User login

Severe Acne Fulminans Following Low-Dose Isotretinoin and Testosterone Use

To the Editor:

Acne fulminans (AF), the most severe form of acne, is a rare condition with an incidence of less than 1% of total acne cases.1 Adolescent boys are the most susceptible group of patients.2 Painful inflammatory pustules that transform into deep ulcerations covered by abundant hemorrhagic crust are typical of AF. Commonly affected areas include the face, back, neck, and chest. Additionally, fever and polyarthralgia may be present, and there often is myopathy due to rapid weight loss.3,4 Less often, erythema nodosum and splenomegaly may be observed.5 Laboratory testing also may reveal markers of systemic inflammation such as leukocytosis with neutrophilia, elevated C-reactive protein levels, increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and thrombocytosis. Anemia and elevated hepatic enzyme levels also may be present in AF.2 It is suspected that AF may be induced by low doses of isotretinoin therapy with concomitant inherited susceptibility.6

We report the case of a 21-year-old man who was referred to the Department of Dermatology by his primary care physician for evaluation of severe hemorrhagic lesions on the trunk following use of oral isotretinoin (Figure 1). Prior to development of the lesions, the patient had started weekly intramuscular injections of testosterone 500 mg, which he purchased online without consulting a physician, to address muscle mass reduction associated with sudden weight loss from intense physical training. After 8 months of testosterone supplementation along with continued physical training, the patient presented to his primary care physician for treatment of acne vulgaris on the back and trunk of 2 months’ duration. Oral isotretinoin 20 mg once daily was initiated; however, the patient reported that the acne lesions showed progression after 1 month of treatment. Isotretinoin was increased to a more weight-appropriate dosage of 60 mg once daily 2 weeks before admission to our dermatology clinic.

At the current presentation, dermatologic examination revealed numerous inflamed ulcerations covered by a hemorrhagic crust on the back and trunk. The patient also reported knee, elbow, and inguinal pain, especially at night. No fever or loss of appetite was reported. The patient was otherwise healthy and had no remarkable family history of acne or other dermatologic diseases.

Laboratory testing showed leukocytosis (11,000/µL [reference range, 4500–11,000/µL]), an elevated C-reactive protein level (66 mg/L [reference range, 0.08–3.1 mg/L]), and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (46 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]). There were laboratory and clinical signs of a secondary bacterial infection in the affected areas, and a culture of secretions collected from lesions on the back grew Staphylococcus aureus with sensitivity to erythromycin, clindamycin, doxycycline, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and resistance to penicillin. A diagnosis of AF was made based on the clinical presentation and systemic symptoms, and anabolic-androgenic steroids and low-dose isotretinoin were identified as etiologic factors.

Treatment initially included cessation of isotretinoin and administration of prednisone, omeprazole, clindamycin, and doxycycline. Prednisone was given at a dosage of 40 mg once daily for 1 week, then decreased by 5 mg every 7 days. Omeprazole was given concurrently as prophylaxis for the gastrointestinal tract side effects of long-term prednisone use. Clindamycin was given at a dosage of 300 mg 3 times daily. Doxycycline was given for 6 weeks at a dosage of 100 mg twice daily. Topical octenidine dihydrochloride also was given.

Marked improvement was noted after 24 hours (Figure 2) as well as on the third day of treatment (Figure 3A). After 6 weeks, only disfiguring scars were visible (Figure 3B). Oral isotretinoin was reincorporated after 8 weeks and was subsequently discontinued after 5 months of therapy with a cumulative dose of 150 mg/kg.

It is important to differentiate AF from exacerbation of acne vulgaris because patients typically have mild or moderate acne vulgaris before the onset of acute symptoms.1 Acne fulminans is characterized by systemic symptoms such as myalgia, polyarthralgia, fatigue, and osteolytic bone lesions.1,7 Additionally, hematologic symptoms such as fever, leukocytosis, anemia, splenomegaly, and hepatomegaly may be present.1,5,7 Our patient demonstrated the polysymptomatic form of AF. The patient had severe acne with a tendency to scar. There also were some systemic manifestations such as polyarthralgia, weight loss, leukocytosis, an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and an elevated C-reactive protein level.

The clinical diagnosis in our patient also was supported by the hypothesis that heredity, overactive immune reactions, bacterial infections, and use of some drugs (eg, isotretinoin, tetracycline, testosterone) can trigger AF.8 The most well-known theory is that low doses of isotretinoin induce AF.6 The majority of cases are caused by doses of less than 20 mg/kg once daily, but there have been reports of patients using full doses and developing this condition.9 The fact that the use of low- and high-dose isotretinoin can provoke AF suggests an idiosyncratic reaction that is not clearly dose related. The most dangerous triggering factor of AF is concomitant usage of testosterone and isotretinoin.10 Our patient used testosterone injections to increase muscle mass and underwent treatment with isotretinoin for acne.

Treatment of AF is controversial, as there is no standard therapy. Currently, steroids and isotretinoin are the treatments of choice. Antibiotic use is controversial because of a lack of randomized trials.11

In the first stage of treatment, prednisone 0.5 to 1 mg/kg once daily is recommended as an initial anti-inflammatory therapy, with gradual dose reduction. According to evidence-based recommendations, a low dose of isotretinoin can be introduced after crusted lesions have healed. The overlapping therapy with steroids and isotretinoin should be provided for at least 4 weeks. High-potency topical corticosteroids can be used on granulation tissue, which can shorten the systemic treatment with prednisone or can be an alternative treatment for patients with contraindications to systemic corticosteroids.11

Additionally, local care of the lesions including compresses and topical emollients is crucial. There are some case reports in which there is introduction of high doses of isotretinoin, subsequently with systemic steroids.7,8,12 Seukeran and Cunliffe5 proved that it is beneficial to give acne prophylaxis to prevent further episodes. Our patient was similarly treated with systemic steroids and isotretinoin. Treatment guidelines for AF do not recommend oral antibiotics,11 but data are limited in the case of isotretinoin-induced AF. Our patient was given doxycycline concomitant with systemic steroids, which was necessary due to signs of secondary infection from a lesion culture. Doxycycline was stopped when isotretinoin treatment was initiated to prevent pseudotumor cerebri. The patient achieved good clinical improvement with no relapse.

Using isotretinoin to treat acne vulgaris has many benefits, despite the possibility of developing AF as an extremely rare complication. Clinicians should be aware of the risk of this complication to make the diagnosis and provide appropriate care, especially in young men. It is particularly important to consider the possibility of concomitant testosterone and isotretinoin when documenting the patient’s medical history.

- Romiti R, Jansen T, Plewig G. Acne fulminans. An Bras Dermatol. 2000;75:611-617.

- Karvonen SL. Acne fulminans: report of clinical findings and treatment of twenty-four patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:572-579.

- Kelly AP, Burns RE. Acute febrile ulcerative conglobate acne with polyarthralgia. Arch Dermatol. 1971;104:182-187.

- Plewig G, Kligman AM. Vitamin A acid in acneiform dermatoses. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl. 1975;74:119-127.

- Seukeran DC, Cunliffe WJ. The treatment of acne fulminans: a review of 25 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:307-309.

- Kraus SL, Emmert S, Schön MP, et al. The dark side of beauty: acne fulminans induced by anabolic steroids in a male bodybuilder. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1210-1212.

- Jansen T, Plewig G. Acne fulminans. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:254-257.

- Zanelato TP, Gontijo GM, Alves CA, et al. Disabling acne fulminans. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:9-12.

- Azulay DR, Abulafia LA, Costa JAN, et al. Tecido de granulação exuberante. efeito colateral da terapêutica com isotretinoína. An Bras Dermatol. 1985;60:179-182.

- Traupe H, von Mühlendahl KE, Brämswig J, et al. Acne of the fulminans type following testosterone therapy in three excessively tall boys. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:414-417.

- Greywal T, Zaenglein AL, Baldwin HE, et al. Evidence-based recommendations for the management of acne fulminans and its variants. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:109-117.

- Honma M, Murakami M, Iinuma S, et al. Acne fulminans following measles infection. J Dermatol. 2009;36:471-473.

To the Editor:

Acne fulminans (AF), the most severe form of acne, is a rare condition with an incidence of less than 1% of total acne cases.1 Adolescent boys are the most susceptible group of patients.2 Painful inflammatory pustules that transform into deep ulcerations covered by abundant hemorrhagic crust are typical of AF. Commonly affected areas include the face, back, neck, and chest. Additionally, fever and polyarthralgia may be present, and there often is myopathy due to rapid weight loss.3,4 Less often, erythema nodosum and splenomegaly may be observed.5 Laboratory testing also may reveal markers of systemic inflammation such as leukocytosis with neutrophilia, elevated C-reactive protein levels, increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and thrombocytosis. Anemia and elevated hepatic enzyme levels also may be present in AF.2 It is suspected that AF may be induced by low doses of isotretinoin therapy with concomitant inherited susceptibility.6

We report the case of a 21-year-old man who was referred to the Department of Dermatology by his primary care physician for evaluation of severe hemorrhagic lesions on the trunk following use of oral isotretinoin (Figure 1). Prior to development of the lesions, the patient had started weekly intramuscular injections of testosterone 500 mg, which he purchased online without consulting a physician, to address muscle mass reduction associated with sudden weight loss from intense physical training. After 8 months of testosterone supplementation along with continued physical training, the patient presented to his primary care physician for treatment of acne vulgaris on the back and trunk of 2 months’ duration. Oral isotretinoin 20 mg once daily was initiated; however, the patient reported that the acne lesions showed progression after 1 month of treatment. Isotretinoin was increased to a more weight-appropriate dosage of 60 mg once daily 2 weeks before admission to our dermatology clinic.

At the current presentation, dermatologic examination revealed numerous inflamed ulcerations covered by a hemorrhagic crust on the back and trunk. The patient also reported knee, elbow, and inguinal pain, especially at night. No fever or loss of appetite was reported. The patient was otherwise healthy and had no remarkable family history of acne or other dermatologic diseases.

Laboratory testing showed leukocytosis (11,000/µL [reference range, 4500–11,000/µL]), an elevated C-reactive protein level (66 mg/L [reference range, 0.08–3.1 mg/L]), and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (46 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]). There were laboratory and clinical signs of a secondary bacterial infection in the affected areas, and a culture of secretions collected from lesions on the back grew Staphylococcus aureus with sensitivity to erythromycin, clindamycin, doxycycline, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and resistance to penicillin. A diagnosis of AF was made based on the clinical presentation and systemic symptoms, and anabolic-androgenic steroids and low-dose isotretinoin were identified as etiologic factors.

Treatment initially included cessation of isotretinoin and administration of prednisone, omeprazole, clindamycin, and doxycycline. Prednisone was given at a dosage of 40 mg once daily for 1 week, then decreased by 5 mg every 7 days. Omeprazole was given concurrently as prophylaxis for the gastrointestinal tract side effects of long-term prednisone use. Clindamycin was given at a dosage of 300 mg 3 times daily. Doxycycline was given for 6 weeks at a dosage of 100 mg twice daily. Topical octenidine dihydrochloride also was given.

Marked improvement was noted after 24 hours (Figure 2) as well as on the third day of treatment (Figure 3A). After 6 weeks, only disfiguring scars were visible (Figure 3B). Oral isotretinoin was reincorporated after 8 weeks and was subsequently discontinued after 5 months of therapy with a cumulative dose of 150 mg/kg.

It is important to differentiate AF from exacerbation of acne vulgaris because patients typically have mild or moderate acne vulgaris before the onset of acute symptoms.1 Acne fulminans is characterized by systemic symptoms such as myalgia, polyarthralgia, fatigue, and osteolytic bone lesions.1,7 Additionally, hematologic symptoms such as fever, leukocytosis, anemia, splenomegaly, and hepatomegaly may be present.1,5,7 Our patient demonstrated the polysymptomatic form of AF. The patient had severe acne with a tendency to scar. There also were some systemic manifestations such as polyarthralgia, weight loss, leukocytosis, an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and an elevated C-reactive protein level.

The clinical diagnosis in our patient also was supported by the hypothesis that heredity, overactive immune reactions, bacterial infections, and use of some drugs (eg, isotretinoin, tetracycline, testosterone) can trigger AF.8 The most well-known theory is that low doses of isotretinoin induce AF.6 The majority of cases are caused by doses of less than 20 mg/kg once daily, but there have been reports of patients using full doses and developing this condition.9 The fact that the use of low- and high-dose isotretinoin can provoke AF suggests an idiosyncratic reaction that is not clearly dose related. The most dangerous triggering factor of AF is concomitant usage of testosterone and isotretinoin.10 Our patient used testosterone injections to increase muscle mass and underwent treatment with isotretinoin for acne.

Treatment of AF is controversial, as there is no standard therapy. Currently, steroids and isotretinoin are the treatments of choice. Antibiotic use is controversial because of a lack of randomized trials.11

In the first stage of treatment, prednisone 0.5 to 1 mg/kg once daily is recommended as an initial anti-inflammatory therapy, with gradual dose reduction. According to evidence-based recommendations, a low dose of isotretinoin can be introduced after crusted lesions have healed. The overlapping therapy with steroids and isotretinoin should be provided for at least 4 weeks. High-potency topical corticosteroids can be used on granulation tissue, which can shorten the systemic treatment with prednisone or can be an alternative treatment for patients with contraindications to systemic corticosteroids.11

Additionally, local care of the lesions including compresses and topical emollients is crucial. There are some case reports in which there is introduction of high doses of isotretinoin, subsequently with systemic steroids.7,8,12 Seukeran and Cunliffe5 proved that it is beneficial to give acne prophylaxis to prevent further episodes. Our patient was similarly treated with systemic steroids and isotretinoin. Treatment guidelines for AF do not recommend oral antibiotics,11 but data are limited in the case of isotretinoin-induced AF. Our patient was given doxycycline concomitant with systemic steroids, which was necessary due to signs of secondary infection from a lesion culture. Doxycycline was stopped when isotretinoin treatment was initiated to prevent pseudotumor cerebri. The patient achieved good clinical improvement with no relapse.

Using isotretinoin to treat acne vulgaris has many benefits, despite the possibility of developing AF as an extremely rare complication. Clinicians should be aware of the risk of this complication to make the diagnosis and provide appropriate care, especially in young men. It is particularly important to consider the possibility of concomitant testosterone and isotretinoin when documenting the patient’s medical history.

To the Editor:

Acne fulminans (AF), the most severe form of acne, is a rare condition with an incidence of less than 1% of total acne cases.1 Adolescent boys are the most susceptible group of patients.2 Painful inflammatory pustules that transform into deep ulcerations covered by abundant hemorrhagic crust are typical of AF. Commonly affected areas include the face, back, neck, and chest. Additionally, fever and polyarthralgia may be present, and there often is myopathy due to rapid weight loss.3,4 Less often, erythema nodosum and splenomegaly may be observed.5 Laboratory testing also may reveal markers of systemic inflammation such as leukocytosis with neutrophilia, elevated C-reactive protein levels, increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and thrombocytosis. Anemia and elevated hepatic enzyme levels also may be present in AF.2 It is suspected that AF may be induced by low doses of isotretinoin therapy with concomitant inherited susceptibility.6

We report the case of a 21-year-old man who was referred to the Department of Dermatology by his primary care physician for evaluation of severe hemorrhagic lesions on the trunk following use of oral isotretinoin (Figure 1). Prior to development of the lesions, the patient had started weekly intramuscular injections of testosterone 500 mg, which he purchased online without consulting a physician, to address muscle mass reduction associated with sudden weight loss from intense physical training. After 8 months of testosterone supplementation along with continued physical training, the patient presented to his primary care physician for treatment of acne vulgaris on the back and trunk of 2 months’ duration. Oral isotretinoin 20 mg once daily was initiated; however, the patient reported that the acne lesions showed progression after 1 month of treatment. Isotretinoin was increased to a more weight-appropriate dosage of 60 mg once daily 2 weeks before admission to our dermatology clinic.

At the current presentation, dermatologic examination revealed numerous inflamed ulcerations covered by a hemorrhagic crust on the back and trunk. The patient also reported knee, elbow, and inguinal pain, especially at night. No fever or loss of appetite was reported. The patient was otherwise healthy and had no remarkable family history of acne or other dermatologic diseases.

Laboratory testing showed leukocytosis (11,000/µL [reference range, 4500–11,000/µL]), an elevated C-reactive protein level (66 mg/L [reference range, 0.08–3.1 mg/L]), and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (46 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]). There were laboratory and clinical signs of a secondary bacterial infection in the affected areas, and a culture of secretions collected from lesions on the back grew Staphylococcus aureus with sensitivity to erythromycin, clindamycin, doxycycline, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and resistance to penicillin. A diagnosis of AF was made based on the clinical presentation and systemic symptoms, and anabolic-androgenic steroids and low-dose isotretinoin were identified as etiologic factors.

Treatment initially included cessation of isotretinoin and administration of prednisone, omeprazole, clindamycin, and doxycycline. Prednisone was given at a dosage of 40 mg once daily for 1 week, then decreased by 5 mg every 7 days. Omeprazole was given concurrently as prophylaxis for the gastrointestinal tract side effects of long-term prednisone use. Clindamycin was given at a dosage of 300 mg 3 times daily. Doxycycline was given for 6 weeks at a dosage of 100 mg twice daily. Topical octenidine dihydrochloride also was given.

Marked improvement was noted after 24 hours (Figure 2) as well as on the third day of treatment (Figure 3A). After 6 weeks, only disfiguring scars were visible (Figure 3B). Oral isotretinoin was reincorporated after 8 weeks and was subsequently discontinued after 5 months of therapy with a cumulative dose of 150 mg/kg.

It is important to differentiate AF from exacerbation of acne vulgaris because patients typically have mild or moderate acne vulgaris before the onset of acute symptoms.1 Acne fulminans is characterized by systemic symptoms such as myalgia, polyarthralgia, fatigue, and osteolytic bone lesions.1,7 Additionally, hematologic symptoms such as fever, leukocytosis, anemia, splenomegaly, and hepatomegaly may be present.1,5,7 Our patient demonstrated the polysymptomatic form of AF. The patient had severe acne with a tendency to scar. There also were some systemic manifestations such as polyarthralgia, weight loss, leukocytosis, an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and an elevated C-reactive protein level.

The clinical diagnosis in our patient also was supported by the hypothesis that heredity, overactive immune reactions, bacterial infections, and use of some drugs (eg, isotretinoin, tetracycline, testosterone) can trigger AF.8 The most well-known theory is that low doses of isotretinoin induce AF.6 The majority of cases are caused by doses of less than 20 mg/kg once daily, but there have been reports of patients using full doses and developing this condition.9 The fact that the use of low- and high-dose isotretinoin can provoke AF suggests an idiosyncratic reaction that is not clearly dose related. The most dangerous triggering factor of AF is concomitant usage of testosterone and isotretinoin.10 Our patient used testosterone injections to increase muscle mass and underwent treatment with isotretinoin for acne.

Treatment of AF is controversial, as there is no standard therapy. Currently, steroids and isotretinoin are the treatments of choice. Antibiotic use is controversial because of a lack of randomized trials.11

In the first stage of treatment, prednisone 0.5 to 1 mg/kg once daily is recommended as an initial anti-inflammatory therapy, with gradual dose reduction. According to evidence-based recommendations, a low dose of isotretinoin can be introduced after crusted lesions have healed. The overlapping therapy with steroids and isotretinoin should be provided for at least 4 weeks. High-potency topical corticosteroids can be used on granulation tissue, which can shorten the systemic treatment with prednisone or can be an alternative treatment for patients with contraindications to systemic corticosteroids.11

Additionally, local care of the lesions including compresses and topical emollients is crucial. There are some case reports in which there is introduction of high doses of isotretinoin, subsequently with systemic steroids.7,8,12 Seukeran and Cunliffe5 proved that it is beneficial to give acne prophylaxis to prevent further episodes. Our patient was similarly treated with systemic steroids and isotretinoin. Treatment guidelines for AF do not recommend oral antibiotics,11 but data are limited in the case of isotretinoin-induced AF. Our patient was given doxycycline concomitant with systemic steroids, which was necessary due to signs of secondary infection from a lesion culture. Doxycycline was stopped when isotretinoin treatment was initiated to prevent pseudotumor cerebri. The patient achieved good clinical improvement with no relapse.

Using isotretinoin to treat acne vulgaris has many benefits, despite the possibility of developing AF as an extremely rare complication. Clinicians should be aware of the risk of this complication to make the diagnosis and provide appropriate care, especially in young men. It is particularly important to consider the possibility of concomitant testosterone and isotretinoin when documenting the patient’s medical history.

- Romiti R, Jansen T, Plewig G. Acne fulminans. An Bras Dermatol. 2000;75:611-617.

- Karvonen SL. Acne fulminans: report of clinical findings and treatment of twenty-four patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:572-579.

- Kelly AP, Burns RE. Acute febrile ulcerative conglobate acne with polyarthralgia. Arch Dermatol. 1971;104:182-187.

- Plewig G, Kligman AM. Vitamin A acid in acneiform dermatoses. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl. 1975;74:119-127.

- Seukeran DC, Cunliffe WJ. The treatment of acne fulminans: a review of 25 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:307-309.

- Kraus SL, Emmert S, Schön MP, et al. The dark side of beauty: acne fulminans induced by anabolic steroids in a male bodybuilder. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1210-1212.

- Jansen T, Plewig G. Acne fulminans. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:254-257.

- Zanelato TP, Gontijo GM, Alves CA, et al. Disabling acne fulminans. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:9-12.

- Azulay DR, Abulafia LA, Costa JAN, et al. Tecido de granulação exuberante. efeito colateral da terapêutica com isotretinoína. An Bras Dermatol. 1985;60:179-182.

- Traupe H, von Mühlendahl KE, Brämswig J, et al. Acne of the fulminans type following testosterone therapy in three excessively tall boys. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:414-417.

- Greywal T, Zaenglein AL, Baldwin HE, et al. Evidence-based recommendations for the management of acne fulminans and its variants. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:109-117.

- Honma M, Murakami M, Iinuma S, et al. Acne fulminans following measles infection. J Dermatol. 2009;36:471-473.

- Romiti R, Jansen T, Plewig G. Acne fulminans. An Bras Dermatol. 2000;75:611-617.

- Karvonen SL. Acne fulminans: report of clinical findings and treatment of twenty-four patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:572-579.

- Kelly AP, Burns RE. Acute febrile ulcerative conglobate acne with polyarthralgia. Arch Dermatol. 1971;104:182-187.

- Plewig G, Kligman AM. Vitamin A acid in acneiform dermatoses. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl. 1975;74:119-127.

- Seukeran DC, Cunliffe WJ. The treatment of acne fulminans: a review of 25 cases. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:307-309.

- Kraus SL, Emmert S, Schön MP, et al. The dark side of beauty: acne fulminans induced by anabolic steroids in a male bodybuilder. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1210-1212.

- Jansen T, Plewig G. Acne fulminans. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:254-257.

- Zanelato TP, Gontijo GM, Alves CA, et al. Disabling acne fulminans. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:9-12.

- Azulay DR, Abulafia LA, Costa JAN, et al. Tecido de granulação exuberante. efeito colateral da terapêutica com isotretinoína. An Bras Dermatol. 1985;60:179-182.

- Traupe H, von Mühlendahl KE, Brämswig J, et al. Acne of the fulminans type following testosterone therapy in three excessively tall boys. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:414-417.

- Greywal T, Zaenglein AL, Baldwin HE, et al. Evidence-based recommendations for the management of acne fulminans and its variants. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:109-117.

- Honma M, Murakami M, Iinuma S, et al. Acne fulminans following measles infection. J Dermatol. 2009;36:471-473.

Practice Points

- Acne fulminans, the most severe form of acne, is characterized by deep ulcerations covered by a hemorrhagic crust. It is commonly associated with fever, polyarthralgia, and myopathy caused by rapid weight loss.

- This rare condition is recognized as a potential complication of oral isotretinoin therapy.

Allergic Contact Dermatitis With Sparing of Exposed Psoriasis Plaques

To the Editor:

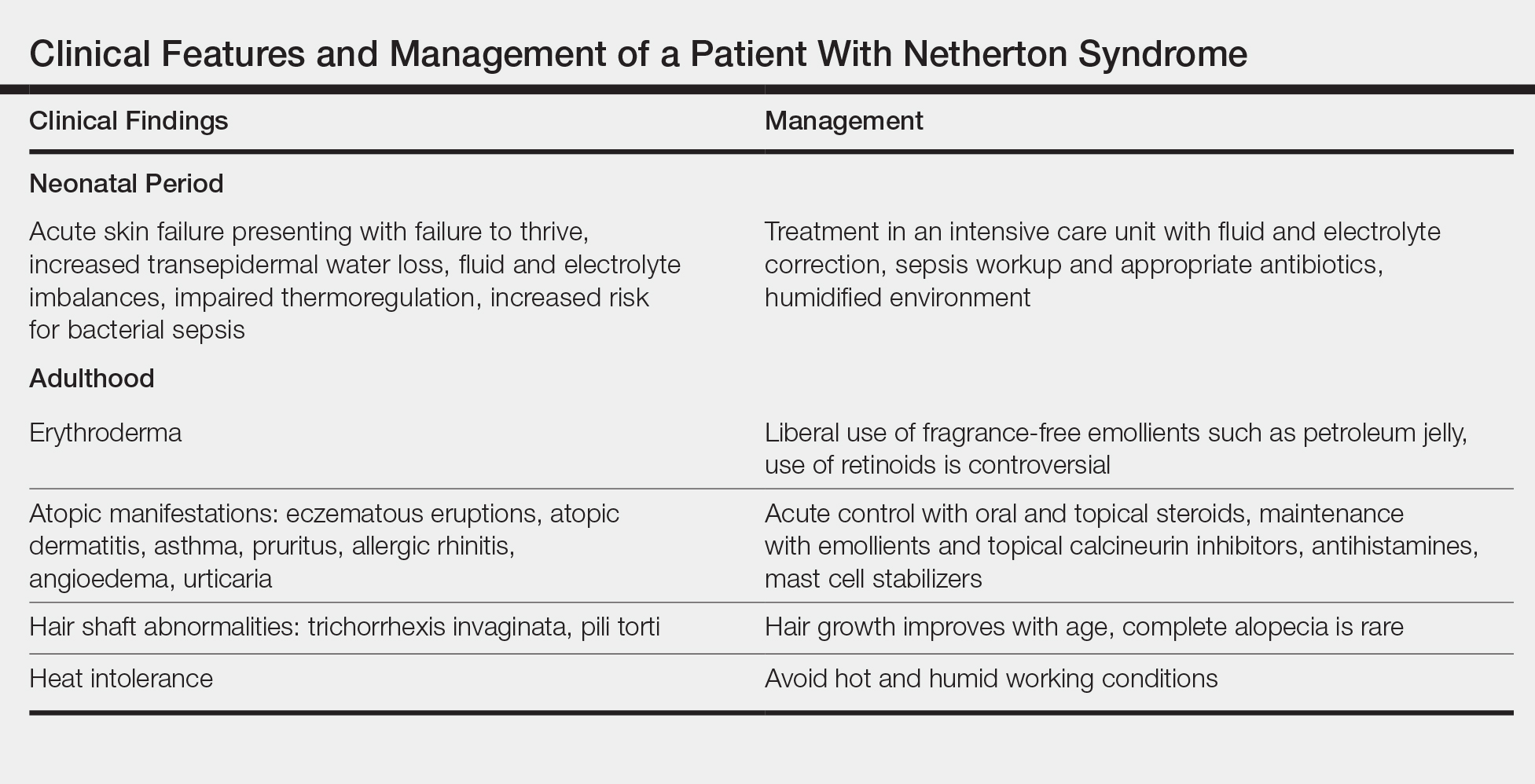

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) is a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction against antigens to which the skin’s immune system was previously sensitized. The initial sensitization requires penetration of the antigen through the stratum corneum. Thus, the ability of a particle to cause ACD is related to its molecular structure and size, lipophilicity, and protein-binding affinity, as well as the dose and duration of exposure.1 Psoriasis typically presents as well-demarcated areas of skin that may be erythematous, indurated, and scaly to variable degrees. Histologically, psoriasis plaques are characterized by epidermal hyperplasia in the presence of a T-cell infiltrate and neutrophilic microabscesses. We report a case of a patient with plaque-type psoriasis who experienced ACD with sparing of exposed psoriatic plaques.

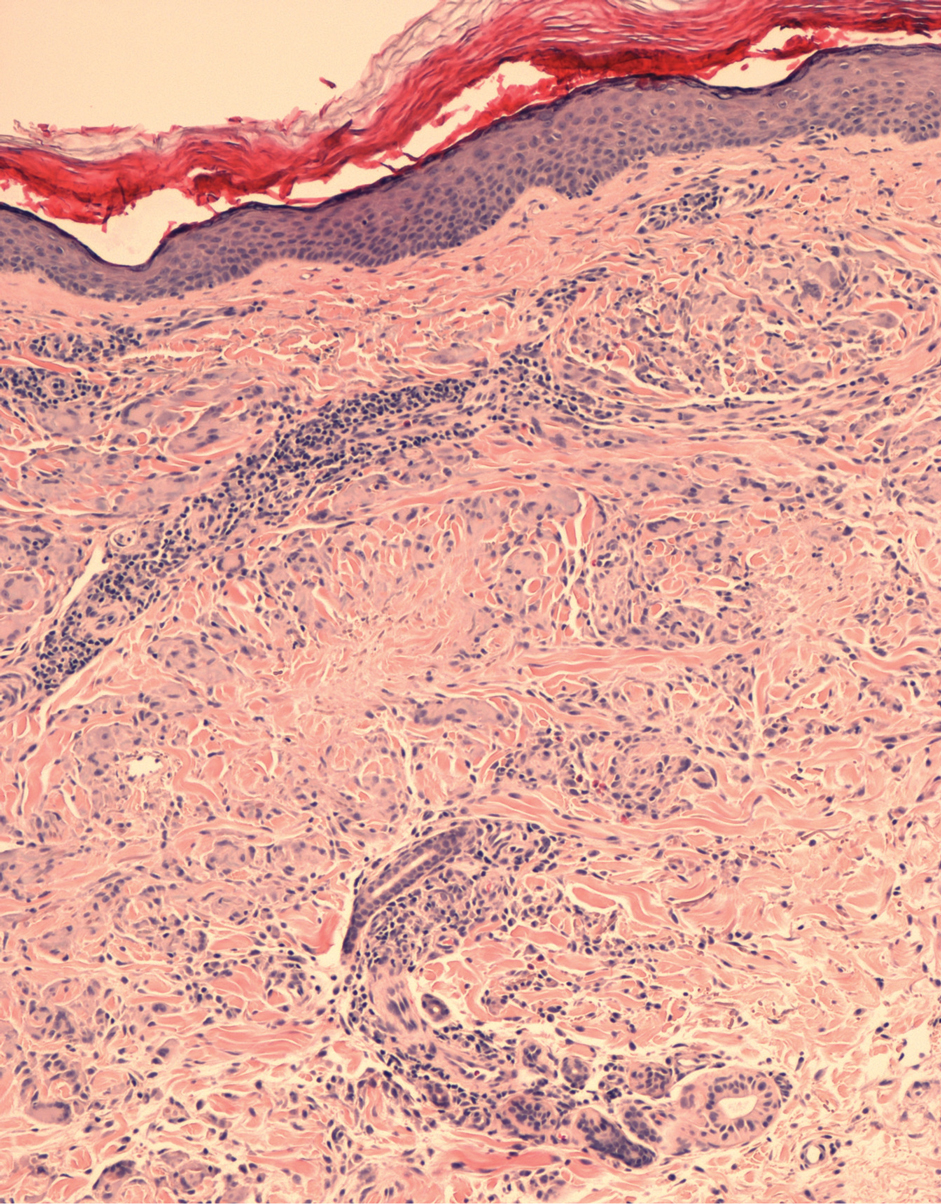

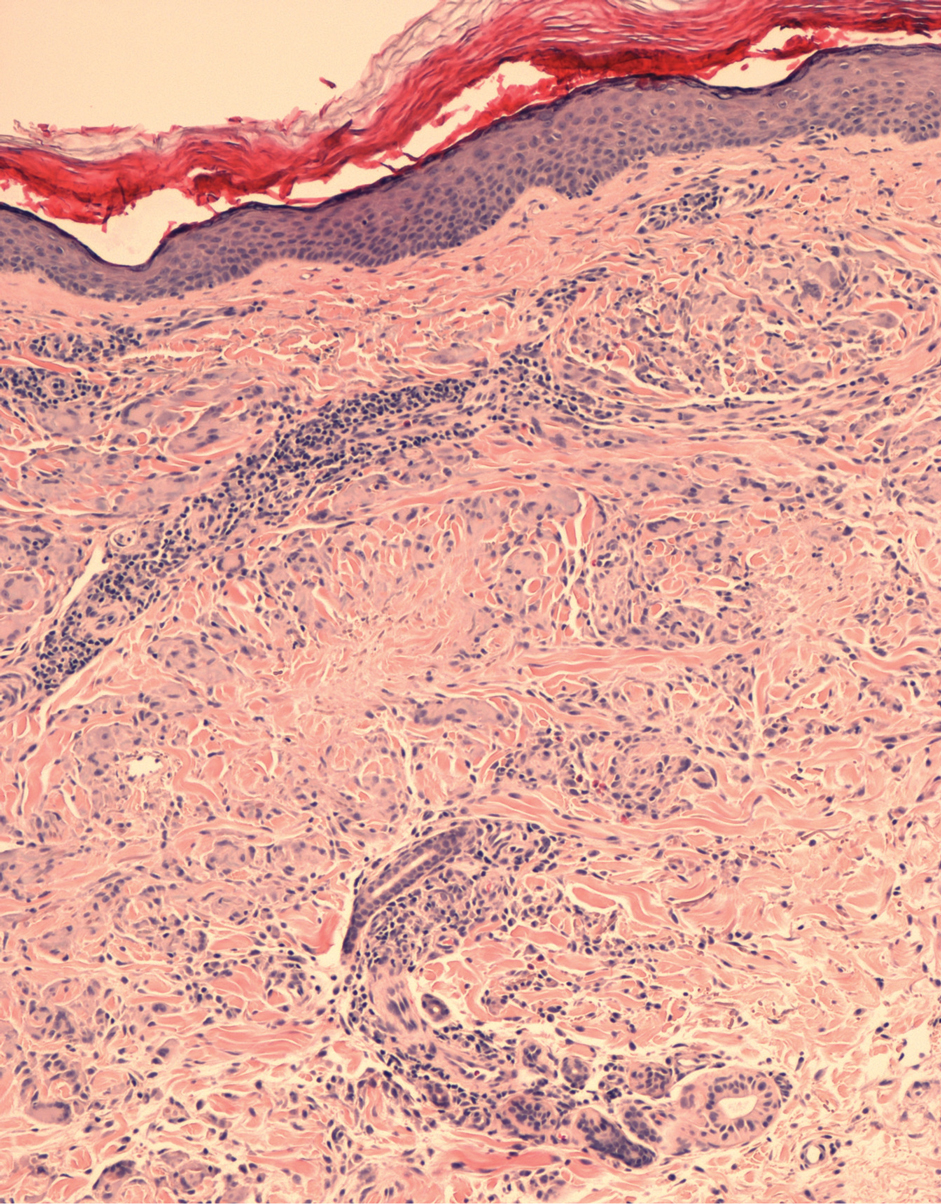

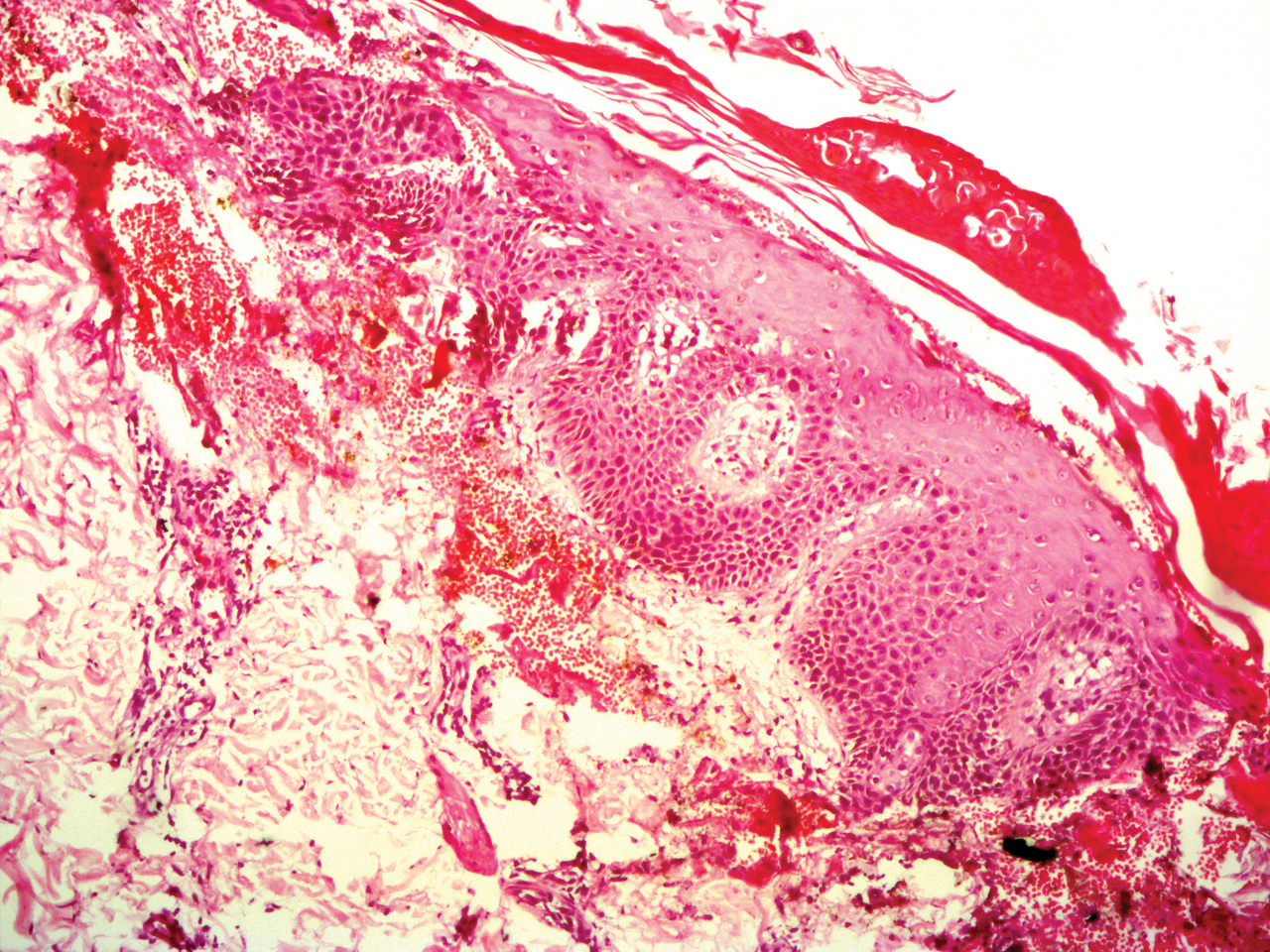

A 45-year-old man with a 5-year history of generalized moderate to severe psoriasis undergoing therapy with ustekinumab 45 mg subcutaneously once every 12 weeks presented to the emergency department with intensely erythematous, pruritic, vesicular lesions on the trunk, arms, and legs within 24 hours of exposure to poison oak while hiking. The patient reported pruritus, pain, and swelling of the affected areas. On physical examination, he was afebrile. Widespread erythematous vesicular lesions were noted on the face, trunk, arms, and legs, sparing the well-demarcated scaly psoriatic plaques on the arms and legs (Figure). The patient was given intravenous fluids and intravenous diphenhydramine. After responding to initial treatment, the patient was discharged with ibuprofen and a tapering dose of oral prednisone from 60 mg 5 times daily, to 40 mg 5 times daily, to 20 mg 5 times daily over 15 days.

star), with a linear border demarcating the ACD lesion and the unaffected psoriatic plaque (black arrow).

Allergic contact dermatitis occurs after sensitization to environmental allergens or haptens. Clinically, ACD is characterized by pruritic, erythematous, vesicular papules and plaques. The predominant effector cells in ACD are CD8+ T cells, along with contributions from helper T cells (TH2). Together, these cell types produce an environment enriched in IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, IL-17, and tumor necrosis factor α.2 Ultimately, the ACD response induces keratinocyte apoptosis via cytotoxic effects.3,4

Plaque psoriasis is a chronic, immune-mediated, inflammatory disease that presents clinically as erythematous well-demarcated plaques with a micaceous scale. The immunologic environment of psoriasis plaques is characterized by infiltration of CD4+ TH17 cells and elevated levels of IL-17, IL-23, tumor necrosis factor α, and IL-1β, which induce keratinocyte hyperproliferation through a complex mechanism resulting in hyperkeratosis composed of orthokeratosis and parakeratosis, a neutrophilic infiltrate, and Munro microabscesses.5

The predominant effector cells and the final effects on keratinocyte survival are divergent in psoriasis and ACD. The possibly antagonistic relationship between these immunologic processes is further supported by epidemiologic studies demonstrating a decreased incidence of ACD in patients with psoriasis.6,7

Our patient demonstrated a typical ACD reaction in response to exposure to urushiol, the allergen present in poison oak, in areas unaffected by psoriasis plaques. Interestingly, the patient displayed this response even while undergoing therapy with ustekinumab, a fully humanized antibody that binds IL-12 and IL-23 and ultimately downregulates TH17 cell-mediated release of IL-17 in the treatment of psoriasis. Although IL-17 also has been implicated in ACD, the lack of inhibition of ACD with ustekinumab treatment was previously demonstrated in a small retrospective study, indicating a potentially different source of IL-17 in ACD.8

Our patient did not demonstrate a typical ACD response in areas of active psoriasis plaques. This phenomenon was of great interest to us. It is possible that the presence of hyperkeratosis, manifested clinically as scaling, served as a mechanical barrier preventing the diffusion and exposure of cutaneous immune cells to urushiol. On the other hand, it is possible that the immunologic environment of the active psoriasis plaque was altered in such a way that it did not demonstrate the typical response to allergen exposure.

We hypothesize that the lack of a typical ACD response at sites of psoriatic plaques in our patient may be attributed to the intensity and duration of exposure to the allergen. Quaranta et al9 reported a typical ACD clinical response and a mixed immunohistologic response to nickel patch testing at sites of active plaques in nickel-sensitized psoriasis patients. Patch testing involves 48 hours of direct contact with an allergen, while our patient experienced an estimated 8 to 10 hours of exposure to the allergen prior to removal via washing. Supporting this line of reasoning, a proportion of patients who are responsive to nickel patch testing do not exhibit clinical symptoms in response to casual nickel exposure.10 Although a physical barrier effect due to hyperkeratosis may have contributed to the lack of ACD response in sites of psoriasis plaques in our patient, it remains possible that a more limited duration of exposure to the allergen is not sufficient to overcome the native immunologic milieu of the psoriasis plaque and induce the immunologic cascade resulting in ACD. Further research into the potentially antagonistic relationship of psoriasis and ACD should be performed to elucidate the interaction between these two common conditions.

- Kimber I, Basketter DA, Gerberick GF, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2002;2:201-211.

- Vocanson M, Hennino A, Cluzel-Tailhardat M, et al. CD8+ T cells are effector cells of contact dermatitis to common skin allergens in mice. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:815-820.

- Akiba H, Kehren J, Ducluzeau MT, et al. Skin inflammation during contact hypersensitivity is mediated by early recruitment of CD8+ T cytotoxic 1 cells inducing keratinocyte apoptosis. J Immunol. 2002;168:3079-3087.

- Trautmann A, Akdis M, Kleemann D, et al. T cell-mediated Fas-induced keratinocyte apoptosis plays a key pathogenetic role in eczematous dermatitis. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:25-35.

- Lynde CW, Poulin Y, Vender R, et al. Interleukin 17A: toward a new understanding of psoriasis pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:141-150.

- Bangsgaard N, Engkilde K, Thyssen JP, et al. Inverse relationship between contact allergy and psoriasis: results from a patient- and a population-based study. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:1119-1123.

- Henseler T, Christophers E. Disease concomitance in psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:982-986.

- Bangsgaard N, Zachariae C, Menne T, et al. Lack of effect of ustekinumab in treatment of allergic contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 2011;65:227-230.

- Quaranta M, Eyerich S, Knapp B, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis in psoriasis patients: typical, delayed, and non-interacting. PLoS One. 2014;9:e101814.

- Kimber I, Basketter DA, Gerberick GF, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2002;2:201-211.

To the Editor:

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) is a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction against antigens to which the skin’s immune system was previously sensitized. The initial sensitization requires penetration of the antigen through the stratum corneum. Thus, the ability of a particle to cause ACD is related to its molecular structure and size, lipophilicity, and protein-binding affinity, as well as the dose and duration of exposure.1 Psoriasis typically presents as well-demarcated areas of skin that may be erythematous, indurated, and scaly to variable degrees. Histologically, psoriasis plaques are characterized by epidermal hyperplasia in the presence of a T-cell infiltrate and neutrophilic microabscesses. We report a case of a patient with plaque-type psoriasis who experienced ACD with sparing of exposed psoriatic plaques.

A 45-year-old man with a 5-year history of generalized moderate to severe psoriasis undergoing therapy with ustekinumab 45 mg subcutaneously once every 12 weeks presented to the emergency department with intensely erythematous, pruritic, vesicular lesions on the trunk, arms, and legs within 24 hours of exposure to poison oak while hiking. The patient reported pruritus, pain, and swelling of the affected areas. On physical examination, he was afebrile. Widespread erythematous vesicular lesions were noted on the face, trunk, arms, and legs, sparing the well-demarcated scaly psoriatic plaques on the arms and legs (Figure). The patient was given intravenous fluids and intravenous diphenhydramine. After responding to initial treatment, the patient was discharged with ibuprofen and a tapering dose of oral prednisone from 60 mg 5 times daily, to 40 mg 5 times daily, to 20 mg 5 times daily over 15 days.

star), with a linear border demarcating the ACD lesion and the unaffected psoriatic plaque (black arrow).

Allergic contact dermatitis occurs after sensitization to environmental allergens or haptens. Clinically, ACD is characterized by pruritic, erythematous, vesicular papules and plaques. The predominant effector cells in ACD are CD8+ T cells, along with contributions from helper T cells (TH2). Together, these cell types produce an environment enriched in IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, IL-17, and tumor necrosis factor α.2 Ultimately, the ACD response induces keratinocyte apoptosis via cytotoxic effects.3,4

Plaque psoriasis is a chronic, immune-mediated, inflammatory disease that presents clinically as erythematous well-demarcated plaques with a micaceous scale. The immunologic environment of psoriasis plaques is characterized by infiltration of CD4+ TH17 cells and elevated levels of IL-17, IL-23, tumor necrosis factor α, and IL-1β, which induce keratinocyte hyperproliferation through a complex mechanism resulting in hyperkeratosis composed of orthokeratosis and parakeratosis, a neutrophilic infiltrate, and Munro microabscesses.5

The predominant effector cells and the final effects on keratinocyte survival are divergent in psoriasis and ACD. The possibly antagonistic relationship between these immunologic processes is further supported by epidemiologic studies demonstrating a decreased incidence of ACD in patients with psoriasis.6,7

Our patient demonstrated a typical ACD reaction in response to exposure to urushiol, the allergen present in poison oak, in areas unaffected by psoriasis plaques. Interestingly, the patient displayed this response even while undergoing therapy with ustekinumab, a fully humanized antibody that binds IL-12 and IL-23 and ultimately downregulates TH17 cell-mediated release of IL-17 in the treatment of psoriasis. Although IL-17 also has been implicated in ACD, the lack of inhibition of ACD with ustekinumab treatment was previously demonstrated in a small retrospective study, indicating a potentially different source of IL-17 in ACD.8

Our patient did not demonstrate a typical ACD response in areas of active psoriasis plaques. This phenomenon was of great interest to us. It is possible that the presence of hyperkeratosis, manifested clinically as scaling, served as a mechanical barrier preventing the diffusion and exposure of cutaneous immune cells to urushiol. On the other hand, it is possible that the immunologic environment of the active psoriasis plaque was altered in such a way that it did not demonstrate the typical response to allergen exposure.

We hypothesize that the lack of a typical ACD response at sites of psoriatic plaques in our patient may be attributed to the intensity and duration of exposure to the allergen. Quaranta et al9 reported a typical ACD clinical response and a mixed immunohistologic response to nickel patch testing at sites of active plaques in nickel-sensitized psoriasis patients. Patch testing involves 48 hours of direct contact with an allergen, while our patient experienced an estimated 8 to 10 hours of exposure to the allergen prior to removal via washing. Supporting this line of reasoning, a proportion of patients who are responsive to nickel patch testing do not exhibit clinical symptoms in response to casual nickel exposure.10 Although a physical barrier effect due to hyperkeratosis may have contributed to the lack of ACD response in sites of psoriasis plaques in our patient, it remains possible that a more limited duration of exposure to the allergen is not sufficient to overcome the native immunologic milieu of the psoriasis plaque and induce the immunologic cascade resulting in ACD. Further research into the potentially antagonistic relationship of psoriasis and ACD should be performed to elucidate the interaction between these two common conditions.

To the Editor:

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) is a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction against antigens to which the skin’s immune system was previously sensitized. The initial sensitization requires penetration of the antigen through the stratum corneum. Thus, the ability of a particle to cause ACD is related to its molecular structure and size, lipophilicity, and protein-binding affinity, as well as the dose and duration of exposure.1 Psoriasis typically presents as well-demarcated areas of skin that may be erythematous, indurated, and scaly to variable degrees. Histologically, psoriasis plaques are characterized by epidermal hyperplasia in the presence of a T-cell infiltrate and neutrophilic microabscesses. We report a case of a patient with plaque-type psoriasis who experienced ACD with sparing of exposed psoriatic plaques.

A 45-year-old man with a 5-year history of generalized moderate to severe psoriasis undergoing therapy with ustekinumab 45 mg subcutaneously once every 12 weeks presented to the emergency department with intensely erythematous, pruritic, vesicular lesions on the trunk, arms, and legs within 24 hours of exposure to poison oak while hiking. The patient reported pruritus, pain, and swelling of the affected areas. On physical examination, he was afebrile. Widespread erythematous vesicular lesions were noted on the face, trunk, arms, and legs, sparing the well-demarcated scaly psoriatic plaques on the arms and legs (Figure). The patient was given intravenous fluids and intravenous diphenhydramine. After responding to initial treatment, the patient was discharged with ibuprofen and a tapering dose of oral prednisone from 60 mg 5 times daily, to 40 mg 5 times daily, to 20 mg 5 times daily over 15 days.

star), with a linear border demarcating the ACD lesion and the unaffected psoriatic plaque (black arrow).

Allergic contact dermatitis occurs after sensitization to environmental allergens or haptens. Clinically, ACD is characterized by pruritic, erythematous, vesicular papules and plaques. The predominant effector cells in ACD are CD8+ T cells, along with contributions from helper T cells (TH2). Together, these cell types produce an environment enriched in IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, IL-17, and tumor necrosis factor α.2 Ultimately, the ACD response induces keratinocyte apoptosis via cytotoxic effects.3,4

Plaque psoriasis is a chronic, immune-mediated, inflammatory disease that presents clinically as erythematous well-demarcated plaques with a micaceous scale. The immunologic environment of psoriasis plaques is characterized by infiltration of CD4+ TH17 cells and elevated levels of IL-17, IL-23, tumor necrosis factor α, and IL-1β, which induce keratinocyte hyperproliferation through a complex mechanism resulting in hyperkeratosis composed of orthokeratosis and parakeratosis, a neutrophilic infiltrate, and Munro microabscesses.5

The predominant effector cells and the final effects on keratinocyte survival are divergent in psoriasis and ACD. The possibly antagonistic relationship between these immunologic processes is further supported by epidemiologic studies demonstrating a decreased incidence of ACD in patients with psoriasis.6,7

Our patient demonstrated a typical ACD reaction in response to exposure to urushiol, the allergen present in poison oak, in areas unaffected by psoriasis plaques. Interestingly, the patient displayed this response even while undergoing therapy with ustekinumab, a fully humanized antibody that binds IL-12 and IL-23 and ultimately downregulates TH17 cell-mediated release of IL-17 in the treatment of psoriasis. Although IL-17 also has been implicated in ACD, the lack of inhibition of ACD with ustekinumab treatment was previously demonstrated in a small retrospective study, indicating a potentially different source of IL-17 in ACD.8

Our patient did not demonstrate a typical ACD response in areas of active psoriasis plaques. This phenomenon was of great interest to us. It is possible that the presence of hyperkeratosis, manifested clinically as scaling, served as a mechanical barrier preventing the diffusion and exposure of cutaneous immune cells to urushiol. On the other hand, it is possible that the immunologic environment of the active psoriasis plaque was altered in such a way that it did not demonstrate the typical response to allergen exposure.

We hypothesize that the lack of a typical ACD response at sites of psoriatic plaques in our patient may be attributed to the intensity and duration of exposure to the allergen. Quaranta et al9 reported a typical ACD clinical response and a mixed immunohistologic response to nickel patch testing at sites of active plaques in nickel-sensitized psoriasis patients. Patch testing involves 48 hours of direct contact with an allergen, while our patient experienced an estimated 8 to 10 hours of exposure to the allergen prior to removal via washing. Supporting this line of reasoning, a proportion of patients who are responsive to nickel patch testing do not exhibit clinical symptoms in response to casual nickel exposure.10 Although a physical barrier effect due to hyperkeratosis may have contributed to the lack of ACD response in sites of psoriasis plaques in our patient, it remains possible that a more limited duration of exposure to the allergen is not sufficient to overcome the native immunologic milieu of the psoriasis plaque and induce the immunologic cascade resulting in ACD. Further research into the potentially antagonistic relationship of psoriasis and ACD should be performed to elucidate the interaction between these two common conditions.

- Kimber I, Basketter DA, Gerberick GF, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2002;2:201-211.

- Vocanson M, Hennino A, Cluzel-Tailhardat M, et al. CD8+ T cells are effector cells of contact dermatitis to common skin allergens in mice. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:815-820.

- Akiba H, Kehren J, Ducluzeau MT, et al. Skin inflammation during contact hypersensitivity is mediated by early recruitment of CD8+ T cytotoxic 1 cells inducing keratinocyte apoptosis. J Immunol. 2002;168:3079-3087.

- Trautmann A, Akdis M, Kleemann D, et al. T cell-mediated Fas-induced keratinocyte apoptosis plays a key pathogenetic role in eczematous dermatitis. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:25-35.

- Lynde CW, Poulin Y, Vender R, et al. Interleukin 17A: toward a new understanding of psoriasis pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:141-150.

- Bangsgaard N, Engkilde K, Thyssen JP, et al. Inverse relationship between contact allergy and psoriasis: results from a patient- and a population-based study. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:1119-1123.

- Henseler T, Christophers E. Disease concomitance in psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:982-986.

- Bangsgaard N, Zachariae C, Menne T, et al. Lack of effect of ustekinumab in treatment of allergic contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 2011;65:227-230.

- Quaranta M, Eyerich S, Knapp B, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis in psoriasis patients: typical, delayed, and non-interacting. PLoS One. 2014;9:e101814.

- Kimber I, Basketter DA, Gerberick GF, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2002;2:201-211.

- Kimber I, Basketter DA, Gerberick GF, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2002;2:201-211.

- Vocanson M, Hennino A, Cluzel-Tailhardat M, et al. CD8+ T cells are effector cells of contact dermatitis to common skin allergens in mice. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:815-820.

- Akiba H, Kehren J, Ducluzeau MT, et al. Skin inflammation during contact hypersensitivity is mediated by early recruitment of CD8+ T cytotoxic 1 cells inducing keratinocyte apoptosis. J Immunol. 2002;168:3079-3087.

- Trautmann A, Akdis M, Kleemann D, et al. T cell-mediated Fas-induced keratinocyte apoptosis plays a key pathogenetic role in eczematous dermatitis. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:25-35.

- Lynde CW, Poulin Y, Vender R, et al. Interleukin 17A: toward a new understanding of psoriasis pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:141-150.

- Bangsgaard N, Engkilde K, Thyssen JP, et al. Inverse relationship between contact allergy and psoriasis: results from a patient- and a population-based study. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:1119-1123.

- Henseler T, Christophers E. Disease concomitance in psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:982-986.

- Bangsgaard N, Zachariae C, Menne T, et al. Lack of effect of ustekinumab in treatment of allergic contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 2011;65:227-230.

- Quaranta M, Eyerich S, Knapp B, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis in psoriasis patients: typical, delayed, and non-interacting. PLoS One. 2014;9:e101814.

- Kimber I, Basketter DA, Gerberick GF, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2002;2:201-211.

Practice Points

- Patients with plaque-type psoriasis who experience allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) may present with sparing of exposed psoriatic plaques.

- The divergent immunologic milieus present in ACD and psoriasis likely underly the decreased incidence of ACD in patients with psoriasis.

Generalized Granuloma Annulare Responsive to Narrowband UVB

To the Editor:

Granuloma annulare (GA) is a common dermatosis that usually presents with dermal papules and annular plaques in a symmetric distribution.1 The etiology is unknown, but a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction is the favored pathogenesis. Several systemic associations have been reported with generalized GA including diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, autoimmune thyroiditis, rheumatoid arthritis, and lymphoproliferative malignancies, as well as other malignancies and viral infections such as human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C. Localized GA often is self-limiting, but generalized disease can be chronic and progressive. Although asymptomatic in most cases, the lesions can be cosmetically bothersome, and many patients desire treatment. There are few well-controlled studies of treatment, and most are limited to case reports and series. A review of GA treatment noted only 3 randomized studies: 2 relating to photodynamic therapy and 1 to cryosurgery. Well-accepted therapies, such as topical and intralesional corticosteroids, antimalarials, immunosuppressants, antibiotics, and phototherapy, are substantiated by lesser-quality evidence.1 Phototherapy has been studied for the treatment of GA and other disorders with altered dermal matrix deposition for which there are limited effective treatment options. UV irradiation promotes degradation of structural components of the dermis and inhibition of collagen production.2 Granuloma annulare generally is resistant to therapy. We report a case of generalized GA of long duration that responded well to phototherapy with narrowband UVB (NB-UVB).

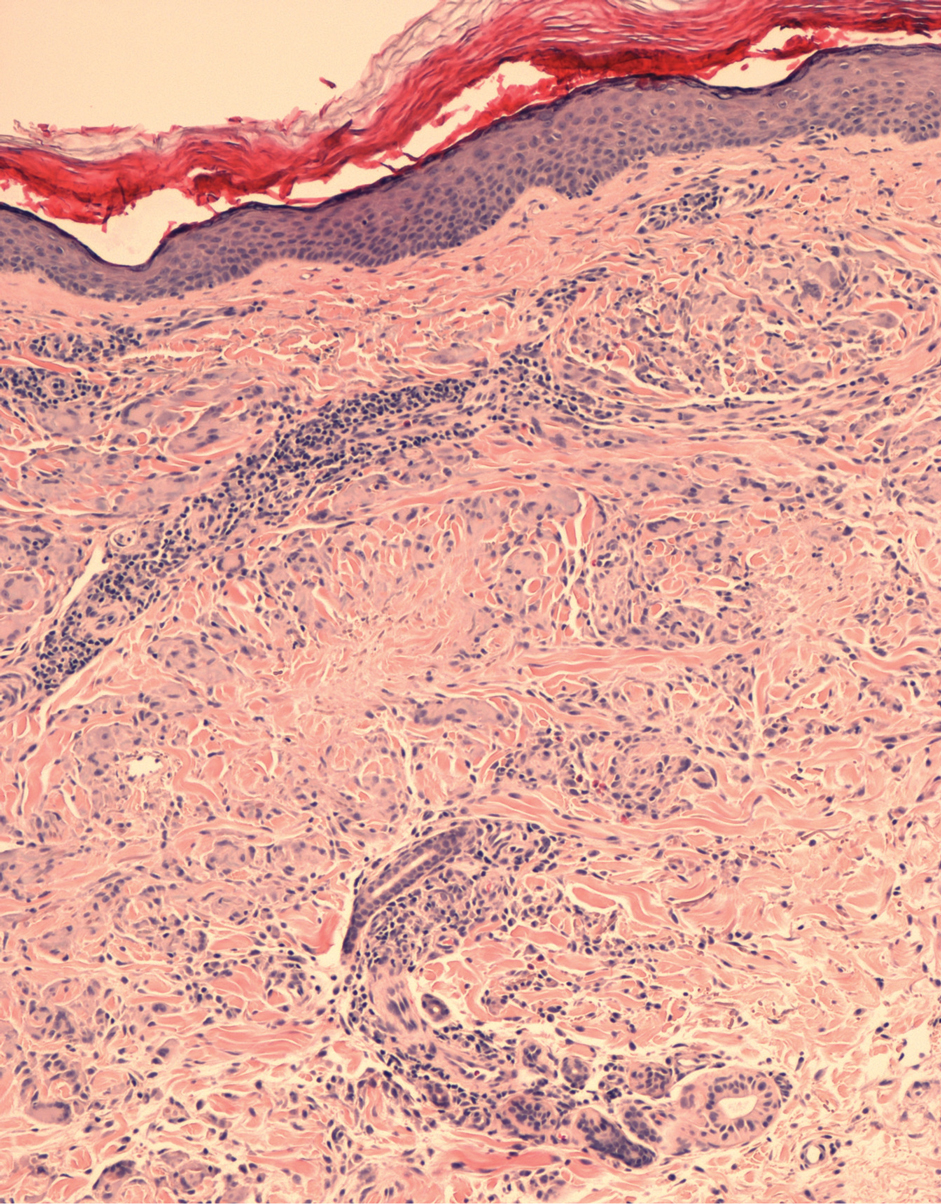

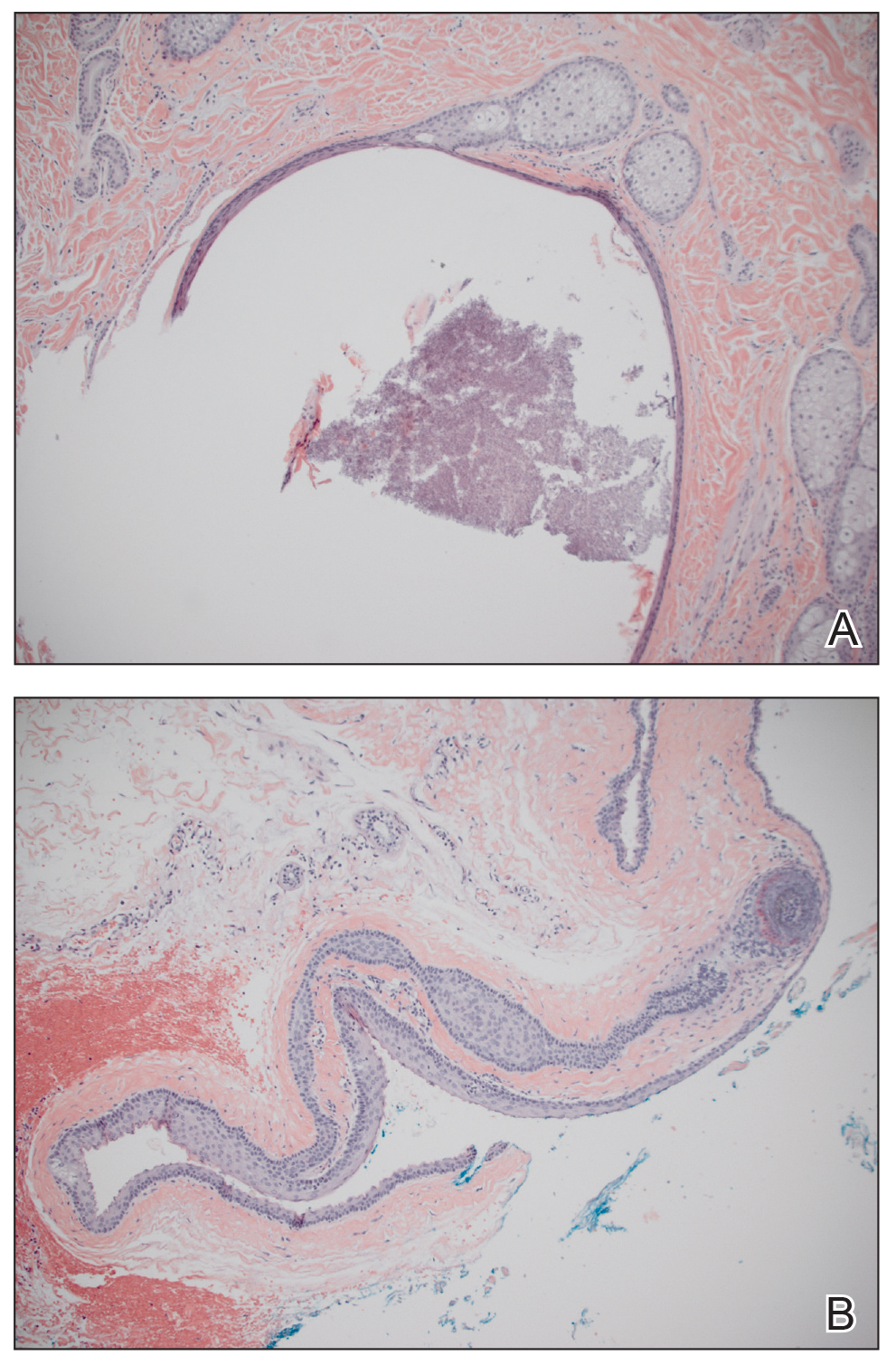

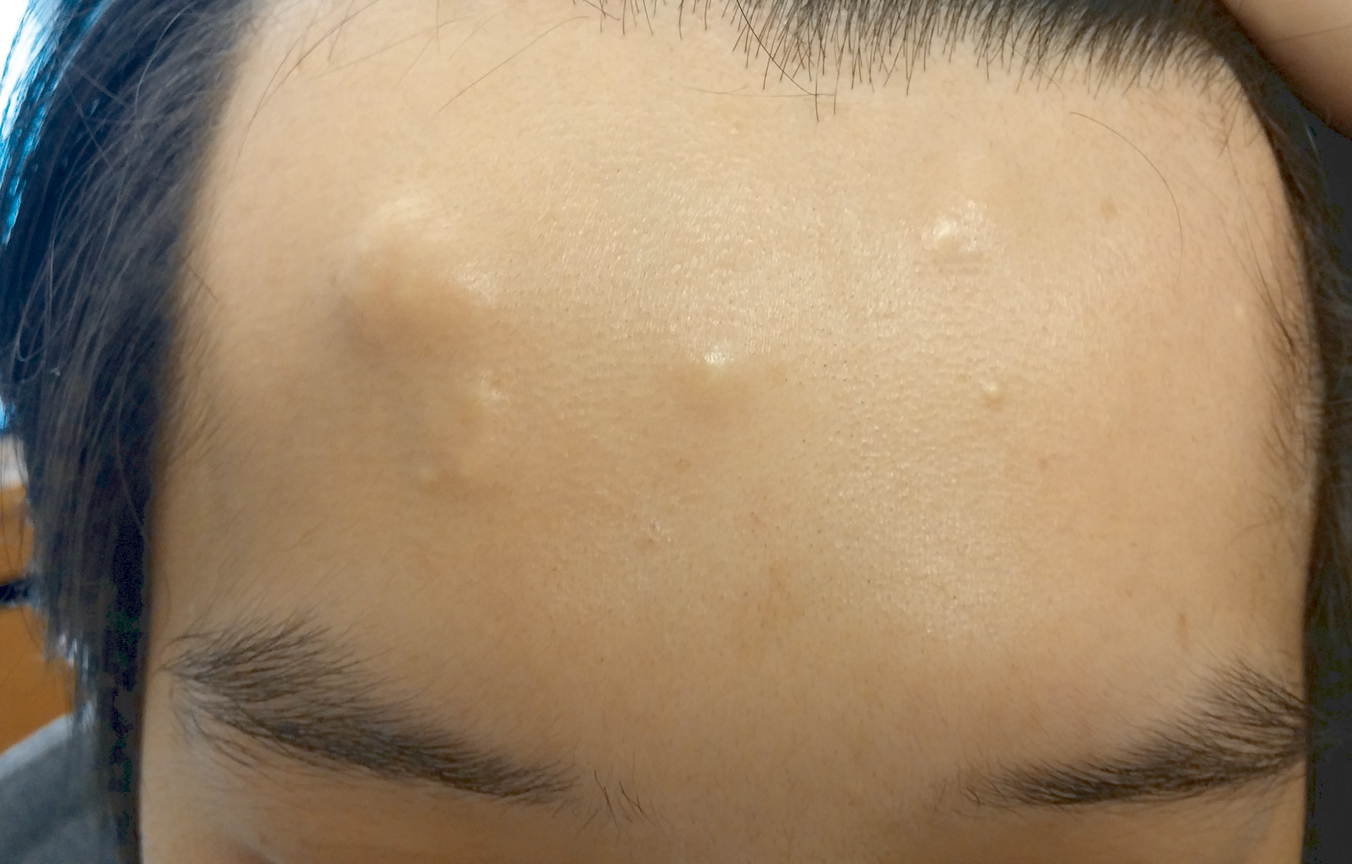

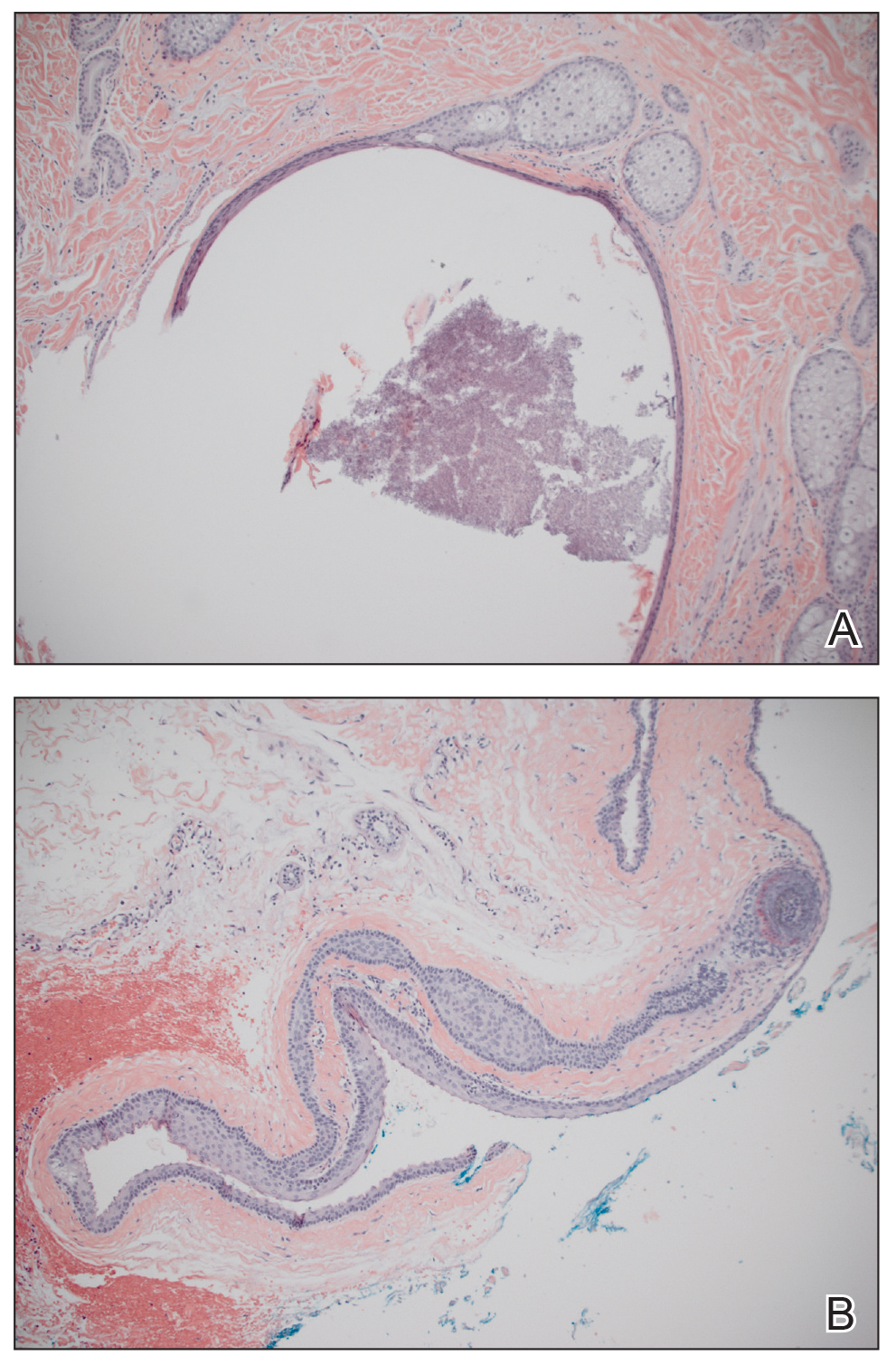

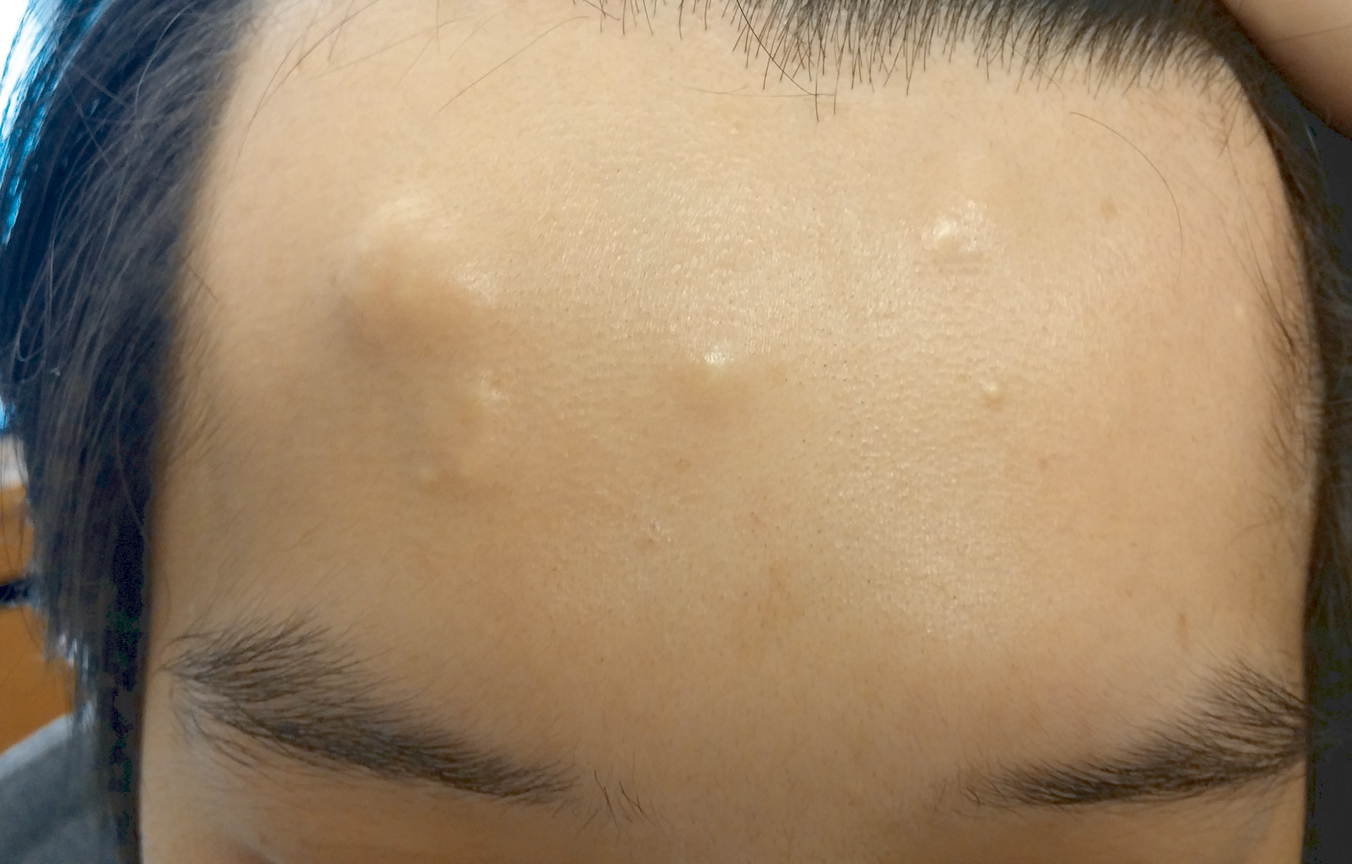

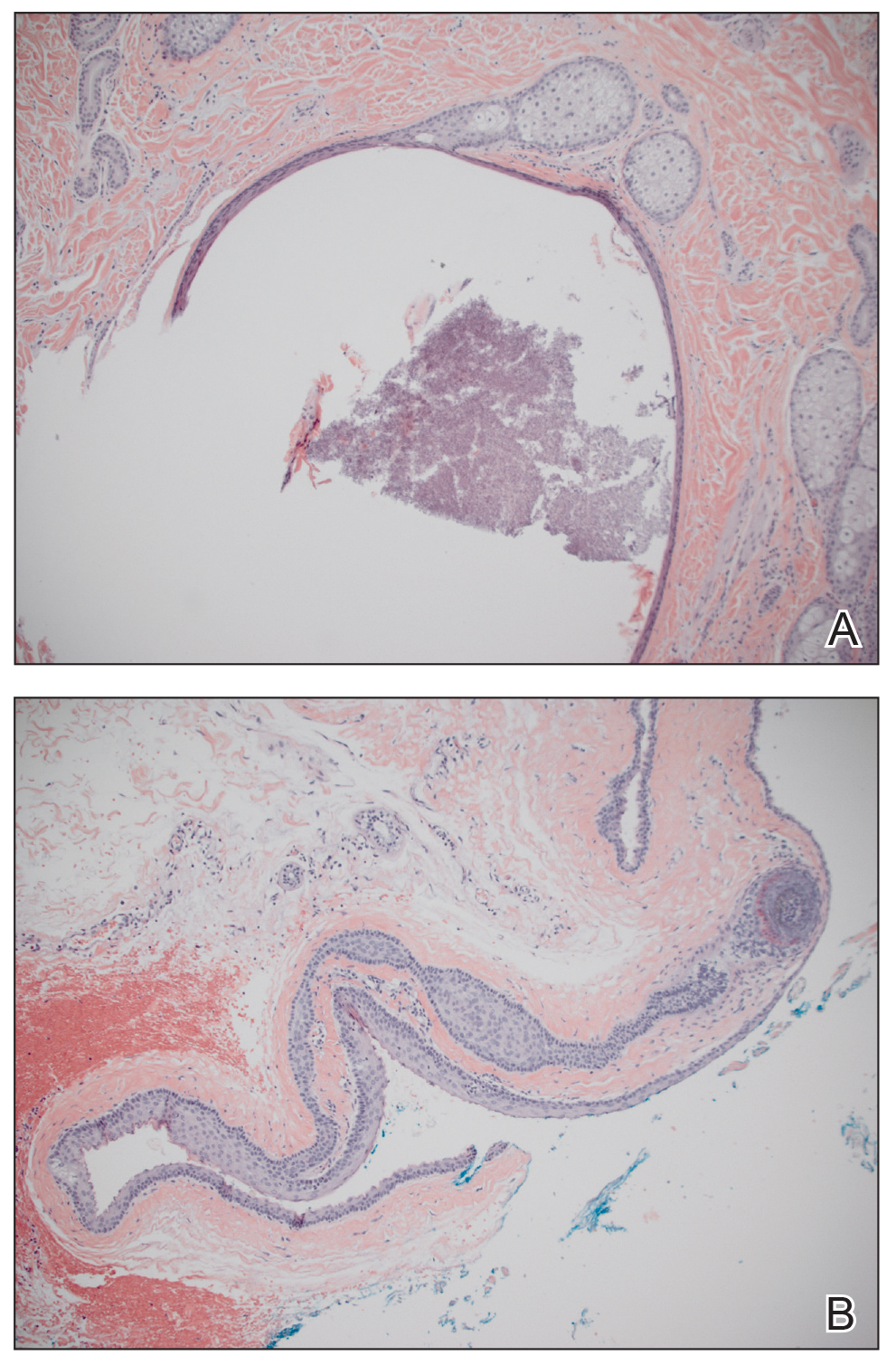

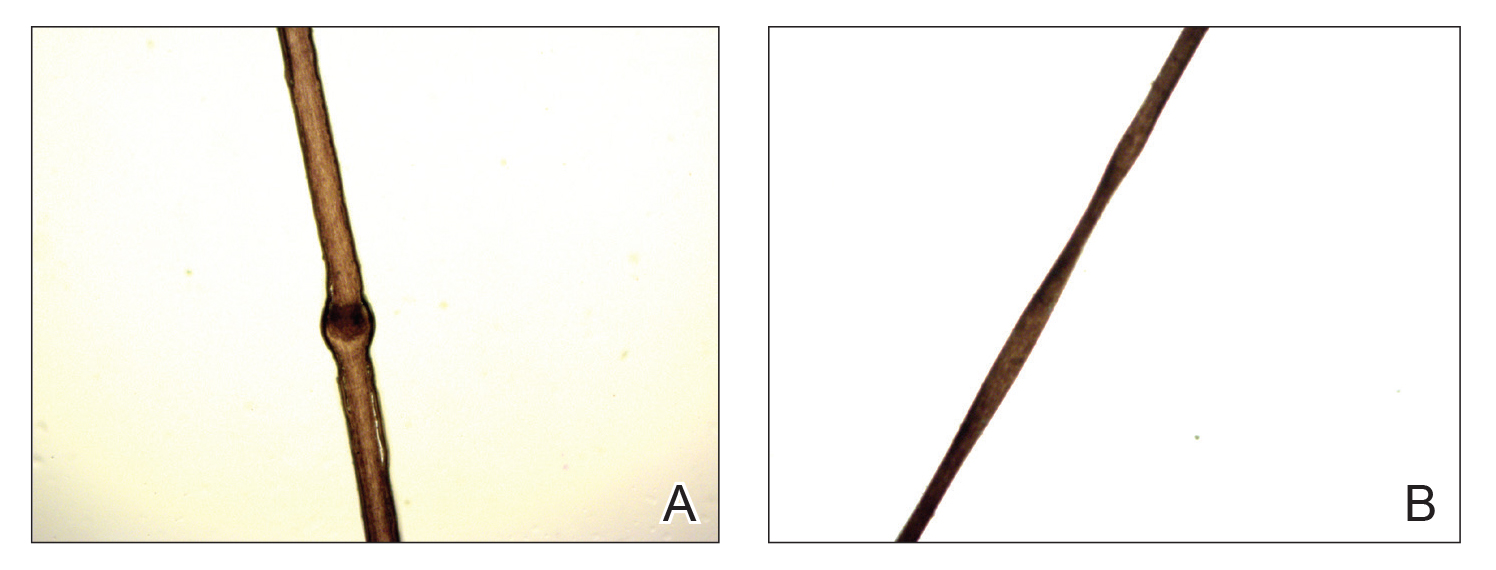

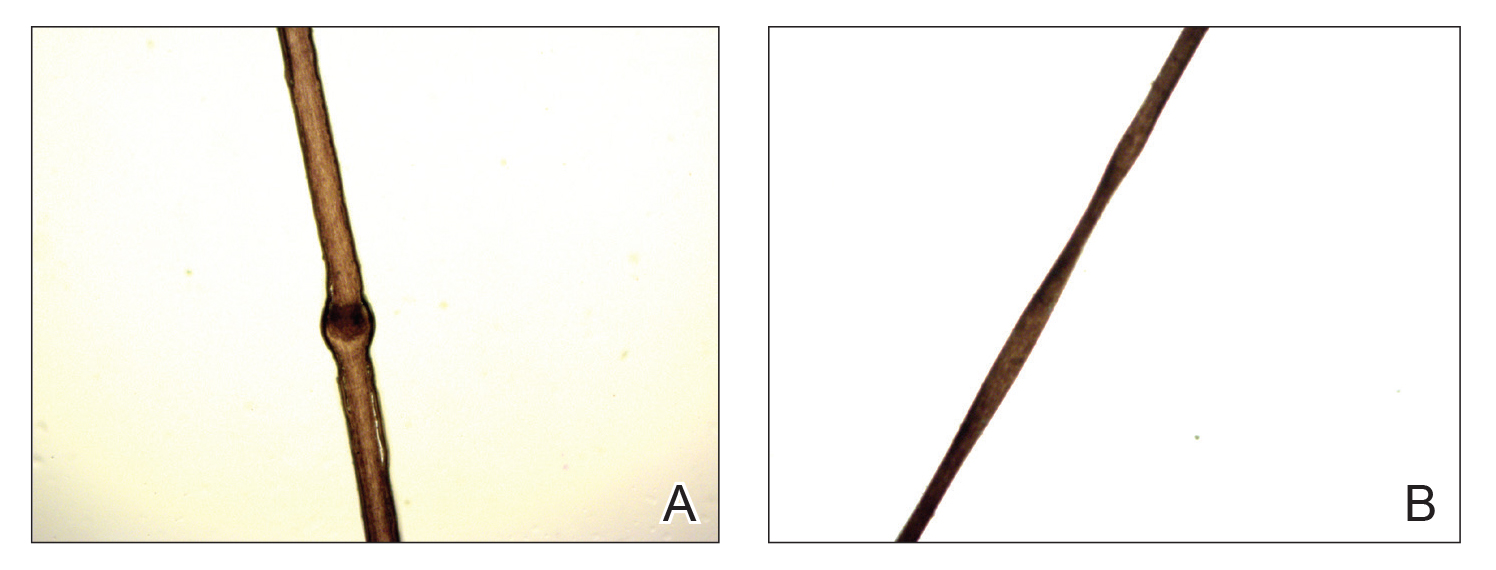

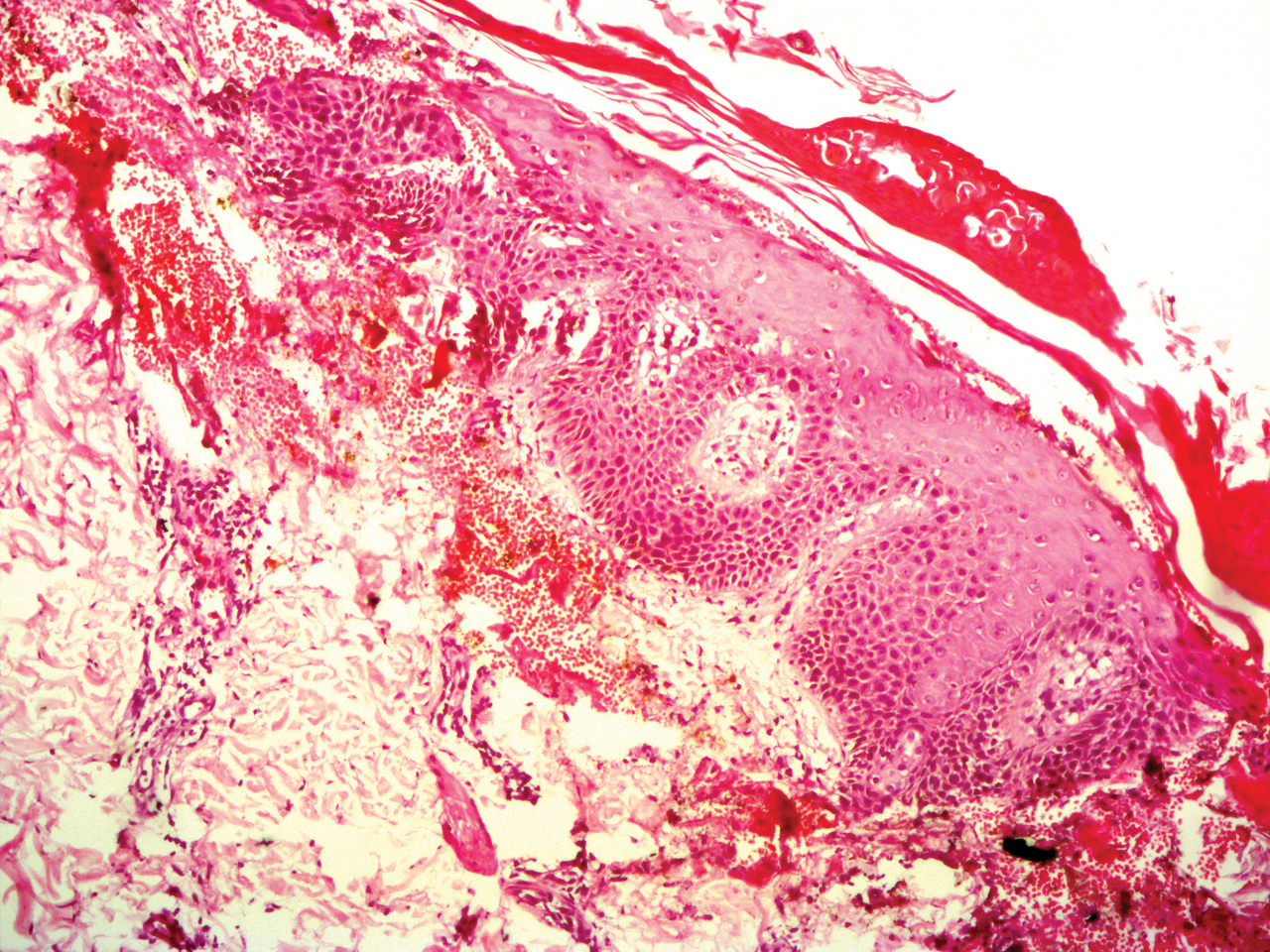

A 60-year-old woman presented with generalized GA of 4 years’ duration that was confirmed on biopsy on 2 occasions (Figure 1). The lesions were asymptomatic but disfiguring and consisted of extensive pink, thin, annular plaques and papules on the torso, arms, and legs (Figure 2A). Apart from mild depression for which she was being treated with paroxetine and trazodone, she was otherwise healthy without evidence of thyroid disease, hyperlipidemia, or diabetes mellitus. Prior treatments for GA had included tapering courses of prednisone (up to 30 mg/d, tapered by 5 mg every 4 days) and betamethasone dipropionate cream 0.05%. She was started on NB-UVB therapy 5 times weekly in incremental doses with no adjuvant therapy. After 100 treatments, there was notable improvement with lesions becoming paler and flatter, with some involuting completely (Figure 2B). The frequency of treatment was reduced to 3 times weekly with continued improvement. An NB-UVB device was used containing 48 TL 100W/01-FS72 lamps with a mean irradiance of 2.9 mW/cm2. Her starting dose was 90 mJ/cm2. The cumulative dose after 100 treatments was 35,600 mJ/cm2. Apart from occasional mild erythema, there were no adverse effects.

Inui et al3 described the successful treatment of generalized GA with NB-UVB. A retrospective review of NB-UVB for vitiligo, pruritus, and inflammatory dermatoses included 2 cases of generalized GA that were noted to have only a minimal to mild improvement.4 Most reports relating to phototherapy of GA have focused on psoralen plus UVA (PUVA). A retrospective study of 33 patients treated with systemic PUVA showed improvement in two-thirds of patients.5 Older studies showed systemic PUVA was effective in 1 patient after 53 treatments6 and in 4 patients using a high-dose protocol7; topical PUVA was effective in 4 patients after an average of 26 treatments.8 Psoralen plus UVA bath was reported as an effective treatment of generalized GA in a child.9 UVA1 phototherapy provided good or excellent results in half of patients (10/20) studied with generalized GA; however, discontinuation of treatment resulted in early recurrence of disease.10 In general, NB-UVB has been preferred over PUVA and UVA1 due to long-term safety, tolerability, and access. Although further clinical trials are needed, our report suggests that NB-UVB could be a useful modality in generalized GA.

- Thornsberry LA, English JC III. Etiology, diagnosis, and therapeutic management of granuloma annulare: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:279-290.

- Fisher GJ, Wang ZQ, Datta SC, et al. Pathophysiology of premature skin aging induced by ultraviolet light. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1419-1428.

- Inui S, Nishida Y, Itami S, et al. Disseminated granuloma annulare responsive to narrowband ultraviolet B therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:532-533.

- Samson Yashar S, Gielczyk R, Scherschun L, et al. Narrow-band ultraviolet B treatment for vitiligo, pruritus, and inflammatory dermatoses. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2003;19:164-168.

- Browne F, Turner D, Goulden V. Psoralen and ultraviolet A in the treatment of granuloma annulare. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2011;27:81-84.

- Setterfield J, Huilgol SC, Black MM. Generalised granuloma annulare successfully treated with PUVA. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1999;24:458-460.

- Munchenberger S, Schopf E, Simon JC. Phototherapy with UVA-1 for generalized granuloma annulare. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1605.

- Grundmann-Kollmann M, Ochsendorf FR, Zollner TM, et al. Cream psoralen plus ultraviolet A therapy for granuloma annulare. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:996-999.

- Batchelor R, Clark S. Clearance of generalized popular umbilicated granuloma annulare in a child with bath PUVA therapy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:72-74.

- Schnopp C, Tzaneva S, Mempel M, et al. UVA1 phototherapy for disseminated granuloma annulare. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2005;21:68-71.

To the Editor:

Granuloma annulare (GA) is a common dermatosis that usually presents with dermal papules and annular plaques in a symmetric distribution.1 The etiology is unknown, but a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction is the favored pathogenesis. Several systemic associations have been reported with generalized GA including diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, autoimmune thyroiditis, rheumatoid arthritis, and lymphoproliferative malignancies, as well as other malignancies and viral infections such as human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C. Localized GA often is self-limiting, but generalized disease can be chronic and progressive. Although asymptomatic in most cases, the lesions can be cosmetically bothersome, and many patients desire treatment. There are few well-controlled studies of treatment, and most are limited to case reports and series. A review of GA treatment noted only 3 randomized studies: 2 relating to photodynamic therapy and 1 to cryosurgery. Well-accepted therapies, such as topical and intralesional corticosteroids, antimalarials, immunosuppressants, antibiotics, and phototherapy, are substantiated by lesser-quality evidence.1 Phototherapy has been studied for the treatment of GA and other disorders with altered dermal matrix deposition for which there are limited effective treatment options. UV irradiation promotes degradation of structural components of the dermis and inhibition of collagen production.2 Granuloma annulare generally is resistant to therapy. We report a case of generalized GA of long duration that responded well to phototherapy with narrowband UVB (NB-UVB).

A 60-year-old woman presented with generalized GA of 4 years’ duration that was confirmed on biopsy on 2 occasions (Figure 1). The lesions were asymptomatic but disfiguring and consisted of extensive pink, thin, annular plaques and papules on the torso, arms, and legs (Figure 2A). Apart from mild depression for which she was being treated with paroxetine and trazodone, she was otherwise healthy without evidence of thyroid disease, hyperlipidemia, or diabetes mellitus. Prior treatments for GA had included tapering courses of prednisone (up to 30 mg/d, tapered by 5 mg every 4 days) and betamethasone dipropionate cream 0.05%. She was started on NB-UVB therapy 5 times weekly in incremental doses with no adjuvant therapy. After 100 treatments, there was notable improvement with lesions becoming paler and flatter, with some involuting completely (Figure 2B). The frequency of treatment was reduced to 3 times weekly with continued improvement. An NB-UVB device was used containing 48 TL 100W/01-FS72 lamps with a mean irradiance of 2.9 mW/cm2. Her starting dose was 90 mJ/cm2. The cumulative dose after 100 treatments was 35,600 mJ/cm2. Apart from occasional mild erythema, there were no adverse effects.

Inui et al3 described the successful treatment of generalized GA with NB-UVB. A retrospective review of NB-UVB for vitiligo, pruritus, and inflammatory dermatoses included 2 cases of generalized GA that were noted to have only a minimal to mild improvement.4 Most reports relating to phototherapy of GA have focused on psoralen plus UVA (PUVA). A retrospective study of 33 patients treated with systemic PUVA showed improvement in two-thirds of patients.5 Older studies showed systemic PUVA was effective in 1 patient after 53 treatments6 and in 4 patients using a high-dose protocol7; topical PUVA was effective in 4 patients after an average of 26 treatments.8 Psoralen plus UVA bath was reported as an effective treatment of generalized GA in a child.9 UVA1 phototherapy provided good or excellent results in half of patients (10/20) studied with generalized GA; however, discontinuation of treatment resulted in early recurrence of disease.10 In general, NB-UVB has been preferred over PUVA and UVA1 due to long-term safety, tolerability, and access. Although further clinical trials are needed, our report suggests that NB-UVB could be a useful modality in generalized GA.

To the Editor:

Granuloma annulare (GA) is a common dermatosis that usually presents with dermal papules and annular plaques in a symmetric distribution.1 The etiology is unknown, but a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction is the favored pathogenesis. Several systemic associations have been reported with generalized GA including diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, autoimmune thyroiditis, rheumatoid arthritis, and lymphoproliferative malignancies, as well as other malignancies and viral infections such as human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C. Localized GA often is self-limiting, but generalized disease can be chronic and progressive. Although asymptomatic in most cases, the lesions can be cosmetically bothersome, and many patients desire treatment. There are few well-controlled studies of treatment, and most are limited to case reports and series. A review of GA treatment noted only 3 randomized studies: 2 relating to photodynamic therapy and 1 to cryosurgery. Well-accepted therapies, such as topical and intralesional corticosteroids, antimalarials, immunosuppressants, antibiotics, and phototherapy, are substantiated by lesser-quality evidence.1 Phototherapy has been studied for the treatment of GA and other disorders with altered dermal matrix deposition for which there are limited effective treatment options. UV irradiation promotes degradation of structural components of the dermis and inhibition of collagen production.2 Granuloma annulare generally is resistant to therapy. We report a case of generalized GA of long duration that responded well to phototherapy with narrowband UVB (NB-UVB).

A 60-year-old woman presented with generalized GA of 4 years’ duration that was confirmed on biopsy on 2 occasions (Figure 1). The lesions were asymptomatic but disfiguring and consisted of extensive pink, thin, annular plaques and papules on the torso, arms, and legs (Figure 2A). Apart from mild depression for which she was being treated with paroxetine and trazodone, she was otherwise healthy without evidence of thyroid disease, hyperlipidemia, or diabetes mellitus. Prior treatments for GA had included tapering courses of prednisone (up to 30 mg/d, tapered by 5 mg every 4 days) and betamethasone dipropionate cream 0.05%. She was started on NB-UVB therapy 5 times weekly in incremental doses with no adjuvant therapy. After 100 treatments, there was notable improvement with lesions becoming paler and flatter, with some involuting completely (Figure 2B). The frequency of treatment was reduced to 3 times weekly with continued improvement. An NB-UVB device was used containing 48 TL 100W/01-FS72 lamps with a mean irradiance of 2.9 mW/cm2. Her starting dose was 90 mJ/cm2. The cumulative dose after 100 treatments was 35,600 mJ/cm2. Apart from occasional mild erythema, there were no adverse effects.

Inui et al3 described the successful treatment of generalized GA with NB-UVB. A retrospective review of NB-UVB for vitiligo, pruritus, and inflammatory dermatoses included 2 cases of generalized GA that were noted to have only a minimal to mild improvement.4 Most reports relating to phototherapy of GA have focused on psoralen plus UVA (PUVA). A retrospective study of 33 patients treated with systemic PUVA showed improvement in two-thirds of patients.5 Older studies showed systemic PUVA was effective in 1 patient after 53 treatments6 and in 4 patients using a high-dose protocol7; topical PUVA was effective in 4 patients after an average of 26 treatments.8 Psoralen plus UVA bath was reported as an effective treatment of generalized GA in a child.9 UVA1 phototherapy provided good or excellent results in half of patients (10/20) studied with generalized GA; however, discontinuation of treatment resulted in early recurrence of disease.10 In general, NB-UVB has been preferred over PUVA and UVA1 due to long-term safety, tolerability, and access. Although further clinical trials are needed, our report suggests that NB-UVB could be a useful modality in generalized GA.

- Thornsberry LA, English JC III. Etiology, diagnosis, and therapeutic management of granuloma annulare: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:279-290.

- Fisher GJ, Wang ZQ, Datta SC, et al. Pathophysiology of premature skin aging induced by ultraviolet light. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1419-1428.

- Inui S, Nishida Y, Itami S, et al. Disseminated granuloma annulare responsive to narrowband ultraviolet B therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:532-533.

- Samson Yashar S, Gielczyk R, Scherschun L, et al. Narrow-band ultraviolet B treatment for vitiligo, pruritus, and inflammatory dermatoses. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2003;19:164-168.

- Browne F, Turner D, Goulden V. Psoralen and ultraviolet A in the treatment of granuloma annulare. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2011;27:81-84.

- Setterfield J, Huilgol SC, Black MM. Generalised granuloma annulare successfully treated with PUVA. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1999;24:458-460.

- Munchenberger S, Schopf E, Simon JC. Phototherapy with UVA-1 for generalized granuloma annulare. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1605.

- Grundmann-Kollmann M, Ochsendorf FR, Zollner TM, et al. Cream psoralen plus ultraviolet A therapy for granuloma annulare. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:996-999.

- Batchelor R, Clark S. Clearance of generalized popular umbilicated granuloma annulare in a child with bath PUVA therapy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:72-74.

- Schnopp C, Tzaneva S, Mempel M, et al. UVA1 phototherapy for disseminated granuloma annulare. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2005;21:68-71.

- Thornsberry LA, English JC III. Etiology, diagnosis, and therapeutic management of granuloma annulare: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:279-290.

- Fisher GJ, Wang ZQ, Datta SC, et al. Pathophysiology of premature skin aging induced by ultraviolet light. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1419-1428.

- Inui S, Nishida Y, Itami S, et al. Disseminated granuloma annulare responsive to narrowband ultraviolet B therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:532-533.

- Samson Yashar S, Gielczyk R, Scherschun L, et al. Narrow-band ultraviolet B treatment for vitiligo, pruritus, and inflammatory dermatoses. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2003;19:164-168.

- Browne F, Turner D, Goulden V. Psoralen and ultraviolet A in the treatment of granuloma annulare. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2011;27:81-84.

- Setterfield J, Huilgol SC, Black MM. Generalised granuloma annulare successfully treated with PUVA. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1999;24:458-460.

- Munchenberger S, Schopf E, Simon JC. Phototherapy with UVA-1 for generalized granuloma annulare. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1605.

- Grundmann-Kollmann M, Ochsendorf FR, Zollner TM, et al. Cream psoralen plus ultraviolet A therapy for granuloma annulare. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:996-999.

- Batchelor R, Clark S. Clearance of generalized popular umbilicated granuloma annulare in a child with bath PUVA therapy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:72-74.

- Schnopp C, Tzaneva S, Mempel M, et al. UVA1 phototherapy for disseminated granuloma annulare. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2005;21:68-71.

Practice Points

- The generalized variant of granuloma annulare (GA) can be persistent, sometimes lasting years to decades; treatment is not always effective.

- The safety profile and tolerability of narrowband UVB phototherapy make it a suitable treatment option for generalized GA.

Pustular Tinea Id Reaction

To the Editor:

A 17-year-old adolescent girl presented to the dermatology clinic with a tender pruritic rash on the left wrist that was spreading to the bilateral arms and legs of several years’ duration. An area of a prior biopsy on the left wrist was healing well with use of petroleum jelly and halcinonide cream. The patient denied any constitutional symptoms.

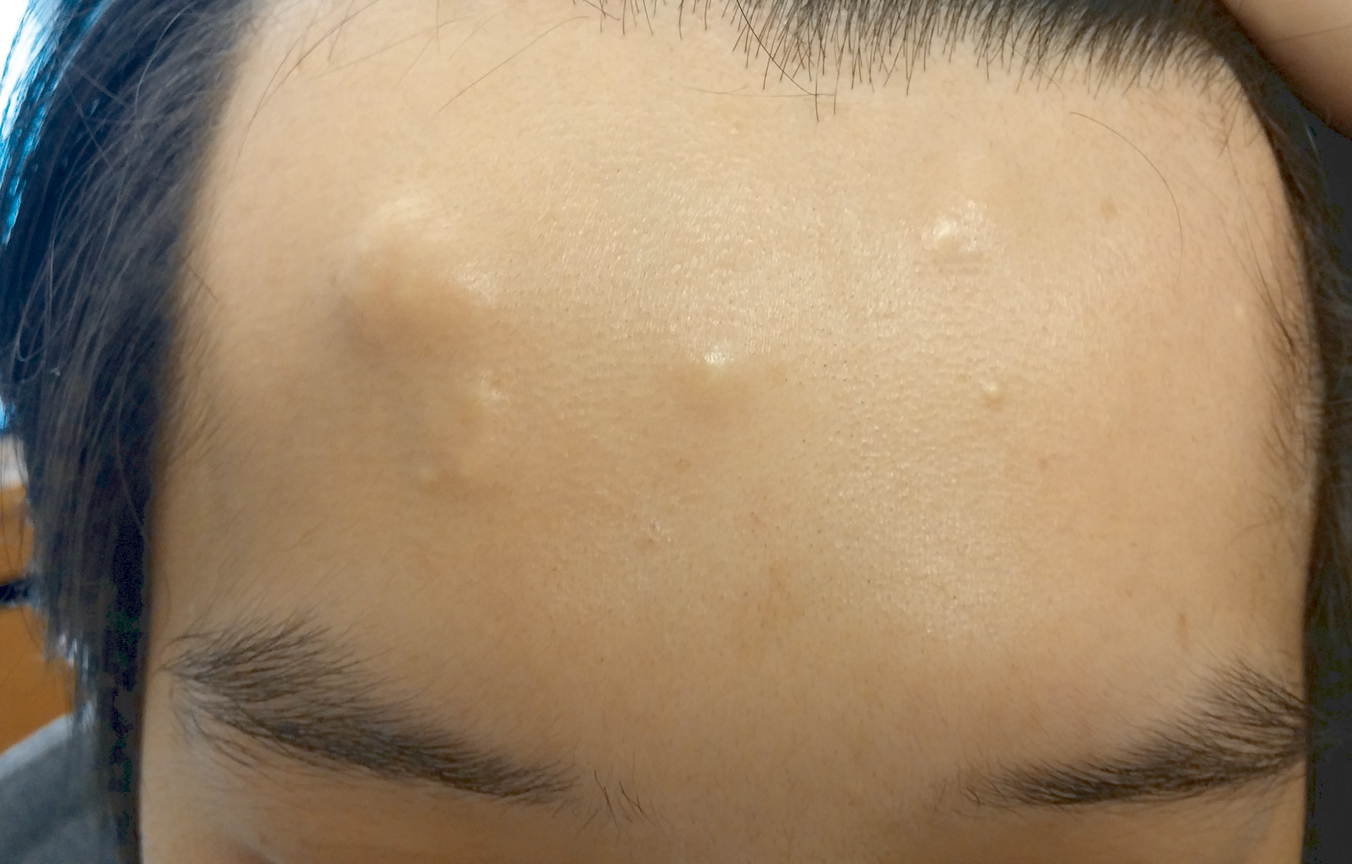

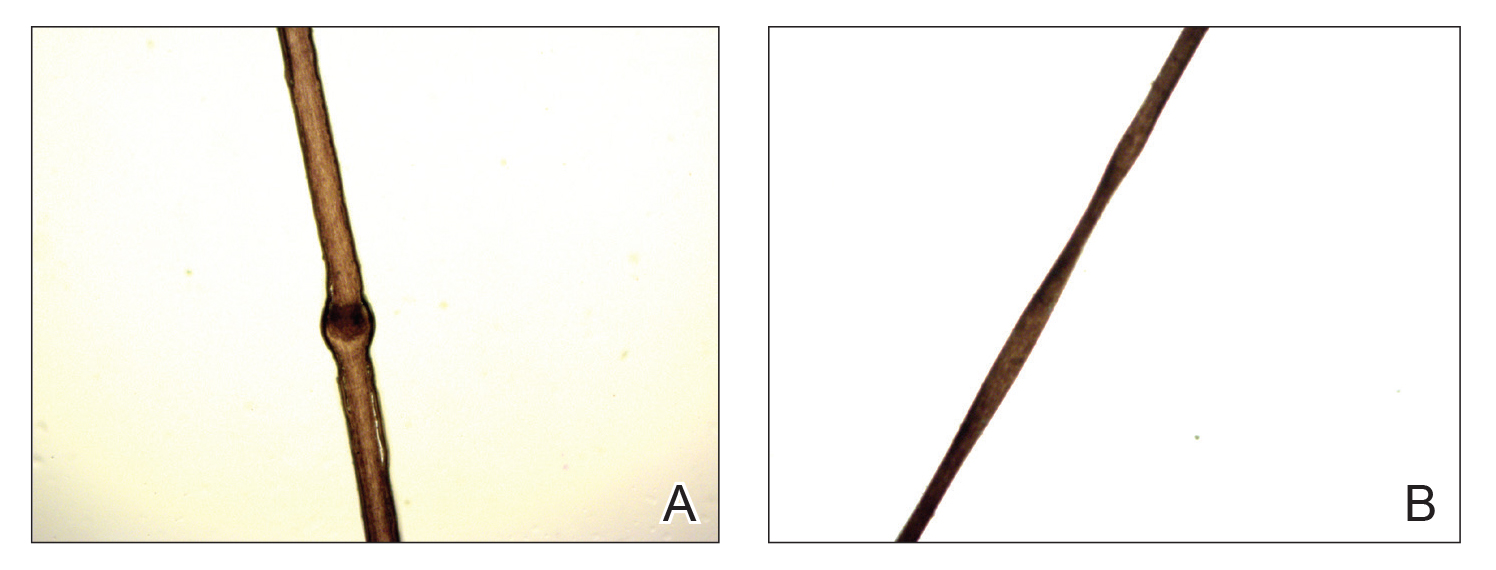

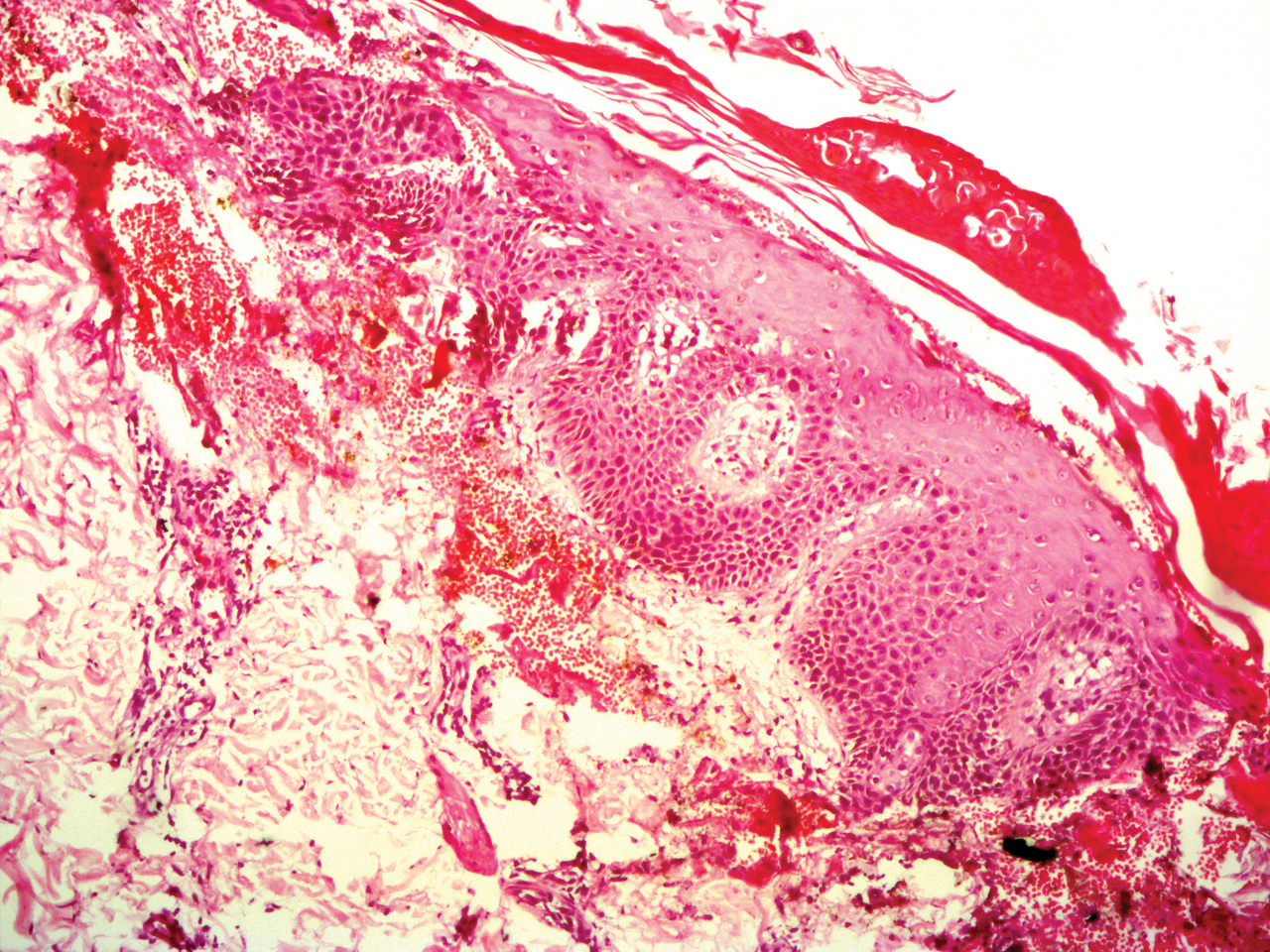

Physical examination revealed numerous erythematous papules coalescing into plaques on the bilateral anterior and posterior arms and legs, including some erythematous macules and papules on the palms and soles. The original area of involvement on the left dorsal medial wrist demonstrated a background of erythema with overlying peripheral scaling and resolving violaceous to erythematous papules with signs of serosanguineous crusting (Figure 1). Scattered perifollicular erythema was present on the posterior aspects of the bilateral thighs and arms (Figure 2). Baseline complete blood cell count and complete metabolic panel were within reference range.

Clinical histopathology showed evidence of a pustular superficial dermatophyte infection, and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain demonstrated numerous fungal hyphae within subcorneal pustules, indicating pustular tinea. Based on the clinicopathologic correlation, the initial presentation was diagnosed as pustular tinea of the entire left wrist, followed by a generalized id reaction 1 week later.

The patient was prescribed oral terbinafine 250 mg once daily to treat the diffuse involvement of the pustular tinea as well as once-daily oral cetirizine, once-daily oral diphenhydramine, a topical emollient, and a topical nonsteroidal antipruritic gel.

Tinea is a superficial fungal infection commonly caused by the dermatophytes Epidermophyton, Trichophyton, and Microsporum. It has a variety of clinical presentations based on the anatomic location, including tinea capitis (hair/scalp), tinea pedis (feet), tinea corporis (face/trunk/extremities), tinea cruris (groin), and tinea unguium (nails).1 Tinea infections occur in the stratum corneum, hair, and nails, thriving on dead keratin in these areas.2 Tinea corporis usually appears as an erythematous ring-shaped lesion with a scaly border, but atypical cases presenting with vesicles, pustules, and bullae also have been reported.3 Additionally, secondary eruptions called id reactions, or autoeczematization, can present in the setting of dermatophyte infections. Such outbreaks may be due to a delayed hypersensitivity reaction to the fungal antigens. Id reactions can manifest in many forms of tinea with patients generally exhibiting pruritic papulovesicular lesions that can present far from the site of origin.4

Patients with id reactions can have atypical and varied presentations. In a case of id reaction due to tinea corporis, a patient presented with vesicles and pustules that grew in number and coalesced to form annular lesions.5 A case of an id reaction caused by tinea pedis also noted the presence of pustules, which are atypical in this form of tinea.6 In another case of tinea pedis, a generalized id reaction was noted, illustrating that such eruptions do not necessarily appear at the original site of infection.7 Additionally, in a rare presentation of tinea invading the nares, a patient developed an erythema multiforme id reaction.8 Id reactions also were noted in 14 patients with refractory otitis externa, illustrating the ability of this fungal infection to persist and infect distant locations.9

Because the differential diagnoses for tinea infection are extensive, pathology or laboratory confirmation is necessary for diagnosis, and potassium hydroxide preparation often is used to diagnose dermatophyte infections.1,2 Additionally, the possibility of a hypersensitivity drug rash should remain in the differential if the patient received allergy-inducing medications prior to the outbreak, which may in turn complicate the diagnosis.

Tinea infections typically can be treated with topical antifungals such as terbinafine, butenafine,1 and luliconazole10; however, more involved cases may require oral antifungal treatment.1 Systemic treatment of tinea corporis includes itraconazole, terbinafine, and fluconazole,11 all of which exhibit fewer side effects and greater efficacy when compared to griseofulvin.12-15

Treatment of id reactions centers on the proper clearance of the dermatophyte infection, and treatment with oral antifungals generally is sufficient. In the cases of id reaction in patients with refractory otitis, some success was achieved with treatment involving immunotherapy with dermatophyte and dust mite allergen extracts coupled with a yeast elimination diet.9 In acute id reactions, topical corticosteroids and antipruritic agents can be applied.4 Rarely, systemic glucocorticoids are required, such as in cases in which the id reaction persists despite proper treatment of the primary infection.16

- Ely JW, Rosenfeld S, Seabury Stone M. Diagnosis and management of tinea infections. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90:702-710.

- Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 5th ed. Hanover, NH: Elsevier, Inc; 2010.

- Ziemer M, Seyfarth F, Elsner P, et al. Atypical manifestations of tinea corporis. Mycoses. 2007;50(suppl 2):31-35.

- Cheng N, Rucker Wright D, Cohen BA. Dermatophytid in tinea capitis: rarely reported common phenomenon with clinical implications [published online July 4, 2011]. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e453-e457.

- Ohno S, Tanabe H, Kawasaki M, et al. Tinea corporis with acute inflammation caused by Trichophyton tonsurans. J Dermatol. 2008;35:590-593.

- Hirschmann JV, Raugi GJ. Pustular tinea pedis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:132-133.

- Iglesias ME, España A, Idoate MA, et al. Generalized skin reaction following tinea pedis (dermatophytids). J Dermatol. 1994;21:31-34.

- Atzori L, Pau M, Aste M. Erythema multiforme ID reaction in atypical dermatophytosis: a case report. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:699-701.

- Derebery J, Berliner KI. Foot and ear disease—the dermatophytid reaction in otology. Laryngoscope. 1996;106(2 Pt 1):181-186.

- Khanna D, Bharti S. Luliconazole for the treatment of fungal infections: an evidence-based review. Core Evid. 2014;9:113-124.

- Korting HC, Schöllmann C. The significance of itraconazole for treatment of fungal infections of skin, nails and mucous membranes. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2009;7:11-20.

- Goldstein AO, Goldstein BG. Dermatophyte (tinea) infections. UpToDate website. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/dermatophyte-tinea-infections. Updated December 28, 2018. Accessed April 24, 2019.

- Cole GW, Stricklin G. A comparison of a new oral antifungal, terbinafine, with griseofulvin as therapy for tinea corporis. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:1537.

- Panagiotidou D, Kousidou T, Chaidemenos G, et al. A comparison of itraconazole and griseofulvin in the treatment of tinea corporis and tinea cruris: a double-blind study. J Int Med Res. 1992;20:392-400.

- Faergemann J, Mörk NJ, Haglund A, et al. A multicentre (double-blind) comparative study to assess the safety and efficacy of fluconazole and griseofulvin in the treatment of tinea corporis and tinea cruris. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:575-577.

- Ilkit M, Durdu M, Karakas M. Cutaneous id reactions: a comprehensive review of clinical manifestations, epidemiology, etiology, and management. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2012;38:191-202.

To the Editor:

A 17-year-old adolescent girl presented to the dermatology clinic with a tender pruritic rash on the left wrist that was spreading to the bilateral arms and legs of several years’ duration. An area of a prior biopsy on the left wrist was healing well with use of petroleum jelly and halcinonide cream. The patient denied any constitutional symptoms.

Physical examination revealed numerous erythematous papules coalescing into plaques on the bilateral anterior and posterior arms and legs, including some erythematous macules and papules on the palms and soles. The original area of involvement on the left dorsal medial wrist demonstrated a background of erythema with overlying peripheral scaling and resolving violaceous to erythematous papules with signs of serosanguineous crusting (Figure 1). Scattered perifollicular erythema was present on the posterior aspects of the bilateral thighs and arms (Figure 2). Baseline complete blood cell count and complete metabolic panel were within reference range.

Clinical histopathology showed evidence of a pustular superficial dermatophyte infection, and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain demonstrated numerous fungal hyphae within subcorneal pustules, indicating pustular tinea. Based on the clinicopathologic correlation, the initial presentation was diagnosed as pustular tinea of the entire left wrist, followed by a generalized id reaction 1 week later.

The patient was prescribed oral terbinafine 250 mg once daily to treat the diffuse involvement of the pustular tinea as well as once-daily oral cetirizine, once-daily oral diphenhydramine, a topical emollient, and a topical nonsteroidal antipruritic gel.

Tinea is a superficial fungal infection commonly caused by the dermatophytes Epidermophyton, Trichophyton, and Microsporum. It has a variety of clinical presentations based on the anatomic location, including tinea capitis (hair/scalp), tinea pedis (feet), tinea corporis (face/trunk/extremities), tinea cruris (groin), and tinea unguium (nails).1 Tinea infections occur in the stratum corneum, hair, and nails, thriving on dead keratin in these areas.2 Tinea corporis usually appears as an erythematous ring-shaped lesion with a scaly border, but atypical cases presenting with vesicles, pustules, and bullae also have been reported.3 Additionally, secondary eruptions called id reactions, or autoeczematization, can present in the setting of dermatophyte infections. Such outbreaks may be due to a delayed hypersensitivity reaction to the fungal antigens. Id reactions can manifest in many forms of tinea with patients generally exhibiting pruritic papulovesicular lesions that can present far from the site of origin.4

Patients with id reactions can have atypical and varied presentations. In a case of id reaction due to tinea corporis, a patient presented with vesicles and pustules that grew in number and coalesced to form annular lesions.5 A case of an id reaction caused by tinea pedis also noted the presence of pustules, which are atypical in this form of tinea.6 In another case of tinea pedis, a generalized id reaction was noted, illustrating that such eruptions do not necessarily appear at the original site of infection.7 Additionally, in a rare presentation of tinea invading the nares, a patient developed an erythema multiforme id reaction.8 Id reactions also were noted in 14 patients with refractory otitis externa, illustrating the ability of this fungal infection to persist and infect distant locations.9

Because the differential diagnoses for tinea infection are extensive, pathology or laboratory confirmation is necessary for diagnosis, and potassium hydroxide preparation often is used to diagnose dermatophyte infections.1,2 Additionally, the possibility of a hypersensitivity drug rash should remain in the differential if the patient received allergy-inducing medications prior to the outbreak, which may in turn complicate the diagnosis.

Tinea infections typically can be treated with topical antifungals such as terbinafine, butenafine,1 and luliconazole10; however, more involved cases may require oral antifungal treatment.1 Systemic treatment of tinea corporis includes itraconazole, terbinafine, and fluconazole,11 all of which exhibit fewer side effects and greater efficacy when compared to griseofulvin.12-15