User login

Can skin care aid use of diabetes devices?

Technologies that allow people to monitor blood sugar and automate the administration of insulin have radically transformed the lives of patients – and children in particular – with type 1 diabetes. But the devices often come with a cost: Insulin pumps and continuous glucose monitors can irritate the skin at the points of contact, causing some people to stop using their pumps or monitors altogether.

Regular use of lipid-rich skin creams can reduce eczema in children who use insulin pumps and continuous glucose monitors to manage type 1 diabetes, Danish researchers reported last month. The article is currently undergoing peer review at The Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology, and the authors said they hope their approach will deter more children from abandoning diabetes technology.

“A simple thing can actually change a lot,” said Anna Korsgaard Berg, MD, a pediatrician who specializes in diabetes care at Copenhagen University Hospital’s Steno Diabetes Center in Herlev, Denmark, and a coauthor of the new study. “Not all skin reactions can be solved by the skin care program, but it can help improve the issue.”

More than 1.5 million children and adolescents worldwide live with type 1 diabetes, a condition that requires continuous insulin infusion. Insulin pumps meet this need in many wealthier countries, and are often used in combination with sensors that measure a child’s glucose level. Both the American Diabetes Association and the International Society for Adolescent and Pediatric Diabetes recommend insulin pumps and continuous glucose monitors as core treatment tools.

Dr. Berg and colleagues, who have previously shown that as many as 90% of children who use these devices experience some kind of skin reaction, want to minimize the rate of such discomfort in hopes that fewer children stop using the devices. According to a 2014 study, 18% of people with type 1 diabetes who stopped using continuous glucose monitors did so because of skin irritation.

Lather on that lipid-rich lotion

Dr. Berg and colleagues studied 170 children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes (average age, 11 years) who use insulin pumps, continuous glucose monitors, or both. From March 2020 to July 2021, 112 children (55 girls) employed a skin care program developed for the study, while the other 58 (34 girls) did not receive any skin care advice.

The skin care group received instructions about how to gently insert and remove their insulin pumps or glucose monitors, to minimize skin damage. They also were told to avoid disinfectants such as alcohol, which can irritate skin. The children in this group used a cream containing 70% lipids to help rehydrate their skin, applying the salve each day a device was not inserted into their skin.

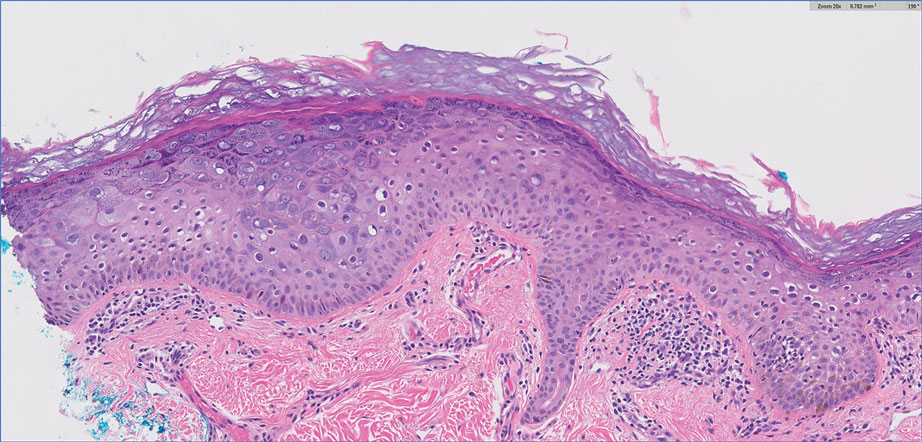

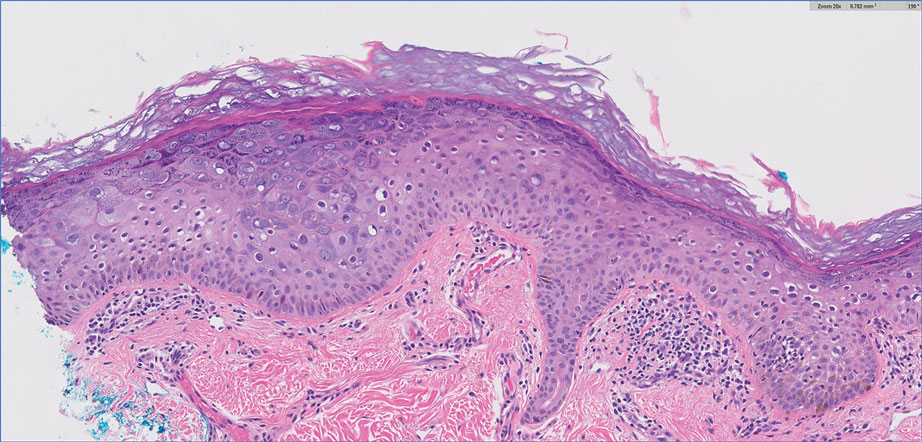

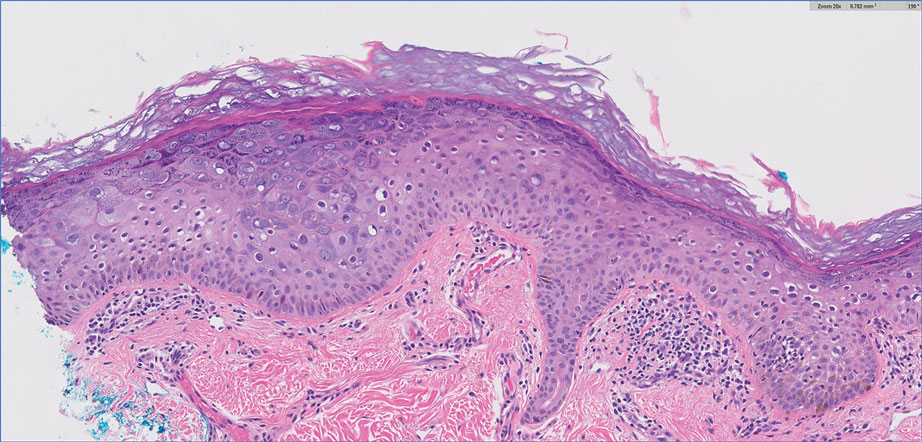

Eczema can be a real problem for kids who use insulin pumps and continuous glucose monitors to manage type 1 diabetes. Researchers found that regular use of lipid-rich skin creams can reduce its incidence.

Although insulin pumps and glucose monitors are kept in place for longer periods of time than they once were, Dr. Berg and colleagues noted, users do periodically remove them when bathing or when undergoing medical tests that involve x-rays. On days when the devices were not in place for a period of time, children in the skin care group were encouraged to follow the protocol.

Study results

One-third of children in the skin care group developed eczema or experienced a wound, compared with almost half of the children in the control group, according to the researchers. The absolute difference in developing eczema or wounds between the two groups was 12.9 % (95% confidence interval, –28.7% to 2.9%).

Children in the skin care group were much less likely to develop wounds, the researchers found, when they focused only on wounds and not eczema (odds ratio, 0.29, 95% CI, 0.12-0.68).

Dr. Berg said she would like to explore whether other techniques, such as a combination of patches, adhesives, or other lotions, yield even better results.

“Anything that can help people use technology more consistently is better for both quality of life and diabetes outcomes,” said Priya Prahalad, MD, a specialist in pediatric endocrinology and diabetes at Stanford Medicine Children’s Health in Palo Alto and Sunnyvale, Calif.

Dr. Prahalad, who was not involved in the Danish study, said that although the sample sizes in the trial were relatively small, the data are “headed in the right direction.”

Pediatricians already recommend using moisturizing creams at the sites where pumps or glucose monitors are inserted into the skin, she noted. But the new study simply employed an especially moisturizing cream to mitigate skin damage.

Although one reason for skin irritation may be the repeated insertion and removal of devices, Dr. Berg and Dr. Prahalad stressed that the medical devices themselves may contain allergy-causing components. Device makers are not required to disclose what’s inside the boxes.

“I do not understand why the full content of a device is not by law mandatory to declare, when declaration by law is mandatory for many other products and drugs but not for medical devices,” Dr. Berg said.

Dr. Berg reports receiving lipid cream from Teva Pharmaceuticals and research support from Medtronic. Dr. Prahalad reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Technologies that allow people to monitor blood sugar and automate the administration of insulin have radically transformed the lives of patients – and children in particular – with type 1 diabetes. But the devices often come with a cost: Insulin pumps and continuous glucose monitors can irritate the skin at the points of contact, causing some people to stop using their pumps or monitors altogether.

Regular use of lipid-rich skin creams can reduce eczema in children who use insulin pumps and continuous glucose monitors to manage type 1 diabetes, Danish researchers reported last month. The article is currently undergoing peer review at The Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology, and the authors said they hope their approach will deter more children from abandoning diabetes technology.

“A simple thing can actually change a lot,” said Anna Korsgaard Berg, MD, a pediatrician who specializes in diabetes care at Copenhagen University Hospital’s Steno Diabetes Center in Herlev, Denmark, and a coauthor of the new study. “Not all skin reactions can be solved by the skin care program, but it can help improve the issue.”

More than 1.5 million children and adolescents worldwide live with type 1 diabetes, a condition that requires continuous insulin infusion. Insulin pumps meet this need in many wealthier countries, and are often used in combination with sensors that measure a child’s glucose level. Both the American Diabetes Association and the International Society for Adolescent and Pediatric Diabetes recommend insulin pumps and continuous glucose monitors as core treatment tools.

Dr. Berg and colleagues, who have previously shown that as many as 90% of children who use these devices experience some kind of skin reaction, want to minimize the rate of such discomfort in hopes that fewer children stop using the devices. According to a 2014 study, 18% of people with type 1 diabetes who stopped using continuous glucose monitors did so because of skin irritation.

Lather on that lipid-rich lotion

Dr. Berg and colleagues studied 170 children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes (average age, 11 years) who use insulin pumps, continuous glucose monitors, or both. From March 2020 to July 2021, 112 children (55 girls) employed a skin care program developed for the study, while the other 58 (34 girls) did not receive any skin care advice.

The skin care group received instructions about how to gently insert and remove their insulin pumps or glucose monitors, to minimize skin damage. They also were told to avoid disinfectants such as alcohol, which can irritate skin. The children in this group used a cream containing 70% lipids to help rehydrate their skin, applying the salve each day a device was not inserted into their skin.

Eczema can be a real problem for kids who use insulin pumps and continuous glucose monitors to manage type 1 diabetes. Researchers found that regular use of lipid-rich skin creams can reduce its incidence.

Although insulin pumps and glucose monitors are kept in place for longer periods of time than they once were, Dr. Berg and colleagues noted, users do periodically remove them when bathing or when undergoing medical tests that involve x-rays. On days when the devices were not in place for a period of time, children in the skin care group were encouraged to follow the protocol.

Study results

One-third of children in the skin care group developed eczema or experienced a wound, compared with almost half of the children in the control group, according to the researchers. The absolute difference in developing eczema or wounds between the two groups was 12.9 % (95% confidence interval, –28.7% to 2.9%).

Children in the skin care group were much less likely to develop wounds, the researchers found, when they focused only on wounds and not eczema (odds ratio, 0.29, 95% CI, 0.12-0.68).

Dr. Berg said she would like to explore whether other techniques, such as a combination of patches, adhesives, or other lotions, yield even better results.

“Anything that can help people use technology more consistently is better for both quality of life and diabetes outcomes,” said Priya Prahalad, MD, a specialist in pediatric endocrinology and diabetes at Stanford Medicine Children’s Health in Palo Alto and Sunnyvale, Calif.

Dr. Prahalad, who was not involved in the Danish study, said that although the sample sizes in the trial were relatively small, the data are “headed in the right direction.”

Pediatricians already recommend using moisturizing creams at the sites where pumps or glucose monitors are inserted into the skin, she noted. But the new study simply employed an especially moisturizing cream to mitigate skin damage.

Although one reason for skin irritation may be the repeated insertion and removal of devices, Dr. Berg and Dr. Prahalad stressed that the medical devices themselves may contain allergy-causing components. Device makers are not required to disclose what’s inside the boxes.

“I do not understand why the full content of a device is not by law mandatory to declare, when declaration by law is mandatory for many other products and drugs but not for medical devices,” Dr. Berg said.

Dr. Berg reports receiving lipid cream from Teva Pharmaceuticals and research support from Medtronic. Dr. Prahalad reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Technologies that allow people to monitor blood sugar and automate the administration of insulin have radically transformed the lives of patients – and children in particular – with type 1 diabetes. But the devices often come with a cost: Insulin pumps and continuous glucose monitors can irritate the skin at the points of contact, causing some people to stop using their pumps or monitors altogether.

Regular use of lipid-rich skin creams can reduce eczema in children who use insulin pumps and continuous glucose monitors to manage type 1 diabetes, Danish researchers reported last month. The article is currently undergoing peer review at The Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology, and the authors said they hope their approach will deter more children from abandoning diabetes technology.

“A simple thing can actually change a lot,” said Anna Korsgaard Berg, MD, a pediatrician who specializes in diabetes care at Copenhagen University Hospital’s Steno Diabetes Center in Herlev, Denmark, and a coauthor of the new study. “Not all skin reactions can be solved by the skin care program, but it can help improve the issue.”

More than 1.5 million children and adolescents worldwide live with type 1 diabetes, a condition that requires continuous insulin infusion. Insulin pumps meet this need in many wealthier countries, and are often used in combination with sensors that measure a child’s glucose level. Both the American Diabetes Association and the International Society for Adolescent and Pediatric Diabetes recommend insulin pumps and continuous glucose monitors as core treatment tools.

Dr. Berg and colleagues, who have previously shown that as many as 90% of children who use these devices experience some kind of skin reaction, want to minimize the rate of such discomfort in hopes that fewer children stop using the devices. According to a 2014 study, 18% of people with type 1 diabetes who stopped using continuous glucose monitors did so because of skin irritation.

Lather on that lipid-rich lotion

Dr. Berg and colleagues studied 170 children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes (average age, 11 years) who use insulin pumps, continuous glucose monitors, or both. From March 2020 to July 2021, 112 children (55 girls) employed a skin care program developed for the study, while the other 58 (34 girls) did not receive any skin care advice.

The skin care group received instructions about how to gently insert and remove their insulin pumps or glucose monitors, to minimize skin damage. They also were told to avoid disinfectants such as alcohol, which can irritate skin. The children in this group used a cream containing 70% lipids to help rehydrate their skin, applying the salve each day a device was not inserted into their skin.

Eczema can be a real problem for kids who use insulin pumps and continuous glucose monitors to manage type 1 diabetes. Researchers found that regular use of lipid-rich skin creams can reduce its incidence.

Although insulin pumps and glucose monitors are kept in place for longer periods of time than they once were, Dr. Berg and colleagues noted, users do periodically remove them when bathing or when undergoing medical tests that involve x-rays. On days when the devices were not in place for a period of time, children in the skin care group were encouraged to follow the protocol.

Study results

One-third of children in the skin care group developed eczema or experienced a wound, compared with almost half of the children in the control group, according to the researchers. The absolute difference in developing eczema or wounds between the two groups was 12.9 % (95% confidence interval, –28.7% to 2.9%).

Children in the skin care group were much less likely to develop wounds, the researchers found, when they focused only on wounds and not eczema (odds ratio, 0.29, 95% CI, 0.12-0.68).

Dr. Berg said she would like to explore whether other techniques, such as a combination of patches, adhesives, or other lotions, yield even better results.

“Anything that can help people use technology more consistently is better for both quality of life and diabetes outcomes,” said Priya Prahalad, MD, a specialist in pediatric endocrinology and diabetes at Stanford Medicine Children’s Health in Palo Alto and Sunnyvale, Calif.

Dr. Prahalad, who was not involved in the Danish study, said that although the sample sizes in the trial were relatively small, the data are “headed in the right direction.”

Pediatricians already recommend using moisturizing creams at the sites where pumps or glucose monitors are inserted into the skin, she noted. But the new study simply employed an especially moisturizing cream to mitigate skin damage.

Although one reason for skin irritation may be the repeated insertion and removal of devices, Dr. Berg and Dr. Prahalad stressed that the medical devices themselves may contain allergy-causing components. Device makers are not required to disclose what’s inside the boxes.

“I do not understand why the full content of a device is not by law mandatory to declare, when declaration by law is mandatory for many other products and drugs but not for medical devices,” Dr. Berg said.

Dr. Berg reports receiving lipid cream from Teva Pharmaceuticals and research support from Medtronic. Dr. Prahalad reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Evidence Behind Topical Hair Loss Remedies on TikTok

Hair loss is an exceedingly common chief concern in outpatient dermatology clinics. An estimated 50% of males and females will experience androgenetic alopecia.1 Approximately 2% of new dermatology outpatient visits in the United States and the United Kingdom are for alopecia areata, the second most common type of hair loss.2 As access to dermatology appointments remains an issue with some studies citing wait times ranging from 2 to 25 days for a dermatologic consultation, the ease of accessibility of medical information on social media continues to grow,3 which leaves many of our patients turning to social media as a first-line source of information. As dermatology resident physicians, it is essential to be aware of popular dermatologic therapies on social media so that we may provide evidence-based opinions to our patients.

Remedies for Hair Loss on Social Media

Many trends on hair loss therapies found on TikTok focus on natural remedies that are produced by ingredients accessible to patients at home and over the counter, which may increase the appeal due to ease of treatment.

Rosemary Oil—The top trends in hair loss remedies I have come across are rosemary oil and rosemary water. Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis) has been known to possess antimicrobial and antioxidant properties but also has shown enhancement of microcapillary perfusion, which could explain its role in the prevention of hair loss and aiding hair growth in a similar mechanism to minoxidil.4,5 Unlike many other natural hair loss remedies, there are randomized controlled trials that assess the efficacy of rosemary oil for the treatment of hair loss. In a 2015 study of 100 patients with androgenetic alopecia, there was no statistically significant difference in mean hair count measured by microphotographic assessment after 6 months of treatment in 2 groups treated with either minoxidil solution 2% or rosemary oil, and both groups experienced a significant increase in hair count at 6 months (P<.05) compared with baseline and 3 months.6 Additionally, essential oils, including a mixture of thyme, rosemary, lavender, and cedarwood oils for alopecia were superior to placebo carrier oils in a posttreatment photographic assessment of their efficacy.7

Rice Water—The use of rice water and rice bran extract is a common hair care practice in Asia. Rice bran extract preparations have been shown in vivo to increase the number of anagen hair follicles as well as the number of anagen-related molecules in the dermal papillae.8,9 However, there are limited clinical data to support the use of rice water for hair growth.10

Onion Juice—Sharquie and Al-Obaidi11 conducted a study comparing crude onion juice to tap water in 38 patients with alopecia areata. They found that onion juice produced hair regrowth in significantly more patients than tap water (P<.0001).11 The mechanism of crude onion juice in hair growth is unknown; however, the induction of irritant or allergic contact dermatitis to components in crude onion juice may stimulate antigenic competition.12

Garlic Gel—Garlic gel, which is in the genus Allium, produces organosulfur compounds that provide antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory benefits.12 Additionally, in a double-blind randomized controlled trial, garlic powder was shown to increase cutaneous capillary perfusion.5 One study in 40 patients with alopecia areata demonstrated garlic gel 5% added to betamethasone valerate cream 0.1% was statistically superior to betamethasone alone in stimulating terminal hair growth (P=.001).13

Limitations and Downsides to Hair Loss Remedies on Social Media

Social media continues to be a prominent source of medical information for our patients, but most sources of hair content on social media are not board-certified dermatologists. A recent review of alopecia-related content found only 4% and 10% of posts were created by medical professionals on Instagram and TikTok, respectively, making misinformation extremely likely.14 Natural hair loss remedies contrived by TikTok have little clinical evidence to support their claims. Few data are available that compare these treatments to gold-standard hair loss therapies. Additionally, while some of these agents may be beneficial, the lack of standardized dosing may counteract these benefits. For example, videos on rosemary water advise the viewer to boil fresh rosemary sprigs in water and apply the solution to the hair daily with a spray bottle or apply cloves of garlic directly to the scalp, as opposed to a measured and standardized percentage. Some preparations may even induce harm to patients. Over-the-counter oils with added fragrances and natural compounds in onion and garlic may cause contact dermatitis. Finally, by using these products, patients may delay consultation with a board-certified dermatologist, leading to delays in applying evidence-based therapies targeted to specific hair loss subtypes while also incurring unnecessary expenses for these preparations.

Final Thoughts

Hair loss affects a notable portion of the population and is a common chief concern in dermatology clinics. Misinformation on social media continues to grow in prevalence. It is important to be aware of the hair loss remedies that are commonly touted to patients online and the evidence behind them.

- Ho CH, Sood T, Zito PM. Androgenetic alopecia. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- McMichael AJ, Pearce DJ, Wasserman D, et al. Alopecia in the United States: outpatient utilization and common prescribing patterns. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(2 suppl):S49-S51.

- Creadore A, Desai S, Li SJ, et al. Insurance acceptance, appointment wait time, and dermatologist access across practice types in the US. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:181-188. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.5173

- Bassino E, Gasparri F, Munaron L. Protective role of nutritional plants containing flavonoids in hair follicle disruption: a review. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:523. doi:10.3390/ijms21020523

- Ezekwe N, King M, Hollinger JC. The use of natural ingredients in the treatment of alopecias with an emphasis on central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: a systematic review [published online August 1, 2020]. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020;13:23-27.

- Panahi Y, Taghizadeh M, Marzony ET, et al. Rosemary oil vs minoxidil 2% for the treatment of androgenetic alopecia: a randomized comparative trial. Skinmed. 2015;13:15-21.

- Hay IC, Jamieson M, Ormerod AD. Randomized trial of aromatherapy. successful treatment for alopecia areata. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1349-1352. doi:10.1001/archderm.134.11.1349

- Choi JS, Jeon MH, Moon WS, et al. In vivo hair growth-promoting effect of rice bran extract prepared by supercritical carbon dioxide fluid. Biol Pharm Bull. 2014;37:44-53. doi:10.1248/bpb.b13-00528

- Kim YM, Kwon SJ, Jang HJ, et al. Rice bran mineral extract increases the expression of anagen-related molecules in human dermal papilla through wnt/catenin pathway. Food Nutr Res. 2017;61:1412792. doi:10.1080/16546628.2017.1412792

- Hashemi K, Pham C, Sung C, et al. A systematic review: application of rice products for hair growth. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21:177-185. doi:10.36849/jdd.6345

- Sharquie KE, Al-Obaidi HK. Onion juice (Allium cepa L.), a new topical treatment for alopecia areata. J Dermatol. 2002;29:343-346. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2002.tb00277.x

- Hosking AM, Juhasz M, Atanaskova Mesinkovska N. Complementary and alternative treatments for alopecia: a comprehensive review. Skin Appendage Disord. 2019;5:72-89. doi:10.1159/000492035

- Hajheydari Z, Jamshidi M, Akbari J, et al. Combination of topical garlic gel and betamethasone valerate cream in the treatment of localized alopecia areata: a double-blind randomized controlled study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007;73:29-32. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.30648

- Laughter M, Anderson J, Kolla A, et al. An analysis of alopecia related content on Instagram and TikTok. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21:1316-1321. doi:10.36849/JDD.6707

Hair loss is an exceedingly common chief concern in outpatient dermatology clinics. An estimated 50% of males and females will experience androgenetic alopecia.1 Approximately 2% of new dermatology outpatient visits in the United States and the United Kingdom are for alopecia areata, the second most common type of hair loss.2 As access to dermatology appointments remains an issue with some studies citing wait times ranging from 2 to 25 days for a dermatologic consultation, the ease of accessibility of medical information on social media continues to grow,3 which leaves many of our patients turning to social media as a first-line source of information. As dermatology resident physicians, it is essential to be aware of popular dermatologic therapies on social media so that we may provide evidence-based opinions to our patients.

Remedies for Hair Loss on Social Media

Many trends on hair loss therapies found on TikTok focus on natural remedies that are produced by ingredients accessible to patients at home and over the counter, which may increase the appeal due to ease of treatment.

Rosemary Oil—The top trends in hair loss remedies I have come across are rosemary oil and rosemary water. Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis) has been known to possess antimicrobial and antioxidant properties but also has shown enhancement of microcapillary perfusion, which could explain its role in the prevention of hair loss and aiding hair growth in a similar mechanism to minoxidil.4,5 Unlike many other natural hair loss remedies, there are randomized controlled trials that assess the efficacy of rosemary oil for the treatment of hair loss. In a 2015 study of 100 patients with androgenetic alopecia, there was no statistically significant difference in mean hair count measured by microphotographic assessment after 6 months of treatment in 2 groups treated with either minoxidil solution 2% or rosemary oil, and both groups experienced a significant increase in hair count at 6 months (P<.05) compared with baseline and 3 months.6 Additionally, essential oils, including a mixture of thyme, rosemary, lavender, and cedarwood oils for alopecia were superior to placebo carrier oils in a posttreatment photographic assessment of their efficacy.7

Rice Water—The use of rice water and rice bran extract is a common hair care practice in Asia. Rice bran extract preparations have been shown in vivo to increase the number of anagen hair follicles as well as the number of anagen-related molecules in the dermal papillae.8,9 However, there are limited clinical data to support the use of rice water for hair growth.10

Onion Juice—Sharquie and Al-Obaidi11 conducted a study comparing crude onion juice to tap water in 38 patients with alopecia areata. They found that onion juice produced hair regrowth in significantly more patients than tap water (P<.0001).11 The mechanism of crude onion juice in hair growth is unknown; however, the induction of irritant or allergic contact dermatitis to components in crude onion juice may stimulate antigenic competition.12

Garlic Gel—Garlic gel, which is in the genus Allium, produces organosulfur compounds that provide antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory benefits.12 Additionally, in a double-blind randomized controlled trial, garlic powder was shown to increase cutaneous capillary perfusion.5 One study in 40 patients with alopecia areata demonstrated garlic gel 5% added to betamethasone valerate cream 0.1% was statistically superior to betamethasone alone in stimulating terminal hair growth (P=.001).13

Limitations and Downsides to Hair Loss Remedies on Social Media

Social media continues to be a prominent source of medical information for our patients, but most sources of hair content on social media are not board-certified dermatologists. A recent review of alopecia-related content found only 4% and 10% of posts were created by medical professionals on Instagram and TikTok, respectively, making misinformation extremely likely.14 Natural hair loss remedies contrived by TikTok have little clinical evidence to support their claims. Few data are available that compare these treatments to gold-standard hair loss therapies. Additionally, while some of these agents may be beneficial, the lack of standardized dosing may counteract these benefits. For example, videos on rosemary water advise the viewer to boil fresh rosemary sprigs in water and apply the solution to the hair daily with a spray bottle or apply cloves of garlic directly to the scalp, as opposed to a measured and standardized percentage. Some preparations may even induce harm to patients. Over-the-counter oils with added fragrances and natural compounds in onion and garlic may cause contact dermatitis. Finally, by using these products, patients may delay consultation with a board-certified dermatologist, leading to delays in applying evidence-based therapies targeted to specific hair loss subtypes while also incurring unnecessary expenses for these preparations.

Final Thoughts

Hair loss affects a notable portion of the population and is a common chief concern in dermatology clinics. Misinformation on social media continues to grow in prevalence. It is important to be aware of the hair loss remedies that are commonly touted to patients online and the evidence behind them.

Hair loss is an exceedingly common chief concern in outpatient dermatology clinics. An estimated 50% of males and females will experience androgenetic alopecia.1 Approximately 2% of new dermatology outpatient visits in the United States and the United Kingdom are for alopecia areata, the second most common type of hair loss.2 As access to dermatology appointments remains an issue with some studies citing wait times ranging from 2 to 25 days for a dermatologic consultation, the ease of accessibility of medical information on social media continues to grow,3 which leaves many of our patients turning to social media as a first-line source of information. As dermatology resident physicians, it is essential to be aware of popular dermatologic therapies on social media so that we may provide evidence-based opinions to our patients.

Remedies for Hair Loss on Social Media

Many trends on hair loss therapies found on TikTok focus on natural remedies that are produced by ingredients accessible to patients at home and over the counter, which may increase the appeal due to ease of treatment.

Rosemary Oil—The top trends in hair loss remedies I have come across are rosemary oil and rosemary water. Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis) has been known to possess antimicrobial and antioxidant properties but also has shown enhancement of microcapillary perfusion, which could explain its role in the prevention of hair loss and aiding hair growth in a similar mechanism to minoxidil.4,5 Unlike many other natural hair loss remedies, there are randomized controlled trials that assess the efficacy of rosemary oil for the treatment of hair loss. In a 2015 study of 100 patients with androgenetic alopecia, there was no statistically significant difference in mean hair count measured by microphotographic assessment after 6 months of treatment in 2 groups treated with either minoxidil solution 2% or rosemary oil, and both groups experienced a significant increase in hair count at 6 months (P<.05) compared with baseline and 3 months.6 Additionally, essential oils, including a mixture of thyme, rosemary, lavender, and cedarwood oils for alopecia were superior to placebo carrier oils in a posttreatment photographic assessment of their efficacy.7

Rice Water—The use of rice water and rice bran extract is a common hair care practice in Asia. Rice bran extract preparations have been shown in vivo to increase the number of anagen hair follicles as well as the number of anagen-related molecules in the dermal papillae.8,9 However, there are limited clinical data to support the use of rice water for hair growth.10

Onion Juice—Sharquie and Al-Obaidi11 conducted a study comparing crude onion juice to tap water in 38 patients with alopecia areata. They found that onion juice produced hair regrowth in significantly more patients than tap water (P<.0001).11 The mechanism of crude onion juice in hair growth is unknown; however, the induction of irritant or allergic contact dermatitis to components in crude onion juice may stimulate antigenic competition.12

Garlic Gel—Garlic gel, which is in the genus Allium, produces organosulfur compounds that provide antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory benefits.12 Additionally, in a double-blind randomized controlled trial, garlic powder was shown to increase cutaneous capillary perfusion.5 One study in 40 patients with alopecia areata demonstrated garlic gel 5% added to betamethasone valerate cream 0.1% was statistically superior to betamethasone alone in stimulating terminal hair growth (P=.001).13

Limitations and Downsides to Hair Loss Remedies on Social Media

Social media continues to be a prominent source of medical information for our patients, but most sources of hair content on social media are not board-certified dermatologists. A recent review of alopecia-related content found only 4% and 10% of posts were created by medical professionals on Instagram and TikTok, respectively, making misinformation extremely likely.14 Natural hair loss remedies contrived by TikTok have little clinical evidence to support their claims. Few data are available that compare these treatments to gold-standard hair loss therapies. Additionally, while some of these agents may be beneficial, the lack of standardized dosing may counteract these benefits. For example, videos on rosemary water advise the viewer to boil fresh rosemary sprigs in water and apply the solution to the hair daily with a spray bottle or apply cloves of garlic directly to the scalp, as opposed to a measured and standardized percentage. Some preparations may even induce harm to patients. Over-the-counter oils with added fragrances and natural compounds in onion and garlic may cause contact dermatitis. Finally, by using these products, patients may delay consultation with a board-certified dermatologist, leading to delays in applying evidence-based therapies targeted to specific hair loss subtypes while also incurring unnecessary expenses for these preparations.

Final Thoughts

Hair loss affects a notable portion of the population and is a common chief concern in dermatology clinics. Misinformation on social media continues to grow in prevalence. It is important to be aware of the hair loss remedies that are commonly touted to patients online and the evidence behind them.

- Ho CH, Sood T, Zito PM. Androgenetic alopecia. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- McMichael AJ, Pearce DJ, Wasserman D, et al. Alopecia in the United States: outpatient utilization and common prescribing patterns. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(2 suppl):S49-S51.

- Creadore A, Desai S, Li SJ, et al. Insurance acceptance, appointment wait time, and dermatologist access across practice types in the US. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:181-188. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.5173

- Bassino E, Gasparri F, Munaron L. Protective role of nutritional plants containing flavonoids in hair follicle disruption: a review. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:523. doi:10.3390/ijms21020523

- Ezekwe N, King M, Hollinger JC. The use of natural ingredients in the treatment of alopecias with an emphasis on central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: a systematic review [published online August 1, 2020]. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020;13:23-27.

- Panahi Y, Taghizadeh M, Marzony ET, et al. Rosemary oil vs minoxidil 2% for the treatment of androgenetic alopecia: a randomized comparative trial. Skinmed. 2015;13:15-21.

- Hay IC, Jamieson M, Ormerod AD. Randomized trial of aromatherapy. successful treatment for alopecia areata. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1349-1352. doi:10.1001/archderm.134.11.1349

- Choi JS, Jeon MH, Moon WS, et al. In vivo hair growth-promoting effect of rice bran extract prepared by supercritical carbon dioxide fluid. Biol Pharm Bull. 2014;37:44-53. doi:10.1248/bpb.b13-00528

- Kim YM, Kwon SJ, Jang HJ, et al. Rice bran mineral extract increases the expression of anagen-related molecules in human dermal papilla through wnt/catenin pathway. Food Nutr Res. 2017;61:1412792. doi:10.1080/16546628.2017.1412792

- Hashemi K, Pham C, Sung C, et al. A systematic review: application of rice products for hair growth. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21:177-185. doi:10.36849/jdd.6345

- Sharquie KE, Al-Obaidi HK. Onion juice (Allium cepa L.), a new topical treatment for alopecia areata. J Dermatol. 2002;29:343-346. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2002.tb00277.x

- Hosking AM, Juhasz M, Atanaskova Mesinkovska N. Complementary and alternative treatments for alopecia: a comprehensive review. Skin Appendage Disord. 2019;5:72-89. doi:10.1159/000492035

- Hajheydari Z, Jamshidi M, Akbari J, et al. Combination of topical garlic gel and betamethasone valerate cream in the treatment of localized alopecia areata: a double-blind randomized controlled study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007;73:29-32. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.30648

- Laughter M, Anderson J, Kolla A, et al. An analysis of alopecia related content on Instagram and TikTok. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21:1316-1321. doi:10.36849/JDD.6707

- Ho CH, Sood T, Zito PM. Androgenetic alopecia. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- McMichael AJ, Pearce DJ, Wasserman D, et al. Alopecia in the United States: outpatient utilization and common prescribing patterns. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(2 suppl):S49-S51.

- Creadore A, Desai S, Li SJ, et al. Insurance acceptance, appointment wait time, and dermatologist access across practice types in the US. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:181-188. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.5173

- Bassino E, Gasparri F, Munaron L. Protective role of nutritional plants containing flavonoids in hair follicle disruption: a review. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:523. doi:10.3390/ijms21020523

- Ezekwe N, King M, Hollinger JC. The use of natural ingredients in the treatment of alopecias with an emphasis on central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: a systematic review [published online August 1, 2020]. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020;13:23-27.

- Panahi Y, Taghizadeh M, Marzony ET, et al. Rosemary oil vs minoxidil 2% for the treatment of androgenetic alopecia: a randomized comparative trial. Skinmed. 2015;13:15-21.

- Hay IC, Jamieson M, Ormerod AD. Randomized trial of aromatherapy. successful treatment for alopecia areata. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1349-1352. doi:10.1001/archderm.134.11.1349

- Choi JS, Jeon MH, Moon WS, et al. In vivo hair growth-promoting effect of rice bran extract prepared by supercritical carbon dioxide fluid. Biol Pharm Bull. 2014;37:44-53. doi:10.1248/bpb.b13-00528

- Kim YM, Kwon SJ, Jang HJ, et al. Rice bran mineral extract increases the expression of anagen-related molecules in human dermal papilla through wnt/catenin pathway. Food Nutr Res. 2017;61:1412792. doi:10.1080/16546628.2017.1412792

- Hashemi K, Pham C, Sung C, et al. A systematic review: application of rice products for hair growth. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21:177-185. doi:10.36849/jdd.6345

- Sharquie KE, Al-Obaidi HK. Onion juice (Allium cepa L.), a new topical treatment for alopecia areata. J Dermatol. 2002;29:343-346. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2002.tb00277.x

- Hosking AM, Juhasz M, Atanaskova Mesinkovska N. Complementary and alternative treatments for alopecia: a comprehensive review. Skin Appendage Disord. 2019;5:72-89. doi:10.1159/000492035

- Hajheydari Z, Jamshidi M, Akbari J, et al. Combination of topical garlic gel and betamethasone valerate cream in the treatment of localized alopecia areata: a double-blind randomized controlled study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007;73:29-32. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.30648

- Laughter M, Anderson J, Kolla A, et al. An analysis of alopecia related content on Instagram and TikTok. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21:1316-1321. doi:10.36849/JDD.6707

Resident Pearl

- With terabytes of information at their fingertips, patients often turn to social media for hair loss advice. Many recommended therapies lack evidence-based research, and some may even be harmful to patients or delay time to efficacious treatments.

Which nonopioid meds are best for easing acute low back pain?

based on data from more than 3,000 individuals.

Acute low back pain (LBP) remains a common cause of disability worldwide, with a high socioeconomic burden, write Alice Baroncini, MD, of RWTH University Hospital, Aachen, Germany, and colleagues.

In an analysis published in the Journal of Orthopaedic Research, a team of investigators from Germany examined which nonopioid drugs are best for treating LBP.

The researchers identified 18 studies totaling 3,478 patients with acute low back pain of less than 12 weeks’ duration. They selected studies that only investigated the lumbar spine, and studies involving opioids were excluded. The mean age of the patients across all the studies was 42.5 years, and 54% were women. The mean duration of symptoms before treatment was 15.1 days.

Overall, muscle relaxants and NSAIDs demonstrated effectiveness in reducing pain and disability for acute LBP patients after about 1 week of use.

In addition, studies of a combination of NSAIDs and paracetamol (also known as acetaminophen) showed a greater improvement than NSAIDs alone, but paracetamol/acetaminophen alone had no significant impact on LBP.

Most patients with acute LBP experience spontaneous recovery and reduction of symptoms, thus the real impact of most medications is uncertain, the researchers write in their discussion. The lack of a placebo effect in the selected studies reinforces the hypothesis that nonopioid medications improve LBP symptoms, they say.

However, “while this work only focuses on the pharmacological management of acute LBP, it is fundamental to highlight that the use of drugs should always be a second-line strategy once other nonpharmacological, noninvasive therapies have proved to be insufficient,” the researchers write.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the inability to distinguish among different NSAID classes, the inability to conduct a subanalysis of the best drug or treatment protocol for a given drug class, and the short follow-up period for the included studies, the researchers note.

More research is needed to address the effects of different drugs on LBP recurrence, they add.

However, the results support the current opinion that NSAIDs can be effectively used for LBP, strengthened by the large number of studies and relatively low risk of bias, the researchers conclude.

The current study addresses a common cause of morbidity among patients and highlights alternatives to opioid analgesics for its management, Suman Pal, MBBS, a specialist in hospital medicine at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, said in an interview.

Dr. Pal said he was not surprised by the results. “The findings of the study mirror prior studies,” he said. “However, the lack of benefit of paracetamol alone needs to be highlighted as important to clinical practice.”

A key message for clinicians is the role of NSAIDs in LBP, Dr. Pal said. “NSAIDs, either alone or in combination with paracetamol or myorelaxants, can be effective therapy for select patients with acute LBP.” However, “further research is needed to better identify which patients would derive most benefit from this approach,” he said.

Other research needs include more evidence to better understand the appropriate duration of therapy, given the potential for adverse effects with chronic NSAID use, Dr. Pal said.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers and Dr. Pal have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

based on data from more than 3,000 individuals.

Acute low back pain (LBP) remains a common cause of disability worldwide, with a high socioeconomic burden, write Alice Baroncini, MD, of RWTH University Hospital, Aachen, Germany, and colleagues.

In an analysis published in the Journal of Orthopaedic Research, a team of investigators from Germany examined which nonopioid drugs are best for treating LBP.

The researchers identified 18 studies totaling 3,478 patients with acute low back pain of less than 12 weeks’ duration. They selected studies that only investigated the lumbar spine, and studies involving opioids were excluded. The mean age of the patients across all the studies was 42.5 years, and 54% were women. The mean duration of symptoms before treatment was 15.1 days.

Overall, muscle relaxants and NSAIDs demonstrated effectiveness in reducing pain and disability for acute LBP patients after about 1 week of use.

In addition, studies of a combination of NSAIDs and paracetamol (also known as acetaminophen) showed a greater improvement than NSAIDs alone, but paracetamol/acetaminophen alone had no significant impact on LBP.

Most patients with acute LBP experience spontaneous recovery and reduction of symptoms, thus the real impact of most medications is uncertain, the researchers write in their discussion. The lack of a placebo effect in the selected studies reinforces the hypothesis that nonopioid medications improve LBP symptoms, they say.

However, “while this work only focuses on the pharmacological management of acute LBP, it is fundamental to highlight that the use of drugs should always be a second-line strategy once other nonpharmacological, noninvasive therapies have proved to be insufficient,” the researchers write.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the inability to distinguish among different NSAID classes, the inability to conduct a subanalysis of the best drug or treatment protocol for a given drug class, and the short follow-up period for the included studies, the researchers note.

More research is needed to address the effects of different drugs on LBP recurrence, they add.

However, the results support the current opinion that NSAIDs can be effectively used for LBP, strengthened by the large number of studies and relatively low risk of bias, the researchers conclude.

The current study addresses a common cause of morbidity among patients and highlights alternatives to opioid analgesics for its management, Suman Pal, MBBS, a specialist in hospital medicine at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, said in an interview.

Dr. Pal said he was not surprised by the results. “The findings of the study mirror prior studies,” he said. “However, the lack of benefit of paracetamol alone needs to be highlighted as important to clinical practice.”

A key message for clinicians is the role of NSAIDs in LBP, Dr. Pal said. “NSAIDs, either alone or in combination with paracetamol or myorelaxants, can be effective therapy for select patients with acute LBP.” However, “further research is needed to better identify which patients would derive most benefit from this approach,” he said.

Other research needs include more evidence to better understand the appropriate duration of therapy, given the potential for adverse effects with chronic NSAID use, Dr. Pal said.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers and Dr. Pal have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

based on data from more than 3,000 individuals.

Acute low back pain (LBP) remains a common cause of disability worldwide, with a high socioeconomic burden, write Alice Baroncini, MD, of RWTH University Hospital, Aachen, Germany, and colleagues.

In an analysis published in the Journal of Orthopaedic Research, a team of investigators from Germany examined which nonopioid drugs are best for treating LBP.

The researchers identified 18 studies totaling 3,478 patients with acute low back pain of less than 12 weeks’ duration. They selected studies that only investigated the lumbar spine, and studies involving opioids were excluded. The mean age of the patients across all the studies was 42.5 years, and 54% were women. The mean duration of symptoms before treatment was 15.1 days.

Overall, muscle relaxants and NSAIDs demonstrated effectiveness in reducing pain and disability for acute LBP patients after about 1 week of use.

In addition, studies of a combination of NSAIDs and paracetamol (also known as acetaminophen) showed a greater improvement than NSAIDs alone, but paracetamol/acetaminophen alone had no significant impact on LBP.

Most patients with acute LBP experience spontaneous recovery and reduction of symptoms, thus the real impact of most medications is uncertain, the researchers write in their discussion. The lack of a placebo effect in the selected studies reinforces the hypothesis that nonopioid medications improve LBP symptoms, they say.

However, “while this work only focuses on the pharmacological management of acute LBP, it is fundamental to highlight that the use of drugs should always be a second-line strategy once other nonpharmacological, noninvasive therapies have proved to be insufficient,” the researchers write.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the inability to distinguish among different NSAID classes, the inability to conduct a subanalysis of the best drug or treatment protocol for a given drug class, and the short follow-up period for the included studies, the researchers note.

More research is needed to address the effects of different drugs on LBP recurrence, they add.

However, the results support the current opinion that NSAIDs can be effectively used for LBP, strengthened by the large number of studies and relatively low risk of bias, the researchers conclude.

The current study addresses a common cause of morbidity among patients and highlights alternatives to opioid analgesics for its management, Suman Pal, MBBS, a specialist in hospital medicine at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, said in an interview.

Dr. Pal said he was not surprised by the results. “The findings of the study mirror prior studies,” he said. “However, the lack of benefit of paracetamol alone needs to be highlighted as important to clinical practice.”

A key message for clinicians is the role of NSAIDs in LBP, Dr. Pal said. “NSAIDs, either alone or in combination with paracetamol or myorelaxants, can be effective therapy for select patients with acute LBP.” However, “further research is needed to better identify which patients would derive most benefit from this approach,” he said.

Other research needs include more evidence to better understand the appropriate duration of therapy, given the potential for adverse effects with chronic NSAID use, Dr. Pal said.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers and Dr. Pal have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF ORTHOPAEDIC RESEARCH

Any level of physical activity tied to better later-life memory

new research suggests.

A prospective study of 1,400 participants showed that those who exercised to any extent in adulthood had significantly better cognitive scores later in life, compared with their peers who were physically inactive.

Maintaining an exercise routine throughout adulthood showed the strongest link to subsequent mental acuity.

Although these associations lessened when investigators controlled for childhood cognitive ability, socioeconomic background, and education, they remained statistically significant.

“Our findings support recommendations for greater participation in physical activity across adulthood,” lead investigator Sarah-Naomi James, PhD, research fellow at the Medical Research Council Unit for Lifelong Health and Ageing at the University College London, told this news organization.

“We provide evidence to encourage inactive adults to be active even to a small extent … at any point during adulthood,” which can improve cognition and memory later in life, Dr. James said.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry.

Exercise timing

Previous studies have established a link between fitness training and cognitive benefit later in life, but the researchers wanted to explore whether the timing or type of exercise influenced cognitive outcomes in later life.

The investigators asked more than 1,400 participants in the 1946 British birth cohort how much they had exercised at ages 36, 43, 60, and 69 years.

The questions changed slightly for each assessment period, but in general, participants were asked whether in the past month they had exercised or participated in such activities as badminton, swimming, fitness exercises, yoga, dancing, football, mountain climbing, jogging, or brisk walks for 30 minutes or more; and if so, how many times they participated per month.

Prior research showed that when the participants were aged 60 years, the most commonly reported activities were walking (71%), swimming (33%), floor exercises (24%), and cycling (15%).

When they turned 69, researchers tested participants’ cognitive performance using the Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination–III, which measures attention and orientation, verbal fluency, memory, language, and visuospatial function. In this study sample, 53% were women, and all were White.

Physical activity levels were classified as inactive, moderately active (one to four times per month), and most active (five or more times per month). In addition, they were summed across all five assessments to create a total score ranging from 0 (inactive at all ages) to 5 (active at all ages).

Overall, 11% of participants were physically inactive at all five time points; 17% were active at one time point; 20% were active at two and three time points; 17% were active at four time points; and 15% were active at all five time points.

‘Cradle to grave’ study?

Results showed that being physically active at all study time points was significantly associated with higher cognitive performance, verbal memory, and processing speed when participants were aged 69 (P < .01).

Those who exercised to any extent in adulthood – even just once a month during one of the time periods, fared better cognitively in later life, compared with physically inactive participants. (P < .01).

Study limitations cited include a lack of diversity among participants and a disproportionately high attrition rate among those who were socially disadvantaged.

“Our findings show that being active during every decade from their 30s on was associated with better cognition at around 70. Indeed, those who were active for longer had the highest cognitive function,” Dr. James said.

“However, it is also never too late to start. People in our study who only started being active in their 50s or 60s still had higher cognitive scores at age 70, compared to people of the same age who had never been active,” she added.

Dr. James intends to continue following the study sample to determine whether physical activity is linked to preserved cognitive aging “and buffers the effects of cognitive deterioration in the presence of disease markers that cause dementia, ultimately delaying dementia onset.

“We hope the cohort we study will be the first ‘cradle to grave’ study in the world, where we have followed people for their entire lives,” she said.

Encouraging finding

In a comment, Joel Hughes, PhD, professor of psychology and director of clinical training at Kent (Ohio) State University, said the study contributes to the idea that “accumulation of physical activity over one’s lifetime fits the data better than a ‘sensitive period’ – which suggests that it’s never too late to start exercising.”

Dr. Hughes, who was not involved in the research, noted that “exercise can improve cerebral blood flow and hemodynamic function, as well as greater activation of relevant brain regions such as the frontal lobes.”

While observing that the effects of exercise on cognition are likely complex from a mechanistic point of view, the finding that “exercise preserves or improves cognition later in life is encouraging,” he said.

The study received funding from the UK Medical Research Council and Alzheimer’s Research UK. The investigators and Dr. Hughes report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests.

A prospective study of 1,400 participants showed that those who exercised to any extent in adulthood had significantly better cognitive scores later in life, compared with their peers who were physically inactive.

Maintaining an exercise routine throughout adulthood showed the strongest link to subsequent mental acuity.

Although these associations lessened when investigators controlled for childhood cognitive ability, socioeconomic background, and education, they remained statistically significant.

“Our findings support recommendations for greater participation in physical activity across adulthood,” lead investigator Sarah-Naomi James, PhD, research fellow at the Medical Research Council Unit for Lifelong Health and Ageing at the University College London, told this news organization.

“We provide evidence to encourage inactive adults to be active even to a small extent … at any point during adulthood,” which can improve cognition and memory later in life, Dr. James said.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry.

Exercise timing

Previous studies have established a link between fitness training and cognitive benefit later in life, but the researchers wanted to explore whether the timing or type of exercise influenced cognitive outcomes in later life.

The investigators asked more than 1,400 participants in the 1946 British birth cohort how much they had exercised at ages 36, 43, 60, and 69 years.

The questions changed slightly for each assessment period, but in general, participants were asked whether in the past month they had exercised or participated in such activities as badminton, swimming, fitness exercises, yoga, dancing, football, mountain climbing, jogging, or brisk walks for 30 minutes or more; and if so, how many times they participated per month.

Prior research showed that when the participants were aged 60 years, the most commonly reported activities were walking (71%), swimming (33%), floor exercises (24%), and cycling (15%).

When they turned 69, researchers tested participants’ cognitive performance using the Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination–III, which measures attention and orientation, verbal fluency, memory, language, and visuospatial function. In this study sample, 53% were women, and all were White.

Physical activity levels were classified as inactive, moderately active (one to four times per month), and most active (five or more times per month). In addition, they were summed across all five assessments to create a total score ranging from 0 (inactive at all ages) to 5 (active at all ages).

Overall, 11% of participants were physically inactive at all five time points; 17% were active at one time point; 20% were active at two and three time points; 17% were active at four time points; and 15% were active at all five time points.

‘Cradle to grave’ study?

Results showed that being physically active at all study time points was significantly associated with higher cognitive performance, verbal memory, and processing speed when participants were aged 69 (P < .01).

Those who exercised to any extent in adulthood – even just once a month during one of the time periods, fared better cognitively in later life, compared with physically inactive participants. (P < .01).

Study limitations cited include a lack of diversity among participants and a disproportionately high attrition rate among those who were socially disadvantaged.

“Our findings show that being active during every decade from their 30s on was associated with better cognition at around 70. Indeed, those who were active for longer had the highest cognitive function,” Dr. James said.

“However, it is also never too late to start. People in our study who only started being active in their 50s or 60s still had higher cognitive scores at age 70, compared to people of the same age who had never been active,” she added.

Dr. James intends to continue following the study sample to determine whether physical activity is linked to preserved cognitive aging “and buffers the effects of cognitive deterioration in the presence of disease markers that cause dementia, ultimately delaying dementia onset.

“We hope the cohort we study will be the first ‘cradle to grave’ study in the world, where we have followed people for their entire lives,” she said.

Encouraging finding

In a comment, Joel Hughes, PhD, professor of psychology and director of clinical training at Kent (Ohio) State University, said the study contributes to the idea that “accumulation of physical activity over one’s lifetime fits the data better than a ‘sensitive period’ – which suggests that it’s never too late to start exercising.”

Dr. Hughes, who was not involved in the research, noted that “exercise can improve cerebral blood flow and hemodynamic function, as well as greater activation of relevant brain regions such as the frontal lobes.”

While observing that the effects of exercise on cognition are likely complex from a mechanistic point of view, the finding that “exercise preserves or improves cognition later in life is encouraging,” he said.

The study received funding from the UK Medical Research Council and Alzheimer’s Research UK. The investigators and Dr. Hughes report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests.

A prospective study of 1,400 participants showed that those who exercised to any extent in adulthood had significantly better cognitive scores later in life, compared with their peers who were physically inactive.

Maintaining an exercise routine throughout adulthood showed the strongest link to subsequent mental acuity.

Although these associations lessened when investigators controlled for childhood cognitive ability, socioeconomic background, and education, they remained statistically significant.

“Our findings support recommendations for greater participation in physical activity across adulthood,” lead investigator Sarah-Naomi James, PhD, research fellow at the Medical Research Council Unit for Lifelong Health and Ageing at the University College London, told this news organization.

“We provide evidence to encourage inactive adults to be active even to a small extent … at any point during adulthood,” which can improve cognition and memory later in life, Dr. James said.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry.

Exercise timing

Previous studies have established a link between fitness training and cognitive benefit later in life, but the researchers wanted to explore whether the timing or type of exercise influenced cognitive outcomes in later life.

The investigators asked more than 1,400 participants in the 1946 British birth cohort how much they had exercised at ages 36, 43, 60, and 69 years.

The questions changed slightly for each assessment period, but in general, participants were asked whether in the past month they had exercised or participated in such activities as badminton, swimming, fitness exercises, yoga, dancing, football, mountain climbing, jogging, or brisk walks for 30 minutes or more; and if so, how many times they participated per month.

Prior research showed that when the participants were aged 60 years, the most commonly reported activities were walking (71%), swimming (33%), floor exercises (24%), and cycling (15%).

When they turned 69, researchers tested participants’ cognitive performance using the Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination–III, which measures attention and orientation, verbal fluency, memory, language, and visuospatial function. In this study sample, 53% were women, and all were White.

Physical activity levels were classified as inactive, moderately active (one to four times per month), and most active (five or more times per month). In addition, they were summed across all five assessments to create a total score ranging from 0 (inactive at all ages) to 5 (active at all ages).

Overall, 11% of participants were physically inactive at all five time points; 17% were active at one time point; 20% were active at two and three time points; 17% were active at four time points; and 15% were active at all five time points.

‘Cradle to grave’ study?

Results showed that being physically active at all study time points was significantly associated with higher cognitive performance, verbal memory, and processing speed when participants were aged 69 (P < .01).

Those who exercised to any extent in adulthood – even just once a month during one of the time periods, fared better cognitively in later life, compared with physically inactive participants. (P < .01).

Study limitations cited include a lack of diversity among participants and a disproportionately high attrition rate among those who were socially disadvantaged.

“Our findings show that being active during every decade from their 30s on was associated with better cognition at around 70. Indeed, those who were active for longer had the highest cognitive function,” Dr. James said.

“However, it is also never too late to start. People in our study who only started being active in their 50s or 60s still had higher cognitive scores at age 70, compared to people of the same age who had never been active,” she added.

Dr. James intends to continue following the study sample to determine whether physical activity is linked to preserved cognitive aging “and buffers the effects of cognitive deterioration in the presence of disease markers that cause dementia, ultimately delaying dementia onset.

“We hope the cohort we study will be the first ‘cradle to grave’ study in the world, where we have followed people for their entire lives,” she said.

Encouraging finding

In a comment, Joel Hughes, PhD, professor of psychology and director of clinical training at Kent (Ohio) State University, said the study contributes to the idea that “accumulation of physical activity over one’s lifetime fits the data better than a ‘sensitive period’ – which suggests that it’s never too late to start exercising.”

Dr. Hughes, who was not involved in the research, noted that “exercise can improve cerebral blood flow and hemodynamic function, as well as greater activation of relevant brain regions such as the frontal lobes.”

While observing that the effects of exercise on cognition are likely complex from a mechanistic point of view, the finding that “exercise preserves or improves cognition later in life is encouraging,” he said.

The study received funding from the UK Medical Research Council and Alzheimer’s Research UK. The investigators and Dr. Hughes report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF NEUROLOGY, NEUROSURGERY & PSYCHIATRY

Swallow this: Tiny tech tracks your gut in real time

From heartburn to hemorrhoids and everything in between, gastrointestinal troubles affect 60 million to 70 million Americans. Part of what makes them so frustrating – besides the frequent flights to the bathroom – are the invasive and uncomfortable tests one must endure for diagnosis, such as endoscopy (feeding a flexible tube into a person’s digestive tract) or x-rays that can involve higher radiation exposure.

But a revolutionary new option promising greater comfort and convenience could become available within the next few years.

The technology is described in Nature Electronics, along with the results of in vitro and animal testing of how well it works.

“You can think of this like a GPS that you can see on your phone as your Lyft or Uber driver is moving around,” says study author Azita Emami, PhD, a professor of electrical engineering and medical engineering at the California Institute of Technology, Pasadena. “You can see the driver coming through the streets, and you can track it in real time, but imagine you can do that with much higher precision for a much smaller device inside the body.”

It’s not the first option for GI testing that can be swallowed. A “capsule endoscopy” camera can take pictures of the digestive tract. And a “wireless motility capsule” uses sensors to measure pH, temperature, and pressure. But these technologies may not work for the entire time it takes to pass through the gut, usually about 1-3 days. And while they gather information, you can’t track their location in the GI tract in real time. Your doctor can learn a lot from this level of detail.

“If a patient has motility problems in their GI tract, it can actually tell the [doctor] where the motility problem is happening, where the slowdown is happening, which is much more informative,” says Dr. Emami. Such slowdowns are common in notoriously frustrating GI issues like irritable bowel syndrome, or IBS, and inflammatory bowel disease, or IBD.

To develop this technology, the research team drew inspiration from magnetic resonance imaging, or MRI. Magnetic fields transmit data from the Bluetooth-enabled device to a smartphone. An external component, a magnetic field generator that looks like a flat mat, powers the device and is small enough to be carried in a backpack – or placed under a bed, attached to a jacket, or mounted to a toilet seat. The part that can be swallowed has tiny chips embedded in a capsulelike package.

Before this technology can go to market, more testing is needed, including clinical trials in humans, says Dr. Emami. That will likely take a few years.

The team also aims to make the device even smaller (it now measures about 1 cm wide and 2 cm long) and less expensive, and they want it to do more things, such as sending medicines to the GI tract. Those innovations could take a few more years.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

From heartburn to hemorrhoids and everything in between, gastrointestinal troubles affect 60 million to 70 million Americans. Part of what makes them so frustrating – besides the frequent flights to the bathroom – are the invasive and uncomfortable tests one must endure for diagnosis, such as endoscopy (feeding a flexible tube into a person’s digestive tract) or x-rays that can involve higher radiation exposure.

But a revolutionary new option promising greater comfort and convenience could become available within the next few years.

The technology is described in Nature Electronics, along with the results of in vitro and animal testing of how well it works.

“You can think of this like a GPS that you can see on your phone as your Lyft or Uber driver is moving around,” says study author Azita Emami, PhD, a professor of electrical engineering and medical engineering at the California Institute of Technology, Pasadena. “You can see the driver coming through the streets, and you can track it in real time, but imagine you can do that with much higher precision for a much smaller device inside the body.”

It’s not the first option for GI testing that can be swallowed. A “capsule endoscopy” camera can take pictures of the digestive tract. And a “wireless motility capsule” uses sensors to measure pH, temperature, and pressure. But these technologies may not work for the entire time it takes to pass through the gut, usually about 1-3 days. And while they gather information, you can’t track their location in the GI tract in real time. Your doctor can learn a lot from this level of detail.

“If a patient has motility problems in their GI tract, it can actually tell the [doctor] where the motility problem is happening, where the slowdown is happening, which is much more informative,” says Dr. Emami. Such slowdowns are common in notoriously frustrating GI issues like irritable bowel syndrome, or IBS, and inflammatory bowel disease, or IBD.

To develop this technology, the research team drew inspiration from magnetic resonance imaging, or MRI. Magnetic fields transmit data from the Bluetooth-enabled device to a smartphone. An external component, a magnetic field generator that looks like a flat mat, powers the device and is small enough to be carried in a backpack – or placed under a bed, attached to a jacket, or mounted to a toilet seat. The part that can be swallowed has tiny chips embedded in a capsulelike package.

Before this technology can go to market, more testing is needed, including clinical trials in humans, says Dr. Emami. That will likely take a few years.

The team also aims to make the device even smaller (it now measures about 1 cm wide and 2 cm long) and less expensive, and they want it to do more things, such as sending medicines to the GI tract. Those innovations could take a few more years.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

From heartburn to hemorrhoids and everything in between, gastrointestinal troubles affect 60 million to 70 million Americans. Part of what makes them so frustrating – besides the frequent flights to the bathroom – are the invasive and uncomfortable tests one must endure for diagnosis, such as endoscopy (feeding a flexible tube into a person’s digestive tract) or x-rays that can involve higher radiation exposure.

But a revolutionary new option promising greater comfort and convenience could become available within the next few years.

The technology is described in Nature Electronics, along with the results of in vitro and animal testing of how well it works.

“You can think of this like a GPS that you can see on your phone as your Lyft or Uber driver is moving around,” says study author Azita Emami, PhD, a professor of electrical engineering and medical engineering at the California Institute of Technology, Pasadena. “You can see the driver coming through the streets, and you can track it in real time, but imagine you can do that with much higher precision for a much smaller device inside the body.”

It’s not the first option for GI testing that can be swallowed. A “capsule endoscopy” camera can take pictures of the digestive tract. And a “wireless motility capsule” uses sensors to measure pH, temperature, and pressure. But these technologies may not work for the entire time it takes to pass through the gut, usually about 1-3 days. And while they gather information, you can’t track their location in the GI tract in real time. Your doctor can learn a lot from this level of detail.

“If a patient has motility problems in their GI tract, it can actually tell the [doctor] where the motility problem is happening, where the slowdown is happening, which is much more informative,” says Dr. Emami. Such slowdowns are common in notoriously frustrating GI issues like irritable bowel syndrome, or IBS, and inflammatory bowel disease, or IBD.

To develop this technology, the research team drew inspiration from magnetic resonance imaging, or MRI. Magnetic fields transmit data from the Bluetooth-enabled device to a smartphone. An external component, a magnetic field generator that looks like a flat mat, powers the device and is small enough to be carried in a backpack – or placed under a bed, attached to a jacket, or mounted to a toilet seat. The part that can be swallowed has tiny chips embedded in a capsulelike package.

Before this technology can go to market, more testing is needed, including clinical trials in humans, says Dr. Emami. That will likely take a few years.

The team also aims to make the device even smaller (it now measures about 1 cm wide and 2 cm long) and less expensive, and they want it to do more things, such as sending medicines to the GI tract. Those innovations could take a few more years.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM NATURE ELECTRONICS

Colorectal cancer incidence doubled in younger adults

according to a new report from the American Cancer Society.

Diagnoses in people younger than 55 years doubled from 11% (1 in 10) in 1995 to 20% (1 in 5) in 2019.

In addition, more advanced disease is being diagnosed; the proportion of individuals of all ages presenting with advanced-stage CRC increased from 52% in the mid-2000s to 60% in 2019.

“We know rates are increasing in young people, but it’s alarming to see how rapidly the whole patient population is shifting younger, despite shrinking numbers in the overall population,” said Rebecca Siegel, MPH, senior scientific director of surveillance research at the American Cancer Society and lead author of the report.

“The trend toward more advanced disease in people of all ages is also surprising and should motivate everyone 45 and older to get screened,” she added.

The report was published online in CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians.

CRC is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer and the third leading cause of cancer death of both men and women in the United States. It is estimated that there will be 153,020 new cases of CRC in the U.S. in 2023, including 106,970 tumors in the colon and 46,050 in the rectum.

Overall, in 2023, an estimated 153,020 people will be diagnosed with CRC in the U.S., and of those, 52,550 people will die from the disease.

The incidence of CRC rapidly decreased during the 2000s among people aged 50 and older, largely because of an increase in cancer screening with colonoscopy. But progress slowed during the past decade, and now the trends toward declining incidence is largely confined to those aged 65 and older.

The authors point out that more than half of all cases and deaths are associated with modifiable risk factors, including smoking, an unhealthy diet, high alcohol consumption, physical inactivity, and excess body weight. A large proportion of CRC incidence and mortality is preventable through recommended screening, surveillance, and high-quality treatment.