User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

I’m a physician battling long COVID. I can assure you it’s real

One in 5. It almost seems unimaginable that this is the real number of people who are struggling with long COVID, especially considering how many people in the United States have had COVID-19 at this point (more than 96 million).

Even more unimaginable at this time is that it’s happening to me. I’ve experienced not only the disabling effects of long COVID, but I’ve also seen, firsthand, the frustration of navigating diagnosis and treatment. It’s given me a taste of what millions of other patients are going through.

Vaxxed, masked, and (too) relaxed

I caught COVID-19 (probably Omicron BA.5) that presented as sniffles, making me think it was probably just allergies. However, my resting heart rate was up on my Garmin watch, so of course I got tested and was positive.

With my symptoms virtually nonexistent, it seemed, at the time, merely an inconvenience, because I was forced to isolate away from family and friends, who all stayed negative.

But 2 weeks later, I began to have urticaria – hives – after physical exertion. Did that mean my mast cells were angry? There’s some evidence these immune cells become overactivated in some patients with COVID. Next, I began to experience lightheadedness and the rapid heartbeat of tachycardia. The tachycardia was especially bad any time I physically exerted myself, including on a walk. Imagine me – a lover of all bargain shopping – cutting short a trip to the outlet mall on a particularly bad day when my heart rate was 140 after taking just a few steps. This was orthostatic intolerance.

Then came the severe worsening of my migraines – which are often vestibular, making me nauseated and dizzy on top of the throbbing.

I was of course familiar with these symptoms, as professor and chair of the department of rehabilitation medicine at the Joe R. and Teresa Lozano Long School of Medicine at University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio. I developed a post-COVID recovery clinic to help patients.

So I knew about postexertional malaise (PEM) and postexertional symptom exacerbation (PESE), but I was now experiencing these distressing symptoms firsthand.

Clinicians really need to look for this cardinal sign of long COVID as well as evidence of myalgic encephalomyelitis or chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). ME/CFS is marked by exacerbation of fatigue or symptoms after an activity that could previously be done without these aftereffects. In my case, as an All-American Masters miler with several marathons under my belt, running 5 miles is a walk in the park. But now, I pay for those 5 miles for the rest of the day on the couch or with palpitations, dizziness, and fatigue the following day. Busy clinic day full of procedures? I would have to be sitting by the end of it. Bed by 9 PM was not always early enough.

Becoming a statistic

Here I am, one of the leading experts in the country on caring for people with long COVID, featured in the national news and having testified in front of Congress, and now I am part of that lived experience. Me – a healthy athlete, with no comorbidities, a normal BMI, vaccinated and boosted, and after an almost asymptomatic bout of COVID-19, a victim to long COVID.

You just never know how your body is going to react. Neuroinflammation occurred in studies with mice with mild respiratory COVID and could be happening to me. I did not want a chronic immune-mediated vasculopathy.

So, I did what any other hyperaware physician-researcher would do. I enrolled in the RECOVER trial – a study my own institution is taking part in and one that I recommend to my own patients.

I also decided that I need to access care and not just ignore my symptoms or try to treat them myself.

That’s when things got difficult. There was a wait of at least a month to see my primary care provider – but I was able to use my privileged position as a physician to get in sooner.

My provider said that she had limited knowledge of long COVID, and she hesitated to order some of the tests and treatments that I recommended because they were not yet considered standard of care. I can understand the hesitation. It is engrained in medical education to follow evidence based on the highest-quality research studies. We are slowly learning more about long COVID, but acknowledging the learning curve offers little to patients who need help now.

This has made me realize that we cannot wait on an evidence-based approach – which can take decades to develop – while people are suffering. And it’s important that everyone on the front line learn about some of the manifestations and disease management of long COVID.

I left this first physician visit feeling more defeated than anything and decided to try to push through. That, I quickly realized, was not the right thing to do.

So again, after a couple of significant crashes and days of severe migraines, I phoned a friend: Ratna Bhavaraju-Sanka, MD, the amazing neurologist who treats patients with long COVID alongside me. She squeezed me in on a non-clinic day. Again, I had the privilege to see a specialist most people wait half a year to see. I was diagnosed with both autonomic dysfunction and intractable migraine.

She ordered some intravenous fluids and IV magnesium that would probably help both. But then another obstacle arose. My institution’s infusion center is focused on patients with cancer, and I was unable to schedule treatments there.

Luckily, I knew about the concierge mobile IV hydration therapy companies that come to your house – mostly offering a hangover treatment service. And I am thankful that I had the health literacy and financial ability to pay for some fluids at home.

On another particularly bad day, I phoned other friends – higher-ups at the hospital – who expedited a slot at the hospital infusion center and approval for the IV magnesium.

Thanks to my access, knowledge, and other privileges, I got fairly quick if imperfect care, enrolled in a research trial, and received medications. I knew to pace myself. The vast majority of others with long COVID lack these advantages.

The patient with long COVID

Things I have learned that others can learn, too:

- Acknowledge and recognize that long COVID is a disease that is affecting 1 in 5 Americans who catch COVID. Many look completely “normal on the outside.” Please listen to your patients.

- Autonomic dysfunction is a common manifestation of long COVID. A 10-minute stand test goes a long way in diagnosing this condition, from the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. It is not just anxiety.

- “That’s only in research” is dismissive and harmful. Think outside the box. Follow guidelines. Consider encouraging patients to sign up for trials.

- Screen for PEM/PESE and teach your patients to pace themselves, because pushing through it or doing graded exercises will be harmful.

- We need to train more physicians to treat postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection () and other postinfectious conditions, such as ME/CFS.

If long COVID is hard for physicians to understand and deal with, imagine how difficult it is for patients with no expertise in this area.

It is exponentially harder for those with fewer resources, time, and health literacy. My lived experience with long COVID has shown me that being a patient is never easy. You put your body and fate into the hands of trusted professionals and expect validation and assistance, not gaslighting or gatekeeping.

Along with millions of others, I am tired of waiting.

Dr. Gutierrez is Professor and Distinguished Chair, department of rehabilitation medicine, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. She reported receiving honoraria for lecturing on long COVID and receiving a research grant from Co-PI for the NIH RECOVER trial.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

One in 5. It almost seems unimaginable that this is the real number of people who are struggling with long COVID, especially considering how many people in the United States have had COVID-19 at this point (more than 96 million).

Even more unimaginable at this time is that it’s happening to me. I’ve experienced not only the disabling effects of long COVID, but I’ve also seen, firsthand, the frustration of navigating diagnosis and treatment. It’s given me a taste of what millions of other patients are going through.

Vaxxed, masked, and (too) relaxed

I caught COVID-19 (probably Omicron BA.5) that presented as sniffles, making me think it was probably just allergies. However, my resting heart rate was up on my Garmin watch, so of course I got tested and was positive.

With my symptoms virtually nonexistent, it seemed, at the time, merely an inconvenience, because I was forced to isolate away from family and friends, who all stayed negative.

But 2 weeks later, I began to have urticaria – hives – after physical exertion. Did that mean my mast cells were angry? There’s some evidence these immune cells become overactivated in some patients with COVID. Next, I began to experience lightheadedness and the rapid heartbeat of tachycardia. The tachycardia was especially bad any time I physically exerted myself, including on a walk. Imagine me – a lover of all bargain shopping – cutting short a trip to the outlet mall on a particularly bad day when my heart rate was 140 after taking just a few steps. This was orthostatic intolerance.

Then came the severe worsening of my migraines – which are often vestibular, making me nauseated and dizzy on top of the throbbing.

I was of course familiar with these symptoms, as professor and chair of the department of rehabilitation medicine at the Joe R. and Teresa Lozano Long School of Medicine at University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio. I developed a post-COVID recovery clinic to help patients.

So I knew about postexertional malaise (PEM) and postexertional symptom exacerbation (PESE), but I was now experiencing these distressing symptoms firsthand.

Clinicians really need to look for this cardinal sign of long COVID as well as evidence of myalgic encephalomyelitis or chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). ME/CFS is marked by exacerbation of fatigue or symptoms after an activity that could previously be done without these aftereffects. In my case, as an All-American Masters miler with several marathons under my belt, running 5 miles is a walk in the park. But now, I pay for those 5 miles for the rest of the day on the couch or with palpitations, dizziness, and fatigue the following day. Busy clinic day full of procedures? I would have to be sitting by the end of it. Bed by 9 PM was not always early enough.

Becoming a statistic

Here I am, one of the leading experts in the country on caring for people with long COVID, featured in the national news and having testified in front of Congress, and now I am part of that lived experience. Me – a healthy athlete, with no comorbidities, a normal BMI, vaccinated and boosted, and after an almost asymptomatic bout of COVID-19, a victim to long COVID.

You just never know how your body is going to react. Neuroinflammation occurred in studies with mice with mild respiratory COVID and could be happening to me. I did not want a chronic immune-mediated vasculopathy.

So, I did what any other hyperaware physician-researcher would do. I enrolled in the RECOVER trial – a study my own institution is taking part in and one that I recommend to my own patients.

I also decided that I need to access care and not just ignore my symptoms or try to treat them myself.

That’s when things got difficult. There was a wait of at least a month to see my primary care provider – but I was able to use my privileged position as a physician to get in sooner.

My provider said that she had limited knowledge of long COVID, and she hesitated to order some of the tests and treatments that I recommended because they were not yet considered standard of care. I can understand the hesitation. It is engrained in medical education to follow evidence based on the highest-quality research studies. We are slowly learning more about long COVID, but acknowledging the learning curve offers little to patients who need help now.

This has made me realize that we cannot wait on an evidence-based approach – which can take decades to develop – while people are suffering. And it’s important that everyone on the front line learn about some of the manifestations and disease management of long COVID.

I left this first physician visit feeling more defeated than anything and decided to try to push through. That, I quickly realized, was not the right thing to do.

So again, after a couple of significant crashes and days of severe migraines, I phoned a friend: Ratna Bhavaraju-Sanka, MD, the amazing neurologist who treats patients with long COVID alongside me. She squeezed me in on a non-clinic day. Again, I had the privilege to see a specialist most people wait half a year to see. I was diagnosed with both autonomic dysfunction and intractable migraine.

She ordered some intravenous fluids and IV magnesium that would probably help both. But then another obstacle arose. My institution’s infusion center is focused on patients with cancer, and I was unable to schedule treatments there.

Luckily, I knew about the concierge mobile IV hydration therapy companies that come to your house – mostly offering a hangover treatment service. And I am thankful that I had the health literacy and financial ability to pay for some fluids at home.

On another particularly bad day, I phoned other friends – higher-ups at the hospital – who expedited a slot at the hospital infusion center and approval for the IV magnesium.

Thanks to my access, knowledge, and other privileges, I got fairly quick if imperfect care, enrolled in a research trial, and received medications. I knew to pace myself. The vast majority of others with long COVID lack these advantages.

The patient with long COVID

Things I have learned that others can learn, too:

- Acknowledge and recognize that long COVID is a disease that is affecting 1 in 5 Americans who catch COVID. Many look completely “normal on the outside.” Please listen to your patients.

- Autonomic dysfunction is a common manifestation of long COVID. A 10-minute stand test goes a long way in diagnosing this condition, from the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. It is not just anxiety.

- “That’s only in research” is dismissive and harmful. Think outside the box. Follow guidelines. Consider encouraging patients to sign up for trials.

- Screen for PEM/PESE and teach your patients to pace themselves, because pushing through it or doing graded exercises will be harmful.

- We need to train more physicians to treat postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection () and other postinfectious conditions, such as ME/CFS.

If long COVID is hard for physicians to understand and deal with, imagine how difficult it is for patients with no expertise in this area.

It is exponentially harder for those with fewer resources, time, and health literacy. My lived experience with long COVID has shown me that being a patient is never easy. You put your body and fate into the hands of trusted professionals and expect validation and assistance, not gaslighting or gatekeeping.

Along with millions of others, I am tired of waiting.

Dr. Gutierrez is Professor and Distinguished Chair, department of rehabilitation medicine, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. She reported receiving honoraria for lecturing on long COVID and receiving a research grant from Co-PI for the NIH RECOVER trial.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

One in 5. It almost seems unimaginable that this is the real number of people who are struggling with long COVID, especially considering how many people in the United States have had COVID-19 at this point (more than 96 million).

Even more unimaginable at this time is that it’s happening to me. I’ve experienced not only the disabling effects of long COVID, but I’ve also seen, firsthand, the frustration of navigating diagnosis and treatment. It’s given me a taste of what millions of other patients are going through.

Vaxxed, masked, and (too) relaxed

I caught COVID-19 (probably Omicron BA.5) that presented as sniffles, making me think it was probably just allergies. However, my resting heart rate was up on my Garmin watch, so of course I got tested and was positive.

With my symptoms virtually nonexistent, it seemed, at the time, merely an inconvenience, because I was forced to isolate away from family and friends, who all stayed negative.

But 2 weeks later, I began to have urticaria – hives – after physical exertion. Did that mean my mast cells were angry? There’s some evidence these immune cells become overactivated in some patients with COVID. Next, I began to experience lightheadedness and the rapid heartbeat of tachycardia. The tachycardia was especially bad any time I physically exerted myself, including on a walk. Imagine me – a lover of all bargain shopping – cutting short a trip to the outlet mall on a particularly bad day when my heart rate was 140 after taking just a few steps. This was orthostatic intolerance.

Then came the severe worsening of my migraines – which are often vestibular, making me nauseated and dizzy on top of the throbbing.

I was of course familiar with these symptoms, as professor and chair of the department of rehabilitation medicine at the Joe R. and Teresa Lozano Long School of Medicine at University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio. I developed a post-COVID recovery clinic to help patients.

So I knew about postexertional malaise (PEM) and postexertional symptom exacerbation (PESE), but I was now experiencing these distressing symptoms firsthand.

Clinicians really need to look for this cardinal sign of long COVID as well as evidence of myalgic encephalomyelitis or chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). ME/CFS is marked by exacerbation of fatigue or symptoms after an activity that could previously be done without these aftereffects. In my case, as an All-American Masters miler with several marathons under my belt, running 5 miles is a walk in the park. But now, I pay for those 5 miles for the rest of the day on the couch or with palpitations, dizziness, and fatigue the following day. Busy clinic day full of procedures? I would have to be sitting by the end of it. Bed by 9 PM was not always early enough.

Becoming a statistic

Here I am, one of the leading experts in the country on caring for people with long COVID, featured in the national news and having testified in front of Congress, and now I am part of that lived experience. Me – a healthy athlete, with no comorbidities, a normal BMI, vaccinated and boosted, and after an almost asymptomatic bout of COVID-19, a victim to long COVID.

You just never know how your body is going to react. Neuroinflammation occurred in studies with mice with mild respiratory COVID and could be happening to me. I did not want a chronic immune-mediated vasculopathy.

So, I did what any other hyperaware physician-researcher would do. I enrolled in the RECOVER trial – a study my own institution is taking part in and one that I recommend to my own patients.

I also decided that I need to access care and not just ignore my symptoms or try to treat them myself.

That’s when things got difficult. There was a wait of at least a month to see my primary care provider – but I was able to use my privileged position as a physician to get in sooner.

My provider said that she had limited knowledge of long COVID, and she hesitated to order some of the tests and treatments that I recommended because they were not yet considered standard of care. I can understand the hesitation. It is engrained in medical education to follow evidence based on the highest-quality research studies. We are slowly learning more about long COVID, but acknowledging the learning curve offers little to patients who need help now.

This has made me realize that we cannot wait on an evidence-based approach – which can take decades to develop – while people are suffering. And it’s important that everyone on the front line learn about some of the manifestations and disease management of long COVID.

I left this first physician visit feeling more defeated than anything and decided to try to push through. That, I quickly realized, was not the right thing to do.

So again, after a couple of significant crashes and days of severe migraines, I phoned a friend: Ratna Bhavaraju-Sanka, MD, the amazing neurologist who treats patients with long COVID alongside me. She squeezed me in on a non-clinic day. Again, I had the privilege to see a specialist most people wait half a year to see. I was diagnosed with both autonomic dysfunction and intractable migraine.

She ordered some intravenous fluids and IV magnesium that would probably help both. But then another obstacle arose. My institution’s infusion center is focused on patients with cancer, and I was unable to schedule treatments there.

Luckily, I knew about the concierge mobile IV hydration therapy companies that come to your house – mostly offering a hangover treatment service. And I am thankful that I had the health literacy and financial ability to pay for some fluids at home.

On another particularly bad day, I phoned other friends – higher-ups at the hospital – who expedited a slot at the hospital infusion center and approval for the IV magnesium.

Thanks to my access, knowledge, and other privileges, I got fairly quick if imperfect care, enrolled in a research trial, and received medications. I knew to pace myself. The vast majority of others with long COVID lack these advantages.

The patient with long COVID

Things I have learned that others can learn, too:

- Acknowledge and recognize that long COVID is a disease that is affecting 1 in 5 Americans who catch COVID. Many look completely “normal on the outside.” Please listen to your patients.

- Autonomic dysfunction is a common manifestation of long COVID. A 10-minute stand test goes a long way in diagnosing this condition, from the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. It is not just anxiety.

- “That’s only in research” is dismissive and harmful. Think outside the box. Follow guidelines. Consider encouraging patients to sign up for trials.

- Screen for PEM/PESE and teach your patients to pace themselves, because pushing through it or doing graded exercises will be harmful.

- We need to train more physicians to treat postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection () and other postinfectious conditions, such as ME/CFS.

If long COVID is hard for physicians to understand and deal with, imagine how difficult it is for patients with no expertise in this area.

It is exponentially harder for those with fewer resources, time, and health literacy. My lived experience with long COVID has shown me that being a patient is never easy. You put your body and fate into the hands of trusted professionals and expect validation and assistance, not gaslighting or gatekeeping.

Along with millions of others, I am tired of waiting.

Dr. Gutierrez is Professor and Distinguished Chair, department of rehabilitation medicine, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. She reported receiving honoraria for lecturing on long COVID and receiving a research grant from Co-PI for the NIH RECOVER trial.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

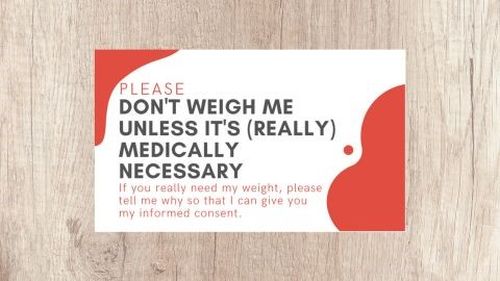

BMI and reproduction – weighing the evidence

Arguably, no topic during an infertility consultation generates more of an emotional reaction than discussing body mass index (BMI), particularly when it is high. Patients have become increasingly sensitive to weight discussions with their physicians because of concerns about body shaming. Among patients with an elevated BMI, criticism on social media of health care professionals’ counseling and a preemptive presentation of “Don’t Weigh Me” cards have become popular responses. Despite the medical evidence on impaired reproduction with an abnormal BMI, patients are choosing to forgo the topic. Research has demonstrated “extensive evidence [of] strong weight bias” in a wide range of health staff.1 A “viral” TikTok study revealed that medical “gaslighting” founded in weight stigma and bias is harmful, as reported on KevinMD.com.2 This month, we review the effect of abnormal BMI, both high and low, on reproduction and pregnancy.

A method to assess relative weight was first described in 1832 as its ratio in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters, or the Quetelet Index. The search for a functional assessment of relative body weight began after World War II when reports by actuaries noted the increased mortality of overweight policyholders. The relationship between weight and cardiovascular disease was further revealed in epidemiologic studies. The Quetelet Index became the BMI in 1972.3

Weight measurement is a mainstay in the assessment of a patient’s vital signs along with blood pressure, pulse rate, respiration rate, and temperature. Weight is vital to the calculation of medication dosage – for instance, administration of conscious sedative drugs, methotrexate, and gonadotropins. Some state boards of medicine, such as Florida, have a limitation on patient BMI at office-based surgery centers (40 kg/m2).

Obesity is a disease

As reported by the World Health Organization in 2022, the disease of obesity is an epidemic afflicting more than 1 billion people worldwide, or 1 in 8 individuals globally.4 The health implications of an elevated BMI include increased mortality, diabetes, heart disease, and stroke, physical limitations to activities of daily living, and complications affecting reproduction.

Female obesity is related to poorer outcomes in natural and assisted conception, including an increased risk of miscarriage. Compared with normal-weight women, those with obesity are three times more likely to have ovulatory dysfunction,5 infertility,6 a lower chance for conception,7 higher rate of miscarriage, and low birth weight.8,9During pregnancy, women with obesity have three to four times higher rates of gestational diabetes and preeclampsia,10 as well as likelihood of delivering preterm,11 having a fetus with macrosomia and birth defects, and a 1.3- to 2.1-times higher risk of stillbirth.12

Obesity is present in 40%-80% of women with polycystic ovary syndrome,13 the most common cause of ovulatory dysfunction from dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis. While PCOS is associated with reproductive and metabolic consequences, even in regularly ovulating women, increasing obesity appears to be associated with decreasing spontaneous pregnancy rates and increased time to pregnancy.14

Obesity and IVF

Women with obesity have reduced success with assisted reproductive technology, an increased number of canceled cycles, and poorer quality oocytes retrieved. A prospective cohort study of nearly 2,000 women reported that every 5 kg of body weight increase (from the patient’s baseline weight at age 18) was associated with a 5% increase in the mean duration of time required for conception (95% confidence interval, 3%-7%).15 Given that approximately 90% of these women had regular menstrual cycles, ovulatory dysfunction was not the suspected pathophysiology.

A meta-analysis of 21 cohort studies reported a lower likelihood of live birth following in vitro fertilization for women with obesity, compared with normal-weight women (risk ratio, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.82-0.87).16 A further subgroup analysis that evaluated only women with PCOS showed a reduction in the live birth rate following IVF for individuals with obesity, compared with normal-weight individuals (RR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.74-0.82).

In a retrospective study of almost 500,000 fresh autologous IVF cycles, women with obesity had a 6% reduction in pregnancy rates and a 13% reduction in live birth rates, compared with normal-weight women. Both high and low BMI were associated with an increased risk of low birth weight and preterm delivery.17 The live birth rates per transfer for normal-weight and higher-weight women were 38% and 33%, respectively.

Contrarily, a randomized controlled trial showed that an intensive weight-reduction program resulted in a large weight loss but did not substantially affect live birth rates in women with obesity scheduled for IVF.18

Low BMI

A noteworthy cause of low BMI is functional hypothalamic amenorrhea (FHA), a disorder with low energy availability either from decreased caloric intake and/or excessive energy expenditure associated with eating disorders, excessive exercise, and stress. Consequently, a reduced GnRH drive results in a decreased pulse frequency and amplitude leading to low levels of follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone, resulting in anovulation. Correction of lifestyle behaviors related to FHA can restore menstrual cycles. After normal weight is achieved, it appears unlikely that fertility is affected.19 In 47% of adolescent patients with anorexia, menses spontaneously returned within the first 12 months after admission, with an improved prognosis in secondary over primary amenorrhea.20,21 Interestingly, mildly and significantly underweight infertile women have pregnancy and live birth rates similar to normal-weight patients after IVF treatment.22

Pregnancy is complicated in underweight women, resulting in an increased risk of anemia, fetal growth retardation, and low birth weight, as well as preterm birth.21

Take-home message

The extremes of BMI both impair natural reproduction. Elevated BMI reduces success with IVF but rapid weight loss prior to IVF does not improve outcomes. A normal BMI is the goal for optimal reproductive and pregnancy health.

Dr. Trolice is director of the IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

References

1. Talumaa B et al. Obesity Rev. 2022;23:e13494.

2. https://bit.ly/3rHCivE.

3. Eknoyan G. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:47-51.

4. Wells JCK. Dis Models Mech. 2012;5:595-607.

5. Brewer CJ and Balen AH. Reproduction. 2010;140:347-64.

6. Silvestris E et al. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2018;16:22.

7. Wise LA et al. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:253-64.

8. Bellver J. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2022;34:114-21.

9. Dickey RP et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209:349.e1.

10. Alwash SM et al. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2021;15:425-30.

11. Cnattingius S et al. JAMA. 2013;309:2362-70.

12. Aune D et al. JAMA. 2014;311:1536-46.

13. Sam S. Obes Manag. 2007;3:69-73.

14. van der Steeg JW et al. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:324-8.

15. Gaskins AJ et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:850-8.

16. Sermondade N et al. Hum Reprod Update. 2019;25:439-519.

17. Kawwass JF et al. Fertil Steril. 2016;106[7]:1742-50.

18. Einarsson S et al. Hum Reprod. 2017;32:1621-30.

19. Chaer R et al. Diseases. 2020;8:46.

20. Dempfle A et al. Psychiatry. 2013;13:308.

21. Verma A and Shrimali L. J Clin Diagn Res. 2012;6:1531-3.

22. Romanski PA et al. Reprod Biomed Online. 2020;42:366-74.

Arguably, no topic during an infertility consultation generates more of an emotional reaction than discussing body mass index (BMI), particularly when it is high. Patients have become increasingly sensitive to weight discussions with their physicians because of concerns about body shaming. Among patients with an elevated BMI, criticism on social media of health care professionals’ counseling and a preemptive presentation of “Don’t Weigh Me” cards have become popular responses. Despite the medical evidence on impaired reproduction with an abnormal BMI, patients are choosing to forgo the topic. Research has demonstrated “extensive evidence [of] strong weight bias” in a wide range of health staff.1 A “viral” TikTok study revealed that medical “gaslighting” founded in weight stigma and bias is harmful, as reported on KevinMD.com.2 This month, we review the effect of abnormal BMI, both high and low, on reproduction and pregnancy.

A method to assess relative weight was first described in 1832 as its ratio in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters, or the Quetelet Index. The search for a functional assessment of relative body weight began after World War II when reports by actuaries noted the increased mortality of overweight policyholders. The relationship between weight and cardiovascular disease was further revealed in epidemiologic studies. The Quetelet Index became the BMI in 1972.3

Weight measurement is a mainstay in the assessment of a patient’s vital signs along with blood pressure, pulse rate, respiration rate, and temperature. Weight is vital to the calculation of medication dosage – for instance, administration of conscious sedative drugs, methotrexate, and gonadotropins. Some state boards of medicine, such as Florida, have a limitation on patient BMI at office-based surgery centers (40 kg/m2).

Obesity is a disease

As reported by the World Health Organization in 2022, the disease of obesity is an epidemic afflicting more than 1 billion people worldwide, or 1 in 8 individuals globally.4 The health implications of an elevated BMI include increased mortality, diabetes, heart disease, and stroke, physical limitations to activities of daily living, and complications affecting reproduction.

Female obesity is related to poorer outcomes in natural and assisted conception, including an increased risk of miscarriage. Compared with normal-weight women, those with obesity are three times more likely to have ovulatory dysfunction,5 infertility,6 a lower chance for conception,7 higher rate of miscarriage, and low birth weight.8,9During pregnancy, women with obesity have three to four times higher rates of gestational diabetes and preeclampsia,10 as well as likelihood of delivering preterm,11 having a fetus with macrosomia and birth defects, and a 1.3- to 2.1-times higher risk of stillbirth.12

Obesity is present in 40%-80% of women with polycystic ovary syndrome,13 the most common cause of ovulatory dysfunction from dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis. While PCOS is associated with reproductive and metabolic consequences, even in regularly ovulating women, increasing obesity appears to be associated with decreasing spontaneous pregnancy rates and increased time to pregnancy.14

Obesity and IVF

Women with obesity have reduced success with assisted reproductive technology, an increased number of canceled cycles, and poorer quality oocytes retrieved. A prospective cohort study of nearly 2,000 women reported that every 5 kg of body weight increase (from the patient’s baseline weight at age 18) was associated with a 5% increase in the mean duration of time required for conception (95% confidence interval, 3%-7%).15 Given that approximately 90% of these women had regular menstrual cycles, ovulatory dysfunction was not the suspected pathophysiology.

A meta-analysis of 21 cohort studies reported a lower likelihood of live birth following in vitro fertilization for women with obesity, compared with normal-weight women (risk ratio, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.82-0.87).16 A further subgroup analysis that evaluated only women with PCOS showed a reduction in the live birth rate following IVF for individuals with obesity, compared with normal-weight individuals (RR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.74-0.82).

In a retrospective study of almost 500,000 fresh autologous IVF cycles, women with obesity had a 6% reduction in pregnancy rates and a 13% reduction in live birth rates, compared with normal-weight women. Both high and low BMI were associated with an increased risk of low birth weight and preterm delivery.17 The live birth rates per transfer for normal-weight and higher-weight women were 38% and 33%, respectively.

Contrarily, a randomized controlled trial showed that an intensive weight-reduction program resulted in a large weight loss but did not substantially affect live birth rates in women with obesity scheduled for IVF.18

Low BMI

A noteworthy cause of low BMI is functional hypothalamic amenorrhea (FHA), a disorder with low energy availability either from decreased caloric intake and/or excessive energy expenditure associated with eating disorders, excessive exercise, and stress. Consequently, a reduced GnRH drive results in a decreased pulse frequency and amplitude leading to low levels of follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone, resulting in anovulation. Correction of lifestyle behaviors related to FHA can restore menstrual cycles. After normal weight is achieved, it appears unlikely that fertility is affected.19 In 47% of adolescent patients with anorexia, menses spontaneously returned within the first 12 months after admission, with an improved prognosis in secondary over primary amenorrhea.20,21 Interestingly, mildly and significantly underweight infertile women have pregnancy and live birth rates similar to normal-weight patients after IVF treatment.22

Pregnancy is complicated in underweight women, resulting in an increased risk of anemia, fetal growth retardation, and low birth weight, as well as preterm birth.21

Take-home message

The extremes of BMI both impair natural reproduction. Elevated BMI reduces success with IVF but rapid weight loss prior to IVF does not improve outcomes. A normal BMI is the goal for optimal reproductive and pregnancy health.

Dr. Trolice is director of the IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

References

1. Talumaa B et al. Obesity Rev. 2022;23:e13494.

2. https://bit.ly/3rHCivE.

3. Eknoyan G. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:47-51.

4. Wells JCK. Dis Models Mech. 2012;5:595-607.

5. Brewer CJ and Balen AH. Reproduction. 2010;140:347-64.

6. Silvestris E et al. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2018;16:22.

7. Wise LA et al. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:253-64.

8. Bellver J. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2022;34:114-21.

9. Dickey RP et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209:349.e1.

10. Alwash SM et al. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2021;15:425-30.

11. Cnattingius S et al. JAMA. 2013;309:2362-70.

12. Aune D et al. JAMA. 2014;311:1536-46.

13. Sam S. Obes Manag. 2007;3:69-73.

14. van der Steeg JW et al. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:324-8.

15. Gaskins AJ et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:850-8.

16. Sermondade N et al. Hum Reprod Update. 2019;25:439-519.

17. Kawwass JF et al. Fertil Steril. 2016;106[7]:1742-50.

18. Einarsson S et al. Hum Reprod. 2017;32:1621-30.

19. Chaer R et al. Diseases. 2020;8:46.

20. Dempfle A et al. Psychiatry. 2013;13:308.

21. Verma A and Shrimali L. J Clin Diagn Res. 2012;6:1531-3.

22. Romanski PA et al. Reprod Biomed Online. 2020;42:366-74.

Arguably, no topic during an infertility consultation generates more of an emotional reaction than discussing body mass index (BMI), particularly when it is high. Patients have become increasingly sensitive to weight discussions with their physicians because of concerns about body shaming. Among patients with an elevated BMI, criticism on social media of health care professionals’ counseling and a preemptive presentation of “Don’t Weigh Me” cards have become popular responses. Despite the medical evidence on impaired reproduction with an abnormal BMI, patients are choosing to forgo the topic. Research has demonstrated “extensive evidence [of] strong weight bias” in a wide range of health staff.1 A “viral” TikTok study revealed that medical “gaslighting” founded in weight stigma and bias is harmful, as reported on KevinMD.com.2 This month, we review the effect of abnormal BMI, both high and low, on reproduction and pregnancy.

A method to assess relative weight was first described in 1832 as its ratio in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters, or the Quetelet Index. The search for a functional assessment of relative body weight began after World War II when reports by actuaries noted the increased mortality of overweight policyholders. The relationship between weight and cardiovascular disease was further revealed in epidemiologic studies. The Quetelet Index became the BMI in 1972.3

Weight measurement is a mainstay in the assessment of a patient’s vital signs along with blood pressure, pulse rate, respiration rate, and temperature. Weight is vital to the calculation of medication dosage – for instance, administration of conscious sedative drugs, methotrexate, and gonadotropins. Some state boards of medicine, such as Florida, have a limitation on patient BMI at office-based surgery centers (40 kg/m2).

Obesity is a disease

As reported by the World Health Organization in 2022, the disease of obesity is an epidemic afflicting more than 1 billion people worldwide, or 1 in 8 individuals globally.4 The health implications of an elevated BMI include increased mortality, diabetes, heart disease, and stroke, physical limitations to activities of daily living, and complications affecting reproduction.

Female obesity is related to poorer outcomes in natural and assisted conception, including an increased risk of miscarriage. Compared with normal-weight women, those with obesity are three times more likely to have ovulatory dysfunction,5 infertility,6 a lower chance for conception,7 higher rate of miscarriage, and low birth weight.8,9During pregnancy, women with obesity have three to four times higher rates of gestational diabetes and preeclampsia,10 as well as likelihood of delivering preterm,11 having a fetus with macrosomia and birth defects, and a 1.3- to 2.1-times higher risk of stillbirth.12

Obesity is present in 40%-80% of women with polycystic ovary syndrome,13 the most common cause of ovulatory dysfunction from dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis. While PCOS is associated with reproductive and metabolic consequences, even in regularly ovulating women, increasing obesity appears to be associated with decreasing spontaneous pregnancy rates and increased time to pregnancy.14

Obesity and IVF

Women with obesity have reduced success with assisted reproductive technology, an increased number of canceled cycles, and poorer quality oocytes retrieved. A prospective cohort study of nearly 2,000 women reported that every 5 kg of body weight increase (from the patient’s baseline weight at age 18) was associated with a 5% increase in the mean duration of time required for conception (95% confidence interval, 3%-7%).15 Given that approximately 90% of these women had regular menstrual cycles, ovulatory dysfunction was not the suspected pathophysiology.

A meta-analysis of 21 cohort studies reported a lower likelihood of live birth following in vitro fertilization for women with obesity, compared with normal-weight women (risk ratio, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.82-0.87).16 A further subgroup analysis that evaluated only women with PCOS showed a reduction in the live birth rate following IVF for individuals with obesity, compared with normal-weight individuals (RR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.74-0.82).

In a retrospective study of almost 500,000 fresh autologous IVF cycles, women with obesity had a 6% reduction in pregnancy rates and a 13% reduction in live birth rates, compared with normal-weight women. Both high and low BMI were associated with an increased risk of low birth weight and preterm delivery.17 The live birth rates per transfer for normal-weight and higher-weight women were 38% and 33%, respectively.

Contrarily, a randomized controlled trial showed that an intensive weight-reduction program resulted in a large weight loss but did not substantially affect live birth rates in women with obesity scheduled for IVF.18

Low BMI

A noteworthy cause of low BMI is functional hypothalamic amenorrhea (FHA), a disorder with low energy availability either from decreased caloric intake and/or excessive energy expenditure associated with eating disorders, excessive exercise, and stress. Consequently, a reduced GnRH drive results in a decreased pulse frequency and amplitude leading to low levels of follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone, resulting in anovulation. Correction of lifestyle behaviors related to FHA can restore menstrual cycles. After normal weight is achieved, it appears unlikely that fertility is affected.19 In 47% of adolescent patients with anorexia, menses spontaneously returned within the first 12 months after admission, with an improved prognosis in secondary over primary amenorrhea.20,21 Interestingly, mildly and significantly underweight infertile women have pregnancy and live birth rates similar to normal-weight patients after IVF treatment.22

Pregnancy is complicated in underweight women, resulting in an increased risk of anemia, fetal growth retardation, and low birth weight, as well as preterm birth.21

Take-home message

The extremes of BMI both impair natural reproduction. Elevated BMI reduces success with IVF but rapid weight loss prior to IVF does not improve outcomes. A normal BMI is the goal for optimal reproductive and pregnancy health.

Dr. Trolice is director of the IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

References

1. Talumaa B et al. Obesity Rev. 2022;23:e13494.

2. https://bit.ly/3rHCivE.

3. Eknoyan G. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:47-51.

4. Wells JCK. Dis Models Mech. 2012;5:595-607.

5. Brewer CJ and Balen AH. Reproduction. 2010;140:347-64.

6. Silvestris E et al. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2018;16:22.

7. Wise LA et al. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:253-64.

8. Bellver J. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2022;34:114-21.

9. Dickey RP et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209:349.e1.

10. Alwash SM et al. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2021;15:425-30.

11. Cnattingius S et al. JAMA. 2013;309:2362-70.

12. Aune D et al. JAMA. 2014;311:1536-46.

13. Sam S. Obes Manag. 2007;3:69-73.

14. van der Steeg JW et al. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:324-8.

15. Gaskins AJ et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:850-8.

16. Sermondade N et al. Hum Reprod Update. 2019;25:439-519.

17. Kawwass JF et al. Fertil Steril. 2016;106[7]:1742-50.

18. Einarsson S et al. Hum Reprod. 2017;32:1621-30.

19. Chaer R et al. Diseases. 2020;8:46.

20. Dempfle A et al. Psychiatry. 2013;13:308.

21. Verma A and Shrimali L. J Clin Diagn Res. 2012;6:1531-3.

22. Romanski PA et al. Reprod Biomed Online. 2020;42:366-74.

Would a national provider directory save docs’ time, help patients?

When a consumer uses a health plan provider directory to look up a physician, there’s a high probability that the entry for that doctor is incomplete or inaccurate. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services would like to change that by creating a National Directory of Healthcare Providers and Services, which the agency believes would be more valuable to consumers.

In asking for public comments on whether and how it should establish the directory, CMS argues that this data repository would help patients locate physicians and could help with care coordination, health information exchange, and public health data reporting.

However, it’s not clear that such a directory would be any better than current insurance company listings or that people would use it. But a national directory could benefit physician practices by reducing their administrative work, according to observers.

In requesting public comment on the proposed national directory, CMS explains that provider organizations face “redundant and burdensome reporting requirements to multiple databases.” The directory could greatly reduce this challenge by requiring health care organizations to report provider information to a single database. Currently, physician practices have to submit these data to an average of 20 payers each, according to CMS.

“Right now, [physicians are] inundated with requests, and it takes a lot of time to update this stuff,” said David Zetter, a practice management consultant in Mechanicsburg, Pa.. “If there were one national repository of this information, that would be a good move.”

CMS envisions the National Directory as a central hub from which payers could obtain the latest provider data, which would be updated through a standardized application programming interface (API). Consequently, the insurers would no longer need to have providers submit this information to them separately.

CMS is soliciting input on what should be included in the directory. It notes that in addition to contact information, insurer directories also include a physicians’ specialties, health plan affiliations, and whether they accept new patients.

CMS’ 60-day public comment period ends Dec. 6. After that, the agency will decide what steps to take if it is decided that CMS has the legal authority to create the directory.

Terrible track record

In its annual reviews of health plan directories, CMS found that, from 2017 to 2022, only 47% of provider entries were complete. Only 73% of the providers could be matched to published directories. And only 28% of the provider names, addresses, and specialties in the directories matched those in the National Provider Identifier (NPI) registry.

Many of the mistakes in provider directories stem from errors made by practice staff, who have many other duties besides updating directory data. Yet an astonishing amount of time and effort is devoted to this task. A 2019 survey found that physician practices spend $2.76 billion annually on directory maintenance, or nearly $1000 per month per practice, on average.

The Council for Affordable Quality Healthcare, which conducted the survey, estimated that placing all directory data collection on a single platform could save the average practice $4,746 per year. For all practices in the United States, that works out to about $1.1 billion annually, CAQH said.

Pros and cons of national directory

For all the money spent on maintaining provider directories, consumers don’t use them very much. According to a 2021 Press Ganey survey, fewer than 5% of consumers seeking a primary care doctor get their information from an insurer or a benefits manager. About half search the internet first, and 24% seek a referral from a physician.

A national provider directory would be useful only if it were done right, Mr. Zetter said. Citing the inaccuracy and incompleteness of health plan directories, he said it was likely that a national directory would have similar problems. Data entered by practice staff would have to be automatically validated, perhaps through use of some kind of AI algorithm.

Effect on coordination of care

Mr. Zetter doubts the directory could improve care coordination, because primary care doctors usually refer patients to specialists they already know.

But Julia Adler-Milstein, PhD, professor of medicine and director of the Center for Clinical Informatics at the University of California, San Francisco, said that a national directory could improve communications among providers when patients select specialists outside of their primary care physician’s referral network.

“Especially if it’s not an established referral relationship, that’s where a national directory would be helpful, not only to locate the physicians but also to understand their preferences in how they’d like to receive information,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Adler-Milstein worries less than Mr. Zetter does about the challenge of ensuring the accuracy of data in the directory. She pointed out that the National Plan and Provider Enumeration System, which includes the NPI registry, has done a good job of validating provider name, address, and specialty information.

Dr. Adler-Milstein is more concerned about whether the proposed directory would address physician preferences as to how they wish to receive information. For example, while some physicians may prefer to be contacted directly, others may prefer or are required to communicate through their practices or health systems.

Efficiency in data exchange

The API used by the proposed directory would be based on the Fast Health Interoperability Resources standard that all electronic health record vendors must now include in their products. That raises the question of whether communications using contact information from the directory would be sent through a secure email system or through integrated EHR systems, Dr. Adler-Milstein said.

“I’m not sure whether the directory could support that [integration],” she said. “If it focuses on the concept of secure email exchange, that’s a relatively inefficient way of doing it,” because providers want clinical messages to pop up in their EHR workflow rather than their inboxes.

Nevertheless, Dr. Milstein-Adler added, the directory “would clearly take a lot of today’s manual work out of the system. I think organizations like UCSF would be very motivated to support the directory, knowing that people were going to a single source to find the updated information, including preferences in how we’d like people to communicate with us. There would be a lot of efficiency reasons for organizations to use this national directory.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

When a consumer uses a health plan provider directory to look up a physician, there’s a high probability that the entry for that doctor is incomplete or inaccurate. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services would like to change that by creating a National Directory of Healthcare Providers and Services, which the agency believes would be more valuable to consumers.

In asking for public comments on whether and how it should establish the directory, CMS argues that this data repository would help patients locate physicians and could help with care coordination, health information exchange, and public health data reporting.

However, it’s not clear that such a directory would be any better than current insurance company listings or that people would use it. But a national directory could benefit physician practices by reducing their administrative work, according to observers.

In requesting public comment on the proposed national directory, CMS explains that provider organizations face “redundant and burdensome reporting requirements to multiple databases.” The directory could greatly reduce this challenge by requiring health care organizations to report provider information to a single database. Currently, physician practices have to submit these data to an average of 20 payers each, according to CMS.

“Right now, [physicians are] inundated with requests, and it takes a lot of time to update this stuff,” said David Zetter, a practice management consultant in Mechanicsburg, Pa.. “If there were one national repository of this information, that would be a good move.”

CMS envisions the National Directory as a central hub from which payers could obtain the latest provider data, which would be updated through a standardized application programming interface (API). Consequently, the insurers would no longer need to have providers submit this information to them separately.

CMS is soliciting input on what should be included in the directory. It notes that in addition to contact information, insurer directories also include a physicians’ specialties, health plan affiliations, and whether they accept new patients.

CMS’ 60-day public comment period ends Dec. 6. After that, the agency will decide what steps to take if it is decided that CMS has the legal authority to create the directory.

Terrible track record

In its annual reviews of health plan directories, CMS found that, from 2017 to 2022, only 47% of provider entries were complete. Only 73% of the providers could be matched to published directories. And only 28% of the provider names, addresses, and specialties in the directories matched those in the National Provider Identifier (NPI) registry.

Many of the mistakes in provider directories stem from errors made by practice staff, who have many other duties besides updating directory data. Yet an astonishing amount of time and effort is devoted to this task. A 2019 survey found that physician practices spend $2.76 billion annually on directory maintenance, or nearly $1000 per month per practice, on average.

The Council for Affordable Quality Healthcare, which conducted the survey, estimated that placing all directory data collection on a single platform could save the average practice $4,746 per year. For all practices in the United States, that works out to about $1.1 billion annually, CAQH said.

Pros and cons of national directory

For all the money spent on maintaining provider directories, consumers don’t use them very much. According to a 2021 Press Ganey survey, fewer than 5% of consumers seeking a primary care doctor get their information from an insurer or a benefits manager. About half search the internet first, and 24% seek a referral from a physician.

A national provider directory would be useful only if it were done right, Mr. Zetter said. Citing the inaccuracy and incompleteness of health plan directories, he said it was likely that a national directory would have similar problems. Data entered by practice staff would have to be automatically validated, perhaps through use of some kind of AI algorithm.

Effect on coordination of care

Mr. Zetter doubts the directory could improve care coordination, because primary care doctors usually refer patients to specialists they already know.

But Julia Adler-Milstein, PhD, professor of medicine and director of the Center for Clinical Informatics at the University of California, San Francisco, said that a national directory could improve communications among providers when patients select specialists outside of their primary care physician’s referral network.

“Especially if it’s not an established referral relationship, that’s where a national directory would be helpful, not only to locate the physicians but also to understand their preferences in how they’d like to receive information,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Adler-Milstein worries less than Mr. Zetter does about the challenge of ensuring the accuracy of data in the directory. She pointed out that the National Plan and Provider Enumeration System, which includes the NPI registry, has done a good job of validating provider name, address, and specialty information.

Dr. Adler-Milstein is more concerned about whether the proposed directory would address physician preferences as to how they wish to receive information. For example, while some physicians may prefer to be contacted directly, others may prefer or are required to communicate through their practices or health systems.

Efficiency in data exchange

The API used by the proposed directory would be based on the Fast Health Interoperability Resources standard that all electronic health record vendors must now include in their products. That raises the question of whether communications using contact information from the directory would be sent through a secure email system or through integrated EHR systems, Dr. Adler-Milstein said.

“I’m not sure whether the directory could support that [integration],” she said. “If it focuses on the concept of secure email exchange, that’s a relatively inefficient way of doing it,” because providers want clinical messages to pop up in their EHR workflow rather than their inboxes.

Nevertheless, Dr. Milstein-Adler added, the directory “would clearly take a lot of today’s manual work out of the system. I think organizations like UCSF would be very motivated to support the directory, knowing that people were going to a single source to find the updated information, including preferences in how we’d like people to communicate with us. There would be a lot of efficiency reasons for organizations to use this national directory.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

When a consumer uses a health plan provider directory to look up a physician, there’s a high probability that the entry for that doctor is incomplete or inaccurate. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services would like to change that by creating a National Directory of Healthcare Providers and Services, which the agency believes would be more valuable to consumers.

In asking for public comments on whether and how it should establish the directory, CMS argues that this data repository would help patients locate physicians and could help with care coordination, health information exchange, and public health data reporting.

However, it’s not clear that such a directory would be any better than current insurance company listings or that people would use it. But a national directory could benefit physician practices by reducing their administrative work, according to observers.

In requesting public comment on the proposed national directory, CMS explains that provider organizations face “redundant and burdensome reporting requirements to multiple databases.” The directory could greatly reduce this challenge by requiring health care organizations to report provider information to a single database. Currently, physician practices have to submit these data to an average of 20 payers each, according to CMS.

“Right now, [physicians are] inundated with requests, and it takes a lot of time to update this stuff,” said David Zetter, a practice management consultant in Mechanicsburg, Pa.. “If there were one national repository of this information, that would be a good move.”

CMS envisions the National Directory as a central hub from which payers could obtain the latest provider data, which would be updated through a standardized application programming interface (API). Consequently, the insurers would no longer need to have providers submit this information to them separately.

CMS is soliciting input on what should be included in the directory. It notes that in addition to contact information, insurer directories also include a physicians’ specialties, health plan affiliations, and whether they accept new patients.

CMS’ 60-day public comment period ends Dec. 6. After that, the agency will decide what steps to take if it is decided that CMS has the legal authority to create the directory.

Terrible track record

In its annual reviews of health plan directories, CMS found that, from 2017 to 2022, only 47% of provider entries were complete. Only 73% of the providers could be matched to published directories. And only 28% of the provider names, addresses, and specialties in the directories matched those in the National Provider Identifier (NPI) registry.

Many of the mistakes in provider directories stem from errors made by practice staff, who have many other duties besides updating directory data. Yet an astonishing amount of time and effort is devoted to this task. A 2019 survey found that physician practices spend $2.76 billion annually on directory maintenance, or nearly $1000 per month per practice, on average.

The Council for Affordable Quality Healthcare, which conducted the survey, estimated that placing all directory data collection on a single platform could save the average practice $4,746 per year. For all practices in the United States, that works out to about $1.1 billion annually, CAQH said.

Pros and cons of national directory

For all the money spent on maintaining provider directories, consumers don’t use them very much. According to a 2021 Press Ganey survey, fewer than 5% of consumers seeking a primary care doctor get their information from an insurer or a benefits manager. About half search the internet first, and 24% seek a referral from a physician.

A national provider directory would be useful only if it were done right, Mr. Zetter said. Citing the inaccuracy and incompleteness of health plan directories, he said it was likely that a national directory would have similar problems. Data entered by practice staff would have to be automatically validated, perhaps through use of some kind of AI algorithm.

Effect on coordination of care

Mr. Zetter doubts the directory could improve care coordination, because primary care doctors usually refer patients to specialists they already know.

But Julia Adler-Milstein, PhD, professor of medicine and director of the Center for Clinical Informatics at the University of California, San Francisco, said that a national directory could improve communications among providers when patients select specialists outside of their primary care physician’s referral network.

“Especially if it’s not an established referral relationship, that’s where a national directory would be helpful, not only to locate the physicians but also to understand their preferences in how they’d like to receive information,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Adler-Milstein worries less than Mr. Zetter does about the challenge of ensuring the accuracy of data in the directory. She pointed out that the National Plan and Provider Enumeration System, which includes the NPI registry, has done a good job of validating provider name, address, and specialty information.

Dr. Adler-Milstein is more concerned about whether the proposed directory would address physician preferences as to how they wish to receive information. For example, while some physicians may prefer to be contacted directly, others may prefer or are required to communicate through their practices or health systems.

Efficiency in data exchange

The API used by the proposed directory would be based on the Fast Health Interoperability Resources standard that all electronic health record vendors must now include in their products. That raises the question of whether communications using contact information from the directory would be sent through a secure email system or through integrated EHR systems, Dr. Adler-Milstein said.

“I’m not sure whether the directory could support that [integration],” she said. “If it focuses on the concept of secure email exchange, that’s a relatively inefficient way of doing it,” because providers want clinical messages to pop up in their EHR workflow rather than their inboxes.

Nevertheless, Dr. Milstein-Adler added, the directory “would clearly take a lot of today’s manual work out of the system. I think organizations like UCSF would be very motivated to support the directory, knowing that people were going to a single source to find the updated information, including preferences in how we’d like people to communicate with us. There would be a lot of efficiency reasons for organizations to use this national directory.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Plant-based diet cut hot flashes 78%: WAVS study

Women eating a reduced-fat vegan diet combined with a daily serving of soybeans experienced a 78% reduction in frequency of menopausal hot flashes over 12 weeks, in a small, nonblinded, randomized-controlled trial.

“We do not fully understand yet why this combination works, but it seems that these three elements are key: avoiding animal products, reducing fat, and adding a serving of soybeans,” lead researcher Neal Barnard, MD, explained in a press release. “These new results suggest that a diet change should be considered as a first-line treatment for troublesome vasomotor symptoms, including night sweats and hot flashes,” added Dr. Barnard, who is president of the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine, and adjunct professor at George Washington University, Washington.

But, while “the findings from this very small study complement everything we know about the benefits of an excellent diet and the health benefits of soy,” they should be interpreted with some caution, commented Susan Reed, MD, president of the North American Menopause Society, and associate program director of the women’s reproductive research program at the University of Washington, Seattle.

For the trial, called WAVS (Women’s Study for the Alleviation of Vasomotor Symptoms), the researchers randomized 84 postmenopausal women with at least two moderate to severe hot flashes daily to either the intervention or usual diet, with a total of 71 subjects completing the 12-week study, published in Menopause. Criteria for exclusion included any cause of vasomotor symptoms other than natural menopause, current use of a low-fat, vegan diet that includes daily soy products, soy allergy, and body mass index < 18.5 kg/m2.

Participants in the intervention group were asked to avoid animal-derived foods, minimize their use of oils and fatty foods such as nuts and avocados, and include half a cup (86 g) of cooked soybeans daily in their diets. They were also offered 1-hour virtual group meetings each week, in which a registered dietitian or research staff provided information on food preparation and managing common dietary challenges.

Control group participants were asked to continue their usual diets and attend four 1-hour group sessions.

At baseline and then after the 12-week study period, dietary intake was self-recorded for 2 weekdays and 1 weekend day, hot flash frequency and severity was recorded for 1 week using a mobile app, and the effect of menopausal symptoms on quality of life was measured using the vasomotor, psychosocial, physical, and sexual domains of the Menopause-Specific Quality of Life (MENQOL) questionnaire.

Equol production was also assessed in a subset of 15 intervention and 12 control participants who had urinary isoflavone concentrations measured after eating half a cup (86 g) of soybeans twice daily for 3 days. This was based on the theory that diets such as the intervention in this study “seem to foster the growth of gut bacteria capable of converting daidzein to equol,” noted the authors. The ability to produce equol is detected more frequently in individuals following vegetarian diets than in omnivores and … has been proposed as a factor in soy’s apparent health benefits.”

The study found that total hot flash frequency decreased by 78% in the intervention group (P < .001) and 39% (P < .001) in the control group (between-group P = .003), and moderate to severe hot flashes decreased by 88% versus 34%, respectively (from 5.0 to 0.6 per day, P < .001 vs. from 4.4 to 2.9 per day, P < .001; between-group P < .001). Among participants with at least seven moderate to severe hot flashes per day at baseline, moderate to severe hot flashes decreased by 93% (from 10.6 to 0.7 per day) in the intervention group (P < .001) and 36% (from 9.0 to 5.8 per day) in the control group (P = .01, between-group P < .001). The changes in hot flashes were paralleled by changes in the MENQOL findings, with significant between-group differences in the vasomotor (P = 0.004), physical (P = 0.01), and sexual (P = 0.03) domains.

Changes in frequency of severe hot flashes correlated directly with changes in fat intake, and inversely with changes in carbohydrate and fiber intake, such that “the greater the reduction in fat intake and the greater the increases in carbohydrate and fiber consumption, the greater the reduction in severe hot flashes,” noted the researchers. Mean body weight also decreased by 3.6 kg in the intervention group and 0.2 kg in the control group (P < .001). “Equol-production status had no apparent effect on hot flashes,” they added.

The study is the second phase of WAVS, which comprises two parts, the first of which showed similar results, but was conducted in the fall, raising questions about whether cooler temperatures were partly responsible for the results. Phase 2 of WAVS enrolled participants in the spring “ruling out the effect of outside temperature,” noted the authors.

“Eating a healthy diet at midlife is so important for long-term health and a sense of well-being for peri- and postmenopausal women,” said Dr Reed, but she urged caution in interpreting the findings. “This was an unblinded study,” she told this news organization. “Women were recruited to this study anticipating that they would be in a study on a soy diet. Individuals who sign up for a study are hoping for benefit from the intervention. The controls who don’t get the soy diet are often disappointed, so there is no benefit from a nonblinded control arm for their hot flashes. And that is exactly what we saw here. Blinded studies can hide what you are getting, so everyone in the study (intervention and controls) has the same anticipated benefit. But you cannot blind a soy diet.”

Dr. Reed also noted that, while the biologic mechanism of benefit should be equol production, this was not shown – given that both equol producers and nonproducers in the soy intervention reported marked symptom reduction.

“Only prior studies with estrogen interventions have observed reductions of hot flashes of the amount reported here,” she concluded. “Hopefully future large studies will clarify the role of soy diet for decreasing hot flashes.”

Dr. Barnard writes books and articles and gives lectures related to nutrition and health and has received royalties and honoraria from these sources. Dr. Reed has no relevant disclosures.

Women eating a reduced-fat vegan diet combined with a daily serving of soybeans experienced a 78% reduction in frequency of menopausal hot flashes over 12 weeks, in a small, nonblinded, randomized-controlled trial.

“We do not fully understand yet why this combination works, but it seems that these three elements are key: avoiding animal products, reducing fat, and adding a serving of soybeans,” lead researcher Neal Barnard, MD, explained in a press release. “These new results suggest that a diet change should be considered as a first-line treatment for troublesome vasomotor symptoms, including night sweats and hot flashes,” added Dr. Barnard, who is president of the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine, and adjunct professor at George Washington University, Washington.

But, while “the findings from this very small study complement everything we know about the benefits of an excellent diet and the health benefits of soy,” they should be interpreted with some caution, commented Susan Reed, MD, president of the North American Menopause Society, and associate program director of the women’s reproductive research program at the University of Washington, Seattle.

For the trial, called WAVS (Women’s Study for the Alleviation of Vasomotor Symptoms), the researchers randomized 84 postmenopausal women with at least two moderate to severe hot flashes daily to either the intervention or usual diet, with a total of 71 subjects completing the 12-week study, published in Menopause. Criteria for exclusion included any cause of vasomotor symptoms other than natural menopause, current use of a low-fat, vegan diet that includes daily soy products, soy allergy, and body mass index < 18.5 kg/m2.

Participants in the intervention group were asked to avoid animal-derived foods, minimize their use of oils and fatty foods such as nuts and avocados, and include half a cup (86 g) of cooked soybeans daily in their diets. They were also offered 1-hour virtual group meetings each week, in which a registered dietitian or research staff provided information on food preparation and managing common dietary challenges.

Control group participants were asked to continue their usual diets and attend four 1-hour group sessions.

At baseline and then after the 12-week study period, dietary intake was self-recorded for 2 weekdays and 1 weekend day, hot flash frequency and severity was recorded for 1 week using a mobile app, and the effect of menopausal symptoms on quality of life was measured using the vasomotor, psychosocial, physical, and sexual domains of the Menopause-Specific Quality of Life (MENQOL) questionnaire.

Equol production was also assessed in a subset of 15 intervention and 12 control participants who had urinary isoflavone concentrations measured after eating half a cup (86 g) of soybeans twice daily for 3 days. This was based on the theory that diets such as the intervention in this study “seem to foster the growth of gut bacteria capable of converting daidzein to equol,” noted the authors. The ability to produce equol is detected more frequently in individuals following vegetarian diets than in omnivores and … has been proposed as a factor in soy’s apparent health benefits.”

The study found that total hot flash frequency decreased by 78% in the intervention group (P < .001) and 39% (P < .001) in the control group (between-group P = .003), and moderate to severe hot flashes decreased by 88% versus 34%, respectively (from 5.0 to 0.6 per day, P < .001 vs. from 4.4 to 2.9 per day, P < .001; between-group P < .001). Among participants with at least seven moderate to severe hot flashes per day at baseline, moderate to severe hot flashes decreased by 93% (from 10.6 to 0.7 per day) in the intervention group (P < .001) and 36% (from 9.0 to 5.8 per day) in the control group (P = .01, between-group P < .001). The changes in hot flashes were paralleled by changes in the MENQOL findings, with significant between-group differences in the vasomotor (P = 0.004), physical (P = 0.01), and sexual (P = 0.03) domains.