User login

HM18: ‘Things we do for no reason’

Be aware of low value care practices

Presenter

Leonard Feldman, MD, SFHM

Session summary

In the current climate of increasing national health care expenditures, the Journal of Hospital Medicine continues to expand its series “Things We Do for No Reason” to shed light on areas for improvement in the delivery of high-value care. Physicians, however, continue to practice low value care because of practice habits and lack of cost transparency. In keeping with the spirit of the journal’s series, three low-value practices were highlighted in this HM18 session, including the benefits of high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) oxygen therapy, the value of serum albumin and prealbumin in malnutrition, and the use of nebulized versus inhaler albuterol.

HFNC oxygen therapy has become a widespread practice internationally, with large variations in implementation across all age ranges. In bronchiolitic infants, variations in time of implementation, duration of therapy, weaning policies, and outcome measures have yielded mixed results to date. Many studies are still underway, but current literature has not shown significant benefits of starting HFNC early in the illness process, and infants receiving HFNC have not had better outcomes than those who received standard therapy (low-flow nasal cannula).

Serum albumin and prealbumin are often cited as markers of malnutrition. In patients on tube feeds, such as those with cerebral palsy and complex medical conditions, current literature shows no benefit in the use of these lab markers for screening or for following to assess improvement. In addition, patients with eating disorders do not have significant correlation of their nutritive status with these markers. Therefore, the use of these labs for screening of malnutrition is of little if any value.

Finally, when comparing albuterol delivery systems, there has been no proof that nebulized albuterol is any better than metered dose inhalers (MDI) in its effect. As long as appropriate dosing of MDIs is done, the benefits are the same. In addition, side effects are fewer, and the length of stay in the ED is shorter. The more a family uses MDI inhalers, the better their technique. Studies have shown it takes approximately three attempts at using an MDI to get the technique correct, so inpatient MDI use would also decrease user error in the outpatient setting.

Key takeaways for HM

- Practice habits, lack of transparency of costs, and regional training lead to low value care practices.

- Early introduction of high-flow nasal cannula in hospitalization of an infant with bronchiolitis has not been shown to decrease length of stay or severity outcomes, according to currently available data.

- Serum albumin and prealbumin have little to no benefit in screening of malnutrition.

- Nebulized albuterol has not been proven to be more beneficial that MDI albuterol at appropriate doses.

- Repeat MDI administration has been shown to positively affect user administration techniques.

- MDI albuterol use has fewer side effects and decreased ED length of stay, compared with nebulized albuterol.

Dr. Schwenk is an associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and a pediatric hospitalist at Norton Children’s Hospital, Louisville.

Be aware of low value care practices

Be aware of low value care practices

Presenter

Leonard Feldman, MD, SFHM

Session summary

In the current climate of increasing national health care expenditures, the Journal of Hospital Medicine continues to expand its series “Things We Do for No Reason” to shed light on areas for improvement in the delivery of high-value care. Physicians, however, continue to practice low value care because of practice habits and lack of cost transparency. In keeping with the spirit of the journal’s series, three low-value practices were highlighted in this HM18 session, including the benefits of high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) oxygen therapy, the value of serum albumin and prealbumin in malnutrition, and the use of nebulized versus inhaler albuterol.

HFNC oxygen therapy has become a widespread practice internationally, with large variations in implementation across all age ranges. In bronchiolitic infants, variations in time of implementation, duration of therapy, weaning policies, and outcome measures have yielded mixed results to date. Many studies are still underway, but current literature has not shown significant benefits of starting HFNC early in the illness process, and infants receiving HFNC have not had better outcomes than those who received standard therapy (low-flow nasal cannula).

Serum albumin and prealbumin are often cited as markers of malnutrition. In patients on tube feeds, such as those with cerebral palsy and complex medical conditions, current literature shows no benefit in the use of these lab markers for screening or for following to assess improvement. In addition, patients with eating disorders do not have significant correlation of their nutritive status with these markers. Therefore, the use of these labs for screening of malnutrition is of little if any value.

Finally, when comparing albuterol delivery systems, there has been no proof that nebulized albuterol is any better than metered dose inhalers (MDI) in its effect. As long as appropriate dosing of MDIs is done, the benefits are the same. In addition, side effects are fewer, and the length of stay in the ED is shorter. The more a family uses MDI inhalers, the better their technique. Studies have shown it takes approximately three attempts at using an MDI to get the technique correct, so inpatient MDI use would also decrease user error in the outpatient setting.

Key takeaways for HM

- Practice habits, lack of transparency of costs, and regional training lead to low value care practices.

- Early introduction of high-flow nasal cannula in hospitalization of an infant with bronchiolitis has not been shown to decrease length of stay or severity outcomes, according to currently available data.

- Serum albumin and prealbumin have little to no benefit in screening of malnutrition.

- Nebulized albuterol has not been proven to be more beneficial that MDI albuterol at appropriate doses.

- Repeat MDI administration has been shown to positively affect user administration techniques.

- MDI albuterol use has fewer side effects and decreased ED length of stay, compared with nebulized albuterol.

Dr. Schwenk is an associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and a pediatric hospitalist at Norton Children’s Hospital, Louisville.

Presenter

Leonard Feldman, MD, SFHM

Session summary

In the current climate of increasing national health care expenditures, the Journal of Hospital Medicine continues to expand its series “Things We Do for No Reason” to shed light on areas for improvement in the delivery of high-value care. Physicians, however, continue to practice low value care because of practice habits and lack of cost transparency. In keeping with the spirit of the journal’s series, three low-value practices were highlighted in this HM18 session, including the benefits of high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) oxygen therapy, the value of serum albumin and prealbumin in malnutrition, and the use of nebulized versus inhaler albuterol.

HFNC oxygen therapy has become a widespread practice internationally, with large variations in implementation across all age ranges. In bronchiolitic infants, variations in time of implementation, duration of therapy, weaning policies, and outcome measures have yielded mixed results to date. Many studies are still underway, but current literature has not shown significant benefits of starting HFNC early in the illness process, and infants receiving HFNC have not had better outcomes than those who received standard therapy (low-flow nasal cannula).

Serum albumin and prealbumin are often cited as markers of malnutrition. In patients on tube feeds, such as those with cerebral palsy and complex medical conditions, current literature shows no benefit in the use of these lab markers for screening or for following to assess improvement. In addition, patients with eating disorders do not have significant correlation of their nutritive status with these markers. Therefore, the use of these labs for screening of malnutrition is of little if any value.

Finally, when comparing albuterol delivery systems, there has been no proof that nebulized albuterol is any better than metered dose inhalers (MDI) in its effect. As long as appropriate dosing of MDIs is done, the benefits are the same. In addition, side effects are fewer, and the length of stay in the ED is shorter. The more a family uses MDI inhalers, the better their technique. Studies have shown it takes approximately three attempts at using an MDI to get the technique correct, so inpatient MDI use would also decrease user error in the outpatient setting.

Key takeaways for HM

- Practice habits, lack of transparency of costs, and regional training lead to low value care practices.

- Early introduction of high-flow nasal cannula in hospitalization of an infant with bronchiolitis has not been shown to decrease length of stay or severity outcomes, according to currently available data.

- Serum albumin and prealbumin have little to no benefit in screening of malnutrition.

- Nebulized albuterol has not been proven to be more beneficial that MDI albuterol at appropriate doses.

- Repeat MDI administration has been shown to positively affect user administration techniques.

- MDI albuterol use has fewer side effects and decreased ED length of stay, compared with nebulized albuterol.

Dr. Schwenk is an associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and a pediatric hospitalist at Norton Children’s Hospital, Louisville.

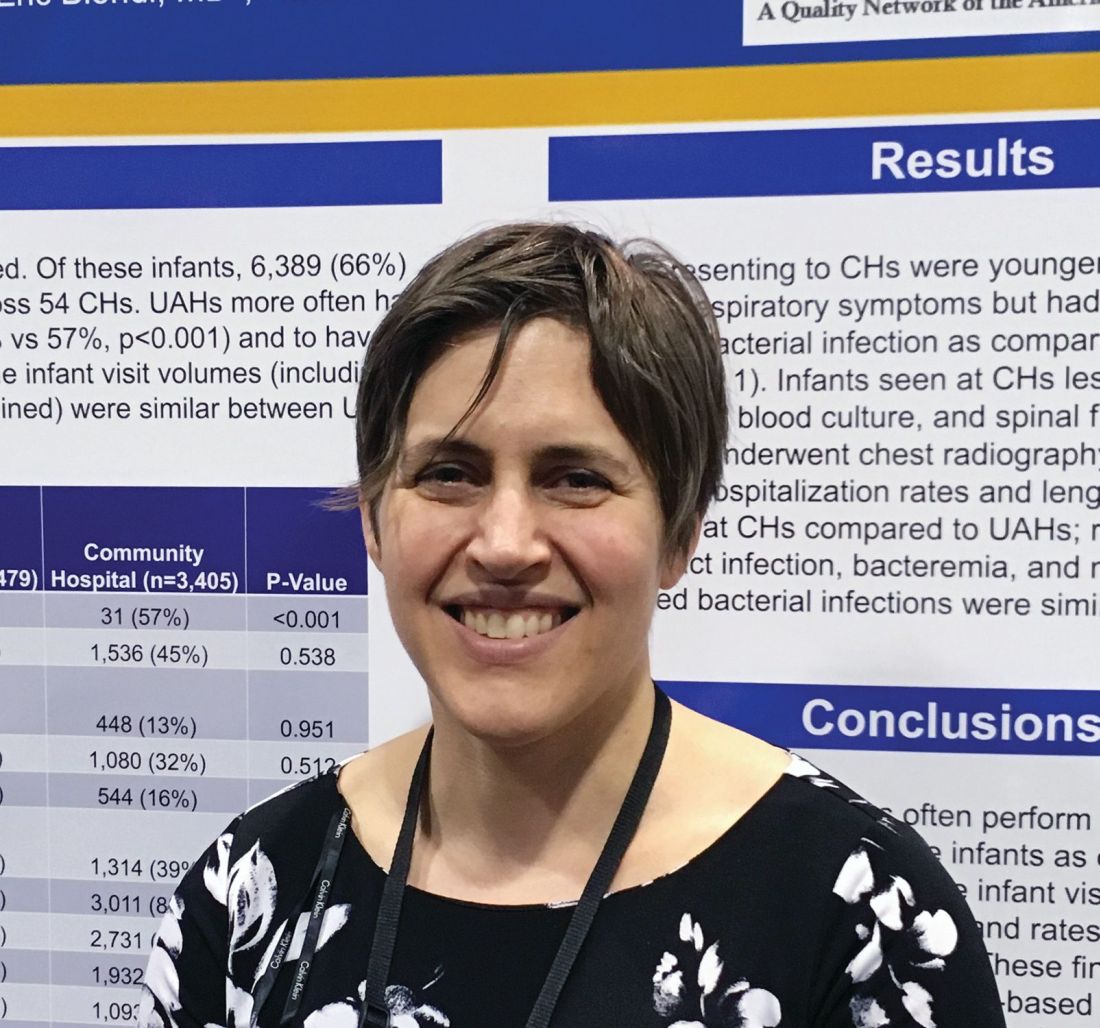

Nearly one-quarter of presurgery patients already using opioids

at a large academic medical center, a cross-sectional observational study has determined.

Prescription or illegal opioid use can have profound implications for surgical outcomes and continued postoperative medication abuse. “Preoperative opioid use was associated with a greater burden of comorbid disease and multiple risk factors for poor recovery. ... Opioid-tolerant patients are at risk for opioid-associated adverse events and are less likely to discontinue opioid-based therapy after their surgery,” wrote Paul E. Hilliard, MD, and a team of researchers at the University of Michigan Health System. Although the question of preoperative opioid use has been examined and the Michigan findings are consistent with earlier estimates of prevalence (Ann Surg. 2017;265[4]:695-701), this study sought a more detailed profile of both the characteristics of these patients and the types of procedures correlated with opioid use.

Patient data were derived primarily from two ongoing institutional registries, the Michigan Genomics Initiative and the Analgesic Outcomes Study. Each of these projects involved recruiting nonemergency surgery patients to participate and self-report on pain and affect issues. Opioid use data were extracted from the preop anesthesia history and from physical examination. A total of 34,186 patients were recruited for this study; 54.2% were women, 89.1% were white, and the mean age was 53.1 years. Overall, 23.1% of these patients were taking opioids of various kinds, mostly by prescription along with nonprescription opioids and illegal drugs of other kinds.

The most common opioids found in this patient sample were hydrocodone bitartrate (59.4%), tramadol hydrochloride (21.2%) and oxycodone hydrochloride (18.5%), although the duration or frequency of use was not determined.

“In our experience, in surveys like this patients are pretty honest. [The data do not] track to their medical record, but was done privately for research. That having been said, I am sure there is significant underreporting,” study coauthor Michael J. Englesbe, MD, FACS, said in an interview. In addition to some nondisclosure by study participants, the exclusion of patients admitted to surgery from the ED could mean that 23.1% is a conservative estimate, he noted.

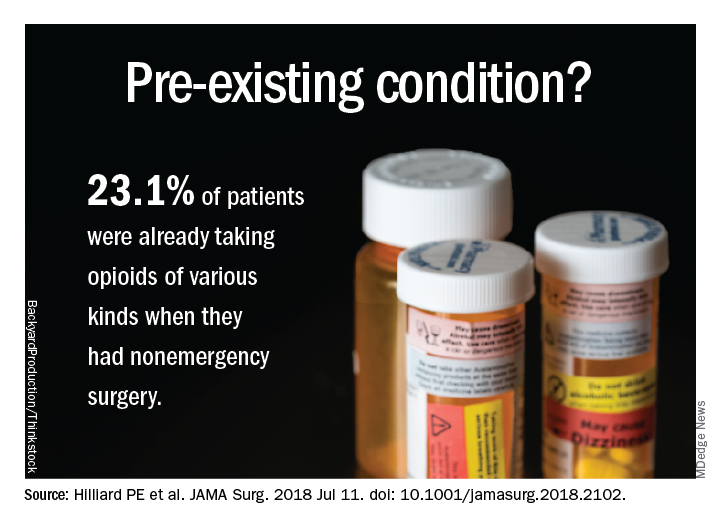

Patient characteristics included in the study (tobacco use, alcohol use, sleep apnea, pain, life satisfaction, depression, anxiety) were self-reported and validated using tools such as the Brief Pain Inventory, the Fibromyalgia Survey, and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Procedural data were derived from patient records and ICD-10 data and rated via the ASA score and Charlson Comorbidity Index.

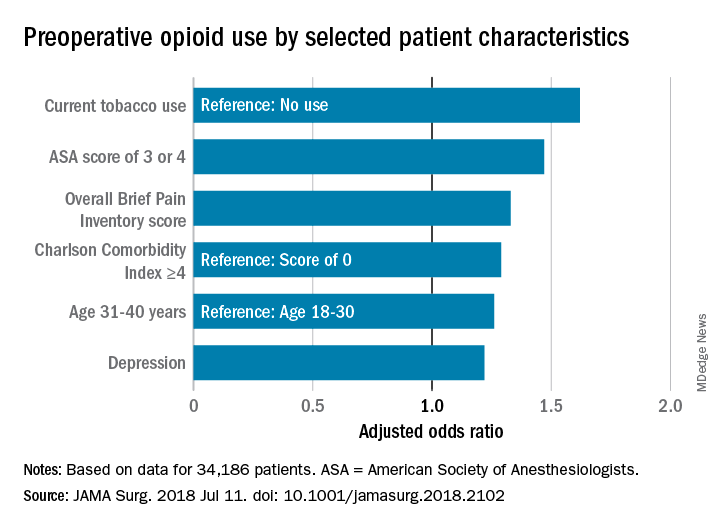

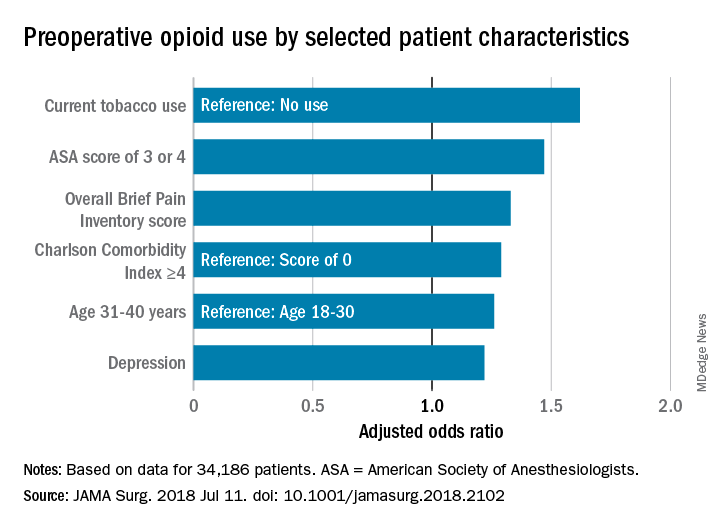

A multivariate analysis of patient characteristics found that age between 31 and 40, tobacco use, heavy alcohol use, pain score, depression, comorbidities reflected in a higher ASA score, and Charlson Comorbidity Score were all significant risk factors for presurgical opiate use.

Patients who were scheduled for surgical procedures involving lower extremities (adjusted odds ratio 3.61, 95% confidence interval, 2.81-4.64) were at the highest risk for opioid use, followed by pelvis surgery, excluding hip (aOR, 3.09, 95% CI, 1.88-5.08), upper arm or elbow (aOR, 3.07, 95% CI, 2.12-4.45), and spine surgery (aOR, 2.68, 95% CI, 2.15-3.32).

The study also broke out the data by presurgery opioid usage and surgery service. Of patients having spine neurosurgery, 55.1% were already taking opioids, and among those having orthopedic spine surgery, 65.1% were taking opioids. General surgery patients were not among those mostly likely to be using opioids (gastrointestinal surgery, 19.3% and endocrine surgery 14.3%). “Certain surgical services may be more likely to encounter patients with high comorbidities for opioid use, and more targeted opioid education strategies aimed at those services may help to mitigate risk in the postoperative period,” the authors wrote.

“All surgeons should take a preop pain history. They should ask about current pain and previous pain experiences. They should also ask about a history of substance use disorder. This should lead into a discussion of the pain expectations from the procedure. Patients should expect to be in pain, that is normal. Pain-free surgery is rare. If a patient has a complex pain history or takes chronic opioids, the surgeon should consider referring them to anesthesia for formal preop pain management planning and potentially weaning of opioid dose prior to elective surgery,” noted Dr. Englesbe, the Cyrenus G. Darling Sr., MD and Cyrenus G Darling Jr., MD Professor of Surgery, and faculty at the Center for Healthcare Outcomes & Policy, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Surgeons are likely to see patients with a past history of opioid dependence or who are recovering from substance abuse. “Every effort should be made to avoid opioids in these patients. We have developed a Pain Optimization Pathway which facilitates no postoperative opioids for these and other patients. These patients are at high risk to relapse and surgeons must know who these patients are so they can provide optimal care,” Dr. Englesbe added.The limitations of this study as reported by the authors include the single-center design, the nondiverse racial makeup of the sample, and the difficulty of ascertaining the dosing and duration of opioid use, both prescription and illegal.

The investigators reported no disclosures relevant to this study. This study was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, the American College of Surgeons, and other noncommercial sources.

SOURCE: Hilliard PE et al. JAMA Surg. 2018 Jul 11. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.2102.

at a large academic medical center, a cross-sectional observational study has determined.

Prescription or illegal opioid use can have profound implications for surgical outcomes and continued postoperative medication abuse. “Preoperative opioid use was associated with a greater burden of comorbid disease and multiple risk factors for poor recovery. ... Opioid-tolerant patients are at risk for opioid-associated adverse events and are less likely to discontinue opioid-based therapy after their surgery,” wrote Paul E. Hilliard, MD, and a team of researchers at the University of Michigan Health System. Although the question of preoperative opioid use has been examined and the Michigan findings are consistent with earlier estimates of prevalence (Ann Surg. 2017;265[4]:695-701), this study sought a more detailed profile of both the characteristics of these patients and the types of procedures correlated with opioid use.

Patient data were derived primarily from two ongoing institutional registries, the Michigan Genomics Initiative and the Analgesic Outcomes Study. Each of these projects involved recruiting nonemergency surgery patients to participate and self-report on pain and affect issues. Opioid use data were extracted from the preop anesthesia history and from physical examination. A total of 34,186 patients were recruited for this study; 54.2% were women, 89.1% were white, and the mean age was 53.1 years. Overall, 23.1% of these patients were taking opioids of various kinds, mostly by prescription along with nonprescription opioids and illegal drugs of other kinds.

The most common opioids found in this patient sample were hydrocodone bitartrate (59.4%), tramadol hydrochloride (21.2%) and oxycodone hydrochloride (18.5%), although the duration or frequency of use was not determined.

“In our experience, in surveys like this patients are pretty honest. [The data do not] track to their medical record, but was done privately for research. That having been said, I am sure there is significant underreporting,” study coauthor Michael J. Englesbe, MD, FACS, said in an interview. In addition to some nondisclosure by study participants, the exclusion of patients admitted to surgery from the ED could mean that 23.1% is a conservative estimate, he noted.

Patient characteristics included in the study (tobacco use, alcohol use, sleep apnea, pain, life satisfaction, depression, anxiety) were self-reported and validated using tools such as the Brief Pain Inventory, the Fibromyalgia Survey, and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Procedural data were derived from patient records and ICD-10 data and rated via the ASA score and Charlson Comorbidity Index.

A multivariate analysis of patient characteristics found that age between 31 and 40, tobacco use, heavy alcohol use, pain score, depression, comorbidities reflected in a higher ASA score, and Charlson Comorbidity Score were all significant risk factors for presurgical opiate use.

Patients who were scheduled for surgical procedures involving lower extremities (adjusted odds ratio 3.61, 95% confidence interval, 2.81-4.64) were at the highest risk for opioid use, followed by pelvis surgery, excluding hip (aOR, 3.09, 95% CI, 1.88-5.08), upper arm or elbow (aOR, 3.07, 95% CI, 2.12-4.45), and spine surgery (aOR, 2.68, 95% CI, 2.15-3.32).

The study also broke out the data by presurgery opioid usage and surgery service. Of patients having spine neurosurgery, 55.1% were already taking opioids, and among those having orthopedic spine surgery, 65.1% were taking opioids. General surgery patients were not among those mostly likely to be using opioids (gastrointestinal surgery, 19.3% and endocrine surgery 14.3%). “Certain surgical services may be more likely to encounter patients with high comorbidities for opioid use, and more targeted opioid education strategies aimed at those services may help to mitigate risk in the postoperative period,” the authors wrote.

“All surgeons should take a preop pain history. They should ask about current pain and previous pain experiences. They should also ask about a history of substance use disorder. This should lead into a discussion of the pain expectations from the procedure. Patients should expect to be in pain, that is normal. Pain-free surgery is rare. If a patient has a complex pain history or takes chronic opioids, the surgeon should consider referring them to anesthesia for formal preop pain management planning and potentially weaning of opioid dose prior to elective surgery,” noted Dr. Englesbe, the Cyrenus G. Darling Sr., MD and Cyrenus G Darling Jr., MD Professor of Surgery, and faculty at the Center for Healthcare Outcomes & Policy, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Surgeons are likely to see patients with a past history of opioid dependence or who are recovering from substance abuse. “Every effort should be made to avoid opioids in these patients. We have developed a Pain Optimization Pathway which facilitates no postoperative opioids for these and other patients. These patients are at high risk to relapse and surgeons must know who these patients are so they can provide optimal care,” Dr. Englesbe added.The limitations of this study as reported by the authors include the single-center design, the nondiverse racial makeup of the sample, and the difficulty of ascertaining the dosing and duration of opioid use, both prescription and illegal.

The investigators reported no disclosures relevant to this study. This study was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, the American College of Surgeons, and other noncommercial sources.

SOURCE: Hilliard PE et al. JAMA Surg. 2018 Jul 11. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.2102.

at a large academic medical center, a cross-sectional observational study has determined.

Prescription or illegal opioid use can have profound implications for surgical outcomes and continued postoperative medication abuse. “Preoperative opioid use was associated with a greater burden of comorbid disease and multiple risk factors for poor recovery. ... Opioid-tolerant patients are at risk for opioid-associated adverse events and are less likely to discontinue opioid-based therapy after their surgery,” wrote Paul E. Hilliard, MD, and a team of researchers at the University of Michigan Health System. Although the question of preoperative opioid use has been examined and the Michigan findings are consistent with earlier estimates of prevalence (Ann Surg. 2017;265[4]:695-701), this study sought a more detailed profile of both the characteristics of these patients and the types of procedures correlated with opioid use.

Patient data were derived primarily from two ongoing institutional registries, the Michigan Genomics Initiative and the Analgesic Outcomes Study. Each of these projects involved recruiting nonemergency surgery patients to participate and self-report on pain and affect issues. Opioid use data were extracted from the preop anesthesia history and from physical examination. A total of 34,186 patients were recruited for this study; 54.2% were women, 89.1% were white, and the mean age was 53.1 years. Overall, 23.1% of these patients were taking opioids of various kinds, mostly by prescription along with nonprescription opioids and illegal drugs of other kinds.

The most common opioids found in this patient sample were hydrocodone bitartrate (59.4%), tramadol hydrochloride (21.2%) and oxycodone hydrochloride (18.5%), although the duration or frequency of use was not determined.

“In our experience, in surveys like this patients are pretty honest. [The data do not] track to their medical record, but was done privately for research. That having been said, I am sure there is significant underreporting,” study coauthor Michael J. Englesbe, MD, FACS, said in an interview. In addition to some nondisclosure by study participants, the exclusion of patients admitted to surgery from the ED could mean that 23.1% is a conservative estimate, he noted.

Patient characteristics included in the study (tobacco use, alcohol use, sleep apnea, pain, life satisfaction, depression, anxiety) were self-reported and validated using tools such as the Brief Pain Inventory, the Fibromyalgia Survey, and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Procedural data were derived from patient records and ICD-10 data and rated via the ASA score and Charlson Comorbidity Index.

A multivariate analysis of patient characteristics found that age between 31 and 40, tobacco use, heavy alcohol use, pain score, depression, comorbidities reflected in a higher ASA score, and Charlson Comorbidity Score were all significant risk factors for presurgical opiate use.

Patients who were scheduled for surgical procedures involving lower extremities (adjusted odds ratio 3.61, 95% confidence interval, 2.81-4.64) were at the highest risk for opioid use, followed by pelvis surgery, excluding hip (aOR, 3.09, 95% CI, 1.88-5.08), upper arm or elbow (aOR, 3.07, 95% CI, 2.12-4.45), and spine surgery (aOR, 2.68, 95% CI, 2.15-3.32).

The study also broke out the data by presurgery opioid usage and surgery service. Of patients having spine neurosurgery, 55.1% were already taking opioids, and among those having orthopedic spine surgery, 65.1% were taking opioids. General surgery patients were not among those mostly likely to be using opioids (gastrointestinal surgery, 19.3% and endocrine surgery 14.3%). “Certain surgical services may be more likely to encounter patients with high comorbidities for opioid use, and more targeted opioid education strategies aimed at those services may help to mitigate risk in the postoperative period,” the authors wrote.

“All surgeons should take a preop pain history. They should ask about current pain and previous pain experiences. They should also ask about a history of substance use disorder. This should lead into a discussion of the pain expectations from the procedure. Patients should expect to be in pain, that is normal. Pain-free surgery is rare. If a patient has a complex pain history or takes chronic opioids, the surgeon should consider referring them to anesthesia for formal preop pain management planning and potentially weaning of opioid dose prior to elective surgery,” noted Dr. Englesbe, the Cyrenus G. Darling Sr., MD and Cyrenus G Darling Jr., MD Professor of Surgery, and faculty at the Center for Healthcare Outcomes & Policy, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Surgeons are likely to see patients with a past history of opioid dependence or who are recovering from substance abuse. “Every effort should be made to avoid opioids in these patients. We have developed a Pain Optimization Pathway which facilitates no postoperative opioids for these and other patients. These patients are at high risk to relapse and surgeons must know who these patients are so they can provide optimal care,” Dr. Englesbe added.The limitations of this study as reported by the authors include the single-center design, the nondiverse racial makeup of the sample, and the difficulty of ascertaining the dosing and duration of opioid use, both prescription and illegal.

The investigators reported no disclosures relevant to this study. This study was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, the American College of Surgeons, and other noncommercial sources.

SOURCE: Hilliard PE et al. JAMA Surg. 2018 Jul 11. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.2102.

FROM JAMA SURGERY

Key clinical point: Preoperative opioid use is prevalent in patients who are having spinal surgery and have depression.

Major finding:

Study details: An observational study of 34,186 surgical patients in the University of Michigan Health system.

Disclosures: The investigators reported no disclosures relevant to this study. This study was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, the American College of Surgeons, and other noncommercial sources.

Source: Hilliard P E et al. JAMA Surg. 2018 Jul 11;. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2018.2102.

Better ICU staff communication with family may improve end-of-life choices

A nurse-led support intervention for the families of critically ill patients did little to ease families’ psychological symptoms, but it did improve their perception of staff communication and family-centered care in the intensive care unit.

The length of ICU stay was also significantly shorter and the in-unit death rate higher among patients whose families received the intervention – a finding that suggests difficult end-of-life choices may have been eased, reported Douglas B. White, MD, and his colleagues (N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2365-75).

“The intervention resulted in significant improvements in markers of the quality of decision making, including the patient- and family-centeredness of care and the quality of clinician-family communication. Taken together, these findings suggest that the intervention allowed surrogates to transition a patient’s treatment to comfort-focused care when doing so aligned with the patient’s values,” wrote Dr. White of the University of Pittsburgh. “A previous study that was conducted in the context of advanced illness suggested that treatment that accords with the patient’s preferences may lead to shorter survival among those who prioritize comfort over longevity.”

The trial randomized 1,420 patients and their family surrogates in five ICUs to usual care, or to the multicomponent family-support intervention. The primary outcome was change in the surrogates’ scores on the Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS) at 6 months. The secondary outcomes were changes in Impact of Event Scale (IES; a measure of posttraumatic stress) the Quality of Communication (QOC) scale, quality of clinician-family communication measured by the Patient Perception of Patient Centeredness (PPPC) scale and the mean length of ICU stay.

The intervention was delivered by nurses who received special training on communication and other skills needed to support the families of critically ill patients. Nurses met with families every day and arranged regular meetings with ICU clinicians. A quality improvement specialist incorporated the family support into daily work flow.

In a fully adjusted model, there was no significant between-group difference in the 6-month HADS scores (11.7 vs. 12 points). Likewise, there was no significant difference between the groups in the mean IES score at 6 months.

Family members in the active group did rate the quality of clinician-family communication as significantly better, and they also gave significantly higher ratings to the quality of patient- and family-centered care during the ICU stay.

The shorter length of stay was reflected in the time to death among patients who died during the stay (4.4 days in the intervention group vs. 6.8 days in the control group), although there was no significant difference in length of stay among patients who survived to discharge. Significantly more patients in the intervention group died in the ICU as well (36% vs. 28.5%); however, there was no significant difference in 6-month mortality (60.4% vs. 55.4%).

The study was supported by an Innovation Award from the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Health System and by the Greenwell Foundation. Dr. White reported having no financial disclosures

Although the results by White and colleagues “cannot be interpreted as clinically directive,” the study offers a glimpse of the path forward in improving the experience of families with critically ill loved ones, Daniela Lamas, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018; 378:2431-2).

The study didn’t meet its primary endpoint of reducing surrogates’ psychological symptoms at 6 months, but it did lead to an improved ICU experience, with better clinician communication. There was another finding that deserves a close look: In the intervention group, ICU length of stay was shorter and in-hospital mortality greater, although mortality among those who survived to discharge was similar at 6 months.

These findings suggest that the intervention did not lead to the premature death of patients who would have otherwise done well, but rather was associated with a shorter dying process for those who faced a dismal prognosis, according to Dr. Lamas.

“As we increasingly look beyond mortality as the primary outcome that matters, seeking to maximize quality of life and minimize suffering, this work represents an ‘end of the beginning’ by suggesting the next steps in moving closer to achieving these goals.”

Dr. Lamas is a pulmonary and critical care doctor at Brigham & Women’s Hospital and on the faculty at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Although the results by White and colleagues “cannot be interpreted as clinically directive,” the study offers a glimpse of the path forward in improving the experience of families with critically ill loved ones, Daniela Lamas, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018; 378:2431-2).

The study didn’t meet its primary endpoint of reducing surrogates’ psychological symptoms at 6 months, but it did lead to an improved ICU experience, with better clinician communication. There was another finding that deserves a close look: In the intervention group, ICU length of stay was shorter and in-hospital mortality greater, although mortality among those who survived to discharge was similar at 6 months.

These findings suggest that the intervention did not lead to the premature death of patients who would have otherwise done well, but rather was associated with a shorter dying process for those who faced a dismal prognosis, according to Dr. Lamas.

“As we increasingly look beyond mortality as the primary outcome that matters, seeking to maximize quality of life and minimize suffering, this work represents an ‘end of the beginning’ by suggesting the next steps in moving closer to achieving these goals.”

Dr. Lamas is a pulmonary and critical care doctor at Brigham & Women’s Hospital and on the faculty at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Although the results by White and colleagues “cannot be interpreted as clinically directive,” the study offers a glimpse of the path forward in improving the experience of families with critically ill loved ones, Daniela Lamas, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018; 378:2431-2).

The study didn’t meet its primary endpoint of reducing surrogates’ psychological symptoms at 6 months, but it did lead to an improved ICU experience, with better clinician communication. There was another finding that deserves a close look: In the intervention group, ICU length of stay was shorter and in-hospital mortality greater, although mortality among those who survived to discharge was similar at 6 months.

These findings suggest that the intervention did not lead to the premature death of patients who would have otherwise done well, but rather was associated with a shorter dying process for those who faced a dismal prognosis, according to Dr. Lamas.

“As we increasingly look beyond mortality as the primary outcome that matters, seeking to maximize quality of life and minimize suffering, this work represents an ‘end of the beginning’ by suggesting the next steps in moving closer to achieving these goals.”

Dr. Lamas is a pulmonary and critical care doctor at Brigham & Women’s Hospital and on the faculty at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

A nurse-led support intervention for the families of critically ill patients did little to ease families’ psychological symptoms, but it did improve their perception of staff communication and family-centered care in the intensive care unit.

The length of ICU stay was also significantly shorter and the in-unit death rate higher among patients whose families received the intervention – a finding that suggests difficult end-of-life choices may have been eased, reported Douglas B. White, MD, and his colleagues (N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2365-75).

“The intervention resulted in significant improvements in markers of the quality of decision making, including the patient- and family-centeredness of care and the quality of clinician-family communication. Taken together, these findings suggest that the intervention allowed surrogates to transition a patient’s treatment to comfort-focused care when doing so aligned with the patient’s values,” wrote Dr. White of the University of Pittsburgh. “A previous study that was conducted in the context of advanced illness suggested that treatment that accords with the patient’s preferences may lead to shorter survival among those who prioritize comfort over longevity.”

The trial randomized 1,420 patients and their family surrogates in five ICUs to usual care, or to the multicomponent family-support intervention. The primary outcome was change in the surrogates’ scores on the Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS) at 6 months. The secondary outcomes were changes in Impact of Event Scale (IES; a measure of posttraumatic stress) the Quality of Communication (QOC) scale, quality of clinician-family communication measured by the Patient Perception of Patient Centeredness (PPPC) scale and the mean length of ICU stay.

The intervention was delivered by nurses who received special training on communication and other skills needed to support the families of critically ill patients. Nurses met with families every day and arranged regular meetings with ICU clinicians. A quality improvement specialist incorporated the family support into daily work flow.

In a fully adjusted model, there was no significant between-group difference in the 6-month HADS scores (11.7 vs. 12 points). Likewise, there was no significant difference between the groups in the mean IES score at 6 months.

Family members in the active group did rate the quality of clinician-family communication as significantly better, and they also gave significantly higher ratings to the quality of patient- and family-centered care during the ICU stay.

The shorter length of stay was reflected in the time to death among patients who died during the stay (4.4 days in the intervention group vs. 6.8 days in the control group), although there was no significant difference in length of stay among patients who survived to discharge. Significantly more patients in the intervention group died in the ICU as well (36% vs. 28.5%); however, there was no significant difference in 6-month mortality (60.4% vs. 55.4%).

The study was supported by an Innovation Award from the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Health System and by the Greenwell Foundation. Dr. White reported having no financial disclosures

A nurse-led support intervention for the families of critically ill patients did little to ease families’ psychological symptoms, but it did improve their perception of staff communication and family-centered care in the intensive care unit.

The length of ICU stay was also significantly shorter and the in-unit death rate higher among patients whose families received the intervention – a finding that suggests difficult end-of-life choices may have been eased, reported Douglas B. White, MD, and his colleagues (N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2365-75).

“The intervention resulted in significant improvements in markers of the quality of decision making, including the patient- and family-centeredness of care and the quality of clinician-family communication. Taken together, these findings suggest that the intervention allowed surrogates to transition a patient’s treatment to comfort-focused care when doing so aligned with the patient’s values,” wrote Dr. White of the University of Pittsburgh. “A previous study that was conducted in the context of advanced illness suggested that treatment that accords with the patient’s preferences may lead to shorter survival among those who prioritize comfort over longevity.”

The trial randomized 1,420 patients and their family surrogates in five ICUs to usual care, or to the multicomponent family-support intervention. The primary outcome was change in the surrogates’ scores on the Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS) at 6 months. The secondary outcomes were changes in Impact of Event Scale (IES; a measure of posttraumatic stress) the Quality of Communication (QOC) scale, quality of clinician-family communication measured by the Patient Perception of Patient Centeredness (PPPC) scale and the mean length of ICU stay.

The intervention was delivered by nurses who received special training on communication and other skills needed to support the families of critically ill patients. Nurses met with families every day and arranged regular meetings with ICU clinicians. A quality improvement specialist incorporated the family support into daily work flow.

In a fully adjusted model, there was no significant between-group difference in the 6-month HADS scores (11.7 vs. 12 points). Likewise, there was no significant difference between the groups in the mean IES score at 6 months.

Family members in the active group did rate the quality of clinician-family communication as significantly better, and they also gave significantly higher ratings to the quality of patient- and family-centered care during the ICU stay.

The shorter length of stay was reflected in the time to death among patients who died during the stay (4.4 days in the intervention group vs. 6.8 days in the control group), although there was no significant difference in length of stay among patients who survived to discharge. Significantly more patients in the intervention group died in the ICU as well (36% vs. 28.5%); however, there was no significant difference in 6-month mortality (60.4% vs. 55.4%).

The study was supported by an Innovation Award from the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Health System and by the Greenwell Foundation. Dr. White reported having no financial disclosures

FROM NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: A family communication intervention didn’t improve 6-month psychological symptoms among those with loved ones in intensive care units.

Major finding: There was no significant difference on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale at 6 months (11.7 vs. 12 points).

Study details: The study randomized 1,420 ICU patients and surrogates to the intervention or to usual care.

Disclosures: The study was supported by an Innovation Award from the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Health System and by the Greenwell Foundation. Dr. White had no financial disclosures.

Source: White et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2365-75.

Intranasal naloxone promising for type 1 hypoglycemia

ORLANDO –

“This has been a clinical problem for a very long time, and we see it all the time. A patient comes into my clinic, the nurses check their blood sugar, it’s 50 mg/dL, and they’re just sitting there without any symptoms,” said lead investigator Sandra Aleksic, MD, of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York.

As blood glucose in the brain drops, people get confused, and their behavioral defenses are compromised. They might crash if they’re driving. “If you have HAAF, it makes you prone to more hypoglycemia, which blunts your response even more. It’s a vicious cycle,” she said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Endogenous opioids are at least partly to blame. Hypoglycemia induces release of beta-endorphin, which in turn inhibits production of epinephrine. Einstein investigators have shown in previous small studies with healthy subjects that morphine blunts the response to induced hypoglycemia, and intravenous naloxone – an opioid blocker – prevents HAAF (Diabetes. 2017 Nov;66[11]:2764-73).

Intravenous naloxone, however, isn’t practical for outpatients, so the team wanted to see whether intranasal naloxone also prevented HAAF. The results “are very promising, but this is preliminary.” If it pans out, though, patients may one day carry intranasal naloxone along with their glucose pills and glucagon to treat hypoglycemia. “Any time they are getting low, they would take the spray,” Dr. Aleksic said.

The team used hypoglycemic, hyperinsulinemic clamps to drop blood glucose levels in seven healthy subjects down to 54 mg/dL for 2 hours twice in one day and gave them hourly sprays of either intranasal saline or 4 mg of intranasal naloxone; hypoglycemia was induced again for 2 hours the following day. The 2-day experiment was repeated 5 weeks later.

Overall, there was no difference in peak epinephrine levels between the first hypoglycemic episode on day 1 and the third episode on day 2 in subjects randomized to naloxone (942 pg/mL plus or minus 190 versus 857 pg/mL plus or minus 134; P = .4). The third episode, meanwhile, placed placebo subjects into HAAF (first hypoglycemic episode 1,375 pg/mL plus or minus 182 versus 858 pg/mL plus or minus 235; P = .004). There was also a trend toward higher hepatic glucose production in the naloxone group.

“These findings suggest that HAAF can be prevented by acute blockade of opioid receptors during hypoglycemia. ... Acute self-administration of intranasal naloxone could be an effective and feasible real-world approach to ameliorate HAAF in type 1 diabetes,” the investigators concluded. A trial in patients with T1DM is being considered.

Dr. Aleksic estimated that patients with T1DM drop blood glucose below 54 mg/dL maybe three or four times a month, on average, depending on how well they manage the condition. For now, it’s unknown how long protection from naloxone would last.

The study subjects were men, 43 years old, on average, with a mean body mass index of 26 kg/m2.

The investigators didn’t have any disclosures, and there was no industry funding for the work.

SOURCE: Aleksic S et al. ADA 2018, Abstract 10-LB.

ORLANDO –

“This has been a clinical problem for a very long time, and we see it all the time. A patient comes into my clinic, the nurses check their blood sugar, it’s 50 mg/dL, and they’re just sitting there without any symptoms,” said lead investigator Sandra Aleksic, MD, of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York.

As blood glucose in the brain drops, people get confused, and their behavioral defenses are compromised. They might crash if they’re driving. “If you have HAAF, it makes you prone to more hypoglycemia, which blunts your response even more. It’s a vicious cycle,” she said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Endogenous opioids are at least partly to blame. Hypoglycemia induces release of beta-endorphin, which in turn inhibits production of epinephrine. Einstein investigators have shown in previous small studies with healthy subjects that morphine blunts the response to induced hypoglycemia, and intravenous naloxone – an opioid blocker – prevents HAAF (Diabetes. 2017 Nov;66[11]:2764-73).

Intravenous naloxone, however, isn’t practical for outpatients, so the team wanted to see whether intranasal naloxone also prevented HAAF. The results “are very promising, but this is preliminary.” If it pans out, though, patients may one day carry intranasal naloxone along with their glucose pills and glucagon to treat hypoglycemia. “Any time they are getting low, they would take the spray,” Dr. Aleksic said.

The team used hypoglycemic, hyperinsulinemic clamps to drop blood glucose levels in seven healthy subjects down to 54 mg/dL for 2 hours twice in one day and gave them hourly sprays of either intranasal saline or 4 mg of intranasal naloxone; hypoglycemia was induced again for 2 hours the following day. The 2-day experiment was repeated 5 weeks later.

Overall, there was no difference in peak epinephrine levels between the first hypoglycemic episode on day 1 and the third episode on day 2 in subjects randomized to naloxone (942 pg/mL plus or minus 190 versus 857 pg/mL plus or minus 134; P = .4). The third episode, meanwhile, placed placebo subjects into HAAF (first hypoglycemic episode 1,375 pg/mL plus or minus 182 versus 858 pg/mL plus or minus 235; P = .004). There was also a trend toward higher hepatic glucose production in the naloxone group.

“These findings suggest that HAAF can be prevented by acute blockade of opioid receptors during hypoglycemia. ... Acute self-administration of intranasal naloxone could be an effective and feasible real-world approach to ameliorate HAAF in type 1 diabetes,” the investigators concluded. A trial in patients with T1DM is being considered.

Dr. Aleksic estimated that patients with T1DM drop blood glucose below 54 mg/dL maybe three or four times a month, on average, depending on how well they manage the condition. For now, it’s unknown how long protection from naloxone would last.

The study subjects were men, 43 years old, on average, with a mean body mass index of 26 kg/m2.

The investigators didn’t have any disclosures, and there was no industry funding for the work.

SOURCE: Aleksic S et al. ADA 2018, Abstract 10-LB.

ORLANDO –

“This has been a clinical problem for a very long time, and we see it all the time. A patient comes into my clinic, the nurses check their blood sugar, it’s 50 mg/dL, and they’re just sitting there without any symptoms,” said lead investigator Sandra Aleksic, MD, of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York.

As blood glucose in the brain drops, people get confused, and their behavioral defenses are compromised. They might crash if they’re driving. “If you have HAAF, it makes you prone to more hypoglycemia, which blunts your response even more. It’s a vicious cycle,” she said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Endogenous opioids are at least partly to blame. Hypoglycemia induces release of beta-endorphin, which in turn inhibits production of epinephrine. Einstein investigators have shown in previous small studies with healthy subjects that morphine blunts the response to induced hypoglycemia, and intravenous naloxone – an opioid blocker – prevents HAAF (Diabetes. 2017 Nov;66[11]:2764-73).

Intravenous naloxone, however, isn’t practical for outpatients, so the team wanted to see whether intranasal naloxone also prevented HAAF. The results “are very promising, but this is preliminary.” If it pans out, though, patients may one day carry intranasal naloxone along with their glucose pills and glucagon to treat hypoglycemia. “Any time they are getting low, they would take the spray,” Dr. Aleksic said.

The team used hypoglycemic, hyperinsulinemic clamps to drop blood glucose levels in seven healthy subjects down to 54 mg/dL for 2 hours twice in one day and gave them hourly sprays of either intranasal saline or 4 mg of intranasal naloxone; hypoglycemia was induced again for 2 hours the following day. The 2-day experiment was repeated 5 weeks later.

Overall, there was no difference in peak epinephrine levels between the first hypoglycemic episode on day 1 and the third episode on day 2 in subjects randomized to naloxone (942 pg/mL plus or minus 190 versus 857 pg/mL plus or minus 134; P = .4). The third episode, meanwhile, placed placebo subjects into HAAF (first hypoglycemic episode 1,375 pg/mL plus or minus 182 versus 858 pg/mL plus or minus 235; P = .004). There was also a trend toward higher hepatic glucose production in the naloxone group.

“These findings suggest that HAAF can be prevented by acute blockade of opioid receptors during hypoglycemia. ... Acute self-administration of intranasal naloxone could be an effective and feasible real-world approach to ameliorate HAAF in type 1 diabetes,” the investigators concluded. A trial in patients with T1DM is being considered.

Dr. Aleksic estimated that patients with T1DM drop blood glucose below 54 mg/dL maybe three or four times a month, on average, depending on how well they manage the condition. For now, it’s unknown how long protection from naloxone would last.

The study subjects were men, 43 years old, on average, with a mean body mass index of 26 kg/m2.

The investigators didn’t have any disclosures, and there was no industry funding for the work.

SOURCE: Aleksic S et al. ADA 2018, Abstract 10-LB.

REPORTING FROM ADA 2018

Key clinical point: Intranasal naloxone might be just the ticket to prevent hypoglycemia-associated autonomic failure in type 1 diabetes mellitus.

Major finding: Overall, there was no difference in peak epinephrine levels between the first day 1 hypoglycemic episode and the third episode on day 2 in subjects randomized to naloxone (942 plus or minus 190 pg/mL versus 857 plus or minus 134 pg/mL; P = 0.4).

Study details: Randomized trial with seven healthy volunteers

Disclosures: There was no industry funding for the work, and the investigators didn’t have any disclosures.

Source: Aleksic S et al. ADA 2018, Abstract 10-LB

More testing of febrile infants at teaching vs. community hospitals, but similar outcomes

TORONTO – according to a study presented at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

“The community hospitals are doing less procedures on the infants, but with basically the exact same outcomes,” said Beth C. Natt, MD, MPH, director of pediatric hospital medicine at Bridgeport (Conn.) Hospital.

Babies who presented to university-affiliated hospitals were more likely to be hospitalized (70% vs. 67%; P = .001) than were those at community hospitals, but had a similar likelihood of being diagnosed with bacteremia, meningitis, or urinary tract infection. The rates of missed bacterial infection were 0.8% for teaching hospitals and 1% for community hospitals (P = .346).

“There is some thought that in community settings, because we’re not completing the workup in the standard, protocolized way seen at teaching hospitals, we might be doing wrong by the children, but these data show we’re actually doing just fine,” Dr. Natt said in an interview.

She and her colleagues reviewed 9,884 febrile infant evaluations occurring at 132 hospitals participating in the Reducing Excessive Variation in the Infant Sepsis Evaluation (REVISE) quality improvement project. Two-thirds of the infants (n = 6,479) were evaluated across 78 university-affiliated hospitals and 3,405 (or 34%) were seen at 54 community hospitals. Hospital status was self-reported.

The teaching hospitals more often had at least one pediatric emergency medicine provider, compared with community hospitals (90% vs. 57%; P = .001) and were more likely to see babies between 7 and 30 days old (90% vs. 57%; P = .001). They also were more likely to obtain urine cultures (92% vs. 88%; P = 0.001), blood cultures (84% vs. 80%; P = .001), and cerebral spinal fluid cultures (62% vs. 57%; P = .001).

On the other hand, community hospitals were significantly more likely to see children presenting with respiratory symptoms (39% vs. 36% for teaching hospitals; P = .014), and were more likely to order chest x-rays on febrile infants (32% vs. 24% for university-affiliated hospitals; P = .001).

“As a community hospitalist, the results weren’t that surprising to me,” said Dr. Natt. “If anything was surprising it was how often we were doing chest x-rays, but I think that had to do with the fact that we had more children with respiratory symptoms coming to community hospitals.

“The American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines for fever were written last in 1993, when I was in high school, so they are very due to be revised,” said Dr. Natt. “I suspect the new guidelines will have us doing fewer spinal taps in children and more watchful waiting.”

TORONTO – according to a study presented at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

“The community hospitals are doing less procedures on the infants, but with basically the exact same outcomes,” said Beth C. Natt, MD, MPH, director of pediatric hospital medicine at Bridgeport (Conn.) Hospital.

Babies who presented to university-affiliated hospitals were more likely to be hospitalized (70% vs. 67%; P = .001) than were those at community hospitals, but had a similar likelihood of being diagnosed with bacteremia, meningitis, or urinary tract infection. The rates of missed bacterial infection were 0.8% for teaching hospitals and 1% for community hospitals (P = .346).

“There is some thought that in community settings, because we’re not completing the workup in the standard, protocolized way seen at teaching hospitals, we might be doing wrong by the children, but these data show we’re actually doing just fine,” Dr. Natt said in an interview.

She and her colleagues reviewed 9,884 febrile infant evaluations occurring at 132 hospitals participating in the Reducing Excessive Variation in the Infant Sepsis Evaluation (REVISE) quality improvement project. Two-thirds of the infants (n = 6,479) were evaluated across 78 university-affiliated hospitals and 3,405 (or 34%) were seen at 54 community hospitals. Hospital status was self-reported.

The teaching hospitals more often had at least one pediatric emergency medicine provider, compared with community hospitals (90% vs. 57%; P = .001) and were more likely to see babies between 7 and 30 days old (90% vs. 57%; P = .001). They also were more likely to obtain urine cultures (92% vs. 88%; P = 0.001), blood cultures (84% vs. 80%; P = .001), and cerebral spinal fluid cultures (62% vs. 57%; P = .001).

On the other hand, community hospitals were significantly more likely to see children presenting with respiratory symptoms (39% vs. 36% for teaching hospitals; P = .014), and were more likely to order chest x-rays on febrile infants (32% vs. 24% for university-affiliated hospitals; P = .001).

“As a community hospitalist, the results weren’t that surprising to me,” said Dr. Natt. “If anything was surprising it was how often we were doing chest x-rays, but I think that had to do with the fact that we had more children with respiratory symptoms coming to community hospitals.

“The American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines for fever were written last in 1993, when I was in high school, so they are very due to be revised,” said Dr. Natt. “I suspect the new guidelines will have us doing fewer spinal taps in children and more watchful waiting.”

TORONTO – according to a study presented at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

“The community hospitals are doing less procedures on the infants, but with basically the exact same outcomes,” said Beth C. Natt, MD, MPH, director of pediatric hospital medicine at Bridgeport (Conn.) Hospital.

Babies who presented to university-affiliated hospitals were more likely to be hospitalized (70% vs. 67%; P = .001) than were those at community hospitals, but had a similar likelihood of being diagnosed with bacteremia, meningitis, or urinary tract infection. The rates of missed bacterial infection were 0.8% for teaching hospitals and 1% for community hospitals (P = .346).

“There is some thought that in community settings, because we’re not completing the workup in the standard, protocolized way seen at teaching hospitals, we might be doing wrong by the children, but these data show we’re actually doing just fine,” Dr. Natt said in an interview.

She and her colleagues reviewed 9,884 febrile infant evaluations occurring at 132 hospitals participating in the Reducing Excessive Variation in the Infant Sepsis Evaluation (REVISE) quality improvement project. Two-thirds of the infants (n = 6,479) were evaluated across 78 university-affiliated hospitals and 3,405 (or 34%) were seen at 54 community hospitals. Hospital status was self-reported.

The teaching hospitals more often had at least one pediatric emergency medicine provider, compared with community hospitals (90% vs. 57%; P = .001) and were more likely to see babies between 7 and 30 days old (90% vs. 57%; P = .001). They also were more likely to obtain urine cultures (92% vs. 88%; P = 0.001), blood cultures (84% vs. 80%; P = .001), and cerebral spinal fluid cultures (62% vs. 57%; P = .001).

On the other hand, community hospitals were significantly more likely to see children presenting with respiratory symptoms (39% vs. 36% for teaching hospitals; P = .014), and were more likely to order chest x-rays on febrile infants (32% vs. 24% for university-affiliated hospitals; P = .001).

“As a community hospitalist, the results weren’t that surprising to me,” said Dr. Natt. “If anything was surprising it was how often we were doing chest x-rays, but I think that had to do with the fact that we had more children with respiratory symptoms coming to community hospitals.

“The American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines for fever were written last in 1993, when I was in high school, so they are very due to be revised,” said Dr. Natt. “I suspect the new guidelines will have us doing fewer spinal taps in children and more watchful waiting.”

AT PAS 18

Key clinical point: University-affiliated hospitals do more invasive testing in febrile infants, but have outcomes similar to those of community hospitals.

Major finding: The rate of missed bacterial infection did not differ between hospital types: 0.8% for teaching hospitals and 1% for community hospitals (P = .346).

Study details: Review of 9,884 febrile infant evaluations occurring at 132 hospitals, 66% of which were university-affiliated hospitals and 34% of which were community hospitals.

Disclosures: The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

Fentanyl analogs nearly double their overdose death toll

, according to preliminary data from 10 states.

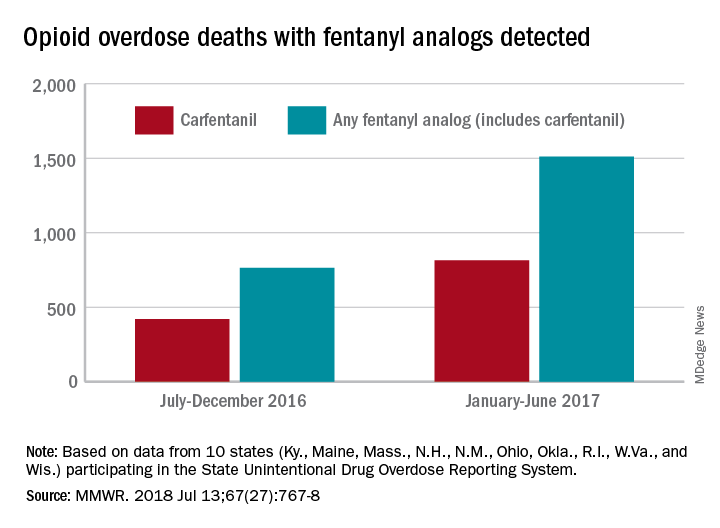

During July 2016 to December 2016, there were 764 opioid overdose deaths that tested positive for any fentanyl analog, with carfentanil being the most common (421 deaths). From January 2017 to June 2017, the respective numbers increased by 98% (1,511) and 94% (815), wrote Julie O’Donnell, PhD, and her associates at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. The report was published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

“The increasing array of fentanyl analogs highlights the need to build forensic toxicological testing capabilities to identify and report emerging threats, and to enhance capacity to rapidly respond to evolving drug trends,” Dr. O’Donnell and her associates said.

Along with carfentanil, 13 other analogs were detected in decedents during the 12-month period: 3-methylfentanyl, 4-fluorobutyrfentanyl, 4-fluorofentanyl, 4-fluoroisobutyrfentanyl, acetylfentanyl, acrylfentanyl, butyrylfentanyl, cyclopropylfentanyl, cyclopentylfentanyl, furanylethylfentanyl, furanylfentanyl, isobutyrylfentanyl, and tetrahydrofuranylfentanyl. Deaths may have involved “more than one analog, as well as ... other opioid and nonopioid substances,” they noted.

The 10 states reporting data to the State Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System (SUDORS) were Kentucky, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Ohio, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, West Virginia, and Wisconsin. Two other SUDORS-reporting states – Missouri and Pennsylvania – did not have their data ready in time to be included in this analysis.

The increasing availability of fentanyl analogs hit Ohio especially hard: More deaths occurred there than in the other 10 states combined. Of the 421 carfentanil-related deaths in July 2016 to December 2016, nearly 400 were in Ohio, and there were 218 Ohio deaths in April 2017 alone. A look at the bigger picture shows that 3 of the 10 states reported carfentanil-related overdose deaths in the second half of 2016, compared with 7 in the first half of 2017, the investigators said.

Carfentanil, which is the most potent of the 14 fentanyl analogs that have been detected so far, “is intended for sedation of large animals, and is estimated to have 10,000 times the potency of morphine,” Dr. O’Donnell and her associates wrote.

SOURCE: O’Donnell J et al. MMWR. 2018 Jul 13;67(27):767-8.

, according to preliminary data from 10 states.

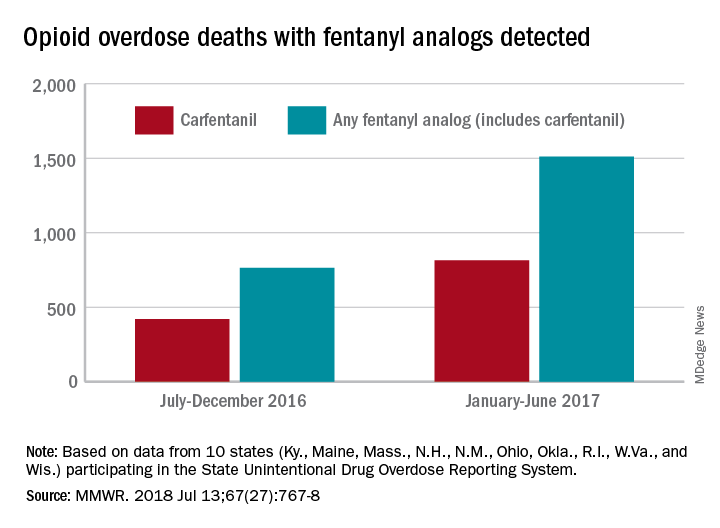

During July 2016 to December 2016, there were 764 opioid overdose deaths that tested positive for any fentanyl analog, with carfentanil being the most common (421 deaths). From January 2017 to June 2017, the respective numbers increased by 98% (1,511) and 94% (815), wrote Julie O’Donnell, PhD, and her associates at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. The report was published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

“The increasing array of fentanyl analogs highlights the need to build forensic toxicological testing capabilities to identify and report emerging threats, and to enhance capacity to rapidly respond to evolving drug trends,” Dr. O’Donnell and her associates said.

Along with carfentanil, 13 other analogs were detected in decedents during the 12-month period: 3-methylfentanyl, 4-fluorobutyrfentanyl, 4-fluorofentanyl, 4-fluoroisobutyrfentanyl, acetylfentanyl, acrylfentanyl, butyrylfentanyl, cyclopropylfentanyl, cyclopentylfentanyl, furanylethylfentanyl, furanylfentanyl, isobutyrylfentanyl, and tetrahydrofuranylfentanyl. Deaths may have involved “more than one analog, as well as ... other opioid and nonopioid substances,” they noted.

The 10 states reporting data to the State Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System (SUDORS) were Kentucky, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Ohio, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, West Virginia, and Wisconsin. Two other SUDORS-reporting states – Missouri and Pennsylvania – did not have their data ready in time to be included in this analysis.

The increasing availability of fentanyl analogs hit Ohio especially hard: More deaths occurred there than in the other 10 states combined. Of the 421 carfentanil-related deaths in July 2016 to December 2016, nearly 400 were in Ohio, and there were 218 Ohio deaths in April 2017 alone. A look at the bigger picture shows that 3 of the 10 states reported carfentanil-related overdose deaths in the second half of 2016, compared with 7 in the first half of 2017, the investigators said.

Carfentanil, which is the most potent of the 14 fentanyl analogs that have been detected so far, “is intended for sedation of large animals, and is estimated to have 10,000 times the potency of morphine,” Dr. O’Donnell and her associates wrote.

SOURCE: O’Donnell J et al. MMWR. 2018 Jul 13;67(27):767-8.

, according to preliminary data from 10 states.

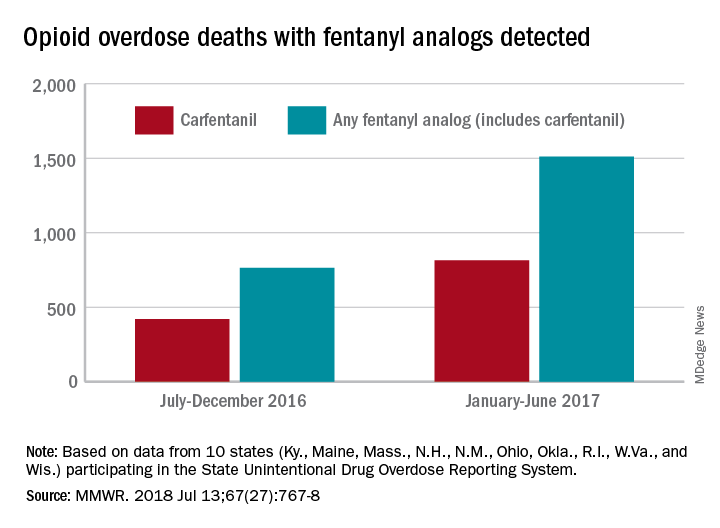

During July 2016 to December 2016, there were 764 opioid overdose deaths that tested positive for any fentanyl analog, with carfentanil being the most common (421 deaths). From January 2017 to June 2017, the respective numbers increased by 98% (1,511) and 94% (815), wrote Julie O’Donnell, PhD, and her associates at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. The report was published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

“The increasing array of fentanyl analogs highlights the need to build forensic toxicological testing capabilities to identify and report emerging threats, and to enhance capacity to rapidly respond to evolving drug trends,” Dr. O’Donnell and her associates said.

Along with carfentanil, 13 other analogs were detected in decedents during the 12-month period: 3-methylfentanyl, 4-fluorobutyrfentanyl, 4-fluorofentanyl, 4-fluoroisobutyrfentanyl, acetylfentanyl, acrylfentanyl, butyrylfentanyl, cyclopropylfentanyl, cyclopentylfentanyl, furanylethylfentanyl, furanylfentanyl, isobutyrylfentanyl, and tetrahydrofuranylfentanyl. Deaths may have involved “more than one analog, as well as ... other opioid and nonopioid substances,” they noted.

The 10 states reporting data to the State Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System (SUDORS) were Kentucky, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Ohio, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, West Virginia, and Wisconsin. Two other SUDORS-reporting states – Missouri and Pennsylvania – did not have their data ready in time to be included in this analysis.

The increasing availability of fentanyl analogs hit Ohio especially hard: More deaths occurred there than in the other 10 states combined. Of the 421 carfentanil-related deaths in July 2016 to December 2016, nearly 400 were in Ohio, and there were 218 Ohio deaths in April 2017 alone. A look at the bigger picture shows that 3 of the 10 states reported carfentanil-related overdose deaths in the second half of 2016, compared with 7 in the first half of 2017, the investigators said.

Carfentanil, which is the most potent of the 14 fentanyl analogs that have been detected so far, “is intended for sedation of large animals, and is estimated to have 10,000 times the potency of morphine,” Dr. O’Donnell and her associates wrote.

SOURCE: O’Donnell J et al. MMWR. 2018 Jul 13;67(27):767-8.

FROM MMWR

Pediatric inpatient seizures treated quickly with new intervention

TORONTO – Researchers at UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital in San Francisco implemented a novel intervention that leveraged existing in-room technology to expedite antiepileptic drug administration to inpatients having a seizure.

With the quality initiative, they were able to decrease median time from seizure onset to benzodiazepine (BZD) administration from 7 minutes (preintervention) to 2 minutes (post intervention) and reduce the median time from order to administration of second-phase non-BZDs from 28 minutes to 11 minutes.

“Leveraging existing patient room technology to mobilize pharmacy to the bedside expedited non-BZD administration by 60%,” reported principal investigator Arpi Bekmezian, MD, a pediatric hospitalist and medical director of quality and safety at Benioff Children’s Hospital. She presented the findings at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

“Furthermore, the rapid-response seizure rescue process may have created an increased sense of urgency helping to expedite initial BZD administration by 70%. ... This may have prevented the need for second-phase therapy and progression to status epilepticus, potentially minimizing the risk of neuronal injury, and all without the additional resources of a Code team.”

Early and rapid escalation of treatment is critical to prevent neuronal injury in patients with status epilepticus. Guidelines recommend initial antiepileptic therapy at 5 minutes, with rapid escalation to second-phase therapy if the seizure persists.

Preintervention baseline data from UCSF Benioff Children’s indicated a 7-minute lag time from seizure onset to BZD therapy and a 28-minute lag from order to administration of non-BZDs (phenobarbital, phenytoin, levetiracetam, valproic acid). Other studies have shown significantly greater delays to antiepileptic treatment.

“That was just too long, and it matched our clinical experience of being at the bedside of a seizing patient and wondering why the medication was taking so long to arrive from the pharmacy.”

The researchers set out to reduce time to BZD administration from 7 minutes to 5 minutes or less and to reduce time to second-phase non-BZD administration to less than 10 minutes. To accomplish this, a multidisciplinary team that included leadership from physicians, pharmacy, and nursing defined primary and secondary drivers of efficiency, with interventions targeting both team communication and medication delivery.

The intervention period lasted 16 months, during which time there were 61 seizure events requiring urgent antiepileptic treatment. Complete data were available for 57 seizures.

Among the interventions they implemented was to stock all medication-dispensing stations with intranasal/buccal BZD available on “nursing override” for easy access and administration.

Because non-BZDs require pharmacy compounding, and the main pharmacy receives many STAT orders with competing priorities, they developed a hospitalwide “seizure rescue” (SR) process by using patient-room staff terminals to activate a dedicated individual from the pharmacy, who would then report to the bedside with a backpack stocked with non-BZDs ready to compound. Nurses were trained to press the SR button for any seizure that may require urgent therapy.

“We didn’t want nurses to waste time on the phone [calling pharmacy], and we considered calling a Code, but we couldn’t really justify the resource utilization as most of these patients didn’t have respiratory compromise, and they didn’t need the whole Code team,” said Dr. Bekmezian. She noted that her hospital strongly discourages bedside compounding by nursing staff.

Instead, they realized they could easily reprogram the patient-room electronic staff terminals to have a dedicated SR button that would directly alert a dedicated pharmacist carrying the SR phone. The pharmacist could then swipe and confirm that they received the alert and let the nurse know they were on the way, “and this would free up the nurse to go ahead and obtain the benzodiazepines and administer them as pharmacy made their way to the room.”

“To our knowledge, this is the first study to report expediting antiepileptic drug delivery to patients in the hospital,” said Dr. Bekmezian. She noted that less than 50% of cases actually required pharmacist response, “but the pharmacy staff chose to be activated earlier in the management algorithm to avoid delays in treatment.”

UCSF Children’s Hospital San Francisco campus is a 183-bed, tertiary care, teaching children’s hospital that has pediatric, neonatal, and cardiac intensive care units and set-down units. They provide liver, bone marrow, kidney, and cardiac transplantation and have more than 10,000 annual admissions.

The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bekmezian A et al. PAS 2018. Abstract 3545.3.

TORONTO – Researchers at UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital in San Francisco implemented a novel intervention that leveraged existing in-room technology to expedite antiepileptic drug administration to inpatients having a seizure.

With the quality initiative, they were able to decrease median time from seizure onset to benzodiazepine (BZD) administration from 7 minutes (preintervention) to 2 minutes (post intervention) and reduce the median time from order to administration of second-phase non-BZDs from 28 minutes to 11 minutes.

“Leveraging existing patient room technology to mobilize pharmacy to the bedside expedited non-BZD administration by 60%,” reported principal investigator Arpi Bekmezian, MD, a pediatric hospitalist and medical director of quality and safety at Benioff Children’s Hospital. She presented the findings at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

“Furthermore, the rapid-response seizure rescue process may have created an increased sense of urgency helping to expedite initial BZD administration by 70%. ... This may have prevented the need for second-phase therapy and progression to status epilepticus, potentially minimizing the risk of neuronal injury, and all without the additional resources of a Code team.”

Early and rapid escalation of treatment is critical to prevent neuronal injury in patients with status epilepticus. Guidelines recommend initial antiepileptic therapy at 5 minutes, with rapid escalation to second-phase therapy if the seizure persists.

Preintervention baseline data from UCSF Benioff Children’s indicated a 7-minute lag time from seizure onset to BZD therapy and a 28-minute lag from order to administration of non-BZDs (phenobarbital, phenytoin, levetiracetam, valproic acid). Other studies have shown significantly greater delays to antiepileptic treatment.

“That was just too long, and it matched our clinical experience of being at the bedside of a seizing patient and wondering why the medication was taking so long to arrive from the pharmacy.”

The researchers set out to reduce time to BZD administration from 7 minutes to 5 minutes or less and to reduce time to second-phase non-BZD administration to less than 10 minutes. To accomplish this, a multidisciplinary team that included leadership from physicians, pharmacy, and nursing defined primary and secondary drivers of efficiency, with interventions targeting both team communication and medication delivery.

The intervention period lasted 16 months, during which time there were 61 seizure events requiring urgent antiepileptic treatment. Complete data were available for 57 seizures.

Among the interventions they implemented was to stock all medication-dispensing stations with intranasal/buccal BZD available on “nursing override” for easy access and administration.

Because non-BZDs require pharmacy compounding, and the main pharmacy receives many STAT orders with competing priorities, they developed a hospitalwide “seizure rescue” (SR) process by using patient-room staff terminals to activate a dedicated individual from the pharmacy, who would then report to the bedside with a backpack stocked with non-BZDs ready to compound. Nurses were trained to press the SR button for any seizure that may require urgent therapy.

“We didn’t want nurses to waste time on the phone [calling pharmacy], and we considered calling a Code, but we couldn’t really justify the resource utilization as most of these patients didn’t have respiratory compromise, and they didn’t need the whole Code team,” said Dr. Bekmezian. She noted that her hospital strongly discourages bedside compounding by nursing staff.

Instead, they realized they could easily reprogram the patient-room electronic staff terminals to have a dedicated SR button that would directly alert a dedicated pharmacist carrying the SR phone. The pharmacist could then swipe and confirm that they received the alert and let the nurse know they were on the way, “and this would free up the nurse to go ahead and obtain the benzodiazepines and administer them as pharmacy made their way to the room.”

“To our knowledge, this is the first study to report expediting antiepileptic drug delivery to patients in the hospital,” said Dr. Bekmezian. She noted that less than 50% of cases actually required pharmacist response, “but the pharmacy staff chose to be activated earlier in the management algorithm to avoid delays in treatment.”

UCSF Children’s Hospital San Francisco campus is a 183-bed, tertiary care, teaching children’s hospital that has pediatric, neonatal, and cardiac intensive care units and set-down units. They provide liver, bone marrow, kidney, and cardiac transplantation and have more than 10,000 annual admissions.

The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bekmezian A et al. PAS 2018. Abstract 3545.3.

TORONTO – Researchers at UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital in San Francisco implemented a novel intervention that leveraged existing in-room technology to expedite antiepileptic drug administration to inpatients having a seizure.