User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Children and COVID: New cases fall again, ED rates rebound for some

The 7-day average percentage of ED visits with diagnosed COVID, which had reached a post-Omicron high of 3.5% in late July for those aged 12-15, began to fall and was down to 3.0% on Aug. 12. That trend reversed, however, and the rate was up to 3.6% on Aug. 19, the last date for which data are available from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That change of COVID fortunes cannot yet be seen for all children. The 7-day average ED visit rate for those aged 0-11 years peaked at 6.8% during the last week of July and has continued to fall, dropping from 5.7% on Aug. 12 to 5.1% on Aug. 19. Children aged 16-17 years seem to be taking a middle path: Their ED-visit rate declined from late July into mid-August but held steady over the last week, according to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker.

There is a hint of the same trend regarding new admissions among children aged 0-17 years. The national rate, which had declined in recent weeks, ticked up from 0.42 to 0.43 new admissions per 100,000 population over the last week of available data, the CDC said.

Weekly cases fall below 80,000

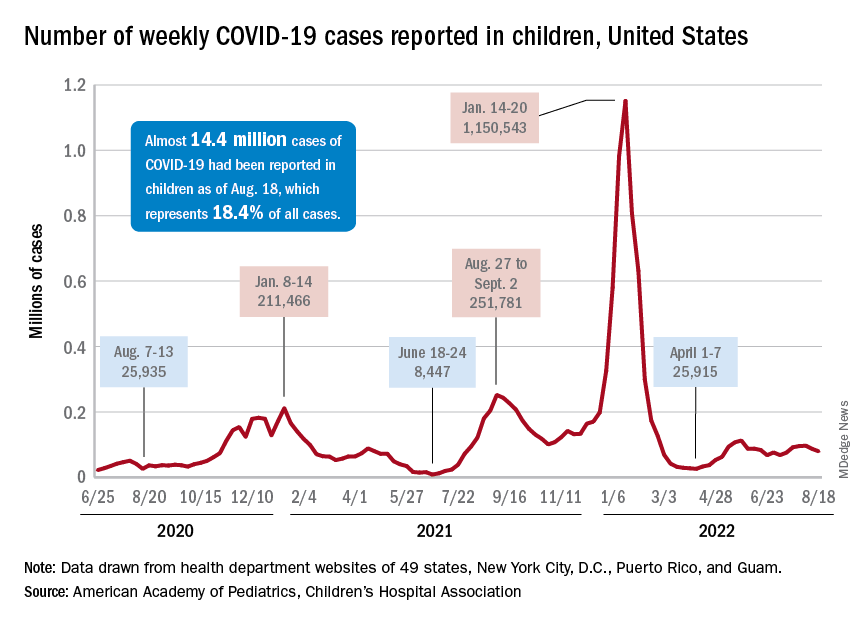

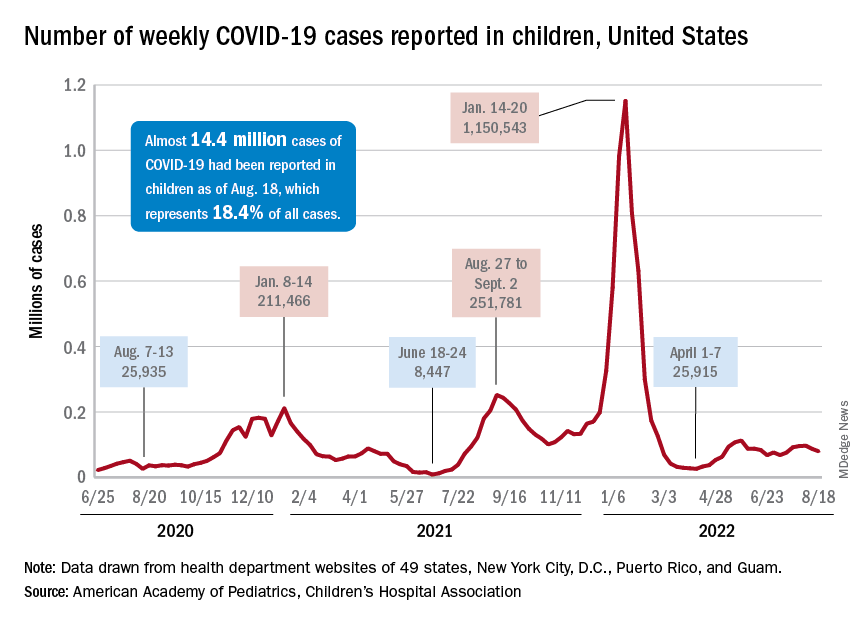

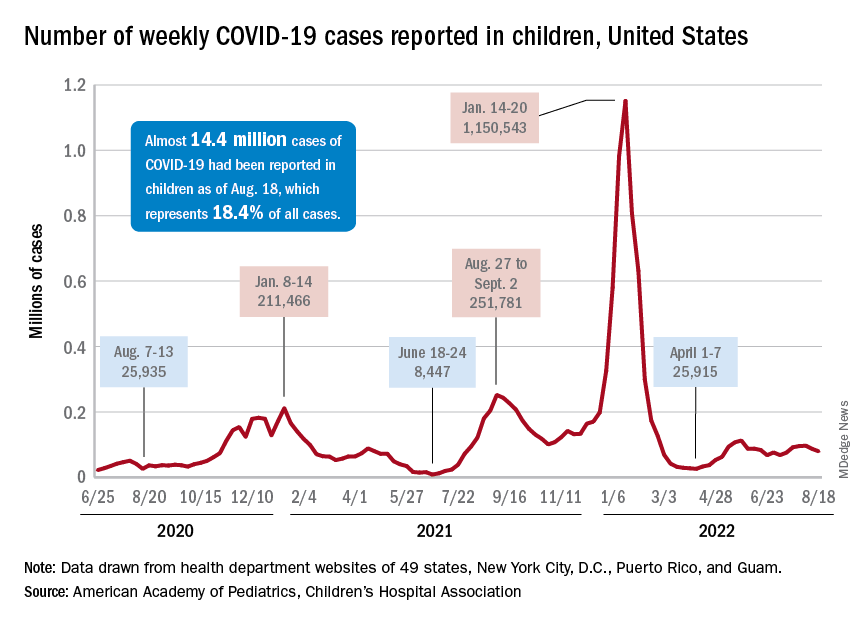

New cases in general were down by 8.5% from the previous week, dropping from 87,902 for the week of Aug. 5-11 to 79,525 for Aug. 12-18. That marked the second straight week with fewer cases after a 4-week period that saw weekly totals increase from almost 68,000 to nearly 97,000, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The AAP and CHA put the cumulative number of child COVID-19 cases at just under 14.4 million since the pandemic began, which represents 18.4% of cases among all ages. The CDC estimates that there have been almost 14.7 million cases in children aged 0-17 years, as well as 1,750 deaths, of which 14 were reported in the last week (Aug. 16-22).

The CDC age subgroups indicate that children aged 0-4 years have experienced fewer cases (2.9 million) than children aged 5-11 years (5.6 million cases) and 12-15 (3.0 million cases) but more deaths: 548 so far, versus 432 for 5- to 11-year-olds and 437 for 12- to 15-year-olds, the COVID Data Tracker shows. Those aged 0-4 make up 6% of the total U.S. population, compared with 8.7% and 5.1%, respectively, for the older children.

Most younger children still not vaccinated

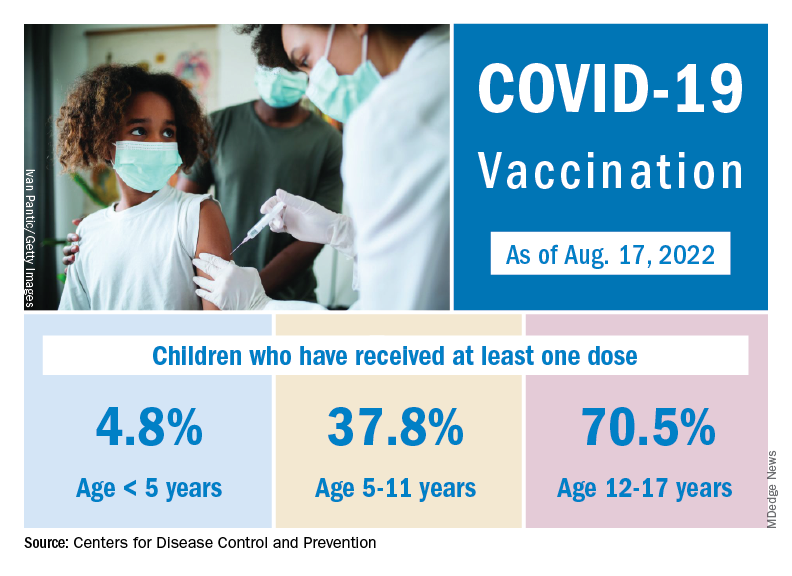

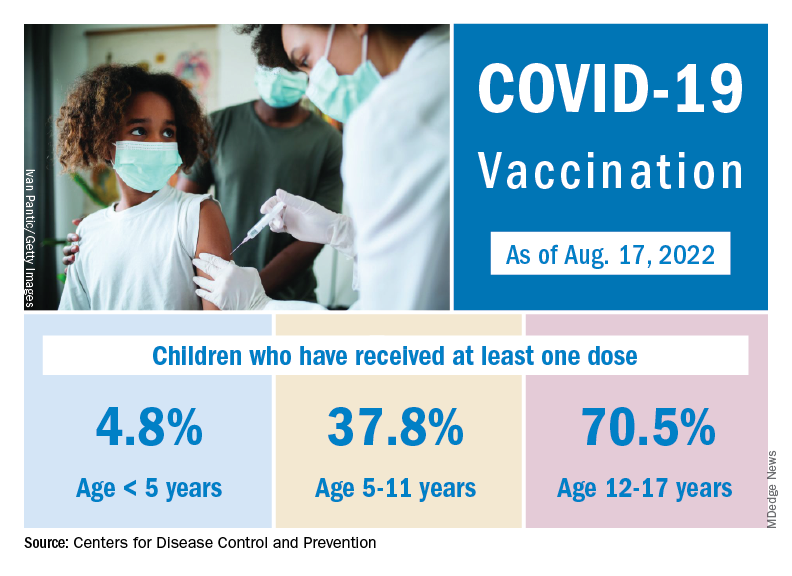

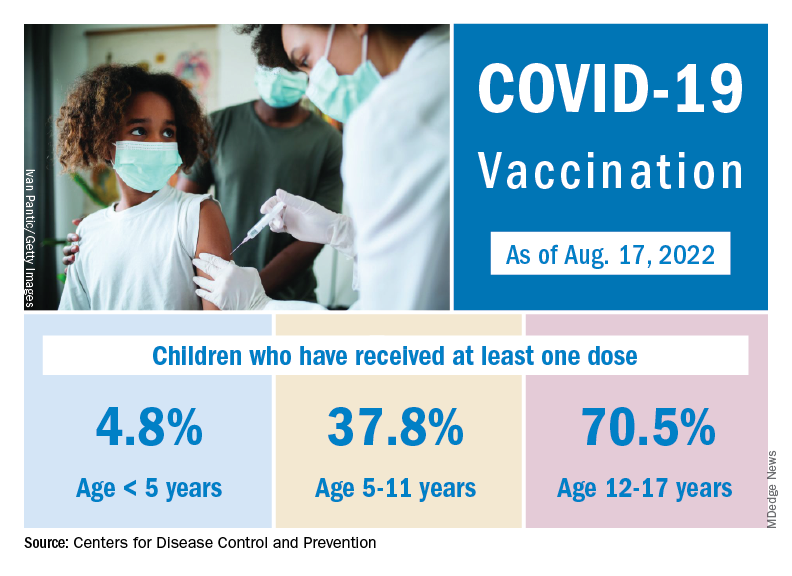

Although it may not qualify as a big push to vaccinate children before the start of the new school year, first-time vaccinations did rise somewhat in late July and August for children aged 5-17 years. Among children younger than 5 years, though, initial doses of the vaccine fell during the second full week of August, especially in 2- to 4-year-olds, based on the CDC data.

Through almost 2 months of vaccine eligibility, 4.8% of children under age 5 have received at least one dose and 0.9% are fully vaccinated as of Aug. 17. The current rates are 37.8% (one dose) and 30.4% (completed) for those aged 5-11 and 70.5% and 60.3% for 12- to 17-year-olds.

The 7-day average percentage of ED visits with diagnosed COVID, which had reached a post-Omicron high of 3.5% in late July for those aged 12-15, began to fall and was down to 3.0% on Aug. 12. That trend reversed, however, and the rate was up to 3.6% on Aug. 19, the last date for which data are available from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That change of COVID fortunes cannot yet be seen for all children. The 7-day average ED visit rate for those aged 0-11 years peaked at 6.8% during the last week of July and has continued to fall, dropping from 5.7% on Aug. 12 to 5.1% on Aug. 19. Children aged 16-17 years seem to be taking a middle path: Their ED-visit rate declined from late July into mid-August but held steady over the last week, according to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker.

There is a hint of the same trend regarding new admissions among children aged 0-17 years. The national rate, which had declined in recent weeks, ticked up from 0.42 to 0.43 new admissions per 100,000 population over the last week of available data, the CDC said.

Weekly cases fall below 80,000

New cases in general were down by 8.5% from the previous week, dropping from 87,902 for the week of Aug. 5-11 to 79,525 for Aug. 12-18. That marked the second straight week with fewer cases after a 4-week period that saw weekly totals increase from almost 68,000 to nearly 97,000, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The AAP and CHA put the cumulative number of child COVID-19 cases at just under 14.4 million since the pandemic began, which represents 18.4% of cases among all ages. The CDC estimates that there have been almost 14.7 million cases in children aged 0-17 years, as well as 1,750 deaths, of which 14 were reported in the last week (Aug. 16-22).

The CDC age subgroups indicate that children aged 0-4 years have experienced fewer cases (2.9 million) than children aged 5-11 years (5.6 million cases) and 12-15 (3.0 million cases) but more deaths: 548 so far, versus 432 for 5- to 11-year-olds and 437 for 12- to 15-year-olds, the COVID Data Tracker shows. Those aged 0-4 make up 6% of the total U.S. population, compared with 8.7% and 5.1%, respectively, for the older children.

Most younger children still not vaccinated

Although it may not qualify as a big push to vaccinate children before the start of the new school year, first-time vaccinations did rise somewhat in late July and August for children aged 5-17 years. Among children younger than 5 years, though, initial doses of the vaccine fell during the second full week of August, especially in 2- to 4-year-olds, based on the CDC data.

Through almost 2 months of vaccine eligibility, 4.8% of children under age 5 have received at least one dose and 0.9% are fully vaccinated as of Aug. 17. The current rates are 37.8% (one dose) and 30.4% (completed) for those aged 5-11 and 70.5% and 60.3% for 12- to 17-year-olds.

The 7-day average percentage of ED visits with diagnosed COVID, which had reached a post-Omicron high of 3.5% in late July for those aged 12-15, began to fall and was down to 3.0% on Aug. 12. That trend reversed, however, and the rate was up to 3.6% on Aug. 19, the last date for which data are available from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That change of COVID fortunes cannot yet be seen for all children. The 7-day average ED visit rate for those aged 0-11 years peaked at 6.8% during the last week of July and has continued to fall, dropping from 5.7% on Aug. 12 to 5.1% on Aug. 19. Children aged 16-17 years seem to be taking a middle path: Their ED-visit rate declined from late July into mid-August but held steady over the last week, according to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker.

There is a hint of the same trend regarding new admissions among children aged 0-17 years. The national rate, which had declined in recent weeks, ticked up from 0.42 to 0.43 new admissions per 100,000 population over the last week of available data, the CDC said.

Weekly cases fall below 80,000

New cases in general were down by 8.5% from the previous week, dropping from 87,902 for the week of Aug. 5-11 to 79,525 for Aug. 12-18. That marked the second straight week with fewer cases after a 4-week period that saw weekly totals increase from almost 68,000 to nearly 97,000, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The AAP and CHA put the cumulative number of child COVID-19 cases at just under 14.4 million since the pandemic began, which represents 18.4% of cases among all ages. The CDC estimates that there have been almost 14.7 million cases in children aged 0-17 years, as well as 1,750 deaths, of which 14 were reported in the last week (Aug. 16-22).

The CDC age subgroups indicate that children aged 0-4 years have experienced fewer cases (2.9 million) than children aged 5-11 years (5.6 million cases) and 12-15 (3.0 million cases) but more deaths: 548 so far, versus 432 for 5- to 11-year-olds and 437 for 12- to 15-year-olds, the COVID Data Tracker shows. Those aged 0-4 make up 6% of the total U.S. population, compared with 8.7% and 5.1%, respectively, for the older children.

Most younger children still not vaccinated

Although it may not qualify as a big push to vaccinate children before the start of the new school year, first-time vaccinations did rise somewhat in late July and August for children aged 5-17 years. Among children younger than 5 years, though, initial doses of the vaccine fell during the second full week of August, especially in 2- to 4-year-olds, based on the CDC data.

Through almost 2 months of vaccine eligibility, 4.8% of children under age 5 have received at least one dose and 0.9% are fully vaccinated as of Aug. 17. The current rates are 37.8% (one dose) and 30.4% (completed) for those aged 5-11 and 70.5% and 60.3% for 12- to 17-year-olds.

How does not getting enough sleep affect the developing brain?

Children who do not get enough sleep for one night can be cranky, groggy, or meltdown prone the next day.

Over time, though, insufficient sleep may impair neurodevelopment in ways that can be measured on brain scans and tests long term, a new study shows.

Research published in The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health found that 9- and 10-year-olds who do not get at least 9 hours of sleep most nights tend to have less gray matter and smaller areas of the brain responsible for attention, memory, and inhibition control, relative to children who do get enough sleep.

The researchers also found a relationship between insufficient sleep and disrupted connections between the basal ganglia and cortical regions of the brain. These disruptions appeared to be linked to depression, thought problems, and impairments in crystallized intelligence, a type of intelligence that depends on memory.

The overall patterns persisted 2 years later, even as those who got enough sleep at baseline gradually slept less over time, while those who were not getting enough sleep to begin with continued to sleep about the same amount, the researchers reported.

The results bolster the case for delaying school start times, as California recently did, according one researcher who was not involved in the study.

The ABCD Study

To examine how insufficient sleep affects children’s mental health, cognition, brain function, and brain structure over 2 years, Ze Wang, PhD, professor of diagnostic radiology and nuclear medicine at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, and colleagues analyzed data from the ongoing Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study. The ABCD Study is tracking the biologic and behavioral development of more than 11,000 children in the United States who were recruited for the study when they were 9 or 10 years old.

For their new analysis, Dr. Wang’s group focused on 6,042 participants: 3,021 children with insufficient sleep who were matched with an equal number of participants who were similar in many respects, including sex, socioeconomic status, and puberty status, except they got at least 9 hours of sleep. They also looked at outcomes 2 years later from 749 of the matched pairs who had results available.

The investigators determined sleep duration based on how parents answered the question: “How many hours of sleep does your child get on most nights in the past 6 months?” Possible answers included at least 9 hours, 8-9 hours, 7-8 hours, 5-7 hours, or less than 5 hours. They also looked at functional and structural MRI scans, test results, and responses to questionnaires.

Negative effects of inadequate sleep were spread over “several different domains including brain structure, function, cognition, behavior, and mental health,” Dr. Wang said.

The strength of the relationship between sleep duration and the various outcomes was “modest” and based on group averages, he said. So, a given child who does not sleep for 9 hours most nights won’t necessarily perform worse than a child who gets enough sleep.

Still, modest effects may accumulate and have lasting consequences, Dr. Wang said.

Crystallized intelligence

The researchers looked at 42 behavioral outcomes, 32 of which were significantly different between the groups. Four outcomes in particular – depression, thought problems, performance on a picture-vocabulary test, and crystallized intelligence – were areas where insufficient sleep seemed to have a larger negative effect.

Sleep duration’s relationship with crystallized intelligence was twice that for fluid intelligence, which does not depend on memory.

“Sleep affects memory,” Dr. Wang said. “Crystallized intelligence depends on learned skills and knowledge, which are memory. In this sense, sleep is related to crystallized intelligence.”

One limitation of the study is that some parents may not accurately report how much sleep their child gets, Dr. Wang acknowledged. Children may be awake when parents think they are asleep, for example.

And although the results show getting 9 hours of sleep may help neurocognitive development, it’s also possible that excessive amounts of sleep could be problematic, the study authors wrote.

Further experiments are needed to prove that insufficient sleep – and not some other, unaccounted for factor – causes the observed impairments in neurodevelopment.

To promote healthy sleep, parents should keep a strict routine for their children, such as a regular bedtime and no electronic devices in the bedroom, Dr. Wang suggested. More physical activity during the day also should help.

If children have high levels of stress and depression, “finding the source is critical,” he said. Likewise, clinicians should consider how mental health can affect their patients’ sleep.

More to healthy sleep than duration

“This study both aligns with and advances existing research on the importance of sufficient sleep for child well-being,” said Ariel A. Williamson, PhD, DBSM, a psychologist and pediatric sleep expert in the department of child and adolescent psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and assistant professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at University of Pennsylvania, also in Philadelphia.

The researchers used rigorous propensity score matching, longitudinal data, and brain imaging, which are “innovative methods that provide more evidence on potential mechanisms linking insufficient sleep and child outcomes,” said Dr. Williamson, who was not involved in the study.

While the investigators focused on sleep duration, child sleep health is multidimensional and includes other elements like timing and perception of sleep quality, Dr. Williamson noted. “For example, some research shows that having a sleep schedule that varies night to night is linked to poor child outcomes.”

Dr. Williamson tells families and clinicians that “sleep is a pillar of health,” equal to diet and exercise. That said, sleep recommendations need to fit within a family’s life – taking into account after school activities and late-night homework sessions. But extending sleep by just “20-30 minutes can make a meaningful difference for daytime functioning,” Dr. Williamson said.

Start school later?

Researchers have only relatively recently begun to understand how insufficient sleep affects adolescent neurocognitive development long term, and this study provides “crucial evidence” about the consequences, Lydia Gabriela Speyer, PhD, said in an editorial published with the study. Dr. Speyer is affiliated with the department of psychology at the University of Cambridge (England).

“Given the novel finding that insufficient sleep is associated with changes in brain structure and connectivity that are long-lasting, early intervention is crucial because such neural changes are probably not reversible and might consequently affect adolescents’ development into adulthood,” Dr. Speyer wrote.

Delaying school start times could be one way to help kids get more sleep. The American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommend that middle schools and high schools start no earlier than 8:30 a.m. to better align with students’ circadian rhythm, Dr. Speyer noted.

As it is in the United States, most schools start closer to 8 a.m. In California, though, a law that went into effect on July 1 prohibits high schools from starting before 8:30 a.m. Other states are weighing similar legislation.

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Wang and his coauthors and Dr. Speyer had no conflict of interest disclosures. Dr. Williamson is a sleep expert for the Pediatric Sleep Council (www.babysleep.com), which provides free information about early childhood sleep, but she does not receive compensation for this role.

Children who do not get enough sleep for one night can be cranky, groggy, or meltdown prone the next day.

Over time, though, insufficient sleep may impair neurodevelopment in ways that can be measured on brain scans and tests long term, a new study shows.

Research published in The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health found that 9- and 10-year-olds who do not get at least 9 hours of sleep most nights tend to have less gray matter and smaller areas of the brain responsible for attention, memory, and inhibition control, relative to children who do get enough sleep.

The researchers also found a relationship between insufficient sleep and disrupted connections between the basal ganglia and cortical regions of the brain. These disruptions appeared to be linked to depression, thought problems, and impairments in crystallized intelligence, a type of intelligence that depends on memory.

The overall patterns persisted 2 years later, even as those who got enough sleep at baseline gradually slept less over time, while those who were not getting enough sleep to begin with continued to sleep about the same amount, the researchers reported.

The results bolster the case for delaying school start times, as California recently did, according one researcher who was not involved in the study.

The ABCD Study

To examine how insufficient sleep affects children’s mental health, cognition, brain function, and brain structure over 2 years, Ze Wang, PhD, professor of diagnostic radiology and nuclear medicine at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, and colleagues analyzed data from the ongoing Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study. The ABCD Study is tracking the biologic and behavioral development of more than 11,000 children in the United States who were recruited for the study when they were 9 or 10 years old.

For their new analysis, Dr. Wang’s group focused on 6,042 participants: 3,021 children with insufficient sleep who were matched with an equal number of participants who were similar in many respects, including sex, socioeconomic status, and puberty status, except they got at least 9 hours of sleep. They also looked at outcomes 2 years later from 749 of the matched pairs who had results available.

The investigators determined sleep duration based on how parents answered the question: “How many hours of sleep does your child get on most nights in the past 6 months?” Possible answers included at least 9 hours, 8-9 hours, 7-8 hours, 5-7 hours, or less than 5 hours. They also looked at functional and structural MRI scans, test results, and responses to questionnaires.

Negative effects of inadequate sleep were spread over “several different domains including brain structure, function, cognition, behavior, and mental health,” Dr. Wang said.

The strength of the relationship between sleep duration and the various outcomes was “modest” and based on group averages, he said. So, a given child who does not sleep for 9 hours most nights won’t necessarily perform worse than a child who gets enough sleep.

Still, modest effects may accumulate and have lasting consequences, Dr. Wang said.

Crystallized intelligence

The researchers looked at 42 behavioral outcomes, 32 of which were significantly different between the groups. Four outcomes in particular – depression, thought problems, performance on a picture-vocabulary test, and crystallized intelligence – were areas where insufficient sleep seemed to have a larger negative effect.

Sleep duration’s relationship with crystallized intelligence was twice that for fluid intelligence, which does not depend on memory.

“Sleep affects memory,” Dr. Wang said. “Crystallized intelligence depends on learned skills and knowledge, which are memory. In this sense, sleep is related to crystallized intelligence.”

One limitation of the study is that some parents may not accurately report how much sleep their child gets, Dr. Wang acknowledged. Children may be awake when parents think they are asleep, for example.

And although the results show getting 9 hours of sleep may help neurocognitive development, it’s also possible that excessive amounts of sleep could be problematic, the study authors wrote.

Further experiments are needed to prove that insufficient sleep – and not some other, unaccounted for factor – causes the observed impairments in neurodevelopment.

To promote healthy sleep, parents should keep a strict routine for their children, such as a regular bedtime and no electronic devices in the bedroom, Dr. Wang suggested. More physical activity during the day also should help.

If children have high levels of stress and depression, “finding the source is critical,” he said. Likewise, clinicians should consider how mental health can affect their patients’ sleep.

More to healthy sleep than duration

“This study both aligns with and advances existing research on the importance of sufficient sleep for child well-being,” said Ariel A. Williamson, PhD, DBSM, a psychologist and pediatric sleep expert in the department of child and adolescent psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and assistant professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at University of Pennsylvania, also in Philadelphia.

The researchers used rigorous propensity score matching, longitudinal data, and brain imaging, which are “innovative methods that provide more evidence on potential mechanisms linking insufficient sleep and child outcomes,” said Dr. Williamson, who was not involved in the study.

While the investigators focused on sleep duration, child sleep health is multidimensional and includes other elements like timing and perception of sleep quality, Dr. Williamson noted. “For example, some research shows that having a sleep schedule that varies night to night is linked to poor child outcomes.”

Dr. Williamson tells families and clinicians that “sleep is a pillar of health,” equal to diet and exercise. That said, sleep recommendations need to fit within a family’s life – taking into account after school activities and late-night homework sessions. But extending sleep by just “20-30 minutes can make a meaningful difference for daytime functioning,” Dr. Williamson said.

Start school later?

Researchers have only relatively recently begun to understand how insufficient sleep affects adolescent neurocognitive development long term, and this study provides “crucial evidence” about the consequences, Lydia Gabriela Speyer, PhD, said in an editorial published with the study. Dr. Speyer is affiliated with the department of psychology at the University of Cambridge (England).

“Given the novel finding that insufficient sleep is associated with changes in brain structure and connectivity that are long-lasting, early intervention is crucial because such neural changes are probably not reversible and might consequently affect adolescents’ development into adulthood,” Dr. Speyer wrote.

Delaying school start times could be one way to help kids get more sleep. The American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommend that middle schools and high schools start no earlier than 8:30 a.m. to better align with students’ circadian rhythm, Dr. Speyer noted.

As it is in the United States, most schools start closer to 8 a.m. In California, though, a law that went into effect on July 1 prohibits high schools from starting before 8:30 a.m. Other states are weighing similar legislation.

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Wang and his coauthors and Dr. Speyer had no conflict of interest disclosures. Dr. Williamson is a sleep expert for the Pediatric Sleep Council (www.babysleep.com), which provides free information about early childhood sleep, but she does not receive compensation for this role.

Children who do not get enough sleep for one night can be cranky, groggy, or meltdown prone the next day.

Over time, though, insufficient sleep may impair neurodevelopment in ways that can be measured on brain scans and tests long term, a new study shows.

Research published in The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health found that 9- and 10-year-olds who do not get at least 9 hours of sleep most nights tend to have less gray matter and smaller areas of the brain responsible for attention, memory, and inhibition control, relative to children who do get enough sleep.

The researchers also found a relationship between insufficient sleep and disrupted connections between the basal ganglia and cortical regions of the brain. These disruptions appeared to be linked to depression, thought problems, and impairments in crystallized intelligence, a type of intelligence that depends on memory.

The overall patterns persisted 2 years later, even as those who got enough sleep at baseline gradually slept less over time, while those who were not getting enough sleep to begin with continued to sleep about the same amount, the researchers reported.

The results bolster the case for delaying school start times, as California recently did, according one researcher who was not involved in the study.

The ABCD Study

To examine how insufficient sleep affects children’s mental health, cognition, brain function, and brain structure over 2 years, Ze Wang, PhD, professor of diagnostic radiology and nuclear medicine at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, and colleagues analyzed data from the ongoing Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study. The ABCD Study is tracking the biologic and behavioral development of more than 11,000 children in the United States who were recruited for the study when they were 9 or 10 years old.

For their new analysis, Dr. Wang’s group focused on 6,042 participants: 3,021 children with insufficient sleep who were matched with an equal number of participants who were similar in many respects, including sex, socioeconomic status, and puberty status, except they got at least 9 hours of sleep. They also looked at outcomes 2 years later from 749 of the matched pairs who had results available.

The investigators determined sleep duration based on how parents answered the question: “How many hours of sleep does your child get on most nights in the past 6 months?” Possible answers included at least 9 hours, 8-9 hours, 7-8 hours, 5-7 hours, or less than 5 hours. They also looked at functional and structural MRI scans, test results, and responses to questionnaires.

Negative effects of inadequate sleep were spread over “several different domains including brain structure, function, cognition, behavior, and mental health,” Dr. Wang said.

The strength of the relationship between sleep duration and the various outcomes was “modest” and based on group averages, he said. So, a given child who does not sleep for 9 hours most nights won’t necessarily perform worse than a child who gets enough sleep.

Still, modest effects may accumulate and have lasting consequences, Dr. Wang said.

Crystallized intelligence

The researchers looked at 42 behavioral outcomes, 32 of which were significantly different between the groups. Four outcomes in particular – depression, thought problems, performance on a picture-vocabulary test, and crystallized intelligence – were areas where insufficient sleep seemed to have a larger negative effect.

Sleep duration’s relationship with crystallized intelligence was twice that for fluid intelligence, which does not depend on memory.

“Sleep affects memory,” Dr. Wang said. “Crystallized intelligence depends on learned skills and knowledge, which are memory. In this sense, sleep is related to crystallized intelligence.”

One limitation of the study is that some parents may not accurately report how much sleep their child gets, Dr. Wang acknowledged. Children may be awake when parents think they are asleep, for example.

And although the results show getting 9 hours of sleep may help neurocognitive development, it’s also possible that excessive amounts of sleep could be problematic, the study authors wrote.

Further experiments are needed to prove that insufficient sleep – and not some other, unaccounted for factor – causes the observed impairments in neurodevelopment.

To promote healthy sleep, parents should keep a strict routine for their children, such as a regular bedtime and no electronic devices in the bedroom, Dr. Wang suggested. More physical activity during the day also should help.

If children have high levels of stress and depression, “finding the source is critical,” he said. Likewise, clinicians should consider how mental health can affect their patients’ sleep.

More to healthy sleep than duration

“This study both aligns with and advances existing research on the importance of sufficient sleep for child well-being,” said Ariel A. Williamson, PhD, DBSM, a psychologist and pediatric sleep expert in the department of child and adolescent psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and assistant professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at University of Pennsylvania, also in Philadelphia.

The researchers used rigorous propensity score matching, longitudinal data, and brain imaging, which are “innovative methods that provide more evidence on potential mechanisms linking insufficient sleep and child outcomes,” said Dr. Williamson, who was not involved in the study.

While the investigators focused on sleep duration, child sleep health is multidimensional and includes other elements like timing and perception of sleep quality, Dr. Williamson noted. “For example, some research shows that having a sleep schedule that varies night to night is linked to poor child outcomes.”

Dr. Williamson tells families and clinicians that “sleep is a pillar of health,” equal to diet and exercise. That said, sleep recommendations need to fit within a family’s life – taking into account after school activities and late-night homework sessions. But extending sleep by just “20-30 minutes can make a meaningful difference for daytime functioning,” Dr. Williamson said.

Start school later?

Researchers have only relatively recently begun to understand how insufficient sleep affects adolescent neurocognitive development long term, and this study provides “crucial evidence” about the consequences, Lydia Gabriela Speyer, PhD, said in an editorial published with the study. Dr. Speyer is affiliated with the department of psychology at the University of Cambridge (England).

“Given the novel finding that insufficient sleep is associated with changes in brain structure and connectivity that are long-lasting, early intervention is crucial because such neural changes are probably not reversible and might consequently affect adolescents’ development into adulthood,” Dr. Speyer wrote.

Delaying school start times could be one way to help kids get more sleep. The American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommend that middle schools and high schools start no earlier than 8:30 a.m. to better align with students’ circadian rhythm, Dr. Speyer noted.

As it is in the United States, most schools start closer to 8 a.m. In California, though, a law that went into effect on July 1 prohibits high schools from starting before 8:30 a.m. Other states are weighing similar legislation.

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Wang and his coauthors and Dr. Speyer had no conflict of interest disclosures. Dr. Williamson is a sleep expert for the Pediatric Sleep Council (www.babysleep.com), which provides free information about early childhood sleep, but she does not receive compensation for this role.

FROM THE LANCET CHILD & ADOLESCENT HEALTH

Consider essential oil allergy in patient with dermatitis

PORTLAND, ORE. – When patients present to Brandon L. Adler, MD, with dermatitis on the eyelid, face, or neck, he routinely asks them if they apply essential oils on their skin, or if they have an essential oil diffuser or nebulizer in their home.

“The answer is frequently ‘yes,’ ” Dr. Adler, clinical assistant professor of dermatology at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, said at the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association. “Essential oils are widely used throughout the wellness industry. They are contained in personal care products, beauty products, natural cleaning products, and they’re being diffused by our patients into the air. More than 75 essential oils are reported to cause allergic contact dermatitis.”

“Linalool is most classically associated with lavender, while limonene is associated with citrus, but they’re found in many different plants,” said Dr. Adler, who directs USC’s contact dermatitis clinic. “On their own, linalool and limonene are not particularly allergenic; they’re not a big deal in the patch test clinic. The problem comes when we add air to the mix, because they oxidize to hydroperoxides of linalool and limonene. These are quite potent allergens.”

According to the most recent North American Contact Dermatitis Group data, 8.9% of patients undergoing patch testing tested positive to linalool hydroperoxides and 2.6% were positive to limonene hydroperoxides.

Dr. Adler discussed the case of a female massage therapist who presented with refractory hand dermatitis and was on methotrexate and dupilumab at the time of consultation but was still symptomatic. She patch-tested positive to limonene and linalool hydroperoxides as well as multiple essential oils that she had been using with her clients, ranging from sacred frankincense oil to basil oil, and she was advised to massage using only coconut or vegetable oils.

Essential oil allergy may also be related to cannabis allergy. According to Dr. Adler, allergic contact dermatitis to cannabis has been rarely reported, but in an analysis of 103 commercial topical cannabinoid preparations that he published with Vincent DeLeo, MD, also with USC, 84% contained a NACDG allergen, frequently essential oils.

More recently, Dr. Adler and colleagues reported the case of a 40-year-old woman who was referred for patch testing for nummular dermatitis that wasn’t responding to treatment. The patient was found to be using topical cannabis and also grew cannabis at home. “She asked to be patch-tested to her homegrown cannabis and had a strong positive patch test to the cannabis, linalool and limonene hydroperoxides, and other essential oils,” Dr. Adler recalled. “We sent her cannabis sample for analysis at a commercial lab and found that it contained limonene and other allergenic terpene chemicals.

“We’re just starting to unravel what this means in terms of our patients and how to manage them, but many are using topical cannabis and topical CBD. I suspect this is a lot less rare than we realize.”

Another recent case from Europe reported allergic contact dermatitis to Cannabis sativa (hemp) seed oil following topical application, with positive patch testing.

Dr. Adler disclosed that he has received research grants from the American Contact Dermatitis Society. He is also an investigator for AbbVie and a consultant for the Skin Research Institute.

PORTLAND, ORE. – When patients present to Brandon L. Adler, MD, with dermatitis on the eyelid, face, or neck, he routinely asks them if they apply essential oils on their skin, or if they have an essential oil diffuser or nebulizer in their home.

“The answer is frequently ‘yes,’ ” Dr. Adler, clinical assistant professor of dermatology at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, said at the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association. “Essential oils are widely used throughout the wellness industry. They are contained in personal care products, beauty products, natural cleaning products, and they’re being diffused by our patients into the air. More than 75 essential oils are reported to cause allergic contact dermatitis.”

“Linalool is most classically associated with lavender, while limonene is associated with citrus, but they’re found in many different plants,” said Dr. Adler, who directs USC’s contact dermatitis clinic. “On their own, linalool and limonene are not particularly allergenic; they’re not a big deal in the patch test clinic. The problem comes when we add air to the mix, because they oxidize to hydroperoxides of linalool and limonene. These are quite potent allergens.”

According to the most recent North American Contact Dermatitis Group data, 8.9% of patients undergoing patch testing tested positive to linalool hydroperoxides and 2.6% were positive to limonene hydroperoxides.

Dr. Adler discussed the case of a female massage therapist who presented with refractory hand dermatitis and was on methotrexate and dupilumab at the time of consultation but was still symptomatic. She patch-tested positive to limonene and linalool hydroperoxides as well as multiple essential oils that she had been using with her clients, ranging from sacred frankincense oil to basil oil, and she was advised to massage using only coconut or vegetable oils.

Essential oil allergy may also be related to cannabis allergy. According to Dr. Adler, allergic contact dermatitis to cannabis has been rarely reported, but in an analysis of 103 commercial topical cannabinoid preparations that he published with Vincent DeLeo, MD, also with USC, 84% contained a NACDG allergen, frequently essential oils.

More recently, Dr. Adler and colleagues reported the case of a 40-year-old woman who was referred for patch testing for nummular dermatitis that wasn’t responding to treatment. The patient was found to be using topical cannabis and also grew cannabis at home. “She asked to be patch-tested to her homegrown cannabis and had a strong positive patch test to the cannabis, linalool and limonene hydroperoxides, and other essential oils,” Dr. Adler recalled. “We sent her cannabis sample for analysis at a commercial lab and found that it contained limonene and other allergenic terpene chemicals.

“We’re just starting to unravel what this means in terms of our patients and how to manage them, but many are using topical cannabis and topical CBD. I suspect this is a lot less rare than we realize.”

Another recent case from Europe reported allergic contact dermatitis to Cannabis sativa (hemp) seed oil following topical application, with positive patch testing.

Dr. Adler disclosed that he has received research grants from the American Contact Dermatitis Society. He is also an investigator for AbbVie and a consultant for the Skin Research Institute.

PORTLAND, ORE. – When patients present to Brandon L. Adler, MD, with dermatitis on the eyelid, face, or neck, he routinely asks them if they apply essential oils on their skin, or if they have an essential oil diffuser or nebulizer in their home.

“The answer is frequently ‘yes,’ ” Dr. Adler, clinical assistant professor of dermatology at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, said at the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association. “Essential oils are widely used throughout the wellness industry. They are contained in personal care products, beauty products, natural cleaning products, and they’re being diffused by our patients into the air. More than 75 essential oils are reported to cause allergic contact dermatitis.”

“Linalool is most classically associated with lavender, while limonene is associated with citrus, but they’re found in many different plants,” said Dr. Adler, who directs USC’s contact dermatitis clinic. “On their own, linalool and limonene are not particularly allergenic; they’re not a big deal in the patch test clinic. The problem comes when we add air to the mix, because they oxidize to hydroperoxides of linalool and limonene. These are quite potent allergens.”

According to the most recent North American Contact Dermatitis Group data, 8.9% of patients undergoing patch testing tested positive to linalool hydroperoxides and 2.6% were positive to limonene hydroperoxides.

Dr. Adler discussed the case of a female massage therapist who presented with refractory hand dermatitis and was on methotrexate and dupilumab at the time of consultation but was still symptomatic. She patch-tested positive to limonene and linalool hydroperoxides as well as multiple essential oils that she had been using with her clients, ranging from sacred frankincense oil to basil oil, and she was advised to massage using only coconut or vegetable oils.

Essential oil allergy may also be related to cannabis allergy. According to Dr. Adler, allergic contact dermatitis to cannabis has been rarely reported, but in an analysis of 103 commercial topical cannabinoid preparations that he published with Vincent DeLeo, MD, also with USC, 84% contained a NACDG allergen, frequently essential oils.

More recently, Dr. Adler and colleagues reported the case of a 40-year-old woman who was referred for patch testing for nummular dermatitis that wasn’t responding to treatment. The patient was found to be using topical cannabis and also grew cannabis at home. “She asked to be patch-tested to her homegrown cannabis and had a strong positive patch test to the cannabis, linalool and limonene hydroperoxides, and other essential oils,” Dr. Adler recalled. “We sent her cannabis sample for analysis at a commercial lab and found that it contained limonene and other allergenic terpene chemicals.

“We’re just starting to unravel what this means in terms of our patients and how to manage them, but many are using topical cannabis and topical CBD. I suspect this is a lot less rare than we realize.”

Another recent case from Europe reported allergic contact dermatitis to Cannabis sativa (hemp) seed oil following topical application, with positive patch testing.

Dr. Adler disclosed that he has received research grants from the American Contact Dermatitis Society. He is also an investigator for AbbVie and a consultant for the Skin Research Institute.

AT PDA 2022

Leukemia rates two to three times higher in children born near fracking

Children born near fracking and other “unconventional” drilling sites are at two to three times greater risk of developing childhood leukemia, according to new research.

The study, published in the journal Environmental Health Perspectives, compared proximity of homes to unconventional oil and gas development (UOGD) sites and risk of the most common form of childhood leukemia, acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

Researchers looked at 405 children aged 2-7 diagnosed with ALL in Pennsylvania from 2009 to 2017. These children were compared to a control group of 2,080 without the disease matched on the year of birth.

“Unconventional oil and gas development can both use and release chemicals that have been linked to cancer,” study coauthor Nicole Deziel, PhD, of the Yale School of Public Health, New Haven, Conn., said in a statement . She noted that the possibility that children living in close proximity to such sites are “exposed to these chemical carcinogens is a major public health concern.”

About 17 million Americans live within a half-mile of active oil and gas production, according to the Oil & Gas Threat Map, Common Dreams reports. That number includes 4 million children.

The Yale study also found that drinking water could be an important pathway of exposure to oil- and gas-related chemicals used in the UOGD methods of extraction.

Researchers used a new metric that measures exposure to contaminated drinking water and distance to a well. They were able to identify UOGD-affected wells that fell within watersheds where children and their families likely obtained their water.

“Previous health studies have found links between proximity to oil and gas drilling and various children’s health outcomes,” said Dr. Deziel. “This study is among the few to focus on drinking water specifically and the first to apply a novel metric designed to capture potential exposure through this pathway.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Children born near fracking and other “unconventional” drilling sites are at two to three times greater risk of developing childhood leukemia, according to new research.

The study, published in the journal Environmental Health Perspectives, compared proximity of homes to unconventional oil and gas development (UOGD) sites and risk of the most common form of childhood leukemia, acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

Researchers looked at 405 children aged 2-7 diagnosed with ALL in Pennsylvania from 2009 to 2017. These children were compared to a control group of 2,080 without the disease matched on the year of birth.

“Unconventional oil and gas development can both use and release chemicals that have been linked to cancer,” study coauthor Nicole Deziel, PhD, of the Yale School of Public Health, New Haven, Conn., said in a statement . She noted that the possibility that children living in close proximity to such sites are “exposed to these chemical carcinogens is a major public health concern.”

About 17 million Americans live within a half-mile of active oil and gas production, according to the Oil & Gas Threat Map, Common Dreams reports. That number includes 4 million children.

The Yale study also found that drinking water could be an important pathway of exposure to oil- and gas-related chemicals used in the UOGD methods of extraction.

Researchers used a new metric that measures exposure to contaminated drinking water and distance to a well. They were able to identify UOGD-affected wells that fell within watersheds where children and their families likely obtained their water.

“Previous health studies have found links between proximity to oil and gas drilling and various children’s health outcomes,” said Dr. Deziel. “This study is among the few to focus on drinking water specifically and the first to apply a novel metric designed to capture potential exposure through this pathway.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Children born near fracking and other “unconventional” drilling sites are at two to three times greater risk of developing childhood leukemia, according to new research.

The study, published in the journal Environmental Health Perspectives, compared proximity of homes to unconventional oil and gas development (UOGD) sites and risk of the most common form of childhood leukemia, acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

Researchers looked at 405 children aged 2-7 diagnosed with ALL in Pennsylvania from 2009 to 2017. These children were compared to a control group of 2,080 without the disease matched on the year of birth.

“Unconventional oil and gas development can both use and release chemicals that have been linked to cancer,” study coauthor Nicole Deziel, PhD, of the Yale School of Public Health, New Haven, Conn., said in a statement . She noted that the possibility that children living in close proximity to such sites are “exposed to these chemical carcinogens is a major public health concern.”

About 17 million Americans live within a half-mile of active oil and gas production, according to the Oil & Gas Threat Map, Common Dreams reports. That number includes 4 million children.

The Yale study also found that drinking water could be an important pathway of exposure to oil- and gas-related chemicals used in the UOGD methods of extraction.

Researchers used a new metric that measures exposure to contaminated drinking water and distance to a well. They were able to identify UOGD-affected wells that fell within watersheds where children and their families likely obtained their water.

“Previous health studies have found links between proximity to oil and gas drilling and various children’s health outcomes,” said Dr. Deziel. “This study is among the few to focus on drinking water specifically and the first to apply a novel metric designed to capture potential exposure through this pathway.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Watching TV, using computer have opposite ties to dementia risk

The relationship to dementia with these activities remained strong no matter how much physical activity a person did, the authors wrote in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Both watching TV and using a computer have been linked to increased risk of chronic disease and mortality, while exercise and physical activity (PA) have shown benefit in reducing cognitive decline, structural brain atrophy, and dementia risk in older adults, the authors wrote.

The authors said they wanted to try to understand the effects of watching TV and using computers on dementia risk, because people in the United States and Europe have been engaging in both of these activities more often.

They concluded that it’s not the sitting part of sedentary behavior (SB) that potentially has the effect on dementia but what people are doing while sitting.

Some of the results were surprising, lead author David Raichlen, PhD, professor of Human and Evolutionary Biology at University of Southern California, Los Angeles, said in an interview.

Previous literature on sedentary behaviors have documented their negative effects on a wide range of health outcomes, rather than finding positive associations, he explained.

More than 140,000 included in study

The researchers conducted their prospective cohort study using data from the United Kingdom Biobank. After excluding people younger than 60, those with prevalent dementia at the start of follow-up, and those without complete data, 146,651 participants were included.

The participants were followed from their baseline visit until they received a dementia diagnosis, died, were lost to follow-up, or were last admitted to the hospital.

TV-watching time was linked with an increased risk of incident dementia (HR [95% confidence interval] = 1.31 [1.23-1.40]), and computer use was linked with a reduced risk of incident dementia HR [95% CI] = 0.80 [0.76-0.85]).

TV’s link with higher dementia risk increased in those who had the highest use, compared with those who had the lowest use (HR [95% CI] = 1.28 [1.18-1.39].

Similarly, the link with risk reduction for dementia with computer use increased with more use.

Both medium and high computer time were associated with reduced risk of incident dementia (HR [95% CI] = 0.70 [0.64-0.76] and HR [95% CI] = 0.76 [0.70-0.83] respectively).

Dr. Raichlen pointed out that the high use of TV in this study was 4 or more hours a day and computer use – which included leisure use, not work use – had benefits on dementia risk after just half an hour.

These results remained significant after researchers adjusted for demographic, health, and lifestyle variables, including time spent on physical activity, sleeping, obesity, alcohol consumption, smoking status, diet scores, education level, body mass index, and employment type.

Physical is still better than sedentary activity

One potential reason for the different effects on dementia risk in the two activities studied, the authors write, is that sitting down to watch TV is associated with “uniquely low levels of muscle activity and energy expenditure, compared with sitting to use a computer.”

Andrew Budson, MD, chief of Cognitive & Behavioral Neurology and Associate Chief of Staff for Education for the VA Boston Healthcare System, Mass., who was not part of the study, said he thinks a more likely explanation for the study findings lies in the active versus passive tasks required in the two kinds of viewing that the authors reference.

“When we’re doing cognitive activity involving using the computer, we’re using large parts of our cortex to carry out that activity, whereas when we’re watching TV, there are probably relatively small amounts of our brain that are actually active,” Dr. Budson, author of Seven Steps to Managing Your Memory, explained in an interview.

“This is one of the first times I’ve been convinced that even when the computer activity isn’t completely new and novel, it may be beneficial,” Dr. Budson said.

It would be much better to do physical activity, but if the choice is sedentary activity, active cognitive activities, such as computer use, are better than TV watching, he continued.

The results of the current study are consistent with previous work showing that the type of sedentary behavior matters, according to the authors.

“Several studies have shown that TV time is associated with mortality and poor cardiometabolic biomarkers, whereas computer time is not,” they wrote.

A limitation of the study is that sedentary behaviors were self-reported via questionnaires, and there may be errors in recall.

“The use of objective methods for measuring both SB and PA are needed in future studies,” they write.

The authors receive support from the National Institutes of Health, the State of Arizona, the Arizona Department of Health Services, and the McKnight Brain Research Foundation. Neither the authors nor Dr. Budson declared relevant financial relationships.

The relationship to dementia with these activities remained strong no matter how much physical activity a person did, the authors wrote in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Both watching TV and using a computer have been linked to increased risk of chronic disease and mortality, while exercise and physical activity (PA) have shown benefit in reducing cognitive decline, structural brain atrophy, and dementia risk in older adults, the authors wrote.

The authors said they wanted to try to understand the effects of watching TV and using computers on dementia risk, because people in the United States and Europe have been engaging in both of these activities more often.

They concluded that it’s not the sitting part of sedentary behavior (SB) that potentially has the effect on dementia but what people are doing while sitting.

Some of the results were surprising, lead author David Raichlen, PhD, professor of Human and Evolutionary Biology at University of Southern California, Los Angeles, said in an interview.

Previous literature on sedentary behaviors have documented their negative effects on a wide range of health outcomes, rather than finding positive associations, he explained.

More than 140,000 included in study

The researchers conducted their prospective cohort study using data from the United Kingdom Biobank. After excluding people younger than 60, those with prevalent dementia at the start of follow-up, and those without complete data, 146,651 participants were included.

The participants were followed from their baseline visit until they received a dementia diagnosis, died, were lost to follow-up, or were last admitted to the hospital.

TV-watching time was linked with an increased risk of incident dementia (HR [95% confidence interval] = 1.31 [1.23-1.40]), and computer use was linked with a reduced risk of incident dementia HR [95% CI] = 0.80 [0.76-0.85]).

TV’s link with higher dementia risk increased in those who had the highest use, compared with those who had the lowest use (HR [95% CI] = 1.28 [1.18-1.39].

Similarly, the link with risk reduction for dementia with computer use increased with more use.

Both medium and high computer time were associated with reduced risk of incident dementia (HR [95% CI] = 0.70 [0.64-0.76] and HR [95% CI] = 0.76 [0.70-0.83] respectively).

Dr. Raichlen pointed out that the high use of TV in this study was 4 or more hours a day and computer use – which included leisure use, not work use – had benefits on dementia risk after just half an hour.

These results remained significant after researchers adjusted for demographic, health, and lifestyle variables, including time spent on physical activity, sleeping, obesity, alcohol consumption, smoking status, diet scores, education level, body mass index, and employment type.

Physical is still better than sedentary activity

One potential reason for the different effects on dementia risk in the two activities studied, the authors write, is that sitting down to watch TV is associated with “uniquely low levels of muscle activity and energy expenditure, compared with sitting to use a computer.”

Andrew Budson, MD, chief of Cognitive & Behavioral Neurology and Associate Chief of Staff for Education for the VA Boston Healthcare System, Mass., who was not part of the study, said he thinks a more likely explanation for the study findings lies in the active versus passive tasks required in the two kinds of viewing that the authors reference.

“When we’re doing cognitive activity involving using the computer, we’re using large parts of our cortex to carry out that activity, whereas when we’re watching TV, there are probably relatively small amounts of our brain that are actually active,” Dr. Budson, author of Seven Steps to Managing Your Memory, explained in an interview.

“This is one of the first times I’ve been convinced that even when the computer activity isn’t completely new and novel, it may be beneficial,” Dr. Budson said.

It would be much better to do physical activity, but if the choice is sedentary activity, active cognitive activities, such as computer use, are better than TV watching, he continued.

The results of the current study are consistent with previous work showing that the type of sedentary behavior matters, according to the authors.

“Several studies have shown that TV time is associated with mortality and poor cardiometabolic biomarkers, whereas computer time is not,” they wrote.

A limitation of the study is that sedentary behaviors were self-reported via questionnaires, and there may be errors in recall.

“The use of objective methods for measuring both SB and PA are needed in future studies,” they write.

The authors receive support from the National Institutes of Health, the State of Arizona, the Arizona Department of Health Services, and the McKnight Brain Research Foundation. Neither the authors nor Dr. Budson declared relevant financial relationships.

The relationship to dementia with these activities remained strong no matter how much physical activity a person did, the authors wrote in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Both watching TV and using a computer have been linked to increased risk of chronic disease and mortality, while exercise and physical activity (PA) have shown benefit in reducing cognitive decline, structural brain atrophy, and dementia risk in older adults, the authors wrote.

The authors said they wanted to try to understand the effects of watching TV and using computers on dementia risk, because people in the United States and Europe have been engaging in both of these activities more often.

They concluded that it’s not the sitting part of sedentary behavior (SB) that potentially has the effect on dementia but what people are doing while sitting.

Some of the results were surprising, lead author David Raichlen, PhD, professor of Human and Evolutionary Biology at University of Southern California, Los Angeles, said in an interview.

Previous literature on sedentary behaviors have documented their negative effects on a wide range of health outcomes, rather than finding positive associations, he explained.

More than 140,000 included in study

The researchers conducted their prospective cohort study using data from the United Kingdom Biobank. After excluding people younger than 60, those with prevalent dementia at the start of follow-up, and those without complete data, 146,651 participants were included.

The participants were followed from their baseline visit until they received a dementia diagnosis, died, were lost to follow-up, or were last admitted to the hospital.

TV-watching time was linked with an increased risk of incident dementia (HR [95% confidence interval] = 1.31 [1.23-1.40]), and computer use was linked with a reduced risk of incident dementia HR [95% CI] = 0.80 [0.76-0.85]).

TV’s link with higher dementia risk increased in those who had the highest use, compared with those who had the lowest use (HR [95% CI] = 1.28 [1.18-1.39].

Similarly, the link with risk reduction for dementia with computer use increased with more use.

Both medium and high computer time were associated with reduced risk of incident dementia (HR [95% CI] = 0.70 [0.64-0.76] and HR [95% CI] = 0.76 [0.70-0.83] respectively).

Dr. Raichlen pointed out that the high use of TV in this study was 4 or more hours a day and computer use – which included leisure use, not work use – had benefits on dementia risk after just half an hour.

These results remained significant after researchers adjusted for demographic, health, and lifestyle variables, including time spent on physical activity, sleeping, obesity, alcohol consumption, smoking status, diet scores, education level, body mass index, and employment type.

Physical is still better than sedentary activity

One potential reason for the different effects on dementia risk in the two activities studied, the authors write, is that sitting down to watch TV is associated with “uniquely low levels of muscle activity and energy expenditure, compared with sitting to use a computer.”

Andrew Budson, MD, chief of Cognitive & Behavioral Neurology and Associate Chief of Staff for Education for the VA Boston Healthcare System, Mass., who was not part of the study, said he thinks a more likely explanation for the study findings lies in the active versus passive tasks required in the two kinds of viewing that the authors reference.

“When we’re doing cognitive activity involving using the computer, we’re using large parts of our cortex to carry out that activity, whereas when we’re watching TV, there are probably relatively small amounts of our brain that are actually active,” Dr. Budson, author of Seven Steps to Managing Your Memory, explained in an interview.

“This is one of the first times I’ve been convinced that even when the computer activity isn’t completely new and novel, it may be beneficial,” Dr. Budson said.

It would be much better to do physical activity, but if the choice is sedentary activity, active cognitive activities, such as computer use, are better than TV watching, he continued.

The results of the current study are consistent with previous work showing that the type of sedentary behavior matters, according to the authors.

“Several studies have shown that TV time is associated with mortality and poor cardiometabolic biomarkers, whereas computer time is not,” they wrote.

A limitation of the study is that sedentary behaviors were self-reported via questionnaires, and there may be errors in recall.

“The use of objective methods for measuring both SB and PA are needed in future studies,” they write.

The authors receive support from the National Institutes of Health, the State of Arizona, the Arizona Department of Health Services, and the McKnight Brain Research Foundation. Neither the authors nor Dr. Budson declared relevant financial relationships.

FROM PROCEEDINGS OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES

Higher rates of group B strep disease found in Black and Asian newborns

Health charities called for action to address racial health disparities after population-wide analysis by the UK Health Security Agency found that Black and Asian neonates had a significantly higher risk of early-onset group B streptococcal disease (GBS), compared with White infants.

One support group said more research was now needed to identify the cause of the disparity, and called for pregnant women to be better informed about the disease and what it could mean for them and their baby.

The study, published in Pediatrics, used UKHSA data on laboratory-confirmed infant group B streptococcal (iGBS) disease cases between Jan. 1, 2016, and Dec. 31, 2020, and were linked to hospital ethnicity records.

Cases of iGBS were defined as isolation of Streptococcus agalactiae from a normally sterile site at 0-6 days of life for early-onset iGBS and 7-90 days for late-onset disease.

Hospital data and parent-reported ethnicity

Researchers found 2,512 iGBS cases in England during the study period, 65.3% were early onset and 34.8% late onset, equivalent to 0.52 and 0.28 cases per 1000 live births respectively.

Researchers were able to link 85.6% of those to ethnicity. Among those 2,149 cases, Black infants had a 48% higher risk, and Asian infants a 40% higher risk of early onset iGBS, compared with White infants. Among those from an Asian background, the risk was 87% higher for Bangladeshi and 38% higher for Pakistani neonates.

Rates of early onset iGBS per 1,000 live births were 0.43 for White infants, 0.63 for Black infants, and 0.60 for those of Asian ethnicity.

In contrast, Indian infants had an early-onset rate of 0.47 per 1,000 live births, which was similar to White infants.

Black infants had 57% higher rates of late-onset iGBS (0.37) than White infants (0.24), the researchers reported.

The study authors highlighted previous research which found higher prevalence of group B streptococcal colonization in mothers from Black and some Asian ethnic groups, but lower prevalence in mothers from the Indian subcontinent. More research was needed to establish causes, the researchers said, including whether higher preterm birth rates in minority ethnic groups led to increased iGBS risk in neonates, or whether maternal group B streptococcal disease led to higher preterm birth rates and subsequent neonatal iGBS.

The researchers concluded: “Understanding the factors underpinning differences in rates of early-onset iGBS within south Asian groups in England may lead to new opportunities for prevention such as prioritized antenatal screening. Strategies to prevent neonatal iGBS must be tailored from high-quality quantitative and qualitative data to reach all women and protect all infants, irrespective of racial or ethnic background.”

‘Shocking but not surprising’

Commenting on the study, Edward Morris, president of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, said: “This research is striking reading, and is yet another example of how far we have to go to tackle health inequalities within women’s health care.”

Philip Steer, professor emeritus at Imperial College London, said that the results were “consistent with previous reports of higher GBS carriage and higher maternal and neonatal mortality rates in minority groups” and “emphasize the importance of studying not just whether, but why, these differences exist.” He added: “We need to understand the reasons for the differences before we can design much-needed intervention to eliminate them.”

Jane Plumb, chief executive of Group B Strep Support, called the findings “shocking, but unfortunately not surprising” and said that they offered “another example of racial disparities in maternal and neonatal health.” She said: “We’re calling for all pregnant women and birthing people to be informed about GBS and its risks, so they can make empowered choices for themselves and their baby. It is also critical that trusts sign up to take part in the internationally significant [National Institute for Health and Care Research]–funded GBS3 clinical trial, designed to improve the prevention of GBS infection.”

Baroness Shaista Gohir, chief executive of the Muslim Women’s Network, said: “With significantly higher rates of group B Strep infection in Black and Asian babies, greater efforts must be made to improve awareness among pregnant women within these communities.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape UK.

Health charities called for action to address racial health disparities after population-wide analysis by the UK Health Security Agency found that Black and Asian neonates had a significantly higher risk of early-onset group B streptococcal disease (GBS), compared with White infants.

One support group said more research was now needed to identify the cause of the disparity, and called for pregnant women to be better informed about the disease and what it could mean for them and their baby.

The study, published in Pediatrics, used UKHSA data on laboratory-confirmed infant group B streptococcal (iGBS) disease cases between Jan. 1, 2016, and Dec. 31, 2020, and were linked to hospital ethnicity records.

Cases of iGBS were defined as isolation of Streptococcus agalactiae from a normally sterile site at 0-6 days of life for early-onset iGBS and 7-90 days for late-onset disease.

Hospital data and parent-reported ethnicity

Researchers found 2,512 iGBS cases in England during the study period, 65.3% were early onset and 34.8% late onset, equivalent to 0.52 and 0.28 cases per 1000 live births respectively.

Researchers were able to link 85.6% of those to ethnicity. Among those 2,149 cases, Black infants had a 48% higher risk, and Asian infants a 40% higher risk of early onset iGBS, compared with White infants. Among those from an Asian background, the risk was 87% higher for Bangladeshi and 38% higher for Pakistani neonates.

Rates of early onset iGBS per 1,000 live births were 0.43 for White infants, 0.63 for Black infants, and 0.60 for those of Asian ethnicity.

In contrast, Indian infants had an early-onset rate of 0.47 per 1,000 live births, which was similar to White infants.

Black infants had 57% higher rates of late-onset iGBS (0.37) than White infants (0.24), the researchers reported.

The study authors highlighted previous research which found higher prevalence of group B streptococcal colonization in mothers from Black and some Asian ethnic groups, but lower prevalence in mothers from the Indian subcontinent. More research was needed to establish causes, the researchers said, including whether higher preterm birth rates in minority ethnic groups led to increased iGBS risk in neonates, or whether maternal group B streptococcal disease led to higher preterm birth rates and subsequent neonatal iGBS.

The researchers concluded: “Understanding the factors underpinning differences in rates of early-onset iGBS within south Asian groups in England may lead to new opportunities for prevention such as prioritized antenatal screening. Strategies to prevent neonatal iGBS must be tailored from high-quality quantitative and qualitative data to reach all women and protect all infants, irrespective of racial or ethnic background.”

‘Shocking but not surprising’

Commenting on the study, Edward Morris, president of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, said: “This research is striking reading, and is yet another example of how far we have to go to tackle health inequalities within women’s health care.”

Philip Steer, professor emeritus at Imperial College London, said that the results were “consistent with previous reports of higher GBS carriage and higher maternal and neonatal mortality rates in minority groups” and “emphasize the importance of studying not just whether, but why, these differences exist.” He added: “We need to understand the reasons for the differences before we can design much-needed intervention to eliminate them.”

Jane Plumb, chief executive of Group B Strep Support, called the findings “shocking, but unfortunately not surprising” and said that they offered “another example of racial disparities in maternal and neonatal health.” She said: “We’re calling for all pregnant women and birthing people to be informed about GBS and its risks, so they can make empowered choices for themselves and their baby. It is also critical that trusts sign up to take part in the internationally significant [National Institute for Health and Care Research]–funded GBS3 clinical trial, designed to improve the prevention of GBS infection.”

Baroness Shaista Gohir, chief executive of the Muslim Women’s Network, said: “With significantly higher rates of group B Strep infection in Black and Asian babies, greater efforts must be made to improve awareness among pregnant women within these communities.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape UK.

Health charities called for action to address racial health disparities after population-wide analysis by the UK Health Security Agency found that Black and Asian neonates had a significantly higher risk of early-onset group B streptococcal disease (GBS), compared with White infants.

One support group said more research was now needed to identify the cause of the disparity, and called for pregnant women to be better informed about the disease and what it could mean for them and their baby.

The study, published in Pediatrics, used UKHSA data on laboratory-confirmed infant group B streptococcal (iGBS) disease cases between Jan. 1, 2016, and Dec. 31, 2020, and were linked to hospital ethnicity records.

Cases of iGBS were defined as isolation of Streptococcus agalactiae from a normally sterile site at 0-6 days of life for early-onset iGBS and 7-90 days for late-onset disease.

Hospital data and parent-reported ethnicity

Researchers found 2,512 iGBS cases in England during the study period, 65.3% were early onset and 34.8% late onset, equivalent to 0.52 and 0.28 cases per 1000 live births respectively.

Researchers were able to link 85.6% of those to ethnicity. Among those 2,149 cases, Black infants had a 48% higher risk, and Asian infants a 40% higher risk of early onset iGBS, compared with White infants. Among those from an Asian background, the risk was 87% higher for Bangladeshi and 38% higher for Pakistani neonates.

Rates of early onset iGBS per 1,000 live births were 0.43 for White infants, 0.63 for Black infants, and 0.60 for those of Asian ethnicity.

In contrast, Indian infants had an early-onset rate of 0.47 per 1,000 live births, which was similar to White infants.

Black infants had 57% higher rates of late-onset iGBS (0.37) than White infants (0.24), the researchers reported.

The study authors highlighted previous research which found higher prevalence of group B streptococcal colonization in mothers from Black and some Asian ethnic groups, but lower prevalence in mothers from the Indian subcontinent. More research was needed to establish causes, the researchers said, including whether higher preterm birth rates in minority ethnic groups led to increased iGBS risk in neonates, or whether maternal group B streptococcal disease led to higher preterm birth rates and subsequent neonatal iGBS.

The researchers concluded: “Understanding the factors underpinning differences in rates of early-onset iGBS within south Asian groups in England may lead to new opportunities for prevention such as prioritized antenatal screening. Strategies to prevent neonatal iGBS must be tailored from high-quality quantitative and qualitative data to reach all women and protect all infants, irrespective of racial or ethnic background.”

‘Shocking but not surprising’

Commenting on the study, Edward Morris, president of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, said: “This research is striking reading, and is yet another example of how far we have to go to tackle health inequalities within women’s health care.”

Philip Steer, professor emeritus at Imperial College London, said that the results were “consistent with previous reports of higher GBS carriage and higher maternal and neonatal mortality rates in minority groups” and “emphasize the importance of studying not just whether, but why, these differences exist.” He added: “We need to understand the reasons for the differences before we can design much-needed intervention to eliminate them.”

Jane Plumb, chief executive of Group B Strep Support, called the findings “shocking, but unfortunately not surprising” and said that they offered “another example of racial disparities in maternal and neonatal health.” She said: “We’re calling for all pregnant women and birthing people to be informed about GBS and its risks, so they can make empowered choices for themselves and their baby. It is also critical that trusts sign up to take part in the internationally significant [National Institute for Health and Care Research]–funded GBS3 clinical trial, designed to improve the prevention of GBS infection.”

Baroness Shaista Gohir, chief executive of the Muslim Women’s Network, said: “With significantly higher rates of group B Strep infection in Black and Asian babies, greater efforts must be made to improve awareness among pregnant women within these communities.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape UK.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Poor physician access linked with unplanned return ED visits

Difficulty in accessing a family physician is associated with a higher risk for unplanned return visits to the emergency department among patients aged 75 years and older, new data indicate.