User login

Codes, Contracts, and Commitments: Who Defines What is a Profession?

Codes, Contracts, and Commitments: Who Defines What is a Profession?

A professional is someone who can do his best work when he doesn’t feel like it.

Alistair Cooke

When I was a young person with no idea about growing up to be something, my father used to tell me there were 4 learned professions: medicine to heal the body, law to protect the body politic, teaching to nurture the mind, and the clergy to care for the soul.1 That adage, or some version of it, is attributed to a variety of sources, likely because it captures something essential and timeless about the learned professions. I write this as a much older person, and it has been my privilege to have worked in some capacity in all 4 of these venerable vocations.

There are many more recognized professions now than in my father’s time with new ones still emerging as the world becomes more complicated and specialized. In November 2025, however, the growth of the professions was dealt a serious blow when the US Department of Education (DOE) redefined what constitutes a profession for the purpose of federal funding of graduate degrees.2 The internet is understandably abuzz with opinions across the political spectrum. What is missing from many of these discussions is an understanding of the criteria for a profession and, even more importantly, who has the authority to decide when an individual or a group has met that standard.

But first, what and why did the DOE make this change? The One Big Beautiful Bill Act charged the DOE with reducing what it claims is massive overspending on graduate education by limiting the programs that meet the definition of a “professional degree” eligible for higher funding. Of my father’s 4, medicine (including dentistry) and law made the cut with students in those professions able to borrow up to $200,000 in direct unsubsidized student loans while those in other programs would be limited to $100,000.2

As one of the oldest and most respected professions in America, nursing has received the most media attention, yet there are also other important and valued professions that are missing from the DOE list.3 The excluded professions also include: physician assistants, physical therapists, audiologists, architects, accountants, educators, and social workers. The proposed regulatory changes are not yet finalized and Congressional representatives, health care experts, and a myriad of professional associations have rightly objected the reclassification will only worsen the critical shortage of nurses, teachers, and other helping professions the country is already facing.4

There are thousands of federal health care professionals who worked long and hard to achieve their goals whom this Act undervalues. Moreover, the regulatory change leaves many students enrolled in education and training programs under federal practice auspices confused and overwhelmed. Perhaps they can take some hope and inspiration from the recognition that historically and philosophically, no agency or administration can unilaterally define what is a profession.

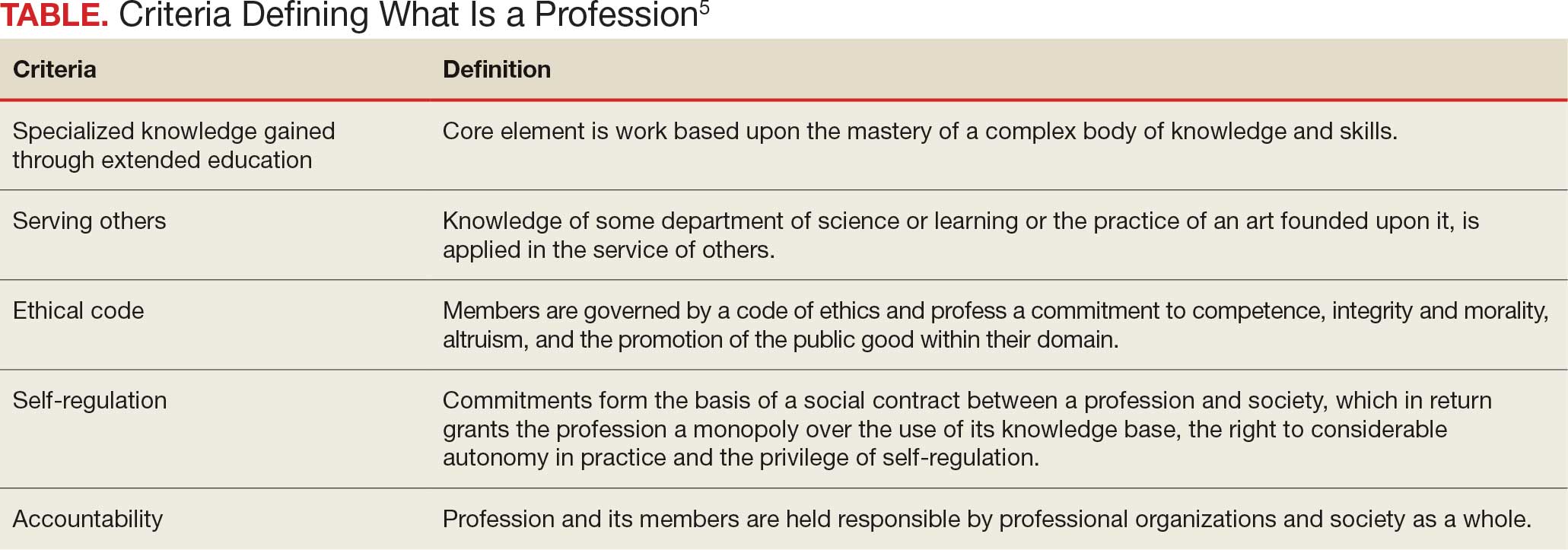

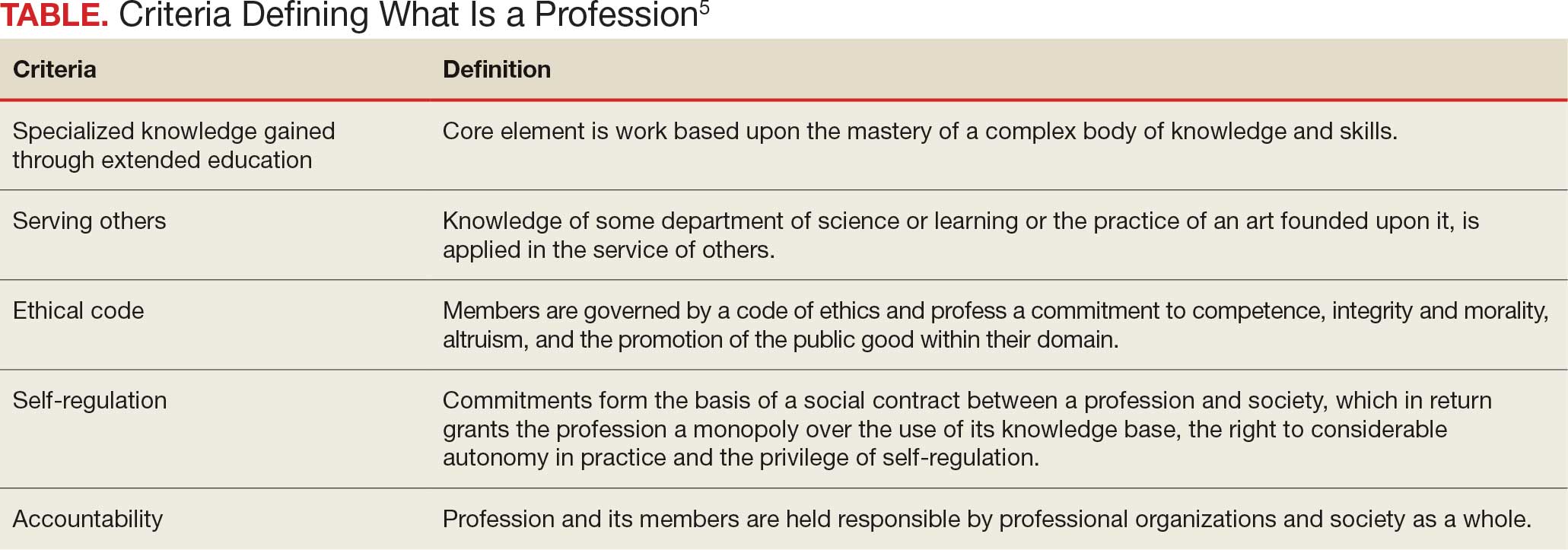

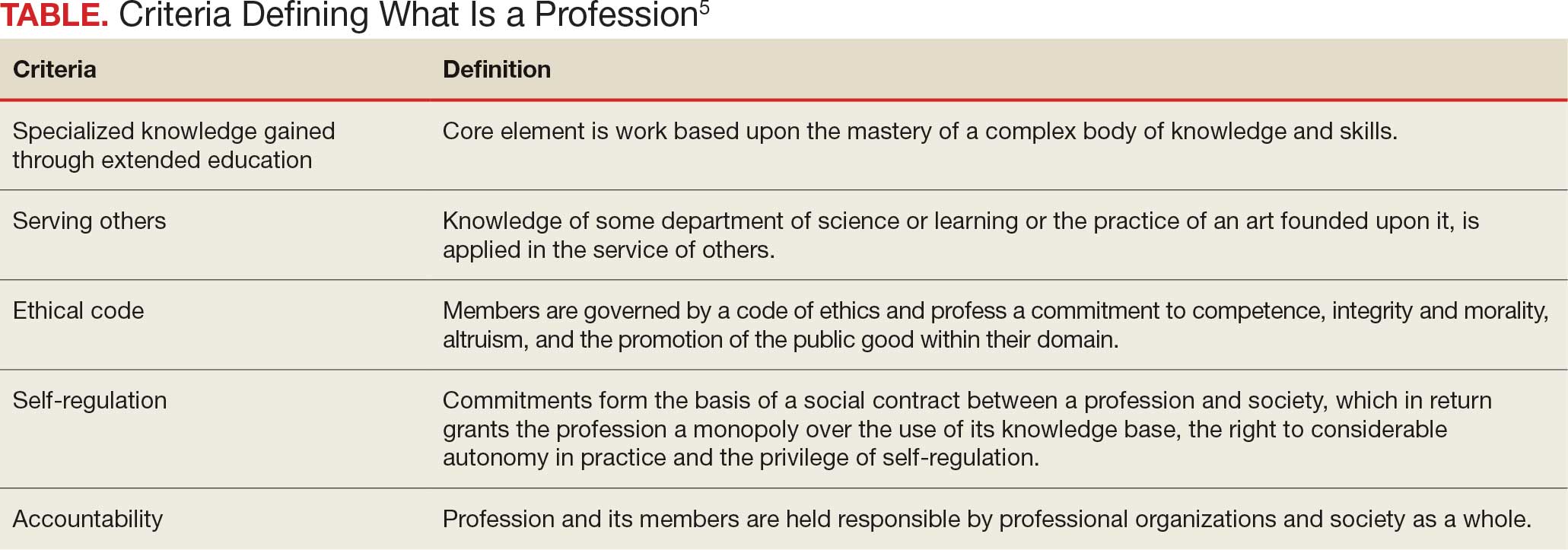

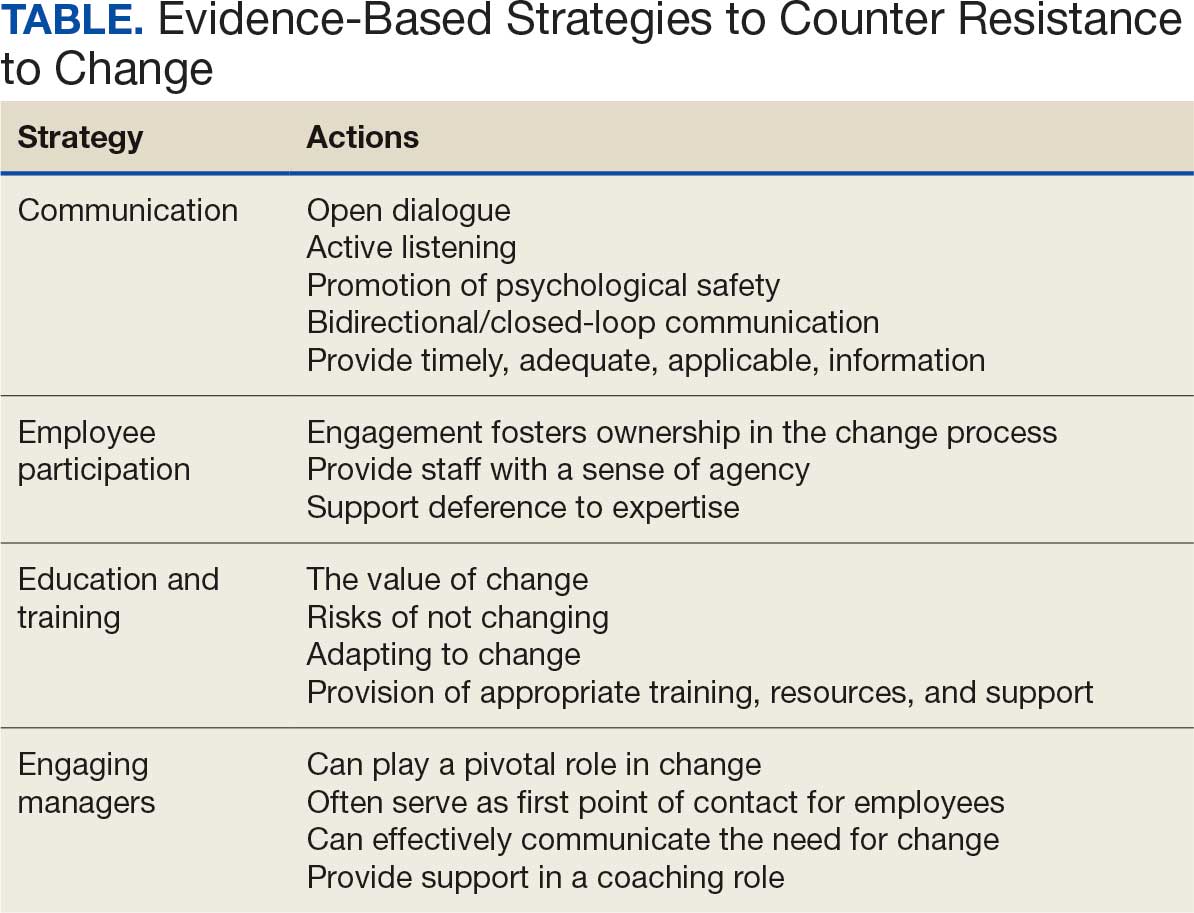

The literature on professionalism is voluminous, in large part because it has been surprisingly difficult to reach a consensus definition. A proposed definition from scholars captures most of the key aspects of a profession. While it is drawn from the medical literature, it applies to most of the caring professions the DOE disqualified. For pedagogic purposes, the definition is parsed into discrete criteria in the Table.5

Even this simple summary makes it obvious that a government agency alone could not possibly have the competence to determine who meets these complex technical and moral criteria. The members of the profession must assume a primary role in that determination. The complicated history of the professions shows that the locus of these decisions has resided in various combinations of educational institutions, such as nursing schools,6 professional societies (eg, National Association of Social Workers),7 and certifying boards (eg, National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants).8 States, not the federal government, have long played a key part in defining professions in the US, through their authority to grant licenses to practice.9

In response to criticism, the DOE has stated that “the definition of a ‘professional degree’ is an internal definition used by the Department of Education to distinguish among programs that qualify for higher loan limits, not a value judgment about the importance of programs. It has no bearing on whether a program is professional in nature or not.”2 Given the ancient compact between society and the professions in which the government subsidizes the training of professionals dedicated to public service, it is hard to see how these changes can be dismissed as merely semantic and not a promissory breach.10

I recognize that this abstract editorial is little comfort to beleaguered and demoralized professionals and students. Still, it offers a voice of support for each federal practitioner or trainee who fulfills the epigraph’s description of a professional day after day. The nurse who works the extra shift without complaint or resentment so that veterans receive the care they deserve, the social worker who responds on a weekend night to an active duty family without food so they do not spend another night hungry, and the physician assistant who makes it into the isolated public health clinic despite the terrible weather so there is someone ready to take care for patients in need. The proposed policy shift cannot in any meaningful sense rob them of their identity as individuals committed to a code of caring. However, without an intact social compact, it may well remove their practical ability to remain and enter the helping professions to the detriment of us all.

- Wade JW. Public responsibilities of the learned professions. Louisiana Law Rev. 1960;21:130-148

- US Department of Education. Myth vs. fact: the definition of professional degrees. Press Release. November 24, 2025. Accessed December 22, 2025. https://www.ed.gov/about/news/press-release/myth-vs-fact-definition-of-professional-degrees

- Laws J. Full list of degrees not classed as “professional” by Trump admin. Newsweek. Updated November 26, 2025. Accessed December 22, 2025. https://www.newsweek.com/full-list-degrees-professional-trump-administration-11085695

- New York Academy of Medicine. Response to stripping “professional status” as proposed by the Department of Education. New York Academy of Medicine. November 24, 2025. Accessed December 22, 2025. https://nyam.org/article/response-to-stripping-professional-status-as-proposed-by-the-department-of-education

- Cruess SR, Johnston S, Cruess RL. “Profession”: a working definition for medical educators. Teach Learn Med. 2004;16:74-76. doi:10.1207/s15328015tlm1601_15

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing. Nursing is a professional degree. American Association of Colleges of Nursing. Accessed December 20, 2025. https://www.aacnnursing.org/policy-advocacy/take-action/nursing-is-a-professional-degree

- National Association of Social Workers. Social work is a profession. Social Workers. Accessed December 20, 2025. https://www.socialworkers.org

- National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. Accessed December 20, 2025. https://www.nccpa.net/about-nccpa/#who-we-are

- The Federation of State Boards of Physical Therapy. Accessed December 20, 2025. https://www.fsbpt.org/About-Us/Staff-Home

- Cruess SR, Cruess RL. Professionalism and medicine’s contract with social contract with society. Virtual Mentor. 2004;6:185-188. doi:10.1001/virtualmentor.2004.6.4.msoc1-040

A professional is someone who can do his best work when he doesn’t feel like it.

Alistair Cooke

When I was a young person with no idea about growing up to be something, my father used to tell me there were 4 learned professions: medicine to heal the body, law to protect the body politic, teaching to nurture the mind, and the clergy to care for the soul.1 That adage, or some version of it, is attributed to a variety of sources, likely because it captures something essential and timeless about the learned professions. I write this as a much older person, and it has been my privilege to have worked in some capacity in all 4 of these venerable vocations.

There are many more recognized professions now than in my father’s time with new ones still emerging as the world becomes more complicated and specialized. In November 2025, however, the growth of the professions was dealt a serious blow when the US Department of Education (DOE) redefined what constitutes a profession for the purpose of federal funding of graduate degrees.2 The internet is understandably abuzz with opinions across the political spectrum. What is missing from many of these discussions is an understanding of the criteria for a profession and, even more importantly, who has the authority to decide when an individual or a group has met that standard.

But first, what and why did the DOE make this change? The One Big Beautiful Bill Act charged the DOE with reducing what it claims is massive overspending on graduate education by limiting the programs that meet the definition of a “professional degree” eligible for higher funding. Of my father’s 4, medicine (including dentistry) and law made the cut with students in those professions able to borrow up to $200,000 in direct unsubsidized student loans while those in other programs would be limited to $100,000.2

As one of the oldest and most respected professions in America, nursing has received the most media attention, yet there are also other important and valued professions that are missing from the DOE list.3 The excluded professions also include: physician assistants, physical therapists, audiologists, architects, accountants, educators, and social workers. The proposed regulatory changes are not yet finalized and Congressional representatives, health care experts, and a myriad of professional associations have rightly objected the reclassification will only worsen the critical shortage of nurses, teachers, and other helping professions the country is already facing.4

There are thousands of federal health care professionals who worked long and hard to achieve their goals whom this Act undervalues. Moreover, the regulatory change leaves many students enrolled in education and training programs under federal practice auspices confused and overwhelmed. Perhaps they can take some hope and inspiration from the recognition that historically and philosophically, no agency or administration can unilaterally define what is a profession.

The literature on professionalism is voluminous, in large part because it has been surprisingly difficult to reach a consensus definition. A proposed definition from scholars captures most of the key aspects of a profession. While it is drawn from the medical literature, it applies to most of the caring professions the DOE disqualified. For pedagogic purposes, the definition is parsed into discrete criteria in the Table.5

Even this simple summary makes it obvious that a government agency alone could not possibly have the competence to determine who meets these complex technical and moral criteria. The members of the profession must assume a primary role in that determination. The complicated history of the professions shows that the locus of these decisions has resided in various combinations of educational institutions, such as nursing schools,6 professional societies (eg, National Association of Social Workers),7 and certifying boards (eg, National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants).8 States, not the federal government, have long played a key part in defining professions in the US, through their authority to grant licenses to practice.9

In response to criticism, the DOE has stated that “the definition of a ‘professional degree’ is an internal definition used by the Department of Education to distinguish among programs that qualify for higher loan limits, not a value judgment about the importance of programs. It has no bearing on whether a program is professional in nature or not.”2 Given the ancient compact between society and the professions in which the government subsidizes the training of professionals dedicated to public service, it is hard to see how these changes can be dismissed as merely semantic and not a promissory breach.10

I recognize that this abstract editorial is little comfort to beleaguered and demoralized professionals and students. Still, it offers a voice of support for each federal practitioner or trainee who fulfills the epigraph’s description of a professional day after day. The nurse who works the extra shift without complaint or resentment so that veterans receive the care they deserve, the social worker who responds on a weekend night to an active duty family without food so they do not spend another night hungry, and the physician assistant who makes it into the isolated public health clinic despite the terrible weather so there is someone ready to take care for patients in need. The proposed policy shift cannot in any meaningful sense rob them of their identity as individuals committed to a code of caring. However, without an intact social compact, it may well remove their practical ability to remain and enter the helping professions to the detriment of us all.

A professional is someone who can do his best work when he doesn’t feel like it.

Alistair Cooke

When I was a young person with no idea about growing up to be something, my father used to tell me there were 4 learned professions: medicine to heal the body, law to protect the body politic, teaching to nurture the mind, and the clergy to care for the soul.1 That adage, or some version of it, is attributed to a variety of sources, likely because it captures something essential and timeless about the learned professions. I write this as a much older person, and it has been my privilege to have worked in some capacity in all 4 of these venerable vocations.

There are many more recognized professions now than in my father’s time with new ones still emerging as the world becomes more complicated and specialized. In November 2025, however, the growth of the professions was dealt a serious blow when the US Department of Education (DOE) redefined what constitutes a profession for the purpose of federal funding of graduate degrees.2 The internet is understandably abuzz with opinions across the political spectrum. What is missing from many of these discussions is an understanding of the criteria for a profession and, even more importantly, who has the authority to decide when an individual or a group has met that standard.

But first, what and why did the DOE make this change? The One Big Beautiful Bill Act charged the DOE with reducing what it claims is massive overspending on graduate education by limiting the programs that meet the definition of a “professional degree” eligible for higher funding. Of my father’s 4, medicine (including dentistry) and law made the cut with students in those professions able to borrow up to $200,000 in direct unsubsidized student loans while those in other programs would be limited to $100,000.2

As one of the oldest and most respected professions in America, nursing has received the most media attention, yet there are also other important and valued professions that are missing from the DOE list.3 The excluded professions also include: physician assistants, physical therapists, audiologists, architects, accountants, educators, and social workers. The proposed regulatory changes are not yet finalized and Congressional representatives, health care experts, and a myriad of professional associations have rightly objected the reclassification will only worsen the critical shortage of nurses, teachers, and other helping professions the country is already facing.4

There are thousands of federal health care professionals who worked long and hard to achieve their goals whom this Act undervalues. Moreover, the regulatory change leaves many students enrolled in education and training programs under federal practice auspices confused and overwhelmed. Perhaps they can take some hope and inspiration from the recognition that historically and philosophically, no agency or administration can unilaterally define what is a profession.

The literature on professionalism is voluminous, in large part because it has been surprisingly difficult to reach a consensus definition. A proposed definition from scholars captures most of the key aspects of a profession. While it is drawn from the medical literature, it applies to most of the caring professions the DOE disqualified. For pedagogic purposes, the definition is parsed into discrete criteria in the Table.5

Even this simple summary makes it obvious that a government agency alone could not possibly have the competence to determine who meets these complex technical and moral criteria. The members of the profession must assume a primary role in that determination. The complicated history of the professions shows that the locus of these decisions has resided in various combinations of educational institutions, such as nursing schools,6 professional societies (eg, National Association of Social Workers),7 and certifying boards (eg, National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants).8 States, not the federal government, have long played a key part in defining professions in the US, through their authority to grant licenses to practice.9

In response to criticism, the DOE has stated that “the definition of a ‘professional degree’ is an internal definition used by the Department of Education to distinguish among programs that qualify for higher loan limits, not a value judgment about the importance of programs. It has no bearing on whether a program is professional in nature or not.”2 Given the ancient compact between society and the professions in which the government subsidizes the training of professionals dedicated to public service, it is hard to see how these changes can be dismissed as merely semantic and not a promissory breach.10

I recognize that this abstract editorial is little comfort to beleaguered and demoralized professionals and students. Still, it offers a voice of support for each federal practitioner or trainee who fulfills the epigraph’s description of a professional day after day. The nurse who works the extra shift without complaint or resentment so that veterans receive the care they deserve, the social worker who responds on a weekend night to an active duty family without food so they do not spend another night hungry, and the physician assistant who makes it into the isolated public health clinic despite the terrible weather so there is someone ready to take care for patients in need. The proposed policy shift cannot in any meaningful sense rob them of their identity as individuals committed to a code of caring. However, without an intact social compact, it may well remove their practical ability to remain and enter the helping professions to the detriment of us all.

- Wade JW. Public responsibilities of the learned professions. Louisiana Law Rev. 1960;21:130-148

- US Department of Education. Myth vs. fact: the definition of professional degrees. Press Release. November 24, 2025. Accessed December 22, 2025. https://www.ed.gov/about/news/press-release/myth-vs-fact-definition-of-professional-degrees

- Laws J. Full list of degrees not classed as “professional” by Trump admin. Newsweek. Updated November 26, 2025. Accessed December 22, 2025. https://www.newsweek.com/full-list-degrees-professional-trump-administration-11085695

- New York Academy of Medicine. Response to stripping “professional status” as proposed by the Department of Education. New York Academy of Medicine. November 24, 2025. Accessed December 22, 2025. https://nyam.org/article/response-to-stripping-professional-status-as-proposed-by-the-department-of-education

- Cruess SR, Johnston S, Cruess RL. “Profession”: a working definition for medical educators. Teach Learn Med. 2004;16:74-76. doi:10.1207/s15328015tlm1601_15

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing. Nursing is a professional degree. American Association of Colleges of Nursing. Accessed December 20, 2025. https://www.aacnnursing.org/policy-advocacy/take-action/nursing-is-a-professional-degree

- National Association of Social Workers. Social work is a profession. Social Workers. Accessed December 20, 2025. https://www.socialworkers.org

- National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. Accessed December 20, 2025. https://www.nccpa.net/about-nccpa/#who-we-are

- The Federation of State Boards of Physical Therapy. Accessed December 20, 2025. https://www.fsbpt.org/About-Us/Staff-Home

- Cruess SR, Cruess RL. Professionalism and medicine’s contract with social contract with society. Virtual Mentor. 2004;6:185-188. doi:10.1001/virtualmentor.2004.6.4.msoc1-040

- Wade JW. Public responsibilities of the learned professions. Louisiana Law Rev. 1960;21:130-148

- US Department of Education. Myth vs. fact: the definition of professional degrees. Press Release. November 24, 2025. Accessed December 22, 2025. https://www.ed.gov/about/news/press-release/myth-vs-fact-definition-of-professional-degrees

- Laws J. Full list of degrees not classed as “professional” by Trump admin. Newsweek. Updated November 26, 2025. Accessed December 22, 2025. https://www.newsweek.com/full-list-degrees-professional-trump-administration-11085695

- New York Academy of Medicine. Response to stripping “professional status” as proposed by the Department of Education. New York Academy of Medicine. November 24, 2025. Accessed December 22, 2025. https://nyam.org/article/response-to-stripping-professional-status-as-proposed-by-the-department-of-education

- Cruess SR, Johnston S, Cruess RL. “Profession”: a working definition for medical educators. Teach Learn Med. 2004;16:74-76. doi:10.1207/s15328015tlm1601_15

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing. Nursing is a professional degree. American Association of Colleges of Nursing. Accessed December 20, 2025. https://www.aacnnursing.org/policy-advocacy/take-action/nursing-is-a-professional-degree

- National Association of Social Workers. Social work is a profession. Social Workers. Accessed December 20, 2025. https://www.socialworkers.org

- National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. Accessed December 20, 2025. https://www.nccpa.net/about-nccpa/#who-we-are

- The Federation of State Boards of Physical Therapy. Accessed December 20, 2025. https://www.fsbpt.org/About-Us/Staff-Home

- Cruess SR, Cruess RL. Professionalism and medicine’s contract with social contract with society. Virtual Mentor. 2004;6:185-188. doi:10.1001/virtualmentor.2004.6.4.msoc1-040

Codes, Contracts, and Commitments: Who Defines What is a Profession?

Codes, Contracts, and Commitments: Who Defines What is a Profession?

Can Telehealth Improve Access to Amyloid-Targeting Therapies for Veterans Living With Alzheimer Disease?

Can Telehealth Improve Access to Amyloid-Targeting Therapies for Veterans Living With Alzheimer Disease?

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is the largest US integrated health care system, providing health care to > 9 million veterans annually. Dementia affects > 7.2 million Americans, and an estimated 450,000 veterans live with Alzheimer disease (AD).1,2 Compared with the general population, veterans have a higher burden of chronic medical conditions and are disproportionately affected by AD due to exposure to military-related risk factors (eg, traumatic brain injury and posttraumatic stress disorder) and the high prevalence of nonmilitary risk factors, such as cardiovascular disease. The VHA is a pioneer in dementia care, having established a Dementia System of Care to provide primary and specialty care to veterans with dementia. The VHA also is leading the way in implementing the Institute for Healthcare Improvement Age-Friendly Health Systems (AFHS) framework for providing goal-concordant care in > 100 VHA medical centers. The VHA aims to be the largest AFHS in the country.

AD profoundly affects individuals and their families. The progressive nature of the most common form of dementia diminishes the quality of life for patients as well as their care partners in an ongoing fashion, often leading to emotional, physical, and financial strain. Costs for health and long-term care for people living with AD and other dementias were projected at $360 billion in 2024, largely due to the need for nursing home care.1 Although several oral medications are available, their capacity to effectively mitigate the negative effects of AD is limited. Cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine may offer temporary symptomatic relief, but they do not alter disease progression.3 The use of these agents is relatively low, with about one-third of patients diagnosed with AD receiving these medications.4

Amyloid-Targeting Therapies

Recent advancements in biologics, particularly amyloid-targeting therapies, such as lecanemab and donanemab, offer new hope for managing AD. Older adults treated with these medications show less decline on measures of cognition and function than those receiving a placebo at 18 months.5,6 However, accessing and using these medications is challenging.

Use of amyloid-targeting therapies poses challenges. The medications are expensive, potentially placing a financial burden on patients, families, and health care systems.7 Determining initial eligibility for treatment requires a battery of cognitive assessments, laboratory tests, advanced radiologic studies (eg, magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] of the brain and amyloid positron emission tomography [PET] scans), and possible cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) testing. Frequent ongoing assessments are necessary to monitor safety and efficacy. These treatments carry substantial risks, particularly amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA) such as cerebral edema, microhemorrhages, and superficial siderosis. Therefore, follow-up assessments typically occur around months 2, 3, 4, and 7, depending on which medication is selected. Finally, at present, both agents must be intravenous (IV)-administered in a monitored clinical setting, which requires additional coordination, transportation, and cost.

Ongoing evaluations and in-person administration particularly affect patients and care partners with limitations regarding transportation, time off work, and navigating complex health care systems.8 VHA clinicians at sites that have implemented or are interested in implementing amyloid-targeting therapy programs endorse similar challenges when implementing these therapies in their US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers (VAMCs).9

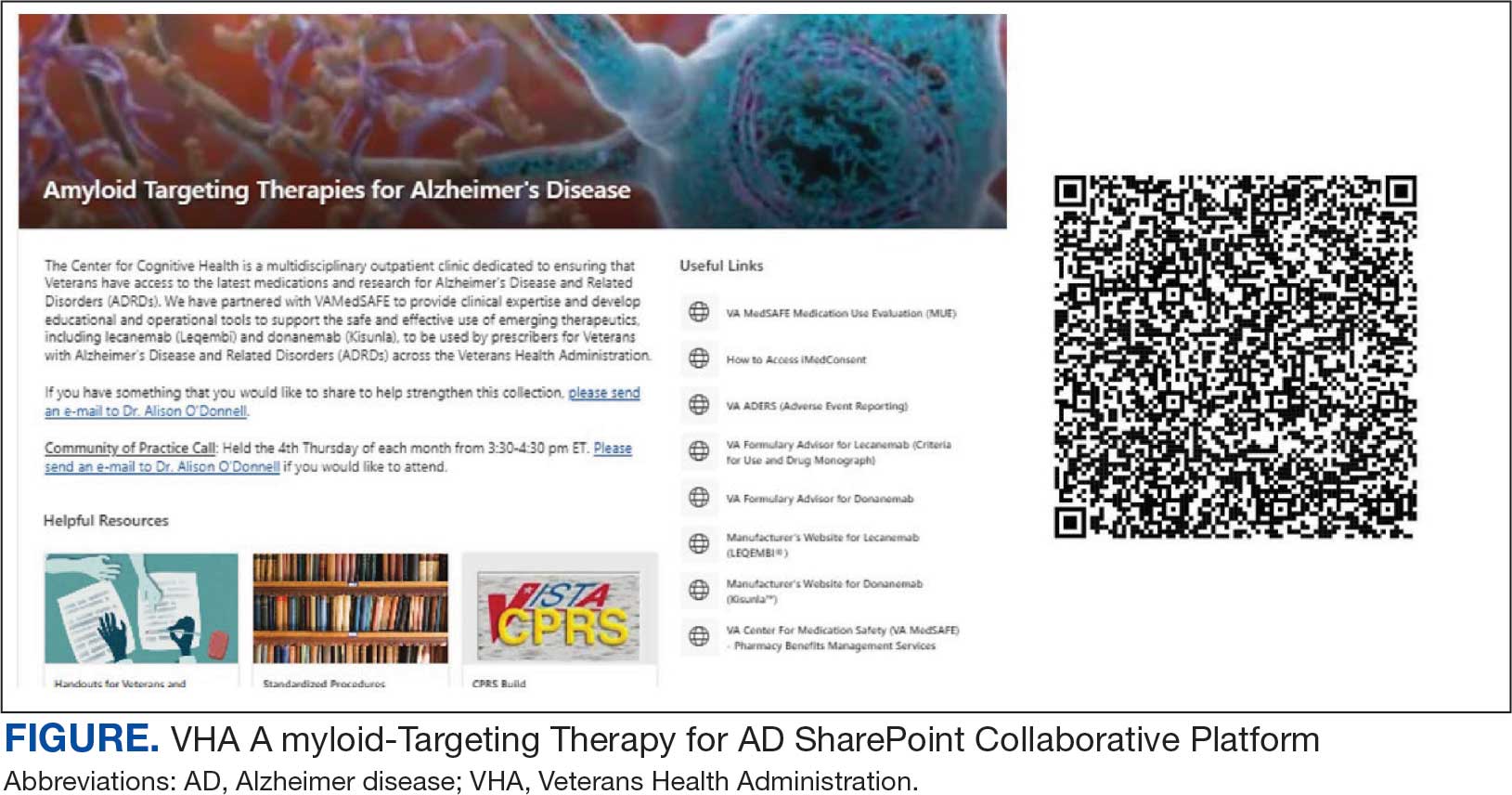

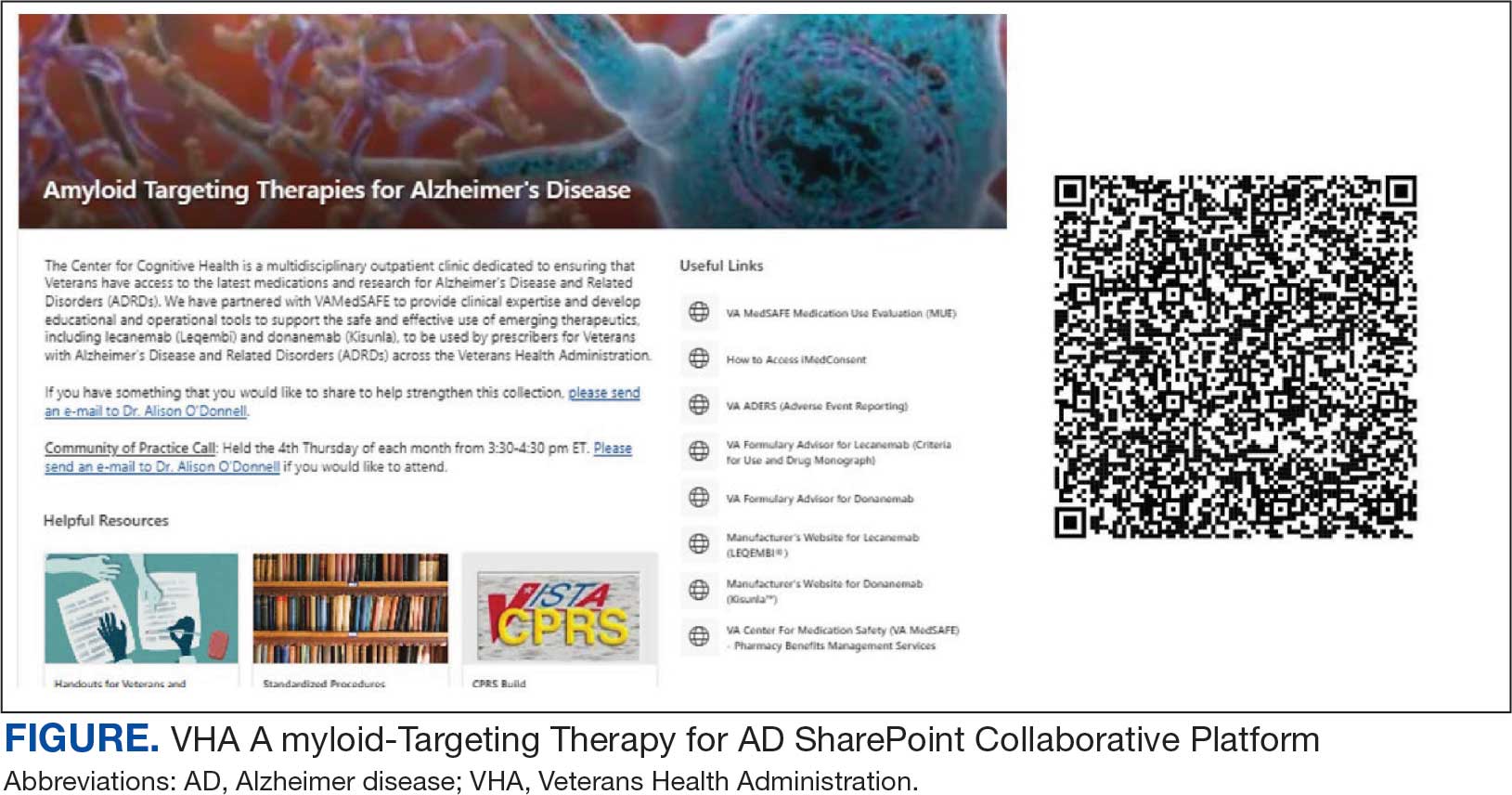

The VHA was one of the first health care systems to use amyloid-targeting therapies, covering the cost of lecanemab and donanemab, in addition to costs associated with concomitant evaluation and testing. However, given the safety concerns with this novel class of medications, the VHA National Formulary Committee developed criteria for use and recommended the VA Center for Medication Safety (VAMedSAFE) conduct a mandatory real-time medication use evaluation (MUE). VAMedSAFE developed the MUE to monitor the safe and appropriate use of amyloid-targeting therapy for AD. Two authors (AJO, SMH) partnered with VAMedSAFE through the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System Technology Enhancing Cognition and Health–Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Center (TECH-GRECC) to provide clinical expertise, substantive feedback for the development of the MUE, and guidance for VHA sites starting amyloid targeting-therapy programs. We started a VHA Amyloid-Targeting Therapy for AD SharePoint collaborative platform and VHA AD Therapeutics Community of Practice (CoP) for shared learning (Figure). The private SharePoint platform houses an array of implementation materials for VAMCs starting programs: key documents and links; educational materials; sample guidelines; note templates; and electronic health record screenshots. The CoP allows VHAs to share best practices and discuss challenges.

Even with these advantages, we found that ensuring the safe and appropriate use of amyloid-targeting therapies did not overcome the barriers associated with their complexity. This was especially true for veterans living in rural areas. Only 4 VAMCs had administered amyloid-targeting therapies in the first year they were available. Preliminary data demonstrated that 27 (84%) of 32 veterans who initiated lecanemab in the VHA between October 2023 and September 2024 resided in urban areas.10 To address the underutilization of amyloid-targeting therapy, we propose leveraging the strengths of VHA telehealth to facilitate expansion of access to these medications for veterans with early AD. Telehealth may substantially increase access to evaluation for veterans with early dementia and, when medically appropriate, to receive amyloid-targeting therapies by reducing transportation needs and mitigating costs while ensuring appropriate monitoring through ongoing clinical assessments.

Using Telehealth

The VHA is a pioneer in telehealth, with programs dating back to 2003.11 Between October 1, 2018, and September 30, 2019, the VHA served > 900,000 veterans through the provision of > 2.6 million episodes of care via telehealth.12 The COVID-19 pandemic further cemented the role of telemedicine as an essential component of health care. Telehealth has demonstrated success in the assessment and management of individuals living with dementia. At the VHA, the GRECC-Connect Project is a partnership between 9 urban GRECC sites that seek to provide consultative geriatric and dementia care to rural veterans through telehealth.13 Additional evidence supports the potential to leverage telehealth to effectively communicate results of amyloid PET scans.14

This approach is not without limitations such as the digital divide, or the gap that separates technology-enabled individuals and those unprepared to adopt technology due to limited digital literacy levels or access to needed hardware, software, and connectivity. The VHA has taken steps to address these digital divide barriers by broadly providing tools—such as tablets and broadband connectivity—to veterans. Specifically, the VHA has instituted digital divide consults to determine whether telehealth could be a potential solution for appropriate veterans and to provide an iPad (if eligible) to connect with VA clinicians. Complementary to the digital divide consult, a VHA-specific telehealth preparedness assessment tool is under development and being tested by 2 authors (JF, SMH). This telehealth preparedness assessment tool is designed to aid in the seamless integration of telehealth services with the support of tailored education materials specific to gaps in digital literacy that a veteran might experience.

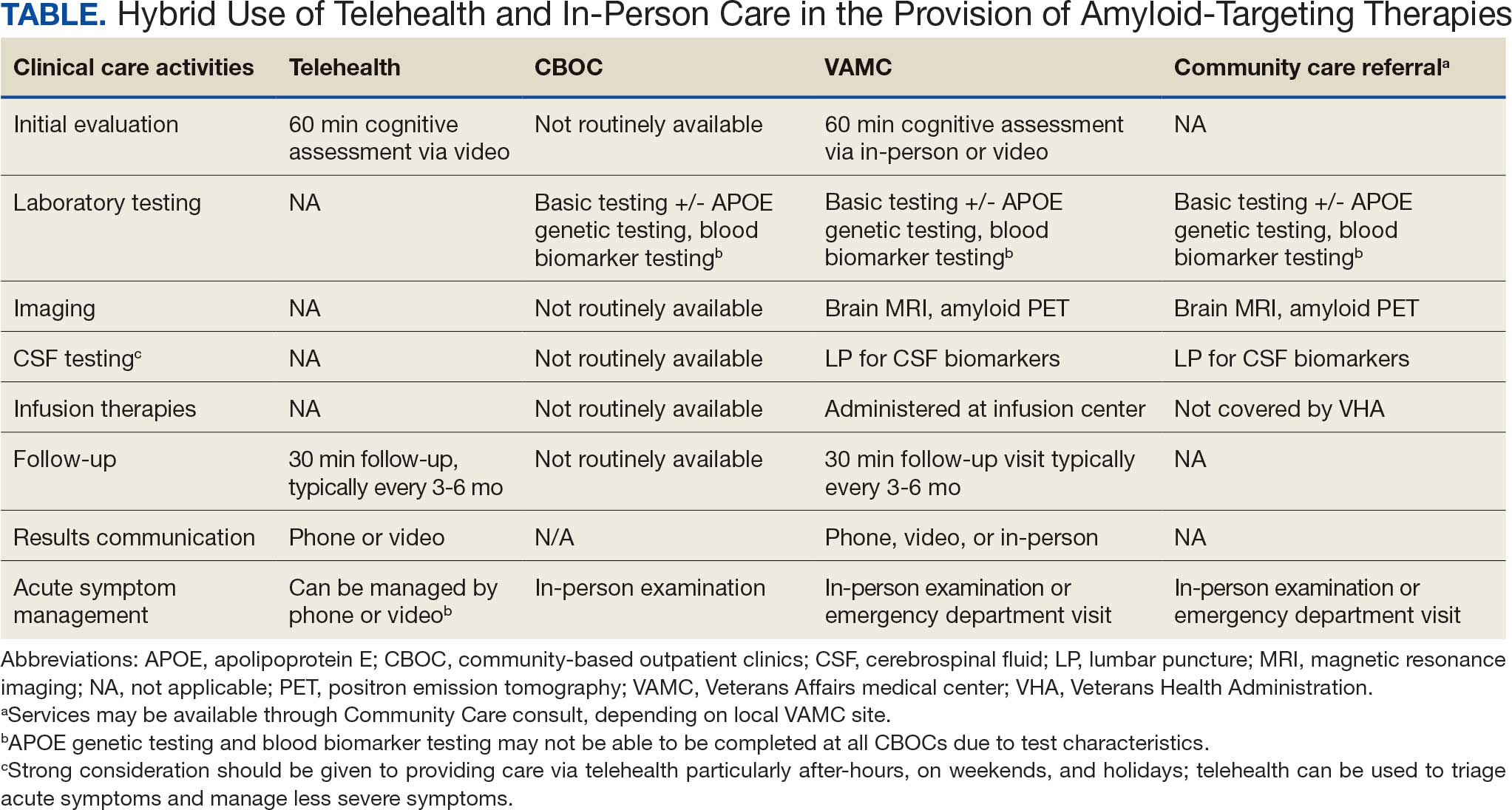

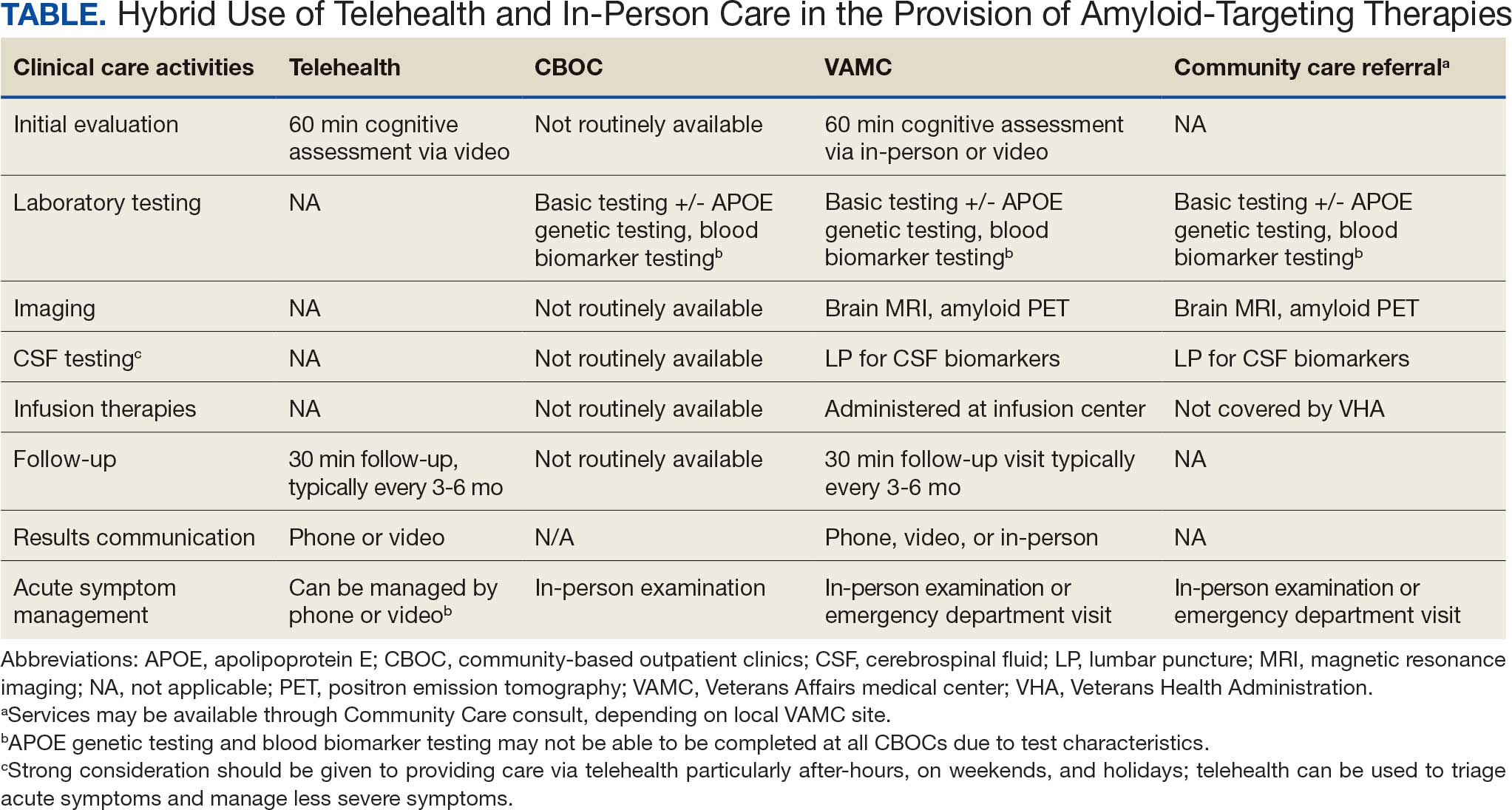

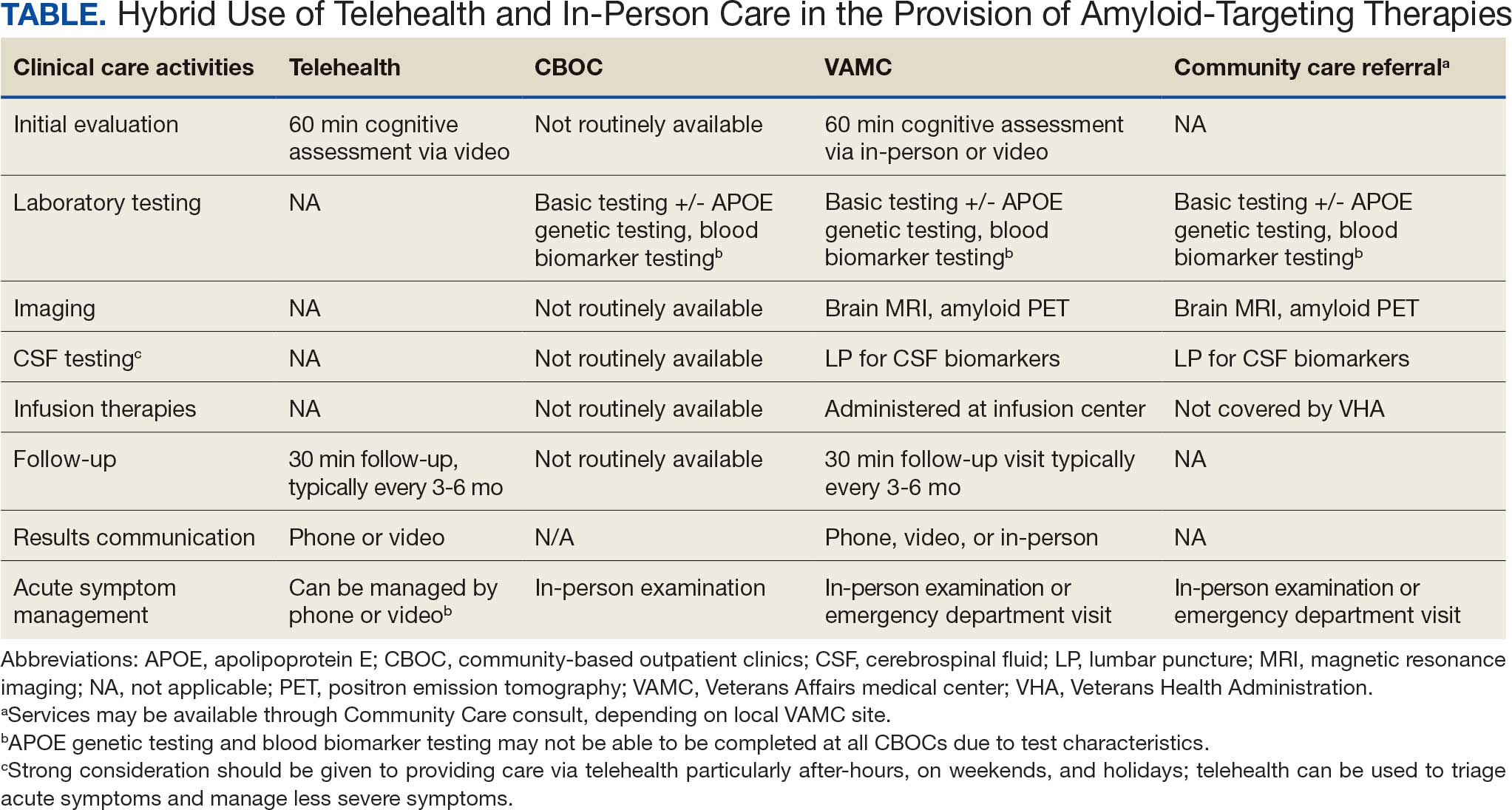

Building on these initiatives, there is an opportunity to expand access to amyloid-targeting therapies, regardless of distance to large VAMCs, by leveraging telehealth as an alternative method of connecting patients with specialty care. Specifically, a hybrid approach could be used to accomplish the myriad initial and follow-up tasks involved in the provision of amyloid-targeting therapies (Table). Not all VHA facilities possess the specialty expertise to prescribe these medications, and local clinicians may not have sufficient knowledge and clinical support to prescribe and monitor these therapies.

The first step is identifying local and regional subject matter experts, followed by the development and expansion of these networks. The National TeleNeurology Program is a good example of a national telehealth program that leverages technology to bring specialty services to rural areas with limited access to care. Although amyloid-targeting therapies often require more complex logistics, such as laboratory tests and imaging, these initial hurdles can be overcome through localized services and collaboration between VAMCs.

While treatment and imaging will most likely need to occur at a VAMC, most basic laboratory studies can be performed at community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs). Some CBOCs may not be able to process more specialized laboratory tests such as apolipoprotein E genetic testing. Samples for these tests can be collected and processed at VAMCs, which usually have contracts with outside laboratories capable of performing these studies. Most, although not all, VAMCs offer advanced imaging, including MRI of the brain and amyloid PETs. VAMCs without those modalities may need to coordinate with other regional VAMCs. Additionally, a pilot program is already underway whereby VAMCs without the ability to quantify the amount of amyloid on PETs are able to leverage technology and collaborations with other VAMCs to obtain these data.

Once the initial phases of evaluation and care are completed, telemedicine can be leveraged for follow-up and ongoing management. Interdisciplinary teams can help facilitate care related to amyloid-targeting therapies, including the close monitoring of veterans for development of ARIA.15 To achieve this monitoring, specialty clinic teams prescribing amyloid-targeting therapies, which may be geographically distant, need to coordinate with local primary care clinical teams and emergency clinicians. All of these health care team members, along with neurologists and neurosurgeons, should be involved in the development and implementation of protocols in the event that patients present to their local primary or specialty care clinics or emergency department with ARIA symptoms.

If amyloid-targeting therapies are to be provided along with other emerging treatments for rural veterans, telehealth must be part of the solution. There is a pressing need to explore innovative evaluation and delivery models for these therapies, particularly as we expect additional diagnostics and therapeutics to be available in the future. With the advent of commercially available blood tests (ie, blood biomarkers) for AD, there is hope for a transition away from PETs and CSF testing given their cost, limited access, and invasiveness for diagnosis and monitoring of AD. These advances will increase the utility of telehealth to help rural veterans access amyloid-targeting therapies.

Additionally, administering the drug at home or at local clinics, supported by a dedicated health care team or home health agency, could further improve accessibility. Telehealth can be leveraged in this scenario, allowing specialty clinics and specialists to connect with patients and clinicians based out of local clinics or even home health agencies. In this scenario, specialists can provide hands-on care guidance and oversight even though they may be geographically distant from care recipients. Transitioning from IV administration to subcutaneous formulations would further enhance convenience and reduce barriers; these formulations may be available soon.16 Addressing logistical challenges to care and access through technology-based solutions will require coordinated efforts and continued VHA investment.

Conclusions

The VHA has a large population of veterans with dementia, and the costs to care for these veterans will only increase. While the current benefits of amyloid-targeting therapies are modest, now is the time to establish care processes that will support future innovations in amyloid-targeting therapies and other treatments and diagnostics. We are developing better ways to detect AD using clinical decision support tools, improving care pathways and the management of AD, and leveraging telehealth to improve access. The VA is conducting research to investigate whether a cognitive screening and laboratory evaluation that includes a telehealth preparedness assessment will be feasible and effective for improving the detection of AD and access to treatment, and we plan to publish the results.

The lessons learned can be extended to non-VHA care settings to help achieve potential benefits for other patients with early AD. Emerging therapies have the potential to improve the quality of life for both patients and care partners, adding life to years and not just years to life. Policymakers and payors must prioritize research funding to evaluate the safety and efficacy of these approaches to the delivery of health services, ensuring that emerging therapies are accessible for all individuals affected by AD.

- Alzheimer’s Association. 2025 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2025;21(4):e70235. doi:10.1002/alz.70235

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Statistical Projections of Alzheimer’s Dementia for VA Patients, VA Enrollees, and US Veterans. December 18, 2020. Accessed November 2, 2025. https://www.va.gov/GERIATRICS/docs/VHA_ALZHEIMERS_DEMENTIA_Statistical_Projections_FY21_and_FY33_sgc121820.pdf

- Casey DA, Antimisiaris D, O’Brien J. Drugs for Alzheimer’s disease: are they effective? P T. 2010;35(4):208-211.

- Barthold D, Joyce G, Ferido P, et al. Pharmaceutical treatment for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias: utilization and disparities. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;76(2):579-589. doi:10.3233/JAD-200133

- Sims JR, Zimmer JA, Evans CD, et al. Donanemab in early symptomatic Alzheimer disease: the TRAILBLAZER-ALZ 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2023;330(6):512-527. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.13239

- van Dyck CH, Swanson CJ, Aisen P, et al. Lecanemab in early Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(1):9-21. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2212948

- Tanne JH. Lecanemab: US Veterans Health Administration will cover cost of new Alzheimer’s drug. BMJ. 2023;380:p628. doi:10.1136/bmj.p628

- Nadeau SE. Lecanemab questions. Neurology. 2024;102(7):e209320. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000209320 9. O’Donnell AJ, Fortunato AT, Spitznogle BL, et al. Implementation of lecanemab for Alzheimer’s disease: facilitators and barriers. Presented at: American Geriatrics Society 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting, Chicago. May 2025.

- O’Donnell AJ, Zhao X, Parr A, et al. Use of lecanemab for Alzheimer’s disease within the Veteran’s Health Foundation: early findings. Abstract presented at: Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2025; July 27, 2025; Toronto, Canada.

- O’Donnell AJ, Zhao X, Parr A, et al. Use of lecanemab for Alzheimer’s disease within the Veteran’s Health Foundation: early findings. Abstract presented at: Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2025; July 27, 2025; Toronto, Canada.

- Hopp F, Whitten P, Subramanian U, et al. Perspectives from the Veterans Health Administration about opportunities and barriers in telemedicine. J Telemed Telecare. 2006;12(8):404-409. doi:10.1258/135763306779378717

- VA reports significant increase in veteran use of telehealth services. News release. US Department of Veterans Affairs. November 22, 2019. Accessed November 19, 2025. https://news.va.gov/press-room/va-reports-significant-increase-in-veteran-use-of-telehealth-services/

- Powers BB, Homer MC, Morone N, et al. Creation of an interprofessional teledementia clinic for rural veterans: preliminary data. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(5):1092-1099. doi:10.1111/jgs.14839

- Erickson CM, Chin NA, Rosario HL, et al. Feasibility of virtual Alzheimer’s biomarker disclosure: findings from an observational cohort. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2023;9(3):e12413. doi:10.1002/trc2.12413

- Turk KW, Knobel MD, Nothern A, et al. An interprofessional team for disease-modifying therapy in Alzheimer disease implementation. Neurol Clin Pract. 2024;14(6):e200346. doi:10.1212/CPJ.0000000000200346

- FDA accepts LEQEMBI® (lecanemab-irmb) biologics license application for subcutaneous maintenance dosing for the treatment of early Alzheimer’s disease. News release. Elsai US. January 13, 2025. Accessed November 2, 2025. https://media-us.eisai.com/2025-01-13-FDA-Accepts-LEQEMBI-R-lecanemab-irmb-Biologics-License-Application-for-Subcutaneous-Maintenance-Dosing-for-the-Treatment-of-Early-Alzheimers-Disease

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is the largest US integrated health care system, providing health care to > 9 million veterans annually. Dementia affects > 7.2 million Americans, and an estimated 450,000 veterans live with Alzheimer disease (AD).1,2 Compared with the general population, veterans have a higher burden of chronic medical conditions and are disproportionately affected by AD due to exposure to military-related risk factors (eg, traumatic brain injury and posttraumatic stress disorder) and the high prevalence of nonmilitary risk factors, such as cardiovascular disease. The VHA is a pioneer in dementia care, having established a Dementia System of Care to provide primary and specialty care to veterans with dementia. The VHA also is leading the way in implementing the Institute for Healthcare Improvement Age-Friendly Health Systems (AFHS) framework for providing goal-concordant care in > 100 VHA medical centers. The VHA aims to be the largest AFHS in the country.

AD profoundly affects individuals and their families. The progressive nature of the most common form of dementia diminishes the quality of life for patients as well as their care partners in an ongoing fashion, often leading to emotional, physical, and financial strain. Costs for health and long-term care for people living with AD and other dementias were projected at $360 billion in 2024, largely due to the need for nursing home care.1 Although several oral medications are available, their capacity to effectively mitigate the negative effects of AD is limited. Cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine may offer temporary symptomatic relief, but they do not alter disease progression.3 The use of these agents is relatively low, with about one-third of patients diagnosed with AD receiving these medications.4

Amyloid-Targeting Therapies

Recent advancements in biologics, particularly amyloid-targeting therapies, such as lecanemab and donanemab, offer new hope for managing AD. Older adults treated with these medications show less decline on measures of cognition and function than those receiving a placebo at 18 months.5,6 However, accessing and using these medications is challenging.

Use of amyloid-targeting therapies poses challenges. The medications are expensive, potentially placing a financial burden on patients, families, and health care systems.7 Determining initial eligibility for treatment requires a battery of cognitive assessments, laboratory tests, advanced radiologic studies (eg, magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] of the brain and amyloid positron emission tomography [PET] scans), and possible cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) testing. Frequent ongoing assessments are necessary to monitor safety and efficacy. These treatments carry substantial risks, particularly amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA) such as cerebral edema, microhemorrhages, and superficial siderosis. Therefore, follow-up assessments typically occur around months 2, 3, 4, and 7, depending on which medication is selected. Finally, at present, both agents must be intravenous (IV)-administered in a monitored clinical setting, which requires additional coordination, transportation, and cost.

Ongoing evaluations and in-person administration particularly affect patients and care partners with limitations regarding transportation, time off work, and navigating complex health care systems.8 VHA clinicians at sites that have implemented or are interested in implementing amyloid-targeting therapy programs endorse similar challenges when implementing these therapies in their US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers (VAMCs).9

The VHA was one of the first health care systems to use amyloid-targeting therapies, covering the cost of lecanemab and donanemab, in addition to costs associated with concomitant evaluation and testing. However, given the safety concerns with this novel class of medications, the VHA National Formulary Committee developed criteria for use and recommended the VA Center for Medication Safety (VAMedSAFE) conduct a mandatory real-time medication use evaluation (MUE). VAMedSAFE developed the MUE to monitor the safe and appropriate use of amyloid-targeting therapy for AD. Two authors (AJO, SMH) partnered with VAMedSAFE through the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System Technology Enhancing Cognition and Health–Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Center (TECH-GRECC) to provide clinical expertise, substantive feedback for the development of the MUE, and guidance for VHA sites starting amyloid targeting-therapy programs. We started a VHA Amyloid-Targeting Therapy for AD SharePoint collaborative platform and VHA AD Therapeutics Community of Practice (CoP) for shared learning (Figure). The private SharePoint platform houses an array of implementation materials for VAMCs starting programs: key documents and links; educational materials; sample guidelines; note templates; and electronic health record screenshots. The CoP allows VHAs to share best practices and discuss challenges.

Even with these advantages, we found that ensuring the safe and appropriate use of amyloid-targeting therapies did not overcome the barriers associated with their complexity. This was especially true for veterans living in rural areas. Only 4 VAMCs had administered amyloid-targeting therapies in the first year they were available. Preliminary data demonstrated that 27 (84%) of 32 veterans who initiated lecanemab in the VHA between October 2023 and September 2024 resided in urban areas.10 To address the underutilization of amyloid-targeting therapy, we propose leveraging the strengths of VHA telehealth to facilitate expansion of access to these medications for veterans with early AD. Telehealth may substantially increase access to evaluation for veterans with early dementia and, when medically appropriate, to receive amyloid-targeting therapies by reducing transportation needs and mitigating costs while ensuring appropriate monitoring through ongoing clinical assessments.

Using Telehealth

The VHA is a pioneer in telehealth, with programs dating back to 2003.11 Between October 1, 2018, and September 30, 2019, the VHA served > 900,000 veterans through the provision of > 2.6 million episodes of care via telehealth.12 The COVID-19 pandemic further cemented the role of telemedicine as an essential component of health care. Telehealth has demonstrated success in the assessment and management of individuals living with dementia. At the VHA, the GRECC-Connect Project is a partnership between 9 urban GRECC sites that seek to provide consultative geriatric and dementia care to rural veterans through telehealth.13 Additional evidence supports the potential to leverage telehealth to effectively communicate results of amyloid PET scans.14

This approach is not without limitations such as the digital divide, or the gap that separates technology-enabled individuals and those unprepared to adopt technology due to limited digital literacy levels or access to needed hardware, software, and connectivity. The VHA has taken steps to address these digital divide barriers by broadly providing tools—such as tablets and broadband connectivity—to veterans. Specifically, the VHA has instituted digital divide consults to determine whether telehealth could be a potential solution for appropriate veterans and to provide an iPad (if eligible) to connect with VA clinicians. Complementary to the digital divide consult, a VHA-specific telehealth preparedness assessment tool is under development and being tested by 2 authors (JF, SMH). This telehealth preparedness assessment tool is designed to aid in the seamless integration of telehealth services with the support of tailored education materials specific to gaps in digital literacy that a veteran might experience.

Building on these initiatives, there is an opportunity to expand access to amyloid-targeting therapies, regardless of distance to large VAMCs, by leveraging telehealth as an alternative method of connecting patients with specialty care. Specifically, a hybrid approach could be used to accomplish the myriad initial and follow-up tasks involved in the provision of amyloid-targeting therapies (Table). Not all VHA facilities possess the specialty expertise to prescribe these medications, and local clinicians may not have sufficient knowledge and clinical support to prescribe and monitor these therapies.

The first step is identifying local and regional subject matter experts, followed by the development and expansion of these networks. The National TeleNeurology Program is a good example of a national telehealth program that leverages technology to bring specialty services to rural areas with limited access to care. Although amyloid-targeting therapies often require more complex logistics, such as laboratory tests and imaging, these initial hurdles can be overcome through localized services and collaboration between VAMCs.

While treatment and imaging will most likely need to occur at a VAMC, most basic laboratory studies can be performed at community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs). Some CBOCs may not be able to process more specialized laboratory tests such as apolipoprotein E genetic testing. Samples for these tests can be collected and processed at VAMCs, which usually have contracts with outside laboratories capable of performing these studies. Most, although not all, VAMCs offer advanced imaging, including MRI of the brain and amyloid PETs. VAMCs without those modalities may need to coordinate with other regional VAMCs. Additionally, a pilot program is already underway whereby VAMCs without the ability to quantify the amount of amyloid on PETs are able to leverage technology and collaborations with other VAMCs to obtain these data.

Once the initial phases of evaluation and care are completed, telemedicine can be leveraged for follow-up and ongoing management. Interdisciplinary teams can help facilitate care related to amyloid-targeting therapies, including the close monitoring of veterans for development of ARIA.15 To achieve this monitoring, specialty clinic teams prescribing amyloid-targeting therapies, which may be geographically distant, need to coordinate with local primary care clinical teams and emergency clinicians. All of these health care team members, along with neurologists and neurosurgeons, should be involved in the development and implementation of protocols in the event that patients present to their local primary or specialty care clinics or emergency department with ARIA symptoms.

If amyloid-targeting therapies are to be provided along with other emerging treatments for rural veterans, telehealth must be part of the solution. There is a pressing need to explore innovative evaluation and delivery models for these therapies, particularly as we expect additional diagnostics and therapeutics to be available in the future. With the advent of commercially available blood tests (ie, blood biomarkers) for AD, there is hope for a transition away from PETs and CSF testing given their cost, limited access, and invasiveness for diagnosis and monitoring of AD. These advances will increase the utility of telehealth to help rural veterans access amyloid-targeting therapies.

Additionally, administering the drug at home or at local clinics, supported by a dedicated health care team or home health agency, could further improve accessibility. Telehealth can be leveraged in this scenario, allowing specialty clinics and specialists to connect with patients and clinicians based out of local clinics or even home health agencies. In this scenario, specialists can provide hands-on care guidance and oversight even though they may be geographically distant from care recipients. Transitioning from IV administration to subcutaneous formulations would further enhance convenience and reduce barriers; these formulations may be available soon.16 Addressing logistical challenges to care and access through technology-based solutions will require coordinated efforts and continued VHA investment.

Conclusions

The VHA has a large population of veterans with dementia, and the costs to care for these veterans will only increase. While the current benefits of amyloid-targeting therapies are modest, now is the time to establish care processes that will support future innovations in amyloid-targeting therapies and other treatments and diagnostics. We are developing better ways to detect AD using clinical decision support tools, improving care pathways and the management of AD, and leveraging telehealth to improve access. The VA is conducting research to investigate whether a cognitive screening and laboratory evaluation that includes a telehealth preparedness assessment will be feasible and effective for improving the detection of AD and access to treatment, and we plan to publish the results.

The lessons learned can be extended to non-VHA care settings to help achieve potential benefits for other patients with early AD. Emerging therapies have the potential to improve the quality of life for both patients and care partners, adding life to years and not just years to life. Policymakers and payors must prioritize research funding to evaluate the safety and efficacy of these approaches to the delivery of health services, ensuring that emerging therapies are accessible for all individuals affected by AD.

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is the largest US integrated health care system, providing health care to > 9 million veterans annually. Dementia affects > 7.2 million Americans, and an estimated 450,000 veterans live with Alzheimer disease (AD).1,2 Compared with the general population, veterans have a higher burden of chronic medical conditions and are disproportionately affected by AD due to exposure to military-related risk factors (eg, traumatic brain injury and posttraumatic stress disorder) and the high prevalence of nonmilitary risk factors, such as cardiovascular disease. The VHA is a pioneer in dementia care, having established a Dementia System of Care to provide primary and specialty care to veterans with dementia. The VHA also is leading the way in implementing the Institute for Healthcare Improvement Age-Friendly Health Systems (AFHS) framework for providing goal-concordant care in > 100 VHA medical centers. The VHA aims to be the largest AFHS in the country.

AD profoundly affects individuals and their families. The progressive nature of the most common form of dementia diminishes the quality of life for patients as well as their care partners in an ongoing fashion, often leading to emotional, physical, and financial strain. Costs for health and long-term care for people living with AD and other dementias were projected at $360 billion in 2024, largely due to the need for nursing home care.1 Although several oral medications are available, their capacity to effectively mitigate the negative effects of AD is limited. Cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine may offer temporary symptomatic relief, but they do not alter disease progression.3 The use of these agents is relatively low, with about one-third of patients diagnosed with AD receiving these medications.4

Amyloid-Targeting Therapies

Recent advancements in biologics, particularly amyloid-targeting therapies, such as lecanemab and donanemab, offer new hope for managing AD. Older adults treated with these medications show less decline on measures of cognition and function than those receiving a placebo at 18 months.5,6 However, accessing and using these medications is challenging.

Use of amyloid-targeting therapies poses challenges. The medications are expensive, potentially placing a financial burden on patients, families, and health care systems.7 Determining initial eligibility for treatment requires a battery of cognitive assessments, laboratory tests, advanced radiologic studies (eg, magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] of the brain and amyloid positron emission tomography [PET] scans), and possible cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) testing. Frequent ongoing assessments are necessary to monitor safety and efficacy. These treatments carry substantial risks, particularly amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA) such as cerebral edema, microhemorrhages, and superficial siderosis. Therefore, follow-up assessments typically occur around months 2, 3, 4, and 7, depending on which medication is selected. Finally, at present, both agents must be intravenous (IV)-administered in a monitored clinical setting, which requires additional coordination, transportation, and cost.

Ongoing evaluations and in-person administration particularly affect patients and care partners with limitations regarding transportation, time off work, and navigating complex health care systems.8 VHA clinicians at sites that have implemented or are interested in implementing amyloid-targeting therapy programs endorse similar challenges when implementing these therapies in their US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers (VAMCs).9

The VHA was one of the first health care systems to use amyloid-targeting therapies, covering the cost of lecanemab and donanemab, in addition to costs associated with concomitant evaluation and testing. However, given the safety concerns with this novel class of medications, the VHA National Formulary Committee developed criteria for use and recommended the VA Center for Medication Safety (VAMedSAFE) conduct a mandatory real-time medication use evaluation (MUE). VAMedSAFE developed the MUE to monitor the safe and appropriate use of amyloid-targeting therapy for AD. Two authors (AJO, SMH) partnered with VAMedSAFE through the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System Technology Enhancing Cognition and Health–Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Center (TECH-GRECC) to provide clinical expertise, substantive feedback for the development of the MUE, and guidance for VHA sites starting amyloid targeting-therapy programs. We started a VHA Amyloid-Targeting Therapy for AD SharePoint collaborative platform and VHA AD Therapeutics Community of Practice (CoP) for shared learning (Figure). The private SharePoint platform houses an array of implementation materials for VAMCs starting programs: key documents and links; educational materials; sample guidelines; note templates; and electronic health record screenshots. The CoP allows VHAs to share best practices and discuss challenges.

Even with these advantages, we found that ensuring the safe and appropriate use of amyloid-targeting therapies did not overcome the barriers associated with their complexity. This was especially true for veterans living in rural areas. Only 4 VAMCs had administered amyloid-targeting therapies in the first year they were available. Preliminary data demonstrated that 27 (84%) of 32 veterans who initiated lecanemab in the VHA between October 2023 and September 2024 resided in urban areas.10 To address the underutilization of amyloid-targeting therapy, we propose leveraging the strengths of VHA telehealth to facilitate expansion of access to these medications for veterans with early AD. Telehealth may substantially increase access to evaluation for veterans with early dementia and, when medically appropriate, to receive amyloid-targeting therapies by reducing transportation needs and mitigating costs while ensuring appropriate monitoring through ongoing clinical assessments.

Using Telehealth

The VHA is a pioneer in telehealth, with programs dating back to 2003.11 Between October 1, 2018, and September 30, 2019, the VHA served > 900,000 veterans through the provision of > 2.6 million episodes of care via telehealth.12 The COVID-19 pandemic further cemented the role of telemedicine as an essential component of health care. Telehealth has demonstrated success in the assessment and management of individuals living with dementia. At the VHA, the GRECC-Connect Project is a partnership between 9 urban GRECC sites that seek to provide consultative geriatric and dementia care to rural veterans through telehealth.13 Additional evidence supports the potential to leverage telehealth to effectively communicate results of amyloid PET scans.14

This approach is not without limitations such as the digital divide, or the gap that separates technology-enabled individuals and those unprepared to adopt technology due to limited digital literacy levels or access to needed hardware, software, and connectivity. The VHA has taken steps to address these digital divide barriers by broadly providing tools—such as tablets and broadband connectivity—to veterans. Specifically, the VHA has instituted digital divide consults to determine whether telehealth could be a potential solution for appropriate veterans and to provide an iPad (if eligible) to connect with VA clinicians. Complementary to the digital divide consult, a VHA-specific telehealth preparedness assessment tool is under development and being tested by 2 authors (JF, SMH). This telehealth preparedness assessment tool is designed to aid in the seamless integration of telehealth services with the support of tailored education materials specific to gaps in digital literacy that a veteran might experience.

Building on these initiatives, there is an opportunity to expand access to amyloid-targeting therapies, regardless of distance to large VAMCs, by leveraging telehealth as an alternative method of connecting patients with specialty care. Specifically, a hybrid approach could be used to accomplish the myriad initial and follow-up tasks involved in the provision of amyloid-targeting therapies (Table). Not all VHA facilities possess the specialty expertise to prescribe these medications, and local clinicians may not have sufficient knowledge and clinical support to prescribe and monitor these therapies.

The first step is identifying local and regional subject matter experts, followed by the development and expansion of these networks. The National TeleNeurology Program is a good example of a national telehealth program that leverages technology to bring specialty services to rural areas with limited access to care. Although amyloid-targeting therapies often require more complex logistics, such as laboratory tests and imaging, these initial hurdles can be overcome through localized services and collaboration between VAMCs.

While treatment and imaging will most likely need to occur at a VAMC, most basic laboratory studies can be performed at community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs). Some CBOCs may not be able to process more specialized laboratory tests such as apolipoprotein E genetic testing. Samples for these tests can be collected and processed at VAMCs, which usually have contracts with outside laboratories capable of performing these studies. Most, although not all, VAMCs offer advanced imaging, including MRI of the brain and amyloid PETs. VAMCs without those modalities may need to coordinate with other regional VAMCs. Additionally, a pilot program is already underway whereby VAMCs without the ability to quantify the amount of amyloid on PETs are able to leverage technology and collaborations with other VAMCs to obtain these data.

Once the initial phases of evaluation and care are completed, telemedicine can be leveraged for follow-up and ongoing management. Interdisciplinary teams can help facilitate care related to amyloid-targeting therapies, including the close monitoring of veterans for development of ARIA.15 To achieve this monitoring, specialty clinic teams prescribing amyloid-targeting therapies, which may be geographically distant, need to coordinate with local primary care clinical teams and emergency clinicians. All of these health care team members, along with neurologists and neurosurgeons, should be involved in the development and implementation of protocols in the event that patients present to their local primary or specialty care clinics or emergency department with ARIA symptoms.

If amyloid-targeting therapies are to be provided along with other emerging treatments for rural veterans, telehealth must be part of the solution. There is a pressing need to explore innovative evaluation and delivery models for these therapies, particularly as we expect additional diagnostics and therapeutics to be available in the future. With the advent of commercially available blood tests (ie, blood biomarkers) for AD, there is hope for a transition away from PETs and CSF testing given their cost, limited access, and invasiveness for diagnosis and monitoring of AD. These advances will increase the utility of telehealth to help rural veterans access amyloid-targeting therapies.

Additionally, administering the drug at home or at local clinics, supported by a dedicated health care team or home health agency, could further improve accessibility. Telehealth can be leveraged in this scenario, allowing specialty clinics and specialists to connect with patients and clinicians based out of local clinics or even home health agencies. In this scenario, specialists can provide hands-on care guidance and oversight even though they may be geographically distant from care recipients. Transitioning from IV administration to subcutaneous formulations would further enhance convenience and reduce barriers; these formulations may be available soon.16 Addressing logistical challenges to care and access through technology-based solutions will require coordinated efforts and continued VHA investment.

Conclusions

The VHA has a large population of veterans with dementia, and the costs to care for these veterans will only increase. While the current benefits of amyloid-targeting therapies are modest, now is the time to establish care processes that will support future innovations in amyloid-targeting therapies and other treatments and diagnostics. We are developing better ways to detect AD using clinical decision support tools, improving care pathways and the management of AD, and leveraging telehealth to improve access. The VA is conducting research to investigate whether a cognitive screening and laboratory evaluation that includes a telehealth preparedness assessment will be feasible and effective for improving the detection of AD and access to treatment, and we plan to publish the results.

The lessons learned can be extended to non-VHA care settings to help achieve potential benefits for other patients with early AD. Emerging therapies have the potential to improve the quality of life for both patients and care partners, adding life to years and not just years to life. Policymakers and payors must prioritize research funding to evaluate the safety and efficacy of these approaches to the delivery of health services, ensuring that emerging therapies are accessible for all individuals affected by AD.

- Alzheimer’s Association. 2025 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2025;21(4):e70235. doi:10.1002/alz.70235

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Statistical Projections of Alzheimer’s Dementia for VA Patients, VA Enrollees, and US Veterans. December 18, 2020. Accessed November 2, 2025. https://www.va.gov/GERIATRICS/docs/VHA_ALZHEIMERS_DEMENTIA_Statistical_Projections_FY21_and_FY33_sgc121820.pdf

- Casey DA, Antimisiaris D, O’Brien J. Drugs for Alzheimer’s disease: are they effective? P T. 2010;35(4):208-211.

- Barthold D, Joyce G, Ferido P, et al. Pharmaceutical treatment for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias: utilization and disparities. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;76(2):579-589. doi:10.3233/JAD-200133

- Sims JR, Zimmer JA, Evans CD, et al. Donanemab in early symptomatic Alzheimer disease: the TRAILBLAZER-ALZ 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2023;330(6):512-527. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.13239

- van Dyck CH, Swanson CJ, Aisen P, et al. Lecanemab in early Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(1):9-21. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2212948

- Tanne JH. Lecanemab: US Veterans Health Administration will cover cost of new Alzheimer’s drug. BMJ. 2023;380:p628. doi:10.1136/bmj.p628

- Nadeau SE. Lecanemab questions. Neurology. 2024;102(7):e209320. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000209320 9. O’Donnell AJ, Fortunato AT, Spitznogle BL, et al. Implementation of lecanemab for Alzheimer’s disease: facilitators and barriers. Presented at: American Geriatrics Society 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting, Chicago. May 2025.

- O’Donnell AJ, Zhao X, Parr A, et al. Use of lecanemab for Alzheimer’s disease within the Veteran’s Health Foundation: early findings. Abstract presented at: Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2025; July 27, 2025; Toronto, Canada.

- O’Donnell AJ, Zhao X, Parr A, et al. Use of lecanemab for Alzheimer’s disease within the Veteran’s Health Foundation: early findings. Abstract presented at: Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2025; July 27, 2025; Toronto, Canada.

- Hopp F, Whitten P, Subramanian U, et al. Perspectives from the Veterans Health Administration about opportunities and barriers in telemedicine. J Telemed Telecare. 2006;12(8):404-409. doi:10.1258/135763306779378717

- VA reports significant increase in veteran use of telehealth services. News release. US Department of Veterans Affairs. November 22, 2019. Accessed November 19, 2025. https://news.va.gov/press-room/va-reports-significant-increase-in-veteran-use-of-telehealth-services/

- Powers BB, Homer MC, Morone N, et al. Creation of an interprofessional teledementia clinic for rural veterans: preliminary data. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(5):1092-1099. doi:10.1111/jgs.14839

- Erickson CM, Chin NA, Rosario HL, et al. Feasibility of virtual Alzheimer’s biomarker disclosure: findings from an observational cohort. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2023;9(3):e12413. doi:10.1002/trc2.12413

- Turk KW, Knobel MD, Nothern A, et al. An interprofessional team for disease-modifying therapy in Alzheimer disease implementation. Neurol Clin Pract. 2024;14(6):e200346. doi:10.1212/CPJ.0000000000200346

- FDA accepts LEQEMBI® (lecanemab-irmb) biologics license application for subcutaneous maintenance dosing for the treatment of early Alzheimer’s disease. News release. Elsai US. January 13, 2025. Accessed November 2, 2025. https://media-us.eisai.com/2025-01-13-FDA-Accepts-LEQEMBI-R-lecanemab-irmb-Biologics-License-Application-for-Subcutaneous-Maintenance-Dosing-for-the-Treatment-of-Early-Alzheimers-Disease

- Alzheimer’s Association. 2025 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2025;21(4):e70235. doi:10.1002/alz.70235

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Statistical Projections of Alzheimer’s Dementia for VA Patients, VA Enrollees, and US Veterans. December 18, 2020. Accessed November 2, 2025. https://www.va.gov/GERIATRICS/docs/VHA_ALZHEIMERS_DEMENTIA_Statistical_Projections_FY21_and_FY33_sgc121820.pdf

- Casey DA, Antimisiaris D, O’Brien J. Drugs for Alzheimer’s disease: are they effective? P T. 2010;35(4):208-211.

- Barthold D, Joyce G, Ferido P, et al. Pharmaceutical treatment for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias: utilization and disparities. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;76(2):579-589. doi:10.3233/JAD-200133

- Sims JR, Zimmer JA, Evans CD, et al. Donanemab in early symptomatic Alzheimer disease: the TRAILBLAZER-ALZ 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2023;330(6):512-527. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.13239

- van Dyck CH, Swanson CJ, Aisen P, et al. Lecanemab in early Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(1):9-21. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2212948

- Tanne JH. Lecanemab: US Veterans Health Administration will cover cost of new Alzheimer’s drug. BMJ. 2023;380:p628. doi:10.1136/bmj.p628

- Nadeau SE. Lecanemab questions. Neurology. 2024;102(7):e209320. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000209320 9. O’Donnell AJ, Fortunato AT, Spitznogle BL, et al. Implementation of lecanemab for Alzheimer’s disease: facilitators and barriers. Presented at: American Geriatrics Society 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting, Chicago. May 2025.

- O’Donnell AJ, Zhao X, Parr A, et al. Use of lecanemab for Alzheimer’s disease within the Veteran’s Health Foundation: early findings. Abstract presented at: Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2025; July 27, 2025; Toronto, Canada.

- O’Donnell AJ, Zhao X, Parr A, et al. Use of lecanemab for Alzheimer’s disease within the Veteran’s Health Foundation: early findings. Abstract presented at: Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2025; July 27, 2025; Toronto, Canada.

- Hopp F, Whitten P, Subramanian U, et al. Perspectives from the Veterans Health Administration about opportunities and barriers in telemedicine. J Telemed Telecare. 2006;12(8):404-409. doi:10.1258/135763306779378717

- VA reports significant increase in veteran use of telehealth services. News release. US Department of Veterans Affairs. November 22, 2019. Accessed November 19, 2025. https://news.va.gov/press-room/va-reports-significant-increase-in-veteran-use-of-telehealth-services/

- Powers BB, Homer MC, Morone N, et al. Creation of an interprofessional teledementia clinic for rural veterans: preliminary data. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(5):1092-1099. doi:10.1111/jgs.14839

- Erickson CM, Chin NA, Rosario HL, et al. Feasibility of virtual Alzheimer’s biomarker disclosure: findings from an observational cohort. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2023;9(3):e12413. doi:10.1002/trc2.12413

- Turk KW, Knobel MD, Nothern A, et al. An interprofessional team for disease-modifying therapy in Alzheimer disease implementation. Neurol Clin Pract. 2024;14(6):e200346. doi:10.1212/CPJ.0000000000200346

- FDA accepts LEQEMBI® (lecanemab-irmb) biologics license application for subcutaneous maintenance dosing for the treatment of early Alzheimer’s disease. News release. Elsai US. January 13, 2025. Accessed November 2, 2025. https://media-us.eisai.com/2025-01-13-FDA-Accepts-LEQEMBI-R-lecanemab-irmb-Biologics-License-Application-for-Subcutaneous-Maintenance-Dosing-for-the-Treatment-of-Early-Alzheimers-Disease

Can Telehealth Improve Access to Amyloid-Targeting Therapies for Veterans Living With Alzheimer Disease?

Can Telehealth Improve Access to Amyloid-Targeting Therapies for Veterans Living With Alzheimer Disease?

The Once and Future Veterans Health Administration

The Once and Future Veterans Health Administration

He who thus considers things in their first growth and origin ... will obtain the clearest view of them. Politics, Book I, Part II by Aristotle

Many seasoned observers of federal practice have signaled that the future of US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care is threatened as never before. Political forces and economic interests are siphoning Veterans Health Administration (VHA) capital and human resources into the community with an ineluctable push toward privatization.1

This Veterans Day, the vitality, if not the very viability of veteran health care, is in serious jeopardy, so it seems fitting to review the rationale for having institutions dedicated to the specialized medical treatment of veterans. Aristotle advises us on how to undertake this intellectual exercise in the epigraph. This column will revisit the historical origins of VA medicine to better appreciate the justification of an agency committed to this unique purpose and what may be sacrificed if it is decimated.

The provision of medical care focused on the injuries and illnesses of warriors is as old as war. The ancient Romans had among the first veterans’ hospital, named a valetudinarium. Sick and injured members of the Roman legions received state-of-the-art medical and surgical care from military doctors inside these facilities.2

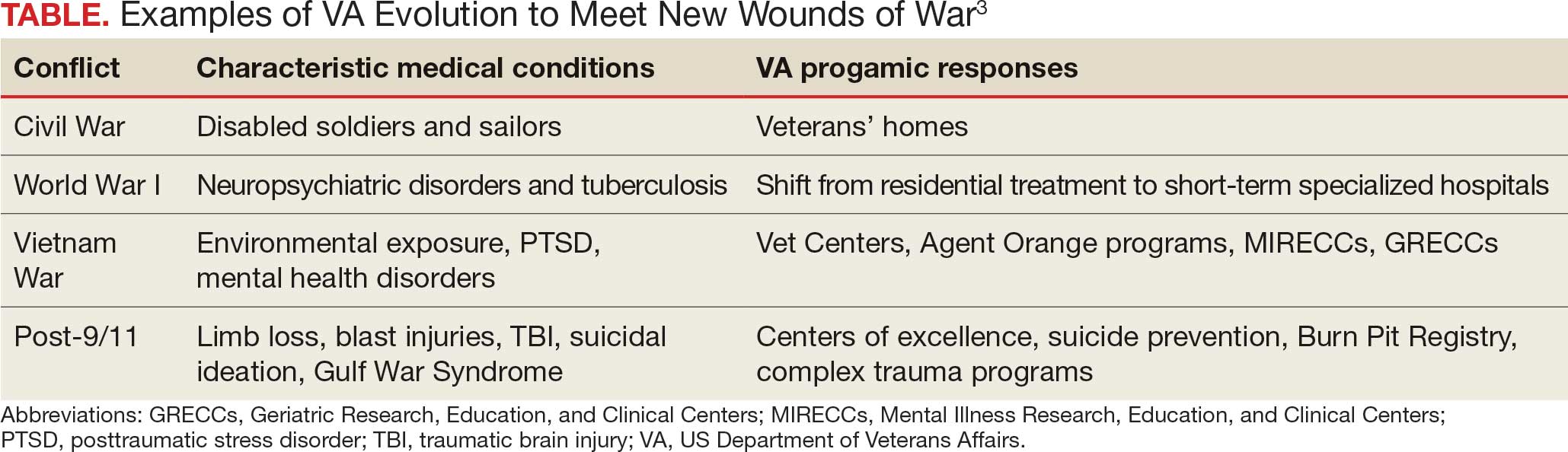

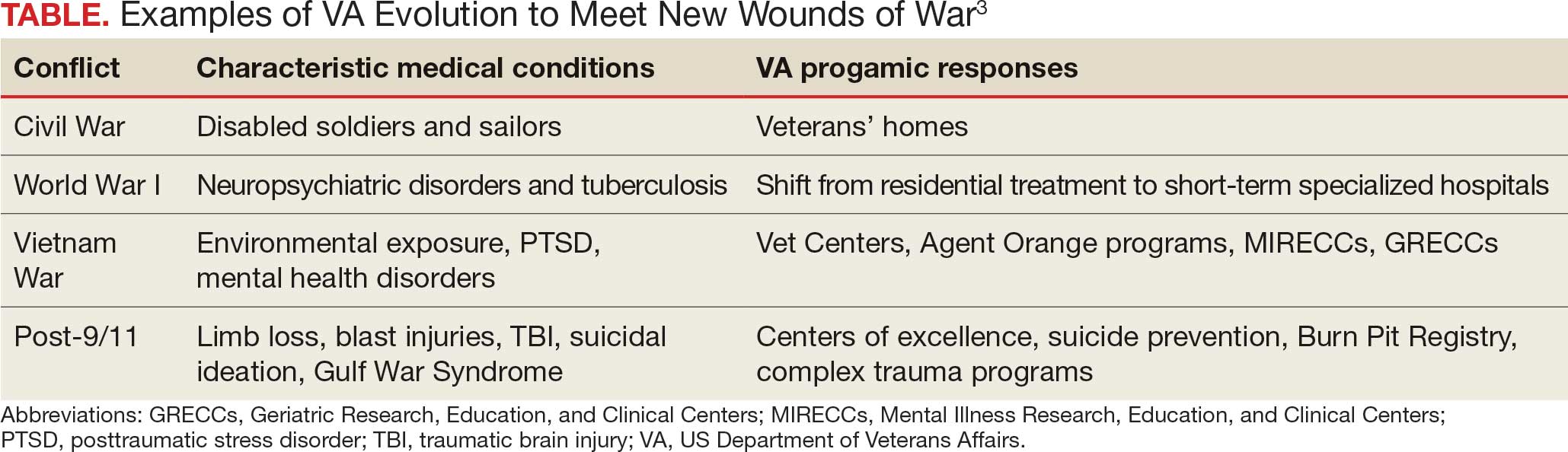

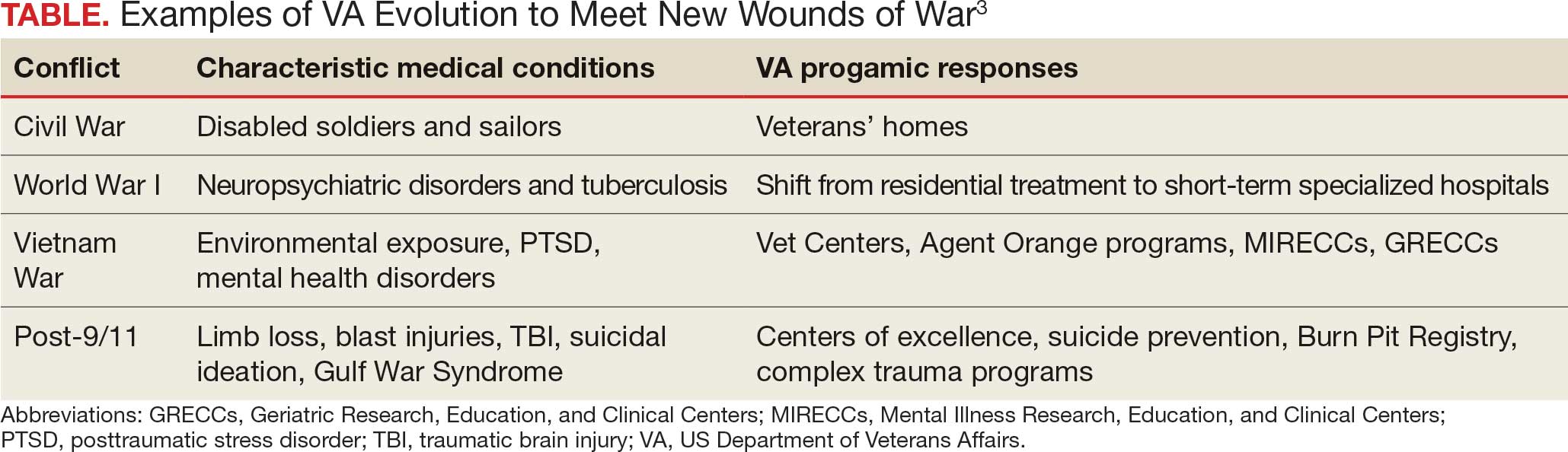

In the United States, federal practice emerged almost simultaneously with the birth of a nation. Wounded troops and families of slain soldiers required rehabilitation and support from the fledgling federal government. This began a pattern of development in which each war generated novel injuries and disorders that required the VA to evolve (Table).3

Many arguments can be marshalled to demonstrate the importance of not just ensuring VA health care survives but also has the resources needed to thrive. I will highlight what I argue are the most important justifications for its existence.

The ethical argument: President Abraham Lincoln and a long line of government officials for more than 2 centuries have called the provision of high-quality health care focused on veterans a sacred trust. Failing to fulfill that promise is a violation of the deepest principles of veracity and fidelity that those who govern owe to the citizens who selflessly sacrificed time, health, and even in some cases life, for the safety and well-being of their country.4

The quality argument: Dozens of studies have found that compared to the community, many areas of veteran medical care are just plain better. Two surveys particularly salient in the aging veteran population illustrate this growing body of positive research. The most recent and largest survey of Medicare patients found that VHA hospitals surpassed community-based hospitals on all 10 metrics.5 A retrospective cohort study of mortality compared veterans transported by ambulance to VHA or community-based hospitals. The researchers found that those taken to VHA facilities had a 30-day all cause adjustment mortality 20 times lower than those taken to civilian hospitals, especially among minoritized populations who generally have higher mortality.6

The cultural argument: Glance at almost any form of communication from veterans or about their health care and you will apprehend common cultural themes. Even when frustrated that the system has not lived up to their expectations, and perhaps because of their sense of belonging, they voice ownership of VHA as their medical home. Surveys of veteran experiences have shown many feel more comfortable receiving care in the company of comrades in arms and from health care professionals with expertise and experience with veterans’ distinctive medical problems and the military values that inform their preferences for care.7

The complexity argument: Anyone who has worked even a short time in a VHA hospital or clinic knows the patients are in general more complicated than similar patients in the community. Multiple medical, geriatric, neuropsychiatric, substance use, and social comorbidities are the expectation, not the exception, as in some civilian systems. Many of the conditions common in the VHA such as traumatic brain injury, service-connected cancers, suicidal ideation, environmental exposures, and posttraumatic stress disorder would be encountered in community health care settings. The differences between VHA and community care led the RAND Corporation to caution that “Community care providers might not be equipped to handle the needs of veterans.”8