User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

Childhood nightmares a prelude to cognitive problems, Parkinson’s?

new research shows.

Compared with children who never had distressing dreams between ages 7 and 11 years, those who had persistent distressing dreams were 76% more likely to develop cognitive impairment and roughly seven times more likely to develop PD by age 50 years.

It’s been shown previously that sleep problems in adulthood, including distressing dreams, can precede the onset of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) or PD by several years, and in some cases decades, study investigator Abidemi Otaiku, BMBS, University of Birmingham (England), told this news organization.

However, no studies have investigated whether distressing dreams during childhood might also be associated with increased risk for cognitive decline or PD.

“As such, these findings provide evidence for the first time that certain sleep problems in childhood (having regular distressing dreams) could be an early indicator of increased dementia and PD risk,” Dr. Otaiku said.

He noted that the findings build on previous studies which showed that regular nightmares in childhood could be an early indicator for psychiatric problems in adolescence, such as borderline personality disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and psychosis.

The study was published online February 26 in The Lancet journal eClinicalMedicine.

Statistically significant

The prospective, longitudinal analysis used data from the 1958 British Birth Cohort Study, a prospective birth cohort which included all people born in Britain during a single week in 1958.

At age 7 years (in 1965) and 11 years (in 1969), mothers were asked to report whether their child experienced “bad dreams or night terrors” in the past 3 months, and cognitive impairment and PD were determined at age 50 (2008).

Among a total of 6,991 children (51% girls), 78.2% never had distressing dreams, 17.9% had transient distressing dreams (either at ages 7 or 11 years), and 3.8% had persistent distressing dreams (at both ages 7 and 11 years).

By age 50, 262 participants had developed cognitive impairment, and five had been diagnosed with PD.

After adjusting for all covariates, having more regular distressing dreams during childhood was “linearly and statistically significantly” associated with higher risk of developing cognitive impairment or PD by age 50 years (P = .037). This was the case in both boys and girls.

Compared with children who never had bad dreams, peers who had persistent distressing dreams (at ages 7 and 11 years) had an 85% increased risk for cognitive impairment or PD by age 50 (adjusted odds ratio, 1.85; 95% confidence interval, 1.10-3.11; P = .019).

The associations remained when incident cognitive impairment and incident PD were analyzed separately.

Compared with children who never had distressing dreams, children who had persistent distressing dreams were 76% more likely to develop cognitive impairment by age 50 years (aOR, 1.76; 95% CI, 1.03-2.99; P = .037), and were about seven times more likely to be diagnosed with PD by age 50 years (aOR, 7.35; 95% CI, 1.03-52.73; P = .047).

The linear association was statistically significant for PD (P = .050) and had a trend toward statistical significance for cognitive impairment (P = .074).

Mechanism unclear

“Early-life nightmares might be causally associated with cognitive impairment and PD, noncausally associated with cognitive impairment and PD, or both. At this stage it remains unclear which of the three options is correct. Therefore, further research on mechanisms is needed,” Dr. Otaiku told this news organization.

“One plausible noncausal explanation is that there are shared genetic factors which predispose individuals to having frequent nightmares in childhood, and to developing neurodegenerative diseases such as AD or PD in adulthood,” he added.

It’s also plausible that having regular nightmares throughout childhood could be a causal risk factor for cognitive impairment and PD by causing chronic sleep disruption, he noted.

“Chronic sleep disruption due to nightmares might lead to impaired glymphatic clearance during sleep – and thus greater accumulation of pathological proteins in the brain, such as amyloid-beta and alpha-synuclein,” Dr. Otaiku said.

Disrupted sleep throughout childhood might also impair normal brain development, which could make children’s brains less resilient to neuropathologic damage, he said.

Clinical implications?

There are established treatments for childhood nightmares, including nonpharmacologic approaches.

“For children who have regular nightmares that lead to impaired daytime functioning, it may well be a good idea for them to see a sleep physician to discuss whether treatment may be needed,” Dr. Otaiku said.

But should doctors treat children with persistent nightmares for the purpose of preventing neurodegenerative diseases in adulthood or psychiatric problems in adolescence?

“It’s an interesting possibility. However, more research is needed to confirm these epidemiological associations and to determine whether or not nightmares are a causal risk factor for these conditions,” Dr. Otaiku concluded.

The study received no external funding. Dr. Otaiku reports no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research shows.

Compared with children who never had distressing dreams between ages 7 and 11 years, those who had persistent distressing dreams were 76% more likely to develop cognitive impairment and roughly seven times more likely to develop PD by age 50 years.

It’s been shown previously that sleep problems in adulthood, including distressing dreams, can precede the onset of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) or PD by several years, and in some cases decades, study investigator Abidemi Otaiku, BMBS, University of Birmingham (England), told this news organization.

However, no studies have investigated whether distressing dreams during childhood might also be associated with increased risk for cognitive decline or PD.

“As such, these findings provide evidence for the first time that certain sleep problems in childhood (having regular distressing dreams) could be an early indicator of increased dementia and PD risk,” Dr. Otaiku said.

He noted that the findings build on previous studies which showed that regular nightmares in childhood could be an early indicator for psychiatric problems in adolescence, such as borderline personality disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and psychosis.

The study was published online February 26 in The Lancet journal eClinicalMedicine.

Statistically significant

The prospective, longitudinal analysis used data from the 1958 British Birth Cohort Study, a prospective birth cohort which included all people born in Britain during a single week in 1958.

At age 7 years (in 1965) and 11 years (in 1969), mothers were asked to report whether their child experienced “bad dreams or night terrors” in the past 3 months, and cognitive impairment and PD were determined at age 50 (2008).

Among a total of 6,991 children (51% girls), 78.2% never had distressing dreams, 17.9% had transient distressing dreams (either at ages 7 or 11 years), and 3.8% had persistent distressing dreams (at both ages 7 and 11 years).

By age 50, 262 participants had developed cognitive impairment, and five had been diagnosed with PD.

After adjusting for all covariates, having more regular distressing dreams during childhood was “linearly and statistically significantly” associated with higher risk of developing cognitive impairment or PD by age 50 years (P = .037). This was the case in both boys and girls.

Compared with children who never had bad dreams, peers who had persistent distressing dreams (at ages 7 and 11 years) had an 85% increased risk for cognitive impairment or PD by age 50 (adjusted odds ratio, 1.85; 95% confidence interval, 1.10-3.11; P = .019).

The associations remained when incident cognitive impairment and incident PD were analyzed separately.

Compared with children who never had distressing dreams, children who had persistent distressing dreams were 76% more likely to develop cognitive impairment by age 50 years (aOR, 1.76; 95% CI, 1.03-2.99; P = .037), and were about seven times more likely to be diagnosed with PD by age 50 years (aOR, 7.35; 95% CI, 1.03-52.73; P = .047).

The linear association was statistically significant for PD (P = .050) and had a trend toward statistical significance for cognitive impairment (P = .074).

Mechanism unclear

“Early-life nightmares might be causally associated with cognitive impairment and PD, noncausally associated with cognitive impairment and PD, or both. At this stage it remains unclear which of the three options is correct. Therefore, further research on mechanisms is needed,” Dr. Otaiku told this news organization.

“One plausible noncausal explanation is that there are shared genetic factors which predispose individuals to having frequent nightmares in childhood, and to developing neurodegenerative diseases such as AD or PD in adulthood,” he added.

It’s also plausible that having regular nightmares throughout childhood could be a causal risk factor for cognitive impairment and PD by causing chronic sleep disruption, he noted.

“Chronic sleep disruption due to nightmares might lead to impaired glymphatic clearance during sleep – and thus greater accumulation of pathological proteins in the brain, such as amyloid-beta and alpha-synuclein,” Dr. Otaiku said.

Disrupted sleep throughout childhood might also impair normal brain development, which could make children’s brains less resilient to neuropathologic damage, he said.

Clinical implications?

There are established treatments for childhood nightmares, including nonpharmacologic approaches.

“For children who have regular nightmares that lead to impaired daytime functioning, it may well be a good idea for them to see a sleep physician to discuss whether treatment may be needed,” Dr. Otaiku said.

But should doctors treat children with persistent nightmares for the purpose of preventing neurodegenerative diseases in adulthood or psychiatric problems in adolescence?

“It’s an interesting possibility. However, more research is needed to confirm these epidemiological associations and to determine whether or not nightmares are a causal risk factor for these conditions,” Dr. Otaiku concluded.

The study received no external funding. Dr. Otaiku reports no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research shows.

Compared with children who never had distressing dreams between ages 7 and 11 years, those who had persistent distressing dreams were 76% more likely to develop cognitive impairment and roughly seven times more likely to develop PD by age 50 years.

It’s been shown previously that sleep problems in adulthood, including distressing dreams, can precede the onset of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) or PD by several years, and in some cases decades, study investigator Abidemi Otaiku, BMBS, University of Birmingham (England), told this news organization.

However, no studies have investigated whether distressing dreams during childhood might also be associated with increased risk for cognitive decline or PD.

“As such, these findings provide evidence for the first time that certain sleep problems in childhood (having regular distressing dreams) could be an early indicator of increased dementia and PD risk,” Dr. Otaiku said.

He noted that the findings build on previous studies which showed that regular nightmares in childhood could be an early indicator for psychiatric problems in adolescence, such as borderline personality disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and psychosis.

The study was published online February 26 in The Lancet journal eClinicalMedicine.

Statistically significant

The prospective, longitudinal analysis used data from the 1958 British Birth Cohort Study, a prospective birth cohort which included all people born in Britain during a single week in 1958.

At age 7 years (in 1965) and 11 years (in 1969), mothers were asked to report whether their child experienced “bad dreams or night terrors” in the past 3 months, and cognitive impairment and PD were determined at age 50 (2008).

Among a total of 6,991 children (51% girls), 78.2% never had distressing dreams, 17.9% had transient distressing dreams (either at ages 7 or 11 years), and 3.8% had persistent distressing dreams (at both ages 7 and 11 years).

By age 50, 262 participants had developed cognitive impairment, and five had been diagnosed with PD.

After adjusting for all covariates, having more regular distressing dreams during childhood was “linearly and statistically significantly” associated with higher risk of developing cognitive impairment or PD by age 50 years (P = .037). This was the case in both boys and girls.

Compared with children who never had bad dreams, peers who had persistent distressing dreams (at ages 7 and 11 years) had an 85% increased risk for cognitive impairment or PD by age 50 (adjusted odds ratio, 1.85; 95% confidence interval, 1.10-3.11; P = .019).

The associations remained when incident cognitive impairment and incident PD were analyzed separately.

Compared with children who never had distressing dreams, children who had persistent distressing dreams were 76% more likely to develop cognitive impairment by age 50 years (aOR, 1.76; 95% CI, 1.03-2.99; P = .037), and were about seven times more likely to be diagnosed with PD by age 50 years (aOR, 7.35; 95% CI, 1.03-52.73; P = .047).

The linear association was statistically significant for PD (P = .050) and had a trend toward statistical significance for cognitive impairment (P = .074).

Mechanism unclear

“Early-life nightmares might be causally associated with cognitive impairment and PD, noncausally associated with cognitive impairment and PD, or both. At this stage it remains unclear which of the three options is correct. Therefore, further research on mechanisms is needed,” Dr. Otaiku told this news organization.

“One plausible noncausal explanation is that there are shared genetic factors which predispose individuals to having frequent nightmares in childhood, and to developing neurodegenerative diseases such as AD or PD in adulthood,” he added.

It’s also plausible that having regular nightmares throughout childhood could be a causal risk factor for cognitive impairment and PD by causing chronic sleep disruption, he noted.

“Chronic sleep disruption due to nightmares might lead to impaired glymphatic clearance during sleep – and thus greater accumulation of pathological proteins in the brain, such as amyloid-beta and alpha-synuclein,” Dr. Otaiku said.

Disrupted sleep throughout childhood might also impair normal brain development, which could make children’s brains less resilient to neuropathologic damage, he said.

Clinical implications?

There are established treatments for childhood nightmares, including nonpharmacologic approaches.

“For children who have regular nightmares that lead to impaired daytime functioning, it may well be a good idea for them to see a sleep physician to discuss whether treatment may be needed,” Dr. Otaiku said.

But should doctors treat children with persistent nightmares for the purpose of preventing neurodegenerative diseases in adulthood or psychiatric problems in adolescence?

“It’s an interesting possibility. However, more research is needed to confirm these epidemiological associations and to determine whether or not nightmares are a causal risk factor for these conditions,” Dr. Otaiku concluded.

The study received no external funding. Dr. Otaiku reports no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ECLINICALMEDICINE

Even mild COVID is hard on the brain

early research suggests.

“Our results suggest a severe pattern of changes in how the brain communicates as well as its structure, mainly in people with anxiety and depression with long-COVID syndrome, which affects so many people,” study investigator Clarissa Yasuda, MD, PhD, from University of Campinas, São Paulo, said in a news release.

“The magnitude of these changes suggests that they could lead to problems with memory and thinking skills, so we need to be exploring holistic treatments even for people mildly affected by COVID-19,” Dr. Yasuda added.

The findings were released March 6 ahead of the study’s scheduled presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

Brain shrinkage

Some studies have shown a high prevalence of symptoms of anxiety and depression in COVID-19 survivors, but few have investigated the associated cerebral changes, Dr. Yasuda told this news organization.

The study included 254 adults (177 women, 77 men, median age 41 years) who had mild COVID-19 a median of 82 days earlier. A total of 102 had symptoms of both anxiety and depression, and 152 had no such symptoms.

On brain imaging, those with COVID-19 and anxiety and depression had atrophy in the limbic area of the brain, which plays a role in memory and emotional processing.

No shrinkage in this area was evident in people who had COVID-19 without anxiety and depression or in a healthy control group of individuals without COVID-19.

The researchers also observed a “severe” pattern of abnormal cerebral functional connectivity in those with COVID-19 and anxiety and depression.

In this functional connectivity analysis, individuals with COVID-19 and anxiety and depression had widespread functional changes in each of the 12 networks assessed, while those with COVID-19 but without symptoms of anxiety and depression showed changes in only 5 networks.

Mechanisms unclear

“Unfortunately, the underpinning mechanisms associated with brain changes and neuropsychiatric dysfunction after COVID-19 infection are unclear,” Dr. Yasuda told this news organization.

“Some studies have demonstrated an association between symptoms of anxiety and depression with inflammation. However, we hypothesize that these cerebral alterations may result from a more complex interaction of social, psychological, and systemic stressors, including inflammation. It is indeed intriguing that such alterations are present in individuals who presented mild acute infection,” Dr. Yasuda added.

“Symptoms of anxiety and depression are frequently observed after COVID-19 and are part of long-COVID syndrome for some individuals. These symptoms require adequate treatment to improve the quality of life, cognition, and work capacity,” she said.

Treating these symptoms may induce “brain plasticity, which may result in some degree of gray matter increase and eventually prevent further structural and functional damage,” Dr. Yasuda said.

A limitation of the study was that symptoms of anxiety and depression were self-reported, meaning people may have misjudged or misreported symptoms.

Commenting on the findings for this news organization, Cyrus Raji, MD, PhD, with the Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology, Washington University, St. Louis, said the idea that COVID-19 is bad for the brain isn’t new. Dr. Raji was not involved with the study.

Early in the pandemic, Dr. Raji and colleagues published a paper detailing COVID-19’s effects on the brain, and Dr. Raji followed it up with a TED talk on the subject.

“Within the growing framework of what we already know about COVID-19 infection and its adverse effects on the brain, this work incrementally adds to this knowledge by identifying functional and structural neuroimaging abnormalities related to anxiety and depression in persons suffering from COVID-19 infection,” Dr. Raji said.

The study was supported by the São Paulo Research Foundation. The authors have no relevant disclosures. Raji is a consultant for Brainreader, Apollo Health, Pacific Neuroscience Foundation, and Neurevolution LLC.

early research suggests.

“Our results suggest a severe pattern of changes in how the brain communicates as well as its structure, mainly in people with anxiety and depression with long-COVID syndrome, which affects so many people,” study investigator Clarissa Yasuda, MD, PhD, from University of Campinas, São Paulo, said in a news release.

“The magnitude of these changes suggests that they could lead to problems with memory and thinking skills, so we need to be exploring holistic treatments even for people mildly affected by COVID-19,” Dr. Yasuda added.

The findings were released March 6 ahead of the study’s scheduled presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

Brain shrinkage

Some studies have shown a high prevalence of symptoms of anxiety and depression in COVID-19 survivors, but few have investigated the associated cerebral changes, Dr. Yasuda told this news organization.

The study included 254 adults (177 women, 77 men, median age 41 years) who had mild COVID-19 a median of 82 days earlier. A total of 102 had symptoms of both anxiety and depression, and 152 had no such symptoms.

On brain imaging, those with COVID-19 and anxiety and depression had atrophy in the limbic area of the brain, which plays a role in memory and emotional processing.

No shrinkage in this area was evident in people who had COVID-19 without anxiety and depression or in a healthy control group of individuals without COVID-19.

The researchers also observed a “severe” pattern of abnormal cerebral functional connectivity in those with COVID-19 and anxiety and depression.

In this functional connectivity analysis, individuals with COVID-19 and anxiety and depression had widespread functional changes in each of the 12 networks assessed, while those with COVID-19 but without symptoms of anxiety and depression showed changes in only 5 networks.

Mechanisms unclear

“Unfortunately, the underpinning mechanisms associated with brain changes and neuropsychiatric dysfunction after COVID-19 infection are unclear,” Dr. Yasuda told this news organization.

“Some studies have demonstrated an association between symptoms of anxiety and depression with inflammation. However, we hypothesize that these cerebral alterations may result from a more complex interaction of social, psychological, and systemic stressors, including inflammation. It is indeed intriguing that such alterations are present in individuals who presented mild acute infection,” Dr. Yasuda added.

“Symptoms of anxiety and depression are frequently observed after COVID-19 and are part of long-COVID syndrome for some individuals. These symptoms require adequate treatment to improve the quality of life, cognition, and work capacity,” she said.

Treating these symptoms may induce “brain plasticity, which may result in some degree of gray matter increase and eventually prevent further structural and functional damage,” Dr. Yasuda said.

A limitation of the study was that symptoms of anxiety and depression were self-reported, meaning people may have misjudged or misreported symptoms.

Commenting on the findings for this news organization, Cyrus Raji, MD, PhD, with the Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology, Washington University, St. Louis, said the idea that COVID-19 is bad for the brain isn’t new. Dr. Raji was not involved with the study.

Early in the pandemic, Dr. Raji and colleagues published a paper detailing COVID-19’s effects on the brain, and Dr. Raji followed it up with a TED talk on the subject.

“Within the growing framework of what we already know about COVID-19 infection and its adverse effects on the brain, this work incrementally adds to this knowledge by identifying functional and structural neuroimaging abnormalities related to anxiety and depression in persons suffering from COVID-19 infection,” Dr. Raji said.

The study was supported by the São Paulo Research Foundation. The authors have no relevant disclosures. Raji is a consultant for Brainreader, Apollo Health, Pacific Neuroscience Foundation, and Neurevolution LLC.

early research suggests.

“Our results suggest a severe pattern of changes in how the brain communicates as well as its structure, mainly in people with anxiety and depression with long-COVID syndrome, which affects so many people,” study investigator Clarissa Yasuda, MD, PhD, from University of Campinas, São Paulo, said in a news release.

“The magnitude of these changes suggests that they could lead to problems with memory and thinking skills, so we need to be exploring holistic treatments even for people mildly affected by COVID-19,” Dr. Yasuda added.

The findings were released March 6 ahead of the study’s scheduled presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

Brain shrinkage

Some studies have shown a high prevalence of symptoms of anxiety and depression in COVID-19 survivors, but few have investigated the associated cerebral changes, Dr. Yasuda told this news organization.

The study included 254 adults (177 women, 77 men, median age 41 years) who had mild COVID-19 a median of 82 days earlier. A total of 102 had symptoms of both anxiety and depression, and 152 had no such symptoms.

On brain imaging, those with COVID-19 and anxiety and depression had atrophy in the limbic area of the brain, which plays a role in memory and emotional processing.

No shrinkage in this area was evident in people who had COVID-19 without anxiety and depression or in a healthy control group of individuals without COVID-19.

The researchers also observed a “severe” pattern of abnormal cerebral functional connectivity in those with COVID-19 and anxiety and depression.

In this functional connectivity analysis, individuals with COVID-19 and anxiety and depression had widespread functional changes in each of the 12 networks assessed, while those with COVID-19 but without symptoms of anxiety and depression showed changes in only 5 networks.

Mechanisms unclear

“Unfortunately, the underpinning mechanisms associated with brain changes and neuropsychiatric dysfunction after COVID-19 infection are unclear,” Dr. Yasuda told this news organization.

“Some studies have demonstrated an association between symptoms of anxiety and depression with inflammation. However, we hypothesize that these cerebral alterations may result from a more complex interaction of social, psychological, and systemic stressors, including inflammation. It is indeed intriguing that such alterations are present in individuals who presented mild acute infection,” Dr. Yasuda added.

“Symptoms of anxiety and depression are frequently observed after COVID-19 and are part of long-COVID syndrome for some individuals. These symptoms require adequate treatment to improve the quality of life, cognition, and work capacity,” she said.

Treating these symptoms may induce “brain plasticity, which may result in some degree of gray matter increase and eventually prevent further structural and functional damage,” Dr. Yasuda said.

A limitation of the study was that symptoms of anxiety and depression were self-reported, meaning people may have misjudged or misreported symptoms.

Commenting on the findings for this news organization, Cyrus Raji, MD, PhD, with the Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology, Washington University, St. Louis, said the idea that COVID-19 is bad for the brain isn’t new. Dr. Raji was not involved with the study.

Early in the pandemic, Dr. Raji and colleagues published a paper detailing COVID-19’s effects on the brain, and Dr. Raji followed it up with a TED talk on the subject.

“Within the growing framework of what we already know about COVID-19 infection and its adverse effects on the brain, this work incrementally adds to this knowledge by identifying functional and structural neuroimaging abnormalities related to anxiety and depression in persons suffering from COVID-19 infection,” Dr. Raji said.

The study was supported by the São Paulo Research Foundation. The authors have no relevant disclosures. Raji is a consultant for Brainreader, Apollo Health, Pacific Neuroscience Foundation, and Neurevolution LLC.

Daily socialization may extend lifespan in elderly

Sometimes more is more.

Correlations between socializing and survival were detected regardless of baseline health status, suggesting that physicians should be recommending daily socialization for all elderly patients, lead author Ziqiong Wang, MD, of Sichuan University West China Hospital, Chengdu, China, and colleagues reported.

These findings align with an array of prior studies reporting physical and mental health benefits from socialization, and negative impacts from isolation, the investigators wrote in the Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. Not all studies have yielded the same picture, however, and most research has been conducted in Western countries, leading to uncertainty about whether different outcomes would be seen in populations in other parts of the world. Furthermore, the authors added that few studies have explored the amount of socialization needed to derive a positive benefit.

To address this knowledge gap, the investigators analyzed survival data from 28,563 participants in the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey with a median age of 89 years at baseline.

“[This analysis] is from a highly respected ongoing longitudinal study of aging in China, which includes a large number of subjects and employs very strong research design and statistical analytical methods, so it has credibility,” John W. Rowe, MD, Julius B. Richmond Professor of Health Policy and Aging at Columbia University, New York, said in a written comment.

The investigators stratified frequency of socialization into five tiers: never, not monthly but sometimes, not weekly but at least once per month, not daily but at least once per week, and almost every day.

Survival proportions were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method after accounting for a range of individual characteristics, including age, sex, household income, smoking status, diabetes, self-rated health, and others. Comparative findings were described in terms of time ratios using multivariable parametric accelerated failure time (AFT) models.

“The AFT model estimates the time ratio (TR), which is interpreted as the expected time to events in one category relative to the reference group,” the investigators wrote. “Unlike the interpretation of proportional hazard model results where hazard ratios larger than 1 are equal to higher risk, a TR of greater than 1 is considered to have a longer time to events, compared with the reference group.”

From baseline to 5 years, each socialization tier was significantly associated with prolonged survival, suggesting a general benefit. Compared with no socialization, socializing sometimes but not monthly was associated with 42% longer survival, at least monthly socialization was associated with 48% longer survival, at least weekly was associated with 110% longer survival, and socializing almost every day was associated with 87% longer survival.

The outsized benefit of daily socialization became clear in a long-term survival analysis, which spanned 5 years through the end of follow-up. Compared with no socialization, daily socialization tripled survival (TR, 3.04; P < .001), compared with prolongations ranging from 5% to 64% for less socialization, with just one of these lower tiers achieving statistical significance (P = .046).

Of note, the benefit of daily socialization was detected regardless of a person’s health status at baseline.

“No matter if elderly participants had chronic diseases or not, [and] no matter if older people had good self-rated health or not, the survival benefits of frequently participating in social activity were the same,” said principal author Sen He, MD, of Sichuan University, in a written comment.

“Socializing almost every day seems to be the most beneficial for a long life,” Dr. Sen added, noting that more research is needed to determine if there is an optimal type of social activity.

Dr. Rowe pointed out two key findings from the study. The first was that it confirmed “prior studies that have identified a beneficial effect of social activity on life expectancy.

“We have known that engagement is essential for successful aging and that isolation is toxic. While this finding is not novel, it is nice to see this confirmation of what we thought we knew,” he wrote.

Secondly, the study has identified “a threshold effect”, which is that “the long-term benefit on life expectancy was only seen in the presence of fairly intense social interactions, essentially daily,” he said.

According to Preeti Malani, MD, professor of medicine and geriatrician at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, the findings are also helpful because they offer data from another part of the world, adding confidence in findings from Western countries.

“This [study] happens to focus on older adults in China, which is helpful since aging is not the same everywhere in the world,” Dr. Malani said. “While the numbers here may not be precise, it’s fair to say that socialization is good for your health – for everyone but especially for older adults.”

Considering the body of evidence now spanning a range of populations, Dr. Malani said physicians should be screening for, and recommending, socialization for all elderly patients, particularly because many aren’t getting enough of it.

“Work that my colleagues and I have done (with the National Poll on Healthy Aging) suggests that there is a portion of older adults that have very little to no social contact,” Dr. Malani said. “A physician may not know this unless they are asking routinely about socialization the way we might ask about diet and exercise. How much is enough? No one knows, but anything is better than nothing and likely more is better.”

She also suggested that personalization is key.

“Physical and emotional health may limit the ability to socialize, so not everyone can engage all the time,” Dr. Malani said. “Also, socialization can look different for different people. Technology allows for socialization even if an individual has trouble leaving their home. I especially worry about this issue for older adults that are also caregivers. Those individuals also need time for themselves” and on way to fulfill that need is by socializing with others.

The study was supported by Sichuan (China) Science and Technology Program, the National Key R&D Program of China, and the National Natural Science Foundation of China. The investigators, Dr. Rowe, and Dr. Malani disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

Sometimes more is more.

Correlations between socializing and survival were detected regardless of baseline health status, suggesting that physicians should be recommending daily socialization for all elderly patients, lead author Ziqiong Wang, MD, of Sichuan University West China Hospital, Chengdu, China, and colleagues reported.

These findings align with an array of prior studies reporting physical and mental health benefits from socialization, and negative impacts from isolation, the investigators wrote in the Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. Not all studies have yielded the same picture, however, and most research has been conducted in Western countries, leading to uncertainty about whether different outcomes would be seen in populations in other parts of the world. Furthermore, the authors added that few studies have explored the amount of socialization needed to derive a positive benefit.

To address this knowledge gap, the investigators analyzed survival data from 28,563 participants in the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey with a median age of 89 years at baseline.

“[This analysis] is from a highly respected ongoing longitudinal study of aging in China, which includes a large number of subjects and employs very strong research design and statistical analytical methods, so it has credibility,” John W. Rowe, MD, Julius B. Richmond Professor of Health Policy and Aging at Columbia University, New York, said in a written comment.

The investigators stratified frequency of socialization into five tiers: never, not monthly but sometimes, not weekly but at least once per month, not daily but at least once per week, and almost every day.

Survival proportions were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method after accounting for a range of individual characteristics, including age, sex, household income, smoking status, diabetes, self-rated health, and others. Comparative findings were described in terms of time ratios using multivariable parametric accelerated failure time (AFT) models.

“The AFT model estimates the time ratio (TR), which is interpreted as the expected time to events in one category relative to the reference group,” the investigators wrote. “Unlike the interpretation of proportional hazard model results where hazard ratios larger than 1 are equal to higher risk, a TR of greater than 1 is considered to have a longer time to events, compared with the reference group.”

From baseline to 5 years, each socialization tier was significantly associated with prolonged survival, suggesting a general benefit. Compared with no socialization, socializing sometimes but not monthly was associated with 42% longer survival, at least monthly socialization was associated with 48% longer survival, at least weekly was associated with 110% longer survival, and socializing almost every day was associated with 87% longer survival.

The outsized benefit of daily socialization became clear in a long-term survival analysis, which spanned 5 years through the end of follow-up. Compared with no socialization, daily socialization tripled survival (TR, 3.04; P < .001), compared with prolongations ranging from 5% to 64% for less socialization, with just one of these lower tiers achieving statistical significance (P = .046).

Of note, the benefit of daily socialization was detected regardless of a person’s health status at baseline.

“No matter if elderly participants had chronic diseases or not, [and] no matter if older people had good self-rated health or not, the survival benefits of frequently participating in social activity were the same,” said principal author Sen He, MD, of Sichuan University, in a written comment.

“Socializing almost every day seems to be the most beneficial for a long life,” Dr. Sen added, noting that more research is needed to determine if there is an optimal type of social activity.

Dr. Rowe pointed out two key findings from the study. The first was that it confirmed “prior studies that have identified a beneficial effect of social activity on life expectancy.

“We have known that engagement is essential for successful aging and that isolation is toxic. While this finding is not novel, it is nice to see this confirmation of what we thought we knew,” he wrote.

Secondly, the study has identified “a threshold effect”, which is that “the long-term benefit on life expectancy was only seen in the presence of fairly intense social interactions, essentially daily,” he said.

According to Preeti Malani, MD, professor of medicine and geriatrician at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, the findings are also helpful because they offer data from another part of the world, adding confidence in findings from Western countries.

“This [study] happens to focus on older adults in China, which is helpful since aging is not the same everywhere in the world,” Dr. Malani said. “While the numbers here may not be precise, it’s fair to say that socialization is good for your health – for everyone but especially for older adults.”

Considering the body of evidence now spanning a range of populations, Dr. Malani said physicians should be screening for, and recommending, socialization for all elderly patients, particularly because many aren’t getting enough of it.

“Work that my colleagues and I have done (with the National Poll on Healthy Aging) suggests that there is a portion of older adults that have very little to no social contact,” Dr. Malani said. “A physician may not know this unless they are asking routinely about socialization the way we might ask about diet and exercise. How much is enough? No one knows, but anything is better than nothing and likely more is better.”

She also suggested that personalization is key.

“Physical and emotional health may limit the ability to socialize, so not everyone can engage all the time,” Dr. Malani said. “Also, socialization can look different for different people. Technology allows for socialization even if an individual has trouble leaving their home. I especially worry about this issue for older adults that are also caregivers. Those individuals also need time for themselves” and on way to fulfill that need is by socializing with others.

The study was supported by Sichuan (China) Science and Technology Program, the National Key R&D Program of China, and the National Natural Science Foundation of China. The investigators, Dr. Rowe, and Dr. Malani disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

Sometimes more is more.

Correlations between socializing and survival were detected regardless of baseline health status, suggesting that physicians should be recommending daily socialization for all elderly patients, lead author Ziqiong Wang, MD, of Sichuan University West China Hospital, Chengdu, China, and colleagues reported.

These findings align with an array of prior studies reporting physical and mental health benefits from socialization, and negative impacts from isolation, the investigators wrote in the Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. Not all studies have yielded the same picture, however, and most research has been conducted in Western countries, leading to uncertainty about whether different outcomes would be seen in populations in other parts of the world. Furthermore, the authors added that few studies have explored the amount of socialization needed to derive a positive benefit.

To address this knowledge gap, the investigators analyzed survival data from 28,563 participants in the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey with a median age of 89 years at baseline.

“[This analysis] is from a highly respected ongoing longitudinal study of aging in China, which includes a large number of subjects and employs very strong research design and statistical analytical methods, so it has credibility,” John W. Rowe, MD, Julius B. Richmond Professor of Health Policy and Aging at Columbia University, New York, said in a written comment.

The investigators stratified frequency of socialization into five tiers: never, not monthly but sometimes, not weekly but at least once per month, not daily but at least once per week, and almost every day.

Survival proportions were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method after accounting for a range of individual characteristics, including age, sex, household income, smoking status, diabetes, self-rated health, and others. Comparative findings were described in terms of time ratios using multivariable parametric accelerated failure time (AFT) models.

“The AFT model estimates the time ratio (TR), which is interpreted as the expected time to events in one category relative to the reference group,” the investigators wrote. “Unlike the interpretation of proportional hazard model results where hazard ratios larger than 1 are equal to higher risk, a TR of greater than 1 is considered to have a longer time to events, compared with the reference group.”

From baseline to 5 years, each socialization tier was significantly associated with prolonged survival, suggesting a general benefit. Compared with no socialization, socializing sometimes but not monthly was associated with 42% longer survival, at least monthly socialization was associated with 48% longer survival, at least weekly was associated with 110% longer survival, and socializing almost every day was associated with 87% longer survival.

The outsized benefit of daily socialization became clear in a long-term survival analysis, which spanned 5 years through the end of follow-up. Compared with no socialization, daily socialization tripled survival (TR, 3.04; P < .001), compared with prolongations ranging from 5% to 64% for less socialization, with just one of these lower tiers achieving statistical significance (P = .046).

Of note, the benefit of daily socialization was detected regardless of a person’s health status at baseline.

“No matter if elderly participants had chronic diseases or not, [and] no matter if older people had good self-rated health or not, the survival benefits of frequently participating in social activity were the same,” said principal author Sen He, MD, of Sichuan University, in a written comment.

“Socializing almost every day seems to be the most beneficial for a long life,” Dr. Sen added, noting that more research is needed to determine if there is an optimal type of social activity.

Dr. Rowe pointed out two key findings from the study. The first was that it confirmed “prior studies that have identified a beneficial effect of social activity on life expectancy.

“We have known that engagement is essential for successful aging and that isolation is toxic. While this finding is not novel, it is nice to see this confirmation of what we thought we knew,” he wrote.

Secondly, the study has identified “a threshold effect”, which is that “the long-term benefit on life expectancy was only seen in the presence of fairly intense social interactions, essentially daily,” he said.

According to Preeti Malani, MD, professor of medicine and geriatrician at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, the findings are also helpful because they offer data from another part of the world, adding confidence in findings from Western countries.

“This [study] happens to focus on older adults in China, which is helpful since aging is not the same everywhere in the world,” Dr. Malani said. “While the numbers here may not be precise, it’s fair to say that socialization is good for your health – for everyone but especially for older adults.”

Considering the body of evidence now spanning a range of populations, Dr. Malani said physicians should be screening for, and recommending, socialization for all elderly patients, particularly because many aren’t getting enough of it.

“Work that my colleagues and I have done (with the National Poll on Healthy Aging) suggests that there is a portion of older adults that have very little to no social contact,” Dr. Malani said. “A physician may not know this unless they are asking routinely about socialization the way we might ask about diet and exercise. How much is enough? No one knows, but anything is better than nothing and likely more is better.”

She also suggested that personalization is key.

“Physical and emotional health may limit the ability to socialize, so not everyone can engage all the time,” Dr. Malani said. “Also, socialization can look different for different people. Technology allows for socialization even if an individual has trouble leaving their home. I especially worry about this issue for older adults that are also caregivers. Those individuals also need time for themselves” and on way to fulfill that need is by socializing with others.

The study was supported by Sichuan (China) Science and Technology Program, the National Key R&D Program of China, and the National Natural Science Foundation of China. The investigators, Dr. Rowe, and Dr. Malani disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF EPIDEMIOLOGY & COMMUNITY HEALTH

Distinct suicidal thought patterns flag those at highest risk

Long-term assessment of suicide risk and ideation in older adults may help identify distinct ideation patterns and predict potential future suicidal behavior, new research suggests.

Investigators studied over 300 older adults, assessing suicidal ideation and behavior for up to 14 years at least once annually. They then identified four suicidal ideation profiles.

They found that In turn, fast-remitting ideators were at higher risk in comparison to low/nonideators with no attempts or suicide.

Chronic severe ideators also showed the most severe levels of dysfunction across personality, social characteristics, and impulsivity measures, while highly variable and fast-remitting ideators displayed more specific deficits.

“We identified longitudinal ideation profiles that convey differential risk of future suicidal behavior to help clinicians recognize high suicide risk patients for preventing suicide,” said lead author Hanga Galfalvy, PhD, associate professor, department of psychiatry, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York.

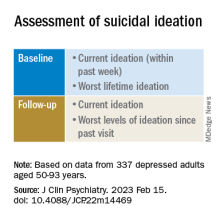

“Clinicians should repeatedly assess suicidal ideation and ask not only about current ideation but also about the worst ideation since the last visit [because] similar levels of ideation during a single assessment can belong to very different risk profiles,” said Dr. Galfalvy, also a professor of biostatistics and a coinvestigator in the Conte Center for Suicide Prevention at Columbia University.

The study was published online in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Vulnerable population

“Older adults in most countries, including the U.S., are at the highest risk of dying of suicide out of all age groups,” said Dr. Galfalvy. “A significant number of depressed older adults experience thoughts of killing themselves, but fortunately, only a few transition from suicidal thoughts to behavior.”

Senior author Katalin Szanto, MD, professor of psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh, said in an interview that currently established clinical and psychosocial suicide risk factors have “low predictive value and provide little insight into the high suicide rate in the elderly.”

These traditional risk factors “poorly distinguish between suicide ideators and suicide attempters and do not take into consideration the heterogeneity of suicidal behavior,” said Dr. Szanto, principal investigator at the University of Pittsburgh’s Longitudinal research Program in Late-Life Suicide, where the study was conducted.

“Suicidal ideation measured at one time point – current or lifetime – may not be enough to accurately predict suicide risk,” the investigators wrote.

The current study, a collaboration between investigators from the Longitudinal Research Program in Late-Life Suicide and the Conte Center for Suicide Prevention, investigates “profiles of suicidal thoughts and behavior in patients with late-life depression over a longer period of time,” Dr. Galfalvy said.

The researchers used latent profile analysis (LPA) in a cohort of adults with nonpsychotic unipolar depression (aged 50-93 years; n = 337; mean age, 65.12 years) to “identify distinct ideation profiles and their clinical correlates” and to “test the profiles’ association with the risk of suicidal behavior before and during follow-up.”

LPA is “a data-driven method of grouping individuals into subgroups, based on quantitative characteristics,” Dr. Galfalvy explained.

The LPA yielded four profiles of ideation.

At baseline, the researchers assessed the presence or absence of suicidal behavior history and the number and lethality of attempts. They prospectively assessed suicidal ideation and attempts at least once annually thereafter over a period ranging from 3 months to 14 years (median, 3 years; IQR, 1.6-4 years).

At baseline and at follow-ups, they assessed ideation severity.

They also assessed depression severity, impulsivity, and personality measures, as well as perception of social support, social problem solving, cognitive performance, and physical comorbidities.

Personalized prevention

Of the original cohort, 92 patients died during the follow-up period, with 13 dying of suicide (or suspected suicide).

Over half (60%) of the chronic severe as well as the highly variable groups and almost half (48%) of the fast-remitting group had a history of past suicide attempt – all significantly higher than the low-nonideators (0%).

Despite comparable current ideation severity at baseline, the risk of suicide attempt/death was greater for chronic severe ideators versus fast-remitting ideators, but not greater than for highly variable ideators. On the other hand, highly variable ideators were at greater risk, compared with fast-remitting ideators.

Cognitive factors “did not significantly discriminate between the ideation profiles, although ... lower global cognitive performance predicted suicidal behavior during follow-up,” the authors wrote.

This finding “aligns with prior studies indicating that late-life suicidal behavior but not ideation may be related to cognition ... and instead, ideation and cognition may act as independent risk factors for suicidal behavior,” they added.

“Patients in the fluctuating ideator group generally had moderate or high levels of worst suicidal ideation between visits, but not when asked about current ideation levels at the time of the follow-up assessment,” Dr. Galfalvy noted. “For them, the time frame of the question made a difference as to the level of ideation reported.”

The study “identified several clinical differences among these subgroups which could lead to more personalized suicide prevention efforts and further research into the heterogeneity of suicidal behavior,” she suggested.

New insight

Commenting on the study, Ari Cuperfain, MD, of the University of Toronto said the study “adds to the nuanced understanding of how changes in suicidal ideation over time can lead to suicidal actions and behavior.”

The study “sheds light on the notion of how older adults who die by suicide can demonstrate a greater degree of premeditated intent relative to younger cohorts, with chronic severe ideators portending the highest risk for suicide in this sample,” added Dr. Cuperfain, who was not involved with the current research.

“Overall, the paper highlights the importance of both screening for current levels of suicidal ideation in addition to the evolution of suicidal ideation in developing a risk assessment and in finding interventions to reduce this risk when it is most prominent,” he stated.

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health. The authors and Dr. Cuperfain disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Long-term assessment of suicide risk and ideation in older adults may help identify distinct ideation patterns and predict potential future suicidal behavior, new research suggests.

Investigators studied over 300 older adults, assessing suicidal ideation and behavior for up to 14 years at least once annually. They then identified four suicidal ideation profiles.

They found that In turn, fast-remitting ideators were at higher risk in comparison to low/nonideators with no attempts or suicide.

Chronic severe ideators also showed the most severe levels of dysfunction across personality, social characteristics, and impulsivity measures, while highly variable and fast-remitting ideators displayed more specific deficits.

“We identified longitudinal ideation profiles that convey differential risk of future suicidal behavior to help clinicians recognize high suicide risk patients for preventing suicide,” said lead author Hanga Galfalvy, PhD, associate professor, department of psychiatry, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York.

“Clinicians should repeatedly assess suicidal ideation and ask not only about current ideation but also about the worst ideation since the last visit [because] similar levels of ideation during a single assessment can belong to very different risk profiles,” said Dr. Galfalvy, also a professor of biostatistics and a coinvestigator in the Conte Center for Suicide Prevention at Columbia University.

The study was published online in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Vulnerable population

“Older adults in most countries, including the U.S., are at the highest risk of dying of suicide out of all age groups,” said Dr. Galfalvy. “A significant number of depressed older adults experience thoughts of killing themselves, but fortunately, only a few transition from suicidal thoughts to behavior.”

Senior author Katalin Szanto, MD, professor of psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh, said in an interview that currently established clinical and psychosocial suicide risk factors have “low predictive value and provide little insight into the high suicide rate in the elderly.”

These traditional risk factors “poorly distinguish between suicide ideators and suicide attempters and do not take into consideration the heterogeneity of suicidal behavior,” said Dr. Szanto, principal investigator at the University of Pittsburgh’s Longitudinal research Program in Late-Life Suicide, where the study was conducted.

“Suicidal ideation measured at one time point – current or lifetime – may not be enough to accurately predict suicide risk,” the investigators wrote.

The current study, a collaboration between investigators from the Longitudinal Research Program in Late-Life Suicide and the Conte Center for Suicide Prevention, investigates “profiles of suicidal thoughts and behavior in patients with late-life depression over a longer period of time,” Dr. Galfalvy said.

The researchers used latent profile analysis (LPA) in a cohort of adults with nonpsychotic unipolar depression (aged 50-93 years; n = 337; mean age, 65.12 years) to “identify distinct ideation profiles and their clinical correlates” and to “test the profiles’ association with the risk of suicidal behavior before and during follow-up.”

LPA is “a data-driven method of grouping individuals into subgroups, based on quantitative characteristics,” Dr. Galfalvy explained.

The LPA yielded four profiles of ideation.

At baseline, the researchers assessed the presence or absence of suicidal behavior history and the number and lethality of attempts. They prospectively assessed suicidal ideation and attempts at least once annually thereafter over a period ranging from 3 months to 14 years (median, 3 years; IQR, 1.6-4 years).

At baseline and at follow-ups, they assessed ideation severity.

They also assessed depression severity, impulsivity, and personality measures, as well as perception of social support, social problem solving, cognitive performance, and physical comorbidities.

Personalized prevention

Of the original cohort, 92 patients died during the follow-up period, with 13 dying of suicide (or suspected suicide).

Over half (60%) of the chronic severe as well as the highly variable groups and almost half (48%) of the fast-remitting group had a history of past suicide attempt – all significantly higher than the low-nonideators (0%).

Despite comparable current ideation severity at baseline, the risk of suicide attempt/death was greater for chronic severe ideators versus fast-remitting ideators, but not greater than for highly variable ideators. On the other hand, highly variable ideators were at greater risk, compared with fast-remitting ideators.

Cognitive factors “did not significantly discriminate between the ideation profiles, although ... lower global cognitive performance predicted suicidal behavior during follow-up,” the authors wrote.

This finding “aligns with prior studies indicating that late-life suicidal behavior but not ideation may be related to cognition ... and instead, ideation and cognition may act as independent risk factors for suicidal behavior,” they added.

“Patients in the fluctuating ideator group generally had moderate or high levels of worst suicidal ideation between visits, but not when asked about current ideation levels at the time of the follow-up assessment,” Dr. Galfalvy noted. “For them, the time frame of the question made a difference as to the level of ideation reported.”

The study “identified several clinical differences among these subgroups which could lead to more personalized suicide prevention efforts and further research into the heterogeneity of suicidal behavior,” she suggested.

New insight

Commenting on the study, Ari Cuperfain, MD, of the University of Toronto said the study “adds to the nuanced understanding of how changes in suicidal ideation over time can lead to suicidal actions and behavior.”

The study “sheds light on the notion of how older adults who die by suicide can demonstrate a greater degree of premeditated intent relative to younger cohorts, with chronic severe ideators portending the highest risk for suicide in this sample,” added Dr. Cuperfain, who was not involved with the current research.

“Overall, the paper highlights the importance of both screening for current levels of suicidal ideation in addition to the evolution of suicidal ideation in developing a risk assessment and in finding interventions to reduce this risk when it is most prominent,” he stated.

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health. The authors and Dr. Cuperfain disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Long-term assessment of suicide risk and ideation in older adults may help identify distinct ideation patterns and predict potential future suicidal behavior, new research suggests.

Investigators studied over 300 older adults, assessing suicidal ideation and behavior for up to 14 years at least once annually. They then identified four suicidal ideation profiles.

They found that In turn, fast-remitting ideators were at higher risk in comparison to low/nonideators with no attempts or suicide.

Chronic severe ideators also showed the most severe levels of dysfunction across personality, social characteristics, and impulsivity measures, while highly variable and fast-remitting ideators displayed more specific deficits.

“We identified longitudinal ideation profiles that convey differential risk of future suicidal behavior to help clinicians recognize high suicide risk patients for preventing suicide,” said lead author Hanga Galfalvy, PhD, associate professor, department of psychiatry, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York.

“Clinicians should repeatedly assess suicidal ideation and ask not only about current ideation but also about the worst ideation since the last visit [because] similar levels of ideation during a single assessment can belong to very different risk profiles,” said Dr. Galfalvy, also a professor of biostatistics and a coinvestigator in the Conte Center for Suicide Prevention at Columbia University.

The study was published online in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Vulnerable population

“Older adults in most countries, including the U.S., are at the highest risk of dying of suicide out of all age groups,” said Dr. Galfalvy. “A significant number of depressed older adults experience thoughts of killing themselves, but fortunately, only a few transition from suicidal thoughts to behavior.”

Senior author Katalin Szanto, MD, professor of psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh, said in an interview that currently established clinical and psychosocial suicide risk factors have “low predictive value and provide little insight into the high suicide rate in the elderly.”

These traditional risk factors “poorly distinguish between suicide ideators and suicide attempters and do not take into consideration the heterogeneity of suicidal behavior,” said Dr. Szanto, principal investigator at the University of Pittsburgh’s Longitudinal research Program in Late-Life Suicide, where the study was conducted.

“Suicidal ideation measured at one time point – current or lifetime – may not be enough to accurately predict suicide risk,” the investigators wrote.

The current study, a collaboration between investigators from the Longitudinal Research Program in Late-Life Suicide and the Conte Center for Suicide Prevention, investigates “profiles of suicidal thoughts and behavior in patients with late-life depression over a longer period of time,” Dr. Galfalvy said.

The researchers used latent profile analysis (LPA) in a cohort of adults with nonpsychotic unipolar depression (aged 50-93 years; n = 337; mean age, 65.12 years) to “identify distinct ideation profiles and their clinical correlates” and to “test the profiles’ association with the risk of suicidal behavior before and during follow-up.”

LPA is “a data-driven method of grouping individuals into subgroups, based on quantitative characteristics,” Dr. Galfalvy explained.

The LPA yielded four profiles of ideation.

At baseline, the researchers assessed the presence or absence of suicidal behavior history and the number and lethality of attempts. They prospectively assessed suicidal ideation and attempts at least once annually thereafter over a period ranging from 3 months to 14 years (median, 3 years; IQR, 1.6-4 years).

At baseline and at follow-ups, they assessed ideation severity.

They also assessed depression severity, impulsivity, and personality measures, as well as perception of social support, social problem solving, cognitive performance, and physical comorbidities.

Personalized prevention

Of the original cohort, 92 patients died during the follow-up period, with 13 dying of suicide (or suspected suicide).

Over half (60%) of the chronic severe as well as the highly variable groups and almost half (48%) of the fast-remitting group had a history of past suicide attempt – all significantly higher than the low-nonideators (0%).

Despite comparable current ideation severity at baseline, the risk of suicide attempt/death was greater for chronic severe ideators versus fast-remitting ideators, but not greater than for highly variable ideators. On the other hand, highly variable ideators were at greater risk, compared with fast-remitting ideators.

Cognitive factors “did not significantly discriminate between the ideation profiles, although ... lower global cognitive performance predicted suicidal behavior during follow-up,” the authors wrote.

This finding “aligns with prior studies indicating that late-life suicidal behavior but not ideation may be related to cognition ... and instead, ideation and cognition may act as independent risk factors for suicidal behavior,” they added.

“Patients in the fluctuating ideator group generally had moderate or high levels of worst suicidal ideation between visits, but not when asked about current ideation levels at the time of the follow-up assessment,” Dr. Galfalvy noted. “For them, the time frame of the question made a difference as to the level of ideation reported.”

The study “identified several clinical differences among these subgroups which could lead to more personalized suicide prevention efforts and further research into the heterogeneity of suicidal behavior,” she suggested.

New insight

Commenting on the study, Ari Cuperfain, MD, of the University of Toronto said the study “adds to the nuanced understanding of how changes in suicidal ideation over time can lead to suicidal actions and behavior.”

The study “sheds light on the notion of how older adults who die by suicide can demonstrate a greater degree of premeditated intent relative to younger cohorts, with chronic severe ideators portending the highest risk for suicide in this sample,” added Dr. Cuperfain, who was not involved with the current research.

“Overall, the paper highlights the importance of both screening for current levels of suicidal ideation in addition to the evolution of suicidal ideation in developing a risk assessment and in finding interventions to reduce this risk when it is most prominent,” he stated.

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health. The authors and Dr. Cuperfain disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL PSYCHIATRY

Encephalitis linked to psychosis, suicidal thoughts

Investigators assessed 120 patients hospitalized in a neurological center and diagnosed with ANMDARE. Most had psychosis and other severe mental health disturbances. Of these, 13% also had suicidal thoughts and behaviors.

However, after medical treatment that included immunotherapy, neurologic and psychiatric pharmacotherapy, and rehabilitation and psychotherapy, almost all patients with suicidal thoughts and behaviors had sustained remission of their suicidality.

“Most patients [with ANMDARE] suffer with severe mental health problems, and it is not infrequent that suicidal thoughts and behaviors emerge in this context – mainly in patients with clinical features of psychotic depression,” senior author Jesús Ramirez-Bermúdez, MD, PhD, from the neuropsychiatry unit, National Institute of Neurology and Neurosurgery of Mexico, told this news organization.

“The good news is that, in most cases, the suicidal thoughts and behaviors as well as the features of psychotic depression improve significantly with the specific immunological therapy. However, careful psychiatric and psychotherapeutic support are helpful to restore the long-term psychological well-being,” Dr. Ramirez-Bermúdez said.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences.

Delayed recognition

ANMDARE is a “frequent form of autoimmune encephalitis,” the authors write. It often begins with an “abrupt onset of behavioral and cognitive symptoms, followed by seizures and movement disorders,” they add.

“The clinical care of persons with encephalitis is challenging because these patients suffer from acute and severe mental health disturbances [and] are often misdiagnosed as having a primary psychiatric disorder, for instance, schizophrenia or bipolar disorder; but, they do not improve with the use of psychiatric medication or psychotherapy,” Dr. Ramirez-Bermúdez said.

Rather, the disease requires specific treatments, such as the use of antiviral medication or immunotherapy, he added. Without these, “the mortality rate is high, and many patients have bad outcomes, including disability related to cognitive and affective disturbances,” he said.

Dr. Ramirez-Bermúdez noted that there are “many cultural problems in the conventional approach to mental health problems, including prejudices, fear, myths, stigma, and discrimination.” And these attitudes can contribute to delayed recognition of ANMDARE.

During recent years, Dr. Ramirez-Bermúdez and colleagues observed that some patients with autoimmune encephalitis and, more specifically, patients suffering from ANMDARE had suicidal behavior. A previous study conducted in China suggested that the problem of suicidal behavior is not infrequent in this population.

“We wanted to make a structured, systematic, and prospective approach to this problem to answer some questions related to ANMDARE,” Dr. Ramirez-Bermúdez said. These questions included: What is the frequency of suicidal thoughts and behaviors, what are the neurological and psychiatric features related to suicidal behavior in this population, and what is the outcome after receiving immunological treatment?

The researchers conducted an observational longitudinal study that included patients hospitalized between 2014 and 2021 who had definite ANMDARE (n = 120).

Patients were diagnosed as having encephalitis by means of clinical interviews, neuropsychological studies, brain imaging, EEG, and analysis of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

All participants had antibodies against the NMDA glutamate receptor in their CSF and were classified as having ANMDARE based on Graus criteria, “which are considered the best current standard for diagnosis,” Dr. Ramirez-Bermúdez noted.

Clinical measures were obtained both before and after treatment with immunotherapy, and all clinical data were registered prospectively and included a “broad scope of neurological and psychiatric variables seen in patients with ANMDARE.”

Information regarding suicidal thoughts and behaviors was gathered from patients as well as relatives, with assessments occurring at admission and at discharge.

Biological signaling

Results showed that 15 patients presented with suicidal thoughts and/or behaviors. Of this subgroup, the median age was 32 years (range, 19-48 years) and 53.3% were women.

All members of this subgroup had psychotic features, including persecutory, grandiose, nihilistic, or jealousy delusion (n = 14), delirium (n = 13), visual or auditory hallucinations (n = 11), psychotic depression (n = 10), and/or catatonia (n = 8).

Most (n = 12) had suicidal ideation with intent, three had preparatory behaviors, and seven actually engaged in suicidal self-directed violence.

Of these 15 patients, 7 had abnormal CSF findings, 8 had MRI abnormalities involving the medial temporal lobe, and all had abnormal EEG involving generalized slowing.

Fourteen suicidal patients were treated with an antipsychotic, 4 with dexmedetomidine, and 12 with lorazepam. In addition, 10 received plasmapheresis and 7 received immunoglobulin.

Of note, at discharge, self-directed violent thoughts and behaviors completely remitted in 14 of the 15 patients. Long-term follow-up showed that they remained free of suicidality.

Dr. Ramirez-Bermúdez noted that in some patients with neuropsychiatric disturbances, “there are autoantibodies against the NR1 subunit of the NMDA glutamate receptor: the main excitatory neurotransmitter in the human brain.”

The NMDA receptor is “particularly important as part of the biological signaling that is required in several cognitive and affective processes leading to complex behaviors,” he said. NMDA receptor dysfunction “may lead to states in which these cognitive and affective processes are disturbed,” frequently resulting in psychosis.

Study coauthor Ava Easton, MD, chief executive of the Encephalitis Society, told this news organization that mental health issues, self-injurious thoughts, and suicidal behaviors after encephalitis “may occur for a number of reasons and stigma around talking about mental health can be a real barrier to speaking up about symptoms; but it is an important barrier to overcome.”

Dr. Easton, an honorary fellow in the department of clinical infection, microbiology, and immunology, University of Liverpool, England, added that their study “provides a platform on which to break taboo, show tangible links which are based on data between suicide and encephalitis, and call for more awareness of the risk of mental health issues during and after encephalitis.”

‘Neglected symptom’

Commenting on the study, Carsten Finke, MD, Heisenberg Professor for Cognitive Neurology and consultant neurologist, department of neurology at Charité, Berlin, and professor at Berlin School of Mind and Brain, said that the research was on “a very important topic on a so far rather neglected symptom of encephalitis.”

Dr. Finke, a founding member of the scientific council of the German Network for Research on Autoimmune Encephalitis, was not involved in the current study.

He noted that 77% of people don’t know what encephalitis is. “This lack of awareness leads to delays in diagnoses and treatment – and poorer outcomes for patients,” Dr. Finke said.

Also commenting, Michael Eriksen Benros, MD, PhD, professor of immune-psychiatry, department of immunology and microbiology, Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen, said that the study “underlines the clinical importance of screening individuals with psychotic symptoms for suicidal ideations during acute phases,” as well as those with definite ANMDARE as a likely underlying cause of the psychotic symptoms.

This is important because patients with ANMDARE “might not necessarily be admitted at psychiatric departments where screenings for suicidal ideation are part of the clinical routine,” said Dr. Benros, who was not involved with the research.

Instead, “many patients with ANMDARE are at neurological departments during acute phases,” he added.

The study was supported by the National Council of Science and Technology of Mexico. Dr. Ramirez-Bermúdez, Dr. Easton, Dr. Benros, and Dr. Finke report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators assessed 120 patients hospitalized in a neurological center and diagnosed with ANMDARE. Most had psychosis and other severe mental health disturbances. Of these, 13% also had suicidal thoughts and behaviors.

However, after medical treatment that included immunotherapy, neurologic and psychiatric pharmacotherapy, and rehabilitation and psychotherapy, almost all patients with suicidal thoughts and behaviors had sustained remission of their suicidality.

“Most patients [with ANMDARE] suffer with severe mental health problems, and it is not infrequent that suicidal thoughts and behaviors emerge in this context – mainly in patients with clinical features of psychotic depression,” senior author Jesús Ramirez-Bermúdez, MD, PhD, from the neuropsychiatry unit, National Institute of Neurology and Neurosurgery of Mexico, told this news organization.