User login

AML study shows transcription factors are ‘druggable’

In developing a compound that exhibits activity against a type of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), investigators have shown that transcription factors are, in fact, “druggable.”

The compound, AI-10-49, selectively binds to the mutated transcription factor CBFβ-SMMHC, and this prevents CBFβ-SMMHC from binding to another transcription factor, RUNX1.

In this way, AI-10-49 restores RUNX1 transcriptional activity, which leads to the death of inv(16) AML cells in vitro and in vivo.

“This drug that we’ve developed is . . . targeting a class of proteins that hasn’t been targeted for drug development very much in the past,” said study author John H. Bushweller, PhD, of the University of Virginia Health System in Charlottesville.

“It’s really a new paradigm, a new approach to try to treat these diseases. This class of proteins is very important for determining how much of many other proteins are made, so it’s a unique way of changing the way the cell behaves.”

Dr Bushweller and his colleagues described their work in Science.

The investigators noted that CBFβ-SMMHC is expressed in AML with the chromosome inversion inv(16)(p13q22). And CBFβ-SMMHC outcompetes wild-type CBFβ for binding to RUNX1, thereby deregulating RUNX1 activity in hematopoiesis and inducing AML.

“When you target a mutated protein in a cancer, you would ideally like to inhibit that mutated form of the protein but not affect the normal form of the protein that’s still there,” Dr Bushweller said. “In the case of [AI-10-49], we’ve achieved that.”

He and his colleagues tested AI-10-49 in 11 leukemia cells lines and found that only ME-1 cells were highly sensitive to the treatment. AI-10-49 effectively dissociated RUNX1 from CBFβ-SMMHC in ME-1 cells, with 90% dissociation after 6 hours of treatment.

But the drug had a modest effect on CBFβ-RUNX1 association. It also had negligible activity in normal human bone marrow cells.

The investigators then tested AI-10-49 in a mouse model of inv(16) AML. Control mice (vehicle-treated) succumbed to leukemia in a median of 33.5 days, compared to a median of 61 days for mice that received AI-10-49.

Dr Bushweller and his colleagues did not evaluate toxicity after long-term exposure to AI-10-49, but they found no evidence of toxicity after 7 days of AI-10-49 treatment.

Next, the investigators tested AI-10-49 in 4 primary inv(16) AML cell samples. They saw a reduction in leukemia cell viability when AI-10-49 was administered at 5 μM and 10 μM concentrations. Bivalent AI-10-49 was more potent than monovalent AI-10-47.

The team said these results suggest that direct inhibition of CBFβ-SMMHC may be an effective therapeutic approach for inv(16) AML, and the findings provide support for therapies targeting transcription factors. ![]()

In developing a compound that exhibits activity against a type of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), investigators have shown that transcription factors are, in fact, “druggable.”

The compound, AI-10-49, selectively binds to the mutated transcription factor CBFβ-SMMHC, and this prevents CBFβ-SMMHC from binding to another transcription factor, RUNX1.

In this way, AI-10-49 restores RUNX1 transcriptional activity, which leads to the death of inv(16) AML cells in vitro and in vivo.

“This drug that we’ve developed is . . . targeting a class of proteins that hasn’t been targeted for drug development very much in the past,” said study author John H. Bushweller, PhD, of the University of Virginia Health System in Charlottesville.

“It’s really a new paradigm, a new approach to try to treat these diseases. This class of proteins is very important for determining how much of many other proteins are made, so it’s a unique way of changing the way the cell behaves.”

Dr Bushweller and his colleagues described their work in Science.

The investigators noted that CBFβ-SMMHC is expressed in AML with the chromosome inversion inv(16)(p13q22). And CBFβ-SMMHC outcompetes wild-type CBFβ for binding to RUNX1, thereby deregulating RUNX1 activity in hematopoiesis and inducing AML.

“When you target a mutated protein in a cancer, you would ideally like to inhibit that mutated form of the protein but not affect the normal form of the protein that’s still there,” Dr Bushweller said. “In the case of [AI-10-49], we’ve achieved that.”

He and his colleagues tested AI-10-49 in 11 leukemia cells lines and found that only ME-1 cells were highly sensitive to the treatment. AI-10-49 effectively dissociated RUNX1 from CBFβ-SMMHC in ME-1 cells, with 90% dissociation after 6 hours of treatment.

But the drug had a modest effect on CBFβ-RUNX1 association. It also had negligible activity in normal human bone marrow cells.

The investigators then tested AI-10-49 in a mouse model of inv(16) AML. Control mice (vehicle-treated) succumbed to leukemia in a median of 33.5 days, compared to a median of 61 days for mice that received AI-10-49.

Dr Bushweller and his colleagues did not evaluate toxicity after long-term exposure to AI-10-49, but they found no evidence of toxicity after 7 days of AI-10-49 treatment.

Next, the investigators tested AI-10-49 in 4 primary inv(16) AML cell samples. They saw a reduction in leukemia cell viability when AI-10-49 was administered at 5 μM and 10 μM concentrations. Bivalent AI-10-49 was more potent than monovalent AI-10-47.

The team said these results suggest that direct inhibition of CBFβ-SMMHC may be an effective therapeutic approach for inv(16) AML, and the findings provide support for therapies targeting transcription factors. ![]()

In developing a compound that exhibits activity against a type of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), investigators have shown that transcription factors are, in fact, “druggable.”

The compound, AI-10-49, selectively binds to the mutated transcription factor CBFβ-SMMHC, and this prevents CBFβ-SMMHC from binding to another transcription factor, RUNX1.

In this way, AI-10-49 restores RUNX1 transcriptional activity, which leads to the death of inv(16) AML cells in vitro and in vivo.

“This drug that we’ve developed is . . . targeting a class of proteins that hasn’t been targeted for drug development very much in the past,” said study author John H. Bushweller, PhD, of the University of Virginia Health System in Charlottesville.

“It’s really a new paradigm, a new approach to try to treat these diseases. This class of proteins is very important for determining how much of many other proteins are made, so it’s a unique way of changing the way the cell behaves.”

Dr Bushweller and his colleagues described their work in Science.

The investigators noted that CBFβ-SMMHC is expressed in AML with the chromosome inversion inv(16)(p13q22). And CBFβ-SMMHC outcompetes wild-type CBFβ for binding to RUNX1, thereby deregulating RUNX1 activity in hematopoiesis and inducing AML.

“When you target a mutated protein in a cancer, you would ideally like to inhibit that mutated form of the protein but not affect the normal form of the protein that’s still there,” Dr Bushweller said. “In the case of [AI-10-49], we’ve achieved that.”

He and his colleagues tested AI-10-49 in 11 leukemia cells lines and found that only ME-1 cells were highly sensitive to the treatment. AI-10-49 effectively dissociated RUNX1 from CBFβ-SMMHC in ME-1 cells, with 90% dissociation after 6 hours of treatment.

But the drug had a modest effect on CBFβ-RUNX1 association. It also had negligible activity in normal human bone marrow cells.

The investigators then tested AI-10-49 in a mouse model of inv(16) AML. Control mice (vehicle-treated) succumbed to leukemia in a median of 33.5 days, compared to a median of 61 days for mice that received AI-10-49.

Dr Bushweller and his colleagues did not evaluate toxicity after long-term exposure to AI-10-49, but they found no evidence of toxicity after 7 days of AI-10-49 treatment.

Next, the investigators tested AI-10-49 in 4 primary inv(16) AML cell samples. They saw a reduction in leukemia cell viability when AI-10-49 was administered at 5 μM and 10 μM concentrations. Bivalent AI-10-49 was more potent than monovalent AI-10-47.

The team said these results suggest that direct inhibition of CBFβ-SMMHC may be an effective therapeutic approach for inv(16) AML, and the findings provide support for therapies targeting transcription factors. ![]()

Prevalence of SDB in SCD may be high

Image by Graham Beards

Results of a small study suggest there may be a high prevalence of sleep disordered breathing (SDB) in adults with sickle cell disease (SCD).

Of the 32 patients included in the study, 44% had a clinical diagnosis of SDB.

These patients had significantly increased REM latency, a significantly higher mean score on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, and a significantly higher oxygen desaturation index (ODI) than patients who did not have SDB.

However, there was no significant difference between SDB and non-SDB patients with regard to insomnia, delayed sleep phase syndrome, nocturia, or SCD complications.

Sunil Sharma, MD, of Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and his colleagues recounted these results in the Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine.

“Previous research identified pain and sleep disturbance as 2 common symptoms of adult sickle cell disorder,” Dr Sharma said. “We wanted to examine the reasons for the sleep disturbances, as it can have a strong impact on our patients’ quality of life and overall health. We discovered a high incidence of sleep disordered breathing in patients with sickle cell disease who also report trouble with sleep.”

Dr Sharma and his colleagues analyzed 32 consecutive adult SCD patients who had reported symptoms suggesting disordered sleep or had an Epworth Sleepiness Scale score of 10 or greater. The patients underwent a comprehensive sleep evaluation and overnight polysomnography in an accredited sleep center.

SDB was defined as having an apnea-hypopnea index (AHI, events/hour) of 5 or greater. SDB was considered mild if the AHI was 5 to < 15, moderate if the AHI was 15 to < 30, and severe if the AHI was ≥ 30. Once they determined which patients had SDB, the researchers compared these patients to those without the condition.

The team found that 44% of patients (n=14) had SDB. It was mild in 8 patients, moderate in 4, and severe in 2.

Compared to non-SDB patients, those with SDB had a significantly higher mean AHI (1.6 and 17, respectively; P=0.0001), a significantly increased REM latency (98 and 159 minutes, respectively; P=0.014), and a significantly higher mean score on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (8.6 and 13, respectively; P=0.017).

Patients with SDB also had a significantly higher ODI than non-SDB patients (13 and 1.6, respectively; P=0.0009). Significant oxygen desaturation was defined as oxygen saturation < 89% for 5 cumulative minutes or more. The ODI was the number of recorded oxygen desaturations ≥ 4% per hour of sleep.

There was no significant difference between SDB and non-SDB patients in the incidence of nocturia (2.3 and 1.6, respectively; P=0.063), insomnia (57% and 72%, respectively; P=0.46), or delayed sleep phase syndrome (57% and 50%, respectively; P=0.73).

Delayed sleep phase syndrome was defined as a delay in sleep onset of 2 hours or greater from the desired sleep time and an inability to awaken at the desired time. Insomnia was defined as difficulty initiating sleep (sleep latency greater than 60 minutes) or difficulty maintaining sleep (more than 2 awakenings requiring more than 20 minutes to fall back asleep) on the majority of nights for more than 4 weeks.

There was no significant difference between SDB and non-SDB patients with regard to SCD complications, including crises during sleep (44% and 39%, respectively; P=0.67), average hospital admissions in the last 5 years (9.1 and 6.0, respectively; P=0.15), or average mini-crises per month (2.7 and 3.6, respectively; P=0.69).

Dr Sharma said the diagnosis of SDB could be missed in adults with SCD because they are not generally obese, a common risk factor for SDB, and daytime sleepiness is attributed to the pain medications used to treat the symptoms of SCD. He hopes this study will increase awareness among physicians who can screen patients for SDB.

“Our study suggests that patients with sickle cell disorder should be screened using a questionnaire to identify problems with sleep,” Dr Sharma said. “For further testing, an oxygen desaturation index is another low-cost screening tool that can identify sleep disordered breathing in this population.” ![]()

Image by Graham Beards

Results of a small study suggest there may be a high prevalence of sleep disordered breathing (SDB) in adults with sickle cell disease (SCD).

Of the 32 patients included in the study, 44% had a clinical diagnosis of SDB.

These patients had significantly increased REM latency, a significantly higher mean score on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, and a significantly higher oxygen desaturation index (ODI) than patients who did not have SDB.

However, there was no significant difference between SDB and non-SDB patients with regard to insomnia, delayed sleep phase syndrome, nocturia, or SCD complications.

Sunil Sharma, MD, of Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and his colleagues recounted these results in the Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine.

“Previous research identified pain and sleep disturbance as 2 common symptoms of adult sickle cell disorder,” Dr Sharma said. “We wanted to examine the reasons for the sleep disturbances, as it can have a strong impact on our patients’ quality of life and overall health. We discovered a high incidence of sleep disordered breathing in patients with sickle cell disease who also report trouble with sleep.”

Dr Sharma and his colleagues analyzed 32 consecutive adult SCD patients who had reported symptoms suggesting disordered sleep or had an Epworth Sleepiness Scale score of 10 or greater. The patients underwent a comprehensive sleep evaluation and overnight polysomnography in an accredited sleep center.

SDB was defined as having an apnea-hypopnea index (AHI, events/hour) of 5 or greater. SDB was considered mild if the AHI was 5 to < 15, moderate if the AHI was 15 to < 30, and severe if the AHI was ≥ 30. Once they determined which patients had SDB, the researchers compared these patients to those without the condition.

The team found that 44% of patients (n=14) had SDB. It was mild in 8 patients, moderate in 4, and severe in 2.

Compared to non-SDB patients, those with SDB had a significantly higher mean AHI (1.6 and 17, respectively; P=0.0001), a significantly increased REM latency (98 and 159 minutes, respectively; P=0.014), and a significantly higher mean score on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (8.6 and 13, respectively; P=0.017).

Patients with SDB also had a significantly higher ODI than non-SDB patients (13 and 1.6, respectively; P=0.0009). Significant oxygen desaturation was defined as oxygen saturation < 89% for 5 cumulative minutes or more. The ODI was the number of recorded oxygen desaturations ≥ 4% per hour of sleep.

There was no significant difference between SDB and non-SDB patients in the incidence of nocturia (2.3 and 1.6, respectively; P=0.063), insomnia (57% and 72%, respectively; P=0.46), or delayed sleep phase syndrome (57% and 50%, respectively; P=0.73).

Delayed sleep phase syndrome was defined as a delay in sleep onset of 2 hours or greater from the desired sleep time and an inability to awaken at the desired time. Insomnia was defined as difficulty initiating sleep (sleep latency greater than 60 minutes) or difficulty maintaining sleep (more than 2 awakenings requiring more than 20 minutes to fall back asleep) on the majority of nights for more than 4 weeks.

There was no significant difference between SDB and non-SDB patients with regard to SCD complications, including crises during sleep (44% and 39%, respectively; P=0.67), average hospital admissions in the last 5 years (9.1 and 6.0, respectively; P=0.15), or average mini-crises per month (2.7 and 3.6, respectively; P=0.69).

Dr Sharma said the diagnosis of SDB could be missed in adults with SCD because they are not generally obese, a common risk factor for SDB, and daytime sleepiness is attributed to the pain medications used to treat the symptoms of SCD. He hopes this study will increase awareness among physicians who can screen patients for SDB.

“Our study suggests that patients with sickle cell disorder should be screened using a questionnaire to identify problems with sleep,” Dr Sharma said. “For further testing, an oxygen desaturation index is another low-cost screening tool that can identify sleep disordered breathing in this population.” ![]()

Image by Graham Beards

Results of a small study suggest there may be a high prevalence of sleep disordered breathing (SDB) in adults with sickle cell disease (SCD).

Of the 32 patients included in the study, 44% had a clinical diagnosis of SDB.

These patients had significantly increased REM latency, a significantly higher mean score on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, and a significantly higher oxygen desaturation index (ODI) than patients who did not have SDB.

However, there was no significant difference between SDB and non-SDB patients with regard to insomnia, delayed sleep phase syndrome, nocturia, or SCD complications.

Sunil Sharma, MD, of Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and his colleagues recounted these results in the Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine.

“Previous research identified pain and sleep disturbance as 2 common symptoms of adult sickle cell disorder,” Dr Sharma said. “We wanted to examine the reasons for the sleep disturbances, as it can have a strong impact on our patients’ quality of life and overall health. We discovered a high incidence of sleep disordered breathing in patients with sickle cell disease who also report trouble with sleep.”

Dr Sharma and his colleagues analyzed 32 consecutive adult SCD patients who had reported symptoms suggesting disordered sleep or had an Epworth Sleepiness Scale score of 10 or greater. The patients underwent a comprehensive sleep evaluation and overnight polysomnography in an accredited sleep center.

SDB was defined as having an apnea-hypopnea index (AHI, events/hour) of 5 or greater. SDB was considered mild if the AHI was 5 to < 15, moderate if the AHI was 15 to < 30, and severe if the AHI was ≥ 30. Once they determined which patients had SDB, the researchers compared these patients to those without the condition.

The team found that 44% of patients (n=14) had SDB. It was mild in 8 patients, moderate in 4, and severe in 2.

Compared to non-SDB patients, those with SDB had a significantly higher mean AHI (1.6 and 17, respectively; P=0.0001), a significantly increased REM latency (98 and 159 minutes, respectively; P=0.014), and a significantly higher mean score on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (8.6 and 13, respectively; P=0.017).

Patients with SDB also had a significantly higher ODI than non-SDB patients (13 and 1.6, respectively; P=0.0009). Significant oxygen desaturation was defined as oxygen saturation < 89% for 5 cumulative minutes or more. The ODI was the number of recorded oxygen desaturations ≥ 4% per hour of sleep.

There was no significant difference between SDB and non-SDB patients in the incidence of nocturia (2.3 and 1.6, respectively; P=0.063), insomnia (57% and 72%, respectively; P=0.46), or delayed sleep phase syndrome (57% and 50%, respectively; P=0.73).

Delayed sleep phase syndrome was defined as a delay in sleep onset of 2 hours or greater from the desired sleep time and an inability to awaken at the desired time. Insomnia was defined as difficulty initiating sleep (sleep latency greater than 60 minutes) or difficulty maintaining sleep (more than 2 awakenings requiring more than 20 minutes to fall back asleep) on the majority of nights for more than 4 weeks.

There was no significant difference between SDB and non-SDB patients with regard to SCD complications, including crises during sleep (44% and 39%, respectively; P=0.67), average hospital admissions in the last 5 years (9.1 and 6.0, respectively; P=0.15), or average mini-crises per month (2.7 and 3.6, respectively; P=0.69).

Dr Sharma said the diagnosis of SDB could be missed in adults with SCD because they are not generally obese, a common risk factor for SDB, and daytime sleepiness is attributed to the pain medications used to treat the symptoms of SCD. He hopes this study will increase awareness among physicians who can screen patients for SDB.

“Our study suggests that patients with sickle cell disorder should be screened using a questionnaire to identify problems with sleep,” Dr Sharma said. “For further testing, an oxygen desaturation index is another low-cost screening tool that can identify sleep disordered breathing in this population.” ![]()

Israel approves ponatinib for CML, Ph+ ALL

Photo courtesy of the US FDA

The Israeli Ministry of Health has granted regulatory approval for the kinase inhibitor ponatinib (Iclusig) to treat certain adults with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) or Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph+ ALL).

The drug can now be used to treat adults with any phase of CML who have the T315I mutation or are resistant to/cannot tolerate dasatinib or nilotinib and for whom subsequent treatment with imatinib is not clinically appropriate.

Ponatinib is also approved to treat patients with Ph+ ALL who have the T315I mutation or are resistant to/cannot tolerate dasatinib and for whom subsequent treatment with imatinib is not clinically appropriate.

Ariad Pharmaceuticals, Inc., the company developing ponatinib, said the drug should be available in Israel in the second quarter of 2015.

Trial results

The Ministry of Health’s decision to approve ponatinib was based on results from the phase 2 PACE trial, which included patients with CML or Ph+ ALL who were resistant to or intolerant of prior tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy, or who had the T315I mutation.

The median follow-up times were 15.3 months in chronic-phase CML patients, 15.8 months in accelerated-phase CML patients, and 6.2 months in patients with blast-phase CML or Ph+ ALL.

In chronic-phase CML, the primary endpoint was major cytogenetic response, and it occurred in 56% of patients. Among chronic-phase patients with the T315I mutation, 70% achieved a major cytogenetic response. Among patients who had failed treatment with dasatinib or nilotinib, 51% achieved a major cytogenetic response.

In accelerated-phase CML, the primary endpoint was major hematologic response. This occurred in 57% of all patients in this group, 50% of patients with the T315I mutation, and 58% of patients who had failed treatment with dasatinib or nilotinib.

The primary endpoint was major hematologic response in blast-phase CML/Ph+ ALL as well. Thirty-four percent of all patients in this group met this endpoint, as did 33% of patients with the T315I mutation and 35% of patients who had failed treatment with dasatinib or nilotinib.

Common non-hematologic adverse events included rash (38%), abdominal pain (38%), headache (35%), dry skin (35%), constipation (34%), fatigue (27%), pyrexia (27%), nausea (26%), arthralgia (25%), hypertension (21%), increased lipase (19%), and increased amylase (7%).

Hematologic events of any grade included thrombocytopenia (42%), neutropenia (24%), and anemia (20%). Serious adverse events of arterial thromboembolism, including arterial stenosis, occurred in patients with cardiovascular risk factors.

Safety issues

Extended follow-up data from the PACE trial, collected in 2013, suggested ponatinib can increase the risk of thrombotic events. When these data came to light, officials in the European Union and the US, where ponatinib had already been approved, began to investigate the drug.

Ponatinib was pulled from the US market for a little over 2 months, and trials of the drug were placed on partial hold while the Food and Drug Administration evaluated the drug’s safety. Ponatinib went back on the market in January 2014, with new safety measures in place.

The drug was not pulled from the market in the European Union, but the European Medicine’s Agency released recommendations for safer use of ponatinib. The Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use reviewed data on ponatinib and decided the drug’s benefits outweigh its risks. ![]()

Photo courtesy of the US FDA

The Israeli Ministry of Health has granted regulatory approval for the kinase inhibitor ponatinib (Iclusig) to treat certain adults with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) or Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph+ ALL).

The drug can now be used to treat adults with any phase of CML who have the T315I mutation or are resistant to/cannot tolerate dasatinib or nilotinib and for whom subsequent treatment with imatinib is not clinically appropriate.

Ponatinib is also approved to treat patients with Ph+ ALL who have the T315I mutation or are resistant to/cannot tolerate dasatinib and for whom subsequent treatment with imatinib is not clinically appropriate.

Ariad Pharmaceuticals, Inc., the company developing ponatinib, said the drug should be available in Israel in the second quarter of 2015.

Trial results

The Ministry of Health’s decision to approve ponatinib was based on results from the phase 2 PACE trial, which included patients with CML or Ph+ ALL who were resistant to or intolerant of prior tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy, or who had the T315I mutation.

The median follow-up times were 15.3 months in chronic-phase CML patients, 15.8 months in accelerated-phase CML patients, and 6.2 months in patients with blast-phase CML or Ph+ ALL.

In chronic-phase CML, the primary endpoint was major cytogenetic response, and it occurred in 56% of patients. Among chronic-phase patients with the T315I mutation, 70% achieved a major cytogenetic response. Among patients who had failed treatment with dasatinib or nilotinib, 51% achieved a major cytogenetic response.

In accelerated-phase CML, the primary endpoint was major hematologic response. This occurred in 57% of all patients in this group, 50% of patients with the T315I mutation, and 58% of patients who had failed treatment with dasatinib or nilotinib.

The primary endpoint was major hematologic response in blast-phase CML/Ph+ ALL as well. Thirty-four percent of all patients in this group met this endpoint, as did 33% of patients with the T315I mutation and 35% of patients who had failed treatment with dasatinib or nilotinib.

Common non-hematologic adverse events included rash (38%), abdominal pain (38%), headache (35%), dry skin (35%), constipation (34%), fatigue (27%), pyrexia (27%), nausea (26%), arthralgia (25%), hypertension (21%), increased lipase (19%), and increased amylase (7%).

Hematologic events of any grade included thrombocytopenia (42%), neutropenia (24%), and anemia (20%). Serious adverse events of arterial thromboembolism, including arterial stenosis, occurred in patients with cardiovascular risk factors.

Safety issues

Extended follow-up data from the PACE trial, collected in 2013, suggested ponatinib can increase the risk of thrombotic events. When these data came to light, officials in the European Union and the US, where ponatinib had already been approved, began to investigate the drug.

Ponatinib was pulled from the US market for a little over 2 months, and trials of the drug were placed on partial hold while the Food and Drug Administration evaluated the drug’s safety. Ponatinib went back on the market in January 2014, with new safety measures in place.

The drug was not pulled from the market in the European Union, but the European Medicine’s Agency released recommendations for safer use of ponatinib. The Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use reviewed data on ponatinib and decided the drug’s benefits outweigh its risks. ![]()

Photo courtesy of the US FDA

The Israeli Ministry of Health has granted regulatory approval for the kinase inhibitor ponatinib (Iclusig) to treat certain adults with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) or Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph+ ALL).

The drug can now be used to treat adults with any phase of CML who have the T315I mutation or are resistant to/cannot tolerate dasatinib or nilotinib and for whom subsequent treatment with imatinib is not clinically appropriate.

Ponatinib is also approved to treat patients with Ph+ ALL who have the T315I mutation or are resistant to/cannot tolerate dasatinib and for whom subsequent treatment with imatinib is not clinically appropriate.

Ariad Pharmaceuticals, Inc., the company developing ponatinib, said the drug should be available in Israel in the second quarter of 2015.

Trial results

The Ministry of Health’s decision to approve ponatinib was based on results from the phase 2 PACE trial, which included patients with CML or Ph+ ALL who were resistant to or intolerant of prior tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy, or who had the T315I mutation.

The median follow-up times were 15.3 months in chronic-phase CML patients, 15.8 months in accelerated-phase CML patients, and 6.2 months in patients with blast-phase CML or Ph+ ALL.

In chronic-phase CML, the primary endpoint was major cytogenetic response, and it occurred in 56% of patients. Among chronic-phase patients with the T315I mutation, 70% achieved a major cytogenetic response. Among patients who had failed treatment with dasatinib or nilotinib, 51% achieved a major cytogenetic response.

In accelerated-phase CML, the primary endpoint was major hematologic response. This occurred in 57% of all patients in this group, 50% of patients with the T315I mutation, and 58% of patients who had failed treatment with dasatinib or nilotinib.

The primary endpoint was major hematologic response in blast-phase CML/Ph+ ALL as well. Thirty-four percent of all patients in this group met this endpoint, as did 33% of patients with the T315I mutation and 35% of patients who had failed treatment with dasatinib or nilotinib.

Common non-hematologic adverse events included rash (38%), abdominal pain (38%), headache (35%), dry skin (35%), constipation (34%), fatigue (27%), pyrexia (27%), nausea (26%), arthralgia (25%), hypertension (21%), increased lipase (19%), and increased amylase (7%).

Hematologic events of any grade included thrombocytopenia (42%), neutropenia (24%), and anemia (20%). Serious adverse events of arterial thromboembolism, including arterial stenosis, occurred in patients with cardiovascular risk factors.

Safety issues

Extended follow-up data from the PACE trial, collected in 2013, suggested ponatinib can increase the risk of thrombotic events. When these data came to light, officials in the European Union and the US, where ponatinib had already been approved, began to investigate the drug.

Ponatinib was pulled from the US market for a little over 2 months, and trials of the drug were placed on partial hold while the Food and Drug Administration evaluated the drug’s safety. Ponatinib went back on the market in January 2014, with new safety measures in place.

The drug was not pulled from the market in the European Union, but the European Medicine’s Agency released recommendations for safer use of ponatinib. The Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use reviewed data on ponatinib and decided the drug’s benefits outweigh its risks. ![]()

Group identifies priorities for lymphoma research

Photo by Darren Baker

By agreeing upon—and addressing—the aspects of lymphoma research that need the most improvement, the research community could advance the treatment of these diseases, according to a report published in Blood.

The report’s authors said limitations in research infrastructure, funding, and collaborative approaches across research centers present potential challenges on the road to developing better treatments.

And they outlined several “priority areas” that, they believe, require particular attention.

“[Our report] draws focus to our most pressing needs, which, if unaddressed, will prevent transformative changes to how we study and treat these diseases,” said David M. Weinstock, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts.

“Directing our collaborative efforts toward the most high-impact areas will enable us to more rapidly bring life-saving treatments to our patients.”

The report lists the following priority areas:

- Infrastructure

- Develop an adequate number of disease models for each lymphoma subtype

- Establish a central repository of biospecimens, cell lines, and in vivo models with open access

- Organize patient advocacy to support research.

- Research

- Catalogue how lymphoma cells differ across disease subtypes

- Better define and identify mutations and other abnormalities associated with the disease

- Develop strategies to identify high-risk patients who may benefit most from clinical trials

- Enhance efforts to use immune therapies to cure lymphoma

- Better understand how lymphoma cells communicate with normal cells.

“[W]e invite clinicians, scientists, advocates, and patients to weigh in on this strategic roadmap so that it reflects the input of everyone in the community,” Dr Weinstock said. “We will share these priorities with funding agencies, advocacy groups, and others who can help us address the challenges we have identified, and thereby accelerate the development of new approaches to understand and eradicate lymphoma.”

To weigh in, visit: http://www.hematology.org/lymphoma-roadmap.

This report was developed after a review of the state of the science in lymphoma that took place at a special ASH Meeting on Lymphoma Biology in August 2014. A second ASH Meeting on Lymphoma Biology is planned for the summer of 2016. ![]()

Photo by Darren Baker

By agreeing upon—and addressing—the aspects of lymphoma research that need the most improvement, the research community could advance the treatment of these diseases, according to a report published in Blood.

The report’s authors said limitations in research infrastructure, funding, and collaborative approaches across research centers present potential challenges on the road to developing better treatments.

And they outlined several “priority areas” that, they believe, require particular attention.

“[Our report] draws focus to our most pressing needs, which, if unaddressed, will prevent transformative changes to how we study and treat these diseases,” said David M. Weinstock, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts.

“Directing our collaborative efforts toward the most high-impact areas will enable us to more rapidly bring life-saving treatments to our patients.”

The report lists the following priority areas:

- Infrastructure

- Develop an adequate number of disease models for each lymphoma subtype

- Establish a central repository of biospecimens, cell lines, and in vivo models with open access

- Organize patient advocacy to support research.

- Research

- Catalogue how lymphoma cells differ across disease subtypes

- Better define and identify mutations and other abnormalities associated with the disease

- Develop strategies to identify high-risk patients who may benefit most from clinical trials

- Enhance efforts to use immune therapies to cure lymphoma

- Better understand how lymphoma cells communicate with normal cells.

“[W]e invite clinicians, scientists, advocates, and patients to weigh in on this strategic roadmap so that it reflects the input of everyone in the community,” Dr Weinstock said. “We will share these priorities with funding agencies, advocacy groups, and others who can help us address the challenges we have identified, and thereby accelerate the development of new approaches to understand and eradicate lymphoma.”

To weigh in, visit: http://www.hematology.org/lymphoma-roadmap.

This report was developed after a review of the state of the science in lymphoma that took place at a special ASH Meeting on Lymphoma Biology in August 2014. A second ASH Meeting on Lymphoma Biology is planned for the summer of 2016. ![]()

Photo by Darren Baker

By agreeing upon—and addressing—the aspects of lymphoma research that need the most improvement, the research community could advance the treatment of these diseases, according to a report published in Blood.

The report’s authors said limitations in research infrastructure, funding, and collaborative approaches across research centers present potential challenges on the road to developing better treatments.

And they outlined several “priority areas” that, they believe, require particular attention.

“[Our report] draws focus to our most pressing needs, which, if unaddressed, will prevent transformative changes to how we study and treat these diseases,” said David M. Weinstock, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts.

“Directing our collaborative efforts toward the most high-impact areas will enable us to more rapidly bring life-saving treatments to our patients.”

The report lists the following priority areas:

- Infrastructure

- Develop an adequate number of disease models for each lymphoma subtype

- Establish a central repository of biospecimens, cell lines, and in vivo models with open access

- Organize patient advocacy to support research.

- Research

- Catalogue how lymphoma cells differ across disease subtypes

- Better define and identify mutations and other abnormalities associated with the disease

- Develop strategies to identify high-risk patients who may benefit most from clinical trials

- Enhance efforts to use immune therapies to cure lymphoma

- Better understand how lymphoma cells communicate with normal cells.

“[W]e invite clinicians, scientists, advocates, and patients to weigh in on this strategic roadmap so that it reflects the input of everyone in the community,” Dr Weinstock said. “We will share these priorities with funding agencies, advocacy groups, and others who can help us address the challenges we have identified, and thereby accelerate the development of new approaches to understand and eradicate lymphoma.”

To weigh in, visit: http://www.hematology.org/lymphoma-roadmap.

This report was developed after a review of the state of the science in lymphoma that took place at a special ASH Meeting on Lymphoma Biology in August 2014. A second ASH Meeting on Lymphoma Biology is planned for the summer of 2016. ![]()

Hospital Management of AECOPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is currently the third leading cause of death in the United States, accounting for over 140,000 deaths in 2009.[1] The economic burden of COPD is felt at all levels of the healthcare system with hospitalizations making up a large proportion of these costs.[2] As the US population ages, the prevalence of this disease is expected to rise, as will its impact on healthcare utilization and healthcare costs. The total estimated US healthcare costs attributable to COPD were $32.1 billion in 2010, with a projected 53% increase to $49.0 billion in 2020.[3] The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) defines an exacerbation as an acute event characterized by a worsening of the patient's respiratory symptoms that is beyond normal day‐to‐day variations.[4] Although there are no well‐established criteria, 3 cardinal symptoms suggest an exacerbation: worsening of dyspnea, increase in sputum volume, and increase in sputum purulence. Additionally, constitutional symptoms and a variable decrease in pulmonary function are also typically encountered in patients with an acute exacerbation.

Exacerbations have a major impact on the course of COPD. They have been shown to negatively affect quality of life, accelerate decline of lung function, and increase risk of mortality. Although the majority of exacerbations are managed in the outpatient setting, severe exacerbations will warrant emergency department visits and often hospital admission. Such exacerbations may often be complicated by respiratory failure and result in death.[4] Indeed, exacerbations requiring hospital admission have an estimated in‐hospital mortality of anywhere from 4% to 30% and are associated with poor long‐term outcomes and increased risk of rehospitalization.[5] Furthermore, the increased risk of mortality from a severe exacerbation remains elevated for approximately 90 days after the index hospitalization.[6] This review will provide an overview of the etiology, assessment, management, and follow‐up care of patients with COPD exacerbation in the hospital setting.

ETIOLOGY

Approximately 70% to 80% of exacerbations can be attributed to respiratory infections, with the remaining 20% to 30% due to environmental pollution or an unknown etiology.[7] Both viral and bacterial infections have been implicated in COPD exacerbations. Rhinoviruses are the most common viruses associated with acute exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD). Common bacteria implicated in triggering AECOPD include Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Moraxella catarrhalis.[8, 9] Coinfection with multiple organisms can worsen severity of exacerbations.[10]

Exacerbations may also occur in the absence of an infectious trigger. Environmental factors may play a role, and increased risk of exacerbations has been reported during periods of higher air pollution. Increased concentrations of pollutants such as black smoke, sulphur dioxide, ozone, and nitrogen dioxide are associated with worsening in respiratory symptoms, increased risk of hospital admissions, and COPD‐associated mortality.[11] Exacerbations can also be precipitated or complicated by the presence of certain comorbid conditions such as aspiration or congestive heart failure (CHF). Other factors associated with increased risk for exacerbations include increased age, severity of airway obstruction, gastroesophageal reflux, chronic mucous hypersecretion, longer duration of COPD, productive cough and wheeze, increases in cough and sputum, and poor health‐related quality of life.[12, 13, 14, 15] Most importantly, a past history of exacerbation is a very good predictor of a subsequent episode.

CLINICAL ASSESSMENT

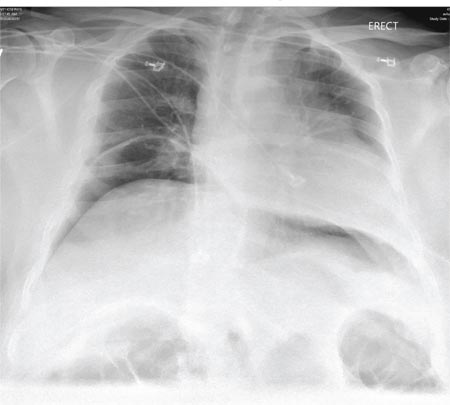

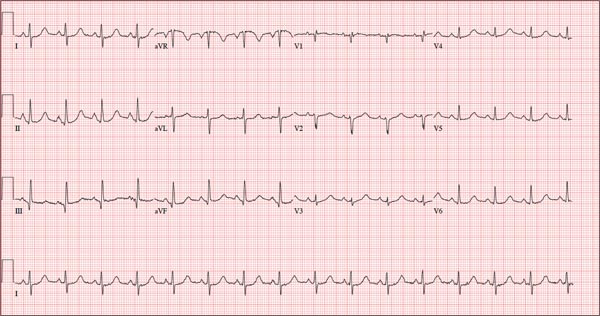

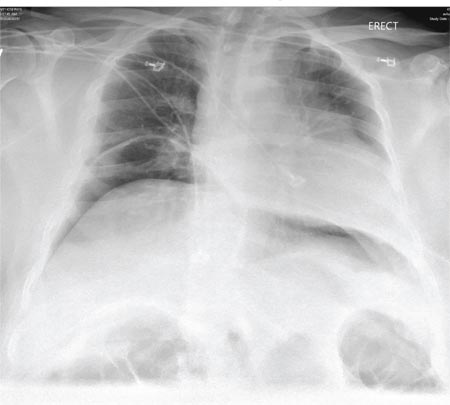

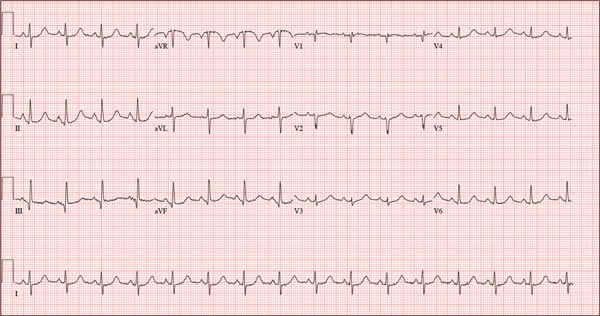

Initial evaluation of a severe exacerbation should include a comprehensive medical history, physical exam, and occasionally laboratory tests. A chest radiograph is often performed to rule out alternative diagnoses such as pneumonia or CHF.[4] Arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis is almost always needed when managing severe exacerbations to evaluate the presence of respiratory failure, which may require noninvasive or mechanical ventilation.[16, 17] Initial laboratory tests for hospitalized patients should include a complete blood cell count to help identify the presence of polycythemia, anemia, or leukocytosis, and a basic metabolic profile to identify any electrolyte abnormalities. Additional testing, such as an electrocardiogram (ECG), should be performed in the appropriate clinical context. Common ECG findings seen in COPD patients include right ventricular hypertrophy, right atrial enlargement, and low voltage QRS complexes.[18] Arrhythmias, such as multifocal atrial tachycardia, atrial fibrillation, and ventricular tachycardia, can also be observed.[19] Although pulmonary function tests performed during an acute exacerbation will have limited diagnostic or prognostic utility because the patient is not at clinical baseline, spirometry testing prior to hospital discharge may be helpful for confirming the diagnosis of COPD in patients who have not had pulmonary function testing before.

Pulmonary embolism (PE) may mimic the clinical presentation of a COPD exacerbation with features such as acute dyspnea, tachycardia, and pleuritic chest pain. Workup for PE should be considered if a clear cause for the exacerbation is not identified.[20] A meta‐analysis of 5 observational studies determined that the prevalence of PE was nearly 25% in hospitalized patients with COPD exacerbation.[21] However, significant heterogeneity in the data examined in this analysis was noted, with a wide range of reported PE incidence in the studies included.

The use of certain biomarkers such as brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) and procalcitonin may be helpful in guiding therapy by ruling out other concomitant disorders such as CHF (BNP) or ruling in a respiratory infection as a trigger (procalcitonin). BNP levels have been found to be significantly higher in patients with diastolic heart failure compared to patients with obstruction lung disease (224 240 pg/mL vs 14 12 pg/mL, P 0.0001).[22] Furthermore, an increase in BNP levels of 100 pg/mL in patients with AECOPD was found to independently predict the need for intensive care unit admission (hazard ratio [HR], 1.13; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.03 to 1.24).[23] Procalcitonin may be helpful in deciding when to use antibiotics in bacterial infection[24]; however, further studies are needed to characterize its use in guiding antibiotic therapy for COPD exacerbations.

Sputum Gram stain and cultures should be considered in patients with purulence or change in sputum color. Additional indications for collecting sputum include frequent exacerbations, severe airflow limitation, and exacerbations requiring mechanical ventilation due to the possibility of antibiotic‐resistant pathogens. The risk for certain organisms such as Pseudomonas include: (1) recent hospitalization with duration of at least 2 days within the past 90 days, (2) frequent antibiotic therapy of >4 courses within the past year, (3) Severe or very severe airflow obstruction (GOLD stage III or IV), (4) isolation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa during a previous exacerbation, and (5) recent systemic glucocorticoid use. Routine use of Gram stain and culture in patients without the above features may be of little yield, as common bacterial pathogens may be difficult to isolate in sputum or may have already been present as a colonizing organism.[25, 26, 27]

Patients who may warrant hospital admission have some of the following features: marked increase in intensity of symptoms, severe underlying COPD, lack of response to initial medical management, presence of serious comorbidities such as heart failure, history of frequent exacerbations, older age, and insufficient home support.[4] Indications for hospital admission and for intensive care unit admission are listed in Table 1.[16, 28]

|

| Consider hospital admission |

| Failure to respond to initial medical management |

| New severe or progressive symptoms (eg, dyspnea at rest, accessory muscle use) |

| Severe COPD |

| History of frequent exacerbations |

| New physical exam findings (eg, cyanosis, peripheral edema) |

| Older age |

| Comorbidities (eg, heart arrhythmias, heart failure) |

| Lack of home support |

| Consider ICU admission |

| Severe dyspnea that responds inadequately to initial treatment |

| Persistent hypoxemia or acidosis not responsive to O2 therapy and NIPPV |

| Impending or active respiratory failure |

| Changes in mental status such as confusion, lethargy, or coma |

| Hemodynamic instability |

MANAGEMENT

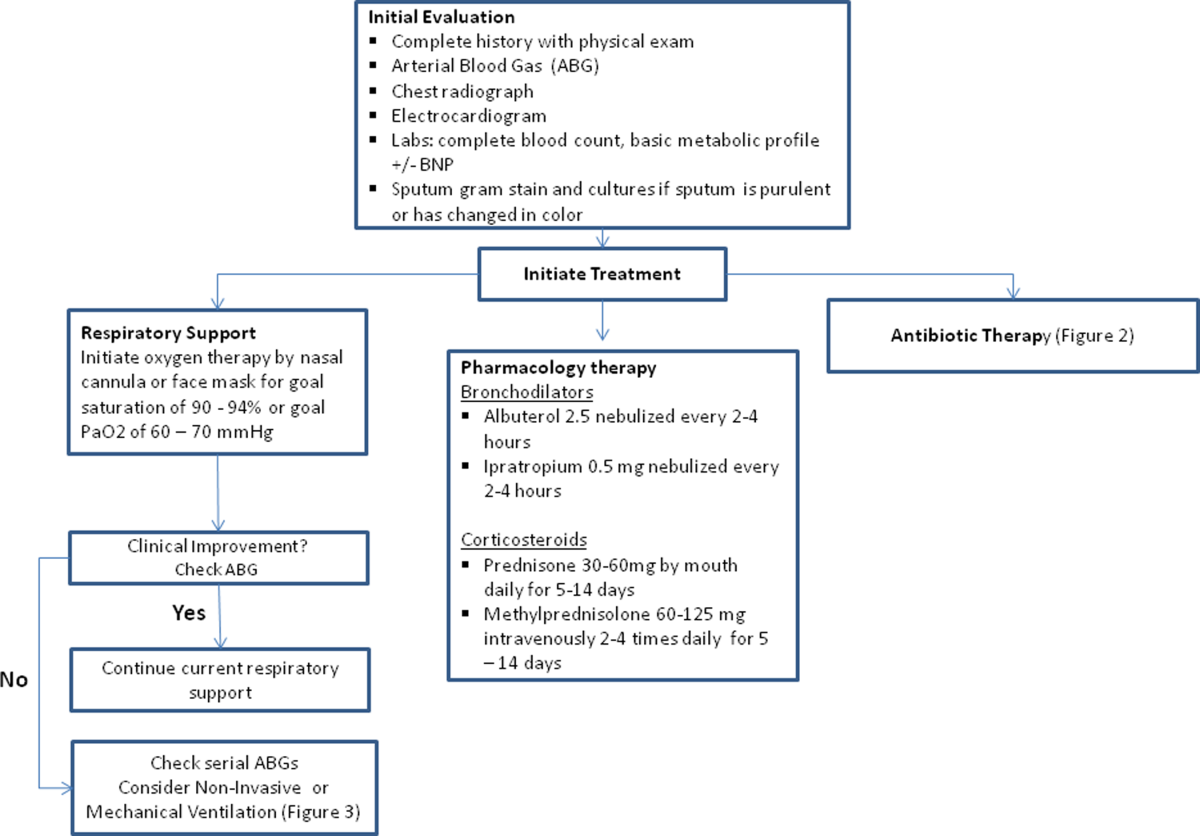

The initial goals of inpatient management of AECOPD are to correct the underlying respiratory dysfunction and hypoxemia, minimize progression of symptoms, and manage underlying triggers and comorbid conditions. Figure 1 outlines initial assessment and management actions to perform once a patient is admitted.[4] Once the patient has been stabilized, objectives change to prevention of subsequent exacerbations through a number of methods including optimization of outpatient pharmacotherapy, establishment of adequate home care, and close hospital follow‐up.

Pharmacologic Therapy

The major components of pharmacologic therapy used in the management of acute exacerbation of COPD in the hospital setting include bronchodilators, systemic corticosteroids, and antibiotics.

Bronchodilators

Short‐acting 2‐adrenergic agonists (eg, albuterol) with or without short‐acting anticholinergic agents (eg, ipratropium bromide) are the mainstay initial bronchodilators in an exacerbation. Short‐acting agents are preferred because of their rapid onset of action and efficacy in achieving bronchodilation. The 2 agents are often used together based on findings in studies that found combination therapy produced bronchodilation beyond what could be achieved with either agent alone.[29] Although a systematic review demonstrated comparable efficacy of bronchodilator delivery with nebulized therapy and meter‐dosed inhaler therapy, nebulization is often the preferred modality due to improved tolerance of administration in acute exacerbations.[30] Typical doses for albuterol are 2.5 mg by nebulizer every 2 to 4 hours as needed. Ipratropium bromide is usually dosed at 0.5 mg by nebulizer every 4 hours as needed. More frequent bronchodilator therapy than every 2 hours, possibly even continuous nebulized treatment, may be considered for severe symptoms. The use of long‐acting bronchodilators is restricted to maintenance therapy and should not be used in the treatment of an acute exacerbation.

Methylxanthines such as aminophylline and theophylline are not recommended for the initial management of acute exacerbations, and should only be considered as second line therapy in the setting of insufficient response to short‐acting bronchodilators.[4] In a review of randomized controlled trials, adding methylxanthines to conventional therapy did not readily reveal a significant improvement in lung function or symptoms.[31] Furthermore, therapy was associated with significantly more nausea and vomiting, tremors, palpitations, and arrhythmias compared to placebo.[31, 32]

Systemic Corticosteroids

Systemic glucocorticoids have an essential role in the management of patients hospitalized for COPD exacerbation. Studies have demonstrated that systemic corticosteroid use shortens recovery time, reduces hospital stays, reduces early treatment failure, and improves lung function. One of the most comprehensive trials establishing the clinical efficacy of systemic corticosteroids is the Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study of Systemic Corticosteroids in COPD Exacerbation.[33] In this study, 271 patients were randomly assigned to receive placebo, an 8‐week course of systemic corticosteroid therapy, or a 2‐week course of systemic corticosteroids. The primary endpoint of analysis was treatment failure as evidenced by an intensification of pharmacologic therapy, readmission, intubation, or death. The groups treated with systemic corticosteroids were found to have lower rates of treatment failure, shorter initial hospital stay, and more rapid improvement in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1). Recent studies have not found significant differences in outcome between patients treated with a shorter duration of systemic corticosteroids (57 days) and those using a longer duration of (1014 days).[34, 35] Furthermore, COPD patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) may potentially have worse outcomes and adverse events when given higher doses of steroids. One cohort study assessing hospital mortality in COPD patients admitted to the ICU and treated with corticosteroids within the first 2 days of admission found that patients who received low doses of steroids (240 mg/d on hospital day 1 or 2) did not have significant reduction in mortality (odds ratio [OR] 0.85; 95% CI, 0.71 to 1.01;P= 0.06) but was associated with reduction in hospital (OR 0.44 d; 95% CI, 0.67 to 0.21; P 0.01) and ICU length of stays (OR 0.31 d; 95% CI, 0.46 to 0.16;P 0.01), hospital costs (OR $2559; 95% CI, $4508 to $609;P= 0.01), length of mechanical ventilation (OR 0.29 d; 95% CI, 0.52 to 0.06;P= 0.01), need for insulin therapy (22.7% vs 25.1%;P 0.01), and fungal infections (3.3% vs 4.4%;P 0.01).[36] Additionally, oral corticosteroids do not appear to be inferior to intravenous therapy.[37] Most patients admitted to the hospital with COPD exacerbation should be treated with a short course of low‐dose systemic corticosteroids such as 40 mg of prednisone daily for 5 days. Patients without adequate initial response to therapy may deserve alteration of dose or duration of steroid treatment. Although the use of a 40‐mg daily dose of prednisone is a suggested regimen of treatment in the majority of cases, the dosing and duration of steroids may need to be increased in more severe cases. The use of inhaled corticosteroids is limited to the maintenance therapy of COPD in conjunction with long‐acting bronchodilators.

Mucoactive Agents

Current literature does not support the routine use of mucoactive agents in the management of AECOPD.[38, 39, 40]

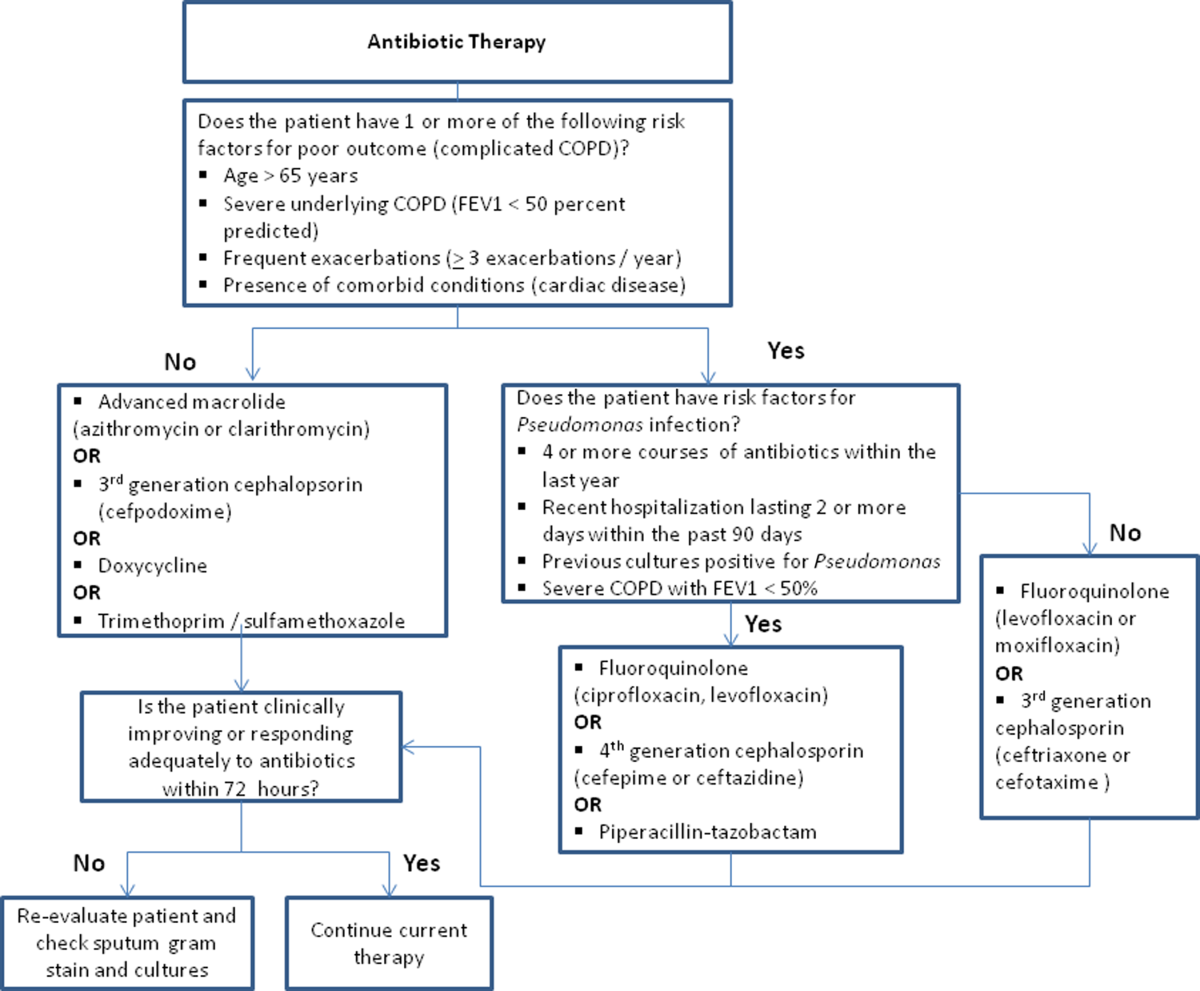

Antibiotics

There is a clear benefit for the use of antibiotics to treat exacerbations of COPD in an inpatient setting, especially given that most exacerbations are triggered by a respiratory infection. A 2012 systematic review of 16 placebo‐controlled studies demonstrated high‐quality evidence that antibiotics significantly reduced risk of treatment failure in hospitalized with severe exacerbations not requiring ICU admission (number needed to treat [NNT] = 10; relative risk [RR] 0.77; 95% CI, 0.65 to 0.91; I2= 47%).[41] However, there was no statistically significant effect on mortality or hospital length of stay. Patient groups treated with antibiotics were more likely to experience adverse events, with diarrhea being the most common side effect.

Of those studies, only 1 addressed antibiotic use in the ICU. In this study, patients with severe exacerbation requiring mechanical ventilation were treated with either ofloxacin 400 mg daily or placebo for 10 days.[42] The treatment group had significantly lower mortality (NNT = 6; absolute risk reduction [ARR] 17.5%; 95% CI, 4.3 to 30.7; P = 0.01) and a decreased need for additional courses of antibiotics (NNT = 4; ARR 28.4%; 95% CI, 12.9 to 43.9; P = 0.0006). Both the duration of mechanical ventilation and duration of hospital stay were significantly shorter in the treatment group (absolute difference 4.2 days; 95% CI, 2.5 to 5.9; and absolute difference 9.6 days; 95% CI, 3.4 to 12.8, respectively). Mortality benefit and reduced length of stay were seen only in patients admitted to the ICU.[42]

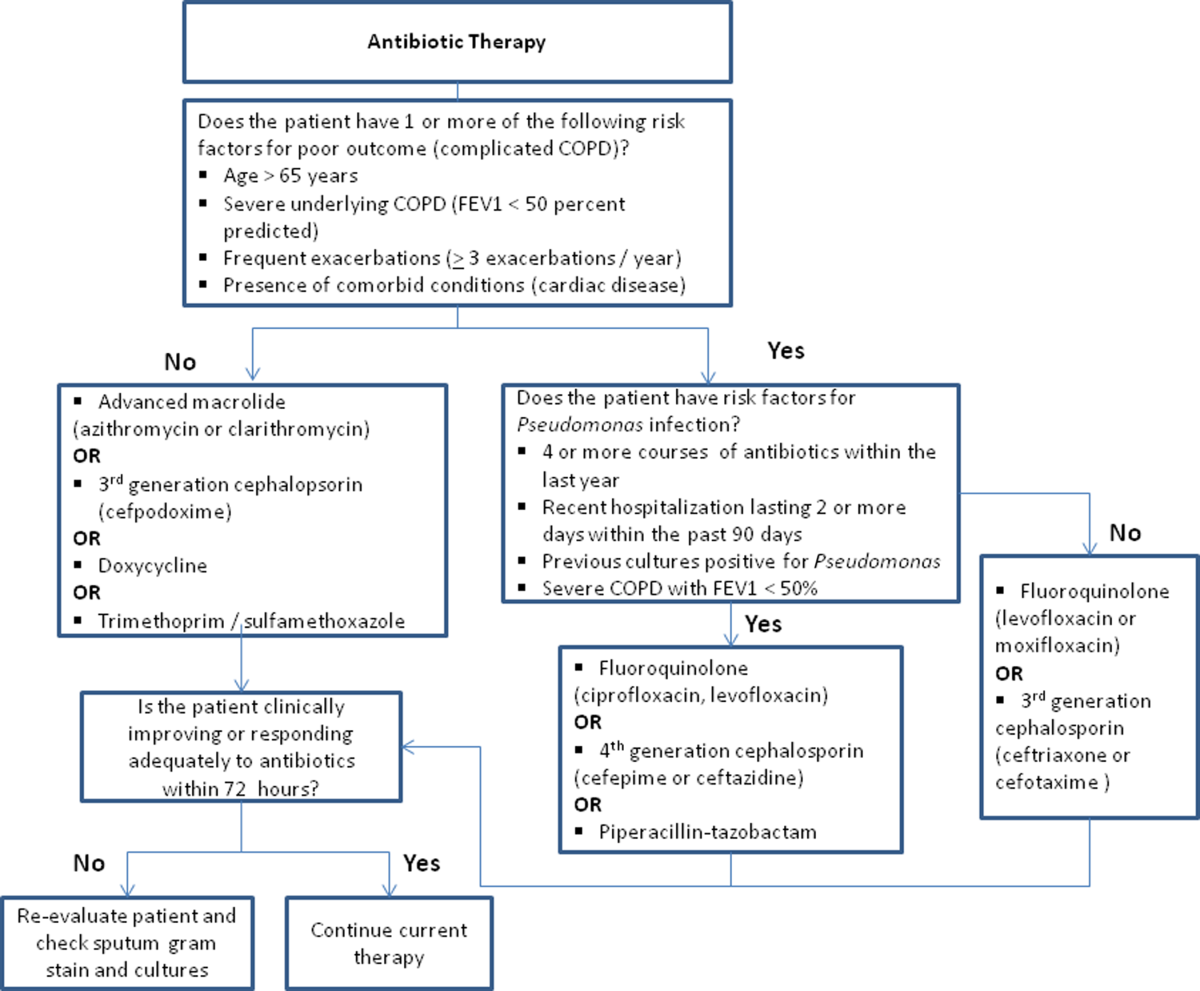

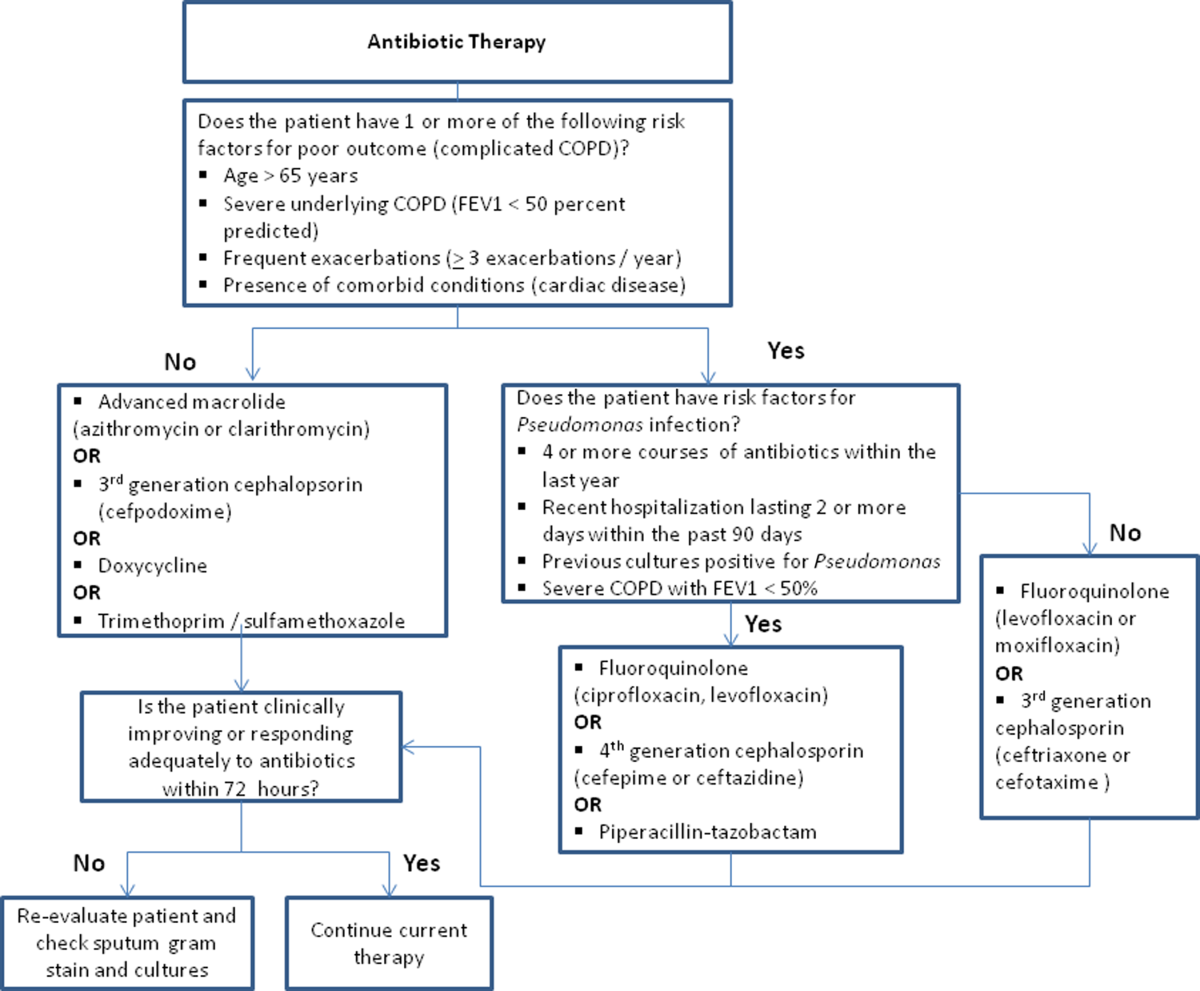

Despite the multitude of studies demonstrating significant benefits of antibiotic use for moderate to severe exacerbations, optimal antibiotic regimens for treatment have not been established. A risk stratification approach to antibiotic therapy has been proposed. In this approach, patients who are diagnosed with moderate or severe exacerbations (defined as having at least 2 of the 3 cardinal symptoms of exacerbation) are differentiated into simple or complicated patients. An algorithm that helps in choosing antibiotics is outlined in Figure 2.[43] Complicated patients are those who had at least 1 or more of the following risk factors for poor outcome: age >65 years, FEV1 50%, comorbid disease such as cardiac disease, or 3 more exacerbations in the previous 12 months. If a specific antibiotic had been used within the last 3 months, a different class of agents is generally recommended. Additionally, patients treated according to this approach should be reassessed in 48 to 72 hours.[16, 43, 44]

Respiratory Support

Oxygen therapy plays an important part in the inpatient management of exacerbations. Correction of hypoxemia takes priority over correction of hypercapnea. Several devices such as nasal cannulas, Venturi masks, and nonrebreathing masks can be utilized to ensure adequate delivery of supplemental oxygen. Controlled oxygen therapy should target an oxygen saturation of >92%, allowing for the treatment of hypoxemia while reducing the risk of hypercapnia and respiratory acidosis related to worsening of ventilation perfusion mismatch.[45] ABGs should ideally be checked 30 to 60 minutes after the initiation of oxygen to assess for adequate oxygenation without interval worsening of carbon dioxide retention or respiratory acidosis.[4]

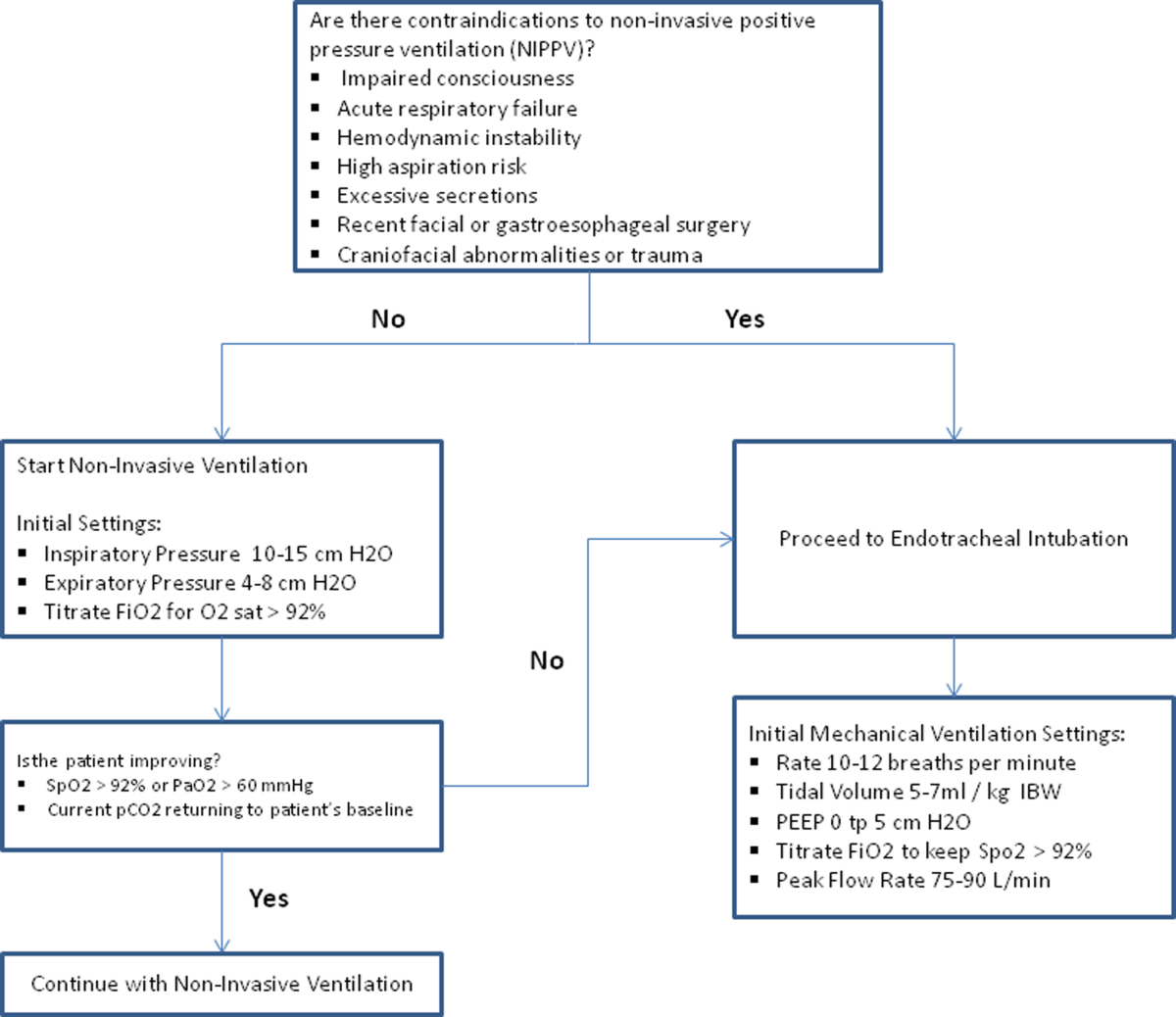

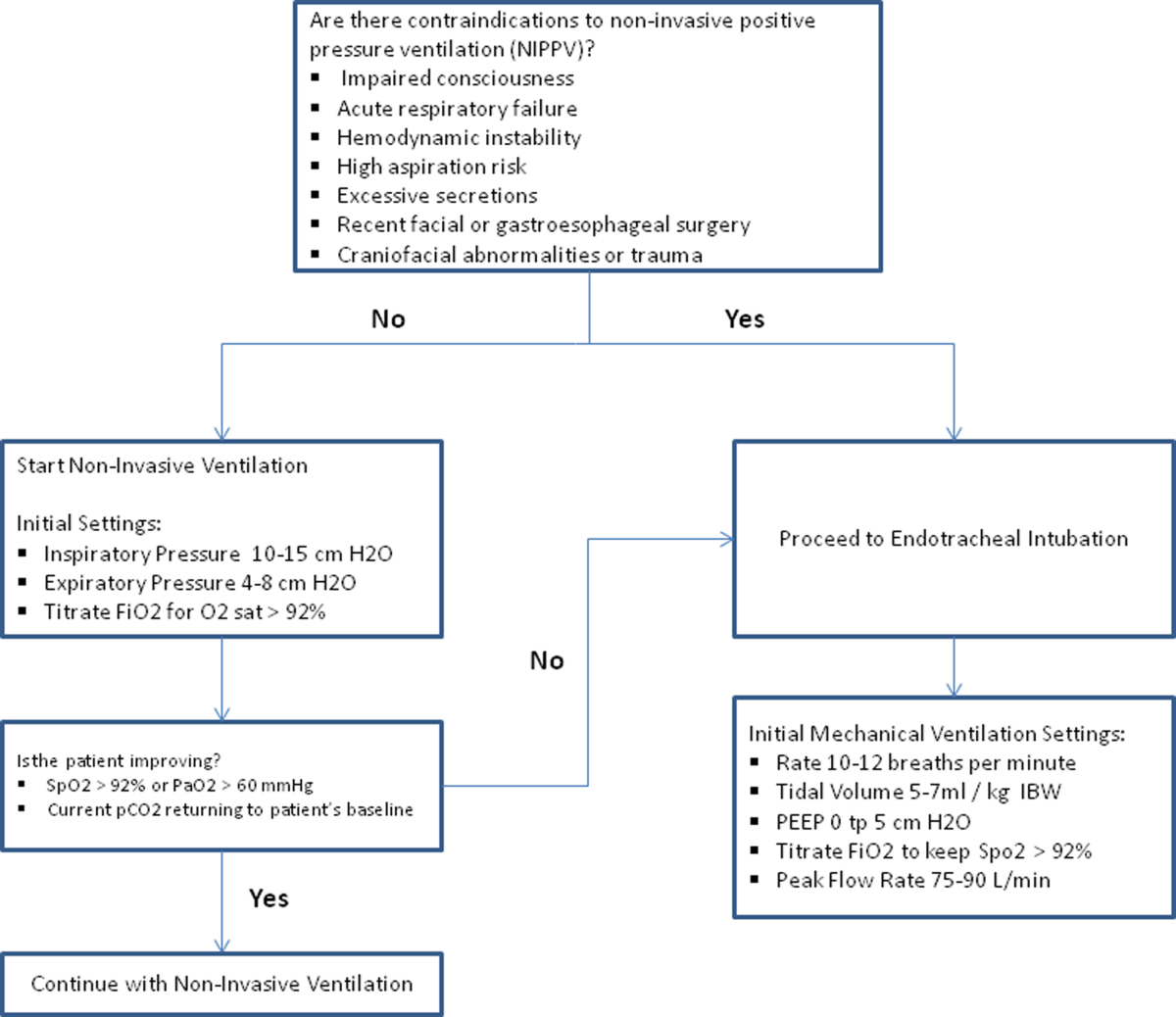

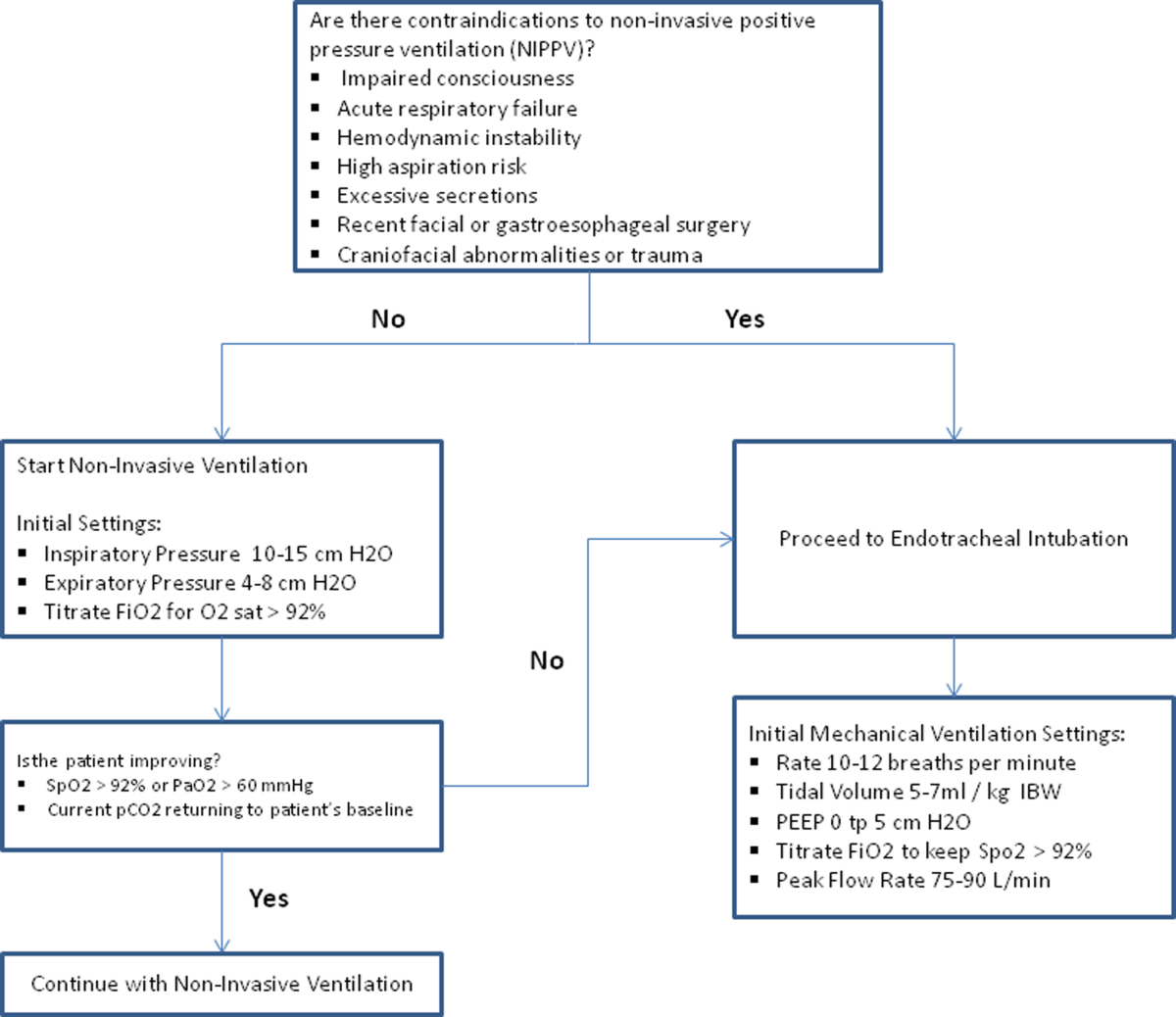

The use of noninvasive or invasive mechanical ventilation should be considered if acidemia (pH 7.35) occurs either on presentation or with continued oxygen therapy, or if symptoms worsen with evidence of respiratory muscle fatigue. The use of noninvasive ventilation has been shown to reduce the work of breathing and tachypnea. More importantly, it significantly improves pH within the first hour of treatment and reduces mortality (NNT 10), need for intubation (NNT 4), and hospital length of stay (reduction of 3.2 days [95% CI, 2.1 to 4.4 days]).[46, 47, 48, 49] Noninvasive positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV) is usually administered in a combination of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) and pressure support ventilation (PSV). Initial settings for CPAP and PSV are 4 to 8 cm H2O and 10 to 15 cm H2O, respectively. Serial ABGs repeated every 30 to 60 minutes after initiating NIPPV or other clinical changes are necessary to correctly assess and guide therapy. Contraindications to NIPPV include significantly altered mental status, respiratory arrest, cardiovascular instability, presence of copious secretions with high aspiration risk, recent facial or gastroesophageal surgery, and facial trauma or anatomic abnormality.[16, 50]

Invasive mechanical ventilation should be considered if a trial of noninvasive ventilation is unsuccessful. Additional indications are outlined in Figure 3.[4] Ventilatory strategies are geared toward correcting gas exchange abnormalities and minimizing lung injury. Minute ventilation should be titrated with the goal of normalizing the pH and returning partial pressure of CO2 back to the patient's baseline. COPD patients can have chronic hypercapnea and may have difficulty weaning from the ventilator if they are ventilated to a normal CO2. Additional considerations in the management of respiratory failure from AECOPD with mechanical ventilation include minimizing regional overdistension and management of dynamic hyperinflation. Overdistension injury or volutrauma can occur when high tidal volumes delivered by the ventilator force the already open alveoli to overdistend and develop stretch injury. Excessive volumes can also increase the risk of hyperinflation and barotrauma. Therefore, lower tidal volumes (eg, 57 mL/kg) have increasingly been utilized in the initial ventilatory management of these patients. Incomplete expiration of an inspired breath prior to initiation of the next breath causes air trapping, which in turn increases the alveolar pressure at the end of expiration or autopeak end expiratory pressure (auto‐PEEP). Increased auto‐PEEP can cause significant negative effects including increased work of breathing, barotrauma, and decreased systemic venous return.[51] Strategies to reduce auto‐PEEP include the following: reducing patient minute ventilation and ventilatory demand, lengthening the expiratory time, and reducing airflow resistance by pharmacologic agents. If auto‐PEEP persists despite management, applying external PEEP may reduce the threshold load for inspiratory effort caused by auto‐PEEP, and thus may decrease the work of breathing. Initial ventilator settings and mode used is dependent on operator and local practices. Suggested appropriate initial settings include the use of volume assist control ventilation with a rate of 10 to 12 breaths/minute, low tidal volumes of 5 to 7 mL/kg, PEEP of 5 cmH2O, and FiO2 needed to keep saturations >92% and/or a PaO2 > 60 mm Hg. Settings can be adjusted based on serial ABG analysis and the patient's tolerance of mechanical ventilation.[51, 52] Sedation may be needed to help patients tolerate ventilatory support.

Management of Comorbidities

Many comorbidities are associated with COPD. Common comorbidities include anxiety, depression, lung cancer, hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.[50] Comorbid conditions complicate the management of COPD by increasing risk of hospitalization and mortality and significantly increasing healthcare costs.[53, 54] The clinical manifestations of these comorbid conditions and COPD are associated by means of the inflammation pathway either as a result of a spillover of inflammatory mediators occurring in the lungs or as a result of a systemic inflammatory state.[55, 56] Although there are no randomized controlled studies evaluating the effects of treating comorbidities in patients with COPD, observational studies have suggested that treating some of these conditions may be beneficial COPD.[50, 57, 58, 59, 60] Treatment of comorbidities should be optimized once the acute problems warranting admission have been stabilized. As a general rule, treatment of comorbidities should not affect the management of COPD and should be treated according to the guidelines for the comorbidity.[4] The management of cardiovascular disease and anxiety and depression will be addressed here.

Cardiovascular Disease

Cardiovascular disease is a major comorbidity in COPD. Several studies have observed the coexistence of the 2 conditions. COPD and cardiovascular disease share tobacco abuse as a risk factor.[61] Common entities in cardiovascular disease include ischemic heart disease, CHF, atrial fibrillation, and hypertension. Treatment of these conditions should generally adhere to current guidelines, as there is no evidence to suggest treatment should negatively impact COPD.[4] If considering the use of ‐blockers as part of a cardiac management regimen, cardioselective ‐blockers such as atenolol or metoprolol are recommended over nonselective blockade due to potential precipitation of bronchospasm in predisposed patients. A systematic review assessing the effect of short‐term and long‐term cardioselective ‐blocker use on the respiratory function of patients with COPD did not reveal significant adverse effects.[62] Regarding inhaled pharmacotherapy in patients with both COPD and cardiovascular disease, treatment should adhere to current GOLD guidelines. There has been concern for adverse cardiovascular effects associated with inhaled long‐acting agonist and long‐acting anticholinergic agents, but data from large long‐term studies have not shown a significant negative effect.[63, 64]

Anxiety and Depression

Comorbid anxiety or depression may complicate management in patients with COPD by worsening prognosis or interfering with therapy. The presence of these comorbid conditions has predicted poor adherence to treatment, lower health‐related quality of life, decreased exercise capacity, increased disability, and increased risk of exacerbation and mortality.[65, 66, 67, 68] A recent meta‐analysis found that the presence of comorbid depression increased the risk of mortality by 83%, and comorbid anxiety increased the risk of exacerbation and mortality by 28%. Additionally, patients with COPD were found to be at 55% to 69% increased risk of developing depression.[69]

Although further study is needed to clearly define screening and management, treatment of these co‐morbid conditions in patients with COPD should adhere to usual guidelines. During an admission for exacerbation, screening for depression and anxiety with a referral to psychiatry should be considered on a case‐by‐case basis. No changes to pharmacologic management for COPD are necessary while a patient is under treatment for anxiety or depression.[4] Exercise training during hospitalization for acute exacerbation of COPD can be considered, as recent data revealed beneficial effects on depression symptoms and overall mood.[70]

Palliative Care

The focus of palliative care in a COPD patient is to provide care aimed at improving symptom control, communication, physical activity, and emotional support to overall better the patient's quality of life.[71] Palliative care in pulmonary disease can be divided into 3 main areas of concentration: support for patient and family, care of the patient, and responsibility of the professional caregiver. Discussions with patients regarding initiation of palliative care should begin at time of diagnosis of COPD.[4] However, there are significant barriers to planning end‐of‐life care in these patients including difficulty with establishing prognosis in end‐stage COPD, patients' lack of awareness regarding progression of disease, and lack of communication between care teams. Given these obstacles, patients admitted with AECOPD often have no care plan in place.[71]

Responsibility of the caregiver during an admission for AECOPD includes advance care planning and medical management for relief of distressing symptoms such as dyspnea, anxiety, or depression. Palliative care teams are becoming more available for consultation on hospitalized patients, and they will help facilitate the palliative care discussion in multiple areas including goals of care, optimization of quality of life, and identification of community/palliative care resources that may be available once the patient is discharged.[4, 72]

DISCHARGE PLANNING

Patients admitted for AECOPD can be considered for discharge once symptoms are improved and their condition is stable enough to permit outpatient management. A discharge checklist is suggested in Table 2 to ensure proper follow‐up and that teaching has been performed prior to discharge.[4] Risk factors for rehospitalization include the following: previous hospital admissions for exacerbation, continuous dyspnea, oral corticosteroid use, long‐term oxygen therapy, poor health‐related quality of life, and lack of routine physical activity.[73, 74] An optimal length of stay has not been established, and more research is needed to identify predictive factors associated with hospitalization/rehospitalization.[75, 76]

|

| Patient and/or caregiver must demonstrate the ability to follow an outpatient regimen for the treatment of COPD |

| Reassess inhaler technique |

| Educate patient on the role of maintenance therapy and completion of steroid and/or antibiotic therapy |

| Establish a care plan for patient's medical problems |

| Patient must be evaluated for and if needed set for oxygen therapy |

| Patient must be scheduled for outpatient follow up in 4 |

There are interventions that can shorten length of stay and expedite recovery from symptoms in the outpatient setting. Establishing home health visits by a nurse has allowed patients to be discharged earlier without significantly increasing readmission rates.[77, 78] Additionally, the use of a written action plan has allowed for more appropriate treatment for exacerbations, which may shorten recovery time, although there was no change in healthcare resource utilization.[79, 80, 81] Prior to discharge, patients should start or restart long‐acting bronchodilator maintenance medications, which usually include long‐acting 2 agonists, long‐acting anticholinergics, or both. In addition, the use of inhaled corticosteroids and phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE‐4) inhibitors should also be considered if appropriate for the severity of the underlying disease. Patients should also have the following performed at time of discharge: optimization of home maintenance pharmacologic therapy, reassessment of inhaler technique, education regarding role of maintenance therapy, instructions regarding antibiotic and steroid use, management plan of comorbidities, scheduled hospital follow‐up, and evaluation of long‐term oxygen use.

There are insufficient data to establish a specific schedule postdischarge that will maximize positive outcomes. One retrospective cohort study found that patients who had a follow‐up visit with their primary care provider or pulmonologist within 30 days of discharge had significantly reduced risk of an emergency room (ER) visit (HR 0.86; 95% CI, 0.83 to 0.9) and reduced readmission rates (HR 0.91; 95% CI, 0.87 to 0.96).[82] Nonetheless, current guidelines recommend follow‐up to occur within 4 to 6 weeks after discharge from the hospital. A shorter follow‐up interval of 1 to 2 weeks after discharge may be needed for patients at higher risk for relapse such as those who have frequent exacerbations or those admitted to the ICU for respiratory failure.[16, 28]

PREVENTION

After hospitalization, most patients are not discharged with appropriate support and medications, which in turn, increases their risk for hospital readmission.[83] Several modalities including vaccination, action plans, long‐acting inhaled bronchodilators, and antibiotics have been shown to be effective in prevention of COPD exacerbations. However, there has been little guidance available to help clinicians choose therapies from the currently available options that would be most appropriate for their patients. This year, the American College of Chest Physicians and the Canadian Thoracic Society published an evidence‐based guideline on the prevention of COPD exacerbations.[84] Recommended therapies (those with level 1 evidence) will be discussed here.

Vaccinations

Annual influenza vaccinations are recommended for COPD patients. A meta‐analysis of 11 trials, with 6 of those trials specifically performed in patients with COPD, demonstrated a reduction in total number of exacerbations per vaccinated patient compared to patients who received placebo (mean difference of 0.037, 0.64 to 0.11; P = 0.006).[85]

Pneumococcal vaccines should also be administered, especially because COPD exacerbations related to pneumococcal infection have had been associated with longer hospitalizations and worsening impairment of lung function compared to noninfectious exacerbations. However, there is insufficient evidence to indicate that pneumococcal vaccination can prevent AECOPD, although a Cochrane systematic review of 7 studies examining this suggests a borderline statistically significant improvement in pneumonia rates in those with COPD versus controls (OR 0.72; 95% CI, 0.51 to 1.01).[86]

Pulmonary Rehabilitation

Pulmonary rehabilitation is a comprehensive program based on exercise training, education, and behavior change that is designed to improve the physical and psychological condition of people with chronic respiratory disease as well as promote long‐term adherence to health enhancing behaviors. Although a pooled analysis of 623 patients from 9 studies demonstrated a significant reduction in hospitalizations in patients who participated in pulmonary rehabilitation compared to those who pursued conventional care (OR 0.4; 95% CI, 0.22 to 0.91; P = 0.03), the overall quality of evidence was low with significant heterogeneity also observed (P = 0.03; I2 = 52%). However, when the studies were categorized by timing of rehabilitation, patients who participated in a rehabilitation program initiated within 1 month after a COPD hospitalization had a reduction in rehospitalizations after completion of rehabilitation (OR 0.24; 95% CI, 0.07 to 0.88; P = 0.03). No reduction was seen in patients without a recent history of AECOPD (>1 month) who underwent rehabilitation (OR 0.79; 95% CI, 0.42 to 1.5; P = 0.47). Based on these findings, pulmonary rehabilitation should be initiated in patients within 4 weeks of an AECOPD.[84]

Education, Action Plans, and Case Management

Education, action plans, and case management are all interventions that focus on enabling patients to be knowledgeable about COPD, equipping them with the necessary skills to manage their chronic disease, and motivating them to be proactive with their healthcare. There are no formal definitions describing these modalities. Patient education is usually a formal delivery of COPD topics in forms such as nurse teaching or classes with the objective of improving knowledge and understanding of the disease process. Action plans are usually written plans created by a clinician for individual patients aiming to teach them how to identify and self‐manage AECOPD. Case management consists of patients either receiving formal follow‐up or consistent communication such as scheduled telephone calls with a healthcare professional allowing for closer monitoring of symptoms, better availability of medical staff, prompt coordination of care, and early identification and treatment of AECOPD.

Although several studies have evaluated the impact on hospitalization rates after implementation of the above interventions as an individual modality or in combination with each other, only the combination of patient education and case management that included direct access to a healthcare specialist at least monthly demonstrated a significant decrease in hospitalization rate with a pooled opportunity risk of 0.82 (95% CI, 0.17 to 3.99) and significant heterogeneity between studies (P = 0.003, I2 = 89%). There was insufficient evidence to recommend use of all 3 interventions together. Use of any of these interventions individually after a COPD hospitalization was not recommended.[84]

Maintenance Pharmacotherapies

The use of long‐acting inhaled bronchodilators with or without inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) as maintenance therapy has been shown to decrease exacerbations. Efficacy of long‐acting 2 agonists (LABAs), long acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs), and combination therapies with or without ICS will be discussed here.

A systematic review of LABAs demonstrated a reduced exacerbation rate with long‐acting 2 agonist use versus placebo.[87] Data from 7 studies with a total of 2859 patients enrolled demonstrated an OR for severe exacerbation requiring admissions of 0.73 (95% CI, 0.56 to 0.95). Data from 7 studies with 3375 patients evaluating rates of moderate exacerbations demonstrated an OR of 0.73 (95% CI, 0.61 to 0.87).[84]

Tiotropium is the best studied inhaled LAMA in the treatment of COPD. Two major trials helped establish role of tiotropium in COPD management. The first by Niewoehner et al. demonstrated that the addition of tiotropium to standard treatment significantly decreased the proportion of patients who experienced 1 or more exacerbations during the 6‐month duration of treatment (27.9% vs 32.3%; P = 0.037).[88] The UPLIFT (Understanding Potential Long‐term Impacts on Function with Tiotropium) trial was published soon after, and found a 14% reduction in exacerbations over 4 years in patients treated with tiotropium compared to those receiving usual care (0.73 vs 0.85 exacerbations per year; RR 0.86; 95% CI, 0.81 to 0.91).[89] A recently published systematic review assessing the effectiveness of tiotropium versus placebo demonstrated a reduction in the rate of acute exacerbations with tiotropium by 22%. The OR was 0.78 (95% CI, 0.70 to 0.87) with a NNT of 16. Additional analysis of 21 studies enrolling 22,852 patients found that tiotropium treatment was associated with fewer hospitalizations due to exacerbations, with an OR of 0.85 (95% CI, 0.72 to 1.00).[90] Studies comparing LAMAs to short‐acting muscarinic antagonist ipratroprium showed that tiotropium was superior in exacerbation prevention (OR 0.71; 95% CI, 0.52 to 0.95).[91] LAMAs have also demonstrated a lower rate of exacerbation when compared to LABAs. In a systematic review of 6 studies enrolling 12,123 patients, those using tiotropium alone had an OR of 0.86 (95% CI, 0.79 to 0.93) compared to patients using LABAs. Further analysis of the 4 studies in this review that reported COPD hospitalization as an outcome showed that rates of hospitalization in subjects receiving tiotropium was significantly lower in subjects who received tiotropium compared to LABA (OR 0.87; 95% CI, 0.77 to 0.99).[92]

The largest clinical trial to date for ICS/LABA combination therapy was the TORCH (Towards a Revolution in COPD Health) study. In this 3‐year study, 6112 patients were randomized to treatment with fluticasone‐salmeterol or placebo. Patients treated with the combination therapy had a 25% reduction in exacerbations when compared to placebo.[64] However, there are few long‐term studies comparing combination ICS/LABA versus single drugs with exacerbations as the primary outcome. A recent Cochrane meta‐analysis found 14 studies that met inclusion criteria that randomized a total of 11,794 patients with severe COPD. Results indicate combination ICS/LABA reduced the number of exacerbations but did not significantly affect the rate of hospitalizations when compared with LABA monotherapy. Additionally, there was a 4% increased risk of pneumonia in the combination therapy group compared with the LABA alone.[93]

There are also little data comparing triple therapy (LABA/ICS and LAMA) to double or single therapy. A recent systematic review compared the efficacy of 3 therapeutic approaches: tiotropium plus LABA (dual therapy), LABA/ICS (combined therapy), and tiotropium plus ICS/LABA. The review consisted of 20 trials with a total of 6803 patients included. Both dual therapy and triple therapy did not have significant impact on risk of exacerbations in comparison to tiotropium monotherapy.[94]

There are no guidelines regarding the step up of maintenance inhaler therapy immediately after COPD‐related hospitalization. That being said, any patient with COPD who is hospitalized for AECOPD is already considered to be at high risk for exacerbation and can therefore be classified as group C or D according to the GOLD combined assessment. Per GOLD guidelines for management of stable COPD, recommended first choice for maintenance therapy in a group C patient would be ICS/LABA or LAMA and in a group D patient would be ICS/LABA LAMA. Further titration of maintenance therapy should be performed on an outpatient basis.[4]

Additional Therapies

There are several additional therapies including long‐term macrolides and PDE4 inhibitors such as roflumilast that have demonstrated significant reduction in exacerbations[95]; more data are needed before these modalities can be fully recommended.[84]

CONCLUSIONS