User login

How Is SIADH Diagnosed and Managed?

Case

A 70-year-old woman with hypertension presents after a fall. Her medications include hydrochlorothiazide. Her blood pressure is 130/70 mm/Hg, with heart rate of 86. She has normal orthostatic vital signs. Her mucus membranes are moist and she has no jugular venous distension, edema, or ascites. Her plasma sodium (PNa) is 125 mmol/L, potassium 3.6 mmol/L, blood urea nitrogen (BUN) 30 mg/dL, and creatinine 0.8 mg/dL. Additional labs include serum thyroid stimulating hormone 1.12 mIU/L, cortisol 15 mcg/dL, serum osmolality 270 mOsm/kg, uric acid 4 mg/dL, urine osmolality 300 mOsm/kg, urine sodium (UNa) 40 mmol/L, fractional excretion of sodium 1.0%, and fractional excretion of urate (FEUrate) 13%. She receives 2 L isotonic saline intravenously over 24 hours, with resulting PNa of 127.

What is the cause of her hyponatremia, and how should her hyponatremia be managed?

Overview

Hyponatremia is one of the most common electrolyte abnormalities; it has a prevalence as high as 30% upon admission to the hospital.1 Hyponatremia is important clinically because of its high risk of mortality in the acute and symptomatic setting, and the risk of central pontine myelinolysis (CPM), or death with too rapid correction.2 Even so-called “asymptomatic” mild hyponatremia is associated with increased falls and impairments in gait and attention in the elderly.3

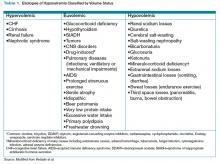

Hyponatremia is a state of excess water compared with the amount of solute in the extracellular fluid. To aid in diagnosing the etiology of hypotonic hyponatremia, the differential is traditionally divided into categories based on extracellular fluid volume (ECV) status, as shown in Table 1 (below), with syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH) being the most common cause of euvolemic hyponatremia.2 However, data show that clinical determination of volume status is often flawed,4 and an algorithmic approach to diagnosis and treatment yields improved results.5

Review of the Data

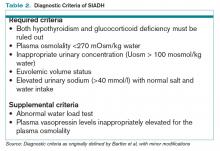

Diagnosis of SIADH. The original diagnostic criteria for SIADH, with minor modifications, are presented in Table 2, page 18).6,7,8 However, applying these criteria in clinical settings presents several difficulties, most notably a determination of ECV. The gold standard for assessing ECV status is by radioisotope, which is not practically feasible.9 Therefore, clinicians must rely on surrogate clinical markers of ECV (orthostatic hypotension, skin turgor, mucus membrane dryness, central venous pressure, BUN, BUN-creatinine ratio, and serum uric acid levels), which lack both sensitivity and specificity.4 Astoundingly, clinical assessment of ECV has been demonstrated to be accurate only 50% of the time when differentiating euvolemic patients from those with hypovolemia.4

Another challenge lies in the interpretation of UNa, which frequently is used as a surrogate for extra-arterial blood volume (EABV) status.10 Unfortunately, in the setting of diuretic use, UNa becomes inaccurate. The FEUrate, however, is unaffected by diuretic use and can be helpful in distinguishing between etiologies of hyponatremia with UNa greater than 30 mmol/L.11 The FEUrate is about 10% in normal euvolemic subjects and is reduced (usually <8%) in patients with low effective arterial blood volume.11,12 A trial of 86 patients demonstrated that a FEUrate of 12% had a specificity and positive predictive value of 100% in accurately identifying SIADH from diuretic-induced hyponatremia in patients on diuretics.11,12 Therefore, the UNa is a valid marker of EABV status when patients are not on diuretics; however, the FEUrate should be used in the setting of diuretic use.

Yet another pitfall is differentiating patients with salt depletion from those with SIADH. In these situations, measurement of the change in PNa concentration after a test infusion of isotonic saline is helpful. In salt depletion, PNa usually increases ≥5 mmol/L after 2 L saline infusion, which is not the case with SIADH.13 Incorrectly diagnosing renal salt wasting (RSW) as SIADH results in fluid restriction and, consequently, ECV depletion and increased morbidity.14 The persistence of hypouricemia and elevated FEUrate after correction of the hyponatremia in RSW differentiates it from SIADH.13, 14

Given these challenges, recommendations to use an algorithmic approach for the evaluation and diagnosis of hyponatremia have surfaced. In a study of 121 patients admitted with hyponatremia, an algorithm-based approach to the diagnosis of hyponatremia yielded an overall diagnostic accuracy of 71%, compared with an accuracy of 32% by experienced clinicians.5 This study also highlighted SIADH as the most frequent false-positive diagnosis that was expected whenever the combination of euvolemia and a UNa >30 mmol/L was present.5 Cases of diuretic-induced hyponatremia often were misclassified due to errors in the accurate assessment of ECV status, as most of these patients appeared clinically euvolemic or hypervolemic.5 Therefore, it is important to use an algorithm in identifying SIADH and to use one that does not rely solely on clinical estimation of ECV status (see Figure 1, below).

Management of acute and symptomatic hyponatremia. When hyponatremia develops acutely, urgent treatment is required (see Figure 2, below).15 Hyponatremia is considered acute when the onset is within 48 hours.15 Acute hyponatremia is most easily identified in the hospital and is commonly iatrogenic. Small case reviews in the 1980s began to associate postoperative deaths with the administration of hypotonic fluids.16 Asymptomatic patients with hyponatremia presenting from home should be considered chronic hyponatremias as the duration often is unclear.

Acute hyponatremia or neurologically symptomatic hyponatremia regardless of duration requires the use of hypertonic saline.15 Traditional sodium correction algorithms are based on early case series, which were focused on limiting neurologic complications from sodium overcorrection.17 This resulted in protocols recommending a conservative rate of correction spread over a 24- to 48-hour period.17 Infusing 3% saline at a rate of 1 ml/kg/hr to 2 ml/kg/hr results in a 1 mmol/L/hr to 2 mmol/L/hr increase in PNa.15 This simplified formula results in similar correction rates as more complex calculations.15 Correction should not exceed 8 mmol/L to 10 mmol/L within the first 24 hours, and 18 mmol/L to 25 mmol/L by 48 hours to avoid CPM.15 PNa should be checked every two hours to ensure that the correction rate is not exceeding the predicted rate, as the formulas do not take into account oral intake and ongoing losses.15

Recent observations focused on the initial four hours from onset of hyponatremia suggest a higher rate of correction can be tolerated without complications.18 Rapid sodium correction of 4 mmol/L to 6 mmol/L often is enough to stop neurologic complications.18 This can be accomplished with a bolus infusion of 100 mL of 3% saline.19 This may be repeated twice at 10-minute intervals until there is neurologic improvement.19 This might sound aggressive, but this would correspond to a rise in PNa of 5 mmol/L to 6 mmol/L in a 50 kg woman. Subsequent treatment with hypertonic fluid might not be needed if symptoms resolve.

Management of chronic hyponatremia. Hyponatremia secondary to SIADH improves with the treatment of the underlying cause, thus an active search for a causative medication or condition should be sought (see Table 1, p. 17).20

Water restriction. Restriction of fluid intake is the first-line treatment for SIADH in patients without hypovolemia. The severity of fluid restriction is guided by the concentration of the urinary solutes.15 Restriction of water intake to 500 ml/day to 1,000 ml/day is generally advised for many patients, as losses from the skin, lungs, and urine exceed this amount, leading to a gradual reduction in total body water.21 The main drawback of fluid restriction is poor compliance due to an intact thirst mechanism.

Saline infusion. The infusion of normal saline theoretically worsens hyponatremia due to SIADH because the water is retained while the salt is excreted. However, a trial of normal saline sometimes is attempted in patients in whom the differentiation between hypovolemia and euvolemia is difficult. From a study of a series of 17 patients with chronic SIADH, Musch and Decaux concluded that the infusion of intravenous normal (0.9%) saline raises PNa when the urine osmolality is less than 530 mosm/L.22

Oral solutes (urea and salt). The oral intake of salt augments water excretion23, and salt tablets are used as a second-line agent in patients with persistent hyponatremia despite fluid restriction.23 The oral administration of urea also results in increased free-water excretion via osmotic diuresis,24 but its poor palatability, lack of availability in the U.S., and limited user experience has restricted its usage.24

Demeclocycline. Demeclo-cycline is a tetracycline derivative that causes a partial nephrogenic diabetes insipidus.25 Its limitations include a slow onset of action (two to five days) and an unpredictable treatment effect with the possibility of causing profound polyuria and hypernatremia. It is also associated with reversible azotemia and sometimes nephrotoxicity, especially in patients with cirrhosis.

Lithium. Lithium also causes nephrogenic diabetes insipidus by downregulating vasopressin-stimulated aquaporin-2 expression and thus improves hyponatremia in SIADH.26 However, its use is significantly limited by its unpredictable response and the risks of interstitial nephritis and end-stage renal disease with chronic use. Therefore, it is no longer recommended for the treatment of SIADH.

Vasopressin receptor antagonists. Due to the role of excessive levels of vasopressin in the pathophysiology of most types of SIADH, antagonists of the vasopressin receptor were developed with the goal of preventing the excess water absorption that causes hyponatremia. Two vasopressin receptor antagonists, or vaptans, have been approved by the FDA for the treatment of nonemergent euvolemic and hypervolemic hyponatremia. Conivaptan is a nonselective vasopressin receptor antagonist that is for IV use only. Tolvaptan is a selective V2 receptor antagonist that is taken orally. Both conivaptan and tolvaptan successfully increase PNa levels while the drugs are being taken.27,28,29,30 Tolvaptan increases PNa levels in hyponatremia due to SIADH and CHF, and modestly so in cirrhosis.30

The most common side effects of the vaptans include dry mouth, increased thirst, and increased urination, although serious side effects (hypernatremia or too-rapid rate of increase in PNa) are possible.29 It is unclear if treating stable, asymptomatic hyponatremia with vaptans has any reduction in morbidity or mortality. One study found that tolvaptan increased the patients’ self-evaluations of mental functioning, but a study of tolvaptan used in combination with diuretics in the setting of CHF did not result in decreased mortality.29,31 Due to their expense, necessity of being started in the hospital, and unclear long-term benefit, the vaptans are only recommended when traditional measures such as fluid restriction and salt tablets have been unsuccessful.

Back to the Case

Our patient has hypotonic hyponatremia based on her low serum osmolality. The duration of her hyponatremia is unclear, but the patient is not experiencing seizures or coma. Therefore, her hyponatremia should be corrected slowly, and hypertonic saline is not indicated.

As is common in clinical practice, her true volume status is difficult to clinically ascertain. By physical exam, she appears euvolemic, but because she is on hydrochlorothiazide, she might be subtly hypovolemic. The UNa of 40 mmol/L is not consistent with hypovolemia, but its accuracy is limited in the setting of diuretics. The failure to improve her sodium by at least 5 mmol/L after a 2 L normal saline infusion argues against low effective arterial blood volume and indicates that the hydrochlorothiazide is unlikely to be the cause of her hyponatremia.

Therefore, the most likely cause of the hyponatremia is SIADH, a diagnosis further corroborated by the elevated FEUrate of 13%. Her chronic hyponatremia should be managed initially with fluid restriction while an investigation for an underlying cause of SIADH is initiated.

Bottom Line

The diagnosis of SIADH relies on the careful evaluation of laboratory values, use of an algorithm, and recognizing the limitations of clinically assessing volume status. The underlying cause of SIADH must also be sought and treated. TH

Dr. Grant is a clinical lecturer in internal medicine, Dr. Cho is a clinical instructor in internal medicine, and Dr. Nichani is an assistant professor of internal medicine at the University of Michigan Hospital and Health Systems in Ann Arbor.

References

- Upadhyay A, Jaber BL, Madias NE. Incidence and prevalence of hyponatremia. Am J Med. 2006;119(7 Suppl 1):S30-35.

- Verbalis JG, Goldsmith SR, Greenberg A, Schrier RW, Sterns RH. Hyponatremia treatment guidelines 2007: expert panel recommendations. Am J Med. 2007;120(11 Suppl 1):S1-21.

- Renneboog B, Musch W, Vandemergel X, Manto MU, Decaux G. Mild chronic hyponatremia is associated with falls, unsteadiness, and attention deficits. Am J Med. 2006;119(1):71.e71-78.

- Chung HM, Kluge R, Schrier RW, Anderson RJ. Clinical assessment of extracellular fluid volume in hyponatremia. Am J Med. 1987;83(5):905-908.

- Fenske W, Maier SK, Blechschmidt A, Allolio B, Störk S. Utility and limitations of the traditional diagnostic approach to hyponatremia: a diagnostic study. Am J Med. 2010;123(7):652-657.

- Bartter FC, Schwartz WB. The syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone. Am J Med. 1967;42(5):790-806.

- Smith DM, McKenna K, Thompson CJ. Hyponatraemia. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2000;52(6):667-678.

- Verbalis JG. Hyponatraemia. Baillieres Clin Endocrinol Metab. Aug 1989;3(2):499-530.

- Maesaka JK, Imbriano LJ, Ali NM, Ilamathi E. Is it cerebral or renal salt wasting? Kidney Int. 2009;76(9):934-938.

- Verbalis JG. Disorders of body water homeostasis. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;17(4):471-503.

- Fenske W, Störk S, Koschker AC, et al. Value of fractional uric acid excretion in differential diagnosis of hyponatremic patients on diuretics. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(8):2991-2997.

- Maesaka JK, Fishbane S. Regulation of renal urate excretion: a critical review. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;32(6):917-933.

- Milionis HJ, Liamis GL, Elisaf MS. The hyponatremic patient: a systematic approach to laboratory diagnosis. CMAJ. 2002;166(8):1056-1062.

- Bitew S, Imbriano L, Miyawaki N, Fishbane S, Maesaka JK. More on renal salt wasting without cerebral disease: response to saline infusion. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(2):309-315.

- Ellison DH, Berl T. Clinical practice. The syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(20):2064-2072.

- Arieff AI. Hyponatremia, convulsions, respiratory arrest, and permanent brain damage after elective surgery in healthy women. N Engl J Med. 1986;314(24):1529-1535.

- Ayus JC, Krothapalli RK, Arieff AI. Treatment of symptomatic hyponatremia and its relation to brain damage. A prospective study. N Engl J Med. 1987;317(19):1190-1195.

- Sterns RH, Nigwekar SU, Hix JK. The treatment of hyponatremia. Semin Nephrol. 2009;29(3):282-299.

- Hew-Butler T, Ayus JC, Kipps C, et al. Statement of the Second International Exercise-Associated Hyponatremia Consensus Development Conference, New Zealand, 2007. Clin J Sport Med. 2008;18(2):111-121.

- List AF, Hainsworth JD, Davis BW, Hande KR, Greco FA, Johnson DH. The syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) in small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1986;4(8):1191-1198.

- Verbalis JG. Managing hyponatremia in patients with syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion. J Hosp Med. 2010;5 Suppl 3:S18-S26.

- Musch W, Decaux G. Treating the syndrome of inappropriate ADH secretion with isotonic saline. QJM. 1998;91(11):749-753.

- Berl T. Impact of solute intake on urine flow and water excretion. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19(6):1076-1078.

- Decaux G, Brimioulle S, Genette F, Mockel J. Treatment of the syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone by urea. Am J Med. 1980;69(1):99-106.

- Forrest JN Jr., Cox M, Hong C, Morrison G, Bia M, Singer I. Superiority of demeclocycline over lithium in the treatment of chronic syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone. N Engl J Med. 1978;298(4):173-177.

- Nielsen J, Hoffert JD, Knepper MA, Agre P, Nielsen S, Fenton RA. Proteomic analysis of lithium-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus: mechanisms for aquaporin 2 down-regulation and cellular proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(9):3634-3639.

- Zeltser D, Rosansky S, van Rensburg H, Verbalis JG, Smith N. Assessment of the efficacy and safety of intravenous conivaptan in euvolemic and hypervolemic hyponatremia. Am J Nephrol. 2007;27(5):447-457.

- Verbalis JG, Zeltser D, Smith N, Barve A, Andoh M. Assessment of the efficacy and safety of intravenous conivaptan in patients with euvolaemic hyponatraemia: subgroup analysis of a randomized, controlled study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2008;69(1):159-168.

- Schrier RW, Gross P, Gheorghiade M, et al. Tolvaptan, a selective oral vasopressin V2-receptor antagonist, for hyponatremia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(20):2099-2112.

- Berl T, Quittnat-Pelletier F, Verbalis JG, et al. Oral tolvaptan is safe and effective in chronic hyponatremia. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21(4):705-712.

- Konstam MA, Gheorghiade M, Burnett JC Jr., et al. Effects of oral tolvaptan in patients hospitalized for worsening heart failure: the EVEREST Outcome Trial. JAMA. 2007;297(12):1319-1331.

Case

A 70-year-old woman with hypertension presents after a fall. Her medications include hydrochlorothiazide. Her blood pressure is 130/70 mm/Hg, with heart rate of 86. She has normal orthostatic vital signs. Her mucus membranes are moist and she has no jugular venous distension, edema, or ascites. Her plasma sodium (PNa) is 125 mmol/L, potassium 3.6 mmol/L, blood urea nitrogen (BUN) 30 mg/dL, and creatinine 0.8 mg/dL. Additional labs include serum thyroid stimulating hormone 1.12 mIU/L, cortisol 15 mcg/dL, serum osmolality 270 mOsm/kg, uric acid 4 mg/dL, urine osmolality 300 mOsm/kg, urine sodium (UNa) 40 mmol/L, fractional excretion of sodium 1.0%, and fractional excretion of urate (FEUrate) 13%. She receives 2 L isotonic saline intravenously over 24 hours, with resulting PNa of 127.

What is the cause of her hyponatremia, and how should her hyponatremia be managed?

Overview

Hyponatremia is one of the most common electrolyte abnormalities; it has a prevalence as high as 30% upon admission to the hospital.1 Hyponatremia is important clinically because of its high risk of mortality in the acute and symptomatic setting, and the risk of central pontine myelinolysis (CPM), or death with too rapid correction.2 Even so-called “asymptomatic” mild hyponatremia is associated with increased falls and impairments in gait and attention in the elderly.3

Hyponatremia is a state of excess water compared with the amount of solute in the extracellular fluid. To aid in diagnosing the etiology of hypotonic hyponatremia, the differential is traditionally divided into categories based on extracellular fluid volume (ECV) status, as shown in Table 1 (below), with syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH) being the most common cause of euvolemic hyponatremia.2 However, data show that clinical determination of volume status is often flawed,4 and an algorithmic approach to diagnosis and treatment yields improved results.5

Review of the Data

Diagnosis of SIADH. The original diagnostic criteria for SIADH, with minor modifications, are presented in Table 2, page 18).6,7,8 However, applying these criteria in clinical settings presents several difficulties, most notably a determination of ECV. The gold standard for assessing ECV status is by radioisotope, which is not practically feasible.9 Therefore, clinicians must rely on surrogate clinical markers of ECV (orthostatic hypotension, skin turgor, mucus membrane dryness, central venous pressure, BUN, BUN-creatinine ratio, and serum uric acid levels), which lack both sensitivity and specificity.4 Astoundingly, clinical assessment of ECV has been demonstrated to be accurate only 50% of the time when differentiating euvolemic patients from those with hypovolemia.4

Another challenge lies in the interpretation of UNa, which frequently is used as a surrogate for extra-arterial blood volume (EABV) status.10 Unfortunately, in the setting of diuretic use, UNa becomes inaccurate. The FEUrate, however, is unaffected by diuretic use and can be helpful in distinguishing between etiologies of hyponatremia with UNa greater than 30 mmol/L.11 The FEUrate is about 10% in normal euvolemic subjects and is reduced (usually <8%) in patients with low effective arterial blood volume.11,12 A trial of 86 patients demonstrated that a FEUrate of 12% had a specificity and positive predictive value of 100% in accurately identifying SIADH from diuretic-induced hyponatremia in patients on diuretics.11,12 Therefore, the UNa is a valid marker of EABV status when patients are not on diuretics; however, the FEUrate should be used in the setting of diuretic use.

Yet another pitfall is differentiating patients with salt depletion from those with SIADH. In these situations, measurement of the change in PNa concentration after a test infusion of isotonic saline is helpful. In salt depletion, PNa usually increases ≥5 mmol/L after 2 L saline infusion, which is not the case with SIADH.13 Incorrectly diagnosing renal salt wasting (RSW) as SIADH results in fluid restriction and, consequently, ECV depletion and increased morbidity.14 The persistence of hypouricemia and elevated FEUrate after correction of the hyponatremia in RSW differentiates it from SIADH.13, 14

Given these challenges, recommendations to use an algorithmic approach for the evaluation and diagnosis of hyponatremia have surfaced. In a study of 121 patients admitted with hyponatremia, an algorithm-based approach to the diagnosis of hyponatremia yielded an overall diagnostic accuracy of 71%, compared with an accuracy of 32% by experienced clinicians.5 This study also highlighted SIADH as the most frequent false-positive diagnosis that was expected whenever the combination of euvolemia and a UNa >30 mmol/L was present.5 Cases of diuretic-induced hyponatremia often were misclassified due to errors in the accurate assessment of ECV status, as most of these patients appeared clinically euvolemic or hypervolemic.5 Therefore, it is important to use an algorithm in identifying SIADH and to use one that does not rely solely on clinical estimation of ECV status (see Figure 1, below).

Management of acute and symptomatic hyponatremia. When hyponatremia develops acutely, urgent treatment is required (see Figure 2, below).15 Hyponatremia is considered acute when the onset is within 48 hours.15 Acute hyponatremia is most easily identified in the hospital and is commonly iatrogenic. Small case reviews in the 1980s began to associate postoperative deaths with the administration of hypotonic fluids.16 Asymptomatic patients with hyponatremia presenting from home should be considered chronic hyponatremias as the duration often is unclear.

Acute hyponatremia or neurologically symptomatic hyponatremia regardless of duration requires the use of hypertonic saline.15 Traditional sodium correction algorithms are based on early case series, which were focused on limiting neurologic complications from sodium overcorrection.17 This resulted in protocols recommending a conservative rate of correction spread over a 24- to 48-hour period.17 Infusing 3% saline at a rate of 1 ml/kg/hr to 2 ml/kg/hr results in a 1 mmol/L/hr to 2 mmol/L/hr increase in PNa.15 This simplified formula results in similar correction rates as more complex calculations.15 Correction should not exceed 8 mmol/L to 10 mmol/L within the first 24 hours, and 18 mmol/L to 25 mmol/L by 48 hours to avoid CPM.15 PNa should be checked every two hours to ensure that the correction rate is not exceeding the predicted rate, as the formulas do not take into account oral intake and ongoing losses.15

Recent observations focused on the initial four hours from onset of hyponatremia suggest a higher rate of correction can be tolerated without complications.18 Rapid sodium correction of 4 mmol/L to 6 mmol/L often is enough to stop neurologic complications.18 This can be accomplished with a bolus infusion of 100 mL of 3% saline.19 This may be repeated twice at 10-minute intervals until there is neurologic improvement.19 This might sound aggressive, but this would correspond to a rise in PNa of 5 mmol/L to 6 mmol/L in a 50 kg woman. Subsequent treatment with hypertonic fluid might not be needed if symptoms resolve.

Management of chronic hyponatremia. Hyponatremia secondary to SIADH improves with the treatment of the underlying cause, thus an active search for a causative medication or condition should be sought (see Table 1, p. 17).20

Water restriction. Restriction of fluid intake is the first-line treatment for SIADH in patients without hypovolemia. The severity of fluid restriction is guided by the concentration of the urinary solutes.15 Restriction of water intake to 500 ml/day to 1,000 ml/day is generally advised for many patients, as losses from the skin, lungs, and urine exceed this amount, leading to a gradual reduction in total body water.21 The main drawback of fluid restriction is poor compliance due to an intact thirst mechanism.

Saline infusion. The infusion of normal saline theoretically worsens hyponatremia due to SIADH because the water is retained while the salt is excreted. However, a trial of normal saline sometimes is attempted in patients in whom the differentiation between hypovolemia and euvolemia is difficult. From a study of a series of 17 patients with chronic SIADH, Musch and Decaux concluded that the infusion of intravenous normal (0.9%) saline raises PNa when the urine osmolality is less than 530 mosm/L.22

Oral solutes (urea and salt). The oral intake of salt augments water excretion23, and salt tablets are used as a second-line agent in patients with persistent hyponatremia despite fluid restriction.23 The oral administration of urea also results in increased free-water excretion via osmotic diuresis,24 but its poor palatability, lack of availability in the U.S., and limited user experience has restricted its usage.24

Demeclocycline. Demeclo-cycline is a tetracycline derivative that causes a partial nephrogenic diabetes insipidus.25 Its limitations include a slow onset of action (two to five days) and an unpredictable treatment effect with the possibility of causing profound polyuria and hypernatremia. It is also associated with reversible azotemia and sometimes nephrotoxicity, especially in patients with cirrhosis.

Lithium. Lithium also causes nephrogenic diabetes insipidus by downregulating vasopressin-stimulated aquaporin-2 expression and thus improves hyponatremia in SIADH.26 However, its use is significantly limited by its unpredictable response and the risks of interstitial nephritis and end-stage renal disease with chronic use. Therefore, it is no longer recommended for the treatment of SIADH.

Vasopressin receptor antagonists. Due to the role of excessive levels of vasopressin in the pathophysiology of most types of SIADH, antagonists of the vasopressin receptor were developed with the goal of preventing the excess water absorption that causes hyponatremia. Two vasopressin receptor antagonists, or vaptans, have been approved by the FDA for the treatment of nonemergent euvolemic and hypervolemic hyponatremia. Conivaptan is a nonselective vasopressin receptor antagonist that is for IV use only. Tolvaptan is a selective V2 receptor antagonist that is taken orally. Both conivaptan and tolvaptan successfully increase PNa levels while the drugs are being taken.27,28,29,30 Tolvaptan increases PNa levels in hyponatremia due to SIADH and CHF, and modestly so in cirrhosis.30

The most common side effects of the vaptans include dry mouth, increased thirst, and increased urination, although serious side effects (hypernatremia or too-rapid rate of increase in PNa) are possible.29 It is unclear if treating stable, asymptomatic hyponatremia with vaptans has any reduction in morbidity or mortality. One study found that tolvaptan increased the patients’ self-evaluations of mental functioning, but a study of tolvaptan used in combination with diuretics in the setting of CHF did not result in decreased mortality.29,31 Due to their expense, necessity of being started in the hospital, and unclear long-term benefit, the vaptans are only recommended when traditional measures such as fluid restriction and salt tablets have been unsuccessful.

Back to the Case

Our patient has hypotonic hyponatremia based on her low serum osmolality. The duration of her hyponatremia is unclear, but the patient is not experiencing seizures or coma. Therefore, her hyponatremia should be corrected slowly, and hypertonic saline is not indicated.

As is common in clinical practice, her true volume status is difficult to clinically ascertain. By physical exam, she appears euvolemic, but because she is on hydrochlorothiazide, she might be subtly hypovolemic. The UNa of 40 mmol/L is not consistent with hypovolemia, but its accuracy is limited in the setting of diuretics. The failure to improve her sodium by at least 5 mmol/L after a 2 L normal saline infusion argues against low effective arterial blood volume and indicates that the hydrochlorothiazide is unlikely to be the cause of her hyponatremia.

Therefore, the most likely cause of the hyponatremia is SIADH, a diagnosis further corroborated by the elevated FEUrate of 13%. Her chronic hyponatremia should be managed initially with fluid restriction while an investigation for an underlying cause of SIADH is initiated.

Bottom Line

The diagnosis of SIADH relies on the careful evaluation of laboratory values, use of an algorithm, and recognizing the limitations of clinically assessing volume status. The underlying cause of SIADH must also be sought and treated. TH

Dr. Grant is a clinical lecturer in internal medicine, Dr. Cho is a clinical instructor in internal medicine, and Dr. Nichani is an assistant professor of internal medicine at the University of Michigan Hospital and Health Systems in Ann Arbor.

References

- Upadhyay A, Jaber BL, Madias NE. Incidence and prevalence of hyponatremia. Am J Med. 2006;119(7 Suppl 1):S30-35.

- Verbalis JG, Goldsmith SR, Greenberg A, Schrier RW, Sterns RH. Hyponatremia treatment guidelines 2007: expert panel recommendations. Am J Med. 2007;120(11 Suppl 1):S1-21.

- Renneboog B, Musch W, Vandemergel X, Manto MU, Decaux G. Mild chronic hyponatremia is associated with falls, unsteadiness, and attention deficits. Am J Med. 2006;119(1):71.e71-78.

- Chung HM, Kluge R, Schrier RW, Anderson RJ. Clinical assessment of extracellular fluid volume in hyponatremia. Am J Med. 1987;83(5):905-908.

- Fenske W, Maier SK, Blechschmidt A, Allolio B, Störk S. Utility and limitations of the traditional diagnostic approach to hyponatremia: a diagnostic study. Am J Med. 2010;123(7):652-657.

- Bartter FC, Schwartz WB. The syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone. Am J Med. 1967;42(5):790-806.

- Smith DM, McKenna K, Thompson CJ. Hyponatraemia. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2000;52(6):667-678.

- Verbalis JG. Hyponatraemia. Baillieres Clin Endocrinol Metab. Aug 1989;3(2):499-530.

- Maesaka JK, Imbriano LJ, Ali NM, Ilamathi E. Is it cerebral or renal salt wasting? Kidney Int. 2009;76(9):934-938.

- Verbalis JG. Disorders of body water homeostasis. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;17(4):471-503.

- Fenske W, Störk S, Koschker AC, et al. Value of fractional uric acid excretion in differential diagnosis of hyponatremic patients on diuretics. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(8):2991-2997.

- Maesaka JK, Fishbane S. Regulation of renal urate excretion: a critical review. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;32(6):917-933.

- Milionis HJ, Liamis GL, Elisaf MS. The hyponatremic patient: a systematic approach to laboratory diagnosis. CMAJ. 2002;166(8):1056-1062.

- Bitew S, Imbriano L, Miyawaki N, Fishbane S, Maesaka JK. More on renal salt wasting without cerebral disease: response to saline infusion. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(2):309-315.

- Ellison DH, Berl T. Clinical practice. The syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(20):2064-2072.

- Arieff AI. Hyponatremia, convulsions, respiratory arrest, and permanent brain damage after elective surgery in healthy women. N Engl J Med. 1986;314(24):1529-1535.

- Ayus JC, Krothapalli RK, Arieff AI. Treatment of symptomatic hyponatremia and its relation to brain damage. A prospective study. N Engl J Med. 1987;317(19):1190-1195.

- Sterns RH, Nigwekar SU, Hix JK. The treatment of hyponatremia. Semin Nephrol. 2009;29(3):282-299.

- Hew-Butler T, Ayus JC, Kipps C, et al. Statement of the Second International Exercise-Associated Hyponatremia Consensus Development Conference, New Zealand, 2007. Clin J Sport Med. 2008;18(2):111-121.

- List AF, Hainsworth JD, Davis BW, Hande KR, Greco FA, Johnson DH. The syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) in small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1986;4(8):1191-1198.

- Verbalis JG. Managing hyponatremia in patients with syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion. J Hosp Med. 2010;5 Suppl 3:S18-S26.

- Musch W, Decaux G. Treating the syndrome of inappropriate ADH secretion with isotonic saline. QJM. 1998;91(11):749-753.

- Berl T. Impact of solute intake on urine flow and water excretion. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19(6):1076-1078.

- Decaux G, Brimioulle S, Genette F, Mockel J. Treatment of the syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone by urea. Am J Med. 1980;69(1):99-106.

- Forrest JN Jr., Cox M, Hong C, Morrison G, Bia M, Singer I. Superiority of demeclocycline over lithium in the treatment of chronic syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone. N Engl J Med. 1978;298(4):173-177.

- Nielsen J, Hoffert JD, Knepper MA, Agre P, Nielsen S, Fenton RA. Proteomic analysis of lithium-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus: mechanisms for aquaporin 2 down-regulation and cellular proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(9):3634-3639.

- Zeltser D, Rosansky S, van Rensburg H, Verbalis JG, Smith N. Assessment of the efficacy and safety of intravenous conivaptan in euvolemic and hypervolemic hyponatremia. Am J Nephrol. 2007;27(5):447-457.

- Verbalis JG, Zeltser D, Smith N, Barve A, Andoh M. Assessment of the efficacy and safety of intravenous conivaptan in patients with euvolaemic hyponatraemia: subgroup analysis of a randomized, controlled study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2008;69(1):159-168.

- Schrier RW, Gross P, Gheorghiade M, et al. Tolvaptan, a selective oral vasopressin V2-receptor antagonist, for hyponatremia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(20):2099-2112.

- Berl T, Quittnat-Pelletier F, Verbalis JG, et al. Oral tolvaptan is safe and effective in chronic hyponatremia. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21(4):705-712.

- Konstam MA, Gheorghiade M, Burnett JC Jr., et al. Effects of oral tolvaptan in patients hospitalized for worsening heart failure: the EVEREST Outcome Trial. JAMA. 2007;297(12):1319-1331.

Case

A 70-year-old woman with hypertension presents after a fall. Her medications include hydrochlorothiazide. Her blood pressure is 130/70 mm/Hg, with heart rate of 86. She has normal orthostatic vital signs. Her mucus membranes are moist and she has no jugular venous distension, edema, or ascites. Her plasma sodium (PNa) is 125 mmol/L, potassium 3.6 mmol/L, blood urea nitrogen (BUN) 30 mg/dL, and creatinine 0.8 mg/dL. Additional labs include serum thyroid stimulating hormone 1.12 mIU/L, cortisol 15 mcg/dL, serum osmolality 270 mOsm/kg, uric acid 4 mg/dL, urine osmolality 300 mOsm/kg, urine sodium (UNa) 40 mmol/L, fractional excretion of sodium 1.0%, and fractional excretion of urate (FEUrate) 13%. She receives 2 L isotonic saline intravenously over 24 hours, with resulting PNa of 127.

What is the cause of her hyponatremia, and how should her hyponatremia be managed?

Overview

Hyponatremia is one of the most common electrolyte abnormalities; it has a prevalence as high as 30% upon admission to the hospital.1 Hyponatremia is important clinically because of its high risk of mortality in the acute and symptomatic setting, and the risk of central pontine myelinolysis (CPM), or death with too rapid correction.2 Even so-called “asymptomatic” mild hyponatremia is associated with increased falls and impairments in gait and attention in the elderly.3

Hyponatremia is a state of excess water compared with the amount of solute in the extracellular fluid. To aid in diagnosing the etiology of hypotonic hyponatremia, the differential is traditionally divided into categories based on extracellular fluid volume (ECV) status, as shown in Table 1 (below), with syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH) being the most common cause of euvolemic hyponatremia.2 However, data show that clinical determination of volume status is often flawed,4 and an algorithmic approach to diagnosis and treatment yields improved results.5

Review of the Data

Diagnosis of SIADH. The original diagnostic criteria for SIADH, with minor modifications, are presented in Table 2, page 18).6,7,8 However, applying these criteria in clinical settings presents several difficulties, most notably a determination of ECV. The gold standard for assessing ECV status is by radioisotope, which is not practically feasible.9 Therefore, clinicians must rely on surrogate clinical markers of ECV (orthostatic hypotension, skin turgor, mucus membrane dryness, central venous pressure, BUN, BUN-creatinine ratio, and serum uric acid levels), which lack both sensitivity and specificity.4 Astoundingly, clinical assessment of ECV has been demonstrated to be accurate only 50% of the time when differentiating euvolemic patients from those with hypovolemia.4

Another challenge lies in the interpretation of UNa, which frequently is used as a surrogate for extra-arterial blood volume (EABV) status.10 Unfortunately, in the setting of diuretic use, UNa becomes inaccurate. The FEUrate, however, is unaffected by diuretic use and can be helpful in distinguishing between etiologies of hyponatremia with UNa greater than 30 mmol/L.11 The FEUrate is about 10% in normal euvolemic subjects and is reduced (usually <8%) in patients with low effective arterial blood volume.11,12 A trial of 86 patients demonstrated that a FEUrate of 12% had a specificity and positive predictive value of 100% in accurately identifying SIADH from diuretic-induced hyponatremia in patients on diuretics.11,12 Therefore, the UNa is a valid marker of EABV status when patients are not on diuretics; however, the FEUrate should be used in the setting of diuretic use.

Yet another pitfall is differentiating patients with salt depletion from those with SIADH. In these situations, measurement of the change in PNa concentration after a test infusion of isotonic saline is helpful. In salt depletion, PNa usually increases ≥5 mmol/L after 2 L saline infusion, which is not the case with SIADH.13 Incorrectly diagnosing renal salt wasting (RSW) as SIADH results in fluid restriction and, consequently, ECV depletion and increased morbidity.14 The persistence of hypouricemia and elevated FEUrate after correction of the hyponatremia in RSW differentiates it from SIADH.13, 14

Given these challenges, recommendations to use an algorithmic approach for the evaluation and diagnosis of hyponatremia have surfaced. In a study of 121 patients admitted with hyponatremia, an algorithm-based approach to the diagnosis of hyponatremia yielded an overall diagnostic accuracy of 71%, compared with an accuracy of 32% by experienced clinicians.5 This study also highlighted SIADH as the most frequent false-positive diagnosis that was expected whenever the combination of euvolemia and a UNa >30 mmol/L was present.5 Cases of diuretic-induced hyponatremia often were misclassified due to errors in the accurate assessment of ECV status, as most of these patients appeared clinically euvolemic or hypervolemic.5 Therefore, it is important to use an algorithm in identifying SIADH and to use one that does not rely solely on clinical estimation of ECV status (see Figure 1, below).

Management of acute and symptomatic hyponatremia. When hyponatremia develops acutely, urgent treatment is required (see Figure 2, below).15 Hyponatremia is considered acute when the onset is within 48 hours.15 Acute hyponatremia is most easily identified in the hospital and is commonly iatrogenic. Small case reviews in the 1980s began to associate postoperative deaths with the administration of hypotonic fluids.16 Asymptomatic patients with hyponatremia presenting from home should be considered chronic hyponatremias as the duration often is unclear.

Acute hyponatremia or neurologically symptomatic hyponatremia regardless of duration requires the use of hypertonic saline.15 Traditional sodium correction algorithms are based on early case series, which were focused on limiting neurologic complications from sodium overcorrection.17 This resulted in protocols recommending a conservative rate of correction spread over a 24- to 48-hour period.17 Infusing 3% saline at a rate of 1 ml/kg/hr to 2 ml/kg/hr results in a 1 mmol/L/hr to 2 mmol/L/hr increase in PNa.15 This simplified formula results in similar correction rates as more complex calculations.15 Correction should not exceed 8 mmol/L to 10 mmol/L within the first 24 hours, and 18 mmol/L to 25 mmol/L by 48 hours to avoid CPM.15 PNa should be checked every two hours to ensure that the correction rate is not exceeding the predicted rate, as the formulas do not take into account oral intake and ongoing losses.15

Recent observations focused on the initial four hours from onset of hyponatremia suggest a higher rate of correction can be tolerated without complications.18 Rapid sodium correction of 4 mmol/L to 6 mmol/L often is enough to stop neurologic complications.18 This can be accomplished with a bolus infusion of 100 mL of 3% saline.19 This may be repeated twice at 10-minute intervals until there is neurologic improvement.19 This might sound aggressive, but this would correspond to a rise in PNa of 5 mmol/L to 6 mmol/L in a 50 kg woman. Subsequent treatment with hypertonic fluid might not be needed if symptoms resolve.

Management of chronic hyponatremia. Hyponatremia secondary to SIADH improves with the treatment of the underlying cause, thus an active search for a causative medication or condition should be sought (see Table 1, p. 17).20

Water restriction. Restriction of fluid intake is the first-line treatment for SIADH in patients without hypovolemia. The severity of fluid restriction is guided by the concentration of the urinary solutes.15 Restriction of water intake to 500 ml/day to 1,000 ml/day is generally advised for many patients, as losses from the skin, lungs, and urine exceed this amount, leading to a gradual reduction in total body water.21 The main drawback of fluid restriction is poor compliance due to an intact thirst mechanism.

Saline infusion. The infusion of normal saline theoretically worsens hyponatremia due to SIADH because the water is retained while the salt is excreted. However, a trial of normal saline sometimes is attempted in patients in whom the differentiation between hypovolemia and euvolemia is difficult. From a study of a series of 17 patients with chronic SIADH, Musch and Decaux concluded that the infusion of intravenous normal (0.9%) saline raises PNa when the urine osmolality is less than 530 mosm/L.22

Oral solutes (urea and salt). The oral intake of salt augments water excretion23, and salt tablets are used as a second-line agent in patients with persistent hyponatremia despite fluid restriction.23 The oral administration of urea also results in increased free-water excretion via osmotic diuresis,24 but its poor palatability, lack of availability in the U.S., and limited user experience has restricted its usage.24

Demeclocycline. Demeclo-cycline is a tetracycline derivative that causes a partial nephrogenic diabetes insipidus.25 Its limitations include a slow onset of action (two to five days) and an unpredictable treatment effect with the possibility of causing profound polyuria and hypernatremia. It is also associated with reversible azotemia and sometimes nephrotoxicity, especially in patients with cirrhosis.

Lithium. Lithium also causes nephrogenic diabetes insipidus by downregulating vasopressin-stimulated aquaporin-2 expression and thus improves hyponatremia in SIADH.26 However, its use is significantly limited by its unpredictable response and the risks of interstitial nephritis and end-stage renal disease with chronic use. Therefore, it is no longer recommended for the treatment of SIADH.

Vasopressin receptor antagonists. Due to the role of excessive levels of vasopressin in the pathophysiology of most types of SIADH, antagonists of the vasopressin receptor were developed with the goal of preventing the excess water absorption that causes hyponatremia. Two vasopressin receptor antagonists, or vaptans, have been approved by the FDA for the treatment of nonemergent euvolemic and hypervolemic hyponatremia. Conivaptan is a nonselective vasopressin receptor antagonist that is for IV use only. Tolvaptan is a selective V2 receptor antagonist that is taken orally. Both conivaptan and tolvaptan successfully increase PNa levels while the drugs are being taken.27,28,29,30 Tolvaptan increases PNa levels in hyponatremia due to SIADH and CHF, and modestly so in cirrhosis.30

The most common side effects of the vaptans include dry mouth, increased thirst, and increased urination, although serious side effects (hypernatremia or too-rapid rate of increase in PNa) are possible.29 It is unclear if treating stable, asymptomatic hyponatremia with vaptans has any reduction in morbidity or mortality. One study found that tolvaptan increased the patients’ self-evaluations of mental functioning, but a study of tolvaptan used in combination with diuretics in the setting of CHF did not result in decreased mortality.29,31 Due to their expense, necessity of being started in the hospital, and unclear long-term benefit, the vaptans are only recommended when traditional measures such as fluid restriction and salt tablets have been unsuccessful.

Back to the Case

Our patient has hypotonic hyponatremia based on her low serum osmolality. The duration of her hyponatremia is unclear, but the patient is not experiencing seizures or coma. Therefore, her hyponatremia should be corrected slowly, and hypertonic saline is not indicated.

As is common in clinical practice, her true volume status is difficult to clinically ascertain. By physical exam, she appears euvolemic, but because she is on hydrochlorothiazide, she might be subtly hypovolemic. The UNa of 40 mmol/L is not consistent with hypovolemia, but its accuracy is limited in the setting of diuretics. The failure to improve her sodium by at least 5 mmol/L after a 2 L normal saline infusion argues against low effective arterial blood volume and indicates that the hydrochlorothiazide is unlikely to be the cause of her hyponatremia.

Therefore, the most likely cause of the hyponatremia is SIADH, a diagnosis further corroborated by the elevated FEUrate of 13%. Her chronic hyponatremia should be managed initially with fluid restriction while an investigation for an underlying cause of SIADH is initiated.

Bottom Line

The diagnosis of SIADH relies on the careful evaluation of laboratory values, use of an algorithm, and recognizing the limitations of clinically assessing volume status. The underlying cause of SIADH must also be sought and treated. TH

Dr. Grant is a clinical lecturer in internal medicine, Dr. Cho is a clinical instructor in internal medicine, and Dr. Nichani is an assistant professor of internal medicine at the University of Michigan Hospital and Health Systems in Ann Arbor.

References

- Upadhyay A, Jaber BL, Madias NE. Incidence and prevalence of hyponatremia. Am J Med. 2006;119(7 Suppl 1):S30-35.

- Verbalis JG, Goldsmith SR, Greenberg A, Schrier RW, Sterns RH. Hyponatremia treatment guidelines 2007: expert panel recommendations. Am J Med. 2007;120(11 Suppl 1):S1-21.

- Renneboog B, Musch W, Vandemergel X, Manto MU, Decaux G. Mild chronic hyponatremia is associated with falls, unsteadiness, and attention deficits. Am J Med. 2006;119(1):71.e71-78.

- Chung HM, Kluge R, Schrier RW, Anderson RJ. Clinical assessment of extracellular fluid volume in hyponatremia. Am J Med. 1987;83(5):905-908.

- Fenske W, Maier SK, Blechschmidt A, Allolio B, Störk S. Utility and limitations of the traditional diagnostic approach to hyponatremia: a diagnostic study. Am J Med. 2010;123(7):652-657.

- Bartter FC, Schwartz WB. The syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone. Am J Med. 1967;42(5):790-806.

- Smith DM, McKenna K, Thompson CJ. Hyponatraemia. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2000;52(6):667-678.

- Verbalis JG. Hyponatraemia. Baillieres Clin Endocrinol Metab. Aug 1989;3(2):499-530.

- Maesaka JK, Imbriano LJ, Ali NM, Ilamathi E. Is it cerebral or renal salt wasting? Kidney Int. 2009;76(9):934-938.

- Verbalis JG. Disorders of body water homeostasis. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;17(4):471-503.

- Fenske W, Störk S, Koschker AC, et al. Value of fractional uric acid excretion in differential diagnosis of hyponatremic patients on diuretics. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(8):2991-2997.

- Maesaka JK, Fishbane S. Regulation of renal urate excretion: a critical review. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;32(6):917-933.

- Milionis HJ, Liamis GL, Elisaf MS. The hyponatremic patient: a systematic approach to laboratory diagnosis. CMAJ. 2002;166(8):1056-1062.

- Bitew S, Imbriano L, Miyawaki N, Fishbane S, Maesaka JK. More on renal salt wasting without cerebral disease: response to saline infusion. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(2):309-315.

- Ellison DH, Berl T. Clinical practice. The syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(20):2064-2072.

- Arieff AI. Hyponatremia, convulsions, respiratory arrest, and permanent brain damage after elective surgery in healthy women. N Engl J Med. 1986;314(24):1529-1535.

- Ayus JC, Krothapalli RK, Arieff AI. Treatment of symptomatic hyponatremia and its relation to brain damage. A prospective study. N Engl J Med. 1987;317(19):1190-1195.

- Sterns RH, Nigwekar SU, Hix JK. The treatment of hyponatremia. Semin Nephrol. 2009;29(3):282-299.

- Hew-Butler T, Ayus JC, Kipps C, et al. Statement of the Second International Exercise-Associated Hyponatremia Consensus Development Conference, New Zealand, 2007. Clin J Sport Med. 2008;18(2):111-121.

- List AF, Hainsworth JD, Davis BW, Hande KR, Greco FA, Johnson DH. The syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) in small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1986;4(8):1191-1198.

- Verbalis JG. Managing hyponatremia in patients with syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion. J Hosp Med. 2010;5 Suppl 3:S18-S26.

- Musch W, Decaux G. Treating the syndrome of inappropriate ADH secretion with isotonic saline. QJM. 1998;91(11):749-753.

- Berl T. Impact of solute intake on urine flow and water excretion. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19(6):1076-1078.

- Decaux G, Brimioulle S, Genette F, Mockel J. Treatment of the syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone by urea. Am J Med. 1980;69(1):99-106.

- Forrest JN Jr., Cox M, Hong C, Morrison G, Bia M, Singer I. Superiority of demeclocycline over lithium in the treatment of chronic syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone. N Engl J Med. 1978;298(4):173-177.

- Nielsen J, Hoffert JD, Knepper MA, Agre P, Nielsen S, Fenton RA. Proteomic analysis of lithium-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus: mechanisms for aquaporin 2 down-regulation and cellular proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(9):3634-3639.

- Zeltser D, Rosansky S, van Rensburg H, Verbalis JG, Smith N. Assessment of the efficacy and safety of intravenous conivaptan in euvolemic and hypervolemic hyponatremia. Am J Nephrol. 2007;27(5):447-457.

- Verbalis JG, Zeltser D, Smith N, Barve A, Andoh M. Assessment of the efficacy and safety of intravenous conivaptan in patients with euvolaemic hyponatraemia: subgroup analysis of a randomized, controlled study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2008;69(1):159-168.

- Schrier RW, Gross P, Gheorghiade M, et al. Tolvaptan, a selective oral vasopressin V2-receptor antagonist, for hyponatremia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(20):2099-2112.

- Berl T, Quittnat-Pelletier F, Verbalis JG, et al. Oral tolvaptan is safe and effective in chronic hyponatremia. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21(4):705-712.

- Konstam MA, Gheorghiade M, Burnett JC Jr., et al. Effects of oral tolvaptan in patients hospitalized for worsening heart failure: the EVEREST Outcome Trial. JAMA. 2007;297(12):1319-1331.

Global Perspective

We’ve all heard the stereotypes: Other countries have socialized medicine, rationed care, endless lines, and little incentive for innovation. OK, there might be a grain of truth to the wait times. But healthcare in other developed nations is surprisingly varied in its mix of public and private providers, and it yields high-quality outcomes for a far better price than in the U.S. And yes, international innovation is alive and well.

Head-to-head comparisons can only go so far, with many countries using vastly different metrics to measure quality and efficiency. Nevertheless, the examples of bundling, reference pricing, and patient-reported outcomes offer a glimpse of how large-scale initiatives can help improve outcomes and bottom lines in the hospital and beyond.

Just the Facts

Last November, the nonprofit Commonwealth Fund in New York funded an analysis of healthcare data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which explains just how expensive healthcare is here.

In 2008, the U.S. spent roughly $7,500 per person on healthcare, an astonishing 50% more than the next closest country: Norway, at about $5,000 per person. And yet we lag behind Norway and almost all of our other peers in mortality rates. Cathy Schoen, senior vice president for policy, research, and evaluation at the Commonwealth Fund, says the OECD statistics also say something about how we use hospitals. Compared with its peers, the U.S. actually spends a smaller fraction of money on hospital care. We’re also on the low end of the number of acute-care hospital beds and hospital discharges per 1,000 people, and below average on the typical length of stay for acute care, at about 5.5 days. “So we’re not using the hospital more, and we’re not staying in it longer,” Schoen says. “Nor do we have way more beds, so it’s not an occupancy issue that’s driving this.”

Instead, the numbers suggest that the tests ordered, the drugs prescribed, the devices implanted, and other medical services offered are driving up costs, at least in part. So what can other countries tell us? As policymakers here debate how to bundle more healthcare payments around episodes of care (see “A Bundle of Nerves,” November 2010, p. 1), European countries including Germany and the Netherlands already are using the payment initiative on a national level to create efficiencies around hospital-based care. And they’ve done it with an American innovation: diagnostic-related groups, or DRGs. Bundling around a hip replacement, for example, includes the cost of the implant, the surgeon, and all of the hospital care. “It gives the hospital overall and all of its physicians an incentive to say, ‘If we could buy supplies cheaper, let’s do it,’ ” Schoen says.

An eye-popping 2007 McKinsey & Company study documents the relative cost of hip and knee replacement surgeries for five countries. In 2004, U.S. doctors performed just over half as many hip replacements per 100,000 people as their German counterparts. Yet the cost of each hip prosthetic averaged more than $4,800 per patient in the U.S.—four times higher than the $1,200 cost in Germany and the $1,400 cost in the United Kingdom.

Part of this difference, Schoen says, is due to supply chain management and involving doctors in the decision-making process. Many countries (and a few integrated health systems in the U.S.) are asking surgeons to help select just one or two prosthetic implants, negotiate for bulk volume pricing, and then track the clinical outcomes of those devices to flag poor performers, she says.

Setting the Bar for New Drugs

Drugs are another big-ticket item, and the U.S. pays almost twice as much per capita as the OECD average. To keep their prices lower, Schoen says, many European countries have information systems that track the relative clinical effectiveness of pharmaceuticals. “And they’re using it to inform the way they cover drugs: not to exclude them from the list of what’s covered, but to do something in Europe that’s called reference pricing,” she adds.

Let’s say a new drug costs 50% more than an older one with roughly equivalent efficacy. Under reference pricing, a doctor can still prescribe the new drug, but the patient must pay all or most of the difference. Such benchmarking has fueled an interesting dynamic. “The brand names that are coming in and want to get some market share will price themselves lower, because if they’re priced really high compared to the reference price, the chances are they just won’t ever get a market share,” Schoen says. As a result, drug prices stay lower.

The concept, although discussed in the U.S., has yet to be widely implemented here. A new study in the April issue of the Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy, however, could cause some cash-strapped governments to take a closer look.1 In the study, the Arkansas State Employee Health Plan used reference pricing for proton-pump inhibitors, using the cost of generic omeprazole as its reference point. Over the 43-month reference-pricing period, net plan costs for the drugs dropped by 49.5% per member per month.

Patient Feedback

A third lesson is that constructive feedback on quality can improve performance, even if no money is attached to outcomes. Like the U.S., Germany is placing a high priority on metrics that evaluate hospital quality. Schoen says the German performance improvement initiative is identifying outliers and providing them with feedback and technical support, but it is not built into the payment system. “They’ve had pretty rapid improvement out of that,” she says, “and I would say we’re learning the same thing in the U.S.”

Initially, Medicare data posted on its Hospital Compare website (www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov) showed a wide hospital-to-hospital variation in mortality rates for pneumonia, heart attacks, and congestive heart failure. But since then, Schoen says, most outliers on the low end have improved dramatically, even though the only payment incentive was to encourage reporting. In fact, CMS is dropping some core measures from its hospital value-based purchasing program.

Public reporting of quality measures, especially mortality rates, is certainly not without controversy. But Schoen says that if handled properly, disseminating information that suggests a facility’s performance is subpar can tap into the professionalism of its staff and create a strong incentive among them to do better. “That’s something true both internationally and in the U.S.,” she says.

In the U.S., Schoen says, the basic questions asked of patients in the HCAHPS (Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems) portion of Medicare’s new VBP system represent a good start. But the experiences of other countries, she says, suggest that patient reporting should be directed more at outcomes, similar to a proposal left out of last year’s healthcare reform bill that would have created a feedback system for patients receiving implantable medical devices.

Even so, hospitals like Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in Lebanon, N.H., are instituting patient feedback systems on their own, and a National Institutes of Health (NIH) initiative called PROMIS (Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System) is gaining traction. “It’s less blaming, and it’s more informing,” Schoen says. TH

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer based in Seattle.

Reference

- Johnson JT, Neill KK, Davis DA. Five-year examination of utilization and drug cost outcomes associated with benefit design changes including reference pricing for proton pump inhibitors in a state employee health plan. J Manag Care Pharm. 2011;17(3):200-212.

We’ve all heard the stereotypes: Other countries have socialized medicine, rationed care, endless lines, and little incentive for innovation. OK, there might be a grain of truth to the wait times. But healthcare in other developed nations is surprisingly varied in its mix of public and private providers, and it yields high-quality outcomes for a far better price than in the U.S. And yes, international innovation is alive and well.

Head-to-head comparisons can only go so far, with many countries using vastly different metrics to measure quality and efficiency. Nevertheless, the examples of bundling, reference pricing, and patient-reported outcomes offer a glimpse of how large-scale initiatives can help improve outcomes and bottom lines in the hospital and beyond.

Just the Facts

Last November, the nonprofit Commonwealth Fund in New York funded an analysis of healthcare data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which explains just how expensive healthcare is here.

In 2008, the U.S. spent roughly $7,500 per person on healthcare, an astonishing 50% more than the next closest country: Norway, at about $5,000 per person. And yet we lag behind Norway and almost all of our other peers in mortality rates. Cathy Schoen, senior vice president for policy, research, and evaluation at the Commonwealth Fund, says the OECD statistics also say something about how we use hospitals. Compared with its peers, the U.S. actually spends a smaller fraction of money on hospital care. We’re also on the low end of the number of acute-care hospital beds and hospital discharges per 1,000 people, and below average on the typical length of stay for acute care, at about 5.5 days. “So we’re not using the hospital more, and we’re not staying in it longer,” Schoen says. “Nor do we have way more beds, so it’s not an occupancy issue that’s driving this.”

Instead, the numbers suggest that the tests ordered, the drugs prescribed, the devices implanted, and other medical services offered are driving up costs, at least in part. So what can other countries tell us? As policymakers here debate how to bundle more healthcare payments around episodes of care (see “A Bundle of Nerves,” November 2010, p. 1), European countries including Germany and the Netherlands already are using the payment initiative on a national level to create efficiencies around hospital-based care. And they’ve done it with an American innovation: diagnostic-related groups, or DRGs. Bundling around a hip replacement, for example, includes the cost of the implant, the surgeon, and all of the hospital care. “It gives the hospital overall and all of its physicians an incentive to say, ‘If we could buy supplies cheaper, let’s do it,’ ” Schoen says.

An eye-popping 2007 McKinsey & Company study documents the relative cost of hip and knee replacement surgeries for five countries. In 2004, U.S. doctors performed just over half as many hip replacements per 100,000 people as their German counterparts. Yet the cost of each hip prosthetic averaged more than $4,800 per patient in the U.S.—four times higher than the $1,200 cost in Germany and the $1,400 cost in the United Kingdom.

Part of this difference, Schoen says, is due to supply chain management and involving doctors in the decision-making process. Many countries (and a few integrated health systems in the U.S.) are asking surgeons to help select just one or two prosthetic implants, negotiate for bulk volume pricing, and then track the clinical outcomes of those devices to flag poor performers, she says.

Setting the Bar for New Drugs

Drugs are another big-ticket item, and the U.S. pays almost twice as much per capita as the OECD average. To keep their prices lower, Schoen says, many European countries have information systems that track the relative clinical effectiveness of pharmaceuticals. “And they’re using it to inform the way they cover drugs: not to exclude them from the list of what’s covered, but to do something in Europe that’s called reference pricing,” she adds.

Let’s say a new drug costs 50% more than an older one with roughly equivalent efficacy. Under reference pricing, a doctor can still prescribe the new drug, but the patient must pay all or most of the difference. Such benchmarking has fueled an interesting dynamic. “The brand names that are coming in and want to get some market share will price themselves lower, because if they’re priced really high compared to the reference price, the chances are they just won’t ever get a market share,” Schoen says. As a result, drug prices stay lower.

The concept, although discussed in the U.S., has yet to be widely implemented here. A new study in the April issue of the Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy, however, could cause some cash-strapped governments to take a closer look.1 In the study, the Arkansas State Employee Health Plan used reference pricing for proton-pump inhibitors, using the cost of generic omeprazole as its reference point. Over the 43-month reference-pricing period, net plan costs for the drugs dropped by 49.5% per member per month.

Patient Feedback

A third lesson is that constructive feedback on quality can improve performance, even if no money is attached to outcomes. Like the U.S., Germany is placing a high priority on metrics that evaluate hospital quality. Schoen says the German performance improvement initiative is identifying outliers and providing them with feedback and technical support, but it is not built into the payment system. “They’ve had pretty rapid improvement out of that,” she says, “and I would say we’re learning the same thing in the U.S.”

Initially, Medicare data posted on its Hospital Compare website (www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov) showed a wide hospital-to-hospital variation in mortality rates for pneumonia, heart attacks, and congestive heart failure. But since then, Schoen says, most outliers on the low end have improved dramatically, even though the only payment incentive was to encourage reporting. In fact, CMS is dropping some core measures from its hospital value-based purchasing program.

Public reporting of quality measures, especially mortality rates, is certainly not without controversy. But Schoen says that if handled properly, disseminating information that suggests a facility’s performance is subpar can tap into the professionalism of its staff and create a strong incentive among them to do better. “That’s something true both internationally and in the U.S.,” she says.

In the U.S., Schoen says, the basic questions asked of patients in the HCAHPS (Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems) portion of Medicare’s new VBP system represent a good start. But the experiences of other countries, she says, suggest that patient reporting should be directed more at outcomes, similar to a proposal left out of last year’s healthcare reform bill that would have created a feedback system for patients receiving implantable medical devices.

Even so, hospitals like Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in Lebanon, N.H., are instituting patient feedback systems on their own, and a National Institutes of Health (NIH) initiative called PROMIS (Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System) is gaining traction. “It’s less blaming, and it’s more informing,” Schoen says. TH

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer based in Seattle.

Reference

- Johnson JT, Neill KK, Davis DA. Five-year examination of utilization and drug cost outcomes associated with benefit design changes including reference pricing for proton pump inhibitors in a state employee health plan. J Manag Care Pharm. 2011;17(3):200-212.

We’ve all heard the stereotypes: Other countries have socialized medicine, rationed care, endless lines, and little incentive for innovation. OK, there might be a grain of truth to the wait times. But healthcare in other developed nations is surprisingly varied in its mix of public and private providers, and it yields high-quality outcomes for a far better price than in the U.S. And yes, international innovation is alive and well.

Head-to-head comparisons can only go so far, with many countries using vastly different metrics to measure quality and efficiency. Nevertheless, the examples of bundling, reference pricing, and patient-reported outcomes offer a glimpse of how large-scale initiatives can help improve outcomes and bottom lines in the hospital and beyond.

Just the Facts

Last November, the nonprofit Commonwealth Fund in New York funded an analysis of healthcare data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which explains just how expensive healthcare is here.

In 2008, the U.S. spent roughly $7,500 per person on healthcare, an astonishing 50% more than the next closest country: Norway, at about $5,000 per person. And yet we lag behind Norway and almost all of our other peers in mortality rates. Cathy Schoen, senior vice president for policy, research, and evaluation at the Commonwealth Fund, says the OECD statistics also say something about how we use hospitals. Compared with its peers, the U.S. actually spends a smaller fraction of money on hospital care. We’re also on the low end of the number of acute-care hospital beds and hospital discharges per 1,000 people, and below average on the typical length of stay for acute care, at about 5.5 days. “So we’re not using the hospital more, and we’re not staying in it longer,” Schoen says. “Nor do we have way more beds, so it’s not an occupancy issue that’s driving this.”

Instead, the numbers suggest that the tests ordered, the drugs prescribed, the devices implanted, and other medical services offered are driving up costs, at least in part. So what can other countries tell us? As policymakers here debate how to bundle more healthcare payments around episodes of care (see “A Bundle of Nerves,” November 2010, p. 1), European countries including Germany and the Netherlands already are using the payment initiative on a national level to create efficiencies around hospital-based care. And they’ve done it with an American innovation: diagnostic-related groups, or DRGs. Bundling around a hip replacement, for example, includes the cost of the implant, the surgeon, and all of the hospital care. “It gives the hospital overall and all of its physicians an incentive to say, ‘If we could buy supplies cheaper, let’s do it,’ ” Schoen says.

An eye-popping 2007 McKinsey & Company study documents the relative cost of hip and knee replacement surgeries for five countries. In 2004, U.S. doctors performed just over half as many hip replacements per 100,000 people as their German counterparts. Yet the cost of each hip prosthetic averaged more than $4,800 per patient in the U.S.—four times higher than the $1,200 cost in Germany and the $1,400 cost in the United Kingdom.

Part of this difference, Schoen says, is due to supply chain management and involving doctors in the decision-making process. Many countries (and a few integrated health systems in the U.S.) are asking surgeons to help select just one or two prosthetic implants, negotiate for bulk volume pricing, and then track the clinical outcomes of those devices to flag poor performers, she says.

Setting the Bar for New Drugs

Drugs are another big-ticket item, and the U.S. pays almost twice as much per capita as the OECD average. To keep their prices lower, Schoen says, many European countries have information systems that track the relative clinical effectiveness of pharmaceuticals. “And they’re using it to inform the way they cover drugs: not to exclude them from the list of what’s covered, but to do something in Europe that’s called reference pricing,” she adds.

Let’s say a new drug costs 50% more than an older one with roughly equivalent efficacy. Under reference pricing, a doctor can still prescribe the new drug, but the patient must pay all or most of the difference. Such benchmarking has fueled an interesting dynamic. “The brand names that are coming in and want to get some market share will price themselves lower, because if they’re priced really high compared to the reference price, the chances are they just won’t ever get a market share,” Schoen says. As a result, drug prices stay lower.

The concept, although discussed in the U.S., has yet to be widely implemented here. A new study in the April issue of the Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy, however, could cause some cash-strapped governments to take a closer look.1 In the study, the Arkansas State Employee Health Plan used reference pricing for proton-pump inhibitors, using the cost of generic omeprazole as its reference point. Over the 43-month reference-pricing period, net plan costs for the drugs dropped by 49.5% per member per month.

Patient Feedback

A third lesson is that constructive feedback on quality can improve performance, even if no money is attached to outcomes. Like the U.S., Germany is placing a high priority on metrics that evaluate hospital quality. Schoen says the German performance improvement initiative is identifying outliers and providing them with feedback and technical support, but it is not built into the payment system. “They’ve had pretty rapid improvement out of that,” she says, “and I would say we’re learning the same thing in the U.S.”

Initially, Medicare data posted on its Hospital Compare website (www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov) showed a wide hospital-to-hospital variation in mortality rates for pneumonia, heart attacks, and congestive heart failure. But since then, Schoen says, most outliers on the low end have improved dramatically, even though the only payment incentive was to encourage reporting. In fact, CMS is dropping some core measures from its hospital value-based purchasing program.

Public reporting of quality measures, especially mortality rates, is certainly not without controversy. But Schoen says that if handled properly, disseminating information that suggests a facility’s performance is subpar can tap into the professionalism of its staff and create a strong incentive among them to do better. “That’s something true both internationally and in the U.S.,” she says.

In the U.S., Schoen says, the basic questions asked of patients in the HCAHPS (Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems) portion of Medicare’s new VBP system represent a good start. But the experiences of other countries, she says, suggest that patient reporting should be directed more at outcomes, similar to a proposal left out of last year’s healthcare reform bill that would have created a feedback system for patients receiving implantable medical devices.

Even so, hospitals like Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in Lebanon, N.H., are instituting patient feedback systems on their own, and a National Institutes of Health (NIH) initiative called PROMIS (Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System) is gaining traction. “It’s less blaming, and it’s more informing,” Schoen says. TH

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer based in Seattle.

Reference

- Johnson JT, Neill KK, Davis DA. Five-year examination of utilization and drug cost outcomes associated with benefit design changes including reference pricing for proton pump inhibitors in a state employee health plan. J Manag Care Pharm. 2011;17(3):200-212.

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: Quick fix eliminates indigent discharge problems

The Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) in Charleston hasn’t solved the issue of care transitions for the indigent, “but we have thought about it a lot,” says Neal Axon, MD, MSCR, FHM, assistant professor in the Division of Hospital Medicine at MUSC. The hospital is experimenting with quality-improvement (QI) techniques learned through participation in SHM’s Project BOOST.

“The first principle I try to teach residents is that a good discharge for a patient without insurance is the same as a good discharge for a patient with insurance,” Dr. Axon says. “Many of the same principles apply.”

If the care plan fails to address basic needs of indigent patients, including access to housing, primary care, and affordable medications, that patient won’t be able to focus on their medical needs.

Affiliated primary-care clinics already see a high percentage of indigent patients, Dr. Axon says, so there might be some pushback when the hospital team attempts a new referral. “We have tried to distinguish between care that needs to be done in the first week or so after discharge versus ongoing follow-up,” he explains. “We have negotiated with the clinic so that patients can come back here for one or two visits for urgent follow-up care without being entered into the [outpatient] system permanently. We are also blessed to have federally qualified health centers in the Charleston area. We have cordial relationships with those clinics, even if it’s not as well-integrated as I might wish.”

Another service that can be helpful with care transitions for uninsured patients is a 14-bed transitional-care unit on the hospital campus. “It provides rehabilitation and long-term care for the small numbers of chronically ill patients with long-term disabilities who don’t qualify for Medicaid or Medicare and can’t be placed elsewhere,” he says. “We’re able to care for these patients in a less costly way on the unit, rather than leaving them in an acute-care bed.” The hospital, he adds, views the unit as a cost-avoidance measure.