User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

The devil in the (masking) details

The Devil’s own face covering?

It’s been over a year and a half since the COVID-19 emergency was declared in the United States, and we’ve been starting to wonder what our good friend SARS-CoV-2 has left to give. The collective cynic/optimist in us figures that the insanity can’t last forever, right?

Maybe not forever, but …

A group of parents is suing the Central Bucks (Pa.) School District over school mask mandates, suggesting that the district has no legal authority to enforce such measures. Most of their arguments, Philadelphia Magazine says, are pretty standard stuff: Masks are causing depression, anxiety, and discomfort in their children; masks are a violation of their constitutional rights; and “masks are being used as a control mechanism over the population.”

There are some unusual claims, though. One of the parents, Shannon Harris, said that “wearing masks interferes with their religious duty to spread the word of God and forces them to participate in a satanic ritual,” according to the Philadelphia Inquirer.

Philadelphia Magazine decided to check on that “satanic ritual” claim by asking an expert, in this case a spokesperson for the Church of Satan. The Reverend Raul Antony said that “simply ‘wearing a mask’ is not a Satanic ritual, and anyone that genuinely thinks otherwise is a blithering idiot,” adding that the group’s rituals were available on its website.

COVID, you never let us down.

You’re the (hurricane) wind beneath my wings

Marriage isn’t easy. From finances to everyday stressors like work and children, maintaining a solid relationship is tough. Then a natural disaster shows up on top of everything else, and marriages actually improve, researchers found.

In a study published by Psychological Science, researchers surveyed 231 newlywed couples about the satisfaction of their marriage before and after Hurricane Harvey in 2017. They found after the hurricane couples had a “significant boost” in the satisfaction of their relationship.

One would think something like this would create what researchers call a “stress spillover,” creating a decrease in relationship satisfaction. Destruction to your home or even displacement after a natural disaster seems pretty stressful. But, “a natural disaster can really put things in perspective. People realize how important their partner is to them when they are jolted out of the day-to-day stress of life,” said Hannah Williamson, PhD, the lead author of the study.

And although everyone saw an increase, the biggest jumps in relationship satisfaction belonged to the people who were most unhappy before the hurricane. Unfortunately, the researchers also found that the effects were only temporary and the dissatisfaction came back within a year.

Dr. Williamson thinks there may be something to these findings that can be beneficial from a therapy standpoint where “couples can shift their perspective in a similar way without having to go through a natural disaster.”

Let’s hope she’s right, because the alternative is to seek out a rampaging hurricane every time your relationship is on the rocks, and that just seems impractical after the second or third year.

Not-so-essential oils

Many people use essential oils as a way to unwind and relax. Stressed? Can’t sleep? There’s probably an essential oil for that. However, it seems like these days a lot of things we love and/or think are good for us have a side that’s not so.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a woman from Georgia died from a rare bacteria called Burkholderia pseudomallei. There have been three previous infections in Kansas, Minnesota, and Texas throughout 2021; two of the four infections were in children. Melioidosis, the disease caused by B. pseudomallei, is usually found in southeast Asia and isn’t obvious or easy to diagnose, especially in places like decidedly untropical Minnesota.

The Georgia case was the real break in this medical mystery, as the infection was traced back to a Walmart product called “Better Homes and Gardens Essential Oil Infused Aromatherapy Room Spray with Gemstones” (a very pithy name). The bacteria were in the lavender and chamomile scent. The CDC is investigating all other product scents, and Walmart has recalled all lots of the product.

If you’ve got that particular essential oil, it’s probably for the best that you stop using it. Don’t worry, we’re sure there’s plenty of other essential oil–infused aromatherapy room sprays with gemstones out there for your scent-based needs.

Welcome to the Ministry of Sleep-Deprived Walks

Walking is simple, right? You put one foot in front of the other, and soon you’re walking out the door. Little kids can do it. Even zombies can walk, and they don’t even have brains.

Research from MIT and the University of São Paulo has shown that walking is a little trickier than we might think. One researcher in particular noticed that student volunteers tended to perform worse toward the end of semesters, as project deadlines and multiple exams crashed over their heads and they were deprived of solid sleep schedules.

In a study published in Scientific Reports, our intrepid walking researchers had a collection of students monitor their sleep patterns for 2 weeks; on average, the students got 6 hours per night, though some were able to compensate on weekends. On the final day of a 14-day period, some students pulled all-nighters while the rest were allowed to sleep as usual. Then all students performed a walking test involving keeping time with a metronome.

To absolutely no one’s surprise, the students who performed all-nighters before being tested walked the worst, but between the other students, the ones who compensated for sleep deprivation on weekends did better than those who got 6 hours every night, despite getting a similar amount of sleep overall. This effect persisted even when the compensating students performed their walking tests late in the week, just before they got their weekend beauty sleep.

The moral of the story? Sleep is good, and you should get more of it. But if you can’t, sleep in on weekends. Science has given you permission. All those suburban dads looking to get their teenagers up at 8 in the morning must be sweating right now.

The Devil’s own face covering?

It’s been over a year and a half since the COVID-19 emergency was declared in the United States, and we’ve been starting to wonder what our good friend SARS-CoV-2 has left to give. The collective cynic/optimist in us figures that the insanity can’t last forever, right?

Maybe not forever, but …

A group of parents is suing the Central Bucks (Pa.) School District over school mask mandates, suggesting that the district has no legal authority to enforce such measures. Most of their arguments, Philadelphia Magazine says, are pretty standard stuff: Masks are causing depression, anxiety, and discomfort in their children; masks are a violation of their constitutional rights; and “masks are being used as a control mechanism over the population.”

There are some unusual claims, though. One of the parents, Shannon Harris, said that “wearing masks interferes with their religious duty to spread the word of God and forces them to participate in a satanic ritual,” according to the Philadelphia Inquirer.

Philadelphia Magazine decided to check on that “satanic ritual” claim by asking an expert, in this case a spokesperson for the Church of Satan. The Reverend Raul Antony said that “simply ‘wearing a mask’ is not a Satanic ritual, and anyone that genuinely thinks otherwise is a blithering idiot,” adding that the group’s rituals were available on its website.

COVID, you never let us down.

You’re the (hurricane) wind beneath my wings

Marriage isn’t easy. From finances to everyday stressors like work and children, maintaining a solid relationship is tough. Then a natural disaster shows up on top of everything else, and marriages actually improve, researchers found.

In a study published by Psychological Science, researchers surveyed 231 newlywed couples about the satisfaction of their marriage before and after Hurricane Harvey in 2017. They found after the hurricane couples had a “significant boost” in the satisfaction of their relationship.

One would think something like this would create what researchers call a “stress spillover,” creating a decrease in relationship satisfaction. Destruction to your home or even displacement after a natural disaster seems pretty stressful. But, “a natural disaster can really put things in perspective. People realize how important their partner is to them when they are jolted out of the day-to-day stress of life,” said Hannah Williamson, PhD, the lead author of the study.

And although everyone saw an increase, the biggest jumps in relationship satisfaction belonged to the people who were most unhappy before the hurricane. Unfortunately, the researchers also found that the effects were only temporary and the dissatisfaction came back within a year.

Dr. Williamson thinks there may be something to these findings that can be beneficial from a therapy standpoint where “couples can shift their perspective in a similar way without having to go through a natural disaster.”

Let’s hope she’s right, because the alternative is to seek out a rampaging hurricane every time your relationship is on the rocks, and that just seems impractical after the second or third year.

Not-so-essential oils

Many people use essential oils as a way to unwind and relax. Stressed? Can’t sleep? There’s probably an essential oil for that. However, it seems like these days a lot of things we love and/or think are good for us have a side that’s not so.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a woman from Georgia died from a rare bacteria called Burkholderia pseudomallei. There have been three previous infections in Kansas, Minnesota, and Texas throughout 2021; two of the four infections were in children. Melioidosis, the disease caused by B. pseudomallei, is usually found in southeast Asia and isn’t obvious or easy to diagnose, especially in places like decidedly untropical Minnesota.

The Georgia case was the real break in this medical mystery, as the infection was traced back to a Walmart product called “Better Homes and Gardens Essential Oil Infused Aromatherapy Room Spray with Gemstones” (a very pithy name). The bacteria were in the lavender and chamomile scent. The CDC is investigating all other product scents, and Walmart has recalled all lots of the product.

If you’ve got that particular essential oil, it’s probably for the best that you stop using it. Don’t worry, we’re sure there’s plenty of other essential oil–infused aromatherapy room sprays with gemstones out there for your scent-based needs.

Welcome to the Ministry of Sleep-Deprived Walks

Walking is simple, right? You put one foot in front of the other, and soon you’re walking out the door. Little kids can do it. Even zombies can walk, and they don’t even have brains.

Research from MIT and the University of São Paulo has shown that walking is a little trickier than we might think. One researcher in particular noticed that student volunteers tended to perform worse toward the end of semesters, as project deadlines and multiple exams crashed over their heads and they were deprived of solid sleep schedules.

In a study published in Scientific Reports, our intrepid walking researchers had a collection of students monitor their sleep patterns for 2 weeks; on average, the students got 6 hours per night, though some were able to compensate on weekends. On the final day of a 14-day period, some students pulled all-nighters while the rest were allowed to sleep as usual. Then all students performed a walking test involving keeping time with a metronome.

To absolutely no one’s surprise, the students who performed all-nighters before being tested walked the worst, but between the other students, the ones who compensated for sleep deprivation on weekends did better than those who got 6 hours every night, despite getting a similar amount of sleep overall. This effect persisted even when the compensating students performed their walking tests late in the week, just before they got their weekend beauty sleep.

The moral of the story? Sleep is good, and you should get more of it. But if you can’t, sleep in on weekends. Science has given you permission. All those suburban dads looking to get their teenagers up at 8 in the morning must be sweating right now.

The Devil’s own face covering?

It’s been over a year and a half since the COVID-19 emergency was declared in the United States, and we’ve been starting to wonder what our good friend SARS-CoV-2 has left to give. The collective cynic/optimist in us figures that the insanity can’t last forever, right?

Maybe not forever, but …

A group of parents is suing the Central Bucks (Pa.) School District over school mask mandates, suggesting that the district has no legal authority to enforce such measures. Most of their arguments, Philadelphia Magazine says, are pretty standard stuff: Masks are causing depression, anxiety, and discomfort in their children; masks are a violation of their constitutional rights; and “masks are being used as a control mechanism over the population.”

There are some unusual claims, though. One of the parents, Shannon Harris, said that “wearing masks interferes with their religious duty to spread the word of God and forces them to participate in a satanic ritual,” according to the Philadelphia Inquirer.

Philadelphia Magazine decided to check on that “satanic ritual” claim by asking an expert, in this case a spokesperson for the Church of Satan. The Reverend Raul Antony said that “simply ‘wearing a mask’ is not a Satanic ritual, and anyone that genuinely thinks otherwise is a blithering idiot,” adding that the group’s rituals were available on its website.

COVID, you never let us down.

You’re the (hurricane) wind beneath my wings

Marriage isn’t easy. From finances to everyday stressors like work and children, maintaining a solid relationship is tough. Then a natural disaster shows up on top of everything else, and marriages actually improve, researchers found.

In a study published by Psychological Science, researchers surveyed 231 newlywed couples about the satisfaction of their marriage before and after Hurricane Harvey in 2017. They found after the hurricane couples had a “significant boost” in the satisfaction of their relationship.

One would think something like this would create what researchers call a “stress spillover,” creating a decrease in relationship satisfaction. Destruction to your home or even displacement after a natural disaster seems pretty stressful. But, “a natural disaster can really put things in perspective. People realize how important their partner is to them when they are jolted out of the day-to-day stress of life,” said Hannah Williamson, PhD, the lead author of the study.

And although everyone saw an increase, the biggest jumps in relationship satisfaction belonged to the people who were most unhappy before the hurricane. Unfortunately, the researchers also found that the effects were only temporary and the dissatisfaction came back within a year.

Dr. Williamson thinks there may be something to these findings that can be beneficial from a therapy standpoint where “couples can shift their perspective in a similar way without having to go through a natural disaster.”

Let’s hope she’s right, because the alternative is to seek out a rampaging hurricane every time your relationship is on the rocks, and that just seems impractical after the second or third year.

Not-so-essential oils

Many people use essential oils as a way to unwind and relax. Stressed? Can’t sleep? There’s probably an essential oil for that. However, it seems like these days a lot of things we love and/or think are good for us have a side that’s not so.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a woman from Georgia died from a rare bacteria called Burkholderia pseudomallei. There have been three previous infections in Kansas, Minnesota, and Texas throughout 2021; two of the four infections were in children. Melioidosis, the disease caused by B. pseudomallei, is usually found in southeast Asia and isn’t obvious or easy to diagnose, especially in places like decidedly untropical Minnesota.

The Georgia case was the real break in this medical mystery, as the infection was traced back to a Walmart product called “Better Homes and Gardens Essential Oil Infused Aromatherapy Room Spray with Gemstones” (a very pithy name). The bacteria were in the lavender and chamomile scent. The CDC is investigating all other product scents, and Walmart has recalled all lots of the product.

If you’ve got that particular essential oil, it’s probably for the best that you stop using it. Don’t worry, we’re sure there’s plenty of other essential oil–infused aromatherapy room sprays with gemstones out there for your scent-based needs.

Welcome to the Ministry of Sleep-Deprived Walks

Walking is simple, right? You put one foot in front of the other, and soon you’re walking out the door. Little kids can do it. Even zombies can walk, and they don’t even have brains.

Research from MIT and the University of São Paulo has shown that walking is a little trickier than we might think. One researcher in particular noticed that student volunteers tended to perform worse toward the end of semesters, as project deadlines and multiple exams crashed over their heads and they were deprived of solid sleep schedules.

In a study published in Scientific Reports, our intrepid walking researchers had a collection of students monitor their sleep patterns for 2 weeks; on average, the students got 6 hours per night, though some were able to compensate on weekends. On the final day of a 14-day period, some students pulled all-nighters while the rest were allowed to sleep as usual. Then all students performed a walking test involving keeping time with a metronome.

To absolutely no one’s surprise, the students who performed all-nighters before being tested walked the worst, but between the other students, the ones who compensated for sleep deprivation on weekends did better than those who got 6 hours every night, despite getting a similar amount of sleep overall. This effect persisted even when the compensating students performed their walking tests late in the week, just before they got their weekend beauty sleep.

The moral of the story? Sleep is good, and you should get more of it. But if you can’t, sleep in on weekends. Science has given you permission. All those suburban dads looking to get their teenagers up at 8 in the morning must be sweating right now.

‘Down to my last diaper’: The anxiety of parenting in poverty

For parents living in poverty, “diaper math” is a familiar and distressingly pressing daily calculation. Babies in the U.S. go through 6-10 disposable diapers a day, at an average cost of $70-$80 a month. Name-brand diapers with high-end absorption sell for as much as a half a dollar each, and can result in upwards of $120 a month in expenses.

One in every three American families cannot afford enough diapers to keep their infants and toddlers clean, dry, and healthy, according to the National Diaper Bank Network. For many parents, that leads to wrenching choices: diapers, food, or rent?

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the situation, both by expanding unemployment rolls and by causing supply chain disruptions that have triggered higher prices for a multitude of products, including diapers. Diaper banks – community-funded programs that offer free diapers to low-income families – distributed 86% more diapers on average in 2020 than in 2019, according to the National Diaper Bank Network. In some locations, distribution increased by as much as 800%.

Yet no federal program helps parents pay for this childhood essential. The government’s food assistance program does not cover diapers, nor do most state-level public aid programs.

California is the only state to directly fund diapers for families, but support is limited. CalWORKS, a financial assistance program for families with children, provides $30 per month to help families pay for diapers for children under age 3. Federal policy shifts also may be in the works: Democratic lawmakers are pushing to include $200 million for diaper distribution in the massive budget reconciliation package.

Without adequate resources, low-income parents are left scrambling for ways to get the most use out of each diaper. This stressful undertaking is the subject of a recent article in American Sociological Review by Jennifer Randles, PhD, professor of sociology at California State University–Fresno. In 2018, Randles conducted phone interviews with 70 mothers in California over nine months. She tried to recruit fathers as well, but only two men responded.

Dr. Randles spoke with KHN’s Jenny Gold about how the cost of diapers weighs on low-income moms, and the “inventive mothering” many low-income women adopt to shield their children from the harms of poverty. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: How do diapers play into day-to-day anxieties for low-income mothers?

In my sample, half of the mothers told me that they worried more about diapers than they worried about food or housing.

I started to ask mothers, “Can you tell me how many diapers you have on hand right now?” Almost every one told me with exact specificity how many they had – 5 or 7 or 12. And they knew exactly how long that number of diapers would last, based on how often their children defecated and urinated, if their kid was sick, if they had a diaper rash at the time. So just all the emotional and cognitive labor that goes into keeping such careful track of diaper supplies.

They were worrying and figuring out, “OK, I’m down to almost my last diaper. What do I do now? Do I go find some cans [to sell]? Do I go sell some things in my house? Who in my social network might have some extra cash right now?” I talked to moms who sell blood plasma just to get their infants diapers.

Q: What coping strategies stood out to you?

Those of us who study diapers often call them diaper-stretching strategies. One was leaving on a diaper a little bit longer than someone might otherwise leave it on and letting it get completely full. Some mothers figured out if they bought a [more expensive] diaper that held more and leaked less, they could leave the diaper on longer.

They would also do things like letting the baby go diaperless, especially when they were at home and felt like they wouldn’t be judged for letting their baby go without a diaper. And they used every household good you can imagine to make makeshift diapers. Mothers are using cloth, sheets, and pillowcases. They’re using things that are disposable like paper towels with duct tape. They’re making diapers out their own period supplies or adult incontinence supplies when they can get a sample.

One of the questions I often get is, “Why don’t they just use cloth?” A lot of the mothers that I spoke with had tried cloth diapers and they found that they were very cost- and labor-prohibitive. If you pay for a full startup set of cloth diapers, you’re looking at anywhere from $500 to $1,000. And these moms never had that much money. Most of them didn’t have in-home washers and dryers. Some of them didn’t even have homes or consistent access to water, and it’s illegal in a lot of laundromats and public laundry facilities to wash your old diapers. So the same conditions that would prevent moms from being able to readily afford disposable diapers are the same conditions that keep them from being able to use cloth.

Q: You found that, for many women, the concept of being a good mother is wrapped up in diapering. Why is that?

Diapers and managing diapers was so fundamental to their identity as good moms. Most of the mothers in my sample went without their own food. They weren’t paying a cellphone bill or buying their own medicine or their own menstrual supplies, as a way of saving diaper money.

I talked to a lot of moms who said, when your baby is hungry, that’s horrible. Obviously, you do everything to prevent that. But there’s something about a diaper that covers this vulnerable part of a very young baby’s body, this very delicate skin. And being able to do something to meet this human need that we all have, and to maintain dignity and cleanliness.

A lot of the moms had been through the welfare system, and so they’re living in this constant fear [of losing their children]. This is especially true among mothers of color, who are much more likely to get wrapped up in the child welfare system. People can’t necessarily see when your baby’s hungry. But people can see a saggy diaper. That’s going to be one of the things that tags you as a bad mom.

Q: Was your work on diapers influenced by your experience as a parent?

When I was doing these interviews, my daughter was about 2 or 3. So still in diapers. When my daughter peed during a diaper change, I thought, “Oh, I can just toss that one. Here, let me get another clean one.” That’s a really easy choice. For me. That’s a crisis for the mothers I interviewed. Many of them told me they have an anxiety attack with every diaper change.

Q: Do you see a clear policy solution to diaper stress?

What’s kind of ironic is how much physical, emotional, and cognitive labor goes into managing something that society and lawmakers don’t even recognize. Diapers are still not really recognized as a basic need, as evidenced by the fact that they’re still taxed in 35 states.

I think what California is doing is an excellent start. And I think diaper banks are a fabulous type of community-based organization that are filling a huge need that is not being filled by safety net policies. So, public support for diaper banks.

The direct cash aid part of the social safety net has been all but dismantled in the last 25 years. California is pretty generous. But there are some states where just the cost of diapers alone would use almost half of the average state TANF [Temporary Assistance for Needy Families] benefit for a family of three. I think we really do have to address the fact that the value of cash aid buys so much less than it used to.

Q: Your body of work on marriage and families is fascinating and unusual. Is there a single animating question behind your research?

The common thread is: How do our safety net policies support low-income families’ parenting goals? And do they equalize the conditions of parenting? I think of it as a reproductive justice issue. The ability to have a child or to not have a child, and then to parent that child in conditions where the child’s basic needs are met.

We like to say that we’re child and family friendly. The diaper issue is just one of many, many issues where we don’t really put our money or our policies where our mouth is, in terms of supporting families and supporting children. I think my work is trying to get people to think more collectively about having a social responsibility to all families and to each other. No country, but especially the richest country on the planet, should have one in three very young children not having one of their basic needs met.

I interviewed one dad who was incarcerated because he wrote a bad check. And as he described it to me, he had a certain amount of money, and they needed both diapers and milk for the baby. And I’ll never forget, he said, “I didn’t make a good choice, but I made the right one.”

These are not fancy shoes. These are not name-brand clothes. This was a dad needing both milk and diapers. I don’t think it gets much more basic than that.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

For parents living in poverty, “diaper math” is a familiar and distressingly pressing daily calculation. Babies in the U.S. go through 6-10 disposable diapers a day, at an average cost of $70-$80 a month. Name-brand diapers with high-end absorption sell for as much as a half a dollar each, and can result in upwards of $120 a month in expenses.

One in every three American families cannot afford enough diapers to keep their infants and toddlers clean, dry, and healthy, according to the National Diaper Bank Network. For many parents, that leads to wrenching choices: diapers, food, or rent?

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the situation, both by expanding unemployment rolls and by causing supply chain disruptions that have triggered higher prices for a multitude of products, including diapers. Diaper banks – community-funded programs that offer free diapers to low-income families – distributed 86% more diapers on average in 2020 than in 2019, according to the National Diaper Bank Network. In some locations, distribution increased by as much as 800%.

Yet no federal program helps parents pay for this childhood essential. The government’s food assistance program does not cover diapers, nor do most state-level public aid programs.

California is the only state to directly fund diapers for families, but support is limited. CalWORKS, a financial assistance program for families with children, provides $30 per month to help families pay for diapers for children under age 3. Federal policy shifts also may be in the works: Democratic lawmakers are pushing to include $200 million for diaper distribution in the massive budget reconciliation package.

Without adequate resources, low-income parents are left scrambling for ways to get the most use out of each diaper. This stressful undertaking is the subject of a recent article in American Sociological Review by Jennifer Randles, PhD, professor of sociology at California State University–Fresno. In 2018, Randles conducted phone interviews with 70 mothers in California over nine months. She tried to recruit fathers as well, but only two men responded.

Dr. Randles spoke with KHN’s Jenny Gold about how the cost of diapers weighs on low-income moms, and the “inventive mothering” many low-income women adopt to shield their children from the harms of poverty. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: How do diapers play into day-to-day anxieties for low-income mothers?

In my sample, half of the mothers told me that they worried more about diapers than they worried about food or housing.

I started to ask mothers, “Can you tell me how many diapers you have on hand right now?” Almost every one told me with exact specificity how many they had – 5 or 7 or 12. And they knew exactly how long that number of diapers would last, based on how often their children defecated and urinated, if their kid was sick, if they had a diaper rash at the time. So just all the emotional and cognitive labor that goes into keeping such careful track of diaper supplies.

They were worrying and figuring out, “OK, I’m down to almost my last diaper. What do I do now? Do I go find some cans [to sell]? Do I go sell some things in my house? Who in my social network might have some extra cash right now?” I talked to moms who sell blood plasma just to get their infants diapers.

Q: What coping strategies stood out to you?

Those of us who study diapers often call them diaper-stretching strategies. One was leaving on a diaper a little bit longer than someone might otherwise leave it on and letting it get completely full. Some mothers figured out if they bought a [more expensive] diaper that held more and leaked less, they could leave the diaper on longer.

They would also do things like letting the baby go diaperless, especially when they were at home and felt like they wouldn’t be judged for letting their baby go without a diaper. And they used every household good you can imagine to make makeshift diapers. Mothers are using cloth, sheets, and pillowcases. They’re using things that are disposable like paper towels with duct tape. They’re making diapers out their own period supplies or adult incontinence supplies when they can get a sample.

One of the questions I often get is, “Why don’t they just use cloth?” A lot of the mothers that I spoke with had tried cloth diapers and they found that they were very cost- and labor-prohibitive. If you pay for a full startup set of cloth diapers, you’re looking at anywhere from $500 to $1,000. And these moms never had that much money. Most of them didn’t have in-home washers and dryers. Some of them didn’t even have homes or consistent access to water, and it’s illegal in a lot of laundromats and public laundry facilities to wash your old diapers. So the same conditions that would prevent moms from being able to readily afford disposable diapers are the same conditions that keep them from being able to use cloth.

Q: You found that, for many women, the concept of being a good mother is wrapped up in diapering. Why is that?

Diapers and managing diapers was so fundamental to their identity as good moms. Most of the mothers in my sample went without their own food. They weren’t paying a cellphone bill or buying their own medicine or their own menstrual supplies, as a way of saving diaper money.

I talked to a lot of moms who said, when your baby is hungry, that’s horrible. Obviously, you do everything to prevent that. But there’s something about a diaper that covers this vulnerable part of a very young baby’s body, this very delicate skin. And being able to do something to meet this human need that we all have, and to maintain dignity and cleanliness.

A lot of the moms had been through the welfare system, and so they’re living in this constant fear [of losing their children]. This is especially true among mothers of color, who are much more likely to get wrapped up in the child welfare system. People can’t necessarily see when your baby’s hungry. But people can see a saggy diaper. That’s going to be one of the things that tags you as a bad mom.

Q: Was your work on diapers influenced by your experience as a parent?

When I was doing these interviews, my daughter was about 2 or 3. So still in diapers. When my daughter peed during a diaper change, I thought, “Oh, I can just toss that one. Here, let me get another clean one.” That’s a really easy choice. For me. That’s a crisis for the mothers I interviewed. Many of them told me they have an anxiety attack with every diaper change.

Q: Do you see a clear policy solution to diaper stress?

What’s kind of ironic is how much physical, emotional, and cognitive labor goes into managing something that society and lawmakers don’t even recognize. Diapers are still not really recognized as a basic need, as evidenced by the fact that they’re still taxed in 35 states.

I think what California is doing is an excellent start. And I think diaper banks are a fabulous type of community-based organization that are filling a huge need that is not being filled by safety net policies. So, public support for diaper banks.

The direct cash aid part of the social safety net has been all but dismantled in the last 25 years. California is pretty generous. But there are some states where just the cost of diapers alone would use almost half of the average state TANF [Temporary Assistance for Needy Families] benefit for a family of three. I think we really do have to address the fact that the value of cash aid buys so much less than it used to.

Q: Your body of work on marriage and families is fascinating and unusual. Is there a single animating question behind your research?

The common thread is: How do our safety net policies support low-income families’ parenting goals? And do they equalize the conditions of parenting? I think of it as a reproductive justice issue. The ability to have a child or to not have a child, and then to parent that child in conditions where the child’s basic needs are met.

We like to say that we’re child and family friendly. The diaper issue is just one of many, many issues where we don’t really put our money or our policies where our mouth is, in terms of supporting families and supporting children. I think my work is trying to get people to think more collectively about having a social responsibility to all families and to each other. No country, but especially the richest country on the planet, should have one in three very young children not having one of their basic needs met.

I interviewed one dad who was incarcerated because he wrote a bad check. And as he described it to me, he had a certain amount of money, and they needed both diapers and milk for the baby. And I’ll never forget, he said, “I didn’t make a good choice, but I made the right one.”

These are not fancy shoes. These are not name-brand clothes. This was a dad needing both milk and diapers. I don’t think it gets much more basic than that.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

For parents living in poverty, “diaper math” is a familiar and distressingly pressing daily calculation. Babies in the U.S. go through 6-10 disposable diapers a day, at an average cost of $70-$80 a month. Name-brand diapers with high-end absorption sell for as much as a half a dollar each, and can result in upwards of $120 a month in expenses.

One in every three American families cannot afford enough diapers to keep their infants and toddlers clean, dry, and healthy, according to the National Diaper Bank Network. For many parents, that leads to wrenching choices: diapers, food, or rent?

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the situation, both by expanding unemployment rolls and by causing supply chain disruptions that have triggered higher prices for a multitude of products, including diapers. Diaper banks – community-funded programs that offer free diapers to low-income families – distributed 86% more diapers on average in 2020 than in 2019, according to the National Diaper Bank Network. In some locations, distribution increased by as much as 800%.

Yet no federal program helps parents pay for this childhood essential. The government’s food assistance program does not cover diapers, nor do most state-level public aid programs.

California is the only state to directly fund diapers for families, but support is limited. CalWORKS, a financial assistance program for families with children, provides $30 per month to help families pay for diapers for children under age 3. Federal policy shifts also may be in the works: Democratic lawmakers are pushing to include $200 million for diaper distribution in the massive budget reconciliation package.

Without adequate resources, low-income parents are left scrambling for ways to get the most use out of each diaper. This stressful undertaking is the subject of a recent article in American Sociological Review by Jennifer Randles, PhD, professor of sociology at California State University–Fresno. In 2018, Randles conducted phone interviews with 70 mothers in California over nine months. She tried to recruit fathers as well, but only two men responded.

Dr. Randles spoke with KHN’s Jenny Gold about how the cost of diapers weighs on low-income moms, and the “inventive mothering” many low-income women adopt to shield their children from the harms of poverty. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: How do diapers play into day-to-day anxieties for low-income mothers?

In my sample, half of the mothers told me that they worried more about diapers than they worried about food or housing.

I started to ask mothers, “Can you tell me how many diapers you have on hand right now?” Almost every one told me with exact specificity how many they had – 5 or 7 or 12. And they knew exactly how long that number of diapers would last, based on how often their children defecated and urinated, if their kid was sick, if they had a diaper rash at the time. So just all the emotional and cognitive labor that goes into keeping such careful track of diaper supplies.

They were worrying and figuring out, “OK, I’m down to almost my last diaper. What do I do now? Do I go find some cans [to sell]? Do I go sell some things in my house? Who in my social network might have some extra cash right now?” I talked to moms who sell blood plasma just to get their infants diapers.

Q: What coping strategies stood out to you?

Those of us who study diapers often call them diaper-stretching strategies. One was leaving on a diaper a little bit longer than someone might otherwise leave it on and letting it get completely full. Some mothers figured out if they bought a [more expensive] diaper that held more and leaked less, they could leave the diaper on longer.

They would also do things like letting the baby go diaperless, especially when they were at home and felt like they wouldn’t be judged for letting their baby go without a diaper. And they used every household good you can imagine to make makeshift diapers. Mothers are using cloth, sheets, and pillowcases. They’re using things that are disposable like paper towels with duct tape. They’re making diapers out their own period supplies or adult incontinence supplies when they can get a sample.

One of the questions I often get is, “Why don’t they just use cloth?” A lot of the mothers that I spoke with had tried cloth diapers and they found that they were very cost- and labor-prohibitive. If you pay for a full startup set of cloth diapers, you’re looking at anywhere from $500 to $1,000. And these moms never had that much money. Most of them didn’t have in-home washers and dryers. Some of them didn’t even have homes or consistent access to water, and it’s illegal in a lot of laundromats and public laundry facilities to wash your old diapers. So the same conditions that would prevent moms from being able to readily afford disposable diapers are the same conditions that keep them from being able to use cloth.

Q: You found that, for many women, the concept of being a good mother is wrapped up in diapering. Why is that?

Diapers and managing diapers was so fundamental to their identity as good moms. Most of the mothers in my sample went without their own food. They weren’t paying a cellphone bill or buying their own medicine or their own menstrual supplies, as a way of saving diaper money.

I talked to a lot of moms who said, when your baby is hungry, that’s horrible. Obviously, you do everything to prevent that. But there’s something about a diaper that covers this vulnerable part of a very young baby’s body, this very delicate skin. And being able to do something to meet this human need that we all have, and to maintain dignity and cleanliness.

A lot of the moms had been through the welfare system, and so they’re living in this constant fear [of losing their children]. This is especially true among mothers of color, who are much more likely to get wrapped up in the child welfare system. People can’t necessarily see when your baby’s hungry. But people can see a saggy diaper. That’s going to be one of the things that tags you as a bad mom.

Q: Was your work on diapers influenced by your experience as a parent?

When I was doing these interviews, my daughter was about 2 or 3. So still in diapers. When my daughter peed during a diaper change, I thought, “Oh, I can just toss that one. Here, let me get another clean one.” That’s a really easy choice. For me. That’s a crisis for the mothers I interviewed. Many of them told me they have an anxiety attack with every diaper change.

Q: Do you see a clear policy solution to diaper stress?

What’s kind of ironic is how much physical, emotional, and cognitive labor goes into managing something that society and lawmakers don’t even recognize. Diapers are still not really recognized as a basic need, as evidenced by the fact that they’re still taxed in 35 states.

I think what California is doing is an excellent start. And I think diaper banks are a fabulous type of community-based organization that are filling a huge need that is not being filled by safety net policies. So, public support for diaper banks.

The direct cash aid part of the social safety net has been all but dismantled in the last 25 years. California is pretty generous. But there are some states where just the cost of diapers alone would use almost half of the average state TANF [Temporary Assistance for Needy Families] benefit for a family of three. I think we really do have to address the fact that the value of cash aid buys so much less than it used to.

Q: Your body of work on marriage and families is fascinating and unusual. Is there a single animating question behind your research?

The common thread is: How do our safety net policies support low-income families’ parenting goals? And do they equalize the conditions of parenting? I think of it as a reproductive justice issue. The ability to have a child or to not have a child, and then to parent that child in conditions where the child’s basic needs are met.

We like to say that we’re child and family friendly. The diaper issue is just one of many, many issues where we don’t really put our money or our policies where our mouth is, in terms of supporting families and supporting children. I think my work is trying to get people to think more collectively about having a social responsibility to all families and to each other. No country, but especially the richest country on the planet, should have one in three very young children not having one of their basic needs met.

I interviewed one dad who was incarcerated because he wrote a bad check. And as he described it to me, he had a certain amount of money, and they needed both diapers and milk for the baby. And I’ll never forget, he said, “I didn’t make a good choice, but I made the right one.”

These are not fancy shoes. These are not name-brand clothes. This was a dad needing both milk and diapers. I don’t think it gets much more basic than that.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Which specialties get the biggest markups over Medicare rates?

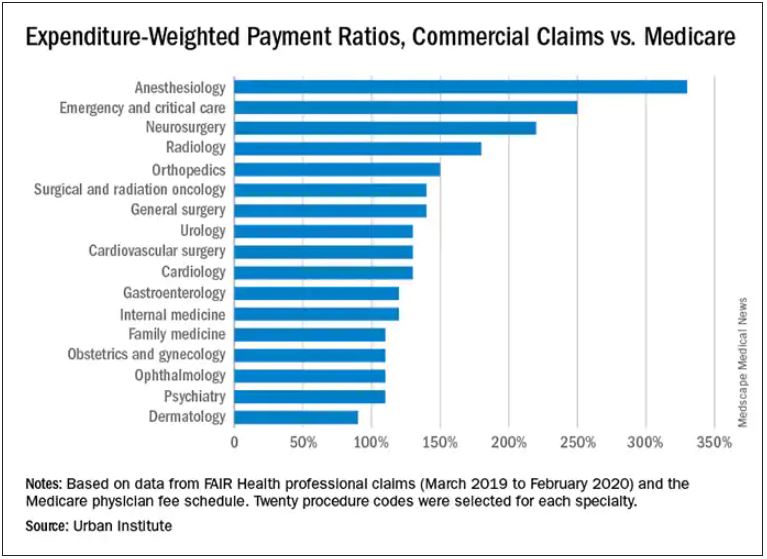

Anesthesiologists charge private insurers more than 300% above Medicare rates, a markup that is higher than that of 16 other specialties, according to a study released by the Urban Institute.

The Washington-based nonprofit institute found that the lowest markups were in psychiatry, ophthalmology, ob.gyn., family medicine, gastroenterology, and internal medicine, at 110%-120% of Medicare rates. .

In the middle are cardiology and cardiovascular surgery (130%), urology (130%), general surgery, surgical and radiation oncology (all at 140%), and orthopedics (150%).

At the top end were radiology (180%), neurosurgery (220%), emergency and critical care (250%), and anesthesiology (330%).

The wide variation in payments could be cited in support of the idea of applying Medicare rates across all physician specialties, say the study authors. Although lowering practitioner payments might lead to savings, it “will also create more pushback from providers, especially if these rates are introduced in the employer market,” write researchers Stacey McMorrow, PhD, Robert A. Berenson, MD, and John Holahan, PhD.

It is not known whether lowering commercial payment rates might decrease patient access, they write.

The authors also note that specialties in which the potential for a fee reduction was greatest were also the specialties for which baseline compensation was highest – from $350,000 annually for emergency physicians to $800,000 a year for neurosurgeons. Annual compensation for ob.gyns., dermatologists, and opthalmologists is about $350,000 a year, which suggests that “these specialties are similarly well compensated by both Medicare and commercial insurers,” the authors write.

The investigators assessed the top 20 procedure codes by expenditure in each of 17 physician specialties. They estimated the commercial-to-Medicare payment ratio for each service and constructed weighted averages across services for each specialty at the national level and for 12 states for which data for all the specialties and services were available.

The researchers analyzed claims from the FAIR Health database between March 2019 and March 2020. That database represents 60 insurers covering 150 million people.

Pediatric and geriatric specialties, nonphysician practitioners, out-of-network clinicians, and ambulatory surgery center claims were excluded. Codes with modifiers, J codes, and clinical laboratory services were also not included.

The charges used in the study were not the actual contracted rates. The authors instead used “imputed allowed amounts” for each claim line. That method was used to protect the confidentiality of the negotiated rates.

With regard to all specialties, the lowest compensated services were procedures, evaluation and management, and tests, which received 140%-150% of the Medicare rate. Treatments and imaging were marked up 160%. Anesthesia was reimbursed at a rate 330% higher than the rate Medicare would pay.

The authors also assessed geographic variation for the 12 states for which they had data.

Similar to findings in other studies, the researchers found that the markup was lowest in Pennsylvania (120%) and highest in Wisconsin (260%). The U.S. average was 160%. California and Missouri were at 150%; Michigan was right at the average.

For physicians in Illinois, Louisiana, Colorado, Texas, and New York, markups were 170%-180% over the Medicare rate. Markups for clinicians in New Jersey (190%) and Arizona (200%) were closest to the Wisconsin rate.

The authors note some study limitations, including the fact that they excluded out-of-network practitioners, “and such payments may disproportionately affect certain specialties.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

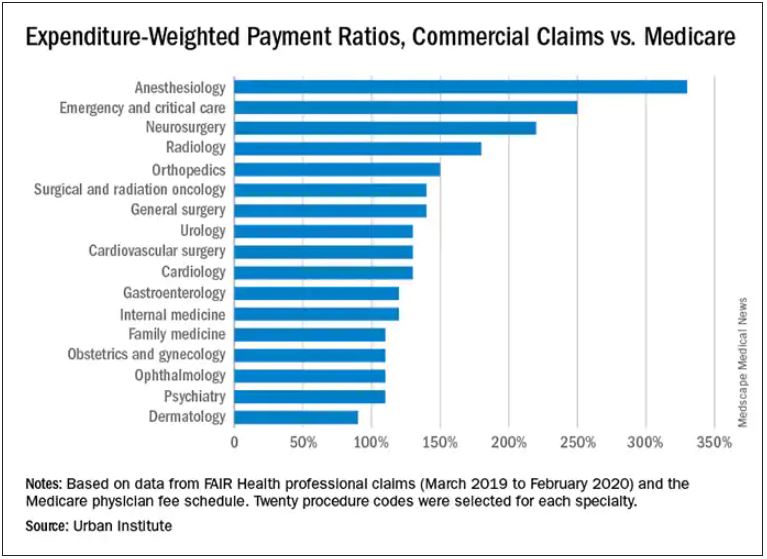

Anesthesiologists charge private insurers more than 300% above Medicare rates, a markup that is higher than that of 16 other specialties, according to a study released by the Urban Institute.

The Washington-based nonprofit institute found that the lowest markups were in psychiatry, ophthalmology, ob.gyn., family medicine, gastroenterology, and internal medicine, at 110%-120% of Medicare rates. .

In the middle are cardiology and cardiovascular surgery (130%), urology (130%), general surgery, surgical and radiation oncology (all at 140%), and orthopedics (150%).

At the top end were radiology (180%), neurosurgery (220%), emergency and critical care (250%), and anesthesiology (330%).

The wide variation in payments could be cited in support of the idea of applying Medicare rates across all physician specialties, say the study authors. Although lowering practitioner payments might lead to savings, it “will also create more pushback from providers, especially if these rates are introduced in the employer market,” write researchers Stacey McMorrow, PhD, Robert A. Berenson, MD, and John Holahan, PhD.

It is not known whether lowering commercial payment rates might decrease patient access, they write.

The authors also note that specialties in which the potential for a fee reduction was greatest were also the specialties for which baseline compensation was highest – from $350,000 annually for emergency physicians to $800,000 a year for neurosurgeons. Annual compensation for ob.gyns., dermatologists, and opthalmologists is about $350,000 a year, which suggests that “these specialties are similarly well compensated by both Medicare and commercial insurers,” the authors write.

The investigators assessed the top 20 procedure codes by expenditure in each of 17 physician specialties. They estimated the commercial-to-Medicare payment ratio for each service and constructed weighted averages across services for each specialty at the national level and for 12 states for which data for all the specialties and services were available.

The researchers analyzed claims from the FAIR Health database between March 2019 and March 2020. That database represents 60 insurers covering 150 million people.

Pediatric and geriatric specialties, nonphysician practitioners, out-of-network clinicians, and ambulatory surgery center claims were excluded. Codes with modifiers, J codes, and clinical laboratory services were also not included.

The charges used in the study were not the actual contracted rates. The authors instead used “imputed allowed amounts” for each claim line. That method was used to protect the confidentiality of the negotiated rates.

With regard to all specialties, the lowest compensated services were procedures, evaluation and management, and tests, which received 140%-150% of the Medicare rate. Treatments and imaging were marked up 160%. Anesthesia was reimbursed at a rate 330% higher than the rate Medicare would pay.

The authors also assessed geographic variation for the 12 states for which they had data.

Similar to findings in other studies, the researchers found that the markup was lowest in Pennsylvania (120%) and highest in Wisconsin (260%). The U.S. average was 160%. California and Missouri were at 150%; Michigan was right at the average.

For physicians in Illinois, Louisiana, Colorado, Texas, and New York, markups were 170%-180% over the Medicare rate. Markups for clinicians in New Jersey (190%) and Arizona (200%) were closest to the Wisconsin rate.

The authors note some study limitations, including the fact that they excluded out-of-network practitioners, “and such payments may disproportionately affect certain specialties.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

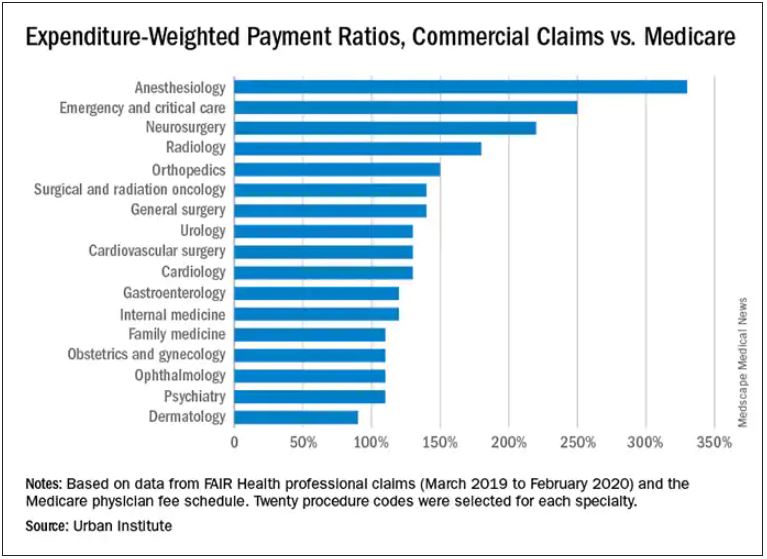

Anesthesiologists charge private insurers more than 300% above Medicare rates, a markup that is higher than that of 16 other specialties, according to a study released by the Urban Institute.

The Washington-based nonprofit institute found that the lowest markups were in psychiatry, ophthalmology, ob.gyn., family medicine, gastroenterology, and internal medicine, at 110%-120% of Medicare rates. .

In the middle are cardiology and cardiovascular surgery (130%), urology (130%), general surgery, surgical and radiation oncology (all at 140%), and orthopedics (150%).

At the top end were radiology (180%), neurosurgery (220%), emergency and critical care (250%), and anesthesiology (330%).

The wide variation in payments could be cited in support of the idea of applying Medicare rates across all physician specialties, say the study authors. Although lowering practitioner payments might lead to savings, it “will also create more pushback from providers, especially if these rates are introduced in the employer market,” write researchers Stacey McMorrow, PhD, Robert A. Berenson, MD, and John Holahan, PhD.

It is not known whether lowering commercial payment rates might decrease patient access, they write.

The authors also note that specialties in which the potential for a fee reduction was greatest were also the specialties for which baseline compensation was highest – from $350,000 annually for emergency physicians to $800,000 a year for neurosurgeons. Annual compensation for ob.gyns., dermatologists, and opthalmologists is about $350,000 a year, which suggests that “these specialties are similarly well compensated by both Medicare and commercial insurers,” the authors write.

The investigators assessed the top 20 procedure codes by expenditure in each of 17 physician specialties. They estimated the commercial-to-Medicare payment ratio for each service and constructed weighted averages across services for each specialty at the national level and for 12 states for which data for all the specialties and services were available.

The researchers analyzed claims from the FAIR Health database between March 2019 and March 2020. That database represents 60 insurers covering 150 million people.

Pediatric and geriatric specialties, nonphysician practitioners, out-of-network clinicians, and ambulatory surgery center claims were excluded. Codes with modifiers, J codes, and clinical laboratory services were also not included.

The charges used in the study were not the actual contracted rates. The authors instead used “imputed allowed amounts” for each claim line. That method was used to protect the confidentiality of the negotiated rates.

With regard to all specialties, the lowest compensated services were procedures, evaluation and management, and tests, which received 140%-150% of the Medicare rate. Treatments and imaging were marked up 160%. Anesthesia was reimbursed at a rate 330% higher than the rate Medicare would pay.

The authors also assessed geographic variation for the 12 states for which they had data.

Similar to findings in other studies, the researchers found that the markup was lowest in Pennsylvania (120%) and highest in Wisconsin (260%). The U.S. average was 160%. California and Missouri were at 150%; Michigan was right at the average.

For physicians in Illinois, Louisiana, Colorado, Texas, and New York, markups were 170%-180% over the Medicare rate. Markups for clinicians in New Jersey (190%) and Arizona (200%) were closest to the Wisconsin rate.

The authors note some study limitations, including the fact that they excluded out-of-network practitioners, “and such payments may disproportionately affect certain specialties.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Autism prevalence in children as high as 10% in some New Jersey communities

Investigators found that up to 10% of children in some of the state’s school districts have an ASD diagnosis vs. the national average of just under 2%.

School districts with higher ASD prevalence in the study have expansive health and educational programs in place to diagnose and support children with ASD, which likely contributed to the higher caseloads, senior investigator Walter Zahorodny, PhD, associate professor of pediatrics at New Jersey Medical School in Newark, said in an interview.

“When you have those players on the ground, it’s likely we’re going to be finding more, if not almost all, of the children with autism in a given district,” said Dr. Zahorodny, director of the New Jersey Autism Study for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The study was published online Oct. 21 in the journal Autism Research.

Local analysis

Researchers used the Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring (ADDM) Network, a surveillance method developed by the CDC that includes data collected from health and special education records of children living in 11 communities across the United States. New Jersey is one of the ADDM participating sites.

National data are important, but Dr. Zahorodny and colleagues wanted to examine ASD prevalence at a more granular level, comparing prevalence district by district.

They examined data from 5,453 children who were 8 years old in 2016 and attended public school in Essex, Hudson, Ocean, and Union counties.

The prevalence of ASD was 36 children per 1,000 overall. Hudson County reported the lowest rate, at 31 cases per 1,000 children, and Ocean County reported the highest, at 54 cases per 1,000 children.

Across the region, ASD prevalence was four times higher in boys vs. girls, mirroring national statistics.

High ASD prevalence was more likely in mid-socioeconomic status districts (prevalence ratio [PR], 1.2; P = .01) and in larger school districts (PR, 1.3; P = .004).

Hispanic children had significantly lower ASD prevalence overall compared with White children (PR, 0.6; P < .001). In fact, prevalence was 30%-60% lower among Hispanic children in three of four counties compared with White children.

Another study is underway to better understand why autism rates were lower in specific districts and Hispanic children overall, but Dr. Zahorodny said one possibility is a lack of resources in those districts.

Will new methodology miss cases?

The study’s methodology was used by the CDC from 2000 to 2016 and includes assessment of children who have an ASD diagnosis, and children who haven’t received a diagnosis but have documented behaviors consistent with ASD.

In 2018, it was replaced with a less comprehensive approach that relies only on children with an ASD diagnosis. Data using this new methodology have not yet been reported.

In the new study from New Jersey, 767 children with autism were diagnosed by a pediatrician, neurologist, or other community provider. The remaining 175 children with autism, 18.6% of the total cohort, did not have an ASD diagnosis but met the ADDM case definition.

Under the new methodology, those children would not be counted.

“Something could be lost in the new methodology in terms of usefulness of the information because when the estimates are incomplete or low, that might lead people to make the wrong judgments when they make decisions about resources,” Dr. Zahorodny said.

The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health. The study authors report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators found that up to 10% of children in some of the state’s school districts have an ASD diagnosis vs. the national average of just under 2%.

School districts with higher ASD prevalence in the study have expansive health and educational programs in place to diagnose and support children with ASD, which likely contributed to the higher caseloads, senior investigator Walter Zahorodny, PhD, associate professor of pediatrics at New Jersey Medical School in Newark, said in an interview.

“When you have those players on the ground, it’s likely we’re going to be finding more, if not almost all, of the children with autism in a given district,” said Dr. Zahorodny, director of the New Jersey Autism Study for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The study was published online Oct. 21 in the journal Autism Research.

Local analysis

Researchers used the Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring (ADDM) Network, a surveillance method developed by the CDC that includes data collected from health and special education records of children living in 11 communities across the United States. New Jersey is one of the ADDM participating sites.

National data are important, but Dr. Zahorodny and colleagues wanted to examine ASD prevalence at a more granular level, comparing prevalence district by district.

They examined data from 5,453 children who were 8 years old in 2016 and attended public school in Essex, Hudson, Ocean, and Union counties.

The prevalence of ASD was 36 children per 1,000 overall. Hudson County reported the lowest rate, at 31 cases per 1,000 children, and Ocean County reported the highest, at 54 cases per 1,000 children.

Across the region, ASD prevalence was four times higher in boys vs. girls, mirroring national statistics.

High ASD prevalence was more likely in mid-socioeconomic status districts (prevalence ratio [PR], 1.2; P = .01) and in larger school districts (PR, 1.3; P = .004).

Hispanic children had significantly lower ASD prevalence overall compared with White children (PR, 0.6; P < .001). In fact, prevalence was 30%-60% lower among Hispanic children in three of four counties compared with White children.

Another study is underway to better understand why autism rates were lower in specific districts and Hispanic children overall, but Dr. Zahorodny said one possibility is a lack of resources in those districts.

Will new methodology miss cases?

The study’s methodology was used by the CDC from 2000 to 2016 and includes assessment of children who have an ASD diagnosis, and children who haven’t received a diagnosis but have documented behaviors consistent with ASD.

In 2018, it was replaced with a less comprehensive approach that relies only on children with an ASD diagnosis. Data using this new methodology have not yet been reported.

In the new study from New Jersey, 767 children with autism were diagnosed by a pediatrician, neurologist, or other community provider. The remaining 175 children with autism, 18.6% of the total cohort, did not have an ASD diagnosis but met the ADDM case definition.

Under the new methodology, those children would not be counted.

“Something could be lost in the new methodology in terms of usefulness of the information because when the estimates are incomplete or low, that might lead people to make the wrong judgments when they make decisions about resources,” Dr. Zahorodny said.

The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health. The study authors report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators found that up to 10% of children in some of the state’s school districts have an ASD diagnosis vs. the national average of just under 2%.

School districts with higher ASD prevalence in the study have expansive health and educational programs in place to diagnose and support children with ASD, which likely contributed to the higher caseloads, senior investigator Walter Zahorodny, PhD, associate professor of pediatrics at New Jersey Medical School in Newark, said in an interview.

“When you have those players on the ground, it’s likely we’re going to be finding more, if not almost all, of the children with autism in a given district,” said Dr. Zahorodny, director of the New Jersey Autism Study for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The study was published online Oct. 21 in the journal Autism Research.

Local analysis

Researchers used the Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring (ADDM) Network, a surveillance method developed by the CDC that includes data collected from health and special education records of children living in 11 communities across the United States. New Jersey is one of the ADDM participating sites.

National data are important, but Dr. Zahorodny and colleagues wanted to examine ASD prevalence at a more granular level, comparing prevalence district by district.

They examined data from 5,453 children who were 8 years old in 2016 and attended public school in Essex, Hudson, Ocean, and Union counties.

The prevalence of ASD was 36 children per 1,000 overall. Hudson County reported the lowest rate, at 31 cases per 1,000 children, and Ocean County reported the highest, at 54 cases per 1,000 children.

Across the region, ASD prevalence was four times higher in boys vs. girls, mirroring national statistics.

High ASD prevalence was more likely in mid-socioeconomic status districts (prevalence ratio [PR], 1.2; P = .01) and in larger school districts (PR, 1.3; P = .004).

Hispanic children had significantly lower ASD prevalence overall compared with White children (PR, 0.6; P < .001). In fact, prevalence was 30%-60% lower among Hispanic children in three of four counties compared with White children.

Another study is underway to better understand why autism rates were lower in specific districts and Hispanic children overall, but Dr. Zahorodny said one possibility is a lack of resources in those districts.

Will new methodology miss cases?

The study’s methodology was used by the CDC from 2000 to 2016 and includes assessment of children who have an ASD diagnosis, and children who haven’t received a diagnosis but have documented behaviors consistent with ASD.

In 2018, it was replaced with a less comprehensive approach that relies only on children with an ASD diagnosis. Data using this new methodology have not yet been reported.

In the new study from New Jersey, 767 children with autism were diagnosed by a pediatrician, neurologist, or other community provider. The remaining 175 children with autism, 18.6% of the total cohort, did not have an ASD diagnosis but met the ADDM case definition.

Under the new methodology, those children would not be counted.

“Something could be lost in the new methodology in terms of usefulness of the information because when the estimates are incomplete or low, that might lead people to make the wrong judgments when they make decisions about resources,” Dr. Zahorodny said.

The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health. The study authors report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Ohio records more deaths than births for first time

In 2020, around 143,661 Ohioans died and 129,313 Ohioans were born, according to The Columbus Dispatch. The trend appears to have continued so far this year, with 107,462 deaths and 100,781 births reported to date.

Deaths haven’t surpassed births in the 112 years since the state began compiling data in 1909, the newspaper reported. The state’s birth rate has been declining for years while the number of deaths has risen, though data shows that the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the shift.

“It doesn’t surprise me at all,” Joseph Gastaldo, MD, the medical director of infectious diseases for OhioHealth, told the newspaper.

Ohio’s birth rate fell by 4% in 2020, which defied public expectations about a pandemic birth boom. In addition, the state reported 13,927 COVID-19 deaths throughout the year.

“It’s COVID, clearly,” he noted.

Alabama also recorded more deaths than births for the first time last year, according to The New York Times. The state reported 64,714 deaths and 57,641 births in 2020.

“Our state literally shrunk in 2020,” Scott Harris, MD, the state health officer for Alabama, said at a news conference in September.

The state had never recorded a gap that large, even during World War I, World War II, and the 1918 flu pandemic, he said. Alabama has kept records on the numbers since 1900.

“We’ve never had a time when deaths exceeded births,” Dr. Harris said.

In fact, about half of U.S. states reported death rates higher than birth rates in 2020, according to a recent study from researchers at the University of New Hampshire. In 2019, only five states --Maine, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Vermont, and West Virginia -- reported more deaths than births.

In 2020, the United States reported a record of nearly 3.4 million deaths, which was 18% more than in 2019, the researchers found. COVID-19 was the primary reason for the increase in deaths, accounting for about 11% of total deaths. Meanwhile, births dropped by 4% to about 3.6 million.

The surplus of births over deaths added 229,000 people to the U.S. population in 2020, as compared to 892,000 in 2019, which means the country’s population growth slowed last year. The decline, paired with lower immigration rates during the pandemic, led to the smallest annual percentage population gain in at least 100 years.

“Deaths will likely exceed births again in many states in 2021,” Kenneth Johnson, PhD, a senior demographer and study author, wrote in a statement.

“How large or protracted these fertility declines and mortality increases will be remains to be seen, but they have already dramatically reduced population growth in the United States,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

In 2020, around 143,661 Ohioans died and 129,313 Ohioans were born, according to The Columbus Dispatch. The trend appears to have continued so far this year, with 107,462 deaths and 100,781 births reported to date.

Deaths haven’t surpassed births in the 112 years since the state began compiling data in 1909, the newspaper reported. The state’s birth rate has been declining for years while the number of deaths has risen, though data shows that the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the shift.

“It doesn’t surprise me at all,” Joseph Gastaldo, MD, the medical director of infectious diseases for OhioHealth, told the newspaper.

Ohio’s birth rate fell by 4% in 2020, which defied public expectations about a pandemic birth boom. In addition, the state reported 13,927 COVID-19 deaths throughout the year.

“It’s COVID, clearly,” he noted.

Alabama also recorded more deaths than births for the first time last year, according to The New York Times. The state reported 64,714 deaths and 57,641 births in 2020.

“Our state literally shrunk in 2020,” Scott Harris, MD, the state health officer for Alabama, said at a news conference in September.

The state had never recorded a gap that large, even during World War I, World War II, and the 1918 flu pandemic, he said. Alabama has kept records on the numbers since 1900.

“We’ve never had a time when deaths exceeded births,” Dr. Harris said.

In fact, about half of U.S. states reported death rates higher than birth rates in 2020, according to a recent study from researchers at the University of New Hampshire. In 2019, only five states --Maine, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Vermont, and West Virginia -- reported more deaths than births.

In 2020, the United States reported a record of nearly 3.4 million deaths, which was 18% more than in 2019, the researchers found. COVID-19 was the primary reason for the increase in deaths, accounting for about 11% of total deaths. Meanwhile, births dropped by 4% to about 3.6 million.

The surplus of births over deaths added 229,000 people to the U.S. population in 2020, as compared to 892,000 in 2019, which means the country’s population growth slowed last year. The decline, paired with lower immigration rates during the pandemic, led to the smallest annual percentage population gain in at least 100 years.

“Deaths will likely exceed births again in many states in 2021,” Kenneth Johnson, PhD, a senior demographer and study author, wrote in a statement.

“How large or protracted these fertility declines and mortality increases will be remains to be seen, but they have already dramatically reduced population growth in the United States,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

In 2020, around 143,661 Ohioans died and 129,313 Ohioans were born, according to The Columbus Dispatch. The trend appears to have continued so far this year, with 107,462 deaths and 100,781 births reported to date.

Deaths haven’t surpassed births in the 112 years since the state began compiling data in 1909, the newspaper reported. The state’s birth rate has been declining for years while the number of deaths has risen, though data shows that the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the shift.

“It doesn’t surprise me at all,” Joseph Gastaldo, MD, the medical director of infectious diseases for OhioHealth, told the newspaper.

Ohio’s birth rate fell by 4% in 2020, which defied public expectations about a pandemic birth boom. In addition, the state reported 13,927 COVID-19 deaths throughout the year.

“It’s COVID, clearly,” he noted.

Alabama also recorded more deaths than births for the first time last year, according to The New York Times. The state reported 64,714 deaths and 57,641 births in 2020.

“Our state literally shrunk in 2020,” Scott Harris, MD, the state health officer for Alabama, said at a news conference in September.

The state had never recorded a gap that large, even during World War I, World War II, and the 1918 flu pandemic, he said. Alabama has kept records on the numbers since 1900.

“We’ve never had a time when deaths exceeded births,” Dr. Harris said.

In fact, about half of U.S. states reported death rates higher than birth rates in 2020, according to a recent study from researchers at the University of New Hampshire. In 2019, only five states --Maine, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Vermont, and West Virginia -- reported more deaths than births.

In 2020, the United States reported a record of nearly 3.4 million deaths, which was 18% more than in 2019, the researchers found. COVID-19 was the primary reason for the increase in deaths, accounting for about 11% of total deaths. Meanwhile, births dropped by 4% to about 3.6 million.

The surplus of births over deaths added 229,000 people to the U.S. population in 2020, as compared to 892,000 in 2019, which means the country’s population growth slowed last year. The decline, paired with lower immigration rates during the pandemic, led to the smallest annual percentage population gain in at least 100 years.

“Deaths will likely exceed births again in many states in 2021,” Kenneth Johnson, PhD, a senior demographer and study author, wrote in a statement.

“How large or protracted these fertility declines and mortality increases will be remains to be seen, but they have already dramatically reduced population growth in the United States,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Hot temperatures in outdoor lockboxes increase sample errors

, according to results from a recent study published in the American Journal of Clinical Pathology.