User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

Immune dysregulation may drive long-term postpartum depression

Postpartum depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder that persist 2-3 years after birth are associated with a dysregulated immune system that is characterized by increased inflammatory signaling, according to investigators.

These findings suggest that mental health screening for women who have given birth should continue beyond the first year post partum, reported lead author Jennifer M. Nicoloro-SantaBarbara, PhD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues.

“Delayed postpartum depression, also known as late-onset postpartum depression, can affect women up to 18 months after delivery,” the investigators wrote in the American Journal of Reproductive Immunology. “It can appear even later in some women, depending on the hormonal changes that occur after having a baby (for example, timing of weaning). However, the majority of research on maternal mental health focuses on the first year post birth, leaving a gap in research beyond 12 months post partum.”

To address this gap, the investigators enrolled 33 women who were 2-3 years post partum. Participants completed self-guided questionnaires on PTSD, depression, and anxiety, and provided blood samples for gene expression analysis.

Sixteen of the 33 women had clinically significant mood disturbances. and significantly reduced activation of genes associated with viral response.

“The results provide preliminary evidence of a mechanism (e.g., immune dysregulation) that might be contributing to mood disorders and bring us closer to the goal of identifying targetable biomarkers for mood disorders,” Dr. Nicoloro-SantaBarbara said in a written comment. “This work highlights the need for standardized and continual depression and anxiety screening in ob.gyn. and primary care settings that extends beyond the 6-week maternal visit and possibly beyond the first postpartum year.”

Findings draw skepticism

“The authors argue that mothers need to be screened for depression/anxiety longer than the first year post partum, and this is true, but it has nothing to do with their findings,” said Jennifer L. Payne, MD, an expert in reproductive psychiatry at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville.

In a written comment, she explained that the cross-sectional design makes it impossible to know whether the mood disturbances were linked with delivery at all.

“It is unclear if the depression/anxiety symptoms began after delivery or not,” Dr. Payne said. “In addition, it is unclear if the findings are causative or a result of depression/anxiety symptoms (the authors admit this in the limitations section). It is likely that the findings are not specific or even related to having delivered a child, but rather reflect a more general process related to depression/anxiety outside of the postpartum time period.”

Only prospective studies can answer these questions, she said.

Dr. Nicoloro-SantaBarbara agreed that further research is needed.

“Our findings are exciting, but still need to be replicated in larger samples with diverse women in order to make sure they generalize,” she said. “More work is needed to understand why inflammation plays a role in postpartum mental illness for some women and not others.”

The study was supported by a Cedars-Sinai Precision Health Grant, the Cousins Center for Psychoneuroimmunology, University of California, Los Angeles, and the National Institute of Mental Health. The investigators and Dr. Payne disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

Postpartum depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder that persist 2-3 years after birth are associated with a dysregulated immune system that is characterized by increased inflammatory signaling, according to investigators.

These findings suggest that mental health screening for women who have given birth should continue beyond the first year post partum, reported lead author Jennifer M. Nicoloro-SantaBarbara, PhD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues.

“Delayed postpartum depression, also known as late-onset postpartum depression, can affect women up to 18 months after delivery,” the investigators wrote in the American Journal of Reproductive Immunology. “It can appear even later in some women, depending on the hormonal changes that occur after having a baby (for example, timing of weaning). However, the majority of research on maternal mental health focuses on the first year post birth, leaving a gap in research beyond 12 months post partum.”

To address this gap, the investigators enrolled 33 women who were 2-3 years post partum. Participants completed self-guided questionnaires on PTSD, depression, and anxiety, and provided blood samples for gene expression analysis.

Sixteen of the 33 women had clinically significant mood disturbances. and significantly reduced activation of genes associated with viral response.

“The results provide preliminary evidence of a mechanism (e.g., immune dysregulation) that might be contributing to mood disorders and bring us closer to the goal of identifying targetable biomarkers for mood disorders,” Dr. Nicoloro-SantaBarbara said in a written comment. “This work highlights the need for standardized and continual depression and anxiety screening in ob.gyn. and primary care settings that extends beyond the 6-week maternal visit and possibly beyond the first postpartum year.”

Findings draw skepticism

“The authors argue that mothers need to be screened for depression/anxiety longer than the first year post partum, and this is true, but it has nothing to do with their findings,” said Jennifer L. Payne, MD, an expert in reproductive psychiatry at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville.

In a written comment, she explained that the cross-sectional design makes it impossible to know whether the mood disturbances were linked with delivery at all.

“It is unclear if the depression/anxiety symptoms began after delivery or not,” Dr. Payne said. “In addition, it is unclear if the findings are causative or a result of depression/anxiety symptoms (the authors admit this in the limitations section). It is likely that the findings are not specific or even related to having delivered a child, but rather reflect a more general process related to depression/anxiety outside of the postpartum time period.”

Only prospective studies can answer these questions, she said.

Dr. Nicoloro-SantaBarbara agreed that further research is needed.

“Our findings are exciting, but still need to be replicated in larger samples with diverse women in order to make sure they generalize,” she said. “More work is needed to understand why inflammation plays a role in postpartum mental illness for some women and not others.”

The study was supported by a Cedars-Sinai Precision Health Grant, the Cousins Center for Psychoneuroimmunology, University of California, Los Angeles, and the National Institute of Mental Health. The investigators and Dr. Payne disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

Postpartum depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder that persist 2-3 years after birth are associated with a dysregulated immune system that is characterized by increased inflammatory signaling, according to investigators.

These findings suggest that mental health screening for women who have given birth should continue beyond the first year post partum, reported lead author Jennifer M. Nicoloro-SantaBarbara, PhD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues.

“Delayed postpartum depression, also known as late-onset postpartum depression, can affect women up to 18 months after delivery,” the investigators wrote in the American Journal of Reproductive Immunology. “It can appear even later in some women, depending on the hormonal changes that occur after having a baby (for example, timing of weaning). However, the majority of research on maternal mental health focuses on the first year post birth, leaving a gap in research beyond 12 months post partum.”

To address this gap, the investigators enrolled 33 women who were 2-3 years post partum. Participants completed self-guided questionnaires on PTSD, depression, and anxiety, and provided blood samples for gene expression analysis.

Sixteen of the 33 women had clinically significant mood disturbances. and significantly reduced activation of genes associated with viral response.

“The results provide preliminary evidence of a mechanism (e.g., immune dysregulation) that might be contributing to mood disorders and bring us closer to the goal of identifying targetable biomarkers for mood disorders,” Dr. Nicoloro-SantaBarbara said in a written comment. “This work highlights the need for standardized and continual depression and anxiety screening in ob.gyn. and primary care settings that extends beyond the 6-week maternal visit and possibly beyond the first postpartum year.”

Findings draw skepticism

“The authors argue that mothers need to be screened for depression/anxiety longer than the first year post partum, and this is true, but it has nothing to do with their findings,” said Jennifer L. Payne, MD, an expert in reproductive psychiatry at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville.

In a written comment, she explained that the cross-sectional design makes it impossible to know whether the mood disturbances were linked with delivery at all.

“It is unclear if the depression/anxiety symptoms began after delivery or not,” Dr. Payne said. “In addition, it is unclear if the findings are causative or a result of depression/anxiety symptoms (the authors admit this in the limitations section). It is likely that the findings are not specific or even related to having delivered a child, but rather reflect a more general process related to depression/anxiety outside of the postpartum time period.”

Only prospective studies can answer these questions, she said.

Dr. Nicoloro-SantaBarbara agreed that further research is needed.

“Our findings are exciting, but still need to be replicated in larger samples with diverse women in order to make sure they generalize,” she said. “More work is needed to understand why inflammation plays a role in postpartum mental illness for some women and not others.”

The study was supported by a Cedars-Sinai Precision Health Grant, the Cousins Center for Psychoneuroimmunology, University of California, Los Angeles, and the National Institute of Mental Health. The investigators and Dr. Payne disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF REPRODUCTIVE IMMUNOLOGY

SSRI tied to improved cognition in comorbid depression, dementia

The results of the 12-week open-label, single-group study are positive, study investigator Michael Cronquist Christensen, MPA, DrPH, a director with the Lundbeck pharmaceutical company, told this news organization before presenting the results in a poster at the 15th Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease conference.

“The study confirms earlier findings of improvement in both depressive symptoms and cognitive performance with vortioxetine in patients with depression and dementia and adds to this research that these clinical effects also extend to improvement in health-related quality of life and patients’ daily functioning,” Dr. Christensen said.

“It also demonstrates that patients with depression and comorbid dementia can be safely treated with 20 mg vortioxetine – starting dose of 5 mg for the first week and up-titration to 10 mg at day 8,” he added.

However, he reported that Lundbeck doesn’t plan to seek approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for a new indication. Vortioxetine received FDA approval in 2013 to treat MDD, but 3 years later the agency rejected an expansion of its indication to include cognitive dysfunction.

“Vortioxetine is approved for MDD, but the product can be used in patients with MDD who have other diseases, including other mental illnesses,” Dr. Christensen said.

Potential neurotransmission modulator

Vortioxetine is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and serotonin receptor modulator. According to Dr. Christensen, evidence suggests the drug’s receptor targets “have the potential to modulate neurotransmitter systems that are essential for regulation of cognitive function.”

The researchers recruited 83 individuals aged 55-85 with recurrent MDD that had started before the age of 55. All had MDD episodes within the previous 6 months and comorbid dementia for at least 6 months.

Of the participants, 65.9% were female. In addition, 42.7% had Alzheimer’s disease, 26.8% had mixed-type dementia, and the rest had other types of dementia.

The daily oral dose of vortioxetine started at 5 mg for up to week 1 and then was increased to 10 mg. It was then increased to 20 mg or decreased to 5 mg “based on investigator judgment and patient response.” The average daily dose was 12.3 mg.

In regard to the primary outcome, at week 12 (n = 70), scores on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) fell by a mean of –12.4 (.78, P < .0001), which researchers deemed to be a significant reduction in severe symptoms.

“A significant and clinically meaningful effect was observed from week 1,” the researchers reported.

“As a basis for comparison, we typically see an improvement around 13-14 points during 8 weeks of antidepressant treatment in adults with MDD who do not have dementia,” Dr. Christensen added.

More than a third of patients (35.7%) saw a reduction in MADRS score by more than 50% at week 12, and 17.2% were considered to have reached MDD depression remission, defined as a MADRS score at or under 10.

For secondary outcomes, the total Digit Symbol Substitution test score grew by 0.65 (standardized effect size) by week 12, showing significant improvement (P < .0001). In addition, participants improved on some other cognitive measures, and Dr. Christensen noted that “significant improvement was also observed in the patients’ health-related quality of life and daily functioning.”

A third of patients had drug-related treatment-emergent adverse events.

Vortioxetine is one of the most expensive antidepressants: It has a list price of $444 a month, and no generic version is currently available.

Small trial, open-label design

In a comment, Claire Sexton, DPhil, senior director of scientific programs and outreach at the Alzheimer’s Association, said the study “reflects a valuable aspect of treatment research because of the close connection between depression and dementia. Depression is a known risk factor for dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease, and those who have dementia may experience depression.”

She cautioned, however, that the trial was small and had an open-label design instead of the “gold standard” of a double-blinded trial with a control group.

The study was funded by Lundbeck, where Dr. Christensen is an employee. Another author is a Lundbeck employee, and a third author reported various disclosures. Dr. Sexton reported no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The results of the 12-week open-label, single-group study are positive, study investigator Michael Cronquist Christensen, MPA, DrPH, a director with the Lundbeck pharmaceutical company, told this news organization before presenting the results in a poster at the 15th Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease conference.

“The study confirms earlier findings of improvement in both depressive symptoms and cognitive performance with vortioxetine in patients with depression and dementia and adds to this research that these clinical effects also extend to improvement in health-related quality of life and patients’ daily functioning,” Dr. Christensen said.

“It also demonstrates that patients with depression and comorbid dementia can be safely treated with 20 mg vortioxetine – starting dose of 5 mg for the first week and up-titration to 10 mg at day 8,” he added.

However, he reported that Lundbeck doesn’t plan to seek approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for a new indication. Vortioxetine received FDA approval in 2013 to treat MDD, but 3 years later the agency rejected an expansion of its indication to include cognitive dysfunction.

“Vortioxetine is approved for MDD, but the product can be used in patients with MDD who have other diseases, including other mental illnesses,” Dr. Christensen said.

Potential neurotransmission modulator

Vortioxetine is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and serotonin receptor modulator. According to Dr. Christensen, evidence suggests the drug’s receptor targets “have the potential to modulate neurotransmitter systems that are essential for regulation of cognitive function.”

The researchers recruited 83 individuals aged 55-85 with recurrent MDD that had started before the age of 55. All had MDD episodes within the previous 6 months and comorbid dementia for at least 6 months.

Of the participants, 65.9% were female. In addition, 42.7% had Alzheimer’s disease, 26.8% had mixed-type dementia, and the rest had other types of dementia.

The daily oral dose of vortioxetine started at 5 mg for up to week 1 and then was increased to 10 mg. It was then increased to 20 mg or decreased to 5 mg “based on investigator judgment and patient response.” The average daily dose was 12.3 mg.

In regard to the primary outcome, at week 12 (n = 70), scores on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) fell by a mean of –12.4 (.78, P < .0001), which researchers deemed to be a significant reduction in severe symptoms.

“A significant and clinically meaningful effect was observed from week 1,” the researchers reported.

“As a basis for comparison, we typically see an improvement around 13-14 points during 8 weeks of antidepressant treatment in adults with MDD who do not have dementia,” Dr. Christensen added.

More than a third of patients (35.7%) saw a reduction in MADRS score by more than 50% at week 12, and 17.2% were considered to have reached MDD depression remission, defined as a MADRS score at or under 10.

For secondary outcomes, the total Digit Symbol Substitution test score grew by 0.65 (standardized effect size) by week 12, showing significant improvement (P < .0001). In addition, participants improved on some other cognitive measures, and Dr. Christensen noted that “significant improvement was also observed in the patients’ health-related quality of life and daily functioning.”

A third of patients had drug-related treatment-emergent adverse events.

Vortioxetine is one of the most expensive antidepressants: It has a list price of $444 a month, and no generic version is currently available.

Small trial, open-label design

In a comment, Claire Sexton, DPhil, senior director of scientific programs and outreach at the Alzheimer’s Association, said the study “reflects a valuable aspect of treatment research because of the close connection between depression and dementia. Depression is a known risk factor for dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease, and those who have dementia may experience depression.”

She cautioned, however, that the trial was small and had an open-label design instead of the “gold standard” of a double-blinded trial with a control group.

The study was funded by Lundbeck, where Dr. Christensen is an employee. Another author is a Lundbeck employee, and a third author reported various disclosures. Dr. Sexton reported no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The results of the 12-week open-label, single-group study are positive, study investigator Michael Cronquist Christensen, MPA, DrPH, a director with the Lundbeck pharmaceutical company, told this news organization before presenting the results in a poster at the 15th Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease conference.

“The study confirms earlier findings of improvement in both depressive symptoms and cognitive performance with vortioxetine in patients with depression and dementia and adds to this research that these clinical effects also extend to improvement in health-related quality of life and patients’ daily functioning,” Dr. Christensen said.

“It also demonstrates that patients with depression and comorbid dementia can be safely treated with 20 mg vortioxetine – starting dose of 5 mg for the first week and up-titration to 10 mg at day 8,” he added.

However, he reported that Lundbeck doesn’t plan to seek approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for a new indication. Vortioxetine received FDA approval in 2013 to treat MDD, but 3 years later the agency rejected an expansion of its indication to include cognitive dysfunction.

“Vortioxetine is approved for MDD, but the product can be used in patients with MDD who have other diseases, including other mental illnesses,” Dr. Christensen said.

Potential neurotransmission modulator

Vortioxetine is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and serotonin receptor modulator. According to Dr. Christensen, evidence suggests the drug’s receptor targets “have the potential to modulate neurotransmitter systems that are essential for regulation of cognitive function.”

The researchers recruited 83 individuals aged 55-85 with recurrent MDD that had started before the age of 55. All had MDD episodes within the previous 6 months and comorbid dementia for at least 6 months.

Of the participants, 65.9% were female. In addition, 42.7% had Alzheimer’s disease, 26.8% had mixed-type dementia, and the rest had other types of dementia.

The daily oral dose of vortioxetine started at 5 mg for up to week 1 and then was increased to 10 mg. It was then increased to 20 mg or decreased to 5 mg “based on investigator judgment and patient response.” The average daily dose was 12.3 mg.

In regard to the primary outcome, at week 12 (n = 70), scores on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) fell by a mean of –12.4 (.78, P < .0001), which researchers deemed to be a significant reduction in severe symptoms.

“A significant and clinically meaningful effect was observed from week 1,” the researchers reported.

“As a basis for comparison, we typically see an improvement around 13-14 points during 8 weeks of antidepressant treatment in adults with MDD who do not have dementia,” Dr. Christensen added.

More than a third of patients (35.7%) saw a reduction in MADRS score by more than 50% at week 12, and 17.2% were considered to have reached MDD depression remission, defined as a MADRS score at or under 10.

For secondary outcomes, the total Digit Symbol Substitution test score grew by 0.65 (standardized effect size) by week 12, showing significant improvement (P < .0001). In addition, participants improved on some other cognitive measures, and Dr. Christensen noted that “significant improvement was also observed in the patients’ health-related quality of life and daily functioning.”

A third of patients had drug-related treatment-emergent adverse events.

Vortioxetine is one of the most expensive antidepressants: It has a list price of $444 a month, and no generic version is currently available.

Small trial, open-label design

In a comment, Claire Sexton, DPhil, senior director of scientific programs and outreach at the Alzheimer’s Association, said the study “reflects a valuable aspect of treatment research because of the close connection between depression and dementia. Depression is a known risk factor for dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease, and those who have dementia may experience depression.”

She cautioned, however, that the trial was small and had an open-label design instead of the “gold standard” of a double-blinded trial with a control group.

The study was funded by Lundbeck, where Dr. Christensen is an employee. Another author is a Lundbeck employee, and a third author reported various disclosures. Dr. Sexton reported no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM CTAD 2022

Let people take illegal drugs under medical supervision?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Hi. I’m Art Caplan. I’m the director of the division of medical ethics at New York University.

One is up in Washington Heights in Manhattan; the other, I believe, is over in Harlem.

These two centers will supervise people taking drugs. They have available all of the anti-overdose medications, such as Narcan. If you overdose, they will help you and try to counsel you to get off drugs, but they don’t insist that you do so. You can go there, even if you’re an addict, and continue to take drugs under supervision. This is called a risk-reduction strategy.

Some people note that there are over 100 centers like this worldwide. They’re in Canada, Switzerland, and many other countries, and they seem to work. “Working” means more people seem to come off drugs slowly – not huge numbers, but some – than if you don’t do something like this, and death rates from overdose go way down.

By the way, having these centers in place has other benefits. They save money because when someone overdoses out in the community, you have to pay all the costs of the ambulances and emergency rooms, and there are risks to the first responders due to fentanyl or other things. There are fewer syringes littering parks and public places where people shoot up. You have everything controlled when they come into a center, so that’s less burden on the community.

It turns out that you have less crime because people just aren’t out there harming or robbing other people to get money to get their next fix. The drugs are provided for them. Crime rates in neighborhoods around the world where these centers operate seem to dip. There are many positives.

There are also some negatives. People say it shouldn’t be the job of the state to keep people addicted. It’s just not the right role. Everything should be aimed at getting people off drugs, maybe including criminal penalties if that’s what it takes to get them to stop using.

My own view is that hasn’t worked. Implementing tough prison sentences in trying to fight the war on drugs just doesn’t seem to work. We had 100,000 deaths last year from drug overdoses. That number has been climbing. We all know that we’ve got a terrible epidemic of deaths due to drug overdose.

It seems to me that these centers that are involved in risk reduction are a better option for now, until we figure out some interventions that can cut the desire or the drive to use drugs, or antidotes that are effective for months or years, to prevent people from getting high no matter what drugs they take.

I’m going to come out and say that I think the New York experiment has worked. I think it has saved upward of 600 lives, they estimate, in the past year that would have been overdoses. I think costwise, it’s effective. [Reductions in] related damages and injuries from syringes being scattered around, and robbery, and so forth, are all to the good. There are even a few people coming off drugs due to counseling, which is a better outcome than we get when they’re just out in the streets.

I think other cities want to try this. I know Philadelphia does. I know New York wants to expand its program. The federal government isn’t sure, but I think the time has come to try an expansion. I think we’ve got something that – although far from perfect and I wish we had other tools – may be the best we’ve got. In the war on drugs, little victories ought to be reinforced.

Dr. Caplan disclosed that he has served as a director, officer, partner, employee, adviser, consultant, or trustee for Johnson & Johnson’s Panel for Compassionate Drug Use (unpaid position), and is a contributing author and adviser for Medscape. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Hi. I’m Art Caplan. I’m the director of the division of medical ethics at New York University.

One is up in Washington Heights in Manhattan; the other, I believe, is over in Harlem.

These two centers will supervise people taking drugs. They have available all of the anti-overdose medications, such as Narcan. If you overdose, they will help you and try to counsel you to get off drugs, but they don’t insist that you do so. You can go there, even if you’re an addict, and continue to take drugs under supervision. This is called a risk-reduction strategy.

Some people note that there are over 100 centers like this worldwide. They’re in Canada, Switzerland, and many other countries, and they seem to work. “Working” means more people seem to come off drugs slowly – not huge numbers, but some – than if you don’t do something like this, and death rates from overdose go way down.

By the way, having these centers in place has other benefits. They save money because when someone overdoses out in the community, you have to pay all the costs of the ambulances and emergency rooms, and there are risks to the first responders due to fentanyl or other things. There are fewer syringes littering parks and public places where people shoot up. You have everything controlled when they come into a center, so that’s less burden on the community.

It turns out that you have less crime because people just aren’t out there harming or robbing other people to get money to get their next fix. The drugs are provided for them. Crime rates in neighborhoods around the world where these centers operate seem to dip. There are many positives.

There are also some negatives. People say it shouldn’t be the job of the state to keep people addicted. It’s just not the right role. Everything should be aimed at getting people off drugs, maybe including criminal penalties if that’s what it takes to get them to stop using.

My own view is that hasn’t worked. Implementing tough prison sentences in trying to fight the war on drugs just doesn’t seem to work. We had 100,000 deaths last year from drug overdoses. That number has been climbing. We all know that we’ve got a terrible epidemic of deaths due to drug overdose.

It seems to me that these centers that are involved in risk reduction are a better option for now, until we figure out some interventions that can cut the desire or the drive to use drugs, or antidotes that are effective for months or years, to prevent people from getting high no matter what drugs they take.

I’m going to come out and say that I think the New York experiment has worked. I think it has saved upward of 600 lives, they estimate, in the past year that would have been overdoses. I think costwise, it’s effective. [Reductions in] related damages and injuries from syringes being scattered around, and robbery, and so forth, are all to the good. There are even a few people coming off drugs due to counseling, which is a better outcome than we get when they’re just out in the streets.

I think other cities want to try this. I know Philadelphia does. I know New York wants to expand its program. The federal government isn’t sure, but I think the time has come to try an expansion. I think we’ve got something that – although far from perfect and I wish we had other tools – may be the best we’ve got. In the war on drugs, little victories ought to be reinforced.

Dr. Caplan disclosed that he has served as a director, officer, partner, employee, adviser, consultant, or trustee for Johnson & Johnson’s Panel for Compassionate Drug Use (unpaid position), and is a contributing author and adviser for Medscape. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Hi. I’m Art Caplan. I’m the director of the division of medical ethics at New York University.

One is up in Washington Heights in Manhattan; the other, I believe, is over in Harlem.

These two centers will supervise people taking drugs. They have available all of the anti-overdose medications, such as Narcan. If you overdose, they will help you and try to counsel you to get off drugs, but they don’t insist that you do so. You can go there, even if you’re an addict, and continue to take drugs under supervision. This is called a risk-reduction strategy.

Some people note that there are over 100 centers like this worldwide. They’re in Canada, Switzerland, and many other countries, and they seem to work. “Working” means more people seem to come off drugs slowly – not huge numbers, but some – than if you don’t do something like this, and death rates from overdose go way down.

By the way, having these centers in place has other benefits. They save money because when someone overdoses out in the community, you have to pay all the costs of the ambulances and emergency rooms, and there are risks to the first responders due to fentanyl or other things. There are fewer syringes littering parks and public places where people shoot up. You have everything controlled when they come into a center, so that’s less burden on the community.

It turns out that you have less crime because people just aren’t out there harming or robbing other people to get money to get their next fix. The drugs are provided for them. Crime rates in neighborhoods around the world where these centers operate seem to dip. There are many positives.

There are also some negatives. People say it shouldn’t be the job of the state to keep people addicted. It’s just not the right role. Everything should be aimed at getting people off drugs, maybe including criminal penalties if that’s what it takes to get them to stop using.

My own view is that hasn’t worked. Implementing tough prison sentences in trying to fight the war on drugs just doesn’t seem to work. We had 100,000 deaths last year from drug overdoses. That number has been climbing. We all know that we’ve got a terrible epidemic of deaths due to drug overdose.

It seems to me that these centers that are involved in risk reduction are a better option for now, until we figure out some interventions that can cut the desire or the drive to use drugs, or antidotes that are effective for months or years, to prevent people from getting high no matter what drugs they take.

I’m going to come out and say that I think the New York experiment has worked. I think it has saved upward of 600 lives, they estimate, in the past year that would have been overdoses. I think costwise, it’s effective. [Reductions in] related damages and injuries from syringes being scattered around, and robbery, and so forth, are all to the good. There are even a few people coming off drugs due to counseling, which is a better outcome than we get when they’re just out in the streets.

I think other cities want to try this. I know Philadelphia does. I know New York wants to expand its program. The federal government isn’t sure, but I think the time has come to try an expansion. I think we’ve got something that – although far from perfect and I wish we had other tools – may be the best we’ve got. In the war on drugs, little victories ought to be reinforced.

Dr. Caplan disclosed that he has served as a director, officer, partner, employee, adviser, consultant, or trustee for Johnson & Johnson’s Panel for Compassionate Drug Use (unpaid position), and is a contributing author and adviser for Medscape. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Why doctors are losing trust in patients; what should be done?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Hi. I’m Art Caplan. I’m at the division of medical ethics at New York University.

I want to talk about a paper that my colleagues in my division just published in Health Affairs.

As they pointed out, there’s a large amount of literature about what makes patients trust their doctor. There are many studies that show that, although patients sometimes have become more critical of the medical profession, in general they still try to trust their individual physician. Nurses remain in fairly high esteem among those who are getting hospital care.

What isn’t studied, as this paper properly points out, is, what can the doctor and the nurse do to trust the patient? How can that be assessed? Isn’t that just as important as saying that patients have to trust their doctors to do and comply with what they’re told?

What if doctors are afraid of violence? What if doctors are fearful that they can’t trust patients to listen, pay attention, or do what they’re being told? What if they think that patients are coming in with all kinds of disinformation, false information, or things they pick up on the Internet, so that even though you try your best to get across accurate and complete information about what to do about infectious diseases, taking care of a kid with strep throat, or whatever it might be, you’re thinking, Can I trust this patient to do what it is that I want them to do?

One particular problem that’s causing distrust is that more and more patients are showing stress and dependence on drugs and alcohol. That doesn’t make them less trustworthy per se, but it means they can’t regulate their own behavior as well.

That obviously has to be something that the physician or the nurse is thinking about. Is this person going to be able to contain anger? Is this person going to be able to handle bad news? Is this person going to deal with me when I tell them that some of the things they believe to be true about what’s good for their health care are false?

I think we have to really start to push administrators and people in positions of power to teach doctors and nurses how to defuse situations and how to make people more comfortable when they come in and the doctor suspects that they might be under the influence, impaired, or angry because of things they’ve seen on social media, whatever those might be – including concerns about racism, bigotry, and bias, which some patients are bringing into the clinic and the hospital setting.

We need more training. We’ve got to address this as a serious issue. What can we do to defuse situations where the doctor or the nurse rightly thinks that they can’t control or they can’t trust what the patient is thinking or how the patient might behave?

It’s also the case that I think we need more backup and quick access to security so that people feel safe and comfortable in providing care. We have to make sure that if you need someone to restrain a patient or to get somebody out of a situation, that they can get there quickly and respond rapidly, and that they know what to do to deescalate a situation.

It’s sad to say, but security in today’s health care world has to be something that we really test and check – not because we’re worried, as many places are, about a shooter entering the premises, which is its own bit of concern – but I’m just talking about when the doctor or the nurse says that this patient might be acting up, could get violent, or is someone I can’t trust.

My coauthors are basically saying that it’s not a one-way street. Yes, we have to figure out ways to make sure that our patients can trust what we say. Trust is absolutely the lubricant that makes health care flow. If patients don’t trust their doctors, they’re not going to do what they say. They’re not going to get their prescriptions filled. They’re not going to be compliant. They’re not going to try to lose weight or control their diabetes.

It also goes the other way. The doctor or the nurse has to trust the patient. They have to believe that they’re safe. They have to believe that the patient is capable of controlling themselves. They have to believe that the patient is capable of listening and hearing what they’re saying, and that they’re competent to follow up on instructions, including to come back if that’s what’s required.

Everybody has to feel secure in the environment in which they’re working. Security, sadly, has to be a priority if we’re going to have a health care workforce that really feels safe and comfortable dealing with a patient population that is increasingly aggressive and perhaps not as trustworthy.

That’s not news I like to read when my colleagues write it up, but it’s important and we have to take it seriously.

Dr. Caplan disclosed that he has served as a director, officer, partner, employee, adviser, consultant, or trustee for Johnson & Johnson’s Panel for Compassionate Drug Use (unpaid position), and is a contributing author and adviser for Medscape. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Hi. I’m Art Caplan. I’m at the division of medical ethics at New York University.

I want to talk about a paper that my colleagues in my division just published in Health Affairs.

As they pointed out, there’s a large amount of literature about what makes patients trust their doctor. There are many studies that show that, although patients sometimes have become more critical of the medical profession, in general they still try to trust their individual physician. Nurses remain in fairly high esteem among those who are getting hospital care.

What isn’t studied, as this paper properly points out, is, what can the doctor and the nurse do to trust the patient? How can that be assessed? Isn’t that just as important as saying that patients have to trust their doctors to do and comply with what they’re told?

What if doctors are afraid of violence? What if doctors are fearful that they can’t trust patients to listen, pay attention, or do what they’re being told? What if they think that patients are coming in with all kinds of disinformation, false information, or things they pick up on the Internet, so that even though you try your best to get across accurate and complete information about what to do about infectious diseases, taking care of a kid with strep throat, or whatever it might be, you’re thinking, Can I trust this patient to do what it is that I want them to do?

One particular problem that’s causing distrust is that more and more patients are showing stress and dependence on drugs and alcohol. That doesn’t make them less trustworthy per se, but it means they can’t regulate their own behavior as well.

That obviously has to be something that the physician or the nurse is thinking about. Is this person going to be able to contain anger? Is this person going to be able to handle bad news? Is this person going to deal with me when I tell them that some of the things they believe to be true about what’s good for their health care are false?

I think we have to really start to push administrators and people in positions of power to teach doctors and nurses how to defuse situations and how to make people more comfortable when they come in and the doctor suspects that they might be under the influence, impaired, or angry because of things they’ve seen on social media, whatever those might be – including concerns about racism, bigotry, and bias, which some patients are bringing into the clinic and the hospital setting.

We need more training. We’ve got to address this as a serious issue. What can we do to defuse situations where the doctor or the nurse rightly thinks that they can’t control or they can’t trust what the patient is thinking or how the patient might behave?

It’s also the case that I think we need more backup and quick access to security so that people feel safe and comfortable in providing care. We have to make sure that if you need someone to restrain a patient or to get somebody out of a situation, that they can get there quickly and respond rapidly, and that they know what to do to deescalate a situation.

It’s sad to say, but security in today’s health care world has to be something that we really test and check – not because we’re worried, as many places are, about a shooter entering the premises, which is its own bit of concern – but I’m just talking about when the doctor or the nurse says that this patient might be acting up, could get violent, or is someone I can’t trust.

My coauthors are basically saying that it’s not a one-way street. Yes, we have to figure out ways to make sure that our patients can trust what we say. Trust is absolutely the lubricant that makes health care flow. If patients don’t trust their doctors, they’re not going to do what they say. They’re not going to get their prescriptions filled. They’re not going to be compliant. They’re not going to try to lose weight or control their diabetes.

It also goes the other way. The doctor or the nurse has to trust the patient. They have to believe that they’re safe. They have to believe that the patient is capable of controlling themselves. They have to believe that the patient is capable of listening and hearing what they’re saying, and that they’re competent to follow up on instructions, including to come back if that’s what’s required.

Everybody has to feel secure in the environment in which they’re working. Security, sadly, has to be a priority if we’re going to have a health care workforce that really feels safe and comfortable dealing with a patient population that is increasingly aggressive and perhaps not as trustworthy.

That’s not news I like to read when my colleagues write it up, but it’s important and we have to take it seriously.

Dr. Caplan disclosed that he has served as a director, officer, partner, employee, adviser, consultant, or trustee for Johnson & Johnson’s Panel for Compassionate Drug Use (unpaid position), and is a contributing author and adviser for Medscape. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Hi. I’m Art Caplan. I’m at the division of medical ethics at New York University.

I want to talk about a paper that my colleagues in my division just published in Health Affairs.

As they pointed out, there’s a large amount of literature about what makes patients trust their doctor. There are many studies that show that, although patients sometimes have become more critical of the medical profession, in general they still try to trust their individual physician. Nurses remain in fairly high esteem among those who are getting hospital care.

What isn’t studied, as this paper properly points out, is, what can the doctor and the nurse do to trust the patient? How can that be assessed? Isn’t that just as important as saying that patients have to trust their doctors to do and comply with what they’re told?

What if doctors are afraid of violence? What if doctors are fearful that they can’t trust patients to listen, pay attention, or do what they’re being told? What if they think that patients are coming in with all kinds of disinformation, false information, or things they pick up on the Internet, so that even though you try your best to get across accurate and complete information about what to do about infectious diseases, taking care of a kid with strep throat, or whatever it might be, you’re thinking, Can I trust this patient to do what it is that I want them to do?

One particular problem that’s causing distrust is that more and more patients are showing stress and dependence on drugs and alcohol. That doesn’t make them less trustworthy per se, but it means they can’t regulate their own behavior as well.

That obviously has to be something that the physician or the nurse is thinking about. Is this person going to be able to contain anger? Is this person going to be able to handle bad news? Is this person going to deal with me when I tell them that some of the things they believe to be true about what’s good for their health care are false?

I think we have to really start to push administrators and people in positions of power to teach doctors and nurses how to defuse situations and how to make people more comfortable when they come in and the doctor suspects that they might be under the influence, impaired, or angry because of things they’ve seen on social media, whatever those might be – including concerns about racism, bigotry, and bias, which some patients are bringing into the clinic and the hospital setting.

We need more training. We’ve got to address this as a serious issue. What can we do to defuse situations where the doctor or the nurse rightly thinks that they can’t control or they can’t trust what the patient is thinking or how the patient might behave?

It’s also the case that I think we need more backup and quick access to security so that people feel safe and comfortable in providing care. We have to make sure that if you need someone to restrain a patient or to get somebody out of a situation, that they can get there quickly and respond rapidly, and that they know what to do to deescalate a situation.

It’s sad to say, but security in today’s health care world has to be something that we really test and check – not because we’re worried, as many places are, about a shooter entering the premises, which is its own bit of concern – but I’m just talking about when the doctor or the nurse says that this patient might be acting up, could get violent, or is someone I can’t trust.

My coauthors are basically saying that it’s not a one-way street. Yes, we have to figure out ways to make sure that our patients can trust what we say. Trust is absolutely the lubricant that makes health care flow. If patients don’t trust their doctors, they’re not going to do what they say. They’re not going to get their prescriptions filled. They’re not going to be compliant. They’re not going to try to lose weight or control their diabetes.

It also goes the other way. The doctor or the nurse has to trust the patient. They have to believe that they’re safe. They have to believe that the patient is capable of controlling themselves. They have to believe that the patient is capable of listening and hearing what they’re saying, and that they’re competent to follow up on instructions, including to come back if that’s what’s required.

Everybody has to feel secure in the environment in which they’re working. Security, sadly, has to be a priority if we’re going to have a health care workforce that really feels safe and comfortable dealing with a patient population that is increasingly aggressive and perhaps not as trustworthy.

That’s not news I like to read when my colleagues write it up, but it’s important and we have to take it seriously.

Dr. Caplan disclosed that he has served as a director, officer, partner, employee, adviser, consultant, or trustee for Johnson & Johnson’s Panel for Compassionate Drug Use (unpaid position), and is a contributing author and adviser for Medscape. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

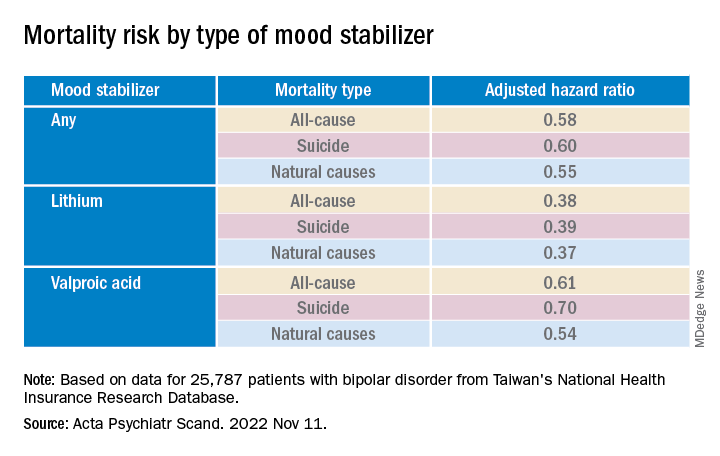

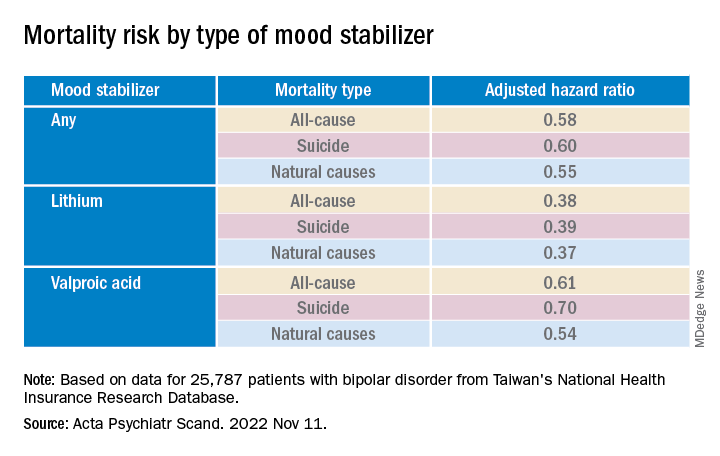

Mood stabilizers, particularly lithium, potential lifesavers in bipolar disorder

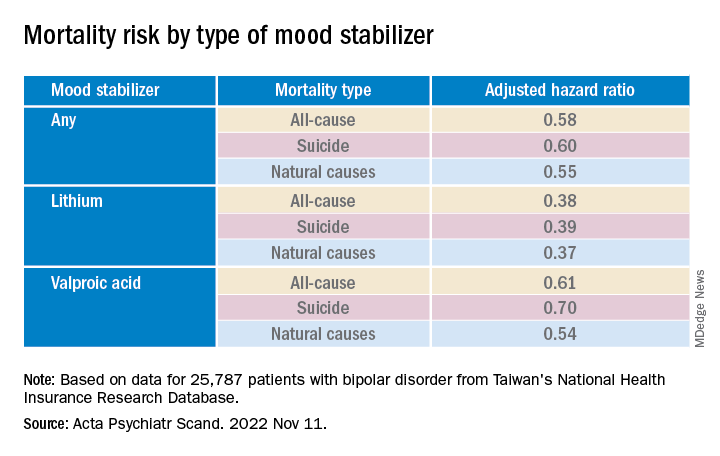

Investigators led by Pao-Huan Chen, MD, of the department of psychiatry, Taipei Medical University Hospital, Taiwan, evaluated the association between the use of mood stabilizers and the risks for all-cause mortality, suicide, and natural mortality in more than 25,000 patients with BD and found that those with BD had higher mortality.

However, they also found that patients with BD had a significantly decreased adjusted 5-year risk of dying from any cause, suicide, and natural causes. Lithium was associated with the largest risk reduction compared with the other mood stabilizers.

“The present findings highlight the potential role of mood stabilizers, particularly lithium, in reducing mortality among patients with bipolar disorder,” the authors write.

“The findings of this study could inform future clinical and mechanistic research evaluating the multifaceted effects of mood stabilizers, particularly lithium, on the psychological and physiological statuses of patients with bipolar disorder,” they add.

The study was published online in Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica.

Research gap

Patients with BD have an elevated risk for multiple comorbidities in addition to mood symptoms and neurocognitive dysfunction, with previous research suggesting a mortality rate due to suicide and natural causes that is at least twice as high as that of the general population, the authors write.

Lithium, in particular, has been associated with decreased risk for all-cause mortality and suicide in patients with BD, but findings regarding anticonvulsant mood stabilizers have been “inconsistent.”

To fill this research gap, the researchers evaluated 16 years of data from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database, which includes information about more than 23 million residents of Taiwan. The current study, which encompassed 25,787 patients with BD, looked at data from the 5-year period after index hospitalization.

The researchers hypothesized that mood stabilizers “would decrease the risk of mortality” among patients with BD and that “different mood stabilizers would exhibit different associations with mortality, owing to their varying effects on mood symptoms and physiological function.”

Covariates included sex, age, employment status, comorbidities, and concomitant drugs.

Of the patients with BD, 4,000 died within the 5-year period. Suicide and natural causes accounted for 19.0% and 73.7% of these deaths, respectively.

Cardioprotective effects?

The standardized mortality ratios (SMRs) – the ratios of observed mortality in the BD cohort to the number of expected deaths in the general population – were 5.26 for all causes (95% confidence interval, 5.10-5.43), 26.02 for suicide (95% CI, 24.20-27.93), and 4.68 for natural causes (95% CI, 4.51-4.85).

The cumulative mortality rate was higher among men vs. women, a difference that was even larger among patients who had died from any cause or natural causes (crude hazard ratios, .60 and .52, respectively; both Ps < .001).

The suicide risk peaked between ages 45 and 65 years, whereas the risks for all-cause and natural mortality increased with age and were highest in those older than 65 years.

Patients who had died from any cause or from natural causes had a higher risk for physical and psychiatric comorbidities, whereas those who had died by suicide had a higher risk for primarily psychiatric comorbidities.

Mood stabilizers were associated with decreased risks for all-cause mortality and natural mortality, with lithium and valproic acid tied to the lowest risk for all three mortality types (all Ps < .001).

Lamotrigine and carbamazepine were “not significantly associated with any type of mortality,” the authors report.

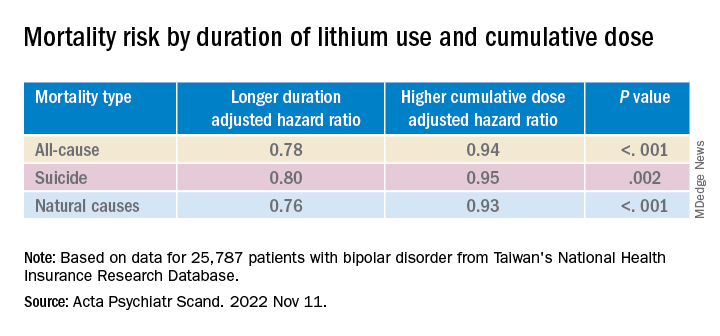

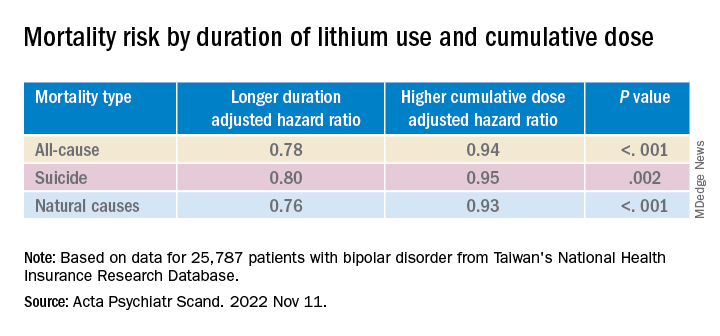

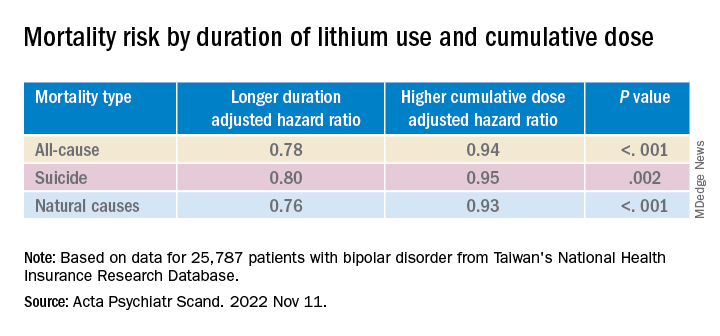

Longer duration of lithium use and a higher cumulative dose of lithium were both associated with lower risks for all three types of mortality (all Ps < .001).

Valproic acid was associated with dose-dependent decreases in all-cause and natural mortality risks.

The findings suggest that mood stabilizers “may improve not only psychosocial outcomes but also the physical health of patients with BD,” the investigators note.

The association between mood stabilizer use and reduced natural mortality risk “may be attributable to the potential benefits of psychiatric care” but may also “have resulted from the direct effects of mood stabilizers on physiological functions,” they add.

Some research suggests lithium treatment may reduce the risk for cardiovascular disease in patients with BD. Mechanistic studies have also pointed to potential cardioprotective effects from valproic acid.

The authors note several study limitations. Focusing on hospitalized patients “may have led to selection bias and overestimated mortality risk.” Moreover, the analyses were “based on the prescription, not the consumption, of mood stabilizers” and information regarding adherence was unavailable.

The absence of a protective mechanism of lamotrigine and carbamazepine may be attributable to “bias toward the relatively poor treatment responses” of these agents, neither of which is used as a first-line medication to treat BD in Taiwan. Patients taking these agents “may not receive medical care at a level equal to those taking lithium, who tend to receive closer surveillance, owing to the narrow therapeutic index.”

First-line treatment

Commenting on the study, Roger S. McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology, University of Toronto, and head of the mood disorders psychopharmacology unit, said that the data “add to a growing confluence of data from observational studies indicating that lithium especially is capable of reducing all-cause mortality, suicide mortality, and natural mortality.”

Dr. McIntyre, chairman and executive director of the Brain and Cognitive Discover Foundation, Toronto, who was not involved with the study, agreed with the authors that lamotrigine is “not a very popular drug in Taiwan, therefore we may not have sufficient assay sensitivity to document the effect.”

But lamotrigine “does have recurrence prevention effects in BD, especially bipolar depression, and it would be expected that it would reduce suicide potentially especially in such a large sample.”

The study’s take-home message “is that the extant evidence now indicates that lithium should be a first-line treatment in persons who live with BD who are experiencing suicidal ideation and/or behavior and these data should inform algorithms of treatment selection and sequencing in clinical practice guidelines,” said Dr. McIntyre.

This research was supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology in Taiwan and Taipei City Hospital. The authors declared no relevant financial relationships. Dr. McIntyre has received research grant support from CIHR/GACD/National Natural Science Foundation of China, and the Milken Institute; and speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Alkermes, Neumora Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sage, Biogen, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Bausch Health, Axsome, Novo Nordisk, Kris, Sanofi, Eisai, Intra-Cellular, NewBridge Pharmaceuticals, Viatris, AbbVie, and Atai Life Sciences. Dr. McIntyre is a CEO of Braxia Scientific.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators led by Pao-Huan Chen, MD, of the department of psychiatry, Taipei Medical University Hospital, Taiwan, evaluated the association between the use of mood stabilizers and the risks for all-cause mortality, suicide, and natural mortality in more than 25,000 patients with BD and found that those with BD had higher mortality.

However, they also found that patients with BD had a significantly decreased adjusted 5-year risk of dying from any cause, suicide, and natural causes. Lithium was associated with the largest risk reduction compared with the other mood stabilizers.

“The present findings highlight the potential role of mood stabilizers, particularly lithium, in reducing mortality among patients with bipolar disorder,” the authors write.

“The findings of this study could inform future clinical and mechanistic research evaluating the multifaceted effects of mood stabilizers, particularly lithium, on the psychological and physiological statuses of patients with bipolar disorder,” they add.

The study was published online in Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica.

Research gap

Patients with BD have an elevated risk for multiple comorbidities in addition to mood symptoms and neurocognitive dysfunction, with previous research suggesting a mortality rate due to suicide and natural causes that is at least twice as high as that of the general population, the authors write.

Lithium, in particular, has been associated with decreased risk for all-cause mortality and suicide in patients with BD, but findings regarding anticonvulsant mood stabilizers have been “inconsistent.”

To fill this research gap, the researchers evaluated 16 years of data from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database, which includes information about more than 23 million residents of Taiwan. The current study, which encompassed 25,787 patients with BD, looked at data from the 5-year period after index hospitalization.

The researchers hypothesized that mood stabilizers “would decrease the risk of mortality” among patients with BD and that “different mood stabilizers would exhibit different associations with mortality, owing to their varying effects on mood symptoms and physiological function.”

Covariates included sex, age, employment status, comorbidities, and concomitant drugs.

Of the patients with BD, 4,000 died within the 5-year period. Suicide and natural causes accounted for 19.0% and 73.7% of these deaths, respectively.

Cardioprotective effects?

The standardized mortality ratios (SMRs) – the ratios of observed mortality in the BD cohort to the number of expected deaths in the general population – were 5.26 for all causes (95% confidence interval, 5.10-5.43), 26.02 for suicide (95% CI, 24.20-27.93), and 4.68 for natural causes (95% CI, 4.51-4.85).

The cumulative mortality rate was higher among men vs. women, a difference that was even larger among patients who had died from any cause or natural causes (crude hazard ratios, .60 and .52, respectively; both Ps < .001).

The suicide risk peaked between ages 45 and 65 years, whereas the risks for all-cause and natural mortality increased with age and were highest in those older than 65 years.

Patients who had died from any cause or from natural causes had a higher risk for physical and psychiatric comorbidities, whereas those who had died by suicide had a higher risk for primarily psychiatric comorbidities.

Mood stabilizers were associated with decreased risks for all-cause mortality and natural mortality, with lithium and valproic acid tied to the lowest risk for all three mortality types (all Ps < .001).

Lamotrigine and carbamazepine were “not significantly associated with any type of mortality,” the authors report.

Longer duration of lithium use and a higher cumulative dose of lithium were both associated with lower risks for all three types of mortality (all Ps < .001).

Valproic acid was associated with dose-dependent decreases in all-cause and natural mortality risks.

The findings suggest that mood stabilizers “may improve not only psychosocial outcomes but also the physical health of patients with BD,” the investigators note.

The association between mood stabilizer use and reduced natural mortality risk “may be attributable to the potential benefits of psychiatric care” but may also “have resulted from the direct effects of mood stabilizers on physiological functions,” they add.

Some research suggests lithium treatment may reduce the risk for cardiovascular disease in patients with BD. Mechanistic studies have also pointed to potential cardioprotective effects from valproic acid.

The authors note several study limitations. Focusing on hospitalized patients “may have led to selection bias and overestimated mortality risk.” Moreover, the analyses were “based on the prescription, not the consumption, of mood stabilizers” and information regarding adherence was unavailable.

The absence of a protective mechanism of lamotrigine and carbamazepine may be attributable to “bias toward the relatively poor treatment responses” of these agents, neither of which is used as a first-line medication to treat BD in Taiwan. Patients taking these agents “may not receive medical care at a level equal to those taking lithium, who tend to receive closer surveillance, owing to the narrow therapeutic index.”

First-line treatment

Commenting on the study, Roger S. McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology, University of Toronto, and head of the mood disorders psychopharmacology unit, said that the data “add to a growing confluence of data from observational studies indicating that lithium especially is capable of reducing all-cause mortality, suicide mortality, and natural mortality.”

Dr. McIntyre, chairman and executive director of the Brain and Cognitive Discover Foundation, Toronto, who was not involved with the study, agreed with the authors that lamotrigine is “not a very popular drug in Taiwan, therefore we may not have sufficient assay sensitivity to document the effect.”

But lamotrigine “does have recurrence prevention effects in BD, especially bipolar depression, and it would be expected that it would reduce suicide potentially especially in such a large sample.”

The study’s take-home message “is that the extant evidence now indicates that lithium should be a first-line treatment in persons who live with BD who are experiencing suicidal ideation and/or behavior and these data should inform algorithms of treatment selection and sequencing in clinical practice guidelines,” said Dr. McIntyre.

This research was supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology in Taiwan and Taipei City Hospital. The authors declared no relevant financial relationships. Dr. McIntyre has received research grant support from CIHR/GACD/National Natural Science Foundation of China, and the Milken Institute; and speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Alkermes, Neumora Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sage, Biogen, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Bausch Health, Axsome, Novo Nordisk, Kris, Sanofi, Eisai, Intra-Cellular, NewBridge Pharmaceuticals, Viatris, AbbVie, and Atai Life Sciences. Dr. McIntyre is a CEO of Braxia Scientific.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators led by Pao-Huan Chen, MD, of the department of psychiatry, Taipei Medical University Hospital, Taiwan, evaluated the association between the use of mood stabilizers and the risks for all-cause mortality, suicide, and natural mortality in more than 25,000 patients with BD and found that those with BD had higher mortality.

However, they also found that patients with BD had a significantly decreased adjusted 5-year risk of dying from any cause, suicide, and natural causes. Lithium was associated with the largest risk reduction compared with the other mood stabilizers.

“The present findings highlight the potential role of mood stabilizers, particularly lithium, in reducing mortality among patients with bipolar disorder,” the authors write.

“The findings of this study could inform future clinical and mechanistic research evaluating the multifaceted effects of mood stabilizers, particularly lithium, on the psychological and physiological statuses of patients with bipolar disorder,” they add.

The study was published online in Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica.

Research gap

Patients with BD have an elevated risk for multiple comorbidities in addition to mood symptoms and neurocognitive dysfunction, with previous research suggesting a mortality rate due to suicide and natural causes that is at least twice as high as that of the general population, the authors write.

Lithium, in particular, has been associated with decreased risk for all-cause mortality and suicide in patients with BD, but findings regarding anticonvulsant mood stabilizers have been “inconsistent.”

To fill this research gap, the researchers evaluated 16 years of data from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database, which includes information about more than 23 million residents of Taiwan. The current study, which encompassed 25,787 patients with BD, looked at data from the 5-year period after index hospitalization.

The researchers hypothesized that mood stabilizers “would decrease the risk of mortality” among patients with BD and that “different mood stabilizers would exhibit different associations with mortality, owing to their varying effects on mood symptoms and physiological function.”

Covariates included sex, age, employment status, comorbidities, and concomitant drugs.

Of the patients with BD, 4,000 died within the 5-year period. Suicide and natural causes accounted for 19.0% and 73.7% of these deaths, respectively.

Cardioprotective effects?

The standardized mortality ratios (SMRs) – the ratios of observed mortality in the BD cohort to the number of expected deaths in the general population – were 5.26 for all causes (95% confidence interval, 5.10-5.43), 26.02 for suicide (95% CI, 24.20-27.93), and 4.68 for natural causes (95% CI, 4.51-4.85).

The cumulative mortality rate was higher among men vs. women, a difference that was even larger among patients who had died from any cause or natural causes (crude hazard ratios, .60 and .52, respectively; both Ps < .001).

The suicide risk peaked between ages 45 and 65 years, whereas the risks for all-cause and natural mortality increased with age and were highest in those older than 65 years.

Patients who had died from any cause or from natural causes had a higher risk for physical and psychiatric comorbidities, whereas those who had died by suicide had a higher risk for primarily psychiatric comorbidities.

Mood stabilizers were associated with decreased risks for all-cause mortality and natural mortality, with lithium and valproic acid tied to the lowest risk for all three mortality types (all Ps < .001).

Lamotrigine and carbamazepine were “not significantly associated with any type of mortality,” the authors report.

Longer duration of lithium use and a higher cumulative dose of lithium were both associated with lower risks for all three types of mortality (all Ps < .001).

Valproic acid was associated with dose-dependent decreases in all-cause and natural mortality risks.

The findings suggest that mood stabilizers “may improve not only psychosocial outcomes but also the physical health of patients with BD,” the investigators note.

The association between mood stabilizer use and reduced natural mortality risk “may be attributable to the potential benefits of psychiatric care” but may also “have resulted from the direct effects of mood stabilizers on physiological functions,” they add.

Some research suggests lithium treatment may reduce the risk for cardiovascular disease in patients with BD. Mechanistic studies have also pointed to potential cardioprotective effects from valproic acid.

The authors note several study limitations. Focusing on hospitalized patients “may have led to selection bias and overestimated mortality risk.” Moreover, the analyses were “based on the prescription, not the consumption, of mood stabilizers” and information regarding adherence was unavailable.

The absence of a protective mechanism of lamotrigine and carbamazepine may be attributable to “bias toward the relatively poor treatment responses” of these agents, neither of which is used as a first-line medication to treat BD in Taiwan. Patients taking these agents “may not receive medical care at a level equal to those taking lithium, who tend to receive closer surveillance, owing to the narrow therapeutic index.”

First-line treatment

Commenting on the study, Roger S. McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology, University of Toronto, and head of the mood disorders psychopharmacology unit, said that the data “add to a growing confluence of data from observational studies indicating that lithium especially is capable of reducing all-cause mortality, suicide mortality, and natural mortality.”

Dr. McIntyre, chairman and executive director of the Brain and Cognitive Discover Foundation, Toronto, who was not involved with the study, agreed with the authors that lamotrigine is “not a very popular drug in Taiwan, therefore we may not have sufficient assay sensitivity to document the effect.”

But lamotrigine “does have recurrence prevention effects in BD, especially bipolar depression, and it would be expected that it would reduce suicide potentially especially in such a large sample.”

The study’s take-home message “is that the extant evidence now indicates that lithium should be a first-line treatment in persons who live with BD who are experiencing suicidal ideation and/or behavior and these data should inform algorithms of treatment selection and sequencing in clinical practice guidelines,” said Dr. McIntyre.

This research was supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology in Taiwan and Taipei City Hospital. The authors declared no relevant financial relationships. Dr. McIntyre has received research grant support from CIHR/GACD/National Natural Science Foundation of China, and the Milken Institute; and speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Alkermes, Neumora Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sage, Biogen, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Bausch Health, Axsome, Novo Nordisk, Kris, Sanofi, Eisai, Intra-Cellular, NewBridge Pharmaceuticals, Viatris, AbbVie, and Atai Life Sciences. Dr. McIntyre is a CEO of Braxia Scientific.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ACTA PSYCHIATRICA SCANDINAVICA

Digital treatment may help relieve PTSD, panic disorder

The 28-day home-based treatment, known as the capnometry guided respiratory intervention (CGRI), uses an app-based feedback protocol to normalize respiration and increase patients’ ability to cope with symptoms of stress, anxiety, and panic by providing real time breath-to-breath feedback of respiratory rate and carbon dioxide (CO2) levels via a nasal cannula.

Results from the large real-world study showed that over 65% of patients with PD and over 72% of those with PTSD responded to the treatment. In addition, almost 75% of participants adhered to the study protocol, with low dropout rates.

“The brief duration of treatment, high adherence rates, and clinical benefit suggests that CGRI provides an important addition to treatment options for PD and PTSD,” the investigators write.

The study was published online in Frontiers in Digital Health.

‘New kid on the block’

The “respiratory dysregulation hypothesis” links CO2 sensitivity to panic attacks and PD, and similar reactivity has been identified in PTSD, but a “common limitation of psychotherapeutic and pharmacologic approaches to PD and PTSD is that neither address the role of respiratory physiology and breathing style,” the investigators note.

The most widely studied treatment for PTSD is trauma-focused psychotherapy, in which the patient reviews and revisits the trauma, but it has a high dropout rate, study investigator Michael Telch, PhD, director of the Laboratory for the Study of Anxiety Disorders, University of Texas, Austin, told this news organization.

He described CGRI for PTSD as a “relatively new kid on the block, so to speak.” The intervention was cleared by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treatment of PD and PTSD in 2013 and 2018, respectively, and is currently available through the Veterans Administration for veterans with PTSD. It is also covered by some commercial insurance plans.

“The underlying assumption [of CGRI] is that a person can learn to develop skills for controlling some of their physiological reactions that are triggered as a result of trauma,” said Dr. Telch.

The device uses a biofeedback approach to give patients “greater control over their physiological reactions, such as hyperventilation and increased respiration rate, and the focus is on providing a sense of mastery,” he said.

Participants with PTSD were assigned to a health coach. The device was delivered to the patient’s home, and patients met with the trained coach weekly and could check in between visits via text or e-mail. Twice-daily sessions were recommended.

“The coach gets feedback about what’s happening with the patient’s respiration and end-tidal CO2 levels [etCO2] and instructs participants how to keep their respiration rate and etCO2 at a more normal level,” said Dr. Telch.

The CGRI “teaches a specific breathing style via a system providing real-time feedback of respiratory rate (RR) and exhaled carbon dioxide levels facilitated by data capture,” the authors note.

Sense of mastery

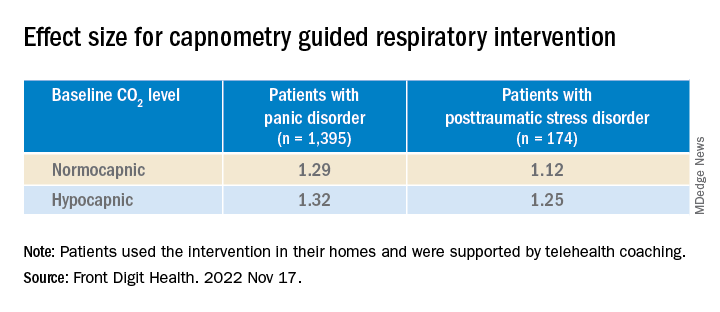

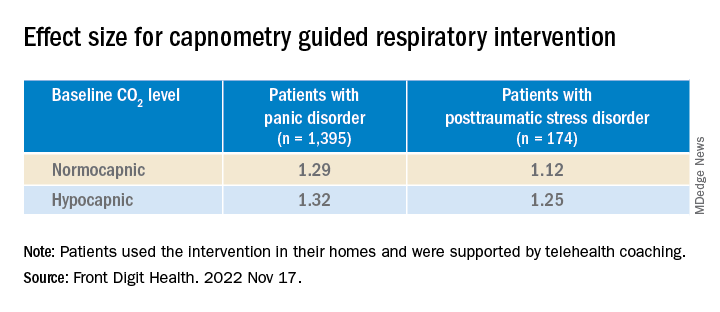

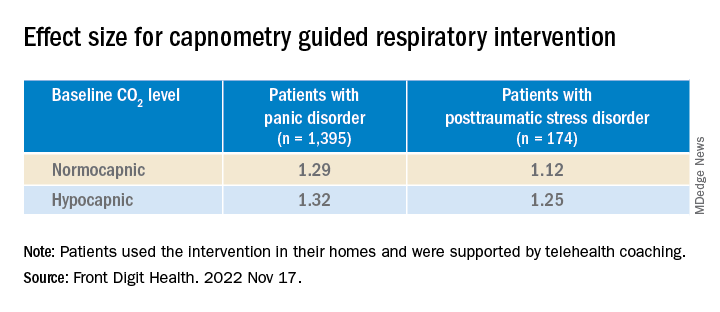

Of the 1,569 participants, 1,395 had PD and 174 had PTSD (mean age, 39.2 [standard deviation, 13.9] years and 40.9 [SD, 14.9] years, respectively; 76% and 73% female, respectively). Those with PD completed the Panic Disorder Severity Scale (PDSS) and those with PTSD completed the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5), before and after the intervention.

The treatment response rate for PD was defined as a 40% or greater reduction in PDSS total scores, whereas treatment response rate for PTSD was defined as a 10-point or greater reduction in PCL-5 scores.

At baseline, patients were classified either as normocapnic or hypocapnic (etCO2 ≥ 37 or < 37, respectively), with 65% classified as normocapnic and 35% classified as hypocapnic.

Among patients with PD, there was a 50.2% mean pre- to posttreatment reduction in total PDSS scores (P < .001; d = 1.31), with a treatment response rate of 65.3% of patients.

Among patients with PTSD, there was a 41.1% pre- to posttreatment reduction in total PCL-5 scores (P < .001; d = 1.16), with a treatment response rate of 72.4%.

When investigators analyzed the response at the individual level, they found that 55.7% of patients with PD and 53.5% of those with PTSD were classified as treatment responders. This determination was based on a two-pronged approach that first calculated the Reliable Change Index (RCI) for each participant, and, in participants showing statistically reliable improvement, whether the posttreatment score was closer to the distribution of scores for patients without or with the given disorder.

“Patients with both normal and below-normal baseline exhaled CO2 levels experienced comparable benefit,” the authors report.

There were high levels of adherence across the full treatment period in both the PD and the PTSD groups (74.8% and 74.9%, respectively), with low dropout rates (10% and 11%, respectively).