User login

Space Available to Attend Quality and Safety Educators Academy in May

Quality improvement education is no longer just an elective for trainees, which is why medical educators need the best possible knowledge and tools for teaching quality and safety. SHM and the Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine (AAIM) have teamed up to present the Quality and Safety Educators Academy, to be held May 1-3 in Tempe, Ariz.

There is still time to register. For more information, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/qsea.

Quality improvement education is no longer just an elective for trainees, which is why medical educators need the best possible knowledge and tools for teaching quality and safety. SHM and the Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine (AAIM) have teamed up to present the Quality and Safety Educators Academy, to be held May 1-3 in Tempe, Ariz.

There is still time to register. For more information, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/qsea.

Quality improvement education is no longer just an elective for trainees, which is why medical educators need the best possible knowledge and tools for teaching quality and safety. SHM and the Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine (AAIM) have teamed up to present the Quality and Safety Educators Academy, to be held May 1-3 in Tempe, Ariz.

There is still time to register. For more information, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/qsea.

Society of Hospital Medicine's Annual Meeting Available On Demand

If you weren’t able to make it to HM14 last month, you can catch up on some of the hottest topics and sessions in the hospitalist movement through On Demand Video from the meeting. HM14 On Demand (www.hospitalmedicine.org/HM14ondemand) is a great way for conference attendees to check out sessions that they missed live, revisit favorite sessions, and share the HM14 experience with colleagues throughout the year.

- Watch sessions that you missed.

- Share your experiences with colleagues.

Revisit your favorite sessions. Topics in HM14 On Demand include:

- Clinical

- Co-Management of Hospitalized Patients

- Bending the Cost Curve

- Rapid Fire Tracks

- Potpourri

- Practice Management

- Quality Improvement

If you weren’t able to make it to HM14 last month, you can catch up on some of the hottest topics and sessions in the hospitalist movement through On Demand Video from the meeting. HM14 On Demand (www.hospitalmedicine.org/HM14ondemand) is a great way for conference attendees to check out sessions that they missed live, revisit favorite sessions, and share the HM14 experience with colleagues throughout the year.

- Watch sessions that you missed.

- Share your experiences with colleagues.

Revisit your favorite sessions. Topics in HM14 On Demand include:

- Clinical

- Co-Management of Hospitalized Patients

- Bending the Cost Curve

- Rapid Fire Tracks

- Potpourri

- Practice Management

- Quality Improvement

If you weren’t able to make it to HM14 last month, you can catch up on some of the hottest topics and sessions in the hospitalist movement through On Demand Video from the meeting. HM14 On Demand (www.hospitalmedicine.org/HM14ondemand) is a great way for conference attendees to check out sessions that they missed live, revisit favorite sessions, and share the HM14 experience with colleagues throughout the year.

- Watch sessions that you missed.

- Share your experiences with colleagues.

Revisit your favorite sessions. Topics in HM14 On Demand include:

- Clinical

- Co-Management of Hospitalized Patients

- Bending the Cost Curve

- Rapid Fire Tracks

- Potpourri

- Practice Management

- Quality Improvement

Tips for Submitting Applications to Society of Hospital Medicine's Project BOOST

Many potential Project BOOST candidate sites apply, but not all are accepted into the program. What makes for a successful application? Ask one of the founding members of Project BOOST and a current mentor, Dr. Jeffrey Greenwald.

- A strong letter of support. Qualified candidates can demonstrate that the hospital’s leadership is already behind their interest to reduce readmission rates through a program like Project BOOST.

- Demonstrate the existing support of the team. Good applications show that it’s not just a good idea to a few people. Good Project BOOST candidates can illustrate that their hospital has an “institutional prioritization for transitions of care.”

- An honest assessment on organizing change. Project BOOST has helped high-performing sites and beginners alike, but a thoughtful assessment of your site’s prior experience in organizing change and process improvement helps program leaders better understand your needs.

Apply Now Project BOOST is accepting applications now through August 30. Visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/projectboost.

Many potential Project BOOST candidate sites apply, but not all are accepted into the program. What makes for a successful application? Ask one of the founding members of Project BOOST and a current mentor, Dr. Jeffrey Greenwald.

- A strong letter of support. Qualified candidates can demonstrate that the hospital’s leadership is already behind their interest to reduce readmission rates through a program like Project BOOST.

- Demonstrate the existing support of the team. Good applications show that it’s not just a good idea to a few people. Good Project BOOST candidates can illustrate that their hospital has an “institutional prioritization for transitions of care.”

- An honest assessment on organizing change. Project BOOST has helped high-performing sites and beginners alike, but a thoughtful assessment of your site’s prior experience in organizing change and process improvement helps program leaders better understand your needs.

Apply Now Project BOOST is accepting applications now through August 30. Visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/projectboost.

Many potential Project BOOST candidate sites apply, but not all are accepted into the program. What makes for a successful application? Ask one of the founding members of Project BOOST and a current mentor, Dr. Jeffrey Greenwald.

- A strong letter of support. Qualified candidates can demonstrate that the hospital’s leadership is already behind their interest to reduce readmission rates through a program like Project BOOST.

- Demonstrate the existing support of the team. Good applications show that it’s not just a good idea to a few people. Good Project BOOST candidates can illustrate that their hospital has an “institutional prioritization for transitions of care.”

- An honest assessment on organizing change. Project BOOST has helped high-performing sites and beginners alike, but a thoughtful assessment of your site’s prior experience in organizing change and process improvement helps program leaders better understand your needs.

Apply Now Project BOOST is accepting applications now through August 30. Visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/projectboost.

Houston-Based Hospital Reduces Readmissions with Society of Hospital Medicine's Project BOOST

Change doesn’t always come easily to hospitals, but once a catalyst comes along, one positive change can set the stage for the next one—and the one after that. At least that’s the lesson from Houston Methodist Hospital (HMH) and their work with SHM’s Project BOOST, a yearlong, mentored implementation program designed to help hospitals nationwide reduce readmission rates.

As the saying goes, every journey begins with a single step. For hospitals ready to start their journey to reduce readmissions rates and tackle other quality improvement challenges, the first step is the application to Project BOOST, which is due at the end of August. Details on the application and fees are available at www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost.

At Houston Methodist Hospital—a hospital U.S. News & World Report ranked one of “America’s Best Hospitals” in a dozen specialties and designated as a magnet hospital for excellence in nursing—taking that first step toward reducing readmissions by applying to Project BOOST has been well worth it.

“I recommend Project BOOST enthusiastically and unequivocally. If implemented efficiently, it could result in a ‘win-win’ situation for patients, the hospital, and the healthcare providers,” says Manasi Kekan, MD, MS, FACP, who serves as HMH’s medical director. “As a hospitalist, at times, I have found it challenging to ration my times between patient contact and documentation to meet the goals set by the healthcare industry. Being involved in BOOST and watching tangible improvements for my patients has provided me with immense personal and professional gratification!”

In fact, Dr. Kekan and her team have been so pleased with the results, both quantitative and qualitative, from their participation in Project BOOST that they enrolled twice: first in 2012 and again in 2013. She cites the program’s adaptability “that would help us develop a higher quality discharge process for our patients.”

Like many fruitful journeys, though, this one did not find Dr. Kekan and the caregivers at HMH alone: They had a guide who made all the difference.

Change implementation can be difficult, says Houston Methodist’s Janice Finder, RN, MSN. “Everyone knows how they want to design the house, so to speak,” she says, “but if you have someone who has done it before and can lead and direct, it goes much smoother.”

That was the true value of their Project BOOST mentor, Jeffrey Greenwald, MD, SFHM, one of the founding developers of Project BOOST.

“Dr. Greenwald gave us great mentorship and guidance,” Finder says. “The guidance about leadership is essential. If you do not have full support and a person who has ‘been there, done that,’ it is hard to envision.”

From his perspective, Dr. Greenwald saw that HMH had many of the critical elements in place to be successful.

“They had a good set of experiences already. They had the will and leadership and skill on the ground in process improvement,” he says, calling HMH an “incredibly well-oiled machine” with buy-in from the kind of inter-professional team that can make Project BOOST a success.

Overall, Dr. Greenwald calls HMH a “good example of a hospital that has married Project BOOST with the hospital’s existing priorities.”

Other Project BOOST sites start at different levels, in terms of basic interventions and process improvement, Dr. Greenwald explains. Many are able to address more advanced challenges, like how to implement change across broader areas in the hospital, working with leadership, addressing political issues, and improving waning interest in groups.

Dr. Greenwald’s interest in mentorship of Project BOOST sites stems from his own experiences early on—and the need for mentors in quality improvement projects.

“I wish I would have had someone like that when I got started,” says Dr. Greenwald, who tries to fill that role for others now. “Hopefully, each group moves down the path of making sure they have the right stakeholders, the right communications styles and skills in how to look at data and work with front-end staff.”

While Project BOOST focuses teams on reducing readmissions rates, Dr. Kekan has found that the skills learned from Project BOOST have created a blueprint that is applicable to many other team-based challenges in the hospital.

“We describe BOOST as a patient-centric quality initiative that mainly helps improve care transitions and encourages patients to stay informed about their health, which, in turn, helps reduce readmissions,” she says. “BOOST can be used as a framework to enhance other disease-specific discharge initiatives, like CHF [congestive heart failure] and delirium.”

Still, the core elements of reducing readmission rates and making a qualitative impact on her, her team, and the hospital resonate the most with Dr. Kekan.

“Providing a good transition plan to our patients provides satisfaction like none other.”

Brendon Shank is SHM’s associate vice president of communications.

Change doesn’t always come easily to hospitals, but once a catalyst comes along, one positive change can set the stage for the next one—and the one after that. At least that’s the lesson from Houston Methodist Hospital (HMH) and their work with SHM’s Project BOOST, a yearlong, mentored implementation program designed to help hospitals nationwide reduce readmission rates.

As the saying goes, every journey begins with a single step. For hospitals ready to start their journey to reduce readmissions rates and tackle other quality improvement challenges, the first step is the application to Project BOOST, which is due at the end of August. Details on the application and fees are available at www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost.

At Houston Methodist Hospital—a hospital U.S. News & World Report ranked one of “America’s Best Hospitals” in a dozen specialties and designated as a magnet hospital for excellence in nursing—taking that first step toward reducing readmissions by applying to Project BOOST has been well worth it.

“I recommend Project BOOST enthusiastically and unequivocally. If implemented efficiently, it could result in a ‘win-win’ situation for patients, the hospital, and the healthcare providers,” says Manasi Kekan, MD, MS, FACP, who serves as HMH’s medical director. “As a hospitalist, at times, I have found it challenging to ration my times between patient contact and documentation to meet the goals set by the healthcare industry. Being involved in BOOST and watching tangible improvements for my patients has provided me with immense personal and professional gratification!”

In fact, Dr. Kekan and her team have been so pleased with the results, both quantitative and qualitative, from their participation in Project BOOST that they enrolled twice: first in 2012 and again in 2013. She cites the program’s adaptability “that would help us develop a higher quality discharge process for our patients.”

Like many fruitful journeys, though, this one did not find Dr. Kekan and the caregivers at HMH alone: They had a guide who made all the difference.

Change implementation can be difficult, says Houston Methodist’s Janice Finder, RN, MSN. “Everyone knows how they want to design the house, so to speak,” she says, “but if you have someone who has done it before and can lead and direct, it goes much smoother.”

That was the true value of their Project BOOST mentor, Jeffrey Greenwald, MD, SFHM, one of the founding developers of Project BOOST.

“Dr. Greenwald gave us great mentorship and guidance,” Finder says. “The guidance about leadership is essential. If you do not have full support and a person who has ‘been there, done that,’ it is hard to envision.”

From his perspective, Dr. Greenwald saw that HMH had many of the critical elements in place to be successful.

“They had a good set of experiences already. They had the will and leadership and skill on the ground in process improvement,” he says, calling HMH an “incredibly well-oiled machine” with buy-in from the kind of inter-professional team that can make Project BOOST a success.

Overall, Dr. Greenwald calls HMH a “good example of a hospital that has married Project BOOST with the hospital’s existing priorities.”

Other Project BOOST sites start at different levels, in terms of basic interventions and process improvement, Dr. Greenwald explains. Many are able to address more advanced challenges, like how to implement change across broader areas in the hospital, working with leadership, addressing political issues, and improving waning interest in groups.

Dr. Greenwald’s interest in mentorship of Project BOOST sites stems from his own experiences early on—and the need for mentors in quality improvement projects.

“I wish I would have had someone like that when I got started,” says Dr. Greenwald, who tries to fill that role for others now. “Hopefully, each group moves down the path of making sure they have the right stakeholders, the right communications styles and skills in how to look at data and work with front-end staff.”

While Project BOOST focuses teams on reducing readmissions rates, Dr. Kekan has found that the skills learned from Project BOOST have created a blueprint that is applicable to many other team-based challenges in the hospital.

“We describe BOOST as a patient-centric quality initiative that mainly helps improve care transitions and encourages patients to stay informed about their health, which, in turn, helps reduce readmissions,” she says. “BOOST can be used as a framework to enhance other disease-specific discharge initiatives, like CHF [congestive heart failure] and delirium.”

Still, the core elements of reducing readmission rates and making a qualitative impact on her, her team, and the hospital resonate the most with Dr. Kekan.

“Providing a good transition plan to our patients provides satisfaction like none other.”

Brendon Shank is SHM’s associate vice president of communications.

Change doesn’t always come easily to hospitals, but once a catalyst comes along, one positive change can set the stage for the next one—and the one after that. At least that’s the lesson from Houston Methodist Hospital (HMH) and their work with SHM’s Project BOOST, a yearlong, mentored implementation program designed to help hospitals nationwide reduce readmission rates.

As the saying goes, every journey begins with a single step. For hospitals ready to start their journey to reduce readmissions rates and tackle other quality improvement challenges, the first step is the application to Project BOOST, which is due at the end of August. Details on the application and fees are available at www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost.

At Houston Methodist Hospital—a hospital U.S. News & World Report ranked one of “America’s Best Hospitals” in a dozen specialties and designated as a magnet hospital for excellence in nursing—taking that first step toward reducing readmissions by applying to Project BOOST has been well worth it.

“I recommend Project BOOST enthusiastically and unequivocally. If implemented efficiently, it could result in a ‘win-win’ situation for patients, the hospital, and the healthcare providers,” says Manasi Kekan, MD, MS, FACP, who serves as HMH’s medical director. “As a hospitalist, at times, I have found it challenging to ration my times between patient contact and documentation to meet the goals set by the healthcare industry. Being involved in BOOST and watching tangible improvements for my patients has provided me with immense personal and professional gratification!”

In fact, Dr. Kekan and her team have been so pleased with the results, both quantitative and qualitative, from their participation in Project BOOST that they enrolled twice: first in 2012 and again in 2013. She cites the program’s adaptability “that would help us develop a higher quality discharge process for our patients.”

Like many fruitful journeys, though, this one did not find Dr. Kekan and the caregivers at HMH alone: They had a guide who made all the difference.

Change implementation can be difficult, says Houston Methodist’s Janice Finder, RN, MSN. “Everyone knows how they want to design the house, so to speak,” she says, “but if you have someone who has done it before and can lead and direct, it goes much smoother.”

That was the true value of their Project BOOST mentor, Jeffrey Greenwald, MD, SFHM, one of the founding developers of Project BOOST.

“Dr. Greenwald gave us great mentorship and guidance,” Finder says. “The guidance about leadership is essential. If you do not have full support and a person who has ‘been there, done that,’ it is hard to envision.”

From his perspective, Dr. Greenwald saw that HMH had many of the critical elements in place to be successful.

“They had a good set of experiences already. They had the will and leadership and skill on the ground in process improvement,” he says, calling HMH an “incredibly well-oiled machine” with buy-in from the kind of inter-professional team that can make Project BOOST a success.

Overall, Dr. Greenwald calls HMH a “good example of a hospital that has married Project BOOST with the hospital’s existing priorities.”

Other Project BOOST sites start at different levels, in terms of basic interventions and process improvement, Dr. Greenwald explains. Many are able to address more advanced challenges, like how to implement change across broader areas in the hospital, working with leadership, addressing political issues, and improving waning interest in groups.

Dr. Greenwald’s interest in mentorship of Project BOOST sites stems from his own experiences early on—and the need for mentors in quality improvement projects.

“I wish I would have had someone like that when I got started,” says Dr. Greenwald, who tries to fill that role for others now. “Hopefully, each group moves down the path of making sure they have the right stakeholders, the right communications styles and skills in how to look at data and work with front-end staff.”

While Project BOOST focuses teams on reducing readmissions rates, Dr. Kekan has found that the skills learned from Project BOOST have created a blueprint that is applicable to many other team-based challenges in the hospital.

“We describe BOOST as a patient-centric quality initiative that mainly helps improve care transitions and encourages patients to stay informed about their health, which, in turn, helps reduce readmissions,” she says. “BOOST can be used as a framework to enhance other disease-specific discharge initiatives, like CHF [congestive heart failure] and delirium.”

Still, the core elements of reducing readmission rates and making a qualitative impact on her, her team, and the hospital resonate the most with Dr. Kekan.

“Providing a good transition plan to our patients provides satisfaction like none other.”

Brendon Shank is SHM’s associate vice president of communications.

Movers and Shakers in Hospital Medicine

Lakshmi Halasyamani, MD, SFHM, is the new chief medical officer (CMO) for Cogent Healthcare, which is based in Brentwood, Tenn. A former SHM board member, Dr. Halasyamani comes to Cogent from her role as CMO at St. Joseph Mercy Health System in Ypsilanti, Mich. She has assumed the role left vacant by Ron Greeno, MD, MHM, after Cogent appointed him executive vice president of strategy and innovation.

Dalibor Hradek, MD, has been named the 2013 physician of the year by the Greenville, S.C.-based OB Hospitalist Group (OBHG). Dr. Hradek is an OB/GYN hospitalist at Lakeland Regional Medical Center in Lakeland, Fla. Dr. Hradek received praise for his clinical expertise and dedication to his patients. OBHG staffs more than 250 OB/GYN hospitalists in over 55 programs nationwide.

Abdul Ftesi, MD, has been named the new hospitalist medical director at the University of Oklahoma Medical Center (OUMC) in Oklahoma City, Okla., by the Dallas, Texas-based provider Questcare Hospitalists. In his new role, Dr. Ftesi will lead and coordinate a team of 12 hospitalists.

Alan Dulit, MD, is the new chief medical officer for St. Anthony Summit Medical Center in Frisco, Colo. Dr. Dulit comes to St. Anthony from his role as OB Hospitalist Group’s vice president of medical affairs at St. Mark’s Hospital in Salt Lake City.

Sujesh Pillai, MD, has been named the 2013 Physician of the Year by Huntsville (Texas) Memorial Hospital (HMH). Dr. Pillai currently serves as hospitalist medical director at HMH. Dr. Pillai is noted for his professionalism and his compassion for his patients and their families.

Christine Meagher, RN, is the first to receive the Hospitalist Nursing Service Award from the Physician Hospitalist group at Heywood Hospital in Gardner, Mass. Meagher serves as a nurse in the ICU at the 134-bed acute care facility.

John Larson, MD, has been named Family Physician of the Year for 2013 by the Wisconsin Academy of Family Physicians. Dr. Larson serves as regional assistant medical director for Mayo Clinic Health System and often plays the role of a hospitalist, among many others, as part of his job.

Charles Clair, MD, recently received a service and gratitude award from the Pocatello (Idaho) Free Clinic. Dr. Clair serves as a hospitalist at Portneuf Medical Center in Pocatello, Idaho, and regularly volunteers at the Free Clinic with his wife, who offers her time maintaining the clinic’s website. The Pocatello Free Clinic has been serving patients in the area since 1971.

Felix Cabrera, MD, is the new director of clinical informatics and medical education for Guam Regional Medical City (GRMC) in Dededo, Guam. Dr. Cabrera was previously a hospitalist and associate medical director at Guam Memorial Hospital. GRMC is a brand new, 130-bed acute care facility privately owned by Philippine healthcare firm The Medical City.

Scott Sears, MD, FACP, has been named the new chief clinical officer for the Tacoma, Wash.-based Sound Physicians. Dr. Sears assumes his new role after serving as Sound’s regional chief medical officer for the Northwest Region.

Talbot “Mac” McCormick, MD, has assumed the role of chief executive officer of the Dallas, Texas-based Eagle Hospital Physicians. Dr. McCormick previously served as Eagle’s president and chief operating officer and has been with Eagle in various roles since 2003.

Lakshmi Halasyamani, MD, SFHM, is the new chief medical officer (CMO) for Cogent Healthcare, which is based in Brentwood, Tenn. A former SHM board member, Dr. Halasyamani comes to Cogent from her role as CMO at St. Joseph Mercy Health System in Ypsilanti, Mich. She has assumed the role left vacant by Ron Greeno, MD, MHM, after Cogent appointed him executive vice president of strategy and innovation.

Dalibor Hradek, MD, has been named the 2013 physician of the year by the Greenville, S.C.-based OB Hospitalist Group (OBHG). Dr. Hradek is an OB/GYN hospitalist at Lakeland Regional Medical Center in Lakeland, Fla. Dr. Hradek received praise for his clinical expertise and dedication to his patients. OBHG staffs more than 250 OB/GYN hospitalists in over 55 programs nationwide.

Abdul Ftesi, MD, has been named the new hospitalist medical director at the University of Oklahoma Medical Center (OUMC) in Oklahoma City, Okla., by the Dallas, Texas-based provider Questcare Hospitalists. In his new role, Dr. Ftesi will lead and coordinate a team of 12 hospitalists.

Alan Dulit, MD, is the new chief medical officer for St. Anthony Summit Medical Center in Frisco, Colo. Dr. Dulit comes to St. Anthony from his role as OB Hospitalist Group’s vice president of medical affairs at St. Mark’s Hospital in Salt Lake City.

Sujesh Pillai, MD, has been named the 2013 Physician of the Year by Huntsville (Texas) Memorial Hospital (HMH). Dr. Pillai currently serves as hospitalist medical director at HMH. Dr. Pillai is noted for his professionalism and his compassion for his patients and their families.

Christine Meagher, RN, is the first to receive the Hospitalist Nursing Service Award from the Physician Hospitalist group at Heywood Hospital in Gardner, Mass. Meagher serves as a nurse in the ICU at the 134-bed acute care facility.

John Larson, MD, has been named Family Physician of the Year for 2013 by the Wisconsin Academy of Family Physicians. Dr. Larson serves as regional assistant medical director for Mayo Clinic Health System and often plays the role of a hospitalist, among many others, as part of his job.

Charles Clair, MD, recently received a service and gratitude award from the Pocatello (Idaho) Free Clinic. Dr. Clair serves as a hospitalist at Portneuf Medical Center in Pocatello, Idaho, and regularly volunteers at the Free Clinic with his wife, who offers her time maintaining the clinic’s website. The Pocatello Free Clinic has been serving patients in the area since 1971.

Felix Cabrera, MD, is the new director of clinical informatics and medical education for Guam Regional Medical City (GRMC) in Dededo, Guam. Dr. Cabrera was previously a hospitalist and associate medical director at Guam Memorial Hospital. GRMC is a brand new, 130-bed acute care facility privately owned by Philippine healthcare firm The Medical City.

Scott Sears, MD, FACP, has been named the new chief clinical officer for the Tacoma, Wash.-based Sound Physicians. Dr. Sears assumes his new role after serving as Sound’s regional chief medical officer for the Northwest Region.

Talbot “Mac” McCormick, MD, has assumed the role of chief executive officer of the Dallas, Texas-based Eagle Hospital Physicians. Dr. McCormick previously served as Eagle’s president and chief operating officer and has been with Eagle in various roles since 2003.

Lakshmi Halasyamani, MD, SFHM, is the new chief medical officer (CMO) for Cogent Healthcare, which is based in Brentwood, Tenn. A former SHM board member, Dr. Halasyamani comes to Cogent from her role as CMO at St. Joseph Mercy Health System in Ypsilanti, Mich. She has assumed the role left vacant by Ron Greeno, MD, MHM, after Cogent appointed him executive vice president of strategy and innovation.

Dalibor Hradek, MD, has been named the 2013 physician of the year by the Greenville, S.C.-based OB Hospitalist Group (OBHG). Dr. Hradek is an OB/GYN hospitalist at Lakeland Regional Medical Center in Lakeland, Fla. Dr. Hradek received praise for his clinical expertise and dedication to his patients. OBHG staffs more than 250 OB/GYN hospitalists in over 55 programs nationwide.

Abdul Ftesi, MD, has been named the new hospitalist medical director at the University of Oklahoma Medical Center (OUMC) in Oklahoma City, Okla., by the Dallas, Texas-based provider Questcare Hospitalists. In his new role, Dr. Ftesi will lead and coordinate a team of 12 hospitalists.

Alan Dulit, MD, is the new chief medical officer for St. Anthony Summit Medical Center in Frisco, Colo. Dr. Dulit comes to St. Anthony from his role as OB Hospitalist Group’s vice president of medical affairs at St. Mark’s Hospital in Salt Lake City.

Sujesh Pillai, MD, has been named the 2013 Physician of the Year by Huntsville (Texas) Memorial Hospital (HMH). Dr. Pillai currently serves as hospitalist medical director at HMH. Dr. Pillai is noted for his professionalism and his compassion for his patients and their families.

Christine Meagher, RN, is the first to receive the Hospitalist Nursing Service Award from the Physician Hospitalist group at Heywood Hospital in Gardner, Mass. Meagher serves as a nurse in the ICU at the 134-bed acute care facility.

John Larson, MD, has been named Family Physician of the Year for 2013 by the Wisconsin Academy of Family Physicians. Dr. Larson serves as regional assistant medical director for Mayo Clinic Health System and often plays the role of a hospitalist, among many others, as part of his job.

Charles Clair, MD, recently received a service and gratitude award from the Pocatello (Idaho) Free Clinic. Dr. Clair serves as a hospitalist at Portneuf Medical Center in Pocatello, Idaho, and regularly volunteers at the Free Clinic with his wife, who offers her time maintaining the clinic’s website. The Pocatello Free Clinic has been serving patients in the area since 1971.

Felix Cabrera, MD, is the new director of clinical informatics and medical education for Guam Regional Medical City (GRMC) in Dededo, Guam. Dr. Cabrera was previously a hospitalist and associate medical director at Guam Memorial Hospital. GRMC is a brand new, 130-bed acute care facility privately owned by Philippine healthcare firm The Medical City.

Scott Sears, MD, FACP, has been named the new chief clinical officer for the Tacoma, Wash.-based Sound Physicians. Dr. Sears assumes his new role after serving as Sound’s regional chief medical officer for the Northwest Region.

Talbot “Mac” McCormick, MD, has assumed the role of chief executive officer of the Dallas, Texas-based Eagle Hospital Physicians. Dr. McCormick previously served as Eagle’s president and chief operating officer and has been with Eagle in various roles since 2003.

Hospital Medicine Group Leaders Need Not Work Clinical Shifts to Achieve Respect

Hospitalist Group Leaders Need Not Work Clinical Shifts to Achieve Respect

The “Survey Insights” article by Dr. Rachel Lovins (“Physician Practice Leaders,” November 2013) makes excellent points about the importance of leadership in hospital medicine groups but perpetuates a fallacy that undercuts the effectiveness of physician leaders. Dr. Lovins states that hospitalist leaders need to work as clinical hospitalists to achieve respect. Consider the example of professional sports, where athletes are highly skilled and earn more than doctors, but the concept of a player/coach has essentially disappeared. The difference is that athletes understand that they are playing on a team that needs a cohesive vision to succeed. They value the insights of a coach who can watch their performance from the sidelines and help them improve, even though that person’s own playing skills may have been undistinguished.

Dr. Lovins states that hospitalist leaders need to experience firsthand the frustrations of hospital practice. Would it not be better to replace anecdotal evidence with systematic communication and analysis of experiences from the entire group? The demand by physicians that their leaders be active clinicians is really a way to ensure that those individuals are unable to secure the time and perspective needed to become effective coaches, and it encroaches upon the autonomy of the individuals.

HM cannot achieve its potential until it develops leaders who can move beyond the level of chief resident and engage meaningfully with the concerns of senior hospital leaders to drive the performance of their teams. Hospitalists must understand that they are part of an organization that will be led by persons with different skill sets than those required to diagnose and treat disease.

—Richard Rohr, MD, SFHM, team leader, United Health Group, Broomall, Pa.

Hospitalist Group Leaders Need Not Work Clinical Shifts to Achieve Respect

The “Survey Insights” article by Dr. Rachel Lovins (“Physician Practice Leaders,” November 2013) makes excellent points about the importance of leadership in hospital medicine groups but perpetuates a fallacy that undercuts the effectiveness of physician leaders. Dr. Lovins states that hospitalist leaders need to work as clinical hospitalists to achieve respect. Consider the example of professional sports, where athletes are highly skilled and earn more than doctors, but the concept of a player/coach has essentially disappeared. The difference is that athletes understand that they are playing on a team that needs a cohesive vision to succeed. They value the insights of a coach who can watch their performance from the sidelines and help them improve, even though that person’s own playing skills may have been undistinguished.

Dr. Lovins states that hospitalist leaders need to experience firsthand the frustrations of hospital practice. Would it not be better to replace anecdotal evidence with systematic communication and analysis of experiences from the entire group? The demand by physicians that their leaders be active clinicians is really a way to ensure that those individuals are unable to secure the time and perspective needed to become effective coaches, and it encroaches upon the autonomy of the individuals.

HM cannot achieve its potential until it develops leaders who can move beyond the level of chief resident and engage meaningfully with the concerns of senior hospital leaders to drive the performance of their teams. Hospitalists must understand that they are part of an organization that will be led by persons with different skill sets than those required to diagnose and treat disease.

—Richard Rohr, MD, SFHM, team leader, United Health Group, Broomall, Pa.

Hospitalist Group Leaders Need Not Work Clinical Shifts to Achieve Respect

The “Survey Insights” article by Dr. Rachel Lovins (“Physician Practice Leaders,” November 2013) makes excellent points about the importance of leadership in hospital medicine groups but perpetuates a fallacy that undercuts the effectiveness of physician leaders. Dr. Lovins states that hospitalist leaders need to work as clinical hospitalists to achieve respect. Consider the example of professional sports, where athletes are highly skilled and earn more than doctors, but the concept of a player/coach has essentially disappeared. The difference is that athletes understand that they are playing on a team that needs a cohesive vision to succeed. They value the insights of a coach who can watch their performance from the sidelines and help them improve, even though that person’s own playing skills may have been undistinguished.

Dr. Lovins states that hospitalist leaders need to experience firsthand the frustrations of hospital practice. Would it not be better to replace anecdotal evidence with systematic communication and analysis of experiences from the entire group? The demand by physicians that their leaders be active clinicians is really a way to ensure that those individuals are unable to secure the time and perspective needed to become effective coaches, and it encroaches upon the autonomy of the individuals.

HM cannot achieve its potential until it develops leaders who can move beyond the level of chief resident and engage meaningfully with the concerns of senior hospital leaders to drive the performance of their teams. Hospitalists must understand that they are part of an organization that will be led by persons with different skill sets than those required to diagnose and treat disease.

—Richard Rohr, MD, SFHM, team leader, United Health Group, Broomall, Pa.

Copper Considered Safe, Effective in Preventing Hospital-Acquired Infections

Concern about Copper’s Effectiveness in Preventing Hospital-Acquired Infections

As public knowledge about the benefits of antimicrobial copper touch surfaces in healthcare facilities continues to grow, questions about this tool naturally arise. Can this copper surface really continuously kill up to 83% of bacteria it comes in contact with? Can it really reduce patient infections by more than half? Can this metal really keep people safer? The answer is “yes,” as has been reported in the Journal of Infection Control, in Hospital Epidemiology, and in the Journal of Clinical Microbiology.

In his “Letter to the Editor (“Concern about Copper’s Effectiveness in Preventing Hospital-Acquired Infections,” November 2013), Dr. Rod Duraski voices cautions about human sensitivity to copper—noting that implanted copper-nickel alloy devices have the potential for severe allergic reactions; however, implanted devices are not part of the EPA-approved products list of antimicrobial copper and, therefore, are not being proposed for use in the fight against hospital infections. Although some patients might experience sensitivity to jewelry, zippers, or buttons, if made from nickel-containing copper alloys, these reactions will be the result of prolonged skin contact, and when removed, the sensitivity will dissipate. The touch-surface components proposed in Karen Appold’s story, “Copper,” (September 2013) come into very brief and intermittent contact with the skin. And, sensitivities are not life-threatening; hospital-acquired infections are.

In fact, three of the four major coin denominations (nickel, dime, quarter) are made from copper-nickel alloys. If these metals are suitable for the everyday exposure we all experience with coinage, they are just as safe when it comes to touch surface components in hospitals. In many instances, the benefits of copper outweigh the relative risk of a rash caused by nickel sensitivity.

Like any surface, copper alloys should be cleaned regularly—especially in hospitals. Copper alloys are compatible with all hospital grade cleaners and disinfectants when the cleaners are used according to manufacturer label instructions. But more importantly, the antimicrobial effect of this metal is not inhibited if the surfaces tarnish. In 2005, a study (www.antimicrobialcopper.com/media/69850/infectious_disease.pdf) found tarnish to be a non-issue when researchers tested the bacterial load on three separate copper alloys, all of which had developed tarnish over time. Additionally, manufacturers are offering components made from tarnish-resistant alloys.

—Harold Michels, PhD, senior vice president of technology and technical services, Copper Development Association, Inc.

Correction: April 4, 2014

A version of this article appeared in print in the April 2014 issue of The Hospitalist. Changes have since been made to the online article per the request of the author.

Concern about Copper’s Effectiveness in Preventing Hospital-Acquired Infections

As public knowledge about the benefits of antimicrobial copper touch surfaces in healthcare facilities continues to grow, questions about this tool naturally arise. Can this copper surface really continuously kill up to 83% of bacteria it comes in contact with? Can it really reduce patient infections by more than half? Can this metal really keep people safer? The answer is “yes,” as has been reported in the Journal of Infection Control, in Hospital Epidemiology, and in the Journal of Clinical Microbiology.

In his “Letter to the Editor (“Concern about Copper’s Effectiveness in Preventing Hospital-Acquired Infections,” November 2013), Dr. Rod Duraski voices cautions about human sensitivity to copper—noting that implanted copper-nickel alloy devices have the potential for severe allergic reactions; however, implanted devices are not part of the EPA-approved products list of antimicrobial copper and, therefore, are not being proposed for use in the fight against hospital infections. Although some patients might experience sensitivity to jewelry, zippers, or buttons, if made from nickel-containing copper alloys, these reactions will be the result of prolonged skin contact, and when removed, the sensitivity will dissipate. The touch-surface components proposed in Karen Appold’s story, “Copper,” (September 2013) come into very brief and intermittent contact with the skin. And, sensitivities are not life-threatening; hospital-acquired infections are.

In fact, three of the four major coin denominations (nickel, dime, quarter) are made from copper-nickel alloys. If these metals are suitable for the everyday exposure we all experience with coinage, they are just as safe when it comes to touch surface components in hospitals. In many instances, the benefits of copper outweigh the relative risk of a rash caused by nickel sensitivity.

Like any surface, copper alloys should be cleaned regularly—especially in hospitals. Copper alloys are compatible with all hospital grade cleaners and disinfectants when the cleaners are used according to manufacturer label instructions. But more importantly, the antimicrobial effect of this metal is not inhibited if the surfaces tarnish. In 2005, a study (www.antimicrobialcopper.com/media/69850/infectious_disease.pdf) found tarnish to be a non-issue when researchers tested the bacterial load on three separate copper alloys, all of which had developed tarnish over time. Additionally, manufacturers are offering components made from tarnish-resistant alloys.

—Harold Michels, PhD, senior vice president of technology and technical services, Copper Development Association, Inc.

Correction: April 4, 2014

A version of this article appeared in print in the April 2014 issue of The Hospitalist. Changes have since been made to the online article per the request of the author.

Concern about Copper’s Effectiveness in Preventing Hospital-Acquired Infections

As public knowledge about the benefits of antimicrobial copper touch surfaces in healthcare facilities continues to grow, questions about this tool naturally arise. Can this copper surface really continuously kill up to 83% of bacteria it comes in contact with? Can it really reduce patient infections by more than half? Can this metal really keep people safer? The answer is “yes,” as has been reported in the Journal of Infection Control, in Hospital Epidemiology, and in the Journal of Clinical Microbiology.

In his “Letter to the Editor (“Concern about Copper’s Effectiveness in Preventing Hospital-Acquired Infections,” November 2013), Dr. Rod Duraski voices cautions about human sensitivity to copper—noting that implanted copper-nickel alloy devices have the potential for severe allergic reactions; however, implanted devices are not part of the EPA-approved products list of antimicrobial copper and, therefore, are not being proposed for use in the fight against hospital infections. Although some patients might experience sensitivity to jewelry, zippers, or buttons, if made from nickel-containing copper alloys, these reactions will be the result of prolonged skin contact, and when removed, the sensitivity will dissipate. The touch-surface components proposed in Karen Appold’s story, “Copper,” (September 2013) come into very brief and intermittent contact with the skin. And, sensitivities are not life-threatening; hospital-acquired infections are.

In fact, three of the four major coin denominations (nickel, dime, quarter) are made from copper-nickel alloys. If these metals are suitable for the everyday exposure we all experience with coinage, they are just as safe when it comes to touch surface components in hospitals. In many instances, the benefits of copper outweigh the relative risk of a rash caused by nickel sensitivity.

Like any surface, copper alloys should be cleaned regularly—especially in hospitals. Copper alloys are compatible with all hospital grade cleaners and disinfectants when the cleaners are used according to manufacturer label instructions. But more importantly, the antimicrobial effect of this metal is not inhibited if the surfaces tarnish. In 2005, a study (www.antimicrobialcopper.com/media/69850/infectious_disease.pdf) found tarnish to be a non-issue when researchers tested the bacterial load on three separate copper alloys, all of which had developed tarnish over time. Additionally, manufacturers are offering components made from tarnish-resistant alloys.

—Harold Michels, PhD, senior vice president of technology and technical services, Copper Development Association, Inc.

Correction: April 4, 2014

A version of this article appeared in print in the April 2014 issue of The Hospitalist. Changes have since been made to the online article per the request of the author.

Delays, Controversy Muddle CMS’ Two-Midnight Rule for Hospital Patient Admissions

A new rule issued by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is at the center of controversy fueled by competing interests and lack of clarity. And, for the fourth time since the two-midnight rule was introduced in the 2014 Hospital Inpatient Prospective Payment System, its implementation has been delayed. Hospitals and providers have until March 31, 2015, before auditors begin scrutinizing patient admission statuses for reimbursement determination.

The rule requires Medicare and Medicaid patients spending fewer than two midnights receiving hospital care to be classified as outpatient or under observation. Patients spending more than two midnights will be considered inpatient. Only physicians can make the determination, and the clock begins ticking the moment care begins.

The rule also cuts hospital inpatient reimbursement by 0.2%, because CMS believes the number of inpatient admissions will increase.

–Joanna Hiatt Kim, vice president of payment policy for the American Hospital Association

The rule pits private Medicare auditors (Medicare Administrative Contractors, MACs, and Recovery Audit Contractors, RACs), who have a financial stake in denying inpatient claims, against hospitals and physicians. It does little to clear confusion for patients when it comes time for them to pay their bills.

Patients generally are unaware whether they’ve been admitted or are under observation. But observation status leaves them on the hook for any skilled nursing care they receive following discharge and for the costs of routine maintenance drugs hospitals give them for chronic conditions.

Beneficiaries also are not eligible for Medicare Part A skilled nursing care coverage if they were an inpatient for fewer than 72 hours, and observation days do not count toward the three-day requirement. The two-midnight rule adds another “layer” to the equation, says Bradley Flansbaum, DO, MPH, FACP, a hospitalist and clinical assistant professor of medicine at NYU School of Medicine in New York City.

At the same time, hospitals now face penalties for patients readmitted within 30 days of discharge for a similar episode of care. Observation status offers a measure of protection in the event patients return.

The number of observation patients increased 69% between 2006 and 2011, according to federal data cited by Kaiser Health News, and the number of observation patients staying more than 48 hours increased from 3% to 8% during this same period.

“The concern is that [the two-midnight rule] sets an arbitrary time threshold that dictates where a patient should be placed,” says Joanna Hiatt Kim, vice president of payment policy for the American Hospital Association. The AHA opposes aspects of the rule and was involved in legislation to delay implementation.

“We feel time should not be the only factor taken into account,” Hiatt Kim adds. “It should be a decision a physician reaches based on a patient’s condition.”

Good Intentions

The rule states that hospital stays fewer than two midnights are generally medically inappropriate for inpatient designation. The services provided are not at issue, but CMS believes those administered during a short stay could be provided on a less expensive outpatient basis.

Dr. Flansbaum, a member of SHM’s Public Policy Committee, says the language of medical necessity that designates status is unclear, though CMS has given physicians the benefit of the doubt.

“We are looking for clear signals from providers for how we determine when someone is appropriately inpatient and when they’re observation,” he explains.

Although medical needs can be quantified, there are often other, nonmedical factors that put patients at risk and influence when and whether a patient is admitted. Physicians routinely weigh these factors on behalf of their patients.

“Risk isn’t necessarily implied by just a dangerous blood value,” Dr. Flansbaum says. “If something is not right in the transition zone or in the community, I think those [factors] need to be taken into account.”

Physicians are being given “a lot of latitude” in CMS’ new rule, he notes.

Clarification

In recent clarification, CMS highlighted exceptions to the rule. If “unforeseen circumstances” shorten the anticipated stay of someone initially deemed inpatient—transfer to another hospital, death, or clinical improvement in fewer than two midnights, for example—CMS can advise auditors to approve the inpatient claim.

Additionally, CMS will maintain a list of services considered “inpatient only,” regardless of stay duration.

But creating a list of every medically necessary service is an “administrative black hole,” says Dr. Flansbaum, though he believes that with enough time and clarity, compliance with the two-midnight rule is possible.

Kelly April Tyrrell is a freelance writer in Wilmington, Del.

A new rule issued by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is at the center of controversy fueled by competing interests and lack of clarity. And, for the fourth time since the two-midnight rule was introduced in the 2014 Hospital Inpatient Prospective Payment System, its implementation has been delayed. Hospitals and providers have until March 31, 2015, before auditors begin scrutinizing patient admission statuses for reimbursement determination.

The rule requires Medicare and Medicaid patients spending fewer than two midnights receiving hospital care to be classified as outpatient or under observation. Patients spending more than two midnights will be considered inpatient. Only physicians can make the determination, and the clock begins ticking the moment care begins.

The rule also cuts hospital inpatient reimbursement by 0.2%, because CMS believes the number of inpatient admissions will increase.

–Joanna Hiatt Kim, vice president of payment policy for the American Hospital Association

The rule pits private Medicare auditors (Medicare Administrative Contractors, MACs, and Recovery Audit Contractors, RACs), who have a financial stake in denying inpatient claims, against hospitals and physicians. It does little to clear confusion for patients when it comes time for them to pay their bills.

Patients generally are unaware whether they’ve been admitted or are under observation. But observation status leaves them on the hook for any skilled nursing care they receive following discharge and for the costs of routine maintenance drugs hospitals give them for chronic conditions.

Beneficiaries also are not eligible for Medicare Part A skilled nursing care coverage if they were an inpatient for fewer than 72 hours, and observation days do not count toward the three-day requirement. The two-midnight rule adds another “layer” to the equation, says Bradley Flansbaum, DO, MPH, FACP, a hospitalist and clinical assistant professor of medicine at NYU School of Medicine in New York City.

At the same time, hospitals now face penalties for patients readmitted within 30 days of discharge for a similar episode of care. Observation status offers a measure of protection in the event patients return.

The number of observation patients increased 69% between 2006 and 2011, according to federal data cited by Kaiser Health News, and the number of observation patients staying more than 48 hours increased from 3% to 8% during this same period.

“The concern is that [the two-midnight rule] sets an arbitrary time threshold that dictates where a patient should be placed,” says Joanna Hiatt Kim, vice president of payment policy for the American Hospital Association. The AHA opposes aspects of the rule and was involved in legislation to delay implementation.

“We feel time should not be the only factor taken into account,” Hiatt Kim adds. “It should be a decision a physician reaches based on a patient’s condition.”

Good Intentions

The rule states that hospital stays fewer than two midnights are generally medically inappropriate for inpatient designation. The services provided are not at issue, but CMS believes those administered during a short stay could be provided on a less expensive outpatient basis.

Dr. Flansbaum, a member of SHM’s Public Policy Committee, says the language of medical necessity that designates status is unclear, though CMS has given physicians the benefit of the doubt.

“We are looking for clear signals from providers for how we determine when someone is appropriately inpatient and when they’re observation,” he explains.

Although medical needs can be quantified, there are often other, nonmedical factors that put patients at risk and influence when and whether a patient is admitted. Physicians routinely weigh these factors on behalf of their patients.

“Risk isn’t necessarily implied by just a dangerous blood value,” Dr. Flansbaum says. “If something is not right in the transition zone or in the community, I think those [factors] need to be taken into account.”

Physicians are being given “a lot of latitude” in CMS’ new rule, he notes.

Clarification

In recent clarification, CMS highlighted exceptions to the rule. If “unforeseen circumstances” shorten the anticipated stay of someone initially deemed inpatient—transfer to another hospital, death, or clinical improvement in fewer than two midnights, for example—CMS can advise auditors to approve the inpatient claim.

Additionally, CMS will maintain a list of services considered “inpatient only,” regardless of stay duration.

But creating a list of every medically necessary service is an “administrative black hole,” says Dr. Flansbaum, though he believes that with enough time and clarity, compliance with the two-midnight rule is possible.

Kelly April Tyrrell is a freelance writer in Wilmington, Del.

A new rule issued by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is at the center of controversy fueled by competing interests and lack of clarity. And, for the fourth time since the two-midnight rule was introduced in the 2014 Hospital Inpatient Prospective Payment System, its implementation has been delayed. Hospitals and providers have until March 31, 2015, before auditors begin scrutinizing patient admission statuses for reimbursement determination.

The rule requires Medicare and Medicaid patients spending fewer than two midnights receiving hospital care to be classified as outpatient or under observation. Patients spending more than two midnights will be considered inpatient. Only physicians can make the determination, and the clock begins ticking the moment care begins.

The rule also cuts hospital inpatient reimbursement by 0.2%, because CMS believes the number of inpatient admissions will increase.

–Joanna Hiatt Kim, vice president of payment policy for the American Hospital Association

The rule pits private Medicare auditors (Medicare Administrative Contractors, MACs, and Recovery Audit Contractors, RACs), who have a financial stake in denying inpatient claims, against hospitals and physicians. It does little to clear confusion for patients when it comes time for them to pay their bills.

Patients generally are unaware whether they’ve been admitted or are under observation. But observation status leaves them on the hook for any skilled nursing care they receive following discharge and for the costs of routine maintenance drugs hospitals give them for chronic conditions.

Beneficiaries also are not eligible for Medicare Part A skilled nursing care coverage if they were an inpatient for fewer than 72 hours, and observation days do not count toward the three-day requirement. The two-midnight rule adds another “layer” to the equation, says Bradley Flansbaum, DO, MPH, FACP, a hospitalist and clinical assistant professor of medicine at NYU School of Medicine in New York City.

At the same time, hospitals now face penalties for patients readmitted within 30 days of discharge for a similar episode of care. Observation status offers a measure of protection in the event patients return.

The number of observation patients increased 69% between 2006 and 2011, according to federal data cited by Kaiser Health News, and the number of observation patients staying more than 48 hours increased from 3% to 8% during this same period.

“The concern is that [the two-midnight rule] sets an arbitrary time threshold that dictates where a patient should be placed,” says Joanna Hiatt Kim, vice president of payment policy for the American Hospital Association. The AHA opposes aspects of the rule and was involved in legislation to delay implementation.

“We feel time should not be the only factor taken into account,” Hiatt Kim adds. “It should be a decision a physician reaches based on a patient’s condition.”

Good Intentions

The rule states that hospital stays fewer than two midnights are generally medically inappropriate for inpatient designation. The services provided are not at issue, but CMS believes those administered during a short stay could be provided on a less expensive outpatient basis.

Dr. Flansbaum, a member of SHM’s Public Policy Committee, says the language of medical necessity that designates status is unclear, though CMS has given physicians the benefit of the doubt.

“We are looking for clear signals from providers for how we determine when someone is appropriately inpatient and when they’re observation,” he explains.

Although medical needs can be quantified, there are often other, nonmedical factors that put patients at risk and influence when and whether a patient is admitted. Physicians routinely weigh these factors on behalf of their patients.

“Risk isn’t necessarily implied by just a dangerous blood value,” Dr. Flansbaum says. “If something is not right in the transition zone or in the community, I think those [factors] need to be taken into account.”

Physicians are being given “a lot of latitude” in CMS’ new rule, he notes.

Clarification

In recent clarification, CMS highlighted exceptions to the rule. If “unforeseen circumstances” shorten the anticipated stay of someone initially deemed inpatient—transfer to another hospital, death, or clinical improvement in fewer than two midnights, for example—CMS can advise auditors to approve the inpatient claim.

Additionally, CMS will maintain a list of services considered “inpatient only,” regardless of stay duration.

But creating a list of every medically necessary service is an “administrative black hole,” says Dr. Flansbaum, though he believes that with enough time and clarity, compliance with the two-midnight rule is possible.

Kelly April Tyrrell is a freelance writer in Wilmington, Del.

Hospitalists’ Skill Sets, Work Experience Perfect for Hospitals' C-Suite Positions

Steve Narang, MD, a pediatrician, hospitalist, and the then-CMO at Banner Health’s Cardon Children’s Medical Center in Phoenix, was attending a leadership summit where all of Banner’s top officials were gathered. It was his third day in his new job.

Banner’s President, Peter Fine, gave a presentation in the future of healthcare and asked for questions. Dr. Narang stepped up to the microphone, asked a question, and made remarks about how the organization needed to ready itself for the changing landscape. Kathy Bollinger, president of the Arizona West Region of Banner, was struck by those remarks. Less than two years later, she made Dr. Narang the CEO at Arizona’s largest teaching hospital, Good Samaritan Medical Center.

His hospitalist background was an important ingredient in the kind of leader Dr. Narang has become, she says.

“The correlation is that hospitalists are leading teams; they are quarterbacking care,” Bollinger adds. “A good hospitalist brings the team together.”

Physicians with a background in hospital medicine are no strangers to C-suite level positions at hospitals. In April, Brian Harte, MD, SFHM, was named president of South Pointe Hospital in Warrenville Heights, Ohio, a center within the Cleveland Clinic system. In January, Patrick Cawley, MD, MBA, MHM, a former SHM president, was named CEO at the Medical University of South Carolina Medical Center in Charleston.

Other recent C-suite arrivals include Nasim Afsar, MD, SFHM, an SHM board member who is associate CMO at UCLA Hospitals in Los Angeles, and Patrick Torcson, MD, MMM, FACP, SFHM, another SHM board member, vice president, and chief integration officer at St. Tammany Parish Hospital in Covington, La.

Although their paths to the C-suite have differed, each agrees that their experience in hospital medicine gave them the knowledge of the system that was required to begin an ascent to the highest levels of leadership. Just as important, or maybe more so, their exposure to the inner workings of a hospital awakened within them a desire to see the system function better. And the necessity of working with all types of healthcare providers within the complicated hospital setting helped them recognize—or at least get others to recognize—their potential for leadership, and helped hone the teamwork skills that are vital in top administrative roles.

They also say that, when they were starting out, they never aspired to high leadership positions. Rather, it was simply following their own interests that ultimately led them there.

By the time Dr. Narang stepped up to the microphone that day in Phoenix, he had more than a dozen years under his belt working as a hospitalist for a children’s hospital and as part of a group that created a pediatric hospitalist company in Louisiana.

And that work helped lay the foundation for him, he says.

“Being a hospitalist was a key strength of my background,” Dr. Narang explains. “Hospitalists are so well-positioned…to get truly at the intersection of operations and find value in a complex puzzle. Hospitalists are able to do that.

“At the end of the day, it’s about leadership. And I learned that from day one as a hospitalist.”

His confidence and sense of the big picture were not lost on Bollinger that day at the leadership summit.

“I thought that took a fair amount of courage,” she says, “on Day 3, to stand up to the mic and have [a] specific conversation with the president of the company. In my mind, he was very enlightened. His comments were very enlightened.”

Firm Foundation

Robert Zipper, MD, MMM, SFHM, chair of SHM’s Leadership Committee, and CMO of Sound Physicians’ West Region, says it’s probably not realistic for a hospitalist to vault up immediately to a chief executive officer position. Pursuing lower-level leadership roles would be a good starting point for hospitalists with C-suite aspirations, he says.

“For those just starting out, I would recommend that they seek out opportunities to lead or be a part of managing change in their hospitals. The right opportunities should feel like a bit of a stretch, but not overwhelming. This might be work in quality, medical staff leadership, etc.,” Dr. Zipper says.

For hospitalists with leadership experience, CMO and vice president of medical affairs have the closest translation, he adds. He also says jobs like chief informatics officer and roles in quality improvement are highly suitable for hospitalists.

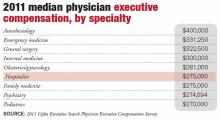

According to the 2011 Cejka Executive Search Physician Executive Compensation Survey, a survey of the American College of Physician Executives’ membership of physicians in management, the median salary of physicians in CEO positions was $393,152. That figure was $343,334 for CMO and $307,500 for chief quality and patient safety officer. The median for all physician executive positions was $305,000. Compensation was typically higher in academic medical centers and lower for hospitals and multi-specialty groups.

Hospitalists in executive positions had a 2011 median income of $275,000, according to the survey.

The survey also showed a wide range of compensation, typically dependent on the size of the institution. Some hospitalist leaders with more than 75% of their full-time-equivalent hours worked clinically “might actually take a small pay cut to make a move,” Dr. Zipper says.

Natural Progression

The hospitalist executives interviewed, for the most part, were emphatic that C-suite level leadership was not something that they imagined for themselves when they began their medical careers.

“In 2007, I could never imagine doing anything less than 100 percent clinical hospitalist work,” UCLA Hospitals’ Dr. Afsar says. “But once I started working and doing my hospitalist job day in and day out, I realized that there were many aspects of our care where I knew we could do better.”

Dr. Harte, president of South Pointe Hospital in Cleveland, says he never really thought about hospital administration as a career ambition. But, “opportunities presented themselves.”

Dr. Torcson says he was so firmly disinterested in administrative positions that when he was asked to join the Medical Executive Committee at his hospital, his first thought was “no way … I’m a doctor, not an administrator.” But after talking to some senior colleagues about it, they reminded him that he was basically obliged to say “yes.” And it ended up being a crucial component in his ascent through the ranks.

Dr. Narang imagined having a career that impacted value fairly early on, after making observations during his pediatric residency. But even he was surprised when he got the call to be CEO, after less than two years on the job.

Now, in retrospect, they all see their years working as a rank-and-file hospitalist as formative.

As a leader in a hospital, you have to be good at recruiting physicians, retaining them and developing them professionally, Dr. Harte says. That requires having clinical credibility, being a decent mentor, being a good role model, and “wearing your integrity on your sleeve.”

“I think one of the things that makes hospitalists fairly natural fits for the hospital leadership positions is that a hospital is a very complicated environment,” Dr. Harte notes. “You have pockets of enormous expertise that sometimes function like silos.

“Being a hospitalist actually trains you well for those things. By nature of what we do, we tend to be folks who do multi-disciplinary rounds. We can sit around a table or walk rounds with nurses, case managers, physical therapists, respiratory therapists, and the like, and actually develop a plan of care that recognizes the expertise of the other individuals within that group. That is a very good incubator for that kind of thinking.”

Hospital leaders also have to know how everything works together within the hospital.

“Hospital medicine has this overlap with that domain as it is,” Dr. Harte continues. “We work in hospitals. It is not such a stretch then, to think that we could be running a hospital.”

Golden Opportunity

Dr. Torcson says the opportunities to lead in the hospital setting abound. A former internist, he says hospitalists are primed to “improve quality and service at the hospital level because of the system-based approach to hospital care.”

Dealing with incomplete information and uncertainty are important challenges for hospital leaders, something Dr. Afsar says are daily hurdles for hospitalists.

“By nature when you’re a hospitalist, you are a problem solver,” she says. “You don’t shy away from problems that you don’t understand.”

That problem-solver outlook is what prompted Neil Martin, MD, chief of neurosurgery at UCLA, to ask Dr. Afsar to join a quality improvement program within the department—first as a participant and then as its leader.

“She was always one of the most active and vocal and solution-oriented people on the committees that I was participating in,” Dr. Martin says. “She was not the kind of person who would describe all of the problems and leave it at that. But, rather, [she] would help identify problems and then propose solutions and then help follow through to implement solutions.”

Hospitalist C-suiters describe days dominated by meetings with executive teams, staff, and individual physicians or groups. Meetings are a necessity, as executives are tasked with crafting a vision, constantly assessing progress, and refining the approach when necessary.

Continuing at least some clinical work is important, Dr. Harte says. It depends on the organization, but he says he sees benefits that help him in his administrative duties.

“It changes the dynamic of the interaction with some of the naysayers on the medical staff,” he says. “That’s still something that I enjoy doing. I think it’s important for me, it’s important for the credibility of my job, and particularly for the organization that I work at.”

A lot of C-suiters sought out formal training in administrative areas—though not necessarily an MBA—once they realized they had an interest in administration.

Dr. Torcson says getting a master’s in medical management degree was “absolutely invaluable.”

“It was obvious to me that I had some needs to develop some additional competencies and capabilities, a different skill set than I gained in medical school and residency,” he says. “The same skill set that makes one a successful or quality physician isn’t necessarily the same skill set that you need to be an effective manager or administrator.”

Dr. Afsar completed an advanced quality improvement training program at Intermountain Healthcare, and Dr. Narang received a master’s in healthcare management from Harvard.

Dr. Harte, who does not have an advanced management degree, says that at some institutions, such as Cleveland Clinic, you can learn on the job the non-clinical areas needed to be a top leader in a hospital, including finance and strategy.

Dr. Zipper says a related degree can be a big leg up.

“If one is specifically looking to enter the C-suite, an advanced business or management degree will make that barrier a lot lower,” he says. Whether that degree is a master’s in business administration, healthcare administration, medical management, or a similar degree doesn’t seem to matter much, he adds.

When she was looking for a new CEO for Good Samaritan Medical Center, Bollinger says that she preferred to hire a physician. That candidate, she says, had to have certain leadership qualities, including the ability to create a suitable vision, curiosity, an “executive presence,” and a “tolerance of ambiguity.”

As it turns out, the value of having a physician CEO has been “probably three times what I anticipated,” she says.

If you’re a hospitalist and have an interest in rising up the leadership ladder, getting involved and getting exposure to areas of interest is where it begins.

“I would say go for it,” Dr. Afsar says. “Raising your hand and being willing to take on responsibility are kind of the first steps in getting involved. I think it’s just as much making sure that you’re the right fit for that type of work, as it is to excel and do well. Not everyone, I think, will thrive and enjoy this type of work. So I think having the opportunity to get exposed to it and see if it’s something that you enjoy is a critical piece.”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in Florida.

Steve Narang, MD, a pediatrician, hospitalist, and the then-CMO at Banner Health’s Cardon Children’s Medical Center in Phoenix, was attending a leadership summit where all of Banner’s top officials were gathered. It was his third day in his new job.

Banner’s President, Peter Fine, gave a presentation in the future of healthcare and asked for questions. Dr. Narang stepped up to the microphone, asked a question, and made remarks about how the organization needed to ready itself for the changing landscape. Kathy Bollinger, president of the Arizona West Region of Banner, was struck by those remarks. Less than two years later, she made Dr. Narang the CEO at Arizona’s largest teaching hospital, Good Samaritan Medical Center.

His hospitalist background was an important ingredient in the kind of leader Dr. Narang has become, she says.

“The correlation is that hospitalists are leading teams; they are quarterbacking care,” Bollinger adds. “A good hospitalist brings the team together.”

Physicians with a background in hospital medicine are no strangers to C-suite level positions at hospitals. In April, Brian Harte, MD, SFHM, was named president of South Pointe Hospital in Warrenville Heights, Ohio, a center within the Cleveland Clinic system. In January, Patrick Cawley, MD, MBA, MHM, a former SHM president, was named CEO at the Medical University of South Carolina Medical Center in Charleston.

Other recent C-suite arrivals include Nasim Afsar, MD, SFHM, an SHM board member who is associate CMO at UCLA Hospitals in Los Angeles, and Patrick Torcson, MD, MMM, FACP, SFHM, another SHM board member, vice president, and chief integration officer at St. Tammany Parish Hospital in Covington, La.

Although their paths to the C-suite have differed, each agrees that their experience in hospital medicine gave them the knowledge of the system that was required to begin an ascent to the highest levels of leadership. Just as important, or maybe more so, their exposure to the inner workings of a hospital awakened within them a desire to see the system function better. And the necessity of working with all types of healthcare providers within the complicated hospital setting helped them recognize—or at least get others to recognize—their potential for leadership, and helped hone the teamwork skills that are vital in top administrative roles.

They also say that, when they were starting out, they never aspired to high leadership positions. Rather, it was simply following their own interests that ultimately led them there.

By the time Dr. Narang stepped up to the microphone that day in Phoenix, he had more than a dozen years under his belt working as a hospitalist for a children’s hospital and as part of a group that created a pediatric hospitalist company in Louisiana.

And that work helped lay the foundation for him, he says.

“Being a hospitalist was a key strength of my background,” Dr. Narang explains. “Hospitalists are so well-positioned…to get truly at the intersection of operations and find value in a complex puzzle. Hospitalists are able to do that.

“At the end of the day, it’s about leadership. And I learned that from day one as a hospitalist.”

His confidence and sense of the big picture were not lost on Bollinger that day at the leadership summit.

“I thought that took a fair amount of courage,” she says, “on Day 3, to stand up to the mic and have [a] specific conversation with the president of the company. In my mind, he was very enlightened. His comments were very enlightened.”

Firm Foundation

Robert Zipper, MD, MMM, SFHM, chair of SHM’s Leadership Committee, and CMO of Sound Physicians’ West Region, says it’s probably not realistic for a hospitalist to vault up immediately to a chief executive officer position. Pursuing lower-level leadership roles would be a good starting point for hospitalists with C-suite aspirations, he says.

“For those just starting out, I would recommend that they seek out opportunities to lead or be a part of managing change in their hospitals. The right opportunities should feel like a bit of a stretch, but not overwhelming. This might be work in quality, medical staff leadership, etc.,” Dr. Zipper says.

For hospitalists with leadership experience, CMO and vice president of medical affairs have the closest translation, he adds. He also says jobs like chief informatics officer and roles in quality improvement are highly suitable for hospitalists.