User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

Pandemic weighing on physicians’ happiness outside of work: survey

One of the unexpected consequences of the pandemic is that many people are rethinking their priorities and lifestyles, and physicians are no exception.

Pets, prayer, and partners

The pandemic has taken a toll on physicians outside of work as well as on the job. Eight in 10 physicians (82% of men and 80% of women) said they were “somewhat” or “very” happy outside of work before the pandemic. This is almost exactly the same result as in last year’s survey.

However, when asked how happy they are outside of work currently, only 6 in 10 (59%) reported being “somewhat” or “very” happy. While the pandemic has made life difficult for everyone, health care professionals face particular stresses even outside of work. Wayne M. Sotile, PhD, founder of the Center for Physician Resilience, says he has counseled doctors who witnessed COVID-related suffering and death at work, then came home to a partner who didn’t believe that the pandemic was real.

Still, physicians reported that spending time with people they love and engaging in favorite activities helps them stay happy. “Spending time with pets” and “religious practice/prayer” were frequent “other” responses to the question, “What do you do to maintain happiness and mental health?” Seven in 10 physicians reported having some kind of religious or spiritual beliefs.

The majority of physicians (83%) are either married or living with a partner, with male physicians edging out their female peers (89% vs. 75%). Among married physicians, 8 in 10 physicians reported that their union is “good” or “very good.” The pandemic may have helped in this respect. Dr. Sotile says he’s heard physicians say that they’ve connected more with their families in the past 18 months. Specialists with the highest rates of happy marriages were otolaryngologists and immunologists (both 91%), followed closely by dermatologists, rheumatologists, and nephrologists (all 90%).

Among physicians balancing a medical career and parenthood, female physicians reported feeling conflicted more often than males (48% vs. 29%). Nicole A. Sparks, MD, an ob.gyn. and a health and lifestyle blogger, cites not being there for her kids as a source of stress. She notes that her two young children notice when she’s not there to help with homework, read bedtime stories, or make their dinner. “Mom guilt can definitely set in if I have to miss important events,” she says.

Work-life balance is an important, if elusive, goal for physicians, and not just females. Sixty percent of female doctors and 53% of male doctors said they would be willing to take a cut in pay if it meant more free time and a better work-life balance. Many doctors do manage to get away from work occasionally, with one-fifth of all physicians taking 5 or more weeks of vacation each year.

Seeking a ‘balanced life’

Alexis Polles, MD, medical director for the Professionals Resource Network, points out the importance of taking time for personal health and wellness. “When we work with professionals who have problems with mental health or substance abuse, they often don’t have a balanced life,” she says. “They are usually in a workaholic mindset and disregard their own needs.”

Few physicians seem to prioritize self-care, with a third indicating they “always” or “most of the time” spend enough time on their own health and wellness. But of those who do, males (38%) are more likely than females (27%) to spend enough time on their own health and wellness. Dr. Polles adds that exercising after a shift can help physicians better make the transition from professional to personal life. Though they did not report when they exercised, about a third of physicians reported doing so four or more times per week. Controlling weight is an issue as well, with 49% of male and 55% of female physicians saying they are currently trying to lose weight.

Of physicians who drink alcohol, about a third have three or more drinks per week. (The CDC defines “heavy drinking” as consuming 15 drinks or more per week for men and eight drinks or more per week for women.)

Of those surveyed, 92% say they do not regularly use cannabidiol or cannabis, and a mere 4% of respondents said they would use at least one of these substances if they were to become legal in their state.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

One of the unexpected consequences of the pandemic is that many people are rethinking their priorities and lifestyles, and physicians are no exception.

Pets, prayer, and partners

The pandemic has taken a toll on physicians outside of work as well as on the job. Eight in 10 physicians (82% of men and 80% of women) said they were “somewhat” or “very” happy outside of work before the pandemic. This is almost exactly the same result as in last year’s survey.

However, when asked how happy they are outside of work currently, only 6 in 10 (59%) reported being “somewhat” or “very” happy. While the pandemic has made life difficult for everyone, health care professionals face particular stresses even outside of work. Wayne M. Sotile, PhD, founder of the Center for Physician Resilience, says he has counseled doctors who witnessed COVID-related suffering and death at work, then came home to a partner who didn’t believe that the pandemic was real.

Still, physicians reported that spending time with people they love and engaging in favorite activities helps them stay happy. “Spending time with pets” and “religious practice/prayer” were frequent “other” responses to the question, “What do you do to maintain happiness and mental health?” Seven in 10 physicians reported having some kind of religious or spiritual beliefs.

The majority of physicians (83%) are either married or living with a partner, with male physicians edging out their female peers (89% vs. 75%). Among married physicians, 8 in 10 physicians reported that their union is “good” or “very good.” The pandemic may have helped in this respect. Dr. Sotile says he’s heard physicians say that they’ve connected more with their families in the past 18 months. Specialists with the highest rates of happy marriages were otolaryngologists and immunologists (both 91%), followed closely by dermatologists, rheumatologists, and nephrologists (all 90%).

Among physicians balancing a medical career and parenthood, female physicians reported feeling conflicted more often than males (48% vs. 29%). Nicole A. Sparks, MD, an ob.gyn. and a health and lifestyle blogger, cites not being there for her kids as a source of stress. She notes that her two young children notice when she’s not there to help with homework, read bedtime stories, or make their dinner. “Mom guilt can definitely set in if I have to miss important events,” she says.

Work-life balance is an important, if elusive, goal for physicians, and not just females. Sixty percent of female doctors and 53% of male doctors said they would be willing to take a cut in pay if it meant more free time and a better work-life balance. Many doctors do manage to get away from work occasionally, with one-fifth of all physicians taking 5 or more weeks of vacation each year.

Seeking a ‘balanced life’

Alexis Polles, MD, medical director for the Professionals Resource Network, points out the importance of taking time for personal health and wellness. “When we work with professionals who have problems with mental health or substance abuse, they often don’t have a balanced life,” she says. “They are usually in a workaholic mindset and disregard their own needs.”

Few physicians seem to prioritize self-care, with a third indicating they “always” or “most of the time” spend enough time on their own health and wellness. But of those who do, males (38%) are more likely than females (27%) to spend enough time on their own health and wellness. Dr. Polles adds that exercising after a shift can help physicians better make the transition from professional to personal life. Though they did not report when they exercised, about a third of physicians reported doing so four or more times per week. Controlling weight is an issue as well, with 49% of male and 55% of female physicians saying they are currently trying to lose weight.

Of physicians who drink alcohol, about a third have three or more drinks per week. (The CDC defines “heavy drinking” as consuming 15 drinks or more per week for men and eight drinks or more per week for women.)

Of those surveyed, 92% say they do not regularly use cannabidiol or cannabis, and a mere 4% of respondents said they would use at least one of these substances if they were to become legal in their state.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

One of the unexpected consequences of the pandemic is that many people are rethinking their priorities and lifestyles, and physicians are no exception.

Pets, prayer, and partners

The pandemic has taken a toll on physicians outside of work as well as on the job. Eight in 10 physicians (82% of men and 80% of women) said they were “somewhat” or “very” happy outside of work before the pandemic. This is almost exactly the same result as in last year’s survey.

However, when asked how happy they are outside of work currently, only 6 in 10 (59%) reported being “somewhat” or “very” happy. While the pandemic has made life difficult for everyone, health care professionals face particular stresses even outside of work. Wayne M. Sotile, PhD, founder of the Center for Physician Resilience, says he has counseled doctors who witnessed COVID-related suffering and death at work, then came home to a partner who didn’t believe that the pandemic was real.

Still, physicians reported that spending time with people they love and engaging in favorite activities helps them stay happy. “Spending time with pets” and “religious practice/prayer” were frequent “other” responses to the question, “What do you do to maintain happiness and mental health?” Seven in 10 physicians reported having some kind of religious or spiritual beliefs.

The majority of physicians (83%) are either married or living with a partner, with male physicians edging out their female peers (89% vs. 75%). Among married physicians, 8 in 10 physicians reported that their union is “good” or “very good.” The pandemic may have helped in this respect. Dr. Sotile says he’s heard physicians say that they’ve connected more with their families in the past 18 months. Specialists with the highest rates of happy marriages were otolaryngologists and immunologists (both 91%), followed closely by dermatologists, rheumatologists, and nephrologists (all 90%).

Among physicians balancing a medical career and parenthood, female physicians reported feeling conflicted more often than males (48% vs. 29%). Nicole A. Sparks, MD, an ob.gyn. and a health and lifestyle blogger, cites not being there for her kids as a source of stress. She notes that her two young children notice when she’s not there to help with homework, read bedtime stories, or make their dinner. “Mom guilt can definitely set in if I have to miss important events,” she says.

Work-life balance is an important, if elusive, goal for physicians, and not just females. Sixty percent of female doctors and 53% of male doctors said they would be willing to take a cut in pay if it meant more free time and a better work-life balance. Many doctors do manage to get away from work occasionally, with one-fifth of all physicians taking 5 or more weeks of vacation each year.

Seeking a ‘balanced life’

Alexis Polles, MD, medical director for the Professionals Resource Network, points out the importance of taking time for personal health and wellness. “When we work with professionals who have problems with mental health or substance abuse, they often don’t have a balanced life,” she says. “They are usually in a workaholic mindset and disregard their own needs.”

Few physicians seem to prioritize self-care, with a third indicating they “always” or “most of the time” spend enough time on their own health and wellness. But of those who do, males (38%) are more likely than females (27%) to spend enough time on their own health and wellness. Dr. Polles adds that exercising after a shift can help physicians better make the transition from professional to personal life. Though they did not report when they exercised, about a third of physicians reported doing so four or more times per week. Controlling weight is an issue as well, with 49% of male and 55% of female physicians saying they are currently trying to lose weight.

Of physicians who drink alcohol, about a third have three or more drinks per week. (The CDC defines “heavy drinking” as consuming 15 drinks or more per week for men and eight drinks or more per week for women.)

Of those surveyed, 92% say they do not regularly use cannabidiol or cannabis, and a mere 4% of respondents said they would use at least one of these substances if they were to become legal in their state.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Dramatic increase in driving high after cannabis legislation

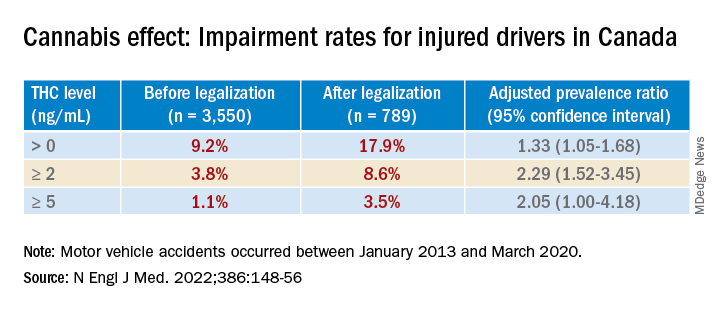

Since Canada legalized marijuana in 2018, there has been a dramatic increase in the number of individuals driving while high, new research shows.

Investigators studied over 4,000 drivers treated after a motor vehicle collision in British Columbia trauma centers and found that, before cannabis was legalized, a THC level greater than 0 ng/mL in the blood was present in roughly 10% of drivers. After the drug was legalized this percentage increased to 18%. The percentages of injured drivers with at least 2 ng/mL, the Canadian legal limit, and at least 5 ng/mL more than doubled.

“It’s concerning that we’re seeing such a dramatic increase,” study investigator Jeffrey Brubacher, MD, associate professor, department of emergency medicine, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, said in a press release.

“There are serious risks associated with driving after cannabis use and our findings suggest more [work] is needed to deter this dangerous behavior in light of legalization,” he said.

The study was published online Jan. 12 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Impact of legalization?

The investigators note that the Canadian government introduced a law aiming to prevent cannabis-impaired driving by establishing penalties and criminal charges for drivers found with a whole-blood THC level of 2 ng/mL, with more severe penalties for those with a THC level of greater than 5 ng/mL or greater than 2.5 ng/mL combined with a blood alcohol level of .05%.

Cannabis use is “associated with cognitive deficits and psychomotor impairment, and there is evidence that it increases the risk of motor vehicle crashes, especially at higher THC levels,” they noted.

“I’m an emergency physician at Vancouver General Hospital’s trauma center. We’ve been measuring drug levels in injured drivers since 2013 here in British Columbia and, in particular, we’ve been measuring THC levels,” Dr. Brubacher said in an interview. “We thought it would be interesting and important to see what would happen after legalization.”

The investigators studied 4,339 drivers – 3,550 whose accident took place before legalization of cannabis, and 789 after legalization – who had been moderately injured in a motor vehicle collision and presented to four British Columbia trauma centers between January 2013 and March 2020.

said Dr. Brubacher. Drivers included in the study had excess blood remaining after the clinical testing had been completed, which was then used for drug analysis.

Insufficient laws

After legalization there was an increased prevalence of drivers with a THC level greater than 0 ng/mL, a TCH level of at least 2 ng/mL, and a THC level of at least 5 ng/mL.

The largest increases in a THC level of at least 2 ng/mL were in drivers 50 years of age or older and among male drivers (adjusted prevalence ratio, 5.18; 95% confidence interval, 2.49-10.78 and aPR, 2.44; 95% CI, 1.60-3.74, respectively).

“There were no significant changes in the prevalence of drivers testing positive for alcohol,” the authors reported.

Dr. Brubacher said the evidence suggests these new laws “are not enough to stop everyone from driving after using cannabis.”

The findings have implications for clinicians and patients and for policymakers, he said. “My moderately conservative recommendations are that, if you are going to smoke cannabis, wait at least 4 hours after smoking before you drive. Edibles last longer, and patients should wait least 8 hours after ingesting [edibles] before driving. And of course, if you continue to feel the effects of the THC, you should avoid driving altogether until the time has elapsed and you no longer feel any effects.”

Dr. Brubacher hopes policy makers will use the study’s findings to “design public information campaigns and enforcement measures that encourage drivers, especially older drivers, to separate cannabis use from driving.”

Additionally, “policy makers shouldn’t lose sight of drinking and driving because that’s an even bigger problem than the risk of driving under the influence of cannabis.”

Focus on older adults

In a comment, Anees Bahji, MD, an International Collaborative Addiction Medicine research fellow at the British Columbia Centre on Substance Use, called the study “interesting and relevant.”

He raised several questions regarding the “correlation between the level of a substance in a person’s system and the degree of impairment.” For example, “does the same level of THC in the blood affect us all the same way? And to what extent do the levels detected at the time of the analysis correlate with the level in the person’s system at the time of driving?”

An additional consideration “is for individuals with cannabis use disorder and for those who have developed tolerance to the psychoactive effects of THC: Does it affect their driving skills in the same way as someone who is cannabis naive?” asked Dr. Bahji, a clinical assistant professor at the University of Calgary (Alta.) who was not involved with the study.

Also commenting, Eric Sevigny, PhD, associate professor of criminal justice and criminology at Georgia State University, Atlanta, described it as a “well-designed study that adds yet another data point for considering appropriate road safety policy responses alongside ongoing cannabis liberalization.”

However, the findings “cannot say much about whether cannabis legalization leads to an increase in cannabis-impaired driving, because current research finds little correlation between biological THC concentrations and driving performance,” said Dr. Sevigny, who was not involved with the study.

The finding of “higher THC prevalence among older adults is also relevant for road safety, as this population has a number of concomitant risk factors, such as cognitive decline and prescription drug use,” Dr. Sevigny added.

The study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Brubacher and Dr. Sevigny disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Bahji reported receiving research funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Calgary Health Trust, the American Psychiatric Association, NIDA, and the University of Calgary.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

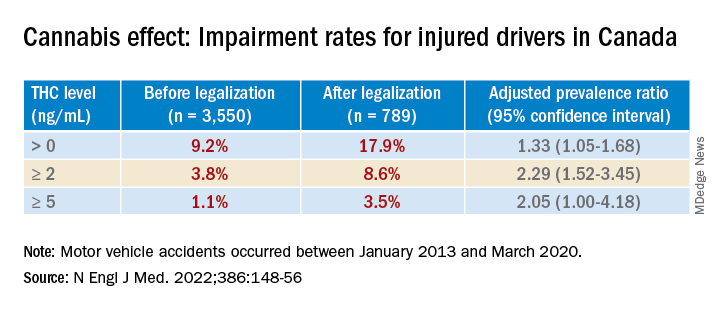

Since Canada legalized marijuana in 2018, there has been a dramatic increase in the number of individuals driving while high, new research shows.

Investigators studied over 4,000 drivers treated after a motor vehicle collision in British Columbia trauma centers and found that, before cannabis was legalized, a THC level greater than 0 ng/mL in the blood was present in roughly 10% of drivers. After the drug was legalized this percentage increased to 18%. The percentages of injured drivers with at least 2 ng/mL, the Canadian legal limit, and at least 5 ng/mL more than doubled.

“It’s concerning that we’re seeing such a dramatic increase,” study investigator Jeffrey Brubacher, MD, associate professor, department of emergency medicine, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, said in a press release.

“There are serious risks associated with driving after cannabis use and our findings suggest more [work] is needed to deter this dangerous behavior in light of legalization,” he said.

The study was published online Jan. 12 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Impact of legalization?

The investigators note that the Canadian government introduced a law aiming to prevent cannabis-impaired driving by establishing penalties and criminal charges for drivers found with a whole-blood THC level of 2 ng/mL, with more severe penalties for those with a THC level of greater than 5 ng/mL or greater than 2.5 ng/mL combined with a blood alcohol level of .05%.

Cannabis use is “associated with cognitive deficits and psychomotor impairment, and there is evidence that it increases the risk of motor vehicle crashes, especially at higher THC levels,” they noted.

“I’m an emergency physician at Vancouver General Hospital’s trauma center. We’ve been measuring drug levels in injured drivers since 2013 here in British Columbia and, in particular, we’ve been measuring THC levels,” Dr. Brubacher said in an interview. “We thought it would be interesting and important to see what would happen after legalization.”

The investigators studied 4,339 drivers – 3,550 whose accident took place before legalization of cannabis, and 789 after legalization – who had been moderately injured in a motor vehicle collision and presented to four British Columbia trauma centers between January 2013 and March 2020.

said Dr. Brubacher. Drivers included in the study had excess blood remaining after the clinical testing had been completed, which was then used for drug analysis.

Insufficient laws

After legalization there was an increased prevalence of drivers with a THC level greater than 0 ng/mL, a TCH level of at least 2 ng/mL, and a THC level of at least 5 ng/mL.

The largest increases in a THC level of at least 2 ng/mL were in drivers 50 years of age or older and among male drivers (adjusted prevalence ratio, 5.18; 95% confidence interval, 2.49-10.78 and aPR, 2.44; 95% CI, 1.60-3.74, respectively).

“There were no significant changes in the prevalence of drivers testing positive for alcohol,” the authors reported.

Dr. Brubacher said the evidence suggests these new laws “are not enough to stop everyone from driving after using cannabis.”

The findings have implications for clinicians and patients and for policymakers, he said. “My moderately conservative recommendations are that, if you are going to smoke cannabis, wait at least 4 hours after smoking before you drive. Edibles last longer, and patients should wait least 8 hours after ingesting [edibles] before driving. And of course, if you continue to feel the effects of the THC, you should avoid driving altogether until the time has elapsed and you no longer feel any effects.”

Dr. Brubacher hopes policy makers will use the study’s findings to “design public information campaigns and enforcement measures that encourage drivers, especially older drivers, to separate cannabis use from driving.”

Additionally, “policy makers shouldn’t lose sight of drinking and driving because that’s an even bigger problem than the risk of driving under the influence of cannabis.”

Focus on older adults

In a comment, Anees Bahji, MD, an International Collaborative Addiction Medicine research fellow at the British Columbia Centre on Substance Use, called the study “interesting and relevant.”

He raised several questions regarding the “correlation between the level of a substance in a person’s system and the degree of impairment.” For example, “does the same level of THC in the blood affect us all the same way? And to what extent do the levels detected at the time of the analysis correlate with the level in the person’s system at the time of driving?”

An additional consideration “is for individuals with cannabis use disorder and for those who have developed tolerance to the psychoactive effects of THC: Does it affect their driving skills in the same way as someone who is cannabis naive?” asked Dr. Bahji, a clinical assistant professor at the University of Calgary (Alta.) who was not involved with the study.

Also commenting, Eric Sevigny, PhD, associate professor of criminal justice and criminology at Georgia State University, Atlanta, described it as a “well-designed study that adds yet another data point for considering appropriate road safety policy responses alongside ongoing cannabis liberalization.”

However, the findings “cannot say much about whether cannabis legalization leads to an increase in cannabis-impaired driving, because current research finds little correlation between biological THC concentrations and driving performance,” said Dr. Sevigny, who was not involved with the study.

The finding of “higher THC prevalence among older adults is also relevant for road safety, as this population has a number of concomitant risk factors, such as cognitive decline and prescription drug use,” Dr. Sevigny added.

The study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Brubacher and Dr. Sevigny disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Bahji reported receiving research funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Calgary Health Trust, the American Psychiatric Association, NIDA, and the University of Calgary.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

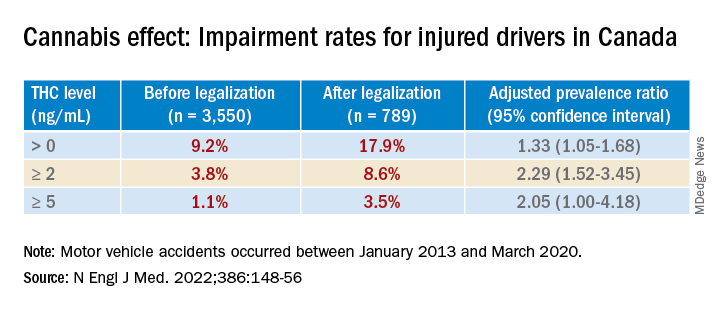

Since Canada legalized marijuana in 2018, there has been a dramatic increase in the number of individuals driving while high, new research shows.

Investigators studied over 4,000 drivers treated after a motor vehicle collision in British Columbia trauma centers and found that, before cannabis was legalized, a THC level greater than 0 ng/mL in the blood was present in roughly 10% of drivers. After the drug was legalized this percentage increased to 18%. The percentages of injured drivers with at least 2 ng/mL, the Canadian legal limit, and at least 5 ng/mL more than doubled.

“It’s concerning that we’re seeing such a dramatic increase,” study investigator Jeffrey Brubacher, MD, associate professor, department of emergency medicine, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, said in a press release.

“There are serious risks associated with driving after cannabis use and our findings suggest more [work] is needed to deter this dangerous behavior in light of legalization,” he said.

The study was published online Jan. 12 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Impact of legalization?

The investigators note that the Canadian government introduced a law aiming to prevent cannabis-impaired driving by establishing penalties and criminal charges for drivers found with a whole-blood THC level of 2 ng/mL, with more severe penalties for those with a THC level of greater than 5 ng/mL or greater than 2.5 ng/mL combined with a blood alcohol level of .05%.

Cannabis use is “associated with cognitive deficits and psychomotor impairment, and there is evidence that it increases the risk of motor vehicle crashes, especially at higher THC levels,” they noted.

“I’m an emergency physician at Vancouver General Hospital’s trauma center. We’ve been measuring drug levels in injured drivers since 2013 here in British Columbia and, in particular, we’ve been measuring THC levels,” Dr. Brubacher said in an interview. “We thought it would be interesting and important to see what would happen after legalization.”

The investigators studied 4,339 drivers – 3,550 whose accident took place before legalization of cannabis, and 789 after legalization – who had been moderately injured in a motor vehicle collision and presented to four British Columbia trauma centers between January 2013 and March 2020.

said Dr. Brubacher. Drivers included in the study had excess blood remaining after the clinical testing had been completed, which was then used for drug analysis.

Insufficient laws

After legalization there was an increased prevalence of drivers with a THC level greater than 0 ng/mL, a TCH level of at least 2 ng/mL, and a THC level of at least 5 ng/mL.

The largest increases in a THC level of at least 2 ng/mL were in drivers 50 years of age or older and among male drivers (adjusted prevalence ratio, 5.18; 95% confidence interval, 2.49-10.78 and aPR, 2.44; 95% CI, 1.60-3.74, respectively).

“There were no significant changes in the prevalence of drivers testing positive for alcohol,” the authors reported.

Dr. Brubacher said the evidence suggests these new laws “are not enough to stop everyone from driving after using cannabis.”

The findings have implications for clinicians and patients and for policymakers, he said. “My moderately conservative recommendations are that, if you are going to smoke cannabis, wait at least 4 hours after smoking before you drive. Edibles last longer, and patients should wait least 8 hours after ingesting [edibles] before driving. And of course, if you continue to feel the effects of the THC, you should avoid driving altogether until the time has elapsed and you no longer feel any effects.”

Dr. Brubacher hopes policy makers will use the study’s findings to “design public information campaigns and enforcement measures that encourage drivers, especially older drivers, to separate cannabis use from driving.”

Additionally, “policy makers shouldn’t lose sight of drinking and driving because that’s an even bigger problem than the risk of driving under the influence of cannabis.”

Focus on older adults

In a comment, Anees Bahji, MD, an International Collaborative Addiction Medicine research fellow at the British Columbia Centre on Substance Use, called the study “interesting and relevant.”

He raised several questions regarding the “correlation between the level of a substance in a person’s system and the degree of impairment.” For example, “does the same level of THC in the blood affect us all the same way? And to what extent do the levels detected at the time of the analysis correlate with the level in the person’s system at the time of driving?”

An additional consideration “is for individuals with cannabis use disorder and for those who have developed tolerance to the psychoactive effects of THC: Does it affect their driving skills in the same way as someone who is cannabis naive?” asked Dr. Bahji, a clinical assistant professor at the University of Calgary (Alta.) who was not involved with the study.

Also commenting, Eric Sevigny, PhD, associate professor of criminal justice and criminology at Georgia State University, Atlanta, described it as a “well-designed study that adds yet another data point for considering appropriate road safety policy responses alongside ongoing cannabis liberalization.”

However, the findings “cannot say much about whether cannabis legalization leads to an increase in cannabis-impaired driving, because current research finds little correlation between biological THC concentrations and driving performance,” said Dr. Sevigny, who was not involved with the study.

The finding of “higher THC prevalence among older adults is also relevant for road safety, as this population has a number of concomitant risk factors, such as cognitive decline and prescription drug use,” Dr. Sevigny added.

The study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Brubacher and Dr. Sevigny disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Bahji reported receiving research funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Calgary Health Trust, the American Psychiatric Association, NIDA, and the University of Calgary.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Psychiatry resident’s viral posts reveal his own mental health battle

First-year psychiatry resident Jake Goodman, MD, knew he was taking a chance when he opened up on his popular social media platforms about his personal mental health battle. He mulled over the decision for several weeks before deciding to take the plunge.

As he voiced recently on his TikTok page, his biggest social media fanbase, with 1.3 million followers, it felt freeing to get his personal struggle off his chest.

“I’m a doctor in training, and most doctors would advise me not to post this,” the 29-year-old from Miami said in the video last month, which garnered 1.2 million views on TikTok alone. “They would say it’s risky for my career. But I didn’t join the medical field to continue the toxic status quo. I’m part of a new generation of health care professionals that are not afraid to be vulnerable and talk about mental health.”

“Dr. Jake,” as he calls himself on social media, admitted he was a physician who treats mental illness and also takes medication for it. “It felt good to say that. And by the way, I’m proud of it,” he said in the TikTok post.

A champion of mental health throughout the pandemic, Dr. Goodman called attention to the illness in the medical field. In a message on Instagram, he stated, “Opening up about your mental health as a medical professional, especially as a doctor who treats mental illness, can be taboo ... So here’s me leading by example.”

He also cited statistics on the challenge: “1 in 2 people will be diagnosed with a mental health illness at some point in their life. Yet many of us will never take medication that can help correct the chemical imbalance in our brains due to medication stigma: the fear that taking medications for our mental health somehow makes us weak.”

Mental health remains an issue among residents. Nearly 70% of residents polled by Medscape in its 2021 Residents Lifestyle & Happiness Report said they strongly or somewhat agree there’s a stigma against seeking mental health help. And nearly half, or 47% of those polled, said they sometimes (36%) or always/most of the time (11%) were depressed. The latter category rose in the past year.

Dr. Goodman told this news organization that he became passionate about mental health when he lost a college friend to suicide. “It really exposed the stigma” of mental health, he said. “I always knew it was there, but it took me seeing someone lose his life and [asking] why didn’t he feel comfortable talking to us, and why didn’t I feel comfortable talking to him?”

Stress of medical training

The decision to pursue psychiatry as his specialty came after a rotation in a clinic for people struggling with substance use disorders. “I was enthralled to see people change their life ... just by mental health care.” It’s why he went into medicine, he tells this news organization. “I always wanted to be in a field to help people [before they hit] rock bottom, when no one else could be there for them.”

Dr. Goodman’s personal battle with mental health didn’t arise until he started residency. “I was not really myself.” He said he felt numb and burned out. “I was not getting as much enjoyment out of things.” A friend pointed out that he might be depressed, so he went to see a therapist and then a psychiatrist and started on medication. “It had a profound impact on how I felt.”

Still, it took a while before Dr. Goodman was comfortable sharing his story with the 1.6 million followers he had already built across his social media platforms.

“I started on social media in 2020 with the goal of advocating for mental health and inspiring future doctors.” He said the message seemed to resonate with people struggling during the early part of the pandemic. On his social media accounts, he also talks about medical school, residency, and being a health care provider. His fiancé is also a resident doctor, in internal medicine.

Dr. Goodman is also trying to create a more realistic image of doctors than the superheroes he believed they were growing up. He wants those who grow up wanting to be doctors and who look up to him to see him as a human being with vulnerabilities, such as mental health.

“You can be a doctor and have mental health issues. Seeking treatment for mental health makes you a better doctor, and for other health care workers suffering in the midst of the pandemic, I want to let them know they are not alone.”

He pointed to the statistic that doctors have one of the highest suicide rates of any professions. “It’s better to talk about that in the early stages of training.”

Students, residents, or attending physicians who have mental health challenges shouldn’t allow their symptoms to go untreated, Dr. Goodman added. “Holding in all the stress and anxiety and feelings in a very traumatic field may be dangerous. ”

One of his goals is to campaign for the removal of a question on state medical licensing forms requiring doctors to report any mental health diagnosis. It’s why doctors may be afraid to admit that they are struggling. “I’m still here. It didn’t ruin my career.”

Doctors who seek treatment for mental health are theoretically protected under the Americans With Disabilities Act from being refused a license on the basis of that diagnosis. Dr. Goodman hopes to advocate at the state level to reduce discrimination and increase accessibility for doctors to seek mental health care.

Still, Dr. Goodman concedes he was initially fearful of the repercussions. “I opened up about it because this post could save lives. I was doing what I believed in.”

So if he runs into barriers to receive his medical license because of his admission, “that’s a serious problem,” he said. “There is already a shortage of doctors. We’ll see what happens in a few years. I am not the only one who will answer ‘yes’ to having sought treatment for a mental illness. The questions do not really need to be there.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

First-year psychiatry resident Jake Goodman, MD, knew he was taking a chance when he opened up on his popular social media platforms about his personal mental health battle. He mulled over the decision for several weeks before deciding to take the plunge.

As he voiced recently on his TikTok page, his biggest social media fanbase, with 1.3 million followers, it felt freeing to get his personal struggle off his chest.

“I’m a doctor in training, and most doctors would advise me not to post this,” the 29-year-old from Miami said in the video last month, which garnered 1.2 million views on TikTok alone. “They would say it’s risky for my career. But I didn’t join the medical field to continue the toxic status quo. I’m part of a new generation of health care professionals that are not afraid to be vulnerable and talk about mental health.”

“Dr. Jake,” as he calls himself on social media, admitted he was a physician who treats mental illness and also takes medication for it. “It felt good to say that. And by the way, I’m proud of it,” he said in the TikTok post.

A champion of mental health throughout the pandemic, Dr. Goodman called attention to the illness in the medical field. In a message on Instagram, he stated, “Opening up about your mental health as a medical professional, especially as a doctor who treats mental illness, can be taboo ... So here’s me leading by example.”

He also cited statistics on the challenge: “1 in 2 people will be diagnosed with a mental health illness at some point in their life. Yet many of us will never take medication that can help correct the chemical imbalance in our brains due to medication stigma: the fear that taking medications for our mental health somehow makes us weak.”

Mental health remains an issue among residents. Nearly 70% of residents polled by Medscape in its 2021 Residents Lifestyle & Happiness Report said they strongly or somewhat agree there’s a stigma against seeking mental health help. And nearly half, or 47% of those polled, said they sometimes (36%) or always/most of the time (11%) were depressed. The latter category rose in the past year.

Dr. Goodman told this news organization that he became passionate about mental health when he lost a college friend to suicide. “It really exposed the stigma” of mental health, he said. “I always knew it was there, but it took me seeing someone lose his life and [asking] why didn’t he feel comfortable talking to us, and why didn’t I feel comfortable talking to him?”

Stress of medical training

The decision to pursue psychiatry as his specialty came after a rotation in a clinic for people struggling with substance use disorders. “I was enthralled to see people change their life ... just by mental health care.” It’s why he went into medicine, he tells this news organization. “I always wanted to be in a field to help people [before they hit] rock bottom, when no one else could be there for them.”

Dr. Goodman’s personal battle with mental health didn’t arise until he started residency. “I was not really myself.” He said he felt numb and burned out. “I was not getting as much enjoyment out of things.” A friend pointed out that he might be depressed, so he went to see a therapist and then a psychiatrist and started on medication. “It had a profound impact on how I felt.”

Still, it took a while before Dr. Goodman was comfortable sharing his story with the 1.6 million followers he had already built across his social media platforms.

“I started on social media in 2020 with the goal of advocating for mental health and inspiring future doctors.” He said the message seemed to resonate with people struggling during the early part of the pandemic. On his social media accounts, he also talks about medical school, residency, and being a health care provider. His fiancé is also a resident doctor, in internal medicine.

Dr. Goodman is also trying to create a more realistic image of doctors than the superheroes he believed they were growing up. He wants those who grow up wanting to be doctors and who look up to him to see him as a human being with vulnerabilities, such as mental health.

“You can be a doctor and have mental health issues. Seeking treatment for mental health makes you a better doctor, and for other health care workers suffering in the midst of the pandemic, I want to let them know they are not alone.”

He pointed to the statistic that doctors have one of the highest suicide rates of any professions. “It’s better to talk about that in the early stages of training.”

Students, residents, or attending physicians who have mental health challenges shouldn’t allow their symptoms to go untreated, Dr. Goodman added. “Holding in all the stress and anxiety and feelings in a very traumatic field may be dangerous. ”

One of his goals is to campaign for the removal of a question on state medical licensing forms requiring doctors to report any mental health diagnosis. It’s why doctors may be afraid to admit that they are struggling. “I’m still here. It didn’t ruin my career.”

Doctors who seek treatment for mental health are theoretically protected under the Americans With Disabilities Act from being refused a license on the basis of that diagnosis. Dr. Goodman hopes to advocate at the state level to reduce discrimination and increase accessibility for doctors to seek mental health care.

Still, Dr. Goodman concedes he was initially fearful of the repercussions. “I opened up about it because this post could save lives. I was doing what I believed in.”

So if he runs into barriers to receive his medical license because of his admission, “that’s a serious problem,” he said. “There is already a shortage of doctors. We’ll see what happens in a few years. I am not the only one who will answer ‘yes’ to having sought treatment for a mental illness. The questions do not really need to be there.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

First-year psychiatry resident Jake Goodman, MD, knew he was taking a chance when he opened up on his popular social media platforms about his personal mental health battle. He mulled over the decision for several weeks before deciding to take the plunge.

As he voiced recently on his TikTok page, his biggest social media fanbase, with 1.3 million followers, it felt freeing to get his personal struggle off his chest.

“I’m a doctor in training, and most doctors would advise me not to post this,” the 29-year-old from Miami said in the video last month, which garnered 1.2 million views on TikTok alone. “They would say it’s risky for my career. But I didn’t join the medical field to continue the toxic status quo. I’m part of a new generation of health care professionals that are not afraid to be vulnerable and talk about mental health.”

“Dr. Jake,” as he calls himself on social media, admitted he was a physician who treats mental illness and also takes medication for it. “It felt good to say that. And by the way, I’m proud of it,” he said in the TikTok post.

A champion of mental health throughout the pandemic, Dr. Goodman called attention to the illness in the medical field. In a message on Instagram, he stated, “Opening up about your mental health as a medical professional, especially as a doctor who treats mental illness, can be taboo ... So here’s me leading by example.”

He also cited statistics on the challenge: “1 in 2 people will be diagnosed with a mental health illness at some point in their life. Yet many of us will never take medication that can help correct the chemical imbalance in our brains due to medication stigma: the fear that taking medications for our mental health somehow makes us weak.”

Mental health remains an issue among residents. Nearly 70% of residents polled by Medscape in its 2021 Residents Lifestyle & Happiness Report said they strongly or somewhat agree there’s a stigma against seeking mental health help. And nearly half, or 47% of those polled, said they sometimes (36%) or always/most of the time (11%) were depressed. The latter category rose in the past year.

Dr. Goodman told this news organization that he became passionate about mental health when he lost a college friend to suicide. “It really exposed the stigma” of mental health, he said. “I always knew it was there, but it took me seeing someone lose his life and [asking] why didn’t he feel comfortable talking to us, and why didn’t I feel comfortable talking to him?”

Stress of medical training

The decision to pursue psychiatry as his specialty came after a rotation in a clinic for people struggling with substance use disorders. “I was enthralled to see people change their life ... just by mental health care.” It’s why he went into medicine, he tells this news organization. “I always wanted to be in a field to help people [before they hit] rock bottom, when no one else could be there for them.”

Dr. Goodman’s personal battle with mental health didn’t arise until he started residency. “I was not really myself.” He said he felt numb and burned out. “I was not getting as much enjoyment out of things.” A friend pointed out that he might be depressed, so he went to see a therapist and then a psychiatrist and started on medication. “It had a profound impact on how I felt.”

Still, it took a while before Dr. Goodman was comfortable sharing his story with the 1.6 million followers he had already built across his social media platforms.

“I started on social media in 2020 with the goal of advocating for mental health and inspiring future doctors.” He said the message seemed to resonate with people struggling during the early part of the pandemic. On his social media accounts, he also talks about medical school, residency, and being a health care provider. His fiancé is also a resident doctor, in internal medicine.

Dr. Goodman is also trying to create a more realistic image of doctors than the superheroes he believed they were growing up. He wants those who grow up wanting to be doctors and who look up to him to see him as a human being with vulnerabilities, such as mental health.

“You can be a doctor and have mental health issues. Seeking treatment for mental health makes you a better doctor, and for other health care workers suffering in the midst of the pandemic, I want to let them know they are not alone.”

He pointed to the statistic that doctors have one of the highest suicide rates of any professions. “It’s better to talk about that in the early stages of training.”

Students, residents, or attending physicians who have mental health challenges shouldn’t allow their symptoms to go untreated, Dr. Goodman added. “Holding in all the stress and anxiety and feelings in a very traumatic field may be dangerous. ”

One of his goals is to campaign for the removal of a question on state medical licensing forms requiring doctors to report any mental health diagnosis. It’s why doctors may be afraid to admit that they are struggling. “I’m still here. It didn’t ruin my career.”

Doctors who seek treatment for mental health are theoretically protected under the Americans With Disabilities Act from being refused a license on the basis of that diagnosis. Dr. Goodman hopes to advocate at the state level to reduce discrimination and increase accessibility for doctors to seek mental health care.

Still, Dr. Goodman concedes he was initially fearful of the repercussions. “I opened up about it because this post could save lives. I was doing what I believed in.”

So if he runs into barriers to receive his medical license because of his admission, “that’s a serious problem,” he said. “There is already a shortage of doctors. We’ll see what happens in a few years. I am not the only one who will answer ‘yes’ to having sought treatment for a mental illness. The questions do not really need to be there.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

When the patient wants to speak to a manager

A patient swore at me the other day. Not as in “she used a curse word.” As in she spewed fury, spitting out a vulgar, adverbial word before “... terrible doctor” while jabbing her finger toward me. In my 15 years of practice, I’d never had that happen before. Equally surprising, I was not surprised by her outburst. The level of incivility from patients is at an all-time high.

Her anger was misdirected. She wanted me to write a letter to her employer excusing her from getting a vaccine. It was neither indicated nor ethical for me to do so. I did my best to redirect her, but without success. As our chief of service, I often help with service concerns and am happy to see patients who want another opinion or want to speak with the department head (aka, “the manager”). Usually I can help. Lately, it’s become harder.

Not only are such rude incidents more frequent, but they are also more dramatic and inappropriate. For example, I cannot imagine writing a complaint against a doctor stating that she must be a foreign medical grad (as it happens, she’s Ivy League-trained) or demanding money back when a biopsy result turned out to be benign, or threatening to report a doctor to the medical board because he failed to schedule a follow-up appointment (that doctor had been retired for months). Patients have hung up on our staff mid-sentence and slammed a clinic door when they left in a huff. Why are so many previously sensible people throwing childlike tantrums?

It’s the same phenomenon happening to our fellow service agents across all industries. The Federal Aviation Administration’s graph of unruly passenger incidents is a flat line from 1995 to 2019, then it goes straight vertical. A recent survey showed that Americans’ sense of civility is low and worse, that people’s expectations that civility will improve is going down. It’s palpable. Last month, I witnessed a man and woman screaming at each other over Christmas lights in a busy store. An army of aproned walkie-talkie staff surrounded them and escorted them out – their coordination and efficiency clearly indicated they’d done this before. Customers everywhere are mad, frustrated, disenfranchised. Lately, a lot of things just are not working out for them. Supplies are out. Kids are sent home from school. No elective surgery appointments are available. The insta-gratification they’ve grown accustomed to from Amazon and DoorDash is colliding with the reality that not everything works that way.

The word “patient’’ you’ll recall comes from the Latin “patior,” meaning to suffer or bear. With virus variants raging, inflation growing, and call center wait times approaching infinity, many of our patients, it seems, cannot bear any more. I’m confident this situation will improve and our patients will be more reasonable in their expectations, but I am afraid that, in the end, we’ll have lost some decorum and dignity that we may never find again in medicine.

For my potty-mouthed patient, I made an excuse to leave the room to get my dermatoscope and walked out. It gave her time to calm down. I returned in a few minutes to do a skin exam. As I was wrapping up, I advised her that she cannot raise her voice or use offensive language and that she should know that I and everyone in our office cares about her and wants to help. She did apologize for her behavior, but then had to add that, if I really cared, I’d write the letter for her.

I guess the customer is not always right.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected]

A patient swore at me the other day. Not as in “she used a curse word.” As in she spewed fury, spitting out a vulgar, adverbial word before “... terrible doctor” while jabbing her finger toward me. In my 15 years of practice, I’d never had that happen before. Equally surprising, I was not surprised by her outburst. The level of incivility from patients is at an all-time high.

Her anger was misdirected. She wanted me to write a letter to her employer excusing her from getting a vaccine. It was neither indicated nor ethical for me to do so. I did my best to redirect her, but without success. As our chief of service, I often help with service concerns and am happy to see patients who want another opinion or want to speak with the department head (aka, “the manager”). Usually I can help. Lately, it’s become harder.

Not only are such rude incidents more frequent, but they are also more dramatic and inappropriate. For example, I cannot imagine writing a complaint against a doctor stating that she must be a foreign medical grad (as it happens, she’s Ivy League-trained) or demanding money back when a biopsy result turned out to be benign, or threatening to report a doctor to the medical board because he failed to schedule a follow-up appointment (that doctor had been retired for months). Patients have hung up on our staff mid-sentence and slammed a clinic door when they left in a huff. Why are so many previously sensible people throwing childlike tantrums?

It’s the same phenomenon happening to our fellow service agents across all industries. The Federal Aviation Administration’s graph of unruly passenger incidents is a flat line from 1995 to 2019, then it goes straight vertical. A recent survey showed that Americans’ sense of civility is low and worse, that people’s expectations that civility will improve is going down. It’s palpable. Last month, I witnessed a man and woman screaming at each other over Christmas lights in a busy store. An army of aproned walkie-talkie staff surrounded them and escorted them out – their coordination and efficiency clearly indicated they’d done this before. Customers everywhere are mad, frustrated, disenfranchised. Lately, a lot of things just are not working out for them. Supplies are out. Kids are sent home from school. No elective surgery appointments are available. The insta-gratification they’ve grown accustomed to from Amazon and DoorDash is colliding with the reality that not everything works that way.

The word “patient’’ you’ll recall comes from the Latin “patior,” meaning to suffer or bear. With virus variants raging, inflation growing, and call center wait times approaching infinity, many of our patients, it seems, cannot bear any more. I’m confident this situation will improve and our patients will be more reasonable in their expectations, but I am afraid that, in the end, we’ll have lost some decorum and dignity that we may never find again in medicine.

For my potty-mouthed patient, I made an excuse to leave the room to get my dermatoscope and walked out. It gave her time to calm down. I returned in a few minutes to do a skin exam. As I was wrapping up, I advised her that she cannot raise her voice or use offensive language and that she should know that I and everyone in our office cares about her and wants to help. She did apologize for her behavior, but then had to add that, if I really cared, I’d write the letter for her.

I guess the customer is not always right.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected]

A patient swore at me the other day. Not as in “she used a curse word.” As in she spewed fury, spitting out a vulgar, adverbial word before “... terrible doctor” while jabbing her finger toward me. In my 15 years of practice, I’d never had that happen before. Equally surprising, I was not surprised by her outburst. The level of incivility from patients is at an all-time high.

Her anger was misdirected. She wanted me to write a letter to her employer excusing her from getting a vaccine. It was neither indicated nor ethical for me to do so. I did my best to redirect her, but without success. As our chief of service, I often help with service concerns and am happy to see patients who want another opinion or want to speak with the department head (aka, “the manager”). Usually I can help. Lately, it’s become harder.

Not only are such rude incidents more frequent, but they are also more dramatic and inappropriate. For example, I cannot imagine writing a complaint against a doctor stating that she must be a foreign medical grad (as it happens, she’s Ivy League-trained) or demanding money back when a biopsy result turned out to be benign, or threatening to report a doctor to the medical board because he failed to schedule a follow-up appointment (that doctor had been retired for months). Patients have hung up on our staff mid-sentence and slammed a clinic door when they left in a huff. Why are so many previously sensible people throwing childlike tantrums?

It’s the same phenomenon happening to our fellow service agents across all industries. The Federal Aviation Administration’s graph of unruly passenger incidents is a flat line from 1995 to 2019, then it goes straight vertical. A recent survey showed that Americans’ sense of civility is low and worse, that people’s expectations that civility will improve is going down. It’s palpable. Last month, I witnessed a man and woman screaming at each other over Christmas lights in a busy store. An army of aproned walkie-talkie staff surrounded them and escorted them out – their coordination and efficiency clearly indicated they’d done this before. Customers everywhere are mad, frustrated, disenfranchised. Lately, a lot of things just are not working out for them. Supplies are out. Kids are sent home from school. No elective surgery appointments are available. The insta-gratification they’ve grown accustomed to from Amazon and DoorDash is colliding with the reality that not everything works that way.

The word “patient’’ you’ll recall comes from the Latin “patior,” meaning to suffer or bear. With virus variants raging, inflation growing, and call center wait times approaching infinity, many of our patients, it seems, cannot bear any more. I’m confident this situation will improve and our patients will be more reasonable in their expectations, but I am afraid that, in the end, we’ll have lost some decorum and dignity that we may never find again in medicine.

For my potty-mouthed patient, I made an excuse to leave the room to get my dermatoscope and walked out. It gave her time to calm down. I returned in a few minutes to do a skin exam. As I was wrapping up, I advised her that she cannot raise her voice or use offensive language and that she should know that I and everyone in our office cares about her and wants to help. She did apologize for her behavior, but then had to add that, if I really cared, I’d write the letter for her.

I guess the customer is not always right.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected]

Mental health problems in kids linked with school closures

Behavior problems, anxiety, and depression in youths were associated with these individuals participating in remote schooling during broader social lockdowns in a new study.

The systematic review, which was published in JAMA Pediatrics on Jan. 18, 2022, was based on data from 36 studies from 11 countries on mental health, physical health, and well-being in children and adolescents aged 0-18 years. The total population included 79,781 children and 18,028 parents or caregivers. The studies reflected the first wave of pandemic school closures and lockdowns from February to July 2020, with the duration of school closure ranging from 1 week to 3 months.

“There are strong theoretical reasons to suggest that school closures may have contributed to a considerable proportion of the harms identified here, particularly mental health harms, through reduction in social contacts with peers and teachers,” Russell Viner, PhD, of UCL Great Ormond St Institute of Child Health, London, and colleagues wrote in their paper.

The researchers included 9 longitudinal pre-post studies, 5 cohort studies, 21 cross-sectional studies, and 1 modeling study in their analysis. Overall, approximately one-third of the studies (36%) were considered high quality, and approximately two-thirds (64%) of the studies were published in journals. Twenty-five of the reports analyzed focused on mental health and well-being.

Schools provide not only education, but also services including meals, health care, and health supplies. Schools also serve as a safety net and source of social support for children, the researchers noted.

The losses children may have experienced during school closures occurred during a time when more than 167,000 children younger than 18 years lost a parent or caregiver to COVID-19, according to a recent report titled “Hidden Pain” by researchers at the University of Pennsylvania, Nemours Children’s Health, and the COVID Collaborative. Although not addressed in the current study, school closures would prevent bereaved children from receiving social-emotional support from friends and teachers. This crisis of loss also prompted the American Academy of Pediatrics to issue a National State of Emergency in Children’s Mental Health in October 2021.

New study results

These studies identified associations between school closures during broader lockdowns and increased emotional and behavioral problems, as well as increased restlessness and inattention. Across these studies, 18%-60% of children and adolescents scored higher than the risk thresholds for diagnoses of distress, especially depressive symptoms and anxiety.

Although two studies showed no significant association with suicide in response to school closures during lockdowns, three studies suggested increased use of screen time, two studies reported increased social media use, and six studies reported lower levels of physical activity.

Three studies of child abuse showed decreases in notifications during lockdowns, likely driven by lack of referrals from schools, the authors noted. A total of 10 studies on sleep and 5 studies on diet showed inconsistent evidence of harm during the specific period of school closures and social lockdowns.

“The contrast of rises in distress with decreases in presentations suggests that there was an escalation of unmet mental health need during lockdowns in already vulnerable children and adolescents,” the researchers wrote. “More troubling still is evidence of a reduction in the ability of the health and social care systems to protect children in many countries, as shown by the large falls in child protection referrals seen in high-quality cohort studies.”

‘Study presents concrete assessments rather than speculation’

“Concerns have been widely expressed in the lay media and beyond that school closures could negatively impact the mental and physical health of children and adolescents,” M. Susan Jay, MD, of the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, said in an interview. “The authors presented a narrative synthesis summarizing available evidence for the first wave of COVID-19 on school closures during the broader social lockdown occurring during this period.”

The “importance” of this research is that “it is not a single convenience sample study, but a systematic review from 11 countries including the United States, United Kingdom, China, and Turkey, among others, and that the quality of the information was graded,” Dr. Jay said. “Although not a meta-analysis, the study presents concrete assessments rather than speculation and overviews its limitations so that the clinician can weigh this information. Importantly, the authors excluded closure of schools with transmission of infection.

“Clearly, school lockdowns as a measure of controlling infectious disease needs balance with potential of negative health behaviors in children and adolescents. Ongoing prospective longitudinal studies are needed as sequential waves of the pandemic continue,” she emphasized.

“Clinically, this study highlights the need for clinicians to consider [asking] about the impact of school closures and remote versus hybrid versus in-person education [as part of their] patients and families question inventory,” Dr. Jay said. “Also, the use of depression inventories can be offered to youth to assess their mental health state at a visit, either via telemedicine or in person, and ideally at sequential visits for a more in-depth assessment.”

Schools play key role in social and emotional development

“It was important to conduct this study now, because this current time is unprecedented,” Peter L. Loper Jr., MD, of the University of South Carolina, Columbia, said in an interview. “We know based on evolutionary biology, anthropology, and developmental psychology, among other disciplines, that meaningful interpersonal interactions embedded in the context of community are vital to supporting human well-being.

“In our current time, the primary framework of community for our children is the school setting; it is the predominant space where they engage in the interpersonal interactions necessary for developing resilience, their sense of purpose, belonging, and fidelity,” he emphasized.

“Rarely in the course of human existence have kids been removed from the broader context of community to this extent and for this duration,” Dr. Loper said. “This study capitalizes on this unprecedented moment to begin to further understand how compromises in our sociocultural infrastructure of community, like school closures and lockdowns, may manifest as mental health problems in children and adolescents. More importantly, it contributes to the exploration of potential unintended consequences of our current infection control measures so we can adapt to support the overall well-being of our children in this ‘new normal.’ ”

Dr. Loper added that he was not surprised by the new study’s findings.

“We were already seeing a decline in pediatric mental health and overall well-being in the years preceding COVID-19 because of the ‘isolation epidemic’ involving many of the factors that this study explored,” he said. “I think this review further illustrates the vital necessity of community to support the health and well-being of humans, and specifically children and adolescents.”

From a clinical standpoint, “we need to be intentional and consistent in balancing infection control measures with our kids’ fundamental psychosocial needs,” Dr. Loper said.

“We need to recognize that, when children and adolescents are isolated from community, their fundamental psychosocial needs go unmet,” he emphasized. “If children and adolescents cannot access the meaningful interpersonal interactions necessary for resilience, then they cannot overcome or navigate distress. They will exhibit the avoidance and withdrawal behaviors that accumulate to manifest as adverse mental health symptoms like anxiety and depression.

“Additional research is needed to further explore how compromises in the psychosocial infrastructure of community manifest as downstream symptom indicators such as anxiety and depression,” which are often manifestations of unmet needs, Dr. Loper said.

Limitations and strengths, according to authors

The findings were limited by several factors, including a lack of examination of school closures’ effects on mental health independent of broader social lockdowns, according to the researchers. Other limitations included the authors potentially having missed studies, inclusion of cross-sectional studies with relatively weak evidence, potential bias from studies using parent reports, and a focus on the first COVID-19 wave, during which many school closures were of limited duration. Also, the researchers said they did not include studies focused on particular groups, such as children with learning difficulties or autism.

The use of large databases from education as well as health care in studies analyzed were strengths of the new research, they said. The investigators received no outside funding for their study. The researchers, Dr. Jay, and Dr. Loper had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Jay serves on the editorial advisory board of Pediatric News.

Behavior problems, anxiety, and depression in youths were associated with these individuals participating in remote schooling during broader social lockdowns in a new study.

The systematic review, which was published in JAMA Pediatrics on Jan. 18, 2022, was based on data from 36 studies from 11 countries on mental health, physical health, and well-being in children and adolescents aged 0-18 years. The total population included 79,781 children and 18,028 parents or caregivers. The studies reflected the first wave of pandemic school closures and lockdowns from February to July 2020, with the duration of school closure ranging from 1 week to 3 months.

“There are strong theoretical reasons to suggest that school closures may have contributed to a considerable proportion of the harms identified here, particularly mental health harms, through reduction in social contacts with peers and teachers,” Russell Viner, PhD, of UCL Great Ormond St Institute of Child Health, London, and colleagues wrote in their paper.

The researchers included 9 longitudinal pre-post studies, 5 cohort studies, 21 cross-sectional studies, and 1 modeling study in their analysis. Overall, approximately one-third of the studies (36%) were considered high quality, and approximately two-thirds (64%) of the studies were published in journals. Twenty-five of the reports analyzed focused on mental health and well-being.

Schools provide not only education, but also services including meals, health care, and health supplies. Schools also serve as a safety net and source of social support for children, the researchers noted.

The losses children may have experienced during school closures occurred during a time when more than 167,000 children younger than 18 years lost a parent or caregiver to COVID-19, according to a recent report titled “Hidden Pain” by researchers at the University of Pennsylvania, Nemours Children’s Health, and the COVID Collaborative. Although not addressed in the current study, school closures would prevent bereaved children from receiving social-emotional support from friends and teachers. This crisis of loss also prompted the American Academy of Pediatrics to issue a National State of Emergency in Children’s Mental Health in October 2021.

New study results

These studies identified associations between school closures during broader lockdowns and increased emotional and behavioral problems, as well as increased restlessness and inattention. Across these studies, 18%-60% of children and adolescents scored higher than the risk thresholds for diagnoses of distress, especially depressive symptoms and anxiety.

Although two studies showed no significant association with suicide in response to school closures during lockdowns, three studies suggested increased use of screen time, two studies reported increased social media use, and six studies reported lower levels of physical activity.

Three studies of child abuse showed decreases in notifications during lockdowns, likely driven by lack of referrals from schools, the authors noted. A total of 10 studies on sleep and 5 studies on diet showed inconsistent evidence of harm during the specific period of school closures and social lockdowns.

“The contrast of rises in distress with decreases in presentations suggests that there was an escalation of unmet mental health need during lockdowns in already vulnerable children and adolescents,” the researchers wrote. “More troubling still is evidence of a reduction in the ability of the health and social care systems to protect children in many countries, as shown by the large falls in child protection referrals seen in high-quality cohort studies.”

‘Study presents concrete assessments rather than speculation’

“Concerns have been widely expressed in the lay media and beyond that school closures could negatively impact the mental and physical health of children and adolescents,” M. Susan Jay, MD, of the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, said in an interview. “The authors presented a narrative synthesis summarizing available evidence for the first wave of COVID-19 on school closures during the broader social lockdown occurring during this period.”

The “importance” of this research is that “it is not a single convenience sample study, but a systematic review from 11 countries including the United States, United Kingdom, China, and Turkey, among others, and that the quality of the information was graded,” Dr. Jay said. “Although not a meta-analysis, the study presents concrete assessments rather than speculation and overviews its limitations so that the clinician can weigh this information. Importantly, the authors excluded closure of schools with transmission of infection.

“Clearly, school lockdowns as a measure of controlling infectious disease needs balance with potential of negative health behaviors in children and adolescents. Ongoing prospective longitudinal studies are needed as sequential waves of the pandemic continue,” she emphasized.

“Clinically, this study highlights the need for clinicians to consider [asking] about the impact of school closures and remote versus hybrid versus in-person education [as part of their] patients and families question inventory,” Dr. Jay said. “Also, the use of depression inventories can be offered to youth to assess their mental health state at a visit, either via telemedicine or in person, and ideally at sequential visits for a more in-depth assessment.”

Schools play key role in social and emotional development

“It was important to conduct this study now, because this current time is unprecedented,” Peter L. Loper Jr., MD, of the University of South Carolina, Columbia, said in an interview. “We know based on evolutionary biology, anthropology, and developmental psychology, among other disciplines, that meaningful interpersonal interactions embedded in the context of community are vital to supporting human well-being.

“In our current time, the primary framework of community for our children is the school setting; it is the predominant space where they engage in the interpersonal interactions necessary for developing resilience, their sense of purpose, belonging, and fidelity,” he emphasized.

“Rarely in the course of human existence have kids been removed from the broader context of community to this extent and for this duration,” Dr. Loper said. “This study capitalizes on this unprecedented moment to begin to further understand how compromises in our sociocultural infrastructure of community, like school closures and lockdowns, may manifest as mental health problems in children and adolescents. More importantly, it contributes to the exploration of potential unintended consequences of our current infection control measures so we can adapt to support the overall well-being of our children in this ‘new normal.’ ”

Dr. Loper added that he was not surprised by the new study’s findings.

“We were already seeing a decline in pediatric mental health and overall well-being in the years preceding COVID-19 because of the ‘isolation epidemic’ involving many of the factors that this study explored,” he said. “I think this review further illustrates the vital necessity of community to support the health and well-being of humans, and specifically children and adolescents.”

From a clinical standpoint, “we need to be intentional and consistent in balancing infection control measures with our kids’ fundamental psychosocial needs,” Dr. Loper said.