User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'medstat-accordion-set article-series')]

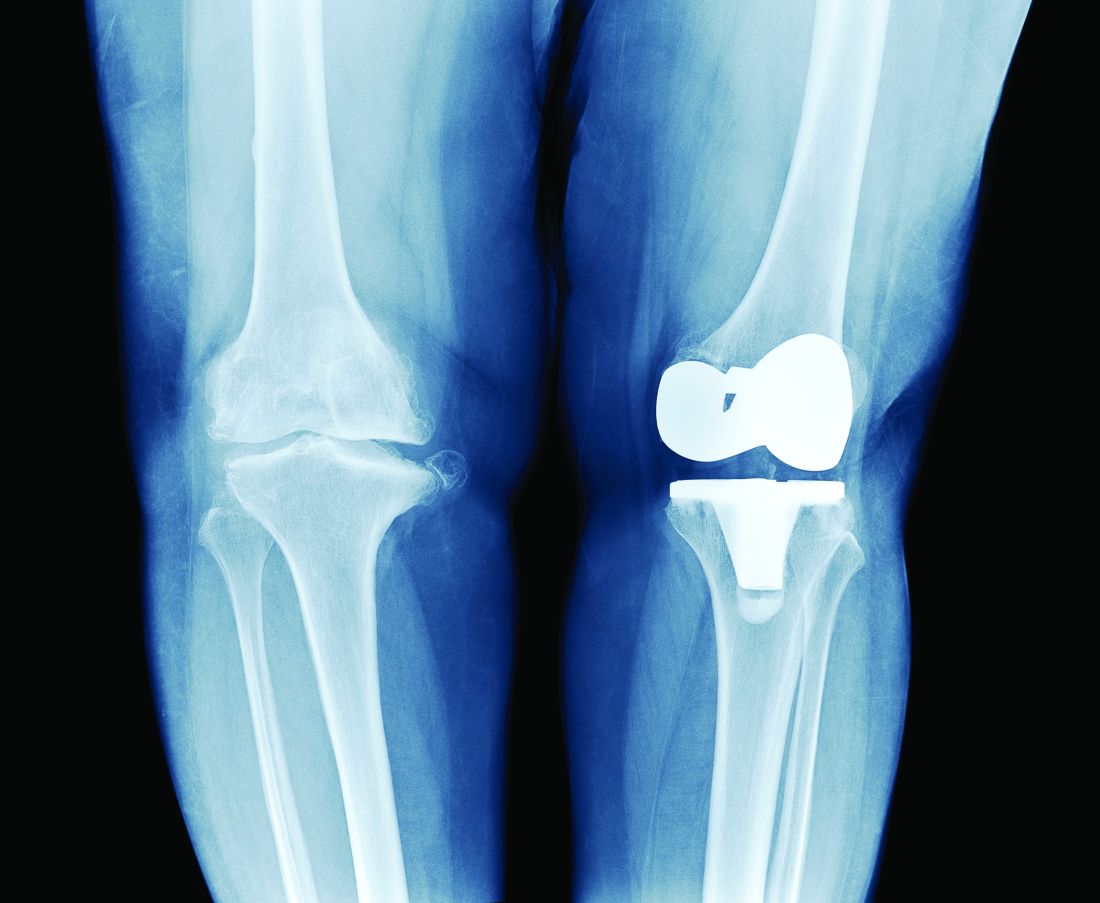

PT may lower risk of long-term opioid use after knee replacement

A new study has found that physical therapy may lead to a reduced risk of long-term opioid use in patients who have undergone total knee replacement (TKR).

“Greater number of PT intervention sessions and earlier initiation of outpatient PT care after TKR were associated with lower odds of long-term opioid use,” authors from Boston University wrote in their report on the study, which was published online Oct. 27 in JAMA Network Open.

“In previous large studies, we’ve seen that physical therapy can reduce pain in people with knee osteoarthritis, which is usually the primary indication for TKR,” study coauthor Deepak Kumar, PT, PhD, said in an interview. “But the association of physical therapy with opioid use in people with knee replacement has not yet been explored.

“The reason we focused on opioid use in these patients is because the number of knee replacement surgeries is going up exponentially,” Dr. Kumar said. “And, depending on which data you look at, from one-third to up to half of people who undergo knee replacement and have used opioids before end up becoming long-term users. Even in people who have not used them before, 5%-8% become long-term users after the surgery.

“Given how many surgeries are happening – and that number is expected to keep going up – the number of people who are becoming long-term opioid users is not trivial,” he said.

Study details

To assess the value of PT in reducing opioid use in this subset of patients, the authors reviewed records from the OptumLabs Data Warehouse insurance claims database to identify 67,322 eligible participants aged 40 or older who underwent TKR from Jan. 1, 2001, to Dec. 31, 2016. Of those patients, 38,408 were opioid naive and 28,914 had taken opioids before. The authors evaluated long-term opioid use – defined as 90 days or more of filled prescriptions – during a 12-month outcome assessment period that varied depending on differences in post-TKR PT start date and duration.

The researchers found a significantly lower likelihood of long-term opioid use associated with receipt of any PT before TKR among patients who had not taken opioids before (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.75; 95% confidence interval, 0.60-0.95) and those who had taken opioids in the past (aOR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.70-0.80).

Investigators found that 2.2% of participants in the opioid-naive group and 32.5% of those in the opioid-experienced group used opioids long-term after TKR. Approximately 76% of participants overall received outpatient PT within the 90 days after surgery, and the receipt of post-TKR PT at any point was associated with lower odds of long-term opioid use in the opioid-experienced group (aOR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.70-0.79).

Among the opioid-experienced group, receiving between 6 and 12 PT sessions (aOR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.75-0.90) or ≥ 13 sessions (aOR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.65-0.77) were both associated with lower odds of long-term opioid use, compared with those who received 1-5 sessions. Beginning PT 31-60 days or 61-90 days after surgery was associated with greater odds of long-term opioid use across both cohorts, compared with those who initiated therapy within 30 days of TKR.

Physical therapy: Underexplored option for pain in knee replacement

One finding caught the researchers slightly off guard: There was no association between active physical therapy and reduced odds of long-term opioid use. “From prior studies, at least in people with knee osteoarthritis, we know that active interventions were more useful than passive interventions,” Dr. Kumar said.

That said, he added that there is still some professional uncertainty regarding “the right type or the right components of physical therapy for managing pain in this population.” Regardless, he believes their study emphasizes the benefits of PT as a pain alleviator in these patients, especially those who have previously used opioids.

“Pharmaceuticals have side effects. Injections are not super effective,” he said. “The idea behind focusing on physical therapy interventions is that it’s widely available, it does you no harm, and it could potentially be lower cost to both the payers and the providers.”

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including not adjusting for opioid use within the 90 days after surgery as well as the different outcome assessment periods for pre-TKR and post-TKR PT exposures. In addition, they admitted that some of the patients who received PT could have been among those less likely to be treated with opioids, and vice versa. “A randomized clinical trial,” they wrote, “would be required to disentangle these issues.”

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Dr. Kumar reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health during the conduct of the study and grants from Pfizer for unrelated projects outside the submitted work. The full list of author disclosures can be found with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new study has found that physical therapy may lead to a reduced risk of long-term opioid use in patients who have undergone total knee replacement (TKR).

“Greater number of PT intervention sessions and earlier initiation of outpatient PT care after TKR were associated with lower odds of long-term opioid use,” authors from Boston University wrote in their report on the study, which was published online Oct. 27 in JAMA Network Open.

“In previous large studies, we’ve seen that physical therapy can reduce pain in people with knee osteoarthritis, which is usually the primary indication for TKR,” study coauthor Deepak Kumar, PT, PhD, said in an interview. “But the association of physical therapy with opioid use in people with knee replacement has not yet been explored.

“The reason we focused on opioid use in these patients is because the number of knee replacement surgeries is going up exponentially,” Dr. Kumar said. “And, depending on which data you look at, from one-third to up to half of people who undergo knee replacement and have used opioids before end up becoming long-term users. Even in people who have not used them before, 5%-8% become long-term users after the surgery.

“Given how many surgeries are happening – and that number is expected to keep going up – the number of people who are becoming long-term opioid users is not trivial,” he said.

Study details

To assess the value of PT in reducing opioid use in this subset of patients, the authors reviewed records from the OptumLabs Data Warehouse insurance claims database to identify 67,322 eligible participants aged 40 or older who underwent TKR from Jan. 1, 2001, to Dec. 31, 2016. Of those patients, 38,408 were opioid naive and 28,914 had taken opioids before. The authors evaluated long-term opioid use – defined as 90 days or more of filled prescriptions – during a 12-month outcome assessment period that varied depending on differences in post-TKR PT start date and duration.

The researchers found a significantly lower likelihood of long-term opioid use associated with receipt of any PT before TKR among patients who had not taken opioids before (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.75; 95% confidence interval, 0.60-0.95) and those who had taken opioids in the past (aOR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.70-0.80).

Investigators found that 2.2% of participants in the opioid-naive group and 32.5% of those in the opioid-experienced group used opioids long-term after TKR. Approximately 76% of participants overall received outpatient PT within the 90 days after surgery, and the receipt of post-TKR PT at any point was associated with lower odds of long-term opioid use in the opioid-experienced group (aOR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.70-0.79).

Among the opioid-experienced group, receiving between 6 and 12 PT sessions (aOR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.75-0.90) or ≥ 13 sessions (aOR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.65-0.77) were both associated with lower odds of long-term opioid use, compared with those who received 1-5 sessions. Beginning PT 31-60 days or 61-90 days after surgery was associated with greater odds of long-term opioid use across both cohorts, compared with those who initiated therapy within 30 days of TKR.

Physical therapy: Underexplored option for pain in knee replacement

One finding caught the researchers slightly off guard: There was no association between active physical therapy and reduced odds of long-term opioid use. “From prior studies, at least in people with knee osteoarthritis, we know that active interventions were more useful than passive interventions,” Dr. Kumar said.

That said, he added that there is still some professional uncertainty regarding “the right type or the right components of physical therapy for managing pain in this population.” Regardless, he believes their study emphasizes the benefits of PT as a pain alleviator in these patients, especially those who have previously used opioids.

“Pharmaceuticals have side effects. Injections are not super effective,” he said. “The idea behind focusing on physical therapy interventions is that it’s widely available, it does you no harm, and it could potentially be lower cost to both the payers and the providers.”

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including not adjusting for opioid use within the 90 days after surgery as well as the different outcome assessment periods for pre-TKR and post-TKR PT exposures. In addition, they admitted that some of the patients who received PT could have been among those less likely to be treated with opioids, and vice versa. “A randomized clinical trial,” they wrote, “would be required to disentangle these issues.”

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Dr. Kumar reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health during the conduct of the study and grants from Pfizer for unrelated projects outside the submitted work. The full list of author disclosures can be found with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new study has found that physical therapy may lead to a reduced risk of long-term opioid use in patients who have undergone total knee replacement (TKR).

“Greater number of PT intervention sessions and earlier initiation of outpatient PT care after TKR were associated with lower odds of long-term opioid use,” authors from Boston University wrote in their report on the study, which was published online Oct. 27 in JAMA Network Open.

“In previous large studies, we’ve seen that physical therapy can reduce pain in people with knee osteoarthritis, which is usually the primary indication for TKR,” study coauthor Deepak Kumar, PT, PhD, said in an interview. “But the association of physical therapy with opioid use in people with knee replacement has not yet been explored.

“The reason we focused on opioid use in these patients is because the number of knee replacement surgeries is going up exponentially,” Dr. Kumar said. “And, depending on which data you look at, from one-third to up to half of people who undergo knee replacement and have used opioids before end up becoming long-term users. Even in people who have not used them before, 5%-8% become long-term users after the surgery.

“Given how many surgeries are happening – and that number is expected to keep going up – the number of people who are becoming long-term opioid users is not trivial,” he said.

Study details

To assess the value of PT in reducing opioid use in this subset of patients, the authors reviewed records from the OptumLabs Data Warehouse insurance claims database to identify 67,322 eligible participants aged 40 or older who underwent TKR from Jan. 1, 2001, to Dec. 31, 2016. Of those patients, 38,408 were opioid naive and 28,914 had taken opioids before. The authors evaluated long-term opioid use – defined as 90 days or more of filled prescriptions – during a 12-month outcome assessment period that varied depending on differences in post-TKR PT start date and duration.

The researchers found a significantly lower likelihood of long-term opioid use associated with receipt of any PT before TKR among patients who had not taken opioids before (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.75; 95% confidence interval, 0.60-0.95) and those who had taken opioids in the past (aOR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.70-0.80).

Investigators found that 2.2% of participants in the opioid-naive group and 32.5% of those in the opioid-experienced group used opioids long-term after TKR. Approximately 76% of participants overall received outpatient PT within the 90 days after surgery, and the receipt of post-TKR PT at any point was associated with lower odds of long-term opioid use in the opioid-experienced group (aOR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.70-0.79).

Among the opioid-experienced group, receiving between 6 and 12 PT sessions (aOR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.75-0.90) or ≥ 13 sessions (aOR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.65-0.77) were both associated with lower odds of long-term opioid use, compared with those who received 1-5 sessions. Beginning PT 31-60 days or 61-90 days after surgery was associated with greater odds of long-term opioid use across both cohorts, compared with those who initiated therapy within 30 days of TKR.

Physical therapy: Underexplored option for pain in knee replacement

One finding caught the researchers slightly off guard: There was no association between active physical therapy and reduced odds of long-term opioid use. “From prior studies, at least in people with knee osteoarthritis, we know that active interventions were more useful than passive interventions,” Dr. Kumar said.

That said, he added that there is still some professional uncertainty regarding “the right type or the right components of physical therapy for managing pain in this population.” Regardless, he believes their study emphasizes the benefits of PT as a pain alleviator in these patients, especially those who have previously used opioids.

“Pharmaceuticals have side effects. Injections are not super effective,” he said. “The idea behind focusing on physical therapy interventions is that it’s widely available, it does you no harm, and it could potentially be lower cost to both the payers and the providers.”

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including not adjusting for opioid use within the 90 days after surgery as well as the different outcome assessment periods for pre-TKR and post-TKR PT exposures. In addition, they admitted that some of the patients who received PT could have been among those less likely to be treated with opioids, and vice versa. “A randomized clinical trial,” they wrote, “would be required to disentangle these issues.”

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Dr. Kumar reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health during the conduct of the study and grants from Pfizer for unrelated projects outside the submitted work. The full list of author disclosures can be found with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Boxed warnings: Legal risks that many physicians never see coming

Almost all physicians write prescriptions, and each prescription requires a physician to assess the risks and benefits of the drug. If an adverse drug reaction occurs, physicians may be called on to defend their risk-benefit assessment in court.

The assessment of risk is complicated when there is a boxed warning that describes potentially serious and life-threatening adverse reactions associated with a drug. Some of our most commonly prescribed drugs have boxed warnings, and drugs that were initially approved by the Food and Drug Administration without boxed warnings may have them added years later.

One serious problem with boxed warnings is that there are no reliable mechanisms for making sure that physicians are aware of them. The warnings are typically not seen by physicians as printed product labels, just as physicians often don’t see the pills and capsules that they prescribe. Pharmacists who receive packaged drugs from manufacturers may be the only ones to see an actual printed boxed warning, but even those pharmacists have little reason to read each label and note changes when handling many bulk packages.

This problem is aggravated by misperceptions that many physicians have about boxed warnings and the increasingly intense scrutiny given to them by mass media and the courts. Lawyers can use boxed warnings to make a drug look dangerous, even when it’s not, and to make physicians look reckless when prescribing it. Therefore, it is important for physicians to understand what boxed warnings are, what they are not, the problems they cause, and how to minimize these problems.

What is a ‘boxed warning’?

The marketing and sale of drugs in the United States requires approval by the FDA. Approval requires manufacturers to prepare a document containing “Full Prescribing Information” for the drug and to include a printed copy in every package of the drug that is sold. This document is commonly called a “package insert,” but the FDA designates this document as the manufacturer’s product “label.”

In 1979, the FDA began requiring some labels to appear within thick, black rectangular borders; these have come to be known as boxed warnings. Boxed warnings are usually placed at the beginning of a label. They may be added to the label of a previously approved drug already on the market or included in the product label when first approved and marketed.

The requirement for a boxed warning most often arises when a signal appears during review of postmarketing surveillance data suggesting a possible and plausible association between a drug and an adverse reaction. Warnings may also be initiated in response to petitions from public interest groups, or upon the discovery of serious toxicity in animals. Regardless of their origin, the intent of a boxed warning is to highlight information that may have important therapeutic consequences and warrants heightened awareness among physicians.

What a boxed warning is not

A boxed warning is not “issued” by the FDA; it is merely required by the FDA. Specific wording or a template may be suggested by the FDA, but product labels and boxed warnings are written and issued by the manufacturer. This distinction may seem minor, but extensive litigation has occurred over whether manufacturers have met their duty to warn consumers about possible risks when using their products, and this duty cannot be shifted to the FDA.

A boxed warning may not be added to a product label at the option of a manufacturer. The FDA allows a boxed warning only if it requires the warning, to preserve its impact. It should be noted that some medical information sources (e.g., PDR.net) may include a “BOXED WARNING” in their drug monographs, but monographs not written by a manufacturer are not regulated by the FDA, and the text of their boxed warnings do not always correspond to the boxed warning that was approved by the FDA.

A boxed warning is not an indication that revocation of FDA approval is being considered or that it is likely to be revoked. FDA approval is subject to ongoing review and may be revoked at any time, without a prior boxed warning.

A boxed warning is not the highest level of warning. The FDA may require a manufacturer to send out a “Dear Health Care Provider” (DHCP) letter when an even higher or more urgent level of warning is deemed necessary. DHCP letters are usually accompanied by revisions of the product label, but most label revisions – and even most boxed warnings – are not accompanied by DHCP letters.

A boxed warning is not a statement about causation. Most warnings describe an “association” between a drug and an adverse effect, or “increased risk,” or instances of a particular adverse effect that “have been reported” in persons taking a drug. The words in a boxed warning are carefully chosen and require careful reading; in most cases they refrain from stating that a drug actually causes an adverse effect. The postmarketing surveillance data on which most warnings are based generally cannot provide the kind of evidence required to establish causation, and an association may be nothing more than an uncommon manifestation of the disorder for which the drug has been prescribed.

A boxed warning is not a statement about the probability of an adverse reaction occurring. The requirement for a boxed warning correlates better to the new recognition of a possible association than to the probability of an association. For example, penicillin has long been known to cause fatal anaphylaxis in 1/100,000 first-time administrations, but it does not have a boxed warning. The adverse consequences described in boxed warnings are often far less frequent – so much so that most physicians will never see them.

A boxed warning does not define the standard of care. The warning is a requirement imposed on the manufacturer, not on the practice of medicine. For legal purposes, the “standard of care” for the practice of medicine is defined state by state and is typically cast in terms such as “what most physicians would do in similar circumstances.” Physicians often prescribe drugs in spite of boxed warnings, just as they often prescribe drugs for “off label” indications, always balancing risk versus benefit.

A boxed warning does not constitute a contraindication to the use of a medication. Some warnings state that a drug is contraindicated in some situations, but product labels have another mandated section for listing contraindications, and most boxed warnings have no corresponding entry in that section.

A boxed warning does not necessarily constitute current information, nor is it always updated when new or contrary information becomes available. Revisions to boxed warnings, and to product labels in general, are made only after detailed review at the FDA, and the process of deciding whether an existing boxed warning continues to be appropriate may divert limited regulatory resources from more urgent priorities. Consequently, revisions to a boxed warning may lag behind the data that justify a revision by months or years. Revisions may never occur if softening or eliminating a boxed warning is deemed to be not worth the cost by a manufacturer.

Boxed warning problems for physicians

There is no reliable mechanism for manufacturers or the FDA to communicate boxed warnings directly to physicians, so it’s not clear how physicians are expected to stay informed about the issuance or revision of boxed warnings. They may first learn about new or revised warnings in the mass media, which is paying ever-increasing attention to press releases from the FDA. However, it can be difficult for the media to accurately convey the subtle and complex nature of a boxed warning in nontechnical terms.

Many physicians subscribe to various medical news alerts and attend continuing medical education (CME) programs, which often do an excellent job of highlighting new warnings, while hospitals, clinics, and pharmacies may broadcast news about boxed warnings in newsletters or other notices. But these notifications are ephemeral and may be missed by physicians who are overwhelmed by email, notices, newsletters, and CME programs.

The warnings that pop up in electronic medical records systems are often so numerous that physicians become trained to ignore them. Printed advertisements in professional journals must include mandated boxed warnings, but their visibility is waning as physicians increasingly read journals online.

Another conundrum is how to inform the public about boxed warnings.

Manufacturers are prohibited from direct-to-consumer advertising of drugs with boxed warnings, although the warnings are easily found on the Internet. Some patients expect and welcome detailed information from their physicians, so it’s a good policy to always and repeatedly review this information with them, especially if they are members of an identified risk group. However, that policy may be counterproductive if it dissuades anxious patients from needed therapy despite risk-benefit considerations that strongly favor it. Boxed warnings are well known to have “spillover effects” in which the aspersions cast by a boxed warning for a relatively small subgroup of patients causes use of a drug to decline among all patients.

Compounding this conundrum is that physicians rarely have sufficient information to gauge the magnitude of a risk, given that boxed warnings are often based on information from surveillance systems that cannot accurately quantify the risk or even establish a causal relationship. The text of a boxed warning generally does not provide the information needed for evidence-based clinical practice such as a quantitative estimate of effect, information about source and trustworthiness of the evidence, and guidance on implementation. For these and other reasons, FDA policies about various boxed warnings have been the target of significant criticism.

Medication guides are one mechanism to address the challenge of informing patients about the risks of drugs they are taking. FDA-approved medication guides are available for most drugs dispensed as outpatient prescriptions, they’re written in plain language for the consumer, and they include paraphrased versions of any boxed warning. Ideally, patients review these guides with their physicians or pharmacists, but the guides may be lengthy and raise questions that may not be answerable (e.g., about incidence rates). Patients may decline to review this information when a drug is prescribed or dispensed, and they may discard printed copies given to them without reading.

What can physicians do to minimize boxed warning problems?

Physicians should periodically review the product labels for drugs they commonly prescribe, including drugs they’ve prescribed for a long time. Prescription renewal requests can be used as a prompt to check for changes in a patient’s condition or other medications that might place a patient in the target population of a boxed warning. Physicians can subscribe to newsletters that announce and discuss significant product label changes, including alerts directly from the FDA. Physicians may also enlist their office staff to find and review boxed warnings for drugs being prescribed, noting which ones should require a conversation with any patient who has been or will be receiving this drug. They may want to make explicit mention in their encounter record that a boxed warning, medication guide, or overall risk-benefit assessment has been discussed.

Summary

The nature of boxed warnings, the means by which they are disseminated, and their role in clinical practice are all in great need of improvement. Until that occurs, boxed warnings offer some, but only very limited, help to patients and physicians who struggle to understand the risks of medications.

Dr. Axelsen is professor in the departments of pharmacology, biochemistry, and biophysics, and of medicine, infectious diseases section, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. He disclosed no relevant financial relationships. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Almost all physicians write prescriptions, and each prescription requires a physician to assess the risks and benefits of the drug. If an adverse drug reaction occurs, physicians may be called on to defend their risk-benefit assessment in court.

The assessment of risk is complicated when there is a boxed warning that describes potentially serious and life-threatening adverse reactions associated with a drug. Some of our most commonly prescribed drugs have boxed warnings, and drugs that were initially approved by the Food and Drug Administration without boxed warnings may have them added years later.

One serious problem with boxed warnings is that there are no reliable mechanisms for making sure that physicians are aware of them. The warnings are typically not seen by physicians as printed product labels, just as physicians often don’t see the pills and capsules that they prescribe. Pharmacists who receive packaged drugs from manufacturers may be the only ones to see an actual printed boxed warning, but even those pharmacists have little reason to read each label and note changes when handling many bulk packages.

This problem is aggravated by misperceptions that many physicians have about boxed warnings and the increasingly intense scrutiny given to them by mass media and the courts. Lawyers can use boxed warnings to make a drug look dangerous, even when it’s not, and to make physicians look reckless when prescribing it. Therefore, it is important for physicians to understand what boxed warnings are, what they are not, the problems they cause, and how to minimize these problems.

What is a ‘boxed warning’?

The marketing and sale of drugs in the United States requires approval by the FDA. Approval requires manufacturers to prepare a document containing “Full Prescribing Information” for the drug and to include a printed copy in every package of the drug that is sold. This document is commonly called a “package insert,” but the FDA designates this document as the manufacturer’s product “label.”

In 1979, the FDA began requiring some labels to appear within thick, black rectangular borders; these have come to be known as boxed warnings. Boxed warnings are usually placed at the beginning of a label. They may be added to the label of a previously approved drug already on the market or included in the product label when first approved and marketed.

The requirement for a boxed warning most often arises when a signal appears during review of postmarketing surveillance data suggesting a possible and plausible association between a drug and an adverse reaction. Warnings may also be initiated in response to petitions from public interest groups, or upon the discovery of serious toxicity in animals. Regardless of their origin, the intent of a boxed warning is to highlight information that may have important therapeutic consequences and warrants heightened awareness among physicians.

What a boxed warning is not

A boxed warning is not “issued” by the FDA; it is merely required by the FDA. Specific wording or a template may be suggested by the FDA, but product labels and boxed warnings are written and issued by the manufacturer. This distinction may seem minor, but extensive litigation has occurred over whether manufacturers have met their duty to warn consumers about possible risks when using their products, and this duty cannot be shifted to the FDA.

A boxed warning may not be added to a product label at the option of a manufacturer. The FDA allows a boxed warning only if it requires the warning, to preserve its impact. It should be noted that some medical information sources (e.g., PDR.net) may include a “BOXED WARNING” in their drug monographs, but monographs not written by a manufacturer are not regulated by the FDA, and the text of their boxed warnings do not always correspond to the boxed warning that was approved by the FDA.

A boxed warning is not an indication that revocation of FDA approval is being considered or that it is likely to be revoked. FDA approval is subject to ongoing review and may be revoked at any time, without a prior boxed warning.

A boxed warning is not the highest level of warning. The FDA may require a manufacturer to send out a “Dear Health Care Provider” (DHCP) letter when an even higher or more urgent level of warning is deemed necessary. DHCP letters are usually accompanied by revisions of the product label, but most label revisions – and even most boxed warnings – are not accompanied by DHCP letters.

A boxed warning is not a statement about causation. Most warnings describe an “association” between a drug and an adverse effect, or “increased risk,” or instances of a particular adverse effect that “have been reported” in persons taking a drug. The words in a boxed warning are carefully chosen and require careful reading; in most cases they refrain from stating that a drug actually causes an adverse effect. The postmarketing surveillance data on which most warnings are based generally cannot provide the kind of evidence required to establish causation, and an association may be nothing more than an uncommon manifestation of the disorder for which the drug has been prescribed.

A boxed warning is not a statement about the probability of an adverse reaction occurring. The requirement for a boxed warning correlates better to the new recognition of a possible association than to the probability of an association. For example, penicillin has long been known to cause fatal anaphylaxis in 1/100,000 first-time administrations, but it does not have a boxed warning. The adverse consequences described in boxed warnings are often far less frequent – so much so that most physicians will never see them.

A boxed warning does not define the standard of care. The warning is a requirement imposed on the manufacturer, not on the practice of medicine. For legal purposes, the “standard of care” for the practice of medicine is defined state by state and is typically cast in terms such as “what most physicians would do in similar circumstances.” Physicians often prescribe drugs in spite of boxed warnings, just as they often prescribe drugs for “off label” indications, always balancing risk versus benefit.

A boxed warning does not constitute a contraindication to the use of a medication. Some warnings state that a drug is contraindicated in some situations, but product labels have another mandated section for listing contraindications, and most boxed warnings have no corresponding entry in that section.

A boxed warning does not necessarily constitute current information, nor is it always updated when new or contrary information becomes available. Revisions to boxed warnings, and to product labels in general, are made only after detailed review at the FDA, and the process of deciding whether an existing boxed warning continues to be appropriate may divert limited regulatory resources from more urgent priorities. Consequently, revisions to a boxed warning may lag behind the data that justify a revision by months or years. Revisions may never occur if softening or eliminating a boxed warning is deemed to be not worth the cost by a manufacturer.

Boxed warning problems for physicians

There is no reliable mechanism for manufacturers or the FDA to communicate boxed warnings directly to physicians, so it’s not clear how physicians are expected to stay informed about the issuance or revision of boxed warnings. They may first learn about new or revised warnings in the mass media, which is paying ever-increasing attention to press releases from the FDA. However, it can be difficult for the media to accurately convey the subtle and complex nature of a boxed warning in nontechnical terms.

Many physicians subscribe to various medical news alerts and attend continuing medical education (CME) programs, which often do an excellent job of highlighting new warnings, while hospitals, clinics, and pharmacies may broadcast news about boxed warnings in newsletters or other notices. But these notifications are ephemeral and may be missed by physicians who are overwhelmed by email, notices, newsletters, and CME programs.

The warnings that pop up in electronic medical records systems are often so numerous that physicians become trained to ignore them. Printed advertisements in professional journals must include mandated boxed warnings, but their visibility is waning as physicians increasingly read journals online.

Another conundrum is how to inform the public about boxed warnings.

Manufacturers are prohibited from direct-to-consumer advertising of drugs with boxed warnings, although the warnings are easily found on the Internet. Some patients expect and welcome detailed information from their physicians, so it’s a good policy to always and repeatedly review this information with them, especially if they are members of an identified risk group. However, that policy may be counterproductive if it dissuades anxious patients from needed therapy despite risk-benefit considerations that strongly favor it. Boxed warnings are well known to have “spillover effects” in which the aspersions cast by a boxed warning for a relatively small subgroup of patients causes use of a drug to decline among all patients.

Compounding this conundrum is that physicians rarely have sufficient information to gauge the magnitude of a risk, given that boxed warnings are often based on information from surveillance systems that cannot accurately quantify the risk or even establish a causal relationship. The text of a boxed warning generally does not provide the information needed for evidence-based clinical practice such as a quantitative estimate of effect, information about source and trustworthiness of the evidence, and guidance on implementation. For these and other reasons, FDA policies about various boxed warnings have been the target of significant criticism.

Medication guides are one mechanism to address the challenge of informing patients about the risks of drugs they are taking. FDA-approved medication guides are available for most drugs dispensed as outpatient prescriptions, they’re written in plain language for the consumer, and they include paraphrased versions of any boxed warning. Ideally, patients review these guides with their physicians or pharmacists, but the guides may be lengthy and raise questions that may not be answerable (e.g., about incidence rates). Patients may decline to review this information when a drug is prescribed or dispensed, and they may discard printed copies given to them without reading.

What can physicians do to minimize boxed warning problems?

Physicians should periodically review the product labels for drugs they commonly prescribe, including drugs they’ve prescribed for a long time. Prescription renewal requests can be used as a prompt to check for changes in a patient’s condition or other medications that might place a patient in the target population of a boxed warning. Physicians can subscribe to newsletters that announce and discuss significant product label changes, including alerts directly from the FDA. Physicians may also enlist their office staff to find and review boxed warnings for drugs being prescribed, noting which ones should require a conversation with any patient who has been or will be receiving this drug. They may want to make explicit mention in their encounter record that a boxed warning, medication guide, or overall risk-benefit assessment has been discussed.

Summary

The nature of boxed warnings, the means by which they are disseminated, and their role in clinical practice are all in great need of improvement. Until that occurs, boxed warnings offer some, but only very limited, help to patients and physicians who struggle to understand the risks of medications.

Dr. Axelsen is professor in the departments of pharmacology, biochemistry, and biophysics, and of medicine, infectious diseases section, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. He disclosed no relevant financial relationships. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Almost all physicians write prescriptions, and each prescription requires a physician to assess the risks and benefits of the drug. If an adverse drug reaction occurs, physicians may be called on to defend their risk-benefit assessment in court.

The assessment of risk is complicated when there is a boxed warning that describes potentially serious and life-threatening adverse reactions associated with a drug. Some of our most commonly prescribed drugs have boxed warnings, and drugs that were initially approved by the Food and Drug Administration without boxed warnings may have them added years later.

One serious problem with boxed warnings is that there are no reliable mechanisms for making sure that physicians are aware of them. The warnings are typically not seen by physicians as printed product labels, just as physicians often don’t see the pills and capsules that they prescribe. Pharmacists who receive packaged drugs from manufacturers may be the only ones to see an actual printed boxed warning, but even those pharmacists have little reason to read each label and note changes when handling many bulk packages.

This problem is aggravated by misperceptions that many physicians have about boxed warnings and the increasingly intense scrutiny given to them by mass media and the courts. Lawyers can use boxed warnings to make a drug look dangerous, even when it’s not, and to make physicians look reckless when prescribing it. Therefore, it is important for physicians to understand what boxed warnings are, what they are not, the problems they cause, and how to minimize these problems.

What is a ‘boxed warning’?

The marketing and sale of drugs in the United States requires approval by the FDA. Approval requires manufacturers to prepare a document containing “Full Prescribing Information” for the drug and to include a printed copy in every package of the drug that is sold. This document is commonly called a “package insert,” but the FDA designates this document as the manufacturer’s product “label.”

In 1979, the FDA began requiring some labels to appear within thick, black rectangular borders; these have come to be known as boxed warnings. Boxed warnings are usually placed at the beginning of a label. They may be added to the label of a previously approved drug already on the market or included in the product label when first approved and marketed.

The requirement for a boxed warning most often arises when a signal appears during review of postmarketing surveillance data suggesting a possible and plausible association between a drug and an adverse reaction. Warnings may also be initiated in response to petitions from public interest groups, or upon the discovery of serious toxicity in animals. Regardless of their origin, the intent of a boxed warning is to highlight information that may have important therapeutic consequences and warrants heightened awareness among physicians.

What a boxed warning is not

A boxed warning is not “issued” by the FDA; it is merely required by the FDA. Specific wording or a template may be suggested by the FDA, but product labels and boxed warnings are written and issued by the manufacturer. This distinction may seem minor, but extensive litigation has occurred over whether manufacturers have met their duty to warn consumers about possible risks when using their products, and this duty cannot be shifted to the FDA.

A boxed warning may not be added to a product label at the option of a manufacturer. The FDA allows a boxed warning only if it requires the warning, to preserve its impact. It should be noted that some medical information sources (e.g., PDR.net) may include a “BOXED WARNING” in their drug monographs, but monographs not written by a manufacturer are not regulated by the FDA, and the text of their boxed warnings do not always correspond to the boxed warning that was approved by the FDA.

A boxed warning is not an indication that revocation of FDA approval is being considered or that it is likely to be revoked. FDA approval is subject to ongoing review and may be revoked at any time, without a prior boxed warning.

A boxed warning is not the highest level of warning. The FDA may require a manufacturer to send out a “Dear Health Care Provider” (DHCP) letter when an even higher or more urgent level of warning is deemed necessary. DHCP letters are usually accompanied by revisions of the product label, but most label revisions – and even most boxed warnings – are not accompanied by DHCP letters.

A boxed warning is not a statement about causation. Most warnings describe an “association” between a drug and an adverse effect, or “increased risk,” or instances of a particular adverse effect that “have been reported” in persons taking a drug. The words in a boxed warning are carefully chosen and require careful reading; in most cases they refrain from stating that a drug actually causes an adverse effect. The postmarketing surveillance data on which most warnings are based generally cannot provide the kind of evidence required to establish causation, and an association may be nothing more than an uncommon manifestation of the disorder for which the drug has been prescribed.

A boxed warning is not a statement about the probability of an adverse reaction occurring. The requirement for a boxed warning correlates better to the new recognition of a possible association than to the probability of an association. For example, penicillin has long been known to cause fatal anaphylaxis in 1/100,000 first-time administrations, but it does not have a boxed warning. The adverse consequences described in boxed warnings are often far less frequent – so much so that most physicians will never see them.

A boxed warning does not define the standard of care. The warning is a requirement imposed on the manufacturer, not on the practice of medicine. For legal purposes, the “standard of care” for the practice of medicine is defined state by state and is typically cast in terms such as “what most physicians would do in similar circumstances.” Physicians often prescribe drugs in spite of boxed warnings, just as they often prescribe drugs for “off label” indications, always balancing risk versus benefit.

A boxed warning does not constitute a contraindication to the use of a medication. Some warnings state that a drug is contraindicated in some situations, but product labels have another mandated section for listing contraindications, and most boxed warnings have no corresponding entry in that section.

A boxed warning does not necessarily constitute current information, nor is it always updated when new or contrary information becomes available. Revisions to boxed warnings, and to product labels in general, are made only after detailed review at the FDA, and the process of deciding whether an existing boxed warning continues to be appropriate may divert limited regulatory resources from more urgent priorities. Consequently, revisions to a boxed warning may lag behind the data that justify a revision by months or years. Revisions may never occur if softening or eliminating a boxed warning is deemed to be not worth the cost by a manufacturer.

Boxed warning problems for physicians

There is no reliable mechanism for manufacturers or the FDA to communicate boxed warnings directly to physicians, so it’s not clear how physicians are expected to stay informed about the issuance or revision of boxed warnings. They may first learn about new or revised warnings in the mass media, which is paying ever-increasing attention to press releases from the FDA. However, it can be difficult for the media to accurately convey the subtle and complex nature of a boxed warning in nontechnical terms.

Many physicians subscribe to various medical news alerts and attend continuing medical education (CME) programs, which often do an excellent job of highlighting new warnings, while hospitals, clinics, and pharmacies may broadcast news about boxed warnings in newsletters or other notices. But these notifications are ephemeral and may be missed by physicians who are overwhelmed by email, notices, newsletters, and CME programs.

The warnings that pop up in electronic medical records systems are often so numerous that physicians become trained to ignore them. Printed advertisements in professional journals must include mandated boxed warnings, but their visibility is waning as physicians increasingly read journals online.

Another conundrum is how to inform the public about boxed warnings.

Manufacturers are prohibited from direct-to-consumer advertising of drugs with boxed warnings, although the warnings are easily found on the Internet. Some patients expect and welcome detailed information from their physicians, so it’s a good policy to always and repeatedly review this information with them, especially if they are members of an identified risk group. However, that policy may be counterproductive if it dissuades anxious patients from needed therapy despite risk-benefit considerations that strongly favor it. Boxed warnings are well known to have “spillover effects” in which the aspersions cast by a boxed warning for a relatively small subgroup of patients causes use of a drug to decline among all patients.

Compounding this conundrum is that physicians rarely have sufficient information to gauge the magnitude of a risk, given that boxed warnings are often based on information from surveillance systems that cannot accurately quantify the risk or even establish a causal relationship. The text of a boxed warning generally does not provide the information needed for evidence-based clinical practice such as a quantitative estimate of effect, information about source and trustworthiness of the evidence, and guidance on implementation. For these and other reasons, FDA policies about various boxed warnings have been the target of significant criticism.

Medication guides are one mechanism to address the challenge of informing patients about the risks of drugs they are taking. FDA-approved medication guides are available for most drugs dispensed as outpatient prescriptions, they’re written in plain language for the consumer, and they include paraphrased versions of any boxed warning. Ideally, patients review these guides with their physicians or pharmacists, but the guides may be lengthy and raise questions that may not be answerable (e.g., about incidence rates). Patients may decline to review this information when a drug is prescribed or dispensed, and they may discard printed copies given to them without reading.

What can physicians do to minimize boxed warning problems?

Physicians should periodically review the product labels for drugs they commonly prescribe, including drugs they’ve prescribed for a long time. Prescription renewal requests can be used as a prompt to check for changes in a patient’s condition or other medications that might place a patient in the target population of a boxed warning. Physicians can subscribe to newsletters that announce and discuss significant product label changes, including alerts directly from the FDA. Physicians may also enlist their office staff to find and review boxed warnings for drugs being prescribed, noting which ones should require a conversation with any patient who has been or will be receiving this drug. They may want to make explicit mention in their encounter record that a boxed warning, medication guide, or overall risk-benefit assessment has been discussed.

Summary

The nature of boxed warnings, the means by which they are disseminated, and their role in clinical practice are all in great need of improvement. Until that occurs, boxed warnings offer some, but only very limited, help to patients and physicians who struggle to understand the risks of medications.

Dr. Axelsen is professor in the departments of pharmacology, biochemistry, and biophysics, and of medicine, infectious diseases section, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. He disclosed no relevant financial relationships. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Clinical Edge Journal Scan Commentary: RA November 2021

Biosimilar medications have received significant attention recently in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA), though the effects of switching from the reference drug to a biosimilar is not known. The study by Fleischmann et al1 looks at the safety and efficacy, as well as immunogenicity, of biosimilar adalimumab (ADL-PF) compared to the reference ADL-EU (European Union sourced adalimumab) in a randomized double-blind study. Patients were randomized to start and continue ADL-PF or start ADL-EU and switch to ADL-PF at week 26 or 52. Immunogenicity was measured using anti-drug antibodies (ADA). American College of Rheumatology (ACR20) response rates were similar among all groups, while ACR50 and ACR70 response rates were numerically lower in the week 52 switch group. ADA development was comparable between groups. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, but overall, safety, efficacy, and immunogenicity were similar between patients maintained on ADL-PF and those switched from ADL-EU at week 26 or 52.

Statins have long been associated with musculoskeletal symptoms in patients, but have also been postulated to have anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects. Complicating the relationship is the knowledge that inflammation increases cardiovascular risk in RA patients. In a case-control study, Peterson et al2 used an administrative database to examine the influence of statin use on development of RA. Cases were identified based on ICD-9 coding as well as a prescription for methotrexate after diagnosis. They were matched 1:1 with controls based on demographics and year of diagnosis. Statin use was evaluated. Statin use was associated with a small increase in risk of RA, which was diminished after adjusting for hyperlipidemia; a trend towards increase in risk with higher dose and duration of statin use was not statistically significant. Beyond this, the reduced risk after adjustment for hyperlipidemia is hard to interpret as an explanation of cause or effect of autoimmunity, and, given the small magnitude of increases and decreases in risk, may not be clinically meaningful.

In addition to patients with RA having a higher burden of cardiovascular disease necessitating use of statins, they also have a high risk of progressive secondary osteoarthritis requiring joint replacement surgery. Chang et al3 used a national claims-based dataset from China to examine risk of total knee or hip replacement (TKR and THR, respectively) in patients with RA. From 2000-2013 (ie, the onset of the biologic era), TKR and THR rates were examined in a cohort of biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (bDMARD) users compared to conventional synthetic DMARD (csDMARD) users. Adjusted hazard ratios (HR) were lower for both TKD and THR in bDMARD users. Though RA activity was not examined, combined with the knowledge of the association of disease severity with bDMARD use, this study lends evidence to the benefits of more aggressive treatment.

Finally, much is made of the link between bDMARD and targeted synthetic DMARD use and malignancy due to reduced immunosurveillance, but concrete evidence is conflicting. Wetzman et al4 performed a systematic review of studies of patients with inflammatory arthritis (RA, psoriatic arthritis, and Ankylosing spondylitis) looking at cancer relapse or occurrence of new cancer. An increase in skin cancers (HR 1.32) was noted, but reassuringly no other increase in risk of recurrent or new cancer was seen.

References

- Fleischmann R et al. Long-term efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity of the adalimumab biosimilar, PF-06410293, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis after switching from reference adalimumab (Humira®) or continuing biosimilar therapy: week 52–92 data from a randomized, double-blind, phase 3 trialArthritis Res Ther. 2021(Sep 25);23:248.

- Peterson MN et al. Risk of rheumatoid arthritis diagnosis in statin users in a large nationwide US study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2021(Sep 18):23:244.

- Chang YS et al. Effects of biologics on reducing the risks of total knee replacement and total hip replacement in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021(Sep 17):keab671.

- Wetzman A et al. Risk of cancer after initiation of targeted therapies in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and a prior cancer: systematic review with meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2021(Sep 21): acr.24784.

Biosimilar medications have received significant attention recently in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA), though the effects of switching from the reference drug to a biosimilar is not known. The study by Fleischmann et al1 looks at the safety and efficacy, as well as immunogenicity, of biosimilar adalimumab (ADL-PF) compared to the reference ADL-EU (European Union sourced adalimumab) in a randomized double-blind study. Patients were randomized to start and continue ADL-PF or start ADL-EU and switch to ADL-PF at week 26 or 52. Immunogenicity was measured using anti-drug antibodies (ADA). American College of Rheumatology (ACR20) response rates were similar among all groups, while ACR50 and ACR70 response rates were numerically lower in the week 52 switch group. ADA development was comparable between groups. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, but overall, safety, efficacy, and immunogenicity were similar between patients maintained on ADL-PF and those switched from ADL-EU at week 26 or 52.

Statins have long been associated with musculoskeletal symptoms in patients, but have also been postulated to have anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects. Complicating the relationship is the knowledge that inflammation increases cardiovascular risk in RA patients. In a case-control study, Peterson et al2 used an administrative database to examine the influence of statin use on development of RA. Cases were identified based on ICD-9 coding as well as a prescription for methotrexate after diagnosis. They were matched 1:1 with controls based on demographics and year of diagnosis. Statin use was evaluated. Statin use was associated with a small increase in risk of RA, which was diminished after adjusting for hyperlipidemia; a trend towards increase in risk with higher dose and duration of statin use was not statistically significant. Beyond this, the reduced risk after adjustment for hyperlipidemia is hard to interpret as an explanation of cause or effect of autoimmunity, and, given the small magnitude of increases and decreases in risk, may not be clinically meaningful.

In addition to patients with RA having a higher burden of cardiovascular disease necessitating use of statins, they also have a high risk of progressive secondary osteoarthritis requiring joint replacement surgery. Chang et al3 used a national claims-based dataset from China to examine risk of total knee or hip replacement (TKR and THR, respectively) in patients with RA. From 2000-2013 (ie, the onset of the biologic era), TKR and THR rates were examined in a cohort of biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (bDMARD) users compared to conventional synthetic DMARD (csDMARD) users. Adjusted hazard ratios (HR) were lower for both TKD and THR in bDMARD users. Though RA activity was not examined, combined with the knowledge of the association of disease severity with bDMARD use, this study lends evidence to the benefits of more aggressive treatment.

Finally, much is made of the link between bDMARD and targeted synthetic DMARD use and malignancy due to reduced immunosurveillance, but concrete evidence is conflicting. Wetzman et al4 performed a systematic review of studies of patients with inflammatory arthritis (RA, psoriatic arthritis, and Ankylosing spondylitis) looking at cancer relapse or occurrence of new cancer. An increase in skin cancers (HR 1.32) was noted, but reassuringly no other increase in risk of recurrent or new cancer was seen.

References

- Fleischmann R et al. Long-term efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity of the adalimumab biosimilar, PF-06410293, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis after switching from reference adalimumab (Humira®) or continuing biosimilar therapy: week 52–92 data from a randomized, double-blind, phase 3 trialArthritis Res Ther. 2021(Sep 25);23:248.

- Peterson MN et al. Risk of rheumatoid arthritis diagnosis in statin users in a large nationwide US study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2021(Sep 18):23:244.

- Chang YS et al. Effects of biologics on reducing the risks of total knee replacement and total hip replacement in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021(Sep 17):keab671.

- Wetzman A et al. Risk of cancer after initiation of targeted therapies in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and a prior cancer: systematic review with meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2021(Sep 21): acr.24784.

Biosimilar medications have received significant attention recently in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA), though the effects of switching from the reference drug to a biosimilar is not known. The study by Fleischmann et al1 looks at the safety and efficacy, as well as immunogenicity, of biosimilar adalimumab (ADL-PF) compared to the reference ADL-EU (European Union sourced adalimumab) in a randomized double-blind study. Patients were randomized to start and continue ADL-PF or start ADL-EU and switch to ADL-PF at week 26 or 52. Immunogenicity was measured using anti-drug antibodies (ADA). American College of Rheumatology (ACR20) response rates were similar among all groups, while ACR50 and ACR70 response rates were numerically lower in the week 52 switch group. ADA development was comparable between groups. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, but overall, safety, efficacy, and immunogenicity were similar between patients maintained on ADL-PF and those switched from ADL-EU at week 26 or 52.

Statins have long been associated with musculoskeletal symptoms in patients, but have also been postulated to have anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects. Complicating the relationship is the knowledge that inflammation increases cardiovascular risk in RA patients. In a case-control study, Peterson et al2 used an administrative database to examine the influence of statin use on development of RA. Cases were identified based on ICD-9 coding as well as a prescription for methotrexate after diagnosis. They were matched 1:1 with controls based on demographics and year of diagnosis. Statin use was evaluated. Statin use was associated with a small increase in risk of RA, which was diminished after adjusting for hyperlipidemia; a trend towards increase in risk with higher dose and duration of statin use was not statistically significant. Beyond this, the reduced risk after adjustment for hyperlipidemia is hard to interpret as an explanation of cause or effect of autoimmunity, and, given the small magnitude of increases and decreases in risk, may not be clinically meaningful.

In addition to patients with RA having a higher burden of cardiovascular disease necessitating use of statins, they also have a high risk of progressive secondary osteoarthritis requiring joint replacement surgery. Chang et al3 used a national claims-based dataset from China to examine risk of total knee or hip replacement (TKR and THR, respectively) in patients with RA. From 2000-2013 (ie, the onset of the biologic era), TKR and THR rates were examined in a cohort of biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (bDMARD) users compared to conventional synthetic DMARD (csDMARD) users. Adjusted hazard ratios (HR) were lower for both TKD and THR in bDMARD users. Though RA activity was not examined, combined with the knowledge of the association of disease severity with bDMARD use, this study lends evidence to the benefits of more aggressive treatment.

Finally, much is made of the link between bDMARD and targeted synthetic DMARD use and malignancy due to reduced immunosurveillance, but concrete evidence is conflicting. Wetzman et al4 performed a systematic review of studies of patients with inflammatory arthritis (RA, psoriatic arthritis, and Ankylosing spondylitis) looking at cancer relapse or occurrence of new cancer. An increase in skin cancers (HR 1.32) was noted, but reassuringly no other increase in risk of recurrent or new cancer was seen.

References

- Fleischmann R et al. Long-term efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity of the adalimumab biosimilar, PF-06410293, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis after switching from reference adalimumab (Humira®) or continuing biosimilar therapy: week 52–92 data from a randomized, double-blind, phase 3 trialArthritis Res Ther. 2021(Sep 25);23:248.

- Peterson MN et al. Risk of rheumatoid arthritis diagnosis in statin users in a large nationwide US study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2021(Sep 18):23:244.

- Chang YS et al. Effects of biologics on reducing the risks of total knee replacement and total hip replacement in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021(Sep 17):keab671.

- Wetzman A et al. Risk of cancer after initiation of targeted therapies in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and a prior cancer: systematic review with meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2021(Sep 21): acr.24784.

Clinical Edge Journal Scan Commentary: PsA November 2021

There have been quite a few papers published in October that have provided further insights into psoriatic arthritis (PsA). Understanding risk factors for developing PsA in patients with psoriasis is of ongoing interest, but there is limited data on the relationship between the severity of psoriasis and the risk of developing PsA especially in the USA population. Using the Optum electronic health records (EHR) database, Merola et al1 assessed the incidence, prevalence, and predictors of PsA among 114,868 patients with psoriasis between January 1, 2009, and March 31, 2019. The severity of psoriasis was determined by treatment received during the 1 year after psoriasis diagnosis as follows: mild (89.3%) topicals and phototherapy only; moderate (5.5%) nonbiologic systemic therapies (acitretin, apremilast, cyclosporine, methotrexate), and severe (5.2%) biologic therapies (adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, golimumab, guselkumab, infliximab, ixekizumab, secukinumab, ustekinumab). They found that the overall incidence of PsA was 2.9 (95% CI 2.9-3.0) events per 100 patient-years of follow up (PY). The incidence (100 PY, 95% CI) by severity was lowest (2.1 [95% CI 2.1-2.1]) in the mild, higher in the moderate (9.9 [95% CI 9.5-10.4]), and highest (17.6 [95% CI 16.9-18.3]) in the severe psoriasis category. The study thus confirms that patients with more severe psoriasis have higher risk of developing PsA.

The effect of treatment of psoriasis on the development of PsA is also have great interest. Recent studies2 have indicated that biologic treatment of psoriasis may reduce the incidence of PsA. However, Meer et al3 in a retrospective cohort study using of 1,93,709 patients with psoriasis without PsA in the Optum Insights EHR database report that biologic use was associated with the development of PsA among patients with psoriasis. After propensity score matching, the hazard ratio was 2.14 (95% CI 2.00-2.28) for patients on biologics compared to those on oral therapy or phototherapy. Such studies are influenced by confounding factors ,by indication, and protopathic bias and hence prospective studies are warranted.

Better treatment outcomes are likely if patient priorities are taken into account when choosing a therapy. However, there are few studies addressing this issue. Sumpton et al4 conducted a discrete choice experiment in patients with PsA in Sydney, Australia, to assess preferences for different attributes of biologics. They identified the following attributes in order of preference: oral route (compared to subcutaneous and intravenous routes), avoiding severe side effects, increasing ability to attend to normal activities, avoiding infections, improvement in enthesitis pain, improvement in psoriasis, increasing chance of remission and improvement in joint pain. Thus, patients valued ease of administration, avoiding side effects, and physical function more when choosing a therapy. With increased availability of treatment choices, developing decision support systems that facilitate shared decision making between patients and clinicians is required to improve care of PsA patients.

Ultrasound is increasingly being used at the point of care in rheumatology, but until now ultrasound was not used as a primary outcome in a clinical trial. In the first randomized, placebo-controlled, phase III study using power Doppler ultrasound (PDUS) D’Agostino et al5 demonstrated that treatment with secukinumab (dosed according to psoriasis severity) led to statistically significant improvement in synovitis measured using the Global European League Against Rheumatism and Outcome Measures in Rheumatoid Arthritis Clinical Trials Synovitis Score (GLOESS) compared to placebo. Thus, secukinumab, an IL-17A inhibitor, reduces synovitis as detected by ultrasound as well as symptoms and clinical signs of PsA.

References

- Merola JF et al. Incidence and Prevalence of Psoriatic Arthritis in Patients With Psoriasis Stratified by Psoriasis Disease Severity: Retrospective Analysis of a US Electronic Health Records Database. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021(Sep 18):S0190-9622(21)02494-4.

- Acosta Felquer ML et al. Treating the skin with biologics in patients with psoriasis decreases the incidence of psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021 (Jul 19):annrheumdis-2021-220865.

- Meer E et al. Does biologic therapy impact the development of PsA among patients with psoriasis? Ann Rheum Dis. 2021(Oct 6):annrheumdis-2021-220761.

- Sumpton D et al. Preferences for biologic treatment in patients with psoriatic arthritis: a discrete choice experiment. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2021(Sep 13):acr.24782

- D'Agostino MA et al. Response to secukinumab on synovitis using power Doppler ultrasound in psoriatic arthritis: 12-week results from a phase III study, ULTIMATE. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021(Sep 16):keab628.

There have been quite a few papers published in October that have provided further insights into psoriatic arthritis (PsA). Understanding risk factors for developing PsA in patients with psoriasis is of ongoing interest, but there is limited data on the relationship between the severity of psoriasis and the risk of developing PsA especially in the USA population. Using the Optum electronic health records (EHR) database, Merola et al1 assessed the incidence, prevalence, and predictors of PsA among 114,868 patients with psoriasis between January 1, 2009, and March 31, 2019. The severity of psoriasis was determined by treatment received during the 1 year after psoriasis diagnosis as follows: mild (89.3%) topicals and phototherapy only; moderate (5.5%) nonbiologic systemic therapies (acitretin, apremilast, cyclosporine, methotrexate), and severe (5.2%) biologic therapies (adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, golimumab, guselkumab, infliximab, ixekizumab, secukinumab, ustekinumab). They found that the overall incidence of PsA was 2.9 (95% CI 2.9-3.0) events per 100 patient-years of follow up (PY). The incidence (100 PY, 95% CI) by severity was lowest (2.1 [95% CI 2.1-2.1]) in the mild, higher in the moderate (9.9 [95% CI 9.5-10.4]), and highest (17.6 [95% CI 16.9-18.3]) in the severe psoriasis category. The study thus confirms that patients with more severe psoriasis have higher risk of developing PsA.

The effect of treatment of psoriasis on the development of PsA is also have great interest. Recent studies2 have indicated that biologic treatment of psoriasis may reduce the incidence of PsA. However, Meer et al3 in a retrospective cohort study using of 1,93,709 patients with psoriasis without PsA in the Optum Insights EHR database report that biologic use was associated with the development of PsA among patients with psoriasis. After propensity score matching, the hazard ratio was 2.14 (95% CI 2.00-2.28) for patients on biologics compared to those on oral therapy or phototherapy. Such studies are influenced by confounding factors ,by indication, and protopathic bias and hence prospective studies are warranted.

Better treatment outcomes are likely if patient priorities are taken into account when choosing a therapy. However, there are few studies addressing this issue. Sumpton et al4 conducted a discrete choice experiment in patients with PsA in Sydney, Australia, to assess preferences for different attributes of biologics. They identified the following attributes in order of preference: oral route (compared to subcutaneous and intravenous routes), avoiding severe side effects, increasing ability to attend to normal activities, avoiding infections, improvement in enthesitis pain, improvement in psoriasis, increasing chance of remission and improvement in joint pain. Thus, patients valued ease of administration, avoiding side effects, and physical function more when choosing a therapy. With increased availability of treatment choices, developing decision support systems that facilitate shared decision making between patients and clinicians is required to improve care of PsA patients.

Ultrasound is increasingly being used at the point of care in rheumatology, but until now ultrasound was not used as a primary outcome in a clinical trial. In the first randomized, placebo-controlled, phase III study using power Doppler ultrasound (PDUS) D’Agostino et al5 demonstrated that treatment with secukinumab (dosed according to psoriasis severity) led to statistically significant improvement in synovitis measured using the Global European League Against Rheumatism and Outcome Measures in Rheumatoid Arthritis Clinical Trials Synovitis Score (GLOESS) compared to placebo. Thus, secukinumab, an IL-17A inhibitor, reduces synovitis as detected by ultrasound as well as symptoms and clinical signs of PsA.

References

- Merola JF et al. Incidence and Prevalence of Psoriatic Arthritis in Patients With Psoriasis Stratified by Psoriasis Disease Severity: Retrospective Analysis of a US Electronic Health Records Database. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021(Sep 18):S0190-9622(21)02494-4.

- Acosta Felquer ML et al. Treating the skin with biologics in patients with psoriasis decreases the incidence of psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021 (Jul 19):annrheumdis-2021-220865.

- Meer E et al. Does biologic therapy impact the development of PsA among patients with psoriasis? Ann Rheum Dis. 2021(Oct 6):annrheumdis-2021-220761.

- Sumpton D et al. Preferences for biologic treatment in patients with psoriatic arthritis: a discrete choice experiment. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2021(Sep 13):acr.24782

- D'Agostino MA et al. Response to secukinumab on synovitis using power Doppler ultrasound in psoriatic arthritis: 12-week results from a phase III study, ULTIMATE. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021(Sep 16):keab628.

There have been quite a few papers published in October that have provided further insights into psoriatic arthritis (PsA). Understanding risk factors for developing PsA in patients with psoriasis is of ongoing interest, but there is limited data on the relationship between the severity of psoriasis and the risk of developing PsA especially in the USA population. Using the Optum electronic health records (EHR) database, Merola et al1 assessed the incidence, prevalence, and predictors of PsA among 114,868 patients with psoriasis between January 1, 2009, and March 31, 2019. The severity of psoriasis was determined by treatment received during the 1 year after psoriasis diagnosis as follows: mild (89.3%) topicals and phototherapy only; moderate (5.5%) nonbiologic systemic therapies (acitretin, apremilast, cyclosporine, methotrexate), and severe (5.2%) biologic therapies (adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, golimumab, guselkumab, infliximab, ixekizumab, secukinumab, ustekinumab). They found that the overall incidence of PsA was 2.9 (95% CI 2.9-3.0) events per 100 patient-years of follow up (PY). The incidence (100 PY, 95% CI) by severity was lowest (2.1 [95% CI 2.1-2.1]) in the mild, higher in the moderate (9.9 [95% CI 9.5-10.4]), and highest (17.6 [95% CI 16.9-18.3]) in the severe psoriasis category. The study thus confirms that patients with more severe psoriasis have higher risk of developing PsA.

The effect of treatment of psoriasis on the development of PsA is also have great interest. Recent studies2 have indicated that biologic treatment of psoriasis may reduce the incidence of PsA. However, Meer et al3 in a retrospective cohort study using of 1,93,709 patients with psoriasis without PsA in the Optum Insights EHR database report that biologic use was associated with the development of PsA among patients with psoriasis. After propensity score matching, the hazard ratio was 2.14 (95% CI 2.00-2.28) for patients on biologics compared to those on oral therapy or phototherapy. Such studies are influenced by confounding factors ,by indication, and protopathic bias and hence prospective studies are warranted.

Better treatment outcomes are likely if patient priorities are taken into account when choosing a therapy. However, there are few studies addressing this issue. Sumpton et al4 conducted a discrete choice experiment in patients with PsA in Sydney, Australia, to assess preferences for different attributes of biologics. They identified the following attributes in order of preference: oral route (compared to subcutaneous and intravenous routes), avoiding severe side effects, increasing ability to attend to normal activities, avoiding infections, improvement in enthesitis pain, improvement in psoriasis, increasing chance of remission and improvement in joint pain. Thus, patients valued ease of administration, avoiding side effects, and physical function more when choosing a therapy. With increased availability of treatment choices, developing decision support systems that facilitate shared decision making between patients and clinicians is required to improve care of PsA patients.