User login

From the Editors: Your call is important to us

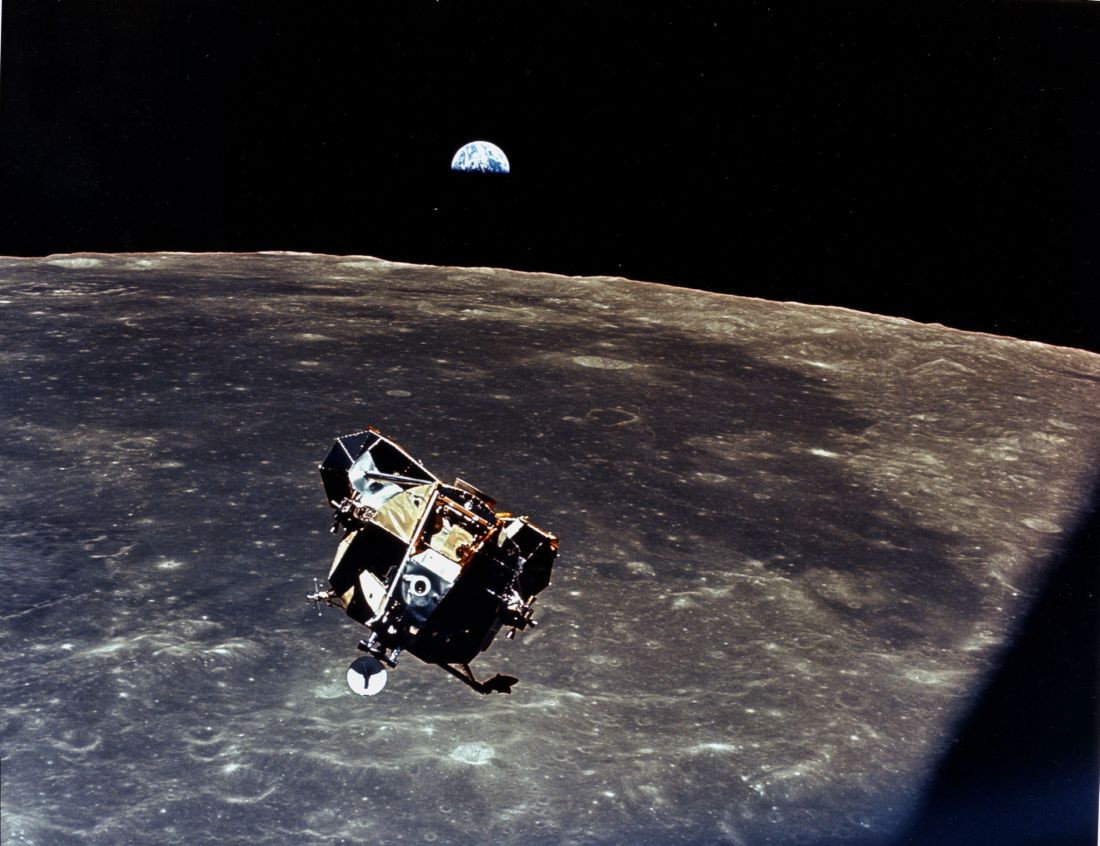

There they were – dropping like a stone toward the lunar surface some 48 years ago. Buzz Aldrin looked at his onboard computer and it reported Error 1202, and alarms started going off in the Lunar Module. Fortunately for Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin, they had a healthy relationship with their computer systems and IT support. Mission control was only 1.5 seconds away and had a huge team of experts that told them they could ignore the error message. The rest is, of course, history. Human beings, not computer software, landed the Eagle. They used their own judgment and experience and data provided by the computer to make their landing decisions.

At 25,000 feet Mission Control answers. Buzz describes the error code. Mission Control reports that his computer is made by Grumman and that Mission Control uses Lockheed-based software. He is advised to call the Grumman help line. At 15,000 feet Grumman responds. They report that Buzz’s password expired about the time the lunar descent burn occurred. He needs to put in a new password and confirm it. He will receive a confirmation email within the next 24 hours. Neil is getting increasingly restive despite his famously bland emotional responses in crises.

At 10,000 feet Buzz gets a new password confirmation, but Error 1202 remains on the display. The moon is enormous in the windshield. Grumman support responds that the error is likely because Buzz put in the wrong weight for the Lunar Module. Buzz begins again feeding in the data to the onboard computer. Grumman suggests that had Buzz simply created the right template, this problem would not have occurred. Buzz, through gritted teeth, asks how he was supposed to create a template for a problem that no one seemed to expect.

They are down to 150 feet now. Neil tells Buzz what he thinks of the computer systems and is told by Mission Control his microphone is hot and that such comments are not appropriate. At Mission Control, a notation is made on their system that Neil will need to discuss this pilot error with the astronaut office upon his return. Neil simply turns off the onboard computer and lands the Lunar Module with seconds of fuel left as he avoids a large boulder field and finds just the right spot. Tranquility Base reports in to Mission Control. Mankind has landed on the Moon.

The alternative history is what surgeons are experiencing every day because of the unhealthy relationship existing between American health care today and our institutional computer systems. Like Neil and Buzz, these surgeons are heroes who avoid boulder fields despite so many obstacles unrelated to their missions. No wonder burnout (a missile term) is so prevalent. We’ve gone from inconvenient to intolerable. Our health care computer systems must be interoperable to have any meaningful use. Our formats need to be understandable. Surgeons need computers to help them make judgments based on easily accessible data in real time. Surgeons need to “fly” the missions and computer systems need to be our servants, not our masters.

Dr. Hughes is clinical professor in the department of surgery and director of medical education at the Kansas University School of Medicine, Salina Campus, and Co-Editor of ACS Surgery News.

There they were – dropping like a stone toward the lunar surface some 48 years ago. Buzz Aldrin looked at his onboard computer and it reported Error 1202, and alarms started going off in the Lunar Module. Fortunately for Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin, they had a healthy relationship with their computer systems and IT support. Mission control was only 1.5 seconds away and had a huge team of experts that told them they could ignore the error message. The rest is, of course, history. Human beings, not computer software, landed the Eagle. They used their own judgment and experience and data provided by the computer to make their landing decisions.

At 25,000 feet Mission Control answers. Buzz describes the error code. Mission Control reports that his computer is made by Grumman and that Mission Control uses Lockheed-based software. He is advised to call the Grumman help line. At 15,000 feet Grumman responds. They report that Buzz’s password expired about the time the lunar descent burn occurred. He needs to put in a new password and confirm it. He will receive a confirmation email within the next 24 hours. Neil is getting increasingly restive despite his famously bland emotional responses in crises.

At 10,000 feet Buzz gets a new password confirmation, but Error 1202 remains on the display. The moon is enormous in the windshield. Grumman support responds that the error is likely because Buzz put in the wrong weight for the Lunar Module. Buzz begins again feeding in the data to the onboard computer. Grumman suggests that had Buzz simply created the right template, this problem would not have occurred. Buzz, through gritted teeth, asks how he was supposed to create a template for a problem that no one seemed to expect.

They are down to 150 feet now. Neil tells Buzz what he thinks of the computer systems and is told by Mission Control his microphone is hot and that such comments are not appropriate. At Mission Control, a notation is made on their system that Neil will need to discuss this pilot error with the astronaut office upon his return. Neil simply turns off the onboard computer and lands the Lunar Module with seconds of fuel left as he avoids a large boulder field and finds just the right spot. Tranquility Base reports in to Mission Control. Mankind has landed on the Moon.

The alternative history is what surgeons are experiencing every day because of the unhealthy relationship existing between American health care today and our institutional computer systems. Like Neil and Buzz, these surgeons are heroes who avoid boulder fields despite so many obstacles unrelated to their missions. No wonder burnout (a missile term) is so prevalent. We’ve gone from inconvenient to intolerable. Our health care computer systems must be interoperable to have any meaningful use. Our formats need to be understandable. Surgeons need computers to help them make judgments based on easily accessible data in real time. Surgeons need to “fly” the missions and computer systems need to be our servants, not our masters.

Dr. Hughes is clinical professor in the department of surgery and director of medical education at the Kansas University School of Medicine, Salina Campus, and Co-Editor of ACS Surgery News.

There they were – dropping like a stone toward the lunar surface some 48 years ago. Buzz Aldrin looked at his onboard computer and it reported Error 1202, and alarms started going off in the Lunar Module. Fortunately for Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin, they had a healthy relationship with their computer systems and IT support. Mission control was only 1.5 seconds away and had a huge team of experts that told them they could ignore the error message. The rest is, of course, history. Human beings, not computer software, landed the Eagle. They used their own judgment and experience and data provided by the computer to make their landing decisions.

At 25,000 feet Mission Control answers. Buzz describes the error code. Mission Control reports that his computer is made by Grumman and that Mission Control uses Lockheed-based software. He is advised to call the Grumman help line. At 15,000 feet Grumman responds. They report that Buzz’s password expired about the time the lunar descent burn occurred. He needs to put in a new password and confirm it. He will receive a confirmation email within the next 24 hours. Neil is getting increasingly restive despite his famously bland emotional responses in crises.

At 10,000 feet Buzz gets a new password confirmation, but Error 1202 remains on the display. The moon is enormous in the windshield. Grumman support responds that the error is likely because Buzz put in the wrong weight for the Lunar Module. Buzz begins again feeding in the data to the onboard computer. Grumman suggests that had Buzz simply created the right template, this problem would not have occurred. Buzz, through gritted teeth, asks how he was supposed to create a template for a problem that no one seemed to expect.

They are down to 150 feet now. Neil tells Buzz what he thinks of the computer systems and is told by Mission Control his microphone is hot and that such comments are not appropriate. At Mission Control, a notation is made on their system that Neil will need to discuss this pilot error with the astronaut office upon his return. Neil simply turns off the onboard computer and lands the Lunar Module with seconds of fuel left as he avoids a large boulder field and finds just the right spot. Tranquility Base reports in to Mission Control. Mankind has landed on the Moon.

The alternative history is what surgeons are experiencing every day because of the unhealthy relationship existing between American health care today and our institutional computer systems. Like Neil and Buzz, these surgeons are heroes who avoid boulder fields despite so many obstacles unrelated to their missions. No wonder burnout (a missile term) is so prevalent. We’ve gone from inconvenient to intolerable. Our health care computer systems must be interoperable to have any meaningful use. Our formats need to be understandable. Surgeons need computers to help them make judgments based on easily accessible data in real time. Surgeons need to “fly” the missions and computer systems need to be our servants, not our masters.

Dr. Hughes is clinical professor in the department of surgery and director of medical education at the Kansas University School of Medicine, Salina Campus, and Co-Editor of ACS Surgery News.

Here There Be Dragons …

For the public, navigating the complex world of vascular care must seem like being adrift on the high seas, with brigands and pirates galore. Vascular surgeons, cardiac surgeons, interventional radiologists, and interventional cardiologists all raise their friendly flags to lure patients. How about vascular medicine, interventional nephrology, and other specialties that sound like a Medical Mad Libs game gone bad? Where to go for care? What is a Heart and Vascular Center? And what about those freestanding labs? You can practically hear the sweet sound of unindicated atherectomies from the streets outside.

Renal stents, EVAR, SFA interventions, EVLT. The question is not who can do them, but who should? When I was a child, I assumed adults were smart. Adults must always have a plan. Now, faced with daily incontrovertible evidence to the contrary, I am ready to cede these points. There is no plan, but there should be.

In the mid-2000s, interventional cardiologists, faced with declining coronary interventions, expanded their interest in other vascular territories. Somehow, despite every metric showing a reduction in their case volume, interventional cardiologists grew their workforce in historic fashion. Between 2008 and 2013, the U.S. workforce of interventional cardiologists nearly doubled, the largest expansion of any medical or surgical specialty. Number two on the list? Interventional Radiology.

I believe the crux of this matter lies in the training of physicians. In the United States, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) sets standards and accredits residency and fellowship programs. Let us review their educational requirements and expectations for these programs with regard to peripheral vascular disease and treatment. First, throw out Vascular Medicine and Interventional Nephrology. The ACGME recognizes 150 specialties and subspecialties, but not these 2. Similarly, the American Board of Medical Specialties offers no certification in these self-designated fields.

Interventional cardiology, according to the ACGME, is “the practice of techniques that improve coronary circulation, alleviate valvular stenosis and regurgitation, and treat other structural heart disease.” Sounds good to me. Looking through the 33-page document that details the requirements for training in interventional cardiology, how often does the word carotid appear? Never. Venous? Zero. Aortic aneurysm? Nada. Any reference to peripheral vascular disease at all? Nope. Indeed the only requirement for knowledge of the peripheral vascular anatomy is in reference to percutaneous approaches to the heart. There is, however, a prerequisite for “application of evidence to patient care and advocacy for quality of care.” It seems the ACGME has my back here.

For other specialties, the training requirements have a tenuous, at best, relationship with vascular interventions. Thoracic Surgery trainees are required to have knowledge of abnormalities of the great vessels and thoracic aorta, but nothing beyond. Interventional radiology trainees must learn to perform “arterial and venous interventions;” but no specific vascular regions are given. Dermatologists need knowledge of vein therapies but neither performance of these procedures nor even direct observation are required.

What then of the trainee case logs? Evidence of their clinical experience? Trainees in interventional cardiology and interventional radiology are not required to use the ACGME case logs. Interventional cardiology fellows only use self-reported case logs and the sole requirement is 250 coronary interventions. In fact, of all the germane specialties, only vascular surgery requires detailed reporting with minimum requirements in multiple vascular trees. Vascular surgery is also the only relevant specialty to report the national averages of the graduates’ case volumes on the public ACGME website.

Education is a process; we acquire competence from the competent. The treatment of peripheral vascular disease is a vocation, not a hobby. “Interest” or even “experience” does not translate to aptitude and proficiency. Whatever one’s issues with the ACGME, they have laid out the most rigorous standards for medical training that exist. Vascular surgery is the only specialty requiring and documenting comprehensive vascular training in all six competencies mandated by the ACGME. Who will tell my trainees, after years of residency, that someone doing a series of unregulated extracurricular activities has had an “equivalent experience”?

Technical teaching without cognitive instruction often results in inappropriate application of treatments. Costs rise and quality falls. Repeated exposure to a technique without consequence or accountability is not training. My 5 year old likes to sit on my lap and steer the car around the parking lot but I do not recommend you let him take you to the airport. What-to-do takes longer to learn than how-to-do-it. In the early years after your training finished, when you called your mentor about a case, what did you ask? In most instances, the question was not how to technically perform a task, but rather what task to do.

The public’s trust in our training and motivation is implicit and necessary. But even doctors have difficulty determining the legitimacy of other specialties’ training in vascular pathology. To say nothing of the public or credentialing committees. Institutions like the ACGME should condemn physicians who chose to practice medicine that bears little resemblance to their intended training.

Peter Lawrence, MD, commenting on this issue in a letter to the New York Times (Feb. 12, 2015), wrote “Vascular Specialists need an in-depth understanding of vascular disease, as well as technical skill, but they also need the ethics to treat patients like a brother or sister, not the source of a payment for a new car.” Allowing so many practitioners to use unregulated pathways to gain credentialing in vascular interventions is folly. Vascular surgeons are the only specialists who have undergone comprehensive accredited training in the care of the vascular patient. We have more than seen it. We have more than done it. We have understood it.

Marriage, and 13 years working for a state institution, have taught me that it is far easier to change one’s own behavior than another’s. As a specialty, we share in the blame for this quagmire. We have been slow to grow our training programs thereby creating a shortage of vascular surgeons. Where we do not exist, others are happy to take up the slack. We cannot make the argument that these are our cases if we cannot cover them. Secondly, we have little public identity. Many medical students do not even understand the role of the vascular surgeon.

We have seemingly failed to brand ourselves to anyone but ourselves. The public must know who we are, where we are, and what we do. This is essential.

Dr. Sheahan is a professor of surgery and Program Director, Vascular Surgery Residency and Fellowship Programs, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, School of Medicine, New Orleans. He is also the Deputy Medical Editor of Vascular Specialist.

For the public, navigating the complex world of vascular care must seem like being adrift on the high seas, with brigands and pirates galore. Vascular surgeons, cardiac surgeons, interventional radiologists, and interventional cardiologists all raise their friendly flags to lure patients. How about vascular medicine, interventional nephrology, and other specialties that sound like a Medical Mad Libs game gone bad? Where to go for care? What is a Heart and Vascular Center? And what about those freestanding labs? You can practically hear the sweet sound of unindicated atherectomies from the streets outside.

Renal stents, EVAR, SFA interventions, EVLT. The question is not who can do them, but who should? When I was a child, I assumed adults were smart. Adults must always have a plan. Now, faced with daily incontrovertible evidence to the contrary, I am ready to cede these points. There is no plan, but there should be.

In the mid-2000s, interventional cardiologists, faced with declining coronary interventions, expanded their interest in other vascular territories. Somehow, despite every metric showing a reduction in their case volume, interventional cardiologists grew their workforce in historic fashion. Between 2008 and 2013, the U.S. workforce of interventional cardiologists nearly doubled, the largest expansion of any medical or surgical specialty. Number two on the list? Interventional Radiology.

I believe the crux of this matter lies in the training of physicians. In the United States, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) sets standards and accredits residency and fellowship programs. Let us review their educational requirements and expectations for these programs with regard to peripheral vascular disease and treatment. First, throw out Vascular Medicine and Interventional Nephrology. The ACGME recognizes 150 specialties and subspecialties, but not these 2. Similarly, the American Board of Medical Specialties offers no certification in these self-designated fields.

Interventional cardiology, according to the ACGME, is “the practice of techniques that improve coronary circulation, alleviate valvular stenosis and regurgitation, and treat other structural heart disease.” Sounds good to me. Looking through the 33-page document that details the requirements for training in interventional cardiology, how often does the word carotid appear? Never. Venous? Zero. Aortic aneurysm? Nada. Any reference to peripheral vascular disease at all? Nope. Indeed the only requirement for knowledge of the peripheral vascular anatomy is in reference to percutaneous approaches to the heart. There is, however, a prerequisite for “application of evidence to patient care and advocacy for quality of care.” It seems the ACGME has my back here.

For other specialties, the training requirements have a tenuous, at best, relationship with vascular interventions. Thoracic Surgery trainees are required to have knowledge of abnormalities of the great vessels and thoracic aorta, but nothing beyond. Interventional radiology trainees must learn to perform “arterial and venous interventions;” but no specific vascular regions are given. Dermatologists need knowledge of vein therapies but neither performance of these procedures nor even direct observation are required.

What then of the trainee case logs? Evidence of their clinical experience? Trainees in interventional cardiology and interventional radiology are not required to use the ACGME case logs. Interventional cardiology fellows only use self-reported case logs and the sole requirement is 250 coronary interventions. In fact, of all the germane specialties, only vascular surgery requires detailed reporting with minimum requirements in multiple vascular trees. Vascular surgery is also the only relevant specialty to report the national averages of the graduates’ case volumes on the public ACGME website.

Education is a process; we acquire competence from the competent. The treatment of peripheral vascular disease is a vocation, not a hobby. “Interest” or even “experience” does not translate to aptitude and proficiency. Whatever one’s issues with the ACGME, they have laid out the most rigorous standards for medical training that exist. Vascular surgery is the only specialty requiring and documenting comprehensive vascular training in all six competencies mandated by the ACGME. Who will tell my trainees, after years of residency, that someone doing a series of unregulated extracurricular activities has had an “equivalent experience”?

Technical teaching without cognitive instruction often results in inappropriate application of treatments. Costs rise and quality falls. Repeated exposure to a technique without consequence or accountability is not training. My 5 year old likes to sit on my lap and steer the car around the parking lot but I do not recommend you let him take you to the airport. What-to-do takes longer to learn than how-to-do-it. In the early years after your training finished, when you called your mentor about a case, what did you ask? In most instances, the question was not how to technically perform a task, but rather what task to do.

The public’s trust in our training and motivation is implicit and necessary. But even doctors have difficulty determining the legitimacy of other specialties’ training in vascular pathology. To say nothing of the public or credentialing committees. Institutions like the ACGME should condemn physicians who chose to practice medicine that bears little resemblance to their intended training.

Peter Lawrence, MD, commenting on this issue in a letter to the New York Times (Feb. 12, 2015), wrote “Vascular Specialists need an in-depth understanding of vascular disease, as well as technical skill, but they also need the ethics to treat patients like a brother or sister, not the source of a payment for a new car.” Allowing so many practitioners to use unregulated pathways to gain credentialing in vascular interventions is folly. Vascular surgeons are the only specialists who have undergone comprehensive accredited training in the care of the vascular patient. We have more than seen it. We have more than done it. We have understood it.

Marriage, and 13 years working for a state institution, have taught me that it is far easier to change one’s own behavior than another’s. As a specialty, we share in the blame for this quagmire. We have been slow to grow our training programs thereby creating a shortage of vascular surgeons. Where we do not exist, others are happy to take up the slack. We cannot make the argument that these are our cases if we cannot cover them. Secondly, we have little public identity. Many medical students do not even understand the role of the vascular surgeon.

We have seemingly failed to brand ourselves to anyone but ourselves. The public must know who we are, where we are, and what we do. This is essential.

Dr. Sheahan is a professor of surgery and Program Director, Vascular Surgery Residency and Fellowship Programs, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, School of Medicine, New Orleans. He is also the Deputy Medical Editor of Vascular Specialist.

For the public, navigating the complex world of vascular care must seem like being adrift on the high seas, with brigands and pirates galore. Vascular surgeons, cardiac surgeons, interventional radiologists, and interventional cardiologists all raise their friendly flags to lure patients. How about vascular medicine, interventional nephrology, and other specialties that sound like a Medical Mad Libs game gone bad? Where to go for care? What is a Heart and Vascular Center? And what about those freestanding labs? You can practically hear the sweet sound of unindicated atherectomies from the streets outside.

Renal stents, EVAR, SFA interventions, EVLT. The question is not who can do them, but who should? When I was a child, I assumed adults were smart. Adults must always have a plan. Now, faced with daily incontrovertible evidence to the contrary, I am ready to cede these points. There is no plan, but there should be.

In the mid-2000s, interventional cardiologists, faced with declining coronary interventions, expanded their interest in other vascular territories. Somehow, despite every metric showing a reduction in their case volume, interventional cardiologists grew their workforce in historic fashion. Between 2008 and 2013, the U.S. workforce of interventional cardiologists nearly doubled, the largest expansion of any medical or surgical specialty. Number two on the list? Interventional Radiology.

I believe the crux of this matter lies in the training of physicians. In the United States, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) sets standards and accredits residency and fellowship programs. Let us review their educational requirements and expectations for these programs with regard to peripheral vascular disease and treatment. First, throw out Vascular Medicine and Interventional Nephrology. The ACGME recognizes 150 specialties and subspecialties, but not these 2. Similarly, the American Board of Medical Specialties offers no certification in these self-designated fields.

Interventional cardiology, according to the ACGME, is “the practice of techniques that improve coronary circulation, alleviate valvular stenosis and regurgitation, and treat other structural heart disease.” Sounds good to me. Looking through the 33-page document that details the requirements for training in interventional cardiology, how often does the word carotid appear? Never. Venous? Zero. Aortic aneurysm? Nada. Any reference to peripheral vascular disease at all? Nope. Indeed the only requirement for knowledge of the peripheral vascular anatomy is in reference to percutaneous approaches to the heart. There is, however, a prerequisite for “application of evidence to patient care and advocacy for quality of care.” It seems the ACGME has my back here.

For other specialties, the training requirements have a tenuous, at best, relationship with vascular interventions. Thoracic Surgery trainees are required to have knowledge of abnormalities of the great vessels and thoracic aorta, but nothing beyond. Interventional radiology trainees must learn to perform “arterial and venous interventions;” but no specific vascular regions are given. Dermatologists need knowledge of vein therapies but neither performance of these procedures nor even direct observation are required.

What then of the trainee case logs? Evidence of their clinical experience? Trainees in interventional cardiology and interventional radiology are not required to use the ACGME case logs. Interventional cardiology fellows only use self-reported case logs and the sole requirement is 250 coronary interventions. In fact, of all the germane specialties, only vascular surgery requires detailed reporting with minimum requirements in multiple vascular trees. Vascular surgery is also the only relevant specialty to report the national averages of the graduates’ case volumes on the public ACGME website.

Education is a process; we acquire competence from the competent. The treatment of peripheral vascular disease is a vocation, not a hobby. “Interest” or even “experience” does not translate to aptitude and proficiency. Whatever one’s issues with the ACGME, they have laid out the most rigorous standards for medical training that exist. Vascular surgery is the only specialty requiring and documenting comprehensive vascular training in all six competencies mandated by the ACGME. Who will tell my trainees, after years of residency, that someone doing a series of unregulated extracurricular activities has had an “equivalent experience”?

Technical teaching without cognitive instruction often results in inappropriate application of treatments. Costs rise and quality falls. Repeated exposure to a technique without consequence or accountability is not training. My 5 year old likes to sit on my lap and steer the car around the parking lot but I do not recommend you let him take you to the airport. What-to-do takes longer to learn than how-to-do-it. In the early years after your training finished, when you called your mentor about a case, what did you ask? In most instances, the question was not how to technically perform a task, but rather what task to do.

The public’s trust in our training and motivation is implicit and necessary. But even doctors have difficulty determining the legitimacy of other specialties’ training in vascular pathology. To say nothing of the public or credentialing committees. Institutions like the ACGME should condemn physicians who chose to practice medicine that bears little resemblance to their intended training.

Peter Lawrence, MD, commenting on this issue in a letter to the New York Times (Feb. 12, 2015), wrote “Vascular Specialists need an in-depth understanding of vascular disease, as well as technical skill, but they also need the ethics to treat patients like a brother or sister, not the source of a payment for a new car.” Allowing so many practitioners to use unregulated pathways to gain credentialing in vascular interventions is folly. Vascular surgeons are the only specialists who have undergone comprehensive accredited training in the care of the vascular patient. We have more than seen it. We have more than done it. We have understood it.

Marriage, and 13 years working for a state institution, have taught me that it is far easier to change one’s own behavior than another’s. As a specialty, we share in the blame for this quagmire. We have been slow to grow our training programs thereby creating a shortage of vascular surgeons. Where we do not exist, others are happy to take up the slack. We cannot make the argument that these are our cases if we cannot cover them. Secondly, we have little public identity. Many medical students do not even understand the role of the vascular surgeon.

We have seemingly failed to brand ourselves to anyone but ourselves. The public must know who we are, where we are, and what we do. This is essential.

Dr. Sheahan is a professor of surgery and Program Director, Vascular Surgery Residency and Fellowship Programs, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, School of Medicine, New Orleans. He is also the Deputy Medical Editor of Vascular Specialist.

Understanding the bell-ringing of concussion

We well recall, back in the day, getting our “bell rung” from some form of sports-related head contact. If we could count the coach’s fingers clearly, run fast and straight, and know the plays, we could happily go back into the game. There was little additional thought given to short-term or lasting effects. I recall hearing tales from my grandfather, a boxing enthusiast, of retired punch-drunk fighters working as bouncers and greeters at sports-focused restaurants and clubs. I certainly didn’t draw any link to a few episodes of personally feeling spacey or dizzy after playing football.

But now, as parents, we are all highly tuned in to the issue of wrongly minimized “minor” head contact and concussion in our children playing sports. There is a growing research-based understanding of the mechanisms of concussion, which remains a clinical syndrome diagnosed on the basis of symptoms and sometimes subtle objective findings that occur in the appropriate environmental context. Intracranial brain impact sets the stage for locally spreading firing of neurons outside their usual pattern. This can result in a diffuse jamming of some normal electrochemical pathways of cognitive function, as well as create additional mismatch between neuronal metabolic needs and the local blood flow providing oxygen and nutrients. This disruption in autoregulation of blood flow sets the stage for enhanced brain sensitivity to any second injurious event, even a minimal one. Hence the aggressive implementation of enforced rest and recovery time for athletes and others with concussion.

It is critical to realize that the patient may not have had a loss of consciousness. Equally important is to consider the need for imaging and protection of patients who are not recovering as expected in 7 to 10 days, as well as for initial imaging of those with severe head impact or baseline neurologic disease, the aged, and those on anticoagulation.

We well recall, back in the day, getting our “bell rung” from some form of sports-related head contact. If we could count the coach’s fingers clearly, run fast and straight, and know the plays, we could happily go back into the game. There was little additional thought given to short-term or lasting effects. I recall hearing tales from my grandfather, a boxing enthusiast, of retired punch-drunk fighters working as bouncers and greeters at sports-focused restaurants and clubs. I certainly didn’t draw any link to a few episodes of personally feeling spacey or dizzy after playing football.

But now, as parents, we are all highly tuned in to the issue of wrongly minimized “minor” head contact and concussion in our children playing sports. There is a growing research-based understanding of the mechanisms of concussion, which remains a clinical syndrome diagnosed on the basis of symptoms and sometimes subtle objective findings that occur in the appropriate environmental context. Intracranial brain impact sets the stage for locally spreading firing of neurons outside their usual pattern. This can result in a diffuse jamming of some normal electrochemical pathways of cognitive function, as well as create additional mismatch between neuronal metabolic needs and the local blood flow providing oxygen and nutrients. This disruption in autoregulation of blood flow sets the stage for enhanced brain sensitivity to any second injurious event, even a minimal one. Hence the aggressive implementation of enforced rest and recovery time for athletes and others with concussion.

It is critical to realize that the patient may not have had a loss of consciousness. Equally important is to consider the need for imaging and protection of patients who are not recovering as expected in 7 to 10 days, as well as for initial imaging of those with severe head impact or baseline neurologic disease, the aged, and those on anticoagulation.

We well recall, back in the day, getting our “bell rung” from some form of sports-related head contact. If we could count the coach’s fingers clearly, run fast and straight, and know the plays, we could happily go back into the game. There was little additional thought given to short-term or lasting effects. I recall hearing tales from my grandfather, a boxing enthusiast, of retired punch-drunk fighters working as bouncers and greeters at sports-focused restaurants and clubs. I certainly didn’t draw any link to a few episodes of personally feeling spacey or dizzy after playing football.

But now, as parents, we are all highly tuned in to the issue of wrongly minimized “minor” head contact and concussion in our children playing sports. There is a growing research-based understanding of the mechanisms of concussion, which remains a clinical syndrome diagnosed on the basis of symptoms and sometimes subtle objective findings that occur in the appropriate environmental context. Intracranial brain impact sets the stage for locally spreading firing of neurons outside their usual pattern. This can result in a diffuse jamming of some normal electrochemical pathways of cognitive function, as well as create additional mismatch between neuronal metabolic needs and the local blood flow providing oxygen and nutrients. This disruption in autoregulation of blood flow sets the stage for enhanced brain sensitivity to any second injurious event, even a minimal one. Hence the aggressive implementation of enforced rest and recovery time for athletes and others with concussion.

It is critical to realize that the patient may not have had a loss of consciousness. Equally important is to consider the need for imaging and protection of patients who are not recovering as expected in 7 to 10 days, as well as for initial imaging of those with severe head impact or baseline neurologic disease, the aged, and those on anticoagulation.

For first-episode psychosis, psychiatrists should behave like cardiologists

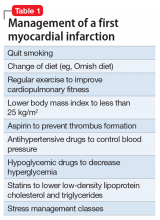

Myocardial infarction (MI) is the leading cause of death in the United States, and schizophrenia is the leading cause of disability. But while cardiologists manage the first heart attack very aggressively to prevent a second MI, we psychiatrists generally do not manage first-episode psychosis (FEP) as aggressively to prevent the more malignant second psychotic episode. Yet abundant evidence indicates that psychiatrists must behave like cardiologists at the onset of schizophrenia and other serious psychosis.

Individuals who survive the first heart attack, which permanently destroys part of the myocardium, are at high risk for a second MI, which may lead to death or weaken the heart so much that heart transplantation becomes necessary. Only implementation of aggressive medical intervention will prevent the likelihood of death due to a second MI in a person who has already suffered a first MI.

Similarly, the FEP of schizophrenia destroys brain tissue, about 10 to 12 cc containing millions of glial cells and billions of synapses.2 This neurotoxicity of psychosis is mediated by neuroinflammation and oxidative stress.3 In most FEP patients, the risk of a second psychotic episode is high, and the tissue destruction of the brain’s gray and white matter infrastructure is even more extensive, leading to clinical deterioration, treatment resistance, and functional disability. That is the grim turning point in the trajectory of schizophrenia.

Although most FEP patients respond well to antipsychotic medications and often return to their baseline social and vocational functioning, after a second episode, they are much more likely to become disabled. Unlike physical death, the mental, cognitive, social, and vocational death of chronic schizophrenia goes on for decades with much suffering, misery, and inability to have love and work, which is what life is all about (according to Freud).

But what is the most common psychiatric practice for a patient who suffers a FEP after he (she) is admitted to an acute inpatient ward? The patient is started on an oral antipsychotic but a long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotic, which is the best protection against future episodes, is never considered, let alone recommended. The patient is given a prescription for an oral antipsychotic at discharge and the family is told to find a private psychiatrist or a community mental health center for follow-up. This practice pattern will likely guarantee a relapse into a second psychotic episode for the following reasons:

- patients’ lack of insight (anosognosia) and refusal to believe they are sick or need medications

- adverse effects, especially extrapyramidal symptoms, to which FEP patients are particularly vulnerable unless they are started on small doses

- apathy and lack of motivation to take medication due to negative symptoms, which impair ability to initiate actions (avolition)

- severe memory impairment that leads to forgetting medications

- substance use, such as marijuana, stimulants, and hallucinogens, as well as alcohol, interferes with adherence.

Most patients and families are ignorant about FEP of schizophrenia and its recurrence and devastating effects.

Thus, because of the almost ubiquitous inability to adhere fully to antipsychotic medications after discharge, FEP patients are essentially destined (ie, doomed) to experience a destructive second psychotic episode, whose neurotoxicity starts the patient on a downhill journey of lifetime disability.4 LAI antipsychotics are the optimal solution to this serious problem, yet 99.99% of psychiatrists never start LAI during a FEP. This is inexplicable considering the body of evidence that supports early use of LAI to prevent relapse. Of the multipronged strategy that should be used for FEP patients to circumvent a second episode and avoid disability, starting LAI in FEP is the most important interventional tactic.5 Consider the following studies that support initiating LAIs during the FEP:

In South Africa, Emsley et al6 conducted the first study of LAI in FEP. In a 2-year follow-up, 64% of patients had complete remission and returned to their baseline functioning with restoration of insight and good quality of life. When the study ended and patients were returned to their referring psychiatrists after 2 years, all patients were switched to oral antipsychotics, because it was the standard practice among psychiatrists there. All patients relapsed within a few months due to poor adherence to oral medications. When they were placed back on the LAI they had received, a sobering (even shocking) clinical finding emerged: 16% of those who had responded so well to LAI for 2 years no longer responded!7 This rapid emergence of treatment resistance after only a second psychotic episode demonstrates how the brain changes drastically after a second episode and validates the recent adoption of “stages” in schizophrenia, similar to cancer stages.8 Many more patients will develop treatment resistance after subsequent episodes.

Subotnik et al9 compared LAI vs oral risperidone in 86 FEP patients. At the end of 1 year, they reported a 650% higher relapse rate in the oral medication group compared with the LAI group (33% vs 5%).9 This well-done study is a wake-up call for psychiatrists to help FEP patients avoid a brain-damaging second episode by using LAI as a first-line option in FEP.

In a separate study, Subotnik et al10 reported that when the blood level of a patient receiving an antipsychotic is measured at the time of discharge from FEP and every month for a year, all it took for a relapse was a drop of 25%.10 Thus, skipping an antipsychotic just 1 day out of 4 (partial nonadherence) is enough to cause a psychotic relapse.

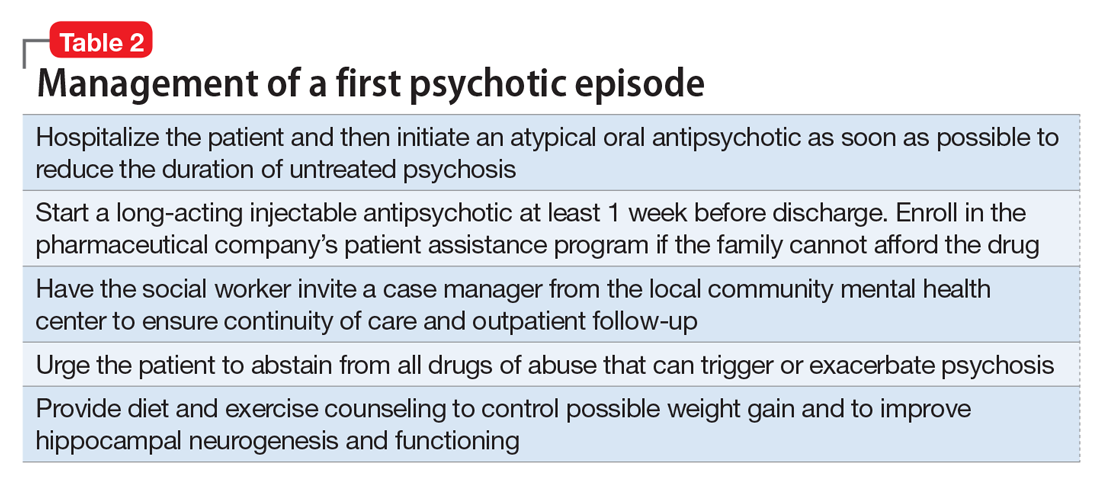

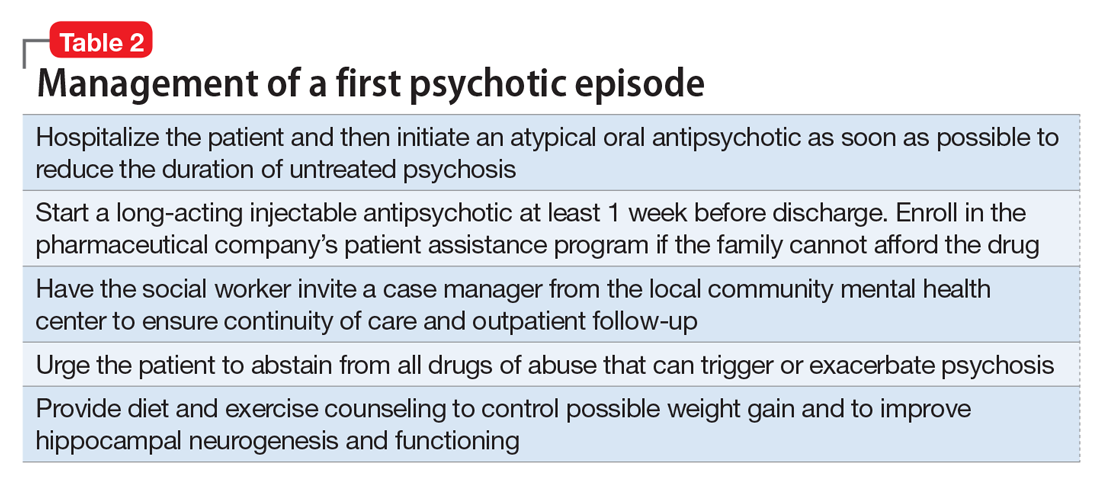

So what should psychiatrists and nurse practitioners do to protect FEP patients from losing their lives to the permanent disability that begins with a second psychotic episode? They must simply change their attitude and their old-fashioned (antiquated?) prescribing habits that keep failing, and start administering LAI during the initial hospitalization right after a few (usually 3 or 4) days of receiving oral antipsychotics (with nursing-assured swallowing of pills) (Table 2). By starting the patient with oral antipsychotics, the presence of an allergic reaction is ruled out, and efficacy onset begins within 2 to 3 days.11 LAI can then be administered several days before discharge and continued in the outpatient setting.

However, various essential psychosocial interventions should be provided along with LAI to ensure progress toward remission and functional recovery after an FEP. The recently published National Institute of Mental Health-sponsored RAISE study12 is a prime example of the synergy between a multimodal and multidisciplinary team-based approach and antipsychotic medication to improve outcome and quality of life after emerging from FEP.

As psychiatric practitioners, we must be clinically aggressive during the “FEP window of opportunity” to avoid a second episode, thereby bending the curve of the downhill trajectory that occurs after second episodes. We must behave like cardiologists, and relentlessly protect patients who suffer a first “brain attack” from experiencing a relapse. No doubt, any psychiatrists who have a family member with FEP would channel their inner cardiologist and implement the evidence-based recommendations described above. But then, shouldn’t we apply the same standard of care to every FEP patient we see?

1. Where next with psychiatric illness? Nature. 1988;336(6195):95-96.

2. Cahn W, Hulshoff Pol HE, Lems EB, et al. Brain volume changes in first episode schizophrenia: a 1-year follow-up study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(11):1002-1010.

3. Monji A, Kato TA, Mizoguchi Y, et al. Neuroinflammation in schizophrenia especially focused on the role of microglia. Prog

4. Alvarez-Jiménoz M, Parker AG, Hetrick SE, et al. Preventing the second episode: a systematic review and meta-analysis of psychosocial and pharmacological trials in first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(3):619-630.

5. Gardner KN, Nasrallah HA. Managing first-episode psychosis: rationale and evidence for nonstandard first-line treatments for schizophrenia. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(7):33,38-45,e3.

6. Emsley R, Oosthuizen P, Koen L, et al. Remission in patients with first-episode schizophrenia receiving assured antipsychotic medication: a study with risperidone long-acting injection. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(6):325-331.

7. Emsley R, Oosthuizen P, Koen L, et al. Comparison of treatment response in second-episode versus first-episode schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;33(1):80-83.

8. McGorry P, Nelson B. Why we need a transdiagnostic staging approach to emerging psychopathology, early diagnosis, and treatment. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(3):191-192.

9. Subotnik KL, Casaus LR, Ventura J, et al. Long-acting injectable risperidone for relapse prevention and control of breakthrough symptoms after a recent first episode of schizophrenia. A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(8):822-829.

10. Subotnik KL, Nuechterlein KH, Ventura J, et al. Risperidone nonadherence and return of positive symptoms in the early course of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(3):286-292.

11. Agid O, Kapur S, Arenovich T, et al. Delayed-onset hypothesis of antipsychotic action: a hypothesis tested and rejected. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(12):1228-1235.

12. Kane JM, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, et al. Comprehensive versus usual community care for first-episode psychosis: 2-year outcomes from the NIMH RAISE early treatment program. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(4):362-372.

Myocardial infarction (MI) is the leading cause of death in the United States, and schizophrenia is the leading cause of disability. But while cardiologists manage the first heart attack very aggressively to prevent a second MI, we psychiatrists generally do not manage first-episode psychosis (FEP) as aggressively to prevent the more malignant second psychotic episode. Yet abundant evidence indicates that psychiatrists must behave like cardiologists at the onset of schizophrenia and other serious psychosis.

Individuals who survive the first heart attack, which permanently destroys part of the myocardium, are at high risk for a second MI, which may lead to death or weaken the heart so much that heart transplantation becomes necessary. Only implementation of aggressive medical intervention will prevent the likelihood of death due to a second MI in a person who has already suffered a first MI.

Similarly, the FEP of schizophrenia destroys brain tissue, about 10 to 12 cc containing millions of glial cells and billions of synapses.2 This neurotoxicity of psychosis is mediated by neuroinflammation and oxidative stress.3 In most FEP patients, the risk of a second psychotic episode is high, and the tissue destruction of the brain’s gray and white matter infrastructure is even more extensive, leading to clinical deterioration, treatment resistance, and functional disability. That is the grim turning point in the trajectory of schizophrenia.

Although most FEP patients respond well to antipsychotic medications and often return to their baseline social and vocational functioning, after a second episode, they are much more likely to become disabled. Unlike physical death, the mental, cognitive, social, and vocational death of chronic schizophrenia goes on for decades with much suffering, misery, and inability to have love and work, which is what life is all about (according to Freud).

But what is the most common psychiatric practice for a patient who suffers a FEP after he (she) is admitted to an acute inpatient ward? The patient is started on an oral antipsychotic but a long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotic, which is the best protection against future episodes, is never considered, let alone recommended. The patient is given a prescription for an oral antipsychotic at discharge and the family is told to find a private psychiatrist or a community mental health center for follow-up. This practice pattern will likely guarantee a relapse into a second psychotic episode for the following reasons:

- patients’ lack of insight (anosognosia) and refusal to believe they are sick or need medications

- adverse effects, especially extrapyramidal symptoms, to which FEP patients are particularly vulnerable unless they are started on small doses

- apathy and lack of motivation to take medication due to negative symptoms, which impair ability to initiate actions (avolition)

- severe memory impairment that leads to forgetting medications

- substance use, such as marijuana, stimulants, and hallucinogens, as well as alcohol, interferes with adherence.

Most patients and families are ignorant about FEP of schizophrenia and its recurrence and devastating effects.

Thus, because of the almost ubiquitous inability to adhere fully to antipsychotic medications after discharge, FEP patients are essentially destined (ie, doomed) to experience a destructive second psychotic episode, whose neurotoxicity starts the patient on a downhill journey of lifetime disability.4 LAI antipsychotics are the optimal solution to this serious problem, yet 99.99% of psychiatrists never start LAI during a FEP. This is inexplicable considering the body of evidence that supports early use of LAI to prevent relapse. Of the multipronged strategy that should be used for FEP patients to circumvent a second episode and avoid disability, starting LAI in FEP is the most important interventional tactic.5 Consider the following studies that support initiating LAIs during the FEP:

In South Africa, Emsley et al6 conducted the first study of LAI in FEP. In a 2-year follow-up, 64% of patients had complete remission and returned to their baseline functioning with restoration of insight and good quality of life. When the study ended and patients were returned to their referring psychiatrists after 2 years, all patients were switched to oral antipsychotics, because it was the standard practice among psychiatrists there. All patients relapsed within a few months due to poor adherence to oral medications. When they were placed back on the LAI they had received, a sobering (even shocking) clinical finding emerged: 16% of those who had responded so well to LAI for 2 years no longer responded!7 This rapid emergence of treatment resistance after only a second psychotic episode demonstrates how the brain changes drastically after a second episode and validates the recent adoption of “stages” in schizophrenia, similar to cancer stages.8 Many more patients will develop treatment resistance after subsequent episodes.

Subotnik et al9 compared LAI vs oral risperidone in 86 FEP patients. At the end of 1 year, they reported a 650% higher relapse rate in the oral medication group compared with the LAI group (33% vs 5%).9 This well-done study is a wake-up call for psychiatrists to help FEP patients avoid a brain-damaging second episode by using LAI as a first-line option in FEP.

In a separate study, Subotnik et al10 reported that when the blood level of a patient receiving an antipsychotic is measured at the time of discharge from FEP and every month for a year, all it took for a relapse was a drop of 25%.10 Thus, skipping an antipsychotic just 1 day out of 4 (partial nonadherence) is enough to cause a psychotic relapse.

So what should psychiatrists and nurse practitioners do to protect FEP patients from losing their lives to the permanent disability that begins with a second psychotic episode? They must simply change their attitude and their old-fashioned (antiquated?) prescribing habits that keep failing, and start administering LAI during the initial hospitalization right after a few (usually 3 or 4) days of receiving oral antipsychotics (with nursing-assured swallowing of pills) (Table 2). By starting the patient with oral antipsychotics, the presence of an allergic reaction is ruled out, and efficacy onset begins within 2 to 3 days.11 LAI can then be administered several days before discharge and continued in the outpatient setting.

However, various essential psychosocial interventions should be provided along with LAI to ensure progress toward remission and functional recovery after an FEP. The recently published National Institute of Mental Health-sponsored RAISE study12 is a prime example of the synergy between a multimodal and multidisciplinary team-based approach and antipsychotic medication to improve outcome and quality of life after emerging from FEP.

As psychiatric practitioners, we must be clinically aggressive during the “FEP window of opportunity” to avoid a second episode, thereby bending the curve of the downhill trajectory that occurs after second episodes. We must behave like cardiologists, and relentlessly protect patients who suffer a first “brain attack” from experiencing a relapse. No doubt, any psychiatrists who have a family member with FEP would channel their inner cardiologist and implement the evidence-based recommendations described above. But then, shouldn’t we apply the same standard of care to every FEP patient we see?

Myocardial infarction (MI) is the leading cause of death in the United States, and schizophrenia is the leading cause of disability. But while cardiologists manage the first heart attack very aggressively to prevent a second MI, we psychiatrists generally do not manage first-episode psychosis (FEP) as aggressively to prevent the more malignant second psychotic episode. Yet abundant evidence indicates that psychiatrists must behave like cardiologists at the onset of schizophrenia and other serious psychosis.

Individuals who survive the first heart attack, which permanently destroys part of the myocardium, are at high risk for a second MI, which may lead to death or weaken the heart so much that heart transplantation becomes necessary. Only implementation of aggressive medical intervention will prevent the likelihood of death due to a second MI in a person who has already suffered a first MI.

Similarly, the FEP of schizophrenia destroys brain tissue, about 10 to 12 cc containing millions of glial cells and billions of synapses.2 This neurotoxicity of psychosis is mediated by neuroinflammation and oxidative stress.3 In most FEP patients, the risk of a second psychotic episode is high, and the tissue destruction of the brain’s gray and white matter infrastructure is even more extensive, leading to clinical deterioration, treatment resistance, and functional disability. That is the grim turning point in the trajectory of schizophrenia.

Although most FEP patients respond well to antipsychotic medications and often return to their baseline social and vocational functioning, after a second episode, they are much more likely to become disabled. Unlike physical death, the mental, cognitive, social, and vocational death of chronic schizophrenia goes on for decades with much suffering, misery, and inability to have love and work, which is what life is all about (according to Freud).

But what is the most common psychiatric practice for a patient who suffers a FEP after he (she) is admitted to an acute inpatient ward? The patient is started on an oral antipsychotic but a long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotic, which is the best protection against future episodes, is never considered, let alone recommended. The patient is given a prescription for an oral antipsychotic at discharge and the family is told to find a private psychiatrist or a community mental health center for follow-up. This practice pattern will likely guarantee a relapse into a second psychotic episode for the following reasons:

- patients’ lack of insight (anosognosia) and refusal to believe they are sick or need medications

- adverse effects, especially extrapyramidal symptoms, to which FEP patients are particularly vulnerable unless they are started on small doses

- apathy and lack of motivation to take medication due to negative symptoms, which impair ability to initiate actions (avolition)

- severe memory impairment that leads to forgetting medications

- substance use, such as marijuana, stimulants, and hallucinogens, as well as alcohol, interferes with adherence.

Most patients and families are ignorant about FEP of schizophrenia and its recurrence and devastating effects.

Thus, because of the almost ubiquitous inability to adhere fully to antipsychotic medications after discharge, FEP patients are essentially destined (ie, doomed) to experience a destructive second psychotic episode, whose neurotoxicity starts the patient on a downhill journey of lifetime disability.4 LAI antipsychotics are the optimal solution to this serious problem, yet 99.99% of psychiatrists never start LAI during a FEP. This is inexplicable considering the body of evidence that supports early use of LAI to prevent relapse. Of the multipronged strategy that should be used for FEP patients to circumvent a second episode and avoid disability, starting LAI in FEP is the most important interventional tactic.5 Consider the following studies that support initiating LAIs during the FEP:

In South Africa, Emsley et al6 conducted the first study of LAI in FEP. In a 2-year follow-up, 64% of patients had complete remission and returned to their baseline functioning with restoration of insight and good quality of life. When the study ended and patients were returned to their referring psychiatrists after 2 years, all patients were switched to oral antipsychotics, because it was the standard practice among psychiatrists there. All patients relapsed within a few months due to poor adherence to oral medications. When they were placed back on the LAI they had received, a sobering (even shocking) clinical finding emerged: 16% of those who had responded so well to LAI for 2 years no longer responded!7 This rapid emergence of treatment resistance after only a second psychotic episode demonstrates how the brain changes drastically after a second episode and validates the recent adoption of “stages” in schizophrenia, similar to cancer stages.8 Many more patients will develop treatment resistance after subsequent episodes.

Subotnik et al9 compared LAI vs oral risperidone in 86 FEP patients. At the end of 1 year, they reported a 650% higher relapse rate in the oral medication group compared with the LAI group (33% vs 5%).9 This well-done study is a wake-up call for psychiatrists to help FEP patients avoid a brain-damaging second episode by using LAI as a first-line option in FEP.

In a separate study, Subotnik et al10 reported that when the blood level of a patient receiving an antipsychotic is measured at the time of discharge from FEP and every month for a year, all it took for a relapse was a drop of 25%.10 Thus, skipping an antipsychotic just 1 day out of 4 (partial nonadherence) is enough to cause a psychotic relapse.

So what should psychiatrists and nurse practitioners do to protect FEP patients from losing their lives to the permanent disability that begins with a second psychotic episode? They must simply change their attitude and their old-fashioned (antiquated?) prescribing habits that keep failing, and start administering LAI during the initial hospitalization right after a few (usually 3 or 4) days of receiving oral antipsychotics (with nursing-assured swallowing of pills) (Table 2). By starting the patient with oral antipsychotics, the presence of an allergic reaction is ruled out, and efficacy onset begins within 2 to 3 days.11 LAI can then be administered several days before discharge and continued in the outpatient setting.

However, various essential psychosocial interventions should be provided along with LAI to ensure progress toward remission and functional recovery after an FEP. The recently published National Institute of Mental Health-sponsored RAISE study12 is a prime example of the synergy between a multimodal and multidisciplinary team-based approach and antipsychotic medication to improve outcome and quality of life after emerging from FEP.

As psychiatric practitioners, we must be clinically aggressive during the “FEP window of opportunity” to avoid a second episode, thereby bending the curve of the downhill trajectory that occurs after second episodes. We must behave like cardiologists, and relentlessly protect patients who suffer a first “brain attack” from experiencing a relapse. No doubt, any psychiatrists who have a family member with FEP would channel their inner cardiologist and implement the evidence-based recommendations described above. But then, shouldn’t we apply the same standard of care to every FEP patient we see?

1. Where next with psychiatric illness? Nature. 1988;336(6195):95-96.

2. Cahn W, Hulshoff Pol HE, Lems EB, et al. Brain volume changes in first episode schizophrenia: a 1-year follow-up study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(11):1002-1010.

3. Monji A, Kato TA, Mizoguchi Y, et al. Neuroinflammation in schizophrenia especially focused on the role of microglia. Prog

4. Alvarez-Jiménoz M, Parker AG, Hetrick SE, et al. Preventing the second episode: a systematic review and meta-analysis of psychosocial and pharmacological trials in first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(3):619-630.

5. Gardner KN, Nasrallah HA. Managing first-episode psychosis: rationale and evidence for nonstandard first-line treatments for schizophrenia. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(7):33,38-45,e3.

6. Emsley R, Oosthuizen P, Koen L, et al. Remission in patients with first-episode schizophrenia receiving assured antipsychotic medication: a study with risperidone long-acting injection. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(6):325-331.

7. Emsley R, Oosthuizen P, Koen L, et al. Comparison of treatment response in second-episode versus first-episode schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;33(1):80-83.

8. McGorry P, Nelson B. Why we need a transdiagnostic staging approach to emerging psychopathology, early diagnosis, and treatment. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(3):191-192.

9. Subotnik KL, Casaus LR, Ventura J, et al. Long-acting injectable risperidone for relapse prevention and control of breakthrough symptoms after a recent first episode of schizophrenia. A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(8):822-829.

10. Subotnik KL, Nuechterlein KH, Ventura J, et al. Risperidone nonadherence and return of positive symptoms in the early course of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(3):286-292.

11. Agid O, Kapur S, Arenovich T, et al. Delayed-onset hypothesis of antipsychotic action: a hypothesis tested and rejected. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(12):1228-1235.

12. Kane JM, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, et al. Comprehensive versus usual community care for first-episode psychosis: 2-year outcomes from the NIMH RAISE early treatment program. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(4):362-372.

1. Where next with psychiatric illness? Nature. 1988;336(6195):95-96.

2. Cahn W, Hulshoff Pol HE, Lems EB, et al. Brain volume changes in first episode schizophrenia: a 1-year follow-up study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(11):1002-1010.

3. Monji A, Kato TA, Mizoguchi Y, et al. Neuroinflammation in schizophrenia especially focused on the role of microglia. Prog

4. Alvarez-Jiménoz M, Parker AG, Hetrick SE, et al. Preventing the second episode: a systematic review and meta-analysis of psychosocial and pharmacological trials in first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(3):619-630.

5. Gardner KN, Nasrallah HA. Managing first-episode psychosis: rationale and evidence for nonstandard first-line treatments for schizophrenia. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(7):33,38-45,e3.

6. Emsley R, Oosthuizen P, Koen L, et al. Remission in patients with first-episode schizophrenia receiving assured antipsychotic medication: a study with risperidone long-acting injection. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(6):325-331.

7. Emsley R, Oosthuizen P, Koen L, et al. Comparison of treatment response in second-episode versus first-episode schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;33(1):80-83.

8. McGorry P, Nelson B. Why we need a transdiagnostic staging approach to emerging psychopathology, early diagnosis, and treatment. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(3):191-192.

9. Subotnik KL, Casaus LR, Ventura J, et al. Long-acting injectable risperidone for relapse prevention and control of breakthrough symptoms after a recent first episode of schizophrenia. A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(8):822-829.

10. Subotnik KL, Nuechterlein KH, Ventura J, et al. Risperidone nonadherence and return of positive symptoms in the early course of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(3):286-292.

11. Agid O, Kapur S, Arenovich T, et al. Delayed-onset hypothesis of antipsychotic action: a hypothesis tested and rejected. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(12):1228-1235.

12. Kane JM, Robinson DG, Schooler NR, et al. Comprehensive versus usual community care for first-episode psychosis: 2-year outcomes from the NIMH RAISE early treatment program. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(4):362-372.

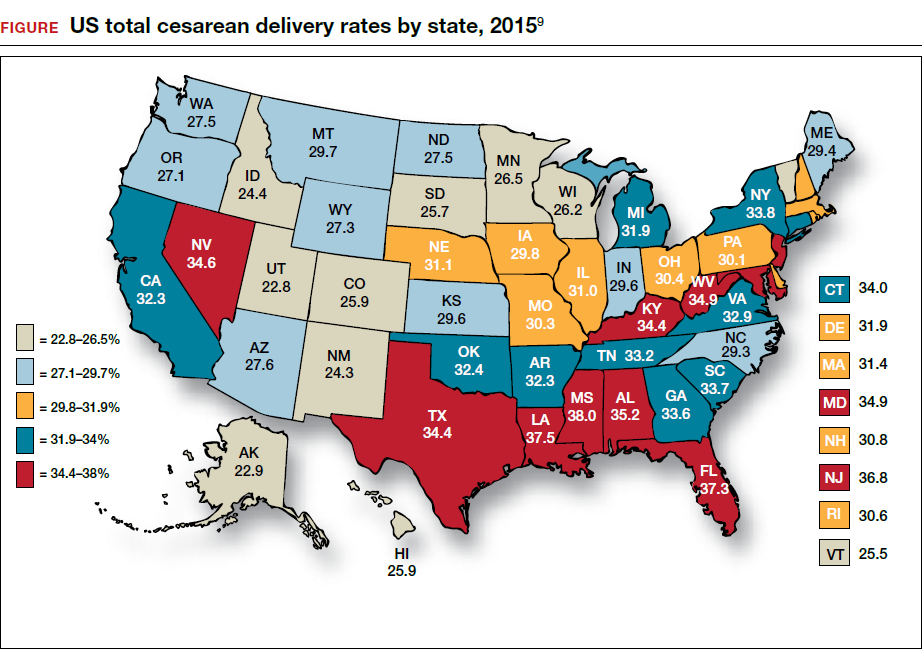

For the management of labor, patience is a virtue

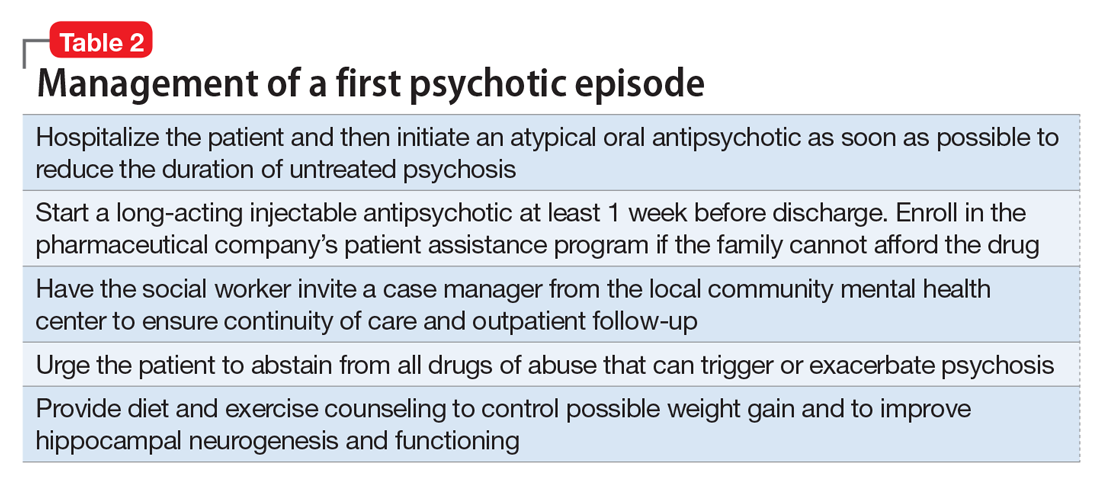

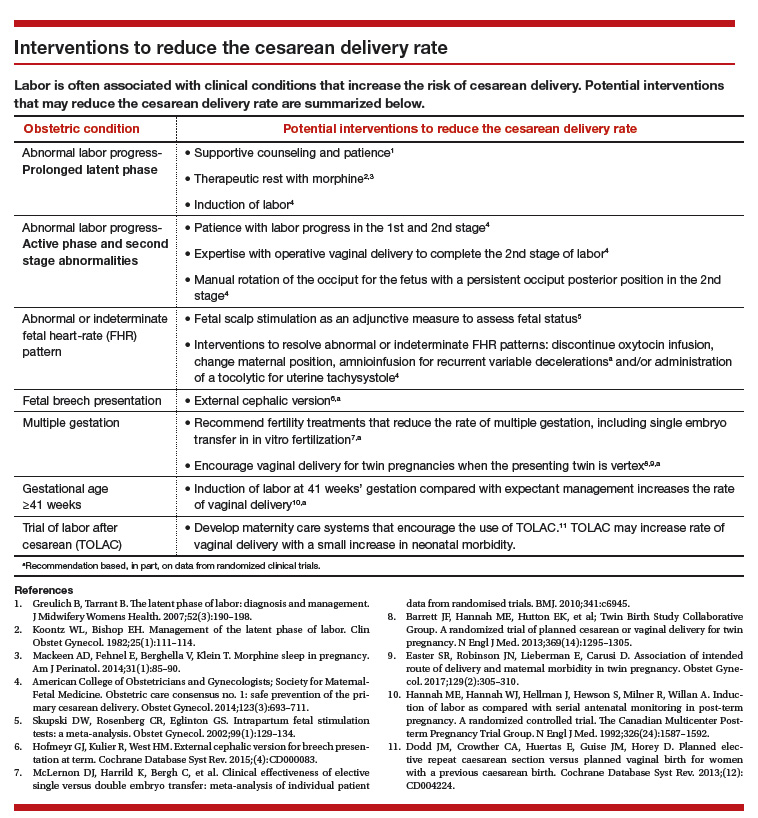

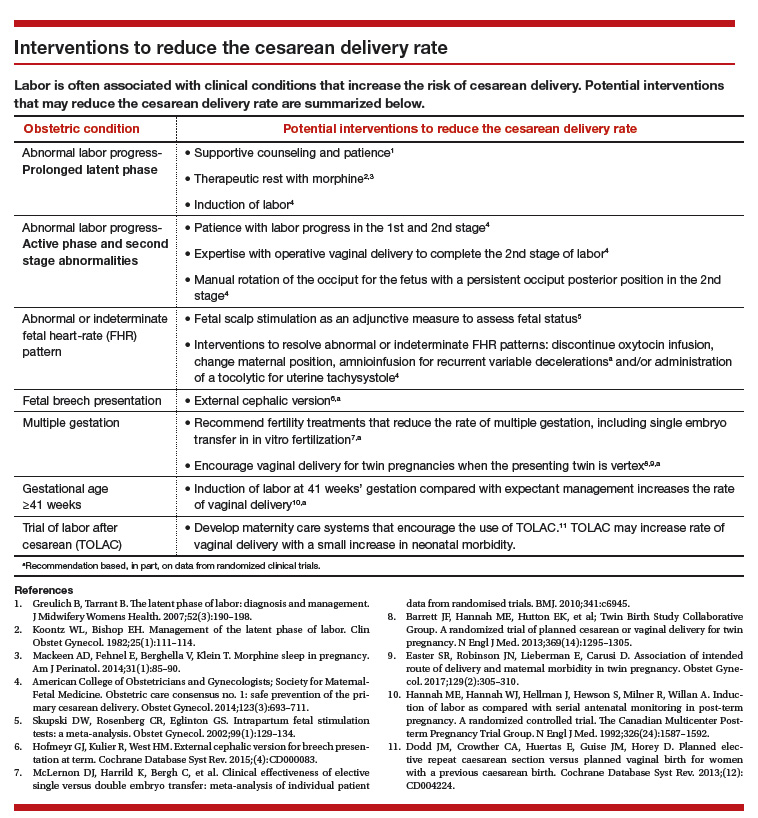

During the past 45 years, the cesarean delivery (CD) rate in the United States has increased from 5.5% in 1970 to 33% from 2009 to 2013, followed by a small decrease to 32% in 2014 and 2015.1 Many clinical problems cause clinicians and patients to decide that CD is an optimal birth route, including: abnormal labor progress, abnormal or indeterminate fetal heart rate pattern, breech presentation, multiple gestation, macrosomia, placental and cord abnormalities, preeclampsia, prior uterine surgery, and prior CD.2 Recent secular trends that contribute to the current rate of CD include an adversarial liability environment,3,4 increasing rates of maternal obesity,5 and widespread use of continuous fetal-heart monitoring during labor.6

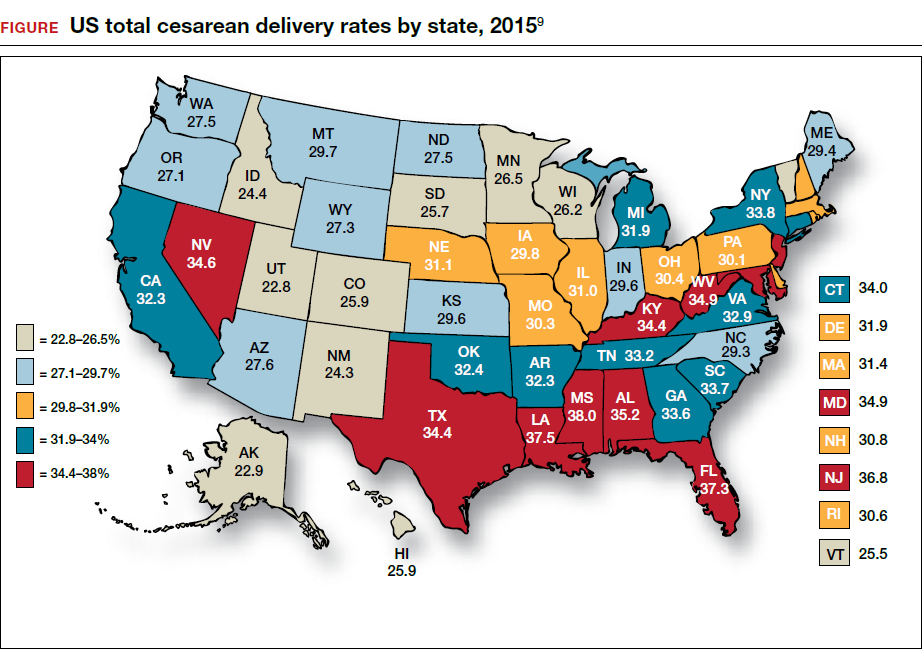

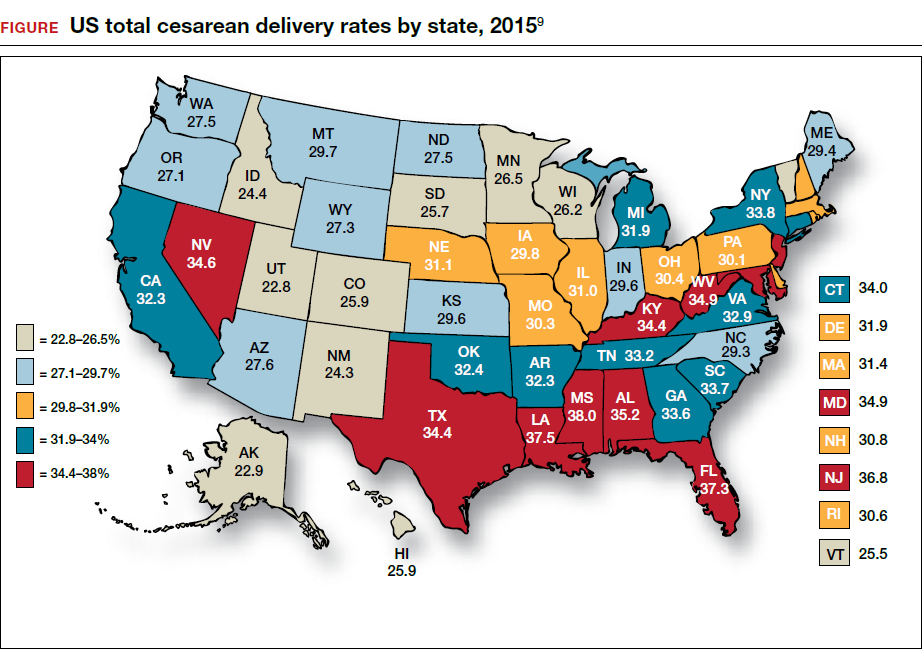

Wide variation in CD rate has been reported among countries, states, and hospitals. The variation is due, in part, to different perspectives about balancing the harms and benefits of vaginal delivery versus CD. In Europe, in 2010 the CD rates in Sweden and Italy were 17.1% and 38%, respectively.7 In 2010, among the states, Alaska had the lowest rate of CD at 22% and Kentucky had the highest rate at 40%.8 In 2015, the highest rate was 38%, in Mississippi (FIGURE).9 In 2014, among Massachusetts hospitals with more than 2,500 births, the CD rate ranged from a low of 22% to a high of 37%.10

Clinicians, patients, policy experts, and the media are perplexed and troubled by the “high” US CD rate and the major variation in rate among countries, states, and hospitals. Labor management practices likely influence the rate of CD and diverse approaches to labor management likely account for the wide variation in CD rates.

A nationwide effort to standardize and continuously improve labor management might result in a decrease in the CD rate. Building on this opportunity, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the Society of Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) have jointly recommended new labor management guidelines that may reduce the primary CD rate.8

The ACOG/SMFM guidelines encourage obstetricians to extend the time for labor progress in both the 1st and 2nd stages prior to recommending a CD.8 These new guidelines emphasize that for a modern obstetrician, patience is a virtue. There are 2 important caveats to this statement: to safely extend the length of time of labor requires both (1) a reassuring fetal heart rate tracing and (2) stable maternal health. If the fetus demonstrates a persistent worrisome Category II or a Category IIIheart-rate tracing, decisive intervention is necessary and permitting an extended labor would not be optimal. Similarly, if the mother has rapidly worsening preeclampsia it may not be wise to extend an induction of labor (IOL) over many days.

There are risks with extending the length of labor. An extended duration of the 1st stage of labor is associated with an increased rate of maternal chorioamnionitis and shoulder dystocia at birth.11 An extended duration of the 2nd stage of labor is associated with an increase in the rate of maternal chorioamnionitis, anal sphincter injury, uterine atony, and neonatal admission to an intensive care unit.12 Clinicians who adopt practices that permit an extended length of labor must weigh the benefits of avoiding a CD against these maternal and fetal complications.

Active phase redefined

Central to the ACOG/SMFM guidelines is a new definition of the active phase of labor. The research of Dr. Emmanuel Friedman indicated that at approximately 4 cm of cervical dilation many women in labor transition from the latent phase, a time of slow change in cervical dilation, to the active phase, a time of more rapid change in cervical dilation.13,14 However, more recent research indicates that the transition between the latent and active phase is difficult to precisely define, but more often occurs at about 6 cm of cervical dilation and not 4 cm of dilation.15 Adopting these new norms means that laboring women will spend much more time in the latent phase, a phase of labor in which patience is a virtue.

The ACOG/SMFM guidelines

Main takeaways from the ACOG/SMFM guidelines are summarized below. Interventions that address common obstetric issues and labor abnormalities are outlined below.

Do not perform CD for a prolonged latent phase of labor, defined as regular contractions of >20 hours duration in nulliparous women and >14 hours duration in multiparous women. Patience with a prolonged latent phase will be rewarded by the majority of women entering the active phase of labor. Alternatively, if appropriate, cervical ripening followed by oxytocin IOL and amniotomy will help the patient with a prolonged latent phase to enter the active phase of labor.16

For women with an unfavorable cervix as assessed by the Bishop score, cervical ripening should be performed prior to IOL. Use of cervical ripening prior to IOL increases the chance of achieving vaginal delivery within 24 hours and may result in a modest decrease in the rate of CD.17,18

Related article:

Should oxytocin and a Foley catheter be used concurrently for cervical ripening in induction of labor?

Failed IOL in the latent phase should only be diagnosed following 12 to 18 hours of both ruptured membranes and adequate contractions stimulated with oxytocin. The key ingredients for the successful management of the latent phase of labor are patience, oxytocin, and amniotomy.16

CD for the indication of active phase arrest requires cervical dilation ≥6 cm with ruptured membranes and no change in cervical dilation for ≥4 hours of adequate uterine activity. In the past, most obstetricians defined active phase arrest, a potential indication for CD, as the absence of cervical change for 2 or more hours in the presence of adequate uterine contractions and cervical dilation of at least 4 cm. Given the new definition of active phase arrest, slow but progressive progress in the 1st stage of labor is not an indication for CD.11,19

“A specific absolute maximum length of time spent in the 2nd stage beyond which all women should be offered an operative delivery has not been identified.”8 Diagnosis of arrest of labor in the 2nd stage may be considered after at least 2 hours of pushing in multiparous women and 3 hours of pushing in nulliparous women, especially if no fetal descent is occurring. The guidelines also state “longer durations may be appropriate on an individualized basis (eg, with use of epidural analgesia or with fetal malposition)” as long as fetal descent is observed.

Patience is a virtue, especially in the management of the 2nd stage of labor. Extending the 2nd stage up to 4 hours appears to be reasonably safe if the fetal status is reassuring and the mother is physiologically stable. In a study from San Francisco of 42,268 births with normal newborn outcomes, the 95th percentile for the length of the 2nd stage of labor for nulliparous women was 3.3 hours without an epidural and 5.6 hours with an epidural.20

In a study of 53,285 births, longer duration of pushing was associated with a small increase in the rate of neonatal adverse outcomes. In nulliparous women the rate of adverse neonatal outcomes increased from 1.3% with less than 60 minutes of pushing to 2.4% with greater than 240 minutes of pushing. Remarkably, even after 4 hours of pushing, 78% of nulliparous women who continued to push had a vaginal delivery.21 In this study, among nulliparous women the rate of anal sphincter injury increased from 5% with less than 60 minutes of pushing to 16% with greater than 240 minutes of pushing, and the rate of postpartum hemorrhage increased from 1% with less than 60 minutes of pushing to 3.3% with greater than 240 minutes of pushing.

I am not enthusiastic about patiently watching a labor extend into the 5th hour of the 2nd stage, especially if the fetus is at +2 station or lower. In a nulliparous woman, after 4 hours of managing the 2nd stage of labor, my patience is exhausted and I am inclined to identify a clear plan for delivery, either by enhanced labor coaching, operative vaginal delivery, or CD.

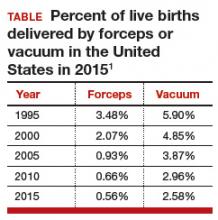

Operative vaginal delivery in the 2nd stage of labor is an acceptable alternative to CD. The rate of operative vaginal delivery in the United States has declined over the past 2 decades (TABLE). In Sweden in 2010 the operative vaginal delivery rate was 7.6% with a CD rate of 17.1%.7 In the United States in 2010 the operative delivery rate was 3.6%, and the CD rate was 33%.1 A renewed focus on operative vaginal delivery with ongoing training and team simulation for the procedure would increase our use of operative delivery and decrease the overall rate of CD.

Related article:

STOP using instruments to assist with delivery of the head at cesarean

Encourage the detection of persistent fetal occiput posterior position by physical examination and/or ultrasound and consider manual rotation of the fetal occiput from the posterior to anterior position in the 2nd stage. Persistent occiput posterior is the most common fetal malposition.22 This malposition is associated with an increased rate of CD.23 There are few randomized trials of manual rotation of the fetal occiput from posterior to anterior position in the 2nd stage of labor, and the evidence is insufficient to determine the efficacy of manual rotation.24 Small nonrandomized studies report that manual rotation of the occiput from posterior to anterior position may reduce the CD rate.25–27

For persistent 2nd stage fetal occiput posterior position in a woman with an adequate pelvis, where manual rotation was not successful and the fetus is at +2 station or below, operative vaginal delivery is an option. “Vacuum or forceps?” and “If forceps, to rotate or not to rotate?” those are the clinical questions. Forceps delivery is more likely to be successfulthan vacuum delivery.28 Direct forceps delivery of the occiput posterior fetus is associated with more anal sphincter injuries than forceps delivery after successful rotation, but few clinicians regularly perform rotational forceps.29 In a study of 2,351 women in the 2nd stage of labor with the fetus at +2 station or below, compared with either forceps or vacuum delivery, CD was associated with more maternal infections and fewer perineal lacerations. Neonatal composite morbidity was not significantly different among the 3 routes of operative delivery.30

Amnioinfusion for repetitive variable decelerations of the fetal heart rate may reduce the risk of CD for an indeterminate fetal heart-rate pattern.31

IOL in a well-dated pregnancy at 41 weeks will reduce the risk of CD. In a large clinical trial, 3,407 women at 41 weeks of gestation were randomly assigned to IOL or expectant management. The rate of CD was significantly lower in the women assigned to IOL compared with expectant management (21% vs 25%, respectively; P = .03).32 The rate of neonatal morbidity was similar in the 2 groups.

Women with twin gestations and the first twin in a cephalic presentation may elect vaginal delivery. In a large clinical trial, 1,398 women with a twin gestation and the first twin in a cephalic presentation were randomly assigned to planned vaginal delivery (with cesarean only if necessary) or planned CD.33 The rate of CD was 44% and 91% for the women in the planned-vaginal and planned-cesarean groups, respectively. There was no significant difference in composite fetal or neonatal death or serious morbidity. The authors concluded that, for twin pregnancy with the presenting twin in the cephalic presentation, there were no demonstrated benefits of planned CD.

Develop maternity care systems that encourage the use of trial of labor after cesarean (TOLAC). The ACOG/SMFM guidelines focus on interventions to reduce the rate of primary CD and do not address the role of TOLAC in reducing CD rates. There are little data from clinical trials to assess the benefits and harms from TOLAC versus scheduled repeat CD.34 However, our experience with TOLAC in the 1990s strongly suggests that encouraging TOLAC will decrease the rate of CD. In 1996 the US rate of vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) peaked at 28%, and the rate of CD achieved a recent historic nadir of 21%. Growing concerns that TOLAC occasionally results in fetal harm was followed by a decrease in the VBAC rate to 12% in 2015.1 A recent study of obstetric practices in countries with high and low VBAC rates concluded that patient and clinician commitment and comfort with prioritizing TOLAC over scheduled repeat CD greatly influenced the VBAC rate.35

Related article: