User login

Cutaneous Pemphigus Vegetans Co-occurring With Oral Pemphigus Vulgaris

To the Editor:

A 74-year-old man with a history of colon cancer and no history of sexually transmitted diseases presented with tender, moist, vegetating, and verrucous plaques localized to the inguinal creases and behind the scrotum of 3 weeks’ duration (Figure 1). The patient recently had taken lisinopril prescribed by his primary care physician for a couple of years for hypertension before switching to losartan prior to the current presentation. He later noticed the groin eruptions. He also noticed white tongue plaques temporally associated with the groin plaques and a long history of recurrent oral ulcerations. Prior to being seen in our clinic, outside physicians cultured methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus from the groin plaques and treated him with oral clindamycin, cephalexin, and topical mupirocin without a clinical response.

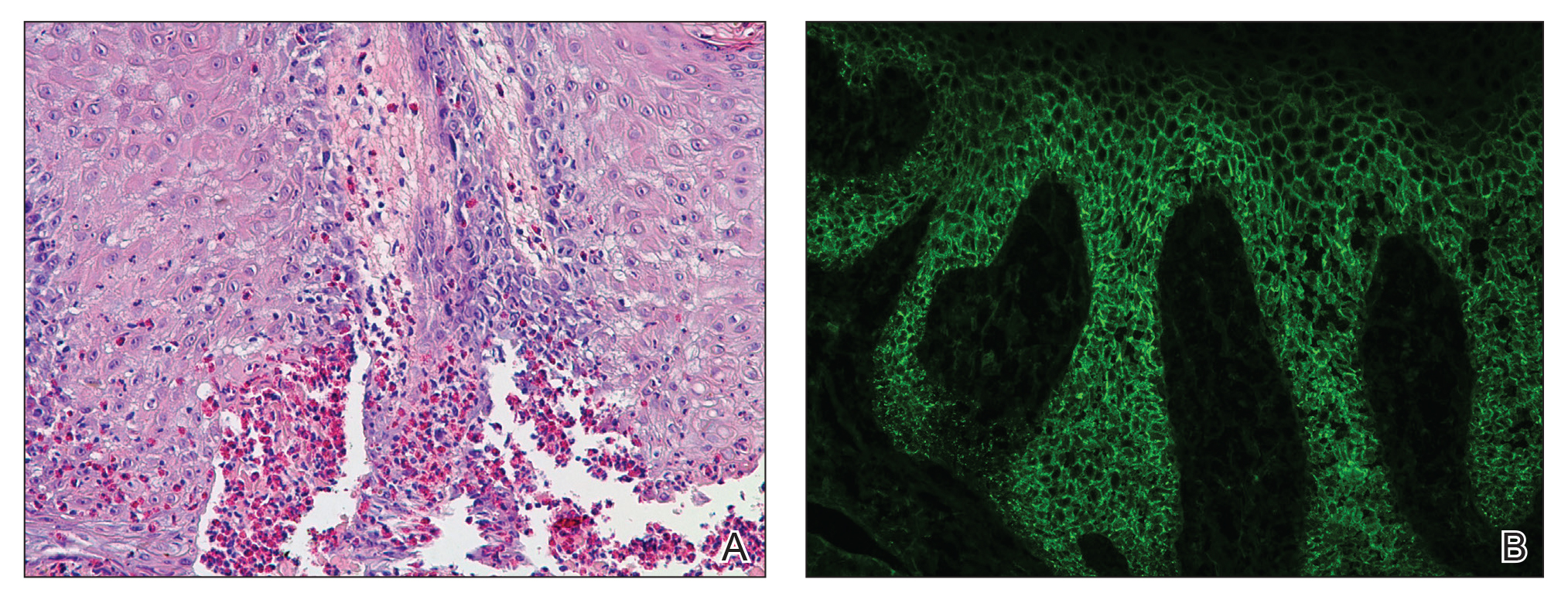

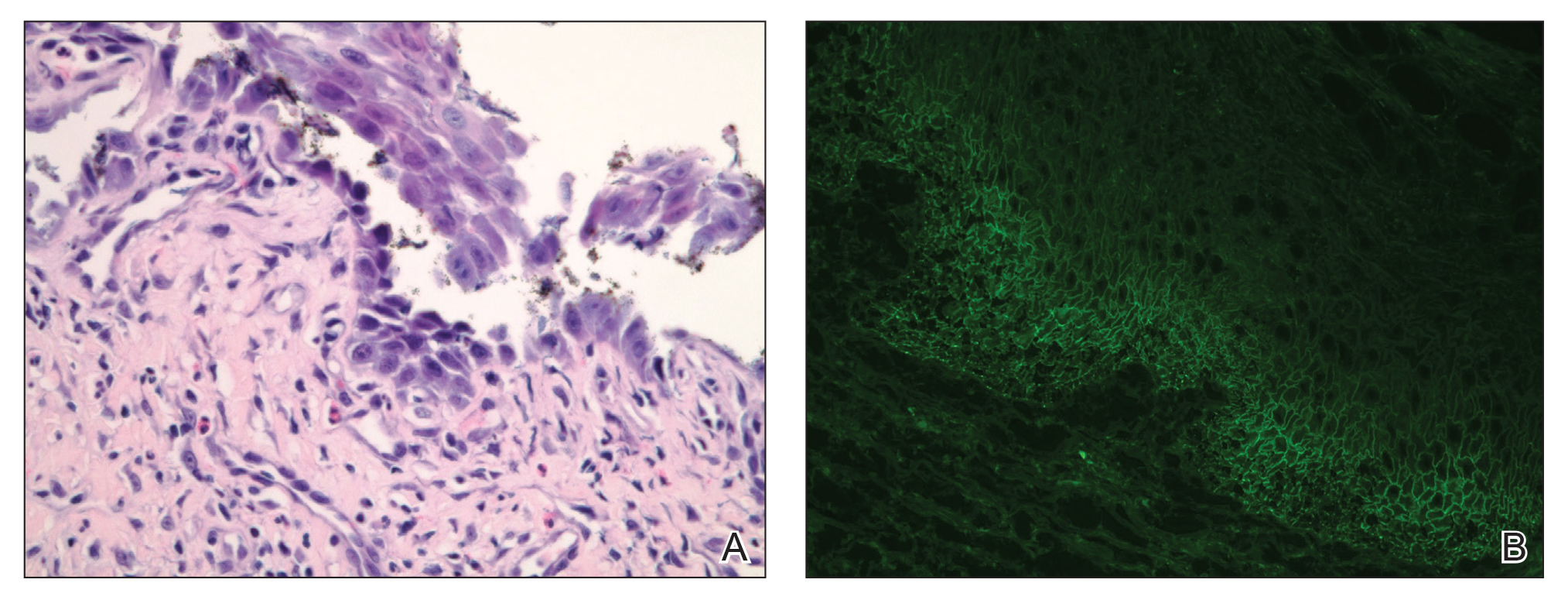

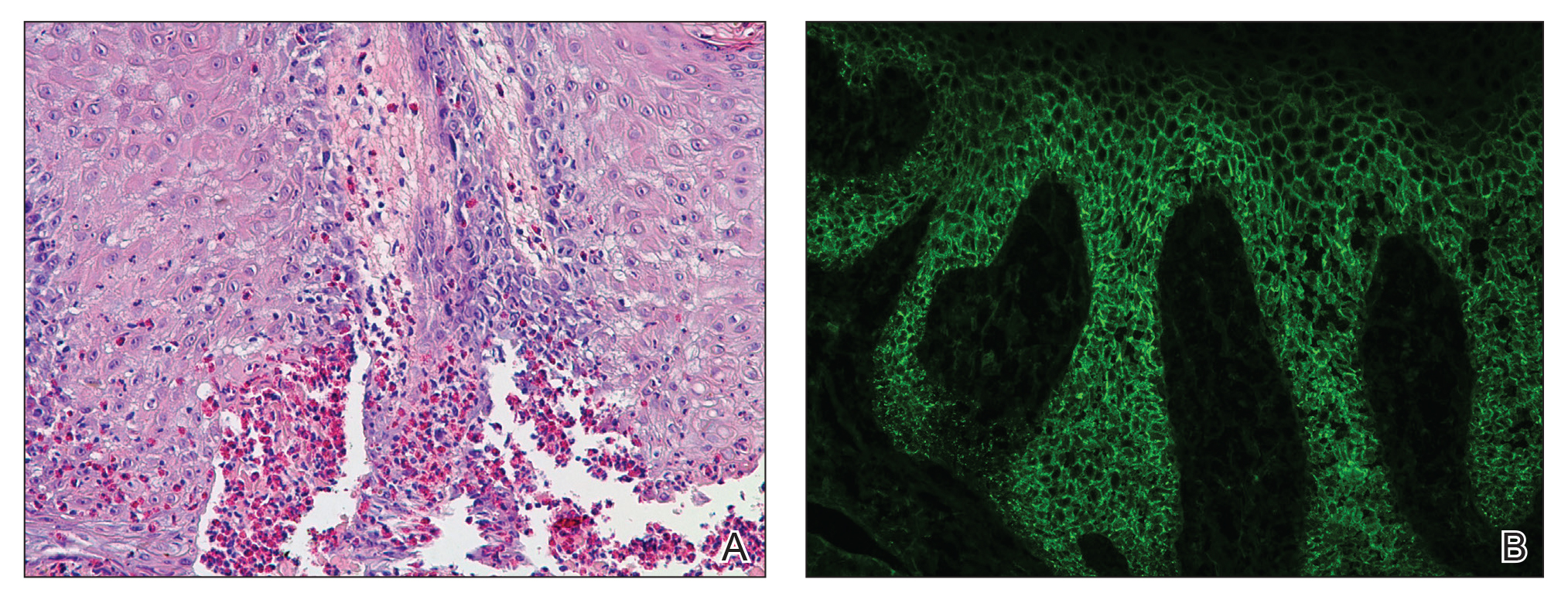

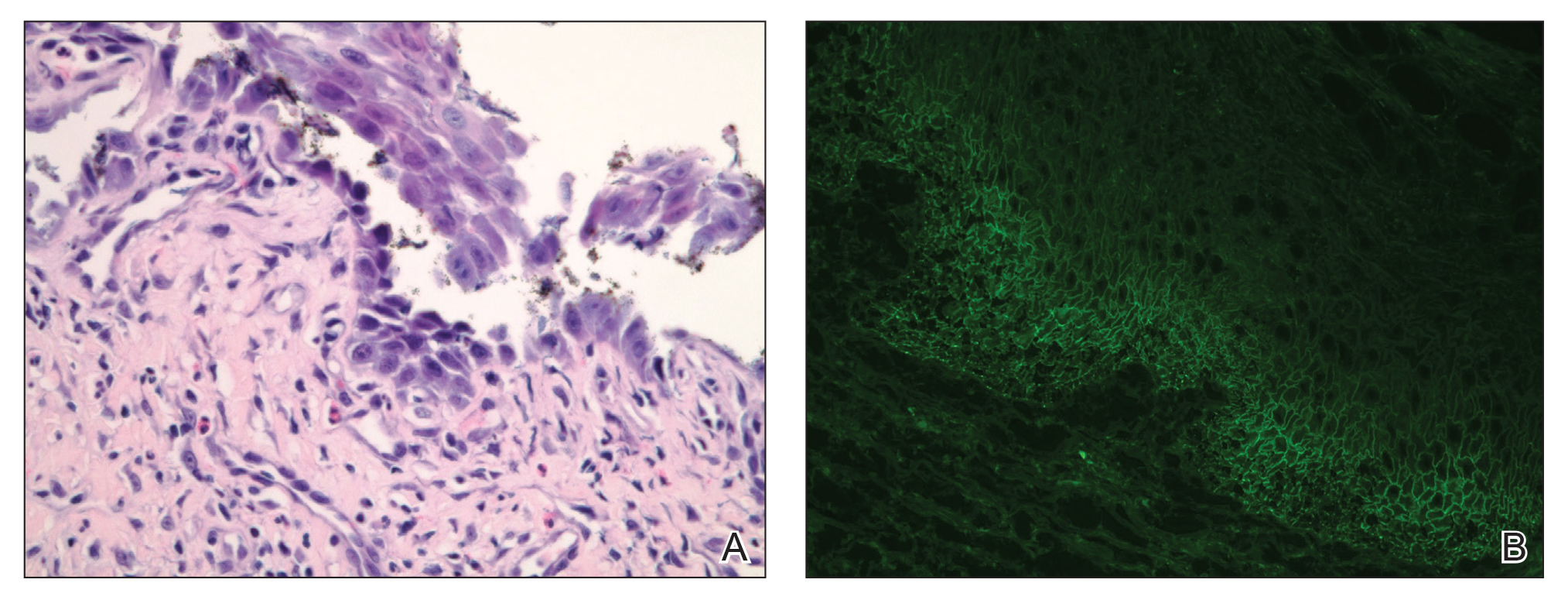

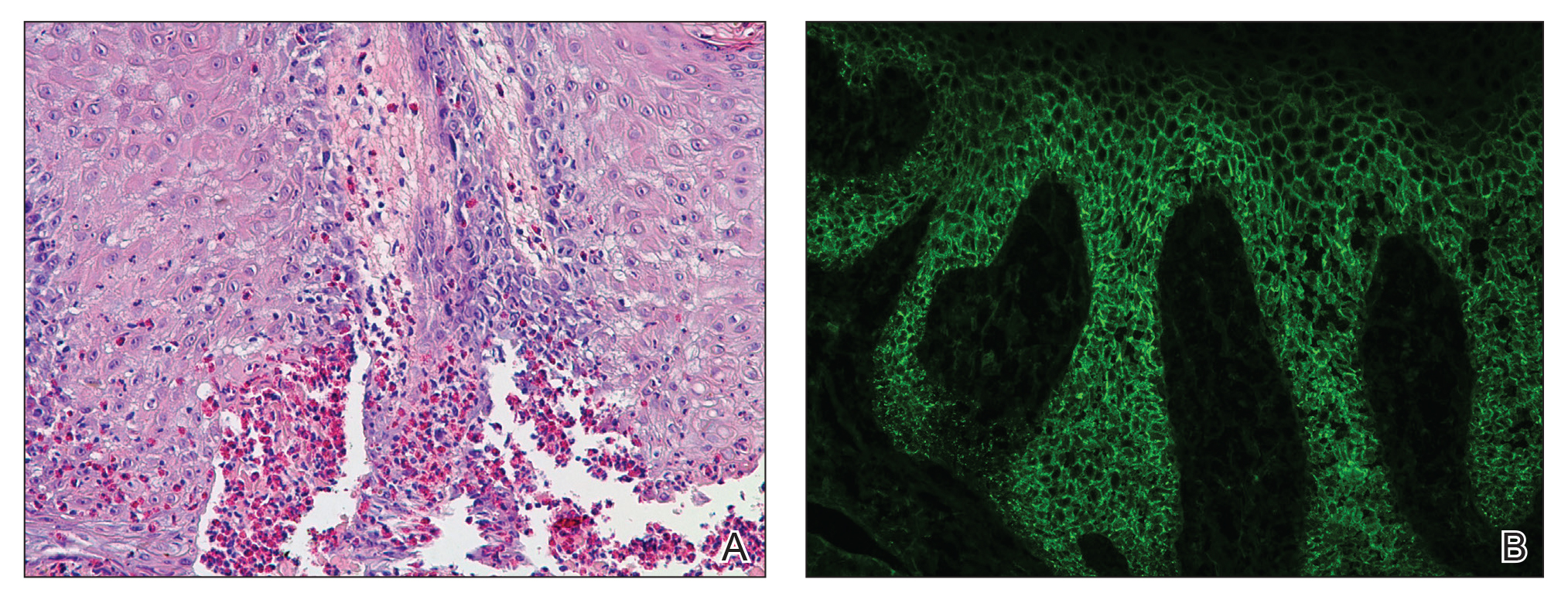

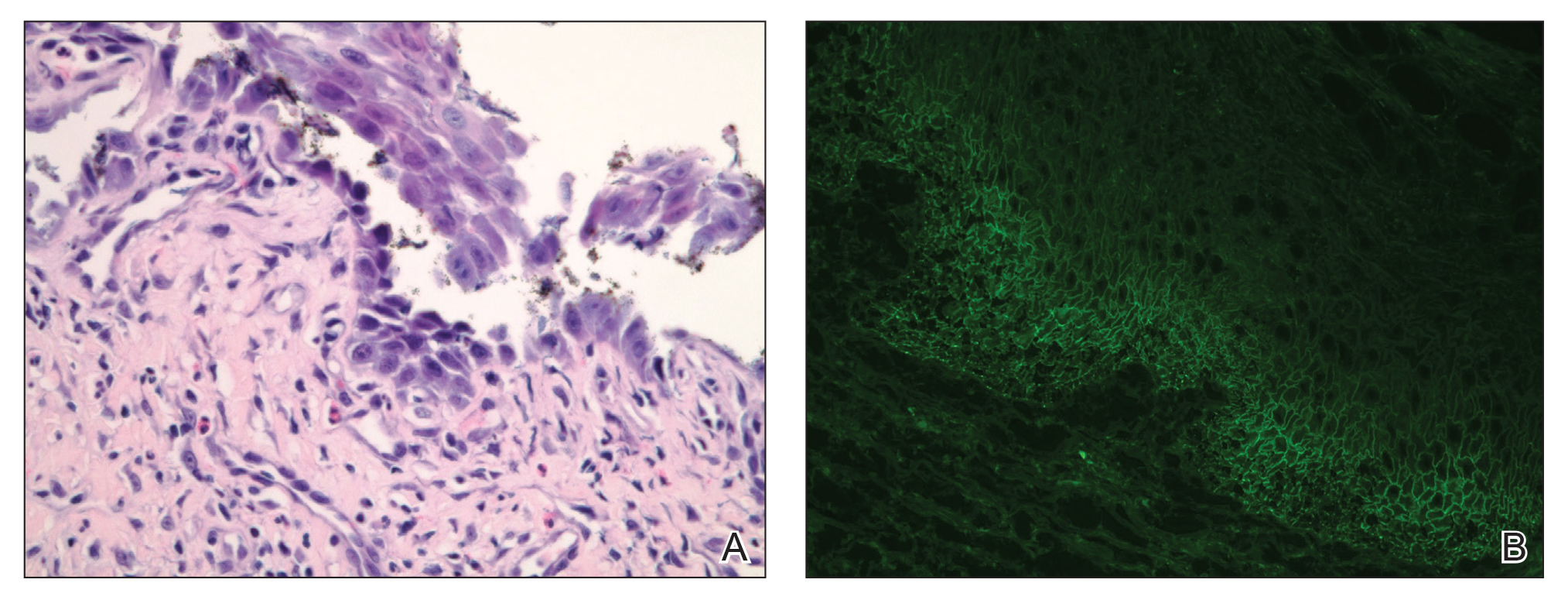

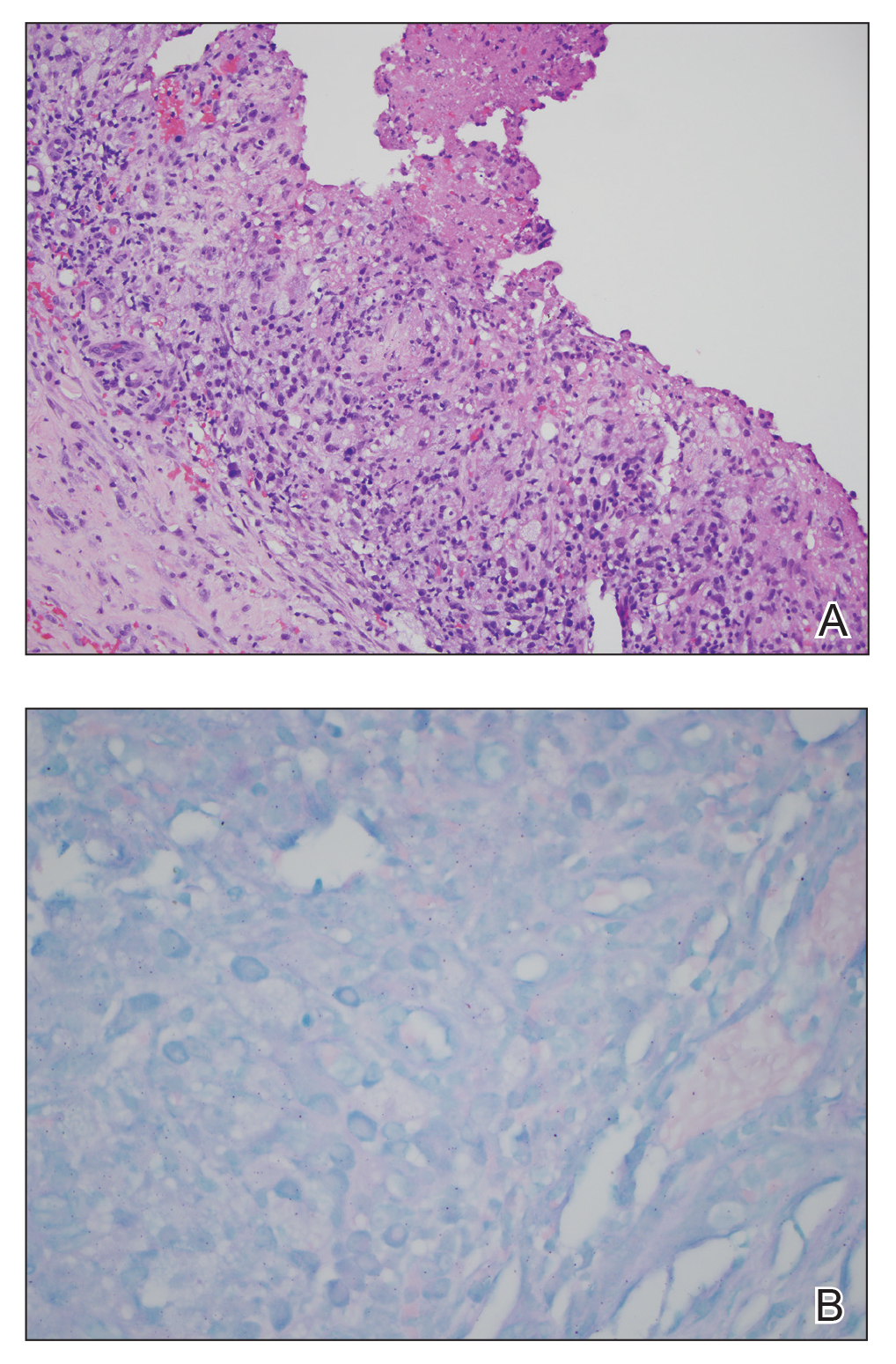

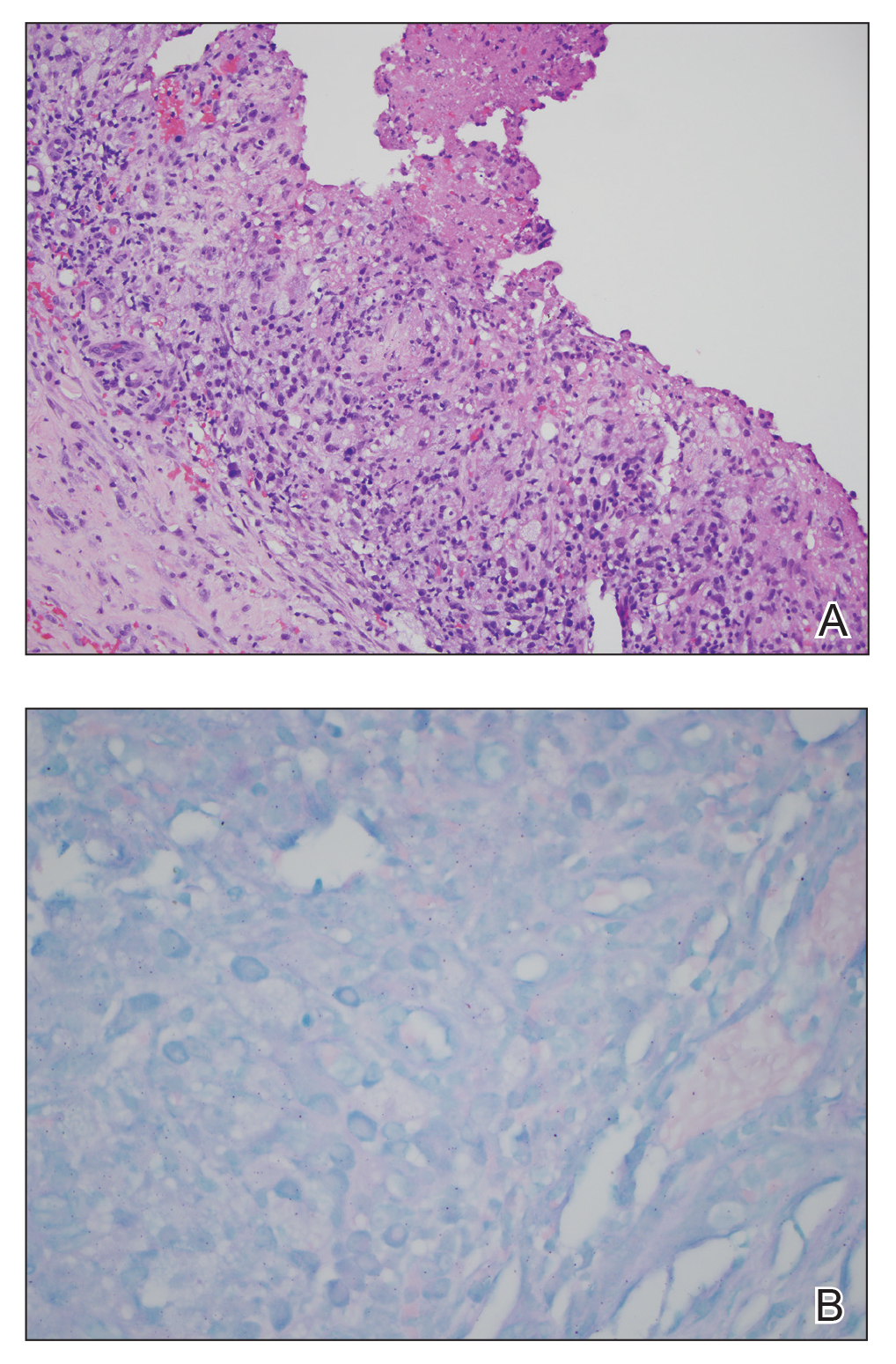

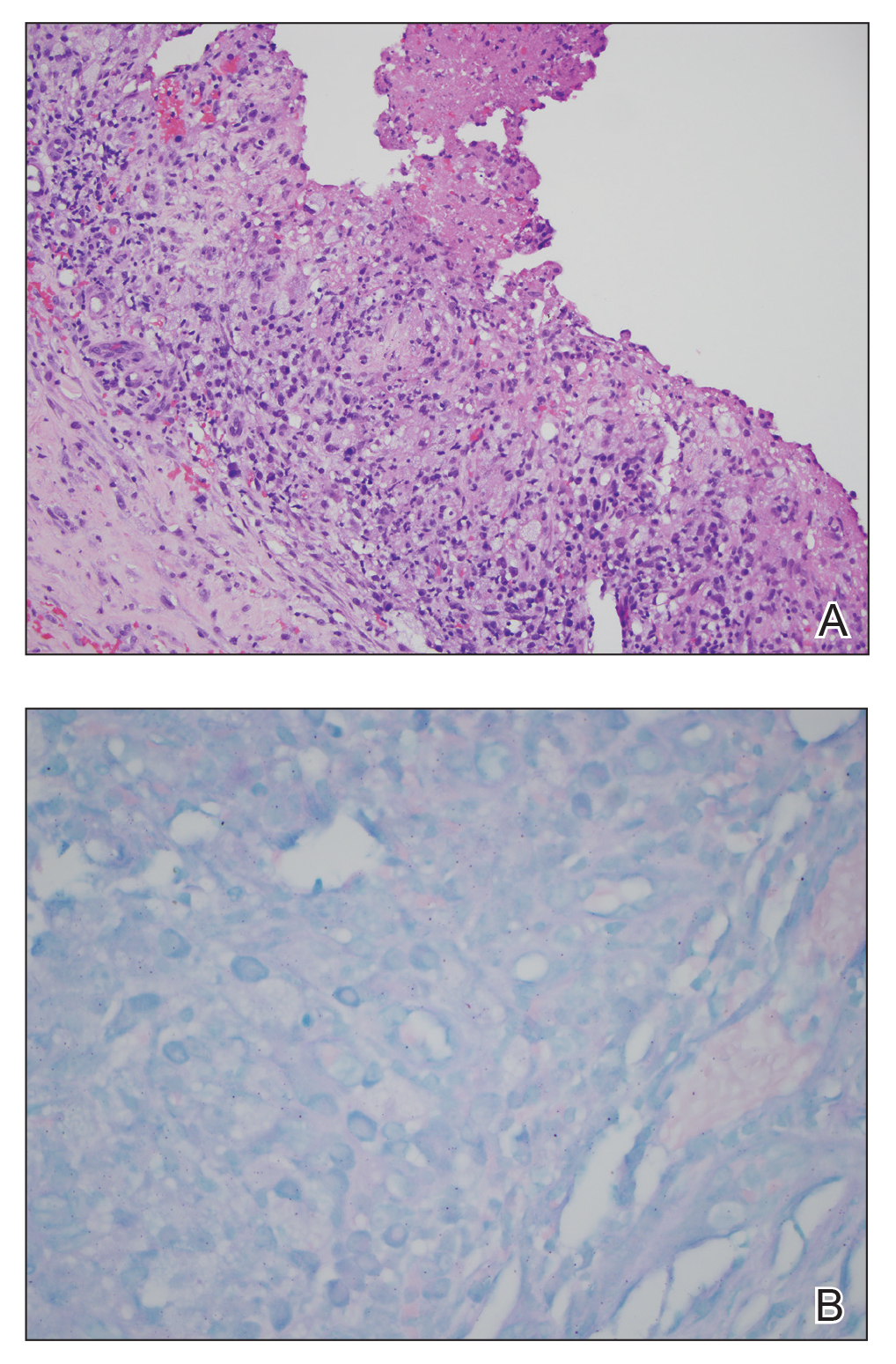

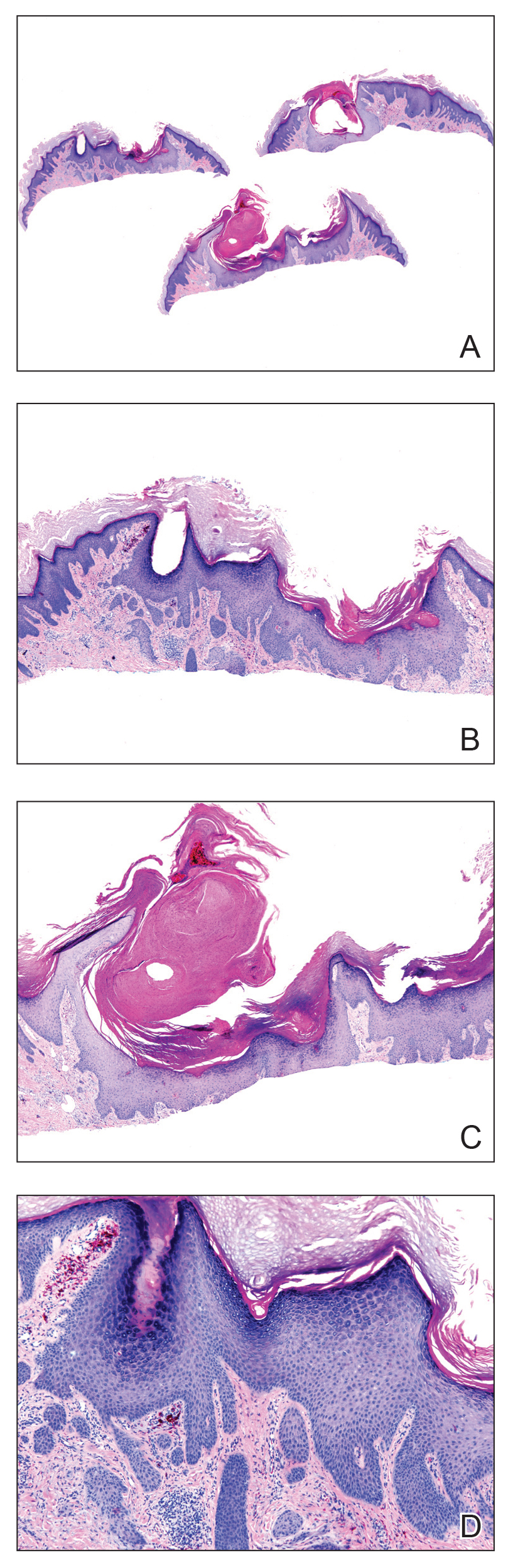

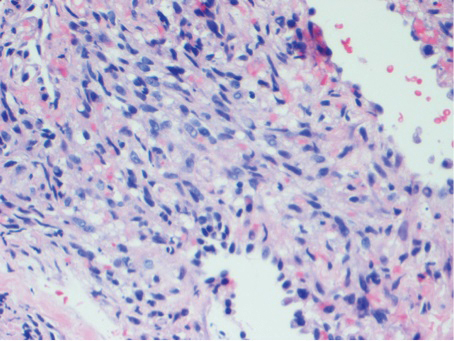

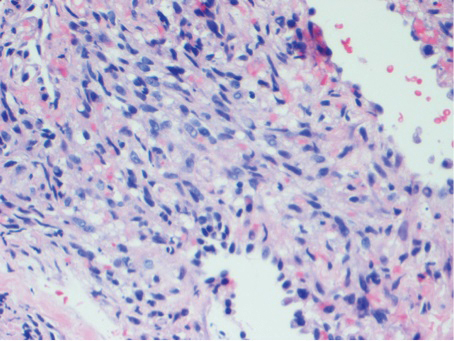

Our differential diagnosis included condyloma acuminata, condyloma lata, and cutaneous pemphigus vegetans. Laboratory testing revealed a nonreactive rapid plasma reagin test and peripheral eosinophilia of 14.9% (reference range, 0%–6%). Biopsy of a left groin plaque revealed epidermal hyperplasia with spongiosis and an eosinophilic-rich infiltrate on hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 2A), and direct immunofluorescence revealed diffuse epidermal intercellular IgG deposits (Figure 2B). The patient’s clinical and histologic presentation was consistent with cutaneous pemphigus vegetans. Biopsy of an oral ulcer revealed denuded acantholytic mucositis with eosinophilic-rich submucosal infiltrate and fibrosis (Figure 3A). Direct immunofluorescence was positive for lacelike intercellular staining for IgG and C3 within the squamous epithelium (Figure 3B). Together the clinical and histologic findings were consistent with oral pemphigus vulgaris.

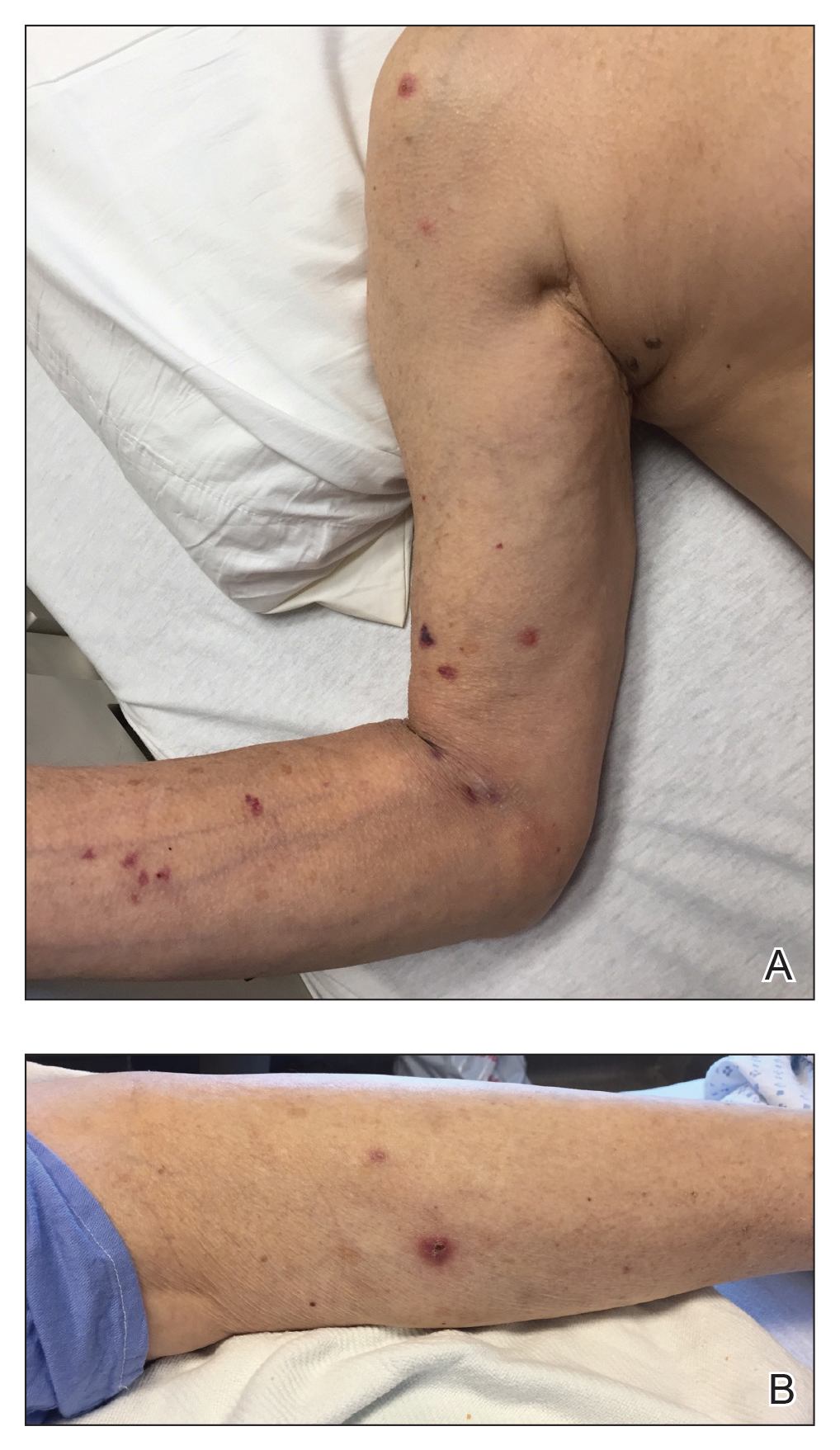

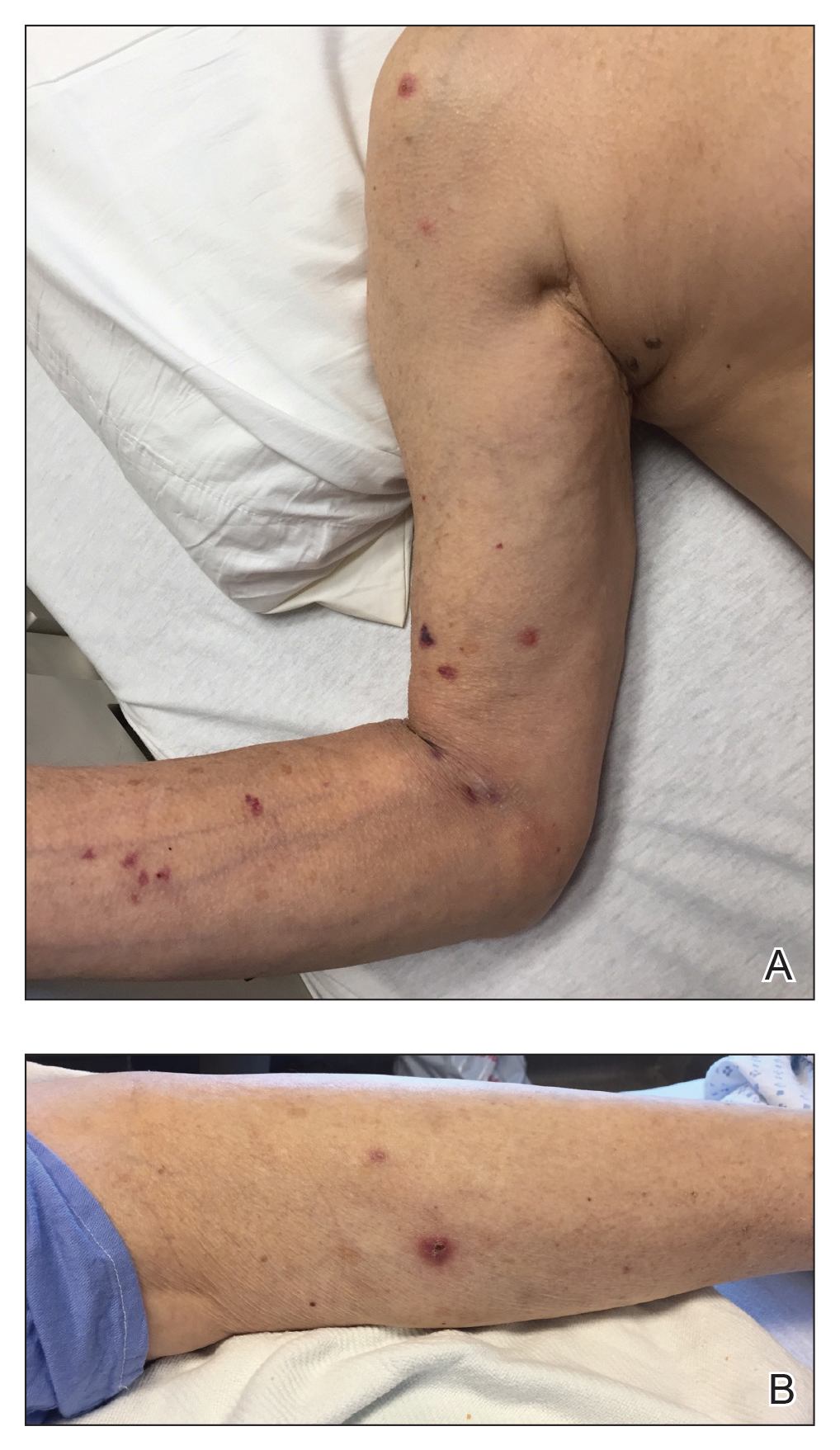

The patient initially was started on oral minocycline 100 mg twice daily and mometasone furoate cream 0.1% twice daily to affected groin areas. With these interventions, the groin plaques almost completely resolved after several months, leaving only residual hyperpigmentation (Figure 4). The oral pemphigus vulgaris initially was treated with dexamethasone 0.5 mg/5 mL solution 2 to 3 times daily, but the lesions were refractory to this approach and also did not improve after the losartan was discontinued for several months. As such, mycophenolate mofetil was started. He was titrated to the lowest effective dose and showed near-complete resolution with 500 mg 3 times daily.

Cutaneous pemphigus vegetans, a rare variant of pemphigus vulgaris, is characterized by vegetating plaques commonly localized to the skin folds, scalp, face, and mucous membranes.1 Involvement of the oral mucosa occurs in a majority of cases. Although our patient had oral ulcerations, he did not have characteristic cerebriform changes of the dorsal tongue or associated verrucous hyperkeratotic lesions involving the buccal mucosa, hard and soft palate, or vermilion border of the lips that typically are seen in pemphigus vegetans.2-5 Subsequent biopsy of the oral mucosa confirmed oral pemphigus vulgaris in our patient.

This case presentation of co-occurring cutaneous pemphigus vegetans and oral pemphigus vulgaris is uncommonly reported in the literature. Although the etiology of this co-occurrence is not clear, it could represent a form of epitope spread, with the mechanism similar to that proposed for the progression of pemphigus vulgaris from the mucosal to the mucocutaneous stage by Chan et al,6 who suggested that an autoimmune reaction against specific desmoglein 3 epitopes (an important protein component for desmosomes and the autoantigen in pemphigus vulgaris) on mucosal membranes could induce local damage. These injuries could then expose the autoreactive immune cells to a secondary desmoglein 3 epitope present in the skin, leading to the development of cutaneous lesions.6 Salato et al7 also supported this idea of intramolecular epitope spread in pemphigus vulgaris, explaining that at various stages of the disease (mucosal and mucocutaneous), the antibodies have “different tissue-binding patterns and pathogenic activities, suggesting that they may recognize distinct epitopes.” This concept of epitope spread from the oral mucosal form to the cutaneous form of pemphigus vulgaris also could help explain our patient’s presentation, as he had a long history of recurrent oral ulcerations prior to developing the vegetating cutaneous plaques of cutaneous pemphigus vegetans.

We also appreciate that either the cutaneous pemphigus vegetans or oral pemphigus vulgaris could have been drug induced in our case. Captopril has been reported to cause pemphigus vulgaris,8 so it is conceivable that the related medication lisinopril was the culprit in our case. A prior case report described an elderly man who developed lisinopril-induced pemphigus foliaceus; however, there was no oral involvement in this case and no further blister formation within 48 hours of discontinuing lisinopril.9 An additional case report implicated lisinopril in the development of a bullous eruption on the oral mucosa in a female patient, though direct and indirect immunofluorescence did not reveal the autoantibodies that typically are seen in pemphigus vulgaris.10 Our patient’s blood eosinophilia also could support an adverse drug reaction. Our patient’s losartan was discontinued for several months without respite of the oral ulcerations and thus was restarted. The cutaneous pemphigus vegetans continues to be in remission and was unaffected by restarting the losartan, making it a less likely culprit for his presentation.

We identified another case in the literature in which an individual with a history of colon cancer was diagnosed with cutaneous pemphigus vegetans.11 As such, we considered a possible link between the 2 diagnoses; however, the temporal disconnect between both conditions in our patient makes this less likely, unlike the other reported case in which the internal neoplasm and pemphigus vegetans appeared nearly simultaneously.11

Finally, our case supports a combination of topical steroids and minocycline for treatment of cutaneous pemphigus vegetans.

Our case demonstrates the importance of considering cutaneous pemphigus vegetans in the differential diagnosis, despite its rarity, when patients present with vegetating plaques. In addition, although oral involvement is common with this condition, if the patient’s oral lesions do not fit the characteristic oral findings seen in pemphigus vegetans, alternative diagnoses should be considered.

- de Almeida HL Jr, Neugebauer MG, Guarenti IM, et al. Pemphigus vegetans associated with verrucous lesions: expanding a phenotype. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2006;61:279-282.

- Danopoulou I, Stavropoulos P, Stratigos A, et al. Pemphigus vegetans confined to the scalp. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1008-1009.

- Markopoulos AK, Antoniades DZ, Zaraboukas T. Pemphigus vegetans of the oral cavity. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:425-428.

- Woo TY, Solomon AR, Fairley JA. Pemphigus vegetans limited to the lips and oral mucosa. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:271-272.

- Yuen KL, Yau KC. An old gentleman with vegetative plaques and erosions: a case of pemphigus vegetans. Hong Kong J Dermatol Venereol. 2012;20:179-182.

- Chan LS, Vanderlugt CJ, Hashimoto T, et al. Epitope spreading: lessons from autoimmune skin diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;110:103-109.

- Salato VK, Hacker-Foegen MK, Lazarova Z, et al. Role of intramolecular epitope spreading in pemphigus vulgaris. Clin Immunol. 2005;116:54-64.

- Dashore A, Choudhary SD. Captopril induced pemphigus vulgaris. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1987;53:293-294.

- Patterson CR, Davies MG. Pemphigus foliaceus: an adverse reaction to lisinopril. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:60-62.

- Baričević M, Mravak Stipeti´c M, Situm M, et al. Oral bullous eruption after taking lisinopril—case report and literature review. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2013;125:408-411.

- Torres T, Ferreira M, Sanches M, et al. Pemphigus vegetans in a patient with colonic cancer. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:603-605.

To the Editor:

A 74-year-old man with a history of colon cancer and no history of sexually transmitted diseases presented with tender, moist, vegetating, and verrucous plaques localized to the inguinal creases and behind the scrotum of 3 weeks’ duration (Figure 1). The patient recently had taken lisinopril prescribed by his primary care physician for a couple of years for hypertension before switching to losartan prior to the current presentation. He later noticed the groin eruptions. He also noticed white tongue plaques temporally associated with the groin plaques and a long history of recurrent oral ulcerations. Prior to being seen in our clinic, outside physicians cultured methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus from the groin plaques and treated him with oral clindamycin, cephalexin, and topical mupirocin without a clinical response.

Our differential diagnosis included condyloma acuminata, condyloma lata, and cutaneous pemphigus vegetans. Laboratory testing revealed a nonreactive rapid plasma reagin test and peripheral eosinophilia of 14.9% (reference range, 0%–6%). Biopsy of a left groin plaque revealed epidermal hyperplasia with spongiosis and an eosinophilic-rich infiltrate on hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 2A), and direct immunofluorescence revealed diffuse epidermal intercellular IgG deposits (Figure 2B). The patient’s clinical and histologic presentation was consistent with cutaneous pemphigus vegetans. Biopsy of an oral ulcer revealed denuded acantholytic mucositis with eosinophilic-rich submucosal infiltrate and fibrosis (Figure 3A). Direct immunofluorescence was positive for lacelike intercellular staining for IgG and C3 within the squamous epithelium (Figure 3B). Together the clinical and histologic findings were consistent with oral pemphigus vulgaris.

The patient initially was started on oral minocycline 100 mg twice daily and mometasone furoate cream 0.1% twice daily to affected groin areas. With these interventions, the groin plaques almost completely resolved after several months, leaving only residual hyperpigmentation (Figure 4). The oral pemphigus vulgaris initially was treated with dexamethasone 0.5 mg/5 mL solution 2 to 3 times daily, but the lesions were refractory to this approach and also did not improve after the losartan was discontinued for several months. As such, mycophenolate mofetil was started. He was titrated to the lowest effective dose and showed near-complete resolution with 500 mg 3 times daily.

Cutaneous pemphigus vegetans, a rare variant of pemphigus vulgaris, is characterized by vegetating plaques commonly localized to the skin folds, scalp, face, and mucous membranes.1 Involvement of the oral mucosa occurs in a majority of cases. Although our patient had oral ulcerations, he did not have characteristic cerebriform changes of the dorsal tongue or associated verrucous hyperkeratotic lesions involving the buccal mucosa, hard and soft palate, or vermilion border of the lips that typically are seen in pemphigus vegetans.2-5 Subsequent biopsy of the oral mucosa confirmed oral pemphigus vulgaris in our patient.

This case presentation of co-occurring cutaneous pemphigus vegetans and oral pemphigus vulgaris is uncommonly reported in the literature. Although the etiology of this co-occurrence is not clear, it could represent a form of epitope spread, with the mechanism similar to that proposed for the progression of pemphigus vulgaris from the mucosal to the mucocutaneous stage by Chan et al,6 who suggested that an autoimmune reaction against specific desmoglein 3 epitopes (an important protein component for desmosomes and the autoantigen in pemphigus vulgaris) on mucosal membranes could induce local damage. These injuries could then expose the autoreactive immune cells to a secondary desmoglein 3 epitope present in the skin, leading to the development of cutaneous lesions.6 Salato et al7 also supported this idea of intramolecular epitope spread in pemphigus vulgaris, explaining that at various stages of the disease (mucosal and mucocutaneous), the antibodies have “different tissue-binding patterns and pathogenic activities, suggesting that they may recognize distinct epitopes.” This concept of epitope spread from the oral mucosal form to the cutaneous form of pemphigus vulgaris also could help explain our patient’s presentation, as he had a long history of recurrent oral ulcerations prior to developing the vegetating cutaneous plaques of cutaneous pemphigus vegetans.

We also appreciate that either the cutaneous pemphigus vegetans or oral pemphigus vulgaris could have been drug induced in our case. Captopril has been reported to cause pemphigus vulgaris,8 so it is conceivable that the related medication lisinopril was the culprit in our case. A prior case report described an elderly man who developed lisinopril-induced pemphigus foliaceus; however, there was no oral involvement in this case and no further blister formation within 48 hours of discontinuing lisinopril.9 An additional case report implicated lisinopril in the development of a bullous eruption on the oral mucosa in a female patient, though direct and indirect immunofluorescence did not reveal the autoantibodies that typically are seen in pemphigus vulgaris.10 Our patient’s blood eosinophilia also could support an adverse drug reaction. Our patient’s losartan was discontinued for several months without respite of the oral ulcerations and thus was restarted. The cutaneous pemphigus vegetans continues to be in remission and was unaffected by restarting the losartan, making it a less likely culprit for his presentation.

We identified another case in the literature in which an individual with a history of colon cancer was diagnosed with cutaneous pemphigus vegetans.11 As such, we considered a possible link between the 2 diagnoses; however, the temporal disconnect between both conditions in our patient makes this less likely, unlike the other reported case in which the internal neoplasm and pemphigus vegetans appeared nearly simultaneously.11

Finally, our case supports a combination of topical steroids and minocycline for treatment of cutaneous pemphigus vegetans.

Our case demonstrates the importance of considering cutaneous pemphigus vegetans in the differential diagnosis, despite its rarity, when patients present with vegetating plaques. In addition, although oral involvement is common with this condition, if the patient’s oral lesions do not fit the characteristic oral findings seen in pemphigus vegetans, alternative diagnoses should be considered.

To the Editor:

A 74-year-old man with a history of colon cancer and no history of sexually transmitted diseases presented with tender, moist, vegetating, and verrucous plaques localized to the inguinal creases and behind the scrotum of 3 weeks’ duration (Figure 1). The patient recently had taken lisinopril prescribed by his primary care physician for a couple of years for hypertension before switching to losartan prior to the current presentation. He later noticed the groin eruptions. He also noticed white tongue plaques temporally associated with the groin plaques and a long history of recurrent oral ulcerations. Prior to being seen in our clinic, outside physicians cultured methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus from the groin plaques and treated him with oral clindamycin, cephalexin, and topical mupirocin without a clinical response.

Our differential diagnosis included condyloma acuminata, condyloma lata, and cutaneous pemphigus vegetans. Laboratory testing revealed a nonreactive rapid plasma reagin test and peripheral eosinophilia of 14.9% (reference range, 0%–6%). Biopsy of a left groin plaque revealed epidermal hyperplasia with spongiosis and an eosinophilic-rich infiltrate on hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 2A), and direct immunofluorescence revealed diffuse epidermal intercellular IgG deposits (Figure 2B). The patient’s clinical and histologic presentation was consistent with cutaneous pemphigus vegetans. Biopsy of an oral ulcer revealed denuded acantholytic mucositis with eosinophilic-rich submucosal infiltrate and fibrosis (Figure 3A). Direct immunofluorescence was positive for lacelike intercellular staining for IgG and C3 within the squamous epithelium (Figure 3B). Together the clinical and histologic findings were consistent with oral pemphigus vulgaris.

The patient initially was started on oral minocycline 100 mg twice daily and mometasone furoate cream 0.1% twice daily to affected groin areas. With these interventions, the groin plaques almost completely resolved after several months, leaving only residual hyperpigmentation (Figure 4). The oral pemphigus vulgaris initially was treated with dexamethasone 0.5 mg/5 mL solution 2 to 3 times daily, but the lesions were refractory to this approach and also did not improve after the losartan was discontinued for several months. As such, mycophenolate mofetil was started. He was titrated to the lowest effective dose and showed near-complete resolution with 500 mg 3 times daily.

Cutaneous pemphigus vegetans, a rare variant of pemphigus vulgaris, is characterized by vegetating plaques commonly localized to the skin folds, scalp, face, and mucous membranes.1 Involvement of the oral mucosa occurs in a majority of cases. Although our patient had oral ulcerations, he did not have characteristic cerebriform changes of the dorsal tongue or associated verrucous hyperkeratotic lesions involving the buccal mucosa, hard and soft palate, or vermilion border of the lips that typically are seen in pemphigus vegetans.2-5 Subsequent biopsy of the oral mucosa confirmed oral pemphigus vulgaris in our patient.

This case presentation of co-occurring cutaneous pemphigus vegetans and oral pemphigus vulgaris is uncommonly reported in the literature. Although the etiology of this co-occurrence is not clear, it could represent a form of epitope spread, with the mechanism similar to that proposed for the progression of pemphigus vulgaris from the mucosal to the mucocutaneous stage by Chan et al,6 who suggested that an autoimmune reaction against specific desmoglein 3 epitopes (an important protein component for desmosomes and the autoantigen in pemphigus vulgaris) on mucosal membranes could induce local damage. These injuries could then expose the autoreactive immune cells to a secondary desmoglein 3 epitope present in the skin, leading to the development of cutaneous lesions.6 Salato et al7 also supported this idea of intramolecular epitope spread in pemphigus vulgaris, explaining that at various stages of the disease (mucosal and mucocutaneous), the antibodies have “different tissue-binding patterns and pathogenic activities, suggesting that they may recognize distinct epitopes.” This concept of epitope spread from the oral mucosal form to the cutaneous form of pemphigus vulgaris also could help explain our patient’s presentation, as he had a long history of recurrent oral ulcerations prior to developing the vegetating cutaneous plaques of cutaneous pemphigus vegetans.

We also appreciate that either the cutaneous pemphigus vegetans or oral pemphigus vulgaris could have been drug induced in our case. Captopril has been reported to cause pemphigus vulgaris,8 so it is conceivable that the related medication lisinopril was the culprit in our case. A prior case report described an elderly man who developed lisinopril-induced pemphigus foliaceus; however, there was no oral involvement in this case and no further blister formation within 48 hours of discontinuing lisinopril.9 An additional case report implicated lisinopril in the development of a bullous eruption on the oral mucosa in a female patient, though direct and indirect immunofluorescence did not reveal the autoantibodies that typically are seen in pemphigus vulgaris.10 Our patient’s blood eosinophilia also could support an adverse drug reaction. Our patient’s losartan was discontinued for several months without respite of the oral ulcerations and thus was restarted. The cutaneous pemphigus vegetans continues to be in remission and was unaffected by restarting the losartan, making it a less likely culprit for his presentation.

We identified another case in the literature in which an individual with a history of colon cancer was diagnosed with cutaneous pemphigus vegetans.11 As such, we considered a possible link between the 2 diagnoses; however, the temporal disconnect between both conditions in our patient makes this less likely, unlike the other reported case in which the internal neoplasm and pemphigus vegetans appeared nearly simultaneously.11

Finally, our case supports a combination of topical steroids and minocycline for treatment of cutaneous pemphigus vegetans.

Our case demonstrates the importance of considering cutaneous pemphigus vegetans in the differential diagnosis, despite its rarity, when patients present with vegetating plaques. In addition, although oral involvement is common with this condition, if the patient’s oral lesions do not fit the characteristic oral findings seen in pemphigus vegetans, alternative diagnoses should be considered.

- de Almeida HL Jr, Neugebauer MG, Guarenti IM, et al. Pemphigus vegetans associated with verrucous lesions: expanding a phenotype. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2006;61:279-282.

- Danopoulou I, Stavropoulos P, Stratigos A, et al. Pemphigus vegetans confined to the scalp. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1008-1009.

- Markopoulos AK, Antoniades DZ, Zaraboukas T. Pemphigus vegetans of the oral cavity. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:425-428.

- Woo TY, Solomon AR, Fairley JA. Pemphigus vegetans limited to the lips and oral mucosa. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:271-272.

- Yuen KL, Yau KC. An old gentleman with vegetative plaques and erosions: a case of pemphigus vegetans. Hong Kong J Dermatol Venereol. 2012;20:179-182.

- Chan LS, Vanderlugt CJ, Hashimoto T, et al. Epitope spreading: lessons from autoimmune skin diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;110:103-109.

- Salato VK, Hacker-Foegen MK, Lazarova Z, et al. Role of intramolecular epitope spreading in pemphigus vulgaris. Clin Immunol. 2005;116:54-64.

- Dashore A, Choudhary SD. Captopril induced pemphigus vulgaris. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1987;53:293-294.

- Patterson CR, Davies MG. Pemphigus foliaceus: an adverse reaction to lisinopril. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:60-62.

- Baričević M, Mravak Stipeti´c M, Situm M, et al. Oral bullous eruption after taking lisinopril—case report and literature review. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2013;125:408-411.

- Torres T, Ferreira M, Sanches M, et al. Pemphigus vegetans in a patient with colonic cancer. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:603-605.

- de Almeida HL Jr, Neugebauer MG, Guarenti IM, et al. Pemphigus vegetans associated with verrucous lesions: expanding a phenotype. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2006;61:279-282.

- Danopoulou I, Stavropoulos P, Stratigos A, et al. Pemphigus vegetans confined to the scalp. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1008-1009.

- Markopoulos AK, Antoniades DZ, Zaraboukas T. Pemphigus vegetans of the oral cavity. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:425-428.

- Woo TY, Solomon AR, Fairley JA. Pemphigus vegetans limited to the lips and oral mucosa. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:271-272.

- Yuen KL, Yau KC. An old gentleman with vegetative plaques and erosions: a case of pemphigus vegetans. Hong Kong J Dermatol Venereol. 2012;20:179-182.

- Chan LS, Vanderlugt CJ, Hashimoto T, et al. Epitope spreading: lessons from autoimmune skin diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;110:103-109.

- Salato VK, Hacker-Foegen MK, Lazarova Z, et al. Role of intramolecular epitope spreading in pemphigus vulgaris. Clin Immunol. 2005;116:54-64.

- Dashore A, Choudhary SD. Captopril induced pemphigus vulgaris. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1987;53:293-294.

- Patterson CR, Davies MG. Pemphigus foliaceus: an adverse reaction to lisinopril. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:60-62.

- Baričević M, Mravak Stipeti´c M, Situm M, et al. Oral bullous eruption after taking lisinopril—case report and literature review. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2013;125:408-411.

- Torres T, Ferreira M, Sanches M, et al. Pemphigus vegetans in a patient with colonic cancer. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:603-605.

Practice Points

- Recognize the clinical and histologic features of pemphigus vegetans, a rare variant of pemphigus vulgaris.

- Consider mechanisms of co-occurring cutaneous pemphigus vegetans and oral pemphigus vulgaris.

Verrucous Psoriasis Treated With Methotrexate and Acitretin Combination Therapy

To the Editor:

A 76-year-old woman with venous insufficiency presented with numerous thick, hyperkeratotic, confluent papules and plaques involving both legs and thighs as well as the lower back. She initially developed lesions on the distal legs, which progressed to involve the thighs and lower back, slowly enlarging over 7 years (Figure 1). The eruption was associated with pruritus and was profoundly malodorous. The patient had been unsuccessfully treated with triamcinolone ointment, bleach baths, and several courses of oral antibiotics. Her history was remarkable for marked venous insufficiency and mild anemia, with a hemoglobin level of 11.9 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL). She had no other abnormalities on a comprehensive blood test, basic metabolic panel, or liver function test.

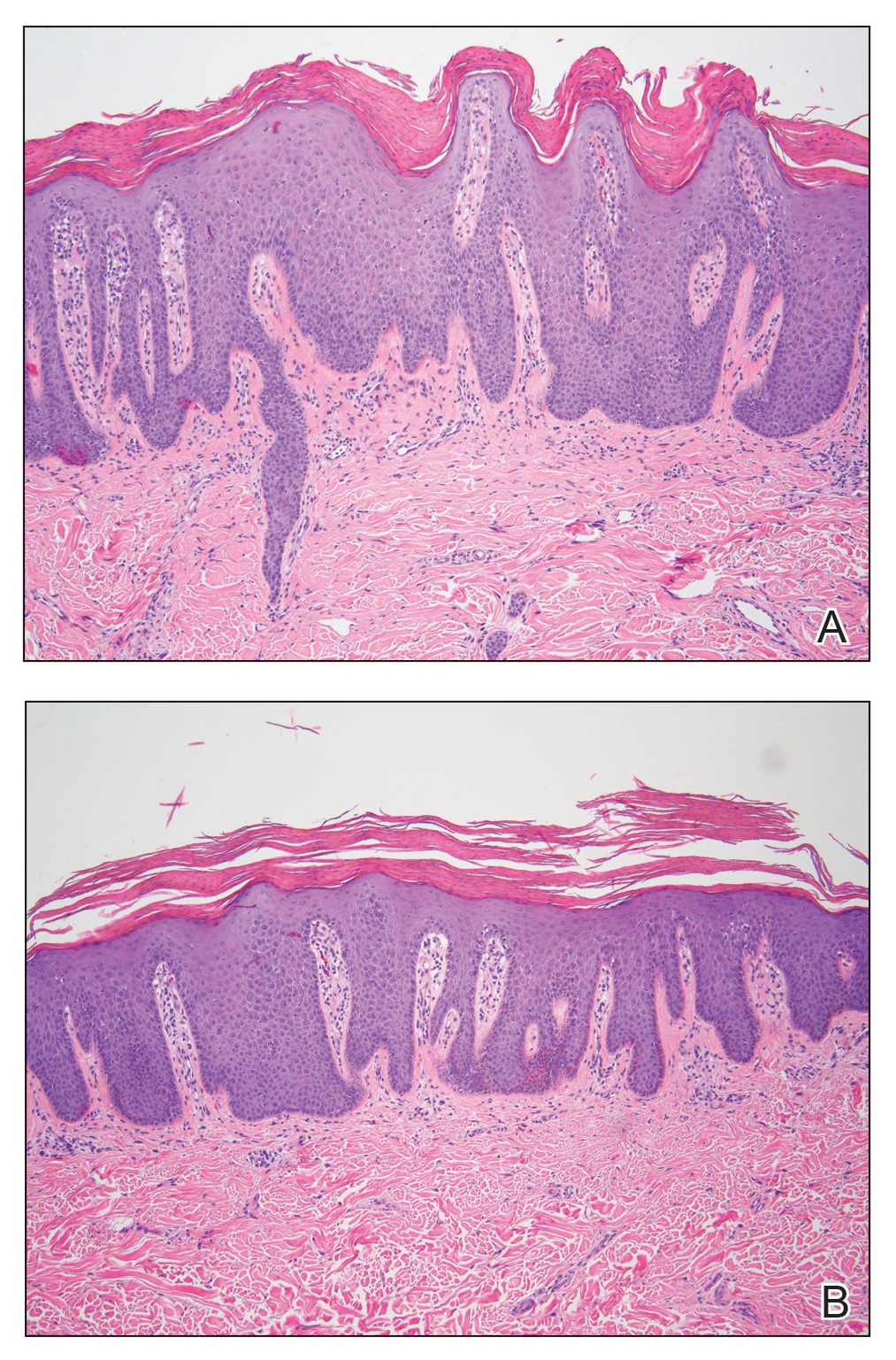

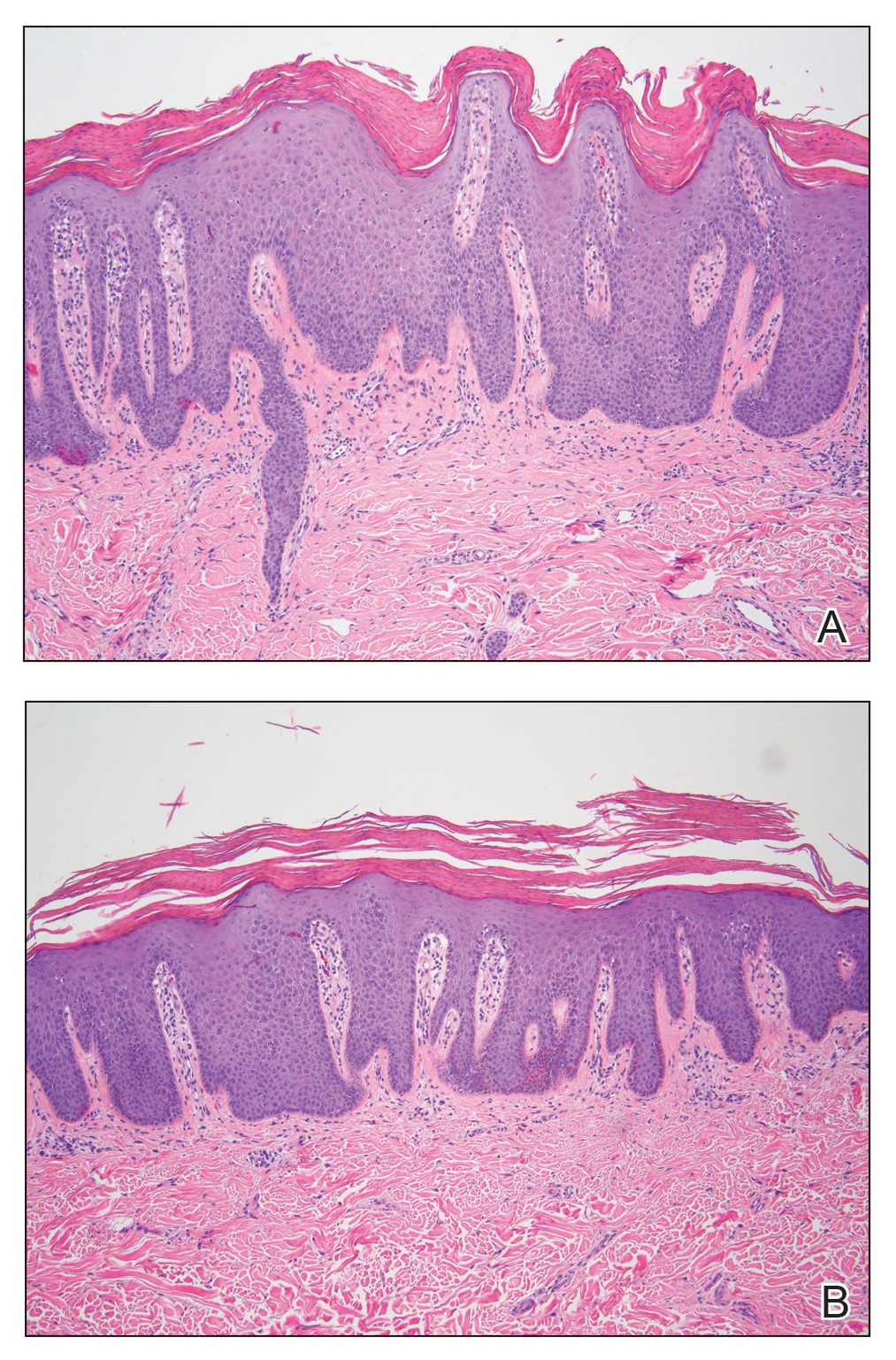

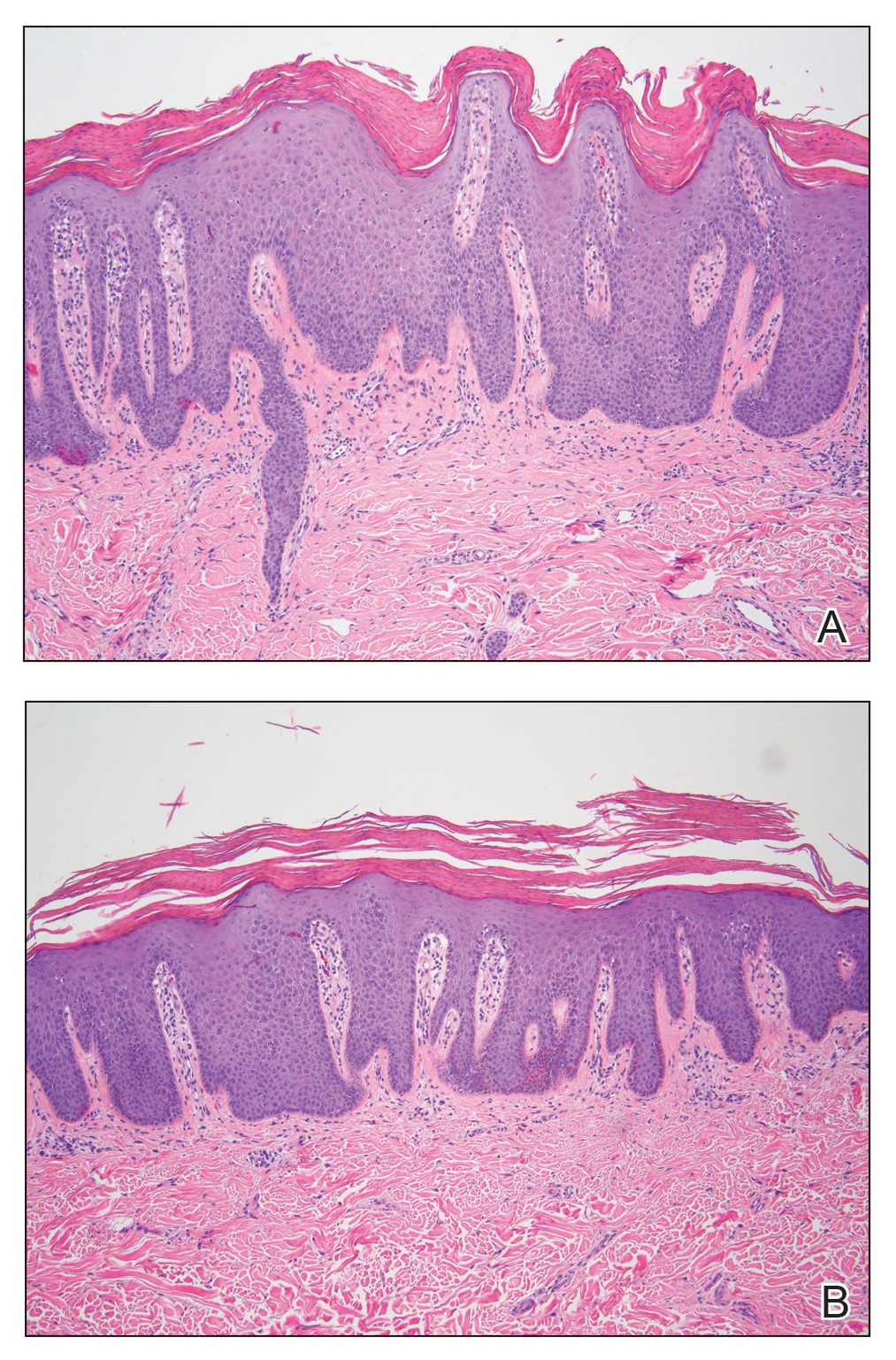

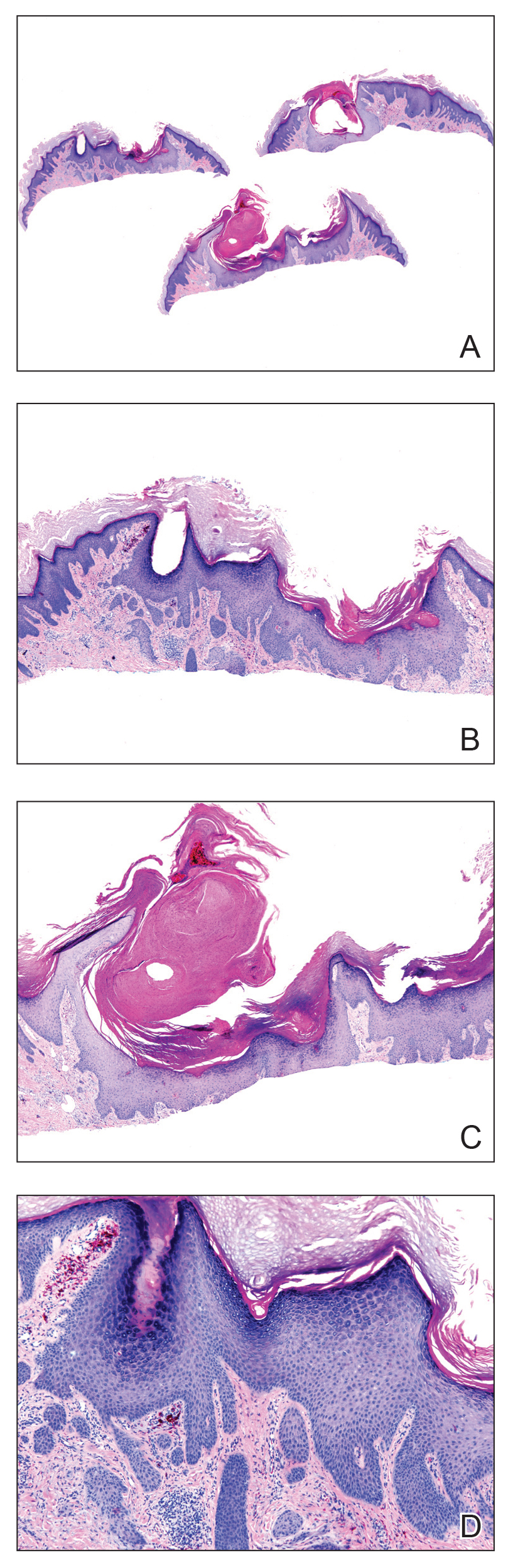

A punch biopsy specimen from the left lower back was obtained and demonstrated papillomatous psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with broad parakeratosis, few intracorneal neutrophils, hypogranulosis, and suprapapillary thinning (Figure 2). She was initially treated with oral methotrexate (20 mg weekly), resulting in partial improvement of plaques and complete resolution of pruritus and malodor. After 15 months of treatment with methotrexate, low-dose methotrexate (10 mg weekly) in combination with acitretin 25 mg daily was started, resulting in further improvement of hyperkeratosis (Figure 3). The patient also was given a compounded corticosteroid ointment containing liquor carbonis detergens, salicylic acid, and fluocinonide ointment, achieving minor additional benefit. Comprehensive metabolic panel, lipid panel, and liver function tests were obtained quarterly. Hemoglobin levels remained low, similar to baseline (11.3–12.5 g/dL), while all other values were within reference range. The patient tolerated treatment well, reporting mild dryness of lips on review of systems, which was attributed to acitretin and was treated with emollients.

Verrucous psoriasis is an uncommon variant of psoriasis that presents as localized annular, erythrodermic, or drug-induced disease, as reported in a patient with preexisting psoriasis after interferon treatment of hepatitis C.1,2 It is characterized by symmetric hypertrophic verrucous plaques that may have an erythematous base and involve the legs, arms, trunk, and dorsal aspect of the hands3; malodor is frequent.1 Histopathologically, overlapping features of verruca vulgaris and psoriasis have been described. Specifically, lesions display typical psoriasiform changes, including parakeratosis, epidermal acanthosis with elongation of rete ridges, suprapapillary thinning, epidermal hypogranulosis, dilated or tortuous capillaries, and neutrophil collections in the stratum corneum (Munro microabscesses) or stratum spinosum (spongiform pustules of Kogoj).3 Additional findings of papillomatosis and epithelial buttressing are highly suggestive of verrucous psoriasis,3 though epithelial buttressing is not universally present.4-6 Similarly, although eosinophils and plasma cells have been described in some patients with verrucous psoriasis, this finding has not been consistently reported.4-6 Our biopsy specimen (Figure 2) lacks the epithelial buttressing but does exhibit subtle papillomatous hyperplasia consistent with the diagnosis of psoriasis.

The etiology of this entity is unknown. An association with diabetes mellitus, pulmonary disease, lymphatic circulation disorders, and immunosuppression has been proposed. Others have reported repeated trauma as contributing to the pathogenesis.1 For our patient, trauma secondary to scratching, long-standing venous insufficiency, and neglect likely contributed to the development of verrucous plaques.

The diagnosis of verrucous psoriasis can be challenging because of its similarity to several other entities, including verruca vulgaris; epidermal nevus; and squamous cell carcinoma, particularly verrucous carcinoma.4,6,7 The diagnosis has been less challenging in areas where prior typical psoriatic lesions evolved into a verrucous morphology. Our patient presented a diagnostic challenge and draws attention to this unique variant of psoriasis that could easily be misdiagnosed and lead to inappropriate treatment.

Verrucous psoriasis can be recalcitrant to therapy. Although studies addressing treatment modalities are lacking, several recommendations can be derived from case reports and our patient. The use of topical therapies, including topical corticosteroids (eg, fluocinonide, clobetasol, halobetasol), keratolytic agents (eg, urea, salicylic acid), and calcipotriene, provide only minimal improvement when used as monotherapy.1 Better success has been reported with systemic therapies, mainly methotrexate and acitretin, with anecdotal reports favoring the use of oral retinoids.1,6 Conversely, biologic medications such as etanercept, ustekinumab, adalimumab, and infliximab have only provided a partial response.1 Combination therapies including intralesional triamcinolone plus methotrexate4 or methotrexate plus acitretin, as in our patient, seem to provide additional benefit. Methotrexate and acitretin combination therapy has traditionally been avoided because of the risk for hepatotoxicity. However, a case series has demonstrated a moderate safety profile with concurrent use of these drugs in treatment-resistant psoriasis.8 In our case, clinical response was most pronounced with combination therapy of methotrexate 10 mg weekly and acitretin 25 mg daily. Thus, strong consideration should be given for combination methotrexate-acitretin therapy in patients with recalcitrant verrucous psoriasis who lack comorbid conditions.

We present a case of verrucous psoriasis, a variant of psoriasis characterized by hypertrophic plaques. We propose that venous insufficiency and long-standing untreated disease was instrumental to the development of these lesions. Furthermore, retinoids, particularly in combination with methotrexate, provided the most benefit for our patient.

Acknowledgment

We thank Stephen Somach, MD (Cleveland, Ohio), for his help interpreting the microscopic findings in our biopsy specimen. He received no compensation.

- Curtis AR, Yosipovitch G. Erythrodermic verrucous psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2012;23:215-218.

- Scavo S, Gurrera A, Mazzaglia C, et al. Verrucous psoriasis in a patient with chronic C hepatitis treated with interferon. Clin Drug Investig. 2004;24:427-429.

- Khalil FK, Keehn CA, Saeed S, et al. Verrucous psoriasis: a distinctive clinicopathologic variant of psoriasis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:204-207.

- Hall L, Marks V, Tyler W. Verrucous psoriasis: a clinical and histopathologic mimicker of verruca vulgaris [abstract]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68(suppl 1):AB218.

- Monroe HR, Hillman JD, Chiu MW. A case of verrucous psoriasis. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:10.

- Larsen F, Susa JS, Cockerell CJ, et al. Case of multiple verrucous carcinomas responding to treatment with acetretin more likely to have been a case of verrucous psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:534-535.

- Kuan YZ, Hsu HC, Kuo TT, et al. Multiple verrucous carcinomas treated with acitretin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(2 suppl):S29-S32.

- Lowenthal KE, Horn PJ, Kalb RE. Concurrent use of methotrexate and acitretin revisited. J Dermatolog Treat. 2008;19:22-26.

To the Editor:

A 76-year-old woman with venous insufficiency presented with numerous thick, hyperkeratotic, confluent papules and plaques involving both legs and thighs as well as the lower back. She initially developed lesions on the distal legs, which progressed to involve the thighs and lower back, slowly enlarging over 7 years (Figure 1). The eruption was associated with pruritus and was profoundly malodorous. The patient had been unsuccessfully treated with triamcinolone ointment, bleach baths, and several courses of oral antibiotics. Her history was remarkable for marked venous insufficiency and mild anemia, with a hemoglobin level of 11.9 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL). She had no other abnormalities on a comprehensive blood test, basic metabolic panel, or liver function test.

A punch biopsy specimen from the left lower back was obtained and demonstrated papillomatous psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with broad parakeratosis, few intracorneal neutrophils, hypogranulosis, and suprapapillary thinning (Figure 2). She was initially treated with oral methotrexate (20 mg weekly), resulting in partial improvement of plaques and complete resolution of pruritus and malodor. After 15 months of treatment with methotrexate, low-dose methotrexate (10 mg weekly) in combination with acitretin 25 mg daily was started, resulting in further improvement of hyperkeratosis (Figure 3). The patient also was given a compounded corticosteroid ointment containing liquor carbonis detergens, salicylic acid, and fluocinonide ointment, achieving minor additional benefit. Comprehensive metabolic panel, lipid panel, and liver function tests were obtained quarterly. Hemoglobin levels remained low, similar to baseline (11.3–12.5 g/dL), while all other values were within reference range. The patient tolerated treatment well, reporting mild dryness of lips on review of systems, which was attributed to acitretin and was treated with emollients.

Verrucous psoriasis is an uncommon variant of psoriasis that presents as localized annular, erythrodermic, or drug-induced disease, as reported in a patient with preexisting psoriasis after interferon treatment of hepatitis C.1,2 It is characterized by symmetric hypertrophic verrucous plaques that may have an erythematous base and involve the legs, arms, trunk, and dorsal aspect of the hands3; malodor is frequent.1 Histopathologically, overlapping features of verruca vulgaris and psoriasis have been described. Specifically, lesions display typical psoriasiform changes, including parakeratosis, epidermal acanthosis with elongation of rete ridges, suprapapillary thinning, epidermal hypogranulosis, dilated or tortuous capillaries, and neutrophil collections in the stratum corneum (Munro microabscesses) or stratum spinosum (spongiform pustules of Kogoj).3 Additional findings of papillomatosis and epithelial buttressing are highly suggestive of verrucous psoriasis,3 though epithelial buttressing is not universally present.4-6 Similarly, although eosinophils and plasma cells have been described in some patients with verrucous psoriasis, this finding has not been consistently reported.4-6 Our biopsy specimen (Figure 2) lacks the epithelial buttressing but does exhibit subtle papillomatous hyperplasia consistent with the diagnosis of psoriasis.

The etiology of this entity is unknown. An association with diabetes mellitus, pulmonary disease, lymphatic circulation disorders, and immunosuppression has been proposed. Others have reported repeated trauma as contributing to the pathogenesis.1 For our patient, trauma secondary to scratching, long-standing venous insufficiency, and neglect likely contributed to the development of verrucous plaques.

The diagnosis of verrucous psoriasis can be challenging because of its similarity to several other entities, including verruca vulgaris; epidermal nevus; and squamous cell carcinoma, particularly verrucous carcinoma.4,6,7 The diagnosis has been less challenging in areas where prior typical psoriatic lesions evolved into a verrucous morphology. Our patient presented a diagnostic challenge and draws attention to this unique variant of psoriasis that could easily be misdiagnosed and lead to inappropriate treatment.

Verrucous psoriasis can be recalcitrant to therapy. Although studies addressing treatment modalities are lacking, several recommendations can be derived from case reports and our patient. The use of topical therapies, including topical corticosteroids (eg, fluocinonide, clobetasol, halobetasol), keratolytic agents (eg, urea, salicylic acid), and calcipotriene, provide only minimal improvement when used as monotherapy.1 Better success has been reported with systemic therapies, mainly methotrexate and acitretin, with anecdotal reports favoring the use of oral retinoids.1,6 Conversely, biologic medications such as etanercept, ustekinumab, adalimumab, and infliximab have only provided a partial response.1 Combination therapies including intralesional triamcinolone plus methotrexate4 or methotrexate plus acitretin, as in our patient, seem to provide additional benefit. Methotrexate and acitretin combination therapy has traditionally been avoided because of the risk for hepatotoxicity. However, a case series has demonstrated a moderate safety profile with concurrent use of these drugs in treatment-resistant psoriasis.8 In our case, clinical response was most pronounced with combination therapy of methotrexate 10 mg weekly and acitretin 25 mg daily. Thus, strong consideration should be given for combination methotrexate-acitretin therapy in patients with recalcitrant verrucous psoriasis who lack comorbid conditions.

We present a case of verrucous psoriasis, a variant of psoriasis characterized by hypertrophic plaques. We propose that venous insufficiency and long-standing untreated disease was instrumental to the development of these lesions. Furthermore, retinoids, particularly in combination with methotrexate, provided the most benefit for our patient.

Acknowledgment

We thank Stephen Somach, MD (Cleveland, Ohio), for his help interpreting the microscopic findings in our biopsy specimen. He received no compensation.

To the Editor:

A 76-year-old woman with venous insufficiency presented with numerous thick, hyperkeratotic, confluent papules and plaques involving both legs and thighs as well as the lower back. She initially developed lesions on the distal legs, which progressed to involve the thighs and lower back, slowly enlarging over 7 years (Figure 1). The eruption was associated with pruritus and was profoundly malodorous. The patient had been unsuccessfully treated with triamcinolone ointment, bleach baths, and several courses of oral antibiotics. Her history was remarkable for marked venous insufficiency and mild anemia, with a hemoglobin level of 11.9 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL). She had no other abnormalities on a comprehensive blood test, basic metabolic panel, or liver function test.

A punch biopsy specimen from the left lower back was obtained and demonstrated papillomatous psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with broad parakeratosis, few intracorneal neutrophils, hypogranulosis, and suprapapillary thinning (Figure 2). She was initially treated with oral methotrexate (20 mg weekly), resulting in partial improvement of plaques and complete resolution of pruritus and malodor. After 15 months of treatment with methotrexate, low-dose methotrexate (10 mg weekly) in combination with acitretin 25 mg daily was started, resulting in further improvement of hyperkeratosis (Figure 3). The patient also was given a compounded corticosteroid ointment containing liquor carbonis detergens, salicylic acid, and fluocinonide ointment, achieving minor additional benefit. Comprehensive metabolic panel, lipid panel, and liver function tests were obtained quarterly. Hemoglobin levels remained low, similar to baseline (11.3–12.5 g/dL), while all other values were within reference range. The patient tolerated treatment well, reporting mild dryness of lips on review of systems, which was attributed to acitretin and was treated with emollients.

Verrucous psoriasis is an uncommon variant of psoriasis that presents as localized annular, erythrodermic, or drug-induced disease, as reported in a patient with preexisting psoriasis after interferon treatment of hepatitis C.1,2 It is characterized by symmetric hypertrophic verrucous plaques that may have an erythematous base and involve the legs, arms, trunk, and dorsal aspect of the hands3; malodor is frequent.1 Histopathologically, overlapping features of verruca vulgaris and psoriasis have been described. Specifically, lesions display typical psoriasiform changes, including parakeratosis, epidermal acanthosis with elongation of rete ridges, suprapapillary thinning, epidermal hypogranulosis, dilated or tortuous capillaries, and neutrophil collections in the stratum corneum (Munro microabscesses) or stratum spinosum (spongiform pustules of Kogoj).3 Additional findings of papillomatosis and epithelial buttressing are highly suggestive of verrucous psoriasis,3 though epithelial buttressing is not universally present.4-6 Similarly, although eosinophils and plasma cells have been described in some patients with verrucous psoriasis, this finding has not been consistently reported.4-6 Our biopsy specimen (Figure 2) lacks the epithelial buttressing but does exhibit subtle papillomatous hyperplasia consistent with the diagnosis of psoriasis.

The etiology of this entity is unknown. An association with diabetes mellitus, pulmonary disease, lymphatic circulation disorders, and immunosuppression has been proposed. Others have reported repeated trauma as contributing to the pathogenesis.1 For our patient, trauma secondary to scratching, long-standing venous insufficiency, and neglect likely contributed to the development of verrucous plaques.

The diagnosis of verrucous psoriasis can be challenging because of its similarity to several other entities, including verruca vulgaris; epidermal nevus; and squamous cell carcinoma, particularly verrucous carcinoma.4,6,7 The diagnosis has been less challenging in areas where prior typical psoriatic lesions evolved into a verrucous morphology. Our patient presented a diagnostic challenge and draws attention to this unique variant of psoriasis that could easily be misdiagnosed and lead to inappropriate treatment.

Verrucous psoriasis can be recalcitrant to therapy. Although studies addressing treatment modalities are lacking, several recommendations can be derived from case reports and our patient. The use of topical therapies, including topical corticosteroids (eg, fluocinonide, clobetasol, halobetasol), keratolytic agents (eg, urea, salicylic acid), and calcipotriene, provide only minimal improvement when used as monotherapy.1 Better success has been reported with systemic therapies, mainly methotrexate and acitretin, with anecdotal reports favoring the use of oral retinoids.1,6 Conversely, biologic medications such as etanercept, ustekinumab, adalimumab, and infliximab have only provided a partial response.1 Combination therapies including intralesional triamcinolone plus methotrexate4 or methotrexate plus acitretin, as in our patient, seem to provide additional benefit. Methotrexate and acitretin combination therapy has traditionally been avoided because of the risk for hepatotoxicity. However, a case series has demonstrated a moderate safety profile with concurrent use of these drugs in treatment-resistant psoriasis.8 In our case, clinical response was most pronounced with combination therapy of methotrexate 10 mg weekly and acitretin 25 mg daily. Thus, strong consideration should be given for combination methotrexate-acitretin therapy in patients with recalcitrant verrucous psoriasis who lack comorbid conditions.

We present a case of verrucous psoriasis, a variant of psoriasis characterized by hypertrophic plaques. We propose that venous insufficiency and long-standing untreated disease was instrumental to the development of these lesions. Furthermore, retinoids, particularly in combination with methotrexate, provided the most benefit for our patient.

Acknowledgment

We thank Stephen Somach, MD (Cleveland, Ohio), for his help interpreting the microscopic findings in our biopsy specimen. He received no compensation.

- Curtis AR, Yosipovitch G. Erythrodermic verrucous psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2012;23:215-218.

- Scavo S, Gurrera A, Mazzaglia C, et al. Verrucous psoriasis in a patient with chronic C hepatitis treated with interferon. Clin Drug Investig. 2004;24:427-429.

- Khalil FK, Keehn CA, Saeed S, et al. Verrucous psoriasis: a distinctive clinicopathologic variant of psoriasis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:204-207.

- Hall L, Marks V, Tyler W. Verrucous psoriasis: a clinical and histopathologic mimicker of verruca vulgaris [abstract]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68(suppl 1):AB218.

- Monroe HR, Hillman JD, Chiu MW. A case of verrucous psoriasis. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:10.

- Larsen F, Susa JS, Cockerell CJ, et al. Case of multiple verrucous carcinomas responding to treatment with acetretin more likely to have been a case of verrucous psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:534-535.

- Kuan YZ, Hsu HC, Kuo TT, et al. Multiple verrucous carcinomas treated with acitretin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(2 suppl):S29-S32.

- Lowenthal KE, Horn PJ, Kalb RE. Concurrent use of methotrexate and acitretin revisited. J Dermatolog Treat. 2008;19:22-26.

- Curtis AR, Yosipovitch G. Erythrodermic verrucous psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2012;23:215-218.

- Scavo S, Gurrera A, Mazzaglia C, et al. Verrucous psoriasis in a patient with chronic C hepatitis treated with interferon. Clin Drug Investig. 2004;24:427-429.

- Khalil FK, Keehn CA, Saeed S, et al. Verrucous psoriasis: a distinctive clinicopathologic variant of psoriasis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:204-207.

- Hall L, Marks V, Tyler W. Verrucous psoriasis: a clinical and histopathologic mimicker of verruca vulgaris [abstract]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68(suppl 1):AB218.

- Monroe HR, Hillman JD, Chiu MW. A case of verrucous psoriasis. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:10.

- Larsen F, Susa JS, Cockerell CJ, et al. Case of multiple verrucous carcinomas responding to treatment with acetretin more likely to have been a case of verrucous psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:534-535.

- Kuan YZ, Hsu HC, Kuo TT, et al. Multiple verrucous carcinomas treated with acitretin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(2 suppl):S29-S32.

- Lowenthal KE, Horn PJ, Kalb RE. Concurrent use of methotrexate and acitretin revisited. J Dermatolog Treat. 2008;19:22-26.

Practice Points

- Verrucous psoriasis in an uncommon but recalcitrant-to-treatment variant of psoriasis that is characterized by hypertrophic plaques.

- The diagnosis of verrucous psoriasis is challenging, as it can mimic other entities such as verruca vulgaris and squamous cell carcinoma.

- Although the etiology of this entity is unknown, an association with diabetes mellitus, pulmonary disease, lymphatic circulation disorders, and immunosuppression has been described.

- The combination of methotrexate and acitretin is a safe and effective option for these patients in the absence of comorbid conditions.

Melanoma In Situ Within a Port-Wine Stain

To the Editor:

Port-wine stains (PWSs) are the most common type of vascular malformations. Patients rarely develop cancers in the overlying skin. However, we describe a case of melanoma in situ occurring within a long-standing facial PWS.

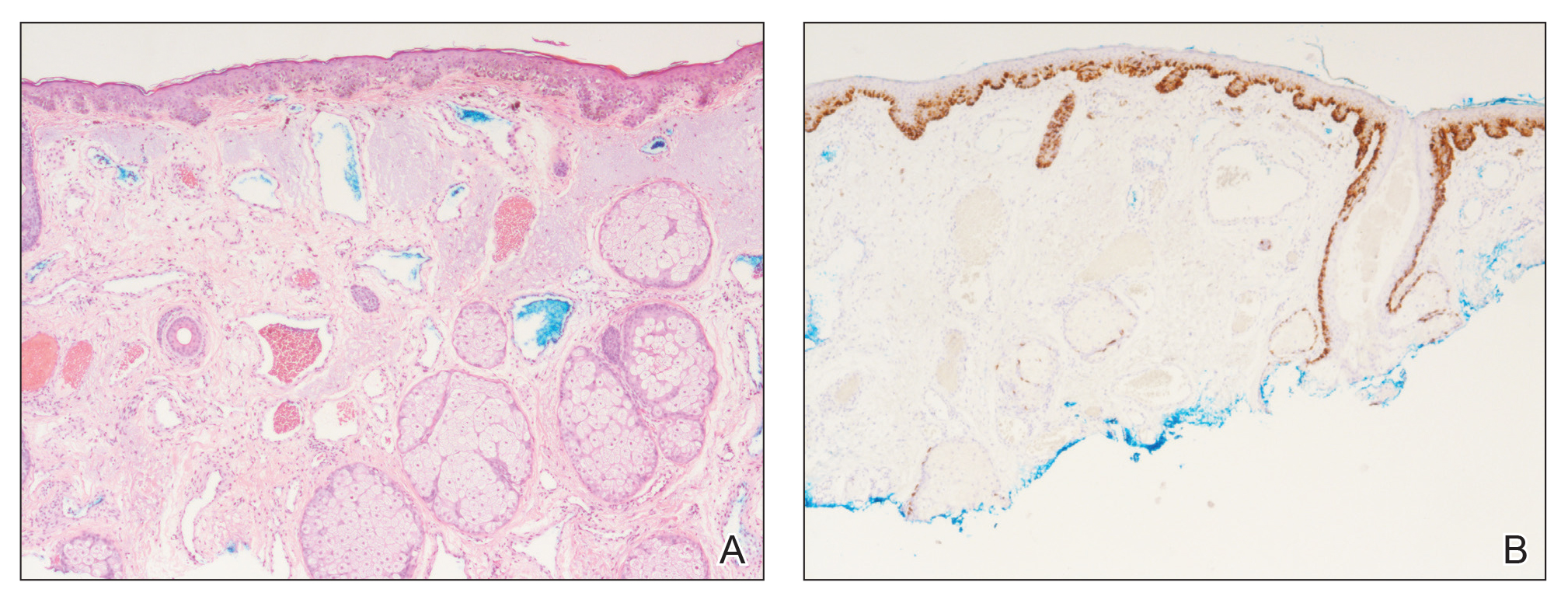

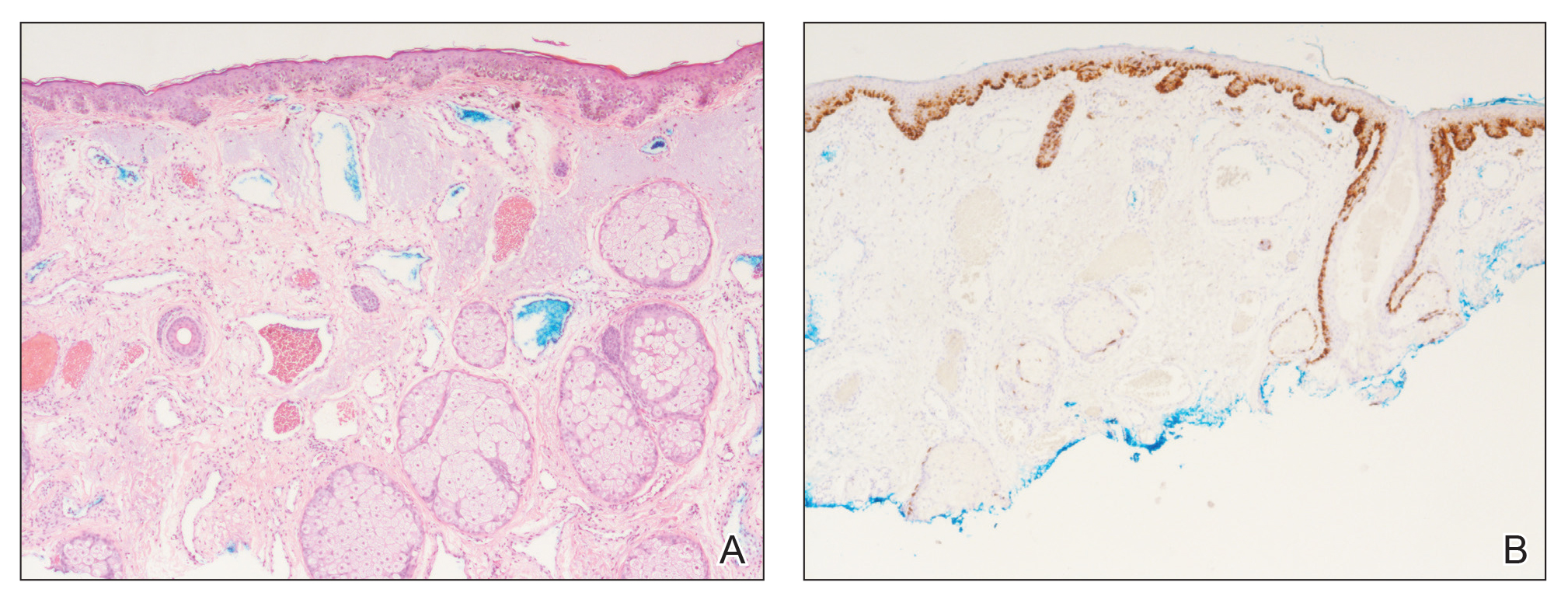

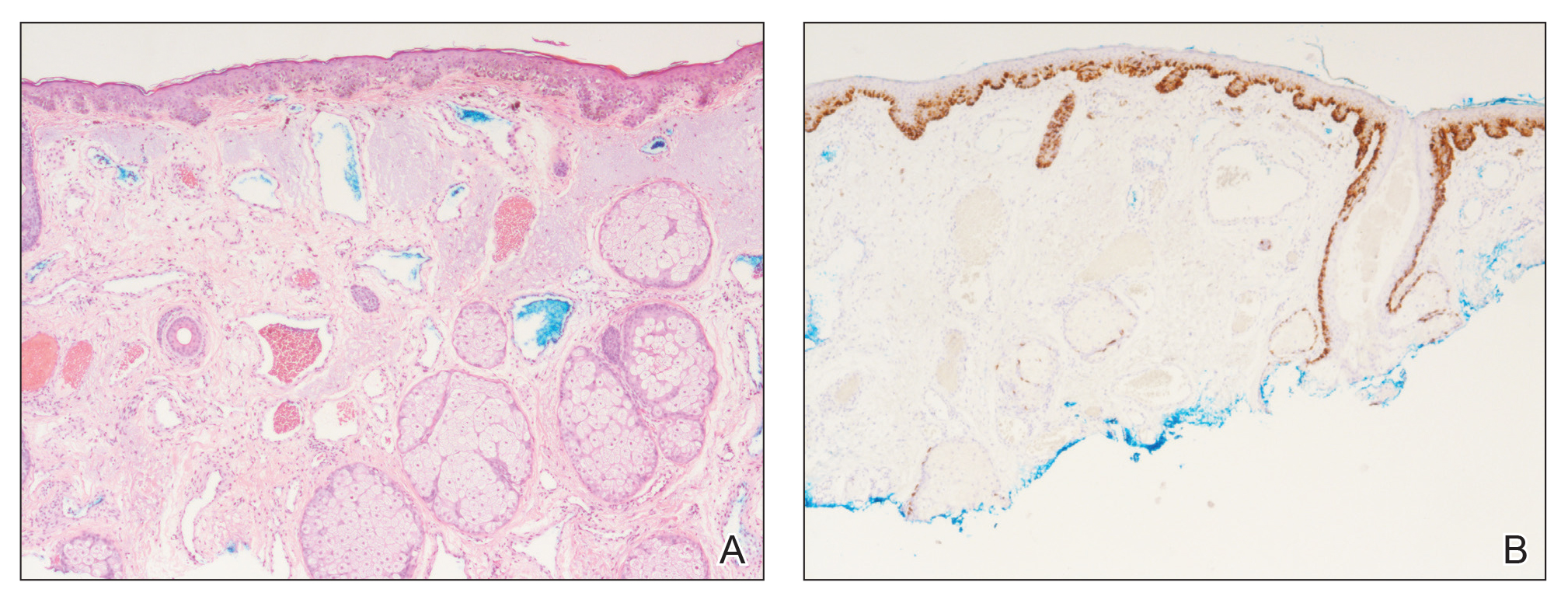

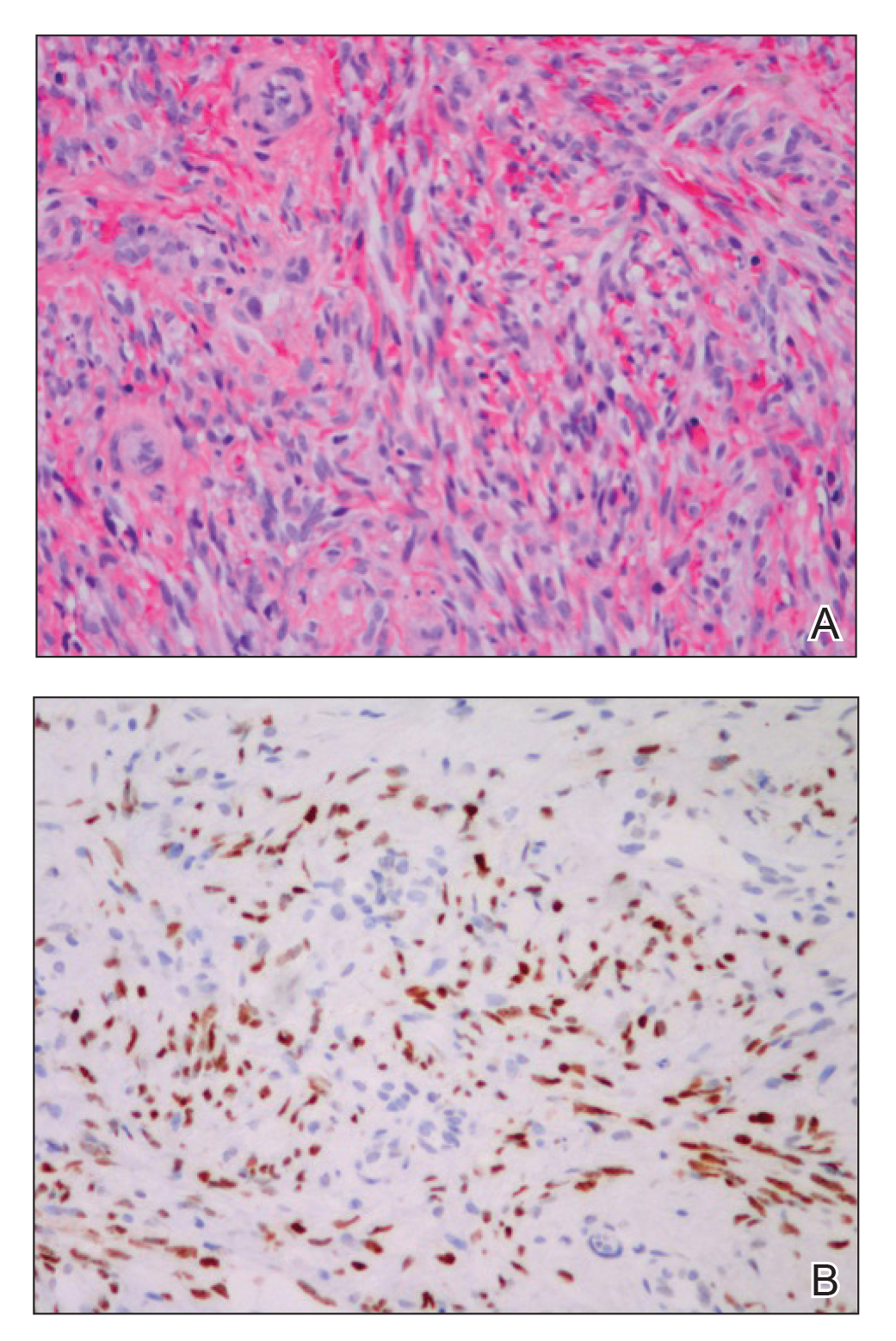

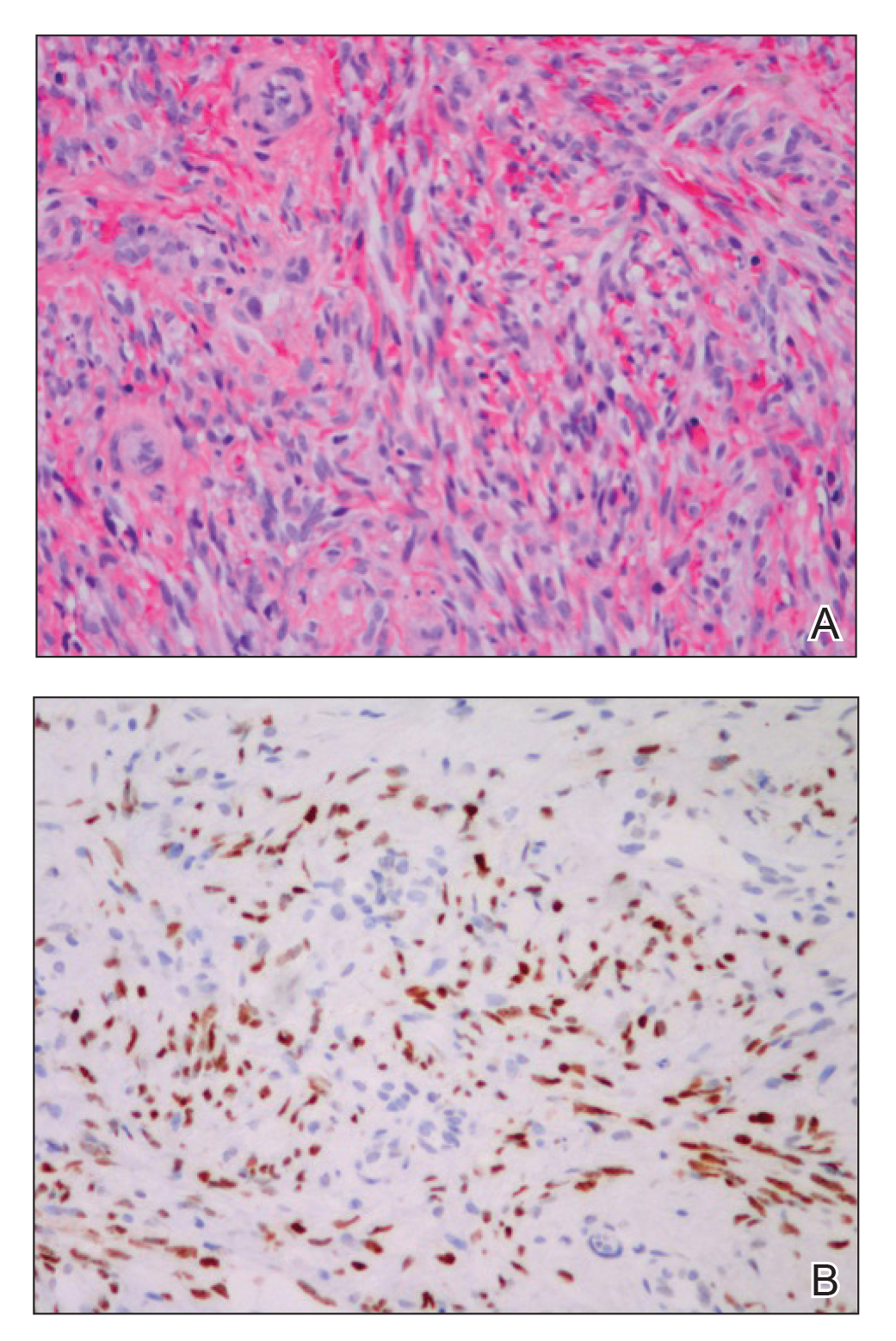

A 60-year-old white man with a history of a large unilateral facial PWS covering the right ear, lateral cheek, jaw, and neck presented to clinic with a new dark lesion on the right ear that had been growing for a few weeks or more. His PWS had been previously treated intermittently with a pulsed dye laser (PDL) for decades with variable improvement. He had not undergone any laser procedures in the last 8 months but wanted to restart treatment with the PDL. Upon further discussion, he reported a new darker area on the right earlobe that was growing. He had no personal or family history of skin cancer and was otherwise healthy. Physical examination revealed a large red vascular patch encompassing the ear, cheek, chin, and lateral neck. Within the PWS there was a black and dark brown patch with irregular borders on the right earlobe (Figure 1A). A shave biopsy was performed for histopathologic examination. The biopsy showed a confluent proliferation of atypical melanocytes along the dermoepidermal junction extending down adnexal structures (Figure 2A) that stained positive for MART-1/Melan-A (Figure 2B). In the dermis, solar elastosis and prominent dilated and thin-walled vessels were present. These findings were consistent with a melanoma in situ, lentigo maligna type, overlying a capillary malformation.

The patient underwent a wedge excision of the lesion with 5-mm margins, resulting in a final postoperative size of 2.5×3.5 cm. There was no excessive bleeding with surgery. A delayed repair was done after clear margins were confirmed by pathology (Figure 1B).

Port-wine stains are congenital vascular malformations that affect approximately 0.3% of individuals.1 Most are located on the head and neck along the distribution of the trigeminal nerve. Cases are thought to occur sporadically, with recent evidence for somatic GNAQ mutations in both nonsyndromic cases and in Sturge-Weber syndrome.2 These lesions become progressively larger with time due to dilation of the capillary proliferation.3 Melanoma in situ, lentigo maligna type, usually affects white men in the sixth and seventh decades of life. It commonly arises on skin with chronic sun damage, particularly on the head and neck.4

Although uncommon, skin cancers have been known to arise in PWSs. Reports of basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) and squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) have been published, but to date, there are no reports of melanoma or melanoma in situ arising in a PWS. According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms melanoma and port wine stain, squamous cell carcinoma and port wine stain, and basal cell carcinoma and port wine stain, fewer than 30 cases of BCCs in a PWS and only 4 cases of SCCs in a PWS have been documented, with 1 patient developing multiple BCCs and SCCs.1,5 Most BCCs (approximately 75%) and SCCs have been associated with historical treatments used to treat PWS before the development of laser therapy, such as grenz rays, topical thorium X, and other radiotherapy techniques.5,6 Interestingly, our patient’s PWS had only been treated with a PDL. Other risk factors for skin cancer in a PWS include sun exposure and smoking.5 There is no evidence that a PDL contributes to the development of skin cancer, but radiotherapy is a major factor.7

Treatment of these skin cancers is no different, with both Mohs micrographic surgery and standard excision used when appropriate. Despite the vascular nature of the lesion, there is only a minimal increase in bleeding risk.3 Most reports indicate no increase in perioperative bleeding.5,7 One case documented a hematoma developing postoperatively.6

This case of melanoma in situ arising in a PWS expands the range of skin cancer types known to arise in these malformations. Because of the potential for skin cancer to develop in a PWS, it is important to routinely examine these vascular proliferations.

- Hackett CB, Langtry JA. Basal cell carcinoma of the ala nasi arising in a port wine stain treated using Mohs micrographic surgery and local flap reconstruction. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:590-592.

- Shirley MD, Tang H, Gallione CJ, et al. Sturge-Weber syndrome and port-wine stains caused by somatic mutation in GNAQ. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1971-1979.

- Cerrati EW, O TM, Binetter D, et al. Surgical treatment of head and neck port-wine stains by means of a staged zonal approach. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134:1003-1012.

- Kallini JR, Jain SK, Khachemoune A. Lentigo maligna: review of salient characteristics and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:473-480.

- Rajan N, Ryan J, Langtry JA. Squamous cell carcinoma arising within a facial port-wine stain treated by Mohs micrographic surgical excision. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:864-866.

- Silapunt S, Goldberg LH, Thurber M, et al. Basal cell carcinoma arising in a port-wine stain. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:1241-1245.

- Jasim ZF, Woo WK, Walsh MY, et al. Multifocal basal cell carcinoma developing in a facial port wine stain treated with argon and pulsed dye laser: a possible role for previous radiotherapy. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:1155-1157.

To the Editor:

Port-wine stains (PWSs) are the most common type of vascular malformations. Patients rarely develop cancers in the overlying skin. However, we describe a case of melanoma in situ occurring within a long-standing facial PWS.

A 60-year-old white man with a history of a large unilateral facial PWS covering the right ear, lateral cheek, jaw, and neck presented to clinic with a new dark lesion on the right ear that had been growing for a few weeks or more. His PWS had been previously treated intermittently with a pulsed dye laser (PDL) for decades with variable improvement. He had not undergone any laser procedures in the last 8 months but wanted to restart treatment with the PDL. Upon further discussion, he reported a new darker area on the right earlobe that was growing. He had no personal or family history of skin cancer and was otherwise healthy. Physical examination revealed a large red vascular patch encompassing the ear, cheek, chin, and lateral neck. Within the PWS there was a black and dark brown patch with irregular borders on the right earlobe (Figure 1A). A shave biopsy was performed for histopathologic examination. The biopsy showed a confluent proliferation of atypical melanocytes along the dermoepidermal junction extending down adnexal structures (Figure 2A) that stained positive for MART-1/Melan-A (Figure 2B). In the dermis, solar elastosis and prominent dilated and thin-walled vessels were present. These findings were consistent with a melanoma in situ, lentigo maligna type, overlying a capillary malformation.

The patient underwent a wedge excision of the lesion with 5-mm margins, resulting in a final postoperative size of 2.5×3.5 cm. There was no excessive bleeding with surgery. A delayed repair was done after clear margins were confirmed by pathology (Figure 1B).

Port-wine stains are congenital vascular malformations that affect approximately 0.3% of individuals.1 Most are located on the head and neck along the distribution of the trigeminal nerve. Cases are thought to occur sporadically, with recent evidence for somatic GNAQ mutations in both nonsyndromic cases and in Sturge-Weber syndrome.2 These lesions become progressively larger with time due to dilation of the capillary proliferation.3 Melanoma in situ, lentigo maligna type, usually affects white men in the sixth and seventh decades of life. It commonly arises on skin with chronic sun damage, particularly on the head and neck.4

Although uncommon, skin cancers have been known to arise in PWSs. Reports of basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) and squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) have been published, but to date, there are no reports of melanoma or melanoma in situ arising in a PWS. According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms melanoma and port wine stain, squamous cell carcinoma and port wine stain, and basal cell carcinoma and port wine stain, fewer than 30 cases of BCCs in a PWS and only 4 cases of SCCs in a PWS have been documented, with 1 patient developing multiple BCCs and SCCs.1,5 Most BCCs (approximately 75%) and SCCs have been associated with historical treatments used to treat PWS before the development of laser therapy, such as grenz rays, topical thorium X, and other radiotherapy techniques.5,6 Interestingly, our patient’s PWS had only been treated with a PDL. Other risk factors for skin cancer in a PWS include sun exposure and smoking.5 There is no evidence that a PDL contributes to the development of skin cancer, but radiotherapy is a major factor.7

Treatment of these skin cancers is no different, with both Mohs micrographic surgery and standard excision used when appropriate. Despite the vascular nature of the lesion, there is only a minimal increase in bleeding risk.3 Most reports indicate no increase in perioperative bleeding.5,7 One case documented a hematoma developing postoperatively.6

This case of melanoma in situ arising in a PWS expands the range of skin cancer types known to arise in these malformations. Because of the potential for skin cancer to develop in a PWS, it is important to routinely examine these vascular proliferations.

To the Editor:

Port-wine stains (PWSs) are the most common type of vascular malformations. Patients rarely develop cancers in the overlying skin. However, we describe a case of melanoma in situ occurring within a long-standing facial PWS.

A 60-year-old white man with a history of a large unilateral facial PWS covering the right ear, lateral cheek, jaw, and neck presented to clinic with a new dark lesion on the right ear that had been growing for a few weeks or more. His PWS had been previously treated intermittently with a pulsed dye laser (PDL) for decades with variable improvement. He had not undergone any laser procedures in the last 8 months but wanted to restart treatment with the PDL. Upon further discussion, he reported a new darker area on the right earlobe that was growing. He had no personal or family history of skin cancer and was otherwise healthy. Physical examination revealed a large red vascular patch encompassing the ear, cheek, chin, and lateral neck. Within the PWS there was a black and dark brown patch with irregular borders on the right earlobe (Figure 1A). A shave biopsy was performed for histopathologic examination. The biopsy showed a confluent proliferation of atypical melanocytes along the dermoepidermal junction extending down adnexal structures (Figure 2A) that stained positive for MART-1/Melan-A (Figure 2B). In the dermis, solar elastosis and prominent dilated and thin-walled vessels were present. These findings were consistent with a melanoma in situ, lentigo maligna type, overlying a capillary malformation.

The patient underwent a wedge excision of the lesion with 5-mm margins, resulting in a final postoperative size of 2.5×3.5 cm. There was no excessive bleeding with surgery. A delayed repair was done after clear margins were confirmed by pathology (Figure 1B).

Port-wine stains are congenital vascular malformations that affect approximately 0.3% of individuals.1 Most are located on the head and neck along the distribution of the trigeminal nerve. Cases are thought to occur sporadically, with recent evidence for somatic GNAQ mutations in both nonsyndromic cases and in Sturge-Weber syndrome.2 These lesions become progressively larger with time due to dilation of the capillary proliferation.3 Melanoma in situ, lentigo maligna type, usually affects white men in the sixth and seventh decades of life. It commonly arises on skin with chronic sun damage, particularly on the head and neck.4

Although uncommon, skin cancers have been known to arise in PWSs. Reports of basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) and squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) have been published, but to date, there are no reports of melanoma or melanoma in situ arising in a PWS. According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms melanoma and port wine stain, squamous cell carcinoma and port wine stain, and basal cell carcinoma and port wine stain, fewer than 30 cases of BCCs in a PWS and only 4 cases of SCCs in a PWS have been documented, with 1 patient developing multiple BCCs and SCCs.1,5 Most BCCs (approximately 75%) and SCCs have been associated with historical treatments used to treat PWS before the development of laser therapy, such as grenz rays, topical thorium X, and other radiotherapy techniques.5,6 Interestingly, our patient’s PWS had only been treated with a PDL. Other risk factors for skin cancer in a PWS include sun exposure and smoking.5 There is no evidence that a PDL contributes to the development of skin cancer, but radiotherapy is a major factor.7

Treatment of these skin cancers is no different, with both Mohs micrographic surgery and standard excision used when appropriate. Despite the vascular nature of the lesion, there is only a minimal increase in bleeding risk.3 Most reports indicate no increase in perioperative bleeding.5,7 One case documented a hematoma developing postoperatively.6

This case of melanoma in situ arising in a PWS expands the range of skin cancer types known to arise in these malformations. Because of the potential for skin cancer to develop in a PWS, it is important to routinely examine these vascular proliferations.

- Hackett CB, Langtry JA. Basal cell carcinoma of the ala nasi arising in a port wine stain treated using Mohs micrographic surgery and local flap reconstruction. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:590-592.

- Shirley MD, Tang H, Gallione CJ, et al. Sturge-Weber syndrome and port-wine stains caused by somatic mutation in GNAQ. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1971-1979.

- Cerrati EW, O TM, Binetter D, et al. Surgical treatment of head and neck port-wine stains by means of a staged zonal approach. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134:1003-1012.

- Kallini JR, Jain SK, Khachemoune A. Lentigo maligna: review of salient characteristics and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:473-480.

- Rajan N, Ryan J, Langtry JA. Squamous cell carcinoma arising within a facial port-wine stain treated by Mohs micrographic surgical excision. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:864-866.

- Silapunt S, Goldberg LH, Thurber M, et al. Basal cell carcinoma arising in a port-wine stain. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:1241-1245.

- Jasim ZF, Woo WK, Walsh MY, et al. Multifocal basal cell carcinoma developing in a facial port wine stain treated with argon and pulsed dye laser: a possible role for previous radiotherapy. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:1155-1157.

- Hackett CB, Langtry JA. Basal cell carcinoma of the ala nasi arising in a port wine stain treated using Mohs micrographic surgery and local flap reconstruction. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:590-592.

- Shirley MD, Tang H, Gallione CJ, et al. Sturge-Weber syndrome and port-wine stains caused by somatic mutation in GNAQ. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1971-1979.

- Cerrati EW, O TM, Binetter D, et al. Surgical treatment of head and neck port-wine stains by means of a staged zonal approach. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134:1003-1012.

- Kallini JR, Jain SK, Khachemoune A. Lentigo maligna: review of salient characteristics and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:473-480.

- Rajan N, Ryan J, Langtry JA. Squamous cell carcinoma arising within a facial port-wine stain treated by Mohs micrographic surgical excision. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:864-866.

- Silapunt S, Goldberg LH, Thurber M, et al. Basal cell carcinoma arising in a port-wine stain. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:1241-1245.

- Jasim ZF, Woo WK, Walsh MY, et al. Multifocal basal cell carcinoma developing in a facial port wine stain treated with argon and pulsed dye laser: a possible role for previous radiotherapy. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:1155-1157.

Practice Points

- Nonmelanoma skin cancer is known to develop in port-wine stains, most commonly basal cell carcinoma.

- The range of skin cancer types known to arise in these malformations can be expanded to include melanoma in situ.

- It is important to routinely examine these vascular proliferations for new lesions.

Kaposi Sarcoma in a Patient With Postpolio Syndrome

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a low-grade vascular tumor that is rare among the general US population, with an incidence rate of less than 1 per 100,000.1 The tumor is more common among certain groups of individuals due to geographic differences in the prevalence of KS-associated herpesvirus (also referred to as human herpesvirus 8) as well as host immune factors.2 Kaposi sarcoma often is defined by the patient's predisposing characteristics yielding the following distinct epidemiologic subtypes: (1) classic KS is a rare disease affecting older men of Mediterranean descent; (2) African KS is an endemic cancer with male predominance in sub-Saharan Africa; (3) AIDS-associated KS is an often aggressive AIDS-defining illness; and (4) iatrogenic KS occurs in patients on immunosuppressive therapy.3 When evaluating a patient without any of these risk factors, the clinical suspicion for KS may be low. We report a patient with postpolio syndrome (PPS) who presented with KS of the right leg, ankle, and foot.

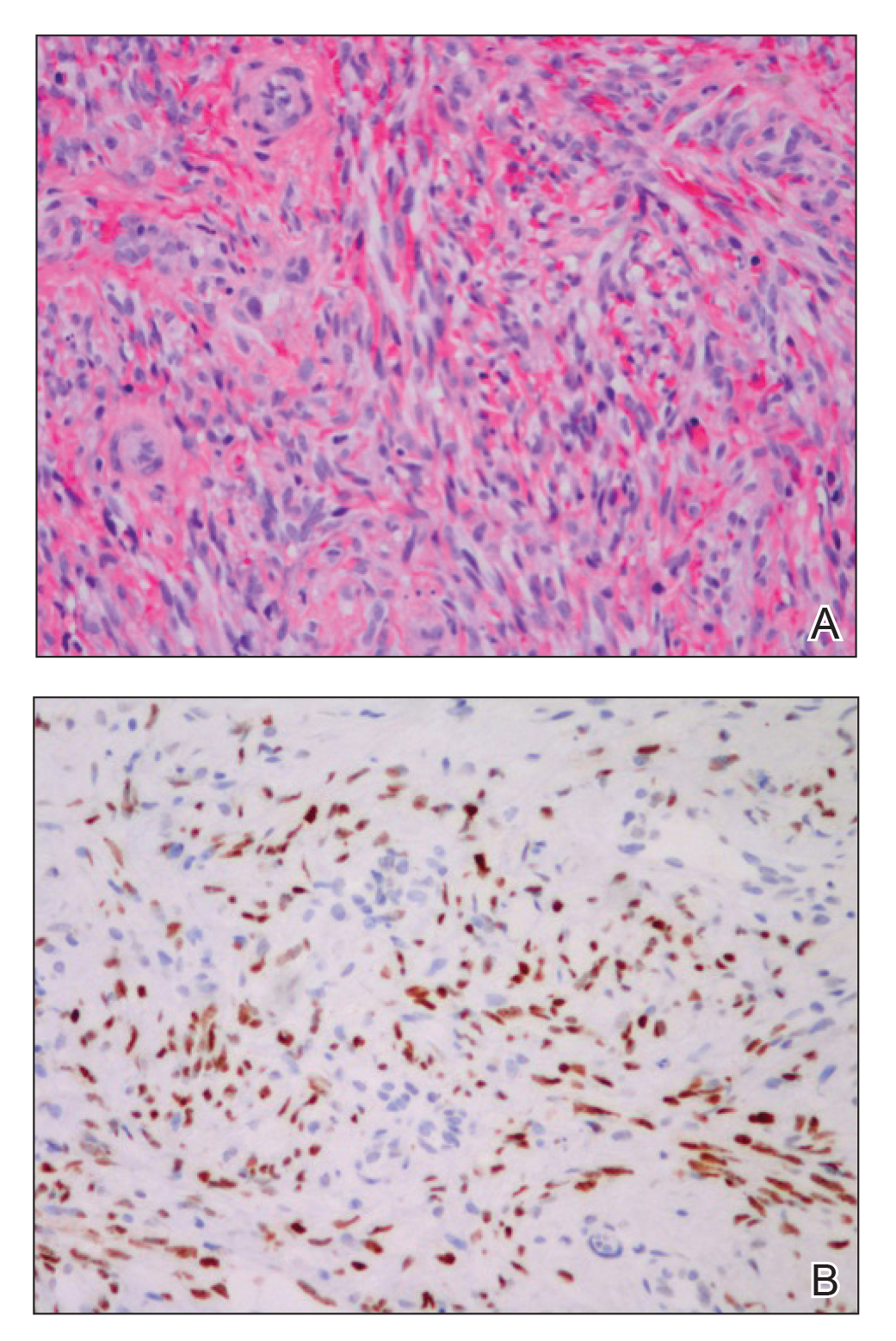

A 77-year-old man with a distant history of paralytic poliomyelitis presented for an annual skin examination with concern for a new lesion on the right ankle. The patient had a history of PPS primarily affecting the right leg. Physical examination revealed residual weakness in an atrophic right lower extremity with a mottled appearance and mild pitting edema to the knee. Two red, dome-shaped, vascular papules were appreciated on the medial aspect of the right ankle (Figure 1), and a shave biopsy of the larger papule was performed. Microscopic examination of the biopsy specimen was consistent with KS (Figure 2). This patient had no history of human immunodeficiency virus or immunosuppressive therapy and was not of Mediterranean descent.

Because KS is a radiosensitive vascular neoplasm and radiation therapy (RT) alone can achieve local control,4 the patient was treated with 6 megaelectron-volt electron-beam RT. He received 30 Gy in 10 fractions to the affected area of the medial ankle. The patient tolerated RT well. Three weeks after completing treatment, he was found to have mild lichenification on the right medial ankle with no clinical evidence of disease. Four months later, he presented with multiple additional vascular papules on the right third toe and in the interdigital web space (Figure 3). Shave biopsy of one of these lesions was consistent with KS. Contrast computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was performed, revealing no evidence of metastatic disease. The patient was treated with 30 Gy in 15 fractions using opposed lateral 6 megaelectron-volt photon fields to the entire right lower extremity below the knee to treat all of the skin affected by the PPS. His posttreatment course was complicated by edema in the affected leg that resolved after daily pneumatic compression. He had no evidence of residual or recurrent disease 6 months after completing RT (Figure 4).

Cutaneous KS is a human herpesvirus 8-positive tumor of endothelial origin typically seen in older men of Mediterranean or African descent and among immunosuppressed patients.4 Our patient did not have any classic risk factors for KS, but his disease did arise in the setting of a right lower extremity that was notably affected by PPS. Postpolio syndrome is characterized by muscle atrophy due to denervation of the motor unit.5 Bruno et al6 found that such deficits in motor innervation could lead to impairments in venous outflow causing cutaneous venous congestion. Acroangiodermatitis clinically resembles KS but is a benign reactive vasoproliferative disorder and is well known to occur in the lower extremities as a sequela of chronic venous insufficiency.7 A case of bilateral lower extremity pseudo-KS was reported in a patient with notable PPS.8 A report of 2 patients describes KS arising in the setting of chronic venous insufficiency without any classic risk factors.9 Therefore, patients with PPS characterized by venous insufficiency may represent a population at increased risk for KS.

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. US Population Data--1969-2017. https://seer.cancer.gov/popdata/. Published January 2019. Accessed November 25, 2019.

- Uldrick TS, Whitby D. Update on KSHV epidemiology, kaposi sarcoma pathogenesis, and treatment of saposi sarcoma. Cancer Lett. 2011;305:150-162.

- Schwartz RA, Micali G, Nasca MR, et al. Kaposi sarcoma: a continuing conundrum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:179-206.

- Arnold HL, Odom RB, James WD, et al. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 1990.

- Boyer FV, Tiffreau V, Rapin A, et al. Post-polio syndrome: pathophysiological hypotheses, diagnosis criteria, drug therapy. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2010;53:34-41.

- Bruno RL, Johnson JC, Berman WS. Vasomotor abnormalities as post-polio sequelae: functional and clinical implications. Orthopedics. 1985;8:865-869.

- Palmer B, Xia Y, Cho S, Lewis FS. Acroangiodermatitis secondary to chronic venous insufficiency. Cutis. 2010;86:239-240.

- Rotbart G. Kaposi's disease and venous insufficiency. Phlebologie. 1978;31:439-443.

- Que SK, DeFelice T, Abdulla FR, et al. Non-HIV-related kaposi sarcoma in 2 Hispanic patients arising in the setting of chronic venous insufficiency. Cutis. 2015;95:E30-E33.

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a low-grade vascular tumor that is rare among the general US population, with an incidence rate of less than 1 per 100,000.1 The tumor is more common among certain groups of individuals due to geographic differences in the prevalence of KS-associated herpesvirus (also referred to as human herpesvirus 8) as well as host immune factors.2 Kaposi sarcoma often is defined by the patient's predisposing characteristics yielding the following distinct epidemiologic subtypes: (1) classic KS is a rare disease affecting older men of Mediterranean descent; (2) African KS is an endemic cancer with male predominance in sub-Saharan Africa; (3) AIDS-associated KS is an often aggressive AIDS-defining illness; and (4) iatrogenic KS occurs in patients on immunosuppressive therapy.3 When evaluating a patient without any of these risk factors, the clinical suspicion for KS may be low. We report a patient with postpolio syndrome (PPS) who presented with KS of the right leg, ankle, and foot.

A 77-year-old man with a distant history of paralytic poliomyelitis presented for an annual skin examination with concern for a new lesion on the right ankle. The patient had a history of PPS primarily affecting the right leg. Physical examination revealed residual weakness in an atrophic right lower extremity with a mottled appearance and mild pitting edema to the knee. Two red, dome-shaped, vascular papules were appreciated on the medial aspect of the right ankle (Figure 1), and a shave biopsy of the larger papule was performed. Microscopic examination of the biopsy specimen was consistent with KS (Figure 2). This patient had no history of human immunodeficiency virus or immunosuppressive therapy and was not of Mediterranean descent.

Because KS is a radiosensitive vascular neoplasm and radiation therapy (RT) alone can achieve local control,4 the patient was treated with 6 megaelectron-volt electron-beam RT. He received 30 Gy in 10 fractions to the affected area of the medial ankle. The patient tolerated RT well. Three weeks after completing treatment, he was found to have mild lichenification on the right medial ankle with no clinical evidence of disease. Four months later, he presented with multiple additional vascular papules on the right third toe and in the interdigital web space (Figure 3). Shave biopsy of one of these lesions was consistent with KS. Contrast computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was performed, revealing no evidence of metastatic disease. The patient was treated with 30 Gy in 15 fractions using opposed lateral 6 megaelectron-volt photon fields to the entire right lower extremity below the knee to treat all of the skin affected by the PPS. His posttreatment course was complicated by edema in the affected leg that resolved after daily pneumatic compression. He had no evidence of residual or recurrent disease 6 months after completing RT (Figure 4).

Cutaneous KS is a human herpesvirus 8-positive tumor of endothelial origin typically seen in older men of Mediterranean or African descent and among immunosuppressed patients.4 Our patient did not have any classic risk factors for KS, but his disease did arise in the setting of a right lower extremity that was notably affected by PPS. Postpolio syndrome is characterized by muscle atrophy due to denervation of the motor unit.5 Bruno et al6 found that such deficits in motor innervation could lead to impairments in venous outflow causing cutaneous venous congestion. Acroangiodermatitis clinically resembles KS but is a benign reactive vasoproliferative disorder and is well known to occur in the lower extremities as a sequela of chronic venous insufficiency.7 A case of bilateral lower extremity pseudo-KS was reported in a patient with notable PPS.8 A report of 2 patients describes KS arising in the setting of chronic venous insufficiency without any classic risk factors.9 Therefore, patients with PPS characterized by venous insufficiency may represent a population at increased risk for KS.

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a low-grade vascular tumor that is rare among the general US population, with an incidence rate of less than 1 per 100,000.1 The tumor is more common among certain groups of individuals due to geographic differences in the prevalence of KS-associated herpesvirus (also referred to as human herpesvirus 8) as well as host immune factors.2 Kaposi sarcoma often is defined by the patient's predisposing characteristics yielding the following distinct epidemiologic subtypes: (1) classic KS is a rare disease affecting older men of Mediterranean descent; (2) African KS is an endemic cancer with male predominance in sub-Saharan Africa; (3) AIDS-associated KS is an often aggressive AIDS-defining illness; and (4) iatrogenic KS occurs in patients on immunosuppressive therapy.3 When evaluating a patient without any of these risk factors, the clinical suspicion for KS may be low. We report a patient with postpolio syndrome (PPS) who presented with KS of the right leg, ankle, and foot.

A 77-year-old man with a distant history of paralytic poliomyelitis presented for an annual skin examination with concern for a new lesion on the right ankle. The patient had a history of PPS primarily affecting the right leg. Physical examination revealed residual weakness in an atrophic right lower extremity with a mottled appearance and mild pitting edema to the knee. Two red, dome-shaped, vascular papules were appreciated on the medial aspect of the right ankle (Figure 1), and a shave biopsy of the larger papule was performed. Microscopic examination of the biopsy specimen was consistent with KS (Figure 2). This patient had no history of human immunodeficiency virus or immunosuppressive therapy and was not of Mediterranean descent.

Because KS is a radiosensitive vascular neoplasm and radiation therapy (RT) alone can achieve local control,4 the patient was treated with 6 megaelectron-volt electron-beam RT. He received 30 Gy in 10 fractions to the affected area of the medial ankle. The patient tolerated RT well. Three weeks after completing treatment, he was found to have mild lichenification on the right medial ankle with no clinical evidence of disease. Four months later, he presented with multiple additional vascular papules on the right third toe and in the interdigital web space (Figure 3). Shave biopsy of one of these lesions was consistent with KS. Contrast computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was performed, revealing no evidence of metastatic disease. The patient was treated with 30 Gy in 15 fractions using opposed lateral 6 megaelectron-volt photon fields to the entire right lower extremity below the knee to treat all of the skin affected by the PPS. His posttreatment course was complicated by edema in the affected leg that resolved after daily pneumatic compression. He had no evidence of residual or recurrent disease 6 months after completing RT (Figure 4).

Cutaneous KS is a human herpesvirus 8-positive tumor of endothelial origin typically seen in older men of Mediterranean or African descent and among immunosuppressed patients.4 Our patient did not have any classic risk factors for KS, but his disease did arise in the setting of a right lower extremity that was notably affected by PPS. Postpolio syndrome is characterized by muscle atrophy due to denervation of the motor unit.5 Bruno et al6 found that such deficits in motor innervation could lead to impairments in venous outflow causing cutaneous venous congestion. Acroangiodermatitis clinically resembles KS but is a benign reactive vasoproliferative disorder and is well known to occur in the lower extremities as a sequela of chronic venous insufficiency.7 A case of bilateral lower extremity pseudo-KS was reported in a patient with notable PPS.8 A report of 2 patients describes KS arising in the setting of chronic venous insufficiency without any classic risk factors.9 Therefore, patients with PPS characterized by venous insufficiency may represent a population at increased risk for KS.

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. US Population Data--1969-2017. https://seer.cancer.gov/popdata/. Published January 2019. Accessed November 25, 2019.

- Uldrick TS, Whitby D. Update on KSHV epidemiology, kaposi sarcoma pathogenesis, and treatment of saposi sarcoma. Cancer Lett. 2011;305:150-162.

- Schwartz RA, Micali G, Nasca MR, et al. Kaposi sarcoma: a continuing conundrum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:179-206.

- Arnold HL, Odom RB, James WD, et al. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 1990.

- Boyer FV, Tiffreau V, Rapin A, et al. Post-polio syndrome: pathophysiological hypotheses, diagnosis criteria, drug therapy. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2010;53:34-41.

- Bruno RL, Johnson JC, Berman WS. Vasomotor abnormalities as post-polio sequelae: functional and clinical implications. Orthopedics. 1985;8:865-869.

- Palmer B, Xia Y, Cho S, Lewis FS. Acroangiodermatitis secondary to chronic venous insufficiency. Cutis. 2010;86:239-240.

- Rotbart G. Kaposi's disease and venous insufficiency. Phlebologie. 1978;31:439-443.

- Que SK, DeFelice T, Abdulla FR, et al. Non-HIV-related kaposi sarcoma in 2 Hispanic patients arising in the setting of chronic venous insufficiency. Cutis. 2015;95:E30-E33.

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. US Population Data--1969-2017. https://seer.cancer.gov/popdata/. Published January 2019. Accessed November 25, 2019.

- Uldrick TS, Whitby D. Update on KSHV epidemiology, kaposi sarcoma pathogenesis, and treatment of saposi sarcoma. Cancer Lett. 2011;305:150-162.

- Schwartz RA, Micali G, Nasca MR, et al. Kaposi sarcoma: a continuing conundrum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:179-206.