User login

Intimate partner violence: Screen others, besides heterosexual women

We were happy to learn in “Time to routinely screen for intimate partner violence?” (PURLs. J Fam Pract. 2013;62:90-92) that the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) agrees with the Institute of Medicine (IOM) that all women of childbearing age should be screened for intimate partner violence (IPV).1 Although the USPSTF recommendation comes 2 years after that of the IOM, it is truly better late than never.

Two populations with known IPV issues require special consideration: lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender (LGBT) patients and heterosexual men. The rate of IPV is higher in the LGBT population than in heterosexual men and women cohabitating with their partners.2 Despite high rates of IPV within the LGBT population, women in this group frequently are overlooked for IPV screening.2

We must remember to screen men in heterosexual relationships, as well. In 2000, the National Violence Against Women survey found that 7% of men reported having experienced IPV in their lifetime.2 Given this data, we believe that all patients ages 14 years and older—regardless of gender or sexual orientation—should be screened for IPV. This would be a much-needed step towards addressing a major public health problem.

Barbara McMillan-Persaud, MD

Kyra P. Clark, MD

Riba Kelsey-Harris, MD

Folashade Omole, MD, FAAFP

Atlanta, Ga

1. Screening for intimate partner violence and abuse of elderly and vulnerable adults. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsipv.htm. Accessed September 16, 2013.

2. Artd KL, Makadon HJ. Addressing intimate partner violence in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:930-933.

We were happy to learn in “Time to routinely screen for intimate partner violence?” (PURLs. J Fam Pract. 2013;62:90-92) that the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) agrees with the Institute of Medicine (IOM) that all women of childbearing age should be screened for intimate partner violence (IPV).1 Although the USPSTF recommendation comes 2 years after that of the IOM, it is truly better late than never.

Two populations with known IPV issues require special consideration: lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender (LGBT) patients and heterosexual men. The rate of IPV is higher in the LGBT population than in heterosexual men and women cohabitating with their partners.2 Despite high rates of IPV within the LGBT population, women in this group frequently are overlooked for IPV screening.2

We must remember to screen men in heterosexual relationships, as well. In 2000, the National Violence Against Women survey found that 7% of men reported having experienced IPV in their lifetime.2 Given this data, we believe that all patients ages 14 years and older—regardless of gender or sexual orientation—should be screened for IPV. This would be a much-needed step towards addressing a major public health problem.

Barbara McMillan-Persaud, MD

Kyra P. Clark, MD

Riba Kelsey-Harris, MD

Folashade Omole, MD, FAAFP

Atlanta, Ga

We were happy to learn in “Time to routinely screen for intimate partner violence?” (PURLs. J Fam Pract. 2013;62:90-92) that the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) agrees with the Institute of Medicine (IOM) that all women of childbearing age should be screened for intimate partner violence (IPV).1 Although the USPSTF recommendation comes 2 years after that of the IOM, it is truly better late than never.

Two populations with known IPV issues require special consideration: lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender (LGBT) patients and heterosexual men. The rate of IPV is higher in the LGBT population than in heterosexual men and women cohabitating with their partners.2 Despite high rates of IPV within the LGBT population, women in this group frequently are overlooked for IPV screening.2

We must remember to screen men in heterosexual relationships, as well. In 2000, the National Violence Against Women survey found that 7% of men reported having experienced IPV in their lifetime.2 Given this data, we believe that all patients ages 14 years and older—regardless of gender or sexual orientation—should be screened for IPV. This would be a much-needed step towards addressing a major public health problem.

Barbara McMillan-Persaud, MD

Kyra P. Clark, MD

Riba Kelsey-Harris, MD

Folashade Omole, MD, FAAFP

Atlanta, Ga

1. Screening for intimate partner violence and abuse of elderly and vulnerable adults. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsipv.htm. Accessed September 16, 2013.

2. Artd KL, Makadon HJ. Addressing intimate partner violence in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:930-933.

1. Screening for intimate partner violence and abuse of elderly and vulnerable adults. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsipv.htm. Accessed September 16, 2013.

2. Artd KL, Makadon HJ. Addressing intimate partner violence in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:930-933.

Persistent fever, left-sided neck pain, night sweats—Dx?

THE CASE

A previously healthy 35-year-old man with a one-week history of left-sided neck pain and fever as high as 104°F sought care at our emergency department. He was given a diagnosis of viral pharyngitis and discharged. He returned the next day and indicated that he was now experiencing drenching night sweats and weakness.

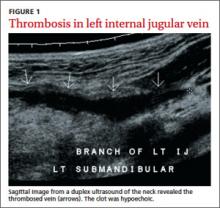

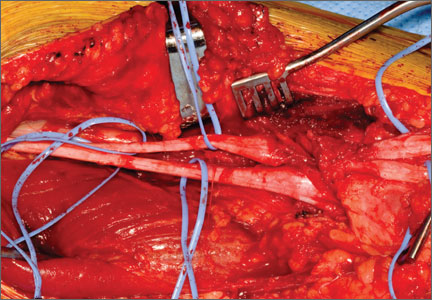

The patient was anxious, but not distressed. His temperature was 100.1°F; blood pressure, 113/65 mm Hg; heart rate, 150 beats per minute; respiratory rate, 18 breaths per minute; and oxygen saturation, 95% on room air. Head and neck examination revealed bilateral cervical lymphadenopathy with pronounced tenderness on the left side of his neck. Oral exam revealed dry mucous membranes, halitosis, and bilateral tonsillar enlargement without exudate. The cardiopulmonary exam was within normal limits. Lab tests showed a white blood cell (WBC) count of 5.9 x 109/L. An ultrasound of the neck revealed thrombosis in the left submandibular branch of the left internal jugular vein (IJV) (FIGURE 1).

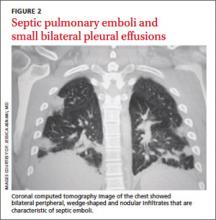

The next day, the patient remained febrile (102.8°F) and developed rigors, diarrhea, pleuritic chest pain, and an elevated WBC count (14.5). A blood culture grew gramnegative rods. The patient was started on piperacillin/tazobactam, and doxycycline was added to treat possible tick-borne infections. Computed tomography (CT) scans of the chest showed the presence of septic pulmonary emboli and small bilateral pleural effusions (FIGURE 2).

THE DIAGNOSIS

We made a diagnosis of Lemierre’s syndrome because our patient met all 4 criteria for the condition:1,2

• a recent oropharyngeal infection

• clinical or radiological evidence of IJV thrombosis

• isolation of anaerobic pathogens (mainly Fusobacterium necrophorum)

• evidence of at least one septic focus, most commonly in the lungs.

We changed the patient’s antibiotic therapy to intravenous (IV) meropenem. His WBC and fever improved, and on Day 10 he was discharged to complete a 28-day course of IV meropenem via a peripherally inserted central catheter.

DISCUSSION

Lemierre’s—A “forgotten” condition that’s making a comeback

In 1936, French microbiologist Andrew Lemierre formally characterized the syndrome in a review of 20 patients who had sepsis, metastatic pulmonary lesions, and isolation of Bacillus funduliformis (now known as F necrophorum).1,2 Other organisms that have been identified in this syndrome include Fusobacterium nucleatum, Candida, Staphylococcus, and Streptococcus.2

Before the antibiotic era, Lemierre’s syndrome was common and often fatal. But with the introduction of penicillin in the 1940s, the incidence of the syndrome dropped, and it eventually became known as “the forgotten disease.”2 Since the 1990s, however, there has been a marked resurgence of Lemierre’s syndrome.3 The incidence of Lemierre’s syndrome today is 0.6 to 2.3 cases per 1 million people per year, with a mortality rate of up to 18%.3,4

This resurgence of Lemierre’s syndrome has been linked to the restricted use of antibiotics for throat infections.3 (One study found the number of prescriptions written for antibiotics decreased by 23% from 1992 to 2000.5) Other factors cited for the increased incidence of Lemierre’s syndrome include improved identification of anaerobic organisms, more effective blood culture methods, and an increased awareness of this syndrome among clinical microbiologists.6

Diagnosis requires a high degree of suspicion

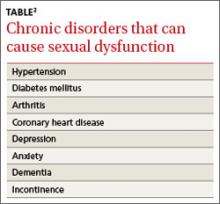

Lemierre’s syndrome typically occurs in healthy young adults. Pharyngitis is the most common initial symptom, occurring in 87% of patients.2 This is followed by a fever (102.2°F - 105.8°F) usually 4 to 5 days after the onset of sore throat.3 Other common symptoms include chills, dysphagia, dyspnea, chest pain, hemoptysis, cervical neck discomfort, arthralgia, malaise, and night sweats.2 Following suppurative thrombophlebitis of the IJV, infection spreads to other organ systems. Pulmonary involvement is the most common site (97% of cases).3 Other complications of this syndrome are listed in the TABLE.3

The differential includes mononucleosis

The differential diagnosis encompasses several common illnesses, including mononucleosis, Group A streptococcal pharyngitis, and peritonsillar abscess. However, while patients with these conditions might have a fever and an elevated WBC count, they typically would not have the pleuritic chest pain that is characteristic of Lemierre’s syndrome. In addition, while patients with peritonsillar abscess would have tonsillar exudates, patients with Lemierre’s syndrome would not likely have them.

Influenza is also part of the differential, although focal neck pain usually isn’t a finding in patients who have the flu.

Once other common illnesses have been ruled out, it’s important to have a high index of suspicion for Lemierre’s syndrome because the oropharyngeal infection may resolve by the time of presentation, and there may be few findings on physical exam.7 Therefore, suspect Lemierre’s if a patient comes in with neck pain and/or pleuritic chest pain and has a recent history of oropharyngeal infection and fever.

CT scan of the neck and chest with contrast is the optimal diagnostic modality because it allows physicians to visualize the IJV8 and detect pulmonary emboli.9 Doppler ultrasound also can be used to diagnose IJV thrombosis. Ultrasound findings would reveal an echogenic focus within a dilated IJV or a complex mass of cystic and solid components.10

Prompt antibiotic treatment is essential

Patients with Lemierre’s syndrome require prompt and appropriate antimicrobial therapy. Researchers have reported mortality rates of 25% among patients who received delayed antibiotic therapy, compared with rates of up to 18% with prompt therapy.3 Metronidazole is the most commonly prescribed antibiotic.8 When combined with ceftriaxone, it provides coverage for both F necrophorum and streptococci, a common copathogen. Monotherapy with a carbapenem antibiotic, clindamycin, ampicillin/sulbactam, or antipseudomonal penicillin also are appropriate options.5 Antimicrobial treatment for 3 to 6 weeks is recommended because relapses have been noted in patients treated for less than 2 weeks.11

Anticoagulation is controversial.2 Proponents of anticoagulation to treat Lemierre’s syndrome believe it may prevent formation of septic emboli and could expedite recovery.4,12 Others believe that clots associated with Lemierre’s syndrome dissolve on their own and that anticoagulation may increase the likelihood of septic emboli.13 Many case reports, including this one, have demonstrated that complete recovery is possible without anticoagulation.10,13-15 Anticoagulation therapy can be considered for patients with Lemierre’s syndrome in the absence of any contraindications such as gastrointestinal or intracranial bleeding.

THE TAKEAWAY

Suspect Lemierre’s syndrome when a patient complains of neck pain, high fever, rigors, dry cough, and pleuritic chest pain and mentions a sore throat that he or she had in the pretceding 7 days. Diagnosis can be confirmed by radiological findings and blood cultures positive for F. necrophorum. Patients with Lemierre’s syndrome should be promptly treated with antibiotics; evidence for anticoagulation is inconclusive.

1. Golpe R, Marin B, Alonso M. Lemierre’s syndrome (necrobacillosis). Postgrad Med J. 1999;75:141-144.

2. Wright WF, Shiner CN, Ribes JA. Lemierre syndrome. South Med J. 2012;105:283-288.

3. Riordan T, Wilson M. Lemierre’s syndrome: more than a historical curiosa. Postgrad Med J. 2004;80:328-334.

4. Ridgway JM, Parikh DA, Wright R, et al. Lemierre syndrome: a pediatric case series and review of literature. Am J Otolaryngol. 2010;31:38-45.

5. McCaig LF, Besser RE, Hughes JM. Antimicrobial drug prescription in ambulatory care settings, United States, 1992–2000. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:432-437.

6. Hagelskjaer Kristensen L, Prag J. Human necrobacillosis, with emphasis on Lemierre’s syndrome. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:524-532.

7. Kupalli K, Livorsi D, Talati N, et al. Lemierre’s syndrome due to fusobacterium necrophorum. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:808-815.

8. Armstrong AW, Spooner K, Sanders JW. Lemierre’s syndrome. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2000;2:168-173.

9. Screaton NJ, Ravenel JG, Lehner PJ, et al. Lemierre syndrome: forgotten but not extinct--report of four cases. Radiology. 1999;213:369-374.

10. Chirinos JA, Lichtstein DM, Garcia J, et al. The evolution of Lemierre syndrome: report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2002;81:458-465.

11. Karkos PD, Asrani S, Karkos CD, et al. Lemierre syndrome: a systematic review. Laryngoscope. 2009;119:1552-1559.

12. Phan T, So TY. Use of anticoagulation therapy for jugular vein thrombus in pediatric patients with Lemierre’s syndrome. Int J Clin Pharm. 2012;34:818-821.

13. O’Brien WT, Cohen RA. Lemierre’ syndrome. Applied Radiology. 2011;40:37-38.

14. Vandenberg SJ, Hartig GK. Lemierre’s syndrome. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;119:516-518.

15. Goldhagen J, Alford BA, Prewitt LH, et al. Suppurative thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein: report of three cases and review of the pediatric literature. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1988;7:410-414.

THE CASE

A previously healthy 35-year-old man with a one-week history of left-sided neck pain and fever as high as 104°F sought care at our emergency department. He was given a diagnosis of viral pharyngitis and discharged. He returned the next day and indicated that he was now experiencing drenching night sweats and weakness.

The patient was anxious, but not distressed. His temperature was 100.1°F; blood pressure, 113/65 mm Hg; heart rate, 150 beats per minute; respiratory rate, 18 breaths per minute; and oxygen saturation, 95% on room air. Head and neck examination revealed bilateral cervical lymphadenopathy with pronounced tenderness on the left side of his neck. Oral exam revealed dry mucous membranes, halitosis, and bilateral tonsillar enlargement without exudate. The cardiopulmonary exam was within normal limits. Lab tests showed a white blood cell (WBC) count of 5.9 x 109/L. An ultrasound of the neck revealed thrombosis in the left submandibular branch of the left internal jugular vein (IJV) (FIGURE 1).

The next day, the patient remained febrile (102.8°F) and developed rigors, diarrhea, pleuritic chest pain, and an elevated WBC count (14.5). A blood culture grew gramnegative rods. The patient was started on piperacillin/tazobactam, and doxycycline was added to treat possible tick-borne infections. Computed tomography (CT) scans of the chest showed the presence of septic pulmonary emboli and small bilateral pleural effusions (FIGURE 2).

THE DIAGNOSIS

We made a diagnosis of Lemierre’s syndrome because our patient met all 4 criteria for the condition:1,2

• a recent oropharyngeal infection

• clinical or radiological evidence of IJV thrombosis

• isolation of anaerobic pathogens (mainly Fusobacterium necrophorum)

• evidence of at least one septic focus, most commonly in the lungs.

We changed the patient’s antibiotic therapy to intravenous (IV) meropenem. His WBC and fever improved, and on Day 10 he was discharged to complete a 28-day course of IV meropenem via a peripherally inserted central catheter.

DISCUSSION

Lemierre’s—A “forgotten” condition that’s making a comeback

In 1936, French microbiologist Andrew Lemierre formally characterized the syndrome in a review of 20 patients who had sepsis, metastatic pulmonary lesions, and isolation of Bacillus funduliformis (now known as F necrophorum).1,2 Other organisms that have been identified in this syndrome include Fusobacterium nucleatum, Candida, Staphylococcus, and Streptococcus.2

Before the antibiotic era, Lemierre’s syndrome was common and often fatal. But with the introduction of penicillin in the 1940s, the incidence of the syndrome dropped, and it eventually became known as “the forgotten disease.”2 Since the 1990s, however, there has been a marked resurgence of Lemierre’s syndrome.3 The incidence of Lemierre’s syndrome today is 0.6 to 2.3 cases per 1 million people per year, with a mortality rate of up to 18%.3,4

This resurgence of Lemierre’s syndrome has been linked to the restricted use of antibiotics for throat infections.3 (One study found the number of prescriptions written for antibiotics decreased by 23% from 1992 to 2000.5) Other factors cited for the increased incidence of Lemierre’s syndrome include improved identification of anaerobic organisms, more effective blood culture methods, and an increased awareness of this syndrome among clinical microbiologists.6

Diagnosis requires a high degree of suspicion

Lemierre’s syndrome typically occurs in healthy young adults. Pharyngitis is the most common initial symptom, occurring in 87% of patients.2 This is followed by a fever (102.2°F - 105.8°F) usually 4 to 5 days after the onset of sore throat.3 Other common symptoms include chills, dysphagia, dyspnea, chest pain, hemoptysis, cervical neck discomfort, arthralgia, malaise, and night sweats.2 Following suppurative thrombophlebitis of the IJV, infection spreads to other organ systems. Pulmonary involvement is the most common site (97% of cases).3 Other complications of this syndrome are listed in the TABLE.3

The differential includes mononucleosis

The differential diagnosis encompasses several common illnesses, including mononucleosis, Group A streptococcal pharyngitis, and peritonsillar abscess. However, while patients with these conditions might have a fever and an elevated WBC count, they typically would not have the pleuritic chest pain that is characteristic of Lemierre’s syndrome. In addition, while patients with peritonsillar abscess would have tonsillar exudates, patients with Lemierre’s syndrome would not likely have them.

Influenza is also part of the differential, although focal neck pain usually isn’t a finding in patients who have the flu.

Once other common illnesses have been ruled out, it’s important to have a high index of suspicion for Lemierre’s syndrome because the oropharyngeal infection may resolve by the time of presentation, and there may be few findings on physical exam.7 Therefore, suspect Lemierre’s if a patient comes in with neck pain and/or pleuritic chest pain and has a recent history of oropharyngeal infection and fever.

CT scan of the neck and chest with contrast is the optimal diagnostic modality because it allows physicians to visualize the IJV8 and detect pulmonary emboli.9 Doppler ultrasound also can be used to diagnose IJV thrombosis. Ultrasound findings would reveal an echogenic focus within a dilated IJV or a complex mass of cystic and solid components.10

Prompt antibiotic treatment is essential

Patients with Lemierre’s syndrome require prompt and appropriate antimicrobial therapy. Researchers have reported mortality rates of 25% among patients who received delayed antibiotic therapy, compared with rates of up to 18% with prompt therapy.3 Metronidazole is the most commonly prescribed antibiotic.8 When combined with ceftriaxone, it provides coverage for both F necrophorum and streptococci, a common copathogen. Monotherapy with a carbapenem antibiotic, clindamycin, ampicillin/sulbactam, or antipseudomonal penicillin also are appropriate options.5 Antimicrobial treatment for 3 to 6 weeks is recommended because relapses have been noted in patients treated for less than 2 weeks.11

Anticoagulation is controversial.2 Proponents of anticoagulation to treat Lemierre’s syndrome believe it may prevent formation of septic emboli and could expedite recovery.4,12 Others believe that clots associated with Lemierre’s syndrome dissolve on their own and that anticoagulation may increase the likelihood of septic emboli.13 Many case reports, including this one, have demonstrated that complete recovery is possible without anticoagulation.10,13-15 Anticoagulation therapy can be considered for patients with Lemierre’s syndrome in the absence of any contraindications such as gastrointestinal or intracranial bleeding.

THE TAKEAWAY

Suspect Lemierre’s syndrome when a patient complains of neck pain, high fever, rigors, dry cough, and pleuritic chest pain and mentions a sore throat that he or she had in the pretceding 7 days. Diagnosis can be confirmed by radiological findings and blood cultures positive for F. necrophorum. Patients with Lemierre’s syndrome should be promptly treated with antibiotics; evidence for anticoagulation is inconclusive.

THE CASE

A previously healthy 35-year-old man with a one-week history of left-sided neck pain and fever as high as 104°F sought care at our emergency department. He was given a diagnosis of viral pharyngitis and discharged. He returned the next day and indicated that he was now experiencing drenching night sweats and weakness.

The patient was anxious, but not distressed. His temperature was 100.1°F; blood pressure, 113/65 mm Hg; heart rate, 150 beats per minute; respiratory rate, 18 breaths per minute; and oxygen saturation, 95% on room air. Head and neck examination revealed bilateral cervical lymphadenopathy with pronounced tenderness on the left side of his neck. Oral exam revealed dry mucous membranes, halitosis, and bilateral tonsillar enlargement without exudate. The cardiopulmonary exam was within normal limits. Lab tests showed a white blood cell (WBC) count of 5.9 x 109/L. An ultrasound of the neck revealed thrombosis in the left submandibular branch of the left internal jugular vein (IJV) (FIGURE 1).

The next day, the patient remained febrile (102.8°F) and developed rigors, diarrhea, pleuritic chest pain, and an elevated WBC count (14.5). A blood culture grew gramnegative rods. The patient was started on piperacillin/tazobactam, and doxycycline was added to treat possible tick-borne infections. Computed tomography (CT) scans of the chest showed the presence of septic pulmonary emboli and small bilateral pleural effusions (FIGURE 2).

THE DIAGNOSIS

We made a diagnosis of Lemierre’s syndrome because our patient met all 4 criteria for the condition:1,2

• a recent oropharyngeal infection

• clinical or radiological evidence of IJV thrombosis

• isolation of anaerobic pathogens (mainly Fusobacterium necrophorum)

• evidence of at least one septic focus, most commonly in the lungs.

We changed the patient’s antibiotic therapy to intravenous (IV) meropenem. His WBC and fever improved, and on Day 10 he was discharged to complete a 28-day course of IV meropenem via a peripherally inserted central catheter.

DISCUSSION

Lemierre’s—A “forgotten” condition that’s making a comeback

In 1936, French microbiologist Andrew Lemierre formally characterized the syndrome in a review of 20 patients who had sepsis, metastatic pulmonary lesions, and isolation of Bacillus funduliformis (now known as F necrophorum).1,2 Other organisms that have been identified in this syndrome include Fusobacterium nucleatum, Candida, Staphylococcus, and Streptococcus.2

Before the antibiotic era, Lemierre’s syndrome was common and often fatal. But with the introduction of penicillin in the 1940s, the incidence of the syndrome dropped, and it eventually became known as “the forgotten disease.”2 Since the 1990s, however, there has been a marked resurgence of Lemierre’s syndrome.3 The incidence of Lemierre’s syndrome today is 0.6 to 2.3 cases per 1 million people per year, with a mortality rate of up to 18%.3,4

This resurgence of Lemierre’s syndrome has been linked to the restricted use of antibiotics for throat infections.3 (One study found the number of prescriptions written for antibiotics decreased by 23% from 1992 to 2000.5) Other factors cited for the increased incidence of Lemierre’s syndrome include improved identification of anaerobic organisms, more effective blood culture methods, and an increased awareness of this syndrome among clinical microbiologists.6

Diagnosis requires a high degree of suspicion

Lemierre’s syndrome typically occurs in healthy young adults. Pharyngitis is the most common initial symptom, occurring in 87% of patients.2 This is followed by a fever (102.2°F - 105.8°F) usually 4 to 5 days after the onset of sore throat.3 Other common symptoms include chills, dysphagia, dyspnea, chest pain, hemoptysis, cervical neck discomfort, arthralgia, malaise, and night sweats.2 Following suppurative thrombophlebitis of the IJV, infection spreads to other organ systems. Pulmonary involvement is the most common site (97% of cases).3 Other complications of this syndrome are listed in the TABLE.3

The differential includes mononucleosis

The differential diagnosis encompasses several common illnesses, including mononucleosis, Group A streptococcal pharyngitis, and peritonsillar abscess. However, while patients with these conditions might have a fever and an elevated WBC count, they typically would not have the pleuritic chest pain that is characteristic of Lemierre’s syndrome. In addition, while patients with peritonsillar abscess would have tonsillar exudates, patients with Lemierre’s syndrome would not likely have them.

Influenza is also part of the differential, although focal neck pain usually isn’t a finding in patients who have the flu.

Once other common illnesses have been ruled out, it’s important to have a high index of suspicion for Lemierre’s syndrome because the oropharyngeal infection may resolve by the time of presentation, and there may be few findings on physical exam.7 Therefore, suspect Lemierre’s if a patient comes in with neck pain and/or pleuritic chest pain and has a recent history of oropharyngeal infection and fever.

CT scan of the neck and chest with contrast is the optimal diagnostic modality because it allows physicians to visualize the IJV8 and detect pulmonary emboli.9 Doppler ultrasound also can be used to diagnose IJV thrombosis. Ultrasound findings would reveal an echogenic focus within a dilated IJV or a complex mass of cystic and solid components.10

Prompt antibiotic treatment is essential

Patients with Lemierre’s syndrome require prompt and appropriate antimicrobial therapy. Researchers have reported mortality rates of 25% among patients who received delayed antibiotic therapy, compared with rates of up to 18% with prompt therapy.3 Metronidazole is the most commonly prescribed antibiotic.8 When combined with ceftriaxone, it provides coverage for both F necrophorum and streptococci, a common copathogen. Monotherapy with a carbapenem antibiotic, clindamycin, ampicillin/sulbactam, or antipseudomonal penicillin also are appropriate options.5 Antimicrobial treatment for 3 to 6 weeks is recommended because relapses have been noted in patients treated for less than 2 weeks.11

Anticoagulation is controversial.2 Proponents of anticoagulation to treat Lemierre’s syndrome believe it may prevent formation of septic emboli and could expedite recovery.4,12 Others believe that clots associated with Lemierre’s syndrome dissolve on their own and that anticoagulation may increase the likelihood of septic emboli.13 Many case reports, including this one, have demonstrated that complete recovery is possible without anticoagulation.10,13-15 Anticoagulation therapy can be considered for patients with Lemierre’s syndrome in the absence of any contraindications such as gastrointestinal or intracranial bleeding.

THE TAKEAWAY

Suspect Lemierre’s syndrome when a patient complains of neck pain, high fever, rigors, dry cough, and pleuritic chest pain and mentions a sore throat that he or she had in the pretceding 7 days. Diagnosis can be confirmed by radiological findings and blood cultures positive for F. necrophorum. Patients with Lemierre’s syndrome should be promptly treated with antibiotics; evidence for anticoagulation is inconclusive.

1. Golpe R, Marin B, Alonso M. Lemierre’s syndrome (necrobacillosis). Postgrad Med J. 1999;75:141-144.

2. Wright WF, Shiner CN, Ribes JA. Lemierre syndrome. South Med J. 2012;105:283-288.

3. Riordan T, Wilson M. Lemierre’s syndrome: more than a historical curiosa. Postgrad Med J. 2004;80:328-334.

4. Ridgway JM, Parikh DA, Wright R, et al. Lemierre syndrome: a pediatric case series and review of literature. Am J Otolaryngol. 2010;31:38-45.

5. McCaig LF, Besser RE, Hughes JM. Antimicrobial drug prescription in ambulatory care settings, United States, 1992–2000. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:432-437.

6. Hagelskjaer Kristensen L, Prag J. Human necrobacillosis, with emphasis on Lemierre’s syndrome. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:524-532.

7. Kupalli K, Livorsi D, Talati N, et al. Lemierre’s syndrome due to fusobacterium necrophorum. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:808-815.

8. Armstrong AW, Spooner K, Sanders JW. Lemierre’s syndrome. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2000;2:168-173.

9. Screaton NJ, Ravenel JG, Lehner PJ, et al. Lemierre syndrome: forgotten but not extinct--report of four cases. Radiology. 1999;213:369-374.

10. Chirinos JA, Lichtstein DM, Garcia J, et al. The evolution of Lemierre syndrome: report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2002;81:458-465.

11. Karkos PD, Asrani S, Karkos CD, et al. Lemierre syndrome: a systematic review. Laryngoscope. 2009;119:1552-1559.

12. Phan T, So TY. Use of anticoagulation therapy for jugular vein thrombus in pediatric patients with Lemierre’s syndrome. Int J Clin Pharm. 2012;34:818-821.

13. O’Brien WT, Cohen RA. Lemierre’ syndrome. Applied Radiology. 2011;40:37-38.

14. Vandenberg SJ, Hartig GK. Lemierre’s syndrome. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;119:516-518.

15. Goldhagen J, Alford BA, Prewitt LH, et al. Suppurative thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein: report of three cases and review of the pediatric literature. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1988;7:410-414.

1. Golpe R, Marin B, Alonso M. Lemierre’s syndrome (necrobacillosis). Postgrad Med J. 1999;75:141-144.

2. Wright WF, Shiner CN, Ribes JA. Lemierre syndrome. South Med J. 2012;105:283-288.

3. Riordan T, Wilson M. Lemierre’s syndrome: more than a historical curiosa. Postgrad Med J. 2004;80:328-334.

4. Ridgway JM, Parikh DA, Wright R, et al. Lemierre syndrome: a pediatric case series and review of literature. Am J Otolaryngol. 2010;31:38-45.

5. McCaig LF, Besser RE, Hughes JM. Antimicrobial drug prescription in ambulatory care settings, United States, 1992–2000. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:432-437.

6. Hagelskjaer Kristensen L, Prag J. Human necrobacillosis, with emphasis on Lemierre’s syndrome. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:524-532.

7. Kupalli K, Livorsi D, Talati N, et al. Lemierre’s syndrome due to fusobacterium necrophorum. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:808-815.

8. Armstrong AW, Spooner K, Sanders JW. Lemierre’s syndrome. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2000;2:168-173.

9. Screaton NJ, Ravenel JG, Lehner PJ, et al. Lemierre syndrome: forgotten but not extinct--report of four cases. Radiology. 1999;213:369-374.

10. Chirinos JA, Lichtstein DM, Garcia J, et al. The evolution of Lemierre syndrome: report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2002;81:458-465.

11. Karkos PD, Asrani S, Karkos CD, et al. Lemierre syndrome: a systematic review. Laryngoscope. 2009;119:1552-1559.

12. Phan T, So TY. Use of anticoagulation therapy for jugular vein thrombus in pediatric patients with Lemierre’s syndrome. Int J Clin Pharm. 2012;34:818-821.

13. O’Brien WT, Cohen RA. Lemierre’ syndrome. Applied Radiology. 2011;40:37-38.

14. Vandenberg SJ, Hartig GK. Lemierre’s syndrome. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;119:516-518.

15. Goldhagen J, Alford BA, Prewitt LH, et al. Suppurative thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein: report of three cases and review of the pediatric literature. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1988;7:410-414.

What you should know about patients who bring a list to their office visit

ABSTRACT

Purpose Little is known about patients who present a written list during a medical consultation. In this preliminary study, we sought to examine and characterize patients who use a prepared list.

Methods The design was an open observational case-controlled study that took place at 2 urban primary care clinics. We enrolled patients consecutively as they arrived with a written list for consultation. Consecutive patients presenting without a list served as the control group. Physician interviews and completed questionnaires provided demographic and medical characteristics of this group and explanations for list preparation.

Results Fifty-four patients presented with a list and were compared with controls. Statistically, patients arriving with a list were significantly more likely to be older and retired, and less likely to be salaried workers or housewives. These patients had more chronic diseases and consumed more long-term medications. They had a greater number of doctor visits in the past year compared with controls, and perceived an increase in memory loss. There were no differences between the groups in terms of psychiatric disease or personality disorders.

Conclusions Aside from certain demographic and health characteristics, patients who use written lists do not differ substantially from those who don’t. They have no discernible ill intention, and the list serves as a memory aid to make the most of the visit.

Nonverbal communication is a significant part of the physician-patient encounter, in part revealing clues to underlying attitudes and emotions or indicating whether one agrees or disagrees with expressed statements.1 Nonverbal communication exhibited by both doctor and patient strongly influences how each participant perceives the encounter and helps determine how the physician-patient relationship will develop.2-4

Patients, for example, are affected by the amount of physician eye contact and computer use. Less eye contact and greater attention to the computer tend to lower patients’ opinions of the consultation.1,5 These and other behaviors may contribute to the finding that 30% to 80% of patients feel their expectations are not met in routine primary care visits.6

Physicians, despite attempts to remain nonjudgmental, can be affected by a patient’s demeanor on entering the consulting room. Subtle prejudices may be evoked by age, gender, ethnicity, manner of dress, tone of voice, mannerisms, cell phone interruptions, and the like.7,8 Negative reactions can create barriers to good communication. Awareness of them may be the first step to preventing or removing hindrances to meaningful dialogue.9

One aspect of a patient’s presentation that may be viewed negatively is possession of a list. But this need not be the case. The list, if viewed as a patient-initiated agenda, can lead to a gratifying encounter for both patient and physician. In fact, there is reason to believe that a list representing a set agenda at the start of a visit may enhance patient satisfaction without increasing visit length.10 In fact, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) advises patients to “Write down your questions before your visit. List the most important ones first to make sure they get asked and answered.”11

To learn more about the people who arrive at a consultation with a written list, we conducted a study at 2 clinics in Clalit Health Services—Southern District (CHS-SD), which we designed to focus on answering the following questions:

1. Do patients with lists have a unique sociodemographic profile?

2. Do they present with specific medical ailments but have a high frequency of psychiatric disorders?

3. What are the underlying motives leading to list use?

METHODS

Design

This was an open observational case-controlled study, approved by the institutional review board and the clinical research board of the Department of Family Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beer-Sheva, Israel.

Setting

We conducted our study at 2 urban primary care clinics serving a population of 7000 people of diverse ages, 10% of whom are recent immigrants.

Selection of participants

We consecutively recruited patients who carried a list to use during the consultation. After obtaining patients’ informed consent to participate in the study, we asked them to spend the time necessary to disclose requested information. We excluded those who were not fluent in the language of their physicians.

Intervention

Family physicians at the participating clinics distributed a questionnaire to patients arriving with a written list, then conducted guided interviews. We defined “list use” as the patient’s choice to refer to a list as an agenda for that visit, whether to remind one’s self to cover all complaints, to accurately describe symptoms, to request medication prescriptions, or to ask about test results.

First, through interview or questionnaire, we gathered standard sociodemographic data. Second, we focused on general health issues, chronic medical disorders, psychiatric disorders, chronic medication consumption, and number of visits. We derived this information from computerized medical records. Third, through the questionnaire, we inquired about the reason patients used a list, and asked patients to subjectively rate their memory and give the general reasons for their visit.

The control group consisted of patients recruited consecutively at arbitrary points in time until its size matched that of the study group. These patients volunteered information to the same line of inquiry. Some members of the groups chose to complete the questionnaires in writing without the physician’s assistance.

Statistical analysis

We processed results using SPSS software. We applied the x2 test for statistical interpretation and set statistical significance at P<.05.

RESULTS

Twenty-five men and twenty-nine women ages 21 to 82 years of age comprised the group of patients presenting with a list. All patients who met inclusion criteria agreed to cooperate. TABLE 1 summarizes the sociodemographic data. The control group consisted of 30 men and 22 women ages 20 to 86 years of age.

There was no statistically meaningful difference in gender ratio between the groups. In the study and control groups, respectively, the average number of children of each subject was 4.1 and 3.5, years of formal education were 10.8 and 10.6, and years since immigration were 40.5 and 37.8 (P=.42). Marital status and average household income were also similar in both groups.

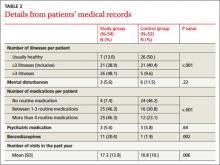

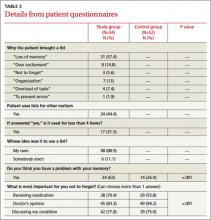

Statistically significant findings with the study group were relatively older ages and likelihood to be pensioners. The study group included fewer employed individuals and fewer housewives (P<.001). They also were more likely to have more than 3 chronic diseases (48.1% vs. 9.6%; P<.001) and took more long-term medications, including benzodiazepines (TABLE 2). They had a greater number of doctor visits in the past year compared with controls and reported a perceived increase in memory loss (TABLE 3). There were no significant differences between the groups in psychiatric or personality disorders, as determined by surveying patients’ electronic records.

The reasons most commonly given for using a list indicated a desire to completely satisfy the objectives of the visit. Most of the individuals decided to prepare a list on their own initiative without persuasion from any external source.

DISCUSSION

In an survey of 216 family physicians and internists at the University of Wisconsin, >60% of respondents said their patients bring in lists very often or sometimes.11 This figure seems much higher than would be found in our country (Israel). However, the practice is certainly common; although the actual frequency is unknown.

Other published observations about list use. Middleton et al12 studied the effects of planned use of agenda forms, completed by patients and handed to physicians at the outset of a primary care visit. The written agenda significantly increased the number of problems identified in each consultation. Patient satisfaction increased and deepened the doctor-patient relationship. However, the duration of consultations also increased.

A commentary by Schrager et al11 acknowledges that lists are dreaded by some physicians. Particularly if the expectation is for a patient to present with a single complaint, the appearance of a list may be an unwelcome surprise, suggesting a collection of separate complaints. And compulsive and somatizing patients can raise a series of overwhelming issues that encumber a short visit. But the commentary points out that, in general, fear of a list is unfounded, and that acceptance without prejudging can lead to a constructive outcome.

A number of researchers have examined the relationship between negative physician attitudes and certain patient attributes such as sociodemographic characteristics or a persistent emotional component to their ailments.13 Katz14 reported that patients who generated the most frustration were those who demanded a cure, those who added unrelated complaints at the end of the visit, malingerers, and those who refused to accept responsibility for their own maladies. List users, we believe, should not be lumped in with this group automatically.

In our study, patients with lists did request more frequent consultations. However, this correlated closely with a heavier burden of disease. Using patient-centered communication to set the agenda for the visit and address the entirety of patients’ concerns has been shown to improve not only patient satisfaction but also adherence to treatment recommendations.15,16 One way for patients to become more involved in their care is to bring a list of questions to each visit, as advised by AHRQ.

What our study revealed about list users. Our results show that those who made use of a list were older than the ones who did not, more likely to be pensioners, and less likely to be employed or be housewives. They had more chronic diseases, were receiving more medications including benzodiazepines, and had a significantly higher rate of medical appointments than did the controls. Psychiatric diagnoses were no more common among the list users, and reasons given for list use were congruent with aging and an increased burden of disease and medication. We could not discern the exact contribution of each independent factor of advanced age or disease burden. This would be an interesting issue to address in more elaborate research, as would be the actual frequency of list use.

Limitations of our study. The weaknesses of our study include its questionable generalizability and the possibility that a number of list bearers may not have been recruited due to time constraints on patients or physicians. Randomization could have been improved if we had selected the controls consecutively after selecting the study patients, and not at a separate time. We did not time the length of the consultations, something that should be done in future studies.

The fact that the study group consumed more benzodiazepine medications may hint that its members suffer from greater levels of anxiety or depression. Nevertheless, we assumed that such conditions were likely of modest intensity since they were not included in the medical records.

Large-scale research could yield far more trustworthy results by adjusting for age, country of origin, and disease burden.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sody Naimer, MD, Department of Family Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, POB 653, Beer-Sheva 84105, Israel; [email protected]

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Dr. Joseph Herman and Mrs. Barbra Schipper for their assistance in preparing this manuscript.

1. Silverman J, Kinnersley P. Doctors’ non-verbal behaviour in consultations: look at the patient before you look at the computer. Br J Gen Pract. 2010;60:76-78.

2. Hall JA, Harrigan JA, Rosenthal R. Nonverbal behavior in clinician-patient interaction. Appl Prev Psychol. 1995;4:21-37.

3. Mast MS. On the importance of nonverbal communication in the physician-patient interaction. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;67:315-318.

4. Roter DL, Frankel RM, Hall JA, et al. The expression of emotion through nonverbal behavior in medical visits. Mechanisms and outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21 suppl 1:S28-S34.

5. Marcinowicz L, Konstantynowicz J, Godlewski C. Patients’ perceptions of GP non-verbal communication: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2010;60:83-87.

6. Kravitz RL. Patients’ expectations for medical care: an expanded formulation based on review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev. 1996;53:3-27.

7. Hooper EM, Comstock LM, Goodwin JM, et al. Patient characteristics that influence physician behavior. Med Care. 1982;20:630-638.

8. Naimer SA, Biton A. A pilot study of behaviour and impact of cellular telephone ringing interrupting the medical consultation. Isr J Fam Pr. 2002;19:35-39.

9. Quill TE. Recognizing and adjusting to barriers in doctor-patient communication. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111:51-57.

10. Brock DM, Mauksch LB, Witteborn S, et al. Effectiveness of intensive physician training in upfront agenda setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:1317-1323.

11. Schrager S, Gaard S. What should you do when your patient brings a list? Fam Pract Manag. 2009;16:23-27.

12. Middleton JF, McKinley RK, Gillies CL. Effect of patient completed agenda forms and doctors’ education about the agenda on the outcome of consultations: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2006;332:1238-1242.

13. Aaker E, Knudsen A, Wynn R, et al. General practitioners’ reactions to non-compliant patients. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2001;19:103-106.

14. Katz RC. “Difficult patients” as family physicians perceive them. Psychol Rep. 1996;79:539-544.

15. Epstein RM, Mauksch L, Carroll J, et al. Have you really addressed your patient’s concerns? Fam Pract Manag. 2008;15:35-40.

16. Bergeson SC, Dean JD. A systems approach to patient-centered care. JAMA. 2006;296:2848-2851.

ABSTRACT

Purpose Little is known about patients who present a written list during a medical consultation. In this preliminary study, we sought to examine and characterize patients who use a prepared list.

Methods The design was an open observational case-controlled study that took place at 2 urban primary care clinics. We enrolled patients consecutively as they arrived with a written list for consultation. Consecutive patients presenting without a list served as the control group. Physician interviews and completed questionnaires provided demographic and medical characteristics of this group and explanations for list preparation.

Results Fifty-four patients presented with a list and were compared with controls. Statistically, patients arriving with a list were significantly more likely to be older and retired, and less likely to be salaried workers or housewives. These patients had more chronic diseases and consumed more long-term medications. They had a greater number of doctor visits in the past year compared with controls, and perceived an increase in memory loss. There were no differences between the groups in terms of psychiatric disease or personality disorders.

Conclusions Aside from certain demographic and health characteristics, patients who use written lists do not differ substantially from those who don’t. They have no discernible ill intention, and the list serves as a memory aid to make the most of the visit.

Nonverbal communication is a significant part of the physician-patient encounter, in part revealing clues to underlying attitudes and emotions or indicating whether one agrees or disagrees with expressed statements.1 Nonverbal communication exhibited by both doctor and patient strongly influences how each participant perceives the encounter and helps determine how the physician-patient relationship will develop.2-4

Patients, for example, are affected by the amount of physician eye contact and computer use. Less eye contact and greater attention to the computer tend to lower patients’ opinions of the consultation.1,5 These and other behaviors may contribute to the finding that 30% to 80% of patients feel their expectations are not met in routine primary care visits.6

Physicians, despite attempts to remain nonjudgmental, can be affected by a patient’s demeanor on entering the consulting room. Subtle prejudices may be evoked by age, gender, ethnicity, manner of dress, tone of voice, mannerisms, cell phone interruptions, and the like.7,8 Negative reactions can create barriers to good communication. Awareness of them may be the first step to preventing or removing hindrances to meaningful dialogue.9

One aspect of a patient’s presentation that may be viewed negatively is possession of a list. But this need not be the case. The list, if viewed as a patient-initiated agenda, can lead to a gratifying encounter for both patient and physician. In fact, there is reason to believe that a list representing a set agenda at the start of a visit may enhance patient satisfaction without increasing visit length.10 In fact, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) advises patients to “Write down your questions before your visit. List the most important ones first to make sure they get asked and answered.”11

To learn more about the people who arrive at a consultation with a written list, we conducted a study at 2 clinics in Clalit Health Services—Southern District (CHS-SD), which we designed to focus on answering the following questions:

1. Do patients with lists have a unique sociodemographic profile?

2. Do they present with specific medical ailments but have a high frequency of psychiatric disorders?

3. What are the underlying motives leading to list use?

METHODS

Design

This was an open observational case-controlled study, approved by the institutional review board and the clinical research board of the Department of Family Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beer-Sheva, Israel.

Setting

We conducted our study at 2 urban primary care clinics serving a population of 7000 people of diverse ages, 10% of whom are recent immigrants.

Selection of participants

We consecutively recruited patients who carried a list to use during the consultation. After obtaining patients’ informed consent to participate in the study, we asked them to spend the time necessary to disclose requested information. We excluded those who were not fluent in the language of their physicians.

Intervention

Family physicians at the participating clinics distributed a questionnaire to patients arriving with a written list, then conducted guided interviews. We defined “list use” as the patient’s choice to refer to a list as an agenda for that visit, whether to remind one’s self to cover all complaints, to accurately describe symptoms, to request medication prescriptions, or to ask about test results.

First, through interview or questionnaire, we gathered standard sociodemographic data. Second, we focused on general health issues, chronic medical disorders, psychiatric disorders, chronic medication consumption, and number of visits. We derived this information from computerized medical records. Third, through the questionnaire, we inquired about the reason patients used a list, and asked patients to subjectively rate their memory and give the general reasons for their visit.

The control group consisted of patients recruited consecutively at arbitrary points in time until its size matched that of the study group. These patients volunteered information to the same line of inquiry. Some members of the groups chose to complete the questionnaires in writing without the physician’s assistance.

Statistical analysis

We processed results using SPSS software. We applied the x2 test for statistical interpretation and set statistical significance at P<.05.

RESULTS

Twenty-five men and twenty-nine women ages 21 to 82 years of age comprised the group of patients presenting with a list. All patients who met inclusion criteria agreed to cooperate. TABLE 1 summarizes the sociodemographic data. The control group consisted of 30 men and 22 women ages 20 to 86 years of age.

There was no statistically meaningful difference in gender ratio between the groups. In the study and control groups, respectively, the average number of children of each subject was 4.1 and 3.5, years of formal education were 10.8 and 10.6, and years since immigration were 40.5 and 37.8 (P=.42). Marital status and average household income were also similar in both groups.

Statistically significant findings with the study group were relatively older ages and likelihood to be pensioners. The study group included fewer employed individuals and fewer housewives (P<.001). They also were more likely to have more than 3 chronic diseases (48.1% vs. 9.6%; P<.001) and took more long-term medications, including benzodiazepines (TABLE 2). They had a greater number of doctor visits in the past year compared with controls and reported a perceived increase in memory loss (TABLE 3). There were no significant differences between the groups in psychiatric or personality disorders, as determined by surveying patients’ electronic records.

The reasons most commonly given for using a list indicated a desire to completely satisfy the objectives of the visit. Most of the individuals decided to prepare a list on their own initiative without persuasion from any external source.

DISCUSSION

In an survey of 216 family physicians and internists at the University of Wisconsin, >60% of respondents said their patients bring in lists very often or sometimes.11 This figure seems much higher than would be found in our country (Israel). However, the practice is certainly common; although the actual frequency is unknown.

Other published observations about list use. Middleton et al12 studied the effects of planned use of agenda forms, completed by patients and handed to physicians at the outset of a primary care visit. The written agenda significantly increased the number of problems identified in each consultation. Patient satisfaction increased and deepened the doctor-patient relationship. However, the duration of consultations also increased.

A commentary by Schrager et al11 acknowledges that lists are dreaded by some physicians. Particularly if the expectation is for a patient to present with a single complaint, the appearance of a list may be an unwelcome surprise, suggesting a collection of separate complaints. And compulsive and somatizing patients can raise a series of overwhelming issues that encumber a short visit. But the commentary points out that, in general, fear of a list is unfounded, and that acceptance without prejudging can lead to a constructive outcome.

A number of researchers have examined the relationship between negative physician attitudes and certain patient attributes such as sociodemographic characteristics or a persistent emotional component to their ailments.13 Katz14 reported that patients who generated the most frustration were those who demanded a cure, those who added unrelated complaints at the end of the visit, malingerers, and those who refused to accept responsibility for their own maladies. List users, we believe, should not be lumped in with this group automatically.

In our study, patients with lists did request more frequent consultations. However, this correlated closely with a heavier burden of disease. Using patient-centered communication to set the agenda for the visit and address the entirety of patients’ concerns has been shown to improve not only patient satisfaction but also adherence to treatment recommendations.15,16 One way for patients to become more involved in their care is to bring a list of questions to each visit, as advised by AHRQ.

What our study revealed about list users. Our results show that those who made use of a list were older than the ones who did not, more likely to be pensioners, and less likely to be employed or be housewives. They had more chronic diseases, were receiving more medications including benzodiazepines, and had a significantly higher rate of medical appointments than did the controls. Psychiatric diagnoses were no more common among the list users, and reasons given for list use were congruent with aging and an increased burden of disease and medication. We could not discern the exact contribution of each independent factor of advanced age or disease burden. This would be an interesting issue to address in more elaborate research, as would be the actual frequency of list use.

Limitations of our study. The weaknesses of our study include its questionable generalizability and the possibility that a number of list bearers may not have been recruited due to time constraints on patients or physicians. Randomization could have been improved if we had selected the controls consecutively after selecting the study patients, and not at a separate time. We did not time the length of the consultations, something that should be done in future studies.

The fact that the study group consumed more benzodiazepine medications may hint that its members suffer from greater levels of anxiety or depression. Nevertheless, we assumed that such conditions were likely of modest intensity since they were not included in the medical records.

Large-scale research could yield far more trustworthy results by adjusting for age, country of origin, and disease burden.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sody Naimer, MD, Department of Family Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, POB 653, Beer-Sheva 84105, Israel; [email protected]

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Dr. Joseph Herman and Mrs. Barbra Schipper for their assistance in preparing this manuscript.

ABSTRACT

Purpose Little is known about patients who present a written list during a medical consultation. In this preliminary study, we sought to examine and characterize patients who use a prepared list.

Methods The design was an open observational case-controlled study that took place at 2 urban primary care clinics. We enrolled patients consecutively as they arrived with a written list for consultation. Consecutive patients presenting without a list served as the control group. Physician interviews and completed questionnaires provided demographic and medical characteristics of this group and explanations for list preparation.

Results Fifty-four patients presented with a list and were compared with controls. Statistically, patients arriving with a list were significantly more likely to be older and retired, and less likely to be salaried workers or housewives. These patients had more chronic diseases and consumed more long-term medications. They had a greater number of doctor visits in the past year compared with controls, and perceived an increase in memory loss. There were no differences between the groups in terms of psychiatric disease or personality disorders.

Conclusions Aside from certain demographic and health characteristics, patients who use written lists do not differ substantially from those who don’t. They have no discernible ill intention, and the list serves as a memory aid to make the most of the visit.

Nonverbal communication is a significant part of the physician-patient encounter, in part revealing clues to underlying attitudes and emotions or indicating whether one agrees or disagrees with expressed statements.1 Nonverbal communication exhibited by both doctor and patient strongly influences how each participant perceives the encounter and helps determine how the physician-patient relationship will develop.2-4

Patients, for example, are affected by the amount of physician eye contact and computer use. Less eye contact and greater attention to the computer tend to lower patients’ opinions of the consultation.1,5 These and other behaviors may contribute to the finding that 30% to 80% of patients feel their expectations are not met in routine primary care visits.6

Physicians, despite attempts to remain nonjudgmental, can be affected by a patient’s demeanor on entering the consulting room. Subtle prejudices may be evoked by age, gender, ethnicity, manner of dress, tone of voice, mannerisms, cell phone interruptions, and the like.7,8 Negative reactions can create barriers to good communication. Awareness of them may be the first step to preventing or removing hindrances to meaningful dialogue.9

One aspect of a patient’s presentation that may be viewed negatively is possession of a list. But this need not be the case. The list, if viewed as a patient-initiated agenda, can lead to a gratifying encounter for both patient and physician. In fact, there is reason to believe that a list representing a set agenda at the start of a visit may enhance patient satisfaction without increasing visit length.10 In fact, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) advises patients to “Write down your questions before your visit. List the most important ones first to make sure they get asked and answered.”11

To learn more about the people who arrive at a consultation with a written list, we conducted a study at 2 clinics in Clalit Health Services—Southern District (CHS-SD), which we designed to focus on answering the following questions:

1. Do patients with lists have a unique sociodemographic profile?

2. Do they present with specific medical ailments but have a high frequency of psychiatric disorders?

3. What are the underlying motives leading to list use?

METHODS

Design

This was an open observational case-controlled study, approved by the institutional review board and the clinical research board of the Department of Family Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beer-Sheva, Israel.

Setting

We conducted our study at 2 urban primary care clinics serving a population of 7000 people of diverse ages, 10% of whom are recent immigrants.

Selection of participants

We consecutively recruited patients who carried a list to use during the consultation. After obtaining patients’ informed consent to participate in the study, we asked them to spend the time necessary to disclose requested information. We excluded those who were not fluent in the language of their physicians.

Intervention

Family physicians at the participating clinics distributed a questionnaire to patients arriving with a written list, then conducted guided interviews. We defined “list use” as the patient’s choice to refer to a list as an agenda for that visit, whether to remind one’s self to cover all complaints, to accurately describe symptoms, to request medication prescriptions, or to ask about test results.

First, through interview or questionnaire, we gathered standard sociodemographic data. Second, we focused on general health issues, chronic medical disorders, psychiatric disorders, chronic medication consumption, and number of visits. We derived this information from computerized medical records. Third, through the questionnaire, we inquired about the reason patients used a list, and asked patients to subjectively rate their memory and give the general reasons for their visit.

The control group consisted of patients recruited consecutively at arbitrary points in time until its size matched that of the study group. These patients volunteered information to the same line of inquiry. Some members of the groups chose to complete the questionnaires in writing without the physician’s assistance.

Statistical analysis

We processed results using SPSS software. We applied the x2 test for statistical interpretation and set statistical significance at P<.05.

RESULTS

Twenty-five men and twenty-nine women ages 21 to 82 years of age comprised the group of patients presenting with a list. All patients who met inclusion criteria agreed to cooperate. TABLE 1 summarizes the sociodemographic data. The control group consisted of 30 men and 22 women ages 20 to 86 years of age.

There was no statistically meaningful difference in gender ratio between the groups. In the study and control groups, respectively, the average number of children of each subject was 4.1 and 3.5, years of formal education were 10.8 and 10.6, and years since immigration were 40.5 and 37.8 (P=.42). Marital status and average household income were also similar in both groups.

Statistically significant findings with the study group were relatively older ages and likelihood to be pensioners. The study group included fewer employed individuals and fewer housewives (P<.001). They also were more likely to have more than 3 chronic diseases (48.1% vs. 9.6%; P<.001) and took more long-term medications, including benzodiazepines (TABLE 2). They had a greater number of doctor visits in the past year compared with controls and reported a perceived increase in memory loss (TABLE 3). There were no significant differences between the groups in psychiatric or personality disorders, as determined by surveying patients’ electronic records.

The reasons most commonly given for using a list indicated a desire to completely satisfy the objectives of the visit. Most of the individuals decided to prepare a list on their own initiative without persuasion from any external source.

DISCUSSION

In an survey of 216 family physicians and internists at the University of Wisconsin, >60% of respondents said their patients bring in lists very often or sometimes.11 This figure seems much higher than would be found in our country (Israel). However, the practice is certainly common; although the actual frequency is unknown.

Other published observations about list use. Middleton et al12 studied the effects of planned use of agenda forms, completed by patients and handed to physicians at the outset of a primary care visit. The written agenda significantly increased the number of problems identified in each consultation. Patient satisfaction increased and deepened the doctor-patient relationship. However, the duration of consultations also increased.

A commentary by Schrager et al11 acknowledges that lists are dreaded by some physicians. Particularly if the expectation is for a patient to present with a single complaint, the appearance of a list may be an unwelcome surprise, suggesting a collection of separate complaints. And compulsive and somatizing patients can raise a series of overwhelming issues that encumber a short visit. But the commentary points out that, in general, fear of a list is unfounded, and that acceptance without prejudging can lead to a constructive outcome.

A number of researchers have examined the relationship between negative physician attitudes and certain patient attributes such as sociodemographic characteristics or a persistent emotional component to their ailments.13 Katz14 reported that patients who generated the most frustration were those who demanded a cure, those who added unrelated complaints at the end of the visit, malingerers, and those who refused to accept responsibility for their own maladies. List users, we believe, should not be lumped in with this group automatically.

In our study, patients with lists did request more frequent consultations. However, this correlated closely with a heavier burden of disease. Using patient-centered communication to set the agenda for the visit and address the entirety of patients’ concerns has been shown to improve not only patient satisfaction but also adherence to treatment recommendations.15,16 One way for patients to become more involved in their care is to bring a list of questions to each visit, as advised by AHRQ.

What our study revealed about list users. Our results show that those who made use of a list were older than the ones who did not, more likely to be pensioners, and less likely to be employed or be housewives. They had more chronic diseases, were receiving more medications including benzodiazepines, and had a significantly higher rate of medical appointments than did the controls. Psychiatric diagnoses were no more common among the list users, and reasons given for list use were congruent with aging and an increased burden of disease and medication. We could not discern the exact contribution of each independent factor of advanced age or disease burden. This would be an interesting issue to address in more elaborate research, as would be the actual frequency of list use.

Limitations of our study. The weaknesses of our study include its questionable generalizability and the possibility that a number of list bearers may not have been recruited due to time constraints on patients or physicians. Randomization could have been improved if we had selected the controls consecutively after selecting the study patients, and not at a separate time. We did not time the length of the consultations, something that should be done in future studies.

The fact that the study group consumed more benzodiazepine medications may hint that its members suffer from greater levels of anxiety or depression. Nevertheless, we assumed that such conditions were likely of modest intensity since they were not included in the medical records.

Large-scale research could yield far more trustworthy results by adjusting for age, country of origin, and disease burden.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sody Naimer, MD, Department of Family Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, POB 653, Beer-Sheva 84105, Israel; [email protected]

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Dr. Joseph Herman and Mrs. Barbra Schipper for their assistance in preparing this manuscript.

1. Silverman J, Kinnersley P. Doctors’ non-verbal behaviour in consultations: look at the patient before you look at the computer. Br J Gen Pract. 2010;60:76-78.

2. Hall JA, Harrigan JA, Rosenthal R. Nonverbal behavior in clinician-patient interaction. Appl Prev Psychol. 1995;4:21-37.

3. Mast MS. On the importance of nonverbal communication in the physician-patient interaction. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;67:315-318.

4. Roter DL, Frankel RM, Hall JA, et al. The expression of emotion through nonverbal behavior in medical visits. Mechanisms and outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21 suppl 1:S28-S34.

5. Marcinowicz L, Konstantynowicz J, Godlewski C. Patients’ perceptions of GP non-verbal communication: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2010;60:83-87.

6. Kravitz RL. Patients’ expectations for medical care: an expanded formulation based on review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev. 1996;53:3-27.

7. Hooper EM, Comstock LM, Goodwin JM, et al. Patient characteristics that influence physician behavior. Med Care. 1982;20:630-638.

8. Naimer SA, Biton A. A pilot study of behaviour and impact of cellular telephone ringing interrupting the medical consultation. Isr J Fam Pr. 2002;19:35-39.

9. Quill TE. Recognizing and adjusting to barriers in doctor-patient communication. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111:51-57.

10. Brock DM, Mauksch LB, Witteborn S, et al. Effectiveness of intensive physician training in upfront agenda setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:1317-1323.

11. Schrager S, Gaard S. What should you do when your patient brings a list? Fam Pract Manag. 2009;16:23-27.

12. Middleton JF, McKinley RK, Gillies CL. Effect of patient completed agenda forms and doctors’ education about the agenda on the outcome of consultations: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2006;332:1238-1242.

13. Aaker E, Knudsen A, Wynn R, et al. General practitioners’ reactions to non-compliant patients. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2001;19:103-106.

14. Katz RC. “Difficult patients” as family physicians perceive them. Psychol Rep. 1996;79:539-544.

15. Epstein RM, Mauksch L, Carroll J, et al. Have you really addressed your patient’s concerns? Fam Pract Manag. 2008;15:35-40.

16. Bergeson SC, Dean JD. A systems approach to patient-centered care. JAMA. 2006;296:2848-2851.

1. Silverman J, Kinnersley P. Doctors’ non-verbal behaviour in consultations: look at the patient before you look at the computer. Br J Gen Pract. 2010;60:76-78.

2. Hall JA, Harrigan JA, Rosenthal R. Nonverbal behavior in clinician-patient interaction. Appl Prev Psychol. 1995;4:21-37.

3. Mast MS. On the importance of nonverbal communication in the physician-patient interaction. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;67:315-318.

4. Roter DL, Frankel RM, Hall JA, et al. The expression of emotion through nonverbal behavior in medical visits. Mechanisms and outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21 suppl 1:S28-S34.

5. Marcinowicz L, Konstantynowicz J, Godlewski C. Patients’ perceptions of GP non-verbal communication: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2010;60:83-87.

6. Kravitz RL. Patients’ expectations for medical care: an expanded formulation based on review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev. 1996;53:3-27.

7. Hooper EM, Comstock LM, Goodwin JM, et al. Patient characteristics that influence physician behavior. Med Care. 1982;20:630-638.

8. Naimer SA, Biton A. A pilot study of behaviour and impact of cellular telephone ringing interrupting the medical consultation. Isr J Fam Pr. 2002;19:35-39.

9. Quill TE. Recognizing and adjusting to barriers in doctor-patient communication. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111:51-57.

10. Brock DM, Mauksch LB, Witteborn S, et al. Effectiveness of intensive physician training in upfront agenda setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:1317-1323.

11. Schrager S, Gaard S. What should you do when your patient brings a list? Fam Pract Manag. 2009;16:23-27.

12. Middleton JF, McKinley RK, Gillies CL. Effect of patient completed agenda forms and doctors’ education about the agenda on the outcome of consultations: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2006;332:1238-1242.

13. Aaker E, Knudsen A, Wynn R, et al. General practitioners’ reactions to non-compliant patients. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2001;19:103-106.

14. Katz RC. “Difficult patients” as family physicians perceive them. Psychol Rep. 1996;79:539-544.

15. Epstein RM, Mauksch L, Carroll J, et al. Have you really addressed your patient’s concerns? Fam Pract Manag. 2008;15:35-40.

16. Bergeson SC, Dean JD. A systems approach to patient-centered care. JAMA. 2006;296:2848-2851.

Failed First Metatarsophalangeal Arthroplasty Salvaged by Hamstring Interposition Arthroplasty: Metallic Debris From Grommets

joint, arthroplasty, implant, metallic debris, grommets, titanium, synovitis, foot

joint, arthroplasty, implant, metallic debris, grommets, titanium, synovitis, foot

joint, arthroplasty, implant, metallic debris, grommets, titanium, synovitis, foot

New and Noteworthy Information—April 2014

Little evidence suggests that most complementary or alternative medicine therapies treat the symptoms of multiple sclerosis (MS), according to an American Academy of Neurology guideline published March 25 in Neurology. Oral cannabis and oral medical marijuana spray, however, may ease patients’ reported symptoms of spasticity, pain related to spasticity, and frequent urination in MS. Not enough evidence is available to show whether smoking marijuana helps treat MS symptoms, according to the guideline. The authors concluded that magnetic therapy is probably effective for fatigue and probably ineffective for depression. Fish oil is probably ineffective for relapses, disability, fatigue, MRI lesions, and quality of life, according to the guideline. In addition, evidence indicates that ginkgo biloba is ineffective for cognition and possibly effective for fatigue, said the authors.

People who develop diabetes and high blood pressure in middle age are more likely to have brain cell loss and problems with memory and thinking skills than people who never have diabetes or high blood pressure or who develop them in old age, according to a study published online ahead of print March 19 in Neurology. Investigators evaluated the thinking and memory skills of 1,437 people (average age, 80), conducted brain scans, and reviewed participants’ medical records to determine whether the latter had been diagnosed with diabetes or high blood pressure in middle age or later. Midlife diabetes was associated with subcortical infarctions, reduced hippocampal volume, reduced whole brain volume, and prevalent mild cognitive impairment. Midlife hypertension was associated with infarctions and white matter hyperintensity volume.