User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

Similar brain atrophy in obesity and Alzheimer’s disease

Comparisons of MRI scans for more than 1,000 participants indicate correlations between the two conditions, especially in areas of gray matter thinning, suggesting that managing excess weight might slow cognitive decline and lower the risk for AD, according to the researchers.

However, brain maps of obesity did not correlate with maps of amyloid or tau protein accumulation.

“The fact that obesity-related brain atrophy did not correlate with the distribution of amyloid and tau proteins in AD was not what we expected,” study author Filip Morys, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher at McGill University, Montreal, said in an interview. “But it might just show that the specific mechanisms underpinning obesity- and Alzheimer’s disease–related neurodegeneration are different. This remains to be confirmed.”

The study was published in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Cortical Thinning

The current study was prompted by the team’s earlier study, which showed that obesity-related neurodegeneration patterns were visually similar to those of AD, said Dr. Morys. “It was known previously that obesity is a risk factor for AD, but we wanted to directly compare brain atrophy patterns in both, which is what we did in this new study.”

The researchers analyzed data from a pooled sample of more than 1,300 participants. From the ADNI database, the researchers selected participants with AD and age- and sex-matched cognitively healthy controls. From the UK Biobank, the researchers drew a sample of lean, overweight, and obese participants without neurologic disease.

To determine how the weight status of patients with AD affects the correspondence between AD and obesity maps, they categorized participants with AD and healthy controls from the ADNI database into lean, overweight, and obese subgroups.

Then, to investigate mechanisms that might drive the similarities between obesity-related brain atrophy and AD-related amyloid-beta accumulation, they looked for overlapping areas in PET brain maps between patients with these outcomes.

The investigations showed that obesity maps were highly correlated with AD maps, but not with amyloid-beta or tau protein maps. The researchers also found significant correlations between obesity and the lean individuals with AD.

Brain regions with the highest similarities between obesity and AD were located mainly in the left temporal and bilateral prefrontal cortices.

“Our research confirms that obesity-related gray matter atrophy resembles that of AD,” the authors concluded. “Excess weight management could lead to improved health outcomes, slow down cognitive decline in aging, and lower the risk for AD.”

Upcoming research “will focus on investigating how weight loss can affect the risk for AD, other dementias, and cognitive decline in general,” said Dr. Morys. “At this point, our study suggests that obesity prevention, weight loss, but also decreasing other metabolic risk factors related to obesity, such as type-2 diabetes or hypertension, might reduce the risk for AD and have beneficial effects on cognition.”

Lifestyle habits

Commenting on the findings, Claire Sexton, DPhil, vice president of scientific programs and outreach at the Alzheimer’s Association, cautioned that a single cross-sectional study isn’t conclusive. “Previous studies have illustrated that the relationship between obesity and dementia is complex. Growing evidence indicates that people can reduce their risk of cognitive decline by adopting key lifestyle habits, like regular exercise, a heart-healthy diet and staying socially and cognitively engaged.”

The Alzheimer’s Association is leading a 2-year clinical trial, U.S. Pointer, to study how targeting these risk factors in combination may reduce risk for cognitive decline in older adults.

The work was supported by a Foundation Scheme award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Morys received a postdoctoral fellowship from Fonds de Recherche du Quebec – Santé. Data collection and sharing were funded by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and multiple pharmaceutical companies and other private sector organizations. Dr. Morys and Dr. Sexton reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Comparisons of MRI scans for more than 1,000 participants indicate correlations between the two conditions, especially in areas of gray matter thinning, suggesting that managing excess weight might slow cognitive decline and lower the risk for AD, according to the researchers.

However, brain maps of obesity did not correlate with maps of amyloid or tau protein accumulation.

“The fact that obesity-related brain atrophy did not correlate with the distribution of amyloid and tau proteins in AD was not what we expected,” study author Filip Morys, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher at McGill University, Montreal, said in an interview. “But it might just show that the specific mechanisms underpinning obesity- and Alzheimer’s disease–related neurodegeneration are different. This remains to be confirmed.”

The study was published in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Cortical Thinning

The current study was prompted by the team’s earlier study, which showed that obesity-related neurodegeneration patterns were visually similar to those of AD, said Dr. Morys. “It was known previously that obesity is a risk factor for AD, but we wanted to directly compare brain atrophy patterns in both, which is what we did in this new study.”

The researchers analyzed data from a pooled sample of more than 1,300 participants. From the ADNI database, the researchers selected participants with AD and age- and sex-matched cognitively healthy controls. From the UK Biobank, the researchers drew a sample of lean, overweight, and obese participants without neurologic disease.

To determine how the weight status of patients with AD affects the correspondence between AD and obesity maps, they categorized participants with AD and healthy controls from the ADNI database into lean, overweight, and obese subgroups.

Then, to investigate mechanisms that might drive the similarities between obesity-related brain atrophy and AD-related amyloid-beta accumulation, they looked for overlapping areas in PET brain maps between patients with these outcomes.

The investigations showed that obesity maps were highly correlated with AD maps, but not with amyloid-beta or tau protein maps. The researchers also found significant correlations between obesity and the lean individuals with AD.

Brain regions with the highest similarities between obesity and AD were located mainly in the left temporal and bilateral prefrontal cortices.

“Our research confirms that obesity-related gray matter atrophy resembles that of AD,” the authors concluded. “Excess weight management could lead to improved health outcomes, slow down cognitive decline in aging, and lower the risk for AD.”

Upcoming research “will focus on investigating how weight loss can affect the risk for AD, other dementias, and cognitive decline in general,” said Dr. Morys. “At this point, our study suggests that obesity prevention, weight loss, but also decreasing other metabolic risk factors related to obesity, such as type-2 diabetes or hypertension, might reduce the risk for AD and have beneficial effects on cognition.”

Lifestyle habits

Commenting on the findings, Claire Sexton, DPhil, vice president of scientific programs and outreach at the Alzheimer’s Association, cautioned that a single cross-sectional study isn’t conclusive. “Previous studies have illustrated that the relationship between obesity and dementia is complex. Growing evidence indicates that people can reduce their risk of cognitive decline by adopting key lifestyle habits, like regular exercise, a heart-healthy diet and staying socially and cognitively engaged.”

The Alzheimer’s Association is leading a 2-year clinical trial, U.S. Pointer, to study how targeting these risk factors in combination may reduce risk for cognitive decline in older adults.

The work was supported by a Foundation Scheme award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Morys received a postdoctoral fellowship from Fonds de Recherche du Quebec – Santé. Data collection and sharing were funded by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and multiple pharmaceutical companies and other private sector organizations. Dr. Morys and Dr. Sexton reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Comparisons of MRI scans for more than 1,000 participants indicate correlations between the two conditions, especially in areas of gray matter thinning, suggesting that managing excess weight might slow cognitive decline and lower the risk for AD, according to the researchers.

However, brain maps of obesity did not correlate with maps of amyloid or tau protein accumulation.

“The fact that obesity-related brain atrophy did not correlate with the distribution of amyloid and tau proteins in AD was not what we expected,” study author Filip Morys, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher at McGill University, Montreal, said in an interview. “But it might just show that the specific mechanisms underpinning obesity- and Alzheimer’s disease–related neurodegeneration are different. This remains to be confirmed.”

The study was published in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Cortical Thinning

The current study was prompted by the team’s earlier study, which showed that obesity-related neurodegeneration patterns were visually similar to those of AD, said Dr. Morys. “It was known previously that obesity is a risk factor for AD, but we wanted to directly compare brain atrophy patterns in both, which is what we did in this new study.”

The researchers analyzed data from a pooled sample of more than 1,300 participants. From the ADNI database, the researchers selected participants with AD and age- and sex-matched cognitively healthy controls. From the UK Biobank, the researchers drew a sample of lean, overweight, and obese participants without neurologic disease.

To determine how the weight status of patients with AD affects the correspondence between AD and obesity maps, they categorized participants with AD and healthy controls from the ADNI database into lean, overweight, and obese subgroups.

Then, to investigate mechanisms that might drive the similarities between obesity-related brain atrophy and AD-related amyloid-beta accumulation, they looked for overlapping areas in PET brain maps between patients with these outcomes.

The investigations showed that obesity maps were highly correlated with AD maps, but not with amyloid-beta or tau protein maps. The researchers also found significant correlations between obesity and the lean individuals with AD.

Brain regions with the highest similarities between obesity and AD were located mainly in the left temporal and bilateral prefrontal cortices.

“Our research confirms that obesity-related gray matter atrophy resembles that of AD,” the authors concluded. “Excess weight management could lead to improved health outcomes, slow down cognitive decline in aging, and lower the risk for AD.”

Upcoming research “will focus on investigating how weight loss can affect the risk for AD, other dementias, and cognitive decline in general,” said Dr. Morys. “At this point, our study suggests that obesity prevention, weight loss, but also decreasing other metabolic risk factors related to obesity, such as type-2 diabetes or hypertension, might reduce the risk for AD and have beneficial effects on cognition.”

Lifestyle habits

Commenting on the findings, Claire Sexton, DPhil, vice president of scientific programs and outreach at the Alzheimer’s Association, cautioned that a single cross-sectional study isn’t conclusive. “Previous studies have illustrated that the relationship between obesity and dementia is complex. Growing evidence indicates that people can reduce their risk of cognitive decline by adopting key lifestyle habits, like regular exercise, a heart-healthy diet and staying socially and cognitively engaged.”

The Alzheimer’s Association is leading a 2-year clinical trial, U.S. Pointer, to study how targeting these risk factors in combination may reduce risk for cognitive decline in older adults.

The work was supported by a Foundation Scheme award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Morys received a postdoctoral fellowship from Fonds de Recherche du Quebec – Santé. Data collection and sharing were funded by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and multiple pharmaceutical companies and other private sector organizations. Dr. Morys and Dr. Sexton reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

Psychiatric illnesses share common brain network

Investigators used coordinate and lesion network mapping to assess whether there was a shared brain network common to multiple psychiatric disorders. In a meta-analysis of almost 200 studies encompassing more than 15,000 individuals, they found that atrophy coordinates across these six psychiatric conditions all mapped to a common brain network.

Moreover, lesion damage to this network in patients with penetrating head trauma correlated with the number of psychiatric illnesses that the patients were diagnosed with post trauma.

The findings have “bigger-picture potential implications,” lead author Joseph Taylor, MD, PhD, medical director of transcranial magnetic stimulation at Brigham and Women’s Hospital’s Center for Brain Circuit Therapeutics, Boston, told this news organization.

“In psychiatry, we talk about symptoms and define our disorders based on symptom checklists, which are fairly reliable but don’t have neurobiological underpinnings,” said Dr. Taylor, who is also an associate psychiatrist in Brigham’s department of psychiatry.

By contrast, “in neurology, we ask: ‘Where is the lesion?’ Studying brain networks could potentially help us diagnose and treat people with psychiatric illness more effectively, just as we treat neurological disorders,” he added.

The findings were published online in Nature Human Behavior.

Beyond symptom checklists

Dr. Taylor noted that, in the field of psychiatry, “we often study disorders in isolation,” such as generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder.

“But what see clinically is that half of patients meet the criteria for more than one psychiatric disorder,” he said. “It can be difficult to diagnose and treat these patients, and there are worse treatment outcomes.”

There is also a “discrepancy” between how these disorders are studied (one at a time) and how patients are treated in clinic, Dr. Taylor noted. And there is increasing evidence that psychiatric disorders may share a common neurobiology.

This “highlights the possibility of potentially developing transdiagnostic treatments based on common neurobiology, not just symptom checklists,” Dr. Taylor said.

Prior work “has attempted to map abnormalities to common brain regions rather than to a common brain network,” the investigators wrote. Moreover, “prior studies have rarely tested specificity by comparing psychiatric disorders to other brain disorders.”

In the current study, the researchers used “morphometric brain lesion datasets coupled with a wiring diagram of the human brain to derive a convergent brain network for psychiatric illness.”

They analyzed four large published datasets. Dataset 1 was sourced from an activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis (ALE) of whole-brain voxel-based studies that compared patients with psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, BD, depression, addiction, OCD, and anxiety to healthy controls (n = 193 studies; 15,892 individuals in total).

Dataset 2 was drawn from published neuroimaging studies involving patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other neurodegenerative conditions (n = 72 studies). They reported coordinates regarding which patients with these disorders had more atrophy compared with control persons.

Dataset 3 was sourced from the Vietnam Head Injury study, which followed veterans with and those without penetrating head injuries (n = 194 veterans with injuries). Dataset 4 was sourced from published neurosurgical ablation coordinates for depression.

Shared neurobiology

Upon analyzing dataset 1, the researchers found decreased gray matter in the bilateral anterior insula, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, thalamus, amygdala, hippocampus, and parietal operculum – findings that are “consistent with prior work.”

However, fewer than 35% of the studies contributed to any single cluster; and no cluster was specific to psychiatric versus neurodegenerative coordinates (drawn from dataset 2).

On the other hand, coordinate network mapping yielded “more statistically robust” (P < .001) results, which were found in 85% of the studies. “Psychiatric atrophy coordinates were functionally connected to the same network of brain regions,” the researchers reported.

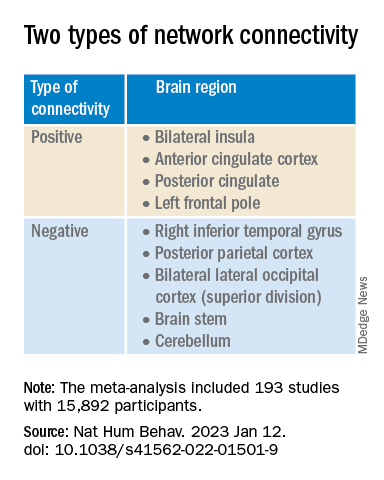

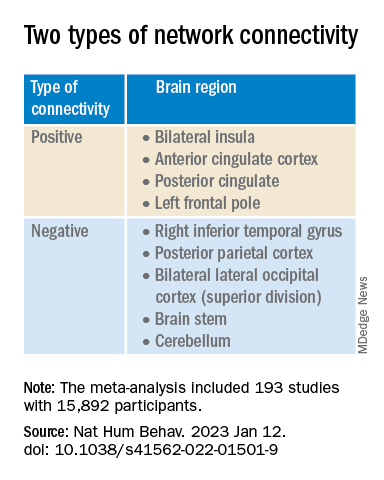

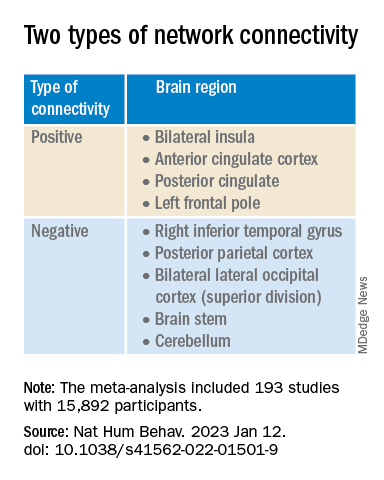

This network was defined by two types of connectivity, positive and negative.

“The topography of this transdiagnostic network was independent of the statistical threshold and specific to psychiatric (vs. neurodegenerative) disorders, with the strongest peak occurring in the posterior parietal cortex (Brodmann Area 7) near the intraparietal sulcus,” the investigators wrote.

When lesions from dataset 3 were overlaid onto the ALE map and the transdiagnostic network in order to evaluate whether damage to either map correlated with number of post-lesion psychiatric diagnosis, results showed no evidence of a correlation between psychiatric comorbidity and damage on the ALE map (Pearson r, 0.02; P = .766).

However, when the same approach was applied to the transdiagnostic network, a statistically significant correlation was found between psychiatric comorbidity and lesion damage (Pearson r, –0.21; P = .01). A multiple regression model showed that the transdiagnostic, but not the ALE, network “independently predicted the number of post-lesion psychiatric diagnoses” (P = .003 vs. P = .1), the investigators reported.

All four neurosurgical ablative targets for psychiatric disorders found on analysis of dataset 4 “intersected” and aligned with the transdiagnostic network.

“The study does not immediately impact clinical practice, but it would be helpful for practicing clinicians to know that psychiatric disorders commonly co-occur and might share common neurobiology and a convergent brain network,” Dr. Taylor said.

“Future work based on our findings could potentially influence clinical trials and clinical practice, especially in the area of brain stimulation,” he added.

‘Exciting new targets’

In a comment, Desmond Oathes, PhD, associate director, Center for Neuromodulation and Stress, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said the “next step in the science is to combine individual brain imaging, aka, ‘individualized connectomes,’ with these promising group maps to determine something meaningful at the individual patient level.”

Dr. Oathes, who is also a faculty clinician at the Center for the Treatment and Study of Anxiety and was not involved with the study, noted that an open question is whether the brain volume abnormalities/atrophy “can be changed with treatment and in what direction.”

A “strong take-home message from this paper is that brain volume measures from single coordinates are noisy as measures of psychiatric abnormality, whereas network effects seem to be especially sensitive for capturing these effects,” Dr. Oathes said.

The “abnormal networks across these disorders do not fit easily into well-known networks from healthy participants. However, they map well onto other databases relevant to psychiatric disorders and offer exciting new potential targets for prospective treatment studies,” he added.

The investigators received no specific funding for this work. Dr. Taylor reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Oathes reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators used coordinate and lesion network mapping to assess whether there was a shared brain network common to multiple psychiatric disorders. In a meta-analysis of almost 200 studies encompassing more than 15,000 individuals, they found that atrophy coordinates across these six psychiatric conditions all mapped to a common brain network.

Moreover, lesion damage to this network in patients with penetrating head trauma correlated with the number of psychiatric illnesses that the patients were diagnosed with post trauma.

The findings have “bigger-picture potential implications,” lead author Joseph Taylor, MD, PhD, medical director of transcranial magnetic stimulation at Brigham and Women’s Hospital’s Center for Brain Circuit Therapeutics, Boston, told this news organization.

“In psychiatry, we talk about symptoms and define our disorders based on symptom checklists, which are fairly reliable but don’t have neurobiological underpinnings,” said Dr. Taylor, who is also an associate psychiatrist in Brigham’s department of psychiatry.

By contrast, “in neurology, we ask: ‘Where is the lesion?’ Studying brain networks could potentially help us diagnose and treat people with psychiatric illness more effectively, just as we treat neurological disorders,” he added.

The findings were published online in Nature Human Behavior.

Beyond symptom checklists

Dr. Taylor noted that, in the field of psychiatry, “we often study disorders in isolation,” such as generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder.

“But what see clinically is that half of patients meet the criteria for more than one psychiatric disorder,” he said. “It can be difficult to diagnose and treat these patients, and there are worse treatment outcomes.”

There is also a “discrepancy” between how these disorders are studied (one at a time) and how patients are treated in clinic, Dr. Taylor noted. And there is increasing evidence that psychiatric disorders may share a common neurobiology.

This “highlights the possibility of potentially developing transdiagnostic treatments based on common neurobiology, not just symptom checklists,” Dr. Taylor said.

Prior work “has attempted to map abnormalities to common brain regions rather than to a common brain network,” the investigators wrote. Moreover, “prior studies have rarely tested specificity by comparing psychiatric disorders to other brain disorders.”

In the current study, the researchers used “morphometric brain lesion datasets coupled with a wiring diagram of the human brain to derive a convergent brain network for psychiatric illness.”

They analyzed four large published datasets. Dataset 1 was sourced from an activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis (ALE) of whole-brain voxel-based studies that compared patients with psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, BD, depression, addiction, OCD, and anxiety to healthy controls (n = 193 studies; 15,892 individuals in total).

Dataset 2 was drawn from published neuroimaging studies involving patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other neurodegenerative conditions (n = 72 studies). They reported coordinates regarding which patients with these disorders had more atrophy compared with control persons.

Dataset 3 was sourced from the Vietnam Head Injury study, which followed veterans with and those without penetrating head injuries (n = 194 veterans with injuries). Dataset 4 was sourced from published neurosurgical ablation coordinates for depression.

Shared neurobiology

Upon analyzing dataset 1, the researchers found decreased gray matter in the bilateral anterior insula, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, thalamus, amygdala, hippocampus, and parietal operculum – findings that are “consistent with prior work.”

However, fewer than 35% of the studies contributed to any single cluster; and no cluster was specific to psychiatric versus neurodegenerative coordinates (drawn from dataset 2).

On the other hand, coordinate network mapping yielded “more statistically robust” (P < .001) results, which were found in 85% of the studies. “Psychiatric atrophy coordinates were functionally connected to the same network of brain regions,” the researchers reported.

This network was defined by two types of connectivity, positive and negative.

“The topography of this transdiagnostic network was independent of the statistical threshold and specific to psychiatric (vs. neurodegenerative) disorders, with the strongest peak occurring in the posterior parietal cortex (Brodmann Area 7) near the intraparietal sulcus,” the investigators wrote.

When lesions from dataset 3 were overlaid onto the ALE map and the transdiagnostic network in order to evaluate whether damage to either map correlated with number of post-lesion psychiatric diagnosis, results showed no evidence of a correlation between psychiatric comorbidity and damage on the ALE map (Pearson r, 0.02; P = .766).

However, when the same approach was applied to the transdiagnostic network, a statistically significant correlation was found between psychiatric comorbidity and lesion damage (Pearson r, –0.21; P = .01). A multiple regression model showed that the transdiagnostic, but not the ALE, network “independently predicted the number of post-lesion psychiatric diagnoses” (P = .003 vs. P = .1), the investigators reported.

All four neurosurgical ablative targets for psychiatric disorders found on analysis of dataset 4 “intersected” and aligned with the transdiagnostic network.

“The study does not immediately impact clinical practice, but it would be helpful for practicing clinicians to know that psychiatric disorders commonly co-occur and might share common neurobiology and a convergent brain network,” Dr. Taylor said.

“Future work based on our findings could potentially influence clinical trials and clinical practice, especially in the area of brain stimulation,” he added.

‘Exciting new targets’

In a comment, Desmond Oathes, PhD, associate director, Center for Neuromodulation and Stress, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said the “next step in the science is to combine individual brain imaging, aka, ‘individualized connectomes,’ with these promising group maps to determine something meaningful at the individual patient level.”

Dr. Oathes, who is also a faculty clinician at the Center for the Treatment and Study of Anxiety and was not involved with the study, noted that an open question is whether the brain volume abnormalities/atrophy “can be changed with treatment and in what direction.”

A “strong take-home message from this paper is that brain volume measures from single coordinates are noisy as measures of psychiatric abnormality, whereas network effects seem to be especially sensitive for capturing these effects,” Dr. Oathes said.

The “abnormal networks across these disorders do not fit easily into well-known networks from healthy participants. However, they map well onto other databases relevant to psychiatric disorders and offer exciting new potential targets for prospective treatment studies,” he added.

The investigators received no specific funding for this work. Dr. Taylor reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Oathes reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators used coordinate and lesion network mapping to assess whether there was a shared brain network common to multiple psychiatric disorders. In a meta-analysis of almost 200 studies encompassing more than 15,000 individuals, they found that atrophy coordinates across these six psychiatric conditions all mapped to a common brain network.

Moreover, lesion damage to this network in patients with penetrating head trauma correlated with the number of psychiatric illnesses that the patients were diagnosed with post trauma.

The findings have “bigger-picture potential implications,” lead author Joseph Taylor, MD, PhD, medical director of transcranial magnetic stimulation at Brigham and Women’s Hospital’s Center for Brain Circuit Therapeutics, Boston, told this news organization.

“In psychiatry, we talk about symptoms and define our disorders based on symptom checklists, which are fairly reliable but don’t have neurobiological underpinnings,” said Dr. Taylor, who is also an associate psychiatrist in Brigham’s department of psychiatry.

By contrast, “in neurology, we ask: ‘Where is the lesion?’ Studying brain networks could potentially help us diagnose and treat people with psychiatric illness more effectively, just as we treat neurological disorders,” he added.

The findings were published online in Nature Human Behavior.

Beyond symptom checklists

Dr. Taylor noted that, in the field of psychiatry, “we often study disorders in isolation,” such as generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder.

“But what see clinically is that half of patients meet the criteria for more than one psychiatric disorder,” he said. “It can be difficult to diagnose and treat these patients, and there are worse treatment outcomes.”

There is also a “discrepancy” between how these disorders are studied (one at a time) and how patients are treated in clinic, Dr. Taylor noted. And there is increasing evidence that psychiatric disorders may share a common neurobiology.

This “highlights the possibility of potentially developing transdiagnostic treatments based on common neurobiology, not just symptom checklists,” Dr. Taylor said.

Prior work “has attempted to map abnormalities to common brain regions rather than to a common brain network,” the investigators wrote. Moreover, “prior studies have rarely tested specificity by comparing psychiatric disorders to other brain disorders.”

In the current study, the researchers used “morphometric brain lesion datasets coupled with a wiring diagram of the human brain to derive a convergent brain network for psychiatric illness.”

They analyzed four large published datasets. Dataset 1 was sourced from an activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis (ALE) of whole-brain voxel-based studies that compared patients with psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, BD, depression, addiction, OCD, and anxiety to healthy controls (n = 193 studies; 15,892 individuals in total).

Dataset 2 was drawn from published neuroimaging studies involving patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other neurodegenerative conditions (n = 72 studies). They reported coordinates regarding which patients with these disorders had more atrophy compared with control persons.

Dataset 3 was sourced from the Vietnam Head Injury study, which followed veterans with and those without penetrating head injuries (n = 194 veterans with injuries). Dataset 4 was sourced from published neurosurgical ablation coordinates for depression.

Shared neurobiology

Upon analyzing dataset 1, the researchers found decreased gray matter in the bilateral anterior insula, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, thalamus, amygdala, hippocampus, and parietal operculum – findings that are “consistent with prior work.”

However, fewer than 35% of the studies contributed to any single cluster; and no cluster was specific to psychiatric versus neurodegenerative coordinates (drawn from dataset 2).

On the other hand, coordinate network mapping yielded “more statistically robust” (P < .001) results, which were found in 85% of the studies. “Psychiatric atrophy coordinates were functionally connected to the same network of brain regions,” the researchers reported.

This network was defined by two types of connectivity, positive and negative.

“The topography of this transdiagnostic network was independent of the statistical threshold and specific to psychiatric (vs. neurodegenerative) disorders, with the strongest peak occurring in the posterior parietal cortex (Brodmann Area 7) near the intraparietal sulcus,” the investigators wrote.

When lesions from dataset 3 were overlaid onto the ALE map and the transdiagnostic network in order to evaluate whether damage to either map correlated with number of post-lesion psychiatric diagnosis, results showed no evidence of a correlation between psychiatric comorbidity and damage on the ALE map (Pearson r, 0.02; P = .766).

However, when the same approach was applied to the transdiagnostic network, a statistically significant correlation was found between psychiatric comorbidity and lesion damage (Pearson r, –0.21; P = .01). A multiple regression model showed that the transdiagnostic, but not the ALE, network “independently predicted the number of post-lesion psychiatric diagnoses” (P = .003 vs. P = .1), the investigators reported.

All four neurosurgical ablative targets for psychiatric disorders found on analysis of dataset 4 “intersected” and aligned with the transdiagnostic network.

“The study does not immediately impact clinical practice, but it would be helpful for practicing clinicians to know that psychiatric disorders commonly co-occur and might share common neurobiology and a convergent brain network,” Dr. Taylor said.

“Future work based on our findings could potentially influence clinical trials and clinical practice, especially in the area of brain stimulation,” he added.

‘Exciting new targets’

In a comment, Desmond Oathes, PhD, associate director, Center for Neuromodulation and Stress, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said the “next step in the science is to combine individual brain imaging, aka, ‘individualized connectomes,’ with these promising group maps to determine something meaningful at the individual patient level.”

Dr. Oathes, who is also a faculty clinician at the Center for the Treatment and Study of Anxiety and was not involved with the study, noted that an open question is whether the brain volume abnormalities/atrophy “can be changed with treatment and in what direction.”

A “strong take-home message from this paper is that brain volume measures from single coordinates are noisy as measures of psychiatric abnormality, whereas network effects seem to be especially sensitive for capturing these effects,” Dr. Oathes said.

The “abnormal networks across these disorders do not fit easily into well-known networks from healthy participants. However, they map well onto other databases relevant to psychiatric disorders and offer exciting new potential targets for prospective treatment studies,” he added.

The investigators received no specific funding for this work. Dr. Taylor reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Oathes reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM NATURE HUMAN BEHAVIOR

Can a ‘smart’ skin patch detect early neurodegenerative diseases?

A new “smart patch” composed of microneedles that can detect proinflammatory markers via simulated skin interstitial fluid (ISF) may help diagnose neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease very early on.

Originally developed to deliver medications and vaccines via the skin in a minimally invasive manner, the microneedle arrays were fitted with molecular sensors that, when placed on the skin, detect neuroinflammatory biomarkers such as interleukin-6 in as little as 6 minutes.

The literature suggests that these biomarkers of neurodegenerative disease are present years before patients become symptomatic, said study investigator Sanjiv Sharma, PhD.

“Neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease are [characterized by] progressive loss in nerve cell and brain cells, which leads to memory problems and a loss of mental ability. That is why early diagnosis is key to preventing the loss of brain tissue in dementia, which can go undetected for years,” added Dr. Sharma, who is a lecturer in medical engineering at Swansea (Wales) University.

Dr. Sharma developed the patch with scientists at the Polytechnic of Porto (Portugal) School of Engineering in Portugal. In 2022, they designed, and are currently testing, a microneedle patch that will deliver the COVID vaccine.

The investigators describe their research on the patch’s ability to detect IL-6 in an article published in ACS Omega.

At-home diagnosis?

“The skin is the largest organ in the body – it contains more skin interstitial fluid than the total blood volume,” Dr. Sharma noted. “This fluid is an ultrafiltrate of blood and holds biomarkers that complement other biofluids, such as sweat, saliva, and urine. It can be sampled in a minimally invasive manner and used either for point-of-care testing or real-time using microneedle devices.”

Dr. Sharma and associates tested the microneedle patch in artificial ISF that contained the inflammatory cytokine IL-6. They found that the patch accurately detected IL-6 concentrations as low as 1 pg/mL in the fabricated ISF solution.

“In general, the transdermal sensor presented here showed simplicity in designing, short measuring time, high accuracy, and low detection limit. This approach seems a successful tool for the screening of inflammatory biomarkers in point of care testing wherein the skin acts as a window to the body,” the investigators reported.

Dr. Sharma noted that early detection of neurodegenerative diseases is crucial, as once symptoms appear, the disease may have already progressed significantly, and meaningful intervention is challenging.

The device has yet to be tested in humans, which is the next step, said Dr. Sharma.

“We will have to test the hypothesis through extensive preclinical and clinical studies to determine if bloodless, transdermal (skin) diagnostics can offer a cost-effective device that could allow testing in simpler settings such as a clinician’s practice or even home settings,” he noted.

Early days

Commenting on the research, David K. Simon, MD, PhD, professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said it is “a promising step regarding validation of a potentially beneficial method for rapidly and accurately measuring IL-6.”

However, he added, “many additional steps are needed to validate the method in actual human skin and to determine whether or not measuring these biomarkers in skin will be useful in studies of neurodegenerative diseases.”

He noted that one study limitation is that inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 are highly nonspecific, and levels are elevated in various diseases associated with inflammation.

“It is highly unlikely that measuring IL-6 will be useful as a diagnostic tool. However, it does have potential as a biomarker for measuring the impact of treatments aimed at reducing inflammation. As the authors point out, it’s more likely that clinicians will require a panel of biomarkers rather than only measuring IL-6,” he said.

The study was funded by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia. The investigators disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new “smart patch” composed of microneedles that can detect proinflammatory markers via simulated skin interstitial fluid (ISF) may help diagnose neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease very early on.

Originally developed to deliver medications and vaccines via the skin in a minimally invasive manner, the microneedle arrays were fitted with molecular sensors that, when placed on the skin, detect neuroinflammatory biomarkers such as interleukin-6 in as little as 6 minutes.

The literature suggests that these biomarkers of neurodegenerative disease are present years before patients become symptomatic, said study investigator Sanjiv Sharma, PhD.

“Neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease are [characterized by] progressive loss in nerve cell and brain cells, which leads to memory problems and a loss of mental ability. That is why early diagnosis is key to preventing the loss of brain tissue in dementia, which can go undetected for years,” added Dr. Sharma, who is a lecturer in medical engineering at Swansea (Wales) University.

Dr. Sharma developed the patch with scientists at the Polytechnic of Porto (Portugal) School of Engineering in Portugal. In 2022, they designed, and are currently testing, a microneedle patch that will deliver the COVID vaccine.

The investigators describe their research on the patch’s ability to detect IL-6 in an article published in ACS Omega.

At-home diagnosis?

“The skin is the largest organ in the body – it contains more skin interstitial fluid than the total blood volume,” Dr. Sharma noted. “This fluid is an ultrafiltrate of blood and holds biomarkers that complement other biofluids, such as sweat, saliva, and urine. It can be sampled in a minimally invasive manner and used either for point-of-care testing or real-time using microneedle devices.”

Dr. Sharma and associates tested the microneedle patch in artificial ISF that contained the inflammatory cytokine IL-6. They found that the patch accurately detected IL-6 concentrations as low as 1 pg/mL in the fabricated ISF solution.

“In general, the transdermal sensor presented here showed simplicity in designing, short measuring time, high accuracy, and low detection limit. This approach seems a successful tool for the screening of inflammatory biomarkers in point of care testing wherein the skin acts as a window to the body,” the investigators reported.

Dr. Sharma noted that early detection of neurodegenerative diseases is crucial, as once symptoms appear, the disease may have already progressed significantly, and meaningful intervention is challenging.

The device has yet to be tested in humans, which is the next step, said Dr. Sharma.

“We will have to test the hypothesis through extensive preclinical and clinical studies to determine if bloodless, transdermal (skin) diagnostics can offer a cost-effective device that could allow testing in simpler settings such as a clinician’s practice or even home settings,” he noted.

Early days

Commenting on the research, David K. Simon, MD, PhD, professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said it is “a promising step regarding validation of a potentially beneficial method for rapidly and accurately measuring IL-6.”

However, he added, “many additional steps are needed to validate the method in actual human skin and to determine whether or not measuring these biomarkers in skin will be useful in studies of neurodegenerative diseases.”

He noted that one study limitation is that inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 are highly nonspecific, and levels are elevated in various diseases associated with inflammation.

“It is highly unlikely that measuring IL-6 will be useful as a diagnostic tool. However, it does have potential as a biomarker for measuring the impact of treatments aimed at reducing inflammation. As the authors point out, it’s more likely that clinicians will require a panel of biomarkers rather than only measuring IL-6,” he said.

The study was funded by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia. The investigators disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new “smart patch” composed of microneedles that can detect proinflammatory markers via simulated skin interstitial fluid (ISF) may help diagnose neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease very early on.

Originally developed to deliver medications and vaccines via the skin in a minimally invasive manner, the microneedle arrays were fitted with molecular sensors that, when placed on the skin, detect neuroinflammatory biomarkers such as interleukin-6 in as little as 6 minutes.

The literature suggests that these biomarkers of neurodegenerative disease are present years before patients become symptomatic, said study investigator Sanjiv Sharma, PhD.

“Neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease are [characterized by] progressive loss in nerve cell and brain cells, which leads to memory problems and a loss of mental ability. That is why early diagnosis is key to preventing the loss of brain tissue in dementia, which can go undetected for years,” added Dr. Sharma, who is a lecturer in medical engineering at Swansea (Wales) University.

Dr. Sharma developed the patch with scientists at the Polytechnic of Porto (Portugal) School of Engineering in Portugal. In 2022, they designed, and are currently testing, a microneedle patch that will deliver the COVID vaccine.

The investigators describe their research on the patch’s ability to detect IL-6 in an article published in ACS Omega.

At-home diagnosis?

“The skin is the largest organ in the body – it contains more skin interstitial fluid than the total blood volume,” Dr. Sharma noted. “This fluid is an ultrafiltrate of blood and holds biomarkers that complement other biofluids, such as sweat, saliva, and urine. It can be sampled in a minimally invasive manner and used either for point-of-care testing or real-time using microneedle devices.”

Dr. Sharma and associates tested the microneedle patch in artificial ISF that contained the inflammatory cytokine IL-6. They found that the patch accurately detected IL-6 concentrations as low as 1 pg/mL in the fabricated ISF solution.

“In general, the transdermal sensor presented here showed simplicity in designing, short measuring time, high accuracy, and low detection limit. This approach seems a successful tool for the screening of inflammatory biomarkers in point of care testing wherein the skin acts as a window to the body,” the investigators reported.

Dr. Sharma noted that early detection of neurodegenerative diseases is crucial, as once symptoms appear, the disease may have already progressed significantly, and meaningful intervention is challenging.

The device has yet to be tested in humans, which is the next step, said Dr. Sharma.

“We will have to test the hypothesis through extensive preclinical and clinical studies to determine if bloodless, transdermal (skin) diagnostics can offer a cost-effective device that could allow testing in simpler settings such as a clinician’s practice or even home settings,” he noted.

Early days

Commenting on the research, David K. Simon, MD, PhD, professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said it is “a promising step regarding validation of a potentially beneficial method for rapidly and accurately measuring IL-6.”

However, he added, “many additional steps are needed to validate the method in actual human skin and to determine whether or not measuring these biomarkers in skin will be useful in studies of neurodegenerative diseases.”

He noted that one study limitation is that inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 are highly nonspecific, and levels are elevated in various diseases associated with inflammation.

“It is highly unlikely that measuring IL-6 will be useful as a diagnostic tool. However, it does have potential as a biomarker for measuring the impact of treatments aimed at reducing inflammation. As the authors point out, it’s more likely that clinicians will require a panel of biomarkers rather than only measuring IL-6,” he said.

The study was funded by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia. The investigators disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ACS OMEGA

Citing workplace violence, one-fourth of critical care workers are ready to quit

A surgeon in Tulsa shot by a disgruntled patient. A doctor in India beaten by a group of bereaved family members. A general practitioner in the United Kingdom threatened with stabbing. A new study identifies this trend and finds that 25% of health care workers polled were willing to quit because of such violence.

“That was pretty appalling,” Rahul Kashyap, MD, MBA, MBBS, recalls. Dr. Kashyap is one of the leaders of the Violence Study of Healthcare Workers and Systems (ViSHWaS), which polled an international sample of physicians, nurses, and hospital staff. This study has worrying implications, Dr. Kashyap says. In a time when hospital staff are reporting burnout in record numbers, further deterrents may be the last thing our health care system needs. But Dr. Kashyap hopes that bringing awareness to these trends may allow physicians, policymakers, and the public to mobilize and intervene before it’s too late.

Previous studies have revealed similar trends. The rate of workplace violence directed at U.S. health care workers is five times that of workers in any other industry, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The same study found that attacks had increased 63% from 2011 to 2018. Other polls that focus on the pandemic show that nearly half of U.S. nurses believe that violence increased since the world shut down. Well before the pandemic, however, a study from the Indian Medical Association found that 75% of doctors experienced workplace violence.

With this history in mind, perhaps it’s not surprising that the idea for the study came from the authors’ personal experiences. They had seen coworkers go through attacks, or they had endured attacks themselves, Dr. Kashyap says. But they couldn’t find any global data to back up these experiences. So Dr. Kashyap and his colleagues formed a web of volunteers dedicated to creating a cross-sectional study.

They got in touch with researchers from countries across Asia, the Middle East, South America, North America, and Africa. The initial group agreed to reach out to their contacts, casting a wide net. Researchers used WhatsApp, LinkedIn, and text messages to distribute the survey. Health care workers in each country completed the brief questionnaire, recalling their prepandemic world and evaluating their current one.

Within 2 months, they had reached health care workers in more than 100 countries. They concluded the study when they received about 5,000 results, according to Dr. Kashyap, and then began the process of stratifying the data. For this report, they focused on critical care, emergency medicine, and anesthesiology, which resulted in 598 responses from 69 countries. Of these, India and the United States had the highest number of participants.

In all, 73% of participants reported facing physical or verbal violence while in the hospital; 48% said they felt less motivated to work because of that violence; 39% of respondents believed that the amount of violence they experienced was the same as before the COVID-19 pandemic; and 36% of respondents believed that violence had increased. Even though they were trained on guidelines from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, 20% of participants felt unprepared to face violence.

Although the study didn’t analyze the reasons workers felt this way, Dr. Kashyap speculates that it could be related to the medical distrust that grew during the pandemic or the stress patients and health care professionals experienced during its peak.

Regardless, the researchers say their study is a starting point. Now that the trend has been highlighted, it may be acted on.

Moving forward, Dr. Kashyap believes that controlling for different variables could determine whether factors like gender or shift time put a worker at higher risk for violence. He hopes it’s possible to interrupt these patterns and reestablish trust in the hospital environment. “It’s aspirational, but you’re hoping that through studies like ViSHWaS, which means trust in Hindi ... [we could restore] the trust and confidence among health care providers for the patients and family members.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A surgeon in Tulsa shot by a disgruntled patient. A doctor in India beaten by a group of bereaved family members. A general practitioner in the United Kingdom threatened with stabbing. A new study identifies this trend and finds that 25% of health care workers polled were willing to quit because of such violence.

“That was pretty appalling,” Rahul Kashyap, MD, MBA, MBBS, recalls. Dr. Kashyap is one of the leaders of the Violence Study of Healthcare Workers and Systems (ViSHWaS), which polled an international sample of physicians, nurses, and hospital staff. This study has worrying implications, Dr. Kashyap says. In a time when hospital staff are reporting burnout in record numbers, further deterrents may be the last thing our health care system needs. But Dr. Kashyap hopes that bringing awareness to these trends may allow physicians, policymakers, and the public to mobilize and intervene before it’s too late.

Previous studies have revealed similar trends. The rate of workplace violence directed at U.S. health care workers is five times that of workers in any other industry, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The same study found that attacks had increased 63% from 2011 to 2018. Other polls that focus on the pandemic show that nearly half of U.S. nurses believe that violence increased since the world shut down. Well before the pandemic, however, a study from the Indian Medical Association found that 75% of doctors experienced workplace violence.

With this history in mind, perhaps it’s not surprising that the idea for the study came from the authors’ personal experiences. They had seen coworkers go through attacks, or they had endured attacks themselves, Dr. Kashyap says. But they couldn’t find any global data to back up these experiences. So Dr. Kashyap and his colleagues formed a web of volunteers dedicated to creating a cross-sectional study.

They got in touch with researchers from countries across Asia, the Middle East, South America, North America, and Africa. The initial group agreed to reach out to their contacts, casting a wide net. Researchers used WhatsApp, LinkedIn, and text messages to distribute the survey. Health care workers in each country completed the brief questionnaire, recalling their prepandemic world and evaluating their current one.

Within 2 months, they had reached health care workers in more than 100 countries. They concluded the study when they received about 5,000 results, according to Dr. Kashyap, and then began the process of stratifying the data. For this report, they focused on critical care, emergency medicine, and anesthesiology, which resulted in 598 responses from 69 countries. Of these, India and the United States had the highest number of participants.

In all, 73% of participants reported facing physical or verbal violence while in the hospital; 48% said they felt less motivated to work because of that violence; 39% of respondents believed that the amount of violence they experienced was the same as before the COVID-19 pandemic; and 36% of respondents believed that violence had increased. Even though they were trained on guidelines from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, 20% of participants felt unprepared to face violence.

Although the study didn’t analyze the reasons workers felt this way, Dr. Kashyap speculates that it could be related to the medical distrust that grew during the pandemic or the stress patients and health care professionals experienced during its peak.

Regardless, the researchers say their study is a starting point. Now that the trend has been highlighted, it may be acted on.

Moving forward, Dr. Kashyap believes that controlling for different variables could determine whether factors like gender or shift time put a worker at higher risk for violence. He hopes it’s possible to interrupt these patterns and reestablish trust in the hospital environment. “It’s aspirational, but you’re hoping that through studies like ViSHWaS, which means trust in Hindi ... [we could restore] the trust and confidence among health care providers for the patients and family members.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A surgeon in Tulsa shot by a disgruntled patient. A doctor in India beaten by a group of bereaved family members. A general practitioner in the United Kingdom threatened with stabbing. A new study identifies this trend and finds that 25% of health care workers polled were willing to quit because of such violence.

“That was pretty appalling,” Rahul Kashyap, MD, MBA, MBBS, recalls. Dr. Kashyap is one of the leaders of the Violence Study of Healthcare Workers and Systems (ViSHWaS), which polled an international sample of physicians, nurses, and hospital staff. This study has worrying implications, Dr. Kashyap says. In a time when hospital staff are reporting burnout in record numbers, further deterrents may be the last thing our health care system needs. But Dr. Kashyap hopes that bringing awareness to these trends may allow physicians, policymakers, and the public to mobilize and intervene before it’s too late.

Previous studies have revealed similar trends. The rate of workplace violence directed at U.S. health care workers is five times that of workers in any other industry, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The same study found that attacks had increased 63% from 2011 to 2018. Other polls that focus on the pandemic show that nearly half of U.S. nurses believe that violence increased since the world shut down. Well before the pandemic, however, a study from the Indian Medical Association found that 75% of doctors experienced workplace violence.

With this history in mind, perhaps it’s not surprising that the idea for the study came from the authors’ personal experiences. They had seen coworkers go through attacks, or they had endured attacks themselves, Dr. Kashyap says. But they couldn’t find any global data to back up these experiences. So Dr. Kashyap and his colleagues formed a web of volunteers dedicated to creating a cross-sectional study.

They got in touch with researchers from countries across Asia, the Middle East, South America, North America, and Africa. The initial group agreed to reach out to their contacts, casting a wide net. Researchers used WhatsApp, LinkedIn, and text messages to distribute the survey. Health care workers in each country completed the brief questionnaire, recalling their prepandemic world and evaluating their current one.

Within 2 months, they had reached health care workers in more than 100 countries. They concluded the study when they received about 5,000 results, according to Dr. Kashyap, and then began the process of stratifying the data. For this report, they focused on critical care, emergency medicine, and anesthesiology, which resulted in 598 responses from 69 countries. Of these, India and the United States had the highest number of participants.

In all, 73% of participants reported facing physical or verbal violence while in the hospital; 48% said they felt less motivated to work because of that violence; 39% of respondents believed that the amount of violence they experienced was the same as before the COVID-19 pandemic; and 36% of respondents believed that violence had increased. Even though they were trained on guidelines from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, 20% of participants felt unprepared to face violence.

Although the study didn’t analyze the reasons workers felt this way, Dr. Kashyap speculates that it could be related to the medical distrust that grew during the pandemic or the stress patients and health care professionals experienced during its peak.

Regardless, the researchers say their study is a starting point. Now that the trend has been highlighted, it may be acted on.

Moving forward, Dr. Kashyap believes that controlling for different variables could determine whether factors like gender or shift time put a worker at higher risk for violence. He hopes it’s possible to interrupt these patterns and reestablish trust in the hospital environment. “It’s aspirational, but you’re hoping that through studies like ViSHWaS, which means trust in Hindi ... [we could restore] the trust and confidence among health care providers for the patients and family members.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Feds charge 25 nursing school execs, staff in fake diploma scheme

The U.S. Department of Justice recently announced charges against 25 owners, operators, and employees of three Florida nursing schools in a fraud scheme in which they sold as many as 7,600 fake nursing degrees.

The purchasers in the diploma scheme paid $10,000 to $15,000 for degrees and transcripts and some 2,800 of the buyers passed the national nursing licensing exam to become registered nurses (RNs) and licensed practice nurses/vocational nurses (LPN/VNs) around the country, according to The New York Times.

Many of the degree recipients went on to work at hospitals, nursing homes, and Veterans Affairs medical centers, according to the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of Florida.

Several national nursing organizations cooperated with the investigation, and the Delaware Division of Professional Regulation already annulled 26 licenses, according to the Delaware Nurses Association. Fake licenses were issued in five states, according to federal reports.

“We are deeply unsettled by this egregious act,” DNA President Stephanie McClellan, MSN, RN, CMSRN, said in the group’s press statement. “We want all Delaware nurses to be aware of this active issue and to speak up if there is a concern regarding capacity to practice safely by a colleague/peer,” she said.

The Oregon State Board of Nursing is also investigating at least a dozen nurses who may have paid for their degrees, according to a Portland CBS affiliate.

The National Council of State Boards of Nursing said in a statement that it had helped authorities identify and monitor the individuals who allegedly provided the false degrees.

Nursing community reacts

News of the fraud scheme spread through the nursing community, including social media. “The recent report on falsified nursing school degrees is both heartbreaking and serves as an eye-opener,” tweeted Usha Menon, PhD, RN, FAAN, dean and health professor of the University of South Florida Health College of Nursing. “There was enough of a need that prompted these bad actors to develop a scheme that could’ve endangered dozens of lives.”

Jennifer Mensik Kennedy, PhD, MBA, RN, the new president of the American Nurses Association, also weighed in. “The accusation that personnel at once-accredited nursing schools allegedly participated in this scheme is simply deplorable. These unlawful and unethical acts disparage the reputation of actual nurses everywhere who have rightfully earned [their titles] through their education, hard work, dedication, and time.”

The false degrees and transcripts were issued by three once-accredited and now-shuttered nursing schools in South Florida: Palm Beach School of Nursing, Sacred Heart International Institute, and Sienna College.

The alleged co-conspirators reportedly made $114 million from the scheme, which dates back to 2016, according to several news reports. Each defendant faces up to 20 years in prison.

Most LPN programs charge $10,000 to $15,000 to complete a program, Robert Rosseter, a spokesperson for the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN), told this news organization.

None were AACN members, and none were accredited by the Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education, which is AACN’s autonomous accrediting agency, Mr. Rosseter said. AACN membership is voluntary and is open to schools offering baccalaureate or higher degrees, he explained.

“What is disturbing about this investigation is that there are over 7,600 people around the country with fraudulent nursing credentials who are potentially in critical health care roles treating patients,” Chad Yarbrough, acting special agent in charge for the FBI in Miami, said in the federal justice department release.

‘Operation Nightingale’ based on tip

The federal action, dubbed “Operation Nightingale” after the nursing pioneer Florence Nightingale, began in 2019. It was based on a tip related to a case in Maryland, according to Nurse.org.

That case ensnared Palm Beach School of Nursing owner Johanah Napoleon, who reportedly was selling fake degrees for $6,000 to $18,000 each to two individuals in Maryland and Virginia. Ms. Napoleon was charged in 2021 and eventually pled guilty. The Florida Board of Nursing shut down the Palm Beach school in 2017 owing to its students’ low passing rate on the national licensing exam.

Two participants in the bigger scheme who had also worked with Ms. Napoleon – Geralda Adrien and Woosvelt Predestin – were indicted in 2021. Ms. Adrien owned private education companies for people who at aspired to be nurses, and Mr. Predestin was an employee. They were sentenced to 27 months in prison last year and helped the federal officials build the larger case.

The 25 individuals who were charged Jan. 25 operated in Delaware, New York, New Jersey, Texas, and Florida.

Schemes lured immigrants

In the scheme involving Siena College, some of the individuals acted as recruiters to direct nurses who were looking for employment to the school, where they allegedly would then pay for an RN or LPN/VN degree. The recipients of the false documents then used them to obtain jobs, including at a hospital in Georgia and a Veterans Affairs medical center in Maryland, according to one indictment. The president of Siena and her co-conspirators sold more than 2,000 fake diplomas, according to charging documents.

At the Palm Beach College of Nursing, individuals at various nursing prep and education programs allegedly helped others obtain fake degrees and transcripts, which were then used to pass RN and LPN/VN licensing exams in states that included Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, and Ohio, according to the indictment.

Some individuals then secured employment with a nursing home in Ohio, a home health agency for pediatric patients in Massachusetts, and skilled nursing facilities in New York and New Jersey.

Prosecutors allege that the president of Sacred Heart International Institute and two other co-conspirators sold 588 fake diplomas.

The FBI said that some of the aspiring nurses who were talked into buying the degrees were LPNs who wanted to become RNs and that most of those lured into the scheme were from South Florida’s Haitian American immigrant community, Nurse.org reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The U.S. Department of Justice recently announced charges against 25 owners, operators, and employees of three Florida nursing schools in a fraud scheme in which they sold as many as 7,600 fake nursing degrees.

The purchasers in the diploma scheme paid $10,000 to $15,000 for degrees and transcripts and some 2,800 of the buyers passed the national nursing licensing exam to become registered nurses (RNs) and licensed practice nurses/vocational nurses (LPN/VNs) around the country, according to The New York Times.

Many of the degree recipients went on to work at hospitals, nursing homes, and Veterans Affairs medical centers, according to the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of Florida.

Several national nursing organizations cooperated with the investigation, and the Delaware Division of Professional Regulation already annulled 26 licenses, according to the Delaware Nurses Association. Fake licenses were issued in five states, according to federal reports.

“We are deeply unsettled by this egregious act,” DNA President Stephanie McClellan, MSN, RN, CMSRN, said in the group’s press statement. “We want all Delaware nurses to be aware of this active issue and to speak up if there is a concern regarding capacity to practice safely by a colleague/peer,” she said.

The Oregon State Board of Nursing is also investigating at least a dozen nurses who may have paid for their degrees, according to a Portland CBS affiliate.

The National Council of State Boards of Nursing said in a statement that it had helped authorities identify and monitor the individuals who allegedly provided the false degrees.

Nursing community reacts

News of the fraud scheme spread through the nursing community, including social media. “The recent report on falsified nursing school degrees is both heartbreaking and serves as an eye-opener,” tweeted Usha Menon, PhD, RN, FAAN, dean and health professor of the University of South Florida Health College of Nursing. “There was enough of a need that prompted these bad actors to develop a scheme that could’ve endangered dozens of lives.”

Jennifer Mensik Kennedy, PhD, MBA, RN, the new president of the American Nurses Association, also weighed in. “The accusation that personnel at once-accredited nursing schools allegedly participated in this scheme is simply deplorable. These unlawful and unethical acts disparage the reputation of actual nurses everywhere who have rightfully earned [their titles] through their education, hard work, dedication, and time.”

The false degrees and transcripts were issued by three once-accredited and now-shuttered nursing schools in South Florida: Palm Beach School of Nursing, Sacred Heart International Institute, and Sienna College.

The alleged co-conspirators reportedly made $114 million from the scheme, which dates back to 2016, according to several news reports. Each defendant faces up to 20 years in prison.

Most LPN programs charge $10,000 to $15,000 to complete a program, Robert Rosseter, a spokesperson for the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN), told this news organization.

None were AACN members, and none were accredited by the Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education, which is AACN’s autonomous accrediting agency, Mr. Rosseter said. AACN membership is voluntary and is open to schools offering baccalaureate or higher degrees, he explained.

“What is disturbing about this investigation is that there are over 7,600 people around the country with fraudulent nursing credentials who are potentially in critical health care roles treating patients,” Chad Yarbrough, acting special agent in charge for the FBI in Miami, said in the federal justice department release.

‘Operation Nightingale’ based on tip

The federal action, dubbed “Operation Nightingale” after the nursing pioneer Florence Nightingale, began in 2019. It was based on a tip related to a case in Maryland, according to Nurse.org.

That case ensnared Palm Beach School of Nursing owner Johanah Napoleon, who reportedly was selling fake degrees for $6,000 to $18,000 each to two individuals in Maryland and Virginia. Ms. Napoleon was charged in 2021 and eventually pled guilty. The Florida Board of Nursing shut down the Palm Beach school in 2017 owing to its students’ low passing rate on the national licensing exam.

Two participants in the bigger scheme who had also worked with Ms. Napoleon – Geralda Adrien and Woosvelt Predestin – were indicted in 2021. Ms. Adrien owned private education companies for people who at aspired to be nurses, and Mr. Predestin was an employee. They were sentenced to 27 months in prison last year and helped the federal officials build the larger case.

The 25 individuals who were charged Jan. 25 operated in Delaware, New York, New Jersey, Texas, and Florida.

Schemes lured immigrants

In the scheme involving Siena College, some of the individuals acted as recruiters to direct nurses who were looking for employment to the school, where they allegedly would then pay for an RN or LPN/VN degree. The recipients of the false documents then used them to obtain jobs, including at a hospital in Georgia and a Veterans Affairs medical center in Maryland, according to one indictment. The president of Siena and her co-conspirators sold more than 2,000 fake diplomas, according to charging documents.

At the Palm Beach College of Nursing, individuals at various nursing prep and education programs allegedly helped others obtain fake degrees and transcripts, which were then used to pass RN and LPN/VN licensing exams in states that included Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, and Ohio, according to the indictment.

Some individuals then secured employment with a nursing home in Ohio, a home health agency for pediatric patients in Massachusetts, and skilled nursing facilities in New York and New Jersey.

Prosecutors allege that the president of Sacred Heart International Institute and two other co-conspirators sold 588 fake diplomas.

The FBI said that some of the aspiring nurses who were talked into buying the degrees were LPNs who wanted to become RNs and that most of those lured into the scheme were from South Florida’s Haitian American immigrant community, Nurse.org reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The U.S. Department of Justice recently announced charges against 25 owners, operators, and employees of three Florida nursing schools in a fraud scheme in which they sold as many as 7,600 fake nursing degrees.

The purchasers in the diploma scheme paid $10,000 to $15,000 for degrees and transcripts and some 2,800 of the buyers passed the national nursing licensing exam to become registered nurses (RNs) and licensed practice nurses/vocational nurses (LPN/VNs) around the country, according to The New York Times.

Many of the degree recipients went on to work at hospitals, nursing homes, and Veterans Affairs medical centers, according to the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of Florida.

Several national nursing organizations cooperated with the investigation, and the Delaware Division of Professional Regulation already annulled 26 licenses, according to the Delaware Nurses Association. Fake licenses were issued in five states, according to federal reports.

“We are deeply unsettled by this egregious act,” DNA President Stephanie McClellan, MSN, RN, CMSRN, said in the group’s press statement. “We want all Delaware nurses to be aware of this active issue and to speak up if there is a concern regarding capacity to practice safely by a colleague/peer,” she said.

The Oregon State Board of Nursing is also investigating at least a dozen nurses who may have paid for their degrees, according to a Portland CBS affiliate.

The National Council of State Boards of Nursing said in a statement that it had helped authorities identify and monitor the individuals who allegedly provided the false degrees.

Nursing community reacts

News of the fraud scheme spread through the nursing community, including social media. “The recent report on falsified nursing school degrees is both heartbreaking and serves as an eye-opener,” tweeted Usha Menon, PhD, RN, FAAN, dean and health professor of the University of South Florida Health College of Nursing. “There was enough of a need that prompted these bad actors to develop a scheme that could’ve endangered dozens of lives.”

Jennifer Mensik Kennedy, PhD, MBA, RN, the new president of the American Nurses Association, also weighed in. “The accusation that personnel at once-accredited nursing schools allegedly participated in this scheme is simply deplorable. These unlawful and unethical acts disparage the reputation of actual nurses everywhere who have rightfully earned [their titles] through their education, hard work, dedication, and time.”

The false degrees and transcripts were issued by three once-accredited and now-shuttered nursing schools in South Florida: Palm Beach School of Nursing, Sacred Heart International Institute, and Sienna College.

The alleged co-conspirators reportedly made $114 million from the scheme, which dates back to 2016, according to several news reports. Each defendant faces up to 20 years in prison.

Most LPN programs charge $10,000 to $15,000 to complete a program, Robert Rosseter, a spokesperson for the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN), told this news organization.

None were AACN members, and none were accredited by the Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education, which is AACN’s autonomous accrediting agency, Mr. Rosseter said. AACN membership is voluntary and is open to schools offering baccalaureate or higher degrees, he explained.

“What is disturbing about this investigation is that there are over 7,600 people around the country with fraudulent nursing credentials who are potentially in critical health care roles treating patients,” Chad Yarbrough, acting special agent in charge for the FBI in Miami, said in the federal justice department release.

‘Operation Nightingale’ based on tip

The federal action, dubbed “Operation Nightingale” after the nursing pioneer Florence Nightingale, began in 2019. It was based on a tip related to a case in Maryland, according to Nurse.org.

That case ensnared Palm Beach School of Nursing owner Johanah Napoleon, who reportedly was selling fake degrees for $6,000 to $18,000 each to two individuals in Maryland and Virginia. Ms. Napoleon was charged in 2021 and eventually pled guilty. The Florida Board of Nursing shut down the Palm Beach school in 2017 owing to its students’ low passing rate on the national licensing exam.