User login

A Pennsylvania Practice

More than 20 years before the term hospitalist was coined, the Brockie Medical Group, a strong internal medicine practice led by Benjamin Hoover, MD, relished its hospital work at York Hospital in York, Pa. Back then, the doctors didn’t call themselves hospitalists, but the time they spent on hospital duties made them the forebears of today’s hospitalists.

According to John McConville, MD, chairman of York Hospital’s department of medicine and a hospital fixture since 1976, some of Brockie Internal Medicine group’s physicians devoted 60% to 70% of their practice time to inpatient tasks. “That was the culture when I arrived on the scene,” he recounts. Shortly thereafter, the group grew stronger when The Brockie Internal Medicine Group’s main competition—a sizable family practice group—fell apart. Brockie absorbed its like-minded physicians.

York, pa.

The Brockie Internal Medical Group is firmly anchored in York, Pa., home to factories that produce barbells and Harley-Davidson motorcycles. York has a soft side, though—it produced the first Peppermint Pattie, a mint-chocolate candy. It is an affordable, rapidly growing suburb, a place where commuters to Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington, D.C., can have a comfortable lifestyle without big city housing prices and the hassles of urban life.

The medical community is close-knit, described by Jonathan Whitney, MD, a Brockie hospitalist leader, as “a collegial environment with a growing population and plenty of patients, so there’s not a sense of competition among physicians.” Dr. Whitney, along with William “Tex” Landis, MD, and Michael Lamanteer, MD, form the Brockie Hospitalist Group’s executive committee, elected decision makers who deal with WellSpan Health and York Hospital on behalf of their colleagues.

WellSpan’s Role

As York grew, so did the Brockie Internal Medical Group. Then came managed care in the 1980s and 1990s, and Brockie’s internists were not happy. “We saw the medical landscape changing everywhere, and we didn’t want managed care pushing us around,” explains Dr. Landis, a Lancaster, Pa., native and now the Brockie Hospitalist Group’s lead physician. “Analyzing how medicine was changing, we felt vulnerable as a single specialty group. We considered various scenarios for becoming a multi-specialty practice, but decided that wasn’t right for us.”

So, in 1995, five group partners decided to sell the practice to WellSpan Health, an integrated nonprofit healthcare system located in South Central Pennsylvania. Their expectation? That WellSpan’s administrative support and financial muscle would protect them against managed care’s encroachment.

Affiliating with WellSpan Health aligned Brockie with the medical services line of York Hospital, providing the administrative support they needed to grow and thrive. Working together, Brockie’s medical leaders and WellSpan administrators oversee the following areas: strategic planning; budgeting, compensation, benefits, and incentives; collections and coding; care management and performance improvement; recruiting and other personnel issues; and scheduling and coverage.

The Hospitalist Program

York Hospital and its surrounding community continued to grow, as did the need for more office-based and inpatient physician services. By 2001, York Hospital’s top executives recognized that a dedicated hospitalist group was the best solution for its overflowing emergency department (ED), booming admissions, and climbing average daily census. As specialists in internal medicine already heavily involved in inpatient care, the Brockie Internal Medical Group was York Hospital’s obvious choice to pioneer a hospital medicine program. Five Brockie physicians chose to join the newly minted inpatient hospital group (the Brockie Hospitalist Group), with four others continuing outpatient care. Over time, seven more hospitalists came on board, with more anticipated in late 2006 through mid-2007.

Part of the York Hospital mindset is that the demand for inpatient services would keep climbing as the community continued to attract newcomers. An unanticipated consequence of having a hospital medicine program was that outpatient practices quickly grew by 20% because they had offloaded their hospital work, in turn generating more hospital admissions. Brockie and York leaders, recognizing the possibility of stress and burnout on hospitalists as their volume of work grew, took steps to avert problems. “We’re in a sustained growth mode and we need the hospitalists to be satisfied with their compensation and schedules to be able to recruit new physicians,” says Dr. McConville. “Hospital administration underwrites the hospitalist program’s shortfall so that we can pay [the hospitalists] a salary commensurate with MGMA [Medical Group Management Association] guidelines plus productivity. It’s a substantial amount annually and well worth it,” he adds.

Unlike many hospitalist programs, York Hospital’s did not arise because physicians wanted to avoid driving to the hospital to make rounds. “Some groups are five minutes away and they gave us their inpatient work, while a group that’s 45 minutes away still does hospital rounds. What drives physicians here is their view of continuity of care,” says Dr. McConville.

Brockie is York’s only hospitalist group, although three other medical groups have hired two doctors to handle their inpatient work. “It’s not a problem for us. We don’t have a sense of competition,” says Dr. Whitney.

The Nuts and Bolts

Perhaps it’s Brockie’s long tenure as a medical group, its acquisition by WellSpan and the performance expectations that such an acquisition denotes, the thoroughness of its hospitalist leaders, or some combination of the above, but the hospitalists have their schedules and compensation calculations down pat.

Dr. Lamanteer spends much time and thought on the hospitalists’ compensation package. He studies national salary data and factors them into a sophisticated system of relative value units (RVUs) and case-based data to maintain a “competitive compensation package that provides incentives for both our physicians and the hospital to balance productivity with keeping length of stay in check,” he says. That’s not as easy as he makes it sound, because bumping up RVUs and volume has to be balanced with a length of stay that is both efficient and safe for patients.

Compensation begins with base salary—either Level I for 132 hours or Level II for 147 hours over three weeks. Productivity bonuses start with one point awarded for each admission, discharge, consult, and ED evaluation. Point values are then adjusted for average professional revenue generated per patient. The threshold for bonus pay is 806 points. Additionally, three clinical performance criteria, chosen annually, impact the bonus. For example, recent targets include ordering a tentative discharge time one or more days in advance (>65%), abiding by the “do not use” abbreviation list created by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) (>90%), and complying with diagnostic coding rules (>75% accuracy).

The hospitalists’ schedule is challenging, particularly for doctors way past residency, involving 8 a.m. to 10 p.m. shifts on a three-week cycle that starts on a Friday. Physicians work eight 14-hour days, followed by a weekend off, then five days on (Monday-Friday) and six days off (Saturday-Thursday). The hospitalists don’t routinely cover night call. A full-time nocturnist, who started in 1992, and moonlighters cover the 10 p.m. to 8 a.m. shift seven days a week, with hospitalists covering only for major emergencies.

Avoiding Burnout

York Hospital’s ED and a cap on residents’ hours keep the Brockie hospitalists busy. But, early in 2005, it looked as if the workload had reached a plateau. Although Dr. Whitney suspected that the breather wouldn’t last, the group had no evidence that the tempo would increase and voted to maintain the number of hospitalists. The tempo picked up.

“We had estimated an 11 percent growth in RVUs, which actually grew by 23 percent last year,” says Dr. Whitney. Then a large primary care group agreed to shift its inpatient work to Brockie in 2006. Dr. Whitney estimated that assuming that practice’s hospital patients would add 5,000 RVUs and 600 more admissions.

“We realized we could approach a point of stress and burnout with the increased workload, so we recruited two new hospitalists,” says Dr. Whitney.

Still, the hospitalists face a balancing act of census peaks and valleys. “The variations with census and admissions go well beyond the bell curve,” says Whitney, who prepares for crunches by finding volunteers among the hospitalists to cover unexpected peaks.

If Brockie sounds like a Harvard case study on hospitalist medicine, it should. Its long tenure, physician leadership, and administrative support have shaped the business practices that facilitated the program’s growth. For one, the sophisticated compensation/productivity scheme didn’t come about by accident. Dr. McConville, a representative of WellSpan’s medical service line, meets with three Brockie hospitalists to fine-tune the program’s metrics. QI measures that are newly written each year, regular individual feedback, and inclusion of evidence-based guidelines contribute to measures and practices that address many of hospital medicine’s problems.

A Big Step to Little Things

But Brockie isn’t perfect. The responsibility of 24/7 coverage and 14-hour days allows little things to fall through the cracks—things like finding the time to promote the hospitalist service on the Web site, getting new formulary updates out quickly, and immediately informing all of those concerned that a patient has died. Brockie has addressed those and other issues that are the mortar to the bricks of a hospitalist practice by hiring David Orskey, an ex-Navy corpsman, as its senior practice manager in July 2006.

Orskey, co-chair of the medical group’s process improvement committee, sees his work as finding efficiencies, working for better care, and increasing patient satisfaction, plus attending to the budget and human resources issues and networking with outpatient practices.

“Twenty-one years in Navy medicine prepared me for this job,” says Orskey. “I’m enjoying this community, which has everything from farmland to executive homes and an influx of Hispanic migrants.”

He’s able to focus on both the details and the big picture, such as making sure that everyone works toward implementing and using the electronic medical record and improving after-hours answering services, as well as refining credentialing and risk management.

LTAC Unit

Brockie’s hospitalists also serve Mechanicsburg, Pa.,-based Select Medical Corporation’s long-term acute care (LTAC) unit, a 30-bed unit within York Hospital that supports patients needing a bridge between an acute hospital and skilled nursing care. The patients run the gamut in their needs—some have pulmonary/ventilator issues; others present medically complex situations such as heart failure, multi-system organ impairment, and cancer; some are neurosurgical/post trauma; and others need specialized wound care.

Dr. Whitney explains that all Brockie hospitalists add the LTAC to their rounds, usually leaving them for the end of the day, when the physicians can better attend to their complex situations. “Many of these patients are older, have been in the ICU with complicated medical issues, and face weeks of care in the LTAC before they can go to a nursing home or another long-term care setting,” he says. “It’s a whole different LOS, and it’s good that we have the LTAC because it reduces the hospital’s burden of caring for them as acute patients, when they really need what the LTAC offers.”

Conclusion

Dr. Lamanteer keeps an eye on the Brockie hospitalists’ future. “It’s clear that we benefit patients, that we provide excellent care, and that we need a large subsidy to do it,” he says. And the big picture means keeping focused on the peaks and valleys of admissions and wondering how volume will grow in the next ten years. He’d like to limit the number of 14-hour shifts to help physicians avoid burnout and to limit weekend duty to one out of three (sustainable) or one out of four (heaven). TH

Marlene Piturro is based in New York.

More than 20 years before the term hospitalist was coined, the Brockie Medical Group, a strong internal medicine practice led by Benjamin Hoover, MD, relished its hospital work at York Hospital in York, Pa. Back then, the doctors didn’t call themselves hospitalists, but the time they spent on hospital duties made them the forebears of today’s hospitalists.

According to John McConville, MD, chairman of York Hospital’s department of medicine and a hospital fixture since 1976, some of Brockie Internal Medicine group’s physicians devoted 60% to 70% of their practice time to inpatient tasks. “That was the culture when I arrived on the scene,” he recounts. Shortly thereafter, the group grew stronger when The Brockie Internal Medicine Group’s main competition—a sizable family practice group—fell apart. Brockie absorbed its like-minded physicians.

York, pa.

The Brockie Internal Medical Group is firmly anchored in York, Pa., home to factories that produce barbells and Harley-Davidson motorcycles. York has a soft side, though—it produced the first Peppermint Pattie, a mint-chocolate candy. It is an affordable, rapidly growing suburb, a place where commuters to Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington, D.C., can have a comfortable lifestyle without big city housing prices and the hassles of urban life.

The medical community is close-knit, described by Jonathan Whitney, MD, a Brockie hospitalist leader, as “a collegial environment with a growing population and plenty of patients, so there’s not a sense of competition among physicians.” Dr. Whitney, along with William “Tex” Landis, MD, and Michael Lamanteer, MD, form the Brockie Hospitalist Group’s executive committee, elected decision makers who deal with WellSpan Health and York Hospital on behalf of their colleagues.

WellSpan’s Role

As York grew, so did the Brockie Internal Medical Group. Then came managed care in the 1980s and 1990s, and Brockie’s internists were not happy. “We saw the medical landscape changing everywhere, and we didn’t want managed care pushing us around,” explains Dr. Landis, a Lancaster, Pa., native and now the Brockie Hospitalist Group’s lead physician. “Analyzing how medicine was changing, we felt vulnerable as a single specialty group. We considered various scenarios for becoming a multi-specialty practice, but decided that wasn’t right for us.”

So, in 1995, five group partners decided to sell the practice to WellSpan Health, an integrated nonprofit healthcare system located in South Central Pennsylvania. Their expectation? That WellSpan’s administrative support and financial muscle would protect them against managed care’s encroachment.

Affiliating with WellSpan Health aligned Brockie with the medical services line of York Hospital, providing the administrative support they needed to grow and thrive. Working together, Brockie’s medical leaders and WellSpan administrators oversee the following areas: strategic planning; budgeting, compensation, benefits, and incentives; collections and coding; care management and performance improvement; recruiting and other personnel issues; and scheduling and coverage.

The Hospitalist Program

York Hospital and its surrounding community continued to grow, as did the need for more office-based and inpatient physician services. By 2001, York Hospital’s top executives recognized that a dedicated hospitalist group was the best solution for its overflowing emergency department (ED), booming admissions, and climbing average daily census. As specialists in internal medicine already heavily involved in inpatient care, the Brockie Internal Medical Group was York Hospital’s obvious choice to pioneer a hospital medicine program. Five Brockie physicians chose to join the newly minted inpatient hospital group (the Brockie Hospitalist Group), with four others continuing outpatient care. Over time, seven more hospitalists came on board, with more anticipated in late 2006 through mid-2007.

Part of the York Hospital mindset is that the demand for inpatient services would keep climbing as the community continued to attract newcomers. An unanticipated consequence of having a hospital medicine program was that outpatient practices quickly grew by 20% because they had offloaded their hospital work, in turn generating more hospital admissions. Brockie and York leaders, recognizing the possibility of stress and burnout on hospitalists as their volume of work grew, took steps to avert problems. “We’re in a sustained growth mode and we need the hospitalists to be satisfied with their compensation and schedules to be able to recruit new physicians,” says Dr. McConville. “Hospital administration underwrites the hospitalist program’s shortfall so that we can pay [the hospitalists] a salary commensurate with MGMA [Medical Group Management Association] guidelines plus productivity. It’s a substantial amount annually and well worth it,” he adds.

Unlike many hospitalist programs, York Hospital’s did not arise because physicians wanted to avoid driving to the hospital to make rounds. “Some groups are five minutes away and they gave us their inpatient work, while a group that’s 45 minutes away still does hospital rounds. What drives physicians here is their view of continuity of care,” says Dr. McConville.

Brockie is York’s only hospitalist group, although three other medical groups have hired two doctors to handle their inpatient work. “It’s not a problem for us. We don’t have a sense of competition,” says Dr. Whitney.

The Nuts and Bolts

Perhaps it’s Brockie’s long tenure as a medical group, its acquisition by WellSpan and the performance expectations that such an acquisition denotes, the thoroughness of its hospitalist leaders, or some combination of the above, but the hospitalists have their schedules and compensation calculations down pat.

Dr. Lamanteer spends much time and thought on the hospitalists’ compensation package. He studies national salary data and factors them into a sophisticated system of relative value units (RVUs) and case-based data to maintain a “competitive compensation package that provides incentives for both our physicians and the hospital to balance productivity with keeping length of stay in check,” he says. That’s not as easy as he makes it sound, because bumping up RVUs and volume has to be balanced with a length of stay that is both efficient and safe for patients.

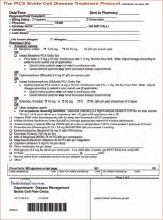

Compensation begins with base salary—either Level I for 132 hours or Level II for 147 hours over three weeks. Productivity bonuses start with one point awarded for each admission, discharge, consult, and ED evaluation. Point values are then adjusted for average professional revenue generated per patient. The threshold for bonus pay is 806 points. Additionally, three clinical performance criteria, chosen annually, impact the bonus. For example, recent targets include ordering a tentative discharge time one or more days in advance (>65%), abiding by the “do not use” abbreviation list created by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) (>90%), and complying with diagnostic coding rules (>75% accuracy).

The hospitalists’ schedule is challenging, particularly for doctors way past residency, involving 8 a.m. to 10 p.m. shifts on a three-week cycle that starts on a Friday. Physicians work eight 14-hour days, followed by a weekend off, then five days on (Monday-Friday) and six days off (Saturday-Thursday). The hospitalists don’t routinely cover night call. A full-time nocturnist, who started in 1992, and moonlighters cover the 10 p.m. to 8 a.m. shift seven days a week, with hospitalists covering only for major emergencies.

Avoiding Burnout

York Hospital’s ED and a cap on residents’ hours keep the Brockie hospitalists busy. But, early in 2005, it looked as if the workload had reached a plateau. Although Dr. Whitney suspected that the breather wouldn’t last, the group had no evidence that the tempo would increase and voted to maintain the number of hospitalists. The tempo picked up.

“We had estimated an 11 percent growth in RVUs, which actually grew by 23 percent last year,” says Dr. Whitney. Then a large primary care group agreed to shift its inpatient work to Brockie in 2006. Dr. Whitney estimated that assuming that practice’s hospital patients would add 5,000 RVUs and 600 more admissions.

“We realized we could approach a point of stress and burnout with the increased workload, so we recruited two new hospitalists,” says Dr. Whitney.

Still, the hospitalists face a balancing act of census peaks and valleys. “The variations with census and admissions go well beyond the bell curve,” says Whitney, who prepares for crunches by finding volunteers among the hospitalists to cover unexpected peaks.

If Brockie sounds like a Harvard case study on hospitalist medicine, it should. Its long tenure, physician leadership, and administrative support have shaped the business practices that facilitated the program’s growth. For one, the sophisticated compensation/productivity scheme didn’t come about by accident. Dr. McConville, a representative of WellSpan’s medical service line, meets with three Brockie hospitalists to fine-tune the program’s metrics. QI measures that are newly written each year, regular individual feedback, and inclusion of evidence-based guidelines contribute to measures and practices that address many of hospital medicine’s problems.

A Big Step to Little Things

But Brockie isn’t perfect. The responsibility of 24/7 coverage and 14-hour days allows little things to fall through the cracks—things like finding the time to promote the hospitalist service on the Web site, getting new formulary updates out quickly, and immediately informing all of those concerned that a patient has died. Brockie has addressed those and other issues that are the mortar to the bricks of a hospitalist practice by hiring David Orskey, an ex-Navy corpsman, as its senior practice manager in July 2006.

Orskey, co-chair of the medical group’s process improvement committee, sees his work as finding efficiencies, working for better care, and increasing patient satisfaction, plus attending to the budget and human resources issues and networking with outpatient practices.

“Twenty-one years in Navy medicine prepared me for this job,” says Orskey. “I’m enjoying this community, which has everything from farmland to executive homes and an influx of Hispanic migrants.”

He’s able to focus on both the details and the big picture, such as making sure that everyone works toward implementing and using the electronic medical record and improving after-hours answering services, as well as refining credentialing and risk management.

LTAC Unit

Brockie’s hospitalists also serve Mechanicsburg, Pa.,-based Select Medical Corporation’s long-term acute care (LTAC) unit, a 30-bed unit within York Hospital that supports patients needing a bridge between an acute hospital and skilled nursing care. The patients run the gamut in their needs—some have pulmonary/ventilator issues; others present medically complex situations such as heart failure, multi-system organ impairment, and cancer; some are neurosurgical/post trauma; and others need specialized wound care.

Dr. Whitney explains that all Brockie hospitalists add the LTAC to their rounds, usually leaving them for the end of the day, when the physicians can better attend to their complex situations. “Many of these patients are older, have been in the ICU with complicated medical issues, and face weeks of care in the LTAC before they can go to a nursing home or another long-term care setting,” he says. “It’s a whole different LOS, and it’s good that we have the LTAC because it reduces the hospital’s burden of caring for them as acute patients, when they really need what the LTAC offers.”

Conclusion

Dr. Lamanteer keeps an eye on the Brockie hospitalists’ future. “It’s clear that we benefit patients, that we provide excellent care, and that we need a large subsidy to do it,” he says. And the big picture means keeping focused on the peaks and valleys of admissions and wondering how volume will grow in the next ten years. He’d like to limit the number of 14-hour shifts to help physicians avoid burnout and to limit weekend duty to one out of three (sustainable) or one out of four (heaven). TH

Marlene Piturro is based in New York.

More than 20 years before the term hospitalist was coined, the Brockie Medical Group, a strong internal medicine practice led by Benjamin Hoover, MD, relished its hospital work at York Hospital in York, Pa. Back then, the doctors didn’t call themselves hospitalists, but the time they spent on hospital duties made them the forebears of today’s hospitalists.

According to John McConville, MD, chairman of York Hospital’s department of medicine and a hospital fixture since 1976, some of Brockie Internal Medicine group’s physicians devoted 60% to 70% of their practice time to inpatient tasks. “That was the culture when I arrived on the scene,” he recounts. Shortly thereafter, the group grew stronger when The Brockie Internal Medicine Group’s main competition—a sizable family practice group—fell apart. Brockie absorbed its like-minded physicians.

York, pa.

The Brockie Internal Medical Group is firmly anchored in York, Pa., home to factories that produce barbells and Harley-Davidson motorcycles. York has a soft side, though—it produced the first Peppermint Pattie, a mint-chocolate candy. It is an affordable, rapidly growing suburb, a place where commuters to Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington, D.C., can have a comfortable lifestyle without big city housing prices and the hassles of urban life.

The medical community is close-knit, described by Jonathan Whitney, MD, a Brockie hospitalist leader, as “a collegial environment with a growing population and plenty of patients, so there’s not a sense of competition among physicians.” Dr. Whitney, along with William “Tex” Landis, MD, and Michael Lamanteer, MD, form the Brockie Hospitalist Group’s executive committee, elected decision makers who deal with WellSpan Health and York Hospital on behalf of their colleagues.

WellSpan’s Role

As York grew, so did the Brockie Internal Medical Group. Then came managed care in the 1980s and 1990s, and Brockie’s internists were not happy. “We saw the medical landscape changing everywhere, and we didn’t want managed care pushing us around,” explains Dr. Landis, a Lancaster, Pa., native and now the Brockie Hospitalist Group’s lead physician. “Analyzing how medicine was changing, we felt vulnerable as a single specialty group. We considered various scenarios for becoming a multi-specialty practice, but decided that wasn’t right for us.”

So, in 1995, five group partners decided to sell the practice to WellSpan Health, an integrated nonprofit healthcare system located in South Central Pennsylvania. Their expectation? That WellSpan’s administrative support and financial muscle would protect them against managed care’s encroachment.

Affiliating with WellSpan Health aligned Brockie with the medical services line of York Hospital, providing the administrative support they needed to grow and thrive. Working together, Brockie’s medical leaders and WellSpan administrators oversee the following areas: strategic planning; budgeting, compensation, benefits, and incentives; collections and coding; care management and performance improvement; recruiting and other personnel issues; and scheduling and coverage.

The Hospitalist Program

York Hospital and its surrounding community continued to grow, as did the need for more office-based and inpatient physician services. By 2001, York Hospital’s top executives recognized that a dedicated hospitalist group was the best solution for its overflowing emergency department (ED), booming admissions, and climbing average daily census. As specialists in internal medicine already heavily involved in inpatient care, the Brockie Internal Medical Group was York Hospital’s obvious choice to pioneer a hospital medicine program. Five Brockie physicians chose to join the newly minted inpatient hospital group (the Brockie Hospitalist Group), with four others continuing outpatient care. Over time, seven more hospitalists came on board, with more anticipated in late 2006 through mid-2007.

Part of the York Hospital mindset is that the demand for inpatient services would keep climbing as the community continued to attract newcomers. An unanticipated consequence of having a hospital medicine program was that outpatient practices quickly grew by 20% because they had offloaded their hospital work, in turn generating more hospital admissions. Brockie and York leaders, recognizing the possibility of stress and burnout on hospitalists as their volume of work grew, took steps to avert problems. “We’re in a sustained growth mode and we need the hospitalists to be satisfied with their compensation and schedules to be able to recruit new physicians,” says Dr. McConville. “Hospital administration underwrites the hospitalist program’s shortfall so that we can pay [the hospitalists] a salary commensurate with MGMA [Medical Group Management Association] guidelines plus productivity. It’s a substantial amount annually and well worth it,” he adds.

Unlike many hospitalist programs, York Hospital’s did not arise because physicians wanted to avoid driving to the hospital to make rounds. “Some groups are five minutes away and they gave us their inpatient work, while a group that’s 45 minutes away still does hospital rounds. What drives physicians here is their view of continuity of care,” says Dr. McConville.

Brockie is York’s only hospitalist group, although three other medical groups have hired two doctors to handle their inpatient work. “It’s not a problem for us. We don’t have a sense of competition,” says Dr. Whitney.

The Nuts and Bolts

Perhaps it’s Brockie’s long tenure as a medical group, its acquisition by WellSpan and the performance expectations that such an acquisition denotes, the thoroughness of its hospitalist leaders, or some combination of the above, but the hospitalists have their schedules and compensation calculations down pat.

Dr. Lamanteer spends much time and thought on the hospitalists’ compensation package. He studies national salary data and factors them into a sophisticated system of relative value units (RVUs) and case-based data to maintain a “competitive compensation package that provides incentives for both our physicians and the hospital to balance productivity with keeping length of stay in check,” he says. That’s not as easy as he makes it sound, because bumping up RVUs and volume has to be balanced with a length of stay that is both efficient and safe for patients.

Compensation begins with base salary—either Level I for 132 hours or Level II for 147 hours over three weeks. Productivity bonuses start with one point awarded for each admission, discharge, consult, and ED evaluation. Point values are then adjusted for average professional revenue generated per patient. The threshold for bonus pay is 806 points. Additionally, three clinical performance criteria, chosen annually, impact the bonus. For example, recent targets include ordering a tentative discharge time one or more days in advance (>65%), abiding by the “do not use” abbreviation list created by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) (>90%), and complying with diagnostic coding rules (>75% accuracy).

The hospitalists’ schedule is challenging, particularly for doctors way past residency, involving 8 a.m. to 10 p.m. shifts on a three-week cycle that starts on a Friday. Physicians work eight 14-hour days, followed by a weekend off, then five days on (Monday-Friday) and six days off (Saturday-Thursday). The hospitalists don’t routinely cover night call. A full-time nocturnist, who started in 1992, and moonlighters cover the 10 p.m. to 8 a.m. shift seven days a week, with hospitalists covering only for major emergencies.

Avoiding Burnout

York Hospital’s ED and a cap on residents’ hours keep the Brockie hospitalists busy. But, early in 2005, it looked as if the workload had reached a plateau. Although Dr. Whitney suspected that the breather wouldn’t last, the group had no evidence that the tempo would increase and voted to maintain the number of hospitalists. The tempo picked up.

“We had estimated an 11 percent growth in RVUs, which actually grew by 23 percent last year,” says Dr. Whitney. Then a large primary care group agreed to shift its inpatient work to Brockie in 2006. Dr. Whitney estimated that assuming that practice’s hospital patients would add 5,000 RVUs and 600 more admissions.

“We realized we could approach a point of stress and burnout with the increased workload, so we recruited two new hospitalists,” says Dr. Whitney.

Still, the hospitalists face a balancing act of census peaks and valleys. “The variations with census and admissions go well beyond the bell curve,” says Whitney, who prepares for crunches by finding volunteers among the hospitalists to cover unexpected peaks.

If Brockie sounds like a Harvard case study on hospitalist medicine, it should. Its long tenure, physician leadership, and administrative support have shaped the business practices that facilitated the program’s growth. For one, the sophisticated compensation/productivity scheme didn’t come about by accident. Dr. McConville, a representative of WellSpan’s medical service line, meets with three Brockie hospitalists to fine-tune the program’s metrics. QI measures that are newly written each year, regular individual feedback, and inclusion of evidence-based guidelines contribute to measures and practices that address many of hospital medicine’s problems.

A Big Step to Little Things

But Brockie isn’t perfect. The responsibility of 24/7 coverage and 14-hour days allows little things to fall through the cracks—things like finding the time to promote the hospitalist service on the Web site, getting new formulary updates out quickly, and immediately informing all of those concerned that a patient has died. Brockie has addressed those and other issues that are the mortar to the bricks of a hospitalist practice by hiring David Orskey, an ex-Navy corpsman, as its senior practice manager in July 2006.

Orskey, co-chair of the medical group’s process improvement committee, sees his work as finding efficiencies, working for better care, and increasing patient satisfaction, plus attending to the budget and human resources issues and networking with outpatient practices.

“Twenty-one years in Navy medicine prepared me for this job,” says Orskey. “I’m enjoying this community, which has everything from farmland to executive homes and an influx of Hispanic migrants.”

He’s able to focus on both the details and the big picture, such as making sure that everyone works toward implementing and using the electronic medical record and improving after-hours answering services, as well as refining credentialing and risk management.

LTAC Unit

Brockie’s hospitalists also serve Mechanicsburg, Pa.,-based Select Medical Corporation’s long-term acute care (LTAC) unit, a 30-bed unit within York Hospital that supports patients needing a bridge between an acute hospital and skilled nursing care. The patients run the gamut in their needs—some have pulmonary/ventilator issues; others present medically complex situations such as heart failure, multi-system organ impairment, and cancer; some are neurosurgical/post trauma; and others need specialized wound care.

Dr. Whitney explains that all Brockie hospitalists add the LTAC to their rounds, usually leaving them for the end of the day, when the physicians can better attend to their complex situations. “Many of these patients are older, have been in the ICU with complicated medical issues, and face weeks of care in the LTAC before they can go to a nursing home or another long-term care setting,” he says. “It’s a whole different LOS, and it’s good that we have the LTAC because it reduces the hospital’s burden of caring for them as acute patients, when they really need what the LTAC offers.”

Conclusion

Dr. Lamanteer keeps an eye on the Brockie hospitalists’ future. “It’s clear that we benefit patients, that we provide excellent care, and that we need a large subsidy to do it,” he says. And the big picture means keeping focused on the peaks and valleys of admissions and wondering how volume will grow in the next ten years. He’d like to limit the number of 14-hour shifts to help physicians avoid burnout and to limit weekend duty to one out of three (sustainable) or one out of four (heaven). TH

Marlene Piturro is based in New York.

Brazil Blossoms

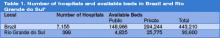

The establishment of a hospital medicine program in Brazil and the attempt to develop the specialty nationwide is both fascinating and challenging. Brazil has about 7,155 hospitals, with 443,210 beds available (including 2,727 public hospitals with 148,966 beds and 4,428 private facilities with 294,244 beds). 1 (See Table 1, p. 44.)

Historical problems in the public health system—also found in private sectors—have motivated physicians to address and improve inefficient management, insufficient financial support, the high number of frequent unnecessary admissions and re-admissions, extended length of stays, limited access to beds and medical services of high complexity, and overcrowded emergency departments.

SUS—Principles and Problems

The Brazilian public health system, called Sistema Único de Saúde, or SUS, is based on universal care and health as a right of citizenship and a state responsibility. Its main principles are universality, integrality, equity, decentralization, and social control.2 Less than half of the Brazilian population uses the SUS system exclusively. They use private health systems as a complement. This situation reflects the difficulties in the Brazilian public health system. The reasons for this duplicity highlight the challenges of our situation.

At the same time, physicians face serious problems. Most are employed by both the public and private sectors. Average salaries in the public system (by far the largest employer) are extremely low. Medical doctors are forced to work many extra hours, including numerous night shifts, creating a major barrier to the growth of physicians dedicated to horizontal inpatient care.

The government, in an attempt to improve medical—and hospital—assistance in the country with “a new kind of health assistance focused on high quality and efficient services,” has created the following projects: Humaniza SUS and QualiSUS.3,4 Theoretical support, operational contours, extent, and applicability are still not clear, however. For many medical doctors, these are merely abstract ideas. QualiSUS has renovated emergency departments in Brazil, but service quality has not improved enough. In our opinion, there are no public policies capable of providing good hospital services and efficient management in Brazilian hospitals, and—even if they existed—we would need to stop corruption in order to meet public commitments.

In Rio Grande do Sul, the Brazilian state where we work as medical doctors, the inadequate SUS reimbursement points to a calamitous future. Here, most hospital care is provided by philanthropic hospitals, which are more vulnerable in financial terms.5 (See Table 2, p. 44.) Despite being in a pioneer state in terms of hospital administration schools, with more than 2,000 graduates in recent years, these philanthropic hospitals have an estimated reimbursement deficit of more than 80%, an unattainable amount even for the best administrator.

Could Hospitalists Be Part of a Solution?

On top of these growing deficits, we have witnessed the closing of more than 2,000 available beds in the last four years, as well as the loss of 10,000 hospital positions and the complete closing of eight hospitals. Aiming to ensure the survival of this hospital system, physicians, health professionals, and organizations involved with hospitals have joined forces to find a solution. Their logo is best translated as “More Health for the Hospitals,” and our group supports their goals.6

Looking at the situation from a different perspective, we see many opportunities for Brazilian hospitalists. Their potential contribution to the quality and safety of medical care is an obvious advantage for hospital management and patients. We predict that this scenario can be accomplished—even in our state. It is possible to make a profit in public as well as in lucrative private institutions. In public institutions, a profit can be made as long as hospital administrators use adequate policy. We believe that in private institutions, though not in philanthropic ones, the key point is hospital administration cooperation and goodwill. Elucidation of hospitalists’ capabilities will open the necessary doors. We are ready to reduce the hospitalization fee and length of stay—among other costs. In this way, we can work with the administrator to develop tools for systems and quality improvements.

Hospital Medicine’s Emergence in Brazil

The implementation of hospital medicine, especially those aspects that involve more than just having a general medicine physician dealing with inpatient care, is brand new in Brazil. So far, the U.S. hospitalist model of care is unfamiliar to most Brazilian medical doctors and healthcare managers. Some institutions have hired hospitalists to be part of rapid response teams, neglecting the more specialized dimension of this new model of care; they are not aware of this title’s real meaning. There is a long way to go until the hospitalist is seen as a specialist, and we hope all our efforts will earn this new specialty official recognition in Brazil.

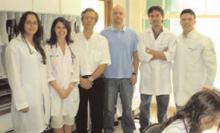

Our group is based in the Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul, mainly in Porto Alegre, its capital. Most of our time is dedicated to inpatient care, and we started our movement after studying the model of care delineated by Wachter and Lee.7-9 In 2005, we formed a local association called GEAMH (Grupo de Estudos e Atualização em Medicina Hospitalar) to promote the understanding and diffusion of hospitalist principles, integrated by the professors and former and current residents of a large local internal medicine residence program from the Internal Medicine Department of Nossa Senhora da Conceição Hospital (HNSC).

We have created a Web site (www.medicinahospitalar.com.br) where you can find history, news, and information about hospital medicine fellowships in the United States, as well as online hospital medicine continuing education. As you can see, we are spreading SHM’s ideas.

The third year of the HNSC Internal Medicine Residence Program (R3) focused on hospital medicine was developed in 2005. We believe this to be the first initiative of its kind in Brazil. HNSC is part of Conceição Hospital Group, which is composed of four hospital units and is one of the biggest public hospital networks in Brazil.

The Internal Medicine Residence Program started at HNSC in 1968. The department itself has more than 100 hospital beds. Medical residents’ activities all take place in the hospital, and there are nine professors: Eduardo Fernandes, Guilherme Barcellos, Janete Brauner, José Luiz F. Soares, Nelson Roessler, Paulo Almeida, Paulo Ricardo Cardoso, Sergio Dedavid, and Sergio Prezzi. We would like to make special mention of our colleagues Eduardo Fernandes, current head of HNSC Internal Medicine Medical Residence Program, and Sergio Prezzi, the R3 coordinator.

The HNSC Internal Medicine Service is well known for graduating internists skilled in hospital practices, mainly because the program is run by professors who specialize in that area. The R3 is a one-year training program. Our goal is to train physicians to provide outstanding and comprehensive inpatient care. Through supervised training, our residents are able to treat common hospital illnesses; we are also training them in consultative medicine and in the clinical management of surgical patients. Other areas of medical residents’ education include medical ethics, end-of-life care, inpatient nutritional support, risk management, rational use of drugs, and technology and evidence-based medicine.

Our third-year residents have the opportunity to try bone marrow biopsy, pleural biopsy, and thorax draining—all of which are usually handled by other medical specialists. In general, residents also have many opportunities to learn about and practice endotracheal intubations, ventilator management, central vein access, and many other procedures.

Based on HNSC experience, a formal stage in hospital medicine under the supervision of Luciano Bauer Grohs, MD, one of the founders of GEAMH, has also been integrated into internal medicine training at Nossa Senhora de Pompéia Hospital in the city of Caxias do Sul, located 125 kilometers from Porto Alegre.

Our group has developed medical education in the inpatient setting. Because there is no hospital medicine society in Brazil, we have tried to coordinate with the Brazilian Society of Internal Medicine, encouraging discussions about hospital care and promoting workshops about mechanical ventilation, central vein access, and early goal-directed therapy for sepsis. More recently, we have chosen to work independently, believing that hospital medicine is distinct from internal medicine.

When we organized the Brazilian Annual Congress of Medical Residents in 2006, we had the opportunity to bring together medical residents and professors from different medical areas. The Congress’ main focuses were rational use of drugs and technology and the relationship between the young physician and the pharmaceutical industry. The participation of Robert Goodman (of No Free Lunch fame) was an important part of the convention.10

Slow and Steady Growth

We understand that there is a long journey ahead, beyond educational and medical assistance. Our group is still far from promoting research. But hospital medicine specialization has launched in Brazil. Dr. Watcher has said to us, “In the United States, the hospitalist field is the fastest growing specialty in the country—and probably in the history of the country. Hospitalists are transforming the delivery of American hospital care and improving quality, patient safety, education, end-of-life care, and more. We are thrilled to partner with our Brazilian colleagues as, together, we try to improve the quality of care for hospitalized patients everywhere.” We are confident that his vision will become a reality in Brazil in the near future. TH

Note: We are in debt to the professors at the Hospital Conceição Internal Medicine Residency Program, without whom our initiatives would never have blossomed. Special thanks to Eduardo Fernandes, Sergio Prezzi, and Paulo Ricardo Cardoso.

Dr. Barcellos is a specialist in internal medicine, emergency medicine, and critical care. He is professor in Nossa Senhora da Conceição Hospital’s Hospital Medicine Residence Program and president of GEAMH, a local association designed to promote the understanding and diffusion of hospitalist principles.

Dr. Wajner is a specialist in internal medicine and emergency medicine and a Master of Science student at Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul.

Dr. de Waldemar is a specialist in internal medicine and emergency medicine.

References

- Departamento de População e Indicadores Sociais. Estatísticas da saúde: assistência médico-sanitária 2005/IBGE. Departamento de População e Indicadores Sociais. 2006. Available at: www.ibge.gov.br/home/estatistica/populacao/condicaodevida/ams/2005/ams2005.pdf. Last accessed January 28, 2007.

- Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária. Lei nº 8080. D.O.U. - Diário Oficial da União; Poder Executivo. September 20, 1990. Available at: http://e-legis.bvs.br/leisref/public/showAct.php?id=16619&word=. Last accessed January 28, 2007.

- Brazilian Ministry of Health Web site. Available at: http://portal.saude.gov.br/saude. Last accessed January 28, 2007.

- Deslandes SF. Análise do discurso oficial sobre a humanização da assistência hospitalar. Ciência e saúde coletiva. 2004;9:7-14. Available at: www.scielo.br/pdf/csc/v9n1/19819.pdf. Last ccessed January 28, 2007.

- Portela MC, Lima SML, Barbosa PR, et al. Caracterização assistencial de hospitais filantrópicos no Brasil. Rev Saúde Pública. 2004;38:811-818. Available at: www.scielo.br/pdf/rsp/v38n6/09.pdf. Last accessed January 28, 2007.

- Sindicato Médico do Rio Grande do Sul Web site. Available at: www.simers.org.br/entquerem.php. Last accessed January 28, 2007.

- Wachter RM, Goldman L. The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system. N Engl J Med. 1996 Aug 15;335(7):514-517.

- Wachter RM, Goldman L. The hospitalist movement 5 years later. JAMA. 2002 Feb 16;287:487–494. Review.

- Wachter RM. An introduction to the hospitalist model. Ann Intern Med. 1999 Feb 16;130(4 Pt 2):338–342.

- No Free Lunch Web site. Available at: www.nofreelunch.org. Last accessed January 28, 2007.

The establishment of a hospital medicine program in Brazil and the attempt to develop the specialty nationwide is both fascinating and challenging. Brazil has about 7,155 hospitals, with 443,210 beds available (including 2,727 public hospitals with 148,966 beds and 4,428 private facilities with 294,244 beds). 1 (See Table 1, p. 44.)

Historical problems in the public health system—also found in private sectors—have motivated physicians to address and improve inefficient management, insufficient financial support, the high number of frequent unnecessary admissions and re-admissions, extended length of stays, limited access to beds and medical services of high complexity, and overcrowded emergency departments.

SUS—Principles and Problems

The Brazilian public health system, called Sistema Único de Saúde, or SUS, is based on universal care and health as a right of citizenship and a state responsibility. Its main principles are universality, integrality, equity, decentralization, and social control.2 Less than half of the Brazilian population uses the SUS system exclusively. They use private health systems as a complement. This situation reflects the difficulties in the Brazilian public health system. The reasons for this duplicity highlight the challenges of our situation.

At the same time, physicians face serious problems. Most are employed by both the public and private sectors. Average salaries in the public system (by far the largest employer) are extremely low. Medical doctors are forced to work many extra hours, including numerous night shifts, creating a major barrier to the growth of physicians dedicated to horizontal inpatient care.

The government, in an attempt to improve medical—and hospital—assistance in the country with “a new kind of health assistance focused on high quality and efficient services,” has created the following projects: Humaniza SUS and QualiSUS.3,4 Theoretical support, operational contours, extent, and applicability are still not clear, however. For many medical doctors, these are merely abstract ideas. QualiSUS has renovated emergency departments in Brazil, but service quality has not improved enough. In our opinion, there are no public policies capable of providing good hospital services and efficient management in Brazilian hospitals, and—even if they existed—we would need to stop corruption in order to meet public commitments.

In Rio Grande do Sul, the Brazilian state where we work as medical doctors, the inadequate SUS reimbursement points to a calamitous future. Here, most hospital care is provided by philanthropic hospitals, which are more vulnerable in financial terms.5 (See Table 2, p. 44.) Despite being in a pioneer state in terms of hospital administration schools, with more than 2,000 graduates in recent years, these philanthropic hospitals have an estimated reimbursement deficit of more than 80%, an unattainable amount even for the best administrator.

Could Hospitalists Be Part of a Solution?

On top of these growing deficits, we have witnessed the closing of more than 2,000 available beds in the last four years, as well as the loss of 10,000 hospital positions and the complete closing of eight hospitals. Aiming to ensure the survival of this hospital system, physicians, health professionals, and organizations involved with hospitals have joined forces to find a solution. Their logo is best translated as “More Health for the Hospitals,” and our group supports their goals.6

Looking at the situation from a different perspective, we see many opportunities for Brazilian hospitalists. Their potential contribution to the quality and safety of medical care is an obvious advantage for hospital management and patients. We predict that this scenario can be accomplished—even in our state. It is possible to make a profit in public as well as in lucrative private institutions. In public institutions, a profit can be made as long as hospital administrators use adequate policy. We believe that in private institutions, though not in philanthropic ones, the key point is hospital administration cooperation and goodwill. Elucidation of hospitalists’ capabilities will open the necessary doors. We are ready to reduce the hospitalization fee and length of stay—among other costs. In this way, we can work with the administrator to develop tools for systems and quality improvements.

Hospital Medicine’s Emergence in Brazil

The implementation of hospital medicine, especially those aspects that involve more than just having a general medicine physician dealing with inpatient care, is brand new in Brazil. So far, the U.S. hospitalist model of care is unfamiliar to most Brazilian medical doctors and healthcare managers. Some institutions have hired hospitalists to be part of rapid response teams, neglecting the more specialized dimension of this new model of care; they are not aware of this title’s real meaning. There is a long way to go until the hospitalist is seen as a specialist, and we hope all our efforts will earn this new specialty official recognition in Brazil.

Our group is based in the Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul, mainly in Porto Alegre, its capital. Most of our time is dedicated to inpatient care, and we started our movement after studying the model of care delineated by Wachter and Lee.7-9 In 2005, we formed a local association called GEAMH (Grupo de Estudos e Atualização em Medicina Hospitalar) to promote the understanding and diffusion of hospitalist principles, integrated by the professors and former and current residents of a large local internal medicine residence program from the Internal Medicine Department of Nossa Senhora da Conceição Hospital (HNSC).

We have created a Web site (www.medicinahospitalar.com.br) where you can find history, news, and information about hospital medicine fellowships in the United States, as well as online hospital medicine continuing education. As you can see, we are spreading SHM’s ideas.

The third year of the HNSC Internal Medicine Residence Program (R3) focused on hospital medicine was developed in 2005. We believe this to be the first initiative of its kind in Brazil. HNSC is part of Conceição Hospital Group, which is composed of four hospital units and is one of the biggest public hospital networks in Brazil.

The Internal Medicine Residence Program started at HNSC in 1968. The department itself has more than 100 hospital beds. Medical residents’ activities all take place in the hospital, and there are nine professors: Eduardo Fernandes, Guilherme Barcellos, Janete Brauner, José Luiz F. Soares, Nelson Roessler, Paulo Almeida, Paulo Ricardo Cardoso, Sergio Dedavid, and Sergio Prezzi. We would like to make special mention of our colleagues Eduardo Fernandes, current head of HNSC Internal Medicine Medical Residence Program, and Sergio Prezzi, the R3 coordinator.

The HNSC Internal Medicine Service is well known for graduating internists skilled in hospital practices, mainly because the program is run by professors who specialize in that area. The R3 is a one-year training program. Our goal is to train physicians to provide outstanding and comprehensive inpatient care. Through supervised training, our residents are able to treat common hospital illnesses; we are also training them in consultative medicine and in the clinical management of surgical patients. Other areas of medical residents’ education include medical ethics, end-of-life care, inpatient nutritional support, risk management, rational use of drugs, and technology and evidence-based medicine.

Our third-year residents have the opportunity to try bone marrow biopsy, pleural biopsy, and thorax draining—all of which are usually handled by other medical specialists. In general, residents also have many opportunities to learn about and practice endotracheal intubations, ventilator management, central vein access, and many other procedures.

Based on HNSC experience, a formal stage in hospital medicine under the supervision of Luciano Bauer Grohs, MD, one of the founders of GEAMH, has also been integrated into internal medicine training at Nossa Senhora de Pompéia Hospital in the city of Caxias do Sul, located 125 kilometers from Porto Alegre.

Our group has developed medical education in the inpatient setting. Because there is no hospital medicine society in Brazil, we have tried to coordinate with the Brazilian Society of Internal Medicine, encouraging discussions about hospital care and promoting workshops about mechanical ventilation, central vein access, and early goal-directed therapy for sepsis. More recently, we have chosen to work independently, believing that hospital medicine is distinct from internal medicine.

When we organized the Brazilian Annual Congress of Medical Residents in 2006, we had the opportunity to bring together medical residents and professors from different medical areas. The Congress’ main focuses were rational use of drugs and technology and the relationship between the young physician and the pharmaceutical industry. The participation of Robert Goodman (of No Free Lunch fame) was an important part of the convention.10

Slow and Steady Growth

We understand that there is a long journey ahead, beyond educational and medical assistance. Our group is still far from promoting research. But hospital medicine specialization has launched in Brazil. Dr. Watcher has said to us, “In the United States, the hospitalist field is the fastest growing specialty in the country—and probably in the history of the country. Hospitalists are transforming the delivery of American hospital care and improving quality, patient safety, education, end-of-life care, and more. We are thrilled to partner with our Brazilian colleagues as, together, we try to improve the quality of care for hospitalized patients everywhere.” We are confident that his vision will become a reality in Brazil in the near future. TH

Note: We are in debt to the professors at the Hospital Conceição Internal Medicine Residency Program, without whom our initiatives would never have blossomed. Special thanks to Eduardo Fernandes, Sergio Prezzi, and Paulo Ricardo Cardoso.

Dr. Barcellos is a specialist in internal medicine, emergency medicine, and critical care. He is professor in Nossa Senhora da Conceição Hospital’s Hospital Medicine Residence Program and president of GEAMH, a local association designed to promote the understanding and diffusion of hospitalist principles.

Dr. Wajner is a specialist in internal medicine and emergency medicine and a Master of Science student at Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul.

Dr. de Waldemar is a specialist in internal medicine and emergency medicine.

References

- Departamento de População e Indicadores Sociais. Estatísticas da saúde: assistência médico-sanitária 2005/IBGE. Departamento de População e Indicadores Sociais. 2006. Available at: www.ibge.gov.br/home/estatistica/populacao/condicaodevida/ams/2005/ams2005.pdf. Last accessed January 28, 2007.

- Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária. Lei nº 8080. D.O.U. - Diário Oficial da União; Poder Executivo. September 20, 1990. Available at: http://e-legis.bvs.br/leisref/public/showAct.php?id=16619&word=. Last accessed January 28, 2007.

- Brazilian Ministry of Health Web site. Available at: http://portal.saude.gov.br/saude. Last accessed January 28, 2007.

- Deslandes SF. Análise do discurso oficial sobre a humanização da assistência hospitalar. Ciência e saúde coletiva. 2004;9:7-14. Available at: www.scielo.br/pdf/csc/v9n1/19819.pdf. Last ccessed January 28, 2007.

- Portela MC, Lima SML, Barbosa PR, et al. Caracterização assistencial de hospitais filantrópicos no Brasil. Rev Saúde Pública. 2004;38:811-818. Available at: www.scielo.br/pdf/rsp/v38n6/09.pdf. Last accessed January 28, 2007.

- Sindicato Médico do Rio Grande do Sul Web site. Available at: www.simers.org.br/entquerem.php. Last accessed January 28, 2007.

- Wachter RM, Goldman L. The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system. N Engl J Med. 1996 Aug 15;335(7):514-517.

- Wachter RM, Goldman L. The hospitalist movement 5 years later. JAMA. 2002 Feb 16;287:487–494. Review.

- Wachter RM. An introduction to the hospitalist model. Ann Intern Med. 1999 Feb 16;130(4 Pt 2):338–342.

- No Free Lunch Web site. Available at: www.nofreelunch.org. Last accessed January 28, 2007.

The establishment of a hospital medicine program in Brazil and the attempt to develop the specialty nationwide is both fascinating and challenging. Brazil has about 7,155 hospitals, with 443,210 beds available (including 2,727 public hospitals with 148,966 beds and 4,428 private facilities with 294,244 beds). 1 (See Table 1, p. 44.)

Historical problems in the public health system—also found in private sectors—have motivated physicians to address and improve inefficient management, insufficient financial support, the high number of frequent unnecessary admissions and re-admissions, extended length of stays, limited access to beds and medical services of high complexity, and overcrowded emergency departments.

SUS—Principles and Problems

The Brazilian public health system, called Sistema Único de Saúde, or SUS, is based on universal care and health as a right of citizenship and a state responsibility. Its main principles are universality, integrality, equity, decentralization, and social control.2 Less than half of the Brazilian population uses the SUS system exclusively. They use private health systems as a complement. This situation reflects the difficulties in the Brazilian public health system. The reasons for this duplicity highlight the challenges of our situation.

At the same time, physicians face serious problems. Most are employed by both the public and private sectors. Average salaries in the public system (by far the largest employer) are extremely low. Medical doctors are forced to work many extra hours, including numerous night shifts, creating a major barrier to the growth of physicians dedicated to horizontal inpatient care.

The government, in an attempt to improve medical—and hospital—assistance in the country with “a new kind of health assistance focused on high quality and efficient services,” has created the following projects: Humaniza SUS and QualiSUS.3,4 Theoretical support, operational contours, extent, and applicability are still not clear, however. For many medical doctors, these are merely abstract ideas. QualiSUS has renovated emergency departments in Brazil, but service quality has not improved enough. In our opinion, there are no public policies capable of providing good hospital services and efficient management in Brazilian hospitals, and—even if they existed—we would need to stop corruption in order to meet public commitments.

In Rio Grande do Sul, the Brazilian state where we work as medical doctors, the inadequate SUS reimbursement points to a calamitous future. Here, most hospital care is provided by philanthropic hospitals, which are more vulnerable in financial terms.5 (See Table 2, p. 44.) Despite being in a pioneer state in terms of hospital administration schools, with more than 2,000 graduates in recent years, these philanthropic hospitals have an estimated reimbursement deficit of more than 80%, an unattainable amount even for the best administrator.

Could Hospitalists Be Part of a Solution?

On top of these growing deficits, we have witnessed the closing of more than 2,000 available beds in the last four years, as well as the loss of 10,000 hospital positions and the complete closing of eight hospitals. Aiming to ensure the survival of this hospital system, physicians, health professionals, and organizations involved with hospitals have joined forces to find a solution. Their logo is best translated as “More Health for the Hospitals,” and our group supports their goals.6

Looking at the situation from a different perspective, we see many opportunities for Brazilian hospitalists. Their potential contribution to the quality and safety of medical care is an obvious advantage for hospital management and patients. We predict that this scenario can be accomplished—even in our state. It is possible to make a profit in public as well as in lucrative private institutions. In public institutions, a profit can be made as long as hospital administrators use adequate policy. We believe that in private institutions, though not in philanthropic ones, the key point is hospital administration cooperation and goodwill. Elucidation of hospitalists’ capabilities will open the necessary doors. We are ready to reduce the hospitalization fee and length of stay—among other costs. In this way, we can work with the administrator to develop tools for systems and quality improvements.

Hospital Medicine’s Emergence in Brazil

The implementation of hospital medicine, especially those aspects that involve more than just having a general medicine physician dealing with inpatient care, is brand new in Brazil. So far, the U.S. hospitalist model of care is unfamiliar to most Brazilian medical doctors and healthcare managers. Some institutions have hired hospitalists to be part of rapid response teams, neglecting the more specialized dimension of this new model of care; they are not aware of this title’s real meaning. There is a long way to go until the hospitalist is seen as a specialist, and we hope all our efforts will earn this new specialty official recognition in Brazil.

Our group is based in the Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul, mainly in Porto Alegre, its capital. Most of our time is dedicated to inpatient care, and we started our movement after studying the model of care delineated by Wachter and Lee.7-9 In 2005, we formed a local association called GEAMH (Grupo de Estudos e Atualização em Medicina Hospitalar) to promote the understanding and diffusion of hospitalist principles, integrated by the professors and former and current residents of a large local internal medicine residence program from the Internal Medicine Department of Nossa Senhora da Conceição Hospital (HNSC).

We have created a Web site (www.medicinahospitalar.com.br) where you can find history, news, and information about hospital medicine fellowships in the United States, as well as online hospital medicine continuing education. As you can see, we are spreading SHM’s ideas.

The third year of the HNSC Internal Medicine Residence Program (R3) focused on hospital medicine was developed in 2005. We believe this to be the first initiative of its kind in Brazil. HNSC is part of Conceição Hospital Group, which is composed of four hospital units and is one of the biggest public hospital networks in Brazil.

The Internal Medicine Residence Program started at HNSC in 1968. The department itself has more than 100 hospital beds. Medical residents’ activities all take place in the hospital, and there are nine professors: Eduardo Fernandes, Guilherme Barcellos, Janete Brauner, José Luiz F. Soares, Nelson Roessler, Paulo Almeida, Paulo Ricardo Cardoso, Sergio Dedavid, and Sergio Prezzi. We would like to make special mention of our colleagues Eduardo Fernandes, current head of HNSC Internal Medicine Medical Residence Program, and Sergio Prezzi, the R3 coordinator.

The HNSC Internal Medicine Service is well known for graduating internists skilled in hospital practices, mainly because the program is run by professors who specialize in that area. The R3 is a one-year training program. Our goal is to train physicians to provide outstanding and comprehensive inpatient care. Through supervised training, our residents are able to treat common hospital illnesses; we are also training them in consultative medicine and in the clinical management of surgical patients. Other areas of medical residents’ education include medical ethics, end-of-life care, inpatient nutritional support, risk management, rational use of drugs, and technology and evidence-based medicine.

Our third-year residents have the opportunity to try bone marrow biopsy, pleural biopsy, and thorax draining—all of which are usually handled by other medical specialists. In general, residents also have many opportunities to learn about and practice endotracheal intubations, ventilator management, central vein access, and many other procedures.

Based on HNSC experience, a formal stage in hospital medicine under the supervision of Luciano Bauer Grohs, MD, one of the founders of GEAMH, has also been integrated into internal medicine training at Nossa Senhora de Pompéia Hospital in the city of Caxias do Sul, located 125 kilometers from Porto Alegre.

Our group has developed medical education in the inpatient setting. Because there is no hospital medicine society in Brazil, we have tried to coordinate with the Brazilian Society of Internal Medicine, encouraging discussions about hospital care and promoting workshops about mechanical ventilation, central vein access, and early goal-directed therapy for sepsis. More recently, we have chosen to work independently, believing that hospital medicine is distinct from internal medicine.

When we organized the Brazilian Annual Congress of Medical Residents in 2006, we had the opportunity to bring together medical residents and professors from different medical areas. The Congress’ main focuses were rational use of drugs and technology and the relationship between the young physician and the pharmaceutical industry. The participation of Robert Goodman (of No Free Lunch fame) was an important part of the convention.10

Slow and Steady Growth

We understand that there is a long journey ahead, beyond educational and medical assistance. Our group is still far from promoting research. But hospital medicine specialization has launched in Brazil. Dr. Watcher has said to us, “In the United States, the hospitalist field is the fastest growing specialty in the country—and probably in the history of the country. Hospitalists are transforming the delivery of American hospital care and improving quality, patient safety, education, end-of-life care, and more. We are thrilled to partner with our Brazilian colleagues as, together, we try to improve the quality of care for hospitalized patients everywhere.” We are confident that his vision will become a reality in Brazil in the near future. TH

Note: We are in debt to the professors at the Hospital Conceição Internal Medicine Residency Program, without whom our initiatives would never have blossomed. Special thanks to Eduardo Fernandes, Sergio Prezzi, and Paulo Ricardo Cardoso.

Dr. Barcellos is a specialist in internal medicine, emergency medicine, and critical care. He is professor in Nossa Senhora da Conceição Hospital’s Hospital Medicine Residence Program and president of GEAMH, a local association designed to promote the understanding and diffusion of hospitalist principles.

Dr. Wajner is a specialist in internal medicine and emergency medicine and a Master of Science student at Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul.

Dr. de Waldemar is a specialist in internal medicine and emergency medicine.

References

- Departamento de População e Indicadores Sociais. Estatísticas da saúde: assistência médico-sanitária 2005/IBGE. Departamento de População e Indicadores Sociais. 2006. Available at: www.ibge.gov.br/home/estatistica/populacao/condicaodevida/ams/2005/ams2005.pdf. Last accessed January 28, 2007.

- Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária. Lei nº 8080. D.O.U. - Diário Oficial da União; Poder Executivo. September 20, 1990. Available at: http://e-legis.bvs.br/leisref/public/showAct.php?id=16619&word=. Last accessed January 28, 2007.

- Brazilian Ministry of Health Web site. Available at: http://portal.saude.gov.br/saude. Last accessed January 28, 2007.

- Deslandes SF. Análise do discurso oficial sobre a humanização da assistência hospitalar. Ciência e saúde coletiva. 2004;9:7-14. Available at: www.scielo.br/pdf/csc/v9n1/19819.pdf. Last ccessed January 28, 2007.

- Portela MC, Lima SML, Barbosa PR, et al. Caracterização assistencial de hospitais filantrópicos no Brasil. Rev Saúde Pública. 2004;38:811-818. Available at: www.scielo.br/pdf/rsp/v38n6/09.pdf. Last accessed January 28, 2007.

- Sindicato Médico do Rio Grande do Sul Web site. Available at: www.simers.org.br/entquerem.php. Last accessed January 28, 2007.

- Wachter RM, Goldman L. The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system. N Engl J Med. 1996 Aug 15;335(7):514-517.

- Wachter RM, Goldman L. The hospitalist movement 5 years later. JAMA. 2002 Feb 16;287:487–494. Review.

- Wachter RM. An introduction to the hospitalist model. Ann Intern Med. 1999 Feb 16;130(4 Pt 2):338–342.

- No Free Lunch Web site. Available at: www.nofreelunch.org. Last accessed January 28, 2007.

Perfect Pain Control

Skillful use of intravenous pain medications can be a powerful tool in the clinician’s pain management armamentarium. Yet many physicians are uncomfortable prescribing IV pain medications, especially opioids, even when their patients are experiencing severe pain—7-10 on the verbal analogue scale (VAS). This reticence, say the palliative care specialists interviewed for this article, may be due to a lack of training and knowledge, as well as misperceptions about proper use of IV opioids. The end result for patients can be inadequate pain control, which, according to researchers, continues to be a problem in U.S. hospitals.1

Even hospitalists not affiliated with a surgical service who do not treat perioperative patients are likely to encounter many different scenarios in which IV pain medications could appropriately address patients’ discomfort. David Ling, MD, a member of SHM’s Palliative Care Task Force, a hospitalist at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass., and assistant professor of medicine at Tufts University School of Medicine (Boston), says patients who need IV pain medicines range from those with acute abdominal pain, pancreatitis, or small bowel obstructions to patients with end-stage cancer, renal disease, or congestive heart failure.

“It’s probably a bigger number on the medical service than most people realize,” he says.

The Short List

When it comes to effective IV pain medications very few choices exist, according to recommendations from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network and other pain advocacy organizations. An informal poll of interview sources corroborates this revelation.

“Morphine is the gold standard in pain control,” says Thomas Bookwalter, PharmD, clinical pharmacist on the General Medicine Service at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) Medical Center, a Health Sciences associate clinical professor at the UCSF School of Pharmacy, and a member of SHM’s Palliative Care Task Force.

Preferences for morphine or other opioids vary by practitioner and institution. For instance, says Dr. Bookwalter, the pain service at UCSF has been using hydromorphone more frequently of late.

Nicole L. Artz, MD, director of the Adult Sickle Cell Disease Care Team at the University of Chicago Hospitals and instructor of medicine at the University of Chicago Medical School, also occasionally uses IV infusions of ketorolac—a powerful NSAID designed for short-term management of moderately severe pain in adults. But, like morphine, it is contraindicated in patients with renal insufficiency and can have GI side effects.

Common Missteps

That opioids remain the drugs of choice for controlling severe pain puts some physicians outside their comfort zone. Dr. Ling, who has extensive experience with IV opioids, has observed two common tendencies among physicians inexperienced with prescribing opioids. “There is a tendency, based on the traditional teaching, to prescribe a lower-than-necessary first dose and for those doses to not be frequent enough,” he says.

Dr. Artz, who has a special interest in pain management, lectures on effectively using opioids to house staff at the University of Chicago. She has observed a deficit in physician training in pain management and has seen physicians make many errors when writing orders for opioids, including mixing IV and short-acting oral opioids or two long-acting opioids, not distinguishing between patients who are opioid-naïve and opioid-tolerant in choosing a starting dose, failing to titrate short-acting opioids rapidly despite inadequate pain control, and giving orders for repeated doses of morphine in patients with renal insufficiency.

Dr. Bookwalter says the World Health Organization’s stepladder approach to treating pain (starting with oral NSAIDs and moving up to opioids) does not align with current scientific thinking on prescribing pain medication. For severe pain, a clinician should consider immediately starting an IV opioid, reassessing the patient every 15-30 minutes to see whether the dose is effectively decreasing the pain. National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Guidelines for Adult Cancer Pain recommend rapid dose escalation to address the level of the patient’s pain.2

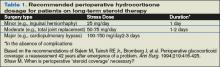

Skill Sets to Acquire