User login

News and Views that Matter to Pediatricians

The leading independent newspaper covering news and commentary in pediatrics.

‘Reassuring’ findings for second-generation antipsychotics during pregnancy

Second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) taken by pregnant women are linked to a low rate of adverse effects in their children, new research suggests.

Data from a large registry study of almost 2,000 women showed that 2.5% of the live births in a group that had been exposed to antipsychotics had confirmed major malformations compared with 2% of the live births in a non-exposed group. This translated into an estimated odds ratio of 1.5 for major malformations.

“The 2.5% absolute risk for major malformations is consistent with the estimates of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s national baseline rate of major malformations in the general population,” lead author Adele Viguera, MD, MPH, director of research for women’s mental health, Cleveland Clinic Neurological Institute, told this news organization.

“Our results are reassuring and suggest that second-generation antipsychotics, as a class, do not substantially increase the risk of major malformations,” Dr. Viguera said.

The findings were published online August 3 in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Safety data scarce

Despite the increasing use of SGAs to treat a “spectrum of psychiatric disorders,” relatively little data are available on the reproductive safety of these agents, Dr. Viguera said.

The National Pregnancy Registry for Atypical Antipsychotics (NPRAA) was established in 2008 to determine risk for major malformation among infants exposed to these medications during the first trimester, relative to a comparison group of unexposed infants of mothers with histories of psychiatric morbidity.

The NPRAA follows pregnant women (aged 18 to 45 years) with psychiatric illness who are exposed or unexposed to SGAs during pregnancy. Participants are recruited through nationwide provider referral, self-referral, and advertisement through the Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Women’s Mental Health website.

Specific data collected are shown in the following table.

Since publication of the first results in 2015, the sample size for the trial has increased – and the absolute and relative risk for major malformations observed in the study population are “more precise,” the investigators note. The current study presented updated previous findings.

Demographic differences

Of the 1,906 women who enrolled as of April 2020, 1,311 (mean age, 32.6 years; 81.3% White) completed the study and were eligible for inclusion in the analysis.

Although the groups had a virtually identical mean age, fewer women in the exposure group were married compared with those in the non-exposure group (77% vs. 90%, respectively) and fewer had a college education (71.2% vs. 87.8%). There was also a higher percentage of first-trimester cigarette smokers in the exposure group (18.4% vs. 5.1%).

On the other hand, more women in the non-exposure group used alcohol than in the exposure group (28.6% vs. 21.4%, respectively).

The most frequent psychiatric disorder in the exposure group was bipolar disorder (63.9%), followed by major depression (12.9%), anxiety (5.8%), and schizophrenia (4.5%). Only 11.4% of women in the non-exposure group were diagnosed with bipolar disorder, whereas 34.1% were diagnosed with major depression, 31.3% with anxiety, and none with schizophrenia.

Notably, a large percentage of women in both groups had a history of postpartum depression and/or psychosis (41.4% and 35.5%, respectively).

The most frequently used SGAs in the exposure group were quetiapine (Seroquel), aripiprazole (Abilify), and lurasidone (Latuda).

Participants in the exposure group had a higher age at initial onset of primary psychiatric diagnosis and a lower proportion of lifetime illness compared with those in the non-exposure group.

Major clinical implication?

Among 640 live births in the exposure group, which included 17 twin pregnancies and 1 triplet pregnancy, 2.5% reported major malformations. Among 704 live births in the control group, which included 14 twin pregnancies, 1.99% reported major malformations.

The estimated OR for major malformations comparing exposed and unexposed infants was 1.48 (95% confidence interval, 0.625-3.517).

The authors note that their findings were consistent with one of the largest studies to date, which included a nationwide sample of more than 1 million women. Its results showed that, among infants exposed to SGAs versus those who were not exposed, the estimated risk ratio after adjusting for psychiatric conditions was 1.05 (95% CI, 0.96-1.16).

Additionally, “a hallmark of a teratogen is that it tends to cause a specific type or pattern of malformations, and we found no preponderance of one single type of major malformation or specific pattern of malformations among the exposed and unexposed groups,” Dr. Viguera said

“A major clinical implication of these findings is that for women with major mood and/or psychotic disorders, treatment with an atypical antipsychotic during pregnancy may be the most prudent clinical decision, much as continued treatment is recommended for pregnant women with other serious and chronic medical conditions, such as epilepsy,” she added.

The concept of ‘satisficing’

Commenting on the study, Vivien Burt, MD, PhD, founder and director/consultant of the Women’s Life Center at the Resnick University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Neuropsychiatric Hospital, called the findings “reassuring.”

The results “support the conclusion that in pregnant women with serious psychiatric illnesses, the use of SGAs is often a better option than avoiding these medications and exposing both the women and their offspring to the adverse consequences of maternal mental illness,” she said.

An accompanying editorial co-authored by Dr. Burt and colleague Sonya Rasminsky, MD, introduced the concept of “satisficing” – a term coined by Herbert Simon, a behavioral economist and Nobel Laureate. “Satisficing” is a “decision-making strategy that aims for a satisfactory (‘good enough’) outcome rather than a perfect one.”

The concept applies to decision-making beyond the field of economics “and is critical to how physicians help patients make decisions when they are faced with multiple treatment options,” said Dr. Burt, a professor emeritus of psychiatry at UCLA.

“The goal of ‘satisficing’ is to plan for the most satisfactory outcome, knowing that there are always unknowns, so in an uncertain world, clinicians should carefully help their patients make decisions that will allow them to achieve an outcome they can best live with,” she noted.

The investigators note that their findings may not be generalizable to the larger population of women taking SGAs, given that their participants were “overwhelmingly White, married, and well-educated women.”

They add that enrollment into the NPRAA registry is ongoing and larger sample sizes will “further narrow the confidence interval around the risk estimates and allow for adjustment of likely sources of confounding.”

The NPRAA is supported by Alkermes, Johnson & Johnson/Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, SAGE Therapeutics, Teva Pharmaceuticals, and Aurobindo Pharma. Past sponsors of the NPRAA are listed in the original paper. Dr. Viguera receives research support from the NPRAA, Alkermes Biopharmaceuticals, Aurobindo Pharma, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Teva Pharmaceuticals, and SAGE Therapeutics and receives adviser/consulting fees from Up-to-Date. Dr. Burt has been a consultant/speaker for Sage Therapeutics. Dr. Rasminsky has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) taken by pregnant women are linked to a low rate of adverse effects in their children, new research suggests.

Data from a large registry study of almost 2,000 women showed that 2.5% of the live births in a group that had been exposed to antipsychotics had confirmed major malformations compared with 2% of the live births in a non-exposed group. This translated into an estimated odds ratio of 1.5 for major malformations.

“The 2.5% absolute risk for major malformations is consistent with the estimates of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s national baseline rate of major malformations in the general population,” lead author Adele Viguera, MD, MPH, director of research for women’s mental health, Cleveland Clinic Neurological Institute, told this news organization.

“Our results are reassuring and suggest that second-generation antipsychotics, as a class, do not substantially increase the risk of major malformations,” Dr. Viguera said.

The findings were published online August 3 in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Safety data scarce

Despite the increasing use of SGAs to treat a “spectrum of psychiatric disorders,” relatively little data are available on the reproductive safety of these agents, Dr. Viguera said.

The National Pregnancy Registry for Atypical Antipsychotics (NPRAA) was established in 2008 to determine risk for major malformation among infants exposed to these medications during the first trimester, relative to a comparison group of unexposed infants of mothers with histories of psychiatric morbidity.

The NPRAA follows pregnant women (aged 18 to 45 years) with psychiatric illness who are exposed or unexposed to SGAs during pregnancy. Participants are recruited through nationwide provider referral, self-referral, and advertisement through the Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Women’s Mental Health website.

Specific data collected are shown in the following table.

Since publication of the first results in 2015, the sample size for the trial has increased – and the absolute and relative risk for major malformations observed in the study population are “more precise,” the investigators note. The current study presented updated previous findings.

Demographic differences

Of the 1,906 women who enrolled as of April 2020, 1,311 (mean age, 32.6 years; 81.3% White) completed the study and were eligible for inclusion in the analysis.

Although the groups had a virtually identical mean age, fewer women in the exposure group were married compared with those in the non-exposure group (77% vs. 90%, respectively) and fewer had a college education (71.2% vs. 87.8%). There was also a higher percentage of first-trimester cigarette smokers in the exposure group (18.4% vs. 5.1%).

On the other hand, more women in the non-exposure group used alcohol than in the exposure group (28.6% vs. 21.4%, respectively).

The most frequent psychiatric disorder in the exposure group was bipolar disorder (63.9%), followed by major depression (12.9%), anxiety (5.8%), and schizophrenia (4.5%). Only 11.4% of women in the non-exposure group were diagnosed with bipolar disorder, whereas 34.1% were diagnosed with major depression, 31.3% with anxiety, and none with schizophrenia.

Notably, a large percentage of women in both groups had a history of postpartum depression and/or psychosis (41.4% and 35.5%, respectively).

The most frequently used SGAs in the exposure group were quetiapine (Seroquel), aripiprazole (Abilify), and lurasidone (Latuda).

Participants in the exposure group had a higher age at initial onset of primary psychiatric diagnosis and a lower proportion of lifetime illness compared with those in the non-exposure group.

Major clinical implication?

Among 640 live births in the exposure group, which included 17 twin pregnancies and 1 triplet pregnancy, 2.5% reported major malformations. Among 704 live births in the control group, which included 14 twin pregnancies, 1.99% reported major malformations.

The estimated OR for major malformations comparing exposed and unexposed infants was 1.48 (95% confidence interval, 0.625-3.517).

The authors note that their findings were consistent with one of the largest studies to date, which included a nationwide sample of more than 1 million women. Its results showed that, among infants exposed to SGAs versus those who were not exposed, the estimated risk ratio after adjusting for psychiatric conditions was 1.05 (95% CI, 0.96-1.16).

Additionally, “a hallmark of a teratogen is that it tends to cause a specific type or pattern of malformations, and we found no preponderance of one single type of major malformation or specific pattern of malformations among the exposed and unexposed groups,” Dr. Viguera said

“A major clinical implication of these findings is that for women with major mood and/or psychotic disorders, treatment with an atypical antipsychotic during pregnancy may be the most prudent clinical decision, much as continued treatment is recommended for pregnant women with other serious and chronic medical conditions, such as epilepsy,” she added.

The concept of ‘satisficing’

Commenting on the study, Vivien Burt, MD, PhD, founder and director/consultant of the Women’s Life Center at the Resnick University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Neuropsychiatric Hospital, called the findings “reassuring.”

The results “support the conclusion that in pregnant women with serious psychiatric illnesses, the use of SGAs is often a better option than avoiding these medications and exposing both the women and their offspring to the adverse consequences of maternal mental illness,” she said.

An accompanying editorial co-authored by Dr. Burt and colleague Sonya Rasminsky, MD, introduced the concept of “satisficing” – a term coined by Herbert Simon, a behavioral economist and Nobel Laureate. “Satisficing” is a “decision-making strategy that aims for a satisfactory (‘good enough’) outcome rather than a perfect one.”

The concept applies to decision-making beyond the field of economics “and is critical to how physicians help patients make decisions when they are faced with multiple treatment options,” said Dr. Burt, a professor emeritus of psychiatry at UCLA.

“The goal of ‘satisficing’ is to plan for the most satisfactory outcome, knowing that there are always unknowns, so in an uncertain world, clinicians should carefully help their patients make decisions that will allow them to achieve an outcome they can best live with,” she noted.

The investigators note that their findings may not be generalizable to the larger population of women taking SGAs, given that their participants were “overwhelmingly White, married, and well-educated women.”

They add that enrollment into the NPRAA registry is ongoing and larger sample sizes will “further narrow the confidence interval around the risk estimates and allow for adjustment of likely sources of confounding.”

The NPRAA is supported by Alkermes, Johnson & Johnson/Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, SAGE Therapeutics, Teva Pharmaceuticals, and Aurobindo Pharma. Past sponsors of the NPRAA are listed in the original paper. Dr. Viguera receives research support from the NPRAA, Alkermes Biopharmaceuticals, Aurobindo Pharma, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Teva Pharmaceuticals, and SAGE Therapeutics and receives adviser/consulting fees from Up-to-Date. Dr. Burt has been a consultant/speaker for Sage Therapeutics. Dr. Rasminsky has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) taken by pregnant women are linked to a low rate of adverse effects in their children, new research suggests.

Data from a large registry study of almost 2,000 women showed that 2.5% of the live births in a group that had been exposed to antipsychotics had confirmed major malformations compared with 2% of the live births in a non-exposed group. This translated into an estimated odds ratio of 1.5 for major malformations.

“The 2.5% absolute risk for major malformations is consistent with the estimates of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s national baseline rate of major malformations in the general population,” lead author Adele Viguera, MD, MPH, director of research for women’s mental health, Cleveland Clinic Neurological Institute, told this news organization.

“Our results are reassuring and suggest that second-generation antipsychotics, as a class, do not substantially increase the risk of major malformations,” Dr. Viguera said.

The findings were published online August 3 in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Safety data scarce

Despite the increasing use of SGAs to treat a “spectrum of psychiatric disorders,” relatively little data are available on the reproductive safety of these agents, Dr. Viguera said.

The National Pregnancy Registry for Atypical Antipsychotics (NPRAA) was established in 2008 to determine risk for major malformation among infants exposed to these medications during the first trimester, relative to a comparison group of unexposed infants of mothers with histories of psychiatric morbidity.

The NPRAA follows pregnant women (aged 18 to 45 years) with psychiatric illness who are exposed or unexposed to SGAs during pregnancy. Participants are recruited through nationwide provider referral, self-referral, and advertisement through the Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Women’s Mental Health website.

Specific data collected are shown in the following table.

Since publication of the first results in 2015, the sample size for the trial has increased – and the absolute and relative risk for major malformations observed in the study population are “more precise,” the investigators note. The current study presented updated previous findings.

Demographic differences

Of the 1,906 women who enrolled as of April 2020, 1,311 (mean age, 32.6 years; 81.3% White) completed the study and were eligible for inclusion in the analysis.

Although the groups had a virtually identical mean age, fewer women in the exposure group were married compared with those in the non-exposure group (77% vs. 90%, respectively) and fewer had a college education (71.2% vs. 87.8%). There was also a higher percentage of first-trimester cigarette smokers in the exposure group (18.4% vs. 5.1%).

On the other hand, more women in the non-exposure group used alcohol than in the exposure group (28.6% vs. 21.4%, respectively).

The most frequent psychiatric disorder in the exposure group was bipolar disorder (63.9%), followed by major depression (12.9%), anxiety (5.8%), and schizophrenia (4.5%). Only 11.4% of women in the non-exposure group were diagnosed with bipolar disorder, whereas 34.1% were diagnosed with major depression, 31.3% with anxiety, and none with schizophrenia.

Notably, a large percentage of women in both groups had a history of postpartum depression and/or psychosis (41.4% and 35.5%, respectively).

The most frequently used SGAs in the exposure group were quetiapine (Seroquel), aripiprazole (Abilify), and lurasidone (Latuda).

Participants in the exposure group had a higher age at initial onset of primary psychiatric diagnosis and a lower proportion of lifetime illness compared with those in the non-exposure group.

Major clinical implication?

Among 640 live births in the exposure group, which included 17 twin pregnancies and 1 triplet pregnancy, 2.5% reported major malformations. Among 704 live births in the control group, which included 14 twin pregnancies, 1.99% reported major malformations.

The estimated OR for major malformations comparing exposed and unexposed infants was 1.48 (95% confidence interval, 0.625-3.517).

The authors note that their findings were consistent with one of the largest studies to date, which included a nationwide sample of more than 1 million women. Its results showed that, among infants exposed to SGAs versus those who were not exposed, the estimated risk ratio after adjusting for psychiatric conditions was 1.05 (95% CI, 0.96-1.16).

Additionally, “a hallmark of a teratogen is that it tends to cause a specific type or pattern of malformations, and we found no preponderance of one single type of major malformation or specific pattern of malformations among the exposed and unexposed groups,” Dr. Viguera said

“A major clinical implication of these findings is that for women with major mood and/or psychotic disorders, treatment with an atypical antipsychotic during pregnancy may be the most prudent clinical decision, much as continued treatment is recommended for pregnant women with other serious and chronic medical conditions, such as epilepsy,” she added.

The concept of ‘satisficing’

Commenting on the study, Vivien Burt, MD, PhD, founder and director/consultant of the Women’s Life Center at the Resnick University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Neuropsychiatric Hospital, called the findings “reassuring.”

The results “support the conclusion that in pregnant women with serious psychiatric illnesses, the use of SGAs is often a better option than avoiding these medications and exposing both the women and their offspring to the adverse consequences of maternal mental illness,” she said.

An accompanying editorial co-authored by Dr. Burt and colleague Sonya Rasminsky, MD, introduced the concept of “satisficing” – a term coined by Herbert Simon, a behavioral economist and Nobel Laureate. “Satisficing” is a “decision-making strategy that aims for a satisfactory (‘good enough’) outcome rather than a perfect one.”

The concept applies to decision-making beyond the field of economics “and is critical to how physicians help patients make decisions when they are faced with multiple treatment options,” said Dr. Burt, a professor emeritus of psychiatry at UCLA.

“The goal of ‘satisficing’ is to plan for the most satisfactory outcome, knowing that there are always unknowns, so in an uncertain world, clinicians should carefully help their patients make decisions that will allow them to achieve an outcome they can best live with,” she noted.

The investigators note that their findings may not be generalizable to the larger population of women taking SGAs, given that their participants were “overwhelmingly White, married, and well-educated women.”

They add that enrollment into the NPRAA registry is ongoing and larger sample sizes will “further narrow the confidence interval around the risk estimates and allow for adjustment of likely sources of confounding.”

The NPRAA is supported by Alkermes, Johnson & Johnson/Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, SAGE Therapeutics, Teva Pharmaceuticals, and Aurobindo Pharma. Past sponsors of the NPRAA are listed in the original paper. Dr. Viguera receives research support from the NPRAA, Alkermes Biopharmaceuticals, Aurobindo Pharma, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Teva Pharmaceuticals, and SAGE Therapeutics and receives adviser/consulting fees from Up-to-Date. Dr. Burt has been a consultant/speaker for Sage Therapeutics. Dr. Rasminsky has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AAP ‘silencing debate’ on gender dysphoria, says doctor group

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) is at the center of a row with an international group of doctors who question whether hormone treatment is the most appropriate way to treat adolescents with gender dysphoria.

After initially accepting the application and payment from the Society for Evidence-Based Gender Medicine (SEGM) for the organization to have an information booth at the AAP annual meeting in October, the AAP did a U-turn earlier this month and canceled the registration, with no explanation as to why.

“Just days earlier,” says SEGM in a statement on its website, “over 80% of AAP members” had indicated they wanted more discussion on the topic of “addressing alternatives to the use of hormone therapies for gender dysphoric youth.”

“This rejection sends a strong signal that the AAP does not want to see any debate on what constitutes evidence-based care for gender-diverse youth,” they add.

Asked for an explanation as to why it accepted but later rescinded SEGM’s application for a booth, the AAP has given no response to date.

A Wall Street Journal article on the furor, published last week, has clocked up 785 comments to date.

There has been an exponential increase in the number of adolescents who identify as transgender – reporting discomfort with their birth sex – in Western countries, and the debate has been covered in detail, having intensified worldwide in the last 12 months, regarding how best to treat youth with gender dysphoria.

Although “affirmative” medical care, defined as treatment with puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones to transition to the opposite sex, is supported by the AAP and other medical organizations, there is growing concern among many doctors and other health care professionals as to whether this is, in fact, the best way to proceed, given that there are a number of irreversible changes associated with treatment. There is also a growing number of “detransitioners” – mostly young people who transitioned and then changed their minds, and “detransitioned” back to their birth sex.

“Because of the low quality of the available evidence and the marked change in the presentation of gender dysphoria in youth in the last several years (many more adolescents with recently emerging transgender identities and significant mental health comorbidities are presenting for care), what constitutes good health care for this patient group is far from clear,” notes SEGM.

“Quelling the debate will not help America’s pediatricians guide patients and their families based on best available evidence. The politicization of the field of gender medicine must end, if we care about gender-variant youth and their long-term health,” they conclude.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) is at the center of a row with an international group of doctors who question whether hormone treatment is the most appropriate way to treat adolescents with gender dysphoria.

After initially accepting the application and payment from the Society for Evidence-Based Gender Medicine (SEGM) for the organization to have an information booth at the AAP annual meeting in October, the AAP did a U-turn earlier this month and canceled the registration, with no explanation as to why.

“Just days earlier,” says SEGM in a statement on its website, “over 80% of AAP members” had indicated they wanted more discussion on the topic of “addressing alternatives to the use of hormone therapies for gender dysphoric youth.”

“This rejection sends a strong signal that the AAP does not want to see any debate on what constitutes evidence-based care for gender-diverse youth,” they add.

Asked for an explanation as to why it accepted but later rescinded SEGM’s application for a booth, the AAP has given no response to date.

A Wall Street Journal article on the furor, published last week, has clocked up 785 comments to date.

There has been an exponential increase in the number of adolescents who identify as transgender – reporting discomfort with their birth sex – in Western countries, and the debate has been covered in detail, having intensified worldwide in the last 12 months, regarding how best to treat youth with gender dysphoria.

Although “affirmative” medical care, defined as treatment with puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones to transition to the opposite sex, is supported by the AAP and other medical organizations, there is growing concern among many doctors and other health care professionals as to whether this is, in fact, the best way to proceed, given that there are a number of irreversible changes associated with treatment. There is also a growing number of “detransitioners” – mostly young people who transitioned and then changed their minds, and “detransitioned” back to their birth sex.

“Because of the low quality of the available evidence and the marked change in the presentation of gender dysphoria in youth in the last several years (many more adolescents with recently emerging transgender identities and significant mental health comorbidities are presenting for care), what constitutes good health care for this patient group is far from clear,” notes SEGM.

“Quelling the debate will not help America’s pediatricians guide patients and their families based on best available evidence. The politicization of the field of gender medicine must end, if we care about gender-variant youth and their long-term health,” they conclude.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) is at the center of a row with an international group of doctors who question whether hormone treatment is the most appropriate way to treat adolescents with gender dysphoria.

After initially accepting the application and payment from the Society for Evidence-Based Gender Medicine (SEGM) for the organization to have an information booth at the AAP annual meeting in October, the AAP did a U-turn earlier this month and canceled the registration, with no explanation as to why.

“Just days earlier,” says SEGM in a statement on its website, “over 80% of AAP members” had indicated they wanted more discussion on the topic of “addressing alternatives to the use of hormone therapies for gender dysphoric youth.”

“This rejection sends a strong signal that the AAP does not want to see any debate on what constitutes evidence-based care for gender-diverse youth,” they add.

Asked for an explanation as to why it accepted but later rescinded SEGM’s application for a booth, the AAP has given no response to date.

A Wall Street Journal article on the furor, published last week, has clocked up 785 comments to date.

There has been an exponential increase in the number of adolescents who identify as transgender – reporting discomfort with their birth sex – in Western countries, and the debate has been covered in detail, having intensified worldwide in the last 12 months, regarding how best to treat youth with gender dysphoria.

Although “affirmative” medical care, defined as treatment with puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones to transition to the opposite sex, is supported by the AAP and other medical organizations, there is growing concern among many doctors and other health care professionals as to whether this is, in fact, the best way to proceed, given that there are a number of irreversible changes associated with treatment. There is also a growing number of “detransitioners” – mostly young people who transitioned and then changed their minds, and “detransitioned” back to their birth sex.

“Because of the low quality of the available evidence and the marked change in the presentation of gender dysphoria in youth in the last several years (many more adolescents with recently emerging transgender identities and significant mental health comorbidities are presenting for care), what constitutes good health care for this patient group is far from clear,” notes SEGM.

“Quelling the debate will not help America’s pediatricians guide patients and their families based on best available evidence. The politicization of the field of gender medicine must end, if we care about gender-variant youth and their long-term health,” they conclude.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

What’s under my toenail?

After the teledermatology consultation, an x-ray was recommended. The x-ray showed an elongated irregular radiopaque mass projecting from the anterior medial aspect of the midshaft of the distal phalanx of the great toe (Picture 3). With these findings, subungual exostosis was suspected, and she was referred to orthopedic surgery for excision of the lesion. Histopathology showed a stack of trabecular bone with a fibrocartilaginous cap, confirming the diagnosis of subungual exostosis.

Subungual exostosis is a benign osteocartilaginous tumor, first described by Dupuytren in 1874. These lesions are rare and are seen mainly in children and young adults. Females appear to be affected more often than males.1 In a systematic review by DaCambra and colleagues, 55% of the cases occur in patients aged younger than 18 years, and the hallux was the most commonly affected digit, though any finger or toe can be affected.2 There are reported case of congenital multiple exostosis delineated to translocation t(X;6)(q22;q13-14).3

The exact cause of these lesions is unknown, but there are multiple theories, which include a reactive process secondary to trauma, infection, or genetic causes. Pathologic examination of the lesions shows an osseous center covered by a fibrocartilaginous cap. There is proliferation of spindle cells that generate cartilage, which later forms trabecular bone.4

On physical examination, subungual exostosis appear like a firm, fixed nodule with a hyperkeratotic smooth surface at the distal end of the nail bed, that slowly grows and can distort and lift up the nail. Dermoscopy features of these lesions include vascular ectasia, hyperkeratosis, onycholysis, and ulceration.

The differential diagnosis of subungual growths includes osteochondromas, which can present in a similar way but are rarer. Pathologic examination is usually required to differentiate between both lesions.5 In exostoses, bone is formed directly from fibrous tissue, whereas in osteochondromas they derive from enchondral ossification.6 The cartilaginous cap of this lesion is what helps to differentiate it in histopathology. In subungual exostosis, the cap is composed of fibrocartilage, while in osteochondromas it is made of hyaline cartilage similar to what is seen in normal growing epiphysis.5 Subungual exostosis can be confused with pyogenic granulomas and verruca, and often are treated as such, which delays appropriate surgical management.

Firm, slow-growing tumors in the fingers or toes of children should raise suspicion for underlying bony lesions like subungual exostosis and osteochondromas. X-rays of the lesion should be performed in order to clarify the diagnosis. Referral to orthopedic surgery is needed for definitive surgical management.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

References

1. Zhang W et al. JAAD Case Rep. 2020 Jun 1;6(8):725-6.

2. DaCambra MP et al. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014 Apr;472(4):1251-9.

3. Torlazzi C et al. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:1972-6.

4. Calonje E et al. McKee’s pathology of the skin: With clinical correlations. (4th ed.) Philadelphia: Elsevier/Saunders, 2012.

5. Lee SK et al. Foot Ankle Int. 2007 May;28(5):595-601.

6. Mavrogenis A et al. Orthopedics. 2008 Oct;31(10).

After the teledermatology consultation, an x-ray was recommended. The x-ray showed an elongated irregular radiopaque mass projecting from the anterior medial aspect of the midshaft of the distal phalanx of the great toe (Picture 3). With these findings, subungual exostosis was suspected, and she was referred to orthopedic surgery for excision of the lesion. Histopathology showed a stack of trabecular bone with a fibrocartilaginous cap, confirming the diagnosis of subungual exostosis.

Subungual exostosis is a benign osteocartilaginous tumor, first described by Dupuytren in 1874. These lesions are rare and are seen mainly in children and young adults. Females appear to be affected more often than males.1 In a systematic review by DaCambra and colleagues, 55% of the cases occur in patients aged younger than 18 years, and the hallux was the most commonly affected digit, though any finger or toe can be affected.2 There are reported case of congenital multiple exostosis delineated to translocation t(X;6)(q22;q13-14).3

The exact cause of these lesions is unknown, but there are multiple theories, which include a reactive process secondary to trauma, infection, or genetic causes. Pathologic examination of the lesions shows an osseous center covered by a fibrocartilaginous cap. There is proliferation of spindle cells that generate cartilage, which later forms trabecular bone.4

On physical examination, subungual exostosis appear like a firm, fixed nodule with a hyperkeratotic smooth surface at the distal end of the nail bed, that slowly grows and can distort and lift up the nail. Dermoscopy features of these lesions include vascular ectasia, hyperkeratosis, onycholysis, and ulceration.

The differential diagnosis of subungual growths includes osteochondromas, which can present in a similar way but are rarer. Pathologic examination is usually required to differentiate between both lesions.5 In exostoses, bone is formed directly from fibrous tissue, whereas in osteochondromas they derive from enchondral ossification.6 The cartilaginous cap of this lesion is what helps to differentiate it in histopathology. In subungual exostosis, the cap is composed of fibrocartilage, while in osteochondromas it is made of hyaline cartilage similar to what is seen in normal growing epiphysis.5 Subungual exostosis can be confused with pyogenic granulomas and verruca, and often are treated as such, which delays appropriate surgical management.

Firm, slow-growing tumors in the fingers or toes of children should raise suspicion for underlying bony lesions like subungual exostosis and osteochondromas. X-rays of the lesion should be performed in order to clarify the diagnosis. Referral to orthopedic surgery is needed for definitive surgical management.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

References

1. Zhang W et al. JAAD Case Rep. 2020 Jun 1;6(8):725-6.

2. DaCambra MP et al. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014 Apr;472(4):1251-9.

3. Torlazzi C et al. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:1972-6.

4. Calonje E et al. McKee’s pathology of the skin: With clinical correlations. (4th ed.) Philadelphia: Elsevier/Saunders, 2012.

5. Lee SK et al. Foot Ankle Int. 2007 May;28(5):595-601.

6. Mavrogenis A et al. Orthopedics. 2008 Oct;31(10).

After the teledermatology consultation, an x-ray was recommended. The x-ray showed an elongated irregular radiopaque mass projecting from the anterior medial aspect of the midshaft of the distal phalanx of the great toe (Picture 3). With these findings, subungual exostosis was suspected, and she was referred to orthopedic surgery for excision of the lesion. Histopathology showed a stack of trabecular bone with a fibrocartilaginous cap, confirming the diagnosis of subungual exostosis.

Subungual exostosis is a benign osteocartilaginous tumor, first described by Dupuytren in 1874. These lesions are rare and are seen mainly in children and young adults. Females appear to be affected more often than males.1 In a systematic review by DaCambra and colleagues, 55% of the cases occur in patients aged younger than 18 years, and the hallux was the most commonly affected digit, though any finger or toe can be affected.2 There are reported case of congenital multiple exostosis delineated to translocation t(X;6)(q22;q13-14).3

The exact cause of these lesions is unknown, but there are multiple theories, which include a reactive process secondary to trauma, infection, or genetic causes. Pathologic examination of the lesions shows an osseous center covered by a fibrocartilaginous cap. There is proliferation of spindle cells that generate cartilage, which later forms trabecular bone.4

On physical examination, subungual exostosis appear like a firm, fixed nodule with a hyperkeratotic smooth surface at the distal end of the nail bed, that slowly grows and can distort and lift up the nail. Dermoscopy features of these lesions include vascular ectasia, hyperkeratosis, onycholysis, and ulceration.

The differential diagnosis of subungual growths includes osteochondromas, which can present in a similar way but are rarer. Pathologic examination is usually required to differentiate between both lesions.5 In exostoses, bone is formed directly from fibrous tissue, whereas in osteochondromas they derive from enchondral ossification.6 The cartilaginous cap of this lesion is what helps to differentiate it in histopathology. In subungual exostosis, the cap is composed of fibrocartilage, while in osteochondromas it is made of hyaline cartilage similar to what is seen in normal growing epiphysis.5 Subungual exostosis can be confused with pyogenic granulomas and verruca, and often are treated as such, which delays appropriate surgical management.

Firm, slow-growing tumors in the fingers or toes of children should raise suspicion for underlying bony lesions like subungual exostosis and osteochondromas. X-rays of the lesion should be performed in order to clarify the diagnosis. Referral to orthopedic surgery is needed for definitive surgical management.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

References

1. Zhang W et al. JAAD Case Rep. 2020 Jun 1;6(8):725-6.

2. DaCambra MP et al. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014 Apr;472(4):1251-9.

3. Torlazzi C et al. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:1972-6.

4. Calonje E et al. McKee’s pathology of the skin: With clinical correlations. (4th ed.) Philadelphia: Elsevier/Saunders, 2012.

5. Lee SK et al. Foot Ankle Int. 2007 May;28(5):595-601.

6. Mavrogenis A et al. Orthopedics. 2008 Oct;31(10).

A 13-year-old female was seen by her pediatrician for a lesion that had been on her right toe for about 6 months. She is unaware of any trauma to the area. The lesion has been growing slowly and recently it started lifting up the nail, became tender, and was bleeding, which is the reason why she sought care.

At the pediatrician's office, he noted a pink crusted papule under the nail. The nail was lifting up and was tender to the touch. She is a healthy girl who is not taking any medications and has no allergies. There is no family history of similar lesions.

The pediatrician took a picture of the lesion and he send it to our pediatric teledermatology service for consultation.

Children and COVID: New cases rise to winter levels

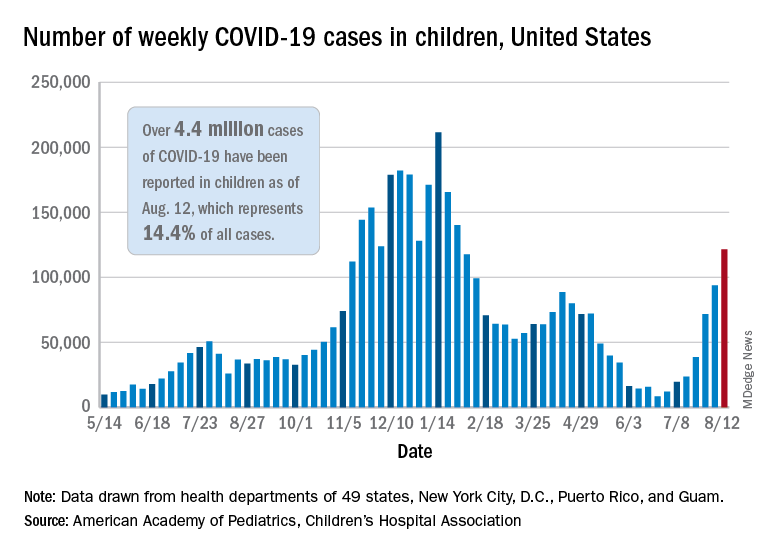

Weekly cases of COVID-19 in children topped 100,000 for the first time since early February, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVD-19 report. The recent surge in child COVID has also brought a record high in hospitalizations and shortages of pediatric ICU beds in some areas.

The 121,000 new cases represent an increase of almost 1,400% since June 18-24, when the weekly tally was just 8,447 and at its lowest point in over a year, the AAP/CHA data show.

On the vaccination front in the last week (Aug. 10-16), vaccine initiation for 12- to 17-year-olds was fairly robust but still down slightly, compared with the previous week. Just over 402,000 children aged 12-15 years received a first vaccination, which was down slightly from 411,000 the week before but still higher than any of the 6 weeks from June 22 to Aug. 2, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccinations were down by a similar margin for 15- to-17-year-olds.

Over 10.9 million children aged 12-17 have had at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine administered, of whom 8.1 million are fully vaccinated. Among those aged 12-15 years, 44.5% have gotten at least one dose and 31.8% are fully vaccinated, with corresponding figures of 53.9% and 42.5% for 16- and 17-year-olds, according to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker.

The number of COVID-19 cases reported in children since the start of the pandemic is up to 4.4 million, which makes up 14.4% of all cases in the United States, the AAP and CHA said. Other cumulative figures through Aug. 12 include almost 18,000 hospitalizations – reported by 23 states and New York City – and 378 deaths – reported by 43 states, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

In the latest edition of their ongoing report, compiled using state data since the summer of 2020, the two groups noted that, “in the summer of 2021, some states have revised cases counts previously reported, begun reporting less frequently, or dropped metrics previously reported.” Among those states are Nebraska, which shut down its online COVID dashboard in late June, and Alabama, which stopped reporting cumulative cases and deaths after July 29.

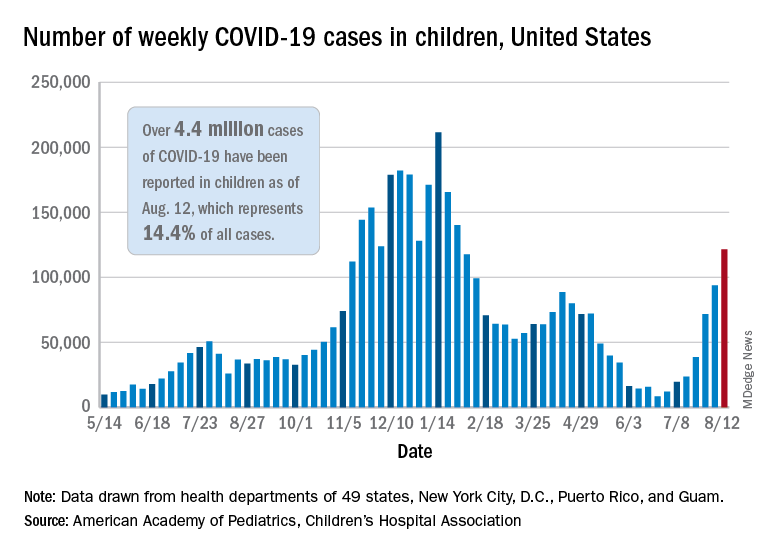

Weekly cases of COVID-19 in children topped 100,000 for the first time since early February, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVD-19 report. The recent surge in child COVID has also brought a record high in hospitalizations and shortages of pediatric ICU beds in some areas.

The 121,000 new cases represent an increase of almost 1,400% since June 18-24, when the weekly tally was just 8,447 and at its lowest point in over a year, the AAP/CHA data show.

On the vaccination front in the last week (Aug. 10-16), vaccine initiation for 12- to 17-year-olds was fairly robust but still down slightly, compared with the previous week. Just over 402,000 children aged 12-15 years received a first vaccination, which was down slightly from 411,000 the week before but still higher than any of the 6 weeks from June 22 to Aug. 2, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccinations were down by a similar margin for 15- to-17-year-olds.

Over 10.9 million children aged 12-17 have had at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine administered, of whom 8.1 million are fully vaccinated. Among those aged 12-15 years, 44.5% have gotten at least one dose and 31.8% are fully vaccinated, with corresponding figures of 53.9% and 42.5% for 16- and 17-year-olds, according to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker.

The number of COVID-19 cases reported in children since the start of the pandemic is up to 4.4 million, which makes up 14.4% of all cases in the United States, the AAP and CHA said. Other cumulative figures through Aug. 12 include almost 18,000 hospitalizations – reported by 23 states and New York City – and 378 deaths – reported by 43 states, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

In the latest edition of their ongoing report, compiled using state data since the summer of 2020, the two groups noted that, “in the summer of 2021, some states have revised cases counts previously reported, begun reporting less frequently, or dropped metrics previously reported.” Among those states are Nebraska, which shut down its online COVID dashboard in late June, and Alabama, which stopped reporting cumulative cases and deaths after July 29.

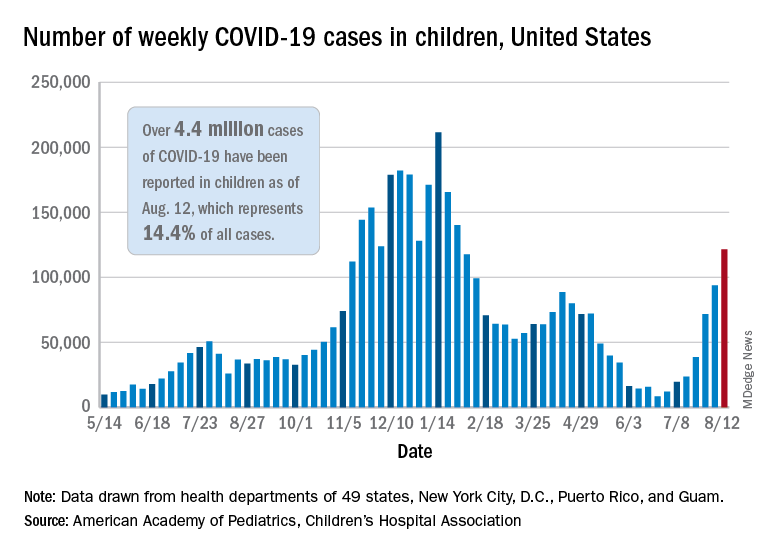

Weekly cases of COVID-19 in children topped 100,000 for the first time since early February, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVD-19 report. The recent surge in child COVID has also brought a record high in hospitalizations and shortages of pediatric ICU beds in some areas.

The 121,000 new cases represent an increase of almost 1,400% since June 18-24, when the weekly tally was just 8,447 and at its lowest point in over a year, the AAP/CHA data show.

On the vaccination front in the last week (Aug. 10-16), vaccine initiation for 12- to 17-year-olds was fairly robust but still down slightly, compared with the previous week. Just over 402,000 children aged 12-15 years received a first vaccination, which was down slightly from 411,000 the week before but still higher than any of the 6 weeks from June 22 to Aug. 2, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccinations were down by a similar margin for 15- to-17-year-olds.

Over 10.9 million children aged 12-17 have had at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine administered, of whom 8.1 million are fully vaccinated. Among those aged 12-15 years, 44.5% have gotten at least one dose and 31.8% are fully vaccinated, with corresponding figures of 53.9% and 42.5% for 16- and 17-year-olds, according to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker.

The number of COVID-19 cases reported in children since the start of the pandemic is up to 4.4 million, which makes up 14.4% of all cases in the United States, the AAP and CHA said. Other cumulative figures through Aug. 12 include almost 18,000 hospitalizations – reported by 23 states and New York City – and 378 deaths – reported by 43 states, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

In the latest edition of their ongoing report, compiled using state data since the summer of 2020, the two groups noted that, “in the summer of 2021, some states have revised cases counts previously reported, begun reporting less frequently, or dropped metrics previously reported.” Among those states are Nebraska, which shut down its online COVID dashboard in late June, and Alabama, which stopped reporting cumulative cases and deaths after July 29.

U.S. pediatric hospitals in peril as Delta hits children

Over the course of the pandemic, COVID-19 has been a less serious illness for children than it has been for adults, and that continues to be true. But with the arrival of Delta, the risk for kids is rising, and that’s creating a perilous situation for hospitals across the United States that treat them.

Roughly 1,800 kids were hospitalized with COVID-19 in the United States last week, a 500% increase in the rate of COVID-19 hospitalizations for children since early July, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Emerging data from a large study in Canada suggest that children who test positive for COVID-19 during the Delta wave may be more than twice as likely to be hospitalized as they were when previous variants were dominating transmission. The new data support what many pediatric infectious disease experts say they’ve been seeing: Younger kids with more serious symptoms.

That may sound concerning, but keep in mind that the overall risk of hospitalization for kids who have COVID-19 is still very low – about one child for every hundred who test positive for the virus will end up needing hospital care for their symptoms, according to current statistics maintained by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

‘This is different’

At Le Bonheur Children’s Hospital in Memphis, they saw Delta coming.

Since last year, every kid that comes to the emergency department at the hospital gets a screening test for COVID-19.

In past waves, doctors usually found kids who were infected by accident – they tested positive after coming in for some other problem, a broken leg or appendicitis, said Nick Hysmith, MD, medical director of infection prevention at the hospital. But within the last few weeks, kids with fevers, sore throats, coughs, and runny noses started testing positive for COVID-19.

“We have seen our positive numbers go from, you know, close to about 8%-10% jump up to 20%, and then in recent weeks, we can get as high as 26% or 30%,” Dr. Hysmith said. “Then we started seeing kids sick enough to be admitted.”

“Over the last week, we’ve really seen an increase,” he said. As of August 16, the hospital had 24 children with COVID-19 admitted. Seven of the children were in the PICU, and two were on ventilators.

Arkansas Children’s Hospital had 23 young COVID-19 patients, 10 in intensive care, and five on ventilators, as of Friday, according to the Washington Post. At Children’s of Mississippi, the only hospital for kids in that state, 22 youth were hospitalized as of Monday, with three in intensive care as of August 16, according to the hospital. The nonprofit relief organization Samaritan’s Purse is setting up a second field hospital in the basement of Children’s to expand the hospital’s capacity.

“This is different,” Dr. Hysmith said. “What we’re seeing now is previously healthy kids coming in with symptomatic infection.”

This increased virulence is happening at a bad time. Schools around the United States are reopening for in-person classes, some for the first time in more than a year. Eight states have blocked districts from requiring masks, while many more have made them optional.

Children under 12 still have no access to a vaccine, so they are facing increased exposure to a germ that’s become more dangerous with little protection, especially in schools that have eschewed masks.

More than just COVID-19

Then there are the latent effects of the virus to contend with.

“We’re not only seeing more children now with acute SARS-CoV-2 in the hospital, we’re starting also to see an uptick of MISC – or Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children,” said Charlotte Hobbs, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Mississippi Children’s Hospital. “We are just beginning to [see] those cases, and we anticipate that’s going to get worse.”

Adding to COVID-19’s misery, another virus is also capitalizing on this increased mixing of kids back into the community. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) hospitalizes about 58,000 children under age 5 in the United States each year. The typical RSV season starts in the fall and peaks in February, along with influenza. This year, the RSV season is early, and it is ferocious.

The combination of the two infections is hitting children’s hospitals hard, and it’s layered on top of the indirect effects of the pandemic, such as the increased population of kids and teens who need mental health care in the wake of the crisis.

“It’s all these things happening at the same time,” said Mark Wietecha, CEO of the Children’s Hospital Association. “To have our hospitals this crowded in August is unusual.

And children’s hospitals are grappling with the same workforce shortages as hospitals that treat adults, while their pool of potential staff is much smaller.

“We can’t easily recruit physicians and nurses from adult hospitals in any practical way to staff a kids’ hospital,” Mr. Wietecha said.

Although pediatric doctors and nurses were trained to care for adults before they specialized, clinicians who primarily care for adults typically haven’t been taught how to care for kids.

Clinicians have fewer tools to fight COVID-19 infections in children than are available for adults.

“There have been many studies in terms of therapies and treatments for acute SARS-CoV-2 infection in adults. We have less data and information in children, and on top of that, some of these treatments aren’t even available under an EUA [emergency use authorization] to children: For example, the monoclonal antibodies,” Dr. Hobbs said.

Antibody treatments are being widely deployed to ease the pressure on hospitals that treat adults. But these therapies aren’t available for kids.

That means children’s hospitals could quickly become overwhelmed, especially in areas where community transmission is high, vaccination rates are low, and parents are screaming about masks.

“So we really have this constellation of events that really doesn’t favor children under the age of 12,” Dr. Hobbs said.

“Universal masking shouldn’t be a debate, because it’s the one thing, with adult vaccination, that can be done to protect this vulnerable population,” she said. “This isn’t a political issue. It’s a public health issue. Period.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Over the course of the pandemic, COVID-19 has been a less serious illness for children than it has been for adults, and that continues to be true. But with the arrival of Delta, the risk for kids is rising, and that’s creating a perilous situation for hospitals across the United States that treat them.

Roughly 1,800 kids were hospitalized with COVID-19 in the United States last week, a 500% increase in the rate of COVID-19 hospitalizations for children since early July, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Emerging data from a large study in Canada suggest that children who test positive for COVID-19 during the Delta wave may be more than twice as likely to be hospitalized as they were when previous variants were dominating transmission. The new data support what many pediatric infectious disease experts say they’ve been seeing: Younger kids with more serious symptoms.

That may sound concerning, but keep in mind that the overall risk of hospitalization for kids who have COVID-19 is still very low – about one child for every hundred who test positive for the virus will end up needing hospital care for their symptoms, according to current statistics maintained by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

‘This is different’

At Le Bonheur Children’s Hospital in Memphis, they saw Delta coming.

Since last year, every kid that comes to the emergency department at the hospital gets a screening test for COVID-19.

In past waves, doctors usually found kids who were infected by accident – they tested positive after coming in for some other problem, a broken leg or appendicitis, said Nick Hysmith, MD, medical director of infection prevention at the hospital. But within the last few weeks, kids with fevers, sore throats, coughs, and runny noses started testing positive for COVID-19.

“We have seen our positive numbers go from, you know, close to about 8%-10% jump up to 20%, and then in recent weeks, we can get as high as 26% or 30%,” Dr. Hysmith said. “Then we started seeing kids sick enough to be admitted.”

“Over the last week, we’ve really seen an increase,” he said. As of August 16, the hospital had 24 children with COVID-19 admitted. Seven of the children were in the PICU, and two were on ventilators.

Arkansas Children’s Hospital had 23 young COVID-19 patients, 10 in intensive care, and five on ventilators, as of Friday, according to the Washington Post. At Children’s of Mississippi, the only hospital for kids in that state, 22 youth were hospitalized as of Monday, with three in intensive care as of August 16, according to the hospital. The nonprofit relief organization Samaritan’s Purse is setting up a second field hospital in the basement of Children’s to expand the hospital’s capacity.

“This is different,” Dr. Hysmith said. “What we’re seeing now is previously healthy kids coming in with symptomatic infection.”

This increased virulence is happening at a bad time. Schools around the United States are reopening for in-person classes, some for the first time in more than a year. Eight states have blocked districts from requiring masks, while many more have made them optional.

Children under 12 still have no access to a vaccine, so they are facing increased exposure to a germ that’s become more dangerous with little protection, especially in schools that have eschewed masks.

More than just COVID-19

Then there are the latent effects of the virus to contend with.

“We’re not only seeing more children now with acute SARS-CoV-2 in the hospital, we’re starting also to see an uptick of MISC – or Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children,” said Charlotte Hobbs, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Mississippi Children’s Hospital. “We are just beginning to [see] those cases, and we anticipate that’s going to get worse.”

Adding to COVID-19’s misery, another virus is also capitalizing on this increased mixing of kids back into the community. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) hospitalizes about 58,000 children under age 5 in the United States each year. The typical RSV season starts in the fall and peaks in February, along with influenza. This year, the RSV season is early, and it is ferocious.

The combination of the two infections is hitting children’s hospitals hard, and it’s layered on top of the indirect effects of the pandemic, such as the increased population of kids and teens who need mental health care in the wake of the crisis.

“It’s all these things happening at the same time,” said Mark Wietecha, CEO of the Children’s Hospital Association. “To have our hospitals this crowded in August is unusual.

And children’s hospitals are grappling with the same workforce shortages as hospitals that treat adults, while their pool of potential staff is much smaller.

“We can’t easily recruit physicians and nurses from adult hospitals in any practical way to staff a kids’ hospital,” Mr. Wietecha said.

Although pediatric doctors and nurses were trained to care for adults before they specialized, clinicians who primarily care for adults typically haven’t been taught how to care for kids.

Clinicians have fewer tools to fight COVID-19 infections in children than are available for adults.

“There have been many studies in terms of therapies and treatments for acute SARS-CoV-2 infection in adults. We have less data and information in children, and on top of that, some of these treatments aren’t even available under an EUA [emergency use authorization] to children: For example, the monoclonal antibodies,” Dr. Hobbs said.

Antibody treatments are being widely deployed to ease the pressure on hospitals that treat adults. But these therapies aren’t available for kids.

That means children’s hospitals could quickly become overwhelmed, especially in areas where community transmission is high, vaccination rates are low, and parents are screaming about masks.

“So we really have this constellation of events that really doesn’t favor children under the age of 12,” Dr. Hobbs said.

“Universal masking shouldn’t be a debate, because it’s the one thing, with adult vaccination, that can be done to protect this vulnerable population,” she said. “This isn’t a political issue. It’s a public health issue. Period.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Over the course of the pandemic, COVID-19 has been a less serious illness for children than it has been for adults, and that continues to be true. But with the arrival of Delta, the risk for kids is rising, and that’s creating a perilous situation for hospitals across the United States that treat them.

Roughly 1,800 kids were hospitalized with COVID-19 in the United States last week, a 500% increase in the rate of COVID-19 hospitalizations for children since early July, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Emerging data from a large study in Canada suggest that children who test positive for COVID-19 during the Delta wave may be more than twice as likely to be hospitalized as they were when previous variants were dominating transmission. The new data support what many pediatric infectious disease experts say they’ve been seeing: Younger kids with more serious symptoms.

That may sound concerning, but keep in mind that the overall risk of hospitalization for kids who have COVID-19 is still very low – about one child for every hundred who test positive for the virus will end up needing hospital care for their symptoms, according to current statistics maintained by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

‘This is different’

At Le Bonheur Children’s Hospital in Memphis, they saw Delta coming.

Since last year, every kid that comes to the emergency department at the hospital gets a screening test for COVID-19.

In past waves, doctors usually found kids who were infected by accident – they tested positive after coming in for some other problem, a broken leg or appendicitis, said Nick Hysmith, MD, medical director of infection prevention at the hospital. But within the last few weeks, kids with fevers, sore throats, coughs, and runny noses started testing positive for COVID-19.

“We have seen our positive numbers go from, you know, close to about 8%-10% jump up to 20%, and then in recent weeks, we can get as high as 26% or 30%,” Dr. Hysmith said. “Then we started seeing kids sick enough to be admitted.”

“Over the last week, we’ve really seen an increase,” he said. As of August 16, the hospital had 24 children with COVID-19 admitted. Seven of the children were in the PICU, and two were on ventilators.

Arkansas Children’s Hospital had 23 young COVID-19 patients, 10 in intensive care, and five on ventilators, as of Friday, according to the Washington Post. At Children’s of Mississippi, the only hospital for kids in that state, 22 youth were hospitalized as of Monday, with three in intensive care as of August 16, according to the hospital. The nonprofit relief organization Samaritan’s Purse is setting up a second field hospital in the basement of Children’s to expand the hospital’s capacity.

“This is different,” Dr. Hysmith said. “What we’re seeing now is previously healthy kids coming in with symptomatic infection.”

This increased virulence is happening at a bad time. Schools around the United States are reopening for in-person classes, some for the first time in more than a year. Eight states have blocked districts from requiring masks, while many more have made them optional.

Children under 12 still have no access to a vaccine, so they are facing increased exposure to a germ that’s become more dangerous with little protection, especially in schools that have eschewed masks.

More than just COVID-19

Then there are the latent effects of the virus to contend with.

“We’re not only seeing more children now with acute SARS-CoV-2 in the hospital, we’re starting also to see an uptick of MISC – or Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children,” said Charlotte Hobbs, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Mississippi Children’s Hospital. “We are just beginning to [see] those cases, and we anticipate that’s going to get worse.”

Adding to COVID-19’s misery, another virus is also capitalizing on this increased mixing of kids back into the community. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) hospitalizes about 58,000 children under age 5 in the United States each year. The typical RSV season starts in the fall and peaks in February, along with influenza. This year, the RSV season is early, and it is ferocious.

The combination of the two infections is hitting children’s hospitals hard, and it’s layered on top of the indirect effects of the pandemic, such as the increased population of kids and teens who need mental health care in the wake of the crisis.

“It’s all these things happening at the same time,” said Mark Wietecha, CEO of the Children’s Hospital Association. “To have our hospitals this crowded in August is unusual.

And children’s hospitals are grappling with the same workforce shortages as hospitals that treat adults, while their pool of potential staff is much smaller.

“We can’t easily recruit physicians and nurses from adult hospitals in any practical way to staff a kids’ hospital,” Mr. Wietecha said.

Although pediatric doctors and nurses were trained to care for adults before they specialized, clinicians who primarily care for adults typically haven’t been taught how to care for kids.

Clinicians have fewer tools to fight COVID-19 infections in children than are available for adults.

“There have been many studies in terms of therapies and treatments for acute SARS-CoV-2 infection in adults. We have less data and information in children, and on top of that, some of these treatments aren’t even available under an EUA [emergency use authorization] to children: For example, the monoclonal antibodies,” Dr. Hobbs said.

Antibody treatments are being widely deployed to ease the pressure on hospitals that treat adults. But these therapies aren’t available for kids.

That means children’s hospitals could quickly become overwhelmed, especially in areas where community transmission is high, vaccination rates are low, and parents are screaming about masks.

“So we really have this constellation of events that really doesn’t favor children under the age of 12,” Dr. Hobbs said.

“Universal masking shouldn’t be a debate, because it’s the one thing, with adult vaccination, that can be done to protect this vulnerable population,” she said. “This isn’t a political issue. It’s a public health issue. Period.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Youngest children more likely to spread SARS-CoV-2 to family: Study

Young children are more likely than are their older siblings to transmit SARS-CoV-2 in their households, according to an analysis of public health records in Ontario, Canada – a finding that upends the common belief that children play a minimal role in COVID-19 spread.

The study by researchers from Public Health Ontario, published online in JAMA Pediatrics, found that teenagers (14- to 17-year-olds) were more likely than were their younger siblings to bring the virus into the household, while infants and toddlers (up to age 3) were about 43% more likely than were the older teens to spread it to others in the home.

Children or teens were the source of SARS-CoV-2 in about 1 in 13 Ontario households between June and December 2020, the study shows. The researchers analyzed health records from 6,280 households with a pediatric COVID-19 case and a subset of 1,717 households in which a child up to age 17 was the source of transmission in a household.

When analyzing the data, the researchers controlled for gender differences, month of disease onset, testing delay, and mean family size.

The role of young children in transmission seemed logical to some experts who have been tracking the evolution of the pandemic. “I think what was more surprising was how long the narrative persisted that children weren’t transmitting SARS-CoV-2,” said Samuel Scarpino, PhD, managing director of pathogen surveillance at the Rockefeller Foundation.

Meanwhile, less mask-wearing, the return to school and activities, and the onslaught of the Delta variant have changed the dynamics of spread, said Andrew Pavia, MD, chief of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at the University of Utah.

“Adolescents and high-school-aged kids have had much, much higher rates of infection in the past,” he said. “Now when we look at the rates of school-aged kids, they are the same as high-school-aged kids, and we’re seeing more and more in the preschool age groups.”

Cases may be underestimated

If anything, the study may underestimate the role young children play in spreading COVID-19 in families, since it included only symptomatic cases as the initial source and young children are more likely to be asymptomatic, Dr. Pavia said.

The Delta variant heightens the concern; it is more than twice as infectious as previous strains and has spurred a rise in pediatric cases, including some coinfection with other circulating respiratory diseases, such as respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).

The Ontario study covers a period before vaccination and the spread of the Delta variant. “As the number of pediatric cases increases worldwide, the role of children in household transmission will continue to grow,” the authors concluded.

Following recommended respiratory hygiene is clearly more difficult with very young children. For example, parents, caregivers, and older siblings aren’t going to stay 6 feet away from a sick baby or toddler, Susan Coffin, MD, MPH, a pediatric infectious disease physician, and David Rubin, MD, a pediatrician and director of PolicyLab at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, noted in an accompanying commentary.

“Cuddling and touching are part and parcel of taking care of a sick young child, and that will obviously come with an increased risk of transmission to parents as well as to older siblings who may be helping to care for their sick brother or sister,” they wrote.

While parents may wash their hands more frequently when caring for a sick child, they aren’t likely to wear a mask, said William Schaffner, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn.

“I imagine some moms even take a sick child into bed with them,” he said. “It’s probably just the extensive contact one has with a sick, very small child that augments their capacity to transmit this infection.”

What can be done

What can be done, then, to reduce the household spread of COVID-19? “The obvious solution to protect a household with a sick young infant or toddler is to make sure that all eligible members of the household are vaccinated,” Dr. Coffin and Dr. Rubin stated in their commentary.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recently wrote to Janet Woodcock, MD, acting commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration, asking for the agency to authorize use of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines for children under age 12 “as soon as possible,” noting that “the Delta variant has created a new and pressing risk to children and adolescents across this country, as it has also done for unvaccinated adults.”

The FDA reportedly asked vaccine makers Pfizer and Moderna to expand the clinical trials of children, which may delay authorization for younger age groups. Pfizer has said it plans to submit a request for emergency use authorization of its vaccine for 5- to 11-year-olds in September or October.

As with adult vaccination, hesitancy is likely to be a barrier. Less than half of parents said they are very or somewhat likely to have their children get a COVID-19 vaccine, according to a national survey conducted by researchers at the University of California, Los Angeles.

The Ontario study provides valuable evidence to support taking steps to protect children from transmission in schools, including mask requirements, frequent testing, and improved ventilation, said Dr. Scarpino.

“We’re not going to be able to control COVID without vaccinating younger individuals,” he said.

Dr. Pavia has consulted for GlaxoSmithKline on non–COVID-19–related issues. Sarah Buchan, PhD, study author and scientist at Public Health Ontario, reported grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research for research on influenza, RSV, and COVID-19, and grants from the Canadian Immunity Task Force for COVID-19 outside the submitted work. Dr. Coffin reported grants as a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention coinvestigator at a Vaccine and Treatment Evaluation Unit site conducting COVID-19 vaccine trials in children. Dr. Scarpino holds unexercised options in ILiAD Biotechnologies, which is focused on the prevention and treatment of pertussis. Dr. Schaffner is a consultant for VBI Vaccines.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Young children are more likely than are their older siblings to transmit SARS-CoV-2 in their households, according to an analysis of public health records in Ontario, Canada – a finding that upends the common belief that children play a minimal role in COVID-19 spread.

The study by researchers from Public Health Ontario, published online in JAMA Pediatrics, found that teenagers (14- to 17-year-olds) were more likely than were their younger siblings to bring the virus into the household, while infants and toddlers (up to age 3) were about 43% more likely than were the older teens to spread it to others in the home.

Children or teens were the source of SARS-CoV-2 in about 1 in 13 Ontario households between June and December 2020, the study shows. The researchers analyzed health records from 6,280 households with a pediatric COVID-19 case and a subset of 1,717 households in which a child up to age 17 was the source of transmission in a household.

When analyzing the data, the researchers controlled for gender differences, month of disease onset, testing delay, and mean family size.

The role of young children in transmission seemed logical to some experts who have been tracking the evolution of the pandemic. “I think what was more surprising was how long the narrative persisted that children weren’t transmitting SARS-CoV-2,” said Samuel Scarpino, PhD, managing director of pathogen surveillance at the Rockefeller Foundation.

Meanwhile, less mask-wearing, the return to school and activities, and the onslaught of the Delta variant have changed the dynamics of spread, said Andrew Pavia, MD, chief of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at the University of Utah.

“Adolescents and high-school-aged kids have had much, much higher rates of infection in the past,” he said. “Now when we look at the rates of school-aged kids, they are the same as high-school-aged kids, and we’re seeing more and more in the preschool age groups.”

Cases may be underestimated

If anything, the study may underestimate the role young children play in spreading COVID-19 in families, since it included only symptomatic cases as the initial source and young children are more likely to be asymptomatic, Dr. Pavia said.

The Delta variant heightens the concern; it is more than twice as infectious as previous strains and has spurred a rise in pediatric cases, including some coinfection with other circulating respiratory diseases, such as respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).

The Ontario study covers a period before vaccination and the spread of the Delta variant. “As the number of pediatric cases increases worldwide, the role of children in household transmission will continue to grow,” the authors concluded.

Following recommended respiratory hygiene is clearly more difficult with very young children. For example, parents, caregivers, and older siblings aren’t going to stay 6 feet away from a sick baby or toddler, Susan Coffin, MD, MPH, a pediatric infectious disease physician, and David Rubin, MD, a pediatrician and director of PolicyLab at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, noted in an accompanying commentary.

“Cuddling and touching are part and parcel of taking care of a sick young child, and that will obviously come with an increased risk of transmission to parents as well as to older siblings who may be helping to care for their sick brother or sister,” they wrote.

While parents may wash their hands more frequently when caring for a sick child, they aren’t likely to wear a mask, said William Schaffner, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn.

“I imagine some moms even take a sick child into bed with them,” he said. “It’s probably just the extensive contact one has with a sick, very small child that augments their capacity to transmit this infection.”

What can be done