User login

Music in the OR

I am sure that even though Theodor Billroth and Johannes Brahms were close friends, Billroth never listened to music in his operating room. I’m pretty sure because the Victrola was invented around 1906 and the first commercial radio broadcast was in 1920. So unless Billroth hired a Viennese string quartet to play in his amphitheater, it is likely the operating room was a pretty quiet place.

Radios were the size of a small refrigerator into the 1940s when Bell Laboratories’ invention of the transistor technology permitted small units to play tinny music through speakers about 2 inches across. So, I would guess that Alfred Blalock didn’t listen to Elvis Presley or Buddy Holly during his pioneering days at Hopkins.

By the late 1960s high-quality, recorded music was available on 8-track tapes invented by the Lear Jet Corporation. Music at that point was literally available everywhere and the OR became a theater once more for some surgeons. Cassette tapes followed, and Johnny Paycheck echoed in the heart room where I trained in Dallas – usually at high volume. When Apple changed the world with the iPod in 2001 and then the Internet streaming services emerged, it became possible to take out a gall bladder accompanied by Vladimir Horowitz or Madonna. And it happens routinely.

As I write this, I am listening to a jazz streaming station. Music is one of the most important elements of my life. Yet, my operating room has had music on only one occasion since I became an attending surgeon. I love music too much for it to be in my OR. It not only relaxes me, which may not be entirely a good thing in surgery, but it engages my intellect, taking up needed CPU time which might be useful in avoiding catastrophe for the patient before me.

Not long ago this subject was the focus of a discussion thread on the ACS Communities. Many reported that they never listen to music in the OR, others said it was essential to their performance, and still others took a middle ground. Everyone said the music shouldn’t be loud; however, I can recall visiting a number of operating rooms in which loud was the standard volume setting. Most respondents spoke in terms of what they needed and like. Several felt that as captain of the SS Operating Room they had the final say of whether, what, and when music would be played.

I noted in the conversation justification, defensiveness, authoritarianism mixed with personal insight that is so characteristic of many surgeons. Of course, there isn’t a “right” answer here any more than there is in a number of OR traditions. The evidence is all over the place except when it comes to volume. There, it is clear that loud music causes or exacerbates communications errors due to inability of the OR team to hear one another or distraction of the team from their primary task.

Music affects everyone in the OR. It represents one of many operating room components that hold the potential of both betterment of care or endangerment of the patient. To say that music in the OR is wrong is like saying propellers on aircraft are somehow wrong. Among the most serious injuries at general aviation airports is individuals walking into a spinning propeller; however, without the propeller the plane can’t fly and deliver its benefits enjoyed at large. The problem isn’t that propellers are evil. It is that they are invisible to the victim who ignores their dangers.

My point is that music is an example of the need for us to be aware of the primary and secondary effects of even the small things we do in the OR because innocuous as they seem, they have potential dangers. The Council on Surgical and Perioperative Care of which the ACS is a member, has more data and resources on their homepage (cspsteam.org) for those interested in the subject on distractions in the OR.

So, what I’ve learned through listening to the music of my colleagues opinions is that when it comes to music, we need to be aware of the spinning propeller of noise pollution in the OR. Many invisible dangers inhabit the OR. Take a moment and listen for them.

Dr. Hughes is clinical professor in the department of surgery and director of medical education at the Kansas University School of Medicine, Salina Campus, and Co-Editor of ACS Surgery News.

I am sure that even though Theodor Billroth and Johannes Brahms were close friends, Billroth never listened to music in his operating room. I’m pretty sure because the Victrola was invented around 1906 and the first commercial radio broadcast was in 1920. So unless Billroth hired a Viennese string quartet to play in his amphitheater, it is likely the operating room was a pretty quiet place.

Radios were the size of a small refrigerator into the 1940s when Bell Laboratories’ invention of the transistor technology permitted small units to play tinny music through speakers about 2 inches across. So, I would guess that Alfred Blalock didn’t listen to Elvis Presley or Buddy Holly during his pioneering days at Hopkins.

By the late 1960s high-quality, recorded music was available on 8-track tapes invented by the Lear Jet Corporation. Music at that point was literally available everywhere and the OR became a theater once more for some surgeons. Cassette tapes followed, and Johnny Paycheck echoed in the heart room where I trained in Dallas – usually at high volume. When Apple changed the world with the iPod in 2001 and then the Internet streaming services emerged, it became possible to take out a gall bladder accompanied by Vladimir Horowitz or Madonna. And it happens routinely.

As I write this, I am listening to a jazz streaming station. Music is one of the most important elements of my life. Yet, my operating room has had music on only one occasion since I became an attending surgeon. I love music too much for it to be in my OR. It not only relaxes me, which may not be entirely a good thing in surgery, but it engages my intellect, taking up needed CPU time which might be useful in avoiding catastrophe for the patient before me.

Not long ago this subject was the focus of a discussion thread on the ACS Communities. Many reported that they never listen to music in the OR, others said it was essential to their performance, and still others took a middle ground. Everyone said the music shouldn’t be loud; however, I can recall visiting a number of operating rooms in which loud was the standard volume setting. Most respondents spoke in terms of what they needed and like. Several felt that as captain of the SS Operating Room they had the final say of whether, what, and when music would be played.

I noted in the conversation justification, defensiveness, authoritarianism mixed with personal insight that is so characteristic of many surgeons. Of course, there isn’t a “right” answer here any more than there is in a number of OR traditions. The evidence is all over the place except when it comes to volume. There, it is clear that loud music causes or exacerbates communications errors due to inability of the OR team to hear one another or distraction of the team from their primary task.

Music affects everyone in the OR. It represents one of many operating room components that hold the potential of both betterment of care or endangerment of the patient. To say that music in the OR is wrong is like saying propellers on aircraft are somehow wrong. Among the most serious injuries at general aviation airports is individuals walking into a spinning propeller; however, without the propeller the plane can’t fly and deliver its benefits enjoyed at large. The problem isn’t that propellers are evil. It is that they are invisible to the victim who ignores their dangers.

My point is that music is an example of the need for us to be aware of the primary and secondary effects of even the small things we do in the OR because innocuous as they seem, they have potential dangers. The Council on Surgical and Perioperative Care of which the ACS is a member, has more data and resources on their homepage (cspsteam.org) for those interested in the subject on distractions in the OR.

So, what I’ve learned through listening to the music of my colleagues opinions is that when it comes to music, we need to be aware of the spinning propeller of noise pollution in the OR. Many invisible dangers inhabit the OR. Take a moment and listen for them.

Dr. Hughes is clinical professor in the department of surgery and director of medical education at the Kansas University School of Medicine, Salina Campus, and Co-Editor of ACS Surgery News.

I am sure that even though Theodor Billroth and Johannes Brahms were close friends, Billroth never listened to music in his operating room. I’m pretty sure because the Victrola was invented around 1906 and the first commercial radio broadcast was in 1920. So unless Billroth hired a Viennese string quartet to play in his amphitheater, it is likely the operating room was a pretty quiet place.

Radios were the size of a small refrigerator into the 1940s when Bell Laboratories’ invention of the transistor technology permitted small units to play tinny music through speakers about 2 inches across. So, I would guess that Alfred Blalock didn’t listen to Elvis Presley or Buddy Holly during his pioneering days at Hopkins.

By the late 1960s high-quality, recorded music was available on 8-track tapes invented by the Lear Jet Corporation. Music at that point was literally available everywhere and the OR became a theater once more for some surgeons. Cassette tapes followed, and Johnny Paycheck echoed in the heart room where I trained in Dallas – usually at high volume. When Apple changed the world with the iPod in 2001 and then the Internet streaming services emerged, it became possible to take out a gall bladder accompanied by Vladimir Horowitz or Madonna. And it happens routinely.

As I write this, I am listening to a jazz streaming station. Music is one of the most important elements of my life. Yet, my operating room has had music on only one occasion since I became an attending surgeon. I love music too much for it to be in my OR. It not only relaxes me, which may not be entirely a good thing in surgery, but it engages my intellect, taking up needed CPU time which might be useful in avoiding catastrophe for the patient before me.

Not long ago this subject was the focus of a discussion thread on the ACS Communities. Many reported that they never listen to music in the OR, others said it was essential to their performance, and still others took a middle ground. Everyone said the music shouldn’t be loud; however, I can recall visiting a number of operating rooms in which loud was the standard volume setting. Most respondents spoke in terms of what they needed and like. Several felt that as captain of the SS Operating Room they had the final say of whether, what, and when music would be played.

I noted in the conversation justification, defensiveness, authoritarianism mixed with personal insight that is so characteristic of many surgeons. Of course, there isn’t a “right” answer here any more than there is in a number of OR traditions. The evidence is all over the place except when it comes to volume. There, it is clear that loud music causes or exacerbates communications errors due to inability of the OR team to hear one another or distraction of the team from their primary task.

Music affects everyone in the OR. It represents one of many operating room components that hold the potential of both betterment of care or endangerment of the patient. To say that music in the OR is wrong is like saying propellers on aircraft are somehow wrong. Among the most serious injuries at general aviation airports is individuals walking into a spinning propeller; however, without the propeller the plane can’t fly and deliver its benefits enjoyed at large. The problem isn’t that propellers are evil. It is that they are invisible to the victim who ignores their dangers.

My point is that music is an example of the need for us to be aware of the primary and secondary effects of even the small things we do in the OR because innocuous as they seem, they have potential dangers. The Council on Surgical and Perioperative Care of which the ACS is a member, has more data and resources on their homepage (cspsteam.org) for those interested in the subject on distractions in the OR.

So, what I’ve learned through listening to the music of my colleagues opinions is that when it comes to music, we need to be aware of the spinning propeller of noise pollution in the OR. Many invisible dangers inhabit the OR. Take a moment and listen for them.

Dr. Hughes is clinical professor in the department of surgery and director of medical education at the Kansas University School of Medicine, Salina Campus, and Co-Editor of ACS Surgery News.

Channeling the flow of medical information

New, changing technologies are being incorporated into every aspect of medical care and education, and the impact cannot be overstated. While the ultimate qualitative impact (beneficial, intrusive, efficient, obstructive, or neutral) of specific individual implementations remains to be seen, there is no doubt that the faces of patient care and the financial management of healthcare delivery have been forever altered.

The amount of information now literally at our fingertips is overwhelming. Some of my patients bring the latest from www.clinicaltrials.gov to their appointments. One patient recently brought downloaded online testimony from patients who were being given an oil supplement to treat disorders including gout, neuropathy, carpal tunnel, sinusitis, headache, and postop hip and knee pain and wanted to know why I hadn’t suggested it for her. Accessing the information pipeline is like drinking from a firehose, and there is no perfect valve that can adjust the flow to every thirst.

Lest we think that only patients use sites of variable reliability in getting their online medical information, in a recent survey by Kantar Media, when 508 physicians were asked which of 49 sites they looked at most often, Wikipedia came in at number 3 (UpToDate was number 1 and Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine was number 25). But when asked to rate the 49 sites for “quality clinical content,” responders listed Wikipedia as 47 (UpToDate was still number 1 and CCJM was number 6).

We healthcare providers can assess the accuracy and quality of clinical content. But it is not always easy, especially when trying to access, digest, and utilize information within the real-time constraints of an office visit or inpatient consultation. The now almost universal use of electronic medical records (EMRs) in major health systems provides access to true point-of-care information to assist in clinical decision-making, but how we filter and channel this information and apply it to the patient sitting in the exam room is not always straightforward. It is naïve to think that one source can fit all of our information needs.

A “smart” EMR can reflexively direct me to diagnosis-linked clinical guidelines or care paths. But without knowing the specifics of how the guidelines were written, I can’t know if they are ideally applicable to the patient in front of me. Guidelines based solely on clinical trial data may not be ideal for a given patient due to constraints of the clinical trial design and the tested clinical populations. There are times in areas outside my clinical field that I seek clinically nuanced expertise in interpreting clinical trials rather than the actual clinical trial data. Other times, when approaching problems within my own expertise, I want to see the raw data to reach a conclusion on its applicability and likely magnitude of effect in a specific patient. Using a trusted source of predigested, summarized data (as opposed to the raw data), knowing whether an author has a relationship with a specific company, and knowing that the clinical trials of a specific therapy are not intrinsically bad or good—all of these contribute to contextual decisions that lead to my clinical recommendations. I always want to know the nature of authors’ commercial relationships, as well as the track record of my information sources.

It is in this context that the paper by Andrews et al in this issue of the Journal addresses in a very practical way some of the nuances in using several popular point-of-care information resources. This is the second of 2 papers that these authors have contributed to the CCJM in an effort to inform and direct us how to quench our thirst for information without getting bloated.

New, changing technologies are being incorporated into every aspect of medical care and education, and the impact cannot be overstated. While the ultimate qualitative impact (beneficial, intrusive, efficient, obstructive, or neutral) of specific individual implementations remains to be seen, there is no doubt that the faces of patient care and the financial management of healthcare delivery have been forever altered.

The amount of information now literally at our fingertips is overwhelming. Some of my patients bring the latest from www.clinicaltrials.gov to their appointments. One patient recently brought downloaded online testimony from patients who were being given an oil supplement to treat disorders including gout, neuropathy, carpal tunnel, sinusitis, headache, and postop hip and knee pain and wanted to know why I hadn’t suggested it for her. Accessing the information pipeline is like drinking from a firehose, and there is no perfect valve that can adjust the flow to every thirst.

Lest we think that only patients use sites of variable reliability in getting their online medical information, in a recent survey by Kantar Media, when 508 physicians were asked which of 49 sites they looked at most often, Wikipedia came in at number 3 (UpToDate was number 1 and Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine was number 25). But when asked to rate the 49 sites for “quality clinical content,” responders listed Wikipedia as 47 (UpToDate was still number 1 and CCJM was number 6).

We healthcare providers can assess the accuracy and quality of clinical content. But it is not always easy, especially when trying to access, digest, and utilize information within the real-time constraints of an office visit or inpatient consultation. The now almost universal use of electronic medical records (EMRs) in major health systems provides access to true point-of-care information to assist in clinical decision-making, but how we filter and channel this information and apply it to the patient sitting in the exam room is not always straightforward. It is naïve to think that one source can fit all of our information needs.

A “smart” EMR can reflexively direct me to diagnosis-linked clinical guidelines or care paths. But without knowing the specifics of how the guidelines were written, I can’t know if they are ideally applicable to the patient in front of me. Guidelines based solely on clinical trial data may not be ideal for a given patient due to constraints of the clinical trial design and the tested clinical populations. There are times in areas outside my clinical field that I seek clinically nuanced expertise in interpreting clinical trials rather than the actual clinical trial data. Other times, when approaching problems within my own expertise, I want to see the raw data to reach a conclusion on its applicability and likely magnitude of effect in a specific patient. Using a trusted source of predigested, summarized data (as opposed to the raw data), knowing whether an author has a relationship with a specific company, and knowing that the clinical trials of a specific therapy are not intrinsically bad or good—all of these contribute to contextual decisions that lead to my clinical recommendations. I always want to know the nature of authors’ commercial relationships, as well as the track record of my information sources.

It is in this context that the paper by Andrews et al in this issue of the Journal addresses in a very practical way some of the nuances in using several popular point-of-care information resources. This is the second of 2 papers that these authors have contributed to the CCJM in an effort to inform and direct us how to quench our thirst for information without getting bloated.

New, changing technologies are being incorporated into every aspect of medical care and education, and the impact cannot be overstated. While the ultimate qualitative impact (beneficial, intrusive, efficient, obstructive, or neutral) of specific individual implementations remains to be seen, there is no doubt that the faces of patient care and the financial management of healthcare delivery have been forever altered.

The amount of information now literally at our fingertips is overwhelming. Some of my patients bring the latest from www.clinicaltrials.gov to their appointments. One patient recently brought downloaded online testimony from patients who were being given an oil supplement to treat disorders including gout, neuropathy, carpal tunnel, sinusitis, headache, and postop hip and knee pain and wanted to know why I hadn’t suggested it for her. Accessing the information pipeline is like drinking from a firehose, and there is no perfect valve that can adjust the flow to every thirst.

Lest we think that only patients use sites of variable reliability in getting their online medical information, in a recent survey by Kantar Media, when 508 physicians were asked which of 49 sites they looked at most often, Wikipedia came in at number 3 (UpToDate was number 1 and Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine was number 25). But when asked to rate the 49 sites for “quality clinical content,” responders listed Wikipedia as 47 (UpToDate was still number 1 and CCJM was number 6).

We healthcare providers can assess the accuracy and quality of clinical content. But it is not always easy, especially when trying to access, digest, and utilize information within the real-time constraints of an office visit or inpatient consultation. The now almost universal use of electronic medical records (EMRs) in major health systems provides access to true point-of-care information to assist in clinical decision-making, but how we filter and channel this information and apply it to the patient sitting in the exam room is not always straightforward. It is naïve to think that one source can fit all of our information needs.

A “smart” EMR can reflexively direct me to diagnosis-linked clinical guidelines or care paths. But without knowing the specifics of how the guidelines were written, I can’t know if they are ideally applicable to the patient in front of me. Guidelines based solely on clinical trial data may not be ideal for a given patient due to constraints of the clinical trial design and the tested clinical populations. There are times in areas outside my clinical field that I seek clinically nuanced expertise in interpreting clinical trials rather than the actual clinical trial data. Other times, when approaching problems within my own expertise, I want to see the raw data to reach a conclusion on its applicability and likely magnitude of effect in a specific patient. Using a trusted source of predigested, summarized data (as opposed to the raw data), knowing whether an author has a relationship with a specific company, and knowing that the clinical trials of a specific therapy are not intrinsically bad or good—all of these contribute to contextual decisions that lead to my clinical recommendations. I always want to know the nature of authors’ commercial relationships, as well as the track record of my information sources.

It is in this context that the paper by Andrews et al in this issue of the Journal addresses in a very practical way some of the nuances in using several popular point-of-care information resources. This is the second of 2 papers that these authors have contributed to the CCJM in an effort to inform and direct us how to quench our thirst for information without getting bloated.

Why are there delays in the diagnosis of endometriosis?

Endometriosis is a common gynecologic problem in adolescents and women. It often presents with pelvic pain, an ovarian endometrioma, and/or subfertility. In a prospective study of 116,678 nurses, the incidence of a new surgical diagnosis of endometriosis was greatest among women aged 25 to 29 years and lowest among women older than age 44.1 Using the incidence data from this study, the calculated prevalence of endometriosis in this large cohort of women of reproductive age was approximately 8%.

Although endometriosis is known to be a very common gynecologic problem, many studies report that there can be long delays between onset of pelvic pain symptoms and the diagnosis of endometriosis (Figure 1).2−6 Combining the results from 5 studies, involving 1,187 women, the mean age of onset of pelvic pain symptoms was 22.1 years, and the mean age at the diagnosis of endometriosis was 30.7 years. This is a difference of 8.6 years between the age of symptom onset and age at diagnosis.2−6

What factors contribute to the diagnosis delay?

Both patient and physician factors contribute to the reported lengthy delay between symptom onset and endometriosis diagnosis.7,8 Differentiating dysmenorrhea due to primary and secondary causes is difficult for both patients and physicians. Women may conceal the severity of menstrual pain to avoid both the embarrassment of drawing attention to themselves and being stigmatized as unable to cope. Most disappointing is that many women with endometriosis reported that they asked their clinician if endometriosis could be the cause of their severe dysmenorrhea and were told, “No.”7,8

Of interest, the reported delay in the diagnosis of endometriosis is much shorter for women who pre-sent with infertility than for women who present with pelvic pain. In one study from the United States, the delay to diagnosis was 3.13 years for women who presented with infertility and 6.35 years for women who presented with severe pelvic pain.3 This suggests that clinicians and patients more rapidly pursue the diagnosis of endometriosis in women with infertility, but not pelvic pain.

Related article:

Endometriosis: Expert answers to 7 crucial questions on diagnosis

Initial treatment of pelvic pain with NSAIDs and estrogen—progestin contraceptives

Many women with undiagnosed endometriosis present with pelvic pain symptoms including moderate to severe dysmenorrhea. These women are often empirically treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and combination estrogen−progestin contraceptives in either a cyclic or continuous manner.9,10 Since many women with endometriosis will have a reduction in their pelvic pain with NSAID and contraceptive treatment, diagnosis of their endometriosis may be delayed until their disease progresses years after their initial presentation. It is important to gently alert these women to the possibility that they have undiagnosed endometriosis as the cause of their pain symptoms and encourage them to report any worsening pain symptoms in a timely manner.

Sometimes women with pelvic pain are treated with NSAIDs and contraceptives but no significant reduction in pain symptoms occurs. For these women, speedy consideration should be given to offering a laparoscopy to determine the cause of their pain.

Related article:

Avoiding “shotgun” treatment: New thoughts on endometriosis-associated pelvic pain

Diagnosing endometriosis relies on identifying flags in the patient’s history

The gold standard for endometriosis diagnosis is surgical visualization of endometriosis lesions, most often with laparoscopy, plus histologic confirmation of endometriosis on a tissue biopsy.9,10 A key to reducing the time between onset of symptoms and diagnosis of endometriosis is identifying adolescents and women who are at high risk for having the disease. These women should be offered a laparoscopy procedure. In women with moderate to severe pelvic pain of at least 6 months duration, medical history, physical examination, and imaging studies can be helpful in identifying those at increased risk for endometriosis.

Items from the patient history that might raise the likelihood of endometriosis include:

- abdominopelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, menorrhagia, subfertility, dyspareunia and/or postcoital bleeding11

- symptoms of dysmenorrhea and/or dyspareunia that are not responsive to NSAIDs or estrogen−progestin contraceptives12

- symptoms of dysmenorrhea and/or dyspareunia associated with absenteeism from school or work13

- multiple visits to the emergency department for severe dysmenorrhea

- endometriosis in the patient’s mother or sister

- subfertility with regular ovulation, patent fallopian tubes, and a partner with a normal semen analysis

- urinary frequency, urgency, and/or pain on urination

- diarrhea, constipation, nausea, dyschezia, bowel cramping, abdominal distention, and early satiety.

A daunting clinical challenge is that symptoms of endometriosis overlap with other gynecologic and nongynecologic problems including pelvic infection, adhesions, ovarian cysts, fibroids, irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, interstitial cystitis, myofascial pain, depression, and history of sexual abuse.

Diagnosing endometriosis relies on identifying flags on physical exam

Physical examination findings that raise the likelihood that the patient has endometriosis include:

- fixed and retroverted uterus

- adnexal mass

- lesions of the cervix or posterior fornix that visually appear to be endometriosis

- uterosacral ligament abnormalities, including tenderness, thickening, and/or nodularity14,15

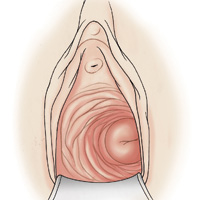

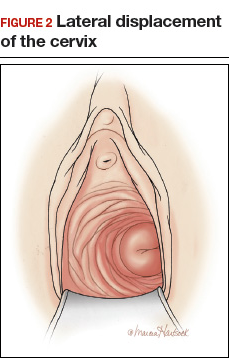

- lateral displacement of the cervix (FIGURE 2)16,17

- severe cervical stenosis.

In one study of 57 women with a surgical diagnosis of endometriosis, uterosacral ligament abnormalities, lateral displacement of the cervix, and cervical stenosis were observed in 47%, 28%, and 19% of the women, respectively.17 In this same study 22 women had none of these findings, but 8 had a complex ovarian mass consistent with endometriosis.

The possibility of endometriosis increases as the number of history and physical examination findings suggestive of endometriosis increase.

Related article:

Endometriosis and pain: Expert answers to 6 questions targeting your management options

When transvaginal ultrasound can aid diagnosis

Most women with endometriosis have normal transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) results because ultrasound cannot detect small isolated peritoneal lesions of endometriosis present in Stage I disease, the most common stage of endometriosis. However, ultrasound is useful in detecting both ovarian endometriomas and nodules of deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE).18 TVUS has excellent sensitivity (>90%) and specificity (>90%) for the detection of ovarian endometriomas because these cysts have characteristic, homogenous, low-level internal echoes.19,20 For the diagnosis of DIE of the uterosacral ligaments and rectovaginal septum, TVUS has fair sensitivity (>50%) and excellent specificity (>90%).21 In most studies, magnetic resonance imaging performs no better than TVUS for imaging ovarian endometriomas and DIE. Hence, TVUS is the preferred imaging modality for detecting endometriosis.22

- Endometriosis is a common gynecologic disease. Approximately 8% of women of reproductive age have the condition.

- Many patients report lengthy delays between the onset of symptoms of pelvic pain and the diagnosis of endometriosis.

- Both patients and clinicians contribute to the delay in the diagnosis of endometriosis: Women are often reluctant to report the severity of their pelvic pain symptoms, and clinicians often under-respond to a patient's report of severe pelvic pain symptoms.

- First-line therapy for the treatment of moderate to severe dysmenorrhea is nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and estrogen−progestin contraceptives.

- Increasing vigilance for endometriosis will shorten the time between onset of symptoms and definitive diagnosis.

- Reducing the time between the onset of symptoms and diagnosis of endometriosis will improve the quality of life of women with the disease because they will receive timely treatment.

This is a practice gap we can close

Clinicians take great pride in accurately solving patient problems in a timely and efficient manner. Substantial research indicates that we can improve the timeliness of our diagnosis of endometriosis. By acknowledging patients’ pain symptoms and recognizing the myriad symptoms and physical examination and imaging findings that are associated with endometriosis, we will close the gap and make this diagnosis with greater speed.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Missmer SA, Hankinson SE, Spiegelman D, Barbieri RL, Marshall LM, Hunter DJ. Incidence of laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis by demographic, anthropometric, and lifestyle factors. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(8):784−796.

- Hadfield R, Mardon H, Barlow D, Kennedy S. Delay in the diagnosis of endometriosis: a survey of women from the USA and UK. Hum Reprod. 1996;11(4):878−880.

- Dmowski WP, Lesniewicz R, Rana N, Pepping P, Noursalehi M. Changing trends in the diagnosis of endometriosis: a comparative study of women with pelvic endometriosis presenting with chronic pelvic pain or infertility. Fertil Steril. 1997;67(2):238−243.

- Arruda MS, Petta CA, Abrão MS, Benetti-Pinto CL. Time elapsed from onset of symptoms to diagnosis of endometriosis in a cohort study of Brazilian women. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(4):756−759.

- Husby GK, Haugen RS, Moen MH. Diagnostic delay in women with pain and endometriosis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82(7):649−653.

- Hudelist G, Fritzer N, Thomas A, et al. Diagnostic delay for endometriosis in Austria and Germany: causes and possible consequences. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(12):3412−3416.

- Ballard K, Lowton K, Wright J. What's the delay? A qualitative study of women's experiences of reaching a diagnosis of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2006;86(5):1296−1301.

- Seear K. The etiquette of endometriosis: stigmatisation, menstrual concealment and the diagnostic delay. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(8):1220−1227.

- Falcone T, Lebovic DI. Clinical management of endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(3):691−705.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 114: Management of endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(1):223−236.

- Ballard KD, Seaman HE, de Vries CS, Wright JT. Can symptomatology help in the diagnosis of endometriosis? Findings from a national case-control study--Part 1. BJOG. 2008;115(11):1382−1391.

- Steenberg CK, Tanbo TG, Qvigstad E. Endometriosis in adolescence: predictive markers and management. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2013;92(5):491−495.

- Zannoni L, Giorgi M, Spagnolo E, Montanari G, Villa G, Seracchioli R. Dysmenorrhea, absenteeism from school, and symptoms suspicious for endometriosis in adolescents. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2014;27(5):258−265.

- Cheewadhanaraks S, Peeyananjarassri K, Dhanaworavibul K, Liabsuetrakul T. Positive predictive value of clinical diagnosis of endometriosis. J Med Assoc Thai. 2004;87(7):740−744.

- Guerriero S, Ajossa S, Gerada M, Virgilio B, Angioni S, Melis GB. Diagnostic value of transvaginal 'tenderness-guided' ultrasonography for the prediction of location of deep endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2008;23(11):2452−2457.

- Propst AM, Storti K, Barbieri RL. Lateral cervical displacement is associated with endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1998;70(3):568−570.

- Barbieri RL, Propst AM. Physical examination findings in women with endometriosis: uterosacral ligament abnormalities, lateral cervical displacement and cervical stenosis. J Gynecol Techniques. 1999;5:157−159.

- Guerriero S, Condous G, van den Bosch T, et al. Systematic approach to sonographic evaluation of the pelvis in women with suspected endometriosis, including terms, definitions and measurements: a consensus opinion from the International Deep Endometriosis Analysis (IDEA) group. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;48(3):318−332.

- Nisenblat V, Bossuyt PM, Farquhar C, Johnson N, Hull ML. Imaging modalities for the non-invasive diagnosis of endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2:CD009591.

- Somigliana E, Vercellini P, Vigano P, Benaglia L, Crosignani PG, Fedele L. Non-invasive diagnosis of endometriosis: the goal or own goal? Hum Reprod. 2010;25(8):1863−1868.

- Guerriero S, Ajossa S, Minguez JA, et al. Accuracy of transvaginal ultrasound for diagnosis of deep endometriosis in uterosacral ligaments, rectovaginal septum, vagina and bladder: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015;46(5):534−545.

- Benacerraf BR, Groszmann Y. Sonography should be the first imaging examination done to evaluate patients with suspected endometriosis. J Ultrasound Med. 2012;31(4):651−653.

Endometriosis is a common gynecologic problem in adolescents and women. It often presents with pelvic pain, an ovarian endometrioma, and/or subfertility. In a prospective study of 116,678 nurses, the incidence of a new surgical diagnosis of endometriosis was greatest among women aged 25 to 29 years and lowest among women older than age 44.1 Using the incidence data from this study, the calculated prevalence of endometriosis in this large cohort of women of reproductive age was approximately 8%.

Although endometriosis is known to be a very common gynecologic problem, many studies report that there can be long delays between onset of pelvic pain symptoms and the diagnosis of endometriosis (Figure 1).2−6 Combining the results from 5 studies, involving 1,187 women, the mean age of onset of pelvic pain symptoms was 22.1 years, and the mean age at the diagnosis of endometriosis was 30.7 years. This is a difference of 8.6 years between the age of symptom onset and age at diagnosis.2−6

What factors contribute to the diagnosis delay?

Both patient and physician factors contribute to the reported lengthy delay between symptom onset and endometriosis diagnosis.7,8 Differentiating dysmenorrhea due to primary and secondary causes is difficult for both patients and physicians. Women may conceal the severity of menstrual pain to avoid both the embarrassment of drawing attention to themselves and being stigmatized as unable to cope. Most disappointing is that many women with endometriosis reported that they asked their clinician if endometriosis could be the cause of their severe dysmenorrhea and were told, “No.”7,8

Of interest, the reported delay in the diagnosis of endometriosis is much shorter for women who pre-sent with infertility than for women who present with pelvic pain. In one study from the United States, the delay to diagnosis was 3.13 years for women who presented with infertility and 6.35 years for women who presented with severe pelvic pain.3 This suggests that clinicians and patients more rapidly pursue the diagnosis of endometriosis in women with infertility, but not pelvic pain.

Related article:

Endometriosis: Expert answers to 7 crucial questions on diagnosis

Initial treatment of pelvic pain with NSAIDs and estrogen—progestin contraceptives

Many women with undiagnosed endometriosis present with pelvic pain symptoms including moderate to severe dysmenorrhea. These women are often empirically treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and combination estrogen−progestin contraceptives in either a cyclic or continuous manner.9,10 Since many women with endometriosis will have a reduction in their pelvic pain with NSAID and contraceptive treatment, diagnosis of their endometriosis may be delayed until their disease progresses years after their initial presentation. It is important to gently alert these women to the possibility that they have undiagnosed endometriosis as the cause of their pain symptoms and encourage them to report any worsening pain symptoms in a timely manner.

Sometimes women with pelvic pain are treated with NSAIDs and contraceptives but no significant reduction in pain symptoms occurs. For these women, speedy consideration should be given to offering a laparoscopy to determine the cause of their pain.

Related article:

Avoiding “shotgun” treatment: New thoughts on endometriosis-associated pelvic pain

Diagnosing endometriosis relies on identifying flags in the patient’s history

The gold standard for endometriosis diagnosis is surgical visualization of endometriosis lesions, most often with laparoscopy, plus histologic confirmation of endometriosis on a tissue biopsy.9,10 A key to reducing the time between onset of symptoms and diagnosis of endometriosis is identifying adolescents and women who are at high risk for having the disease. These women should be offered a laparoscopy procedure. In women with moderate to severe pelvic pain of at least 6 months duration, medical history, physical examination, and imaging studies can be helpful in identifying those at increased risk for endometriosis.

Items from the patient history that might raise the likelihood of endometriosis include:

- abdominopelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, menorrhagia, subfertility, dyspareunia and/or postcoital bleeding11

- symptoms of dysmenorrhea and/or dyspareunia that are not responsive to NSAIDs or estrogen−progestin contraceptives12

- symptoms of dysmenorrhea and/or dyspareunia associated with absenteeism from school or work13

- multiple visits to the emergency department for severe dysmenorrhea

- endometriosis in the patient’s mother or sister

- subfertility with regular ovulation, patent fallopian tubes, and a partner with a normal semen analysis

- urinary frequency, urgency, and/or pain on urination

- diarrhea, constipation, nausea, dyschezia, bowel cramping, abdominal distention, and early satiety.

A daunting clinical challenge is that symptoms of endometriosis overlap with other gynecologic and nongynecologic problems including pelvic infection, adhesions, ovarian cysts, fibroids, irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, interstitial cystitis, myofascial pain, depression, and history of sexual abuse.

Diagnosing endometriosis relies on identifying flags on physical exam

Physical examination findings that raise the likelihood that the patient has endometriosis include:

- fixed and retroverted uterus

- adnexal mass

- lesions of the cervix or posterior fornix that visually appear to be endometriosis

- uterosacral ligament abnormalities, including tenderness, thickening, and/or nodularity14,15

- lateral displacement of the cervix (FIGURE 2)16,17

- severe cervical stenosis.

In one study of 57 women with a surgical diagnosis of endometriosis, uterosacral ligament abnormalities, lateral displacement of the cervix, and cervical stenosis were observed in 47%, 28%, and 19% of the women, respectively.17 In this same study 22 women had none of these findings, but 8 had a complex ovarian mass consistent with endometriosis.

The possibility of endometriosis increases as the number of history and physical examination findings suggestive of endometriosis increase.

Related article:

Endometriosis and pain: Expert answers to 6 questions targeting your management options

When transvaginal ultrasound can aid diagnosis

Most women with endometriosis have normal transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) results because ultrasound cannot detect small isolated peritoneal lesions of endometriosis present in Stage I disease, the most common stage of endometriosis. However, ultrasound is useful in detecting both ovarian endometriomas and nodules of deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE).18 TVUS has excellent sensitivity (>90%) and specificity (>90%) for the detection of ovarian endometriomas because these cysts have characteristic, homogenous, low-level internal echoes.19,20 For the diagnosis of DIE of the uterosacral ligaments and rectovaginal septum, TVUS has fair sensitivity (>50%) and excellent specificity (>90%).21 In most studies, magnetic resonance imaging performs no better than TVUS for imaging ovarian endometriomas and DIE. Hence, TVUS is the preferred imaging modality for detecting endometriosis.22

- Endometriosis is a common gynecologic disease. Approximately 8% of women of reproductive age have the condition.

- Many patients report lengthy delays between the onset of symptoms of pelvic pain and the diagnosis of endometriosis.

- Both patients and clinicians contribute to the delay in the diagnosis of endometriosis: Women are often reluctant to report the severity of their pelvic pain symptoms, and clinicians often under-respond to a patient's report of severe pelvic pain symptoms.

- First-line therapy for the treatment of moderate to severe dysmenorrhea is nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and estrogen−progestin contraceptives.

- Increasing vigilance for endometriosis will shorten the time between onset of symptoms and definitive diagnosis.

- Reducing the time between the onset of symptoms and diagnosis of endometriosis will improve the quality of life of women with the disease because they will receive timely treatment.

This is a practice gap we can close

Clinicians take great pride in accurately solving patient problems in a timely and efficient manner. Substantial research indicates that we can improve the timeliness of our diagnosis of endometriosis. By acknowledging patients’ pain symptoms and recognizing the myriad symptoms and physical examination and imaging findings that are associated with endometriosis, we will close the gap and make this diagnosis with greater speed.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Endometriosis is a common gynecologic problem in adolescents and women. It often presents with pelvic pain, an ovarian endometrioma, and/or subfertility. In a prospective study of 116,678 nurses, the incidence of a new surgical diagnosis of endometriosis was greatest among women aged 25 to 29 years and lowest among women older than age 44.1 Using the incidence data from this study, the calculated prevalence of endometriosis in this large cohort of women of reproductive age was approximately 8%.

Although endometriosis is known to be a very common gynecologic problem, many studies report that there can be long delays between onset of pelvic pain symptoms and the diagnosis of endometriosis (Figure 1).2−6 Combining the results from 5 studies, involving 1,187 women, the mean age of onset of pelvic pain symptoms was 22.1 years, and the mean age at the diagnosis of endometriosis was 30.7 years. This is a difference of 8.6 years between the age of symptom onset and age at diagnosis.2−6

What factors contribute to the diagnosis delay?

Both patient and physician factors contribute to the reported lengthy delay between symptom onset and endometriosis diagnosis.7,8 Differentiating dysmenorrhea due to primary and secondary causes is difficult for both patients and physicians. Women may conceal the severity of menstrual pain to avoid both the embarrassment of drawing attention to themselves and being stigmatized as unable to cope. Most disappointing is that many women with endometriosis reported that they asked their clinician if endometriosis could be the cause of their severe dysmenorrhea and were told, “No.”7,8

Of interest, the reported delay in the diagnosis of endometriosis is much shorter for women who pre-sent with infertility than for women who present with pelvic pain. In one study from the United States, the delay to diagnosis was 3.13 years for women who presented with infertility and 6.35 years for women who presented with severe pelvic pain.3 This suggests that clinicians and patients more rapidly pursue the diagnosis of endometriosis in women with infertility, but not pelvic pain.

Related article:

Endometriosis: Expert answers to 7 crucial questions on diagnosis

Initial treatment of pelvic pain with NSAIDs and estrogen—progestin contraceptives

Many women with undiagnosed endometriosis present with pelvic pain symptoms including moderate to severe dysmenorrhea. These women are often empirically treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and combination estrogen−progestin contraceptives in either a cyclic or continuous manner.9,10 Since many women with endometriosis will have a reduction in their pelvic pain with NSAID and contraceptive treatment, diagnosis of their endometriosis may be delayed until their disease progresses years after their initial presentation. It is important to gently alert these women to the possibility that they have undiagnosed endometriosis as the cause of their pain symptoms and encourage them to report any worsening pain symptoms in a timely manner.

Sometimes women with pelvic pain are treated with NSAIDs and contraceptives but no significant reduction in pain symptoms occurs. For these women, speedy consideration should be given to offering a laparoscopy to determine the cause of their pain.

Related article:

Avoiding “shotgun” treatment: New thoughts on endometriosis-associated pelvic pain

Diagnosing endometriosis relies on identifying flags in the patient’s history

The gold standard for endometriosis diagnosis is surgical visualization of endometriosis lesions, most often with laparoscopy, plus histologic confirmation of endometriosis on a tissue biopsy.9,10 A key to reducing the time between onset of symptoms and diagnosis of endometriosis is identifying adolescents and women who are at high risk for having the disease. These women should be offered a laparoscopy procedure. In women with moderate to severe pelvic pain of at least 6 months duration, medical history, physical examination, and imaging studies can be helpful in identifying those at increased risk for endometriosis.

Items from the patient history that might raise the likelihood of endometriosis include:

- abdominopelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, menorrhagia, subfertility, dyspareunia and/or postcoital bleeding11

- symptoms of dysmenorrhea and/or dyspareunia that are not responsive to NSAIDs or estrogen−progestin contraceptives12

- symptoms of dysmenorrhea and/or dyspareunia associated with absenteeism from school or work13

- multiple visits to the emergency department for severe dysmenorrhea

- endometriosis in the patient’s mother or sister

- subfertility with regular ovulation, patent fallopian tubes, and a partner with a normal semen analysis

- urinary frequency, urgency, and/or pain on urination

- diarrhea, constipation, nausea, dyschezia, bowel cramping, abdominal distention, and early satiety.

A daunting clinical challenge is that symptoms of endometriosis overlap with other gynecologic and nongynecologic problems including pelvic infection, adhesions, ovarian cysts, fibroids, irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, interstitial cystitis, myofascial pain, depression, and history of sexual abuse.

Diagnosing endometriosis relies on identifying flags on physical exam

Physical examination findings that raise the likelihood that the patient has endometriosis include:

- fixed and retroverted uterus

- adnexal mass

- lesions of the cervix or posterior fornix that visually appear to be endometriosis

- uterosacral ligament abnormalities, including tenderness, thickening, and/or nodularity14,15

- lateral displacement of the cervix (FIGURE 2)16,17

- severe cervical stenosis.

In one study of 57 women with a surgical diagnosis of endometriosis, uterosacral ligament abnormalities, lateral displacement of the cervix, and cervical stenosis were observed in 47%, 28%, and 19% of the women, respectively.17 In this same study 22 women had none of these findings, but 8 had a complex ovarian mass consistent with endometriosis.

The possibility of endometriosis increases as the number of history and physical examination findings suggestive of endometriosis increase.

Related article:

Endometriosis and pain: Expert answers to 6 questions targeting your management options

When transvaginal ultrasound can aid diagnosis

Most women with endometriosis have normal transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) results because ultrasound cannot detect small isolated peritoneal lesions of endometriosis present in Stage I disease, the most common stage of endometriosis. However, ultrasound is useful in detecting both ovarian endometriomas and nodules of deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE).18 TVUS has excellent sensitivity (>90%) and specificity (>90%) for the detection of ovarian endometriomas because these cysts have characteristic, homogenous, low-level internal echoes.19,20 For the diagnosis of DIE of the uterosacral ligaments and rectovaginal septum, TVUS has fair sensitivity (>50%) and excellent specificity (>90%).21 In most studies, magnetic resonance imaging performs no better than TVUS for imaging ovarian endometriomas and DIE. Hence, TVUS is the preferred imaging modality for detecting endometriosis.22

- Endometriosis is a common gynecologic disease. Approximately 8% of women of reproductive age have the condition.

- Many patients report lengthy delays between the onset of symptoms of pelvic pain and the diagnosis of endometriosis.

- Both patients and clinicians contribute to the delay in the diagnosis of endometriosis: Women are often reluctant to report the severity of their pelvic pain symptoms, and clinicians often under-respond to a patient's report of severe pelvic pain symptoms.

- First-line therapy for the treatment of moderate to severe dysmenorrhea is nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and estrogen−progestin contraceptives.

- Increasing vigilance for endometriosis will shorten the time between onset of symptoms and definitive diagnosis.

- Reducing the time between the onset of symptoms and diagnosis of endometriosis will improve the quality of life of women with the disease because they will receive timely treatment.

This is a practice gap we can close

Clinicians take great pride in accurately solving patient problems in a timely and efficient manner. Substantial research indicates that we can improve the timeliness of our diagnosis of endometriosis. By acknowledging patients’ pain symptoms and recognizing the myriad symptoms and physical examination and imaging findings that are associated with endometriosis, we will close the gap and make this diagnosis with greater speed.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Missmer SA, Hankinson SE, Spiegelman D, Barbieri RL, Marshall LM, Hunter DJ. Incidence of laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis by demographic, anthropometric, and lifestyle factors. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(8):784−796.

- Hadfield R, Mardon H, Barlow D, Kennedy S. Delay in the diagnosis of endometriosis: a survey of women from the USA and UK. Hum Reprod. 1996;11(4):878−880.

- Dmowski WP, Lesniewicz R, Rana N, Pepping P, Noursalehi M. Changing trends in the diagnosis of endometriosis: a comparative study of women with pelvic endometriosis presenting with chronic pelvic pain or infertility. Fertil Steril. 1997;67(2):238−243.

- Arruda MS, Petta CA, Abrão MS, Benetti-Pinto CL. Time elapsed from onset of symptoms to diagnosis of endometriosis in a cohort study of Brazilian women. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(4):756−759.

- Husby GK, Haugen RS, Moen MH. Diagnostic delay in women with pain and endometriosis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82(7):649−653.

- Hudelist G, Fritzer N, Thomas A, et al. Diagnostic delay for endometriosis in Austria and Germany: causes and possible consequences. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(12):3412−3416.

- Ballard K, Lowton K, Wright J. What's the delay? A qualitative study of women's experiences of reaching a diagnosis of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2006;86(5):1296−1301.

- Seear K. The etiquette of endometriosis: stigmatisation, menstrual concealment and the diagnostic delay. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(8):1220−1227.

- Falcone T, Lebovic DI. Clinical management of endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(3):691−705.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 114: Management of endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(1):223−236.

- Ballard KD, Seaman HE, de Vries CS, Wright JT. Can symptomatology help in the diagnosis of endometriosis? Findings from a national case-control study--Part 1. BJOG. 2008;115(11):1382−1391.

- Steenberg CK, Tanbo TG, Qvigstad E. Endometriosis in adolescence: predictive markers and management. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2013;92(5):491−495.

- Zannoni L, Giorgi M, Spagnolo E, Montanari G, Villa G, Seracchioli R. Dysmenorrhea, absenteeism from school, and symptoms suspicious for endometriosis in adolescents. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2014;27(5):258−265.

- Cheewadhanaraks S, Peeyananjarassri K, Dhanaworavibul K, Liabsuetrakul T. Positive predictive value of clinical diagnosis of endometriosis. J Med Assoc Thai. 2004;87(7):740−744.

- Guerriero S, Ajossa S, Gerada M, Virgilio B, Angioni S, Melis GB. Diagnostic value of transvaginal 'tenderness-guided' ultrasonography for the prediction of location of deep endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2008;23(11):2452−2457.

- Propst AM, Storti K, Barbieri RL. Lateral cervical displacement is associated with endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1998;70(3):568−570.

- Barbieri RL, Propst AM. Physical examination findings in women with endometriosis: uterosacral ligament abnormalities, lateral cervical displacement and cervical stenosis. J Gynecol Techniques. 1999;5:157−159.

- Guerriero S, Condous G, van den Bosch T, et al. Systematic approach to sonographic evaluation of the pelvis in women with suspected endometriosis, including terms, definitions and measurements: a consensus opinion from the International Deep Endometriosis Analysis (IDEA) group. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;48(3):318−332.

- Nisenblat V, Bossuyt PM, Farquhar C, Johnson N, Hull ML. Imaging modalities for the non-invasive diagnosis of endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2:CD009591.

- Somigliana E, Vercellini P, Vigano P, Benaglia L, Crosignani PG, Fedele L. Non-invasive diagnosis of endometriosis: the goal or own goal? Hum Reprod. 2010;25(8):1863−1868.

- Guerriero S, Ajossa S, Minguez JA, et al. Accuracy of transvaginal ultrasound for diagnosis of deep endometriosis in uterosacral ligaments, rectovaginal septum, vagina and bladder: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015;46(5):534−545.

- Benacerraf BR, Groszmann Y. Sonography should be the first imaging examination done to evaluate patients with suspected endometriosis. J Ultrasound Med. 2012;31(4):651−653.

- Missmer SA, Hankinson SE, Spiegelman D, Barbieri RL, Marshall LM, Hunter DJ. Incidence of laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis by demographic, anthropometric, and lifestyle factors. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(8):784−796.

- Hadfield R, Mardon H, Barlow D, Kennedy S. Delay in the diagnosis of endometriosis: a survey of women from the USA and UK. Hum Reprod. 1996;11(4):878−880.

- Dmowski WP, Lesniewicz R, Rana N, Pepping P, Noursalehi M. Changing trends in the diagnosis of endometriosis: a comparative study of women with pelvic endometriosis presenting with chronic pelvic pain or infertility. Fertil Steril. 1997;67(2):238−243.

- Arruda MS, Petta CA, Abrão MS, Benetti-Pinto CL. Time elapsed from onset of symptoms to diagnosis of endometriosis in a cohort study of Brazilian women. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(4):756−759.

- Husby GK, Haugen RS, Moen MH. Diagnostic delay in women with pain and endometriosis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82(7):649−653.

- Hudelist G, Fritzer N, Thomas A, et al. Diagnostic delay for endometriosis in Austria and Germany: causes and possible consequences. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(12):3412−3416.

- Ballard K, Lowton K, Wright J. What's the delay? A qualitative study of women's experiences of reaching a diagnosis of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2006;86(5):1296−1301.

- Seear K. The etiquette of endometriosis: stigmatisation, menstrual concealment and the diagnostic delay. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(8):1220−1227.

- Falcone T, Lebovic DI. Clinical management of endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(3):691−705.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 114: Management of endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(1):223−236.

- Ballard KD, Seaman HE, de Vries CS, Wright JT. Can symptomatology help in the diagnosis of endometriosis? Findings from a national case-control study--Part 1. BJOG. 2008;115(11):1382−1391.

- Steenberg CK, Tanbo TG, Qvigstad E. Endometriosis in adolescence: predictive markers and management. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2013;92(5):491−495.

- Zannoni L, Giorgi M, Spagnolo E, Montanari G, Villa G, Seracchioli R. Dysmenorrhea, absenteeism from school, and symptoms suspicious for endometriosis in adolescents. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2014;27(5):258−265.

- Cheewadhanaraks S, Peeyananjarassri K, Dhanaworavibul K, Liabsuetrakul T. Positive predictive value of clinical diagnosis of endometriosis. J Med Assoc Thai. 2004;87(7):740−744.

- Guerriero S, Ajossa S, Gerada M, Virgilio B, Angioni S, Melis GB. Diagnostic value of transvaginal 'tenderness-guided' ultrasonography for the prediction of location of deep endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2008;23(11):2452−2457.

- Propst AM, Storti K, Barbieri RL. Lateral cervical displacement is associated with endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1998;70(3):568−570.

- Barbieri RL, Propst AM. Physical examination findings in women with endometriosis: uterosacral ligament abnormalities, lateral cervical displacement and cervical stenosis. J Gynecol Techniques. 1999;5:157−159.

- Guerriero S, Condous G, van den Bosch T, et al. Systematic approach to sonographic evaluation of the pelvis in women with suspected endometriosis, including terms, definitions and measurements: a consensus opinion from the International Deep Endometriosis Analysis (IDEA) group. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;48(3):318−332.

- Nisenblat V, Bossuyt PM, Farquhar C, Johnson N, Hull ML. Imaging modalities for the non-invasive diagnosis of endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2:CD009591.

- Somigliana E, Vercellini P, Vigano P, Benaglia L, Crosignani PG, Fedele L. Non-invasive diagnosis of endometriosis: the goal or own goal? Hum Reprod. 2010;25(8):1863−1868.

- Guerriero S, Ajossa S, Minguez JA, et al. Accuracy of transvaginal ultrasound for diagnosis of deep endometriosis in uterosacral ligaments, rectovaginal septum, vagina and bladder: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015;46(5):534−545.

- Benacerraf BR, Groszmann Y. Sonography should be the first imaging examination done to evaluate patients with suspected endometriosis. J Ultrasound Med. 2012;31(4):651−653.

Strength in Community

No question about it, we are entering another uncertain time in health care.

Those of us of a “certain age” may yearn for a return to the days when we surgeons faced few restrictions on our practice or our decisions. Each of us has developed his/her own perspective on the state of U.S. health care and the best path forward, most frequently shaped by our background, geographical location, and practice environment. The tendency among a great many of us has been to erect walls rather than bridges and to view our own situation as unique and more threatened than that of others. Specialists and generalists, urbanites and rural dwellers, all tend to view their own worlds as uniquely challenging.

If there was ever a need to reach out and communicate with one another and understand that the overwhelming desire of every surgeon is to provide his/her patients with the best possible care, it is now. After all, we’re all surgeons who face the same sets of challenges in the OR. There is far more in our professional lives that unites us than separates us. It is critically important that surgeons maintain open lines of communication and solidarity, no matter what other characteristics of politics or place separate us. How do we accomplish this seemingly Herculean task in the midst of the dissension and disintegration occurring all around us?

One powerful tool that can help break down barriers to honest dialogue and reinforce solidarity among surgeons is the ACS Communities. This hugely successful communication platform, which grew out of the old ACS Rural List, is now an electronic meeting place and venue for dialogue for all members of the College. The Communities is a safe place where participants, despite their many differences in specialty, location, practice type, and political views, share the common goal of improving the care available to our patients. Postings range across a wide spectrum of topics – from clinical to fiscal, social, personal and philosophical, sometimes all in the same thread. All ACS Fellows are free to sign up and post on any subject that is of concern to them, as long as their postings adhere to a baseline respect for other members. The contributions are curated by Tyler G Hughes, MD, FACS, coeditor of ACS Surgery News, but they rarely stray from the boundaries of civil discourse.

The diversity of voices on the Communities is gratifying. Midcareer surgeons, recent grads, and retired specialists all converse with each other in this space. Surgeons from different practice types and locales, including from those who work in rural critical access hospitals and those in academic medical centers, all come to discuss, ask for opinions, exchange information, and debate. These colleagues offer opinions based on long years of practice and from article of the highest quality from the literature. The whole is somehow greater than the sum of its parts. Divergent opinions add depth and breadth to any conversation and lead to a greater understanding of the entirety of a subject. I always learn something from these dialogues.

Most threads involve questions about clinical issues that have arisen in the author’s practice. One recent topic was interval cholecystectomy in which the question was raised about whether the gallbladder needs to be removed after placement of a tube cholecystostomy (usually by Interventional Radiology) for acute cholecystitis, a practice that seems to be proliferating in many areas. Over a two-week period, responses poured in from a wide variety of practice sites and types and ranged from expert opinion to references from the literature. Other threads involve less commonly encountered conditions such as coccydynia or splenic cysts or offer opinions about such “hot-button” items” as attire in the OR or music in the OR. Almost every subject is interesting and provides the reader with food for thought.

Other topics stray from the purely clinical or surgical to the health care system itself. One current ongoing and timely subject of a thread on the ACS General Surgery community is entitled “Care for the Vulnerable vs. Cash for the Powerful.” Opinions have been expressed from many perspectives and have truly been educational and enlightening. While the general public discourse has been fraught and divisive, the Communities discussions have been respectful and collegial. This basic unity underlying our diversity is the foundation of the Communities and it is a source of strength for the surgical profession.

The ACS Communities is the work of many hands and hearts over many years, and I am truly grateful to those who made it happen and to the ACS for sponsoring this great platform for communication.

Dr. Deveney is professor of surgery and vice chair of education in the department of surgery, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. She is the Coeditor of ACS Surgery News.

No question about it, we are entering another uncertain time in health care.

Those of us of a “certain age” may yearn for a return to the days when we surgeons faced few restrictions on our practice or our decisions. Each of us has developed his/her own perspective on the state of U.S. health care and the best path forward, most frequently shaped by our background, geographical location, and practice environment. The tendency among a great many of us has been to erect walls rather than bridges and to view our own situation as unique and more threatened than that of others. Specialists and generalists, urbanites and rural dwellers, all tend to view their own worlds as uniquely challenging.

If there was ever a need to reach out and communicate with one another and understand that the overwhelming desire of every surgeon is to provide his/her patients with the best possible care, it is now. After all, we’re all surgeons who face the same sets of challenges in the OR. There is far more in our professional lives that unites us than separates us. It is critically important that surgeons maintain open lines of communication and solidarity, no matter what other characteristics of politics or place separate us. How do we accomplish this seemingly Herculean task in the midst of the dissension and disintegration occurring all around us?

One powerful tool that can help break down barriers to honest dialogue and reinforce solidarity among surgeons is the ACS Communities. This hugely successful communication platform, which grew out of the old ACS Rural List, is now an electronic meeting place and venue for dialogue for all members of the College. The Communities is a safe place where participants, despite their many differences in specialty, location, practice type, and political views, share the common goal of improving the care available to our patients. Postings range across a wide spectrum of topics – from clinical to fiscal, social, personal and philosophical, sometimes all in the same thread. All ACS Fellows are free to sign up and post on any subject that is of concern to them, as long as their postings adhere to a baseline respect for other members. The contributions are curated by Tyler G Hughes, MD, FACS, coeditor of ACS Surgery News, but they rarely stray from the boundaries of civil discourse.

The diversity of voices on the Communities is gratifying. Midcareer surgeons, recent grads, and retired specialists all converse with each other in this space. Surgeons from different practice types and locales, including from those who work in rural critical access hospitals and those in academic medical centers, all come to discuss, ask for opinions, exchange information, and debate. These colleagues offer opinions based on long years of practice and from article of the highest quality from the literature. The whole is somehow greater than the sum of its parts. Divergent opinions add depth and breadth to any conversation and lead to a greater understanding of the entirety of a subject. I always learn something from these dialogues.

Most threads involve questions about clinical issues that have arisen in the author’s practice. One recent topic was interval cholecystectomy in which the question was raised about whether the gallbladder needs to be removed after placement of a tube cholecystostomy (usually by Interventional Radiology) for acute cholecystitis, a practice that seems to be proliferating in many areas. Over a two-week period, responses poured in from a wide variety of practice sites and types and ranged from expert opinion to references from the literature. Other threads involve less commonly encountered conditions such as coccydynia or splenic cysts or offer opinions about such “hot-button” items” as attire in the OR or music in the OR. Almost every subject is interesting and provides the reader with food for thought.

Other topics stray from the purely clinical or surgical to the health care system itself. One current ongoing and timely subject of a thread on the ACS General Surgery community is entitled “Care for the Vulnerable vs. Cash for the Powerful.” Opinions have been expressed from many perspectives and have truly been educational and enlightening. While the general public discourse has been fraught and divisive, the Communities discussions have been respectful and collegial. This basic unity underlying our diversity is the foundation of the Communities and it is a source of strength for the surgical profession.

The ACS Communities is the work of many hands and hearts over many years, and I am truly grateful to those who made it happen and to the ACS for sponsoring this great platform for communication.

Dr. Deveney is professor of surgery and vice chair of education in the department of surgery, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. She is the Coeditor of ACS Surgery News.

No question about it, we are entering another uncertain time in health care.

Those of us of a “certain age” may yearn for a return to the days when we surgeons faced few restrictions on our practice or our decisions. Each of us has developed his/her own perspective on the state of U.S. health care and the best path forward, most frequently shaped by our background, geographical location, and practice environment. The tendency among a great many of us has been to erect walls rather than bridges and to view our own situation as unique and more threatened than that of others. Specialists and generalists, urbanites and rural dwellers, all tend to view their own worlds as uniquely challenging.

If there was ever a need to reach out and communicate with one another and understand that the overwhelming desire of every surgeon is to provide his/her patients with the best possible care, it is now. After all, we’re all surgeons who face the same sets of challenges in the OR. There is far more in our professional lives that unites us than separates us. It is critically important that surgeons maintain open lines of communication and solidarity, no matter what other characteristics of politics or place separate us. How do we accomplish this seemingly Herculean task in the midst of the dissension and disintegration occurring all around us?

One powerful tool that can help break down barriers to honest dialogue and reinforce solidarity among surgeons is the ACS Communities. This hugely successful communication platform, which grew out of the old ACS Rural List, is now an electronic meeting place and venue for dialogue for all members of the College. The Communities is a safe place where participants, despite their many differences in specialty, location, practice type, and political views, share the common goal of improving the care available to our patients. Postings range across a wide spectrum of topics – from clinical to fiscal, social, personal and philosophical, sometimes all in the same thread. All ACS Fellows are free to sign up and post on any subject that is of concern to them, as long as their postings adhere to a baseline respect for other members. The contributions are curated by Tyler G Hughes, MD, FACS, coeditor of ACS Surgery News, but they rarely stray from the boundaries of civil discourse.

The diversity of voices on the Communities is gratifying. Midcareer surgeons, recent grads, and retired specialists all converse with each other in this space. Surgeons from different practice types and locales, including from those who work in rural critical access hospitals and those in academic medical centers, all come to discuss, ask for opinions, exchange information, and debate. These colleagues offer opinions based on long years of practice and from article of the highest quality from the literature. The whole is somehow greater than the sum of its parts. Divergent opinions add depth and breadth to any conversation and lead to a greater understanding of the entirety of a subject. I always learn something from these dialogues.

Most threads involve questions about clinical issues that have arisen in the author’s practice. One recent topic was interval cholecystectomy in which the question was raised about whether the gallbladder needs to be removed after placement of a tube cholecystostomy (usually by Interventional Radiology) for acute cholecystitis, a practice that seems to be proliferating in many areas. Over a two-week period, responses poured in from a wide variety of practice sites and types and ranged from expert opinion to references from the literature. Other threads involve less commonly encountered conditions such as coccydynia or splenic cysts or offer opinions about such “hot-button” items” as attire in the OR or music in the OR. Almost every subject is interesting and provides the reader with food for thought.

Other topics stray from the purely clinical or surgical to the health care system itself. One current ongoing and timely subject of a thread on the ACS General Surgery community is entitled “Care for the Vulnerable vs. Cash for the Powerful.” Opinions have been expressed from many perspectives and have truly been educational and enlightening. While the general public discourse has been fraught and divisive, the Communities discussions have been respectful and collegial. This basic unity underlying our diversity is the foundation of the Communities and it is a source of strength for the surgical profession.

The ACS Communities is the work of many hands and hearts over many years, and I am truly grateful to those who made it happen and to the ACS for sponsoring this great platform for communication.

Dr. Deveney is professor of surgery and vice chair of education in the department of surgery, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. She is the Coeditor of ACS Surgery News.

Evidence helps, but some decisions remain within the art of medicine

Despite advances in therapy, more than 10% of patients with acute bacterial meningitis still die of it, and more suffer significant morbidity, including cognitive dysfunction and deafness. Well-defined protocols that include empiric antibiotics and systemic corticosteroids have improved the outcomes of patients with meningitis. But, as with other closed-space infections such as septic arthritis, any delay in providing appropriate antibiotic treatment is associated with a worse prognosis. In the case of bacterial meningitis, a retrospective analysis concluded that each hour of delay in delivering antibiotics and a corticosteroid can be associated with a relative (not absolute) increase in mortality of 13%.1