User login

COVID-19: Greater mortality among psych patients remains a mystery

Antipsychotics are not responsible for the increased COVID-related death rate among patients with serious mental illness (SMI), new research shows.

The significant increase in COVID-19 mortality that continues to be reported among those with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder “underscores the importance of protective interventions for this group, including priority vaccination,” study investigator Katlyn Nemani, MD, research assistant professor, department of psychiatry, New York University, told this news organization.

The study was published online September 22 in JAMA Psychiatry.

Threefold increase in death

Previous research has linked a diagnosis of a schizophrenia spectrum disorder, which includes schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder, to an almost threefold increase in mortality among patients with COVID-19.

Some population-based research has also reported a link between antipsychotic medication use and increased risk for COVID-related mortality, but these studies did not take psychiatric diagnoses into account.

“This raised the question of whether the increased risk observed in this population is related to underlying psychiatric illness or its treatment,” said Dr. Nemani.

The retrospective cohort study included 464 adults (mean age, 53 years) who were diagnosed with COVID-19 between March 3, 2020, and Feb. 17, 2021, and who had previously been diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorder or bipolar disorder. Of these, 42.2% were treated with an antipsychotic medication.

The primary endpoint was death within 60 days of COVID-19 diagnosis. Covariates included sociodemographic characteristics, such as patient-reported race and ethnicity, age, and insurance type, a psychiatric diagnosis, medical comorbidities, and smoking status.

Of the total, 41 patients (8.8%) died. The 60-day fatality rate was 13.7% among patients with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder (n = 182) and 5.7% among patients with bipolar disorder (n = 282).

Antipsychotic treatment was not significantly associated with mortality (odds ratio, 1.00; 95% confidence interval, 0.48-2.08; P = .99).

“This suggests that antipsychotic medication is unlikely to be responsible for the increased risk we’ve observed in this population, although this finding needs to be replicated,” said Dr. Nemani.

Surprise finding

A diagnosis of a schizophrenia spectrum disorder was associated with an almost threefold increased risk for mortality compared with bipolar disorder (OR, 2.88; 95% CI, 1.36-6.11; P = .006).

“This was a surprising finding,” said Dr. Nemani.

She noted that there is evidence suggesting the immune system may play a role in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia, and research has shown that pneumonia and infection are among the leading causes of premature mortality in this population.

As well, several potential risk factors disproportionately affect people with serious mental illness, including an increase in the prevalence of medical comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes, socioeconomic disadvantages, and barriers to accessing timely care. Prior studies have also found that people with SMI are less likely to receive preventive care interventions, including vaccination, said Dr. Nemani.

However, these factors are unlikely to fully account for the increased risk found in the study, she said.

“Our study population was limited to people who had received treatment within the NYU Langone Health System. We took a comprehensive list of sociodemographic and medical risk factors into account, and our research was conducted prior to the availability of COVID-19 vaccines,” she said.

Further research is necessary to understand what underlies the increase in susceptibility to severe infection among patients with schizophrenia and to identify interventions that may mitigate risk, said Dr. Nemani.

“This includes evaluating systems-level factors, such as access to preventive interventions and treatment, as well as investigating underlying immune mechanisms that may contribute to severe and fatal infection,” she said.

The researchers could not validate psychiatric diagnoses or capture deaths not documented in the electronic health record. In addition, the limited sample size precluded analysis of the use of individual antipsychotic medications, which may differ in their associated effects.

“It’s possible individual antipsychotic medications may be associated with harmful or protective effects,” said Dr. Nemani.

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Antipsychotics are not responsible for the increased COVID-related death rate among patients with serious mental illness (SMI), new research shows.

The significant increase in COVID-19 mortality that continues to be reported among those with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder “underscores the importance of protective interventions for this group, including priority vaccination,” study investigator Katlyn Nemani, MD, research assistant professor, department of psychiatry, New York University, told this news organization.

The study was published online September 22 in JAMA Psychiatry.

Threefold increase in death

Previous research has linked a diagnosis of a schizophrenia spectrum disorder, which includes schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder, to an almost threefold increase in mortality among patients with COVID-19.

Some population-based research has also reported a link between antipsychotic medication use and increased risk for COVID-related mortality, but these studies did not take psychiatric diagnoses into account.

“This raised the question of whether the increased risk observed in this population is related to underlying psychiatric illness or its treatment,” said Dr. Nemani.

The retrospective cohort study included 464 adults (mean age, 53 years) who were diagnosed with COVID-19 between March 3, 2020, and Feb. 17, 2021, and who had previously been diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorder or bipolar disorder. Of these, 42.2% were treated with an antipsychotic medication.

The primary endpoint was death within 60 days of COVID-19 diagnosis. Covariates included sociodemographic characteristics, such as patient-reported race and ethnicity, age, and insurance type, a psychiatric diagnosis, medical comorbidities, and smoking status.

Of the total, 41 patients (8.8%) died. The 60-day fatality rate was 13.7% among patients with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder (n = 182) and 5.7% among patients with bipolar disorder (n = 282).

Antipsychotic treatment was not significantly associated with mortality (odds ratio, 1.00; 95% confidence interval, 0.48-2.08; P = .99).

“This suggests that antipsychotic medication is unlikely to be responsible for the increased risk we’ve observed in this population, although this finding needs to be replicated,” said Dr. Nemani.

Surprise finding

A diagnosis of a schizophrenia spectrum disorder was associated with an almost threefold increased risk for mortality compared with bipolar disorder (OR, 2.88; 95% CI, 1.36-6.11; P = .006).

“This was a surprising finding,” said Dr. Nemani.

She noted that there is evidence suggesting the immune system may play a role in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia, and research has shown that pneumonia and infection are among the leading causes of premature mortality in this population.

As well, several potential risk factors disproportionately affect people with serious mental illness, including an increase in the prevalence of medical comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes, socioeconomic disadvantages, and barriers to accessing timely care. Prior studies have also found that people with SMI are less likely to receive preventive care interventions, including vaccination, said Dr. Nemani.

However, these factors are unlikely to fully account for the increased risk found in the study, she said.

“Our study population was limited to people who had received treatment within the NYU Langone Health System. We took a comprehensive list of sociodemographic and medical risk factors into account, and our research was conducted prior to the availability of COVID-19 vaccines,” she said.

Further research is necessary to understand what underlies the increase in susceptibility to severe infection among patients with schizophrenia and to identify interventions that may mitigate risk, said Dr. Nemani.

“This includes evaluating systems-level factors, such as access to preventive interventions and treatment, as well as investigating underlying immune mechanisms that may contribute to severe and fatal infection,” she said.

The researchers could not validate psychiatric diagnoses or capture deaths not documented in the electronic health record. In addition, the limited sample size precluded analysis of the use of individual antipsychotic medications, which may differ in their associated effects.

“It’s possible individual antipsychotic medications may be associated with harmful or protective effects,” said Dr. Nemani.

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Antipsychotics are not responsible for the increased COVID-related death rate among patients with serious mental illness (SMI), new research shows.

The significant increase in COVID-19 mortality that continues to be reported among those with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder “underscores the importance of protective interventions for this group, including priority vaccination,” study investigator Katlyn Nemani, MD, research assistant professor, department of psychiatry, New York University, told this news organization.

The study was published online September 22 in JAMA Psychiatry.

Threefold increase in death

Previous research has linked a diagnosis of a schizophrenia spectrum disorder, which includes schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder, to an almost threefold increase in mortality among patients with COVID-19.

Some population-based research has also reported a link between antipsychotic medication use and increased risk for COVID-related mortality, but these studies did not take psychiatric diagnoses into account.

“This raised the question of whether the increased risk observed in this population is related to underlying psychiatric illness or its treatment,” said Dr. Nemani.

The retrospective cohort study included 464 adults (mean age, 53 years) who were diagnosed with COVID-19 between March 3, 2020, and Feb. 17, 2021, and who had previously been diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorder or bipolar disorder. Of these, 42.2% were treated with an antipsychotic medication.

The primary endpoint was death within 60 days of COVID-19 diagnosis. Covariates included sociodemographic characteristics, such as patient-reported race and ethnicity, age, and insurance type, a psychiatric diagnosis, medical comorbidities, and smoking status.

Of the total, 41 patients (8.8%) died. The 60-day fatality rate was 13.7% among patients with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder (n = 182) and 5.7% among patients with bipolar disorder (n = 282).

Antipsychotic treatment was not significantly associated with mortality (odds ratio, 1.00; 95% confidence interval, 0.48-2.08; P = .99).

“This suggests that antipsychotic medication is unlikely to be responsible for the increased risk we’ve observed in this population, although this finding needs to be replicated,” said Dr. Nemani.

Surprise finding

A diagnosis of a schizophrenia spectrum disorder was associated with an almost threefold increased risk for mortality compared with bipolar disorder (OR, 2.88; 95% CI, 1.36-6.11; P = .006).

“This was a surprising finding,” said Dr. Nemani.

She noted that there is evidence suggesting the immune system may play a role in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia, and research has shown that pneumonia and infection are among the leading causes of premature mortality in this population.

As well, several potential risk factors disproportionately affect people with serious mental illness, including an increase in the prevalence of medical comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes, socioeconomic disadvantages, and barriers to accessing timely care. Prior studies have also found that people with SMI are less likely to receive preventive care interventions, including vaccination, said Dr. Nemani.

However, these factors are unlikely to fully account for the increased risk found in the study, she said.

“Our study population was limited to people who had received treatment within the NYU Langone Health System. We took a comprehensive list of sociodemographic and medical risk factors into account, and our research was conducted prior to the availability of COVID-19 vaccines,” she said.

Further research is necessary to understand what underlies the increase in susceptibility to severe infection among patients with schizophrenia and to identify interventions that may mitigate risk, said Dr. Nemani.

“This includes evaluating systems-level factors, such as access to preventive interventions and treatment, as well as investigating underlying immune mechanisms that may contribute to severe and fatal infection,” she said.

The researchers could not validate psychiatric diagnoses or capture deaths not documented in the electronic health record. In addition, the limited sample size precluded analysis of the use of individual antipsychotic medications, which may differ in their associated effects.

“It’s possible individual antipsychotic medications may be associated with harmful or protective effects,” said Dr. Nemani.

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID vaccination rates among pregnant people remain low

COVID vaccination rates among pregnant people remain low, despite data that shows the vaccines can prevent the high risk of severe disease during pregnancy.

About 30% of pregnant people are vaccinated, according to the latest CDC data, with only 18% obtaining a dose during pregnancy. Health officials have been tracking the timing of vaccination before and during pregnancy.

The vaccination rates are even lower among pregnant Black people, CDC data shows. About 15% are fully vaccinated, compared with 25% of pregnant Hispanic and Latino people, 34% of pregnant White people, and 46% of pregnant Asian people.

“This puts them at severe risk of severe disease from COVID-19,” Rochelle Walensky, MD, the CDC director, said during a news briefing with the White House COVID-19 Response Team.

“We know that pregnant women are at increased risk of severe disease, of hospitalization and ventilation,” she said. “They’re also at increased risk for adverse events to their baby.”

Those who give birth while infected with COVID-19 had “significantly higher rates” of intensive care unit admission, intubation, ventilation, and death, according to a recent study published in JAMA Network Open.

Dr. Walensky said on Sept. 28 that studies show COVID-19 vaccines can be taken at any time while pregnant or breastfeeding. She noted that the vaccines are safe for both mothers and their babies.

“We’ve actually seen that some antibody from the vaccine traverses [the placenta] to the baby and, in fact, could potentially protect the baby,” she said.

Public health officials say the low vaccination rates can be attributed to caution around the time of pregnancy, concern for the baby, barriers to health care, and misinformation promoted online.

“Pregnancy is a precious time. It’s also a time that a lot of women have fear,” Pam Oliver, MD, an obstetrics and gynecology doctor and executive vice president of North Carolina’s Novant Health, told USA Today.

“It is natural to have questions,” she said. “So, let’s talk about what we know, let’s put it in perspective.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID vaccination rates among pregnant people remain low, despite data that shows the vaccines can prevent the high risk of severe disease during pregnancy.

About 30% of pregnant people are vaccinated, according to the latest CDC data, with only 18% obtaining a dose during pregnancy. Health officials have been tracking the timing of vaccination before and during pregnancy.

The vaccination rates are even lower among pregnant Black people, CDC data shows. About 15% are fully vaccinated, compared with 25% of pregnant Hispanic and Latino people, 34% of pregnant White people, and 46% of pregnant Asian people.

“This puts them at severe risk of severe disease from COVID-19,” Rochelle Walensky, MD, the CDC director, said during a news briefing with the White House COVID-19 Response Team.

“We know that pregnant women are at increased risk of severe disease, of hospitalization and ventilation,” she said. “They’re also at increased risk for adverse events to their baby.”

Those who give birth while infected with COVID-19 had “significantly higher rates” of intensive care unit admission, intubation, ventilation, and death, according to a recent study published in JAMA Network Open.

Dr. Walensky said on Sept. 28 that studies show COVID-19 vaccines can be taken at any time while pregnant or breastfeeding. She noted that the vaccines are safe for both mothers and their babies.

“We’ve actually seen that some antibody from the vaccine traverses [the placenta] to the baby and, in fact, could potentially protect the baby,” she said.

Public health officials say the low vaccination rates can be attributed to caution around the time of pregnancy, concern for the baby, barriers to health care, and misinformation promoted online.

“Pregnancy is a precious time. It’s also a time that a lot of women have fear,” Pam Oliver, MD, an obstetrics and gynecology doctor and executive vice president of North Carolina’s Novant Health, told USA Today.

“It is natural to have questions,” she said. “So, let’s talk about what we know, let’s put it in perspective.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID vaccination rates among pregnant people remain low, despite data that shows the vaccines can prevent the high risk of severe disease during pregnancy.

About 30% of pregnant people are vaccinated, according to the latest CDC data, with only 18% obtaining a dose during pregnancy. Health officials have been tracking the timing of vaccination before and during pregnancy.

The vaccination rates are even lower among pregnant Black people, CDC data shows. About 15% are fully vaccinated, compared with 25% of pregnant Hispanic and Latino people, 34% of pregnant White people, and 46% of pregnant Asian people.

“This puts them at severe risk of severe disease from COVID-19,” Rochelle Walensky, MD, the CDC director, said during a news briefing with the White House COVID-19 Response Team.

“We know that pregnant women are at increased risk of severe disease, of hospitalization and ventilation,” she said. “They’re also at increased risk for adverse events to their baby.”

Those who give birth while infected with COVID-19 had “significantly higher rates” of intensive care unit admission, intubation, ventilation, and death, according to a recent study published in JAMA Network Open.

Dr. Walensky said on Sept. 28 that studies show COVID-19 vaccines can be taken at any time while pregnant or breastfeeding. She noted that the vaccines are safe for both mothers and their babies.

“We’ve actually seen that some antibody from the vaccine traverses [the placenta] to the baby and, in fact, could potentially protect the baby,” she said.

Public health officials say the low vaccination rates can be attributed to caution around the time of pregnancy, concern for the baby, barriers to health care, and misinformation promoted online.

“Pregnancy is a precious time. It’s also a time that a lot of women have fear,” Pam Oliver, MD, an obstetrics and gynecology doctor and executive vice president of North Carolina’s Novant Health, told USA Today.

“It is natural to have questions,” she said. “So, let’s talk about what we know, let’s put it in perspective.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Age, C-reactive protein predict COVID-19 death in diabetes

The data, from the retrospective ACCREDIT cohort study, were presented at the virtual annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD 2021) by Daniel Kevin Llanera, MD.

The combination of older age and high levels of the inflammatory marker CRP were linked to a tripled risk for death by day 7 after hospitalization for COVID-19 among people with diabetes. But, in contrast to other studies, recent A1c and body mass index did not predict COVID-19 outcomes.

“Both of these variables are easily available upon admission to hospital,” Dr. Llanera, who now works at Imperial College, London, said in an EASD press release.

“This means we can easily identify patients early on in their hospital stay who will likely require more aggressive interventions to try and improve survival.”

“It makes sense that CRP and age are important,” said Simon Heller, MB BChir, DM, of the University of Sheffield, England. “It may be that diabetes alone overwhelmed the additional effects of obesity and A1c.

“Certainly in other studies, age was the overwhelming bad prognostic sign among people with diabetes, and perhaps long-term diabetes has effects on the immune system which we haven’t yet identified.”

Kidney disease in younger patients also linked to poorer outcomes

The study, conducted when Dr. Llanera worked for the Countess of Chester NHS Foundation Trust, involved 1,004 patients with diabetes admitted with COVID-19 to seven hospitals in northwest England from Jan. 1 through June 30, 2020. The patients were a mean age of 74.1 years, 60.7% were male, and 45% were in the most deprived quintile based on the U.K. government deprivation index. Overall, 56.2% had macrovascular complications and 49.6% had microvascular complications.

They had a median BMI of 27.6 kg/m2, which is lower than that reported in previous studies and might explain the difference, Dr. Llanera noted.

The primary outcome, death within 7 days of admission, occurred in 24%. By day 30, 33% had died. These rates are higher than the rate found in previous studies, possibly because of greater socioeconomic deprivation and older age of the population, Dr. Llanera speculated.

A total of 7.5% of patients received intensive care by day 7 and 9.8% required intravenous insulin infusions.

On univariate analysis, insulin infusion was found to be protective, with those receiving it half as likely to die as those who didn’t need IV insulin (odds ratio [OR], 0.5).

In contrast, chronic kidney disease in people younger than 70 years increased the risk of death more than twofold (OR, 2.74), as did type 2 diabetes compared with other diabetes types (OR, 2.52).

As in previous studies, use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers were not associated with COVID-19 outcomes, nor was the presence of diabetes-related complications.

In multivariate analysis, CRP and age emerged as the most significant predictors of the primary outcome, with those deemed high risk by a logistic regression model having an OR of 3.44 for death by day 7 compared with those at lower risk based on the two factors.

Data for glycemic control during the time of hospitalization weren’t available for this study, Dr. Llanera said in response to a question.

“We didn’t look into glycemic control during admission, just at entry, so I can’t answer whether strict glucose control is of benefit. I think it’s worth exploring further whether the use of IV insulin may be of benefit.”

Dr. Llanera also pointed out that people with diabetic kidney disease are in a chronic proinflammatory state and have immune dysregulation, thus potentially hindering their ability to “fight off” the virus.

“In addition, ACE2 receptors are upregulated in the kidneys of patients with diabetic kidney disease. These are molecules that facilitate entry of SARS-CoV-2 into the cells. This may lead to direct attack of the kidneys by the virus, possibly leading to worse overall outcomes,” he said.

Dr. Llanera has reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Heller has reported serving as consultant or speaker for Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly, Sanofi Aventis, Mannkind, Zealand, MSD, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The data, from the retrospective ACCREDIT cohort study, were presented at the virtual annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD 2021) by Daniel Kevin Llanera, MD.

The combination of older age and high levels of the inflammatory marker CRP were linked to a tripled risk for death by day 7 after hospitalization for COVID-19 among people with diabetes. But, in contrast to other studies, recent A1c and body mass index did not predict COVID-19 outcomes.

“Both of these variables are easily available upon admission to hospital,” Dr. Llanera, who now works at Imperial College, London, said in an EASD press release.

“This means we can easily identify patients early on in their hospital stay who will likely require more aggressive interventions to try and improve survival.”

“It makes sense that CRP and age are important,” said Simon Heller, MB BChir, DM, of the University of Sheffield, England. “It may be that diabetes alone overwhelmed the additional effects of obesity and A1c.

“Certainly in other studies, age was the overwhelming bad prognostic sign among people with diabetes, and perhaps long-term diabetes has effects on the immune system which we haven’t yet identified.”

Kidney disease in younger patients also linked to poorer outcomes

The study, conducted when Dr. Llanera worked for the Countess of Chester NHS Foundation Trust, involved 1,004 patients with diabetes admitted with COVID-19 to seven hospitals in northwest England from Jan. 1 through June 30, 2020. The patients were a mean age of 74.1 years, 60.7% were male, and 45% were in the most deprived quintile based on the U.K. government deprivation index. Overall, 56.2% had macrovascular complications and 49.6% had microvascular complications.

They had a median BMI of 27.6 kg/m2, which is lower than that reported in previous studies and might explain the difference, Dr. Llanera noted.

The primary outcome, death within 7 days of admission, occurred in 24%. By day 30, 33% had died. These rates are higher than the rate found in previous studies, possibly because of greater socioeconomic deprivation and older age of the population, Dr. Llanera speculated.

A total of 7.5% of patients received intensive care by day 7 and 9.8% required intravenous insulin infusions.

On univariate analysis, insulin infusion was found to be protective, with those receiving it half as likely to die as those who didn’t need IV insulin (odds ratio [OR], 0.5).

In contrast, chronic kidney disease in people younger than 70 years increased the risk of death more than twofold (OR, 2.74), as did type 2 diabetes compared with other diabetes types (OR, 2.52).

As in previous studies, use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers were not associated with COVID-19 outcomes, nor was the presence of diabetes-related complications.

In multivariate analysis, CRP and age emerged as the most significant predictors of the primary outcome, with those deemed high risk by a logistic regression model having an OR of 3.44 for death by day 7 compared with those at lower risk based on the two factors.

Data for glycemic control during the time of hospitalization weren’t available for this study, Dr. Llanera said in response to a question.

“We didn’t look into glycemic control during admission, just at entry, so I can’t answer whether strict glucose control is of benefit. I think it’s worth exploring further whether the use of IV insulin may be of benefit.”

Dr. Llanera also pointed out that people with diabetic kidney disease are in a chronic proinflammatory state and have immune dysregulation, thus potentially hindering their ability to “fight off” the virus.

“In addition, ACE2 receptors are upregulated in the kidneys of patients with diabetic kidney disease. These are molecules that facilitate entry of SARS-CoV-2 into the cells. This may lead to direct attack of the kidneys by the virus, possibly leading to worse overall outcomes,” he said.

Dr. Llanera has reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Heller has reported serving as consultant or speaker for Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly, Sanofi Aventis, Mannkind, Zealand, MSD, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The data, from the retrospective ACCREDIT cohort study, were presented at the virtual annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD 2021) by Daniel Kevin Llanera, MD.

The combination of older age and high levels of the inflammatory marker CRP were linked to a tripled risk for death by day 7 after hospitalization for COVID-19 among people with diabetes. But, in contrast to other studies, recent A1c and body mass index did not predict COVID-19 outcomes.

“Both of these variables are easily available upon admission to hospital,” Dr. Llanera, who now works at Imperial College, London, said in an EASD press release.

“This means we can easily identify patients early on in their hospital stay who will likely require more aggressive interventions to try and improve survival.”

“It makes sense that CRP and age are important,” said Simon Heller, MB BChir, DM, of the University of Sheffield, England. “It may be that diabetes alone overwhelmed the additional effects of obesity and A1c.

“Certainly in other studies, age was the overwhelming bad prognostic sign among people with diabetes, and perhaps long-term diabetes has effects on the immune system which we haven’t yet identified.”

Kidney disease in younger patients also linked to poorer outcomes

The study, conducted when Dr. Llanera worked for the Countess of Chester NHS Foundation Trust, involved 1,004 patients with diabetes admitted with COVID-19 to seven hospitals in northwest England from Jan. 1 through June 30, 2020. The patients were a mean age of 74.1 years, 60.7% were male, and 45% were in the most deprived quintile based on the U.K. government deprivation index. Overall, 56.2% had macrovascular complications and 49.6% had microvascular complications.

They had a median BMI of 27.6 kg/m2, which is lower than that reported in previous studies and might explain the difference, Dr. Llanera noted.

The primary outcome, death within 7 days of admission, occurred in 24%. By day 30, 33% had died. These rates are higher than the rate found in previous studies, possibly because of greater socioeconomic deprivation and older age of the population, Dr. Llanera speculated.

A total of 7.5% of patients received intensive care by day 7 and 9.8% required intravenous insulin infusions.

On univariate analysis, insulin infusion was found to be protective, with those receiving it half as likely to die as those who didn’t need IV insulin (odds ratio [OR], 0.5).

In contrast, chronic kidney disease in people younger than 70 years increased the risk of death more than twofold (OR, 2.74), as did type 2 diabetes compared with other diabetes types (OR, 2.52).

As in previous studies, use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers were not associated with COVID-19 outcomes, nor was the presence of diabetes-related complications.

In multivariate analysis, CRP and age emerged as the most significant predictors of the primary outcome, with those deemed high risk by a logistic regression model having an OR of 3.44 for death by day 7 compared with those at lower risk based on the two factors.

Data for glycemic control during the time of hospitalization weren’t available for this study, Dr. Llanera said in response to a question.

“We didn’t look into glycemic control during admission, just at entry, so I can’t answer whether strict glucose control is of benefit. I think it’s worth exploring further whether the use of IV insulin may be of benefit.”

Dr. Llanera also pointed out that people with diabetic kidney disease are in a chronic proinflammatory state and have immune dysregulation, thus potentially hindering their ability to “fight off” the virus.

“In addition, ACE2 receptors are upregulated in the kidneys of patients with diabetic kidney disease. These are molecules that facilitate entry of SARS-CoV-2 into the cells. This may lead to direct attack of the kidneys by the virus, possibly leading to worse overall outcomes,” he said.

Dr. Llanera has reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Heller has reported serving as consultant or speaker for Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly, Sanofi Aventis, Mannkind, Zealand, MSD, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19 hospitalization 80% more likely for smokers

Observational data was analyzed alongside hospital coronavirus test data and UK Biobank genetic information for the first time, and the findings are published in Thorax.

The data cover 421,469 people overall. Of these, 3.2% took a polymerase chain reaction swab test, 0.4% of these tested positive, 0.2% of them required hospitalization for COVID-19, and 0.1% of them died because of COVID-19.

When it came to smoking status, 59% had never smoked, 37% were ex-smokers, and 3% were current smokers.

Current smokers were 80% more likely to be admitted to hospital, and significantly more likely to die from COVID-19, than nonsmokers.

Time to quit

Heavy smokers who smoked more than 20 cigarettes a day were 6.11 times more likely to die from COVID-19 than people who had never smoked.

Analysis also showed those with a genetic predisposition to being smokers had a 45% higher infection risk, and 60% higher hospitalization risk.

The authors wrote: “Overall, the congruence of observational analyses indicating associations with recent smoking behaviors and [Mendelian randomization] analyses indicating associations with lifelong predisposition to smoking and smoking heaviness support a causal effect of smoking on COVID-19 severity.”

In a linked podcast, lead researcher Dr. Ashley Clift, said: “Our results strongly suggest that smoking is related to your risk of getting severe COVID, and just as smoking affects your risk of heart disease, different cancers, and all those other conditions we know smoking is linked to, it appears that it’s the same for COVID. So now might be as good a time as any to quit cigarettes and quit smoking.”

These results contrast with previous studies that have suggested a protective effect of smoking against COVID-19. In a linked editorial, Anthony Laverty, PhD, and Christopher Millet, PhD, Imperial College London, wrote: “The idea that tobacco smoking may protect against COVID-19 was always an improbable one.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Observational data was analyzed alongside hospital coronavirus test data and UK Biobank genetic information for the first time, and the findings are published in Thorax.

The data cover 421,469 people overall. Of these, 3.2% took a polymerase chain reaction swab test, 0.4% of these tested positive, 0.2% of them required hospitalization for COVID-19, and 0.1% of them died because of COVID-19.

When it came to smoking status, 59% had never smoked, 37% were ex-smokers, and 3% were current smokers.

Current smokers were 80% more likely to be admitted to hospital, and significantly more likely to die from COVID-19, than nonsmokers.

Time to quit

Heavy smokers who smoked more than 20 cigarettes a day were 6.11 times more likely to die from COVID-19 than people who had never smoked.

Analysis also showed those with a genetic predisposition to being smokers had a 45% higher infection risk, and 60% higher hospitalization risk.

The authors wrote: “Overall, the congruence of observational analyses indicating associations with recent smoking behaviors and [Mendelian randomization] analyses indicating associations with lifelong predisposition to smoking and smoking heaviness support a causal effect of smoking on COVID-19 severity.”

In a linked podcast, lead researcher Dr. Ashley Clift, said: “Our results strongly suggest that smoking is related to your risk of getting severe COVID, and just as smoking affects your risk of heart disease, different cancers, and all those other conditions we know smoking is linked to, it appears that it’s the same for COVID. So now might be as good a time as any to quit cigarettes and quit smoking.”

These results contrast with previous studies that have suggested a protective effect of smoking against COVID-19. In a linked editorial, Anthony Laverty, PhD, and Christopher Millet, PhD, Imperial College London, wrote: “The idea that tobacco smoking may protect against COVID-19 was always an improbable one.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Observational data was analyzed alongside hospital coronavirus test data and UK Biobank genetic information for the first time, and the findings are published in Thorax.

The data cover 421,469 people overall. Of these, 3.2% took a polymerase chain reaction swab test, 0.4% of these tested positive, 0.2% of them required hospitalization for COVID-19, and 0.1% of them died because of COVID-19.

When it came to smoking status, 59% had never smoked, 37% were ex-smokers, and 3% were current smokers.

Current smokers were 80% more likely to be admitted to hospital, and significantly more likely to die from COVID-19, than nonsmokers.

Time to quit

Heavy smokers who smoked more than 20 cigarettes a day were 6.11 times more likely to die from COVID-19 than people who had never smoked.

Analysis also showed those with a genetic predisposition to being smokers had a 45% higher infection risk, and 60% higher hospitalization risk.

The authors wrote: “Overall, the congruence of observational analyses indicating associations with recent smoking behaviors and [Mendelian randomization] analyses indicating associations with lifelong predisposition to smoking and smoking heaviness support a causal effect of smoking on COVID-19 severity.”

In a linked podcast, lead researcher Dr. Ashley Clift, said: “Our results strongly suggest that smoking is related to your risk of getting severe COVID, and just as smoking affects your risk of heart disease, different cancers, and all those other conditions we know smoking is linked to, it appears that it’s the same for COVID. So now might be as good a time as any to quit cigarettes and quit smoking.”

These results contrast with previous studies that have suggested a protective effect of smoking against COVID-19. In a linked editorial, Anthony Laverty, PhD, and Christopher Millet, PhD, Imperial College London, wrote: “The idea that tobacco smoking may protect against COVID-19 was always an improbable one.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Children and COVID: New cases topped 200,000 after 3 weeks of declines

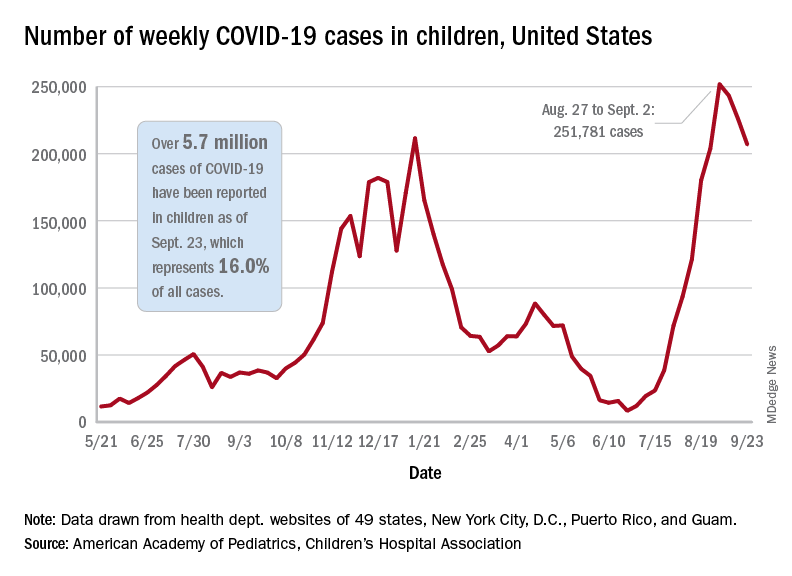

Weekly COVID-19 cases in children dropped again, but the count remained above 200,000 for the fifth consecutive week, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

based on the data in the AAP/CHA joint weekly report on COVID in children.

In the most recent week, Sept. 17-23, there were almost 207,000 new cases of COVID-19 in children, which represented 26.7% of all cases reported in the 46 states that are currently posting data by age on their COVID dashboards, the AAP and CHA said. (New York has never reported such data by age, and Alabama, Nebraska, and Texas have not updated their websites since July 29, June 24, and Aug. 26, respectively.)

The decline in new vaccinations among children, however, began before the summer surge in new cases hit its peak – 251,781 during the week of Aug. 27 to Sept. 2 – and has continued for 7 straight weeks in children aged 12-17 years, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

There were about 172,000 COVID vaccine initiations in children aged 12-17 for the week of Sept. 21-27, the lowest number since April, before it was approved for use in 12- to 15-year-olds. That figure is down by almost a third from the previous week and by more than two-thirds since early August, just before the decline in vaccinations began, according to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker.

The cumulative vaccine situation looks like this: Just over 13 million children under age 18 years have received at least one dose as of Sept. 27, and almost 10.6 million are fully vaccinated. By age group, 53.9% of 12- to 15-year-olds and 61.6% of 16- to 17-year-olds have received at least one dose, with corresponding figures of 43.3% and 51.3% for full vaccination, the CDC said.

COVID-related hospital admissions also continue to fall after peaking at 0.51 children aged 0-17 per 100,000 population on Sept. 4. The admission rate was down to 0.45 per 100,000 as of Sept. 17, and the latest 7-day average (Sept. 19-25) was 258 admissions, compared with a peak of 371 for the week of Aug. 29 to Sept. 4, the CDC reported.

“Although we have seen slight improvements in COVID-19 volumes in the past week, we are at the beginning of an anticipated increase in” multi-inflammatory syndrome in children, Margaret Rush, MD, president of Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., said at a recent hearing of the House Committee on Energy and Commerce’s Oversight subcommittee. That increase would be expected to produce “a secondary wave of seriously ill children 3-6 weeks after acute infection peaks in the community,” the American Hospital Association said.

Meanwhile, Dr. Rush noted, there are signs that seasonal viruses are coming into play. “With the emergence of the Delta variant, we’ve experienced a steep increase in COVID-19 hospitalizations among children on top of an early surge of [respiratory syncytial virus], a serious respiratory illness we usually see in the winter months,” she said in a prepared statement before her testimony.

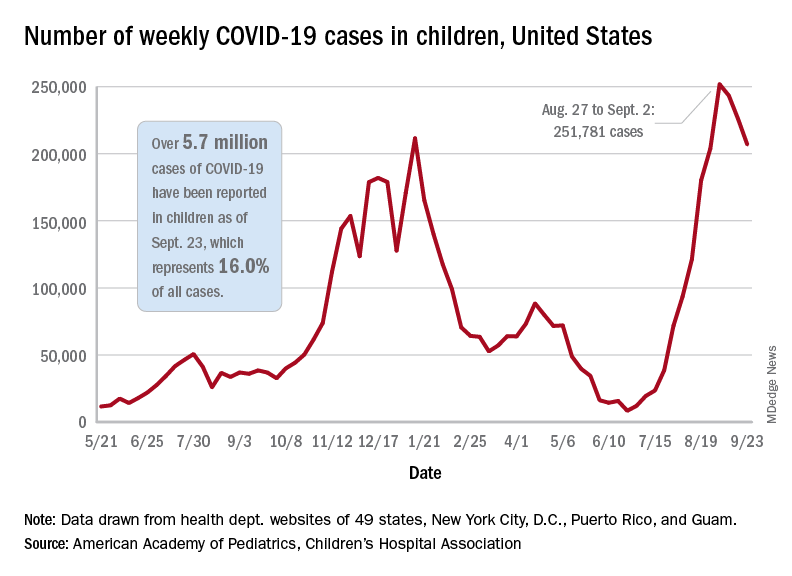

Weekly COVID-19 cases in children dropped again, but the count remained above 200,000 for the fifth consecutive week, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

based on the data in the AAP/CHA joint weekly report on COVID in children.

In the most recent week, Sept. 17-23, there were almost 207,000 new cases of COVID-19 in children, which represented 26.7% of all cases reported in the 46 states that are currently posting data by age on their COVID dashboards, the AAP and CHA said. (New York has never reported such data by age, and Alabama, Nebraska, and Texas have not updated their websites since July 29, June 24, and Aug. 26, respectively.)

The decline in new vaccinations among children, however, began before the summer surge in new cases hit its peak – 251,781 during the week of Aug. 27 to Sept. 2 – and has continued for 7 straight weeks in children aged 12-17 years, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

There were about 172,000 COVID vaccine initiations in children aged 12-17 for the week of Sept. 21-27, the lowest number since April, before it was approved for use in 12- to 15-year-olds. That figure is down by almost a third from the previous week and by more than two-thirds since early August, just before the decline in vaccinations began, according to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker.

The cumulative vaccine situation looks like this: Just over 13 million children under age 18 years have received at least one dose as of Sept. 27, and almost 10.6 million are fully vaccinated. By age group, 53.9% of 12- to 15-year-olds and 61.6% of 16- to 17-year-olds have received at least one dose, with corresponding figures of 43.3% and 51.3% for full vaccination, the CDC said.

COVID-related hospital admissions also continue to fall after peaking at 0.51 children aged 0-17 per 100,000 population on Sept. 4. The admission rate was down to 0.45 per 100,000 as of Sept. 17, and the latest 7-day average (Sept. 19-25) was 258 admissions, compared with a peak of 371 for the week of Aug. 29 to Sept. 4, the CDC reported.

“Although we have seen slight improvements in COVID-19 volumes in the past week, we are at the beginning of an anticipated increase in” multi-inflammatory syndrome in children, Margaret Rush, MD, president of Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., said at a recent hearing of the House Committee on Energy and Commerce’s Oversight subcommittee. That increase would be expected to produce “a secondary wave of seriously ill children 3-6 weeks after acute infection peaks in the community,” the American Hospital Association said.

Meanwhile, Dr. Rush noted, there are signs that seasonal viruses are coming into play. “With the emergence of the Delta variant, we’ve experienced a steep increase in COVID-19 hospitalizations among children on top of an early surge of [respiratory syncytial virus], a serious respiratory illness we usually see in the winter months,” she said in a prepared statement before her testimony.

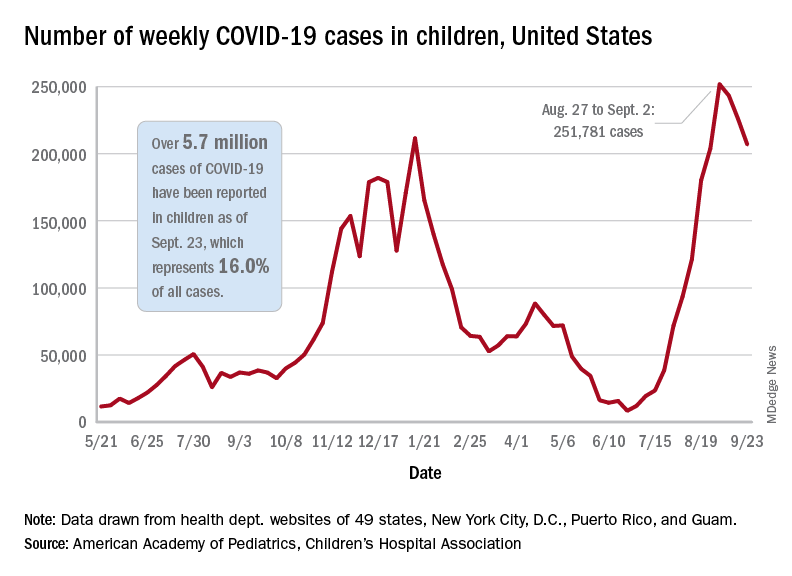

Weekly COVID-19 cases in children dropped again, but the count remained above 200,000 for the fifth consecutive week, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

based on the data in the AAP/CHA joint weekly report on COVID in children.

In the most recent week, Sept. 17-23, there were almost 207,000 new cases of COVID-19 in children, which represented 26.7% of all cases reported in the 46 states that are currently posting data by age on their COVID dashboards, the AAP and CHA said. (New York has never reported such data by age, and Alabama, Nebraska, and Texas have not updated their websites since July 29, June 24, and Aug. 26, respectively.)

The decline in new vaccinations among children, however, began before the summer surge in new cases hit its peak – 251,781 during the week of Aug. 27 to Sept. 2 – and has continued for 7 straight weeks in children aged 12-17 years, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

There were about 172,000 COVID vaccine initiations in children aged 12-17 for the week of Sept. 21-27, the lowest number since April, before it was approved for use in 12- to 15-year-olds. That figure is down by almost a third from the previous week and by more than two-thirds since early August, just before the decline in vaccinations began, according to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker.

The cumulative vaccine situation looks like this: Just over 13 million children under age 18 years have received at least one dose as of Sept. 27, and almost 10.6 million are fully vaccinated. By age group, 53.9% of 12- to 15-year-olds and 61.6% of 16- to 17-year-olds have received at least one dose, with corresponding figures of 43.3% and 51.3% for full vaccination, the CDC said.

COVID-related hospital admissions also continue to fall after peaking at 0.51 children aged 0-17 per 100,000 population on Sept. 4. The admission rate was down to 0.45 per 100,000 as of Sept. 17, and the latest 7-day average (Sept. 19-25) was 258 admissions, compared with a peak of 371 for the week of Aug. 29 to Sept. 4, the CDC reported.

“Although we have seen slight improvements in COVID-19 volumes in the past week, we are at the beginning of an anticipated increase in” multi-inflammatory syndrome in children, Margaret Rush, MD, president of Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., said at a recent hearing of the House Committee on Energy and Commerce’s Oversight subcommittee. That increase would be expected to produce “a secondary wave of seriously ill children 3-6 weeks after acute infection peaks in the community,” the American Hospital Association said.

Meanwhile, Dr. Rush noted, there are signs that seasonal viruses are coming into play. “With the emergence of the Delta variant, we’ve experienced a steep increase in COVID-19 hospitalizations among children on top of an early surge of [respiratory syncytial virus], a serious respiratory illness we usually see in the winter months,” she said in a prepared statement before her testimony.

Polyethylene glycol linked to rare allergic reactions seen with mRNA COVID-19 vaccines

A common inert ingredient may be the culprit behind the rare allergic reactions reported among individuals who have received mRNA COVID-19 vaccines, according to investigators at a large regional health center that was among the first to administer the shots.

Blood samples from 10 of 11 individuals with suspected allergic reactions reacted to polyethylene glycol (PEG), a component of both the Pfizer and Moderna mRNA vaccines, according to a report in JAMA Network Open.

In total, only 22 individuals had suspected allergic reactions out of nearly 39,000 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine doses administered, the investigators reported, noting that the reactions were generally mild and all fully resolved.

Those findings should be reassuring to individuals who are reticent to sign up for a COVID-19 vaccine because of fear of an allergic reaction, said study senior author Kari Nadeau, MD, PhD, director of the Parker Center for Allergy and Asthma Research at Stanford (Calif.) University.

“We’re hoping that this word will get out and then that the companies could also think about making vaccines that have other products in them that don’t include polyethylene glycol,” Dr. Nadeau said in an interview.

PEG is a compound used in many products, including pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, and food. In the mRNA COVID-19 vaccines, PEG serves to stabilize the lipid nanoparticles that help protect and transport mRNA. However, its use in this setting has been linked to allergic reactions in this and previous studies.

No immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies to PEG were detected among the 22 individuals with suspected allergic reactions to mRNA COVID-19 vaccine, but PEG immunoglobulin G (IgG) was present. That suggests non-IgE mediated allergic reactions to PEG may be implicated for the majority of cases, Dr. Nadeau said.

This case series provides interesting new evidence to confirm previous reports that a mechanism other than the classic IgE-mediated allergic response is behind the suspected allergic reactions that are occurring after mRNA COVID-19 vaccine, said Aleena Banerji, MD, associate professor at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and clinical director of the Drug Allergy Program at Massachusetts General Hospital.

“We need to further understand the mechanism of these reactions, but what we know is that IGE mediated allergy to excipients like PEG is probably not the main cause,” Dr. Banerji, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview.

In a recent research letter published in JAMA Internal Medicine, Dr. Banerji and coauthors reported that all individuals with immediate suspected allergic reactions to mRNA COVID-19 vaccine went on to tolerate the second dose, with mild symptoms reported in the minority of patients (32 out of 159, or about 20%).

“Again, that is very consistent with not having an IgE-mediated allergy, so it seems to all be fitting with that picture,” Dr. Banerji said.

The case series by Dr. Nadeau and coauthors was based on review of nearly 39,000 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine doses administered between December 18, 2020 and January 26, 2021. Most mRNA vaccine recipients were Stanford-affiliated health care workers, according to the report.

Among recipients of those doses, they identified 148 individuals who had anaphylaxis-related ICD-10 codes recorded over the same time period. In a review of medical records, investigators pinpointed 22 individuals as having suspected allergy and invited them to participate in follow-up allergy testing.

A total of 11 individuals underwent skin prick testing, but none of them tested positive to PEG or to polysorbate 80, another excipient that has been linked to vaccine-related allergic reactions. One of the patients tested positive to the same mRNA vaccine they had previously received, according to the report.

Those same 11 individuals also underwent basophil activation testing (BAT). In contrast to the skin testing results, BAT results were positive for PEG in 10 of 11 cases (or 91%) and positive for their administered vaccine in all 11 cases, the report shows.

High levels of IgG to PEG were identified in blood samples of individuals with an allergy to the vaccine. Investigators said it’s possible that the BAT results were activated due to IgG via complement activation–related pseudoallergy, or CARPA, as has been hypothesized by some other investigators.

The negative skin prick testing results for PEG, which contrast with the positive BAT results to PEG, suggest that the former may not be appropriate for use as a predictive marker of potential vaccine allergy, according to Dr. Nadeau.

“The take-home message for doctors is to be careful,” she said. “Don’t assume that just because the person skin-tests negative to PEG or to the vaccine itself that you’re out of the woods, because the skin test would be often negative in those scenarios.”

The study was supported by a grants from the Asthma and Allergic Diseases Cooperative Research Centers, a grant from the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease SARS Vaccine study, the Parker Foundation, the Crown Foundation, and the Sunshine Foundation. Dr. Nadeau reports numerous conflicts with various sources in the industry. Dr. Banerji has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A common inert ingredient may be the culprit behind the rare allergic reactions reported among individuals who have received mRNA COVID-19 vaccines, according to investigators at a large regional health center that was among the first to administer the shots.

Blood samples from 10 of 11 individuals with suspected allergic reactions reacted to polyethylene glycol (PEG), a component of both the Pfizer and Moderna mRNA vaccines, according to a report in JAMA Network Open.

In total, only 22 individuals had suspected allergic reactions out of nearly 39,000 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine doses administered, the investigators reported, noting that the reactions were generally mild and all fully resolved.

Those findings should be reassuring to individuals who are reticent to sign up for a COVID-19 vaccine because of fear of an allergic reaction, said study senior author Kari Nadeau, MD, PhD, director of the Parker Center for Allergy and Asthma Research at Stanford (Calif.) University.

“We’re hoping that this word will get out and then that the companies could also think about making vaccines that have other products in them that don’t include polyethylene glycol,” Dr. Nadeau said in an interview.

PEG is a compound used in many products, including pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, and food. In the mRNA COVID-19 vaccines, PEG serves to stabilize the lipid nanoparticles that help protect and transport mRNA. However, its use in this setting has been linked to allergic reactions in this and previous studies.

No immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies to PEG were detected among the 22 individuals with suspected allergic reactions to mRNA COVID-19 vaccine, but PEG immunoglobulin G (IgG) was present. That suggests non-IgE mediated allergic reactions to PEG may be implicated for the majority of cases, Dr. Nadeau said.

This case series provides interesting new evidence to confirm previous reports that a mechanism other than the classic IgE-mediated allergic response is behind the suspected allergic reactions that are occurring after mRNA COVID-19 vaccine, said Aleena Banerji, MD, associate professor at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and clinical director of the Drug Allergy Program at Massachusetts General Hospital.

“We need to further understand the mechanism of these reactions, but what we know is that IGE mediated allergy to excipients like PEG is probably not the main cause,” Dr. Banerji, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview.

In a recent research letter published in JAMA Internal Medicine, Dr. Banerji and coauthors reported that all individuals with immediate suspected allergic reactions to mRNA COVID-19 vaccine went on to tolerate the second dose, with mild symptoms reported in the minority of patients (32 out of 159, or about 20%).

“Again, that is very consistent with not having an IgE-mediated allergy, so it seems to all be fitting with that picture,” Dr. Banerji said.

The case series by Dr. Nadeau and coauthors was based on review of nearly 39,000 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine doses administered between December 18, 2020 and January 26, 2021. Most mRNA vaccine recipients were Stanford-affiliated health care workers, according to the report.

Among recipients of those doses, they identified 148 individuals who had anaphylaxis-related ICD-10 codes recorded over the same time period. In a review of medical records, investigators pinpointed 22 individuals as having suspected allergy and invited them to participate in follow-up allergy testing.

A total of 11 individuals underwent skin prick testing, but none of them tested positive to PEG or to polysorbate 80, another excipient that has been linked to vaccine-related allergic reactions. One of the patients tested positive to the same mRNA vaccine they had previously received, according to the report.

Those same 11 individuals also underwent basophil activation testing (BAT). In contrast to the skin testing results, BAT results were positive for PEG in 10 of 11 cases (or 91%) and positive for their administered vaccine in all 11 cases, the report shows.

High levels of IgG to PEG were identified in blood samples of individuals with an allergy to the vaccine. Investigators said it’s possible that the BAT results were activated due to IgG via complement activation–related pseudoallergy, or CARPA, as has been hypothesized by some other investigators.

The negative skin prick testing results for PEG, which contrast with the positive BAT results to PEG, suggest that the former may not be appropriate for use as a predictive marker of potential vaccine allergy, according to Dr. Nadeau.

“The take-home message for doctors is to be careful,” she said. “Don’t assume that just because the person skin-tests negative to PEG or to the vaccine itself that you’re out of the woods, because the skin test would be often negative in those scenarios.”

The study was supported by a grants from the Asthma and Allergic Diseases Cooperative Research Centers, a grant from the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease SARS Vaccine study, the Parker Foundation, the Crown Foundation, and the Sunshine Foundation. Dr. Nadeau reports numerous conflicts with various sources in the industry. Dr. Banerji has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A common inert ingredient may be the culprit behind the rare allergic reactions reported among individuals who have received mRNA COVID-19 vaccines, according to investigators at a large regional health center that was among the first to administer the shots.

Blood samples from 10 of 11 individuals with suspected allergic reactions reacted to polyethylene glycol (PEG), a component of both the Pfizer and Moderna mRNA vaccines, according to a report in JAMA Network Open.

In total, only 22 individuals had suspected allergic reactions out of nearly 39,000 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine doses administered, the investigators reported, noting that the reactions were generally mild and all fully resolved.

Those findings should be reassuring to individuals who are reticent to sign up for a COVID-19 vaccine because of fear of an allergic reaction, said study senior author Kari Nadeau, MD, PhD, director of the Parker Center for Allergy and Asthma Research at Stanford (Calif.) University.

“We’re hoping that this word will get out and then that the companies could also think about making vaccines that have other products in them that don’t include polyethylene glycol,” Dr. Nadeau said in an interview.

PEG is a compound used in many products, including pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, and food. In the mRNA COVID-19 vaccines, PEG serves to stabilize the lipid nanoparticles that help protect and transport mRNA. However, its use in this setting has been linked to allergic reactions in this and previous studies.

No immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies to PEG were detected among the 22 individuals with suspected allergic reactions to mRNA COVID-19 vaccine, but PEG immunoglobulin G (IgG) was present. That suggests non-IgE mediated allergic reactions to PEG may be implicated for the majority of cases, Dr. Nadeau said.

This case series provides interesting new evidence to confirm previous reports that a mechanism other than the classic IgE-mediated allergic response is behind the suspected allergic reactions that are occurring after mRNA COVID-19 vaccine, said Aleena Banerji, MD, associate professor at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and clinical director of the Drug Allergy Program at Massachusetts General Hospital.

“We need to further understand the mechanism of these reactions, but what we know is that IGE mediated allergy to excipients like PEG is probably not the main cause,” Dr. Banerji, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview.

In a recent research letter published in JAMA Internal Medicine, Dr. Banerji and coauthors reported that all individuals with immediate suspected allergic reactions to mRNA COVID-19 vaccine went on to tolerate the second dose, with mild symptoms reported in the minority of patients (32 out of 159, or about 20%).

“Again, that is very consistent with not having an IgE-mediated allergy, so it seems to all be fitting with that picture,” Dr. Banerji said.

The case series by Dr. Nadeau and coauthors was based on review of nearly 39,000 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine doses administered between December 18, 2020 and January 26, 2021. Most mRNA vaccine recipients were Stanford-affiliated health care workers, according to the report.

Among recipients of those doses, they identified 148 individuals who had anaphylaxis-related ICD-10 codes recorded over the same time period. In a review of medical records, investigators pinpointed 22 individuals as having suspected allergy and invited them to participate in follow-up allergy testing.

A total of 11 individuals underwent skin prick testing, but none of them tested positive to PEG or to polysorbate 80, another excipient that has been linked to vaccine-related allergic reactions. One of the patients tested positive to the same mRNA vaccine they had previously received, according to the report.

Those same 11 individuals also underwent basophil activation testing (BAT). In contrast to the skin testing results, BAT results were positive for PEG in 10 of 11 cases (or 91%) and positive for their administered vaccine in all 11 cases, the report shows.

High levels of IgG to PEG were identified in blood samples of individuals with an allergy to the vaccine. Investigators said it’s possible that the BAT results were activated due to IgG via complement activation–related pseudoallergy, or CARPA, as has been hypothesized by some other investigators.

The negative skin prick testing results for PEG, which contrast with the positive BAT results to PEG, suggest that the former may not be appropriate for use as a predictive marker of potential vaccine allergy, according to Dr. Nadeau.

“The take-home message for doctors is to be careful,” she said. “Don’t assume that just because the person skin-tests negative to PEG or to the vaccine itself that you’re out of the woods, because the skin test would be often negative in those scenarios.”

The study was supported by a grants from the Asthma and Allergic Diseases Cooperative Research Centers, a grant from the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease SARS Vaccine study, the Parker Foundation, the Crown Foundation, and the Sunshine Foundation. Dr. Nadeau reports numerous conflicts with various sources in the industry. Dr. Banerji has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

These schools use weekly testing to keep kids in class – and COVID out

On a recent Monday morning, a group of preschoolers filed into the gymnasium at Hillside School in the west Chicago suburbs. These 4- and 5-year-olds were the first of more than 200 students to get tested for the coronavirus that day – and every Monday – for the foreseeable future.

At the front of the line, a girl in a unicorn headband and sparkly pink skirt clutched a zip-close bag with her name on it. She pulled out a plastic tube with a small funnel attached. Next, Hillside superintendent Kevin Suchinski led the student to a spot marked off with red tape. Mr. Suchinski coached her how to carefully release – but not “spit” – about a half-teaspoon’s worth of saliva into the tube.

“You wait a second, you build up your saliva,” he told her. “You don’t talk, you think about pizza, hamburgers, French fries, ice cream. And you drop it right in there, OK?”

The results will come back within 24 hours. Any students who test positive are instructed to isolate, and the school nurse and administrative staff carry out contact tracing.

Hillside was among the first in Illinois to start regular testing. Now, almost half of Illinois’ 2 million students in grades K-12 attend schools rolling out similar programs. The initiative is supported by federal funding channeled through the state health department.

Schools in other states – such as Massachusetts, Maryland, New York and Colorado – also offer regular testing; Los Angeles public schools have gone further by making it mandatory.

These measures stand in sharp contrast to the confusion in states where people are still fighting about wearing masks in the classroom and other anti-COVID strategies, places where some schools have experienced outbreaks and even teacher deaths.

Within a few weeks of schools reopening, tens of thousands of students across the United States were sent home to quarantine. It’s a concern because options for K-12 students in quarantine are all over the map – with some schools offering virtual instruction and others providing little or no at-home options.

Mr. Suchinski hopes this investment in testing prevents virus detected at Hillside School from spreading into the wider community – and keeps kids learning.

“What we say to ourselves is: If we don’t do this program, we could be losing instruction because we’ve had to close down the school,” he said.

So far, the parents and guardians of two-thirds of all Hillside students have consented to testing. Mr. Suchinski said the school is working hard to get the remaining families on board by educating them about the importance – and benefit – of regular testing.

Every school that can manage it should consider testing students weekly – even twice a week, if possible, said Becky Smith, PhD. She’s an epidemiologist at the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign, which developed the saliva test Hillside and other Illinois schools are using. Smith pointed to several studies – including both peer-reviewed and preliminary research – that suggest rigorous testing and contact tracing are key to keeping the virus at bay in K-12 schools.

“If you’re lucky, you can get away without doing testing, [if] nobody comes to school with a raging infection and takes their mask off at lunchtime and infects everybody sitting at the table with them,” Dr. Smith said. “But relying on luck isn’t what we like to do.”

Julian Hernandez, a Hillside seventh grader, said he feels safer knowing that classmates infected with the virus will be prevented from spreading it to others.

“One of my friends – he got it a couple months ago while we was in school,” Julian recalled. “[He] and his brother had to go back home. ... They were OK. They only had mild symptoms.”

Brandon Muñoz, who’s in the fifth grade, said he’s glad to get tested because he’s too young for the vaccine – and he really doesn’t want to go back to Zoom school.

“Because I wanna really meet more people and friends and just not stay on the computer for too long,” Brandon explained.

Mr. Suchinski said Hillside also improved ventilation throughout the building, installing a new HVAC system and windows with screens in the cafeteria to bring more fresh air in the building.

Regular testing is an added layer of protection, though not the only thing Hillside is relying on: About 90% of Hillside staff are vaccinated, Suchinski said, and students and staffers also wear masks.

Setting up a regular mass-testing program inside a K-12 school takes a good amount of coordination, which Mr. Suchinski can vouch for.

Last school year, Hillside school administrators facilitated the saliva sample collection without outside help. This year, the school tapped funding earmarked for K-12 coronavirus testing to hire COVID testers – who coordinate the collecting, transporting and processing of samples, and reporting results.

A couple of Hillside administrators help oversee the process on Mondays, and also facilitate testing for staff members, plus more frequent testing for a limited group of students: Athletes and children in band and extracurriculars test twice a week because they face greater risks of exposure to the virus from these activities.

Compared with a year ago, COVID testing is now both more affordable and much less invasive, said Mara Aspinall, who studies biomedical testing at Arizona State University. There’s also more help to cover costs.

“The Biden administration has allocated $11 billion to different programs for testing,” Ms. Aspinall said. “There should be no school – public, private or charter – that can’t access that money for testing.”

Creating a mass testing program from scratch is a big lift. But more than half of all states have announced programs to help schools access the money and handle the logistics.

If every school tested every student once a week, the roughly $11 billion earmarked for testing would likely run out in a couple of months. (This assumes $20 to buy and process each test.) Put another way, if a quarter of all U.S. schools tested students weekly, the funds could last the rest of the school year, Ms. Aspinall said.

In its guidance to K-12 schools, updated Aug. 5, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention does not make a firm recommendation for this surveillance testing.

Instead, the CDC advises schools that choose to offer testing to work with public health officials to determine a suitable approach, given rates of community transmission and other factors.

The agency previously recommended screening at least once a week in all areas experiencing moderate to high levels of community transmission. As of Sept. 21, that included 95% of U.S. counties.

For school leaders looking to explore options, Ms. Aspinall suggests a resource she helped write, which is cited within the CDC guidance to schools: the Rockefeller Foundation’s National Testing Action Plan.

This spring – when Hillside was operating at about half capacity and before the more contagious delta variant took over – the school identified 13 positive cases among students and staffers via its weekly testing program. The overall positivity rate of about half a percent made some wonder if all that testing was necessary.

But Mr. Suchinski said that, by identifying the 13 positive cases, the school perhaps avoided more than a dozen potential outbreaks. Some of the positive cases were among people who weren’t showing symptoms but still could’ve spread the virus.

A couple of weeks into the new school year at Hillside, operating at full capacity, Mr. Suchinski said the excitement is palpable. Nowadays he’s balancing feelings of optimism with caution.

“It is great to hear kids laughing. It’s great to see kids on playgrounds,” Mr. Suchinski said.

“At the same time,” he added, “we know that we’re still fighting against the Delta variant and we have to keep our guard up.”

This story is from a partnership that includes Illinois Public Media, Side Effects Public Media, NPR, and KHN (Kaiser Health News). KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

On a recent Monday morning, a group of preschoolers filed into the gymnasium at Hillside School in the west Chicago suburbs. These 4- and 5-year-olds were the first of more than 200 students to get tested for the coronavirus that day – and every Monday – for the foreseeable future.

At the front of the line, a girl in a unicorn headband and sparkly pink skirt clutched a zip-close bag with her name on it. She pulled out a plastic tube with a small funnel attached. Next, Hillside superintendent Kevin Suchinski led the student to a spot marked off with red tape. Mr. Suchinski coached her how to carefully release – but not “spit” – about a half-teaspoon’s worth of saliva into the tube.

“You wait a second, you build up your saliva,” he told her. “You don’t talk, you think about pizza, hamburgers, French fries, ice cream. And you drop it right in there, OK?”

The results will come back within 24 hours. Any students who test positive are instructed to isolate, and the school nurse and administrative staff carry out contact tracing.

Hillside was among the first in Illinois to start regular testing. Now, almost half of Illinois’ 2 million students in grades K-12 attend schools rolling out similar programs. The initiative is supported by federal funding channeled through the state health department.

Schools in other states – such as Massachusetts, Maryland, New York and Colorado – also offer regular testing; Los Angeles public schools have gone further by making it mandatory.

These measures stand in sharp contrast to the confusion in states where people are still fighting about wearing masks in the classroom and other anti-COVID strategies, places where some schools have experienced outbreaks and even teacher deaths.

Within a few weeks of schools reopening, tens of thousands of students across the United States were sent home to quarantine. It’s a concern because options for K-12 students in quarantine are all over the map – with some schools offering virtual instruction and others providing little or no at-home options.

Mr. Suchinski hopes this investment in testing prevents virus detected at Hillside School from spreading into the wider community – and keeps kids learning.

“What we say to ourselves is: If we don’t do this program, we could be losing instruction because we’ve had to close down the school,” he said.

So far, the parents and guardians of two-thirds of all Hillside students have consented to testing. Mr. Suchinski said the school is working hard to get the remaining families on board by educating them about the importance – and benefit – of regular testing.

Every school that can manage it should consider testing students weekly – even twice a week, if possible, said Becky Smith, PhD. She’s an epidemiologist at the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign, which developed the saliva test Hillside and other Illinois schools are using. Smith pointed to several studies – including both peer-reviewed and preliminary research – that suggest rigorous testing and contact tracing are key to keeping the virus at bay in K-12 schools.

“If you’re lucky, you can get away without doing testing, [if] nobody comes to school with a raging infection and takes their mask off at lunchtime and infects everybody sitting at the table with them,” Dr. Smith said. “But relying on luck isn’t what we like to do.”

Julian Hernandez, a Hillside seventh grader, said he feels safer knowing that classmates infected with the virus will be prevented from spreading it to others.

“One of my friends – he got it a couple months ago while we was in school,” Julian recalled. “[He] and his brother had to go back home. ... They were OK. They only had mild symptoms.”

Brandon Muñoz, who’s in the fifth grade, said he’s glad to get tested because he’s too young for the vaccine – and he really doesn’t want to go back to Zoom school.

“Because I wanna really meet more people and friends and just not stay on the computer for too long,” Brandon explained.

Mr. Suchinski said Hillside also improved ventilation throughout the building, installing a new HVAC system and windows with screens in the cafeteria to bring more fresh air in the building.

Regular testing is an added layer of protection, though not the only thing Hillside is relying on: About 90% of Hillside staff are vaccinated, Suchinski said, and students and staffers also wear masks.

Setting up a regular mass-testing program inside a K-12 school takes a good amount of coordination, which Mr. Suchinski can vouch for.

Last school year, Hillside school administrators facilitated the saliva sample collection without outside help. This year, the school tapped funding earmarked for K-12 coronavirus testing to hire COVID testers – who coordinate the collecting, transporting and processing of samples, and reporting results.