User login

Therapeutic hypothermia for newborns who suffer hypoxic–ischemic birth injury

CASE: Risky decision to let labor continue

The baby was born blue and limp, after a long labor complicated by maternal fever and a prolonged fetal heart rate deceleration.

Earlier, just before the mother was raced to the OR for emergency cesarean delivery, the fetal heart rate had increased sufficiently for the OB to decide to permit labor to continue— the goal being rapid vaginal delivery.

In hindsight, that decision appears to have been potentially fateful for this newborn: Apgar scores were 1 at 5 minutes and 3 at 10 minutes. Umbilical artery pH was 6.98; base deficit, –13 mmol/L. The pediatricians made a preliminary diagnosis of hypoxic-ischemic injury and recommended whole-body cooling of the newborn to limit neural damage.

The frightened parents prayed the treatment would work. Later, recalling news reports that they had read about spinal cord-injured football players and survivors of cardiac arrest who received therapeutic cooling with apparent success, they grew more optimistic about the potential benefit of this treatment for their baby.

In animal models of hypoxic-ischemic neural injury, reducing core body temperature minimizes long-term neural consequences of the injury. Experiments have demonstrated that the optimal course is to induce hypothermia immediately after the neural injury, but initiating hypothermia even as long as 6 hours after injury has a protective effect.

Reducing core temperature appears to limit neural injury by decreasing oxygen requirements and suppressing the accumulation of harmful cytotoxic amino acids, cytokines, and free radicals. In contrast to the beneficial effect of hypothermia, raising body temperature by only 1°C or 2°C in experimental animals that have undergone an isolated hypoxic-ischemic event makes neural damage worse.

Clinical trials in newborns

The beneficial effect of whole-body cooling for newborns who have hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy has been reported in several randomized clinical trials.

In a multicenter trial, supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, 208 newborns in severe acidosis at birth were randomized to whole-body cooling or usual care.1 Whole-body cooling, initiated within 6 hours of birth, was achieved by:

- placing subjects on a cooling blanket precooled to 5°C

- inserting an esophageal temperature probe

- adjusting the temperature of the cooling blanket to achieve an esophageal temperature of 33.5°C for 72 hours

- slow rewarming.

Abdominal-wall skin temperature was also monitored in these newborns.

Subjects in the usual care group were nursed in an incubator, with the radiant heat element adjusted to maintain skin temperature of 36.5°C to 37°C.

Investigators determined that the composite end-point of risk of death or disability at 20 months of life was significantly reduced by whole-body cooling (relative risk, 0.72; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.54–0.95; P=.01).

Death occurred in 24% of subjects in the hypothermia group and in 37% of subjects in the usual care group (risk ratio, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.44–1.05; P=.08). The rate of cerebral palsy was 19% in the hypothermia group and 30% in the usual care group (risk ratio, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.38–1.22; P=.20).

The rate of blindness was 7% in the hypothermia group and 14% in usual care group. The rate of hearing impairment was 4% and 6% percent (P - not significant).1

In a second clinical trial, the Total Body Hypothermia for Neonatal Encephalopathy (TOBY) trial of whole-body cooling, 325 newborns with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy were randomized to whole-body cooling or usual care.2 Whole-body cooling was achieved by nursing the infant in an incubator on a cooling blanket set at 25°C to 30°C, with the goal of maintaining a rectal temperature in the newborn of 33°C to 34°C. In this group, the heat element in the incubator was turned off.

Newborns assigned to the usual care group were nursed in an incubator with the heat element turned on and set to maintain a rectal temperature of 37°C.

The rate of death was similar in the two groups, and the rate of severe neurodevelopmental disability in each of the groups was not significantly different. Among surviving infants, however, whole-body cooling was associated with a higher rate of intact neurologic function and a diminished risk of cerebral palsy (compared to what was seen in the usual-care group). Among surviving newborns, cerebral palsy occurred in 28% of those treated with whole-body cooling and in 41% of those receiving usual care (relative risk 0.67; 95% CI, 0.47–0.96; P=.03).

No major adverse effects were observed with whole-body cooling, when compare d against usual care. A 2007 meta-analysis of four trials of therapeutic hypothermia in newborns reported a significant reduction in the composite endpoint of death or in moderate or severe neurodevelopmental disability (relative risk 0.76; 95% CI, 0.65–0.88). The number that needed to be treated to prevent one endpoint event was 6 (95% CI, 4–14).3

Note that some pediatricians remain cautious about using therapeutic hypothermia, because long-term data on the safety and efficacy of the practice have not been reported.

A devastating complication of cardiac arrest is coma and long-term neurologic dysfunction. Randomized trials have reported that therapeutic hypothermia is beneficial for comatose survivors of cardiac arrest.

In one study, 275 comatose survivors of cardiac arrest were randomized to therapeutic hypothermia (core temperature, 32°C to 34°C) or usual care. At 6 months, mortality was 41% in the hypothermia group and 55% in the usual care group (risk ratio 0.74; 95% Ci, 0.58–0.95). At 6 months, the rate of favorable neurologic recovery among survivors was 93% in those who had been treated with hypothermia and 87% in those given usual care.1

One protocol for inducing moderate hypothermia that has been studied in adults is to infuse, intravenously, approximately 2 L of cold (4°C) lactated Ringer’s solution and to cover the body with refrigerated cooling pads. The typical target is a core temperature of 32°C to 34°C, maintained for 24 hours.

Reference

1. The Hypothermia after Cardiac Arrest Study Group Mild therapeutic hypothermia to improve the neurologic outcome after cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(8):549-556.

Impact on your practice

For decades, newborns in neonatal intensive care units received their care in warm incubators designed to maintain a body temperature of approximately 37°C. Could the standard practice of warming newborns have contributed to neurologic problems in those who suffered hypoxic-ischemic injury?

Whole-body cooling appears to reduce the rate of cerebral palsy in newborns after hypoxic-ischemic injury. For OBs, this treatment could significantly reduce their exposure to litigation that is based on a theory of hypoxic-ischemic birth injury—by reducing the number of surviving infants who have cerebral palsy.

Does your nursery have a protocol for rapidly instituting therapeutic cooling?

How does the partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO2) in a newborn compare with that of an adult breathing ambient air near the summit of Mount Everest?

Take the INSTANT QUIZ.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Shankaran S, Laptook AR, Ehrenkranz RA, et al. for National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. Whole-body hypothermia for neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(15):1574-1584.

2. Azzopardi DV, Strohm B, Edwards AD, et al. Moderate hypothermia to treat perinatal asphyxial encephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(14):1349-1358.

3. Shah PS, Ohlsson A, Perlman M. Hypothermia to treat neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy: systematic review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(10):951-958.

CASE: Risky decision to let labor continue

The baby was born blue and limp, after a long labor complicated by maternal fever and a prolonged fetal heart rate deceleration.

Earlier, just before the mother was raced to the OR for emergency cesarean delivery, the fetal heart rate had increased sufficiently for the OB to decide to permit labor to continue— the goal being rapid vaginal delivery.

In hindsight, that decision appears to have been potentially fateful for this newborn: Apgar scores were 1 at 5 minutes and 3 at 10 minutes. Umbilical artery pH was 6.98; base deficit, –13 mmol/L. The pediatricians made a preliminary diagnosis of hypoxic-ischemic injury and recommended whole-body cooling of the newborn to limit neural damage.

The frightened parents prayed the treatment would work. Later, recalling news reports that they had read about spinal cord-injured football players and survivors of cardiac arrest who received therapeutic cooling with apparent success, they grew more optimistic about the potential benefit of this treatment for their baby.

In animal models of hypoxic-ischemic neural injury, reducing core body temperature minimizes long-term neural consequences of the injury. Experiments have demonstrated that the optimal course is to induce hypothermia immediately after the neural injury, but initiating hypothermia even as long as 6 hours after injury has a protective effect.

Reducing core temperature appears to limit neural injury by decreasing oxygen requirements and suppressing the accumulation of harmful cytotoxic amino acids, cytokines, and free radicals. In contrast to the beneficial effect of hypothermia, raising body temperature by only 1°C or 2°C in experimental animals that have undergone an isolated hypoxic-ischemic event makes neural damage worse.

Clinical trials in newborns

The beneficial effect of whole-body cooling for newborns who have hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy has been reported in several randomized clinical trials.

In a multicenter trial, supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, 208 newborns in severe acidosis at birth were randomized to whole-body cooling or usual care.1 Whole-body cooling, initiated within 6 hours of birth, was achieved by:

- placing subjects on a cooling blanket precooled to 5°C

- inserting an esophageal temperature probe

- adjusting the temperature of the cooling blanket to achieve an esophageal temperature of 33.5°C for 72 hours

- slow rewarming.

Abdominal-wall skin temperature was also monitored in these newborns.

Subjects in the usual care group were nursed in an incubator, with the radiant heat element adjusted to maintain skin temperature of 36.5°C to 37°C.

Investigators determined that the composite end-point of risk of death or disability at 20 months of life was significantly reduced by whole-body cooling (relative risk, 0.72; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.54–0.95; P=.01).

Death occurred in 24% of subjects in the hypothermia group and in 37% of subjects in the usual care group (risk ratio, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.44–1.05; P=.08). The rate of cerebral palsy was 19% in the hypothermia group and 30% in the usual care group (risk ratio, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.38–1.22; P=.20).

The rate of blindness was 7% in the hypothermia group and 14% in usual care group. The rate of hearing impairment was 4% and 6% percent (P - not significant).1

In a second clinical trial, the Total Body Hypothermia for Neonatal Encephalopathy (TOBY) trial of whole-body cooling, 325 newborns with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy were randomized to whole-body cooling or usual care.2 Whole-body cooling was achieved by nursing the infant in an incubator on a cooling blanket set at 25°C to 30°C, with the goal of maintaining a rectal temperature in the newborn of 33°C to 34°C. In this group, the heat element in the incubator was turned off.

Newborns assigned to the usual care group were nursed in an incubator with the heat element turned on and set to maintain a rectal temperature of 37°C.

The rate of death was similar in the two groups, and the rate of severe neurodevelopmental disability in each of the groups was not significantly different. Among surviving infants, however, whole-body cooling was associated with a higher rate of intact neurologic function and a diminished risk of cerebral palsy (compared to what was seen in the usual-care group). Among surviving newborns, cerebral palsy occurred in 28% of those treated with whole-body cooling and in 41% of those receiving usual care (relative risk 0.67; 95% CI, 0.47–0.96; P=.03).

No major adverse effects were observed with whole-body cooling, when compare d against usual care. A 2007 meta-analysis of four trials of therapeutic hypothermia in newborns reported a significant reduction in the composite endpoint of death or in moderate or severe neurodevelopmental disability (relative risk 0.76; 95% CI, 0.65–0.88). The number that needed to be treated to prevent one endpoint event was 6 (95% CI, 4–14).3

Note that some pediatricians remain cautious about using therapeutic hypothermia, because long-term data on the safety and efficacy of the practice have not been reported.

A devastating complication of cardiac arrest is coma and long-term neurologic dysfunction. Randomized trials have reported that therapeutic hypothermia is beneficial for comatose survivors of cardiac arrest.

In one study, 275 comatose survivors of cardiac arrest were randomized to therapeutic hypothermia (core temperature, 32°C to 34°C) or usual care. At 6 months, mortality was 41% in the hypothermia group and 55% in the usual care group (risk ratio 0.74; 95% Ci, 0.58–0.95). At 6 months, the rate of favorable neurologic recovery among survivors was 93% in those who had been treated with hypothermia and 87% in those given usual care.1

One protocol for inducing moderate hypothermia that has been studied in adults is to infuse, intravenously, approximately 2 L of cold (4°C) lactated Ringer’s solution and to cover the body with refrigerated cooling pads. The typical target is a core temperature of 32°C to 34°C, maintained for 24 hours.

Reference

1. The Hypothermia after Cardiac Arrest Study Group Mild therapeutic hypothermia to improve the neurologic outcome after cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(8):549-556.

Impact on your practice

For decades, newborns in neonatal intensive care units received their care in warm incubators designed to maintain a body temperature of approximately 37°C. Could the standard practice of warming newborns have contributed to neurologic problems in those who suffered hypoxic-ischemic injury?

Whole-body cooling appears to reduce the rate of cerebral palsy in newborns after hypoxic-ischemic injury. For OBs, this treatment could significantly reduce their exposure to litigation that is based on a theory of hypoxic-ischemic birth injury—by reducing the number of surviving infants who have cerebral palsy.

Does your nursery have a protocol for rapidly instituting therapeutic cooling?

How does the partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO2) in a newborn compare with that of an adult breathing ambient air near the summit of Mount Everest?

Take the INSTANT QUIZ.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

CASE: Risky decision to let labor continue

The baby was born blue and limp, after a long labor complicated by maternal fever and a prolonged fetal heart rate deceleration.

Earlier, just before the mother was raced to the OR for emergency cesarean delivery, the fetal heart rate had increased sufficiently for the OB to decide to permit labor to continue— the goal being rapid vaginal delivery.

In hindsight, that decision appears to have been potentially fateful for this newborn: Apgar scores were 1 at 5 minutes and 3 at 10 minutes. Umbilical artery pH was 6.98; base deficit, –13 mmol/L. The pediatricians made a preliminary diagnosis of hypoxic-ischemic injury and recommended whole-body cooling of the newborn to limit neural damage.

The frightened parents prayed the treatment would work. Later, recalling news reports that they had read about spinal cord-injured football players and survivors of cardiac arrest who received therapeutic cooling with apparent success, they grew more optimistic about the potential benefit of this treatment for their baby.

In animal models of hypoxic-ischemic neural injury, reducing core body temperature minimizes long-term neural consequences of the injury. Experiments have demonstrated that the optimal course is to induce hypothermia immediately after the neural injury, but initiating hypothermia even as long as 6 hours after injury has a protective effect.

Reducing core temperature appears to limit neural injury by decreasing oxygen requirements and suppressing the accumulation of harmful cytotoxic amino acids, cytokines, and free radicals. In contrast to the beneficial effect of hypothermia, raising body temperature by only 1°C or 2°C in experimental animals that have undergone an isolated hypoxic-ischemic event makes neural damage worse.

Clinical trials in newborns

The beneficial effect of whole-body cooling for newborns who have hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy has been reported in several randomized clinical trials.

In a multicenter trial, supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, 208 newborns in severe acidosis at birth were randomized to whole-body cooling or usual care.1 Whole-body cooling, initiated within 6 hours of birth, was achieved by:

- placing subjects on a cooling blanket precooled to 5°C

- inserting an esophageal temperature probe

- adjusting the temperature of the cooling blanket to achieve an esophageal temperature of 33.5°C for 72 hours

- slow rewarming.

Abdominal-wall skin temperature was also monitored in these newborns.

Subjects in the usual care group were nursed in an incubator, with the radiant heat element adjusted to maintain skin temperature of 36.5°C to 37°C.

Investigators determined that the composite end-point of risk of death or disability at 20 months of life was significantly reduced by whole-body cooling (relative risk, 0.72; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.54–0.95; P=.01).

Death occurred in 24% of subjects in the hypothermia group and in 37% of subjects in the usual care group (risk ratio, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.44–1.05; P=.08). The rate of cerebral palsy was 19% in the hypothermia group and 30% in the usual care group (risk ratio, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.38–1.22; P=.20).

The rate of blindness was 7% in the hypothermia group and 14% in usual care group. The rate of hearing impairment was 4% and 6% percent (P - not significant).1

In a second clinical trial, the Total Body Hypothermia for Neonatal Encephalopathy (TOBY) trial of whole-body cooling, 325 newborns with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy were randomized to whole-body cooling or usual care.2 Whole-body cooling was achieved by nursing the infant in an incubator on a cooling blanket set at 25°C to 30°C, with the goal of maintaining a rectal temperature in the newborn of 33°C to 34°C. In this group, the heat element in the incubator was turned off.

Newborns assigned to the usual care group were nursed in an incubator with the heat element turned on and set to maintain a rectal temperature of 37°C.

The rate of death was similar in the two groups, and the rate of severe neurodevelopmental disability in each of the groups was not significantly different. Among surviving infants, however, whole-body cooling was associated with a higher rate of intact neurologic function and a diminished risk of cerebral palsy (compared to what was seen in the usual-care group). Among surviving newborns, cerebral palsy occurred in 28% of those treated with whole-body cooling and in 41% of those receiving usual care (relative risk 0.67; 95% CI, 0.47–0.96; P=.03).

No major adverse effects were observed with whole-body cooling, when compare d against usual care. A 2007 meta-analysis of four trials of therapeutic hypothermia in newborns reported a significant reduction in the composite endpoint of death or in moderate or severe neurodevelopmental disability (relative risk 0.76; 95% CI, 0.65–0.88). The number that needed to be treated to prevent one endpoint event was 6 (95% CI, 4–14).3

Note that some pediatricians remain cautious about using therapeutic hypothermia, because long-term data on the safety and efficacy of the practice have not been reported.

A devastating complication of cardiac arrest is coma and long-term neurologic dysfunction. Randomized trials have reported that therapeutic hypothermia is beneficial for comatose survivors of cardiac arrest.

In one study, 275 comatose survivors of cardiac arrest were randomized to therapeutic hypothermia (core temperature, 32°C to 34°C) or usual care. At 6 months, mortality was 41% in the hypothermia group and 55% in the usual care group (risk ratio 0.74; 95% Ci, 0.58–0.95). At 6 months, the rate of favorable neurologic recovery among survivors was 93% in those who had been treated with hypothermia and 87% in those given usual care.1

One protocol for inducing moderate hypothermia that has been studied in adults is to infuse, intravenously, approximately 2 L of cold (4°C) lactated Ringer’s solution and to cover the body with refrigerated cooling pads. The typical target is a core temperature of 32°C to 34°C, maintained for 24 hours.

Reference

1. The Hypothermia after Cardiac Arrest Study Group Mild therapeutic hypothermia to improve the neurologic outcome after cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(8):549-556.

Impact on your practice

For decades, newborns in neonatal intensive care units received their care in warm incubators designed to maintain a body temperature of approximately 37°C. Could the standard practice of warming newborns have contributed to neurologic problems in those who suffered hypoxic-ischemic injury?

Whole-body cooling appears to reduce the rate of cerebral palsy in newborns after hypoxic-ischemic injury. For OBs, this treatment could significantly reduce their exposure to litigation that is based on a theory of hypoxic-ischemic birth injury—by reducing the number of surviving infants who have cerebral palsy.

Does your nursery have a protocol for rapidly instituting therapeutic cooling?

How does the partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO2) in a newborn compare with that of an adult breathing ambient air near the summit of Mount Everest?

Take the INSTANT QUIZ.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Shankaran S, Laptook AR, Ehrenkranz RA, et al. for National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. Whole-body hypothermia for neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(15):1574-1584.

2. Azzopardi DV, Strohm B, Edwards AD, et al. Moderate hypothermia to treat perinatal asphyxial encephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(14):1349-1358.

3. Shah PS, Ohlsson A, Perlman M. Hypothermia to treat neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy: systematic review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(10):951-958.

1. Shankaran S, Laptook AR, Ehrenkranz RA, et al. for National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. Whole-body hypothermia for neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(15):1574-1584.

2. Azzopardi DV, Strohm B, Edwards AD, et al. Moderate hypothermia to treat perinatal asphyxial encephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(14):1349-1358.

3. Shah PS, Ohlsson A, Perlman M. Hypothermia to treat neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy: systematic review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(10):951-958.

Chronic pain after vaginal wall repair…and more

What caused chronic pain after repair of the vaginal wall?

A WOMAN IN HER THIRTIES underwent anterior and posterior repair of the vaginal wall, including repair of a cystocele and a rectocystocele. Postoperatively, the patient developed a chronic pain syndrome.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ObGyn failed to properly perform the surgery, and damaged the pudendal nerve, which causes chronic pain. The ObGyn moved the levator ani muscle; the muscle shifted into the vaginal canal and damaged the pudendal nerve. Informed consent was not obtained.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The patient was fully informed of all the procedure’s risks. The injury could not have been from displacement of the levator ani muscle because the muscle cannot reach the vaginal canal. Pain is from scar formation that is entrapping a nerve.

VERDICT A New York defense verdict was returned.

DVT + estrogen-based contraception=stroke?

AFTER A DEEP VENOUS THROMBOSIS (DVT) in her leg at age 29, a woman was told by her family physician to avoid birth control that contained estrogen. She claimed she told her ObGyn of the history of DVT and the no-estrogen advice, but he prescribed and inserted a Nuva Ring, which contains ethinyl estradiol. A few months later, the woman was hospitalized with a severe headache, and suffered a stroke that affected her speech and cognitive functions.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ObGyn was negligent in prescribing a contraceptive that contained estrogen, knowing the patient’s history of blood clot.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE An injury caused the first clot; the Nuva Ring did not cause the second clot or stroke.

VERDICT A $523,000 Georgia verdict was returned.

New mother dies; was preeclampsia treated properly?

AT HER SEVENTH-MONTH VISIT to her ObGyn (Dr. A), a woman began to show signs of preeclampsia. Two weeks later, she went to the emergency department (ED) with chest pain, cough, and shortness of breath; she was found to have hypertension and tachycardia. She was examined by an emergency medicine physician (Dr. B), and discharged with a diagnosis of bronchitis and a finding of dyspnea.

At a scheduled prenatal visit 2 days later, she was hypertensive. Dr. A sent her to the ED, where a physician assistant noted signs of edema in her extremities. Attempts to draw arterial blood were unsuccessful, and crackles were heard in her lungs. She was diagnosed as having worsening preeclampsia with pulmonary edema, and admitted.

Dr. C, another ObGyn, decided to perform a cesarean delivery, but on the way to the OR, the patient became unresponsive. After delivery, she went into cardiopulmonary arrest and sustained anoxic brain injury. She died after life support was removed. An autopsy determined cause of death was anoxic encephalopathy due to respiratory arrest caused by preeclampsia.

ESTATE’S CLAIM Dr. A failed to provide proper prenatal care, and failed to recognize preeclampsia. Dr. B failed to recognize preeclampsia, failed to contact a specialist, and failed to immediately admit the patient for monitoring and treatment. Dr. C negligently administered a bolus of IV fluids when the patient showed signs of preeclampsia. He failed to administer medication to reduce fluid retention, and failed to timely admit the patient to the hospital.

PHYSICIANS’ DEFENSE All three physicians denied negligence.

VERDICT A $1.5 million Michigan settlement was reached.

Did resident use forceful traction with shoulder dystocia?

SHOULDER DYSTOCIA was encountered during vaginal delivery, and managed by a resident. The child suffered a brachial plexus injury.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The attending physician failed to 1) properly supervise the resident who was delivering the infant, and 2) prevent the use of traction after it was determined that shoulder dystocia was present.

PHYSICIANS’ DEFENSE The resident, under full supervision of the attending physician, utilized traction after the baby’s head was delivered and shoulder dystocia became evident—but traction was gentle. The maternal forces of labor caused the injury.

VERDICT A $950,000 Virginia settlement was reached.

Was patient informed that tubal ligation had not been performed?

PREGNANT WITH HER FOURTH CHILD despite birth control, a woman and her husband told the ObGyn that they did not want, nor could they afford, a fifth child. They requested bilateral tubal ligation during cesarean delivery. Two days before the scheduled birth, the mother went into labor. Her prenatal records could not be found, and the ObGyn’s office was closed. The ObGyn delivered the baby, but did not perform tubal ligation. She claimed she was never told that the tubal ligation had not been completed, even at the 6-week postpartum visit. She did not take precautions to prevent pregnancy, and later conceived a fifth child.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ObGyn was negligent in not performing the tubal ligation and in not telling the patient until after the fifth child’s conception.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The mother was told that tubal ligation had not been performed at the 6-week visit. She was advised to use birth control until she recovered from the cesarean delivery and could undergo a tubal ligation procedure. The ObGyn acknowledged he had forgotten to perform the tubal ligation at delivery, but insisted there was no negligence under the circumstances.

VERDICT A California defense verdict was returned.

Patient claims stomach injury caused GERD

DUE TO PELVIC PAIN, a woman underwent laparoscopy by her ObGyn. During the procedure, a trocar punctured her stomach. The injury was discovered, the procedure converted to a laparotomy with a vertical incision, and the injury repaired.

PATIENT’S CLAIM She developed gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) because of the puncture wound, and anxiety because of the scar.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE Gastric perforation is a rare but recognized complication of abdominal laparoscopy, and can occur without negligence. Her GERD is either due to a hiatal hernia or pychosomatic disorder.

VERDICT A Virginia defense verdict was returned.

Physicians not responsible for stroke

SEVERAL DAYS AFTER GIVING BIRTH, a 33-year-old woman visited the ED with chest pain, headache, and abdominal pain. An emergency medicine physician and an ObGyn ordered a chest CT scan and administered anticoagulants. By the time the CT scan was completed, the woman denied having chest pain. No pulmonary emboli (PE) were detected on chest CT, and she was discharged.

The next day, she went to another hospital’s ED with a headache and right-side weakness. A CT scan revealed a large left parietal-lobe intracerebral hematoma. A ventricular catheter was placed and she underwent a stereotactic craniotomy for evacuation of the hematoma. She was transferred to a rehabilitation facility a month later.

She suffers permanent neurologic damage, including short-term memory loss and an inability to lift or walk for any great distance.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ED physicians failed to diagnose and treat an acute neurologic event in a timely manner, and did not obtain specialist consults. Administration of anticoagulants was negligent; protamine therapy should have been started to reverse the anticoagulant effects. Laboratory testing of clotting times and a ventilation-perfusion lung scan should have been conducted to confirm the presence of PE.

PHYSICIANS’ DEFENSE The patient’s condition was appropriately diagnosed and treated in the ED. Administration of anticoagulants was necessary because of suspected PE. There is no evidence that the heparin given to the plaintiff the day before her stroke was related to the stroke.

VERDICT A Florida defense verdict was returned.

Did failure to diagnose preeclampsia lead to infant’s death?

AT 38-WEEKS’ GESTATION, a 21-year-old woman was seen at a hospital’s obstetric clinic, and sent to the ED with complaints of leaking fluid and lack of fetal movement. She claimed she showed signs of preeclampsia, pregnancy-induced hypertension, and oligohydramnios, but was not admitted to the hospital. The baby was born 2 days later with persistent pulmonary hypertension (PPH), which led to the child’s death at 33 days of age.

PATIENT’S CLAIM There was negligence in failing to diagnose preeclampsia, pregnancy-induced hypertension, and oligohydramnios, which caused the baby to be born with PPH.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The cause of the infant’s PPH was unknown, and most likely arose in utero prior to birth. An earlier delivery would not have resulted in a different outcome.

VERDICT A Illinois defense verdict was returned.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

What caused chronic pain after repair of the vaginal wall?

A WOMAN IN HER THIRTIES underwent anterior and posterior repair of the vaginal wall, including repair of a cystocele and a rectocystocele. Postoperatively, the patient developed a chronic pain syndrome.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ObGyn failed to properly perform the surgery, and damaged the pudendal nerve, which causes chronic pain. The ObGyn moved the levator ani muscle; the muscle shifted into the vaginal canal and damaged the pudendal nerve. Informed consent was not obtained.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The patient was fully informed of all the procedure’s risks. The injury could not have been from displacement of the levator ani muscle because the muscle cannot reach the vaginal canal. Pain is from scar formation that is entrapping a nerve.

VERDICT A New York defense verdict was returned.

DVT + estrogen-based contraception=stroke?

AFTER A DEEP VENOUS THROMBOSIS (DVT) in her leg at age 29, a woman was told by her family physician to avoid birth control that contained estrogen. She claimed she told her ObGyn of the history of DVT and the no-estrogen advice, but he prescribed and inserted a Nuva Ring, which contains ethinyl estradiol. A few months later, the woman was hospitalized with a severe headache, and suffered a stroke that affected her speech and cognitive functions.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ObGyn was negligent in prescribing a contraceptive that contained estrogen, knowing the patient’s history of blood clot.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE An injury caused the first clot; the Nuva Ring did not cause the second clot or stroke.

VERDICT A $523,000 Georgia verdict was returned.

New mother dies; was preeclampsia treated properly?

AT HER SEVENTH-MONTH VISIT to her ObGyn (Dr. A), a woman began to show signs of preeclampsia. Two weeks later, she went to the emergency department (ED) with chest pain, cough, and shortness of breath; she was found to have hypertension and tachycardia. She was examined by an emergency medicine physician (Dr. B), and discharged with a diagnosis of bronchitis and a finding of dyspnea.

At a scheduled prenatal visit 2 days later, she was hypertensive. Dr. A sent her to the ED, where a physician assistant noted signs of edema in her extremities. Attempts to draw arterial blood were unsuccessful, and crackles were heard in her lungs. She was diagnosed as having worsening preeclampsia with pulmonary edema, and admitted.

Dr. C, another ObGyn, decided to perform a cesarean delivery, but on the way to the OR, the patient became unresponsive. After delivery, she went into cardiopulmonary arrest and sustained anoxic brain injury. She died after life support was removed. An autopsy determined cause of death was anoxic encephalopathy due to respiratory arrest caused by preeclampsia.

ESTATE’S CLAIM Dr. A failed to provide proper prenatal care, and failed to recognize preeclampsia. Dr. B failed to recognize preeclampsia, failed to contact a specialist, and failed to immediately admit the patient for monitoring and treatment. Dr. C negligently administered a bolus of IV fluids when the patient showed signs of preeclampsia. He failed to administer medication to reduce fluid retention, and failed to timely admit the patient to the hospital.

PHYSICIANS’ DEFENSE All three physicians denied negligence.

VERDICT A $1.5 million Michigan settlement was reached.

Did resident use forceful traction with shoulder dystocia?

SHOULDER DYSTOCIA was encountered during vaginal delivery, and managed by a resident. The child suffered a brachial plexus injury.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The attending physician failed to 1) properly supervise the resident who was delivering the infant, and 2) prevent the use of traction after it was determined that shoulder dystocia was present.

PHYSICIANS’ DEFENSE The resident, under full supervision of the attending physician, utilized traction after the baby’s head was delivered and shoulder dystocia became evident—but traction was gentle. The maternal forces of labor caused the injury.

VERDICT A $950,000 Virginia settlement was reached.

Was patient informed that tubal ligation had not been performed?

PREGNANT WITH HER FOURTH CHILD despite birth control, a woman and her husband told the ObGyn that they did not want, nor could they afford, a fifth child. They requested bilateral tubal ligation during cesarean delivery. Two days before the scheduled birth, the mother went into labor. Her prenatal records could not be found, and the ObGyn’s office was closed. The ObGyn delivered the baby, but did not perform tubal ligation. She claimed she was never told that the tubal ligation had not been completed, even at the 6-week postpartum visit. She did not take precautions to prevent pregnancy, and later conceived a fifth child.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ObGyn was negligent in not performing the tubal ligation and in not telling the patient until after the fifth child’s conception.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The mother was told that tubal ligation had not been performed at the 6-week visit. She was advised to use birth control until she recovered from the cesarean delivery and could undergo a tubal ligation procedure. The ObGyn acknowledged he had forgotten to perform the tubal ligation at delivery, but insisted there was no negligence under the circumstances.

VERDICT A California defense verdict was returned.

Patient claims stomach injury caused GERD

DUE TO PELVIC PAIN, a woman underwent laparoscopy by her ObGyn. During the procedure, a trocar punctured her stomach. The injury was discovered, the procedure converted to a laparotomy with a vertical incision, and the injury repaired.

PATIENT’S CLAIM She developed gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) because of the puncture wound, and anxiety because of the scar.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE Gastric perforation is a rare but recognized complication of abdominal laparoscopy, and can occur without negligence. Her GERD is either due to a hiatal hernia or pychosomatic disorder.

VERDICT A Virginia defense verdict was returned.

Physicians not responsible for stroke

SEVERAL DAYS AFTER GIVING BIRTH, a 33-year-old woman visited the ED with chest pain, headache, and abdominal pain. An emergency medicine physician and an ObGyn ordered a chest CT scan and administered anticoagulants. By the time the CT scan was completed, the woman denied having chest pain. No pulmonary emboli (PE) were detected on chest CT, and she was discharged.

The next day, she went to another hospital’s ED with a headache and right-side weakness. A CT scan revealed a large left parietal-lobe intracerebral hematoma. A ventricular catheter was placed and she underwent a stereotactic craniotomy for evacuation of the hematoma. She was transferred to a rehabilitation facility a month later.

She suffers permanent neurologic damage, including short-term memory loss and an inability to lift or walk for any great distance.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ED physicians failed to diagnose and treat an acute neurologic event in a timely manner, and did not obtain specialist consults. Administration of anticoagulants was negligent; protamine therapy should have been started to reverse the anticoagulant effects. Laboratory testing of clotting times and a ventilation-perfusion lung scan should have been conducted to confirm the presence of PE.

PHYSICIANS’ DEFENSE The patient’s condition was appropriately diagnosed and treated in the ED. Administration of anticoagulants was necessary because of suspected PE. There is no evidence that the heparin given to the plaintiff the day before her stroke was related to the stroke.

VERDICT A Florida defense verdict was returned.

Did failure to diagnose preeclampsia lead to infant’s death?

AT 38-WEEKS’ GESTATION, a 21-year-old woman was seen at a hospital’s obstetric clinic, and sent to the ED with complaints of leaking fluid and lack of fetal movement. She claimed she showed signs of preeclampsia, pregnancy-induced hypertension, and oligohydramnios, but was not admitted to the hospital. The baby was born 2 days later with persistent pulmonary hypertension (PPH), which led to the child’s death at 33 days of age.

PATIENT’S CLAIM There was negligence in failing to diagnose preeclampsia, pregnancy-induced hypertension, and oligohydramnios, which caused the baby to be born with PPH.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The cause of the infant’s PPH was unknown, and most likely arose in utero prior to birth. An earlier delivery would not have resulted in a different outcome.

VERDICT A Illinois defense verdict was returned.

What caused chronic pain after repair of the vaginal wall?

A WOMAN IN HER THIRTIES underwent anterior and posterior repair of the vaginal wall, including repair of a cystocele and a rectocystocele. Postoperatively, the patient developed a chronic pain syndrome.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ObGyn failed to properly perform the surgery, and damaged the pudendal nerve, which causes chronic pain. The ObGyn moved the levator ani muscle; the muscle shifted into the vaginal canal and damaged the pudendal nerve. Informed consent was not obtained.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The patient was fully informed of all the procedure’s risks. The injury could not have been from displacement of the levator ani muscle because the muscle cannot reach the vaginal canal. Pain is from scar formation that is entrapping a nerve.

VERDICT A New York defense verdict was returned.

DVT + estrogen-based contraception=stroke?

AFTER A DEEP VENOUS THROMBOSIS (DVT) in her leg at age 29, a woman was told by her family physician to avoid birth control that contained estrogen. She claimed she told her ObGyn of the history of DVT and the no-estrogen advice, but he prescribed and inserted a Nuva Ring, which contains ethinyl estradiol. A few months later, the woman was hospitalized with a severe headache, and suffered a stroke that affected her speech and cognitive functions.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ObGyn was negligent in prescribing a contraceptive that contained estrogen, knowing the patient’s history of blood clot.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE An injury caused the first clot; the Nuva Ring did not cause the second clot or stroke.

VERDICT A $523,000 Georgia verdict was returned.

New mother dies; was preeclampsia treated properly?

AT HER SEVENTH-MONTH VISIT to her ObGyn (Dr. A), a woman began to show signs of preeclampsia. Two weeks later, she went to the emergency department (ED) with chest pain, cough, and shortness of breath; she was found to have hypertension and tachycardia. She was examined by an emergency medicine physician (Dr. B), and discharged with a diagnosis of bronchitis and a finding of dyspnea.

At a scheduled prenatal visit 2 days later, she was hypertensive. Dr. A sent her to the ED, where a physician assistant noted signs of edema in her extremities. Attempts to draw arterial blood were unsuccessful, and crackles were heard in her lungs. She was diagnosed as having worsening preeclampsia with pulmonary edema, and admitted.

Dr. C, another ObGyn, decided to perform a cesarean delivery, but on the way to the OR, the patient became unresponsive. After delivery, she went into cardiopulmonary arrest and sustained anoxic brain injury. She died after life support was removed. An autopsy determined cause of death was anoxic encephalopathy due to respiratory arrest caused by preeclampsia.

ESTATE’S CLAIM Dr. A failed to provide proper prenatal care, and failed to recognize preeclampsia. Dr. B failed to recognize preeclampsia, failed to contact a specialist, and failed to immediately admit the patient for monitoring and treatment. Dr. C negligently administered a bolus of IV fluids when the patient showed signs of preeclampsia. He failed to administer medication to reduce fluid retention, and failed to timely admit the patient to the hospital.

PHYSICIANS’ DEFENSE All three physicians denied negligence.

VERDICT A $1.5 million Michigan settlement was reached.

Did resident use forceful traction with shoulder dystocia?

SHOULDER DYSTOCIA was encountered during vaginal delivery, and managed by a resident. The child suffered a brachial plexus injury.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The attending physician failed to 1) properly supervise the resident who was delivering the infant, and 2) prevent the use of traction after it was determined that shoulder dystocia was present.

PHYSICIANS’ DEFENSE The resident, under full supervision of the attending physician, utilized traction after the baby’s head was delivered and shoulder dystocia became evident—but traction was gentle. The maternal forces of labor caused the injury.

VERDICT A $950,000 Virginia settlement was reached.

Was patient informed that tubal ligation had not been performed?

PREGNANT WITH HER FOURTH CHILD despite birth control, a woman and her husband told the ObGyn that they did not want, nor could they afford, a fifth child. They requested bilateral tubal ligation during cesarean delivery. Two days before the scheduled birth, the mother went into labor. Her prenatal records could not be found, and the ObGyn’s office was closed. The ObGyn delivered the baby, but did not perform tubal ligation. She claimed she was never told that the tubal ligation had not been completed, even at the 6-week postpartum visit. She did not take precautions to prevent pregnancy, and later conceived a fifth child.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ObGyn was negligent in not performing the tubal ligation and in not telling the patient until after the fifth child’s conception.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The mother was told that tubal ligation had not been performed at the 6-week visit. She was advised to use birth control until she recovered from the cesarean delivery and could undergo a tubal ligation procedure. The ObGyn acknowledged he had forgotten to perform the tubal ligation at delivery, but insisted there was no negligence under the circumstances.

VERDICT A California defense verdict was returned.

Patient claims stomach injury caused GERD

DUE TO PELVIC PAIN, a woman underwent laparoscopy by her ObGyn. During the procedure, a trocar punctured her stomach. The injury was discovered, the procedure converted to a laparotomy with a vertical incision, and the injury repaired.

PATIENT’S CLAIM She developed gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) because of the puncture wound, and anxiety because of the scar.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE Gastric perforation is a rare but recognized complication of abdominal laparoscopy, and can occur without negligence. Her GERD is either due to a hiatal hernia or pychosomatic disorder.

VERDICT A Virginia defense verdict was returned.

Physicians not responsible for stroke

SEVERAL DAYS AFTER GIVING BIRTH, a 33-year-old woman visited the ED with chest pain, headache, and abdominal pain. An emergency medicine physician and an ObGyn ordered a chest CT scan and administered anticoagulants. By the time the CT scan was completed, the woman denied having chest pain. No pulmonary emboli (PE) were detected on chest CT, and she was discharged.

The next day, she went to another hospital’s ED with a headache and right-side weakness. A CT scan revealed a large left parietal-lobe intracerebral hematoma. A ventricular catheter was placed and she underwent a stereotactic craniotomy for evacuation of the hematoma. She was transferred to a rehabilitation facility a month later.

She suffers permanent neurologic damage, including short-term memory loss and an inability to lift or walk for any great distance.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ED physicians failed to diagnose and treat an acute neurologic event in a timely manner, and did not obtain specialist consults. Administration of anticoagulants was negligent; protamine therapy should have been started to reverse the anticoagulant effects. Laboratory testing of clotting times and a ventilation-perfusion lung scan should have been conducted to confirm the presence of PE.

PHYSICIANS’ DEFENSE The patient’s condition was appropriately diagnosed and treated in the ED. Administration of anticoagulants was necessary because of suspected PE. There is no evidence that the heparin given to the plaintiff the day before her stroke was related to the stroke.

VERDICT A Florida defense verdict was returned.

Did failure to diagnose preeclampsia lead to infant’s death?

AT 38-WEEKS’ GESTATION, a 21-year-old woman was seen at a hospital’s obstetric clinic, and sent to the ED with complaints of leaking fluid and lack of fetal movement. She claimed she showed signs of preeclampsia, pregnancy-induced hypertension, and oligohydramnios, but was not admitted to the hospital. The baby was born 2 days later with persistent pulmonary hypertension (PPH), which led to the child’s death at 33 days of age.

PATIENT’S CLAIM There was negligence in failing to diagnose preeclampsia, pregnancy-induced hypertension, and oligohydramnios, which caused the baby to be born with PPH.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The cause of the infant’s PPH was unknown, and most likely arose in utero prior to birth. An earlier delivery would not have resulted in a different outcome.

VERDICT A Illinois defense verdict was returned.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

What Should I Do If I Get a Needlestick?

Case

While placing a central line, you sustain a needlestick. You’ve washed the area thoroughly with soap and water, but you are concerned about contracting a bloodborne pathogen. What is the risk of contracting such a pathogen, and what can be done to reduce this risk?

Overview

Needlestick injuries are a common occupational hazard in the hospital setting. According to the International Health Care Worker Safety Center (IHCWSC), approximately 295,000 hospital-based healthcare workers experience occupational percutaneous injuries annually. In 1991, Mangione et al surveyed internal-medicine house staff and found an annual incidence of 674 needlestick injuries per 1,000 participants.1 Other retrospective data estimate this risk to be as high as 839 per 1,000 healthcare workers annually.2 Evidence from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2004 suggests that because these are only self-reported injuries, the annual incidence of such injuries is in fact much higher than the current estimates suggest.2,3,4

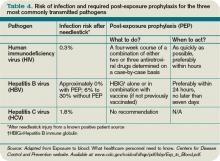

More than 20 bloodborne pathogens (see Table 1, right) might be transmitted from contaminated needles or sharps, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), and hepatitis C virus (HCV). A quick and appropriate response to a needlestick injury can greatly decrease the risk of disease transmission following an occupational exposure to potentially infectious materials.

Review of the Data

After any needlestick injury, an affected healthcare worker should wash the area with soap and water immediately. There is no contraindication to using antiseptic solutions, but there is also no evidence to suggest that this reduces the rates of disease transmission.

As decisions for post-exposure prophylaxis often need to be made within hours, a healthcare worker should seek care in the facility areas responsible for managing occupational exposures. Healthcare providers should always be encouraged and supported to report all sharps-related injuries to such departments.

The source patient should be identified and evaluated for potentially transmissible diseases, including HIV, HBV, and HCV. If indicated, the source patient should then undergo appropriate serological testing, and any indicated antiviral prophylaxis should be initiated (see Table 2, p. 19).

Risk of Seroconversion

For all bloodborne pathogens, a needlestick injury carries a greater risk for transmission than other occupational exposures (e.g. mucous membrane exposure). If a needlestick injury occurs in the setting of an infected patient source, the risk of disease transmission varies for HIV, HBV, and HCV (see Table 3, p. 19). In general, risk for seroconversion is increased with a deep injury, an injury with a device visibly contaminated with the source patient’s blood, or an injury involving a needle placed in the source patient’s artery or vein.3,5,6

Human immunodeficiency virus. Contracting HIV after needlestick injury is rare. From 1981 to 2006, the CDC documented only 57 cases of HIV/AIDS in healthcare workers following occupational exposure and identified an additional “possible” 140 cases post-exposure.5,6 Of the 57 documented cases, 48 sustained a percutaneous injury.

Following needlestick injury involving a known HIV-positive source, the one-year risk of seroconversion has been estimated to be 0.3%.5,6 In 1997, Cardo and colleagues identified four factors associated with increased risk for seroconversion after a needlestick/sharps injury from a known positive-HIV source:

- Deep injury;

- Injury with a device visibly contaminated with the source patient’s blood;

- A procedure involving a needle placed in the source patient’s artery or vein; and

- Exposure to a source patient who died of AIDS in the two months following the occupational exposure.5

Hepatitis B virus. Wides-pread immunization of healthcare workers has led to a dramatic decline in occupationally acquired HBV. The CDC estimated that in 1985, approximately 12,500 new HBV infections occurred in healthcare workers.3 This estimate plummeted to approximately 500 new occupationally acquired HBV infections in 1997.3

Despite this, hospital-based healthcare personnel remain at risk for HBV transmission after a needlestick injury from a known positive patient source. Few studies have evaluated the occupational risk of HBV transmission after a needlestick injury. Buergler et al reported that following a needlestick injury involving a known HBV-positive source, the one-year risk of seroconversion was 0.76% to 7.35% for nonimmunized surgeons, and 0.23% to 2.28% for nonimmunized anesthesiologists.7

In the absence of post-exposure prophylaxis, an exposed healthcare worker has a 6% to 30% risk of becoming infected with HBV.3,8 The risk is greatest if the patient source is known to be hepatitis B e antigen-positive, a marker for greater disease infectivity. When given within one week of injury, post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) with multiple doses of hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG) provides an estimated 75% protection from transmission.

Healthcare workers who have received the hepatitis B vaccine and developed immunity have virtually no risk for infection.6,7

Hepatitis C virus. Prospective evaluation has demonstrated that the average risk of HCV transmission after percutaneous exposure to a known HCV-positive source is from 0% to 7%.3 The Italian Study Group on Occupational Risk of HIV and Other Bloodborne Infections evaluated HCV seroconversion within six months of a reported exposure with enzyme immunoassay and immunoblot assay. In this study, the authors found a seroconversion rate of 1.2%.9

Further, they suggested that HCV seroconversion only occurred from hollow-bore needles, as no seroconversions were noted in healthcare workers who sustained injuries with solid sharp objects.

Post-Exposure Management

The CDC does not recommend prophylaxis when source fluids make contact with intact skin. However, if a percutaneous occupational exposure has occurred, PEPs exist for HIV and HBV but not for HCV.3,6 If a source patient’s HIV, HBV, and HCV statuses are unknown, occupational-health personnel can interview the patient to evaluate his or her risks and initiate testing. Specific information about the time and nature of exposure should be documented.

When testing is indicated, it should be done following institutional and state-specific exposure-control policies and informed consent guidelines. In all situations, the decision to begin antiviral PEP should be carefully considered, weighing benefits of PEP versus the risks and toxicity of treatment.

Human immunodeficiency virus. If a source patient is known to be HIV-positive, has a positive rapid HIV test, or if HIV status cannot be quickly determined, PEP is indicated. Healthcare providers should be aware of rare cases in which the source patient initially tested HIV-seronegative but was subsequently found to have primary HIV infection.

Per 2004 CDC recommendations, PEP is indicated for all healthcare workers who sustain a percuanteous injury from a known HIV-positive source.3,8 For a less severe injury (e.g. solid needle or superficial injury), PEP with either a basic two-drug or three-drug regimen is indicated, depending on the source patient’s viral load.3,5,6,8

If the source patient has unknown HIV status, two-drug PEP is indicated based on the source patient’s HIV risk factors. In such patients, rapid HIV testing also is indicated to aid in determining the need for PEP. When the source HIV status is unknown, PEP is indicated in settings where exposure to HIV-infected persons is likely.

If PEP is indicated, it should be started as quickly as possible. The 2005 U.S. Public Health Service Recommendations for PEP recommend initiating two nucleosides for low-risk exposures and two nucleosides plus a boosted protease inhibitor for high-risk exposures.

Examples of commonly used dual nucleoside regimens are Zidovudine plus Lamivudine (coformulated as Combivir) or Tenofovir plus Emtricitabine (coformulated as Truvada). Current recommendations indicate that PEP should be continued for four weeks, with concurrent clinical and laboratory evaluation for drug toxicity.

Hepatitis B virus. Numerous prospective studies have evaluated the post-exposure effectiveness of HBIG. When administered within 24 hours of exposure, HBIG might offer immediate passive protection against HBV infection. Additionally, if initiated within one week of percutaneous injury with a known HBV-positive source, multiple doses of HGIB provide an estimated 75% protection from transmission.

Although the combination of HBIG and the hepatitis vaccine B series has not been evaluated as PEP in the occupational setting, evidence in the perinatal setting suggests this regimen is more effective than HBIG alone.3,6,8

Hepatitis C virus. No PEP exists for HCV, and current recommendations for post-exposure management focus on early identification and treatment of chronic disease. There are insufficient data for a treatment recommendation for patients with acute HCV infection with no evidence of disease; the appropriate dosing of such a regimen is unknown. Further, evidence suggests that treatment started early in the course of chronic infection could be just as effective and might eliminate the need to treat persons whose infection will spontaneously resolve.7

Back to the Case

Your needlestick occurred while using a hollow-bore needle to cannulate a source patient’s vein, placing you at higher risk for seroconversion. You immediately reported the exposure to the department of occupational health at your hospital. The source patient’s HIV, HBV, and HCV serological statuses were tested, and the patient was found to be HBV-positive. After appropriate counseling, you decide to receive HGIB prophylaxis to reduce your chances of becoming infected with HBV infection.

Bottom Line

Healthcare workers who suffer occupational needlestick injuries require immediate identification and attention to avoid transmission of such infectious diseases as HIV, HBV, and HCV. Source patients should undergo rapid serological testing to determine appropriate PEP. TH

Dr. Zehnder is a hospitalist in the Section of Hospital Medicine at the University of Colorado Denver.

References

- Mangione CM, Gerberding JL, Cummings, SR. Occupational exposure to HIV: Frequency and rates of underreporting of percutaneous and mucocutaneous exposures by medical housestaff. Am J Med. 1991;90(1):85-90.

- Lee JM, Botteman MF, Nicklasson L, et al. Needlestick injury in acute care nurses caring for patients with diabetes mellitus: a retrospective study. Curr Med Res Opinion. 2005;21(5):741-747.

- Workbook for designing, implementing, and evaluating a sharps injury prevention program. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Available at: www.cdc.gov/sharpssafety/pdf/WorkbookComplete.pdf. Accessed Sept. 13, 2010.

- Lee JM, Botteman MF, Xanthakos N, Nicklasson L. Needlestick injuries in the United States. Epidemiologic, economic, and quality of life issues. AAOHN J. 2005;53(3):117-133.

- Cardo DM, Culver DH, Ciesielski CA, et al. A case-control study of HIV seroconversion in health care workers after percutaneous exposure. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Needlestick Surveillance Group. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(21):1485-1490.

- Exposure to blood: What healthcare personnel need to know. CDC website. Available at: www.cdc.gov/ncidod /dhqp/pdf/bbp/Exp_to_Blood.pdf. Accessed Aug. 31, 2010.

- Buergler JM, Kim R, Thisted RA, Cohn SJ, Lichtor JL, Roizen MF. Risk of human immunodeficiency virus in surgeons, anesthesiologists, and medical students. Anesth Analg. 1992;75(1):118-124.

- Updated U.S. Public Health Service guidelines for the management of occupational exposures to HBV, HCV, and HIV and recommendations for postexposure prophylaxis. CDC website. Available at: www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5011a1.htm. Accessed Aug. 31, 2010.

- Puro V, Petrosillo N, Ippolito G. Risk of hepatitis C seroconversion after occupational exposure in health care workers. Italian Study Group on Occupational Risk of HIV and Other Bloodborne Infections. Am J Infect Control. 1995;23(5):273-277.

Case

While placing a central line, you sustain a needlestick. You’ve washed the area thoroughly with soap and water, but you are concerned about contracting a bloodborne pathogen. What is the risk of contracting such a pathogen, and what can be done to reduce this risk?

Overview

Needlestick injuries are a common occupational hazard in the hospital setting. According to the International Health Care Worker Safety Center (IHCWSC), approximately 295,000 hospital-based healthcare workers experience occupational percutaneous injuries annually. In 1991, Mangione et al surveyed internal-medicine house staff and found an annual incidence of 674 needlestick injuries per 1,000 participants.1 Other retrospective data estimate this risk to be as high as 839 per 1,000 healthcare workers annually.2 Evidence from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2004 suggests that because these are only self-reported injuries, the annual incidence of such injuries is in fact much higher than the current estimates suggest.2,3,4

More than 20 bloodborne pathogens (see Table 1, right) might be transmitted from contaminated needles or sharps, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), and hepatitis C virus (HCV). A quick and appropriate response to a needlestick injury can greatly decrease the risk of disease transmission following an occupational exposure to potentially infectious materials.

Review of the Data

After any needlestick injury, an affected healthcare worker should wash the area with soap and water immediately. There is no contraindication to using antiseptic solutions, but there is also no evidence to suggest that this reduces the rates of disease transmission.

As decisions for post-exposure prophylaxis often need to be made within hours, a healthcare worker should seek care in the facility areas responsible for managing occupational exposures. Healthcare providers should always be encouraged and supported to report all sharps-related injuries to such departments.

The source patient should be identified and evaluated for potentially transmissible diseases, including HIV, HBV, and HCV. If indicated, the source patient should then undergo appropriate serological testing, and any indicated antiviral prophylaxis should be initiated (see Table 2, p. 19).

Risk of Seroconversion

For all bloodborne pathogens, a needlestick injury carries a greater risk for transmission than other occupational exposures (e.g. mucous membrane exposure). If a needlestick injury occurs in the setting of an infected patient source, the risk of disease transmission varies for HIV, HBV, and HCV (see Table 3, p. 19). In general, risk for seroconversion is increased with a deep injury, an injury with a device visibly contaminated with the source patient’s blood, or an injury involving a needle placed in the source patient’s artery or vein.3,5,6

Human immunodeficiency virus. Contracting HIV after needlestick injury is rare. From 1981 to 2006, the CDC documented only 57 cases of HIV/AIDS in healthcare workers following occupational exposure and identified an additional “possible” 140 cases post-exposure.5,6 Of the 57 documented cases, 48 sustained a percutaneous injury.

Following needlestick injury involving a known HIV-positive source, the one-year risk of seroconversion has been estimated to be 0.3%.5,6 In 1997, Cardo and colleagues identified four factors associated with increased risk for seroconversion after a needlestick/sharps injury from a known positive-HIV source:

- Deep injury;

- Injury with a device visibly contaminated with the source patient’s blood;

- A procedure involving a needle placed in the source patient’s artery or vein; and

- Exposure to a source patient who died of AIDS in the two months following the occupational exposure.5

Hepatitis B virus. Wides-pread immunization of healthcare workers has led to a dramatic decline in occupationally acquired HBV. The CDC estimated that in 1985, approximately 12,500 new HBV infections occurred in healthcare workers.3 This estimate plummeted to approximately 500 new occupationally acquired HBV infections in 1997.3

Despite this, hospital-based healthcare personnel remain at risk for HBV transmission after a needlestick injury from a known positive patient source. Few studies have evaluated the occupational risk of HBV transmission after a needlestick injury. Buergler et al reported that following a needlestick injury involving a known HBV-positive source, the one-year risk of seroconversion was 0.76% to 7.35% for nonimmunized surgeons, and 0.23% to 2.28% for nonimmunized anesthesiologists.7

In the absence of post-exposure prophylaxis, an exposed healthcare worker has a 6% to 30% risk of becoming infected with HBV.3,8 The risk is greatest if the patient source is known to be hepatitis B e antigen-positive, a marker for greater disease infectivity. When given within one week of injury, post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) with multiple doses of hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG) provides an estimated 75% protection from transmission.

Healthcare workers who have received the hepatitis B vaccine and developed immunity have virtually no risk for infection.6,7

Hepatitis C virus. Prospective evaluation has demonstrated that the average risk of HCV transmission after percutaneous exposure to a known HCV-positive source is from 0% to 7%.3 The Italian Study Group on Occupational Risk of HIV and Other Bloodborne Infections evaluated HCV seroconversion within six months of a reported exposure with enzyme immunoassay and immunoblot assay. In this study, the authors found a seroconversion rate of 1.2%.9

Further, they suggested that HCV seroconversion only occurred from hollow-bore needles, as no seroconversions were noted in healthcare workers who sustained injuries with solid sharp objects.

Post-Exposure Management

The CDC does not recommend prophylaxis when source fluids make contact with intact skin. However, if a percutaneous occupational exposure has occurred, PEPs exist for HIV and HBV but not for HCV.3,6 If a source patient’s HIV, HBV, and HCV statuses are unknown, occupational-health personnel can interview the patient to evaluate his or her risks and initiate testing. Specific information about the time and nature of exposure should be documented.

When testing is indicated, it should be done following institutional and state-specific exposure-control policies and informed consent guidelines. In all situations, the decision to begin antiviral PEP should be carefully considered, weighing benefits of PEP versus the risks and toxicity of treatment.

Human immunodeficiency virus. If a source patient is known to be HIV-positive, has a positive rapid HIV test, or if HIV status cannot be quickly determined, PEP is indicated. Healthcare providers should be aware of rare cases in which the source patient initially tested HIV-seronegative but was subsequently found to have primary HIV infection.

Per 2004 CDC recommendations, PEP is indicated for all healthcare workers who sustain a percuanteous injury from a known HIV-positive source.3,8 For a less severe injury (e.g. solid needle or superficial injury), PEP with either a basic two-drug or three-drug regimen is indicated, depending on the source patient’s viral load.3,5,6,8

If the source patient has unknown HIV status, two-drug PEP is indicated based on the source patient’s HIV risk factors. In such patients, rapid HIV testing also is indicated to aid in determining the need for PEP. When the source HIV status is unknown, PEP is indicated in settings where exposure to HIV-infected persons is likely.

If PEP is indicated, it should be started as quickly as possible. The 2005 U.S. Public Health Service Recommendations for PEP recommend initiating two nucleosides for low-risk exposures and two nucleosides plus a boosted protease inhibitor for high-risk exposures.

Examples of commonly used dual nucleoside regimens are Zidovudine plus Lamivudine (coformulated as Combivir) or Tenofovir plus Emtricitabine (coformulated as Truvada). Current recommendations indicate that PEP should be continued for four weeks, with concurrent clinical and laboratory evaluation for drug toxicity.

Hepatitis B virus. Numerous prospective studies have evaluated the post-exposure effectiveness of HBIG. When administered within 24 hours of exposure, HBIG might offer immediate passive protection against HBV infection. Additionally, if initiated within one week of percutaneous injury with a known HBV-positive source, multiple doses of HGIB provide an estimated 75% protection from transmission.

Although the combination of HBIG and the hepatitis vaccine B series has not been evaluated as PEP in the occupational setting, evidence in the perinatal setting suggests this regimen is more effective than HBIG alone.3,6,8

Hepatitis C virus. No PEP exists for HCV, and current recommendations for post-exposure management focus on early identification and treatment of chronic disease. There are insufficient data for a treatment recommendation for patients with acute HCV infection with no evidence of disease; the appropriate dosing of such a regimen is unknown. Further, evidence suggests that treatment started early in the course of chronic infection could be just as effective and might eliminate the need to treat persons whose infection will spontaneously resolve.7

Back to the Case

Your needlestick occurred while using a hollow-bore needle to cannulate a source patient’s vein, placing you at higher risk for seroconversion. You immediately reported the exposure to the department of occupational health at your hospital. The source patient’s HIV, HBV, and HCV serological statuses were tested, and the patient was found to be HBV-positive. After appropriate counseling, you decide to receive HGIB prophylaxis to reduce your chances of becoming infected with HBV infection.

Bottom Line

Healthcare workers who suffer occupational needlestick injuries require immediate identification and attention to avoid transmission of such infectious diseases as HIV, HBV, and HCV. Source patients should undergo rapid serological testing to determine appropriate PEP. TH

Dr. Zehnder is a hospitalist in the Section of Hospital Medicine at the University of Colorado Denver.

References

- Mangione CM, Gerberding JL, Cummings, SR. Occupational exposure to HIV: Frequency and rates of underreporting of percutaneous and mucocutaneous exposures by medical housestaff. Am J Med. 1991;90(1):85-90.

- Lee JM, Botteman MF, Nicklasson L, et al. Needlestick injury in acute care nurses caring for patients with diabetes mellitus: a retrospective study. Curr Med Res Opinion. 2005;21(5):741-747.

- Workbook for designing, implementing, and evaluating a sharps injury prevention program. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Available at: www.cdc.gov/sharpssafety/pdf/WorkbookComplete.pdf. Accessed Sept. 13, 2010.

- Lee JM, Botteman MF, Xanthakos N, Nicklasson L. Needlestick injuries in the United States. Epidemiologic, economic, and quality of life issues. AAOHN J. 2005;53(3):117-133.

- Cardo DM, Culver DH, Ciesielski CA, et al. A case-control study of HIV seroconversion in health care workers after percutaneous exposure. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Needlestick Surveillance Group. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(21):1485-1490.

- Exposure to blood: What healthcare personnel need to know. CDC website. Available at: www.cdc.gov/ncidod /dhqp/pdf/bbp/Exp_to_Blood.pdf. Accessed Aug. 31, 2010.

- Buergler JM, Kim R, Thisted RA, Cohn SJ, Lichtor JL, Roizen MF. Risk of human immunodeficiency virus in surgeons, anesthesiologists, and medical students. Anesth Analg. 1992;75(1):118-124.

- Updated U.S. Public Health Service guidelines for the management of occupational exposures to HBV, HCV, and HIV and recommendations for postexposure prophylaxis. CDC website. Available at: www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5011a1.htm. Accessed Aug. 31, 2010.

- Puro V, Petrosillo N, Ippolito G. Risk of hepatitis C seroconversion after occupational exposure in health care workers. Italian Study Group on Occupational Risk of HIV and Other Bloodborne Infections. Am J Infect Control. 1995;23(5):273-277.

Case

While placing a central line, you sustain a needlestick. You’ve washed the area thoroughly with soap and water, but you are concerned about contracting a bloodborne pathogen. What is the risk of contracting such a pathogen, and what can be done to reduce this risk?

Overview

Needlestick injuries are a common occupational hazard in the hospital setting. According to the International Health Care Worker Safety Center (IHCWSC), approximately 295,000 hospital-based healthcare workers experience occupational percutaneous injuries annually. In 1991, Mangione et al surveyed internal-medicine house staff and found an annual incidence of 674 needlestick injuries per 1,000 participants.1 Other retrospective data estimate this risk to be as high as 839 per 1,000 healthcare workers annually.2 Evidence from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2004 suggests that because these are only self-reported injuries, the annual incidence of such injuries is in fact much higher than the current estimates suggest.2,3,4

More than 20 bloodborne pathogens (see Table 1, right) might be transmitted from contaminated needles or sharps, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), and hepatitis C virus (HCV). A quick and appropriate response to a needlestick injury can greatly decrease the risk of disease transmission following an occupational exposure to potentially infectious materials.

Review of the Data

After any needlestick injury, an affected healthcare worker should wash the area with soap and water immediately. There is no contraindication to using antiseptic solutions, but there is also no evidence to suggest that this reduces the rates of disease transmission.

As decisions for post-exposure prophylaxis often need to be made within hours, a healthcare worker should seek care in the facility areas responsible for managing occupational exposures. Healthcare providers should always be encouraged and supported to report all sharps-related injuries to such departments.

The source patient should be identified and evaluated for potentially transmissible diseases, including HIV, HBV, and HCV. If indicated, the source patient should then undergo appropriate serological testing, and any indicated antiviral prophylaxis should be initiated (see Table 2, p. 19).

Risk of Seroconversion