User login

Women’s Preventive Services Initiative Guidelines provide consensus for practicing ObGyns

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA) intended that women have access to critical preventive health services without a copay or deductible. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) was asked to help identify those critical preventive women’s health services. In 2011, the IOM Committee on Preventive Services for Women recommended that all women have access to 9 preventive services, among them1:

- screening for gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM)

- human papilloma virus testing

- contraceptive methods and counseling

- well-woman visits.

The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the US Department of Health and Human Services agreed to update the recommended preventive services every 5 years.

In March 2016, HRSA entered into a 5-year cooperative agreement with the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) to update the guidelines and to develop additional recommendations to enhance women’s health.2 ACOG launched the Women’s Preventive Services Initiative (WPSI) to develop the 2016 update.

The 5-year grant with HRSA will address many more preventive health services for women across their lifespan as well as implementation strategies so that women receive consistent and appropriate care, regardless of the health care provider’s specialty. The WPSI recognizes that the selection of a provider for well-woman care will be determined as much by a woman’s needs and preferences as by her access to health care services and health plan availability.

The WPSI draft recommendations were released for public comment in September 2016,2 and HRSA approved the recommendations in December 2016.3 In this editorial, I provide a look at which organizations comprise the WPSI and a summary of the 9 recommended preventive health services.

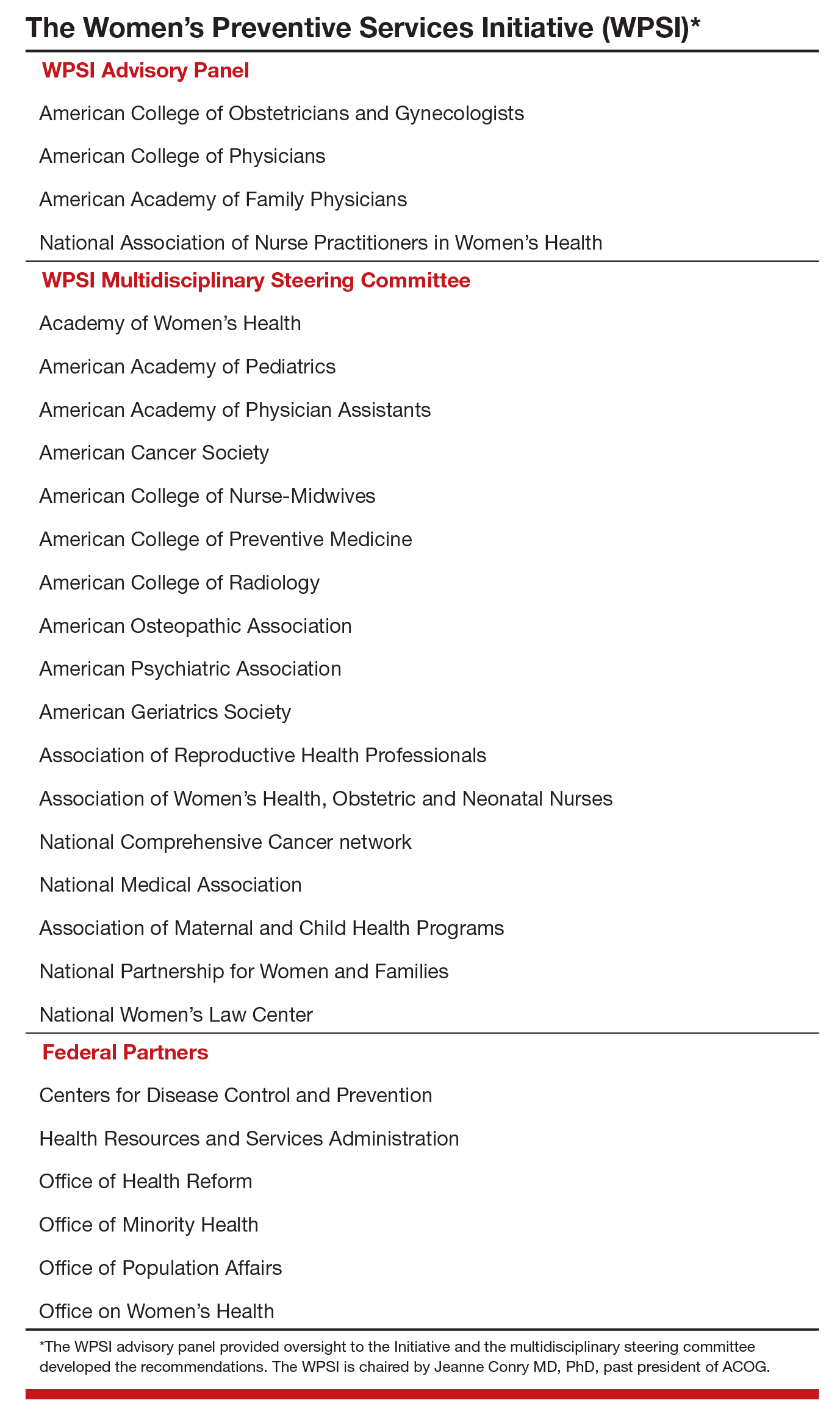

Who makes up the Women’s Preventive Services Initiative?

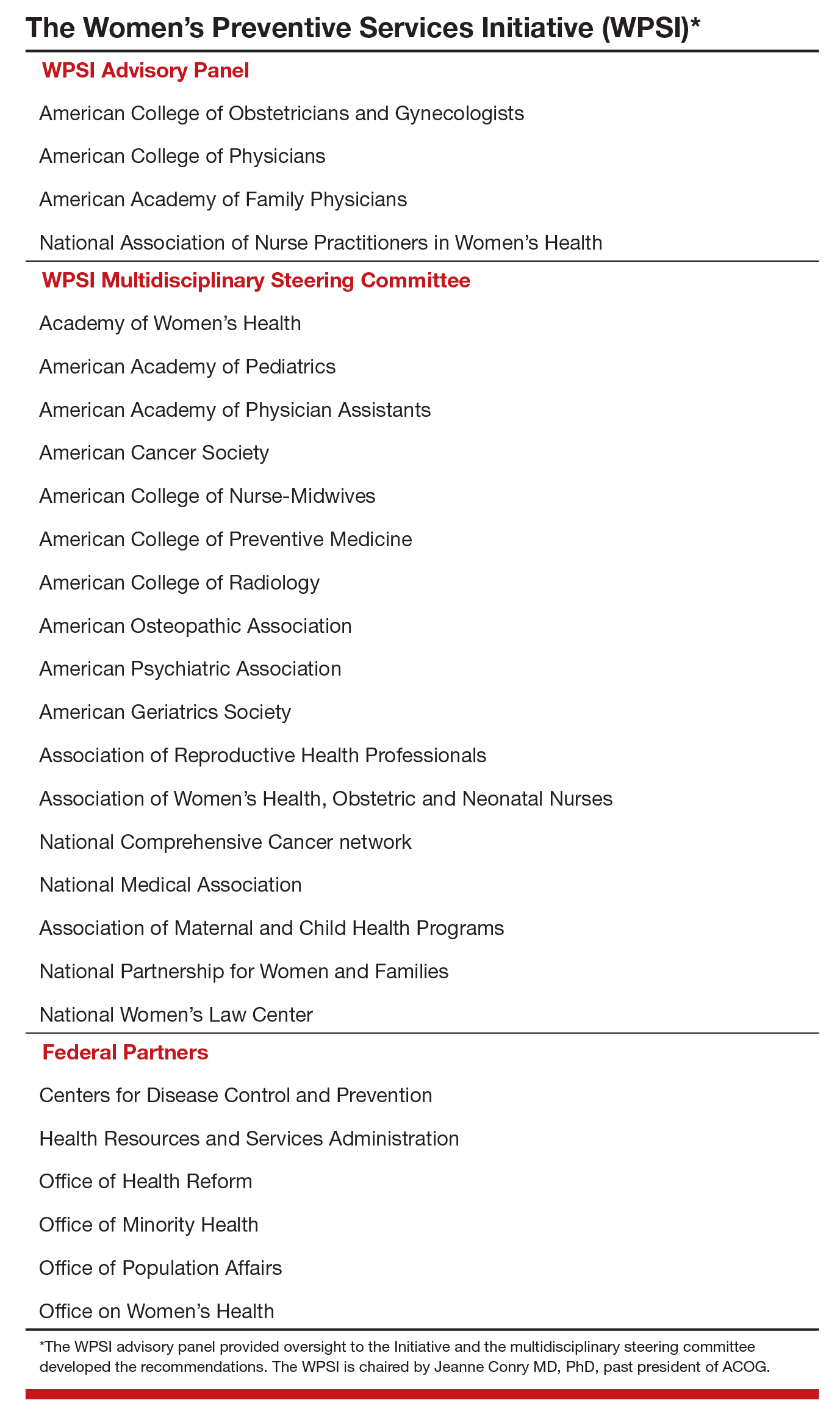

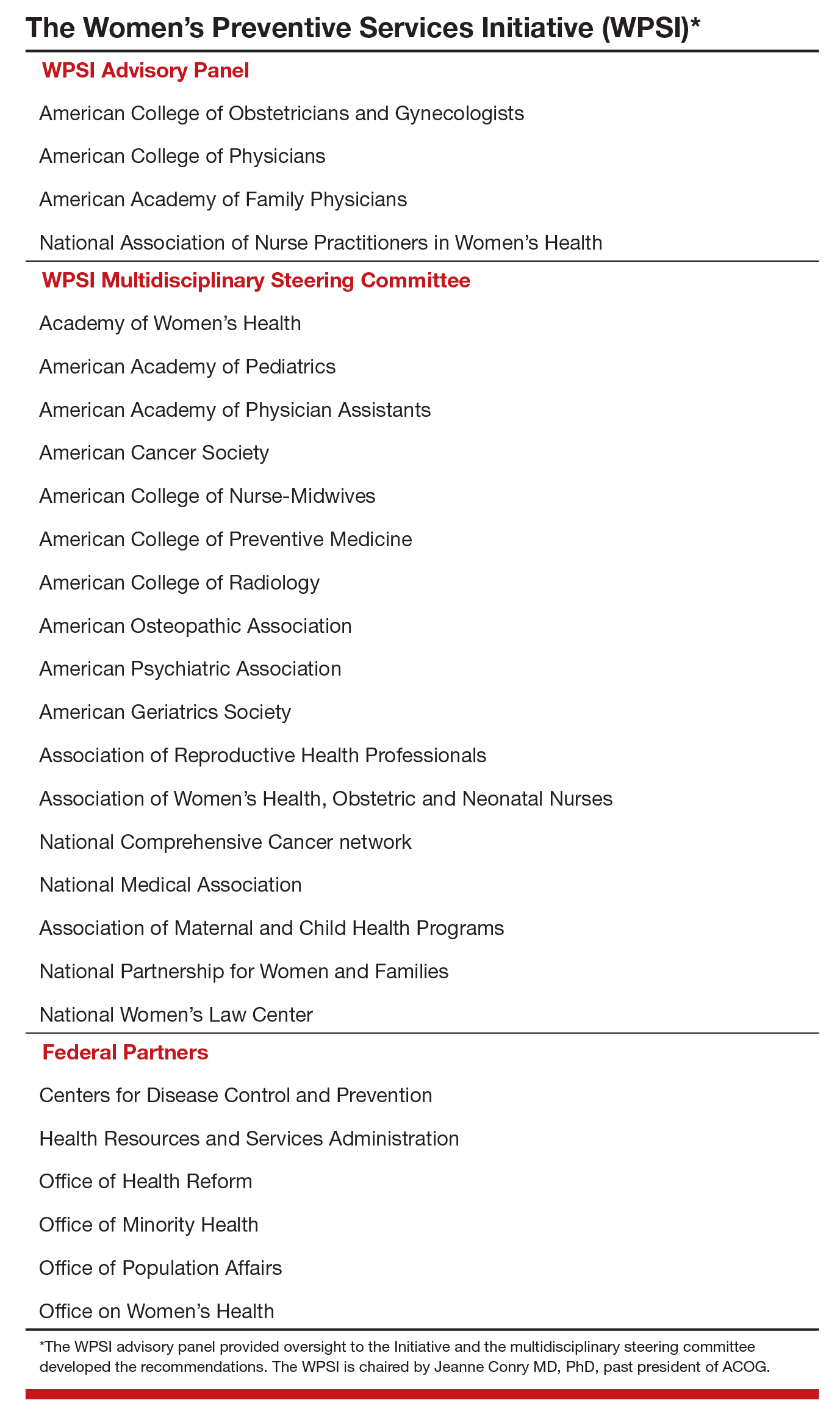

The WPSI is a collaboration between professional societies and consumer organizations. The goal of the WPSI is “to promote health over the course of a woman’s lifetime through disease prevention and preventive healthcare.” The WPSI advisory panel provides oversight to the effort and the multidisciplinary steering committee develops the recommendations. The WPSI advisory panel includes leaders and experts from 4 major professional organizations, whose members provide the majority of women’s health care in the United States:

- ACOG

- American College of Physicians (ACP)

- American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP)

- National Association of Nurse Practitioners in Women’s Health (NPWH).

The multidisciplinary steering committee includes the members of the advisory panel, representatives from 17 professional and consumer organizations, a patient representative, and representatives from 6 federal agencies. The WPSI is currently chaired by Jeanne Conry, MD, PhD, past president of ACOG. The steering committee used evidence-based best practices to develop the guidelines and relied heavily on the foundation provided by the 2011 IOM report.1

The 9 WPSI recommendations

Much of the text below is directly quoted from the final recommendations. When a recommendation is paraphrased it is not placed in quotations.

Recommendation 1: Breast cancer screening for average-risk women

“Average-risk women should initiate mammography screening for breast cancer no earlier than age 40 and no later than age 50 years. Screeningmammography should occur at least biennially and as frequently as annually. Screening should continue through at least age 74 years and age alone should not be the basis to stop screening.”

Decisions about when to initiate screening for women between 40 and 50 years of age, how often to screen, and when to stop screening should be based on shared decision making involving the woman and her clinician.

Recommendation 2: Breastfeeding services and supplies

Women should be provided “comprehensive lactation support services including counseling, education and breast feeding equipment and supplies during the antenatal, perinatal, and postpartum periods.” These services will support the successful initiation and maintenance of breastfeeding. Women should have access to double electric breast pumps.

Recommendation 3: Screening for cervical cancer

Average-risk women should initiate cervical cancer screening with cervical cytology at age 21 years and have cervical cytology testing every 3 years from 21 to 29 years of age. “Cotesting with cytology and human papillomavirus (HPV) testing is not recommended for women younger than 30 years. Women aged 30 to 65 years should be screened with cytology and HPV testing every 5 years or cytology alone every 3 years.” Women who have received the HPV vaccine should be screened using these guidelines. Cervical cancer screening is not recommended for women younger than 21 years or older than 65 years who have had adequate prior screening and are not at high risk for cervical cancer. Cervical cancer screening is also not recommended for women who have had a hysterectomy with removal of the cervix and no personal history of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or 3 within the past 20 years.

Recommendation 4: Contraception

Adolescent and adult women should have access to the full range of US Food and Drug Administration–approved female-controlled contraceptives to prevent unintended pregnancy and improve birth outcomes. Multiple visits with a clinician may be needed to select an optimal contraceptive.

Recommendation 5: Screening for gestational diabetes mellitus

Pregnant women should be screened for GDM between 24 and 28 weeks’ gestation to prevent adverse birth outcomes. Screening should be performed with a “50 gm oral glucose challenge test followed by a 3-hour 100 gm oral glucose tolerance test” if the results on the initial oral glucose tolerance test are abnormal. This testing sequence has high sensitivity and specificity. Women with risk factors for diabetes mellitus should be screened for diabetes at the first prenatal visit using current best clinical practice.

Recommendation 6: Screening for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection

Adolescents and women should receive education and risk assessment for HIV annually and should be tested for HIV at least once during their lifetime. Based on assessed risk, screening annually may be appropriate. “Screening for HIV is recommended for all pregnant women upon initiation of prenatal care with retesting during pregnancy based on risk factors. Rapid HIV testing is recommended for pregnant women who present in active labor with an undocumented HIV status.” Risk-based screening does not identify approximately 20% of HIV-infected people. Hence screening annually may be reasonable.

Recommendation 7: Screening for interpersonal and domestic violence

All adolescents and women should be screened annually for both interpersonal violence (IPV) and domestic violence (DV). Intervention services should be available to all adolescents and women. IPV and DV are prevalent problems, and they are often undetected by clinicians. Hence annual screening is recommended.

Recommendation 8: Counseling for sexually transmitted infections

Adolescents and women should be assessed for sexually transmittedinfection (STI) risk. Risk factors include:

- “age younger than 25 years,

- a recent STI,

- a new sex partner,

- multiple partners,

- a partner with concurrent partners,

- a partner with an STI, and

- a lack of or inconsistent condom use.”

Women at increased risk for an STI should receive behavioral counseling.

Recommendation 9: Well-woman preventive visits

Women should “receive at least one preventive care visit per year beginning in adolescence and continuing across the lifespan to ensure that the recommended preventive services including preconception and many services necessary for prenatal and interconception care are obtained. The primary purpose of these visits is the delivery and coordination of recommended preventive services as determined by age and risk factors.”

- Abridged guidelines for the Women's Preventive Services Initiative can be found here: http://www.womenspreventivehealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/WPSI_2016AbridgedReport.pdf.

- Evidence-based summaries and appendices are available at this link: http://www.womenspreventivehealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Evidence-Summaries-and-Appendices.pdf.

I plan on using these recommendations to guide my practice

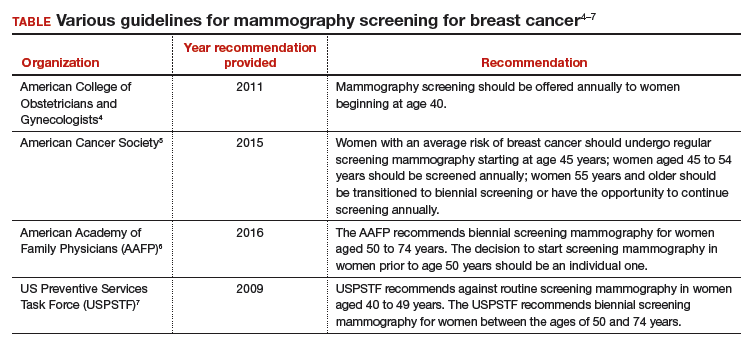

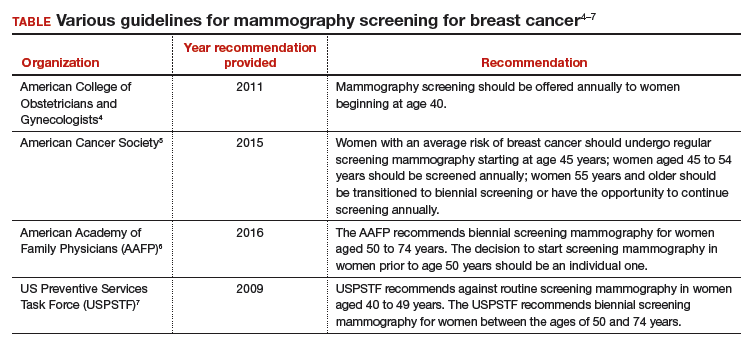

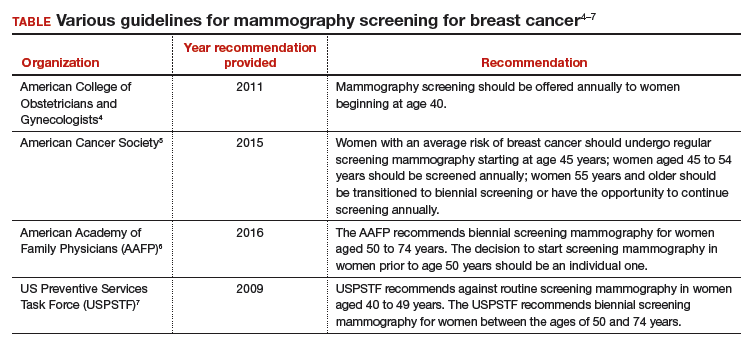

Historically, many high-profile expert professional groups have developed their own women’s health services guidelines. The proliferation of conflicting guidelines confused both patients and clinicians. Dueling guidelines likely undermine public health because they result in confusion among patients and inconsistent care across the many disciplines that provide medical services to women.

The proliferation of conflicting guidelines for mammography screening for breast cancer is a good example of how dueling guidelines can undermine public health (TABLE).4−7 The WPSI has done a great service to women and clinicians by creating a shared framework for consistently providing critical services across a woman’s entire life. I plan on using these recommendations to guide my practice. Patients and clinicians will greatly benefit from the exceptionally thoughtful women’s preventive services guidelines provided by the WPSI.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Institute of Medicine. Clinical preventive services for women: closing the gaps. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. http://nap.edu/13181. Accessed January 16, 2017.

- American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Women's Preventive Services Initiative (WPSI). http://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/ACOG-Departments/Annual-Womens-Health-Care/Womens-Preventive-Services-Initiative. Accessed January 16, 2017.

- Health Resources and Services Administration website. Women's preventive services guidelines. https://www.hrsa.gov/womensguidelines/. Accessed January 16, 2017.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 122: breast cancer screening. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(2 pt 1):372-382.

- Oeffinger KC, Fontham ET, Etzioni R, et al. Breast cancer screening for women at average risk: 2015 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. JAMA. 2015;314(15):1599-1614.

- American Academy of Family Physicians website. Clinical preventive service recommendation: breast cancer. http://www.aafp.org/patient-care/clinical-recommendations/all/breast-cancer.html. Accessed January 16, 2017.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for breast cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(10):716-726.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA) intended that women have access to critical preventive health services without a copay or deductible. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) was asked to help identify those critical preventive women’s health services. In 2011, the IOM Committee on Preventive Services for Women recommended that all women have access to 9 preventive services, among them1:

- screening for gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM)

- human papilloma virus testing

- contraceptive methods and counseling

- well-woman visits.

The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the US Department of Health and Human Services agreed to update the recommended preventive services every 5 years.

In March 2016, HRSA entered into a 5-year cooperative agreement with the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) to update the guidelines and to develop additional recommendations to enhance women’s health.2 ACOG launched the Women’s Preventive Services Initiative (WPSI) to develop the 2016 update.

The 5-year grant with HRSA will address many more preventive health services for women across their lifespan as well as implementation strategies so that women receive consistent and appropriate care, regardless of the health care provider’s specialty. The WPSI recognizes that the selection of a provider for well-woman care will be determined as much by a woman’s needs and preferences as by her access to health care services and health plan availability.

The WPSI draft recommendations were released for public comment in September 2016,2 and HRSA approved the recommendations in December 2016.3 In this editorial, I provide a look at which organizations comprise the WPSI and a summary of the 9 recommended preventive health services.

Who makes up the Women’s Preventive Services Initiative?

The WPSI is a collaboration between professional societies and consumer organizations. The goal of the WPSI is “to promote health over the course of a woman’s lifetime through disease prevention and preventive healthcare.” The WPSI advisory panel provides oversight to the effort and the multidisciplinary steering committee develops the recommendations. The WPSI advisory panel includes leaders and experts from 4 major professional organizations, whose members provide the majority of women’s health care in the United States:

- ACOG

- American College of Physicians (ACP)

- American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP)

- National Association of Nurse Practitioners in Women’s Health (NPWH).

The multidisciplinary steering committee includes the members of the advisory panel, representatives from 17 professional and consumer organizations, a patient representative, and representatives from 6 federal agencies. The WPSI is currently chaired by Jeanne Conry, MD, PhD, past president of ACOG. The steering committee used evidence-based best practices to develop the guidelines and relied heavily on the foundation provided by the 2011 IOM report.1

The 9 WPSI recommendations

Much of the text below is directly quoted from the final recommendations. When a recommendation is paraphrased it is not placed in quotations.

Recommendation 1: Breast cancer screening for average-risk women

“Average-risk women should initiate mammography screening for breast cancer no earlier than age 40 and no later than age 50 years. Screeningmammography should occur at least biennially and as frequently as annually. Screening should continue through at least age 74 years and age alone should not be the basis to stop screening.”

Decisions about when to initiate screening for women between 40 and 50 years of age, how often to screen, and when to stop screening should be based on shared decision making involving the woman and her clinician.

Recommendation 2: Breastfeeding services and supplies

Women should be provided “comprehensive lactation support services including counseling, education and breast feeding equipment and supplies during the antenatal, perinatal, and postpartum periods.” These services will support the successful initiation and maintenance of breastfeeding. Women should have access to double electric breast pumps.

Recommendation 3: Screening for cervical cancer

Average-risk women should initiate cervical cancer screening with cervical cytology at age 21 years and have cervical cytology testing every 3 years from 21 to 29 years of age. “Cotesting with cytology and human papillomavirus (HPV) testing is not recommended for women younger than 30 years. Women aged 30 to 65 years should be screened with cytology and HPV testing every 5 years or cytology alone every 3 years.” Women who have received the HPV vaccine should be screened using these guidelines. Cervical cancer screening is not recommended for women younger than 21 years or older than 65 years who have had adequate prior screening and are not at high risk for cervical cancer. Cervical cancer screening is also not recommended for women who have had a hysterectomy with removal of the cervix and no personal history of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or 3 within the past 20 years.

Recommendation 4: Contraception

Adolescent and adult women should have access to the full range of US Food and Drug Administration–approved female-controlled contraceptives to prevent unintended pregnancy and improve birth outcomes. Multiple visits with a clinician may be needed to select an optimal contraceptive.

Recommendation 5: Screening for gestational diabetes mellitus

Pregnant women should be screened for GDM between 24 and 28 weeks’ gestation to prevent adverse birth outcomes. Screening should be performed with a “50 gm oral glucose challenge test followed by a 3-hour 100 gm oral glucose tolerance test” if the results on the initial oral glucose tolerance test are abnormal. This testing sequence has high sensitivity and specificity. Women with risk factors for diabetes mellitus should be screened for diabetes at the first prenatal visit using current best clinical practice.

Recommendation 6: Screening for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection

Adolescents and women should receive education and risk assessment for HIV annually and should be tested for HIV at least once during their lifetime. Based on assessed risk, screening annually may be appropriate. “Screening for HIV is recommended for all pregnant women upon initiation of prenatal care with retesting during pregnancy based on risk factors. Rapid HIV testing is recommended for pregnant women who present in active labor with an undocumented HIV status.” Risk-based screening does not identify approximately 20% of HIV-infected people. Hence screening annually may be reasonable.

Recommendation 7: Screening for interpersonal and domestic violence

All adolescents and women should be screened annually for both interpersonal violence (IPV) and domestic violence (DV). Intervention services should be available to all adolescents and women. IPV and DV are prevalent problems, and they are often undetected by clinicians. Hence annual screening is recommended.

Recommendation 8: Counseling for sexually transmitted infections

Adolescents and women should be assessed for sexually transmittedinfection (STI) risk. Risk factors include:

- “age younger than 25 years,

- a recent STI,

- a new sex partner,

- multiple partners,

- a partner with concurrent partners,

- a partner with an STI, and

- a lack of or inconsistent condom use.”

Women at increased risk for an STI should receive behavioral counseling.

Recommendation 9: Well-woman preventive visits

Women should “receive at least one preventive care visit per year beginning in adolescence and continuing across the lifespan to ensure that the recommended preventive services including preconception and many services necessary for prenatal and interconception care are obtained. The primary purpose of these visits is the delivery and coordination of recommended preventive services as determined by age and risk factors.”

- Abridged guidelines for the Women's Preventive Services Initiative can be found here: http://www.womenspreventivehealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/WPSI_2016AbridgedReport.pdf.

- Evidence-based summaries and appendices are available at this link: http://www.womenspreventivehealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Evidence-Summaries-and-Appendices.pdf.

I plan on using these recommendations to guide my practice

Historically, many high-profile expert professional groups have developed their own women’s health services guidelines. The proliferation of conflicting guidelines confused both patients and clinicians. Dueling guidelines likely undermine public health because they result in confusion among patients and inconsistent care across the many disciplines that provide medical services to women.

The proliferation of conflicting guidelines for mammography screening for breast cancer is a good example of how dueling guidelines can undermine public health (TABLE).4−7 The WPSI has done a great service to women and clinicians by creating a shared framework for consistently providing critical services across a woman’s entire life. I plan on using these recommendations to guide my practice. Patients and clinicians will greatly benefit from the exceptionally thoughtful women’s preventive services guidelines provided by the WPSI.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA) intended that women have access to critical preventive health services without a copay or deductible. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) was asked to help identify those critical preventive women’s health services. In 2011, the IOM Committee on Preventive Services for Women recommended that all women have access to 9 preventive services, among them1:

- screening for gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM)

- human papilloma virus testing

- contraceptive methods and counseling

- well-woman visits.

The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the US Department of Health and Human Services agreed to update the recommended preventive services every 5 years.

In March 2016, HRSA entered into a 5-year cooperative agreement with the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) to update the guidelines and to develop additional recommendations to enhance women’s health.2 ACOG launched the Women’s Preventive Services Initiative (WPSI) to develop the 2016 update.

The 5-year grant with HRSA will address many more preventive health services for women across their lifespan as well as implementation strategies so that women receive consistent and appropriate care, regardless of the health care provider’s specialty. The WPSI recognizes that the selection of a provider for well-woman care will be determined as much by a woman’s needs and preferences as by her access to health care services and health plan availability.

The WPSI draft recommendations were released for public comment in September 2016,2 and HRSA approved the recommendations in December 2016.3 In this editorial, I provide a look at which organizations comprise the WPSI and a summary of the 9 recommended preventive health services.

Who makes up the Women’s Preventive Services Initiative?

The WPSI is a collaboration between professional societies and consumer organizations. The goal of the WPSI is “to promote health over the course of a woman’s lifetime through disease prevention and preventive healthcare.” The WPSI advisory panel provides oversight to the effort and the multidisciplinary steering committee develops the recommendations. The WPSI advisory panel includes leaders and experts from 4 major professional organizations, whose members provide the majority of women’s health care in the United States:

- ACOG

- American College of Physicians (ACP)

- American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP)

- National Association of Nurse Practitioners in Women’s Health (NPWH).

The multidisciplinary steering committee includes the members of the advisory panel, representatives from 17 professional and consumer organizations, a patient representative, and representatives from 6 federal agencies. The WPSI is currently chaired by Jeanne Conry, MD, PhD, past president of ACOG. The steering committee used evidence-based best practices to develop the guidelines and relied heavily on the foundation provided by the 2011 IOM report.1

The 9 WPSI recommendations

Much of the text below is directly quoted from the final recommendations. When a recommendation is paraphrased it is not placed in quotations.

Recommendation 1: Breast cancer screening for average-risk women

“Average-risk women should initiate mammography screening for breast cancer no earlier than age 40 and no later than age 50 years. Screeningmammography should occur at least biennially and as frequently as annually. Screening should continue through at least age 74 years and age alone should not be the basis to stop screening.”

Decisions about when to initiate screening for women between 40 and 50 years of age, how often to screen, and when to stop screening should be based on shared decision making involving the woman and her clinician.

Recommendation 2: Breastfeeding services and supplies

Women should be provided “comprehensive lactation support services including counseling, education and breast feeding equipment and supplies during the antenatal, perinatal, and postpartum periods.” These services will support the successful initiation and maintenance of breastfeeding. Women should have access to double electric breast pumps.

Recommendation 3: Screening for cervical cancer

Average-risk women should initiate cervical cancer screening with cervical cytology at age 21 years and have cervical cytology testing every 3 years from 21 to 29 years of age. “Cotesting with cytology and human papillomavirus (HPV) testing is not recommended for women younger than 30 years. Women aged 30 to 65 years should be screened with cytology and HPV testing every 5 years or cytology alone every 3 years.” Women who have received the HPV vaccine should be screened using these guidelines. Cervical cancer screening is not recommended for women younger than 21 years or older than 65 years who have had adequate prior screening and are not at high risk for cervical cancer. Cervical cancer screening is also not recommended for women who have had a hysterectomy with removal of the cervix and no personal history of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or 3 within the past 20 years.

Recommendation 4: Contraception

Adolescent and adult women should have access to the full range of US Food and Drug Administration–approved female-controlled contraceptives to prevent unintended pregnancy and improve birth outcomes. Multiple visits with a clinician may be needed to select an optimal contraceptive.

Recommendation 5: Screening for gestational diabetes mellitus

Pregnant women should be screened for GDM between 24 and 28 weeks’ gestation to prevent adverse birth outcomes. Screening should be performed with a “50 gm oral glucose challenge test followed by a 3-hour 100 gm oral glucose tolerance test” if the results on the initial oral glucose tolerance test are abnormal. This testing sequence has high sensitivity and specificity. Women with risk factors for diabetes mellitus should be screened for diabetes at the first prenatal visit using current best clinical practice.

Recommendation 6: Screening for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection

Adolescents and women should receive education and risk assessment for HIV annually and should be tested for HIV at least once during their lifetime. Based on assessed risk, screening annually may be appropriate. “Screening for HIV is recommended for all pregnant women upon initiation of prenatal care with retesting during pregnancy based on risk factors. Rapid HIV testing is recommended for pregnant women who present in active labor with an undocumented HIV status.” Risk-based screening does not identify approximately 20% of HIV-infected people. Hence screening annually may be reasonable.

Recommendation 7: Screening for interpersonal and domestic violence

All adolescents and women should be screened annually for both interpersonal violence (IPV) and domestic violence (DV). Intervention services should be available to all adolescents and women. IPV and DV are prevalent problems, and they are often undetected by clinicians. Hence annual screening is recommended.

Recommendation 8: Counseling for sexually transmitted infections

Adolescents and women should be assessed for sexually transmittedinfection (STI) risk. Risk factors include:

- “age younger than 25 years,

- a recent STI,

- a new sex partner,

- multiple partners,

- a partner with concurrent partners,

- a partner with an STI, and

- a lack of or inconsistent condom use.”

Women at increased risk for an STI should receive behavioral counseling.

Recommendation 9: Well-woman preventive visits

Women should “receive at least one preventive care visit per year beginning in adolescence and continuing across the lifespan to ensure that the recommended preventive services including preconception and many services necessary for prenatal and interconception care are obtained. The primary purpose of these visits is the delivery and coordination of recommended preventive services as determined by age and risk factors.”

- Abridged guidelines for the Women's Preventive Services Initiative can be found here: http://www.womenspreventivehealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/WPSI_2016AbridgedReport.pdf.

- Evidence-based summaries and appendices are available at this link: http://www.womenspreventivehealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Evidence-Summaries-and-Appendices.pdf.

I plan on using these recommendations to guide my practice

Historically, many high-profile expert professional groups have developed their own women’s health services guidelines. The proliferation of conflicting guidelines confused both patients and clinicians. Dueling guidelines likely undermine public health because they result in confusion among patients and inconsistent care across the many disciplines that provide medical services to women.

The proliferation of conflicting guidelines for mammography screening for breast cancer is a good example of how dueling guidelines can undermine public health (TABLE).4−7 The WPSI has done a great service to women and clinicians by creating a shared framework for consistently providing critical services across a woman’s entire life. I plan on using these recommendations to guide my practice. Patients and clinicians will greatly benefit from the exceptionally thoughtful women’s preventive services guidelines provided by the WPSI.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Institute of Medicine. Clinical preventive services for women: closing the gaps. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. http://nap.edu/13181. Accessed January 16, 2017.

- American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Women's Preventive Services Initiative (WPSI). http://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/ACOG-Departments/Annual-Womens-Health-Care/Womens-Preventive-Services-Initiative. Accessed January 16, 2017.

- Health Resources and Services Administration website. Women's preventive services guidelines. https://www.hrsa.gov/womensguidelines/. Accessed January 16, 2017.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 122: breast cancer screening. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(2 pt 1):372-382.

- Oeffinger KC, Fontham ET, Etzioni R, et al. Breast cancer screening for women at average risk: 2015 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. JAMA. 2015;314(15):1599-1614.

- American Academy of Family Physicians website. Clinical preventive service recommendation: breast cancer. http://www.aafp.org/patient-care/clinical-recommendations/all/breast-cancer.html. Accessed January 16, 2017.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for breast cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(10):716-726.

- Institute of Medicine. Clinical preventive services for women: closing the gaps. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. http://nap.edu/13181. Accessed January 16, 2017.

- American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Women's Preventive Services Initiative (WPSI). http://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/ACOG-Departments/Annual-Womens-Health-Care/Womens-Preventive-Services-Initiative. Accessed January 16, 2017.

- Health Resources and Services Administration website. Women's preventive services guidelines. https://www.hrsa.gov/womensguidelines/. Accessed January 16, 2017.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 122: breast cancer screening. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(2 pt 1):372-382.

- Oeffinger KC, Fontham ET, Etzioni R, et al. Breast cancer screening for women at average risk: 2015 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. JAMA. 2015;314(15):1599-1614.

- American Academy of Family Physicians website. Clinical preventive service recommendation: breast cancer. http://www.aafp.org/patient-care/clinical-recommendations/all/breast-cancer.html. Accessed January 16, 2017.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for breast cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(10):716-726.

From the Editors: One pebble at a time

This is a story about Sarah Prince, FRCS, and thousands of others here and abroad who are surgeons. Only a few of you may have heard of Miss Prince, consultant surgeon from Fort William, Scotland; but she represents to me one of thousands of stories that make surgery such a rich subject that spans more than pure science. Sarah achieved immortality in what she accomplished in 43 short years.

Sarah was trained in the United Kingdom system, attaining specialty training in hepatobiliary disease. While she loved that sort of work she decided, with her internist husband Patrick Byrne, to work in a rural town in northern Scotland. In nine years she built up the hospital there and its training paradigm. She went on to work toward creating a better rural surgical system in Scotland, eventually becoming an expert who spoke all over the world about rural surgery and allocating resources to build surgical capacity in rural areas. She understood the volume debate and the need for rural surgeons to have a connection that was substantive with a larger center in a collaborative way benefiting both locales.

I bring her up because she represents something we all can do. A few surgeons become academic giants known far and wide, but all surgeons have the ability to be local giants, unknown but immortal and essential in their own way. Sarah’s accomplishments confirm that.

Unlike surgery in the United States, the U.K. system is more regimented in many ways and even more political than what the average U.S. surgeon experiences. It is a single-payer system that was there long before Sarah became a surgeon and will be there long after. The fact that the system into which she was born was not of her making did not deter Sarah from taking on that very system to make her corner of the world a better place. I was always surprised when speaking with her that the problems she faced in Scotland were much the same as what I’ve seen in rural surgery in the United States and in other countries. She didn’t bend the whole system but she made a significant dent in how things were done. Isn’t that the challenge for us all?

Recently on the ACS Communities and elsewhere, the debate on single-payer, multitier, and market-driven health care is being argued. In light of the current political environment, the path forward seems bewilderingly tangled. Most surgeons just want to operate. The OR may be the last bastion of control we surgeons have in our professional lives. There may be a barrage of obstacles getting to the OR and hordes of explanations and details postoperatively, but in the OR we still get to do what we think is best at the moment using all those skills we so painfully acquired during a career of learning and practice. To despair is easy until one takes a look at what so many surgeons achieve in their lives.

Like Sarah, most of us try to make the profession a little better. In small town Iowa, that may be getting sonography privileges for FAST exams that improves the lot of trauma patients in that town. In an exburbia hospital, the surgeon may bring new expertise not previously available. It goes on and on with each of us contributing one pebble at a time to a mountain of effort. Any one pebble seems so insignificant in itself and sometimes just placing it on the mountain takes enormous effort, but each is worth the toil to put it there.

Which brings us back to Miss Prince (it is a faux pas to call a consultant surgeon in the U.K. by the honorific doctor). Sarah faced just as many challenges and perhaps more than surgeons elsewhere. Yet she brought her best every day to her hospital until cruel fate delivered her a fatal blow at a young age. Even then facing her imminent death, Sarah made sure that her patients and trainees would be well cared for after her passing. Her indomitable approach to surgical life shows that no matter what the opposition, a surgeon can with grit and wit make life better in his or her town, region, and maybe even the world.

As we face 2017 with all its potential for defeat or victory for our patients, let us remember surgeons like Sarah Prince who made a difference and commit ourselves to the same goal. We can do it one pebble at a time until we’ve created a mountain of accomplishment.

Dr. Hughes is clinical professor in the department of surgery and director of medical education at the Kansas University School of Medicine, Salina Campus, and Co-Editor of ACS Surgery News.

This is a story about Sarah Prince, FRCS, and thousands of others here and abroad who are surgeons. Only a few of you may have heard of Miss Prince, consultant surgeon from Fort William, Scotland; but she represents to me one of thousands of stories that make surgery such a rich subject that spans more than pure science. Sarah achieved immortality in what she accomplished in 43 short years.

Sarah was trained in the United Kingdom system, attaining specialty training in hepatobiliary disease. While she loved that sort of work she decided, with her internist husband Patrick Byrne, to work in a rural town in northern Scotland. In nine years she built up the hospital there and its training paradigm. She went on to work toward creating a better rural surgical system in Scotland, eventually becoming an expert who spoke all over the world about rural surgery and allocating resources to build surgical capacity in rural areas. She understood the volume debate and the need for rural surgeons to have a connection that was substantive with a larger center in a collaborative way benefiting both locales.

I bring her up because she represents something we all can do. A few surgeons become academic giants known far and wide, but all surgeons have the ability to be local giants, unknown but immortal and essential in their own way. Sarah’s accomplishments confirm that.

Unlike surgery in the United States, the U.K. system is more regimented in many ways and even more political than what the average U.S. surgeon experiences. It is a single-payer system that was there long before Sarah became a surgeon and will be there long after. The fact that the system into which she was born was not of her making did not deter Sarah from taking on that very system to make her corner of the world a better place. I was always surprised when speaking with her that the problems she faced in Scotland were much the same as what I’ve seen in rural surgery in the United States and in other countries. She didn’t bend the whole system but she made a significant dent in how things were done. Isn’t that the challenge for us all?

Recently on the ACS Communities and elsewhere, the debate on single-payer, multitier, and market-driven health care is being argued. In light of the current political environment, the path forward seems bewilderingly tangled. Most surgeons just want to operate. The OR may be the last bastion of control we surgeons have in our professional lives. There may be a barrage of obstacles getting to the OR and hordes of explanations and details postoperatively, but in the OR we still get to do what we think is best at the moment using all those skills we so painfully acquired during a career of learning and practice. To despair is easy until one takes a look at what so many surgeons achieve in their lives.

Like Sarah, most of us try to make the profession a little better. In small town Iowa, that may be getting sonography privileges for FAST exams that improves the lot of trauma patients in that town. In an exburbia hospital, the surgeon may bring new expertise not previously available. It goes on and on with each of us contributing one pebble at a time to a mountain of effort. Any one pebble seems so insignificant in itself and sometimes just placing it on the mountain takes enormous effort, but each is worth the toil to put it there.

Which brings us back to Miss Prince (it is a faux pas to call a consultant surgeon in the U.K. by the honorific doctor). Sarah faced just as many challenges and perhaps more than surgeons elsewhere. Yet she brought her best every day to her hospital until cruel fate delivered her a fatal blow at a young age. Even then facing her imminent death, Sarah made sure that her patients and trainees would be well cared for after her passing. Her indomitable approach to surgical life shows that no matter what the opposition, a surgeon can with grit and wit make life better in his or her town, region, and maybe even the world.

As we face 2017 with all its potential for defeat or victory for our patients, let us remember surgeons like Sarah Prince who made a difference and commit ourselves to the same goal. We can do it one pebble at a time until we’ve created a mountain of accomplishment.

Dr. Hughes is clinical professor in the department of surgery and director of medical education at the Kansas University School of Medicine, Salina Campus, and Co-Editor of ACS Surgery News.

This is a story about Sarah Prince, FRCS, and thousands of others here and abroad who are surgeons. Only a few of you may have heard of Miss Prince, consultant surgeon from Fort William, Scotland; but she represents to me one of thousands of stories that make surgery such a rich subject that spans more than pure science. Sarah achieved immortality in what she accomplished in 43 short years.

Sarah was trained in the United Kingdom system, attaining specialty training in hepatobiliary disease. While she loved that sort of work she decided, with her internist husband Patrick Byrne, to work in a rural town in northern Scotland. In nine years she built up the hospital there and its training paradigm. She went on to work toward creating a better rural surgical system in Scotland, eventually becoming an expert who spoke all over the world about rural surgery and allocating resources to build surgical capacity in rural areas. She understood the volume debate and the need for rural surgeons to have a connection that was substantive with a larger center in a collaborative way benefiting both locales.

I bring her up because she represents something we all can do. A few surgeons become academic giants known far and wide, but all surgeons have the ability to be local giants, unknown but immortal and essential in their own way. Sarah’s accomplishments confirm that.

Unlike surgery in the United States, the U.K. system is more regimented in many ways and even more political than what the average U.S. surgeon experiences. It is a single-payer system that was there long before Sarah became a surgeon and will be there long after. The fact that the system into which she was born was not of her making did not deter Sarah from taking on that very system to make her corner of the world a better place. I was always surprised when speaking with her that the problems she faced in Scotland were much the same as what I’ve seen in rural surgery in the United States and in other countries. She didn’t bend the whole system but she made a significant dent in how things were done. Isn’t that the challenge for us all?

Recently on the ACS Communities and elsewhere, the debate on single-payer, multitier, and market-driven health care is being argued. In light of the current political environment, the path forward seems bewilderingly tangled. Most surgeons just want to operate. The OR may be the last bastion of control we surgeons have in our professional lives. There may be a barrage of obstacles getting to the OR and hordes of explanations and details postoperatively, but in the OR we still get to do what we think is best at the moment using all those skills we so painfully acquired during a career of learning and practice. To despair is easy until one takes a look at what so many surgeons achieve in their lives.

Like Sarah, most of us try to make the profession a little better. In small town Iowa, that may be getting sonography privileges for FAST exams that improves the lot of trauma patients in that town. In an exburbia hospital, the surgeon may bring new expertise not previously available. It goes on and on with each of us contributing one pebble at a time to a mountain of effort. Any one pebble seems so insignificant in itself and sometimes just placing it on the mountain takes enormous effort, but each is worth the toil to put it there.

Which brings us back to Miss Prince (it is a faux pas to call a consultant surgeon in the U.K. by the honorific doctor). Sarah faced just as many challenges and perhaps more than surgeons elsewhere. Yet she brought her best every day to her hospital until cruel fate delivered her a fatal blow at a young age. Even then facing her imminent death, Sarah made sure that her patients and trainees would be well cared for after her passing. Her indomitable approach to surgical life shows that no matter what the opposition, a surgeon can with grit and wit make life better in his or her town, region, and maybe even the world.

As we face 2017 with all its potential for defeat or victory for our patients, let us remember surgeons like Sarah Prince who made a difference and commit ourselves to the same goal. We can do it one pebble at a time until we’ve created a mountain of accomplishment.

Dr. Hughes is clinical professor in the department of surgery and director of medical education at the Kansas University School of Medicine, Salina Campus, and Co-Editor of ACS Surgery News.

Long-acting reversible contraceptives and acne in adolescents

Examining the impact of contraception on acne in adolescents is clinically important because acne affects about 85% of adolescents, and contraceptives may influence the course of acne disease. Estrogen-progestin contraceptives cause a significant improvement in acne.1,2 By contrast, the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device and the etonogestrel contraceptive implant may exacerbate acne. In this editorial we review the hormonal contraception−acne relationship, available acne treatments, and appropriate management.

Related article:

Your teenage patient and contraception: Think “long-acting” first

Combination oral contraception and acne

As noted, combination oral contraceptives generally result in acne improvement.1,2 Estrogen-progestin contraceptives improve the condition through two mechanisms. Primarily, estrogen-progestin contraceptives suppress pituitary luteinizing hormone secretion, thereby decreasing ovarian testosterone production. These contraceptives also increase liver production of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), thereby increasing bound testosterone and decreasing free testosterone. The decrease in ovarian testosterone production and the increase in SHBG-bound testosterone reduce sebum production, resulting in acne improvement.

The US Food and Drug Administration has approved 4 estrogen-progestin contraceptives for acne treatment:

- Estrostep (norethindrone acetate-ethinyl estradiol plus ferrous fumarate)

- Ortho Tri-Cyclen (norgestimate-ethinyl estradiol)

- Yaz (drospirenone-ethinyl estradiol)

- BeYaz (drospirenone-ethinyl estradiol plus levomefolate).

LARC and acne

The levonorgestrel intrauterine devices (LNG-IUDs), including the levonorgestrel intrauterine systems Mirena, Liletta, Skyla, and Kyleena, and the etonogestrel implant (Nexplanon) are among the most effective contraceptives available for women. Over the last decade there has been a marked increase in the use of LARC. In 2002, 1.3% of women aged 15 to 24 years used an IUD or progestin implant, and this percentage increased to 10% by 2013.3

Progestin-containing LARC may cause acne to worsen. In a large 3-year prospective study of more than 2,900 women using the progestin implant or the copper IUD (ParaGard), use of the progestin implant was associated with a higher rate of reported acne than the copper IUD (18% vs 13%, respectively; relative risk, 1.4; 95% confidence interval, 1.20−1.56; P<.0001).4 In a retrospective review of 991 women who used the etonogestrel implant, 24% of the women requested that the implant be removed; the 3 most common reasons for removal were: bleeding disturbances (45%), worsening acne, (12%) and desire to conceive (12%).5

Similar differences in reported acne are seen between the LNG-IUD and the copper IUD. In a study of 320 women using the LNG-IUD and the copper IUD, an increase in acne was reported by 17% and 7%, respectively (P<.025).6 In a small prospective study of the LNG-IUD versus the copper IUD over the first 12 months of use, use of the LNG-IUD was associated with a statistically significant worsening of acne scores while use of the copper IUD had no impact on acne scores.7

Related article:

Overcoming LARC complications: 7 case challenges

In a study of 2,147 consecutive women using a hormonal contraceptive who presented to a dermatologist for the treatment of acne, patients were asked to assess how the contraceptive affected their acne. By type of contraceptive, the percent of women who reported that the contraceptive made their acne worse was: LNG-IUD, 36%; progestin implant, 33%; depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), 27%; levonorgestrel-ethinyl estradiol oral contraceptive, 10%; norgestimate-ethinyl estradiol (EE), 6%; etonogestrel-EE vaginal ring, 4%; drospirenone-EE, 3%; and desogestrel-EE, 2%. The percent of women who reported that the contraceptive significantly improved their acne was: drospirenone-EE, 26%; norgestimate-EE, 17%; desogestrel-EE, 15%; etonogestrel-EE vaginal ring, 14%; norethindrone-EE, 8%; levonorgestrel-EE, 6%; depot MPA, 5%; LNG-IUD, 3%; and progestin implant, 1%.8

In adolescents with acne, switching from an estrogen-progestin contraceptive to a LNG-IUD or an etonogestrel implant may cause the patient to report that her acne has worsened. As mentioned, combination estrogen-progestin contraceptives reduce free testosterone, thereby improving acne. When an estrogen-progestin contraceptive is discontinued, free testosterone levels will increase. If a LARC method is initiated and the patient’s acne worsens, the patient may attribute this change to the LARC. For clinicians planning on switching a patient from an estrogen-progestin contraceptive to a LNG-IUD or etonogestrel implant, evaluation of current acne symptoms and acne history may be particularly important.

Acne treatment

Acne is caused by follicular hyperproliferation and abnormal desquamation, excess sebum production, proliferation of Propionibacterium acnes, and inflammation.

First-line agents. An expert guideline developed under the auspices of the American Academy of Dermatology recommends that topical agents including retinoids and antimicrobials be first-line treatments for acne.9,10

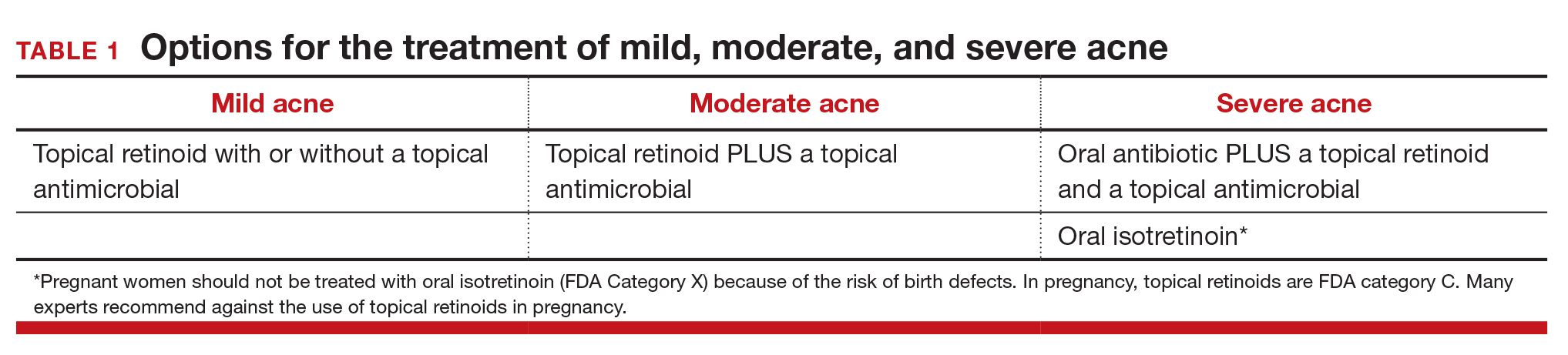

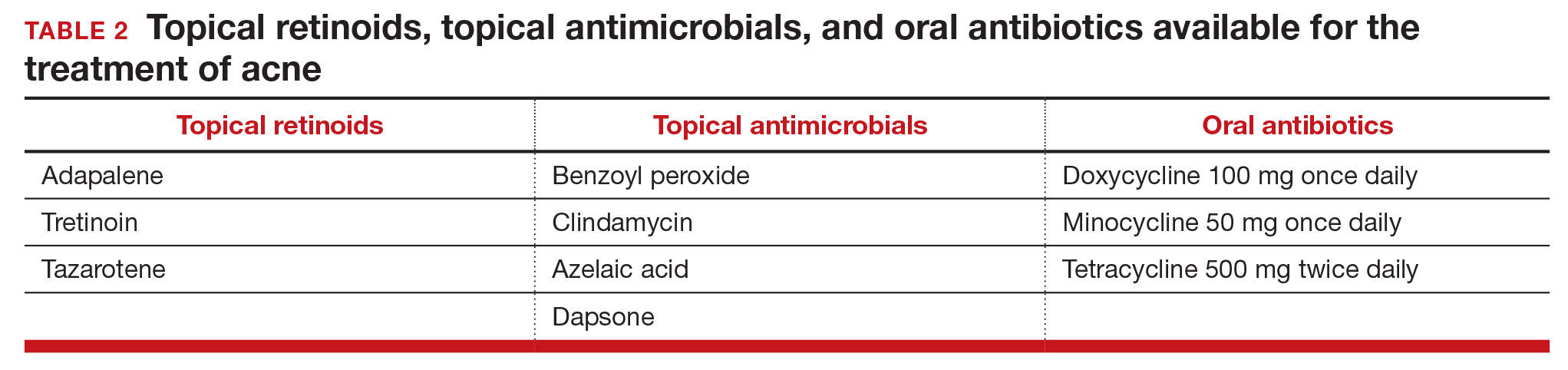

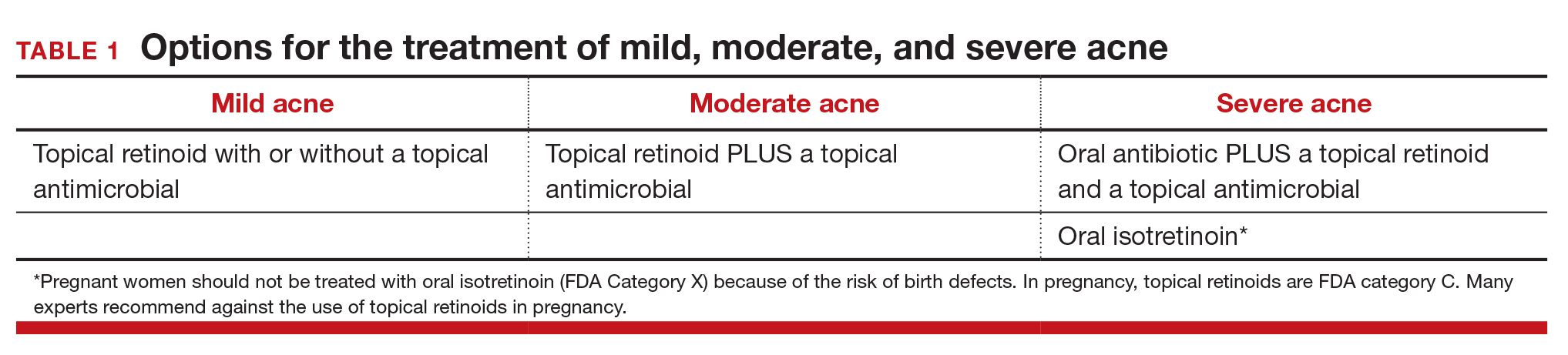

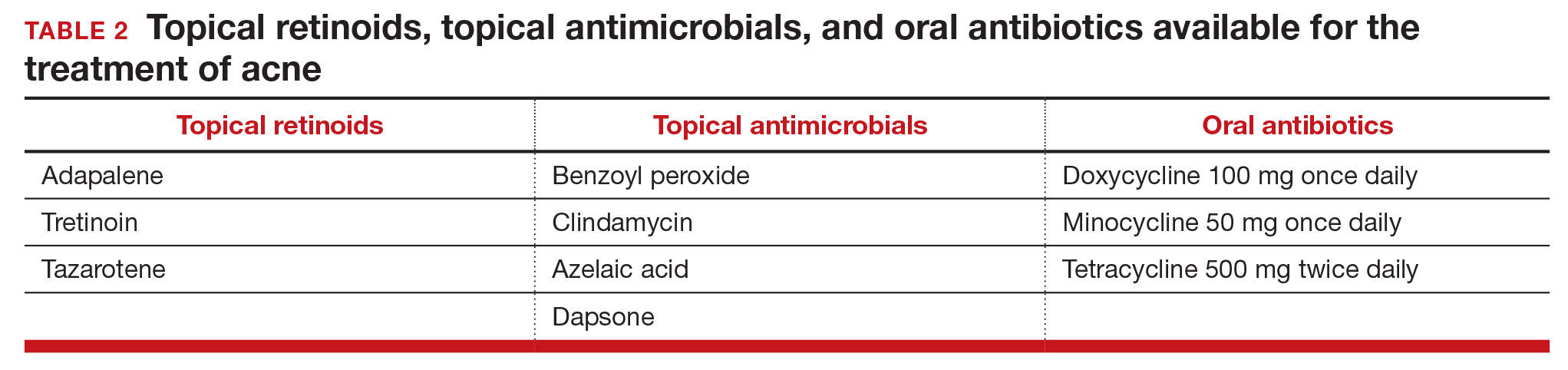

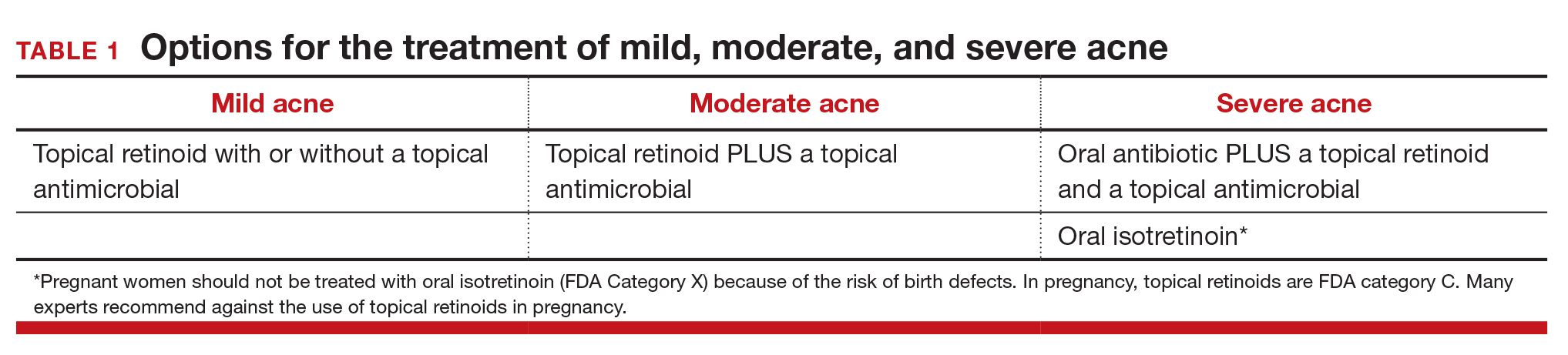

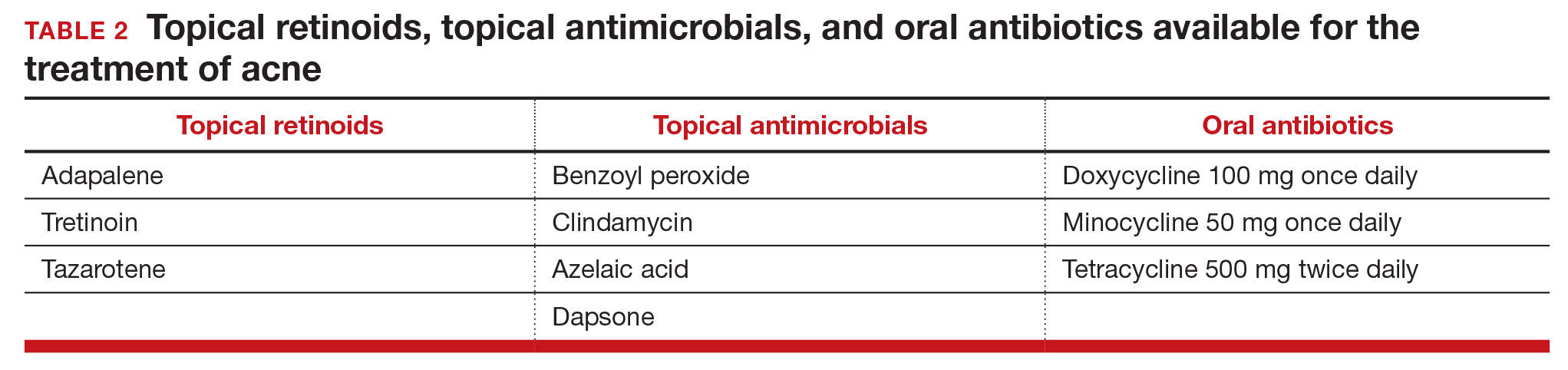

Topical retinoids are the primary component of topical acne treatment and can be used as monotherapy or in combination with topical antimicrobials (TABLE 1). Three topical retinoids are approved for use in the United States: tretinoin, adapalene, and tazarotene. Adapalene is available by prescription, 0.1% and 0.3% gel, and over the counter, 0.1% gel (Differin Gel) (TABLE 2). The topical retinoids are applied once daily at bedtime and can cause local skin irritation and dryness. Pregnant women should not be treated with topical retinoids.

Topical antimicrobials for the treatment of acne include: benzoyl peroxide, clindamycin, azelaic acid, and dapsone. Clindamycin is only recommended for use in combination with benzoyl peroxide in order to reduce the development of bacterial resistance to the antibiotic.

Related article:

Does the risk of unplanned pregnancy outweigh the risk of VTE from hormonal contraception?

Approach to mild, moderate, and severe acne. In adolescents with mild acne a topical retinoid or benzoyl peroxide can be used as monotherapy or used together. Referral to a dermatologist is recommended for moderate to severe acne. Moderate acne is treated with combination topical therapy (benzoyl peroxide plus a topical retinoid, a topical antibiotic, or both). Severe acne is treated with 3 months of oral antibiotics plus topical combination therapy (benzoyl peroxide plus a topical retinoid, a topical antibiotic, or both). In cases of severe nodular acne or acne that produces scarring the patient may require oral isotretinoin treatment.

Acne management for adolescents seeking LARC

Given the data that the LNG-IUD and the etonogestrel implant may worsen acne, it may be wise to preemptively ensure that adolescents with acne who are initiating these contraceptives are also being adequately treated for their acne. Gynecologists should provide anticipatory guidance for adolescents with mild acne who initiate progestin-based LARC. Topical benzoyl peroxide is available over-the-counter and can be recommended to these patients. Follow-up in clinic a few months after initiation also may be helpful to assess side effects.

In moderate and severe cases, coordination with dermatology is recommended. For these patients, gynecologists could consider prescribing a topical retinoid or antibiotic medication in conjunction with a new progestin-based LARC method. Those with severe acne also may benefit from concurrent use of oral contraceptives. In adolescents who do not tolerate progestin-based LARC, the copper IUD is a highly effective alternative and can be paired with estrogen-progestin contraception for acne treatment.

Related article:

With no budge in more than 20 years, are US unintended pregnancy rates finally on the decline?

Acne is but one consideration for contraceptive choice

With the above methods, acne can be managed in adolescents seeking a LNG-IUD or implant and should not be considered a contraindication or reason to avoid progestin-based LARC. Adolescents are more likely to continue LARC than estrogen-progestin contraceptives and LARC methods are associated with substantially lower pregnancy rates in this patient population.11 LARC is recommended as first-line contraception for adolescents by both the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.12,13

In choosing contraception with your adolescent patient, the risk of unintended pregnancy should be weighed against the risk of acne and other potential side effects. Do not select a contraceptive based on the presence or absence of acne disease. However, be aware that contraceptives can either improve or worsen acne. Patients with mild and moderate acne disease should be considered for treatment with topical retinoids and/or antimicrobial agents.

Dr. Barbieri reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Dr. Roe reports receiving grant or research support from the Society of Family Planning.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Arowojolu AO, Gallo MF, Lopez LM, Grimes DA. Combined oral contraceptive pills for treatment of acne. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(7):CD004425.

- Koo EB, Petersen TD, Kimball AB. Meta-analysis comparing efficacy of antibiotics versus oral contraceptives in acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(3):450-459.

- Daniels K, Daugherty J, Jones J, Mosher W. Current contraceptive use and variation by selected characteristics among women aged 15 to 44: United States 2011-2013. Natl Health Stat Report. 2015;(86):1-14.

- Bahamondes L, Brache V, Meirik O, Ali M, Habib N, Landoulsi S; WHO Study Group on Contraceptive Implants for Women. A 3-year multicentre randomized controlled trial of etonogestrel- and levonorgestrel-releasing contraceptive implants, with non-randomized matched copper-intrauterine device controls. Hum Reprod. 2015;30(11):2527-2538.

- Bitzer J, Tschudin S, Adler J; Swiss Implanon Study Group. Acceptability and side-effects of Implanon in Switzerland: a retrospective study by the Implanon Swiss Study Group. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2004;9(4):278-284.

- Nilsson CG, Luukkainen T, Diaz J, Allonen H. Clinical performance of a new levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device. A randomized comparison with a Nova-T-copper device. Contraception. 1982;25(4):345-356.

- Kelekci S, Kelecki KH, Yilmaz B. Effects of levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and T380A intrauterine copper device on dysmenorrhea and days of bleeding in women with and without adenomyosis. Contraception. 2012;86(5):458-463.

- Lortscher D, Admani S, Satur N, Eichenfield LF. Hormonal contraceptives and acne: a retrospective analysis of 2147 patients. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15(6):670-674.

- Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(5):945-973.

- Roman CJ, Cifu AD, Stein SL. Management of acne vulgaris. JAMA. 2016;316(13):1402-1403.

- Winner B, Peipert JF, Zhao Q, et al. Effectiveness of long-acting reversible contraception. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(21):1998-2007.

- American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Adolescence. Contraception for adolescents. Pediatrics. 2014;134(4):e1244-e1256.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Adolescent Health Care Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Working Group. Committee Opinion No. 539. Adolescents and long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol 2012;120(4):983-988.

Examining the impact of contraception on acne in adolescents is clinically important because acne affects about 85% of adolescents, and contraceptives may influence the course of acne disease. Estrogen-progestin contraceptives cause a significant improvement in acne.1,2 By contrast, the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device and the etonogestrel contraceptive implant may exacerbate acne. In this editorial we review the hormonal contraception−acne relationship, available acne treatments, and appropriate management.

Related article:

Your teenage patient and contraception: Think “long-acting” first

Combination oral contraception and acne

As noted, combination oral contraceptives generally result in acne improvement.1,2 Estrogen-progestin contraceptives improve the condition through two mechanisms. Primarily, estrogen-progestin contraceptives suppress pituitary luteinizing hormone secretion, thereby decreasing ovarian testosterone production. These contraceptives also increase liver production of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), thereby increasing bound testosterone and decreasing free testosterone. The decrease in ovarian testosterone production and the increase in SHBG-bound testosterone reduce sebum production, resulting in acne improvement.

The US Food and Drug Administration has approved 4 estrogen-progestin contraceptives for acne treatment:

- Estrostep (norethindrone acetate-ethinyl estradiol plus ferrous fumarate)

- Ortho Tri-Cyclen (norgestimate-ethinyl estradiol)

- Yaz (drospirenone-ethinyl estradiol)

- BeYaz (drospirenone-ethinyl estradiol plus levomefolate).

LARC and acne

The levonorgestrel intrauterine devices (LNG-IUDs), including the levonorgestrel intrauterine systems Mirena, Liletta, Skyla, and Kyleena, and the etonogestrel implant (Nexplanon) are among the most effective contraceptives available for women. Over the last decade there has been a marked increase in the use of LARC. In 2002, 1.3% of women aged 15 to 24 years used an IUD or progestin implant, and this percentage increased to 10% by 2013.3

Progestin-containing LARC may cause acne to worsen. In a large 3-year prospective study of more than 2,900 women using the progestin implant or the copper IUD (ParaGard), use of the progestin implant was associated with a higher rate of reported acne than the copper IUD (18% vs 13%, respectively; relative risk, 1.4; 95% confidence interval, 1.20−1.56; P<.0001).4 In a retrospective review of 991 women who used the etonogestrel implant, 24% of the women requested that the implant be removed; the 3 most common reasons for removal were: bleeding disturbances (45%), worsening acne, (12%) and desire to conceive (12%).5

Similar differences in reported acne are seen between the LNG-IUD and the copper IUD. In a study of 320 women using the LNG-IUD and the copper IUD, an increase in acne was reported by 17% and 7%, respectively (P<.025).6 In a small prospective study of the LNG-IUD versus the copper IUD over the first 12 months of use, use of the LNG-IUD was associated with a statistically significant worsening of acne scores while use of the copper IUD had no impact on acne scores.7

Related article:

Overcoming LARC complications: 7 case challenges

In a study of 2,147 consecutive women using a hormonal contraceptive who presented to a dermatologist for the treatment of acne, patients were asked to assess how the contraceptive affected their acne. By type of contraceptive, the percent of women who reported that the contraceptive made their acne worse was: LNG-IUD, 36%; progestin implant, 33%; depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), 27%; levonorgestrel-ethinyl estradiol oral contraceptive, 10%; norgestimate-ethinyl estradiol (EE), 6%; etonogestrel-EE vaginal ring, 4%; drospirenone-EE, 3%; and desogestrel-EE, 2%. The percent of women who reported that the contraceptive significantly improved their acne was: drospirenone-EE, 26%; norgestimate-EE, 17%; desogestrel-EE, 15%; etonogestrel-EE vaginal ring, 14%; norethindrone-EE, 8%; levonorgestrel-EE, 6%; depot MPA, 5%; LNG-IUD, 3%; and progestin implant, 1%.8

In adolescents with acne, switching from an estrogen-progestin contraceptive to a LNG-IUD or an etonogestrel implant may cause the patient to report that her acne has worsened. As mentioned, combination estrogen-progestin contraceptives reduce free testosterone, thereby improving acne. When an estrogen-progestin contraceptive is discontinued, free testosterone levels will increase. If a LARC method is initiated and the patient’s acne worsens, the patient may attribute this change to the LARC. For clinicians planning on switching a patient from an estrogen-progestin contraceptive to a LNG-IUD or etonogestrel implant, evaluation of current acne symptoms and acne history may be particularly important.

Acne treatment

Acne is caused by follicular hyperproliferation and abnormal desquamation, excess sebum production, proliferation of Propionibacterium acnes, and inflammation.

First-line agents. An expert guideline developed under the auspices of the American Academy of Dermatology recommends that topical agents including retinoids and antimicrobials be first-line treatments for acne.9,10

Topical retinoids are the primary component of topical acne treatment and can be used as monotherapy or in combination with topical antimicrobials (TABLE 1). Three topical retinoids are approved for use in the United States: tretinoin, adapalene, and tazarotene. Adapalene is available by prescription, 0.1% and 0.3% gel, and over the counter, 0.1% gel (Differin Gel) (TABLE 2). The topical retinoids are applied once daily at bedtime and can cause local skin irritation and dryness. Pregnant women should not be treated with topical retinoids.

Topical antimicrobials for the treatment of acne include: benzoyl peroxide, clindamycin, azelaic acid, and dapsone. Clindamycin is only recommended for use in combination with benzoyl peroxide in order to reduce the development of bacterial resistance to the antibiotic.

Related article:

Does the risk of unplanned pregnancy outweigh the risk of VTE from hormonal contraception?

Approach to mild, moderate, and severe acne. In adolescents with mild acne a topical retinoid or benzoyl peroxide can be used as monotherapy or used together. Referral to a dermatologist is recommended for moderate to severe acne. Moderate acne is treated with combination topical therapy (benzoyl peroxide plus a topical retinoid, a topical antibiotic, or both). Severe acne is treated with 3 months of oral antibiotics plus topical combination therapy (benzoyl peroxide plus a topical retinoid, a topical antibiotic, or both). In cases of severe nodular acne or acne that produces scarring the patient may require oral isotretinoin treatment.

Acne management for adolescents seeking LARC

Given the data that the LNG-IUD and the etonogestrel implant may worsen acne, it may be wise to preemptively ensure that adolescents with acne who are initiating these contraceptives are also being adequately treated for their acne. Gynecologists should provide anticipatory guidance for adolescents with mild acne who initiate progestin-based LARC. Topical benzoyl peroxide is available over-the-counter and can be recommended to these patients. Follow-up in clinic a few months after initiation also may be helpful to assess side effects.

In moderate and severe cases, coordination with dermatology is recommended. For these patients, gynecologists could consider prescribing a topical retinoid or antibiotic medication in conjunction with a new progestin-based LARC method. Those with severe acne also may benefit from concurrent use of oral contraceptives. In adolescents who do not tolerate progestin-based LARC, the copper IUD is a highly effective alternative and can be paired with estrogen-progestin contraception for acne treatment.

Related article:

With no budge in more than 20 years, are US unintended pregnancy rates finally on the decline?

Acne is but one consideration for contraceptive choice

With the above methods, acne can be managed in adolescents seeking a LNG-IUD or implant and should not be considered a contraindication or reason to avoid progestin-based LARC. Adolescents are more likely to continue LARC than estrogen-progestin contraceptives and LARC methods are associated with substantially lower pregnancy rates in this patient population.11 LARC is recommended as first-line contraception for adolescents by both the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.12,13

In choosing contraception with your adolescent patient, the risk of unintended pregnancy should be weighed against the risk of acne and other potential side effects. Do not select a contraceptive based on the presence or absence of acne disease. However, be aware that contraceptives can either improve or worsen acne. Patients with mild and moderate acne disease should be considered for treatment with topical retinoids and/or antimicrobial agents.

Dr. Barbieri reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Dr. Roe reports receiving grant or research support from the Society of Family Planning.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Examining the impact of contraception on acne in adolescents is clinically important because acne affects about 85% of adolescents, and contraceptives may influence the course of acne disease. Estrogen-progestin contraceptives cause a significant improvement in acne.1,2 By contrast, the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device and the etonogestrel contraceptive implant may exacerbate acne. In this editorial we review the hormonal contraception−acne relationship, available acne treatments, and appropriate management.

Related article:

Your teenage patient and contraception: Think “long-acting” first

Combination oral contraception and acne

As noted, combination oral contraceptives generally result in acne improvement.1,2 Estrogen-progestin contraceptives improve the condition through two mechanisms. Primarily, estrogen-progestin contraceptives suppress pituitary luteinizing hormone secretion, thereby decreasing ovarian testosterone production. These contraceptives also increase liver production of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), thereby increasing bound testosterone and decreasing free testosterone. The decrease in ovarian testosterone production and the increase in SHBG-bound testosterone reduce sebum production, resulting in acne improvement.

The US Food and Drug Administration has approved 4 estrogen-progestin contraceptives for acne treatment:

- Estrostep (norethindrone acetate-ethinyl estradiol plus ferrous fumarate)

- Ortho Tri-Cyclen (norgestimate-ethinyl estradiol)

- Yaz (drospirenone-ethinyl estradiol)

- BeYaz (drospirenone-ethinyl estradiol plus levomefolate).

LARC and acne

The levonorgestrel intrauterine devices (LNG-IUDs), including the levonorgestrel intrauterine systems Mirena, Liletta, Skyla, and Kyleena, and the etonogestrel implant (Nexplanon) are among the most effective contraceptives available for women. Over the last decade there has been a marked increase in the use of LARC. In 2002, 1.3% of women aged 15 to 24 years used an IUD or progestin implant, and this percentage increased to 10% by 2013.3

Progestin-containing LARC may cause acne to worsen. In a large 3-year prospective study of more than 2,900 women using the progestin implant or the copper IUD (ParaGard), use of the progestin implant was associated with a higher rate of reported acne than the copper IUD (18% vs 13%, respectively; relative risk, 1.4; 95% confidence interval, 1.20−1.56; P<.0001).4 In a retrospective review of 991 women who used the etonogestrel implant, 24% of the women requested that the implant be removed; the 3 most common reasons for removal were: bleeding disturbances (45%), worsening acne, (12%) and desire to conceive (12%).5

Similar differences in reported acne are seen between the LNG-IUD and the copper IUD. In a study of 320 women using the LNG-IUD and the copper IUD, an increase in acne was reported by 17% and 7%, respectively (P<.025).6 In a small prospective study of the LNG-IUD versus the copper IUD over the first 12 months of use, use of the LNG-IUD was associated with a statistically significant worsening of acne scores while use of the copper IUD had no impact on acne scores.7

Related article:

Overcoming LARC complications: 7 case challenges

In a study of 2,147 consecutive women using a hormonal contraceptive who presented to a dermatologist for the treatment of acne, patients were asked to assess how the contraceptive affected their acne. By type of contraceptive, the percent of women who reported that the contraceptive made their acne worse was: LNG-IUD, 36%; progestin implant, 33%; depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), 27%; levonorgestrel-ethinyl estradiol oral contraceptive, 10%; norgestimate-ethinyl estradiol (EE), 6%; etonogestrel-EE vaginal ring, 4%; drospirenone-EE, 3%; and desogestrel-EE, 2%. The percent of women who reported that the contraceptive significantly improved their acne was: drospirenone-EE, 26%; norgestimate-EE, 17%; desogestrel-EE, 15%; etonogestrel-EE vaginal ring, 14%; norethindrone-EE, 8%; levonorgestrel-EE, 6%; depot MPA, 5%; LNG-IUD, 3%; and progestin implant, 1%.8

In adolescents with acne, switching from an estrogen-progestin contraceptive to a LNG-IUD or an etonogestrel implant may cause the patient to report that her acne has worsened. As mentioned, combination estrogen-progestin contraceptives reduce free testosterone, thereby improving acne. When an estrogen-progestin contraceptive is discontinued, free testosterone levels will increase. If a LARC method is initiated and the patient’s acne worsens, the patient may attribute this change to the LARC. For clinicians planning on switching a patient from an estrogen-progestin contraceptive to a LNG-IUD or etonogestrel implant, evaluation of current acne symptoms and acne history may be particularly important.

Acne treatment

Acne is caused by follicular hyperproliferation and abnormal desquamation, excess sebum production, proliferation of Propionibacterium acnes, and inflammation.

First-line agents. An expert guideline developed under the auspices of the American Academy of Dermatology recommends that topical agents including retinoids and antimicrobials be first-line treatments for acne.9,10

Topical retinoids are the primary component of topical acne treatment and can be used as monotherapy or in combination with topical antimicrobials (TABLE 1). Three topical retinoids are approved for use in the United States: tretinoin, adapalene, and tazarotene. Adapalene is available by prescription, 0.1% and 0.3% gel, and over the counter, 0.1% gel (Differin Gel) (TABLE 2). The topical retinoids are applied once daily at bedtime and can cause local skin irritation and dryness. Pregnant women should not be treated with topical retinoids.

Topical antimicrobials for the treatment of acne include: benzoyl peroxide, clindamycin, azelaic acid, and dapsone. Clindamycin is only recommended for use in combination with benzoyl peroxide in order to reduce the development of bacterial resistance to the antibiotic.

Related article:

Does the risk of unplanned pregnancy outweigh the risk of VTE from hormonal contraception?

Approach to mild, moderate, and severe acne. In adolescents with mild acne a topical retinoid or benzoyl peroxide can be used as monotherapy or used together. Referral to a dermatologist is recommended for moderate to severe acne. Moderate acne is treated with combination topical therapy (benzoyl peroxide plus a topical retinoid, a topical antibiotic, or both). Severe acne is treated with 3 months of oral antibiotics plus topical combination therapy (benzoyl peroxide plus a topical retinoid, a topical antibiotic, or both). In cases of severe nodular acne or acne that produces scarring the patient may require oral isotretinoin treatment.

Acne management for adolescents seeking LARC

Given the data that the LNG-IUD and the etonogestrel implant may worsen acne, it may be wise to preemptively ensure that adolescents with acne who are initiating these contraceptives are also being adequately treated for their acne. Gynecologists should provide anticipatory guidance for adolescents with mild acne who initiate progestin-based LARC. Topical benzoyl peroxide is available over-the-counter and can be recommended to these patients. Follow-up in clinic a few months after initiation also may be helpful to assess side effects.

In moderate and severe cases, coordination with dermatology is recommended. For these patients, gynecologists could consider prescribing a topical retinoid or antibiotic medication in conjunction with a new progestin-based LARC method. Those with severe acne also may benefit from concurrent use of oral contraceptives. In adolescents who do not tolerate progestin-based LARC, the copper IUD is a highly effective alternative and can be paired with estrogen-progestin contraception for acne treatment.

Related article:

With no budge in more than 20 years, are US unintended pregnancy rates finally on the decline?

Acne is but one consideration for contraceptive choice

With the above methods, acne can be managed in adolescents seeking a LNG-IUD or implant and should not be considered a contraindication or reason to avoid progestin-based LARC. Adolescents are more likely to continue LARC than estrogen-progestin contraceptives and LARC methods are associated with substantially lower pregnancy rates in this patient population.11 LARC is recommended as first-line contraception for adolescents by both the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.12,13

In choosing contraception with your adolescent patient, the risk of unintended pregnancy should be weighed against the risk of acne and other potential side effects. Do not select a contraceptive based on the presence or absence of acne disease. However, be aware that contraceptives can either improve or worsen acne. Patients with mild and moderate acne disease should be considered for treatment with topical retinoids and/or antimicrobial agents.

Dr. Barbieri reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Dr. Roe reports receiving grant or research support from the Society of Family Planning.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Arowojolu AO, Gallo MF, Lopez LM, Grimes DA. Combined oral contraceptive pills for treatment of acne. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(7):CD004425.

- Koo EB, Petersen TD, Kimball AB. Meta-analysis comparing efficacy of antibiotics versus oral contraceptives in acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(3):450-459.

- Daniels K, Daugherty J, Jones J, Mosher W. Current contraceptive use and variation by selected characteristics among women aged 15 to 44: United States 2011-2013. Natl Health Stat Report. 2015;(86):1-14.

- Bahamondes L, Brache V, Meirik O, Ali M, Habib N, Landoulsi S; WHO Study Group on Contraceptive Implants for Women. A 3-year multicentre randomized controlled trial of etonogestrel- and levonorgestrel-releasing contraceptive implants, with non-randomized matched copper-intrauterine device controls. Hum Reprod. 2015;30(11):2527-2538.

- Bitzer J, Tschudin S, Adler J; Swiss Implanon Study Group. Acceptability and side-effects of Implanon in Switzerland: a retrospective study by the Implanon Swiss Study Group. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2004;9(4):278-284.

- Nilsson CG, Luukkainen T, Diaz J, Allonen H. Clinical performance of a new levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device. A randomized comparison with a Nova-T-copper device. Contraception. 1982;25(4):345-356.

- Kelekci S, Kelecki KH, Yilmaz B. Effects of levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and T380A intrauterine copper device on dysmenorrhea and days of bleeding in women with and without adenomyosis. Contraception. 2012;86(5):458-463.

- Lortscher D, Admani S, Satur N, Eichenfield LF. Hormonal contraceptives and acne: a retrospective analysis of 2147 patients. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15(6):670-674.