User login

Armored CAR T cells next on the production line

NEW YORK—Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells have “remarkable” activity, according to a speaker at the NCCN 9th Annual Congress: Hematologic Malignancies.

“[T]his chimera binds like an antibody, but it acts like a T cell, so it combines the best of both worlds,” said Jae H. Park, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) in New York.

He then traced the evolution of CAR T-cell design, discussed clinical trials using CD19-targed T cells, and described how investigators are working at building a better T cell.

Researchers found that T-cell activation and proliferation require signaling through a costimulatory receptor, such as CD28, 4-1BB, or OX-40. Without costimulation, the T cell becomes unresponsive or undergoes apoptosis.

So based on this observation, Dr Park said, several research groups created second- and third-generation CARs to incorporate the costimulatory signal.

The first generation was typically fused to the CD8 domain. Second-generation CARs include a costimulatory signaling domain, such as CD28, 4-1BB, or OX40. And the third generation contains signaling domains from 2 costimulatory receptors, CD28 with 4-1BB and CD28 with OX40.

The built-in costimulatory signal proved superior to the first-generation CAR T cells.

In NOD/SCID mice inoculated with NALM-6 lymphoma cells, Dr Park said, about 50% more were “cured,” in terms of survival, using a CD80 costimulatory ligand with CD19-targeted T cells compared to those without the ligand.

Clinical trials

Clinical trials using second-generation CD19-targeted T cells in relapsed B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) at MSKCC produced an overall complete response (CR) rate of 88% in a median of 22.1 days. And 72% of the CRs were minimal residual disease (MRD) negative.

So the CAR T cells produce a “very rapid and deep remission,” Dr Park said.

CAR T-cell therapy, however, comes with adverse events, most notably, cytokine release syndrome (CRS), which results from T-cell activation. CRS causes fevers, hypotension, and neurologic toxicities including mental status changes, obtundation, and seizures.

“CRS is not unique to CAR T-cell therapy,” Dr Park said. “Any therapy that activates T cells can have this type of side effect.”

Dr Park noted that CRS is associated with disease burden at the time of treatment. “The larger the disease burden pre T-cell therapy,” he said, “the more likely [patients are] to develop CRS.”

In the MSKCC trial, no patient with very low disease burden—5% blasts in the bone marrow—developed CRS.

However, there is also a correlation between tumor burden and T-cell expansion, he added. T cells expand much better with a larger disease burden, because there is a greater antigen load.

The investigators found that serum C-reactive protein can serve as a surrogate marker for the severity of CRS. Patients with levels above 20 mg/dL are more likely to experience CRS.

And Dr Park pointed out that CRS symptoms respond pretty rapidly to steroids or interleukin-6 receptor blockade.

CAR T-cell therapy has also been used to treat chronic lymphocytic leukemia, but with much more modest response rates than in ALL. Both University of Pennsylvania and MSKCC trials in CLL have produced overall response rates around 40%.

Building a better T cell

Dr Park described efforts underway to develop the fourth-generation “armored” CAR T cells to overcome the hostile tumor microenvironment, which contains multiple inhibitory factors designed to suppress effector T cells.

Armored T cells can actually secrete some of the inflammatory cytokines to change the tumor microenvironment and overcome the inhibitory effect.

Dr Park described a potential scenario: The armored CAR T cells secrete IL-12, enhance the central memory phenotype, enhance cytotoxicity, enhance persistence, modify the endogenous immune system and T-cell activation, and reactivate tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes.

He said future studies will focus on translation of these armored CAR T cells to the clinical setting in both hematologic and solid tumor malignancies. ![]()

NEW YORK—Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells have “remarkable” activity, according to a speaker at the NCCN 9th Annual Congress: Hematologic Malignancies.

“[T]his chimera binds like an antibody, but it acts like a T cell, so it combines the best of both worlds,” said Jae H. Park, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) in New York.

He then traced the evolution of CAR T-cell design, discussed clinical trials using CD19-targed T cells, and described how investigators are working at building a better T cell.

Researchers found that T-cell activation and proliferation require signaling through a costimulatory receptor, such as CD28, 4-1BB, or OX-40. Without costimulation, the T cell becomes unresponsive or undergoes apoptosis.

So based on this observation, Dr Park said, several research groups created second- and third-generation CARs to incorporate the costimulatory signal.

The first generation was typically fused to the CD8 domain. Second-generation CARs include a costimulatory signaling domain, such as CD28, 4-1BB, or OX40. And the third generation contains signaling domains from 2 costimulatory receptors, CD28 with 4-1BB and CD28 with OX40.

The built-in costimulatory signal proved superior to the first-generation CAR T cells.

In NOD/SCID mice inoculated with NALM-6 lymphoma cells, Dr Park said, about 50% more were “cured,” in terms of survival, using a CD80 costimulatory ligand with CD19-targeted T cells compared to those without the ligand.

Clinical trials

Clinical trials using second-generation CD19-targeted T cells in relapsed B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) at MSKCC produced an overall complete response (CR) rate of 88% in a median of 22.1 days. And 72% of the CRs were minimal residual disease (MRD) negative.

So the CAR T cells produce a “very rapid and deep remission,” Dr Park said.

CAR T-cell therapy, however, comes with adverse events, most notably, cytokine release syndrome (CRS), which results from T-cell activation. CRS causes fevers, hypotension, and neurologic toxicities including mental status changes, obtundation, and seizures.

“CRS is not unique to CAR T-cell therapy,” Dr Park said. “Any therapy that activates T cells can have this type of side effect.”

Dr Park noted that CRS is associated with disease burden at the time of treatment. “The larger the disease burden pre T-cell therapy,” he said, “the more likely [patients are] to develop CRS.”

In the MSKCC trial, no patient with very low disease burden—5% blasts in the bone marrow—developed CRS.

However, there is also a correlation between tumor burden and T-cell expansion, he added. T cells expand much better with a larger disease burden, because there is a greater antigen load.

The investigators found that serum C-reactive protein can serve as a surrogate marker for the severity of CRS. Patients with levels above 20 mg/dL are more likely to experience CRS.

And Dr Park pointed out that CRS symptoms respond pretty rapidly to steroids or interleukin-6 receptor blockade.

CAR T-cell therapy has also been used to treat chronic lymphocytic leukemia, but with much more modest response rates than in ALL. Both University of Pennsylvania and MSKCC trials in CLL have produced overall response rates around 40%.

Building a better T cell

Dr Park described efforts underway to develop the fourth-generation “armored” CAR T cells to overcome the hostile tumor microenvironment, which contains multiple inhibitory factors designed to suppress effector T cells.

Armored T cells can actually secrete some of the inflammatory cytokines to change the tumor microenvironment and overcome the inhibitory effect.

Dr Park described a potential scenario: The armored CAR T cells secrete IL-12, enhance the central memory phenotype, enhance cytotoxicity, enhance persistence, modify the endogenous immune system and T-cell activation, and reactivate tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes.

He said future studies will focus on translation of these armored CAR T cells to the clinical setting in both hematologic and solid tumor malignancies. ![]()

NEW YORK—Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells have “remarkable” activity, according to a speaker at the NCCN 9th Annual Congress: Hematologic Malignancies.

“[T]his chimera binds like an antibody, but it acts like a T cell, so it combines the best of both worlds,” said Jae H. Park, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) in New York.

He then traced the evolution of CAR T-cell design, discussed clinical trials using CD19-targed T cells, and described how investigators are working at building a better T cell.

Researchers found that T-cell activation and proliferation require signaling through a costimulatory receptor, such as CD28, 4-1BB, or OX-40. Without costimulation, the T cell becomes unresponsive or undergoes apoptosis.

So based on this observation, Dr Park said, several research groups created second- and third-generation CARs to incorporate the costimulatory signal.

The first generation was typically fused to the CD8 domain. Second-generation CARs include a costimulatory signaling domain, such as CD28, 4-1BB, or OX40. And the third generation contains signaling domains from 2 costimulatory receptors, CD28 with 4-1BB and CD28 with OX40.

The built-in costimulatory signal proved superior to the first-generation CAR T cells.

In NOD/SCID mice inoculated with NALM-6 lymphoma cells, Dr Park said, about 50% more were “cured,” in terms of survival, using a CD80 costimulatory ligand with CD19-targeted T cells compared to those without the ligand.

Clinical trials

Clinical trials using second-generation CD19-targeted T cells in relapsed B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) at MSKCC produced an overall complete response (CR) rate of 88% in a median of 22.1 days. And 72% of the CRs were minimal residual disease (MRD) negative.

So the CAR T cells produce a “very rapid and deep remission,” Dr Park said.

CAR T-cell therapy, however, comes with adverse events, most notably, cytokine release syndrome (CRS), which results from T-cell activation. CRS causes fevers, hypotension, and neurologic toxicities including mental status changes, obtundation, and seizures.

“CRS is not unique to CAR T-cell therapy,” Dr Park said. “Any therapy that activates T cells can have this type of side effect.”

Dr Park noted that CRS is associated with disease burden at the time of treatment. “The larger the disease burden pre T-cell therapy,” he said, “the more likely [patients are] to develop CRS.”

In the MSKCC trial, no patient with very low disease burden—5% blasts in the bone marrow—developed CRS.

However, there is also a correlation between tumor burden and T-cell expansion, he added. T cells expand much better with a larger disease burden, because there is a greater antigen load.

The investigators found that serum C-reactive protein can serve as a surrogate marker for the severity of CRS. Patients with levels above 20 mg/dL are more likely to experience CRS.

And Dr Park pointed out that CRS symptoms respond pretty rapidly to steroids or interleukin-6 receptor blockade.

CAR T-cell therapy has also been used to treat chronic lymphocytic leukemia, but with much more modest response rates than in ALL. Both University of Pennsylvania and MSKCC trials in CLL have produced overall response rates around 40%.

Building a better T cell

Dr Park described efforts underway to develop the fourth-generation “armored” CAR T cells to overcome the hostile tumor microenvironment, which contains multiple inhibitory factors designed to suppress effector T cells.

Armored T cells can actually secrete some of the inflammatory cytokines to change the tumor microenvironment and overcome the inhibitory effect.

Dr Park described a potential scenario: The armored CAR T cells secrete IL-12, enhance the central memory phenotype, enhance cytotoxicity, enhance persistence, modify the endogenous immune system and T-cell activation, and reactivate tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes.

He said future studies will focus on translation of these armored CAR T cells to the clinical setting in both hematologic and solid tumor malignancies. ![]()

Bacterium could help control malaria, dengue

Credit: CDC

A bacterium isolated from a mosquito’s gut could aid the fight against malaria and dengue, according to a study published in PLOS Pathogens.

With previous research, scientists isolated Csp_P, a member of the family of chromobacteria, from the gut of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes.

Now, the team has found that Csp_P can directly inhibit malaria and dengue pathogens in vitro and shorten the life span of the mosquitoes that transmit both diseases.

George Dimopoulos, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, and his colleagues examined Csp_P’s actions on both mosquitoes and pathogens, and the results suggest that Csp_P might help to fight malaria and dengue at different levels.

The researchers added Csp_P to sugar water fed to mosquitoes and found that the bacteria are able to quickly colonize the gut of the two most important mosquito disease vectors—Aedes aegypti and Anopheles gambiae.

Moreover, the presence of Csp_P in the gut reduced the susceptibility of the respective mosquitoes to infection with the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum or with dengue virus.

Even without gut colonization, exposure to Csp_P through food or breeding water shortened the lifespan of adult mosquitoes and mosquito larvae of both species.

When the researchers tested whether Csp_P could act against the malaria or dengue pathogens directly, they found that the bacterium, likely through the production of toxic metabolites, can inhibit the growth of Plasmodium at various stages during the parasite’s life cycle and also abolish dengue virus infectivity.

The team said these toxic metabolites could potentially be developed into drugs to treat malaria and dengue.

Overall, the researchers concluded that Csp_P’s broad-spectrum antipathogen properties and ability to kill mosquitoes make it a good candidate for the development of novel control strategies for malaria and dengue, so it warrants further study. ![]()

Credit: CDC

A bacterium isolated from a mosquito’s gut could aid the fight against malaria and dengue, according to a study published in PLOS Pathogens.

With previous research, scientists isolated Csp_P, a member of the family of chromobacteria, from the gut of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes.

Now, the team has found that Csp_P can directly inhibit malaria and dengue pathogens in vitro and shorten the life span of the mosquitoes that transmit both diseases.

George Dimopoulos, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, and his colleagues examined Csp_P’s actions on both mosquitoes and pathogens, and the results suggest that Csp_P might help to fight malaria and dengue at different levels.

The researchers added Csp_P to sugar water fed to mosquitoes and found that the bacteria are able to quickly colonize the gut of the two most important mosquito disease vectors—Aedes aegypti and Anopheles gambiae.

Moreover, the presence of Csp_P in the gut reduced the susceptibility of the respective mosquitoes to infection with the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum or with dengue virus.

Even without gut colonization, exposure to Csp_P through food or breeding water shortened the lifespan of adult mosquitoes and mosquito larvae of both species.

When the researchers tested whether Csp_P could act against the malaria or dengue pathogens directly, they found that the bacterium, likely through the production of toxic metabolites, can inhibit the growth of Plasmodium at various stages during the parasite’s life cycle and also abolish dengue virus infectivity.

The team said these toxic metabolites could potentially be developed into drugs to treat malaria and dengue.

Overall, the researchers concluded that Csp_P’s broad-spectrum antipathogen properties and ability to kill mosquitoes make it a good candidate for the development of novel control strategies for malaria and dengue, so it warrants further study. ![]()

Credit: CDC

A bacterium isolated from a mosquito’s gut could aid the fight against malaria and dengue, according to a study published in PLOS Pathogens.

With previous research, scientists isolated Csp_P, a member of the family of chromobacteria, from the gut of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes.

Now, the team has found that Csp_P can directly inhibit malaria and dengue pathogens in vitro and shorten the life span of the mosquitoes that transmit both diseases.

George Dimopoulos, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, and his colleagues examined Csp_P’s actions on both mosquitoes and pathogens, and the results suggest that Csp_P might help to fight malaria and dengue at different levels.

The researchers added Csp_P to sugar water fed to mosquitoes and found that the bacteria are able to quickly colonize the gut of the two most important mosquito disease vectors—Aedes aegypti and Anopheles gambiae.

Moreover, the presence of Csp_P in the gut reduced the susceptibility of the respective mosquitoes to infection with the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum or with dengue virus.

Even without gut colonization, exposure to Csp_P through food or breeding water shortened the lifespan of adult mosquitoes and mosquito larvae of both species.

When the researchers tested whether Csp_P could act against the malaria or dengue pathogens directly, they found that the bacterium, likely through the production of toxic metabolites, can inhibit the growth of Plasmodium at various stages during the parasite’s life cycle and also abolish dengue virus infectivity.

The team said these toxic metabolites could potentially be developed into drugs to treat malaria and dengue.

Overall, the researchers concluded that Csp_P’s broad-spectrum antipathogen properties and ability to kill mosquitoes make it a good candidate for the development of novel control strategies for malaria and dengue, so it warrants further study. ![]()

Paracentesis in Cirrhosis Patients/

Ascites is the most common complication of cirrhosis leading to hospital admission.[1] Approximately 12% of hospitalized patients who present with decompensated cirrhosis and ascites have spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP); half of these patients do not present with abdominal pain, fever, nausea, or vomiting.[2] Guidelines published by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) recommend paracentesis for all hospitalized patients with cirrhosis and ascites and also recommend long‐term antibiotic prophylaxis for survivors of an SBP episode.[3] Despite evidence that in‐hospital mortality is reduced in those patients who receive paracentesis in a timely manner,[4, 5] only 40% to 60% of eligible patients receive paracentesis.[4, 6, 7] We aimed to describe clinical predictors of paracentesis and use of antibiotics following an episode of SBP in patients with decompensated cirrhosis and ascites.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of adults admitted to a single tertiary care center between January 1, 2009 and December 31, 2009.7 We included patients with an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision discharge code consistent with decompensated cirrhosis who met clinical criteria for decompensated cirrhosis (see

RESULTS

We identified 193 admissions for 103 patients with decompensated cirrhosis and ascites (Table 1). Of these, 41% (80/193) received diagnostic paracentesis. Mean/standard deviation for age was 53.6/12.4 years; 71% of patients were male and 63% were English speaking. Common comorbidities included diabetes mellitus (33%), psychiatric diagnosis (29%), substance abuse (18%), and renal failure (17%). Excluding SBP, 31% of patients had another documented infection. Gastroenterology was consulted in 50% of the admissions. Fever was present in 27% of patients, elevated white blood cell (WBC) count (ie, WBC >11 k/mm3) was present in 27% of patients, International Normalized Ratio (INR) was elevated (>1.1) in 92% of patients, and 16% of patients had a platelet count of 50,000/mm3. Patients who received paracentesis were less likely to have a fever on presentation (19% vs 32%, P=0.06), low (ie, 50,000/mm3) platelet count (11% vs 19%, P=0.14), or concurrent gastrointestinal (GI) bleed (6% vs 16%, P=0.05). In a multiple logistic regression model including characteristics associated at P0.2 with paracentesis, fever, low platelet count, and concurrent GI bleeding were associated with decreased odds of receiving paracentesis (Appendix 1).

| Overall, N=193, Mean/SD or N (%)* | Paracentesis (), n=113, Mean/SD or N (%) | Paracentesis (+), n=80, Mean/SD or N (%) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Age, y | 53.6/12.4 | 54.1/13.4 | 53.2/11.7 | 1.00 (0.981.03) |

| Sex (male) | 137 (71.0%) | 78 (69.0%) | 59 (73.8%) | 1.26 (0.672.39) |

| English speaking | 122 (63.2%) | 69 (61.1%) | 53 (66.3%) | 1.25 (0.692.28) |

| Etiology | ||||

| Alcohol | 120 (62.2%) | 74 (65.5%) | 46 (57.5%) | 0.71 (0.401.29) |

| Hepatitis C | 94 (48.7%) | 57 (50.4%) | 37 (46.3%) | 0.85 (0.481.50) |

| Hepatitis B | 16 (8.3%) | 7 (6.2%) | 9 (11.3%) | 1.92 (0.685.39) |

| NASH | 8 (4.2%) | 4 (3.5%) | 4 (5.0%) | 1.43 (0.355.91) |

| Cryptogenic | 11 (5.7%) | 6 (5.3%) | 5 (6.3%) | 1.19 (0.354.04) |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Substance abuse | 34 (17.6%) | 22 (19.5%) | 12 (15.0%) | 0.73 (0.341.58) |

| Psychiatric diagnosis | 55 (28.5%) | 38 (33.6%) | 17 (21.3%) | 0.53 (0.271.03) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 63 (32.6%) | 37 (32.7%) | 26 (32.5%) | 0.99 (0.541.82) |

| Renal failure | 33 (17.1%) | 20 (17.7%) | 13 (16.3%) | 0.90 (0.421.94) |

| GI bleed | 23 (11.9%) | 18 (15.9%) | 5 (6.3%) | 0.35 (0.120.99) |

| Admission MELD | 17.3/7.3 | 17.5/7.3 | 17.0/7.3 | 0.99 (0.951.03) |

| Creatinine, median/IQR | 0.9/0.7 | 0.9/0.7 | 0.9/0.8 | 1.02 (0.821.27) |

| Gastroenterology consult | 97 (50.3%) | 46 (40.7%) | 51 (63.8%) | 2.56 (1.424.63) |

| Infection, UTI, pneumonia, other | 60 (31.1%) | 38 (33.6%) | 22 (27.5%) | 0.75 (0.401.40) |

| Temperature 100.4F | 49 (26.8%) | 34 (32.4%) | 15 (19.2%) | 0.50 (0.251.00) |

| WBC >11 k/mm3 | 50 (27.3%) | 28 (26.7%) | 22 (28.2%) | 1.08 (0.562.08) |

| WBC 4 k/mm3 | 43 (23.5%) | 23 (21.9%) | 20 (25.6%) | 1.23 (0.622.44) |

| INR >1.1 | 149 (92.0%) | 83 (93.3%) | 66 (90.4%) | 0.68 (0.222.13) |

| Highest temperature, F | 98.9/1.1 | 99.1/1.3 | 98.8/0.8 | 0.82 (0.621.09) |

| Highest HR | 98.2/20.4 | 97.4/22.4 | 99.2/17.4 | 1.00 (0.991.02) |

| Highest RR | 24.5/13.7 | 25.2/16.8 | 23.5/7.8 | 0.99 (0.961.02) |

| Lowest SBP | 101.0/20.0 | 99.4/20.3 | 102.2/19.7 | 0.99 (0.981.01) |

| Lowest MAP | 73.0/12.2 | 73.2/13.3 | 72.7/10.6 | 1.00 (0.971.02) |

| Lowest O2Sat | 92.6/13.6 | 91.0/17.7 | 94.9/2.8 | 1.04 (0.991.10) |

| Highest PT | 15.8/3.8 | 15.9/3.7 | 15.7/3.9 | 0.98 (0.901.08) |

| Platelets 50 k/mm3 | 30 (15.9%) | 21 (19.3%) | 9 (11.3%) | 0.53 (0.231.23) |

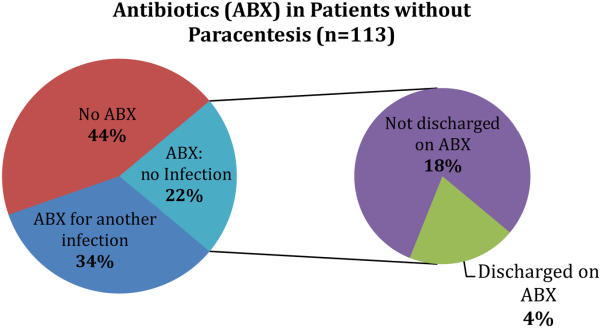

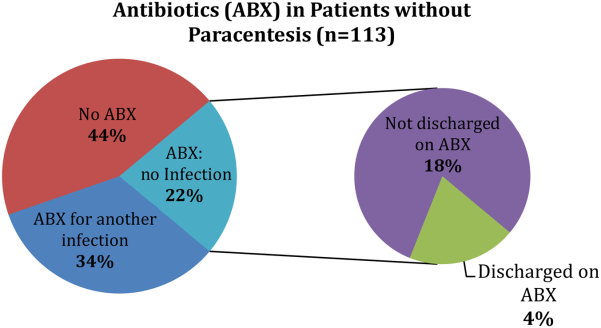

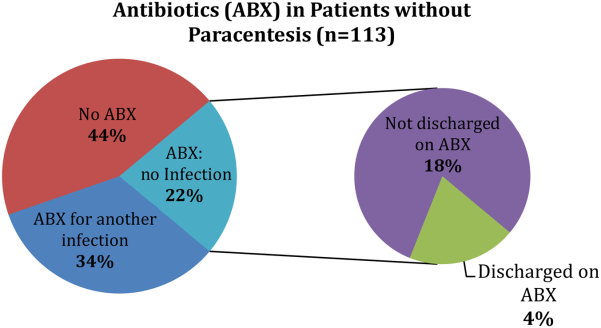

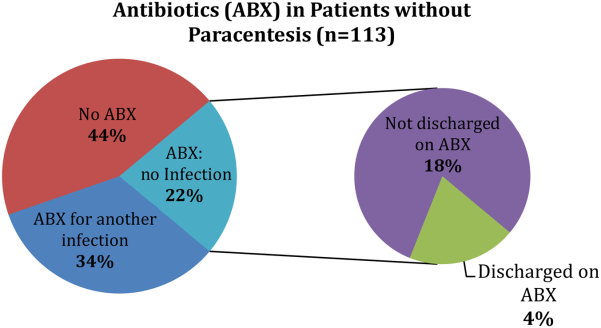

Of the patients who received paracentesis (n=80), 14% were diagnosed with SBP. Of these, 55% received prophylaxis on discharge. Among the patients who did not receive paracentesis (n=113), 38 (34%) received antibiotics for another documented infection (eg, pneumonia), and 25 patients (22%) received antibiotics with no other documented infection or evidence of variceal bleeding. Of these 25 patients who were presumed to be empirically treated for SBP (Figure 1), only 20% were prescribed prophylactic antibiotics on discharge.

CONCLUSION

We found that many patients with decompensated cirrhosis and ascites did not receive paracentesis when hospitalized, which is similar to previously published data.[4, 6, 7] Clinical evidence of infection, such as fever or elevated WBC count, did not increase the odds of receiving paracentesis. Many patients treated for SBP were not discharged on prophylaxis.

This study is limited by its small single‐center design. We could only use data from 1 year (2009), because study data collection was part of a quality‐improvement project that took place for that year only. We did not adjust for the number of red blood cells in the ascitic fluid samples. We were also unable to determine the timing of gastroenterology consultation (whether it was done prior to paracentesis), admission venue (floor vs intensive care), or patient history of SBP.

Despite these limitations, there are important implications. First, the decision to perform paracentesis was not associated with symptoms of infection, although some clinical factors (eg, low platelets or GI bleeding) were associated with reduced odds of receiving paracentesis. Second, a majority of patients treated for SBP did not receive prophylactic antibiotics at discharge. These findings suggest a clear opportunity to increase awareness and acceptance of AASLD guidelines among hospital medicine practitioners. Quality‐improvement efforts should focus on the education of providers, and future research should identify barriers to paracentesis at both the practitioner and system levels (eg, availability of interventional radiology). Checklists or decision support within electronic order entry systems may also help reduce the low rates of paracentesis seen in our and prior studies.[4, 6, 7]

Disclosures: Dr. Lagu is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number K01HL114745. Drs. Lagu, Ghaoui, and Brooling had full access to all of the data in the study. They take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Drs. Lagu, Ghaoui, and Brooling conceived of the study. Dr. Ghaoui acquired the data. Ms. Friderici carried out the statistical analyses. Drs. Lagu, Ghaoui, Brooling, Lindenauer, and Ms. Friderici analyzed and interpreted the data, drafted the manuscript, and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , , , , ; Spanish Collaborative Study Group On Therapeutic Management In Liver Disease. Multicenter hospital study on prescribing patterns for prophylaxis and treatment of complications of cirrhosis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;58(6):435–440.

- , , , et al. Bacterial infection in patients with advanced cirrhosis: a multicentre prospective study. Dig Liver Dis. 2001;33(1):41–48.

- , AASLD. Introduction to the revised American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases Practice Guideline management of adult patients with ascites due to cirrhosis 2012. Hepatology. 2013;57(4):1651–1653.

- , , , . Paracentesis is associated with reduced mortality in patients hospitalized with cirrhosis and ascites. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(3):496–503.e1.

- , , , et al. Delayed paracentesis is associated with increased in‐hospital mortality in patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(9):1436–1442.

- , , , et al. The quality of care provided to patients with cirrhosis and ascites in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(1):70–77.

- , , , , , . Measurement of the quality of care of patients admitted with decompensated cirrhosis. Liver Int. 2014;34(2):204–210.

Ascites is the most common complication of cirrhosis leading to hospital admission.[1] Approximately 12% of hospitalized patients who present with decompensated cirrhosis and ascites have spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP); half of these patients do not present with abdominal pain, fever, nausea, or vomiting.[2] Guidelines published by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) recommend paracentesis for all hospitalized patients with cirrhosis and ascites and also recommend long‐term antibiotic prophylaxis for survivors of an SBP episode.[3] Despite evidence that in‐hospital mortality is reduced in those patients who receive paracentesis in a timely manner,[4, 5] only 40% to 60% of eligible patients receive paracentesis.[4, 6, 7] We aimed to describe clinical predictors of paracentesis and use of antibiotics following an episode of SBP in patients with decompensated cirrhosis and ascites.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of adults admitted to a single tertiary care center between January 1, 2009 and December 31, 2009.7 We included patients with an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision discharge code consistent with decompensated cirrhosis who met clinical criteria for decompensated cirrhosis (see

RESULTS

We identified 193 admissions for 103 patients with decompensated cirrhosis and ascites (Table 1). Of these, 41% (80/193) received diagnostic paracentesis. Mean/standard deviation for age was 53.6/12.4 years; 71% of patients were male and 63% were English speaking. Common comorbidities included diabetes mellitus (33%), psychiatric diagnosis (29%), substance abuse (18%), and renal failure (17%). Excluding SBP, 31% of patients had another documented infection. Gastroenterology was consulted in 50% of the admissions. Fever was present in 27% of patients, elevated white blood cell (WBC) count (ie, WBC >11 k/mm3) was present in 27% of patients, International Normalized Ratio (INR) was elevated (>1.1) in 92% of patients, and 16% of patients had a platelet count of 50,000/mm3. Patients who received paracentesis were less likely to have a fever on presentation (19% vs 32%, P=0.06), low (ie, 50,000/mm3) platelet count (11% vs 19%, P=0.14), or concurrent gastrointestinal (GI) bleed (6% vs 16%, P=0.05). In a multiple logistic regression model including characteristics associated at P0.2 with paracentesis, fever, low platelet count, and concurrent GI bleeding were associated with decreased odds of receiving paracentesis (Appendix 1).

| Overall, N=193, Mean/SD or N (%)* | Paracentesis (), n=113, Mean/SD or N (%) | Paracentesis (+), n=80, Mean/SD or N (%) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Age, y | 53.6/12.4 | 54.1/13.4 | 53.2/11.7 | 1.00 (0.981.03) |

| Sex (male) | 137 (71.0%) | 78 (69.0%) | 59 (73.8%) | 1.26 (0.672.39) |

| English speaking | 122 (63.2%) | 69 (61.1%) | 53 (66.3%) | 1.25 (0.692.28) |

| Etiology | ||||

| Alcohol | 120 (62.2%) | 74 (65.5%) | 46 (57.5%) | 0.71 (0.401.29) |

| Hepatitis C | 94 (48.7%) | 57 (50.4%) | 37 (46.3%) | 0.85 (0.481.50) |

| Hepatitis B | 16 (8.3%) | 7 (6.2%) | 9 (11.3%) | 1.92 (0.685.39) |

| NASH | 8 (4.2%) | 4 (3.5%) | 4 (5.0%) | 1.43 (0.355.91) |

| Cryptogenic | 11 (5.7%) | 6 (5.3%) | 5 (6.3%) | 1.19 (0.354.04) |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Substance abuse | 34 (17.6%) | 22 (19.5%) | 12 (15.0%) | 0.73 (0.341.58) |

| Psychiatric diagnosis | 55 (28.5%) | 38 (33.6%) | 17 (21.3%) | 0.53 (0.271.03) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 63 (32.6%) | 37 (32.7%) | 26 (32.5%) | 0.99 (0.541.82) |

| Renal failure | 33 (17.1%) | 20 (17.7%) | 13 (16.3%) | 0.90 (0.421.94) |

| GI bleed | 23 (11.9%) | 18 (15.9%) | 5 (6.3%) | 0.35 (0.120.99) |

| Admission MELD | 17.3/7.3 | 17.5/7.3 | 17.0/7.3 | 0.99 (0.951.03) |

| Creatinine, median/IQR | 0.9/0.7 | 0.9/0.7 | 0.9/0.8 | 1.02 (0.821.27) |

| Gastroenterology consult | 97 (50.3%) | 46 (40.7%) | 51 (63.8%) | 2.56 (1.424.63) |

| Infection, UTI, pneumonia, other | 60 (31.1%) | 38 (33.6%) | 22 (27.5%) | 0.75 (0.401.40) |

| Temperature 100.4F | 49 (26.8%) | 34 (32.4%) | 15 (19.2%) | 0.50 (0.251.00) |

| WBC >11 k/mm3 | 50 (27.3%) | 28 (26.7%) | 22 (28.2%) | 1.08 (0.562.08) |

| WBC 4 k/mm3 | 43 (23.5%) | 23 (21.9%) | 20 (25.6%) | 1.23 (0.622.44) |

| INR >1.1 | 149 (92.0%) | 83 (93.3%) | 66 (90.4%) | 0.68 (0.222.13) |

| Highest temperature, F | 98.9/1.1 | 99.1/1.3 | 98.8/0.8 | 0.82 (0.621.09) |

| Highest HR | 98.2/20.4 | 97.4/22.4 | 99.2/17.4 | 1.00 (0.991.02) |

| Highest RR | 24.5/13.7 | 25.2/16.8 | 23.5/7.8 | 0.99 (0.961.02) |

| Lowest SBP | 101.0/20.0 | 99.4/20.3 | 102.2/19.7 | 0.99 (0.981.01) |

| Lowest MAP | 73.0/12.2 | 73.2/13.3 | 72.7/10.6 | 1.00 (0.971.02) |

| Lowest O2Sat | 92.6/13.6 | 91.0/17.7 | 94.9/2.8 | 1.04 (0.991.10) |

| Highest PT | 15.8/3.8 | 15.9/3.7 | 15.7/3.9 | 0.98 (0.901.08) |

| Platelets 50 k/mm3 | 30 (15.9%) | 21 (19.3%) | 9 (11.3%) | 0.53 (0.231.23) |

Of the patients who received paracentesis (n=80), 14% were diagnosed with SBP. Of these, 55% received prophylaxis on discharge. Among the patients who did not receive paracentesis (n=113), 38 (34%) received antibiotics for another documented infection (eg, pneumonia), and 25 patients (22%) received antibiotics with no other documented infection or evidence of variceal bleeding. Of these 25 patients who were presumed to be empirically treated for SBP (Figure 1), only 20% were prescribed prophylactic antibiotics on discharge.

CONCLUSION

We found that many patients with decompensated cirrhosis and ascites did not receive paracentesis when hospitalized, which is similar to previously published data.[4, 6, 7] Clinical evidence of infection, such as fever or elevated WBC count, did not increase the odds of receiving paracentesis. Many patients treated for SBP were not discharged on prophylaxis.

This study is limited by its small single‐center design. We could only use data from 1 year (2009), because study data collection was part of a quality‐improvement project that took place for that year only. We did not adjust for the number of red blood cells in the ascitic fluid samples. We were also unable to determine the timing of gastroenterology consultation (whether it was done prior to paracentesis), admission venue (floor vs intensive care), or patient history of SBP.

Despite these limitations, there are important implications. First, the decision to perform paracentesis was not associated with symptoms of infection, although some clinical factors (eg, low platelets or GI bleeding) were associated with reduced odds of receiving paracentesis. Second, a majority of patients treated for SBP did not receive prophylactic antibiotics at discharge. These findings suggest a clear opportunity to increase awareness and acceptance of AASLD guidelines among hospital medicine practitioners. Quality‐improvement efforts should focus on the education of providers, and future research should identify barriers to paracentesis at both the practitioner and system levels (eg, availability of interventional radiology). Checklists or decision support within electronic order entry systems may also help reduce the low rates of paracentesis seen in our and prior studies.[4, 6, 7]

Disclosures: Dr. Lagu is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number K01HL114745. Drs. Lagu, Ghaoui, and Brooling had full access to all of the data in the study. They take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Drs. Lagu, Ghaoui, and Brooling conceived of the study. Dr. Ghaoui acquired the data. Ms. Friderici carried out the statistical analyses. Drs. Lagu, Ghaoui, Brooling, Lindenauer, and Ms. Friderici analyzed and interpreted the data, drafted the manuscript, and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Ascites is the most common complication of cirrhosis leading to hospital admission.[1] Approximately 12% of hospitalized patients who present with decompensated cirrhosis and ascites have spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP); half of these patients do not present with abdominal pain, fever, nausea, or vomiting.[2] Guidelines published by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) recommend paracentesis for all hospitalized patients with cirrhosis and ascites and also recommend long‐term antibiotic prophylaxis for survivors of an SBP episode.[3] Despite evidence that in‐hospital mortality is reduced in those patients who receive paracentesis in a timely manner,[4, 5] only 40% to 60% of eligible patients receive paracentesis.[4, 6, 7] We aimed to describe clinical predictors of paracentesis and use of antibiotics following an episode of SBP in patients with decompensated cirrhosis and ascites.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of adults admitted to a single tertiary care center between January 1, 2009 and December 31, 2009.7 We included patients with an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision discharge code consistent with decompensated cirrhosis who met clinical criteria for decompensated cirrhosis (see

RESULTS

We identified 193 admissions for 103 patients with decompensated cirrhosis and ascites (Table 1). Of these, 41% (80/193) received diagnostic paracentesis. Mean/standard deviation for age was 53.6/12.4 years; 71% of patients were male and 63% were English speaking. Common comorbidities included diabetes mellitus (33%), psychiatric diagnosis (29%), substance abuse (18%), and renal failure (17%). Excluding SBP, 31% of patients had another documented infection. Gastroenterology was consulted in 50% of the admissions. Fever was present in 27% of patients, elevated white blood cell (WBC) count (ie, WBC >11 k/mm3) was present in 27% of patients, International Normalized Ratio (INR) was elevated (>1.1) in 92% of patients, and 16% of patients had a platelet count of 50,000/mm3. Patients who received paracentesis were less likely to have a fever on presentation (19% vs 32%, P=0.06), low (ie, 50,000/mm3) platelet count (11% vs 19%, P=0.14), or concurrent gastrointestinal (GI) bleed (6% vs 16%, P=0.05). In a multiple logistic regression model including characteristics associated at P0.2 with paracentesis, fever, low platelet count, and concurrent GI bleeding were associated with decreased odds of receiving paracentesis (Appendix 1).

| Overall, N=193, Mean/SD or N (%)* | Paracentesis (), n=113, Mean/SD or N (%) | Paracentesis (+), n=80, Mean/SD or N (%) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Age, y | 53.6/12.4 | 54.1/13.4 | 53.2/11.7 | 1.00 (0.981.03) |

| Sex (male) | 137 (71.0%) | 78 (69.0%) | 59 (73.8%) | 1.26 (0.672.39) |

| English speaking | 122 (63.2%) | 69 (61.1%) | 53 (66.3%) | 1.25 (0.692.28) |

| Etiology | ||||

| Alcohol | 120 (62.2%) | 74 (65.5%) | 46 (57.5%) | 0.71 (0.401.29) |

| Hepatitis C | 94 (48.7%) | 57 (50.4%) | 37 (46.3%) | 0.85 (0.481.50) |

| Hepatitis B | 16 (8.3%) | 7 (6.2%) | 9 (11.3%) | 1.92 (0.685.39) |

| NASH | 8 (4.2%) | 4 (3.5%) | 4 (5.0%) | 1.43 (0.355.91) |

| Cryptogenic | 11 (5.7%) | 6 (5.3%) | 5 (6.3%) | 1.19 (0.354.04) |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Substance abuse | 34 (17.6%) | 22 (19.5%) | 12 (15.0%) | 0.73 (0.341.58) |

| Psychiatric diagnosis | 55 (28.5%) | 38 (33.6%) | 17 (21.3%) | 0.53 (0.271.03) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 63 (32.6%) | 37 (32.7%) | 26 (32.5%) | 0.99 (0.541.82) |

| Renal failure | 33 (17.1%) | 20 (17.7%) | 13 (16.3%) | 0.90 (0.421.94) |

| GI bleed | 23 (11.9%) | 18 (15.9%) | 5 (6.3%) | 0.35 (0.120.99) |

| Admission MELD | 17.3/7.3 | 17.5/7.3 | 17.0/7.3 | 0.99 (0.951.03) |

| Creatinine, median/IQR | 0.9/0.7 | 0.9/0.7 | 0.9/0.8 | 1.02 (0.821.27) |

| Gastroenterology consult | 97 (50.3%) | 46 (40.7%) | 51 (63.8%) | 2.56 (1.424.63) |

| Infection, UTI, pneumonia, other | 60 (31.1%) | 38 (33.6%) | 22 (27.5%) | 0.75 (0.401.40) |

| Temperature 100.4F | 49 (26.8%) | 34 (32.4%) | 15 (19.2%) | 0.50 (0.251.00) |

| WBC >11 k/mm3 | 50 (27.3%) | 28 (26.7%) | 22 (28.2%) | 1.08 (0.562.08) |

| WBC 4 k/mm3 | 43 (23.5%) | 23 (21.9%) | 20 (25.6%) | 1.23 (0.622.44) |

| INR >1.1 | 149 (92.0%) | 83 (93.3%) | 66 (90.4%) | 0.68 (0.222.13) |

| Highest temperature, F | 98.9/1.1 | 99.1/1.3 | 98.8/0.8 | 0.82 (0.621.09) |

| Highest HR | 98.2/20.4 | 97.4/22.4 | 99.2/17.4 | 1.00 (0.991.02) |

| Highest RR | 24.5/13.7 | 25.2/16.8 | 23.5/7.8 | 0.99 (0.961.02) |

| Lowest SBP | 101.0/20.0 | 99.4/20.3 | 102.2/19.7 | 0.99 (0.981.01) |

| Lowest MAP | 73.0/12.2 | 73.2/13.3 | 72.7/10.6 | 1.00 (0.971.02) |

| Lowest O2Sat | 92.6/13.6 | 91.0/17.7 | 94.9/2.8 | 1.04 (0.991.10) |

| Highest PT | 15.8/3.8 | 15.9/3.7 | 15.7/3.9 | 0.98 (0.901.08) |

| Platelets 50 k/mm3 | 30 (15.9%) | 21 (19.3%) | 9 (11.3%) | 0.53 (0.231.23) |

Of the patients who received paracentesis (n=80), 14% were diagnosed with SBP. Of these, 55% received prophylaxis on discharge. Among the patients who did not receive paracentesis (n=113), 38 (34%) received antibiotics for another documented infection (eg, pneumonia), and 25 patients (22%) received antibiotics with no other documented infection or evidence of variceal bleeding. Of these 25 patients who were presumed to be empirically treated for SBP (Figure 1), only 20% were prescribed prophylactic antibiotics on discharge.

CONCLUSION

We found that many patients with decompensated cirrhosis and ascites did not receive paracentesis when hospitalized, which is similar to previously published data.[4, 6, 7] Clinical evidence of infection, such as fever or elevated WBC count, did not increase the odds of receiving paracentesis. Many patients treated for SBP were not discharged on prophylaxis.

This study is limited by its small single‐center design. We could only use data from 1 year (2009), because study data collection was part of a quality‐improvement project that took place for that year only. We did not adjust for the number of red blood cells in the ascitic fluid samples. We were also unable to determine the timing of gastroenterology consultation (whether it was done prior to paracentesis), admission venue (floor vs intensive care), or patient history of SBP.

Despite these limitations, there are important implications. First, the decision to perform paracentesis was not associated with symptoms of infection, although some clinical factors (eg, low platelets or GI bleeding) were associated with reduced odds of receiving paracentesis. Second, a majority of patients treated for SBP did not receive prophylactic antibiotics at discharge. These findings suggest a clear opportunity to increase awareness and acceptance of AASLD guidelines among hospital medicine practitioners. Quality‐improvement efforts should focus on the education of providers, and future research should identify barriers to paracentesis at both the practitioner and system levels (eg, availability of interventional radiology). Checklists or decision support within electronic order entry systems may also help reduce the low rates of paracentesis seen in our and prior studies.[4, 6, 7]

Disclosures: Dr. Lagu is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number K01HL114745. Drs. Lagu, Ghaoui, and Brooling had full access to all of the data in the study. They take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Drs. Lagu, Ghaoui, and Brooling conceived of the study. Dr. Ghaoui acquired the data. Ms. Friderici carried out the statistical analyses. Drs. Lagu, Ghaoui, Brooling, Lindenauer, and Ms. Friderici analyzed and interpreted the data, drafted the manuscript, and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , , , , ; Spanish Collaborative Study Group On Therapeutic Management In Liver Disease. Multicenter hospital study on prescribing patterns for prophylaxis and treatment of complications of cirrhosis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;58(6):435–440.

- , , , et al. Bacterial infection in patients with advanced cirrhosis: a multicentre prospective study. Dig Liver Dis. 2001;33(1):41–48.

- , AASLD. Introduction to the revised American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases Practice Guideline management of adult patients with ascites due to cirrhosis 2012. Hepatology. 2013;57(4):1651–1653.

- , , , . Paracentesis is associated with reduced mortality in patients hospitalized with cirrhosis and ascites. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(3):496–503.e1.

- , , , et al. Delayed paracentesis is associated with increased in‐hospital mortality in patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(9):1436–1442.

- , , , et al. The quality of care provided to patients with cirrhosis and ascites in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(1):70–77.

- , , , , , . Measurement of the quality of care of patients admitted with decompensated cirrhosis. Liver Int. 2014;34(2):204–210.

- , , , , ; Spanish Collaborative Study Group On Therapeutic Management In Liver Disease. Multicenter hospital study on prescribing patterns for prophylaxis and treatment of complications of cirrhosis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;58(6):435–440.

- , , , et al. Bacterial infection in patients with advanced cirrhosis: a multicentre prospective study. Dig Liver Dis. 2001;33(1):41–48.

- , AASLD. Introduction to the revised American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases Practice Guideline management of adult patients with ascites due to cirrhosis 2012. Hepatology. 2013;57(4):1651–1653.

- , , , . Paracentesis is associated with reduced mortality in patients hospitalized with cirrhosis and ascites. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(3):496–503.e1.

- , , , et al. Delayed paracentesis is associated with increased in‐hospital mortality in patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(9):1436–1442.

- , , , et al. The quality of care provided to patients with cirrhosis and ascites in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(1):70–77.

- , , , , , . Measurement of the quality of care of patients admitted with decompensated cirrhosis. Liver Int. 2014;34(2):204–210.

Lungs donated after cardiac arrest, brain death yield similar survival rates

AUSTIN, TEX. – The risk of death at 1 year after lung transplantation with organs donated either after cardiac arrest or after brain death was virtually the same, an analysis of the literature has shown.

“Donation after cardiac death appears to be a safe and effective method to expand the donor pool,” said Dr. Dustin Krutsinger of the University of Iowa, Iowa City, who presented the findings during the Hot Topics in Pulmonary Critical Care session at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

Over the years, the demand for organ donations for lung transplant candidates has steadily increased while the number of available organs has remained static. This is due, in part, to physicians being concerned about injury to the organs during the ischemic period, as well as what can often be as much as an hour before organ procurement after withdrawal of life support. However, Dr. Krutsinger said the similarities between the two cohorts could result from the fact that before procurement, systemic circulation allows the lungs to oxygenate by perfusion, and so there is less impact during the ischemic period.

“There is also a thought that the ischemic period might actually protect the lungs and the liver from reperfusion injury. And we’re avoiding brain death, which is not a completely benign state,” he told the audience.

After conducting an extensive review of the literature for 1-year survival rates post lung transplantation, the investigators found 519 unique citations, including 58 citations selected for full text review, 10 observational cohort studies for systematic review, and another 5 such studies for meta-analysis.

Dr. Krutsinger and his colleagues found no significant difference in 1-year survival rates between the donation after cardiac death and the donation after brain death cohorts (P = .658). In a pooled analysis of the five studies, no significant difference in risk of death was found at 1 year after either transplantation procedure (relative risk, 0.66; 95% confidence interval, 0.38-1.15; P = .15). Although he thought the findings were limited by shortcomings in the data, such as the fact that the study was a retrospective analysis of unmatched cohorts and that the follow-up period was short, Dr. Krutsinger said in an interview that he thought the data were compelling enough for institutions to begin rethinking organ procurement and transplantation protocols. In addition to his own study, he cited a 2013 study which he said indicated that if lungs donated after cardiac arrest were included, the pool of available organs would increase by as much as 50% (Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2013;10:73-80).

But challenges remain.

“There are some things you can do to the potential donors that are questionable ethicswise, such as administering heparin premortem, which would be beneficial to the actual recipients. But, up until they are pronounced dead, they are still a patient. You don’t really have that complication with a donation after brain death, since once brain death is determined, the person is officially dead. Things you then do to them to benefit the eventual recipients aren’t being done to a ‘patient.’ ”

Still, Dr. Krutsinger said that if organs procured after cardiac arrest were to become more common than after brain death, he would be “disappointed” since the data showed “the outcomes are similar, not inferior.”

Dr. Krutsinger said he had no relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

AUSTIN, TEX. – The risk of death at 1 year after lung transplantation with organs donated either after cardiac arrest or after brain death was virtually the same, an analysis of the literature has shown.

“Donation after cardiac death appears to be a safe and effective method to expand the donor pool,” said Dr. Dustin Krutsinger of the University of Iowa, Iowa City, who presented the findings during the Hot Topics in Pulmonary Critical Care session at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

Over the years, the demand for organ donations for lung transplant candidates has steadily increased while the number of available organs has remained static. This is due, in part, to physicians being concerned about injury to the organs during the ischemic period, as well as what can often be as much as an hour before organ procurement after withdrawal of life support. However, Dr. Krutsinger said the similarities between the two cohorts could result from the fact that before procurement, systemic circulation allows the lungs to oxygenate by perfusion, and so there is less impact during the ischemic period.

“There is also a thought that the ischemic period might actually protect the lungs and the liver from reperfusion injury. And we’re avoiding brain death, which is not a completely benign state,” he told the audience.

After conducting an extensive review of the literature for 1-year survival rates post lung transplantation, the investigators found 519 unique citations, including 58 citations selected for full text review, 10 observational cohort studies for systematic review, and another 5 such studies for meta-analysis.

Dr. Krutsinger and his colleagues found no significant difference in 1-year survival rates between the donation after cardiac death and the donation after brain death cohorts (P = .658). In a pooled analysis of the five studies, no significant difference in risk of death was found at 1 year after either transplantation procedure (relative risk, 0.66; 95% confidence interval, 0.38-1.15; P = .15). Although he thought the findings were limited by shortcomings in the data, such as the fact that the study was a retrospective analysis of unmatched cohorts and that the follow-up period was short, Dr. Krutsinger said in an interview that he thought the data were compelling enough for institutions to begin rethinking organ procurement and transplantation protocols. In addition to his own study, he cited a 2013 study which he said indicated that if lungs donated after cardiac arrest were included, the pool of available organs would increase by as much as 50% (Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2013;10:73-80).

But challenges remain.

“There are some things you can do to the potential donors that are questionable ethicswise, such as administering heparin premortem, which would be beneficial to the actual recipients. But, up until they are pronounced dead, they are still a patient. You don’t really have that complication with a donation after brain death, since once brain death is determined, the person is officially dead. Things you then do to them to benefit the eventual recipients aren’t being done to a ‘patient.’ ”

Still, Dr. Krutsinger said that if organs procured after cardiac arrest were to become more common than after brain death, he would be “disappointed” since the data showed “the outcomes are similar, not inferior.”

Dr. Krutsinger said he had no relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

AUSTIN, TEX. – The risk of death at 1 year after lung transplantation with organs donated either after cardiac arrest or after brain death was virtually the same, an analysis of the literature has shown.

“Donation after cardiac death appears to be a safe and effective method to expand the donor pool,” said Dr. Dustin Krutsinger of the University of Iowa, Iowa City, who presented the findings during the Hot Topics in Pulmonary Critical Care session at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

Over the years, the demand for organ donations for lung transplant candidates has steadily increased while the number of available organs has remained static. This is due, in part, to physicians being concerned about injury to the organs during the ischemic period, as well as what can often be as much as an hour before organ procurement after withdrawal of life support. However, Dr. Krutsinger said the similarities between the two cohorts could result from the fact that before procurement, systemic circulation allows the lungs to oxygenate by perfusion, and so there is less impact during the ischemic period.

“There is also a thought that the ischemic period might actually protect the lungs and the liver from reperfusion injury. And we’re avoiding brain death, which is not a completely benign state,” he told the audience.

After conducting an extensive review of the literature for 1-year survival rates post lung transplantation, the investigators found 519 unique citations, including 58 citations selected for full text review, 10 observational cohort studies for systematic review, and another 5 such studies for meta-analysis.

Dr. Krutsinger and his colleagues found no significant difference in 1-year survival rates between the donation after cardiac death and the donation after brain death cohorts (P = .658). In a pooled analysis of the five studies, no significant difference in risk of death was found at 1 year after either transplantation procedure (relative risk, 0.66; 95% confidence interval, 0.38-1.15; P = .15). Although he thought the findings were limited by shortcomings in the data, such as the fact that the study was a retrospective analysis of unmatched cohorts and that the follow-up period was short, Dr. Krutsinger said in an interview that he thought the data were compelling enough for institutions to begin rethinking organ procurement and transplantation protocols. In addition to his own study, he cited a 2013 study which he said indicated that if lungs donated after cardiac arrest were included, the pool of available organs would increase by as much as 50% (Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2013;10:73-80).

But challenges remain.

“There are some things you can do to the potential donors that are questionable ethicswise, such as administering heparin premortem, which would be beneficial to the actual recipients. But, up until they are pronounced dead, they are still a patient. You don’t really have that complication with a donation after brain death, since once brain death is determined, the person is officially dead. Things you then do to them to benefit the eventual recipients aren’t being done to a ‘patient.’ ”

Still, Dr. Krutsinger said that if organs procured after cardiac arrest were to become more common than after brain death, he would be “disappointed” since the data showed “the outcomes are similar, not inferior.”

Dr. Krutsinger said he had no relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

AT CHEST 2014

Key clinical point: Expansion of organ donation programs to include organs donated after cardiac death could help meet a growing demand for donated lungs.

Major finding: No significant difference was seen in lung transplantation 1-year survival rates between donation after cardiac arrest and donation after brain death.

Data source: A systematic review of 10 observational cohort studies and a meta-analysis of 5 studies, chosen from more than 500 citations that included 1-year survival data for lung transplantation occuring after either cardiac arrest or brain death.

Disclosures: Dr. Krutsinger said he had no relevant disclosures.

Hospitalists Less-Likely Targets of Malpractice Claims Than Other Physicians

In the article "Liability Impact of the Hospitalist Model of Care," Adam Schaffer, MD, a hospitalist at Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston, writes that hospitalists average 0.52 malpractice claims per 100 physician coverage years (PCYs), while non-hospitalist internal medicine physicians have a rate of 1.91 claims per 100 PCYs. By comparison, ED physicians average 3.5 claims per 100 PYCs, general surgeons average 4.7 claims, and OB/GYNs average 5.56 claims (P<0.001 for all comparisons).

"I was fairly surprised because the magnitude of the decreased risk…was fairly significant and statistically significant," Dr. Schaffer says. He notes that having relatively short interactions with patients and the difficulties of care transitions would appear to make it difficult for hospitalists to establish the type of close relationships with patients that can help prevent malpractice claims. However, hospitalists have overcome that hurdle.

An editorial that accompanies the JHM study contends that hospitalists develop and hone skills "which allow them to quickly establish rapport with patients and families." The editorial was penned by hospitalist Kevin O'Leary, MD, MS, SFHM, of Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, and JHM Editor-in-Chief Andrew Auerbach, MD, MPH, SFHM, of the University of California, San Francisco.

"Even though you may have a relatively brief relationship with the patient," Dr. Schaffer adds, "the fact that you're in the hospital, able to see them, meet with them, answer their questions multiple times a day if need be, that may actually help establish a strong and robust physician-patient relationship."

Visit SHM's blog, "The Hospital Leader," for an exploration of malpractice suits and a Q&A with study author Adam Schaffer.

In the article "Liability Impact of the Hospitalist Model of Care," Adam Schaffer, MD, a hospitalist at Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston, writes that hospitalists average 0.52 malpractice claims per 100 physician coverage years (PCYs), while non-hospitalist internal medicine physicians have a rate of 1.91 claims per 100 PCYs. By comparison, ED physicians average 3.5 claims per 100 PYCs, general surgeons average 4.7 claims, and OB/GYNs average 5.56 claims (P<0.001 for all comparisons).

"I was fairly surprised because the magnitude of the decreased risk…was fairly significant and statistically significant," Dr. Schaffer says. He notes that having relatively short interactions with patients and the difficulties of care transitions would appear to make it difficult for hospitalists to establish the type of close relationships with patients that can help prevent malpractice claims. However, hospitalists have overcome that hurdle.

An editorial that accompanies the JHM study contends that hospitalists develop and hone skills "which allow them to quickly establish rapport with patients and families." The editorial was penned by hospitalist Kevin O'Leary, MD, MS, SFHM, of Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, and JHM Editor-in-Chief Andrew Auerbach, MD, MPH, SFHM, of the University of California, San Francisco.

"Even though you may have a relatively brief relationship with the patient," Dr. Schaffer adds, "the fact that you're in the hospital, able to see them, meet with them, answer their questions multiple times a day if need be, that may actually help establish a strong and robust physician-patient relationship."

Visit SHM's blog, "The Hospital Leader," for an exploration of malpractice suits and a Q&A with study author Adam Schaffer.

In the article "Liability Impact of the Hospitalist Model of Care," Adam Schaffer, MD, a hospitalist at Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston, writes that hospitalists average 0.52 malpractice claims per 100 physician coverage years (PCYs), while non-hospitalist internal medicine physicians have a rate of 1.91 claims per 100 PCYs. By comparison, ED physicians average 3.5 claims per 100 PYCs, general surgeons average 4.7 claims, and OB/GYNs average 5.56 claims (P<0.001 for all comparisons).

"I was fairly surprised because the magnitude of the decreased risk…was fairly significant and statistically significant," Dr. Schaffer says. He notes that having relatively short interactions with patients and the difficulties of care transitions would appear to make it difficult for hospitalists to establish the type of close relationships with patients that can help prevent malpractice claims. However, hospitalists have overcome that hurdle.

An editorial that accompanies the JHM study contends that hospitalists develop and hone skills "which allow them to quickly establish rapport with patients and families." The editorial was penned by hospitalist Kevin O'Leary, MD, MS, SFHM, of Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, and JHM Editor-in-Chief Andrew Auerbach, MD, MPH, SFHM, of the University of California, San Francisco.

"Even though you may have a relatively brief relationship with the patient," Dr. Schaffer adds, "the fact that you're in the hospital, able to see them, meet with them, answer their questions multiple times a day if need be, that may actually help establish a strong and robust physician-patient relationship."

Visit SHM's blog, "The Hospital Leader," for an exploration of malpractice suits and a Q&A with study author Adam Schaffer.

Once-Weekly Antibiotic Might Be Effective for Treatment of Acute Bacterial Skin Infections

Background: Acute bacterial skin infections are common and often require hospitalization for intravenous antibiotic administration. Treatment covering gram-positive bacteria usually is indicated. Dalbavancin is effective against gram-positives, including MRSA. Its long half-life makes it an attractive alternative to other commonly used antibiotics, which require more frequent dosing.

Study design: Phase 3, double-blinded RCT.

Setting: Multiple international centers.

Synopsis: Researchers randomized 1,312 patients with acute bacterial skin and skin-structure infections with signs of systemic infection requiring intravenous antibiotics to receive dalbavancin on days one and eight, with placebo on other days, or several doses of vancomycin with an option to switch to oral linezolid. The primary endpoint was cessation of spread of erythema and temperature of =37.6°C at 48–72 hours. Secondary endpoints included a decrease in lesion area of =20% at 48–72 hours and clinical success at end of therapy (determined by clinical and historical features). Results of the primary endpoint were similar with dalbavancin and vancomycin-linezolid groups (79.7% and 79.8%, respectively) and were within 10 percentage points of noninferiority. The secondary endpoints were similar between both groups. Limitations of the study were the early primary endpoint, lack of noninferiority analysis of the secondary endpoints, and cost-effective analysis.

Bottom line: Once-weekly dalbavancin appears to be similarly efficacious to intravenous vancomycin in the treatment of acute bacterial skin infections in terms of outcomes within 48–72 hours of therapy and might provide an alternative to continued inpatient hospitalization for intravenous antibiotics in stable patients.

Citation: Boucher HW, Wilcox M, Talbot GH, Puttagunta S, Das AF, Dunne MW. Once-weekly dalbavancin versus daily conventional therapy for skin infection. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(23):2169-2179.

Background: Acute bacterial skin infections are common and often require hospitalization for intravenous antibiotic administration. Treatment covering gram-positive bacteria usually is indicated. Dalbavancin is effective against gram-positives, including MRSA. Its long half-life makes it an attractive alternative to other commonly used antibiotics, which require more frequent dosing.

Study design: Phase 3, double-blinded RCT.

Setting: Multiple international centers.

Synopsis: Researchers randomized 1,312 patients with acute bacterial skin and skin-structure infections with signs of systemic infection requiring intravenous antibiotics to receive dalbavancin on days one and eight, with placebo on other days, or several doses of vancomycin with an option to switch to oral linezolid. The primary endpoint was cessation of spread of erythema and temperature of =37.6°C at 48–72 hours. Secondary endpoints included a decrease in lesion area of =20% at 48–72 hours and clinical success at end of therapy (determined by clinical and historical features). Results of the primary endpoint were similar with dalbavancin and vancomycin-linezolid groups (79.7% and 79.8%, respectively) and were within 10 percentage points of noninferiority. The secondary endpoints were similar between both groups. Limitations of the study were the early primary endpoint, lack of noninferiority analysis of the secondary endpoints, and cost-effective analysis.

Bottom line: Once-weekly dalbavancin appears to be similarly efficacious to intravenous vancomycin in the treatment of acute bacterial skin infections in terms of outcomes within 48–72 hours of therapy and might provide an alternative to continued inpatient hospitalization for intravenous antibiotics in stable patients.

Citation: Boucher HW, Wilcox M, Talbot GH, Puttagunta S, Das AF, Dunne MW. Once-weekly dalbavancin versus daily conventional therapy for skin infection. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(23):2169-2179.

Background: Acute bacterial skin infections are common and often require hospitalization for intravenous antibiotic administration. Treatment covering gram-positive bacteria usually is indicated. Dalbavancin is effective against gram-positives, including MRSA. Its long half-life makes it an attractive alternative to other commonly used antibiotics, which require more frequent dosing.

Study design: Phase 3, double-blinded RCT.

Setting: Multiple international centers.

Synopsis: Researchers randomized 1,312 patients with acute bacterial skin and skin-structure infections with signs of systemic infection requiring intravenous antibiotics to receive dalbavancin on days one and eight, with placebo on other days, or several doses of vancomycin with an option to switch to oral linezolid. The primary endpoint was cessation of spread of erythema and temperature of =37.6°C at 48–72 hours. Secondary endpoints included a decrease in lesion area of =20% at 48–72 hours and clinical success at end of therapy (determined by clinical and historical features). Results of the primary endpoint were similar with dalbavancin and vancomycin-linezolid groups (79.7% and 79.8%, respectively) and were within 10 percentage points of noninferiority. The secondary endpoints were similar between both groups. Limitations of the study were the early primary endpoint, lack of noninferiority analysis of the secondary endpoints, and cost-effective analysis.

Bottom line: Once-weekly dalbavancin appears to be similarly efficacious to intravenous vancomycin in the treatment of acute bacterial skin infections in terms of outcomes within 48–72 hours of therapy and might provide an alternative to continued inpatient hospitalization for intravenous antibiotics in stable patients.

Citation: Boucher HW, Wilcox M, Talbot GH, Puttagunta S, Das AF, Dunne MW. Once-weekly dalbavancin versus daily conventional therapy for skin infection. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(23):2169-2179.

Holding Chambers (Spacers) vs. Nebulizers for Acute Asthma

Clinical question: Are beta-2 agonists as effective when administered through a holding chamber (spacer) as they are when administered by a nebulizer?

Background: During an acute asthma attack, beta-2 agonists must be delivered to the peripheral airways. There has been considerable controversy regarding the use of a spacer compared with a nebulizer. Aside from admission rates and length of stay, factors taken into account include cost, maintenance of nebulizer machines, and infection control (potential of cross-infection via nebulizers).

Study design: Meta-analysis review of randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Setting: Multi-centered, worldwide studies from community setting and EDs.

Synopsis: In 39 studies of patients with an acute asthma attack (selected from Cochrane Airways Group Specialized Register), the hospital admission rates did not differ on the basis of delivery method in 729 adults (risk ratio=0.94, confidence interval 0.61-1.43) or in 1,897 children (risk ratio=0.71, confidence interval 0.47-1.08). Secondary outcomes included the duration of time in the ED and the duration of hospital admission. Time spent in the ED varied for adults but was shorter for children with spacers (based on three studies). Duration of hospital admission also did not differ when modes of delivery were compared.

Bottom line: Providing beta-2 agonists using nebulizers during an acute asthma attack is not more effective than administration using a spacer.

Citation: Cates CJ, Welsh EJ, Rowe BH. Holding chambers (spacers) versus nebulisers for beta-agonist treatment of acute asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;9:CD000052.

Clinical question: Are beta-2 agonists as effective when administered through a holding chamber (spacer) as they are when administered by a nebulizer?

Background: During an acute asthma attack, beta-2 agonists must be delivered to the peripheral airways. There has been considerable controversy regarding the use of a spacer compared with a nebulizer. Aside from admission rates and length of stay, factors taken into account include cost, maintenance of nebulizer machines, and infection control (potential of cross-infection via nebulizers).

Study design: Meta-analysis review of randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Setting: Multi-centered, worldwide studies from community setting and EDs.

Synopsis: In 39 studies of patients with an acute asthma attack (selected from Cochrane Airways Group Specialized Register), the hospital admission rates did not differ on the basis of delivery method in 729 adults (risk ratio=0.94, confidence interval 0.61-1.43) or in 1,897 children (risk ratio=0.71, confidence interval 0.47-1.08). Secondary outcomes included the duration of time in the ED and the duration of hospital admission. Time spent in the ED varied for adults but was shorter for children with spacers (based on three studies). Duration of hospital admission also did not differ when modes of delivery were compared.

Bottom line: Providing beta-2 agonists using nebulizers during an acute asthma attack is not more effective than administration using a spacer.

Citation: Cates CJ, Welsh EJ, Rowe BH. Holding chambers (spacers) versus nebulisers for beta-agonist treatment of acute asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;9:CD000052.

Clinical question: Are beta-2 agonists as effective when administered through a holding chamber (spacer) as they are when administered by a nebulizer?

Background: During an acute asthma attack, beta-2 agonists must be delivered to the peripheral airways. There has been considerable controversy regarding the use of a spacer compared with a nebulizer. Aside from admission rates and length of stay, factors taken into account include cost, maintenance of nebulizer machines, and infection control (potential of cross-infection via nebulizers).

Study design: Meta-analysis review of randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Setting: Multi-centered, worldwide studies from community setting and EDs.

Synopsis: In 39 studies of patients with an acute asthma attack (selected from Cochrane Airways Group Specialized Register), the hospital admission rates did not differ on the basis of delivery method in 729 adults (risk ratio=0.94, confidence interval 0.61-1.43) or in 1,897 children (risk ratio=0.71, confidence interval 0.47-1.08). Secondary outcomes included the duration of time in the ED and the duration of hospital admission. Time spent in the ED varied for adults but was shorter for children with spacers (based on three studies). Duration of hospital admission also did not differ when modes of delivery were compared.

Bottom line: Providing beta-2 agonists using nebulizers during an acute asthma attack is not more effective than administration using a spacer.

Citation: Cates CJ, Welsh EJ, Rowe BH. Holding chambers (spacers) versus nebulisers for beta-agonist treatment of acute asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;9:CD000052.

Long-Term Cognitive Impairment after Critical Illness

Clinical question: Are a longer duration of delirium and higher doses of sedatives associated with cognitive impairment in the hospital?

Background: Survivors of critical illness are at risk for prolonged cognitive dysfunction. Delirium (and factors associated with delirium, namely sedative and analgesic medications) has been implicated in cognitive dysfunction.

Study design: Prospective cohort study.

Setting: Multi-center, academic, and acute care hospitals.

Synopsis: The study examined 821 adults admitted to the ICU with respiratory failure, cardiogenic shock, or septic shock. Patients excluded were those with pre-existing cognitive impairment, those with psychotic disorders, and those for whom follow-up would not be possible. Two risk factors measured were duration of delirium and use of sedative/analgesics. Delirium was assessed at three and 12 months using the CAM-ICU algorithm in the ICU by trained psychology professionals who were unaware of the patients’ in-hospital course.

At three months, 40% of patients had global cognition scores that were 1.5 standard deviations (SD) below population mean (similar to traumatic brain injury), and 26% had scores two SD below population mean (similar to mild Alzheimer’s). At 12 months, 34% had scores similar to traumatic brain injury patients, and 24% had scores similar to mild Alzheimer’s. A longer duration of delirium was associated with worse global cognition at three and 12 months. Use of sedatives/analgesics was not associated with cognitive impairment.

Bottom line: Critically ill patients in the ICU who experience a longer duration of delirium are at risk of long-term cognitive impairments lasting 12 months.

Citation: Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Jackson JC, et al. Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(14):1306-1316.

Clinical question: Are a longer duration of delirium and higher doses of sedatives associated with cognitive impairment in the hospital?

Background: Survivors of critical illness are at risk for prolonged cognitive dysfunction. Delirium (and factors associated with delirium, namely sedative and analgesic medications) has been implicated in cognitive dysfunction.

Study design: Prospective cohort study.

Setting: Multi-center, academic, and acute care hospitals.

Synopsis: The study examined 821 adults admitted to the ICU with respiratory failure, cardiogenic shock, or septic shock. Patients excluded were those with pre-existing cognitive impairment, those with psychotic disorders, and those for whom follow-up would not be possible. Two risk factors measured were duration of delirium and use of sedative/analgesics. Delirium was assessed at three and 12 months using the CAM-ICU algorithm in the ICU by trained psychology professionals who were unaware of the patients’ in-hospital course.

At three months, 40% of patients had global cognition scores that were 1.5 standard deviations (SD) below population mean (similar to traumatic brain injury), and 26% had scores two SD below population mean (similar to mild Alzheimer’s). At 12 months, 34% had scores similar to traumatic brain injury patients, and 24% had scores similar to mild Alzheimer’s. A longer duration of delirium was associated with worse global cognition at three and 12 months. Use of sedatives/analgesics was not associated with cognitive impairment.

Bottom line: Critically ill patients in the ICU who experience a longer duration of delirium are at risk of long-term cognitive impairments lasting 12 months.

Citation: Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Jackson JC, et al. Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(14):1306-1316.

Clinical question: Are a longer duration of delirium and higher doses of sedatives associated with cognitive impairment in the hospital?

Background: Survivors of critical illness are at risk for prolonged cognitive dysfunction. Delirium (and factors associated with delirium, namely sedative and analgesic medications) has been implicated in cognitive dysfunction.

Study design: Prospective cohort study.

Setting: Multi-center, academic, and acute care hospitals.

Synopsis: The study examined 821 adults admitted to the ICU with respiratory failure, cardiogenic shock, or septic shock. Patients excluded were those with pre-existing cognitive impairment, those with psychotic disorders, and those for whom follow-up would not be possible. Two risk factors measured were duration of delirium and use of sedative/analgesics. Delirium was assessed at three and 12 months using the CAM-ICU algorithm in the ICU by trained psychology professionals who were unaware of the patients’ in-hospital course.