User login

Prescribing is the culmination of extensive medical training and psychologists don’t qualify

Practicing medicine without a license is a crime, but it seems to have become a hollow law. Politicians are now cynically legalizing it by granting prescribing privileges to individuals with no prior foundation of medical training. Perhaps it is because of serious ignorance of the difference between psychiatry and psychology or MD and PhD degrees. Or perhaps it is a quid pro quo to generous donors to their re-election campaigns who seek a convenient shortcut to the 28,000 hours it takes to become a psychiatrist in 8 years of medical school and psychiatric residency—and that comes after 4 years of college.

I recently consulted an attorney to discuss some legal documents. When he asked me what my line of work is, I then asked him if he knew the difference between a psychiatrist and a psychologist. He hesitated before admitting in an embarrassed tone that he did not really know and thought that they were all “shrinks” and very similar. I then informed him that both go through undergraduate college education, albeit taking very different courses, with pre-med scientific emphasis for future psychiatric physicians and predominately psychology emphasis for future psychologists.

However, psychiatrists then attend medical school for 4 years and rotate on multiple hospital-based medical specialties, such as internal medicine, surgery, pediatrics, obstetrics and gynecology, family medicine, neurology, pathology, psychiatry, ophthalmology, dermatology, anesthesia, radiology, otolaryngology, etc.

Psychologists, on the other hand, take additional advanced psychology courses in graduate school and write a dissertation that requires quite a bit of library time. After getting a MD, future psychiatrists spend 4 years in extensive training in residency programs across inpatient wards and outpatient clinics, assessing the physical and mental health of seriously sick patients with emphasis on both pharmacological and psychotherapeutic treatments for serious psychiatric disorders in patients, the majority of whom have comorbid medical conditions as well. Psychologists, on the other hand, spend 1 year of internship after getting their PhD or PsyD degree, essentially focused on developing counseling and psychotherapy skills. By the time they complete their training, psychologists and psychiatrists have disparate skills: heavily medical and pharmacological skills in psychiatrists and strong psychotherapeutic skills in psychologists.

After this long explanation, I asked the attorney what he thought about psychologists seeking prescription privileges. He was astounded that psychologists would attempt to expand this scope of practice through state legislations rather than going through medical training like all physicians. “That would be like practicing medicine without a license, which is a felony,” he said. He wryly added that his fellow malpractice and litigation lawyers will be the big winners while poorly treated patients will be the biggest losers. Being an avid runner, he also added that such a short-cut to prescribe without the requisite years of medial training reminded him of Rosie Ruiz, who snuck into the Boston marathon a couple of miles before the finish line and “won” the race, before she was caught and discredited.1

Psychology is a respected mental health discipline with strong psychotherapy training and orientation. For decades, psychologists have vigorously criticized the medical model of mental disorders that psychiatric physicians employ to diagnose and treat brain disorders that disrupt thinking, emotions, mood, cognition, and behavior. However, about 25 years ago, a small group of militant psychologists brazenly decided to lobby state legislatures to give them the right to prescribe psychotropics, although they have no formal medical training. Psychiatric physicians, represented by the American Psychiatric Association (APA), strongly opposed this initiative and regarded it as reckless disregard of the obvious need for extensive medical training to be able to prescribe drugs that affect every organ in the body, not only the brain. Psychiatric medications are associated with serious risks of morbidity and mortality.2 The ability to safely prescribe any medication represents the tip of a huge iceberg of 8 years of rigorous medical school education and specialty training. Yet, one of the early proponents of prescription privileges for psychologists, Patrick De Leon, sarcastically likened the ability to prescribe drugs to learning how to operate a desktop computer!

Not all psychologists agreed with the political campaign to lobby state legislatures to pass a law authorizing prescriptive privileges for psychologists.3-6 In fact, most academic psychologists oppose it.7 Most of the early supporters had a PsyD degree from professional schools of psychology, not a PhD degree in psychology, which is obtained from a university department of psychology. The National Alliance on Mental Illness is opposed to psychologists prescribing medications.8 Psychiatrists are outraged by this hazardous “solution” to the shortage of psychiatrists and point to the many potential dangers to patients. Some suggested that this is a quick way to enhance psychologists’ income and to generate more revenue for their professional journals and meetings with lucrative pharmaceutical ads and exhibit booths.

The campaign is ongoing, as Idaho became the fifth state to adopt such an ill-conceived “solution” to increasing access to mental health care, despite valiant effort by the APA to lobby against such laws. Although New Mexico (2002), Louisiana (2004), Illinois (2014), and Iowa (2016) have passed prescriptive authority for psychologists before Idaho, the APA has defeated such measures in numerous other states. But the painful truth is that this has been a lengthy political chess game in which psychologists have been gradually gaining ground and “capturing more pieces.”

Here is a brief, common sense rationale as to the need for full medical training necessary before safely and accurately prescribing medications, most of which are synthetic molecules, which are essentially foreign substances, with both benefits and risks detailed in the FDA-approved label of each drug that reaches the medical marketplace.

First: Making an accurate clinical diagnosis. If a patient presents with depression, the clinician must rule out other possible causes before diagnosing it as primary major depressive disorder for which an antidepressant can be prescribed. The panoply of secondary depressions, which are not treated with antidepressants, includes a variety of recreational drug-induced mood changes and dysphoria and depression induced by numerous prescription drugs (such as antihypertensives, hormonal contraceptives, steroids, interferon, proton pump inhibitors, H2 blockers, malaria drugs, etc.).

After drug-induced depression is ruled out, the clinician must rule out the possibility that an underlying medical condition might be causing the depression, which includes disorders such as hypothyroidism and other endocrinopathies, anemia, stroke, heart disease, hyperkalemia, lupus and other autoimmune disorders, cancer, Parkinsonism, etc. Therefore, a targeted exploration of past and current medical history, accompanied by a battery of lab tests (complete blood count, electrolytes, liver and kidney function tests, metabolic profile, thyroid-stimulating hormone, etc.) must be done to systematically arrive at the correct diagnosis. Only then can the proper treatment plan be determined, which may or may not include prescribing an antidepressant.

Conclusion: Medical training and psychiatric residency are required for an accurate diagnosis of a mental disorder. Even physicians with no psychiatric training might not have the full repertoire of knowledge needed to systematically rule out secondary depression.

Second: Drug selection. Psychiatric drugs can have various iatrogenic effects. Thus, the selection of an appropriate prescription medication from the available array of drugs approved for a given psychiatric indication must be safe and consistent with the patient’s medical history and must not potentially exacerbate ≥1 comorbid medical conditions.

Conclusion: Medical training and psychiatric residency are required.

Third: Knowledge of metabolic pathways of each psychiatric medication to be prescribed as well as the metabolic pathway of all other medications (psychiatric and non-psychiatric) the patient receives is essential to avoid adverse drug–drug interactions. This includes the hepatic enzymes (cytochromes), which often are responsible for metabolizing all the psychiatric and non-psychiatric drugs a patient is receiving. Knowledge of inhibitors and inducers of various cytochrome enzymes is vital for selecting a medication that does not cause a pharmacokinetic adverse reaction that can produce serious adverse effects (even death, such as with QTc prolongation) or can cause loss of efficacy of ≥1 medications that the patient is receiving, in addition to the antidepressant. Also, in addition to evaluating hepatic pathways, knowledge of renal excretion of the drug to be selected and the status of the patient’s kidney function or impairment must be evaluated.

Conclusion: Medical training is required.

Fourth: Laboratory ordering and monitoring. Ordering laboratory data during follow-up of a patient receiving a psychotropic drug is necessary to monitor serum concentrations and ensure a therapeutic range, or to check for serious adverse effects on various organ systems that could be affected by many psychiatric drugs (CNS, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, sexual, endocrine, pulmonary, hepatic, renal, dermatologic, ophthalmologic, etc.).

Conclusion: Medical training is required.

Fifth: General medical treatment. Many patients might require combination drug therapy because of inadequate response to monotherapy. Clinicians must know what is rational and evidence-based polypharmacy and what is irrational, dangerous, or absurd polypharmacy.9 When possible, parsimonious pharmacotherapy should be employed to minimize the number of medications prescribed.10 A patient could experience severe drug–drug reactions that could lead to cardiopulmonary crises. The clinician must be able to examine, intervene, and manage the patient’s medical distress until help arrives.

Conclusion: Medical training is required.

Sixth: Pregnancy. Knowledge about the pharmacotherapeutic aspects of pregnant women with mental illness is critical. Full knowledge about what can or should not be prescribed during pregnancy (ie, avoiding teratogenic agents) is vital for physicians treating women with psychiatric illness who become pregnant.

Conclusion: Medical training is required.

Although I am against prescriptive privileges for psychologists, I want to emphasize how much I appreciate and respect what psychologists do for patients with mental illness. Their psychotherapy skills often are honed beyond those of psychiatrists who, by necessity, focus on medical diagnosis and pharmacotherapeutic management. Combination of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy has been demonstrated to be superior to medications alone. In the 25 years since psychologists have been eagerly pursuing prescriptive privileges, neuroscience research has revealed the neurobiologic effects of psychotherapy. Many studies have shown that evidence-based psychotherapy can induce the same structural and functional brain changes as medications11,12 and can influence biomarkers that accompany psychiatric disorders just as medications do.13

Psychologists should reconsider the many potential hazards of prescription drugs compared with the relative safety and efficacy of psychotherapy. They should focus on their qualifications and main strength, which is psychotherapy, and collaborate with psychiatrists and nurse practitioners on a biopsychosocial approach to mental illness. They also should realize how physically ill most psychiatric patients are and the complex medical management they need for their myriad comorbidities.

Just as I began this editorial with an anecdote, I will end with an illustrative one as well. As an academic professor for the past 3 decades who has trained and supervised numerous psychiatric residents, I once closely supervised a former PhD psychologist who decided to become a psychiatrist by going to medical school, followed by a 4-year psychiatric residency. I asked her to compare her experience and functioning as a psychologist with her current work as a fourth-year psychiatric resident. Her response was enlightening: She said the 2 professions are vastly different in their knowledge base and in terms of how they conceptualize mental illness from a psychological vs medical model. As for prescribing medications, she added that even after 8 years of extensive medical training as a physician and a psychiatrist, she feels there is still much to learn about psychopharmacology to ensure not only efficacy but also safety, because a majority of psychiatric patients have ≥1 coexisting medical conditions and substance use as well. Based on her own experience as a psychologist who became a psychiatric physician, she was completely opposed to prescriptive privileges for psychologists unless they go to medical school and become eligible to prescribe safely.

This former resident is now a successful academic psychiatrist who continues to hone her psychopharmacology skills. State legislators should listen to professionals like her before they pass a law giving prescriptive authority to psychologists without having to go through the rigors of 28,000 hours of training in the 8 years of medical school and psychiatric residency. Legislators should also understand that like psychologists, social work counselors have hardly any medical training, yet they have never sought prescriptive privileges. That’s clearly rational and wise.

1. Rosie Ruiz tries to steal the Boston marathon. Runner’s World. http://www.runnersworld.com/running-times-info/rosie-ruiz-tries-to-steal-the-boston-marathon. Published July 1, 1980. Accessed May 15, 2017.

2. Nelson, JC, Spyker DA. Morbidity and mortality associated with medications used in the treatment of depression: an analysis of cases reported to U.S. Poison Control Centers, 2000-2014. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(5):438-450.

3. Robiner WN, Bearman DL, Berman M, et al. Prescriptive authority for psychologists: despite deficits in education and knowledge? J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2003;10(3):211-221.

4. Robiner WN, Bearman DL, Berman M, et al. Prescriptive authority for psychologists: a looming health hazard? Clinical Psychology Science and Practice. 2002;9(3):231-248.

5. Kingsbury SJ. Some effects of prescribing privileges. Am Psychol. 1992;47(3):426-427.

6. Pollitt B. Fools gold: psychologists using disingenuous reasoning to mislead legislatures into granting psychologists prescriptive authority. Am J Law Med. 2003;29:489-524.

7. DeNelsky GY. The case against prescription privileges for psychologists. Am Psychol. 1996;51(3):207-212.

8. Walker K. An ethical dilemma: clinical psychologists prescribing psychotropic medications. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2002;23(1):17-29.

9. Nasrallah HA. Polypharmacy subtypes: the necessary, the reasonable, the ridiculous and the hazardous. Current Psychiatry. 2011;10(4):10-12.

10. Nasrallah HA. Parsimonious pharmacotherapy. Current Psychiatry. 2011;10(5):12-16.

11. Shou H, Yang Z, Satterthwaite TD, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy increases amygdala connectivity with the cognitive control network in both MDD and PTSD. Neuroimage Clin. 2017;14:464-470.

12. Månsson KN, Salami A, Frick A, et al. Neuroplasticity in response to cognitive behavior therapy for social anxiety disorder. Transl Psychiatry. 2015;5:e727.

13. Redei EE, Andrus BM, Kwasny MJ, et al. Blood transcriptomic biomarkers in adult primary care patients with major depressive disorder undergoing cognitive behavioral therapy. Transl Psychiatry. 2014;4:e442.

Practicing medicine without a license is a crime, but it seems to have become a hollow law. Politicians are now cynically legalizing it by granting prescribing privileges to individuals with no prior foundation of medical training. Perhaps it is because of serious ignorance of the difference between psychiatry and psychology or MD and PhD degrees. Or perhaps it is a quid pro quo to generous donors to their re-election campaigns who seek a convenient shortcut to the 28,000 hours it takes to become a psychiatrist in 8 years of medical school and psychiatric residency—and that comes after 4 years of college.

I recently consulted an attorney to discuss some legal documents. When he asked me what my line of work is, I then asked him if he knew the difference between a psychiatrist and a psychologist. He hesitated before admitting in an embarrassed tone that he did not really know and thought that they were all “shrinks” and very similar. I then informed him that both go through undergraduate college education, albeit taking very different courses, with pre-med scientific emphasis for future psychiatric physicians and predominately psychology emphasis for future psychologists.

However, psychiatrists then attend medical school for 4 years and rotate on multiple hospital-based medical specialties, such as internal medicine, surgery, pediatrics, obstetrics and gynecology, family medicine, neurology, pathology, psychiatry, ophthalmology, dermatology, anesthesia, radiology, otolaryngology, etc.

Psychologists, on the other hand, take additional advanced psychology courses in graduate school and write a dissertation that requires quite a bit of library time. After getting a MD, future psychiatrists spend 4 years in extensive training in residency programs across inpatient wards and outpatient clinics, assessing the physical and mental health of seriously sick patients with emphasis on both pharmacological and psychotherapeutic treatments for serious psychiatric disorders in patients, the majority of whom have comorbid medical conditions as well. Psychologists, on the other hand, spend 1 year of internship after getting their PhD or PsyD degree, essentially focused on developing counseling and psychotherapy skills. By the time they complete their training, psychologists and psychiatrists have disparate skills: heavily medical and pharmacological skills in psychiatrists and strong psychotherapeutic skills in psychologists.

After this long explanation, I asked the attorney what he thought about psychologists seeking prescription privileges. He was astounded that psychologists would attempt to expand this scope of practice through state legislations rather than going through medical training like all physicians. “That would be like practicing medicine without a license, which is a felony,” he said. He wryly added that his fellow malpractice and litigation lawyers will be the big winners while poorly treated patients will be the biggest losers. Being an avid runner, he also added that such a short-cut to prescribe without the requisite years of medial training reminded him of Rosie Ruiz, who snuck into the Boston marathon a couple of miles before the finish line and “won” the race, before she was caught and discredited.1

Psychology is a respected mental health discipline with strong psychotherapy training and orientation. For decades, psychologists have vigorously criticized the medical model of mental disorders that psychiatric physicians employ to diagnose and treat brain disorders that disrupt thinking, emotions, mood, cognition, and behavior. However, about 25 years ago, a small group of militant psychologists brazenly decided to lobby state legislatures to give them the right to prescribe psychotropics, although they have no formal medical training. Psychiatric physicians, represented by the American Psychiatric Association (APA), strongly opposed this initiative and regarded it as reckless disregard of the obvious need for extensive medical training to be able to prescribe drugs that affect every organ in the body, not only the brain. Psychiatric medications are associated with serious risks of morbidity and mortality.2 The ability to safely prescribe any medication represents the tip of a huge iceberg of 8 years of rigorous medical school education and specialty training. Yet, one of the early proponents of prescription privileges for psychologists, Patrick De Leon, sarcastically likened the ability to prescribe drugs to learning how to operate a desktop computer!

Not all psychologists agreed with the political campaign to lobby state legislatures to pass a law authorizing prescriptive privileges for psychologists.3-6 In fact, most academic psychologists oppose it.7 Most of the early supporters had a PsyD degree from professional schools of psychology, not a PhD degree in psychology, which is obtained from a university department of psychology. The National Alliance on Mental Illness is opposed to psychologists prescribing medications.8 Psychiatrists are outraged by this hazardous “solution” to the shortage of psychiatrists and point to the many potential dangers to patients. Some suggested that this is a quick way to enhance psychologists’ income and to generate more revenue for their professional journals and meetings with lucrative pharmaceutical ads and exhibit booths.

The campaign is ongoing, as Idaho became the fifth state to adopt such an ill-conceived “solution” to increasing access to mental health care, despite valiant effort by the APA to lobby against such laws. Although New Mexico (2002), Louisiana (2004), Illinois (2014), and Iowa (2016) have passed prescriptive authority for psychologists before Idaho, the APA has defeated such measures in numerous other states. But the painful truth is that this has been a lengthy political chess game in which psychologists have been gradually gaining ground and “capturing more pieces.”

Here is a brief, common sense rationale as to the need for full medical training necessary before safely and accurately prescribing medications, most of which are synthetic molecules, which are essentially foreign substances, with both benefits and risks detailed in the FDA-approved label of each drug that reaches the medical marketplace.

First: Making an accurate clinical diagnosis. If a patient presents with depression, the clinician must rule out other possible causes before diagnosing it as primary major depressive disorder for which an antidepressant can be prescribed. The panoply of secondary depressions, which are not treated with antidepressants, includes a variety of recreational drug-induced mood changes and dysphoria and depression induced by numerous prescription drugs (such as antihypertensives, hormonal contraceptives, steroids, interferon, proton pump inhibitors, H2 blockers, malaria drugs, etc.).

After drug-induced depression is ruled out, the clinician must rule out the possibility that an underlying medical condition might be causing the depression, which includes disorders such as hypothyroidism and other endocrinopathies, anemia, stroke, heart disease, hyperkalemia, lupus and other autoimmune disorders, cancer, Parkinsonism, etc. Therefore, a targeted exploration of past and current medical history, accompanied by a battery of lab tests (complete blood count, electrolytes, liver and kidney function tests, metabolic profile, thyroid-stimulating hormone, etc.) must be done to systematically arrive at the correct diagnosis. Only then can the proper treatment plan be determined, which may or may not include prescribing an antidepressant.

Conclusion: Medical training and psychiatric residency are required for an accurate diagnosis of a mental disorder. Even physicians with no psychiatric training might not have the full repertoire of knowledge needed to systematically rule out secondary depression.

Second: Drug selection. Psychiatric drugs can have various iatrogenic effects. Thus, the selection of an appropriate prescription medication from the available array of drugs approved for a given psychiatric indication must be safe and consistent with the patient’s medical history and must not potentially exacerbate ≥1 comorbid medical conditions.

Conclusion: Medical training and psychiatric residency are required.

Third: Knowledge of metabolic pathways of each psychiatric medication to be prescribed as well as the metabolic pathway of all other medications (psychiatric and non-psychiatric) the patient receives is essential to avoid adverse drug–drug interactions. This includes the hepatic enzymes (cytochromes), which often are responsible for metabolizing all the psychiatric and non-psychiatric drugs a patient is receiving. Knowledge of inhibitors and inducers of various cytochrome enzymes is vital for selecting a medication that does not cause a pharmacokinetic adverse reaction that can produce serious adverse effects (even death, such as with QTc prolongation) or can cause loss of efficacy of ≥1 medications that the patient is receiving, in addition to the antidepressant. Also, in addition to evaluating hepatic pathways, knowledge of renal excretion of the drug to be selected and the status of the patient’s kidney function or impairment must be evaluated.

Conclusion: Medical training is required.

Fourth: Laboratory ordering and monitoring. Ordering laboratory data during follow-up of a patient receiving a psychotropic drug is necessary to monitor serum concentrations and ensure a therapeutic range, or to check for serious adverse effects on various organ systems that could be affected by many psychiatric drugs (CNS, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, sexual, endocrine, pulmonary, hepatic, renal, dermatologic, ophthalmologic, etc.).

Conclusion: Medical training is required.

Fifth: General medical treatment. Many patients might require combination drug therapy because of inadequate response to monotherapy. Clinicians must know what is rational and evidence-based polypharmacy and what is irrational, dangerous, or absurd polypharmacy.9 When possible, parsimonious pharmacotherapy should be employed to minimize the number of medications prescribed.10 A patient could experience severe drug–drug reactions that could lead to cardiopulmonary crises. The clinician must be able to examine, intervene, and manage the patient’s medical distress until help arrives.

Conclusion: Medical training is required.

Sixth: Pregnancy. Knowledge about the pharmacotherapeutic aspects of pregnant women with mental illness is critical. Full knowledge about what can or should not be prescribed during pregnancy (ie, avoiding teratogenic agents) is vital for physicians treating women with psychiatric illness who become pregnant.

Conclusion: Medical training is required.

Although I am against prescriptive privileges for psychologists, I want to emphasize how much I appreciate and respect what psychologists do for patients with mental illness. Their psychotherapy skills often are honed beyond those of psychiatrists who, by necessity, focus on medical diagnosis and pharmacotherapeutic management. Combination of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy has been demonstrated to be superior to medications alone. In the 25 years since psychologists have been eagerly pursuing prescriptive privileges, neuroscience research has revealed the neurobiologic effects of psychotherapy. Many studies have shown that evidence-based psychotherapy can induce the same structural and functional brain changes as medications11,12 and can influence biomarkers that accompany psychiatric disorders just as medications do.13

Psychologists should reconsider the many potential hazards of prescription drugs compared with the relative safety and efficacy of psychotherapy. They should focus on their qualifications and main strength, which is psychotherapy, and collaborate with psychiatrists and nurse practitioners on a biopsychosocial approach to mental illness. They also should realize how physically ill most psychiatric patients are and the complex medical management they need for their myriad comorbidities.

Just as I began this editorial with an anecdote, I will end with an illustrative one as well. As an academic professor for the past 3 decades who has trained and supervised numerous psychiatric residents, I once closely supervised a former PhD psychologist who decided to become a psychiatrist by going to medical school, followed by a 4-year psychiatric residency. I asked her to compare her experience and functioning as a psychologist with her current work as a fourth-year psychiatric resident. Her response was enlightening: She said the 2 professions are vastly different in their knowledge base and in terms of how they conceptualize mental illness from a psychological vs medical model. As for prescribing medications, she added that even after 8 years of extensive medical training as a physician and a psychiatrist, she feels there is still much to learn about psychopharmacology to ensure not only efficacy but also safety, because a majority of psychiatric patients have ≥1 coexisting medical conditions and substance use as well. Based on her own experience as a psychologist who became a psychiatric physician, she was completely opposed to prescriptive privileges for psychologists unless they go to medical school and become eligible to prescribe safely.

This former resident is now a successful academic psychiatrist who continues to hone her psychopharmacology skills. State legislators should listen to professionals like her before they pass a law giving prescriptive authority to psychologists without having to go through the rigors of 28,000 hours of training in the 8 years of medical school and psychiatric residency. Legislators should also understand that like psychologists, social work counselors have hardly any medical training, yet they have never sought prescriptive privileges. That’s clearly rational and wise.

Practicing medicine without a license is a crime, but it seems to have become a hollow law. Politicians are now cynically legalizing it by granting prescribing privileges to individuals with no prior foundation of medical training. Perhaps it is because of serious ignorance of the difference between psychiatry and psychology or MD and PhD degrees. Or perhaps it is a quid pro quo to generous donors to their re-election campaigns who seek a convenient shortcut to the 28,000 hours it takes to become a psychiatrist in 8 years of medical school and psychiatric residency—and that comes after 4 years of college.

I recently consulted an attorney to discuss some legal documents. When he asked me what my line of work is, I then asked him if he knew the difference between a psychiatrist and a psychologist. He hesitated before admitting in an embarrassed tone that he did not really know and thought that they were all “shrinks” and very similar. I then informed him that both go through undergraduate college education, albeit taking very different courses, with pre-med scientific emphasis for future psychiatric physicians and predominately psychology emphasis for future psychologists.

However, psychiatrists then attend medical school for 4 years and rotate on multiple hospital-based medical specialties, such as internal medicine, surgery, pediatrics, obstetrics and gynecology, family medicine, neurology, pathology, psychiatry, ophthalmology, dermatology, anesthesia, radiology, otolaryngology, etc.

Psychologists, on the other hand, take additional advanced psychology courses in graduate school and write a dissertation that requires quite a bit of library time. After getting a MD, future psychiatrists spend 4 years in extensive training in residency programs across inpatient wards and outpatient clinics, assessing the physical and mental health of seriously sick patients with emphasis on both pharmacological and psychotherapeutic treatments for serious psychiatric disorders in patients, the majority of whom have comorbid medical conditions as well. Psychologists, on the other hand, spend 1 year of internship after getting their PhD or PsyD degree, essentially focused on developing counseling and psychotherapy skills. By the time they complete their training, psychologists and psychiatrists have disparate skills: heavily medical and pharmacological skills in psychiatrists and strong psychotherapeutic skills in psychologists.

After this long explanation, I asked the attorney what he thought about psychologists seeking prescription privileges. He was astounded that psychologists would attempt to expand this scope of practice through state legislations rather than going through medical training like all physicians. “That would be like practicing medicine without a license, which is a felony,” he said. He wryly added that his fellow malpractice and litigation lawyers will be the big winners while poorly treated patients will be the biggest losers. Being an avid runner, he also added that such a short-cut to prescribe without the requisite years of medial training reminded him of Rosie Ruiz, who snuck into the Boston marathon a couple of miles before the finish line and “won” the race, before she was caught and discredited.1

Psychology is a respected mental health discipline with strong psychotherapy training and orientation. For decades, psychologists have vigorously criticized the medical model of mental disorders that psychiatric physicians employ to diagnose and treat brain disorders that disrupt thinking, emotions, mood, cognition, and behavior. However, about 25 years ago, a small group of militant psychologists brazenly decided to lobby state legislatures to give them the right to prescribe psychotropics, although they have no formal medical training. Psychiatric physicians, represented by the American Psychiatric Association (APA), strongly opposed this initiative and regarded it as reckless disregard of the obvious need for extensive medical training to be able to prescribe drugs that affect every organ in the body, not only the brain. Psychiatric medications are associated with serious risks of morbidity and mortality.2 The ability to safely prescribe any medication represents the tip of a huge iceberg of 8 years of rigorous medical school education and specialty training. Yet, one of the early proponents of prescription privileges for psychologists, Patrick De Leon, sarcastically likened the ability to prescribe drugs to learning how to operate a desktop computer!

Not all psychologists agreed with the political campaign to lobby state legislatures to pass a law authorizing prescriptive privileges for psychologists.3-6 In fact, most academic psychologists oppose it.7 Most of the early supporters had a PsyD degree from professional schools of psychology, not a PhD degree in psychology, which is obtained from a university department of psychology. The National Alliance on Mental Illness is opposed to psychologists prescribing medications.8 Psychiatrists are outraged by this hazardous “solution” to the shortage of psychiatrists and point to the many potential dangers to patients. Some suggested that this is a quick way to enhance psychologists’ income and to generate more revenue for their professional journals and meetings with lucrative pharmaceutical ads and exhibit booths.

The campaign is ongoing, as Idaho became the fifth state to adopt such an ill-conceived “solution” to increasing access to mental health care, despite valiant effort by the APA to lobby against such laws. Although New Mexico (2002), Louisiana (2004), Illinois (2014), and Iowa (2016) have passed prescriptive authority for psychologists before Idaho, the APA has defeated such measures in numerous other states. But the painful truth is that this has been a lengthy political chess game in which psychologists have been gradually gaining ground and “capturing more pieces.”

Here is a brief, common sense rationale as to the need for full medical training necessary before safely and accurately prescribing medications, most of which are synthetic molecules, which are essentially foreign substances, with both benefits and risks detailed in the FDA-approved label of each drug that reaches the medical marketplace.

First: Making an accurate clinical diagnosis. If a patient presents with depression, the clinician must rule out other possible causes before diagnosing it as primary major depressive disorder for which an antidepressant can be prescribed. The panoply of secondary depressions, which are not treated with antidepressants, includes a variety of recreational drug-induced mood changes and dysphoria and depression induced by numerous prescription drugs (such as antihypertensives, hormonal contraceptives, steroids, interferon, proton pump inhibitors, H2 blockers, malaria drugs, etc.).

After drug-induced depression is ruled out, the clinician must rule out the possibility that an underlying medical condition might be causing the depression, which includes disorders such as hypothyroidism and other endocrinopathies, anemia, stroke, heart disease, hyperkalemia, lupus and other autoimmune disorders, cancer, Parkinsonism, etc. Therefore, a targeted exploration of past and current medical history, accompanied by a battery of lab tests (complete blood count, electrolytes, liver and kidney function tests, metabolic profile, thyroid-stimulating hormone, etc.) must be done to systematically arrive at the correct diagnosis. Only then can the proper treatment plan be determined, which may or may not include prescribing an antidepressant.

Conclusion: Medical training and psychiatric residency are required for an accurate diagnosis of a mental disorder. Even physicians with no psychiatric training might not have the full repertoire of knowledge needed to systematically rule out secondary depression.

Second: Drug selection. Psychiatric drugs can have various iatrogenic effects. Thus, the selection of an appropriate prescription medication from the available array of drugs approved for a given psychiatric indication must be safe and consistent with the patient’s medical history and must not potentially exacerbate ≥1 comorbid medical conditions.

Conclusion: Medical training and psychiatric residency are required.

Third: Knowledge of metabolic pathways of each psychiatric medication to be prescribed as well as the metabolic pathway of all other medications (psychiatric and non-psychiatric) the patient receives is essential to avoid adverse drug–drug interactions. This includes the hepatic enzymes (cytochromes), which often are responsible for metabolizing all the psychiatric and non-psychiatric drugs a patient is receiving. Knowledge of inhibitors and inducers of various cytochrome enzymes is vital for selecting a medication that does not cause a pharmacokinetic adverse reaction that can produce serious adverse effects (even death, such as with QTc prolongation) or can cause loss of efficacy of ≥1 medications that the patient is receiving, in addition to the antidepressant. Also, in addition to evaluating hepatic pathways, knowledge of renal excretion of the drug to be selected and the status of the patient’s kidney function or impairment must be evaluated.

Conclusion: Medical training is required.

Fourth: Laboratory ordering and monitoring. Ordering laboratory data during follow-up of a patient receiving a psychotropic drug is necessary to monitor serum concentrations and ensure a therapeutic range, or to check for serious adverse effects on various organ systems that could be affected by many psychiatric drugs (CNS, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, sexual, endocrine, pulmonary, hepatic, renal, dermatologic, ophthalmologic, etc.).

Conclusion: Medical training is required.

Fifth: General medical treatment. Many patients might require combination drug therapy because of inadequate response to monotherapy. Clinicians must know what is rational and evidence-based polypharmacy and what is irrational, dangerous, or absurd polypharmacy.9 When possible, parsimonious pharmacotherapy should be employed to minimize the number of medications prescribed.10 A patient could experience severe drug–drug reactions that could lead to cardiopulmonary crises. The clinician must be able to examine, intervene, and manage the patient’s medical distress until help arrives.

Conclusion: Medical training is required.

Sixth: Pregnancy. Knowledge about the pharmacotherapeutic aspects of pregnant women with mental illness is critical. Full knowledge about what can or should not be prescribed during pregnancy (ie, avoiding teratogenic agents) is vital for physicians treating women with psychiatric illness who become pregnant.

Conclusion: Medical training is required.

Although I am against prescriptive privileges for psychologists, I want to emphasize how much I appreciate and respect what psychologists do for patients with mental illness. Their psychotherapy skills often are honed beyond those of psychiatrists who, by necessity, focus on medical diagnosis and pharmacotherapeutic management. Combination of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy has been demonstrated to be superior to medications alone. In the 25 years since psychologists have been eagerly pursuing prescriptive privileges, neuroscience research has revealed the neurobiologic effects of psychotherapy. Many studies have shown that evidence-based psychotherapy can induce the same structural and functional brain changes as medications11,12 and can influence biomarkers that accompany psychiatric disorders just as medications do.13

Psychologists should reconsider the many potential hazards of prescription drugs compared with the relative safety and efficacy of psychotherapy. They should focus on their qualifications and main strength, which is psychotherapy, and collaborate with psychiatrists and nurse practitioners on a biopsychosocial approach to mental illness. They also should realize how physically ill most psychiatric patients are and the complex medical management they need for their myriad comorbidities.

Just as I began this editorial with an anecdote, I will end with an illustrative one as well. As an academic professor for the past 3 decades who has trained and supervised numerous psychiatric residents, I once closely supervised a former PhD psychologist who decided to become a psychiatrist by going to medical school, followed by a 4-year psychiatric residency. I asked her to compare her experience and functioning as a psychologist with her current work as a fourth-year psychiatric resident. Her response was enlightening: She said the 2 professions are vastly different in their knowledge base and in terms of how they conceptualize mental illness from a psychological vs medical model. As for prescribing medications, she added that even after 8 years of extensive medical training as a physician and a psychiatrist, she feels there is still much to learn about psychopharmacology to ensure not only efficacy but also safety, because a majority of psychiatric patients have ≥1 coexisting medical conditions and substance use as well. Based on her own experience as a psychologist who became a psychiatric physician, she was completely opposed to prescriptive privileges for psychologists unless they go to medical school and become eligible to prescribe safely.

This former resident is now a successful academic psychiatrist who continues to hone her psychopharmacology skills. State legislators should listen to professionals like her before they pass a law giving prescriptive authority to psychologists without having to go through the rigors of 28,000 hours of training in the 8 years of medical school and psychiatric residency. Legislators should also understand that like psychologists, social work counselors have hardly any medical training, yet they have never sought prescriptive privileges. That’s clearly rational and wise.

1. Rosie Ruiz tries to steal the Boston marathon. Runner’s World. http://www.runnersworld.com/running-times-info/rosie-ruiz-tries-to-steal-the-boston-marathon. Published July 1, 1980. Accessed May 15, 2017.

2. Nelson, JC, Spyker DA. Morbidity and mortality associated with medications used in the treatment of depression: an analysis of cases reported to U.S. Poison Control Centers, 2000-2014. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(5):438-450.

3. Robiner WN, Bearman DL, Berman M, et al. Prescriptive authority for psychologists: despite deficits in education and knowledge? J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2003;10(3):211-221.

4. Robiner WN, Bearman DL, Berman M, et al. Prescriptive authority for psychologists: a looming health hazard? Clinical Psychology Science and Practice. 2002;9(3):231-248.

5. Kingsbury SJ. Some effects of prescribing privileges. Am Psychol. 1992;47(3):426-427.

6. Pollitt B. Fools gold: psychologists using disingenuous reasoning to mislead legislatures into granting psychologists prescriptive authority. Am J Law Med. 2003;29:489-524.

7. DeNelsky GY. The case against prescription privileges for psychologists. Am Psychol. 1996;51(3):207-212.

8. Walker K. An ethical dilemma: clinical psychologists prescribing psychotropic medications. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2002;23(1):17-29.

9. Nasrallah HA. Polypharmacy subtypes: the necessary, the reasonable, the ridiculous and the hazardous. Current Psychiatry. 2011;10(4):10-12.

10. Nasrallah HA. Parsimonious pharmacotherapy. Current Psychiatry. 2011;10(5):12-16.

11. Shou H, Yang Z, Satterthwaite TD, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy increases amygdala connectivity with the cognitive control network in both MDD and PTSD. Neuroimage Clin. 2017;14:464-470.

12. Månsson KN, Salami A, Frick A, et al. Neuroplasticity in response to cognitive behavior therapy for social anxiety disorder. Transl Psychiatry. 2015;5:e727.

13. Redei EE, Andrus BM, Kwasny MJ, et al. Blood transcriptomic biomarkers in adult primary care patients with major depressive disorder undergoing cognitive behavioral therapy. Transl Psychiatry. 2014;4:e442.

1. Rosie Ruiz tries to steal the Boston marathon. Runner’s World. http://www.runnersworld.com/running-times-info/rosie-ruiz-tries-to-steal-the-boston-marathon. Published July 1, 1980. Accessed May 15, 2017.

2. Nelson, JC, Spyker DA. Morbidity and mortality associated with medications used in the treatment of depression: an analysis of cases reported to U.S. Poison Control Centers, 2000-2014. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(5):438-450.

3. Robiner WN, Bearman DL, Berman M, et al. Prescriptive authority for psychologists: despite deficits in education and knowledge? J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2003;10(3):211-221.

4. Robiner WN, Bearman DL, Berman M, et al. Prescriptive authority for psychologists: a looming health hazard? Clinical Psychology Science and Practice. 2002;9(3):231-248.

5. Kingsbury SJ. Some effects of prescribing privileges. Am Psychol. 1992;47(3):426-427.

6. Pollitt B. Fools gold: psychologists using disingenuous reasoning to mislead legislatures into granting psychologists prescriptive authority. Am J Law Med. 2003;29:489-524.

7. DeNelsky GY. The case against prescription privileges for psychologists. Am Psychol. 1996;51(3):207-212.

8. Walker K. An ethical dilemma: clinical psychologists prescribing psychotropic medications. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2002;23(1):17-29.

9. Nasrallah HA. Polypharmacy subtypes: the necessary, the reasonable, the ridiculous and the hazardous. Current Psychiatry. 2011;10(4):10-12.

10. Nasrallah HA. Parsimonious pharmacotherapy. Current Psychiatry. 2011;10(5):12-16.

11. Shou H, Yang Z, Satterthwaite TD, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy increases amygdala connectivity with the cognitive control network in both MDD and PTSD. Neuroimage Clin. 2017;14:464-470.

12. Månsson KN, Salami A, Frick A, et al. Neuroplasticity in response to cognitive behavior therapy for social anxiety disorder. Transl Psychiatry. 2015;5:e727.

13. Redei EE, Andrus BM, Kwasny MJ, et al. Blood transcriptomic biomarkers in adult primary care patients with major depressive disorder undergoing cognitive behavioral therapy. Transl Psychiatry. 2014;4:e442.

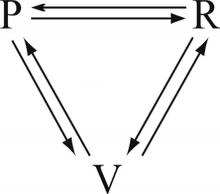

Leadership hacks: The drama triangle

There are plenty of leadership books, seminars, podcasts, and websites available for the aspiring physician leader. However, not all of them are pertinent to the health care environment. As chairman of a large academic department, I have sifted through some of these resources and have found a few that have been particularly helpful to me. One of the more useful is the drama triangle.

Here’s an example: Pat, the administrator, just sent Sam an email stating that, starting today, all computers will be automatically turned off at 5 p.m. and cannot be restarted until 8 a.m. the next day. The reasons are many but unimportant to Sam because they pale in comparison to the inconvenience this places on Sam’s ability to finish work in the evening. No one asked about this change or even gave advance warning.

Anger builds in Sam, especially toward Pat. Something has to be done about this! That something becomes a petition to Kelly, a supervisor/manager/director/chairman with authority. Sam recounts the surprise of the order, details the inefficiencies created, expresses indignation at not being consulted first, lists the personal failings of Pat, and demands an immediate resolution to the problem. Kelly wants to help Sam and approaches Pat to reverse the order. Kelly feels good about helping Sam, and Sam feels great about going to Kelly. Pat doesn’t feel good at all.

Sam started, and Kelly completed, the drama triangle.

Breaking a drama triangle requires uncomfortable work building trust and a more functional relationship between the three players. Ideally, the victim becomes challenged, not threatened. The rescuer becomes a coach, not an enabler. The persecutor raises the bar rather than creating obstacles. With roles redefined, trust is restored. There are many methods and techniques to develop psychological safety and interdependent trust, but the work is the critical first step toward improving the function of a team (Lencioni, P. (2002). The Five Dysfunctions of a Team. Jossey-Bass).

What could Kelly have done to stop a triangle from forming? Sam wanted help, and Kelly’s first instinct is to do just that. However, by completing the triangle with a visit to Pat, Kelly creates more tension between Pat and Sam. To help both Sam and Pat, Kelly has to resist the temptation to rescue Sam from Pat and instead leverage Sam’s trust to begin asking Sam questions that lead Sam toward resolution of Sam’s own problem.

Aware of drama triangles, Kelly asks Sam what the ideal situation would be. Sam replies that all the work would get done by the end of the day. Kelly then asks what the current situation is. According to Pat, the computers turn off at 5, but the work is not done by then. Then, Kelly asks Sam what could be done before 5 that would help get the work done. Sam considers the question and then begins to list some changes to work flow that could allow greater efficiency during the day. Sam also decides to meet with Pat to explain how the two of them can improve communication in the future. Through coaching, Kelly defuses Sam’s anger, avoids a drama triangle, and gets Sam to start considering previously unknown solutions. The model Kelly uses to begin the work of breaking the triangle is sometimes called structural, or dynamic, tension.

Drama triangles compromise trust. The workplace culture can either enable simmering tensions and resentments to persist or it can foster psychological safety that allows for open and honest debate whereby all are heard and validated when change inevitably occurs. Exploring structural tension can build a sense of team and restore trust. A more robust discussion of structural tension will have to wait until my next column. In the meantime, as yourselves, Where do you see drama triangles? What worked to break them? What failed?

For more reading: Emerald, D. (2010). The Power of Ted* (The Empowerment Dynamic). Bainbridge Island, WA: Polaris Publishing.

I invite you to reply to [email protected] to initiate a broader discussion of physician leadership. Responses will be posted to hematologynews.com. Dr. Kalaycio is editor in chief of Hematology News. Dr. Kalaycio chairs the department of hematologic oncology and blood disorders at Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute. Contact him at [email protected].

There are plenty of leadership books, seminars, podcasts, and websites available for the aspiring physician leader. However, not all of them are pertinent to the health care environment. As chairman of a large academic department, I have sifted through some of these resources and have found a few that have been particularly helpful to me. One of the more useful is the drama triangle.

Here’s an example: Pat, the administrator, just sent Sam an email stating that, starting today, all computers will be automatically turned off at 5 p.m. and cannot be restarted until 8 a.m. the next day. The reasons are many but unimportant to Sam because they pale in comparison to the inconvenience this places on Sam’s ability to finish work in the evening. No one asked about this change or even gave advance warning.

Anger builds in Sam, especially toward Pat. Something has to be done about this! That something becomes a petition to Kelly, a supervisor/manager/director/chairman with authority. Sam recounts the surprise of the order, details the inefficiencies created, expresses indignation at not being consulted first, lists the personal failings of Pat, and demands an immediate resolution to the problem. Kelly wants to help Sam and approaches Pat to reverse the order. Kelly feels good about helping Sam, and Sam feels great about going to Kelly. Pat doesn’t feel good at all.

Sam started, and Kelly completed, the drama triangle.

Breaking a drama triangle requires uncomfortable work building trust and a more functional relationship between the three players. Ideally, the victim becomes challenged, not threatened. The rescuer becomes a coach, not an enabler. The persecutor raises the bar rather than creating obstacles. With roles redefined, trust is restored. There are many methods and techniques to develop psychological safety and interdependent trust, but the work is the critical first step toward improving the function of a team (Lencioni, P. (2002). The Five Dysfunctions of a Team. Jossey-Bass).

What could Kelly have done to stop a triangle from forming? Sam wanted help, and Kelly’s first instinct is to do just that. However, by completing the triangle with a visit to Pat, Kelly creates more tension between Pat and Sam. To help both Sam and Pat, Kelly has to resist the temptation to rescue Sam from Pat and instead leverage Sam’s trust to begin asking Sam questions that lead Sam toward resolution of Sam’s own problem.

Aware of drama triangles, Kelly asks Sam what the ideal situation would be. Sam replies that all the work would get done by the end of the day. Kelly then asks what the current situation is. According to Pat, the computers turn off at 5, but the work is not done by then. Then, Kelly asks Sam what could be done before 5 that would help get the work done. Sam considers the question and then begins to list some changes to work flow that could allow greater efficiency during the day. Sam also decides to meet with Pat to explain how the two of them can improve communication in the future. Through coaching, Kelly defuses Sam’s anger, avoids a drama triangle, and gets Sam to start considering previously unknown solutions. The model Kelly uses to begin the work of breaking the triangle is sometimes called structural, or dynamic, tension.

Drama triangles compromise trust. The workplace culture can either enable simmering tensions and resentments to persist or it can foster psychological safety that allows for open and honest debate whereby all are heard and validated when change inevitably occurs. Exploring structural tension can build a sense of team and restore trust. A more robust discussion of structural tension will have to wait until my next column. In the meantime, as yourselves, Where do you see drama triangles? What worked to break them? What failed?

For more reading: Emerald, D. (2010). The Power of Ted* (The Empowerment Dynamic). Bainbridge Island, WA: Polaris Publishing.

I invite you to reply to [email protected] to initiate a broader discussion of physician leadership. Responses will be posted to hematologynews.com. Dr. Kalaycio is editor in chief of Hematology News. Dr. Kalaycio chairs the department of hematologic oncology and blood disorders at Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute. Contact him at [email protected].

There are plenty of leadership books, seminars, podcasts, and websites available for the aspiring physician leader. However, not all of them are pertinent to the health care environment. As chairman of a large academic department, I have sifted through some of these resources and have found a few that have been particularly helpful to me. One of the more useful is the drama triangle.

Here’s an example: Pat, the administrator, just sent Sam an email stating that, starting today, all computers will be automatically turned off at 5 p.m. and cannot be restarted until 8 a.m. the next day. The reasons are many but unimportant to Sam because they pale in comparison to the inconvenience this places on Sam’s ability to finish work in the evening. No one asked about this change or even gave advance warning.

Anger builds in Sam, especially toward Pat. Something has to be done about this! That something becomes a petition to Kelly, a supervisor/manager/director/chairman with authority. Sam recounts the surprise of the order, details the inefficiencies created, expresses indignation at not being consulted first, lists the personal failings of Pat, and demands an immediate resolution to the problem. Kelly wants to help Sam and approaches Pat to reverse the order. Kelly feels good about helping Sam, and Sam feels great about going to Kelly. Pat doesn’t feel good at all.

Sam started, and Kelly completed, the drama triangle.

Breaking a drama triangle requires uncomfortable work building trust and a more functional relationship between the three players. Ideally, the victim becomes challenged, not threatened. The rescuer becomes a coach, not an enabler. The persecutor raises the bar rather than creating obstacles. With roles redefined, trust is restored. There are many methods and techniques to develop psychological safety and interdependent trust, but the work is the critical first step toward improving the function of a team (Lencioni, P. (2002). The Five Dysfunctions of a Team. Jossey-Bass).

What could Kelly have done to stop a triangle from forming? Sam wanted help, and Kelly’s first instinct is to do just that. However, by completing the triangle with a visit to Pat, Kelly creates more tension between Pat and Sam. To help both Sam and Pat, Kelly has to resist the temptation to rescue Sam from Pat and instead leverage Sam’s trust to begin asking Sam questions that lead Sam toward resolution of Sam’s own problem.

Aware of drama triangles, Kelly asks Sam what the ideal situation would be. Sam replies that all the work would get done by the end of the day. Kelly then asks what the current situation is. According to Pat, the computers turn off at 5, but the work is not done by then. Then, Kelly asks Sam what could be done before 5 that would help get the work done. Sam considers the question and then begins to list some changes to work flow that could allow greater efficiency during the day. Sam also decides to meet with Pat to explain how the two of them can improve communication in the future. Through coaching, Kelly defuses Sam’s anger, avoids a drama triangle, and gets Sam to start considering previously unknown solutions. The model Kelly uses to begin the work of breaking the triangle is sometimes called structural, or dynamic, tension.

Drama triangles compromise trust. The workplace culture can either enable simmering tensions and resentments to persist or it can foster psychological safety that allows for open and honest debate whereby all are heard and validated when change inevitably occurs. Exploring structural tension can build a sense of team and restore trust. A more robust discussion of structural tension will have to wait until my next column. In the meantime, as yourselves, Where do you see drama triangles? What worked to break them? What failed?

For more reading: Emerald, D. (2010). The Power of Ted* (The Empowerment Dynamic). Bainbridge Island, WA: Polaris Publishing.

I invite you to reply to [email protected] to initiate a broader discussion of physician leadership. Responses will be posted to hematologynews.com. Dr. Kalaycio is editor in chief of Hematology News. Dr. Kalaycio chairs the department of hematologic oncology and blood disorders at Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute. Contact him at [email protected].

Doing a lot with little – health care in Cuba

Although Cuba lies less than 100 miles from the United States, we Americans tend to know far less about the island nation than about almost any other country in our hemisphere. Only since 2014 has the United States begun to allow its citizens to travel directly to Cuba and has opened official diplomatic relations, although direct trade still remains blocked.

Cuba’s health care system has been touted as providing universal access to primary care services, whose goals are promoting health and preventing disease as well as providing free medical education to a veritable army of health care workers. Less well known are the quality and standards of their surgical services.

Although the Cuban government is a centralized, one-party state that follows the Marxist-Leninist ideology, every individual with whom we met answered our many questions with apparent candor. Perhaps our easy rapport was based to some degree on our common profession and our shared commitment to patient care. Although they were clearly proud of the quality of their free education and medical care, they were also quick to admit the shortcomings in their system: widespread poverty, shortages of food and advanced pharmaceuticals, and old medical facilities. We were not restricted in any way from moving around Havana or speaking with anyone, although our free time was admittedly limited because our busy schedule was crammed with at least two visits per day with the groups listed above.

We were interested in looking at how primary care was delivered in Cuba. We met with a primary care doctor in her office, which was situated on the ground floor of the apartment complex in which she and her patients lived. We also visited a polyclinic, two blocks from the primary care doctor’s office that serves as the next step up the chain and is the site where medical and surgical specialists come to consult with patients from 40-60 primary care practices clustered around the polyclinic. The walls of the polyclinic have posters that educate the patients about the importance of handwashing and prevention of hypertension and cancer. The polyclinic also has an epidemiologist who monitors such basic preventive services as immunizations and prenatal care, both of which achieve nearly 100% compliance in a society in which acceptance of these services is not optional. Pap smears are performed in the primary care clinics, as is comprehensive medical care.

As interesting and impressive as we found the primary care clinics, it was the visits with the surgeons in their hospitals that intrigued us the most. The surgeons we met were modest and collegial, yet proud of what they had accomplished under challenging resource constraints. The hospitals that we visited were reminiscent of the city and county hospitals in the United States in which many of us on the trip had trained in the 1970s: older facilities that were clean and serviceable, but with older, basic equipment. Nevertheless, C. Julian F. Ruiz Torres, MD, has developed minimally invasive surgery in a hospital dedicated to such technological advances. Although he is 72 years old, he still works tirelessly to obtain the resources to build a state-of-the-art surgical simulation center, now under construction. Basic minimally invasive surgical procedures are available in most hospitals, although advanced procedures are restricted to centers such as Dr. Ruiz Torres’ facility, Centro Nacional De Cirugia De Minimo Acceso, of which he is justifiably proud.

In the short time that we were in Cuba, we obviously could observe only a fraction of their entire system. We were unable to determine how representative the health care workers we met were; those we did meet, however, were committed, hard working, and idealistic. Their rewards are clearly not financial, as they are equally (and poorly) paid, earning the same $70/month, no matter what their “rank” in the system.

Whatever the political realities of life in Cuba may be outside of the medical setting, we connected with our fellow physicians and bonded over our shared passion for patient care. This trip was about meeting them and gaining some understanding of their professional challenges and their efforts to work with what they have. Their system has evolved in the unique cultural, political, and economic circumstances of Cuba, and so of course, such a system could never work here. And yet, it was refreshing and inspiring to see medical professionals dedicated to the ideals of our profession – serving the people by delivering the best care they could for all of their patients. My hat is off to them for accomplishing so much despite their limited resources.

Dr. Deveney is professor of surgery and vice chair of education in the department of surgery, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. She is the coeditor of ACS Surgery News.

Although Cuba lies less than 100 miles from the United States, we Americans tend to know far less about the island nation than about almost any other country in our hemisphere. Only since 2014 has the United States begun to allow its citizens to travel directly to Cuba and has opened official diplomatic relations, although direct trade still remains blocked.

Cuba’s health care system has been touted as providing universal access to primary care services, whose goals are promoting health and preventing disease as well as providing free medical education to a veritable army of health care workers. Less well known are the quality and standards of their surgical services.

Although the Cuban government is a centralized, one-party state that follows the Marxist-Leninist ideology, every individual with whom we met answered our many questions with apparent candor. Perhaps our easy rapport was based to some degree on our common profession and our shared commitment to patient care. Although they were clearly proud of the quality of their free education and medical care, they were also quick to admit the shortcomings in their system: widespread poverty, shortages of food and advanced pharmaceuticals, and old medical facilities. We were not restricted in any way from moving around Havana or speaking with anyone, although our free time was admittedly limited because our busy schedule was crammed with at least two visits per day with the groups listed above.

We were interested in looking at how primary care was delivered in Cuba. We met with a primary care doctor in her office, which was situated on the ground floor of the apartment complex in which she and her patients lived. We also visited a polyclinic, two blocks from the primary care doctor’s office that serves as the next step up the chain and is the site where medical and surgical specialists come to consult with patients from 40-60 primary care practices clustered around the polyclinic. The walls of the polyclinic have posters that educate the patients about the importance of handwashing and prevention of hypertension and cancer. The polyclinic also has an epidemiologist who monitors such basic preventive services as immunizations and prenatal care, both of which achieve nearly 100% compliance in a society in which acceptance of these services is not optional. Pap smears are performed in the primary care clinics, as is comprehensive medical care.

As interesting and impressive as we found the primary care clinics, it was the visits with the surgeons in their hospitals that intrigued us the most. The surgeons we met were modest and collegial, yet proud of what they had accomplished under challenging resource constraints. The hospitals that we visited were reminiscent of the city and county hospitals in the United States in which many of us on the trip had trained in the 1970s: older facilities that were clean and serviceable, but with older, basic equipment. Nevertheless, C. Julian F. Ruiz Torres, MD, has developed minimally invasive surgery in a hospital dedicated to such technological advances. Although he is 72 years old, he still works tirelessly to obtain the resources to build a state-of-the-art surgical simulation center, now under construction. Basic minimally invasive surgical procedures are available in most hospitals, although advanced procedures are restricted to centers such as Dr. Ruiz Torres’ facility, Centro Nacional De Cirugia De Minimo Acceso, of which he is justifiably proud.

In the short time that we were in Cuba, we obviously could observe only a fraction of their entire system. We were unable to determine how representative the health care workers we met were; those we did meet, however, were committed, hard working, and idealistic. Their rewards are clearly not financial, as they are equally (and poorly) paid, earning the same $70/month, no matter what their “rank” in the system.

Whatever the political realities of life in Cuba may be outside of the medical setting, we connected with our fellow physicians and bonded over our shared passion for patient care. This trip was about meeting them and gaining some understanding of their professional challenges and their efforts to work with what they have. Their system has evolved in the unique cultural, political, and economic circumstances of Cuba, and so of course, such a system could never work here. And yet, it was refreshing and inspiring to see medical professionals dedicated to the ideals of our profession – serving the people by delivering the best care they could for all of their patients. My hat is off to them for accomplishing so much despite their limited resources.

Dr. Deveney is professor of surgery and vice chair of education in the department of surgery, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. She is the coeditor of ACS Surgery News.

Although Cuba lies less than 100 miles from the United States, we Americans tend to know far less about the island nation than about almost any other country in our hemisphere. Only since 2014 has the United States begun to allow its citizens to travel directly to Cuba and has opened official diplomatic relations, although direct trade still remains blocked.

Cuba’s health care system has been touted as providing universal access to primary care services, whose goals are promoting health and preventing disease as well as providing free medical education to a veritable army of health care workers. Less well known are the quality and standards of their surgical services.

Although the Cuban government is a centralized, one-party state that follows the Marxist-Leninist ideology, every individual with whom we met answered our many questions with apparent candor. Perhaps our easy rapport was based to some degree on our common profession and our shared commitment to patient care. Although they were clearly proud of the quality of their free education and medical care, they were also quick to admit the shortcomings in their system: widespread poverty, shortages of food and advanced pharmaceuticals, and old medical facilities. We were not restricted in any way from moving around Havana or speaking with anyone, although our free time was admittedly limited because our busy schedule was crammed with at least two visits per day with the groups listed above.

We were interested in looking at how primary care was delivered in Cuba. We met with a primary care doctor in her office, which was situated on the ground floor of the apartment complex in which she and her patients lived. We also visited a polyclinic, two blocks from the primary care doctor’s office that serves as the next step up the chain and is the site where medical and surgical specialists come to consult with patients from 40-60 primary care practices clustered around the polyclinic. The walls of the polyclinic have posters that educate the patients about the importance of handwashing and prevention of hypertension and cancer. The polyclinic also has an epidemiologist who monitors such basic preventive services as immunizations and prenatal care, both of which achieve nearly 100% compliance in a society in which acceptance of these services is not optional. Pap smears are performed in the primary care clinics, as is comprehensive medical care.

As interesting and impressive as we found the primary care clinics, it was the visits with the surgeons in their hospitals that intrigued us the most. The surgeons we met were modest and collegial, yet proud of what they had accomplished under challenging resource constraints. The hospitals that we visited were reminiscent of the city and county hospitals in the United States in which many of us on the trip had trained in the 1970s: older facilities that were clean and serviceable, but with older, basic equipment. Nevertheless, C. Julian F. Ruiz Torres, MD, has developed minimally invasive surgery in a hospital dedicated to such technological advances. Although he is 72 years old, he still works tirelessly to obtain the resources to build a state-of-the-art surgical simulation center, now under construction. Basic minimally invasive surgical procedures are available in most hospitals, although advanced procedures are restricted to centers such as Dr. Ruiz Torres’ facility, Centro Nacional De Cirugia De Minimo Acceso, of which he is justifiably proud.

In the short time that we were in Cuba, we obviously could observe only a fraction of their entire system. We were unable to determine how representative the health care workers we met were; those we did meet, however, were committed, hard working, and idealistic. Their rewards are clearly not financial, as they are equally (and poorly) paid, earning the same $70/month, no matter what their “rank” in the system.

Whatever the political realities of life in Cuba may be outside of the medical setting, we connected with our fellow physicians and bonded over our shared passion for patient care. This trip was about meeting them and gaining some understanding of their professional challenges and their efforts to work with what they have. Their system has evolved in the unique cultural, political, and economic circumstances of Cuba, and so of course, such a system could never work here. And yet, it was refreshing and inspiring to see medical professionals dedicated to the ideals of our profession – serving the people by delivering the best care they could for all of their patients. My hat is off to them for accomplishing so much despite their limited resources.

Dr. Deveney is professor of surgery and vice chair of education in the department of surgery, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. She is the coeditor of ACS Surgery News.

Repeal and replace? How about retain, review, and refine?

A suggestion for Congress: keep what’s working in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA), adjust what isn’t working – just make the whole thing better and call it what you will.

A good thing, but needing work

The PPACA, which is also referred to as Obama care, had a lot in it that any reasonable person would consider good. Let’s take a look. As Dr Valerie Arkoosh wrote in our journal in 2012,2 the law attempted to expand access to health care to the embarrassingly large 30 million or more Americans who were not insured. How would it do this? By expanding Medicaid, enhancing consumer protections in the private health insurance market, requiring large employers to offer insurance or pay a fine, giving tax credits to increase affordability of insurance for small businesses, creating state-based competitive market places, and requiring individuals to purchase health insurance plans (the so-called insurance mandate), thereby creating a pool of large numbers of healthy people who would help defray the costs of those not so fortunate.The law also guaranteed insurability despite any preexisting condition, surely a step in the right direction. Likewise, the need for employers to provide health insurance, the state-based health insurance exchanges, and especially the individual mandate to buy insurance or pay a fine, were all steps in the right direction.

And the law went further – it also addressed preventive care. Medicare and all new insurance plans would have to cover, without copay, co-insurance, or deductible, high-certainty preventive services such as screening for breast, cervical, colorectal, lung, and skin cancers, the annual well-woman visit, breast cancer preventative medications, and many others.3 Medicare recipients would be eligible for one non-copay annual wellness visit to their caregiver. Beyond providing increased access to health care, the PPACA added incentives to caregivers who were coming out of training programs to serve in underserved areas and benefit from a decrease in their med school loans or in their loan repayments.

Finally, and especially important, under the PPACA, our age-old insurance system of fee for service, which tends to incentivize more care, would change to incentivizing high-quality, outcomes-based care , thus replacing “quantity of care” with quality of care. So what’s wrong with the features of the law outlined in the preceding paragraphs? Well, of course, for every 100 ideas, only a few will be implemented and actually pay off. Certainly some of the PPACA could have been better implemented, and perhaps the task now facing Congress, if it could ever abandon its current pitched-camp approach, should be to take the ideas that health care policy scientists have established as being valid and find a way to make them work. Surely that would be best for all players, rather than carping about the repeal-replace approach versus staying with the PPACA.

So my response to the repeal-replace assertion? Retain, review, and refine.

Practitioner-friendly content