User login

77 Million U.S. Residents Have Difficulty Understanding Basic Health Information

The number of U.S. residents who have difficulty understanding basic health information, according to a report developed by the University of California at San Francisco and San Francisco General Hospital and published by the Institute of Medicine.1 The report also suggests ways to bridge the gaps to understanding, such as how to make this a priority at every level of the health organization, avoid stigmatizing patients over literacy issues, and adopt proven educational techniques such as teach-back (see “Teach-Back,” September 2012).

Reference

The number of U.S. residents who have difficulty understanding basic health information, according to a report developed by the University of California at San Francisco and San Francisco General Hospital and published by the Institute of Medicine.1 The report also suggests ways to bridge the gaps to understanding, such as how to make this a priority at every level of the health organization, avoid stigmatizing patients over literacy issues, and adopt proven educational techniques such as teach-back (see “Teach-Back,” September 2012).

Reference

The number of U.S. residents who have difficulty understanding basic health information, according to a report developed by the University of California at San Francisco and San Francisco General Hospital and published by the Institute of Medicine.1 The report also suggests ways to bridge the gaps to understanding, such as how to make this a priority at every level of the health organization, avoid stigmatizing patients over literacy issues, and adopt proven educational techniques such as teach-back (see “Teach-Back,” September 2012).

Reference

Win Whitcomb: Hospital Readmissions Penalties Start Now

The uproar and confusion over readmissions penalties has consumed umpteen hours of senior leaders’ time (especially that of CFOs), not to mention that of front-line nurses, case managers, quality-improvement (QI) coordinators, hospitalists, and others involved in discharge planning and ensuring a safe transition for patients out of the hospital. For many, the math is fuzzy, and for most, the return on investment is even fuzzier. After all, avoided readmissions are lost revenue to those who are running a business known as an acute-care hospital.

Let me start with the conclusion: Eliminating avoidable readmissions is the right thing to do, period. But the financial downside to doing so is probably greater than any upside realized through avoidance of the penalties that began affecting hospital payments on Oct. 1—at least in the fee-for-service world we live in. At some point in the future, when most patients are under a global payment, the math might be clearer, but today, penalties probably won’t offset lost revenue from reduced readmissions added to the cost of paying lots of people to work in meetings (and at the bedside) to devise better care transitions. (Caveat: If your hospital is bursting at the seams with full occupancy, reducing readmissions and replacing them with higher-reimbursing patients, such as those undergoing elective major surgery, likely will be a net financial gain for your hospital.)

Part of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) will reduce total Medicare DRG reimbursement for hospitals beginning in fiscal-year 2013 based on actual 30-day readmission rates for myocardial infarction (MI), heart failure (HF), and pneumonia that are in excess of risk-adjusted expected rates. The reduction is capped at 1% in 2013, 2% in 2014, and 3% in 2015 and beyond. Hospital readmission rates are based on calculated baseline rates using Medicare data from July 1, 2008, to June 30, 2011.

Cost of a Readmissions-Reduction Program

How much does it cost for a hospital to implement a care-transitions program—such as SHM’s Project BOOST—to reduce readmissions? Last year, I interviewed a dozen hospitals that successfully implemented SHM’s formal mentored implementation program. The result? In the first year of the program, hospitals spent about $170,000 on training and staff time devoted to the project.

Lost Revenue

Let’s look at a sample penalty calculation, then examine a scenario sizing up how revenue is lost when a hospital is successful in reducing readmissions. The ACA defines the payments for excess readmissions as:

The number of patients with the applicable condition (HF, MI, or pneumonia) multiplied by the base DRG payment made for those patients multiplied by the percentage of readmissions beyond the expected.

As an example, let’s take a hospital that treats 500 pneumonia patients (# with the applicable condition), has a base DRG payment for pneumonia of $5,000, and a readmission rate that is 4% higher than expected (in this example, the actual rate is 25% and the expected rate is 24%; 1/25=4%). The penalty is 500 X $5,000 X .04, or $100,000. We’ll assume that the readmission rate for myocardial infarction and heart failure are less than expected, so the total penalty is $100,000.

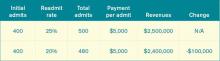

Let’s say the hospital works hard to decrease pneumonia readmissions from 25% to 20% and avoids the penalty. As outlined in Table 1, the hospital will lose $100,000 in revenue (admittedly, reducing readmissions to 20% from 25% represents a big jump, but this is for illustration purposes—we haven’t added in lost revenue from reduced readmissions for other conditions). What’s the final cost of avoiding the $100,000 readmission penalty? Lost revenue of $100,000 plus the cost of implementing the readmission reduction program of $170,000=$270,000.

Why Are We Doing This?

I see the value in care transitions and readmissions-reduction programs, such as Project BOOST, first and foremost as a way to improve patient safety; as such, if implemented effectively, they are likely worth the investment. Second, their value lies in the preparation all hospitals and health systems should be undergoing to remain market-competitive and solvent under global payment systems. Because the penalties in the HRRP might come with lost revenues and the costs of program implementation, be clear about your team’s motivation for reducing readmissions. Your CFO will see to it if I don’t.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

The uproar and confusion over readmissions penalties has consumed umpteen hours of senior leaders’ time (especially that of CFOs), not to mention that of front-line nurses, case managers, quality-improvement (QI) coordinators, hospitalists, and others involved in discharge planning and ensuring a safe transition for patients out of the hospital. For many, the math is fuzzy, and for most, the return on investment is even fuzzier. After all, avoided readmissions are lost revenue to those who are running a business known as an acute-care hospital.

Let me start with the conclusion: Eliminating avoidable readmissions is the right thing to do, period. But the financial downside to doing so is probably greater than any upside realized through avoidance of the penalties that began affecting hospital payments on Oct. 1—at least in the fee-for-service world we live in. At some point in the future, when most patients are under a global payment, the math might be clearer, but today, penalties probably won’t offset lost revenue from reduced readmissions added to the cost of paying lots of people to work in meetings (and at the bedside) to devise better care transitions. (Caveat: If your hospital is bursting at the seams with full occupancy, reducing readmissions and replacing them with higher-reimbursing patients, such as those undergoing elective major surgery, likely will be a net financial gain for your hospital.)

Part of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) will reduce total Medicare DRG reimbursement for hospitals beginning in fiscal-year 2013 based on actual 30-day readmission rates for myocardial infarction (MI), heart failure (HF), and pneumonia that are in excess of risk-adjusted expected rates. The reduction is capped at 1% in 2013, 2% in 2014, and 3% in 2015 and beyond. Hospital readmission rates are based on calculated baseline rates using Medicare data from July 1, 2008, to June 30, 2011.

Cost of a Readmissions-Reduction Program

How much does it cost for a hospital to implement a care-transitions program—such as SHM’s Project BOOST—to reduce readmissions? Last year, I interviewed a dozen hospitals that successfully implemented SHM’s formal mentored implementation program. The result? In the first year of the program, hospitals spent about $170,000 on training and staff time devoted to the project.

Lost Revenue

Let’s look at a sample penalty calculation, then examine a scenario sizing up how revenue is lost when a hospital is successful in reducing readmissions. The ACA defines the payments for excess readmissions as:

The number of patients with the applicable condition (HF, MI, or pneumonia) multiplied by the base DRG payment made for those patients multiplied by the percentage of readmissions beyond the expected.

As an example, let’s take a hospital that treats 500 pneumonia patients (# with the applicable condition), has a base DRG payment for pneumonia of $5,000, and a readmission rate that is 4% higher than expected (in this example, the actual rate is 25% and the expected rate is 24%; 1/25=4%). The penalty is 500 X $5,000 X .04, or $100,000. We’ll assume that the readmission rate for myocardial infarction and heart failure are less than expected, so the total penalty is $100,000.

Let’s say the hospital works hard to decrease pneumonia readmissions from 25% to 20% and avoids the penalty. As outlined in Table 1, the hospital will lose $100,000 in revenue (admittedly, reducing readmissions to 20% from 25% represents a big jump, but this is for illustration purposes—we haven’t added in lost revenue from reduced readmissions for other conditions). What’s the final cost of avoiding the $100,000 readmission penalty? Lost revenue of $100,000 plus the cost of implementing the readmission reduction program of $170,000=$270,000.

Why Are We Doing This?

I see the value in care transitions and readmissions-reduction programs, such as Project BOOST, first and foremost as a way to improve patient safety; as such, if implemented effectively, they are likely worth the investment. Second, their value lies in the preparation all hospitals and health systems should be undergoing to remain market-competitive and solvent under global payment systems. Because the penalties in the HRRP might come with lost revenues and the costs of program implementation, be clear about your team’s motivation for reducing readmissions. Your CFO will see to it if I don’t.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

The uproar and confusion over readmissions penalties has consumed umpteen hours of senior leaders’ time (especially that of CFOs), not to mention that of front-line nurses, case managers, quality-improvement (QI) coordinators, hospitalists, and others involved in discharge planning and ensuring a safe transition for patients out of the hospital. For many, the math is fuzzy, and for most, the return on investment is even fuzzier. After all, avoided readmissions are lost revenue to those who are running a business known as an acute-care hospital.

Let me start with the conclusion: Eliminating avoidable readmissions is the right thing to do, period. But the financial downside to doing so is probably greater than any upside realized through avoidance of the penalties that began affecting hospital payments on Oct. 1—at least in the fee-for-service world we live in. At some point in the future, when most patients are under a global payment, the math might be clearer, but today, penalties probably won’t offset lost revenue from reduced readmissions added to the cost of paying lots of people to work in meetings (and at the bedside) to devise better care transitions. (Caveat: If your hospital is bursting at the seams with full occupancy, reducing readmissions and replacing them with higher-reimbursing patients, such as those undergoing elective major surgery, likely will be a net financial gain for your hospital.)

Part of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) will reduce total Medicare DRG reimbursement for hospitals beginning in fiscal-year 2013 based on actual 30-day readmission rates for myocardial infarction (MI), heart failure (HF), and pneumonia that are in excess of risk-adjusted expected rates. The reduction is capped at 1% in 2013, 2% in 2014, and 3% in 2015 and beyond. Hospital readmission rates are based on calculated baseline rates using Medicare data from July 1, 2008, to June 30, 2011.

Cost of a Readmissions-Reduction Program

How much does it cost for a hospital to implement a care-transitions program—such as SHM’s Project BOOST—to reduce readmissions? Last year, I interviewed a dozen hospitals that successfully implemented SHM’s formal mentored implementation program. The result? In the first year of the program, hospitals spent about $170,000 on training and staff time devoted to the project.

Lost Revenue

Let’s look at a sample penalty calculation, then examine a scenario sizing up how revenue is lost when a hospital is successful in reducing readmissions. The ACA defines the payments for excess readmissions as:

The number of patients with the applicable condition (HF, MI, or pneumonia) multiplied by the base DRG payment made for those patients multiplied by the percentage of readmissions beyond the expected.

As an example, let’s take a hospital that treats 500 pneumonia patients (# with the applicable condition), has a base DRG payment for pneumonia of $5,000, and a readmission rate that is 4% higher than expected (in this example, the actual rate is 25% and the expected rate is 24%; 1/25=4%). The penalty is 500 X $5,000 X .04, or $100,000. We’ll assume that the readmission rate for myocardial infarction and heart failure are less than expected, so the total penalty is $100,000.

Let’s say the hospital works hard to decrease pneumonia readmissions from 25% to 20% and avoids the penalty. As outlined in Table 1, the hospital will lose $100,000 in revenue (admittedly, reducing readmissions to 20% from 25% represents a big jump, but this is for illustration purposes—we haven’t added in lost revenue from reduced readmissions for other conditions). What’s the final cost of avoiding the $100,000 readmission penalty? Lost revenue of $100,000 plus the cost of implementing the readmission reduction program of $170,000=$270,000.

Why Are We Doing This?

I see the value in care transitions and readmissions-reduction programs, such as Project BOOST, first and foremost as a way to improve patient safety; as such, if implemented effectively, they are likely worth the investment. Second, their value lies in the preparation all hospitals and health systems should be undergoing to remain market-competitive and solvent under global payment systems. Because the penalties in the HRRP might come with lost revenues and the costs of program implementation, be clear about your team’s motivation for reducing readmissions. Your CFO will see to it if I don’t.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

Alternative Healthcare Models Aim to Boost Sagging Critical-Care Workforce

Amid the struggle to boost the country’s sagging critical-care workforce, experts have most commonly proposed creating a tiered or regionalized model of care, investing more in tele-ICU services, and augmenting the role of midlevel providers.

The University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, with 20 hospitals and roughly 500 ICU beds throughout its network, is adopting a regionalized healthcare delivery system. Some of the center’s most high-risk services, such as its big transplant programs, are centralized within the main university campus hospitals, as are about half of the ICU beds.

“In those hospitals, we’ve decided that we need 24/7 in-house, intensive-care attendings,” says Derek Angus, MD, the center’s chair of critical-care medicine. The doctors work with fellows and a rapidly growing expansion of midlevel providers.

In some of the smaller hospitals, however, some ICU patients are seen and managed by hospitalists. The medical center’s eventual goal is to be more systematic about the kinds of patients managed by intensivists as well as those managed by hospitalists. It’s a task made easier by the specialists’ close working relationship within the same department.

Dr. Angus believes telemedicine could help by providing a sort of mission control that can help track critically ill patients and those at risk of being admitted to ICUs across all 20 hospitals. He concedes, however, that telemedicine for ICU assistance has had mixed results in the medical literature, suggesting that a major key is working out the proper roles and responsibilities of those using the technology.

To improve the consistency of its own frontline providers, the Emory University Center for Critical Care in Atlanta developed a competency-based, critical-care training program for nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs).

“It’s very clear that if you have a group of NP and PA providers who can do 90 percent of what the physician does, it really begins to unload the physician to focus on what I call the big-picture pieces of critical care,” says center director Timothy Buchman, PhD, MD.

That attending physician can be trained as a care executive to ensure well-coordinated care and to focus on any process that isn’t working well. “At a big academic health sciences center, that should probably be a critical-care physician,” Dr. Buchman notes. “But for the smaller community and regional hospitals that have a relatively less sick population, the person who will be well-positioned to oversee this nonphysician provider staff could well be a hospitalist who’s received additional guidance and training in critical care.”

For mild or moderate complexity of care, he says, the added training need not necessarily include a traditional two-year fellowship. Under a value-based system, sicker patients could be rapidly transferred to a higher level of care, and telemedicine could provide a “backstop” for providers in smaller hospitals who lack the training and experience of someone with a full critical-care fellowship.

Amid the struggle to boost the country’s sagging critical-care workforce, experts have most commonly proposed creating a tiered or regionalized model of care, investing more in tele-ICU services, and augmenting the role of midlevel providers.

The University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, with 20 hospitals and roughly 500 ICU beds throughout its network, is adopting a regionalized healthcare delivery system. Some of the center’s most high-risk services, such as its big transplant programs, are centralized within the main university campus hospitals, as are about half of the ICU beds.

“In those hospitals, we’ve decided that we need 24/7 in-house, intensive-care attendings,” says Derek Angus, MD, the center’s chair of critical-care medicine. The doctors work with fellows and a rapidly growing expansion of midlevel providers.

In some of the smaller hospitals, however, some ICU patients are seen and managed by hospitalists. The medical center’s eventual goal is to be more systematic about the kinds of patients managed by intensivists as well as those managed by hospitalists. It’s a task made easier by the specialists’ close working relationship within the same department.

Dr. Angus believes telemedicine could help by providing a sort of mission control that can help track critically ill patients and those at risk of being admitted to ICUs across all 20 hospitals. He concedes, however, that telemedicine for ICU assistance has had mixed results in the medical literature, suggesting that a major key is working out the proper roles and responsibilities of those using the technology.

To improve the consistency of its own frontline providers, the Emory University Center for Critical Care in Atlanta developed a competency-based, critical-care training program for nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs).

“It’s very clear that if you have a group of NP and PA providers who can do 90 percent of what the physician does, it really begins to unload the physician to focus on what I call the big-picture pieces of critical care,” says center director Timothy Buchman, PhD, MD.

That attending physician can be trained as a care executive to ensure well-coordinated care and to focus on any process that isn’t working well. “At a big academic health sciences center, that should probably be a critical-care physician,” Dr. Buchman notes. “But for the smaller community and regional hospitals that have a relatively less sick population, the person who will be well-positioned to oversee this nonphysician provider staff could well be a hospitalist who’s received additional guidance and training in critical care.”

For mild or moderate complexity of care, he says, the added training need not necessarily include a traditional two-year fellowship. Under a value-based system, sicker patients could be rapidly transferred to a higher level of care, and telemedicine could provide a “backstop” for providers in smaller hospitals who lack the training and experience of someone with a full critical-care fellowship.

Amid the struggle to boost the country’s sagging critical-care workforce, experts have most commonly proposed creating a tiered or regionalized model of care, investing more in tele-ICU services, and augmenting the role of midlevel providers.

The University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, with 20 hospitals and roughly 500 ICU beds throughout its network, is adopting a regionalized healthcare delivery system. Some of the center’s most high-risk services, such as its big transplant programs, are centralized within the main university campus hospitals, as are about half of the ICU beds.

“In those hospitals, we’ve decided that we need 24/7 in-house, intensive-care attendings,” says Derek Angus, MD, the center’s chair of critical-care medicine. The doctors work with fellows and a rapidly growing expansion of midlevel providers.

In some of the smaller hospitals, however, some ICU patients are seen and managed by hospitalists. The medical center’s eventual goal is to be more systematic about the kinds of patients managed by intensivists as well as those managed by hospitalists. It’s a task made easier by the specialists’ close working relationship within the same department.

Dr. Angus believes telemedicine could help by providing a sort of mission control that can help track critically ill patients and those at risk of being admitted to ICUs across all 20 hospitals. He concedes, however, that telemedicine for ICU assistance has had mixed results in the medical literature, suggesting that a major key is working out the proper roles and responsibilities of those using the technology.

To improve the consistency of its own frontline providers, the Emory University Center for Critical Care in Atlanta developed a competency-based, critical-care training program for nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs).

“It’s very clear that if you have a group of NP and PA providers who can do 90 percent of what the physician does, it really begins to unload the physician to focus on what I call the big-picture pieces of critical care,” says center director Timothy Buchman, PhD, MD.

That attending physician can be trained as a care executive to ensure well-coordinated care and to focus on any process that isn’t working well. “At a big academic health sciences center, that should probably be a critical-care physician,” Dr. Buchman notes. “But for the smaller community and regional hospitals that have a relatively less sick population, the person who will be well-positioned to oversee this nonphysician provider staff could well be a hospitalist who’s received additional guidance and training in critical care.”

For mild or moderate complexity of care, he says, the added training need not necessarily include a traditional two-year fellowship. Under a value-based system, sicker patients could be rapidly transferred to a higher level of care, and telemedicine could provide a “backstop” for providers in smaller hospitals who lack the training and experience of someone with a full critical-care fellowship.

Guidelines Drive Optimal Care for Heart Failure Patients

Cardiologists aren’t shy about repeating it: guidelines, guidelines, guidelines. That is, follow them.

“Evidence-based, guideline-driven optimal care for heart failure truly is beneficial,” Dr. Yancy says. “Every effort should be made to strive to achieve ideal thresholds and meeting best practices.”

There is now compelling evidence that, for patients with heart failure, the higher the degree of adherence to Class I-recommended therapies, the greater the reduction in 24-month mortality risk.5

“It would seem as if practicing best quality is almost a perfunctory statement, but consistently, when we look at surveys of quality improvement and adherence to evidence-based strategies, persistent gaps remain in the broader community,” Dr. Yancy says. “We know what we need to do. We’re still striving to get closer and closer to optimal care.”

Dr. Harold says the guidelines are there to make things simpler. So take advantage of them.

“If anything, hospitalists tend to be ahead of most other groups in terms of knowing evidence-based pathways and really tracking very specific protocols,” he says. “I think one of the advantages of hospitalist care is very often, it is guideline-driven. You have less variation in terms of care and quality outcomes.”

Cardiologists aren’t shy about repeating it: guidelines, guidelines, guidelines. That is, follow them.

“Evidence-based, guideline-driven optimal care for heart failure truly is beneficial,” Dr. Yancy says. “Every effort should be made to strive to achieve ideal thresholds and meeting best practices.”

There is now compelling evidence that, for patients with heart failure, the higher the degree of adherence to Class I-recommended therapies, the greater the reduction in 24-month mortality risk.5

“It would seem as if practicing best quality is almost a perfunctory statement, but consistently, when we look at surveys of quality improvement and adherence to evidence-based strategies, persistent gaps remain in the broader community,” Dr. Yancy says. “We know what we need to do. We’re still striving to get closer and closer to optimal care.”

Dr. Harold says the guidelines are there to make things simpler. So take advantage of them.

“If anything, hospitalists tend to be ahead of most other groups in terms of knowing evidence-based pathways and really tracking very specific protocols,” he says. “I think one of the advantages of hospitalist care is very often, it is guideline-driven. You have less variation in terms of care and quality outcomes.”

Cardiologists aren’t shy about repeating it: guidelines, guidelines, guidelines. That is, follow them.

“Evidence-based, guideline-driven optimal care for heart failure truly is beneficial,” Dr. Yancy says. “Every effort should be made to strive to achieve ideal thresholds and meeting best practices.”

There is now compelling evidence that, for patients with heart failure, the higher the degree of adherence to Class I-recommended therapies, the greater the reduction in 24-month mortality risk.5

“It would seem as if practicing best quality is almost a perfunctory statement, but consistently, when we look at surveys of quality improvement and adherence to evidence-based strategies, persistent gaps remain in the broader community,” Dr. Yancy says. “We know what we need to do. We’re still striving to get closer and closer to optimal care.”

Dr. Harold says the guidelines are there to make things simpler. So take advantage of them.

“If anything, hospitalists tend to be ahead of most other groups in terms of knowing evidence-based pathways and really tracking very specific protocols,” he says. “I think one of the advantages of hospitalist care is very often, it is guideline-driven. You have less variation in terms of care and quality outcomes.”

12 Things Cardiologists Think Hospitalists Need to Know

Only about a third of ideal candidates with heart failure are currently treated with [aldosterone antagonists], even though it markedly improves outcome and is Class I-recommended in the guidelines.

—Gregg Fonarow, MD, co-chief, University of California at Los Angeles division of cardiology, chair, American Heart Association’s Get With The Guidelines program steering committee

You might not have done a fellowship in cardiology, but quite often you probably feel like a cardiologist. Hospitalists frequently attend to patients on observation for heart problems and help manage even the most complex patients.

Often, you are working alongside the cardiologist. But other times, you’re on your own. Hospitalists are expected to carry an increasingly heavy load when it comes to heart-failure patients and many other kinds of patients with specialized disorders. It can be hard to keep up with what you need to know.

Top Twelve

- Recognize the new importance of beta-blockers for heart failure, and go with the best of them.

- It’s not readmissions that are the problem—it’s avoidable readmissions.

- New interventional technologies will mean more complex patients, so be ready.

- Aldosterone antagonists, though probably underutilized, can be very effective but require caution.

- Switching from IV diuretics to an oral regimen calls for careful monitoring.

- Patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction have outcomes over the longer haul similar to those with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. And in preserved ejection fraction cases, the contributing illnesses must be addressed.

- Inotropic agents can do more harm than good.

- Pay attention to the ins and outs of new antiplatelet therapies.

- Bridging anticoagulant therapy in patients going for electrophysiology procedures should be done only some, not most, of the time.

- Some non-STEMI patients might benefit from getting to the catheterization lab quickly.

- Beware the idiosyncrasies of new anticoagulants.

- Be cognizant of stent thrombosis and how to manage it.

The Hospitalist spoke to several cardiologists about the latest in treatments, technologies, and HM’s role in the system of care. The following are their suggestions for what you really need to know about treating patients with heart conditions.

1) Recognize the new importance of beta-blockers for heart failure, and go with the best of them.

Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensive receptor blockers have been part of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS) core measures for heart failure for a long time, but beta-blockers at hospital discharge only recently have been added as American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/American Medical Association–Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement measures for heart failure.1

“For those with heart failure and reduced left ventricular ejection fraction, very old and outdated concepts would have talked about potentially holding the beta-blocker during hospitalization for heart failure—or not initiating until the patient was an outpatient,” says Gregg Fonarow, MD, co-chief of the University of California at Los Angeles’ division of cardiology and chair of the steering committee for the American Heart Association’s Get With The Guidelines program. “[But] the guidelines and evidence, and often performance measures, linked to them are now explicit about initiating or maintaining beta-blockers during the heart-failure hospitalization.”

Beta-blockers should be initiated as patients are stabilized before discharge. Dr. Fonarow suggests hospitalists use only one of the three evidence-based therapies: carvedilol, metoprolol succinate, or bisoprolol.

“Many physicians have been using metoprolol tartrate or atenolol in heart-failure patients,” Dr. Fonarow says. “These are not known to improve clinical outcomes. So here’s an example where the specific medication is absolutely, critically important.”

2) It’s not readmissions that are the problem—it’s avoidable readmissions.

“The modifier is very important,” says Clyde Yancy, MD, chief of the division of cardiology at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago. “Heart failure continues to be a problematic disease. Many patients now do really well, but some do not. Those patients are symptomatic and may require frequent hospitalizations for stabilization. We should not disallow or misdirect those patients who need inpatient care from receiving such because of an arbitrary incentive to reduce rehospitalizations out of fear of punitive financial damages. The unforeseen risks here are real.”

Dr. Yancy says studies based on CMS data have found that institutions with higher readmission rates have lower 30-day mortality rates.2 He cautions hospitalists to be “very thoughtful about an overzealous embrace of reducing all readmissions for heart failure.” Instead, the goal should be to limit the “avoidable readmissions.”

“And for the patient that clearly has advanced disease,” he says, “rather than triaging them away from the hospital, we really should be very respectful of their disease. Keep those patients where disease-modifying interventions can be deployed, and we can work to achieve the best possible outcome for those that have the most advanced disease.”

3) New interventional technologies will mean more complex patients, so be ready.

Advances in interventional procedures, including transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) and endoscopic mitral valve repair, will translate into a new population of highly complex patients. Many of these patients will be in their 80s or 90s.

“It’s a whole new paradigm shift of technology,” says John Harold, MD, president-elect of the American College of Cardiology and past chief of staff and department of medicine clinical chief of staff at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. “Very often, the hospitalist is at the front dealing with all of these issues.”

Many of these patients have other problems, including renal insufficiency, diabetes, and the like.

“They have all sorts of other things going on simultaneously, so very often the hospitalist becomes … the point person in dealing with all of these issues,” Dr. Harold says.

4) Aldosterone antagonists, though probably underutilized, can be very effective but require caution.

Aldosterone antagonists can greatly improve outcomes and reduce hospitalization in heart-failure patients, but they have to be used with very careful dosing and patient selection, Dr. Fonarow says. And they require early follow-up once patients are discharged.

“Only about a third of ideal candidates with heart failure are currently treated with this agent, even though it markedly improves outcome and is Class I-recommended in the guidelines,” Dr. Fonarow says. “But this is one where it needs to be started at appropriate low doses, with meticulous monitoring in both the inpatient and the outpatient setting, early follow-up, and early laboratory checks.”

5) Switching from IV diuretics to an oral regimen calls for careful monitoring.

Transitioning patients from IV diuretics to oral regimens is an area rife with mistakes, Dr. Fonarow says. It requires a lot of “meticulous attention to proper potassium supplementation and monitoring of renal function and electrolyte levels,” he says.

Medication reconciliation—“med rec”—is especially important during the transition from inpatient to outpatient.

“There are common medication errors that are made during this transition,” Dr. Fonarow says. “Hospitalists, along with other [care team] members, can really play a critically important role in trying to reduce that risk.”

6) Patients with heart failure with preserved ejection

fraction have outcomes over the longer haul similar to those with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. And in preserved ejection fraction cases, the contributing illnesses must be addressed.

“We really can’t exercise a thought economy that just says, ‘Extrapolate the evidence-based therapies for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction to heart failure with preserved ejection fraction’ and expect good outcomes,” Dr. Yancy says. “That’s not the case. We don’t have an evidence base to substantiate that.”

He says one or more common comorbidities (e.g. atrial fibrillation, hypertension, obesity, diabetes, renal insufficiency) are present in 90% of patients with preserved ejection fraction. Treatment of those comorbidities—for example, rate control in afib patients, lowering the blood pressure in hypertension patients—has to be done with care.

“We should recognize that the therapy for this condition, albeit absent any specifically indicated interventions that will change its natural history, can still be skillfully constructed,” Dr. Yancy says. “But that construct needs to reflect the recommended, guideline-driven interventions for the concomitant other comorbidities.”

7) Inotropic agents can do more harm than good.

For patients who aren’t in cardiogenic shock, using inotropic agents doesn’t help. In fact, it might actually hurt. Dr. Fonarow says studies have shown these agents can “prolong length of stay, cause complications, and increase mortality risk.”

He notes that the use of inotropes should be avoided, or if it’s being considered, a cardiologist with knowledge and experience in heart failure should be involved in the treatment and care.

Statements about avoiding inotropes in heart failure, except under very specific circumstances, have been “incredibly strengthened” recently in the American College of Cardiology and Heart Failure Society of America guidelines.3

8) Pay attention to the ins and outs of new antiplatelet therapies.

—John Harold, MD, president-elect, American College of Cardiology, former chief of staff, department of medicine, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles

Hospitalists caring for acute coronary syndrome patients need to familiarize themselves with updated guidelines and additional therapies that are now available, Dr. Fonarow says. New antiplatelet therapies (e.g. prasugrel and ticagrelor) are available as part of the armamentarium, along with the mainstay clopidogrel.

“These therapies lower the risk of recurrent events, lowered the risk of stent thrombosis,” he says. “In the case of ticagrelor, it actually lowered all-cause mortality. These are important new therapies, with new guideline recommendations, that all hospitalists should be aware of.”

9) Bridging anticoagulant therapy in patients going for electrophysiology procedures should be done only some, not most, of the time.

“Patients getting such devices as pacemakers or implantable cardioverter defribrillators (ICD) installed tend not to need bridging,” says Joaquin Cigarroa, MD, clinical chief of cardiology at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland.

He says it’s actually “safer” to do the procedure when patients “are on oral antithrombotics than switching them from an oral agent, and bridging with low- molecular-weight- or unfractionated heparin.”

“It’s a big deal,” Dr. Cigarroa adds, because it is risky to have elderly and frail patients on multiple antithrombotics. “Hemorrhagic complications in cardiology patients still occurs very frequently, so really be attuned to estimating bleeding risk and making sure that we’re dosing antithrombotics appropriately. Bridging should be the minority of patients, not the majority of patients.”

10) Some non-STEMI patients might benefit from getting to the catheterization lab quickly.

Door-to-balloon time is recognized as critical for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients, but more recent work—such as in the TIMACS trial—finds benefits of early revascularization for some non-STEMI patients as well.2

“This trial showed that among higher-risk patients, using a validated risk score, that those patients did benefit from an early approach, meaning going to the cath lab in the first 12 hours of hospitalization,” Dr. Fonarow says. “We now have more information about the optimal timing of coronary angiography and potential revascularization of higher-risk patients with non-ST-segment elevation MI.”

11) Beware the idiosyncrasies of new anticoagulants.

The introduction of dabigatran and rivaroxaban (and, perhaps soon, apixaban) to the array of anticoagulant therapies brings a new slate of considerations for hospitalists, Dr. Harold says.

“For the majority of these, there’s no specific way to reverse the anticoagulant effect in the event of a major bleeding event,” he says. “There’s no simple antidote. And the effect can last up to 12 to 24 hours, depending on the renal function. This is what the hospitalist will be called to deal with: bleeding complications in patients who have these newer anticoagulants on board.”

Dr. Fonarow says that the new CHA2DS2-VASc score has been found to do a better job than the traditional CHADS2 score in assessing afib stroke risk.4

12) Be cognizant of stent thrombosis and how to manage it.

Dr. Harold says that most hospitalists probably are up to date on drug-eluting stents and the risk of stopping dual antiplatelet therapy within several months of implant, but that doesn’t mean they won’t treat patients whose primary-care physicians (PCPs) aren’t up to date. He recommends working on these cases with hematologists.

“That knowledge is not widespread in terms of the internal-medicine community,” he says. “I’ve seen situations where patients have had their Plavix stopped for colonoscopies and they’ve had stent thrombosis. It’s this knowledge of cardiac patients who come in with recent deployment of drug-eluting stents who may end up having other issues.”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida.

References

- 2009 Focused Update: ACCF/AHA Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in Adults. Circulation. 2009;119:1977-2016 an HFSA 2010 Comprehensive Heart Failure Practice Guideline. J Cardiac Failure. 2010;16(6):475-539.

- Gorodeski EZ, Starling RC, Blackstone EH. Are all readmissions bad readmissions? N Engl J Med. 2010;363:297-298.

- Mehta SR, Granger CB, Boden WE, et al. Early versus delayed invasive intervention in acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(21):2165-2175.

- Olesen JB, Torp-Pedersen C, Hansen ML, Lip GY. The value of the CHA2DS2-VASc score for refining stroke risk stratification in patients with atrial fibrillation with a CHADS2 score 0-1: a nationwide cohort study. Thromb Haemost. 2012;107(6):1172-1179.

- Associations between outpatient heart failure process-of-care measures and mortality. Circulation. 2011;123(15):1601-1610.

Only about a third of ideal candidates with heart failure are currently treated with [aldosterone antagonists], even though it markedly improves outcome and is Class I-recommended in the guidelines.

—Gregg Fonarow, MD, co-chief, University of California at Los Angeles division of cardiology, chair, American Heart Association’s Get With The Guidelines program steering committee

You might not have done a fellowship in cardiology, but quite often you probably feel like a cardiologist. Hospitalists frequently attend to patients on observation for heart problems and help manage even the most complex patients.

Often, you are working alongside the cardiologist. But other times, you’re on your own. Hospitalists are expected to carry an increasingly heavy load when it comes to heart-failure patients and many other kinds of patients with specialized disorders. It can be hard to keep up with what you need to know.

Top Twelve

- Recognize the new importance of beta-blockers for heart failure, and go with the best of them.

- It’s not readmissions that are the problem—it’s avoidable readmissions.

- New interventional technologies will mean more complex patients, so be ready.

- Aldosterone antagonists, though probably underutilized, can be very effective but require caution.

- Switching from IV diuretics to an oral regimen calls for careful monitoring.

- Patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction have outcomes over the longer haul similar to those with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. And in preserved ejection fraction cases, the contributing illnesses must be addressed.

- Inotropic agents can do more harm than good.

- Pay attention to the ins and outs of new antiplatelet therapies.

- Bridging anticoagulant therapy in patients going for electrophysiology procedures should be done only some, not most, of the time.

- Some non-STEMI patients might benefit from getting to the catheterization lab quickly.

- Beware the idiosyncrasies of new anticoagulants.

- Be cognizant of stent thrombosis and how to manage it.

The Hospitalist spoke to several cardiologists about the latest in treatments, technologies, and HM’s role in the system of care. The following are their suggestions for what you really need to know about treating patients with heart conditions.

1) Recognize the new importance of beta-blockers for heart failure, and go with the best of them.

Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensive receptor blockers have been part of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS) core measures for heart failure for a long time, but beta-blockers at hospital discharge only recently have been added as American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/American Medical Association–Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement measures for heart failure.1

“For those with heart failure and reduced left ventricular ejection fraction, very old and outdated concepts would have talked about potentially holding the beta-blocker during hospitalization for heart failure—or not initiating until the patient was an outpatient,” says Gregg Fonarow, MD, co-chief of the University of California at Los Angeles’ division of cardiology and chair of the steering committee for the American Heart Association’s Get With The Guidelines program. “[But] the guidelines and evidence, and often performance measures, linked to them are now explicit about initiating or maintaining beta-blockers during the heart-failure hospitalization.”

Beta-blockers should be initiated as patients are stabilized before discharge. Dr. Fonarow suggests hospitalists use only one of the three evidence-based therapies: carvedilol, metoprolol succinate, or bisoprolol.

“Many physicians have been using metoprolol tartrate or atenolol in heart-failure patients,” Dr. Fonarow says. “These are not known to improve clinical outcomes. So here’s an example where the specific medication is absolutely, critically important.”

2) It’s not readmissions that are the problem—it’s avoidable readmissions.

“The modifier is very important,” says Clyde Yancy, MD, chief of the division of cardiology at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago. “Heart failure continues to be a problematic disease. Many patients now do really well, but some do not. Those patients are symptomatic and may require frequent hospitalizations for stabilization. We should not disallow or misdirect those patients who need inpatient care from receiving such because of an arbitrary incentive to reduce rehospitalizations out of fear of punitive financial damages. The unforeseen risks here are real.”

Dr. Yancy says studies based on CMS data have found that institutions with higher readmission rates have lower 30-day mortality rates.2 He cautions hospitalists to be “very thoughtful about an overzealous embrace of reducing all readmissions for heart failure.” Instead, the goal should be to limit the “avoidable readmissions.”

“And for the patient that clearly has advanced disease,” he says, “rather than triaging them away from the hospital, we really should be very respectful of their disease. Keep those patients where disease-modifying interventions can be deployed, and we can work to achieve the best possible outcome for those that have the most advanced disease.”

3) New interventional technologies will mean more complex patients, so be ready.

Advances in interventional procedures, including transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) and endoscopic mitral valve repair, will translate into a new population of highly complex patients. Many of these patients will be in their 80s or 90s.

“It’s a whole new paradigm shift of technology,” says John Harold, MD, president-elect of the American College of Cardiology and past chief of staff and department of medicine clinical chief of staff at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. “Very often, the hospitalist is at the front dealing with all of these issues.”

Many of these patients have other problems, including renal insufficiency, diabetes, and the like.

“They have all sorts of other things going on simultaneously, so very often the hospitalist becomes … the point person in dealing with all of these issues,” Dr. Harold says.

4) Aldosterone antagonists, though probably underutilized, can be very effective but require caution.

Aldosterone antagonists can greatly improve outcomes and reduce hospitalization in heart-failure patients, but they have to be used with very careful dosing and patient selection, Dr. Fonarow says. And they require early follow-up once patients are discharged.

“Only about a third of ideal candidates with heart failure are currently treated with this agent, even though it markedly improves outcome and is Class I-recommended in the guidelines,” Dr. Fonarow says. “But this is one where it needs to be started at appropriate low doses, with meticulous monitoring in both the inpatient and the outpatient setting, early follow-up, and early laboratory checks.”

5) Switching from IV diuretics to an oral regimen calls for careful monitoring.

Transitioning patients from IV diuretics to oral regimens is an area rife with mistakes, Dr. Fonarow says. It requires a lot of “meticulous attention to proper potassium supplementation and monitoring of renal function and electrolyte levels,” he says.

Medication reconciliation—“med rec”—is especially important during the transition from inpatient to outpatient.

“There are common medication errors that are made during this transition,” Dr. Fonarow says. “Hospitalists, along with other [care team] members, can really play a critically important role in trying to reduce that risk.”

6) Patients with heart failure with preserved ejection

fraction have outcomes over the longer haul similar to those with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. And in preserved ejection fraction cases, the contributing illnesses must be addressed.

“We really can’t exercise a thought economy that just says, ‘Extrapolate the evidence-based therapies for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction to heart failure with preserved ejection fraction’ and expect good outcomes,” Dr. Yancy says. “That’s not the case. We don’t have an evidence base to substantiate that.”

He says one or more common comorbidities (e.g. atrial fibrillation, hypertension, obesity, diabetes, renal insufficiency) are present in 90% of patients with preserved ejection fraction. Treatment of those comorbidities—for example, rate control in afib patients, lowering the blood pressure in hypertension patients—has to be done with care.

“We should recognize that the therapy for this condition, albeit absent any specifically indicated interventions that will change its natural history, can still be skillfully constructed,” Dr. Yancy says. “But that construct needs to reflect the recommended, guideline-driven interventions for the concomitant other comorbidities.”

7) Inotropic agents can do more harm than good.

For patients who aren’t in cardiogenic shock, using inotropic agents doesn’t help. In fact, it might actually hurt. Dr. Fonarow says studies have shown these agents can “prolong length of stay, cause complications, and increase mortality risk.”

He notes that the use of inotropes should be avoided, or if it’s being considered, a cardiologist with knowledge and experience in heart failure should be involved in the treatment and care.

Statements about avoiding inotropes in heart failure, except under very specific circumstances, have been “incredibly strengthened” recently in the American College of Cardiology and Heart Failure Society of America guidelines.3

8) Pay attention to the ins and outs of new antiplatelet therapies.

—John Harold, MD, president-elect, American College of Cardiology, former chief of staff, department of medicine, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles

Hospitalists caring for acute coronary syndrome patients need to familiarize themselves with updated guidelines and additional therapies that are now available, Dr. Fonarow says. New antiplatelet therapies (e.g. prasugrel and ticagrelor) are available as part of the armamentarium, along with the mainstay clopidogrel.

“These therapies lower the risk of recurrent events, lowered the risk of stent thrombosis,” he says. “In the case of ticagrelor, it actually lowered all-cause mortality. These are important new therapies, with new guideline recommendations, that all hospitalists should be aware of.”

9) Bridging anticoagulant therapy in patients going for electrophysiology procedures should be done only some, not most, of the time.

“Patients getting such devices as pacemakers or implantable cardioverter defribrillators (ICD) installed tend not to need bridging,” says Joaquin Cigarroa, MD, clinical chief of cardiology at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland.

He says it’s actually “safer” to do the procedure when patients “are on oral antithrombotics than switching them from an oral agent, and bridging with low- molecular-weight- or unfractionated heparin.”

“It’s a big deal,” Dr. Cigarroa adds, because it is risky to have elderly and frail patients on multiple antithrombotics. “Hemorrhagic complications in cardiology patients still occurs very frequently, so really be attuned to estimating bleeding risk and making sure that we’re dosing antithrombotics appropriately. Bridging should be the minority of patients, not the majority of patients.”

10) Some non-STEMI patients might benefit from getting to the catheterization lab quickly.

Door-to-balloon time is recognized as critical for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients, but more recent work—such as in the TIMACS trial—finds benefits of early revascularization for some non-STEMI patients as well.2

“This trial showed that among higher-risk patients, using a validated risk score, that those patients did benefit from an early approach, meaning going to the cath lab in the first 12 hours of hospitalization,” Dr. Fonarow says. “We now have more information about the optimal timing of coronary angiography and potential revascularization of higher-risk patients with non-ST-segment elevation MI.”

11) Beware the idiosyncrasies of new anticoagulants.

The introduction of dabigatran and rivaroxaban (and, perhaps soon, apixaban) to the array of anticoagulant therapies brings a new slate of considerations for hospitalists, Dr. Harold says.

“For the majority of these, there’s no specific way to reverse the anticoagulant effect in the event of a major bleeding event,” he says. “There’s no simple antidote. And the effect can last up to 12 to 24 hours, depending on the renal function. This is what the hospitalist will be called to deal with: bleeding complications in patients who have these newer anticoagulants on board.”

Dr. Fonarow says that the new CHA2DS2-VASc score has been found to do a better job than the traditional CHADS2 score in assessing afib stroke risk.4

12) Be cognizant of stent thrombosis and how to manage it.

Dr. Harold says that most hospitalists probably are up to date on drug-eluting stents and the risk of stopping dual antiplatelet therapy within several months of implant, but that doesn’t mean they won’t treat patients whose primary-care physicians (PCPs) aren’t up to date. He recommends working on these cases with hematologists.

“That knowledge is not widespread in terms of the internal-medicine community,” he says. “I’ve seen situations where patients have had their Plavix stopped for colonoscopies and they’ve had stent thrombosis. It’s this knowledge of cardiac patients who come in with recent deployment of drug-eluting stents who may end up having other issues.”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida.

References

- 2009 Focused Update: ACCF/AHA Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in Adults. Circulation. 2009;119:1977-2016 an HFSA 2010 Comprehensive Heart Failure Practice Guideline. J Cardiac Failure. 2010;16(6):475-539.

- Gorodeski EZ, Starling RC, Blackstone EH. Are all readmissions bad readmissions? N Engl J Med. 2010;363:297-298.

- Mehta SR, Granger CB, Boden WE, et al. Early versus delayed invasive intervention in acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(21):2165-2175.

- Olesen JB, Torp-Pedersen C, Hansen ML, Lip GY. The value of the CHA2DS2-VASc score for refining stroke risk stratification in patients with atrial fibrillation with a CHADS2 score 0-1: a nationwide cohort study. Thromb Haemost. 2012;107(6):1172-1179.

- Associations between outpatient heart failure process-of-care measures and mortality. Circulation. 2011;123(15):1601-1610.

Only about a third of ideal candidates with heart failure are currently treated with [aldosterone antagonists], even though it markedly improves outcome and is Class I-recommended in the guidelines.

—Gregg Fonarow, MD, co-chief, University of California at Los Angeles division of cardiology, chair, American Heart Association’s Get With The Guidelines program steering committee

You might not have done a fellowship in cardiology, but quite often you probably feel like a cardiologist. Hospitalists frequently attend to patients on observation for heart problems and help manage even the most complex patients.

Often, you are working alongside the cardiologist. But other times, you’re on your own. Hospitalists are expected to carry an increasingly heavy load when it comes to heart-failure patients and many other kinds of patients with specialized disorders. It can be hard to keep up with what you need to know.

Top Twelve

- Recognize the new importance of beta-blockers for heart failure, and go with the best of them.

- It’s not readmissions that are the problem—it’s avoidable readmissions.

- New interventional technologies will mean more complex patients, so be ready.

- Aldosterone antagonists, though probably underutilized, can be very effective but require caution.

- Switching from IV diuretics to an oral regimen calls for careful monitoring.

- Patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction have outcomes over the longer haul similar to those with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. And in preserved ejection fraction cases, the contributing illnesses must be addressed.

- Inotropic agents can do more harm than good.

- Pay attention to the ins and outs of new antiplatelet therapies.

- Bridging anticoagulant therapy in patients going for electrophysiology procedures should be done only some, not most, of the time.

- Some non-STEMI patients might benefit from getting to the catheterization lab quickly.

- Beware the idiosyncrasies of new anticoagulants.

- Be cognizant of stent thrombosis and how to manage it.

The Hospitalist spoke to several cardiologists about the latest in treatments, technologies, and HM’s role in the system of care. The following are their suggestions for what you really need to know about treating patients with heart conditions.

1) Recognize the new importance of beta-blockers for heart failure, and go with the best of them.

Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensive receptor blockers have been part of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS) core measures for heart failure for a long time, but beta-blockers at hospital discharge only recently have been added as American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/American Medical Association–Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement measures for heart failure.1

“For those with heart failure and reduced left ventricular ejection fraction, very old and outdated concepts would have talked about potentially holding the beta-blocker during hospitalization for heart failure—or not initiating until the patient was an outpatient,” says Gregg Fonarow, MD, co-chief of the University of California at Los Angeles’ division of cardiology and chair of the steering committee for the American Heart Association’s Get With The Guidelines program. “[But] the guidelines and evidence, and often performance measures, linked to them are now explicit about initiating or maintaining beta-blockers during the heart-failure hospitalization.”

Beta-blockers should be initiated as patients are stabilized before discharge. Dr. Fonarow suggests hospitalists use only one of the three evidence-based therapies: carvedilol, metoprolol succinate, or bisoprolol.

“Many physicians have been using metoprolol tartrate or atenolol in heart-failure patients,” Dr. Fonarow says. “These are not known to improve clinical outcomes. So here’s an example where the specific medication is absolutely, critically important.”

2) It’s not readmissions that are the problem—it’s avoidable readmissions.

“The modifier is very important,” says Clyde Yancy, MD, chief of the division of cardiology at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago. “Heart failure continues to be a problematic disease. Many patients now do really well, but some do not. Those patients are symptomatic and may require frequent hospitalizations for stabilization. We should not disallow or misdirect those patients who need inpatient care from receiving such because of an arbitrary incentive to reduce rehospitalizations out of fear of punitive financial damages. The unforeseen risks here are real.”

Dr. Yancy says studies based on CMS data have found that institutions with higher readmission rates have lower 30-day mortality rates.2 He cautions hospitalists to be “very thoughtful about an overzealous embrace of reducing all readmissions for heart failure.” Instead, the goal should be to limit the “avoidable readmissions.”

“And for the patient that clearly has advanced disease,” he says, “rather than triaging them away from the hospital, we really should be very respectful of their disease. Keep those patients where disease-modifying interventions can be deployed, and we can work to achieve the best possible outcome for those that have the most advanced disease.”

3) New interventional technologies will mean more complex patients, so be ready.

Advances in interventional procedures, including transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) and endoscopic mitral valve repair, will translate into a new population of highly complex patients. Many of these patients will be in their 80s or 90s.

“It’s a whole new paradigm shift of technology,” says John Harold, MD, president-elect of the American College of Cardiology and past chief of staff and department of medicine clinical chief of staff at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. “Very often, the hospitalist is at the front dealing with all of these issues.”

Many of these patients have other problems, including renal insufficiency, diabetes, and the like.

“They have all sorts of other things going on simultaneously, so very often the hospitalist becomes … the point person in dealing with all of these issues,” Dr. Harold says.

4) Aldosterone antagonists, though probably underutilized, can be very effective but require caution.

Aldosterone antagonists can greatly improve outcomes and reduce hospitalization in heart-failure patients, but they have to be used with very careful dosing and patient selection, Dr. Fonarow says. And they require early follow-up once patients are discharged.

“Only about a third of ideal candidates with heart failure are currently treated with this agent, even though it markedly improves outcome and is Class I-recommended in the guidelines,” Dr. Fonarow says. “But this is one where it needs to be started at appropriate low doses, with meticulous monitoring in both the inpatient and the outpatient setting, early follow-up, and early laboratory checks.”

5) Switching from IV diuretics to an oral regimen calls for careful monitoring.

Transitioning patients from IV diuretics to oral regimens is an area rife with mistakes, Dr. Fonarow says. It requires a lot of “meticulous attention to proper potassium supplementation and monitoring of renal function and electrolyte levels,” he says.

Medication reconciliation—“med rec”—is especially important during the transition from inpatient to outpatient.

“There are common medication errors that are made during this transition,” Dr. Fonarow says. “Hospitalists, along with other [care team] members, can really play a critically important role in trying to reduce that risk.”

6) Patients with heart failure with preserved ejection

fraction have outcomes over the longer haul similar to those with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. And in preserved ejection fraction cases, the contributing illnesses must be addressed.

“We really can’t exercise a thought economy that just says, ‘Extrapolate the evidence-based therapies for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction to heart failure with preserved ejection fraction’ and expect good outcomes,” Dr. Yancy says. “That’s not the case. We don’t have an evidence base to substantiate that.”

He says one or more common comorbidities (e.g. atrial fibrillation, hypertension, obesity, diabetes, renal insufficiency) are present in 90% of patients with preserved ejection fraction. Treatment of those comorbidities—for example, rate control in afib patients, lowering the blood pressure in hypertension patients—has to be done with care.

“We should recognize that the therapy for this condition, albeit absent any specifically indicated interventions that will change its natural history, can still be skillfully constructed,” Dr. Yancy says. “But that construct needs to reflect the recommended, guideline-driven interventions for the concomitant other comorbidities.”

7) Inotropic agents can do more harm than good.

For patients who aren’t in cardiogenic shock, using inotropic agents doesn’t help. In fact, it might actually hurt. Dr. Fonarow says studies have shown these agents can “prolong length of stay, cause complications, and increase mortality risk.”

He notes that the use of inotropes should be avoided, or if it’s being considered, a cardiologist with knowledge and experience in heart failure should be involved in the treatment and care.

Statements about avoiding inotropes in heart failure, except under very specific circumstances, have been “incredibly strengthened” recently in the American College of Cardiology and Heart Failure Society of America guidelines.3

8) Pay attention to the ins and outs of new antiplatelet therapies.

—John Harold, MD, president-elect, American College of Cardiology, former chief of staff, department of medicine, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles

Hospitalists caring for acute coronary syndrome patients need to familiarize themselves with updated guidelines and additional therapies that are now available, Dr. Fonarow says. New antiplatelet therapies (e.g. prasugrel and ticagrelor) are available as part of the armamentarium, along with the mainstay clopidogrel.

“These therapies lower the risk of recurrent events, lowered the risk of stent thrombosis,” he says. “In the case of ticagrelor, it actually lowered all-cause mortality. These are important new therapies, with new guideline recommendations, that all hospitalists should be aware of.”

9) Bridging anticoagulant therapy in patients going for electrophysiology procedures should be done only some, not most, of the time.

“Patients getting such devices as pacemakers or implantable cardioverter defribrillators (ICD) installed tend not to need bridging,” says Joaquin Cigarroa, MD, clinical chief of cardiology at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland.

He says it’s actually “safer” to do the procedure when patients “are on oral antithrombotics than switching them from an oral agent, and bridging with low- molecular-weight- or unfractionated heparin.”

“It’s a big deal,” Dr. Cigarroa adds, because it is risky to have elderly and frail patients on multiple antithrombotics. “Hemorrhagic complications in cardiology patients still occurs very frequently, so really be attuned to estimating bleeding risk and making sure that we’re dosing antithrombotics appropriately. Bridging should be the minority of patients, not the majority of patients.”

10) Some non-STEMI patients might benefit from getting to the catheterization lab quickly.

Door-to-balloon time is recognized as critical for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients, but more recent work—such as in the TIMACS trial—finds benefits of early revascularization for some non-STEMI patients as well.2

“This trial showed that among higher-risk patients, using a validated risk score, that those patients did benefit from an early approach, meaning going to the cath lab in the first 12 hours of hospitalization,” Dr. Fonarow says. “We now have more information about the optimal timing of coronary angiography and potential revascularization of higher-risk patients with non-ST-segment elevation MI.”

11) Beware the idiosyncrasies of new anticoagulants.

The introduction of dabigatran and rivaroxaban (and, perhaps soon, apixaban) to the array of anticoagulant therapies brings a new slate of considerations for hospitalists, Dr. Harold says.

“For the majority of these, there’s no specific way to reverse the anticoagulant effect in the event of a major bleeding event,” he says. “There’s no simple antidote. And the effect can last up to 12 to 24 hours, depending on the renal function. This is what the hospitalist will be called to deal with: bleeding complications in patients who have these newer anticoagulants on board.”

Dr. Fonarow says that the new CHA2DS2-VASc score has been found to do a better job than the traditional CHADS2 score in assessing afib stroke risk.4

12) Be cognizant of stent thrombosis and how to manage it.

Dr. Harold says that most hospitalists probably are up to date on drug-eluting stents and the risk of stopping dual antiplatelet therapy within several months of implant, but that doesn’t mean they won’t treat patients whose primary-care physicians (PCPs) aren’t up to date. He recommends working on these cases with hematologists.

“That knowledge is not widespread in terms of the internal-medicine community,” he says. “I’ve seen situations where patients have had their Plavix stopped for colonoscopies and they’ve had stent thrombosis. It’s this knowledge of cardiac patients who come in with recent deployment of drug-eluting stents who may end up having other issues.”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida.

References

- 2009 Focused Update: ACCF/AHA Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in Adults. Circulation. 2009;119:1977-2016 an HFSA 2010 Comprehensive Heart Failure Practice Guideline. J Cardiac Failure. 2010;16(6):475-539.

- Gorodeski EZ, Starling RC, Blackstone EH. Are all readmissions bad readmissions? N Engl J Med. 2010;363:297-298.

- Mehta SR, Granger CB, Boden WE, et al. Early versus delayed invasive intervention in acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(21):2165-2175.

- Olesen JB, Torp-Pedersen C, Hansen ML, Lip GY. The value of the CHA2DS2-VASc score for refining stroke risk stratification in patients with atrial fibrillation with a CHADS2 score 0-1: a nationwide cohort study. Thromb Haemost. 2012;107(6):1172-1179.

- Associations between outpatient heart failure process-of-care measures and mortality. Circulation. 2011;123(15):1601-1610.

Follow-Up Appointments Essential for Heart Failure Patients

When heart-failure patients have follow-up appointments with their outpatient doctors, outcomes are good, Dr. Fonarow says. However, they are not done nearly enough.

“Early follow-up is essential,” he says. “Follow-up within seven days—in higher-risk patients, even earlier, within three days—is something that has been associated with a lower risk of rehospitalization.”

Despite the research, only about 30% to 40% of patients hospitalized with heart failure are seen by any outpatient provider in the first week post-discharge.

“We have a real opportunity there,” Dr. Fonarow says. “The inpatient physicians can play a really critical role in ensuring that there’s early and appropriate follow-up, and good communication and handoff to the outpatient physician.”

When heart-failure patients have follow-up appointments with their outpatient doctors, outcomes are good, Dr. Fonarow says. However, they are not done nearly enough.

“Early follow-up is essential,” he says. “Follow-up within seven days—in higher-risk patients, even earlier, within three days—is something that has been associated with a lower risk of rehospitalization.”

Despite the research, only about 30% to 40% of patients hospitalized with heart failure are seen by any outpatient provider in the first week post-discharge.

“We have a real opportunity there,” Dr. Fonarow says. “The inpatient physicians can play a really critical role in ensuring that there’s early and appropriate follow-up, and good communication and handoff to the outpatient physician.”

When heart-failure patients have follow-up appointments with their outpatient doctors, outcomes are good, Dr. Fonarow says. However, they are not done nearly enough.

“Early follow-up is essential,” he says. “Follow-up within seven days—in higher-risk patients, even earlier, within three days—is something that has been associated with a lower risk of rehospitalization.”

Despite the research, only about 30% to 40% of patients hospitalized with heart failure are seen by any outpatient provider in the first week post-discharge.

“We have a real opportunity there,” Dr. Fonarow says. “The inpatient physicians can play a really critical role in ensuring that there’s early and appropriate follow-up, and good communication and handoff to the outpatient physician.”

Managing the Customer Care Experience in Hospital Care

I needed an oil change, so I took my car to Jiffy Lube. I had just pulled into the entrance to one of the service bays when a smiling man whose nametag read “Tony” approached me. “Welcome back, Mr. Wellikson. What can we help you with today?” Well, that was nice and so unexpected, as I had not remembered ever going to that Jiffy Lube. As it turns out, they have a video camera that shows incoming cars in their control room. They can read my license plate and call up my car on their computer system, access my record, and create a personal greeting. They also used my car’s past history as a starting point for this encounter. We were off to a good start.

Once I indicated I just wanted a routine oil change, Tony indicated he would be back in five to 10 minutes. He told me I should wait in the waiting room where they had wireless Internet, TV, magazines, and comfortable chairs.

In less than 10 minutes, Tony was back, clipboard in hand, with an assessment of my car’s status, including previous work and manufacturer’s recommendations, based on my car’s age and mileage. Once we negotiated not replacing all of the fluids and filters, Tony smiled and said the work should be completed in 10 minutes.

Soon, Tony came back to lead me out to my car, which had been wheeled out to the front of the garage bay with an open driver’s door waiting for me. After helping me into my seat, Tony came around and sat in the passenger seat and, once again with his ready clipboard, walked me through the 29 steps of inspections and fluid changes that had been made on my visit, reviewed the frequency of future needs for my vehicle, put a sticker on my inside windshield as a reminder, included $5 off for my next service, then patiently asked me if I had any questions.

Total time at Jiffy Lube: less than 30 minutes. Total cost: $29.99. Total customer experience: exceptional. Considering it was the third Jiffy Lube location I had used in the past three years, I can tell you the experience and system is the same throughout the company, whether the uniform name is Tony or Jose or Gladys.

Can such experiences offer hospitalists lessons about how we manage the customer experience in hospital care?

Scalable Innovation

In August 2012, Atul Gawande, MD, wrote a thought-provoking article in The New Yorker in which he coupled his detailed observation of how the restaurant chain The Cheesecake Factory manages to deliver 8 million meals annually nationwide with high quality at a reasonable cost and strong corporate profits with the emerging trend of healthcare delivery innovations being sought by large hospital chains and such innovations as ICU telemedicine.1