User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

The challenges of managing CMV infection during pregnancy

CASE Anomalous findings on fetal anatomic survey

A 27-year-old previously healthy primigravid woman is at 18 weeks’ gestation. She is a first-grade schoolteacher. On her fetal anatomic survey, the estimated fetal weight was in the eighth percentile. Echogenic bowel and a small amount of ascitic fluid were noted in the fetal abdomen. The lateral and third ventricles were mildly dilated, the head circumference was 2 standard deviations below normal, and the placenta was slightly thickened and edematous.

What is the most likely diagnosis?

What diagnostic tests are indicated?

What management options are available for this patient?

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is the most common of the perinatally transmitted infections, affecting 1% to 4% of all pregnancies. Although the virus typically causes either asymptomatic infection or only mild illness in immunocompetent individuals, it can cause life-threatening disease in immunocompromised persons and in the developing fetus. In this article, we review the virology and epidemiology of CMV infection and then focus on the key methods to diagnose infection in the mother and fetus. We conclude by considering measures that may be of at least modest value in treating CMV in pregnancy.

Virology of CMV infection

Cytomegalovirus is a double-stranded DNA virus in the Herpesviridae family. This ubiquitous virus is present in virtually all secretions and excretions of an infected host, including blood, urine, saliva, breast milk, genital secretions, and tissues and organs used for donation. Infection is transmitted through direct contact with any of the substances listed; contact with infected urine or saliva is the most common mode of transmission. Disease occurrence does not show seasonal variation.

After exposure, an incubation period of 28 to 60 days ensues, followed by development of viremia and clinical symptoms. In the majority of exposed individuals, CMV establishes a lifelong latent infection, and recurrent episodes of illness can occur as a result of reactivation of latent virus (also known as secondary infection) or, more rarely, infection with a new viral strain. In fact, most CMV illness episodes in pregnancy represent a reactivation of a previous infection rather than a new infection.

Following initial infection, both IgM (immunoglobulin M) and IgG (immunoglobulin G) antibodies develop rapidly and can be detected in blood within 1 to 2 weeks. IgM levels typically wane within 30 to 60 days, although persistence for several months is not unusual, and levels also can increase with viral reactivation (secondary infection). IgG antibodies typically persist for many years after a primary infection.

Intrauterine CMV infection occurs through hematogenous transplacental passage during maternal viremia. The risk of transmission and severity of fetal effects depend on whether or not the infection is primary or secondary in nature as well as the gestational age at fetal exposure.1,2

Additionally, postnatal vertical transmission can occur through exposure to viral particles in genital secretions as well as breast milk. CMV acquired in the postnatal period rarely produces severe sequelae in a healthy term neonate, but it has been associated with an increased rate of complications in very low birth weight and premature newborns.3

Continue to: Who is at risk...

Who is at risk

Congenital CMV, which occurs in 2.1 to 7.7 per 10,000 live births in the United States, is both the most common congenital infection and the leading cause of nonhereditary congenital hearing loss in children.4,5 The main reservoir of CMV in the United States is young children in day care settings, with approximately 50% of this population showing evidence of viral shedding in saliva.1 Adult populations in North America have a high prevalence of CMV IgG antibodies indicative of prior infection, with rates reaching 50% to 80%. Among seronegative individuals aged 12 to 49, the rate of seroconversion is approximately 1 in 60 annually.6 Significant racial disparities have been noted in rates of seroprevalence and seroconversion, with higher rates of infection in non-Hispanic Black and Mexican American individuals.6 Overall, the rate of new CMV infection among pregnant women in the United States is 0.7% to 4%.7

Clinical manifestations

Manifestations of infection differ depending on whether or not infection is primary or recurrent (secondary) and whether or not the host is immunocompetent or has a compromised immune system. Unique manifestations develop in the fetus.

CMV infection in children and adults. Among individuals with a normal immune response, the typical course of CMV is either no symptoms or a mononucleosis-like illness. In symptomatic patients, the most common symptoms include malaise, fever, and night sweats, and the most common associated laboratory abnormalities are elevation in liver function tests and a decreased white blood cell count, with a predominance of lymphocytes.8

Immunocompromised individuals are at risk for significant morbidity and mortality resulting from CMV. Illness may be the result of reactivation of latent infection due to decreased immune function or may be acquired as a result of treatment such as transplantation of CMV-positive organs or tissues, including bone marrow. Virtually any organ system can be affected, with potential for permanent organ damage and death. Severe systemic infection also can occur.

CMV infection in the fetus and neonate. As noted previously, fetal infection develops as a result of transplacental passage coincident with maternal infection. The risk of CMV transmission to the fetus and the severity of fetal injury vary based on gestational age at fetal infection and whether or not maternal infection is primary or secondary.

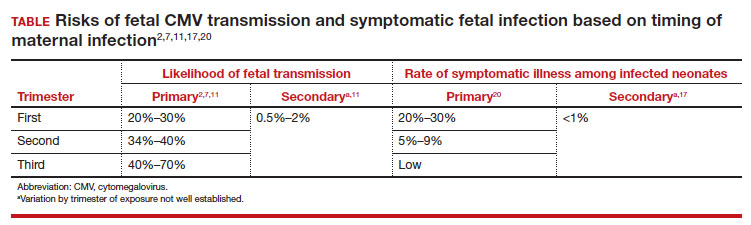

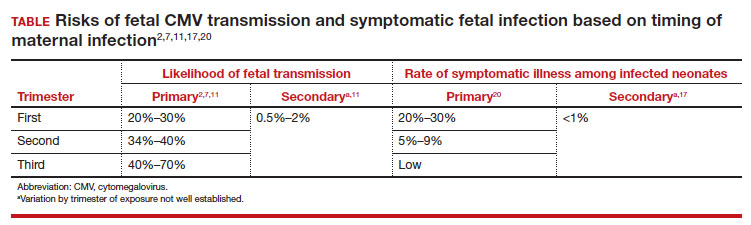

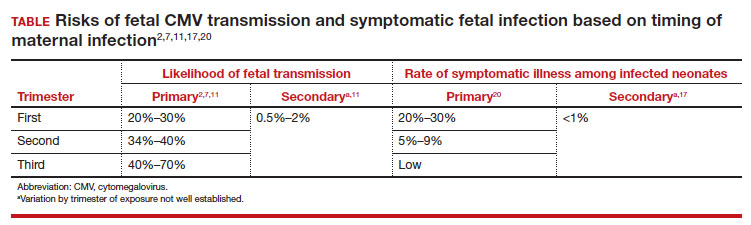

In most studies, primary maternal infections are associated with higher rates of fetal infection and more severe fetal and neonatal disease manifestations.2,7,9,10 Primary infections carry an overall 30% to 40% risk of transmission to the fetus.7,11 The risk of fetal transmission is much lower with a recurrent infection and is usually less than 2%.11 Due to their greater overall incidence, secondary infections account for the majority of cases of fetal and neonatal CMV disease.7 Importantly, although secondary infections generally have been regarded as having a lower risk and lower severity of fetal and neonatal disease, several recent studies have demonstrated rates of complications similar to, and even exceeding, those of primary infections.12-15 The TABLE provides a summary of the risks of fetal transmission and symptomatic fetal infection based on trimester of pregnancy.2,11,16-18

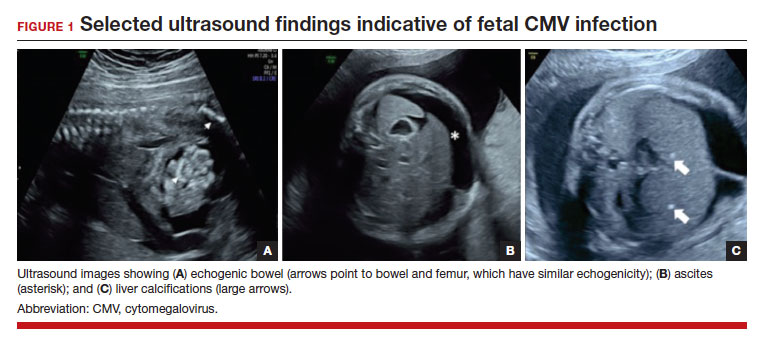

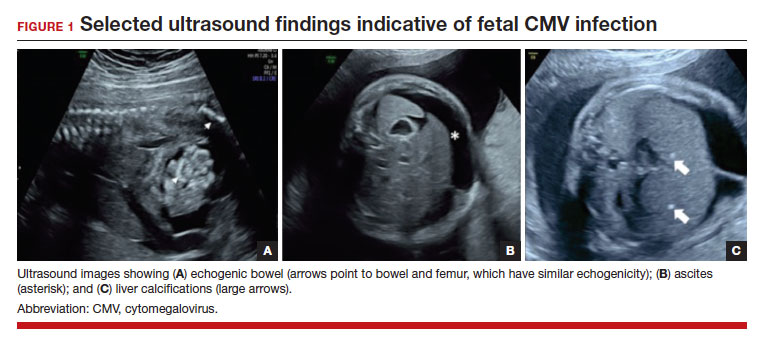

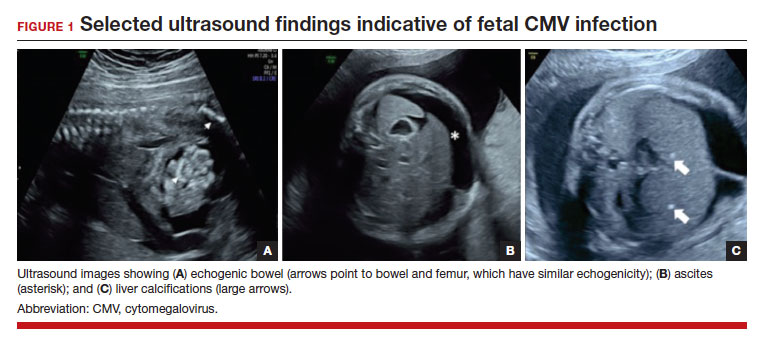

In the fetus, CMV may affect multiple organ systems. Among sonographic and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings, central nervous system (CNS) anomalies are the most common.19,20 These can include microcephaly, ventriculomegaly, and periventricular calcifications. The gastrointestinal system also is frequently affected, and findings include echogenic bowel, hepatosplenomegaly, and liver calcifications. Lastly, isolated effusions, placentomegaly, fetal growth restriction, and even frank hydrops can develop. More favorable neurologic outcomes have been demonstrated in infants with no prenatal brain imaging abnormalities.20,21 However, the role of MRI in prenatal prognosis currently is not well defined.

FIGURE 1 illustrates selected sonographic findings associated with fetal CMV infection.

About 85% to 90% of infants with congenital CMV that results from primary maternal infection have no symptoms at birth. Among the 10% to 15% of infants that do have symptoms, petechial rash, jaundice, and hepatosplenomegaly are the most common manifestations (“blueberry muffin baby”). Approximately 10% to 20% of infants in this group have evidence of chorioretinitis on ophthalmologic examination, and 50% show either microcephaly or low birth weight.22Among survivors of symptomatic congenital CMV, more than 50% have long-term neurologic morbidities that may include sensorineural hearing loss, seizures, vision impairment, and developmental disabilities. Note that even when neonates appear asymptomatic at birth (regardless of whether infection is primary or secondary), 5% may develop microcephaly and motor deficits, 10% go on to develop sensorineural hearing loss, and the overall rate of neurologic morbidity reaches 13% to 15%.12,23 Some of the observed deficits manifest at several years of age, and, currently, no models exist for prediction of outcome.

Continue to: Diagnosing CMV infection...

Diagnosing CMV infection

Maternal infection

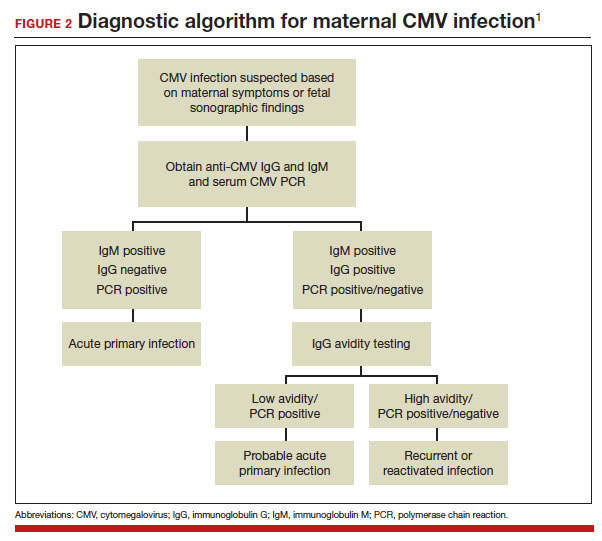

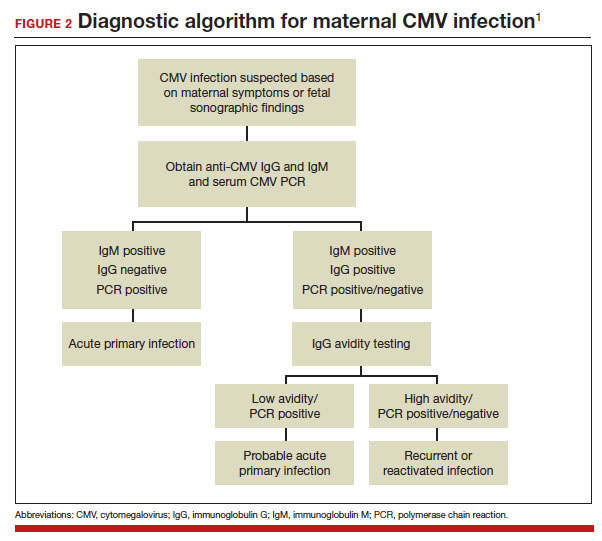

If maternal CMV infection is suspected based on a symptomatic illness or an abnormal fetal ultrasound exam, the first diagnostic test should be an assessment of IgM and IgG serology. If the former test results are positive and the latter negative, the diagnosis of acute CMV infection is confirmed. A positive serum CMV DNA polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test adds additional assurance that the diagnosis is correct. Primary infection, as noted above, poses the greatest risk of serious injury to the fetus.1

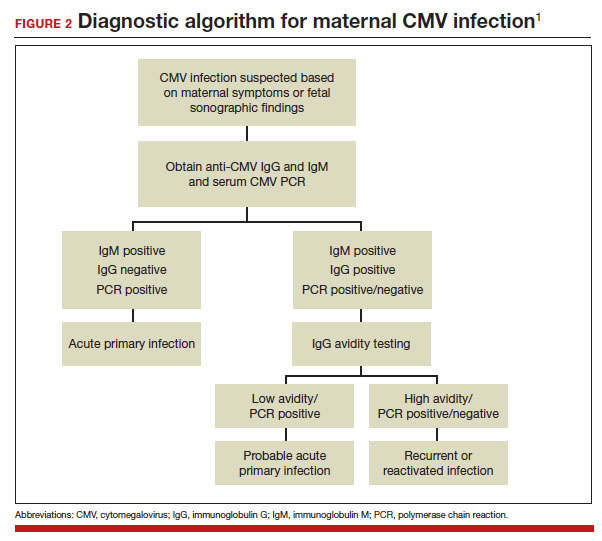

A frequent diagnostic dilemma arises when both the IgM and IgG antibody are positive. Remember that CMV IgM antibody can remain positive for 9 to 12 months after a primary infection and can reappear in the maternal serum in the face of a recurrent or reactivated infection. When confronted by both a positive IgM and positive IgG result, the clinician should then order IgG avidity testing. If the avidity is low to moderate, which reflects poor binding of antibody to the virus, the patient likely has an acute infection. If the avidity is high, which reflects enhanced binding of antibody to virus, the patient probably has a recurrent or reactivated infection; this scenario poses less danger to the developing fetus. The presence of CMV DNA in serum is also more consistent with acute infection, although viremia still can occur with recurrent infection. FIGURE 2 presents a suggested algorithm for the diagnosis of CMV in the pregnant patient.1

If a diagnosis of maternal CMV infection is confirmed, liver function tests should be obtained to determine if CMV hepatitis is present. If the liver function tests are abnormal, a coagulation profile also should be performed to identify the mother who might be at risk for peripartum hemorrhage.

Fetal infection

The single best test for confirmation of congenital CMV infection is detection of viral DNA and quantitation of viral load in the amniotic fluid by PCR. If the amniocentesis is performed prior to 20 weeks’ gestation and is negative, the test should be repeated in approximately 4 weeks.1,19,24

Detection of viral DNA indicates congenital infection. The ultimate task, however, is to determine if the infection has injured the fetus. Detailed ultrasound examination is the key to identifying fetal injury. As noted previously, the principal ultrasonographic findings that suggest congenital CMV infection include2,19,20,21,25:

- hydropic placenta

- fetal growth restriction

- microcephaly (head circumference more than 3 standard deviations below the mean)

- periventricular calcifications

- enlarged liver

- echogenic bowel

- ascites

- fetal hydrops.

Management: Evidence on CMV hyperimmune globulin, valacyclovir

If the immunocompetent mother has clinical manifestations of infection, she should receive symptomatic treatment. She should be encouraged to rest as much as possible, stay well hydrated, and use acetaminophen (1,000 mg every 6 to 8 hours) as needed for malaise and fever.

However, if the mother is immunocompromised and has signs of serious complications, such as chorioretinitis, hepatitis, or pneumonia, more aggressive therapy is indicated. Drugs used in this setting include foscarnet and ganciclovir and are best prescribed in consultation with a medical infectious disease specialist.

At this time, no consistently effective therapy for congenital infection is available. Therefore, if a patient has primary CMV infection in the first half of pregnancy, particularly in the first trimester, she should be counseled that the risk of fetal infection is approximately 40% and that approximately 5% to 15% of infants will be severely affected at birth. Given this information, some patients may opt for pregnancy termination.

In 2005, a report from Nigro and colleagues stimulated great hope that CMV-specific hyperimmune globulin (CytoGam) might be of value for both treatment and prophylaxis for congenital infection.26 These authors studied 157 women with confirmed primary CMV infection. One-hundred forty-eight women were asymptomatic and were identified by routine serologic screening, 8 had symptomatic infection, and 1 was identified because of abnormal fetal ultrasound findings. Forty-five women had CMV detected in amniotic fluid by PCR or culture more than 6 weeks before study enrollment. Thirty-one of these women were treated with intravenous hyperimmune globulin (200 U or 200 mg/kg maternal body weight); 14 declined treatment. Seven of the latter women had infants who were acutely symptomatic at the time of delivery; only 1 of the 31 treated women had an affected neonate (adjusted odds ratio [OR], 0.02; P<.001). In this same study, 84 women did not have a diagnostic amniocentesis because their infection occurred within 6 weeks of enrollment, their gestational age was less than 20 weeks, or they declined the procedure. Thirty-seven of these women received hyperimmune globulin (100 U or 100 mg/kg) every month until delivery, and 47 declined treatment. Six of the treated women delivered infected infants compared with 19 of the untreated women (adjusted OR, 0.32; P<.04).

Although these results were quite encouraging, several problems existed with the study’s design, as noted in an editorial that accompanied the study’s publication.27 First, the study was not randomized or placebo controlled. Second, patients were not stratified based on the severity of fetal ultrasound abnormalities. Third, the dosing of hyperimmune globulin varied; 9 of the 31 patients in the treatment group received additional infusions of drug into either the amniotic fluid or fetal umbilical vein. Moreover, patients in the prophylaxis group actually received a higher cumulative dose of hyperimmune globulin than patients in the treatment group.

Two subsequent investigations that were better designed were unable to verify the effectiveness of hyperimmune globulin. In 2014, Revello and colleagues reported the results of a prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blinded study of 124 women at 5 to 26 weeks’ gestation with confirmed primary CMV infection.28 The rate of congenital infection was 30% in the group treated with hyperimmune globulin and 44% in the placebo group (P=.13). There also was no significant difference in the concentration of serum CMV DNA in treated versus untreated mothers. Moreover, the number of adverse obstetric events (preterm delivery, fetal growth restriction, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, and postpartum preeclampsia) in the treatment group was higher than in the placebo group, 13% versus 2%.

In 2021, Hughes and colleagues published the results of a multicenter, double-blind trial in 399 women who had a diagnosis of primary CMV infection before 23 weeks’ gestation.29 The primary outcome was defined as a composite of congenital CMV infection or fetal/neonatal death. An adverse primary outcome occurred in 22.7% of the patients who received hyperimmune globulin and 19.4% of those who received placebo (relative risk, 1.17; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.80–1.72; P=.42).

Continue to: Jacquemard and colleagues...

Jacquemard and colleagues then proposed a different approach.30 In a small pilot study of 20 patients, these authors used high doses of oral valacylovir (2 g 4 times daily) and documented therapeutic drug concentrations and a decline in CMV viral load in fetal serum. Patients were not stratified by severity of fetal injury at onset of treatment, so the authors were unable to define which fetuses were most likely to benefit from treatment.

In a follow-up investigation, Leruez-Ville and colleagues reported another small series in which high-dose oral valacyclovir (8 g daily) was used for treatment.31 They excluded fetuses with severe brain anomalies and fetuses with no sonographic evidence of injury. The median gestational age at diagnosis was 26 weeks. Thirty-four of 43 treated fetuses were free of injury at birth. In addition, the viral load in the neonate’s serum decreased significantly after treatment, and the platelet count increased. The authors then compared these outcomes to a historical cohort and confirmed that treatment increased the proportion of asymptomatic neonates from 43% without treatment to 82% with treatment (P<.05 with no overlapping confidence intervals).

We conclude from these investigations that hyperimmune globulin is unlikely to be of value in treating congenital CMV infection, especially if the fetus already has sonographic findings of severe injury. High-dose oral valacyclovir also is unlikely to be of value in severely affected fetuses, particularly those with evidence of CNS injury. However, antiviral therapy may be of modest value in situations when the fetus is less severely injured.

Preventive measures

Since no definitive treatment is available for congenital CMV infection, our efforts as clinicians should focus on measures that may prevent transmission of infection to the pregnant patient. These measures include:

- Encouraging patients to use careful handwashing techniques when handling infant diapers and toys.

- Encouraging patients to adopt safe sexual practices if not already engaged in a mutually faithful, monogamous relationship.

- Using CMV-negative blood when transfusing a pregnant woman or a fetus.

At the present time, unfortunately, a readily available and highly effective therapy for prevention of CMV infection is not available.

CASE Congenital infection diagnosed

The ultrasound findings are most consistent with congenital CMV infection, especially given the patient’s work as an elementary schoolteacher. The diagnosis of maternal infection is best established by conventional serology (positive IgM, negative IgM) and detection of viral DNA in maternal blood by PCR testing. The diagnosis of congenital infection is best confirmed by documentation of viral DNA in the amniotic fluid by PCR testing. Given that this fetus already has evidence of moderate to severe injury, no treatment is likely to be effective in reversing the abnormal ultrasound findings. Pregnancy termination may be an option, depending upon the patient’s desires and the legal restrictions prevalent in the patient’s geographic area. ●

- Cytomegalovirus infection is the most common of the perinatally transmitted infections.

- Maternal infection is often asymptomatic. When symptoms are present, they resemble those of an influenza-like illness. In immunocompromised persons, however, CMV may cause serious complications, including pneumonia, hepatitis, and chorioretinitis.

- The virus is transmitted by contact with contaminated body fluids, such as saliva, urine, blood, and genital secretions.

- The greatest risk of severe fetal injury results from primary maternal infection in the first trimester of pregnancy.

- Manifestations of severe congenital CMV infection include growth restriction, microcephaly, ventriculomegaly, hepatosplenomegaly, ascites, chorioretinitis, thrombocytopenia, purpura, and hydrops (“blueberry muffin baby”).

- Late manifestations of infection, which usually follow recurrent maternal infection, may appear as a child enters elementary school and include visual and auditory deficits, developmental delays, and learning disabilities.

- The diagnosis of maternal infection is confirmed by serology and detection of viral DNA in the serum by PCR testing.

- The diagnosis of fetal infection is best made by a combination of abnormal ultrasound findings and detection of CMV DNA in amniotic fluid. The characteristic ultrasound findings include placentomegaly, microcephaly, ventriculomegaly, growth restriction, echogenic bowel, and serous effusions/hydrops.

- Treatment of the mother with antiviral medications such as valacyclovir may be of modest value in reducing placental edema, decreasing viral load in the fetus, and hastening the resolution of some ultrasound findings, such as echogenic bowel.

- While initial studies seemed promising, the use of hyperimmune globulin has not proven to be consistently effective in treating congenital infection.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TR, et al, eds. Creasy and Resnik’s Maternal Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. 2019:888-890.

- Chatzakis C, Ville Y, Makrydimas G, et al. Timing of primary maternal cytomegalovirus infection and rates of vertical transmission and fetal consequences. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:870-883.e11. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2020.05.038

- Kelly MS, Benjamin DK, Puopolo KM, et al. Postnatal cytomegalovirus infection and the risk for bronchopulmonary dysplasia. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:e153785. doi:10.1001 /jamapediatrics.2015.3785

- Messinger CJ, Lipsitch M, Bateman BT, et al. Association between congenital cytomegalovirus and the prevalence at birth of microcephaly in the United States. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174:1159-1167. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.3009

- De Cuyper E, Acke F, Keymeulen A, et al. Risk factors for hearing loss at birth in newborns with congenital cytomegalovirus infection. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2023;149:122-130. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2022.4109

- Colugnati FA, Staras SA, Dollard SC, et al. Incidence of cytomegalovirus infection among the general population and pregnant women in the United States. BMC Infect Dis. 2007;7:71. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-7-71

- Stagno S, Pass RF, Cloud G, et al. Primary cytomegalovirus infection in pregnancy. Incidence, transmission to fetus, and clinical outcome. JAMA. 1986;256:1904-1908.

- Wreghitt TG, Teare EL, Sule O, et al. Cytomegalovirus infection in immunocompetent patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:1603-1606. doi:10.1086/379711

- Fowler KB, Stagno S, Pass RF, et al. The outcome of congenital cytomegalovirus infection in relation to maternal antibody status. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:663-667. doi:10.1056 /NEJM199203053261003

- Faure-Bardon V, Magny JF, Parodi M, et al. Sequelae of congenital cytomegalovirus following maternal primary infections are limited to those acquired in the first trimester of pregnancy. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;69:1526-1532. doi:10.1093/ cid/ciy1128

- Kenneson A, Cannon MJ. Review and meta-analysis of the epidemiology of congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection. Rev Med Virol. 2007;17:253-276. doi:10.1002/ rmv.535

- Boppana SB, Pass RF, Britt WJ, et al. Symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus infection: neonatal morbidity and mortality. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1992;11:93-99. doi:10.1097/00006454-199202000-00007

- Ross SA, Fowler KB, Ashrith G, et al. Hearing loss in children with congenital cytomegalovirus infection born to mothers with preexisting immunity. J Pediatr. 2006;148:332-336. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.09.003

- Zalel Y, Gilboa Y, Berkenshtat M, et al. Secondary cytomegalovirus infection can cause severe fetal sequelae despite maternal preconceptional immunity. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 31:417-420. doi:10.1002/uog.5255

- Scaramuzzino F, Di Pastena M, Chiurchiu S, et al. Secondary cytomegalovirus infections: how much do we still not know? Comparison of children with symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus born to mothers with primary and secondary infection. Front Pediatr. 2022;10:885926. doi:10.3389/fped.2022.885926

- Gindes L, Teperberg-Oikawa M, Sherman D, et al. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection following primary maternal infection in the third trimester. BJOG. 2008;115:830-835. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01651.x

- Hadar E, Dorfman E, Bardin R, et al. Symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus disease following non-primary maternal infection: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17:31. doi:10.1186/s12879-016-2161-3

- Elkan Miller T, Weisz B, Yinon Y, et al. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection following second and third trimester maternal infection is associated with mild childhood adverse outcome not predicted by prenatal imaging. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2021;10:562-568. doi:10.1093/jpids/ piaa154

- Lipitz S, Yinon Y, Malinger G, et al. Risk of cytomegalovirusassociated sequelae in relation to time of infection and findings on prenatal imaging. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;41:508-514. doi:10.1002/uog.12377

- Lipitz S, Elkan Miller T, Yinon Y, et al. Revisiting short- and long-term outcome after fetal first-trimester primary cytomegalovirus infection in relation to prenatal imaging findings. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2020;56:572-578. doi:10.1002/uog.21946

- Buca D, Di Mascio D, Rizzo G, et al. Outcome of fetuses with congenital cytomegalovirus infection and normal ultrasound at diagnosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2021;57:551-559. doi:10.1002/uog.23143

- Boppana SB, Ross SA, Fowler KB. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection: clinical outcome. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57 (suppl 4):S178-S181. doi:10.1093/cid/cit629

- Dollard SC, Grosse SD, Ross DS. New estimates of the prevalence of neurological and sensory sequelae and mortality associated with congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Rev Med Virol. 2007;17:355-363. doi:10.1002/rmv.544

- Hughes BL, Gyamfi-Bannerman C. Diagnosis and antenatal management of congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214:B5-11. doi:10.1016 /j.ajog.2016.02.042

- Rouse DJ, Fette LM, Hughes BL, et al. Noninvasive prediction of congenital cytomegalovirus infection after maternal primary infection. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;139:400-406. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000004691

- Nigro G, Adler SP, La Torre R, et al; Congenital Cytomegalovirus Collaborating Group. Passive immunization during pregnancy for congenital cytomegalovirus infection. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1350-1362. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa043337

- Duff P. Immunotherapy for congenital cytomegalovirus infection. N Engl J Med. 2005;355:1402-1404. doi:10.1056 /NEJMe058172

- Revello MG, Lazzarotto T, Guerra B, et al. A randomized trial of hyperimmune globulin to prevent congenital cytomegalovirus. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1316-1326. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1310214

- Hughes BL, Clifton RG, Rouse DJ, et al. A trial of hyperimmune globulin to prevent congenital cytomegalovirus infection. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:436-444. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1913569

- Jacquemard F, Yamamoto M, Costa JM, et al. Maternal administration of valaciclovir in symptomatic intrauterine cytomegalovirus infection. BJOG. 2007;114:1113-1121. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01308.x

- Leruez-Ville M, Ghout I, Bussières L, et al. In utero treatment of congenital cytomegalovirus infection with valacyclovir in a multicenter, open-label, phase II study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:462.e1-462.e10. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2016.04.003

CASE Anomalous findings on fetal anatomic survey

A 27-year-old previously healthy primigravid woman is at 18 weeks’ gestation. She is a first-grade schoolteacher. On her fetal anatomic survey, the estimated fetal weight was in the eighth percentile. Echogenic bowel and a small amount of ascitic fluid were noted in the fetal abdomen. The lateral and third ventricles were mildly dilated, the head circumference was 2 standard deviations below normal, and the placenta was slightly thickened and edematous.

What is the most likely diagnosis?

What diagnostic tests are indicated?

What management options are available for this patient?

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is the most common of the perinatally transmitted infections, affecting 1% to 4% of all pregnancies. Although the virus typically causes either asymptomatic infection or only mild illness in immunocompetent individuals, it can cause life-threatening disease in immunocompromised persons and in the developing fetus. In this article, we review the virology and epidemiology of CMV infection and then focus on the key methods to diagnose infection in the mother and fetus. We conclude by considering measures that may be of at least modest value in treating CMV in pregnancy.

Virology of CMV infection

Cytomegalovirus is a double-stranded DNA virus in the Herpesviridae family. This ubiquitous virus is present in virtually all secretions and excretions of an infected host, including blood, urine, saliva, breast milk, genital secretions, and tissues and organs used for donation. Infection is transmitted through direct contact with any of the substances listed; contact with infected urine or saliva is the most common mode of transmission. Disease occurrence does not show seasonal variation.

After exposure, an incubation period of 28 to 60 days ensues, followed by development of viremia and clinical symptoms. In the majority of exposed individuals, CMV establishes a lifelong latent infection, and recurrent episodes of illness can occur as a result of reactivation of latent virus (also known as secondary infection) or, more rarely, infection with a new viral strain. In fact, most CMV illness episodes in pregnancy represent a reactivation of a previous infection rather than a new infection.

Following initial infection, both IgM (immunoglobulin M) and IgG (immunoglobulin G) antibodies develop rapidly and can be detected in blood within 1 to 2 weeks. IgM levels typically wane within 30 to 60 days, although persistence for several months is not unusual, and levels also can increase with viral reactivation (secondary infection). IgG antibodies typically persist for many years after a primary infection.

Intrauterine CMV infection occurs through hematogenous transplacental passage during maternal viremia. The risk of transmission and severity of fetal effects depend on whether or not the infection is primary or secondary in nature as well as the gestational age at fetal exposure.1,2

Additionally, postnatal vertical transmission can occur through exposure to viral particles in genital secretions as well as breast milk. CMV acquired in the postnatal period rarely produces severe sequelae in a healthy term neonate, but it has been associated with an increased rate of complications in very low birth weight and premature newborns.3

Continue to: Who is at risk...

Who is at risk

Congenital CMV, which occurs in 2.1 to 7.7 per 10,000 live births in the United States, is both the most common congenital infection and the leading cause of nonhereditary congenital hearing loss in children.4,5 The main reservoir of CMV in the United States is young children in day care settings, with approximately 50% of this population showing evidence of viral shedding in saliva.1 Adult populations in North America have a high prevalence of CMV IgG antibodies indicative of prior infection, with rates reaching 50% to 80%. Among seronegative individuals aged 12 to 49, the rate of seroconversion is approximately 1 in 60 annually.6 Significant racial disparities have been noted in rates of seroprevalence and seroconversion, with higher rates of infection in non-Hispanic Black and Mexican American individuals.6 Overall, the rate of new CMV infection among pregnant women in the United States is 0.7% to 4%.7

Clinical manifestations

Manifestations of infection differ depending on whether or not infection is primary or recurrent (secondary) and whether or not the host is immunocompetent or has a compromised immune system. Unique manifestations develop in the fetus.

CMV infection in children and adults. Among individuals with a normal immune response, the typical course of CMV is either no symptoms or a mononucleosis-like illness. In symptomatic patients, the most common symptoms include malaise, fever, and night sweats, and the most common associated laboratory abnormalities are elevation in liver function tests and a decreased white blood cell count, with a predominance of lymphocytes.8

Immunocompromised individuals are at risk for significant morbidity and mortality resulting from CMV. Illness may be the result of reactivation of latent infection due to decreased immune function or may be acquired as a result of treatment such as transplantation of CMV-positive organs or tissues, including bone marrow. Virtually any organ system can be affected, with potential for permanent organ damage and death. Severe systemic infection also can occur.

CMV infection in the fetus and neonate. As noted previously, fetal infection develops as a result of transplacental passage coincident with maternal infection. The risk of CMV transmission to the fetus and the severity of fetal injury vary based on gestational age at fetal infection and whether or not maternal infection is primary or secondary.

In most studies, primary maternal infections are associated with higher rates of fetal infection and more severe fetal and neonatal disease manifestations.2,7,9,10 Primary infections carry an overall 30% to 40% risk of transmission to the fetus.7,11 The risk of fetal transmission is much lower with a recurrent infection and is usually less than 2%.11 Due to their greater overall incidence, secondary infections account for the majority of cases of fetal and neonatal CMV disease.7 Importantly, although secondary infections generally have been regarded as having a lower risk and lower severity of fetal and neonatal disease, several recent studies have demonstrated rates of complications similar to, and even exceeding, those of primary infections.12-15 The TABLE provides a summary of the risks of fetal transmission and symptomatic fetal infection based on trimester of pregnancy.2,11,16-18

In the fetus, CMV may affect multiple organ systems. Among sonographic and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings, central nervous system (CNS) anomalies are the most common.19,20 These can include microcephaly, ventriculomegaly, and periventricular calcifications. The gastrointestinal system also is frequently affected, and findings include echogenic bowel, hepatosplenomegaly, and liver calcifications. Lastly, isolated effusions, placentomegaly, fetal growth restriction, and even frank hydrops can develop. More favorable neurologic outcomes have been demonstrated in infants with no prenatal brain imaging abnormalities.20,21 However, the role of MRI in prenatal prognosis currently is not well defined.

FIGURE 1 illustrates selected sonographic findings associated with fetal CMV infection.

About 85% to 90% of infants with congenital CMV that results from primary maternal infection have no symptoms at birth. Among the 10% to 15% of infants that do have symptoms, petechial rash, jaundice, and hepatosplenomegaly are the most common manifestations (“blueberry muffin baby”). Approximately 10% to 20% of infants in this group have evidence of chorioretinitis on ophthalmologic examination, and 50% show either microcephaly or low birth weight.22Among survivors of symptomatic congenital CMV, more than 50% have long-term neurologic morbidities that may include sensorineural hearing loss, seizures, vision impairment, and developmental disabilities. Note that even when neonates appear asymptomatic at birth (regardless of whether infection is primary or secondary), 5% may develop microcephaly and motor deficits, 10% go on to develop sensorineural hearing loss, and the overall rate of neurologic morbidity reaches 13% to 15%.12,23 Some of the observed deficits manifest at several years of age, and, currently, no models exist for prediction of outcome.

Continue to: Diagnosing CMV infection...

Diagnosing CMV infection

Maternal infection

If maternal CMV infection is suspected based on a symptomatic illness or an abnormal fetal ultrasound exam, the first diagnostic test should be an assessment of IgM and IgG serology. If the former test results are positive and the latter negative, the diagnosis of acute CMV infection is confirmed. A positive serum CMV DNA polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test adds additional assurance that the diagnosis is correct. Primary infection, as noted above, poses the greatest risk of serious injury to the fetus.1

A frequent diagnostic dilemma arises when both the IgM and IgG antibody are positive. Remember that CMV IgM antibody can remain positive for 9 to 12 months after a primary infection and can reappear in the maternal serum in the face of a recurrent or reactivated infection. When confronted by both a positive IgM and positive IgG result, the clinician should then order IgG avidity testing. If the avidity is low to moderate, which reflects poor binding of antibody to the virus, the patient likely has an acute infection. If the avidity is high, which reflects enhanced binding of antibody to virus, the patient probably has a recurrent or reactivated infection; this scenario poses less danger to the developing fetus. The presence of CMV DNA in serum is also more consistent with acute infection, although viremia still can occur with recurrent infection. FIGURE 2 presents a suggested algorithm for the diagnosis of CMV in the pregnant patient.1

If a diagnosis of maternal CMV infection is confirmed, liver function tests should be obtained to determine if CMV hepatitis is present. If the liver function tests are abnormal, a coagulation profile also should be performed to identify the mother who might be at risk for peripartum hemorrhage.

Fetal infection

The single best test for confirmation of congenital CMV infection is detection of viral DNA and quantitation of viral load in the amniotic fluid by PCR. If the amniocentesis is performed prior to 20 weeks’ gestation and is negative, the test should be repeated in approximately 4 weeks.1,19,24

Detection of viral DNA indicates congenital infection. The ultimate task, however, is to determine if the infection has injured the fetus. Detailed ultrasound examination is the key to identifying fetal injury. As noted previously, the principal ultrasonographic findings that suggest congenital CMV infection include2,19,20,21,25:

- hydropic placenta

- fetal growth restriction

- microcephaly (head circumference more than 3 standard deviations below the mean)

- periventricular calcifications

- enlarged liver

- echogenic bowel

- ascites

- fetal hydrops.

Management: Evidence on CMV hyperimmune globulin, valacyclovir

If the immunocompetent mother has clinical manifestations of infection, she should receive symptomatic treatment. She should be encouraged to rest as much as possible, stay well hydrated, and use acetaminophen (1,000 mg every 6 to 8 hours) as needed for malaise and fever.

However, if the mother is immunocompromised and has signs of serious complications, such as chorioretinitis, hepatitis, or pneumonia, more aggressive therapy is indicated. Drugs used in this setting include foscarnet and ganciclovir and are best prescribed in consultation with a medical infectious disease specialist.

At this time, no consistently effective therapy for congenital infection is available. Therefore, if a patient has primary CMV infection in the first half of pregnancy, particularly in the first trimester, she should be counseled that the risk of fetal infection is approximately 40% and that approximately 5% to 15% of infants will be severely affected at birth. Given this information, some patients may opt for pregnancy termination.

In 2005, a report from Nigro and colleagues stimulated great hope that CMV-specific hyperimmune globulin (CytoGam) might be of value for both treatment and prophylaxis for congenital infection.26 These authors studied 157 women with confirmed primary CMV infection. One-hundred forty-eight women were asymptomatic and were identified by routine serologic screening, 8 had symptomatic infection, and 1 was identified because of abnormal fetal ultrasound findings. Forty-five women had CMV detected in amniotic fluid by PCR or culture more than 6 weeks before study enrollment. Thirty-one of these women were treated with intravenous hyperimmune globulin (200 U or 200 mg/kg maternal body weight); 14 declined treatment. Seven of the latter women had infants who were acutely symptomatic at the time of delivery; only 1 of the 31 treated women had an affected neonate (adjusted odds ratio [OR], 0.02; P<.001). In this same study, 84 women did not have a diagnostic amniocentesis because their infection occurred within 6 weeks of enrollment, their gestational age was less than 20 weeks, or they declined the procedure. Thirty-seven of these women received hyperimmune globulin (100 U or 100 mg/kg) every month until delivery, and 47 declined treatment. Six of the treated women delivered infected infants compared with 19 of the untreated women (adjusted OR, 0.32; P<.04).

Although these results were quite encouraging, several problems existed with the study’s design, as noted in an editorial that accompanied the study’s publication.27 First, the study was not randomized or placebo controlled. Second, patients were not stratified based on the severity of fetal ultrasound abnormalities. Third, the dosing of hyperimmune globulin varied; 9 of the 31 patients in the treatment group received additional infusions of drug into either the amniotic fluid or fetal umbilical vein. Moreover, patients in the prophylaxis group actually received a higher cumulative dose of hyperimmune globulin than patients in the treatment group.

Two subsequent investigations that were better designed were unable to verify the effectiveness of hyperimmune globulin. In 2014, Revello and colleagues reported the results of a prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blinded study of 124 women at 5 to 26 weeks’ gestation with confirmed primary CMV infection.28 The rate of congenital infection was 30% in the group treated with hyperimmune globulin and 44% in the placebo group (P=.13). There also was no significant difference in the concentration of serum CMV DNA in treated versus untreated mothers. Moreover, the number of adverse obstetric events (preterm delivery, fetal growth restriction, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, and postpartum preeclampsia) in the treatment group was higher than in the placebo group, 13% versus 2%.

In 2021, Hughes and colleagues published the results of a multicenter, double-blind trial in 399 women who had a diagnosis of primary CMV infection before 23 weeks’ gestation.29 The primary outcome was defined as a composite of congenital CMV infection or fetal/neonatal death. An adverse primary outcome occurred in 22.7% of the patients who received hyperimmune globulin and 19.4% of those who received placebo (relative risk, 1.17; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.80–1.72; P=.42).

Continue to: Jacquemard and colleagues...

Jacquemard and colleagues then proposed a different approach.30 In a small pilot study of 20 patients, these authors used high doses of oral valacylovir (2 g 4 times daily) and documented therapeutic drug concentrations and a decline in CMV viral load in fetal serum. Patients were not stratified by severity of fetal injury at onset of treatment, so the authors were unable to define which fetuses were most likely to benefit from treatment.

In a follow-up investigation, Leruez-Ville and colleagues reported another small series in which high-dose oral valacyclovir (8 g daily) was used for treatment.31 They excluded fetuses with severe brain anomalies and fetuses with no sonographic evidence of injury. The median gestational age at diagnosis was 26 weeks. Thirty-four of 43 treated fetuses were free of injury at birth. In addition, the viral load in the neonate’s serum decreased significantly after treatment, and the platelet count increased. The authors then compared these outcomes to a historical cohort and confirmed that treatment increased the proportion of asymptomatic neonates from 43% without treatment to 82% with treatment (P<.05 with no overlapping confidence intervals).

We conclude from these investigations that hyperimmune globulin is unlikely to be of value in treating congenital CMV infection, especially if the fetus already has sonographic findings of severe injury. High-dose oral valacyclovir also is unlikely to be of value in severely affected fetuses, particularly those with evidence of CNS injury. However, antiviral therapy may be of modest value in situations when the fetus is less severely injured.

Preventive measures

Since no definitive treatment is available for congenital CMV infection, our efforts as clinicians should focus on measures that may prevent transmission of infection to the pregnant patient. These measures include:

- Encouraging patients to use careful handwashing techniques when handling infant diapers and toys.

- Encouraging patients to adopt safe sexual practices if not already engaged in a mutually faithful, monogamous relationship.

- Using CMV-negative blood when transfusing a pregnant woman or a fetus.

At the present time, unfortunately, a readily available and highly effective therapy for prevention of CMV infection is not available.

CASE Congenital infection diagnosed

The ultrasound findings are most consistent with congenital CMV infection, especially given the patient’s work as an elementary schoolteacher. The diagnosis of maternal infection is best established by conventional serology (positive IgM, negative IgM) and detection of viral DNA in maternal blood by PCR testing. The diagnosis of congenital infection is best confirmed by documentation of viral DNA in the amniotic fluid by PCR testing. Given that this fetus already has evidence of moderate to severe injury, no treatment is likely to be effective in reversing the abnormal ultrasound findings. Pregnancy termination may be an option, depending upon the patient’s desires and the legal restrictions prevalent in the patient’s geographic area. ●

- Cytomegalovirus infection is the most common of the perinatally transmitted infections.

- Maternal infection is often asymptomatic. When symptoms are present, they resemble those of an influenza-like illness. In immunocompromised persons, however, CMV may cause serious complications, including pneumonia, hepatitis, and chorioretinitis.

- The virus is transmitted by contact with contaminated body fluids, such as saliva, urine, blood, and genital secretions.

- The greatest risk of severe fetal injury results from primary maternal infection in the first trimester of pregnancy.

- Manifestations of severe congenital CMV infection include growth restriction, microcephaly, ventriculomegaly, hepatosplenomegaly, ascites, chorioretinitis, thrombocytopenia, purpura, and hydrops (“blueberry muffin baby”).

- Late manifestations of infection, which usually follow recurrent maternal infection, may appear as a child enters elementary school and include visual and auditory deficits, developmental delays, and learning disabilities.

- The diagnosis of maternal infection is confirmed by serology and detection of viral DNA in the serum by PCR testing.

- The diagnosis of fetal infection is best made by a combination of abnormal ultrasound findings and detection of CMV DNA in amniotic fluid. The characteristic ultrasound findings include placentomegaly, microcephaly, ventriculomegaly, growth restriction, echogenic bowel, and serous effusions/hydrops.

- Treatment of the mother with antiviral medications such as valacyclovir may be of modest value in reducing placental edema, decreasing viral load in the fetus, and hastening the resolution of some ultrasound findings, such as echogenic bowel.

- While initial studies seemed promising, the use of hyperimmune globulin has not proven to be consistently effective in treating congenital infection.

CASE Anomalous findings on fetal anatomic survey

A 27-year-old previously healthy primigravid woman is at 18 weeks’ gestation. She is a first-grade schoolteacher. On her fetal anatomic survey, the estimated fetal weight was in the eighth percentile. Echogenic bowel and a small amount of ascitic fluid were noted in the fetal abdomen. The lateral and third ventricles were mildly dilated, the head circumference was 2 standard deviations below normal, and the placenta was slightly thickened and edematous.

What is the most likely diagnosis?

What diagnostic tests are indicated?

What management options are available for this patient?

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is the most common of the perinatally transmitted infections, affecting 1% to 4% of all pregnancies. Although the virus typically causes either asymptomatic infection or only mild illness in immunocompetent individuals, it can cause life-threatening disease in immunocompromised persons and in the developing fetus. In this article, we review the virology and epidemiology of CMV infection and then focus on the key methods to diagnose infection in the mother and fetus. We conclude by considering measures that may be of at least modest value in treating CMV in pregnancy.

Virology of CMV infection

Cytomegalovirus is a double-stranded DNA virus in the Herpesviridae family. This ubiquitous virus is present in virtually all secretions and excretions of an infected host, including blood, urine, saliva, breast milk, genital secretions, and tissues and organs used for donation. Infection is transmitted through direct contact with any of the substances listed; contact with infected urine or saliva is the most common mode of transmission. Disease occurrence does not show seasonal variation.

After exposure, an incubation period of 28 to 60 days ensues, followed by development of viremia and clinical symptoms. In the majority of exposed individuals, CMV establishes a lifelong latent infection, and recurrent episodes of illness can occur as a result of reactivation of latent virus (also known as secondary infection) or, more rarely, infection with a new viral strain. In fact, most CMV illness episodes in pregnancy represent a reactivation of a previous infection rather than a new infection.

Following initial infection, both IgM (immunoglobulin M) and IgG (immunoglobulin G) antibodies develop rapidly and can be detected in blood within 1 to 2 weeks. IgM levels typically wane within 30 to 60 days, although persistence for several months is not unusual, and levels also can increase with viral reactivation (secondary infection). IgG antibodies typically persist for many years after a primary infection.

Intrauterine CMV infection occurs through hematogenous transplacental passage during maternal viremia. The risk of transmission and severity of fetal effects depend on whether or not the infection is primary or secondary in nature as well as the gestational age at fetal exposure.1,2

Additionally, postnatal vertical transmission can occur through exposure to viral particles in genital secretions as well as breast milk. CMV acquired in the postnatal period rarely produces severe sequelae in a healthy term neonate, but it has been associated with an increased rate of complications in very low birth weight and premature newborns.3

Continue to: Who is at risk...

Who is at risk

Congenital CMV, which occurs in 2.1 to 7.7 per 10,000 live births in the United States, is both the most common congenital infection and the leading cause of nonhereditary congenital hearing loss in children.4,5 The main reservoir of CMV in the United States is young children in day care settings, with approximately 50% of this population showing evidence of viral shedding in saliva.1 Adult populations in North America have a high prevalence of CMV IgG antibodies indicative of prior infection, with rates reaching 50% to 80%. Among seronegative individuals aged 12 to 49, the rate of seroconversion is approximately 1 in 60 annually.6 Significant racial disparities have been noted in rates of seroprevalence and seroconversion, with higher rates of infection in non-Hispanic Black and Mexican American individuals.6 Overall, the rate of new CMV infection among pregnant women in the United States is 0.7% to 4%.7

Clinical manifestations

Manifestations of infection differ depending on whether or not infection is primary or recurrent (secondary) and whether or not the host is immunocompetent or has a compromised immune system. Unique manifestations develop in the fetus.

CMV infection in children and adults. Among individuals with a normal immune response, the typical course of CMV is either no symptoms or a mononucleosis-like illness. In symptomatic patients, the most common symptoms include malaise, fever, and night sweats, and the most common associated laboratory abnormalities are elevation in liver function tests and a decreased white blood cell count, with a predominance of lymphocytes.8

Immunocompromised individuals are at risk for significant morbidity and mortality resulting from CMV. Illness may be the result of reactivation of latent infection due to decreased immune function or may be acquired as a result of treatment such as transplantation of CMV-positive organs or tissues, including bone marrow. Virtually any organ system can be affected, with potential for permanent organ damage and death. Severe systemic infection also can occur.

CMV infection in the fetus and neonate. As noted previously, fetal infection develops as a result of transplacental passage coincident with maternal infection. The risk of CMV transmission to the fetus and the severity of fetal injury vary based on gestational age at fetal infection and whether or not maternal infection is primary or secondary.

In most studies, primary maternal infections are associated with higher rates of fetal infection and more severe fetal and neonatal disease manifestations.2,7,9,10 Primary infections carry an overall 30% to 40% risk of transmission to the fetus.7,11 The risk of fetal transmission is much lower with a recurrent infection and is usually less than 2%.11 Due to their greater overall incidence, secondary infections account for the majority of cases of fetal and neonatal CMV disease.7 Importantly, although secondary infections generally have been regarded as having a lower risk and lower severity of fetal and neonatal disease, several recent studies have demonstrated rates of complications similar to, and even exceeding, those of primary infections.12-15 The TABLE provides a summary of the risks of fetal transmission and symptomatic fetal infection based on trimester of pregnancy.2,11,16-18

In the fetus, CMV may affect multiple organ systems. Among sonographic and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings, central nervous system (CNS) anomalies are the most common.19,20 These can include microcephaly, ventriculomegaly, and periventricular calcifications. The gastrointestinal system also is frequently affected, and findings include echogenic bowel, hepatosplenomegaly, and liver calcifications. Lastly, isolated effusions, placentomegaly, fetal growth restriction, and even frank hydrops can develop. More favorable neurologic outcomes have been demonstrated in infants with no prenatal brain imaging abnormalities.20,21 However, the role of MRI in prenatal prognosis currently is not well defined.

FIGURE 1 illustrates selected sonographic findings associated with fetal CMV infection.

About 85% to 90% of infants with congenital CMV that results from primary maternal infection have no symptoms at birth. Among the 10% to 15% of infants that do have symptoms, petechial rash, jaundice, and hepatosplenomegaly are the most common manifestations (“blueberry muffin baby”). Approximately 10% to 20% of infants in this group have evidence of chorioretinitis on ophthalmologic examination, and 50% show either microcephaly or low birth weight.22Among survivors of symptomatic congenital CMV, more than 50% have long-term neurologic morbidities that may include sensorineural hearing loss, seizures, vision impairment, and developmental disabilities. Note that even when neonates appear asymptomatic at birth (regardless of whether infection is primary or secondary), 5% may develop microcephaly and motor deficits, 10% go on to develop sensorineural hearing loss, and the overall rate of neurologic morbidity reaches 13% to 15%.12,23 Some of the observed deficits manifest at several years of age, and, currently, no models exist for prediction of outcome.

Continue to: Diagnosing CMV infection...

Diagnosing CMV infection

Maternal infection

If maternal CMV infection is suspected based on a symptomatic illness or an abnormal fetal ultrasound exam, the first diagnostic test should be an assessment of IgM and IgG serology. If the former test results are positive and the latter negative, the diagnosis of acute CMV infection is confirmed. A positive serum CMV DNA polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test adds additional assurance that the diagnosis is correct. Primary infection, as noted above, poses the greatest risk of serious injury to the fetus.1

A frequent diagnostic dilemma arises when both the IgM and IgG antibody are positive. Remember that CMV IgM antibody can remain positive for 9 to 12 months after a primary infection and can reappear in the maternal serum in the face of a recurrent or reactivated infection. When confronted by both a positive IgM and positive IgG result, the clinician should then order IgG avidity testing. If the avidity is low to moderate, which reflects poor binding of antibody to the virus, the patient likely has an acute infection. If the avidity is high, which reflects enhanced binding of antibody to virus, the patient probably has a recurrent or reactivated infection; this scenario poses less danger to the developing fetus. The presence of CMV DNA in serum is also more consistent with acute infection, although viremia still can occur with recurrent infection. FIGURE 2 presents a suggested algorithm for the diagnosis of CMV in the pregnant patient.1

If a diagnosis of maternal CMV infection is confirmed, liver function tests should be obtained to determine if CMV hepatitis is present. If the liver function tests are abnormal, a coagulation profile also should be performed to identify the mother who might be at risk for peripartum hemorrhage.

Fetal infection

The single best test for confirmation of congenital CMV infection is detection of viral DNA and quantitation of viral load in the amniotic fluid by PCR. If the amniocentesis is performed prior to 20 weeks’ gestation and is negative, the test should be repeated in approximately 4 weeks.1,19,24

Detection of viral DNA indicates congenital infection. The ultimate task, however, is to determine if the infection has injured the fetus. Detailed ultrasound examination is the key to identifying fetal injury. As noted previously, the principal ultrasonographic findings that suggest congenital CMV infection include2,19,20,21,25:

- hydropic placenta

- fetal growth restriction

- microcephaly (head circumference more than 3 standard deviations below the mean)

- periventricular calcifications

- enlarged liver

- echogenic bowel

- ascites

- fetal hydrops.

Management: Evidence on CMV hyperimmune globulin, valacyclovir

If the immunocompetent mother has clinical manifestations of infection, she should receive symptomatic treatment. She should be encouraged to rest as much as possible, stay well hydrated, and use acetaminophen (1,000 mg every 6 to 8 hours) as needed for malaise and fever.

However, if the mother is immunocompromised and has signs of serious complications, such as chorioretinitis, hepatitis, or pneumonia, more aggressive therapy is indicated. Drugs used in this setting include foscarnet and ganciclovir and are best prescribed in consultation with a medical infectious disease specialist.

At this time, no consistently effective therapy for congenital infection is available. Therefore, if a patient has primary CMV infection in the first half of pregnancy, particularly in the first trimester, she should be counseled that the risk of fetal infection is approximately 40% and that approximately 5% to 15% of infants will be severely affected at birth. Given this information, some patients may opt for pregnancy termination.

In 2005, a report from Nigro and colleagues stimulated great hope that CMV-specific hyperimmune globulin (CytoGam) might be of value for both treatment and prophylaxis for congenital infection.26 These authors studied 157 women with confirmed primary CMV infection. One-hundred forty-eight women were asymptomatic and were identified by routine serologic screening, 8 had symptomatic infection, and 1 was identified because of abnormal fetal ultrasound findings. Forty-five women had CMV detected in amniotic fluid by PCR or culture more than 6 weeks before study enrollment. Thirty-one of these women were treated with intravenous hyperimmune globulin (200 U or 200 mg/kg maternal body weight); 14 declined treatment. Seven of the latter women had infants who were acutely symptomatic at the time of delivery; only 1 of the 31 treated women had an affected neonate (adjusted odds ratio [OR], 0.02; P<.001). In this same study, 84 women did not have a diagnostic amniocentesis because their infection occurred within 6 weeks of enrollment, their gestational age was less than 20 weeks, or they declined the procedure. Thirty-seven of these women received hyperimmune globulin (100 U or 100 mg/kg) every month until delivery, and 47 declined treatment. Six of the treated women delivered infected infants compared with 19 of the untreated women (adjusted OR, 0.32; P<.04).

Although these results were quite encouraging, several problems existed with the study’s design, as noted in an editorial that accompanied the study’s publication.27 First, the study was not randomized or placebo controlled. Second, patients were not stratified based on the severity of fetal ultrasound abnormalities. Third, the dosing of hyperimmune globulin varied; 9 of the 31 patients in the treatment group received additional infusions of drug into either the amniotic fluid or fetal umbilical vein. Moreover, patients in the prophylaxis group actually received a higher cumulative dose of hyperimmune globulin than patients in the treatment group.

Two subsequent investigations that were better designed were unable to verify the effectiveness of hyperimmune globulin. In 2014, Revello and colleagues reported the results of a prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blinded study of 124 women at 5 to 26 weeks’ gestation with confirmed primary CMV infection.28 The rate of congenital infection was 30% in the group treated with hyperimmune globulin and 44% in the placebo group (P=.13). There also was no significant difference in the concentration of serum CMV DNA in treated versus untreated mothers. Moreover, the number of adverse obstetric events (preterm delivery, fetal growth restriction, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, and postpartum preeclampsia) in the treatment group was higher than in the placebo group, 13% versus 2%.

In 2021, Hughes and colleagues published the results of a multicenter, double-blind trial in 399 women who had a diagnosis of primary CMV infection before 23 weeks’ gestation.29 The primary outcome was defined as a composite of congenital CMV infection or fetal/neonatal death. An adverse primary outcome occurred in 22.7% of the patients who received hyperimmune globulin and 19.4% of those who received placebo (relative risk, 1.17; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.80–1.72; P=.42).

Continue to: Jacquemard and colleagues...

Jacquemard and colleagues then proposed a different approach.30 In a small pilot study of 20 patients, these authors used high doses of oral valacylovir (2 g 4 times daily) and documented therapeutic drug concentrations and a decline in CMV viral load in fetal serum. Patients were not stratified by severity of fetal injury at onset of treatment, so the authors were unable to define which fetuses were most likely to benefit from treatment.

In a follow-up investigation, Leruez-Ville and colleagues reported another small series in which high-dose oral valacyclovir (8 g daily) was used for treatment.31 They excluded fetuses with severe brain anomalies and fetuses with no sonographic evidence of injury. The median gestational age at diagnosis was 26 weeks. Thirty-four of 43 treated fetuses were free of injury at birth. In addition, the viral load in the neonate’s serum decreased significantly after treatment, and the platelet count increased. The authors then compared these outcomes to a historical cohort and confirmed that treatment increased the proportion of asymptomatic neonates from 43% without treatment to 82% with treatment (P<.05 with no overlapping confidence intervals).

We conclude from these investigations that hyperimmune globulin is unlikely to be of value in treating congenital CMV infection, especially if the fetus already has sonographic findings of severe injury. High-dose oral valacyclovir also is unlikely to be of value in severely affected fetuses, particularly those with evidence of CNS injury. However, antiviral therapy may be of modest value in situations when the fetus is less severely injured.

Preventive measures

Since no definitive treatment is available for congenital CMV infection, our efforts as clinicians should focus on measures that may prevent transmission of infection to the pregnant patient. These measures include:

- Encouraging patients to use careful handwashing techniques when handling infant diapers and toys.

- Encouraging patients to adopt safe sexual practices if not already engaged in a mutually faithful, monogamous relationship.

- Using CMV-negative blood when transfusing a pregnant woman or a fetus.

At the present time, unfortunately, a readily available and highly effective therapy for prevention of CMV infection is not available.

CASE Congenital infection diagnosed

The ultrasound findings are most consistent with congenital CMV infection, especially given the patient’s work as an elementary schoolteacher. The diagnosis of maternal infection is best established by conventional serology (positive IgM, negative IgM) and detection of viral DNA in maternal blood by PCR testing. The diagnosis of congenital infection is best confirmed by documentation of viral DNA in the amniotic fluid by PCR testing. Given that this fetus already has evidence of moderate to severe injury, no treatment is likely to be effective in reversing the abnormal ultrasound findings. Pregnancy termination may be an option, depending upon the patient’s desires and the legal restrictions prevalent in the patient’s geographic area. ●

- Cytomegalovirus infection is the most common of the perinatally transmitted infections.

- Maternal infection is often asymptomatic. When symptoms are present, they resemble those of an influenza-like illness. In immunocompromised persons, however, CMV may cause serious complications, including pneumonia, hepatitis, and chorioretinitis.

- The virus is transmitted by contact with contaminated body fluids, such as saliva, urine, blood, and genital secretions.

- The greatest risk of severe fetal injury results from primary maternal infection in the first trimester of pregnancy.

- Manifestations of severe congenital CMV infection include growth restriction, microcephaly, ventriculomegaly, hepatosplenomegaly, ascites, chorioretinitis, thrombocytopenia, purpura, and hydrops (“blueberry muffin baby”).

- Late manifestations of infection, which usually follow recurrent maternal infection, may appear as a child enters elementary school and include visual and auditory deficits, developmental delays, and learning disabilities.

- The diagnosis of maternal infection is confirmed by serology and detection of viral DNA in the serum by PCR testing.

- The diagnosis of fetal infection is best made by a combination of abnormal ultrasound findings and detection of CMV DNA in amniotic fluid. The characteristic ultrasound findings include placentomegaly, microcephaly, ventriculomegaly, growth restriction, echogenic bowel, and serous effusions/hydrops.

- Treatment of the mother with antiviral medications such as valacyclovir may be of modest value in reducing placental edema, decreasing viral load in the fetus, and hastening the resolution of some ultrasound findings, such as echogenic bowel.

- While initial studies seemed promising, the use of hyperimmune globulin has not proven to be consistently effective in treating congenital infection.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TR, et al, eds. Creasy and Resnik’s Maternal Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. 2019:888-890.

- Chatzakis C, Ville Y, Makrydimas G, et al. Timing of primary maternal cytomegalovirus infection and rates of vertical transmission and fetal consequences. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:870-883.e11. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2020.05.038

- Kelly MS, Benjamin DK, Puopolo KM, et al. Postnatal cytomegalovirus infection and the risk for bronchopulmonary dysplasia. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:e153785. doi:10.1001 /jamapediatrics.2015.3785

- Messinger CJ, Lipsitch M, Bateman BT, et al. Association between congenital cytomegalovirus and the prevalence at birth of microcephaly in the United States. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174:1159-1167. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.3009

- De Cuyper E, Acke F, Keymeulen A, et al. Risk factors for hearing loss at birth in newborns with congenital cytomegalovirus infection. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2023;149:122-130. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2022.4109

- Colugnati FA, Staras SA, Dollard SC, et al. Incidence of cytomegalovirus infection among the general population and pregnant women in the United States. BMC Infect Dis. 2007;7:71. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-7-71

- Stagno S, Pass RF, Cloud G, et al. Primary cytomegalovirus infection in pregnancy. Incidence, transmission to fetus, and clinical outcome. JAMA. 1986;256:1904-1908.

- Wreghitt TG, Teare EL, Sule O, et al. Cytomegalovirus infection in immunocompetent patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:1603-1606. doi:10.1086/379711

- Fowler KB, Stagno S, Pass RF, et al. The outcome of congenital cytomegalovirus infection in relation to maternal antibody status. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:663-667. doi:10.1056 /NEJM199203053261003

- Faure-Bardon V, Magny JF, Parodi M, et al. Sequelae of congenital cytomegalovirus following maternal primary infections are limited to those acquired in the first trimester of pregnancy. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;69:1526-1532. doi:10.1093/ cid/ciy1128

- Kenneson A, Cannon MJ. Review and meta-analysis of the epidemiology of congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection. Rev Med Virol. 2007;17:253-276. doi:10.1002/ rmv.535

- Boppana SB, Pass RF, Britt WJ, et al. Symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus infection: neonatal morbidity and mortality. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1992;11:93-99. doi:10.1097/00006454-199202000-00007

- Ross SA, Fowler KB, Ashrith G, et al. Hearing loss in children with congenital cytomegalovirus infection born to mothers with preexisting immunity. J Pediatr. 2006;148:332-336. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.09.003

- Zalel Y, Gilboa Y, Berkenshtat M, et al. Secondary cytomegalovirus infection can cause severe fetal sequelae despite maternal preconceptional immunity. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 31:417-420. doi:10.1002/uog.5255

- Scaramuzzino F, Di Pastena M, Chiurchiu S, et al. Secondary cytomegalovirus infections: how much do we still not know? Comparison of children with symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus born to mothers with primary and secondary infection. Front Pediatr. 2022;10:885926. doi:10.3389/fped.2022.885926

- Gindes L, Teperberg-Oikawa M, Sherman D, et al. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection following primary maternal infection in the third trimester. BJOG. 2008;115:830-835. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01651.x

- Hadar E, Dorfman E, Bardin R, et al. Symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus disease following non-primary maternal infection: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17:31. doi:10.1186/s12879-016-2161-3

- Elkan Miller T, Weisz B, Yinon Y, et al. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection following second and third trimester maternal infection is associated with mild childhood adverse outcome not predicted by prenatal imaging. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2021;10:562-568. doi:10.1093/jpids/ piaa154

- Lipitz S, Yinon Y, Malinger G, et al. Risk of cytomegalovirusassociated sequelae in relation to time of infection and findings on prenatal imaging. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;41:508-514. doi:10.1002/uog.12377

- Lipitz S, Elkan Miller T, Yinon Y, et al. Revisiting short- and long-term outcome after fetal first-trimester primary cytomegalovirus infection in relation to prenatal imaging findings. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2020;56:572-578. doi:10.1002/uog.21946

- Buca D, Di Mascio D, Rizzo G, et al. Outcome of fetuses with congenital cytomegalovirus infection and normal ultrasound at diagnosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2021;57:551-559. doi:10.1002/uog.23143

- Boppana SB, Ross SA, Fowler KB. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection: clinical outcome. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57 (suppl 4):S178-S181. doi:10.1093/cid/cit629

- Dollard SC, Grosse SD, Ross DS. New estimates of the prevalence of neurological and sensory sequelae and mortality associated with congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Rev Med Virol. 2007;17:355-363. doi:10.1002/rmv.544

- Hughes BL, Gyamfi-Bannerman C. Diagnosis and antenatal management of congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214:B5-11. doi:10.1016 /j.ajog.2016.02.042

- Rouse DJ, Fette LM, Hughes BL, et al. Noninvasive prediction of congenital cytomegalovirus infection after maternal primary infection. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;139:400-406. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000004691

- Nigro G, Adler SP, La Torre R, et al; Congenital Cytomegalovirus Collaborating Group. Passive immunization during pregnancy for congenital cytomegalovirus infection. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1350-1362. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa043337

- Duff P. Immunotherapy for congenital cytomegalovirus infection. N Engl J Med. 2005;355:1402-1404. doi:10.1056 /NEJMe058172

- Revello MG, Lazzarotto T, Guerra B, et al. A randomized trial of hyperimmune globulin to prevent congenital cytomegalovirus. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1316-1326. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1310214

- Hughes BL, Clifton RG, Rouse DJ, et al. A trial of hyperimmune globulin to prevent congenital cytomegalovirus infection. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:436-444. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1913569

- Jacquemard F, Yamamoto M, Costa JM, et al. Maternal administration of valaciclovir in symptomatic intrauterine cytomegalovirus infection. BJOG. 2007;114:1113-1121. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01308.x

- Leruez-Ville M, Ghout I, Bussières L, et al. In utero treatment of congenital cytomegalovirus infection with valacyclovir in a multicenter, open-label, phase II study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:462.e1-462.e10. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2016.04.003

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TR, et al, eds. Creasy and Resnik’s Maternal Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. 2019:888-890.

- Chatzakis C, Ville Y, Makrydimas G, et al. Timing of primary maternal cytomegalovirus infection and rates of vertical transmission and fetal consequences. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:870-883.e11. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2020.05.038

- Kelly MS, Benjamin DK, Puopolo KM, et al. Postnatal cytomegalovirus infection and the risk for bronchopulmonary dysplasia. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:e153785. doi:10.1001 /jamapediatrics.2015.3785

- Messinger CJ, Lipsitch M, Bateman BT, et al. Association between congenital cytomegalovirus and the prevalence at birth of microcephaly in the United States. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174:1159-1167. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.3009

- De Cuyper E, Acke F, Keymeulen A, et al. Risk factors for hearing loss at birth in newborns with congenital cytomegalovirus infection. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2023;149:122-130. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2022.4109

- Colugnati FA, Staras SA, Dollard SC, et al. Incidence of cytomegalovirus infection among the general population and pregnant women in the United States. BMC Infect Dis. 2007;7:71. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-7-71

- Stagno S, Pass RF, Cloud G, et al. Primary cytomegalovirus infection in pregnancy. Incidence, transmission to fetus, and clinical outcome. JAMA. 1986;256:1904-1908.

- Wreghitt TG, Teare EL, Sule O, et al. Cytomegalovirus infection in immunocompetent patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:1603-1606. doi:10.1086/379711

- Fowler KB, Stagno S, Pass RF, et al. The outcome of congenital cytomegalovirus infection in relation to maternal antibody status. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:663-667. doi:10.1056 /NEJM199203053261003

- Faure-Bardon V, Magny JF, Parodi M, et al. Sequelae of congenital cytomegalovirus following maternal primary infections are limited to those acquired in the first trimester of pregnancy. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;69:1526-1532. doi:10.1093/ cid/ciy1128

- Kenneson A, Cannon MJ. Review and meta-analysis of the epidemiology of congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection. Rev Med Virol. 2007;17:253-276. doi:10.1002/ rmv.535

- Boppana SB, Pass RF, Britt WJ, et al. Symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus infection: neonatal morbidity and mortality. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1992;11:93-99. doi:10.1097/00006454-199202000-00007