User login

Hospitalist Time‐Motion

The hospitalist model of care has experienced dramatic growth. In 2003 it was estimated that there were 8000 US hospitalists, a number projected to ultimately reach more than 19 000.1, 2 This rapid growth has largely been driven by improvements in clinical efficiency as a result of hospitalist programs. There is a substantial body of evidence showing that hospitalists reduce length of stay and inpatient costs.3 Despite the rapid growth and proven benefit to clinical efficiency, no studies have evaluated the type and frequency of activities that hospitalists perform during routine work. Although the use of hospitalists improves clinical efficiency for the hospital, relatively little is known about how the hospital can improve efficiency for the hospitalist.

Our institution greatly expanded our hospitalist program in June 2003 to create a resident‐uncovered hospitalist service. The impetus for this change was the need to comply with newly revised Accreditation Council for Graduate Medicine Education (ACGME) program requirements regarding resident duty hours. Many teaching hospitals have implemented similar resident‐uncovered hospitalist services.4 Inefficiencies in their work activities quickly became apparent to our hospitalists. Furthermore, our hospitalists believed that they frequently performed simultaneous activities and that they were excessively interrupted by pages.

To evaluate the type and frequency of activities that the hospitalists performed during routine work, we performed a time‐motion study of hospitalist physicians on the resident‐uncovered hospitalist service. Our goal was to identify areas for systems improvements and activities that were better suited for nonphysician providers and to quantify the time spent multitasking and the frequency of paging interruptions.

METHODS

Northwestern Memorial Hospital (NMH) is a 753‐bed hospital in Chicago, Illinois. NMH is the primary teaching hospital affiliated with the Feinberg School of Medicine of Northwestern University. There are 2 general medicine services at NMH: a traditional resident‐covered ward service and the resident‐uncovered hospitalist service. Patients are admitted to one of these 2 services on the basis of, in order of importance, capacity of the services, preference of the outpatient physician, and potential educational value of the admission. Patients admitted to the hospitalist service are preferentially given beds on specific wards intended for hospitalist service patients. Fourth‐year medical students are frequently paired with hospitalists during their medicine subinternship.

The resident‐uncovered hospitalist service comprises 5 daytime hospitalists on duty at a time. The hospitalists are on service for 7 consecutive days, usually followed by 7 consecutive days off. Hospitalists pick up new patients from the night float hospitalist each morning. Daytime admitting duties rotate on a daily basis. One hospitalist accepts new admissions each morning from 7:00 AM until noon. Two hospitalists accept admissions from noon until 5:00 PM. One hospitalist accepts admissions from 5:00 PM until 9:00 PM. One hospitalist is free from accepting new admissions each day. All daytime hospitalists begin the workday at 7:00 AM and leave when their duties are completed for the day. One night float hospitalist is on duty each night of the week. The night float hospitalist performs admissions and all cross cover activities from 7:00 PM until 7:00 AM.

We first conducted a pilot study to help identify specific activities that our hospitalists routinely perform. Broad categories and subcategories of activities were created based on the results of our pilot study, and a published time‐motion study performed on emergency medicine physicians5 (Table 1). Once activities were defined and codes established, our research assistant unobtrusively shadowed hospitalist physicians for periods lasting 3‐5 hours. The observation periods were distributed in order to sample all activities that a daytime hospitalist would perform throughout a typical week. Observation periods included 2 morning admitting periods, 4 morning nonadmitting periods, 4 afternoon admitting periods, 4 afternoon nonadmitting periods, and 2 admitting periods from 5:00 PM to 9:00 PM. Activities were recorded on a standardized data collection form in 1‐minute intervals. When multiple activities were performed at the same time, all activities were recorded in the same 1‐minute interval. Incoming pages were recorded as well. To minimize the possibility that observation would affect hospitalist behavior, the research assistant was instructed not to initiate conversation with the hospitalists.

| Direct patient care |

| Taking initial history and physical exam |

| Seeing patient in follow‐up visit |

| Going over discharge instructions |

| Family meetings |

| Indirect patient care |

| Reviewing test results and medical records |

| Documentation |

| Documenting history and physical, daily notes, filling out discharge instructions, writing out prescriptions |

| Communication |

| Taking report from night float, taking admission report, face‐to‐face discussion, initiating and returning pages |

| Orders |

| Writing/emnputting orders, calling radiology |

| Professional development |

| Going to conferences, grand rounds, etc |

| Reading articles, textbooks, online references |

| Education |

| Teaching during work rounds |

| Didactic sessions with subintern |

| Travel |

| Walking, taking elevator, etc |

| Personal |

| Lunch, washroom break, etc. |

The data collection forms were manually abstracted and minutes tallied for each category and subcategory, for which summary statistics were converted to percentage of total minutes.

RESULTS

Ten hospitalists were shadowed by a single research assistant for a total of 4467 minutes. Seven hospitalists were male and 3 were female. The hospitalists were a mean age of 31 1.6 years of age and had been practicing as a hospitalist for a mean of 2.1 1.0 years. The hospitalists saw an average of 9.4 4.0 patients on the days they were shadowed by the research assistant. Because simultaneous activities were recorded, a total of 5557 minutes of activities were recorded.

The distribution of total minutes recorded in each activity category is shown in Figure 1. Hospitalists spent 18% of their time doing direct patient care, 69% on indirect patient care, 4% on personal activities, and 3% each on professional development, education, and travel.

Of the time hospitalists directly cared for patients, 18% was spent obtaining histories and performing physical examinations on new patients, 53% seeing patients in follow‐up visits, 16% going over discharge instructions, and 13% in family meetings (Figure 2). Of the time hospitalists spent doing indirect patient care, 37% was taken up by documentation, 21% by reviewing results, 7% by orders, and 35% by communication (Figure 2).

As just explained, communication accounted for 35% of indirect patient care activities; it also accounted for 24% of the total activity minutes. The time spent by hospitalists on communication was further broken down as 23% paging other physicians, 31% returning pages, 34% in face‐to‐face communication, 5% taking report on new admissions, 4% on sign‐out to the night float hospitalist, and 3% receiving sign‐out from the night float hospitalist.

Multitasking, performing more than 1 activity at the same time, was done 21% of the time. Hospitalists received an average of 3.4 1.5 pages per hour, and 7% of total activity time was spent returning pages. Other forms of interruption were not evaluated.

DISCUSSION

Our study had several important findings. First, hospitalists spent most of their time on indirect patient care activities and relatively little time on direct patient care. Time‐motion studies of nonhospitalist physicians have reported similar findings.5, 6 A considerable amount of hospitalist time was spent on documentation. This finding also has been reported in studies of nonhospitalist physicians.5, 7

A unique finding in our study was the large amount of time, 24% of total minutes, spent on communication. A study of emergency medicine physicians by Hollingsworth found that 13% of their time was spent on communication activities.5 The large amount of time spent on communication in our study underscores the need for hospitalists to have outstanding communication skills and systems that support efficient communication. Hospitalists spent 6% of their total time paging other physicians and 7% returning pages. Improvements in the efficiency of paging communication could greatly reduce the amount of time communicating by page. Our paging system provides unidirectional alphanumeric paging. In an effort to improve the efficiency of paging, we have asked nurses and consultants to include FYI and callback in the text of the page so it is clear whether the person who has paged the hospitalist needs to be called back. This simple solution to help reduce the number of unnecessary callbacks has previously been proposed by others.8

Another part of solving this problem is adopting the use of 2‐way pagers instead of alphanumeric pagers. Two‐way paging can increase the efficiency of communication even further. For example, a nurse sends a hospitalist a page that asks if the previous diet orders for a patient just returned from a procedure can be resumed. This hospitalist is on another floor in another patient's room. Rather than spending time leaving the other patient's room, finding a phone, calling the floor, waiting for an answer, and then waiting on hold, the hospitalist simply texts a 1‐word answer, Yes, in the 2‐way paging system. In addition to the time occupied by paging activities, hospitalists spent a large amount of time in face‐to‐face communication (8% of total activity time). On the one hand, having hospitalists discuss patient care with consultants and nurses in person on an ongoing basis throughout the day may improve clinical efficiency. On the other hand, the constant potential for interruption may be problematic. Similarly, 2‐way paging could facilitate communication to such a degree that it could actually increase the frequency of interruptions. Research on improvements in communications systems, interventions to improve communication skills, and team‐based care is warranted in order to evaluate the impact on hospitalist workflow.

An important finding in our study was that multitasking and paging interruptions were common. Although this may come as no surprise to practicing hospitalists, the distraction caused by interruptions and multitasking is an important potential cause of medical errors.911 A thorough examination of the types of activities performed simultaneously and whether they contributed to medical error was beyond the scope of our study. Some activities, such as documenting a note on a patient while reviewing the patient's lab results, are concordant (ie, conducted for the same patient) and therefore may be unlikely to contribute to medical error. Other combinations of activities, such as returning a page about one patient while documenting a note on a different patient or having face‐to‐face communication about one patient while entering an order on another patient, are discordant. Discordant activities may contribute to medical error. Further research of the effect of hospitalist multitasking and interruption on medical error is warranted and should be conducted within the framework of concordant versus discordant activities.

We had hoped to find activities that could be performed by non‐physician providers. No high impact activities were discovered that would be better suited for a non‐physician provider in this study. Clerical tasks, such as calling for radiology orders or obtaining medical records, amounted to a small percentage of hospitalist time (less than 1% combined). We did identify several activities in which automation or process improvement would be helpful. Hospitalists spent 5% of time on the combined activity of documenting discharge instructions and writing out prescriptions. Our institution is in the process of implementing an electronic medical record and computerized physician order entry. We are currently working on an automated process to generate printed discharge instructions and prescriptions. This has the potential not only to improve efficiency, but also to eliminate medication errors, as care is transitioned to the outpatient setting.

Our study had several limitations. First, our findings reflect the experience at one institution. Hospitalist practices vary widely in their staffing and scheduling models as well as in their organizational support. The amount of time that hospitalists spend on activities may differ between practices and between individual hospitalists in the same practice. Another limitation to our study pertains to the workflow of our hospitalists and the locations of their patients. As discussed earlier, patients were assigned to a hospitalist according to time of admission, not location of admission. Because of this, the hospitalists were caring for patients on as many as 5 wards. Although travel time amounted to only 3% of total minutes, it is possible that communication time could have been reduced if patients were distributed to hospitalists on the basis of patient location rather than time of admission of patient. For example, physicians and nurses might spend less time communicating in person compared to communicating via unidirectional paging, which frequently requires waiting for a callback. Finally, our study only observed activities performed by the daytime hospitalists at our hospital. The distribution and types of activities performed by nighttime hospitalists may be somewhat different.

Our study may serve as a model for hospitalist time‐motion studies in other settings. Our findings are of particular importance to resident‐uncovered hospitalist programs in academic hospitals, a setting in which operational inefficiencies may be abundant as house staff members have been poorly positioned in the hospital organization to lobby for process change. We hope that our study is a precursor to research evaluating modifications to the environments and systems in which hospitalists work. Such modifications have the potential to improve productivity and work conditions and promote career satisfaction.

Acknowledgements

We thank Patricia Georgas for shadowing the hospitalists and collecting the data in this study.

- Society of Hospital Medicine. Available at http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=FAQs106:441–445.

- ,.The hospitalist movement 5 years later.JAMA.2002;287:487–494.

- ,.Hospitalists in teaching hospitals: opportunities but not without danger.J Gen Intern Med.2004;4:392–393.

- ,,,,.How do physicians and nurses spend their time in the Emergency Department?Ann Emerg Med.1998;31:97–91.

- ,,,,.A time‐motion study of the activities of attending physicians in an Internal Medicine and Internal Medicine‐Pediatrics resident continuity clinic.Acad Med.2000;75:1138–1143.

- ,,,.Work interrupted: a comparison of workplace interruptions in emergency departments and primary care offices.Ann Emerg Med.2001;38:146–151.

- ,.Residents' suggestions for reducing errors in teaching hospitals.N Engl J Med.2003;348:851–855.

- ,,,.Emergency department workplace interruptions: are emergency physicians “interrupt‐driven” and “multitasking”?Acad Emerg Med.2000;7:1239–243.

- ,,.Understanding medical error and improving patient safety in the inpatient setting.Med Clin N Am.2002;86:847–867.

- ,,,.Sharps‐related injuries in health care workers: a case‐crossover study.Am J Med.2003;114:687–694.

The hospitalist model of care has experienced dramatic growth. In 2003 it was estimated that there were 8000 US hospitalists, a number projected to ultimately reach more than 19 000.1, 2 This rapid growth has largely been driven by improvements in clinical efficiency as a result of hospitalist programs. There is a substantial body of evidence showing that hospitalists reduce length of stay and inpatient costs.3 Despite the rapid growth and proven benefit to clinical efficiency, no studies have evaluated the type and frequency of activities that hospitalists perform during routine work. Although the use of hospitalists improves clinical efficiency for the hospital, relatively little is known about how the hospital can improve efficiency for the hospitalist.

Our institution greatly expanded our hospitalist program in June 2003 to create a resident‐uncovered hospitalist service. The impetus for this change was the need to comply with newly revised Accreditation Council for Graduate Medicine Education (ACGME) program requirements regarding resident duty hours. Many teaching hospitals have implemented similar resident‐uncovered hospitalist services.4 Inefficiencies in their work activities quickly became apparent to our hospitalists. Furthermore, our hospitalists believed that they frequently performed simultaneous activities and that they were excessively interrupted by pages.

To evaluate the type and frequency of activities that the hospitalists performed during routine work, we performed a time‐motion study of hospitalist physicians on the resident‐uncovered hospitalist service. Our goal was to identify areas for systems improvements and activities that were better suited for nonphysician providers and to quantify the time spent multitasking and the frequency of paging interruptions.

METHODS

Northwestern Memorial Hospital (NMH) is a 753‐bed hospital in Chicago, Illinois. NMH is the primary teaching hospital affiliated with the Feinberg School of Medicine of Northwestern University. There are 2 general medicine services at NMH: a traditional resident‐covered ward service and the resident‐uncovered hospitalist service. Patients are admitted to one of these 2 services on the basis of, in order of importance, capacity of the services, preference of the outpatient physician, and potential educational value of the admission. Patients admitted to the hospitalist service are preferentially given beds on specific wards intended for hospitalist service patients. Fourth‐year medical students are frequently paired with hospitalists during their medicine subinternship.

The resident‐uncovered hospitalist service comprises 5 daytime hospitalists on duty at a time. The hospitalists are on service for 7 consecutive days, usually followed by 7 consecutive days off. Hospitalists pick up new patients from the night float hospitalist each morning. Daytime admitting duties rotate on a daily basis. One hospitalist accepts new admissions each morning from 7:00 AM until noon. Two hospitalists accept admissions from noon until 5:00 PM. One hospitalist accepts admissions from 5:00 PM until 9:00 PM. One hospitalist is free from accepting new admissions each day. All daytime hospitalists begin the workday at 7:00 AM and leave when their duties are completed for the day. One night float hospitalist is on duty each night of the week. The night float hospitalist performs admissions and all cross cover activities from 7:00 PM until 7:00 AM.

We first conducted a pilot study to help identify specific activities that our hospitalists routinely perform. Broad categories and subcategories of activities were created based on the results of our pilot study, and a published time‐motion study performed on emergency medicine physicians5 (Table 1). Once activities were defined and codes established, our research assistant unobtrusively shadowed hospitalist physicians for periods lasting 3‐5 hours. The observation periods were distributed in order to sample all activities that a daytime hospitalist would perform throughout a typical week. Observation periods included 2 morning admitting periods, 4 morning nonadmitting periods, 4 afternoon admitting periods, 4 afternoon nonadmitting periods, and 2 admitting periods from 5:00 PM to 9:00 PM. Activities were recorded on a standardized data collection form in 1‐minute intervals. When multiple activities were performed at the same time, all activities were recorded in the same 1‐minute interval. Incoming pages were recorded as well. To minimize the possibility that observation would affect hospitalist behavior, the research assistant was instructed not to initiate conversation with the hospitalists.

| Direct patient care |

| Taking initial history and physical exam |

| Seeing patient in follow‐up visit |

| Going over discharge instructions |

| Family meetings |

| Indirect patient care |

| Reviewing test results and medical records |

| Documentation |

| Documenting history and physical, daily notes, filling out discharge instructions, writing out prescriptions |

| Communication |

| Taking report from night float, taking admission report, face‐to‐face discussion, initiating and returning pages |

| Orders |

| Writing/emnputting orders, calling radiology |

| Professional development |

| Going to conferences, grand rounds, etc |

| Reading articles, textbooks, online references |

| Education |

| Teaching during work rounds |

| Didactic sessions with subintern |

| Travel |

| Walking, taking elevator, etc |

| Personal |

| Lunch, washroom break, etc. |

The data collection forms were manually abstracted and minutes tallied for each category and subcategory, for which summary statistics were converted to percentage of total minutes.

RESULTS

Ten hospitalists were shadowed by a single research assistant for a total of 4467 minutes. Seven hospitalists were male and 3 were female. The hospitalists were a mean age of 31 1.6 years of age and had been practicing as a hospitalist for a mean of 2.1 1.0 years. The hospitalists saw an average of 9.4 4.0 patients on the days they were shadowed by the research assistant. Because simultaneous activities were recorded, a total of 5557 minutes of activities were recorded.

The distribution of total minutes recorded in each activity category is shown in Figure 1. Hospitalists spent 18% of their time doing direct patient care, 69% on indirect patient care, 4% on personal activities, and 3% each on professional development, education, and travel.

Of the time hospitalists directly cared for patients, 18% was spent obtaining histories and performing physical examinations on new patients, 53% seeing patients in follow‐up visits, 16% going over discharge instructions, and 13% in family meetings (Figure 2). Of the time hospitalists spent doing indirect patient care, 37% was taken up by documentation, 21% by reviewing results, 7% by orders, and 35% by communication (Figure 2).

As just explained, communication accounted for 35% of indirect patient care activities; it also accounted for 24% of the total activity minutes. The time spent by hospitalists on communication was further broken down as 23% paging other physicians, 31% returning pages, 34% in face‐to‐face communication, 5% taking report on new admissions, 4% on sign‐out to the night float hospitalist, and 3% receiving sign‐out from the night float hospitalist.

Multitasking, performing more than 1 activity at the same time, was done 21% of the time. Hospitalists received an average of 3.4 1.5 pages per hour, and 7% of total activity time was spent returning pages. Other forms of interruption were not evaluated.

DISCUSSION

Our study had several important findings. First, hospitalists spent most of their time on indirect patient care activities and relatively little time on direct patient care. Time‐motion studies of nonhospitalist physicians have reported similar findings.5, 6 A considerable amount of hospitalist time was spent on documentation. This finding also has been reported in studies of nonhospitalist physicians.5, 7

A unique finding in our study was the large amount of time, 24% of total minutes, spent on communication. A study of emergency medicine physicians by Hollingsworth found that 13% of their time was spent on communication activities.5 The large amount of time spent on communication in our study underscores the need for hospitalists to have outstanding communication skills and systems that support efficient communication. Hospitalists spent 6% of their total time paging other physicians and 7% returning pages. Improvements in the efficiency of paging communication could greatly reduce the amount of time communicating by page. Our paging system provides unidirectional alphanumeric paging. In an effort to improve the efficiency of paging, we have asked nurses and consultants to include FYI and callback in the text of the page so it is clear whether the person who has paged the hospitalist needs to be called back. This simple solution to help reduce the number of unnecessary callbacks has previously been proposed by others.8

Another part of solving this problem is adopting the use of 2‐way pagers instead of alphanumeric pagers. Two‐way paging can increase the efficiency of communication even further. For example, a nurse sends a hospitalist a page that asks if the previous diet orders for a patient just returned from a procedure can be resumed. This hospitalist is on another floor in another patient's room. Rather than spending time leaving the other patient's room, finding a phone, calling the floor, waiting for an answer, and then waiting on hold, the hospitalist simply texts a 1‐word answer, Yes, in the 2‐way paging system. In addition to the time occupied by paging activities, hospitalists spent a large amount of time in face‐to‐face communication (8% of total activity time). On the one hand, having hospitalists discuss patient care with consultants and nurses in person on an ongoing basis throughout the day may improve clinical efficiency. On the other hand, the constant potential for interruption may be problematic. Similarly, 2‐way paging could facilitate communication to such a degree that it could actually increase the frequency of interruptions. Research on improvements in communications systems, interventions to improve communication skills, and team‐based care is warranted in order to evaluate the impact on hospitalist workflow.

An important finding in our study was that multitasking and paging interruptions were common. Although this may come as no surprise to practicing hospitalists, the distraction caused by interruptions and multitasking is an important potential cause of medical errors.911 A thorough examination of the types of activities performed simultaneously and whether they contributed to medical error was beyond the scope of our study. Some activities, such as documenting a note on a patient while reviewing the patient's lab results, are concordant (ie, conducted for the same patient) and therefore may be unlikely to contribute to medical error. Other combinations of activities, such as returning a page about one patient while documenting a note on a different patient or having face‐to‐face communication about one patient while entering an order on another patient, are discordant. Discordant activities may contribute to medical error. Further research of the effect of hospitalist multitasking and interruption on medical error is warranted and should be conducted within the framework of concordant versus discordant activities.

We had hoped to find activities that could be performed by non‐physician providers. No high impact activities were discovered that would be better suited for a non‐physician provider in this study. Clerical tasks, such as calling for radiology orders or obtaining medical records, amounted to a small percentage of hospitalist time (less than 1% combined). We did identify several activities in which automation or process improvement would be helpful. Hospitalists spent 5% of time on the combined activity of documenting discharge instructions and writing out prescriptions. Our institution is in the process of implementing an electronic medical record and computerized physician order entry. We are currently working on an automated process to generate printed discharge instructions and prescriptions. This has the potential not only to improve efficiency, but also to eliminate medication errors, as care is transitioned to the outpatient setting.

Our study had several limitations. First, our findings reflect the experience at one institution. Hospitalist practices vary widely in their staffing and scheduling models as well as in their organizational support. The amount of time that hospitalists spend on activities may differ between practices and between individual hospitalists in the same practice. Another limitation to our study pertains to the workflow of our hospitalists and the locations of their patients. As discussed earlier, patients were assigned to a hospitalist according to time of admission, not location of admission. Because of this, the hospitalists were caring for patients on as many as 5 wards. Although travel time amounted to only 3% of total minutes, it is possible that communication time could have been reduced if patients were distributed to hospitalists on the basis of patient location rather than time of admission of patient. For example, physicians and nurses might spend less time communicating in person compared to communicating via unidirectional paging, which frequently requires waiting for a callback. Finally, our study only observed activities performed by the daytime hospitalists at our hospital. The distribution and types of activities performed by nighttime hospitalists may be somewhat different.

Our study may serve as a model for hospitalist time‐motion studies in other settings. Our findings are of particular importance to resident‐uncovered hospitalist programs in academic hospitals, a setting in which operational inefficiencies may be abundant as house staff members have been poorly positioned in the hospital organization to lobby for process change. We hope that our study is a precursor to research evaluating modifications to the environments and systems in which hospitalists work. Such modifications have the potential to improve productivity and work conditions and promote career satisfaction.

Acknowledgements

We thank Patricia Georgas for shadowing the hospitalists and collecting the data in this study.

The hospitalist model of care has experienced dramatic growth. In 2003 it was estimated that there were 8000 US hospitalists, a number projected to ultimately reach more than 19 000.1, 2 This rapid growth has largely been driven by improvements in clinical efficiency as a result of hospitalist programs. There is a substantial body of evidence showing that hospitalists reduce length of stay and inpatient costs.3 Despite the rapid growth and proven benefit to clinical efficiency, no studies have evaluated the type and frequency of activities that hospitalists perform during routine work. Although the use of hospitalists improves clinical efficiency for the hospital, relatively little is known about how the hospital can improve efficiency for the hospitalist.

Our institution greatly expanded our hospitalist program in June 2003 to create a resident‐uncovered hospitalist service. The impetus for this change was the need to comply with newly revised Accreditation Council for Graduate Medicine Education (ACGME) program requirements regarding resident duty hours. Many teaching hospitals have implemented similar resident‐uncovered hospitalist services.4 Inefficiencies in their work activities quickly became apparent to our hospitalists. Furthermore, our hospitalists believed that they frequently performed simultaneous activities and that they were excessively interrupted by pages.

To evaluate the type and frequency of activities that the hospitalists performed during routine work, we performed a time‐motion study of hospitalist physicians on the resident‐uncovered hospitalist service. Our goal was to identify areas for systems improvements and activities that were better suited for nonphysician providers and to quantify the time spent multitasking and the frequency of paging interruptions.

METHODS

Northwestern Memorial Hospital (NMH) is a 753‐bed hospital in Chicago, Illinois. NMH is the primary teaching hospital affiliated with the Feinberg School of Medicine of Northwestern University. There are 2 general medicine services at NMH: a traditional resident‐covered ward service and the resident‐uncovered hospitalist service. Patients are admitted to one of these 2 services on the basis of, in order of importance, capacity of the services, preference of the outpatient physician, and potential educational value of the admission. Patients admitted to the hospitalist service are preferentially given beds on specific wards intended for hospitalist service patients. Fourth‐year medical students are frequently paired with hospitalists during their medicine subinternship.

The resident‐uncovered hospitalist service comprises 5 daytime hospitalists on duty at a time. The hospitalists are on service for 7 consecutive days, usually followed by 7 consecutive days off. Hospitalists pick up new patients from the night float hospitalist each morning. Daytime admitting duties rotate on a daily basis. One hospitalist accepts new admissions each morning from 7:00 AM until noon. Two hospitalists accept admissions from noon until 5:00 PM. One hospitalist accepts admissions from 5:00 PM until 9:00 PM. One hospitalist is free from accepting new admissions each day. All daytime hospitalists begin the workday at 7:00 AM and leave when their duties are completed for the day. One night float hospitalist is on duty each night of the week. The night float hospitalist performs admissions and all cross cover activities from 7:00 PM until 7:00 AM.

We first conducted a pilot study to help identify specific activities that our hospitalists routinely perform. Broad categories and subcategories of activities were created based on the results of our pilot study, and a published time‐motion study performed on emergency medicine physicians5 (Table 1). Once activities were defined and codes established, our research assistant unobtrusively shadowed hospitalist physicians for periods lasting 3‐5 hours. The observation periods were distributed in order to sample all activities that a daytime hospitalist would perform throughout a typical week. Observation periods included 2 morning admitting periods, 4 morning nonadmitting periods, 4 afternoon admitting periods, 4 afternoon nonadmitting periods, and 2 admitting periods from 5:00 PM to 9:00 PM. Activities were recorded on a standardized data collection form in 1‐minute intervals. When multiple activities were performed at the same time, all activities were recorded in the same 1‐minute interval. Incoming pages were recorded as well. To minimize the possibility that observation would affect hospitalist behavior, the research assistant was instructed not to initiate conversation with the hospitalists.

| Direct patient care |

| Taking initial history and physical exam |

| Seeing patient in follow‐up visit |

| Going over discharge instructions |

| Family meetings |

| Indirect patient care |

| Reviewing test results and medical records |

| Documentation |

| Documenting history and physical, daily notes, filling out discharge instructions, writing out prescriptions |

| Communication |

| Taking report from night float, taking admission report, face‐to‐face discussion, initiating and returning pages |

| Orders |

| Writing/emnputting orders, calling radiology |

| Professional development |

| Going to conferences, grand rounds, etc |

| Reading articles, textbooks, online references |

| Education |

| Teaching during work rounds |

| Didactic sessions with subintern |

| Travel |

| Walking, taking elevator, etc |

| Personal |

| Lunch, washroom break, etc. |

The data collection forms were manually abstracted and minutes tallied for each category and subcategory, for which summary statistics were converted to percentage of total minutes.

RESULTS

Ten hospitalists were shadowed by a single research assistant for a total of 4467 minutes. Seven hospitalists were male and 3 were female. The hospitalists were a mean age of 31 1.6 years of age and had been practicing as a hospitalist for a mean of 2.1 1.0 years. The hospitalists saw an average of 9.4 4.0 patients on the days they were shadowed by the research assistant. Because simultaneous activities were recorded, a total of 5557 minutes of activities were recorded.

The distribution of total minutes recorded in each activity category is shown in Figure 1. Hospitalists spent 18% of their time doing direct patient care, 69% on indirect patient care, 4% on personal activities, and 3% each on professional development, education, and travel.

Of the time hospitalists directly cared for patients, 18% was spent obtaining histories and performing physical examinations on new patients, 53% seeing patients in follow‐up visits, 16% going over discharge instructions, and 13% in family meetings (Figure 2). Of the time hospitalists spent doing indirect patient care, 37% was taken up by documentation, 21% by reviewing results, 7% by orders, and 35% by communication (Figure 2).

As just explained, communication accounted for 35% of indirect patient care activities; it also accounted for 24% of the total activity minutes. The time spent by hospitalists on communication was further broken down as 23% paging other physicians, 31% returning pages, 34% in face‐to‐face communication, 5% taking report on new admissions, 4% on sign‐out to the night float hospitalist, and 3% receiving sign‐out from the night float hospitalist.

Multitasking, performing more than 1 activity at the same time, was done 21% of the time. Hospitalists received an average of 3.4 1.5 pages per hour, and 7% of total activity time was spent returning pages. Other forms of interruption were not evaluated.

DISCUSSION

Our study had several important findings. First, hospitalists spent most of their time on indirect patient care activities and relatively little time on direct patient care. Time‐motion studies of nonhospitalist physicians have reported similar findings.5, 6 A considerable amount of hospitalist time was spent on documentation. This finding also has been reported in studies of nonhospitalist physicians.5, 7

A unique finding in our study was the large amount of time, 24% of total minutes, spent on communication. A study of emergency medicine physicians by Hollingsworth found that 13% of their time was spent on communication activities.5 The large amount of time spent on communication in our study underscores the need for hospitalists to have outstanding communication skills and systems that support efficient communication. Hospitalists spent 6% of their total time paging other physicians and 7% returning pages. Improvements in the efficiency of paging communication could greatly reduce the amount of time communicating by page. Our paging system provides unidirectional alphanumeric paging. In an effort to improve the efficiency of paging, we have asked nurses and consultants to include FYI and callback in the text of the page so it is clear whether the person who has paged the hospitalist needs to be called back. This simple solution to help reduce the number of unnecessary callbacks has previously been proposed by others.8

Another part of solving this problem is adopting the use of 2‐way pagers instead of alphanumeric pagers. Two‐way paging can increase the efficiency of communication even further. For example, a nurse sends a hospitalist a page that asks if the previous diet orders for a patient just returned from a procedure can be resumed. This hospitalist is on another floor in another patient's room. Rather than spending time leaving the other patient's room, finding a phone, calling the floor, waiting for an answer, and then waiting on hold, the hospitalist simply texts a 1‐word answer, Yes, in the 2‐way paging system. In addition to the time occupied by paging activities, hospitalists spent a large amount of time in face‐to‐face communication (8% of total activity time). On the one hand, having hospitalists discuss patient care with consultants and nurses in person on an ongoing basis throughout the day may improve clinical efficiency. On the other hand, the constant potential for interruption may be problematic. Similarly, 2‐way paging could facilitate communication to such a degree that it could actually increase the frequency of interruptions. Research on improvements in communications systems, interventions to improve communication skills, and team‐based care is warranted in order to evaluate the impact on hospitalist workflow.

An important finding in our study was that multitasking and paging interruptions were common. Although this may come as no surprise to practicing hospitalists, the distraction caused by interruptions and multitasking is an important potential cause of medical errors.911 A thorough examination of the types of activities performed simultaneously and whether they contributed to medical error was beyond the scope of our study. Some activities, such as documenting a note on a patient while reviewing the patient's lab results, are concordant (ie, conducted for the same patient) and therefore may be unlikely to contribute to medical error. Other combinations of activities, such as returning a page about one patient while documenting a note on a different patient or having face‐to‐face communication about one patient while entering an order on another patient, are discordant. Discordant activities may contribute to medical error. Further research of the effect of hospitalist multitasking and interruption on medical error is warranted and should be conducted within the framework of concordant versus discordant activities.

We had hoped to find activities that could be performed by non‐physician providers. No high impact activities were discovered that would be better suited for a non‐physician provider in this study. Clerical tasks, such as calling for radiology orders or obtaining medical records, amounted to a small percentage of hospitalist time (less than 1% combined). We did identify several activities in which automation or process improvement would be helpful. Hospitalists spent 5% of time on the combined activity of documenting discharge instructions and writing out prescriptions. Our institution is in the process of implementing an electronic medical record and computerized physician order entry. We are currently working on an automated process to generate printed discharge instructions and prescriptions. This has the potential not only to improve efficiency, but also to eliminate medication errors, as care is transitioned to the outpatient setting.

Our study had several limitations. First, our findings reflect the experience at one institution. Hospitalist practices vary widely in their staffing and scheduling models as well as in their organizational support. The amount of time that hospitalists spend on activities may differ between practices and between individual hospitalists in the same practice. Another limitation to our study pertains to the workflow of our hospitalists and the locations of their patients. As discussed earlier, patients were assigned to a hospitalist according to time of admission, not location of admission. Because of this, the hospitalists were caring for patients on as many as 5 wards. Although travel time amounted to only 3% of total minutes, it is possible that communication time could have been reduced if patients were distributed to hospitalists on the basis of patient location rather than time of admission of patient. For example, physicians and nurses might spend less time communicating in person compared to communicating via unidirectional paging, which frequently requires waiting for a callback. Finally, our study only observed activities performed by the daytime hospitalists at our hospital. The distribution and types of activities performed by nighttime hospitalists may be somewhat different.

Our study may serve as a model for hospitalist time‐motion studies in other settings. Our findings are of particular importance to resident‐uncovered hospitalist programs in academic hospitals, a setting in which operational inefficiencies may be abundant as house staff members have been poorly positioned in the hospital organization to lobby for process change. We hope that our study is a precursor to research evaluating modifications to the environments and systems in which hospitalists work. Such modifications have the potential to improve productivity and work conditions and promote career satisfaction.

Acknowledgements

We thank Patricia Georgas for shadowing the hospitalists and collecting the data in this study.

- Society of Hospital Medicine. Available at http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=FAQs106:441–445.

- ,.The hospitalist movement 5 years later.JAMA.2002;287:487–494.

- ,.Hospitalists in teaching hospitals: opportunities but not without danger.J Gen Intern Med.2004;4:392–393.

- ,,,,.How do physicians and nurses spend their time in the Emergency Department?Ann Emerg Med.1998;31:97–91.

- ,,,,.A time‐motion study of the activities of attending physicians in an Internal Medicine and Internal Medicine‐Pediatrics resident continuity clinic.Acad Med.2000;75:1138–1143.

- ,,,.Work interrupted: a comparison of workplace interruptions in emergency departments and primary care offices.Ann Emerg Med.2001;38:146–151.

- ,.Residents' suggestions for reducing errors in teaching hospitals.N Engl J Med.2003;348:851–855.

- ,,,.Emergency department workplace interruptions: are emergency physicians “interrupt‐driven” and “multitasking”?Acad Emerg Med.2000;7:1239–243.

- ,,.Understanding medical error and improving patient safety in the inpatient setting.Med Clin N Am.2002;86:847–867.

- ,,,.Sharps‐related injuries in health care workers: a case‐crossover study.Am J Med.2003;114:687–694.

- Society of Hospital Medicine. Available at http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=FAQs106:441–445.

- ,.The hospitalist movement 5 years later.JAMA.2002;287:487–494.

- ,.Hospitalists in teaching hospitals: opportunities but not without danger.J Gen Intern Med.2004;4:392–393.

- ,,,,.How do physicians and nurses spend their time in the Emergency Department?Ann Emerg Med.1998;31:97–91.

- ,,,,.A time‐motion study of the activities of attending physicians in an Internal Medicine and Internal Medicine‐Pediatrics resident continuity clinic.Acad Med.2000;75:1138–1143.

- ,,,.Work interrupted: a comparison of workplace interruptions in emergency departments and primary care offices.Ann Emerg Med.2001;38:146–151.

- ,.Residents' suggestions for reducing errors in teaching hospitals.N Engl J Med.2003;348:851–855.

- ,,,.Emergency department workplace interruptions: are emergency physicians “interrupt‐driven” and “multitasking”?Acad Emerg Med.2000;7:1239–243.

- ,,.Understanding medical error and improving patient safety in the inpatient setting.Med Clin N Am.2002;86:847–867.

- ,,,.Sharps‐related injuries in health care workers: a case‐crossover study.Am J Med.2003;114:687–694.

Copyright © 2006 Society of Hospital Medicine

Acute Aortic Dissection

Aortic dissection is an uncommon but highly lethal disease with an incidence of approximately 2,000 cases per year in the United States.1 It is often mistaken for less serious pathology. In one series, aortic dissection was missed in 38% of patients at presentation, with 28% of patients first diagnosed at autopsy.2 Early recognition and management are crucial. If untreated, the mortality rate for acute aortic dissection increases by approximately 1% per hour over the first 48 hours and may reach 70% at 1 week. As many as 90% of untreated patients who suffer aortic dissection die within 3 months of presentation.3, 4 Generally, cardiothoracic surgeons or cardiologists experienced with managing aortic dissection should direct patient evaluation and treatment. Hospitalists, however, are increasingly assuming responsibility for the initial triage and management of patients with acute chest pain syndromes and therefore must be able to rapidly identify aortic dissection, initiate supportive therapy, and refer patients to appropriate specialty care.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Aortic dissection occurs when layers of the aortic wall separate because of infiltration of high‐pressure arterial blood. The proximate causes are elevated shear stress across the aortic lumen in the setting of a concomitant defect in the aortic media. Shear stress is caused by the rapid increase in luminal pressure per unit of time (dP/dt) that results from cardiac systole. As the aorta traverses away from the heart, an increasing proportion of the kinetic energy of left ventricular systole is stored in the aortic wall as potential energy, which facilitates anterograde propagation of cardiac output during diastole. This conversion of kinetic to potential energy also attenuates shear stress. As the proximal aorta is subject to the steepest fluctuations in pressure, it is at the highest risk of dissection. Degeneration of the aortic media is part of the normal aging process but is accelerated in persons with a bicuspid aortic valve, Turner's syndrome, inflammatory arteritis, or inherited diseases of collagen formation.

Once the aortic intima is compromised, blood dissects longitudinally through the aortic media and propagates proximally or distally, creating a false lumen that may communicate with the true lumen of the aorta. Blood may flow through the true lumen, the false lumen, or both. Propagation of the dissection causes much of the morbidity associated with aortic dissection by disrupting blood flow across branch vessels or by directly compromising the pericardium or aortic valve. Over time, the dissection may traverse the entire aortic wall, causing aortic rupture and exsanguination.

CLASSIFICATION

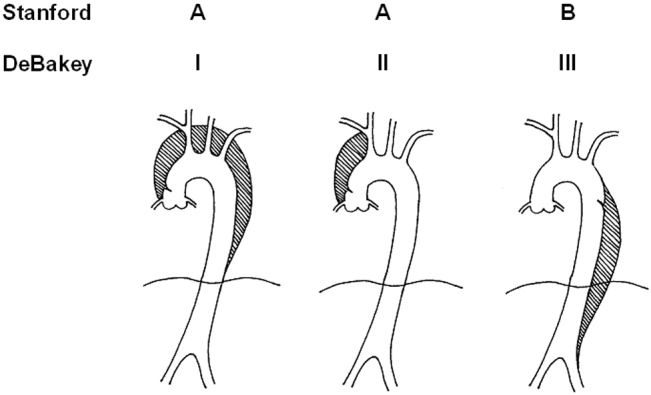

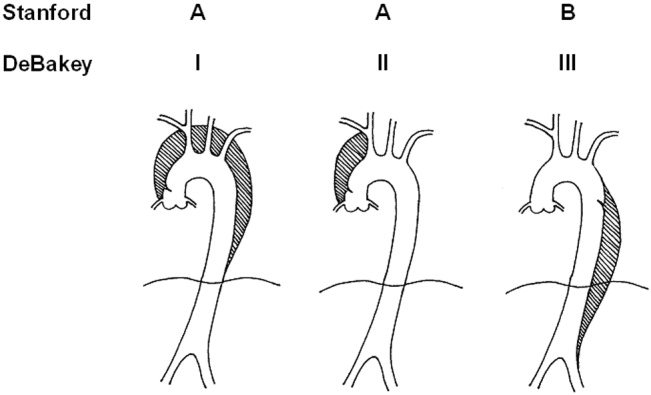

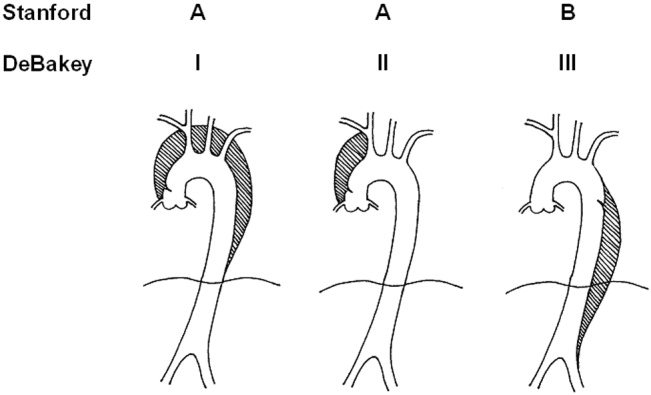

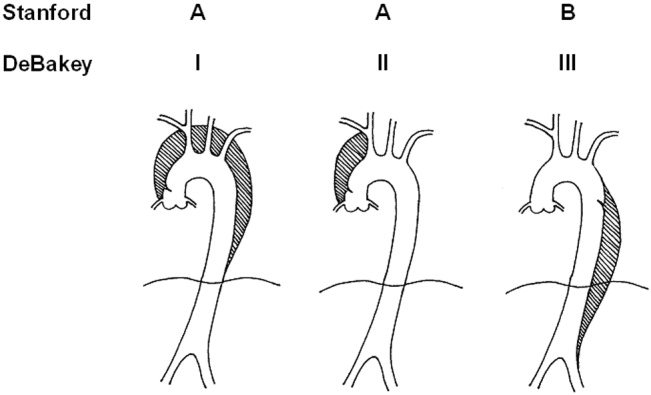

Acute aortic dissection is classified as any aortic dissection diagnosed within 2 weeks of the onset of symptoms, which is the period of highest risk of mortality. Patients who survive more than 2 weeks without treatment are considered to have chronic dissection. Aortic dissections are further classified according to their anatomic location. The fundamental distinction is whether the dissection is proximal (involving the aortic root or ascending aorta) or distal (below the left subclavian artery). The Stanford and DeBakey classification systems are the classification systems most commonly used (Figure 1).

Some variants of aortic dissection are not described in either the Stanford or DeBakey systems. Aortic intramural hematomas (IMH) are caused by intramural hemorrhage of the vasa vasorum without an identifiable intimal tear.57 Penetrating atherosclerotic ulcers (PAUs) are focal defects in the aortic wall with surrounding hematoma but no longitudinal dissection across tissue planes, typically resulting from advanced atherosclerotic disease.8 The pathophysiologic distinctions between IMH, PAU, and classic aortic dissection remain somewhat controversial. Both IMH and PAU may progress to aortic aneurysm formation, frank dissection, or aortic rupture, suggesting that these entities represent a spectrum of diseases with broad overlap (Table 1).9, 10

| Acuity | |

| Acute 2 weeks after onset | |

| Chronic: >2 weeks after onset | |

| Anatomic location: | |

| Ascending aorta: | Stanford Type A, Debakey Type II |

| Ascending and descending aorta: | Stanford Type A, Debakey Type I |

| Descending aorta: | Stanford Type B, Debakey Type III |

| Pathophysiology: | |

| Class 1: Classical aortic dissection with initimal flap between true and false lumen | |

| Class 2: Aortic intramural hematoma without identifiable intimal flap | |

| Class 3: Intimal tear without hematoma (limited dissection) | |

| Class 4: Atherosclerotic plaque rupture with aortic penetrating ulcer | |

| Class 5: Iatrogenic or traumatic aortic dissection (intra‐aortic catherterization, high‐speed deceleration injury, blunt chest trauma) | |

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Aortic dissection is a rare disease, with an estimated incidence of approximately 5‐30 cases per 1 million people per year.1114 Fewer than 0.5% of patients presenting to an emergency department with chest or back pain suffer from aortic dissection.15 Two thirds of patients are male, with an average age at presentation of approximately 65 years. A history of systemic hypertension, found in up to 72% of patients, is by far the most common risk factor.2, 14, 16 Atherosclerosis, a history of prior cardiac surgery, and known aortic aneurysm are other major risk factors.14 The epidemiology of aortic dissection is substantially different in young patients (40 years of age). Hypertension and atherosclerosis become significantly less common, as other risk factors, such as Marfan syndrome, take precedence17 (Table 2). Other risk factors for aortic dissection include:

-

Collagen diseases (eg, Marfan syndrome and Ehlers‐Danlos): In the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD), the largest prospective analysis of aortic dissection to date, 50% of the young patients presenting with aortic dissection had Marfan syndrome.17

-

Bicuspid aortic valve (BAV): Individuals with BAV are 5‐18 times more likely to suffer aortic dissection than those with a trileaflet valve.18, 19 In one survey, 52% of asymptomatic young men with BAV were found to have aortic root dilatation, a frequent precursor of dissection.20 Vascular tissue in individuals with BAV has been found to have increased levels of matrix metalloproteinases, which may degrade elastic matrix components and accelerate medial necrosis.21

-

Aortic coarctation: Aortic coarctation is associated with upper extremity hypertension, BAV and aortic dilatation, all of which predispose to aortic dissection.

-

Turner syndrome: Aortic root dilatation with or without dissection has been incidentally noted in 6%‐9% of patients with Turner syndrome.22, 23

-

Strenuous exercise: Multiple case reports have associated aortic dissection with high‐intensity weightlifting. Many affected individuals were subsequently found to have at least one other risk factor, including hypertension, anabolic steroid abuse, and cocaine abuse.2426

-

Large vessel arteritis: Large vessel arteritides, specifically giant cell arteritis, Takayasu's disease, and tertiary syphilis have long been associated with aortic dilatation and dissection.

-

Cocaine and methamphetamine ingestion: Sympathomimetic drugs cause rapid increases in heart rate and blood pressure, markedly increasing aortic intraluminal shear stress. Furthermore, cocaine is thought to be directly toxic to vascular endothelium and may accelerate medial necrosis.2730

-

Third trimester pregnancy, especially in patients with diseases of collagen31; The significance of pregnancy has recently been called into question by data from the IRAD trial. Of 346 enrolled women with aortic dissection, only 2 were pregnant, suggesting that the previously held association of pregnancy with aortic dissection may be an artifact of selective reporting.1

-

Blunt chest trauma or high‐speed deceleration injury.

-

Iatrogenic injury, typically from intra‐aortic catheterization.

| Hypertension |

| Atherosclerotic disease |

| History of cardiac surgery |

| Aortic aneurysm |

| Collagen diseases (eg, Marfan syndrome and Ehlers‐Danlos) |

| Bicuspid aortic valve (BAV) |

| Aortic coarctation |

| Turner syndrome |

| Strenuous exercise |

| Large vessel arteritis: giant cell, Takayasu's, syphilis |

| Cocaine and methamphetamine ingestion |

| Third‐trimester pregnancy |

| Blunt chest trauma or high‐speed deceleration injury |

| Iatrogenic injury, typically from intra‐aortic catheterization |

INITIAL EVALUATION

The differential diagnosis for acute aortic dissection includes acute coronary syndrome, pulmonary embolus, pneumothorax, pneumonia, musculoskeletal pain, acute cholecystitis, esophageal spasm or rupture, acute pancreatitis, and acute pericarditis. Acute aortic dissections are rarely asymptomatic; in fact, the absence of sudden‐onset chest pain decreases the likelihood of dissection (negative LR 0.3).32 In the IRAD trial, approximately 95% of patients with aortic dissection complained of pain in the chest, back, or abdomen, with 90% characterizing their pain as either severe or the worst ever and 64% describing it as sharp.14 Although the presence of tearing or ripping chest or back pain suggests aortic dissection (positive LR 1.2‐10.8), its absence does not reliably exclude this diagnosis.32 The wide variability in the presentation of aortic dissection increases the challenge of establishing a diagnosis. Clinical findings depend largely on the anatomical location of the dissection and may include pulse deficits, neurologic deficits, hypotension, hypertension, and end‐organ ischemia. Women who develop aortic dissection are generally older and present later than men. Their symptoms are less typical and are likely to be confounded by altered mental status.1 A diagnosis of aortic dissection should be strongly considered for patients presenting with acute chest or back pain and otherwise unexplained aortic insufficiency, focal neurologic deficits, pulse deficits, or end‐organ injury (Table 3).

| Hypotension or shock due to: |

| a. Hemopericardium and pericardial tamponade |

| b. Acute aortic insufficiency due to dilatation of the aortic annulus |

| c. Aortic rupture |

| d. Lactic acidosis |

| e. Spinal shock |

| Acute myocardial ischemia/emnfarction due to coronary ostial occlusion |

| Pericardial friction rub due to hemopericardium |

| Syncope |

| Pleural effusion or frank hemothorax |

| Acute renal failure due to dissection across renal arteries |

| Mesenteric ischemia due to dissection across intra‐abdominal arteries |

| Neurologic deficits: |

| a. Stroke due to occlusion of arch vessels |

| b. Limb weakness |

| c. Spinal cord deficits due to cord ischemia |

| d. Horner syndrome due to compression of superior sympathetic ganglion. |

| e. Hoarseness due to compression of left recurrent laryngeal nerve |

Electrocardiogram: Electrocardiographic abnormalities are commonly seen in aortic dissection and may include ST‐segment or T‐wave abnormalities or left ventricular hypertrophy.14 Proximal aortic dissections may compromise coronary artery perfusion, generating electrocardiogram (ECG) findings compatible with acute myocardial infarction, which may lead the clinician to diagnose and treat myocardial infarction while missing the underlying diagnosis.33 In a recent survey, 9 of 44 patients (21%) presenting with acute aortic dissection were initially diagnosed with acute coronary syndrome and anticoagulated, with 2 deaths.34 ECGs must therefore be interpreted with extreme caution in aortic dissection.

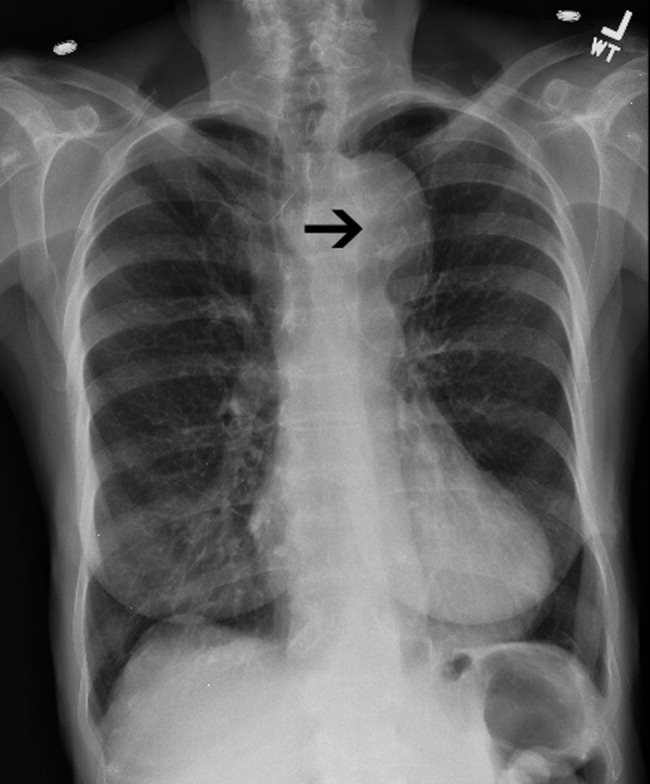

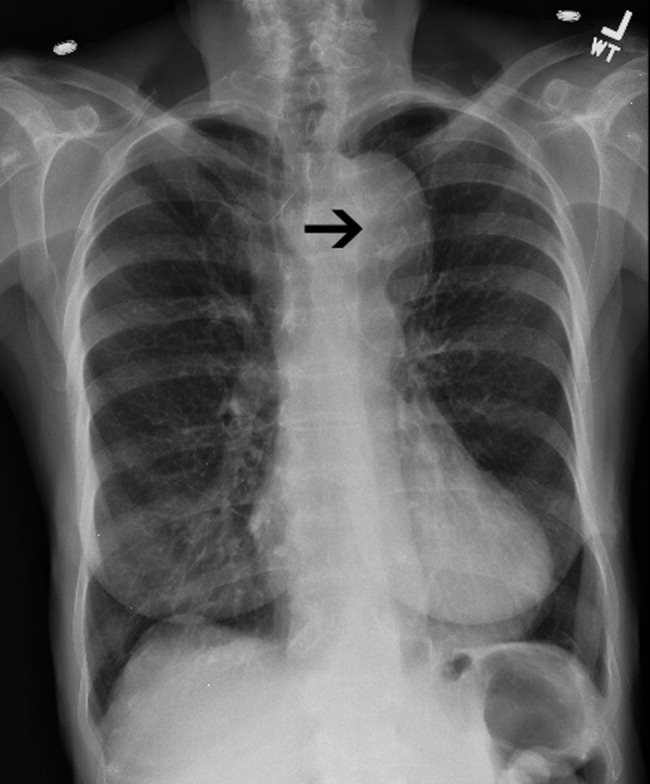

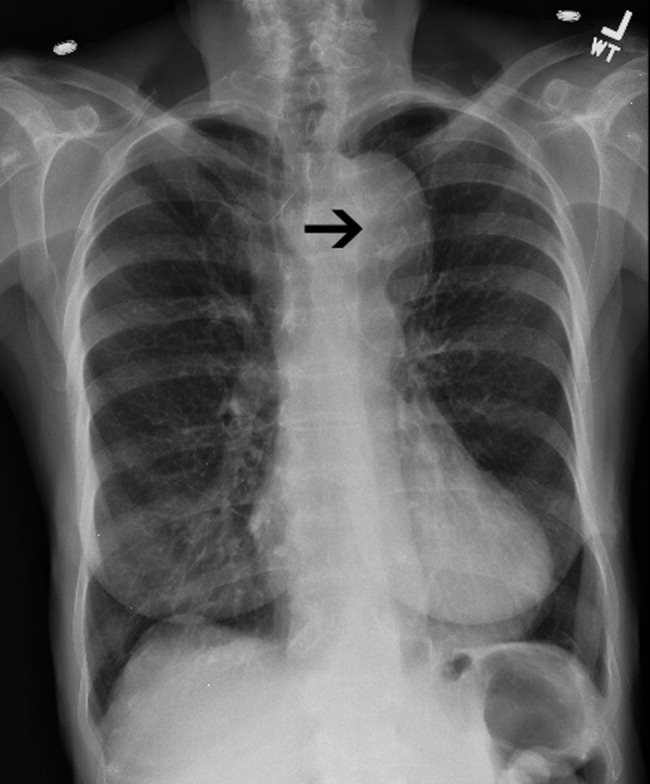

Chest x‐ray: In the emergency department, chest radiography is a mainstay of the evaluation of acute chest pain. Unfortunately, plain‐film radiography has limited utility for diagnosing aortic dissection.35 In the IRAD trial, mediastinal widening (>8 cm) and abnormal aortic contour, the classic radiographic findings in aortic dissection, were present in only 50%‐60% of cases. Twelve percent of patients had a completely normal chest x‐ray.14 A pooled analysis of previous studies demonstrated that the sensitivity of widened mediastinum and abnormal aortic contour was 65% and 71%, respectively.32 Nonspecific radiographic findings, most notably pleural effusion, were common.36 Thus, if the index of suspicion for aortic dissection is elevated, a confirmatory study must be obtained (Figure 2).

Clinical Prediction Tool

Three clinical features were demonstrated to be effective in identifying aortic dissection in patients presenting with acute chest or back pain: immediate onset of tearing or ripping chest pain, mediastinal widening or aortic enlargement/displacement observed on chest x‐ray, and arm pulse or blood pressure differential exceeding 20 mm Hg. When all 3 findings were absent, dissection was unlikely (7% probability, negative LR 0.07 [CI 0.03‐0.17]). If either chest pain or radiographic findings were present, the likelihood was intermediate (31%‐39% probability). With any other combination of findings, dissection was likely (83‐100% probability). This prediction tool effectively identified 96% of all patients who presented to an emergency department with acute aortic dissection.15 However, 4% of patients categorized as low risk were ultimately diagnosed with aortic dissection. Given the exceptionally high mortality resulting from a missed diagnosis, a 4% false‐negative rate is unacceptably high. Thus, the absence of any of the aforementioned findings should not dissuade the clinician from obtaining a confirmatory imaging study if the pretest probability for acute aortic dissection is elevated.

CONFIRMATORY IMAGING STUDIES

The ideal confirmatory imaging modality should identify aortic dissection with high sensitivity and specificity. It should also identify the entry and exit points of the dissection and provide information about the extent of compromise of the aortic valve, pericardium, and great vessels. Four imaging modalities sufficiently meet these criteria in order to be considered diagnostically useful.

Aortography: Previously the gold standard for diagnosing aortic dissection, aortography is no longer a first‐line imaging modality. The sensitivity and specificity of aortography are at best equivalent and probably inferior to less invasive imaging modalities.37, 38 False negatives may occur if both the true and false lumens opacify equally with contrast, or if the false lumen is sufficiently thrombosed to preclude any instillation of contrast. Aortography cannot identify aortic intramural hematomas, is invasive and highly operator dependent, requires nephrotoxic contrast, and generally takes longer to obtain than other modalities.39

Aortography uniquely offers excellent visualization of the coronary arteries and great vessels and is preferred when such information is necessary. Percutaneous aortic endovascular stent grafting has been recently employed to repair distal aortic dissections.4043 As a result, aortography is gaining new life as a therapeutic modality.

CT angiography: Spiral CT angiography (CTA) is the most commonly used modality for diagnosing aortic dissection.44 It is emergently available at most hospitals, and images can be obtained in minutes. Sensitivity and specificity may approach 100%, and CTA may be more sensitive than MRA or TEE in evaluating arch vessel involvement.4547 Like conventional angiography, CTA requires administration of nephrotoxic contrast. It frequently cannot visualize the entry and exit sites (intimal flaps) of a dissection and provides limited information about the coronary arteries and no information about the competency of the aortic valve.48, 49 Thus, if aortic dissection is identified by CTA, a second study may be needed to provide further diagnostic information and to guide surgical intervention (Figures 3 and 4).

Magnetic Resonance Angiography: Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) offers excellent noninvasive evaluation of the thoracic aorta. Sensitivity and specificity are probably superior to spiral CTA, and MRA generally identifies the location of the intimal tear and provides some functional information about the aortic valve.44, 50, 51 MRA is not emergently available at many hospitals. Scanning is time intensive, requiring the patient to remain motionless and relatively inaccessible for up to an hour. Furthermore, patient claustrophobia and the presence of implanted devices such as pacemakers or ferromagnetic foreign bodies may preclude MRA.

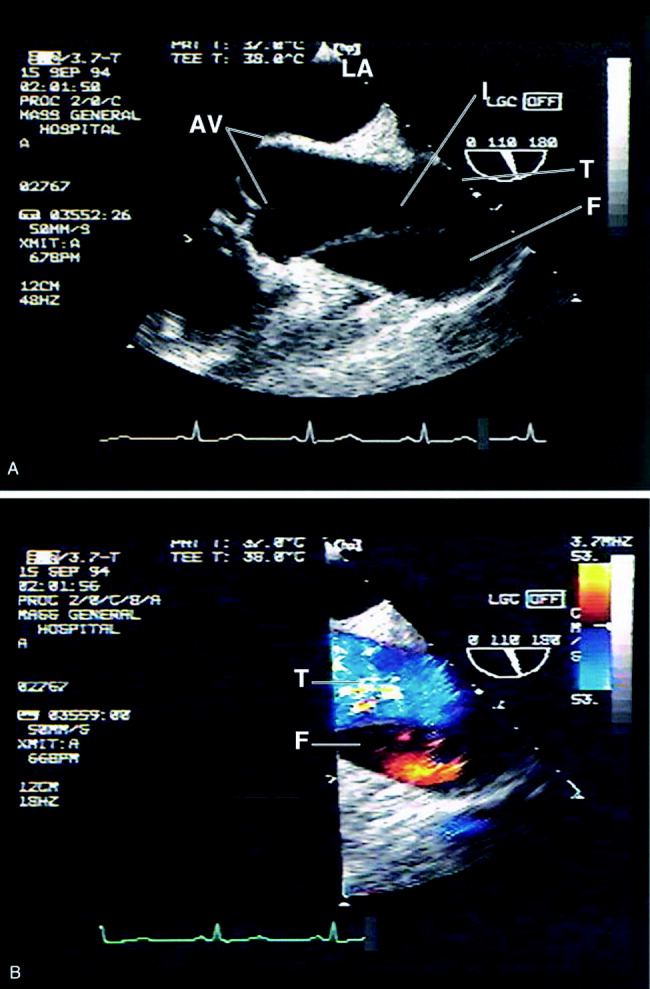

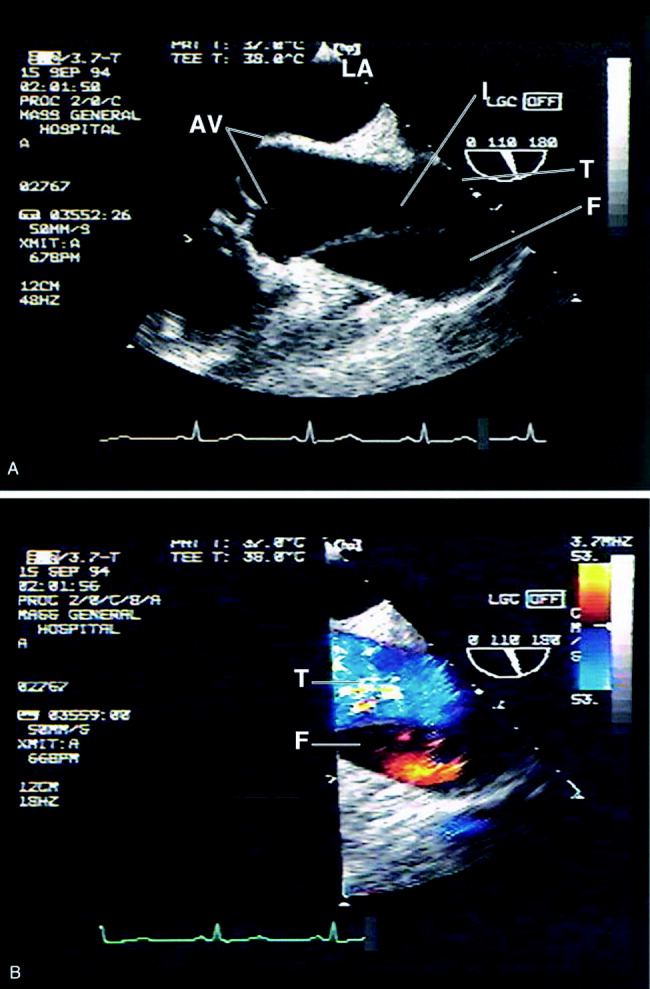

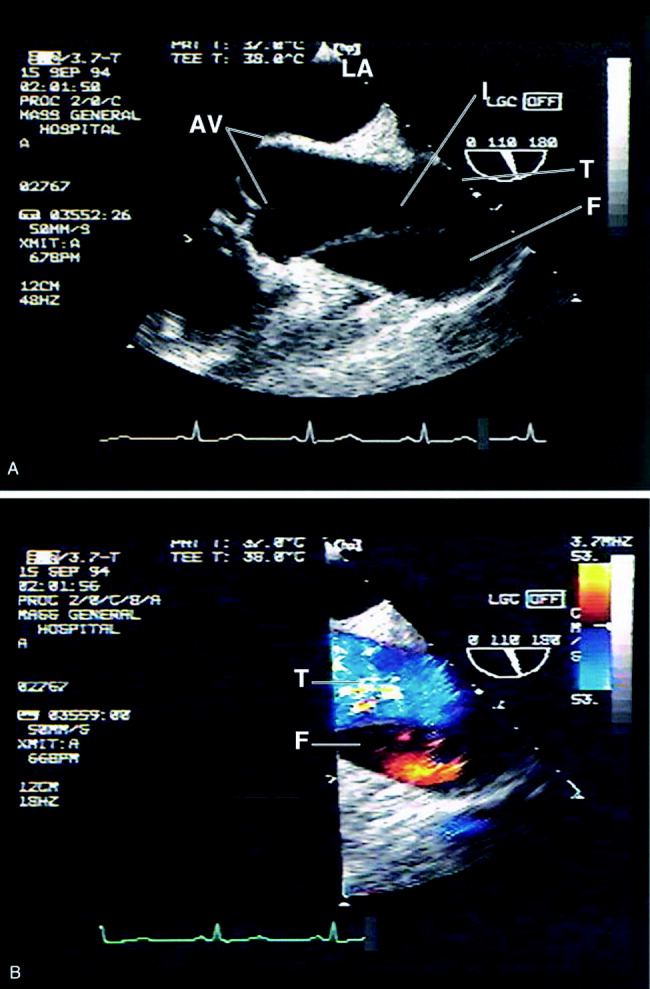

Transesophageal echocardiography: The sensitivity and specificity of transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) are also excellenton a par with CTA and MRA. In addition to providing excellent visualization of the thoracic aorta, TEE provides superb images of the pericardium and detailed assessment of aortic valve function.52 It also is extremely effective at visualizing the aortic intimal flap.44, 49, 53 A significant advantage of TEE is its portability, allowing rapid diagnosis at the bedside. For this reason, it is particularly useful for evaluation of patients who are hemodynamically unstable and are suspected to have an aortic dissection. Because of the anatomic relationship of the aorta with the esophagus and the trachea, TEE more effectively identifies proximal than distal dissections.43 TEE is also somewhat invasive, usually requires patient sedation, and is highly operator dependent, requiring the availability of an experienced and technically skilled operator (Figure 5).

Transthoracic echocardiography: Although it is an excellent tool for the evaluation of many aspects of cardiac anatomy and function, surface echocardiography can reliably visualize only limited portions of the ascending and descending aorta.54, 55 As a consequence, it is neither sensitive nor specific enough to diagnose aortic dissection. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) does, however, play a role in rapidly assessing patients at the bedside for aortic valve or pericardial compromise when these complications are suspected.

Recommendations

CTA, MRA, and TEE are all highly sensitive and specific modalities for diagnosing aortic dissection. Therefore, the condition of the patient, the information needed, and the resources and expertise immediately available should drive the choice of study. MRA is considered the gold standard diagnostic study and is the preferred modality for hemodynamically stable patients with suspected aortic dissection. Because of slow data acquisition and the inaccessibility of patients in the scanner, it is generally unsuited for unstable patients, including those with ongoing pain. Bedside TEE is an excellent choice for patients who are too unstable for MRA but is less effective at visualizing distal dissections. Arch aortography is generally reserved for the confirmation of questionable diagnoses or to image specific branch arteries (Tables 4 and 5).

| Overall | Proximal | Distal | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| TEE | 88% | 90% | 80% |

| CTA | 93% | 93% | 93% |

| MRA | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Aortogram | 87% | 87% | 87% |

| TEE | CTA | MRA | Aortography | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Sensitivity | ++ | ++ | +++ | ++ |

| Specificity | +++ | ++ | +++ | ++ |

| Classification | +++ | ++ | ++ | + |

| Intimal flap | +++ | ‐ | ++ | + |

| Aortic regurgitation | +++ | ++ | ++ | |

| Pericardial effusion | +++ | ++ | ++ | |

| Branch vessel involvement | + | ++ | ++ | +++ |

| Coronary artery involvement | ++ | + | + | +++ |

Most trials comparing CTA, MRA, and TEE were performed in the early 1990s. Computed tomography has evolved significantly over the intervening decade, and some of the diagnostic limitations previously ascribed to CTA, such as the inability to generate 3‐D reconstructed images, no longer exist. Furthermore, CT angiography is widely available and is gaining increasing acceptance as a first‐line imaging modality for patients with noncardiac chest pain.48 Medical centers that maintain round‐the‐clock CT capability may have limited or delayed access to TEE, MRA, or aortography. Given the potential for rapid and dramatic patient deterioration, it is imperative that a diagnosis be established quickly when aortic dissection is suspected. Thus, when the choice is obtaining an immediate CTA or a delayed TEE or MRA, CTA is generally the better choice (Figure 6).

MANAGEMENT

Acute Management:

Approximately half of all patients who present with acute aortic dissection are acutely hypertensive.14 Hypertensive aortic dissection is a hypertensive emergency that mandates immediate decrease in blood pressure to the lowest level that maintains organ perfusion. As a rule, short‐acting, parenteral, titratable antihypertensive agents should be used (Table 6). Intravenous beta‐adrenergic blockers are the mainstay of acute and chronic therapy. Their negative inotropic and chronotropic effects decrease shear stress across the aortic lumen and decrease the likelihood of dissection propagation and aortic dilatation.56, 57 Parenteral vasodilators (eg, nitroprusside and nitroglycerin) should be initiated if beta‐blockers prove insufficient for lowering blood pressure. They should never be used alone, as they may cause reflex tachycardia and consequently may increase intraluminal shear stress. The use of opiates for analgesia and benzodiazepines for anxiolysis further decreases blood pressure by controlling the severe pain and anxiety often associated with acute dissection.

| Name | Mechanism | Dose | Cautions/contraindications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Esmolol | Cardioselective beta‐1 blocker | Load: 500 g/kg IV | Asthma or bronchospasm |

| Drip: 50 g kg1 min1 IV. | Bradycardia | ||

| Increase by increments of 50 g/min | 2nd‐ or 3rd‐degree AV block | ||

| Cocaine or methamphetamine abuse | |||

| Labetalol | Nonselective beta 1,2 blocker | Load: 20 mg IV | Asthma or bronchospasm |

| Selective alpha‐1 blocker | Drip: 2 mg/min IV | Bradycardia | |

| 2nd or 3rd degree AV block | |||

| Cocaine or methamphetamine abuse | |||

| Enalaprilat | ACE inhibitor | 0.625‐1.25 mg IV q 6 hours. | Angioedema |

| Max dose: 5 mg q 6 hours. | Pregnancy | ||

| Renal artery stenosis | |||

| Severe renal insufficiency | |||

| Nitroprusside | Direct arterial vasodilator | Begin at 0.3 g kg1 min1 IV. | May cause reflex tachycardia |

| Max dose 10 g kg1 min1 | Cyanide/thiocyanate toxicityespecially in renal or hepatic insufficiency | ||

| Nitroglycerin | Vascular smooth muscle relaxation | 5‐200 g/min IV | Decreases preloadcontraindicated in tamponade or other preload‐dependent states |

| Concomitant use of sildenafil or similar agents |

Hypotension or shock, which develop in 15%‐30% of patients with acute aortic dissection, are ominous findings that frequently portends impending hemodynamic collapse.14, 58 Patients who develop hypotension are at a fivefold increased risk of death (55.0% vs. 10.3%) and are at markedly increased risk of developing neurologic deficits, as well as myocardial, mesenteric, and limb ischemia. Hypotension may result from pump failure (due to acute aortic insufficiency, pericardial tamponade, or myocardial ischemia), aortic rupture, systemic lactic acidosis, or spinal shock. Bedside transthoracic echocardiography may be particularly useful for the evaluation of hypotensive patients, as it can be used to quickly and noninvasively determine the integrity of the aortic valve and pericardium. Although hypotension may transiently respond to volume resuscitation, all hypotensive patients with aortic dissection, regardless of type, should be immediately referred for emergent surgical evaluation. Pericardiocentesis in the setting of pericardial tamponade remains controversial; a small study suggested that decompression of the pericardial sac may hasten hemodynamic collapse by accelerating blood loss.59

Facilities that do not maintain urgent cardiopulmonary bypass capability should emergently transport patients with aortic dissection to a facility that provides a higher level of care. Transfer should not be delayed to confirm a questionable diagnosis. Proximal aortic dissection frequently compromises the pericardium, aortic valve, and arch vessels, and therefore emergent surgical repair is indicated. When treated medically, proximal dissection carries a dismal 60% in‐hospital mortality rate.14, 60 In contrast, distal aortic dissection is generally treated medically, with surgical intervention generally reserved for patients with an expanding aortic aneurysm, elevated risk of aortic rupture, refractory hypertension, intractable pain, visceral hypoperfusion, and limb ischemia or paresis.11, 61, 62 Individual branch vessel occlusion may be effectively ameliorated with conventional arterial stenting or balloon fenestration.

Endovascular stent grafting has been used successfully in lieu of surgery for patients with acute or chronic distal (type B) aortic dissections.39, 4042, 63 The stent graft is deployed across the proximal intimal tear, obliterating the false lumen and facilitating aortic healing. Early studies suggested that endovascular stent grafting may be safer and more efficacious than conventional surgical repair of distal dissection.41 A recent meta‐analysis of published trials of endovascular aortic stenting found procedural success rates exceeding 95% and a major complication rate of 11%. Thirty‐day mortality was approximately 5%, with 6‐, 12‐ and 24‐month mortality rates plateauing at 10%. Centers with high patient volume had fewer complications and much lower acute mortality rates.14, 64 These medium‐term outcomes compare favorably with conventional therapy. Endovascular stenting has not been prospectively compared against conventional therapy in randomized trials, and it therefore remains unclear who should be referred for endovascular stenting instead of conventional therapy.

Long‐term Management

Survivors of aortic dissection, especially those with diseases of collagen, have a systemic disease that predisposes them to further aortic and great vessel events. Almost one third of survivors of acute aortic dissection will develop dissection propagation or aortic rupture or will require aortic surgery within 5 years of presentation.41, 60 Young patients who present for aortic dissection should be screened for Marfan syndrome according to the Gent nosology.65 To reduce shear stress to the aortic lumen, all patients should be treated with beta‐blockers for life, with blood pressure targeted to be below 135/80.60, 66 Patients who do not tolerate beta blockade may benefit from treatment with diltiazem or verapamil. Progression to aortic aneurysm is common, and patients should undergo serial imaging of the aorta at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months after discharge and annually thereafter. Dilatation of the proximal aorta to >5.0 cm and of the distal aorta to >6.0 cm should prompt referral for surgical or possibly endovascular repair.41, 67 Although supporting data are limited, it is generally accepted that patients should moderate their physical activity to avoid extremes of tachycardia and blood pressure elevation. Sports that involve high speed or sudden deceleration, such as ice hockey, downhill skiing, and football, should be strictly avoided. Patients should be warned to seek immediate medical attention if they develop recurrent chest or back pain or focal neurologic deficits.

PROGNOSIS

Despite significant medical and surgical advances, aortic dissection remains exceptionally lethal. Patients with proximal dissections are more likely to die than those with distal dissections. Using data from the IRAD trial, Mehta et al determined that age 70 years (OR, 1.70), abrupt onset of chest pain (OR 2.60), hypotension/shock/tamponade (OR, 2.97), renal failure (OR, 4.77), pulse deficit (OR, 2.03), and abnormal ECG (OR, 1.77) were independent determinants of death.59 Medical treatment of proximal dissection is generally reserved for patients too ill, unstable, or frail to undergo surgery. In contrast, most patients with distal dissection are managed medically, with surgery generally reserved for those with acute complications. Hence, patients with proximal dissections who are managed medically and those with distal dissections who are managed surgically have the worst outcomes. Outcomes for women are worse than those for men, which is probably attributable to several factors. Women dissect at an older age, present later after the onset of symptoms, and are more likely to have confounding symptoms that may delay timely diagnosis1 (Table 7).

| Proximal (DeBakey I, II; Stanford A) | Distal (DeBakey III; Stanford B) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical | Medical | Surgical | Medical | |

| In‐hospital mortality | 26% | 58% | 31% | 11% |

| Average | 35% | 15% | ||

CONCLUSION

Aortic dissection is a rare and acutely life‐threatening cause of acute chest and back pain. Delays in diagnosis and misdiagnoses are common, frequently with catastrophic consequences. The key to diagnosis is maintaining a high index of suspicion for dissection, especially in patients who present with acute severe chest, back, or abdominal pain in the setting of unexplained acute pulse deficits, neurologic deficits, or acute end‐organ injury. Three clinical findings have been shown to be diagnostically useful: immediate onset of tearing or ripping chest or back pain, mediastinal widening or abnormal aortic contour on chest radiograph, and peripheral pulse deficits or variable pulse pressure (>20 mm Hg). If all 3 findings are absent, acute aortic dissection is unlikely. The presence of any of these findings should prompt further workup. A normal chest radiograph does not rule out aortic dissection. Only TEE, CT, and MR angiography are sufficiently specific to rule out dissection. Aortography is rarely used as a first‐line diagnostic tool but may be useful as a confirmatory test or to provide additional anatomic information. Patients who present with proximal aortic dissection or with any aortic dissection with concomitant hypotension are at exceptionally high risk of death and should be immediately referred for surgical evaluation. Beta‐blockers are the mainstay of acute and chronic therapy of aortic dissection. Survivors of aortic dissection are at a markedly elevated risk for further aortic events and should be followed vigilantly posthospitalization.

- ,,, et al.Gender‐related differences in acute aortic dissection.Circulation.2004;109:3014–3021.

- ,,, et al.Clinical features and differential diagnosis of aortic dissection: Experience with 236 cases.Mayo Clin Proc.1993;68:642–651.

- ,.The natural history of thoracic aortic aneurysm disease: an overview.J Card Surg.1997;12(suppl):270–278.

- ,,.Dissecting aneurysms of the aorta: a review of 505 cases.Medicine.1958;37:217–279.