User login

Educational Impact of Smartphones

Medical residents are rapidly adopting smartphones. Recent statistics revealed that 85% of medical providers currently own a smartphone, and the majority use it in their clinical work.[1] Smartphone capabilities that include the use of text messaging, e‐mail, and mobile phone functions in the clinical setting may improve efficiency and quality of care by reducing the response time for urgent issues.[2] There is, however, increasing recognition that healthcare information technology can create unintended negative consequences. For example, studies have suggested that healthcare information technologies, such as the computerized physician order entry, may actually increase errors by creating new work, changing clinical workflow, and altering communication patterns.[3, 4, 5]

Smartphone use for clinical communication can have unintended consequences by increasing interruptions, reducing interprofessional relationships, and widening the gap between what nurses and physicians perceive as urgent clinical problems.[6] However, no studies have evaluated the impact of smartphones on the educational experience of medical trainees. Although previous studies have described the use of smartphones by trainees for rapid access to electronic medical resources,[7, 8, 9] we did not identify in our literature review any previous studies on the impact of using the smartphone's primary functionas a communication deviceon the educational experience of residents and medical students. Therefore, our study aimed to examine the impact of using smartphones for clinical communication on medical education.

METHODS

Design

The design of the study was qualitative research methodology using interview data, ethnographic data, and content analysis of text‐based messages.

Setting

From June 2009 to September 2010, we conducted a multisite evaluation study on general internal medicine (GIM) wards at 5 large academic teaching hospitals in the city of Toronto, Canada at St. Michael's Hospital, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Toronto General Hospital, Toronto Western Hospital, and Mount Sinai Hospital. Each hospital has clinical teaching units consisting typically of 4 medical teams. Each team includes 1 attending physician, 1 senior resident, 2 or more junior residents, and 2 to 4 medical students. Each hospital had 2 to 4 GIM wards in different geographic locations.

Communication Systems

To make it easier for nurses and other health professionals to communicate with the physician teams, all sites centralized communication to 1 team member, who acts as the single point of contact on behalf of their assigned team in the communication of patient‐related issues. We facilitated this communication through a shared device (either a pager or a smartphone). The senior resident typically carried the shared device during the day and the on‐call junior resident at night and on the weekends. Two hospitals provided smartphones to all residents, whereas a third site provided smartphones only to the senior residents. The standard processes of communication required that physicians respond to all calls and text messages. At the 3 sites with institutional smartphones, nurses could send text messages with patient information using a Web‐based system. We encrypted data sent to institutional smartphones to protect patient information.

Data Collection

Using a mixed‐methods ethnographic approach, we collected data using semistructured interviews, ethnographic observations, and content analysis of text messages. The original larger study focused primarily on examining the overall clinical impact of smartphone use.[10] For our current study, we analyzed the data with a focus on evaluating the impact of smartphones on the educational experience of medical trainees on the GIM teaching service. The respective institutions' research ethics boards approved the study.

Interviews

We conducted semistructured interviews with residents, medical students, attending physicians, and other clinicians across all of the sites to examine how clinicians perceived the impact of smartphones on medical education. We used a purposeful sampling strategy where we interviewed different groups of healthcare professionals who we suspected would represent different viewpoints on the use of smartphones for clinical communication. To obtain diverse perspectives, we snowball sampled by asking interviewees to suggest colleagues with differing views to participate in the interviews. The interview guide consisted of open‐ended questions with additional probes to elicit more detailed information from these frontline clinicians who initiate and receive communication. One of the study investigators (V.L.) conducted interviews that varied from 15 to 45 minutes in duration. We recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed the interviews using NVivo software (QSR International, Doncaster, Victoria, Australia). We added additional questions iteratively as themes emerged from the initial interviews. One of the study investigators (V.L.) encouraged participants to speak freely, to raise issues that they perceived to be important, and to support their responses with examples.

Observations

We observed the communication processes in the hospitals by conducting a work‐shadowing approach that followed individual residents in their work environments. These observations included 1‐on‐1 supervision encounters involving attending staff, medical students, and other residents, and informal and formal teaching rounds. The observation periods included the usual working day (from 8 am to 6 pm) as well as the busiest times on call, typically from 6 pm until 11 pm. We sampled different residents for different time periods. We adopted a nonparticipatory observation technique where we observed all interruptions, communication interactions, and patterns from a distance. We defined workflow interruptions as an intrusion of an unplanned and unscheduled task, causing a discontinuation of tasks, a noticeable break, or task switch behaviour.[11] Data collection included timing of events and writing field notes. One of the study investigators (V.L.) performed all the work‐shadowing observations.

E‐mail

To study the volume and content of messages, we collected e‐mail communications between January 2009 and June 2009 from consenting residents at the 2 hospitals that provided smartphones to all GIM residents. E‐mail information included the sender, the receiver, the time of message, and the message content. To look at usage, we calculated the average number of e‐mails sent and received. To assess interruptions on formal teaching sessions, we paid particular attention to e‐mails received and sent during protected educational timeweekdays from 8 am to 9 am (morning report) and 12 pm to 1 pm (noon rounds). We randomly sampled 20% of all e‐mails sent between residents for content analysis and organized content related to medical education into thematic categories.

Analysis

We used a deductive approach to analyze the interview transcripts by applying a conceptual framework that assessed the educational impact of patient safety interventions.[12] This framework identified 5 educational domains (learning, teaching, supervision, assessment, and feedback). Three study investigators mapped interview data, work‐shadowing data, and e‐mail content to themes (V.L., B.W., and R.W.), and grouped data that did not translate into themes into new categories. We then triangulated the data to develop themes of the educational impact of smartphone communication by both perceived use and actual use, and subsequently constructed a framework of how smartphone communication affected education.

RESULTS

We conducted 124 semistructured interviews with residents, medical students, attending physicians, and other clinicians across all the sites to examine how clinicians perceived the impact of smartphones on medical education. We work‐shadowed 40 individual residents for a total of 196 hours (Table 1). We analyzed the 13,714 e‐mails sent from or received to 34 residents. To analyze e‐mail content, we reviewed 1179 e‐mails sent among residents.

| Methods | Sites | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| St. Michael's Hospital | Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Toronto General Hospital | Toronto Western Hospital | Mount Sinai Hospital | All Hospitals | |

| ||||||

| Work‐shadowing residents | ||||||

| Hours | 60 hours | 35 hours | 57 hours 55 minutes | 27 hours 46 minutes | 15 hours | 196 hours |

| No. of residents | 12 | 7 | 12 | 6 | 3 | 40 |

| Interviews with clinicians | ||||||

| Physicians | 10 | 5 | 13 | 5 | 33 | |

| Medical students | 5 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 11 | |

| Nurses | 9 | 11 | 15 | 14 | 49 | |

| Other health professionsa | 7 | 10 | 8 | 6 | 31 | |

| Total | 31 | 30 | 37 | 26 | 124 | |

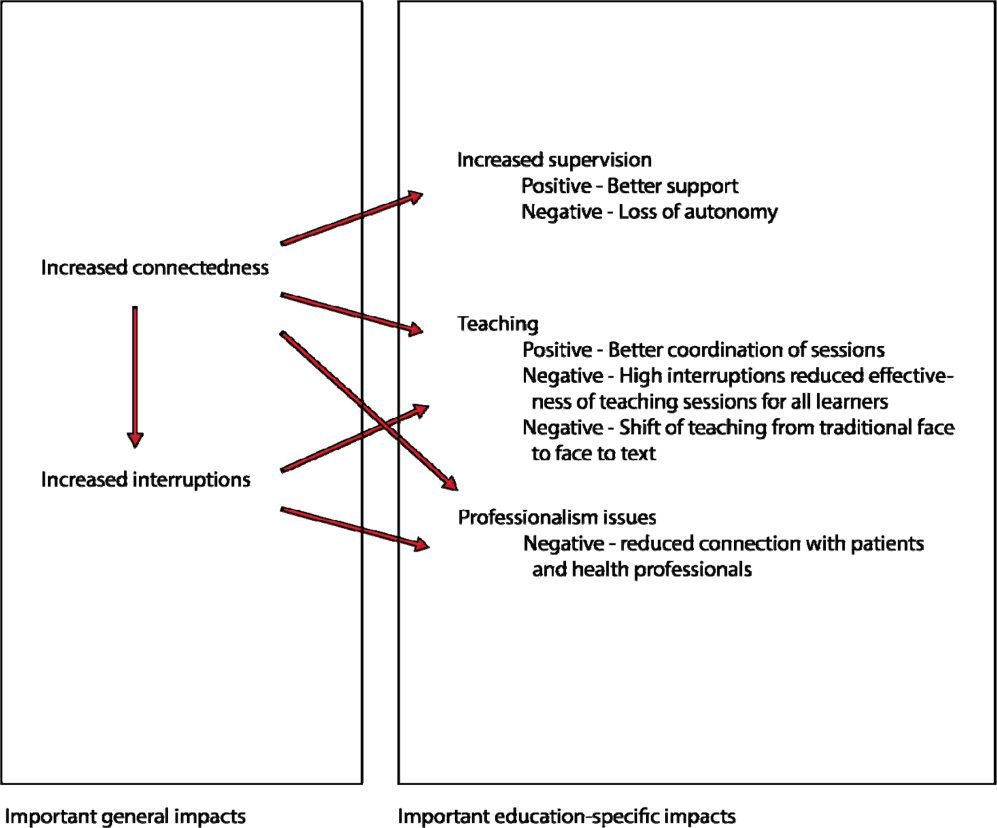

We found that 2 key characteristics of smartphone use for clinical communication, namely an increase in connectedness leading to an increase in interruptions, impacted 3 educational domains: teaching, supervision, and professionalism (Figure 1).

Increased Connectedness

As a communication device, smartphones increase the ability to receive and respond to messages through voice, e‐mail, and text messaging. Not surprisingly, with the improved ability and mobility to communicate, medical trainees perceived being more connected with their team members, who included other residents, medical students, and attending staff as well as with other clinical services and professions. These smartphone communication activities appeared to be pervasive, occurring on the wards, at the bedside, while in transit, and in teaching sessions (Box 1: increased connectedness).

Box

Increased connectedness

I've used the Blackberry system and it's nice to be able to quickly text each other little messages especially for meeting times because then you don't have to page them and wait by the phone. So that's been great for in the team. (Interview Resident 3)

It's incredibly useful for when you're paging somebody else. Often times I'll be consulting with another physician on a patient and I'll say This is my BlackBerry. Call me back after you've seen the patient' or Call me back when you have a plan' or, you know, whatever. So that's extremely valuable which we never had with pages and no one would ever page you for that because it was too much of a pain. (Interview Resident 1)

My personal experience has been that if you need to speak to a more senior individual it's much easier to contact them via the BlackBerry. (Interview Medical Student 1)

At 7:25 pm, MD11 returns to the patient's room and continues examining her. While in the patient's room, I could see her talking on the BlackBerrys. I asked her later what calls she had while in the room. It turns out she had 3 phone calls and 2 texts. Two of the calls were from the radiation oncologists and 1 call from the pathologist. She also received 1 text on the Team BlackBerry and 1 text on the Senior's BlackBerry from the pharmacist. (Field Notes, Work-shadowing MD11)

Interruptions

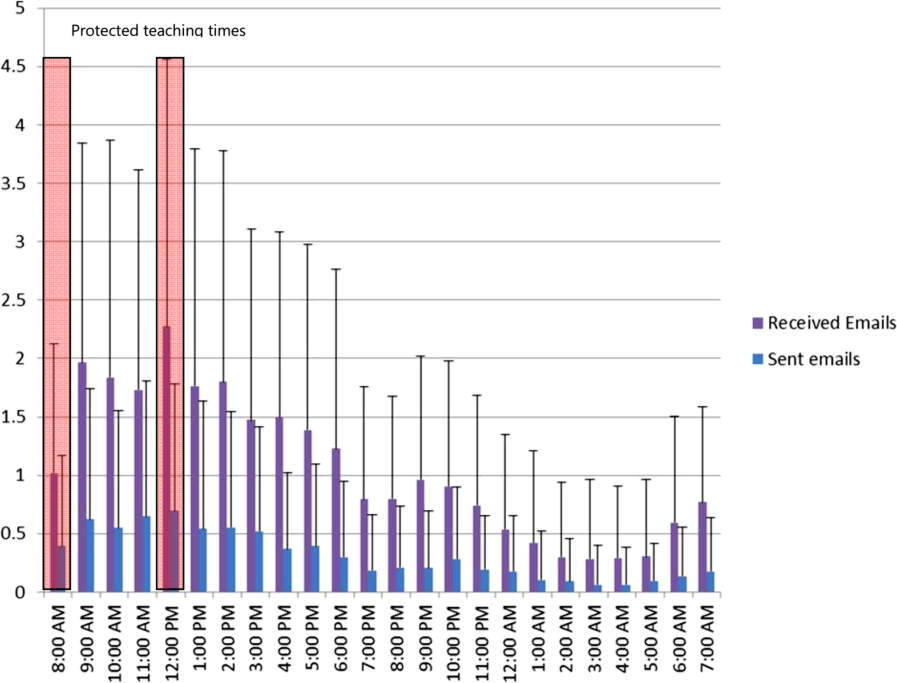

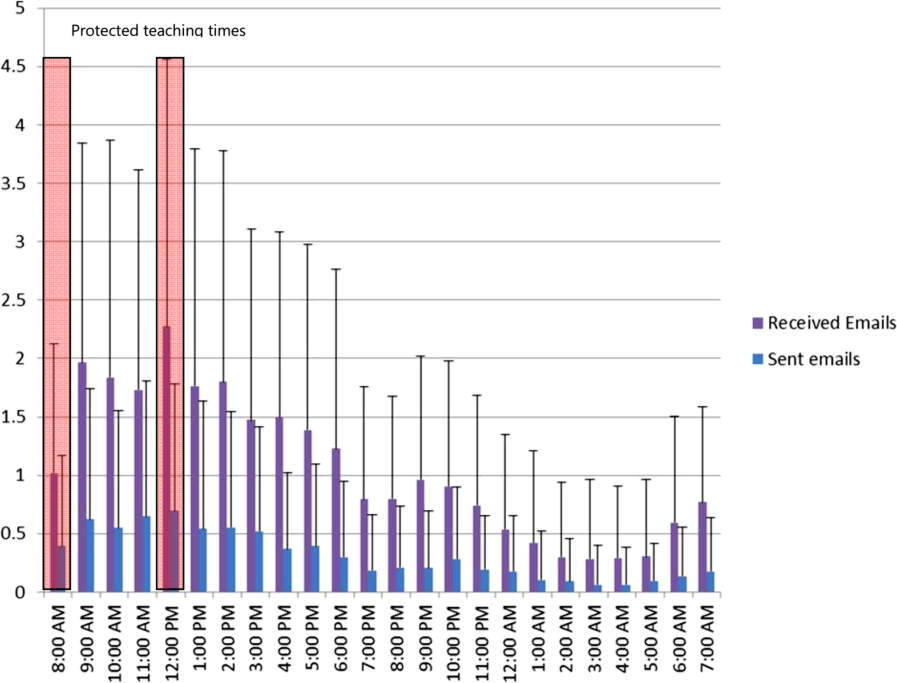

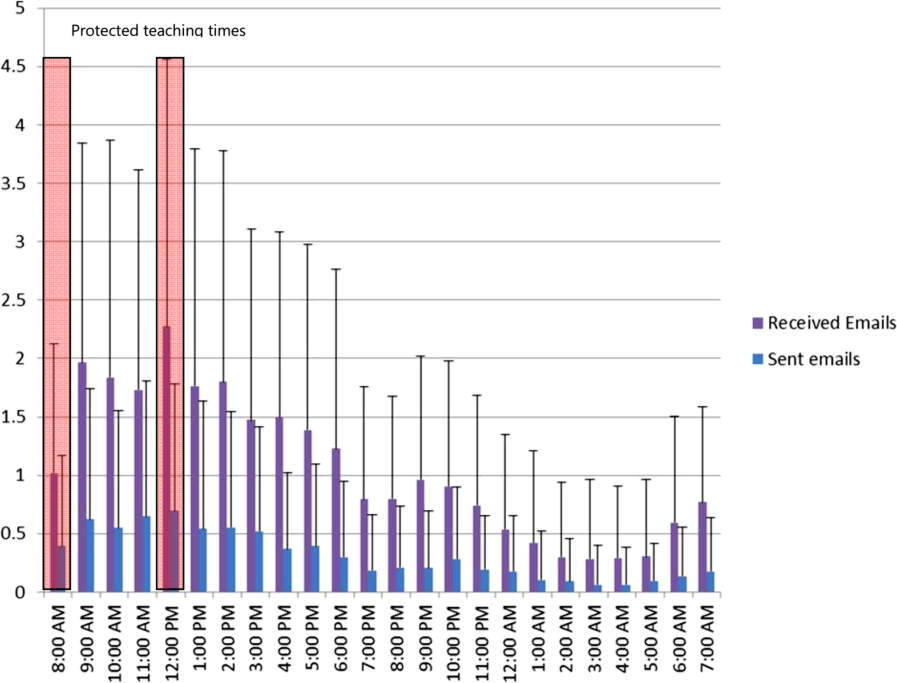

The increased connectedness caused by smartphone use led residents to perceive an increase in the frequency of interruptions. The multitude of communication and contact options made available by smartphones to health providers created an expansive network of connected individuals who were in constant communication with each other. Instead of the difficulties associated with numeric paging and waiting for a response, nurses typically found it easier to call directly or send a text message to residents' smartphones. From the e‐mail analysis, residents received, on a daily basis, on average 25.7 e‐mails, (median, 20; interquartile range [IQR]: 1428) to the team smartphone and sent 7.5 e‐mails (median, 6; IQR: 410). During protected educational time, each resident received an average of 1.0 e‐mail (median, 1; IQR: 01) between 8 am and 9 am and an average of 2.3 e‐mails (median, 2; IQR: 13) during 12 pm to 1 pm (Figure 2). Each of these communication events, whether a phone call, e‐mail, or text‐message, led to an interruption (Box 2). Given that smartphones made it easier for nurses to contact residents, some residents attributed the increase in interruptions to a reduction in the threshold for nurses to communicate.

Box

Increased interruptions

The only negative I can think of is just the incredible number of communications that you get, you know, text messages and e‐mails and everything else. So just the, the number can sometimes be overwhelming. (Interview Resident 1)

Some of [the nurses] rely a little bit more on the BlackBerry so that they will tend to call you a bit more frequently for things that maybe sometimes they should try to find answer for themselves (Interview Resident 2)

And now with the option of being able to, if you really needed to, call them and talk to them directly, I think that kind of improves communication. They're easier to find. (Interview Nurse 4)

Supervision

Smartphone communication appeared to positively impact trainee supervision. Increased connectedness between team members allowed junior trainees to have access and rapidly communicate with a more experienced clinician, which provided them with greater support. Residents found smartphones particularly useful in situations where they felt uncomfortable or where they did not feel competent. Some of these instances related to procedural competence, with residents feeling more comfortable knowing they have rapid access to support (Box 3: increased support).

Box

Supervision

Increased support

It makes me feel more comfortable in the sense that I can instantly make a call or a text and have a question answered if I need an answer. Or if it were an emergency having the ability to talk on the phone and be talked through an emergency situation, or a procedure for example like if you were in a remote area or the physician was in a remote area and you were in hospital and you would need some of that guidance or counselling, there's no substitution. (Interview Medical Student 1)

I'm ready can u dblchk [sic] that I landmarked correctly. (Email from Junior to Senior)

MD3 returns to the patient's room to do a paracentesis with [junior resident]. He calls on his BB to [senior resident] to inform her that they are starting and then hangs up. [Senior resident] arrives at the patient's room. (Field Notes, Workshadowing MD3)

Decreased autonomy

The difference with the Blackberry is they're more likely to say By the way, this happened. Should I do this?' And I write back Yes', No.' If they didn't have that contact like I said they probably would have done something and then because they're making a decision on their own they could very easily have spent the time to research whatever to figure whether that was the right thing to do before doing it. Now they have an outlet where they can pass an idea off of me and then have me make, it's easier for me to make a decision for them. So that can negatively impact education. (Interview Attending 1)

What do I do for a high phosphate?(Email from Junior to Senior)

Hey Pt X's k is 5.5. Was going to shift her. What do u think? (Email from Junior to Senior)

You probably saw the hb 92. Let's give prbc asap while he's on HD.(Email from Staff to Residents on the team)

hb‐ hemoglobin, prbc packed red blood cells, HD ‐ hemodialysis

Hi. Just checking the bloodwork. What is happening to ms X? [sic] Creatinine rising still. Is a foley in? Urology reconsulted? (Email from Attending Staff to Junior Resident)

On the other hand, supervisors perceived that the easy rapid access afforded by smartphone use lowered the threshold for trainees to contact them. In some instances, these attending physicians felt that their trainees would text them for advice when they could have looked up the information themselves. As a result, the increased reliance on the attending physician's input prior to committing to a management plan decreased the trainee's autonomy and independent decision making (Box 3: decreased autonomy). In addition to trainee requests for increased staff involvement, smartphone use made it easier for attending physicians to initiate text messages to their residents as well. In some instances, staff physicians adopted a more hands‐on approach by directing their residents on how to manage their patients. It is unclear if trainees perceived this taking over of care as negatively influencing their education.

Teaching

Medical teams also frequently used smartphones to communicate the location and timing of educational rounds. We observed instances where residents communicated updated information relating to scheduled rounds, as well as for informing team members about spontaneous teaching sessions (Box 4: communicating rounds). Despite this initial benefit, staff physicians worried that interruptions resulting from smartphone use during educational sessions lowered the effectiveness of these sessions for all learners by creating a fragmented learning experience (Box 4: fragmented learning). Our data indicated that residents carrying the team smartphones received and sent a high number of e‐mails throughout the day, which continued at a similar rate during the protected educational time (Figure 2). Additionally, some of the teaching experiences that traditionally would occur in a face‐to‐face manner appeared to have migrated to text‐based interactions. It is unclear whether trainees perceive these text‐based interactions as more or less effective teaching encounters (Box 4: text‐based teaching).

Box

Teaching

Communicating rounds

One is that they can more efficiently communicate about the timing and location of education rounds in case they forget or sort of as an organizer for them (Interview Attending 3)

Physical Exam rounds is at 1:00 outside the morning report room. K. has kindly volunteered! If you miss us then the exam will be on the 3rd floor in room X. Pt X. See you there (Email from chief medical resident to trainees)

Fragmented learning

Because Blackberry is there, it's something that is potentially time occupying and can take the attention away from things and this is true of any Blackberries. People who have Blackberries they always look at their Blackberries so, you know, there are times when I'm sitting face to face with people and residents are looking at their Blackberries. So it's another way that they can be distracted. (Interview Attending 1).

I've seen that be an issue. I've certainly seen them losing concentration during a teaching session because they're being Blackberried, getting Blackberry messages. (Interview Attending 3)

2:06 Team meeting with Attending in a conference room.

2:29 Team BlackBerry (BB) beeps. Senior glances at BB. She dials a number on the Team BB. Speaks on the Team BB and turns to [Junior resident] to inform her that the family is here. She returns to the caller. Senior then hangs up and resumes to her teaching.

2:35 Attending's BB rings. She takes a look and ends the BB call.

2:39 Senior's BB rings. Senior picks up and talks about a patient's case and condition. Senior turns to [junior resident] and asks a question. Team members resume talking among themselves.

2:46 Senior hangs up on the phone call.

2:49 Team discusses another patient's condition/case.

2:57 Junior resident uses her BB to text.

3:02 Team BB beeps. It is a message about a patient's case.

3:05 Meeting ends. (Field Note excerpts, Work‐shadowing MD6)

Text‐based teaching

The resident would get very frustrated with how many questions we have once we've started. Like if three different medical students or four different medical students or four different places all texting him with, oh by the way, what does this stand for?, and he's responding to each of them individually then he has to answer it four different times as opposed to just in person when he can get us all together in a group and it's actually a learning experience. If questions are answered in an email, it's not really helpful for the rest of us. (Interview, medical student SB1)

That would be a great unifying diagnosis, but there may be some underlying element of ROH/NASH also I would hold off on A/C as we do not know if he has varices. Will need to review noncontrast CT ?HCC. Thx (Email from Consulting Staff to Junior)

A/C anticoagulation, CT computed tomography, HCC‐ hepatocellular carcinoma, NASH non‐alcoholic steatohepatitis, ROH alcohol

Professionalism

Our data revealed that smartphone interruptions occurred during teaching rounds and interactions with patients and with other clinical staff. Often these interruptions involved messages or phone calls pertaining to clinical concerns or tasks that nurses communicated to the residents via their smartphone (Box 5). Yet, by responding to these interruptions and initiating communications on their smartphones during patient care encounters and formal teaching sessions, trainees were perceived by other clinicians who were in attendance with them as being rude or disrespectful. Attending staff also tended to role model similar smartphone behaviors. Although we did not specifically work‐shadow attending staff, we did observe frequent usage of their personal smartphones during their interactions with residents.

Box

Professionalism

I don't like it when I see them checking messages when you're trying to talk to them. I think you're losing some of that communication sort of polite behaviour that maybe we knew a little bit more before all this texting and Blackberry. (Interview Allied Health 5)

I think that the etiquette of the Blackberry can be offensive, could be offensive especially with some of our older patients (Interview Allied Health 6)

Senior walks out of the patient's room while typing on the BlackBerry. She finishes typing and returns to the room at 5:36. Senior looks at her BlackBerry and starts typing inside the room in front of the patient. She paused to look at the patient and the resident doing the procedure [paracentesis]. She resumes texting again and walks out of the room at 5:38. Another resident walks out and Senior speaks with the resident. Senior returns to the room and speaks with the patient. She asks the patient if he has ever gotten a successful tap before. Senior looks at her BlackBerry and starts typing. (Field NotesWork‐shadowing MD2)

I think it is almost completely negative in terms of its medical education [Any positive] factors are grossly outweighed by the significant disruptions to their ability to concentrate and participate in the educational session. And I think almost to some extent it's an implicit permission that gets granted to the house staff to disrupt their own teaching experience and disrupt others around them because everybody is doing it because everybody is being Blackberried. So it almost becomes the new social norm and while that may be a new social norm I'm not sure that that's a good thing How big is the negative impact? That's much harder to say. It's probably not a big impact on top of the endless other disruptions in the day to teaching, but it is measurable because it's a new factor so it's observable by me on top of all the other factors which have been there for years. (Interview Attending 3)

2:10‐Attending goes to the whiteboard to teach research methods to the team. Spotted Medical student#1 looking at his IPhone and typing.

2:15‐Med student#1 using the calculator function on his IPhone.

2:20‐Attending glances at his BB quickly.

2:28‐Attending resumes discussion of the patients' cases (Field notes, Work‐shadowing MD7).

DISCUSSION

The educational impacts of smartphone use for communication appear to center on increased connectedness of medical trainees and increased interruptions, which have positive and negative impacts in the areas of teaching, supervision, and professionalism. Smartphone communication provided potential educational benefits through (1) safer supervision with rapid access to help and (2) easier coordination of teaching sessions. Threats to the educational experience included (1) a high level of interruptions to both teachers and learners, which may reduce the effectiveness of formal and informal teaching; (2) replacement of face‐to‐face teaching with texting; (3) a potential erosion of autonomy and independence due to easy access to supervisors and easy ability for supervisors to take over; and (4) professionalism issues with difficulties balancing between clinical service demands and communication during patient and interprofessional encounters.

This study is the first to describe the intersection of clinical communication with smartphones and medical education. A recent study found that residents reported high use of smartphones during rounds for patient care as well as personal issues.[13] We have previously described the perceived impacts of smartphones on clinical communication, which included improved efficiency but concerns for increased interruptions and threats to professionalism.[6] We also observed that sites that used smartphones had increased interruptions compared to those with just pagers.[10] We have also described the content of e‐mail messages between clinicians and found that all e‐mails from nurses to physicians involved clinical care, but e‐mail exchanges between physicians were split between clinical care (60.4%), coordination within the team (53.5%), medical education (9.4%), and social communication (3.9%).[14] This study adds to the literature by focusing on the impacts of smartphone use to medical education and describing the perceived and observed impacts. This study provides a further example of how healthcare information technology can cause unintended consequences on medical education and appear to relate to the linked impacts of increased connectivity and the increased interruptions.[3] In essence, the trainee becomes more global, less local. Being more global translates to increased connections with people separated in physical space. Yet, this increased global connectedness resulted in the trainee being less local, with attention diverted elsewhere, taking away from the quality of patient interactions and interactions with other interprofessional team members. It also reduces the effectiveness of educational sessions for all participants. Although the level of supervision and autonomy are independently related, being too connected to supervisors may lower trainee autonomy by reducing independent thinking around patient issues.[15] It may also move teaching and learning from face‐to‐face conversations to text‐based messages. Although there have been existing tensions between service delivery and medical education, increased connectedness may tilt the balance toward the demands of service delivery and efficiency optimization at the expense of the educational experience. Finally, smartphone use appeared to create an internal tension among trainees, who have to juggle balancing professional behaviors and expectations in their dual role as learner and care provider; it would be educationally unprofessional to interrupt a teaching session and respond to a text message. However, failing to respond to a nurse who has sent a message and is expecting a response would be clinically unprofessional.

To address these threats, we advocate improving systems and processes to reduce interruptions and provide education on the tensions created by increased connectedness. Smarter communication systems could limit interrupting messages to urgent messages and queue nonurgent messages.[16] They could also inform senders about protected educational time. Even more sophisticated systems could inform the sender on the status of the receiver. For example, systems could indicate if they are available or if they are busy in an educational session or an important meeting with a patient and their family. Processes to reduce interruptions include interprofessional consensus on what constitutes an urgent issue and giving explicit permission to learners to ignore their smartphones during educational sessions except for critical communications purposes. Finally, education around smartphone communication for both learners and teachers may help minimize threats to learner autonomy, to face‐to‐face teaching, and to professionalism.[17]

Our study has several limitations. We derived this information from a general study of the impact of smartphones on clinical communication. Our study can be seen as hypothesis generating, and further research is warranted to validate these findings. There may be limits to generalizability as all sites adopted similar communication processes that included centralizing communications to make it easier for senders to reach a responsible physician.

In conclusion, we have provided a summary of the impact of rapidly emerging information technology on the educational experience of medical trainees and identified both positive and negative impacts. Of note, the negative impacts appear to be related to being more global and less local and high interruptions. Further research is required to confirm these unintended consequences as well as to develop solutions to address them. Educators should be aware of these findings and the need to develop curriculum to address and manage the negative impacts of smartphone use in the clinical training environment.

Acknowledgments

Disclosure: Nothing to report.

- , . Smartphone app use among medical providers in ACGME training programs. J Med Syst. 2012;36:3135–3139.

- , , , et al. The use of smartphones for clinical communication on internal medicine wards. J Hosp Med. 2010;5:553–559.

- , , , , , . Anticipating and addressing the unintended consequences of health IT and policy: a report from the AMIA 2009 Health Policy Meeting. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18(1):82–90.

- , , , , . Types of unintended consequences related to computerized provider order entry. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2006;13(5):547–556.

- , , , . “e‐Iatrogenesis”: the most critical unintended consequence of CPOE and other HIT. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2007;14(3):387–388.

- , , , et al. An evaluation of the use of smartphones to communicate between clinicians: a mixed‐methods study. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(3):e59.

- . Smartphones in clinical practice, medical education, and research. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(14):1294–1296.

- , , , . Use of handheld computers in medical education. A systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(5):531–537.

- , , , . A review and a framework of handheld computer adoption in healthcare. Int J Med Inform. 2005;74(5):409–422.

- , , , et al. The intended and unintended consequences of communication systems on General Internal Medicine inpatient care delivery: a prospective observational case study of five teaching hospitals [published online ahead of print January 25, 2013]. J Am Med Inform Assoc. doi:10.1136/amiajnl‐2012‐001160.

- , , , , . Hospital doctors' workflow interruptions and activities: an observation study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20(6):491–497.

- , , , et al. Computerised provider order entry and residency education in an academic medical centre. Med Educ. 2012;46:795–806.

- , , , . Smartphone use during inpatient attending rounds: Prevalence, patterns and potential for distraction. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(8):595–599.

- , , , et al. Understanding interprofessional communication: a content analysis of email communications between doctors and nurses. Applied Clinical Informatics. 2012;3:38–51.

- , , , . Preserving professional credibility: grounded theory study of medical trainees' requests for clinical support. BMJ. 2009;338:b128.

- , , , , . Beyond paging: building a web‐based communication tool for nurses and physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(1):105–110.

- , . Distracted doctoring: smartphones before patients? CMAJ. 2012;184:1440.

Medical residents are rapidly adopting smartphones. Recent statistics revealed that 85% of medical providers currently own a smartphone, and the majority use it in their clinical work.[1] Smartphone capabilities that include the use of text messaging, e‐mail, and mobile phone functions in the clinical setting may improve efficiency and quality of care by reducing the response time for urgent issues.[2] There is, however, increasing recognition that healthcare information technology can create unintended negative consequences. For example, studies have suggested that healthcare information technologies, such as the computerized physician order entry, may actually increase errors by creating new work, changing clinical workflow, and altering communication patterns.[3, 4, 5]

Smartphone use for clinical communication can have unintended consequences by increasing interruptions, reducing interprofessional relationships, and widening the gap between what nurses and physicians perceive as urgent clinical problems.[6] However, no studies have evaluated the impact of smartphones on the educational experience of medical trainees. Although previous studies have described the use of smartphones by trainees for rapid access to electronic medical resources,[7, 8, 9] we did not identify in our literature review any previous studies on the impact of using the smartphone's primary functionas a communication deviceon the educational experience of residents and medical students. Therefore, our study aimed to examine the impact of using smartphones for clinical communication on medical education.

METHODS

Design

The design of the study was qualitative research methodology using interview data, ethnographic data, and content analysis of text‐based messages.

Setting

From June 2009 to September 2010, we conducted a multisite evaluation study on general internal medicine (GIM) wards at 5 large academic teaching hospitals in the city of Toronto, Canada at St. Michael's Hospital, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Toronto General Hospital, Toronto Western Hospital, and Mount Sinai Hospital. Each hospital has clinical teaching units consisting typically of 4 medical teams. Each team includes 1 attending physician, 1 senior resident, 2 or more junior residents, and 2 to 4 medical students. Each hospital had 2 to 4 GIM wards in different geographic locations.

Communication Systems

To make it easier for nurses and other health professionals to communicate with the physician teams, all sites centralized communication to 1 team member, who acts as the single point of contact on behalf of their assigned team in the communication of patient‐related issues. We facilitated this communication through a shared device (either a pager or a smartphone). The senior resident typically carried the shared device during the day and the on‐call junior resident at night and on the weekends. Two hospitals provided smartphones to all residents, whereas a third site provided smartphones only to the senior residents. The standard processes of communication required that physicians respond to all calls and text messages. At the 3 sites with institutional smartphones, nurses could send text messages with patient information using a Web‐based system. We encrypted data sent to institutional smartphones to protect patient information.

Data Collection

Using a mixed‐methods ethnographic approach, we collected data using semistructured interviews, ethnographic observations, and content analysis of text messages. The original larger study focused primarily on examining the overall clinical impact of smartphone use.[10] For our current study, we analyzed the data with a focus on evaluating the impact of smartphones on the educational experience of medical trainees on the GIM teaching service. The respective institutions' research ethics boards approved the study.

Interviews

We conducted semistructured interviews with residents, medical students, attending physicians, and other clinicians across all of the sites to examine how clinicians perceived the impact of smartphones on medical education. We used a purposeful sampling strategy where we interviewed different groups of healthcare professionals who we suspected would represent different viewpoints on the use of smartphones for clinical communication. To obtain diverse perspectives, we snowball sampled by asking interviewees to suggest colleagues with differing views to participate in the interviews. The interview guide consisted of open‐ended questions with additional probes to elicit more detailed information from these frontline clinicians who initiate and receive communication. One of the study investigators (V.L.) conducted interviews that varied from 15 to 45 minutes in duration. We recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed the interviews using NVivo software (QSR International, Doncaster, Victoria, Australia). We added additional questions iteratively as themes emerged from the initial interviews. One of the study investigators (V.L.) encouraged participants to speak freely, to raise issues that they perceived to be important, and to support their responses with examples.

Observations

We observed the communication processes in the hospitals by conducting a work‐shadowing approach that followed individual residents in their work environments. These observations included 1‐on‐1 supervision encounters involving attending staff, medical students, and other residents, and informal and formal teaching rounds. The observation periods included the usual working day (from 8 am to 6 pm) as well as the busiest times on call, typically from 6 pm until 11 pm. We sampled different residents for different time periods. We adopted a nonparticipatory observation technique where we observed all interruptions, communication interactions, and patterns from a distance. We defined workflow interruptions as an intrusion of an unplanned and unscheduled task, causing a discontinuation of tasks, a noticeable break, or task switch behaviour.[11] Data collection included timing of events and writing field notes. One of the study investigators (V.L.) performed all the work‐shadowing observations.

E‐mail

To study the volume and content of messages, we collected e‐mail communications between January 2009 and June 2009 from consenting residents at the 2 hospitals that provided smartphones to all GIM residents. E‐mail information included the sender, the receiver, the time of message, and the message content. To look at usage, we calculated the average number of e‐mails sent and received. To assess interruptions on formal teaching sessions, we paid particular attention to e‐mails received and sent during protected educational timeweekdays from 8 am to 9 am (morning report) and 12 pm to 1 pm (noon rounds). We randomly sampled 20% of all e‐mails sent between residents for content analysis and organized content related to medical education into thematic categories.

Analysis

We used a deductive approach to analyze the interview transcripts by applying a conceptual framework that assessed the educational impact of patient safety interventions.[12] This framework identified 5 educational domains (learning, teaching, supervision, assessment, and feedback). Three study investigators mapped interview data, work‐shadowing data, and e‐mail content to themes (V.L., B.W., and R.W.), and grouped data that did not translate into themes into new categories. We then triangulated the data to develop themes of the educational impact of smartphone communication by both perceived use and actual use, and subsequently constructed a framework of how smartphone communication affected education.

RESULTS

We conducted 124 semistructured interviews with residents, medical students, attending physicians, and other clinicians across all the sites to examine how clinicians perceived the impact of smartphones on medical education. We work‐shadowed 40 individual residents for a total of 196 hours (Table 1). We analyzed the 13,714 e‐mails sent from or received to 34 residents. To analyze e‐mail content, we reviewed 1179 e‐mails sent among residents.

| Methods | Sites | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| St. Michael's Hospital | Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Toronto General Hospital | Toronto Western Hospital | Mount Sinai Hospital | All Hospitals | |

| ||||||

| Work‐shadowing residents | ||||||

| Hours | 60 hours | 35 hours | 57 hours 55 minutes | 27 hours 46 minutes | 15 hours | 196 hours |

| No. of residents | 12 | 7 | 12 | 6 | 3 | 40 |

| Interviews with clinicians | ||||||

| Physicians | 10 | 5 | 13 | 5 | 33 | |

| Medical students | 5 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 11 | |

| Nurses | 9 | 11 | 15 | 14 | 49 | |

| Other health professionsa | 7 | 10 | 8 | 6 | 31 | |

| Total | 31 | 30 | 37 | 26 | 124 | |

We found that 2 key characteristics of smartphone use for clinical communication, namely an increase in connectedness leading to an increase in interruptions, impacted 3 educational domains: teaching, supervision, and professionalism (Figure 1).

Increased Connectedness

As a communication device, smartphones increase the ability to receive and respond to messages through voice, e‐mail, and text messaging. Not surprisingly, with the improved ability and mobility to communicate, medical trainees perceived being more connected with their team members, who included other residents, medical students, and attending staff as well as with other clinical services and professions. These smartphone communication activities appeared to be pervasive, occurring on the wards, at the bedside, while in transit, and in teaching sessions (Box 1: increased connectedness).

Box

Increased connectedness

I've used the Blackberry system and it's nice to be able to quickly text each other little messages especially for meeting times because then you don't have to page them and wait by the phone. So that's been great for in the team. (Interview Resident 3)

It's incredibly useful for when you're paging somebody else. Often times I'll be consulting with another physician on a patient and I'll say This is my BlackBerry. Call me back after you've seen the patient' or Call me back when you have a plan' or, you know, whatever. So that's extremely valuable which we never had with pages and no one would ever page you for that because it was too much of a pain. (Interview Resident 1)

My personal experience has been that if you need to speak to a more senior individual it's much easier to contact them via the BlackBerry. (Interview Medical Student 1)

At 7:25 pm, MD11 returns to the patient's room and continues examining her. While in the patient's room, I could see her talking on the BlackBerrys. I asked her later what calls she had while in the room. It turns out she had 3 phone calls and 2 texts. Two of the calls were from the radiation oncologists and 1 call from the pathologist. She also received 1 text on the Team BlackBerry and 1 text on the Senior's BlackBerry from the pharmacist. (Field Notes, Work-shadowing MD11)

Interruptions

The increased connectedness caused by smartphone use led residents to perceive an increase in the frequency of interruptions. The multitude of communication and contact options made available by smartphones to health providers created an expansive network of connected individuals who were in constant communication with each other. Instead of the difficulties associated with numeric paging and waiting for a response, nurses typically found it easier to call directly or send a text message to residents' smartphones. From the e‐mail analysis, residents received, on a daily basis, on average 25.7 e‐mails, (median, 20; interquartile range [IQR]: 1428) to the team smartphone and sent 7.5 e‐mails (median, 6; IQR: 410). During protected educational time, each resident received an average of 1.0 e‐mail (median, 1; IQR: 01) between 8 am and 9 am and an average of 2.3 e‐mails (median, 2; IQR: 13) during 12 pm to 1 pm (Figure 2). Each of these communication events, whether a phone call, e‐mail, or text‐message, led to an interruption (Box 2). Given that smartphones made it easier for nurses to contact residents, some residents attributed the increase in interruptions to a reduction in the threshold for nurses to communicate.

Box

Increased interruptions

The only negative I can think of is just the incredible number of communications that you get, you know, text messages and e‐mails and everything else. So just the, the number can sometimes be overwhelming. (Interview Resident 1)

Some of [the nurses] rely a little bit more on the BlackBerry so that they will tend to call you a bit more frequently for things that maybe sometimes they should try to find answer for themselves (Interview Resident 2)

And now with the option of being able to, if you really needed to, call them and talk to them directly, I think that kind of improves communication. They're easier to find. (Interview Nurse 4)

Supervision

Smartphone communication appeared to positively impact trainee supervision. Increased connectedness between team members allowed junior trainees to have access and rapidly communicate with a more experienced clinician, which provided them with greater support. Residents found smartphones particularly useful in situations where they felt uncomfortable or where they did not feel competent. Some of these instances related to procedural competence, with residents feeling more comfortable knowing they have rapid access to support (Box 3: increased support).

Box

Supervision

Increased support

It makes me feel more comfortable in the sense that I can instantly make a call or a text and have a question answered if I need an answer. Or if it were an emergency having the ability to talk on the phone and be talked through an emergency situation, or a procedure for example like if you were in a remote area or the physician was in a remote area and you were in hospital and you would need some of that guidance or counselling, there's no substitution. (Interview Medical Student 1)

I'm ready can u dblchk [sic] that I landmarked correctly. (Email from Junior to Senior)

MD3 returns to the patient's room to do a paracentesis with [junior resident]. He calls on his BB to [senior resident] to inform her that they are starting and then hangs up. [Senior resident] arrives at the patient's room. (Field Notes, Workshadowing MD3)

Decreased autonomy

The difference with the Blackberry is they're more likely to say By the way, this happened. Should I do this?' And I write back Yes', No.' If they didn't have that contact like I said they probably would have done something and then because they're making a decision on their own they could very easily have spent the time to research whatever to figure whether that was the right thing to do before doing it. Now they have an outlet where they can pass an idea off of me and then have me make, it's easier for me to make a decision for them. So that can negatively impact education. (Interview Attending 1)

What do I do for a high phosphate?(Email from Junior to Senior)

Hey Pt X's k is 5.5. Was going to shift her. What do u think? (Email from Junior to Senior)

You probably saw the hb 92. Let's give prbc asap while he's on HD.(Email from Staff to Residents on the team)

hb‐ hemoglobin, prbc packed red blood cells, HD ‐ hemodialysis

Hi. Just checking the bloodwork. What is happening to ms X? [sic] Creatinine rising still. Is a foley in? Urology reconsulted? (Email from Attending Staff to Junior Resident)

On the other hand, supervisors perceived that the easy rapid access afforded by smartphone use lowered the threshold for trainees to contact them. In some instances, these attending physicians felt that their trainees would text them for advice when they could have looked up the information themselves. As a result, the increased reliance on the attending physician's input prior to committing to a management plan decreased the trainee's autonomy and independent decision making (Box 3: decreased autonomy). In addition to trainee requests for increased staff involvement, smartphone use made it easier for attending physicians to initiate text messages to their residents as well. In some instances, staff physicians adopted a more hands‐on approach by directing their residents on how to manage their patients. It is unclear if trainees perceived this taking over of care as negatively influencing their education.

Teaching

Medical teams also frequently used smartphones to communicate the location and timing of educational rounds. We observed instances where residents communicated updated information relating to scheduled rounds, as well as for informing team members about spontaneous teaching sessions (Box 4: communicating rounds). Despite this initial benefit, staff physicians worried that interruptions resulting from smartphone use during educational sessions lowered the effectiveness of these sessions for all learners by creating a fragmented learning experience (Box 4: fragmented learning). Our data indicated that residents carrying the team smartphones received and sent a high number of e‐mails throughout the day, which continued at a similar rate during the protected educational time (Figure 2). Additionally, some of the teaching experiences that traditionally would occur in a face‐to‐face manner appeared to have migrated to text‐based interactions. It is unclear whether trainees perceive these text‐based interactions as more or less effective teaching encounters (Box 4: text‐based teaching).

Box

Teaching

Communicating rounds

One is that they can more efficiently communicate about the timing and location of education rounds in case they forget or sort of as an organizer for them (Interview Attending 3)

Physical Exam rounds is at 1:00 outside the morning report room. K. has kindly volunteered! If you miss us then the exam will be on the 3rd floor in room X. Pt X. See you there (Email from chief medical resident to trainees)

Fragmented learning

Because Blackberry is there, it's something that is potentially time occupying and can take the attention away from things and this is true of any Blackberries. People who have Blackberries they always look at their Blackberries so, you know, there are times when I'm sitting face to face with people and residents are looking at their Blackberries. So it's another way that they can be distracted. (Interview Attending 1).

I've seen that be an issue. I've certainly seen them losing concentration during a teaching session because they're being Blackberried, getting Blackberry messages. (Interview Attending 3)

2:06 Team meeting with Attending in a conference room.

2:29 Team BlackBerry (BB) beeps. Senior glances at BB. She dials a number on the Team BB. Speaks on the Team BB and turns to [Junior resident] to inform her that the family is here. She returns to the caller. Senior then hangs up and resumes to her teaching.

2:35 Attending's BB rings. She takes a look and ends the BB call.

2:39 Senior's BB rings. Senior picks up and talks about a patient's case and condition. Senior turns to [junior resident] and asks a question. Team members resume talking among themselves.

2:46 Senior hangs up on the phone call.

2:49 Team discusses another patient's condition/case.

2:57 Junior resident uses her BB to text.

3:02 Team BB beeps. It is a message about a patient's case.

3:05 Meeting ends. (Field Note excerpts, Work‐shadowing MD6)

Text‐based teaching

The resident would get very frustrated with how many questions we have once we've started. Like if three different medical students or four different medical students or four different places all texting him with, oh by the way, what does this stand for?, and he's responding to each of them individually then he has to answer it four different times as opposed to just in person when he can get us all together in a group and it's actually a learning experience. If questions are answered in an email, it's not really helpful for the rest of us. (Interview, medical student SB1)

That would be a great unifying diagnosis, but there may be some underlying element of ROH/NASH also I would hold off on A/C as we do not know if he has varices. Will need to review noncontrast CT ?HCC. Thx (Email from Consulting Staff to Junior)

A/C anticoagulation, CT computed tomography, HCC‐ hepatocellular carcinoma, NASH non‐alcoholic steatohepatitis, ROH alcohol

Professionalism

Our data revealed that smartphone interruptions occurred during teaching rounds and interactions with patients and with other clinical staff. Often these interruptions involved messages or phone calls pertaining to clinical concerns or tasks that nurses communicated to the residents via their smartphone (Box 5). Yet, by responding to these interruptions and initiating communications on their smartphones during patient care encounters and formal teaching sessions, trainees were perceived by other clinicians who were in attendance with them as being rude or disrespectful. Attending staff also tended to role model similar smartphone behaviors. Although we did not specifically work‐shadow attending staff, we did observe frequent usage of their personal smartphones during their interactions with residents.

Box

Professionalism

I don't like it when I see them checking messages when you're trying to talk to them. I think you're losing some of that communication sort of polite behaviour that maybe we knew a little bit more before all this texting and Blackberry. (Interview Allied Health 5)

I think that the etiquette of the Blackberry can be offensive, could be offensive especially with some of our older patients (Interview Allied Health 6)

Senior walks out of the patient's room while typing on the BlackBerry. She finishes typing and returns to the room at 5:36. Senior looks at her BlackBerry and starts typing inside the room in front of the patient. She paused to look at the patient and the resident doing the procedure [paracentesis]. She resumes texting again and walks out of the room at 5:38. Another resident walks out and Senior speaks with the resident. Senior returns to the room and speaks with the patient. She asks the patient if he has ever gotten a successful tap before. Senior looks at her BlackBerry and starts typing. (Field NotesWork‐shadowing MD2)

I think it is almost completely negative in terms of its medical education [Any positive] factors are grossly outweighed by the significant disruptions to their ability to concentrate and participate in the educational session. And I think almost to some extent it's an implicit permission that gets granted to the house staff to disrupt their own teaching experience and disrupt others around them because everybody is doing it because everybody is being Blackberried. So it almost becomes the new social norm and while that may be a new social norm I'm not sure that that's a good thing How big is the negative impact? That's much harder to say. It's probably not a big impact on top of the endless other disruptions in the day to teaching, but it is measurable because it's a new factor so it's observable by me on top of all the other factors which have been there for years. (Interview Attending 3)

2:10‐Attending goes to the whiteboard to teach research methods to the team. Spotted Medical student#1 looking at his IPhone and typing.

2:15‐Med student#1 using the calculator function on his IPhone.

2:20‐Attending glances at his BB quickly.

2:28‐Attending resumes discussion of the patients' cases (Field notes, Work‐shadowing MD7).

DISCUSSION

The educational impacts of smartphone use for communication appear to center on increased connectedness of medical trainees and increased interruptions, which have positive and negative impacts in the areas of teaching, supervision, and professionalism. Smartphone communication provided potential educational benefits through (1) safer supervision with rapid access to help and (2) easier coordination of teaching sessions. Threats to the educational experience included (1) a high level of interruptions to both teachers and learners, which may reduce the effectiveness of formal and informal teaching; (2) replacement of face‐to‐face teaching with texting; (3) a potential erosion of autonomy and independence due to easy access to supervisors and easy ability for supervisors to take over; and (4) professionalism issues with difficulties balancing between clinical service demands and communication during patient and interprofessional encounters.

This study is the first to describe the intersection of clinical communication with smartphones and medical education. A recent study found that residents reported high use of smartphones during rounds for patient care as well as personal issues.[13] We have previously described the perceived impacts of smartphones on clinical communication, which included improved efficiency but concerns for increased interruptions and threats to professionalism.[6] We also observed that sites that used smartphones had increased interruptions compared to those with just pagers.[10] We have also described the content of e‐mail messages between clinicians and found that all e‐mails from nurses to physicians involved clinical care, but e‐mail exchanges between physicians were split between clinical care (60.4%), coordination within the team (53.5%), medical education (9.4%), and social communication (3.9%).[14] This study adds to the literature by focusing on the impacts of smartphone use to medical education and describing the perceived and observed impacts. This study provides a further example of how healthcare information technology can cause unintended consequences on medical education and appear to relate to the linked impacts of increased connectivity and the increased interruptions.[3] In essence, the trainee becomes more global, less local. Being more global translates to increased connections with people separated in physical space. Yet, this increased global connectedness resulted in the trainee being less local, with attention diverted elsewhere, taking away from the quality of patient interactions and interactions with other interprofessional team members. It also reduces the effectiveness of educational sessions for all participants. Although the level of supervision and autonomy are independently related, being too connected to supervisors may lower trainee autonomy by reducing independent thinking around patient issues.[15] It may also move teaching and learning from face‐to‐face conversations to text‐based messages. Although there have been existing tensions between service delivery and medical education, increased connectedness may tilt the balance toward the demands of service delivery and efficiency optimization at the expense of the educational experience. Finally, smartphone use appeared to create an internal tension among trainees, who have to juggle balancing professional behaviors and expectations in their dual role as learner and care provider; it would be educationally unprofessional to interrupt a teaching session and respond to a text message. However, failing to respond to a nurse who has sent a message and is expecting a response would be clinically unprofessional.

To address these threats, we advocate improving systems and processes to reduce interruptions and provide education on the tensions created by increased connectedness. Smarter communication systems could limit interrupting messages to urgent messages and queue nonurgent messages.[16] They could also inform senders about protected educational time. Even more sophisticated systems could inform the sender on the status of the receiver. For example, systems could indicate if they are available or if they are busy in an educational session or an important meeting with a patient and their family. Processes to reduce interruptions include interprofessional consensus on what constitutes an urgent issue and giving explicit permission to learners to ignore their smartphones during educational sessions except for critical communications purposes. Finally, education around smartphone communication for both learners and teachers may help minimize threats to learner autonomy, to face‐to‐face teaching, and to professionalism.[17]

Our study has several limitations. We derived this information from a general study of the impact of smartphones on clinical communication. Our study can be seen as hypothesis generating, and further research is warranted to validate these findings. There may be limits to generalizability as all sites adopted similar communication processes that included centralizing communications to make it easier for senders to reach a responsible physician.

In conclusion, we have provided a summary of the impact of rapidly emerging information technology on the educational experience of medical trainees and identified both positive and negative impacts. Of note, the negative impacts appear to be related to being more global and less local and high interruptions. Further research is required to confirm these unintended consequences as well as to develop solutions to address them. Educators should be aware of these findings and the need to develop curriculum to address and manage the negative impacts of smartphone use in the clinical training environment.

Acknowledgments

Disclosure: Nothing to report.

Medical residents are rapidly adopting smartphones. Recent statistics revealed that 85% of medical providers currently own a smartphone, and the majority use it in their clinical work.[1] Smartphone capabilities that include the use of text messaging, e‐mail, and mobile phone functions in the clinical setting may improve efficiency and quality of care by reducing the response time for urgent issues.[2] There is, however, increasing recognition that healthcare information technology can create unintended negative consequences. For example, studies have suggested that healthcare information technologies, such as the computerized physician order entry, may actually increase errors by creating new work, changing clinical workflow, and altering communication patterns.[3, 4, 5]

Smartphone use for clinical communication can have unintended consequences by increasing interruptions, reducing interprofessional relationships, and widening the gap between what nurses and physicians perceive as urgent clinical problems.[6] However, no studies have evaluated the impact of smartphones on the educational experience of medical trainees. Although previous studies have described the use of smartphones by trainees for rapid access to electronic medical resources,[7, 8, 9] we did not identify in our literature review any previous studies on the impact of using the smartphone's primary functionas a communication deviceon the educational experience of residents and medical students. Therefore, our study aimed to examine the impact of using smartphones for clinical communication on medical education.

METHODS

Design

The design of the study was qualitative research methodology using interview data, ethnographic data, and content analysis of text‐based messages.

Setting

From June 2009 to September 2010, we conducted a multisite evaluation study on general internal medicine (GIM) wards at 5 large academic teaching hospitals in the city of Toronto, Canada at St. Michael's Hospital, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Toronto General Hospital, Toronto Western Hospital, and Mount Sinai Hospital. Each hospital has clinical teaching units consisting typically of 4 medical teams. Each team includes 1 attending physician, 1 senior resident, 2 or more junior residents, and 2 to 4 medical students. Each hospital had 2 to 4 GIM wards in different geographic locations.

Communication Systems

To make it easier for nurses and other health professionals to communicate with the physician teams, all sites centralized communication to 1 team member, who acts as the single point of contact on behalf of their assigned team in the communication of patient‐related issues. We facilitated this communication through a shared device (either a pager or a smartphone). The senior resident typically carried the shared device during the day and the on‐call junior resident at night and on the weekends. Two hospitals provided smartphones to all residents, whereas a third site provided smartphones only to the senior residents. The standard processes of communication required that physicians respond to all calls and text messages. At the 3 sites with institutional smartphones, nurses could send text messages with patient information using a Web‐based system. We encrypted data sent to institutional smartphones to protect patient information.

Data Collection

Using a mixed‐methods ethnographic approach, we collected data using semistructured interviews, ethnographic observations, and content analysis of text messages. The original larger study focused primarily on examining the overall clinical impact of smartphone use.[10] For our current study, we analyzed the data with a focus on evaluating the impact of smartphones on the educational experience of medical trainees on the GIM teaching service. The respective institutions' research ethics boards approved the study.

Interviews

We conducted semistructured interviews with residents, medical students, attending physicians, and other clinicians across all of the sites to examine how clinicians perceived the impact of smartphones on medical education. We used a purposeful sampling strategy where we interviewed different groups of healthcare professionals who we suspected would represent different viewpoints on the use of smartphones for clinical communication. To obtain diverse perspectives, we snowball sampled by asking interviewees to suggest colleagues with differing views to participate in the interviews. The interview guide consisted of open‐ended questions with additional probes to elicit more detailed information from these frontline clinicians who initiate and receive communication. One of the study investigators (V.L.) conducted interviews that varied from 15 to 45 minutes in duration. We recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed the interviews using NVivo software (QSR International, Doncaster, Victoria, Australia). We added additional questions iteratively as themes emerged from the initial interviews. One of the study investigators (V.L.) encouraged participants to speak freely, to raise issues that they perceived to be important, and to support their responses with examples.

Observations

We observed the communication processes in the hospitals by conducting a work‐shadowing approach that followed individual residents in their work environments. These observations included 1‐on‐1 supervision encounters involving attending staff, medical students, and other residents, and informal and formal teaching rounds. The observation periods included the usual working day (from 8 am to 6 pm) as well as the busiest times on call, typically from 6 pm until 11 pm. We sampled different residents for different time periods. We adopted a nonparticipatory observation technique where we observed all interruptions, communication interactions, and patterns from a distance. We defined workflow interruptions as an intrusion of an unplanned and unscheduled task, causing a discontinuation of tasks, a noticeable break, or task switch behaviour.[11] Data collection included timing of events and writing field notes. One of the study investigators (V.L.) performed all the work‐shadowing observations.

E‐mail

To study the volume and content of messages, we collected e‐mail communications between January 2009 and June 2009 from consenting residents at the 2 hospitals that provided smartphones to all GIM residents. E‐mail information included the sender, the receiver, the time of message, and the message content. To look at usage, we calculated the average number of e‐mails sent and received. To assess interruptions on formal teaching sessions, we paid particular attention to e‐mails received and sent during protected educational timeweekdays from 8 am to 9 am (morning report) and 12 pm to 1 pm (noon rounds). We randomly sampled 20% of all e‐mails sent between residents for content analysis and organized content related to medical education into thematic categories.

Analysis

We used a deductive approach to analyze the interview transcripts by applying a conceptual framework that assessed the educational impact of patient safety interventions.[12] This framework identified 5 educational domains (learning, teaching, supervision, assessment, and feedback). Three study investigators mapped interview data, work‐shadowing data, and e‐mail content to themes (V.L., B.W., and R.W.), and grouped data that did not translate into themes into new categories. We then triangulated the data to develop themes of the educational impact of smartphone communication by both perceived use and actual use, and subsequently constructed a framework of how smartphone communication affected education.

RESULTS

We conducted 124 semistructured interviews with residents, medical students, attending physicians, and other clinicians across all the sites to examine how clinicians perceived the impact of smartphones on medical education. We work‐shadowed 40 individual residents for a total of 196 hours (Table 1). We analyzed the 13,714 e‐mails sent from or received to 34 residents. To analyze e‐mail content, we reviewed 1179 e‐mails sent among residents.

| Methods | Sites | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| St. Michael's Hospital | Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Toronto General Hospital | Toronto Western Hospital | Mount Sinai Hospital | All Hospitals | |

| ||||||

| Work‐shadowing residents | ||||||

| Hours | 60 hours | 35 hours | 57 hours 55 minutes | 27 hours 46 minutes | 15 hours | 196 hours |

| No. of residents | 12 | 7 | 12 | 6 | 3 | 40 |

| Interviews with clinicians | ||||||

| Physicians | 10 | 5 | 13 | 5 | 33 | |

| Medical students | 5 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 11 | |

| Nurses | 9 | 11 | 15 | 14 | 49 | |

| Other health professionsa | 7 | 10 | 8 | 6 | 31 | |

| Total | 31 | 30 | 37 | 26 | 124 | |

We found that 2 key characteristics of smartphone use for clinical communication, namely an increase in connectedness leading to an increase in interruptions, impacted 3 educational domains: teaching, supervision, and professionalism (Figure 1).

Increased Connectedness

As a communication device, smartphones increase the ability to receive and respond to messages through voice, e‐mail, and text messaging. Not surprisingly, with the improved ability and mobility to communicate, medical trainees perceived being more connected with their team members, who included other residents, medical students, and attending staff as well as with other clinical services and professions. These smartphone communication activities appeared to be pervasive, occurring on the wards, at the bedside, while in transit, and in teaching sessions (Box 1: increased connectedness).

Box

Increased connectedness

I've used the Blackberry system and it's nice to be able to quickly text each other little messages especially for meeting times because then you don't have to page them and wait by the phone. So that's been great for in the team. (Interview Resident 3)

It's incredibly useful for when you're paging somebody else. Often times I'll be consulting with another physician on a patient and I'll say This is my BlackBerry. Call me back after you've seen the patient' or Call me back when you have a plan' or, you know, whatever. So that's extremely valuable which we never had with pages and no one would ever page you for that because it was too much of a pain. (Interview Resident 1)

My personal experience has been that if you need to speak to a more senior individual it's much easier to contact them via the BlackBerry. (Interview Medical Student 1)

At 7:25 pm, MD11 returns to the patient's room and continues examining her. While in the patient's room, I could see her talking on the BlackBerrys. I asked her later what calls she had while in the room. It turns out she had 3 phone calls and 2 texts. Two of the calls were from the radiation oncologists and 1 call from the pathologist. She also received 1 text on the Team BlackBerry and 1 text on the Senior's BlackBerry from the pharmacist. (Field Notes, Work-shadowing MD11)

Interruptions

The increased connectedness caused by smartphone use led residents to perceive an increase in the frequency of interruptions. The multitude of communication and contact options made available by smartphones to health providers created an expansive network of connected individuals who were in constant communication with each other. Instead of the difficulties associated with numeric paging and waiting for a response, nurses typically found it easier to call directly or send a text message to residents' smartphones. From the e‐mail analysis, residents received, on a daily basis, on average 25.7 e‐mails, (median, 20; interquartile range [IQR]: 1428) to the team smartphone and sent 7.5 e‐mails (median, 6; IQR: 410). During protected educational time, each resident received an average of 1.0 e‐mail (median, 1; IQR: 01) between 8 am and 9 am and an average of 2.3 e‐mails (median, 2; IQR: 13) during 12 pm to 1 pm (Figure 2). Each of these communication events, whether a phone call, e‐mail, or text‐message, led to an interruption (Box 2). Given that smartphones made it easier for nurses to contact residents, some residents attributed the increase in interruptions to a reduction in the threshold for nurses to communicate.

Box

Increased interruptions

The only negative I can think of is just the incredible number of communications that you get, you know, text messages and e‐mails and everything else. So just the, the number can sometimes be overwhelming. (Interview Resident 1)

Some of [the nurses] rely a little bit more on the BlackBerry so that they will tend to call you a bit more frequently for things that maybe sometimes they should try to find answer for themselves (Interview Resident 2)

And now with the option of being able to, if you really needed to, call them and talk to them directly, I think that kind of improves communication. They're easier to find. (Interview Nurse 4)

Supervision

Smartphone communication appeared to positively impact trainee supervision. Increased connectedness between team members allowed junior trainees to have access and rapidly communicate with a more experienced clinician, which provided them with greater support. Residents found smartphones particularly useful in situations where they felt uncomfortable or where they did not feel competent. Some of these instances related to procedural competence, with residents feeling more comfortable knowing they have rapid access to support (Box 3: increased support).

Box

Supervision

Increased support

It makes me feel more comfortable in the sense that I can instantly make a call or a text and have a question answered if I need an answer. Or if it were an emergency having the ability to talk on the phone and be talked through an emergency situation, or a procedure for example like if you were in a remote area or the physician was in a remote area and you were in hospital and you would need some of that guidance or counselling, there's no substitution. (Interview Medical Student 1)

I'm ready can u dblchk [sic] that I landmarked correctly. (Email from Junior to Senior)

MD3 returns to the patient's room to do a paracentesis with [junior resident]. He calls on his BB to [senior resident] to inform her that they are starting and then hangs up. [Senior resident] arrives at the patient's room. (Field Notes, Workshadowing MD3)

Decreased autonomy

The difference with the Blackberry is they're more likely to say By the way, this happened. Should I do this?' And I write back Yes', No.' If they didn't have that contact like I said they probably would have done something and then because they're making a decision on their own they could very easily have spent the time to research whatever to figure whether that was the right thing to do before doing it. Now they have an outlet where they can pass an idea off of me and then have me make, it's easier for me to make a decision for them. So that can negatively impact education. (Interview Attending 1)

What do I do for a high phosphate?(Email from Junior to Senior)

Hey Pt X's k is 5.5. Was going to shift her. What do u think? (Email from Junior to Senior)

You probably saw the hb 92. Let's give prbc asap while he's on HD.(Email from Staff to Residents on the team)

hb‐ hemoglobin, prbc packed red blood cells, HD ‐ hemodialysis

Hi. Just checking the bloodwork. What is happening to ms X? [sic] Creatinine rising still. Is a foley in? Urology reconsulted? (Email from Attending Staff to Junior Resident)

On the other hand, supervisors perceived that the easy rapid access afforded by smartphone use lowered the threshold for trainees to contact them. In some instances, these attending physicians felt that their trainees would text them for advice when they could have looked up the information themselves. As a result, the increased reliance on the attending physician's input prior to committing to a management plan decreased the trainee's autonomy and independent decision making (Box 3: decreased autonomy). In addition to trainee requests for increased staff involvement, smartphone use made it easier for attending physicians to initiate text messages to their residents as well. In some instances, staff physicians adopted a more hands‐on approach by directing their residents on how to manage their patients. It is unclear if trainees perceived this taking over of care as negatively influencing their education.

Teaching