User login

Acantholytic Anaplastic Extramammary Paget Disease

To the Editor:

Extramammary Paget disease (EMPD) is a rare intraepidermal neoplasm with glandular differentiation that is classically known as a mimicker of Bowen disease (squamous cell carcinoma in situ of the skin) due to their histologic similarities.1,2 However, acantholytic anaplastic EMPD (AAEMPD) is a rare variant that can pose a particularly difficult diagnostic challenge because of its histologic similarity to benign acantholytic disorders and other malignant neoplasms. Major histologic features suggestive of AAEMPD include full-thickness atypia of the epidermis, loss of nuclear polarity, marked cytologic anaplasia, intraepidermal acantholysis, and Paget cells.3 The differential diagnosis of EMPD typically includes Bowen disease and pagetoid Bowen disease, but the acantholytic anaplastic variant more often is confused with intraepidermal acantholytic lesions such as acantholytic dyskeratosis of the genitocrural area, familial benign pemphigus (Hailey-Hailey disease), pemphigus vulgaris, and acantholytic Bowen disease. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) studies to assist in the definitive diagnosis of AAEMPD are strongly advised because of these difficulties in diagnosis.4 Cases of EMPD with an acantholytic appearance have rarely been reported in the literature.5-7

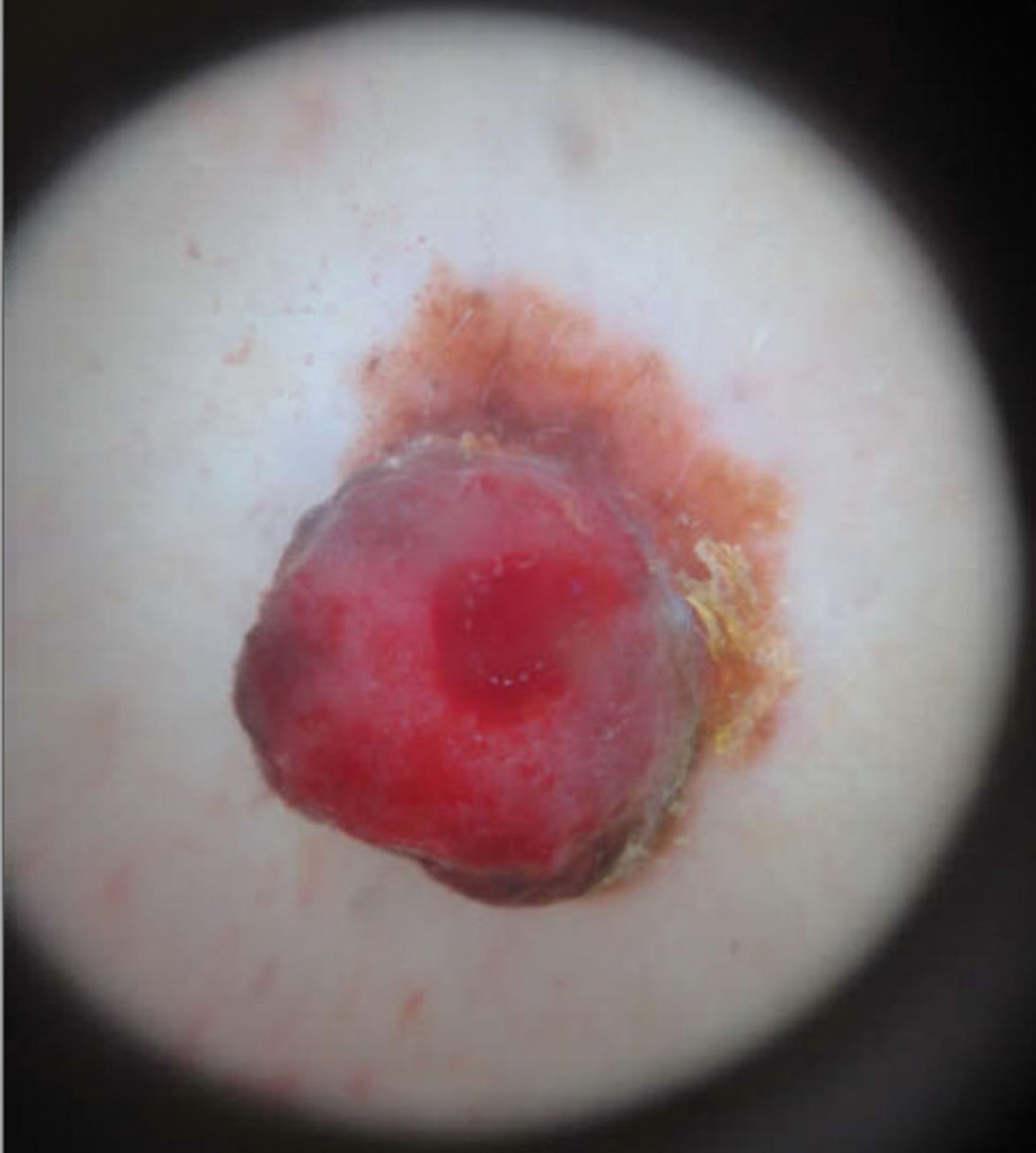

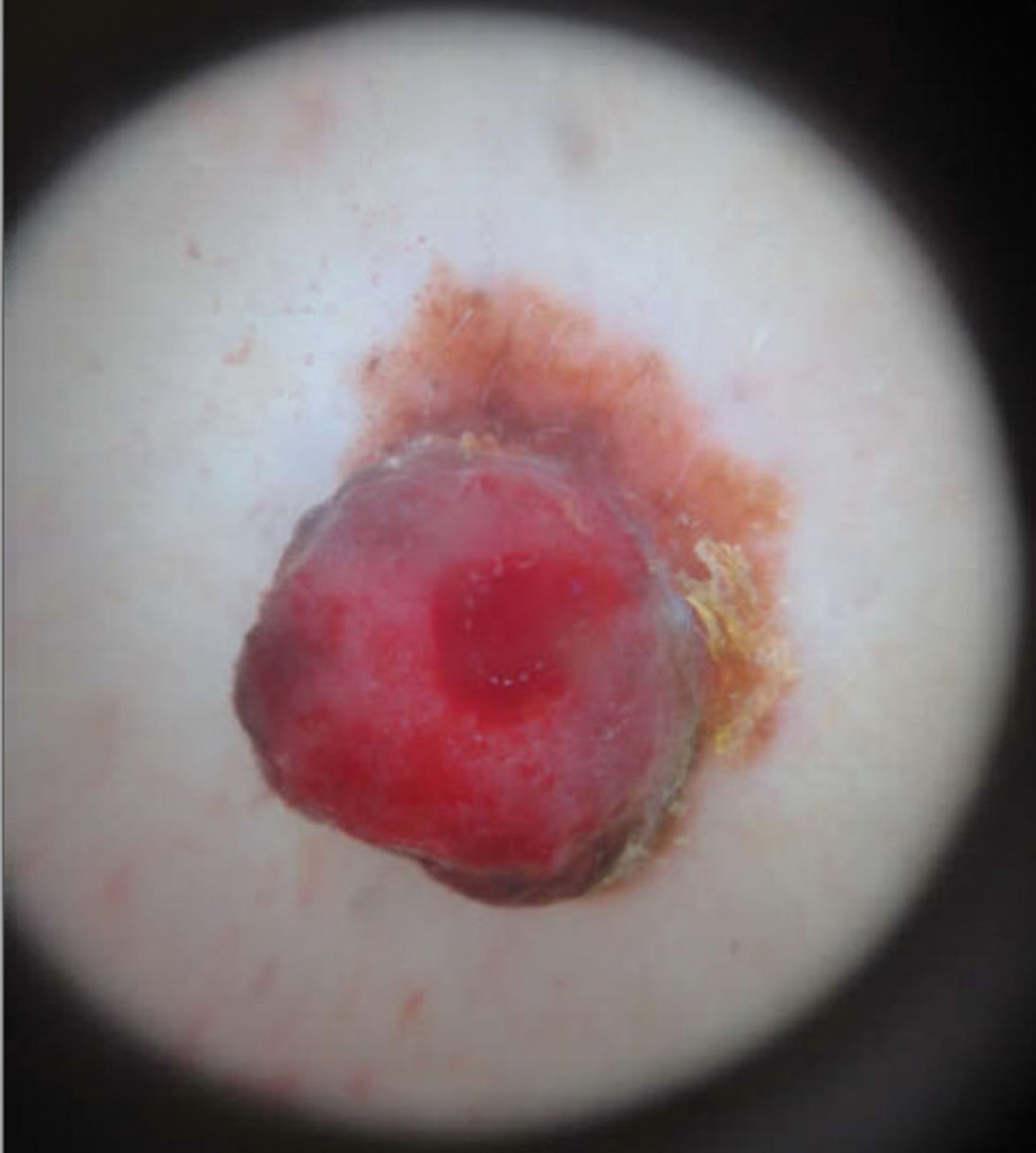

A 78-year-old man with a history of arthritis, heart disease, hypertension, and gastrointestinal disease presented for evaluation of a tender lesion of the right genitocrural crease of 5 years’ duration. He had no history of cutaneous or internal malignancy. Previously the lesion had been treated by dermatology with a variety of topical products including antifungal and antibiotic creams with no improvement. Physical examination revealed a well-defined, 7×5-cm, tender, erythematous, macerated plaque on the right upper inner thigh adjacent to the scrotum with an odor possibly due to secondary infection (Figure 1).

plaque on the right upper inner thigh adjacent to the scrotum.

A biopsy of the lesion was performed, and the specimen was submitted for pathologic examination. Bacterial cultures taken at the time of biopsy revealed polybacterial colonization with Acinetobacter, Morganella, and mixed skin flora. The patient was treated with a 10-day course of oral sulfamethoxazole 800 mg and trimethoprim 160 mg twice daily once culture results returned. The biopsy results were communicated to the patient; however, he subsequently relocated, assumed care at another facility, and has since been lost to follow-up.

The biopsy specimen was examined grossly, serially sectioned, and submitted for routine processing with hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid–Schiff, and Hale colloidal iron staining. Routine IHC was performed with antibodies to cytokeratin (CK) 7, CK20, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), pancytokeratin (CKAE1/AE3), and low- molecular-weight cytokeratin (LMWCK).

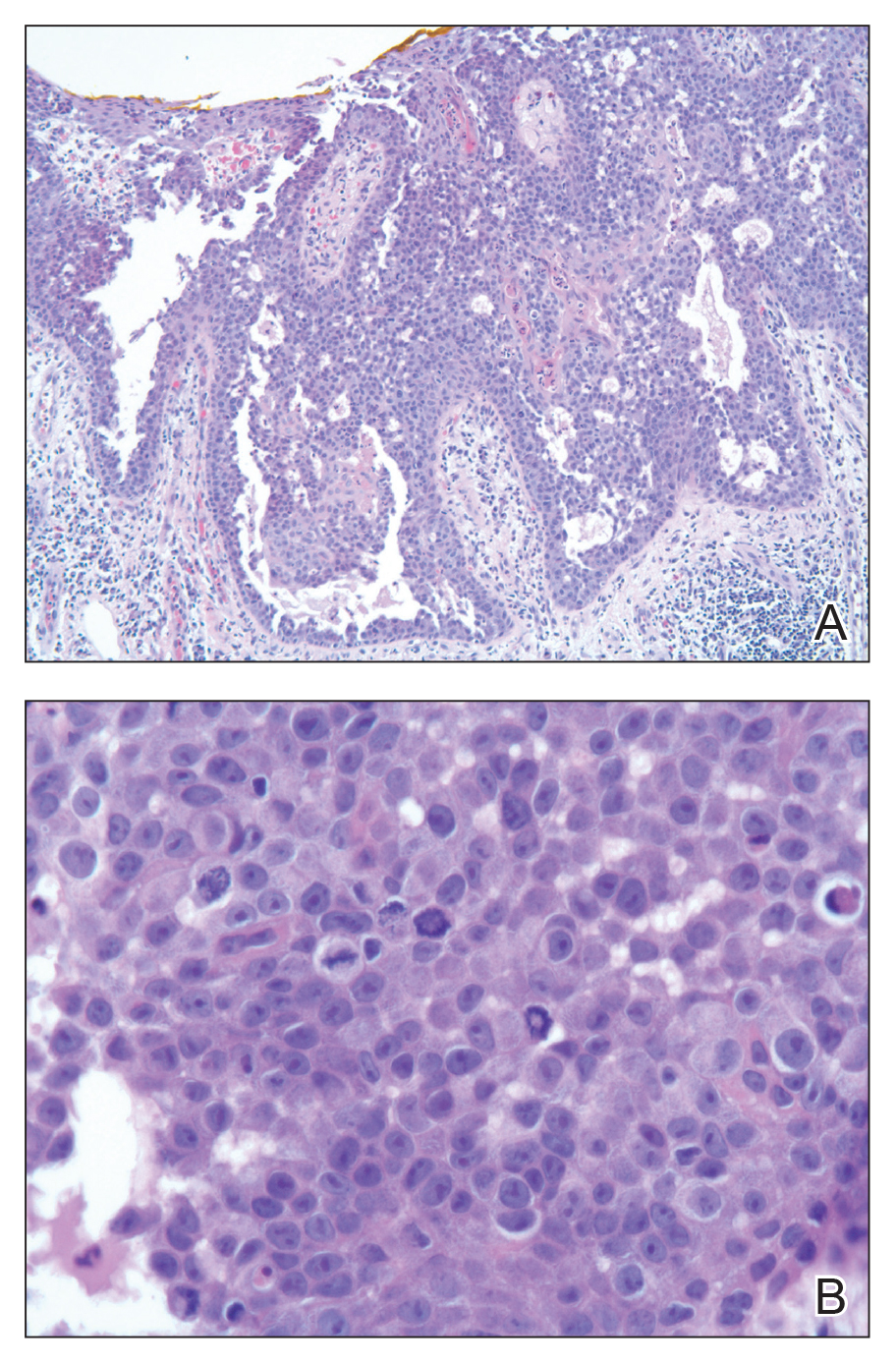

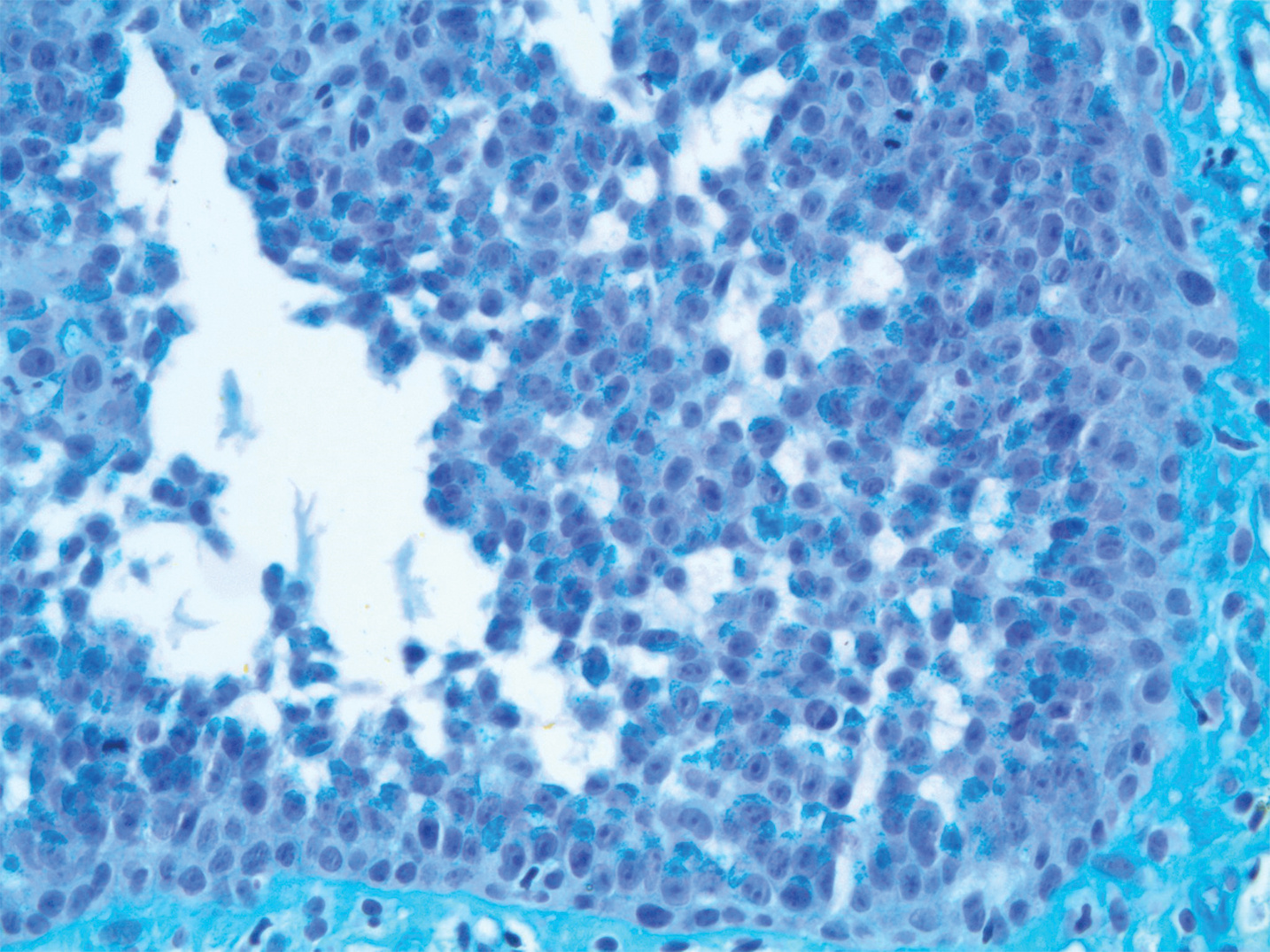

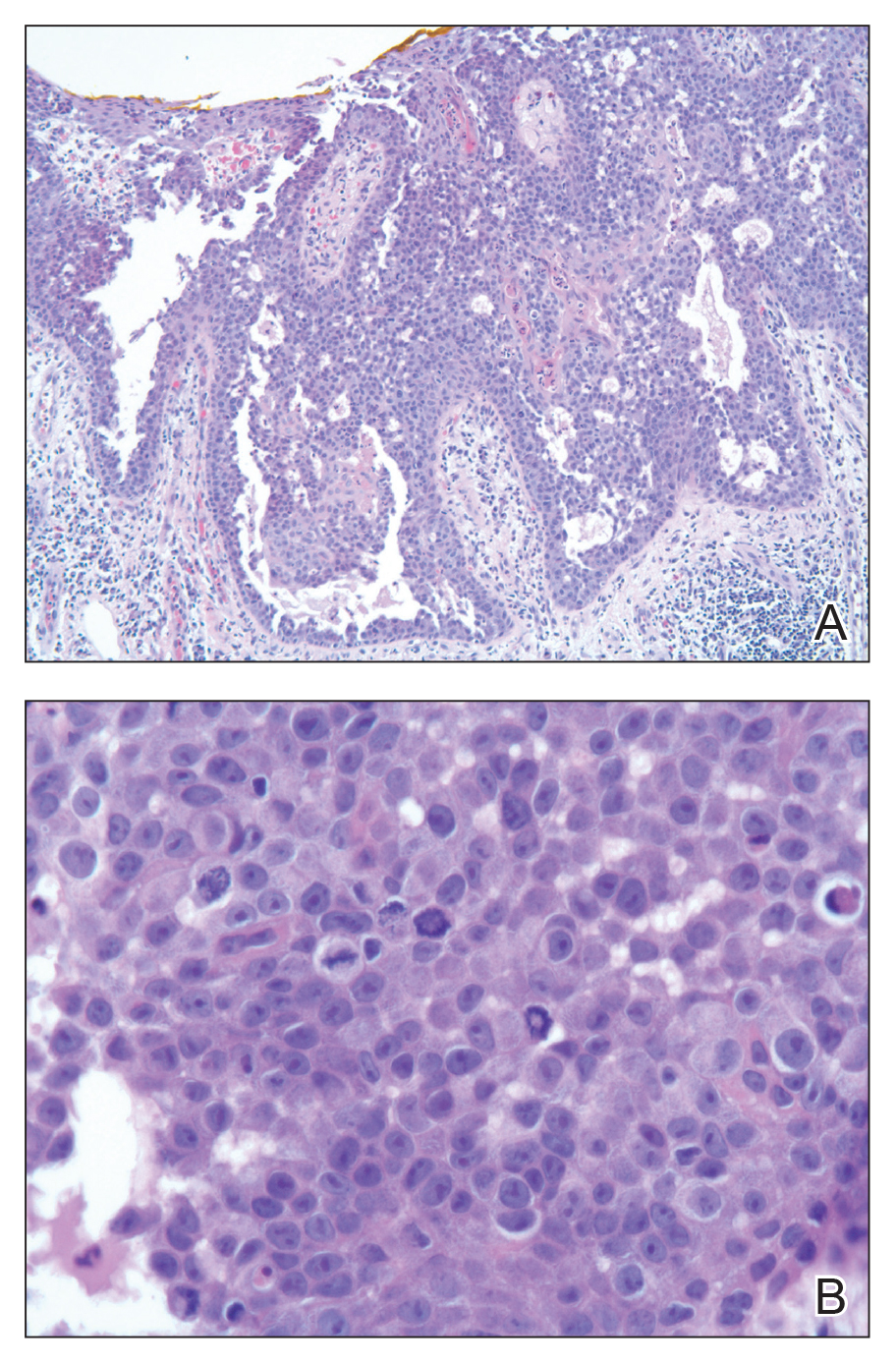

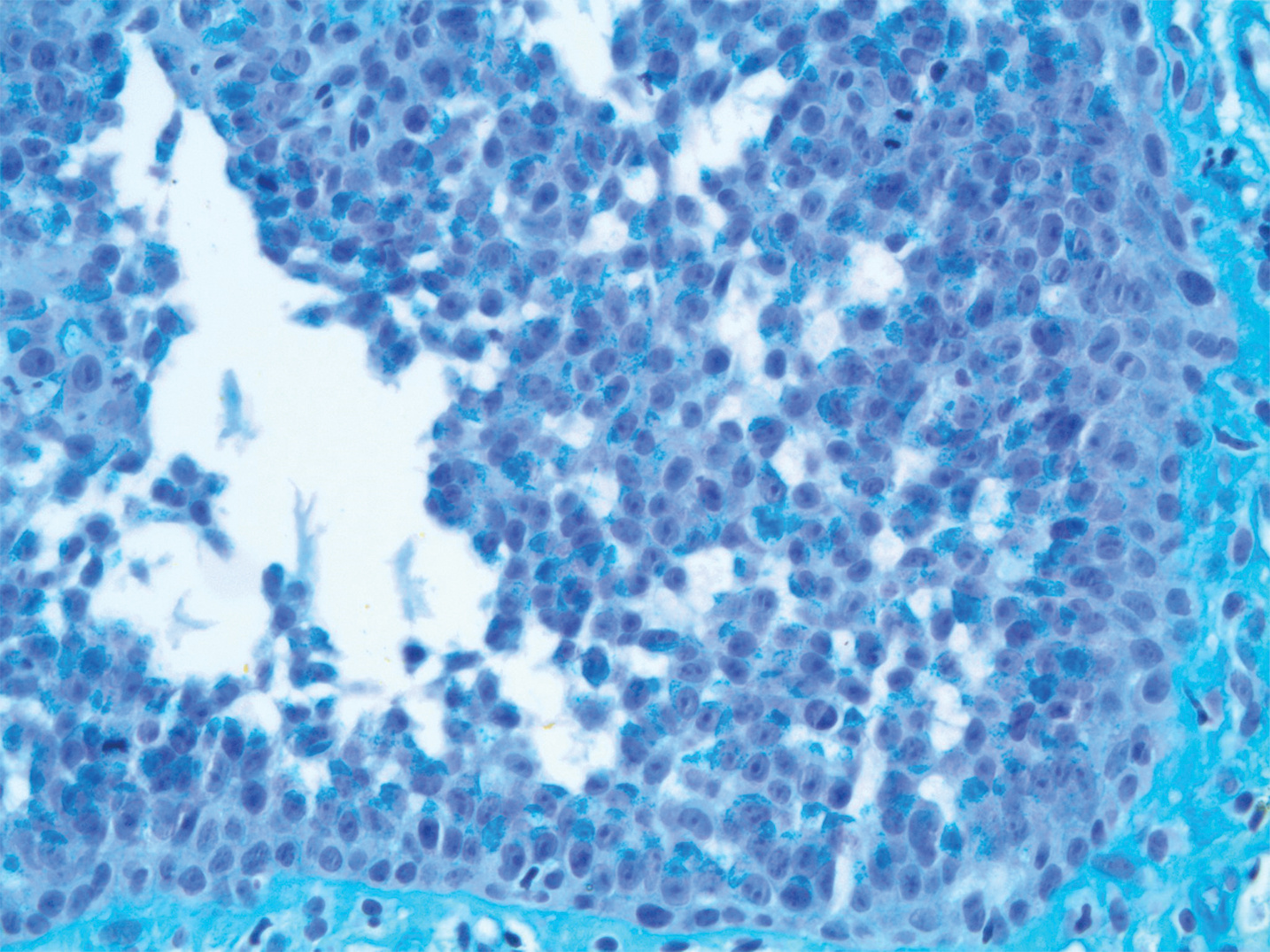

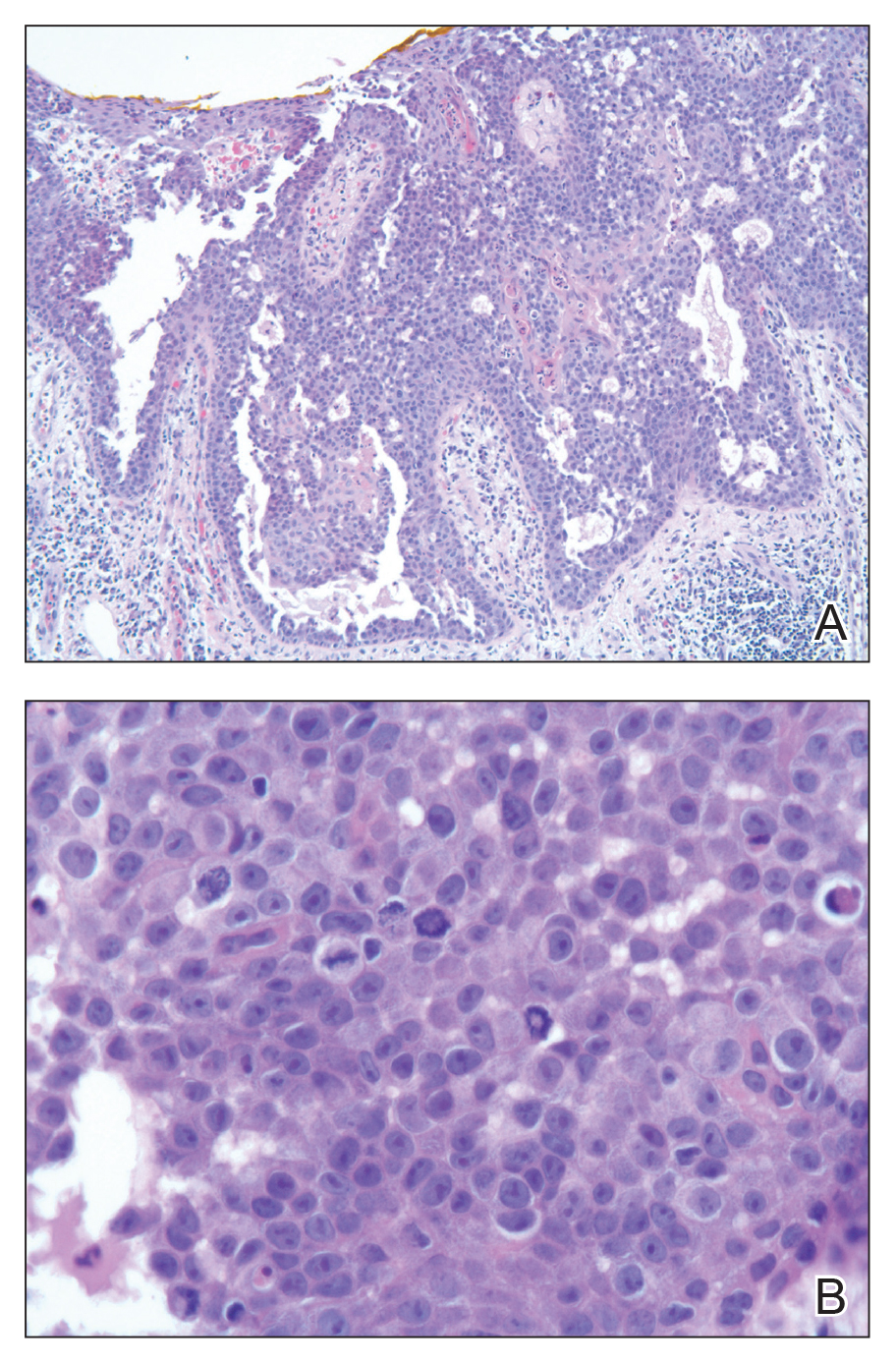

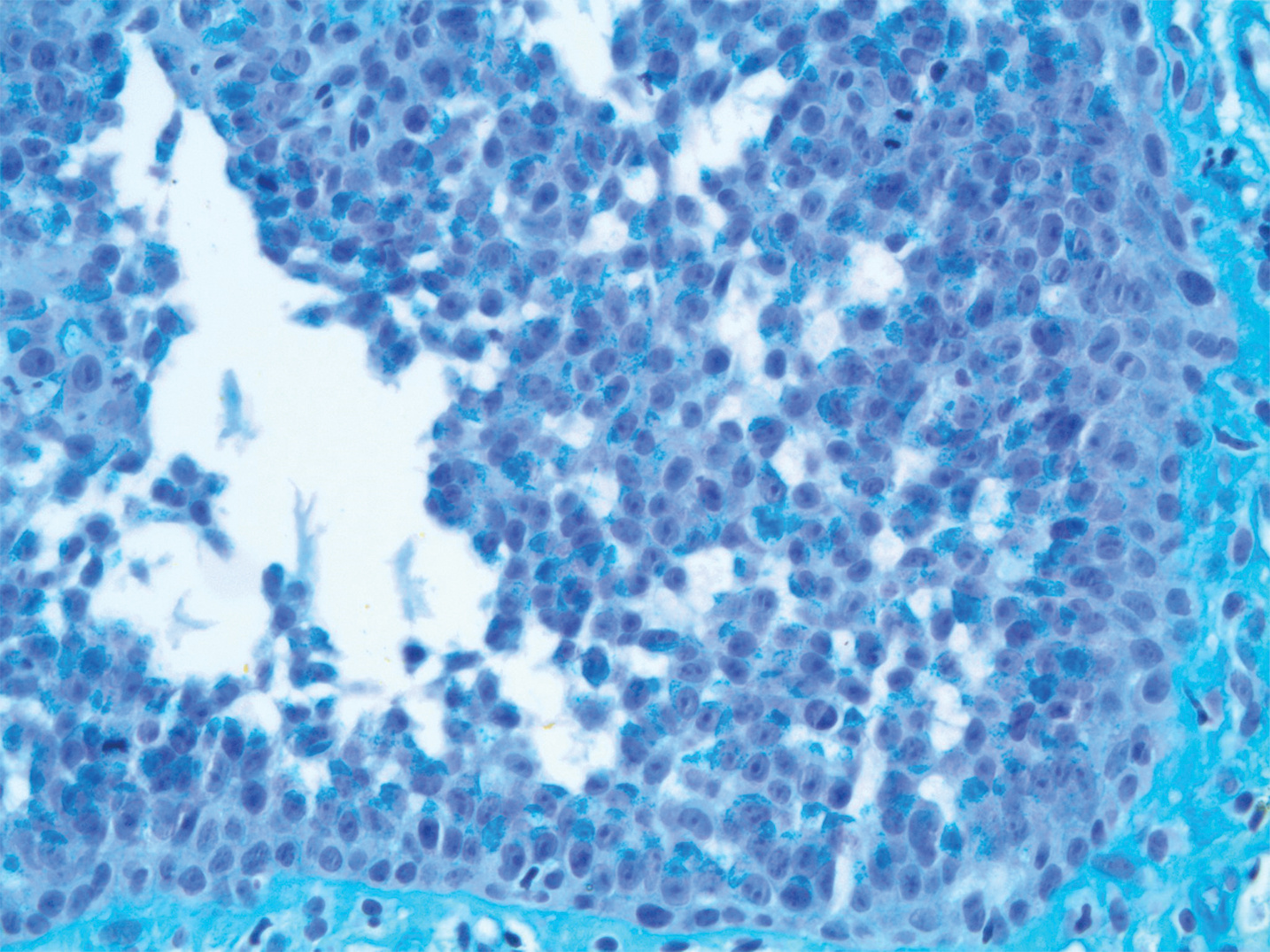

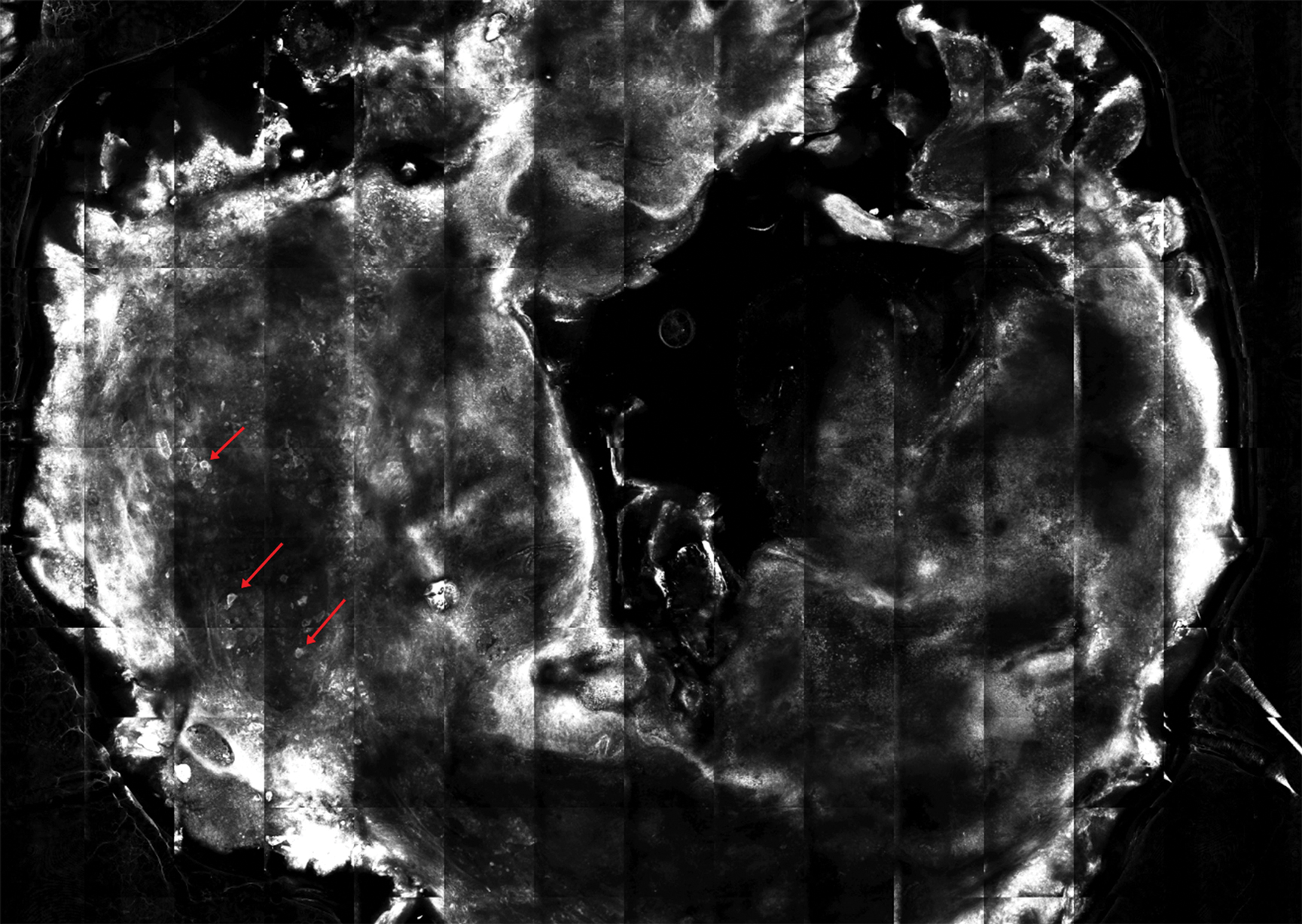

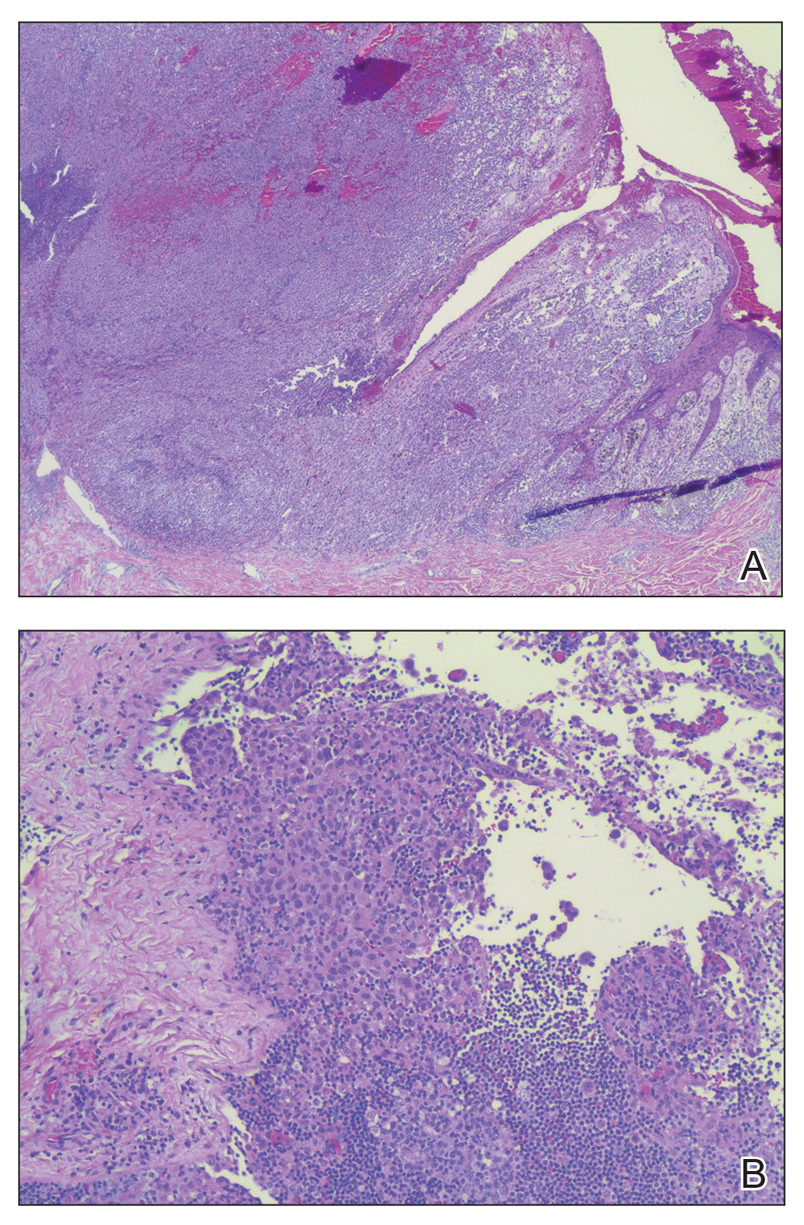

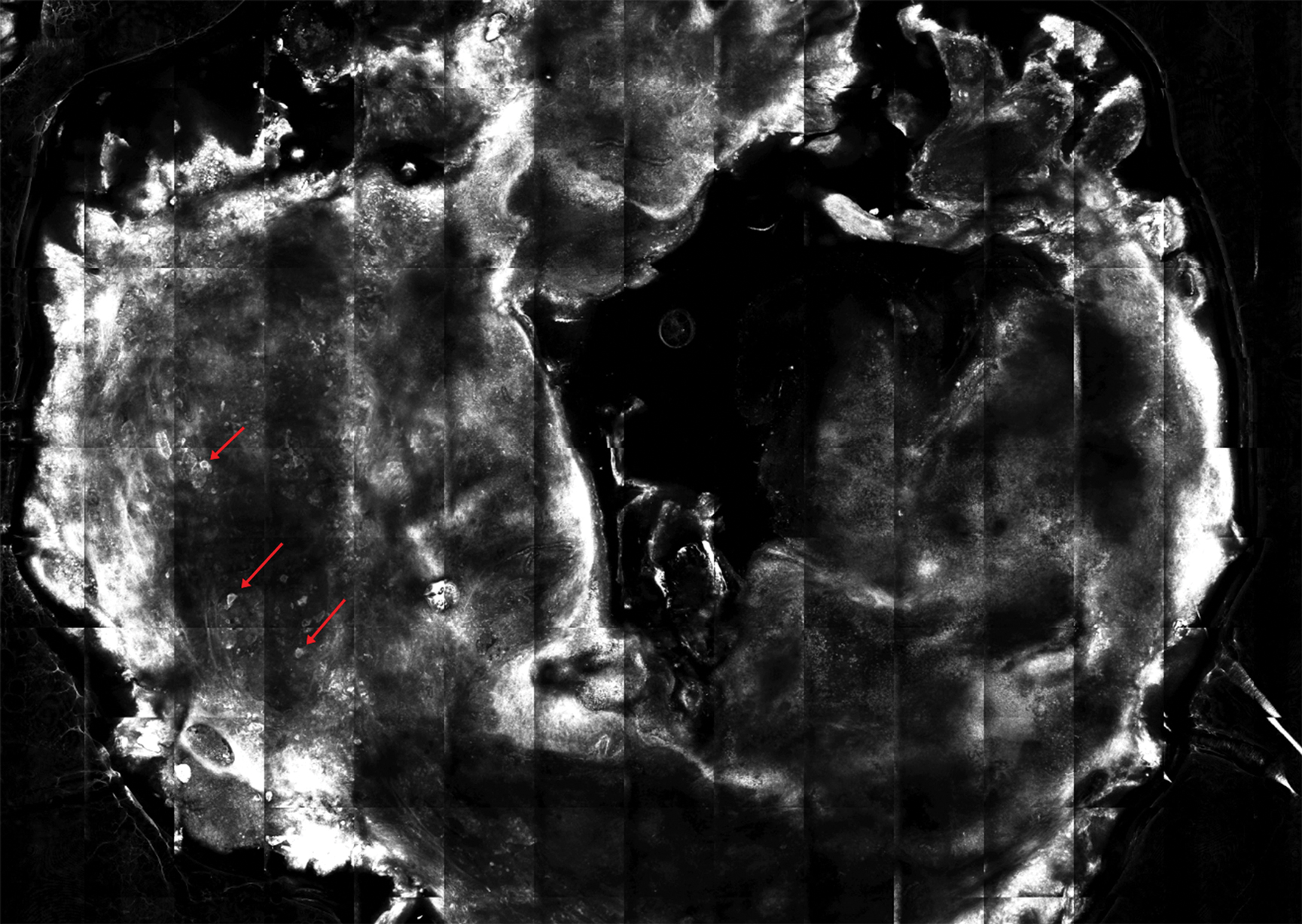

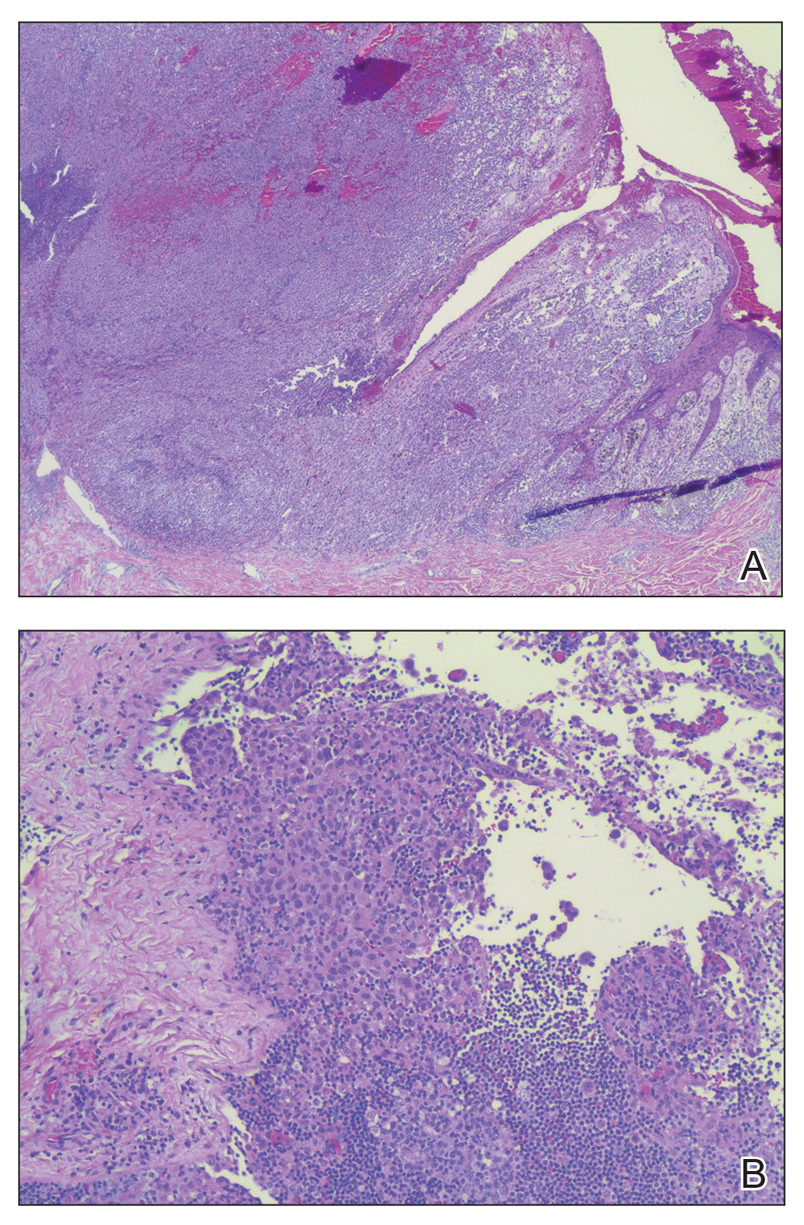

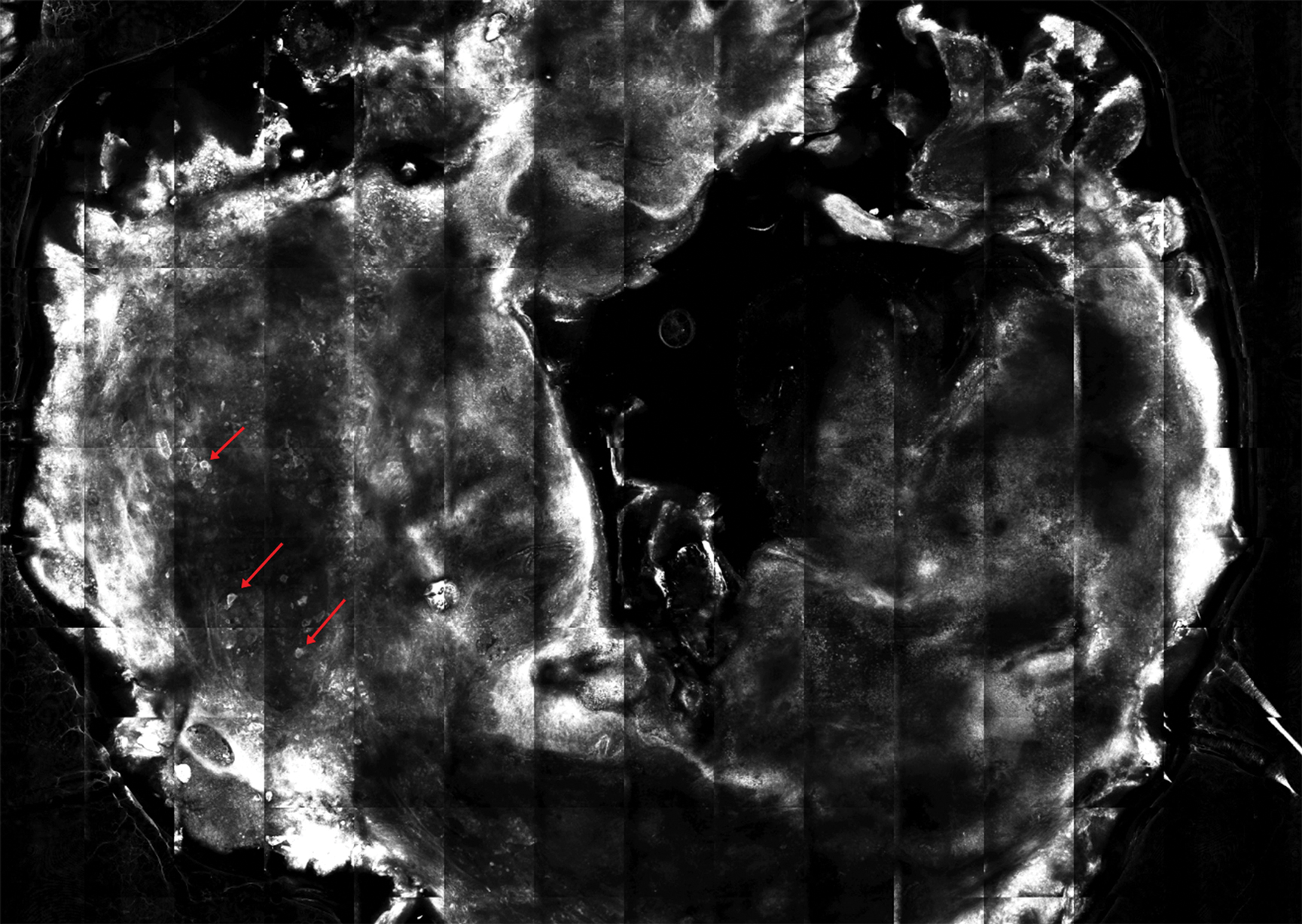

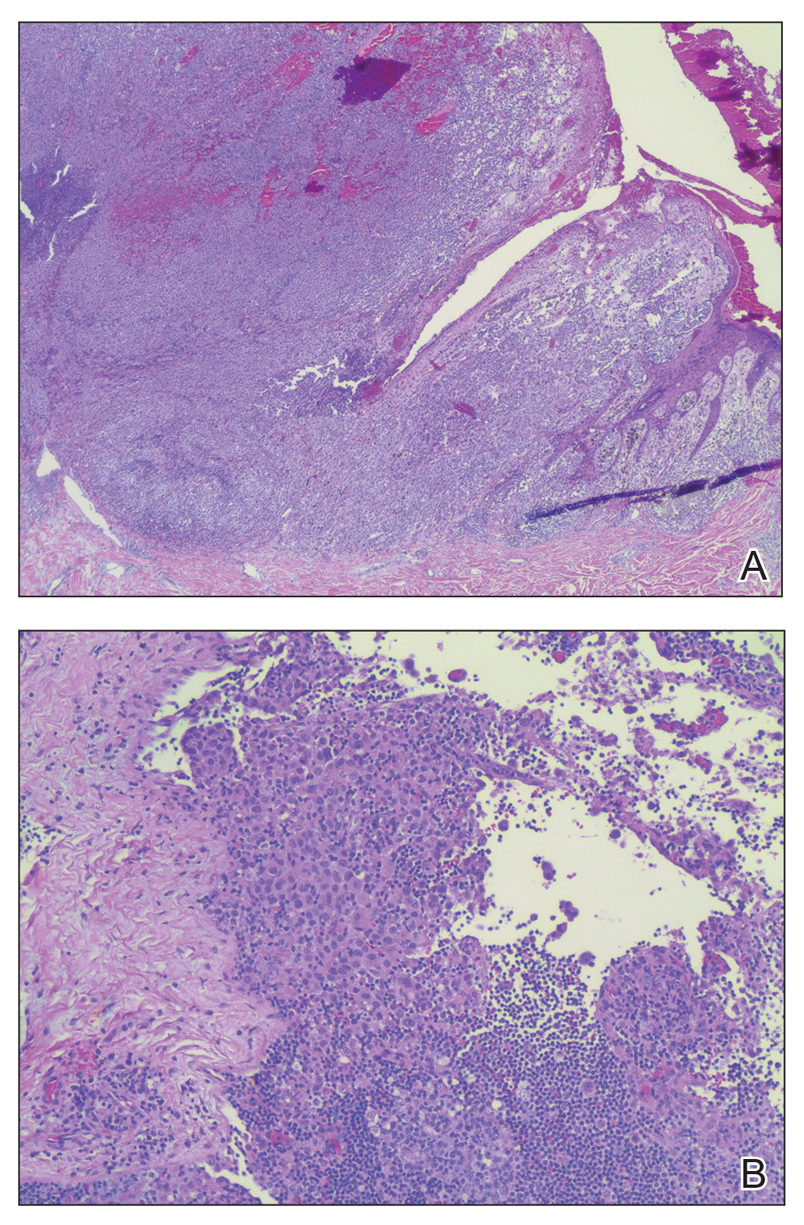

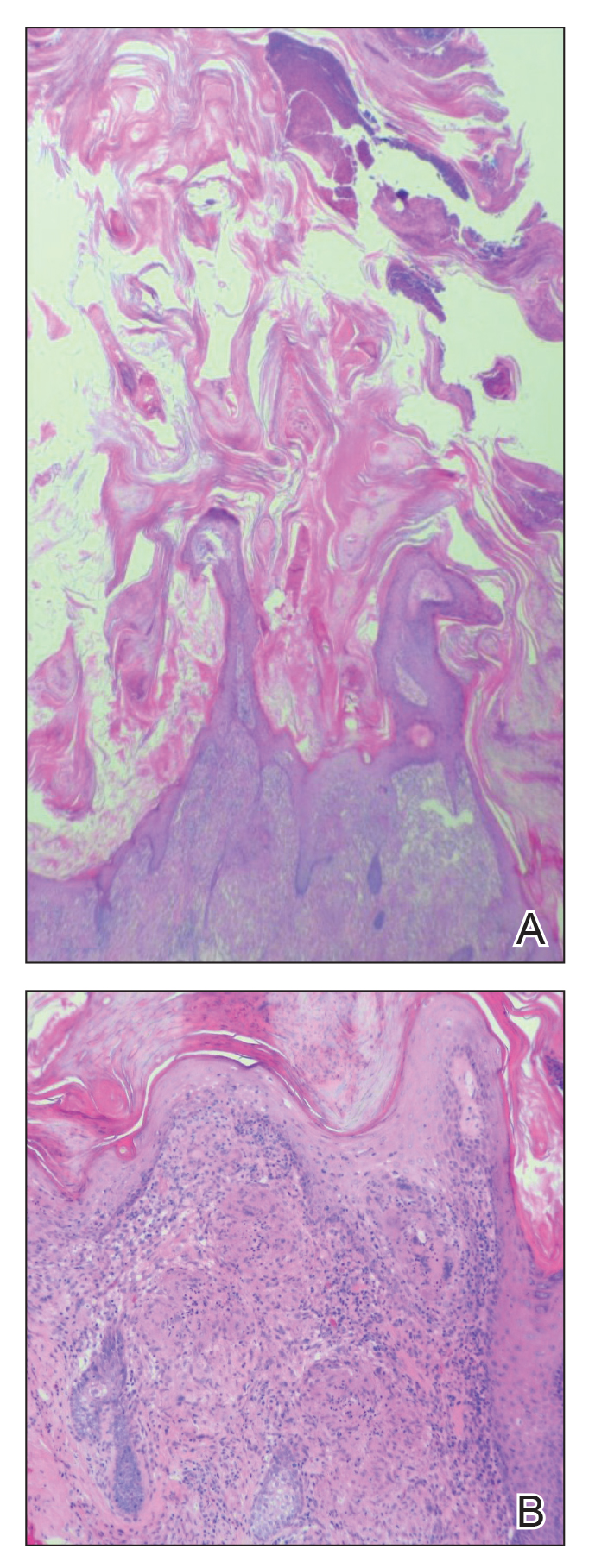

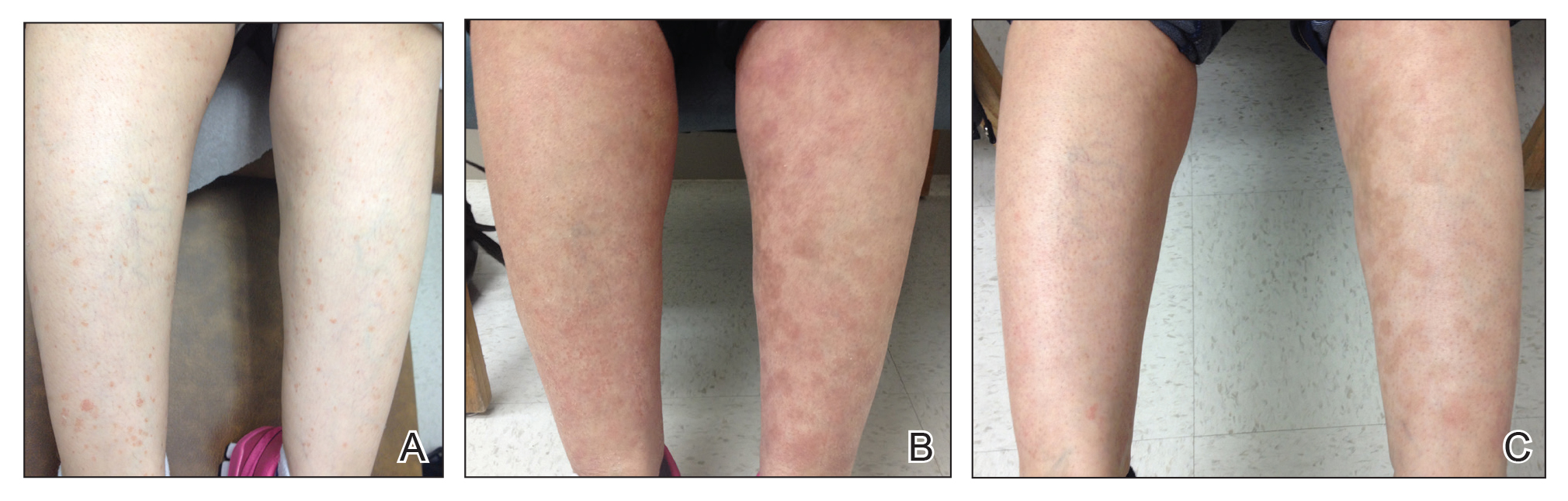

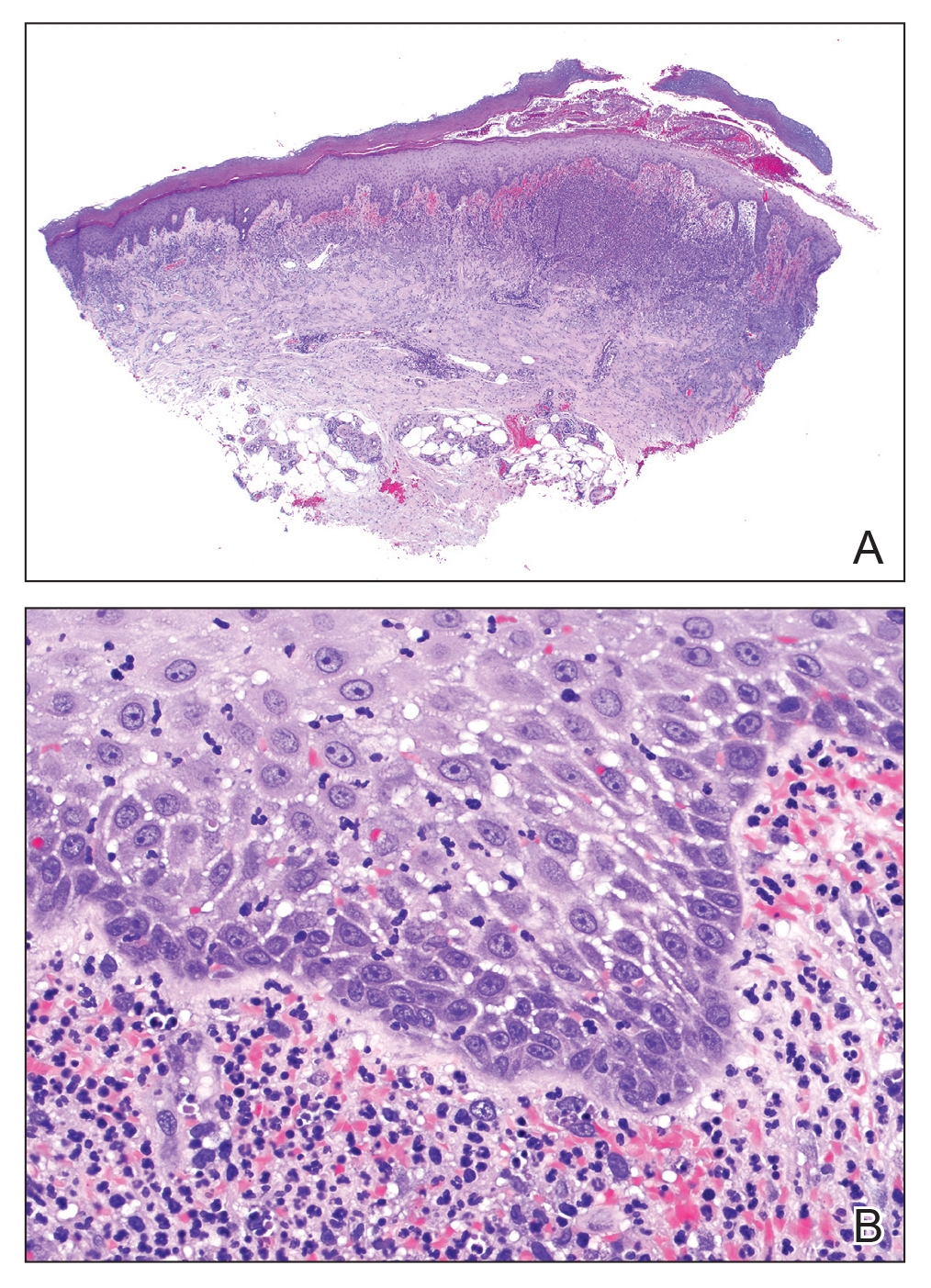

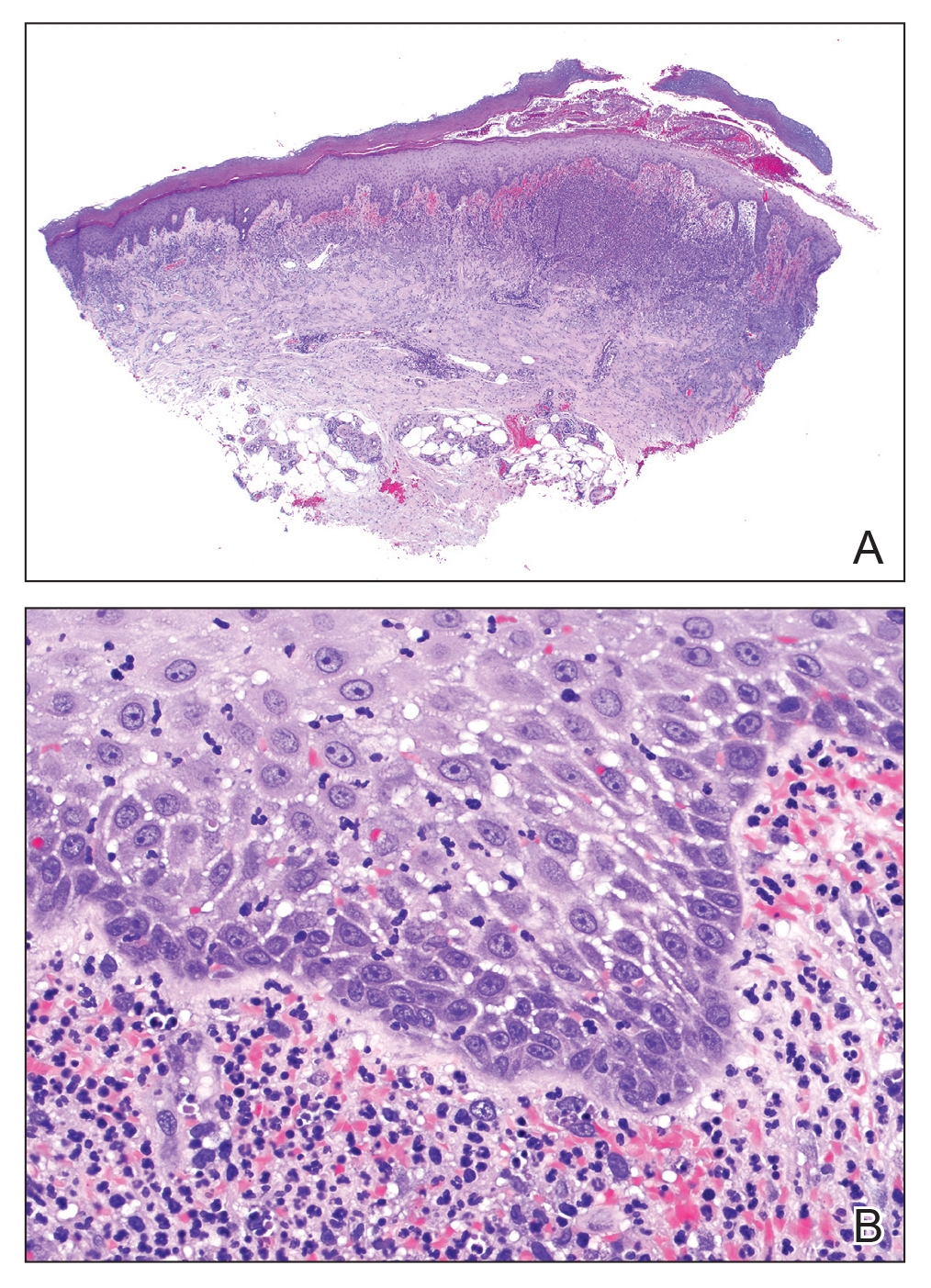

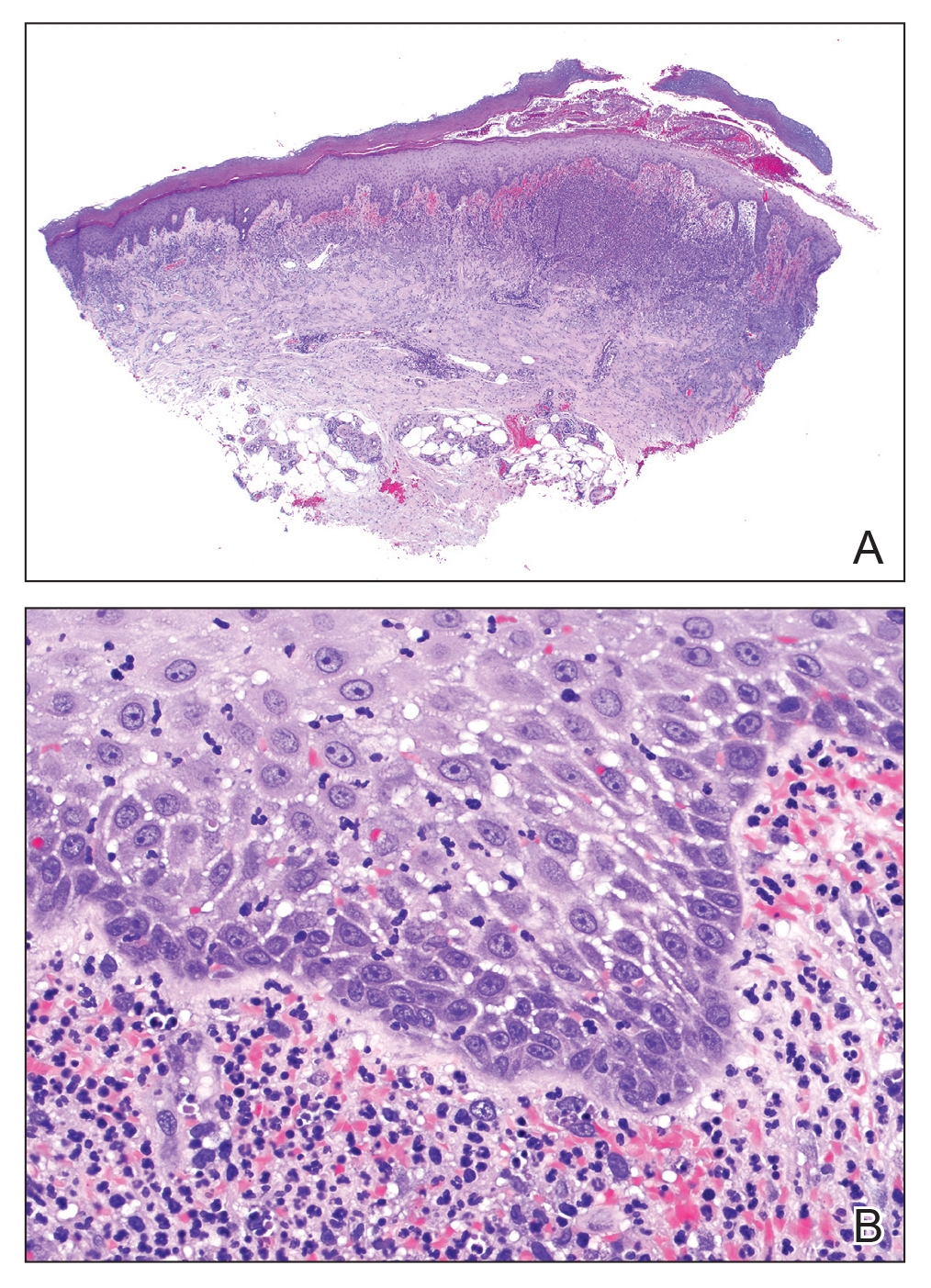

Pathologic examination of the biopsy showed prominent acanthosis of the epidermis composed of a proliferation of epithelial cells with associated full-thickness suprabasal acantholysis (Figure 2A). On inspection at higher magnification, the neoplastic cells demonstrated anaplasia as cytologic atypia with prominent and frequently multiple nucleoli, scant cytoplasm, and a high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio (Figure 2B). There was a marked increase in mitotic activity with as many as 5 mitotic figures per high-power field. A fairly dense mixed inflammatory infiltrate comprised of lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils, and eosinophils was present in the dermis. No fungal elements were observed on periodic acid–Schiff staining. The vast majority of tumor cells demonstrated moderate to abundant cytoplasmic mucin on Hale colloidal iron staining (Figure 3).

(H&E, original magnification ×400).

Immunohistochemistry staining of tumor cells was positive for CK7, CEA, pancytokeratin (CKAE1/AE3), and LMWCK. The tumor cells were negative for CK20. On the basis of the histopathologic and IHC findings, the patient was diagnosed with AAEMPD.

Extramammary Paget disease is a rare intraepidermal neoplasm with glandular differentiation. The most commonly involved sites are the anogenital areas including the vulvar, perianal, perineal, scrotal, and penile regions, as well as other areas rich in apocrine glands such as the axillae.8 Extramammary Paget disease most commonly originates as a primary intraepidermal neoplasm (type 1 EMPD), but an underlying malignant neoplasm that spreads intraepithelially is seen in a minority of cases (types 2 and 3 EMPD). In the vulva, type 1a refers to cutaneous noninvasive Paget disease, type 1b refers to dermal invasion of Paget disease, type 1c refers to vulvar adenocarcinoma–associated Paget disease, type 2 refers to rectal/anal adenocarcinoma–associated Paget disease, and type 3 refers to urogenital neoplasia–associated Paget disease.9

The acantholytic anaplastic variant of EMPD can be challenging to diagnose because of its similarities to many other lesions, including acantholytic dyskeratosis of the genitocrural area, familial benign pemphigus (Hailey-Hailey disease), pemphigus vulgaris, Bowen disease, pagetoid Bowen disease, and acantholytic Bowen disease. Major histologic features of AAEMPD include full-thickness atypia of the epidermis, loss of nuclear polarity, marked cytologic anaplasia, intraepidermal acantholysis, and Paget cells.3 The acantholytic anaplastic variant of EMPD can be differentiated from other diagnoses using IHC studies, with findings indicative of AAEMPD outlined below.

The proliferative neoplastic cell in EMPD is the Paget cell, which can be identified as a large round cell located in the epidermis with pale-staining cytoplasm, a large nucleus, and sometimes a prominent nucleolus. Paget cells can be distributed singly or in clusters, nests, or glandular structures within the epidermis and adjacent to adnexal structures.10 Extramammary Paget disease can have many patterns, including glandular, acantholysis-like, upper nest, tall nest, budding, and sheetlike.11

Immunohistochemically, Paget cells in EMPD typically express pancytokeratins (CKAE1/AE3), low-molecular-weight/simple epithelial type keratins (CK7, CAM 5.2), sweat gland antigens (epithelial membrane antigen, CEA, gross cystic disease fluid protein 15 [GCDFP15]), mucin 5AC (MUC5AC), and often androgen receptor.12-18 Paget cells contain cytoplasmic mucin and demonstrate prominent cytoplasmic staining with Hale colloidal iron.17 Paget cells typically do not express high-molecular-weight cytokeratin (eg, CK5/6), melanocytic antigens, estrogen receptor, or progesterone receptor.15,18

Immunohistochemical staining has been shown to differ between primary cutaneous (type 1) and secondary (types 2 and 3) EMPD. Primary cutaneous EMPD typically expresses sweat gland markers (CK7+, CK20−, GCDFP15+). Secondary EMPD typically expresses an endodermal phenotype (CK7+, CK20+, GCDFP15−).12

Acantholytic dyskeratosis of the genitocrural area is a rare lesion included in the spectrum of focal acantholytic dyskeratoses described by Ackerman.19 It also has been referred to as papular acantholytic dyskeratosis of the vulva, though histologically similar lesions also have been reported in men.20-22 Histologically, acantholytic dyskeratosis of the genitocrural area has prominent acantholysis and dyskeratosis with corps ronds and grains.19 Familial benign pemphigus (Hailey-Hailey disease) is caused by mutations of the ATP2C1 gene, which encodes for a secretory pathway Ca2+/Mn2+-ATPase pump type 1 (SPCA1) in the Golgi apparatus in keratinocytes.23 Familial benign pemphigus has a histologic appearance similar to acantholytic dyskeratosis of the genitocrural area, but a positive family history of familial benign pemphigus can be used to differentiate the 2 entities from each other due to the autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern of familial benign pemphigus. Both of these disorders can appear similar to AAEMPD because of their extensive intraepidermal acantholysis, but they differ in the lack of Paget cells, intraepidermal atypia, and increased mitotic activity.

Acantholytic Bowen disease is a histologic variant that can be difficult to distinguish from AAEMPD on hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections because of their similar histologic features but can be differentiated by IHC stains.5 Acantholytic Bowen disease expresses high-molecular-weight cytokeratin (eg, CK5/6) but is negative for CK7, CAM 5.2, and CEA. Extramammary Paget disease generally has the opposite pattern: positive staining for CK7, CAM 5.2, and CEA, but negative for high-molecular-weight cytokeratin.13,14,24

Primary cutaneous adenosquamous carcinoma is a rare malignancy of squamous and glandular differentiation known for being locally aggressive and metastatic.25 Histologically, cutaneous adenosquamous carcinoma shows infiltrating nests of neoplastic cells with both squamous and glandular features. It differs notably from AAEMPD in that cutaneous adenosquamous carcinomas tend to arise in the head and arm regions, and their histologic morphology is different. The IHC profiles are similar, with positive staining for CEA, CK7, and mucin; however, they differ in that AAEMPD is negative for high-molecular-weight keratin while cutaneous adenosquamous carcinoma is positive.25

Verrucous carcinoma is an uncommon variant of squamous cell carcinoma with well-differentiated keratinocytes and a blunt pushing border.24 Similar to AAEMPD, this neoplasm can arise in the genital and perineal areas; however, the 2 entities differ considerably in morphology on histologic examination.

Pemphigus vulgaris is an autoimmune intraepidermal blistering disorder of the skin and mucous membranes of which pemphigus vegetans is a subtype.26,27 Pemphigus vulgaris is another diagnosis that can possibly be mimicked by AAEMPD.28 Histologic features of pemphigus vulgaris include intraepidermal acantholysis of keratinocytes immediately above the basal layer of the epidermis. Pemphigus vegetans is similar with the addition of papillomatosis, hyperkeratosis, and an eosinophilic infiltrate.26,27 Immunofluorescence typically demonstrates intercellular C3 and IgG deposits.26 These diseases mimic AAEMPD histologically but differ in their relative lack of atypia and Paget cells.

In summary, we report a case of AAEMPD in a 78-year-old man in whom routine histologic specimens showed marked intraepidermal acantholysis and atypical tumor cells with increased mitoses. The latter finding prompted IHC studies that revealed positive CK7, CEA, pancytokeratin, and LMWCK staining with negative CK20 staining. Hale colloidal iron staining showed moderate to abundant cytoplasmic mucin. The patient was diagnosed with AAEMPD. It is imperative to maintain clinical suspicion for AAEMPD and to examine acantholytic disorders with scrutiny. When there is evidence of atypia or mitoses, use of IHC stains can assist in fully characterizing the lesion.

- Bowen JT. Precancerous dermatosis: a study of two cases of chronic atypical epithelial proliferation. J Cutan Dis. 1912;30:241-255.

- Jones RE Jr, Austin C, Ackerman AB. Extramammary Paget’s disease: a critical reexamination. Am J Dermatopathol. 1979;1:101-132.

- Rayne SC, Santa Cruz DJ. Anaplastic Paget’s disease. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992;16:1085-1091.

- Wang EC, Kwah YC, Tan WP, et al. Extramammary Paget disease: immunohistochemistry is critical to distinguish potential mimickers. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:4.

- Du X, Yin X, Zhou N, et al. Extramammary Paget’s disease mimicking acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma in situ: a case report. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:683.

- Mobini N. Acantholytic anaplastic Paget’s disease. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:374-380.

- Oh YJ, Lew BL, Sim WY. Acantholytic anaplastic extramammary Paget’s disease: a case report and review of the literature. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:226-230.

- Zollo JD, Zeitouni NC. The Roswell Park Cancer Institute experience with extramammary Paget’s disease. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:59-65.

- Wilkinson EJ, Brown HM. Vulvar Paget disease of urothelial origin: a report of three cases and a proposed classification of vulvar Paget disease. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:549-554.

- Lam C, Funaro D. Extramammary Paget’s disease: summary of current knowledge. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:807-826.

- Shiomi T, Yoshida Y, Shomori K, et al. Extramammary Paget’s disease: evaluation of the histopathological patterns of Paget cell proliferation in the epidermis. J Dermatol. 2011;38:1054-1057.

- Goldblum JR, Hart WR. Vulvar Paget’s disease: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 19 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:1178-1187.

- Alhumaidi A. Practical immunohistochemistry of epithelial skin tumor. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 2012;78:698-708.

- Battles O, Page D, Johnson J. Cytokeratins, CEA and mucin histochemistry in the diagnosis and characterization of extramammary Paget’s disease. Am J Clin Pathol. 1997;108:6-12.

- Kanitakis J. Mammary and extramammary Paget’s disease. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:581-590.

- Krishna M. Diagnosis of metastatic neoplasms: an immunohistochemical approach. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:207-215.

- Helm KF, Goellner JR, Peters MS. Immunohistochemical stain in extramammary Paget’s disease. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:402-407.

- Liegl B, Horn L, Moinfar F. Androgen receptors are frequently expressed in mammary and extramammary Paget’s disease. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:1283-288.

- Ackerman AB. Focal acantholytic dyskeratosis. Arch Derm. 1972;106:702-706.

- Dittmer CJ, Hornemann A, Rose C, et al. Successful laser therapy of a papular acantholytic dyskeratosis of the vulva: case report and review of literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2010;291:723-725.

- Roh MR, Choi YJ, Lee KG. Papular acantholytic dyskeratosis of the vulva. J Dermatol. 2009;36:427-429.

- Wong KT, Mihm MC Jr. Acantholytic dermatosis localized to genitalia and crural areas of male patients: a report of three cases. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:27-32.

- Hu Z, Bonifas JM, Beech J, et al. Mutations in ATP2C1, encoding a calcium pump, cause Hailey-Hailey disease. Nat Genet. 2000; 24:61-65.

- Elston DM. Malignant tumors of the epidermis. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, eds. Requisites in Dermatology: Dermatopathology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Limited; 2012:53-68.

- Fu JM, McCalmont T, Yu SS. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the skin: a case series. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1152-1158.

- Becker BA, Gaspari AA. Pemphigus vulgaris and vegetans. Dermatol Clin. 1993;11:429-452.

- Rados J. Autoimmune blistering diseases: histologic meaning. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:377-388.

- Kohler S, Smoller BR. A case of extramammary Paget’s disease mimicking pemphigus vulgaris on histologic examination. Dermatology. 1997;195:54-56.

To the Editor:

Extramammary Paget disease (EMPD) is a rare intraepidermal neoplasm with glandular differentiation that is classically known as a mimicker of Bowen disease (squamous cell carcinoma in situ of the skin) due to their histologic similarities.1,2 However, acantholytic anaplastic EMPD (AAEMPD) is a rare variant that can pose a particularly difficult diagnostic challenge because of its histologic similarity to benign acantholytic disorders and other malignant neoplasms. Major histologic features suggestive of AAEMPD include full-thickness atypia of the epidermis, loss of nuclear polarity, marked cytologic anaplasia, intraepidermal acantholysis, and Paget cells.3 The differential diagnosis of EMPD typically includes Bowen disease and pagetoid Bowen disease, but the acantholytic anaplastic variant more often is confused with intraepidermal acantholytic lesions such as acantholytic dyskeratosis of the genitocrural area, familial benign pemphigus (Hailey-Hailey disease), pemphigus vulgaris, and acantholytic Bowen disease. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) studies to assist in the definitive diagnosis of AAEMPD are strongly advised because of these difficulties in diagnosis.4 Cases of EMPD with an acantholytic appearance have rarely been reported in the literature.5-7

A 78-year-old man with a history of arthritis, heart disease, hypertension, and gastrointestinal disease presented for evaluation of a tender lesion of the right genitocrural crease of 5 years’ duration. He had no history of cutaneous or internal malignancy. Previously the lesion had been treated by dermatology with a variety of topical products including antifungal and antibiotic creams with no improvement. Physical examination revealed a well-defined, 7×5-cm, tender, erythematous, macerated plaque on the right upper inner thigh adjacent to the scrotum with an odor possibly due to secondary infection (Figure 1).

plaque on the right upper inner thigh adjacent to the scrotum.

A biopsy of the lesion was performed, and the specimen was submitted for pathologic examination. Bacterial cultures taken at the time of biopsy revealed polybacterial colonization with Acinetobacter, Morganella, and mixed skin flora. The patient was treated with a 10-day course of oral sulfamethoxazole 800 mg and trimethoprim 160 mg twice daily once culture results returned. The biopsy results were communicated to the patient; however, he subsequently relocated, assumed care at another facility, and has since been lost to follow-up.

The biopsy specimen was examined grossly, serially sectioned, and submitted for routine processing with hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid–Schiff, and Hale colloidal iron staining. Routine IHC was performed with antibodies to cytokeratin (CK) 7, CK20, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), pancytokeratin (CKAE1/AE3), and low- molecular-weight cytokeratin (LMWCK).

Pathologic examination of the biopsy showed prominent acanthosis of the epidermis composed of a proliferation of epithelial cells with associated full-thickness suprabasal acantholysis (Figure 2A). On inspection at higher magnification, the neoplastic cells demonstrated anaplasia as cytologic atypia with prominent and frequently multiple nucleoli, scant cytoplasm, and a high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio (Figure 2B). There was a marked increase in mitotic activity with as many as 5 mitotic figures per high-power field. A fairly dense mixed inflammatory infiltrate comprised of lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils, and eosinophils was present in the dermis. No fungal elements were observed on periodic acid–Schiff staining. The vast majority of tumor cells demonstrated moderate to abundant cytoplasmic mucin on Hale colloidal iron staining (Figure 3).

(H&E, original magnification ×400).

Immunohistochemistry staining of tumor cells was positive for CK7, CEA, pancytokeratin (CKAE1/AE3), and LMWCK. The tumor cells were negative for CK20. On the basis of the histopathologic and IHC findings, the patient was diagnosed with AAEMPD.

Extramammary Paget disease is a rare intraepidermal neoplasm with glandular differentiation. The most commonly involved sites are the anogenital areas including the vulvar, perianal, perineal, scrotal, and penile regions, as well as other areas rich in apocrine glands such as the axillae.8 Extramammary Paget disease most commonly originates as a primary intraepidermal neoplasm (type 1 EMPD), but an underlying malignant neoplasm that spreads intraepithelially is seen in a minority of cases (types 2 and 3 EMPD). In the vulva, type 1a refers to cutaneous noninvasive Paget disease, type 1b refers to dermal invasion of Paget disease, type 1c refers to vulvar adenocarcinoma–associated Paget disease, type 2 refers to rectal/anal adenocarcinoma–associated Paget disease, and type 3 refers to urogenital neoplasia–associated Paget disease.9

The acantholytic anaplastic variant of EMPD can be challenging to diagnose because of its similarities to many other lesions, including acantholytic dyskeratosis of the genitocrural area, familial benign pemphigus (Hailey-Hailey disease), pemphigus vulgaris, Bowen disease, pagetoid Bowen disease, and acantholytic Bowen disease. Major histologic features of AAEMPD include full-thickness atypia of the epidermis, loss of nuclear polarity, marked cytologic anaplasia, intraepidermal acantholysis, and Paget cells.3 The acantholytic anaplastic variant of EMPD can be differentiated from other diagnoses using IHC studies, with findings indicative of AAEMPD outlined below.

The proliferative neoplastic cell in EMPD is the Paget cell, which can be identified as a large round cell located in the epidermis with pale-staining cytoplasm, a large nucleus, and sometimes a prominent nucleolus. Paget cells can be distributed singly or in clusters, nests, or glandular structures within the epidermis and adjacent to adnexal structures.10 Extramammary Paget disease can have many patterns, including glandular, acantholysis-like, upper nest, tall nest, budding, and sheetlike.11

Immunohistochemically, Paget cells in EMPD typically express pancytokeratins (CKAE1/AE3), low-molecular-weight/simple epithelial type keratins (CK7, CAM 5.2), sweat gland antigens (epithelial membrane antigen, CEA, gross cystic disease fluid protein 15 [GCDFP15]), mucin 5AC (MUC5AC), and often androgen receptor.12-18 Paget cells contain cytoplasmic mucin and demonstrate prominent cytoplasmic staining with Hale colloidal iron.17 Paget cells typically do not express high-molecular-weight cytokeratin (eg, CK5/6), melanocytic antigens, estrogen receptor, or progesterone receptor.15,18

Immunohistochemical staining has been shown to differ between primary cutaneous (type 1) and secondary (types 2 and 3) EMPD. Primary cutaneous EMPD typically expresses sweat gland markers (CK7+, CK20−, GCDFP15+). Secondary EMPD typically expresses an endodermal phenotype (CK7+, CK20+, GCDFP15−).12

Acantholytic dyskeratosis of the genitocrural area is a rare lesion included in the spectrum of focal acantholytic dyskeratoses described by Ackerman.19 It also has been referred to as papular acantholytic dyskeratosis of the vulva, though histologically similar lesions also have been reported in men.20-22 Histologically, acantholytic dyskeratosis of the genitocrural area has prominent acantholysis and dyskeratosis with corps ronds and grains.19 Familial benign pemphigus (Hailey-Hailey disease) is caused by mutations of the ATP2C1 gene, which encodes for a secretory pathway Ca2+/Mn2+-ATPase pump type 1 (SPCA1) in the Golgi apparatus in keratinocytes.23 Familial benign pemphigus has a histologic appearance similar to acantholytic dyskeratosis of the genitocrural area, but a positive family history of familial benign pemphigus can be used to differentiate the 2 entities from each other due to the autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern of familial benign pemphigus. Both of these disorders can appear similar to AAEMPD because of their extensive intraepidermal acantholysis, but they differ in the lack of Paget cells, intraepidermal atypia, and increased mitotic activity.

Acantholytic Bowen disease is a histologic variant that can be difficult to distinguish from AAEMPD on hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections because of their similar histologic features but can be differentiated by IHC stains.5 Acantholytic Bowen disease expresses high-molecular-weight cytokeratin (eg, CK5/6) but is negative for CK7, CAM 5.2, and CEA. Extramammary Paget disease generally has the opposite pattern: positive staining for CK7, CAM 5.2, and CEA, but negative for high-molecular-weight cytokeratin.13,14,24

Primary cutaneous adenosquamous carcinoma is a rare malignancy of squamous and glandular differentiation known for being locally aggressive and metastatic.25 Histologically, cutaneous adenosquamous carcinoma shows infiltrating nests of neoplastic cells with both squamous and glandular features. It differs notably from AAEMPD in that cutaneous adenosquamous carcinomas tend to arise in the head and arm regions, and their histologic morphology is different. The IHC profiles are similar, with positive staining for CEA, CK7, and mucin; however, they differ in that AAEMPD is negative for high-molecular-weight keratin while cutaneous adenosquamous carcinoma is positive.25

Verrucous carcinoma is an uncommon variant of squamous cell carcinoma with well-differentiated keratinocytes and a blunt pushing border.24 Similar to AAEMPD, this neoplasm can arise in the genital and perineal areas; however, the 2 entities differ considerably in morphology on histologic examination.

Pemphigus vulgaris is an autoimmune intraepidermal blistering disorder of the skin and mucous membranes of which pemphigus vegetans is a subtype.26,27 Pemphigus vulgaris is another diagnosis that can possibly be mimicked by AAEMPD.28 Histologic features of pemphigus vulgaris include intraepidermal acantholysis of keratinocytes immediately above the basal layer of the epidermis. Pemphigus vegetans is similar with the addition of papillomatosis, hyperkeratosis, and an eosinophilic infiltrate.26,27 Immunofluorescence typically demonstrates intercellular C3 and IgG deposits.26 These diseases mimic AAEMPD histologically but differ in their relative lack of atypia and Paget cells.

In summary, we report a case of AAEMPD in a 78-year-old man in whom routine histologic specimens showed marked intraepidermal acantholysis and atypical tumor cells with increased mitoses. The latter finding prompted IHC studies that revealed positive CK7, CEA, pancytokeratin, and LMWCK staining with negative CK20 staining. Hale colloidal iron staining showed moderate to abundant cytoplasmic mucin. The patient was diagnosed with AAEMPD. It is imperative to maintain clinical suspicion for AAEMPD and to examine acantholytic disorders with scrutiny. When there is evidence of atypia or mitoses, use of IHC stains can assist in fully characterizing the lesion.

To the Editor:

Extramammary Paget disease (EMPD) is a rare intraepidermal neoplasm with glandular differentiation that is classically known as a mimicker of Bowen disease (squamous cell carcinoma in situ of the skin) due to their histologic similarities.1,2 However, acantholytic anaplastic EMPD (AAEMPD) is a rare variant that can pose a particularly difficult diagnostic challenge because of its histologic similarity to benign acantholytic disorders and other malignant neoplasms. Major histologic features suggestive of AAEMPD include full-thickness atypia of the epidermis, loss of nuclear polarity, marked cytologic anaplasia, intraepidermal acantholysis, and Paget cells.3 The differential diagnosis of EMPD typically includes Bowen disease and pagetoid Bowen disease, but the acantholytic anaplastic variant more often is confused with intraepidermal acantholytic lesions such as acantholytic dyskeratosis of the genitocrural area, familial benign pemphigus (Hailey-Hailey disease), pemphigus vulgaris, and acantholytic Bowen disease. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) studies to assist in the definitive diagnosis of AAEMPD are strongly advised because of these difficulties in diagnosis.4 Cases of EMPD with an acantholytic appearance have rarely been reported in the literature.5-7

A 78-year-old man with a history of arthritis, heart disease, hypertension, and gastrointestinal disease presented for evaluation of a tender lesion of the right genitocrural crease of 5 years’ duration. He had no history of cutaneous or internal malignancy. Previously the lesion had been treated by dermatology with a variety of topical products including antifungal and antibiotic creams with no improvement. Physical examination revealed a well-defined, 7×5-cm, tender, erythematous, macerated plaque on the right upper inner thigh adjacent to the scrotum with an odor possibly due to secondary infection (Figure 1).

plaque on the right upper inner thigh adjacent to the scrotum.

A biopsy of the lesion was performed, and the specimen was submitted for pathologic examination. Bacterial cultures taken at the time of biopsy revealed polybacterial colonization with Acinetobacter, Morganella, and mixed skin flora. The patient was treated with a 10-day course of oral sulfamethoxazole 800 mg and trimethoprim 160 mg twice daily once culture results returned. The biopsy results were communicated to the patient; however, he subsequently relocated, assumed care at another facility, and has since been lost to follow-up.

The biopsy specimen was examined grossly, serially sectioned, and submitted for routine processing with hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid–Schiff, and Hale colloidal iron staining. Routine IHC was performed with antibodies to cytokeratin (CK) 7, CK20, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), pancytokeratin (CKAE1/AE3), and low- molecular-weight cytokeratin (LMWCK).

Pathologic examination of the biopsy showed prominent acanthosis of the epidermis composed of a proliferation of epithelial cells with associated full-thickness suprabasal acantholysis (Figure 2A). On inspection at higher magnification, the neoplastic cells demonstrated anaplasia as cytologic atypia with prominent and frequently multiple nucleoli, scant cytoplasm, and a high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio (Figure 2B). There was a marked increase in mitotic activity with as many as 5 mitotic figures per high-power field. A fairly dense mixed inflammatory infiltrate comprised of lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils, and eosinophils was present in the dermis. No fungal elements were observed on periodic acid–Schiff staining. The vast majority of tumor cells demonstrated moderate to abundant cytoplasmic mucin on Hale colloidal iron staining (Figure 3).

(H&E, original magnification ×400).

Immunohistochemistry staining of tumor cells was positive for CK7, CEA, pancytokeratin (CKAE1/AE3), and LMWCK. The tumor cells were negative for CK20. On the basis of the histopathologic and IHC findings, the patient was diagnosed with AAEMPD.

Extramammary Paget disease is a rare intraepidermal neoplasm with glandular differentiation. The most commonly involved sites are the anogenital areas including the vulvar, perianal, perineal, scrotal, and penile regions, as well as other areas rich in apocrine glands such as the axillae.8 Extramammary Paget disease most commonly originates as a primary intraepidermal neoplasm (type 1 EMPD), but an underlying malignant neoplasm that spreads intraepithelially is seen in a minority of cases (types 2 and 3 EMPD). In the vulva, type 1a refers to cutaneous noninvasive Paget disease, type 1b refers to dermal invasion of Paget disease, type 1c refers to vulvar adenocarcinoma–associated Paget disease, type 2 refers to rectal/anal adenocarcinoma–associated Paget disease, and type 3 refers to urogenital neoplasia–associated Paget disease.9

The acantholytic anaplastic variant of EMPD can be challenging to diagnose because of its similarities to many other lesions, including acantholytic dyskeratosis of the genitocrural area, familial benign pemphigus (Hailey-Hailey disease), pemphigus vulgaris, Bowen disease, pagetoid Bowen disease, and acantholytic Bowen disease. Major histologic features of AAEMPD include full-thickness atypia of the epidermis, loss of nuclear polarity, marked cytologic anaplasia, intraepidermal acantholysis, and Paget cells.3 The acantholytic anaplastic variant of EMPD can be differentiated from other diagnoses using IHC studies, with findings indicative of AAEMPD outlined below.

The proliferative neoplastic cell in EMPD is the Paget cell, which can be identified as a large round cell located in the epidermis with pale-staining cytoplasm, a large nucleus, and sometimes a prominent nucleolus. Paget cells can be distributed singly or in clusters, nests, or glandular structures within the epidermis and adjacent to adnexal structures.10 Extramammary Paget disease can have many patterns, including glandular, acantholysis-like, upper nest, tall nest, budding, and sheetlike.11

Immunohistochemically, Paget cells in EMPD typically express pancytokeratins (CKAE1/AE3), low-molecular-weight/simple epithelial type keratins (CK7, CAM 5.2), sweat gland antigens (epithelial membrane antigen, CEA, gross cystic disease fluid protein 15 [GCDFP15]), mucin 5AC (MUC5AC), and often androgen receptor.12-18 Paget cells contain cytoplasmic mucin and demonstrate prominent cytoplasmic staining with Hale colloidal iron.17 Paget cells typically do not express high-molecular-weight cytokeratin (eg, CK5/6), melanocytic antigens, estrogen receptor, or progesterone receptor.15,18

Immunohistochemical staining has been shown to differ between primary cutaneous (type 1) and secondary (types 2 and 3) EMPD. Primary cutaneous EMPD typically expresses sweat gland markers (CK7+, CK20−, GCDFP15+). Secondary EMPD typically expresses an endodermal phenotype (CK7+, CK20+, GCDFP15−).12

Acantholytic dyskeratosis of the genitocrural area is a rare lesion included in the spectrum of focal acantholytic dyskeratoses described by Ackerman.19 It also has been referred to as papular acantholytic dyskeratosis of the vulva, though histologically similar lesions also have been reported in men.20-22 Histologically, acantholytic dyskeratosis of the genitocrural area has prominent acantholysis and dyskeratosis with corps ronds and grains.19 Familial benign pemphigus (Hailey-Hailey disease) is caused by mutations of the ATP2C1 gene, which encodes for a secretory pathway Ca2+/Mn2+-ATPase pump type 1 (SPCA1) in the Golgi apparatus in keratinocytes.23 Familial benign pemphigus has a histologic appearance similar to acantholytic dyskeratosis of the genitocrural area, but a positive family history of familial benign pemphigus can be used to differentiate the 2 entities from each other due to the autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern of familial benign pemphigus. Both of these disorders can appear similar to AAEMPD because of their extensive intraepidermal acantholysis, but they differ in the lack of Paget cells, intraepidermal atypia, and increased mitotic activity.

Acantholytic Bowen disease is a histologic variant that can be difficult to distinguish from AAEMPD on hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections because of their similar histologic features but can be differentiated by IHC stains.5 Acantholytic Bowen disease expresses high-molecular-weight cytokeratin (eg, CK5/6) but is negative for CK7, CAM 5.2, and CEA. Extramammary Paget disease generally has the opposite pattern: positive staining for CK7, CAM 5.2, and CEA, but negative for high-molecular-weight cytokeratin.13,14,24

Primary cutaneous adenosquamous carcinoma is a rare malignancy of squamous and glandular differentiation known for being locally aggressive and metastatic.25 Histologically, cutaneous adenosquamous carcinoma shows infiltrating nests of neoplastic cells with both squamous and glandular features. It differs notably from AAEMPD in that cutaneous adenosquamous carcinomas tend to arise in the head and arm regions, and their histologic morphology is different. The IHC profiles are similar, with positive staining for CEA, CK7, and mucin; however, they differ in that AAEMPD is negative for high-molecular-weight keratin while cutaneous adenosquamous carcinoma is positive.25

Verrucous carcinoma is an uncommon variant of squamous cell carcinoma with well-differentiated keratinocytes and a blunt pushing border.24 Similar to AAEMPD, this neoplasm can arise in the genital and perineal areas; however, the 2 entities differ considerably in morphology on histologic examination.

Pemphigus vulgaris is an autoimmune intraepidermal blistering disorder of the skin and mucous membranes of which pemphigus vegetans is a subtype.26,27 Pemphigus vulgaris is another diagnosis that can possibly be mimicked by AAEMPD.28 Histologic features of pemphigus vulgaris include intraepidermal acantholysis of keratinocytes immediately above the basal layer of the epidermis. Pemphigus vegetans is similar with the addition of papillomatosis, hyperkeratosis, and an eosinophilic infiltrate.26,27 Immunofluorescence typically demonstrates intercellular C3 and IgG deposits.26 These diseases mimic AAEMPD histologically but differ in their relative lack of atypia and Paget cells.

In summary, we report a case of AAEMPD in a 78-year-old man in whom routine histologic specimens showed marked intraepidermal acantholysis and atypical tumor cells with increased mitoses. The latter finding prompted IHC studies that revealed positive CK7, CEA, pancytokeratin, and LMWCK staining with negative CK20 staining. Hale colloidal iron staining showed moderate to abundant cytoplasmic mucin. The patient was diagnosed with AAEMPD. It is imperative to maintain clinical suspicion for AAEMPD and to examine acantholytic disorders with scrutiny. When there is evidence of atypia or mitoses, use of IHC stains can assist in fully characterizing the lesion.

- Bowen JT. Precancerous dermatosis: a study of two cases of chronic atypical epithelial proliferation. J Cutan Dis. 1912;30:241-255.

- Jones RE Jr, Austin C, Ackerman AB. Extramammary Paget’s disease: a critical reexamination. Am J Dermatopathol. 1979;1:101-132.

- Rayne SC, Santa Cruz DJ. Anaplastic Paget’s disease. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992;16:1085-1091.

- Wang EC, Kwah YC, Tan WP, et al. Extramammary Paget disease: immunohistochemistry is critical to distinguish potential mimickers. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:4.

- Du X, Yin X, Zhou N, et al. Extramammary Paget’s disease mimicking acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma in situ: a case report. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:683.

- Mobini N. Acantholytic anaplastic Paget’s disease. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:374-380.

- Oh YJ, Lew BL, Sim WY. Acantholytic anaplastic extramammary Paget’s disease: a case report and review of the literature. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:226-230.

- Zollo JD, Zeitouni NC. The Roswell Park Cancer Institute experience with extramammary Paget’s disease. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:59-65.

- Wilkinson EJ, Brown HM. Vulvar Paget disease of urothelial origin: a report of three cases and a proposed classification of vulvar Paget disease. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:549-554.

- Lam C, Funaro D. Extramammary Paget’s disease: summary of current knowledge. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:807-826.

- Shiomi T, Yoshida Y, Shomori K, et al. Extramammary Paget’s disease: evaluation of the histopathological patterns of Paget cell proliferation in the epidermis. J Dermatol. 2011;38:1054-1057.

- Goldblum JR, Hart WR. Vulvar Paget’s disease: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 19 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:1178-1187.

- Alhumaidi A. Practical immunohistochemistry of epithelial skin tumor. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 2012;78:698-708.

- Battles O, Page D, Johnson J. Cytokeratins, CEA and mucin histochemistry in the diagnosis and characterization of extramammary Paget’s disease. Am J Clin Pathol. 1997;108:6-12.

- Kanitakis J. Mammary and extramammary Paget’s disease. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:581-590.

- Krishna M. Diagnosis of metastatic neoplasms: an immunohistochemical approach. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:207-215.

- Helm KF, Goellner JR, Peters MS. Immunohistochemical stain in extramammary Paget’s disease. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:402-407.

- Liegl B, Horn L, Moinfar F. Androgen receptors are frequently expressed in mammary and extramammary Paget’s disease. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:1283-288.

- Ackerman AB. Focal acantholytic dyskeratosis. Arch Derm. 1972;106:702-706.

- Dittmer CJ, Hornemann A, Rose C, et al. Successful laser therapy of a papular acantholytic dyskeratosis of the vulva: case report and review of literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2010;291:723-725.

- Roh MR, Choi YJ, Lee KG. Papular acantholytic dyskeratosis of the vulva. J Dermatol. 2009;36:427-429.

- Wong KT, Mihm MC Jr. Acantholytic dermatosis localized to genitalia and crural areas of male patients: a report of three cases. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:27-32.

- Hu Z, Bonifas JM, Beech J, et al. Mutations in ATP2C1, encoding a calcium pump, cause Hailey-Hailey disease. Nat Genet. 2000; 24:61-65.

- Elston DM. Malignant tumors of the epidermis. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, eds. Requisites in Dermatology: Dermatopathology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Limited; 2012:53-68.

- Fu JM, McCalmont T, Yu SS. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the skin: a case series. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1152-1158.

- Becker BA, Gaspari AA. Pemphigus vulgaris and vegetans. Dermatol Clin. 1993;11:429-452.

- Rados J. Autoimmune blistering diseases: histologic meaning. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:377-388.

- Kohler S, Smoller BR. A case of extramammary Paget’s disease mimicking pemphigus vulgaris on histologic examination. Dermatology. 1997;195:54-56.

- Bowen JT. Precancerous dermatosis: a study of two cases of chronic atypical epithelial proliferation. J Cutan Dis. 1912;30:241-255.

- Jones RE Jr, Austin C, Ackerman AB. Extramammary Paget’s disease: a critical reexamination. Am J Dermatopathol. 1979;1:101-132.

- Rayne SC, Santa Cruz DJ. Anaplastic Paget’s disease. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992;16:1085-1091.

- Wang EC, Kwah YC, Tan WP, et al. Extramammary Paget disease: immunohistochemistry is critical to distinguish potential mimickers. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:4.

- Du X, Yin X, Zhou N, et al. Extramammary Paget’s disease mimicking acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma in situ: a case report. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:683.

- Mobini N. Acantholytic anaplastic Paget’s disease. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:374-380.

- Oh YJ, Lew BL, Sim WY. Acantholytic anaplastic extramammary Paget’s disease: a case report and review of the literature. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:226-230.

- Zollo JD, Zeitouni NC. The Roswell Park Cancer Institute experience with extramammary Paget’s disease. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:59-65.

- Wilkinson EJ, Brown HM. Vulvar Paget disease of urothelial origin: a report of three cases and a proposed classification of vulvar Paget disease. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:549-554.

- Lam C, Funaro D. Extramammary Paget’s disease: summary of current knowledge. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:807-826.

- Shiomi T, Yoshida Y, Shomori K, et al. Extramammary Paget’s disease: evaluation of the histopathological patterns of Paget cell proliferation in the epidermis. J Dermatol. 2011;38:1054-1057.

- Goldblum JR, Hart WR. Vulvar Paget’s disease: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 19 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:1178-1187.

- Alhumaidi A. Practical immunohistochemistry of epithelial skin tumor. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 2012;78:698-708.

- Battles O, Page D, Johnson J. Cytokeratins, CEA and mucin histochemistry in the diagnosis and characterization of extramammary Paget’s disease. Am J Clin Pathol. 1997;108:6-12.

- Kanitakis J. Mammary and extramammary Paget’s disease. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:581-590.

- Krishna M. Diagnosis of metastatic neoplasms: an immunohistochemical approach. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:207-215.

- Helm KF, Goellner JR, Peters MS. Immunohistochemical stain in extramammary Paget’s disease. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:402-407.

- Liegl B, Horn L, Moinfar F. Androgen receptors are frequently expressed in mammary and extramammary Paget’s disease. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:1283-288.

- Ackerman AB. Focal acantholytic dyskeratosis. Arch Derm. 1972;106:702-706.

- Dittmer CJ, Hornemann A, Rose C, et al. Successful laser therapy of a papular acantholytic dyskeratosis of the vulva: case report and review of literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2010;291:723-725.

- Roh MR, Choi YJ, Lee KG. Papular acantholytic dyskeratosis of the vulva. J Dermatol. 2009;36:427-429.

- Wong KT, Mihm MC Jr. Acantholytic dermatosis localized to genitalia and crural areas of male patients: a report of three cases. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:27-32.

- Hu Z, Bonifas JM, Beech J, et al. Mutations in ATP2C1, encoding a calcium pump, cause Hailey-Hailey disease. Nat Genet. 2000; 24:61-65.

- Elston DM. Malignant tumors of the epidermis. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, eds. Requisites in Dermatology: Dermatopathology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Limited; 2012:53-68.

- Fu JM, McCalmont T, Yu SS. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the skin: a case series. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1152-1158.

- Becker BA, Gaspari AA. Pemphigus vulgaris and vegetans. Dermatol Clin. 1993;11:429-452.

- Rados J. Autoimmune blistering diseases: histologic meaning. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:377-388.

- Kohler S, Smoller BR. A case of extramammary Paget’s disease mimicking pemphigus vulgaris on histologic examination. Dermatology. 1997;195:54-56.

Practice Points

- The acantholytic anaplastic variant of extramammary Paget disease (EMPD) can be mimicked by many other entities including Bowen disease, acantholytic dyskeratosis of the genitocrural area, and pemphigus vulgaris.

- A good immunohistochemical panel to evaluate for EMPD includes cytokeratin (CK) 7, pancytokeratin (CKAE1/AE3), CK20, and carcinoembryonic antigen.

Barber’s Sinus Between the Toes of a Female Hairdresser

To the Editor:

Barber’s sinus, or interdigital pilonidal sinus, is an occupational dermatosis with a pathognomonic clinical picture. Nearly all reports of barber’s sinus in the literature have involved the hands of male barbers and hairdressers. We present an uncommon case of barber’s sinus between the toes of a female hairdresser. If left untreated, potential complications of barber’s sinus include abscess formation, cellulitis, lymphangitis, and osteomyelitis. Clinicians should advise patients with an occupational risk of barber’s sinus to wear protective footwear and maintain hygiene in the interdigital spaces.

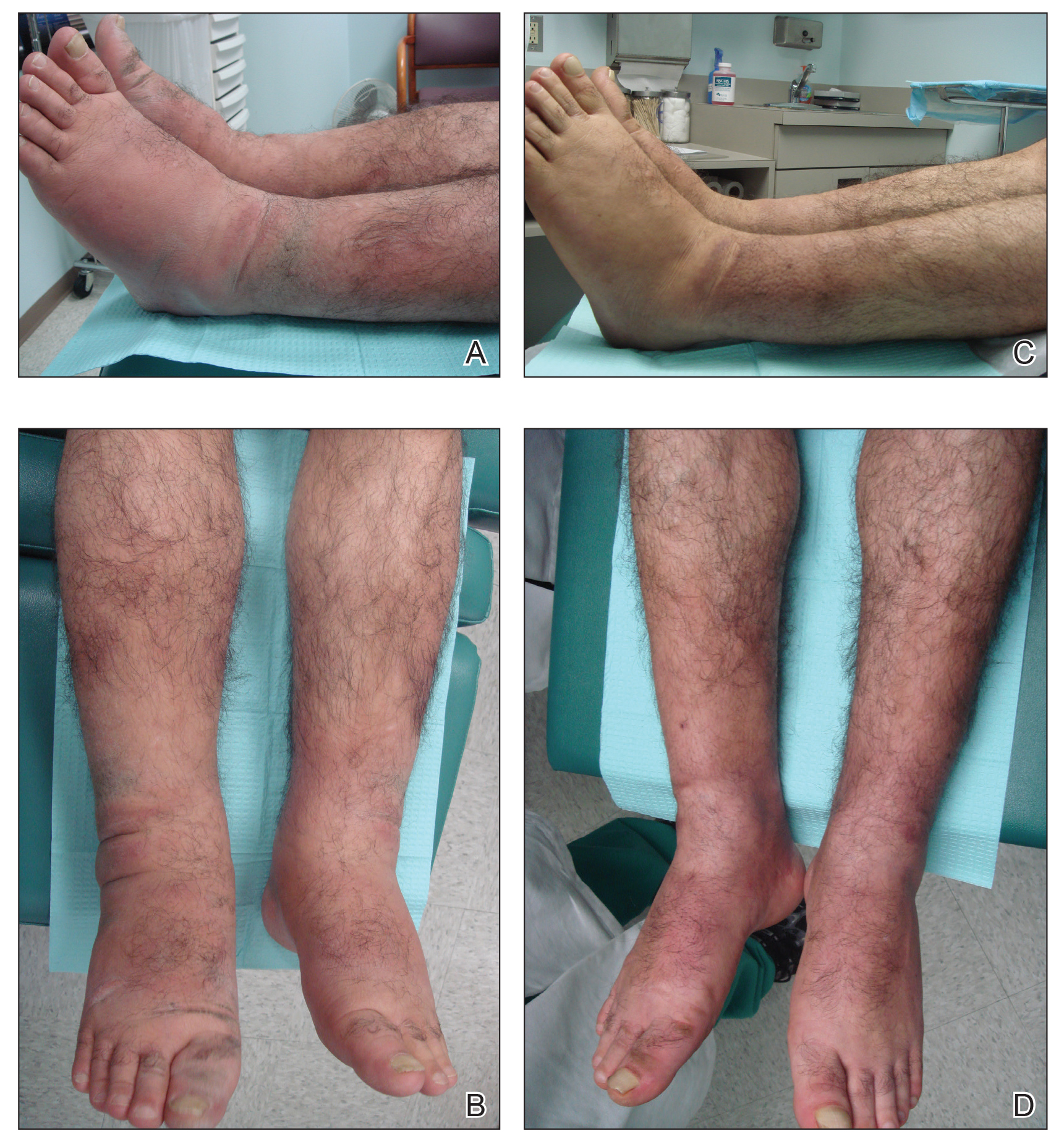

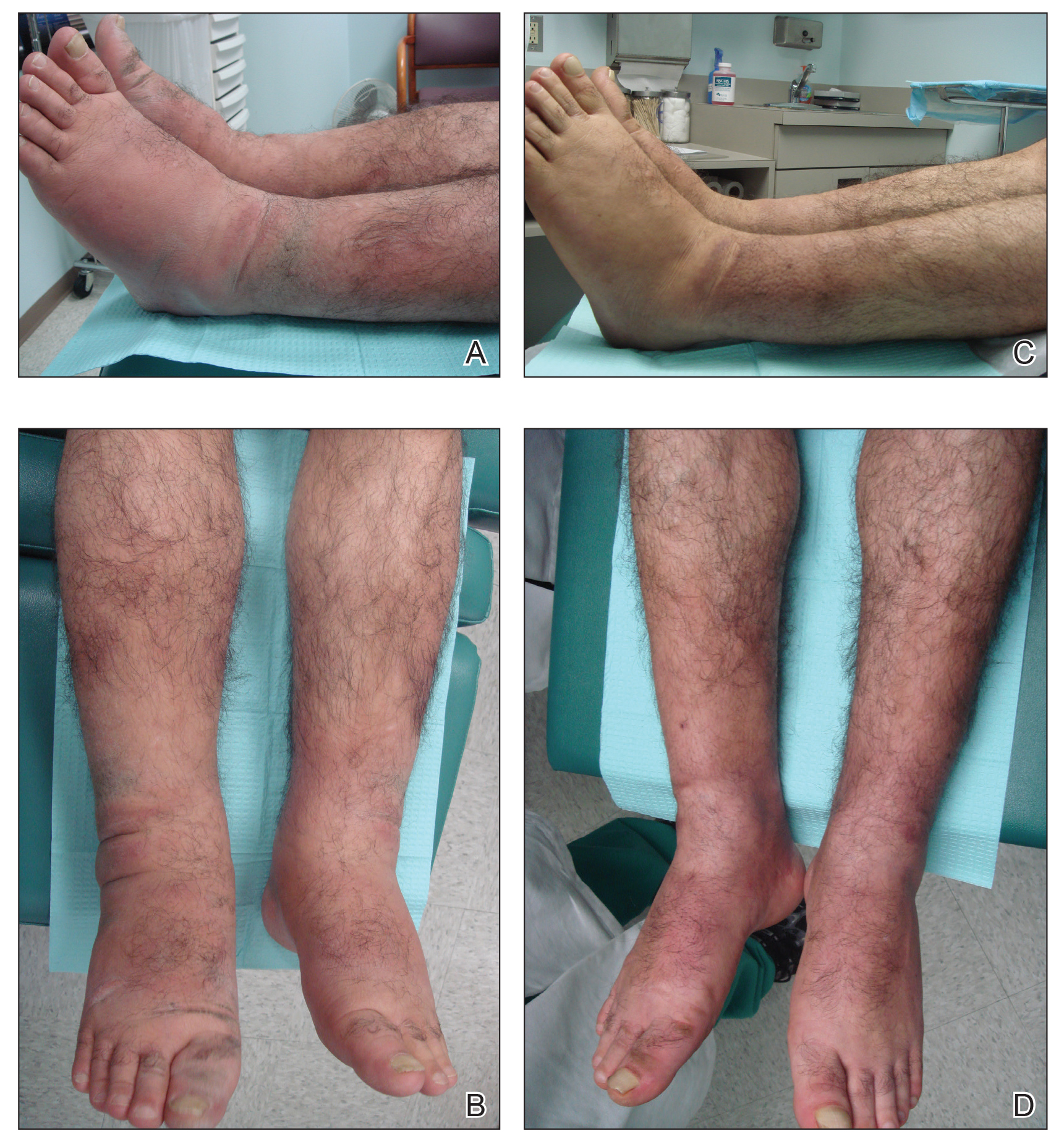

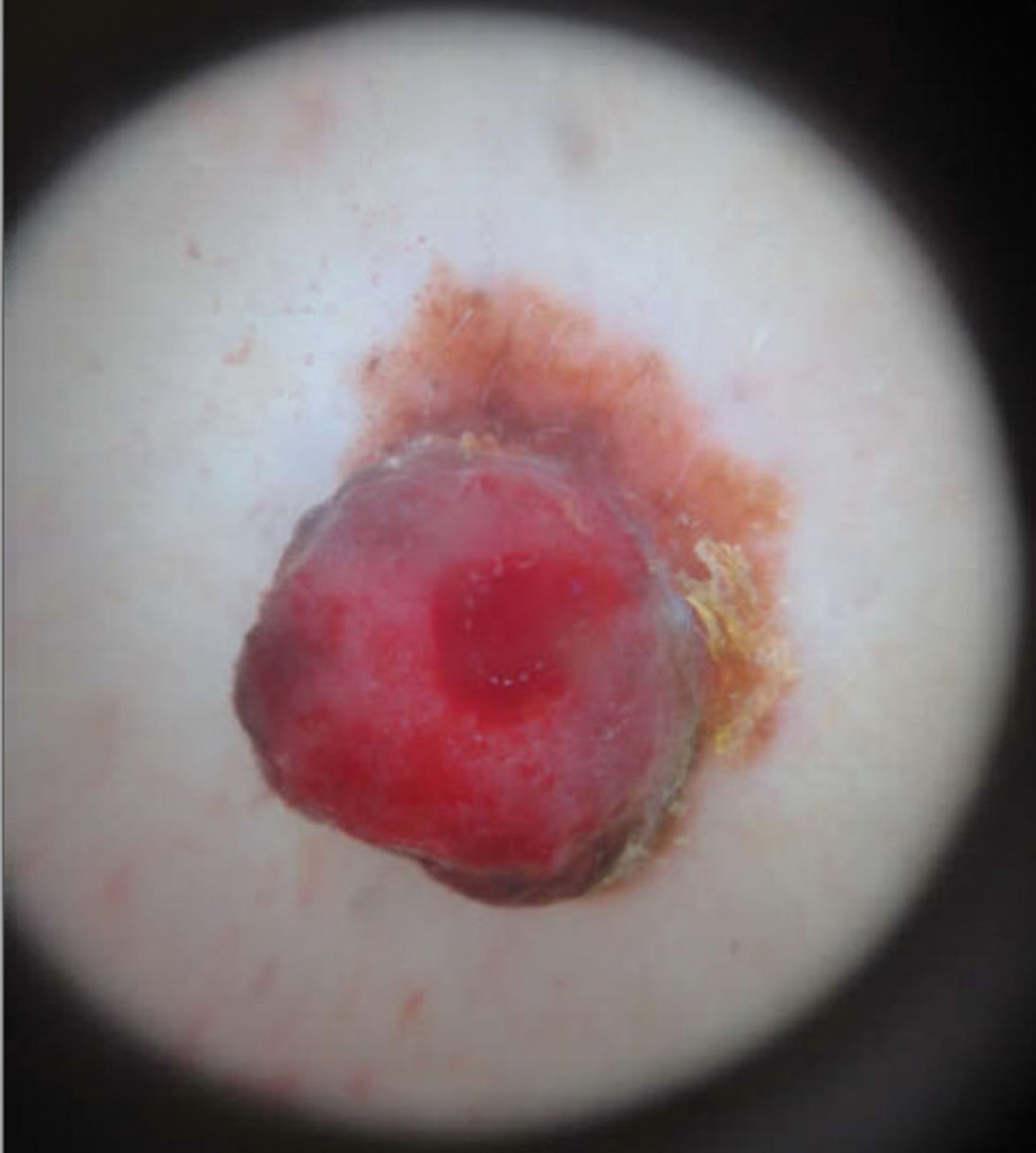

A 23-year-old female hairdresser was referred to our outpatient dermatology clinic by general surgery for evaluation of an asymptomatic interdigital toe lesion of several months’ duration. She was otherwise healthy. Physical examination revealed a 3-mm sinus in the interdigital web space between the fourth and fifth digits of the left foot, creating a partial fistula terminating in an umbilicated pink papule on the dorsal aspect of the interdigital space (Figure). While at work, the patient reported that she usually wore open-toed flip-flops. A diagnosis of barber’s sinus was made clinically. She returned for follow-up to the referring surgeon within 2 months and was offered surgical debridement, but the patient declined treatment, instead opting to wait and monitor for any potential complications. The lesion showed no change in clinical appearance and remained asymptomatic.

Barber’s sinus is caused by sharp fragments of clipped hair that penetrate the fragile interdigital skin and cause a foreign-body reaction. Males are almost exclusively contributory to the reported cases of barber’s sinus in the literature.1,2

The clinical picture of barber’s sinus is pathognomonic, as demonstrated in our case. Other potential diagnoses to consider include atypical mycobacterial infection, deep fungal infection, other foreign-body granuloma, and erosio interdigitalis blastomycetica. Although thorough removal of embedded hair fragments may be curative, most cases require surgical excision, often by curette, and subsequent skin closure. Pathology shows a foreign-body granulomatous reaction to hair fragments. If left untreated, potential complications of barber’s sinus include abscess formation, cellulitis, lymphangitis, and osteomyelitis. This lesion is preventable by maintaining hygiene of the interdigital spaces, use of barrier creams, and wearing protective footwear.3,4

- Efthimiadis C, Kosmidis C, Anthimidis G, et al. Barber’s hair sinus in a female hairdresser: uncommon manifestation of an occupational disease: a case report. Cases J. 2008;1:214.

- O’Neill AC, Purcell EM, Regan PJ. Interdigital pilonidal sinus of the foot [published online May 31, 2009]. Foot (Edinb). 2009;19:227-228.

- Schröder CM, Merk HF, Frank J. Barber’s hair sinus in a female hairdresser: uncommon manifestation of an occupational dermatosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:209-211.

- Joseph HL, Gifford H. Barber’s interdigital pilonidal sinus: the incidence, pathology, and pathogenesis. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1954;70:616-624.

To the Editor:

Barber’s sinus, or interdigital pilonidal sinus, is an occupational dermatosis with a pathognomonic clinical picture. Nearly all reports of barber’s sinus in the literature have involved the hands of male barbers and hairdressers. We present an uncommon case of barber’s sinus between the toes of a female hairdresser. If left untreated, potential complications of barber’s sinus include abscess formation, cellulitis, lymphangitis, and osteomyelitis. Clinicians should advise patients with an occupational risk of barber’s sinus to wear protective footwear and maintain hygiene in the interdigital spaces.

A 23-year-old female hairdresser was referred to our outpatient dermatology clinic by general surgery for evaluation of an asymptomatic interdigital toe lesion of several months’ duration. She was otherwise healthy. Physical examination revealed a 3-mm sinus in the interdigital web space between the fourth and fifth digits of the left foot, creating a partial fistula terminating in an umbilicated pink papule on the dorsal aspect of the interdigital space (Figure). While at work, the patient reported that she usually wore open-toed flip-flops. A diagnosis of barber’s sinus was made clinically. She returned for follow-up to the referring surgeon within 2 months and was offered surgical debridement, but the patient declined treatment, instead opting to wait and monitor for any potential complications. The lesion showed no change in clinical appearance and remained asymptomatic.

Barber’s sinus is caused by sharp fragments of clipped hair that penetrate the fragile interdigital skin and cause a foreign-body reaction. Males are almost exclusively contributory to the reported cases of barber’s sinus in the literature.1,2

The clinical picture of barber’s sinus is pathognomonic, as demonstrated in our case. Other potential diagnoses to consider include atypical mycobacterial infection, deep fungal infection, other foreign-body granuloma, and erosio interdigitalis blastomycetica. Although thorough removal of embedded hair fragments may be curative, most cases require surgical excision, often by curette, and subsequent skin closure. Pathology shows a foreign-body granulomatous reaction to hair fragments. If left untreated, potential complications of barber’s sinus include abscess formation, cellulitis, lymphangitis, and osteomyelitis. This lesion is preventable by maintaining hygiene of the interdigital spaces, use of barrier creams, and wearing protective footwear.3,4

To the Editor:

Barber’s sinus, or interdigital pilonidal sinus, is an occupational dermatosis with a pathognomonic clinical picture. Nearly all reports of barber’s sinus in the literature have involved the hands of male barbers and hairdressers. We present an uncommon case of barber’s sinus between the toes of a female hairdresser. If left untreated, potential complications of barber’s sinus include abscess formation, cellulitis, lymphangitis, and osteomyelitis. Clinicians should advise patients with an occupational risk of barber’s sinus to wear protective footwear and maintain hygiene in the interdigital spaces.

A 23-year-old female hairdresser was referred to our outpatient dermatology clinic by general surgery for evaluation of an asymptomatic interdigital toe lesion of several months’ duration. She was otherwise healthy. Physical examination revealed a 3-mm sinus in the interdigital web space between the fourth and fifth digits of the left foot, creating a partial fistula terminating in an umbilicated pink papule on the dorsal aspect of the interdigital space (Figure). While at work, the patient reported that she usually wore open-toed flip-flops. A diagnosis of barber’s sinus was made clinically. She returned for follow-up to the referring surgeon within 2 months and was offered surgical debridement, but the patient declined treatment, instead opting to wait and monitor for any potential complications. The lesion showed no change in clinical appearance and remained asymptomatic.

Barber’s sinus is caused by sharp fragments of clipped hair that penetrate the fragile interdigital skin and cause a foreign-body reaction. Males are almost exclusively contributory to the reported cases of barber’s sinus in the literature.1,2

The clinical picture of barber’s sinus is pathognomonic, as demonstrated in our case. Other potential diagnoses to consider include atypical mycobacterial infection, deep fungal infection, other foreign-body granuloma, and erosio interdigitalis blastomycetica. Although thorough removal of embedded hair fragments may be curative, most cases require surgical excision, often by curette, and subsequent skin closure. Pathology shows a foreign-body granulomatous reaction to hair fragments. If left untreated, potential complications of barber’s sinus include abscess formation, cellulitis, lymphangitis, and osteomyelitis. This lesion is preventable by maintaining hygiene of the interdigital spaces, use of barrier creams, and wearing protective footwear.3,4

- Efthimiadis C, Kosmidis C, Anthimidis G, et al. Barber’s hair sinus in a female hairdresser: uncommon manifestation of an occupational disease: a case report. Cases J. 2008;1:214.

- O’Neill AC, Purcell EM, Regan PJ. Interdigital pilonidal sinus of the foot [published online May 31, 2009]. Foot (Edinb). 2009;19:227-228.

- Schröder CM, Merk HF, Frank J. Barber’s hair sinus in a female hairdresser: uncommon manifestation of an occupational dermatosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:209-211.

- Joseph HL, Gifford H. Barber’s interdigital pilonidal sinus: the incidence, pathology, and pathogenesis. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1954;70:616-624.

- Efthimiadis C, Kosmidis C, Anthimidis G, et al. Barber’s hair sinus in a female hairdresser: uncommon manifestation of an occupational disease: a case report. Cases J. 2008;1:214.

- O’Neill AC, Purcell EM, Regan PJ. Interdigital pilonidal sinus of the foot [published online May 31, 2009]. Foot (Edinb). 2009;19:227-228.

- Schröder CM, Merk HF, Frank J. Barber’s hair sinus in a female hairdresser: uncommon manifestation of an occupational dermatosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:209-211.

- Joseph HL, Gifford H. Barber’s interdigital pilonidal sinus: the incidence, pathology, and pathogenesis. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1954;70:616-624.

Practice Points

- This case illustrates a disease in which a medical history and simple clinical examination can lead to the diagnosis.

- Patients may value a diagnosis without treatment. A patient with barber’s sinus may be satisfied with watchful waiting.

Management of Refractory Pain From Hereditary Cutaneous Leiomyomas With Nifedipine and Gabapentin

To the Editor:

Leiomyomas are benign smooth muscle tumors. There are 3 types of cutaneous leiomyomas: (1) piloleiomyomas, arising from the arrector pili muscles; (2) angioleiomyomas, arising from the muscles surrounding dermal blood vessels; and (3) leiomyomas of the external genitalia, arising from the dartoic, vulvar, or mammary smooth muscles.1 There is no gender predilection for cutaneous leiomyomas, and lesions present on average at approximately 40 to 45 years of age.2

Piloleiomyomas are the most common type of cutaneous leiomyomas and typically present as red-brown papules and nodules on the trunk, arms, and legs.3 Piloleiomyomas often are associated with spontaneous or induced pain (eg, with cold exposure). The pain associated with piloleiomyomas can be severely debilitating to patients and may have a considerable impact on their quality of life.

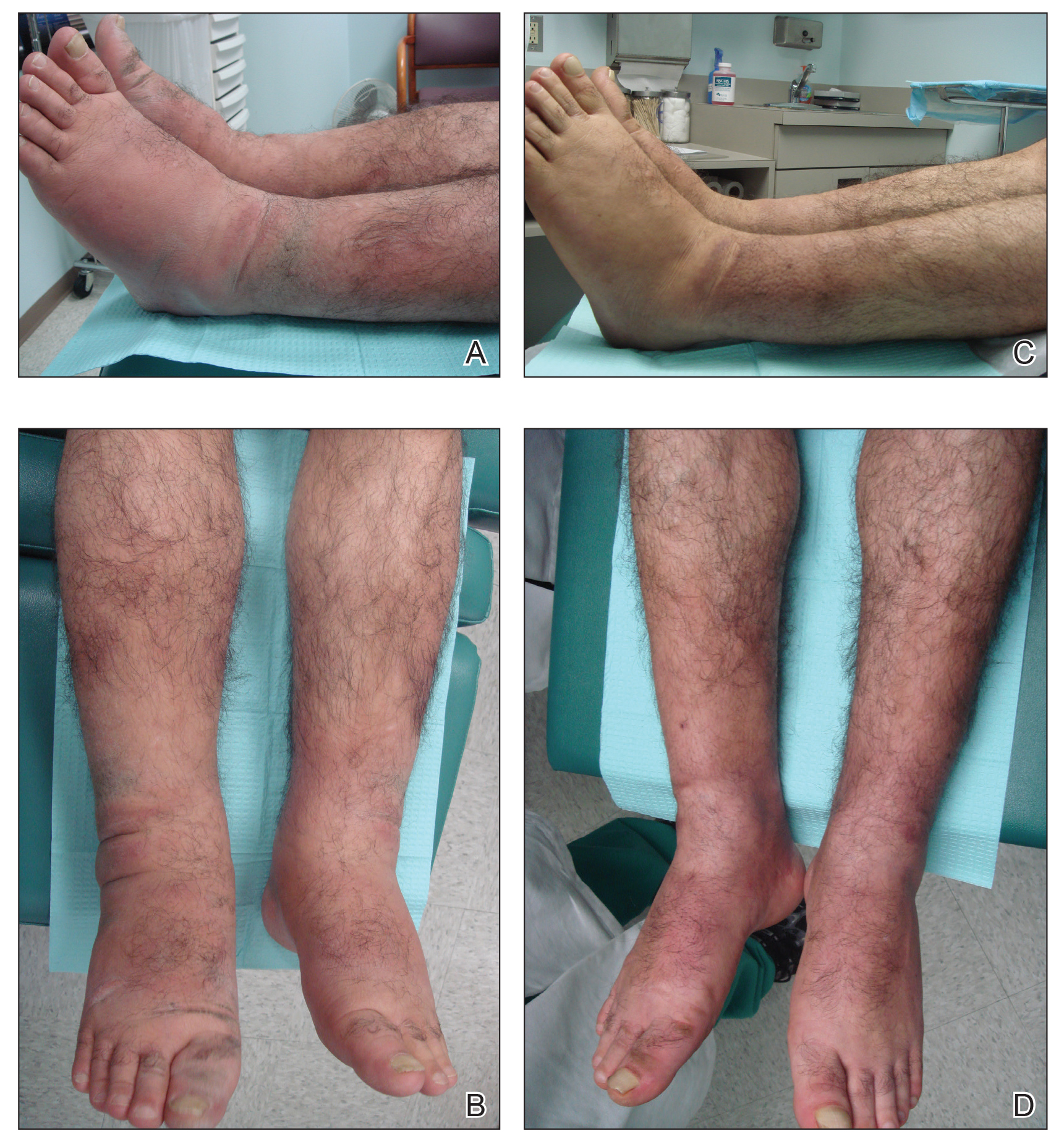

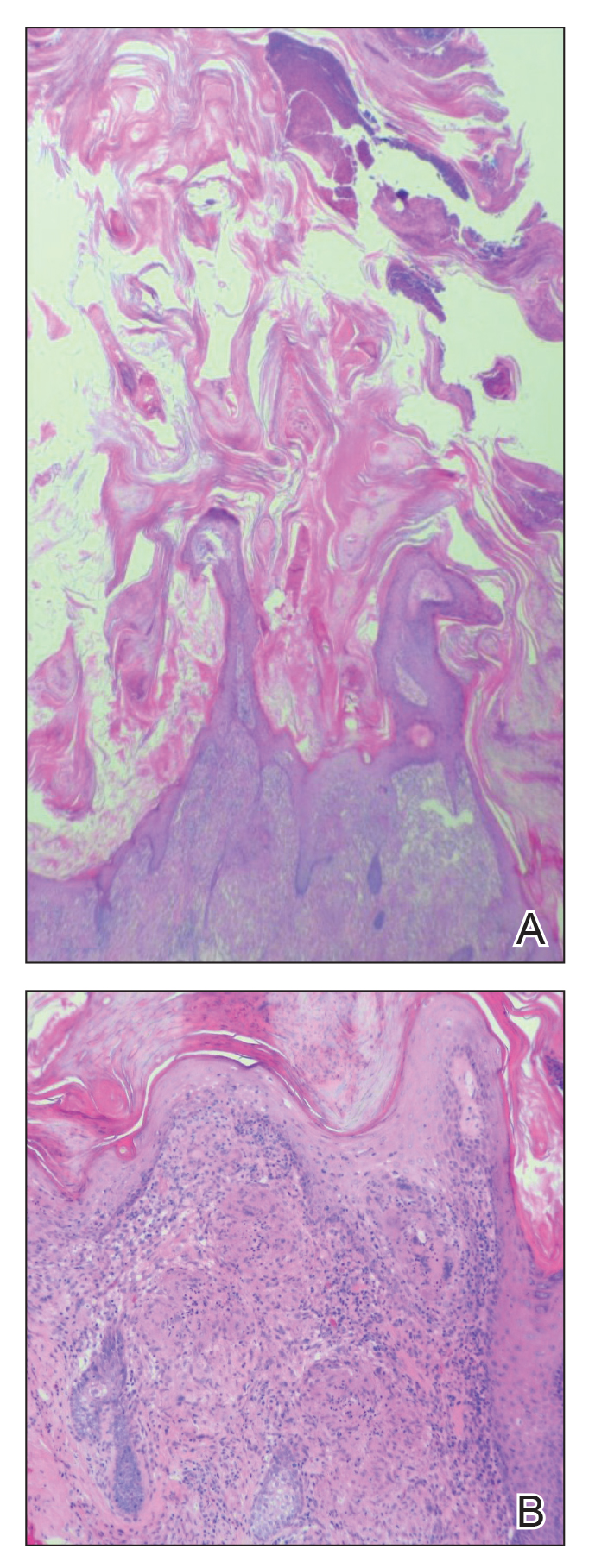

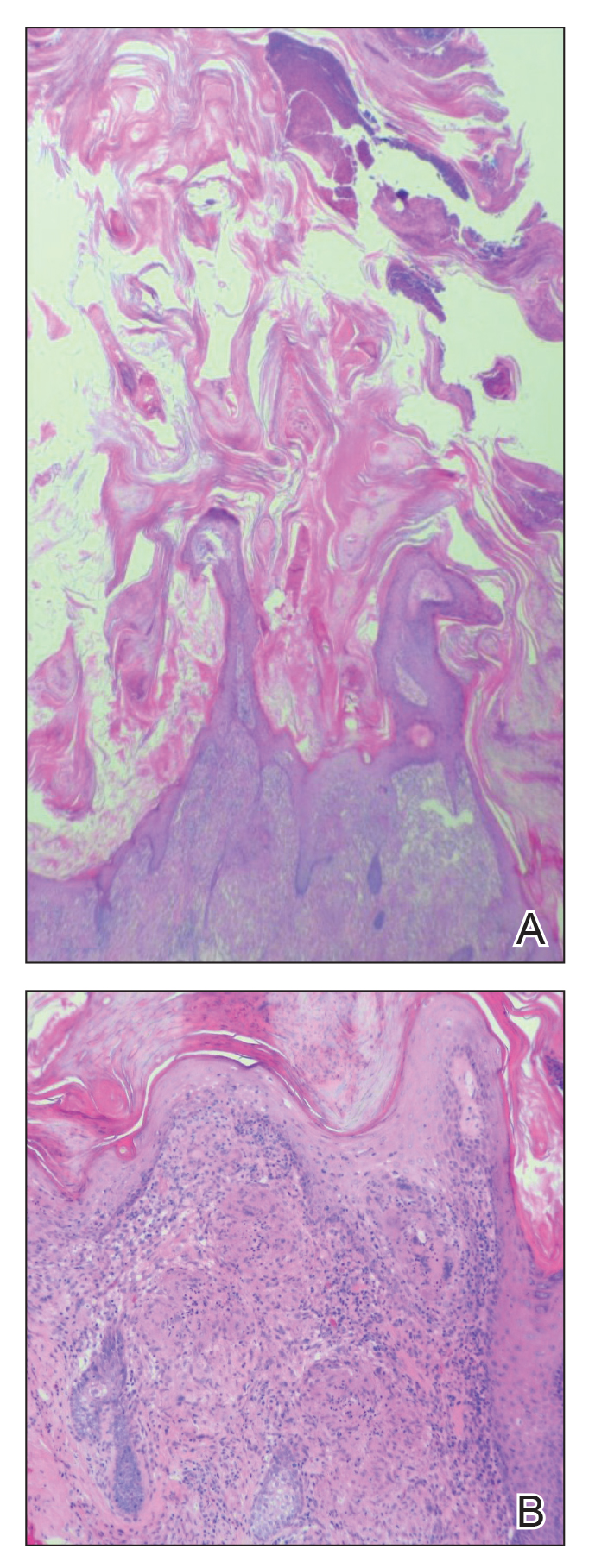

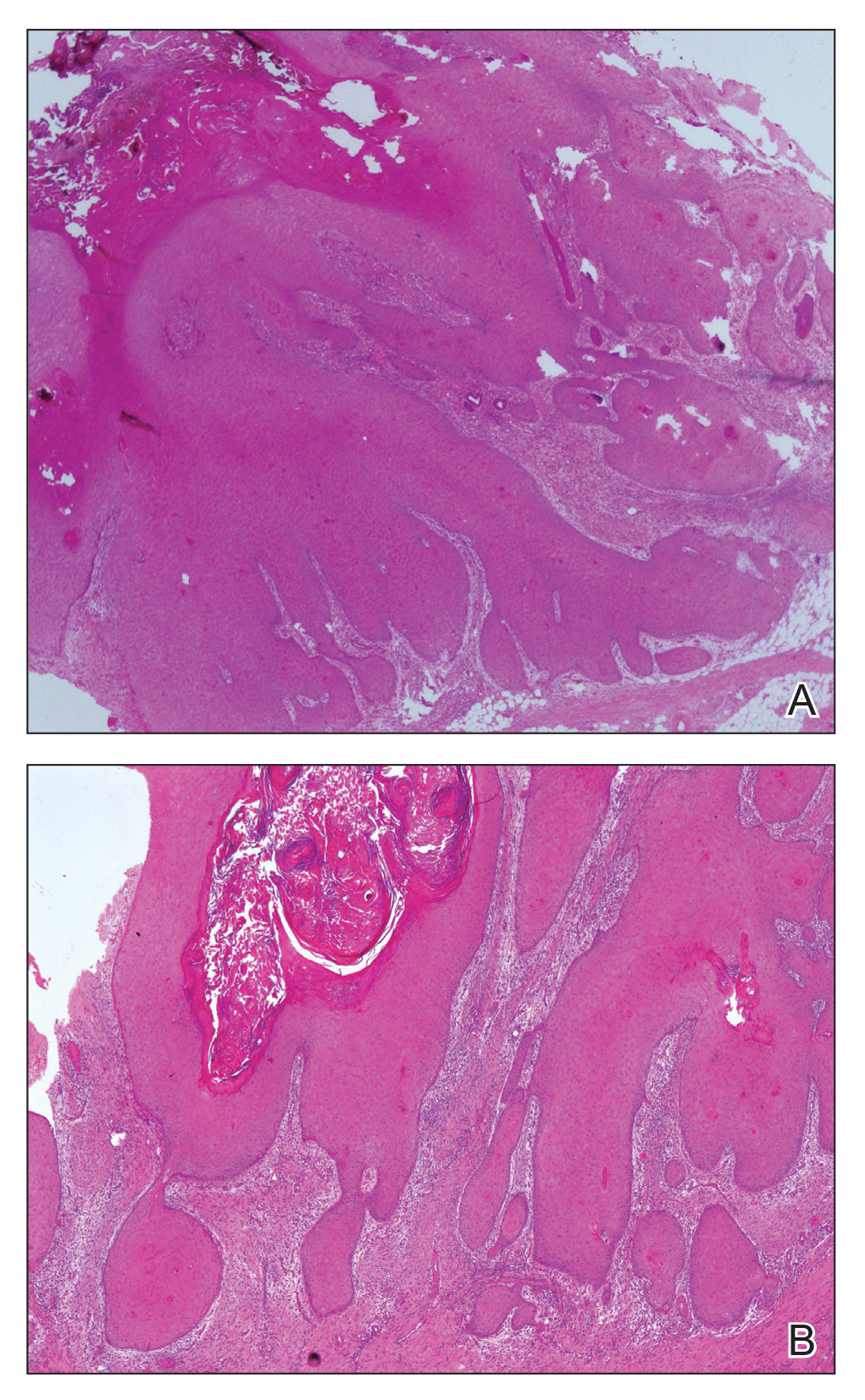

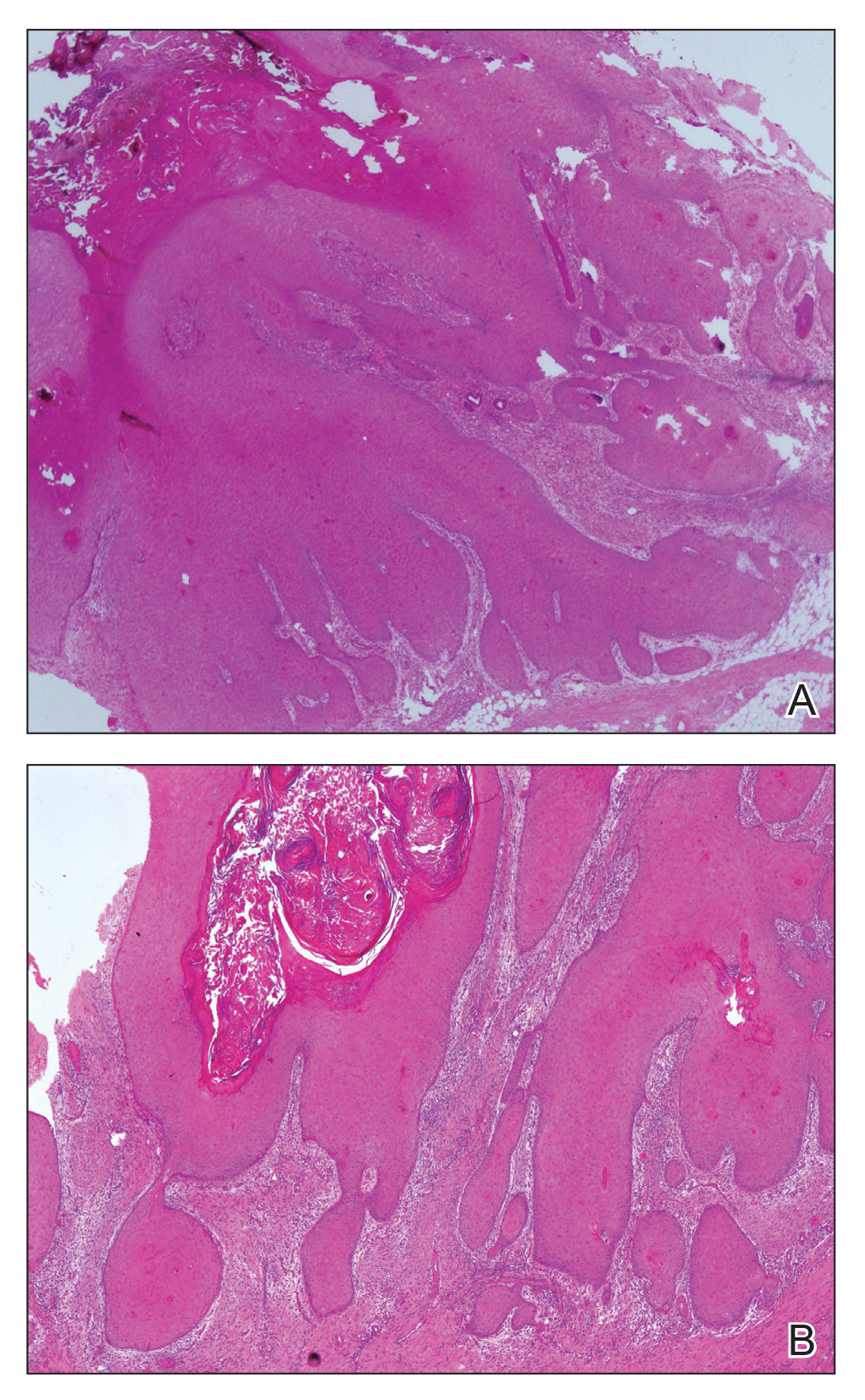

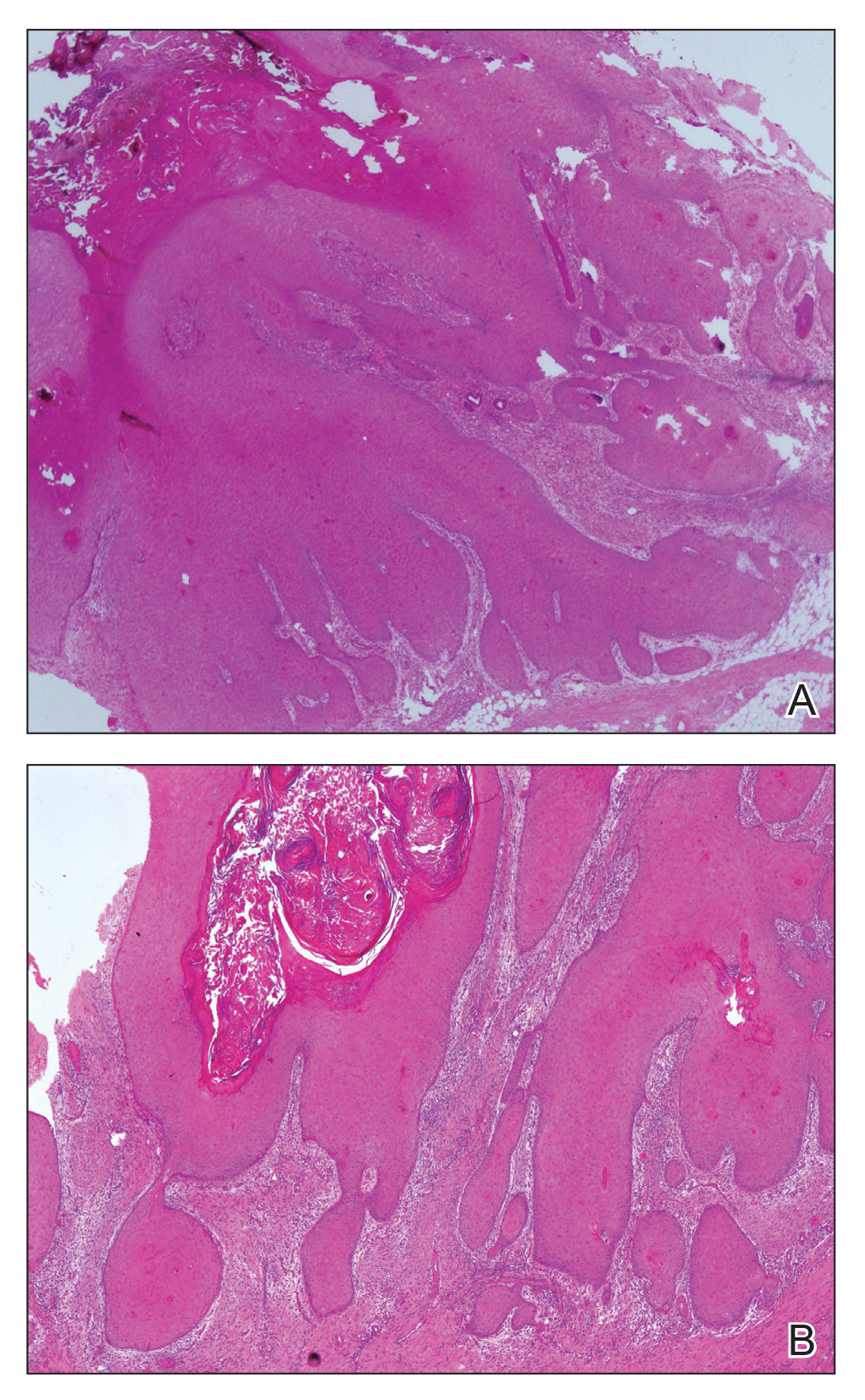

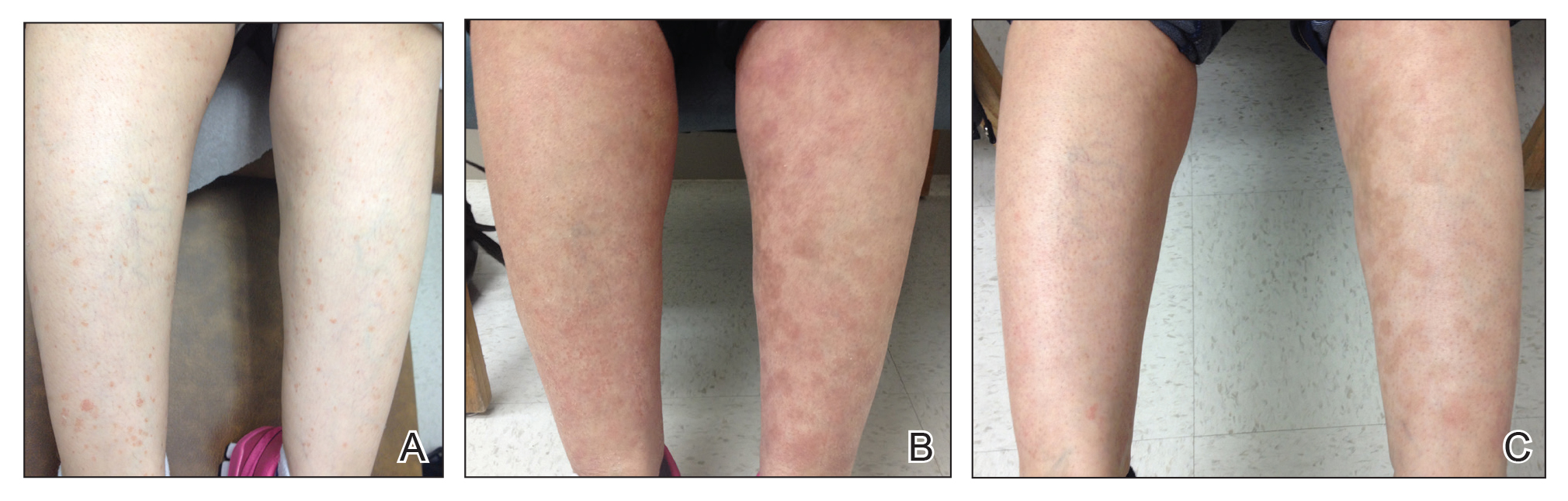

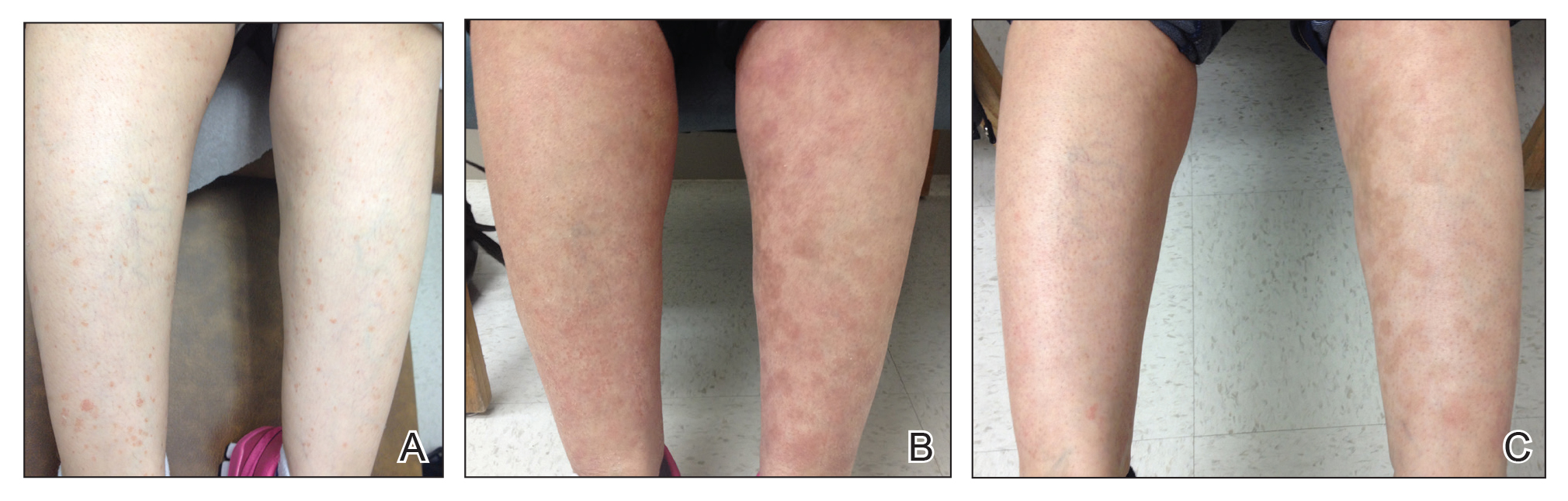

A 40-year-old woman presented to our clinic with numerous widespread, painful, red-brown papules and nodules on the head, neck, chest, abdomen, back, arms, and legs of 6 years’ duration that were increasing in number (Figure 1). She had a history of uterine leiomyomas and type 2 renal papillary carcinoma following a left nephrectomy at 38 years of age. The patient’s mother had a history of similar skin lesions as well as uterine cancer. Multiple excisional biopsies were performed, all of which showed piloleiomyomas on histopathology (Figure 2). The pain associated with the patient’s extensive cutaneous leiomyomas considerably impaired her quality of life. Although she experienced pain in all affected areas of the body, the pain was the worst in the upper arms. She reported having requested a nerve ablation procedure from an outside pain management clinic, which was denied for unknown reasons.

Two years prior to the current presentation, the patient had been treated by a pain management specialist with gabapentin 300 mg twice daily as needed for pain associated with leiomyomas. The patient followed this regimen approximately 3 times weekly for the preceding 1 to 2 years with reduction in her pain symptoms; however, the painful episodes became more frequent and severe over time. The patient reported being unable to further increase the gabapentin dosing frequency because it made her too drowsy and impacted her ability to work a job that required heavy lifting. Thus, the patient requested additional therapy and was subsequently treated at our clinic with numerous excisional biopsies of the most painful lesions during the 2 years prior to her current presentation.

When the patient re-presented to our clinic, she requested additional lesion excisions given that she had experienced some pain relief from this treatment modality in the past; however, these prior excisions only resulted in local pain relief limited to the site of the excision. Because of the extent of the lesions and the patient’s inability to tolerate pain from the lidocaine injections, we did not feel multiple excisions were a practical treatment option. The patient subsequently was offered a trial of cryotherapy for symptom relief based on a reported case in which this modality was successfully used.4 After discussing the risks and benefits associated with this treatment, cryotherapy was attempted on a few of the leiomyomas on the patient’s right shoulder; however, she experienced severe pain during cryotherapy treatment, and the procedure had to be aborted.

We then increased the patient’s gabapentin regimen to 300 mg in the morning and 600 mg in the evening, as tolerated. The patient reported that she was better able to tolerate the sedating side effects of the increased dose of gabapentin because she had stopped working due to her severe pain episodes. We also added oral nifedipine 10 mg 3 times daily, as needed. Within 30 minutes of starting this treatment regimen, the pain associated with the lesions remarkably improved (10/10 severity before starting treatment vs 3/10 after starting treatment). Her pain levels remained stable (3/10 severity) during 3 weeks of treatment with this combination regimen, but unfortunately she developed headaches and malaise, which she associated with the nifedipine at the 3 times daily dose.

The patient was able to better tolerate the nifedipine after reducing the dose to once daily on an as-needed basis. On average, the patient took nifedipine once every 3 days; however, she reported that she had to periodically increase the frequency of the nifedipine to once daily for up to 2 weeks at a time for periods of more frequent pain flares. The patient reported a consistent pattern of the breakthrough symptoms rapidly improving with each dose of nifedipine, though she did feel that taking consistent gabapentin enhanced baseline symptom control. The patient also noticed on a few occasions when she did not have access to her nifedipine that her pain would flare to 10/10 severity and would decrease to 4/10 severity 30 minutes after restarting nifedipine at 10 mg once daily. She experienced breakthrough pain due to exacerbating factors including her menstrual cycle; exposure to the sun and cold temperatures or water; excessive physical activity; and mild trauma. Due to exacerbations from sun exposure, the patient often wore long-sleeved shirts, which helped reduce the severity of the pain episodes while she was outdoors.

The exact mechanism for the pain associated with cutaneous leiomyomas is unknown but is thought to be due to infringement of the lesion on the surrounding cutaneous nerves. In addition, norepinephrine activates alpha receptors on the smooth muscle to contract through an influx of ions such as calcium. When smooth muscle contracts, the compression of nerves likely is worsened.

There are a limited number of case reports in the literature that have demonstrated successful treatment of the pain associated with cutaneous leiomyomas. Previously reported treatment modalities have included phenoxybenzamine, an alpha-blocking agent that may reduce pain through its antiadrenergic effects2; nitroglycerin, a venous and arterial dilator that may reduce pain by decreasing muscle oxygen requirements2; gabapentin, an antiepileptic and analgesic medication with structural similarity to the gamma-aminobutyric acid neurotransmitter for which the exact mechanism of action is unknown3; botulinum toxin, a neuromuscular blocker that prevents the release of presynaptic acetylcholine and may decrease neuropathic pain by reducing hyperactive nerves5,6; hyoscine butylbromide and topical hyoscine hydrobromide, both antispasmodics that may reduce pain through their anticholinergic effects, which relax smooth muscle7,8; and the CO2 laser, a treatment that has been utilized for its resurfacing, excisional, and ablative properties.9,10

Calcium channel blockers such as amlodipine, verapamil, and nifedipine also have been used to treat the pain associated with piloleiomyomas.11 Calcium ion channel antagonists inhibit the influx of calcium ions across the cell membrane; therefore, nifedipine and other calcium channel blockers may prevent the smooth muscle contraction that is hypothesized to cause pain in patients with cutaneous leiomyomas.12

Mean plasma concentration of nifedipine has been shown to reach maximum values of 160 +/− 49 µg/L after 30 to 60 minutes following oral administration of 10 mg of nifedipine.13 After 8 hours, the mean concentration drops to 3.4 +/− 1.2 µg/L. The clinical response in our patient appeared consistent with the reported pharmacokinetics of the drug, as she was able to consistently obtain considerable reduction in her pain symptoms within 30 minutes of starting nifedipine, coinciding with the period of time it takes for the nifedipine to reach maximum plasma concentrations.13

Interestingly, our patient had worsening pain episodes associated with sun exposure, which typically is not reported as one of the usual triggers for cutaneous leiomyomas. We are not aware of any described mechanisms that would explain this phenomenon.

Importantly, any patient presenting with multiple cutaneous and uterine (if female) leiomyomas should be screened for hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma syndrome (HLRCC), an autosomal-dominant disorder linked to a mutation in the fumarate hydratase tumor suppressor gene. Clinically, HLRCC patients typically present with multiple cutaneous leiomyomas, uterine leiomyomas, and renal cell cancer (most often type 2 papillary renal cell carcinoma).14 Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma syndrome (also known as multiple cutaneous and uterine leiomyomatosis syndrome) previously was thought to be a separate disease entity from Reed syndrome; however, after the same mutation in the fumarate hydratase tumor suppressor gene was found to be responsible for both Reed syndrome and HLRCC, they are now thought to be the same disease process.15

Diagnosis of HLRCC is likely when the patient meets the major criterion of multiple cutaneous piloleiomyomas confirmed histopathologically. Clinical diagnosis of HLRCC is suspected if 2 or more of the following minor criteria are present: type 2 papillary renal cell carcinoma before 40 years of age; onset of severely symptomatic (requiring surgery) uterine fibroids before 40 years of age in females; and first-degree family member who meets 1 or more of these criteria.15 At the time of presentation, the patient met clinical criteria for HLRCC, including multiple cutaneous leiomyomas (major criterion) and type 2 papillary renal cell carcinoma before 40 years of age (minor criterion). The patient also had a history of uterine leiomyomas, but these lesions did not fulfill the criterion of being severely symptomatic requiring surgery. Furthermore, the patient’s mother had similar cutaneous leiomyomas and a history of uterine cancer, which fulfilled additional minor criterion, consistent with an autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern (with variable penetrance) seen in HLRCC. An important issue for counseling and monitoring patients is that premenopausal women with HLRCC are at an increased risk of developing uterine leiomyosarcoma.15 Our patient followed up with an oncologist for tumor surveillance and subsequently underwent genetic testing, which revealed a mutation in the fumarate hydratase gene.

Treatment of painful cutaneous leiomyomas, particularly in patients with HLRCC, remains a therapeutic challenge. Although surgical and/or destructive treatments can provide pain relief for patients who have a limited number of lesions, these options are impracticable when a patient has numerous widespread leiomyomas; therefore, systemic therapies may be more beneficial. Clinicians should be aware of nifedipine, which may be used in combination with gabapentin as a viable treatment option in the management of acute and breakthrough pain associated with cutaneous leiomyomas.

Acknowledgment

The a

- Holst VA, Junkins-Hopkins JM, Elenitsas R. Cutaneous smooth muscle neoplasms: clinical features, histologic findings, and treatment options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:477-494.

- Raj S, Calonje E, Kraus M, et al. Cutaneous pilar leiomyoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 53 lesions in 45 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:2-9.

- Alam M, Rabinowitz AD, Engler DE. Gabapentin treatment of multiple piloleiomyoma-related pain. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:S27-S29.

- Basendwh MA, Fatani M, Baltow B. Reed’s syndrome: a case of multiple cutaneous leiomyomas treated with liquid nitrogen cryotherapy. Case Rep Dermatol. 2016;8:65-70.

- Sifaki MK, Krueger-Krasagakis S, Koutsopoulos A, et al. Botulinum toxin type A–treatment of a patient with multiple cutaneous piloleiomyomas. Dermatology. 2008;218:44-47.

- Onder M, Adıs¸en E. A new indication of botulinum toxin: leiomyoma-related pain. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:325-328.

- Kaliyadan F, Manoj J, Dharmaratnam AD. Multiple cutaneous leiomyomas: pain relief with pulsed hysocine butyl bromide. Indian J Dermatol. 2009;54:72.

- Archer CB, Whittaker S, Greaves MW. Pharmacological modulation of cold‐induced pain in cutaneous leiomyomata. Br J Dermatol. 1988;118:255-260.

- Christenson LJ, Smith K, Arpey CJ. Treatment of multiple cutaneous leiomyomas with CO2 laser ablation. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:319-322.

- Michajłowski I, Błaz˙ewicz I, Karpinsky G, et al. Successful treatment of multiple cutaneous leiomyomas with carbon dioxide laser ablation. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2015;32:480-482.

- Archer CB, Greaves MW. Assessment of treatment for painful cutaneous leiomyomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:141-142.

- Thompson JA. Therapy for painful cutaneous leiomyomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13:865-867.

- Raemsch KD, Sommer J. Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of nifedipine. Hypertension. 1983;5(4 pt 2):II18-II24.

- Toro JR, Nickerson ML, Wei MH, et al. Mutations in the fumarate hydratase gene cause hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer in families in North America. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73:95-106.

- Smit DL, Mensenkamp AR, Badeloe S, et al. Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer in families referred for fumarate hydratase germline mutation analysis. Clin Genet. 2011;79:49-59.

To the Editor:

Leiomyomas are benign smooth muscle tumors. There are 3 types of cutaneous leiomyomas: (1) piloleiomyomas, arising from the arrector pili muscles; (2) angioleiomyomas, arising from the muscles surrounding dermal blood vessels; and (3) leiomyomas of the external genitalia, arising from the dartoic, vulvar, or mammary smooth muscles.1 There is no gender predilection for cutaneous leiomyomas, and lesions present on average at approximately 40 to 45 years of age.2

Piloleiomyomas are the most common type of cutaneous leiomyomas and typically present as red-brown papules and nodules on the trunk, arms, and legs.3 Piloleiomyomas often are associated with spontaneous or induced pain (eg, with cold exposure). The pain associated with piloleiomyomas can be severely debilitating to patients and may have a considerable impact on their quality of life.

A 40-year-old woman presented to our clinic with numerous widespread, painful, red-brown papules and nodules on the head, neck, chest, abdomen, back, arms, and legs of 6 years’ duration that were increasing in number (Figure 1). She had a history of uterine leiomyomas and type 2 renal papillary carcinoma following a left nephrectomy at 38 years of age. The patient’s mother had a history of similar skin lesions as well as uterine cancer. Multiple excisional biopsies were performed, all of which showed piloleiomyomas on histopathology (Figure 2). The pain associated with the patient’s extensive cutaneous leiomyomas considerably impaired her quality of life. Although she experienced pain in all affected areas of the body, the pain was the worst in the upper arms. She reported having requested a nerve ablation procedure from an outside pain management clinic, which was denied for unknown reasons.

Two years prior to the current presentation, the patient had been treated by a pain management specialist with gabapentin 300 mg twice daily as needed for pain associated with leiomyomas. The patient followed this regimen approximately 3 times weekly for the preceding 1 to 2 years with reduction in her pain symptoms; however, the painful episodes became more frequent and severe over time. The patient reported being unable to further increase the gabapentin dosing frequency because it made her too drowsy and impacted her ability to work a job that required heavy lifting. Thus, the patient requested additional therapy and was subsequently treated at our clinic with numerous excisional biopsies of the most painful lesions during the 2 years prior to her current presentation.

When the patient re-presented to our clinic, she requested additional lesion excisions given that she had experienced some pain relief from this treatment modality in the past; however, these prior excisions only resulted in local pain relief limited to the site of the excision. Because of the extent of the lesions and the patient’s inability to tolerate pain from the lidocaine injections, we did not feel multiple excisions were a practical treatment option. The patient subsequently was offered a trial of cryotherapy for symptom relief based on a reported case in which this modality was successfully used.4 After discussing the risks and benefits associated with this treatment, cryotherapy was attempted on a few of the leiomyomas on the patient’s right shoulder; however, she experienced severe pain during cryotherapy treatment, and the procedure had to be aborted.

We then increased the patient’s gabapentin regimen to 300 mg in the morning and 600 mg in the evening, as tolerated. The patient reported that she was better able to tolerate the sedating side effects of the increased dose of gabapentin because she had stopped working due to her severe pain episodes. We also added oral nifedipine 10 mg 3 times daily, as needed. Within 30 minutes of starting this treatment regimen, the pain associated with the lesions remarkably improved (10/10 severity before starting treatment vs 3/10 after starting treatment). Her pain levels remained stable (3/10 severity) during 3 weeks of treatment with this combination regimen, but unfortunately she developed headaches and malaise, which she associated with the nifedipine at the 3 times daily dose.

The patient was able to better tolerate the nifedipine after reducing the dose to once daily on an as-needed basis. On average, the patient took nifedipine once every 3 days; however, she reported that she had to periodically increase the frequency of the nifedipine to once daily for up to 2 weeks at a time for periods of more frequent pain flares. The patient reported a consistent pattern of the breakthrough symptoms rapidly improving with each dose of nifedipine, though she did feel that taking consistent gabapentin enhanced baseline symptom control. The patient also noticed on a few occasions when she did not have access to her nifedipine that her pain would flare to 10/10 severity and would decrease to 4/10 severity 30 minutes after restarting nifedipine at 10 mg once daily. She experienced breakthrough pain due to exacerbating factors including her menstrual cycle; exposure to the sun and cold temperatures or water; excessive physical activity; and mild trauma. Due to exacerbations from sun exposure, the patient often wore long-sleeved shirts, which helped reduce the severity of the pain episodes while she was outdoors.

The exact mechanism for the pain associated with cutaneous leiomyomas is unknown but is thought to be due to infringement of the lesion on the surrounding cutaneous nerves. In addition, norepinephrine activates alpha receptors on the smooth muscle to contract through an influx of ions such as calcium. When smooth muscle contracts, the compression of nerves likely is worsened.

There are a limited number of case reports in the literature that have demonstrated successful treatment of the pain associated with cutaneous leiomyomas. Previously reported treatment modalities have included phenoxybenzamine, an alpha-blocking agent that may reduce pain through its antiadrenergic effects2; nitroglycerin, a venous and arterial dilator that may reduce pain by decreasing muscle oxygen requirements2; gabapentin, an antiepileptic and analgesic medication with structural similarity to the gamma-aminobutyric acid neurotransmitter for which the exact mechanism of action is unknown3; botulinum toxin, a neuromuscular blocker that prevents the release of presynaptic acetylcholine and may decrease neuropathic pain by reducing hyperactive nerves5,6; hyoscine butylbromide and topical hyoscine hydrobromide, both antispasmodics that may reduce pain through their anticholinergic effects, which relax smooth muscle7,8; and the CO2 laser, a treatment that has been utilized for its resurfacing, excisional, and ablative properties.9,10

Calcium channel blockers such as amlodipine, verapamil, and nifedipine also have been used to treat the pain associated with piloleiomyomas.11 Calcium ion channel antagonists inhibit the influx of calcium ions across the cell membrane; therefore, nifedipine and other calcium channel blockers may prevent the smooth muscle contraction that is hypothesized to cause pain in patients with cutaneous leiomyomas.12

Mean plasma concentration of nifedipine has been shown to reach maximum values of 160 +/− 49 µg/L after 30 to 60 minutes following oral administration of 10 mg of nifedipine.13 After 8 hours, the mean concentration drops to 3.4 +/− 1.2 µg/L. The clinical response in our patient appeared consistent with the reported pharmacokinetics of the drug, as she was able to consistently obtain considerable reduction in her pain symptoms within 30 minutes of starting nifedipine, coinciding with the period of time it takes for the nifedipine to reach maximum plasma concentrations.13

Interestingly, our patient had worsening pain episodes associated with sun exposure, which typically is not reported as one of the usual triggers for cutaneous leiomyomas. We are not aware of any described mechanisms that would explain this phenomenon.

Importantly, any patient presenting with multiple cutaneous and uterine (if female) leiomyomas should be screened for hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma syndrome (HLRCC), an autosomal-dominant disorder linked to a mutation in the fumarate hydratase tumor suppressor gene. Clinically, HLRCC patients typically present with multiple cutaneous leiomyomas, uterine leiomyomas, and renal cell cancer (most often type 2 papillary renal cell carcinoma).14 Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma syndrome (also known as multiple cutaneous and uterine leiomyomatosis syndrome) previously was thought to be a separate disease entity from Reed syndrome; however, after the same mutation in the fumarate hydratase tumor suppressor gene was found to be responsible for both Reed syndrome and HLRCC, they are now thought to be the same disease process.15

Diagnosis of HLRCC is likely when the patient meets the major criterion of multiple cutaneous piloleiomyomas confirmed histopathologically. Clinical diagnosis of HLRCC is suspected if 2 or more of the following minor criteria are present: type 2 papillary renal cell carcinoma before 40 years of age; onset of severely symptomatic (requiring surgery) uterine fibroids before 40 years of age in females; and first-degree family member who meets 1 or more of these criteria.15 At the time of presentation, the patient met clinical criteria for HLRCC, including multiple cutaneous leiomyomas (major criterion) and type 2 papillary renal cell carcinoma before 40 years of age (minor criterion). The patient also had a history of uterine leiomyomas, but these lesions did not fulfill the criterion of being severely symptomatic requiring surgery. Furthermore, the patient’s mother had similar cutaneous leiomyomas and a history of uterine cancer, which fulfilled additional minor criterion, consistent with an autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern (with variable penetrance) seen in HLRCC. An important issue for counseling and monitoring patients is that premenopausal women with HLRCC are at an increased risk of developing uterine leiomyosarcoma.15 Our patient followed up with an oncologist for tumor surveillance and subsequently underwent genetic testing, which revealed a mutation in the fumarate hydratase gene.

Treatment of painful cutaneous leiomyomas, particularly in patients with HLRCC, remains a therapeutic challenge. Although surgical and/or destructive treatments can provide pain relief for patients who have a limited number of lesions, these options are impracticable when a patient has numerous widespread leiomyomas; therefore, systemic therapies may be more beneficial. Clinicians should be aware of nifedipine, which may be used in combination with gabapentin as a viable treatment option in the management of acute and breakthrough pain associated with cutaneous leiomyomas.

Acknowledgment

The a

To the Editor: