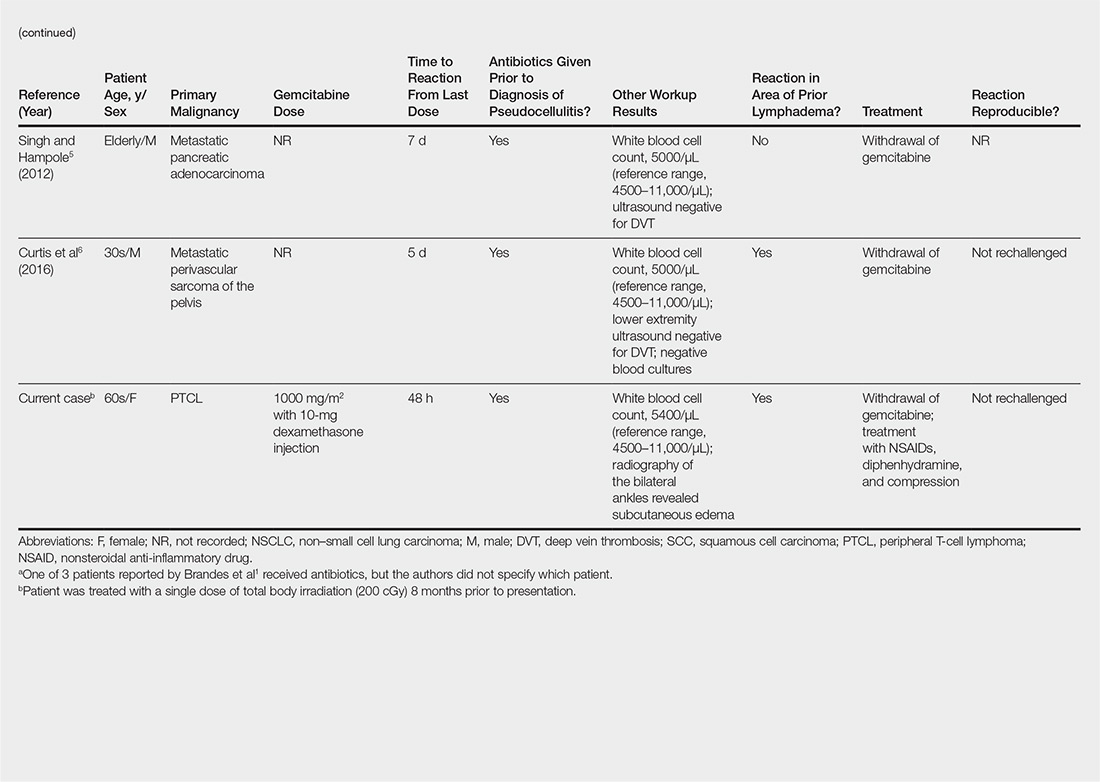

User login

Oral Bowenoid Papulosis

To the Editor:

A 22-year-old Somali woman presented to our institution with oral lesions of 2 years’ duration. The lesions started as small papules in the corners of the mouth that gradually continued to spread to the mucosal lips and gums. The lesions did not drain any material. The patient reported that they were not painful and had not regressed. She was concerned about the cosmetic appearance of the lesions. The patient believed the lesions had developed from working in a chicken factory and was concerned that they appeared possibly due to contact with a substance in the factory. Additionally, she noted that her voice had become hoarse. She was otherwise healthy and denied any sexual contact or ever having a blood transfusion.

Physical examination revealed 10 to 15 flesh-colored papules measuring 2 to 3 mm in diameter on the vermilion, mucosal surfaces of the lips, and upper and lower gingivae (Figure 1). No lesions were seen on the hard and soft palate, tongue, buccal mucosa, or posterior pharynx.

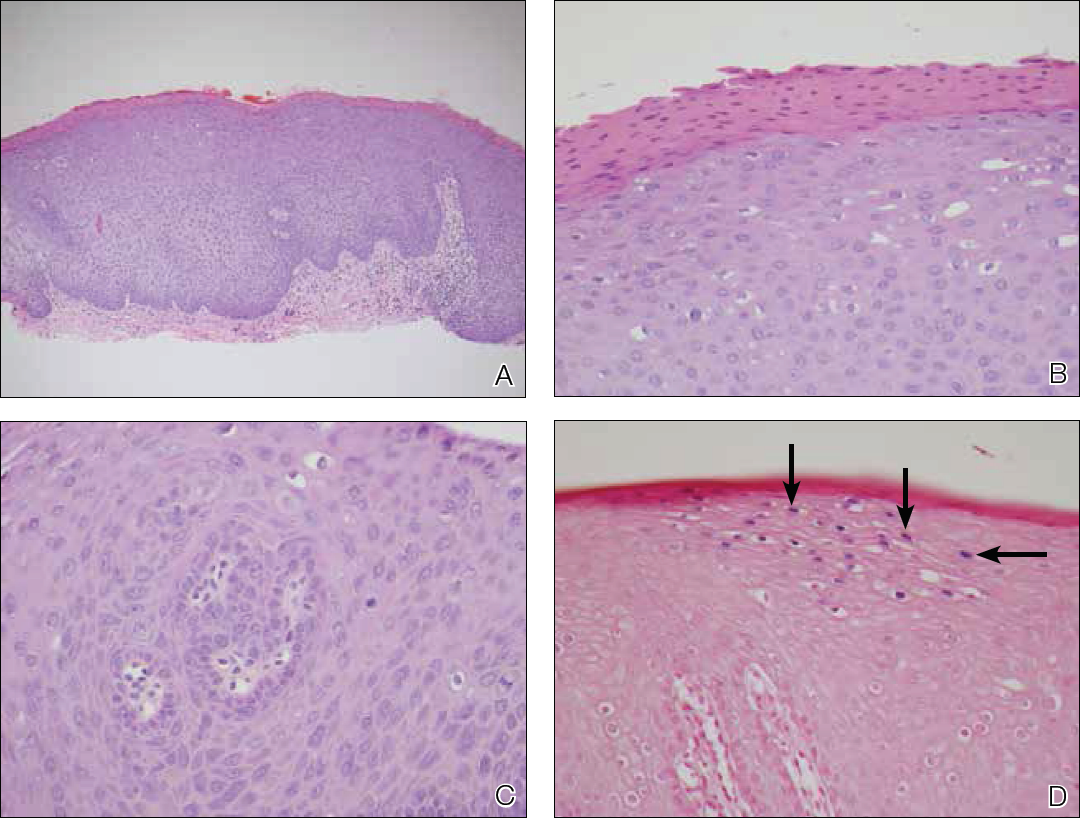

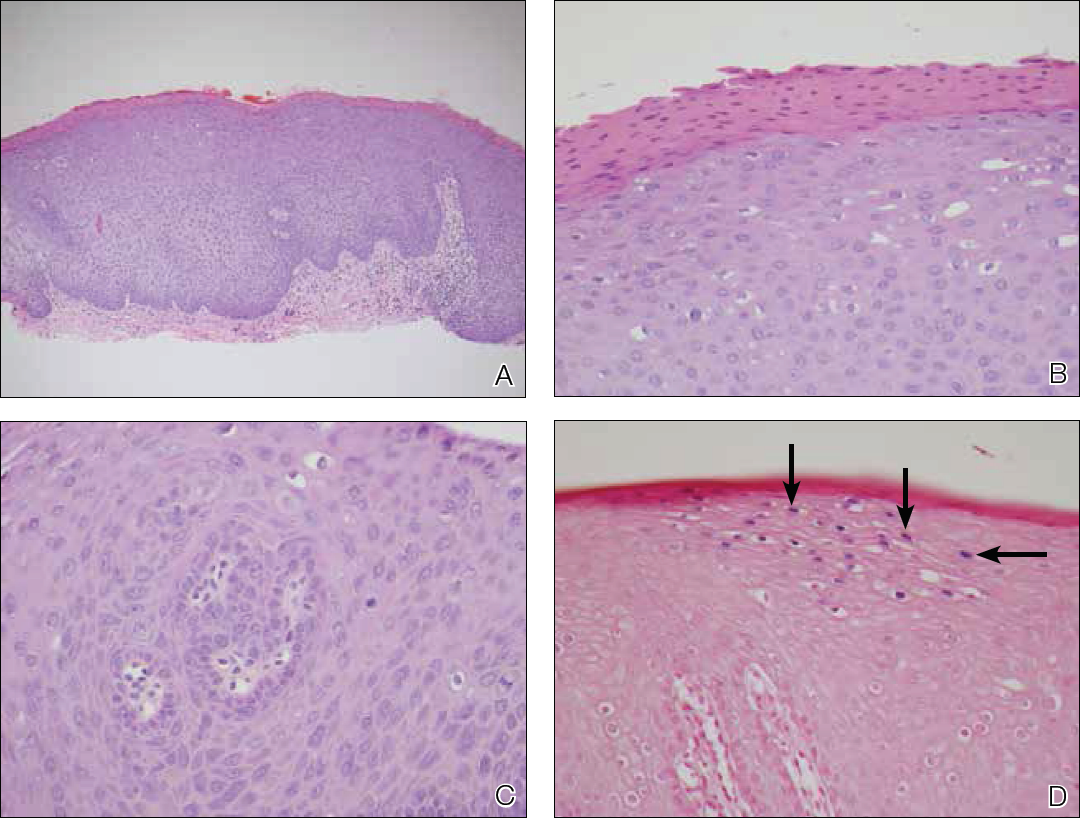

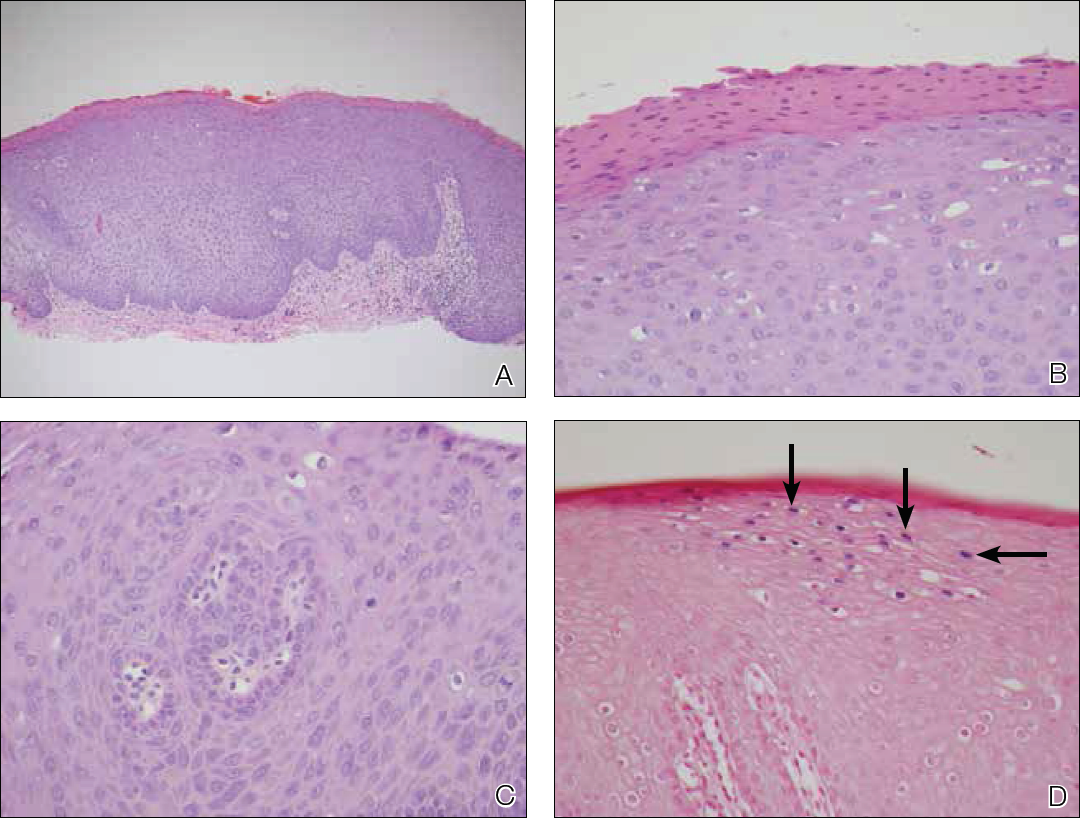

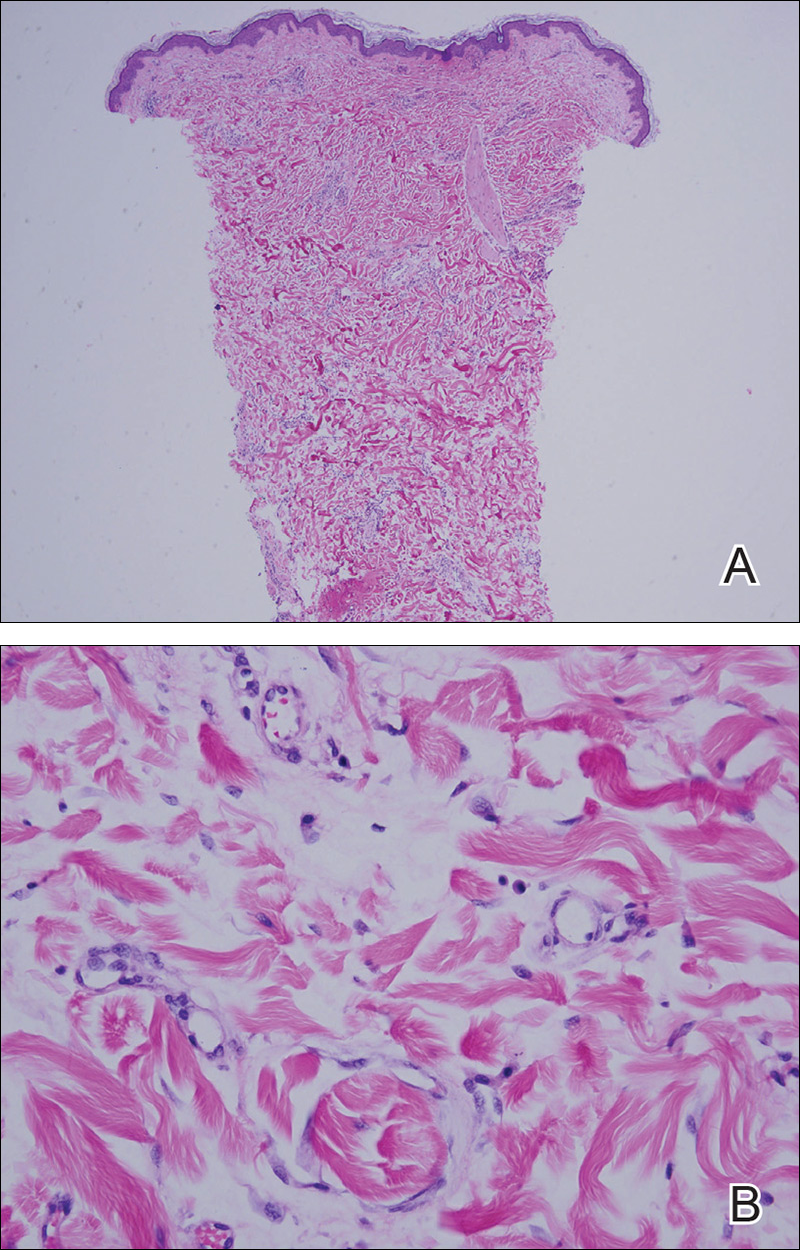

Skin biopsy of the left lower mucosal lip revealed parakeratosis, acanthosis, superficial koilocytes, and atypical keratinocytes with frequent mitoses (Figures 2A–2C). In situ hybridization testing for human papillomavirus (HPV) was negative for low-risk types 6 and 11 but positive for high-risk types 16 and 18 (Figure 2D). Laboratory investigations including complete blood cell count, electrolyte panel, and liver function studies were normal, and serum was negative for syphilis and human immunodeficiency virus antibodies.

The combined clinical and histologic findings were diagnostic of oral bowenoid papulosis. Gynecologic evaluation showed that the patient had undergone female circumcision, and she had a normal Papanicolaou test. The patient was referred to both the ear, nose, and throat clinic as well as the dermatologic surgery department to discuss treatment options, but she was lost to follow-up.

Bowenoid papulosis is triggered by HPV infection and manifests clinically as solitary or multiple verrucous papules and plaques that are usually located on the genitalia.1 Only a few cases of bowenoid papulosis have been reported in the oral cavity.1-5 Because this disease is sexually transmitted, the mean age of onset of bowenoid papulosis is 31 years.2 There is a small risk (2%–3%) of developing invasive carcinoma in bowenoid papulosis.1-3,6 Most lesions are associated with HPV type 16; however, bowenoid papulosis also has been associated with HPV types 18, 31, 32, 35, and 39.2

Some investigators consider bowenoid papulosis and Bowen disease (a type of squamous cell carcinoma [SCC] in situ) to be histologically identical1,6; however, some histologic differences have been reported.1-3,6 Bowenoid papulosis has more dilated and tortuous dermal capillaries and less atypia and dyskeratosis than Bowen disease.1,6 In contrast to bowenoid papulosis, Bowen disease is characterized clinically as well-defined scaly plaques on sun-exposed areas of the skin in older adults. Invasive SCC can be seen in 5% of skin lesions and 30% of penile lesions associated with Bowen disease.2 Risk factors for Bowen disease include sun exposure; arsenic poisoning; and infection with HPV types 2, 16, 18, 31, 33, 52, and 67.1,6

Oral bowenoid papulosis is rare. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term oral bowenoid papulosis yielded 7 additional cases, which are summarized in the Table. In 1987 Lookingbill et al2 described one of the first reported cases of oral disease in a 33-year-old immunosuppressed man receiving prednisone therapy for systemic lupus erythematosus who had both mouth and genital lesions. All lesions were positive for HPV type 16. The patient subsequently developed SCC of the tongue.2

The risk for progression of oral bowenoid papulosis to invasive SCC is not known. Our search yielded only 1 case of this occurrence.2

Two of 3 cases of solitary lip lesions in oral bowenoid papulosis were treated with surgical excision.1 Other treatment options include CO2 laser therapy, cryotherapy, 5-fluorouracil, bleomycin, intralesional interferon alfa, and imiquimod.1-3,5,6

Our case represents a rare report of oral bowenoid papulosis. Recognition of this unusual presentation is important for the diagnosis and management of this disease.

- Daley T, Birek C, Wysocki GP. Oral bowenoid lesions: differential diagnosis and pathogenetic insights. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;90:466-473.

- Lookingbill DP, Kreider JW, Howett MK, et al. Human papillomavirus type 16 in bowenoid papulosis, intraoral papillomas, and squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:363-368.

- Kratochvil FJ, Cioffi GA, Auclair PL, et al. Virus-associated dysplasia (bowenoid papulosis?) of the oral cavity. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989;68:312-316.

- Degener AM, Latino L, Pierangeli A, et al. Human papilloma virus-32-positive extragenital bowenoid papulosis in a HIV patient with typical genital bowenoid papulosis localization. Sex Transm Dis. 2004;31:619-622.

- Rinaggio J, Glick M, Lambert WC. Oral bowenoid papulosis in an HIV-positive male [published online October 14, 2005]. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:328-332.

- Regezi JA, Dekker NP, Ramos DM, et al. Proliferation and invasion factors in HIV-associated dysplastic and nondysplastic oral warts and in oral squamous cell carcinoma: an immunohistochemical and RT-PCR evaluation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;94:724-731.

To the Editor:

A 22-year-old Somali woman presented to our institution with oral lesions of 2 years’ duration. The lesions started as small papules in the corners of the mouth that gradually continued to spread to the mucosal lips and gums. The lesions did not drain any material. The patient reported that they were not painful and had not regressed. She was concerned about the cosmetic appearance of the lesions. The patient believed the lesions had developed from working in a chicken factory and was concerned that they appeared possibly due to contact with a substance in the factory. Additionally, she noted that her voice had become hoarse. She was otherwise healthy and denied any sexual contact or ever having a blood transfusion.

Physical examination revealed 10 to 15 flesh-colored papules measuring 2 to 3 mm in diameter on the vermilion, mucosal surfaces of the lips, and upper and lower gingivae (Figure 1). No lesions were seen on the hard and soft palate, tongue, buccal mucosa, or posterior pharynx.

Skin biopsy of the left lower mucosal lip revealed parakeratosis, acanthosis, superficial koilocytes, and atypical keratinocytes with frequent mitoses (Figures 2A–2C). In situ hybridization testing for human papillomavirus (HPV) was negative for low-risk types 6 and 11 but positive for high-risk types 16 and 18 (Figure 2D). Laboratory investigations including complete blood cell count, electrolyte panel, and liver function studies were normal, and serum was negative for syphilis and human immunodeficiency virus antibodies.

The combined clinical and histologic findings were diagnostic of oral bowenoid papulosis. Gynecologic evaluation showed that the patient had undergone female circumcision, and she had a normal Papanicolaou test. The patient was referred to both the ear, nose, and throat clinic as well as the dermatologic surgery department to discuss treatment options, but she was lost to follow-up.

Bowenoid papulosis is triggered by HPV infection and manifests clinically as solitary or multiple verrucous papules and plaques that are usually located on the genitalia.1 Only a few cases of bowenoid papulosis have been reported in the oral cavity.1-5 Because this disease is sexually transmitted, the mean age of onset of bowenoid papulosis is 31 years.2 There is a small risk (2%–3%) of developing invasive carcinoma in bowenoid papulosis.1-3,6 Most lesions are associated with HPV type 16; however, bowenoid papulosis also has been associated with HPV types 18, 31, 32, 35, and 39.2

Some investigators consider bowenoid papulosis and Bowen disease (a type of squamous cell carcinoma [SCC] in situ) to be histologically identical1,6; however, some histologic differences have been reported.1-3,6 Bowenoid papulosis has more dilated and tortuous dermal capillaries and less atypia and dyskeratosis than Bowen disease.1,6 In contrast to bowenoid papulosis, Bowen disease is characterized clinically as well-defined scaly plaques on sun-exposed areas of the skin in older adults. Invasive SCC can be seen in 5% of skin lesions and 30% of penile lesions associated with Bowen disease.2 Risk factors for Bowen disease include sun exposure; arsenic poisoning; and infection with HPV types 2, 16, 18, 31, 33, 52, and 67.1,6

Oral bowenoid papulosis is rare. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term oral bowenoid papulosis yielded 7 additional cases, which are summarized in the Table. In 1987 Lookingbill et al2 described one of the first reported cases of oral disease in a 33-year-old immunosuppressed man receiving prednisone therapy for systemic lupus erythematosus who had both mouth and genital lesions. All lesions were positive for HPV type 16. The patient subsequently developed SCC of the tongue.2

The risk for progression of oral bowenoid papulosis to invasive SCC is not known. Our search yielded only 1 case of this occurrence.2

Two of 3 cases of solitary lip lesions in oral bowenoid papulosis were treated with surgical excision.1 Other treatment options include CO2 laser therapy, cryotherapy, 5-fluorouracil, bleomycin, intralesional interferon alfa, and imiquimod.1-3,5,6

Our case represents a rare report of oral bowenoid papulosis. Recognition of this unusual presentation is important for the diagnosis and management of this disease.

To the Editor:

A 22-year-old Somali woman presented to our institution with oral lesions of 2 years’ duration. The lesions started as small papules in the corners of the mouth that gradually continued to spread to the mucosal lips and gums. The lesions did not drain any material. The patient reported that they were not painful and had not regressed. She was concerned about the cosmetic appearance of the lesions. The patient believed the lesions had developed from working in a chicken factory and was concerned that they appeared possibly due to contact with a substance in the factory. Additionally, she noted that her voice had become hoarse. She was otherwise healthy and denied any sexual contact or ever having a blood transfusion.

Physical examination revealed 10 to 15 flesh-colored papules measuring 2 to 3 mm in diameter on the vermilion, mucosal surfaces of the lips, and upper and lower gingivae (Figure 1). No lesions were seen on the hard and soft palate, tongue, buccal mucosa, or posterior pharynx.

Skin biopsy of the left lower mucosal lip revealed parakeratosis, acanthosis, superficial koilocytes, and atypical keratinocytes with frequent mitoses (Figures 2A–2C). In situ hybridization testing for human papillomavirus (HPV) was negative for low-risk types 6 and 11 but positive for high-risk types 16 and 18 (Figure 2D). Laboratory investigations including complete blood cell count, electrolyte panel, and liver function studies were normal, and serum was negative for syphilis and human immunodeficiency virus antibodies.

The combined clinical and histologic findings were diagnostic of oral bowenoid papulosis. Gynecologic evaluation showed that the patient had undergone female circumcision, and she had a normal Papanicolaou test. The patient was referred to both the ear, nose, and throat clinic as well as the dermatologic surgery department to discuss treatment options, but she was lost to follow-up.

Bowenoid papulosis is triggered by HPV infection and manifests clinically as solitary or multiple verrucous papules and plaques that are usually located on the genitalia.1 Only a few cases of bowenoid papulosis have been reported in the oral cavity.1-5 Because this disease is sexually transmitted, the mean age of onset of bowenoid papulosis is 31 years.2 There is a small risk (2%–3%) of developing invasive carcinoma in bowenoid papulosis.1-3,6 Most lesions are associated with HPV type 16; however, bowenoid papulosis also has been associated with HPV types 18, 31, 32, 35, and 39.2

Some investigators consider bowenoid papulosis and Bowen disease (a type of squamous cell carcinoma [SCC] in situ) to be histologically identical1,6; however, some histologic differences have been reported.1-3,6 Bowenoid papulosis has more dilated and tortuous dermal capillaries and less atypia and dyskeratosis than Bowen disease.1,6 In contrast to bowenoid papulosis, Bowen disease is characterized clinically as well-defined scaly plaques on sun-exposed areas of the skin in older adults. Invasive SCC can be seen in 5% of skin lesions and 30% of penile lesions associated with Bowen disease.2 Risk factors for Bowen disease include sun exposure; arsenic poisoning; and infection with HPV types 2, 16, 18, 31, 33, 52, and 67.1,6

Oral bowenoid papulosis is rare. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term oral bowenoid papulosis yielded 7 additional cases, which are summarized in the Table. In 1987 Lookingbill et al2 described one of the first reported cases of oral disease in a 33-year-old immunosuppressed man receiving prednisone therapy for systemic lupus erythematosus who had both mouth and genital lesions. All lesions were positive for HPV type 16. The patient subsequently developed SCC of the tongue.2

The risk for progression of oral bowenoid papulosis to invasive SCC is not known. Our search yielded only 1 case of this occurrence.2

Two of 3 cases of solitary lip lesions in oral bowenoid papulosis were treated with surgical excision.1 Other treatment options include CO2 laser therapy, cryotherapy, 5-fluorouracil, bleomycin, intralesional interferon alfa, and imiquimod.1-3,5,6

Our case represents a rare report of oral bowenoid papulosis. Recognition of this unusual presentation is important for the diagnosis and management of this disease.

- Daley T, Birek C, Wysocki GP. Oral bowenoid lesions: differential diagnosis and pathogenetic insights. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;90:466-473.

- Lookingbill DP, Kreider JW, Howett MK, et al. Human papillomavirus type 16 in bowenoid papulosis, intraoral papillomas, and squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:363-368.

- Kratochvil FJ, Cioffi GA, Auclair PL, et al. Virus-associated dysplasia (bowenoid papulosis?) of the oral cavity. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989;68:312-316.

- Degener AM, Latino L, Pierangeli A, et al. Human papilloma virus-32-positive extragenital bowenoid papulosis in a HIV patient with typical genital bowenoid papulosis localization. Sex Transm Dis. 2004;31:619-622.

- Rinaggio J, Glick M, Lambert WC. Oral bowenoid papulosis in an HIV-positive male [published online October 14, 2005]. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:328-332.

- Regezi JA, Dekker NP, Ramos DM, et al. Proliferation and invasion factors in HIV-associated dysplastic and nondysplastic oral warts and in oral squamous cell carcinoma: an immunohistochemical and RT-PCR evaluation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;94:724-731.

- Daley T, Birek C, Wysocki GP. Oral bowenoid lesions: differential diagnosis and pathogenetic insights. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;90:466-473.

- Lookingbill DP, Kreider JW, Howett MK, et al. Human papillomavirus type 16 in bowenoid papulosis, intraoral papillomas, and squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:363-368.

- Kratochvil FJ, Cioffi GA, Auclair PL, et al. Virus-associated dysplasia (bowenoid papulosis?) of the oral cavity. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989;68:312-316.

- Degener AM, Latino L, Pierangeli A, et al. Human papilloma virus-32-positive extragenital bowenoid papulosis in a HIV patient with typical genital bowenoid papulosis localization. Sex Transm Dis. 2004;31:619-622.

- Rinaggio J, Glick M, Lambert WC. Oral bowenoid papulosis in an HIV-positive male [published online October 14, 2005]. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:328-332.

- Regezi JA, Dekker NP, Ramos DM, et al. Proliferation and invasion factors in HIV-associated dysplastic and nondysplastic oral warts and in oral squamous cell carcinoma: an immunohistochemical and RT-PCR evaluation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;94:724-731.

Practice Points

- Bowenoid papulosis is triggered by human papillomavirus infection and manifests clinically as solitary or multiple verrucous papules and plaques that usually are located on the genitalia.

- Oral bowenoid papulosis is rare, and recognition of this unusual presentation is important for the diagnosis and management of this disease.

Gemcitabine-Induced Pseudocellulitis

To the Editor:

Gemcitabine is a nucleoside analogue used to treat a variety of solid and hematologic malignancies. Cutaneous toxicities include radiation recall dermatitis and erysipelaslike reactions that occur in areas not previously treated with radiation. Often referred to as pseudocellulitis, these reactions generally have been reported in areas of lymphedema in patients with solid malignancies.1-6 Herein, we report a rare case of gemcitabine-induced pseudocellulitis on the legs in a patient with a history of hematologic malignancy and total body irradiation (TBI).

A 61-year-old woman with history of peripheral T-cell lymphoma presented to the emergency department at our institution with acute-onset redness, tenderness, and swelling of the legs that was concerning for cellulitis. The patient’s history was notable for receiving gemcitabine 1000 mg/m2 for treatment of refractory lymphoma (12 and 4 days prior to presentation) as well as lymphedema of the legs. Her complete treatment course included multiple rounds of chemotherapy and matched unrelated donor nonmyeloablative allogeneic stem cell transplantation with a single dose of TBI at 200 cGy at our institution. Her transplant was complicated only by mild cutaneous graft-versus-host disease, which resolved with prednisone and tacrolimus.

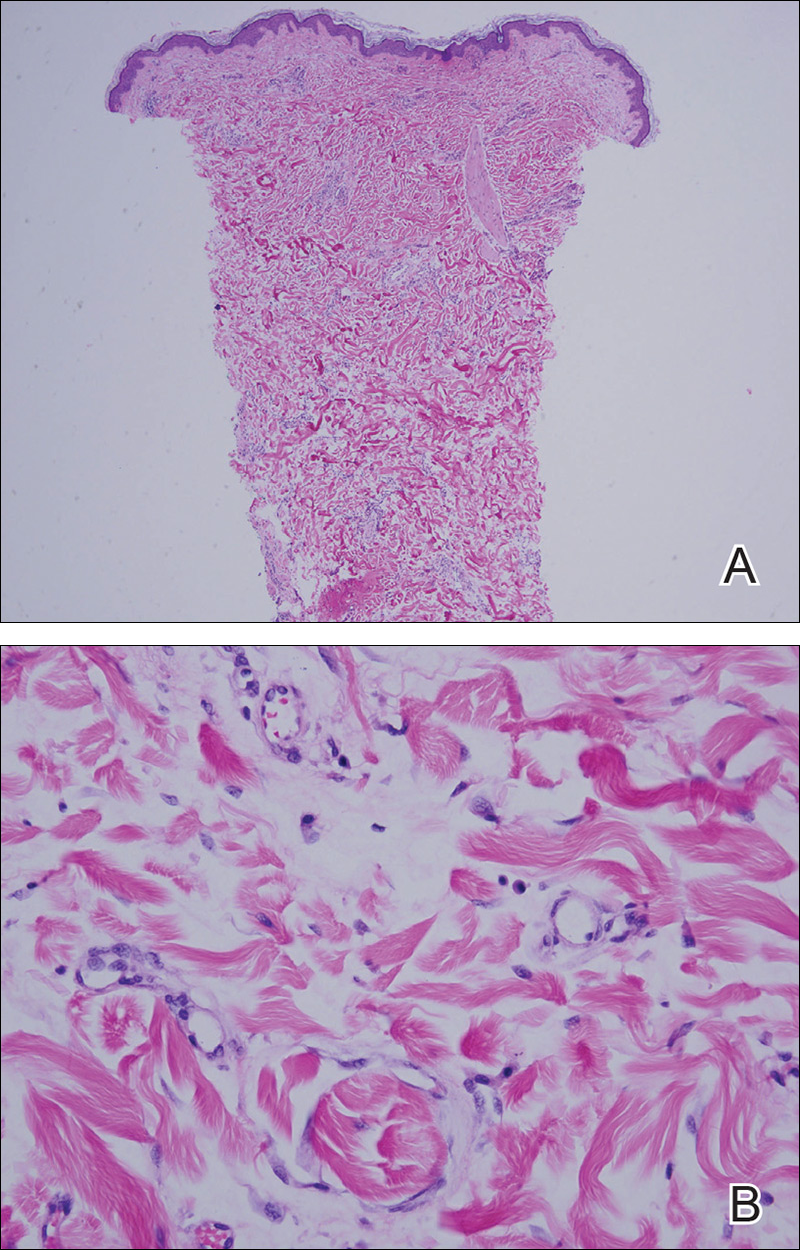

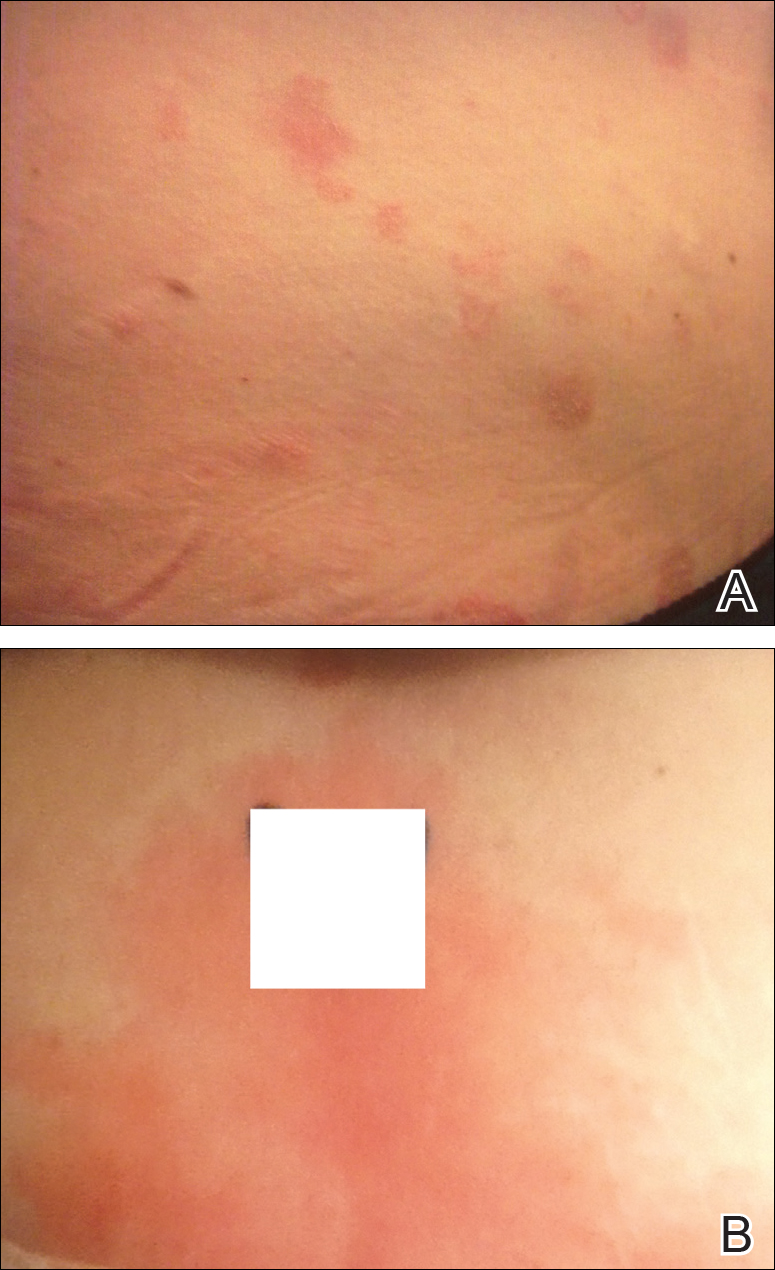

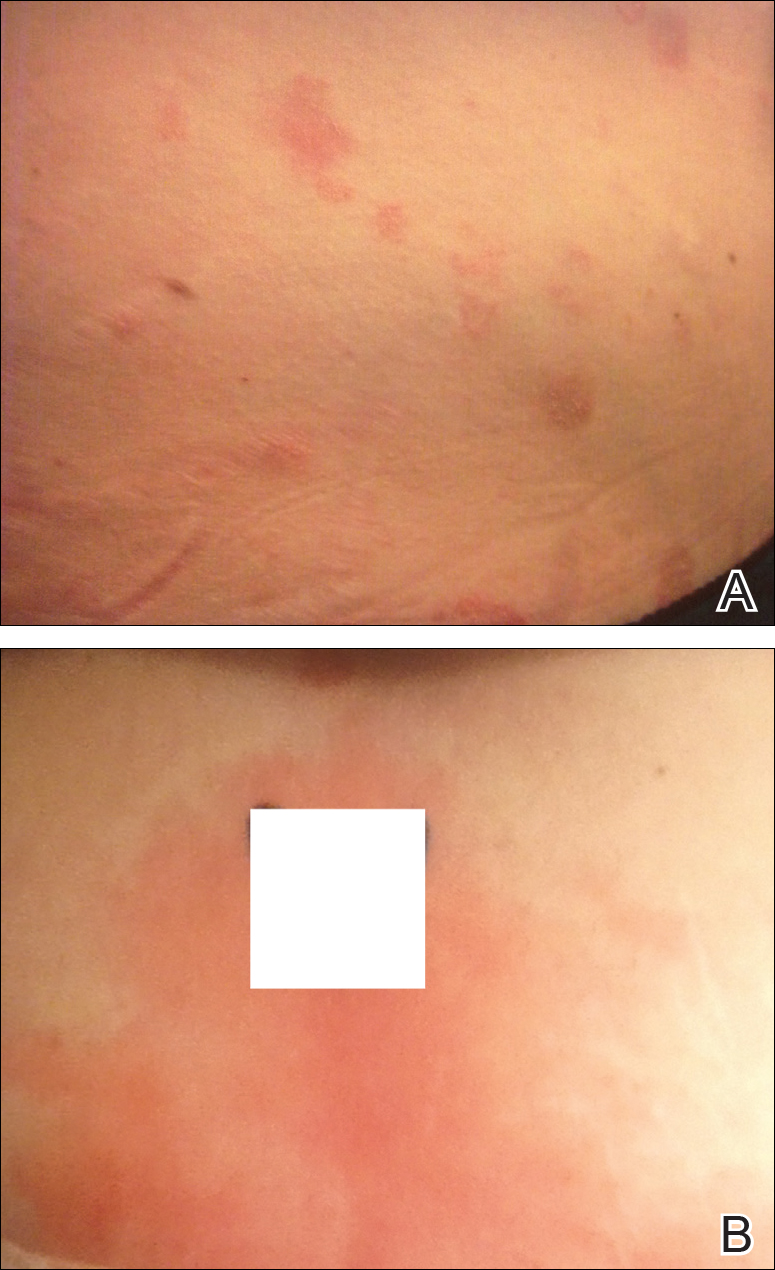

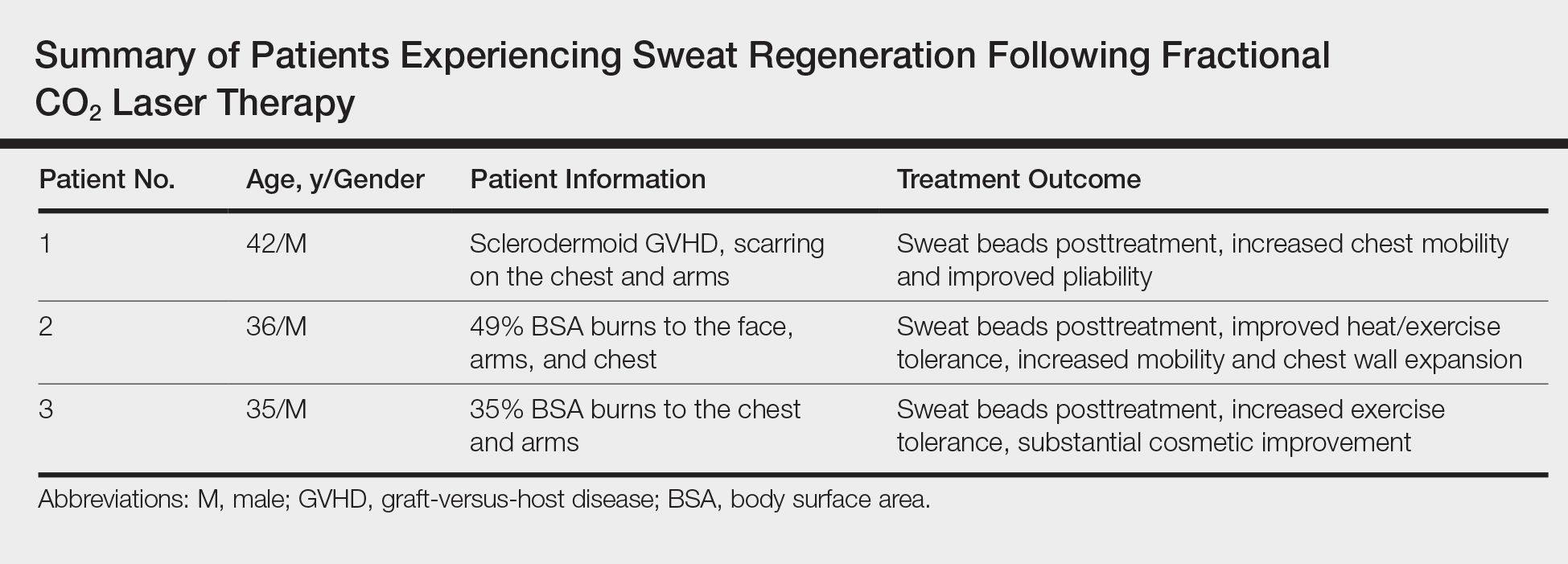

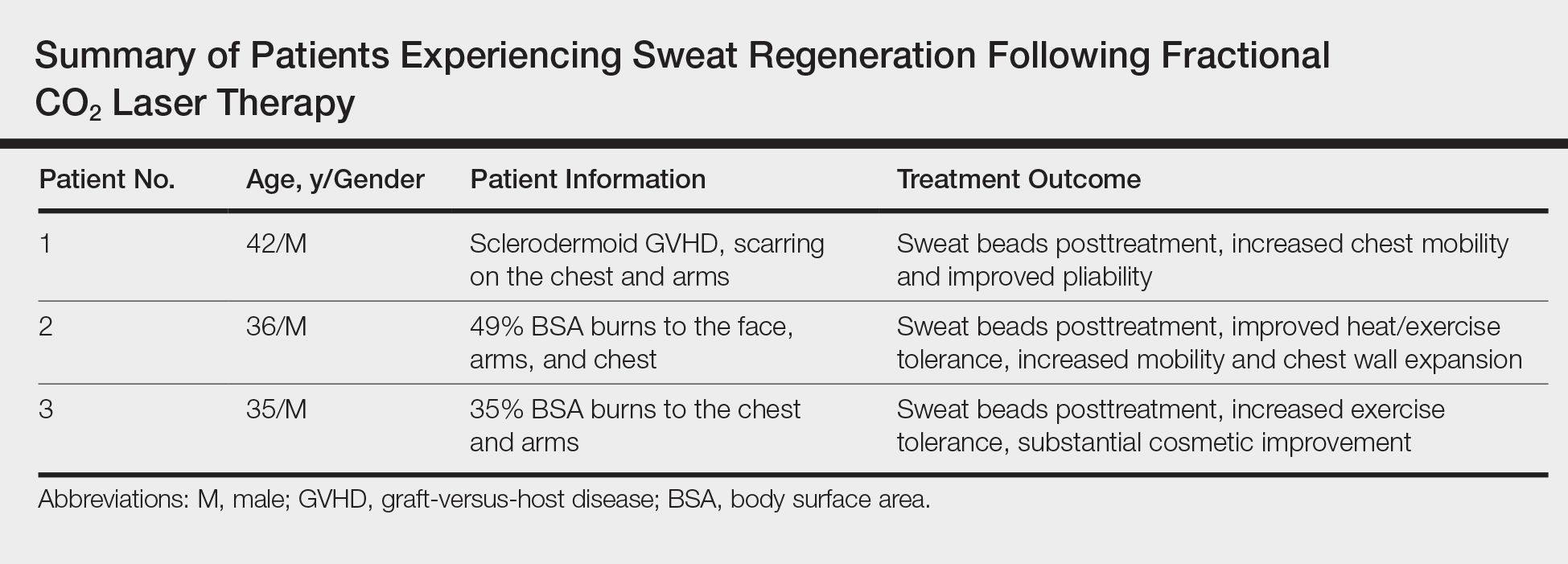

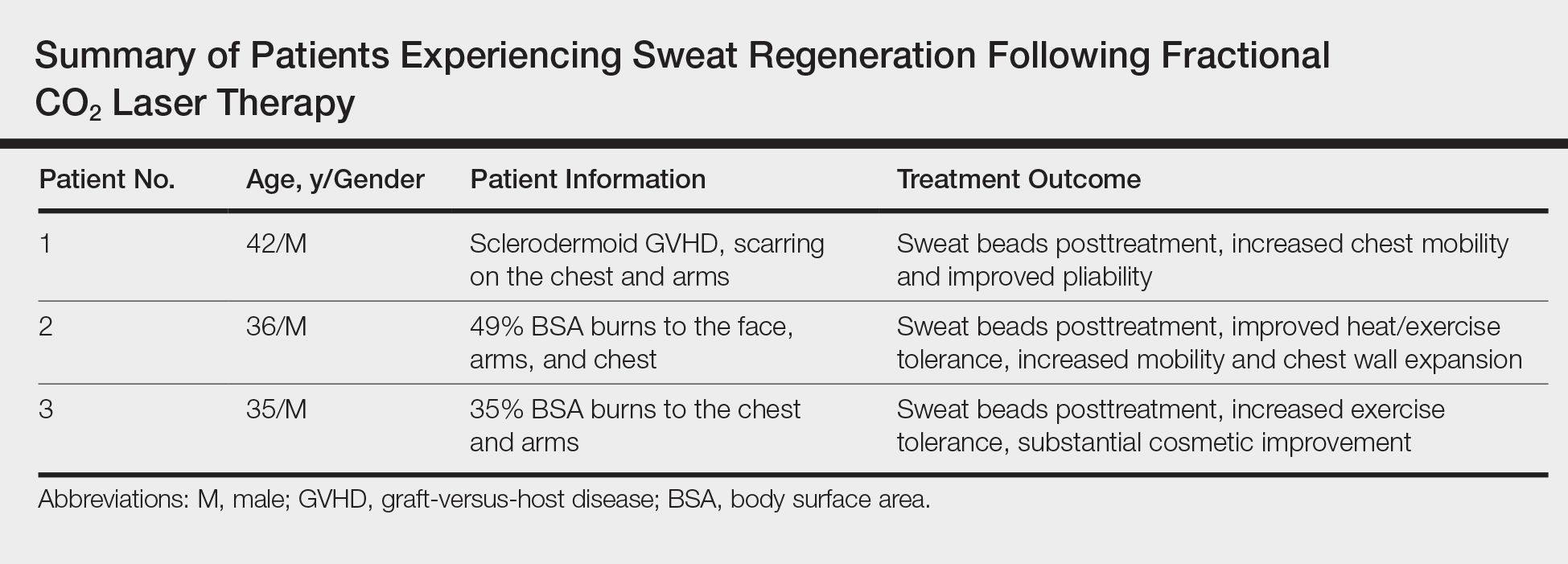

On physical examination, the patient was afebrile with symmetric erythema and induration extending from the bilateral knees to the dorsal feet. A complete blood cell count was notable for a white blood cell count of 5400/µL (reference range, 4500–11,000/µL) and a platelet count of 96,000/µL (reference range, 150,000–400,000/µL). Plain film radiographs of the bilateral ankles were remarkable only for moderate subcutaneous edema. She received vancomycin in the emergency department and was admitted to the oncology service. Blood cultures drawn on admission were negative. Dermatology was consulted on admission, and a diagnosis of pseudocellulitis was made in conjunction with oncology (Figure). Antibiotics were held, and the patient was treated symptomatically with ibuprofen and was discharged 1 day after admission. The reaction resolved after 1 week with the use of diphenhydramine, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and compression. The patient was not rechallenged with gemcitabine.

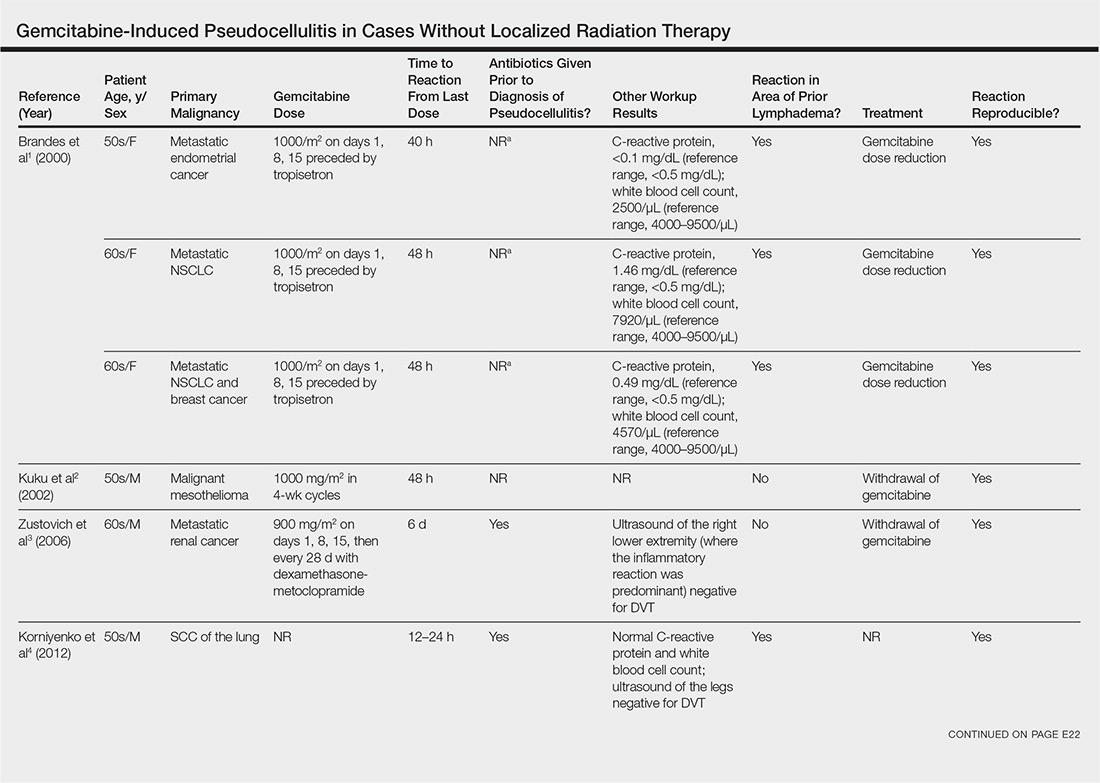

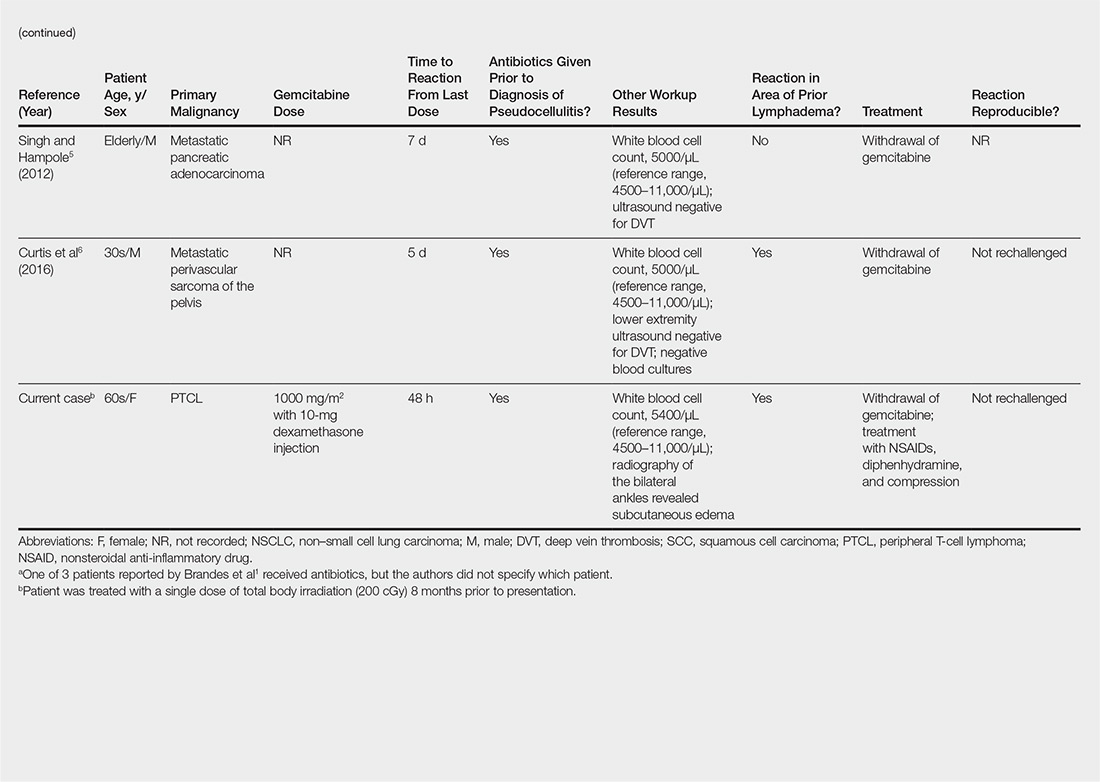

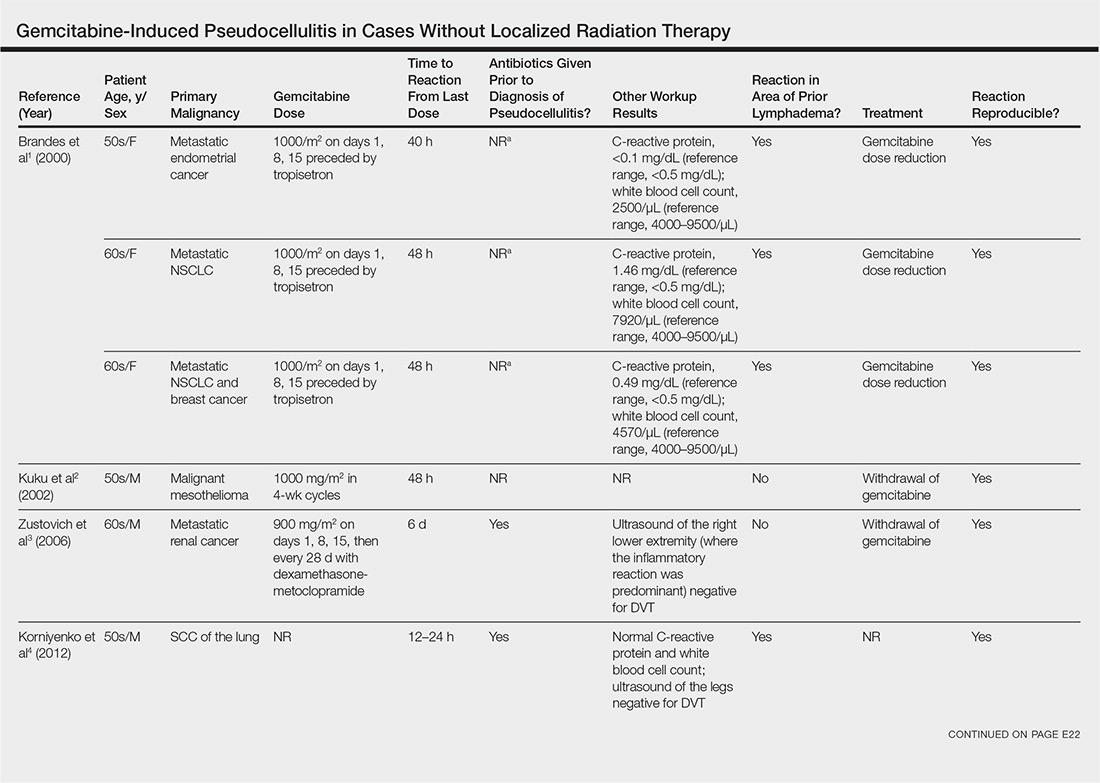

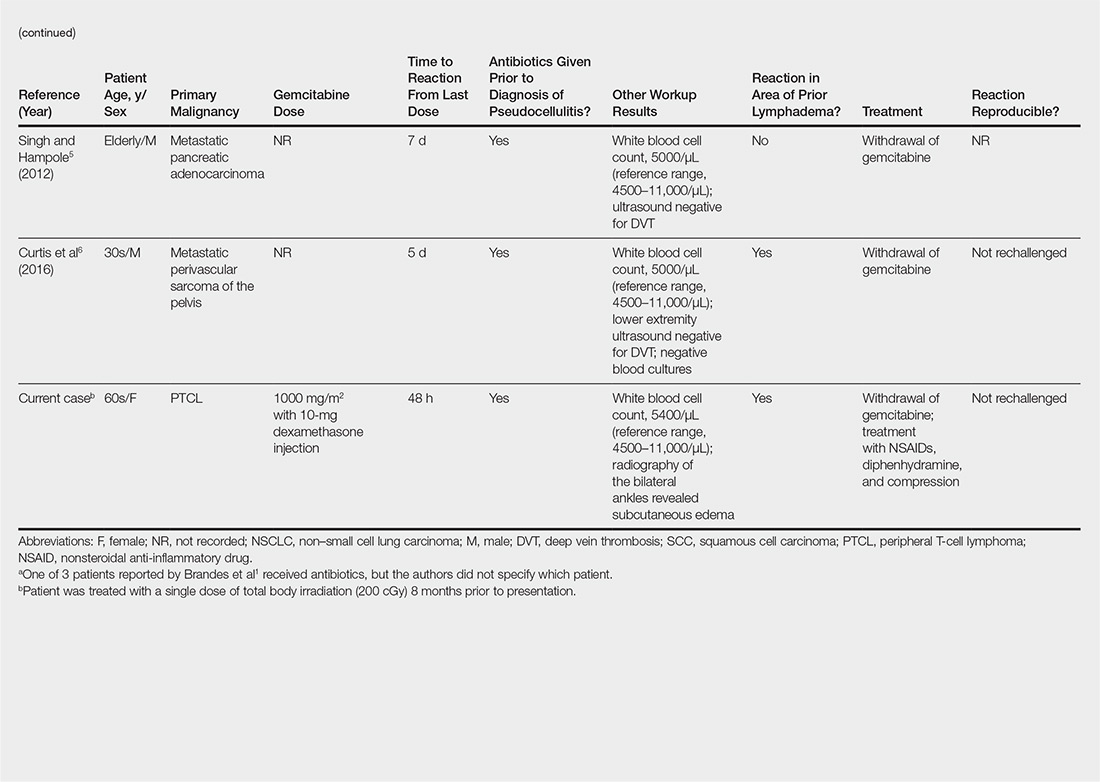

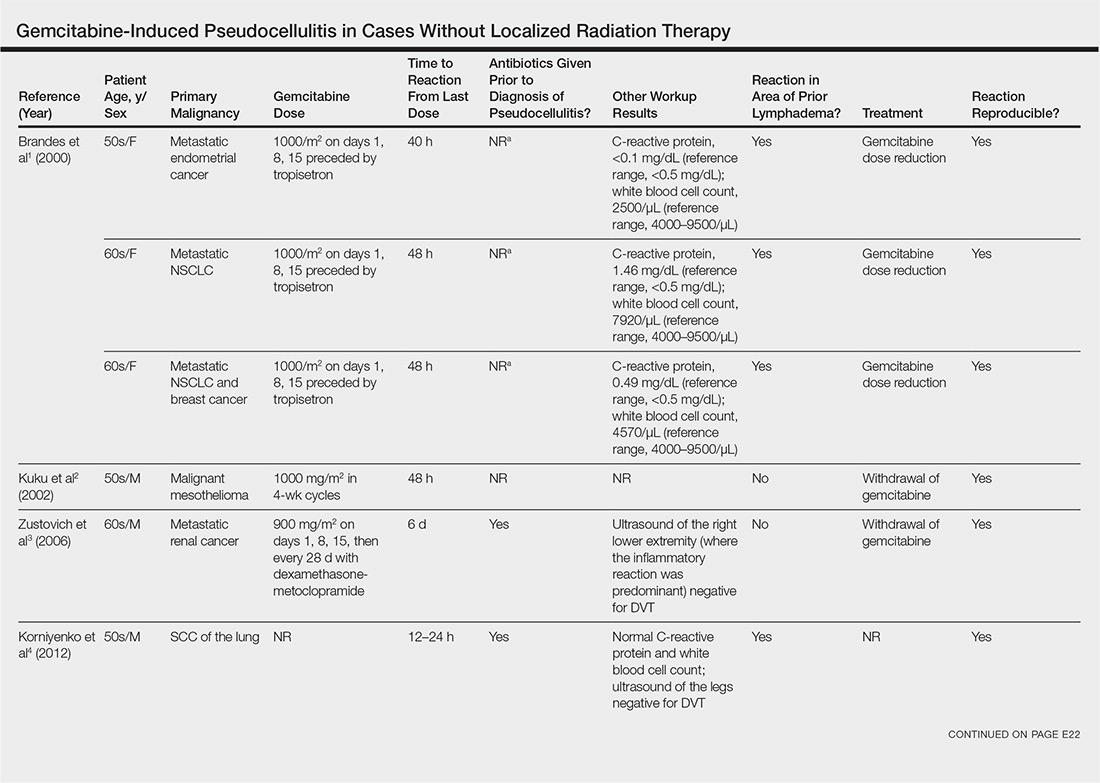

Gemcitabine-induced pseudocellulitis is a rare cutaneous side effect of gemcitabine therapy. Reported cases have suggested key characteristics of pseudocellulitis (Table). The reaction is characterized by localized erythema, edema, and tenderness of the skin, with onset generally 48 hours to 1 week after receiving gemcitabine.1-6 Lymphedema appears to be a risk factor.1,3-5 Six cases (including the current case) demonstrated confinement of these findings to areas of prior lymphedema.1,4,6 Infectious workup is negative, and rechallenging with gemcitabine likely will reproduce the reaction. Unlike radiation recall dermatitis, there is no prior localized radiation exposure.

Our patient had a history of hematologic malignancy and a one-time low-dose TBI of 200 cGy, unlike the other reported cases described in the Table. It is difficult to attribute our patient’s localized eruption to radiation recall given the history of TBI. The clinical examination, laboratory findings, and time frame of the reaction were consistent with gemcitabine-induced pseudocellulitis.

It is important to be aware of pseudocellulitis as a possible complication of gemcitabine therapy in patients without history of localized radiation. Early recognition of pseudocellulitis may prevent unnecessary exposure to broad-spectrum antibiotics. Patients’ temperature, white blood cell count, clinical examination, and potentially ancillary studies (eg, vascular studies, inflammatory markers) should be reviewed carefully to determine whether there is an infectious or alternate etiology. In patients with known prior lymphedema, it may be beneficial to educate clinicians and patients alike about this potential adverse effect of gemcitabine and the high likelihood of recurrence on re-exposure.

- Brandes A, Reichmann U, Plasswilm L, et al. Time- and dose-limiting erysipeloid rash confined to areas of lymphedema following treatment with gemcitabine—a report of three cases. Anticancer Drugs. 2000;11:15-17.

- Kuku I, Kaya E, Sevinc A, et al. Gemcitabine-induced erysipeloid skin lesions in a patient with malignant mesothelioma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2002;16:271-272.

- Zustovich F, Pavei P, Cartei G. Erysipeloid skin toxicity induced by gemcitabine. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:757-758.

- Korniyenko A, Lozada J, Ranade A, et al. Recurrent lower extremity pseudocellulitis. Am J Ther. 2012;19:e141-e142.

- Singh A, Hampole H. Gemcitabine associated pseudocellulitis [published online June 14, 2012]. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:1721.

- Curtis S, Hong S, Gucalp R, et al. Gemcitabine-induced pseudocellulitis in a patient with recurrent lymphedema: a case report and review of the current literature. Am J Ther. 2016;23:e321-323.

To the Editor:

Gemcitabine is a nucleoside analogue used to treat a variety of solid and hematologic malignancies. Cutaneous toxicities include radiation recall dermatitis and erysipelaslike reactions that occur in areas not previously treated with radiation. Often referred to as pseudocellulitis, these reactions generally have been reported in areas of lymphedema in patients with solid malignancies.1-6 Herein, we report a rare case of gemcitabine-induced pseudocellulitis on the legs in a patient with a history of hematologic malignancy and total body irradiation (TBI).

A 61-year-old woman with history of peripheral T-cell lymphoma presented to the emergency department at our institution with acute-onset redness, tenderness, and swelling of the legs that was concerning for cellulitis. The patient’s history was notable for receiving gemcitabine 1000 mg/m2 for treatment of refractory lymphoma (12 and 4 days prior to presentation) as well as lymphedema of the legs. Her complete treatment course included multiple rounds of chemotherapy and matched unrelated donor nonmyeloablative allogeneic stem cell transplantation with a single dose of TBI at 200 cGy at our institution. Her transplant was complicated only by mild cutaneous graft-versus-host disease, which resolved with prednisone and tacrolimus.

On physical examination, the patient was afebrile with symmetric erythema and induration extending from the bilateral knees to the dorsal feet. A complete blood cell count was notable for a white blood cell count of 5400/µL (reference range, 4500–11,000/µL) and a platelet count of 96,000/µL (reference range, 150,000–400,000/µL). Plain film radiographs of the bilateral ankles were remarkable only for moderate subcutaneous edema. She received vancomycin in the emergency department and was admitted to the oncology service. Blood cultures drawn on admission were negative. Dermatology was consulted on admission, and a diagnosis of pseudocellulitis was made in conjunction with oncology (Figure). Antibiotics were held, and the patient was treated symptomatically with ibuprofen and was discharged 1 day after admission. The reaction resolved after 1 week with the use of diphenhydramine, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and compression. The patient was not rechallenged with gemcitabine.

Gemcitabine-induced pseudocellulitis is a rare cutaneous side effect of gemcitabine therapy. Reported cases have suggested key characteristics of pseudocellulitis (Table). The reaction is characterized by localized erythema, edema, and tenderness of the skin, with onset generally 48 hours to 1 week after receiving gemcitabine.1-6 Lymphedema appears to be a risk factor.1,3-5 Six cases (including the current case) demonstrated confinement of these findings to areas of prior lymphedema.1,4,6 Infectious workup is negative, and rechallenging with gemcitabine likely will reproduce the reaction. Unlike radiation recall dermatitis, there is no prior localized radiation exposure.

Our patient had a history of hematologic malignancy and a one-time low-dose TBI of 200 cGy, unlike the other reported cases described in the Table. It is difficult to attribute our patient’s localized eruption to radiation recall given the history of TBI. The clinical examination, laboratory findings, and time frame of the reaction were consistent with gemcitabine-induced pseudocellulitis.

It is important to be aware of pseudocellulitis as a possible complication of gemcitabine therapy in patients without history of localized radiation. Early recognition of pseudocellulitis may prevent unnecessary exposure to broad-spectrum antibiotics. Patients’ temperature, white blood cell count, clinical examination, and potentially ancillary studies (eg, vascular studies, inflammatory markers) should be reviewed carefully to determine whether there is an infectious or alternate etiology. In patients with known prior lymphedema, it may be beneficial to educate clinicians and patients alike about this potential adverse effect of gemcitabine and the high likelihood of recurrence on re-exposure.

To the Editor:

Gemcitabine is a nucleoside analogue used to treat a variety of solid and hematologic malignancies. Cutaneous toxicities include radiation recall dermatitis and erysipelaslike reactions that occur in areas not previously treated with radiation. Often referred to as pseudocellulitis, these reactions generally have been reported in areas of lymphedema in patients with solid malignancies.1-6 Herein, we report a rare case of gemcitabine-induced pseudocellulitis on the legs in a patient with a history of hematologic malignancy and total body irradiation (TBI).

A 61-year-old woman with history of peripheral T-cell lymphoma presented to the emergency department at our institution with acute-onset redness, tenderness, and swelling of the legs that was concerning for cellulitis. The patient’s history was notable for receiving gemcitabine 1000 mg/m2 for treatment of refractory lymphoma (12 and 4 days prior to presentation) as well as lymphedema of the legs. Her complete treatment course included multiple rounds of chemotherapy and matched unrelated donor nonmyeloablative allogeneic stem cell transplantation with a single dose of TBI at 200 cGy at our institution. Her transplant was complicated only by mild cutaneous graft-versus-host disease, which resolved with prednisone and tacrolimus.

On physical examination, the patient was afebrile with symmetric erythema and induration extending from the bilateral knees to the dorsal feet. A complete blood cell count was notable for a white blood cell count of 5400/µL (reference range, 4500–11,000/µL) and a platelet count of 96,000/µL (reference range, 150,000–400,000/µL). Plain film radiographs of the bilateral ankles were remarkable only for moderate subcutaneous edema. She received vancomycin in the emergency department and was admitted to the oncology service. Blood cultures drawn on admission were negative. Dermatology was consulted on admission, and a diagnosis of pseudocellulitis was made in conjunction with oncology (Figure). Antibiotics were held, and the patient was treated symptomatically with ibuprofen and was discharged 1 day after admission. The reaction resolved after 1 week with the use of diphenhydramine, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and compression. The patient was not rechallenged with gemcitabine.

Gemcitabine-induced pseudocellulitis is a rare cutaneous side effect of gemcitabine therapy. Reported cases have suggested key characteristics of pseudocellulitis (Table). The reaction is characterized by localized erythema, edema, and tenderness of the skin, with onset generally 48 hours to 1 week after receiving gemcitabine.1-6 Lymphedema appears to be a risk factor.1,3-5 Six cases (including the current case) demonstrated confinement of these findings to areas of prior lymphedema.1,4,6 Infectious workup is negative, and rechallenging with gemcitabine likely will reproduce the reaction. Unlike radiation recall dermatitis, there is no prior localized radiation exposure.

Our patient had a history of hematologic malignancy and a one-time low-dose TBI of 200 cGy, unlike the other reported cases described in the Table. It is difficult to attribute our patient’s localized eruption to radiation recall given the history of TBI. The clinical examination, laboratory findings, and time frame of the reaction were consistent with gemcitabine-induced pseudocellulitis.

It is important to be aware of pseudocellulitis as a possible complication of gemcitabine therapy in patients without history of localized radiation. Early recognition of pseudocellulitis may prevent unnecessary exposure to broad-spectrum antibiotics. Patients’ temperature, white blood cell count, clinical examination, and potentially ancillary studies (eg, vascular studies, inflammatory markers) should be reviewed carefully to determine whether there is an infectious or alternate etiology. In patients with known prior lymphedema, it may be beneficial to educate clinicians and patients alike about this potential adverse effect of gemcitabine and the high likelihood of recurrence on re-exposure.

- Brandes A, Reichmann U, Plasswilm L, et al. Time- and dose-limiting erysipeloid rash confined to areas of lymphedema following treatment with gemcitabine—a report of three cases. Anticancer Drugs. 2000;11:15-17.

- Kuku I, Kaya E, Sevinc A, et al. Gemcitabine-induced erysipeloid skin lesions in a patient with malignant mesothelioma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2002;16:271-272.

- Zustovich F, Pavei P, Cartei G. Erysipeloid skin toxicity induced by gemcitabine. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:757-758.

- Korniyenko A, Lozada J, Ranade A, et al. Recurrent lower extremity pseudocellulitis. Am J Ther. 2012;19:e141-e142.

- Singh A, Hampole H. Gemcitabine associated pseudocellulitis [published online June 14, 2012]. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:1721.

- Curtis S, Hong S, Gucalp R, et al. Gemcitabine-induced pseudocellulitis in a patient with recurrent lymphedema: a case report and review of the current literature. Am J Ther. 2016;23:e321-323.

- Brandes A, Reichmann U, Plasswilm L, et al. Time- and dose-limiting erysipeloid rash confined to areas of lymphedema following treatment with gemcitabine—a report of three cases. Anticancer Drugs. 2000;11:15-17.

- Kuku I, Kaya E, Sevinc A, et al. Gemcitabine-induced erysipeloid skin lesions in a patient with malignant mesothelioma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2002;16:271-272.

- Zustovich F, Pavei P, Cartei G. Erysipeloid skin toxicity induced by gemcitabine. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:757-758.

- Korniyenko A, Lozada J, Ranade A, et al. Recurrent lower extremity pseudocellulitis. Am J Ther. 2012;19:e141-e142.

- Singh A, Hampole H. Gemcitabine associated pseudocellulitis [published online June 14, 2012]. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:1721.

- Curtis S, Hong S, Gucalp R, et al. Gemcitabine-induced pseudocellulitis in a patient with recurrent lymphedema: a case report and review of the current literature. Am J Ther. 2016;23:e321-323.

Practice Points

- Gemcitabine is a nucleoside analogue used to treat a variety of solid and hematologic malignancies.

- Gemcitabine-induced pseudocellulitis is a rare cutaneous side effect of gemcitabine therapy.

- Early recognition of pseudocellulitis may prevent unnecessary exposure to broad-spectrum antibiotics.

DRESS Syndrome Induced by Telaprevir: A Potentially Fatal Adverse Event in Chronic Hepatitis C Therapy

To the Editor:

A 58-year-old woman with a history of hyperprolactinemia and gastrointestinal angiodysplasia presented to the dermatology department with a generalized skin rash of 3 weeks’ duration. She did not have a history of toxic habits. She had a history of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 1b (IL-28B locus) with severe hepatic fibrosis (stage 4) as assessed by ultrasound-based elastography. Due to lack of response, plasma HCV RNA was still detectable at week 12 of pegylated interferon and ribavirin (RIB) therapy, and triple therapy with pegylated interferon, RIB, and telaprevir was initiated.

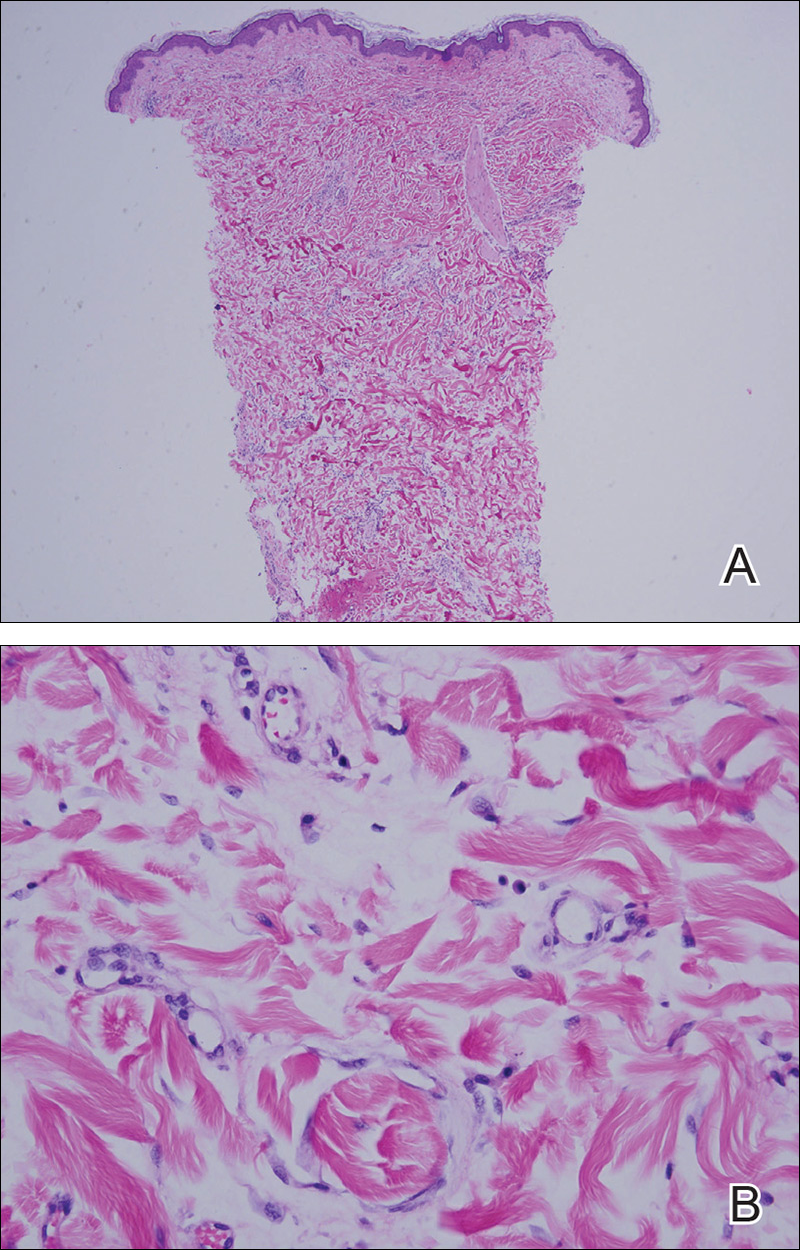

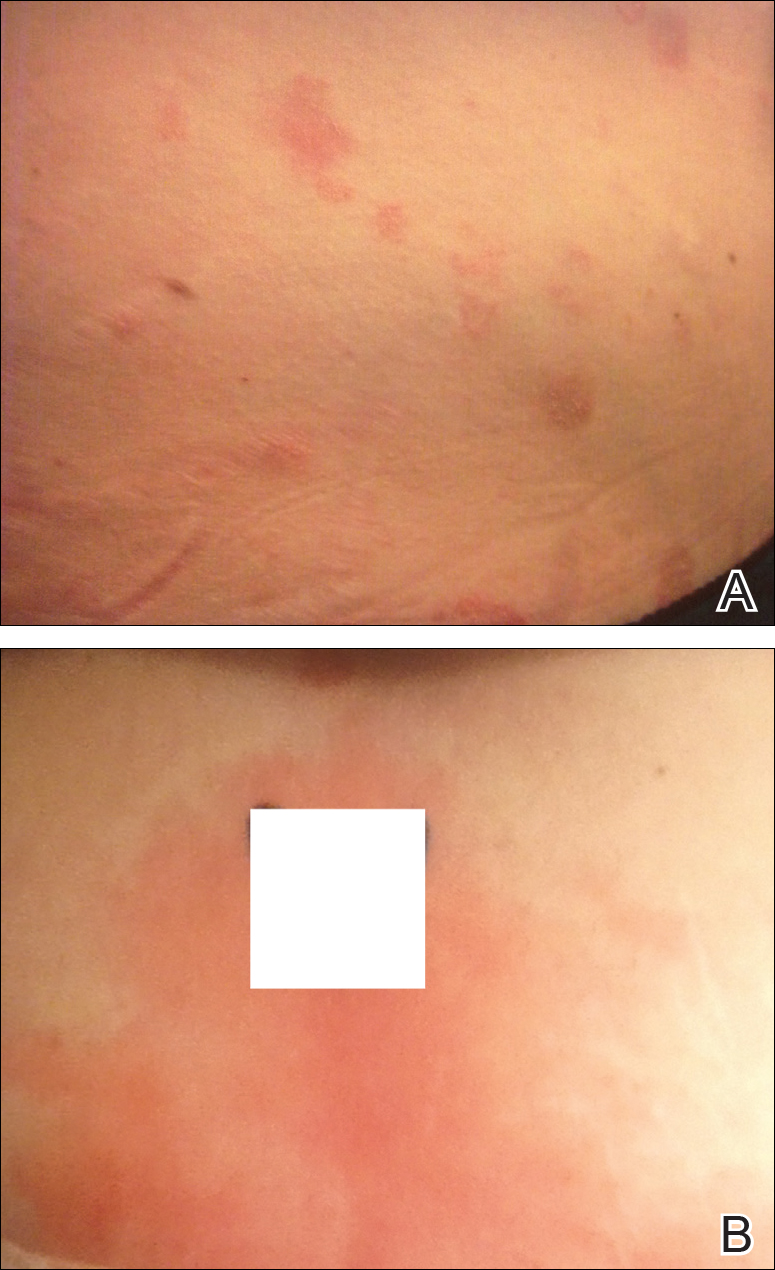

Two months later, she was admitted to the hospital after developing a generalized cutaneous rash that covered 90% of the body surface area (BSA) along with fever (temperature, 38.5°C). Laboratory blood tests showed an elevated absolute eosinophil count (2000 cells/µL [reference range, 0–500 cells/µL]), anemia (hemoglobin, 6.5 g/dL [reference range, 12–16 g/dL]), thrombocytopenia (26×103/µL [reference range, 150–400×103/µL]), and altered liver function tests (serum alanine aminotransferase, 60 U/L [reference range, 0–45 U/L]; aspartate aminotransferase, 80 U/L [reference range, 0–40 U/L]). Plasma HCV RNA was undetectable at this visit. On physical examination a generalized exanthema with coalescing plaques was observed, as well as crusted vesicles covering the arms, legs, chest, abdomen, and back. Palmoplantar papules (Figure, A) and facial swelling (Figure, B) also were present. A skin biopsy specimen taken from a papule on the left arm showed superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltration with dermal edema. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of DRESS (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms) syndrome. Application of the Adverse Drug Reaction Probability Scale1 in our patient (total score of 5) suggested that DRESS syndrome was a moderate adverse event likely related to the use of telaprevir.

After diagnosis of DRESS syndrome, telaprevir was discontinued, and the doses of RIB and pegylated interferon were reduced to 200 mg and 180 µg weekly, respectively. Laboratory test values including liver function tests normalized within 3 weeks and remained normal on follow-up. Plasma HCV RNA continued to be undetectable.

Hepatitis C virus is relatively common with an incidence of 3% worldwide.2 It may present as an acute hepatitis or, more frequently, as asymptomatic chronic hepatitis. The acute process is self-limited and rarely causes hepatic failure. It usually leads to a chronic infection, which can result in cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and the need for liver transplantation. The aim of treatment is eradication of HCV RNA, which is predicted by the attainment of a sustained virologic response. The latter is defined by the absence of HCV RNA by a polymerase chain reaction within 3 to 6 months after cessation of treatment.

Treatment of chronic HCV was based on the combination of pegylated interferon alfa-2a or -2b with RIB until 2015. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of HCV infection have been published by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America.2 These guidelines include new protease inhibitors, telaprevir and boceprevir, in the therapeutic approach of these patients. The main limitation of both drugs is the cutaneous toxicity.

Factors to be considered when treating HCV include viral genotype, if the patient is naïve or pretreated, the degree of fibrosis, established cirrhosis, and the treatment response. For patients with genotype 1,2 as in our case, combination therapy with 3 drugs is recommended: pegylated interferon 180 µg subcutaneous injection weekly, RIB 15 mg/kg daily, and telaprevir 2250 mg or boceprevir 2400 mg daily. Triple therapy has been shown to achieve a successful response in 75% of naïve patients and in 50% of patients refractory to standard therapy.3

Telaprevir is an NS3/4A protease inhibitor approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency for treatment of chronic HCV infection in naïve patients and in those unresponsive to double therapy. In phase 2 clinical trials, 41% to 61% of patients treated with telaprevir developed cutaneous reactions, of which 5% to 8% required cessation of treatment.4 The predicting risk factors for developing a secondary rash to telaprevir include age older than 45 years, body mass index less than 30, Caucasian ethnicity, and receiving HCV therapy for the first time.4

This cutaneous side effect is managed depending on the extension of the lesions, the presence of systemic symptoms, and laboratory abnormalities.5 Therefore, the severity of the skin reaction can be divided into 4 stages4,5: (1) grade I or mild, defined as a localized rash with no systemic signs or mucosal involvement; (2) grade II or moderate, a maximum of 50% BSA involvement without epidermal detachment, and inflammation of the mucous membranes may be present without ulcers, as well as systemic symptoms such as fever, arthralgia, or eosinophilia; (3) grade III or severe, skin lesions affecting more than 50% BSA or less if any of the following lesions are present: vesicles or blisters, ulcers, epidermal detachment, palpable purpura, or erythema that does not blanch under pressure; (4) grade IV or life-threatening, when the clinical picture is consistent with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, DRESS syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, or Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

DRESS syndrome is a condition clinically characterized by a generalized skin rash, facial angioedema, high fever, lymph node enlargement, and leukocytosis with eosinophilia or atypical lymphocytosis, along with abnormal renal and hepatic function tests. Cutaneous histopathologic examination may be unspecific, though atypical lymphocytes with a marked epidermotropism mimicking fungoid mycosis also have been described.6 In addition, human herpesvirus 6 serology may be negative, despite infection with this herpesvirus subtype having been associated with the development of DRESS syndrome. The pathophysiologic mechanism of DRESS syndrome is not completely understood; however, one theory ascribes an immunologic activation due to drug metabolite formation as the main mechanism.1

Eleven patients7 with possible DRESS syndrome have been reported in clinical trials (less than 5% of the total of patients), with an addition of 1 more by Montaudié et al.8 No notable differences were found between telaprevir levels in these patients with respect to those of the control group.

For the management of DRESS syndrome, the occurrence of early signs of a severe acute skin reaction requires the immediate cessation of the drug, telaprevir in this case. The withdrawal of the dual therapy will depend on the short-term clinical course, according to the general condition of the patient, as well as the analytical abnormalities observed.9

In conclusion, telaprevir is a promising novel therapy for the treatment of HCV infection, but its cutaneous side effects still need to be properly established.

- Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharacol Ther. 1981;30:239-245.

- HCV guidance: recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. HCV Guidelines website. http://www.hcvguidelines.org. Accessed August 11, 2018.

- Jacobson IM, McHutchison JG, Dusheiko G, et al; ADVANCE Study Team. Telaprevir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2405-2416.

- Kardaun SH, Sidoroff A, Valeyrie-Allanore L, et al. Variability in the clinical pattern of cutaneous side-effects of drugs with systemic symptoms: does a DRESS syndrome really exist? Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:609-611.

- Roujeau JC, Mockenhaupt M, Tahan SR, et al. Telaprevir-related dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:152-158.

- De Vriese AS, Philippe J, Van Renterghem DM, et al. Carbamazepine hypersensitivity syndrome: report of 4 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1995;74:144-151.

- Cacoub P, Musette P, Descamps V, et al. The DRESS syndrome: a literature review [published online May 17, 2011]. Am J Med. 2011;124:588-597.

- Montaudié H, Passeron T, Cardot-Leccia N, et al. Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms due to telaprevir. Dermatology. 2010;221:303-305.

- Tas S, Simonart T. Management of drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS syndrome): an update. Dermatology. 2003;206:353-356.

To the Editor:

A 58-year-old woman with a history of hyperprolactinemia and gastrointestinal angiodysplasia presented to the dermatology department with a generalized skin rash of 3 weeks’ duration. She did not have a history of toxic habits. She had a history of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 1b (IL-28B locus) with severe hepatic fibrosis (stage 4) as assessed by ultrasound-based elastography. Due to lack of response, plasma HCV RNA was still detectable at week 12 of pegylated interferon and ribavirin (RIB) therapy, and triple therapy with pegylated interferon, RIB, and telaprevir was initiated.

Two months later, she was admitted to the hospital after developing a generalized cutaneous rash that covered 90% of the body surface area (BSA) along with fever (temperature, 38.5°C). Laboratory blood tests showed an elevated absolute eosinophil count (2000 cells/µL [reference range, 0–500 cells/µL]), anemia (hemoglobin, 6.5 g/dL [reference range, 12–16 g/dL]), thrombocytopenia (26×103/µL [reference range, 150–400×103/µL]), and altered liver function tests (serum alanine aminotransferase, 60 U/L [reference range, 0–45 U/L]; aspartate aminotransferase, 80 U/L [reference range, 0–40 U/L]). Plasma HCV RNA was undetectable at this visit. On physical examination a generalized exanthema with coalescing plaques was observed, as well as crusted vesicles covering the arms, legs, chest, abdomen, and back. Palmoplantar papules (Figure, A) and facial swelling (Figure, B) also were present. A skin biopsy specimen taken from a papule on the left arm showed superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltration with dermal edema. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of DRESS (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms) syndrome. Application of the Adverse Drug Reaction Probability Scale1 in our patient (total score of 5) suggested that DRESS syndrome was a moderate adverse event likely related to the use of telaprevir.

After diagnosis of DRESS syndrome, telaprevir was discontinued, and the doses of RIB and pegylated interferon were reduced to 200 mg and 180 µg weekly, respectively. Laboratory test values including liver function tests normalized within 3 weeks and remained normal on follow-up. Plasma HCV RNA continued to be undetectable.

Hepatitis C virus is relatively common with an incidence of 3% worldwide.2 It may present as an acute hepatitis or, more frequently, as asymptomatic chronic hepatitis. The acute process is self-limited and rarely causes hepatic failure. It usually leads to a chronic infection, which can result in cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and the need for liver transplantation. The aim of treatment is eradication of HCV RNA, which is predicted by the attainment of a sustained virologic response. The latter is defined by the absence of HCV RNA by a polymerase chain reaction within 3 to 6 months after cessation of treatment.

Treatment of chronic HCV was based on the combination of pegylated interferon alfa-2a or -2b with RIB until 2015. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of HCV infection have been published by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America.2 These guidelines include new protease inhibitors, telaprevir and boceprevir, in the therapeutic approach of these patients. The main limitation of both drugs is the cutaneous toxicity.

Factors to be considered when treating HCV include viral genotype, if the patient is naïve or pretreated, the degree of fibrosis, established cirrhosis, and the treatment response. For patients with genotype 1,2 as in our case, combination therapy with 3 drugs is recommended: pegylated interferon 180 µg subcutaneous injection weekly, RIB 15 mg/kg daily, and telaprevir 2250 mg or boceprevir 2400 mg daily. Triple therapy has been shown to achieve a successful response in 75% of naïve patients and in 50% of patients refractory to standard therapy.3

Telaprevir is an NS3/4A protease inhibitor approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency for treatment of chronic HCV infection in naïve patients and in those unresponsive to double therapy. In phase 2 clinical trials, 41% to 61% of patients treated with telaprevir developed cutaneous reactions, of which 5% to 8% required cessation of treatment.4 The predicting risk factors for developing a secondary rash to telaprevir include age older than 45 years, body mass index less than 30, Caucasian ethnicity, and receiving HCV therapy for the first time.4

This cutaneous side effect is managed depending on the extension of the lesions, the presence of systemic symptoms, and laboratory abnormalities.5 Therefore, the severity of the skin reaction can be divided into 4 stages4,5: (1) grade I or mild, defined as a localized rash with no systemic signs or mucosal involvement; (2) grade II or moderate, a maximum of 50% BSA involvement without epidermal detachment, and inflammation of the mucous membranes may be present without ulcers, as well as systemic symptoms such as fever, arthralgia, or eosinophilia; (3) grade III or severe, skin lesions affecting more than 50% BSA or less if any of the following lesions are present: vesicles or blisters, ulcers, epidermal detachment, palpable purpura, or erythema that does not blanch under pressure; (4) grade IV or life-threatening, when the clinical picture is consistent with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, DRESS syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, or Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

DRESS syndrome is a condition clinically characterized by a generalized skin rash, facial angioedema, high fever, lymph node enlargement, and leukocytosis with eosinophilia or atypical lymphocytosis, along with abnormal renal and hepatic function tests. Cutaneous histopathologic examination may be unspecific, though atypical lymphocytes with a marked epidermotropism mimicking fungoid mycosis also have been described.6 In addition, human herpesvirus 6 serology may be negative, despite infection with this herpesvirus subtype having been associated with the development of DRESS syndrome. The pathophysiologic mechanism of DRESS syndrome is not completely understood; however, one theory ascribes an immunologic activation due to drug metabolite formation as the main mechanism.1

Eleven patients7 with possible DRESS syndrome have been reported in clinical trials (less than 5% of the total of patients), with an addition of 1 more by Montaudié et al.8 No notable differences were found between telaprevir levels in these patients with respect to those of the control group.

For the management of DRESS syndrome, the occurrence of early signs of a severe acute skin reaction requires the immediate cessation of the drug, telaprevir in this case. The withdrawal of the dual therapy will depend on the short-term clinical course, according to the general condition of the patient, as well as the analytical abnormalities observed.9

In conclusion, telaprevir is a promising novel therapy for the treatment of HCV infection, but its cutaneous side effects still need to be properly established.

To the Editor:

A 58-year-old woman with a history of hyperprolactinemia and gastrointestinal angiodysplasia presented to the dermatology department with a generalized skin rash of 3 weeks’ duration. She did not have a history of toxic habits. She had a history of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 1b (IL-28B locus) with severe hepatic fibrosis (stage 4) as assessed by ultrasound-based elastography. Due to lack of response, plasma HCV RNA was still detectable at week 12 of pegylated interferon and ribavirin (RIB) therapy, and triple therapy with pegylated interferon, RIB, and telaprevir was initiated.

Two months later, she was admitted to the hospital after developing a generalized cutaneous rash that covered 90% of the body surface area (BSA) along with fever (temperature, 38.5°C). Laboratory blood tests showed an elevated absolute eosinophil count (2000 cells/µL [reference range, 0–500 cells/µL]), anemia (hemoglobin, 6.5 g/dL [reference range, 12–16 g/dL]), thrombocytopenia (26×103/µL [reference range, 150–400×103/µL]), and altered liver function tests (serum alanine aminotransferase, 60 U/L [reference range, 0–45 U/L]; aspartate aminotransferase, 80 U/L [reference range, 0–40 U/L]). Plasma HCV RNA was undetectable at this visit. On physical examination a generalized exanthema with coalescing plaques was observed, as well as crusted vesicles covering the arms, legs, chest, abdomen, and back. Palmoplantar papules (Figure, A) and facial swelling (Figure, B) also were present. A skin biopsy specimen taken from a papule on the left arm showed superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltration with dermal edema. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of DRESS (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms) syndrome. Application of the Adverse Drug Reaction Probability Scale1 in our patient (total score of 5) suggested that DRESS syndrome was a moderate adverse event likely related to the use of telaprevir.

After diagnosis of DRESS syndrome, telaprevir was discontinued, and the doses of RIB and pegylated interferon were reduced to 200 mg and 180 µg weekly, respectively. Laboratory test values including liver function tests normalized within 3 weeks and remained normal on follow-up. Plasma HCV RNA continued to be undetectable.

Hepatitis C virus is relatively common with an incidence of 3% worldwide.2 It may present as an acute hepatitis or, more frequently, as asymptomatic chronic hepatitis. The acute process is self-limited and rarely causes hepatic failure. It usually leads to a chronic infection, which can result in cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and the need for liver transplantation. The aim of treatment is eradication of HCV RNA, which is predicted by the attainment of a sustained virologic response. The latter is defined by the absence of HCV RNA by a polymerase chain reaction within 3 to 6 months after cessation of treatment.

Treatment of chronic HCV was based on the combination of pegylated interferon alfa-2a or -2b with RIB until 2015. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of HCV infection have been published by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America.2 These guidelines include new protease inhibitors, telaprevir and boceprevir, in the therapeutic approach of these patients. The main limitation of both drugs is the cutaneous toxicity.

Factors to be considered when treating HCV include viral genotype, if the patient is naïve or pretreated, the degree of fibrosis, established cirrhosis, and the treatment response. For patients with genotype 1,2 as in our case, combination therapy with 3 drugs is recommended: pegylated interferon 180 µg subcutaneous injection weekly, RIB 15 mg/kg daily, and telaprevir 2250 mg or boceprevir 2400 mg daily. Triple therapy has been shown to achieve a successful response in 75% of naïve patients and in 50% of patients refractory to standard therapy.3

Telaprevir is an NS3/4A protease inhibitor approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency for treatment of chronic HCV infection in naïve patients and in those unresponsive to double therapy. In phase 2 clinical trials, 41% to 61% of patients treated with telaprevir developed cutaneous reactions, of which 5% to 8% required cessation of treatment.4 The predicting risk factors for developing a secondary rash to telaprevir include age older than 45 years, body mass index less than 30, Caucasian ethnicity, and receiving HCV therapy for the first time.4

This cutaneous side effect is managed depending on the extension of the lesions, the presence of systemic symptoms, and laboratory abnormalities.5 Therefore, the severity of the skin reaction can be divided into 4 stages4,5: (1) grade I or mild, defined as a localized rash with no systemic signs or mucosal involvement; (2) grade II or moderate, a maximum of 50% BSA involvement without epidermal detachment, and inflammation of the mucous membranes may be present without ulcers, as well as systemic symptoms such as fever, arthralgia, or eosinophilia; (3) grade III or severe, skin lesions affecting more than 50% BSA or less if any of the following lesions are present: vesicles or blisters, ulcers, epidermal detachment, palpable purpura, or erythema that does not blanch under pressure; (4) grade IV or life-threatening, when the clinical picture is consistent with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, DRESS syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, or Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

DRESS syndrome is a condition clinically characterized by a generalized skin rash, facial angioedema, high fever, lymph node enlargement, and leukocytosis with eosinophilia or atypical lymphocytosis, along with abnormal renal and hepatic function tests. Cutaneous histopathologic examination may be unspecific, though atypical lymphocytes with a marked epidermotropism mimicking fungoid mycosis also have been described.6 In addition, human herpesvirus 6 serology may be negative, despite infection with this herpesvirus subtype having been associated with the development of DRESS syndrome. The pathophysiologic mechanism of DRESS syndrome is not completely understood; however, one theory ascribes an immunologic activation due to drug metabolite formation as the main mechanism.1

Eleven patients7 with possible DRESS syndrome have been reported in clinical trials (less than 5% of the total of patients), with an addition of 1 more by Montaudié et al.8 No notable differences were found between telaprevir levels in these patients with respect to those of the control group.

For the management of DRESS syndrome, the occurrence of early signs of a severe acute skin reaction requires the immediate cessation of the drug, telaprevir in this case. The withdrawal of the dual therapy will depend on the short-term clinical course, according to the general condition of the patient, as well as the analytical abnormalities observed.9

In conclusion, telaprevir is a promising novel therapy for the treatment of HCV infection, but its cutaneous side effects still need to be properly established.

- Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharacol Ther. 1981;30:239-245.

- HCV guidance: recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. HCV Guidelines website. http://www.hcvguidelines.org. Accessed August 11, 2018.

- Jacobson IM, McHutchison JG, Dusheiko G, et al; ADVANCE Study Team. Telaprevir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2405-2416.

- Kardaun SH, Sidoroff A, Valeyrie-Allanore L, et al. Variability in the clinical pattern of cutaneous side-effects of drugs with systemic symptoms: does a DRESS syndrome really exist? Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:609-611.

- Roujeau JC, Mockenhaupt M, Tahan SR, et al. Telaprevir-related dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:152-158.

- De Vriese AS, Philippe J, Van Renterghem DM, et al. Carbamazepine hypersensitivity syndrome: report of 4 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1995;74:144-151.

- Cacoub P, Musette P, Descamps V, et al. The DRESS syndrome: a literature review [published online May 17, 2011]. Am J Med. 2011;124:588-597.

- Montaudié H, Passeron T, Cardot-Leccia N, et al. Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms due to telaprevir. Dermatology. 2010;221:303-305.

- Tas S, Simonart T. Management of drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS syndrome): an update. Dermatology. 2003;206:353-356.

- Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharacol Ther. 1981;30:239-245.

- HCV guidance: recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. HCV Guidelines website. http://www.hcvguidelines.org. Accessed August 11, 2018.

- Jacobson IM, McHutchison JG, Dusheiko G, et al; ADVANCE Study Team. Telaprevir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2405-2416.

- Kardaun SH, Sidoroff A, Valeyrie-Allanore L, et al. Variability in the clinical pattern of cutaneous side-effects of drugs with systemic symptoms: does a DRESS syndrome really exist? Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:609-611.

- Roujeau JC, Mockenhaupt M, Tahan SR, et al. Telaprevir-related dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:152-158.

- De Vriese AS, Philippe J, Van Renterghem DM, et al. Carbamazepine hypersensitivity syndrome: report of 4 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1995;74:144-151.

- Cacoub P, Musette P, Descamps V, et al. The DRESS syndrome: a literature review [published online May 17, 2011]. Am J Med. 2011;124:588-597.

- Montaudié H, Passeron T, Cardot-Leccia N, et al. Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms due to telaprevir. Dermatology. 2010;221:303-305.

- Tas S, Simonart T. Management of drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS syndrome): an update. Dermatology. 2003;206:353-356.

Practice Points

- DRESS syndrome is characterized by a generalized skin rash, facial angioedema, high fever, lymph node enlargement, and leukocytosis with eosinophilia or atypical lymphocytosis, along with abnormal renal and hepatic function tests.

- Severity of the skin reaction can be divided into 4 stages; in the third and fourth stages, adequate patient monitoring is necessary.

- Telaprevir is an NS3/4A protease inhibitor approved for treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus infection in naïve patients and in those unresponsive to double therapy. Its cutaneous side effects still need to be properly established.

Eumycetoma Pedis in an Albanian Farmer

To the Editor:

Mycetoma is a noncontagious chronic infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissue caused by exogenous fungi or bacteria that can involve deeper structures such as the fasciae, muscles, and bones. Clinically it is characterized by increased swelling of the affected area, fibrosis, nodules, tumefaction, formation of draining sinuses, and abscesses that drain pus-containing grains through fistulae.1 The initiation of the infection is related to local trauma and can involve muscle, underlying bone, and adjacent organs. The feet are the most commonly affected region, and the incubation period is variable. Patients rarely report prior trauma to the affected area and only seek medical consultation when the nodules and draining sinuses become evident. The etiopathogenesis of mycetoma is associated with aerobic actinomycetes (ie, Nocardia, Actinomadura, Streptomyces), known as actinomycetoma, and fungal infections, known as eumycetomas.1

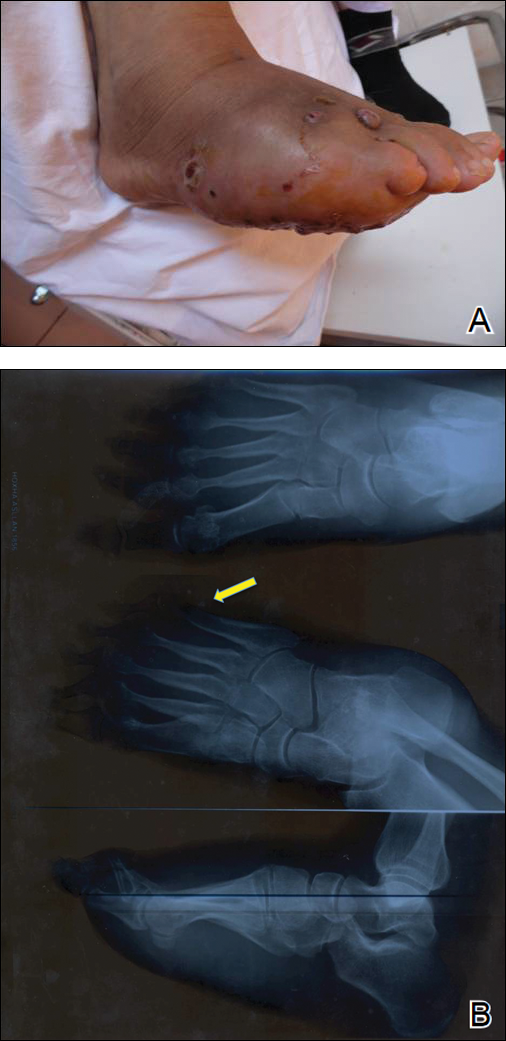

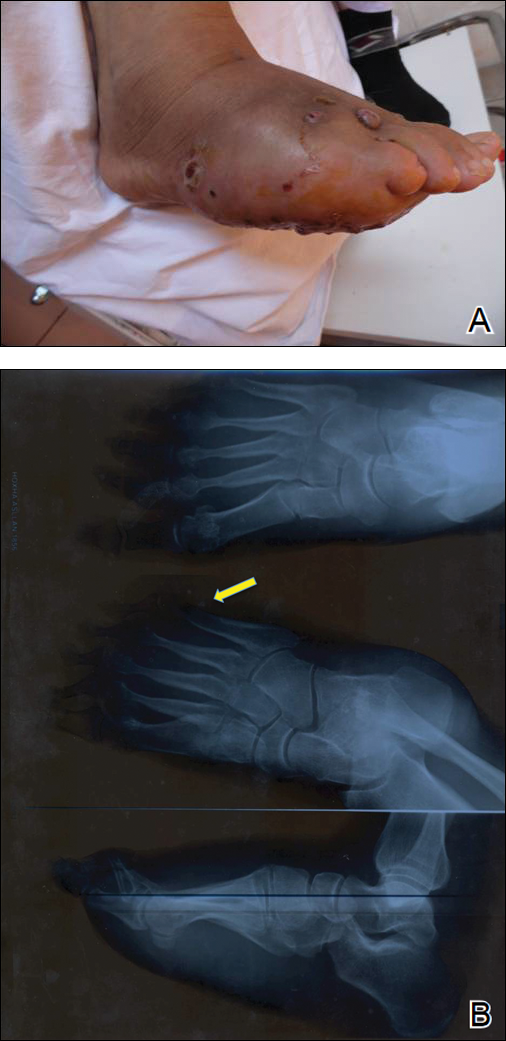

We report the case of a 57-year-old Albanian man who was referred to the outpatient clinic of our dermatology department for diagnosis and treatment of a chronic, suppurative, subcutaneous infection on the right foot presenting as abscesses and draining sinuses. The patient was a farmer and reported that the condition appeared 4 years prior following a laceration he sustained while at work. Dermatologic examination revealed local tumefaction, fistulated nodules, and abscesses discharging a serohemorrhagic fluid on the right foot (Figure 1). Perilesional erythema and subcutaneous swelling were evident. There was no regional lymphadenopathy. Standard laboratory examination was normal. Radiography of the right foot showed no osteolytic lesions or evidence of osteomyelitis.

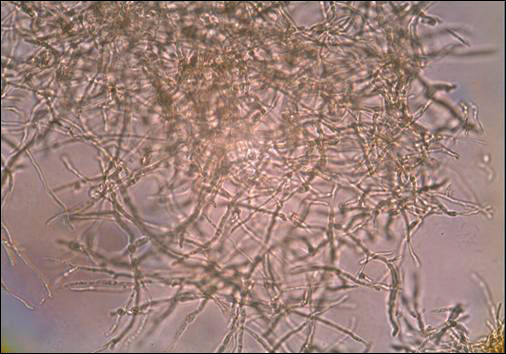

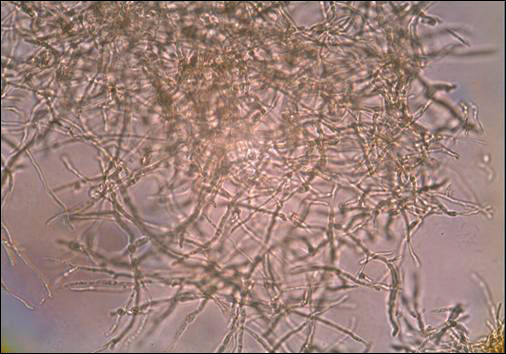

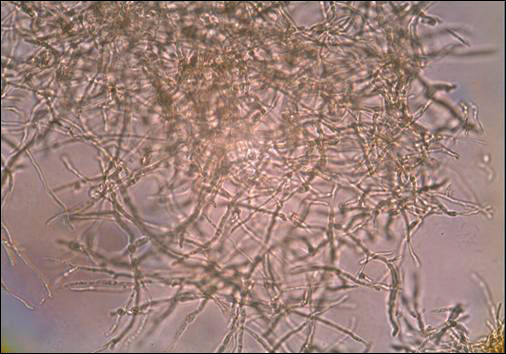

A skin biopsy from a lesion on the right foot was performed, and identification of the possible etiologic agent was based on direct microscopic examination of the granules, culture isolation of the agent, and fungal microscopic morphology.2 Granules were studied under direct examination with potassium hydroxide solution 20% and showed septate branching hyphae (Figure 2). The culture produced colonies that were white, yellow, and brown. Colonies were comprised of dense mycelium with melanin pigment and were grown at 37°C. A lactose tolerance test was positive.2 Therefore, the strain was identified as Madurella mycetomatis, and a diagnosis of eumycetoma pedis was made.

The patient was hospitalized for 2 weeks and treated with intravenous fluconazole, then treatment with oral itraconazole 200 mg once daily was initiated. At 4-month follow-up, he had self-discontinued treatment but demonstrated partial improvement of the tumefaction, healing of sinus tracts, and functional recovery of the right foot.

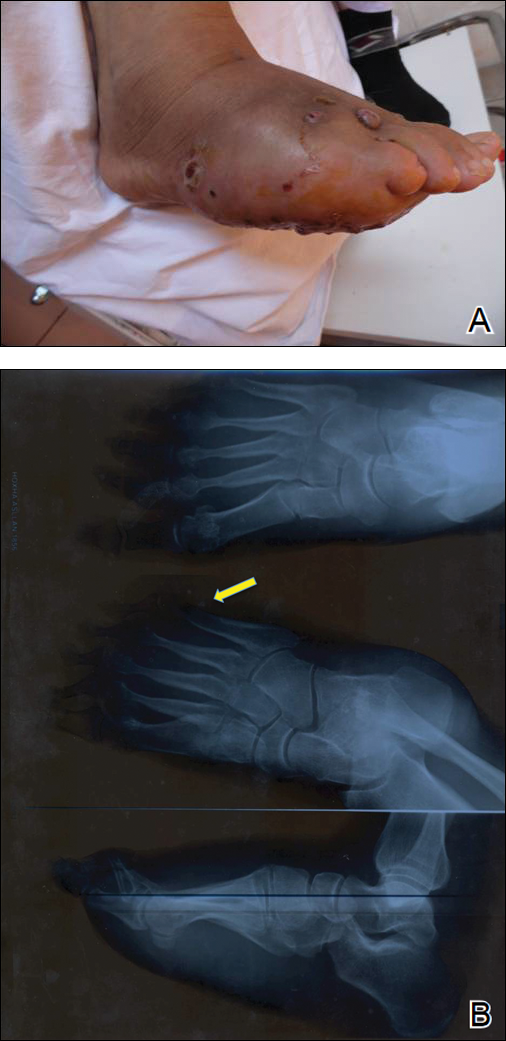

One year following the initial presentation, the patient’s clinical condition worsened (Figure 3A). Radiography of the right foot showed osteolytic lesions on bones in the right foot (Figure 3B), and a repeat culture showed the presence of Staphylococcus aureus; thus, treatment with itraconazole 200 mg once daily along with antibiotics (cefuroxime and gentamicin) was started immediately. Surgical treatment was recommended, but the patient refused treatment.

Mycetomas are rare in Albania but are common in countries of tropical and subtropical regions. K

Clinical features of eumycetoma include lesions with clear margins, few sinuses, black grains, slow progression, and long-term involvement of bone. The grains represent an aggregate of hyphae produced by fungi; thus, the characteristic feature of eumycetoma is the formation of large granules that can involve bone.1 A critical diagnostic step is to distinguish between eumycetoma and actinomycetoma. If possible, it is important to culture the organism because treatment varies depending on the cause of the infection.

Fungal identification is crucial in the diagnosis of mycetoma. In our case, diagnosis of eumycetoma pedis was based on clinical examination and detection of fungal species by microscopic examination and culture. The color of small granules (black grains) is a parameter used to identify different pathogens on histology but is not sufficient for diagnosis.5 The examination by potassium hydroxide preparation is helpful to identify the hyphae; however, culture is necessary.2

Therapeutic management of eumycetoma needs a combined strategy that includes systemic treatment and surgical therapy. Eumycetomas generally are more difficult to treat then actinomycetomas. Some authors recommend a high dose of amphotericin B as the treatment of choice for eumycetoma,6,7 but there are some that emphasize that amphotericin B is partially effective.8,9 There also is evidence in the literature of resistance of eumycetoma to ketoconazole treatment10,11 and successful treatment with fluconazole and itraconazole.10-13 For this reason, we treated our patient with the latter agents. In cases of osteolysis, amputation often is required.

In conclusion, eumycetoma pedis is a rare deep fungal infection that can cause considerable morbidity. P

- Rook A, Burns T. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. West Sussex, UK; Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010.

- Balows A, Hausler WJ, eds. Manual of Clinical Microbiology. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology; 1991.

- Carter HV. On a new striking form of fungus disease principally affecting the foot and prevailing endemically in many parts of India. Trans Med Phys Soc Bombay. 1860;6:104-142.

- Kwon-Chung KJ, Bennet JE. Medical Mycology. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1992.

- Venugopal PV, Venugopal TV. Pale grain eumycetomas in Madras. Australas J Dermatol. 1995;36:149-151.

- Guarro J, Gams W, Pujol I, et al. Acremonium species: new emerging fungal opportunists—in vitro antifungal susceptibilities and review. Clin Infec Dis. 1997;25:1222-1229.

- Lau YL, Yuen KY, Lee CW, et al. Invasive Acremonium falciforme infection in a patient with severe combined immunodeficiency. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:197-198.

- Fincher RM, Fisher JF, Lovell RD, et al. Infection due to the fungus Acremonium (cephalosporium). Medicine (Baltimore). 1991;70:398-409.

- Milburn PB, Papayanopulos DM, Pomerantz BM. Mycetoma due to Acremonium falciforme. Int J Dermatol. 1988;27:408-410.

- Welsh O, Salinas MC, Rodriguez MA. Treatment of eumycetoma and actinomycetoma. Cur Top Med Mycol. 1995;6:47-71.

- Restrepo A. Treatment of tropical mycoses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:S91-S102.

- Gugnani HC, Ezeanolue BC, Khalil M, et al. Fluconazole in the therapy of tropical deep mycoses. Mycoses. 1995;38:485-488.

- Welsh O. Mycetoma. current concepts in treatment. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:387-398.

To the Editor:

Mycetoma is a noncontagious chronic infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissue caused by exogenous fungi or bacteria that can involve deeper structures such as the fasciae, muscles, and bones. Clinically it is characterized by increased swelling of the affected area, fibrosis, nodules, tumefaction, formation of draining sinuses, and abscesses that drain pus-containing grains through fistulae.1 The initiation of the infection is related to local trauma and can involve muscle, underlying bone, and adjacent organs. The feet are the most commonly affected region, and the incubation period is variable. Patients rarely report prior trauma to the affected area and only seek medical consultation when the nodules and draining sinuses become evident. The etiopathogenesis of mycetoma is associated with aerobic actinomycetes (ie, Nocardia, Actinomadura, Streptomyces), known as actinomycetoma, and fungal infections, known as eumycetomas.1

We report the case of a 57-year-old Albanian man who was referred to the outpatient clinic of our dermatology department for diagnosis and treatment of a chronic, suppurative, subcutaneous infection on the right foot presenting as abscesses and draining sinuses. The patient was a farmer and reported that the condition appeared 4 years prior following a laceration he sustained while at work. Dermatologic examination revealed local tumefaction, fistulated nodules, and abscesses discharging a serohemorrhagic fluid on the right foot (Figure 1). Perilesional erythema and subcutaneous swelling were evident. There was no regional lymphadenopathy. Standard laboratory examination was normal. Radiography of the right foot showed no osteolytic lesions or evidence of osteomyelitis.

A skin biopsy from a lesion on the right foot was performed, and identification of the possible etiologic agent was based on direct microscopic examination of the granules, culture isolation of the agent, and fungal microscopic morphology.2 Granules were studied under direct examination with potassium hydroxide solution 20% and showed septate branching hyphae (Figure 2). The culture produced colonies that were white, yellow, and brown. Colonies were comprised of dense mycelium with melanin pigment and were grown at 37°C. A lactose tolerance test was positive.2 Therefore, the strain was identified as Madurella mycetomatis, and a diagnosis of eumycetoma pedis was made.

The patient was hospitalized for 2 weeks and treated with intravenous fluconazole, then treatment with oral itraconazole 200 mg once daily was initiated. At 4-month follow-up, he had self-discontinued treatment but demonstrated partial improvement of the tumefaction, healing of sinus tracts, and functional recovery of the right foot.

One year following the initial presentation, the patient’s clinical condition worsened (Figure 3A). Radiography of the right foot showed osteolytic lesions on bones in the right foot (Figure 3B), and a repeat culture showed the presence of Staphylococcus aureus; thus, treatment with itraconazole 200 mg once daily along with antibiotics (cefuroxime and gentamicin) was started immediately. Surgical treatment was recommended, but the patient refused treatment.

Mycetomas are rare in Albania but are common in countries of tropical and subtropical regions. K

Clinical features of eumycetoma include lesions with clear margins, few sinuses, black grains, slow progression, and long-term involvement of bone. The grains represent an aggregate of hyphae produced by fungi; thus, the characteristic feature of eumycetoma is the formation of large granules that can involve bone.1 A critical diagnostic step is to distinguish between eumycetoma and actinomycetoma. If possible, it is important to culture the organism because treatment varies depending on the cause of the infection.

Fungal identification is crucial in the diagnosis of mycetoma. In our case, diagnosis of eumycetoma pedis was based on clinical examination and detection of fungal species by microscopic examination and culture. The color of small granules (black grains) is a parameter used to identify different pathogens on histology but is not sufficient for diagnosis.5 The examination by potassium hydroxide preparation is helpful to identify the hyphae; however, culture is necessary.2

Therapeutic management of eumycetoma needs a combined strategy that includes systemic treatment and surgical therapy. Eumycetomas generally are more difficult to treat then actinomycetomas. Some authors recommend a high dose of amphotericin B as the treatment of choice for eumycetoma,6,7 but there are some that emphasize that amphotericin B is partially effective.8,9 There also is evidence in the literature of resistance of eumycetoma to ketoconazole treatment10,11 and successful treatment with fluconazole and itraconazole.10-13 For this reason, we treated our patient with the latter agents. In cases of osteolysis, amputation often is required.

In conclusion, eumycetoma pedis is a rare deep fungal infection that can cause considerable morbidity. P

To the Editor:

Mycetoma is a noncontagious chronic infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissue caused by exogenous fungi or bacteria that can involve deeper structures such as the fasciae, muscles, and bones. Clinically it is characterized by increased swelling of the affected area, fibrosis, nodules, tumefaction, formation of draining sinuses, and abscesses that drain pus-containing grains through fistulae.1 The initiation of the infection is related to local trauma and can involve muscle, underlying bone, and adjacent organs. The feet are the most commonly affected region, and the incubation period is variable. Patients rarely report prior trauma to the affected area and only seek medical consultation when the nodules and draining sinuses become evident. The etiopathogenesis of mycetoma is associated with aerobic actinomycetes (ie, Nocardia, Actinomadura, Streptomyces), known as actinomycetoma, and fungal infections, known as eumycetomas.1

We report the case of a 57-year-old Albanian man who was referred to the outpatient clinic of our dermatology department for diagnosis and treatment of a chronic, suppurative, subcutaneous infection on the right foot presenting as abscesses and draining sinuses. The patient was a farmer and reported that the condition appeared 4 years prior following a laceration he sustained while at work. Dermatologic examination revealed local tumefaction, fistulated nodules, and abscesses discharging a serohemorrhagic fluid on the right foot (Figure 1). Perilesional erythema and subcutaneous swelling were evident. There was no regional lymphadenopathy. Standard laboratory examination was normal. Radiography of the right foot showed no osteolytic lesions or evidence of osteomyelitis.

A skin biopsy from a lesion on the right foot was performed, and identification of the possible etiologic agent was based on direct microscopic examination of the granules, culture isolation of the agent, and fungal microscopic morphology.2 Granules were studied under direct examination with potassium hydroxide solution 20% and showed septate branching hyphae (Figure 2). The culture produced colonies that were white, yellow, and brown. Colonies were comprised of dense mycelium with melanin pigment and were grown at 37°C. A lactose tolerance test was positive.2 Therefore, the strain was identified as Madurella mycetomatis, and a diagnosis of eumycetoma pedis was made.

The patient was hospitalized for 2 weeks and treated with intravenous fluconazole, then treatment with oral itraconazole 200 mg once daily was initiated. At 4-month follow-up, he had self-discontinued treatment but demonstrated partial improvement of the tumefaction, healing of sinus tracts, and functional recovery of the right foot.

One year following the initial presentation, the patient’s clinical condition worsened (Figure 3A). Radiography of the right foot showed osteolytic lesions on bones in the right foot (Figure 3B), and a repeat culture showed the presence of Staphylococcus aureus; thus, treatment with itraconazole 200 mg once daily along with antibiotics (cefuroxime and gentamicin) was started immediately. Surgical treatment was recommended, but the patient refused treatment.

Mycetomas are rare in Albania but are common in countries of tropical and subtropical regions. K

Clinical features of eumycetoma include lesions with clear margins, few sinuses, black grains, slow progression, and long-term involvement of bone. The grains represent an aggregate of hyphae produced by fungi; thus, the characteristic feature of eumycetoma is the formation of large granules that can involve bone.1 A critical diagnostic step is to distinguish between eumycetoma and actinomycetoma. If possible, it is important to culture the organism because treatment varies depending on the cause of the infection.

Fungal identification is crucial in the diagnosis of mycetoma. In our case, diagnosis of eumycetoma pedis was based on clinical examination and detection of fungal species by microscopic examination and culture. The color of small granules (black grains) is a parameter used to identify different pathogens on histology but is not sufficient for diagnosis.5 The examination by potassium hydroxide preparation is helpful to identify the hyphae; however, culture is necessary.2

Therapeutic management of eumycetoma needs a combined strategy that includes systemic treatment and surgical therapy. Eumycetomas generally are more difficult to treat then actinomycetomas. Some authors recommend a high dose of amphotericin B as the treatment of choice for eumycetoma,6,7 but there are some that emphasize that amphotericin B is partially effective.8,9 There also is evidence in the literature of resistance of eumycetoma to ketoconazole treatment10,11 and successful treatment with fluconazole and itraconazole.10-13 For this reason, we treated our patient with the latter agents. In cases of osteolysis, amputation often is required.

In conclusion, eumycetoma pedis is a rare deep fungal infection that can cause considerable morbidity. P

- Rook A, Burns T. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. West Sussex, UK; Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010.

- Balows A, Hausler WJ, eds. Manual of Clinical Microbiology. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology; 1991.

- Carter HV. On a new striking form of fungus disease principally affecting the foot and prevailing endemically in many parts of India. Trans Med Phys Soc Bombay. 1860;6:104-142.

- Kwon-Chung KJ, Bennet JE. Medical Mycology. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1992.

- Venugopal PV, Venugopal TV. Pale grain eumycetomas in Madras. Australas J Dermatol. 1995;36:149-151.

- Guarro J, Gams W, Pujol I, et al. Acremonium species: new emerging fungal opportunists—in vitro antifungal susceptibilities and review. Clin Infec Dis. 1997;25:1222-1229.

- Lau YL, Yuen KY, Lee CW, et al. Invasive Acremonium falciforme infection in a patient with severe combined immunodeficiency. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:197-198.

- Fincher RM, Fisher JF, Lovell RD, et al. Infection due to the fungus Acremonium (cephalosporium). Medicine (Baltimore). 1991;70:398-409.

- Milburn PB, Papayanopulos DM, Pomerantz BM. Mycetoma due to Acremonium falciforme. Int J Dermatol. 1988;27:408-410.

- Welsh O, Salinas MC, Rodriguez MA. Treatment of eumycetoma and actinomycetoma. Cur Top Med Mycol. 1995;6:47-71.

- Restrepo A. Treatment of tropical mycoses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:S91-S102.

- Gugnani HC, Ezeanolue BC, Khalil M, et al. Fluconazole in the therapy of tropical deep mycoses. Mycoses. 1995;38:485-488.

- Welsh O. Mycetoma. current concepts in treatment. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:387-398.

- Rook A, Burns T. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. West Sussex, UK; Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010.

- Balows A, Hausler WJ, eds. Manual of Clinical Microbiology. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology; 1991.

- Carter HV. On a new striking form of fungus disease principally affecting the foot and prevailing endemically in many parts of India. Trans Med Phys Soc Bombay. 1860;6:104-142.

- Kwon-Chung KJ, Bennet JE. Medical Mycology. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1992.

- Venugopal PV, Venugopal TV. Pale grain eumycetomas in Madras. Australas J Dermatol. 1995;36:149-151.

- Guarro J, Gams W, Pujol I, et al. Acremonium species: new emerging fungal opportunists—in vitro antifungal susceptibilities and review. Clin Infec Dis. 1997;25:1222-1229.

- Lau YL, Yuen KY, Lee CW, et al. Invasive Acremonium falciforme infection in a patient with severe combined immunodeficiency. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:197-198.

- Fincher RM, Fisher JF, Lovell RD, et al. Infection due to the fungus Acremonium (cephalosporium). Medicine (Baltimore). 1991;70:398-409.

- Milburn PB, Papayanopulos DM, Pomerantz BM. Mycetoma due to Acremonium falciforme. Int J Dermatol. 1988;27:408-410.

- Welsh O, Salinas MC, Rodriguez MA. Treatment of eumycetoma and actinomycetoma. Cur Top Med Mycol. 1995;6:47-71.