User login

Medication-Nonadherent Hypothyroidism Requiring Frequent Primary Care Visits to Achieve Euthyroidism

Nonadherence to medications is an issue across health care. In endocrinology, hypothyroidism, a deficiency of thyroid hormones, is most often treated with levothyroxine and if left untreated can lead to myxedema coma, which can lead to death due to multiorgan dysfunction.1 Therefore, adherence to levothyroxine is very important in preventing fatal complications.

We present the case of a patient with persistent primary hypothyroidism who was suspected to be nonadherent to levothyroxine, although the patient consistently claimed adherence. The patient’s plasma thyrotropin (TSH) level improved to reference range after 6 weeks of weekly primary care clinic visits. After stopping the visits, his plasma TSH level increased again, so 9 more weeks of visits resumed, which again helped bring down his plasma TSH levels.

Case Presentation

A male patient aged 67 years presented to the Dayton Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) endocrinology clinic for evaluation of thyroid nodules. The patient reported no history of neck irradiation and a physical examination was unremarkable. At that time, laboratory results showed a slightly elevated plasma TSH level of 4.35 uIU/mL (reference range, 0.35-4.00 uIU/mL) and normal free thyroxine (T4) of 1.00 ng/dL (reference range, 0.74-1.46 ng/dL). Later that year, the patient underwent a total thyroidectomy at the Cincinnati VAMC for Hurthle cell variant papillary thyroid carcinoma that was noted on biopsy at the Dayton VAMC. After surgical pathology results were available, the patient started levothyroxine 200 mcg daily, although 224 mcg would have been more appropriate based on his 142 kg weight. Due to a history of arrhythmia, the goal plasma TSH level was 0.10 to 0.50 uIU/mL. The patient subsequently underwent radioactive iodine ablation. After levothyroxine dose adjustments, the patient’s plasma TSH level was noted to be within his target range at 0.28 uIU/mL 3 months postablation.

Over the next 5 years the patient had regular laboratory tests during which his plasma TSH level rose and were typically high despite adjusting levothyroxine doses between 200 mcg and 325 mcg. The patient received counseling on taking the medication in the morning on an empty stomach and waiting at least 1 hour before consuming anything, and he went to many follow-up visits at the Dayton VAMC endocrinology clinic. He reported no vomiting or diarrhea but endorsed weight gain once. The patient also had high free T4 at times and did not take extra levothyroxine before undergoing laboratory tests.

Nonadherence to levothyroxine was suspected, but the patient insisted he was adherent. He received the medication in the mail regularly, generally had 90-day refills unless a dose change was made, used a pill box, and had social support from his son, but he did not use a phone alarm to remind him to take it. A home care nurse made weekly visits to make sure the remaining levothyroxine pill counts were correct; however, the patient continued to have difficulty maintaining daily adherence at home as indicated by the nurse’s pill counts not aligning with the number of pills which should have been left if the patient was talking the pills daily.

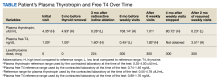

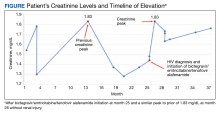

The patient was asked to visit a local community-based outpatient clinic (CBOC) weekly (to avoid patient travel time to Dayton VAMC > 1 hour) to check pill counts and assess adherence. The patient went to the CBOC clinic for these visits, during which pill counts indicated much better but not 100% adherence. After 6 weeks of clinic visits, his plasma TSH decreased to 1.01 uIU/mL, which was within the reference range, and the patient stopped coming to the weekly clinic visits (Table). Four months later, the patient's plasma TSH levels increased to 80.72 uIU/mL. Nonadherence to levothyroxine was suspected again. He was asked to resume weekly clinic visits, and the life-threatening effects of hypothyroidism and not taking levothyroxine were discussed with the patient and his son. The patient made CBOC clinic visits for 9 weeks, after which his plasma TSH level was low at 0.23 uIU/mL.

Discussion

There are multiple important causes to consider in patients with persistent hypothyroidism. One is medication nonadherence, which was most likely seen in the patient in this case. Missing even 1 day of levothyroxine can affect TSH and thyroid hormone levels for several days due to the long half-life of the medication.2 Hepp and colleagues found that patients with hypothyroidism were significantly more likely to be nonadherent to levothyroxine if they had comorbid conditions such as type 2 diabetes or were obese.3 Another study of levothyroxine adherence found that the most common reason for missing doses was forgetfulness.4 However, memory and cognition impairments can also be symptoms of hypothyroidism itself; Haskard-Zolnierek and colleagues found a significant association between nonadherence to levothyroxine and self-reported brain fog in patients with hypothyroidism.5

Another cause of persistent hypothyroidism is malabsorption. Absorption of levothyroxine can be affected by intestinal malabsorption due to inflammatory bowel disease, lactose intolerance, or gastrointestinal infection, as well as several foods, drinks (eg, coffee), medications, vitamins, and supplements (eg, proton-pump inhibitors and calcium).2,6 Levothyroxine is absorbed mainly at the jejunum and upper ileum, so any pathologies or ingested items that would directly or indirectly affect absorption at those sites can affect levothyroxine absorption.2

A liquid levothyroxine formulation can help with malabsorption.2 Alternatively, weight gain may lead to a need for increasing the dosage of levothyroxine.2,6 Other factors that can affect TSH levels include Addison disease, dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis, and TSH heterophile antibodies.2

Research describes methods that have effectively treated hypothyroidism in patients struggling with levothyroxine adherence. Two case reports describe weekly visits for levothyroxine administration successfully treating uncontrolled hypothyroidism.7,8 A meta-analysis found that while weekly levothyroxine tablets led to a higher mean TSH level than daily use, weekly use still led to reference-range TSH levels, suggesting that weekly levothyroxine may be a helpful alternative for nonadherent patients.9 Alternatively, patients taking levothyroxine tablets have been shown to forget to take their medication more frequently compared to those taking the liquid formulation.10,11 Additionally, a study by El Helou and colleagues found that adherence to levothyroxine was significantly improved when patients had endocrinology visits once a month and when the endocrinologist provided information about hypothyroidism.12

Another method that may improve adherence to levothyroxine is telehealth visits. This would be especially helpful for patients who live far from the clinic or do not have the time, transportation, or financial means to visit the clinic for weekly visits to assess medication adherence. Additionally, patients may be afraid of admitting to a health care professional that they are nonadherent. Clinicians must be tactful when asking about adherence to make the patient feel comfortable with admitting to nonadherence if their cognition is not impaired. Then, a patient-led conversation can occur regarding realistic ways the patient feels they can work toward adherence.

To our knowledge, the patient in this case report had no symptoms of intestinal malabsorption, and weight gain was not thought to be the issue, as levothyroxine dosage was adjusted multiple times. His plasma TSH levels returned to reference range after weekly pill count visits for 6 weeks and after weekly pill count visits for 9 weeks. Therefore, nonadherence to levothyroxine was suspected to be the cause of frequently elevated plasma TSH levels despite the patient’s insistence on adherence. While the patient did not report memory issues, cognitive impairments due to hypothyroidism may have been contributing to his probable nonadherence. Additionally, he had comorbidities, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity, which may have made adherence more difficult.

Levothyroxine was also only prescribed in daily tablet form, so the frequency and formulation may have also contributed to nonadherence. While the home nurse was originally sent to assess the patient’s adherence, the care team could have had the nurse start giving the patient weekly levothyroxine once nonadherence was determined to be a likely issue. The patient’s adherence only improved when he went to the clinic for pill counts but not when the home nurse came to his house weekly; this could be because the patient knew he had to invest the time to physically go to clinic visits for pill checks, motivating him to increase adherence.

Conclusions

This case reports a patient with frequently high plasma TSH levels achieving normalization of plasma TSH levels after weekly medication adherence checks at a primary care clinic. Weekly visits to a clinic seem impractical compared to weekly dosing with a visiting nurse; however, after review of the literature, this may be an approach to consider in the future. This strategy may especially help in cases of persistent abnormal plasma TSH levels in which no etiology can be found other than suspected medication nonadherence. Knowing their medication use will be checked at weekly clinic visits may motivate patients to be adherent.

1. Chaker L, Bianco AC, Jonklaas J, Peeters RP. Hypothyroidism. Lancet. 2017;390(10101):1550-1562. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30703-1

2. Centanni M, Benvenga S, Sachmechi I. Diagnosis and management of treatment-refractory hypothyroidism: an expert consensus report. J Endocrinol Invest. 2017;40(12):1289-1301. doi:10.1007/s40618-017-0706-y

3. Hepp Z, Lage MJ, Espaillat R, Gossain VV. The association between adherence to levothyroxine and economic and clinical outcomes in patients with hypothyroidism in the US. J Med Econ. 2018;21(9):912-919. doi:10.1080/13696998.2018.1484749

4. Shakya Shrestha S, Risal K, Shrestha R, Bhatta RD. Medication Adherence to Levothyroxine Therapy among Hypothyroid Patients and their Clinical Outcomes with Special Reference to Thyroid Function Parameters. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ). 2018;16(62):129-137.

5. Haskard-Zolnierek K, Wilson C, Pruin J, Deason R, Howard K. The Relationship Between Brain Fog and Medication Adherence for Individuals With Hypothyroidism. Clin Nurs Res. 2022;31(3):445-452. doi:10.1177/10547738211038127

6. McNally LJ, Ofiaeli CI, Oyibo SO. Treatment-refractory hypothyroidism. BMJ. 2019;364:l579. Published 2019 Feb 25. doi:10.1136/bmj.l579

7. Nakano Y, Hashimoto K, Ohkiba N, et al. A Case of Refractory Hypothyroidism due to Poor Compliance Treated with the Weekly Intravenous and Oral Levothyroxine Administration. Case Rep Endocrinol. 2019;2019:5986014. Published 2019 Feb 5. doi:10.1155/2019/5986014

8. Kiran Z, Shaikh KS, Fatima N, Tariq N, Baloch AA. Levothyroxine absorption test followed by directly observed treatment on an outpatient basis to address long-term high TSH levels in a hypothyroid patient: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2023;17(1):24. Published 2023 Jan 25. doi:10.1186/s13256-023-03760-0

9. Chiu HH, Larrazabal R Jr, Uy AB, Jimeno C. Weekly Versus Daily Levothyroxine Tablet Replacement in Adults with Hypothyroidism: A Meta-Analysis. J ASEAN Fed Endocr Soc. 2021;36(2):156-160. doi:10.15605/jafes.036.02.07

10. Cappelli C, Castello R, Marini F, et al. Adherence to Levothyroxine Treatment Among Patients With Hypothyroidism: A Northeastern Italian Survey. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2018;9:699. Published 2018 Nov 23. doi:10.3389/fendo.2018.00699

11. Bocale R, Desideri G, Barini A, et al. Long-Term Adherence to Levothyroxine Replacement Therapy in Thyroidectomized Patients. J Clin Med. 2022;11(15):4296. Published 2022 Jul 24. doi:10.3390/jcm11154296

12. El Helou S, Hallit S, Awada S, et al. Adherence to levothyroxine among patients with hypothyroidism in Lebanon. East Mediterr Health J. 2019;25(3):149-159. Published 2019 Apr 25. doi:10.26719/emhj.18.022

Nonadherence to medications is an issue across health care. In endocrinology, hypothyroidism, a deficiency of thyroid hormones, is most often treated with levothyroxine and if left untreated can lead to myxedema coma, which can lead to death due to multiorgan dysfunction.1 Therefore, adherence to levothyroxine is very important in preventing fatal complications.

We present the case of a patient with persistent primary hypothyroidism who was suspected to be nonadherent to levothyroxine, although the patient consistently claimed adherence. The patient’s plasma thyrotropin (TSH) level improved to reference range after 6 weeks of weekly primary care clinic visits. After stopping the visits, his plasma TSH level increased again, so 9 more weeks of visits resumed, which again helped bring down his plasma TSH levels.

Case Presentation

A male patient aged 67 years presented to the Dayton Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) endocrinology clinic for evaluation of thyroid nodules. The patient reported no history of neck irradiation and a physical examination was unremarkable. At that time, laboratory results showed a slightly elevated plasma TSH level of 4.35 uIU/mL (reference range, 0.35-4.00 uIU/mL) and normal free thyroxine (T4) of 1.00 ng/dL (reference range, 0.74-1.46 ng/dL). Later that year, the patient underwent a total thyroidectomy at the Cincinnati VAMC for Hurthle cell variant papillary thyroid carcinoma that was noted on biopsy at the Dayton VAMC. After surgical pathology results were available, the patient started levothyroxine 200 mcg daily, although 224 mcg would have been more appropriate based on his 142 kg weight. Due to a history of arrhythmia, the goal plasma TSH level was 0.10 to 0.50 uIU/mL. The patient subsequently underwent radioactive iodine ablation. After levothyroxine dose adjustments, the patient’s plasma TSH level was noted to be within his target range at 0.28 uIU/mL 3 months postablation.

Over the next 5 years the patient had regular laboratory tests during which his plasma TSH level rose and were typically high despite adjusting levothyroxine doses between 200 mcg and 325 mcg. The patient received counseling on taking the medication in the morning on an empty stomach and waiting at least 1 hour before consuming anything, and he went to many follow-up visits at the Dayton VAMC endocrinology clinic. He reported no vomiting or diarrhea but endorsed weight gain once. The patient also had high free T4 at times and did not take extra levothyroxine before undergoing laboratory tests.

Nonadherence to levothyroxine was suspected, but the patient insisted he was adherent. He received the medication in the mail regularly, generally had 90-day refills unless a dose change was made, used a pill box, and had social support from his son, but he did not use a phone alarm to remind him to take it. A home care nurse made weekly visits to make sure the remaining levothyroxine pill counts were correct; however, the patient continued to have difficulty maintaining daily adherence at home as indicated by the nurse’s pill counts not aligning with the number of pills which should have been left if the patient was talking the pills daily.

The patient was asked to visit a local community-based outpatient clinic (CBOC) weekly (to avoid patient travel time to Dayton VAMC > 1 hour) to check pill counts and assess adherence. The patient went to the CBOC clinic for these visits, during which pill counts indicated much better but not 100% adherence. After 6 weeks of clinic visits, his plasma TSH decreased to 1.01 uIU/mL, which was within the reference range, and the patient stopped coming to the weekly clinic visits (Table). Four months later, the patient's plasma TSH levels increased to 80.72 uIU/mL. Nonadherence to levothyroxine was suspected again. He was asked to resume weekly clinic visits, and the life-threatening effects of hypothyroidism and not taking levothyroxine were discussed with the patient and his son. The patient made CBOC clinic visits for 9 weeks, after which his plasma TSH level was low at 0.23 uIU/mL.

Discussion

There are multiple important causes to consider in patients with persistent hypothyroidism. One is medication nonadherence, which was most likely seen in the patient in this case. Missing even 1 day of levothyroxine can affect TSH and thyroid hormone levels for several days due to the long half-life of the medication.2 Hepp and colleagues found that patients with hypothyroidism were significantly more likely to be nonadherent to levothyroxine if they had comorbid conditions such as type 2 diabetes or were obese.3 Another study of levothyroxine adherence found that the most common reason for missing doses was forgetfulness.4 However, memory and cognition impairments can also be symptoms of hypothyroidism itself; Haskard-Zolnierek and colleagues found a significant association between nonadherence to levothyroxine and self-reported brain fog in patients with hypothyroidism.5

Another cause of persistent hypothyroidism is malabsorption. Absorption of levothyroxine can be affected by intestinal malabsorption due to inflammatory bowel disease, lactose intolerance, or gastrointestinal infection, as well as several foods, drinks (eg, coffee), medications, vitamins, and supplements (eg, proton-pump inhibitors and calcium).2,6 Levothyroxine is absorbed mainly at the jejunum and upper ileum, so any pathologies or ingested items that would directly or indirectly affect absorption at those sites can affect levothyroxine absorption.2

A liquid levothyroxine formulation can help with malabsorption.2 Alternatively, weight gain may lead to a need for increasing the dosage of levothyroxine.2,6 Other factors that can affect TSH levels include Addison disease, dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis, and TSH heterophile antibodies.2

Research describes methods that have effectively treated hypothyroidism in patients struggling with levothyroxine adherence. Two case reports describe weekly visits for levothyroxine administration successfully treating uncontrolled hypothyroidism.7,8 A meta-analysis found that while weekly levothyroxine tablets led to a higher mean TSH level than daily use, weekly use still led to reference-range TSH levels, suggesting that weekly levothyroxine may be a helpful alternative for nonadherent patients.9 Alternatively, patients taking levothyroxine tablets have been shown to forget to take their medication more frequently compared to those taking the liquid formulation.10,11 Additionally, a study by El Helou and colleagues found that adherence to levothyroxine was significantly improved when patients had endocrinology visits once a month and when the endocrinologist provided information about hypothyroidism.12

Another method that may improve adherence to levothyroxine is telehealth visits. This would be especially helpful for patients who live far from the clinic or do not have the time, transportation, or financial means to visit the clinic for weekly visits to assess medication adherence. Additionally, patients may be afraid of admitting to a health care professional that they are nonadherent. Clinicians must be tactful when asking about adherence to make the patient feel comfortable with admitting to nonadherence if their cognition is not impaired. Then, a patient-led conversation can occur regarding realistic ways the patient feels they can work toward adherence.

To our knowledge, the patient in this case report had no symptoms of intestinal malabsorption, and weight gain was not thought to be the issue, as levothyroxine dosage was adjusted multiple times. His plasma TSH levels returned to reference range after weekly pill count visits for 6 weeks and after weekly pill count visits for 9 weeks. Therefore, nonadherence to levothyroxine was suspected to be the cause of frequently elevated plasma TSH levels despite the patient’s insistence on adherence. While the patient did not report memory issues, cognitive impairments due to hypothyroidism may have been contributing to his probable nonadherence. Additionally, he had comorbidities, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity, which may have made adherence more difficult.

Levothyroxine was also only prescribed in daily tablet form, so the frequency and formulation may have also contributed to nonadherence. While the home nurse was originally sent to assess the patient’s adherence, the care team could have had the nurse start giving the patient weekly levothyroxine once nonadherence was determined to be a likely issue. The patient’s adherence only improved when he went to the clinic for pill counts but not when the home nurse came to his house weekly; this could be because the patient knew he had to invest the time to physically go to clinic visits for pill checks, motivating him to increase adherence.

Conclusions

This case reports a patient with frequently high plasma TSH levels achieving normalization of plasma TSH levels after weekly medication adherence checks at a primary care clinic. Weekly visits to a clinic seem impractical compared to weekly dosing with a visiting nurse; however, after review of the literature, this may be an approach to consider in the future. This strategy may especially help in cases of persistent abnormal plasma TSH levels in which no etiology can be found other than suspected medication nonadherence. Knowing their medication use will be checked at weekly clinic visits may motivate patients to be adherent.

Nonadherence to medications is an issue across health care. In endocrinology, hypothyroidism, a deficiency of thyroid hormones, is most often treated with levothyroxine and if left untreated can lead to myxedema coma, which can lead to death due to multiorgan dysfunction.1 Therefore, adherence to levothyroxine is very important in preventing fatal complications.

We present the case of a patient with persistent primary hypothyroidism who was suspected to be nonadherent to levothyroxine, although the patient consistently claimed adherence. The patient’s plasma thyrotropin (TSH) level improved to reference range after 6 weeks of weekly primary care clinic visits. After stopping the visits, his plasma TSH level increased again, so 9 more weeks of visits resumed, which again helped bring down his plasma TSH levels.

Case Presentation

A male patient aged 67 years presented to the Dayton Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) endocrinology clinic for evaluation of thyroid nodules. The patient reported no history of neck irradiation and a physical examination was unremarkable. At that time, laboratory results showed a slightly elevated plasma TSH level of 4.35 uIU/mL (reference range, 0.35-4.00 uIU/mL) and normal free thyroxine (T4) of 1.00 ng/dL (reference range, 0.74-1.46 ng/dL). Later that year, the patient underwent a total thyroidectomy at the Cincinnati VAMC for Hurthle cell variant papillary thyroid carcinoma that was noted on biopsy at the Dayton VAMC. After surgical pathology results were available, the patient started levothyroxine 200 mcg daily, although 224 mcg would have been more appropriate based on his 142 kg weight. Due to a history of arrhythmia, the goal plasma TSH level was 0.10 to 0.50 uIU/mL. The patient subsequently underwent radioactive iodine ablation. After levothyroxine dose adjustments, the patient’s plasma TSH level was noted to be within his target range at 0.28 uIU/mL 3 months postablation.

Over the next 5 years the patient had regular laboratory tests during which his plasma TSH level rose and were typically high despite adjusting levothyroxine doses between 200 mcg and 325 mcg. The patient received counseling on taking the medication in the morning on an empty stomach and waiting at least 1 hour before consuming anything, and he went to many follow-up visits at the Dayton VAMC endocrinology clinic. He reported no vomiting or diarrhea but endorsed weight gain once. The patient also had high free T4 at times and did not take extra levothyroxine before undergoing laboratory tests.

Nonadherence to levothyroxine was suspected, but the patient insisted he was adherent. He received the medication in the mail regularly, generally had 90-day refills unless a dose change was made, used a pill box, and had social support from his son, but he did not use a phone alarm to remind him to take it. A home care nurse made weekly visits to make sure the remaining levothyroxine pill counts were correct; however, the patient continued to have difficulty maintaining daily adherence at home as indicated by the nurse’s pill counts not aligning with the number of pills which should have been left if the patient was talking the pills daily.

The patient was asked to visit a local community-based outpatient clinic (CBOC) weekly (to avoid patient travel time to Dayton VAMC > 1 hour) to check pill counts and assess adherence. The patient went to the CBOC clinic for these visits, during which pill counts indicated much better but not 100% adherence. After 6 weeks of clinic visits, his plasma TSH decreased to 1.01 uIU/mL, which was within the reference range, and the patient stopped coming to the weekly clinic visits (Table). Four months later, the patient's plasma TSH levels increased to 80.72 uIU/mL. Nonadherence to levothyroxine was suspected again. He was asked to resume weekly clinic visits, and the life-threatening effects of hypothyroidism and not taking levothyroxine were discussed with the patient and his son. The patient made CBOC clinic visits for 9 weeks, after which his plasma TSH level was low at 0.23 uIU/mL.

Discussion

There are multiple important causes to consider in patients with persistent hypothyroidism. One is medication nonadherence, which was most likely seen in the patient in this case. Missing even 1 day of levothyroxine can affect TSH and thyroid hormone levels for several days due to the long half-life of the medication.2 Hepp and colleagues found that patients with hypothyroidism were significantly more likely to be nonadherent to levothyroxine if they had comorbid conditions such as type 2 diabetes or were obese.3 Another study of levothyroxine adherence found that the most common reason for missing doses was forgetfulness.4 However, memory and cognition impairments can also be symptoms of hypothyroidism itself; Haskard-Zolnierek and colleagues found a significant association between nonadherence to levothyroxine and self-reported brain fog in patients with hypothyroidism.5

Another cause of persistent hypothyroidism is malabsorption. Absorption of levothyroxine can be affected by intestinal malabsorption due to inflammatory bowel disease, lactose intolerance, or gastrointestinal infection, as well as several foods, drinks (eg, coffee), medications, vitamins, and supplements (eg, proton-pump inhibitors and calcium).2,6 Levothyroxine is absorbed mainly at the jejunum and upper ileum, so any pathologies or ingested items that would directly or indirectly affect absorption at those sites can affect levothyroxine absorption.2

A liquid levothyroxine formulation can help with malabsorption.2 Alternatively, weight gain may lead to a need for increasing the dosage of levothyroxine.2,6 Other factors that can affect TSH levels include Addison disease, dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis, and TSH heterophile antibodies.2

Research describes methods that have effectively treated hypothyroidism in patients struggling with levothyroxine adherence. Two case reports describe weekly visits for levothyroxine administration successfully treating uncontrolled hypothyroidism.7,8 A meta-analysis found that while weekly levothyroxine tablets led to a higher mean TSH level than daily use, weekly use still led to reference-range TSH levels, suggesting that weekly levothyroxine may be a helpful alternative for nonadherent patients.9 Alternatively, patients taking levothyroxine tablets have been shown to forget to take their medication more frequently compared to those taking the liquid formulation.10,11 Additionally, a study by El Helou and colleagues found that adherence to levothyroxine was significantly improved when patients had endocrinology visits once a month and when the endocrinologist provided information about hypothyroidism.12

Another method that may improve adherence to levothyroxine is telehealth visits. This would be especially helpful for patients who live far from the clinic or do not have the time, transportation, or financial means to visit the clinic for weekly visits to assess medication adherence. Additionally, patients may be afraid of admitting to a health care professional that they are nonadherent. Clinicians must be tactful when asking about adherence to make the patient feel comfortable with admitting to nonadherence if their cognition is not impaired. Then, a patient-led conversation can occur regarding realistic ways the patient feels they can work toward adherence.

To our knowledge, the patient in this case report had no symptoms of intestinal malabsorption, and weight gain was not thought to be the issue, as levothyroxine dosage was adjusted multiple times. His plasma TSH levels returned to reference range after weekly pill count visits for 6 weeks and after weekly pill count visits for 9 weeks. Therefore, nonadherence to levothyroxine was suspected to be the cause of frequently elevated plasma TSH levels despite the patient’s insistence on adherence. While the patient did not report memory issues, cognitive impairments due to hypothyroidism may have been contributing to his probable nonadherence. Additionally, he had comorbidities, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity, which may have made adherence more difficult.

Levothyroxine was also only prescribed in daily tablet form, so the frequency and formulation may have also contributed to nonadherence. While the home nurse was originally sent to assess the patient’s adherence, the care team could have had the nurse start giving the patient weekly levothyroxine once nonadherence was determined to be a likely issue. The patient’s adherence only improved when he went to the clinic for pill counts but not when the home nurse came to his house weekly; this could be because the patient knew he had to invest the time to physically go to clinic visits for pill checks, motivating him to increase adherence.

Conclusions

This case reports a patient with frequently high plasma TSH levels achieving normalization of plasma TSH levels after weekly medication adherence checks at a primary care clinic. Weekly visits to a clinic seem impractical compared to weekly dosing with a visiting nurse; however, after review of the literature, this may be an approach to consider in the future. This strategy may especially help in cases of persistent abnormal plasma TSH levels in which no etiology can be found other than suspected medication nonadherence. Knowing their medication use will be checked at weekly clinic visits may motivate patients to be adherent.

1. Chaker L, Bianco AC, Jonklaas J, Peeters RP. Hypothyroidism. Lancet. 2017;390(10101):1550-1562. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30703-1

2. Centanni M, Benvenga S, Sachmechi I. Diagnosis and management of treatment-refractory hypothyroidism: an expert consensus report. J Endocrinol Invest. 2017;40(12):1289-1301. doi:10.1007/s40618-017-0706-y

3. Hepp Z, Lage MJ, Espaillat R, Gossain VV. The association between adherence to levothyroxine and economic and clinical outcomes in patients with hypothyroidism in the US. J Med Econ. 2018;21(9):912-919. doi:10.1080/13696998.2018.1484749

4. Shakya Shrestha S, Risal K, Shrestha R, Bhatta RD. Medication Adherence to Levothyroxine Therapy among Hypothyroid Patients and their Clinical Outcomes with Special Reference to Thyroid Function Parameters. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ). 2018;16(62):129-137.

5. Haskard-Zolnierek K, Wilson C, Pruin J, Deason R, Howard K. The Relationship Between Brain Fog and Medication Adherence for Individuals With Hypothyroidism. Clin Nurs Res. 2022;31(3):445-452. doi:10.1177/10547738211038127

6. McNally LJ, Ofiaeli CI, Oyibo SO. Treatment-refractory hypothyroidism. BMJ. 2019;364:l579. Published 2019 Feb 25. doi:10.1136/bmj.l579

7. Nakano Y, Hashimoto K, Ohkiba N, et al. A Case of Refractory Hypothyroidism due to Poor Compliance Treated with the Weekly Intravenous and Oral Levothyroxine Administration. Case Rep Endocrinol. 2019;2019:5986014. Published 2019 Feb 5. doi:10.1155/2019/5986014

8. Kiran Z, Shaikh KS, Fatima N, Tariq N, Baloch AA. Levothyroxine absorption test followed by directly observed treatment on an outpatient basis to address long-term high TSH levels in a hypothyroid patient: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2023;17(1):24. Published 2023 Jan 25. doi:10.1186/s13256-023-03760-0

9. Chiu HH, Larrazabal R Jr, Uy AB, Jimeno C. Weekly Versus Daily Levothyroxine Tablet Replacement in Adults with Hypothyroidism: A Meta-Analysis. J ASEAN Fed Endocr Soc. 2021;36(2):156-160. doi:10.15605/jafes.036.02.07

10. Cappelli C, Castello R, Marini F, et al. Adherence to Levothyroxine Treatment Among Patients With Hypothyroidism: A Northeastern Italian Survey. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2018;9:699. Published 2018 Nov 23. doi:10.3389/fendo.2018.00699

11. Bocale R, Desideri G, Barini A, et al. Long-Term Adherence to Levothyroxine Replacement Therapy in Thyroidectomized Patients. J Clin Med. 2022;11(15):4296. Published 2022 Jul 24. doi:10.3390/jcm11154296

12. El Helou S, Hallit S, Awada S, et al. Adherence to levothyroxine among patients with hypothyroidism in Lebanon. East Mediterr Health J. 2019;25(3):149-159. Published 2019 Apr 25. doi:10.26719/emhj.18.022

1. Chaker L, Bianco AC, Jonklaas J, Peeters RP. Hypothyroidism. Lancet. 2017;390(10101):1550-1562. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30703-1

2. Centanni M, Benvenga S, Sachmechi I. Diagnosis and management of treatment-refractory hypothyroidism: an expert consensus report. J Endocrinol Invest. 2017;40(12):1289-1301. doi:10.1007/s40618-017-0706-y

3. Hepp Z, Lage MJ, Espaillat R, Gossain VV. The association between adherence to levothyroxine and economic and clinical outcomes in patients with hypothyroidism in the US. J Med Econ. 2018;21(9):912-919. doi:10.1080/13696998.2018.1484749

4. Shakya Shrestha S, Risal K, Shrestha R, Bhatta RD. Medication Adherence to Levothyroxine Therapy among Hypothyroid Patients and their Clinical Outcomes with Special Reference to Thyroid Function Parameters. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ). 2018;16(62):129-137.

5. Haskard-Zolnierek K, Wilson C, Pruin J, Deason R, Howard K. The Relationship Between Brain Fog and Medication Adherence for Individuals With Hypothyroidism. Clin Nurs Res. 2022;31(3):445-452. doi:10.1177/10547738211038127

6. McNally LJ, Ofiaeli CI, Oyibo SO. Treatment-refractory hypothyroidism. BMJ. 2019;364:l579. Published 2019 Feb 25. doi:10.1136/bmj.l579

7. Nakano Y, Hashimoto K, Ohkiba N, et al. A Case of Refractory Hypothyroidism due to Poor Compliance Treated with the Weekly Intravenous and Oral Levothyroxine Administration. Case Rep Endocrinol. 2019;2019:5986014. Published 2019 Feb 5. doi:10.1155/2019/5986014

8. Kiran Z, Shaikh KS, Fatima N, Tariq N, Baloch AA. Levothyroxine absorption test followed by directly observed treatment on an outpatient basis to address long-term high TSH levels in a hypothyroid patient: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2023;17(1):24. Published 2023 Jan 25. doi:10.1186/s13256-023-03760-0

9. Chiu HH, Larrazabal R Jr, Uy AB, Jimeno C. Weekly Versus Daily Levothyroxine Tablet Replacement in Adults with Hypothyroidism: A Meta-Analysis. J ASEAN Fed Endocr Soc. 2021;36(2):156-160. doi:10.15605/jafes.036.02.07

10. Cappelli C, Castello R, Marini F, et al. Adherence to Levothyroxine Treatment Among Patients With Hypothyroidism: A Northeastern Italian Survey. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2018;9:699. Published 2018 Nov 23. doi:10.3389/fendo.2018.00699

11. Bocale R, Desideri G, Barini A, et al. Long-Term Adherence to Levothyroxine Replacement Therapy in Thyroidectomized Patients. J Clin Med. 2022;11(15):4296. Published 2022 Jul 24. doi:10.3390/jcm11154296

12. El Helou S, Hallit S, Awada S, et al. Adherence to levothyroxine among patients with hypothyroidism in Lebanon. East Mediterr Health J. 2019;25(3):149-159. Published 2019 Apr 25. doi:10.26719/emhj.18.022

Dermatologic Reactions Following COVID-19 Vaccination: A Case Series

Cutaneous reactions associated with the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine have been reported worldwide since December 2020. Local injection site reactions (<1%) such as erythema, swelling, delayed local reactions (1%–10%), morbilliform rash, urticarial reactions, pityriasis rosea, Rowell syndrome, and lichen planus have been reported following the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine.1 Cutaneous reactions reported in association with the Sinovac-Coronavac COVID-19 vaccine include swelling, redness, itching, discoloration, induration (1%–10%), urticaria, petechial rash, and exacerbation of psoriasis at the local injection site (<1%).2

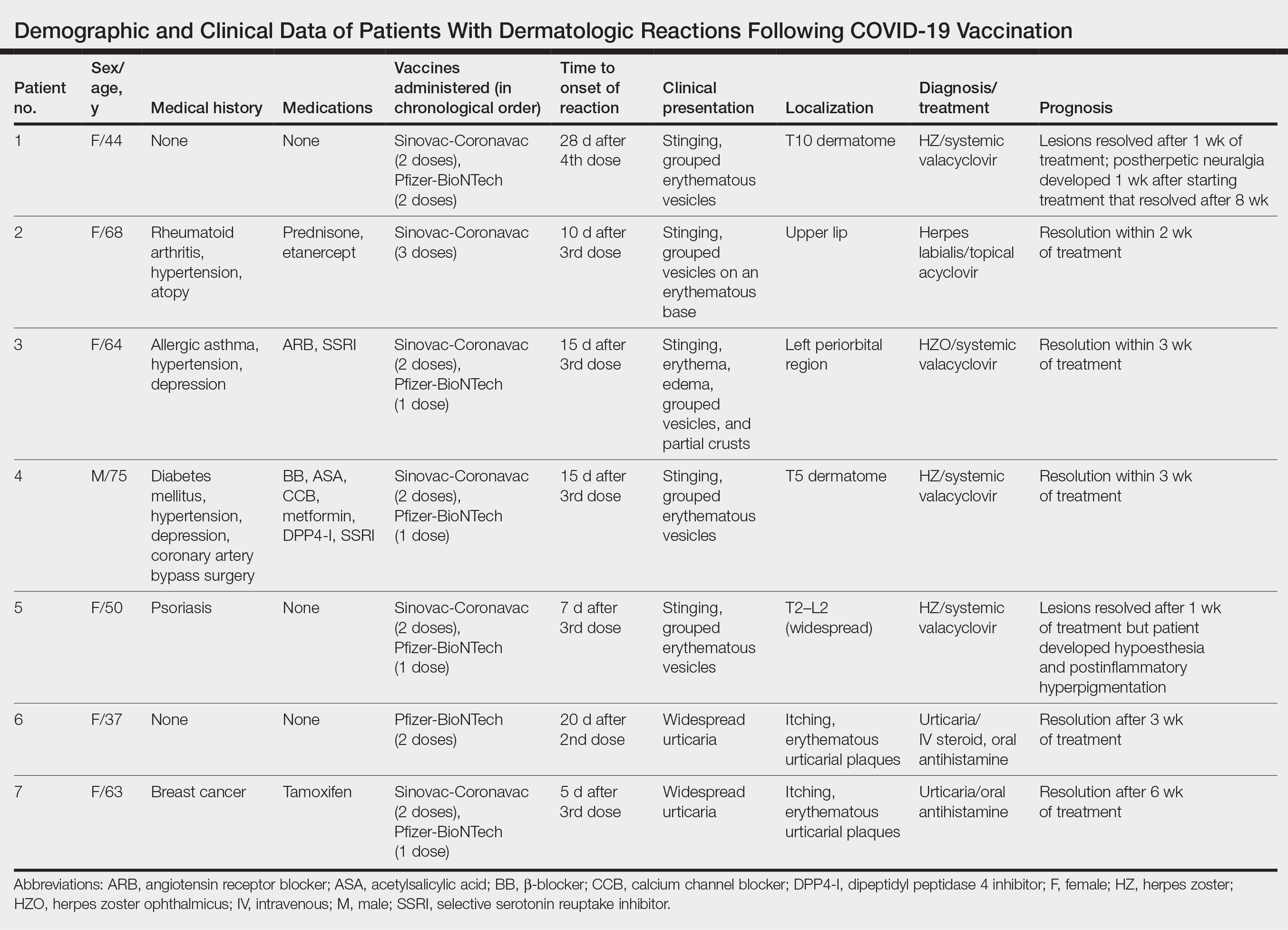

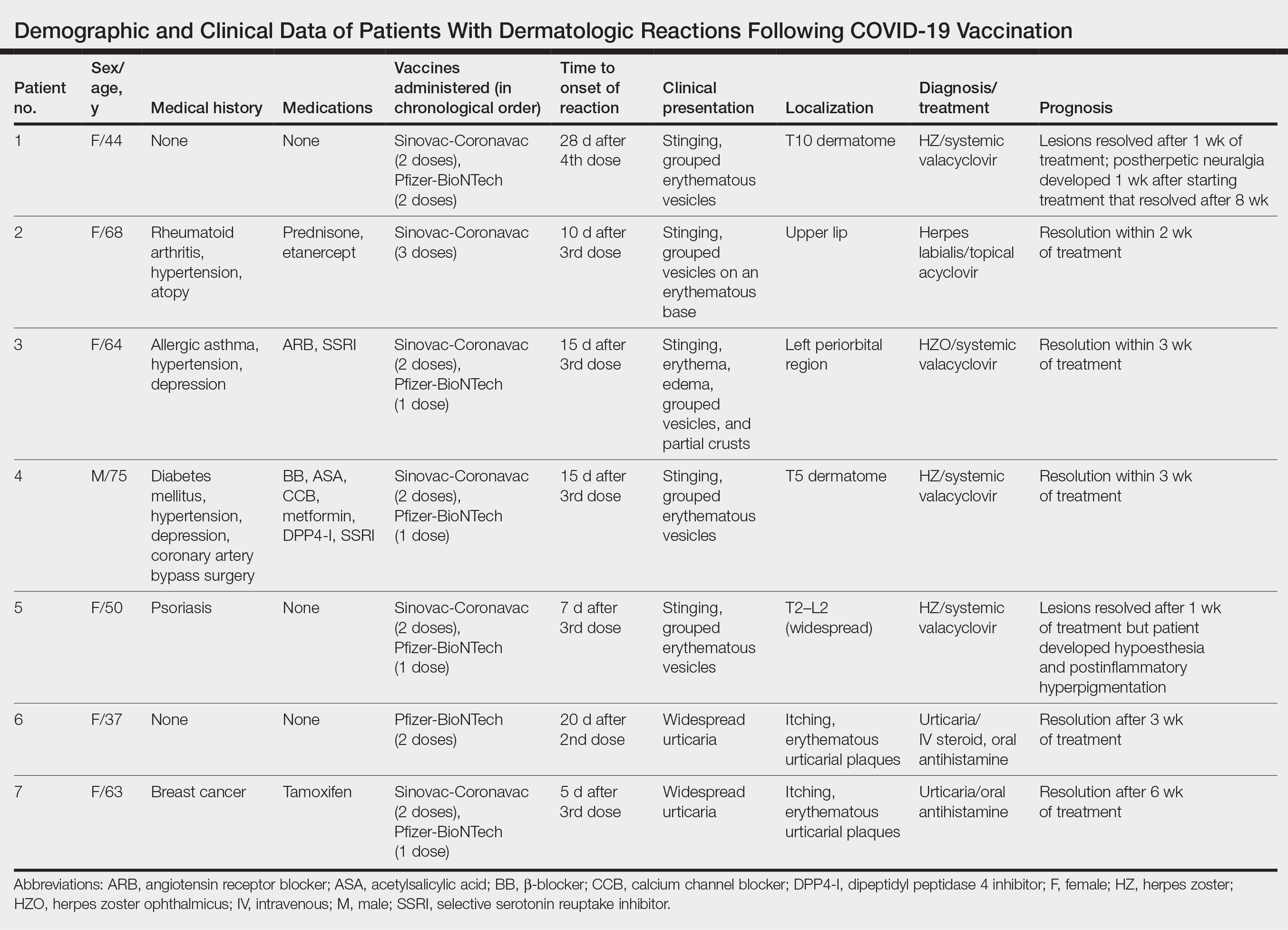

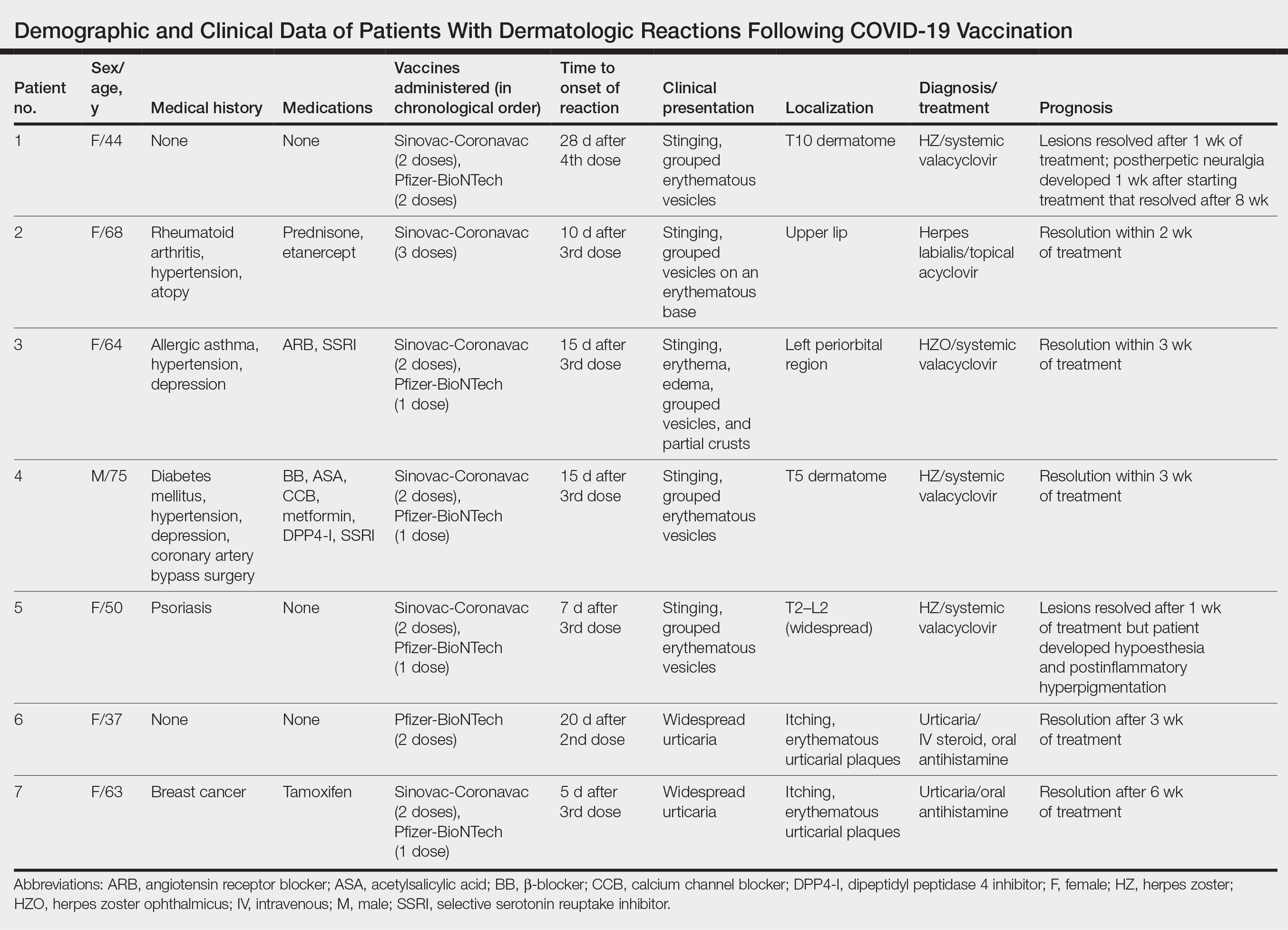

We describe 7 patients from Turkey who presented with various dermatologic problems 5 to 28 days after COVID-19 vaccination, highlighting the possibility of early and late cutaneous reactions related to the vaccine (Table).

Case Reports

Patient 1—A 44-year-old woman was admitted to the dermatology clinic with painful lesions on the trunk of 3 days’ duration. Dermatologic examination revealed grouped erythematous vesicles showing dermatomal spread in the right thoracolumbar (dermatome T10) region. The patient reported that she had received 2 doses of the Sinovac-Coronavac vaccine (doses 1 and 2) and 2 doses of the BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine (doses 3 and 4); the rash had developed 28 days after she received the 4th dose. Her medical history was unremarkable. The lesions regressed after 1 week of treatment with oral valacyclovir 1000 mg 3 times daily, but she developed postherpetic neuralgia 1 week after starting treatment, which resolved after 8 weeks.

Patient 2—A 68-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of painful sores on the upper lip of 1 day’s duration. She had a history of rheumatoid arthritis, hypertension, and atopy and was currently taking prednisone and etanercept. Dermatologic examination revealed grouped vesicles on an erythematous base on the upper lip. A diagnosis of herpes labialis was made. The patient reported that she had received a third dose of the Sinovac-Coronavac vaccine 10 days prior to the appearance of the lesions. Her symptoms resolved completely within 2 weeks of treatment with topical acyclovir.

Patient 3—A 64-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital with pain, redness, and watery sores on and around the left eyelid of 2 days’ duration. Dermatologic evaluation revealed the erythematous surface of the left eyelid and periorbital area showed partial crusts, clustered vesicles, erythema, and edema. Additionally, the conjunctiva was purulent and erythematous. The patient’s medical history was notable for allergic asthma, hypertension, anxiety, and depression. For this reason, the patient was prescribed an angiotensin receptor blocker and a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. She noted that a similar rash had developed around the left eye 6 years prior that was diagnosed as herpes zoster (HZ). She also reported that she had received 2 doses of the Sinovac-Coronavac COVID-19 vaccine followed by 1 dose of the BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine, which she had received 2 weeks before the rash developed. The patient was treated at the eye clinic and was found to have ocular involvement. Ophthalmology was consulted and a diagnosis of herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO) was made. Systemic valacyclovir treatment was initiated, resulting in clinical improvement within 3 weeks.

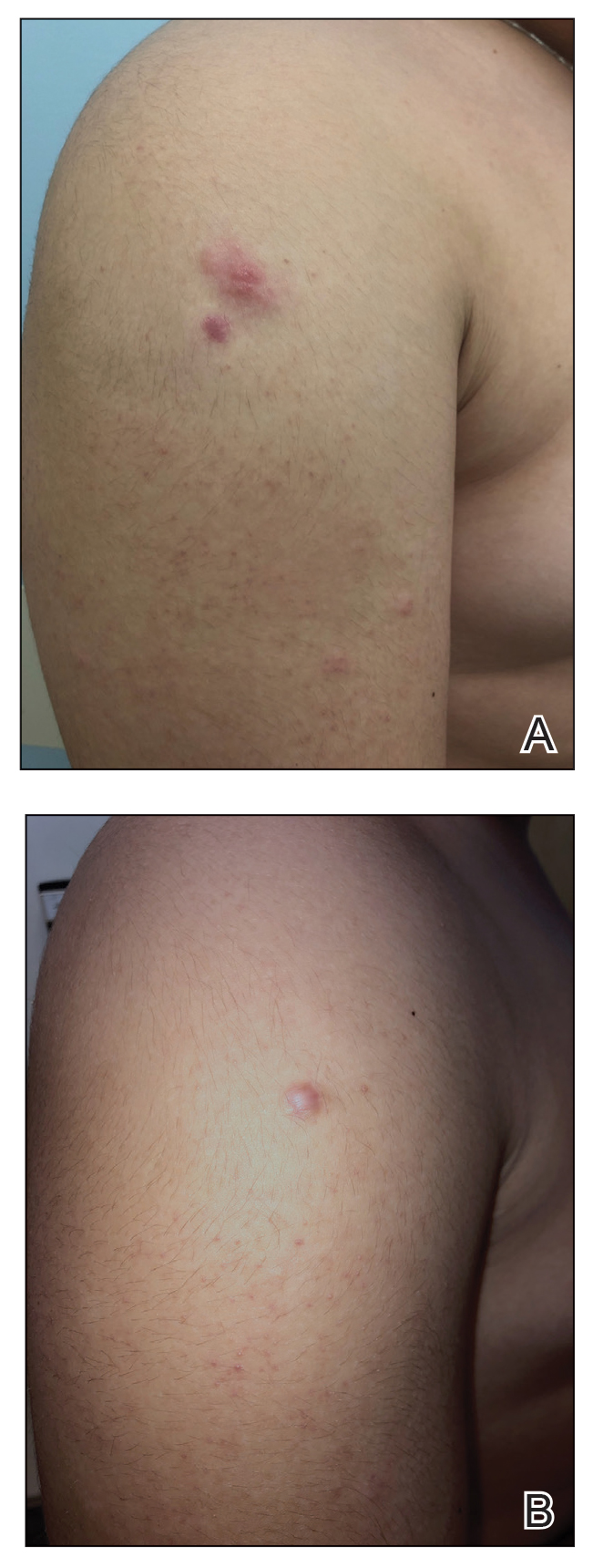

Patient 4—A 75-year-old man was admitted to the hospital with chest and back pain and widespread muscle pain of several days’ duration. His medical history was remarkable for diabetes mellitus, hypertension, depression, and coronary artery bypass surgery. A medication history revealed treatment with a β-blocker, acetylsalicylic acid, a calcium channel blocker, a dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitor, and a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. Dermatologic examination revealed grouped vesicles on an erythematous background in dermatome T5 on the right chest and back. A diagnosis of HZ was made. The patient reported that he had received 2 doses of the Sinovac-Coronavac vaccine followed by 1 dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine 2 weeks prior to the current presentation. He was treated with valacyclovir for 1 week, and his symptoms resolved entirely within 3 weeks.

Patient 5—A 50-year-old woman presented to the hospital for evaluation of painful sores on the back, chest, groin, and abdomen of 10 days’ duration. The lesions initially had developed 7 days after receiving the BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine; she previously had received 2 doses of the Sinovac-Coronavac vaccine. The patient had a history of untreated psoriasis. Dermatologic examination revealed grouped vesicles on an erythematous background in the T2–L2 dermatomes on the left side of the trunk. A diagnosis of HZ was made. The lesions resolved after 1 week of treatment with systemic valacyclovir; however, she subsequently developed postherpetic neuralgia, hypoesthesia, and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in the affected regions.

Patient 6—A 37-year-old woman presented to the hospital with redness, swelling, and itching all over the body of 3 days’ duration. The patient noted that the rash would subside and reappear throughout the day. Her medical history was unremarkable, except for COVID-19 infection 6 months prior. She had received a second dose of the BioNTech vaccine 20 days prior to development of symptoms. Dermatologic examination revealed widespread erythematous urticarial plaques. A diagnosis of acute urticaria was made. The patient recovered completely after 1 week of treatment with a systemic steroid and 3 weeks of antihistamine treatment.

Patient 7—A 63-year-old woman presented to the hospital with widespread itching and rash that appeared 5 days after the first dose of the BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. The patient reported that the rash resolved spontaneously within a few hours but then reappeared. Her medical history revealed that she was taking tamoxifen for breast cancer and that she previously had received 2 doses of the Sinovac-Coronavac vaccine. Dermatologic examination revealed erythematous urticarial plaques on the trunk and arms. A diagnosis of urticaria was made, and her symptoms resolved after 6 weeks of antihistamine treatment.

Comment

Skin lesions associated with COVID-19 infection have been reported worldwide3,4 as well as dermatologic reactions following COVID-19 vaccination. In one case from Turkey, HZ infection was reported in a 68-year-old man 5 days after he received a second dose of the COVID-19 vaccine.5 In another case, HZ infection developed in a 78-year-old man 5 days after COVID-19 vaccination.6 Numerous cases of HZ infection developing within 1 to 26 days of COVID-19 vaccination have been reported worldwide.7-9

In a study conducted in the United States, 40 skin reactions associated with the COVID-19 vaccine were investigated; of these cases, 87.5% (35/40) were reported as varicella-zoster virus, and 12.5% (5/40) were reported as herpes simplex reactivation; 54% (19/35) and 80% (4/5) of these cases, respectively, were associated with the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine.10 The average age of patients who developed a skin reaction was 46 years, and 70% (28/40) were women. The time to onset of the reaction was 2 to 13 days after vaccination, and symptoms were reported to improve within 7 days on average.10

Another study from Spain examined 405 vaccine-related skin reactions, 40.2% of which were related to the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine. Among them, 80.2% occurred in women; 13.8% of cases were diagnosed as varicella-zoster virus or HZ virus reactivation, and 14.6% were urticaria. Eighty reactions (21%) were classified as severe/very severe and 81% required treatment.11 One study reported 414 skin reactions from the COVID-19 vaccine from December 2020 to February 2021; of these cases, 83% occurred after the Moderna vaccine, which is not available in Turkey, and 17% occurred after the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine.12A systematic review of 91 patients who developed HZ infection after COVID-19 vaccination reported that 10% (9/91) of cases were receiving immunosuppressive therapy and 13% (12/91) had an autoimmune disease.7 In our case series, it is known that at least 2 of the patients (patients 2 and 5), including 1 patient with rheumatoid arthritis (patient 2) who was on immunosuppressive treatment, had autoimmune disorders. However, reports in the literature indicate that most patients with autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic diseases remain stable after vaccination.13

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus is a rare form of HZ caused by involvement of the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve that manifests as vesicular lesions and retinitis, uveitis, keratitis, conjunctivitis, and pain on an erythematous background. Two cases of women who developed HZO infection after Pfizer-BioNTech vaccination were reported in the literature.14 Although patient 3 in our case series had a history of HZO 6 years prior, the possibility of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine triggering HZO should be taken into consideration.

Although cutaneous reactions after the Sinovac-Coronavac vaccine were observed in only 1 of 7 patients in our case series, skin reactions after Sinovac-Coronavac (an inactivated viral vaccine) have been reported in the literature. In one study, after a total of 35,229 injections, the incidence of cutaneous adverse events due to Sinovac-Coronavac was reported to be 0.94% and 0.70% after the first and second doses, respectively.15 Therefore, further study results are needed to directly attribute the reactions to COVID-19 vaccination.

Conclusion

Our case series highlights that clinicians should be vigilant in diagnosing cutaneous reactions following COVID-19 vaccination early to prevent potential complications. Early recognition of reactions is crucial, and the prognosis can be improved with appropriate treatment. Despite the potential dermatologic adverse effects of the COVID-19 vaccine, the most effective way to protect against serious COVID-19 infection is to continue to be vaccinated.

- Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2603-2615.

- Zhang Y, Zeng G, Pan H, et al. Safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in healthy adults aged 18–59 years: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1/2 clinical trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21:181-192.

- Tan SW, Tam YC, Oh CC. Skin manifestations of COVID-19: a worldwide review. JAAD Int. 2021;2:119-133.

- Singh H, Kaur H, Singh K, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19: a systematic review. advances in wound care. 2021;10:51-80.

- Aksu SB, Öztürk GZ. A rare case of shingles after COVID-19 vaccine: is it a possible adverse effect? clinical and experimental vaccine research. 2021;10:198-201.

- Bostan E, Yalici-Armagan B. Herpes zoster following inactivated COVID-19 vaccine: a coexistence or coincidence? J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:1566-1567.

- Katsikas Triantafyllidis K, Giannos P, Mian IT, et al. Varicella zoster virus reactivation following COVID-19 vaccination: a systematic review of case reports. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9:1013. doi:10.3390/vaccines9091013

- Rodríguez-Jiménez P, Chicharro P, Cabrera LM, et al. Varicella-zoster virus reactivation after SARS-CoV-2 BNT162b2 mRNA vaccination: report of 5 cases. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;12:58-59. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2021.04.014

- Lee C, Cotter D, Basa J, et al. 20 Post-COVID-19 vaccine-related shingles cases seen at the Las Vegas Dermatology clinic and sent to us via social media. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:1960-1964.

- Fathy RA, McMahon DE, Lee C, et al. Varicella-zoster and herpes simplex virus reactivation post-COVID-19 vaccination: a review of 40 cases in an International Dermatology Registry. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venerol. 2022;36:E6-E9.

- Català A, Muñoz-Santos C, Galván-Casas C, et al. Cutaneous reactions after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: a cross-sectional Spanish nationwide study of 405 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2022;186:142-152.

- McMahon DE, Amerson E, Rosenbach M, et al. Cutaneous reactions reported after Moderna and Pfizer COVID-19 vaccination: a registry-based study of 414 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:46-55.

- Furer V, Eviatar T, Zisman D, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in adult patients with autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic diseases and in the general population: a multicentre study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:1330-1338.

- Bernardini N, Skroza N, Mambrin A, et al. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus in two women after Pfizer-BioNTech (BNT162b2) vaccine. J Med Virol. 2022;94:817-818.

- Rerknimitr P, Puaratanaarunkon T, Wongtada C, et al. Cutaneous adverse reactions from 35,229 doses of Sinovac and AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccination: a prospective cohort study in healthcare workers. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:E158-E161.

Cutaneous reactions associated with the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine have been reported worldwide since December 2020. Local injection site reactions (<1%) such as erythema, swelling, delayed local reactions (1%–10%), morbilliform rash, urticarial reactions, pityriasis rosea, Rowell syndrome, and lichen planus have been reported following the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine.1 Cutaneous reactions reported in association with the Sinovac-Coronavac COVID-19 vaccine include swelling, redness, itching, discoloration, induration (1%–10%), urticaria, petechial rash, and exacerbation of psoriasis at the local injection site (<1%).2

We describe 7 patients from Turkey who presented with various dermatologic problems 5 to 28 days after COVID-19 vaccination, highlighting the possibility of early and late cutaneous reactions related to the vaccine (Table).

Case Reports

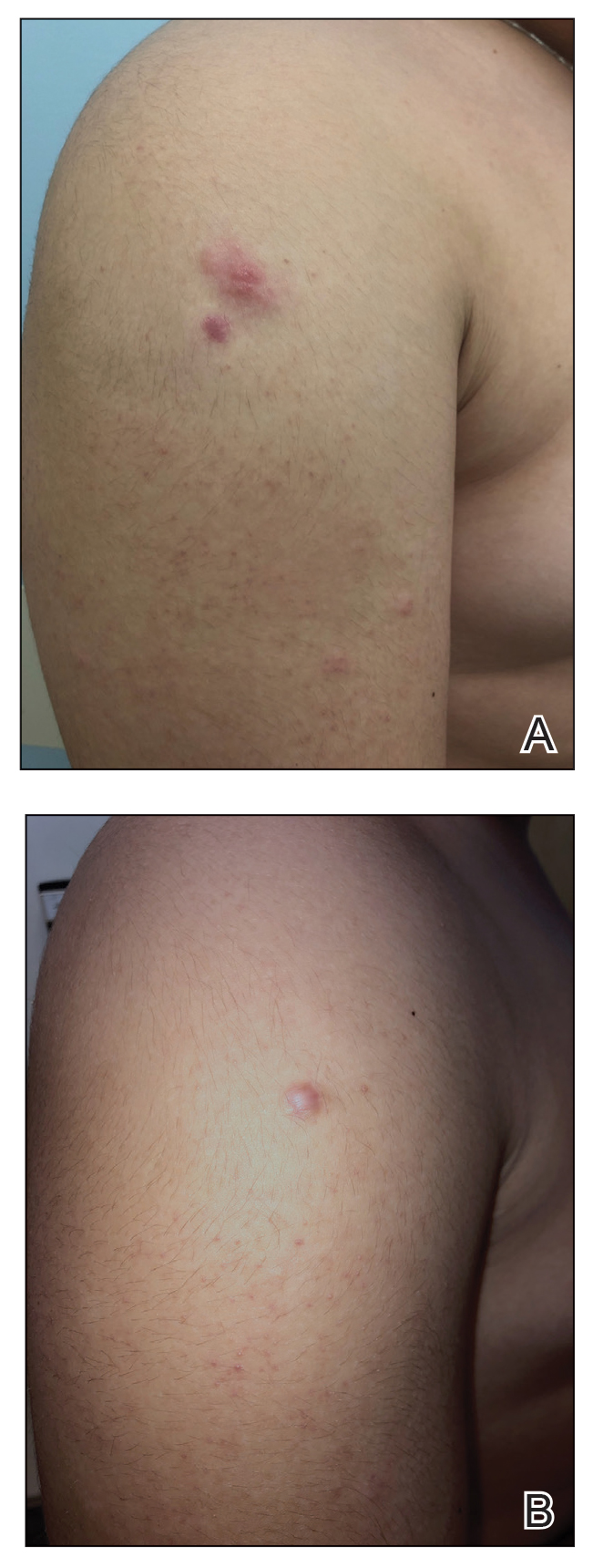

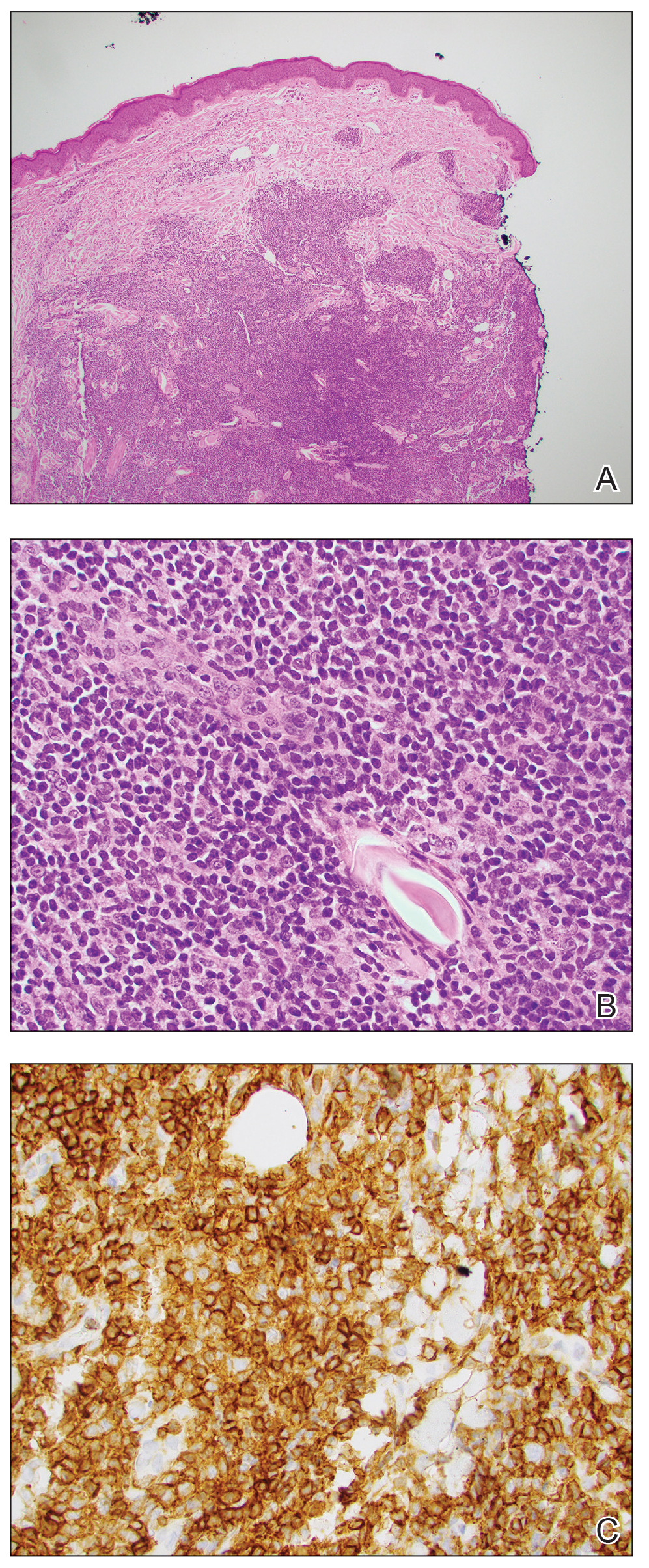

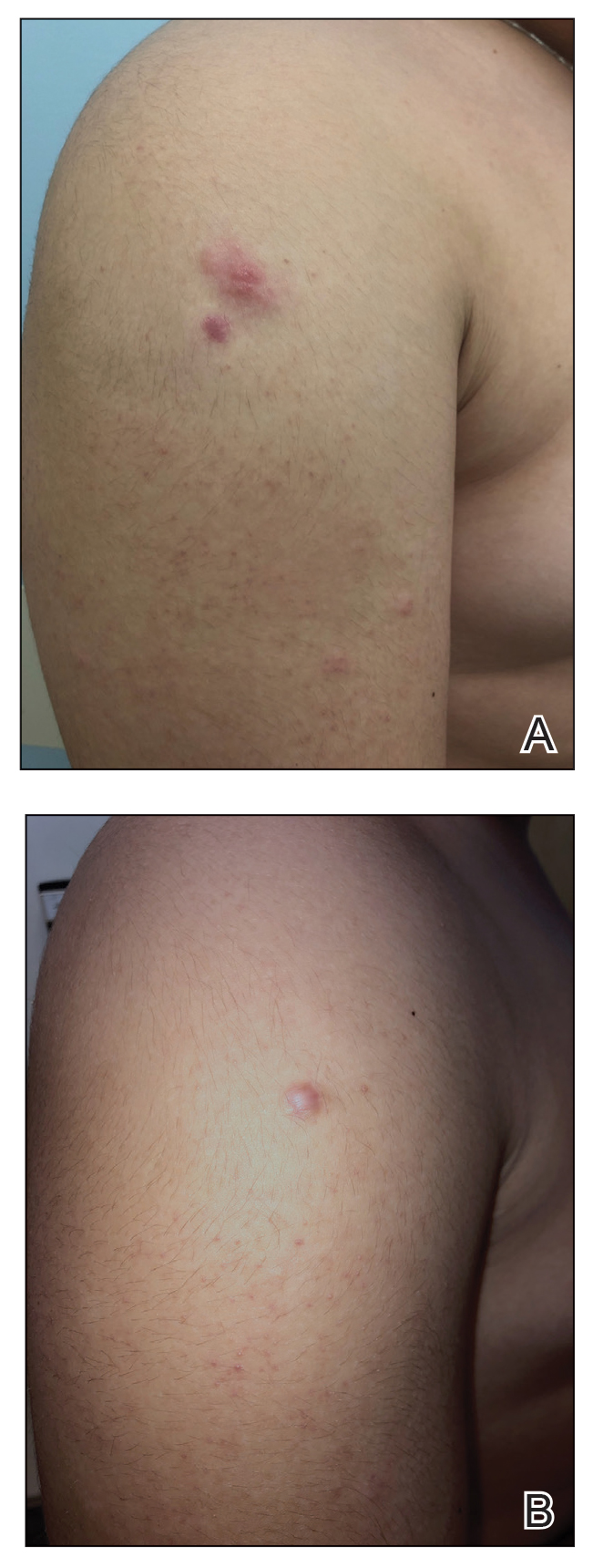

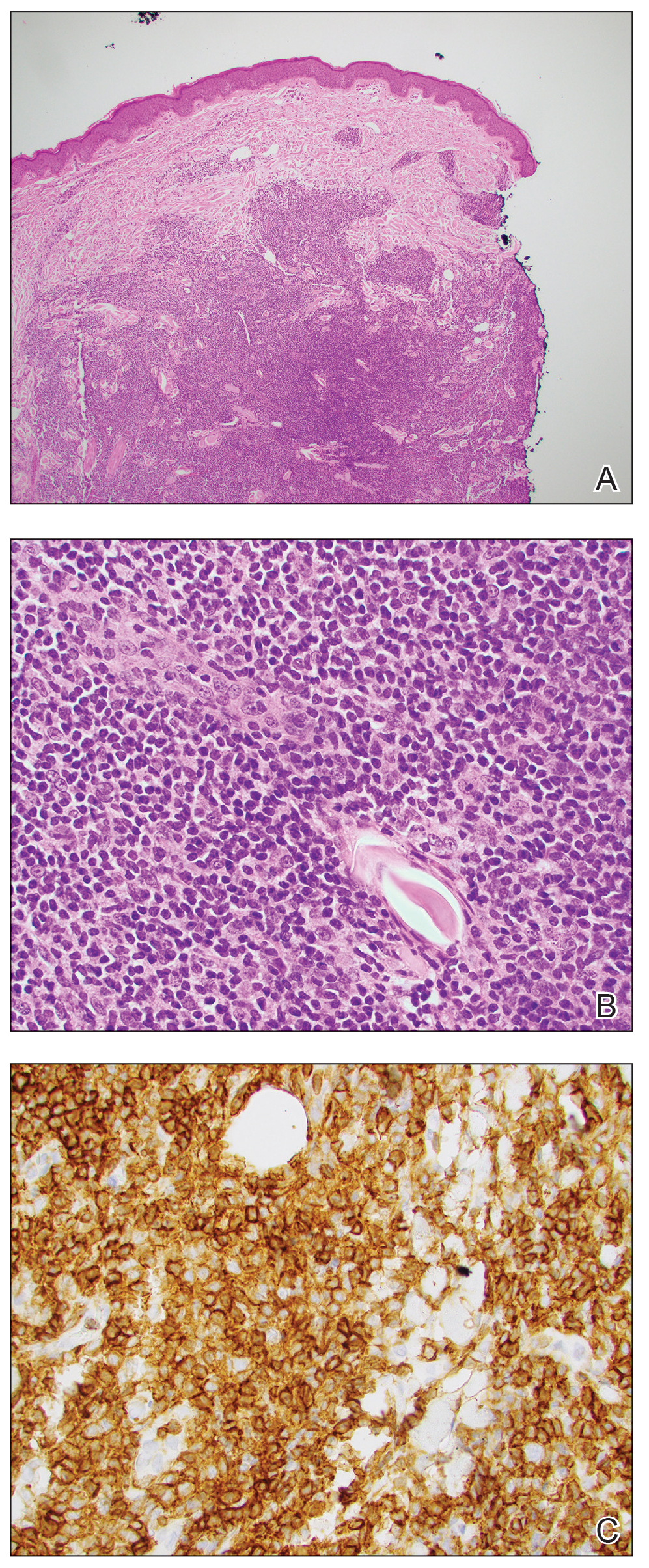

Patient 1—A 44-year-old woman was admitted to the dermatology clinic with painful lesions on the trunk of 3 days’ duration. Dermatologic examination revealed grouped erythematous vesicles showing dermatomal spread in the right thoracolumbar (dermatome T10) region. The patient reported that she had received 2 doses of the Sinovac-Coronavac vaccine (doses 1 and 2) and 2 doses of the BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine (doses 3 and 4); the rash had developed 28 days after she received the 4th dose. Her medical history was unremarkable. The lesions regressed after 1 week of treatment with oral valacyclovir 1000 mg 3 times daily, but she developed postherpetic neuralgia 1 week after starting treatment, which resolved after 8 weeks.

Patient 2—A 68-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of painful sores on the upper lip of 1 day’s duration. She had a history of rheumatoid arthritis, hypertension, and atopy and was currently taking prednisone and etanercept. Dermatologic examination revealed grouped vesicles on an erythematous base on the upper lip. A diagnosis of herpes labialis was made. The patient reported that she had received a third dose of the Sinovac-Coronavac vaccine 10 days prior to the appearance of the lesions. Her symptoms resolved completely within 2 weeks of treatment with topical acyclovir.

Patient 3—A 64-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital with pain, redness, and watery sores on and around the left eyelid of 2 days’ duration. Dermatologic evaluation revealed the erythematous surface of the left eyelid and periorbital area showed partial crusts, clustered vesicles, erythema, and edema. Additionally, the conjunctiva was purulent and erythematous. The patient’s medical history was notable for allergic asthma, hypertension, anxiety, and depression. For this reason, the patient was prescribed an angiotensin receptor blocker and a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. She noted that a similar rash had developed around the left eye 6 years prior that was diagnosed as herpes zoster (HZ). She also reported that she had received 2 doses of the Sinovac-Coronavac COVID-19 vaccine followed by 1 dose of the BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine, which she had received 2 weeks before the rash developed. The patient was treated at the eye clinic and was found to have ocular involvement. Ophthalmology was consulted and a diagnosis of herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO) was made. Systemic valacyclovir treatment was initiated, resulting in clinical improvement within 3 weeks.

Patient 4—A 75-year-old man was admitted to the hospital with chest and back pain and widespread muscle pain of several days’ duration. His medical history was remarkable for diabetes mellitus, hypertension, depression, and coronary artery bypass surgery. A medication history revealed treatment with a β-blocker, acetylsalicylic acid, a calcium channel blocker, a dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitor, and a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. Dermatologic examination revealed grouped vesicles on an erythematous background in dermatome T5 on the right chest and back. A diagnosis of HZ was made. The patient reported that he had received 2 doses of the Sinovac-Coronavac vaccine followed by 1 dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine 2 weeks prior to the current presentation. He was treated with valacyclovir for 1 week, and his symptoms resolved entirely within 3 weeks.

Patient 5—A 50-year-old woman presented to the hospital for evaluation of painful sores on the back, chest, groin, and abdomen of 10 days’ duration. The lesions initially had developed 7 days after receiving the BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine; she previously had received 2 doses of the Sinovac-Coronavac vaccine. The patient had a history of untreated psoriasis. Dermatologic examination revealed grouped vesicles on an erythematous background in the T2–L2 dermatomes on the left side of the trunk. A diagnosis of HZ was made. The lesions resolved after 1 week of treatment with systemic valacyclovir; however, she subsequently developed postherpetic neuralgia, hypoesthesia, and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in the affected regions.

Patient 6—A 37-year-old woman presented to the hospital with redness, swelling, and itching all over the body of 3 days’ duration. The patient noted that the rash would subside and reappear throughout the day. Her medical history was unremarkable, except for COVID-19 infection 6 months prior. She had received a second dose of the BioNTech vaccine 20 days prior to development of symptoms. Dermatologic examination revealed widespread erythematous urticarial plaques. A diagnosis of acute urticaria was made. The patient recovered completely after 1 week of treatment with a systemic steroid and 3 weeks of antihistamine treatment.

Patient 7—A 63-year-old woman presented to the hospital with widespread itching and rash that appeared 5 days after the first dose of the BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. The patient reported that the rash resolved spontaneously within a few hours but then reappeared. Her medical history revealed that she was taking tamoxifen for breast cancer and that she previously had received 2 doses of the Sinovac-Coronavac vaccine. Dermatologic examination revealed erythematous urticarial plaques on the trunk and arms. A diagnosis of urticaria was made, and her symptoms resolved after 6 weeks of antihistamine treatment.

Comment

Skin lesions associated with COVID-19 infection have been reported worldwide3,4 as well as dermatologic reactions following COVID-19 vaccination. In one case from Turkey, HZ infection was reported in a 68-year-old man 5 days after he received a second dose of the COVID-19 vaccine.5 In another case, HZ infection developed in a 78-year-old man 5 days after COVID-19 vaccination.6 Numerous cases of HZ infection developing within 1 to 26 days of COVID-19 vaccination have been reported worldwide.7-9

In a study conducted in the United States, 40 skin reactions associated with the COVID-19 vaccine were investigated; of these cases, 87.5% (35/40) were reported as varicella-zoster virus, and 12.5% (5/40) were reported as herpes simplex reactivation; 54% (19/35) and 80% (4/5) of these cases, respectively, were associated with the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine.10 The average age of patients who developed a skin reaction was 46 years, and 70% (28/40) were women. The time to onset of the reaction was 2 to 13 days after vaccination, and symptoms were reported to improve within 7 days on average.10

Another study from Spain examined 405 vaccine-related skin reactions, 40.2% of which were related to the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine. Among them, 80.2% occurred in women; 13.8% of cases were diagnosed as varicella-zoster virus or HZ virus reactivation, and 14.6% were urticaria. Eighty reactions (21%) were classified as severe/very severe and 81% required treatment.11 One study reported 414 skin reactions from the COVID-19 vaccine from December 2020 to February 2021; of these cases, 83% occurred after the Moderna vaccine, which is not available in Turkey, and 17% occurred after the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine.12A systematic review of 91 patients who developed HZ infection after COVID-19 vaccination reported that 10% (9/91) of cases were receiving immunosuppressive therapy and 13% (12/91) had an autoimmune disease.7 In our case series, it is known that at least 2 of the patients (patients 2 and 5), including 1 patient with rheumatoid arthritis (patient 2) who was on immunosuppressive treatment, had autoimmune disorders. However, reports in the literature indicate that most patients with autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic diseases remain stable after vaccination.13

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus is a rare form of HZ caused by involvement of the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve that manifests as vesicular lesions and retinitis, uveitis, keratitis, conjunctivitis, and pain on an erythematous background. Two cases of women who developed HZO infection after Pfizer-BioNTech vaccination were reported in the literature.14 Although patient 3 in our case series had a history of HZO 6 years prior, the possibility of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine triggering HZO should be taken into consideration.

Although cutaneous reactions after the Sinovac-Coronavac vaccine were observed in only 1 of 7 patients in our case series, skin reactions after Sinovac-Coronavac (an inactivated viral vaccine) have been reported in the literature. In one study, after a total of 35,229 injections, the incidence of cutaneous adverse events due to Sinovac-Coronavac was reported to be 0.94% and 0.70% after the first and second doses, respectively.15 Therefore, further study results are needed to directly attribute the reactions to COVID-19 vaccination.

Conclusion

Our case series highlights that clinicians should be vigilant in diagnosing cutaneous reactions following COVID-19 vaccination early to prevent potential complications. Early recognition of reactions is crucial, and the prognosis can be improved with appropriate treatment. Despite the potential dermatologic adverse effects of the COVID-19 vaccine, the most effective way to protect against serious COVID-19 infection is to continue to be vaccinated.

Cutaneous reactions associated with the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine have been reported worldwide since December 2020. Local injection site reactions (<1%) such as erythema, swelling, delayed local reactions (1%–10%), morbilliform rash, urticarial reactions, pityriasis rosea, Rowell syndrome, and lichen planus have been reported following the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine.1 Cutaneous reactions reported in association with the Sinovac-Coronavac COVID-19 vaccine include swelling, redness, itching, discoloration, induration (1%–10%), urticaria, petechial rash, and exacerbation of psoriasis at the local injection site (<1%).2

We describe 7 patients from Turkey who presented with various dermatologic problems 5 to 28 days after COVID-19 vaccination, highlighting the possibility of early and late cutaneous reactions related to the vaccine (Table).

Case Reports

Patient 1—A 44-year-old woman was admitted to the dermatology clinic with painful lesions on the trunk of 3 days’ duration. Dermatologic examination revealed grouped erythematous vesicles showing dermatomal spread in the right thoracolumbar (dermatome T10) region. The patient reported that she had received 2 doses of the Sinovac-Coronavac vaccine (doses 1 and 2) and 2 doses of the BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine (doses 3 and 4); the rash had developed 28 days after she received the 4th dose. Her medical history was unremarkable. The lesions regressed after 1 week of treatment with oral valacyclovir 1000 mg 3 times daily, but she developed postherpetic neuralgia 1 week after starting treatment, which resolved after 8 weeks.

Patient 2—A 68-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of painful sores on the upper lip of 1 day’s duration. She had a history of rheumatoid arthritis, hypertension, and atopy and was currently taking prednisone and etanercept. Dermatologic examination revealed grouped vesicles on an erythematous base on the upper lip. A diagnosis of herpes labialis was made. The patient reported that she had received a third dose of the Sinovac-Coronavac vaccine 10 days prior to the appearance of the lesions. Her symptoms resolved completely within 2 weeks of treatment with topical acyclovir.

Patient 3—A 64-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital with pain, redness, and watery sores on and around the left eyelid of 2 days’ duration. Dermatologic evaluation revealed the erythematous surface of the left eyelid and periorbital area showed partial crusts, clustered vesicles, erythema, and edema. Additionally, the conjunctiva was purulent and erythematous. The patient’s medical history was notable for allergic asthma, hypertension, anxiety, and depression. For this reason, the patient was prescribed an angiotensin receptor blocker and a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. She noted that a similar rash had developed around the left eye 6 years prior that was diagnosed as herpes zoster (HZ). She also reported that she had received 2 doses of the Sinovac-Coronavac COVID-19 vaccine followed by 1 dose of the BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine, which she had received 2 weeks before the rash developed. The patient was treated at the eye clinic and was found to have ocular involvement. Ophthalmology was consulted and a diagnosis of herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO) was made. Systemic valacyclovir treatment was initiated, resulting in clinical improvement within 3 weeks.

Patient 4—A 75-year-old man was admitted to the hospital with chest and back pain and widespread muscle pain of several days’ duration. His medical history was remarkable for diabetes mellitus, hypertension, depression, and coronary artery bypass surgery. A medication history revealed treatment with a β-blocker, acetylsalicylic acid, a calcium channel blocker, a dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitor, and a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. Dermatologic examination revealed grouped vesicles on an erythematous background in dermatome T5 on the right chest and back. A diagnosis of HZ was made. The patient reported that he had received 2 doses of the Sinovac-Coronavac vaccine followed by 1 dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine 2 weeks prior to the current presentation. He was treated with valacyclovir for 1 week, and his symptoms resolved entirely within 3 weeks.

Patient 5—A 50-year-old woman presented to the hospital for evaluation of painful sores on the back, chest, groin, and abdomen of 10 days’ duration. The lesions initially had developed 7 days after receiving the BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine; she previously had received 2 doses of the Sinovac-Coronavac vaccine. The patient had a history of untreated psoriasis. Dermatologic examination revealed grouped vesicles on an erythematous background in the T2–L2 dermatomes on the left side of the trunk. A diagnosis of HZ was made. The lesions resolved after 1 week of treatment with systemic valacyclovir; however, she subsequently developed postherpetic neuralgia, hypoesthesia, and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in the affected regions.

Patient 6—A 37-year-old woman presented to the hospital with redness, swelling, and itching all over the body of 3 days’ duration. The patient noted that the rash would subside and reappear throughout the day. Her medical history was unremarkable, except for COVID-19 infection 6 months prior. She had received a second dose of the BioNTech vaccine 20 days prior to development of symptoms. Dermatologic examination revealed widespread erythematous urticarial plaques. A diagnosis of acute urticaria was made. The patient recovered completely after 1 week of treatment with a systemic steroid and 3 weeks of antihistamine treatment.

Patient 7—A 63-year-old woman presented to the hospital with widespread itching and rash that appeared 5 days after the first dose of the BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. The patient reported that the rash resolved spontaneously within a few hours but then reappeared. Her medical history revealed that she was taking tamoxifen for breast cancer and that she previously had received 2 doses of the Sinovac-Coronavac vaccine. Dermatologic examination revealed erythematous urticarial plaques on the trunk and arms. A diagnosis of urticaria was made, and her symptoms resolved after 6 weeks of antihistamine treatment.

Comment

Skin lesions associated with COVID-19 infection have been reported worldwide3,4 as well as dermatologic reactions following COVID-19 vaccination. In one case from Turkey, HZ infection was reported in a 68-year-old man 5 days after he received a second dose of the COVID-19 vaccine.5 In another case, HZ infection developed in a 78-year-old man 5 days after COVID-19 vaccination.6 Numerous cases of HZ infection developing within 1 to 26 days of COVID-19 vaccination have been reported worldwide.7-9

In a study conducted in the United States, 40 skin reactions associated with the COVID-19 vaccine were investigated; of these cases, 87.5% (35/40) were reported as varicella-zoster virus, and 12.5% (5/40) were reported as herpes simplex reactivation; 54% (19/35) and 80% (4/5) of these cases, respectively, were associated with the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine.10 The average age of patients who developed a skin reaction was 46 years, and 70% (28/40) were women. The time to onset of the reaction was 2 to 13 days after vaccination, and symptoms were reported to improve within 7 days on average.10

Another study from Spain examined 405 vaccine-related skin reactions, 40.2% of which were related to the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine. Among them, 80.2% occurred in women; 13.8% of cases were diagnosed as varicella-zoster virus or HZ virus reactivation, and 14.6% were urticaria. Eighty reactions (21%) were classified as severe/very severe and 81% required treatment.11 One study reported 414 skin reactions from the COVID-19 vaccine from December 2020 to February 2021; of these cases, 83% occurred after the Moderna vaccine, which is not available in Turkey, and 17% occurred after the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine.12A systematic review of 91 patients who developed HZ infection after COVID-19 vaccination reported that 10% (9/91) of cases were receiving immunosuppressive therapy and 13% (12/91) had an autoimmune disease.7 In our case series, it is known that at least 2 of the patients (patients 2 and 5), including 1 patient with rheumatoid arthritis (patient 2) who was on immunosuppressive treatment, had autoimmune disorders. However, reports in the literature indicate that most patients with autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic diseases remain stable after vaccination.13

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus is a rare form of HZ caused by involvement of the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve that manifests as vesicular lesions and retinitis, uveitis, keratitis, conjunctivitis, and pain on an erythematous background. Two cases of women who developed HZO infection after Pfizer-BioNTech vaccination were reported in the literature.14 Although patient 3 in our case series had a history of HZO 6 years prior, the possibility of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine triggering HZO should be taken into consideration.

Although cutaneous reactions after the Sinovac-Coronavac vaccine were observed in only 1 of 7 patients in our case series, skin reactions after Sinovac-Coronavac (an inactivated viral vaccine) have been reported in the literature. In one study, after a total of 35,229 injections, the incidence of cutaneous adverse events due to Sinovac-Coronavac was reported to be 0.94% and 0.70% after the first and second doses, respectively.15 Therefore, further study results are needed to directly attribute the reactions to COVID-19 vaccination.

Conclusion

Our case series highlights that clinicians should be vigilant in diagnosing cutaneous reactions following COVID-19 vaccination early to prevent potential complications. Early recognition of reactions is crucial, and the prognosis can be improved with appropriate treatment. Despite the potential dermatologic adverse effects of the COVID-19 vaccine, the most effective way to protect against serious COVID-19 infection is to continue to be vaccinated.

- Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2603-2615.

- Zhang Y, Zeng G, Pan H, et al. Safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in healthy adults aged 18–59 years: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1/2 clinical trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21:181-192.

- Tan SW, Tam YC, Oh CC. Skin manifestations of COVID-19: a worldwide review. JAAD Int. 2021;2:119-133.

- Singh H, Kaur H, Singh K, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19: a systematic review. advances in wound care. 2021;10:51-80.

- Aksu SB, Öztürk GZ. A rare case of shingles after COVID-19 vaccine: is it a possible adverse effect? clinical and experimental vaccine research. 2021;10:198-201.

- Bostan E, Yalici-Armagan B. Herpes zoster following inactivated COVID-19 vaccine: a coexistence or coincidence? J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:1566-1567.

- Katsikas Triantafyllidis K, Giannos P, Mian IT, et al. Varicella zoster virus reactivation following COVID-19 vaccination: a systematic review of case reports. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9:1013. doi:10.3390/vaccines9091013

- Rodríguez-Jiménez P, Chicharro P, Cabrera LM, et al. Varicella-zoster virus reactivation after SARS-CoV-2 BNT162b2 mRNA vaccination: report of 5 cases. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;12:58-59. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2021.04.014

- Lee C, Cotter D, Basa J, et al. 20 Post-COVID-19 vaccine-related shingles cases seen at the Las Vegas Dermatology clinic and sent to us via social media. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:1960-1964.

- Fathy RA, McMahon DE, Lee C, et al. Varicella-zoster and herpes simplex virus reactivation post-COVID-19 vaccination: a review of 40 cases in an International Dermatology Registry. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venerol. 2022;36:E6-E9.

- Català A, Muñoz-Santos C, Galván-Casas C, et al. Cutaneous reactions after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: a cross-sectional Spanish nationwide study of 405 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2022;186:142-152.

- McMahon DE, Amerson E, Rosenbach M, et al. Cutaneous reactions reported after Moderna and Pfizer COVID-19 vaccination: a registry-based study of 414 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:46-55.

- Furer V, Eviatar T, Zisman D, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in adult patients with autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic diseases and in the general population: a multicentre study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:1330-1338.

- Bernardini N, Skroza N, Mambrin A, et al. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus in two women after Pfizer-BioNTech (BNT162b2) vaccine. J Med Virol. 2022;94:817-818.

- Rerknimitr P, Puaratanaarunkon T, Wongtada C, et al. Cutaneous adverse reactions from 35,229 doses of Sinovac and AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccination: a prospective cohort study in healthcare workers. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:E158-E161.

- Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2603-2615.

- Zhang Y, Zeng G, Pan H, et al. Safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in healthy adults aged 18–59 years: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1/2 clinical trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21:181-192.

- Tan SW, Tam YC, Oh CC. Skin manifestations of COVID-19: a worldwide review. JAAD Int. 2021;2:119-133.

- Singh H, Kaur H, Singh K, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19: a systematic review. advances in wound care. 2021;10:51-80.

- Aksu SB, Öztürk GZ. A rare case of shingles after COVID-19 vaccine: is it a possible adverse effect? clinical and experimental vaccine research. 2021;10:198-201.

- Bostan E, Yalici-Armagan B. Herpes zoster following inactivated COVID-19 vaccine: a coexistence or coincidence? J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:1566-1567.

- Katsikas Triantafyllidis K, Giannos P, Mian IT, et al. Varicella zoster virus reactivation following COVID-19 vaccination: a systematic review of case reports. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9:1013. doi:10.3390/vaccines9091013

- Rodríguez-Jiménez P, Chicharro P, Cabrera LM, et al. Varicella-zoster virus reactivation after SARS-CoV-2 BNT162b2 mRNA vaccination: report of 5 cases. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;12:58-59. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2021.04.014

- Lee C, Cotter D, Basa J, et al. 20 Post-COVID-19 vaccine-related shingles cases seen at the Las Vegas Dermatology clinic and sent to us via social media. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:1960-1964.

- Fathy RA, McMahon DE, Lee C, et al. Varicella-zoster and herpes simplex virus reactivation post-COVID-19 vaccination: a review of 40 cases in an International Dermatology Registry. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venerol. 2022;36:E6-E9.

- Català A, Muñoz-Santos C, Galván-Casas C, et al. Cutaneous reactions after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: a cross-sectional Spanish nationwide study of 405 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2022;186:142-152.

- McMahon DE, Amerson E, Rosenbach M, et al. Cutaneous reactions reported after Moderna and Pfizer COVID-19 vaccination: a registry-based study of 414 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:46-55.

- Furer V, Eviatar T, Zisman D, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in adult patients with autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic diseases and in the general population: a multicentre study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:1330-1338.

- Bernardini N, Skroza N, Mambrin A, et al. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus in two women after Pfizer-BioNTech (BNT162b2) vaccine. J Med Virol. 2022;94:817-818.

- Rerknimitr P, Puaratanaarunkon T, Wongtada C, et al. Cutaneous adverse reactions from 35,229 doses of Sinovac and AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccination: a prospective cohort study in healthcare workers. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:E158-E161.

Practice Points

- Cutaneous reactions have been reported following COVID-19 vaccination.

- Herpes infections and urticarial reactions can be associated with COVID-19 vaccination, regardless of the delay in onset between the injection and symptom development.

My Kidney Is Fine, Can’t You Cystatin C?

Clinicians usually measure renal function by using surrogate markers because directly measuring glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is not routinely feasible in a clinical setting.1,2 Creatinine (Cr) and cystatin C (CysC) are the 2 main surrogate molecules used to estimate GFR.3

Creatine is a molecule nonenzymatically converted into Cr, weighing only 113 Da in skeletal muscles.4 It is then filtered at the glomeruli and secreted at the proximal tubules of the kidneys. However, serum Cr (sCr) levels are affected by several factors, including age, biological sex, liver function, diet, and muscle mass.5 Historically, sCr levels also are affected by race.5 In an early study of factors affecting accurate GFR, researchers reported that self-identified African American patients had a 16% higher GFR than those who did not when using Cr.6 Despite this, the inclusion of Cr on a basic metabolic panel has allowed automatic reporting of an estimated GFR using sCr (eGFRCr) to be readily available.7

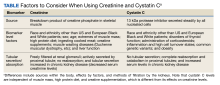

In comparison to Cr, CysC is an endogenous protein weighing 13 kDa produced by all nucleated cells.8,9 CysC is filtered by the kidney at the glomeruli and completely reabsorbed and catabolized by epithelial cells at the proximal tubule.9 Since production is not dependent on skeletal muscle, there are fewer physiological impacts on serum concentration of CysC. Levels of CysC may be elevated by factors shown in the Table.

Estimating Glomerular Filtration Rates

Multiple equations were developed to mitigate the impact of extraneous factors on the accuracy of an eGFRCr. The first widely used equation that included a variable adjustment for race was the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease study, presented in 2006.10 The equation increased the accuracy of eGFRCr further by adjusting for sex and age. It was followed by the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation in 2009, which was more accurate at higher GFR levels.11

CysC was simultaneously studied as an alternative to Cr with multiple equation iterations shown to be viable in various populations as early as 2003.12-15 However, it was not until 2012 that an equation for the use of CysC was offered for widespread use as an alternative to Cr alongside further refinement of the CKD-EPI equation for Cr.16 A new formula was presented in 2021 to use both sCr and serum CysC levels to obtain a more accurate estimation of GFR.17 Research continues its effort to accurately estimate GFR for diagnosing kidney disease and assessing comorbidities relating to decreased kidney function.3