User login

Venous Thromboembolism and Weight Changes in Veteran Patients Using Megestrol Acetate as an Appetite Stimulant

New and Noteworthy Information—October

Transient ischemic attack (TIA) is linked with a substantial risk of disability, researchers reported in the September 13 online Stroke. The 510 consecutive patients prospectively enrolled in the study had minor stroke or TIA, were not previously disabled, and had a CT or CT angiography completed within 24 hours of symptom onset. After assessing disability 90 days following the event, the investigators found that 15% of patients had a disabled outcome. Those who experienced recurrent strokes were more likely to be disabled—53% of patients with recurrent strokes were disabled, compared with 12% of those who did not have a recurrent stroke. “In terms of absolute numbers, most patients have disability as a result of their presenting event; however, recurrent events have the largest relative impact on outcome,” the study authors concluded.

Persons with high plasma glucose levels that are still within the normal range are more likely to have atrophy of brain structures associated with neurodegenerative processes, according to a study published in the September 4 Neurology. Investigators used MRI scans to assess hippocampal and amygdalar volumes in a sample of 266 cognitively healthy persons ages 60 to 64 who did not have type 2 diabetes. Results showed that plasma glucose levels were significantly linked with hippocampal and amygdalar atrophy. After controlling for age, sex, BMI, hypertension, alcohol, and smoking, the researchers found that plasma glucose levels accounted for a 6% to 10% change in volume. “These findings suggest that even in the subclinical range and in the absence of diabetes, monitoring and management of plasma glucose levels could have an impact on cerebral health,” the study authors wrote.

The FDA has approved once-a-day tablet Aubagio (teriflunomide) for treatment of adults with relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis (MS). During a clinical trial, patients taking teriflunomide had a relapse rate that was 30% lower than that of patients taking placebo. The most common side effects observed during clinical trials were diarrhea, abnormal liver tests, nausea, and hair loss, and physicians should conduct blood tests to check patients’ liver function before the drug is prescribed as well as periodically during treatment, researchers said. In addition, because of a risk of fetal harm, women of childbearing age must have a negative pregnancy test before beginning teriflunomide and should use birth control throughout treatment. Teriflunomide is the second oral treatment therapy for MS to be approved in the United States.

Patients who appear likely to have sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease may benefit from CSF 14-3-3 assays to clarify the diagnosis, researchers reported in the online September 19 Neurology. In a systematic literature review, the investigators identified articles from 1995 to January 1, 2011, that involved patients who had CSF analysis for protein 14-3-3. Based on data from 1,849 patients, the researchers determined that assays for CSF 14-3-3 are probably moderately accurate in diagnosing Creutzfeldt-Jakob—the assays had a sensitivity of 92%, specificity of 80%, likelihood ratio of 4.7, and negative likelihood ratio of 0.10. The study authors recommend CSF 14-3-3 assays “for patients who have rapidly progressive dementia and are strongly suspected of having sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob and for whom diagnosis remains uncertain (pretest probably of between 20% and 90%).”

Children with migraine and children with tension-type headaches are significantly more likely to have behavioral and emotional symptoms, and the frequency of headaches affects the likelihood of these symptoms, according to a study published in the online September 17 Cephalagia. After examining a sample of 1,856 children ages 5 to 11, investigators found that those with migraine were significantly more likely to experience abnormalities in somatic, anxiety-depressive, social, attention, internalizing, and total score domains of the Child Behavior Checklist. Children with tension-type headaches had a lower rate of abnormalities than children with migraine, but those with tension-type headaches still had significantly more abnormalities than controls. Children with headaches are more likely to have internalizing symptoms than externalizing symptoms such as rule breaking and aggressivity, the researchers found.

Heavy alcohol intake is associated with experiencing intracerebral hemorrhage at a younger age, according to a study published in the September 11 Neurology. Researchers prospectively followed 562 adults with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage and recorded information about their alcohol intake. A total of 137 patients were heavy alcohol drinkers, and these patients were more likely to be younger (median age, 60), to have a history of ischemic heart disease, and to be smokers. Furthermore, heavy alcohol drinkers had significantly lower platelet counts and prothrombin ratio. The investigators noted that although heavy alcohol intake is associated with intracerebral hemorrhage at a younger age, “the underlying vasculopathy remains unexplored in these patients. Indirect markers suggest small-vessel disease at an early stage that might be enhanced by moderate hemostatic disorders,” the authors concluded.

Long-term use of ginkgo biloba extract does not prevent the onset of Alzheimer’s disease in older patients, according to a study published in the online September 5 Lancet Neurology. Researchers enrolled 2,854 participants in a parallel-group, double-blind clinical trial in which 1,406 persons were randomized to receive ginkgo biloba extract and 1,414 persons were randomized to placebo. After five years of follow-up, 61 participants taking ginkgo biloba were diagnosed with probable Alzheimer’s disease, while 73 participants in the placebo group received a diagnosis of probable Alzheimer’s disease, though the risk was not proportional over time. The incidence of adverse events, as well as hemorrhagic or cardiovascular events, did not differ between groups. “Long-term use of standardized ginkgo biloba extract in this trial did not reduce the risk of progression to Alzheimer’s disease compared with placebo,” the researchers concluded.

The 13.3–mg/24 h dosage strength of the Exelon Patch (rivastigmine transdermal system) has been approved by the FDA for treatment of mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Approval was based on the performance of the 13.3–mg/24 h dosage in the 48-week, double-blind phase of the OPTIMA study, which analyzed patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease who met predefined functional and cognitive decline criteria for the 9.5–mg/24 h dose. Compared with patients taking the 9.5–mg/24 h dose, patients taking the 13.3–mg/24 h dose showed statistically significant improvement in overall function. In addition, the overall safety profile of the 13.3–mg/24 h dose was the same as that of the lower dose, and fewer patients on the 13.3–mg/24 h dose needed to discontinue treatment than patients on the 9.5–mg/24 h dose.

The FDA has approved Nucynta (tapentadol) for management of neuropathic pain associated with diabetic peripheral neuropathy when a continuous, around-the-clock opioid analgesic is needed for an extended period of time. According to preclinical studies, the drug is a centrally acting synthetic analgesic, though the exact mechanism of action is unknown. In two randomized-withdrawal, placebo-controlled phase III trials, researchers studied patients who had at least a one-point reduction in pain intensity during three weeks of treatment and then continued for an additional 12 weeks on the same dose, which was titrated to balance individual tolerability and efficacy. These patients had significantly better pain control than those who switched to placebo. The most common adverse events associated with the drug were nausea, constipation, vomiting, dizziness, headache, and somnolence, but tapentadol was generally well tolerated.

A mouse model of abnormal adult-generated granule cells (DGCs) has provided the first direct evidence that abnormal DGCs are linked to seizures, researchers reported in the September 20 Neuron. To isolate the effects of the abnormal cells, investigators used a transgenic mouse model to selectively delete PTEN from DGCs generated after birth. As a result of PTEN deletion, the mammalian target of rapamycin pathway was hyperactivated, which produced abnormal DGCs that resembled those in epilepsy. “Strikingly, animals in which PTEN was deleted from 9% or more of the DGC population developed spontaneous seizures in about four weeks, confirming that abnormal DGCs, which are present in both animals and humans with epilepsy, are capable of causing the disease,” the researchers stated.

Patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) who receive gingko biloba 120 mg twice a day do not show improved cognitive performance, researchers reported in the September 18 Neurology. The investigators compared the performance of two groups of patients with MS who scored 1 SD or more below the mean on one of four neuropsychologic tests. Sixty-one patients received 120 mg of ginkgo biloba twice a day for 12 weeks, and 59 patients received placebo. The researchers evaluated participants’ cognitive performance following treatment and found no statistically significant difference in scores between the two groups. Furthermore, no significant adverse events related to gingko biloba treatment occurred, according to the study authors. Overall, the investigators concluded that gingko biloba does not improve cognitive function in patients with MS.

The Solitaire Flow Restoration device performs substantially better than the Merci Retrieval System in treating acute ischemic stroke, according to a study published in the online August 24 Lancet. In a randomized, parallel-group, noninferiority trial, the efficacy and safety of the Solitaire device, a self-expanding stent retriever designed to quickly restore blood flow, was compared with the efficacy and safety of the standard Merci Retrieval system. The 58 patients in the Solitaire group achieved the primary efficacy outcome 61% of the time, compared with 24% of patients in the Merci group, investigators said. Furthermore, patients in the Solitaire group had lower 90-day mortality than patients in the Merci group (17 versus 38). “The Solitaire device might be a future treatment of choice for endovascular recanalization in acute ischemic stroke,” the researchers concluded.

—Lauren LeBano

Transient ischemic attack (TIA) is linked with a substantial risk of disability, researchers reported in the September 13 online Stroke. The 510 consecutive patients prospectively enrolled in the study had minor stroke or TIA, were not previously disabled, and had a CT or CT angiography completed within 24 hours of symptom onset. After assessing disability 90 days following the event, the investigators found that 15% of patients had a disabled outcome. Those who experienced recurrent strokes were more likely to be disabled—53% of patients with recurrent strokes were disabled, compared with 12% of those who did not have a recurrent stroke. “In terms of absolute numbers, most patients have disability as a result of their presenting event; however, recurrent events have the largest relative impact on outcome,” the study authors concluded.

Persons with high plasma glucose levels that are still within the normal range are more likely to have atrophy of brain structures associated with neurodegenerative processes, according to a study published in the September 4 Neurology. Investigators used MRI scans to assess hippocampal and amygdalar volumes in a sample of 266 cognitively healthy persons ages 60 to 64 who did not have type 2 diabetes. Results showed that plasma glucose levels were significantly linked with hippocampal and amygdalar atrophy. After controlling for age, sex, BMI, hypertension, alcohol, and smoking, the researchers found that plasma glucose levels accounted for a 6% to 10% change in volume. “These findings suggest that even in the subclinical range and in the absence of diabetes, monitoring and management of plasma glucose levels could have an impact on cerebral health,” the study authors wrote.

The FDA has approved once-a-day tablet Aubagio (teriflunomide) for treatment of adults with relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis (MS). During a clinical trial, patients taking teriflunomide had a relapse rate that was 30% lower than that of patients taking placebo. The most common side effects observed during clinical trials were diarrhea, abnormal liver tests, nausea, and hair loss, and physicians should conduct blood tests to check patients’ liver function before the drug is prescribed as well as periodically during treatment, researchers said. In addition, because of a risk of fetal harm, women of childbearing age must have a negative pregnancy test before beginning teriflunomide and should use birth control throughout treatment. Teriflunomide is the second oral treatment therapy for MS to be approved in the United States.

Patients who appear likely to have sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease may benefit from CSF 14-3-3 assays to clarify the diagnosis, researchers reported in the online September 19 Neurology. In a systematic literature review, the investigators identified articles from 1995 to January 1, 2011, that involved patients who had CSF analysis for protein 14-3-3. Based on data from 1,849 patients, the researchers determined that assays for CSF 14-3-3 are probably moderately accurate in diagnosing Creutzfeldt-Jakob—the assays had a sensitivity of 92%, specificity of 80%, likelihood ratio of 4.7, and negative likelihood ratio of 0.10. The study authors recommend CSF 14-3-3 assays “for patients who have rapidly progressive dementia and are strongly suspected of having sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob and for whom diagnosis remains uncertain (pretest probably of between 20% and 90%).”

Children with migraine and children with tension-type headaches are significantly more likely to have behavioral and emotional symptoms, and the frequency of headaches affects the likelihood of these symptoms, according to a study published in the online September 17 Cephalagia. After examining a sample of 1,856 children ages 5 to 11, investigators found that those with migraine were significantly more likely to experience abnormalities in somatic, anxiety-depressive, social, attention, internalizing, and total score domains of the Child Behavior Checklist. Children with tension-type headaches had a lower rate of abnormalities than children with migraine, but those with tension-type headaches still had significantly more abnormalities than controls. Children with headaches are more likely to have internalizing symptoms than externalizing symptoms such as rule breaking and aggressivity, the researchers found.

Heavy alcohol intake is associated with experiencing intracerebral hemorrhage at a younger age, according to a study published in the September 11 Neurology. Researchers prospectively followed 562 adults with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage and recorded information about their alcohol intake. A total of 137 patients were heavy alcohol drinkers, and these patients were more likely to be younger (median age, 60), to have a history of ischemic heart disease, and to be smokers. Furthermore, heavy alcohol drinkers had significantly lower platelet counts and prothrombin ratio. The investigators noted that although heavy alcohol intake is associated with intracerebral hemorrhage at a younger age, “the underlying vasculopathy remains unexplored in these patients. Indirect markers suggest small-vessel disease at an early stage that might be enhanced by moderate hemostatic disorders,” the authors concluded.

Long-term use of ginkgo biloba extract does not prevent the onset of Alzheimer’s disease in older patients, according to a study published in the online September 5 Lancet Neurology. Researchers enrolled 2,854 participants in a parallel-group, double-blind clinical trial in which 1,406 persons were randomized to receive ginkgo biloba extract and 1,414 persons were randomized to placebo. After five years of follow-up, 61 participants taking ginkgo biloba were diagnosed with probable Alzheimer’s disease, while 73 participants in the placebo group received a diagnosis of probable Alzheimer’s disease, though the risk was not proportional over time. The incidence of adverse events, as well as hemorrhagic or cardiovascular events, did not differ between groups. “Long-term use of standardized ginkgo biloba extract in this trial did not reduce the risk of progression to Alzheimer’s disease compared with placebo,” the researchers concluded.

The 13.3–mg/24 h dosage strength of the Exelon Patch (rivastigmine transdermal system) has been approved by the FDA for treatment of mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Approval was based on the performance of the 13.3–mg/24 h dosage in the 48-week, double-blind phase of the OPTIMA study, which analyzed patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease who met predefined functional and cognitive decline criteria for the 9.5–mg/24 h dose. Compared with patients taking the 9.5–mg/24 h dose, patients taking the 13.3–mg/24 h dose showed statistically significant improvement in overall function. In addition, the overall safety profile of the 13.3–mg/24 h dose was the same as that of the lower dose, and fewer patients on the 13.3–mg/24 h dose needed to discontinue treatment than patients on the 9.5–mg/24 h dose.

The FDA has approved Nucynta (tapentadol) for management of neuropathic pain associated with diabetic peripheral neuropathy when a continuous, around-the-clock opioid analgesic is needed for an extended period of time. According to preclinical studies, the drug is a centrally acting synthetic analgesic, though the exact mechanism of action is unknown. In two randomized-withdrawal, placebo-controlled phase III trials, researchers studied patients who had at least a one-point reduction in pain intensity during three weeks of treatment and then continued for an additional 12 weeks on the same dose, which was titrated to balance individual tolerability and efficacy. These patients had significantly better pain control than those who switched to placebo. The most common adverse events associated with the drug were nausea, constipation, vomiting, dizziness, headache, and somnolence, but tapentadol was generally well tolerated.

A mouse model of abnormal adult-generated granule cells (DGCs) has provided the first direct evidence that abnormal DGCs are linked to seizures, researchers reported in the September 20 Neuron. To isolate the effects of the abnormal cells, investigators used a transgenic mouse model to selectively delete PTEN from DGCs generated after birth. As a result of PTEN deletion, the mammalian target of rapamycin pathway was hyperactivated, which produced abnormal DGCs that resembled those in epilepsy. “Strikingly, animals in which PTEN was deleted from 9% or more of the DGC population developed spontaneous seizures in about four weeks, confirming that abnormal DGCs, which are present in both animals and humans with epilepsy, are capable of causing the disease,” the researchers stated.

Patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) who receive gingko biloba 120 mg twice a day do not show improved cognitive performance, researchers reported in the September 18 Neurology. The investigators compared the performance of two groups of patients with MS who scored 1 SD or more below the mean on one of four neuropsychologic tests. Sixty-one patients received 120 mg of ginkgo biloba twice a day for 12 weeks, and 59 patients received placebo. The researchers evaluated participants’ cognitive performance following treatment and found no statistically significant difference in scores between the two groups. Furthermore, no significant adverse events related to gingko biloba treatment occurred, according to the study authors. Overall, the investigators concluded that gingko biloba does not improve cognitive function in patients with MS.

The Solitaire Flow Restoration device performs substantially better than the Merci Retrieval System in treating acute ischemic stroke, according to a study published in the online August 24 Lancet. In a randomized, parallel-group, noninferiority trial, the efficacy and safety of the Solitaire device, a self-expanding stent retriever designed to quickly restore blood flow, was compared with the efficacy and safety of the standard Merci Retrieval system. The 58 patients in the Solitaire group achieved the primary efficacy outcome 61% of the time, compared with 24% of patients in the Merci group, investigators said. Furthermore, patients in the Solitaire group had lower 90-day mortality than patients in the Merci group (17 versus 38). “The Solitaire device might be a future treatment of choice for endovascular recanalization in acute ischemic stroke,” the researchers concluded.

—Lauren LeBano

Transient ischemic attack (TIA) is linked with a substantial risk of disability, researchers reported in the September 13 online Stroke. The 510 consecutive patients prospectively enrolled in the study had minor stroke or TIA, were not previously disabled, and had a CT or CT angiography completed within 24 hours of symptom onset. After assessing disability 90 days following the event, the investigators found that 15% of patients had a disabled outcome. Those who experienced recurrent strokes were more likely to be disabled—53% of patients with recurrent strokes were disabled, compared with 12% of those who did not have a recurrent stroke. “In terms of absolute numbers, most patients have disability as a result of their presenting event; however, recurrent events have the largest relative impact on outcome,” the study authors concluded.

Persons with high plasma glucose levels that are still within the normal range are more likely to have atrophy of brain structures associated with neurodegenerative processes, according to a study published in the September 4 Neurology. Investigators used MRI scans to assess hippocampal and amygdalar volumes in a sample of 266 cognitively healthy persons ages 60 to 64 who did not have type 2 diabetes. Results showed that plasma glucose levels were significantly linked with hippocampal and amygdalar atrophy. After controlling for age, sex, BMI, hypertension, alcohol, and smoking, the researchers found that plasma glucose levels accounted for a 6% to 10% change in volume. “These findings suggest that even in the subclinical range and in the absence of diabetes, monitoring and management of plasma glucose levels could have an impact on cerebral health,” the study authors wrote.

The FDA has approved once-a-day tablet Aubagio (teriflunomide) for treatment of adults with relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis (MS). During a clinical trial, patients taking teriflunomide had a relapse rate that was 30% lower than that of patients taking placebo. The most common side effects observed during clinical trials were diarrhea, abnormal liver tests, nausea, and hair loss, and physicians should conduct blood tests to check patients’ liver function before the drug is prescribed as well as periodically during treatment, researchers said. In addition, because of a risk of fetal harm, women of childbearing age must have a negative pregnancy test before beginning teriflunomide and should use birth control throughout treatment. Teriflunomide is the second oral treatment therapy for MS to be approved in the United States.

Patients who appear likely to have sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease may benefit from CSF 14-3-3 assays to clarify the diagnosis, researchers reported in the online September 19 Neurology. In a systematic literature review, the investigators identified articles from 1995 to January 1, 2011, that involved patients who had CSF analysis for protein 14-3-3. Based on data from 1,849 patients, the researchers determined that assays for CSF 14-3-3 are probably moderately accurate in diagnosing Creutzfeldt-Jakob—the assays had a sensitivity of 92%, specificity of 80%, likelihood ratio of 4.7, and negative likelihood ratio of 0.10. The study authors recommend CSF 14-3-3 assays “for patients who have rapidly progressive dementia and are strongly suspected of having sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob and for whom diagnosis remains uncertain (pretest probably of between 20% and 90%).”

Children with migraine and children with tension-type headaches are significantly more likely to have behavioral and emotional symptoms, and the frequency of headaches affects the likelihood of these symptoms, according to a study published in the online September 17 Cephalagia. After examining a sample of 1,856 children ages 5 to 11, investigators found that those with migraine were significantly more likely to experience abnormalities in somatic, anxiety-depressive, social, attention, internalizing, and total score domains of the Child Behavior Checklist. Children with tension-type headaches had a lower rate of abnormalities than children with migraine, but those with tension-type headaches still had significantly more abnormalities than controls. Children with headaches are more likely to have internalizing symptoms than externalizing symptoms such as rule breaking and aggressivity, the researchers found.

Heavy alcohol intake is associated with experiencing intracerebral hemorrhage at a younger age, according to a study published in the September 11 Neurology. Researchers prospectively followed 562 adults with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage and recorded information about their alcohol intake. A total of 137 patients were heavy alcohol drinkers, and these patients were more likely to be younger (median age, 60), to have a history of ischemic heart disease, and to be smokers. Furthermore, heavy alcohol drinkers had significantly lower platelet counts and prothrombin ratio. The investigators noted that although heavy alcohol intake is associated with intracerebral hemorrhage at a younger age, “the underlying vasculopathy remains unexplored in these patients. Indirect markers suggest small-vessel disease at an early stage that might be enhanced by moderate hemostatic disorders,” the authors concluded.

Long-term use of ginkgo biloba extract does not prevent the onset of Alzheimer’s disease in older patients, according to a study published in the online September 5 Lancet Neurology. Researchers enrolled 2,854 participants in a parallel-group, double-blind clinical trial in which 1,406 persons were randomized to receive ginkgo biloba extract and 1,414 persons were randomized to placebo. After five years of follow-up, 61 participants taking ginkgo biloba were diagnosed with probable Alzheimer’s disease, while 73 participants in the placebo group received a diagnosis of probable Alzheimer’s disease, though the risk was not proportional over time. The incidence of adverse events, as well as hemorrhagic or cardiovascular events, did not differ between groups. “Long-term use of standardized ginkgo biloba extract in this trial did not reduce the risk of progression to Alzheimer’s disease compared with placebo,” the researchers concluded.

The 13.3–mg/24 h dosage strength of the Exelon Patch (rivastigmine transdermal system) has been approved by the FDA for treatment of mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Approval was based on the performance of the 13.3–mg/24 h dosage in the 48-week, double-blind phase of the OPTIMA study, which analyzed patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease who met predefined functional and cognitive decline criteria for the 9.5–mg/24 h dose. Compared with patients taking the 9.5–mg/24 h dose, patients taking the 13.3–mg/24 h dose showed statistically significant improvement in overall function. In addition, the overall safety profile of the 13.3–mg/24 h dose was the same as that of the lower dose, and fewer patients on the 13.3–mg/24 h dose needed to discontinue treatment than patients on the 9.5–mg/24 h dose.

The FDA has approved Nucynta (tapentadol) for management of neuropathic pain associated with diabetic peripheral neuropathy when a continuous, around-the-clock opioid analgesic is needed for an extended period of time. According to preclinical studies, the drug is a centrally acting synthetic analgesic, though the exact mechanism of action is unknown. In two randomized-withdrawal, placebo-controlled phase III trials, researchers studied patients who had at least a one-point reduction in pain intensity during three weeks of treatment and then continued for an additional 12 weeks on the same dose, which was titrated to balance individual tolerability and efficacy. These patients had significantly better pain control than those who switched to placebo. The most common adverse events associated with the drug were nausea, constipation, vomiting, dizziness, headache, and somnolence, but tapentadol was generally well tolerated.

A mouse model of abnormal adult-generated granule cells (DGCs) has provided the first direct evidence that abnormal DGCs are linked to seizures, researchers reported in the September 20 Neuron. To isolate the effects of the abnormal cells, investigators used a transgenic mouse model to selectively delete PTEN from DGCs generated after birth. As a result of PTEN deletion, the mammalian target of rapamycin pathway was hyperactivated, which produced abnormal DGCs that resembled those in epilepsy. “Strikingly, animals in which PTEN was deleted from 9% or more of the DGC population developed spontaneous seizures in about four weeks, confirming that abnormal DGCs, which are present in both animals and humans with epilepsy, are capable of causing the disease,” the researchers stated.

Patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) who receive gingko biloba 120 mg twice a day do not show improved cognitive performance, researchers reported in the September 18 Neurology. The investigators compared the performance of two groups of patients with MS who scored 1 SD or more below the mean on one of four neuropsychologic tests. Sixty-one patients received 120 mg of ginkgo biloba twice a day for 12 weeks, and 59 patients received placebo. The researchers evaluated participants’ cognitive performance following treatment and found no statistically significant difference in scores between the two groups. Furthermore, no significant adverse events related to gingko biloba treatment occurred, according to the study authors. Overall, the investigators concluded that gingko biloba does not improve cognitive function in patients with MS.

The Solitaire Flow Restoration device performs substantially better than the Merci Retrieval System in treating acute ischemic stroke, according to a study published in the online August 24 Lancet. In a randomized, parallel-group, noninferiority trial, the efficacy and safety of the Solitaire device, a self-expanding stent retriever designed to quickly restore blood flow, was compared with the efficacy and safety of the standard Merci Retrieval system. The 58 patients in the Solitaire group achieved the primary efficacy outcome 61% of the time, compared with 24% of patients in the Merci group, investigators said. Furthermore, patients in the Solitaire group had lower 90-day mortality than patients in the Merci group (17 versus 38). “The Solitaire device might be a future treatment of choice for endovascular recanalization in acute ischemic stroke,” the researchers concluded.

—Lauren LeBano

Livedoid Vasculopathy

What's Eating You? Bedbugs Revisited (Cimex lectularius)

Menkes Syndrome Presenting as Possible Child Abuse

Stalked by a ‘patient’

CASE: Delusions and threats

For over 20 months, Ms. I, age 48, sends a psychiatric resident letters and postcards that total approximately 3,000 pages and come from dozens of return addresses. Ms. I expresses romantic feelings toward the resident and believes that he was her physician and prescribed medications, including “mood stabilizers.” The resident never treated Ms. I; to his knowledge, he has never interacted with her.

Ms. I describes the resident’s refusal to continue treating her as “abandonment” and states that she is contemplating self-harm because of this rejection. In her letters, Ms. I admits that she was a long-term patient in a state psychiatric hospital in her home state and suffers from persistent auditory hallucinations. She also wants a romantic relationship with the resident and repeatedly threatens the resident’s female acquaintances and former romantic partners whose relationships she had surmised from news articles available on the Internet. Ms. I also threatens to strangle the resident. The resident sends her multiple written requests that she cease contact, but they are not acknowledged.

The authors’ observations

Stalking—repeated, unwanted attention or communication that would cause a reasonable person fear—is a serious threat for many psychiatric clinicians.1 Prevalence rates among mental health care providers range from 3% to 21%.2,3 Most stalkers have engaged in previous stalking behavior.3

Being stalked is highly distressing,4 and mental health professionals often do not reveal such experiences to colleagues.5 Irrational feelings of guilt or embarrassment, such as being thought to have poorly managed interactions with the stalker, often motivate a self-imposed silence (Table 1).6 This isolation may foster anxiety, interfere with receiving problem-solving advice, and increase physical vulnerability. In the case involving Ms. I, the psychiatric resident’s primary responsibility is safeguarding his own physical and psychological welfare.

Clinicians who work in a hospital or other institutional setting who are being stalked should inform their supervisors and the facility’s security personnel. Security personnel may be able to gather data about the stalker, decrease the stalker’s ability to communicate with the victim, and reduce unwanted physical access to the victim by distributing a photo of the stalker or installing a camera or receptionist-controlled door lock in patient entryways. Security personnel also may collaborate with local law enforcement. Having a third party respond to a stalker’s aggressive behavior—rather than the victim responding directly—avoids rewarding the stalker, which may generate further unwanted contact.7 Any intervention by the victim may increase the risk of violence, creating an “intervention dilemma.” Resnick8 argues that before deciding how best to address the stalker’s behavior, a stalking victim must “first separate the risk of continued stalking from the risk that the stalker will commit a violent act.”

Mental health professionals in private practice who are being stalked should consider retaining an attorney. An attorney often can maintain privacy of communications regarding the stalker via the attorney-client and attorney-work product privileges, which may help during legal proceedings.

Table 1

Factors that can impede psychiatrists from reporting stalking

| Fear of being perceived as a failure |

| Embarrassment |

| High professional tolerance for antisocial and threatening behavior |

| Misplaced sense of duty |

| Source: Reference 6 |

RESPONSE: Involving police

Over 2 months, Ms. I phones the resident’s home 105 times (the resident screens the calls). During 1 call, she states that she is hidden in a closet in her home and will hurt herself unless the resident “resumes” her psychiatric care. The resident contacts police in his city and Ms. I’s community, but authorities are reluctant to act when he acknowledges that he is not Ms. I’s psychiatrist and does not know her. Police officers in Ms. I’s hometown tell the resident no one answered the door when they visited her home. They state that they would enter the residence forcibly only if Ms. I’s physician or a family member asked them to do so, and because the resident admits that he is not her psychiatrist, they cannot take further action. Ms. I leaves the resident a phone message several hours later to inform him she is safe.

The authors’ observations

Stalking-induced countertransference responses may lead a psychiatrist to unwittingly place himself in harm’s way. For example, intense rage at a stalker’s request for treatment may generate guilt that motivates the psychiatrist to agree to treat the stalker. Feelings of helplessness may produce a frantic desire to do something even when such activity is ill-advised. Psychiatrists may develop a tolerance for antisocial or threatening behavior—which is common in mental health settings—and could accept unnecessary risks.

A psychiatrist who is being stalked may be able to assist a mentally ill stalker in a way that does not create a duty to treat and does not expose the psychiatrist to harm, such as contacting a mobile crisis intervention team, a mental health professional who recently treated the stalker, a family member of the stalker, or law enforcement personnel. A psychiatrist who is thrust from the role of helper to victim and must protect his or her own well-being instead of attending to a patient’s welfare is prone to suffer substantial countertransference distress.

The situation with Ms. I was particularly challenging because the resident did not know her complete history and therefore had little information to gauge how likely she was to act on her aggressive threats. Factors that predict future violence include:

- a history of violence

- significant prior criminality

- young age at first arrest

- concomitant substance abuse

- male sex.9

Unfortunately, other than sex, this data regarding Ms. I could not be readily obtained.

A psychiatrist’s duty

Although sympathetic to his stalker’s distress, the resident did not want to treat this woman, nor was he ethically or legally obligated to do so. An individual’s wish to be treated by a particular psychiatrist does not create a duty for the psychiatrist to satisfy this wish.10 State-based “Good Samaritan” laws encourage physicians to assist those in acute need by shielding them from liability, as long as they reasonably act within the scope of their expertise.11 However, they do not require a physician to care for an individual in acute need. A delusional wish for treatment or a false belief of already being in treatment does not create a duty to care for a person.

OUTCOME: Seeking help

Ms. I’s phone calls and letters continue. The resident discusses the situation with his associate residency director, who refers him to the hospital’s legal and investigative staffs. Based on advice from the hospital’s private investigator, the resident sends Ms. I a formal “cease and desist” letter that threatens her with legal action and possible jail time. The staff at the front desk of the clinic where the resident works and the hospital’s security department are instructed to watch for a visitor with Ms. I’s name and description, although the hospital’s investigator is unable to obtain a photograph of her. Shortly after the resident sends the letter, Ms. I ceases communication.

The authors’ observations

This case is unusual because most stalking victims know their stalkers. Identifying a stalker’s motivation can be helpful in formulating a risk assessment. One classification system recognizes 5 categories of stalkers: rejected, intimacy seeking, incompetent, resentful, and predatory (Table 2).1 Rejected stalkers appear to pose the greatest risk of violence and homicide.8 However, all stalkers may pose a risk of violence and therefore all stalking behavior should be treated seriously.

Table 2

Classification of stalkers

| Category | Common features |

|---|---|

| Rejected | Most have a personality disorder; often seeking reconciliation and revenge; most frequent victims are ex-romantic partners, but also target estranged relatives, former friends |

| Intimacy seeking | Erotomania; “morbid infatuation” |

| Incompetent | Lacking social skills; often have stalked others |

| Resentful | Pursuing a vendetta; generally feeling aggrieved |

| Predatory | Often comorbid with paraphilias; may have past convictions for sex offenses |

| Source: Adapted from reference 1 | |

Responding to a stalker

The approach should be tailored to the stalker’s characteristics.12 Silence—ie, lack of acknowledgement of a stalker’s intrusions—is one tactic.13 Consistent and persistent lack of engagement may bore the stalker, but also may provoke frustration or narcissistic or paranoia-fueled rage, and increased efforts to interact with the mental health professional. Other responses include:

- obtaining a protection or restraining order

- promoting the stalker’s participation in adversarial civil litigation, such as a lawsuit

- issuing verbal counterthreats.

Restraining orders are controversial and assessments of their effectiveness vary.14 How well a restraining order works may depend on the stalker’s:

- ability to appreciate reality, and how likely he or she is to experience anxiety when confronted with adverse consequences of his or her actions

- how consistently, rapidly, and harshly the criminal justice system responds to violations of restraining orders.

Restraining orders also may provide the victim a false sense of security.15 One of her letters revealed that Ms. I violated a criminal plea arrangement years earlier, which suggests she was capable of violating a restraining order.

Litigation. A stalker may initiate civil litigation against the victim to feel that he or she has an impact on the victim, which may reduce the stalker’s risk of violence if he or she is emotionally engaged in the litigation. Based on the authors’ experience, as long as the stalker is talking, he or she generally is less likely to act out violently and terminate a satisfying process. Adversarial civil litigation could give a stalker the opportunity to be “close” to the victim and a means of expressing aggressive wishes. The benefit of litigation lasts only as long as the case persists and the stalker believes he or she may prevail. In one of her letters, Ms. I bragged that she had represented herself as a pro se litigant in a complex civil matter, suggesting that she might be constructively channeled into litigation.

Promoting litigation carries significant risk.16 Being a defendant in pro se litigation may be emotionally and financially stressful. This approach may be desirable if the psychiatrist’s institution is willing to offer substantial support. For example, an institution may provide legal assistance—including helping to defray the cost of litigation—and litigation-related scheduling flexibility. An attorney may serve as a boundary between the victim and the pro se litigant’s sometimes ceaseless, time-devouring, anxiety-inducing legal maneuvers.

Counterthreats. Warning a stalker that he or she will face severe civil and criminal consequences if his or her behavior continues can make clear that his or her conduct is unacceptable.17 Such warnings may be delivered verbally or in writing by a legal representative, law enforcement personnel, a private security agent, or the victim.

Issuing a counterthreat can be risky. Stalkers with antisocial or narcissistic personality features may perceive a counterthreat as narcissistically diminishing, and to save face will escalate their stalking in retaliation. Avoid counterthreats if you believe the stalker might be psychotic because destabilizing such an individual—such as by precipitating a short psychotic episode—may increase unpredictability and diminish their responsive to interventions.

Ms. I’s contact with the resident lasted approximately 20 months, slightly less than the average 26 months reported in a survey of mental health professionals.3 Because stalkers are unpredictable, the psychiatric resident remains cautious.

Related Resources

- National Center for Victims of Crime. Stalking resource center. www.victimsofcrime.org/our-programs/stalking-resource-center.

- Mullen PE, Pathé M, Purcell R. Stalkers and their victims. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2009.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Mullen PE, Pathé M, Purcell R, et al. Study of stalkers. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(8):1244-1249.

2. Sandberg DA, McNiel DE, Binder RL. Stalking threatening, and harassing behavior by psychiatric patients toward clinicians. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2002;30(2):221-229.

3. McIvor R, Potter L, Davies L. Stalking behavior by patients towards psychiatrists in a large mental health organization. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2008;54(4):350-357.

4. Mullen PE, Pathé M. Stalking. Crime and Justice. 2002;29:273-318.

5. Bird S. Strategies for managing and minimizing the impact of harassment and stalking by patients. ANZ J Surg. 2009;79(7-8):537-538.

6. Sinwelski SA, Vinton L. Stalking: the constant threat of violence. Affilia. 2001;16(1):46-65.

7. Meloy JR. Commentary: stalking threatening, and harassing behavior by patients—the risk-management response. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2002;30(2):230-231.

8. Resnick PJ. Stalking risk assessment. In: Pinals DA, ed. Stalking: psychiatric perspectives and practical approaches. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007:61–84.

9. Dietz PE. Defenses against dangerous people when arrest and commitment fail. In: Simon RI, ed. American Psychiatric Press review of clinical psychiatry and the law. 1st ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1989:205–219.

10. Hilliard J. Termination of treatment with troublesome patients. In: Lifson LE, Simon RI, eds. The mental health practitioner and the law: a comprehensive handbook. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1998:216–224.

11. Paterick TJ, Paterick BB, Paterick TE. Implications of Good Samaritan laws for physicians. J Med Pract Manage. 2008;23(6):372-375.

12. MacKenzie RD, James DV. Management and treatment of stalkers: problems options, and solutions. Behav Sci Law. 2011;29(2):220-239.

13. Fremouw WJ, Westrup D, Pennypacker J. Stalking on campus: the prevalence and strategies for coping with stalking. J Forensic Sci. 1997;42(4):666-669.

14. Nicastro AM, Cousins AV, Spitzberg BH. The tactical face of stalking. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2000;28(1):69-82.

15. Spitzberg BH. The tactical topography of stalking victimization and management. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2002;3(4):261-288.

16. Pathé M, MacKenzie R, Mullen PE. Stalking by law: damaging victims and rewarding offenders. J Law Med. 2004;12(1):103-111.

17. Lion JR, Herschler JA. The stalking of physicians by their patients. In: Meloy JR. The psychology of stalking: clinical and forensic perspectives. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1998:163–173.

CASE: Delusions and threats

For over 20 months, Ms. I, age 48, sends a psychiatric resident letters and postcards that total approximately 3,000 pages and come from dozens of return addresses. Ms. I expresses romantic feelings toward the resident and believes that he was her physician and prescribed medications, including “mood stabilizers.” The resident never treated Ms. I; to his knowledge, he has never interacted with her.

Ms. I describes the resident’s refusal to continue treating her as “abandonment” and states that she is contemplating self-harm because of this rejection. In her letters, Ms. I admits that she was a long-term patient in a state psychiatric hospital in her home state and suffers from persistent auditory hallucinations. She also wants a romantic relationship with the resident and repeatedly threatens the resident’s female acquaintances and former romantic partners whose relationships she had surmised from news articles available on the Internet. Ms. I also threatens to strangle the resident. The resident sends her multiple written requests that she cease contact, but they are not acknowledged.

The authors’ observations

Stalking—repeated, unwanted attention or communication that would cause a reasonable person fear—is a serious threat for many psychiatric clinicians.1 Prevalence rates among mental health care providers range from 3% to 21%.2,3 Most stalkers have engaged in previous stalking behavior.3

Being stalked is highly distressing,4 and mental health professionals often do not reveal such experiences to colleagues.5 Irrational feelings of guilt or embarrassment, such as being thought to have poorly managed interactions with the stalker, often motivate a self-imposed silence (Table 1).6 This isolation may foster anxiety, interfere with receiving problem-solving advice, and increase physical vulnerability. In the case involving Ms. I, the psychiatric resident’s primary responsibility is safeguarding his own physical and psychological welfare.

Clinicians who work in a hospital or other institutional setting who are being stalked should inform their supervisors and the facility’s security personnel. Security personnel may be able to gather data about the stalker, decrease the stalker’s ability to communicate with the victim, and reduce unwanted physical access to the victim by distributing a photo of the stalker or installing a camera or receptionist-controlled door lock in patient entryways. Security personnel also may collaborate with local law enforcement. Having a third party respond to a stalker’s aggressive behavior—rather than the victim responding directly—avoids rewarding the stalker, which may generate further unwanted contact.7 Any intervention by the victim may increase the risk of violence, creating an “intervention dilemma.” Resnick8 argues that before deciding how best to address the stalker’s behavior, a stalking victim must “first separate the risk of continued stalking from the risk that the stalker will commit a violent act.”

Mental health professionals in private practice who are being stalked should consider retaining an attorney. An attorney often can maintain privacy of communications regarding the stalker via the attorney-client and attorney-work product privileges, which may help during legal proceedings.

Table 1

Factors that can impede psychiatrists from reporting stalking

| Fear of being perceived as a failure |

| Embarrassment |

| High professional tolerance for antisocial and threatening behavior |

| Misplaced sense of duty |

| Source: Reference 6 |

RESPONSE: Involving police

Over 2 months, Ms. I phones the resident’s home 105 times (the resident screens the calls). During 1 call, she states that she is hidden in a closet in her home and will hurt herself unless the resident “resumes” her psychiatric care. The resident contacts police in his city and Ms. I’s community, but authorities are reluctant to act when he acknowledges that he is not Ms. I’s psychiatrist and does not know her. Police officers in Ms. I’s hometown tell the resident no one answered the door when they visited her home. They state that they would enter the residence forcibly only if Ms. I’s physician or a family member asked them to do so, and because the resident admits that he is not her psychiatrist, they cannot take further action. Ms. I leaves the resident a phone message several hours later to inform him she is safe.

The authors’ observations

Stalking-induced countertransference responses may lead a psychiatrist to unwittingly place himself in harm’s way. For example, intense rage at a stalker’s request for treatment may generate guilt that motivates the psychiatrist to agree to treat the stalker. Feelings of helplessness may produce a frantic desire to do something even when such activity is ill-advised. Psychiatrists may develop a tolerance for antisocial or threatening behavior—which is common in mental health settings—and could accept unnecessary risks.

A psychiatrist who is being stalked may be able to assist a mentally ill stalker in a way that does not create a duty to treat and does not expose the psychiatrist to harm, such as contacting a mobile crisis intervention team, a mental health professional who recently treated the stalker, a family member of the stalker, or law enforcement personnel. A psychiatrist who is thrust from the role of helper to victim and must protect his or her own well-being instead of attending to a patient’s welfare is prone to suffer substantial countertransference distress.

The situation with Ms. I was particularly challenging because the resident did not know her complete history and therefore had little information to gauge how likely she was to act on her aggressive threats. Factors that predict future violence include:

- a history of violence

- significant prior criminality

- young age at first arrest

- concomitant substance abuse

- male sex.9

Unfortunately, other than sex, this data regarding Ms. I could not be readily obtained.

A psychiatrist’s duty

Although sympathetic to his stalker’s distress, the resident did not want to treat this woman, nor was he ethically or legally obligated to do so. An individual’s wish to be treated by a particular psychiatrist does not create a duty for the psychiatrist to satisfy this wish.10 State-based “Good Samaritan” laws encourage physicians to assist those in acute need by shielding them from liability, as long as they reasonably act within the scope of their expertise.11 However, they do not require a physician to care for an individual in acute need. A delusional wish for treatment or a false belief of already being in treatment does not create a duty to care for a person.

OUTCOME: Seeking help

Ms. I’s phone calls and letters continue. The resident discusses the situation with his associate residency director, who refers him to the hospital’s legal and investigative staffs. Based on advice from the hospital’s private investigator, the resident sends Ms. I a formal “cease and desist” letter that threatens her with legal action and possible jail time. The staff at the front desk of the clinic where the resident works and the hospital’s security department are instructed to watch for a visitor with Ms. I’s name and description, although the hospital’s investigator is unable to obtain a photograph of her. Shortly after the resident sends the letter, Ms. I ceases communication.

The authors’ observations

This case is unusual because most stalking victims know their stalkers. Identifying a stalker’s motivation can be helpful in formulating a risk assessment. One classification system recognizes 5 categories of stalkers: rejected, intimacy seeking, incompetent, resentful, and predatory (Table 2).1 Rejected stalkers appear to pose the greatest risk of violence and homicide.8 However, all stalkers may pose a risk of violence and therefore all stalking behavior should be treated seriously.

Table 2

Classification of stalkers

| Category | Common features |

|---|---|

| Rejected | Most have a personality disorder; often seeking reconciliation and revenge; most frequent victims are ex-romantic partners, but also target estranged relatives, former friends |

| Intimacy seeking | Erotomania; “morbid infatuation” |

| Incompetent | Lacking social skills; often have stalked others |

| Resentful | Pursuing a vendetta; generally feeling aggrieved |

| Predatory | Often comorbid with paraphilias; may have past convictions for sex offenses |

| Source: Adapted from reference 1 | |

Responding to a stalker

The approach should be tailored to the stalker’s characteristics.12 Silence—ie, lack of acknowledgement of a stalker’s intrusions—is one tactic.13 Consistent and persistent lack of engagement may bore the stalker, but also may provoke frustration or narcissistic or paranoia-fueled rage, and increased efforts to interact with the mental health professional. Other responses include:

- obtaining a protection or restraining order

- promoting the stalker’s participation in adversarial civil litigation, such as a lawsuit

- issuing verbal counterthreats.

Restraining orders are controversial and assessments of their effectiveness vary.14 How well a restraining order works may depend on the stalker’s:

- ability to appreciate reality, and how likely he or she is to experience anxiety when confronted with adverse consequences of his or her actions

- how consistently, rapidly, and harshly the criminal justice system responds to violations of restraining orders.

Restraining orders also may provide the victim a false sense of security.15 One of her letters revealed that Ms. I violated a criminal plea arrangement years earlier, which suggests she was capable of violating a restraining order.

Litigation. A stalker may initiate civil litigation against the victim to feel that he or she has an impact on the victim, which may reduce the stalker’s risk of violence if he or she is emotionally engaged in the litigation. Based on the authors’ experience, as long as the stalker is talking, he or she generally is less likely to act out violently and terminate a satisfying process. Adversarial civil litigation could give a stalker the opportunity to be “close” to the victim and a means of expressing aggressive wishes. The benefit of litigation lasts only as long as the case persists and the stalker believes he or she may prevail. In one of her letters, Ms. I bragged that she had represented herself as a pro se litigant in a complex civil matter, suggesting that she might be constructively channeled into litigation.

Promoting litigation carries significant risk.16 Being a defendant in pro se litigation may be emotionally and financially stressful. This approach may be desirable if the psychiatrist’s institution is willing to offer substantial support. For example, an institution may provide legal assistance—including helping to defray the cost of litigation—and litigation-related scheduling flexibility. An attorney may serve as a boundary between the victim and the pro se litigant’s sometimes ceaseless, time-devouring, anxiety-inducing legal maneuvers.

Counterthreats. Warning a stalker that he or she will face severe civil and criminal consequences if his or her behavior continues can make clear that his or her conduct is unacceptable.17 Such warnings may be delivered verbally or in writing by a legal representative, law enforcement personnel, a private security agent, or the victim.

Issuing a counterthreat can be risky. Stalkers with antisocial or narcissistic personality features may perceive a counterthreat as narcissistically diminishing, and to save face will escalate their stalking in retaliation. Avoid counterthreats if you believe the stalker might be psychotic because destabilizing such an individual—such as by precipitating a short psychotic episode—may increase unpredictability and diminish their responsive to interventions.

Ms. I’s contact with the resident lasted approximately 20 months, slightly less than the average 26 months reported in a survey of mental health professionals.3 Because stalkers are unpredictable, the psychiatric resident remains cautious.

Related Resources

- National Center for Victims of Crime. Stalking resource center. www.victimsofcrime.org/our-programs/stalking-resource-center.

- Mullen PE, Pathé M, Purcell R. Stalkers and their victims. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2009.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

CASE: Delusions and threats

For over 20 months, Ms. I, age 48, sends a psychiatric resident letters and postcards that total approximately 3,000 pages and come from dozens of return addresses. Ms. I expresses romantic feelings toward the resident and believes that he was her physician and prescribed medications, including “mood stabilizers.” The resident never treated Ms. I; to his knowledge, he has never interacted with her.

Ms. I describes the resident’s refusal to continue treating her as “abandonment” and states that she is contemplating self-harm because of this rejection. In her letters, Ms. I admits that she was a long-term patient in a state psychiatric hospital in her home state and suffers from persistent auditory hallucinations. She also wants a romantic relationship with the resident and repeatedly threatens the resident’s female acquaintances and former romantic partners whose relationships she had surmised from news articles available on the Internet. Ms. I also threatens to strangle the resident. The resident sends her multiple written requests that she cease contact, but they are not acknowledged.

The authors’ observations

Stalking—repeated, unwanted attention or communication that would cause a reasonable person fear—is a serious threat for many psychiatric clinicians.1 Prevalence rates among mental health care providers range from 3% to 21%.2,3 Most stalkers have engaged in previous stalking behavior.3

Being stalked is highly distressing,4 and mental health professionals often do not reveal such experiences to colleagues.5 Irrational feelings of guilt or embarrassment, such as being thought to have poorly managed interactions with the stalker, often motivate a self-imposed silence (Table 1).6 This isolation may foster anxiety, interfere with receiving problem-solving advice, and increase physical vulnerability. In the case involving Ms. I, the psychiatric resident’s primary responsibility is safeguarding his own physical and psychological welfare.

Clinicians who work in a hospital or other institutional setting who are being stalked should inform their supervisors and the facility’s security personnel. Security personnel may be able to gather data about the stalker, decrease the stalker’s ability to communicate with the victim, and reduce unwanted physical access to the victim by distributing a photo of the stalker or installing a camera or receptionist-controlled door lock in patient entryways. Security personnel also may collaborate with local law enforcement. Having a third party respond to a stalker’s aggressive behavior—rather than the victim responding directly—avoids rewarding the stalker, which may generate further unwanted contact.7 Any intervention by the victim may increase the risk of violence, creating an “intervention dilemma.” Resnick8 argues that before deciding how best to address the stalker’s behavior, a stalking victim must “first separate the risk of continued stalking from the risk that the stalker will commit a violent act.”

Mental health professionals in private practice who are being stalked should consider retaining an attorney. An attorney often can maintain privacy of communications regarding the stalker via the attorney-client and attorney-work product privileges, which may help during legal proceedings.

Table 1

Factors that can impede psychiatrists from reporting stalking

| Fear of being perceived as a failure |

| Embarrassment |

| High professional tolerance for antisocial and threatening behavior |

| Misplaced sense of duty |

| Source: Reference 6 |

RESPONSE: Involving police

Over 2 months, Ms. I phones the resident’s home 105 times (the resident screens the calls). During 1 call, she states that she is hidden in a closet in her home and will hurt herself unless the resident “resumes” her psychiatric care. The resident contacts police in his city and Ms. I’s community, but authorities are reluctant to act when he acknowledges that he is not Ms. I’s psychiatrist and does not know her. Police officers in Ms. I’s hometown tell the resident no one answered the door when they visited her home. They state that they would enter the residence forcibly only if Ms. I’s physician or a family member asked them to do so, and because the resident admits that he is not her psychiatrist, they cannot take further action. Ms. I leaves the resident a phone message several hours later to inform him she is safe.

The authors’ observations

Stalking-induced countertransference responses may lead a psychiatrist to unwittingly place himself in harm’s way. For example, intense rage at a stalker’s request for treatment may generate guilt that motivates the psychiatrist to agree to treat the stalker. Feelings of helplessness may produce a frantic desire to do something even when such activity is ill-advised. Psychiatrists may develop a tolerance for antisocial or threatening behavior—which is common in mental health settings—and could accept unnecessary risks.

A psychiatrist who is being stalked may be able to assist a mentally ill stalker in a way that does not create a duty to treat and does not expose the psychiatrist to harm, such as contacting a mobile crisis intervention team, a mental health professional who recently treated the stalker, a family member of the stalker, or law enforcement personnel. A psychiatrist who is thrust from the role of helper to victim and must protect his or her own well-being instead of attending to a patient’s welfare is prone to suffer substantial countertransference distress.

The situation with Ms. I was particularly challenging because the resident did not know her complete history and therefore had little information to gauge how likely she was to act on her aggressive threats. Factors that predict future violence include:

- a history of violence

- significant prior criminality

- young age at first arrest

- concomitant substance abuse

- male sex.9

Unfortunately, other than sex, this data regarding Ms. I could not be readily obtained.

A psychiatrist’s duty

Although sympathetic to his stalker’s distress, the resident did not want to treat this woman, nor was he ethically or legally obligated to do so. An individual’s wish to be treated by a particular psychiatrist does not create a duty for the psychiatrist to satisfy this wish.10 State-based “Good Samaritan” laws encourage physicians to assist those in acute need by shielding them from liability, as long as they reasonably act within the scope of their expertise.11 However, they do not require a physician to care for an individual in acute need. A delusional wish for treatment or a false belief of already being in treatment does not create a duty to care for a person.

OUTCOME: Seeking help

Ms. I’s phone calls and letters continue. The resident discusses the situation with his associate residency director, who refers him to the hospital’s legal and investigative staffs. Based on advice from the hospital’s private investigator, the resident sends Ms. I a formal “cease and desist” letter that threatens her with legal action and possible jail time. The staff at the front desk of the clinic where the resident works and the hospital’s security department are instructed to watch for a visitor with Ms. I’s name and description, although the hospital’s investigator is unable to obtain a photograph of her. Shortly after the resident sends the letter, Ms. I ceases communication.

The authors’ observations

This case is unusual because most stalking victims know their stalkers. Identifying a stalker’s motivation can be helpful in formulating a risk assessment. One classification system recognizes 5 categories of stalkers: rejected, intimacy seeking, incompetent, resentful, and predatory (Table 2).1 Rejected stalkers appear to pose the greatest risk of violence and homicide.8 However, all stalkers may pose a risk of violence and therefore all stalking behavior should be treated seriously.

Table 2

Classification of stalkers

| Category | Common features |

|---|---|

| Rejected | Most have a personality disorder; often seeking reconciliation and revenge; most frequent victims are ex-romantic partners, but also target estranged relatives, former friends |

| Intimacy seeking | Erotomania; “morbid infatuation” |

| Incompetent | Lacking social skills; often have stalked others |

| Resentful | Pursuing a vendetta; generally feeling aggrieved |

| Predatory | Often comorbid with paraphilias; may have past convictions for sex offenses |

| Source: Adapted from reference 1 | |

Responding to a stalker

The approach should be tailored to the stalker’s characteristics.12 Silence—ie, lack of acknowledgement of a stalker’s intrusions—is one tactic.13 Consistent and persistent lack of engagement may bore the stalker, but also may provoke frustration or narcissistic or paranoia-fueled rage, and increased efforts to interact with the mental health professional. Other responses include:

- obtaining a protection or restraining order

- promoting the stalker’s participation in adversarial civil litigation, such as a lawsuit

- issuing verbal counterthreats.

Restraining orders are controversial and assessments of their effectiveness vary.14 How well a restraining order works may depend on the stalker’s:

- ability to appreciate reality, and how likely he or she is to experience anxiety when confronted with adverse consequences of his or her actions

- how consistently, rapidly, and harshly the criminal justice system responds to violations of restraining orders.

Restraining orders also may provide the victim a false sense of security.15 One of her letters revealed that Ms. I violated a criminal plea arrangement years earlier, which suggests she was capable of violating a restraining order.

Litigation. A stalker may initiate civil litigation against the victim to feel that he or she has an impact on the victim, which may reduce the stalker’s risk of violence if he or she is emotionally engaged in the litigation. Based on the authors’ experience, as long as the stalker is talking, he or she generally is less likely to act out violently and terminate a satisfying process. Adversarial civil litigation could give a stalker the opportunity to be “close” to the victim and a means of expressing aggressive wishes. The benefit of litigation lasts only as long as the case persists and the stalker believes he or she may prevail. In one of her letters, Ms. I bragged that she had represented herself as a pro se litigant in a complex civil matter, suggesting that she might be constructively channeled into litigation.

Promoting litigation carries significant risk.16 Being a defendant in pro se litigation may be emotionally and financially stressful. This approach may be desirable if the psychiatrist’s institution is willing to offer substantial support. For example, an institution may provide legal assistance—including helping to defray the cost of litigation—and litigation-related scheduling flexibility. An attorney may serve as a boundary between the victim and the pro se litigant’s sometimes ceaseless, time-devouring, anxiety-inducing legal maneuvers.

Counterthreats. Warning a stalker that he or she will face severe civil and criminal consequences if his or her behavior continues can make clear that his or her conduct is unacceptable.17 Such warnings may be delivered verbally or in writing by a legal representative, law enforcement personnel, a private security agent, or the victim.

Issuing a counterthreat can be risky. Stalkers with antisocial or narcissistic personality features may perceive a counterthreat as narcissistically diminishing, and to save face will escalate their stalking in retaliation. Avoid counterthreats if you believe the stalker might be psychotic because destabilizing such an individual—such as by precipitating a short psychotic episode—may increase unpredictability and diminish their responsive to interventions.

Ms. I’s contact with the resident lasted approximately 20 months, slightly less than the average 26 months reported in a survey of mental health professionals.3 Because stalkers are unpredictable, the psychiatric resident remains cautious.

Related Resources

- National Center for Victims of Crime. Stalking resource center. www.victimsofcrime.org/our-programs/stalking-resource-center.

- Mullen PE, Pathé M, Purcell R. Stalkers and their victims. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2009.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Mullen PE, Pathé M, Purcell R, et al. Study of stalkers. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(8):1244-1249.

2. Sandberg DA, McNiel DE, Binder RL. Stalking threatening, and harassing behavior by psychiatric patients toward clinicians. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2002;30(2):221-229.

3. McIvor R, Potter L, Davies L. Stalking behavior by patients towards psychiatrists in a large mental health organization. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2008;54(4):350-357.

4. Mullen PE, Pathé M. Stalking. Crime and Justice. 2002;29:273-318.

5. Bird S. Strategies for managing and minimizing the impact of harassment and stalking by patients. ANZ J Surg. 2009;79(7-8):537-538.

6. Sinwelski SA, Vinton L. Stalking: the constant threat of violence. Affilia. 2001;16(1):46-65.

7. Meloy JR. Commentary: stalking threatening, and harassing behavior by patients—the risk-management response. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2002;30(2):230-231.

8. Resnick PJ. Stalking risk assessment. In: Pinals DA, ed. Stalking: psychiatric perspectives and practical approaches. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007:61–84.

9. Dietz PE. Defenses against dangerous people when arrest and commitment fail. In: Simon RI, ed. American Psychiatric Press review of clinical psychiatry and the law. 1st ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1989:205–219.

10. Hilliard J. Termination of treatment with troublesome patients. In: Lifson LE, Simon RI, eds. The mental health practitioner and the law: a comprehensive handbook. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1998:216–224.

11. Paterick TJ, Paterick BB, Paterick TE. Implications of Good Samaritan laws for physicians. J Med Pract Manage. 2008;23(6):372-375.

12. MacKenzie RD, James DV. Management and treatment of stalkers: problems options, and solutions. Behav Sci Law. 2011;29(2):220-239.

13. Fremouw WJ, Westrup D, Pennypacker J. Stalking on campus: the prevalence and strategies for coping with stalking. J Forensic Sci. 1997;42(4):666-669.

14. Nicastro AM, Cousins AV, Spitzberg BH. The tactical face of stalking. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2000;28(1):69-82.

15. Spitzberg BH. The tactical topography of stalking victimization and management. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2002;3(4):261-288.

16. Pathé M, MacKenzie R, Mullen PE. Stalking by law: damaging victims and rewarding offenders. J Law Med. 2004;12(1):103-111.

17. Lion JR, Herschler JA. The stalking of physicians by their patients. In: Meloy JR. The psychology of stalking: clinical and forensic perspectives. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1998:163–173.

1. Mullen PE, Pathé M, Purcell R, et al. Study of stalkers. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(8):1244-1249.

2. Sandberg DA, McNiel DE, Binder RL. Stalking threatening, and harassing behavior by psychiatric patients toward clinicians. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2002;30(2):221-229.

3. McIvor R, Potter L, Davies L. Stalking behavior by patients towards psychiatrists in a large mental health organization. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2008;54(4):350-357.

4. Mullen PE, Pathé M. Stalking. Crime and Justice. 2002;29:273-318.

5. Bird S. Strategies for managing and minimizing the impact of harassment and stalking by patients. ANZ J Surg. 2009;79(7-8):537-538.

6. Sinwelski SA, Vinton L. Stalking: the constant threat of violence. Affilia. 2001;16(1):46-65.

7. Meloy JR. Commentary: stalking threatening, and harassing behavior by patients—the risk-management response. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2002;30(2):230-231.

8. Resnick PJ. Stalking risk assessment. In: Pinals DA, ed. Stalking: psychiatric perspectives and practical approaches. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007:61–84.

9. Dietz PE. Defenses against dangerous people when arrest and commitment fail. In: Simon RI, ed. American Psychiatric Press review of clinical psychiatry and the law. 1st ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1989:205–219.

10. Hilliard J. Termination of treatment with troublesome patients. In: Lifson LE, Simon RI, eds. The mental health practitioner and the law: a comprehensive handbook. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1998:216–224.

11. Paterick TJ, Paterick BB, Paterick TE. Implications of Good Samaritan laws for physicians. J Med Pract Manage. 2008;23(6):372-375.

12. MacKenzie RD, James DV. Management and treatment of stalkers: problems options, and solutions. Behav Sci Law. 2011;29(2):220-239.

13. Fremouw WJ, Westrup D, Pennypacker J. Stalking on campus: the prevalence and strategies for coping with stalking. J Forensic Sci. 1997;42(4):666-669.

14. Nicastro AM, Cousins AV, Spitzberg BH. The tactical face of stalking. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2000;28(1):69-82.

15. Spitzberg BH. The tactical topography of stalking victimization and management. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2002;3(4):261-288.

16. Pathé M, MacKenzie R, Mullen PE. Stalking by law: damaging victims and rewarding offenders. J Law Med. 2004;12(1):103-111.

17. Lion JR, Herschler JA. The stalking of physicians by their patients. In: Meloy JR. The psychology of stalking: clinical and forensic perspectives. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1998:163–173.

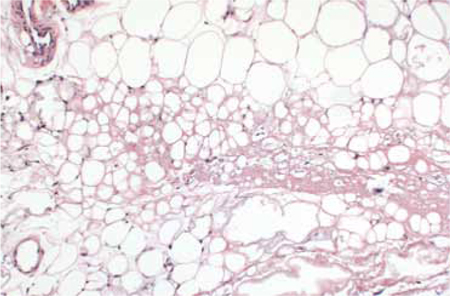

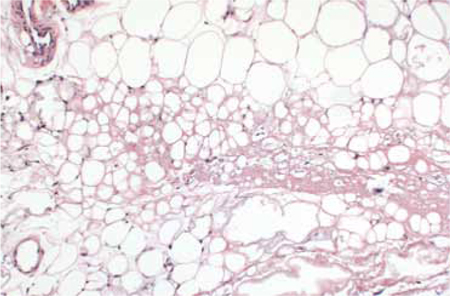

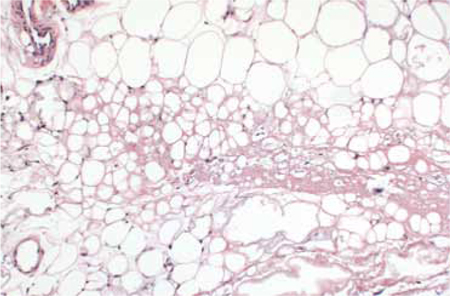

Hyperpigmentation and atrophy

A 35-year-old woman sought care at our clinic for a plaque on her upper left arm. She said that it had started 3 months earlier as a small indentation, but had recently became larger and hyperpigmented. The lesion was not pruritic or painful, and she had no associated weakness or systemic symptoms. The patient denied any insect bites, instrumentation, topical ointments, or trauma to the area.

Physical examination revealed a 3.5 × 2.5 cm area of hyperpigmentation on the posterior aspect of the left arm, overlying the musculotendinous junction of the lateral head of the triceps (FIGURE 1). The lesion had an irregular border and a central region approximately 1 cm in diameter associated with a nontender subcutaneous mass that felt tethered to the skin. There was significant thinning of the subcutaneous fat beneath the hyperpigmentation relative to the normal surrounding skin. The patient had normal triceps function and a normal distal neurovascular exam.