User login

Team Rapid

The origin of the RRT can be found in medical emergency teams (METs). METs began in Australia as a result of the realization that earlier intervention could lead to better outcomes.1 In December 2004, in response to persistent problems with patient safety, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement launched its “100,000 Lives Campaign.”2 The Institute’s key plan for saving some of these 100,000 lives was to create RRTs at every participating medical center. Participating facilities would also submit data on mortality.

Olive View-UCLA Medical Center (OV-UCLA) signed on to participate in the campaign, and part of that effort was the creation and implementation of an RRT. We joined a University Health Consortium “Commit to Action” team, which assisted us by providing support as we began the creation and implementation of the RRT. What follows is the story of how we created an RRT.

We chose team members from all disciplines that were to be part of the RRT response—both at and behind the scenes: RNs, nursing administrators, hospital administrators, ICU attendings, house staff, laboratory personnel, nursing educators, radiology technicians, and hospital operators. The group was further organized into specific teams to solve problems and present solutions. At this point we learned our first important lesson: We needed to meet individually with all inpatient department chairs to discuss the effect of RRTs.

Activation and Notification

How would the RRT call be activated—overhead or beeper? Who could call, and what would the indications be? The OV-UCLA activation and notification team decided that the RRT could be activated by any staff member. Criteria, including vital signs, mental status, or simply “concern about the patient,” were created and posted. A telephone line in the ICU (X4415) was dedicated for RRT calls, and all other activation was overhead due to the lack of an adequate beeper system. (Other than code pagers, our beeper system can’t be simultaneously activated, and ancillaries don’t have beepers.)

The primary nurse’s responsibilities included calling the primary team or cross-covering team and obtaining a fingerstick glucose on all patients while waiting for the team. In discussions the primary team, we learned our second important lesson: As we presented the RRT to the hospital staff, everyone was concerned about the primary team. Ensuring that a mechanism for notifying the primary team was in place and reassuring staff that the primary team would be involved emerged as essential tasks. It was also imperative to identify the chain of command.

With this need in mind, we decided the primary team would always be the captain and would, therefore, have the authority to dismiss whomever they wanted from the RRT. An ICU attending was assigned to RRT call as supervision for the ICU resident responder. At OV-UCLA, our attending is not in-house and, to date, has not been called.

Documentation

The OV-UCLA documentation team was called on to answer the following questions: How would the RRT call be documented? How would medication orders be sent to the pharmacy? How would quality indicators (QI) and data be collected on the calls?

The team’s solution involved creating a one-page, primarily check-based document. The ICU nurse who answered the X4415 telephone in the ICU would begin documentation, which included the time of the call and the chief complaint. When the RRT reached the patient, however, the documentation duties were transferred to the primary RN. All providers were to document on the same page—similar to a code sheet. The RRT nurse and the attending doctor were to check vitals and perform the physical exam, as all information was called out to the documenter.

Medications were to be verbally ordered by the doctor, then read back and verified by the nurses documenting and administering for the RRT. For the most part, medication orders were restricted to what was carried in the RRT bag. The document was eventually copied three times: The original was placed in the chart, one copy was sent to the pharmacy for a record of medication, and the other was saved for QI. The primary team was expected to write a note in the chart’s disposition and time of disposition were to be included in this message.

Equipment

The OV-UCLA equipment team had one important question to answer: What supplies did we need at the bedside?

Although equipment and medications are readily available outside the ICU, the team didn’t want to spend time looking for equipment during an RRT call. “I don’t want a quick RRT call to evolve into a three-hour scavenger hunt,” says one team member.

Because OV-UCLA does not have a 24-hour pharmacist, the group felt it essential to bring medications to the bedside to avoid delays. Our solution to this potential problem was simple. The medication box is prepared by the pharmacy and sealed with one expiration date. Once the box is opened, it is exchanged for a new sealed box. The team chose a rolling duffle to store and transport the supplies, which are compartmentalized into the following sections: infection control, medications, airway and respiratory, IV access and blood draw, and IV start. Medications include respiratory treatments, antibiotics, furosemide, nitroglycerin, metoprolol, heparin and low molecular weight heparin, naloxone, ephedrine, dopamine, glucose, glucagons, and so on. The bag is restocked upon its return to the ICU.

Because of the stress involved in maintaining emergency equipment, we opted to call the supplies a “convenience bag.” This label ensured that only the sealed medication box would require a mandatory check; the rest of the equipment would be monitored on a more informal basis. Because all equipment is available on every floor, and because any RRT call can be converted to a code blue, the team felt that this was reasonable. The committee also purchased a five-pound patient monitor that has a screen for a cardiac tracing, a pulse oximeter, a noninvasive blood pressure monitor, and a temperature probe. This monitor fits easily in a pocket of the duffle.

Education and Publicity

How would staff know to call the RRT? The OV-UCLA team, anticipating that the majority of RRT calls would be activated by the primary RNs, decided that educating all nursing staff was essential.

The hospital nursing education office trained all nurses on all shifts in a short period of time. All nursing staff were taught to use SBAR (situation, background, assessment, and recommendation) communication and to identify early warning signs.1 The importance of recognizing the early warning signs was stressed during the nursing and physician training sessions. Staff were reassured that they didn’t have to know what was wrong with the patient to know that something was wrong and that help was required.

Publicity was accomplished in a variety of ways. The facility purchased pencils in our official color—lime green—that said “Rapid Response Team X4415.” The duffle was wheeled to all nursing stations so that staff could see it. We also ordered custom green-and-white M&M candy (available at www.mms.com) labeled “RRT X4415” to give as a promotional gift when an RRT was called.

Staffing

One last question remained for our team members: Who would respond to the RRT?

The committee felt strongly that an ICU nurse, an ICU resident, and a respiratory therapist should respond. Many physicians on the team did not want a doctor to respond, mostly due to concerns over chain of command. Who would be responsible for decisions made by the RRT? What if an ICU R2 disagreed with a surgery R4? Could they write a “do not call RRT order?” Nursing, on the other hand, wanted physician response; they wanted to be able to stabilize the patient.

Standardized protocols were discussed, but the team felt that the they would unreasonably delay the start. Radiology, which has no code blue response, volunteered to respond to all calls and hand-deliver the film to a computerized viewing system. The lab volunteered to run all RRT labs—designated with a lime green sticker—as quickly as possible.

The medical staff wanted to pilot the RRT, but because we are a small facility (220 beds) and to avoid confusion we launched the RRT for all inpatients. We went live in October 2005. The original plan was to staff an ICU nurse/RRT position. This RRT RN would relieve ICU nurses for breaks to maintain staffing ratios and provide RRT coverage. Because of the omnipresent nursing shortage, however, the RRT position is often pulled and the charge nurse must cover calls. Nurses sign up for RRT overtime and get pulled for patient care duties.

Mock RRT Calls

We performed three RRT drills to determine problem areas. For the first call, we involved a physician who had been vocal about the need for an RRT. The call was for a patient with shortness of breath. Two problems occurred during this drill: The primary team was never called, and there was no overhead page. So a member of our team worked with the hospital operator on our committee and clarified our protocols.

At the second drill, the main problem was documentation. The ICU nurse was so busy documenting that he wasn’t involved with the patient. Because the expertise of the ICU nurse is essential (in fact, there are times when this RN is the most experienced person on the team) we restructured the response so that the primary nurse would document and the ICU nurse was free to provide the hands-on care required.

At the final mock RRT, the major problem was again communication; that is, everyone spoke at once. The team members were encouraged to direct all comments to the team leader and keep any other conversation to a minimum.

A Successful RRT

The following case example, which describes the successful use of our OV-UCLA’s RRT, provides an illuminating look at its effectiveness. In this case, the RRT comprised the ICU nurse, the ICU physician, and the respiratory therapist. The team carried the following equipment: a patient monitor, medications, an IV start, blood sampling tubes, a central line, oxygen masks, and suctioning equipment.

The case began when the primary nurse activated the call. The patient—a 36-year-old HIV-positive male with acute rectal bleeding—was found to have a systolic blood pressure (SBP) reading of 70 and a heart rate of 144. The patient was admitted for anal warts but was noted to have acute bright red blood per rectum. The primary physician team had been called, but had not yet arrived. The primary nurse used the bedside phone to call X4415, and the RRT arrived within three minutes.

Upon arrival, the RRT started a wide bore IV and a central line. The team then called for O-negative blood from the blood bank. The transfusion began seven minutes after the team’s arrival in the patient’s room. The patient was transferred to the ICU and was discharged to the floor the following day.

Results

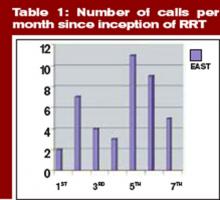

In four-and-a-half months, we have had 43 calls. The warning signs that precipitated the calls include:

- Respiratory distress: 14 (resulting in eight intubations);

- Cardiac problems: six;

- Altered mental status: four;

- Hypotension: four;

- Post-procedure oversedation: three;

- Vomiting: two;

- Bleeding: two;

- Gastrointestinal: one;

- Mouth bleeding: one;

- Hypoglycemia: one; and

- Unclear etiology: five. TH

Dr. Stein is the medical director, Intensive Care Unit/SDU, at Olive View UCLA Medical Center.

References

- Bellomo R, Goldsmith D, Uchino S, et al. A prospective before-and-after trial of a medical emergency team. Med J Aust. 2003 Sep 15:179(6):283-287

- The Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s 100,000 Lives Campaign. Available at: www.ihi.org. Last accessed July 10, 2006.

- Leonard MS, Graham S, Taggart B. The human factor: effective teamwork and communication in patient strategy. In: Leonard M, Frankel A, Simmonds T, eds. Achieving safe and reliable health care strategies and solutions. 1st ed. ACHE Management Series; 2004. p.37-65.

- Schein RM, Hazday N, Pena M, et al. Clinical antecedents to in-hospital cardiopulmonary arrests. Chest. 1990;98:1388-1392.

- Franklin C, Matthew J. Developing strategies to prevent-in hospital cardiac arrest: analyzing responses of physicians and nurses in the hours before the event. Crit Care Med. 1994;22(2):244-247.

The origin of the RRT can be found in medical emergency teams (METs). METs began in Australia as a result of the realization that earlier intervention could lead to better outcomes.1 In December 2004, in response to persistent problems with patient safety, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement launched its “100,000 Lives Campaign.”2 The Institute’s key plan for saving some of these 100,000 lives was to create RRTs at every participating medical center. Participating facilities would also submit data on mortality.

Olive View-UCLA Medical Center (OV-UCLA) signed on to participate in the campaign, and part of that effort was the creation and implementation of an RRT. We joined a University Health Consortium “Commit to Action” team, which assisted us by providing support as we began the creation and implementation of the RRT. What follows is the story of how we created an RRT.

We chose team members from all disciplines that were to be part of the RRT response—both at and behind the scenes: RNs, nursing administrators, hospital administrators, ICU attendings, house staff, laboratory personnel, nursing educators, radiology technicians, and hospital operators. The group was further organized into specific teams to solve problems and present solutions. At this point we learned our first important lesson: We needed to meet individually with all inpatient department chairs to discuss the effect of RRTs.

Activation and Notification

How would the RRT call be activated—overhead or beeper? Who could call, and what would the indications be? The OV-UCLA activation and notification team decided that the RRT could be activated by any staff member. Criteria, including vital signs, mental status, or simply “concern about the patient,” were created and posted. A telephone line in the ICU (X4415) was dedicated for RRT calls, and all other activation was overhead due to the lack of an adequate beeper system. (Other than code pagers, our beeper system can’t be simultaneously activated, and ancillaries don’t have beepers.)

The primary nurse’s responsibilities included calling the primary team or cross-covering team and obtaining a fingerstick glucose on all patients while waiting for the team. In discussions the primary team, we learned our second important lesson: As we presented the RRT to the hospital staff, everyone was concerned about the primary team. Ensuring that a mechanism for notifying the primary team was in place and reassuring staff that the primary team would be involved emerged as essential tasks. It was also imperative to identify the chain of command.

With this need in mind, we decided the primary team would always be the captain and would, therefore, have the authority to dismiss whomever they wanted from the RRT. An ICU attending was assigned to RRT call as supervision for the ICU resident responder. At OV-UCLA, our attending is not in-house and, to date, has not been called.

Documentation

The OV-UCLA documentation team was called on to answer the following questions: How would the RRT call be documented? How would medication orders be sent to the pharmacy? How would quality indicators (QI) and data be collected on the calls?

The team’s solution involved creating a one-page, primarily check-based document. The ICU nurse who answered the X4415 telephone in the ICU would begin documentation, which included the time of the call and the chief complaint. When the RRT reached the patient, however, the documentation duties were transferred to the primary RN. All providers were to document on the same page—similar to a code sheet. The RRT nurse and the attending doctor were to check vitals and perform the physical exam, as all information was called out to the documenter.

Medications were to be verbally ordered by the doctor, then read back and verified by the nurses documenting and administering for the RRT. For the most part, medication orders were restricted to what was carried in the RRT bag. The document was eventually copied three times: The original was placed in the chart, one copy was sent to the pharmacy for a record of medication, and the other was saved for QI. The primary team was expected to write a note in the chart’s disposition and time of disposition were to be included in this message.

Equipment

The OV-UCLA equipment team had one important question to answer: What supplies did we need at the bedside?

Although equipment and medications are readily available outside the ICU, the team didn’t want to spend time looking for equipment during an RRT call. “I don’t want a quick RRT call to evolve into a three-hour scavenger hunt,” says one team member.

Because OV-UCLA does not have a 24-hour pharmacist, the group felt it essential to bring medications to the bedside to avoid delays. Our solution to this potential problem was simple. The medication box is prepared by the pharmacy and sealed with one expiration date. Once the box is opened, it is exchanged for a new sealed box. The team chose a rolling duffle to store and transport the supplies, which are compartmentalized into the following sections: infection control, medications, airway and respiratory, IV access and blood draw, and IV start. Medications include respiratory treatments, antibiotics, furosemide, nitroglycerin, metoprolol, heparin and low molecular weight heparin, naloxone, ephedrine, dopamine, glucose, glucagons, and so on. The bag is restocked upon its return to the ICU.

Because of the stress involved in maintaining emergency equipment, we opted to call the supplies a “convenience bag.” This label ensured that only the sealed medication box would require a mandatory check; the rest of the equipment would be monitored on a more informal basis. Because all equipment is available on every floor, and because any RRT call can be converted to a code blue, the team felt that this was reasonable. The committee also purchased a five-pound patient monitor that has a screen for a cardiac tracing, a pulse oximeter, a noninvasive blood pressure monitor, and a temperature probe. This monitor fits easily in a pocket of the duffle.

Education and Publicity

How would staff know to call the RRT? The OV-UCLA team, anticipating that the majority of RRT calls would be activated by the primary RNs, decided that educating all nursing staff was essential.

The hospital nursing education office trained all nurses on all shifts in a short period of time. All nursing staff were taught to use SBAR (situation, background, assessment, and recommendation) communication and to identify early warning signs.1 The importance of recognizing the early warning signs was stressed during the nursing and physician training sessions. Staff were reassured that they didn’t have to know what was wrong with the patient to know that something was wrong and that help was required.

Publicity was accomplished in a variety of ways. The facility purchased pencils in our official color—lime green—that said “Rapid Response Team X4415.” The duffle was wheeled to all nursing stations so that staff could see it. We also ordered custom green-and-white M&M candy (available at www.mms.com) labeled “RRT X4415” to give as a promotional gift when an RRT was called.

Staffing

One last question remained for our team members: Who would respond to the RRT?

The committee felt strongly that an ICU nurse, an ICU resident, and a respiratory therapist should respond. Many physicians on the team did not want a doctor to respond, mostly due to concerns over chain of command. Who would be responsible for decisions made by the RRT? What if an ICU R2 disagreed with a surgery R4? Could they write a “do not call RRT order?” Nursing, on the other hand, wanted physician response; they wanted to be able to stabilize the patient.

Standardized protocols were discussed, but the team felt that the they would unreasonably delay the start. Radiology, which has no code blue response, volunteered to respond to all calls and hand-deliver the film to a computerized viewing system. The lab volunteered to run all RRT labs—designated with a lime green sticker—as quickly as possible.

The medical staff wanted to pilot the RRT, but because we are a small facility (220 beds) and to avoid confusion we launched the RRT for all inpatients. We went live in October 2005. The original plan was to staff an ICU nurse/RRT position. This RRT RN would relieve ICU nurses for breaks to maintain staffing ratios and provide RRT coverage. Because of the omnipresent nursing shortage, however, the RRT position is often pulled and the charge nurse must cover calls. Nurses sign up for RRT overtime and get pulled for patient care duties.

Mock RRT Calls

We performed three RRT drills to determine problem areas. For the first call, we involved a physician who had been vocal about the need for an RRT. The call was for a patient with shortness of breath. Two problems occurred during this drill: The primary team was never called, and there was no overhead page. So a member of our team worked with the hospital operator on our committee and clarified our protocols.

At the second drill, the main problem was documentation. The ICU nurse was so busy documenting that he wasn’t involved with the patient. Because the expertise of the ICU nurse is essential (in fact, there are times when this RN is the most experienced person on the team) we restructured the response so that the primary nurse would document and the ICU nurse was free to provide the hands-on care required.

At the final mock RRT, the major problem was again communication; that is, everyone spoke at once. The team members were encouraged to direct all comments to the team leader and keep any other conversation to a minimum.

A Successful RRT

The following case example, which describes the successful use of our OV-UCLA’s RRT, provides an illuminating look at its effectiveness. In this case, the RRT comprised the ICU nurse, the ICU physician, and the respiratory therapist. The team carried the following equipment: a patient monitor, medications, an IV start, blood sampling tubes, a central line, oxygen masks, and suctioning equipment.

The case began when the primary nurse activated the call. The patient—a 36-year-old HIV-positive male with acute rectal bleeding—was found to have a systolic blood pressure (SBP) reading of 70 and a heart rate of 144. The patient was admitted for anal warts but was noted to have acute bright red blood per rectum. The primary physician team had been called, but had not yet arrived. The primary nurse used the bedside phone to call X4415, and the RRT arrived within three minutes.

Upon arrival, the RRT started a wide bore IV and a central line. The team then called for O-negative blood from the blood bank. The transfusion began seven minutes after the team’s arrival in the patient’s room. The patient was transferred to the ICU and was discharged to the floor the following day.

Results

In four-and-a-half months, we have had 43 calls. The warning signs that precipitated the calls include:

- Respiratory distress: 14 (resulting in eight intubations);

- Cardiac problems: six;

- Altered mental status: four;

- Hypotension: four;

- Post-procedure oversedation: three;

- Vomiting: two;

- Bleeding: two;

- Gastrointestinal: one;

- Mouth bleeding: one;

- Hypoglycemia: one; and

- Unclear etiology: five. TH

Dr. Stein is the medical director, Intensive Care Unit/SDU, at Olive View UCLA Medical Center.

References

- Bellomo R, Goldsmith D, Uchino S, et al. A prospective before-and-after trial of a medical emergency team. Med J Aust. 2003 Sep 15:179(6):283-287

- The Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s 100,000 Lives Campaign. Available at: www.ihi.org. Last accessed July 10, 2006.

- Leonard MS, Graham S, Taggart B. The human factor: effective teamwork and communication in patient strategy. In: Leonard M, Frankel A, Simmonds T, eds. Achieving safe and reliable health care strategies and solutions. 1st ed. ACHE Management Series; 2004. p.37-65.

- Schein RM, Hazday N, Pena M, et al. Clinical antecedents to in-hospital cardiopulmonary arrests. Chest. 1990;98:1388-1392.

- Franklin C, Matthew J. Developing strategies to prevent-in hospital cardiac arrest: analyzing responses of physicians and nurses in the hours before the event. Crit Care Med. 1994;22(2):244-247.

The origin of the RRT can be found in medical emergency teams (METs). METs began in Australia as a result of the realization that earlier intervention could lead to better outcomes.1 In December 2004, in response to persistent problems with patient safety, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement launched its “100,000 Lives Campaign.”2 The Institute’s key plan for saving some of these 100,000 lives was to create RRTs at every participating medical center. Participating facilities would also submit data on mortality.

Olive View-UCLA Medical Center (OV-UCLA) signed on to participate in the campaign, and part of that effort was the creation and implementation of an RRT. We joined a University Health Consortium “Commit to Action” team, which assisted us by providing support as we began the creation and implementation of the RRT. What follows is the story of how we created an RRT.

We chose team members from all disciplines that were to be part of the RRT response—both at and behind the scenes: RNs, nursing administrators, hospital administrators, ICU attendings, house staff, laboratory personnel, nursing educators, radiology technicians, and hospital operators. The group was further organized into specific teams to solve problems and present solutions. At this point we learned our first important lesson: We needed to meet individually with all inpatient department chairs to discuss the effect of RRTs.

Activation and Notification

How would the RRT call be activated—overhead or beeper? Who could call, and what would the indications be? The OV-UCLA activation and notification team decided that the RRT could be activated by any staff member. Criteria, including vital signs, mental status, or simply “concern about the patient,” were created and posted. A telephone line in the ICU (X4415) was dedicated for RRT calls, and all other activation was overhead due to the lack of an adequate beeper system. (Other than code pagers, our beeper system can’t be simultaneously activated, and ancillaries don’t have beepers.)

The primary nurse’s responsibilities included calling the primary team or cross-covering team and obtaining a fingerstick glucose on all patients while waiting for the team. In discussions the primary team, we learned our second important lesson: As we presented the RRT to the hospital staff, everyone was concerned about the primary team. Ensuring that a mechanism for notifying the primary team was in place and reassuring staff that the primary team would be involved emerged as essential tasks. It was also imperative to identify the chain of command.

With this need in mind, we decided the primary team would always be the captain and would, therefore, have the authority to dismiss whomever they wanted from the RRT. An ICU attending was assigned to RRT call as supervision for the ICU resident responder. At OV-UCLA, our attending is not in-house and, to date, has not been called.

Documentation

The OV-UCLA documentation team was called on to answer the following questions: How would the RRT call be documented? How would medication orders be sent to the pharmacy? How would quality indicators (QI) and data be collected on the calls?

The team’s solution involved creating a one-page, primarily check-based document. The ICU nurse who answered the X4415 telephone in the ICU would begin documentation, which included the time of the call and the chief complaint. When the RRT reached the patient, however, the documentation duties were transferred to the primary RN. All providers were to document on the same page—similar to a code sheet. The RRT nurse and the attending doctor were to check vitals and perform the physical exam, as all information was called out to the documenter.

Medications were to be verbally ordered by the doctor, then read back and verified by the nurses documenting and administering for the RRT. For the most part, medication orders were restricted to what was carried in the RRT bag. The document was eventually copied three times: The original was placed in the chart, one copy was sent to the pharmacy for a record of medication, and the other was saved for QI. The primary team was expected to write a note in the chart’s disposition and time of disposition were to be included in this message.

Equipment

The OV-UCLA equipment team had one important question to answer: What supplies did we need at the bedside?

Although equipment and medications are readily available outside the ICU, the team didn’t want to spend time looking for equipment during an RRT call. “I don’t want a quick RRT call to evolve into a three-hour scavenger hunt,” says one team member.

Because OV-UCLA does not have a 24-hour pharmacist, the group felt it essential to bring medications to the bedside to avoid delays. Our solution to this potential problem was simple. The medication box is prepared by the pharmacy and sealed with one expiration date. Once the box is opened, it is exchanged for a new sealed box. The team chose a rolling duffle to store and transport the supplies, which are compartmentalized into the following sections: infection control, medications, airway and respiratory, IV access and blood draw, and IV start. Medications include respiratory treatments, antibiotics, furosemide, nitroglycerin, metoprolol, heparin and low molecular weight heparin, naloxone, ephedrine, dopamine, glucose, glucagons, and so on. The bag is restocked upon its return to the ICU.

Because of the stress involved in maintaining emergency equipment, we opted to call the supplies a “convenience bag.” This label ensured that only the sealed medication box would require a mandatory check; the rest of the equipment would be monitored on a more informal basis. Because all equipment is available on every floor, and because any RRT call can be converted to a code blue, the team felt that this was reasonable. The committee also purchased a five-pound patient monitor that has a screen for a cardiac tracing, a pulse oximeter, a noninvasive blood pressure monitor, and a temperature probe. This monitor fits easily in a pocket of the duffle.

Education and Publicity

How would staff know to call the RRT? The OV-UCLA team, anticipating that the majority of RRT calls would be activated by the primary RNs, decided that educating all nursing staff was essential.

The hospital nursing education office trained all nurses on all shifts in a short period of time. All nursing staff were taught to use SBAR (situation, background, assessment, and recommendation) communication and to identify early warning signs.1 The importance of recognizing the early warning signs was stressed during the nursing and physician training sessions. Staff were reassured that they didn’t have to know what was wrong with the patient to know that something was wrong and that help was required.

Publicity was accomplished in a variety of ways. The facility purchased pencils in our official color—lime green—that said “Rapid Response Team X4415.” The duffle was wheeled to all nursing stations so that staff could see it. We also ordered custom green-and-white M&M candy (available at www.mms.com) labeled “RRT X4415” to give as a promotional gift when an RRT was called.

Staffing

One last question remained for our team members: Who would respond to the RRT?

The committee felt strongly that an ICU nurse, an ICU resident, and a respiratory therapist should respond. Many physicians on the team did not want a doctor to respond, mostly due to concerns over chain of command. Who would be responsible for decisions made by the RRT? What if an ICU R2 disagreed with a surgery R4? Could they write a “do not call RRT order?” Nursing, on the other hand, wanted physician response; they wanted to be able to stabilize the patient.

Standardized protocols were discussed, but the team felt that the they would unreasonably delay the start. Radiology, which has no code blue response, volunteered to respond to all calls and hand-deliver the film to a computerized viewing system. The lab volunteered to run all RRT labs—designated with a lime green sticker—as quickly as possible.

The medical staff wanted to pilot the RRT, but because we are a small facility (220 beds) and to avoid confusion we launched the RRT for all inpatients. We went live in October 2005. The original plan was to staff an ICU nurse/RRT position. This RRT RN would relieve ICU nurses for breaks to maintain staffing ratios and provide RRT coverage. Because of the omnipresent nursing shortage, however, the RRT position is often pulled and the charge nurse must cover calls. Nurses sign up for RRT overtime and get pulled for patient care duties.

Mock RRT Calls

We performed three RRT drills to determine problem areas. For the first call, we involved a physician who had been vocal about the need for an RRT. The call was for a patient with shortness of breath. Two problems occurred during this drill: The primary team was never called, and there was no overhead page. So a member of our team worked with the hospital operator on our committee and clarified our protocols.

At the second drill, the main problem was documentation. The ICU nurse was so busy documenting that he wasn’t involved with the patient. Because the expertise of the ICU nurse is essential (in fact, there are times when this RN is the most experienced person on the team) we restructured the response so that the primary nurse would document and the ICU nurse was free to provide the hands-on care required.

At the final mock RRT, the major problem was again communication; that is, everyone spoke at once. The team members were encouraged to direct all comments to the team leader and keep any other conversation to a minimum.

A Successful RRT

The following case example, which describes the successful use of our OV-UCLA’s RRT, provides an illuminating look at its effectiveness. In this case, the RRT comprised the ICU nurse, the ICU physician, and the respiratory therapist. The team carried the following equipment: a patient monitor, medications, an IV start, blood sampling tubes, a central line, oxygen masks, and suctioning equipment.

The case began when the primary nurse activated the call. The patient—a 36-year-old HIV-positive male with acute rectal bleeding—was found to have a systolic blood pressure (SBP) reading of 70 and a heart rate of 144. The patient was admitted for anal warts but was noted to have acute bright red blood per rectum. The primary physician team had been called, but had not yet arrived. The primary nurse used the bedside phone to call X4415, and the RRT arrived within three minutes.

Upon arrival, the RRT started a wide bore IV and a central line. The team then called for O-negative blood from the blood bank. The transfusion began seven minutes after the team’s arrival in the patient’s room. The patient was transferred to the ICU and was discharged to the floor the following day.

Results

In four-and-a-half months, we have had 43 calls. The warning signs that precipitated the calls include:

- Respiratory distress: 14 (resulting in eight intubations);

- Cardiac problems: six;

- Altered mental status: four;

- Hypotension: four;

- Post-procedure oversedation: three;

- Vomiting: two;

- Bleeding: two;

- Gastrointestinal: one;

- Mouth bleeding: one;

- Hypoglycemia: one; and

- Unclear etiology: five. TH

Dr. Stein is the medical director, Intensive Care Unit/SDU, at Olive View UCLA Medical Center.

References

- Bellomo R, Goldsmith D, Uchino S, et al. A prospective before-and-after trial of a medical emergency team. Med J Aust. 2003 Sep 15:179(6):283-287

- The Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s 100,000 Lives Campaign. Available at: www.ihi.org. Last accessed July 10, 2006.

- Leonard MS, Graham S, Taggart B. The human factor: effective teamwork and communication in patient strategy. In: Leonard M, Frankel A, Simmonds T, eds. Achieving safe and reliable health care strategies and solutions. 1st ed. ACHE Management Series; 2004. p.37-65.

- Schein RM, Hazday N, Pena M, et al. Clinical antecedents to in-hospital cardiopulmonary arrests. Chest. 1990;98:1388-1392.

- Franklin C, Matthew J. Developing strategies to prevent-in hospital cardiac arrest: analyzing responses of physicians and nurses in the hours before the event. Crit Care Med. 1994;22(2):244-247.

Doctors of the American Frontier

Discussions of the mid-19th century American physician often conjure up images of the surgeons of the Civil War who tirelessly plied their trade during battle: “During the rest of the night and early morning, he [amputated] arms below the elbow and legs below the knee in less than five minutes. The deep incision … the sweeping cut … pull back the soft parts to expose the bone … saw swiftly.”1

However, in the same period but some thousand miles west, frontier physicians faced similar battle wounds sustained in campaigns against American Indians, as well as a myriad of other duties. Some frontier physicians met these challenges with remarkable ingenuity, while others resorted to treatments later deemed quackery. They often practiced alone in the wilderness without a hospital or colleagues for support.

The first and most obvious task of a military physician on the frontier was to attend to soldiers wounded during battle. The first hurdle was reaching the soldier. In 1874, Surgeon George Miller Sternberg faced daunting challenges in aiding seriously wounded soldiers of General Oliver Otis Howard’s company after a melee with Chief Joseph’s Nez Percé tribe. As dark settled across Clearwater River, Idaho, “Surgeon George Miller Sternberg and an aide crawled out onto the battlefield looking for the wounded. They crept so close to the enemy that they could hear the Indians talking.”1 Dr. Sternberg worked tirelessly throughout the night ligating pulsing arteries and soothing the suffering soldiers with whatever means he had, from opium balls to whiskey. During the course of the evening, an American Indian sentinel spotted Dr. Sternberg’s lantern and shot it out, forcing Dr. Sternberg to continue his treatment in darkness.

In other conflicts, the frontier physician often found himself an active participant in a battle. In the Battle of the Lava Beds fought in Oregon in 1873, Dr. George Martin Kober received a gunshot wound in the arm during the course of the battle. Despite his wound he continued to “treat the wounded before he allowed Dr. Skinner to come to his relief.”1

In the Battle of Bates Creek, fought in the summer of 1874, Dr. Thomas Maghee “was the object of the direct fire of an Indian. Until, laying down his instruments for a moment, he took his carbine and killed the Indian and then returned quietly to his work.”1

When the battle concluded and the soldiers returned to camp, the physicians began to wage a fierce war with disease. Among the plagues that stalked the camps: cholera, scurvy, yellow fever, tuberculosis, and typhoid fever. On one occasion in 1874 cholera struck in the heat of the summer at Fort Riley in Kansas. The pestilence devastated the fort by swiftly taking the lives of dozens of soldiers and compelling a hundred more to desert the fort in fear. One ignorant physician attempted in vain to combat the disease by “burning barrels of pine tar beneath the open windows of the fort hospital.”1

Eventually, Dr. Sternberg conquered the outbreak by implementing a strict disinfection and isolation campaign. In the battle against scurvy, military physicians noted that the typical diet of “meat, white bread, soda biscuits, syrup, lard, and black coffee” was insufficient and often attempted to plant and harvest their own supply of vegetables to treat the vitamin C-deficient soldiers.1

The frontier physician’s duties often expanded outside of the realms of medicine because “by order of the Secretary of War they also studied weather, geography, plants, fauna, Indian customs, and antiquities.”1 In fulfilling these duties, physicians made remarkable contributions to the preservation of the history of the American West, such as Dr. James Kimball’s purchase of the autobiography of Sitting Bull. Indeed, life as a military physician on the American frontier tested the courage, durability, and ingenuity of the early American doctor. TH

John Bois is a second-year medical student at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minn.

Reference

- Dunlop R. Doctors of the American Frontier. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company; 1965: 73.

Discussions of the mid-19th century American physician often conjure up images of the surgeons of the Civil War who tirelessly plied their trade during battle: “During the rest of the night and early morning, he [amputated] arms below the elbow and legs below the knee in less than five minutes. The deep incision … the sweeping cut … pull back the soft parts to expose the bone … saw swiftly.”1

However, in the same period but some thousand miles west, frontier physicians faced similar battle wounds sustained in campaigns against American Indians, as well as a myriad of other duties. Some frontier physicians met these challenges with remarkable ingenuity, while others resorted to treatments later deemed quackery. They often practiced alone in the wilderness without a hospital or colleagues for support.

The first and most obvious task of a military physician on the frontier was to attend to soldiers wounded during battle. The first hurdle was reaching the soldier. In 1874, Surgeon George Miller Sternberg faced daunting challenges in aiding seriously wounded soldiers of General Oliver Otis Howard’s company after a melee with Chief Joseph’s Nez Percé tribe. As dark settled across Clearwater River, Idaho, “Surgeon George Miller Sternberg and an aide crawled out onto the battlefield looking for the wounded. They crept so close to the enemy that they could hear the Indians talking.”1 Dr. Sternberg worked tirelessly throughout the night ligating pulsing arteries and soothing the suffering soldiers with whatever means he had, from opium balls to whiskey. During the course of the evening, an American Indian sentinel spotted Dr. Sternberg’s lantern and shot it out, forcing Dr. Sternberg to continue his treatment in darkness.

In other conflicts, the frontier physician often found himself an active participant in a battle. In the Battle of the Lava Beds fought in Oregon in 1873, Dr. George Martin Kober received a gunshot wound in the arm during the course of the battle. Despite his wound he continued to “treat the wounded before he allowed Dr. Skinner to come to his relief.”1

In the Battle of Bates Creek, fought in the summer of 1874, Dr. Thomas Maghee “was the object of the direct fire of an Indian. Until, laying down his instruments for a moment, he took his carbine and killed the Indian and then returned quietly to his work.”1

When the battle concluded and the soldiers returned to camp, the physicians began to wage a fierce war with disease. Among the plagues that stalked the camps: cholera, scurvy, yellow fever, tuberculosis, and typhoid fever. On one occasion in 1874 cholera struck in the heat of the summer at Fort Riley in Kansas. The pestilence devastated the fort by swiftly taking the lives of dozens of soldiers and compelling a hundred more to desert the fort in fear. One ignorant physician attempted in vain to combat the disease by “burning barrels of pine tar beneath the open windows of the fort hospital.”1

Eventually, Dr. Sternberg conquered the outbreak by implementing a strict disinfection and isolation campaign. In the battle against scurvy, military physicians noted that the typical diet of “meat, white bread, soda biscuits, syrup, lard, and black coffee” was insufficient and often attempted to plant and harvest their own supply of vegetables to treat the vitamin C-deficient soldiers.1

The frontier physician’s duties often expanded outside of the realms of medicine because “by order of the Secretary of War they also studied weather, geography, plants, fauna, Indian customs, and antiquities.”1 In fulfilling these duties, physicians made remarkable contributions to the preservation of the history of the American West, such as Dr. James Kimball’s purchase of the autobiography of Sitting Bull. Indeed, life as a military physician on the American frontier tested the courage, durability, and ingenuity of the early American doctor. TH

John Bois is a second-year medical student at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minn.

Reference

- Dunlop R. Doctors of the American Frontier. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company; 1965: 73.

Discussions of the mid-19th century American physician often conjure up images of the surgeons of the Civil War who tirelessly plied their trade during battle: “During the rest of the night and early morning, he [amputated] arms below the elbow and legs below the knee in less than five minutes. The deep incision … the sweeping cut … pull back the soft parts to expose the bone … saw swiftly.”1

However, in the same period but some thousand miles west, frontier physicians faced similar battle wounds sustained in campaigns against American Indians, as well as a myriad of other duties. Some frontier physicians met these challenges with remarkable ingenuity, while others resorted to treatments later deemed quackery. They often practiced alone in the wilderness without a hospital or colleagues for support.

The first and most obvious task of a military physician on the frontier was to attend to soldiers wounded during battle. The first hurdle was reaching the soldier. In 1874, Surgeon George Miller Sternberg faced daunting challenges in aiding seriously wounded soldiers of General Oliver Otis Howard’s company after a melee with Chief Joseph’s Nez Percé tribe. As dark settled across Clearwater River, Idaho, “Surgeon George Miller Sternberg and an aide crawled out onto the battlefield looking for the wounded. They crept so close to the enemy that they could hear the Indians talking.”1 Dr. Sternberg worked tirelessly throughout the night ligating pulsing arteries and soothing the suffering soldiers with whatever means he had, from opium balls to whiskey. During the course of the evening, an American Indian sentinel spotted Dr. Sternberg’s lantern and shot it out, forcing Dr. Sternberg to continue his treatment in darkness.

In other conflicts, the frontier physician often found himself an active participant in a battle. In the Battle of the Lava Beds fought in Oregon in 1873, Dr. George Martin Kober received a gunshot wound in the arm during the course of the battle. Despite his wound he continued to “treat the wounded before he allowed Dr. Skinner to come to his relief.”1

In the Battle of Bates Creek, fought in the summer of 1874, Dr. Thomas Maghee “was the object of the direct fire of an Indian. Until, laying down his instruments for a moment, he took his carbine and killed the Indian and then returned quietly to his work.”1

When the battle concluded and the soldiers returned to camp, the physicians began to wage a fierce war with disease. Among the plagues that stalked the camps: cholera, scurvy, yellow fever, tuberculosis, and typhoid fever. On one occasion in 1874 cholera struck in the heat of the summer at Fort Riley in Kansas. The pestilence devastated the fort by swiftly taking the lives of dozens of soldiers and compelling a hundred more to desert the fort in fear. One ignorant physician attempted in vain to combat the disease by “burning barrels of pine tar beneath the open windows of the fort hospital.”1

Eventually, Dr. Sternberg conquered the outbreak by implementing a strict disinfection and isolation campaign. In the battle against scurvy, military physicians noted that the typical diet of “meat, white bread, soda biscuits, syrup, lard, and black coffee” was insufficient and often attempted to plant and harvest their own supply of vegetables to treat the vitamin C-deficient soldiers.1

The frontier physician’s duties often expanded outside of the realms of medicine because “by order of the Secretary of War they also studied weather, geography, plants, fauna, Indian customs, and antiquities.”1 In fulfilling these duties, physicians made remarkable contributions to the preservation of the history of the American West, such as Dr. James Kimball’s purchase of the autobiography of Sitting Bull. Indeed, life as a military physician on the American frontier tested the courage, durability, and ingenuity of the early American doctor. TH

John Bois is a second-year medical student at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minn.

Reference

- Dunlop R. Doctors of the American Frontier. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company; 1965: 73.

The Yuk Factor

Despite modern wound treatment and broad-spectrum antibiotic treatment, patients with chronic wounds still exist. The appearance of antibiotic resistant bacteria, such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in the 1980s and ’90s, gave rise to a search for other remedies. One of the remedies that has been rediscovered and subsequently successfully reintroduced is maggot debridement therapy (MDT).1 The fact that more than 100 articles were published on the subject in the past two decades indicates that the use of maggots is making a strong comeback in medicine.2 In January 2004, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued 510(k)#33391, allowing production and marketing of maggots as a medical device. In this article, we discuss the use of MDT in patients with a chronic wound.

A Long History of Maggot Therapy

MDT has been used in many cultures and has been known for centuries.3 Ambroise Parè is credited as the father of modern MDT. Unfortunately, no evidence can be found of Parè using maggots as a means to clean or heal wounds. The only reference is the often-cited case that occurred in 1557 at the battle of St. Quentin, when Parè observed soldiers whose wounds were covered by maggots. He mainly described the negative effects of the maggots, and, above all, believed they were spontaneously produced by the wound itself, not by the eggs of fly.4

Baron Larey (1766-1842) a famous surgeon in the army of Napoleon Bonaparte, wrote about soldiers who had larvae-infested wounds, but was frustrated that it was difficult to persuade his patients to leave the maggots in place, believing that “they promoted healing without leaving any damage.”5

The first surgeon to use MDT in patients in the hospital was the orthopedic surgeon William Baer. In the 1920s he was faced with a group of untreatable patients with severe osteomyelitis (antibiotics had not yet been discovered). He successfully treated many patients with maggots, and because of his success the therapy became regularly used in the United States.6

By 1934 more than 1,000 surgeons were using maggot therapy. Surgical Maggots were available commercially from Lederle Corporation.7 But with the introduction of antibiotics in the 1940s, the use of maggots dropped off. In the following years, case reports were published only occasionally.

The Negative Image of Maggots

A large problem of MDT is the difficulty of this type of therapy to gain acceptance in the medical community. Maggots are associated with rotting and decay. The image is of filthy, low-life creatures that are ugly and disgusting. Although a nice recent example for the general public is the scene in the movie Gladiator. The main character (played by Russell Crow) is advised to leave the maggots that spontaneously infested a wound on his shoulder in place so that the wound would heal. He leaves them in place and the wound heals without any problem, enabling Crow’s character to fight many battles.

In contrast, in an oral presentation we held recently at a Dutch scientific surgical meeting, a surgical professor in the audience said, “I will never allow those creatures in my ward.”8 This remark shows that widespread use and acceptance of MDT has not yet been reached. It seems there is still much work to do before MDT is generally accepted as a therapeutic method.

Fortunately, the negative image that seems to exist among nurses and physicians does not seem to bother patients.9 We have treated more than 100 patients in our clinic with MDT. All patients to whom we proposed MDT agreed to the therapy. All were allowed to discontinue the therapy whenever they wanted; none did. In a survey of the first 38 MDT-treated patients, 89% agreed to another session of MDT if the surgeon believed it would be beneficial, and 94% of the patients said that they would recommend it to others. This is despite the fact that the therapy was not successful in all patients (there was a below-knee of above the knee amputation-rate of 19% among patients who underwent MDT).10

Indications and Evidence

Indications and contra-indications for maggot therapy are not well defined. Some state that all kind of wounds that contain necrosis or slough can be good candidates for MDT. In our own study of 101 patients with 116 wounds treated with maggots, we had an overall success rate of 67%. (Seventy-eight out of 116 wounds had a beneficial outcome.) However, in 13 patients with septic arthritis, all wounds failed. Success rates where significantly reduced in cases of chronic limb ischemia, visible tendon or bone, and in cases of duration longer than three months before the start of MDT.11

Most physicians who start MDT use it mainly for worst-case scenarios. From our previous studies, it is clear that success rates in those patients are low. After witnessing a few failures, the physician is naturally reluctant to use it again.

What about evidence? Large randomized studies are lacking, although one containing 600 venous ulcer patients was initiated in 2004.12 There have been three randomized studies performed. Wayman, et al., have shown the cost-effectiveness of larval therapy in venous ulcers compared with hydrogel dressing.13 Contreras, et al., could not find a difference between MDT and curettage and topical silver sulfadiazine in patients with venous leg ulcers.14 At the 36th annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, Markevich, et al., reported on a randomized, multicenter, double-blind controlled clinical trial (n=140) for neuropathic diabetic foot lesions compared to conventional treatment. They found a significant higher percentage of granulation tissue after 10 days, compared with the hydrogel group.15 Results from large case-series indicate that MDT works and could even save limbs.2,16-18 The mechanism of action has not been unraveled yet.

Factors Influencing Effectiveness of MDT

Unfortunately, the statement made by Thomas, who said that maggot therapy works by “secreting proteolytic enzymes that break down dead tissue, turning it into a soup, which they then ingest,” still holds.19 It is known that there are mechanical effects, tissue growth effects, that direct killing of bacteria in the alimentary tract of the maggot takes place, and that maggots produce antibacterial factors.2,17,20-31

Although maggots are suitable agents for chronic wound treatment, it is likely that some wounds are more eligible than others for this type of treatment. In our opinion, all wounds that contain gangrenous or necrotic tissue with infection seem to be suited for MDT.32 Success rates of MDT reported in literature vary, but seem to be around 80% to 90%.16,17,33 In our own series, success rate is about 70%.

Patient-selection (case-mix) and method of outcome measurement play essential roles in these percentages. In our opinion, all wounds that contain necrotic tissue can be debrided effectively with MDT. However, if for example wound ischemia is the major etiologic factor, this should also be addressed. In our experience, diabetic foot, venous ulcers, traumatic ulcers, and infections after surgical procedures are all good candidates for MDT.

Absolute contraindications in our opinion are wounds close to large, uncovered blood vessels and wounds that need immediate surgical debridement (e.g., in the case of a septic patient). A relative contraindication is patients with natural of medically induced coagulopathies, but also patient preference could play a role.34 We have had very bad results with infected small joints of the foot; all wounds (n=13) eventually needed a small or large amputation.

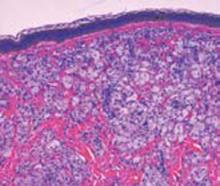

Even the technique of application has an effect on outcome. There are two different application techniques: the free-range and the contained technique. The free-range technique is more effective in vitro and in-vivo and has become our standard application technique—not only in the outpatient department, but also in the intra-mural setting.35,36 (Figure 1, p. 16, shows a patient with a necrotic wound on the leg after radiation therapy and a surgical excision for a malignant tumor was performed.) Earlier surgical debridement combined with split skin graft failed. After four applications of maggots, the wound was free of necrosis and could be subsequently closed. (See Figure 2, p. 16.)

The contained technique is used in patients with bleeding tendencies and wounds that do not have enough healthy skin surrounding the wound; in other words, where the covering “cage” needed in case of the free-range technique can’t be applied. (This problem is shown in Figure 3, p. 16: A patient with necrotizing fasciitis of the left upper leg was treated with the contained technique—BiologiQ, Apeldoorn, Netherlands—as there is no proximal skin border. Of course, patient preference plays a role as well in the choice of application technique.37

Wound Clinic

In the Netherlands maggots can be ordered easily and are delivered within 24 hours. We started a wound clinic in 2002. First it was for MDT alone, but now the scope is broader, and we treat chronic wounds with different kind of wound therapies. We have two nurses, one nurse practitioner, one resident-surgeon, and one vascular surgeon who apply the maggots.

Patients do not need to be admitted for MDT. Fifty-nine percent of our patients are treated in the outpatient department. We are able to treat as many as 10 or 15 patients in one session, but MDT-treated patients make up only two or three patients at a time.

We found that after fast, successful biological debridement with MDT we were left with a lot of patients with red, granulating wounds that needed our attention in order to prevent relapses. In our opinion, there are many different treatment methods after MDT. Plaster casting in case of diabetic feet, secondary closure, and split skin grafting are different methods. However, other therapies like VAC-therapy and recently OASIS are promising.

At this time, all patients are prospectively followed after MDT. We are especially interested in patient selection and are now also aiming to find the ideal wound therapy after MDT. TH

Dr. Steenvoorde is a resident surgeon at Rijnland Hospital Leiderdorp, the Netherlands. van Doorn is a nurse-practitioner at Rijnland Hospital Leiderdorp. Jacobi is a senior researcher in the Medical Decision Department at Leiden University Medical Center, in the Netherlands. Dr. Oskam is a vascular surgeon at Rijnland Hospital Leiderdorp.

References

- Beasley WD, Hirst G. Making a meal of MRSA-the role of biosurgery inhospital-acquired infection. J Hosp Infect. 2004;56(1):6-9.

- Jukema GN, Menon AG, Bernards AT. et al. Amputation-sparing treatment by nature: “surgical” maggots revisited. Clin Infect Dis. 2002 Dec 15;35(12):1566-1571.

- Church JC. The traditional use of maggots in wound healing, and the development of larva therapy (biosurgery) in modern medicine. J Altern Complement Med. 1996 Winter;2(4):525-527.

- Coppi C. I dressed your wounds, God healed you—a wounded person’s psychology according to Ambroise Parè. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2005;51:62-64.

- Goldstein HI. Maggots in the treatment of wound and bone infections. J Bone Joint Surg. 1931;13:476-478.

- Baer WS. The treatment of chronic osteomyelitis with the maggot (larva of the blow fly). J Bone Joint Surg. 1931;13:438-475.

- Puckner WA. New and nonofficial remedies, surgical maggots-Lederle. J Am Med Assoc. 1932;98(5):401.

- Steenvoorde P, Doorn Lv, Jacobi CE, et al. Maggot therapy: retrospective study comparing two different application-techniques. (Dutch). Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Heelkunde. 2006;15:86.

- Contreras RJ, Fuentes SA, Karam-Orantes M, et al. Larval debridement therapy in Mexico. Wound Care Canada. 2005;3:42-46.

- Steenvoorde P, Budding TJ, Engeland Av, et al. Maggot therapy and the “yuk factor”: an issue for the patient? Wound Repair Regen. 2005 May-Jun;13(3):350-352.

- Steenvoorde P, Jacobi CA, Doorn Lv, et al. Maggot debridement therapy of infected ulcers: patient and wound factors influencing outcome. Ann Royal Coll Surg Eng. 2006.

- Raynor P, Dumville J, Cullum N. A new clinical trial of the effect of larval therapy. J Tissue Viability. 2004 Jul;14(3):104-105.

- Wayman J, Nirojogi V, Walker A, et al. The cost effectiveness of larval therapy in venous ulcers. J Tissue Viability. 2001 Jan;11(1):51.

- Contreras RJ, Fuentes SA, Arroyo ES, et al. Larval debridement therapy and infection control in venous ulcers: a comparative study. Presented at: the Second World Union of Wound Healing Societies Meeting; July 8-13, 2004.

- Markevich YO, McLeod-Roberts J, Mousley M, et al. Maggot therapy for diabetic neuropathic foot wounds: a randomized study. Presented at: the 36th Annual Meeting of the EASD; September 17-21, 2000. Ref Type: Conference Proceeding.

- Wolff H, Hansson C. Larval therapy—an effective method for ulcer debridement. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:137.

- Mumcuoglu KY, Ingber A, Gilead L, et al. Maggot therapy for the treatment of intractable wounds. Int J Dermatol. 1999 Aug;38(8):623-627.

- Courtenay M. The use of larval therapy in wound management in the UK. J Wound Care. 1999 Apr;8 (4):177-179.

- Bonn D. Maggot therapy: an alternative for wound infection. Lancet. 2000 Sep 30;356 (9236):1174.

- Robinson W. Stimulation of healing in non-healing wounds. J Bone Joint Surgery. 1935;17:267-271.

- Robinson W. Ammonium bicarbonate secreted by surgical maggots stimulates healing in purulent wounds. Am J Surg. 1940;47:111-115.

- Mumcuoglu KY, Ingber A, Gilead L, et al. Maggot therapy for the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetes Care. 1998 Nov;21(11):2030-2031.

- Simmons S. A bactericidal principle in excretions of surgical maggots which destroys important etiological agents of pyogenic infections. J Bacteriol. 1935;30:253-267.

- Simmons S. The bactericidal properties of excretions of the maggot of Lucilia sericata. Bull Entomol Res. 1935;26:559-563.

- Mumcuoglu KY. Clinical applications for maggots in wound care. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2001;2:219-227.

- Armstrong DG, Short B, Martin BR, et al. Maggot therapy in lower extremity hospice wound care. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2005;95(3):254-257.

- Robinson W, Norwood VH. The role of surgical maggots in the disinfection of osteomyelitis and other infected wounds. J Bone Joint Surgery. 1933;15:409-412.

- Robinson W, Norwood VH. Destruction of pyogenic bacteria in the alimentary tract of surgical maggots implanted in infected wounds. J Lab Clin Med. 1933;19:581-585.

- Mumcuoglu KY, Miller J, Mumcuoglu M. et al. Destruction of bacteria in the digestive tract of the maggot of Lucilia sericata (Diptera: Calliphoridae). J Med Entomol. 2001 Mar;38(2):161-166.

- Sherman RA, Hall MJ, Thomas S. Medicinal maggots: an ancient remedy for some contemporary afflictions. Annu Rev Entomol. 2000;45:55-81.

- Prete PE. Growth effects of Phaenicia sericata larval extracts on fibroblasts: mechanism for wound healing by maggot therapy. Life Sci. 1997;60(8):505-510.

- Church JCT, Courtenay M. Maggot debridement therapy for chronic wounds. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2002 Jun;1(2):129-134.

- Courtenay M, Church JC, Ryan TJ. Larva therapy in wound management. J R Soc Med. 2000 Feb;93:72-74.

- 34. Steenvoorde P, Oskam J. Bleeding c omplications in patients treated with maggot debridement therapy (MDT). Letter to the editor. IJLEW. 2005;4:57-58.

- Thomas S, Wynn K, Fowler T, et al. The effect of containment on the properties of sterile maggots. Br J Nurs. 2002 Jun;11(12 Suppl):S21-S22, S24, S26 passim.

- Steenvoorde P, Jacobi CE, Oskam J. Maggot debridement therapy: free-range or contained? An in-vivo study. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2005;18:430-435.

- Steenvoorde P, Oskam J. Use of larval therapy to combat infection after breast-conserving surgery. J Wound Care. 2005 May;14(5):212-213.

Despite modern wound treatment and broad-spectrum antibiotic treatment, patients with chronic wounds still exist. The appearance of antibiotic resistant bacteria, such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in the 1980s and ’90s, gave rise to a search for other remedies. One of the remedies that has been rediscovered and subsequently successfully reintroduced is maggot debridement therapy (MDT).1 The fact that more than 100 articles were published on the subject in the past two decades indicates that the use of maggots is making a strong comeback in medicine.2 In January 2004, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued 510(k)#33391, allowing production and marketing of maggots as a medical device. In this article, we discuss the use of MDT in patients with a chronic wound.

A Long History of Maggot Therapy

MDT has been used in many cultures and has been known for centuries.3 Ambroise Parè is credited as the father of modern MDT. Unfortunately, no evidence can be found of Parè using maggots as a means to clean or heal wounds. The only reference is the often-cited case that occurred in 1557 at the battle of St. Quentin, when Parè observed soldiers whose wounds were covered by maggots. He mainly described the negative effects of the maggots, and, above all, believed they were spontaneously produced by the wound itself, not by the eggs of fly.4

Baron Larey (1766-1842) a famous surgeon in the army of Napoleon Bonaparte, wrote about soldiers who had larvae-infested wounds, but was frustrated that it was difficult to persuade his patients to leave the maggots in place, believing that “they promoted healing without leaving any damage.”5

The first surgeon to use MDT in patients in the hospital was the orthopedic surgeon William Baer. In the 1920s he was faced with a group of untreatable patients with severe osteomyelitis (antibiotics had not yet been discovered). He successfully treated many patients with maggots, and because of his success the therapy became regularly used in the United States.6

By 1934 more than 1,000 surgeons were using maggot therapy. Surgical Maggots were available commercially from Lederle Corporation.7 But with the introduction of antibiotics in the 1940s, the use of maggots dropped off. In the following years, case reports were published only occasionally.

The Negative Image of Maggots

A large problem of MDT is the difficulty of this type of therapy to gain acceptance in the medical community. Maggots are associated with rotting and decay. The image is of filthy, low-life creatures that are ugly and disgusting. Although a nice recent example for the general public is the scene in the movie Gladiator. The main character (played by Russell Crow) is advised to leave the maggots that spontaneously infested a wound on his shoulder in place so that the wound would heal. He leaves them in place and the wound heals without any problem, enabling Crow’s character to fight many battles.

In contrast, in an oral presentation we held recently at a Dutch scientific surgical meeting, a surgical professor in the audience said, “I will never allow those creatures in my ward.”8 This remark shows that widespread use and acceptance of MDT has not yet been reached. It seems there is still much work to do before MDT is generally accepted as a therapeutic method.

Fortunately, the negative image that seems to exist among nurses and physicians does not seem to bother patients.9 We have treated more than 100 patients in our clinic with MDT. All patients to whom we proposed MDT agreed to the therapy. All were allowed to discontinue the therapy whenever they wanted; none did. In a survey of the first 38 MDT-treated patients, 89% agreed to another session of MDT if the surgeon believed it would be beneficial, and 94% of the patients said that they would recommend it to others. This is despite the fact that the therapy was not successful in all patients (there was a below-knee of above the knee amputation-rate of 19% among patients who underwent MDT).10

Indications and Evidence

Indications and contra-indications for maggot therapy are not well defined. Some state that all kind of wounds that contain necrosis or slough can be good candidates for MDT. In our own study of 101 patients with 116 wounds treated with maggots, we had an overall success rate of 67%. (Seventy-eight out of 116 wounds had a beneficial outcome.) However, in 13 patients with septic arthritis, all wounds failed. Success rates where significantly reduced in cases of chronic limb ischemia, visible tendon or bone, and in cases of duration longer than three months before the start of MDT.11

Most physicians who start MDT use it mainly for worst-case scenarios. From our previous studies, it is clear that success rates in those patients are low. After witnessing a few failures, the physician is naturally reluctant to use it again.

What about evidence? Large randomized studies are lacking, although one containing 600 venous ulcer patients was initiated in 2004.12 There have been three randomized studies performed. Wayman, et al., have shown the cost-effectiveness of larval therapy in venous ulcers compared with hydrogel dressing.13 Contreras, et al., could not find a difference between MDT and curettage and topical silver sulfadiazine in patients with venous leg ulcers.14 At the 36th annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, Markevich, et al., reported on a randomized, multicenter, double-blind controlled clinical trial (n=140) for neuropathic diabetic foot lesions compared to conventional treatment. They found a significant higher percentage of granulation tissue after 10 days, compared with the hydrogel group.15 Results from large case-series indicate that MDT works and could even save limbs.2,16-18 The mechanism of action has not been unraveled yet.

Factors Influencing Effectiveness of MDT

Unfortunately, the statement made by Thomas, who said that maggot therapy works by “secreting proteolytic enzymes that break down dead tissue, turning it into a soup, which they then ingest,” still holds.19 It is known that there are mechanical effects, tissue growth effects, that direct killing of bacteria in the alimentary tract of the maggot takes place, and that maggots produce antibacterial factors.2,17,20-31

Although maggots are suitable agents for chronic wound treatment, it is likely that some wounds are more eligible than others for this type of treatment. In our opinion, all wounds that contain gangrenous or necrotic tissue with infection seem to be suited for MDT.32 Success rates of MDT reported in literature vary, but seem to be around 80% to 90%.16,17,33 In our own series, success rate is about 70%.

Patient-selection (case-mix) and method of outcome measurement play essential roles in these percentages. In our opinion, all wounds that contain necrotic tissue can be debrided effectively with MDT. However, if for example wound ischemia is the major etiologic factor, this should also be addressed. In our experience, diabetic foot, venous ulcers, traumatic ulcers, and infections after surgical procedures are all good candidates for MDT.

Absolute contraindications in our opinion are wounds close to large, uncovered blood vessels and wounds that need immediate surgical debridement (e.g., in the case of a septic patient). A relative contraindication is patients with natural of medically induced coagulopathies, but also patient preference could play a role.34 We have had very bad results with infected small joints of the foot; all wounds (n=13) eventually needed a small or large amputation.

Even the technique of application has an effect on outcome. There are two different application techniques: the free-range and the contained technique. The free-range technique is more effective in vitro and in-vivo and has become our standard application technique—not only in the outpatient department, but also in the intra-mural setting.35,36 (Figure 1, p. 16, shows a patient with a necrotic wound on the leg after radiation therapy and a surgical excision for a malignant tumor was performed.) Earlier surgical debridement combined with split skin graft failed. After four applications of maggots, the wound was free of necrosis and could be subsequently closed. (See Figure 2, p. 16.)

The contained technique is used in patients with bleeding tendencies and wounds that do not have enough healthy skin surrounding the wound; in other words, where the covering “cage” needed in case of the free-range technique can’t be applied. (This problem is shown in Figure 3, p. 16: A patient with necrotizing fasciitis of the left upper leg was treated with the contained technique—BiologiQ, Apeldoorn, Netherlands—as there is no proximal skin border. Of course, patient preference plays a role as well in the choice of application technique.37

Wound Clinic

In the Netherlands maggots can be ordered easily and are delivered within 24 hours. We started a wound clinic in 2002. First it was for MDT alone, but now the scope is broader, and we treat chronic wounds with different kind of wound therapies. We have two nurses, one nurse practitioner, one resident-surgeon, and one vascular surgeon who apply the maggots.

Patients do not need to be admitted for MDT. Fifty-nine percent of our patients are treated in the outpatient department. We are able to treat as many as 10 or 15 patients in one session, but MDT-treated patients make up only two or three patients at a time.

We found that after fast, successful biological debridement with MDT we were left with a lot of patients with red, granulating wounds that needed our attention in order to prevent relapses. In our opinion, there are many different treatment methods after MDT. Plaster casting in case of diabetic feet, secondary closure, and split skin grafting are different methods. However, other therapies like VAC-therapy and recently OASIS are promising.

At this time, all patients are prospectively followed after MDT. We are especially interested in patient selection and are now also aiming to find the ideal wound therapy after MDT. TH

Dr. Steenvoorde is a resident surgeon at Rijnland Hospital Leiderdorp, the Netherlands. van Doorn is a nurse-practitioner at Rijnland Hospital Leiderdorp. Jacobi is a senior researcher in the Medical Decision Department at Leiden University Medical Center, in the Netherlands. Dr. Oskam is a vascular surgeon at Rijnland Hospital Leiderdorp.

References

- Beasley WD, Hirst G. Making a meal of MRSA-the role of biosurgery inhospital-acquired infection. J Hosp Infect. 2004;56(1):6-9.

- Jukema GN, Menon AG, Bernards AT. et al. Amputation-sparing treatment by nature: “surgical” maggots revisited. Clin Infect Dis. 2002 Dec 15;35(12):1566-1571.

- Church JC. The traditional use of maggots in wound healing, and the development of larva therapy (biosurgery) in modern medicine. J Altern Complement Med. 1996 Winter;2(4):525-527.

- Coppi C. I dressed your wounds, God healed you—a wounded person’s psychology according to Ambroise Parè. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2005;51:62-64.

- Goldstein HI. Maggots in the treatment of wound and bone infections. J Bone Joint Surg. 1931;13:476-478.

- Baer WS. The treatment of chronic osteomyelitis with the maggot (larva of the blow fly). J Bone Joint Surg. 1931;13:438-475.

- Puckner WA. New and nonofficial remedies, surgical maggots-Lederle. J Am Med Assoc. 1932;98(5):401.

- Steenvoorde P, Doorn Lv, Jacobi CE, et al. Maggot therapy: retrospective study comparing two different application-techniques. (Dutch). Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Heelkunde. 2006;15:86.

- Contreras RJ, Fuentes SA, Karam-Orantes M, et al. Larval debridement therapy in Mexico. Wound Care Canada. 2005;3:42-46.

- Steenvoorde P, Budding TJ, Engeland Av, et al. Maggot therapy and the “yuk factor”: an issue for the patient? Wound Repair Regen. 2005 May-Jun;13(3):350-352.

- Steenvoorde P, Jacobi CA, Doorn Lv, et al. Maggot debridement therapy of infected ulcers: patient and wound factors influencing outcome. Ann Royal Coll Surg Eng. 2006.

- Raynor P, Dumville J, Cullum N. A new clinical trial of the effect of larval therapy. J Tissue Viability. 2004 Jul;14(3):104-105.

- Wayman J, Nirojogi V, Walker A, et al. The cost effectiveness of larval therapy in venous ulcers. J Tissue Viability. 2001 Jan;11(1):51.

- Contreras RJ, Fuentes SA, Arroyo ES, et al. Larval debridement therapy and infection control in venous ulcers: a comparative study. Presented at: the Second World Union of Wound Healing Societies Meeting; July 8-13, 2004.

- Markevich YO, McLeod-Roberts J, Mousley M, et al. Maggot therapy for diabetic neuropathic foot wounds: a randomized study. Presented at: the 36th Annual Meeting of the EASD; September 17-21, 2000. Ref Type: Conference Proceeding.

- Wolff H, Hansson C. Larval therapy—an effective method for ulcer debridement. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:137.

- Mumcuoglu KY, Ingber A, Gilead L, et al. Maggot therapy for the treatment of intractable wounds. Int J Dermatol. 1999 Aug;38(8):623-627.

- Courtenay M. The use of larval therapy in wound management in the UK. J Wound Care. 1999 Apr;8 (4):177-179.