User login

Lower glucose targets show improved mortality in cardiac patients

Tighter glucose control while minimizing the risk of severe hypoglycemia is associated with lower mortality among critically ill cardiac patents, new research suggests.

Researchers reported in CHEST on the outcomes of a multicenter retrospective cohort study in 1,809 adults in cardiac ICUs. Patients were treated either to a blood glucose target of 80-110 mg/dL or 90-140 mg/dL, based on the clinician’s preference, but using a computerized ICU insulin infusion protocol that the authors said had resulted in low rates of severe hypoglycemia.

The study found patients treated to the 80-110 mg/dL blood glucose target had a significantly lower unadjusted 30-day mortality compared to patients treated to the 90-140 mg/dL target (4.3% vs. 9.2%; P less than .001). The lower mortality in the lower target group was evident among both diabetic (4.7% vs. 12.9%; P less than .001) and nondiabetic patients (4.1% vs. 7.4%; P = .02).

Researchers also saw that unadjusted 30-day mortality increased with increasing median glucose levels; 5.5% in patients with a blood glucose of 70-110 mg/dL, 8.3% mortality in those with blood glucose levels of 141-180 mg/dL, and 25% in those with a blood glucose level higher than 180 mg/dL.

Patients treated to the 80-110 mg/dL blood glucose target were more likely to experience an episode of moderate hypoglycemia, compared with those in the higher target group (18.6% vs. 8.3%; P less than .001). However, the rates of severe hypoglycemia were low in both groups, and the difference between the low and high target groups did not reach statistical significance (1.16% vs. 0.35%; P = .051).

The authors did note that patients whose blood glucose dropped below 60 mg/dL showed increased mortality, regardless of what target they was set for them. The 30-day unadjusted mortality in these patients was 15%, compared with 5.2% for patients in either group who did not experience a blood glucose level below 60 mg/dL.

“Our results further the discussion about the appropriate BG [blood glucose] target in the critically ill because they suggest that the BG target and severe hypoglycemia effects can be separated,” wrote Andrew M. Hersh, MD, of the division of pulmonary and critical care at San Antonio Military Medical Center, and his coauthors.

But they said the large differences in mortality seen between the two treatment targets should be interpreted with caution, as it was difficult to attribute that difference solely to an 18 mg/dL difference in blood glucose treatment targets.

“While we attempted to capture factors that influenced clinician choice, and while our model successfully achieved balance, suggesting that residual confounding was minimized, we suspect that some of the mortality signal may be attributable to residual confounding,” they wrote.

Another explanation could be that hypoglycemia was an ‘epiphenomenon’ of multiorgan failure, as some studies have found that both spontaneous and iatrogenic hypoglycemia were independently associated with mortality. “However, given the very-low rates of severe hypoglycemia found in both groups it is unlikely that this was a main driver of the mortality difference found,” the investigators wrote.

The majority of patients in the study had been admitted to the hospital for chest pain or acute coronary syndrome (43.3%), while 31.9% were admitted for cardiothoracic surgery, 6.8% for heart failure including cardiogenic shock, and 6% for vascular surgery.

The authors commented that a safe and reliable protocol for intensive insulin therapy, with high clinician compliance, could be the key to realizing its benefits, and could be aided by recent advances such as closed-loop insulin delivery systems.

They also stressed that their results did not support a rejection of current guidelines and instead called for large randomized, clinical trials to find a balance between benefits and harms of intensive insulin therapy.

“Instead our analysis suggests that trials such as NICE-SUGAR, and the conclusion they drew, may have been accurate only in the setting of technologies, which led to high rates of severe hypoglycemia.”

No conflicts of interest were declared.

After the multicenter NICE-SUGAR trial showed higher 90-day mortality in patients treated with intensive insulin therapy to lower blood glucose targets, compared with more moderate targets, enthusiasm has waned for tighter blood glucose control, James S. Krinsley, MD, argued in an editorial accompanying the study (CHEST 2018; 154[5]:1004-5). But the assumption of a “one-size-fits-all” approach to glucose control in the critically ill is a potential flaw of randomized clinical trials, he noted, and some patients may be better suited to tighter control than others. This study has shown that standardized protocols, including frequent measurement of blood glucose, can safely achieve tight blood glucose control in the ICU with low rates of hypoglycemia. If these findings are confirmed in larger multicenter clinical trials, it should prompt a rethink of blood glucose targets in the critically ill, he concluded.

Dr. Krinsley is director of critical care at Stamford (Conn.) Hospital and clinical professor of medicine at the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York. He declared consultancies or advisory board positions with Edwards Life Sciences, Medtronic, OptiScan Biomedical, and Roche Diagnostics.

After the multicenter NICE-SUGAR trial showed higher 90-day mortality in patients treated with intensive insulin therapy to lower blood glucose targets, compared with more moderate targets, enthusiasm has waned for tighter blood glucose control, James S. Krinsley, MD, argued in an editorial accompanying the study (CHEST 2018; 154[5]:1004-5). But the assumption of a “one-size-fits-all” approach to glucose control in the critically ill is a potential flaw of randomized clinical trials, he noted, and some patients may be better suited to tighter control than others. This study has shown that standardized protocols, including frequent measurement of blood glucose, can safely achieve tight blood glucose control in the ICU with low rates of hypoglycemia. If these findings are confirmed in larger multicenter clinical trials, it should prompt a rethink of blood glucose targets in the critically ill, he concluded.

Dr. Krinsley is director of critical care at Stamford (Conn.) Hospital and clinical professor of medicine at the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York. He declared consultancies or advisory board positions with Edwards Life Sciences, Medtronic, OptiScan Biomedical, and Roche Diagnostics.

After the multicenter NICE-SUGAR trial showed higher 90-day mortality in patients treated with intensive insulin therapy to lower blood glucose targets, compared with more moderate targets, enthusiasm has waned for tighter blood glucose control, James S. Krinsley, MD, argued in an editorial accompanying the study (CHEST 2018; 154[5]:1004-5). But the assumption of a “one-size-fits-all” approach to glucose control in the critically ill is a potential flaw of randomized clinical trials, he noted, and some patients may be better suited to tighter control than others. This study has shown that standardized protocols, including frequent measurement of blood glucose, can safely achieve tight blood glucose control in the ICU with low rates of hypoglycemia. If these findings are confirmed in larger multicenter clinical trials, it should prompt a rethink of blood glucose targets in the critically ill, he concluded.

Dr. Krinsley is director of critical care at Stamford (Conn.) Hospital and clinical professor of medicine at the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York. He declared consultancies or advisory board positions with Edwards Life Sciences, Medtronic, OptiScan Biomedical, and Roche Diagnostics.

Tighter glucose control while minimizing the risk of severe hypoglycemia is associated with lower mortality among critically ill cardiac patents, new research suggests.

Researchers reported in CHEST on the outcomes of a multicenter retrospective cohort study in 1,809 adults in cardiac ICUs. Patients were treated either to a blood glucose target of 80-110 mg/dL or 90-140 mg/dL, based on the clinician’s preference, but using a computerized ICU insulin infusion protocol that the authors said had resulted in low rates of severe hypoglycemia.

The study found patients treated to the 80-110 mg/dL blood glucose target had a significantly lower unadjusted 30-day mortality compared to patients treated to the 90-140 mg/dL target (4.3% vs. 9.2%; P less than .001). The lower mortality in the lower target group was evident among both diabetic (4.7% vs. 12.9%; P less than .001) and nondiabetic patients (4.1% vs. 7.4%; P = .02).

Researchers also saw that unadjusted 30-day mortality increased with increasing median glucose levels; 5.5% in patients with a blood glucose of 70-110 mg/dL, 8.3% mortality in those with blood glucose levels of 141-180 mg/dL, and 25% in those with a blood glucose level higher than 180 mg/dL.

Patients treated to the 80-110 mg/dL blood glucose target were more likely to experience an episode of moderate hypoglycemia, compared with those in the higher target group (18.6% vs. 8.3%; P less than .001). However, the rates of severe hypoglycemia were low in both groups, and the difference between the low and high target groups did not reach statistical significance (1.16% vs. 0.35%; P = .051).

The authors did note that patients whose blood glucose dropped below 60 mg/dL showed increased mortality, regardless of what target they was set for them. The 30-day unadjusted mortality in these patients was 15%, compared with 5.2% for patients in either group who did not experience a blood glucose level below 60 mg/dL.

“Our results further the discussion about the appropriate BG [blood glucose] target in the critically ill because they suggest that the BG target and severe hypoglycemia effects can be separated,” wrote Andrew M. Hersh, MD, of the division of pulmonary and critical care at San Antonio Military Medical Center, and his coauthors.

But they said the large differences in mortality seen between the two treatment targets should be interpreted with caution, as it was difficult to attribute that difference solely to an 18 mg/dL difference in blood glucose treatment targets.

“While we attempted to capture factors that influenced clinician choice, and while our model successfully achieved balance, suggesting that residual confounding was minimized, we suspect that some of the mortality signal may be attributable to residual confounding,” they wrote.

Another explanation could be that hypoglycemia was an ‘epiphenomenon’ of multiorgan failure, as some studies have found that both spontaneous and iatrogenic hypoglycemia were independently associated with mortality. “However, given the very-low rates of severe hypoglycemia found in both groups it is unlikely that this was a main driver of the mortality difference found,” the investigators wrote.

The majority of patients in the study had been admitted to the hospital for chest pain or acute coronary syndrome (43.3%), while 31.9% were admitted for cardiothoracic surgery, 6.8% for heart failure including cardiogenic shock, and 6% for vascular surgery.

The authors commented that a safe and reliable protocol for intensive insulin therapy, with high clinician compliance, could be the key to realizing its benefits, and could be aided by recent advances such as closed-loop insulin delivery systems.

They also stressed that their results did not support a rejection of current guidelines and instead called for large randomized, clinical trials to find a balance between benefits and harms of intensive insulin therapy.

“Instead our analysis suggests that trials such as NICE-SUGAR, and the conclusion they drew, may have been accurate only in the setting of technologies, which led to high rates of severe hypoglycemia.”

No conflicts of interest were declared.

Tighter glucose control while minimizing the risk of severe hypoglycemia is associated with lower mortality among critically ill cardiac patents, new research suggests.

Researchers reported in CHEST on the outcomes of a multicenter retrospective cohort study in 1,809 adults in cardiac ICUs. Patients were treated either to a blood glucose target of 80-110 mg/dL or 90-140 mg/dL, based on the clinician’s preference, but using a computerized ICU insulin infusion protocol that the authors said had resulted in low rates of severe hypoglycemia.

The study found patients treated to the 80-110 mg/dL blood glucose target had a significantly lower unadjusted 30-day mortality compared to patients treated to the 90-140 mg/dL target (4.3% vs. 9.2%; P less than .001). The lower mortality in the lower target group was evident among both diabetic (4.7% vs. 12.9%; P less than .001) and nondiabetic patients (4.1% vs. 7.4%; P = .02).

Researchers also saw that unadjusted 30-day mortality increased with increasing median glucose levels; 5.5% in patients with a blood glucose of 70-110 mg/dL, 8.3% mortality in those with blood glucose levels of 141-180 mg/dL, and 25% in those with a blood glucose level higher than 180 mg/dL.

Patients treated to the 80-110 mg/dL blood glucose target were more likely to experience an episode of moderate hypoglycemia, compared with those in the higher target group (18.6% vs. 8.3%; P less than .001). However, the rates of severe hypoglycemia were low in both groups, and the difference between the low and high target groups did not reach statistical significance (1.16% vs. 0.35%; P = .051).

The authors did note that patients whose blood glucose dropped below 60 mg/dL showed increased mortality, regardless of what target they was set for them. The 30-day unadjusted mortality in these patients was 15%, compared with 5.2% for patients in either group who did not experience a blood glucose level below 60 mg/dL.

“Our results further the discussion about the appropriate BG [blood glucose] target in the critically ill because they suggest that the BG target and severe hypoglycemia effects can be separated,” wrote Andrew M. Hersh, MD, of the division of pulmonary and critical care at San Antonio Military Medical Center, and his coauthors.

But they said the large differences in mortality seen between the two treatment targets should be interpreted with caution, as it was difficult to attribute that difference solely to an 18 mg/dL difference in blood glucose treatment targets.

“While we attempted to capture factors that influenced clinician choice, and while our model successfully achieved balance, suggesting that residual confounding was minimized, we suspect that some of the mortality signal may be attributable to residual confounding,” they wrote.

Another explanation could be that hypoglycemia was an ‘epiphenomenon’ of multiorgan failure, as some studies have found that both spontaneous and iatrogenic hypoglycemia were independently associated with mortality. “However, given the very-low rates of severe hypoglycemia found in both groups it is unlikely that this was a main driver of the mortality difference found,” the investigators wrote.

The majority of patients in the study had been admitted to the hospital for chest pain or acute coronary syndrome (43.3%), while 31.9% were admitted for cardiothoracic surgery, 6.8% for heart failure including cardiogenic shock, and 6% for vascular surgery.

The authors commented that a safe and reliable protocol for intensive insulin therapy, with high clinician compliance, could be the key to realizing its benefits, and could be aided by recent advances such as closed-loop insulin delivery systems.

They also stressed that their results did not support a rejection of current guidelines and instead called for large randomized, clinical trials to find a balance between benefits and harms of intensive insulin therapy.

“Instead our analysis suggests that trials such as NICE-SUGAR, and the conclusion they drew, may have been accurate only in the setting of technologies, which led to high rates of severe hypoglycemia.”

No conflicts of interest were declared.

FROM CHEST

Key clinical point: Tighter blood glucose control may reduce 30-day mortality in critically ill cardiac patients.

Major finding: Unadjusted 30-day mortality increased with increasing median glucose levels; 5.5% in patients with a blood glucose between 70 and 110 mg/dL, and 25% in those above 180 mg/dL.

Study details: A retrospective cohort study in 1,809 adults in cardiac intensive care units.

Disclosures: No conflicts of interest were declared.

Source: Hersh AM et al. Chest. 2018 Nov;154(5):1044-51.

Liberal oxygen therapy associated with increased mortality

Background: An increasing body of literature suggests that hyperoxia may be harmful, yet liberal use of supplemental oxygen remains widespread.

Study design: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Acutely ill hospitalized adults.

Synopsis: The authors performed a meta-analysis of 25 randomized controlled trials of oxygen therapy in acutely ill adults, encompassing 16,037 patients comparing liberal oxygen strategy (median fraction of inspired oxygen,, 0.52; interquartile range, 0.39-0.85) to conservative oxygen strategy (median FiO2, 0.21; IQR, 0.21-025). Results showed the liberal oxygen strategy was associated with higher in-hospital (risk ratio, 1.21; 95% confidence interval, 1.03-1.43) and 30-day (RR, 1.14, 95% CI, 1.01-1.28) mortality, without a difference in length of stay or disability.

Much like transfusion thresholds, more may not always be better when it comes to supplemental oxygen. Hospitalists should consider the harmful effects of hyperoxia when caring for patients on supplemental oxygen. Unfortunately, median blood oxygen saturation during therapy was not available for each group in this trial, so more research is needed to clearly define the upper limit of oxygen saturation at which harm outweighs benefit.

Bottom line: When compared to conservative oxygen administration, liberal oxygen therapy increases mortality in acutely ill adults.

Citation: Chu DK et al. Mortality and morbidity in acutely ill adults treated with liberal versus conservative oxygen therapy (IOTA): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2018;391:1693-705.

Dr. Metter is an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, University of Colorado, Denver.

Background: An increasing body of literature suggests that hyperoxia may be harmful, yet liberal use of supplemental oxygen remains widespread.

Study design: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Acutely ill hospitalized adults.

Synopsis: The authors performed a meta-analysis of 25 randomized controlled trials of oxygen therapy in acutely ill adults, encompassing 16,037 patients comparing liberal oxygen strategy (median fraction of inspired oxygen,, 0.52; interquartile range, 0.39-0.85) to conservative oxygen strategy (median FiO2, 0.21; IQR, 0.21-025). Results showed the liberal oxygen strategy was associated with higher in-hospital (risk ratio, 1.21; 95% confidence interval, 1.03-1.43) and 30-day (RR, 1.14, 95% CI, 1.01-1.28) mortality, without a difference in length of stay or disability.

Much like transfusion thresholds, more may not always be better when it comes to supplemental oxygen. Hospitalists should consider the harmful effects of hyperoxia when caring for patients on supplemental oxygen. Unfortunately, median blood oxygen saturation during therapy was not available for each group in this trial, so more research is needed to clearly define the upper limit of oxygen saturation at which harm outweighs benefit.

Bottom line: When compared to conservative oxygen administration, liberal oxygen therapy increases mortality in acutely ill adults.

Citation: Chu DK et al. Mortality and morbidity in acutely ill adults treated with liberal versus conservative oxygen therapy (IOTA): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2018;391:1693-705.

Dr. Metter is an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, University of Colorado, Denver.

Background: An increasing body of literature suggests that hyperoxia may be harmful, yet liberal use of supplemental oxygen remains widespread.

Study design: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Acutely ill hospitalized adults.

Synopsis: The authors performed a meta-analysis of 25 randomized controlled trials of oxygen therapy in acutely ill adults, encompassing 16,037 patients comparing liberal oxygen strategy (median fraction of inspired oxygen,, 0.52; interquartile range, 0.39-0.85) to conservative oxygen strategy (median FiO2, 0.21; IQR, 0.21-025). Results showed the liberal oxygen strategy was associated with higher in-hospital (risk ratio, 1.21; 95% confidence interval, 1.03-1.43) and 30-day (RR, 1.14, 95% CI, 1.01-1.28) mortality, without a difference in length of stay or disability.

Much like transfusion thresholds, more may not always be better when it comes to supplemental oxygen. Hospitalists should consider the harmful effects of hyperoxia when caring for patients on supplemental oxygen. Unfortunately, median blood oxygen saturation during therapy was not available for each group in this trial, so more research is needed to clearly define the upper limit of oxygen saturation at which harm outweighs benefit.

Bottom line: When compared to conservative oxygen administration, liberal oxygen therapy increases mortality in acutely ill adults.

Citation: Chu DK et al. Mortality and morbidity in acutely ill adults treated with liberal versus conservative oxygen therapy (IOTA): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2018;391:1693-705.

Dr. Metter is an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, University of Colorado, Denver.

Portable hematology analyzer gets FDA nod

The Food and Drug Administration has granted .

HemoScreen requires a single drop of blood and uses disposable cartridges that provide automatic sample preparation.

HemoScreen can analyze 20 standard complete blood count parameters and produces results within 5 minutes.

Study results suggested that HemoScreen provides results comparable to those of another hematology analyzer, Sysmex XE-2100 (J Clin Pathol. 2016 Aug;69[8]:720-5).

“The HemoScreen delivers lab accurate results,” Avishay Bransky, PhD, CEO of PixCell, said in a statement.

HemoScreen “would be especially useful” in physicians’ offices, emergency rooms, intensive care units, oncology clinics, and remote locations, he added.

HemoScreen makes use of a technology called viscoelastic focusing, which employs microfluidics and machine vision algorithms to analyze cells.

The Food and Drug Administration has granted .

HemoScreen requires a single drop of blood and uses disposable cartridges that provide automatic sample preparation.

HemoScreen can analyze 20 standard complete blood count parameters and produces results within 5 minutes.

Study results suggested that HemoScreen provides results comparable to those of another hematology analyzer, Sysmex XE-2100 (J Clin Pathol. 2016 Aug;69[8]:720-5).

“The HemoScreen delivers lab accurate results,” Avishay Bransky, PhD, CEO of PixCell, said in a statement.

HemoScreen “would be especially useful” in physicians’ offices, emergency rooms, intensive care units, oncology clinics, and remote locations, he added.

HemoScreen makes use of a technology called viscoelastic focusing, which employs microfluidics and machine vision algorithms to analyze cells.

The Food and Drug Administration has granted .

HemoScreen requires a single drop of blood and uses disposable cartridges that provide automatic sample preparation.

HemoScreen can analyze 20 standard complete blood count parameters and produces results within 5 minutes.

Study results suggested that HemoScreen provides results comparable to those of another hematology analyzer, Sysmex XE-2100 (J Clin Pathol. 2016 Aug;69[8]:720-5).

“The HemoScreen delivers lab accurate results,” Avishay Bransky, PhD, CEO of PixCell, said in a statement.

HemoScreen “would be especially useful” in physicians’ offices, emergency rooms, intensive care units, oncology clinics, and remote locations, he added.

HemoScreen makes use of a technology called viscoelastic focusing, which employs microfluidics and machine vision algorithms to analyze cells.

Surgical repair of hip fractures in nursing home patients

Clinical question: Does surgical repair of hip fractures in nursing home residents with advanced dementia reduce adverse outcomes?

Background: Hip fractures are common in the advanced dementia nursing home population. The benefit of surgical repair is unclear in this population given significant baseline functional disability and limited life expectancy.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Medicare claims data set.

Synopsis: Among 3,083 nursing home residents with advanced dementia and hip fracture, nearly 85% underwent surgical repair. The 30-day mortality rate in the nonsurgical group was 30.6%, compared with 11.5% in the surgical group. In an adjusted model, the surgical group had decreased risk of death, compared with the nonsurgical group (hazard ratio, 0.88; 95% confidence interval, 0.79-0.98). In additional adjusted models, surgical patients also had decreased risk of pressure ulcers (HR 0.64; 95% CI, 0.47-0.86) and less pain (HR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.61-0.99). Limitations included the observational nature of the study. Although the models were adjusted, unmeasured confounding may have contributed to the findings.

Bottom line: Surgical repair of hip fractures in nursing home patients with advanced dementia reduces post-fracture mortality, pain, and pressure ulcer risk.

Citation: Berry SD et al. Association of clinical outcomes with surgical repair of hip fracture vs. nonsurgical management in nursing home residents with advanced dementia. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(6):774-80.

Dr. Abramowicz is an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, University of Colorado, Denver.

Clinical question: Does surgical repair of hip fractures in nursing home residents with advanced dementia reduce adverse outcomes?

Background: Hip fractures are common in the advanced dementia nursing home population. The benefit of surgical repair is unclear in this population given significant baseline functional disability and limited life expectancy.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Medicare claims data set.

Synopsis: Among 3,083 nursing home residents with advanced dementia and hip fracture, nearly 85% underwent surgical repair. The 30-day mortality rate in the nonsurgical group was 30.6%, compared with 11.5% in the surgical group. In an adjusted model, the surgical group had decreased risk of death, compared with the nonsurgical group (hazard ratio, 0.88; 95% confidence interval, 0.79-0.98). In additional adjusted models, surgical patients also had decreased risk of pressure ulcers (HR 0.64; 95% CI, 0.47-0.86) and less pain (HR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.61-0.99). Limitations included the observational nature of the study. Although the models were adjusted, unmeasured confounding may have contributed to the findings.

Bottom line: Surgical repair of hip fractures in nursing home patients with advanced dementia reduces post-fracture mortality, pain, and pressure ulcer risk.

Citation: Berry SD et al. Association of clinical outcomes with surgical repair of hip fracture vs. nonsurgical management in nursing home residents with advanced dementia. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(6):774-80.

Dr. Abramowicz is an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, University of Colorado, Denver.

Clinical question: Does surgical repair of hip fractures in nursing home residents with advanced dementia reduce adverse outcomes?

Background: Hip fractures are common in the advanced dementia nursing home population. The benefit of surgical repair is unclear in this population given significant baseline functional disability and limited life expectancy.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Medicare claims data set.

Synopsis: Among 3,083 nursing home residents with advanced dementia and hip fracture, nearly 85% underwent surgical repair. The 30-day mortality rate in the nonsurgical group was 30.6%, compared with 11.5% in the surgical group. In an adjusted model, the surgical group had decreased risk of death, compared with the nonsurgical group (hazard ratio, 0.88; 95% confidence interval, 0.79-0.98). In additional adjusted models, surgical patients also had decreased risk of pressure ulcers (HR 0.64; 95% CI, 0.47-0.86) and less pain (HR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.61-0.99). Limitations included the observational nature of the study. Although the models were adjusted, unmeasured confounding may have contributed to the findings.

Bottom line: Surgical repair of hip fractures in nursing home patients with advanced dementia reduces post-fracture mortality, pain, and pressure ulcer risk.

Citation: Berry SD et al. Association of clinical outcomes with surgical repair of hip fracture vs. nonsurgical management in nursing home residents with advanced dementia. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(6):774-80.

Dr. Abramowicz is an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, University of Colorado, Denver.

BNP levels and mortality in patients with and without heart failure

Clinical question: Does B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) have prognostic value outside of heart failure (HF) patients?

Background: BNP levels are influenced by both cardiac and extracardiac stimuli and thus might have prognostic value outside of the traditional use to guide therapy for HF patients.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study of the Vanderbilt electronic health record.

Setting: Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn.

Synopsis: The study evaluated 30,487 patients with at least two BNP values for 2002-2015. Within this cohort, 62% of patients did not have a HF diagnosis. Risk of death was elevated in all patients regardless of HF status as BNP values rose. An increase from the 25th to 75th percentile in BNP value was associated with an increased risk of death in non-HF patients (hazard ratio, 2.08; 95% confidence interval, 1.99-2.2). Additionally, in a multivariate analysis BNP was the strongest predictor of death, compared with traditional risk factors in both HF and non-HF patients. The main limitation to this study was the use of ICD codes for diagnosis of HF.

Bottom line: BNP has predictive value for risk of death in non-HF patients; as BNP levels rise, regardless of HF status, so does risk of death.

Citation: York MK et al. B-type natriuretic peptide levels and mortality in patients with and without heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 May 15;71(19):2079-88.

Dr. Abramowicz is an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, University of Colorado, Denver.

Clinical question: Does B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) have prognostic value outside of heart failure (HF) patients?

Background: BNP levels are influenced by both cardiac and extracardiac stimuli and thus might have prognostic value outside of the traditional use to guide therapy for HF patients.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study of the Vanderbilt electronic health record.

Setting: Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn.

Synopsis: The study evaluated 30,487 patients with at least two BNP values for 2002-2015. Within this cohort, 62% of patients did not have a HF diagnosis. Risk of death was elevated in all patients regardless of HF status as BNP values rose. An increase from the 25th to 75th percentile in BNP value was associated with an increased risk of death in non-HF patients (hazard ratio, 2.08; 95% confidence interval, 1.99-2.2). Additionally, in a multivariate analysis BNP was the strongest predictor of death, compared with traditional risk factors in both HF and non-HF patients. The main limitation to this study was the use of ICD codes for diagnosis of HF.

Bottom line: BNP has predictive value for risk of death in non-HF patients; as BNP levels rise, regardless of HF status, so does risk of death.

Citation: York MK et al. B-type natriuretic peptide levels and mortality in patients with and without heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 May 15;71(19):2079-88.

Dr. Abramowicz is an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, University of Colorado, Denver.

Clinical question: Does B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) have prognostic value outside of heart failure (HF) patients?

Background: BNP levels are influenced by both cardiac and extracardiac stimuli and thus might have prognostic value outside of the traditional use to guide therapy for HF patients.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study of the Vanderbilt electronic health record.

Setting: Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn.

Synopsis: The study evaluated 30,487 patients with at least two BNP values for 2002-2015. Within this cohort, 62% of patients did not have a HF diagnosis. Risk of death was elevated in all patients regardless of HF status as BNP values rose. An increase from the 25th to 75th percentile in BNP value was associated with an increased risk of death in non-HF patients (hazard ratio, 2.08; 95% confidence interval, 1.99-2.2). Additionally, in a multivariate analysis BNP was the strongest predictor of death, compared with traditional risk factors in both HF and non-HF patients. The main limitation to this study was the use of ICD codes for diagnosis of HF.

Bottom line: BNP has predictive value for risk of death in non-HF patients; as BNP levels rise, regardless of HF status, so does risk of death.

Citation: York MK et al. B-type natriuretic peptide levels and mortality in patients with and without heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 May 15;71(19):2079-88.

Dr. Abramowicz is an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, University of Colorado, Denver.

FDA approval of powerful opioid tinged with irony

The timing of the Food and Drug Administration’s Nov. 2 approval of the medication Dsuvia, a sublingual formulation of the synthetic opioid sufentanil, is interesting – to say the least. Dsuvia is a powerful pain medication, said to be 10 times more potent than fentanyl and 1,000 times more potent than morphine. The medication, developed by AcelRx Pharmaceuticals for use in medically supervised settings, has an indication for moderate to severe pain, and is packaged in single-dose applicators.

The chairperson of the FDA’s Anesthetic and Analgesics Drug Product Advisory Committee, Raeford E. Brown Jr., MD, a professor of pediatric anesthesia at the University of Kentucky, Lexington, could not be present Oct. 12 at the committee vote recommending approval. With the consumer advocacy group Public Citizen, Dr. Brown wrote a letter to FDA leaders detailing concerns about the new formulation of sufentanil.

“It is my observation,” Dr. Brown wrote, “that once the FDA approves an opioid compound, there are no safeguards as to the population that will be exposed, the postmarketing analysis of prescribing behavior, or the ongoing analysis of the risks of the drug to the general population relative to its benefit to the public health. Briefly stated, for all of the opioids that have been marketed in the last 10 years, there has not been sufficient demonstration of safety, nor has there been postmarketing assessment of who is taking the drug, how often prescribing is inappropriate, and whether there was ever a reason to risk the health of the general population by having one more opioid on the market.”

Dr. Brown went on to detail his concerns about sufentanil. In the intravenous formulation, the medication has been in use for more than two decades.

“It is so potent that abusers of this intravenous formulation often die when they inject the first dose; I have witnessed this in resuscitating physicians, medical students, technicians, and other health care providers, some successfully, as a part of my duties as a clinician in a major academic medical center. Because it is so potent, the dosing volume, whether in the IV formulation or the sublingual form, can be quite small. It is thus an extremely divertible drug, and I predict that we will encounter diversion, abuse, and death within the early months of its availability on the market.”

The letter finishes by criticizing the fact that the full Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee was not invited to the Oct. 12 meeting, and finally, about the ease of diversion among health care professionals – and anesthesiologists in particular.

Meanwhile, Scott Gottlieb, MD, commissioner of the FDA, posted a lengthy explanation on the organization’s website on Nov. 2, after the vote. In his statement on the agency’s approval of Dsuvia and the FDA’s future consideration of new opioids, Dr. Gottlieb explains: “To address concerns about the potential risks associated with Dsuvia, this product will have strong limitations on its use. It can’t be dispensed to patients for home use and should not be used for more than 72 hours. And it should only be administered by a health care provider using a single-dose applicator. That means it won’t be available at retail pharmacies for patients to take home. These measures to restrict the use of this product only within a supervised health care setting, and not for home use, are important steps to help prevent misuse and abuse of Dsuvia, as well reduce the potential for diversion. Because of the risks of addiction, abuse, and misuse with opioids, Dsuvia also is to be reserved for use in patients for whom alternative pain treatment options have not been tolerated, or are not expected to be tolerated, where existing treatment options have not provided adequate analgesia, or where these alternatives are not expected to provide adequate analgesia.”

In addition to the statement posted on the FDA’s website, Dr. Gottlieb made the approval of Dsuvia the topic of his weekly #SundayTweetorial on Nov. 4. In this venue, Dr. Gottlieb posts tweets on a single topic. On both Twitter and the FDA website, he noted that a major factor in the approval of Dsuvia was advantages it might convey for pain control to soldiers on the battlefield, where oral medications might take time to work and intravenous access might not be possible.

One tweet read: “Whether there’s a need for another powerful opioid in the throes of a massive crisis of addiction is a critical question. As a public health agency, we have an obligation to address this question for patients with pain, for the addiction crisis, for innovators, for all Americans.”

Another tweet stated, “While Dsuvia brings another highly potent opioid to market it fulfills a limited, unmet medical need in treating our nation’s soldiers on the battlefield. That’s why the Pentagon worked closely with the sponsor on developing Dsuvia. FDA committed to prioritize needs of our troops.”

in possible deaths from misdirected use of a very potent agent. And while the new opioid may have been geared toward unmet military needs, Dsuvia will be available for use in civilian medical facilities as well.

There is some irony to the idea that a pharmaceutical company would continue to develop opioids when there is so much need for nonaddictive agents for pain control and so much pressure on physicians to limit access of opiates to pain patients. We are left to stand by and watch as yet another potent opioid preparation is introduced.

Dr. Miller is coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016), and assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

The timing of the Food and Drug Administration’s Nov. 2 approval of the medication Dsuvia, a sublingual formulation of the synthetic opioid sufentanil, is interesting – to say the least. Dsuvia is a powerful pain medication, said to be 10 times more potent than fentanyl and 1,000 times more potent than morphine. The medication, developed by AcelRx Pharmaceuticals for use in medically supervised settings, has an indication for moderate to severe pain, and is packaged in single-dose applicators.

The chairperson of the FDA’s Anesthetic and Analgesics Drug Product Advisory Committee, Raeford E. Brown Jr., MD, a professor of pediatric anesthesia at the University of Kentucky, Lexington, could not be present Oct. 12 at the committee vote recommending approval. With the consumer advocacy group Public Citizen, Dr. Brown wrote a letter to FDA leaders detailing concerns about the new formulation of sufentanil.

“It is my observation,” Dr. Brown wrote, “that once the FDA approves an opioid compound, there are no safeguards as to the population that will be exposed, the postmarketing analysis of prescribing behavior, or the ongoing analysis of the risks of the drug to the general population relative to its benefit to the public health. Briefly stated, for all of the opioids that have been marketed in the last 10 years, there has not been sufficient demonstration of safety, nor has there been postmarketing assessment of who is taking the drug, how often prescribing is inappropriate, and whether there was ever a reason to risk the health of the general population by having one more opioid on the market.”

Dr. Brown went on to detail his concerns about sufentanil. In the intravenous formulation, the medication has been in use for more than two decades.

“It is so potent that abusers of this intravenous formulation often die when they inject the first dose; I have witnessed this in resuscitating physicians, medical students, technicians, and other health care providers, some successfully, as a part of my duties as a clinician in a major academic medical center. Because it is so potent, the dosing volume, whether in the IV formulation or the sublingual form, can be quite small. It is thus an extremely divertible drug, and I predict that we will encounter diversion, abuse, and death within the early months of its availability on the market.”

The letter finishes by criticizing the fact that the full Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee was not invited to the Oct. 12 meeting, and finally, about the ease of diversion among health care professionals – and anesthesiologists in particular.

Meanwhile, Scott Gottlieb, MD, commissioner of the FDA, posted a lengthy explanation on the organization’s website on Nov. 2, after the vote. In his statement on the agency’s approval of Dsuvia and the FDA’s future consideration of new opioids, Dr. Gottlieb explains: “To address concerns about the potential risks associated with Dsuvia, this product will have strong limitations on its use. It can’t be dispensed to patients for home use and should not be used for more than 72 hours. And it should only be administered by a health care provider using a single-dose applicator. That means it won’t be available at retail pharmacies for patients to take home. These measures to restrict the use of this product only within a supervised health care setting, and not for home use, are important steps to help prevent misuse and abuse of Dsuvia, as well reduce the potential for diversion. Because of the risks of addiction, abuse, and misuse with opioids, Dsuvia also is to be reserved for use in patients for whom alternative pain treatment options have not been tolerated, or are not expected to be tolerated, where existing treatment options have not provided adequate analgesia, or where these alternatives are not expected to provide adequate analgesia.”

In addition to the statement posted on the FDA’s website, Dr. Gottlieb made the approval of Dsuvia the topic of his weekly #SundayTweetorial on Nov. 4. In this venue, Dr. Gottlieb posts tweets on a single topic. On both Twitter and the FDA website, he noted that a major factor in the approval of Dsuvia was advantages it might convey for pain control to soldiers on the battlefield, where oral medications might take time to work and intravenous access might not be possible.

One tweet read: “Whether there’s a need for another powerful opioid in the throes of a massive crisis of addiction is a critical question. As a public health agency, we have an obligation to address this question for patients with pain, for the addiction crisis, for innovators, for all Americans.”

Another tweet stated, “While Dsuvia brings another highly potent opioid to market it fulfills a limited, unmet medical need in treating our nation’s soldiers on the battlefield. That’s why the Pentagon worked closely with the sponsor on developing Dsuvia. FDA committed to prioritize needs of our troops.”

in possible deaths from misdirected use of a very potent agent. And while the new opioid may have been geared toward unmet military needs, Dsuvia will be available for use in civilian medical facilities as well.

There is some irony to the idea that a pharmaceutical company would continue to develop opioids when there is so much need for nonaddictive agents for pain control and so much pressure on physicians to limit access of opiates to pain patients. We are left to stand by and watch as yet another potent opioid preparation is introduced.

Dr. Miller is coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016), and assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

The timing of the Food and Drug Administration’s Nov. 2 approval of the medication Dsuvia, a sublingual formulation of the synthetic opioid sufentanil, is interesting – to say the least. Dsuvia is a powerful pain medication, said to be 10 times more potent than fentanyl and 1,000 times more potent than morphine. The medication, developed by AcelRx Pharmaceuticals for use in medically supervised settings, has an indication for moderate to severe pain, and is packaged in single-dose applicators.

The chairperson of the FDA’s Anesthetic and Analgesics Drug Product Advisory Committee, Raeford E. Brown Jr., MD, a professor of pediatric anesthesia at the University of Kentucky, Lexington, could not be present Oct. 12 at the committee vote recommending approval. With the consumer advocacy group Public Citizen, Dr. Brown wrote a letter to FDA leaders detailing concerns about the new formulation of sufentanil.

“It is my observation,” Dr. Brown wrote, “that once the FDA approves an opioid compound, there are no safeguards as to the population that will be exposed, the postmarketing analysis of prescribing behavior, or the ongoing analysis of the risks of the drug to the general population relative to its benefit to the public health. Briefly stated, for all of the opioids that have been marketed in the last 10 years, there has not been sufficient demonstration of safety, nor has there been postmarketing assessment of who is taking the drug, how often prescribing is inappropriate, and whether there was ever a reason to risk the health of the general population by having one more opioid on the market.”

Dr. Brown went on to detail his concerns about sufentanil. In the intravenous formulation, the medication has been in use for more than two decades.

“It is so potent that abusers of this intravenous formulation often die when they inject the first dose; I have witnessed this in resuscitating physicians, medical students, technicians, and other health care providers, some successfully, as a part of my duties as a clinician in a major academic medical center. Because it is so potent, the dosing volume, whether in the IV formulation or the sublingual form, can be quite small. It is thus an extremely divertible drug, and I predict that we will encounter diversion, abuse, and death within the early months of its availability on the market.”

The letter finishes by criticizing the fact that the full Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee was not invited to the Oct. 12 meeting, and finally, about the ease of diversion among health care professionals – and anesthesiologists in particular.

Meanwhile, Scott Gottlieb, MD, commissioner of the FDA, posted a lengthy explanation on the organization’s website on Nov. 2, after the vote. In his statement on the agency’s approval of Dsuvia and the FDA’s future consideration of new opioids, Dr. Gottlieb explains: “To address concerns about the potential risks associated with Dsuvia, this product will have strong limitations on its use. It can’t be dispensed to patients for home use and should not be used for more than 72 hours. And it should only be administered by a health care provider using a single-dose applicator. That means it won’t be available at retail pharmacies for patients to take home. These measures to restrict the use of this product only within a supervised health care setting, and not for home use, are important steps to help prevent misuse and abuse of Dsuvia, as well reduce the potential for diversion. Because of the risks of addiction, abuse, and misuse with opioids, Dsuvia also is to be reserved for use in patients for whom alternative pain treatment options have not been tolerated, or are not expected to be tolerated, where existing treatment options have not provided adequate analgesia, or where these alternatives are not expected to provide adequate analgesia.”

In addition to the statement posted on the FDA’s website, Dr. Gottlieb made the approval of Dsuvia the topic of his weekly #SundayTweetorial on Nov. 4. In this venue, Dr. Gottlieb posts tweets on a single topic. On both Twitter and the FDA website, he noted that a major factor in the approval of Dsuvia was advantages it might convey for pain control to soldiers on the battlefield, where oral medications might take time to work and intravenous access might not be possible.

One tweet read: “Whether there’s a need for another powerful opioid in the throes of a massive crisis of addiction is a critical question. As a public health agency, we have an obligation to address this question for patients with pain, for the addiction crisis, for innovators, for all Americans.”

Another tweet stated, “While Dsuvia brings another highly potent opioid to market it fulfills a limited, unmet medical need in treating our nation’s soldiers on the battlefield. That’s why the Pentagon worked closely with the sponsor on developing Dsuvia. FDA committed to prioritize needs of our troops.”

in possible deaths from misdirected use of a very potent agent. And while the new opioid may have been geared toward unmet military needs, Dsuvia will be available for use in civilian medical facilities as well.

There is some irony to the idea that a pharmaceutical company would continue to develop opioids when there is so much need for nonaddictive agents for pain control and so much pressure on physicians to limit access of opiates to pain patients. We are left to stand by and watch as yet another potent opioid preparation is introduced.

Dr. Miller is coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016), and assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Quick Byte: Palliative care

Rapid adoption of a key program

In 2015, 75% of U.S. hospitals with more than 50 beds had palliative care programs – a sharp increase from the 25% that had palliative care in 2000.

“The rapid adoption of this high-value program, which is voluntary and runs counter to the dominant culture in U.S. hospitals, was catalyzed by tens of millions of dollars in philanthropic support for innovation, dissemination, and professionalization in the palliative care field,” according to research published in Health Affairs.

Reference

Cassel JB et al. Palliative care leadership centers are key to the diffusion of palliative care innovation. Health Aff. 2018 Feb. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1122.

Rapid adoption of a key program

Rapid adoption of a key program

In 2015, 75% of U.S. hospitals with more than 50 beds had palliative care programs – a sharp increase from the 25% that had palliative care in 2000.

“The rapid adoption of this high-value program, which is voluntary and runs counter to the dominant culture in U.S. hospitals, was catalyzed by tens of millions of dollars in philanthropic support for innovation, dissemination, and professionalization in the palliative care field,” according to research published in Health Affairs.

Reference

Cassel JB et al. Palliative care leadership centers are key to the diffusion of palliative care innovation. Health Aff. 2018 Feb. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1122.

In 2015, 75% of U.S. hospitals with more than 50 beds had palliative care programs – a sharp increase from the 25% that had palliative care in 2000.

“The rapid adoption of this high-value program, which is voluntary and runs counter to the dominant culture in U.S. hospitals, was catalyzed by tens of millions of dollars in philanthropic support for innovation, dissemination, and professionalization in the palliative care field,” according to research published in Health Affairs.

Reference

Cassel JB et al. Palliative care leadership centers are key to the diffusion of palliative care innovation. Health Aff. 2018 Feb. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1122.

FDA approves sufentanil for adults with acute pain

The Food and Drug Administration on Nov. 2 approved sufentanil (Dsuvia) for managing acute pain in adult patients in certified, medically supervised health care settings.

Sufentanil, an opioid analgesic manufactured by AcelRx Pharmaceuticals, was approved as a 30-mcg sublingual tablet. The efficacy of Dsuvia was shown in a randomized, clinical trial where patients who received the drug demonstrated significantly greater pain relief after both 15 minutes and 12 hours, compared with placebo.

“As a single-dose, noninvasive medication with a rapid reduction in pain intensity, Dsuvia represents an important alternative for health care providers to offer patients for acute pain management,” David Leiman, MD, of the department of surgery at the University of Texas, Houston, said in the AcelRx press statement.

FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, commented on the approval amid concerns expressed by some, such as the advocacy group Public Citizen, that the drug is “more than 1,000 times more potent than morphine,” and that approval could lead to diversion and abuse – particularly in light of the U.S. opioid epidemic.

In his statement, Dr. Gottlieb identified one broad, significant issue. “Why do we need an oral formulation of sufentanil – a more potent form of fentanyl that’s been approved for intravenous and epidural use in the U.S. since 1984 – on the market?”

In particular, he focused on the needs of the military. The Department of Defense has taken interest in sufentanil as it fulfills a small but specific battlefield need, namely as a means of pain relief in battlefield situations where soldiers cannot swallow oral medication and access to intravenous medication is limited.

Dr. Gottlieb made clear that sufentanil was meant only to be taken in controlled settings and will have strong limitations on its use. It cannot be prescribed for home use, and treatment should be limited to 72 hours. It can only be delivered by health care professionals using a single-dose applicator and will not be available in pharmacies. It is only to be used in patients who have not tolerated or are expected not to tolerate alternative methods of pain management.

“The FDA has implemented a REMS [Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy] that reflects the potential risks associated with this product and mandates that Dsuvia will only be made available for use in a certified medically supervised heath care setting, including its use on the battlefield,” Dr. Gottlieb said.

However, he recognized that the debate runs deeper than how the FDA should mitigate risk over a new drug, and “as a public health agency, we have an obligation to address this question openly and directly. As a physician and regulator, I won’t bypass legitimate questions and concerns related to our role in addressing the opioid crisis,” he said.

Find Dr. Gottlieb’s full statement on the FDA website.

The Food and Drug Administration on Nov. 2 approved sufentanil (Dsuvia) for managing acute pain in adult patients in certified, medically supervised health care settings.

Sufentanil, an opioid analgesic manufactured by AcelRx Pharmaceuticals, was approved as a 30-mcg sublingual tablet. The efficacy of Dsuvia was shown in a randomized, clinical trial where patients who received the drug demonstrated significantly greater pain relief after both 15 minutes and 12 hours, compared with placebo.

“As a single-dose, noninvasive medication with a rapid reduction in pain intensity, Dsuvia represents an important alternative for health care providers to offer patients for acute pain management,” David Leiman, MD, of the department of surgery at the University of Texas, Houston, said in the AcelRx press statement.

FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, commented on the approval amid concerns expressed by some, such as the advocacy group Public Citizen, that the drug is “more than 1,000 times more potent than morphine,” and that approval could lead to diversion and abuse – particularly in light of the U.S. opioid epidemic.

In his statement, Dr. Gottlieb identified one broad, significant issue. “Why do we need an oral formulation of sufentanil – a more potent form of fentanyl that’s been approved for intravenous and epidural use in the U.S. since 1984 – on the market?”

In particular, he focused on the needs of the military. The Department of Defense has taken interest in sufentanil as it fulfills a small but specific battlefield need, namely as a means of pain relief in battlefield situations where soldiers cannot swallow oral medication and access to intravenous medication is limited.

Dr. Gottlieb made clear that sufentanil was meant only to be taken in controlled settings and will have strong limitations on its use. It cannot be prescribed for home use, and treatment should be limited to 72 hours. It can only be delivered by health care professionals using a single-dose applicator and will not be available in pharmacies. It is only to be used in patients who have not tolerated or are expected not to tolerate alternative methods of pain management.

“The FDA has implemented a REMS [Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy] that reflects the potential risks associated with this product and mandates that Dsuvia will only be made available for use in a certified medically supervised heath care setting, including its use on the battlefield,” Dr. Gottlieb said.

However, he recognized that the debate runs deeper than how the FDA should mitigate risk over a new drug, and “as a public health agency, we have an obligation to address this question openly and directly. As a physician and regulator, I won’t bypass legitimate questions and concerns related to our role in addressing the opioid crisis,” he said.

Find Dr. Gottlieb’s full statement on the FDA website.

The Food and Drug Administration on Nov. 2 approved sufentanil (Dsuvia) for managing acute pain in adult patients in certified, medically supervised health care settings.

Sufentanil, an opioid analgesic manufactured by AcelRx Pharmaceuticals, was approved as a 30-mcg sublingual tablet. The efficacy of Dsuvia was shown in a randomized, clinical trial where patients who received the drug demonstrated significantly greater pain relief after both 15 minutes and 12 hours, compared with placebo.

“As a single-dose, noninvasive medication with a rapid reduction in pain intensity, Dsuvia represents an important alternative for health care providers to offer patients for acute pain management,” David Leiman, MD, of the department of surgery at the University of Texas, Houston, said in the AcelRx press statement.

FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, commented on the approval amid concerns expressed by some, such as the advocacy group Public Citizen, that the drug is “more than 1,000 times more potent than morphine,” and that approval could lead to diversion and abuse – particularly in light of the U.S. opioid epidemic.

In his statement, Dr. Gottlieb identified one broad, significant issue. “Why do we need an oral formulation of sufentanil – a more potent form of fentanyl that’s been approved for intravenous and epidural use in the U.S. since 1984 – on the market?”

In particular, he focused on the needs of the military. The Department of Defense has taken interest in sufentanil as it fulfills a small but specific battlefield need, namely as a means of pain relief in battlefield situations where soldiers cannot swallow oral medication and access to intravenous medication is limited.

Dr. Gottlieb made clear that sufentanil was meant only to be taken in controlled settings and will have strong limitations on its use. It cannot be prescribed for home use, and treatment should be limited to 72 hours. It can only be delivered by health care professionals using a single-dose applicator and will not be available in pharmacies. It is only to be used in patients who have not tolerated or are expected not to tolerate alternative methods of pain management.

“The FDA has implemented a REMS [Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy] that reflects the potential risks associated with this product and mandates that Dsuvia will only be made available for use in a certified medically supervised heath care setting, including its use on the battlefield,” Dr. Gottlieb said.

However, he recognized that the debate runs deeper than how the FDA should mitigate risk over a new drug, and “as a public health agency, we have an obligation to address this question openly and directly. As a physician and regulator, I won’t bypass legitimate questions and concerns related to our role in addressing the opioid crisis,” he said.

Find Dr. Gottlieb’s full statement on the FDA website.

In pediatric ICU, being underweight can be deadly

SAN DIEGO – Underweight people don’t get much attention amid the obesity epidemic. But a new analysis of worldwide data finds that underweight pediatric ICU patients worldwide face a higher risk of death within 28 days than all their counterparts, even the overweight and obese.

While the report suggests that underweight patients weren’t sicker than the other children and young adults, they also faced a higher risk of fluid accumulation and all-stage acute kidney injury, compared with overweight children, study lead author Rajit K. Basu, MD, MS, of Emory University and Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, said in an interview. His team’s findings were released at Kidney Week 2018, sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology.

“Obesity gets the lion’s share of the spotlight, but there is a large and likely growing population of children who, for reasons left to be fully parsed out, are underweight,” Dr. Basu said. “These patients have increased attributable risks for poor outcome.”

The new report is a follow-up analysis of a 2017 prospective study by the same team that tracked acute kidney injury and mortality in 4,683 pediatric ICU patients at 32 clinics in Asia, Australia, Europe, and North America. The patients, aged from 3 months to 25 years, were recruited over 3 months in 2014 (N Engl J Med 2017;376:11-20).

The researchers launched the study to better understand the risk facing underweight pediatric patients. “There is a paucity of data linking mortality to weight classification in children,” Dr. Basu said. “There are only a few reports, and there is a suggestion that the ‘obesity paradox’ – protection from morbidity and mortality because of excessive weight – exists.”

For the new analysis, researchers tracked 3,719 patients: 29% were underweight, 44% had normal weight, 11% were overweight, and 16% were obese.

The 28-day mortality rate was 4% overall and highest in the underweight patients at 6%, compared with normal (3%), overweight (2%), and obese patients (2%) (P less than .0001). Underweight patients had a higher adjusted risk of mortality, compared with normal-weight patients (adjusted odds ratio, 1.8; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-2.8).

Underweight patients also had “a higher risk of fluid accumulation and a higher incidence of all-stage acute kidney injury, compared to overweight children,” Dr. Basu said.

The study authors also examined mortality rates in the 14% of patients (n = 542) who had sepsis. Again, underweight patients had the highest risk of 28-day mortality (15%), compared with normal weight (7%), overweight (4%), and obese patients (5%) (P = 0.003).

Who are the underweight children? “Analysis of the comorbidities reveals that nearly one-third of these children had some neuromuscular and/or pulmonary comorbidities, implying that these children were most likely static cerebral palsy children or had neuromuscular developmental disorder,” Dr. Basu said. “The demographic data also interestingly pointed out that the underweight population was predominantly Eastern Asian in origin.”

But there wasn’t a sign of increased illness in the underweight patients. “We can say that these kids were no sicker compared to the overweight kids as assessed by objective severity-of-illness scoring tools used in the critically ill population,” he said.

Is there a link between fluid overload and higher mortality numbers in underweight children? “There is a preponderance of data now, particularly in children, associating excessive fluid accumulation and poor outcome,” Dr. Basu said, who pointed to a 2018 systematic review and analysis that linked fluid overload to a higher risk of in-hospital mortality (OR, 4.34; 95% CI, 3.01-6.26) (JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172[3]:257-68).

Fluid accumulation disrupts organs “via hydrostatic pressure overregulation, causing an imbalance in local mediators of hormonal homeostasis and through vascular congestion,” he said. However, best practices regarding fluid are not yet clear.

“Fluid accumulation does occur frequently,” he said, “and it is likely a very important and relevant part of practice for bedside providers to be mindful on a multiple-times-a-day basis of what is happening with net fluid balance and how that relates to end-organ function, particularly the lungs and the kidneys.”

The National Institutes of Health provided partial funding for the study. One of the authors received fellowship funding from Gambro/Baxter Healthcare.

SAN DIEGO – Underweight people don’t get much attention amid the obesity epidemic. But a new analysis of worldwide data finds that underweight pediatric ICU patients worldwide face a higher risk of death within 28 days than all their counterparts, even the overweight and obese.

While the report suggests that underweight patients weren’t sicker than the other children and young adults, they also faced a higher risk of fluid accumulation and all-stage acute kidney injury, compared with overweight children, study lead author Rajit K. Basu, MD, MS, of Emory University and Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, said in an interview. His team’s findings were released at Kidney Week 2018, sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology.

“Obesity gets the lion’s share of the spotlight, but there is a large and likely growing population of children who, for reasons left to be fully parsed out, are underweight,” Dr. Basu said. “These patients have increased attributable risks for poor outcome.”

The new report is a follow-up analysis of a 2017 prospective study by the same team that tracked acute kidney injury and mortality in 4,683 pediatric ICU patients at 32 clinics in Asia, Australia, Europe, and North America. The patients, aged from 3 months to 25 years, were recruited over 3 months in 2014 (N Engl J Med 2017;376:11-20).

The researchers launched the study to better understand the risk facing underweight pediatric patients. “There is a paucity of data linking mortality to weight classification in children,” Dr. Basu said. “There are only a few reports, and there is a suggestion that the ‘obesity paradox’ – protection from morbidity and mortality because of excessive weight – exists.”

For the new analysis, researchers tracked 3,719 patients: 29% were underweight, 44% had normal weight, 11% were overweight, and 16% were obese.

The 28-day mortality rate was 4% overall and highest in the underweight patients at 6%, compared with normal (3%), overweight (2%), and obese patients (2%) (P less than .0001). Underweight patients had a higher adjusted risk of mortality, compared with normal-weight patients (adjusted odds ratio, 1.8; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-2.8).

Underweight patients also had “a higher risk of fluid accumulation and a higher incidence of all-stage acute kidney injury, compared to overweight children,” Dr. Basu said.

The study authors also examined mortality rates in the 14% of patients (n = 542) who had sepsis. Again, underweight patients had the highest risk of 28-day mortality (15%), compared with normal weight (7%), overweight (4%), and obese patients (5%) (P = 0.003).

Who are the underweight children? “Analysis of the comorbidities reveals that nearly one-third of these children had some neuromuscular and/or pulmonary comorbidities, implying that these children were most likely static cerebral palsy children or had neuromuscular developmental disorder,” Dr. Basu said. “The demographic data also interestingly pointed out that the underweight population was predominantly Eastern Asian in origin.”

But there wasn’t a sign of increased illness in the underweight patients. “We can say that these kids were no sicker compared to the overweight kids as assessed by objective severity-of-illness scoring tools used in the critically ill population,” he said.

Is there a link between fluid overload and higher mortality numbers in underweight children? “There is a preponderance of data now, particularly in children, associating excessive fluid accumulation and poor outcome,” Dr. Basu said, who pointed to a 2018 systematic review and analysis that linked fluid overload to a higher risk of in-hospital mortality (OR, 4.34; 95% CI, 3.01-6.26) (JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172[3]:257-68).

Fluid accumulation disrupts organs “via hydrostatic pressure overregulation, causing an imbalance in local mediators of hormonal homeostasis and through vascular congestion,” he said. However, best practices regarding fluid are not yet clear.

“Fluid accumulation does occur frequently,” he said, “and it is likely a very important and relevant part of practice for bedside providers to be mindful on a multiple-times-a-day basis of what is happening with net fluid balance and how that relates to end-organ function, particularly the lungs and the kidneys.”

The National Institutes of Health provided partial funding for the study. One of the authors received fellowship funding from Gambro/Baxter Healthcare.

SAN DIEGO – Underweight people don’t get much attention amid the obesity epidemic. But a new analysis of worldwide data finds that underweight pediatric ICU patients worldwide face a higher risk of death within 28 days than all their counterparts, even the overweight and obese.

While the report suggests that underweight patients weren’t sicker than the other children and young adults, they also faced a higher risk of fluid accumulation and all-stage acute kidney injury, compared with overweight children, study lead author Rajit K. Basu, MD, MS, of Emory University and Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, said in an interview. His team’s findings were released at Kidney Week 2018, sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology.

“Obesity gets the lion’s share of the spotlight, but there is a large and likely growing population of children who, for reasons left to be fully parsed out, are underweight,” Dr. Basu said. “These patients have increased attributable risks for poor outcome.”

The new report is a follow-up analysis of a 2017 prospective study by the same team that tracked acute kidney injury and mortality in 4,683 pediatric ICU patients at 32 clinics in Asia, Australia, Europe, and North America. The patients, aged from 3 months to 25 years, were recruited over 3 months in 2014 (N Engl J Med 2017;376:11-20).

The researchers launched the study to better understand the risk facing underweight pediatric patients. “There is a paucity of data linking mortality to weight classification in children,” Dr. Basu said. “There are only a few reports, and there is a suggestion that the ‘obesity paradox’ – protection from morbidity and mortality because of excessive weight – exists.”

For the new analysis, researchers tracked 3,719 patients: 29% were underweight, 44% had normal weight, 11% were overweight, and 16% were obese.

The 28-day mortality rate was 4% overall and highest in the underweight patients at 6%, compared with normal (3%), overweight (2%), and obese patients (2%) (P less than .0001). Underweight patients had a higher adjusted risk of mortality, compared with normal-weight patients (adjusted odds ratio, 1.8; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-2.8).

Underweight patients also had “a higher risk of fluid accumulation and a higher incidence of all-stage acute kidney injury, compared to overweight children,” Dr. Basu said.

The study authors also examined mortality rates in the 14% of patients (n = 542) who had sepsis. Again, underweight patients had the highest risk of 28-day mortality (15%), compared with normal weight (7%), overweight (4%), and obese patients (5%) (P = 0.003).

Who are the underweight children? “Analysis of the comorbidities reveals that nearly one-third of these children had some neuromuscular and/or pulmonary comorbidities, implying that these children were most likely static cerebral palsy children or had neuromuscular developmental disorder,” Dr. Basu said. “The demographic data also interestingly pointed out that the underweight population was predominantly Eastern Asian in origin.”

But there wasn’t a sign of increased illness in the underweight patients. “We can say that these kids were no sicker compared to the overweight kids as assessed by objective severity-of-illness scoring tools used in the critically ill population,” he said.

Is there a link between fluid overload and higher mortality numbers in underweight children? “There is a preponderance of data now, particularly in children, associating excessive fluid accumulation and poor outcome,” Dr. Basu said, who pointed to a 2018 systematic review and analysis that linked fluid overload to a higher risk of in-hospital mortality (OR, 4.34; 95% CI, 3.01-6.26) (JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172[3]:257-68).

Fluid accumulation disrupts organs “via hydrostatic pressure overregulation, causing an imbalance in local mediators of hormonal homeostasis and through vascular congestion,” he said. However, best practices regarding fluid are not yet clear.

“Fluid accumulation does occur frequently,” he said, “and it is likely a very important and relevant part of practice for bedside providers to be mindful on a multiple-times-a-day basis of what is happening with net fluid balance and how that relates to end-organ function, particularly the lungs and the kidneys.”

The National Institutes of Health provided partial funding for the study. One of the authors received fellowship funding from Gambro/Baxter Healthcare.

REPORTING FROM KIDNEY WEEK 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Underweight patients had a higher adjusted risk of 28-day mortality than normal-weight patients (adjusted odds ratio, 1.8; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-2.8).

Study details: A follow-up analysis of 3,719 pediatric ICU patients, aged from 3 months to 25 years, recruited in a prospective study over 3 months in 2014 at 32 worldwide centers.

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health provided partial funding for the study. One of the authors received fellowship funding from Gambro/Baxter Healthcare.

How do you evaluate and treat a patient with C. difficile–associated disease?

Metronidazole is no longer recommended

Case

A 45-year-old woman on omeprazole for gastroesophageal reflux disease and recent treatment with ciprofloxacin for a urinary tract infection (UTI), who also has had several days of frequent watery stools, is admitted. She does not appear ill, and her abdominal exam is benign. She has normal renal function and white blood cell count. How should she be evaluated and treated for Clostridium difficile–associated disease (CDAD)?

Brief overview

C. difficile, a gram-positive anaerobic bacillus that exists in vegetative and spore forms, is a leading cause of hospital-associated diarrhea. C. difficile has a variety of presentations, ranging from asymptomatic colonization to CDAD, including severe diarrhea, ileus, and megacolon, and may be associated with a fatal outcome on rare occasions. The incidence of CDAD has been rising since the emergence of a hypervirulent strain (NAP1/BI/027) in the early 2000s and, not surprisingly, the number of deaths attributed to CDAD has also increased.1

CDAD requires acquisition of C. difficile as well as alteration in the colonic microbiota, often precipitated by antibiotics. The vegetative form of C. difficile can produce up to three toxins that are responsible for a cascade of reactions beginning with intestinal epithelial cell death followed by a significant inflammatory response and migration of neutrophils that eventually lead to the formation of the characteristic pseudomembranes.2

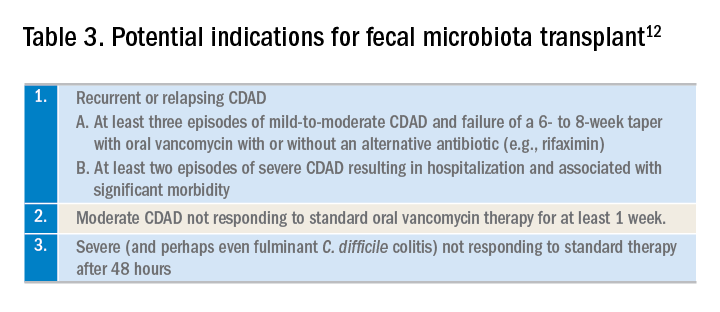

Until recently, the mainstay treatment for CDAD consisted of metronidazole and oral preparations of vancomycin. Recent results from randomized controlled trials and the increasing popularity of fecal microbiota transplant (FMT), however, have changed the therapeutic landscape of CDAD dramatically. Not surprisingly, the 2017 Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America joint guidelines for CDAD represent a significant change to the treatment of CDAD, compared with previous guidelines.3

Overview of data