User login

Universal acceptance of computerized physician order entry: What would it take?

Self‐check‐in kiosks started to appear in airports in the late 1990s, and within a few years, they seem to have become ubiquitous in the airline industry. Today, almost 70% of business travelers use them, and other sectors of the travel industry are beginning to experiment with the technology.1 Compared to this innovation in the airline industry, adoption of computerized physician order entry (CPOE) in U.S. hospitals, first pioneered in the early 1970s,2, 3 has taken a much more leisurely pace. Despite numerous studies documenting its benefits,47 promotion by prominent national patient safety advocacy groups such as LeapFrog,8 and numerous guides on best adoption practices.912 fewer than 10% of U.S. hospitals have fully adopted this technology.13 Moreover, as Lindenauer et al.14 pointed out, most hospitals that have successfully implemented CPOE are academic medical centers that rely on house staff to enter orders. With notable exceptions,3 adoption of CPOE in community hospitals where attending physicians write most orders remains anemic.

Although an increasing number of scholarly articles has documented the reasons for this slow rate of adoption even in hospitals that have the resources to invest in this technology, much of that research is based on expert opinion and case studies.11, 1519 In this context, Lindenauer et al.14 should be commended for using empirical evidence to delineate the predictors of adoption. Lindenauer et al. found that physicians who trained in hospitals with CPOE were more likely to be frequent users of CPOE in their new environment. Although the analysis did not account for possible confounding such as employment status of the physician, this result does confirm the conventional wisdom that physicians‐in‐training are more malleable and that residency is an important opportunity to expose physicians to safety technologies. If this finding is borne out by further research, it would bode well for the adoption of CPOE, as many physicians are trained in academic institutions, which are more likely to have CPOE,20 and almost all physicians spend part of their training in a VA hospital, which has uniformly adopted CPOE. Similarly, Lindenauer et al. found that physicians who use computers for personal purposes are more likely to be frequent users of CPOE. Given the increasingly ubiquitous use of computers in all spheres of life, time is on the side of increasing acceptance of CPOE.

However, a closer examination of the data presented by Lindenauer et al. raises several concerns. First, the substantial number of infrequent users across all demographic subgroups and clinical disciplines, even among users who were exposed to CPOE during training or those who used computers regularly for personal purposes, highlights the absence of shortcuts to the universal acceptance of CPOE. Second, whereas 63% of surveyed physicians believed that CPOE would reduce the incidence of medication errors and 71% believed that CPOE would prevent aspects of care from slipping through the cracks, only 42% of the surveyed physicians were frequent users of CPOE. This implies that even when physicians believe in the safety and quality benefits of CPOE, that belief alone may not be sufficient to convince all of them to adopt this technology wholeheartedly; other factors such as speed, ease of use, and training are likely important prerequisites. Third, although 66% of orders placed in person at the 2 study hospitals were entered through CPOE, acceptance of this technology, as measured by Lindenauer et al, was moderate at both institutions. This suggests that even when organizations have reached the 70% threshold set by Leapfrog as the proportion of orders placed in CPOE that qualifies as full implementation, they may continue to face resistance to full acceptance of the technology.

Compared to their academic counterparts, community hospitals face additional hurdles as they implement CPOE. Not only does their smaller size make it difficult to achieve economies of scale, they are also at a disadvantage because of the relationship the community hospital has with its physicians. Unlike physicians‐in‐training in academic medical centers, physicians in community hospitals function as largely autonomous agents over whom the hospital administration has little control. Although these physicians and their hospitals share the common goals of patient safety and quality, the financial incentives for the adoption of CPOE are often misaligned. For example, a recent cost benefit analysis21 showed the enormous potential for hospitals to cut costs if physicians fully adopt a CPOE system with rich decision support features. However, those savings typically accrue to the hospital, not to the physicians who use the system. Assuming the typical learning curve that accompanies the use of any new technology, physicians in community hospitals may have little incentive to invest the time to learn to use the system efficiently.

So what can be done to overcome these seemingly formidable barriers to full adoption of CPOE? Emerging research, which has so far largely focused on CPOE implementation at academic hospitals, suggests there is no silver bullet. Instead, it has taught us how the complex interplay among vendor capability, organizational behavior, clinician work flow, and implementation strategy determines the success or failure of adoption.11, 17, 18, 22 Although physician characteristics will play a role in determining whether an individual adopts this technology, local factors such as the presence of champions, governance model for the project, support for staff throughout the process, and relationship between administration and physicians are likely important determinants of success at both academic and community hospitals. In addition, organizations that embark on CPOE implementation need to understand the enormity of the task at hand and must devote not only sufficient financial but also human capital over time.11, 18 In the words of a chief medical information officer, Implementing CPOE should not be thought of as an event, but a long‐term commitment.

Beyond following proposed best practices for the implementation of CPOE, community hospitals may need to adopt additional strategies to address their unique challenges. Given the misalignment of incentives for physicians' use of CPOE, leadership in community hospitals must be particularly skilled at articulating the benefits of CPOE to physicians. These benefits include not only decreased professional liability from improved patient safety and better quality of care, but also fewer pharmacy callbacks, remote access, and rapid ordering through order sets. Hospitals may also want to elicit support from physicians early by empowering them to create order sets for their disciplines. Mechanisms for hospitals and physicians to engage in mutual cost‐sharing arrangements may provide addition opportunities for hospitals to entice physicians to adopt the technology. Finally, and of particular interest to the readership of this journal, as hospitalists become more prevalent and take care of an increasing proportion of hospitalized patients,23 they are often ideal candidates to lead the implementation of CPOE in community hospitals. Because hospitalists spend most of their time in the hospital, they are often in the best position to get fully trained on CPOE, to define their own order sets, and to redesign care processes in order to take full advantage of CPOE capabilities. In addition, as many hospitalists are directly employed or supported by the hospital, their goals for quality, safety, and efficiency are usually better aligned with those of the hospital.

The stakes involved in implementing CPOE are high. Hospitals invest enormous sums of money in these systems, and many will not have the financial or political capital to attempt a second implementation after an initial failure. In addition, as recent research has pointed out,24 inappropriate implementation strategies may lead to delays in essential care and direct patient harm. In many ways, the complex task of implementing CPOE is not unlike other endeavors in patient care, where optimal outcomes require sound knowledge and reliable processes and where disaster can strike for lack of attention to detail or common sense. If Hippocrates were alive today, he might have this to say about CPOE implementation: Life is short, the art long, opportunity fleeting, experience treacherous, judgment difficult.

- Travel self‐serve kiosks here to stay.Adelman Group. Available at: http://www.adelmantravel.com/index_news_past.asp?Date=031406. Accessed March 14,2006.

- ,.Computer‐based physician order entry: the state of the art.J Am Med Inform Assoc.1994;1:108–123.

- ,,,.Final report on evaluation of the implementation of a medical information system in a general community hospital.Battelle Laboratories NTIS PB.1975;248:340.

- ,,, et al.Effect of computerized physician order entry and a team intervention on prevention of serious medication errors.JAMA.1998;280:1311–1316.

- ,,,,,.Effects of computerized physician order entry in prescribing practices.Arch Intern Med.2000;160:2741–2747.

- ,,,,,.A computerized reminder system to increase the use of preventive care for hospitalized patients [see comments].N Eng J M.2001;345:965–970.

- ,,,.A randomized trial of “corollary orders” to prevent errors of omission.J Am Med Inform Assoc.1997;4:364–75.

- The Leapfrog Group for Patient Safety: Rewarding Higher Standards.2001. Available at: www.leapfroggroup.org.

- ,,,,,.Understanding hospital readiness for computerized physician order entry.Jt Comm J Qual Saf.2003;29:336–344.

- ,,,,.Antecedents of the people and organizational aspects of medical informatics: review of the literature.J Am Med Informatics Assoc.1997;4:79–93.

- ,,.A consensus statement on considerations for a successful CPOE implementation.J Am Med Informatics Assoc.2003;10:229–234.

- AHA Guide to Computerized Physician Order‐Entry Systems.American Hospital Association:Chicago;2000.

- ,,,.Computerized physician order entry in US hospitals: results of a 2002 survey.J Am Med Inform Assoc.2004;11:95–99.

- ,,, et al.Physician characteristics, attitudes, and use of computerized order entry.J Hosp Med.2006;1:.

- ,.Computerized physician order entry systems in hospitals: mandates and incentives.Health Aff,2002;21(4):180–188.

- ,,.The use of computers for clinical care: a case series of advanced U.S. sites.J Am Med Inform Assoc.2003;10:94–107.

- ,,.Some unintended consequences of information technology in health care: the nature of patient care information system‐related errors.J Am Med Inform Assoc.2003;21:104–112.

- ,,,,,.Overcoming the barriers to implementing computerized physician order entry systems in US hospitals: perspectives from senior management.Health Aff.2004;23(4):184–190.

- ,,.Understanding Implementation: The case of a computerized physician order entry system in a large Dutch university medical cneter.J Am Med Inform Assoc.2004;11:207–216.

- ,,.U.S. adoption of computerized physician order entry systems.Health Aff.2005;24:1654–1663.

- ,,, et al.Return on investment for a computerized physician order entry system.J Am Med Inform Assoc.2006;13:261–266.

- ,,,.A diffusion of innovations model of physician order entry.AMIA Annu Symp Proc.2001;2001:22–26.

- ,,,.The status of hospital medicine groups in the United States.J Hosp Med.2006;1:75–80.

- ,,, et al.Unexpected increased mortality after implementation of a commercially sold computerized physician order entry system.Pediatrics.2005;116:1506–1512.

Self‐check‐in kiosks started to appear in airports in the late 1990s, and within a few years, they seem to have become ubiquitous in the airline industry. Today, almost 70% of business travelers use them, and other sectors of the travel industry are beginning to experiment with the technology.1 Compared to this innovation in the airline industry, adoption of computerized physician order entry (CPOE) in U.S. hospitals, first pioneered in the early 1970s,2, 3 has taken a much more leisurely pace. Despite numerous studies documenting its benefits,47 promotion by prominent national patient safety advocacy groups such as LeapFrog,8 and numerous guides on best adoption practices.912 fewer than 10% of U.S. hospitals have fully adopted this technology.13 Moreover, as Lindenauer et al.14 pointed out, most hospitals that have successfully implemented CPOE are academic medical centers that rely on house staff to enter orders. With notable exceptions,3 adoption of CPOE in community hospitals where attending physicians write most orders remains anemic.

Although an increasing number of scholarly articles has documented the reasons for this slow rate of adoption even in hospitals that have the resources to invest in this technology, much of that research is based on expert opinion and case studies.11, 1519 In this context, Lindenauer et al.14 should be commended for using empirical evidence to delineate the predictors of adoption. Lindenauer et al. found that physicians who trained in hospitals with CPOE were more likely to be frequent users of CPOE in their new environment. Although the analysis did not account for possible confounding such as employment status of the physician, this result does confirm the conventional wisdom that physicians‐in‐training are more malleable and that residency is an important opportunity to expose physicians to safety technologies. If this finding is borne out by further research, it would bode well for the adoption of CPOE, as many physicians are trained in academic institutions, which are more likely to have CPOE,20 and almost all physicians spend part of their training in a VA hospital, which has uniformly adopted CPOE. Similarly, Lindenauer et al. found that physicians who use computers for personal purposes are more likely to be frequent users of CPOE. Given the increasingly ubiquitous use of computers in all spheres of life, time is on the side of increasing acceptance of CPOE.

However, a closer examination of the data presented by Lindenauer et al. raises several concerns. First, the substantial number of infrequent users across all demographic subgroups and clinical disciplines, even among users who were exposed to CPOE during training or those who used computers regularly for personal purposes, highlights the absence of shortcuts to the universal acceptance of CPOE. Second, whereas 63% of surveyed physicians believed that CPOE would reduce the incidence of medication errors and 71% believed that CPOE would prevent aspects of care from slipping through the cracks, only 42% of the surveyed physicians were frequent users of CPOE. This implies that even when physicians believe in the safety and quality benefits of CPOE, that belief alone may not be sufficient to convince all of them to adopt this technology wholeheartedly; other factors such as speed, ease of use, and training are likely important prerequisites. Third, although 66% of orders placed in person at the 2 study hospitals were entered through CPOE, acceptance of this technology, as measured by Lindenauer et al, was moderate at both institutions. This suggests that even when organizations have reached the 70% threshold set by Leapfrog as the proportion of orders placed in CPOE that qualifies as full implementation, they may continue to face resistance to full acceptance of the technology.

Compared to their academic counterparts, community hospitals face additional hurdles as they implement CPOE. Not only does their smaller size make it difficult to achieve economies of scale, they are also at a disadvantage because of the relationship the community hospital has with its physicians. Unlike physicians‐in‐training in academic medical centers, physicians in community hospitals function as largely autonomous agents over whom the hospital administration has little control. Although these physicians and their hospitals share the common goals of patient safety and quality, the financial incentives for the adoption of CPOE are often misaligned. For example, a recent cost benefit analysis21 showed the enormous potential for hospitals to cut costs if physicians fully adopt a CPOE system with rich decision support features. However, those savings typically accrue to the hospital, not to the physicians who use the system. Assuming the typical learning curve that accompanies the use of any new technology, physicians in community hospitals may have little incentive to invest the time to learn to use the system efficiently.

So what can be done to overcome these seemingly formidable barriers to full adoption of CPOE? Emerging research, which has so far largely focused on CPOE implementation at academic hospitals, suggests there is no silver bullet. Instead, it has taught us how the complex interplay among vendor capability, organizational behavior, clinician work flow, and implementation strategy determines the success or failure of adoption.11, 17, 18, 22 Although physician characteristics will play a role in determining whether an individual adopts this technology, local factors such as the presence of champions, governance model for the project, support for staff throughout the process, and relationship between administration and physicians are likely important determinants of success at both academic and community hospitals. In addition, organizations that embark on CPOE implementation need to understand the enormity of the task at hand and must devote not only sufficient financial but also human capital over time.11, 18 In the words of a chief medical information officer, Implementing CPOE should not be thought of as an event, but a long‐term commitment.

Beyond following proposed best practices for the implementation of CPOE, community hospitals may need to adopt additional strategies to address their unique challenges. Given the misalignment of incentives for physicians' use of CPOE, leadership in community hospitals must be particularly skilled at articulating the benefits of CPOE to physicians. These benefits include not only decreased professional liability from improved patient safety and better quality of care, but also fewer pharmacy callbacks, remote access, and rapid ordering through order sets. Hospitals may also want to elicit support from physicians early by empowering them to create order sets for their disciplines. Mechanisms for hospitals and physicians to engage in mutual cost‐sharing arrangements may provide addition opportunities for hospitals to entice physicians to adopt the technology. Finally, and of particular interest to the readership of this journal, as hospitalists become more prevalent and take care of an increasing proportion of hospitalized patients,23 they are often ideal candidates to lead the implementation of CPOE in community hospitals. Because hospitalists spend most of their time in the hospital, they are often in the best position to get fully trained on CPOE, to define their own order sets, and to redesign care processes in order to take full advantage of CPOE capabilities. In addition, as many hospitalists are directly employed or supported by the hospital, their goals for quality, safety, and efficiency are usually better aligned with those of the hospital.

The stakes involved in implementing CPOE are high. Hospitals invest enormous sums of money in these systems, and many will not have the financial or political capital to attempt a second implementation after an initial failure. In addition, as recent research has pointed out,24 inappropriate implementation strategies may lead to delays in essential care and direct patient harm. In many ways, the complex task of implementing CPOE is not unlike other endeavors in patient care, where optimal outcomes require sound knowledge and reliable processes and where disaster can strike for lack of attention to detail or common sense. If Hippocrates were alive today, he might have this to say about CPOE implementation: Life is short, the art long, opportunity fleeting, experience treacherous, judgment difficult.

Self‐check‐in kiosks started to appear in airports in the late 1990s, and within a few years, they seem to have become ubiquitous in the airline industry. Today, almost 70% of business travelers use them, and other sectors of the travel industry are beginning to experiment with the technology.1 Compared to this innovation in the airline industry, adoption of computerized physician order entry (CPOE) in U.S. hospitals, first pioneered in the early 1970s,2, 3 has taken a much more leisurely pace. Despite numerous studies documenting its benefits,47 promotion by prominent national patient safety advocacy groups such as LeapFrog,8 and numerous guides on best adoption practices.912 fewer than 10% of U.S. hospitals have fully adopted this technology.13 Moreover, as Lindenauer et al.14 pointed out, most hospitals that have successfully implemented CPOE are academic medical centers that rely on house staff to enter orders. With notable exceptions,3 adoption of CPOE in community hospitals where attending physicians write most orders remains anemic.

Although an increasing number of scholarly articles has documented the reasons for this slow rate of adoption even in hospitals that have the resources to invest in this technology, much of that research is based on expert opinion and case studies.11, 1519 In this context, Lindenauer et al.14 should be commended for using empirical evidence to delineate the predictors of adoption. Lindenauer et al. found that physicians who trained in hospitals with CPOE were more likely to be frequent users of CPOE in their new environment. Although the analysis did not account for possible confounding such as employment status of the physician, this result does confirm the conventional wisdom that physicians‐in‐training are more malleable and that residency is an important opportunity to expose physicians to safety technologies. If this finding is borne out by further research, it would bode well for the adoption of CPOE, as many physicians are trained in academic institutions, which are more likely to have CPOE,20 and almost all physicians spend part of their training in a VA hospital, which has uniformly adopted CPOE. Similarly, Lindenauer et al. found that physicians who use computers for personal purposes are more likely to be frequent users of CPOE. Given the increasingly ubiquitous use of computers in all spheres of life, time is on the side of increasing acceptance of CPOE.

However, a closer examination of the data presented by Lindenauer et al. raises several concerns. First, the substantial number of infrequent users across all demographic subgroups and clinical disciplines, even among users who were exposed to CPOE during training or those who used computers regularly for personal purposes, highlights the absence of shortcuts to the universal acceptance of CPOE. Second, whereas 63% of surveyed physicians believed that CPOE would reduce the incidence of medication errors and 71% believed that CPOE would prevent aspects of care from slipping through the cracks, only 42% of the surveyed physicians were frequent users of CPOE. This implies that even when physicians believe in the safety and quality benefits of CPOE, that belief alone may not be sufficient to convince all of them to adopt this technology wholeheartedly; other factors such as speed, ease of use, and training are likely important prerequisites. Third, although 66% of orders placed in person at the 2 study hospitals were entered through CPOE, acceptance of this technology, as measured by Lindenauer et al, was moderate at both institutions. This suggests that even when organizations have reached the 70% threshold set by Leapfrog as the proportion of orders placed in CPOE that qualifies as full implementation, they may continue to face resistance to full acceptance of the technology.

Compared to their academic counterparts, community hospitals face additional hurdles as they implement CPOE. Not only does their smaller size make it difficult to achieve economies of scale, they are also at a disadvantage because of the relationship the community hospital has with its physicians. Unlike physicians‐in‐training in academic medical centers, physicians in community hospitals function as largely autonomous agents over whom the hospital administration has little control. Although these physicians and their hospitals share the common goals of patient safety and quality, the financial incentives for the adoption of CPOE are often misaligned. For example, a recent cost benefit analysis21 showed the enormous potential for hospitals to cut costs if physicians fully adopt a CPOE system with rich decision support features. However, those savings typically accrue to the hospital, not to the physicians who use the system. Assuming the typical learning curve that accompanies the use of any new technology, physicians in community hospitals may have little incentive to invest the time to learn to use the system efficiently.

So what can be done to overcome these seemingly formidable barriers to full adoption of CPOE? Emerging research, which has so far largely focused on CPOE implementation at academic hospitals, suggests there is no silver bullet. Instead, it has taught us how the complex interplay among vendor capability, organizational behavior, clinician work flow, and implementation strategy determines the success or failure of adoption.11, 17, 18, 22 Although physician characteristics will play a role in determining whether an individual adopts this technology, local factors such as the presence of champions, governance model for the project, support for staff throughout the process, and relationship between administration and physicians are likely important determinants of success at both academic and community hospitals. In addition, organizations that embark on CPOE implementation need to understand the enormity of the task at hand and must devote not only sufficient financial but also human capital over time.11, 18 In the words of a chief medical information officer, Implementing CPOE should not be thought of as an event, but a long‐term commitment.

Beyond following proposed best practices for the implementation of CPOE, community hospitals may need to adopt additional strategies to address their unique challenges. Given the misalignment of incentives for physicians' use of CPOE, leadership in community hospitals must be particularly skilled at articulating the benefits of CPOE to physicians. These benefits include not only decreased professional liability from improved patient safety and better quality of care, but also fewer pharmacy callbacks, remote access, and rapid ordering through order sets. Hospitals may also want to elicit support from physicians early by empowering them to create order sets for their disciplines. Mechanisms for hospitals and physicians to engage in mutual cost‐sharing arrangements may provide addition opportunities for hospitals to entice physicians to adopt the technology. Finally, and of particular interest to the readership of this journal, as hospitalists become more prevalent and take care of an increasing proportion of hospitalized patients,23 they are often ideal candidates to lead the implementation of CPOE in community hospitals. Because hospitalists spend most of their time in the hospital, they are often in the best position to get fully trained on CPOE, to define their own order sets, and to redesign care processes in order to take full advantage of CPOE capabilities. In addition, as many hospitalists are directly employed or supported by the hospital, their goals for quality, safety, and efficiency are usually better aligned with those of the hospital.

The stakes involved in implementing CPOE are high. Hospitals invest enormous sums of money in these systems, and many will not have the financial or political capital to attempt a second implementation after an initial failure. In addition, as recent research has pointed out,24 inappropriate implementation strategies may lead to delays in essential care and direct patient harm. In many ways, the complex task of implementing CPOE is not unlike other endeavors in patient care, where optimal outcomes require sound knowledge and reliable processes and where disaster can strike for lack of attention to detail or common sense. If Hippocrates were alive today, he might have this to say about CPOE implementation: Life is short, the art long, opportunity fleeting, experience treacherous, judgment difficult.

- Travel self‐serve kiosks here to stay.Adelman Group. Available at: http://www.adelmantravel.com/index_news_past.asp?Date=031406. Accessed March 14,2006.

- ,.Computer‐based physician order entry: the state of the art.J Am Med Inform Assoc.1994;1:108–123.

- ,,,.Final report on evaluation of the implementation of a medical information system in a general community hospital.Battelle Laboratories NTIS PB.1975;248:340.

- ,,, et al.Effect of computerized physician order entry and a team intervention on prevention of serious medication errors.JAMA.1998;280:1311–1316.

- ,,,,,.Effects of computerized physician order entry in prescribing practices.Arch Intern Med.2000;160:2741–2747.

- ,,,,,.A computerized reminder system to increase the use of preventive care for hospitalized patients [see comments].N Eng J M.2001;345:965–970.

- ,,,.A randomized trial of “corollary orders” to prevent errors of omission.J Am Med Inform Assoc.1997;4:364–75.

- The Leapfrog Group for Patient Safety: Rewarding Higher Standards.2001. Available at: www.leapfroggroup.org.

- ,,,,,.Understanding hospital readiness for computerized physician order entry.Jt Comm J Qual Saf.2003;29:336–344.

- ,,,,.Antecedents of the people and organizational aspects of medical informatics: review of the literature.J Am Med Informatics Assoc.1997;4:79–93.

- ,,.A consensus statement on considerations for a successful CPOE implementation.J Am Med Informatics Assoc.2003;10:229–234.

- AHA Guide to Computerized Physician Order‐Entry Systems.American Hospital Association:Chicago;2000.

- ,,,.Computerized physician order entry in US hospitals: results of a 2002 survey.J Am Med Inform Assoc.2004;11:95–99.

- ,,, et al.Physician characteristics, attitudes, and use of computerized order entry.J Hosp Med.2006;1:.

- ,.Computerized physician order entry systems in hospitals: mandates and incentives.Health Aff,2002;21(4):180–188.

- ,,.The use of computers for clinical care: a case series of advanced U.S. sites.J Am Med Inform Assoc.2003;10:94–107.

- ,,.Some unintended consequences of information technology in health care: the nature of patient care information system‐related errors.J Am Med Inform Assoc.2003;21:104–112.

- ,,,,,.Overcoming the barriers to implementing computerized physician order entry systems in US hospitals: perspectives from senior management.Health Aff.2004;23(4):184–190.

- ,,.Understanding Implementation: The case of a computerized physician order entry system in a large Dutch university medical cneter.J Am Med Inform Assoc.2004;11:207–216.

- ,,.U.S. adoption of computerized physician order entry systems.Health Aff.2005;24:1654–1663.

- ,,, et al.Return on investment for a computerized physician order entry system.J Am Med Inform Assoc.2006;13:261–266.

- ,,,.A diffusion of innovations model of physician order entry.AMIA Annu Symp Proc.2001;2001:22–26.

- ,,,.The status of hospital medicine groups in the United States.J Hosp Med.2006;1:75–80.

- ,,, et al.Unexpected increased mortality after implementation of a commercially sold computerized physician order entry system.Pediatrics.2005;116:1506–1512.

- Travel self‐serve kiosks here to stay.Adelman Group. Available at: http://www.adelmantravel.com/index_news_past.asp?Date=031406. Accessed March 14,2006.

- ,.Computer‐based physician order entry: the state of the art.J Am Med Inform Assoc.1994;1:108–123.

- ,,,.Final report on evaluation of the implementation of a medical information system in a general community hospital.Battelle Laboratories NTIS PB.1975;248:340.

- ,,, et al.Effect of computerized physician order entry and a team intervention on prevention of serious medication errors.JAMA.1998;280:1311–1316.

- ,,,,,.Effects of computerized physician order entry in prescribing practices.Arch Intern Med.2000;160:2741–2747.

- ,,,,,.A computerized reminder system to increase the use of preventive care for hospitalized patients [see comments].N Eng J M.2001;345:965–970.

- ,,,.A randomized trial of “corollary orders” to prevent errors of omission.J Am Med Inform Assoc.1997;4:364–75.

- The Leapfrog Group for Patient Safety: Rewarding Higher Standards.2001. Available at: www.leapfroggroup.org.

- ,,,,,.Understanding hospital readiness for computerized physician order entry.Jt Comm J Qual Saf.2003;29:336–344.

- ,,,,.Antecedents of the people and organizational aspects of medical informatics: review of the literature.J Am Med Informatics Assoc.1997;4:79–93.

- ,,.A consensus statement on considerations for a successful CPOE implementation.J Am Med Informatics Assoc.2003;10:229–234.

- AHA Guide to Computerized Physician Order‐Entry Systems.American Hospital Association:Chicago;2000.

- ,,,.Computerized physician order entry in US hospitals: results of a 2002 survey.J Am Med Inform Assoc.2004;11:95–99.

- ,,, et al.Physician characteristics, attitudes, and use of computerized order entry.J Hosp Med.2006;1:.

- ,.Computerized physician order entry systems in hospitals: mandates and incentives.Health Aff,2002;21(4):180–188.

- ,,.The use of computers for clinical care: a case series of advanced U.S. sites.J Am Med Inform Assoc.2003;10:94–107.

- ,,.Some unintended consequences of information technology in health care: the nature of patient care information system‐related errors.J Am Med Inform Assoc.2003;21:104–112.

- ,,,,,.Overcoming the barriers to implementing computerized physician order entry systems in US hospitals: perspectives from senior management.Health Aff.2004;23(4):184–190.

- ,,.Understanding Implementation: The case of a computerized physician order entry system in a large Dutch university medical cneter.J Am Med Inform Assoc.2004;11:207–216.

- ,,.U.S. adoption of computerized physician order entry systems.Health Aff.2005;24:1654–1663.

- ,,, et al.Return on investment for a computerized physician order entry system.J Am Med Inform Assoc.2006;13:261–266.

- ,,,.A diffusion of innovations model of physician order entry.AMIA Annu Symp Proc.2001;2001:22–26.

- ,,,.The status of hospital medicine groups in the United States.J Hosp Med.2006;1:75–80.

- ,,, et al.Unexpected increased mortality after implementation of a commercially sold computerized physician order entry system.Pediatrics.2005;116:1506–1512.

Editorial

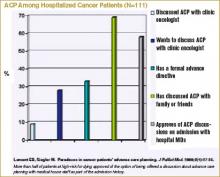

This issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine contains the inaugural article in a planned series addressing key palliative care topics relevant for the practice, teaching, and study of hospital medicine. As was noted by Diane Meier in her article Palliative Care in Hospitals1 and in Steve Pantilat's accompanying editorial, Palliative Care and Hospitalists: A Partnership for Hope,2 hospitalists are well positioned to increase access to palliative care for all hospitalized patients. Achieving this goal will require that hospitalists attain at least basic competence in the components of high‐quality, comprehensive palliative care (assessment and treatment of pain and other symptom distress, communication about goals of care, and provision of practical and psychosocial support, care coordination, continuity, and bereavement services). Palliative care is becoming more prominent in medical school and residency curricula, palliative care fellowship opportunities are proliferating, a number of palliative care resources are available on the Internet, and motivated hospital‐based providers may attain palliative care education via a variety of educational programs and faculty development courses (see Table 1 in the Meier article).1 Some hospital medicine programs have specifically targeted faculty development in palliative care competencies.4

Recognizing the salience of palliative care for the practice of hospital medicine, the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) created the Palliative Care Task Force specifically to raise awareness of the importance of palliative care to hospital medicine and charged it with developing relevant palliative care educational materials. The Palliative Care Task Force has selected the Journal of Hospital Medicine as a means of disseminating palliative care content through a series of peer‐reviewed articles on palliative care topics relevant to hospital medicine. The articles will address practical matters relevant to care at the bedside in addition to policy issues. The article in this issue, Discussing Resuscitation Preferences: Challenges and Rewards,3 addresses the common barriers to and provides practical advice for conducting these frequent, but often difficult, conversations. Planned topics, addressing some of the key domains of palliative care clinical practice, include: pain management, symptom control, communicating bad news, caring for the clinical care provider, and importance of a multidisciplinary team approach to end‐of‐life care. Each of these articles will specifically address the relevance and implications of these topics for the practice of hospital medicine.

The Journal of Hospital Medicine looks forward to reviewing these articles from the Palliative Care Task Force and invites additional submissions relevant to the practice, teaching, or study of palliative care in the hospital setting.

- .Palliative care in hospitals.J Hosp Med.2006;1:21–28.

- .Palliative care and hospitalists: a partnership for hope.J Hosp Med.2006;1:5–6.

- ,,.Discussing resuscitation preferences: challenges and rewards.J Hosp Med.2006;1:231–240.

- ,,.The effect of an intensive palliative care‐focused retreat on hospitalist faculty and resident palliative care knowledge and comfort/confidence.J Hosp Med.2006;1;S2:S9.

This issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine contains the inaugural article in a planned series addressing key palliative care topics relevant for the practice, teaching, and study of hospital medicine. As was noted by Diane Meier in her article Palliative Care in Hospitals1 and in Steve Pantilat's accompanying editorial, Palliative Care and Hospitalists: A Partnership for Hope,2 hospitalists are well positioned to increase access to palliative care for all hospitalized patients. Achieving this goal will require that hospitalists attain at least basic competence in the components of high‐quality, comprehensive palliative care (assessment and treatment of pain and other symptom distress, communication about goals of care, and provision of practical and psychosocial support, care coordination, continuity, and bereavement services). Palliative care is becoming more prominent in medical school and residency curricula, palliative care fellowship opportunities are proliferating, a number of palliative care resources are available on the Internet, and motivated hospital‐based providers may attain palliative care education via a variety of educational programs and faculty development courses (see Table 1 in the Meier article).1 Some hospital medicine programs have specifically targeted faculty development in palliative care competencies.4

Recognizing the salience of palliative care for the practice of hospital medicine, the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) created the Palliative Care Task Force specifically to raise awareness of the importance of palliative care to hospital medicine and charged it with developing relevant palliative care educational materials. The Palliative Care Task Force has selected the Journal of Hospital Medicine as a means of disseminating palliative care content through a series of peer‐reviewed articles on palliative care topics relevant to hospital medicine. The articles will address practical matters relevant to care at the bedside in addition to policy issues. The article in this issue, Discussing Resuscitation Preferences: Challenges and Rewards,3 addresses the common barriers to and provides practical advice for conducting these frequent, but often difficult, conversations. Planned topics, addressing some of the key domains of palliative care clinical practice, include: pain management, symptom control, communicating bad news, caring for the clinical care provider, and importance of a multidisciplinary team approach to end‐of‐life care. Each of these articles will specifically address the relevance and implications of these topics for the practice of hospital medicine.

The Journal of Hospital Medicine looks forward to reviewing these articles from the Palliative Care Task Force and invites additional submissions relevant to the practice, teaching, or study of palliative care in the hospital setting.

This issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine contains the inaugural article in a planned series addressing key palliative care topics relevant for the practice, teaching, and study of hospital medicine. As was noted by Diane Meier in her article Palliative Care in Hospitals1 and in Steve Pantilat's accompanying editorial, Palliative Care and Hospitalists: A Partnership for Hope,2 hospitalists are well positioned to increase access to palliative care for all hospitalized patients. Achieving this goal will require that hospitalists attain at least basic competence in the components of high‐quality, comprehensive palliative care (assessment and treatment of pain and other symptom distress, communication about goals of care, and provision of practical and psychosocial support, care coordination, continuity, and bereavement services). Palliative care is becoming more prominent in medical school and residency curricula, palliative care fellowship opportunities are proliferating, a number of palliative care resources are available on the Internet, and motivated hospital‐based providers may attain palliative care education via a variety of educational programs and faculty development courses (see Table 1 in the Meier article).1 Some hospital medicine programs have specifically targeted faculty development in palliative care competencies.4

Recognizing the salience of palliative care for the practice of hospital medicine, the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) created the Palliative Care Task Force specifically to raise awareness of the importance of palliative care to hospital medicine and charged it with developing relevant palliative care educational materials. The Palliative Care Task Force has selected the Journal of Hospital Medicine as a means of disseminating palliative care content through a series of peer‐reviewed articles on palliative care topics relevant to hospital medicine. The articles will address practical matters relevant to care at the bedside in addition to policy issues. The article in this issue, Discussing Resuscitation Preferences: Challenges and Rewards,3 addresses the common barriers to and provides practical advice for conducting these frequent, but often difficult, conversations. Planned topics, addressing some of the key domains of palliative care clinical practice, include: pain management, symptom control, communicating bad news, caring for the clinical care provider, and importance of a multidisciplinary team approach to end‐of‐life care. Each of these articles will specifically address the relevance and implications of these topics for the practice of hospital medicine.

The Journal of Hospital Medicine looks forward to reviewing these articles from the Palliative Care Task Force and invites additional submissions relevant to the practice, teaching, or study of palliative care in the hospital setting.

- .Palliative care in hospitals.J Hosp Med.2006;1:21–28.

- .Palliative care and hospitalists: a partnership for hope.J Hosp Med.2006;1:5–6.

- ,,.Discussing resuscitation preferences: challenges and rewards.J Hosp Med.2006;1:231–240.

- ,,.The effect of an intensive palliative care‐focused retreat on hospitalist faculty and resident palliative care knowledge and comfort/confidence.J Hosp Med.2006;1;S2:S9.

- .Palliative care in hospitals.J Hosp Med.2006;1:21–28.

- .Palliative care and hospitalists: a partnership for hope.J Hosp Med.2006;1:5–6.

- ,,.Discussing resuscitation preferences: challenges and rewards.J Hosp Med.2006;1:231–240.

- ,,.The effect of an intensive palliative care‐focused retreat on hospitalist faculty and resident palliative care knowledge and comfort/confidence.J Hosp Med.2006;1;S2:S9.

A Piece of Eddie

Who was Eddie and why would anyone want a piece of him? That was the question that troubled me for decades. “Bum bum baba bum bum bum bum … I want a piece of Eddie.” Every time I heard that song by The Ramones, it drove me to distraction. I couldn’t stand the band. It wasn’t their Proto-Punk cacophonic guitar jams or their dysfunctional family antics—it was Eddie. Why did they want a piece of him? It was a mystery I couldn’t solve.

Then last year I was listening to a radio piece on The Ramones when they mentioned that song. It turns out that the lyrics are actually, “I want to be sedated.” I want to be sedated? Not a piece of Eddie? How odd, and then how hilarious. Suddenly I was singing the song in my head. What a relief: There was no Eddie. It would be the prefect theme song for an anesthesiologist. I wanted to be sedated!

Terms that sound alike are called homonyms; whole phrases are called oronyms. Some examples are stuffy nose and stuff he knows; pullet surprise and Pulitzer Prize; and delicate and delegate. There is an oronym poem that has circulated the Internet that goes, “Eye halve a spelling chequer, it came with my pea sea … ”

What Eddie and I had experienced was a mondegreen. This term was coined by Sylvia Wright in an article published in 1954 in Harper’s Magazine. It comes from a 17th-century ballad. Its line sounds like “And Lady Mondegreen,” but in fact it is “and laid him on the green.” The term refers specifically to song lyrics that are misunderstood. Here are some of my favorite examples; the mondegreen is followed by the actual lyric;

- “There’s a bathroom on the right”/”There’s a bad moon on the rise” by Credence Clearwater Revival

- “ ’Scuse me while I kiss this guy”/“ ’Scuse my while I kiss the sky” by Jimi Hendrix

- “The girl with colitis goes by”/“The girl with kaleidoscope eyes” by The Beatles

- “I’ll never leave your pizza burnin’ ”/“I’ll never be your beast of burden” by The Rolling Stones

- “Oh, Louisa Brown”/“All the leaves are brown” by The Mamas and the Papas

- “No ducks of Haslem in the classroom”/“No dark sarcasm in the classroom” by Pink Floyd

- “Bring me an iron lung”/“Bring me a higher love” by Steve Winwood

- “Midnight after you’re wasted”/“Midnight at the oasis” by Maria Muldaur

You get the idea.

It is not always songs that get “misunderheard.” The complex lingo of medicine is also difficult for the neophyte or—worse—the patient to comprehend. When I started medical school, the most practical advice given to me was from my friend Jon’s father, who worked in the related profession of alcohol distribution. He told me to learn the buzzwords. I took his advice to cardia.

So there I was on rounds, a third-year medical student. A patient had an Na of 116. I wisely stroked my beard, and said that we should watch out for central pontoon myelinolysis. I guess they weren’t listening too carefully to what I had exactly said. For the next 14 years, I uttered dire warnings about central pontoon myelinolysis, until a first-year medical student corrected me. Oh, pontine, the pons—now that makes more sense!

I had made a malapropism, which comes from the character Mrs. Malaprop in an 18th-century play. (The name came from mal a propros, or French for “inappropriate”).

There is no specific term for medical malapropisms, or mondegreens. However, I call them roaches, after the famous “roaches in the liver” (cirrhosis). We have all seen these lists of roaches, whether generated by patients or bad dictation skills. Some examples are:

- The patient was treated for Paris Fevers (paresthesias);

- It was a non-respectable (unresectable) tumor;

- A debunking (debulking) procedure was performed;

- Nerve testing was done using a pink prick (pinprick) test;

- I had smiling mighty Jesus (spinal meningitis);

- She used an IOU (IUD) and still got pregnant;

- He has very close veins (varicose);

- She had postmortem (post partum) depression;

- Heart populations and high pretension (palpitations and hypertension);

- A case of headlights (head lice);

- Sick as hell anemia (sickle cell anemia); and

- The blood vessels were ecstatic (ectatic).

These roaches are generally amusing. They are certainly not anything a hospitalist would ever say or hear, though. Our patients are well informed, and our communications skills are flawless. We all know the medical malpractice risk of poor communication, and all of our patients are medically savvy and sesquepedalinistically erudite (whatever that means).

The next time you tell a patient they have a PE, remember they may be wondering what their medical condition has to do with monkey (an APE) and why you need to spell it out, or how their dyspnea is related to a high-school gym class (PE). You will have to excuse me now, I’ve got another hyponatremic patient and have to go hypertonic sailing. TH

Jamie Newman, MD, FACP, is the physician editor of The Hospitalist, consultant, Hospital Internal Medicine, and assistant professor of internal medicine and medical history, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minn.

Who was Eddie and why would anyone want a piece of him? That was the question that troubled me for decades. “Bum bum baba bum bum bum bum … I want a piece of Eddie.” Every time I heard that song by The Ramones, it drove me to distraction. I couldn’t stand the band. It wasn’t their Proto-Punk cacophonic guitar jams or their dysfunctional family antics—it was Eddie. Why did they want a piece of him? It was a mystery I couldn’t solve.

Then last year I was listening to a radio piece on The Ramones when they mentioned that song. It turns out that the lyrics are actually, “I want to be sedated.” I want to be sedated? Not a piece of Eddie? How odd, and then how hilarious. Suddenly I was singing the song in my head. What a relief: There was no Eddie. It would be the prefect theme song for an anesthesiologist. I wanted to be sedated!

Terms that sound alike are called homonyms; whole phrases are called oronyms. Some examples are stuffy nose and stuff he knows; pullet surprise and Pulitzer Prize; and delicate and delegate. There is an oronym poem that has circulated the Internet that goes, “Eye halve a spelling chequer, it came with my pea sea … ”

What Eddie and I had experienced was a mondegreen. This term was coined by Sylvia Wright in an article published in 1954 in Harper’s Magazine. It comes from a 17th-century ballad. Its line sounds like “And Lady Mondegreen,” but in fact it is “and laid him on the green.” The term refers specifically to song lyrics that are misunderstood. Here are some of my favorite examples; the mondegreen is followed by the actual lyric;

- “There’s a bathroom on the right”/”There’s a bad moon on the rise” by Credence Clearwater Revival

- “ ’Scuse me while I kiss this guy”/“ ’Scuse my while I kiss the sky” by Jimi Hendrix

- “The girl with colitis goes by”/“The girl with kaleidoscope eyes” by The Beatles

- “I’ll never leave your pizza burnin’ ”/“I’ll never be your beast of burden” by The Rolling Stones

- “Oh, Louisa Brown”/“All the leaves are brown” by The Mamas and the Papas

- “No ducks of Haslem in the classroom”/“No dark sarcasm in the classroom” by Pink Floyd

- “Bring me an iron lung”/“Bring me a higher love” by Steve Winwood

- “Midnight after you’re wasted”/“Midnight at the oasis” by Maria Muldaur

You get the idea.

It is not always songs that get “misunderheard.” The complex lingo of medicine is also difficult for the neophyte or—worse—the patient to comprehend. When I started medical school, the most practical advice given to me was from my friend Jon’s father, who worked in the related profession of alcohol distribution. He told me to learn the buzzwords. I took his advice to cardia.

So there I was on rounds, a third-year medical student. A patient had an Na of 116. I wisely stroked my beard, and said that we should watch out for central pontoon myelinolysis. I guess they weren’t listening too carefully to what I had exactly said. For the next 14 years, I uttered dire warnings about central pontoon myelinolysis, until a first-year medical student corrected me. Oh, pontine, the pons—now that makes more sense!

I had made a malapropism, which comes from the character Mrs. Malaprop in an 18th-century play. (The name came from mal a propros, or French for “inappropriate”).

There is no specific term for medical malapropisms, or mondegreens. However, I call them roaches, after the famous “roaches in the liver” (cirrhosis). We have all seen these lists of roaches, whether generated by patients or bad dictation skills. Some examples are:

- The patient was treated for Paris Fevers (paresthesias);

- It was a non-respectable (unresectable) tumor;

- A debunking (debulking) procedure was performed;

- Nerve testing was done using a pink prick (pinprick) test;

- I had smiling mighty Jesus (spinal meningitis);

- She used an IOU (IUD) and still got pregnant;

- He has very close veins (varicose);

- She had postmortem (post partum) depression;

- Heart populations and high pretension (palpitations and hypertension);

- A case of headlights (head lice);

- Sick as hell anemia (sickle cell anemia); and

- The blood vessels were ecstatic (ectatic).

These roaches are generally amusing. They are certainly not anything a hospitalist would ever say or hear, though. Our patients are well informed, and our communications skills are flawless. We all know the medical malpractice risk of poor communication, and all of our patients are medically savvy and sesquepedalinistically erudite (whatever that means).

The next time you tell a patient they have a PE, remember they may be wondering what their medical condition has to do with monkey (an APE) and why you need to spell it out, or how their dyspnea is related to a high-school gym class (PE). You will have to excuse me now, I’ve got another hyponatremic patient and have to go hypertonic sailing. TH

Jamie Newman, MD, FACP, is the physician editor of The Hospitalist, consultant, Hospital Internal Medicine, and assistant professor of internal medicine and medical history, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minn.

Who was Eddie and why would anyone want a piece of him? That was the question that troubled me for decades. “Bum bum baba bum bum bum bum … I want a piece of Eddie.” Every time I heard that song by The Ramones, it drove me to distraction. I couldn’t stand the band. It wasn’t their Proto-Punk cacophonic guitar jams or their dysfunctional family antics—it was Eddie. Why did they want a piece of him? It was a mystery I couldn’t solve.

Then last year I was listening to a radio piece on The Ramones when they mentioned that song. It turns out that the lyrics are actually, “I want to be sedated.” I want to be sedated? Not a piece of Eddie? How odd, and then how hilarious. Suddenly I was singing the song in my head. What a relief: There was no Eddie. It would be the prefect theme song for an anesthesiologist. I wanted to be sedated!

Terms that sound alike are called homonyms; whole phrases are called oronyms. Some examples are stuffy nose and stuff he knows; pullet surprise and Pulitzer Prize; and delicate and delegate. There is an oronym poem that has circulated the Internet that goes, “Eye halve a spelling chequer, it came with my pea sea … ”

What Eddie and I had experienced was a mondegreen. This term was coined by Sylvia Wright in an article published in 1954 in Harper’s Magazine. It comes from a 17th-century ballad. Its line sounds like “And Lady Mondegreen,” but in fact it is “and laid him on the green.” The term refers specifically to song lyrics that are misunderstood. Here are some of my favorite examples; the mondegreen is followed by the actual lyric;

- “There’s a bathroom on the right”/”There’s a bad moon on the rise” by Credence Clearwater Revival

- “ ’Scuse me while I kiss this guy”/“ ’Scuse my while I kiss the sky” by Jimi Hendrix

- “The girl with colitis goes by”/“The girl with kaleidoscope eyes” by The Beatles

- “I’ll never leave your pizza burnin’ ”/“I’ll never be your beast of burden” by The Rolling Stones

- “Oh, Louisa Brown”/“All the leaves are brown” by The Mamas and the Papas

- “No ducks of Haslem in the classroom”/“No dark sarcasm in the classroom” by Pink Floyd

- “Bring me an iron lung”/“Bring me a higher love” by Steve Winwood

- “Midnight after you’re wasted”/“Midnight at the oasis” by Maria Muldaur

You get the idea.

It is not always songs that get “misunderheard.” The complex lingo of medicine is also difficult for the neophyte or—worse—the patient to comprehend. When I started medical school, the most practical advice given to me was from my friend Jon’s father, who worked in the related profession of alcohol distribution. He told me to learn the buzzwords. I took his advice to cardia.

So there I was on rounds, a third-year medical student. A patient had an Na of 116. I wisely stroked my beard, and said that we should watch out for central pontoon myelinolysis. I guess they weren’t listening too carefully to what I had exactly said. For the next 14 years, I uttered dire warnings about central pontoon myelinolysis, until a first-year medical student corrected me. Oh, pontine, the pons—now that makes more sense!

I had made a malapropism, which comes from the character Mrs. Malaprop in an 18th-century play. (The name came from mal a propros, or French for “inappropriate”).

There is no specific term for medical malapropisms, or mondegreens. However, I call them roaches, after the famous “roaches in the liver” (cirrhosis). We have all seen these lists of roaches, whether generated by patients or bad dictation skills. Some examples are:

- The patient was treated for Paris Fevers (paresthesias);

- It was a non-respectable (unresectable) tumor;

- A debunking (debulking) procedure was performed;

- Nerve testing was done using a pink prick (pinprick) test;

- I had smiling mighty Jesus (spinal meningitis);

- She used an IOU (IUD) and still got pregnant;

- He has very close veins (varicose);

- She had postmortem (post partum) depression;

- Heart populations and high pretension (palpitations and hypertension);

- A case of headlights (head lice);

- Sick as hell anemia (sickle cell anemia); and

- The blood vessels were ecstatic (ectatic).

These roaches are generally amusing. They are certainly not anything a hospitalist would ever say or hear, though. Our patients are well informed, and our communications skills are flawless. We all know the medical malpractice risk of poor communication, and all of our patients are medically savvy and sesquepedalinistically erudite (whatever that means).

The next time you tell a patient they have a PE, remember they may be wondering what their medical condition has to do with monkey (an APE) and why you need to spell it out, or how their dyspnea is related to a high-school gym class (PE). You will have to excuse me now, I’ve got another hyponatremic patient and have to go hypertonic sailing. TH

Jamie Newman, MD, FACP, is the physician editor of The Hospitalist, consultant, Hospital Internal Medicine, and assistant professor of internal medicine and medical history, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minn.

The Obesity Problem in U.S. Hospitals

The United States is growing. That is, its individual inhabitants are getting bigger. Depending on the source, anywhere from 30% to 50% of the American population is now obese.1-3 By all accounts, the percentage of obese adults in our country has risen considerably over the past two decades and continues to rise.

When asked about challenges in treating the obese patient, many medical professionals will expound on bariatric treatments and surgeries—programs designed to help patients lose weight. Addressed far less frequently are the challenges faced by physicians—specifically hospitalists—in treating the obese patient for a routine or emergency medical problem or traumatic injury.

Complicating Factors

Obesity is a contributing factor to a myriad of medical problems. The American Heart Association lists obesity as one of several modifiable independent risk factors for cardiovascular disease.4 Overweight individuals are also at higher risk for a long list of other diseases, including high blood pressure, high cholesterol, type 2 diabetes, stroke, gallbladder disease, arthritis, sleep disturbances and problems breathing, and certain types of cancers.5 There is also growing evidence that obesity may be a risk factor for asthma.6

Obese patients may delay seeking medical care for a number of reasons, including self-consciousness about their weight, fear of negative comments from physicians and staff, or past negative experiences with hospitals or staff.2 When patients delay seeking appropriate preventive care, they are more likely to end up in the emergency department or be admitted to the hospital and, consequently, under the care of a hospitalist.

The Transport Conundrum

Furniture, equipment, medical supplies, and everything else commonly used in the hospital are designed to accommodate the average-size adult. In fact, for many morbidly obese patients, the difficulty begins immediately upon arrival at (or even before reaching) the hospital.

When a patient suffers an acute illness or traumatic injury, the logical reaction in many cases is to call an ambulance for transport to the hospital. For a large person, this can create the first dilemma in receiving care. Many ambulance companies now have stretchers with weight ratings of up to 700 pounds. However, moving a stretcher loaded with several hundred pounds of patient can be quite a challenge for ambulance personnel—even with extra crew members available.

If the patient is not ambulatory, the crew must find a way to place the patient onto the stretcher and then to move the stretcher into their ambulance. They can face the difficulty of not only lifting and moving such a heavy load, but also moving through doorways, down stairs, and across uneven surfaces. Simply dealing with the logistics of moving the patient safely can be time-consuming and can cause a delay in administering emergency care to the patient.

Upon arrival at the hospital, the same dilemmas will arise in transferring the patient from the ambulance stretcher to a hospital bed. Many devices designed to aid in lifting and moving patients are not rated for use with the morbidly obese patient. There must be sufficient staff on hand to facilitate transfer of the patient, and the staff must be well educated in lifting and moving techniques safe for staff and patient.

The issues regarding the lifting and moving of obese patients present significant safety implications for hospital employees. Michael Allswede, DO, residency program director for Emergency Medicine Residency at Conemaugh Health Systems in Johnstown, Pa., says that this particular issue is compounded by the fact that many hospital employees are overweight themselves. “You basically have obese people trying to lift obese people,” he says.

In a Novation survey of VHA member hospitals released in December 2004, 28% of respondents reported an increase in workplace injuries—primarily back injuries—related to lifting obese patients.7 The National Council of Compensation estimates the average cost per healthcare worker injury to be $8,400.8 This increase in worker’s compensation claims clearly has a significant financial impact on hospitals.

Diagnosis Made Difficult

Once the patient is situated, the medical staff faces the challenge of how to best assess the patient as accurately as possible. Basic vital signs can be difficult to obtain. With several layers of fat between the arteries and skin surface, pulses can be difficult—if not impossible—to palpate. Blood pressure cuffs must be large enough to avoid obtaining false readings. It can be difficult to auscultate lung sounds and cardiac rhythms; it may also be impossible to assess the abdomen by typical hands-on examination techniques. Even visualizing the entire skin surface can be difficult and time-consuming.

Obtaining diagnostic studies presents yet another challenge: Needles used for drawing blood may not be long enough to reach a vein through the layers of fat. CT and MRI images may not be possible if the gantry does not have a high enough weight rating, and there is also the possibility that the patient simply will not fit into the machine. Because body fat basically places a pillow between internal organs and the sensoring unit, ultrasound images may be impossible to obtain. Even something as simple as a chest X-ray may be difficult to interpret because of the difficulty of trying to diagnose the density difference between infected lung lobes versus the chest around it.

Dr. Allswede says that with the usual preferred diagnostic tools often rendered useless doctors have only two choices: “We can watch and wait, or we can perform invasive procedures.”

When an invasive procedure is necessary, Dr. Allswede cautions, physicians cannot rely on normal body landmarks to aid in location of underlying organs. Procedures such as placement of central lines, chest tubes, and peritoneal lavage can become a guessing game for the physician. “The normal body markings don’t align with body cavities,” he explains. “It becomes more difficult to do landmark locating for procedures.”

ABCs of Treating Obese Patients

Even the most basic medical management can be made difficult by obesity. Management of airway, breathing, and circulation is generally straightforward, and the protocols and procedures are standard; however, in the extremely obese patient problems can arise that are generally unseen in the average patient.

Morbidly obese patients desaturate more quickly than other adults. This can make it even more imperative than usual that a patent airway be obtained and maintained. Obesity makes it more difficult for the physician to visualize the laryngeal structures when attempting to intubate. Further, ventilation is made more difficult because of reduced pulmonary compliance, increased chest wall resistance, increased airway resistance, abnormal diaphragmatic position, and increased upper airway resistance.3

These patients have increased blood volumes, increased cardiac output, increased left ventricular volume, and lowered systemic vascular resistance. They may display atypical cardiac rhythms. Obtaining venous access can be extremely difficult in obese patients.3

Some of these problems can be solved by patient positioning, but some may require improvised techniques and/or specialized equipment.

Drug dosages must be modified for a morbidly obese patient; however, this is not simply a matter of larger body equaling larger dose. The physician must differentiate between fat-soluble and water-soluble medications, and obtain an estimate of the patient’s weight and body mass index to determine the proper dose of any given medication. Having a quick reference chart available for the most commonly used medications may be somewhat helpful, but it would be impossible to anticipate every possible drug-dosing dilemma. Figuring the proper dose can take some time, time that is not always available in a life-threatening situation.

Costly Solutions

Rising costs of caring for obese patients results in increased costs for everybody. The Centers for Disease Control estimates that the cost of caring for an overweight or obese patient is an average of 37% more than the cost of caring for a person of normal weight. This adds an average of $732 annually to the medical bill of every patient.8

In an effort to provide quality medical care to larger patients, many hospitals must purchase specialized equipment and supplies. There are hundreds of products available designed to help facilitate medical care of obese patients. Some hospitals are investing a great deal of money in caring for obese individuals, from lifting and moving equipment such as stretchers, wheelchairs, and lifts, to furniture such as beds and chairs, to medical equipment, including blood pressure cuffs, longer needles, and retractors.

Some facilities are making structural changes, such as widening doorways and hallways, to accommodate the passage of the larger equipment loaded with the larger patient. The 2004 Novation survey reported the mean estimated cost of new supplies to be $43,015. The mean cost of renovations in 2004 was $22,000 (compared with $15,250 in 2003).7

Conclusion

There is no doubt that the treatment of obese patients presents unique, sometimes expensive, challenges to hospitals and hospitalists. Hospitals have a responsibility to have the necessary diagnostic and treatment equipment available. Hospitalists have a responsibility to be familiar with the ways they can modify existing procedures and techniques to achieve a more desirable outcome in the obese patient. Above all, every effort must be expended to ensure that the obese patient is given the same respect and the same quality of care as every other patient. TH

Sheri Polley is based in Pennsylvania.

References

- Weight Loss & Obesity Resource Center. Medical Care for Obese Patients. Available at: http://weightlossobesity.com/obesity/medical-care-for-obese-patients.html. Last accessed May 17, 2006.

- Weight Control Information Network. Medical Care for Obese Patients. Available at: http://win.niddk.nih.gov/publications/medical.htm. Last accessed May 17, 2006.

- Brunette DD. Resuscitation of the morbidly obese patient. Am J Emerg Med. 2004 Jan;22(1):40-47.

- Criqui MH. Obesity, risk factors, and predicting cardiovascular events. Circulation. 2005 Apr 19;111 (15):1869-1870. Available online at: http://circ.ahajournals.org/cgi/content/full/111/15/1869. Last accessed May 17, 2006.

- New York Office for the Aging 2001–2004. Overweight & Obesity. Available at: www.agingwell.state.ny.us/prevention/overweight.htm. Last accessed May 22, 2006.

- Medical News Today. Is obesity a risk factor for asthma? Available at: www.medicalnewstoday.com/medicalnews.php?newsid=24118. Last accessed May 17, 2006.

- VHA. 2004 obese patient care survey market research report. Available at: www.vha.com/portal/server.pt/gateway/PTARGS_0_2_1534_234_0_43/http%3B/remote.vha.com/public/research/docs/obestpatientcare.pdf. Last accessed May 6, 2006.

- Akridge J. Bariatrics products help hospitals serve growing market. Healthcare Purchasing News. 2004 Mar. Available at: www.highbeam.com/library/docfree.asp?DOCID=1G1:124790587&num=1&ctrlInfo=Round20%3AMode20a%3ASR%3AResult&ao=&FreePremium=BOTH&tab=lib. Last accessed July19, 2006.

The United States is growing. That is, its individual inhabitants are getting bigger. Depending on the source, anywhere from 30% to 50% of the American population is now obese.1-3 By all accounts, the percentage of obese adults in our country has risen considerably over the past two decades and continues to rise.

When asked about challenges in treating the obese patient, many medical professionals will expound on bariatric treatments and surgeries—programs designed to help patients lose weight. Addressed far less frequently are the challenges faced by physicians—specifically hospitalists—in treating the obese patient for a routine or emergency medical problem or traumatic injury.

Complicating Factors

Obesity is a contributing factor to a myriad of medical problems. The American Heart Association lists obesity as one of several modifiable independent risk factors for cardiovascular disease.4 Overweight individuals are also at higher risk for a long list of other diseases, including high blood pressure, high cholesterol, type 2 diabetes, stroke, gallbladder disease, arthritis, sleep disturbances and problems breathing, and certain types of cancers.5 There is also growing evidence that obesity may be a risk factor for asthma.6

Obese patients may delay seeking medical care for a number of reasons, including self-consciousness about their weight, fear of negative comments from physicians and staff, or past negative experiences with hospitals or staff.2 When patients delay seeking appropriate preventive care, they are more likely to end up in the emergency department or be admitted to the hospital and, consequently, under the care of a hospitalist.

The Transport Conundrum

Furniture, equipment, medical supplies, and everything else commonly used in the hospital are designed to accommodate the average-size adult. In fact, for many morbidly obese patients, the difficulty begins immediately upon arrival at (or even before reaching) the hospital.

When a patient suffers an acute illness or traumatic injury, the logical reaction in many cases is to call an ambulance for transport to the hospital. For a large person, this can create the first dilemma in receiving care. Many ambulance companies now have stretchers with weight ratings of up to 700 pounds. However, moving a stretcher loaded with several hundred pounds of patient can be quite a challenge for ambulance personnel—even with extra crew members available.

If the patient is not ambulatory, the crew must find a way to place the patient onto the stretcher and then to move the stretcher into their ambulance. They can face the difficulty of not only lifting and moving such a heavy load, but also moving through doorways, down stairs, and across uneven surfaces. Simply dealing with the logistics of moving the patient safely can be time-consuming and can cause a delay in administering emergency care to the patient.

Upon arrival at the hospital, the same dilemmas will arise in transferring the patient from the ambulance stretcher to a hospital bed. Many devices designed to aid in lifting and moving patients are not rated for use with the morbidly obese patient. There must be sufficient staff on hand to facilitate transfer of the patient, and the staff must be well educated in lifting and moving techniques safe for staff and patient.

The issues regarding the lifting and moving of obese patients present significant safety implications for hospital employees. Michael Allswede, DO, residency program director for Emergency Medicine Residency at Conemaugh Health Systems in Johnstown, Pa., says that this particular issue is compounded by the fact that many hospital employees are overweight themselves. “You basically have obese people trying to lift obese people,” he says.

In a Novation survey of VHA member hospitals released in December 2004, 28% of respondents reported an increase in workplace injuries—primarily back injuries—related to lifting obese patients.7 The National Council of Compensation estimates the average cost per healthcare worker injury to be $8,400.8 This increase in worker’s compensation claims clearly has a significant financial impact on hospitals.

Diagnosis Made Difficult

Once the patient is situated, the medical staff faces the challenge of how to best assess the patient as accurately as possible. Basic vital signs can be difficult to obtain. With several layers of fat between the arteries and skin surface, pulses can be difficult—if not impossible—to palpate. Blood pressure cuffs must be large enough to avoid obtaining false readings. It can be difficult to auscultate lung sounds and cardiac rhythms; it may also be impossible to assess the abdomen by typical hands-on examination techniques. Even visualizing the entire skin surface can be difficult and time-consuming.

Obtaining diagnostic studies presents yet another challenge: Needles used for drawing blood may not be long enough to reach a vein through the layers of fat. CT and MRI images may not be possible if the gantry does not have a high enough weight rating, and there is also the possibility that the patient simply will not fit into the machine. Because body fat basically places a pillow between internal organs and the sensoring unit, ultrasound images may be impossible to obtain. Even something as simple as a chest X-ray may be difficult to interpret because of the difficulty of trying to diagnose the density difference between infected lung lobes versus the chest around it.

Dr. Allswede says that with the usual preferred diagnostic tools often rendered useless doctors have only two choices: “We can watch and wait, or we can perform invasive procedures.”

When an invasive procedure is necessary, Dr. Allswede cautions, physicians cannot rely on normal body landmarks to aid in location of underlying organs. Procedures such as placement of central lines, chest tubes, and peritoneal lavage can become a guessing game for the physician. “The normal body markings don’t align with body cavities,” he explains. “It becomes more difficult to do landmark locating for procedures.”

ABCs of Treating Obese Patients

Even the most basic medical management can be made difficult by obesity. Management of airway, breathing, and circulation is generally straightforward, and the protocols and procedures are standard; however, in the extremely obese patient problems can arise that are generally unseen in the average patient.

Morbidly obese patients desaturate more quickly than other adults. This can make it even more imperative than usual that a patent airway be obtained and maintained. Obesity makes it more difficult for the physician to visualize the laryngeal structures when attempting to intubate. Further, ventilation is made more difficult because of reduced pulmonary compliance, increased chest wall resistance, increased airway resistance, abnormal diaphragmatic position, and increased upper airway resistance.3