User login

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: Hospitals Forced to Adapt Amid Shifting Slate of Quality Measures

With the arrival of value-based purchasing (VBP), many hospitals have faced hard decisions about where to allocate scarce resources to maximize their performance potential. In some cases, those decisions have been made even more difficult by a set of core measures still very much in flux. For hospitalists, that means the ability to quickly adapt and reprioritize will be in high demand as measures are added or subtracted from the value-based purchasing program.

In the proposed program rules released in mid-January, CMS initially selected 17 core clinical measures from a list of 28 eligible candidates included in the Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting (IQR) Program (https://www.cms.gov/HospitalQualityInits/08_HospitalRHQDAPU.asp) and also listed on the public Hospital Compare website (www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov/) for at least one year. CMS explained its decision to withhold some of the remaining core measures from the program by noting that they were “topped out” and thus provided a poor basis of comparison among hospitals. Others, according to the agency, were of little value or were encouraging bad behavior.

CMS used the latter reason in its explanation for why it was not including an eligible core measure on administering antibiotics to pneumonia patients within six hours of their arrival at a hospital. “We do not believe that this measure is appropriate for inclusion because it could lead to inappropriate antibiotic use,” the rules stated. For that measure and others not recommended for inclusion in the hospital VBP program, CMS added that it would propose retiring them “in the near future.”

—Laura M. Dietzel, program director for High-Tech Meaningful Use, PeaceHealth

Laura M. Dietzel, program director for High-Tech Meaningful Use at PeaceHealth, a faith-based healthcare system that operates eight hospitals in three Western states, says CMS’ short statement caught her health system off-guard and forced a rapid shift in its priorities. “We were really focusing on moving some numbers and making some technology changes for some core measures that now, based on what CMS has in the proposed value-based purchasing, will not be around even as of next year,” she says.

Dietzel says the move to high-tech tools like electronic medical records (EMRs) has further complicated how hospitals and healthcare systems like PeaceHealth are preparing for the VBP program. For two other measures that relate to pneumonia immunization, she says, some of PeaceHealth’s hospitals have “less than ideal” scores that could potentially create some financial risk.

An EMR system on tap for next year, she says, likely will help the hospitals significantly improve their scores. But what should they do between now and then: Reinvent the wheel to prop up their numbers, only to do it again in a year? Or should they take a temporary hit until the more comprehensive system is in place?

Similar questions are likely to confront more healthcare providers as the program expands and evolves. Even as it will likely retire some measures in fiscal year 2014, CMS will add more from a list of 20 related to hospital-acquired conditions and complications, patient safety indicators, inpatient quality indicators, and mortality rates.

With the arrival of value-based purchasing (VBP), many hospitals have faced hard decisions about where to allocate scarce resources to maximize their performance potential. In some cases, those decisions have been made even more difficult by a set of core measures still very much in flux. For hospitalists, that means the ability to quickly adapt and reprioritize will be in high demand as measures are added or subtracted from the value-based purchasing program.

In the proposed program rules released in mid-January, CMS initially selected 17 core clinical measures from a list of 28 eligible candidates included in the Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting (IQR) Program (https://www.cms.gov/HospitalQualityInits/08_HospitalRHQDAPU.asp) and also listed on the public Hospital Compare website (www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov/) for at least one year. CMS explained its decision to withhold some of the remaining core measures from the program by noting that they were “topped out” and thus provided a poor basis of comparison among hospitals. Others, according to the agency, were of little value or were encouraging bad behavior.

CMS used the latter reason in its explanation for why it was not including an eligible core measure on administering antibiotics to pneumonia patients within six hours of their arrival at a hospital. “We do not believe that this measure is appropriate for inclusion because it could lead to inappropriate antibiotic use,” the rules stated. For that measure and others not recommended for inclusion in the hospital VBP program, CMS added that it would propose retiring them “in the near future.”

—Laura M. Dietzel, program director for High-Tech Meaningful Use, PeaceHealth

Laura M. Dietzel, program director for High-Tech Meaningful Use at PeaceHealth, a faith-based healthcare system that operates eight hospitals in three Western states, says CMS’ short statement caught her health system off-guard and forced a rapid shift in its priorities. “We were really focusing on moving some numbers and making some technology changes for some core measures that now, based on what CMS has in the proposed value-based purchasing, will not be around even as of next year,” she says.

Dietzel says the move to high-tech tools like electronic medical records (EMRs) has further complicated how hospitals and healthcare systems like PeaceHealth are preparing for the VBP program. For two other measures that relate to pneumonia immunization, she says, some of PeaceHealth’s hospitals have “less than ideal” scores that could potentially create some financial risk.

An EMR system on tap for next year, she says, likely will help the hospitals significantly improve their scores. But what should they do between now and then: Reinvent the wheel to prop up their numbers, only to do it again in a year? Or should they take a temporary hit until the more comprehensive system is in place?

Similar questions are likely to confront more healthcare providers as the program expands and evolves. Even as it will likely retire some measures in fiscal year 2014, CMS will add more from a list of 20 related to hospital-acquired conditions and complications, patient safety indicators, inpatient quality indicators, and mortality rates.

With the arrival of value-based purchasing (VBP), many hospitals have faced hard decisions about where to allocate scarce resources to maximize their performance potential. In some cases, those decisions have been made even more difficult by a set of core measures still very much in flux. For hospitalists, that means the ability to quickly adapt and reprioritize will be in high demand as measures are added or subtracted from the value-based purchasing program.

In the proposed program rules released in mid-January, CMS initially selected 17 core clinical measures from a list of 28 eligible candidates included in the Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting (IQR) Program (https://www.cms.gov/HospitalQualityInits/08_HospitalRHQDAPU.asp) and also listed on the public Hospital Compare website (www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov/) for at least one year. CMS explained its decision to withhold some of the remaining core measures from the program by noting that they were “topped out” and thus provided a poor basis of comparison among hospitals. Others, according to the agency, were of little value or were encouraging bad behavior.

CMS used the latter reason in its explanation for why it was not including an eligible core measure on administering antibiotics to pneumonia patients within six hours of their arrival at a hospital. “We do not believe that this measure is appropriate for inclusion because it could lead to inappropriate antibiotic use,” the rules stated. For that measure and others not recommended for inclusion in the hospital VBP program, CMS added that it would propose retiring them “in the near future.”

—Laura M. Dietzel, program director for High-Tech Meaningful Use, PeaceHealth

Laura M. Dietzel, program director for High-Tech Meaningful Use at PeaceHealth, a faith-based healthcare system that operates eight hospitals in three Western states, says CMS’ short statement caught her health system off-guard and forced a rapid shift in its priorities. “We were really focusing on moving some numbers and making some technology changes for some core measures that now, based on what CMS has in the proposed value-based purchasing, will not be around even as of next year,” she says.

Dietzel says the move to high-tech tools like electronic medical records (EMRs) has further complicated how hospitals and healthcare systems like PeaceHealth are preparing for the VBP program. For two other measures that relate to pneumonia immunization, she says, some of PeaceHealth’s hospitals have “less than ideal” scores that could potentially create some financial risk.

An EMR system on tap for next year, she says, likely will help the hospitals significantly improve their scores. But what should they do between now and then: Reinvent the wheel to prop up their numbers, only to do it again in a year? Or should they take a temporary hit until the more comprehensive system is in place?

Similar questions are likely to confront more healthcare providers as the program expands and evolves. Even as it will likely retire some measures in fiscal year 2014, CMS will add more from a list of 20 related to hospital-acquired conditions and complications, patient safety indicators, inpatient quality indicators, and mortality rates.

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: Experts explain how hospitalists can thrive in a new era of payment reform

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: Listen to billing and coding consultants discuss the importance of provider buy-in

Click here to listen to Dr. Pinson

Click here to listen to Ms. Leong

Click here to listen to Dr. Pinson

Click here to listen to Ms. Leong

Click here to listen to Dr. Pinson

Click here to listen to Ms. Leong

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: PEERist Program Provides Rural Nebraska Hospital 24/7 HM Coverage

Hospitalist programs take many shapes, and the organizational flowchart typically depends on the number and makeup of the physicians, the hospital, the patients, and the community. Adequately covering the needs of inpatient units can be especially frustrating in rural communities, some hospitalists say.

“There are only five physicians total in our town,” says Gary Ensz, MD, a partner in the Auburn Family Health Center in Auburn, Neb. “In addition to being family practitioners, we are our own hospitalists. Covering the emergency room, seeing patients in clinic, and following hospitalized patients is a big burden.”

To address these issues, Dr. Ensz and his partners developed the Physician Extender Emergency Room Hospitalist (PEERist) program. They utilize physician assistants (PAs) to serve many hospitalist functions under their supervision.

“We hired PAs to work in the hospital and the emergency room,” Dr. Ensz explains. “They do not work in the clinic and then take call. Their only responsibilities are to the hospital and ER.”

—Gary Ensz, MD, partner, Auburn (Neb.) Family Health Center

PEERists work under protocols addressing treatment concerns and give guidance on when physicians should be called. On-call doctors round in the morning with the PA. The physicians like this approach, Dr. Ensz says, because they see the PEERist when it is convenient for them; before, they would leave clinic patients to attend to concerns at the hospital.

Impact of ER Call

“For most of us practicing in rural situations, the demands of ER call force people to retire,” Dr. Ensz says. “Now we have someone at the hospital highly trained and, as they get more experience, actually do some work better simply because they are there all the time. At worst, you now have two sets of hands working on the patient.”

PAs work a rotating schedule of up to 72 hours with as many as nine days off in a row. PAs can be recruited from a much larger area; in fact, one commutes four hours each way. PEERists say the time off makes it easier to do things with their families or work another job.

Other Benefits

In addition to pluses associated with the practice, Dr. Ensz is seeing other benefits, such as closer working relationships with the nurses. He also stresses that his hospital now has 24/7 in-house coverage, something almost unheard of in small rural hospitals.

One of the more subtle improvements might have been in getting people to the hospital quicker. “It wasn’t unusual for someone to come to clinic with symptoms they had for a while,” Dr. Ensz says. “The PEERists being in-house all the time have done away with these concerns.”

Hospitalist programs take many shapes, and the organizational flowchart typically depends on the number and makeup of the physicians, the hospital, the patients, and the community. Adequately covering the needs of inpatient units can be especially frustrating in rural communities, some hospitalists say.

“There are only five physicians total in our town,” says Gary Ensz, MD, a partner in the Auburn Family Health Center in Auburn, Neb. “In addition to being family practitioners, we are our own hospitalists. Covering the emergency room, seeing patients in clinic, and following hospitalized patients is a big burden.”

To address these issues, Dr. Ensz and his partners developed the Physician Extender Emergency Room Hospitalist (PEERist) program. They utilize physician assistants (PAs) to serve many hospitalist functions under their supervision.

“We hired PAs to work in the hospital and the emergency room,” Dr. Ensz explains. “They do not work in the clinic and then take call. Their only responsibilities are to the hospital and ER.”

—Gary Ensz, MD, partner, Auburn (Neb.) Family Health Center

PEERists work under protocols addressing treatment concerns and give guidance on when physicians should be called. On-call doctors round in the morning with the PA. The physicians like this approach, Dr. Ensz says, because they see the PEERist when it is convenient for them; before, they would leave clinic patients to attend to concerns at the hospital.

Impact of ER Call

“For most of us practicing in rural situations, the demands of ER call force people to retire,” Dr. Ensz says. “Now we have someone at the hospital highly trained and, as they get more experience, actually do some work better simply because they are there all the time. At worst, you now have two sets of hands working on the patient.”

PAs work a rotating schedule of up to 72 hours with as many as nine days off in a row. PAs can be recruited from a much larger area; in fact, one commutes four hours each way. PEERists say the time off makes it easier to do things with their families or work another job.

Other Benefits

In addition to pluses associated with the practice, Dr. Ensz is seeing other benefits, such as closer working relationships with the nurses. He also stresses that his hospital now has 24/7 in-house coverage, something almost unheard of in small rural hospitals.

One of the more subtle improvements might have been in getting people to the hospital quicker. “It wasn’t unusual for someone to come to clinic with symptoms they had for a while,” Dr. Ensz says. “The PEERists being in-house all the time have done away with these concerns.”

Hospitalist programs take many shapes, and the organizational flowchart typically depends on the number and makeup of the physicians, the hospital, the patients, and the community. Adequately covering the needs of inpatient units can be especially frustrating in rural communities, some hospitalists say.

“There are only five physicians total in our town,” says Gary Ensz, MD, a partner in the Auburn Family Health Center in Auburn, Neb. “In addition to being family practitioners, we are our own hospitalists. Covering the emergency room, seeing patients in clinic, and following hospitalized patients is a big burden.”

To address these issues, Dr. Ensz and his partners developed the Physician Extender Emergency Room Hospitalist (PEERist) program. They utilize physician assistants (PAs) to serve many hospitalist functions under their supervision.

“We hired PAs to work in the hospital and the emergency room,” Dr. Ensz explains. “They do not work in the clinic and then take call. Their only responsibilities are to the hospital and ER.”

—Gary Ensz, MD, partner, Auburn (Neb.) Family Health Center

PEERists work under protocols addressing treatment concerns and give guidance on when physicians should be called. On-call doctors round in the morning with the PA. The physicians like this approach, Dr. Ensz says, because they see the PEERist when it is convenient for them; before, they would leave clinic patients to attend to concerns at the hospital.

Impact of ER Call

“For most of us practicing in rural situations, the demands of ER call force people to retire,” Dr. Ensz says. “Now we have someone at the hospital highly trained and, as they get more experience, actually do some work better simply because they are there all the time. At worst, you now have two sets of hands working on the patient.”

PAs work a rotating schedule of up to 72 hours with as many as nine days off in a row. PAs can be recruited from a much larger area; in fact, one commutes four hours each way. PEERists say the time off makes it easier to do things with their families or work another job.

Other Benefits

In addition to pluses associated with the practice, Dr. Ensz is seeing other benefits, such as closer working relationships with the nurses. He also stresses that his hospital now has 24/7 in-house coverage, something almost unheard of in small rural hospitals.

One of the more subtle improvements might have been in getting people to the hospital quicker. “It wasn’t unusual for someone to come to clinic with symptoms they had for a while,” Dr. Ensz says. “The PEERists being in-house all the time have done away with these concerns.”

Nurse Practitioners, Physician Assistants to the Rescue

In 2004, the hospitalist group at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor faced a manpower problem: In a refrain common to hospitalist groups around the country, changes in duty-hour regulations were making it harder for medical residents to continue to provide inpatient coverage at the same levels as before.

Addressing the issue was difficult for the HM group and hospital administrators; they were going to need a significant number of new providers, and qualified physicians were in short supply. To address these issues, the HM group chose to add nonphysician providers (NPP) to their service.

“NPPs had worked at UM for a long time in other areas,” says Vikas Parekh, MD, SFHM, associate director of hospitalist management. “We had just created a new service that was hiring new people and thought NPPs would help in providing services.”

Hiring NPPs helped solve the University of Michigan’s problem, and the tactic has helped solve manpower issues at numerous HM groups around the country. But deciding whether your HM group should hire physicians, NPPs—usually nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs)—or some combination of the two will not be easy. It is a complex decision, one that requires following state-level licensing and practice laws as well as local hospital bylaws and federal and private insurance payment rules. Such decisions also mean HM group directors need to keep in mind case mixes and the personalities of the physicians in the practice.

“There is no one-size-fits-all solution,” says Mitchell Wilson, MD, SFHM, corporate medical director for Eagle Hospital Physicians in Atlanta. “Not all environments are well-suited to NPP practice. Even when it is, you can’t just throw an NPP into the mix on their own with the expectation they will be successful.”

Whether it’s covering admissions, streamlining discharges, or working as an integral part of a care team, NPPs can be the solution expanding HM groups are looking for.

“Our physicians depend on NPPs to help them complete patient care in a more efficient manner and work to enhance continuity of care,” says Mary Whitehead, RN, APRN-BC, FNP, of Hospital Medicine Associates in Fort Worth, Texas. “We lower physician rounding time so patients are seen sooner and tests are requested sooner. In addition, the patients really appreciate the extra time we can spend with them.”

Trained, Licensed, Available

NPs must be registered nurses with clinical experience before they can enroll in an advanced degree program, which usually results in a master’s degree or doctorate. Generally, a state board of nursing, or a state board jointly with the state medical board, regulates NPs.

PAs are trained in more of a traditional medical model. They have a variable education level all the way up to a PhD, although more states are requiring at least a master’s degree. Practice and other legal parameters most often come under the authority of state medical boards.

NPPs can provide additional medical expertise to patients, says Ryan Genzink, PA, a physician assistant with Hospitalists of Western Michigan in Grand Rapids and the American Academy of Physician Assistants’ medical liaison to SHM. “One of the challenges faced by physicians is that they often have to be in two places at once,” he says. “There is a recognition that teams provide better care for complicated patients.”

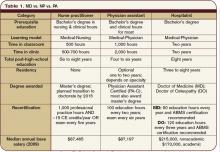

NPPs generally practice under the supervision of a physician hospitalist. Some states allow a greater degree of independence for NPs. However, most NPs and PAs are required to have a practice agreement outlining their responsibilities and the amount of oversight required (see Table 1, p. 39). There is no such thing as a “fire and forget” NPP.

“The practice needs to thoroughly understand the legal environment early in the process,” says John Nelson, MD, MHM, hospitalist director at Bellevue (Wash.) Medical Center, partner in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants, and SHM cofounder. “NPPs are not a ‘hospitalist lite’ that can function entirely like a hospitalist.”

Hospital bylaws, which can vary greatly by city, county, or state, are another important consideration before you hire an NPP.

“In some areas, NPPs may not be able to practice in the ICU,” Dr. Wilson says. “In others, the physician may be required to see the patient instead of consulting with the NPP. The idiosyncrasies of the individual hospital’s bylaws may impact the efficiency of the NPP/MD team.”

Physician Characteristics

Environmental variables—namely, the personality of the physicians within the practice—should be considered before you head down the NPP path. It makes little practical or financial sense to spend the time and effort of hiring an NPP if the physicians still insist on doing all the work.

“[It’s] one of the most significant factors in successfully integrating an NPP program,” Dr. Wilson says. “Will [physicians] be able to tolerate some degree of uncertainty when letting others see their patients? Are they open to adapting to different practice styles? The thing we see most often in practices that use NPPs to their advantage is the recognition that there is an important role for the nonphysician at the bedside.”

Some physicians hesitate to work with NPPs, while others welcome the extra help and unique experience NPPs offer. Experts agree that forcing NPPs on a physician is not a good idea. They also agree that, especially when beginning a new program, group directors should let physicians who are interested in working with NPPs take the lead. As NPP use in the group matures, many of those who were at first unwilling can decide that there is a place for NPPs in their practice.

Case Mix Is Key

The types and kinds of patient seen might limit the use of NPPs in hospitalist practice. “Our experience is that acuity and complexity of the care, especially as it relates to diagnostic and therapeutic decision-making, makes it difficult for NPPs to function independently,” Dr. Parekh says.

Dr. Wilson agrees. “Depending on the specific attributes of the setting, a service with both high-complexity and high-acuity patients may be a more challenging environment to realize the efficiencies of NPPs,” he says. “There is a relationship between complexity, acuity, and physician involvement.”

Even so, a continuum of NPP use in HM practice is achievable. For example, as a patient improves, an NPP might be able to take on a larger role in treatment by participating in discharge planning. In more acute patients, the NPP can save valuable physician time by coordinating with consultants, staying on top of treatments, and consolidating clinically important data for the physician.

Many Models in Use

Historically, the widespread use of alternative providers began in 2004 as a result of the changes to resident duty-hours. The restrictions created a workforce gap, which led to a large number of new positions in hospitals nationwide. Many of HM’s early adopters essentially went with what they knew.

“We work in teams where the physician, NPP, and nurse see a group of patients similar in function to an attending, resident, and RN,” Genzink says. “We see ‘our’ patients in a collaborative fashion.”

There are other models that have proven successful in the correct setting. Some HM groups use specialist NPPs to cover specific clinical areas, such as orthopedics or oncology. This not only develops a cadre of providers with excellent understanding of their patients, but it also frees up physician time for more acute and complicated patients.

“Our physicians depend on us helping them get patient care completed more efficiently, so that length of stay is acceptable, and to enhance continuity of care,” says Whitehead, the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners’ liaison to SHM. “Having an NPP visit the patient daily, documenting progress, greatly enhances communications between physicians and consultants.”

Other groups have NPPs specialize by function—for example, they cover all admissions or work mainly with discharging a patient. Some groups have the physician see the patient on admission, work out a care plan, then turn over management to the NPP. Many agree that most NPPs are best utilized by having them cover specific shifts, such as overnight call or on a swing shift, to help during peak demand.

Monetary and Time Commitments

The financial impact of NPPs on a hospitalist practice depends on many factors. Groups will need to look not only at the salary and benefit costs associated with the position, but also how best to fit that person into the billing system.

Salary and benefit comparisons are fairly straightforward: The State of Hospital Medicine: 2010 Report Based on 2009 Data, produced by SHM and the Medical Group Management Association, shows median total compensation for adult hospitalists at $215,000 per year; NPP compensation is around $87,000.1

The general cost of benefits (health insurance, retirement, etc.) is fairly typical throughout a hospitalist practice, so there should be little difference between a new FTE hospitalist or NPP. Other considerations, including office space and support staff, would be roughly the same if the group hired a physician. The cost of continuing education and malpractice insurance likely will be less with an NPP, but it is best to check before making a new hire.

After the outgo has been established, the next step is to look at the differences in reimbursement for NPPs vs. physicians. Here, again, the math gets tricky. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) pay NPPs at 85% of the physician rate for a specific diagnosis. However, if there is direct physician involvement, the claim can be filed as “shared billing” and reimbursed at 100%.

For some hospitalist practices, adding NPPs is an easy decision to make. Dr. Parekh says his group already has policies in place that require a physician to see the patient every day. In that case, no extra physician time is necessary, so shared billing makes sense. Other hospitals’ bylaws might have similar requirements.

For practices in which the NPP is able to work with less oversight, it might be better to bill at 85% rather than use the physician time to meet shared-billing criteria. Even in practices with greater NPP autonomy, such variables as case mix and patient acuity might enter into the equation. If the patient is sick enough that the physician is involved for a significant amount of time, then shared billing probably is best.

Experts say group directors and hiring managers should look carefully at contracts with private insurers, too. There most likely will be considerable variation in how each plan handles NPP claims.

Managing performance expectations can have an impact on the successful use of NPPs in a hospitalist practice. Setting realistic goals and groupwide understanding of what the NPPs’ roles will be is crucial. The practice should look at the work that needs to be done and decide if that work provides a genuinely valuable role for an NPP.

Hire for Need, Not Desperation

“The mistake I see most often is hiring an NPP because a practice is desperate for help,” says Martin Buser, MPH, FACHE, a partner in Hospitalist Management Resources, LLC, in San Diego. “Smart practices are looking at NPPs, evaluating where they do the most good, and then setting out their role and expectations based on these needs and the practice environment.”

Hiring mistakes can be compounded if the NPP is not a good match to the job description or group expectations. If the practice hires an NPP fresh out of school, the group will need to establish training and have the new hire work more closely with physicians. If, on the other hand, an NP has 10 years of experience in an ICU, or a PA has worked in the ED for the past five years, a higher level of autonomy can be granted sooner. However, NPPs with established backgrounds are almost as rare as experienced hospitalists (see “Integrating NPPs Into HM Practice,” p. 38).

Inevitably, there will be changes in the interactions between patients and the hospitalists, as both physicians and NPPs become more comfortable with the other’s practice style, as well as each other’s strengths and weaknesses.

MD-to-NPP Ratio Varies

The practice structure and optimal mix of NPPs to MDs is something that will be specific to the hospitalist group. “We don’t really have good studies on this subject,” Buser says. “I usually get worried when we exceed two NPPs to one MD.”

Others disagree. Dr. Parekh, who works in an academic center, says his group has been successful having one MD work with as many as three NPPs. At the other end, Dr. Wilson says his 10 years of experience suggest 1:1 is the most efficient ratio.

However, all of them agree that having one NPP work with more than one physician is not sustainable. The NPP will be less familiar with each doctor’s practice style, what kind of information they need, and how things should be presented. If two or more hospitalists share an NPP, there can be internal friction over division of the NPP’s time, as well as extending the time before the MDs have a good feel for the NPP’s strengths and weaknesses.

In the final analysis, the HM group has to look at the amount and type of work available. In some cases, it will make financial and clinical sense to bring on an NPP. Under other circumstances, an FTE hospitalist is the best fit.

“Sustainability, quality, and efficiency are the drivers for NPP/MD teams. Increasing pressure to offset program costs is not,” Dr. Wilson says. “You do it because it helps sustain the program, helps with recruiting, and effects your efficiency.” TH

Kurt Ullman is a freelance medical writer based in Indiana.

Reference

- Medical Group Management Association and the Society of Hospital Medicine. State of Hospital Medicine: 2010 Report Based on 2009 Data. 2010. Philadelphia and Englewood, Colo.

In 2004, the hospitalist group at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor faced a manpower problem: In a refrain common to hospitalist groups around the country, changes in duty-hour regulations were making it harder for medical residents to continue to provide inpatient coverage at the same levels as before.

Addressing the issue was difficult for the HM group and hospital administrators; they were going to need a significant number of new providers, and qualified physicians were in short supply. To address these issues, the HM group chose to add nonphysician providers (NPP) to their service.

“NPPs had worked at UM for a long time in other areas,” says Vikas Parekh, MD, SFHM, associate director of hospitalist management. “We had just created a new service that was hiring new people and thought NPPs would help in providing services.”

Hiring NPPs helped solve the University of Michigan’s problem, and the tactic has helped solve manpower issues at numerous HM groups around the country. But deciding whether your HM group should hire physicians, NPPs—usually nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs)—or some combination of the two will not be easy. It is a complex decision, one that requires following state-level licensing and practice laws as well as local hospital bylaws and federal and private insurance payment rules. Such decisions also mean HM group directors need to keep in mind case mixes and the personalities of the physicians in the practice.

“There is no one-size-fits-all solution,” says Mitchell Wilson, MD, SFHM, corporate medical director for Eagle Hospital Physicians in Atlanta. “Not all environments are well-suited to NPP practice. Even when it is, you can’t just throw an NPP into the mix on their own with the expectation they will be successful.”

Whether it’s covering admissions, streamlining discharges, or working as an integral part of a care team, NPPs can be the solution expanding HM groups are looking for.

“Our physicians depend on NPPs to help them complete patient care in a more efficient manner and work to enhance continuity of care,” says Mary Whitehead, RN, APRN-BC, FNP, of Hospital Medicine Associates in Fort Worth, Texas. “We lower physician rounding time so patients are seen sooner and tests are requested sooner. In addition, the patients really appreciate the extra time we can spend with them.”

Trained, Licensed, Available

NPs must be registered nurses with clinical experience before they can enroll in an advanced degree program, which usually results in a master’s degree or doctorate. Generally, a state board of nursing, or a state board jointly with the state medical board, regulates NPs.

PAs are trained in more of a traditional medical model. They have a variable education level all the way up to a PhD, although more states are requiring at least a master’s degree. Practice and other legal parameters most often come under the authority of state medical boards.

NPPs can provide additional medical expertise to patients, says Ryan Genzink, PA, a physician assistant with Hospitalists of Western Michigan in Grand Rapids and the American Academy of Physician Assistants’ medical liaison to SHM. “One of the challenges faced by physicians is that they often have to be in two places at once,” he says. “There is a recognition that teams provide better care for complicated patients.”

NPPs generally practice under the supervision of a physician hospitalist. Some states allow a greater degree of independence for NPs. However, most NPs and PAs are required to have a practice agreement outlining their responsibilities and the amount of oversight required (see Table 1, p. 39). There is no such thing as a “fire and forget” NPP.

“The practice needs to thoroughly understand the legal environment early in the process,” says John Nelson, MD, MHM, hospitalist director at Bellevue (Wash.) Medical Center, partner in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants, and SHM cofounder. “NPPs are not a ‘hospitalist lite’ that can function entirely like a hospitalist.”

Hospital bylaws, which can vary greatly by city, county, or state, are another important consideration before you hire an NPP.

“In some areas, NPPs may not be able to practice in the ICU,” Dr. Wilson says. “In others, the physician may be required to see the patient instead of consulting with the NPP. The idiosyncrasies of the individual hospital’s bylaws may impact the efficiency of the NPP/MD team.”

Physician Characteristics

Environmental variables—namely, the personality of the physicians within the practice—should be considered before you head down the NPP path. It makes little practical or financial sense to spend the time and effort of hiring an NPP if the physicians still insist on doing all the work.

“[It’s] one of the most significant factors in successfully integrating an NPP program,” Dr. Wilson says. “Will [physicians] be able to tolerate some degree of uncertainty when letting others see their patients? Are they open to adapting to different practice styles? The thing we see most often in practices that use NPPs to their advantage is the recognition that there is an important role for the nonphysician at the bedside.”

Some physicians hesitate to work with NPPs, while others welcome the extra help and unique experience NPPs offer. Experts agree that forcing NPPs on a physician is not a good idea. They also agree that, especially when beginning a new program, group directors should let physicians who are interested in working with NPPs take the lead. As NPP use in the group matures, many of those who were at first unwilling can decide that there is a place for NPPs in their practice.

Case Mix Is Key

The types and kinds of patient seen might limit the use of NPPs in hospitalist practice. “Our experience is that acuity and complexity of the care, especially as it relates to diagnostic and therapeutic decision-making, makes it difficult for NPPs to function independently,” Dr. Parekh says.

Dr. Wilson agrees. “Depending on the specific attributes of the setting, a service with both high-complexity and high-acuity patients may be a more challenging environment to realize the efficiencies of NPPs,” he says. “There is a relationship between complexity, acuity, and physician involvement.”

Even so, a continuum of NPP use in HM practice is achievable. For example, as a patient improves, an NPP might be able to take on a larger role in treatment by participating in discharge planning. In more acute patients, the NPP can save valuable physician time by coordinating with consultants, staying on top of treatments, and consolidating clinically important data for the physician.

Many Models in Use

Historically, the widespread use of alternative providers began in 2004 as a result of the changes to resident duty-hours. The restrictions created a workforce gap, which led to a large number of new positions in hospitals nationwide. Many of HM’s early adopters essentially went with what they knew.

“We work in teams where the physician, NPP, and nurse see a group of patients similar in function to an attending, resident, and RN,” Genzink says. “We see ‘our’ patients in a collaborative fashion.”

There are other models that have proven successful in the correct setting. Some HM groups use specialist NPPs to cover specific clinical areas, such as orthopedics or oncology. This not only develops a cadre of providers with excellent understanding of their patients, but it also frees up physician time for more acute and complicated patients.

“Our physicians depend on us helping them get patient care completed more efficiently, so that length of stay is acceptable, and to enhance continuity of care,” says Whitehead, the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners’ liaison to SHM. “Having an NPP visit the patient daily, documenting progress, greatly enhances communications between physicians and consultants.”

Other groups have NPPs specialize by function—for example, they cover all admissions or work mainly with discharging a patient. Some groups have the physician see the patient on admission, work out a care plan, then turn over management to the NPP. Many agree that most NPPs are best utilized by having them cover specific shifts, such as overnight call or on a swing shift, to help during peak demand.

Monetary and Time Commitments

The financial impact of NPPs on a hospitalist practice depends on many factors. Groups will need to look not only at the salary and benefit costs associated with the position, but also how best to fit that person into the billing system.

Salary and benefit comparisons are fairly straightforward: The State of Hospital Medicine: 2010 Report Based on 2009 Data, produced by SHM and the Medical Group Management Association, shows median total compensation for adult hospitalists at $215,000 per year; NPP compensation is around $87,000.1

The general cost of benefits (health insurance, retirement, etc.) is fairly typical throughout a hospitalist practice, so there should be little difference between a new FTE hospitalist or NPP. Other considerations, including office space and support staff, would be roughly the same if the group hired a physician. The cost of continuing education and malpractice insurance likely will be less with an NPP, but it is best to check before making a new hire.

After the outgo has been established, the next step is to look at the differences in reimbursement for NPPs vs. physicians. Here, again, the math gets tricky. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) pay NPPs at 85% of the physician rate for a specific diagnosis. However, if there is direct physician involvement, the claim can be filed as “shared billing” and reimbursed at 100%.

For some hospitalist practices, adding NPPs is an easy decision to make. Dr. Parekh says his group already has policies in place that require a physician to see the patient every day. In that case, no extra physician time is necessary, so shared billing makes sense. Other hospitals’ bylaws might have similar requirements.

For practices in which the NPP is able to work with less oversight, it might be better to bill at 85% rather than use the physician time to meet shared-billing criteria. Even in practices with greater NPP autonomy, such variables as case mix and patient acuity might enter into the equation. If the patient is sick enough that the physician is involved for a significant amount of time, then shared billing probably is best.

Experts say group directors and hiring managers should look carefully at contracts with private insurers, too. There most likely will be considerable variation in how each plan handles NPP claims.

Managing performance expectations can have an impact on the successful use of NPPs in a hospitalist practice. Setting realistic goals and groupwide understanding of what the NPPs’ roles will be is crucial. The practice should look at the work that needs to be done and decide if that work provides a genuinely valuable role for an NPP.

Hire for Need, Not Desperation

“The mistake I see most often is hiring an NPP because a practice is desperate for help,” says Martin Buser, MPH, FACHE, a partner in Hospitalist Management Resources, LLC, in San Diego. “Smart practices are looking at NPPs, evaluating where they do the most good, and then setting out their role and expectations based on these needs and the practice environment.”

Hiring mistakes can be compounded if the NPP is not a good match to the job description or group expectations. If the practice hires an NPP fresh out of school, the group will need to establish training and have the new hire work more closely with physicians. If, on the other hand, an NP has 10 years of experience in an ICU, or a PA has worked in the ED for the past five years, a higher level of autonomy can be granted sooner. However, NPPs with established backgrounds are almost as rare as experienced hospitalists (see “Integrating NPPs Into HM Practice,” p. 38).

Inevitably, there will be changes in the interactions between patients and the hospitalists, as both physicians and NPPs become more comfortable with the other’s practice style, as well as each other’s strengths and weaknesses.

MD-to-NPP Ratio Varies

The practice structure and optimal mix of NPPs to MDs is something that will be specific to the hospitalist group. “We don’t really have good studies on this subject,” Buser says. “I usually get worried when we exceed two NPPs to one MD.”

Others disagree. Dr. Parekh, who works in an academic center, says his group has been successful having one MD work with as many as three NPPs. At the other end, Dr. Wilson says his 10 years of experience suggest 1:1 is the most efficient ratio.

However, all of them agree that having one NPP work with more than one physician is not sustainable. The NPP will be less familiar with each doctor’s practice style, what kind of information they need, and how things should be presented. If two or more hospitalists share an NPP, there can be internal friction over division of the NPP’s time, as well as extending the time before the MDs have a good feel for the NPP’s strengths and weaknesses.

In the final analysis, the HM group has to look at the amount and type of work available. In some cases, it will make financial and clinical sense to bring on an NPP. Under other circumstances, an FTE hospitalist is the best fit.

“Sustainability, quality, and efficiency are the drivers for NPP/MD teams. Increasing pressure to offset program costs is not,” Dr. Wilson says. “You do it because it helps sustain the program, helps with recruiting, and effects your efficiency.” TH

Kurt Ullman is a freelance medical writer based in Indiana.

Reference

- Medical Group Management Association and the Society of Hospital Medicine. State of Hospital Medicine: 2010 Report Based on 2009 Data. 2010. Philadelphia and Englewood, Colo.

In 2004, the hospitalist group at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor faced a manpower problem: In a refrain common to hospitalist groups around the country, changes in duty-hour regulations were making it harder for medical residents to continue to provide inpatient coverage at the same levels as before.

Addressing the issue was difficult for the HM group and hospital administrators; they were going to need a significant number of new providers, and qualified physicians were in short supply. To address these issues, the HM group chose to add nonphysician providers (NPP) to their service.

“NPPs had worked at UM for a long time in other areas,” says Vikas Parekh, MD, SFHM, associate director of hospitalist management. “We had just created a new service that was hiring new people and thought NPPs would help in providing services.”

Hiring NPPs helped solve the University of Michigan’s problem, and the tactic has helped solve manpower issues at numerous HM groups around the country. But deciding whether your HM group should hire physicians, NPPs—usually nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs)—or some combination of the two will not be easy. It is a complex decision, one that requires following state-level licensing and practice laws as well as local hospital bylaws and federal and private insurance payment rules. Such decisions also mean HM group directors need to keep in mind case mixes and the personalities of the physicians in the practice.

“There is no one-size-fits-all solution,” says Mitchell Wilson, MD, SFHM, corporate medical director for Eagle Hospital Physicians in Atlanta. “Not all environments are well-suited to NPP practice. Even when it is, you can’t just throw an NPP into the mix on their own with the expectation they will be successful.”

Whether it’s covering admissions, streamlining discharges, or working as an integral part of a care team, NPPs can be the solution expanding HM groups are looking for.

“Our physicians depend on NPPs to help them complete patient care in a more efficient manner and work to enhance continuity of care,” says Mary Whitehead, RN, APRN-BC, FNP, of Hospital Medicine Associates in Fort Worth, Texas. “We lower physician rounding time so patients are seen sooner and tests are requested sooner. In addition, the patients really appreciate the extra time we can spend with them.”

Trained, Licensed, Available

NPs must be registered nurses with clinical experience before they can enroll in an advanced degree program, which usually results in a master’s degree or doctorate. Generally, a state board of nursing, or a state board jointly with the state medical board, regulates NPs.

PAs are trained in more of a traditional medical model. They have a variable education level all the way up to a PhD, although more states are requiring at least a master’s degree. Practice and other legal parameters most often come under the authority of state medical boards.

NPPs can provide additional medical expertise to patients, says Ryan Genzink, PA, a physician assistant with Hospitalists of Western Michigan in Grand Rapids and the American Academy of Physician Assistants’ medical liaison to SHM. “One of the challenges faced by physicians is that they often have to be in two places at once,” he says. “There is a recognition that teams provide better care for complicated patients.”

NPPs generally practice under the supervision of a physician hospitalist. Some states allow a greater degree of independence for NPs. However, most NPs and PAs are required to have a practice agreement outlining their responsibilities and the amount of oversight required (see Table 1, p. 39). There is no such thing as a “fire and forget” NPP.

“The practice needs to thoroughly understand the legal environment early in the process,” says John Nelson, MD, MHM, hospitalist director at Bellevue (Wash.) Medical Center, partner in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants, and SHM cofounder. “NPPs are not a ‘hospitalist lite’ that can function entirely like a hospitalist.”

Hospital bylaws, which can vary greatly by city, county, or state, are another important consideration before you hire an NPP.

“In some areas, NPPs may not be able to practice in the ICU,” Dr. Wilson says. “In others, the physician may be required to see the patient instead of consulting with the NPP. The idiosyncrasies of the individual hospital’s bylaws may impact the efficiency of the NPP/MD team.”

Physician Characteristics

Environmental variables—namely, the personality of the physicians within the practice—should be considered before you head down the NPP path. It makes little practical or financial sense to spend the time and effort of hiring an NPP if the physicians still insist on doing all the work.

“[It’s] one of the most significant factors in successfully integrating an NPP program,” Dr. Wilson says. “Will [physicians] be able to tolerate some degree of uncertainty when letting others see their patients? Are they open to adapting to different practice styles? The thing we see most often in practices that use NPPs to their advantage is the recognition that there is an important role for the nonphysician at the bedside.”

Some physicians hesitate to work with NPPs, while others welcome the extra help and unique experience NPPs offer. Experts agree that forcing NPPs on a physician is not a good idea. They also agree that, especially when beginning a new program, group directors should let physicians who are interested in working with NPPs take the lead. As NPP use in the group matures, many of those who were at first unwilling can decide that there is a place for NPPs in their practice.

Case Mix Is Key

The types and kinds of patient seen might limit the use of NPPs in hospitalist practice. “Our experience is that acuity and complexity of the care, especially as it relates to diagnostic and therapeutic decision-making, makes it difficult for NPPs to function independently,” Dr. Parekh says.

Dr. Wilson agrees. “Depending on the specific attributes of the setting, a service with both high-complexity and high-acuity patients may be a more challenging environment to realize the efficiencies of NPPs,” he says. “There is a relationship between complexity, acuity, and physician involvement.”

Even so, a continuum of NPP use in HM practice is achievable. For example, as a patient improves, an NPP might be able to take on a larger role in treatment by participating in discharge planning. In more acute patients, the NPP can save valuable physician time by coordinating with consultants, staying on top of treatments, and consolidating clinically important data for the physician.

Many Models in Use

Historically, the widespread use of alternative providers began in 2004 as a result of the changes to resident duty-hours. The restrictions created a workforce gap, which led to a large number of new positions in hospitals nationwide. Many of HM’s early adopters essentially went with what they knew.

“We work in teams where the physician, NPP, and nurse see a group of patients similar in function to an attending, resident, and RN,” Genzink says. “We see ‘our’ patients in a collaborative fashion.”

There are other models that have proven successful in the correct setting. Some HM groups use specialist NPPs to cover specific clinical areas, such as orthopedics or oncology. This not only develops a cadre of providers with excellent understanding of their patients, but it also frees up physician time for more acute and complicated patients.

“Our physicians depend on us helping them get patient care completed more efficiently, so that length of stay is acceptable, and to enhance continuity of care,” says Whitehead, the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners’ liaison to SHM. “Having an NPP visit the patient daily, documenting progress, greatly enhances communications between physicians and consultants.”

Other groups have NPPs specialize by function—for example, they cover all admissions or work mainly with discharging a patient. Some groups have the physician see the patient on admission, work out a care plan, then turn over management to the NPP. Many agree that most NPPs are best utilized by having them cover specific shifts, such as overnight call or on a swing shift, to help during peak demand.

Monetary and Time Commitments

The financial impact of NPPs on a hospitalist practice depends on many factors. Groups will need to look not only at the salary and benefit costs associated with the position, but also how best to fit that person into the billing system.

Salary and benefit comparisons are fairly straightforward: The State of Hospital Medicine: 2010 Report Based on 2009 Data, produced by SHM and the Medical Group Management Association, shows median total compensation for adult hospitalists at $215,000 per year; NPP compensation is around $87,000.1

The general cost of benefits (health insurance, retirement, etc.) is fairly typical throughout a hospitalist practice, so there should be little difference between a new FTE hospitalist or NPP. Other considerations, including office space and support staff, would be roughly the same if the group hired a physician. The cost of continuing education and malpractice insurance likely will be less with an NPP, but it is best to check before making a new hire.

After the outgo has been established, the next step is to look at the differences in reimbursement for NPPs vs. physicians. Here, again, the math gets tricky. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) pay NPPs at 85% of the physician rate for a specific diagnosis. However, if there is direct physician involvement, the claim can be filed as “shared billing” and reimbursed at 100%.

For some hospitalist practices, adding NPPs is an easy decision to make. Dr. Parekh says his group already has policies in place that require a physician to see the patient every day. In that case, no extra physician time is necessary, so shared billing makes sense. Other hospitals’ bylaws might have similar requirements.

For practices in which the NPP is able to work with less oversight, it might be better to bill at 85% rather than use the physician time to meet shared-billing criteria. Even in practices with greater NPP autonomy, such variables as case mix and patient acuity might enter into the equation. If the patient is sick enough that the physician is involved for a significant amount of time, then shared billing probably is best.

Experts say group directors and hiring managers should look carefully at contracts with private insurers, too. There most likely will be considerable variation in how each plan handles NPP claims.

Managing performance expectations can have an impact on the successful use of NPPs in a hospitalist practice. Setting realistic goals and groupwide understanding of what the NPPs’ roles will be is crucial. The practice should look at the work that needs to be done and decide if that work provides a genuinely valuable role for an NPP.

Hire for Need, Not Desperation

“The mistake I see most often is hiring an NPP because a practice is desperate for help,” says Martin Buser, MPH, FACHE, a partner in Hospitalist Management Resources, LLC, in San Diego. “Smart practices are looking at NPPs, evaluating where they do the most good, and then setting out their role and expectations based on these needs and the practice environment.”

Hiring mistakes can be compounded if the NPP is not a good match to the job description or group expectations. If the practice hires an NPP fresh out of school, the group will need to establish training and have the new hire work more closely with physicians. If, on the other hand, an NP has 10 years of experience in an ICU, or a PA has worked in the ED for the past five years, a higher level of autonomy can be granted sooner. However, NPPs with established backgrounds are almost as rare as experienced hospitalists (see “Integrating NPPs Into HM Practice,” p. 38).

Inevitably, there will be changes in the interactions between patients and the hospitalists, as both physicians and NPPs become more comfortable with the other’s practice style, as well as each other’s strengths and weaknesses.

MD-to-NPP Ratio Varies

The practice structure and optimal mix of NPPs to MDs is something that will be specific to the hospitalist group. “We don’t really have good studies on this subject,” Buser says. “I usually get worried when we exceed two NPPs to one MD.”

Others disagree. Dr. Parekh, who works in an academic center, says his group has been successful having one MD work with as many as three NPPs. At the other end, Dr. Wilson says his 10 years of experience suggest 1:1 is the most efficient ratio.

However, all of them agree that having one NPP work with more than one physician is not sustainable. The NPP will be less familiar with each doctor’s practice style, what kind of information they need, and how things should be presented. If two or more hospitalists share an NPP, there can be internal friction over division of the NPP’s time, as well as extending the time before the MDs have a good feel for the NPP’s strengths and weaknesses.

In the final analysis, the HM group has to look at the amount and type of work available. In some cases, it will make financial and clinical sense to bring on an NPP. Under other circumstances, an FTE hospitalist is the best fit.

“Sustainability, quality, and efficiency are the drivers for NPP/MD teams. Increasing pressure to offset program costs is not,” Dr. Wilson says. “You do it because it helps sustain the program, helps with recruiting, and effects your efficiency.” TH

Kurt Ullman is a freelance medical writer based in Indiana.

Reference

- Medical Group Management Association and the Society of Hospital Medicine. State of Hospital Medicine: 2010 Report Based on 2009 Data. 2010. Philadelphia and Englewood, Colo.

Hospitalists Are the Answer

Earlier this year, the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) published the article “A Physician Management Infrastructure,” by Peter Pronovost and Jill Marsteller.1 Pronovost and Marsteller’s commentary gets to the very heart of the need for change in healthcare delivery and the major barriers to that change.

As they note, quality improvement (QI) continues to receive attention from every sector of the healthcare market, but systematic and widespread benefits—actual improvement in quality of care—are years away from reaching the patient. The major impediments to delivering performance changes at the front lines of healthcare are both attitudinal and structural.

However, such obstacles can be overcome, starting today.

The authors rightly cite the development of physician leadership as a significant factor in the long-term success of QI. For too long, healthcare leaders have taken a “learn as you go” approach to leadership development. This antiquated philosophy that the best physician leaders ascend naturally to leadership falsely assumes that today’s leaders are perfectly suited for their jobs.

Training Tomorrow’s Leaders Today

In order for meaningful QI to succeed, systematic leadership development in healthcare must be a priority. Those hospitals and healthcare systems that acknowledge this reality already are reaping the benefits. Across the country, more than 1,200 hospitalists have participated in SHM’s Leadership Academy, a rigorous multicourse program that trains physicians in the fundamentals of hospital-based leadership. Leadership Academy participants then go on to lead new programs, many of which are QI-related, in their hospitals. This year, SHM will announce a Certification for Leaders in Hospital Medicine, which will further raise the bar, and mentor, enable, and define the future leaders for our hospitals.

The collective experience of HM also indicates that formal mentorship programs are a critical element to systematic leadership development. The exponential growth of SHM’s mentor-based QI programs to reduce readmissions, prevent VTEs, and improve glycemic control in hospitals—now implemented in more than 300 hospital sites across the country—is a testament to the need for one-on-one mentorship and leadership development and the impact it can have on patient care.

SHM continues to provide broad training in performance improvement and patient safety in its one-day “Quality Improvement Skills” pre-course at the annual meeting (HM11, May 10-13, Grapevine, Texas, www. hospitalmedicine2011.org). In the coming months, SHM will debut a nine-part series of Web-based modules that are essential to any hospitalist now charged with taking an active role in improving performance at their hospital.

Teamwork Is Key

Looking at the evolved present-day hospital, but more to the future, SHM and hospitalists recognize that empowered and coordinated teams of health professionals will deliver the best care. SHM is working to promote the development of high-performing teams (HPTs) with the rest of the Hospital Care Collaborative (HCC), which includes national organizations for nurses, pharmacists, case managers, medical social workers, and respiratory therapists. SHM also has convened a senior group from C-suites, nursing executives, and the American Hospital Association; the plan is to publish a roadmap to promoting the growth and success of HPTs.

All the good intentions and teams and physician champions will still be hamstrung to affect real change in the current payment system, which still rewards healthcare in a transactional fashion, where we pay by the unit of the visit or the procedure. That is why SHM has taken our message to Washington and why we are supporting innovations that reward performance.

The value-based purchasing initiatives that will move substantial dollars to those hospitals that show they can deliver better performance (we’re talking millions of dollars, even at the start) is a beginning of hopefully a sea change in how we think about paying for healthcare (see “Value-Based Purchasing Raises the Stakes,” p. 1). And SHM continues to actively promote having national hospitalist thought leaders be right in the middle of setting the new standards of healthcare at the National Quality Forum, the Joint Commission, and AMA’s Physician Consortium on Performance Improvement, along with other national organizations.

Dr. Pronovost sees the gaps and barriers in having a management structure at our nation’s hospitals that is staffed, financed, and trained to deliver high performance. He does specifically call out hospitalists as a new specialty that is better organized to potentially be part of the solution. SHM and our hospitalists want to move this from a possibility and a potential to affect real change, consistently, day after day, at as many hospitals as we can reach. That is the promise of hospital medicine, and that is the vision of SHM. TH

Dr. Wellikson is CEO of SHM.

Reference

- Pronovost PJ, Marstellar JA. A physician management infrastructure. JAMA. 2011;305(5):500-501.

Earlier this year, the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) published the article “A Physician Management Infrastructure,” by Peter Pronovost and Jill Marsteller.1 Pronovost and Marsteller’s commentary gets to the very heart of the need for change in healthcare delivery and the major barriers to that change.

As they note, quality improvement (QI) continues to receive attention from every sector of the healthcare market, but systematic and widespread benefits—actual improvement in quality of care—are years away from reaching the patient. The major impediments to delivering performance changes at the front lines of healthcare are both attitudinal and structural.

However, such obstacles can be overcome, starting today.

The authors rightly cite the development of physician leadership as a significant factor in the long-term success of QI. For too long, healthcare leaders have taken a “learn as you go” approach to leadership development. This antiquated philosophy that the best physician leaders ascend naturally to leadership falsely assumes that today’s leaders are perfectly suited for their jobs.

Training Tomorrow’s Leaders Today

In order for meaningful QI to succeed, systematic leadership development in healthcare must be a priority. Those hospitals and healthcare systems that acknowledge this reality already are reaping the benefits. Across the country, more than 1,200 hospitalists have participated in SHM’s Leadership Academy, a rigorous multicourse program that trains physicians in the fundamentals of hospital-based leadership. Leadership Academy participants then go on to lead new programs, many of which are QI-related, in their hospitals. This year, SHM will announce a Certification for Leaders in Hospital Medicine, which will further raise the bar, and mentor, enable, and define the future leaders for our hospitals.

The collective experience of HM also indicates that formal mentorship programs are a critical element to systematic leadership development. The exponential growth of SHM’s mentor-based QI programs to reduce readmissions, prevent VTEs, and improve glycemic control in hospitals—now implemented in more than 300 hospital sites across the country—is a testament to the need for one-on-one mentorship and leadership development and the impact it can have on patient care.

SHM continues to provide broad training in performance improvement and patient safety in its one-day “Quality Improvement Skills” pre-course at the annual meeting (HM11, May 10-13, Grapevine, Texas, www. hospitalmedicine2011.org). In the coming months, SHM will debut a nine-part series of Web-based modules that are essential to any hospitalist now charged with taking an active role in improving performance at their hospital.

Teamwork Is Key

Looking at the evolved present-day hospital, but more to the future, SHM and hospitalists recognize that empowered and coordinated teams of health professionals will deliver the best care. SHM is working to promote the development of high-performing teams (HPTs) with the rest of the Hospital Care Collaborative (HCC), which includes national organizations for nurses, pharmacists, case managers, medical social workers, and respiratory therapists. SHM also has convened a senior group from C-suites, nursing executives, and the American Hospital Association; the plan is to publish a roadmap to promoting the growth and success of HPTs.

All the good intentions and teams and physician champions will still be hamstrung to affect real change in the current payment system, which still rewards healthcare in a transactional fashion, where we pay by the unit of the visit or the procedure. That is why SHM has taken our message to Washington and why we are supporting innovations that reward performance.

The value-based purchasing initiatives that will move substantial dollars to those hospitals that show they can deliver better performance (we’re talking millions of dollars, even at the start) is a beginning of hopefully a sea change in how we think about paying for healthcare (see “Value-Based Purchasing Raises the Stakes,” p. 1). And SHM continues to actively promote having national hospitalist thought leaders be right in the middle of setting the new standards of healthcare at the National Quality Forum, the Joint Commission, and AMA’s Physician Consortium on Performance Improvement, along with other national organizations.

Dr. Pronovost sees the gaps and barriers in having a management structure at our nation’s hospitals that is staffed, financed, and trained to deliver high performance. He does specifically call out hospitalists as a new specialty that is better organized to potentially be part of the solution. SHM and our hospitalists want to move this from a possibility and a potential to affect real change, consistently, day after day, at as many hospitals as we can reach. That is the promise of hospital medicine, and that is the vision of SHM. TH

Dr. Wellikson is CEO of SHM.

Reference

- Pronovost PJ, Marstellar JA. A physician management infrastructure. JAMA. 2011;305(5):500-501.

Earlier this year, the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) published the article “A Physician Management Infrastructure,” by Peter Pronovost and Jill Marsteller.1 Pronovost and Marsteller’s commentary gets to the very heart of the need for change in healthcare delivery and the major barriers to that change.

As they note, quality improvement (QI) continues to receive attention from every sector of the healthcare market, but systematic and widespread benefits—actual improvement in quality of care—are years away from reaching the patient. The major impediments to delivering performance changes at the front lines of healthcare are both attitudinal and structural.

However, such obstacles can be overcome, starting today.

The authors rightly cite the development of physician leadership as a significant factor in the long-term success of QI. For too long, healthcare leaders have taken a “learn as you go” approach to leadership development. This antiquated philosophy that the best physician leaders ascend naturally to leadership falsely assumes that today’s leaders are perfectly suited for their jobs.

Training Tomorrow’s Leaders Today

In order for meaningful QI to succeed, systematic leadership development in healthcare must be a priority. Those hospitals and healthcare systems that acknowledge this reality already are reaping the benefits. Across the country, more than 1,200 hospitalists have participated in SHM’s Leadership Academy, a rigorous multicourse program that trains physicians in the fundamentals of hospital-based leadership. Leadership Academy participants then go on to lead new programs, many of which are QI-related, in their hospitals. This year, SHM will announce a Certification for Leaders in Hospital Medicine, which will further raise the bar, and mentor, enable, and define the future leaders for our hospitals.

The collective experience of HM also indicates that formal mentorship programs are a critical element to systematic leadership development. The exponential growth of SHM’s mentor-based QI programs to reduce readmissions, prevent VTEs, and improve glycemic control in hospitals—now implemented in more than 300 hospital sites across the country—is a testament to the need for one-on-one mentorship and leadership development and the impact it can have on patient care.

SHM continues to provide broad training in performance improvement and patient safety in its one-day “Quality Improvement Skills” pre-course at the annual meeting (HM11, May 10-13, Grapevine, Texas, www. hospitalmedicine2011.org). In the coming months, SHM will debut a nine-part series of Web-based modules that are essential to any hospitalist now charged with taking an active role in improving performance at their hospital.

Teamwork Is Key

Looking at the evolved present-day hospital, but more to the future, SHM and hospitalists recognize that empowered and coordinated teams of health professionals will deliver the best care. SHM is working to promote the development of high-performing teams (HPTs) with the rest of the Hospital Care Collaborative (HCC), which includes national organizations for nurses, pharmacists, case managers, medical social workers, and respiratory therapists. SHM also has convened a senior group from C-suites, nursing executives, and the American Hospital Association; the plan is to publish a roadmap to promoting the growth and success of HPTs.

All the good intentions and teams and physician champions will still be hamstrung to affect real change in the current payment system, which still rewards healthcare in a transactional fashion, where we pay by the unit of the visit or the procedure. That is why SHM has taken our message to Washington and why we are supporting innovations that reward performance.

The value-based purchasing initiatives that will move substantial dollars to those hospitals that show they can deliver better performance (we’re talking millions of dollars, even at the start) is a beginning of hopefully a sea change in how we think about paying for healthcare (see “Value-Based Purchasing Raises the Stakes,” p. 1). And SHM continues to actively promote having national hospitalist thought leaders be right in the middle of setting the new standards of healthcare at the National Quality Forum, the Joint Commission, and AMA’s Physician Consortium on Performance Improvement, along with other national organizations.

Dr. Pronovost sees the gaps and barriers in having a management structure at our nation’s hospitals that is staffed, financed, and trained to deliver high performance. He does specifically call out hospitalists as a new specialty that is better organized to potentially be part of the solution. SHM and our hospitalists want to move this from a possibility and a potential to affect real change, consistently, day after day, at as many hospitals as we can reach. That is the promise of hospital medicine, and that is the vision of SHM. TH

Dr. Wellikson is CEO of SHM.

Reference

- Pronovost PJ, Marstellar JA. A physician management infrastructure. JAMA. 2011;305(5):500-501.

Paid For Being Special

It’s official. I am a “recognized” hospitalist. I’m certified. I’m special.

Although I’ve always felt that HM was special, that it’s a field with its own defined body of knowledge, area of expertise, and dedicated providers, it is now official. It is special; I am special. I got the letter in the mail the other day to prove it.

The correspondence arrived in an important-looking white envelope, with a return address stamped with the “American Board of Internal Medicine” insignia. The letter itself congratulated me on becoming a member of the first class of internists to complete their Maintenance of Certification (MOC) with Recognition of Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine (FPHM). As you’ve no doubt heard, the ABIM developed this MOC process to recognize hospitalists who’ve been in practice for at least three years after their initial certification in internal medicine (IM).

This is the first ABIM certification program that recognizes physician expertise in a field that is not tied directly to either residency or specialty fellowship training. In other words, unlike the cardiology certification exam, which requires a physician to have completed a fellowship training program, the FPHM allows for clinical experience to substitute for fellowship training. While the FPHM does not confer true “specialty status” (like the cardiology certification exam does), it does, as the moniker implies, recognize that we have focused our practice.

Implicit within that is the understanding that this focus brings with it a level of expertise that distinguishes hospitalists from nonhospitalists. This is a massive step forward for HM, as it lends significant credibility to the work we do and helps the public better understand what a hospitalist is and does. Most important, it helps set apart that cadre of true hospitalists who are dedicating their careers to fundamentally improving the care and outcomes of hospitalized patients.

It is this last point that came to mind as I reviewed this month’s cover story on value-based purchasing (see “Value-Based Purchasing Raises the Stakes,” p. 1).

Sticky Yet Crucial Point

One of the sticking points that I’ve heard from some hospitalists is that the FPHM requires a three-year cycle of self-evaluation. For those new to this process, let’s clear up some of the nomenclature. When IM residents graduate, they are eligible to sit for the ABIM certification exam. Upon passage, they are board-certified internists and can choose to enter into the maintenance of certification process. This is a 10-year process whereby diplomates (ABIM-speak for those certified as a specialist, with a diploma in medicine; not to be confused with a diplomat—a person who conducts negotiations and maintains political rest through the tactful handling of delicate situations, something perhaps more appropriate to the bulk of patient situations we encounter) must complete self-evaluation of medical knowledge modules, self-evaluation of practice performance, and ultimately a secure exam. This is where the FPHM differs.