User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

Aerobic exercise augments PTSD therapy

Investigators randomly assigned individuals with PTSD to receive either exposure therapy with aerobic exercise or exposure therapy with passive stretching for 9 weeks. At 6 months post intervention, participants in the aerobic exercise group showed greater reductions in PTSD severity, compared with those in the stretching group.

“There is a critical need to improve outcomes for treating people with PTSD, and this finding points to one potentially cheap and ready-to-use strategy that all clinicians could employ with most patients,” lead author Richard Bryant, MPsych, PhD, DSc, director of the Traumatic Stress Clinic and Scientia Professor of Psychology at the University of New South Wales, Sydney, told this news organization.

The study was published online in The Lancet Psychiatry.

Promoting BDNF

“Trauma-focused psychotherapy is the recommended treatment for PTSD, but up to half of patients do not respond to this treatment,” Dr. Bryant said.

“We know that brain-derived neurotrophic factors [BDNF] are critical for synaptic plasticity, which underpins the learning that occurs in therapy so that reminders of trauma are no longer fear-provoking,” he continued. “Preclinical animal and human research inform us that brief aerobic exercise can promote BDNF and new learning that inhibits fear responses.”

The researchers “hypothesized that brief exercise after exposure therapy to trauma memories – which is the key ingredient of trauma-focused psychotherapy – would lead to greater reductions in PTSD, relative to standard trauma-focused therapy,” he said.

To investigate the question, the researchers randomly assigned 130 adults with PTSD (mean age, 39 years; 61% female; 76% White) to receive nine 90-minute sessions of exposure therapy with either aerobic exercise or passive stretching (n = 65 in each group).

There were no differences at baseline in sociodemographic characteristics or psychopathology measures, although the mean age of the stretching group was slightly older than that of the aerobic group (40 years vs. 37 years, respectively), and there was a slightly higher proportion of women in the stretching group (68% vs. 54%).

Participants did not differ on weekly exercise either at baseline, immediately post treatment, or at 6-week follow-up.

PTSD severity (the primary outcome) was measured using the clinician-administered PTSD scale CAPS-2, with assessments conducted at baseline, 1 week post treatment, and 6 months post treatment.

The aerobic exercise regimen was tailored to each participant, based on an assessment of his/her aerobic target zone.

The exposure therapy sessions were identical for both groups. Following the exposure sessions, participants engaged in their respective exercises: Those in the passive stretching group engaged in 20 minutes of exercise, while those in the aerobic group participated in a total of 20 minutes of exercise, with 10 conducted at their personal aerobic target heart rate.

“This level of exercise was chosen because BDNF concentration in the serum is increased by two 3-minute bouts of aerobic exercise, and 10 minutes of aerobic exercise can facilitate extinction learning,” the authors explained.

The aerobic activity consisted of running on a stepper exercise platform while having cardiac activity recorded. A small portion (10%) of the therapy sessions were recorded and rated for treatment fidelity.

Change in PTSD was the primary outcome, with secondary outcomes consisting of changes in depression, anxiety, alcohol use disorder, and posttraumatic cognitions.

Few barriers

The researchers found no significant differences in PTSD severity, as measured by CAPS-2 score, between treatment groups at 10 weeks – that is, immediately post treatment (mean difference, 7.0; 95% confidence interval, –2.3 to 16.4; P = .14).

However, significantly greater reductions in PTSD severity were found in the aerobic versus the stretching group at 6-month follow-up (mean difference, 12.1;95% CI, 2.4-21.8; P = .023), pointing to a “moderate effect size” (d = 0.6; 95% CI, 0.1-1.1]).

Although there were no differences found at 6-month assessment between rates of PTSD diagnosis (25% of the aerobic vs 27% of the stretching group), more participants in the aerobic group reached a “minimal clinically important difference,” compared to those in the stretching group (96% vs. 84%, respectively, x2 = 4.4; P = .036).

There were also superior benefits found in the aerobic versus the stretching group on depression severity at 6 months (a secondary outcome), with a mean difference in Beck Depression Inventory-2 score of 5.7 (95% CI, 0.5-10.9; P = .022), yielding a “moderate effect size” (d = 0.5; 95% CI, 0.1-1.0]).

There were no adverse events associated with the intervention, and almost all the sessions (88%) complied with the treatment protocol.

The researchers noted several limitations. For example, they did not obtain plasma to measure BDNF concentrations, so they could not “infer whether the mechanism of change involved BDNF.”

In addition, they did not perform sex-specific analyses. “Future studies could increase the sample size to investigate sex differences because females display less BDNF change following exercise than do males,” they wrote.

Nevertheless, the study “provides initial evidence of a simple and accessible strategy that clinicians could readily apply in combination with exposure therapy,” they stated. “Whereas many pharmacologic interventions pose barriers, including cost, requirement for prescriptions, and patient resistance to drugs, exercise offers clinicians a strategy that can be implemented with few barriers.”

Dr. Bryant emphasized that one study “does not represent a body of evidence, and so it is essential that this finding be replicated in other trials before it can be recommended for clinical use.” He noted that other trials are “currently underway.”

Easy augmentation

In a comment, Barbara Rothbaum, PhD, professor in psychiatry and director of the Trauma and Anxiety Recovery Program at Emory University, Atlanta, called it a “well-controlled trial augmenting exposure therapy for PTSD with brief aerobic exercise and finding some benefits of the augmented condition at 6 months posttreatment but not immediately posttreatment.”

The study’s methodology – that is, using independent standard assessment of PTSD and rating audio recordings of therapy sessions for treatment fidelity and quality – can lead us to “be confident in their [the researchers’] conclusions,” she said.

Dr. Rothbaum, who was not associated with this study, described research into methods to augment exposure therapy for PTSD as “timely and clinically relevant.”

Exercise “would be an easy augmentation for many clinicians if it is helpful,” she noted.

The study was funded by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council. The authors and Dr. Rothbaum reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators randomly assigned individuals with PTSD to receive either exposure therapy with aerobic exercise or exposure therapy with passive stretching for 9 weeks. At 6 months post intervention, participants in the aerobic exercise group showed greater reductions in PTSD severity, compared with those in the stretching group.

“There is a critical need to improve outcomes for treating people with PTSD, and this finding points to one potentially cheap and ready-to-use strategy that all clinicians could employ with most patients,” lead author Richard Bryant, MPsych, PhD, DSc, director of the Traumatic Stress Clinic and Scientia Professor of Psychology at the University of New South Wales, Sydney, told this news organization.

The study was published online in The Lancet Psychiatry.

Promoting BDNF

“Trauma-focused psychotherapy is the recommended treatment for PTSD, but up to half of patients do not respond to this treatment,” Dr. Bryant said.

“We know that brain-derived neurotrophic factors [BDNF] are critical for synaptic plasticity, which underpins the learning that occurs in therapy so that reminders of trauma are no longer fear-provoking,” he continued. “Preclinical animal and human research inform us that brief aerobic exercise can promote BDNF and new learning that inhibits fear responses.”

The researchers “hypothesized that brief exercise after exposure therapy to trauma memories – which is the key ingredient of trauma-focused psychotherapy – would lead to greater reductions in PTSD, relative to standard trauma-focused therapy,” he said.

To investigate the question, the researchers randomly assigned 130 adults with PTSD (mean age, 39 years; 61% female; 76% White) to receive nine 90-minute sessions of exposure therapy with either aerobic exercise or passive stretching (n = 65 in each group).

There were no differences at baseline in sociodemographic characteristics or psychopathology measures, although the mean age of the stretching group was slightly older than that of the aerobic group (40 years vs. 37 years, respectively), and there was a slightly higher proportion of women in the stretching group (68% vs. 54%).

Participants did not differ on weekly exercise either at baseline, immediately post treatment, or at 6-week follow-up.

PTSD severity (the primary outcome) was measured using the clinician-administered PTSD scale CAPS-2, with assessments conducted at baseline, 1 week post treatment, and 6 months post treatment.

The aerobic exercise regimen was tailored to each participant, based on an assessment of his/her aerobic target zone.

The exposure therapy sessions were identical for both groups. Following the exposure sessions, participants engaged in their respective exercises: Those in the passive stretching group engaged in 20 minutes of exercise, while those in the aerobic group participated in a total of 20 minutes of exercise, with 10 conducted at their personal aerobic target heart rate.

“This level of exercise was chosen because BDNF concentration in the serum is increased by two 3-minute bouts of aerobic exercise, and 10 minutes of aerobic exercise can facilitate extinction learning,” the authors explained.

The aerobic activity consisted of running on a stepper exercise platform while having cardiac activity recorded. A small portion (10%) of the therapy sessions were recorded and rated for treatment fidelity.

Change in PTSD was the primary outcome, with secondary outcomes consisting of changes in depression, anxiety, alcohol use disorder, and posttraumatic cognitions.

Few barriers

The researchers found no significant differences in PTSD severity, as measured by CAPS-2 score, between treatment groups at 10 weeks – that is, immediately post treatment (mean difference, 7.0; 95% confidence interval, –2.3 to 16.4; P = .14).

However, significantly greater reductions in PTSD severity were found in the aerobic versus the stretching group at 6-month follow-up (mean difference, 12.1;95% CI, 2.4-21.8; P = .023), pointing to a “moderate effect size” (d = 0.6; 95% CI, 0.1-1.1]).

Although there were no differences found at 6-month assessment between rates of PTSD diagnosis (25% of the aerobic vs 27% of the stretching group), more participants in the aerobic group reached a “minimal clinically important difference,” compared to those in the stretching group (96% vs. 84%, respectively, x2 = 4.4; P = .036).

There were also superior benefits found in the aerobic versus the stretching group on depression severity at 6 months (a secondary outcome), with a mean difference in Beck Depression Inventory-2 score of 5.7 (95% CI, 0.5-10.9; P = .022), yielding a “moderate effect size” (d = 0.5; 95% CI, 0.1-1.0]).

There were no adverse events associated with the intervention, and almost all the sessions (88%) complied with the treatment protocol.

The researchers noted several limitations. For example, they did not obtain plasma to measure BDNF concentrations, so they could not “infer whether the mechanism of change involved BDNF.”

In addition, they did not perform sex-specific analyses. “Future studies could increase the sample size to investigate sex differences because females display less BDNF change following exercise than do males,” they wrote.

Nevertheless, the study “provides initial evidence of a simple and accessible strategy that clinicians could readily apply in combination with exposure therapy,” they stated. “Whereas many pharmacologic interventions pose barriers, including cost, requirement for prescriptions, and patient resistance to drugs, exercise offers clinicians a strategy that can be implemented with few barriers.”

Dr. Bryant emphasized that one study “does not represent a body of evidence, and so it is essential that this finding be replicated in other trials before it can be recommended for clinical use.” He noted that other trials are “currently underway.”

Easy augmentation

In a comment, Barbara Rothbaum, PhD, professor in psychiatry and director of the Trauma and Anxiety Recovery Program at Emory University, Atlanta, called it a “well-controlled trial augmenting exposure therapy for PTSD with brief aerobic exercise and finding some benefits of the augmented condition at 6 months posttreatment but not immediately posttreatment.”

The study’s methodology – that is, using independent standard assessment of PTSD and rating audio recordings of therapy sessions for treatment fidelity and quality – can lead us to “be confident in their [the researchers’] conclusions,” she said.

Dr. Rothbaum, who was not associated with this study, described research into methods to augment exposure therapy for PTSD as “timely and clinically relevant.”

Exercise “would be an easy augmentation for many clinicians if it is helpful,” she noted.

The study was funded by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council. The authors and Dr. Rothbaum reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators randomly assigned individuals with PTSD to receive either exposure therapy with aerobic exercise or exposure therapy with passive stretching for 9 weeks. At 6 months post intervention, participants in the aerobic exercise group showed greater reductions in PTSD severity, compared with those in the stretching group.

“There is a critical need to improve outcomes for treating people with PTSD, and this finding points to one potentially cheap and ready-to-use strategy that all clinicians could employ with most patients,” lead author Richard Bryant, MPsych, PhD, DSc, director of the Traumatic Stress Clinic and Scientia Professor of Psychology at the University of New South Wales, Sydney, told this news organization.

The study was published online in The Lancet Psychiatry.

Promoting BDNF

“Trauma-focused psychotherapy is the recommended treatment for PTSD, but up to half of patients do not respond to this treatment,” Dr. Bryant said.

“We know that brain-derived neurotrophic factors [BDNF] are critical for synaptic plasticity, which underpins the learning that occurs in therapy so that reminders of trauma are no longer fear-provoking,” he continued. “Preclinical animal and human research inform us that brief aerobic exercise can promote BDNF and new learning that inhibits fear responses.”

The researchers “hypothesized that brief exercise after exposure therapy to trauma memories – which is the key ingredient of trauma-focused psychotherapy – would lead to greater reductions in PTSD, relative to standard trauma-focused therapy,” he said.

To investigate the question, the researchers randomly assigned 130 adults with PTSD (mean age, 39 years; 61% female; 76% White) to receive nine 90-minute sessions of exposure therapy with either aerobic exercise or passive stretching (n = 65 in each group).

There were no differences at baseline in sociodemographic characteristics or psychopathology measures, although the mean age of the stretching group was slightly older than that of the aerobic group (40 years vs. 37 years, respectively), and there was a slightly higher proportion of women in the stretching group (68% vs. 54%).

Participants did not differ on weekly exercise either at baseline, immediately post treatment, or at 6-week follow-up.

PTSD severity (the primary outcome) was measured using the clinician-administered PTSD scale CAPS-2, with assessments conducted at baseline, 1 week post treatment, and 6 months post treatment.

The aerobic exercise regimen was tailored to each participant, based on an assessment of his/her aerobic target zone.

The exposure therapy sessions were identical for both groups. Following the exposure sessions, participants engaged in their respective exercises: Those in the passive stretching group engaged in 20 minutes of exercise, while those in the aerobic group participated in a total of 20 minutes of exercise, with 10 conducted at their personal aerobic target heart rate.

“This level of exercise was chosen because BDNF concentration in the serum is increased by two 3-minute bouts of aerobic exercise, and 10 minutes of aerobic exercise can facilitate extinction learning,” the authors explained.

The aerobic activity consisted of running on a stepper exercise platform while having cardiac activity recorded. A small portion (10%) of the therapy sessions were recorded and rated for treatment fidelity.

Change in PTSD was the primary outcome, with secondary outcomes consisting of changes in depression, anxiety, alcohol use disorder, and posttraumatic cognitions.

Few barriers

The researchers found no significant differences in PTSD severity, as measured by CAPS-2 score, between treatment groups at 10 weeks – that is, immediately post treatment (mean difference, 7.0; 95% confidence interval, –2.3 to 16.4; P = .14).

However, significantly greater reductions in PTSD severity were found in the aerobic versus the stretching group at 6-month follow-up (mean difference, 12.1;95% CI, 2.4-21.8; P = .023), pointing to a “moderate effect size” (d = 0.6; 95% CI, 0.1-1.1]).

Although there were no differences found at 6-month assessment between rates of PTSD diagnosis (25% of the aerobic vs 27% of the stretching group), more participants in the aerobic group reached a “minimal clinically important difference,” compared to those in the stretching group (96% vs. 84%, respectively, x2 = 4.4; P = .036).

There were also superior benefits found in the aerobic versus the stretching group on depression severity at 6 months (a secondary outcome), with a mean difference in Beck Depression Inventory-2 score of 5.7 (95% CI, 0.5-10.9; P = .022), yielding a “moderate effect size” (d = 0.5; 95% CI, 0.1-1.0]).

There were no adverse events associated with the intervention, and almost all the sessions (88%) complied with the treatment protocol.

The researchers noted several limitations. For example, they did not obtain plasma to measure BDNF concentrations, so they could not “infer whether the mechanism of change involved BDNF.”

In addition, they did not perform sex-specific analyses. “Future studies could increase the sample size to investigate sex differences because females display less BDNF change following exercise than do males,” they wrote.

Nevertheless, the study “provides initial evidence of a simple and accessible strategy that clinicians could readily apply in combination with exposure therapy,” they stated. “Whereas many pharmacologic interventions pose barriers, including cost, requirement for prescriptions, and patient resistance to drugs, exercise offers clinicians a strategy that can be implemented with few barriers.”

Dr. Bryant emphasized that one study “does not represent a body of evidence, and so it is essential that this finding be replicated in other trials before it can be recommended for clinical use.” He noted that other trials are “currently underway.”

Easy augmentation

In a comment, Barbara Rothbaum, PhD, professor in psychiatry and director of the Trauma and Anxiety Recovery Program at Emory University, Atlanta, called it a “well-controlled trial augmenting exposure therapy for PTSD with brief aerobic exercise and finding some benefits of the augmented condition at 6 months posttreatment but not immediately posttreatment.”

The study’s methodology – that is, using independent standard assessment of PTSD and rating audio recordings of therapy sessions for treatment fidelity and quality – can lead us to “be confident in their [the researchers’] conclusions,” she said.

Dr. Rothbaum, who was not associated with this study, described research into methods to augment exposure therapy for PTSD as “timely and clinically relevant.”

Exercise “would be an easy augmentation for many clinicians if it is helpful,” she noted.

The study was funded by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council. The authors and Dr. Rothbaum reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE LANCET PSYCHIATRY

Antipsychotic shows benefit for Alzheimer’s agitation

SAN FRANCISCO – In a widely anticipated report,

Members of a panel of dementia specialists here at the 15th Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease (CTAD) conference said that the results were encouraging. But they also noted that the available data make it difficult to understand the impact of the drug on the day-to-day life on patients.

“I’d like to be able to translate that into something else to understand the risk benefit calculus,” said neurologist and neuroscientist Alireza Atri, MD, PhD, of Banner Sun Health Research Institute in Phoenix. “How does it affect the patients themselves, their quality of life, and the family members and their burden?”

Currently, there’s no Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment for agitation in AD.

In 2015, the FDA approved brexpiprazole, an oral medication, as a treatment for schizophrenia and an adjunctive treatment for major depressive disorder (MDD). It is an expensive drug with an average retail price per GoodRx of $1,582 per month, and no generic is available.

Researchers released the results of a trio of phase 3 clinical trials at CTAD that examined various doses of brexpiprazole. The results of the first two trials had been released earlier in 2018.

Three trials

All trials were multicenter, 12-week, randomized, double-blind and placebo-controlled.

Study participants were aged 55-90 years, had probable AD diagnoses, and had agitation per various scales. The average age in the groups was 74 years, 56.0%-61.7% were women, and 94.3%-98.1% were White.

The first trial examined two fixed doses (1 mg/d, n = 137; and 2 mg/d, n = 140) or placebo (n = 136). “The study initially included a 0.5 mg/day arm,” the researchers reported, “which was removed in a protocol amendment, and patients randomized to that arm were not included in efficacy analyses.”

The second trial looked at a flexible dose (0.5-2 mg/d, n = 133) or placebo (n = 137).

In a CTAD presentation, Nanco Hefting of Lundbeck, a codeveloper of the drug, said that the researchers learned from the first two trials that 2 mg/d might be an appropriate dose, and the FDA recommended they also examine 3 mg/day. As a result, the third trial examined two fixed doses (2 mg/d, n = 75; 3 mg/d, n = 153; or placebo, n = 117).

In the third trial, both the placebo and drug groups improved per a measurement of agitation; those in the drug group improved somewhat more.

The mean change in baseline on the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory scale – the primary endpoint – was –5.32 for the 2-mg/d and 3-mg/d groups vs. placebo (P = .0026); the score in the placebo group fell by about 18 and by about 22 in the drug group.

The key secondary endpoint was an improvement from baseline to week 12 in the Clinical Global Impression–Severity (CGI-S) score related to agitation. Compared with the placebo group, this score was –0.27 in the drug group (P = .0078). Both scores hovered around –1.0.

Safety data show the percentage of treatment-emergent events ranged from 45.9% in the placebo group to 49.0%-56.8% for brexpiprazole in the three trials. The percentage of these events leading to discontinuation was 6.3% among those receiving the drug and 3.4% in the placebo group.

University of Exeter dementia researcher Clive Ballard, MD, MB ChB, one of the panelists who discussed the research after the CTAD presentation, praised the trials as “well-conducted” and said that he was pleased that subjects in institutions were included. “It’s not an easy environment to do trials in. They should be really commended for doing for doing that.”

But he echoed fellow panelist Dr. Atri by noting that more data are needed to understand how well the drug works. “I would like to see the effect sizes and a little bit more detail to understand the clinical meaningfulness of that level of benefit.”

What’s next? A spokeswoman for Otsuka, a codeveloper of brexpiprazole, said that it hopes to hear in 2023 about a supplemental new drug application that was filed in November 2022.

Otsuka and Lundbeck funded the research. Mr. Hefting is an employee of Lundbeck, and several other authors work for Lundbeck or Otsuka. The single non-employee author reports various disclosures. Disclosures for Dr. Atri and Dr. Ballard were not provided.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN FRANCISCO – In a widely anticipated report,

Members of a panel of dementia specialists here at the 15th Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease (CTAD) conference said that the results were encouraging. But they also noted that the available data make it difficult to understand the impact of the drug on the day-to-day life on patients.

“I’d like to be able to translate that into something else to understand the risk benefit calculus,” said neurologist and neuroscientist Alireza Atri, MD, PhD, of Banner Sun Health Research Institute in Phoenix. “How does it affect the patients themselves, their quality of life, and the family members and their burden?”

Currently, there’s no Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment for agitation in AD.

In 2015, the FDA approved brexpiprazole, an oral medication, as a treatment for schizophrenia and an adjunctive treatment for major depressive disorder (MDD). It is an expensive drug with an average retail price per GoodRx of $1,582 per month, and no generic is available.

Researchers released the results of a trio of phase 3 clinical trials at CTAD that examined various doses of brexpiprazole. The results of the first two trials had been released earlier in 2018.

Three trials

All trials were multicenter, 12-week, randomized, double-blind and placebo-controlled.

Study participants were aged 55-90 years, had probable AD diagnoses, and had agitation per various scales. The average age in the groups was 74 years, 56.0%-61.7% were women, and 94.3%-98.1% were White.

The first trial examined two fixed doses (1 mg/d, n = 137; and 2 mg/d, n = 140) or placebo (n = 136). “The study initially included a 0.5 mg/day arm,” the researchers reported, “which was removed in a protocol amendment, and patients randomized to that arm were not included in efficacy analyses.”

The second trial looked at a flexible dose (0.5-2 mg/d, n = 133) or placebo (n = 137).

In a CTAD presentation, Nanco Hefting of Lundbeck, a codeveloper of the drug, said that the researchers learned from the first two trials that 2 mg/d might be an appropriate dose, and the FDA recommended they also examine 3 mg/day. As a result, the third trial examined two fixed doses (2 mg/d, n = 75; 3 mg/d, n = 153; or placebo, n = 117).

In the third trial, both the placebo and drug groups improved per a measurement of agitation; those in the drug group improved somewhat more.

The mean change in baseline on the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory scale – the primary endpoint – was –5.32 for the 2-mg/d and 3-mg/d groups vs. placebo (P = .0026); the score in the placebo group fell by about 18 and by about 22 in the drug group.

The key secondary endpoint was an improvement from baseline to week 12 in the Clinical Global Impression–Severity (CGI-S) score related to agitation. Compared with the placebo group, this score was –0.27 in the drug group (P = .0078). Both scores hovered around –1.0.

Safety data show the percentage of treatment-emergent events ranged from 45.9% in the placebo group to 49.0%-56.8% for brexpiprazole in the three trials. The percentage of these events leading to discontinuation was 6.3% among those receiving the drug and 3.4% in the placebo group.

University of Exeter dementia researcher Clive Ballard, MD, MB ChB, one of the panelists who discussed the research after the CTAD presentation, praised the trials as “well-conducted” and said that he was pleased that subjects in institutions were included. “It’s not an easy environment to do trials in. They should be really commended for doing for doing that.”

But he echoed fellow panelist Dr. Atri by noting that more data are needed to understand how well the drug works. “I would like to see the effect sizes and a little bit more detail to understand the clinical meaningfulness of that level of benefit.”

What’s next? A spokeswoman for Otsuka, a codeveloper of brexpiprazole, said that it hopes to hear in 2023 about a supplemental new drug application that was filed in November 2022.

Otsuka and Lundbeck funded the research. Mr. Hefting is an employee of Lundbeck, and several other authors work for Lundbeck or Otsuka. The single non-employee author reports various disclosures. Disclosures for Dr. Atri and Dr. Ballard were not provided.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN FRANCISCO – In a widely anticipated report,

Members of a panel of dementia specialists here at the 15th Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease (CTAD) conference said that the results were encouraging. But they also noted that the available data make it difficult to understand the impact of the drug on the day-to-day life on patients.

“I’d like to be able to translate that into something else to understand the risk benefit calculus,” said neurologist and neuroscientist Alireza Atri, MD, PhD, of Banner Sun Health Research Institute in Phoenix. “How does it affect the patients themselves, their quality of life, and the family members and their burden?”

Currently, there’s no Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment for agitation in AD.

In 2015, the FDA approved brexpiprazole, an oral medication, as a treatment for schizophrenia and an adjunctive treatment for major depressive disorder (MDD). It is an expensive drug with an average retail price per GoodRx of $1,582 per month, and no generic is available.

Researchers released the results of a trio of phase 3 clinical trials at CTAD that examined various doses of brexpiprazole. The results of the first two trials had been released earlier in 2018.

Three trials

All trials were multicenter, 12-week, randomized, double-blind and placebo-controlled.

Study participants were aged 55-90 years, had probable AD diagnoses, and had agitation per various scales. The average age in the groups was 74 years, 56.0%-61.7% were women, and 94.3%-98.1% were White.

The first trial examined two fixed doses (1 mg/d, n = 137; and 2 mg/d, n = 140) or placebo (n = 136). “The study initially included a 0.5 mg/day arm,” the researchers reported, “which was removed in a protocol amendment, and patients randomized to that arm were not included in efficacy analyses.”

The second trial looked at a flexible dose (0.5-2 mg/d, n = 133) or placebo (n = 137).

In a CTAD presentation, Nanco Hefting of Lundbeck, a codeveloper of the drug, said that the researchers learned from the first two trials that 2 mg/d might be an appropriate dose, and the FDA recommended they also examine 3 mg/day. As a result, the third trial examined two fixed doses (2 mg/d, n = 75; 3 mg/d, n = 153; or placebo, n = 117).

In the third trial, both the placebo and drug groups improved per a measurement of agitation; those in the drug group improved somewhat more.

The mean change in baseline on the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory scale – the primary endpoint – was –5.32 for the 2-mg/d and 3-mg/d groups vs. placebo (P = .0026); the score in the placebo group fell by about 18 and by about 22 in the drug group.

The key secondary endpoint was an improvement from baseline to week 12 in the Clinical Global Impression–Severity (CGI-S) score related to agitation. Compared with the placebo group, this score was –0.27 in the drug group (P = .0078). Both scores hovered around –1.0.

Safety data show the percentage of treatment-emergent events ranged from 45.9% in the placebo group to 49.0%-56.8% for brexpiprazole in the three trials. The percentage of these events leading to discontinuation was 6.3% among those receiving the drug and 3.4% in the placebo group.

University of Exeter dementia researcher Clive Ballard, MD, MB ChB, one of the panelists who discussed the research after the CTAD presentation, praised the trials as “well-conducted” and said that he was pleased that subjects in institutions were included. “It’s not an easy environment to do trials in. They should be really commended for doing for doing that.”

But he echoed fellow panelist Dr. Atri by noting that more data are needed to understand how well the drug works. “I would like to see the effect sizes and a little bit more detail to understand the clinical meaningfulness of that level of benefit.”

What’s next? A spokeswoman for Otsuka, a codeveloper of brexpiprazole, said that it hopes to hear in 2023 about a supplemental new drug application that was filed in November 2022.

Otsuka and Lundbeck funded the research. Mr. Hefting is an employee of Lundbeck, and several other authors work for Lundbeck or Otsuka. The single non-employee author reports various disclosures. Disclosures for Dr. Atri and Dr. Ballard were not provided.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT CTAD 2022

Mindfulness, exercise strike out in memory trial

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

We are coming to the end of the year, which always makes me think about getting older. Much like the search for the fountain of youth, many promising leads have ultimately led to dead ends. And yet, I had high hopes for a trial that focused on two cornerstones of wellness – exercise and mindfulness – to address the subjective loss of memory that comes with aging. Alas, meditation and exercise do not appear to be the fountain of youth.

I’m talking about this study, appearing in JAMA, known as the MEDEX trial.

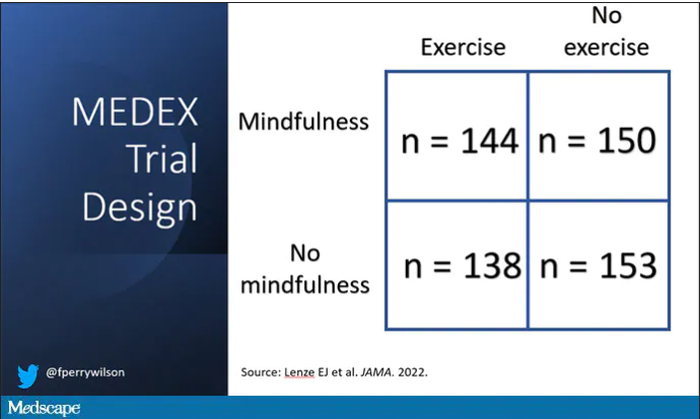

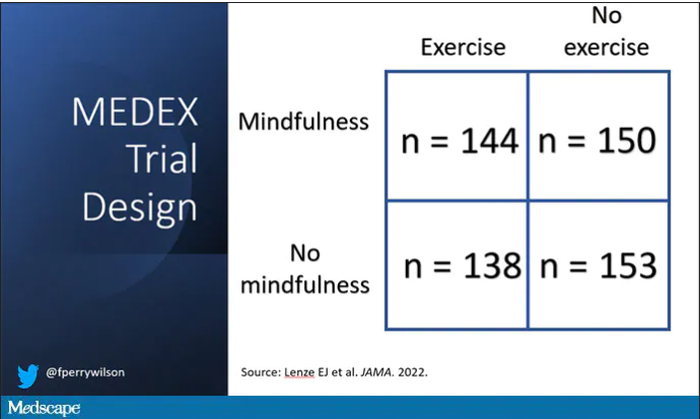

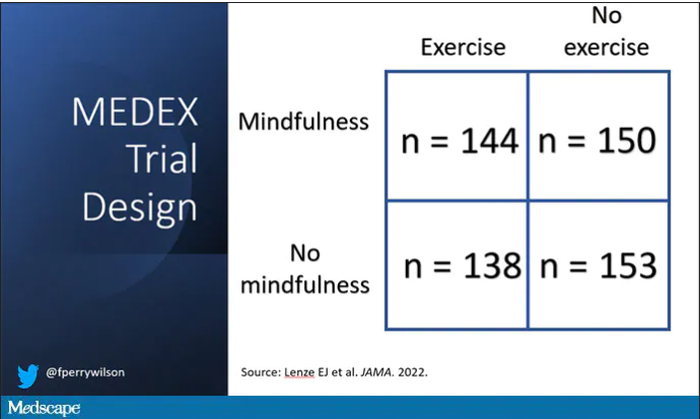

It’s a clever design: a 2 x 2 factorial randomized trial where participants could be randomized to a mindfulness intervention, an exercise intervention, both, or neither.

In this manner, you can test multiple hypotheses exploiting a shared control group. Or as a mentor of mine used to say, you get two trials for the price of one and a half.

The participants were older adults, aged 65-84, living in the community. They had to be relatively sedentary at baseline and not engaging in mindfulness practices. They had to subjectively report some memory or concentration issues but had to be cognitively intact, based on a standard dementia screening test. In other words, these are your average older people who are worried that they aren’t as sharp as they used to be.

The interventions themselves were fairly intense. The exercise group had instructor-led sessions for 90 minutes twice a week for the first 6 months of the study, once a week thereafter. And participants were encouraged to exercise at home such that they had a total of 300 minutes of weekly exercise.

The mindfulness program was characterized by eight weekly classes of 2.5 hours each as well as a half-day retreat to teach the tenets of mindfulness and meditation, with monthly refreshers thereafter. Participants were instructed to meditate for 60 minutes a day in addition to the classes.

For the 144 people who were randomized to both meditation and exercise, this trial amounted to something of a part-time job. So you might think that adherence to the interventions was low, but apparently that’s not the case. Attendance to the mindfulness classes was over 90%, and over 80% for the exercise classes. And diary-based reporting of home efforts was also pretty good.

The control group wasn’t left to their own devices. Recognizing that the community aspect of exercise or mindfulness classes might convey a benefit independent of the actual exercise or mindfulness, the control group met on a similar schedule to discuss health education, but no mention of exercise or mindfulness occurred in that setting.

The primary outcome was change in memory and executive function scores across a battery of neuropsychologic testing, but the story is told in just a few pictures.

Memory scores improved in all three groups – mindfulness, exercise, and health education – over time. Cognitive composite score improved in all three groups similarly. There was no synergistic effect of mindfulness and exercise either. Basically, everyone got a bit better.

But the study did way more than look at scores on tests. Researchers used MRI to measure brain anatomic outcomes as well. And the surprising thing is that virtually none of these outcomes were different between the groups either.

Hippocampal volume decreased a bit in all the groups. Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex volume was flat. There was no change in scores measuring tasks of daily living.

When you see negative results like this, right away you worry that the intervention wasn’t properly delivered. Were these people really exercising and meditating? Well, the authors showed that individuals randomized to exercise, at least, had less sleep latency, greater aerobic fitness, and greater strength. So we know something was happening.

They then asked, would the people in the exercise group with the greatest changes in those physiologic parameters show some improvement in cognitive parameters? In other words, we know you were exercising because you got stronger and are sleeping better; is your memory better? The answer? Surprisingly, still no. Even in that honestly somewhat cherry-picked group, the interventions had no effect.

Could it be that the control was inappropriate, that the “health education” intervention was actually so helpful that it obscured the benefits of exercise and meditation? After all, cognitive scores did improve in all groups. The authors doubt it. They say they think the improvement in cognitive scores reflects the fact that patients had learned a bit about how to take the tests. This is pretty common in the neuropsychiatric literature.

So here we are and I just want to say, well, shoot. This is not the result I wanted. And I think the reason I’m so disappointed is because aging and the loss of cognitive faculties that comes with aging are just sort of scary. We are all looking for some control over that fear, and how nice it would be to be able to tell ourselves not to worry – that we won’t have those problems as we get older because we exercise, or meditate, or drink red wine, or don’t drink wine, or whatever. And while I have no doubt that staying healthier physically will keep you healthier mentally, it may take more than one simple thing to move the needle.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor, department of medicine, and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

We are coming to the end of the year, which always makes me think about getting older. Much like the search for the fountain of youth, many promising leads have ultimately led to dead ends. And yet, I had high hopes for a trial that focused on two cornerstones of wellness – exercise and mindfulness – to address the subjective loss of memory that comes with aging. Alas, meditation and exercise do not appear to be the fountain of youth.

I’m talking about this study, appearing in JAMA, known as the MEDEX trial.

It’s a clever design: a 2 x 2 factorial randomized trial where participants could be randomized to a mindfulness intervention, an exercise intervention, both, or neither.

In this manner, you can test multiple hypotheses exploiting a shared control group. Or as a mentor of mine used to say, you get two trials for the price of one and a half.

The participants were older adults, aged 65-84, living in the community. They had to be relatively sedentary at baseline and not engaging in mindfulness practices. They had to subjectively report some memory or concentration issues but had to be cognitively intact, based on a standard dementia screening test. In other words, these are your average older people who are worried that they aren’t as sharp as they used to be.

The interventions themselves were fairly intense. The exercise group had instructor-led sessions for 90 minutes twice a week for the first 6 months of the study, once a week thereafter. And participants were encouraged to exercise at home such that they had a total of 300 minutes of weekly exercise.

The mindfulness program was characterized by eight weekly classes of 2.5 hours each as well as a half-day retreat to teach the tenets of mindfulness and meditation, with monthly refreshers thereafter. Participants were instructed to meditate for 60 minutes a day in addition to the classes.

For the 144 people who were randomized to both meditation and exercise, this trial amounted to something of a part-time job. So you might think that adherence to the interventions was low, but apparently that’s not the case. Attendance to the mindfulness classes was over 90%, and over 80% for the exercise classes. And diary-based reporting of home efforts was also pretty good.

The control group wasn’t left to their own devices. Recognizing that the community aspect of exercise or mindfulness classes might convey a benefit independent of the actual exercise or mindfulness, the control group met on a similar schedule to discuss health education, but no mention of exercise or mindfulness occurred in that setting.

The primary outcome was change in memory and executive function scores across a battery of neuropsychologic testing, but the story is told in just a few pictures.

Memory scores improved in all three groups – mindfulness, exercise, and health education – over time. Cognitive composite score improved in all three groups similarly. There was no synergistic effect of mindfulness and exercise either. Basically, everyone got a bit better.

But the study did way more than look at scores on tests. Researchers used MRI to measure brain anatomic outcomes as well. And the surprising thing is that virtually none of these outcomes were different between the groups either.

Hippocampal volume decreased a bit in all the groups. Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex volume was flat. There was no change in scores measuring tasks of daily living.

When you see negative results like this, right away you worry that the intervention wasn’t properly delivered. Were these people really exercising and meditating? Well, the authors showed that individuals randomized to exercise, at least, had less sleep latency, greater aerobic fitness, and greater strength. So we know something was happening.

They then asked, would the people in the exercise group with the greatest changes in those physiologic parameters show some improvement in cognitive parameters? In other words, we know you were exercising because you got stronger and are sleeping better; is your memory better? The answer? Surprisingly, still no. Even in that honestly somewhat cherry-picked group, the interventions had no effect.

Could it be that the control was inappropriate, that the “health education” intervention was actually so helpful that it obscured the benefits of exercise and meditation? After all, cognitive scores did improve in all groups. The authors doubt it. They say they think the improvement in cognitive scores reflects the fact that patients had learned a bit about how to take the tests. This is pretty common in the neuropsychiatric literature.

So here we are and I just want to say, well, shoot. This is not the result I wanted. And I think the reason I’m so disappointed is because aging and the loss of cognitive faculties that comes with aging are just sort of scary. We are all looking for some control over that fear, and how nice it would be to be able to tell ourselves not to worry – that we won’t have those problems as we get older because we exercise, or meditate, or drink red wine, or don’t drink wine, or whatever. And while I have no doubt that staying healthier physically will keep you healthier mentally, it may take more than one simple thing to move the needle.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor, department of medicine, and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

We are coming to the end of the year, which always makes me think about getting older. Much like the search for the fountain of youth, many promising leads have ultimately led to dead ends. And yet, I had high hopes for a trial that focused on two cornerstones of wellness – exercise and mindfulness – to address the subjective loss of memory that comes with aging. Alas, meditation and exercise do not appear to be the fountain of youth.

I’m talking about this study, appearing in JAMA, known as the MEDEX trial.

It’s a clever design: a 2 x 2 factorial randomized trial where participants could be randomized to a mindfulness intervention, an exercise intervention, both, or neither.

In this manner, you can test multiple hypotheses exploiting a shared control group. Or as a mentor of mine used to say, you get two trials for the price of one and a half.

The participants were older adults, aged 65-84, living in the community. They had to be relatively sedentary at baseline and not engaging in mindfulness practices. They had to subjectively report some memory or concentration issues but had to be cognitively intact, based on a standard dementia screening test. In other words, these are your average older people who are worried that they aren’t as sharp as they used to be.

The interventions themselves were fairly intense. The exercise group had instructor-led sessions for 90 minutes twice a week for the first 6 months of the study, once a week thereafter. And participants were encouraged to exercise at home such that they had a total of 300 minutes of weekly exercise.

The mindfulness program was characterized by eight weekly classes of 2.5 hours each as well as a half-day retreat to teach the tenets of mindfulness and meditation, with monthly refreshers thereafter. Participants were instructed to meditate for 60 minutes a day in addition to the classes.

For the 144 people who were randomized to both meditation and exercise, this trial amounted to something of a part-time job. So you might think that adherence to the interventions was low, but apparently that’s not the case. Attendance to the mindfulness classes was over 90%, and over 80% for the exercise classes. And diary-based reporting of home efforts was also pretty good.

The control group wasn’t left to their own devices. Recognizing that the community aspect of exercise or mindfulness classes might convey a benefit independent of the actual exercise or mindfulness, the control group met on a similar schedule to discuss health education, but no mention of exercise or mindfulness occurred in that setting.

The primary outcome was change in memory and executive function scores across a battery of neuropsychologic testing, but the story is told in just a few pictures.

Memory scores improved in all three groups – mindfulness, exercise, and health education – over time. Cognitive composite score improved in all three groups similarly. There was no synergistic effect of mindfulness and exercise either. Basically, everyone got a bit better.

But the study did way more than look at scores on tests. Researchers used MRI to measure brain anatomic outcomes as well. And the surprising thing is that virtually none of these outcomes were different between the groups either.

Hippocampal volume decreased a bit in all the groups. Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex volume was flat. There was no change in scores measuring tasks of daily living.

When you see negative results like this, right away you worry that the intervention wasn’t properly delivered. Were these people really exercising and meditating? Well, the authors showed that individuals randomized to exercise, at least, had less sleep latency, greater aerobic fitness, and greater strength. So we know something was happening.

They then asked, would the people in the exercise group with the greatest changes in those physiologic parameters show some improvement in cognitive parameters? In other words, we know you were exercising because you got stronger and are sleeping better; is your memory better? The answer? Surprisingly, still no. Even in that honestly somewhat cherry-picked group, the interventions had no effect.

Could it be that the control was inappropriate, that the “health education” intervention was actually so helpful that it obscured the benefits of exercise and meditation? After all, cognitive scores did improve in all groups. The authors doubt it. They say they think the improvement in cognitive scores reflects the fact that patients had learned a bit about how to take the tests. This is pretty common in the neuropsychiatric literature.

So here we are and I just want to say, well, shoot. This is not the result I wanted. And I think the reason I’m so disappointed is because aging and the loss of cognitive faculties that comes with aging are just sort of scary. We are all looking for some control over that fear, and how nice it would be to be able to tell ourselves not to worry – that we won’t have those problems as we get older because we exercise, or meditate, or drink red wine, or don’t drink wine, or whatever. And while I have no doubt that staying healthier physically will keep you healthier mentally, it may take more than one simple thing to move the needle.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor, department of medicine, and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Have you heard the one about the cow in the doctor’s office?

Maybe the cow was late for its appointment

It’s been a long day running the front desk at your doctor’s office. People calling in prescriptions, a million appointments, you’ve been running yourself ragged keeping things together. Finally, it’s almost closing time. The last patient of the day has just checked out and you turn back to the waiting room, expecting to see it blessedly empty.

Instead, a 650-pound cow is staring at you.

“I’m sorry, sir or madam, we’re about to close.”

Moo.

“I understand it’s important, but seriously, the doctor’s about to …”

Moo.

“Fine, I’ll see what we can do for you. What’s your insurance?”

Moo Cross Moo Shield.

“Sorry, we don’t take that. You’ll have to go someplace else.”

This is probably not how things went down recently at Orange (Va.) Family Physicians, when they had a cow break into the office. Cows don’t have health insurance.

The intrepid bovine was being transferred to a new home when it jumped off the trailer and wandered an eighth of a mile to Orange Family Physicians, where the cow wranglers found it hanging around outside. Unfortunately, this was a smart cow, and it bolted as it saw the wranglers, crashing through the glass doors into the doctor’s office. Though neither man had ever wrangled a cow from inside a building, they ultimately secured a rope around the cow’s neck and escorted it back outside, tying it to a nearby pole to keep it from further adventures.

One of the wranglers summed up the situation quite nicely on his Facebook page: “You ain’t no cowboy if you don’t rope a calf out of a [doctor’s] office.”

We can see that decision in your eyes

The cliché that eyes are the windows to the soul doesn’t tell the whole story about how telling eyes really are. It’s all about how they move. In a recent study, researchers determined that a type of eye movement known as a saccade reveals your choice before you even decide.

Saccades involve the eyes jumping from one fixation point to another, senior author Alaa Ahmed of the University of Colorado, Boulder, explained in a statement from the university. Saccade vigor was the key in how aligned the type of decisions were made by the 22 study participants.

In the study, subjects walked on a treadmill at varied inclines for a period of time. Then they sat in front of a monitor and a high-speed camera that tracked their eye movements as the monitor presented them with a series of exercise options. The participants had only 4 seconds to choose between them.

After they made their choices, participants went back on the treadmill to perform the exercises they had chosen. The researchers found that participants’ eyes jumped between the options slowly then faster to the option they eventually picked. The more impulsive decision-makers also tended to move their eyes even more rapidly before slowing down after a decision was made, making it pretty conclusive that the eyes were revealing their choices.

The way your eyes shift gives you away without saying a thing. Might be wise, then, to wear sunglasses to your next poker tournament.

Let them eat soap

Okay, we admit it: LOTME spends a lot of time in the bathroom. Today, though, we’re interested in the sinks. Specifically, the P-traps under the sinks. You know, the curvy bit that keeps sewer gas from wafting back into the room?

Well, researchers from the University of Reading (England) recently found some fungi while examining a bunch of sinks on the university’s Whiteknights campus. “It isn’t a big surprise to find fungi in a warm, wet environment. But sinks and P-traps have thus far been overlooked as potential reservoirs of these microorganisms,” they said in a written statement.

Samples collected from 289 P-traps contained “a very similar community of yeasts and molds, showing that sinks in use in public environments share a role as reservoirs of fungal organisms,” they noted.

The fungi living in the traps survived conditions with high temperatures, low pH, and little in the way of nutrients. So what were they eating? Some varieties, they said, “use detergents, found in soap, as a source of carbon-rich food.” We’ll repeat that last part: They used the soap as food.

WARNING: Rant Ahead.

There are a lot of cleaning products for sale that say they will make your home safe by killing 99.9% of germs and bacteria. Not fungi, exactly, but we’re still talking microorganisms. Molds, bacteria, and viruses are all stuff that can infect humans and make them sick.

So you kill 99.9% of them. Great, but that leaves 0.1% that you just made angry. And what do they do next? They learn to eat soap. Then University of Reading investigators find out that all the extra hand washing going on during the COVID-19 pandemic was “clogging up sinks with nasty disease-causing bacteria.”

These are microorganisms we’re talking about people. They’ve been at this for a billion years! Rats can’t beat them, cockroaches won’t stop them – Earth’s ultimate survivors are powerless against the invisible horde.

We’re doomed.

Maybe the cow was late for its appointment

It’s been a long day running the front desk at your doctor’s office. People calling in prescriptions, a million appointments, you’ve been running yourself ragged keeping things together. Finally, it’s almost closing time. The last patient of the day has just checked out and you turn back to the waiting room, expecting to see it blessedly empty.

Instead, a 650-pound cow is staring at you.

“I’m sorry, sir or madam, we’re about to close.”

Moo.

“I understand it’s important, but seriously, the doctor’s about to …”

Moo.

“Fine, I’ll see what we can do for you. What’s your insurance?”

Moo Cross Moo Shield.

“Sorry, we don’t take that. You’ll have to go someplace else.”

This is probably not how things went down recently at Orange (Va.) Family Physicians, when they had a cow break into the office. Cows don’t have health insurance.

The intrepid bovine was being transferred to a new home when it jumped off the trailer and wandered an eighth of a mile to Orange Family Physicians, where the cow wranglers found it hanging around outside. Unfortunately, this was a smart cow, and it bolted as it saw the wranglers, crashing through the glass doors into the doctor’s office. Though neither man had ever wrangled a cow from inside a building, they ultimately secured a rope around the cow’s neck and escorted it back outside, tying it to a nearby pole to keep it from further adventures.

One of the wranglers summed up the situation quite nicely on his Facebook page: “You ain’t no cowboy if you don’t rope a calf out of a [doctor’s] office.”

We can see that decision in your eyes

The cliché that eyes are the windows to the soul doesn’t tell the whole story about how telling eyes really are. It’s all about how they move. In a recent study, researchers determined that a type of eye movement known as a saccade reveals your choice before you even decide.

Saccades involve the eyes jumping from one fixation point to another, senior author Alaa Ahmed of the University of Colorado, Boulder, explained in a statement from the university. Saccade vigor was the key in how aligned the type of decisions were made by the 22 study participants.

In the study, subjects walked on a treadmill at varied inclines for a period of time. Then they sat in front of a monitor and a high-speed camera that tracked their eye movements as the monitor presented them with a series of exercise options. The participants had only 4 seconds to choose between them.

After they made their choices, participants went back on the treadmill to perform the exercises they had chosen. The researchers found that participants’ eyes jumped between the options slowly then faster to the option they eventually picked. The more impulsive decision-makers also tended to move their eyes even more rapidly before slowing down after a decision was made, making it pretty conclusive that the eyes were revealing their choices.

The way your eyes shift gives you away without saying a thing. Might be wise, then, to wear sunglasses to your next poker tournament.

Let them eat soap

Okay, we admit it: LOTME spends a lot of time in the bathroom. Today, though, we’re interested in the sinks. Specifically, the P-traps under the sinks. You know, the curvy bit that keeps sewer gas from wafting back into the room?

Well, researchers from the University of Reading (England) recently found some fungi while examining a bunch of sinks on the university’s Whiteknights campus. “It isn’t a big surprise to find fungi in a warm, wet environment. But sinks and P-traps have thus far been overlooked as potential reservoirs of these microorganisms,” they said in a written statement.

Samples collected from 289 P-traps contained “a very similar community of yeasts and molds, showing that sinks in use in public environments share a role as reservoirs of fungal organisms,” they noted.

The fungi living in the traps survived conditions with high temperatures, low pH, and little in the way of nutrients. So what were they eating? Some varieties, they said, “use detergents, found in soap, as a source of carbon-rich food.” We’ll repeat that last part: They used the soap as food.

WARNING: Rant Ahead.

There are a lot of cleaning products for sale that say they will make your home safe by killing 99.9% of germs and bacteria. Not fungi, exactly, but we’re still talking microorganisms. Molds, bacteria, and viruses are all stuff that can infect humans and make them sick.

So you kill 99.9% of them. Great, but that leaves 0.1% that you just made angry. And what do they do next? They learn to eat soap. Then University of Reading investigators find out that all the extra hand washing going on during the COVID-19 pandemic was “clogging up sinks with nasty disease-causing bacteria.”

These are microorganisms we’re talking about people. They’ve been at this for a billion years! Rats can’t beat them, cockroaches won’t stop them – Earth’s ultimate survivors are powerless against the invisible horde.

We’re doomed.

Maybe the cow was late for its appointment

It’s been a long day running the front desk at your doctor’s office. People calling in prescriptions, a million appointments, you’ve been running yourself ragged keeping things together. Finally, it’s almost closing time. The last patient of the day has just checked out and you turn back to the waiting room, expecting to see it blessedly empty.

Instead, a 650-pound cow is staring at you.

“I’m sorry, sir or madam, we’re about to close.”

Moo.

“I understand it’s important, but seriously, the doctor’s about to …”

Moo.

“Fine, I’ll see what we can do for you. What’s your insurance?”

Moo Cross Moo Shield.

“Sorry, we don’t take that. You’ll have to go someplace else.”

This is probably not how things went down recently at Orange (Va.) Family Physicians, when they had a cow break into the office. Cows don’t have health insurance.

The intrepid bovine was being transferred to a new home when it jumped off the trailer and wandered an eighth of a mile to Orange Family Physicians, where the cow wranglers found it hanging around outside. Unfortunately, this was a smart cow, and it bolted as it saw the wranglers, crashing through the glass doors into the doctor’s office. Though neither man had ever wrangled a cow from inside a building, they ultimately secured a rope around the cow’s neck and escorted it back outside, tying it to a nearby pole to keep it from further adventures.

One of the wranglers summed up the situation quite nicely on his Facebook page: “You ain’t no cowboy if you don’t rope a calf out of a [doctor’s] office.”

We can see that decision in your eyes

The cliché that eyes are the windows to the soul doesn’t tell the whole story about how telling eyes really are. It’s all about how they move. In a recent study, researchers determined that a type of eye movement known as a saccade reveals your choice before you even decide.

Saccades involve the eyes jumping from one fixation point to another, senior author Alaa Ahmed of the University of Colorado, Boulder, explained in a statement from the university. Saccade vigor was the key in how aligned the type of decisions were made by the 22 study participants.

In the study, subjects walked on a treadmill at varied inclines for a period of time. Then they sat in front of a monitor and a high-speed camera that tracked their eye movements as the monitor presented them with a series of exercise options. The participants had only 4 seconds to choose between them.

After they made their choices, participants went back on the treadmill to perform the exercises they had chosen. The researchers found that participants’ eyes jumped between the options slowly then faster to the option they eventually picked. The more impulsive decision-makers also tended to move their eyes even more rapidly before slowing down after a decision was made, making it pretty conclusive that the eyes were revealing their choices.

The way your eyes shift gives you away without saying a thing. Might be wise, then, to wear sunglasses to your next poker tournament.

Let them eat soap

Okay, we admit it: LOTME spends a lot of time in the bathroom. Today, though, we’re interested in the sinks. Specifically, the P-traps under the sinks. You know, the curvy bit that keeps sewer gas from wafting back into the room?

Well, researchers from the University of Reading (England) recently found some fungi while examining a bunch of sinks on the university’s Whiteknights campus. “It isn’t a big surprise to find fungi in a warm, wet environment. But sinks and P-traps have thus far been overlooked as potential reservoirs of these microorganisms,” they said in a written statement.

Samples collected from 289 P-traps contained “a very similar community of yeasts and molds, showing that sinks in use in public environments share a role as reservoirs of fungal organisms,” they noted.

The fungi living in the traps survived conditions with high temperatures, low pH, and little in the way of nutrients. So what were they eating? Some varieties, they said, “use detergents, found in soap, as a source of carbon-rich food.” We’ll repeat that last part: They used the soap as food.

WARNING: Rant Ahead.

There are a lot of cleaning products for sale that say they will make your home safe by killing 99.9% of germs and bacteria. Not fungi, exactly, but we’re still talking microorganisms. Molds, bacteria, and viruses are all stuff that can infect humans and make them sick.

So you kill 99.9% of them. Great, but that leaves 0.1% that you just made angry. And what do they do next? They learn to eat soap. Then University of Reading investigators find out that all the extra hand washing going on during the COVID-19 pandemic was “clogging up sinks with nasty disease-causing bacteria.”

These are microorganisms we’re talking about people. They’ve been at this for a billion years! Rats can’t beat them, cockroaches won’t stop them – Earth’s ultimate survivors are powerless against the invisible horde.

We’re doomed.

Can a Mediterranean diet ease depression in young men?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Drew Ramsey, MD: Welcome back, everyone. I’m Dr. Drew Ramsey. I’m on the editorial board with Medscape Psychiatry and I’m an assistant clinical professor of psychiatry at Columbia University. We have a special guest today.

I’m here with nutritionist Jessica Bayes, who’s at the University of Technology Sydney, and she’s the lead author of the AMMEND trial. [Editor’s note: Since completing her PhD, Bayes is now at Southern Cross University.]

Jessica, welcome to Medscape.

Jessica Bayes, PhD: Thank you for having me.

The AMMEND Trial

Dr. Ramsey: Thank you for coming on board and helping all of us as clinicians understand some of your research and some of what is suggested by your research – that young men can change their diet and it helped their depression. Tell us a little bit about the AMMEND trial.

Dr. Bayes: The AMMEND trial was a 12-week randomized controlled trial in young men, 18-25 years old, who had diagnosed moderate to severe clinical depression. They had a poor baseline diet and we got them to eat a healthy Mediterranean diet, which improved their symptoms of depression.

Dr. Ramsey: It was a remarkable trial. Jessica, if I recall, you helped individuals improve the Mediterranean dietary pattern score by 8 points on a 14-point scale. That led to a 20-point reduction in their Beck Depression Inventory. Tell us what that looked like on the ground.

Dr. Bayes: It’s a huge improvement. Obviously, they were feeling much better in the end in terms of their depressive symptoms, but we also measured their energy, sleep, and quality of life. Many of them at the end were at a score cutoff that suggests no depression or in remission.

Dr. Ramsey: There were 72 people in your total trial, so 36% in your intervention arm went into full remission.

Dr. Bayes: Which is just amazing.

Dr. Ramsey: It also follows up the SMILES trial, which was a little bit of a different trial. You had two nutritional counseling sessions and the SMILES trial had seven, but in the SMILES trial, 32.3% of the patients went into full remission when they adopted a Mediterranean-style diet.

Jessica, what is the secret that you and your team know? I think many clinicians, especially clinicians who are parents and have teens, are kind of shaking their heads in disbelief. They’ve been telling their kids to eat healthy. What do you guys know about how to help young men change their diet?

How to Aid Adherence to Mediterranean Diet

Dr. Bayes: Prior to starting this, when I would say this idea to people, everyone would say, “Great idea. There’s no way you’re going to get depressed young men to change their diet. Not going to happen.” We went to them and we asked them. We said, “We’re going to do this study. What do you want from us? What resources would you need? How many appointments would you like? What’s too little or too many?”

We really got their feedback on board when we designed the study, and that obviously paid off. We had a personalized approach and we met them where they were at. We gave them the skills, resources, recipes, meal ideas – all those things – so we could really set them up to succeed.

Dr. Ramsey: You were telling me earlier about a few of the dietary changes that you felt made a big difference for these young men. What were those?

Dr. Bayes: Increasing the vegetables, olive oil, and legumes are probably the big ones that most of them were really not doing beforehand. They were really able to take that on board and make significant improvements in those areas.

Dr. Ramsey: These are really some of the top food categories in nutritional psychiatry as we think about how we help our efforts to improve mental health by thinking about nutrition, nutritional quality, and nutritional density. Certainly, those food categories – nuts and legumes, plants, and olive oil – are really what help get us there.

You also gave the students a food hamper. If you were going to be in charge of mental health in Australia and America and you got to give every college freshman a little box with a note, what would be in that box?

Dr. Bayes: I’d want to put everything in that box! It would be full of brightly colored fruits and vegetables, different nuts and seeds, and legumes. It would be full of recipes and ideas of how to cook things and how to prepare really delicious things. It would be full of different herbs and spices and all of those things to get people really excited about food.

Dr. Ramsey: Did the young men pick up on your enthusiasm and excitement around food? Did they begin to adopt some of that, shifting their view of how they saw the food and how they saw that it is related to their depression?

Dr. Bayes: Hopefully. I do think energy is infectious. I’m sure that played a role somewhat, but trying to get them excited about food can be really quite daunting, thinking, I’ve got to change my entire diet and I’ve got to learn to cook and go out and buy groceries. I don’t even know what to do with a piece of salmon. Trying to get them curious, interested, and just reminding them that it’s not all-or-nothing. Make small changes, give it a go, and have fun.

Dr. Ramsey: You also have a unique aspect of your research that you’re interested in male mental health, and that’s not something that’s been widely researched. Can you tell us a little bit about what these men were like in terms of coming into your trial as depressed young men?

Dr. Bayes: In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, mental health was at the forefront of many people’s minds. They joined the study saying, “I’ve never seen anything like this before. I’ve never seen myself represented in research. I wanted to contribute. I want to add to that conversation because I feel like we are overlooked.”

Dr. Ramsey: I love hearing this notion that maybe young men aren’t quite who we think they are. They are wanting to be seen around their mental health. They can learn to use olive oil and to cook, and they can engage in mental health interventions that work. We just need to ask, give them some food, encourage them, and it makes a big difference.

Jessica Bayes, thank you so much for joining us and sharing some of your research. Everyone, it’s the AMMEND trial. We will drop a link to the trial below so you can take a peek and tell us what you think.

Please, in the comments, let us know what you think about this notion of helping young men with depression through nutritional interventions. Take a peek at the great work that Jessica and Professor Sibbritt from the University of Technology Sydney have published and put out into the scientific literature for us all.

Thanks so much, Jessica. I look forward to seeing you soon.

Dr. Bayes: Thank you.

Dr. Ramsey is assistant clinical professor, department of psychiatry, Columbia University, New York. He has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for InterContinental Hotels Group; National Kale Day 501(c)3. Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Sharecare. Dr. Bayes is a postdoctoral research fellow; clinical nutritionist, Southern Cross University, National Center for Naturopathic Medicine, Lismore, New South Wales, Australia. She has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: Received research grant from Endeavour College. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Drew Ramsey, MD: Welcome back, everyone. I’m Dr. Drew Ramsey. I’m on the editorial board with Medscape Psychiatry and I’m an assistant clinical professor of psychiatry at Columbia University. We have a special guest today.

I’m here with nutritionist Jessica Bayes, who’s at the University of Technology Sydney, and she’s the lead author of the AMMEND trial. [Editor’s note: Since completing her PhD, Bayes is now at Southern Cross University.]

Jessica, welcome to Medscape.

Jessica Bayes, PhD: Thank you for having me.

The AMMEND Trial

Dr. Ramsey: Thank you for coming on board and helping all of us as clinicians understand some of your research and some of what is suggested by your research – that young men can change their diet and it helped their depression. Tell us a little bit about the AMMEND trial.

Dr. Bayes: The AMMEND trial was a 12-week randomized controlled trial in young men, 18-25 years old, who had diagnosed moderate to severe clinical depression. They had a poor baseline diet and we got them to eat a healthy Mediterranean diet, which improved their symptoms of depression.

Dr. Ramsey: It was a remarkable trial. Jessica, if I recall, you helped individuals improve the Mediterranean dietary pattern score by 8 points on a 14-point scale. That led to a 20-point reduction in their Beck Depression Inventory. Tell us what that looked like on the ground.

Dr. Bayes: It’s a huge improvement. Obviously, they were feeling much better in the end in terms of their depressive symptoms, but we also measured their energy, sleep, and quality of life. Many of them at the end were at a score cutoff that suggests no depression or in remission.

Dr. Ramsey: There were 72 people in your total trial, so 36% in your intervention arm went into full remission.

Dr. Bayes: Which is just amazing.

Dr. Ramsey: It also follows up the SMILES trial, which was a little bit of a different trial. You had two nutritional counseling sessions and the SMILES trial had seven, but in the SMILES trial, 32.3% of the patients went into full remission when they adopted a Mediterranean-style diet.

Jessica, what is the secret that you and your team know? I think many clinicians, especially clinicians who are parents and have teens, are kind of shaking their heads in disbelief. They’ve been telling their kids to eat healthy. What do you guys know about how to help young men change their diet?

How to Aid Adherence to Mediterranean Diet

Dr. Bayes: Prior to starting this, when I would say this idea to people, everyone would say, “Great idea. There’s no way you’re going to get depressed young men to change their diet. Not going to happen.” We went to them and we asked them. We said, “We’re going to do this study. What do you want from us? What resources would you need? How many appointments would you like? What’s too little or too many?”

We really got their feedback on board when we designed the study, and that obviously paid off. We had a personalized approach and we met them where they were at. We gave them the skills, resources, recipes, meal ideas – all those things – so we could really set them up to succeed.

Dr. Ramsey: You were telling me earlier about a few of the dietary changes that you felt made a big difference for these young men. What were those?

Dr. Bayes: Increasing the vegetables, olive oil, and legumes are probably the big ones that most of them were really not doing beforehand. They were really able to take that on board and make significant improvements in those areas.