User login

Synthetic legal intoxicating drugs

To the Editor: I greatly appreciate the well-presented article by Drs. Jerry, Collins, and Streem in your April 2012 issue.1

As a specialist in integrative addiction medicine, I have had first-hand experience with many of the medical concerns described by the authors, and I expect to learn more about optimal management strategies as we learn more as a profession.

The lone case report cited in the article suggests a relatively short time to onset of seizure of 30 minutes following intentional ingestion of synthetic cannabinoids (JWH-018).2

In the residential treatment (“rehab”) setting where I work, I am seeing a latency to seizure onset of 24 to 72 hours with patients reporting use of synthetic cannabinoids.

Given this experience to date, I have two questions for the authors regarding new-onset seizures.

Are the authors aware of this trend in patients who present to non-emergency-department treatment settings such as residential treatment facilities? And in these cases, what if any recommendations would the authors make regarding seizure prophylaxis in patients with no history of seizure?

- Jerry J, Collins G, Streem D. Synthetic legal intoxicating drugs: the emerging ‘incense’ and ‘bath salt’ phenomenon. Cleve Clin J Med 2012; 79:258–264.

- Lapoint J, James LP, Moran CL, Nelson LS, Hoffman RS, Moran JH. Severe toxicity following synthetic cannabinoid ingestion. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2011; 49:760–764.

To the Editor: I greatly appreciate the well-presented article by Drs. Jerry, Collins, and Streem in your April 2012 issue.1

As a specialist in integrative addiction medicine, I have had first-hand experience with many of the medical concerns described by the authors, and I expect to learn more about optimal management strategies as we learn more as a profession.

The lone case report cited in the article suggests a relatively short time to onset of seizure of 30 minutes following intentional ingestion of synthetic cannabinoids (JWH-018).2

In the residential treatment (“rehab”) setting where I work, I am seeing a latency to seizure onset of 24 to 72 hours with patients reporting use of synthetic cannabinoids.

Given this experience to date, I have two questions for the authors regarding new-onset seizures.

Are the authors aware of this trend in patients who present to non-emergency-department treatment settings such as residential treatment facilities? And in these cases, what if any recommendations would the authors make regarding seizure prophylaxis in patients with no history of seizure?

To the Editor: I greatly appreciate the well-presented article by Drs. Jerry, Collins, and Streem in your April 2012 issue.1

As a specialist in integrative addiction medicine, I have had first-hand experience with many of the medical concerns described by the authors, and I expect to learn more about optimal management strategies as we learn more as a profession.

The lone case report cited in the article suggests a relatively short time to onset of seizure of 30 minutes following intentional ingestion of synthetic cannabinoids (JWH-018).2

In the residential treatment (“rehab”) setting where I work, I am seeing a latency to seizure onset of 24 to 72 hours with patients reporting use of synthetic cannabinoids.

Given this experience to date, I have two questions for the authors regarding new-onset seizures.

Are the authors aware of this trend in patients who present to non-emergency-department treatment settings such as residential treatment facilities? And in these cases, what if any recommendations would the authors make regarding seizure prophylaxis in patients with no history of seizure?

- Jerry J, Collins G, Streem D. Synthetic legal intoxicating drugs: the emerging ‘incense’ and ‘bath salt’ phenomenon. Cleve Clin J Med 2012; 79:258–264.

- Lapoint J, James LP, Moran CL, Nelson LS, Hoffman RS, Moran JH. Severe toxicity following synthetic cannabinoid ingestion. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2011; 49:760–764.

- Jerry J, Collins G, Streem D. Synthetic legal intoxicating drugs: the emerging ‘incense’ and ‘bath salt’ phenomenon. Cleve Clin J Med 2012; 79:258–264.

- Lapoint J, James LP, Moran CL, Nelson LS, Hoffman RS, Moran JH. Severe toxicity following synthetic cannabinoid ingestion. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2011; 49:760–764.

In reply: Synthetic legal intoxicating drugs

In Reply: We thank Dr. Chandiramani for his thoughtful comments.

Only four cases of seizure-like activity associated with synthetic cannabinoids have been reported in the literature. In addition to the case reported in our paper,1 there was another in which a 19-year-old had two seizures soon after smoking a spice product, and the second seizure was witnessed by paramedics on the way to the hospital.2 Though this patient’s urine was not analyzed for synthetic cannabinoids, the spice product that was reportedly smoked by the patient was later sent to a laboratory for analysis and was found to contain four synthetic cannabinoids: JWH-018, JWH-081, JWH-250, and AM-2201.

In another case,3 seizure occurred after use of an incense product called “Spicy XXX,” but neither the incense sample nor the patient’s urine was tested for synthetic cannabinoids.

The final case reported in the literature involved a 25-year-old man who was brought to an emergency department by coworkers who had witnessed seizure-like activity.4 He was reported to have smoked an incense product about “45 minutes prior to presentation,”4 indicating that the seizure-like activity happened within that time frame. Two synthetic cannabinoids (JWH-018 and JWH-073) were detected in the patient’s urine.

In the case by Lapoint et al1 that we referred to in our paper,1 seizure activity recurred in the hospital and was successfully treated with lorazepam. The case reported by Schneir and Baumbacher2 described treatment of the second seizure with intranasal midazolam, with no recurrence of seizure activity.

In summary, the literature on seizure activity related to synthetic cannabinoids is sparse. When the time course has been documented in these few cases, seizures seem to occur “soon” after using these products,2 or from 45 minutes to 1 hour after use.1,4 Although benzodiazepines have been used to treat seizure activity, there have been no published reports of using medications to prevent seizures in individuals who have been using spice products. Furthermore, the routine employment of seizure prophylaxis of any kind would probably be premature at this point given the uncertainty of the actual seizure risk among all synthetic cannabinoid users. We would consider giving a benzodiazepine to prevent possible seizures after drug ingestion in cases in which prior seizures have occurred, in cases of extreme excitement or agitation, or in those with marked alterations of mental state.

- Lapoint J, James LP, Moran CL, Nelson LS, Hoffman RS, Moran JH. Severe toxicity following synthetic cannabinoid ingestion. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2011; 49:760–764.

- Schneir AB, Baumbacher T. Convulsions associated with the use of a synthetic cannabinoid product. J Med Toxicol 2012; 8:62–64.

- Simmons JR, Skinner CG, Williams J, Kang CS, Schwartz MD, Wills BK. Intoxication from smoking “spice” (letter). Ann Emerg Med 2011; 57:187–188.

- Simmons J, Cookman L, Kang C, Skinner C. Three cases of ‘spice’ exposure. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2011; 49:431–433.

In Reply: We thank Dr. Chandiramani for his thoughtful comments.

Only four cases of seizure-like activity associated with synthetic cannabinoids have been reported in the literature. In addition to the case reported in our paper,1 there was another in which a 19-year-old had two seizures soon after smoking a spice product, and the second seizure was witnessed by paramedics on the way to the hospital.2 Though this patient’s urine was not analyzed for synthetic cannabinoids, the spice product that was reportedly smoked by the patient was later sent to a laboratory for analysis and was found to contain four synthetic cannabinoids: JWH-018, JWH-081, JWH-250, and AM-2201.

In another case,3 seizure occurred after use of an incense product called “Spicy XXX,” but neither the incense sample nor the patient’s urine was tested for synthetic cannabinoids.

The final case reported in the literature involved a 25-year-old man who was brought to an emergency department by coworkers who had witnessed seizure-like activity.4 He was reported to have smoked an incense product about “45 minutes prior to presentation,”4 indicating that the seizure-like activity happened within that time frame. Two synthetic cannabinoids (JWH-018 and JWH-073) were detected in the patient’s urine.

In the case by Lapoint et al1 that we referred to in our paper,1 seizure activity recurred in the hospital and was successfully treated with lorazepam. The case reported by Schneir and Baumbacher2 described treatment of the second seizure with intranasal midazolam, with no recurrence of seizure activity.

In summary, the literature on seizure activity related to synthetic cannabinoids is sparse. When the time course has been documented in these few cases, seizures seem to occur “soon” after using these products,2 or from 45 minutes to 1 hour after use.1,4 Although benzodiazepines have been used to treat seizure activity, there have been no published reports of using medications to prevent seizures in individuals who have been using spice products. Furthermore, the routine employment of seizure prophylaxis of any kind would probably be premature at this point given the uncertainty of the actual seizure risk among all synthetic cannabinoid users. We would consider giving a benzodiazepine to prevent possible seizures after drug ingestion in cases in which prior seizures have occurred, in cases of extreme excitement or agitation, or in those with marked alterations of mental state.

In Reply: We thank Dr. Chandiramani for his thoughtful comments.

Only four cases of seizure-like activity associated with synthetic cannabinoids have been reported in the literature. In addition to the case reported in our paper,1 there was another in which a 19-year-old had two seizures soon after smoking a spice product, and the second seizure was witnessed by paramedics on the way to the hospital.2 Though this patient’s urine was not analyzed for synthetic cannabinoids, the spice product that was reportedly smoked by the patient was later sent to a laboratory for analysis and was found to contain four synthetic cannabinoids: JWH-018, JWH-081, JWH-250, and AM-2201.

In another case,3 seizure occurred after use of an incense product called “Spicy XXX,” but neither the incense sample nor the patient’s urine was tested for synthetic cannabinoids.

The final case reported in the literature involved a 25-year-old man who was brought to an emergency department by coworkers who had witnessed seizure-like activity.4 He was reported to have smoked an incense product about “45 minutes prior to presentation,”4 indicating that the seizure-like activity happened within that time frame. Two synthetic cannabinoids (JWH-018 and JWH-073) were detected in the patient’s urine.

In the case by Lapoint et al1 that we referred to in our paper,1 seizure activity recurred in the hospital and was successfully treated with lorazepam. The case reported by Schneir and Baumbacher2 described treatment of the second seizure with intranasal midazolam, with no recurrence of seizure activity.

In summary, the literature on seizure activity related to synthetic cannabinoids is sparse. When the time course has been documented in these few cases, seizures seem to occur “soon” after using these products,2 or from 45 minutes to 1 hour after use.1,4 Although benzodiazepines have been used to treat seizure activity, there have been no published reports of using medications to prevent seizures in individuals who have been using spice products. Furthermore, the routine employment of seizure prophylaxis of any kind would probably be premature at this point given the uncertainty of the actual seizure risk among all synthetic cannabinoid users. We would consider giving a benzodiazepine to prevent possible seizures after drug ingestion in cases in which prior seizures have occurred, in cases of extreme excitement or agitation, or in those with marked alterations of mental state.

- Lapoint J, James LP, Moran CL, Nelson LS, Hoffman RS, Moran JH. Severe toxicity following synthetic cannabinoid ingestion. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2011; 49:760–764.

- Schneir AB, Baumbacher T. Convulsions associated with the use of a synthetic cannabinoid product. J Med Toxicol 2012; 8:62–64.

- Simmons JR, Skinner CG, Williams J, Kang CS, Schwartz MD, Wills BK. Intoxication from smoking “spice” (letter). Ann Emerg Med 2011; 57:187–188.

- Simmons J, Cookman L, Kang C, Skinner C. Three cases of ‘spice’ exposure. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2011; 49:431–433.

- Lapoint J, James LP, Moran CL, Nelson LS, Hoffman RS, Moran JH. Severe toxicity following synthetic cannabinoid ingestion. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2011; 49:760–764.

- Schneir AB, Baumbacher T. Convulsions associated with the use of a synthetic cannabinoid product. J Med Toxicol 2012; 8:62–64.

- Simmons JR, Skinner CG, Williams J, Kang CS, Schwartz MD, Wills BK. Intoxication from smoking “spice” (letter). Ann Emerg Med 2011; 57:187–188.

- Simmons J, Cookman L, Kang C, Skinner C. Three cases of ‘spice’ exposure. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2011; 49:431–433.

Geriatric patient-centered medical home

To the Editor: The discussion by Gennari and colleagues1 on how to obtain certification from the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) for a geriatric patient-centered medical home was very timely and instructive. The great effort that must be put into getting one’s practice certified was thoroughly documented.

Some community-based physicians will not require financial incentives to undertake this laborious process, finding sufficient reward in continuous quality improvement. However, economic reality dictates that time spent on certification must be taken away from other, productive (ie, income-generating) activities. Therefore, it is reasonable to ask what kind of financial incentives will be provided to physicians who obtain NCQA certification, and which organization or entity will pay for these incentives.

- Gennari A, Fedor K, Bakow E, Resnick NM. A geriatric patient-centered medical home: how to obtain NCQA certification. Cleve Clin J Med 2012; 79:359–366.

To the Editor: The discussion by Gennari and colleagues1 on how to obtain certification from the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) for a geriatric patient-centered medical home was very timely and instructive. The great effort that must be put into getting one’s practice certified was thoroughly documented.

Some community-based physicians will not require financial incentives to undertake this laborious process, finding sufficient reward in continuous quality improvement. However, economic reality dictates that time spent on certification must be taken away from other, productive (ie, income-generating) activities. Therefore, it is reasonable to ask what kind of financial incentives will be provided to physicians who obtain NCQA certification, and which organization or entity will pay for these incentives.

To the Editor: The discussion by Gennari and colleagues1 on how to obtain certification from the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) for a geriatric patient-centered medical home was very timely and instructive. The great effort that must be put into getting one’s practice certified was thoroughly documented.

Some community-based physicians will not require financial incentives to undertake this laborious process, finding sufficient reward in continuous quality improvement. However, economic reality dictates that time spent on certification must be taken away from other, productive (ie, income-generating) activities. Therefore, it is reasonable to ask what kind of financial incentives will be provided to physicians who obtain NCQA certification, and which organization or entity will pay for these incentives.

- Gennari A, Fedor K, Bakow E, Resnick NM. A geriatric patient-centered medical home: how to obtain NCQA certification. Cleve Clin J Med 2012; 79:359–366.

- Gennari A, Fedor K, Bakow E, Resnick NM. A geriatric patient-centered medical home: how to obtain NCQA certification. Cleve Clin J Med 2012; 79:359–366.

In reply: Geriatric patient-centered medical home

In Reply: At this time, the financial incentives for acquiring NCQA medical home certification depend on your geographic location. According to a June 5th publication in Health Care Payer News,1 26 states have adopted policies to make payments to healthcare providers that have met medical home standards. These payments and their specific requirements vary from state to state.

Your question underscores the importance of our recommendation to partner with your local health insurance provider. By reaching out to them, you can learn about what incentive programs are in place in your area or are under development. The model that many insurance companies have used is to give higher reimbursements for practices that are medical homes or that meet certain quality insurance markers. If you align your medical home quality insurance markers with your local insurance company’s incentive plan, then your medical home work can translate into real dollars for your practice. This concept of an incentive plan for quality care is becoming more and more prevalent. Furthermore, the public (ie, patients) are also becoming more savvy about the concepts of the medical home and quality. Becoming a medical home has great marketing potential that can turn into financial benefits for a practice, as well.

- Mosquera M. States make progress with medical homes. Healthcare Payer News. June 5, 2012. Available at www.healthcarepayernews.com/content/states-make-progressmedical-homes. Accessed July 5, 2012.

In Reply: At this time, the financial incentives for acquiring NCQA medical home certification depend on your geographic location. According to a June 5th publication in Health Care Payer News,1 26 states have adopted policies to make payments to healthcare providers that have met medical home standards. These payments and their specific requirements vary from state to state.

Your question underscores the importance of our recommendation to partner with your local health insurance provider. By reaching out to them, you can learn about what incentive programs are in place in your area or are under development. The model that many insurance companies have used is to give higher reimbursements for practices that are medical homes or that meet certain quality insurance markers. If you align your medical home quality insurance markers with your local insurance company’s incentive plan, then your medical home work can translate into real dollars for your practice. This concept of an incentive plan for quality care is becoming more and more prevalent. Furthermore, the public (ie, patients) are also becoming more savvy about the concepts of the medical home and quality. Becoming a medical home has great marketing potential that can turn into financial benefits for a practice, as well.

In Reply: At this time, the financial incentives for acquiring NCQA medical home certification depend on your geographic location. According to a June 5th publication in Health Care Payer News,1 26 states have adopted policies to make payments to healthcare providers that have met medical home standards. These payments and their specific requirements vary from state to state.

Your question underscores the importance of our recommendation to partner with your local health insurance provider. By reaching out to them, you can learn about what incentive programs are in place in your area or are under development. The model that many insurance companies have used is to give higher reimbursements for practices that are medical homes or that meet certain quality insurance markers. If you align your medical home quality insurance markers with your local insurance company’s incentive plan, then your medical home work can translate into real dollars for your practice. This concept of an incentive plan for quality care is becoming more and more prevalent. Furthermore, the public (ie, patients) are also becoming more savvy about the concepts of the medical home and quality. Becoming a medical home has great marketing potential that can turn into financial benefits for a practice, as well.

- Mosquera M. States make progress with medical homes. Healthcare Payer News. June 5, 2012. Available at www.healthcarepayernews.com/content/states-make-progressmedical-homes. Accessed July 5, 2012.

- Mosquera M. States make progress with medical homes. Healthcare Payer News. June 5, 2012. Available at www.healthcarepayernews.com/content/states-make-progressmedical-homes. Accessed July 5, 2012.

Autoinflammatory syndromes: Fever is not always a sign of infection

A 22-year-old man of Turkish ancestry presents to your office for an urgent visit. One day before the visit, he abruptly developed a fever with temperatures as high as 104°F (40°C), abdominal pain, joint pain, and a red rash on the lower right leg. He has no cough, nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, ear or eye pain, oral ulcers, vomiting, or diarrhea. After reviewing his chart, it becomes apparent that he has experienced similar intermittent, random, and self-limited episodes over the last 4 years.

On examination, he is febrile with diffuse abdominal tenderness and guarding. Bowel sounds are normal, and there is no rebound. The left knee is slightly swollen and limited in range of motion, and there is a large, non-palpable, blanching, erythematous lesion over the anterior lower leg.

While pondering diagnostic possibilities, you remember reading about autoinflammatory syndromes that result in recurrent episodes of fever and multisystemic inflammatory symptoms but cannot recall the evaluation and therapeutic options for these conditions.

These syndromes pose diagnostic challenges for physicians. Although these conditions are uncommon and may mimic malignancy or infection, they should be considered in patients who have recurrent febrile illness. While the autoinflammatory syndrome of familial Mediterranean fever (FMF), the diagnosis in the case above, is well known, our growing understanding of genetics and the immune system has unearthed a growing number of autoinflammatory syndromes.

A GENETICALLY DIVERSE BUT CLINICALLY SIMILAR GROUP OF CONDITIONS

The autoinflammatory syndromes are a group of genetically diverse but clinically similar conditions characterized by recurrent attacks of fever, rash, serositis, lymphadenopathy, and musculoskeletal involvement. This category of diseases is rapidly expanding and was built on the discovery of the genetics behind FMF, hyperimmunoglobulin D syndrome (HIDS), tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS), and the cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS). More recent additions to the list include Blau syndrome and the syndrome of pyogenic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum, and acne (PAPA).

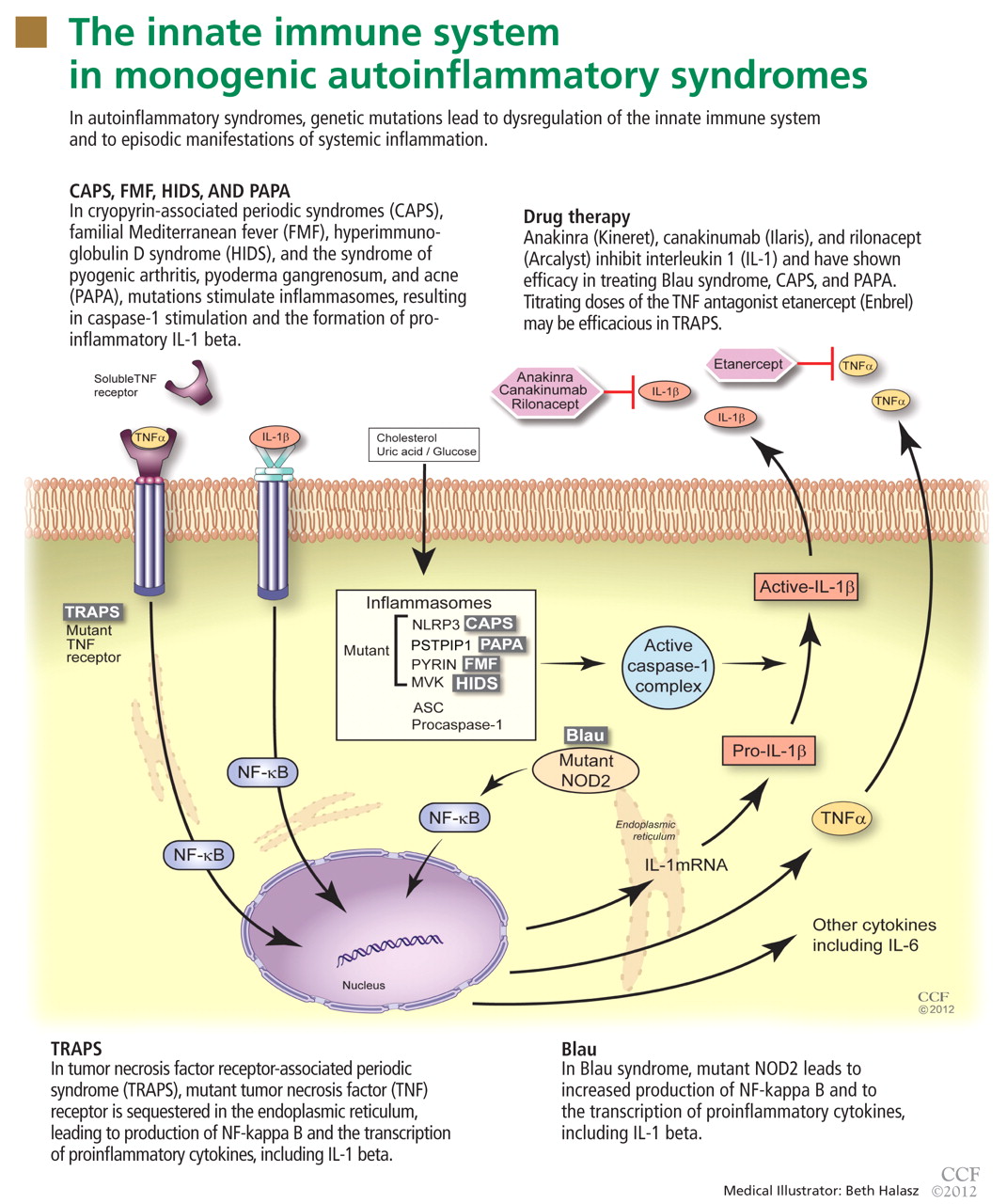

In autoinflammatory syndromes, genetic mutations lead to dysregulation of the innate immune system and to episodic manifestations of systemic inflammation. Many patients have first- or second-degree relatives with similar symptoms, reflecting the genetic abnormalities underlying this class of conditions. Unlike patients with other rheumatic diseases, patients with autoinflammatory diseases do not have autoreactive T lymphocytes, and they typically lack pathogenic autoantibodies.

The characterization of genetic autoinflammatory syndromes shows the importance of a well-regulated innate immune system and sheds light on the role of the innate immune system in common medical conditions such as gout and type 2 diabetes (see below).

THE INNATE IMMUNE SYSTEM : OUR FIRST LINE OF DEFENSE

The innate immune system is the first line of immune defense. It is evolutionarily conserved. Unlike the adaptive immune response, the innate immune response is not antigen-specific, and its activation does not produce a memory response. Generally speaking, it is composed of certain white blood cells (neutrophils, dendritic cells, macrophages, natural killer cells), proinflammatory signaling proteins (cytokines), and the complement system. Interleukin 1 (IL-1), interleukin 6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha are the critical and most potent proinflammatory cytokines of the innate immune system.

To date, nearly all mutations that have been linked to the autoinflammatory syndromes disrupt regulation of inflammatory signaling within the innate immune system. This disruption generates a proinflammatory state, often leading to a final common pathway ending with activation of the inflammasome.

The inflammasome is a complex of distinct proteins which, when brought together, serve to convert inactive prointerleukin 1 beta to the active proinflammatory cytokine IL-1 beta.1 Formation of the inflammasome can be mediated by multiple different signals including microbial products, endogenously produced substances such as cholesterol and uric acid, or by proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines (Figure 1).

FAMILIAL MEDITERRANEAN FEVER

FMF is the most common and well characterized autoinflammatory syndrome. Described in 1949, its etiology was not understood until the genetic mutation that causes it was discovered in 1997.2–4

The Mediterranean fever gene MEFV encodes pyrin, a protein with an important role in controlling IL-1 production. Mutations in MEFV affect pyrin-mediated regulation, and IL-1 production increases.

Classically, FMF is described as autosomal recessive, although many patients have only one abnormal allele.5 Possibly, the abnormal allele confers an evolutionary advantage in resisting an endemic pathogen, an idea reflected in the carrier frequencies of different MEFV mutations in certain Mediterranean and Middle Eastern ethnic populations (Sephardic Jews, Turks, Arabs, Armenians).6,7 Also, carriage of mutations in MEFV in patients with Crohn disease has been associated with a higher risk of extraintestinal manifestations and colonic stricture,8 and their carriage in patients with multiple sclerosis has been associated with a rapid progression of that disease.9

Brief episodes of fever and serositis

Although FMF usually presents at ages 5 to 15, about 20% of patients with FMF suffer their first inflammatory attack after age 20 years.

Attacks are characterized by brief episodes of fever with temperatures higher than 102°F (38.9°C), lasting less than 72 hours, accompanied by intense serositis. Abdominal serositis may be severe enough to mimic appendicitis and lead to exploratory surgery.

About 70% of patients experience arthritis (predominantly in the legs), and 40% develop erysipeloid erythema, an intensely erythematous, warm, tender, and plaque-like lesion on the lower extremities. Biopsy of involved skin shows a diffuse, primarily neutrophilic, inflammatory cell infiltrate.

Laboratory examination reveals marked elevation of acute-phase reactants, which may normalize between episodes. The diagnosis can be made using a combination of clinical suspicion, sequencing of the MEFV gene, and a positive response to a trial of colchicine (Colcrys).

Without treatment, repetitive attacks of inflammation may result in amyloidosis of the kidneys or liver. The risk of amyloidosis is related to several discrete risk factors, such as country of residence, MEFV genotype, and serum amyloid A genotype.10–12 Patients should be monitored for physical manifestations of amyloidosis at least annually.

FMF patients have also been described who develop vasculitides such as Henoch-Schönlein purpura, polyarteritis nodosa, or Behçet disease.

Colchicine is the mainstay of FMF treatment

Colchicine has been the mainstay of therapy for patients with FMF for almost 40 years.13–15 Its benefits in FMF are clear: symptoms cease in nearly 70% of patients treated with colchicine, and an additional 25% have a reduction in the severity and frequency of attacks.

Only 5% to 10% of patients have no response to colchicine; this may be partially due to individual dose limitations imposed by common drug-associated gastrointestinal side effects.16–18 For these patients, newer biologic drugs that inhibit IL-1 activity, such as anakinra (Kineret) and rilonacept (Arcalyst), offer great promise.

Typically, FMF attacks become less frequent and less severe with age. However, the overall prognosis in FMF is related mainly to the individual’s genotype and the associated risk of amyloidosis.19

HYPERIMMUNOGLOBULIN D SYNDROME

HIDS is another autosomal recessive autoinflammatory syndrome.20

The genetic defect underlying HIDS lies within the mevalonate kinase gene MVK.21 Mevalonate kinase, an enzyme, plays an important role in the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway, following the initial step by 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-CoA (HMG-CoA) reductase. Mutations are primarily missense mutations in highly conserved areas of protein that result in decreased MVK activity (1% to 5% of normal).22,23 Decreased production of geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate resulting from disruption in the HMG-CoA reductase pathway subsequently leads to increased release of IL-1 beta from peripheral blood mononuclear cells and triggers inflammatory symptoms.24

Attacks of HIDS begin early in life

HIDS attacks begin early in life, with more than 70% of patients suffering their first attack before age 2, but adult-onset disease has been reported. Patients may report that routine childhood vaccinations triggered attacks, a historical finding unique to HIDS.

Attacks typically last 4 days; a longer duration can help the clinician differentiate HIDS from FMF.

More than 90% of patients have cervical lymphadenopathy, and 80% have an erythematous rash characteristically located on the palms and soles. About 70% of patients have headache, arthritis, and abdominal pain.

During attacks, laboratory examination reveals elevated acute inflammatory reactants. As the name implies, serum levels of immunoglobulin D (IgD) are elevated. However, this finding is not specific to HIDS and may also be found in patients with Still disease or FMF or in those who smoke cigarettes. Serum IgD levels fluctuate throughout life, and the sensitivity of commercially available IgD test kits is variable.

Assessment of mevalonic acid levels in the urine during febrile attacks offers a more sensitive, specific, and reliable diagnostic test for HIDS.25 While genetic sequencing is the gold standard of diagnostic testing, close to 30% of patients meeting clinical criteria for HIDS have no definable mutation.26

Treatment of HIDS can be challenging

Oral corticosteroids are effective in HIDS, but their long-term side effects are undesirable. Patients rarely respond to colchicine, differentiating them from FMF patients.

Etanercept (Enbrel), a fusion protein composed of the soluble TNF receptor and the Fc portion of the human IgG1 protein, has been efficacious in some patients.27,28 IL-1 inhibitors have also been used with increasing efficacy in the treatment of HIDS attacks.29,30

Although the frequency of attacks decreases with age, long-term follow-up of 28 Dutch HIDS patients found that their quality of life was still lower than that in country-matched controls.31

TUMOR NECROSIS FACTOR RECEPTOR-ASSOCIATED PERIODIC SYNDROME

In 1982, a large multiplex family from Scotland and Ireland was described who had a newly recognized syndrome termed familial Hibernian fever, characterized by recurrent fever, rash, and abdominal pain.32 In 1998, the genetics of this autosomal dominant condition were characterized,33–35 and it is now known by the acronym TRAPS.

TRAPS has a variable presentation owing to a variety of mutations in the gene encoding the cell surface receptor for TNF (TNFRSF1A). TNFRSF1A mutations affecting conserved cysteine residues important for protein folding correspond to severe disease phenotypes.

The R92Q mutation has an allele frequency of up to 4% of the population. It has no impact on the structure and function of the TNF receptor protein and is associated with a heterogeneous disease course. In contrast, the P46L mutation has an allele frequency of 1% of the population and typically is associated with a milder disease course characterized by older age of onset, shorter episodes, and a low frequency of amyloidosis.36–39

The R92Q and T61I mutations, which have low penetrance, have been increasingly reported in adult patients with the autoimmune diseases systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and multiple sclerosis.40–42 Their influence is believed to contribute to proinflammatory responses but not to provide additional genetic susceptibility as provided by human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genotypes for susceptibility for these autoimmune diseases.

TRAPS attacks last longer than FMF and HIDS attacks

TRAPS attacks last 7 days or more, differentiating TRAPS from FMF and HIDS. Patients may present from infancy into adulthood, but more typically present in the toddler period.

Most patients experience intense myalgia as well as abdominal and pleuritic chest pain. A single-center series in 2002 described close to half of patients diagnosed with TRAPS as having had an intra-abdominal surgical procedure; in 10% necrotic bowel was identified, yet the biopsy typically revealed only a serosal mononuclear infiltrate.43

Like FMF and HIDS, TRAPS can cause an erythematous rash. The rash usually appears on an extremity, is centrifugal, and travels proximal-to-distal in concert with symptoms of myalgia. Deep tissue biopsy often demonstrates an intense, neutrophilic fasciitis sparing the underlying musculature. Painful conjunctivitis with periorbital edema also may occur.

Laboratory values reflecting widespread systemic inflammation and elevated acute-phase reactants are encountered during attacks and in some cases may persist between episodes.

Genetic testing can be used to confirm the diagnosis. The probability of finding a mutation in TNFRSF1A depends highly on whether the patient has affected relatives. In a series of 28 patients with recurrent inflammatory syndromes and TNFRSF1A mutations, 9 (32%) had a family history of recurrent inflammatory syndromes, while in 176 patients with sporadic, nonfamilial “TRAPS-like” symptoms, TNFRSF1A mutations were uncommon.37,38

Etanercept is effective for TRAPS

Systemic corticosteroids may be effective for treating TRAPS, but ever-increasing doses are often required.

Etanercept’s ability to bind both soluble and bound TNF explains its relative efficacy in treating TRAPS even though other TNF inhibitors have proven ineffective.44,45 With etanercept, the prognosis of TRAPS patients is typically good. Etanercept has even been effective in treating cases of renal amyloidosis from long-standing TRAPS, although it has not been shown to facilitate regression of renal amyloid mass.46,47 However, responses to treatment with etanercept may wane with time, and resistant cases have been reported.

IL-1 blockade with anakinra has been shown to be effective in the short term and long term in small case series, providing a reasonable alternative for patients who are difficult to manage.

CRYOPYRIN-ASSOCIATED PERIODIC SYNDROMES

- Perhaps the most clinically diverse hereditary autoinflammatory syndromes are the cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS). There are three overlapping phenotypes: Familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome (FCAS)

- Muckle-Wells syndrome (MWS)

- Neonatal-onset multisystemic inflammatory disorder (NOMID).

Mutations in NLRP3

CAPS symptoms stem from mutations within the NLRP3 gene (NOD-like receptor family, pyrin domain), which encodes the protein, cyropyrin.48NLRP3 mutations result in an abnormal cryopyrin structure, abnormal inflammasome activity, and increased IL-1 beta production.49,50

There is poor genotype-phenotype association in CAPS; the same NLRP3 point mutation can result in variable features, typically of either FCAS and MWS or MWS and NOMID overlapping phenotypes, supporting the hypothesis that modifier genes play a role in phenotypic expression.

Inheritance patterns in CAPS are autosomal dominant, but spontaneous mutations are also common. In fact, approximately two-thirds of patients with mutation-negative NOMID have somatic NLRP3 mutations, indicating that somatic NLRP3 mosaicism contributes to the clinical syndrome.51

Clinical features of the CAPS

The hallmarks of the CAPS include recurrent fevers, urticarial rash, and central nervous system inflammation. Characteristically, CAPS patients present in the neonatal period through early childhood, but adult-onset cases, which may have less typical features, have been reported.

Patients with FCAS develop brief episodes (< 24 hours) of fever, joint pain, and urticarial rash when exposed to sudden drops in ambient temperature.

Patients with MWS have more frequent, prolonged attacks, which may or may not be related to changes in ambient temperature. They also develop fever and urticarial rash and may develop arthritis and headaches from aseptic meningitis.

Patients with NOMID often present with fever and persistent urticarial rash shortly after birth and suffer from chronic aseptic meningitis, which can lead to papilledema and optic nerve atrophy. Frontal bossing of the skull and overgrowth of the epiphyseal regions of long bones with accompanying growth delay are also characteristic of NOMID.

IL-1 antagonists offer relief from CAPS

Many patients with FCAS do not require treatment and may move to a warmer climate to avoid rapid swings in ambient temperature. Otherwise, control of IL-1 beta activity is essential to the successful treatment of CAPS. Patients with MWS and NOMID require treatment with IL-1 antagonists, and the biologic drugs anakinra, rilonacept, and canakinumab (Ilaris) offer the possibility of symptomatic relief and long-term control of the disease.52–54

Prognosis depends on the phenotype

The overall prognosis for patients with CAPS largely depends on phenotype.

Patients with FCAS generally have progressive improvement in attack frequency and severity over time and are at minimal risk of amyloidosis.

Patients with MWS have a relatively good prognosis when treated with IL-1 antagonists, making them at low risk of amyloidosis and sensorineural hearing loss.

However, patients with NOMID are at high risk of sensorineural hearing loss, growth delay, and amyloidosis unless the condition is recognized and treated early in its course. Mortality rates historically are as high as 20% in untreated patients with NOMID.55

OTHER AUTOINFLAMMATORY SYNDROMES

More recently, other autoinflammatory syndromes of known genetic etiology have been described.

NLRP12-associated autoinflammatory disorders

A subset of patients with clinical manifestations attributable to CAPS but without mutations at the NLRP3 locus have mutations in another NLRP family member expressed in peripheral blood mononuclear cells on the NLRP12 gene. They are therefore labeled as having an NLRP12-associated autoinflammatory disorder.56,57

Deficiency of interleukin 1 receptor antagonist

IL-1 receptor antagonist is a naturally occurring antagonist of IL-1 alpha and IL-1 beta. In patients with deficiency of IL-1 receptor antagonist (DIRA), the action of these potent proinflammatory proteins is unopposed, leading to severe pustular rash and osteitis.58,59

Pyogenic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum, and acne syndrome

Patients with PAPA syndrome also have increased IL-1 production, in this case due to a mutation in the cytoplasmic adapter protein proline-serine-threonine phosphatase-interacting protein (PSTPIP1) gene, leading to the development of the symptoms included in the PAPA acronym.60

Majeed syndrome

Majeed syndrome is caused by a mutation in the LPIN2 gene, resulting in the early onset of chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis, neutrophilic dermatosis, and dyserythropoietic anemia.61

Blau syndrome

Some patients with Blau syndrome (granulomatosis, arthritis, and uveitis) have NOD2/CARD15 gene mutations.62 Cases of DIRA, PAPA, and Blau syndrome have been reported that responded favorably to treatment with IL-1 antagonists.

Periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and adenopathy syndrome

Although symptoms of the periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and adenopathy (PFAPA) syndrome typically begin in childhood, adult-onset cases have been reported.63

Patients with PFAPA syndrome develop predictable, stereotypic febrile attacks that last on average 5 days and occur approximately every 4 weeks. Between attacks, patients are healthy; during attacks, they may experience oral ulceration (aphthous stomatitis), exudative or nonexudative pharyngitis, and enlarged and tender cervical lymph nodes. Up to 60% of PFAPA patients also experience abdominal pain.

No single genetic mutation has been identified, although it has been shown that 45% of PFAPA patients have a parent or sibling with recurrent fever and 12% have a parent or sibling with a PFAPA-like phenotype, suggesting that the disease has a genetic basis.64 Recent studies have demonstrated that T-cell–regulated complement activation and IL-1 production are altered in PFAPA patients, thus supporting the hypothesis that PFAPA is an autoinflammatory syndrome.65

Treatment. In view of the syndrome’s self-limited nature, treatment is reserved for patients with a severe presentation or for patients whose condition is especially burdensome.

The fever’s height may partially respond to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, but these drugs have little effect on the duration or frequency of fever.

One or two doses of prednisone (1 mg/kg) within 6 hours of fever onset is effective in aborting the febrile episode in 90% of patients; however, up to 50% of patients may experience an increased frequency of attacks after treatment with systemic corticosteroids.66,67

Additional options include daily colchicine, which may lengthen the time between attacks, and cimetidine (Tagamet), which has been shown to prevent PFAPA attacks in approximately one-third of patients.67–69

The prognosis of PFAPA is quite favorable, and without intervention 40% of patients experience a significant reduction in the severity and frequency of fever attacks within 5 years of diagnosis. To date, there have been no reports of amyloidosis or hearing loss in PFAPA patients.

DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION OF SUSPECTED AUTOINFLAMMATORY DISEASE

The autoinflammatory syndromes pose a true diagnostic challenge for physicians. Tremendous advances have been made in molecular and genetic testing. Nevertheless, the history and careful physical examination can lead the astute clinician to the proper diagnosis when evaluating a patient with a suspected autoinflammatory syndrome.

Critical elements in the history include age at the onset of attacks, duration of attacks, associated symptoms (serositis, adenopathy, myalgias, arthralgias, arthritis, ocular symptoms, central nervous system symptoms, rash), family members with similar symptoms, and ethnic background.

Internists should remember that autoinflammatory syndromes are part of the differential diagnosis in adult patients with a recurrent febrile illness. A vigorous search for malignancy and infection (especially tuberculosis) should be conducted in all patients. However, the repetitive, stereotypic nature of autoinflammatory syndromes differentiates them from typical confounders.

The utility of acute-phase reactants in the diagnostic evaluation is limited, as many conditions result in abnormal values. However, serial monitoring of inflammatory markers such as the erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level in patients with a formally diagnosed autoinflammatory syndrome can be useful in tracking disease activity, identifying flares, and monitoring the efficacy of therapy.

In cases of suspected HIDS, assessment of IgD levels is not recommended, since IgD can be elevated in a number of autoinflammatory and rheumatologic conditions. Instead, preference should be given to testing mevalonic acid levels in the urine in patients with HIDS or suspected HIDS.

Patients with central nervous system symptoms should undergo a thorough examination, including a formal ophthalmologic evaluation, imaging, and possibly lumbar puncture to assess intracranial pressure and inflammatory changes in the cerebrospinal fluid.

Dermatologic manifestations should be examined firsthand and assessed as needed with magnetic resonance imaging to elucidate fascial inflammation or with full-thickness biopsy.

Gross bony abnormalities should be evaluated with plain radiography.

Audiologic testing may be indicated in the diagnostic evaluation of patients with recurrent fever.

Renal or hepatic biopsy may be indicated in the evaluation for amyloidosis; amyloid deposition has been reported in patients with TRAPS and clinical FMF not presenting with fever.70,71

Genetic testing is commercially available for patients with suspected hereditary autoinflammatory syndromes. However, clinicians should be cautioned that up to 30% of patients with phenotypic manifestations characteristic of a given autoinflammatory syndrome have normal results on genetic testing. In addition, the results of genetic testing may take several months to return and may cost patients and families up to several thousand dollars, as some insurers refuse to cover this procedure. Genetic testing may ultimately be indicated for proper counseling of reproductive risk.

Responses to short courses of medications such as colchicine, prednisone, and IL-1 receptor antagonists also represent diagnostic tools.

Figure 2 provides a proposed diagnostic algorithm for patients with suspected recurrent fever syndromes. Table 1 summarizes clinical and genetic features of the common autoinflammatory syndromes.

NEW INSIGHT INTO MORE COMMON CONDITIONS

Advances in the understanding of the autoinflammatory syndromes have provided new insight into the role of the innate immune system in other, more common conditions.72 Indeed, abnormal regulation of the innate inflammatory pathway has been implicated in the pathogenesis of conditions as phenotypically diverse as gout, type 2 diabetes, atherosclerosis, and epilepsy.73,74

Table 2 presents examples of the innate immune system’s involvement in the pathogenesis of several common chronic conditions.

Further study of autoinflammatory syndromes will add to our understanding of the innate immune system. These advances will lead to continued improvement in the care we give patients, both for the classic autoinflammatory syndromes and for other, more common, genetically complex conditions.

Our 22-year-old patient’s fever, abdominal pain (presumed peritonitis), erysipelas-like skin lesion, and arthritis are typical of FMF. Therefore, genetic testing was performed, which revealed a single MEFV gene mutation (M694V). Colchicine has been efficacious in preventing flares of his disease.

- Martinon F, Burns K, Tschopp J. The inflammasome: a molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of proIL-beta. Mol Cell 2002; 10:417–426.

- Siegal S. Benign paroxysmal peritonitis. Gastroenterology 1949; 12:234–247.

- International FMF Consortium. Ancient missense mutations in a new member of the RoRet gene family are likely to cause familial Mediterranean fever. Cell 1997; 90:797–807.

- French FMF Consortium. A candidate gene for familial Mediterranean fever. Nat Genet 1997; 17:25–31.

- Marek-Yagel D, Berkun Y, Padeh S, et al. Clinical disease among patients heterozygous for familial Mediterranean fever. Arthritis Rheum 2009; 60:1862–1866.

- Cattan D. Familial Mediterranean fever: is low mortality from tuberculosis a specific advantage for MEFV mutations carriers? Mortality from tuberculosis among Muslims, Jewish, French, Italian and Maltese patients in Tunis (Tunisia) in the first half of the 20th century. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2003; 21(suppl 30):S53–S54.

- Masters SL, Simon A, Aksentijevich I, Kastner DL. Horror autoinflammaticus: the molecular pathophysiology of autoinflammatory disease. Annu Rev Immunol 2009; 27:621–668.

- Fidder H, Chowers Y, Ackerman Z, et al. The familial Mediterranean fever (MEVF) gene as a modifier of Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2005; 100:338–343.

- Shinar Y, Livneh A, Villa Y, et al. Common mutations in the familial Mediterranean fever gene associate with rapid progression to disability in non-Ashkenazi Jewish multiple sclerosis patients. Genes Immun 2003; 4:197–203.

- Medlej-Hashim M, Delague V, Chouery E, et al. Amyloidosis in familial Mediterranean fever patients: correlation with MEFV genotype and SAA1 and MICA polymorphisms effects. BMC Med Genet 2004; 5:4.

- Mimouni A, Magal N, Stoffman N, et al. Familial Mediterranean fever: effects of genotype and ethnicity on inflammatory attacks and amyloidosis. Pediatrics 2000; 105:E70.

- Touitou I, Sarkisian T, Medlej-Hashim M, et al; International Study Group for Phenotype-Genotype Correlation in Familial Mediterranean Fever. Country as the primary risk factor for renal amyloidosis in familial Mediterranean fever. Arthritis Rheum 2007; 56:1706–1712.

- Goldfinger SE. Colchicine for familial Mediterranean fever. N Engl J Med 1972; 287:1302.

- Wolff SM, Dinarello CA, Dale DC, Goldfinger SE, Alling DW. Colchicine therapy of familial Mediterranean fever. Trans Assoc Am Physicians 1974; 87:186–194.

- Dinarello CA, Wolff SM, Goldfinger SE, Dale DC, Alling DW. Colchicine therapy for familial mediterranean fever. A double-blind trial. N Engl J Med 1974; 291:934–937.

- Putterman C, Ben-Chetrit E, Caraco Y, Levy M. Colchicine intoxication: clinical pharmacology, risk factors, features, and management. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1991; 21:143–155.

- Lidar M, Scherrmann JM, Shinar Y, et al. Colchicine nonresponsiveness in familial Mediterranean fever: clinical, genetic, pharmacokinetic, and socioeconomic characterization. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2004; 33:273–282.

- Ben-Chetrit E, Ozdogan H. Non-response to colchicine in FMF—definition, causes and suggested solutions. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2008; 26(suppl 50):S49–S51.

- Ben-Chetrit E, Touitou I. Familial Mediterranean fever in the world. Arthritis Rheum 2009; 61:1447–1453.

- van der Meer JW, Vossen JM, Radl J, et al. Hyperimmunoglobulinaemia D and periodic fever: a new syndrome. Lancet 1984; 1:1087–1090.

- Drenth JP, Cuisset L, Grateau G, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding mevalonate kinase cause hyper-IgD and periodic fever syndrome. International Hyper-IgD Study Group. Nat Genet 1999; 22:178–181.

- Houten SM, Frenkel J, Kuis W, Wanders RJ, Poll-The BT, Waterham HR. Molecular basis of classical mevalonic aciduria and the hyperimmunoglobulinaemia D and periodic fever syndrome: high frequency of 3 mutations in the mevalonate kinase gene. J Inherit Metab Dis 2000; 23:367–370.

- Poll-The BT, Frenkel J, Houten SM, et al. Mevalonic aciduria in 12 unrelated patients with hyperimmunoglobulinaemia D and periodic fever syndrome. J Inherit Metab Dis 2000; 23:363–366.

- Mandey SH, Kuijk LM, Frenkel J, Waterham HR. A role for geranylgeranylation in interleukin-1beta secretion. Arthritis Rheum 2006; 54:3690–3695.

- van der Hilst JC, Frenkel J. Hyperimmunoglobulin D syndrome in childhood. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2010; 12:101–107.

- Simon A, Cuisset L, Vincent MF, et al. Molecular analysis of the mevalonate kinase gene in a cohort of patients with the hyper-igd and periodic fever syndrome: its application as a diagnostic tool. Ann Intern Med 2001; 135:338–343.

- Takada K, Aksentijevich I, Mahadevan V, Dean JA, Kelley RI, Kastner DL. Favorable preliminary experience with etanercept in two patients with the hyperimmunoglobulinemia D and periodic fever syndrome. Arthritis Rheum 2003; 48:2645–2651.

- Korppi M, Van Gijn ME, Antila K. Hyperimmunoglobulinemia D and periodic fever syndrome in children. Review on therapy with biological drugs and case report. Acta Paediatr 2011; 100:21–25.

- Rigante D, Ansuini V, Bertoni B, et al. Treatment with anakinra in the hyperimmunoglobulinemia D/periodic fever syndrome. Rheumatol Int 2006; 27:97–100.

- Bodar EJ, Kuijk LM, Drenth JP, van der Meer JW, Simon A, Frenkel J. On-demand anakinra treatment is effective in mevalonate kinase deficiency. Ann Rheum Dis 2011; 70:2155–2158.

- van der Hilst JC, Bodar EJ, Barron KS, et al; International HIDS Study Group. Long-term follow-up, clinical features, and quality of life in a series of 103 patients with hyperimmunoglobulinemia D syndrome. Medicine (Baltimore) 2008; 87:301–310.

- Williamson LM, Hull D, Mehta R, Reeves WG, Robinson BH, Toghill PJ. Familial Hibernian fever. Q J Med 1982; 51:469–480.

- Mulley J, Saar K, Hewitt G, et al. Gene localization for an autosomal dominant familial periodic fever to 12p13. Am J Hum Genet 1998; 62:884–889.

- McDermott MF, Ogunkolade BW, McDermott EM, et al. Linkage of familial Hibernian fever to chromosome 12p13. Am J Hum Genet 1998; 62:1446–1451.

- McDermott MF, Aksentijevich I, Galon J, et al. Germline mutations in the extracellular domains of the 55 kDa TNF receptor, TNFR1, define a family of dominantly inherited autoinflammatory syndromes. Cell 1999; 97:133–144.

- Aksentijevich I, Galon J, Soares M, et al. The tumor-necrosis-factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome: new mutations in TNFRSF1A, ancestral origins, genotype-phenotype studies, and evidence for further genetic heterogeneity of periodic fevers. Am J Hum Genet 2001; 69:301–314.

- Dodé C, André M, Bienvenu T, et al; French Heraditary Recurrent Inflammatory Disorder Study Group. The enlarging clinical, genetic, and population spectrum of tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome. Arthritis Rheum 2002; 46:2181–2188.

- Aganna E, Hammond L, Hawkins PN, et al. Heterogeneity among patients with tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome phenotypes. Arthritis Rheum 2003; 48:2632–2644.

- Ravet N, Rouaghe S, Dodé C, et al. Clinical significance of P46L and R92Q substitutions in the tumour necrosis factor superfamily 1A gene. Ann Rheum Dis 2006; 65:1158–1162.

- Dieudé P, Goossens M, Cornélis F, Michou L, Bardin T, Tchernitchko DO; European Consortium on Rheumatoid Arthritis Families. The TNFRSF1A R92Q mutation is frequent in rheumatoid arthritis but shows no evidence for association or linkage with the disease. Ann Rheum Dis 2007; 66:1113–1115.

- Ida H, Kawasaki E, Miyashita T, et al. A novel mutation (T61I) in the gene encoding tumour necrosis factor receptor superfamily 1A (TNFRSF1A) in a Japanese patient with tumour necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS) associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2004; 43:1292–1299.

- Kümpfel T, Hoffmann LA, Pellkofer H, et al. Multiple sclerosis and the TNFRSF1A R92Q mutation: clinical characteristics of 21 cases. Neurology 2008; 71:1812–1820.

- Hull KM, Drewe E, Aksentijevich I, et al. The TNF receptor-associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS): emerging concepts of an autoinflammatory disorder. Medicine (Baltimore) 2002; 81:349–368.

- Drewe E, McDermott EM, Powell PT, Isaacs JD, Powell RJ. Prospective study of anti-tumour necrosis factor receptor superfamily 1B fusion protein, and case study of anti-tumour necrosis factor receptor superfamily 1A fusion protein, in tumour necrosis factor receptor associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS): clinical and laboratory findings in a series of seven patients. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2003; 42:235–239.

- Bulua AC, Mogul DB, Aksentijevich I, et al. Efficacy of etanercept in the tumor necrosis factor receptor–associated periodic syndrome: a prospective, open-label, dose-escalation study. Arthritis Rheum 2012; 64:908–913.

- Drewe E, McDermott EM, Powell RJ. Treatment of the nephrotic syndrome with etanercept in patients with the tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome. N Engl J Med 2000; 343:1044–1045.

- Simsek I, Kaya A, Erdem H, Pay S, Yenicesu M, Dinc A. No regression of renal amyloid mass despite remission of nephrotic syndrome in a patient with TRAPS following etanercept therapy. J Nephrol 2010; 23:119–123.

- Hoffman HM, Mueller JL, Broide DH, Wanderer AA, Kolodner RD. Mutation of a new gene encoding a putative pyrin-like protein causes familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome and Muckle-Wells syndrome. Nat Genet 2001; 29:301–315.

- Aganna E, Martinon F, Hawkins PN, et al. Association of mutations in the NALP3/CIAS1/PYPAF1 gene with a broad phenotype including recurrent fever, cold sensitivity, sensorineural deafness, and AA amyloidosis. Arthritis Rheum 2002; 46:2445–2452.

- Aksentijevich I, Nowak M, Mallah M, et al. De novo CIAS1 mutations, cytokine activation, and evidence for genetic heterogeneity in patients with neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease (NOMID): a new member of the expanding family of pyrin-associated autoinflammatory diseases. Arthritis Rheum 2002; 46:3340–3348.

- Tanaka N, Izawa K, Saito MK, et al. High incidence of NLRP3 somatic mosaicism in patients with chronic infantile neurologic, cutaneous, articular syndrome: results of an International Multicenter Collaborative Study. Arthritis Rheum 2011; 63:3625–3632.

- Hoffman HM, Throne ML, Amar NJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of rilonacept (interleukin-1 Trap) in patients with cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes: results from two sequential placebo-controlled studies. Arthritis Rheum 2008; 58:2443–2652.

- Lachmann HJ, Kone-Paut I, Kuemmerle-Deschner JB, et al. Use of canakinumab in the cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome. N Engl J Med 2009; 360:2416–2425.

- Kuemmerle-Deschner JB, Tyrrell PN, Koetter I, et al. Efficacy and safety of anakinra therapy in pediatric and adult patients with the autoinflammatory Muckle-Wells syndrome. Arthritis Rheum 2011; 63:840–849.

- Prieur AM, Griscelli C, Lampert F, et al. A chronic, infantile, neurological, cutaneous and articular (CINCA) syndrome. A specific entity analysed in 30 patients. Scand J Rheumatol Suppl 1987; 66:57–68.

- Jéru I, Duquesnoy P, Fernandes-Alnemri T, et al. Mutations in NALP12 cause hereditary periodic fever syndromes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008; 105:1614–1619.

- Borghini S, Tassi S, Chiesa S, et al. Clinical presentation and pathogenesis of cold-induced autoinflammatory disease in a family with recurrence of an NLRP12 mutation. Arthritis Rheum 2011; 63:830–839.

- Aksentijevich I, Masters SL, Ferguson PJ, et al. An autoinflammatory disease with deficiency of the interleukin-1-receptor antagonist. N Engl J Med 2009; 360:2426–2437.

- Reddy S, Jia S, Geoffrey R, et al. An autoinflammatory disease due to homozygous deletion of the IL1RN locus. N Engl J Med 2009; 360:2438–2444.

- Wise CA, Gillum JD, Seidman CE, et al. Mutations in CD2BP1 disrupt binding to PTP PEST and are responsible for PAPA syndrome, an autoinflammatory disorder. Hum Mol Genet 2002; 11:961–969.

- Ferguson PJ, Chen S, Tayeh MK, et al. Homozygous mutations in LPIN2 are responsible for the syndrome of chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis and congenital dyserythropoietic anaemia (Majeed syndrome). J Med Genet 2005; 42:551–557.

- Miceli-Richard C, Lesage S, Rybojad M, et al. CARD15 mutations in Blau syndrome. Nat Genet 2001; 29:19–20.

- Padeh S, Stoffman N, Berkun Y. Periodic fever accompanied by aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis and cervical adenitis syndrome (PFAPA syndrome) in adults. Isr Med Assoc J 2008; 10:358–360.

- Cochard M, Clet J, Le L, et al. PFAPA syndrome is not a sporadic disease. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010; 49:1984–1987.

- Stojanov S, Lapidus S, Chitkara P, et al. Periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and adenitis (PFAPA) is a disorder of innate immunity and Th1 activation responsive to IL-1 blockade. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011; 108:7148–7153.

- Thomas KT, Feder HM, Lawton AR, Edwards KM. Periodic fever syndrome in children. J Pediatr 1999; 135:15–21.

- Feder HM. Cimetidine treatment for periodic fever associated with aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis and cervical adenitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1992; 11:318–321.

- Tasher D, Stein M, Dalal I, Somekh E. Colchicine prophylaxis for frequent periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis and adenitis episodes. Acta Paediatr 2008; 97:1090–1092.

- Pillet P, Ansoborlo S, Carrère A, Perel Y, Guillard JM. [(P)FAPA syndrome: value of cimetidine]. In French. Arch Pediatr 2000; 7:54–57.

- Kallinich T, Haffner D, Rudolph B, et al. ”Periodic fever” without fever: two cases of non-febrile TRAPS with mutations in the TNFRSF1A gene presenting with episodes of inflammation or monosymptomatic amyloidosis. Ann Rheum Dis 2006; 65:958–960.

- Sohar E, Gafni J, Pras M, Heller H. Familial Mediterranean fever. A survey of 470 cases and review of the literature. Am J Med 1967; 43:227–253.

- Goldbach-Mansky R, Kastner DL. Autoinflammation: the prominent role of IL-1 in monogenic autoinflammatory diseases and implications for common illnesses. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2009; 124:1141–1149.

- Martinon F, Pétrilli V, Mayor A, Tardivel A, Tschopp J. Gout-associated uric acid crystals activate the NALP3 inflammasome. Nature 2006; 440:237–241.

- Masters SL, Dunne A, Subramanian SL, et al. Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome by islet amyloid polypeptide provides a mechanism for enhanced IL-1ß in type 2 diabetes. Nat Immunol 2010; 11:897–904.

A 22-year-old man of Turkish ancestry presents to your office for an urgent visit. One day before the visit, he abruptly developed a fever with temperatures as high as 104°F (40°C), abdominal pain, joint pain, and a red rash on the lower right leg. He has no cough, nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, ear or eye pain, oral ulcers, vomiting, or diarrhea. After reviewing his chart, it becomes apparent that he has experienced similar intermittent, random, and self-limited episodes over the last 4 years.

On examination, he is febrile with diffuse abdominal tenderness and guarding. Bowel sounds are normal, and there is no rebound. The left knee is slightly swollen and limited in range of motion, and there is a large, non-palpable, blanching, erythematous lesion over the anterior lower leg.

While pondering diagnostic possibilities, you remember reading about autoinflammatory syndromes that result in recurrent episodes of fever and multisystemic inflammatory symptoms but cannot recall the evaluation and therapeutic options for these conditions.

These syndromes pose diagnostic challenges for physicians. Although these conditions are uncommon and may mimic malignancy or infection, they should be considered in patients who have recurrent febrile illness. While the autoinflammatory syndrome of familial Mediterranean fever (FMF), the diagnosis in the case above, is well known, our growing understanding of genetics and the immune system has unearthed a growing number of autoinflammatory syndromes.

A GENETICALLY DIVERSE BUT CLINICALLY SIMILAR GROUP OF CONDITIONS

The autoinflammatory syndromes are a group of genetically diverse but clinically similar conditions characterized by recurrent attacks of fever, rash, serositis, lymphadenopathy, and musculoskeletal involvement. This category of diseases is rapidly expanding and was built on the discovery of the genetics behind FMF, hyperimmunoglobulin D syndrome (HIDS), tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS), and the cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS). More recent additions to the list include Blau syndrome and the syndrome of pyogenic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum, and acne (PAPA).

In autoinflammatory syndromes, genetic mutations lead to dysregulation of the innate immune system and to episodic manifestations of systemic inflammation. Many patients have first- or second-degree relatives with similar symptoms, reflecting the genetic abnormalities underlying this class of conditions. Unlike patients with other rheumatic diseases, patients with autoinflammatory diseases do not have autoreactive T lymphocytes, and they typically lack pathogenic autoantibodies.

The characterization of genetic autoinflammatory syndromes shows the importance of a well-regulated innate immune system and sheds light on the role of the innate immune system in common medical conditions such as gout and type 2 diabetes (see below).

THE INNATE IMMUNE SYSTEM : OUR FIRST LINE OF DEFENSE

The innate immune system is the first line of immune defense. It is evolutionarily conserved. Unlike the adaptive immune response, the innate immune response is not antigen-specific, and its activation does not produce a memory response. Generally speaking, it is composed of certain white blood cells (neutrophils, dendritic cells, macrophages, natural killer cells), proinflammatory signaling proteins (cytokines), and the complement system. Interleukin 1 (IL-1), interleukin 6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha are the critical and most potent proinflammatory cytokines of the innate immune system.

To date, nearly all mutations that have been linked to the autoinflammatory syndromes disrupt regulation of inflammatory signaling within the innate immune system. This disruption generates a proinflammatory state, often leading to a final common pathway ending with activation of the inflammasome.

The inflammasome is a complex of distinct proteins which, when brought together, serve to convert inactive prointerleukin 1 beta to the active proinflammatory cytokine IL-1 beta.1 Formation of the inflammasome can be mediated by multiple different signals including microbial products, endogenously produced substances such as cholesterol and uric acid, or by proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines (Figure 1).

FAMILIAL MEDITERRANEAN FEVER

FMF is the most common and well characterized autoinflammatory syndrome. Described in 1949, its etiology was not understood until the genetic mutation that causes it was discovered in 1997.2–4

The Mediterranean fever gene MEFV encodes pyrin, a protein with an important role in controlling IL-1 production. Mutations in MEFV affect pyrin-mediated regulation, and IL-1 production increases.

Classically, FMF is described as autosomal recessive, although many patients have only one abnormal allele.5 Possibly, the abnormal allele confers an evolutionary advantage in resisting an endemic pathogen, an idea reflected in the carrier frequencies of different MEFV mutations in certain Mediterranean and Middle Eastern ethnic populations (Sephardic Jews, Turks, Arabs, Armenians).6,7 Also, carriage of mutations in MEFV in patients with Crohn disease has been associated with a higher risk of extraintestinal manifestations and colonic stricture,8 and their carriage in patients with multiple sclerosis has been associated with a rapid progression of that disease.9

Brief episodes of fever and serositis

Although FMF usually presents at ages 5 to 15, about 20% of patients with FMF suffer their first inflammatory attack after age 20 years.

Attacks are characterized by brief episodes of fever with temperatures higher than 102°F (38.9°C), lasting less than 72 hours, accompanied by intense serositis. Abdominal serositis may be severe enough to mimic appendicitis and lead to exploratory surgery.

About 70% of patients experience arthritis (predominantly in the legs), and 40% develop erysipeloid erythema, an intensely erythematous, warm, tender, and plaque-like lesion on the lower extremities. Biopsy of involved skin shows a diffuse, primarily neutrophilic, inflammatory cell infiltrate.

Laboratory examination reveals marked elevation of acute-phase reactants, which may normalize between episodes. The diagnosis can be made using a combination of clinical suspicion, sequencing of the MEFV gene, and a positive response to a trial of colchicine (Colcrys).

Without treatment, repetitive attacks of inflammation may result in amyloidosis of the kidneys or liver. The risk of amyloidosis is related to several discrete risk factors, such as country of residence, MEFV genotype, and serum amyloid A genotype.10–12 Patients should be monitored for physical manifestations of amyloidosis at least annually.

FMF patients have also been described who develop vasculitides such as Henoch-Schönlein purpura, polyarteritis nodosa, or Behçet disease.

Colchicine is the mainstay of FMF treatment

Colchicine has been the mainstay of therapy for patients with FMF for almost 40 years.13–15 Its benefits in FMF are clear: symptoms cease in nearly 70% of patients treated with colchicine, and an additional 25% have a reduction in the severity and frequency of attacks.

Only 5% to 10% of patients have no response to colchicine; this may be partially due to individual dose limitations imposed by common drug-associated gastrointestinal side effects.16–18 For these patients, newer biologic drugs that inhibit IL-1 activity, such as anakinra (Kineret) and rilonacept (Arcalyst), offer great promise.

Typically, FMF attacks become less frequent and less severe with age. However, the overall prognosis in FMF is related mainly to the individual’s genotype and the associated risk of amyloidosis.19

HYPERIMMUNOGLOBULIN D SYNDROME

HIDS is another autosomal recessive autoinflammatory syndrome.20

The genetic defect underlying HIDS lies within the mevalonate kinase gene MVK.21 Mevalonate kinase, an enzyme, plays an important role in the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway, following the initial step by 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-CoA (HMG-CoA) reductase. Mutations are primarily missense mutations in highly conserved areas of protein that result in decreased MVK activity (1% to 5% of normal).22,23 Decreased production of geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate resulting from disruption in the HMG-CoA reductase pathway subsequently leads to increased release of IL-1 beta from peripheral blood mononuclear cells and triggers inflammatory symptoms.24

Attacks of HIDS begin early in life

HIDS attacks begin early in life, with more than 70% of patients suffering their first attack before age 2, but adult-onset disease has been reported. Patients may report that routine childhood vaccinations triggered attacks, a historical finding unique to HIDS.

Attacks typically last 4 days; a longer duration can help the clinician differentiate HIDS from FMF.

More than 90% of patients have cervical lymphadenopathy, and 80% have an erythematous rash characteristically located on the palms and soles. About 70% of patients have headache, arthritis, and abdominal pain.

During attacks, laboratory examination reveals elevated acute inflammatory reactants. As the name implies, serum levels of immunoglobulin D (IgD) are elevated. However, this finding is not specific to HIDS and may also be found in patients with Still disease or FMF or in those who smoke cigarettes. Serum IgD levels fluctuate throughout life, and the sensitivity of commercially available IgD test kits is variable.

Assessment of mevalonic acid levels in the urine during febrile attacks offers a more sensitive, specific, and reliable diagnostic test for HIDS.25 While genetic sequencing is the gold standard of diagnostic testing, close to 30% of patients meeting clinical criteria for HIDS have no definable mutation.26

Treatment of HIDS can be challenging

Oral corticosteroids are effective in HIDS, but their long-term side effects are undesirable. Patients rarely respond to colchicine, differentiating them from FMF patients.

Etanercept (Enbrel), a fusion protein composed of the soluble TNF receptor and the Fc portion of the human IgG1 protein, has been efficacious in some patients.27,28 IL-1 inhibitors have also been used with increasing efficacy in the treatment of HIDS attacks.29,30

Although the frequency of attacks decreases with age, long-term follow-up of 28 Dutch HIDS patients found that their quality of life was still lower than that in country-matched controls.31

TUMOR NECROSIS FACTOR RECEPTOR-ASSOCIATED PERIODIC SYNDROME

In 1982, a large multiplex family from Scotland and Ireland was described who had a newly recognized syndrome termed familial Hibernian fever, characterized by recurrent fever, rash, and abdominal pain.32 In 1998, the genetics of this autosomal dominant condition were characterized,33–35 and it is now known by the acronym TRAPS.

TRAPS has a variable presentation owing to a variety of mutations in the gene encoding the cell surface receptor for TNF (TNFRSF1A). TNFRSF1A mutations affecting conserved cysteine residues important for protein folding correspond to severe disease phenotypes.

The R92Q mutation has an allele frequency of up to 4% of the population. It has no impact on the structure and function of the TNF receptor protein and is associated with a heterogeneous disease course. In contrast, the P46L mutation has an allele frequency of 1% of the population and typically is associated with a milder disease course characterized by older age of onset, shorter episodes, and a low frequency of amyloidosis.36–39

The R92Q and T61I mutations, which have low penetrance, have been increasingly reported in adult patients with the autoimmune diseases systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and multiple sclerosis.40–42 Their influence is believed to contribute to proinflammatory responses but not to provide additional genetic susceptibility as provided by human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genotypes for susceptibility for these autoimmune diseases.

TRAPS attacks last longer than FMF and HIDS attacks

TRAPS attacks last 7 days or more, differentiating TRAPS from FMF and HIDS. Patients may present from infancy into adulthood, but more typically present in the toddler period.

Most patients experience intense myalgia as well as abdominal and pleuritic chest pain. A single-center series in 2002 described close to half of patients diagnosed with TRAPS as having had an intra-abdominal surgical procedure; in 10% necrotic bowel was identified, yet the biopsy typically revealed only a serosal mononuclear infiltrate.43

Like FMF and HIDS, TRAPS can cause an erythematous rash. The rash usually appears on an extremity, is centrifugal, and travels proximal-to-distal in concert with symptoms of myalgia. Deep tissue biopsy often demonstrates an intense, neutrophilic fasciitis sparing the underlying musculature. Painful conjunctivitis with periorbital edema also may occur.

Laboratory values reflecting widespread systemic inflammation and elevated acute-phase reactants are encountered during attacks and in some cases may persist between episodes.

Genetic testing can be used to confirm the diagnosis. The probability of finding a mutation in TNFRSF1A depends highly on whether the patient has affected relatives. In a series of 28 patients with recurrent inflammatory syndromes and TNFRSF1A mutations, 9 (32%) had a family history of recurrent inflammatory syndromes, while in 176 patients with sporadic, nonfamilial “TRAPS-like” symptoms, TNFRSF1A mutations were uncommon.37,38

Etanercept is effective for TRAPS

Systemic corticosteroids may be effective for treating TRAPS, but ever-increasing doses are often required.

Etanercept’s ability to bind both soluble and bound TNF explains its relative efficacy in treating TRAPS even though other TNF inhibitors have proven ineffective.44,45 With etanercept, the prognosis of TRAPS patients is typically good. Etanercept has even been effective in treating cases of renal amyloidosis from long-standing TRAPS, although it has not been shown to facilitate regression of renal amyloid mass.46,47 However, responses to treatment with etanercept may wane with time, and resistant cases have been reported.

IL-1 blockade with anakinra has been shown to be effective in the short term and long term in small case series, providing a reasonable alternative for patients who are difficult to manage.

CRYOPYRIN-ASSOCIATED PERIODIC SYNDROMES

- Perhaps the most clinically diverse hereditary autoinflammatory syndromes are the cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS). There are three overlapping phenotypes: Familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome (FCAS)

- Muckle-Wells syndrome (MWS)

- Neonatal-onset multisystemic inflammatory disorder (NOMID).

Mutations in NLRP3

CAPS symptoms stem from mutations within the NLRP3 gene (NOD-like receptor family, pyrin domain), which encodes the protein, cyropyrin.48NLRP3 mutations result in an abnormal cryopyrin structure, abnormal inflammasome activity, and increased IL-1 beta production.49,50

There is poor genotype-phenotype association in CAPS; the same NLRP3 point mutation can result in variable features, typically of either FCAS and MWS or MWS and NOMID overlapping phenotypes, supporting the hypothesis that modifier genes play a role in phenotypic expression.

Inheritance patterns in CAPS are autosomal dominant, but spontaneous mutations are also common. In fact, approximately two-thirds of patients with mutation-negative NOMID have somatic NLRP3 mutations, indicating that somatic NLRP3 mosaicism contributes to the clinical syndrome.51

Clinical features of the CAPS

The hallmarks of the CAPS include recurrent fevers, urticarial rash, and central nervous system inflammation. Characteristically, CAPS patients present in the neonatal period through early childhood, but adult-onset cases, which may have less typical features, have been reported.

Patients with FCAS develop brief episodes (< 24 hours) of fever, joint pain, and urticarial rash when exposed to sudden drops in ambient temperature.

Patients with MWS have more frequent, prolonged attacks, which may or may not be related to changes in ambient temperature. They also develop fever and urticarial rash and may develop arthritis and headaches from aseptic meningitis.