User login

Three days in the life of a surgeon

By sheer happenstance, I was visiting a surgery program on the day after “the Match.” As all of you know, four days before the official release of the placement of every new surgical trainee, both the medical students involved and the programs affected are informed as to whether they have been matched. Students don’t know where they are going, just that the last rung of training is now in place. They have a job and a relatively secure future. Those who have not been matched and those programs that did not fill all their slots now enter into a scramble (officially called SOAP) to find students for the remaining slots. This year, the scramble occurred on a Wednesday and was orchestrated by a set of rules I’d never been privy to before.

On Tuesday night, all the programs in need of students for their open slots, whether categorical or preliminary, looked over the list of candidates remaining and made their choices. So did the students now hoping to find a place. At 10 a.m., the offers went out to students in the first round. Next, in precisely timed order, the programs found out who had accepted the offers. And, if slots were left over, the programs had a short time to put up another set of offers – and so on throughout the day until all the slots were gone. Like a game of musical chairs, the music finally stopped and the Match was over for the entering class of residents for 2017.

Dr. Hughes is clinical professor in the department of surgery and director of medical education at the Kansas University School of Medicine, Salina Campus, and coeditor of ACS Surgery News.

By sheer happenstance, I was visiting a surgery program on the day after “the Match.” As all of you know, four days before the official release of the placement of every new surgical trainee, both the medical students involved and the programs affected are informed as to whether they have been matched. Students don’t know where they are going, just that the last rung of training is now in place. They have a job and a relatively secure future. Those who have not been matched and those programs that did not fill all their slots now enter into a scramble (officially called SOAP) to find students for the remaining slots. This year, the scramble occurred on a Wednesday and was orchestrated by a set of rules I’d never been privy to before.

On Tuesday night, all the programs in need of students for their open slots, whether categorical or preliminary, looked over the list of candidates remaining and made their choices. So did the students now hoping to find a place. At 10 a.m., the offers went out to students in the first round. Next, in precisely timed order, the programs found out who had accepted the offers. And, if slots were left over, the programs had a short time to put up another set of offers – and so on throughout the day until all the slots were gone. Like a game of musical chairs, the music finally stopped and the Match was over for the entering class of residents for 2017.

Dr. Hughes is clinical professor in the department of surgery and director of medical education at the Kansas University School of Medicine, Salina Campus, and coeditor of ACS Surgery News.

By sheer happenstance, I was visiting a surgery program on the day after “the Match.” As all of you know, four days before the official release of the placement of every new surgical trainee, both the medical students involved and the programs affected are informed as to whether they have been matched. Students don’t know where they are going, just that the last rung of training is now in place. They have a job and a relatively secure future. Those who have not been matched and those programs that did not fill all their slots now enter into a scramble (officially called SOAP) to find students for the remaining slots. This year, the scramble occurred on a Wednesday and was orchestrated by a set of rules I’d never been privy to before.

On Tuesday night, all the programs in need of students for their open slots, whether categorical or preliminary, looked over the list of candidates remaining and made their choices. So did the students now hoping to find a place. At 10 a.m., the offers went out to students in the first round. Next, in precisely timed order, the programs found out who had accepted the offers. And, if slots were left over, the programs had a short time to put up another set of offers – and so on throughout the day until all the slots were gone. Like a game of musical chairs, the music finally stopped and the Match was over for the entering class of residents for 2017.

Dr. Hughes is clinical professor in the department of surgery and director of medical education at the Kansas University School of Medicine, Salina Campus, and coeditor of ACS Surgery News.

Defining high reliability

When the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations came to our hospital for a survey last fall, our administration was confident that the review would be favorable. The Joint Commission was stressing the reliability of hospitals and so were we. We had chartered a “High-Reliability Organization Enterprise Steering Committee” that was “empowered to make recommendations to the (executive board) on what is needed to achieve the goals of high reliability across the enterprise.” High reliability was a priority for our administration and for the Joint Commission. Unfortunately, nearly no one else knew what high reliability meant.

In 2001, Karl E. Weick and Kathleen M. Sutcliffe published their book, “Managing the Unexpected: Resilient Performance in an Age of Uncertainty,” (Hoboken, N.J.: Jossey-Bass, 2001), which defined high-reliability organizations as those that reliably prevent error. They included examples from the military and from aviation. They proffered five principles to guide those organizations wishing to become highly reliable:

1. Preoccupation with failure.

2. Reluctance to simplify interpretations.

3. Sensitivity to operations.

4. Commitment to resilience.

5. Deference to expertise.

In September 2005, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality created a document to adapt the concepts developed by Mr. Weick and Ms. Sutcliffe to the health care industry, where opportunities to avoid error and prevent catastrophe abound. The eventual result has been steady progress in measuring avoidable health care errors, such as avoiding central line–associated blood stream infections and holding health care organizations accountable for their reduction. However, organizational cultures are difficult to change, and there is still a long way to go.

In contrast to large systems, individual providers can change quickly, especially if there is incentive to do so. What principles would increase our own ability to become a high-reliability individuals (HRIs):

• Recognize failure as systemic, not personal. Health care providers are humans, and humans make mistakes. Unfortunately, we come from a tradition that rewards success and penalizes failure. Research shows that is better to recognize failure as something to be prevented next time rather than to be punished now. Admonitions to pay attention, focus more, and remember better rely on fallible humans and reliably fail. Systems solutions, such as checklists, timeouts, and hard stops reliably succeed. HRIs should blame error less often on people, and more often on system failures.

• Simple solutions are preferred to complex requirements. Chemotherapy was once calculated and written by hand. Every cancer center can recall tragic disasters that occurred as a result of errors either by the ordering physician or by interpretations made by pharmacists and nurses. The introduction of electronic chemotherapy ordering has nearly eliminated these mistakes. HRIs can initiate technology solutions to their work to help reduce the risk of errors.

• Sensitivity to patients. Patients often desire to be included as partners in their care. In addition to being present and attentive to patients, why not enlist them as colleagues in care? For example, the patient who has their own calendar of chemotherapy treatments – complete with agents, doses, and schedules – will be more likely to question perceived errors. HRIs are transparent.

• Resilience in character. Learning to accept the potential for error requires acceptance that others also are trying to prevent error and are not judging your competence. The physician who attacks those who are trying to help reduces the psychological safety required for colleagues to speak up when potential errors are identified. Physicians will become HRIs only when they lower their defenses and become more teammates rather than a soloists.

• Deference to evidence. The “way it has always been” must give way to the way things are. Anecdotes and personal conviction do not meet scientific standards and should be abandoned in the face of evidence. Yet, this seemingly obvious principle often is disregarded when clinicians are presented with standardized treatment pathways and limited formularies in the name of autonomy; autonomy is fine until patients are endangered by it. The HRI practices evidence-based medicine.

Marty Makary, MD, explores most of these principles in his book “Unaccountable: What Hospitals Won’t Tell You and How Transparency Can Revolutionize Health Care”(London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2012). While written from a surgeon’s perspective, Dr. Makary exposes the dangerous state of modern medical care across all specialties. I recommend it as a sobering assessment of the way things are and as a prescription for health care systems and physicians to help them become more reliable.

How are you driving safety in your area? What are some best practices we can share with others? I invite you to reply to [email protected] to initiate a broader discussion of patient safety and reliability. Responses will be posted to hematologynews.com.

Dr. Kalaycio is Editor in Chief of Hematology News. Dr. Kalaycio chairs the department of hematologic oncology and blood disorders at Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute. Contact him at [email protected].

When the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations came to our hospital for a survey last fall, our administration was confident that the review would be favorable. The Joint Commission was stressing the reliability of hospitals and so were we. We had chartered a “High-Reliability Organization Enterprise Steering Committee” that was “empowered to make recommendations to the (executive board) on what is needed to achieve the goals of high reliability across the enterprise.” High reliability was a priority for our administration and for the Joint Commission. Unfortunately, nearly no one else knew what high reliability meant.

In 2001, Karl E. Weick and Kathleen M. Sutcliffe published their book, “Managing the Unexpected: Resilient Performance in an Age of Uncertainty,” (Hoboken, N.J.: Jossey-Bass, 2001), which defined high-reliability organizations as those that reliably prevent error. They included examples from the military and from aviation. They proffered five principles to guide those organizations wishing to become highly reliable:

1. Preoccupation with failure.

2. Reluctance to simplify interpretations.

3. Sensitivity to operations.

4. Commitment to resilience.

5. Deference to expertise.

In September 2005, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality created a document to adapt the concepts developed by Mr. Weick and Ms. Sutcliffe to the health care industry, where opportunities to avoid error and prevent catastrophe abound. The eventual result has been steady progress in measuring avoidable health care errors, such as avoiding central line–associated blood stream infections and holding health care organizations accountable for their reduction. However, organizational cultures are difficult to change, and there is still a long way to go.

In contrast to large systems, individual providers can change quickly, especially if there is incentive to do so. What principles would increase our own ability to become a high-reliability individuals (HRIs):

• Recognize failure as systemic, not personal. Health care providers are humans, and humans make mistakes. Unfortunately, we come from a tradition that rewards success and penalizes failure. Research shows that is better to recognize failure as something to be prevented next time rather than to be punished now. Admonitions to pay attention, focus more, and remember better rely on fallible humans and reliably fail. Systems solutions, such as checklists, timeouts, and hard stops reliably succeed. HRIs should blame error less often on people, and more often on system failures.

• Simple solutions are preferred to complex requirements. Chemotherapy was once calculated and written by hand. Every cancer center can recall tragic disasters that occurred as a result of errors either by the ordering physician or by interpretations made by pharmacists and nurses. The introduction of electronic chemotherapy ordering has nearly eliminated these mistakes. HRIs can initiate technology solutions to their work to help reduce the risk of errors.

• Sensitivity to patients. Patients often desire to be included as partners in their care. In addition to being present and attentive to patients, why not enlist them as colleagues in care? For example, the patient who has their own calendar of chemotherapy treatments – complete with agents, doses, and schedules – will be more likely to question perceived errors. HRIs are transparent.

• Resilience in character. Learning to accept the potential for error requires acceptance that others also are trying to prevent error and are not judging your competence. The physician who attacks those who are trying to help reduces the psychological safety required for colleagues to speak up when potential errors are identified. Physicians will become HRIs only when they lower their defenses and become more teammates rather than a soloists.

• Deference to evidence. The “way it has always been” must give way to the way things are. Anecdotes and personal conviction do not meet scientific standards and should be abandoned in the face of evidence. Yet, this seemingly obvious principle often is disregarded when clinicians are presented with standardized treatment pathways and limited formularies in the name of autonomy; autonomy is fine until patients are endangered by it. The HRI practices evidence-based medicine.

Marty Makary, MD, explores most of these principles in his book “Unaccountable: What Hospitals Won’t Tell You and How Transparency Can Revolutionize Health Care”(London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2012). While written from a surgeon’s perspective, Dr. Makary exposes the dangerous state of modern medical care across all specialties. I recommend it as a sobering assessment of the way things are and as a prescription for health care systems and physicians to help them become more reliable.

How are you driving safety in your area? What are some best practices we can share with others? I invite you to reply to [email protected] to initiate a broader discussion of patient safety and reliability. Responses will be posted to hematologynews.com.

Dr. Kalaycio is Editor in Chief of Hematology News. Dr. Kalaycio chairs the department of hematologic oncology and blood disorders at Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute. Contact him at [email protected].

When the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations came to our hospital for a survey last fall, our administration was confident that the review would be favorable. The Joint Commission was stressing the reliability of hospitals and so were we. We had chartered a “High-Reliability Organization Enterprise Steering Committee” that was “empowered to make recommendations to the (executive board) on what is needed to achieve the goals of high reliability across the enterprise.” High reliability was a priority for our administration and for the Joint Commission. Unfortunately, nearly no one else knew what high reliability meant.

In 2001, Karl E. Weick and Kathleen M. Sutcliffe published their book, “Managing the Unexpected: Resilient Performance in an Age of Uncertainty,” (Hoboken, N.J.: Jossey-Bass, 2001), which defined high-reliability organizations as those that reliably prevent error. They included examples from the military and from aviation. They proffered five principles to guide those organizations wishing to become highly reliable:

1. Preoccupation with failure.

2. Reluctance to simplify interpretations.

3. Sensitivity to operations.

4. Commitment to resilience.

5. Deference to expertise.

In September 2005, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality created a document to adapt the concepts developed by Mr. Weick and Ms. Sutcliffe to the health care industry, where opportunities to avoid error and prevent catastrophe abound. The eventual result has been steady progress in measuring avoidable health care errors, such as avoiding central line–associated blood stream infections and holding health care organizations accountable for their reduction. However, organizational cultures are difficult to change, and there is still a long way to go.

In contrast to large systems, individual providers can change quickly, especially if there is incentive to do so. What principles would increase our own ability to become a high-reliability individuals (HRIs):

• Recognize failure as systemic, not personal. Health care providers are humans, and humans make mistakes. Unfortunately, we come from a tradition that rewards success and penalizes failure. Research shows that is better to recognize failure as something to be prevented next time rather than to be punished now. Admonitions to pay attention, focus more, and remember better rely on fallible humans and reliably fail. Systems solutions, such as checklists, timeouts, and hard stops reliably succeed. HRIs should blame error less often on people, and more often on system failures.

• Simple solutions are preferred to complex requirements. Chemotherapy was once calculated and written by hand. Every cancer center can recall tragic disasters that occurred as a result of errors either by the ordering physician or by interpretations made by pharmacists and nurses. The introduction of electronic chemotherapy ordering has nearly eliminated these mistakes. HRIs can initiate technology solutions to their work to help reduce the risk of errors.

• Sensitivity to patients. Patients often desire to be included as partners in their care. In addition to being present and attentive to patients, why not enlist them as colleagues in care? For example, the patient who has their own calendar of chemotherapy treatments – complete with agents, doses, and schedules – will be more likely to question perceived errors. HRIs are transparent.

• Resilience in character. Learning to accept the potential for error requires acceptance that others also are trying to prevent error and are not judging your competence. The physician who attacks those who are trying to help reduces the psychological safety required for colleagues to speak up when potential errors are identified. Physicians will become HRIs only when they lower their defenses and become more teammates rather than a soloists.

• Deference to evidence. The “way it has always been” must give way to the way things are. Anecdotes and personal conviction do not meet scientific standards and should be abandoned in the face of evidence. Yet, this seemingly obvious principle often is disregarded when clinicians are presented with standardized treatment pathways and limited formularies in the name of autonomy; autonomy is fine until patients are endangered by it. The HRI practices evidence-based medicine.

Marty Makary, MD, explores most of these principles in his book “Unaccountable: What Hospitals Won’t Tell You and How Transparency Can Revolutionize Health Care”(London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2012). While written from a surgeon’s perspective, Dr. Makary exposes the dangerous state of modern medical care across all specialties. I recommend it as a sobering assessment of the way things are and as a prescription for health care systems and physicians to help them become more reliable.

How are you driving safety in your area? What are some best practices we can share with others? I invite you to reply to [email protected] to initiate a broader discussion of patient safety and reliability. Responses will be posted to hematologynews.com.

Dr. Kalaycio is Editor in Chief of Hematology News. Dr. Kalaycio chairs the department of hematologic oncology and blood disorders at Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute. Contact him at [email protected].

Blending classic clinical skills with new technology

Now that we can order MRI studies on a break from rounds walking to Starbucks, utilize portable ultrasounds to direct IV line placement, and use dual-energy CT to detect a gout attack that has not yet occurred, it seems like a romantic anachronism to extol the ongoing virtues of the seemingly lost art of the physical examination. Back “in the day,” the giants of medicine roamed the halls with their natural instruments of palpation and percussion and their skills in observation and auscultation. They were giants because they stood out then, just as skilled diagnosticians stand out today using an upgraded set of tools. Some physicians a few decades ago were able to recognize, describe, and diagnose late-stage endocarditis with a stethoscope, a magnifying glass, and an ophthalmoscope. The giants of today recognize the patient with endocarditis and document its presence using transesophageal echocardiography before the peripheral eponymous stigmata of Janeway and Osler appear or the blood cultures turn positive. The physical examination, history, diagnostic reasoning, and clinical technology are all essential for a blend that provides efficient and effective medical care. The blending is the challenge.

Clinicians are not created equal. We learn and prioritize our skills in different ways. But if we are not taught to value and trust the physical examination, if we don’t have the opportunity to see it influence patient management in positive ways, we may eschew it and instead indiscriminately use easily available laboratory and imaging tests—a more expensive and often misleading strategic approach. Today while in clinic, I saw a 54-year-old woman for evaluation of possible lupus who had arthritis of the hands and a high positive antinuclear antibody titer, but negative or normal results on other, previously ordered tests, including anti-DNA, rheumatoid factor, anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide, hepatitis C studies, complement levels, and another half-dozen immune serologic tests. On examination, she had typical nodular osteoarthritis of the proximal and distal interphalangeal joints of her hand with squaring of her thumbs. The antinuclear antibody was most likely associated with her previously diagnosed autoimmune thyroid disease.

In an editorial in this issue of the Journal, Dr. Salvatore Mangione, the author of a book on physical diagnosis,1 cites a recent study indicating that the most common recognized diagnostic error related to the physical examination is that the appropriate examination isn’t done.2 I would add to that my concerns over the new common custom of cutting and pasting the findings from earlier physical examinations into later progress notes in the electronic record. So much for the value of being able to recognize “changing murmurs” when diagnosing infectious endocarditis.

The apparent efficiency (reflected in length of stay) and availability of technology, as well as a lack of physician skill and time, are often cited as reasons for the demise of the physical examination. Yet this does not need to be the case. If I had trained with portable ultrasonography readily available to confirm or refute my impressions, my skills at detecting low-grade synovitis would surely be better than they are. With a gold standard at hand, which may be technology or at times a skilled mentor, our examinations can be refined if we want them to be.

But the issue of limited physician time must be addressed. Efficiency is a critical concept in preserving how we practice and perform the physical examination. When we know what we are looking for, we are more likely to find it if it is present, or to have confidence that it is not present. I am far more likely to recognize a loud pulmonic second heart sound if I suspect that the dyspneic patient I am examining has pulmonary hypertension associated with her scleroderma than if I am doing a perfunctory cardiac auscultation in a patient admitted with cellulitis. Appropriate focus provides power to the directed physical examination. If I am looking for the cause of unexplained fevers, I will do a purposeful axillary and epitrochlear lymph node examination. I am not mindlessly probing the flesh.

Nishigori and colleagues have written of the “hypothesis-driven” physical examination.3 Busy clinicians, they say, don’t have time to perform a head-to-toe, by-the-book physical examination. Instead, we should, by a dynamic process, formulate a differential diagnosis from the history and other initial information, and then perform the directed physical examination in earnest, looking for evidence to support or refute our diagnostic hypothesis—and thus redirect it. Plus, in a nice break from electronic charting, we can actually explain our thought processes to the patient as we perform the examination.

This approach makes sense to me as both intellectually satisfying and clinically efficient. And then we can consider which lab tests and technologic gadgetry we should order, while walking to get the café latte we ordered with our cell phone app.

New technology can support and not necessarily replace old habits.

- Mangione S. Physical Diagnosis Secrets, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Mosby/Elsevier, 2008.

- Verghese A, Charlton B, Kassirer JP, Ramsey M, Ioannidis JP. Inadequacies of physical examination as a cause of medical errors and adverse events: a collection of vignettes. Am J Med 2015; 128:1322–1324.

- Nishigori H, Masuda K, Kikukawa M, et al. A model teaching session for the hypothesis-driven physical examination. Medical Teacher 2011; 33:410–417.

Now that we can order MRI studies on a break from rounds walking to Starbucks, utilize portable ultrasounds to direct IV line placement, and use dual-energy CT to detect a gout attack that has not yet occurred, it seems like a romantic anachronism to extol the ongoing virtues of the seemingly lost art of the physical examination. Back “in the day,” the giants of medicine roamed the halls with their natural instruments of palpation and percussion and their skills in observation and auscultation. They were giants because they stood out then, just as skilled diagnosticians stand out today using an upgraded set of tools. Some physicians a few decades ago were able to recognize, describe, and diagnose late-stage endocarditis with a stethoscope, a magnifying glass, and an ophthalmoscope. The giants of today recognize the patient with endocarditis and document its presence using transesophageal echocardiography before the peripheral eponymous stigmata of Janeway and Osler appear or the blood cultures turn positive. The physical examination, history, diagnostic reasoning, and clinical technology are all essential for a blend that provides efficient and effective medical care. The blending is the challenge.

Clinicians are not created equal. We learn and prioritize our skills in different ways. But if we are not taught to value and trust the physical examination, if we don’t have the opportunity to see it influence patient management in positive ways, we may eschew it and instead indiscriminately use easily available laboratory and imaging tests—a more expensive and often misleading strategic approach. Today while in clinic, I saw a 54-year-old woman for evaluation of possible lupus who had arthritis of the hands and a high positive antinuclear antibody titer, but negative or normal results on other, previously ordered tests, including anti-DNA, rheumatoid factor, anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide, hepatitis C studies, complement levels, and another half-dozen immune serologic tests. On examination, she had typical nodular osteoarthritis of the proximal and distal interphalangeal joints of her hand with squaring of her thumbs. The antinuclear antibody was most likely associated with her previously diagnosed autoimmune thyroid disease.

In an editorial in this issue of the Journal, Dr. Salvatore Mangione, the author of a book on physical diagnosis,1 cites a recent study indicating that the most common recognized diagnostic error related to the physical examination is that the appropriate examination isn’t done.2 I would add to that my concerns over the new common custom of cutting and pasting the findings from earlier physical examinations into later progress notes in the electronic record. So much for the value of being able to recognize “changing murmurs” when diagnosing infectious endocarditis.

The apparent efficiency (reflected in length of stay) and availability of technology, as well as a lack of physician skill and time, are often cited as reasons for the demise of the physical examination. Yet this does not need to be the case. If I had trained with portable ultrasonography readily available to confirm or refute my impressions, my skills at detecting low-grade synovitis would surely be better than they are. With a gold standard at hand, which may be technology or at times a skilled mentor, our examinations can be refined if we want them to be.

But the issue of limited physician time must be addressed. Efficiency is a critical concept in preserving how we practice and perform the physical examination. When we know what we are looking for, we are more likely to find it if it is present, or to have confidence that it is not present. I am far more likely to recognize a loud pulmonic second heart sound if I suspect that the dyspneic patient I am examining has pulmonary hypertension associated with her scleroderma than if I am doing a perfunctory cardiac auscultation in a patient admitted with cellulitis. Appropriate focus provides power to the directed physical examination. If I am looking for the cause of unexplained fevers, I will do a purposeful axillary and epitrochlear lymph node examination. I am not mindlessly probing the flesh.

Nishigori and colleagues have written of the “hypothesis-driven” physical examination.3 Busy clinicians, they say, don’t have time to perform a head-to-toe, by-the-book physical examination. Instead, we should, by a dynamic process, formulate a differential diagnosis from the history and other initial information, and then perform the directed physical examination in earnest, looking for evidence to support or refute our diagnostic hypothesis—and thus redirect it. Plus, in a nice break from electronic charting, we can actually explain our thought processes to the patient as we perform the examination.

This approach makes sense to me as both intellectually satisfying and clinically efficient. And then we can consider which lab tests and technologic gadgetry we should order, while walking to get the café latte we ordered with our cell phone app.

New technology can support and not necessarily replace old habits.

Now that we can order MRI studies on a break from rounds walking to Starbucks, utilize portable ultrasounds to direct IV line placement, and use dual-energy CT to detect a gout attack that has not yet occurred, it seems like a romantic anachronism to extol the ongoing virtues of the seemingly lost art of the physical examination. Back “in the day,” the giants of medicine roamed the halls with their natural instruments of palpation and percussion and their skills in observation and auscultation. They were giants because they stood out then, just as skilled diagnosticians stand out today using an upgraded set of tools. Some physicians a few decades ago were able to recognize, describe, and diagnose late-stage endocarditis with a stethoscope, a magnifying glass, and an ophthalmoscope. The giants of today recognize the patient with endocarditis and document its presence using transesophageal echocardiography before the peripheral eponymous stigmata of Janeway and Osler appear or the blood cultures turn positive. The physical examination, history, diagnostic reasoning, and clinical technology are all essential for a blend that provides efficient and effective medical care. The blending is the challenge.

Clinicians are not created equal. We learn and prioritize our skills in different ways. But if we are not taught to value and trust the physical examination, if we don’t have the opportunity to see it influence patient management in positive ways, we may eschew it and instead indiscriminately use easily available laboratory and imaging tests—a more expensive and often misleading strategic approach. Today while in clinic, I saw a 54-year-old woman for evaluation of possible lupus who had arthritis of the hands and a high positive antinuclear antibody titer, but negative or normal results on other, previously ordered tests, including anti-DNA, rheumatoid factor, anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide, hepatitis C studies, complement levels, and another half-dozen immune serologic tests. On examination, she had typical nodular osteoarthritis of the proximal and distal interphalangeal joints of her hand with squaring of her thumbs. The antinuclear antibody was most likely associated with her previously diagnosed autoimmune thyroid disease.

In an editorial in this issue of the Journal, Dr. Salvatore Mangione, the author of a book on physical diagnosis,1 cites a recent study indicating that the most common recognized diagnostic error related to the physical examination is that the appropriate examination isn’t done.2 I would add to that my concerns over the new common custom of cutting and pasting the findings from earlier physical examinations into later progress notes in the electronic record. So much for the value of being able to recognize “changing murmurs” when diagnosing infectious endocarditis.

The apparent efficiency (reflected in length of stay) and availability of technology, as well as a lack of physician skill and time, are often cited as reasons for the demise of the physical examination. Yet this does not need to be the case. If I had trained with portable ultrasonography readily available to confirm or refute my impressions, my skills at detecting low-grade synovitis would surely be better than they are. With a gold standard at hand, which may be technology or at times a skilled mentor, our examinations can be refined if we want them to be.

But the issue of limited physician time must be addressed. Efficiency is a critical concept in preserving how we practice and perform the physical examination. When we know what we are looking for, we are more likely to find it if it is present, or to have confidence that it is not present. I am far more likely to recognize a loud pulmonic second heart sound if I suspect that the dyspneic patient I am examining has pulmonary hypertension associated with her scleroderma than if I am doing a perfunctory cardiac auscultation in a patient admitted with cellulitis. Appropriate focus provides power to the directed physical examination. If I am looking for the cause of unexplained fevers, I will do a purposeful axillary and epitrochlear lymph node examination. I am not mindlessly probing the flesh.

Nishigori and colleagues have written of the “hypothesis-driven” physical examination.3 Busy clinicians, they say, don’t have time to perform a head-to-toe, by-the-book physical examination. Instead, we should, by a dynamic process, formulate a differential diagnosis from the history and other initial information, and then perform the directed physical examination in earnest, looking for evidence to support or refute our diagnostic hypothesis—and thus redirect it. Plus, in a nice break from electronic charting, we can actually explain our thought processes to the patient as we perform the examination.

This approach makes sense to me as both intellectually satisfying and clinically efficient. And then we can consider which lab tests and technologic gadgetry we should order, while walking to get the café latte we ordered with our cell phone app.

New technology can support and not necessarily replace old habits.

- Mangione S. Physical Diagnosis Secrets, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Mosby/Elsevier, 2008.

- Verghese A, Charlton B, Kassirer JP, Ramsey M, Ioannidis JP. Inadequacies of physical examination as a cause of medical errors and adverse events: a collection of vignettes. Am J Med 2015; 128:1322–1324.

- Nishigori H, Masuda K, Kikukawa M, et al. A model teaching session for the hypothesis-driven physical examination. Medical Teacher 2011; 33:410–417.

- Mangione S. Physical Diagnosis Secrets, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Mosby/Elsevier, 2008.

- Verghese A, Charlton B, Kassirer JP, Ramsey M, Ioannidis JP. Inadequacies of physical examination as a cause of medical errors and adverse events: a collection of vignettes. Am J Med 2015; 128:1322–1324.

- Nishigori H, Masuda K, Kikukawa M, et al. A model teaching session for the hypothesis-driven physical examination. Medical Teacher 2011; 33:410–417.

Treating polycystic ovary syndrome: Start using dual medical therapy

Using the Rotterdam criteria, the diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is made in the presence of 2 of the following 3 criteria1:

- oligo-ovulation or anovulation

- hyperandrogenism manifested by the presence of either hirsutism or elevated hormone levels (including serum testosterone androstenedione and/or dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate)

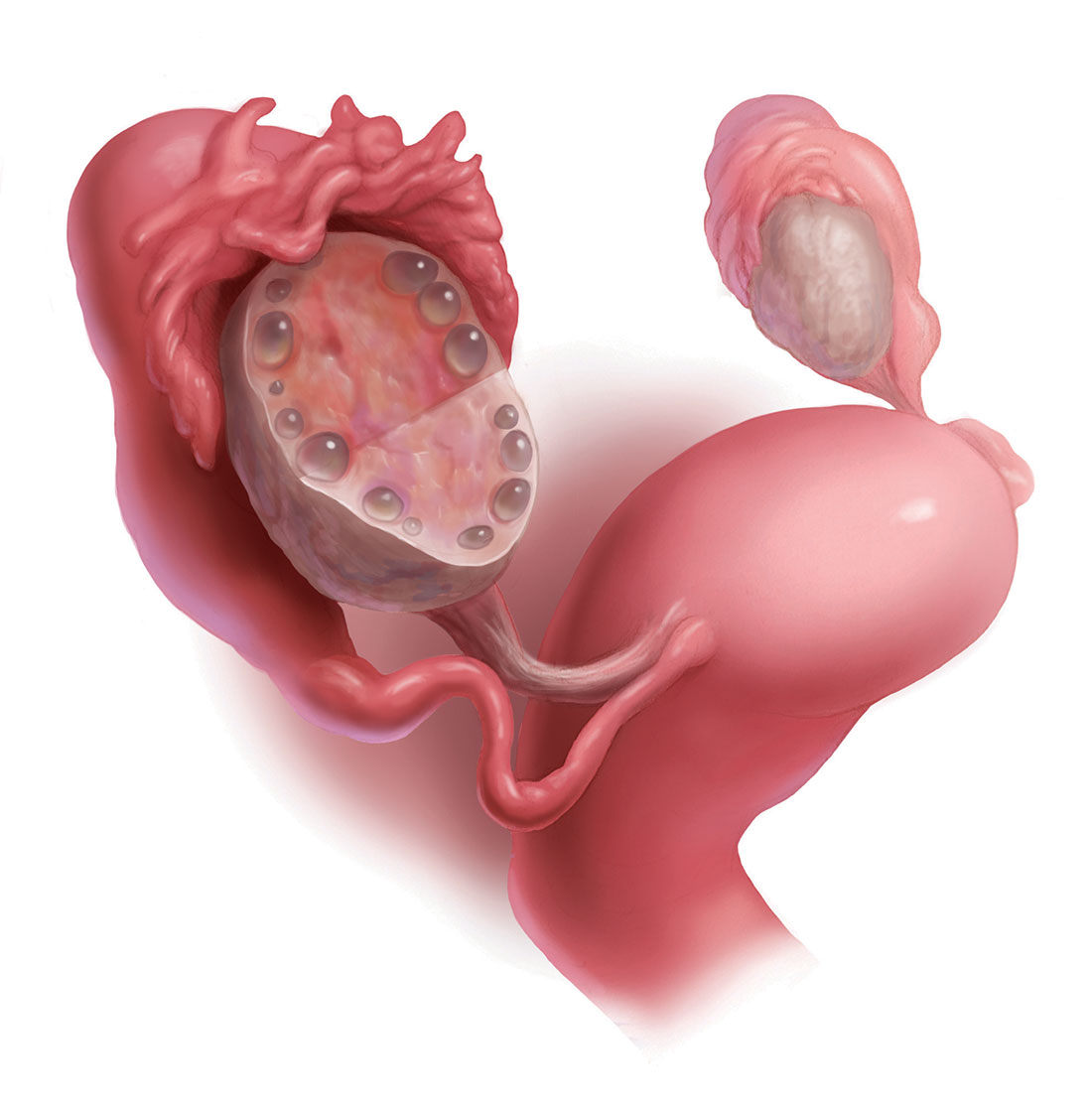

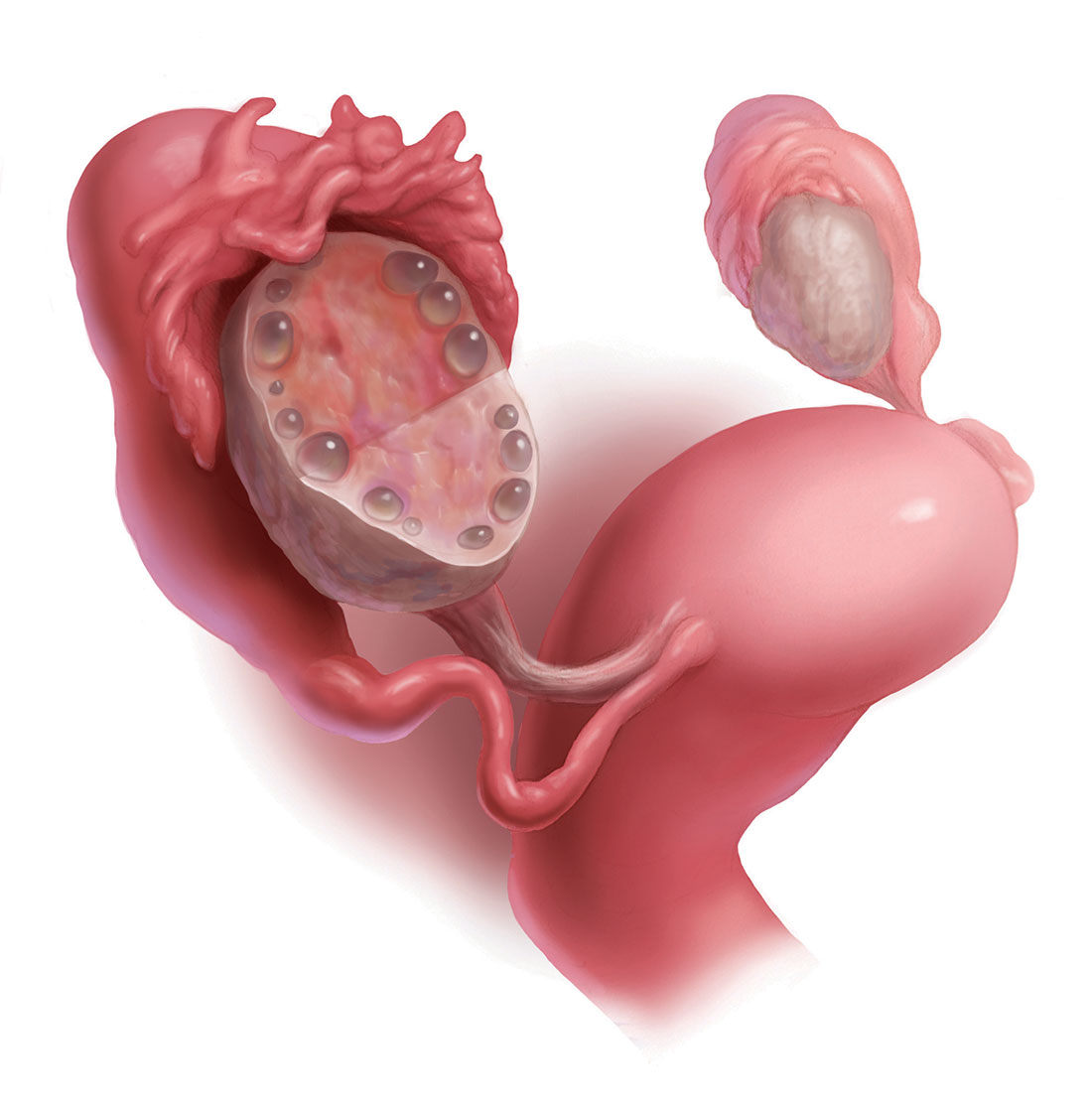

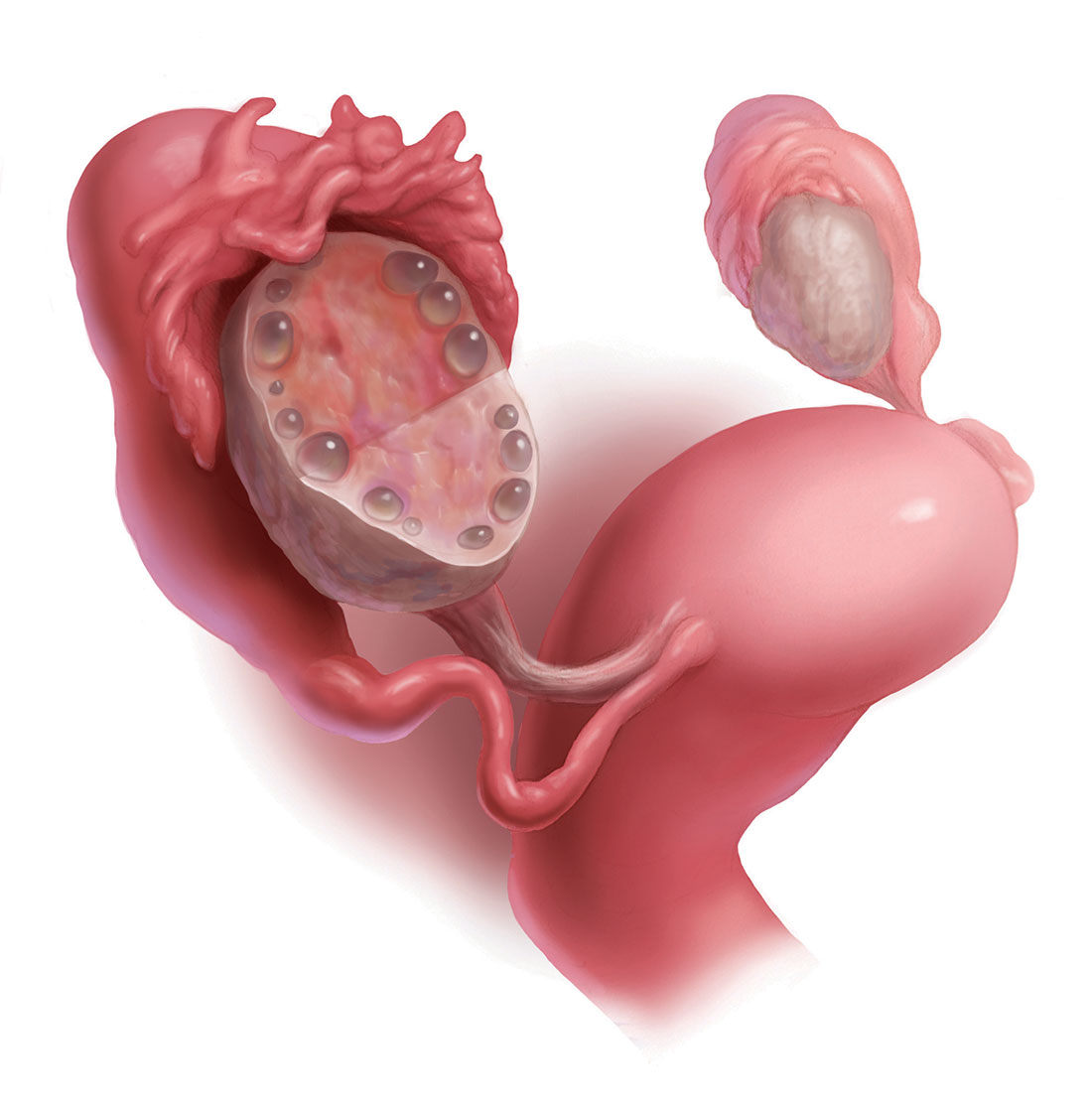

- ultrasonography evidence of multifollicular ovaries (≥12 follicles with a diameter of 2 mm to 9 mm in one or both ovaries; FIGURE) or ovarian stromal volume of 10 mL or more.

Among reproductive-age women, the prevalence of PCOS has been reported to range from 8% to 13% for different populations.2 Most clinicians initiate treatment for PCOS with oral estrogen−progestin (OEP) monotherapy. OEP treatment has many beneficial hormonal effects, including:

- a resulting decrease in pituitary luteinizing hormone (LH) secretion, which decreases ovarian androgen production

- an increase in liver production of sex hormone−binding globulin (SHBG), which decreases free testosterone levels

- protection against the development of endometrial hyperplasia

- induction of regular uterine withdrawal bleeding.

However, OEP therapy neither improves metabolic indices (insulin sensitivity and visceral fat secretion of adipokines) nor blocks androgen action in the skin.

Dual medical treatment for PCOS can address the issues that monotherapy cannot and, along with providing guidance on improving diet and exercise, many experts support the initial therapy of PCOS with dual medical therapy (OEP plus metformin or spironolactone).

Advantages of OEP plus metformin

For many women with PCOS, the syndrome is characterized by abnormalities in both the reproductive (increase in LH secretion) and metabolic (insulin resistance and increased adipokines) systems. OEP monotherapy does not improve the metabolic abnormalities of PCOS. Combination treatment with both OEP plus metformin, along with diet and exercise, can best treat these combined abnormalities.

Data support dual therapy with metformin. In one small, randomized trial in women with PCOS, OEP plus metformin (1,500 mg daily) resulted in a greater reduction in serum androstenedione and a greater increase in SHBG than OEP monotherapy.3 In addition, weight loss and a reduction in waist-to-hip ratio only occurred in the OEP plus metformin group.3 In another small randomized study in women with PCOS, OEP plus metformin (1,500 mg daily) resulted in a greater decrease in free androgen index than OEP monotherapy.4

In my clinical opinion, women who may best benefit from OEP plus metformin therapy have one of the following factors indicating the presence of insulin resistance5:

- body mass index >30 kg/m2

- waist-to-hip ratio ≥0.85

- waist circumference >35 in (89 cm)

- acanthosis nigricans

- personal history of gestational diabetes

- family history of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in a first-degree relative

- diagnosis of the metabolic syndrome.

My preferred treatment approach

Metformin is a low cost and safe treatment for metabolic dysfunction due to insulin resistance and excess adipokines. I often start PCOS treatment for my patients with an OEP plus metformin extended release (XR) 750 mg with dinner. If the patient tolerates this dose, I increase the dose to metformin XR 1,500 mg with dinner.

Adverse effects. The most common side effects of metformin are gastrointestinal, including abdominal discomfort, flatulence, borborygmi, diarrhea, and nausea. Metformin reduces serum vitamin B12 levels by 5% to 10%; therefore, ensuring adequate vitamin B12 intake (2.6 µg daily) is helpful.6 Although metformin does reduce vitamin B12 levels, there is no strong relationship between metformin and anemia or peripheral neuropathy.7 Lactic acidosis is a rare complication of metformin.

Beneficial effects. In the treatment of PCOS, metformin may have many beneficial effects, including8:

- decrease in insulin resistance

- decrease in harmful adipokines

- reduction in visceral fat

- reduction in the incidence of T2DM.

- oral norethindrone acetate 5 mg daily (which can lower luteinizing hormone levels and block ovulation) plus metformin

- norethindrone acetate 5 mg plus spironolactone

- levonorgestrel-intrauterine device plus metformin or spironolactone.

OEP plus spironolactone

Many women with PCOS have increased LH secretion and increased androgen activity in the skin due to increased 5-alpha reductase enzyme activity, which catalyzes the conversion of testosterone to the powerful intracellular androgen dihydrotestosterone.9 Women with PCOS may present with a chief problem report of hirsutism, acne, or female androgenetic alopecia. OEP plus spironolactone may be an optimal initial treatment for women with a dominant dermatologic manifestation of PCOS. OEP treatment results in a decrease in pituitary LH secretion and ovarian androgen production. Spironolactone adds to this therapeutic effect by blocking androgen action in the skin.

The data on dual therapy with spironolactone. Many dermatologists recommend spironolactone in combination with cosmetic measures for the treatment of acne, but there are only a few randomized trials that demonstrate its efficacy.10 In one trial spironolactone was demonstrated to be superior to placebo for the treatment of inflammatory acne.10 Authors of multiple randomized trials report that the antiandrogens, spironolactone, or finasteride are superior to metformin to treat hirsutism.11 In addition, a few small trials report that spironolactone plus OEP is superior to either OEP or metformin monotherapy for hirsutism.11 Clinical trials of spironolactone for hirsutism have been rated as “low quality” and additional controlled trials of OEP monotherapy versus OEP plus spironolactone are warranted.12

My preferred treatment approach

Spironolactone is effective in the treatment of hirsutism at doses ranging from 50 mg to 200 mg daily. I routinely use a dose of spironolactone 100 mg daily because this dose is near of the top of the dose-response curve and has few adverse effects (such as intermittent uterine bleeding or spotting). With spironolactone monotherapy at a dose of 200 mg, irregular uterine bleeding or spotting is common, but concomitant treatment with an OEP tends to minimize this side effect. In my practice I rarely have patients report irregular uterine bleeding or spotting with the combination treatment of an OEP and spironolactone 100 mg daily.

Contraindications. Spironolactone should not be given to women with renal insufficiency because it can cause hyperkalemia. However, it is not necessary to check potassium levels in young women taking spironolactone with normal creatinine levels.13

Triple therapy: OEP plus metformin plus spironolactone

Some experts strongly recommend the initial treatment of PCOS in adolescents and young women with triple therapy: OEP plus an insulin sensitizer plus an antiandrogen.14 This recommendation is based in part on the observation that OEP monotherapy may be associated with an increase in circulating adipokines and visceral fat mass as determined by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry.15 By contrast, triple treatment with an OEP plus metformin plus an antiandrogen is associated with a decrease in circulating adipokines and visceral fat mass.

What is the best progestin for PCOS?

Any OEP is better than no OEP, regardless of the progestin used to treat the PCOS because ethinyl estradiol plus any synthetic progestin suppresses pituitary secretion of LH and decreases ovarian androgen production. However, for the treatment of acne, using a progestin that is less androgenic may be beneficial.16

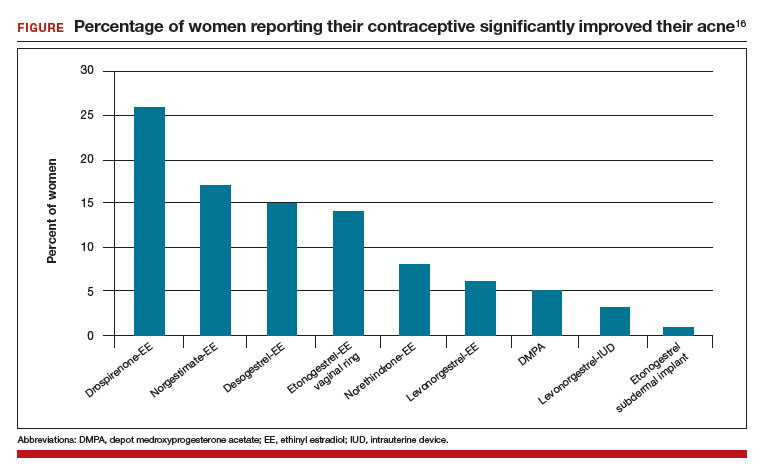

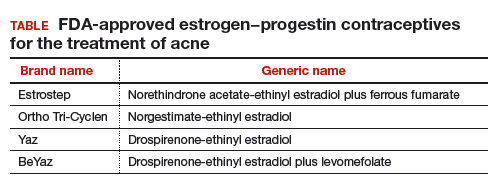

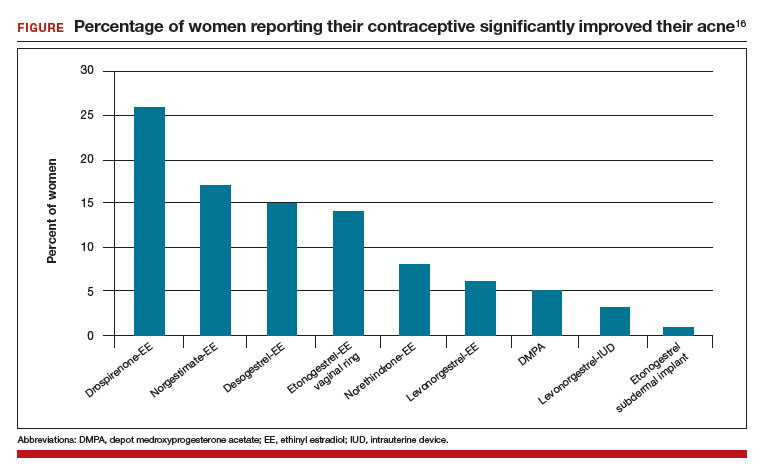

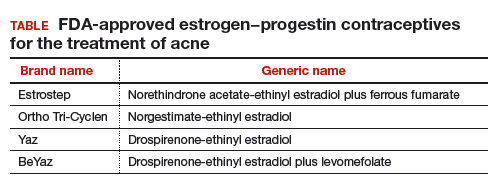

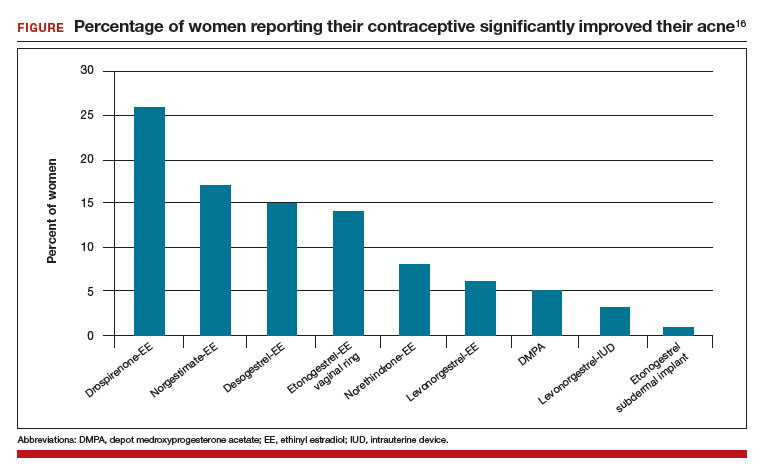

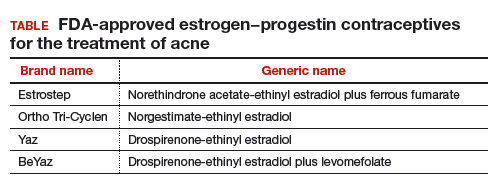

In one study, 2,147 consecutive women who were taking a contraceptive and presented for treatment of acne were asked if their contraceptive had a positive impact on their acne. The percentage of women reporting that their contraceptive significantly improved their acne ranged from 26% for those taking drospirenone-ethinyl estradiol (EE) to 1% for those taking the etonogestrel subdermal implant (FIGURE).16 The US Food and Drug Administration has approved 4 OEP contraceptives for the treatment of acne (TABLE). The OEPs with drospirenone, norgestimate, desogestrel, or norethindrone acetate may be optimal choices for the treatment of acne caused by PCOS.

The bottom line

PCOS is a common endocrine disorder treated primarily by obstetricians-gynecologists. Among adolescents and young women with PCOS chief problem reports include irregular menses, hirsutism, obesity, acne, and infertility. Among mid-life women the presentation of PCOS often evolves into chronic medical problems, including obesity, metabolic syndrome, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, T2DM, cardiovascular disease, and endometrial cancer.17–19 To optimally treat the multiple pathophysiologic disorders manifested in PCOS, I recommend initial dual medical therapy with an OEP plus metformin or an OEP plus spironolactone.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Hum Reprod. 2004;19(1):41-47.

- Bozdag G, Mumusoglu S, Zengin D, Karabulut E, Yildiz BO. The prevalence and phenotypic features of polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(12):2841-2855.

- Elter K, Imir G, Durmusoglu F. Clinical, endocrine and metabolic effects of metformin added to ethinyl estradiol-cyproterone acetate in non-obese women with polycystic ovarian syndrome: a randomized controlled study. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(7):1729-1737.

- Cibula D, Fanta M, Vrbikova J, et al. The effect of combination therapy with metformin and combined oral contraceptives (COC) versus COC alone on insulin sensitivity, hyperandrogenism, SHBG and lipids in PCOS patients. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(1):180-184.

- Grundy SM, Brewer HB, Cleeman JI, Smith SC Jr, Lenfant C; American Heart Association; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Definition of metabolic syndrome: Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Circulation. 2004;109(3):433-438.

- Niafar M, Hai F, Porhomayon J, Nader ND. The role of metformin on vitamin B12 deficiency: a meta-analysis review. Intern Emerg Med. 2015;10(1):93-102.

- de Groot-Kamphuis DM, van Dijk PR, Groenier KH, Houweling St, Bilo HJ, Kleefstra N. Vitamin B12 deficiency and the lack of its consequences in type 2 diabetes patients using metformin. Neth J Med. 2013;71(7):386-390.

- Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Christakou CD, Kandaraki E, Economou FN. Metformin: an old medication of new fashion: evolving new molecular mechanisms and clinical implications in polycystic ovary syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol. 2010;162(2):193-212.

- Skalba P, Dabkowska-Huc A, Kazimierczak W, Samojedny A, Samojedny MP, Chelmicki Z. Content of 5-alph-reductase (type 1 and type 2) mRNA in dermal papillae from the lower abdominal region in women with hirsutism. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31(4):564-570.

- Layton AM, Eady EA, Whitehouse H, Del Rosso JQ, Fedorowicz Z, van Zuuren EJ. Oral spironolactone for acne vulgaris in adult females: a hybrid systematic review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18(2):169-191.

- Swiglo BA, Cosma M, Flynn DN, et al. Clinical review: antiandrogens for the treatment of hirsutism: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(4):1153-1160.

- van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z. Interventions for hirsutism excluding laser and photoepilation therapy alone: abridged Cochrane systematic review including GRADE assessments. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175(1):45-61.

- Plovanich M, Weng QY, Mostaghimi A. Low usefulness of potassium monitoring among healthy young women taking spironolactone for acne. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(9):941-944.

- Ibanez L, de Zegher F. Low-dose combination of flutamide, metformin and an oral contraceptive for non-obese, young women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(1):57-60.

- Ibanez L, de Zegher F. Ethinyl estradiol-drospirenone, flutamide-metformin or both for adolescents and women with hyperinsulinemic hyperandrogenism: opposite effects on adipocytokines and body adiposity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(4):1592-1597.

- Lortscher D, Admani S, Stur N, Eichenfield LF. Hormonal contraceptives and acne: a retrospective analysis of 2147 patients. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15(6):670-674.

- Wang ET, Calderon-Margalit R, Cedars MI, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome and risk for long-term diabetes and dyslipidemia. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(1):6-13.

- Joham AE, Raniasinha S, Zoungas S, Moran L, Teede HJ. Gestational diabetes and type 2 diabetes in reproductive aged women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(3):e447-e452.

- Gottschau M, Kjaer SK, Jensen A, Munk C, Mellemkjaer L. Risk of cancer among women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a Danish cohort study. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136(1):99-103.

Using the Rotterdam criteria, the diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is made in the presence of 2 of the following 3 criteria1:

- oligo-ovulation or anovulation

- hyperandrogenism manifested by the presence of either hirsutism or elevated hormone levels (including serum testosterone androstenedione and/or dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate)

- ultrasonography evidence of multifollicular ovaries (≥12 follicles with a diameter of 2 mm to 9 mm in one or both ovaries; FIGURE) or ovarian stromal volume of 10 mL or more.

Among reproductive-age women, the prevalence of PCOS has been reported to range from 8% to 13% for different populations.2 Most clinicians initiate treatment for PCOS with oral estrogen−progestin (OEP) monotherapy. OEP treatment has many beneficial hormonal effects, including:

- a resulting decrease in pituitary luteinizing hormone (LH) secretion, which decreases ovarian androgen production

- an increase in liver production of sex hormone−binding globulin (SHBG), which decreases free testosterone levels

- protection against the development of endometrial hyperplasia

- induction of regular uterine withdrawal bleeding.

However, OEP therapy neither improves metabolic indices (insulin sensitivity and visceral fat secretion of adipokines) nor blocks androgen action in the skin.

Dual medical treatment for PCOS can address the issues that monotherapy cannot and, along with providing guidance on improving diet and exercise, many experts support the initial therapy of PCOS with dual medical therapy (OEP plus metformin or spironolactone).

Advantages of OEP plus metformin

For many women with PCOS, the syndrome is characterized by abnormalities in both the reproductive (increase in LH secretion) and metabolic (insulin resistance and increased adipokines) systems. OEP monotherapy does not improve the metabolic abnormalities of PCOS. Combination treatment with both OEP plus metformin, along with diet and exercise, can best treat these combined abnormalities.

Data support dual therapy with metformin. In one small, randomized trial in women with PCOS, OEP plus metformin (1,500 mg daily) resulted in a greater reduction in serum androstenedione and a greater increase in SHBG than OEP monotherapy.3 In addition, weight loss and a reduction in waist-to-hip ratio only occurred in the OEP plus metformin group.3 In another small randomized study in women with PCOS, OEP plus metformin (1,500 mg daily) resulted in a greater decrease in free androgen index than OEP monotherapy.4

In my clinical opinion, women who may best benefit from OEP plus metformin therapy have one of the following factors indicating the presence of insulin resistance5:

- body mass index >30 kg/m2

- waist-to-hip ratio ≥0.85

- waist circumference >35 in (89 cm)

- acanthosis nigricans

- personal history of gestational diabetes

- family history of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in a first-degree relative

- diagnosis of the metabolic syndrome.

My preferred treatment approach

Metformin is a low cost and safe treatment for metabolic dysfunction due to insulin resistance and excess adipokines. I often start PCOS treatment for my patients with an OEP plus metformin extended release (XR) 750 mg with dinner. If the patient tolerates this dose, I increase the dose to metformin XR 1,500 mg with dinner.

Adverse effects. The most common side effects of metformin are gastrointestinal, including abdominal discomfort, flatulence, borborygmi, diarrhea, and nausea. Metformin reduces serum vitamin B12 levels by 5% to 10%; therefore, ensuring adequate vitamin B12 intake (2.6 µg daily) is helpful.6 Although metformin does reduce vitamin B12 levels, there is no strong relationship between metformin and anemia or peripheral neuropathy.7 Lactic acidosis is a rare complication of metformin.

Beneficial effects. In the treatment of PCOS, metformin may have many beneficial effects, including8:

- decrease in insulin resistance

- decrease in harmful adipokines

- reduction in visceral fat

- reduction in the incidence of T2DM.

- oral norethindrone acetate 5 mg daily (which can lower luteinizing hormone levels and block ovulation) plus metformin

- norethindrone acetate 5 mg plus spironolactone

- levonorgestrel-intrauterine device plus metformin or spironolactone.

OEP plus spironolactone

Many women with PCOS have increased LH secretion and increased androgen activity in the skin due to increased 5-alpha reductase enzyme activity, which catalyzes the conversion of testosterone to the powerful intracellular androgen dihydrotestosterone.9 Women with PCOS may present with a chief problem report of hirsutism, acne, or female androgenetic alopecia. OEP plus spironolactone may be an optimal initial treatment for women with a dominant dermatologic manifestation of PCOS. OEP treatment results in a decrease in pituitary LH secretion and ovarian androgen production. Spironolactone adds to this therapeutic effect by blocking androgen action in the skin.

The data on dual therapy with spironolactone. Many dermatologists recommend spironolactone in combination with cosmetic measures for the treatment of acne, but there are only a few randomized trials that demonstrate its efficacy.10 In one trial spironolactone was demonstrated to be superior to placebo for the treatment of inflammatory acne.10 Authors of multiple randomized trials report that the antiandrogens, spironolactone, or finasteride are superior to metformin to treat hirsutism.11 In addition, a few small trials report that spironolactone plus OEP is superior to either OEP or metformin monotherapy for hirsutism.11 Clinical trials of spironolactone for hirsutism have been rated as “low quality” and additional controlled trials of OEP monotherapy versus OEP plus spironolactone are warranted.12

My preferred treatment approach

Spironolactone is effective in the treatment of hirsutism at doses ranging from 50 mg to 200 mg daily. I routinely use a dose of spironolactone 100 mg daily because this dose is near of the top of the dose-response curve and has few adverse effects (such as intermittent uterine bleeding or spotting). With spironolactone monotherapy at a dose of 200 mg, irregular uterine bleeding or spotting is common, but concomitant treatment with an OEP tends to minimize this side effect. In my practice I rarely have patients report irregular uterine bleeding or spotting with the combination treatment of an OEP and spironolactone 100 mg daily.

Contraindications. Spironolactone should not be given to women with renal insufficiency because it can cause hyperkalemia. However, it is not necessary to check potassium levels in young women taking spironolactone with normal creatinine levels.13

Triple therapy: OEP plus metformin plus spironolactone

Some experts strongly recommend the initial treatment of PCOS in adolescents and young women with triple therapy: OEP plus an insulin sensitizer plus an antiandrogen.14 This recommendation is based in part on the observation that OEP monotherapy may be associated with an increase in circulating adipokines and visceral fat mass as determined by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry.15 By contrast, triple treatment with an OEP plus metformin plus an antiandrogen is associated with a decrease in circulating adipokines and visceral fat mass.

What is the best progestin for PCOS?

Any OEP is better than no OEP, regardless of the progestin used to treat the PCOS because ethinyl estradiol plus any synthetic progestin suppresses pituitary secretion of LH and decreases ovarian androgen production. However, for the treatment of acne, using a progestin that is less androgenic may be beneficial.16

In one study, 2,147 consecutive women who were taking a contraceptive and presented for treatment of acne were asked if their contraceptive had a positive impact on their acne. The percentage of women reporting that their contraceptive significantly improved their acne ranged from 26% for those taking drospirenone-ethinyl estradiol (EE) to 1% for those taking the etonogestrel subdermal implant (FIGURE).16 The US Food and Drug Administration has approved 4 OEP contraceptives for the treatment of acne (TABLE). The OEPs with drospirenone, norgestimate, desogestrel, or norethindrone acetate may be optimal choices for the treatment of acne caused by PCOS.

The bottom line

PCOS is a common endocrine disorder treated primarily by obstetricians-gynecologists. Among adolescents and young women with PCOS chief problem reports include irregular menses, hirsutism, obesity, acne, and infertility. Among mid-life women the presentation of PCOS often evolves into chronic medical problems, including obesity, metabolic syndrome, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, T2DM, cardiovascular disease, and endometrial cancer.17–19 To optimally treat the multiple pathophysiologic disorders manifested in PCOS, I recommend initial dual medical therapy with an OEP plus metformin or an OEP plus spironolactone.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Using the Rotterdam criteria, the diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is made in the presence of 2 of the following 3 criteria1:

- oligo-ovulation or anovulation

- hyperandrogenism manifested by the presence of either hirsutism or elevated hormone levels (including serum testosterone androstenedione and/or dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate)

- ultrasonography evidence of multifollicular ovaries (≥12 follicles with a diameter of 2 mm to 9 mm in one or both ovaries; FIGURE) or ovarian stromal volume of 10 mL or more.

Among reproductive-age women, the prevalence of PCOS has been reported to range from 8% to 13% for different populations.2 Most clinicians initiate treatment for PCOS with oral estrogen−progestin (OEP) monotherapy. OEP treatment has many beneficial hormonal effects, including:

- a resulting decrease in pituitary luteinizing hormone (LH) secretion, which decreases ovarian androgen production

- an increase in liver production of sex hormone−binding globulin (SHBG), which decreases free testosterone levels

- protection against the development of endometrial hyperplasia

- induction of regular uterine withdrawal bleeding.

However, OEP therapy neither improves metabolic indices (insulin sensitivity and visceral fat secretion of adipokines) nor blocks androgen action in the skin.

Dual medical treatment for PCOS can address the issues that monotherapy cannot and, along with providing guidance on improving diet and exercise, many experts support the initial therapy of PCOS with dual medical therapy (OEP plus metformin or spironolactone).

Advantages of OEP plus metformin

For many women with PCOS, the syndrome is characterized by abnormalities in both the reproductive (increase in LH secretion) and metabolic (insulin resistance and increased adipokines) systems. OEP monotherapy does not improve the metabolic abnormalities of PCOS. Combination treatment with both OEP plus metformin, along with diet and exercise, can best treat these combined abnormalities.

Data support dual therapy with metformin. In one small, randomized trial in women with PCOS, OEP plus metformin (1,500 mg daily) resulted in a greater reduction in serum androstenedione and a greater increase in SHBG than OEP monotherapy.3 In addition, weight loss and a reduction in waist-to-hip ratio only occurred in the OEP plus metformin group.3 In another small randomized study in women with PCOS, OEP plus metformin (1,500 mg daily) resulted in a greater decrease in free androgen index than OEP monotherapy.4

In my clinical opinion, women who may best benefit from OEP plus metformin therapy have one of the following factors indicating the presence of insulin resistance5:

- body mass index >30 kg/m2

- waist-to-hip ratio ≥0.85

- waist circumference >35 in (89 cm)

- acanthosis nigricans

- personal history of gestational diabetes

- family history of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in a first-degree relative

- diagnosis of the metabolic syndrome.

My preferred treatment approach

Metformin is a low cost and safe treatment for metabolic dysfunction due to insulin resistance and excess adipokines. I often start PCOS treatment for my patients with an OEP plus metformin extended release (XR) 750 mg with dinner. If the patient tolerates this dose, I increase the dose to metformin XR 1,500 mg with dinner.

Adverse effects. The most common side effects of metformin are gastrointestinal, including abdominal discomfort, flatulence, borborygmi, diarrhea, and nausea. Metformin reduces serum vitamin B12 levels by 5% to 10%; therefore, ensuring adequate vitamin B12 intake (2.6 µg daily) is helpful.6 Although metformin does reduce vitamin B12 levels, there is no strong relationship between metformin and anemia or peripheral neuropathy.7 Lactic acidosis is a rare complication of metformin.

Beneficial effects. In the treatment of PCOS, metformin may have many beneficial effects, including8:

- decrease in insulin resistance

- decrease in harmful adipokines

- reduction in visceral fat

- reduction in the incidence of T2DM.

- oral norethindrone acetate 5 mg daily (which can lower luteinizing hormone levels and block ovulation) plus metformin

- norethindrone acetate 5 mg plus spironolactone

- levonorgestrel-intrauterine device plus metformin or spironolactone.

OEP plus spironolactone

Many women with PCOS have increased LH secretion and increased androgen activity in the skin due to increased 5-alpha reductase enzyme activity, which catalyzes the conversion of testosterone to the powerful intracellular androgen dihydrotestosterone.9 Women with PCOS may present with a chief problem report of hirsutism, acne, or female androgenetic alopecia. OEP plus spironolactone may be an optimal initial treatment for women with a dominant dermatologic manifestation of PCOS. OEP treatment results in a decrease in pituitary LH secretion and ovarian androgen production. Spironolactone adds to this therapeutic effect by blocking androgen action in the skin.

The data on dual therapy with spironolactone. Many dermatologists recommend spironolactone in combination with cosmetic measures for the treatment of acne, but there are only a few randomized trials that demonstrate its efficacy.10 In one trial spironolactone was demonstrated to be superior to placebo for the treatment of inflammatory acne.10 Authors of multiple randomized trials report that the antiandrogens, spironolactone, or finasteride are superior to metformin to treat hirsutism.11 In addition, a few small trials report that spironolactone plus OEP is superior to either OEP or metformin monotherapy for hirsutism.11 Clinical trials of spironolactone for hirsutism have been rated as “low quality” and additional controlled trials of OEP monotherapy versus OEP plus spironolactone are warranted.12

My preferred treatment approach

Spironolactone is effective in the treatment of hirsutism at doses ranging from 50 mg to 200 mg daily. I routinely use a dose of spironolactone 100 mg daily because this dose is near of the top of the dose-response curve and has few adverse effects (such as intermittent uterine bleeding or spotting). With spironolactone monotherapy at a dose of 200 mg, irregular uterine bleeding or spotting is common, but concomitant treatment with an OEP tends to minimize this side effect. In my practice I rarely have patients report irregular uterine bleeding or spotting with the combination treatment of an OEP and spironolactone 100 mg daily.

Contraindications. Spironolactone should not be given to women with renal insufficiency because it can cause hyperkalemia. However, it is not necessary to check potassium levels in young women taking spironolactone with normal creatinine levels.13

Triple therapy: OEP plus metformin plus spironolactone

Some experts strongly recommend the initial treatment of PCOS in adolescents and young women with triple therapy: OEP plus an insulin sensitizer plus an antiandrogen.14 This recommendation is based in part on the observation that OEP monotherapy may be associated with an increase in circulating adipokines and visceral fat mass as determined by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry.15 By contrast, triple treatment with an OEP plus metformin plus an antiandrogen is associated with a decrease in circulating adipokines and visceral fat mass.

What is the best progestin for PCOS?

Any OEP is better than no OEP, regardless of the progestin used to treat the PCOS because ethinyl estradiol plus any synthetic progestin suppresses pituitary secretion of LH and decreases ovarian androgen production. However, for the treatment of acne, using a progestin that is less androgenic may be beneficial.16

In one study, 2,147 consecutive women who were taking a contraceptive and presented for treatment of acne were asked if their contraceptive had a positive impact on their acne. The percentage of women reporting that their contraceptive significantly improved their acne ranged from 26% for those taking drospirenone-ethinyl estradiol (EE) to 1% for those taking the etonogestrel subdermal implant (FIGURE).16 The US Food and Drug Administration has approved 4 OEP contraceptives for the treatment of acne (TABLE). The OEPs with drospirenone, norgestimate, desogestrel, or norethindrone acetate may be optimal choices for the treatment of acne caused by PCOS.

The bottom line

PCOS is a common endocrine disorder treated primarily by obstetricians-gynecologists. Among adolescents and young women with PCOS chief problem reports include irregular menses, hirsutism, obesity, acne, and infertility. Among mid-life women the presentation of PCOS often evolves into chronic medical problems, including obesity, metabolic syndrome, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, T2DM, cardiovascular disease, and endometrial cancer.17–19 To optimally treat the multiple pathophysiologic disorders manifested in PCOS, I recommend initial dual medical therapy with an OEP plus metformin or an OEP plus spironolactone.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Hum Reprod. 2004;19(1):41-47.

- Bozdag G, Mumusoglu S, Zengin D, Karabulut E, Yildiz BO. The prevalence and phenotypic features of polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(12):2841-2855.

- Elter K, Imir G, Durmusoglu F. Clinical, endocrine and metabolic effects of metformin added to ethinyl estradiol-cyproterone acetate in non-obese women with polycystic ovarian syndrome: a randomized controlled study. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(7):1729-1737.

- Cibula D, Fanta M, Vrbikova J, et al. The effect of combination therapy with metformin and combined oral contraceptives (COC) versus COC alone on insulin sensitivity, hyperandrogenism, SHBG and lipids in PCOS patients. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(1):180-184.

- Grundy SM, Brewer HB, Cleeman JI, Smith SC Jr, Lenfant C; American Heart Association; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Definition of metabolic syndrome: Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Circulation. 2004;109(3):433-438.

- Niafar M, Hai F, Porhomayon J, Nader ND. The role of metformin on vitamin B12 deficiency: a meta-analysis review. Intern Emerg Med. 2015;10(1):93-102.

- de Groot-Kamphuis DM, van Dijk PR, Groenier KH, Houweling St, Bilo HJ, Kleefstra N. Vitamin B12 deficiency and the lack of its consequences in type 2 diabetes patients using metformin. Neth J Med. 2013;71(7):386-390.

- Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Christakou CD, Kandaraki E, Economou FN. Metformin: an old medication of new fashion: evolving new molecular mechanisms and clinical implications in polycystic ovary syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol. 2010;162(2):193-212.

- Skalba P, Dabkowska-Huc A, Kazimierczak W, Samojedny A, Samojedny MP, Chelmicki Z. Content of 5-alph-reductase (type 1 and type 2) mRNA in dermal papillae from the lower abdominal region in women with hirsutism. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31(4):564-570.

- Layton AM, Eady EA, Whitehouse H, Del Rosso JQ, Fedorowicz Z, van Zuuren EJ. Oral spironolactone for acne vulgaris in adult females: a hybrid systematic review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18(2):169-191.

- Swiglo BA, Cosma M, Flynn DN, et al. Clinical review: antiandrogens for the treatment of hirsutism: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(4):1153-1160.

- van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z. Interventions for hirsutism excluding laser and photoepilation therapy alone: abridged Cochrane systematic review including GRADE assessments. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175(1):45-61.

- Plovanich M, Weng QY, Mostaghimi A. Low usefulness of potassium monitoring among healthy young women taking spironolactone for acne. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(9):941-944.

- Ibanez L, de Zegher F. Low-dose combination of flutamide, metformin and an oral contraceptive for non-obese, young women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(1):57-60.

- Ibanez L, de Zegher F. Ethinyl estradiol-drospirenone, flutamide-metformin or both for adolescents and women with hyperinsulinemic hyperandrogenism: opposite effects on adipocytokines and body adiposity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(4):1592-1597.

- Lortscher D, Admani S, Stur N, Eichenfield LF. Hormonal contraceptives and acne: a retrospective analysis of 2147 patients. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15(6):670-674.

- Wang ET, Calderon-Margalit R, Cedars MI, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome and risk for long-term diabetes and dyslipidemia. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(1):6-13.

- Joham AE, Raniasinha S, Zoungas S, Moran L, Teede HJ. Gestational diabetes and type 2 diabetes in reproductive aged women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(3):e447-e452.

- Gottschau M, Kjaer SK, Jensen A, Munk C, Mellemkjaer L. Risk of cancer among women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a Danish cohort study. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136(1):99-103.

- Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Hum Reprod. 2004;19(1):41-47.

- Bozdag G, Mumusoglu S, Zengin D, Karabulut E, Yildiz BO. The prevalence and phenotypic features of polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(12):2841-2855.

- Elter K, Imir G, Durmusoglu F. Clinical, endocrine and metabolic effects of metformin added to ethinyl estradiol-cyproterone acetate in non-obese women with polycystic ovarian syndrome: a randomized controlled study. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(7):1729-1737.

- Cibula D, Fanta M, Vrbikova J, et al. The effect of combination therapy with metformin and combined oral contraceptives (COC) versus COC alone on insulin sensitivity, hyperandrogenism, SHBG and lipids in PCOS patients. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(1):180-184.

- Grundy SM, Brewer HB, Cleeman JI, Smith SC Jr, Lenfant C; American Heart Association; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Definition of metabolic syndrome: Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Circulation. 2004;109(3):433-438.

- Niafar M, Hai F, Porhomayon J, Nader ND. The role of metformin on vitamin B12 deficiency: a meta-analysis review. Intern Emerg Med. 2015;10(1):93-102.

- de Groot-Kamphuis DM, van Dijk PR, Groenier KH, Houweling St, Bilo HJ, Kleefstra N. Vitamin B12 deficiency and the lack of its consequences in type 2 diabetes patients using metformin. Neth J Med. 2013;71(7):386-390.

- Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Christakou CD, Kandaraki E, Economou FN. Metformin: an old medication of new fashion: evolving new molecular mechanisms and clinical implications in polycystic ovary syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol. 2010;162(2):193-212.

- Skalba P, Dabkowska-Huc A, Kazimierczak W, Samojedny A, Samojedny MP, Chelmicki Z. Content of 5-alph-reductase (type 1 and type 2) mRNA in dermal papillae from the lower abdominal region in women with hirsutism. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31(4):564-570.

- Layton AM, Eady EA, Whitehouse H, Del Rosso JQ, Fedorowicz Z, van Zuuren EJ. Oral spironolactone for acne vulgaris in adult females: a hybrid systematic review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18(2):169-191.

- Swiglo BA, Cosma M, Flynn DN, et al. Clinical review: antiandrogens for the treatment of hirsutism: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(4):1153-1160.

- van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z. Interventions for hirsutism excluding laser and photoepilation therapy alone: abridged Cochrane systematic review including GRADE assessments. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175(1):45-61.

- Plovanich M, Weng QY, Mostaghimi A. Low usefulness of potassium monitoring among healthy young women taking spironolactone for acne. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(9):941-944.

- Ibanez L, de Zegher F. Low-dose combination of flutamide, metformin and an oral contraceptive for non-obese, young women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(1):57-60.

- Ibanez L, de Zegher F. Ethinyl estradiol-drospirenone, flutamide-metformin or both for adolescents and women with hyperinsulinemic hyperandrogenism: opposite effects on adipocytokines and body adiposity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(4):1592-1597.

- Lortscher D, Admani S, Stur N, Eichenfield LF. Hormonal contraceptives and acne: a retrospective analysis of 2147 patients. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15(6):670-674.

- Wang ET, Calderon-Margalit R, Cedars MI, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome and risk for long-term diabetes and dyslipidemia. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(1):6-13.

- Joham AE, Raniasinha S, Zoungas S, Moran L, Teede HJ. Gestational diabetes and type 2 diabetes in reproductive aged women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(3):e447-e452.

- Gottschau M, Kjaer SK, Jensen A, Munk C, Mellemkjaer L. Risk of cancer among women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a Danish cohort study. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136(1):99-103.

ACS: Ensuring the integrity of the profession and the quality of patient care

With a new administration and Congress in place, as well as many exciting internal changes, the American College of Surgeons (ACS) is looking forward to an exciting year ahead.

Quality improvement

Making certain that surgeons have the tools they need to measure and evaluate their performance is a key mission of the College. To this end, we have initiated the database integration system, which will bring together under a single platform the ACS National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS NSQIP®), National Cancer Database, National Trauma Data Bank, and Surgeon Specific Registry (SSRTM). This project, which is being implemented incrementally, will make it easier for surgeons to meet American Board of Surgery (ABS) Maintenance of Certification requirements and Medicare payment mandates.

Furthermore, the College intends to publish an ACS quality manual this year. This comprehensive guidebook will outline strategies and resources needed to ensure the delivery of optimal surgical care.

Advocacy