User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

More medical schools build training in transgender care

Klay Noto wants to be the kind of doctor he never had when he began to question his gender identity.

A second-year student at Tulane University in New Orleans, he wants to listen compassionately to patients’ concerns and recognize the hurt when they question who they are. He will be the kind of doctor who knows that a breast exam can be traumatizing if someone has been breast binding or that instructing a patient to take everything off and put on a gown can be triggering for someone with gender dysphoria.

Being in the room for hard conversations is part of why he pursued med school. “There aren’t many LGBT people in medicine and as I started to understand all the dynamics that go into it, I started to see that I could do it and I could be that different kind of doctor,” he told this news organization.

Mr. Noto, who transitioned after college, wants to see more transgender people like himself teaching gender medicine, and for all medical students to be trained in what it means to be transgender and how to give compassionate and comprehensive care to all patients.

Gains have been made in providing curriculum in transgender care that trains medical students in such concepts as how to approach gender identity with sensitivity and how to manage hormone therapy and surgery for transitioning patients who request that, according to those interviewed for this story.

But they agree there’s a long way to go to having widespread medical school integration of the health care needs of about 1.4 million transgender people in the United States.

According to the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) Curriculum Inventory data collected from 131 U.S. medical schools, more than 65% offered some form of transgender-related education in 2018, and more than 80% of those provided such curriculum in required courses.

Lack of transgender, nonbinary faculty

Jason Klein, MD, is a pediatric endocrinologist and medical director of the Transgender Youth Health Program at New York (N.Y.) University.

He said in an interview that the number of programs nationally that have gender medicine as a structured part of their curriculum has increased over the last 5-10 years, but that education is not standardized from program to program.

The program at NYU includes lecture-style learning, case presentations, real-world conversations with people in the community, group discussions, and patient care, Dr. Klein said. There are formal lectures as part of adolescent medicine where students learn the differences between gender and sexual identity, and education on medical treatment of transgender and nonbinary adolescents, starting with puberty blockers and moving into affirming hormones.

Doctors also learn to know their limits and decide when to refer patients to a specialist.

“The focus is really about empathic and supportive care,” said Dr. Klein, assistant professor in the department of pediatrics at Hassenfeld Children’s Hospital at NYU Langone Health. “It’s about communication and understanding and the language we use and how to deliver affirming care in a health care setting in general.”

Imagine the potential stressors, he said, of a transgender person entering a typical health care setting. The electronic health record may only have room for the legal name of a person and not the name a person may currently be using. The intake form typically asks patients to check either male or female. The bathrooms give the same two choices.

“Every physician should know how to speak with, treat, emote with, and empathize with care for the trans and nonbinary individual,” Dr. Klein said.

Dr. Klein noted there is a glaring shortage of trans and nonbinary physicians to lead efforts to expand education on integrating the medical, psychological, and psychosocial care that patients will receive.

Currently, gender medicine is not included on board exams for adolescent medicine or endocrinology, he said.

“Adding formal training in gender medicine to board exams would really help solidify the importance of this arena of medicine,” he noted.

First AAMC standards

In 2014, the AAMC released the first standards to guide curricula across medical school and residency to support training doctors to be competent in caring for transgender patients.

The standards include recommending that all doctors be able to communicate with patients related to their gender identity and understand how to deliver high-quality care to transgender and gender-diverse patients within their specialty, Kristen L. Eckstrand, MD, a coauthor of the guidelines, told this news organization.

“Many medical schools have developed their own curricula to meet these standards,” said Dr. Eckstrand, medical director for LGBTQIA+ Health at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

Norma Poll-Hunter, PhD, AAMC’s senior director for workforce diversity, noted that the organization recently released its diversity, equity, and inclusion competencies that guide the medical education of students, residents, and faculty.

Dr. Poll-Hunter told this news organization that AAMC partners with the Building the Next Generation of Academic Physicians LGBT Health Workforce Conference “to support safe spaces for scholarly efforts and mentorship to advance this area of work.”

Team approach at Rutgers

Among the medical schools that incorporate comprehensive transgender care into the curriculum is Rutgers University’s Robert Wood Johnson Medical School in New Brunswick, N.J.

Gloria Bachmann, MD, is professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the school and medical director of its partner, the PROUD Gender Center of New Jersey. PROUD stands for “Promoting Respect, Outreach, Understanding, and Dignity,” and the center provides comprehensive care for transgender and nonbinary patients in one location.

Dr. Bachmann said Rutgers takes a team approach with both instructors and learners teaching medical students about transgender care. The teachers are not only professors in traditional classroom lectures, but patient navigators and nurses at the PROUD center, established as part of the medical school in 2020. Students learn from the navigators, for instance, how to help patients through the spectrum of inpatient and outpatient care.

“All of our learners do get to care for individuals who identify as transgender,” said Dr. Bachmann.

Among the improvements in educating students on transgender care over the years, she said, is the emphasis on social determinants of health. In the transgender population, initial questions may include whether the person is able to access care through insurance as laws vary widely on what care and procedures are covered.

As another example, Dr. Bachmann cites: “If they are seen on an emergency basis and are sent home with medication and follow-up, can they afford it?”

Another consideration is whether there is a home to which they can return.

“Many individuals who are transgender may not have a home. Their family may not be accepting of them. Therefore, it’s the social determinants of health as well as their transgender identity that have to be put into the equation of best care,” she said.

Giving back to the trans community

Mr. Noto doesn’t know whether he will specialize in gender medicine, but he is committed to serving the transgender community in whatever physician path he chooses.

He said he realizes he is fortunate to have strong family support and good insurance and that he can afford fees, such as the copay to see transgender care specialists. Many in the community do not have those resources and are likely to get care “only if they have to.”

At Tulane, training in transgender care starts during orientation week and continues on different levels, with different options, throughout medical school and residency, he added.

Mr. Noto said he would like to see more mandatory learning such as a “queer-centered exam, where you have to give an organ inventory and you have to ask patients if it’s OK to talk about X, Y, and Z.” He’d also like more opportunities for clinical interaction with transgender patients, such as queer-centered rotations.

When physicians aren’t well trained in transgender care, you have patients educating the doctors, which, Mr. Noto said, should not be acceptable.

“People come to you on their worst day. And to not be informed about them in my mind is negligent. In what other population can you choose not to learn about someone just because you don’t want to?” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Klay Noto wants to be the kind of doctor he never had when he began to question his gender identity.

A second-year student at Tulane University in New Orleans, he wants to listen compassionately to patients’ concerns and recognize the hurt when they question who they are. He will be the kind of doctor who knows that a breast exam can be traumatizing if someone has been breast binding or that instructing a patient to take everything off and put on a gown can be triggering for someone with gender dysphoria.

Being in the room for hard conversations is part of why he pursued med school. “There aren’t many LGBT people in medicine and as I started to understand all the dynamics that go into it, I started to see that I could do it and I could be that different kind of doctor,” he told this news organization.

Mr. Noto, who transitioned after college, wants to see more transgender people like himself teaching gender medicine, and for all medical students to be trained in what it means to be transgender and how to give compassionate and comprehensive care to all patients.

Gains have been made in providing curriculum in transgender care that trains medical students in such concepts as how to approach gender identity with sensitivity and how to manage hormone therapy and surgery for transitioning patients who request that, according to those interviewed for this story.

But they agree there’s a long way to go to having widespread medical school integration of the health care needs of about 1.4 million transgender people in the United States.

According to the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) Curriculum Inventory data collected from 131 U.S. medical schools, more than 65% offered some form of transgender-related education in 2018, and more than 80% of those provided such curriculum in required courses.

Lack of transgender, nonbinary faculty

Jason Klein, MD, is a pediatric endocrinologist and medical director of the Transgender Youth Health Program at New York (N.Y.) University.

He said in an interview that the number of programs nationally that have gender medicine as a structured part of their curriculum has increased over the last 5-10 years, but that education is not standardized from program to program.

The program at NYU includes lecture-style learning, case presentations, real-world conversations with people in the community, group discussions, and patient care, Dr. Klein said. There are formal lectures as part of adolescent medicine where students learn the differences between gender and sexual identity, and education on medical treatment of transgender and nonbinary adolescents, starting with puberty blockers and moving into affirming hormones.

Doctors also learn to know their limits and decide when to refer patients to a specialist.

“The focus is really about empathic and supportive care,” said Dr. Klein, assistant professor in the department of pediatrics at Hassenfeld Children’s Hospital at NYU Langone Health. “It’s about communication and understanding and the language we use and how to deliver affirming care in a health care setting in general.”

Imagine the potential stressors, he said, of a transgender person entering a typical health care setting. The electronic health record may only have room for the legal name of a person and not the name a person may currently be using. The intake form typically asks patients to check either male or female. The bathrooms give the same two choices.

“Every physician should know how to speak with, treat, emote with, and empathize with care for the trans and nonbinary individual,” Dr. Klein said.

Dr. Klein noted there is a glaring shortage of trans and nonbinary physicians to lead efforts to expand education on integrating the medical, psychological, and psychosocial care that patients will receive.

Currently, gender medicine is not included on board exams for adolescent medicine or endocrinology, he said.

“Adding formal training in gender medicine to board exams would really help solidify the importance of this arena of medicine,” he noted.

First AAMC standards

In 2014, the AAMC released the first standards to guide curricula across medical school and residency to support training doctors to be competent in caring for transgender patients.

The standards include recommending that all doctors be able to communicate with patients related to their gender identity and understand how to deliver high-quality care to transgender and gender-diverse patients within their specialty, Kristen L. Eckstrand, MD, a coauthor of the guidelines, told this news organization.

“Many medical schools have developed their own curricula to meet these standards,” said Dr. Eckstrand, medical director for LGBTQIA+ Health at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

Norma Poll-Hunter, PhD, AAMC’s senior director for workforce diversity, noted that the organization recently released its diversity, equity, and inclusion competencies that guide the medical education of students, residents, and faculty.

Dr. Poll-Hunter told this news organization that AAMC partners with the Building the Next Generation of Academic Physicians LGBT Health Workforce Conference “to support safe spaces for scholarly efforts and mentorship to advance this area of work.”

Team approach at Rutgers

Among the medical schools that incorporate comprehensive transgender care into the curriculum is Rutgers University’s Robert Wood Johnson Medical School in New Brunswick, N.J.

Gloria Bachmann, MD, is professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the school and medical director of its partner, the PROUD Gender Center of New Jersey. PROUD stands for “Promoting Respect, Outreach, Understanding, and Dignity,” and the center provides comprehensive care for transgender and nonbinary patients in one location.

Dr. Bachmann said Rutgers takes a team approach with both instructors and learners teaching medical students about transgender care. The teachers are not only professors in traditional classroom lectures, but patient navigators and nurses at the PROUD center, established as part of the medical school in 2020. Students learn from the navigators, for instance, how to help patients through the spectrum of inpatient and outpatient care.

“All of our learners do get to care for individuals who identify as transgender,” said Dr. Bachmann.

Among the improvements in educating students on transgender care over the years, she said, is the emphasis on social determinants of health. In the transgender population, initial questions may include whether the person is able to access care through insurance as laws vary widely on what care and procedures are covered.

As another example, Dr. Bachmann cites: “If they are seen on an emergency basis and are sent home with medication and follow-up, can they afford it?”

Another consideration is whether there is a home to which they can return.

“Many individuals who are transgender may not have a home. Their family may not be accepting of them. Therefore, it’s the social determinants of health as well as their transgender identity that have to be put into the equation of best care,” she said.

Giving back to the trans community

Mr. Noto doesn’t know whether he will specialize in gender medicine, but he is committed to serving the transgender community in whatever physician path he chooses.

He said he realizes he is fortunate to have strong family support and good insurance and that he can afford fees, such as the copay to see transgender care specialists. Many in the community do not have those resources and are likely to get care “only if they have to.”

At Tulane, training in transgender care starts during orientation week and continues on different levels, with different options, throughout medical school and residency, he added.

Mr. Noto said he would like to see more mandatory learning such as a “queer-centered exam, where you have to give an organ inventory and you have to ask patients if it’s OK to talk about X, Y, and Z.” He’d also like more opportunities for clinical interaction with transgender patients, such as queer-centered rotations.

When physicians aren’t well trained in transgender care, you have patients educating the doctors, which, Mr. Noto said, should not be acceptable.

“People come to you on their worst day. And to not be informed about them in my mind is negligent. In what other population can you choose not to learn about someone just because you don’t want to?” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Klay Noto wants to be the kind of doctor he never had when he began to question his gender identity.

A second-year student at Tulane University in New Orleans, he wants to listen compassionately to patients’ concerns and recognize the hurt when they question who they are. He will be the kind of doctor who knows that a breast exam can be traumatizing if someone has been breast binding or that instructing a patient to take everything off and put on a gown can be triggering for someone with gender dysphoria.

Being in the room for hard conversations is part of why he pursued med school. “There aren’t many LGBT people in medicine and as I started to understand all the dynamics that go into it, I started to see that I could do it and I could be that different kind of doctor,” he told this news organization.

Mr. Noto, who transitioned after college, wants to see more transgender people like himself teaching gender medicine, and for all medical students to be trained in what it means to be transgender and how to give compassionate and comprehensive care to all patients.

Gains have been made in providing curriculum in transgender care that trains medical students in such concepts as how to approach gender identity with sensitivity and how to manage hormone therapy and surgery for transitioning patients who request that, according to those interviewed for this story.

But they agree there’s a long way to go to having widespread medical school integration of the health care needs of about 1.4 million transgender people in the United States.

According to the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) Curriculum Inventory data collected from 131 U.S. medical schools, more than 65% offered some form of transgender-related education in 2018, and more than 80% of those provided such curriculum in required courses.

Lack of transgender, nonbinary faculty

Jason Klein, MD, is a pediatric endocrinologist and medical director of the Transgender Youth Health Program at New York (N.Y.) University.

He said in an interview that the number of programs nationally that have gender medicine as a structured part of their curriculum has increased over the last 5-10 years, but that education is not standardized from program to program.

The program at NYU includes lecture-style learning, case presentations, real-world conversations with people in the community, group discussions, and patient care, Dr. Klein said. There are formal lectures as part of adolescent medicine where students learn the differences between gender and sexual identity, and education on medical treatment of transgender and nonbinary adolescents, starting with puberty blockers and moving into affirming hormones.

Doctors also learn to know their limits and decide when to refer patients to a specialist.

“The focus is really about empathic and supportive care,” said Dr. Klein, assistant professor in the department of pediatrics at Hassenfeld Children’s Hospital at NYU Langone Health. “It’s about communication and understanding and the language we use and how to deliver affirming care in a health care setting in general.”

Imagine the potential stressors, he said, of a transgender person entering a typical health care setting. The electronic health record may only have room for the legal name of a person and not the name a person may currently be using. The intake form typically asks patients to check either male or female. The bathrooms give the same two choices.

“Every physician should know how to speak with, treat, emote with, and empathize with care for the trans and nonbinary individual,” Dr. Klein said.

Dr. Klein noted there is a glaring shortage of trans and nonbinary physicians to lead efforts to expand education on integrating the medical, psychological, and psychosocial care that patients will receive.

Currently, gender medicine is not included on board exams for adolescent medicine or endocrinology, he said.

“Adding formal training in gender medicine to board exams would really help solidify the importance of this arena of medicine,” he noted.

First AAMC standards

In 2014, the AAMC released the first standards to guide curricula across medical school and residency to support training doctors to be competent in caring for transgender patients.

The standards include recommending that all doctors be able to communicate with patients related to their gender identity and understand how to deliver high-quality care to transgender and gender-diverse patients within their specialty, Kristen L. Eckstrand, MD, a coauthor of the guidelines, told this news organization.

“Many medical schools have developed their own curricula to meet these standards,” said Dr. Eckstrand, medical director for LGBTQIA+ Health at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

Norma Poll-Hunter, PhD, AAMC’s senior director for workforce diversity, noted that the organization recently released its diversity, equity, and inclusion competencies that guide the medical education of students, residents, and faculty.

Dr. Poll-Hunter told this news organization that AAMC partners with the Building the Next Generation of Academic Physicians LGBT Health Workforce Conference “to support safe spaces for scholarly efforts and mentorship to advance this area of work.”

Team approach at Rutgers

Among the medical schools that incorporate comprehensive transgender care into the curriculum is Rutgers University’s Robert Wood Johnson Medical School in New Brunswick, N.J.

Gloria Bachmann, MD, is professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the school and medical director of its partner, the PROUD Gender Center of New Jersey. PROUD stands for “Promoting Respect, Outreach, Understanding, and Dignity,” and the center provides comprehensive care for transgender and nonbinary patients in one location.

Dr. Bachmann said Rutgers takes a team approach with both instructors and learners teaching medical students about transgender care. The teachers are not only professors in traditional classroom lectures, but patient navigators and nurses at the PROUD center, established as part of the medical school in 2020. Students learn from the navigators, for instance, how to help patients through the spectrum of inpatient and outpatient care.

“All of our learners do get to care for individuals who identify as transgender,” said Dr. Bachmann.

Among the improvements in educating students on transgender care over the years, she said, is the emphasis on social determinants of health. In the transgender population, initial questions may include whether the person is able to access care through insurance as laws vary widely on what care and procedures are covered.

As another example, Dr. Bachmann cites: “If they are seen on an emergency basis and are sent home with medication and follow-up, can they afford it?”

Another consideration is whether there is a home to which they can return.

“Many individuals who are transgender may not have a home. Their family may not be accepting of them. Therefore, it’s the social determinants of health as well as their transgender identity that have to be put into the equation of best care,” she said.

Giving back to the trans community

Mr. Noto doesn’t know whether he will specialize in gender medicine, but he is committed to serving the transgender community in whatever physician path he chooses.

He said he realizes he is fortunate to have strong family support and good insurance and that he can afford fees, such as the copay to see transgender care specialists. Many in the community do not have those resources and are likely to get care “only if they have to.”

At Tulane, training in transgender care starts during orientation week and continues on different levels, with different options, throughout medical school and residency, he added.

Mr. Noto said he would like to see more mandatory learning such as a “queer-centered exam, where you have to give an organ inventory and you have to ask patients if it’s OK to talk about X, Y, and Z.” He’d also like more opportunities for clinical interaction with transgender patients, such as queer-centered rotations.

When physicians aren’t well trained in transgender care, you have patients educating the doctors, which, Mr. Noto said, should not be acceptable.

“People come to you on their worst day. And to not be informed about them in my mind is negligent. In what other population can you choose not to learn about someone just because you don’t want to?” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

MammoRisk: A novel tool for assessing breast cancer risk

, according to a recent study. The assessment is based on a patient’s clinical data and breast density, with or without a polygenic risk score (PRS). Adding the latter criterion to the model led to four out of 10 women being assigned a different risk category. Of note, three out of 10 women were changed to a higher risk category.

A multifaceted assessment

In France, biennial mammographic screening is recommended for women aged 50-74 years. A personalized risk assessment approach based not only on age, but also on various risk factors, is a promising strategy that is currently being studied for several types of cancer. These personalized screening approaches seek to contribute to early diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer at an early and curable stage, as well as to decrease overall health costs for society.

Women aged 40 years or older, with no more than one first-degree relative with breast cancer diagnosed after the age of 40 years, were eligible for risk assessment using MammoRisk. Women previously identified as high risk were, therefore, not enrolled. MammoRisk is a machine learning–based tool that evaluates a patient’s risk with or without considering PRS. A PRS reflects the individual’s genetic risk of developing breast cancer. To calculate this risk, DNA was extracted from saliva samples for genotyping of 76 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Patients underwent a complete breast cancer assessment, including a questionnaire, mammogram with evaluation of breast density, collection of saliva sample, and consultations with a radiologist and a breast cancer specialist, the investigators said.

PRS influenced risk

Out of the 290 women who underwent breast cancer assessment between January 2019 and May 2021, 68% were eligible for risk assessment using MammoRisk (median age, 52 years). The others were not eligible because they were younger than 40 years of age, had a history of atypical hyperplasia, were directed to oncogenetic consultation, had a non-White origin, or were considered for Tyrer–Cuzick risk assessment.

Following risk assessment using MammoRisk without PRS, 16% of patients were classified as moderate risk, 53% as intermediate risk, 31% as high risk, and 0% as very high risk. The median risk score (estimated risk at 5 years) was 1.5.

When PRS was added to MammoRisk, 25% were classified as moderate risk, 33% as intermediate risk, 42% as high risk, and 0% as very high risk. Again, the median risk score was 1.5.

A total of 40% of patients were assigned a different risk category when PRS was added to MammoRisk. Importantly, 28% of patients changed from intermediate risk to moderate or high risk.

One author has received speaker honorarium from Predilife, the company commercializing MammoRisk. The others report no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to a recent study. The assessment is based on a patient’s clinical data and breast density, with or without a polygenic risk score (PRS). Adding the latter criterion to the model led to four out of 10 women being assigned a different risk category. Of note, three out of 10 women were changed to a higher risk category.

A multifaceted assessment

In France, biennial mammographic screening is recommended for women aged 50-74 years. A personalized risk assessment approach based not only on age, but also on various risk factors, is a promising strategy that is currently being studied for several types of cancer. These personalized screening approaches seek to contribute to early diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer at an early and curable stage, as well as to decrease overall health costs for society.

Women aged 40 years or older, with no more than one first-degree relative with breast cancer diagnosed after the age of 40 years, were eligible for risk assessment using MammoRisk. Women previously identified as high risk were, therefore, not enrolled. MammoRisk is a machine learning–based tool that evaluates a patient’s risk with or without considering PRS. A PRS reflects the individual’s genetic risk of developing breast cancer. To calculate this risk, DNA was extracted from saliva samples for genotyping of 76 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Patients underwent a complete breast cancer assessment, including a questionnaire, mammogram with evaluation of breast density, collection of saliva sample, and consultations with a radiologist and a breast cancer specialist, the investigators said.

PRS influenced risk

Out of the 290 women who underwent breast cancer assessment between January 2019 and May 2021, 68% were eligible for risk assessment using MammoRisk (median age, 52 years). The others were not eligible because they were younger than 40 years of age, had a history of atypical hyperplasia, were directed to oncogenetic consultation, had a non-White origin, or were considered for Tyrer–Cuzick risk assessment.

Following risk assessment using MammoRisk without PRS, 16% of patients were classified as moderate risk, 53% as intermediate risk, 31% as high risk, and 0% as very high risk. The median risk score (estimated risk at 5 years) was 1.5.

When PRS was added to MammoRisk, 25% were classified as moderate risk, 33% as intermediate risk, 42% as high risk, and 0% as very high risk. Again, the median risk score was 1.5.

A total of 40% of patients were assigned a different risk category when PRS was added to MammoRisk. Importantly, 28% of patients changed from intermediate risk to moderate or high risk.

One author has received speaker honorarium from Predilife, the company commercializing MammoRisk. The others report no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to a recent study. The assessment is based on a patient’s clinical data and breast density, with or without a polygenic risk score (PRS). Adding the latter criterion to the model led to four out of 10 women being assigned a different risk category. Of note, three out of 10 women were changed to a higher risk category.

A multifaceted assessment

In France, biennial mammographic screening is recommended for women aged 50-74 years. A personalized risk assessment approach based not only on age, but also on various risk factors, is a promising strategy that is currently being studied for several types of cancer. These personalized screening approaches seek to contribute to early diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer at an early and curable stage, as well as to decrease overall health costs for society.

Women aged 40 years or older, with no more than one first-degree relative with breast cancer diagnosed after the age of 40 years, were eligible for risk assessment using MammoRisk. Women previously identified as high risk were, therefore, not enrolled. MammoRisk is a machine learning–based tool that evaluates a patient’s risk with or without considering PRS. A PRS reflects the individual’s genetic risk of developing breast cancer. To calculate this risk, DNA was extracted from saliva samples for genotyping of 76 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Patients underwent a complete breast cancer assessment, including a questionnaire, mammogram with evaluation of breast density, collection of saliva sample, and consultations with a radiologist and a breast cancer specialist, the investigators said.

PRS influenced risk

Out of the 290 women who underwent breast cancer assessment between January 2019 and May 2021, 68% were eligible for risk assessment using MammoRisk (median age, 52 years). The others were not eligible because they were younger than 40 years of age, had a history of atypical hyperplasia, were directed to oncogenetic consultation, had a non-White origin, or were considered for Tyrer–Cuzick risk assessment.

Following risk assessment using MammoRisk without PRS, 16% of patients were classified as moderate risk, 53% as intermediate risk, 31% as high risk, and 0% as very high risk. The median risk score (estimated risk at 5 years) was 1.5.

When PRS was added to MammoRisk, 25% were classified as moderate risk, 33% as intermediate risk, 42% as high risk, and 0% as very high risk. Again, the median risk score was 1.5.

A total of 40% of patients were assigned a different risk category when PRS was added to MammoRisk. Importantly, 28% of patients changed from intermediate risk to moderate or high risk.

One author has received speaker honorarium from Predilife, the company commercializing MammoRisk. The others report no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM BREAST CANCER RESEARCH AND TREATMENT

U.S. life expectancy dropped by 2 years in 2020: Study

according to a new study.

The study, published in medRxiv, said U.S. life expectancy went from 78.86 years in 2019 to 76.99 years in 2020, during the thick of the global COVID-19 pandemic. Though vaccines were widely available in 2021, the U.S. life expectancy was expected to keep going down, to 76.60 years.

In “peer countries” – Austria, Belgium, Denmark, England and Wales, Finland, France, Germany, Israel, Italy, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Northern Ireland, Norway, Portugal, Scotland, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland – life expectancy went down only 0.57 years from 2019 to 2020 and increased by 0.28 years in 2021, the study said. The peer countries now have a life expectancy that’s 5 years longer than in the United States.

“The fact the U.S. lost so many more lives than other high-income countries speaks not only to how we managed the pandemic, but also to more deeply rooted problems that predated the pandemic,” said Steven H. Woolf, MD, one of the study authors and a professor of family medicine and population health at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, according to Reuters.

“U.S. life expectancy has been falling behind other countries since the 1980s, and the gap has widened over time, especially in the last decade.”

Lack of universal health care, income and educational inequality, and less-healthy physical and social environments helped lead to the decline in American life expectancy, according to Dr. Woolf.

The life expectancy drop from 2019 to 2020 hit Black and Hispanic people hardest, according to the study. But the drop from 2020 to 2021 affected White people the most, with average life expectancy among them going down about a third of a year.

Researchers looked at death data from the National Center for Health Statistics, the Human Mortality Database, and overseas statistical agencies. Life expectancy for 2021 was estimated “using a previously validated modeling method,” the study said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

according to a new study.

The study, published in medRxiv, said U.S. life expectancy went from 78.86 years in 2019 to 76.99 years in 2020, during the thick of the global COVID-19 pandemic. Though vaccines were widely available in 2021, the U.S. life expectancy was expected to keep going down, to 76.60 years.

In “peer countries” – Austria, Belgium, Denmark, England and Wales, Finland, France, Germany, Israel, Italy, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Northern Ireland, Norway, Portugal, Scotland, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland – life expectancy went down only 0.57 years from 2019 to 2020 and increased by 0.28 years in 2021, the study said. The peer countries now have a life expectancy that’s 5 years longer than in the United States.

“The fact the U.S. lost so many more lives than other high-income countries speaks not only to how we managed the pandemic, but also to more deeply rooted problems that predated the pandemic,” said Steven H. Woolf, MD, one of the study authors and a professor of family medicine and population health at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, according to Reuters.

“U.S. life expectancy has been falling behind other countries since the 1980s, and the gap has widened over time, especially in the last decade.”

Lack of universal health care, income and educational inequality, and less-healthy physical and social environments helped lead to the decline in American life expectancy, according to Dr. Woolf.

The life expectancy drop from 2019 to 2020 hit Black and Hispanic people hardest, according to the study. But the drop from 2020 to 2021 affected White people the most, with average life expectancy among them going down about a third of a year.

Researchers looked at death data from the National Center for Health Statistics, the Human Mortality Database, and overseas statistical agencies. Life expectancy for 2021 was estimated “using a previously validated modeling method,” the study said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

according to a new study.

The study, published in medRxiv, said U.S. life expectancy went from 78.86 years in 2019 to 76.99 years in 2020, during the thick of the global COVID-19 pandemic. Though vaccines were widely available in 2021, the U.S. life expectancy was expected to keep going down, to 76.60 years.

In “peer countries” – Austria, Belgium, Denmark, England and Wales, Finland, France, Germany, Israel, Italy, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Northern Ireland, Norway, Portugal, Scotland, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland – life expectancy went down only 0.57 years from 2019 to 2020 and increased by 0.28 years in 2021, the study said. The peer countries now have a life expectancy that’s 5 years longer than in the United States.

“The fact the U.S. lost so many more lives than other high-income countries speaks not only to how we managed the pandemic, but also to more deeply rooted problems that predated the pandemic,” said Steven H. Woolf, MD, one of the study authors and a professor of family medicine and population health at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, according to Reuters.

“U.S. life expectancy has been falling behind other countries since the 1980s, and the gap has widened over time, especially in the last decade.”

Lack of universal health care, income and educational inequality, and less-healthy physical and social environments helped lead to the decline in American life expectancy, according to Dr. Woolf.

The life expectancy drop from 2019 to 2020 hit Black and Hispanic people hardest, according to the study. But the drop from 2020 to 2021 affected White people the most, with average life expectancy among them going down about a third of a year.

Researchers looked at death data from the National Center for Health Statistics, the Human Mortality Database, and overseas statistical agencies. Life expectancy for 2021 was estimated “using a previously validated modeling method,” the study said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM MEDRXIV

Infectious disease pop quiz: Clinical challenge #23 for the ObGyn

What are the most common organisms that cause chorioamnionitis and puerperal endometritis?

Continue to the answer...

Chorioamnionitis and puerperal endometritis are polymicrobial, mixed aerobic-anaerobic infections. The dominant organisms are anaerobic gram-negative bacilli (Bacteroides and Prevotella species); anaerobic gram-positive cocci (Peptococcus species and Peptostreptococcus species); aerobic gram-negative bacilli (principally, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Proteus species); and aerobic gram-positive cocci (enterococci, staphylococci, and group B streptococci).

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

What are the most common organisms that cause chorioamnionitis and puerperal endometritis?

Continue to the answer...

Chorioamnionitis and puerperal endometritis are polymicrobial, mixed aerobic-anaerobic infections. The dominant organisms are anaerobic gram-negative bacilli (Bacteroides and Prevotella species); anaerobic gram-positive cocci (Peptococcus species and Peptostreptococcus species); aerobic gram-negative bacilli (principally, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Proteus species); and aerobic gram-positive cocci (enterococci, staphylococci, and group B streptococci).

What are the most common organisms that cause chorioamnionitis and puerperal endometritis?

Continue to the answer...

Chorioamnionitis and puerperal endometritis are polymicrobial, mixed aerobic-anaerobic infections. The dominant organisms are anaerobic gram-negative bacilli (Bacteroides and Prevotella species); anaerobic gram-positive cocci (Peptococcus species and Peptostreptococcus species); aerobic gram-negative bacilli (principally, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Proteus species); and aerobic gram-positive cocci (enterococci, staphylococci, and group B streptococci).

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

Unraveling primary ovarian insufficiency

In the presentation of secondary amenorrhea, pregnancy is the No. 1 differential diagnosis. Once this has been excluded, an algorithm is initiated to determine the etiology, including an assessment of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis. While the early onset of ovarian failure can be physically and psychologically disrupting, the effect on fertility is an especially devastating event. Previously identified by terms including premature ovarian failure and premature menopause, “primary ovarian insufficiency” (POI) is now the preferred designation. This month’s article will address the diagnosis, evaluation, and management of POI.

The definition of POI is the development of primary hypogonadism before the age of 40 years. Spontaneous POI occurs in approximately 1 in 250 women by age 35 years and 1 in 100 by age 40 years. After excluding pregnancy, the clinician should determine signs and symptoms that can lead to expedited and cost-efficient testing.

Consequences

POI is an important risk factor for bone loss and osteoporosis, especially in young women who develop ovarian dysfunction before they achieve peak adult bone mass. At the time of diagnosis of POI, a bone density test (dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry) should be obtained. Women with POI may also develop depression and anxiety as well as experience an increased risk for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, possibly related to endothelial dysfunction.

Young women with spontaneous POI are at increased risk of developing autoimmune adrenal insufficiency (AAI), a potentially fatal disorder. Consequently, to diagnose AAI, serum adrenal cortical and 21-hydroxylase antibodies should be measured in all women who have a karyotype of 46,XX and experience spontaneous POI. Women with AAI have a 50% risk of developing adrenal insufficiency. Despite initial normal adrenal function, women with positive adrenal cortical antibodies should be followed annually.

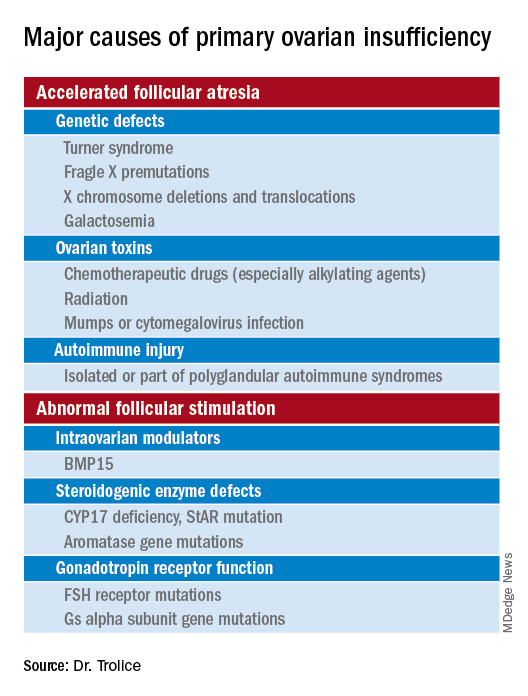

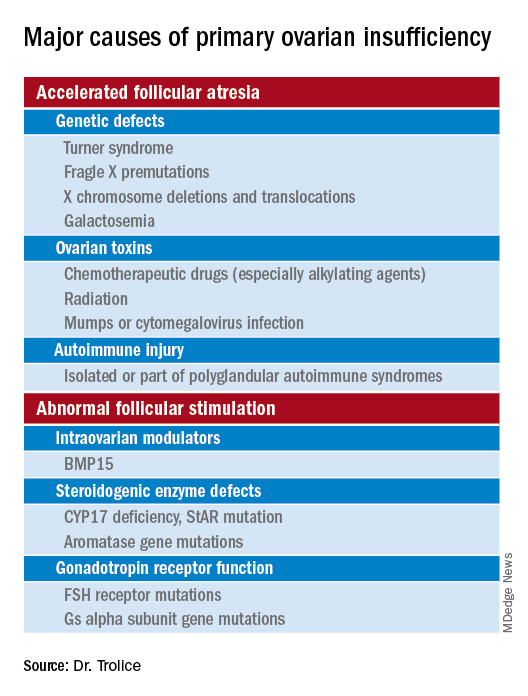

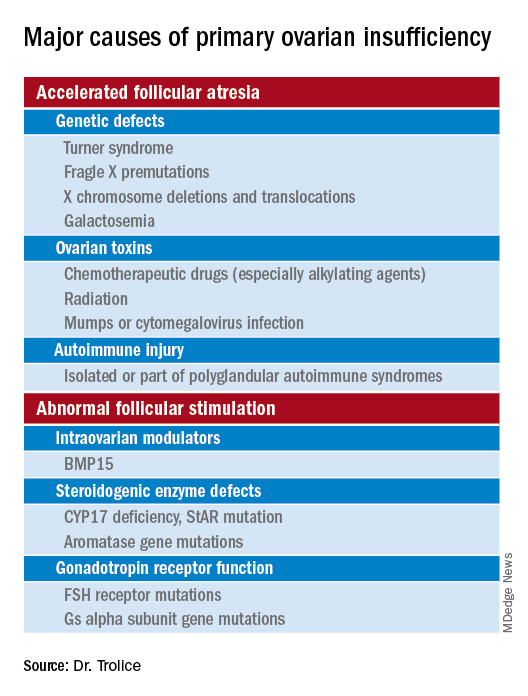

Causes (see table for a more complete list)

Iatrogenic

Known causes of POI include chemotherapy/radiation often in the setting of cancer treatment. The three most commonly used drugs, cyclophosphamide, cisplatin, and doxorubicin, cause POI by inducing death and/or accelerated activation of primordial follicles and increased atresia of growing follicles. The most damaging agents are alkylating drugs. A cyclophosphamide equivalent dose calculator has been established for ovarian failure risk stratification from chemotherapy based on the cumulative dose of alkylating agents received.

One study estimated the radiosensitivity of the oocyte to be less than 2 Gy. Based upon this estimate, the authors calculated the dose of radiotherapy that would result in immediate and permanent ovarian failure in 97.5% of patients as follows:

- 20.3 Gy at birth

- 18.4 Gy at age 10 years

- 16.5 Gy at age 20 years

- 14.3 Gy at age 30 years

Genetic

Approximately 10% of cases are familial. A family history of POI raises concern for a fragile X premutation. Fragile X syndrome is an X-linked form of intellectual disability that is one of the most common causes of mental retardation worldwide. There is a strong relationship between age at menopause, including POI, and premutations for fragile X syndrome. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that women with POI or an elevated follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) level before age 40 years without known cause be screened for FMR1 premutations. Approximately 6% of cases of POI are associated with premutations in the FMR1 gene.

Turner syndrome is one of the most common causes of POI and results from the lack of a second X chromosome. The most common chromosomal defect in humans, TS occurs in up to 1.5% of conceptions, 10% of spontaneous abortions, and 1 of 2,500 live births.

Serum antiadrenal and/or anti–21-hydroxylase antibodies and antithyroid antiperoxidase antibodies, can aid in the diagnosis of adrenal gland, ovary, and thyroid autoimmune causes, which is found in 4% of women with spontaneous POI. Testing for the presence of 21-hydroxylase autoantibodies or adrenal autoantibodies is sufficient to make the diagnosis of autoimmune oophoritis in women with proven spontaneous POI.

The etiology of POI remains unknown in approximately 75%-90% of cases. However, studies using whole exome or whole genome sequencing have identified genetic variants in approximately 30%-35% of these patients.

Risk factors

Factors that are thought to play a role in determining the age of menopause, include genetics (e.g., FMR1 premutation and mosaic Turner syndrome), ethnicity (earlier among Hispanic women and later in Japanese American women when compared with White women), and smoking (reduced by approximately 2 years ).

Regarding ovarian aging, the holy grail of the reproductive life span is to predict menopause. While the definitive age eludes us, anti-Müllerian hormone levels appear to show promise. An ultrasensitive anti-Müllerian hormone assay (< 0.01 ng/mL) predicted a 79% probability of menopause within 12 months for women aged 51 and above; the probability was 51% for women below age 48.

Diagnosis

The three P’s of secondary amenorrhea are physiological, pharmacological, or pathological and can guide the clinician to a targeted evaluation. Physiological causes are pregnancy, the first 6 months of continuous breastfeeding (from elevated prolactin), and natural menopause. Pharmacological etiologies, excluding hormonal treatment that suppresses ovulation (combined oral contraceptives, gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist/antagonist, or danazol), include agents that inhibit dopamine thereby increasing serum prolactin, such as metoclopramide; phenothiazine antipsychotics, such as haloperidol; and tardive dystonia dopamine-depleting medications, such as reserpine. Pathological causes include pituitary adenomas, thyroid disease, functional hypothalamic amenorrhea from changes in weight, exercise regimen, and stress.

Management

About 50%-75% of women with 46,XX spontaneous POI experience intermittent ovarian function and 5%-10% of women remain able to conceive. Anecdotally, a 32-year-old woman presented to me with primary infertility, secondary amenorrhea, and suspected POI based on vasomotor symptoms and elevated FSH levels. Pelvic ultrasound showed a hemorrhagic cyst, suspicious for a corpus luteum. Two weeks thereafter she reported a positive home urine human chorionic gonadotropin test and ultimately delivered twins. Her diagnosis of POI with amenorrhea remained postpartum.

Unless there is an absolute contraindication, estrogen therapy should be prescribed to women with POI to reduce the risk of osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease, and urogenital atrophy as well as to maintain sexual health and quality of life. For those with an intact uterus, women should receive progesterone because of the risk of endometrial hyperplasia from unopposed estrogen. Rather than oral estrogen, the use of transdermal or vaginal delivery of estrogen is a more physiological approach and provides lower risks of venous thromboembolism and gallbladder disease. Of note, standard postmenopausal hormone therapy, which has a much lower dose of estrogen than combined estrogen-progestin contraceptives, does not provide effective contraception. Per ACOG, systemic hormone treatment should be prescribed until age 50-51 years to all women with POI.

For fertility, women with spontaneous POI can be offered oocyte or embryo donation. The uterus does not age reproductively, unlike oocytes, therefore women can achieve reasonable pregnancy success rates through egg donation despite experiencing menopause.

Future potential options

Female germline stem cells have been isolated from neonatal mice and transplanted into sterile adult mice, who then were able to produce offspring. In a second study, oogonial stem cells were isolated from neonatal and adult mouse ovaries; pups were subsequently born from the oocytes. Further experiments are needed before the implications for humans can be determined.

Emotionally traumatic for most women, POI disrupts life plans, hopes, and dreams of raising a family. The approach to the patient with POI involves the above evidence-based testing along with empathy from the health care provider.

Dr. Trolice is director of The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

In the presentation of secondary amenorrhea, pregnancy is the No. 1 differential diagnosis. Once this has been excluded, an algorithm is initiated to determine the etiology, including an assessment of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis. While the early onset of ovarian failure can be physically and psychologically disrupting, the effect on fertility is an especially devastating event. Previously identified by terms including premature ovarian failure and premature menopause, “primary ovarian insufficiency” (POI) is now the preferred designation. This month’s article will address the diagnosis, evaluation, and management of POI.

The definition of POI is the development of primary hypogonadism before the age of 40 years. Spontaneous POI occurs in approximately 1 in 250 women by age 35 years and 1 in 100 by age 40 years. After excluding pregnancy, the clinician should determine signs and symptoms that can lead to expedited and cost-efficient testing.

Consequences

POI is an important risk factor for bone loss and osteoporosis, especially in young women who develop ovarian dysfunction before they achieve peak adult bone mass. At the time of diagnosis of POI, a bone density test (dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry) should be obtained. Women with POI may also develop depression and anxiety as well as experience an increased risk for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, possibly related to endothelial dysfunction.

Young women with spontaneous POI are at increased risk of developing autoimmune adrenal insufficiency (AAI), a potentially fatal disorder. Consequently, to diagnose AAI, serum adrenal cortical and 21-hydroxylase antibodies should be measured in all women who have a karyotype of 46,XX and experience spontaneous POI. Women with AAI have a 50% risk of developing adrenal insufficiency. Despite initial normal adrenal function, women with positive adrenal cortical antibodies should be followed annually.

Causes (see table for a more complete list)

Iatrogenic

Known causes of POI include chemotherapy/radiation often in the setting of cancer treatment. The three most commonly used drugs, cyclophosphamide, cisplatin, and doxorubicin, cause POI by inducing death and/or accelerated activation of primordial follicles and increased atresia of growing follicles. The most damaging agents are alkylating drugs. A cyclophosphamide equivalent dose calculator has been established for ovarian failure risk stratification from chemotherapy based on the cumulative dose of alkylating agents received.

One study estimated the radiosensitivity of the oocyte to be less than 2 Gy. Based upon this estimate, the authors calculated the dose of radiotherapy that would result in immediate and permanent ovarian failure in 97.5% of patients as follows:

- 20.3 Gy at birth

- 18.4 Gy at age 10 years

- 16.5 Gy at age 20 years

- 14.3 Gy at age 30 years

Genetic

Approximately 10% of cases are familial. A family history of POI raises concern for a fragile X premutation. Fragile X syndrome is an X-linked form of intellectual disability that is one of the most common causes of mental retardation worldwide. There is a strong relationship between age at menopause, including POI, and premutations for fragile X syndrome. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that women with POI or an elevated follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) level before age 40 years without known cause be screened for FMR1 premutations. Approximately 6% of cases of POI are associated with premutations in the FMR1 gene.

Turner syndrome is one of the most common causes of POI and results from the lack of a second X chromosome. The most common chromosomal defect in humans, TS occurs in up to 1.5% of conceptions, 10% of spontaneous abortions, and 1 of 2,500 live births.

Serum antiadrenal and/or anti–21-hydroxylase antibodies and antithyroid antiperoxidase antibodies, can aid in the diagnosis of adrenal gland, ovary, and thyroid autoimmune causes, which is found in 4% of women with spontaneous POI. Testing for the presence of 21-hydroxylase autoantibodies or adrenal autoantibodies is sufficient to make the diagnosis of autoimmune oophoritis in women with proven spontaneous POI.

The etiology of POI remains unknown in approximately 75%-90% of cases. However, studies using whole exome or whole genome sequencing have identified genetic variants in approximately 30%-35% of these patients.

Risk factors

Factors that are thought to play a role in determining the age of menopause, include genetics (e.g., FMR1 premutation and mosaic Turner syndrome), ethnicity (earlier among Hispanic women and later in Japanese American women when compared with White women), and smoking (reduced by approximately 2 years ).

Regarding ovarian aging, the holy grail of the reproductive life span is to predict menopause. While the definitive age eludes us, anti-Müllerian hormone levels appear to show promise. An ultrasensitive anti-Müllerian hormone assay (< 0.01 ng/mL) predicted a 79% probability of menopause within 12 months for women aged 51 and above; the probability was 51% for women below age 48.

Diagnosis

The three P’s of secondary amenorrhea are physiological, pharmacological, or pathological and can guide the clinician to a targeted evaluation. Physiological causes are pregnancy, the first 6 months of continuous breastfeeding (from elevated prolactin), and natural menopause. Pharmacological etiologies, excluding hormonal treatment that suppresses ovulation (combined oral contraceptives, gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist/antagonist, or danazol), include agents that inhibit dopamine thereby increasing serum prolactin, such as metoclopramide; phenothiazine antipsychotics, such as haloperidol; and tardive dystonia dopamine-depleting medications, such as reserpine. Pathological causes include pituitary adenomas, thyroid disease, functional hypothalamic amenorrhea from changes in weight, exercise regimen, and stress.

Management

About 50%-75% of women with 46,XX spontaneous POI experience intermittent ovarian function and 5%-10% of women remain able to conceive. Anecdotally, a 32-year-old woman presented to me with primary infertility, secondary amenorrhea, and suspected POI based on vasomotor symptoms and elevated FSH levels. Pelvic ultrasound showed a hemorrhagic cyst, suspicious for a corpus luteum. Two weeks thereafter she reported a positive home urine human chorionic gonadotropin test and ultimately delivered twins. Her diagnosis of POI with amenorrhea remained postpartum.

Unless there is an absolute contraindication, estrogen therapy should be prescribed to women with POI to reduce the risk of osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease, and urogenital atrophy as well as to maintain sexual health and quality of life. For those with an intact uterus, women should receive progesterone because of the risk of endometrial hyperplasia from unopposed estrogen. Rather than oral estrogen, the use of transdermal or vaginal delivery of estrogen is a more physiological approach and provides lower risks of venous thromboembolism and gallbladder disease. Of note, standard postmenopausal hormone therapy, which has a much lower dose of estrogen than combined estrogen-progestin contraceptives, does not provide effective contraception. Per ACOG, systemic hormone treatment should be prescribed until age 50-51 years to all women with POI.

For fertility, women with spontaneous POI can be offered oocyte or embryo donation. The uterus does not age reproductively, unlike oocytes, therefore women can achieve reasonable pregnancy success rates through egg donation despite experiencing menopause.

Future potential options

Female germline stem cells have been isolated from neonatal mice and transplanted into sterile adult mice, who then were able to produce offspring. In a second study, oogonial stem cells were isolated from neonatal and adult mouse ovaries; pups were subsequently born from the oocytes. Further experiments are needed before the implications for humans can be determined.

Emotionally traumatic for most women, POI disrupts life plans, hopes, and dreams of raising a family. The approach to the patient with POI involves the above evidence-based testing along with empathy from the health care provider.

Dr. Trolice is director of The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

In the presentation of secondary amenorrhea, pregnancy is the No. 1 differential diagnosis. Once this has been excluded, an algorithm is initiated to determine the etiology, including an assessment of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis. While the early onset of ovarian failure can be physically and psychologically disrupting, the effect on fertility is an especially devastating event. Previously identified by terms including premature ovarian failure and premature menopause, “primary ovarian insufficiency” (POI) is now the preferred designation. This month’s article will address the diagnosis, evaluation, and management of POI.

The definition of POI is the development of primary hypogonadism before the age of 40 years. Spontaneous POI occurs in approximately 1 in 250 women by age 35 years and 1 in 100 by age 40 years. After excluding pregnancy, the clinician should determine signs and symptoms that can lead to expedited and cost-efficient testing.

Consequences

POI is an important risk factor for bone loss and osteoporosis, especially in young women who develop ovarian dysfunction before they achieve peak adult bone mass. At the time of diagnosis of POI, a bone density test (dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry) should be obtained. Women with POI may also develop depression and anxiety as well as experience an increased risk for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, possibly related to endothelial dysfunction.

Young women with spontaneous POI are at increased risk of developing autoimmune adrenal insufficiency (AAI), a potentially fatal disorder. Consequently, to diagnose AAI, serum adrenal cortical and 21-hydroxylase antibodies should be measured in all women who have a karyotype of 46,XX and experience spontaneous POI. Women with AAI have a 50% risk of developing adrenal insufficiency. Despite initial normal adrenal function, women with positive adrenal cortical antibodies should be followed annually.

Causes (see table for a more complete list)

Iatrogenic

Known causes of POI include chemotherapy/radiation often in the setting of cancer treatment. The three most commonly used drugs, cyclophosphamide, cisplatin, and doxorubicin, cause POI by inducing death and/or accelerated activation of primordial follicles and increased atresia of growing follicles. The most damaging agents are alkylating drugs. A cyclophosphamide equivalent dose calculator has been established for ovarian failure risk stratification from chemotherapy based on the cumulative dose of alkylating agents received.

One study estimated the radiosensitivity of the oocyte to be less than 2 Gy. Based upon this estimate, the authors calculated the dose of radiotherapy that would result in immediate and permanent ovarian failure in 97.5% of patients as follows:

- 20.3 Gy at birth

- 18.4 Gy at age 10 years

- 16.5 Gy at age 20 years

- 14.3 Gy at age 30 years

Genetic

Approximately 10% of cases are familial. A family history of POI raises concern for a fragile X premutation. Fragile X syndrome is an X-linked form of intellectual disability that is one of the most common causes of mental retardation worldwide. There is a strong relationship between age at menopause, including POI, and premutations for fragile X syndrome. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that women with POI or an elevated follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) level before age 40 years without known cause be screened for FMR1 premutations. Approximately 6% of cases of POI are associated with premutations in the FMR1 gene.

Turner syndrome is one of the most common causes of POI and results from the lack of a second X chromosome. The most common chromosomal defect in humans, TS occurs in up to 1.5% of conceptions, 10% of spontaneous abortions, and 1 of 2,500 live births.

Serum antiadrenal and/or anti–21-hydroxylase antibodies and antithyroid antiperoxidase antibodies, can aid in the diagnosis of adrenal gland, ovary, and thyroid autoimmune causes, which is found in 4% of women with spontaneous POI. Testing for the presence of 21-hydroxylase autoantibodies or adrenal autoantibodies is sufficient to make the diagnosis of autoimmune oophoritis in women with proven spontaneous POI.

The etiology of POI remains unknown in approximately 75%-90% of cases. However, studies using whole exome or whole genome sequencing have identified genetic variants in approximately 30%-35% of these patients.

Risk factors

Factors that are thought to play a role in determining the age of menopause, include genetics (e.g., FMR1 premutation and mosaic Turner syndrome), ethnicity (earlier among Hispanic women and later in Japanese American women when compared with White women), and smoking (reduced by approximately 2 years ).

Regarding ovarian aging, the holy grail of the reproductive life span is to predict menopause. While the definitive age eludes us, anti-Müllerian hormone levels appear to show promise. An ultrasensitive anti-Müllerian hormone assay (< 0.01 ng/mL) predicted a 79% probability of menopause within 12 months for women aged 51 and above; the probability was 51% for women below age 48.

Diagnosis

The three P’s of secondary amenorrhea are physiological, pharmacological, or pathological and can guide the clinician to a targeted evaluation. Physiological causes are pregnancy, the first 6 months of continuous breastfeeding (from elevated prolactin), and natural menopause. Pharmacological etiologies, excluding hormonal treatment that suppresses ovulation (combined oral contraceptives, gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist/antagonist, or danazol), include agents that inhibit dopamine thereby increasing serum prolactin, such as metoclopramide; phenothiazine antipsychotics, such as haloperidol; and tardive dystonia dopamine-depleting medications, such as reserpine. Pathological causes include pituitary adenomas, thyroid disease, functional hypothalamic amenorrhea from changes in weight, exercise regimen, and stress.

Management

About 50%-75% of women with 46,XX spontaneous POI experience intermittent ovarian function and 5%-10% of women remain able to conceive. Anecdotally, a 32-year-old woman presented to me with primary infertility, secondary amenorrhea, and suspected POI based on vasomotor symptoms and elevated FSH levels. Pelvic ultrasound showed a hemorrhagic cyst, suspicious for a corpus luteum. Two weeks thereafter she reported a positive home urine human chorionic gonadotropin test and ultimately delivered twins. Her diagnosis of POI with amenorrhea remained postpartum.

Unless there is an absolute contraindication, estrogen therapy should be prescribed to women with POI to reduce the risk of osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease, and urogenital atrophy as well as to maintain sexual health and quality of life. For those with an intact uterus, women should receive progesterone because of the risk of endometrial hyperplasia from unopposed estrogen. Rather than oral estrogen, the use of transdermal or vaginal delivery of estrogen is a more physiological approach and provides lower risks of venous thromboembolism and gallbladder disease. Of note, standard postmenopausal hormone therapy, which has a much lower dose of estrogen than combined estrogen-progestin contraceptives, does not provide effective contraception. Per ACOG, systemic hormone treatment should be prescribed until age 50-51 years to all women with POI.

For fertility, women with spontaneous POI can be offered oocyte or embryo donation. The uterus does not age reproductively, unlike oocytes, therefore women can achieve reasonable pregnancy success rates through egg donation despite experiencing menopause.

Future potential options

Female germline stem cells have been isolated from neonatal mice and transplanted into sterile adult mice, who then were able to produce offspring. In a second study, oogonial stem cells were isolated from neonatal and adult mouse ovaries; pups were subsequently born from the oocytes. Further experiments are needed before the implications for humans can be determined.

Emotionally traumatic for most women, POI disrupts life plans, hopes, and dreams of raising a family. The approach to the patient with POI involves the above evidence-based testing along with empathy from the health care provider.

Dr. Trolice is director of The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

Persistent problem: High C-section rates plague the South

All along, Julia Maeda knew she wanted to have her baby naturally. For her, that meant in a hospital, vaginally, without an epidural for pain relief.

This was her first pregnancy. And although she is a nurse, she was working with cancer patients at the time, not with laboring mothers or babies. “I really didn’t know what I was getting into,” said Ms. Maeda, now 32. “I didn’t do much preparation.”

Her home state of Mississippi has the highest cesarean section rate in the United States – nearly 4 in 10 women who give birth there deliver their babies via C-section. Almost 2 weeks past her due date in 2019, Ms. Maeda became one of them after her doctor came to her bedside while she was in labor.

“‘You’re not in distress, and your baby is not in distress – but we don’t want you to get that way, so we need to think about a C-section,’” she recalled her doctor saying. “I was totally defeated. I just gave in.”

C-sections are sometimes necessary and even lifesaving, but public health experts have long contended that too many performed in the U.S. aren’t. They argue it is major surgery accompanied by significant risk and a high price tag.

Overall, 31.8% of all births in the U.S. were C-sections in 2020, just a slight tick up from 31.7% the year before, according to the latest data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But that’s close to the peak in 2009, when it was 32.9%. And the rates are far higher in many states, especially across the South.

These high C-section rates have persisted – and in some states, such as Alabama and Kentucky, even grown slightly – despite continual calls to reduce them. And although the pandemic presented new challenges for pregnant women, research suggests that the U.S. C-section rate was unaffected by COVID. Instead, obstetricians and other health experts say the high rate is an intractable problem.

Some states, such as California and New Jersey, have reduced their rates through a variety of strategies, including sharing C-section data with doctors and hospitals. But change has proved difficult elsewhere, especially in the South and in Texas, where women are generally less healthy heading into their pregnancies and maternal and infant health problems are among the highest in the United States.

“We have to restructure how we think about C-sections,” said Veronica Gillispie-Bell, MD, an ob.gyn. who is medical director of the Louisiana Perinatal Quality Collaborative, Kenner, La., a group of 43 birthing hospitals focused on lowering Louisiana’s C-section rate. “It’s a lifesaving technique, but it’s also not without risks.”

She said C-sections, like any operation, create scar tissue, including in the uterus, which may complicate future pregnancies or abdominal surgeries. C-sections also typically lead to an extended hospital stay and recovery period and increase the chance of infection. Babies face risks, too. In rare cases, they can be nicked or cut during an incision.

Although C-sections are sometimes necessary, public health leaders say these surgeries have been overused in many places. Black women, particularly, are more likely to give birth by C-section than any other racial group in the country. Often, hospitals and even regions have wide, unexplained variations in rates.

“If you were delivering in Miami-Dade County, you had a 75% greater chance of having a cesarean than in northern Florida,” said William Sappenfield, MD, an ob.gyn. and epidemiologist at the University of South Florida, Tampa, who has studied the state’s high C-section rate.

Some physicians say their rates are driven by mothers who request the procedure, not by doctors. But Rebekah Gee, MD, an ob.gyn. at Louisiana State University Healthcare Network, New Orleans, and former secretary of the Louisiana Department of Health, said she saw C-section rates go dramatically up at 4 and 5 p.m. – around the time when doctors tend to want to go home.

She led several initiatives to improve birth outcomes in Louisiana, including leveling Medicaid payment rates to hospitals for vaginal deliveries and C-sections. In most places, C-sections are significantly more expensive than vaginal deliveries, making high C-section rates not only a concern for expectant mothers but also for taxpayers.

Medicaid pays for 60% of all births in Louisiana, according to KFF, and about half of all births in most Southern states, compared with 42% nationally. That’s one reason some states – including Louisiana, Tennessee, and Minnesota – have tried to tackle high C-section rates by changing how much Medicaid pays for them. But payment reform alone isn’t enough, Dr. Gee said.

“There was a guy in central Louisiana who was doing more C-sections and early elective deliveries than anyone in the U.S.,” she said. “When you have a culture like that, it’s hard to shift from it.”

Linda Schwimmer, president and CEO of the New Jersey Health Care Quality Institute, said many hospitals and doctors don’t even know their C-section rates. Sharing this data with doctors and hospitals – and making it public – made some providers uncomfortable, she said, but it ultimately worked. New Jersey’s C-section rate among first-time, low-risk mothers dropped from 33.1% in 2013 to 26.7% 6 years later once the state began sharing these data, among other initiatives.

The New Jersey Health Care Quality Institute and other groups like it around the country focus on reducing a subset of C-sections called “nulliparous, term, singleton, vertex” C-sections, or surgeries on first-time, full-term moms giving birth to a single infant who is positioned head-down in the uterus.

NTSV C-sections are important to track because women who have a C-section during their first pregnancy face a 90% chance of having another in subsequent pregnancies. Across the U.S., the rate for these C-sections was 25.9% in 2020 and 25.6% in 2019.

Elliott Main, MD, a maternal-fetal specialist at Stanford (Calif.) University and the medical director of the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative, coauthored a paper, published in JAMA last year, that outlines interventions the collaborative took that lowered California’s NTSV C-Section rate from 26.0% in 2014 to 22.8% in 2019. Nationally, the rate was unchanged during that period.

Allowing women to labor for longer stretches of time before resorting to surgery is important, he said.

The cervix must be 10 cm dilated before a woman gives birth. The threshold for “active labor” used to be when the cervix was dilated at least 4 cm. In more recent years, though, the onset of active labor has been changed to 5-6 cm.

“People show up at the hospital too early,” said Toni Hill, president of the Mississippi Midwives Alliance. “If you show up to the hospital at 2-3 centimeters, you can be at 2-3 centimeters for weeks. I don’t even consider that labor.”

Too often, she said, women at an early stage of labor end up being induced and deliver via C-section.

“It’s almost like, at this point, C-sections are being handed out like lollipops,” said LA’Patricia Washington, a doula based in Jackson, Miss. Doulas are trained, nonmedical workers who help parents before, during, and after delivery.

Ms. Washington works with a nonprofit group, the Jackson Safer Childbirth Experience, that pays for doulas to help expectant mothers in the region. Some state Medicaid programs, such as New Jersey’s, reimburse for services by doulas because research shows they can reduce C-section rates. California has been trying to roll out the same benefit for its Medicaid members.

In 2020, when Julia Maeda became pregnant again, she paid out-of-pocket for a doula to attend the birth. The experience of having her son via C-section the previous year had been “emotionally and psychologically traumatic,” Ms. Maeda said.

She told her ob.gyn. that she wanted a VBAC, short for “vaginal birth after cesarean.” But, she said, “he just shook his head and said, ‘That’s not a good idea.’”

She had VBAC anyway. Ms. Maeda credits her doula with making it happen.

“Maybe just her presence relayed to the nursing staff that this was something I was serious about,” Ms. Maeda said. “They want you to have your baby during business hours. And biology doesn’t work that way.”