User login

Medical Decision-Making: Avoid These Common Coding & Documentation Mistakes

Medical decision-making (MDM) mistakes are common. Here are the coding and documentation mistakes hospitalists make most often, along with some tips on how to avoid them.

Listing the problem without a plan. Healthcare professionals are able to infer the acuity and severity of a case without superfluous or redundant documentation, but auditors may not have this ability. Adequate documentation for every service date helps to convey patient complexity during a medical record review. Although the problem list may not change dramatically from day to day during a hospitalization, the auditor only reviews the service date in question, not the entire medical record.

Hospitalists should be sure to formulate a complete and accurate description of the patient’s condition with an analogous plan of care for each encounter. Listing problems without a corresponding plan of care does not corroborate physician management of that problem and could cause a downgrade of complexity. Listing problems with a brief, generalized comment (e.g. “DM, CKD, CHF: Continue current treatment plan”) equally diminishes the complexity and effort put forth by the physician.

Clearly document the plan. The care plan represents problems the physician personally manages, along with those that must also be considered when he or she formulates the management options, even if another physician is primarily managing the problem. For example, the hospitalist can monitor the patient’s diabetic management while the nephrologist oversees the chronic kidney disease (CKD). Since the CKD impacts the hospitalist’s diabetic care plan, the hospitalist may also receive credit for any CKD consideration if the documentation supports a hospitalist-related care plan, or comment about CKD that does not overlap or replicate the nephrologist’s plan. In other words, there must be some “value-added” input by the hospitalist.

Credit is given for the quantity of problems addressed as well as the quality. For inpatient care, an established problem is defined as one in which a care plan has been generated by the physician (or same specialty group practice member) during the current hospitalization. Established problems are less complex than new problems, for which a diagnosis, prognosis, or care plan has not been developed. Severity of the problem also influences complexity. A “worsening” problem is considered more complex than an “improving” problem, since the worsening problem likely requires revisions to the current care plan and, thus, more physician effort. Physician documentation should always:

- Identify all problems managed or addressed during each encounter;

- Identify problems as stable or progressing, when appropriate;

- Indicate differential diagnoses when the problem remains undefined;

- Indicate the management/treatment option(s) for each problem; and

- Note management options to be continued somewhere in the progress note for that encounter (e.g. medication list) when documentation indicates a continuation of current management options (e.g. “continue meds”).

Considering relevant data. “Data” is organized as pathology/laboratory testing, radiology, and medicine-based diagnostic testing that contributes to diagnosing or managing patient problems. Pertinent orders or results may appear in the medical record, but most of the background interactions and communications involving testing are undetected when reviewing the progress note. To receive credit:

- Specify tests ordered and rationale in the physician’s progress note, or make an entry that refers to another auditor-accessible location for ordered tests and studies; however, this latter option jeopardizes a medical record review due to potential lack of awareness of the need to submit this extraneous information during a payer record request or appeal.

- Document test review by including a brief entry in the progress note (e.g. “elevated glucose levels” or “CXR shows RLL infiltrates”); credit is not given for entries lacking a comment on the findings (e.g. “CXR reviewed”).

- Summarize key points when reviewing old records or obtaining history from someone other than the patient, as necessary; be sure to identify the increased efforts of reviewing the considerable number of old records by stating, “OSH (outside hospital) records reviewed and shows…” or “Records from previous hospitalization(s) reveal….”

- Indicate when images, tracings, or specimens are “personally reviewed,” or the auditor will assume the physician merely reviewed the written report; be sure to include a comment on the findings.

- Summarize any discussions of unexpected or contradictory test results with the physician performing the procedure or diagnostic study.

Data credit may be more substantial during the initial investigative phase of the hospitalization, before diagnoses or treatment options have been confirmed. Routine monitoring of the stabilized patient may not yield as many “points.”

Undervaluing the patient’s complexity. A general lack of understanding of the MDM component of the documentation guidelines often results in physicians undervaluing their services. Some physicians may consider a case “low complexity” simply because of the frequency with which they encounter the case type. The speed with which the care plan is developed should have no bearing on how complex the patient’s condition really is. Hospitalists need to better identify the risk involved for the patient.

Patient risk is categorized as minimal, low, moderate, or high based on pre-assigned items pertaining to the presenting problem, diagnostic procedures ordered, and management options selected. The single highest-rated item detected on the Table of Risk determines the overall patient risk for an encounter.1 Chronic conditions with exacerbations and invasive procedures offer more patient risk than acute, uncomplicated illnesses or noninvasive procedures. Stable or improving problems are considered “less risky” than progressing problems; conditions that pose a threat to life/bodily function outweigh undiagnosed problems where it is difficult to determine the patient’s prognosis; and medication risk varies with the administration (e.g. oral vs. parenteral), type, and potential for adverse effects. Medication risk for a particular drug is invariable whether the dosage is increased, decreased, or continued without change. Physicians should:

- Provide status for all problems in the plan of care and identify them as stable, worsening, or progressing (mild or severe), when applicable; don’t assume that the auditor can infer this from the documentation details.

- Document all diagnostic or therapeutic procedures considered.

- Identify surgical risk factors involving co-morbid conditions that place the patient at greater risk than the average patient, when appropriate.

- Associate the labs ordered to monitor for medication toxicity with the corresponding medication; don’t assume that the auditor knows which labs are used to check for toxicity.

Varying levels of complexity. Remember that decision-making is just one of three components in evaluation and management (E&M) services, along with history and exam. MDM is identical for both the 1995 and 1997 guidelines, rooted in the complexity of the patient’s problem(s) addressed during a given encounter.1,2 Complexity is categorized as straightforward, low, moderate, or high, and directly correlates to the content of physician documentation.

Each visit level represents a particular level of complexity (see Table 1). Auditors only consider the care plan for a given service date when reviewing MDM. More specifically, the auditor reviews three areas of MDM for each encounter (see Table 2), and the physician receives credit for: a) the number of diagnoses and/or treatment options; b) the amount and/or complexity of data ordered/reviewed; c) the risk of complications/morbidity/mortality.

To determine MDM complexity, each MDM category is assigned a point level. Complexity correlates to the second-highest MDM category. For example, if the auditor assigns “multiple” diagnoses/treatment options, “minimal” data, and “high” risk, the physician attains moderate complexity decision-making (see Table 3).

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 1995 Documentation Guidelines for Evaluation and Management Services. Available at: www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNEdWebGuide/Downloads/95Docguidelines.pdf. Accessed July 7, 2014.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 1997 Documentation Guidelines for Evaluation and Management Services. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNEdWebGuide/Downloads/97Docguidelines.pdf. Accessed July 7, 2014.

- American Medical Association. Current Procedural Terminology: 2014 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association; 2013:14-21.

- Novitas Solutions. Novitas Solutions documentation worksheet. Available at: www.novitas-solutions.com/webcenter/content/conn/UCM_Repository/uuid/dDocName:00004966. Accessed July 7, 2014.

Medical decision-making (MDM) mistakes are common. Here are the coding and documentation mistakes hospitalists make most often, along with some tips on how to avoid them.

Listing the problem without a plan. Healthcare professionals are able to infer the acuity and severity of a case without superfluous or redundant documentation, but auditors may not have this ability. Adequate documentation for every service date helps to convey patient complexity during a medical record review. Although the problem list may not change dramatically from day to day during a hospitalization, the auditor only reviews the service date in question, not the entire medical record.

Hospitalists should be sure to formulate a complete and accurate description of the patient’s condition with an analogous plan of care for each encounter. Listing problems without a corresponding plan of care does not corroborate physician management of that problem and could cause a downgrade of complexity. Listing problems with a brief, generalized comment (e.g. “DM, CKD, CHF: Continue current treatment plan”) equally diminishes the complexity and effort put forth by the physician.

Clearly document the plan. The care plan represents problems the physician personally manages, along with those that must also be considered when he or she formulates the management options, even if another physician is primarily managing the problem. For example, the hospitalist can monitor the patient’s diabetic management while the nephrologist oversees the chronic kidney disease (CKD). Since the CKD impacts the hospitalist’s diabetic care plan, the hospitalist may also receive credit for any CKD consideration if the documentation supports a hospitalist-related care plan, or comment about CKD that does not overlap or replicate the nephrologist’s plan. In other words, there must be some “value-added” input by the hospitalist.

Credit is given for the quantity of problems addressed as well as the quality. For inpatient care, an established problem is defined as one in which a care plan has been generated by the physician (or same specialty group practice member) during the current hospitalization. Established problems are less complex than new problems, for which a diagnosis, prognosis, or care plan has not been developed. Severity of the problem also influences complexity. A “worsening” problem is considered more complex than an “improving” problem, since the worsening problem likely requires revisions to the current care plan and, thus, more physician effort. Physician documentation should always:

- Identify all problems managed or addressed during each encounter;

- Identify problems as stable or progressing, when appropriate;

- Indicate differential diagnoses when the problem remains undefined;

- Indicate the management/treatment option(s) for each problem; and

- Note management options to be continued somewhere in the progress note for that encounter (e.g. medication list) when documentation indicates a continuation of current management options (e.g. “continue meds”).

Considering relevant data. “Data” is organized as pathology/laboratory testing, radiology, and medicine-based diagnostic testing that contributes to diagnosing or managing patient problems. Pertinent orders or results may appear in the medical record, but most of the background interactions and communications involving testing are undetected when reviewing the progress note. To receive credit:

- Specify tests ordered and rationale in the physician’s progress note, or make an entry that refers to another auditor-accessible location for ordered tests and studies; however, this latter option jeopardizes a medical record review due to potential lack of awareness of the need to submit this extraneous information during a payer record request or appeal.

- Document test review by including a brief entry in the progress note (e.g. “elevated glucose levels” or “CXR shows RLL infiltrates”); credit is not given for entries lacking a comment on the findings (e.g. “CXR reviewed”).

- Summarize key points when reviewing old records or obtaining history from someone other than the patient, as necessary; be sure to identify the increased efforts of reviewing the considerable number of old records by stating, “OSH (outside hospital) records reviewed and shows…” or “Records from previous hospitalization(s) reveal….”

- Indicate when images, tracings, or specimens are “personally reviewed,” or the auditor will assume the physician merely reviewed the written report; be sure to include a comment on the findings.

- Summarize any discussions of unexpected or contradictory test results with the physician performing the procedure or diagnostic study.

Data credit may be more substantial during the initial investigative phase of the hospitalization, before diagnoses or treatment options have been confirmed. Routine monitoring of the stabilized patient may not yield as many “points.”

Undervaluing the patient’s complexity. A general lack of understanding of the MDM component of the documentation guidelines often results in physicians undervaluing their services. Some physicians may consider a case “low complexity” simply because of the frequency with which they encounter the case type. The speed with which the care plan is developed should have no bearing on how complex the patient’s condition really is. Hospitalists need to better identify the risk involved for the patient.

Patient risk is categorized as minimal, low, moderate, or high based on pre-assigned items pertaining to the presenting problem, diagnostic procedures ordered, and management options selected. The single highest-rated item detected on the Table of Risk determines the overall patient risk for an encounter.1 Chronic conditions with exacerbations and invasive procedures offer more patient risk than acute, uncomplicated illnesses or noninvasive procedures. Stable or improving problems are considered “less risky” than progressing problems; conditions that pose a threat to life/bodily function outweigh undiagnosed problems where it is difficult to determine the patient’s prognosis; and medication risk varies with the administration (e.g. oral vs. parenteral), type, and potential for adverse effects. Medication risk for a particular drug is invariable whether the dosage is increased, decreased, or continued without change. Physicians should:

- Provide status for all problems in the plan of care and identify them as stable, worsening, or progressing (mild or severe), when applicable; don’t assume that the auditor can infer this from the documentation details.

- Document all diagnostic or therapeutic procedures considered.

- Identify surgical risk factors involving co-morbid conditions that place the patient at greater risk than the average patient, when appropriate.

- Associate the labs ordered to monitor for medication toxicity with the corresponding medication; don’t assume that the auditor knows which labs are used to check for toxicity.

Varying levels of complexity. Remember that decision-making is just one of three components in evaluation and management (E&M) services, along with history and exam. MDM is identical for both the 1995 and 1997 guidelines, rooted in the complexity of the patient’s problem(s) addressed during a given encounter.1,2 Complexity is categorized as straightforward, low, moderate, or high, and directly correlates to the content of physician documentation.

Each visit level represents a particular level of complexity (see Table 1). Auditors only consider the care plan for a given service date when reviewing MDM. More specifically, the auditor reviews three areas of MDM for each encounter (see Table 2), and the physician receives credit for: a) the number of diagnoses and/or treatment options; b) the amount and/or complexity of data ordered/reviewed; c) the risk of complications/morbidity/mortality.

To determine MDM complexity, each MDM category is assigned a point level. Complexity correlates to the second-highest MDM category. For example, if the auditor assigns “multiple” diagnoses/treatment options, “minimal” data, and “high” risk, the physician attains moderate complexity decision-making (see Table 3).

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 1995 Documentation Guidelines for Evaluation and Management Services. Available at: www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNEdWebGuide/Downloads/95Docguidelines.pdf. Accessed July 7, 2014.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 1997 Documentation Guidelines for Evaluation and Management Services. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNEdWebGuide/Downloads/97Docguidelines.pdf. Accessed July 7, 2014.

- American Medical Association. Current Procedural Terminology: 2014 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association; 2013:14-21.

- Novitas Solutions. Novitas Solutions documentation worksheet. Available at: www.novitas-solutions.com/webcenter/content/conn/UCM_Repository/uuid/dDocName:00004966. Accessed July 7, 2014.

Medical decision-making (MDM) mistakes are common. Here are the coding and documentation mistakes hospitalists make most often, along with some tips on how to avoid them.

Listing the problem without a plan. Healthcare professionals are able to infer the acuity and severity of a case without superfluous or redundant documentation, but auditors may not have this ability. Adequate documentation for every service date helps to convey patient complexity during a medical record review. Although the problem list may not change dramatically from day to day during a hospitalization, the auditor only reviews the service date in question, not the entire medical record.

Hospitalists should be sure to formulate a complete and accurate description of the patient’s condition with an analogous plan of care for each encounter. Listing problems without a corresponding plan of care does not corroborate physician management of that problem and could cause a downgrade of complexity. Listing problems with a brief, generalized comment (e.g. “DM, CKD, CHF: Continue current treatment plan”) equally diminishes the complexity and effort put forth by the physician.

Clearly document the plan. The care plan represents problems the physician personally manages, along with those that must also be considered when he or she formulates the management options, even if another physician is primarily managing the problem. For example, the hospitalist can monitor the patient’s diabetic management while the nephrologist oversees the chronic kidney disease (CKD). Since the CKD impacts the hospitalist’s diabetic care plan, the hospitalist may also receive credit for any CKD consideration if the documentation supports a hospitalist-related care plan, or comment about CKD that does not overlap or replicate the nephrologist’s plan. In other words, there must be some “value-added” input by the hospitalist.

Credit is given for the quantity of problems addressed as well as the quality. For inpatient care, an established problem is defined as one in which a care plan has been generated by the physician (or same specialty group practice member) during the current hospitalization. Established problems are less complex than new problems, for which a diagnosis, prognosis, or care plan has not been developed. Severity of the problem also influences complexity. A “worsening” problem is considered more complex than an “improving” problem, since the worsening problem likely requires revisions to the current care plan and, thus, more physician effort. Physician documentation should always:

- Identify all problems managed or addressed during each encounter;

- Identify problems as stable or progressing, when appropriate;

- Indicate differential diagnoses when the problem remains undefined;

- Indicate the management/treatment option(s) for each problem; and

- Note management options to be continued somewhere in the progress note for that encounter (e.g. medication list) when documentation indicates a continuation of current management options (e.g. “continue meds”).

Considering relevant data. “Data” is organized as pathology/laboratory testing, radiology, and medicine-based diagnostic testing that contributes to diagnosing or managing patient problems. Pertinent orders or results may appear in the medical record, but most of the background interactions and communications involving testing are undetected when reviewing the progress note. To receive credit:

- Specify tests ordered and rationale in the physician’s progress note, or make an entry that refers to another auditor-accessible location for ordered tests and studies; however, this latter option jeopardizes a medical record review due to potential lack of awareness of the need to submit this extraneous information during a payer record request or appeal.

- Document test review by including a brief entry in the progress note (e.g. “elevated glucose levels” or “CXR shows RLL infiltrates”); credit is not given for entries lacking a comment on the findings (e.g. “CXR reviewed”).

- Summarize key points when reviewing old records or obtaining history from someone other than the patient, as necessary; be sure to identify the increased efforts of reviewing the considerable number of old records by stating, “OSH (outside hospital) records reviewed and shows…” or “Records from previous hospitalization(s) reveal….”

- Indicate when images, tracings, or specimens are “personally reviewed,” or the auditor will assume the physician merely reviewed the written report; be sure to include a comment on the findings.

- Summarize any discussions of unexpected or contradictory test results with the physician performing the procedure or diagnostic study.

Data credit may be more substantial during the initial investigative phase of the hospitalization, before diagnoses or treatment options have been confirmed. Routine monitoring of the stabilized patient may not yield as many “points.”

Undervaluing the patient’s complexity. A general lack of understanding of the MDM component of the documentation guidelines often results in physicians undervaluing their services. Some physicians may consider a case “low complexity” simply because of the frequency with which they encounter the case type. The speed with which the care plan is developed should have no bearing on how complex the patient’s condition really is. Hospitalists need to better identify the risk involved for the patient.

Patient risk is categorized as minimal, low, moderate, or high based on pre-assigned items pertaining to the presenting problem, diagnostic procedures ordered, and management options selected. The single highest-rated item detected on the Table of Risk determines the overall patient risk for an encounter.1 Chronic conditions with exacerbations and invasive procedures offer more patient risk than acute, uncomplicated illnesses or noninvasive procedures. Stable or improving problems are considered “less risky” than progressing problems; conditions that pose a threat to life/bodily function outweigh undiagnosed problems where it is difficult to determine the patient’s prognosis; and medication risk varies with the administration (e.g. oral vs. parenteral), type, and potential for adverse effects. Medication risk for a particular drug is invariable whether the dosage is increased, decreased, or continued without change. Physicians should:

- Provide status for all problems in the plan of care and identify them as stable, worsening, or progressing (mild or severe), when applicable; don’t assume that the auditor can infer this from the documentation details.

- Document all diagnostic or therapeutic procedures considered.

- Identify surgical risk factors involving co-morbid conditions that place the patient at greater risk than the average patient, when appropriate.

- Associate the labs ordered to monitor for medication toxicity with the corresponding medication; don’t assume that the auditor knows which labs are used to check for toxicity.

Varying levels of complexity. Remember that decision-making is just one of three components in evaluation and management (E&M) services, along with history and exam. MDM is identical for both the 1995 and 1997 guidelines, rooted in the complexity of the patient’s problem(s) addressed during a given encounter.1,2 Complexity is categorized as straightforward, low, moderate, or high, and directly correlates to the content of physician documentation.

Each visit level represents a particular level of complexity (see Table 1). Auditors only consider the care plan for a given service date when reviewing MDM. More specifically, the auditor reviews three areas of MDM for each encounter (see Table 2), and the physician receives credit for: a) the number of diagnoses and/or treatment options; b) the amount and/or complexity of data ordered/reviewed; c) the risk of complications/morbidity/mortality.

To determine MDM complexity, each MDM category is assigned a point level. Complexity correlates to the second-highest MDM category. For example, if the auditor assigns “multiple” diagnoses/treatment options, “minimal” data, and “high” risk, the physician attains moderate complexity decision-making (see Table 3).

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 1995 Documentation Guidelines for Evaluation and Management Services. Available at: www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNEdWebGuide/Downloads/95Docguidelines.pdf. Accessed July 7, 2014.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. 1997 Documentation Guidelines for Evaluation and Management Services. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNEdWebGuide/Downloads/97Docguidelines.pdf. Accessed July 7, 2014.

- American Medical Association. Current Procedural Terminology: 2014 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association; 2013:14-21.

- Novitas Solutions. Novitas Solutions documentation worksheet. Available at: www.novitas-solutions.com/webcenter/content/conn/UCM_Repository/uuid/dDocName:00004966. Accessed July 7, 2014.

Proper Inpatient Documentation, Coding Essential to Avoid a Medicare Audit

Several years ago we sent a CPT coding auditor 15 chart notes generated by each doctor in our group. Among each doctors’ 15 notes were at least one or two billed as initial hospital care, follow up, discharge, critical care, and so on. This coding expert returned a report showing that, out of all the notes reviewed, a significant portion were not billed at the correct level. Most of the incorrectly billed notes were judged to reflect “up-coding,” and a few were seen as “down-coded.”

This was distressing and hard to believe.

So I took the same set of notes and paid a second coding expert for an independent review. She didn’t know about the first audit but returned a report that showed a nearly identical portion of incorrectly coded notes.

Two independent audits showing nearly the same portion of notes coded incorrectly was alarming. But it was difficult for my partners and me to address, because the auditors didn’t agree on the correct code for many of the notes. In some cases, both flagged a note as incorrectly coded but didn’t agree on the correct code. For a number of the notes, one auditor said the visit was “up-coded,” while the other said it was “down-coded.” There was so little agreement between the two of them that we had a hard time coming up with any firm conclusions about what we should do to improve our performance.

If experts who think about coding all the time can’t agree on the right code for a given note, how can hospitalists be expected to code nearly all of our visits accurately?

RAC: Recovery Audit Contractor

Despite what I believe is poor inter-rater reliability among coding auditors, we need to work diligently to comply with coding guidelines. A 2003 Federal law mandated a program of Recovery Audit Contractors, or RAC for short, to find cases of “up-coding” or other overbilling and require the provider to repay any resulting loss.

A number of companies are in the business of conducting RAC audits (one of them, CGI, is the Canadian company blamed for the failed “Obamacare” exchange websites), and there is a reasonable chance one of these companies has reviewed some of your charges—or those of your hospitalist colleagues.

The RAC auditors review information about your charges, and if they determine that you up-coded or overbilled, they send a “demand letter” summarizing their findings, along with the amount of money they have determined you should pay back. (Theoretically, they could notify you of “under-coding,” so that you can be paid more for past work, but I haven’t yet come across an example of that.)

It is common to appeal the RAC findings, but that can be a long process, and many organizations decide to pay back all the money requested by the RAC as quickly as possible to avoid paying interest on a delayed payment if the appeal is unsuccessful. In the case of a successful appeal, the money previously refunded by the doctor would be returned.

Page 338 of the CMS Fiscal Year 2015 “Justification of Estimates for Appropriations Committees” says that “…about 50 percent of the estimated 43,000 appeals [of adverse RAC audit findings] were fully or partially overturned…” This could mean the RACs are a sort of loose cannon, accusing many providers of overbilling while knowing that some won’t bother to appeal because they don’t understand the process or because the dollar amount involved for a single provider is too small to justify the time and expense of conducting the appeal. In this way, a RAC audit is like the $15 rebate on the last electronic gadget you bought. The seller knows that many people, including me, will fail to do the work required to claim the rebate.

Accuracy Strategies

There are a number of ways to help your group ensure appropriate CPT coding and reduce the chance a RAC will ask for money back.

Education. There are many ways to help providers in your practice understand the elements of documentation and coding. Periodic training classes (e.g. during orientation and annually thereafter) are useful but may not be enough. For me, this is a little like learning a foreign language by going to a couple of classes. Instead, I think “immersion training” is more effective. That might mean a doctor spends a few minutes with a certified coder on most working days for a few weeks. For example, they could meet for 15 minutes near lunchtime and review how the doctor plans to bill visits made that morning. Lastly, consider targeted education for each doctor, based on any problems found in an audit of his/her coding.

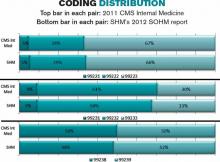

Review coding patterns. As I wrote in my August 2007 column, there is value in ensuring that each doctor in the group can see how her coding pattern differs from the group as a whole or any individual in the group. That is, what portion of follow-up visits was billed at the lowest, middle, and highest levels? What about admissions, discharges, and so on? I provided a sample report in that same column.

It also is worth taking the time to compare each doctor’s coding pattern to both the CMS Internal Medicine data and SHM’s State of Hospital Medicine report. The accompanying figure shows the most current data sets available.

Keep in mind that the goal is not to simply ensure that your coding pattern matches these external data sets; knowing where yours differs from these sets can suggest where you might want to investigate further or seek additional education.

Coding audits. Having a certified coder audit your performance at least annually is a good idea. It can help uncover areas in which you’d benefit from further review and training, and if, heaven forbid, questions are ever raised about whether you’re intentionally up-coding (fraud), showing that you’re audited regularly could help demonstrate your efforts to code correctly. In the latter case, it is probably more valuable if the audit is done independently of your employer.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at [email protected].

Several years ago we sent a CPT coding auditor 15 chart notes generated by each doctor in our group. Among each doctors’ 15 notes were at least one or two billed as initial hospital care, follow up, discharge, critical care, and so on. This coding expert returned a report showing that, out of all the notes reviewed, a significant portion were not billed at the correct level. Most of the incorrectly billed notes were judged to reflect “up-coding,” and a few were seen as “down-coded.”

This was distressing and hard to believe.

So I took the same set of notes and paid a second coding expert for an independent review. She didn’t know about the first audit but returned a report that showed a nearly identical portion of incorrectly coded notes.

Two independent audits showing nearly the same portion of notes coded incorrectly was alarming. But it was difficult for my partners and me to address, because the auditors didn’t agree on the correct code for many of the notes. In some cases, both flagged a note as incorrectly coded but didn’t agree on the correct code. For a number of the notes, one auditor said the visit was “up-coded,” while the other said it was “down-coded.” There was so little agreement between the two of them that we had a hard time coming up with any firm conclusions about what we should do to improve our performance.

If experts who think about coding all the time can’t agree on the right code for a given note, how can hospitalists be expected to code nearly all of our visits accurately?

RAC: Recovery Audit Contractor

Despite what I believe is poor inter-rater reliability among coding auditors, we need to work diligently to comply with coding guidelines. A 2003 Federal law mandated a program of Recovery Audit Contractors, or RAC for short, to find cases of “up-coding” or other overbilling and require the provider to repay any resulting loss.

A number of companies are in the business of conducting RAC audits (one of them, CGI, is the Canadian company blamed for the failed “Obamacare” exchange websites), and there is a reasonable chance one of these companies has reviewed some of your charges—or those of your hospitalist colleagues.

The RAC auditors review information about your charges, and if they determine that you up-coded or overbilled, they send a “demand letter” summarizing their findings, along with the amount of money they have determined you should pay back. (Theoretically, they could notify you of “under-coding,” so that you can be paid more for past work, but I haven’t yet come across an example of that.)

It is common to appeal the RAC findings, but that can be a long process, and many organizations decide to pay back all the money requested by the RAC as quickly as possible to avoid paying interest on a delayed payment if the appeal is unsuccessful. In the case of a successful appeal, the money previously refunded by the doctor would be returned.

Page 338 of the CMS Fiscal Year 2015 “Justification of Estimates for Appropriations Committees” says that “…about 50 percent of the estimated 43,000 appeals [of adverse RAC audit findings] were fully or partially overturned…” This could mean the RACs are a sort of loose cannon, accusing many providers of overbilling while knowing that some won’t bother to appeal because they don’t understand the process or because the dollar amount involved for a single provider is too small to justify the time and expense of conducting the appeal. In this way, a RAC audit is like the $15 rebate on the last electronic gadget you bought. The seller knows that many people, including me, will fail to do the work required to claim the rebate.

Accuracy Strategies

There are a number of ways to help your group ensure appropriate CPT coding and reduce the chance a RAC will ask for money back.

Education. There are many ways to help providers in your practice understand the elements of documentation and coding. Periodic training classes (e.g. during orientation and annually thereafter) are useful but may not be enough. For me, this is a little like learning a foreign language by going to a couple of classes. Instead, I think “immersion training” is more effective. That might mean a doctor spends a few minutes with a certified coder on most working days for a few weeks. For example, they could meet for 15 minutes near lunchtime and review how the doctor plans to bill visits made that morning. Lastly, consider targeted education for each doctor, based on any problems found in an audit of his/her coding.

Review coding patterns. As I wrote in my August 2007 column, there is value in ensuring that each doctor in the group can see how her coding pattern differs from the group as a whole or any individual in the group. That is, what portion of follow-up visits was billed at the lowest, middle, and highest levels? What about admissions, discharges, and so on? I provided a sample report in that same column.

It also is worth taking the time to compare each doctor’s coding pattern to both the CMS Internal Medicine data and SHM’s State of Hospital Medicine report. The accompanying figure shows the most current data sets available.

Keep in mind that the goal is not to simply ensure that your coding pattern matches these external data sets; knowing where yours differs from these sets can suggest where you might want to investigate further or seek additional education.

Coding audits. Having a certified coder audit your performance at least annually is a good idea. It can help uncover areas in which you’d benefit from further review and training, and if, heaven forbid, questions are ever raised about whether you’re intentionally up-coding (fraud), showing that you’re audited regularly could help demonstrate your efforts to code correctly. In the latter case, it is probably more valuable if the audit is done independently of your employer.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at [email protected].

Several years ago we sent a CPT coding auditor 15 chart notes generated by each doctor in our group. Among each doctors’ 15 notes were at least one or two billed as initial hospital care, follow up, discharge, critical care, and so on. This coding expert returned a report showing that, out of all the notes reviewed, a significant portion were not billed at the correct level. Most of the incorrectly billed notes were judged to reflect “up-coding,” and a few were seen as “down-coded.”

This was distressing and hard to believe.

So I took the same set of notes and paid a second coding expert for an independent review. She didn’t know about the first audit but returned a report that showed a nearly identical portion of incorrectly coded notes.

Two independent audits showing nearly the same portion of notes coded incorrectly was alarming. But it was difficult for my partners and me to address, because the auditors didn’t agree on the correct code for many of the notes. In some cases, both flagged a note as incorrectly coded but didn’t agree on the correct code. For a number of the notes, one auditor said the visit was “up-coded,” while the other said it was “down-coded.” There was so little agreement between the two of them that we had a hard time coming up with any firm conclusions about what we should do to improve our performance.

If experts who think about coding all the time can’t agree on the right code for a given note, how can hospitalists be expected to code nearly all of our visits accurately?

RAC: Recovery Audit Contractor

Despite what I believe is poor inter-rater reliability among coding auditors, we need to work diligently to comply with coding guidelines. A 2003 Federal law mandated a program of Recovery Audit Contractors, or RAC for short, to find cases of “up-coding” or other overbilling and require the provider to repay any resulting loss.

A number of companies are in the business of conducting RAC audits (one of them, CGI, is the Canadian company blamed for the failed “Obamacare” exchange websites), and there is a reasonable chance one of these companies has reviewed some of your charges—or those of your hospitalist colleagues.

The RAC auditors review information about your charges, and if they determine that you up-coded or overbilled, they send a “demand letter” summarizing their findings, along with the amount of money they have determined you should pay back. (Theoretically, they could notify you of “under-coding,” so that you can be paid more for past work, but I haven’t yet come across an example of that.)

It is common to appeal the RAC findings, but that can be a long process, and many organizations decide to pay back all the money requested by the RAC as quickly as possible to avoid paying interest on a delayed payment if the appeal is unsuccessful. In the case of a successful appeal, the money previously refunded by the doctor would be returned.

Page 338 of the CMS Fiscal Year 2015 “Justification of Estimates for Appropriations Committees” says that “…about 50 percent of the estimated 43,000 appeals [of adverse RAC audit findings] were fully or partially overturned…” This could mean the RACs are a sort of loose cannon, accusing many providers of overbilling while knowing that some won’t bother to appeal because they don’t understand the process or because the dollar amount involved for a single provider is too small to justify the time and expense of conducting the appeal. In this way, a RAC audit is like the $15 rebate on the last electronic gadget you bought. The seller knows that many people, including me, will fail to do the work required to claim the rebate.

Accuracy Strategies

There are a number of ways to help your group ensure appropriate CPT coding and reduce the chance a RAC will ask for money back.

Education. There are many ways to help providers in your practice understand the elements of documentation and coding. Periodic training classes (e.g. during orientation and annually thereafter) are useful but may not be enough. For me, this is a little like learning a foreign language by going to a couple of classes. Instead, I think “immersion training” is more effective. That might mean a doctor spends a few minutes with a certified coder on most working days for a few weeks. For example, they could meet for 15 minutes near lunchtime and review how the doctor plans to bill visits made that morning. Lastly, consider targeted education for each doctor, based on any problems found in an audit of his/her coding.

Review coding patterns. As I wrote in my August 2007 column, there is value in ensuring that each doctor in the group can see how her coding pattern differs from the group as a whole or any individual in the group. That is, what portion of follow-up visits was billed at the lowest, middle, and highest levels? What about admissions, discharges, and so on? I provided a sample report in that same column.

It also is worth taking the time to compare each doctor’s coding pattern to both the CMS Internal Medicine data and SHM’s State of Hospital Medicine report. The accompanying figure shows the most current data sets available.

Keep in mind that the goal is not to simply ensure that your coding pattern matches these external data sets; knowing where yours differs from these sets can suggest where you might want to investigate further or seek additional education.

Coding audits. Having a certified coder audit your performance at least annually is a good idea. It can help uncover areas in which you’d benefit from further review and training, and if, heaven forbid, questions are ever raised about whether you’re intentionally up-coding (fraud), showing that you’re audited regularly could help demonstrate your efforts to code correctly. In the latter case, it is probably more valuable if the audit is done independently of your employer.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at [email protected].

Delay in ICD-10 Implementation to Impact Hospitalists, Physicians, Payers

On April 1, President Obama signed into law a bill that again delays a permanent fix of the sustainable growth rate formula, or SGR, the so-called “doc fix.” The bill also contained a surprise provision added by Congress to delay implementation of the switch from ICD-9 to ICD-10. The mandated conversion was supposed to take place by October 1 of this year; its delay will have a range of impacts on everyone from physicians to payers.

Hospitalists and others must weigh their options going forward, as many health systems and groups are already well on their way toward compliance with the 2014 deadline.

At this point, prevailing wisdom is that Congress added the delay as an appeasement to physician groups that would be unhappy about its failure to pass an SGR replacement, says Jeffrey Smith, senior director of federal affairs for CHIME, the College of Healthcare Information Management Executives.

“The appeasement, if in fact that was the motivation, was too little too late,” Smith says, adding Congress “caused a lot of unnecessary chaos.”

For instance, according to Modern Healthcare, executives at Catholic Health Initiatives had already invested millions of dollars updating software programs to handle the coding switch ahead of a new electronic health record system roll-out in 89 of its hospitals, which would not have been ready by the ICD-10 deadline.

“Anyone in the process has to circle the wagons again and reconsider their timelines,” Smith says. “The legislation has punished people trying to do the right thing.”

The transition to ICD-10 is a massive update to the 30-year-old ICD-9 codes, which no longer adequately reflect medical diagnoses, procedures, technology, and knowledge. There are five times more diagnosis codes and 21 times more procedural codes in ICD-10. It’s been on the table for at least a decade, and this was not the first delay.

In 2012, when fewer groups were on their way to compliance, CMS estimated that a one-year push-back of ICD-10 conversion could cost up to $306 million. With the latest delay, the American Health Information Management Association says CMS now estimates those costs between $1 billion and $6.6 billion.

However, according to the American Medical Association, which has actively lobbied to stop ICD-10 altogether, the costs of implementing ICD-10 range from $57,000 for small physician practices to as high as $8 million for large practices.

The increased number of codes, the increased number of characters per code, and the increased specificity require significant planning, training, software updates, and financial investments.

The Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) also pushed for ICD-10 delay, concerned that many groups would not be ready by Oct. 1. MGMA surveys showed as much, says Robert Tennant, senior policy advisor for MGMA.“We were concerned that if everyone has to flip the switch at the same time, there will be huge problems, as there were for healthcare.gov,” Tennant explains.

What MGMA would like to see is more thorough end-to-end testing and staggered roll-outs. Hospitals and health plans should be permitted to start using ICD-10 coding when they're ready, even if ahead of the next deadline, Tennant said. MGMA would also like to see a period of dual coding built in.

The ball is now in CMS' court.

“I think that CMS has within its power … the ability to embolden the industry to be more confident,” Smith says. “Even if it’s not going to require ICD-10 codes [by October 2014], hopefully they are still doing testing, still doing benchmarking, and by the time the deadline rolls around, it will touch every sector of the healthcare economy.”

Hospitalists, Smith says, should be more involved in the conversation going forward, to help maintain the momentum and preserve the investments made by their groups and institutions. Those not ready should push for compliance, rather than finding themselves in the same position a year from now.

Many of the hospital CIOs (chief information officers) he has talked to say that while they are stopping the car, they are keeping the engine running. Some will push for dual coding, even if only internally, because it’s proving to be a valuable tool in understanding their patient populations.

“It’s a frustrating time any time you have to kind of stop something with so much momentum, with hundreds of millions, if not billions, spent in advance of the conversion,” Smith says. “It does nothing to help care in this country to stay on ICD-9. Everybody understands those codes are completely exhausted, and the data we are getting out of it, while workable, is certainly not going to get us where we need to be in terms of transforming healthcare.”

Kelly April Tyrrell is a freelance writer in Madison, Wis.

On April 1, President Obama signed into law a bill that again delays a permanent fix of the sustainable growth rate formula, or SGR, the so-called “doc fix.” The bill also contained a surprise provision added by Congress to delay implementation of the switch from ICD-9 to ICD-10. The mandated conversion was supposed to take place by October 1 of this year; its delay will have a range of impacts on everyone from physicians to payers.

Hospitalists and others must weigh their options going forward, as many health systems and groups are already well on their way toward compliance with the 2014 deadline.

At this point, prevailing wisdom is that Congress added the delay as an appeasement to physician groups that would be unhappy about its failure to pass an SGR replacement, says Jeffrey Smith, senior director of federal affairs for CHIME, the College of Healthcare Information Management Executives.

“The appeasement, if in fact that was the motivation, was too little too late,” Smith says, adding Congress “caused a lot of unnecessary chaos.”

For instance, according to Modern Healthcare, executives at Catholic Health Initiatives had already invested millions of dollars updating software programs to handle the coding switch ahead of a new electronic health record system roll-out in 89 of its hospitals, which would not have been ready by the ICD-10 deadline.

“Anyone in the process has to circle the wagons again and reconsider their timelines,” Smith says. “The legislation has punished people trying to do the right thing.”

The transition to ICD-10 is a massive update to the 30-year-old ICD-9 codes, which no longer adequately reflect medical diagnoses, procedures, technology, and knowledge. There are five times more diagnosis codes and 21 times more procedural codes in ICD-10. It’s been on the table for at least a decade, and this was not the first delay.

In 2012, when fewer groups were on their way to compliance, CMS estimated that a one-year push-back of ICD-10 conversion could cost up to $306 million. With the latest delay, the American Health Information Management Association says CMS now estimates those costs between $1 billion and $6.6 billion.

However, according to the American Medical Association, which has actively lobbied to stop ICD-10 altogether, the costs of implementing ICD-10 range from $57,000 for small physician practices to as high as $8 million for large practices.

The increased number of codes, the increased number of characters per code, and the increased specificity require significant planning, training, software updates, and financial investments.

The Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) also pushed for ICD-10 delay, concerned that many groups would not be ready by Oct. 1. MGMA surveys showed as much, says Robert Tennant, senior policy advisor for MGMA.“We were concerned that if everyone has to flip the switch at the same time, there will be huge problems, as there were for healthcare.gov,” Tennant explains.

What MGMA would like to see is more thorough end-to-end testing and staggered roll-outs. Hospitals and health plans should be permitted to start using ICD-10 coding when they're ready, even if ahead of the next deadline, Tennant said. MGMA would also like to see a period of dual coding built in.

The ball is now in CMS' court.

“I think that CMS has within its power … the ability to embolden the industry to be more confident,” Smith says. “Even if it’s not going to require ICD-10 codes [by October 2014], hopefully they are still doing testing, still doing benchmarking, and by the time the deadline rolls around, it will touch every sector of the healthcare economy.”

Hospitalists, Smith says, should be more involved in the conversation going forward, to help maintain the momentum and preserve the investments made by their groups and institutions. Those not ready should push for compliance, rather than finding themselves in the same position a year from now.

Many of the hospital CIOs (chief information officers) he has talked to say that while they are stopping the car, they are keeping the engine running. Some will push for dual coding, even if only internally, because it’s proving to be a valuable tool in understanding their patient populations.

“It’s a frustrating time any time you have to kind of stop something with so much momentum, with hundreds of millions, if not billions, spent in advance of the conversion,” Smith says. “It does nothing to help care in this country to stay on ICD-9. Everybody understands those codes are completely exhausted, and the data we are getting out of it, while workable, is certainly not going to get us where we need to be in terms of transforming healthcare.”

Kelly April Tyrrell is a freelance writer in Madison, Wis.

On April 1, President Obama signed into law a bill that again delays a permanent fix of the sustainable growth rate formula, or SGR, the so-called “doc fix.” The bill also contained a surprise provision added by Congress to delay implementation of the switch from ICD-9 to ICD-10. The mandated conversion was supposed to take place by October 1 of this year; its delay will have a range of impacts on everyone from physicians to payers.

Hospitalists and others must weigh their options going forward, as many health systems and groups are already well on their way toward compliance with the 2014 deadline.

At this point, prevailing wisdom is that Congress added the delay as an appeasement to physician groups that would be unhappy about its failure to pass an SGR replacement, says Jeffrey Smith, senior director of federal affairs for CHIME, the College of Healthcare Information Management Executives.

“The appeasement, if in fact that was the motivation, was too little too late,” Smith says, adding Congress “caused a lot of unnecessary chaos.”

For instance, according to Modern Healthcare, executives at Catholic Health Initiatives had already invested millions of dollars updating software programs to handle the coding switch ahead of a new electronic health record system roll-out in 89 of its hospitals, which would not have been ready by the ICD-10 deadline.

“Anyone in the process has to circle the wagons again and reconsider their timelines,” Smith says. “The legislation has punished people trying to do the right thing.”

The transition to ICD-10 is a massive update to the 30-year-old ICD-9 codes, which no longer adequately reflect medical diagnoses, procedures, technology, and knowledge. There are five times more diagnosis codes and 21 times more procedural codes in ICD-10. It’s been on the table for at least a decade, and this was not the first delay.

In 2012, when fewer groups were on their way to compliance, CMS estimated that a one-year push-back of ICD-10 conversion could cost up to $306 million. With the latest delay, the American Health Information Management Association says CMS now estimates those costs between $1 billion and $6.6 billion.

However, according to the American Medical Association, which has actively lobbied to stop ICD-10 altogether, the costs of implementing ICD-10 range from $57,000 for small physician practices to as high as $8 million for large practices.

The increased number of codes, the increased number of characters per code, and the increased specificity require significant planning, training, software updates, and financial investments.

The Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) also pushed for ICD-10 delay, concerned that many groups would not be ready by Oct. 1. MGMA surveys showed as much, says Robert Tennant, senior policy advisor for MGMA.“We were concerned that if everyone has to flip the switch at the same time, there will be huge problems, as there were for healthcare.gov,” Tennant explains.

What MGMA would like to see is more thorough end-to-end testing and staggered roll-outs. Hospitals and health plans should be permitted to start using ICD-10 coding when they're ready, even if ahead of the next deadline, Tennant said. MGMA would also like to see a period of dual coding built in.

The ball is now in CMS' court.

“I think that CMS has within its power … the ability to embolden the industry to be more confident,” Smith says. “Even if it’s not going to require ICD-10 codes [by October 2014], hopefully they are still doing testing, still doing benchmarking, and by the time the deadline rolls around, it will touch every sector of the healthcare economy.”

Hospitalists, Smith says, should be more involved in the conversation going forward, to help maintain the momentum and preserve the investments made by their groups and institutions. Those not ready should push for compliance, rather than finding themselves in the same position a year from now.

Many of the hospital CIOs (chief information officers) he has talked to say that while they are stopping the car, they are keeping the engine running. Some will push for dual coding, even if only internally, because it’s proving to be a valuable tool in understanding their patient populations.

“It’s a frustrating time any time you have to kind of stop something with so much momentum, with hundreds of millions, if not billions, spent in advance of the conversion,” Smith says. “It does nothing to help care in this country to stay on ICD-9. Everybody understands those codes are completely exhausted, and the data we are getting out of it, while workable, is certainly not going to get us where we need to be in terms of transforming healthcare.”

Kelly April Tyrrell is a freelance writer in Madison, Wis.

Code-H Interactive Tool Helps Hospital Medicine Groups with Coding

Looking for ways to make your HM group run better? SHM is introducing new tools and information to keep you ahead of the curve.

CODE-H Interactive is an industry first: an interactive tool to help hospitalist groups code effectively and efficiently. CODE-H Interactive allows users to validate documentation against coding criteria and provides a guided tour through clinical documentation, allowing users to ensure they are choosing the correct billing code while providing a conceptual framework that enables the user to easily “connect the dots” between clinical documentation and the applicable CPT coding.

CODE-H Interactive includes two modules: one that reviews three admission notes and a second that reviews three daily notes. It also enables users to assess other E/M codes, such as consultations and ED visits. To get started, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/CODEHI.

Looking for ways to make your HM group run better? SHM is introducing new tools and information to keep you ahead of the curve.

CODE-H Interactive is an industry first: an interactive tool to help hospitalist groups code effectively and efficiently. CODE-H Interactive allows users to validate documentation against coding criteria and provides a guided tour through clinical documentation, allowing users to ensure they are choosing the correct billing code while providing a conceptual framework that enables the user to easily “connect the dots” between clinical documentation and the applicable CPT coding.

CODE-H Interactive includes two modules: one that reviews three admission notes and a second that reviews three daily notes. It also enables users to assess other E/M codes, such as consultations and ED visits. To get started, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/CODEHI.

Looking for ways to make your HM group run better? SHM is introducing new tools and information to keep you ahead of the curve.

CODE-H Interactive is an industry first: an interactive tool to help hospitalist groups code effectively and efficiently. CODE-H Interactive allows users to validate documentation against coding criteria and provides a guided tour through clinical documentation, allowing users to ensure they are choosing the correct billing code while providing a conceptual framework that enables the user to easily “connect the dots” between clinical documentation and the applicable CPT coding.

CODE-H Interactive includes two modules: one that reviews three admission notes and a second that reviews three daily notes. It also enables users to assess other E/M codes, such as consultations and ED visits. To get started, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/CODEHI.

SGR Reform, ICD-10 Implementation Delays Frustrate Hospitalists, Physicians

Congress has once again delayed implementation of draconian Medicare cuts tied to the sustainable growth rate (SGR) formula. It was the 17th temporary patch applied to the ailing physician reimbursement program, so the decision caused little surprise.

But with the same legislation—the Protecting Access to Medicare Act of 2014—being used to delay the long-awaited debut of ICD-10, many hospitalists and physicians couldn’t help but wonder whether billing and coding would now be as much of a political football as the SGR fix.1

The upshot: It doesn’t seem that way.

“I think it’s two separate issues,” says Phyllis “PJ” Floyd, RN, BSN, MBA, NE-BC, CCA, director of health information services and clinical documentation improvement at Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) in Charleston, S.C. “The fact that it was all in one bill, I don’t know that it was well thought out as much as it was, ‘Let’s put the ICD-10 in here at the same time.’

“It was just a few sentences, and then it wasn’t even brought up in the discussion on the floor.”

Four policy wonks interviewed by The Hospitalist concurred that while tying the ICD-10 delay to the SGR issue was an unexpected and frustrating development, the coding system likely will be implemented in the relative short term. Meanwhile, a long-term resolution of the SGR dilemma remains much more elusive.

“For about 12 hours, I felt relief about the ICD-10 [being delayed], and then I just realized, it’s still coming, presumably,” says John Nelson, MD, MHM, a co-founder and past president of SHM and medical director of the hospitalist practice at Overlake Hospital Medical Center in Bellevue, Wash. “[It’s] like a patient who needs surgery and finds out it’s canceled for the day and he’ll have it tomorrow. Well, that’s good for right now, but [he] still has to face this eventually.”

“Doc-Pay” Fix Near?

Congress’ recent decision to delay both an SGR fix and the ICD-10 are troubling to some hospitalists and others for different reasons.

The SGR extension through this year’s end means that physicians do not face a 24% cut to physician payments under Medicare. SHM has long lobbied against temporary patches to the SGR, repeatedly backing legislation that would once and for all scrap the formula and replace it with something sustainable.

The SGR formula was first crafted in 1997, but the now often-delayed cuts were a byproduct of the federal sequester that was included in the Budget Control Act of 2011. At the time, the massive reduction to Medicare payments was tied to political brinksmanship over the country’s debt ceiling. The cuts were implemented as a doomsday scenario that was never likely to actually happen, but despite negotiations over the past three years, no long-term compromise can be found. Paying for the reform remains the main stumbling block.

“I think, this year, Congress was as close as it’s been in a long time to enacting a serious fix, aided by the agreement of major professional societies like the American College of Physicians and American College of Surgeons,” says David Howard, PhD, an associate professor in the department of health policy and management at the Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University in Atlanta. “They were all on board with this solution. ... Who knows, maybe if the economic situation continues to improve [and] tax revenues continue to go up...that will create a more favorable environment for compromise.”

Dr. Howard adds that while Congress might be close to a solution in theory, agreement on how to offset the roughly $100 billion in costs “is just very difficult.” That is why the healthcare professor is pessimistic that a long-term fix is truly at hand.

“The places where Congress might have looked for savings to offset the cost of the doc fix, such as hospital reimbursement rates or payment rates to Medicare Advantage plans—those are exactly the areas that the Affordable Care Act is targeting to pay for insurance expansion,” Dr. Howard adds. “So those areas of savings are not going to be available to offset the cost of the doc fix.”

ICD-10 Delays “Unfair”

The medical coding conundrum presents a different set of issues. The delay in transitioning healthcare providers from the ICD-9 medical coding classification system to the more complicated ICD-10 means the upgraded system is now against an Oct. 1, 2015, deadline. This comes after the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) already pushed back the original implementation date for ICD-10 by one year.

SHM Public Policy Committee member Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, SFHM, says he thinks most doctors are content with the delay, particularly in light of some estimates that show that only about 20% of physicians “have actually initiated the ICD-10 transition.” But he also notes that it’s unfair to the health systems that have prepared for ICD-10.

“ICD-9 has a little more than 14,000 diagnostic codes and nearly 4,000 procedural codes. That is to be contrasted to ICD-10, which has more than 68,000 diagnostic codes ... and over 72,000 procedural codes,” Dr. Lenchus says. “So, it is not surprising that many take solace in the delay.”

–Dr. Lenchus

Dr. Nelson says the level of frustration for hospitalists is growing; however, the level of disruption for hospitals and health systems is reaching a boiling point.

“Of course, in some places, hospitalists may be the physician lead on ICD-10 efforts, so [they are] very much wrapped up in the problem of ‘What do we do now?’”

The answer, at least to the Coalition for ICD-10, a group of medical/technology trade groups, is to fight to ensure that the delays go no further. In an April letter to CMS Administrator Marilyn Tavenner, the coalition made that case, noting that in 2012, “CMS estimated the cost to the healthcare industry of a one-year delay to be as much as $6.6 billion, or approximately 30% of the $22 billion that CMS estimated had been invested or budgeted for ICD-10 implementation.”2

The letter went on to explain that the disruption and cost will grow each time the ICD-10 deadline is pushed.

“Furthermore, as CMS stated in 2012, implementation costs will continue to increase considerably with every year of a delay,” according to the letter. “The lost opportunity costs of failing to move to a more effective code set also continue to climb every year.”

Stay Engaged, Switch Gears

One of Floyd’s biggest concerns is that the ICD-10 implementation delays will affect physician engagement. The hospitalist groups at MUSC began training for ICD-10 in January 2013; however, the preparation and training were geared toward a 2014 implementation.

“You have to switch gears a little bit,” she says. “What we plan to do now is begin to do heavy auditing, and then from those audits we can give real-time feedback on what we’re doing well and what we’re not doing well. So I think that will be a method for engagement.”

She urges hospitalists, practice leaders, and informatics professionals to discuss ICD-10 not as a theoretical application, but as one tied to reimbursement that will have major impact in the years ahead. To that end, the American Health Information Management Association highlights the fact that the new coding system will result in higher-quality data that can improve performance measures, provide “increased sensitivity” to reimbursement methodologies, and help with stronger public health surveillance.3

“A lot of physicians see this as a hospital issue, and I think that’s why they shy away,” Floyd says. “Now there are some physicians who are interested in how well the hospital does, but the other piece is that it does affect things like [reduced] risk of mortality [and] comparison of data worldwide—those are things that we just have to continue to reiterate … and give them real examples.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

- Govtrack. H.R. 4302: Protecting Access to Medicare Act of 2014. https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/113/hr4302. Accessed June 5, 2014.

- Coalition for ICD. Letter to CMS Administrator Tavenner, April 11, 2014. http://coalitionforicd10.wordpress.com/2014/03/26/letter-from-the-coalition-for-icd-10. Accessed June 5, 2014.

- American Health Information Management Association. ICD-10-CM/PCS Transition: Planning and Preparation Checklist. http://journal.ahima.org/wp-content/uploads/ICD10-checklist.pdf. Accessed June 5, 2014.

Congress has once again delayed implementation of draconian Medicare cuts tied to the sustainable growth rate (SGR) formula. It was the 17th temporary patch applied to the ailing physician reimbursement program, so the decision caused little surprise.

But with the same legislation—the Protecting Access to Medicare Act of 2014—being used to delay the long-awaited debut of ICD-10, many hospitalists and physicians couldn’t help but wonder whether billing and coding would now be as much of a political football as the SGR fix.1

The upshot: It doesn’t seem that way.

“I think it’s two separate issues,” says Phyllis “PJ” Floyd, RN, BSN, MBA, NE-BC, CCA, director of health information services and clinical documentation improvement at Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) in Charleston, S.C. “The fact that it was all in one bill, I don’t know that it was well thought out as much as it was, ‘Let’s put the ICD-10 in here at the same time.’

“It was just a few sentences, and then it wasn’t even brought up in the discussion on the floor.”

Four policy wonks interviewed by The Hospitalist concurred that while tying the ICD-10 delay to the SGR issue was an unexpected and frustrating development, the coding system likely will be implemented in the relative short term. Meanwhile, a long-term resolution of the SGR dilemma remains much more elusive.

“For about 12 hours, I felt relief about the ICD-10 [being delayed], and then I just realized, it’s still coming, presumably,” says John Nelson, MD, MHM, a co-founder and past president of SHM and medical director of the hospitalist practice at Overlake Hospital Medical Center in Bellevue, Wash. “[It’s] like a patient who needs surgery and finds out it’s canceled for the day and he’ll have it tomorrow. Well, that’s good for right now, but [he] still has to face this eventually.”

“Doc-Pay” Fix Near?

Congress’ recent decision to delay both an SGR fix and the ICD-10 are troubling to some hospitalists and others for different reasons.

The SGR extension through this year’s end means that physicians do not face a 24% cut to physician payments under Medicare. SHM has long lobbied against temporary patches to the SGR, repeatedly backing legislation that would once and for all scrap the formula and replace it with something sustainable.

The SGR formula was first crafted in 1997, but the now often-delayed cuts were a byproduct of the federal sequester that was included in the Budget Control Act of 2011. At the time, the massive reduction to Medicare payments was tied to political brinksmanship over the country’s debt ceiling. The cuts were implemented as a doomsday scenario that was never likely to actually happen, but despite negotiations over the past three years, no long-term compromise can be found. Paying for the reform remains the main stumbling block.

“I think, this year, Congress was as close as it’s been in a long time to enacting a serious fix, aided by the agreement of major professional societies like the American College of Physicians and American College of Surgeons,” says David Howard, PhD, an associate professor in the department of health policy and management at the Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University in Atlanta. “They were all on board with this solution. ... Who knows, maybe if the economic situation continues to improve [and] tax revenues continue to go up...that will create a more favorable environment for compromise.”

Dr. Howard adds that while Congress might be close to a solution in theory, agreement on how to offset the roughly $100 billion in costs “is just very difficult.” That is why the healthcare professor is pessimistic that a long-term fix is truly at hand.

“The places where Congress might have looked for savings to offset the cost of the doc fix, such as hospital reimbursement rates or payment rates to Medicare Advantage plans—those are exactly the areas that the Affordable Care Act is targeting to pay for insurance expansion,” Dr. Howard adds. “So those areas of savings are not going to be available to offset the cost of the doc fix.”

ICD-10 Delays “Unfair”

The medical coding conundrum presents a different set of issues. The delay in transitioning healthcare providers from the ICD-9 medical coding classification system to the more complicated ICD-10 means the upgraded system is now against an Oct. 1, 2015, deadline. This comes after the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) already pushed back the original implementation date for ICD-10 by one year.

SHM Public Policy Committee member Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, SFHM, says he thinks most doctors are content with the delay, particularly in light of some estimates that show that only about 20% of physicians “have actually initiated the ICD-10 transition.” But he also notes that it’s unfair to the health systems that have prepared for ICD-10.

“ICD-9 has a little more than 14,000 diagnostic codes and nearly 4,000 procedural codes. That is to be contrasted to ICD-10, which has more than 68,000 diagnostic codes ... and over 72,000 procedural codes,” Dr. Lenchus says. “So, it is not surprising that many take solace in the delay.”

–Dr. Lenchus

Dr. Nelson says the level of frustration for hospitalists is growing; however, the level of disruption for hospitals and health systems is reaching a boiling point.

“Of course, in some places, hospitalists may be the physician lead on ICD-10 efforts, so [they are] very much wrapped up in the problem of ‘What do we do now?’”

The answer, at least to the Coalition for ICD-10, a group of medical/technology trade groups, is to fight to ensure that the delays go no further. In an April letter to CMS Administrator Marilyn Tavenner, the coalition made that case, noting that in 2012, “CMS estimated the cost to the healthcare industry of a one-year delay to be as much as $6.6 billion, or approximately 30% of the $22 billion that CMS estimated had been invested or budgeted for ICD-10 implementation.”2

The letter went on to explain that the disruption and cost will grow each time the ICD-10 deadline is pushed.

“Furthermore, as CMS stated in 2012, implementation costs will continue to increase considerably with every year of a delay,” according to the letter. “The lost opportunity costs of failing to move to a more effective code set also continue to climb every year.”

Stay Engaged, Switch Gears