User login

Effective treatment of recurrent bacterial vaginosis

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is caused by a complex change in vaginal bacterial flora, with a reduction in lactobacilli (which help maintain an acidic environment) and an increase in anaerobic gram-negative organisms including Gardnerella vaginalis species and Bacteroides, Prevotella, and Mobiluncus genera. Infection with G vaginalis is thought to trigger a cascade of changes in vaginal flora that leads to BV.1

BV is present in 30% to 50% of sexually active women, and of these women 50% to 75% have an abnormal vaginal discharge, which is gray, thin, and homogeneous and may have a fishy odor.2 In addition to causing an abnormal vaginal discharge, BV is a cause of postpartum fever, posthysterectomy vaginal cuff cellulitis, and postabortion infection, and it increases the risk of acquiring HIV, herpes simplex type 2, gonorrhea, chlamydia, and trichomoniasis infection.3

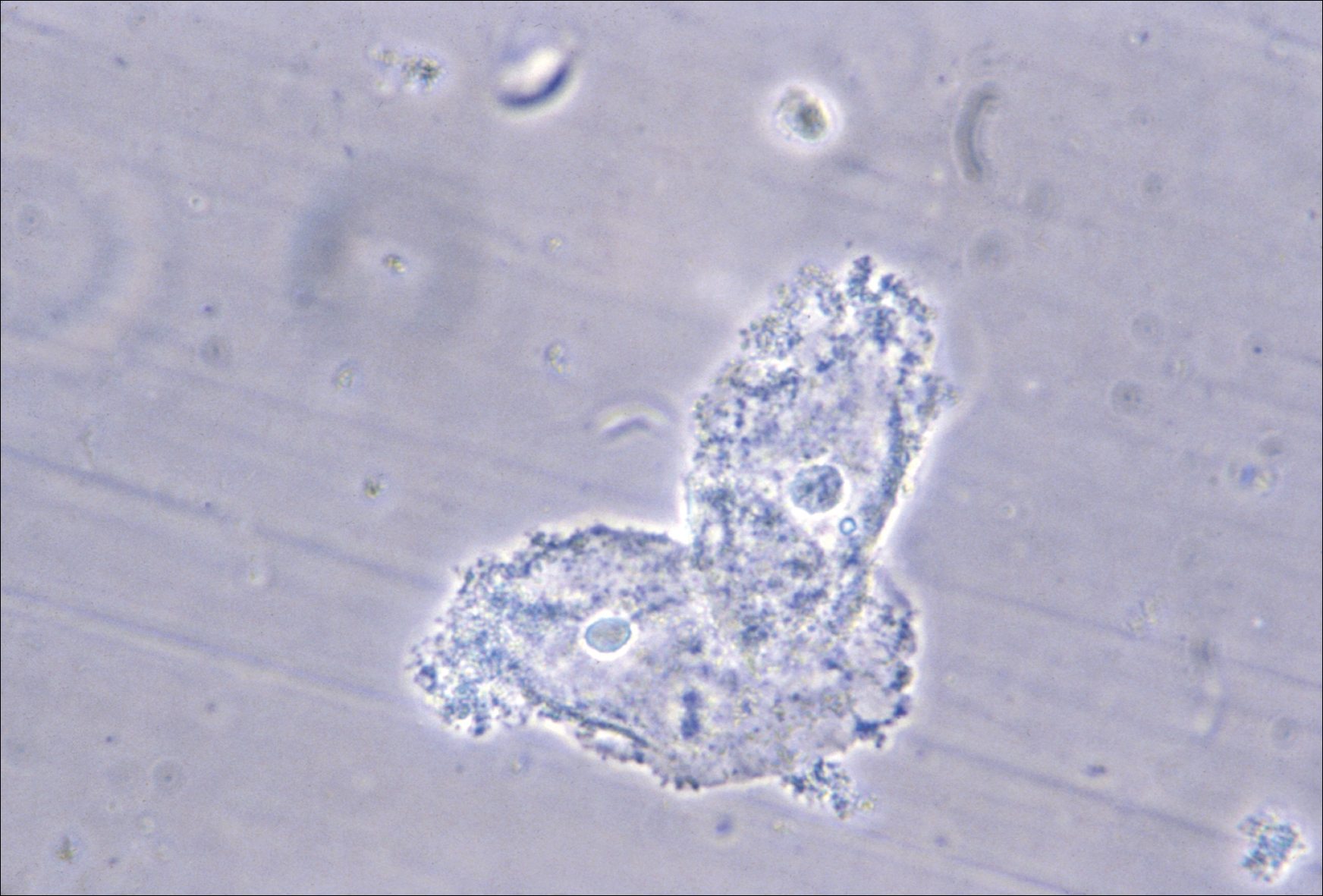

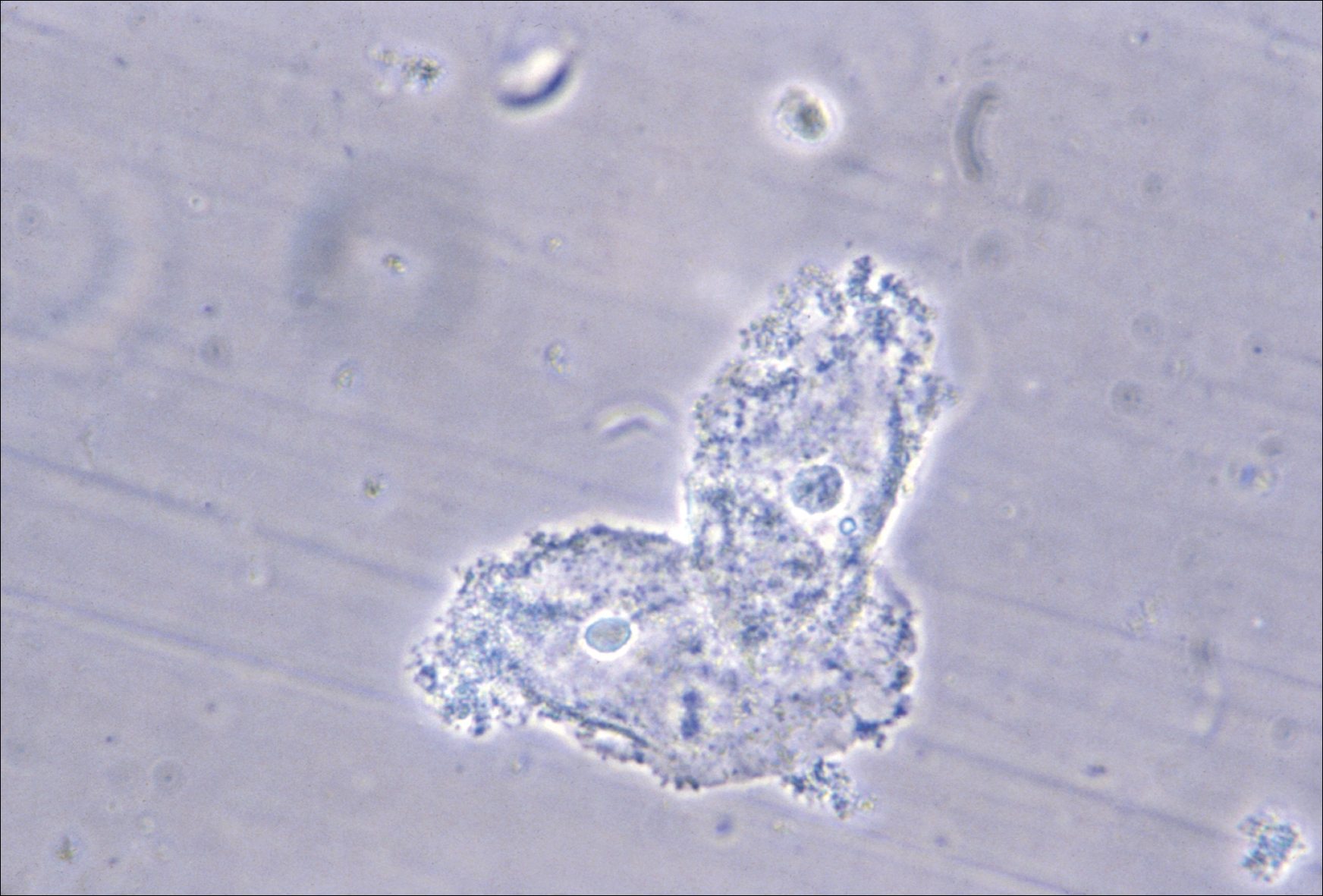

When using microscopy and the Amsel criteria, the diagnosis of BV is made when at least 3 of the following 4 criteria are present:

- homogeneous, thin, gray discharge

- vaginal pH >4.5

- positive whiff-amine test when applying a drop of 10% KOH to a sample of the vaginal discharge

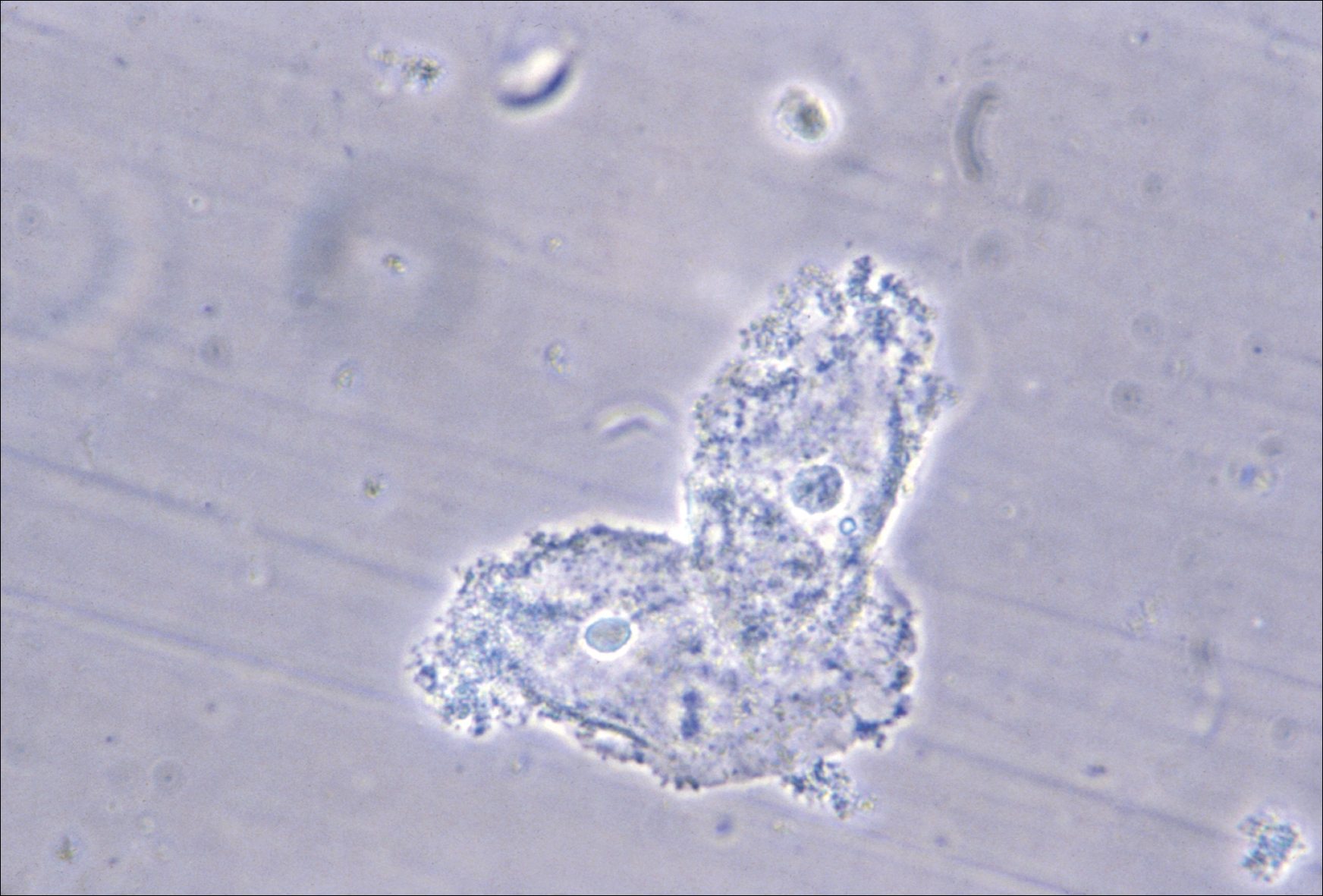

- clue cells detected with microscopy on a saline wet mount.

If microscopy is not available, the Affirm VPIII test (BD Diagnostic Systems, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey) for DNA sequences of G vaginalis has high sensitivity and specificity.4 The OSOM BVBlue test (Sekisui Diagnostics, Lexington, Massachusetts), a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments-waived point of service test, measures vaginal sialidase, which is produced by Gardnerella and other pathogens associated with BV.5 BV may be detected in routine cervical cytology testing and, if the patient is symptomatic, treatment is recommended.

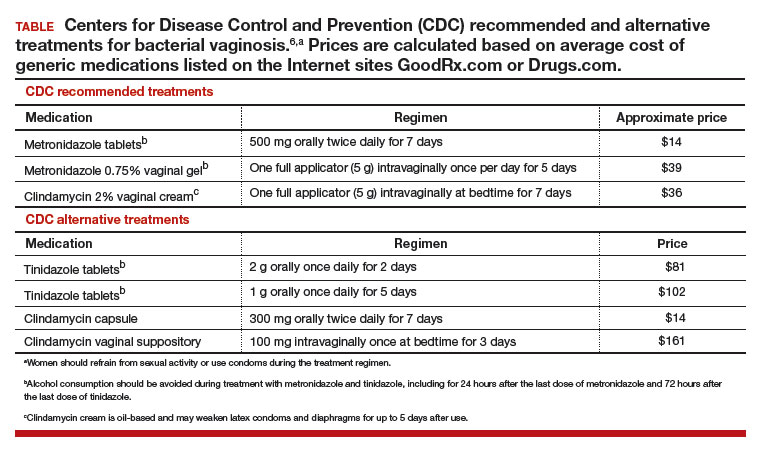

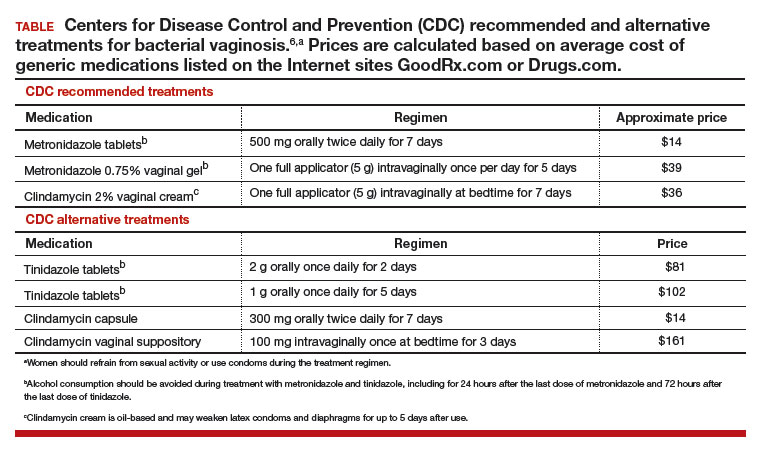

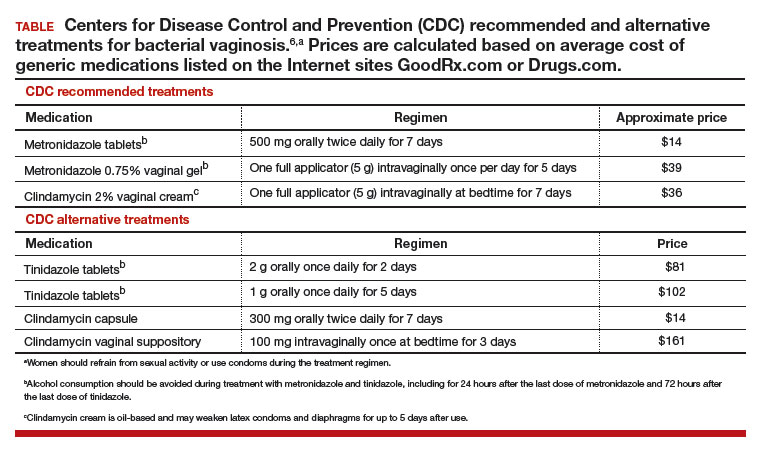

Initial treatment of BV. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has recommended 3 treatment regimens for BV and 4 alternative treatment options (TABLE).6 In addition to antimicrobial treatment, the CDC recommends that women with BV use condoms with sexual intercourse. The CDC also advises that clinicians should con-sider testing women with BV for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections.

Related article:

Successful treatment of chronic vaginitis

Treatment of recurrent BV

A major problem with BV is that, although initial treatment is successful in about 80% of cases, up to 50% of women will have a recurrence of BV within 12 months of initial treatment.2 Preliminary studies suggest that for women with 3 or more episodes of BV, the regimens below may be effective.

Regimen 1

Following the completion of a CDC-recommended treatment regimen (see TABLE), prescribe metronidazole vaginal gel 0.75%, one full applicator, twice weekly for 6 months.7

In a prospective randomized trial examining this regimen, following initial treatment with a 10-day metronidazole vaginal gel regimen 112 women were randomly assigned to chronic suppressive therapy with metronidazole vaginal gel 0.75%, one full applicator, twice weekly for 16 weeks or a placebo. During the treatment period, recurrent BV was diagnosed in 26% of the women taking metronidazole gel and 59% of the women taking placebo.7 This regimen may be complicated by secondary vaginal candidiasis, which may be treated with a vaginal or oral antifungal agent.

Regimen 2

Initiate a 21-day course of vaginal boric acid capsules 600 mg once daily at bedtime and simultaneously prescribe a standard CDC treatment regimen (see TABLE). At the completion of the vaginal boric acid treatment initiate metronidazole vaginal gel 0.75% twice weekly for 6 months.8

NOTE: Boric acid can cause death if consumed orally.9 Boric acid capsules should be stored securely to ensure that they are not accidentally taken orally. Boric acid poisoning may present with vomiting, fever, skin rash, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, metabolic acidosis, and renal failure.10 Boric acid should not be used by pregnant women because it is a teratogen.11

The bacterial organisms responsible for BV reside in a self-produced matrix, referred to as a biofilm, that protect the organisms from antimicrobial agents.12 Boric acid may prevent the formation of a biofilm and increase the effectiveness of anti-microbial treatment.

Regimen 3

Following the completion of a standard treatment regimen (see TABLE), prescribe oral metronidazole 2 g and fluconazole 150 mg administered once every month.13

In a randomized clinical trial, 310 female sex workers were randomly assigned to monthly treatment with oral metronidazole 2 g plus fluconazole 150 mg or placebo for up to 12 months.13 In the treatment and placebo groups episodes of BV were 199 and 326 per 100 person-years, respectively (hazard ratio, 0.55; 95% confidence interval, 0.49-0.63; P<.001). In Canada, a vaginal ovule containing both a high dose of metronidazole (500 mg) and nystatin (10,000 IU) is available and could be used intermittently to prevent recurrence.14

Treatment of partners

The CDC does not recommend treatment of the partners of women with BV because there are no definitive data to support such a recommendation. However, the 6 published clinical trials testing the utility of treating sex partners of women with BV have significant methodologic flaws, including underpowered studies and suboptimal antibiotic treatment regimens.15 Hence, whether partners should be treated remains an open question. Many experts believe that, in most cases, BV is a sexually transmitted disease.16,17 For women who have sex with women, the rate of BV concordance among partners is high. If one woman has diagnosed BV and symptoms are present in her partner, treatment of the partner is reasonable. For women with BV who have sex with men, sexual intercourse influences disease activity, and consistent use of condoms may reduce the rate of recurrence.18 Male circumcision may reduce the risk of BV in female partners.19

Related article:

Bacterial vaginosis: Meet patients' needs with effective diagnosis and treatment

Over-the-counter treatments

In women with BV it is thought that the vaginal administration of lactic acid can help restore the normal acidic pH of the vagina, encourage the growth of lactobacilli, and suppress the growth of the bacteria that cause BV.20 Many products containing lactic acid in a formulation for vaginal use are available (among them Luvena and Gynofit gel).

Lactobacilli play an important role in maintaining vaginal health. Lactobacillus rhamnosus and Lactobacillus reuteri are available for purchase as supplements for oral administration. It is thought that oral administration of lactobacilli can help improve the vaginal microbiome. In one clinical trial, 125 women with BV were randomly assigned to receive the combination of 1 week of metronidazole plus oral Lactobacillus twice daily for 30 days or metronidazole plus placebo.21 Resolution of symptoms was reported as 88% and 40% in the metronidazole-lactobacilli and metronidazole-placebo groups, respectively.21 By contrast, one systematic review of probiotic treatment of BV concluded that there is insufficient evidence to recommend for or against probiotic treatment of BV.22 Patients with recurrent BV commonly report that they believe a probiotic was helpful in resolving their symptoms.

On the horizon

In one trial, a single 2-g oral dose of secnidazole was as effective as a 7-day course of oral metronidazole 500 mg twice daily.23 In a small dose-finding study, a single dose of either secnidazole 1 g or 2 g was equally effective in treating BV.24 An effective single-dose treatment of BV would likely improve patient adherence with therapy. Symbiomix is preparing for FDA review of this medication (secnidazole, Solosec) for use in the United States.

BV is a prevalent problem and often adversely impacts a woman's quality of life and love relationships. BV recurrence is very common. Many women report that their BV was resistant to intermittet treatment and recurred, repetitively over many years. The 3 treatment options presented in this editorial may help to suppress the recurrence rate and improve symptoms.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Schwebke JR, Muzny CA, Josey WE. Role of Gardnerella vaginalis in the pathogenesis of bacterial vaginosis: a conceptual model. J Infect Dis. 2014;210(3):338-343.

- Bradshaw CS, Morton AN, Hocking J, et al. High recurrence rates of bacterial vaginosis over the course of 12 months after oral metronidazole therapy and factors associated with recurrence. J Infect Dis. 2006;193(11):1478-1486.

- Murphy K, Mitchell CM. The interplay of host immunity, environment and the risk of bacterial vaginosis and associated reproductive health outcomes. J Infect Dis. 2016;214(suppl 1):S29-S35.

- Mulhem E, Boyanton BL Jr, Robinson-Dunn B, Ebert C, Dzebo R. Performance of the Affirm VP-III using residual vaginal discharge collected from the speculum to characterize vaginitis in symptomatic women. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2014;18(4):344-346.

- Bradshaw CS, Morton AN, Garland SM, Horvath LB, Kuzevska I, Fairley CK. Evaluation of a point-of-care test, BVBLue, and clinical and laboratory criteria for diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(3):1304-1308.

- 2015 Sexually transmitted disease treatment guidelines: Bacterial vaginosis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/bv.htm. Updated June 4,2015. Accessed June 9, 2017.

- Sobel JD, Ferris D, Schwebke J, et al. Suppressive antibacterial therapy with 0.75% metronidazole vaginal gel to prevent recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(5):1283-1289.

- Reichman O, Akins R, Sobel JD. Boric acid addition to suppressive antimicrobial therapy for recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36(11):732-734.

- Wong LC, Heimbach MD, Truscott DR, Duncan BD. Boric acid poisoning: report of 11 cases. Can Med Assoc J. 1964;90:1018-1023.

- Teshima D, Morishita K, Ueda Y, et al. Clinical management of boric acid ingestion: pharmacokinetic assessment of efficacy of hemodialysis for treatment of acute boric acid poisoning. J Pharmacobiodyn. 1992;15(6):287-294.

- Di Renzo F, Cappelletti G, Broccia ML, Giavini E, Menegola E. Boric acid inhibits embryonic histone deacetylases: a suggested mechanism to explain boric acid-related teratogenicity. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2007;220(2):178-185.

- Muzny CA, Schwebke JR. Biofilms: an underappreciated mechanism of treatment failure and recurrence in vaginal infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(4):601-606.

- McClelland RS, Richardson BA, Hassan WM, et al. Improvement of vaginal health for Kenyan women at risk for acquisition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: results of a randomized trial. J Infect Dis. 2008;197(10):1361-1368.

- Sanchez S, Garcia PJ, Thomas KK, Catlin M, Holmes KK. Intravaginal metronidazole gel versus metronidazole plus nystatin ovules for bacterial vaginosis: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(6):1898-1906.

- Mehta SD. Systematic review of randomized trials of treatment of male sexual partners for improved bacteria vaginosis outcomes in women. Sex Transm Dis. 2012;39(10):822-830.

- Muzny CA, Schwebke JR. Pathogenesis of bacterial vaginosis: discussion of current hypotheses. J Infect Dis. 2016;214(suppl 1):S1-S5.

- Vodstrcil LA, Walker SM, Hocking JS, et al. Incident bacterial vaginosis (BV) in women who have sex with women is associated with behaviors that suggest sexual transmission of BV. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(7):1042-1053.

- Bradshaw CS, Vodstrcil LA, Hocking JS, et al. Recurrence of bacterial vaginosis is significantly associated with posttreatment sexual activities and hormonal contraceptive use. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(6):777-786.

- Gray RH, Kigozi G, Serwadda D, et al. The effects of male circumcision on female partners' genital tract symptoms and vaginal infections in a randomized trial in Rakai, Uganda. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200(1):42.e1-e7.

- O'Hanlon DE, Moench TR, Cone RA. In vaginal fluid, bacteria associated with bacterial vaginosis can be suppressed with lactic acid but not hydrogen peroxide. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:200.

- Anukam K, Osazuwa E, Ahonkhai I, et al. Augmentation of antimicrobial metronidazole therapy of bacterial vaginosis with oral probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1 and Lactobacillus reuteri RC-14: randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. Microbes Infect. 2006;8(6):1450-1454.

- Senok AC, Verstraelen H, Temmerman M, Botta GA. Probiotics for the treatment of bacterial vaginosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(4):CD006289.

- Bohbot JM, Vicaut E, Fagnen D, Brauman M. Treatment of bacterial vaginosis: a multicenter, double-blind, double-dummy, randomised phase III study comparing secnidazole and metronidazole. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2010;2010. doi:10.1155/2010/705692.

- Núñez JT, Gómez G. Low-dose secnidazole in the treatment of bacterial vaginosis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005;88(3):281-285.

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is caused by a complex change in vaginal bacterial flora, with a reduction in lactobacilli (which help maintain an acidic environment) and an increase in anaerobic gram-negative organisms including Gardnerella vaginalis species and Bacteroides, Prevotella, and Mobiluncus genera. Infection with G vaginalis is thought to trigger a cascade of changes in vaginal flora that leads to BV.1

BV is present in 30% to 50% of sexually active women, and of these women 50% to 75% have an abnormal vaginal discharge, which is gray, thin, and homogeneous and may have a fishy odor.2 In addition to causing an abnormal vaginal discharge, BV is a cause of postpartum fever, posthysterectomy vaginal cuff cellulitis, and postabortion infection, and it increases the risk of acquiring HIV, herpes simplex type 2, gonorrhea, chlamydia, and trichomoniasis infection.3

When using microscopy and the Amsel criteria, the diagnosis of BV is made when at least 3 of the following 4 criteria are present:

- homogeneous, thin, gray discharge

- vaginal pH >4.5

- positive whiff-amine test when applying a drop of 10% KOH to a sample of the vaginal discharge

- clue cells detected with microscopy on a saline wet mount.

If microscopy is not available, the Affirm VPIII test (BD Diagnostic Systems, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey) for DNA sequences of G vaginalis has high sensitivity and specificity.4 The OSOM BVBlue test (Sekisui Diagnostics, Lexington, Massachusetts), a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments-waived point of service test, measures vaginal sialidase, which is produced by Gardnerella and other pathogens associated with BV.5 BV may be detected in routine cervical cytology testing and, if the patient is symptomatic, treatment is recommended.

Initial treatment of BV. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has recommended 3 treatment regimens for BV and 4 alternative treatment options (TABLE).6 In addition to antimicrobial treatment, the CDC recommends that women with BV use condoms with sexual intercourse. The CDC also advises that clinicians should con-sider testing women with BV for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections.

Related article:

Successful treatment of chronic vaginitis

Treatment of recurrent BV

A major problem with BV is that, although initial treatment is successful in about 80% of cases, up to 50% of women will have a recurrence of BV within 12 months of initial treatment.2 Preliminary studies suggest that for women with 3 or more episodes of BV, the regimens below may be effective.

Regimen 1

Following the completion of a CDC-recommended treatment regimen (see TABLE), prescribe metronidazole vaginal gel 0.75%, one full applicator, twice weekly for 6 months.7

In a prospective randomized trial examining this regimen, following initial treatment with a 10-day metronidazole vaginal gel regimen 112 women were randomly assigned to chronic suppressive therapy with metronidazole vaginal gel 0.75%, one full applicator, twice weekly for 16 weeks or a placebo. During the treatment period, recurrent BV was diagnosed in 26% of the women taking metronidazole gel and 59% of the women taking placebo.7 This regimen may be complicated by secondary vaginal candidiasis, which may be treated with a vaginal or oral antifungal agent.

Regimen 2

Initiate a 21-day course of vaginal boric acid capsules 600 mg once daily at bedtime and simultaneously prescribe a standard CDC treatment regimen (see TABLE). At the completion of the vaginal boric acid treatment initiate metronidazole vaginal gel 0.75% twice weekly for 6 months.8

NOTE: Boric acid can cause death if consumed orally.9 Boric acid capsules should be stored securely to ensure that they are not accidentally taken orally. Boric acid poisoning may present with vomiting, fever, skin rash, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, metabolic acidosis, and renal failure.10 Boric acid should not be used by pregnant women because it is a teratogen.11

The bacterial organisms responsible for BV reside in a self-produced matrix, referred to as a biofilm, that protect the organisms from antimicrobial agents.12 Boric acid may prevent the formation of a biofilm and increase the effectiveness of anti-microbial treatment.

Regimen 3

Following the completion of a standard treatment regimen (see TABLE), prescribe oral metronidazole 2 g and fluconazole 150 mg administered once every month.13

In a randomized clinical trial, 310 female sex workers were randomly assigned to monthly treatment with oral metronidazole 2 g plus fluconazole 150 mg or placebo for up to 12 months.13 In the treatment and placebo groups episodes of BV were 199 and 326 per 100 person-years, respectively (hazard ratio, 0.55; 95% confidence interval, 0.49-0.63; P<.001). In Canada, a vaginal ovule containing both a high dose of metronidazole (500 mg) and nystatin (10,000 IU) is available and could be used intermittently to prevent recurrence.14

Treatment of partners

The CDC does not recommend treatment of the partners of women with BV because there are no definitive data to support such a recommendation. However, the 6 published clinical trials testing the utility of treating sex partners of women with BV have significant methodologic flaws, including underpowered studies and suboptimal antibiotic treatment regimens.15 Hence, whether partners should be treated remains an open question. Many experts believe that, in most cases, BV is a sexually transmitted disease.16,17 For women who have sex with women, the rate of BV concordance among partners is high. If one woman has diagnosed BV and symptoms are present in her partner, treatment of the partner is reasonable. For women with BV who have sex with men, sexual intercourse influences disease activity, and consistent use of condoms may reduce the rate of recurrence.18 Male circumcision may reduce the risk of BV in female partners.19

Related article:

Bacterial vaginosis: Meet patients' needs with effective diagnosis and treatment

Over-the-counter treatments

In women with BV it is thought that the vaginal administration of lactic acid can help restore the normal acidic pH of the vagina, encourage the growth of lactobacilli, and suppress the growth of the bacteria that cause BV.20 Many products containing lactic acid in a formulation for vaginal use are available (among them Luvena and Gynofit gel).

Lactobacilli play an important role in maintaining vaginal health. Lactobacillus rhamnosus and Lactobacillus reuteri are available for purchase as supplements for oral administration. It is thought that oral administration of lactobacilli can help improve the vaginal microbiome. In one clinical trial, 125 women with BV were randomly assigned to receive the combination of 1 week of metronidazole plus oral Lactobacillus twice daily for 30 days or metronidazole plus placebo.21 Resolution of symptoms was reported as 88% and 40% in the metronidazole-lactobacilli and metronidazole-placebo groups, respectively.21 By contrast, one systematic review of probiotic treatment of BV concluded that there is insufficient evidence to recommend for or against probiotic treatment of BV.22 Patients with recurrent BV commonly report that they believe a probiotic was helpful in resolving their symptoms.

On the horizon

In one trial, a single 2-g oral dose of secnidazole was as effective as a 7-day course of oral metronidazole 500 mg twice daily.23 In a small dose-finding study, a single dose of either secnidazole 1 g or 2 g was equally effective in treating BV.24 An effective single-dose treatment of BV would likely improve patient adherence with therapy. Symbiomix is preparing for FDA review of this medication (secnidazole, Solosec) for use in the United States.

BV is a prevalent problem and often adversely impacts a woman's quality of life and love relationships. BV recurrence is very common. Many women report that their BV was resistant to intermittet treatment and recurred, repetitively over many years. The 3 treatment options presented in this editorial may help to suppress the recurrence rate and improve symptoms.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is caused by a complex change in vaginal bacterial flora, with a reduction in lactobacilli (which help maintain an acidic environment) and an increase in anaerobic gram-negative organisms including Gardnerella vaginalis species and Bacteroides, Prevotella, and Mobiluncus genera. Infection with G vaginalis is thought to trigger a cascade of changes in vaginal flora that leads to BV.1

BV is present in 30% to 50% of sexually active women, and of these women 50% to 75% have an abnormal vaginal discharge, which is gray, thin, and homogeneous and may have a fishy odor.2 In addition to causing an abnormal vaginal discharge, BV is a cause of postpartum fever, posthysterectomy vaginal cuff cellulitis, and postabortion infection, and it increases the risk of acquiring HIV, herpes simplex type 2, gonorrhea, chlamydia, and trichomoniasis infection.3

When using microscopy and the Amsel criteria, the diagnosis of BV is made when at least 3 of the following 4 criteria are present:

- homogeneous, thin, gray discharge

- vaginal pH >4.5

- positive whiff-amine test when applying a drop of 10% KOH to a sample of the vaginal discharge

- clue cells detected with microscopy on a saline wet mount.

If microscopy is not available, the Affirm VPIII test (BD Diagnostic Systems, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey) for DNA sequences of G vaginalis has high sensitivity and specificity.4 The OSOM BVBlue test (Sekisui Diagnostics, Lexington, Massachusetts), a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments-waived point of service test, measures vaginal sialidase, which is produced by Gardnerella and other pathogens associated with BV.5 BV may be detected in routine cervical cytology testing and, if the patient is symptomatic, treatment is recommended.

Initial treatment of BV. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has recommended 3 treatment regimens for BV and 4 alternative treatment options (TABLE).6 In addition to antimicrobial treatment, the CDC recommends that women with BV use condoms with sexual intercourse. The CDC also advises that clinicians should con-sider testing women with BV for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections.

Related article:

Successful treatment of chronic vaginitis

Treatment of recurrent BV

A major problem with BV is that, although initial treatment is successful in about 80% of cases, up to 50% of women will have a recurrence of BV within 12 months of initial treatment.2 Preliminary studies suggest that for women with 3 or more episodes of BV, the regimens below may be effective.

Regimen 1

Following the completion of a CDC-recommended treatment regimen (see TABLE), prescribe metronidazole vaginal gel 0.75%, one full applicator, twice weekly for 6 months.7

In a prospective randomized trial examining this regimen, following initial treatment with a 10-day metronidazole vaginal gel regimen 112 women were randomly assigned to chronic suppressive therapy with metronidazole vaginal gel 0.75%, one full applicator, twice weekly for 16 weeks or a placebo. During the treatment period, recurrent BV was diagnosed in 26% of the women taking metronidazole gel and 59% of the women taking placebo.7 This regimen may be complicated by secondary vaginal candidiasis, which may be treated with a vaginal or oral antifungal agent.

Regimen 2

Initiate a 21-day course of vaginal boric acid capsules 600 mg once daily at bedtime and simultaneously prescribe a standard CDC treatment regimen (see TABLE). At the completion of the vaginal boric acid treatment initiate metronidazole vaginal gel 0.75% twice weekly for 6 months.8

NOTE: Boric acid can cause death if consumed orally.9 Boric acid capsules should be stored securely to ensure that they are not accidentally taken orally. Boric acid poisoning may present with vomiting, fever, skin rash, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, metabolic acidosis, and renal failure.10 Boric acid should not be used by pregnant women because it is a teratogen.11

The bacterial organisms responsible for BV reside in a self-produced matrix, referred to as a biofilm, that protect the organisms from antimicrobial agents.12 Boric acid may prevent the formation of a biofilm and increase the effectiveness of anti-microbial treatment.

Regimen 3

Following the completion of a standard treatment regimen (see TABLE), prescribe oral metronidazole 2 g and fluconazole 150 mg administered once every month.13

In a randomized clinical trial, 310 female sex workers were randomly assigned to monthly treatment with oral metronidazole 2 g plus fluconazole 150 mg or placebo for up to 12 months.13 In the treatment and placebo groups episodes of BV were 199 and 326 per 100 person-years, respectively (hazard ratio, 0.55; 95% confidence interval, 0.49-0.63; P<.001). In Canada, a vaginal ovule containing both a high dose of metronidazole (500 mg) and nystatin (10,000 IU) is available and could be used intermittently to prevent recurrence.14

Treatment of partners

The CDC does not recommend treatment of the partners of women with BV because there are no definitive data to support such a recommendation. However, the 6 published clinical trials testing the utility of treating sex partners of women with BV have significant methodologic flaws, including underpowered studies and suboptimal antibiotic treatment regimens.15 Hence, whether partners should be treated remains an open question. Many experts believe that, in most cases, BV is a sexually transmitted disease.16,17 For women who have sex with women, the rate of BV concordance among partners is high. If one woman has diagnosed BV and symptoms are present in her partner, treatment of the partner is reasonable. For women with BV who have sex with men, sexual intercourse influences disease activity, and consistent use of condoms may reduce the rate of recurrence.18 Male circumcision may reduce the risk of BV in female partners.19

Related article:

Bacterial vaginosis: Meet patients' needs with effective diagnosis and treatment

Over-the-counter treatments

In women with BV it is thought that the vaginal administration of lactic acid can help restore the normal acidic pH of the vagina, encourage the growth of lactobacilli, and suppress the growth of the bacteria that cause BV.20 Many products containing lactic acid in a formulation for vaginal use are available (among them Luvena and Gynofit gel).

Lactobacilli play an important role in maintaining vaginal health. Lactobacillus rhamnosus and Lactobacillus reuteri are available for purchase as supplements for oral administration. It is thought that oral administration of lactobacilli can help improve the vaginal microbiome. In one clinical trial, 125 women with BV were randomly assigned to receive the combination of 1 week of metronidazole plus oral Lactobacillus twice daily for 30 days or metronidazole plus placebo.21 Resolution of symptoms was reported as 88% and 40% in the metronidazole-lactobacilli and metronidazole-placebo groups, respectively.21 By contrast, one systematic review of probiotic treatment of BV concluded that there is insufficient evidence to recommend for or against probiotic treatment of BV.22 Patients with recurrent BV commonly report that they believe a probiotic was helpful in resolving their symptoms.

On the horizon

In one trial, a single 2-g oral dose of secnidazole was as effective as a 7-day course of oral metronidazole 500 mg twice daily.23 In a small dose-finding study, a single dose of either secnidazole 1 g or 2 g was equally effective in treating BV.24 An effective single-dose treatment of BV would likely improve patient adherence with therapy. Symbiomix is preparing for FDA review of this medication (secnidazole, Solosec) for use in the United States.

BV is a prevalent problem and often adversely impacts a woman's quality of life and love relationships. BV recurrence is very common. Many women report that their BV was resistant to intermittet treatment and recurred, repetitively over many years. The 3 treatment options presented in this editorial may help to suppress the recurrence rate and improve symptoms.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Schwebke JR, Muzny CA, Josey WE. Role of Gardnerella vaginalis in the pathogenesis of bacterial vaginosis: a conceptual model. J Infect Dis. 2014;210(3):338-343.

- Bradshaw CS, Morton AN, Hocking J, et al. High recurrence rates of bacterial vaginosis over the course of 12 months after oral metronidazole therapy and factors associated with recurrence. J Infect Dis. 2006;193(11):1478-1486.

- Murphy K, Mitchell CM. The interplay of host immunity, environment and the risk of bacterial vaginosis and associated reproductive health outcomes. J Infect Dis. 2016;214(suppl 1):S29-S35.

- Mulhem E, Boyanton BL Jr, Robinson-Dunn B, Ebert C, Dzebo R. Performance of the Affirm VP-III using residual vaginal discharge collected from the speculum to characterize vaginitis in symptomatic women. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2014;18(4):344-346.

- Bradshaw CS, Morton AN, Garland SM, Horvath LB, Kuzevska I, Fairley CK. Evaluation of a point-of-care test, BVBLue, and clinical and laboratory criteria for diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(3):1304-1308.

- 2015 Sexually transmitted disease treatment guidelines: Bacterial vaginosis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/bv.htm. Updated June 4,2015. Accessed June 9, 2017.

- Sobel JD, Ferris D, Schwebke J, et al. Suppressive antibacterial therapy with 0.75% metronidazole vaginal gel to prevent recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(5):1283-1289.

- Reichman O, Akins R, Sobel JD. Boric acid addition to suppressive antimicrobial therapy for recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36(11):732-734.

- Wong LC, Heimbach MD, Truscott DR, Duncan BD. Boric acid poisoning: report of 11 cases. Can Med Assoc J. 1964;90:1018-1023.

- Teshima D, Morishita K, Ueda Y, et al. Clinical management of boric acid ingestion: pharmacokinetic assessment of efficacy of hemodialysis for treatment of acute boric acid poisoning. J Pharmacobiodyn. 1992;15(6):287-294.

- Di Renzo F, Cappelletti G, Broccia ML, Giavini E, Menegola E. Boric acid inhibits embryonic histone deacetylases: a suggested mechanism to explain boric acid-related teratogenicity. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2007;220(2):178-185.

- Muzny CA, Schwebke JR. Biofilms: an underappreciated mechanism of treatment failure and recurrence in vaginal infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(4):601-606.

- McClelland RS, Richardson BA, Hassan WM, et al. Improvement of vaginal health for Kenyan women at risk for acquisition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: results of a randomized trial. J Infect Dis. 2008;197(10):1361-1368.

- Sanchez S, Garcia PJ, Thomas KK, Catlin M, Holmes KK. Intravaginal metronidazole gel versus metronidazole plus nystatin ovules for bacterial vaginosis: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(6):1898-1906.

- Mehta SD. Systematic review of randomized trials of treatment of male sexual partners for improved bacteria vaginosis outcomes in women. Sex Transm Dis. 2012;39(10):822-830.

- Muzny CA, Schwebke JR. Pathogenesis of bacterial vaginosis: discussion of current hypotheses. J Infect Dis. 2016;214(suppl 1):S1-S5.

- Vodstrcil LA, Walker SM, Hocking JS, et al. Incident bacterial vaginosis (BV) in women who have sex with women is associated with behaviors that suggest sexual transmission of BV. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(7):1042-1053.

- Bradshaw CS, Vodstrcil LA, Hocking JS, et al. Recurrence of bacterial vaginosis is significantly associated with posttreatment sexual activities and hormonal contraceptive use. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(6):777-786.

- Gray RH, Kigozi G, Serwadda D, et al. The effects of male circumcision on female partners' genital tract symptoms and vaginal infections in a randomized trial in Rakai, Uganda. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200(1):42.e1-e7.

- O'Hanlon DE, Moench TR, Cone RA. In vaginal fluid, bacteria associated with bacterial vaginosis can be suppressed with lactic acid but not hydrogen peroxide. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:200.

- Anukam K, Osazuwa E, Ahonkhai I, et al. Augmentation of antimicrobial metronidazole therapy of bacterial vaginosis with oral probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1 and Lactobacillus reuteri RC-14: randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. Microbes Infect. 2006;8(6):1450-1454.

- Senok AC, Verstraelen H, Temmerman M, Botta GA. Probiotics for the treatment of bacterial vaginosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(4):CD006289.

- Bohbot JM, Vicaut E, Fagnen D, Brauman M. Treatment of bacterial vaginosis: a multicenter, double-blind, double-dummy, randomised phase III study comparing secnidazole and metronidazole. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2010;2010. doi:10.1155/2010/705692.

- Núñez JT, Gómez G. Low-dose secnidazole in the treatment of bacterial vaginosis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005;88(3):281-285.

- Schwebke JR, Muzny CA, Josey WE. Role of Gardnerella vaginalis in the pathogenesis of bacterial vaginosis: a conceptual model. J Infect Dis. 2014;210(3):338-343.

- Bradshaw CS, Morton AN, Hocking J, et al. High recurrence rates of bacterial vaginosis over the course of 12 months after oral metronidazole therapy and factors associated with recurrence. J Infect Dis. 2006;193(11):1478-1486.

- Murphy K, Mitchell CM. The interplay of host immunity, environment and the risk of bacterial vaginosis and associated reproductive health outcomes. J Infect Dis. 2016;214(suppl 1):S29-S35.

- Mulhem E, Boyanton BL Jr, Robinson-Dunn B, Ebert C, Dzebo R. Performance of the Affirm VP-III using residual vaginal discharge collected from the speculum to characterize vaginitis in symptomatic women. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2014;18(4):344-346.

- Bradshaw CS, Morton AN, Garland SM, Horvath LB, Kuzevska I, Fairley CK. Evaluation of a point-of-care test, BVBLue, and clinical and laboratory criteria for diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(3):1304-1308.

- 2015 Sexually transmitted disease treatment guidelines: Bacterial vaginosis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/bv.htm. Updated June 4,2015. Accessed June 9, 2017.

- Sobel JD, Ferris D, Schwebke J, et al. Suppressive antibacterial therapy with 0.75% metronidazole vaginal gel to prevent recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(5):1283-1289.

- Reichman O, Akins R, Sobel JD. Boric acid addition to suppressive antimicrobial therapy for recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36(11):732-734.

- Wong LC, Heimbach MD, Truscott DR, Duncan BD. Boric acid poisoning: report of 11 cases. Can Med Assoc J. 1964;90:1018-1023.

- Teshima D, Morishita K, Ueda Y, et al. Clinical management of boric acid ingestion: pharmacokinetic assessment of efficacy of hemodialysis for treatment of acute boric acid poisoning. J Pharmacobiodyn. 1992;15(6):287-294.

- Di Renzo F, Cappelletti G, Broccia ML, Giavini E, Menegola E. Boric acid inhibits embryonic histone deacetylases: a suggested mechanism to explain boric acid-related teratogenicity. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2007;220(2):178-185.

- Muzny CA, Schwebke JR. Biofilms: an underappreciated mechanism of treatment failure and recurrence in vaginal infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(4):601-606.

- McClelland RS, Richardson BA, Hassan WM, et al. Improvement of vaginal health for Kenyan women at risk for acquisition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: results of a randomized trial. J Infect Dis. 2008;197(10):1361-1368.

- Sanchez S, Garcia PJ, Thomas KK, Catlin M, Holmes KK. Intravaginal metronidazole gel versus metronidazole plus nystatin ovules for bacterial vaginosis: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(6):1898-1906.

- Mehta SD. Systematic review of randomized trials of treatment of male sexual partners for improved bacteria vaginosis outcomes in women. Sex Transm Dis. 2012;39(10):822-830.

- Muzny CA, Schwebke JR. Pathogenesis of bacterial vaginosis: discussion of current hypotheses. J Infect Dis. 2016;214(suppl 1):S1-S5.

- Vodstrcil LA, Walker SM, Hocking JS, et al. Incident bacterial vaginosis (BV) in women who have sex with women is associated with behaviors that suggest sexual transmission of BV. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(7):1042-1053.

- Bradshaw CS, Vodstrcil LA, Hocking JS, et al. Recurrence of bacterial vaginosis is significantly associated with posttreatment sexual activities and hormonal contraceptive use. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(6):777-786.

- Gray RH, Kigozi G, Serwadda D, et al. The effects of male circumcision on female partners' genital tract symptoms and vaginal infections in a randomized trial in Rakai, Uganda. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200(1):42.e1-e7.

- O'Hanlon DE, Moench TR, Cone RA. In vaginal fluid, bacteria associated with bacterial vaginosis can be suppressed with lactic acid but not hydrogen peroxide. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:200.

- Anukam K, Osazuwa E, Ahonkhai I, et al. Augmentation of antimicrobial metronidazole therapy of bacterial vaginosis with oral probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1 and Lactobacillus reuteri RC-14: randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. Microbes Infect. 2006;8(6):1450-1454.

- Senok AC, Verstraelen H, Temmerman M, Botta GA. Probiotics for the treatment of bacterial vaginosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(4):CD006289.

- Bohbot JM, Vicaut E, Fagnen D, Brauman M. Treatment of bacterial vaginosis: a multicenter, double-blind, double-dummy, randomised phase III study comparing secnidazole and metronidazole. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2010;2010. doi:10.1155/2010/705692.

- Núñez JT, Gómez G. Low-dose secnidazole in the treatment of bacterial vaginosis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005;88(3):281-285.

Appropriate diagnosis of tickborne infections

As summer is upon us, we enter the peak of tick season. Most reported cases of tickborne disease occur from April to October, and in this issue, Eickhoff and Blaylock offer a timely review of less common (non-Lyme disease) but significant tickborne infections.

In areas endemic for infection with Rickettsia rickettsii, the organism responsible for Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF), physicians and many patients are keenly aware of the signs and symptoms of the disease and are quick to offer and accept empiric antibiotic (doxycycline) therapy. Empiric therapy at the first suspicion of RMSF is appropriate, as untreated infection carries a 20% death rate. Vigilance for early Lyme disease (caused by Borrelia burgdorferi) is also high in true endemic areas, likely because of public awareness and concern for various documented—and some touted but unproven—associated morbidities.

Other tickborne infections are likely underrecognized by physicians who are not experts in infectious disease, and thus are not treated early. There are many reasons for this, including the relative infrequency of severe disease, the nonspecific clinical signs of early infection, and the spreading of infections to geographic areas where they are traditionally not considered endemic.

Additional features likely contribute to delayed diagnosis. Surveys of patients with documented RMSF or Lyme disease show that a large proportion of infections occur in patients who have no history of camping or hiking. Most people are not even aware that they have been harboring a feeding tick, as many ticks are quite small and attachment is painless. Because some ticks survive more than a year, they may stay alive in clothes and closets throughout the winter months and occasionally cause nonseasonal infections.

Geography and entomology matter; the matching of a specific tick vector to a specific disease is tight. With the slow migration of some tick species along with their nonhuman animal hosts into new territories due to temperature changes and urbanization, some diseases are appearing in areas of the country where they had not been previously diagnosed. We must be aware of these changes, and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) offers useful updated infection maps on their website.

The diagnosis of acute infection is often delayed because of late consideration of the possibility of the disease. In addition, some tests are serologic and require the passage of time before a diagnostic result is obtained. But an increasing and distinct problem is the overdiagnosis and long-term treatment of some patients whose infection is undocumented, perpetuating concern over the unproven entity of chronic infection, the most prevalent being the diagnosis and treatment of “chronic Lyme disease.” Close attention must be paid to the manner of diagnosis and the specific tests used to purportedly confirm the diagnosis of infection. This has been an ongoing challenge in managing patients with chronic fatigue and malaise, a vexing and significant clinical problem without a ready solution in patients who have undergone an extensive evaluation. It is obviously tempting for patients to grasp at any “diagnostic” answer. But chronic and repeated therapy for nonexistent infection is not benign. The CDC has published lists of tests for Lyme disease in particular that are considered to have inadequately established accuracy and clinical utility; these include lymphocyte transformation tests, quantitative CD57 lymphocyte assays, and urinary antigen “capture assays.”

Recognizing and treating acute tickborne infections is crucial, as in distinguishing them from their mimics, which include some systemic autoimmune diseases. But we should not allow the fear of undertreatment of early infection to morph into unwarranted overtreatment of nonexistent chronic infection, just as we should not prematurely assume that ongoing symptoms of fatigue and malaise after a presumed tickborne infection are from the psychologically crippling fear of ongoing morbidity. Periodic reappraisal of the patient and his or her symptoms is warranted.

As summer is upon us, we enter the peak of tick season. Most reported cases of tickborne disease occur from April to October, and in this issue, Eickhoff and Blaylock offer a timely review of less common (non-Lyme disease) but significant tickborne infections.

In areas endemic for infection with Rickettsia rickettsii, the organism responsible for Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF), physicians and many patients are keenly aware of the signs and symptoms of the disease and are quick to offer and accept empiric antibiotic (doxycycline) therapy. Empiric therapy at the first suspicion of RMSF is appropriate, as untreated infection carries a 20% death rate. Vigilance for early Lyme disease (caused by Borrelia burgdorferi) is also high in true endemic areas, likely because of public awareness and concern for various documented—and some touted but unproven—associated morbidities.

Other tickborne infections are likely underrecognized by physicians who are not experts in infectious disease, and thus are not treated early. There are many reasons for this, including the relative infrequency of severe disease, the nonspecific clinical signs of early infection, and the spreading of infections to geographic areas where they are traditionally not considered endemic.

Additional features likely contribute to delayed diagnosis. Surveys of patients with documented RMSF or Lyme disease show that a large proportion of infections occur in patients who have no history of camping or hiking. Most people are not even aware that they have been harboring a feeding tick, as many ticks are quite small and attachment is painless. Because some ticks survive more than a year, they may stay alive in clothes and closets throughout the winter months and occasionally cause nonseasonal infections.

Geography and entomology matter; the matching of a specific tick vector to a specific disease is tight. With the slow migration of some tick species along with their nonhuman animal hosts into new territories due to temperature changes and urbanization, some diseases are appearing in areas of the country where they had not been previously diagnosed. We must be aware of these changes, and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) offers useful updated infection maps on their website.

The diagnosis of acute infection is often delayed because of late consideration of the possibility of the disease. In addition, some tests are serologic and require the passage of time before a diagnostic result is obtained. But an increasing and distinct problem is the overdiagnosis and long-term treatment of some patients whose infection is undocumented, perpetuating concern over the unproven entity of chronic infection, the most prevalent being the diagnosis and treatment of “chronic Lyme disease.” Close attention must be paid to the manner of diagnosis and the specific tests used to purportedly confirm the diagnosis of infection. This has been an ongoing challenge in managing patients with chronic fatigue and malaise, a vexing and significant clinical problem without a ready solution in patients who have undergone an extensive evaluation. It is obviously tempting for patients to grasp at any “diagnostic” answer. But chronic and repeated therapy for nonexistent infection is not benign. The CDC has published lists of tests for Lyme disease in particular that are considered to have inadequately established accuracy and clinical utility; these include lymphocyte transformation tests, quantitative CD57 lymphocyte assays, and urinary antigen “capture assays.”

Recognizing and treating acute tickborne infections is crucial, as in distinguishing them from their mimics, which include some systemic autoimmune diseases. But we should not allow the fear of undertreatment of early infection to morph into unwarranted overtreatment of nonexistent chronic infection, just as we should not prematurely assume that ongoing symptoms of fatigue and malaise after a presumed tickborne infection are from the psychologically crippling fear of ongoing morbidity. Periodic reappraisal of the patient and his or her symptoms is warranted.

As summer is upon us, we enter the peak of tick season. Most reported cases of tickborne disease occur from April to October, and in this issue, Eickhoff and Blaylock offer a timely review of less common (non-Lyme disease) but significant tickborne infections.

In areas endemic for infection with Rickettsia rickettsii, the organism responsible for Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF), physicians and many patients are keenly aware of the signs and symptoms of the disease and are quick to offer and accept empiric antibiotic (doxycycline) therapy. Empiric therapy at the first suspicion of RMSF is appropriate, as untreated infection carries a 20% death rate. Vigilance for early Lyme disease (caused by Borrelia burgdorferi) is also high in true endemic areas, likely because of public awareness and concern for various documented—and some touted but unproven—associated morbidities.

Other tickborne infections are likely underrecognized by physicians who are not experts in infectious disease, and thus are not treated early. There are many reasons for this, including the relative infrequency of severe disease, the nonspecific clinical signs of early infection, and the spreading of infections to geographic areas where they are traditionally not considered endemic.

Additional features likely contribute to delayed diagnosis. Surveys of patients with documented RMSF or Lyme disease show that a large proportion of infections occur in patients who have no history of camping or hiking. Most people are not even aware that they have been harboring a feeding tick, as many ticks are quite small and attachment is painless. Because some ticks survive more than a year, they may stay alive in clothes and closets throughout the winter months and occasionally cause nonseasonal infections.

Geography and entomology matter; the matching of a specific tick vector to a specific disease is tight. With the slow migration of some tick species along with their nonhuman animal hosts into new territories due to temperature changes and urbanization, some diseases are appearing in areas of the country where they had not been previously diagnosed. We must be aware of these changes, and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) offers useful updated infection maps on their website.

The diagnosis of acute infection is often delayed because of late consideration of the possibility of the disease. In addition, some tests are serologic and require the passage of time before a diagnostic result is obtained. But an increasing and distinct problem is the overdiagnosis and long-term treatment of some patients whose infection is undocumented, perpetuating concern over the unproven entity of chronic infection, the most prevalent being the diagnosis and treatment of “chronic Lyme disease.” Close attention must be paid to the manner of diagnosis and the specific tests used to purportedly confirm the diagnosis of infection. This has been an ongoing challenge in managing patients with chronic fatigue and malaise, a vexing and significant clinical problem without a ready solution in patients who have undergone an extensive evaluation. It is obviously tempting for patients to grasp at any “diagnostic” answer. But chronic and repeated therapy for nonexistent infection is not benign. The CDC has published lists of tests for Lyme disease in particular that are considered to have inadequately established accuracy and clinical utility; these include lymphocyte transformation tests, quantitative CD57 lymphocyte assays, and urinary antigen “capture assays.”

Recognizing and treating acute tickborne infections is crucial, as in distinguishing them from their mimics, which include some systemic autoimmune diseases. But we should not allow the fear of undertreatment of early infection to morph into unwarranted overtreatment of nonexistent chronic infection, just as we should not prematurely assume that ongoing symptoms of fatigue and malaise after a presumed tickborne infection are from the psychologically crippling fear of ongoing morbidity. Periodic reappraisal of the patient and his or her symptoms is warranted.

Glutamate’s exciting roles in body, brain, and mind: A fertile future pharmacotherapy target

GLU is now recognized as the most abundant neurotransmitter in the brain, and its excitatory properties are vital for brain structure and function. Importantly, it also is the precursor of γ-aminobutyric acid, the ubiquitous inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain. GLU is one of the first molecules produced during fetal life and plays a critical role in brain development and in organ development because it is a building block for protein synthesis and for manufacturing muscle and other body tissue. Therefore, aberrations in GLU activity can have a major impact on neurodevelopment—the underpinning of most psychiatric disorders due to genetic and environmental factors—and the general health of the brain and body.

GLU is derived from glutamic acid, which is not considered an essential amino acid because it is synthesized in the body via the citric acid cycle. It is readily available from many food items, including cheese, soy, and tomatoes. Monosodium GLU2 is used as a food additive to enhance flavor (Chinese food, anyone?). Incidentally, GLU represents >50% of all amino acids in breast milk, which underscores its importance for a baby’s brain and body development.

GLU’s many brain receptors

Amazingly, although it has been long known that GLU is present in all body tissues, the role of GLU in the CNS and brain was not recognized until the 1980s. This was several decades after the discovery of other neurotransmitters, such as acetylcholine, norepinephrine, and serotonin, which are less widely distributed in the CNS. Over the past 30 years, advances in psychiatric research have elucidated the numerous effects of GLU and its receptors on neuropsychiatric disorders. Multiple receptors of GLU have been discovered, including 16 ion channel receptors (7 for N-methyl-

GLU and neurodegeneration

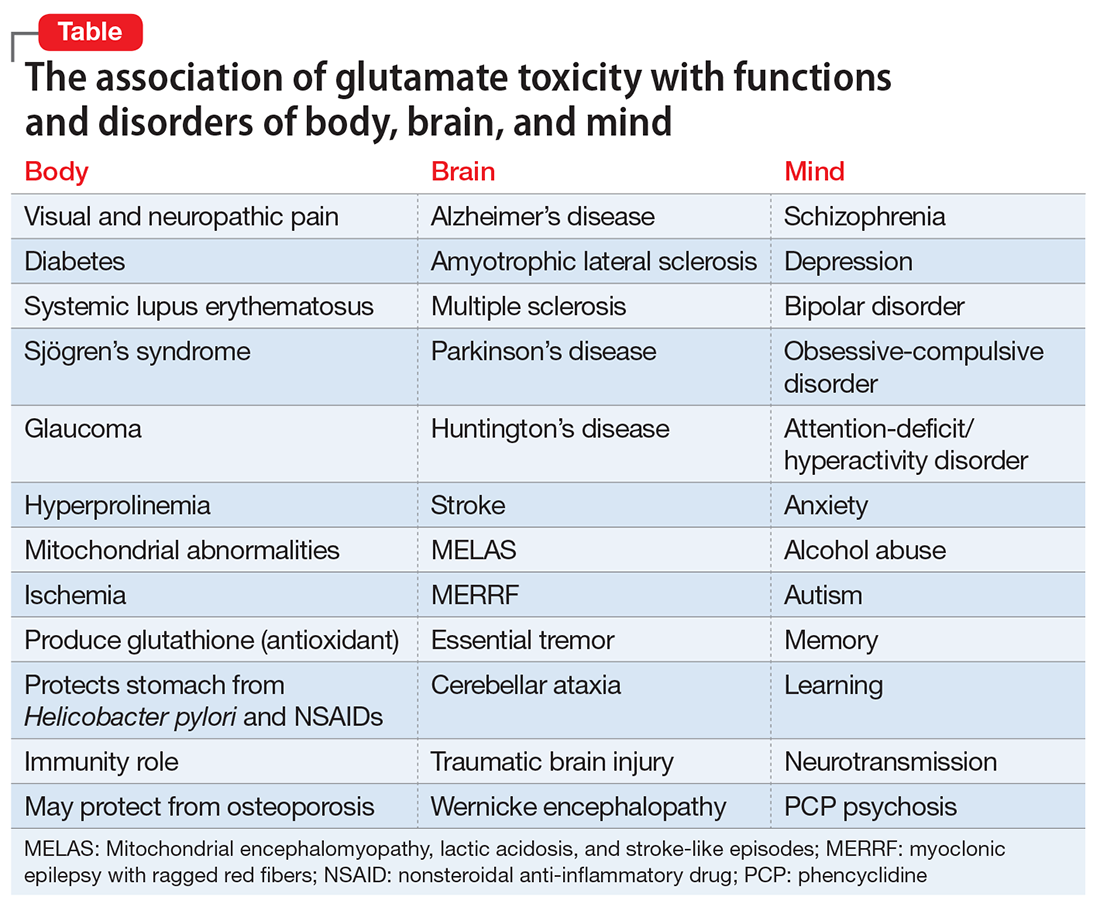

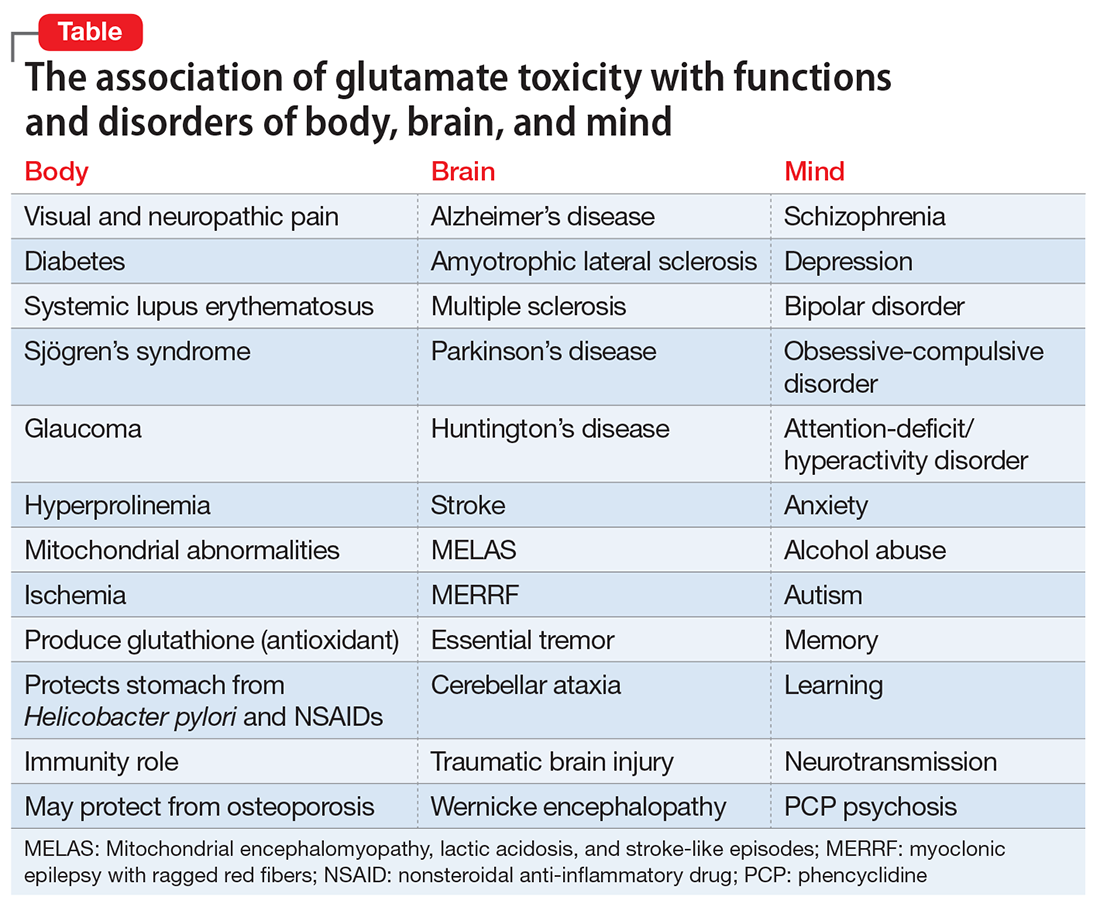

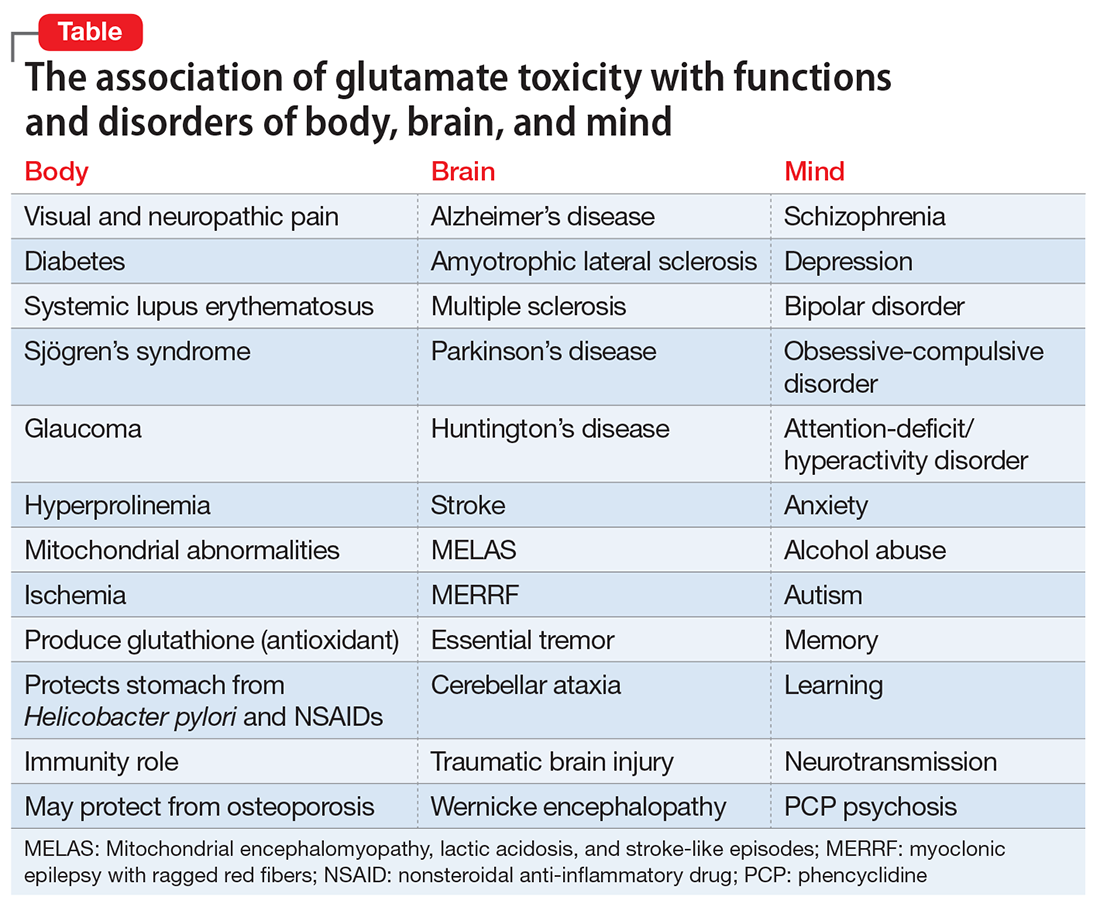

An excess of GLU activity can be neurotoxic and can lead to brain damage.3 Therefore, it is not surprising that excess GLU activity has been found in many neurodegenerative disorders (Table). Similar to other neurologic disorders that are considered neurodegenerative, such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Huntington’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease, major psychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia, depression, and bipolar disorder, also are neurodegenerative if left untreated or if multiple relapses recur because of treatment discontinuation (Table). Several neuroimaging studies have documented brain tissue loss in psychotic and mood disorders after repeated episodes. Therefore, targeting GLU in psychotic and mood disorders is legitimately a “hot” research area in psychiatry.

GLU models of psychiatric neurobiology

Advances in biological psychiatry have moved GLU to the forefront of the neurobiology and pathophysiology of the most serious psychiatric disorders. Overactivity or underactivity of the GLU NMDA receptor has emerged as scientifically plausible mechanisms underlying psychotic and mood disorders. The GLU hypothesis of schizophrenia4 grew out of the observation that phencyclidine, a drug of abuse that is a potent NMDA antagonist (50-fold stronger than ketamine), can trigger in healthy individuals a severe psychosis indistinguishable from schizophrenia, with positive and negative symptoms, cognitive impairment, thought disorder, catatonia, and agitation. Similarly, the recently discovered paraneoplastic encephalitis caused by an ovarian teratoma that secretes antibodies to the NMDA receptor produces acute psychosis, seizures, delirium, dyskinesia, headache, bizarre behavior, confusion, paranoia, auditory and visual hallucinations, and cognitive deficits.5 This demonstrates how the GLU NMDA receptor and its 7 subunits are intimately associated with various psychotic symptoms when genetic or non-genetic factors (antagonists or antibodies) drastically reduce its activity.

On the other hand, there is an impressive body of evidence that, unlike the hypofunction of NMDA receptors in schizophrenia, there appears to be increased activity of NMDA receptors in both unipolar and bipolar depression.6 Several NMDA antagonists have been shown in controlled clinical trials to be highly effective in rapidly reversing severe, chronic depression that did not respond to standard antidepressants.7 A number of NMDA antagonists have been reported to rapidly reverse—within a few hours—severe and chronic depression when administered intravenously (ketamine, rapastinel, scopolamine), intranasally (S-ketamine), or via inhalation (nitrous oxide). NMDA antagonists also show promise in other serious psychiatric disorders such as obsessive-compulsive disorder.8 Riluzole and memantine reduce GLU activity and both are FDA-approved for treating neurodegenerative disorders, such as ALS and AD, respectively.9,10 Therefore, antagonism of GLU is considered neuroprotective and can be therapeutically beneficial in managing neurodegenerative brain disorders.

GLU and the future of psychopharmacology

Based on the wealth of data generated over the past 2 decades regarding the central role of GLU receptors (NMDA, AMPA, kainate, and others) in brain health and disease, modulating GLU pathways is rapidly emerging as a key target for drug development for neuropsychiatric disorders. This approach could help with some medical comorbidities, such as diabetes11 and pain,12 that co-occur frequently with schizophrenia and depression. GLU has been implicated in diabetes via toxicity that destroys pancreatic beta cells.11 It is possible that novel drug development in the future could exploit GLU signaling and pathways to concurrently repair disorders of the brain and body, such as schizophrenia with comorbid diabetes or depression with comorbid pain. It is worth noting that glucose dysregulation has been shown to exist at the onset of schizophrenia before treatment is started.13 This might be related to GLU toxicity occurring simultaneously in the body and the brain. Also worth noting is that ketamine, an NMDA antagonist which has emerged as an ultra-rapid acting antidepressant, is an anesthetic, suggesting that perhaps it may help mitigate the pain symptoms that often accompany major depression.

It is logical to conclude that GLU pathways show exciting prospects for therapeutic advances for the brain, body, and mind. This merits intensive scientific effort for novel drug development in neuropsychiatric disorder that may parsimoniously rectify co-occurring GLU-related diseases of the brain, body, and mind.

1. Meldrum BS. Glutamate as a neurotransmitter in the brain: review of physiology and pathology. J Nutr. 2000;130(4S suppl):1007S-1015S.

2. Freeman M. Reconsidering the effects of monosodium glutamate: a literature review. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2005;18(10):482-486.

3. Novelli A, Pérez-Basterrechea M, Fernández-Sánchez MT. Glutamate and neurodegeneration. In: Schmidt WJ, Reith MEA, eds. Dopamine and glutamate in psychiatric disorders. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2005:447-474.

4. Javitt DC. Glutamate and schizophrenia: phencyclidine, N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors, and dopamine-glutamate interactions. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2007;78:69-108.

5. Dalmau E, Tüzün E, Wu HY, et al. Paraneoplastic anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis associated with ovarian teratoma. Ann Neurol. 2007;61(1):25-36.

6. Iadarola ND, Niciu MJ, Richards EM, et al. Ketamine and other N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists in the treatment of depression: a perspective review. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2015;6(3):97-114.

7. Wohleb ES, Gerhard D, Thomas A, et al. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of rapid-acting antidepressants ketamine and scopolamine. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2017;15(1):11-20.

8. Pittenger C. Glutamate modulators in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatr Ann. 2015;45(6):308-315.

9. Farrimond LE, Roberts E, McShane R. Memantine and cholinesterase inhibitor combination therapy for Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2012;2(3). doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000917.

10. Bensimon G, Lacomblez L, Meininger V. A controlled trial of riluzole in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. ALS/Riluzole Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(9):585-591.

11. Davalli AM, Perego C, Folli FB. The potential role of glutamate in the current diabetes epidemic. Acta Diabetol. 2012;49(3):167-183.

12. Wozniak KM, Rojas C, Wu Y, et al. The role of glutamate signaling in pain processes and its regulation by GCP II inhibition. Curr Med Chem. 2012;19(9):1323-1334.

13. Pillinger T, Beck K, Gobjila C, et al. Impaired glucose homeostasis in first-episode schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(3):261-269.

GLU is now recognized as the most abundant neurotransmitter in the brain, and its excitatory properties are vital for brain structure and function. Importantly, it also is the precursor of γ-aminobutyric acid, the ubiquitous inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain. GLU is one of the first molecules produced during fetal life and plays a critical role in brain development and in organ development because it is a building block for protein synthesis and for manufacturing muscle and other body tissue. Therefore, aberrations in GLU activity can have a major impact on neurodevelopment—the underpinning of most psychiatric disorders due to genetic and environmental factors—and the general health of the brain and body.

GLU is derived from glutamic acid, which is not considered an essential amino acid because it is synthesized in the body via the citric acid cycle. It is readily available from many food items, including cheese, soy, and tomatoes. Monosodium GLU2 is used as a food additive to enhance flavor (Chinese food, anyone?). Incidentally, GLU represents >50% of all amino acids in breast milk, which underscores its importance for a baby’s brain and body development.

GLU’s many brain receptors

Amazingly, although it has been long known that GLU is present in all body tissues, the role of GLU in the CNS and brain was not recognized until the 1980s. This was several decades after the discovery of other neurotransmitters, such as acetylcholine, norepinephrine, and serotonin, which are less widely distributed in the CNS. Over the past 30 years, advances in psychiatric research have elucidated the numerous effects of GLU and its receptors on neuropsychiatric disorders. Multiple receptors of GLU have been discovered, including 16 ion channel receptors (7 for N-methyl-

GLU and neurodegeneration

An excess of GLU activity can be neurotoxic and can lead to brain damage.3 Therefore, it is not surprising that excess GLU activity has been found in many neurodegenerative disorders (Table). Similar to other neurologic disorders that are considered neurodegenerative, such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Huntington’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease, major psychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia, depression, and bipolar disorder, also are neurodegenerative if left untreated or if multiple relapses recur because of treatment discontinuation (Table). Several neuroimaging studies have documented brain tissue loss in psychotic and mood disorders after repeated episodes. Therefore, targeting GLU in psychotic and mood disorders is legitimately a “hot” research area in psychiatry.

GLU models of psychiatric neurobiology

Advances in biological psychiatry have moved GLU to the forefront of the neurobiology and pathophysiology of the most serious psychiatric disorders. Overactivity or underactivity of the GLU NMDA receptor has emerged as scientifically plausible mechanisms underlying psychotic and mood disorders. The GLU hypothesis of schizophrenia4 grew out of the observation that phencyclidine, a drug of abuse that is a potent NMDA antagonist (50-fold stronger than ketamine), can trigger in healthy individuals a severe psychosis indistinguishable from schizophrenia, with positive and negative symptoms, cognitive impairment, thought disorder, catatonia, and agitation. Similarly, the recently discovered paraneoplastic encephalitis caused by an ovarian teratoma that secretes antibodies to the NMDA receptor produces acute psychosis, seizures, delirium, dyskinesia, headache, bizarre behavior, confusion, paranoia, auditory and visual hallucinations, and cognitive deficits.5 This demonstrates how the GLU NMDA receptor and its 7 subunits are intimately associated with various psychotic symptoms when genetic or non-genetic factors (antagonists or antibodies) drastically reduce its activity.

On the other hand, there is an impressive body of evidence that, unlike the hypofunction of NMDA receptors in schizophrenia, there appears to be increased activity of NMDA receptors in both unipolar and bipolar depression.6 Several NMDA antagonists have been shown in controlled clinical trials to be highly effective in rapidly reversing severe, chronic depression that did not respond to standard antidepressants.7 A number of NMDA antagonists have been reported to rapidly reverse—within a few hours—severe and chronic depression when administered intravenously (ketamine, rapastinel, scopolamine), intranasally (S-ketamine), or via inhalation (nitrous oxide). NMDA antagonists also show promise in other serious psychiatric disorders such as obsessive-compulsive disorder.8 Riluzole and memantine reduce GLU activity and both are FDA-approved for treating neurodegenerative disorders, such as ALS and AD, respectively.9,10 Therefore, antagonism of GLU is considered neuroprotective and can be therapeutically beneficial in managing neurodegenerative brain disorders.

GLU and the future of psychopharmacology

Based on the wealth of data generated over the past 2 decades regarding the central role of GLU receptors (NMDA, AMPA, kainate, and others) in brain health and disease, modulating GLU pathways is rapidly emerging as a key target for drug development for neuropsychiatric disorders. This approach could help with some medical comorbidities, such as diabetes11 and pain,12 that co-occur frequently with schizophrenia and depression. GLU has been implicated in diabetes via toxicity that destroys pancreatic beta cells.11 It is possible that novel drug development in the future could exploit GLU signaling and pathways to concurrently repair disorders of the brain and body, such as schizophrenia with comorbid diabetes or depression with comorbid pain. It is worth noting that glucose dysregulation has been shown to exist at the onset of schizophrenia before treatment is started.13 This might be related to GLU toxicity occurring simultaneously in the body and the brain. Also worth noting is that ketamine, an NMDA antagonist which has emerged as an ultra-rapid acting antidepressant, is an anesthetic, suggesting that perhaps it may help mitigate the pain symptoms that often accompany major depression.

It is logical to conclude that GLU pathways show exciting prospects for therapeutic advances for the brain, body, and mind. This merits intensive scientific effort for novel drug development in neuropsychiatric disorder that may parsimoniously rectify co-occurring GLU-related diseases of the brain, body, and mind.

GLU is now recognized as the most abundant neurotransmitter in the brain, and its excitatory properties are vital for brain structure and function. Importantly, it also is the precursor of γ-aminobutyric acid, the ubiquitous inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain. GLU is one of the first molecules produced during fetal life and plays a critical role in brain development and in organ development because it is a building block for protein synthesis and for manufacturing muscle and other body tissue. Therefore, aberrations in GLU activity can have a major impact on neurodevelopment—the underpinning of most psychiatric disorders due to genetic and environmental factors—and the general health of the brain and body.

GLU is derived from glutamic acid, which is not considered an essential amino acid because it is synthesized in the body via the citric acid cycle. It is readily available from many food items, including cheese, soy, and tomatoes. Monosodium GLU2 is used as a food additive to enhance flavor (Chinese food, anyone?). Incidentally, GLU represents >50% of all amino acids in breast milk, which underscores its importance for a baby’s brain and body development.

GLU’s many brain receptors

Amazingly, although it has been long known that GLU is present in all body tissues, the role of GLU in the CNS and brain was not recognized until the 1980s. This was several decades after the discovery of other neurotransmitters, such as acetylcholine, norepinephrine, and serotonin, which are less widely distributed in the CNS. Over the past 30 years, advances in psychiatric research have elucidated the numerous effects of GLU and its receptors on neuropsychiatric disorders. Multiple receptors of GLU have been discovered, including 16 ion channel receptors (7 for N-methyl-

GLU and neurodegeneration

An excess of GLU activity can be neurotoxic and can lead to brain damage.3 Therefore, it is not surprising that excess GLU activity has been found in many neurodegenerative disorders (Table). Similar to other neurologic disorders that are considered neurodegenerative, such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Huntington’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease, major psychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia, depression, and bipolar disorder, also are neurodegenerative if left untreated or if multiple relapses recur because of treatment discontinuation (Table). Several neuroimaging studies have documented brain tissue loss in psychotic and mood disorders after repeated episodes. Therefore, targeting GLU in psychotic and mood disorders is legitimately a “hot” research area in psychiatry.

GLU models of psychiatric neurobiology

Advances in biological psychiatry have moved GLU to the forefront of the neurobiology and pathophysiology of the most serious psychiatric disorders. Overactivity or underactivity of the GLU NMDA receptor has emerged as scientifically plausible mechanisms underlying psychotic and mood disorders. The GLU hypothesis of schizophrenia4 grew out of the observation that phencyclidine, a drug of abuse that is a potent NMDA antagonist (50-fold stronger than ketamine), can trigger in healthy individuals a severe psychosis indistinguishable from schizophrenia, with positive and negative symptoms, cognitive impairment, thought disorder, catatonia, and agitation. Similarly, the recently discovered paraneoplastic encephalitis caused by an ovarian teratoma that secretes antibodies to the NMDA receptor produces acute psychosis, seizures, delirium, dyskinesia, headache, bizarre behavior, confusion, paranoia, auditory and visual hallucinations, and cognitive deficits.5 This demonstrates how the GLU NMDA receptor and its 7 subunits are intimately associated with various psychotic symptoms when genetic or non-genetic factors (antagonists or antibodies) drastically reduce its activity.

On the other hand, there is an impressive body of evidence that, unlike the hypofunction of NMDA receptors in schizophrenia, there appears to be increased activity of NMDA receptors in both unipolar and bipolar depression.6 Several NMDA antagonists have been shown in controlled clinical trials to be highly effective in rapidly reversing severe, chronic depression that did not respond to standard antidepressants.7 A number of NMDA antagonists have been reported to rapidly reverse—within a few hours—severe and chronic depression when administered intravenously (ketamine, rapastinel, scopolamine), intranasally (S-ketamine), or via inhalation (nitrous oxide). NMDA antagonists also show promise in other serious psychiatric disorders such as obsessive-compulsive disorder.8 Riluzole and memantine reduce GLU activity and both are FDA-approved for treating neurodegenerative disorders, such as ALS and AD, respectively.9,10 Therefore, antagonism of GLU is considered neuroprotective and can be therapeutically beneficial in managing neurodegenerative brain disorders.

GLU and the future of psychopharmacology

Based on the wealth of data generated over the past 2 decades regarding the central role of GLU receptors (NMDA, AMPA, kainate, and others) in brain health and disease, modulating GLU pathways is rapidly emerging as a key target for drug development for neuropsychiatric disorders. This approach could help with some medical comorbidities, such as diabetes11 and pain,12 that co-occur frequently with schizophrenia and depression. GLU has been implicated in diabetes via toxicity that destroys pancreatic beta cells.11 It is possible that novel drug development in the future could exploit GLU signaling and pathways to concurrently repair disorders of the brain and body, such as schizophrenia with comorbid diabetes or depression with comorbid pain. It is worth noting that glucose dysregulation has been shown to exist at the onset of schizophrenia before treatment is started.13 This might be related to GLU toxicity occurring simultaneously in the body and the brain. Also worth noting is that ketamine, an NMDA antagonist which has emerged as an ultra-rapid acting antidepressant, is an anesthetic, suggesting that perhaps it may help mitigate the pain symptoms that often accompany major depression.

It is logical to conclude that GLU pathways show exciting prospects for therapeutic advances for the brain, body, and mind. This merits intensive scientific effort for novel drug development in neuropsychiatric disorder that may parsimoniously rectify co-occurring GLU-related diseases of the brain, body, and mind.

1. Meldrum BS. Glutamate as a neurotransmitter in the brain: review of physiology and pathology. J Nutr. 2000;130(4S suppl):1007S-1015S.

2. Freeman M. Reconsidering the effects of monosodium glutamate: a literature review. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2005;18(10):482-486.

3. Novelli A, Pérez-Basterrechea M, Fernández-Sánchez MT. Glutamate and neurodegeneration. In: Schmidt WJ, Reith MEA, eds. Dopamine and glutamate in psychiatric disorders. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2005:447-474.

4. Javitt DC. Glutamate and schizophrenia: phencyclidine, N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors, and dopamine-glutamate interactions. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2007;78:69-108.

5. Dalmau E, Tüzün E, Wu HY, et al. Paraneoplastic anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis associated with ovarian teratoma. Ann Neurol. 2007;61(1):25-36.

6. Iadarola ND, Niciu MJ, Richards EM, et al. Ketamine and other N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists in the treatment of depression: a perspective review. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2015;6(3):97-114.

7. Wohleb ES, Gerhard D, Thomas A, et al. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of rapid-acting antidepressants ketamine and scopolamine. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2017;15(1):11-20.

8. Pittenger C. Glutamate modulators in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatr Ann. 2015;45(6):308-315.

9. Farrimond LE, Roberts E, McShane R. Memantine and cholinesterase inhibitor combination therapy for Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2012;2(3). doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000917.

10. Bensimon G, Lacomblez L, Meininger V. A controlled trial of riluzole in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. ALS/Riluzole Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(9):585-591.

11. Davalli AM, Perego C, Folli FB. The potential role of glutamate in the current diabetes epidemic. Acta Diabetol. 2012;49(3):167-183.

12. Wozniak KM, Rojas C, Wu Y, et al. The role of glutamate signaling in pain processes and its regulation by GCP II inhibition. Curr Med Chem. 2012;19(9):1323-1334.

13. Pillinger T, Beck K, Gobjila C, et al. Impaired glucose homeostasis in first-episode schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(3):261-269.

1. Meldrum BS. Glutamate as a neurotransmitter in the brain: review of physiology and pathology. J Nutr. 2000;130(4S suppl):1007S-1015S.

2. Freeman M. Reconsidering the effects of monosodium glutamate: a literature review. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2005;18(10):482-486.

3. Novelli A, Pérez-Basterrechea M, Fernández-Sánchez MT. Glutamate and neurodegeneration. In: Schmidt WJ, Reith MEA, eds. Dopamine and glutamate in psychiatric disorders. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2005:447-474.

4. Javitt DC. Glutamate and schizophrenia: phencyclidine, N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors, and dopamine-glutamate interactions. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2007;78:69-108.

5. Dalmau E, Tüzün E, Wu HY, et al. Paraneoplastic anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis associated with ovarian teratoma. Ann Neurol. 2007;61(1):25-36.

6. Iadarola ND, Niciu MJ, Richards EM, et al. Ketamine and other N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists in the treatment of depression: a perspective review. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2015;6(3):97-114.

7. Wohleb ES, Gerhard D, Thomas A, et al. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of rapid-acting antidepressants ketamine and scopolamine. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2017;15(1):11-20.

8. Pittenger C. Glutamate modulators in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatr Ann. 2015;45(6):308-315.

9. Farrimond LE, Roberts E, McShane R. Memantine and cholinesterase inhibitor combination therapy for Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2012;2(3). doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000917.

10. Bensimon G, Lacomblez L, Meininger V. A controlled trial of riluzole in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. ALS/Riluzole Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(9):585-591.

11. Davalli AM, Perego C, Folli FB. The potential role of glutamate in the current diabetes epidemic. Acta Diabetol. 2012;49(3):167-183.

12. Wozniak KM, Rojas C, Wu Y, et al. The role of glutamate signaling in pain processes and its regulation by GCP II inhibition. Curr Med Chem. 2012;19(9):1323-1334.

13. Pillinger T, Beck K, Gobjila C, et al. Impaired glucose homeostasis in first-episode schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(3):261-269.

Improving cancer care through modern portfolio theory

We struggle daily to improve cancer care – to improve our therapeutic outcomes in cancer – as individual physicians and as researchers. We work collectively to disseminate information and collaborate, and there are welcome calls for open data sharing to accelerate progress.1 We enroll patients on clinical trials, or we work in a basic science lab to discover mechanisms of carcinogenesis and potential therapeutic targets. We discuss “n of 1” trials and the “paradigm shift of precision oncology,” and we are optimistic about the future of cancer care.