User login

Communication Vital to End-of-Life Care

A year ago in March, I looked my father in the eyes for the last time as he mouthed the words "help me" from his ICU bed. But despite being surrounded by teams of medical personnel and the latest healthcare technology, I felt utterly powerless to make a clear decision—and unclear to whom to turn for sound advice.

After 30 days of care in a well-known teaching hospital in the Northeast, my father was about to succumb to Stage 4 lung cancer, a tumor invading his spine. Moments before his plea, the ICU team had conducted a breathing test that apparently went awry—beginning the trial while my mother and I were downstairs receiving the latest round of conflicting information from a pair of doctors debating his outlook for discharge, physical rehabilitation, and hospice care. They casually informed us that a breathing test was about to occur; we rushed back to my father's side to learn the unfortunate outcome.

Prior to the episode that led to his being moved to the ICU, my father had been residing in a room directly across from a small hospitalist oncology office. What ensued was dizzying to behold: an endless parade of consultations; a narrowly averted million-dollar-plus spinal surgery in the wee hours; a too-zealous resident's further injuring of my father's right leg, which had already been compromised by a tumor degrading the femur.

My mother, my wife, and I struggled to maintain Dad's always-indomitable spirit while parsing the barrage of input regarding his potential for quality of life outside the hospital. We sat in numerous meetings, often with a pair of doctors espousing diametrically opposed outlooks. We tried to keep track of whom we were speaking with and who was in charge at any given moment; the lists we kept looked like the roster of a sports team, amply covered in scribbled-out names, phone numbers—and question marks.

It was only after my father tried feebly to speak his last words to me that the doctor who'd appeared to be most in charge pulled me aside at the door of the ICU. My mother and I hemmed and hawed in trying to decide whether to accede to another round of heroic measures. I was surprised by the somewhat terse tone of voice this senior physician used in dissuading us from allowing further life-extending efforts. I would have welcomed such honesty wholeheartedly far earlier in the process.

One of the value propositions hospitalists tout to their employers and patients is their expertise in coordinating care and facilitating communication among caregivers. Of course, there are nearly as many methods for doing so as there are hospitalist teams.

As the medical process grows more complex and specialized, with more "stakeholders" weighing in on the conversation, the hospitalist's role in taking charge of and energetically managing the flow of information for the benefit of beleaguered kin is more vital than ever. I can't speak for all loved ones who must witness the passage of a parent, a child, or a spouse, but for me, a hospitalist's firm hand would have made a world of difference in how we navigated this inevitable event.

Geoff Giordano was editor of The Hospitalist from 2007 to 2008. His father, Thomas, a lifelong journalist, wrote several articles for the magazine during that period.

A year ago in March, I looked my father in the eyes for the last time as he mouthed the words "help me" from his ICU bed. But despite being surrounded by teams of medical personnel and the latest healthcare technology, I felt utterly powerless to make a clear decision—and unclear to whom to turn for sound advice.

After 30 days of care in a well-known teaching hospital in the Northeast, my father was about to succumb to Stage 4 lung cancer, a tumor invading his spine. Moments before his plea, the ICU team had conducted a breathing test that apparently went awry—beginning the trial while my mother and I were downstairs receiving the latest round of conflicting information from a pair of doctors debating his outlook for discharge, physical rehabilitation, and hospice care. They casually informed us that a breathing test was about to occur; we rushed back to my father's side to learn the unfortunate outcome.

Prior to the episode that led to his being moved to the ICU, my father had been residing in a room directly across from a small hospitalist oncology office. What ensued was dizzying to behold: an endless parade of consultations; a narrowly averted million-dollar-plus spinal surgery in the wee hours; a too-zealous resident's further injuring of my father's right leg, which had already been compromised by a tumor degrading the femur.

My mother, my wife, and I struggled to maintain Dad's always-indomitable spirit while parsing the barrage of input regarding his potential for quality of life outside the hospital. We sat in numerous meetings, often with a pair of doctors espousing diametrically opposed outlooks. We tried to keep track of whom we were speaking with and who was in charge at any given moment; the lists we kept looked like the roster of a sports team, amply covered in scribbled-out names, phone numbers—and question marks.

It was only after my father tried feebly to speak his last words to me that the doctor who'd appeared to be most in charge pulled me aside at the door of the ICU. My mother and I hemmed and hawed in trying to decide whether to accede to another round of heroic measures. I was surprised by the somewhat terse tone of voice this senior physician used in dissuading us from allowing further life-extending efforts. I would have welcomed such honesty wholeheartedly far earlier in the process.

One of the value propositions hospitalists tout to their employers and patients is their expertise in coordinating care and facilitating communication among caregivers. Of course, there are nearly as many methods for doing so as there are hospitalist teams.

As the medical process grows more complex and specialized, with more "stakeholders" weighing in on the conversation, the hospitalist's role in taking charge of and energetically managing the flow of information for the benefit of beleaguered kin is more vital than ever. I can't speak for all loved ones who must witness the passage of a parent, a child, or a spouse, but for me, a hospitalist's firm hand would have made a world of difference in how we navigated this inevitable event.

Geoff Giordano was editor of The Hospitalist from 2007 to 2008. His father, Thomas, a lifelong journalist, wrote several articles for the magazine during that period.

A year ago in March, I looked my father in the eyes for the last time as he mouthed the words "help me" from his ICU bed. But despite being surrounded by teams of medical personnel and the latest healthcare technology, I felt utterly powerless to make a clear decision—and unclear to whom to turn for sound advice.

After 30 days of care in a well-known teaching hospital in the Northeast, my father was about to succumb to Stage 4 lung cancer, a tumor invading his spine. Moments before his plea, the ICU team had conducted a breathing test that apparently went awry—beginning the trial while my mother and I were downstairs receiving the latest round of conflicting information from a pair of doctors debating his outlook for discharge, physical rehabilitation, and hospice care. They casually informed us that a breathing test was about to occur; we rushed back to my father's side to learn the unfortunate outcome.

Prior to the episode that led to his being moved to the ICU, my father had been residing in a room directly across from a small hospitalist oncology office. What ensued was dizzying to behold: an endless parade of consultations; a narrowly averted million-dollar-plus spinal surgery in the wee hours; a too-zealous resident's further injuring of my father's right leg, which had already been compromised by a tumor degrading the femur.

My mother, my wife, and I struggled to maintain Dad's always-indomitable spirit while parsing the barrage of input regarding his potential for quality of life outside the hospital. We sat in numerous meetings, often with a pair of doctors espousing diametrically opposed outlooks. We tried to keep track of whom we were speaking with and who was in charge at any given moment; the lists we kept looked like the roster of a sports team, amply covered in scribbled-out names, phone numbers—and question marks.

It was only after my father tried feebly to speak his last words to me that the doctor who'd appeared to be most in charge pulled me aside at the door of the ICU. My mother and I hemmed and hawed in trying to decide whether to accede to another round of heroic measures. I was surprised by the somewhat terse tone of voice this senior physician used in dissuading us from allowing further life-extending efforts. I would have welcomed such honesty wholeheartedly far earlier in the process.

One of the value propositions hospitalists tout to their employers and patients is their expertise in coordinating care and facilitating communication among caregivers. Of course, there are nearly as many methods for doing so as there are hospitalist teams.

As the medical process grows more complex and specialized, with more "stakeholders" weighing in on the conversation, the hospitalist's role in taking charge of and energetically managing the flow of information for the benefit of beleaguered kin is more vital than ever. I can't speak for all loved ones who must witness the passage of a parent, a child, or a spouse, but for me, a hospitalist's firm hand would have made a world of difference in how we navigated this inevitable event.

Geoff Giordano was editor of The Hospitalist from 2007 to 2008. His father, Thomas, a lifelong journalist, wrote several articles for the magazine during that period.

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: TK

Enter text here

Enter text here

Enter text here

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: TK

Enter text here

Enter text here

Enter text here

Weighing the Pros and Cons of ACOs

Regardless of the fate of federal health reform, accountable care organizations will continue to develop because the current system is completely unsustainable.

These organizations are emerging because of the necessity to shift the unsustainable payment for volume in today’s fee-for-service health care delivery system to one that rewards value. ACOs will be judged on the delivery of quality health care while controlling overall costs. In general, ACOs will usually receive about half of the savings if quality standards are met.

This will necessitate a transformative shift from fragmented, episodic care to care that is delivered by teams following best practices across the continuum. Providers will thus be "accountable" to each other to achieve value (defined as the highest quality at the lowest cost), because they must work together to generate a sizable savings pool and to improve a patient population’s health status.

Why are ACOs empowering to primary care physicians?

ACOs will target the following key drivers of value:

• Prevention and wellness.

• Chronic disease management.

• Reduced hospitalizations.

• Improved care transitions.

• Multispecialty comanagement of complex patients.

Primary care physicians play a central role in each of these categories.

As Harold Miller of the Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform once said: "In order to be accountable for the health and health care of a broad population of patients, an accountable care organization must have one or more primary care practices playing a central role."

In fact, primary care providers are the only type of provider mandated for inclusion in the ACO Shared Savings Program under the Affordable Care Act.

But are ACOs likely to be favorable situations for primary care physicians?

First, let’s consider the pros. Many physicians find that the ACO movement’s emphasis on primary care to be a validation of the reasons they went to medical school. Being asked to guide the health care delivery system and being given the tools to do so is empowering. Leading change that will save lives and improve patient access to care would be deeply fulfilling. There also is, of course, the potential for financial gain. Unlike physicians in other specialties, primary care physicians have many opportunities in ACOs.

On the con side, you are not alone if you feel overworked or burned out, or that you simply do not have the time, resources, or remaining intellectual bandwidth to get involved.

Many have already weathered promises from the "next big thing" that in the end did not work out as advertised. And equal numbers have little capital and no business or legal consultants on retainer, as do other health care stakeholders. Time is stretched tight in many areas of the country that are already feeling the effects of a primary care workforce shortage – and now the ACO model is asking that you take on more responsibility?

But here’s the thing: If primary care physicians do not recognize the magnitude of their role in time, the opportunity for ACO success will pass them by and be replaced by dismal alternatives.

And there are already success stories. Starting with several simple Medicaid initiatives, North Carolina primary care physicians created a statewide confederation of 14 medical home ACO networks. Although the work involved is plentiful, so have been the rewards.

Among them is a renewed empowerment and leverage for their interests when they contract with payers and facilities. In interviews with the networks’ physicians, the consensus is that although much is uncertain, the primary care physicians feel much more prepared to face the changes in health care, having first created the medical home networks that lead to medical home–centric ACOs.

For those primary care physicians who choose to join a hospital, the same pros and cons generally apply. By being on the "inside," employed physicians may actually have more influence to shape a successful ACO that fairly values the role of primary care. However, they may have more difficulty freely associating with an ACO outside of the hospital’s ACO.

Whether you are inside or outside the hospital setting, there is tremendous financial opportunity for primary care providers. Shared savings is based on all costs, including those for hospitalization and drugs. The distribution of the shared savings will be proportional to the relative contribution to the savings. Thus, the percentage going to primary care stands to be considerable.

America cannot afford its current health care system. It is asking physicians to run a new health care system, with primary care at its core. There is a dramatic change of focus, from cost centers in health care to savings centers in health care.

Empowerment is being offered, but primary care must step up in order to enjoy it.

Regardless of the fate of federal health reform, accountable care organizations will continue to develop because the current system is completely unsustainable.

These organizations are emerging because of the necessity to shift the unsustainable payment for volume in today’s fee-for-service health care delivery system to one that rewards value. ACOs will be judged on the delivery of quality health care while controlling overall costs. In general, ACOs will usually receive about half of the savings if quality standards are met.

This will necessitate a transformative shift from fragmented, episodic care to care that is delivered by teams following best practices across the continuum. Providers will thus be "accountable" to each other to achieve value (defined as the highest quality at the lowest cost), because they must work together to generate a sizable savings pool and to improve a patient population’s health status.

Why are ACOs empowering to primary care physicians?

ACOs will target the following key drivers of value:

• Prevention and wellness.

• Chronic disease management.

• Reduced hospitalizations.

• Improved care transitions.

• Multispecialty comanagement of complex patients.

Primary care physicians play a central role in each of these categories.

As Harold Miller of the Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform once said: "In order to be accountable for the health and health care of a broad population of patients, an accountable care organization must have one or more primary care practices playing a central role."

In fact, primary care providers are the only type of provider mandated for inclusion in the ACO Shared Savings Program under the Affordable Care Act.

But are ACOs likely to be favorable situations for primary care physicians?

First, let’s consider the pros. Many physicians find that the ACO movement’s emphasis on primary care to be a validation of the reasons they went to medical school. Being asked to guide the health care delivery system and being given the tools to do so is empowering. Leading change that will save lives and improve patient access to care would be deeply fulfilling. There also is, of course, the potential for financial gain. Unlike physicians in other specialties, primary care physicians have many opportunities in ACOs.

On the con side, you are not alone if you feel overworked or burned out, or that you simply do not have the time, resources, or remaining intellectual bandwidth to get involved.

Many have already weathered promises from the "next big thing" that in the end did not work out as advertised. And equal numbers have little capital and no business or legal consultants on retainer, as do other health care stakeholders. Time is stretched tight in many areas of the country that are already feeling the effects of a primary care workforce shortage – and now the ACO model is asking that you take on more responsibility?

But here’s the thing: If primary care physicians do not recognize the magnitude of their role in time, the opportunity for ACO success will pass them by and be replaced by dismal alternatives.

And there are already success stories. Starting with several simple Medicaid initiatives, North Carolina primary care physicians created a statewide confederation of 14 medical home ACO networks. Although the work involved is plentiful, so have been the rewards.

Among them is a renewed empowerment and leverage for their interests when they contract with payers and facilities. In interviews with the networks’ physicians, the consensus is that although much is uncertain, the primary care physicians feel much more prepared to face the changes in health care, having first created the medical home networks that lead to medical home–centric ACOs.

For those primary care physicians who choose to join a hospital, the same pros and cons generally apply. By being on the "inside," employed physicians may actually have more influence to shape a successful ACO that fairly values the role of primary care. However, they may have more difficulty freely associating with an ACO outside of the hospital’s ACO.

Whether you are inside or outside the hospital setting, there is tremendous financial opportunity for primary care providers. Shared savings is based on all costs, including those for hospitalization and drugs. The distribution of the shared savings will be proportional to the relative contribution to the savings. Thus, the percentage going to primary care stands to be considerable.

America cannot afford its current health care system. It is asking physicians to run a new health care system, with primary care at its core. There is a dramatic change of focus, from cost centers in health care to savings centers in health care.

Empowerment is being offered, but primary care must step up in order to enjoy it.

Regardless of the fate of federal health reform, accountable care organizations will continue to develop because the current system is completely unsustainable.

These organizations are emerging because of the necessity to shift the unsustainable payment for volume in today’s fee-for-service health care delivery system to one that rewards value. ACOs will be judged on the delivery of quality health care while controlling overall costs. In general, ACOs will usually receive about half of the savings if quality standards are met.

This will necessitate a transformative shift from fragmented, episodic care to care that is delivered by teams following best practices across the continuum. Providers will thus be "accountable" to each other to achieve value (defined as the highest quality at the lowest cost), because they must work together to generate a sizable savings pool and to improve a patient population’s health status.

Why are ACOs empowering to primary care physicians?

ACOs will target the following key drivers of value:

• Prevention and wellness.

• Chronic disease management.

• Reduced hospitalizations.

• Improved care transitions.

• Multispecialty comanagement of complex patients.

Primary care physicians play a central role in each of these categories.

As Harold Miller of the Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform once said: "In order to be accountable for the health and health care of a broad population of patients, an accountable care organization must have one or more primary care practices playing a central role."

In fact, primary care providers are the only type of provider mandated for inclusion in the ACO Shared Savings Program under the Affordable Care Act.

But are ACOs likely to be favorable situations for primary care physicians?

First, let’s consider the pros. Many physicians find that the ACO movement’s emphasis on primary care to be a validation of the reasons they went to medical school. Being asked to guide the health care delivery system and being given the tools to do so is empowering. Leading change that will save lives and improve patient access to care would be deeply fulfilling. There also is, of course, the potential for financial gain. Unlike physicians in other specialties, primary care physicians have many opportunities in ACOs.

On the con side, you are not alone if you feel overworked or burned out, or that you simply do not have the time, resources, or remaining intellectual bandwidth to get involved.

Many have already weathered promises from the "next big thing" that in the end did not work out as advertised. And equal numbers have little capital and no business or legal consultants on retainer, as do other health care stakeholders. Time is stretched tight in many areas of the country that are already feeling the effects of a primary care workforce shortage – and now the ACO model is asking that you take on more responsibility?

But here’s the thing: If primary care physicians do not recognize the magnitude of their role in time, the opportunity for ACO success will pass them by and be replaced by dismal alternatives.

And there are already success stories. Starting with several simple Medicaid initiatives, North Carolina primary care physicians created a statewide confederation of 14 medical home ACO networks. Although the work involved is plentiful, so have been the rewards.

Among them is a renewed empowerment and leverage for their interests when they contract with payers and facilities. In interviews with the networks’ physicians, the consensus is that although much is uncertain, the primary care physicians feel much more prepared to face the changes in health care, having first created the medical home networks that lead to medical home–centric ACOs.

For those primary care physicians who choose to join a hospital, the same pros and cons generally apply. By being on the "inside," employed physicians may actually have more influence to shape a successful ACO that fairly values the role of primary care. However, they may have more difficulty freely associating with an ACO outside of the hospital’s ACO.

Whether you are inside or outside the hospital setting, there is tremendous financial opportunity for primary care providers. Shared savings is based on all costs, including those for hospitalization and drugs. The distribution of the shared savings will be proportional to the relative contribution to the savings. Thus, the percentage going to primary care stands to be considerable.

America cannot afford its current health care system. It is asking physicians to run a new health care system, with primary care at its core. There is a dramatic change of focus, from cost centers in health care to savings centers in health care.

Empowerment is being offered, but primary care must step up in order to enjoy it.

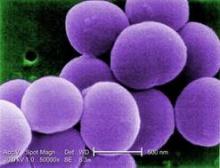

Chlorhexidine-Resistant S. aureus Infections on the Rise

BOSTON – It’s no surprise that antibiotic resistance continues to grow, but now some Staphylococcus aureus are showing off a new trick – resistance to chlorhexidine, the antiseptic relied upon to prevent staph infections.

In a review of isolates from pediatric cancer patients, an increasing number of S. aureus became resistant to the antiseptic, Dr. J. Chase McNeil said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies. The jump from susceptible to resistant occurred around 2006 – 2 years after the Texas Children’s Hospital began using chlorhexidine in the weekly central line dressing changes for its cancer patients, and a year after the facility introduced chlorhexidine mouthwash up to four times each day for patients with acute myeloid leukemia.

"It’s very interesting to see this upward trend [in resistance]," he said in an interview. "Before 2007, we had none, and since then we’ve seen an increase every year."

While the clinical significance of this phenomenon remains unclear, it’s very clear that the bacteria are changing, he added.

Dr. Chase reported a review of a prospectively acquired data set, which includes all children treated at the university’s pediatric oncology facility. He and his coinvestigators looked for infections caused by S. aureus and their related complications. They also assessed the emergence of staph isolates showing the qacA/B gene, which confers a higher minimum inhibitory concentration and minimum bactericidal concentration to chlorhexidine and other quaternary ammonium compound (QAC) antiseptics. The study also examined rates of methicillin resistance.

From 2001 through 2011, 213 S. aureus infections developed in 179 patients. Infections were most commonly associated with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (43%). Other cancers were primary central nervous system malignancies (11%), acute myeloid leukemia (AML), and hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) patients (16%). Among the infections were bacteremias (40%), skin and soft tissue infections (36%) and surgical site infections (15%).

Most of the infections were methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (147); the remaining infections were methicillin resistant. Most of the methicillin-resistant S. aureus isolates were also the USA300 strain, a particularly resistant strain associated with serious, rapidly progressing infections. The USA300 isolates were responsible for 59% of the skin/soft tissue infections and 25% of the bacteremias.

Overall, 8% of the isolates were also qacA/B positive. These were more likely to be resistant to ciprofloxacin than the qacA/B-negative isolates (50% vs. 15%).

Chlorhexidine-cleansed dressing changes and catheter cleansings began in 2004 in response to a sharp increase in staph infections in AML and HSCT patients, Dr. McNeil said. These infections did drop precipitously in the following years. In 2005, AML patients began using a chlorhexidine mouthwash up to four times each day.

However, in 2006, just as the staph infection rate was improving, qacA/B resistance suddenly appeared. By 2009, 10% of infections were positive for qacA/B, and by 2011, this had risen to about 22%.

"We can’t say if the change in the microbiology of these is caused by anything, or causing anything significant, but there is definitely a temporal association," he said.

Chlorhexidine continues to be relied upon in the oncology ward, he said. By 2011, daily chlorhexidine baths became part of the standard care for neutropenic AML patients.

Among the entire group of patients with infections, 19% (37) developed a total of 58 complications. Bacteremias were associated with most of the complications (70%). A multivariate analysis showed a significant association between complicated bacteremias and AMC patients with a low lymphocyte count.

Thirteen patients with bacteremia also developed pulmonary nodules. All of these were associated with methicillin-susceptible S. aureus isolates. The nodules developed rapidly, appearing a median of 5 days after bacteremia onset. Six patients were biopsied, with S. aureus cultured from five. One nodule was a metastatic tumor. One other patient with nodules died before culture. This patient had an invasive pulmonary fungal infection.

Dr. McNeil said several factors were significantly associated with staph infections and pulmonary nodules, including HSCT, a low lymphocyte count, and low platelets.

"This isn’t surprising because it’s well known that children with malignancies are at a high risk for staph disease because of their immune compromise and a high exposure to empiric antibiotics and antiseptics."

Dr. McNeil said he had no financial declarations.

BOSTON – It’s no surprise that antibiotic resistance continues to grow, but now some Staphylococcus aureus are showing off a new trick – resistance to chlorhexidine, the antiseptic relied upon to prevent staph infections.

In a review of isolates from pediatric cancer patients, an increasing number of S. aureus became resistant to the antiseptic, Dr. J. Chase McNeil said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies. The jump from susceptible to resistant occurred around 2006 – 2 years after the Texas Children’s Hospital began using chlorhexidine in the weekly central line dressing changes for its cancer patients, and a year after the facility introduced chlorhexidine mouthwash up to four times each day for patients with acute myeloid leukemia.

"It’s very interesting to see this upward trend [in resistance]," he said in an interview. "Before 2007, we had none, and since then we’ve seen an increase every year."

While the clinical significance of this phenomenon remains unclear, it’s very clear that the bacteria are changing, he added.

Dr. Chase reported a review of a prospectively acquired data set, which includes all children treated at the university’s pediatric oncology facility. He and his coinvestigators looked for infections caused by S. aureus and their related complications. They also assessed the emergence of staph isolates showing the qacA/B gene, which confers a higher minimum inhibitory concentration and minimum bactericidal concentration to chlorhexidine and other quaternary ammonium compound (QAC) antiseptics. The study also examined rates of methicillin resistance.

From 2001 through 2011, 213 S. aureus infections developed in 179 patients. Infections were most commonly associated with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (43%). Other cancers were primary central nervous system malignancies (11%), acute myeloid leukemia (AML), and hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) patients (16%). Among the infections were bacteremias (40%), skin and soft tissue infections (36%) and surgical site infections (15%).

Most of the infections were methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (147); the remaining infections were methicillin resistant. Most of the methicillin-resistant S. aureus isolates were also the USA300 strain, a particularly resistant strain associated with serious, rapidly progressing infections. The USA300 isolates were responsible for 59% of the skin/soft tissue infections and 25% of the bacteremias.

Overall, 8% of the isolates were also qacA/B positive. These were more likely to be resistant to ciprofloxacin than the qacA/B-negative isolates (50% vs. 15%).

Chlorhexidine-cleansed dressing changes and catheter cleansings began in 2004 in response to a sharp increase in staph infections in AML and HSCT patients, Dr. McNeil said. These infections did drop precipitously in the following years. In 2005, AML patients began using a chlorhexidine mouthwash up to four times each day.

However, in 2006, just as the staph infection rate was improving, qacA/B resistance suddenly appeared. By 2009, 10% of infections were positive for qacA/B, and by 2011, this had risen to about 22%.

"We can’t say if the change in the microbiology of these is caused by anything, or causing anything significant, but there is definitely a temporal association," he said.

Chlorhexidine continues to be relied upon in the oncology ward, he said. By 2011, daily chlorhexidine baths became part of the standard care for neutropenic AML patients.

Among the entire group of patients with infections, 19% (37) developed a total of 58 complications. Bacteremias were associated with most of the complications (70%). A multivariate analysis showed a significant association between complicated bacteremias and AMC patients with a low lymphocyte count.

Thirteen patients with bacteremia also developed pulmonary nodules. All of these were associated with methicillin-susceptible S. aureus isolates. The nodules developed rapidly, appearing a median of 5 days after bacteremia onset. Six patients were biopsied, with S. aureus cultured from five. One nodule was a metastatic tumor. One other patient with nodules died before culture. This patient had an invasive pulmonary fungal infection.

Dr. McNeil said several factors were significantly associated with staph infections and pulmonary nodules, including HSCT, a low lymphocyte count, and low platelets.

"This isn’t surprising because it’s well known that children with malignancies are at a high risk for staph disease because of their immune compromise and a high exposure to empiric antibiotics and antiseptics."

Dr. McNeil said he had no financial declarations.

BOSTON – It’s no surprise that antibiotic resistance continues to grow, but now some Staphylococcus aureus are showing off a new trick – resistance to chlorhexidine, the antiseptic relied upon to prevent staph infections.

In a review of isolates from pediatric cancer patients, an increasing number of S. aureus became resistant to the antiseptic, Dr. J. Chase McNeil said at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies. The jump from susceptible to resistant occurred around 2006 – 2 years after the Texas Children’s Hospital began using chlorhexidine in the weekly central line dressing changes for its cancer patients, and a year after the facility introduced chlorhexidine mouthwash up to four times each day for patients with acute myeloid leukemia.

"It’s very interesting to see this upward trend [in resistance]," he said in an interview. "Before 2007, we had none, and since then we’ve seen an increase every year."

While the clinical significance of this phenomenon remains unclear, it’s very clear that the bacteria are changing, he added.

Dr. Chase reported a review of a prospectively acquired data set, which includes all children treated at the university’s pediatric oncology facility. He and his coinvestigators looked for infections caused by S. aureus and their related complications. They also assessed the emergence of staph isolates showing the qacA/B gene, which confers a higher minimum inhibitory concentration and minimum bactericidal concentration to chlorhexidine and other quaternary ammonium compound (QAC) antiseptics. The study also examined rates of methicillin resistance.

From 2001 through 2011, 213 S. aureus infections developed in 179 patients. Infections were most commonly associated with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (43%). Other cancers were primary central nervous system malignancies (11%), acute myeloid leukemia (AML), and hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) patients (16%). Among the infections were bacteremias (40%), skin and soft tissue infections (36%) and surgical site infections (15%).

Most of the infections were methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (147); the remaining infections were methicillin resistant. Most of the methicillin-resistant S. aureus isolates were also the USA300 strain, a particularly resistant strain associated with serious, rapidly progressing infections. The USA300 isolates were responsible for 59% of the skin/soft tissue infections and 25% of the bacteremias.

Overall, 8% of the isolates were also qacA/B positive. These were more likely to be resistant to ciprofloxacin than the qacA/B-negative isolates (50% vs. 15%).

Chlorhexidine-cleansed dressing changes and catheter cleansings began in 2004 in response to a sharp increase in staph infections in AML and HSCT patients, Dr. McNeil said. These infections did drop precipitously in the following years. In 2005, AML patients began using a chlorhexidine mouthwash up to four times each day.

However, in 2006, just as the staph infection rate was improving, qacA/B resistance suddenly appeared. By 2009, 10% of infections were positive for qacA/B, and by 2011, this had risen to about 22%.

"We can’t say if the change in the microbiology of these is caused by anything, or causing anything significant, but there is definitely a temporal association," he said.

Chlorhexidine continues to be relied upon in the oncology ward, he said. By 2011, daily chlorhexidine baths became part of the standard care for neutropenic AML patients.

Among the entire group of patients with infections, 19% (37) developed a total of 58 complications. Bacteremias were associated with most of the complications (70%). A multivariate analysis showed a significant association between complicated bacteremias and AMC patients with a low lymphocyte count.

Thirteen patients with bacteremia also developed pulmonary nodules. All of these were associated with methicillin-susceptible S. aureus isolates. The nodules developed rapidly, appearing a median of 5 days after bacteremia onset. Six patients were biopsied, with S. aureus cultured from five. One nodule was a metastatic tumor. One other patient with nodules died before culture. This patient had an invasive pulmonary fungal infection.

Dr. McNeil said several factors were significantly associated with staph infections and pulmonary nodules, including HSCT, a low lymphocyte count, and low platelets.

"This isn’t surprising because it’s well known that children with malignancies are at a high risk for staph disease because of their immune compromise and a high exposure to empiric antibiotics and antiseptics."

Dr. McNeil said he had no financial declarations.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE PEDIATRIC ACADEMIC SOCIETIES

Major Finding: In a pediatric oncology ward, chlorhexidine-resistant S. aureus–associated infections increased from 0 in 2007 to more than 20% of staph infections in 2011.

Data Source: The data were drawn from an 11-year prospectively acquired series.

Disclosures: Dr. J. Chase McNeil had no financial disclosures.

Treating Alcoholism Is a Family Affair

"My husband is an alcoholic. They tell me I am an enabler! They say I am codependent," Ms. Jasper stated to the nurse as her husband was being admitted for alcohol detox.

"What do they mean?" she continued. "What am I supposed to do when my husband drinks? Wrestle the bottle from him? Then he would just slug me. If I don’t give him what he wants, he starts, you know, getting aggressive with me. I don’t think I am the problem here. He is the one with the problem. I am not to blame for his drinking!"

What is codependency? Who is an enabler? Why would spouses encourage their partners to keep on drinking? Think of these issues from Ms. Jasper’s point of view. It is easier to allow her alcohol-dependent husband to continue drinking rather than confront the problem and face either violence or a break-up of the family.

If he is the main breadwinner, the stakes are even higher. Ms. Jasper might encourage him to continue going to work – and might be eager to make excuses for him so he won’t lose his job.

Besides, people with alcohol dependence might gain sobriety and do well for periods of time, leading the family to believe that the problem is solved.

Another factor that can lead to this dysfunctional way of relating is a desire on the part of the family to preserve its image. As a result, family members might try to hide the problem. In time, they might forget about their own needs and devote their lives to trying to maintain a calm family atmosphere, hoping that the person with alcohol dependence will feel less stress and become sober.

Essentially, families cope as best they can. Whatever behaviors they demonstrate can be understood as normal reactions to the stress of trying to cope with a spouse who has alcohol dependency.

What are the best coping behaviors that provide a supportive environment for recovery without family members becoming overly responsible for their ill relative?

One way to determine this is to use the Behavioral Enabling Scale (BES), a clinically derived instrument that assesses enabling behaviors. The BES emphasizes observable behaviors rather than inferred motives. The BES has two components: the enabling behaviors scale and the enabling beliefs scale. The enabling behaviors scale includes items such as giving money to the patient to buy alcohol, buying alcohol, and taking over neglected chores because she or he was drinking. Enabling behaviors can be subtle, such as making excuses to family or friends. The enabling beliefs scale includes items such as, ‘‘I need to do whatever it takes to hold my relationship with my partner together’’ and ‘‘I should do my best to protect my partner from the negative consequences of his/her alcohol use.’’

Family research can tell us quite a bit about enabling behaviors in families with alcohol dependence. One such study was conducted by Robert J. Rotunda, Ph.D., and his colleagues (J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2004;26:269-76).

That study looked at 42 couples in which one partner met DSM-IV criteria for alcohol dependence. In all, 29 patients were men, and 13 were women. The mean age of the patients was 43.9 years, and their partners’ mean age was 44.3 years. Some 95% of the couples were legally married and had been cohabiting for an average of 13 years. Investigators administered the BES to both partners.

Enabling Behaviors

The study found that enabling behaviors are prevalent but not consistent. For example, "specific items of strong endorsement [that is, collapsing the response categories of sometimes, often, and very often] arising from the partners themselves included admission ... to lying or making excuses to family or friends (69%), performing the client’s neglected chores (69%), threatening separation but then not following through ... (67%), changing or canceling family plans or social activities because of the drinking (49%), and making excuses for the client’s behavior (44%)," the investigators wrote.

"Notably, 30% of the partners sampled indicated they gave money to the client to buy alcohol, or drank in the client’s presence."

All of the enabling behaviors had occurred over the past year, and only one partner of the 42 clients who participated in the survey denied engaging in any of the 20 enabling behaviors.

This study shows the extent to which most partners have engaged in some enabling behavior.

Enabling Beliefs

Another concept that the study explored was the relationship between specific partner beliefs and enabling behaviors. The investigators identified 13 "partner belief items" that factor into the partner’s enabling behaviors.

Examples of enabling beliefs include ‘‘My partner can’t get along without my help’’ and ‘‘It is my duty to take on more responsibility for home and family obligations than my partner in times of stress.’’

What Should the Clinician Do?

How can we help families cope with the psychological and physical strain that might result from interaction with those struggling with alcohol dependence? Enabling behavior might reflect hopelessness, and partners should be assessed for depression or at least demoralization. Clinicians should assess which particular spousal behaviors reinforce drinking or interfere with recovery, and which behaviors are supportive of recovery. As always, it is important to let partners know what they are doing well, and to encourage them to continue.

The couple can be encouraged to enroll in marital family therapy (MFT), which can have excellent results for treating alcohol dependence, according to Timothy J. O’Farrell, Ph.D. (J. Marital Fam. Ther. 2012;38:122-44). Even if the spouse with alcohol dependence is unwilling to seek help, MFT is effective in helping the family cope better and in motivating alcoholics to enter treatment.

In addition, spouse coping-skills training promotes improved coping by family members, as can involvement with groups such as Al-Anon. Behavioral couples therapy is more effective than individual treatment at increasing abstinence and improving relationship functioning.

Take a look Dr. O’Farrell’s program. It is easy to implement some of his couples therapy exercises into your clinical practice.

"My husband is an alcoholic. They tell me I am an enabler! They say I am codependent," Ms. Jasper stated to the nurse as her husband was being admitted for alcohol detox.

"What do they mean?" she continued. "What am I supposed to do when my husband drinks? Wrestle the bottle from him? Then he would just slug me. If I don’t give him what he wants, he starts, you know, getting aggressive with me. I don’t think I am the problem here. He is the one with the problem. I am not to blame for his drinking!"

What is codependency? Who is an enabler? Why would spouses encourage their partners to keep on drinking? Think of these issues from Ms. Jasper’s point of view. It is easier to allow her alcohol-dependent husband to continue drinking rather than confront the problem and face either violence or a break-up of the family.

If he is the main breadwinner, the stakes are even higher. Ms. Jasper might encourage him to continue going to work – and might be eager to make excuses for him so he won’t lose his job.

Besides, people with alcohol dependence might gain sobriety and do well for periods of time, leading the family to believe that the problem is solved.

Another factor that can lead to this dysfunctional way of relating is a desire on the part of the family to preserve its image. As a result, family members might try to hide the problem. In time, they might forget about their own needs and devote their lives to trying to maintain a calm family atmosphere, hoping that the person with alcohol dependence will feel less stress and become sober.

Essentially, families cope as best they can. Whatever behaviors they demonstrate can be understood as normal reactions to the stress of trying to cope with a spouse who has alcohol dependency.

What are the best coping behaviors that provide a supportive environment for recovery without family members becoming overly responsible for their ill relative?

One way to determine this is to use the Behavioral Enabling Scale (BES), a clinically derived instrument that assesses enabling behaviors. The BES emphasizes observable behaviors rather than inferred motives. The BES has two components: the enabling behaviors scale and the enabling beliefs scale. The enabling behaviors scale includes items such as giving money to the patient to buy alcohol, buying alcohol, and taking over neglected chores because she or he was drinking. Enabling behaviors can be subtle, such as making excuses to family or friends. The enabling beliefs scale includes items such as, ‘‘I need to do whatever it takes to hold my relationship with my partner together’’ and ‘‘I should do my best to protect my partner from the negative consequences of his/her alcohol use.’’

Family research can tell us quite a bit about enabling behaviors in families with alcohol dependence. One such study was conducted by Robert J. Rotunda, Ph.D., and his colleagues (J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2004;26:269-76).

That study looked at 42 couples in which one partner met DSM-IV criteria for alcohol dependence. In all, 29 patients were men, and 13 were women. The mean age of the patients was 43.9 years, and their partners’ mean age was 44.3 years. Some 95% of the couples were legally married and had been cohabiting for an average of 13 years. Investigators administered the BES to both partners.

Enabling Behaviors

The study found that enabling behaviors are prevalent but not consistent. For example, "specific items of strong endorsement [that is, collapsing the response categories of sometimes, often, and very often] arising from the partners themselves included admission ... to lying or making excuses to family or friends (69%), performing the client’s neglected chores (69%), threatening separation but then not following through ... (67%), changing or canceling family plans or social activities because of the drinking (49%), and making excuses for the client’s behavior (44%)," the investigators wrote.

"Notably, 30% of the partners sampled indicated they gave money to the client to buy alcohol, or drank in the client’s presence."

All of the enabling behaviors had occurred over the past year, and only one partner of the 42 clients who participated in the survey denied engaging in any of the 20 enabling behaviors.

This study shows the extent to which most partners have engaged in some enabling behavior.

Enabling Beliefs

Another concept that the study explored was the relationship between specific partner beliefs and enabling behaviors. The investigators identified 13 "partner belief items" that factor into the partner’s enabling behaviors.

Examples of enabling beliefs include ‘‘My partner can’t get along without my help’’ and ‘‘It is my duty to take on more responsibility for home and family obligations than my partner in times of stress.’’

What Should the Clinician Do?

How can we help families cope with the psychological and physical strain that might result from interaction with those struggling with alcohol dependence? Enabling behavior might reflect hopelessness, and partners should be assessed for depression or at least demoralization. Clinicians should assess which particular spousal behaviors reinforce drinking or interfere with recovery, and which behaviors are supportive of recovery. As always, it is important to let partners know what they are doing well, and to encourage them to continue.

The couple can be encouraged to enroll in marital family therapy (MFT), which can have excellent results for treating alcohol dependence, according to Timothy J. O’Farrell, Ph.D. (J. Marital Fam. Ther. 2012;38:122-44). Even if the spouse with alcohol dependence is unwilling to seek help, MFT is effective in helping the family cope better and in motivating alcoholics to enter treatment.

In addition, spouse coping-skills training promotes improved coping by family members, as can involvement with groups such as Al-Anon. Behavioral couples therapy is more effective than individual treatment at increasing abstinence and improving relationship functioning.

Take a look Dr. O’Farrell’s program. It is easy to implement some of his couples therapy exercises into your clinical practice.

"My husband is an alcoholic. They tell me I am an enabler! They say I am codependent," Ms. Jasper stated to the nurse as her husband was being admitted for alcohol detox.

"What do they mean?" she continued. "What am I supposed to do when my husband drinks? Wrestle the bottle from him? Then he would just slug me. If I don’t give him what he wants, he starts, you know, getting aggressive with me. I don’t think I am the problem here. He is the one with the problem. I am not to blame for his drinking!"

What is codependency? Who is an enabler? Why would spouses encourage their partners to keep on drinking? Think of these issues from Ms. Jasper’s point of view. It is easier to allow her alcohol-dependent husband to continue drinking rather than confront the problem and face either violence or a break-up of the family.

If he is the main breadwinner, the stakes are even higher. Ms. Jasper might encourage him to continue going to work – and might be eager to make excuses for him so he won’t lose his job.

Besides, people with alcohol dependence might gain sobriety and do well for periods of time, leading the family to believe that the problem is solved.

Another factor that can lead to this dysfunctional way of relating is a desire on the part of the family to preserve its image. As a result, family members might try to hide the problem. In time, they might forget about their own needs and devote their lives to trying to maintain a calm family atmosphere, hoping that the person with alcohol dependence will feel less stress and become sober.

Essentially, families cope as best they can. Whatever behaviors they demonstrate can be understood as normal reactions to the stress of trying to cope with a spouse who has alcohol dependency.

What are the best coping behaviors that provide a supportive environment for recovery without family members becoming overly responsible for their ill relative?

One way to determine this is to use the Behavioral Enabling Scale (BES), a clinically derived instrument that assesses enabling behaviors. The BES emphasizes observable behaviors rather than inferred motives. The BES has two components: the enabling behaviors scale and the enabling beliefs scale. The enabling behaviors scale includes items such as giving money to the patient to buy alcohol, buying alcohol, and taking over neglected chores because she or he was drinking. Enabling behaviors can be subtle, such as making excuses to family or friends. The enabling beliefs scale includes items such as, ‘‘I need to do whatever it takes to hold my relationship with my partner together’’ and ‘‘I should do my best to protect my partner from the negative consequences of his/her alcohol use.’’

Family research can tell us quite a bit about enabling behaviors in families with alcohol dependence. One such study was conducted by Robert J. Rotunda, Ph.D., and his colleagues (J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2004;26:269-76).

That study looked at 42 couples in which one partner met DSM-IV criteria for alcohol dependence. In all, 29 patients were men, and 13 were women. The mean age of the patients was 43.9 years, and their partners’ mean age was 44.3 years. Some 95% of the couples were legally married and had been cohabiting for an average of 13 years. Investigators administered the BES to both partners.

Enabling Behaviors

The study found that enabling behaviors are prevalent but not consistent. For example, "specific items of strong endorsement [that is, collapsing the response categories of sometimes, often, and very often] arising from the partners themselves included admission ... to lying or making excuses to family or friends (69%), performing the client’s neglected chores (69%), threatening separation but then not following through ... (67%), changing or canceling family plans or social activities because of the drinking (49%), and making excuses for the client’s behavior (44%)," the investigators wrote.

"Notably, 30% of the partners sampled indicated they gave money to the client to buy alcohol, or drank in the client’s presence."

All of the enabling behaviors had occurred over the past year, and only one partner of the 42 clients who participated in the survey denied engaging in any of the 20 enabling behaviors.

This study shows the extent to which most partners have engaged in some enabling behavior.

Enabling Beliefs

Another concept that the study explored was the relationship between specific partner beliefs and enabling behaviors. The investigators identified 13 "partner belief items" that factor into the partner’s enabling behaviors.

Examples of enabling beliefs include ‘‘My partner can’t get along without my help’’ and ‘‘It is my duty to take on more responsibility for home and family obligations than my partner in times of stress.’’

What Should the Clinician Do?

How can we help families cope with the psychological and physical strain that might result from interaction with those struggling with alcohol dependence? Enabling behavior might reflect hopelessness, and partners should be assessed for depression or at least demoralization. Clinicians should assess which particular spousal behaviors reinforce drinking or interfere with recovery, and which behaviors are supportive of recovery. As always, it is important to let partners know what they are doing well, and to encourage them to continue.

The couple can be encouraged to enroll in marital family therapy (MFT), which can have excellent results for treating alcohol dependence, according to Timothy J. O’Farrell, Ph.D. (J. Marital Fam. Ther. 2012;38:122-44). Even if the spouse with alcohol dependence is unwilling to seek help, MFT is effective in helping the family cope better and in motivating alcoholics to enter treatment.

In addition, spouse coping-skills training promotes improved coping by family members, as can involvement with groups such as Al-Anon. Behavioral couples therapy is more effective than individual treatment at increasing abstinence and improving relationship functioning.

Take a look Dr. O’Farrell’s program. It is easy to implement some of his couples therapy exercises into your clinical practice.

Vedolizumab Scores on Safety, Efficacy for Ulcerative Colitis

SAN DIEGO – Vedolizumab, a novel drug that selectively blocks lymphocyte trafficking to the gut, was safe and highly effective for inducing and maintaining clinical remission in patients with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis in a pivotal phase III trial.

"If the findings hold up with more detailed analysis, it looks like we’ll have the efficacy of a biologic agent without some of the toxicity issues that we’ve seen with anti-TNF [tumor necrosis factor] drugs," said Dr. William J. Sandborn, professor of medicine and chief of gastroenterology at the University of California, San Diego.

"This potentially could be a first-line drug," for treating moderate to severe ulcerative colitis, said Dr. Sandborn, a coinvestigator in the study.

"Vedolizumab was more effective than placebo for induction and maintenance treatment, including both anti-TNF–exposed and naive patients," Dr. Brian G. Feagan, the study’s lead investigator, said at the annual Digestive Disease Week. In addition, there was little difference between the vedolizumab and placebo groups in terms of adverse events, serious adverse events, and serious infections, said Dr. Feagan, professor of medicine at Western University in London, Ont.

At the end of a year of maintenance treatment, patients kept on the more frequent vedolizumab dosage tested, 300 mg delivered intravenously once every 4 weeks, showed a potent efficacy effect, surpassing the placebo group in corticosteroid-free clinical remissions by 31 percentage points (45% vs. 14%). "Nothing else is that good," Dr. Sandborn said in an interview. "Steroid-free remission with a delta over placebo of 30% is very impressive, especially when you factor in that many of the patients had failed anti-TNF treatment.

"We thought that vedolizumab would be safer than systemic immunosuppression, and I think the data are consistent with that. This will be a first-line treatment," Dr. Feagan said.

Equally important, total worldwide experience with vedolizumab, which now includes about 2,500 patients, has not yet resulted in a single case of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), an adverse effect produced by vedolizumab’s cousin drug, natalizumab (Tysarbi), ’approved for U.S. marketing to treat multiple sclerosis and Crohns disease.

Vedolizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that specifically binds to the alpha-4 beta-7 integrin protein that helps move leukocytes into the gut. Natalizumab is a less specific integrin antagonist that affects the protein’s actions and immune-cell trafficking to a variety of body sites, including the brain. Natalizumab "essentially blocks immune surveillance in the brain, and that allows for the JC virus [carried by about 50% of people] to cause PML," explained Dr. Sandborn. In contrast, vedolizumab does not cause "a systemic blockade of lymphocytes trafficking; it only affects a small fraction of lymphocytes, and leaves the brain completely unaffected."

Patients most at risk for PML are those who previously received immunosuppressive treatment with a drug such as azathioprine, methotrexate, or an anti-TNF drug. Patients with that history who received natalizumab for 1-2 years have about a 1 in 500-600 risk for PML, and those who got natalizumab for more than 2 years have a 1% risk.

By comparison, vedolizomab’s clean record based on 2,500 recipients "looks like it might have a very nice safety profile. If people can get comfortable with vedolizumab being different from natalizumab, then it has the potential to be first-line therapy for patients who have the worst prognosis," those who don’t respond to treatment with mesalamine.

The GEMINI I trial enrolled patients at 105 international sites with ulcerative colitis who had a Mayo score of at least 6 and an endoscopic subscore of at least 2 (indicating moderate disease) despite standard treatments. Patients were an average age of 40 years, their average duration of disease was 7 years, and their average Mayo score at entry was 8.5. Roughly 40% had previously received an anti-TNF treatment, about a third had failed on an anti-TNF drug, and just over half of the patients entered the study on a corticosteroid.

The trial included an induction phase that randomized 225 patients to a 6-week regimen with vedolizumab infusions and 149 patients to placebo. The researchers started another 521 ulcerative colitis patients on an open-label induction regimen, and then randomized 373 patients who responded after 6 weeks to maintenance infusion with vedolizumab every 4 weeks, a vedolizumab infusion every 8 weeks, or placebo.

The primary end point of the induction phase was clinical response, defined as a drop in the Mayo score of at least 3 points and at least 30%, plus a drop in the rectal bleeding score of at least 1 point or an absolute rectal bleeding subscore of 1 point or less. Achievement of this end point occurred in 47% of patients on vedolizumab and in 26% of those on placebo, a statistically significant difference. Among patients previously treated with an anti-TNF drug, 39% had a clinical response after 6 weeks on vedolizumab compared with 21% in the placebo arm, a significant difference. Among anti-TNF–naive patients, the rates were 53% and 26%.

The primary end point of the maintenance phase was clinical remission at 52 weeks, defined as a total Mayo score of 2 or less and no subscore greater than 1 point. This end point was met by 45% of patients who received vedolizumab every 4 weeks, by 42% who received the drug every 8 weeks, and by 16% of the placebo patients. Clinical remission without corticosteroid treatment occurred in 45% of patients who got vedolizumab every 4 weeks, 31% who got the drug every 8 weeks, and 14% who took placebo. Among patients with a history of anti-TNF treatment, clinical remission after 1 year occurred in 35% of patients maintained with the drug every 4 weeks, 37% who got the drug every 8 weeks, and 5% who took placebo. A total of 209 patients remained in the study through the 52-week assessment.

On May 11, Millennium Pharmaceuticals, the company developing vedolizumab, announced that the drug significantly surpassed placebo for the treatment of Crohn’s disease in the pivotal, phase III trial for that indication. The company said that it will soon report the full Crohn’s disease results.

The GEMINI I study was funded by Millennium. Dr. Feagan said he has been a consultant to Millennium and to several other drug companies. Dr. Sandborn said he has been a consultant to several drug companies but has no relationship with Millennium.

Vedolizumab is a biological therapy that blocks alpha-4/beta-7 integrins. This mechanism is novel within our armamentarium of available therapies for ulcerative colitis, and vedolizumab is also the first non-systemically acting biologic therapy. The induction and maintenance results of this phase III trial of vedolizumab in moderate to severe ulcerative colitis are very encouraging and represent a major advance in our field. It appears that the impressive safety profile (infection rate was similar to placebo) seen in this trial is likely due to its gut-specific activity.

Furthermore, it is of interest that despite inhibition of lymphocyte trafficking in the gut, there does not appear to be an increased risk of GI infections. If these impressive results pan out in clinical practice, vedolizumab undoubtedly will become a significant option for the management of our ulcerative colitis patients, and will have a prominent place in our treatment algorithms. We eagerly await FDA review and further studies, including the Crohn’s disease trial results.

David T. Rubin, M.D., AGAF, is Professor of Medicine, Associate Section Chief for Education, and Co-Director, Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, University of Chicago.

Vedolizumab is a biological therapy that blocks alpha-4/beta-7 integrins. This mechanism is novel within our armamentarium of available therapies for ulcerative colitis, and vedolizumab is also the first non-systemically acting biologic therapy. The induction and maintenance results of this phase III trial of vedolizumab in moderate to severe ulcerative colitis are very encouraging and represent a major advance in our field. It appears that the impressive safety profile (infection rate was similar to placebo) seen in this trial is likely due to its gut-specific activity.

Furthermore, it is of interest that despite inhibition of lymphocyte trafficking in the gut, there does not appear to be an increased risk of GI infections. If these impressive results pan out in clinical practice, vedolizumab undoubtedly will become a significant option for the management of our ulcerative colitis patients, and will have a prominent place in our treatment algorithms. We eagerly await FDA review and further studies, including the Crohn’s disease trial results.

David T. Rubin, M.D., AGAF, is Professor of Medicine, Associate Section Chief for Education, and Co-Director, Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, University of Chicago.

Vedolizumab is a biological therapy that blocks alpha-4/beta-7 integrins. This mechanism is novel within our armamentarium of available therapies for ulcerative colitis, and vedolizumab is also the first non-systemically acting biologic therapy. The induction and maintenance results of this phase III trial of vedolizumab in moderate to severe ulcerative colitis are very encouraging and represent a major advance in our field. It appears that the impressive safety profile (infection rate was similar to placebo) seen in this trial is likely due to its gut-specific activity.

Furthermore, it is of interest that despite inhibition of lymphocyte trafficking in the gut, there does not appear to be an increased risk of GI infections. If these impressive results pan out in clinical practice, vedolizumab undoubtedly will become a significant option for the management of our ulcerative colitis patients, and will have a prominent place in our treatment algorithms. We eagerly await FDA review and further studies, including the Crohn’s disease trial results.

David T. Rubin, M.D., AGAF, is Professor of Medicine, Associate Section Chief for Education, and Co-Director, Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center, University of Chicago.

SAN DIEGO – Vedolizumab, a novel drug that selectively blocks lymphocyte trafficking to the gut, was safe and highly effective for inducing and maintaining clinical remission in patients with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis in a pivotal phase III trial.

"If the findings hold up with more detailed analysis, it looks like we’ll have the efficacy of a biologic agent without some of the toxicity issues that we’ve seen with anti-TNF [tumor necrosis factor] drugs," said Dr. William J. Sandborn, professor of medicine and chief of gastroenterology at the University of California, San Diego.

"This potentially could be a first-line drug," for treating moderate to severe ulcerative colitis, said Dr. Sandborn, a coinvestigator in the study.

"Vedolizumab was more effective than placebo for induction and maintenance treatment, including both anti-TNF–exposed and naive patients," Dr. Brian G. Feagan, the study’s lead investigator, said at the annual Digestive Disease Week. In addition, there was little difference between the vedolizumab and placebo groups in terms of adverse events, serious adverse events, and serious infections, said Dr. Feagan, professor of medicine at Western University in London, Ont.

At the end of a year of maintenance treatment, patients kept on the more frequent vedolizumab dosage tested, 300 mg delivered intravenously once every 4 weeks, showed a potent efficacy effect, surpassing the placebo group in corticosteroid-free clinical remissions by 31 percentage points (45% vs. 14%). "Nothing else is that good," Dr. Sandborn said in an interview. "Steroid-free remission with a delta over placebo of 30% is very impressive, especially when you factor in that many of the patients had failed anti-TNF treatment.

"We thought that vedolizumab would be safer than systemic immunosuppression, and I think the data are consistent with that. This will be a first-line treatment," Dr. Feagan said.

Equally important, total worldwide experience with vedolizumab, which now includes about 2,500 patients, has not yet resulted in a single case of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), an adverse effect produced by vedolizumab’s cousin drug, natalizumab (Tysarbi), ’approved for U.S. marketing to treat multiple sclerosis and Crohns disease.

Vedolizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that specifically binds to the alpha-4 beta-7 integrin protein that helps move leukocytes into the gut. Natalizumab is a less specific integrin antagonist that affects the protein’s actions and immune-cell trafficking to a variety of body sites, including the brain. Natalizumab "essentially blocks immune surveillance in the brain, and that allows for the JC virus [carried by about 50% of people] to cause PML," explained Dr. Sandborn. In contrast, vedolizumab does not cause "a systemic blockade of lymphocytes trafficking; it only affects a small fraction of lymphocytes, and leaves the brain completely unaffected."

Patients most at risk for PML are those who previously received immunosuppressive treatment with a drug such as azathioprine, methotrexate, or an anti-TNF drug. Patients with that history who received natalizumab for 1-2 years have about a 1 in 500-600 risk for PML, and those who got natalizumab for more than 2 years have a 1% risk.

By comparison, vedolizomab’s clean record based on 2,500 recipients "looks like it might have a very nice safety profile. If people can get comfortable with vedolizumab being different from natalizumab, then it has the potential to be first-line therapy for patients who have the worst prognosis," those who don’t respond to treatment with mesalamine.

The GEMINI I trial enrolled patients at 105 international sites with ulcerative colitis who had a Mayo score of at least 6 and an endoscopic subscore of at least 2 (indicating moderate disease) despite standard treatments. Patients were an average age of 40 years, their average duration of disease was 7 years, and their average Mayo score at entry was 8.5. Roughly 40% had previously received an anti-TNF treatment, about a third had failed on an anti-TNF drug, and just over half of the patients entered the study on a corticosteroid.

The trial included an induction phase that randomized 225 patients to a 6-week regimen with vedolizumab infusions and 149 patients to placebo. The researchers started another 521 ulcerative colitis patients on an open-label induction regimen, and then randomized 373 patients who responded after 6 weeks to maintenance infusion with vedolizumab every 4 weeks, a vedolizumab infusion every 8 weeks, or placebo.

The primary end point of the induction phase was clinical response, defined as a drop in the Mayo score of at least 3 points and at least 30%, plus a drop in the rectal bleeding score of at least 1 point or an absolute rectal bleeding subscore of 1 point or less. Achievement of this end point occurred in 47% of patients on vedolizumab and in 26% of those on placebo, a statistically significant difference. Among patients previously treated with an anti-TNF drug, 39% had a clinical response after 6 weeks on vedolizumab compared with 21% in the placebo arm, a significant difference. Among anti-TNF–naive patients, the rates were 53% and 26%.

The primary end point of the maintenance phase was clinical remission at 52 weeks, defined as a total Mayo score of 2 or less and no subscore greater than 1 point. This end point was met by 45% of patients who received vedolizumab every 4 weeks, by 42% who received the drug every 8 weeks, and by 16% of the placebo patients. Clinical remission without corticosteroid treatment occurred in 45% of patients who got vedolizumab every 4 weeks, 31% who got the drug every 8 weeks, and 14% who took placebo. Among patients with a history of anti-TNF treatment, clinical remission after 1 year occurred in 35% of patients maintained with the drug every 4 weeks, 37% who got the drug every 8 weeks, and 5% who took placebo. A total of 209 patients remained in the study through the 52-week assessment.

On May 11, Millennium Pharmaceuticals, the company developing vedolizumab, announced that the drug significantly surpassed placebo for the treatment of Crohn’s disease in the pivotal, phase III trial for that indication. The company said that it will soon report the full Crohn’s disease results.

The GEMINI I study was funded by Millennium. Dr. Feagan said he has been a consultant to Millennium and to several other drug companies. Dr. Sandborn said he has been a consultant to several drug companies but has no relationship with Millennium.

SAN DIEGO – Vedolizumab, a novel drug that selectively blocks lymphocyte trafficking to the gut, was safe and highly effective for inducing and maintaining clinical remission in patients with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis in a pivotal phase III trial.

"If the findings hold up with more detailed analysis, it looks like we’ll have the efficacy of a biologic agent without some of the toxicity issues that we’ve seen with anti-TNF [tumor necrosis factor] drugs," said Dr. William J. Sandborn, professor of medicine and chief of gastroenterology at the University of California, San Diego.

"This potentially could be a first-line drug," for treating moderate to severe ulcerative colitis, said Dr. Sandborn, a coinvestigator in the study.

"Vedolizumab was more effective than placebo for induction and maintenance treatment, including both anti-TNF–exposed and naive patients," Dr. Brian G. Feagan, the study’s lead investigator, said at the annual Digestive Disease Week. In addition, there was little difference between the vedolizumab and placebo groups in terms of adverse events, serious adverse events, and serious infections, said Dr. Feagan, professor of medicine at Western University in London, Ont.

At the end of a year of maintenance treatment, patients kept on the more frequent vedolizumab dosage tested, 300 mg delivered intravenously once every 4 weeks, showed a potent efficacy effect, surpassing the placebo group in corticosteroid-free clinical remissions by 31 percentage points (45% vs. 14%). "Nothing else is that good," Dr. Sandborn said in an interview. "Steroid-free remission with a delta over placebo of 30% is very impressive, especially when you factor in that many of the patients had failed anti-TNF treatment.

"We thought that vedolizumab would be safer than systemic immunosuppression, and I think the data are consistent with that. This will be a first-line treatment," Dr. Feagan said.

Equally important, total worldwide experience with vedolizumab, which now includes about 2,500 patients, has not yet resulted in a single case of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), an adverse effect produced by vedolizumab’s cousin drug, natalizumab (Tysarbi), ’approved for U.S. marketing to treat multiple sclerosis and Crohns disease.

Vedolizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that specifically binds to the alpha-4 beta-7 integrin protein that helps move leukocytes into the gut. Natalizumab is a less specific integrin antagonist that affects the protein’s actions and immune-cell trafficking to a variety of body sites, including the brain. Natalizumab "essentially blocks immune surveillance in the brain, and that allows for the JC virus [carried by about 50% of people] to cause PML," explained Dr. Sandborn. In contrast, vedolizumab does not cause "a systemic blockade of lymphocytes trafficking; it only affects a small fraction of lymphocytes, and leaves the brain completely unaffected."

Patients most at risk for PML are those who previously received immunosuppressive treatment with a drug such as azathioprine, methotrexate, or an anti-TNF drug. Patients with that history who received natalizumab for 1-2 years have about a 1 in 500-600 risk for PML, and those who got natalizumab for more than 2 years have a 1% risk.

By comparison, vedolizomab’s clean record based on 2,500 recipients "looks like it might have a very nice safety profile. If people can get comfortable with vedolizumab being different from natalizumab, then it has the potential to be first-line therapy for patients who have the worst prognosis," those who don’t respond to treatment with mesalamine.