User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

Joint effort: CBD not just innocent bystander in weed

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

I visited a legal cannabis dispensary in Massachusetts a few years ago, mostly to see what the hype was about. There I was, knowing basically nothing about pot, as the gentle stoner behind the counter explained to me the differences between the various strains. Acapulco Gold is buoyant and energizing; Purple Kush is sleepy, relaxed, dissociative. Here’s a strain that makes you feel nostalgic; here’s one that helps you focus. It was as complicated and as oddly specific as a fancy wine tasting – and, I had a feeling, about as reliable.

It’s a plant, after all, and though delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is the chemical responsible for its euphoric effects, it is far from the only substance in there.

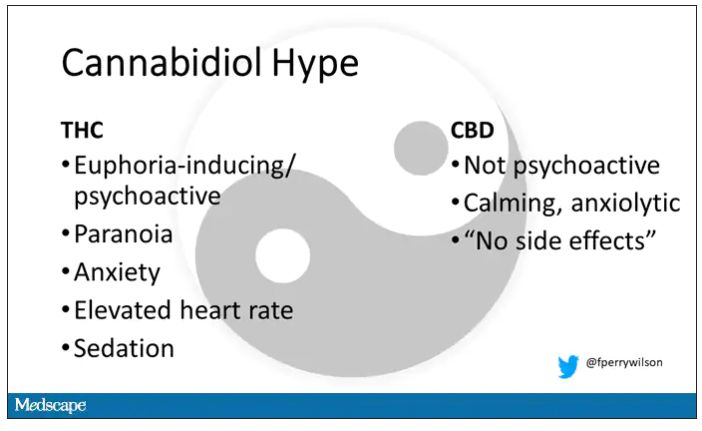

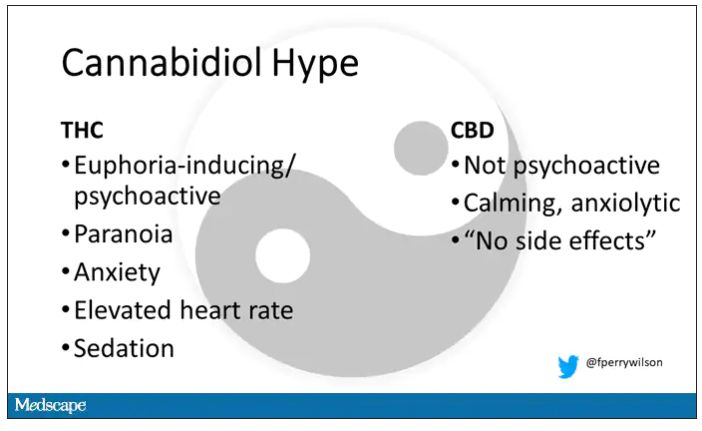

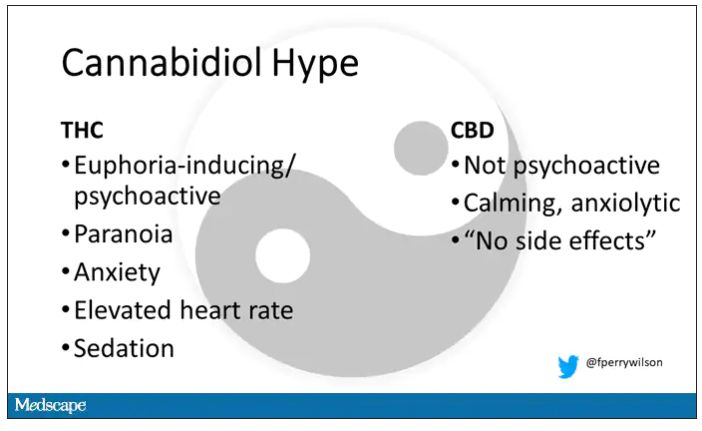

The second most important compound in cannabis is cannabidiol, and most people will tell you that CBD is the gentle yin to THC’s paranoiac yang. Hence your local ganja barista reminding you that, if you don›t want all those anxiety-inducing side effects of THC, grab a strain with a nice CBD balance.

But is it true? A new study appearing in JAMA Network Open suggests, in fact, that it’s quite the opposite. This study is from Austin Zamarripa and colleagues, who clearly sit at the researcher cool kids table.

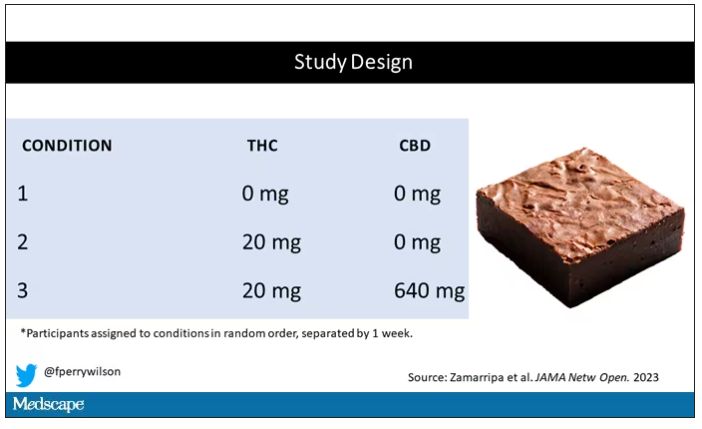

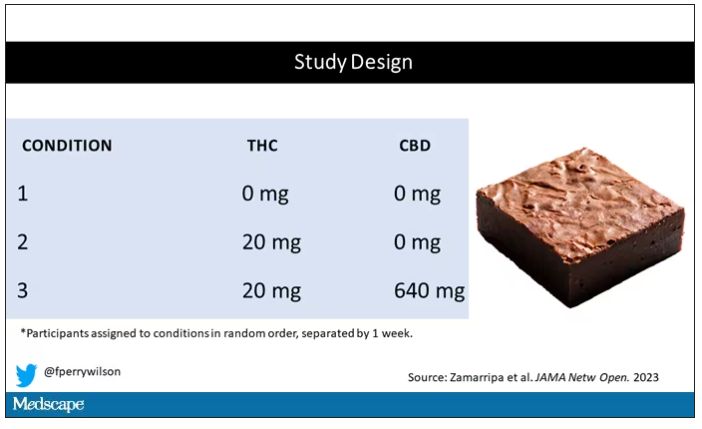

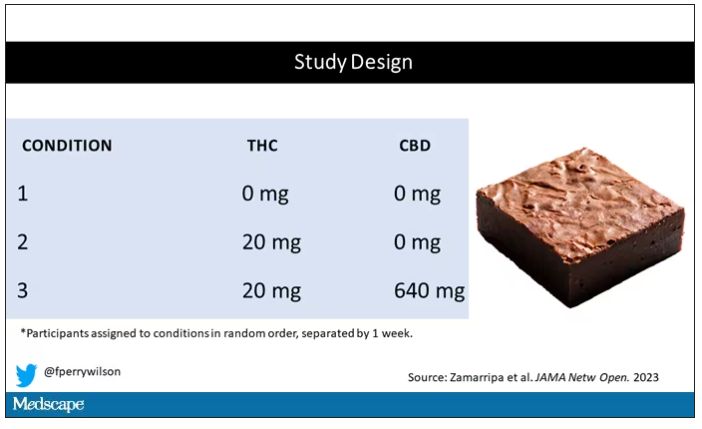

Eighteen adults who had abstained from marijuana use for at least a month participated in this trial (which is way more fun than anything we do in my lab at Yale). In random order, separated by at least a week, they ate some special brownies.

Condition one was a control brownie, condition two was a brownie containing 20 mg of THC, and condition three was a brownie containing 20 mg of THC and 640 mg of CBD. Participants were assigned each condition in random order, separated by at least a week.

A side note on doses for those of you who, like me, are not totally weed literate. A dose of 20 mg of THC is about a third of what you might find in a typical joint these days (though it’s about double the THC content of a joint in the ‘70s – I believe the technical term is “doobie”). And 640 mg of CBD is a decent dose, as 5 mg per kilogram is what some folks start with to achieve therapeutic effects.

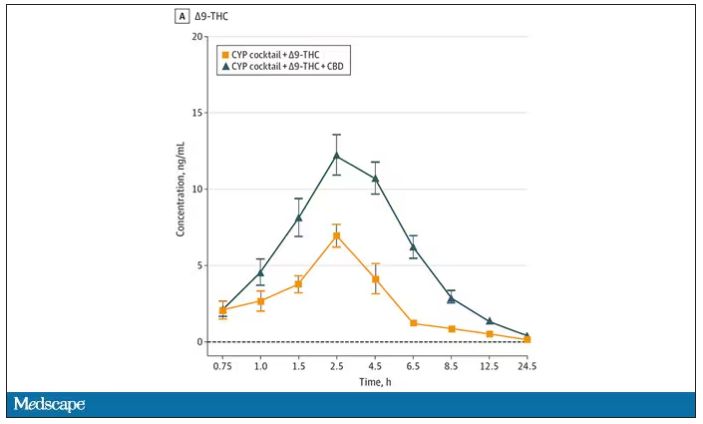

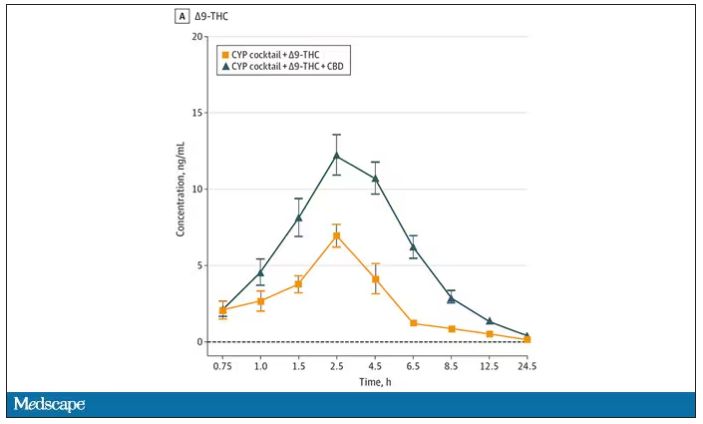

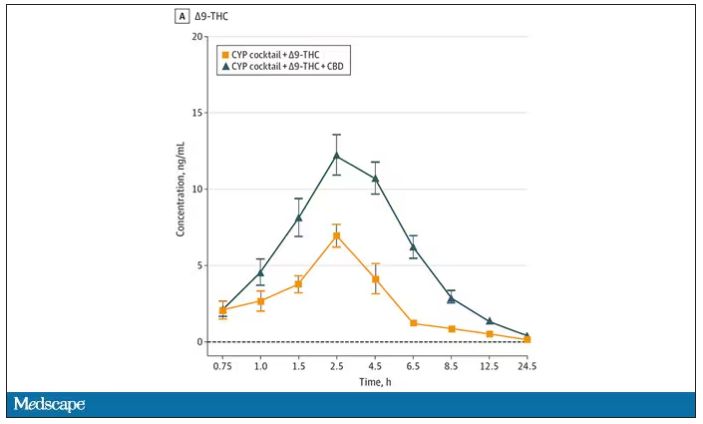

Both THC and CBD interact with the cytochrome p450 system in the liver. This matters when you’re ingesting them instead of smoking them because you have first-pass metabolism to contend with. And, because of that p450 inhibition, it’s possible that CBD might actually increase the amount of THC that gets into your bloodstream from the brownie, or gummy, or pizza sauce, or whatever.

Let’s get to the results, starting with blood THC concentration. It’s not subtle. With CBD on board the THC concentration rises higher faster, with roughly double the area under the curve.

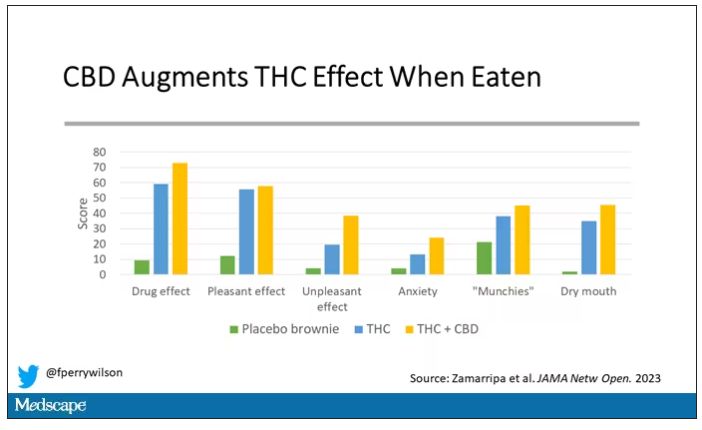

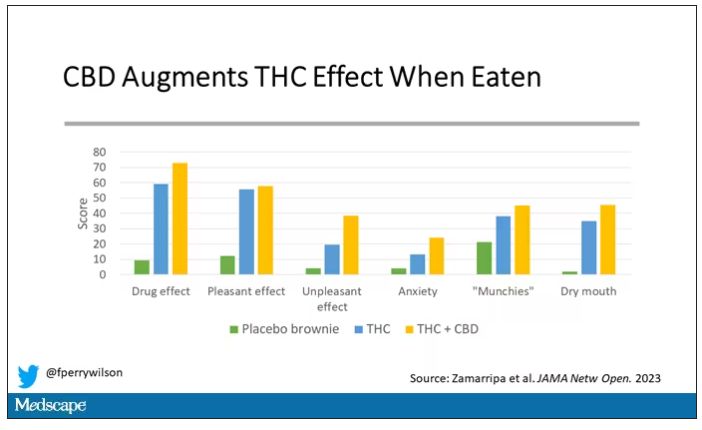

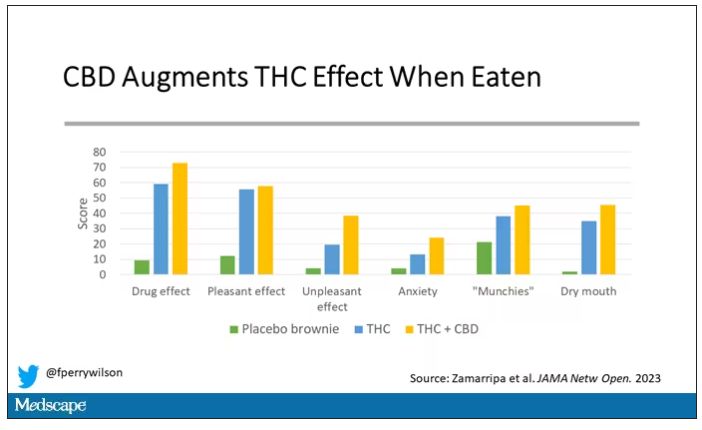

And, unsurprisingly, the subjective experience correlated with those higher levels. Individuals rated the “drug effect” higher with the combo. But, interestingly, the “pleasant” drug effect didn’t change much, while the unpleasant effects were substantially higher. No mitigation of THC anxiety here – quite the opposite. CBD made the anxiety worse.

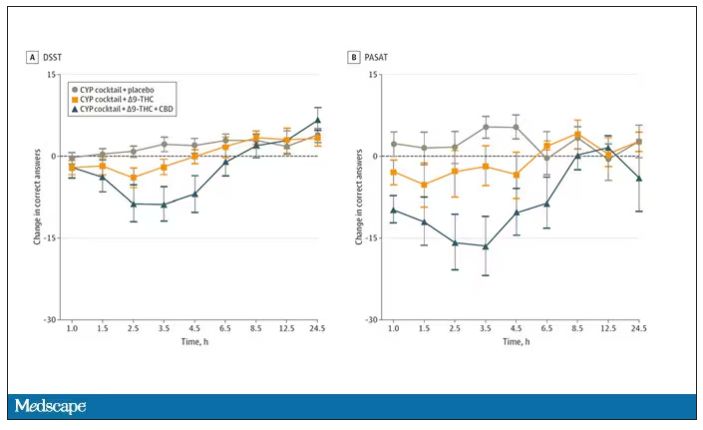

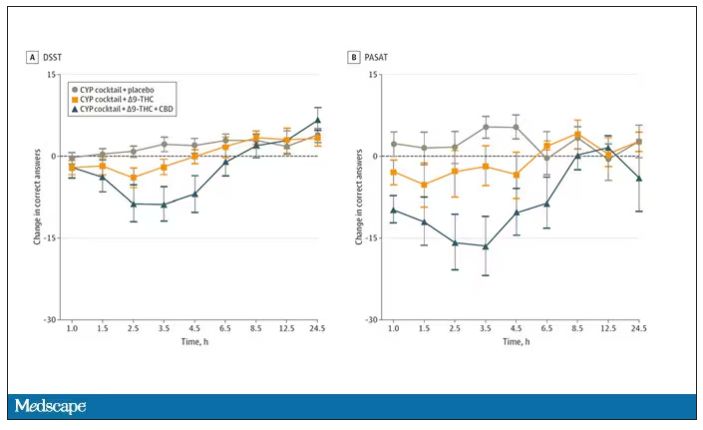

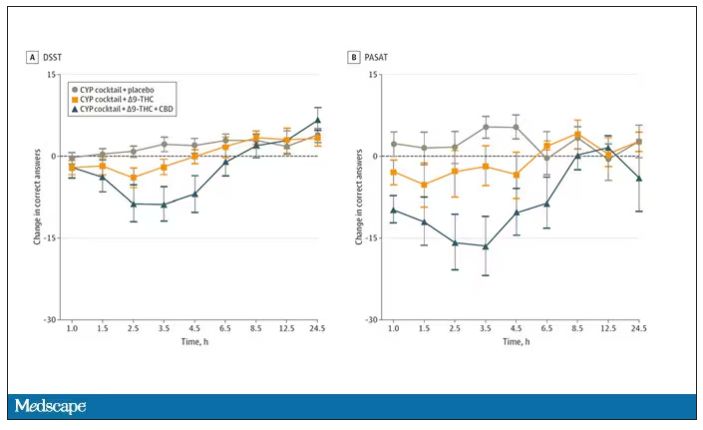

Cognitive effects were equally profound. Scores on a digit symbol substitution test and a paced serial addition task were all substantially worse when CBD was mixed with THC.

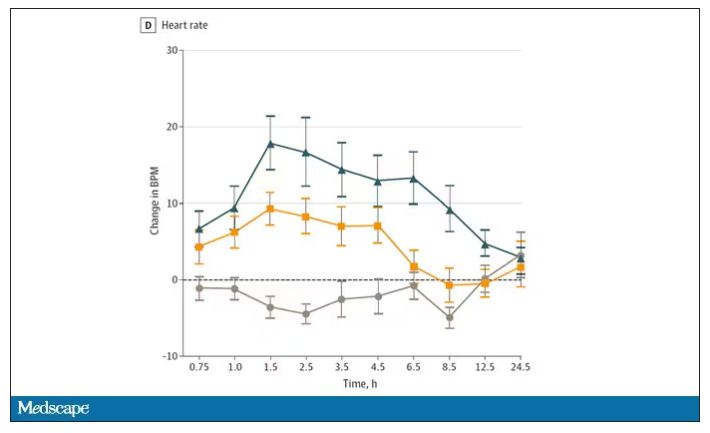

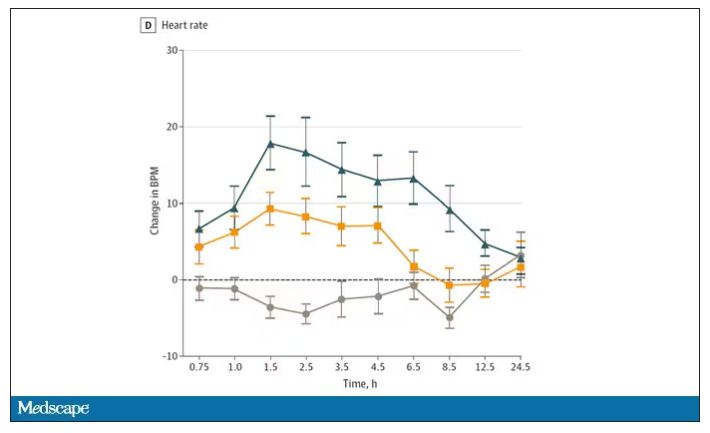

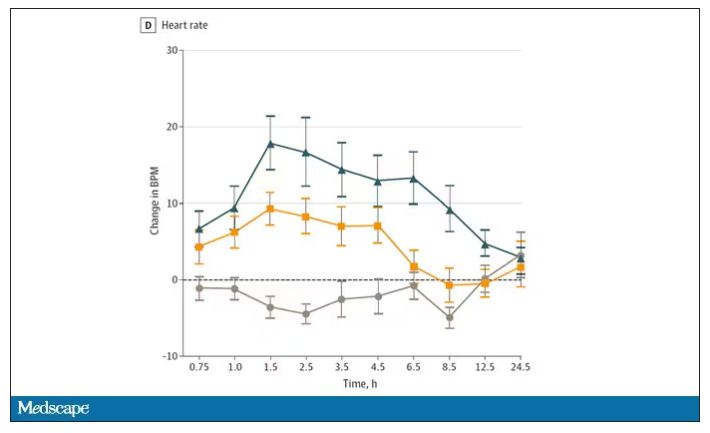

And for those of you who want some more objective measures, check out the heart rate. Despite the purported “calming” nature of CBD, heart rates were way higher when individuals were exposed to both chemicals.

The picture here is quite clear, though the mechanism is not. At least when talking edibles, CBD enhances the effects of THC, and not necessarily for the better. It may be that CBD is competing with some of the proteins that metabolize THC, thus prolonging its effects. CBD may also directly inhibit those enzymes. But whatever the case, I think we can safely say the myth that CBD makes the effects of THC more mild or more tolerable is busted.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale University’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven, Conn.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

I visited a legal cannabis dispensary in Massachusetts a few years ago, mostly to see what the hype was about. There I was, knowing basically nothing about pot, as the gentle stoner behind the counter explained to me the differences between the various strains. Acapulco Gold is buoyant and energizing; Purple Kush is sleepy, relaxed, dissociative. Here’s a strain that makes you feel nostalgic; here’s one that helps you focus. It was as complicated and as oddly specific as a fancy wine tasting – and, I had a feeling, about as reliable.

It’s a plant, after all, and though delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is the chemical responsible for its euphoric effects, it is far from the only substance in there.

The second most important compound in cannabis is cannabidiol, and most people will tell you that CBD is the gentle yin to THC’s paranoiac yang. Hence your local ganja barista reminding you that, if you don›t want all those anxiety-inducing side effects of THC, grab a strain with a nice CBD balance.

But is it true? A new study appearing in JAMA Network Open suggests, in fact, that it’s quite the opposite. This study is from Austin Zamarripa and colleagues, who clearly sit at the researcher cool kids table.

Eighteen adults who had abstained from marijuana use for at least a month participated in this trial (which is way more fun than anything we do in my lab at Yale). In random order, separated by at least a week, they ate some special brownies.

Condition one was a control brownie, condition two was a brownie containing 20 mg of THC, and condition three was a brownie containing 20 mg of THC and 640 mg of CBD. Participants were assigned each condition in random order, separated by at least a week.

A side note on doses for those of you who, like me, are not totally weed literate. A dose of 20 mg of THC is about a third of what you might find in a typical joint these days (though it’s about double the THC content of a joint in the ‘70s – I believe the technical term is “doobie”). And 640 mg of CBD is a decent dose, as 5 mg per kilogram is what some folks start with to achieve therapeutic effects.

Both THC and CBD interact with the cytochrome p450 system in the liver. This matters when you’re ingesting them instead of smoking them because you have first-pass metabolism to contend with. And, because of that p450 inhibition, it’s possible that CBD might actually increase the amount of THC that gets into your bloodstream from the brownie, or gummy, or pizza sauce, or whatever.

Let’s get to the results, starting with blood THC concentration. It’s not subtle. With CBD on board the THC concentration rises higher faster, with roughly double the area under the curve.

And, unsurprisingly, the subjective experience correlated with those higher levels. Individuals rated the “drug effect” higher with the combo. But, interestingly, the “pleasant” drug effect didn’t change much, while the unpleasant effects were substantially higher. No mitigation of THC anxiety here – quite the opposite. CBD made the anxiety worse.

Cognitive effects were equally profound. Scores on a digit symbol substitution test and a paced serial addition task were all substantially worse when CBD was mixed with THC.

And for those of you who want some more objective measures, check out the heart rate. Despite the purported “calming” nature of CBD, heart rates were way higher when individuals were exposed to both chemicals.

The picture here is quite clear, though the mechanism is not. At least when talking edibles, CBD enhances the effects of THC, and not necessarily for the better. It may be that CBD is competing with some of the proteins that metabolize THC, thus prolonging its effects. CBD may also directly inhibit those enzymes. But whatever the case, I think we can safely say the myth that CBD makes the effects of THC more mild or more tolerable is busted.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale University’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven, Conn.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

I visited a legal cannabis dispensary in Massachusetts a few years ago, mostly to see what the hype was about. There I was, knowing basically nothing about pot, as the gentle stoner behind the counter explained to me the differences between the various strains. Acapulco Gold is buoyant and energizing; Purple Kush is sleepy, relaxed, dissociative. Here’s a strain that makes you feel nostalgic; here’s one that helps you focus. It was as complicated and as oddly specific as a fancy wine tasting – and, I had a feeling, about as reliable.

It’s a plant, after all, and though delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is the chemical responsible for its euphoric effects, it is far from the only substance in there.

The second most important compound in cannabis is cannabidiol, and most people will tell you that CBD is the gentle yin to THC’s paranoiac yang. Hence your local ganja barista reminding you that, if you don›t want all those anxiety-inducing side effects of THC, grab a strain with a nice CBD balance.

But is it true? A new study appearing in JAMA Network Open suggests, in fact, that it’s quite the opposite. This study is from Austin Zamarripa and colleagues, who clearly sit at the researcher cool kids table.

Eighteen adults who had abstained from marijuana use for at least a month participated in this trial (which is way more fun than anything we do in my lab at Yale). In random order, separated by at least a week, they ate some special brownies.

Condition one was a control brownie, condition two was a brownie containing 20 mg of THC, and condition three was a brownie containing 20 mg of THC and 640 mg of CBD. Participants were assigned each condition in random order, separated by at least a week.

A side note on doses for those of you who, like me, are not totally weed literate. A dose of 20 mg of THC is about a third of what you might find in a typical joint these days (though it’s about double the THC content of a joint in the ‘70s – I believe the technical term is “doobie”). And 640 mg of CBD is a decent dose, as 5 mg per kilogram is what some folks start with to achieve therapeutic effects.

Both THC and CBD interact with the cytochrome p450 system in the liver. This matters when you’re ingesting them instead of smoking them because you have first-pass metabolism to contend with. And, because of that p450 inhibition, it’s possible that CBD might actually increase the amount of THC that gets into your bloodstream from the brownie, or gummy, or pizza sauce, or whatever.

Let’s get to the results, starting with blood THC concentration. It’s not subtle. With CBD on board the THC concentration rises higher faster, with roughly double the area under the curve.

And, unsurprisingly, the subjective experience correlated with those higher levels. Individuals rated the “drug effect” higher with the combo. But, interestingly, the “pleasant” drug effect didn’t change much, while the unpleasant effects were substantially higher. No mitigation of THC anxiety here – quite the opposite. CBD made the anxiety worse.

Cognitive effects were equally profound. Scores on a digit symbol substitution test and a paced serial addition task were all substantially worse when CBD was mixed with THC.

And for those of you who want some more objective measures, check out the heart rate. Despite the purported “calming” nature of CBD, heart rates were way higher when individuals were exposed to both chemicals.

The picture here is quite clear, though the mechanism is not. At least when talking edibles, CBD enhances the effects of THC, and not necessarily for the better. It may be that CBD is competing with some of the proteins that metabolize THC, thus prolonging its effects. CBD may also directly inhibit those enzymes. But whatever the case, I think we can safely say the myth that CBD makes the effects of THC more mild or more tolerable is busted.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale University’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven, Conn.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Doctors are disappearing from emergency departments as hospitals look to cut costs

She didn’t know much about miscarriage, but this seemed like one.

In the emergency department, she was examined then sent home, she said. She went back when her cramping became excruciating. Then home again. It ultimately took three trips to the ED on 3 consecutive days, generating three separate bills, before she saw a doctor who looked at her blood work and confirmed her fears.

“At the time I wasn’t thinking, ‘Oh, I need to see a doctor,’ ” Ms. Valle recalled. “But when you think about it, it’s like, ‘Well, dang – why didn’t I see a doctor?’ ” It’s unclear whether the repeat visits were due to delays in seeing a physician, but the experience worried her. And she’s still paying the bills.

The hospital declined to discuss Ms. Valle’s care, citing patient privacy. But 17 months before her 3-day ordeal, Tennova had outsourced its emergency departments to American Physician Partners, a medical staffing company owned by private equity investors. APP employs fewer doctors in its EDs as one of its cost-saving initiatives to increase earnings, according to a confidential company document obtained by KHN and NPR.

This staffing strategy has permeated hospitals, and particularly emergency departments, that seek to reduce their top expense: physician labor. While diagnosing and treating patients was once their domain, doctors are increasingly being replaced by nurse practitioners and physician assistants, collectively known as “midlevel practitioners,” who can perform many of the same duties and generate much of the same revenue for less than half of the pay.

“APP has numerous cost saving initiatives underway as part of the Company’s continual focus on cost optimization,” the document says, including a “shift of staffing” between doctors and midlevel practitioners.

In a statement to KHN, American Physician Partners said this strategy is a way to ensure all EDs remain fully staffed, calling it a “blended model” that allows doctors, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants “to provide care to their fullest potential.”

Critics of this strategy say the quest to save money results in treatment meted out by someone with far less training than a physician, leaving patients vulnerable to misdiagnoses, higher medical bills, and inadequate care. And these fears are bolstered by evidence that suggests dropping doctors from EDs may not be good for patients.

A working paper, published in October by the National Bureau of Economic Research, analyzed roughly 1.1 million visits to 44 EDs throughout the Veterans Health Administration, where nurse practitioners can treat patients without oversight from doctors.

Researchers found that treatment by a nurse practitioner resulted on average in a 7% increase in cost of care and an 11% increase in length of stay, extending patients’ time in the ED by minutes for minor visits and hours for longer ones. These gaps widened among patients with more severe diagnoses, the study said, but could be somewhat mitigated by nurse practitioners with more experience.

The study also found that ED patients treated by a nurse practitioner were 20% more likely to be readmitted to the hospital for a preventable reason within 30 days, although the overall risk of readmission remained very small.

Yiqun Chen, PhD, who is an assistant professor of economics at the University of Illinois at Chicago and coauthored the study, said these findings are not an indictment of nurse practitioners in the ED. Instead, she said, she hopes the study will guide how to best deploy nurse practitioners: in treatment of simpler patients or circumstances when no doctor is available.

“It’s not just a simple question of if we can substitute physicians with nurse practitioners or not,” Dr. Chen said. “It depends on how we use them. If we just use them as independent providers, especially ... for relatively complicated patients, it doesn’t seem to be a very good use.”

Dr. Chen’s research echoes smaller studies, like one from The Harvey L. Neiman Health Policy Institute that found nonphysician practitioners in EDs were associated with a 5.3% increase in imaging, which could unnecessarily increase bills for patients. Separately, a study at the Hattiesburg Clinic in Mississippi found that midlevel practitioners in primary care – not in the emergency department – increased the out-of-pocket costs to patients while also leading to worse performance on 9 of 10 quality-of-care metrics, including cancer screenings and vaccination rates.

But definitive evidence remains elusive that replacing ER doctors with nonphysicians has a negative impact on patients, said Cameron Gettel, MD, an assistant professor of emergency medicine at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. Private equity investment and the use of midlevel practitioners rose in lockstep in the ED, Dr. Gettel said, and in the absence of game-changing research, the pattern will likely continue.

“Worse patient outcomes haven’t really been shown across the board,” he said. “And I think until that is shown, then they will continue to play an increasing role.”

For private equity, dropping ED docs is a “simple equation”

Private equity companies pool money from wealthy investors to buy their way into various industries, often slashing spending and seeking to flip businesses in 3 to 7 years. While this business model is a proven moneymaker on Wall Street, it raises concerns in health care, where critics worry the pressure to turn big profits will influence life-or-death decisions that were once left solely to medical professionals.

Nearly $1 trillion in private equity funds have gone into almost 8,000 health care transactions over the past decade, according to industry tracker PitchBook, including buying into medical staffing companies that many hospitals hire to manage their emergency departments.

Two firms dominate the ED staffing industry: TeamHealth, bought by private equity firm Blackstone in 2016, and Envision Healthcare, bought by KKR in 2018. Trying to undercut these staffing giants is American Physician Partners, a rapidly expanding company that runs EDs in at least 17 states and is 50% owned by private equity firm BBH Capital Partners.

These staffing companies have been among the most aggressive in replacing doctors to cut costs, said Robert McNamara, MD, a founder of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine and chair of emergency medicine at Temple University, Philadelphia.

“It’s a relatively simple equation,” Dr. McNamara said. “Their No. 1 expense is the board-certified emergency physician. So they are going to want to keep that expense as low as possible.”

Not everyone sees the trend of private equity in ED staffing in a negative light. Jennifer Orozco, president of the American Academy of Physician Associates, which represents physician assistants, said even if the change – to use more nonphysician providers – is driven by the staffing firms’ desire to make more money, patients are still well served by a team approach that includes nurse practitioners and physician assistants.

“Though I see that shift, it’s not about profits at the end of the day,” Ms. Orozco said. “It’s about the patient.”

The “shift” is nearly invisible to patients because hospitals rarely promote branding from their ED staffing firms and there is little public documentation of private equity investments.

Arthur Smolensky, MD, a Tennessee emergency medicine specialist attempting to measure private equity’s intrusion into EDs, said his review of hospital job postings and employment contracts in 14 major metropolitan areas found that 43% of ED patients were seen in EDs staffed by companies with nonphysician owners, nearly all of whom are private equity investors.

Dr. Smolensky hopes to publish his full study, expanding to 55 metro areas, later this year. But this research will merely quantify what many doctors already know: The ED has changed. Demoralized by an increased focus on profit, and wary of a looming surplus of emergency medicine residents because there are fewer jobs to fill, many experienced doctors are leaving the ED on their own, he said.

“Most of us didn’t go into medicine to supervise an army of people that are not as well trained as we are,” Dr. Smolensky said. “We want to take care of patients.”

“I guess we’re the first guinea pigs for our ER”

Joshua Allen, a nurse practitioner at a small Kentucky hospital, snaked a rubber hose through a rack of pork ribs to practice inserting a chest tube to fix a collapsed lung.

It was 2020, and American Physician Partners was restructuring the ED where Mr. Allen worked, reducing shifts from two doctors to one. Once Mr. Allen had placed 10 tubes under a doctor’s supervision, he would be allowed to do it on his own.

“I guess we’re the first guinea pigs for our ER,” he said. “If we do have a major trauma and multiple victims come in, there’s only one doctor there. ... We need to be prepared.”

Mr. Allen is one of many midlevel practitioners finding work in emergency departments. Nurse practitioners and physician assistants are among the fastest-growing occupations in the nation, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Generally, they have master’s degrees and receive several years of specialized schooling but have significantly less training than doctors. Many are permitted to diagnose patients and prescribe medication with little or no supervision from a doctor, although limitations vary by state.

The Neiman Institute found that the share of ED visits in which a midlevel practitioner was the main clinician increased by more than 172% between 2005 and 2020. Another study, in the Journal of Emergency Medicine, reported that if trends continue there may be equal numbers of midlevel practitioners and doctors in EDs by 2030.

There is little mystery as to why. Federal data shows emergency medicine doctors are paid about $310,000 a year on average, while nurse practitioners and physician assistants earn less than $120,000. Generally, hospitals can bill for care by a midlevel practitioner at 85% the rate of a doctor while paying them less than half as much.

Private equity can make millions in the gap.

For example, Envision once encouraged EDs to employ “the least expensive resource” and treat up to 35% of patients with midlevel practitioners, according to a 2017 PowerPoint presentation. The presentation drew scorn on social media and disappeared from Envision’s website.

Envision declined a request for a phone interview. In a written statement to KHN, spokesperson Aliese Polk said the company does not direct its physician leaders on how to care for patients and called the presentation a “concept guide” that does not represent current views.

American Physician Partners touted roughly the same staffing strategy in 2021 in response to the No Surprises Act, which threatened the company’s profits by outlawing surprise medical bills. In its confidential pitch to lenders, the company estimated it could cut almost $6 million by shifting more staffing from physicians to midlevel practitioners.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

She didn’t know much about miscarriage, but this seemed like one.

In the emergency department, she was examined then sent home, she said. She went back when her cramping became excruciating. Then home again. It ultimately took three trips to the ED on 3 consecutive days, generating three separate bills, before she saw a doctor who looked at her blood work and confirmed her fears.

“At the time I wasn’t thinking, ‘Oh, I need to see a doctor,’ ” Ms. Valle recalled. “But when you think about it, it’s like, ‘Well, dang – why didn’t I see a doctor?’ ” It’s unclear whether the repeat visits were due to delays in seeing a physician, but the experience worried her. And she’s still paying the bills.

The hospital declined to discuss Ms. Valle’s care, citing patient privacy. But 17 months before her 3-day ordeal, Tennova had outsourced its emergency departments to American Physician Partners, a medical staffing company owned by private equity investors. APP employs fewer doctors in its EDs as one of its cost-saving initiatives to increase earnings, according to a confidential company document obtained by KHN and NPR.

This staffing strategy has permeated hospitals, and particularly emergency departments, that seek to reduce their top expense: physician labor. While diagnosing and treating patients was once their domain, doctors are increasingly being replaced by nurse practitioners and physician assistants, collectively known as “midlevel practitioners,” who can perform many of the same duties and generate much of the same revenue for less than half of the pay.

“APP has numerous cost saving initiatives underway as part of the Company’s continual focus on cost optimization,” the document says, including a “shift of staffing” between doctors and midlevel practitioners.

In a statement to KHN, American Physician Partners said this strategy is a way to ensure all EDs remain fully staffed, calling it a “blended model” that allows doctors, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants “to provide care to their fullest potential.”

Critics of this strategy say the quest to save money results in treatment meted out by someone with far less training than a physician, leaving patients vulnerable to misdiagnoses, higher medical bills, and inadequate care. And these fears are bolstered by evidence that suggests dropping doctors from EDs may not be good for patients.

A working paper, published in October by the National Bureau of Economic Research, analyzed roughly 1.1 million visits to 44 EDs throughout the Veterans Health Administration, where nurse practitioners can treat patients without oversight from doctors.

Researchers found that treatment by a nurse practitioner resulted on average in a 7% increase in cost of care and an 11% increase in length of stay, extending patients’ time in the ED by minutes for minor visits and hours for longer ones. These gaps widened among patients with more severe diagnoses, the study said, but could be somewhat mitigated by nurse practitioners with more experience.

The study also found that ED patients treated by a nurse practitioner were 20% more likely to be readmitted to the hospital for a preventable reason within 30 days, although the overall risk of readmission remained very small.

Yiqun Chen, PhD, who is an assistant professor of economics at the University of Illinois at Chicago and coauthored the study, said these findings are not an indictment of nurse practitioners in the ED. Instead, she said, she hopes the study will guide how to best deploy nurse practitioners: in treatment of simpler patients or circumstances when no doctor is available.

“It’s not just a simple question of if we can substitute physicians with nurse practitioners or not,” Dr. Chen said. “It depends on how we use them. If we just use them as independent providers, especially ... for relatively complicated patients, it doesn’t seem to be a very good use.”

Dr. Chen’s research echoes smaller studies, like one from The Harvey L. Neiman Health Policy Institute that found nonphysician practitioners in EDs were associated with a 5.3% increase in imaging, which could unnecessarily increase bills for patients. Separately, a study at the Hattiesburg Clinic in Mississippi found that midlevel practitioners in primary care – not in the emergency department – increased the out-of-pocket costs to patients while also leading to worse performance on 9 of 10 quality-of-care metrics, including cancer screenings and vaccination rates.

But definitive evidence remains elusive that replacing ER doctors with nonphysicians has a negative impact on patients, said Cameron Gettel, MD, an assistant professor of emergency medicine at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. Private equity investment and the use of midlevel practitioners rose in lockstep in the ED, Dr. Gettel said, and in the absence of game-changing research, the pattern will likely continue.

“Worse patient outcomes haven’t really been shown across the board,” he said. “And I think until that is shown, then they will continue to play an increasing role.”

For private equity, dropping ED docs is a “simple equation”

Private equity companies pool money from wealthy investors to buy their way into various industries, often slashing spending and seeking to flip businesses in 3 to 7 years. While this business model is a proven moneymaker on Wall Street, it raises concerns in health care, where critics worry the pressure to turn big profits will influence life-or-death decisions that were once left solely to medical professionals.

Nearly $1 trillion in private equity funds have gone into almost 8,000 health care transactions over the past decade, according to industry tracker PitchBook, including buying into medical staffing companies that many hospitals hire to manage their emergency departments.

Two firms dominate the ED staffing industry: TeamHealth, bought by private equity firm Blackstone in 2016, and Envision Healthcare, bought by KKR in 2018. Trying to undercut these staffing giants is American Physician Partners, a rapidly expanding company that runs EDs in at least 17 states and is 50% owned by private equity firm BBH Capital Partners.

These staffing companies have been among the most aggressive in replacing doctors to cut costs, said Robert McNamara, MD, a founder of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine and chair of emergency medicine at Temple University, Philadelphia.

“It’s a relatively simple equation,” Dr. McNamara said. “Their No. 1 expense is the board-certified emergency physician. So they are going to want to keep that expense as low as possible.”

Not everyone sees the trend of private equity in ED staffing in a negative light. Jennifer Orozco, president of the American Academy of Physician Associates, which represents physician assistants, said even if the change – to use more nonphysician providers – is driven by the staffing firms’ desire to make more money, patients are still well served by a team approach that includes nurse practitioners and physician assistants.

“Though I see that shift, it’s not about profits at the end of the day,” Ms. Orozco said. “It’s about the patient.”

The “shift” is nearly invisible to patients because hospitals rarely promote branding from their ED staffing firms and there is little public documentation of private equity investments.

Arthur Smolensky, MD, a Tennessee emergency medicine specialist attempting to measure private equity’s intrusion into EDs, said his review of hospital job postings and employment contracts in 14 major metropolitan areas found that 43% of ED patients were seen in EDs staffed by companies with nonphysician owners, nearly all of whom are private equity investors.

Dr. Smolensky hopes to publish his full study, expanding to 55 metro areas, later this year. But this research will merely quantify what many doctors already know: The ED has changed. Demoralized by an increased focus on profit, and wary of a looming surplus of emergency medicine residents because there are fewer jobs to fill, many experienced doctors are leaving the ED on their own, he said.

“Most of us didn’t go into medicine to supervise an army of people that are not as well trained as we are,” Dr. Smolensky said. “We want to take care of patients.”

“I guess we’re the first guinea pigs for our ER”

Joshua Allen, a nurse practitioner at a small Kentucky hospital, snaked a rubber hose through a rack of pork ribs to practice inserting a chest tube to fix a collapsed lung.

It was 2020, and American Physician Partners was restructuring the ED where Mr. Allen worked, reducing shifts from two doctors to one. Once Mr. Allen had placed 10 tubes under a doctor’s supervision, he would be allowed to do it on his own.

“I guess we’re the first guinea pigs for our ER,” he said. “If we do have a major trauma and multiple victims come in, there’s only one doctor there. ... We need to be prepared.”

Mr. Allen is one of many midlevel practitioners finding work in emergency departments. Nurse practitioners and physician assistants are among the fastest-growing occupations in the nation, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Generally, they have master’s degrees and receive several years of specialized schooling but have significantly less training than doctors. Many are permitted to diagnose patients and prescribe medication with little or no supervision from a doctor, although limitations vary by state.

The Neiman Institute found that the share of ED visits in which a midlevel practitioner was the main clinician increased by more than 172% between 2005 and 2020. Another study, in the Journal of Emergency Medicine, reported that if trends continue there may be equal numbers of midlevel practitioners and doctors in EDs by 2030.

There is little mystery as to why. Federal data shows emergency medicine doctors are paid about $310,000 a year on average, while nurse practitioners and physician assistants earn less than $120,000. Generally, hospitals can bill for care by a midlevel practitioner at 85% the rate of a doctor while paying them less than half as much.

Private equity can make millions in the gap.

For example, Envision once encouraged EDs to employ “the least expensive resource” and treat up to 35% of patients with midlevel practitioners, according to a 2017 PowerPoint presentation. The presentation drew scorn on social media and disappeared from Envision’s website.

Envision declined a request for a phone interview. In a written statement to KHN, spokesperson Aliese Polk said the company does not direct its physician leaders on how to care for patients and called the presentation a “concept guide” that does not represent current views.

American Physician Partners touted roughly the same staffing strategy in 2021 in response to the No Surprises Act, which threatened the company’s profits by outlawing surprise medical bills. In its confidential pitch to lenders, the company estimated it could cut almost $6 million by shifting more staffing from physicians to midlevel practitioners.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

She didn’t know much about miscarriage, but this seemed like one.

In the emergency department, she was examined then sent home, she said. She went back when her cramping became excruciating. Then home again. It ultimately took three trips to the ED on 3 consecutive days, generating three separate bills, before she saw a doctor who looked at her blood work and confirmed her fears.

“At the time I wasn’t thinking, ‘Oh, I need to see a doctor,’ ” Ms. Valle recalled. “But when you think about it, it’s like, ‘Well, dang – why didn’t I see a doctor?’ ” It’s unclear whether the repeat visits were due to delays in seeing a physician, but the experience worried her. And she’s still paying the bills.

The hospital declined to discuss Ms. Valle’s care, citing patient privacy. But 17 months before her 3-day ordeal, Tennova had outsourced its emergency departments to American Physician Partners, a medical staffing company owned by private equity investors. APP employs fewer doctors in its EDs as one of its cost-saving initiatives to increase earnings, according to a confidential company document obtained by KHN and NPR.

This staffing strategy has permeated hospitals, and particularly emergency departments, that seek to reduce their top expense: physician labor. While diagnosing and treating patients was once their domain, doctors are increasingly being replaced by nurse practitioners and physician assistants, collectively known as “midlevel practitioners,” who can perform many of the same duties and generate much of the same revenue for less than half of the pay.

“APP has numerous cost saving initiatives underway as part of the Company’s continual focus on cost optimization,” the document says, including a “shift of staffing” between doctors and midlevel practitioners.

In a statement to KHN, American Physician Partners said this strategy is a way to ensure all EDs remain fully staffed, calling it a “blended model” that allows doctors, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants “to provide care to their fullest potential.”

Critics of this strategy say the quest to save money results in treatment meted out by someone with far less training than a physician, leaving patients vulnerable to misdiagnoses, higher medical bills, and inadequate care. And these fears are bolstered by evidence that suggests dropping doctors from EDs may not be good for patients.

A working paper, published in October by the National Bureau of Economic Research, analyzed roughly 1.1 million visits to 44 EDs throughout the Veterans Health Administration, where nurse practitioners can treat patients without oversight from doctors.

Researchers found that treatment by a nurse practitioner resulted on average in a 7% increase in cost of care and an 11% increase in length of stay, extending patients’ time in the ED by minutes for minor visits and hours for longer ones. These gaps widened among patients with more severe diagnoses, the study said, but could be somewhat mitigated by nurse practitioners with more experience.

The study also found that ED patients treated by a nurse practitioner were 20% more likely to be readmitted to the hospital for a preventable reason within 30 days, although the overall risk of readmission remained very small.

Yiqun Chen, PhD, who is an assistant professor of economics at the University of Illinois at Chicago and coauthored the study, said these findings are not an indictment of nurse practitioners in the ED. Instead, she said, she hopes the study will guide how to best deploy nurse practitioners: in treatment of simpler patients or circumstances when no doctor is available.

“It’s not just a simple question of if we can substitute physicians with nurse practitioners or not,” Dr. Chen said. “It depends on how we use them. If we just use them as independent providers, especially ... for relatively complicated patients, it doesn’t seem to be a very good use.”

Dr. Chen’s research echoes smaller studies, like one from The Harvey L. Neiman Health Policy Institute that found nonphysician practitioners in EDs were associated with a 5.3% increase in imaging, which could unnecessarily increase bills for patients. Separately, a study at the Hattiesburg Clinic in Mississippi found that midlevel practitioners in primary care – not in the emergency department – increased the out-of-pocket costs to patients while also leading to worse performance on 9 of 10 quality-of-care metrics, including cancer screenings and vaccination rates.

But definitive evidence remains elusive that replacing ER doctors with nonphysicians has a negative impact on patients, said Cameron Gettel, MD, an assistant professor of emergency medicine at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. Private equity investment and the use of midlevel practitioners rose in lockstep in the ED, Dr. Gettel said, and in the absence of game-changing research, the pattern will likely continue.

“Worse patient outcomes haven’t really been shown across the board,” he said. “And I think until that is shown, then they will continue to play an increasing role.”

For private equity, dropping ED docs is a “simple equation”

Private equity companies pool money from wealthy investors to buy their way into various industries, often slashing spending and seeking to flip businesses in 3 to 7 years. While this business model is a proven moneymaker on Wall Street, it raises concerns in health care, where critics worry the pressure to turn big profits will influence life-or-death decisions that were once left solely to medical professionals.

Nearly $1 trillion in private equity funds have gone into almost 8,000 health care transactions over the past decade, according to industry tracker PitchBook, including buying into medical staffing companies that many hospitals hire to manage their emergency departments.

Two firms dominate the ED staffing industry: TeamHealth, bought by private equity firm Blackstone in 2016, and Envision Healthcare, bought by KKR in 2018. Trying to undercut these staffing giants is American Physician Partners, a rapidly expanding company that runs EDs in at least 17 states and is 50% owned by private equity firm BBH Capital Partners.

These staffing companies have been among the most aggressive in replacing doctors to cut costs, said Robert McNamara, MD, a founder of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine and chair of emergency medicine at Temple University, Philadelphia.

“It’s a relatively simple equation,” Dr. McNamara said. “Their No. 1 expense is the board-certified emergency physician. So they are going to want to keep that expense as low as possible.”

Not everyone sees the trend of private equity in ED staffing in a negative light. Jennifer Orozco, president of the American Academy of Physician Associates, which represents physician assistants, said even if the change – to use more nonphysician providers – is driven by the staffing firms’ desire to make more money, patients are still well served by a team approach that includes nurse practitioners and physician assistants.

“Though I see that shift, it’s not about profits at the end of the day,” Ms. Orozco said. “It’s about the patient.”

The “shift” is nearly invisible to patients because hospitals rarely promote branding from their ED staffing firms and there is little public documentation of private equity investments.

Arthur Smolensky, MD, a Tennessee emergency medicine specialist attempting to measure private equity’s intrusion into EDs, said his review of hospital job postings and employment contracts in 14 major metropolitan areas found that 43% of ED patients were seen in EDs staffed by companies with nonphysician owners, nearly all of whom are private equity investors.

Dr. Smolensky hopes to publish his full study, expanding to 55 metro areas, later this year. But this research will merely quantify what many doctors already know: The ED has changed. Demoralized by an increased focus on profit, and wary of a looming surplus of emergency medicine residents because there are fewer jobs to fill, many experienced doctors are leaving the ED on their own, he said.

“Most of us didn’t go into medicine to supervise an army of people that are not as well trained as we are,” Dr. Smolensky said. “We want to take care of patients.”

“I guess we’re the first guinea pigs for our ER”

Joshua Allen, a nurse practitioner at a small Kentucky hospital, snaked a rubber hose through a rack of pork ribs to practice inserting a chest tube to fix a collapsed lung.

It was 2020, and American Physician Partners was restructuring the ED where Mr. Allen worked, reducing shifts from two doctors to one. Once Mr. Allen had placed 10 tubes under a doctor’s supervision, he would be allowed to do it on his own.

“I guess we’re the first guinea pigs for our ER,” he said. “If we do have a major trauma and multiple victims come in, there’s only one doctor there. ... We need to be prepared.”

Mr. Allen is one of many midlevel practitioners finding work in emergency departments. Nurse practitioners and physician assistants are among the fastest-growing occupations in the nation, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Generally, they have master’s degrees and receive several years of specialized schooling but have significantly less training than doctors. Many are permitted to diagnose patients and prescribe medication with little or no supervision from a doctor, although limitations vary by state.

The Neiman Institute found that the share of ED visits in which a midlevel practitioner was the main clinician increased by more than 172% between 2005 and 2020. Another study, in the Journal of Emergency Medicine, reported that if trends continue there may be equal numbers of midlevel practitioners and doctors in EDs by 2030.

There is little mystery as to why. Federal data shows emergency medicine doctors are paid about $310,000 a year on average, while nurse practitioners and physician assistants earn less than $120,000. Generally, hospitals can bill for care by a midlevel practitioner at 85% the rate of a doctor while paying them less than half as much.

Private equity can make millions in the gap.

For example, Envision once encouraged EDs to employ “the least expensive resource” and treat up to 35% of patients with midlevel practitioners, according to a 2017 PowerPoint presentation. The presentation drew scorn on social media and disappeared from Envision’s website.

Envision declined a request for a phone interview. In a written statement to KHN, spokesperson Aliese Polk said the company does not direct its physician leaders on how to care for patients and called the presentation a “concept guide” that does not represent current views.

American Physician Partners touted roughly the same staffing strategy in 2021 in response to the No Surprises Act, which threatened the company’s profits by outlawing surprise medical bills. In its confidential pitch to lenders, the company estimated it could cut almost $6 million by shifting more staffing from physicians to midlevel practitioners.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

New report says suicide rates rising among young Black people

Significant increases in suicide occurred among Native American, Black and Hispanic people, with a startling rise among young Black people. Meanwhile, the rate of suicide among older people declined between 2018 and 2021, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has reported.

In 2021, 48,183 people died by suicide in the United States, which equates to a suicide rate of 14.1 per 100,000 people. That level equals the 2018 suicide rate, which had seen a peak that was followed by declines associated with the pandemic.

Experts said rebounding suicide rates are common following times of crisis, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Suicide declines have also occurred during times of war and natural disaster, when psychological resilience tends to increase and people work together to overcome shared adversity.

“That will wane, and then you will see rebounding in suicide rates. That is, in fact, what we feared would happen. And it has happened, at least in 2021,” Christine Moutier, MD, chief medical officer of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, told the New York Times.

The new CDC report found that the largest increase was among Black people aged 10-24 years, who experienced a 36.6% increase in suicide rate between 2018 and 2021. While Black people experience mental illness at the same rates as that of the general population, historically they have disproportionately limited access to mental health care, according to the American Psychiatric Association.

CDC report authors noted that some of the biggest increases in suicide rates occurred among groups most affected by the pandemic.

From 2018 to 2021, the suicide rate for people aged 25-44 increased among Native Americans by 33.7% and among Black people by 22.9%. Suicide increased among multiracial people by 20.6% and among Hispanic or Latinx people by 19.4%. Among White people of all ages, the suicide rate declined or remained steady.

“As the nation continues to respond to the short- and long-term impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, remaining vigilant in prevention efforts is critical, especially among disproportionately affected populations where longer-term impacts might compound preexisting inequities in suicide risk,” the CDC researchers wrote.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Significant increases in suicide occurred among Native American, Black and Hispanic people, with a startling rise among young Black people. Meanwhile, the rate of suicide among older people declined between 2018 and 2021, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has reported.

In 2021, 48,183 people died by suicide in the United States, which equates to a suicide rate of 14.1 per 100,000 people. That level equals the 2018 suicide rate, which had seen a peak that was followed by declines associated with the pandemic.

Experts said rebounding suicide rates are common following times of crisis, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Suicide declines have also occurred during times of war and natural disaster, when psychological resilience tends to increase and people work together to overcome shared adversity.

“That will wane, and then you will see rebounding in suicide rates. That is, in fact, what we feared would happen. And it has happened, at least in 2021,” Christine Moutier, MD, chief medical officer of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, told the New York Times.

The new CDC report found that the largest increase was among Black people aged 10-24 years, who experienced a 36.6% increase in suicide rate between 2018 and 2021. While Black people experience mental illness at the same rates as that of the general population, historically they have disproportionately limited access to mental health care, according to the American Psychiatric Association.

CDC report authors noted that some of the biggest increases in suicide rates occurred among groups most affected by the pandemic.

From 2018 to 2021, the suicide rate for people aged 25-44 increased among Native Americans by 33.7% and among Black people by 22.9%. Suicide increased among multiracial people by 20.6% and among Hispanic or Latinx people by 19.4%. Among White people of all ages, the suicide rate declined or remained steady.

“As the nation continues to respond to the short- and long-term impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, remaining vigilant in prevention efforts is critical, especially among disproportionately affected populations where longer-term impacts might compound preexisting inequities in suicide risk,” the CDC researchers wrote.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Significant increases in suicide occurred among Native American, Black and Hispanic people, with a startling rise among young Black people. Meanwhile, the rate of suicide among older people declined between 2018 and 2021, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has reported.

In 2021, 48,183 people died by suicide in the United States, which equates to a suicide rate of 14.1 per 100,000 people. That level equals the 2018 suicide rate, which had seen a peak that was followed by declines associated with the pandemic.

Experts said rebounding suicide rates are common following times of crisis, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Suicide declines have also occurred during times of war and natural disaster, when psychological resilience tends to increase and people work together to overcome shared adversity.

“That will wane, and then you will see rebounding in suicide rates. That is, in fact, what we feared would happen. And it has happened, at least in 2021,” Christine Moutier, MD, chief medical officer of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, told the New York Times.

The new CDC report found that the largest increase was among Black people aged 10-24 years, who experienced a 36.6% increase in suicide rate between 2018 and 2021. While Black people experience mental illness at the same rates as that of the general population, historically they have disproportionately limited access to mental health care, according to the American Psychiatric Association.

CDC report authors noted that some of the biggest increases in suicide rates occurred among groups most affected by the pandemic.

From 2018 to 2021, the suicide rate for people aged 25-44 increased among Native Americans by 33.7% and among Black people by 22.9%. Suicide increased among multiracial people by 20.6% and among Hispanic or Latinx people by 19.4%. Among White people of all ages, the suicide rate declined or remained steady.

“As the nation continues to respond to the short- and long-term impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, remaining vigilant in prevention efforts is critical, especially among disproportionately affected populations where longer-term impacts might compound preexisting inequities in suicide risk,” the CDC researchers wrote.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Repetitive TMS effective for comorbid depression, substance use

In a retrospective observational study, participants receiving 20-30 rTMS sessions delivered over a course of 4-6 weeks showed significant reductions in both craving and depression symptom scores.

In addition, the researchers found that the number of rTMS sessions significantly predicted the number of days of drug abstinence, even after controlling for confounders.

“For each additional TMS session, there was an additional 10 days of abstinence in the community,” principal investigator Wael Foad, MD, medical director, Erada Center for Treatment and Rehabilitation, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, told this news organization.

However, Dr. Foad noted that he would need to construct a randomized controlled trial to further explore that “interesting” finding.

The results were published in the Annals of Clinical Psychiatry.

Inpatient program

The researchers retrospectively analyzed medical records of men admitted to the inpatient unit at the Erada Center between June 2019 and September 2020. The vast majority were native to the UAE.

The inpatient program focuses on treating patients with SUDs and is the only dedicated addiction rehabilitation service in Dubai, the investigators noted.

They analyzed outcomes for 55 men with mild to moderate MDD who received rTMS as standard treatment.

Participants were excluded from the data analysis if they had another comorbid diagnosis from the DSM-5 other than SUD or MDD. They were also excluded if they used an illicit substance 2 weeks before the study or used certain medications, including antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, or mood stabilizers.

When patients first arrived on the unit, they were detoxed for a period of time before they began receiving rTMS sessions.

The 55 men received 20-30 high-frequency rTMS sessions over the course of 4-6 weeks in the area of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Each session consisted of 3,000 pulses delivered over a period of 37.5 minutes. Severity of depression was measured with the Clinical Global Impression–Severity Scale (CGI-S), which uses a 7-point Likert scale.

In addition, participants’ scores were tracked on the Brief Substance Craving Scale (BSCS), a self-report scale that measures craving for primary and secondary substances of abuse over a 24-hr period.

Of all participants, 47% said opiates and 35% said methamphetamine were their primary substances of abuse.

Significant improvement

Results showed a statistically significant improvement (P < .05) between baseline and post-rTMS treatment scores in severity of depression and drug craving, as measured by the BSCS and the CGI-S.

The researchers noted that eight participants dropped out of the study after their first rTMS session for various reasons.

Dr. Foad explained that investigators contracted with study participants to receive 20 rTMS sessions; if the sessions were not fully completed during the inpatient stay, the rTMS sessions were continued on an outpatient basis. A study clinician closely monitored patients until they finished their sessions.

For each additional rTMS session the patients completed beyond 20 sessions, there was an associated excess of 10 more days of abstinence from the primary drug in the community.

The investigators speculated that rTMS may reduce drug craving by increasing dopaminergic binding in the striatum, or by releasing dopamine in the caudate nucleus.

Study limitations cited include the lack of a control group and the fact that the study sample was limited to male inpatients, which limits generalizability of the findings to other populations.

Promising intervention

Commenting on the study, Colleen Ann Hanlon, PhD, noted that, from years of work using TMS for depression, “we know that more sessions of TMS during the acute treatment phase tends to lead to stronger and possibly more durable results long-term.”

Dr. Hanlon, who was not involved with the current research, formerly headed a clinical neuromodulation lab at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C. She is now vice president of medical affairs at BrainsWay, an international health technology company specializing in Deep TMS.

She noted that Deep TMS was approved by the Food and Drug Administration for smoking cessation in 2020, “which was a tremendous win for our field at large, and requires only 15 acute sessions followed by 3 weekly sessions” of deep TMS.

“I suspect this is just the beginning of a new era in neuromodulation-based therapeutics for people struggling with drug and alcohol use disorders,” Dr. Hanlon said.

The study behind the FDA approval for smoking approval was a large double-blind, sham-controlled multisite clinical trial where investigators used an H4 coil – a TMS coil that modulates multiple brain areas involved in addictive behaviors simultaneously.

Results from that study showed that 15 sessions of deep TMS significantly improved smoking cessation rates relative to sham (10 Hz, 120% motor threshold, H4 coil, 1,800 pulses/session).

“The difference in cigarette consumption and craving was significant as early as 2 weeks after treatment initiation,” said Dr. Hanlon. “I am looking forward to the future of this field for all people suffering from drug and alcohol use disorders.”

The study and services provided through the Erada Center were funded by the government of Dubai. The investigators reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a retrospective observational study, participants receiving 20-30 rTMS sessions delivered over a course of 4-6 weeks showed significant reductions in both craving and depression symptom scores.

In addition, the researchers found that the number of rTMS sessions significantly predicted the number of days of drug abstinence, even after controlling for confounders.

“For each additional TMS session, there was an additional 10 days of abstinence in the community,” principal investigator Wael Foad, MD, medical director, Erada Center for Treatment and Rehabilitation, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, told this news organization.

However, Dr. Foad noted that he would need to construct a randomized controlled trial to further explore that “interesting” finding.

The results were published in the Annals of Clinical Psychiatry.

Inpatient program

The researchers retrospectively analyzed medical records of men admitted to the inpatient unit at the Erada Center between June 2019 and September 2020. The vast majority were native to the UAE.

The inpatient program focuses on treating patients with SUDs and is the only dedicated addiction rehabilitation service in Dubai, the investigators noted.

They analyzed outcomes for 55 men with mild to moderate MDD who received rTMS as standard treatment.

Participants were excluded from the data analysis if they had another comorbid diagnosis from the DSM-5 other than SUD or MDD. They were also excluded if they used an illicit substance 2 weeks before the study or used certain medications, including antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, or mood stabilizers.

When patients first arrived on the unit, they were detoxed for a period of time before they began receiving rTMS sessions.

The 55 men received 20-30 high-frequency rTMS sessions over the course of 4-6 weeks in the area of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Each session consisted of 3,000 pulses delivered over a period of 37.5 minutes. Severity of depression was measured with the Clinical Global Impression–Severity Scale (CGI-S), which uses a 7-point Likert scale.

In addition, participants’ scores were tracked on the Brief Substance Craving Scale (BSCS), a self-report scale that measures craving for primary and secondary substances of abuse over a 24-hr period.

Of all participants, 47% said opiates and 35% said methamphetamine were their primary substances of abuse.

Significant improvement

Results showed a statistically significant improvement (P < .05) between baseline and post-rTMS treatment scores in severity of depression and drug craving, as measured by the BSCS and the CGI-S.

The researchers noted that eight participants dropped out of the study after their first rTMS session for various reasons.

Dr. Foad explained that investigators contracted with study participants to receive 20 rTMS sessions; if the sessions were not fully completed during the inpatient stay, the rTMS sessions were continued on an outpatient basis. A study clinician closely monitored patients until they finished their sessions.

For each additional rTMS session the patients completed beyond 20 sessions, there was an associated excess of 10 more days of abstinence from the primary drug in the community.

The investigators speculated that rTMS may reduce drug craving by increasing dopaminergic binding in the striatum, or by releasing dopamine in the caudate nucleus.

Study limitations cited include the lack of a control group and the fact that the study sample was limited to male inpatients, which limits generalizability of the findings to other populations.

Promising intervention

Commenting on the study, Colleen Ann Hanlon, PhD, noted that, from years of work using TMS for depression, “we know that more sessions of TMS during the acute treatment phase tends to lead to stronger and possibly more durable results long-term.”

Dr. Hanlon, who was not involved with the current research, formerly headed a clinical neuromodulation lab at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C. She is now vice president of medical affairs at BrainsWay, an international health technology company specializing in Deep TMS.

She noted that Deep TMS was approved by the Food and Drug Administration for smoking cessation in 2020, “which was a tremendous win for our field at large, and requires only 15 acute sessions followed by 3 weekly sessions” of deep TMS.

“I suspect this is just the beginning of a new era in neuromodulation-based therapeutics for people struggling with drug and alcohol use disorders,” Dr. Hanlon said.

The study behind the FDA approval for smoking approval was a large double-blind, sham-controlled multisite clinical trial where investigators used an H4 coil – a TMS coil that modulates multiple brain areas involved in addictive behaviors simultaneously.

Results from that study showed that 15 sessions of deep TMS significantly improved smoking cessation rates relative to sham (10 Hz, 120% motor threshold, H4 coil, 1,800 pulses/session).

“The difference in cigarette consumption and craving was significant as early as 2 weeks after treatment initiation,” said Dr. Hanlon. “I am looking forward to the future of this field for all people suffering from drug and alcohol use disorders.”

The study and services provided through the Erada Center were funded by the government of Dubai. The investigators reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a retrospective observational study, participants receiving 20-30 rTMS sessions delivered over a course of 4-6 weeks showed significant reductions in both craving and depression symptom scores.

In addition, the researchers found that the number of rTMS sessions significantly predicted the number of days of drug abstinence, even after controlling for confounders.

“For each additional TMS session, there was an additional 10 days of abstinence in the community,” principal investigator Wael Foad, MD, medical director, Erada Center for Treatment and Rehabilitation, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, told this news organization.

However, Dr. Foad noted that he would need to construct a randomized controlled trial to further explore that “interesting” finding.

The results were published in the Annals of Clinical Psychiatry.

Inpatient program

The researchers retrospectively analyzed medical records of men admitted to the inpatient unit at the Erada Center between June 2019 and September 2020. The vast majority were native to the UAE.

The inpatient program focuses on treating patients with SUDs and is the only dedicated addiction rehabilitation service in Dubai, the investigators noted.

They analyzed outcomes for 55 men with mild to moderate MDD who received rTMS as standard treatment.

Participants were excluded from the data analysis if they had another comorbid diagnosis from the DSM-5 other than SUD or MDD. They were also excluded if they used an illicit substance 2 weeks before the study or used certain medications, including antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, or mood stabilizers.

When patients first arrived on the unit, they were detoxed for a period of time before they began receiving rTMS sessions.

The 55 men received 20-30 high-frequency rTMS sessions over the course of 4-6 weeks in the area of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Each session consisted of 3,000 pulses delivered over a period of 37.5 minutes. Severity of depression was measured with the Clinical Global Impression–Severity Scale (CGI-S), which uses a 7-point Likert scale.

In addition, participants’ scores were tracked on the Brief Substance Craving Scale (BSCS), a self-report scale that measures craving for primary and secondary substances of abuse over a 24-hr period.

Of all participants, 47% said opiates and 35% said methamphetamine were their primary substances of abuse.

Significant improvement

Results showed a statistically significant improvement (P < .05) between baseline and post-rTMS treatment scores in severity of depression and drug craving, as measured by the BSCS and the CGI-S.

The researchers noted that eight participants dropped out of the study after their first rTMS session for various reasons.

Dr. Foad explained that investigators contracted with study participants to receive 20 rTMS sessions; if the sessions were not fully completed during the inpatient stay, the rTMS sessions were continued on an outpatient basis. A study clinician closely monitored patients until they finished their sessions.

For each additional rTMS session the patients completed beyond 20 sessions, there was an associated excess of 10 more days of abstinence from the primary drug in the community.

The investigators speculated that rTMS may reduce drug craving by increasing dopaminergic binding in the striatum, or by releasing dopamine in the caudate nucleus.

Study limitations cited include the lack of a control group and the fact that the study sample was limited to male inpatients, which limits generalizability of the findings to other populations.

Promising intervention

Commenting on the study, Colleen Ann Hanlon, PhD, noted that, from years of work using TMS for depression, “we know that more sessions of TMS during the acute treatment phase tends to lead to stronger and possibly more durable results long-term.”

Dr. Hanlon, who was not involved with the current research, formerly headed a clinical neuromodulation lab at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C. She is now vice president of medical affairs at BrainsWay, an international health technology company specializing in Deep TMS.

She noted that Deep TMS was approved by the Food and Drug Administration for smoking cessation in 2020, “which was a tremendous win for our field at large, and requires only 15 acute sessions followed by 3 weekly sessions” of deep TMS.

“I suspect this is just the beginning of a new era in neuromodulation-based therapeutics for people struggling with drug and alcohol use disorders,” Dr. Hanlon said.

The study behind the FDA approval for smoking approval was a large double-blind, sham-controlled multisite clinical trial where investigators used an H4 coil – a TMS coil that modulates multiple brain areas involved in addictive behaviors simultaneously.

Results from that study showed that 15 sessions of deep TMS significantly improved smoking cessation rates relative to sham (10 Hz, 120% motor threshold, H4 coil, 1,800 pulses/session).

“The difference in cigarette consumption and craving was significant as early as 2 weeks after treatment initiation,” said Dr. Hanlon. “I am looking forward to the future of this field for all people suffering from drug and alcohol use disorders.”

The study and services provided through the Erada Center were funded by the government of Dubai. The investigators reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE ANNALS OF CLINICAL PSYCHIATRY

Forced hospitalization for mental illness not a permanent solution

I met Eleanor when I was writing a book on involuntary psychiatric treatment. She was very ill when she presented to an emergency department in Northern California. She was looking for help and would have signed herself in, but after waiting 8 hours with no food or medical attention, she walked out and went to another hospital.

At this point, she was agitated and distressed and began screaming uncontrollably. The physician in the second ED did not offer her the option of signing in, and she was placed on a 72-hour hold and subsequently held in the hospital for 3 weeks after a judge committed her.

Like so many issues, involuntary psychiatric care is highly polarized. Some groups favor legislation to make involuntary treatment easier, while patient advocacy and civil rights groups vehemently oppose such legislation.

We don’t hear from these combatants as much as we hear from those who trumpet their views on abortion or gun control, yet this battlefield exists. It is not surprising that when New York City Mayor Eric Adams announced a plan to hospitalize homeless people with mental illnesses – involuntarily if necessary, and at the discretion of the police – people were outraged.

New York City is not the only place using this strategy to address the problem of mental illness and homelessness; California has enacted similar legislation, and every major city has homeless citizens.

Eleanor was not homeless, and fortunately, she recovered and returned to her family. However, she remained distressed and traumatized by her hospitalization for years. “It sticks with you,” she told me. “I would rather die than go in again.”

I wish I could tell you that Eleanor is unique in saying that she would rather die than go to a hospital unit for treatment, but it is not an uncommon sentiment for patients. Some people who are charged with crimes and end up in the judicial system will opt to go to jail rather than to a psychiatric hospital. It is also not easy to access outpatient psychiatric treatment.

Barriers to care

Many psychiatrists don’t participate with insurance networks, and publicly funded clinics may have long waiting lists, so illnesses escalate until there is a crisis and hospitalization is necessary. For many, stigma and fear of potential professional repercussions are significant barriers to care.

What are the issues that legislation attempts to address? The first is the standard for hospitalizing individuals against their will. In some states, the patient must be dangerous, while in others there is a lower standard of “gravely disabled,” and finally there are those that promote a standard of a “need for treatment.”

The second is related to medicating people against their will, a process that can be rightly perceived as an assault if the patient refuses to take oral medications and must be held down for injections. Next, the use of outpatient civil commitment – legally requiring people to get treatment if they are not in the hospital – has been increasingly invoked as a way to prevent mass murders and random violence against strangers.

All but four states have some legislation for outpatient commitment, euphemistically called Assisted Outpatient Treatment (AOT), yet these laws are difficult to enforce and expensive to enact. They are also not fully effective.

In New York City, Kendra’s Law has not eliminated subway violence by people with psychiatric disturbances, and the shooter who killed 32 people and wounded 17 others at Virginia Tech in 2007 had previously been ordered by a judge to go to outpatient treatment, but he simply never showed up for his appointment.

Finally, the battle includes the right of patients to refuse to have their psychiatric information released to their caretakers under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 – a measure that many families believe would help them to get loved ones to take medications and go to appointments.

The concern about how to negotiate the needs of society and the civil rights of people with psychiatric disorders has been with us for centuries. There is a strong antipsychiatry movement that asserts that psychotropic medications are ineffective or harmful and refers to patients as “psychiatric survivors.” We value the right to medical autonomy, and when there is controversy over the validity of a treatment, there is even more controversy over forcing it upon people.

Psychiatric medications are very effective and benefit many people, but they don’t help everyone, and some people experience side effects. Also, we can’t deny that involuntary care can go wrong; the conservatorship of Britney Spears for 13 years is a very public example.

Multiple stakeholders

Many have a stake in how this plays out. There are the patients, who may be suffering and unable to recognize that they are ill, who may have valid reasons for not wanting the treatments, and who ideally should have the right to refuse care.

There are the families who watch their loved ones suffer, deteriorate, and miss the opportunities that life has to offer; who do not want their children to be homeless or incarcerated; and who may be at risk from violent behavior.

There are the mental health professionals who want to do what’s in the best interest of their patients while following legal and ethical mandates, who worry about being sued for tragic outcomes, and who can’t meet the current demand for services.

There is the taxpayer who foots the bill for disability payments, lost productivity, and institutionalization. There is our society that worries that people with psychiatric disorders will commit random acts of violence.

Finally, there are the insurers, who want to pay for as little care as possible and throw up constant hurdles in the treatment process. We must acknowledge that resources used for involuntary treatment are diverted away from those who want care.

Eleanor had many advantages that unhoused people don’t have: a supportive family, health insurance, and the financial means to pay a psychiatrist who respected her wishes to wean off her medications. She returned to a comfortable home and to personal and occupational success.

It is tragic that we have people living on the streets because of a psychiatric disorder, addiction, poverty, or some combination of these. No one should be unhoused. If the rationale of hospitalization is to decrease violence, I am not hopeful. The Epidemiologic Catchment Area study shows that people with psychiatric disorders are responsible for only 4% of all violence.

The logistics of determining which people living on the streets have psychiatric disorders, transporting them safely to medical facilities, and then finding the resources to provide for compassionate and thoughtful care in meaningful and sustained ways are very challenging.