User login

Cosmetic procedures in pregnancy

Cosmetic procedures in general should be postponed until after pregnancy. Factors to consider in a pregnant patient include the hormonal and physiologic changes of the patient during pregnancy, as well as the risk to the fetus.

Many dermatologic changes occur during a pregnancy. Pregnant women may develop hyperpigmentation, formation of vascular lesions and varicose veins, hirsutism, striae, acne, and increased skin growths. These changes may lead pregnant women to seek cosmetic treatments.

However, physiologic changes such as increased blood volume, decreased hematocrit, increased flushing, increased melanocyte stimulation, and decreased wound healing should prompt a delay of cosmetic procedures until 3-6 months after the postpartum period, when these factors return to normal and the risk of complications is reduced.

The safety of many cosmetic treatments during pregnancy remains unknown. This includes microdermabrasion, chemical peels, and laser treatments. Given the increased risk of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, as well as poor wound healing and increased risk of hypertrophic and keloidal scarring in pregnancy, these procedures are often avoided.

The safety of injectable treatments during pregnancy, such as liquid sclerosants and fillers, has not been evaluated. However, the manufacturers list pregnancy and breastfeeding as contraindications to treatment. Neurotoxins are also avoided during pregnancy and breastfeeding, based on teratogenicity in animal studies. There have been no controlled trials in humans.

Though there have been incidental exposures of botulinum toxin in women who did not know they were pregnant, no documented reports of fetal anomaly during these incidental exposures has been reported. In addition, no studies have been conducted to evaluate whether the toxin is excreted in breast milk, or when it is safe to use neurotoxins, fillers, or liquid sclerosants prior to conception.

The 10 months of pregnancy and many months of nursing can be a long stretch to wait for women who get regular cosmetic treatments. The skin changes of pregnancy can be bothersome; however, the risks of complications to the mother and the fetus outweigh the transient benefits of cosmetic procedures. The hormonal and physiologic changes of pregnancy are widely different in each woman, and sometimes the long-term side effects and complications can be completely unpredictable. Thus, patience and thorough counseling are the best strategies for treating our pregnant and nursing moms.

References

Nussbaum, R. and Benedetto, A.V. Cosmetic aspects of pregnancy. Clinics in Dermatology 2006;24:133-41.

Morgan, J.C. et al. Botulinum Toxin and Pregnancy Skinmed 2006;5:308.

Monteiro, E. Botulinum toxin A during pregnancy: a survey of treating physicians. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2006;77:117-9.

Lee, K.C., et al. Safety of cosmetic dermatologic procedures during pregnancy. Dermatol. Surg. 2013;39:1573-86.

Goldberg, D. and Maloney, M. Dermatologic surgery and cosmetic procedures during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Dermatologic Therapy 2013;26:321-30.

Dr. Talakoub and Dr. Wesley are co-contributors to a monthly Aesthetic Dermatology column in Dermatology News. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub.

Cosmetic procedures in general should be postponed until after pregnancy. Factors to consider in a pregnant patient include the hormonal and physiologic changes of the patient during pregnancy, as well as the risk to the fetus.

Many dermatologic changes occur during a pregnancy. Pregnant women may develop hyperpigmentation, formation of vascular lesions and varicose veins, hirsutism, striae, acne, and increased skin growths. These changes may lead pregnant women to seek cosmetic treatments.

However, physiologic changes such as increased blood volume, decreased hematocrit, increased flushing, increased melanocyte stimulation, and decreased wound healing should prompt a delay of cosmetic procedures until 3-6 months after the postpartum period, when these factors return to normal and the risk of complications is reduced.

The safety of many cosmetic treatments during pregnancy remains unknown. This includes microdermabrasion, chemical peels, and laser treatments. Given the increased risk of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, as well as poor wound healing and increased risk of hypertrophic and keloidal scarring in pregnancy, these procedures are often avoided.

The safety of injectable treatments during pregnancy, such as liquid sclerosants and fillers, has not been evaluated. However, the manufacturers list pregnancy and breastfeeding as contraindications to treatment. Neurotoxins are also avoided during pregnancy and breastfeeding, based on teratogenicity in animal studies. There have been no controlled trials in humans.

Though there have been incidental exposures of botulinum toxin in women who did not know they were pregnant, no documented reports of fetal anomaly during these incidental exposures has been reported. In addition, no studies have been conducted to evaluate whether the toxin is excreted in breast milk, or when it is safe to use neurotoxins, fillers, or liquid sclerosants prior to conception.

The 10 months of pregnancy and many months of nursing can be a long stretch to wait for women who get regular cosmetic treatments. The skin changes of pregnancy can be bothersome; however, the risks of complications to the mother and the fetus outweigh the transient benefits of cosmetic procedures. The hormonal and physiologic changes of pregnancy are widely different in each woman, and sometimes the long-term side effects and complications can be completely unpredictable. Thus, patience and thorough counseling are the best strategies for treating our pregnant and nursing moms.

References

Nussbaum, R. and Benedetto, A.V. Cosmetic aspects of pregnancy. Clinics in Dermatology 2006;24:133-41.

Morgan, J.C. et al. Botulinum Toxin and Pregnancy Skinmed 2006;5:308.

Monteiro, E. Botulinum toxin A during pregnancy: a survey of treating physicians. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2006;77:117-9.

Lee, K.C., et al. Safety of cosmetic dermatologic procedures during pregnancy. Dermatol. Surg. 2013;39:1573-86.

Goldberg, D. and Maloney, M. Dermatologic surgery and cosmetic procedures during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Dermatologic Therapy 2013;26:321-30.

Dr. Talakoub and Dr. Wesley are co-contributors to a monthly Aesthetic Dermatology column in Dermatology News. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub.

Cosmetic procedures in general should be postponed until after pregnancy. Factors to consider in a pregnant patient include the hormonal and physiologic changes of the patient during pregnancy, as well as the risk to the fetus.

Many dermatologic changes occur during a pregnancy. Pregnant women may develop hyperpigmentation, formation of vascular lesions and varicose veins, hirsutism, striae, acne, and increased skin growths. These changes may lead pregnant women to seek cosmetic treatments.

However, physiologic changes such as increased blood volume, decreased hematocrit, increased flushing, increased melanocyte stimulation, and decreased wound healing should prompt a delay of cosmetic procedures until 3-6 months after the postpartum period, when these factors return to normal and the risk of complications is reduced.

The safety of many cosmetic treatments during pregnancy remains unknown. This includes microdermabrasion, chemical peels, and laser treatments. Given the increased risk of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, as well as poor wound healing and increased risk of hypertrophic and keloidal scarring in pregnancy, these procedures are often avoided.

The safety of injectable treatments during pregnancy, such as liquid sclerosants and fillers, has not been evaluated. However, the manufacturers list pregnancy and breastfeeding as contraindications to treatment. Neurotoxins are also avoided during pregnancy and breastfeeding, based on teratogenicity in animal studies. There have been no controlled trials in humans.

Though there have been incidental exposures of botulinum toxin in women who did not know they were pregnant, no documented reports of fetal anomaly during these incidental exposures has been reported. In addition, no studies have been conducted to evaluate whether the toxin is excreted in breast milk, or when it is safe to use neurotoxins, fillers, or liquid sclerosants prior to conception.

The 10 months of pregnancy and many months of nursing can be a long stretch to wait for women who get regular cosmetic treatments. The skin changes of pregnancy can be bothersome; however, the risks of complications to the mother and the fetus outweigh the transient benefits of cosmetic procedures. The hormonal and physiologic changes of pregnancy are widely different in each woman, and sometimes the long-term side effects and complications can be completely unpredictable. Thus, patience and thorough counseling are the best strategies for treating our pregnant and nursing moms.

References

Nussbaum, R. and Benedetto, A.V. Cosmetic aspects of pregnancy. Clinics in Dermatology 2006;24:133-41.

Morgan, J.C. et al. Botulinum Toxin and Pregnancy Skinmed 2006;5:308.

Monteiro, E. Botulinum toxin A during pregnancy: a survey of treating physicians. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2006;77:117-9.

Lee, K.C., et al. Safety of cosmetic dermatologic procedures during pregnancy. Dermatol. Surg. 2013;39:1573-86.

Goldberg, D. and Maloney, M. Dermatologic surgery and cosmetic procedures during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Dermatologic Therapy 2013;26:321-30.

Dr. Talakoub and Dr. Wesley are co-contributors to a monthly Aesthetic Dermatology column in Dermatology News. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub.

What Is Your Diagnosis? New World Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

A 40-year-old man presented with a nonhealing ulcer on the right hand of 2 months’ duration. The lesion had started as a pruritic papule while he was visiting Guyana 2 months prior. The area had slowly enlarged with progressive ulceration. He denied any systemic signs including fever, chills, or weight loss, and his medical history was unremarkable. Physical examination revealed a 4-cm fungating ulceration with heaped-up borders on the dorsal aspect of the right hand.

The Diagnosis: New World Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

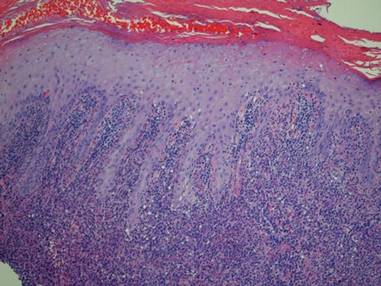

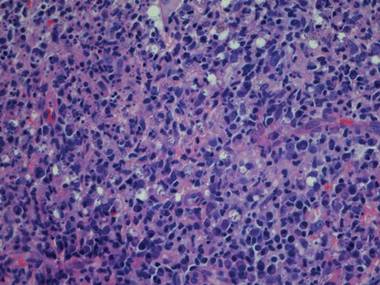

In addition to the ulceration on the right hand, a 2-cm ulcerated plaque also had developed on the right side of the chin a few days later (Figure 1). A biopsy was obtained from the lesion on the hand. Histopathologic examination revealed granulomatous inflammation with numerous histiocytes containing intracellular organisms (Figure 2). The microorganisms had pale pink nuclei with basophilic kinetoplasts (Figure 3). Tissue culture showed a mixed growth of gram-positive and gram-negative organisms but no predominant organism. Fungal and mycobacterial cultures were negative. A diagnosis of New World cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) was made due to visualization of intracellular microorganisms containing basophilic kinetoplasts. Polymerase chain reaction on the tissue block confirmed the presence of Leishmania guyanensis.

|

Cutaneous leishmaniasis is caused by protozoa from the Leishmania species and is transmitted by the bite of the female sandfly. There are 2 classifications for the disease: Old World and New World. Old World CL is transmitted by the sandfly of the genus Phlebotomus, which is endemic in Asia, Africa, the Mediterranean, and the Middle East. New World CL is transmitted by the sandflies of the genus Lutzomyia, which are endemic in Mexico, Central America, and South America. There have been occasional cases of autochthonous transmission reported in Texas and Oklahoma,1 but there has been no known transmission of CL in Australia or the Pacific Islands.2 Human infection can be transmitted by 21 species of Leishmania and can be speciated by designated laboratories such as the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (Silver Spring, Maryland) using tissue culture and polymerase chain reaction.1 The CDC can assist with the collection of specimens and supply of culture medium for cases occurring in the United States. Identification of the species is important because there are associated implications for treatment and prognosis.

There are 3 major forms of leishmaniasis: cutaneous, mucocutaneous, and visceral. Cutaneous leishmaniasis is the most common form. There are approximately 1.5 million new cases of CL each year worldwide,3 and more than 90% of these cases occur in Afghanistan, Algeria, Iran, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Brazil, and Peru.1 New World CL is caused by 2 species complexes: Leishmania mexicana and Leishmania viannia, including the subspecies L guyanensis, which was seen in our patient.

Cutaneous leishmaniasis usually begins as a small, well-defined papule at the site of the insect bite that then enlarges and becomes a nodule or plaque. Next, the lesion becomes ulcerated with raised borders (Figure 1). The ulcer typically is painless unless there is secondary bacterial or fungal infection.3,4 The incubation period usually is 2 to 8 weeks and multiple lesions may be present, as seen in our patient.4

Old World CL can resolve without treatment, but New World CL is less likely to spontaneously resolve. Additionally, there is a greater risk for spread of the infection to mucous membranes or for systemic dissemination if New World CL is left untreated.2,5 Patients with multiple lesions (ie, ≥3); large lesions (ie, >2.5 cm); lesions on the face, hands, feet, or joints; and those who are immunocompromised should be treated promptly.2 Pentavalent antimonials (eg, meglumine antimoniate, sodium stibogluconate) are the treatment of choice for New World CL, except for infections caused by L guyanensis. The most common pentavalent antimonial agent used in the United States is sodium stibogluconate and is given at a standard intravenous dose of 20 mg antimony/kg daily for 20 days.2 The drug is only available through the CDC’s Drug Service under an Investigational New Drug protocol.1

Intramuscular pentamidine (3 mg/kg daily every other day for 4 doses) is the first-line treatment of CL caused by L guyanensis because systemic antimony usually is not effective.2,6,7 Intralesional injection with pentavalent antimonials usually is not recommended for treatment of New World CL because of the possibility of disseminated disease.2 Liposomal amphotericin B has mainly been used to treat visceral and mucosal leishmaniasis, but there have been some small studies and case reports that have showed it to be successful in treating CL.8-10 Larger controlled studies need to be performed. Oral antifungal drugs (eg, fluconazole, ketoconazole, itraconazole) also have been used to treat CL with variable results depending on the Leishmania species.11

There currently are no vaccines or drugs available to prevent against leishmaniasis. Preventive measures such as avoiding outdoor activities from dusk to dawn when sandflies are the most active, wearing protective clothing, and applying insect repellent that contains DEET (diethyltoluamide) can help reduce a traveler’s risk for becoming infected. Mosquito nets also should be treated with permethrin, which acts as an insect repellent, as sandflies are so small that they can penetrate mosquito nets.1,3,11

Acknowledgements—We would like to thank Francis Steurer, MS, and Barbara Herwaldt, MD, MPH, at the CDC in Atlanta, Georgia, for their help with the identification of the Leishmania species.

1. Herwaldt BL, Magill AJ. Infectious diseases related to travel: leishmaniasis, cutaneous. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2010/chapter-5/cutaneous-leish maniasis.htm. Published August 1, 2013. Accessed March 5, 2015.

2. Mitropolos P, Konidas P, Durkin-Konidas M. New World cutaneous leishmaniasis: updated review of current and future diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:309-322.

3. Hepburn NC. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: an overview. J Postgrad Med. 2003;49:50-54.

4. Markle WH, Makhoul K. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: recognition and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69:1455-1460.

5. Couppié P, Clyti E, Sainte Marie D, et al. Disseminated cutaneous leishmaniasis due to Leishmania guyanensis: case of a patient with 425 lesions. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;71:558-560.

6. Nacher M, Carme B, Sainte Marie D, et al. Influence of clinical presentation on the efficacy of a short course of pentamidine in the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis in French Guiana. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2001;95:331-336.

7. Minodier P, Parola P. Cutaneous leishmaniasis treatment. Trav Med Inf Dis. 2007;5:150-158.

8. Solomon M, Baum S, Barzilai A, et al. Liposomal amphotericin B in comparison to sodium stibogluconate for cutaneous infection due to Leishmania braziliensis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:612-616.

9. Konecny P, Stark DJ. An Australian case of New World cutaneous leishmaniasis. Med J Aust. 2007;186:315-317.

10. Brown M, Noursadeghi M, Boyle J, et al. Successful liposomal amphotericin B treatment of Leishmania braziliensis cutaneous leishmaniasis. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:203-205.

11. Parasites: leishmaniasis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/leishmaniasis/index.html. Updated January 10, 2013. Accessed March 5, 2015.

A 40-year-old man presented with a nonhealing ulcer on the right hand of 2 months’ duration. The lesion had started as a pruritic papule while he was visiting Guyana 2 months prior. The area had slowly enlarged with progressive ulceration. He denied any systemic signs including fever, chills, or weight loss, and his medical history was unremarkable. Physical examination revealed a 4-cm fungating ulceration with heaped-up borders on the dorsal aspect of the right hand.

The Diagnosis: New World Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

In addition to the ulceration on the right hand, a 2-cm ulcerated plaque also had developed on the right side of the chin a few days later (Figure 1). A biopsy was obtained from the lesion on the hand. Histopathologic examination revealed granulomatous inflammation with numerous histiocytes containing intracellular organisms (Figure 2). The microorganisms had pale pink nuclei with basophilic kinetoplasts (Figure 3). Tissue culture showed a mixed growth of gram-positive and gram-negative organisms but no predominant organism. Fungal and mycobacterial cultures were negative. A diagnosis of New World cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) was made due to visualization of intracellular microorganisms containing basophilic kinetoplasts. Polymerase chain reaction on the tissue block confirmed the presence of Leishmania guyanensis.

|

Cutaneous leishmaniasis is caused by protozoa from the Leishmania species and is transmitted by the bite of the female sandfly. There are 2 classifications for the disease: Old World and New World. Old World CL is transmitted by the sandfly of the genus Phlebotomus, which is endemic in Asia, Africa, the Mediterranean, and the Middle East. New World CL is transmitted by the sandflies of the genus Lutzomyia, which are endemic in Mexico, Central America, and South America. There have been occasional cases of autochthonous transmission reported in Texas and Oklahoma,1 but there has been no known transmission of CL in Australia or the Pacific Islands.2 Human infection can be transmitted by 21 species of Leishmania and can be speciated by designated laboratories such as the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (Silver Spring, Maryland) using tissue culture and polymerase chain reaction.1 The CDC can assist with the collection of specimens and supply of culture medium for cases occurring in the United States. Identification of the species is important because there are associated implications for treatment and prognosis.

There are 3 major forms of leishmaniasis: cutaneous, mucocutaneous, and visceral. Cutaneous leishmaniasis is the most common form. There are approximately 1.5 million new cases of CL each year worldwide,3 and more than 90% of these cases occur in Afghanistan, Algeria, Iran, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Brazil, and Peru.1 New World CL is caused by 2 species complexes: Leishmania mexicana and Leishmania viannia, including the subspecies L guyanensis, which was seen in our patient.

Cutaneous leishmaniasis usually begins as a small, well-defined papule at the site of the insect bite that then enlarges and becomes a nodule or plaque. Next, the lesion becomes ulcerated with raised borders (Figure 1). The ulcer typically is painless unless there is secondary bacterial or fungal infection.3,4 The incubation period usually is 2 to 8 weeks and multiple lesions may be present, as seen in our patient.4

Old World CL can resolve without treatment, but New World CL is less likely to spontaneously resolve. Additionally, there is a greater risk for spread of the infection to mucous membranes or for systemic dissemination if New World CL is left untreated.2,5 Patients with multiple lesions (ie, ≥3); large lesions (ie, >2.5 cm); lesions on the face, hands, feet, or joints; and those who are immunocompromised should be treated promptly.2 Pentavalent antimonials (eg, meglumine antimoniate, sodium stibogluconate) are the treatment of choice for New World CL, except for infections caused by L guyanensis. The most common pentavalent antimonial agent used in the United States is sodium stibogluconate and is given at a standard intravenous dose of 20 mg antimony/kg daily for 20 days.2 The drug is only available through the CDC’s Drug Service under an Investigational New Drug protocol.1

Intramuscular pentamidine (3 mg/kg daily every other day for 4 doses) is the first-line treatment of CL caused by L guyanensis because systemic antimony usually is not effective.2,6,7 Intralesional injection with pentavalent antimonials usually is not recommended for treatment of New World CL because of the possibility of disseminated disease.2 Liposomal amphotericin B has mainly been used to treat visceral and mucosal leishmaniasis, but there have been some small studies and case reports that have showed it to be successful in treating CL.8-10 Larger controlled studies need to be performed. Oral antifungal drugs (eg, fluconazole, ketoconazole, itraconazole) also have been used to treat CL with variable results depending on the Leishmania species.11

There currently are no vaccines or drugs available to prevent against leishmaniasis. Preventive measures such as avoiding outdoor activities from dusk to dawn when sandflies are the most active, wearing protective clothing, and applying insect repellent that contains DEET (diethyltoluamide) can help reduce a traveler’s risk for becoming infected. Mosquito nets also should be treated with permethrin, which acts as an insect repellent, as sandflies are so small that they can penetrate mosquito nets.1,3,11

Acknowledgements—We would like to thank Francis Steurer, MS, and Barbara Herwaldt, MD, MPH, at the CDC in Atlanta, Georgia, for their help with the identification of the Leishmania species.

A 40-year-old man presented with a nonhealing ulcer on the right hand of 2 months’ duration. The lesion had started as a pruritic papule while he was visiting Guyana 2 months prior. The area had slowly enlarged with progressive ulceration. He denied any systemic signs including fever, chills, or weight loss, and his medical history was unremarkable. Physical examination revealed a 4-cm fungating ulceration with heaped-up borders on the dorsal aspect of the right hand.

The Diagnosis: New World Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

In addition to the ulceration on the right hand, a 2-cm ulcerated plaque also had developed on the right side of the chin a few days later (Figure 1). A biopsy was obtained from the lesion on the hand. Histopathologic examination revealed granulomatous inflammation with numerous histiocytes containing intracellular organisms (Figure 2). The microorganisms had pale pink nuclei with basophilic kinetoplasts (Figure 3). Tissue culture showed a mixed growth of gram-positive and gram-negative organisms but no predominant organism. Fungal and mycobacterial cultures were negative. A diagnosis of New World cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) was made due to visualization of intracellular microorganisms containing basophilic kinetoplasts. Polymerase chain reaction on the tissue block confirmed the presence of Leishmania guyanensis.

|

Cutaneous leishmaniasis is caused by protozoa from the Leishmania species and is transmitted by the bite of the female sandfly. There are 2 classifications for the disease: Old World and New World. Old World CL is transmitted by the sandfly of the genus Phlebotomus, which is endemic in Asia, Africa, the Mediterranean, and the Middle East. New World CL is transmitted by the sandflies of the genus Lutzomyia, which are endemic in Mexico, Central America, and South America. There have been occasional cases of autochthonous transmission reported in Texas and Oklahoma,1 but there has been no known transmission of CL in Australia or the Pacific Islands.2 Human infection can be transmitted by 21 species of Leishmania and can be speciated by designated laboratories such as the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (Silver Spring, Maryland) using tissue culture and polymerase chain reaction.1 The CDC can assist with the collection of specimens and supply of culture medium for cases occurring in the United States. Identification of the species is important because there are associated implications for treatment and prognosis.

There are 3 major forms of leishmaniasis: cutaneous, mucocutaneous, and visceral. Cutaneous leishmaniasis is the most common form. There are approximately 1.5 million new cases of CL each year worldwide,3 and more than 90% of these cases occur in Afghanistan, Algeria, Iran, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Brazil, and Peru.1 New World CL is caused by 2 species complexes: Leishmania mexicana and Leishmania viannia, including the subspecies L guyanensis, which was seen in our patient.

Cutaneous leishmaniasis usually begins as a small, well-defined papule at the site of the insect bite that then enlarges and becomes a nodule or plaque. Next, the lesion becomes ulcerated with raised borders (Figure 1). The ulcer typically is painless unless there is secondary bacterial or fungal infection.3,4 The incubation period usually is 2 to 8 weeks and multiple lesions may be present, as seen in our patient.4

Old World CL can resolve without treatment, but New World CL is less likely to spontaneously resolve. Additionally, there is a greater risk for spread of the infection to mucous membranes or for systemic dissemination if New World CL is left untreated.2,5 Patients with multiple lesions (ie, ≥3); large lesions (ie, >2.5 cm); lesions on the face, hands, feet, or joints; and those who are immunocompromised should be treated promptly.2 Pentavalent antimonials (eg, meglumine antimoniate, sodium stibogluconate) are the treatment of choice for New World CL, except for infections caused by L guyanensis. The most common pentavalent antimonial agent used in the United States is sodium stibogluconate and is given at a standard intravenous dose of 20 mg antimony/kg daily for 20 days.2 The drug is only available through the CDC’s Drug Service under an Investigational New Drug protocol.1

Intramuscular pentamidine (3 mg/kg daily every other day for 4 doses) is the first-line treatment of CL caused by L guyanensis because systemic antimony usually is not effective.2,6,7 Intralesional injection with pentavalent antimonials usually is not recommended for treatment of New World CL because of the possibility of disseminated disease.2 Liposomal amphotericin B has mainly been used to treat visceral and mucosal leishmaniasis, but there have been some small studies and case reports that have showed it to be successful in treating CL.8-10 Larger controlled studies need to be performed. Oral antifungal drugs (eg, fluconazole, ketoconazole, itraconazole) also have been used to treat CL with variable results depending on the Leishmania species.11

There currently are no vaccines or drugs available to prevent against leishmaniasis. Preventive measures such as avoiding outdoor activities from dusk to dawn when sandflies are the most active, wearing protective clothing, and applying insect repellent that contains DEET (diethyltoluamide) can help reduce a traveler’s risk for becoming infected. Mosquito nets also should be treated with permethrin, which acts as an insect repellent, as sandflies are so small that they can penetrate mosquito nets.1,3,11

Acknowledgements—We would like to thank Francis Steurer, MS, and Barbara Herwaldt, MD, MPH, at the CDC in Atlanta, Georgia, for their help with the identification of the Leishmania species.

1. Herwaldt BL, Magill AJ. Infectious diseases related to travel: leishmaniasis, cutaneous. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2010/chapter-5/cutaneous-leish maniasis.htm. Published August 1, 2013. Accessed March 5, 2015.

2. Mitropolos P, Konidas P, Durkin-Konidas M. New World cutaneous leishmaniasis: updated review of current and future diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:309-322.

3. Hepburn NC. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: an overview. J Postgrad Med. 2003;49:50-54.

4. Markle WH, Makhoul K. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: recognition and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69:1455-1460.

5. Couppié P, Clyti E, Sainte Marie D, et al. Disseminated cutaneous leishmaniasis due to Leishmania guyanensis: case of a patient with 425 lesions. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;71:558-560.

6. Nacher M, Carme B, Sainte Marie D, et al. Influence of clinical presentation on the efficacy of a short course of pentamidine in the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis in French Guiana. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2001;95:331-336.

7. Minodier P, Parola P. Cutaneous leishmaniasis treatment. Trav Med Inf Dis. 2007;5:150-158.

8. Solomon M, Baum S, Barzilai A, et al. Liposomal amphotericin B in comparison to sodium stibogluconate for cutaneous infection due to Leishmania braziliensis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:612-616.

9. Konecny P, Stark DJ. An Australian case of New World cutaneous leishmaniasis. Med J Aust. 2007;186:315-317.

10. Brown M, Noursadeghi M, Boyle J, et al. Successful liposomal amphotericin B treatment of Leishmania braziliensis cutaneous leishmaniasis. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:203-205.

11. Parasites: leishmaniasis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/leishmaniasis/index.html. Updated January 10, 2013. Accessed March 5, 2015.

1. Herwaldt BL, Magill AJ. Infectious diseases related to travel: leishmaniasis, cutaneous. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2010/chapter-5/cutaneous-leish maniasis.htm. Published August 1, 2013. Accessed March 5, 2015.

2. Mitropolos P, Konidas P, Durkin-Konidas M. New World cutaneous leishmaniasis: updated review of current and future diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:309-322.

3. Hepburn NC. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: an overview. J Postgrad Med. 2003;49:50-54.

4. Markle WH, Makhoul K. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: recognition and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69:1455-1460.

5. Couppié P, Clyti E, Sainte Marie D, et al. Disseminated cutaneous leishmaniasis due to Leishmania guyanensis: case of a patient with 425 lesions. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;71:558-560.

6. Nacher M, Carme B, Sainte Marie D, et al. Influence of clinical presentation on the efficacy of a short course of pentamidine in the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis in French Guiana. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2001;95:331-336.

7. Minodier P, Parola P. Cutaneous leishmaniasis treatment. Trav Med Inf Dis. 2007;5:150-158.

8. Solomon M, Baum S, Barzilai A, et al. Liposomal amphotericin B in comparison to sodium stibogluconate for cutaneous infection due to Leishmania braziliensis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:612-616.

9. Konecny P, Stark DJ. An Australian case of New World cutaneous leishmaniasis. Med J Aust. 2007;186:315-317.

10. Brown M, Noursadeghi M, Boyle J, et al. Successful liposomal amphotericin B treatment of Leishmania braziliensis cutaneous leishmaniasis. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:203-205.

11. Parasites: leishmaniasis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/leishmaniasis/index.html. Updated January 10, 2013. Accessed March 5, 2015.

Team discovers transmissible leukemia in clams

Photo by Michael J. Metzger

Results of a new study indicate that leukemia may be contagious—at least in clams.

Researchers found that outbreaks of leukemia in soft-shell clams along the east coast of North America can be explained by the spread of cancerous cells from one clam to another.

“The evidence indicates that the tumor cells themselves are contagious—that the cells can spread from one animal to another in the ocean,” said Stephen Goff, PhD, of Columbia University in New York, New York.

“We know this must be true because the genotypes of the tumor cells do not match those of the host animals that acquire the disease, but instead all derive from a single lineage of tumor cells.”

In other words, a leukemia that has killed many clams can be traced to one incidence of disease. The cancer originated in some unfortunate clam and has persisted ever since, as those cancerous cells divide, break free, and make their way to other clams.

Dr Goff and his colleagues described this discovery in Cell.

The researchers noted that only 2 other examples of transmissible cancer are known in the wild. These include the canine transmissible venereal tumor, transmitted by sexual contact, and the Tasmanian devil facial tumor disease, transmitted through biting.

In early studies of the leukemia in clams, Dr Goff and his colleagues found high levels of a particular sequence of DNA they named “Steamer.” While normal cells contain only 2 to 5 copies of Steamer, leukemic cells can have 150 copies. The researchers initially thought this difference was the result of a genetic amplification process occurring within each individual clam.

But when the team analyzed the genomes of leukemia cells collected in New York, Maine, and Prince Edward Island, they discovered something else entirely. The cancerous cells they had collected from clams living at different locations were nearly identical to one another at the genetic level.

“We were astonished to realize that the tumors did not arise from the cells of their diseased host animals, but rather from a rogue clonal cell line spreading over huge geographical distances,” Dr Goff said.

The results showed the cells can survive in seawater long enough to reach and sicken a new host. It is not yet known whether this leukemia can spread to other molluscs or whether there are mechanisms that recognize the malignant cells as foreign invaders and attack them.

Dr Goff said there is plenty the researchers don’t know about this leukemia, including when it first arose and how it spreads from one clam to another. They don’t know what role Steamer played in the cancer’s origin, if any. And they don’t know how often these sorts of cancers might arise in molluscs or other marine animals.

But the findings do suggest that transmissible cancers are more common than anyone suspected. ![]()

Photo by Michael J. Metzger

Results of a new study indicate that leukemia may be contagious—at least in clams.

Researchers found that outbreaks of leukemia in soft-shell clams along the east coast of North America can be explained by the spread of cancerous cells from one clam to another.

“The evidence indicates that the tumor cells themselves are contagious—that the cells can spread from one animal to another in the ocean,” said Stephen Goff, PhD, of Columbia University in New York, New York.

“We know this must be true because the genotypes of the tumor cells do not match those of the host animals that acquire the disease, but instead all derive from a single lineage of tumor cells.”

In other words, a leukemia that has killed many clams can be traced to one incidence of disease. The cancer originated in some unfortunate clam and has persisted ever since, as those cancerous cells divide, break free, and make their way to other clams.

Dr Goff and his colleagues described this discovery in Cell.

The researchers noted that only 2 other examples of transmissible cancer are known in the wild. These include the canine transmissible venereal tumor, transmitted by sexual contact, and the Tasmanian devil facial tumor disease, transmitted through biting.

In early studies of the leukemia in clams, Dr Goff and his colleagues found high levels of a particular sequence of DNA they named “Steamer.” While normal cells contain only 2 to 5 copies of Steamer, leukemic cells can have 150 copies. The researchers initially thought this difference was the result of a genetic amplification process occurring within each individual clam.

But when the team analyzed the genomes of leukemia cells collected in New York, Maine, and Prince Edward Island, they discovered something else entirely. The cancerous cells they had collected from clams living at different locations were nearly identical to one another at the genetic level.

“We were astonished to realize that the tumors did not arise from the cells of their diseased host animals, but rather from a rogue clonal cell line spreading over huge geographical distances,” Dr Goff said.

The results showed the cells can survive in seawater long enough to reach and sicken a new host. It is not yet known whether this leukemia can spread to other molluscs or whether there are mechanisms that recognize the malignant cells as foreign invaders and attack them.

Dr Goff said there is plenty the researchers don’t know about this leukemia, including when it first arose and how it spreads from one clam to another. They don’t know what role Steamer played in the cancer’s origin, if any. And they don’t know how often these sorts of cancers might arise in molluscs or other marine animals.

But the findings do suggest that transmissible cancers are more common than anyone suspected. ![]()

Photo by Michael J. Metzger

Results of a new study indicate that leukemia may be contagious—at least in clams.

Researchers found that outbreaks of leukemia in soft-shell clams along the east coast of North America can be explained by the spread of cancerous cells from one clam to another.

“The evidence indicates that the tumor cells themselves are contagious—that the cells can spread from one animal to another in the ocean,” said Stephen Goff, PhD, of Columbia University in New York, New York.

“We know this must be true because the genotypes of the tumor cells do not match those of the host animals that acquire the disease, but instead all derive from a single lineage of tumor cells.”

In other words, a leukemia that has killed many clams can be traced to one incidence of disease. The cancer originated in some unfortunate clam and has persisted ever since, as those cancerous cells divide, break free, and make their way to other clams.

Dr Goff and his colleagues described this discovery in Cell.

The researchers noted that only 2 other examples of transmissible cancer are known in the wild. These include the canine transmissible venereal tumor, transmitted by sexual contact, and the Tasmanian devil facial tumor disease, transmitted through biting.

In early studies of the leukemia in clams, Dr Goff and his colleagues found high levels of a particular sequence of DNA they named “Steamer.” While normal cells contain only 2 to 5 copies of Steamer, leukemic cells can have 150 copies. The researchers initially thought this difference was the result of a genetic amplification process occurring within each individual clam.

But when the team analyzed the genomes of leukemia cells collected in New York, Maine, and Prince Edward Island, they discovered something else entirely. The cancerous cells they had collected from clams living at different locations were nearly identical to one another at the genetic level.

“We were astonished to realize that the tumors did not arise from the cells of their diseased host animals, but rather from a rogue clonal cell line spreading over huge geographical distances,” Dr Goff said.

The results showed the cells can survive in seawater long enough to reach and sicken a new host. It is not yet known whether this leukemia can spread to other molluscs or whether there are mechanisms that recognize the malignant cells as foreign invaders and attack them.

Dr Goff said there is plenty the researchers don’t know about this leukemia, including when it first arose and how it spreads from one clam to another. They don’t know what role Steamer played in the cancer’s origin, if any. And they don’t know how often these sorts of cancers might arise in molluscs or other marine animals.

But the findings do suggest that transmissible cancers are more common than anyone suspected. ![]()

Regulatory monocytes can inhibit GVHD

Image courtesy of PLOS ONE

Researchers believe they have identified a population of monocytes that can protect against graft-vs-host disease (GVHD).

While analyzing peripheral blood stem cells from healthy donors, the team found CD34+ cells with the features of mature monocytes.

They said these cells are transcriptionally distinct from myeloid and monocytic precursors, but they are similar to mature monocytes and endowed with immunosuppressive properties.

Maud D’Aveni, MD, of INSERM in Paris, France, and colleagues described these cells and their abilities in Science Translational Medicine.

The researchers found that granulocyte colony-stimulating factor mobilized the monocytes, which strongly suppressed the activation of donor T cells.

In fact, patients who received peripheral blood stem cells containing high levels of the monocytes had lower rates of GVHD.

Experiments in mice revealed that the monocytes release nitric oxide, which triggers reactive T cells to self-destruct and activates a subset of T cells that suppress the immune system to produce immune tolerance.

The researchers said these results indicate that boosting this population of monocytes could help prevent GVHD in transplant recipients. ![]()

Image courtesy of PLOS ONE

Researchers believe they have identified a population of monocytes that can protect against graft-vs-host disease (GVHD).

While analyzing peripheral blood stem cells from healthy donors, the team found CD34+ cells with the features of mature monocytes.

They said these cells are transcriptionally distinct from myeloid and monocytic precursors, but they are similar to mature monocytes and endowed with immunosuppressive properties.

Maud D’Aveni, MD, of INSERM in Paris, France, and colleagues described these cells and their abilities in Science Translational Medicine.

The researchers found that granulocyte colony-stimulating factor mobilized the monocytes, which strongly suppressed the activation of donor T cells.

In fact, patients who received peripheral blood stem cells containing high levels of the monocytes had lower rates of GVHD.

Experiments in mice revealed that the monocytes release nitric oxide, which triggers reactive T cells to self-destruct and activates a subset of T cells that suppress the immune system to produce immune tolerance.

The researchers said these results indicate that boosting this population of monocytes could help prevent GVHD in transplant recipients. ![]()

Image courtesy of PLOS ONE

Researchers believe they have identified a population of monocytes that can protect against graft-vs-host disease (GVHD).

While analyzing peripheral blood stem cells from healthy donors, the team found CD34+ cells with the features of mature monocytes.

They said these cells are transcriptionally distinct from myeloid and monocytic precursors, but they are similar to mature monocytes and endowed with immunosuppressive properties.

Maud D’Aveni, MD, of INSERM in Paris, France, and colleagues described these cells and their abilities in Science Translational Medicine.

The researchers found that granulocyte colony-stimulating factor mobilized the monocytes, which strongly suppressed the activation of donor T cells.

In fact, patients who received peripheral blood stem cells containing high levels of the monocytes had lower rates of GVHD.

Experiments in mice revealed that the monocytes release nitric oxide, which triggers reactive T cells to self-destruct and activates a subset of T cells that suppress the immune system to produce immune tolerance.

The researchers said these results indicate that boosting this population of monocytes could help prevent GVHD in transplant recipients. ![]()

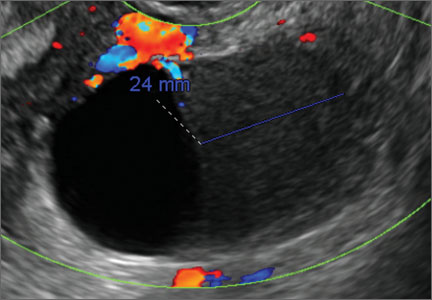

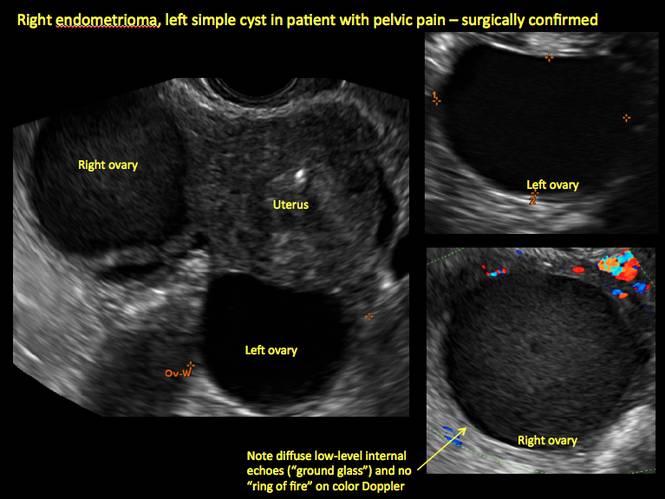

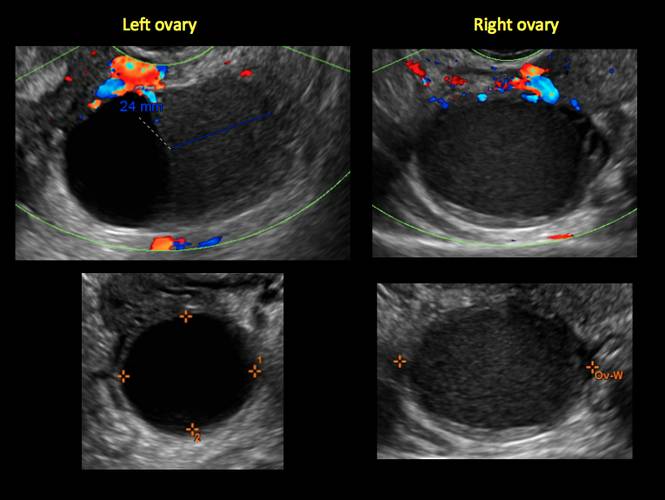

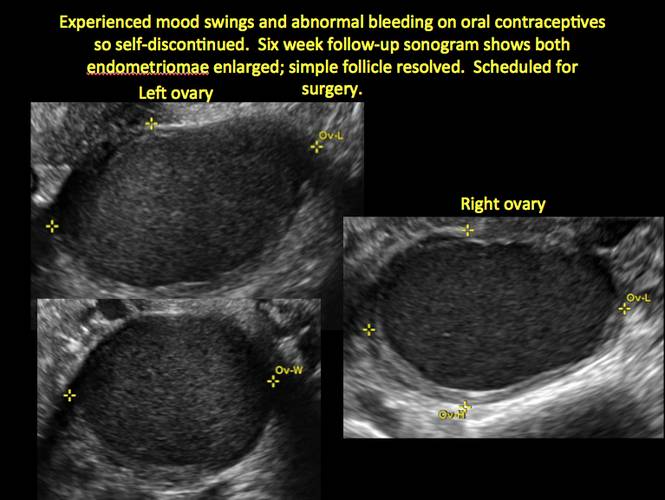

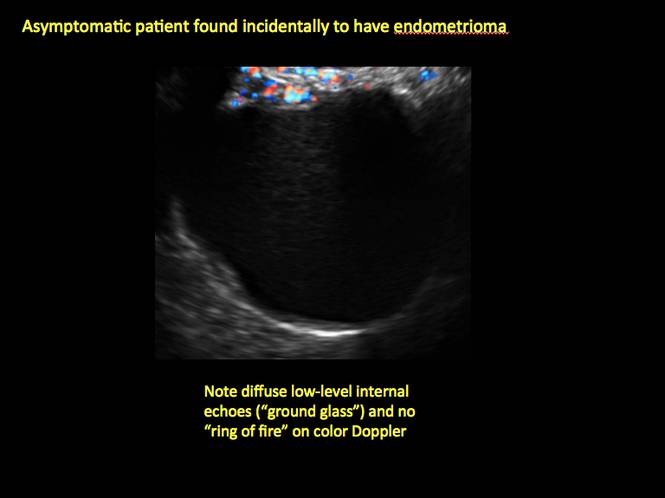

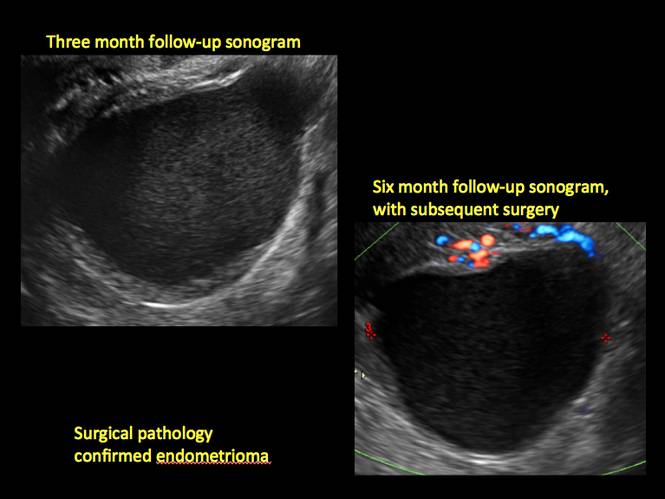

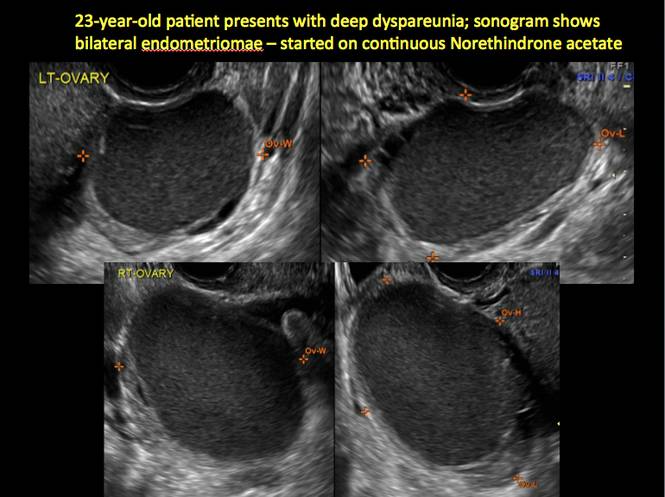

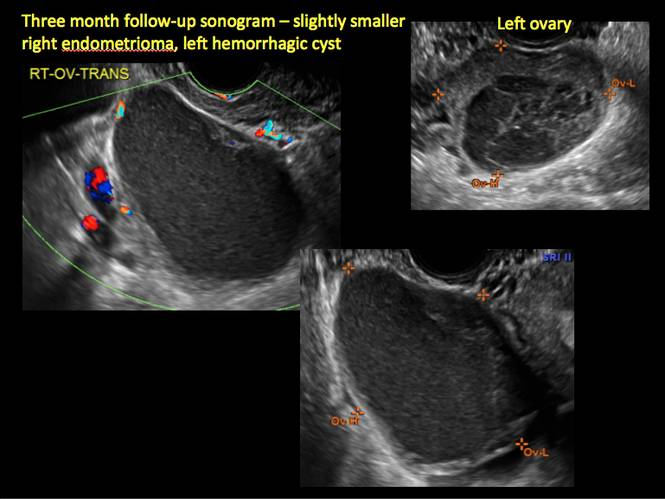

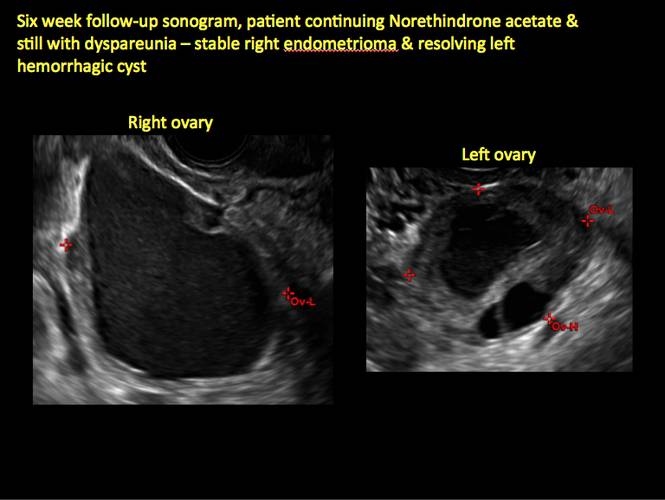

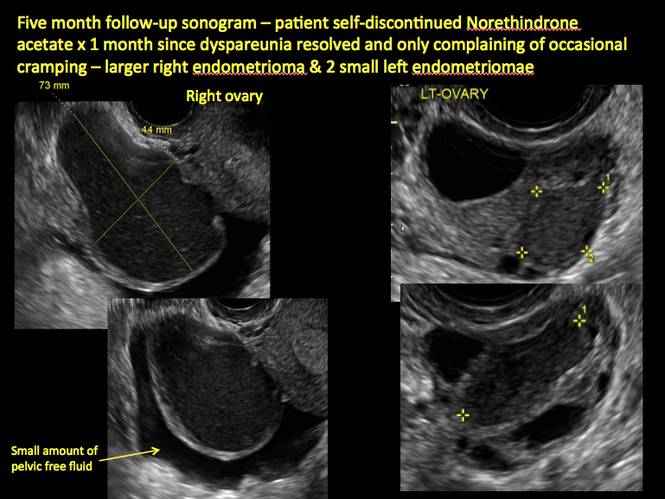

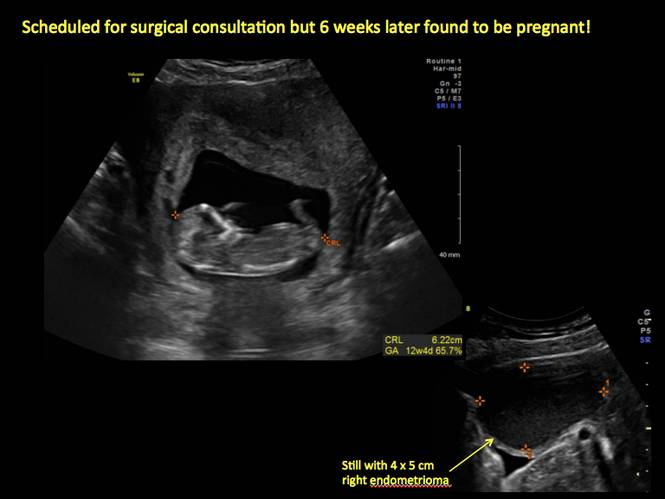

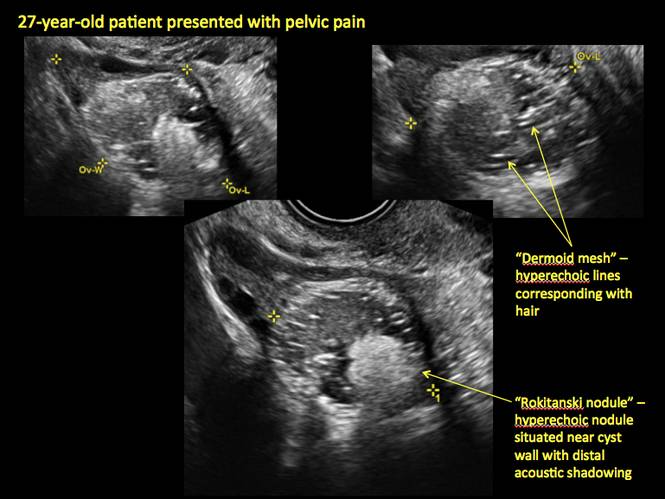

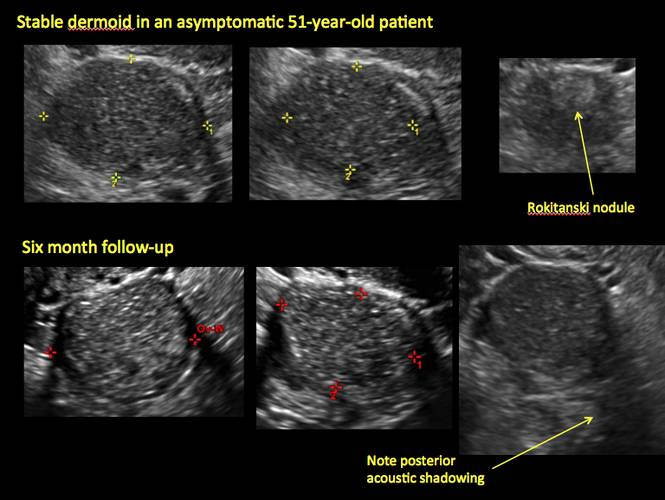

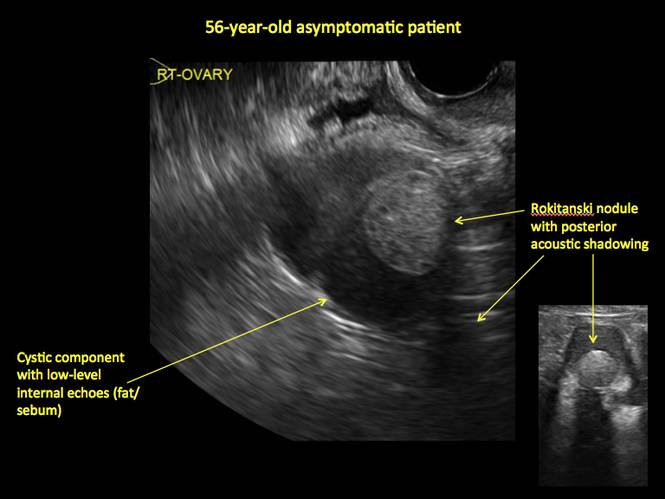

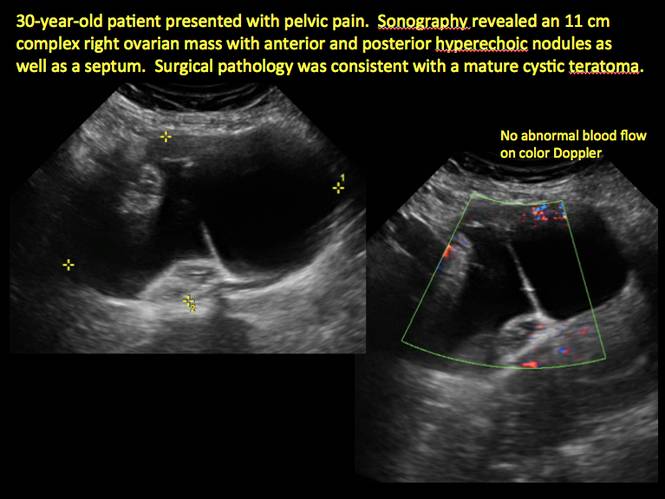

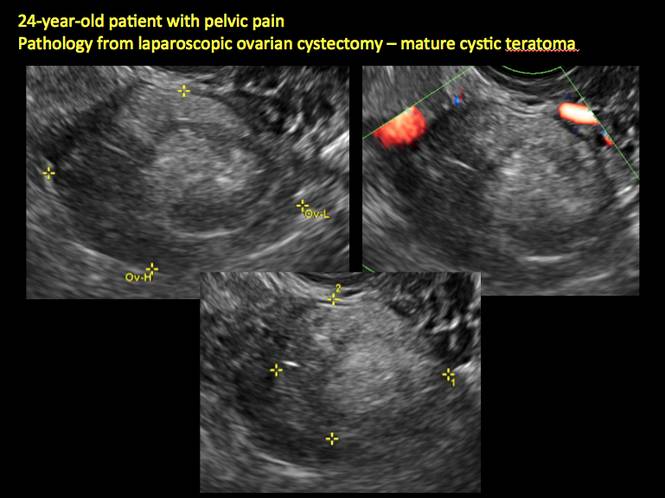

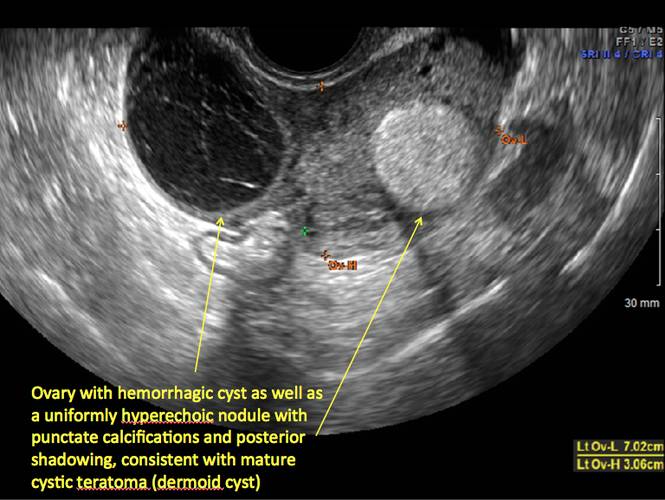

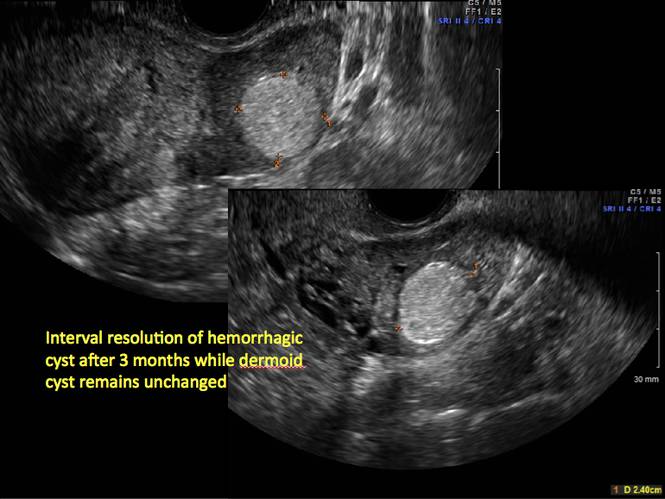

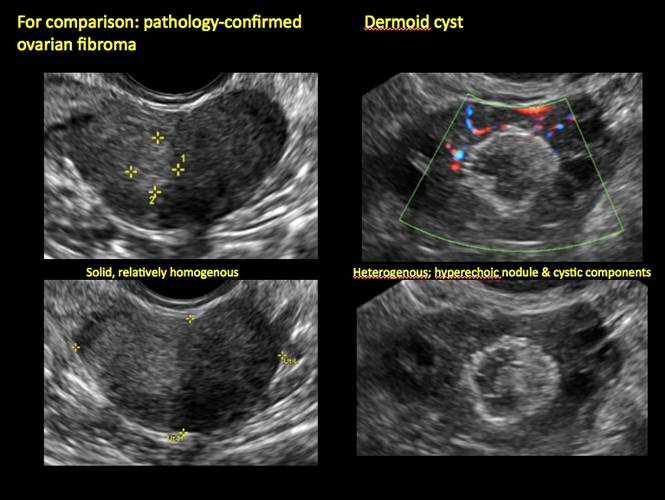

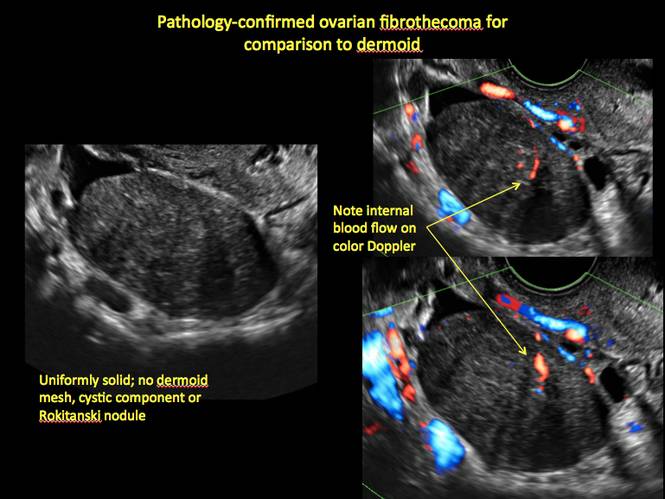

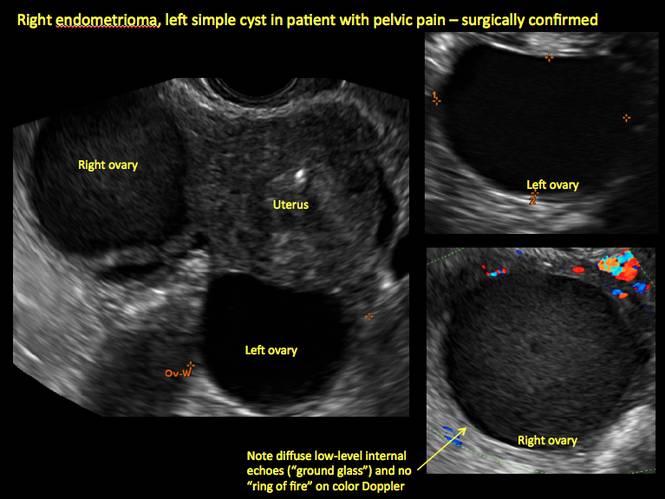

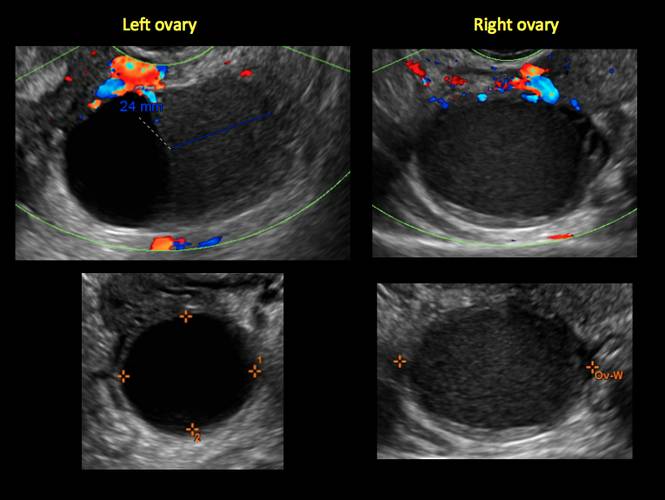

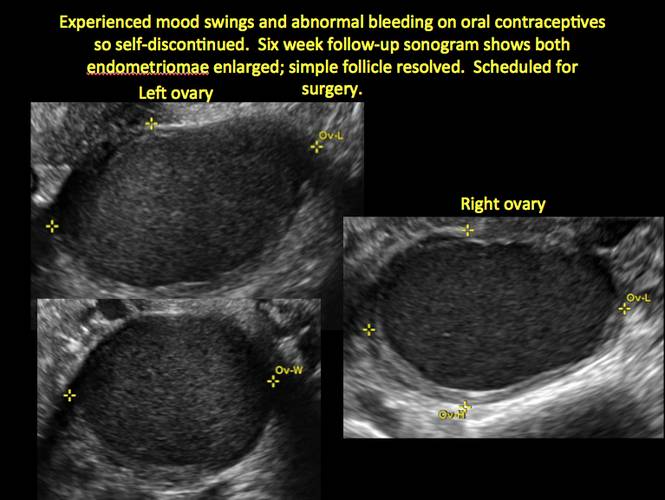

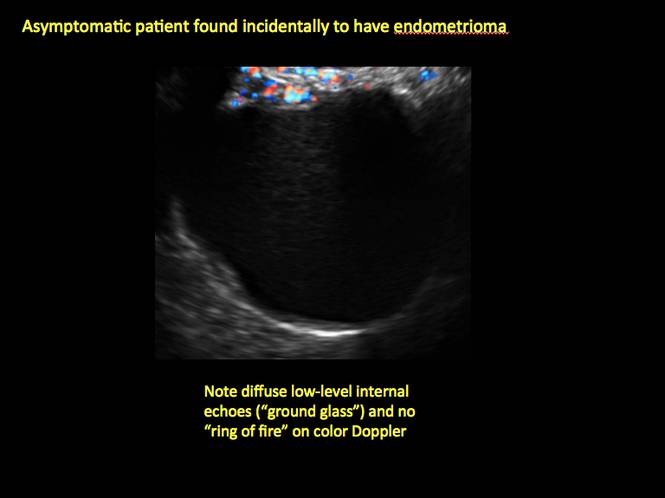

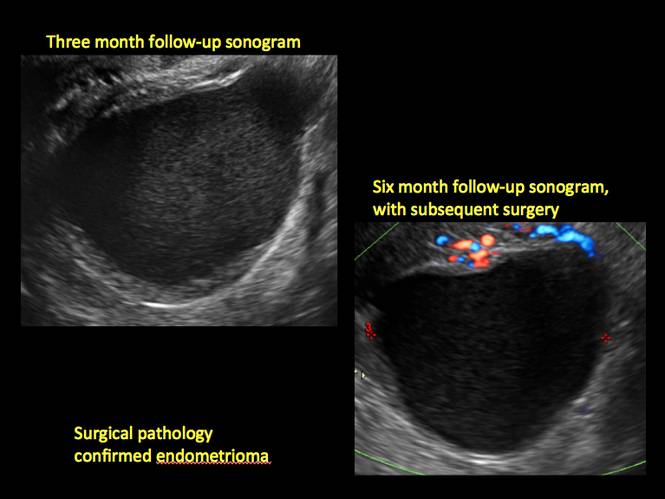

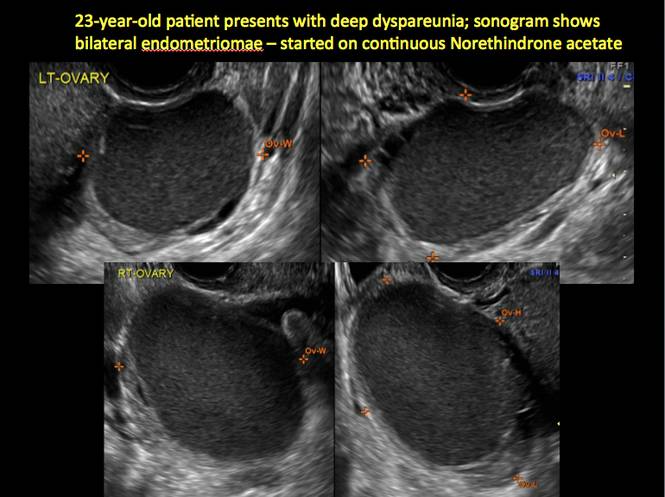

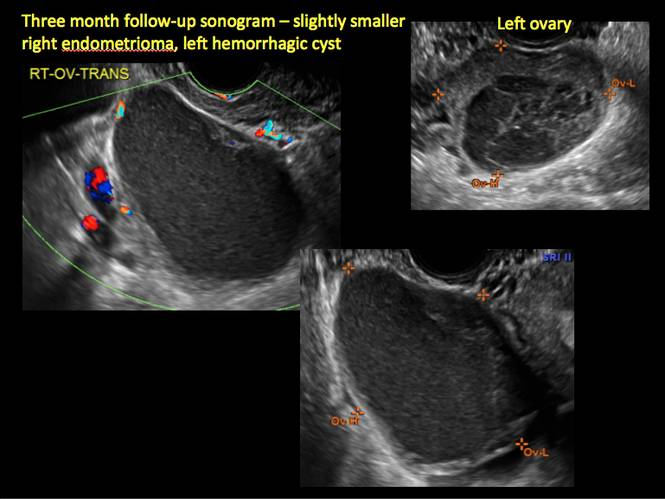

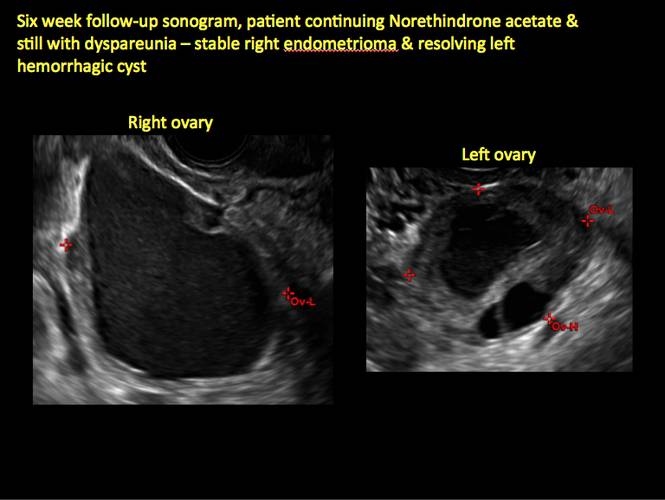

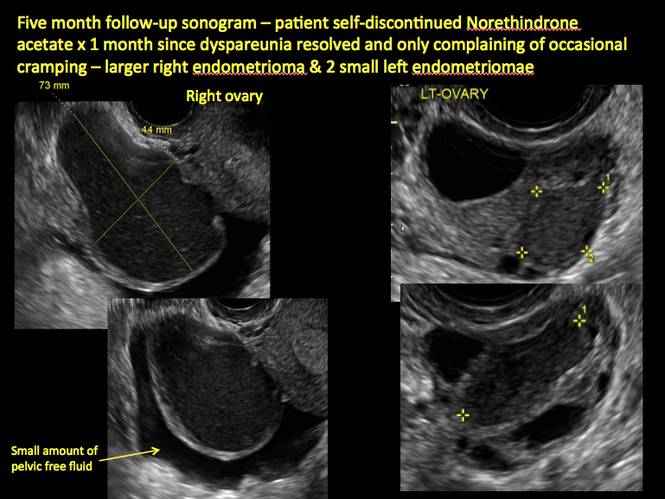

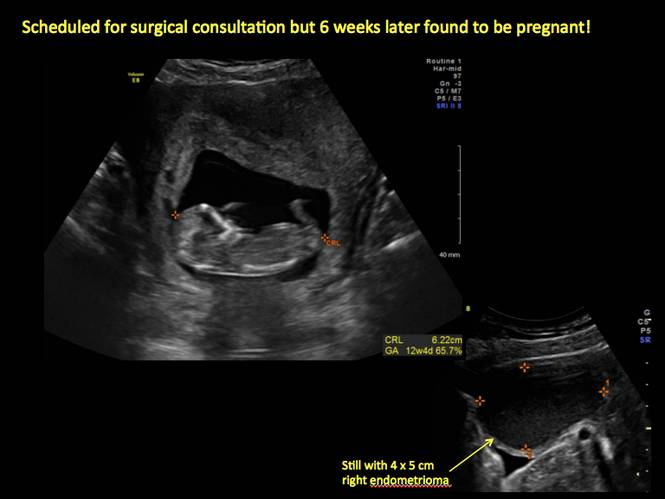

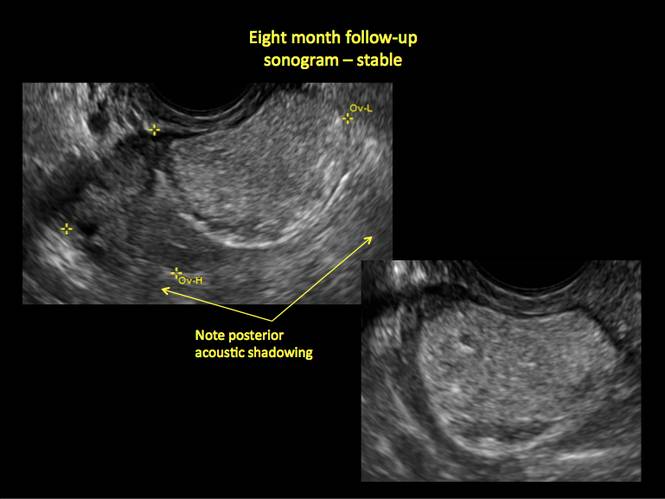

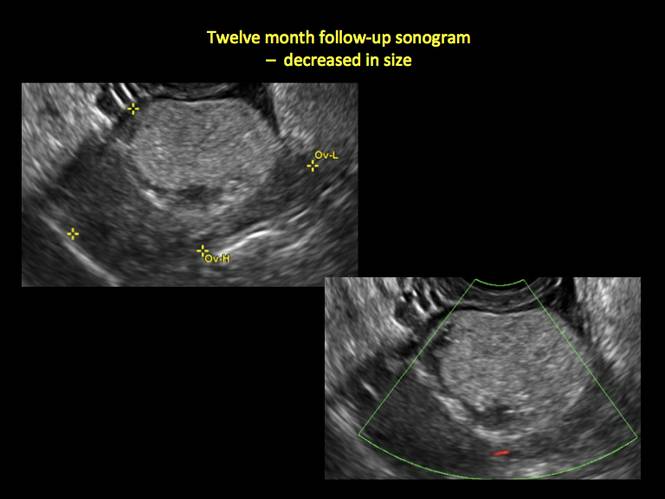

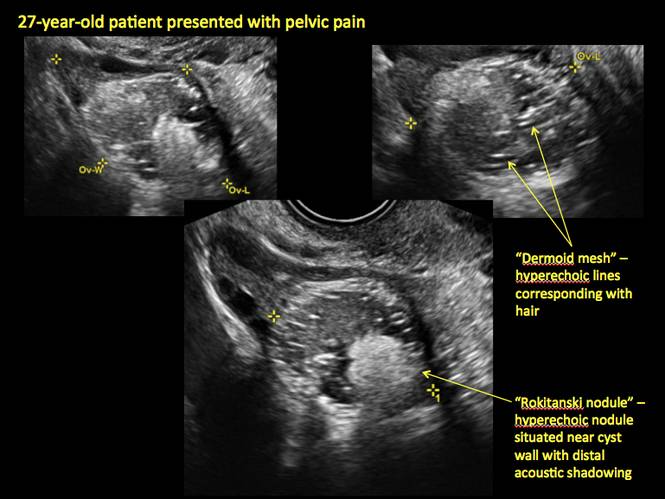

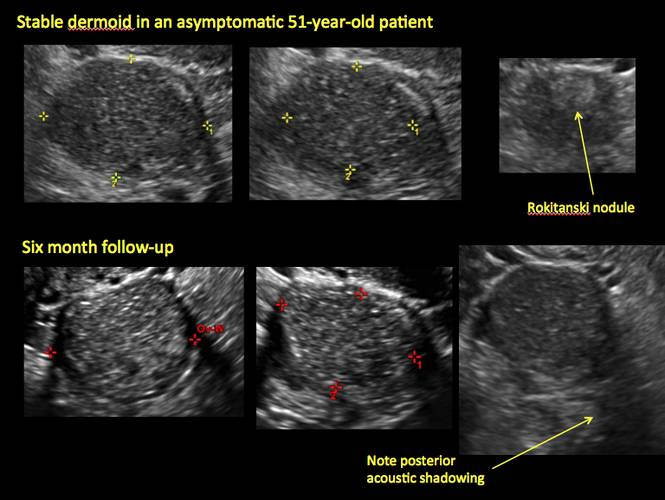

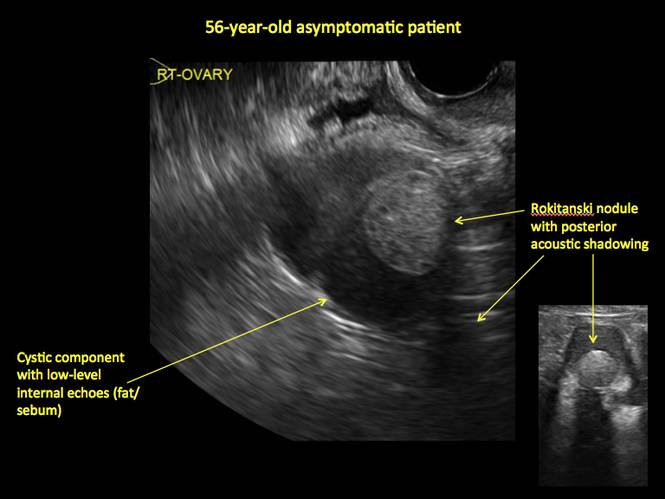

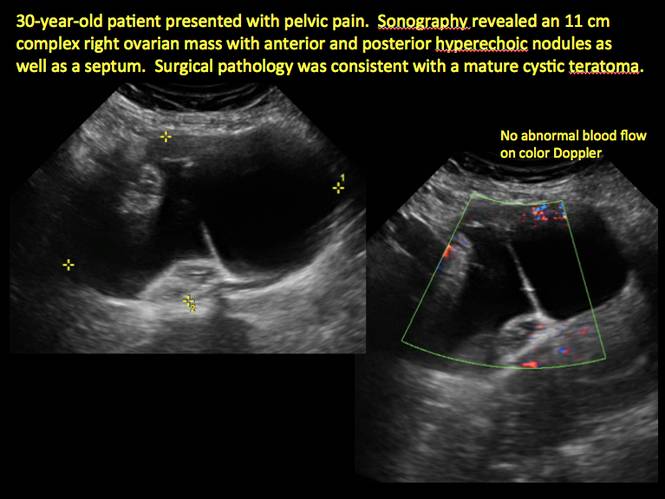

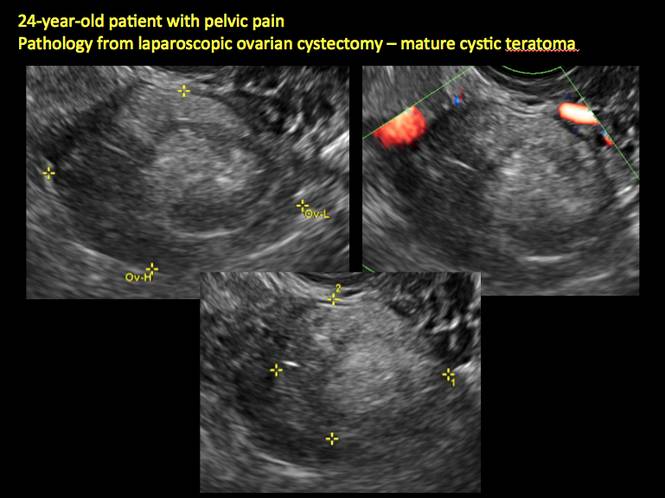

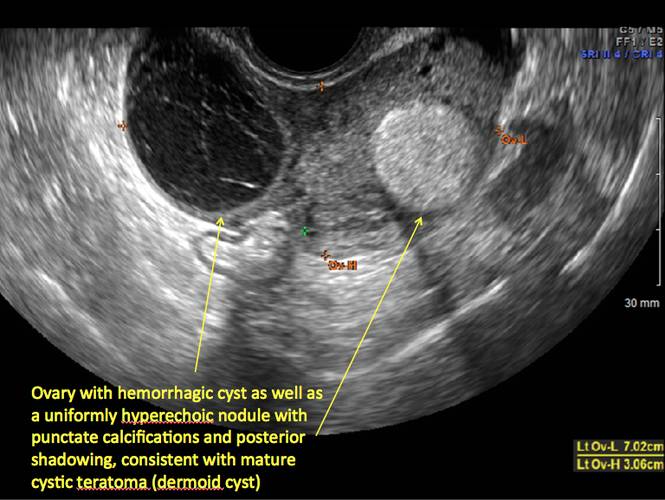

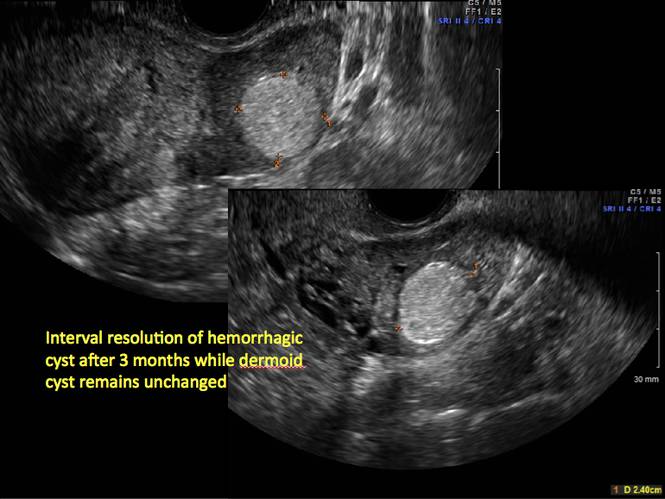

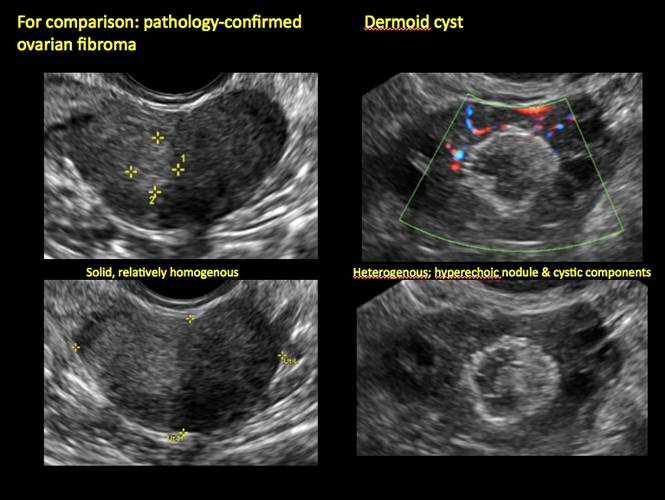

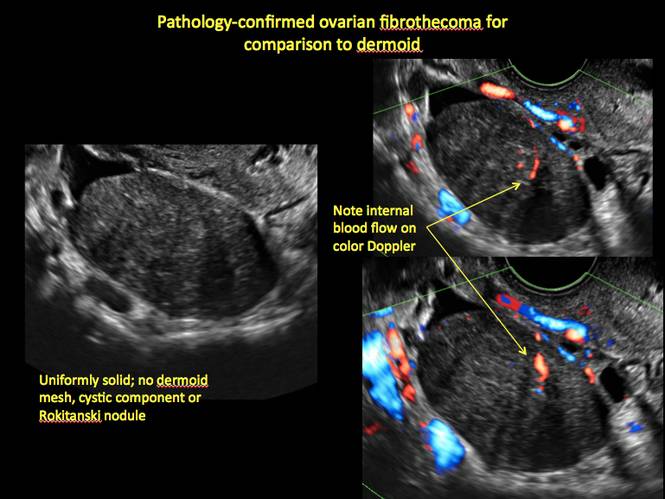

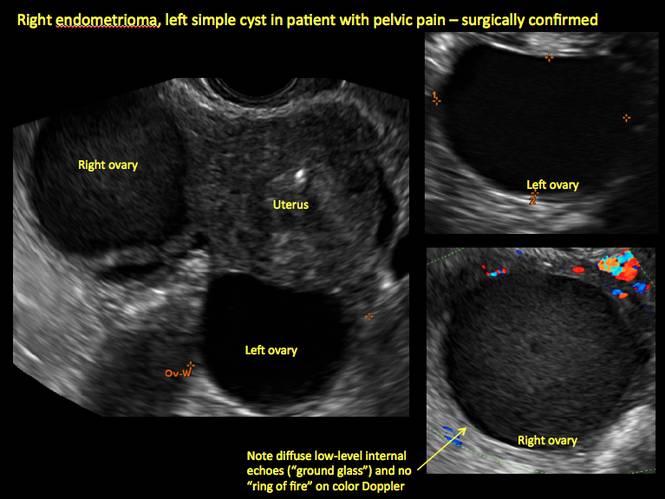

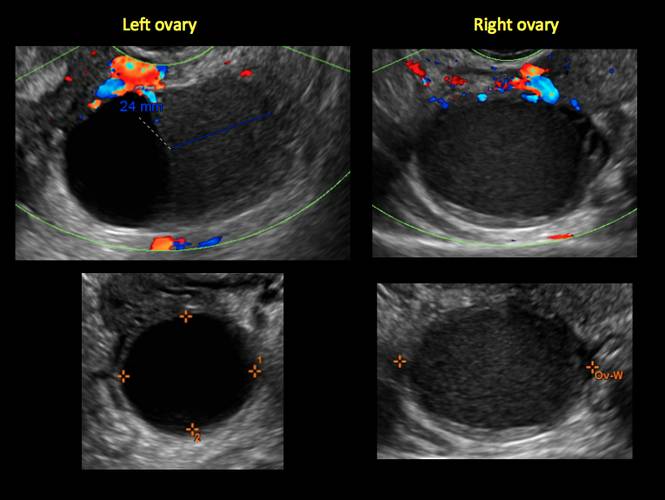

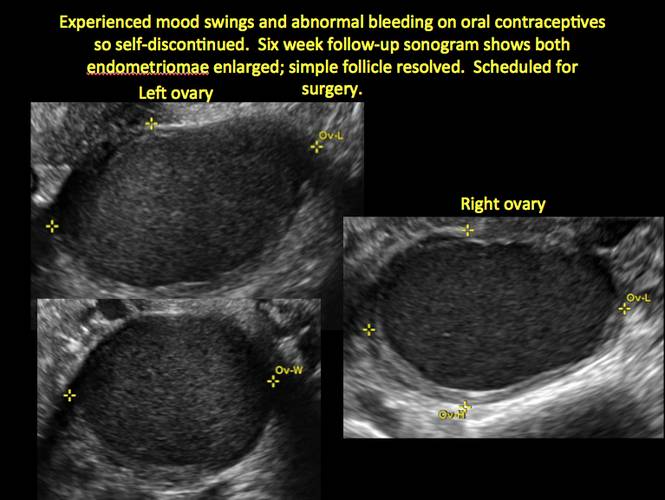

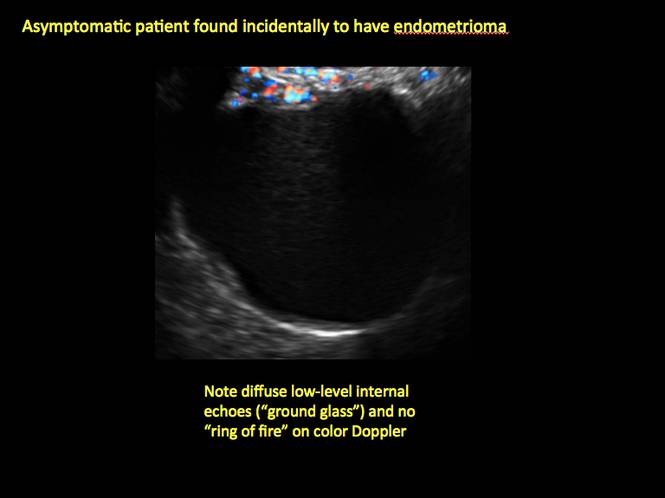

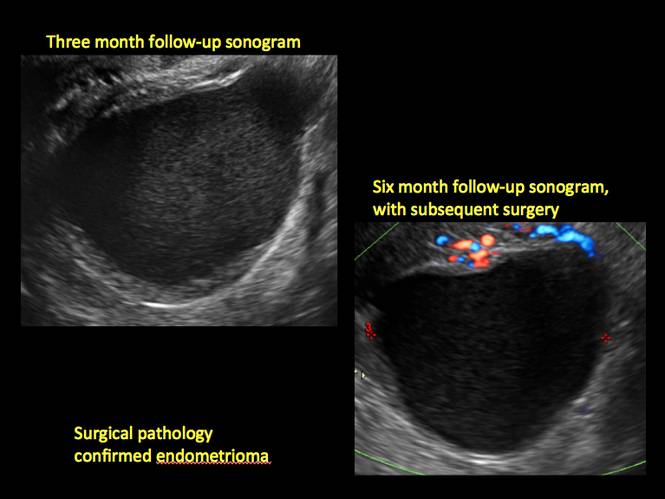

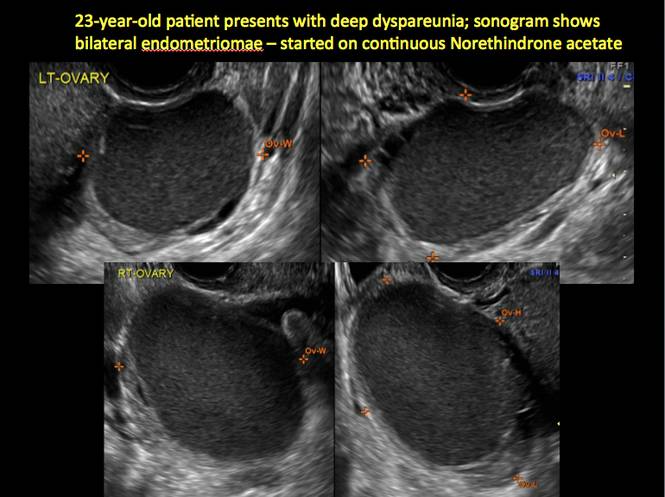

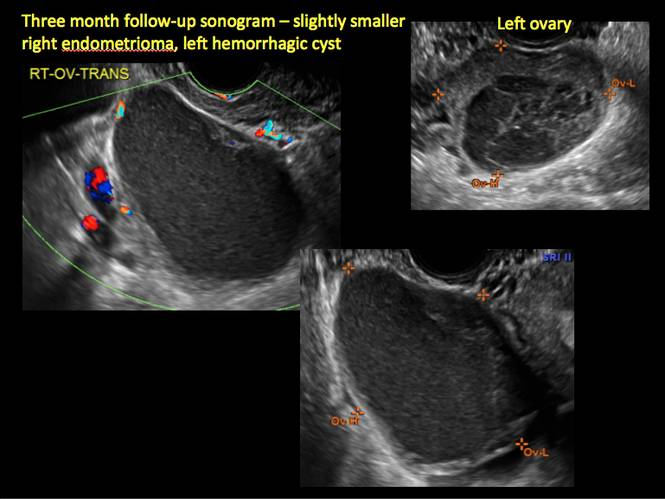

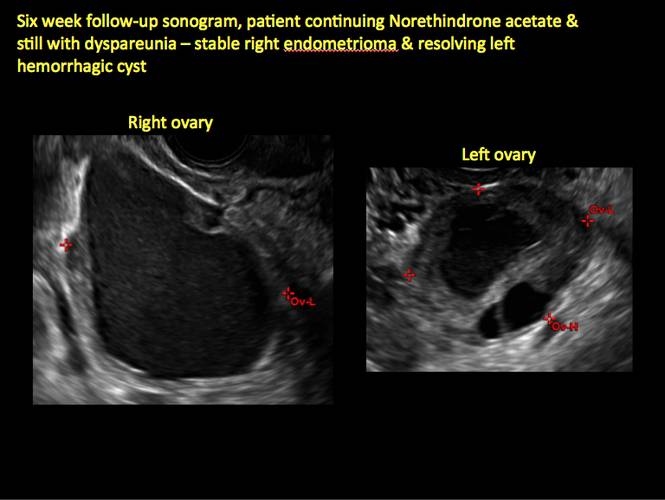

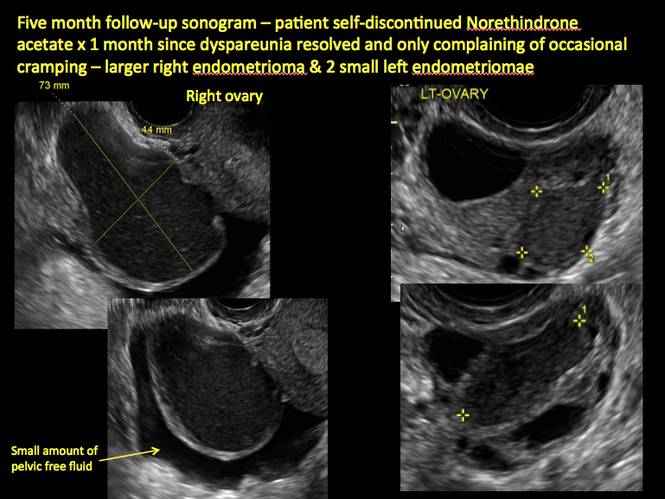

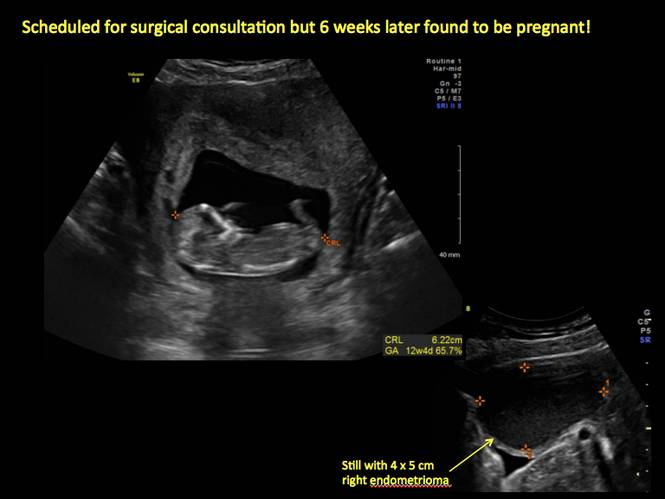

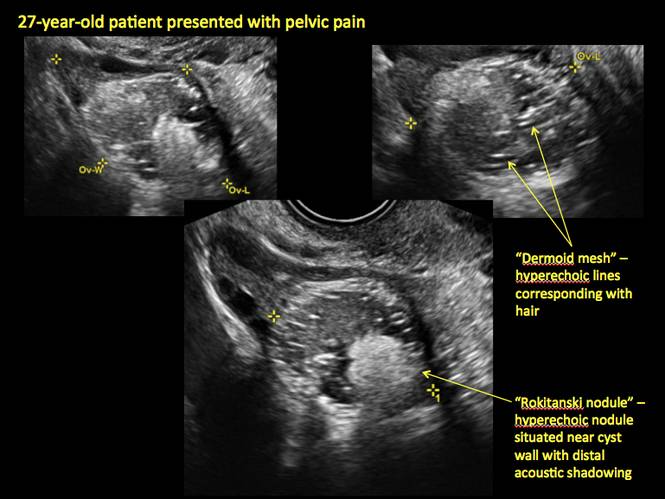

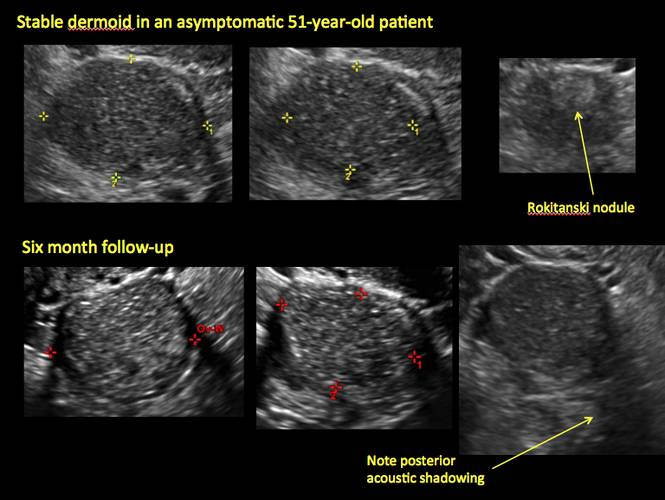

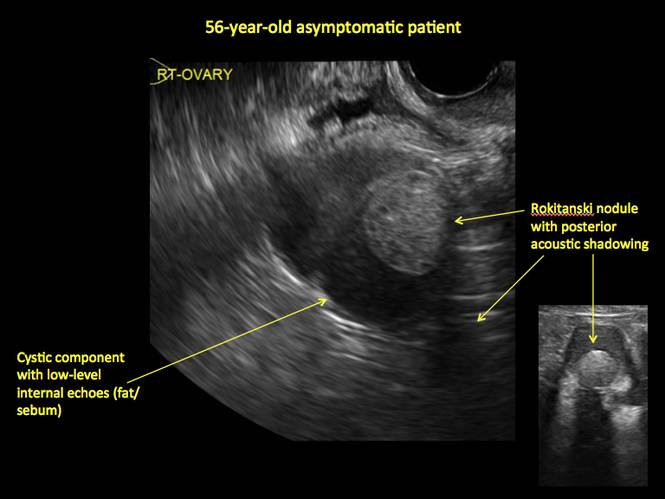

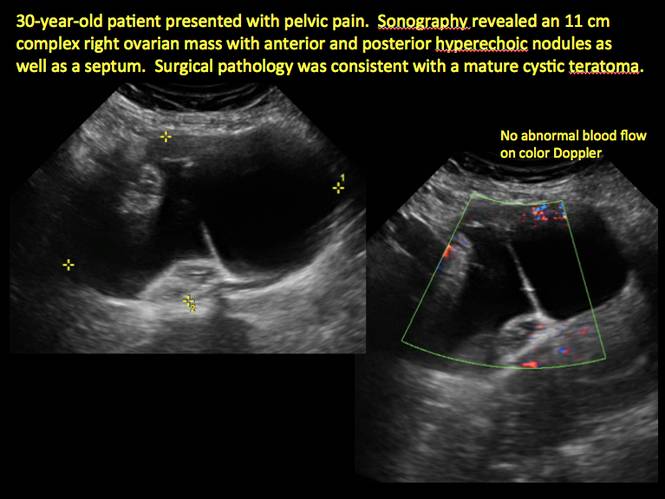

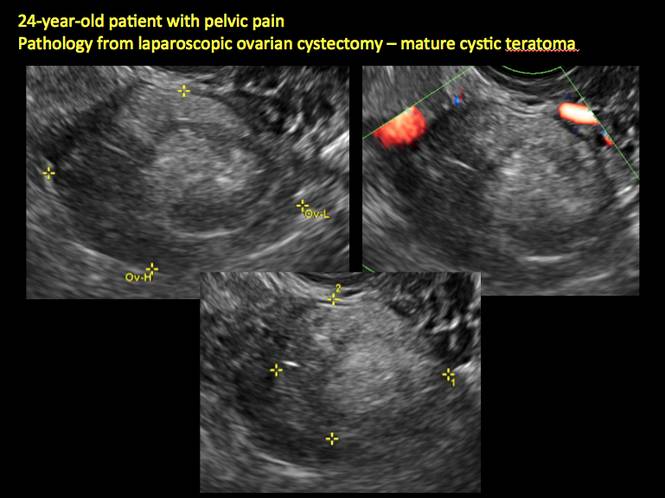

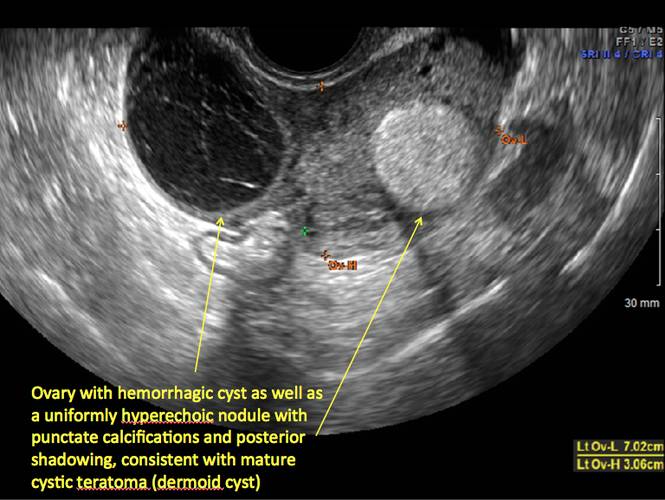

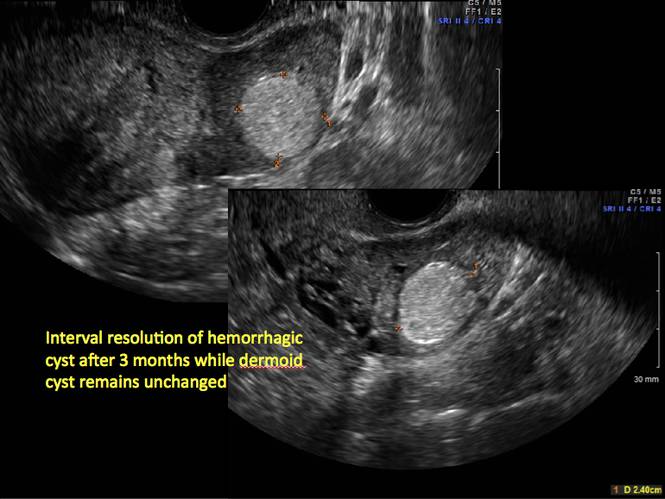

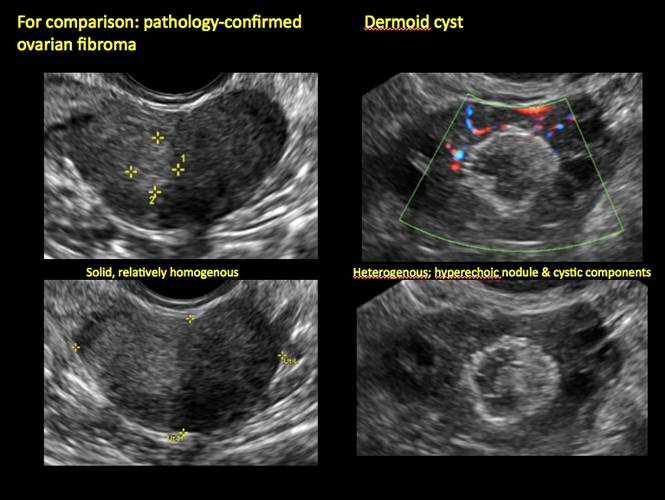

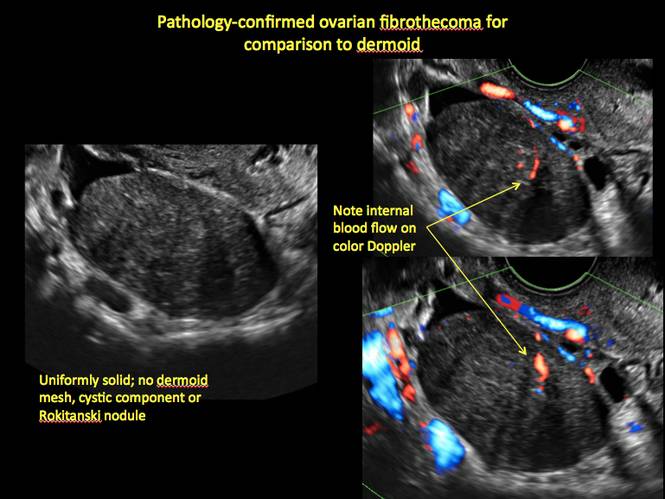

Imaging the endometrioma and mature cystic teratoma

The preferred imaging method to evaluate the majority of adnexal cysts is ultrasonography, which can help characterize the cyst type. Common benign adnexal cyst types include simple, hemorrhagic, endometrioma, and mature teratoma (dermoid cyst). In this part 2 of a 4-part series on cystic adnexal pathology, we focus on imaging signs for, and follow-up of, endometriomas and mature teratomas.

Endometriomas

Endometriomas are common, typically benign, cysts that produce homogenous, low-level internal echoes and a “ground glass” appearance on ultrasonography. No internal flow is apparent on color Doppler. The presence of tiny echogenic wall foci can distinguish an endometrioma from a hemorrhagic cyst.

Rarely, endometriomas may undergo malignant transformation. Usually this occurs with cysts greater than 9 cm and in patients aged 45 years or older. A malignancy often exhibits rapid growth or the development of a solid nodule with flow on color Doppler.

Management

Although surgery remains the first-line management for women with symptomatic or enlarging endometriomas, there appears to be a role for sonographic observation, with continuous progestational treatment, in women with small (< 5 cm) asymptomatic endometriomas.

The Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound 2010 Consensus Conference Statement recommended1:

- Short-interval follow-up (6 to 12 weeks) in reproductive-aged women to ensure acute hemorrhagic cysts are not mistaken for endometriomas

- If not removed surgically, sonographic follow-up is recommended, with frequency of follow up based on patient age and symptoms and cyst size and characteristics.

In FIGURES 1 through 11 (slides of image collections), we present several cases, including one of a 25-year-old patient presenting with pelvic pain and dyspareunia who was later found to have bilateral endometriomas.

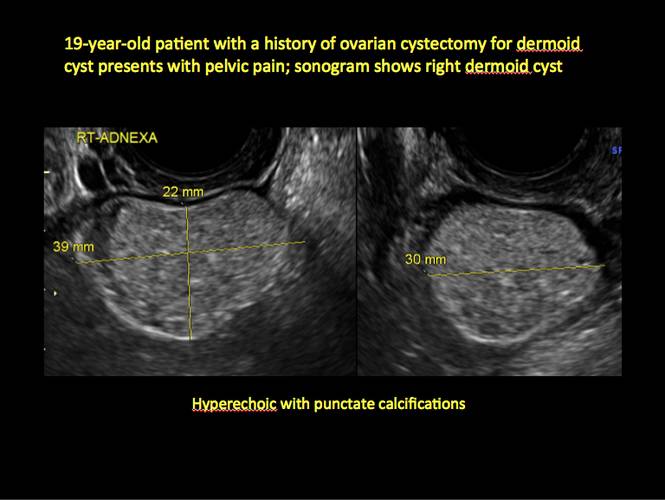

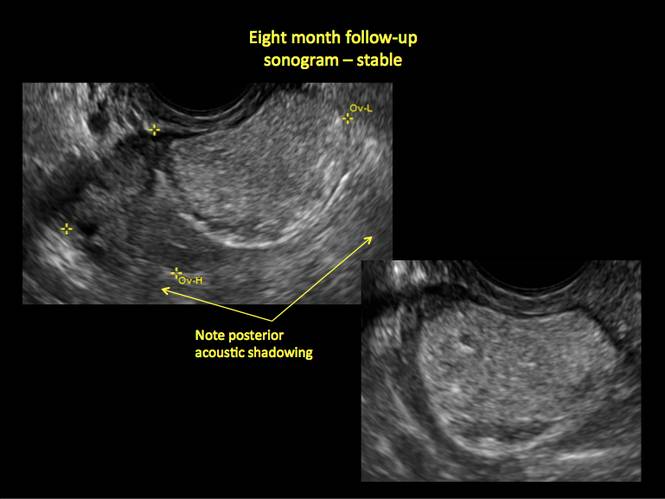

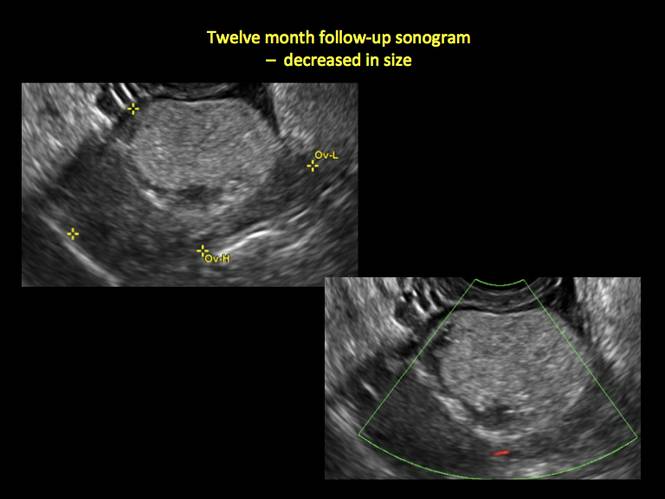

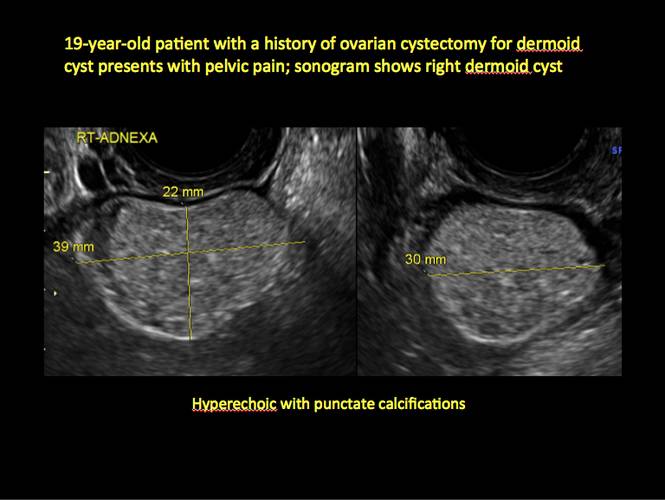

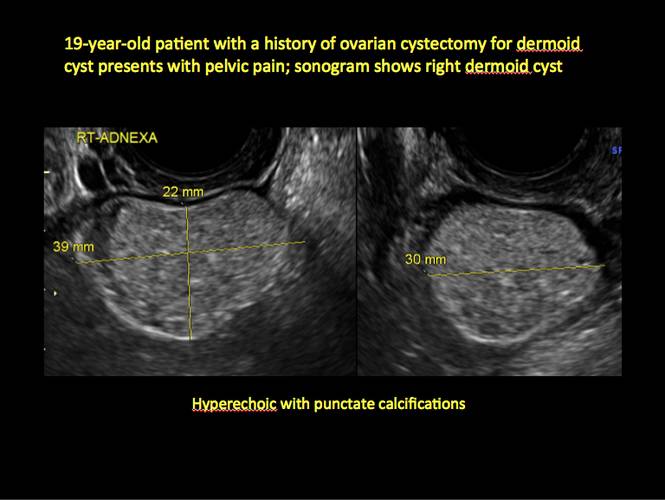

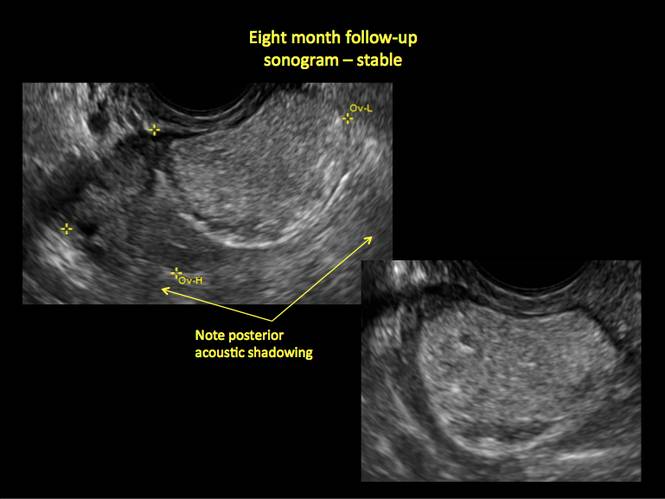

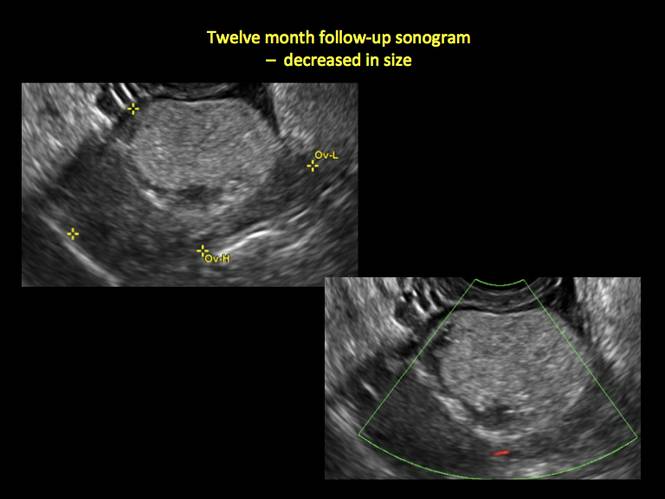

Mature teratomas

Mature cystic teratomas display several telltale signs on imaging, including:

- hyperechoic lines/dots (“dermoid mesh”) corresponding to hair/skeletal components

- “Rokitanski nodule” – a peripherally placed mass of sebum, bones, and hair

- posterior acoustic shadowing

- cystic or floating spherical structures

- no internal flow on color Doppler

Rarely, dermoid cysts may undergo malignant transformation. Usually this occurs in cysts greater than 10 cm and in patients aged 50 years or older. Internal flow on color Doppler, branching, or invasion into adjacent structures can indicate malignancy.

Management

The traditional treatment for dermoid cysts is surgical. However, given the ability for accurate diagnosis with vaginal ultrasonography, there appears to be a role for sonographic observation in asymptomatic women with small dermoids.2

If the cyst is not surgically removed, the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound 2010 Consensus Conference Statement recommended initial sonographic follow up at no more than 6 months to 1 year to ensure no change in size or internal architecture.1

In FIGURES 12 through 24 below (slides of image collections), we offer imaging from the case presentation and follow-up of a 19-year-old patient with pelvic pain who has a history of ovarian cystectomy for dermoid cyst, as well as 6 additional case illustrations.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 9

Figure 10

Figure 11

Figure 12

Figure 13

Figure 14

Figure 15

Figure 16

Figure 17

Figure 18

Figure 19

Figure 20

Figure 21

Figure 22

Figure 23

Figure 24

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Levine D, Brown DL, Andreotti RF, et al. Management of asymptomatic ovarian and other adnexal cysts imaged at US: Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound Consensus Conference Statement. Radiology. 2010;256(3):943–954.

2. Hoo WL, Yazbek WL, Holland T, Mavrelos D, Tong EN, Jurkovic D. Expectant management of ultrasonically diagnosed ovarian dermoid cysts: is it possible to predict outcome? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;36(2): 235–240.

The preferred imaging method to evaluate the majority of adnexal cysts is ultrasonography, which can help characterize the cyst type. Common benign adnexal cyst types include simple, hemorrhagic, endometrioma, and mature teratoma (dermoid cyst). In this part 2 of a 4-part series on cystic adnexal pathology, we focus on imaging signs for, and follow-up of, endometriomas and mature teratomas.

Endometriomas

Endometriomas are common, typically benign, cysts that produce homogenous, low-level internal echoes and a “ground glass” appearance on ultrasonography. No internal flow is apparent on color Doppler. The presence of tiny echogenic wall foci can distinguish an endometrioma from a hemorrhagic cyst.

Rarely, endometriomas may undergo malignant transformation. Usually this occurs with cysts greater than 9 cm and in patients aged 45 years or older. A malignancy often exhibits rapid growth or the development of a solid nodule with flow on color Doppler.

Management

Although surgery remains the first-line management for women with symptomatic or enlarging endometriomas, there appears to be a role for sonographic observation, with continuous progestational treatment, in women with small (< 5 cm) asymptomatic endometriomas.

The Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound 2010 Consensus Conference Statement recommended1:

- Short-interval follow-up (6 to 12 weeks) in reproductive-aged women to ensure acute hemorrhagic cysts are not mistaken for endometriomas

- If not removed surgically, sonographic follow-up is recommended, with frequency of follow up based on patient age and symptoms and cyst size and characteristics.

In FIGURES 1 through 11 (slides of image collections), we present several cases, including one of a 25-year-old patient presenting with pelvic pain and dyspareunia who was later found to have bilateral endometriomas.

Mature teratomas

Mature cystic teratomas display several telltale signs on imaging, including:

- hyperechoic lines/dots (“dermoid mesh”) corresponding to hair/skeletal components

- “Rokitanski nodule” – a peripherally placed mass of sebum, bones, and hair

- posterior acoustic shadowing

- cystic or floating spherical structures

- no internal flow on color Doppler

Rarely, dermoid cysts may undergo malignant transformation. Usually this occurs in cysts greater than 10 cm and in patients aged 50 years or older. Internal flow on color Doppler, branching, or invasion into adjacent structures can indicate malignancy.

Management

The traditional treatment for dermoid cysts is surgical. However, given the ability for accurate diagnosis with vaginal ultrasonography, there appears to be a role for sonographic observation in asymptomatic women with small dermoids.2

If the cyst is not surgically removed, the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound 2010 Consensus Conference Statement recommended initial sonographic follow up at no more than 6 months to 1 year to ensure no change in size or internal architecture.1

In FIGURES 12 through 24 below (slides of image collections), we offer imaging from the case presentation and follow-up of a 19-year-old patient with pelvic pain who has a history of ovarian cystectomy for dermoid cyst, as well as 6 additional case illustrations.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 9

Figure 10

Figure 11

Figure 12

Figure 13

Figure 14

Figure 15

Figure 16

Figure 17

Figure 18

Figure 19

Figure 20

Figure 21

Figure 22

Figure 23

Figure 24

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

The preferred imaging method to evaluate the majority of adnexal cysts is ultrasonography, which can help characterize the cyst type. Common benign adnexal cyst types include simple, hemorrhagic, endometrioma, and mature teratoma (dermoid cyst). In this part 2 of a 4-part series on cystic adnexal pathology, we focus on imaging signs for, and follow-up of, endometriomas and mature teratomas.

Endometriomas

Endometriomas are common, typically benign, cysts that produce homogenous, low-level internal echoes and a “ground glass” appearance on ultrasonography. No internal flow is apparent on color Doppler. The presence of tiny echogenic wall foci can distinguish an endometrioma from a hemorrhagic cyst.

Rarely, endometriomas may undergo malignant transformation. Usually this occurs with cysts greater than 9 cm and in patients aged 45 years or older. A malignancy often exhibits rapid growth or the development of a solid nodule with flow on color Doppler.

Management

Although surgery remains the first-line management for women with symptomatic or enlarging endometriomas, there appears to be a role for sonographic observation, with continuous progestational treatment, in women with small (< 5 cm) asymptomatic endometriomas.

The Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound 2010 Consensus Conference Statement recommended1:

- Short-interval follow-up (6 to 12 weeks) in reproductive-aged women to ensure acute hemorrhagic cysts are not mistaken for endometriomas

- If not removed surgically, sonographic follow-up is recommended, with frequency of follow up based on patient age and symptoms and cyst size and characteristics.

In FIGURES 1 through 11 (slides of image collections), we present several cases, including one of a 25-year-old patient presenting with pelvic pain and dyspareunia who was later found to have bilateral endometriomas.

Mature teratomas

Mature cystic teratomas display several telltale signs on imaging, including:

- hyperechoic lines/dots (“dermoid mesh”) corresponding to hair/skeletal components

- “Rokitanski nodule” – a peripherally placed mass of sebum, bones, and hair

- posterior acoustic shadowing

- cystic or floating spherical structures

- no internal flow on color Doppler

Rarely, dermoid cysts may undergo malignant transformation. Usually this occurs in cysts greater than 10 cm and in patients aged 50 years or older. Internal flow on color Doppler, branching, or invasion into adjacent structures can indicate malignancy.

Management

The traditional treatment for dermoid cysts is surgical. However, given the ability for accurate diagnosis with vaginal ultrasonography, there appears to be a role for sonographic observation in asymptomatic women with small dermoids.2

If the cyst is not surgically removed, the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound 2010 Consensus Conference Statement recommended initial sonographic follow up at no more than 6 months to 1 year to ensure no change in size or internal architecture.1

In FIGURES 12 through 24 below (slides of image collections), we offer imaging from the case presentation and follow-up of a 19-year-old patient with pelvic pain who has a history of ovarian cystectomy for dermoid cyst, as well as 6 additional case illustrations.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 9

Figure 10

Figure 11

Figure 12

Figure 13

Figure 14

Figure 15

Figure 16

Figure 17

Figure 18

Figure 19

Figure 20

Figure 21

Figure 22

Figure 23

Figure 24

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Levine D, Brown DL, Andreotti RF, et al. Management of asymptomatic ovarian and other adnexal cysts imaged at US: Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound Consensus Conference Statement. Radiology. 2010;256(3):943–954.

2. Hoo WL, Yazbek WL, Holland T, Mavrelos D, Tong EN, Jurkovic D. Expectant management of ultrasonically diagnosed ovarian dermoid cysts: is it possible to predict outcome? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;36(2): 235–240.

1. Levine D, Brown DL, Andreotti RF, et al. Management of asymptomatic ovarian and other adnexal cysts imaged at US: Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound Consensus Conference Statement. Radiology. 2010;256(3):943–954.

2. Hoo WL, Yazbek WL, Holland T, Mavrelos D, Tong EN, Jurkovic D. Expectant management of ultrasonically diagnosed ovarian dermoid cysts: is it possible to predict outcome? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;36(2): 235–240.

Try exposure therapy, SSRIs for PTSD

LAS VEGAS– There is no cure for posttraumatic stress disorder, but helping its sufferers reduce symptoms, improve resistance, and achieve a better quality of life is possible.

“We have no idea what the best treatments are for PTSD,” Dr. Charles B. Nemeroff, the Leonard M. Miller Professor, and chairman of the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of Miami, told an audience at the annual psychopharmacology update held by the Nevada Psychiatric Association.

Whether to rely upon psychosocial or pharmacologic interventions, or a combination of the two, to help shift PTSD from a debilitating condition into a manageable, chronic one, it is important to understand PTSD as a brain disease. “To accurately treat PTSD, consider it within a neurobiological context,” Dr. Nemeroff said. “Ordinarily, the brain is evolved to deal with stress, but it can be compromised.”

In chronic PTSD, brain studies have shown a noted shrinkage in the hippocampus, contributing to memory impairment, similar to the reduced hippocampal volume in child-abuse victims. Additionally, cortical function in the brain is affected in PTSD, creating difficulty with exercising judgment and good decision making.

“One way to think about PTSD is that the cortex is unable to reign in the limbic system,” Dr. Nemeroff said. “The hippocampus is impaired, the amygdala is hyperactive, and there is a tremendous emotional drive, so the ‘thinking’ part of the brain can’t [overcome] the emotional, reptilian brain.”

The result is that a person remains stuck in a hyperaroused state. “We know that the neurobiological basis for PTSD involves a prolonged, vigilant response to stress [involving] a multitude of brain circuits ... and of course the sympathetic nervous system and the pituitary and adrenal systems,” Dr. Nemeroff said.

Beyond brain changes, a genetic predisposition to PTSD accounts for a third of all cases, while an additional one-third are attributable to additional biological risk factors, according to Dr. Nemeroff (Nature 2011;470:492-7).

Just as with all anxiety-related disorders, women are more PTSD susceptible than are men. One of the “few things everybody agrees on,” Dr. Nemeroff said, is that early-life trauma such as neglect or abuse is a definite risk factor for PTSD, in part because early-life stress is thought to permanently program the brain regions involved in stress- and anxiety-mediation. Add to that, any adult level trauma, and they two “synergize. The more adult trauma coupled with early childhood abuse or neglect, the higher the level of PTSD.”

Meanwhile, poor social support, especially after the occurrence of a traumatic event, is a traditional prognosticator of poor recovery from PTSD, as are a family history of mood disorders, lower I.Q. and education, and experiencing other stressors the year before or after a traumatic event.

Dr. Nemeroff said that although the goals of treatment are reduced core symptoms, improved quality of life and function, strength, and resilience against subsequent stress, “the sad fact of the matter is that we don’t have a clue what the best treatment is, because we have no predictors of treatment response for PTSD.”

The most common treatments for PTSD are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), although the best data available suggest that prolonged imaginal exposure therapy is the most effective, Dr. Nemeroff said. It can be provided either virtually or in person, and includes breathing techniques, psychoeducation, and cognitive therapy. The Institute of Medicine gives exposure therapy its highest rating for scientific evidence, said Dr. Nemeroff, who is a board member of the institute.

Pharmacologic treatments approved by the Food and Drug Administration for PTSD treatment include sertraline and paroxetine, although other antidepressants can be prescribed off-label to some effect.

With sertraline, there is a “pretty low bar” of efficacy, according to Dr. Nemeroff, since only a 30% improvement in symptoms was recorded in 60% of study participants for FDA approval. It’s important to remember the treatment-response in PTSD is much slower than in major depression, Dr. Nemeroff said. “It can take as much as 9 months, so don’t give up.”

Combining sertraline with prolonged exposure therapy is even more effective, he said (J. Trauma Stress 2006;19:625-38). Meanwhile, other data show what paroxetine alone performed better than placebo, but the data are mixed for the drug in combination with prolonged exposure therapy (Am. J. Psychiatry 2012;169:80-8), (J. Clin. Psychiatry 2008;69:400-5), (J. Clin. Neurosci. 2008;62:646-52), and (Am. J. Psychiatry 2001;158:1982-8).

Dr. Nemeroff said lately, he has been treating PTSD patients with venlafaxine 450 mg, which is much higher than the usual dose of about 220 mg, with “considerably good results” (Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2006;63:1158-65).

Improvements in memory and hippocampal volume generally are found with SSRI treatments, as well as reductions in symptom severity, according to Dr. Nemeroff.

For PTSD patients who are struggling with insomnia and other sleep-related problems, Dr. Nemeroff said prazosin has been “phenomenal,” especially in reducing nightmares (Am. J. Psychiatry 2013;170:1003-10).

One drug class to avoid using with PTSD patients is benzodiazepines, he said. “Every study has shown that benzodiazepines in PTSD do not work, and they come with a high rate of substance abuse in this population.”

*Dr. Nemeroff disclosed that he receives research and grant support from the National Institutes of Health. He also serves as a consultant for several companies, including Xhale, Takeda, SK Pharma, Shire, Roche, Lilly, Allergan, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Development America, Taisho Pharmaceutical, Lundbeck, Prismic Pharmaceuticals, and Clintara LLC. He is a stockholder in Xhale, Celgene, Seattle Genetics, Abbvie, Titan Pharmaceuticals, and OPKO Health.

In addition, he holds financial/proprietary interest in patents for method/devices for the transdermal delivery of lithium and for a method of assessing antidepressant drug therapy.

*Correction, 4/10/2015: An earlier version of this story misstated Dr. Nemeroff's disclosures.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

LAS VEGAS– There is no cure for posttraumatic stress disorder, but helping its sufferers reduce symptoms, improve resistance, and achieve a better quality of life is possible.

“We have no idea what the best treatments are for PTSD,” Dr. Charles B. Nemeroff, the Leonard M. Miller Professor, and chairman of the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of Miami, told an audience at the annual psychopharmacology update held by the Nevada Psychiatric Association.

Whether to rely upon psychosocial or pharmacologic interventions, or a combination of the two, to help shift PTSD from a debilitating condition into a manageable, chronic one, it is important to understand PTSD as a brain disease. “To accurately treat PTSD, consider it within a neurobiological context,” Dr. Nemeroff said. “Ordinarily, the brain is evolved to deal with stress, but it can be compromised.”

In chronic PTSD, brain studies have shown a noted shrinkage in the hippocampus, contributing to memory impairment, similar to the reduced hippocampal volume in child-abuse victims. Additionally, cortical function in the brain is affected in PTSD, creating difficulty with exercising judgment and good decision making.

“One way to think about PTSD is that the cortex is unable to reign in the limbic system,” Dr. Nemeroff said. “The hippocampus is impaired, the amygdala is hyperactive, and there is a tremendous emotional drive, so the ‘thinking’ part of the brain can’t [overcome] the emotional, reptilian brain.”

The result is that a person remains stuck in a hyperaroused state. “We know that the neurobiological basis for PTSD involves a prolonged, vigilant response to stress [involving] a multitude of brain circuits ... and of course the sympathetic nervous system and the pituitary and adrenal systems,” Dr. Nemeroff said.

Beyond brain changes, a genetic predisposition to PTSD accounts for a third of all cases, while an additional one-third are attributable to additional biological risk factors, according to Dr. Nemeroff (Nature 2011;470:492-7).

Just as with all anxiety-related disorders, women are more PTSD susceptible than are men. One of the “few things everybody agrees on,” Dr. Nemeroff said, is that early-life trauma such as neglect or abuse is a definite risk factor for PTSD, in part because early-life stress is thought to permanently program the brain regions involved in stress- and anxiety-mediation. Add to that, any adult level trauma, and they two “synergize. The more adult trauma coupled with early childhood abuse or neglect, the higher the level of PTSD.”

Meanwhile, poor social support, especially after the occurrence of a traumatic event, is a traditional prognosticator of poor recovery from PTSD, as are a family history of mood disorders, lower I.Q. and education, and experiencing other stressors the year before or after a traumatic event.

Dr. Nemeroff said that although the goals of treatment are reduced core symptoms, improved quality of life and function, strength, and resilience against subsequent stress, “the sad fact of the matter is that we don’t have a clue what the best treatment is, because we have no predictors of treatment response for PTSD.”

The most common treatments for PTSD are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), although the best data available suggest that prolonged imaginal exposure therapy is the most effective, Dr. Nemeroff said. It can be provided either virtually or in person, and includes breathing techniques, psychoeducation, and cognitive therapy. The Institute of Medicine gives exposure therapy its highest rating for scientific evidence, said Dr. Nemeroff, who is a board member of the institute.

Pharmacologic treatments approved by the Food and Drug Administration for PTSD treatment include sertraline and paroxetine, although other antidepressants can be prescribed off-label to some effect.

With sertraline, there is a “pretty low bar” of efficacy, according to Dr. Nemeroff, since only a 30% improvement in symptoms was recorded in 60% of study participants for FDA approval. It’s important to remember the treatment-response in PTSD is much slower than in major depression, Dr. Nemeroff said. “It can take as much as 9 months, so don’t give up.”

Combining sertraline with prolonged exposure therapy is even more effective, he said (J. Trauma Stress 2006;19:625-38). Meanwhile, other data show what paroxetine alone performed better than placebo, but the data are mixed for the drug in combination with prolonged exposure therapy (Am. J. Psychiatry 2012;169:80-8), (J. Clin. Psychiatry 2008;69:400-5), (J. Clin. Neurosci. 2008;62:646-52), and (Am. J. Psychiatry 2001;158:1982-8).

Dr. Nemeroff said lately, he has been treating PTSD patients with venlafaxine 450 mg, which is much higher than the usual dose of about 220 mg, with “considerably good results” (Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2006;63:1158-65).

Improvements in memory and hippocampal volume generally are found with SSRI treatments, as well as reductions in symptom severity, according to Dr. Nemeroff.

For PTSD patients who are struggling with insomnia and other sleep-related problems, Dr. Nemeroff said prazosin has been “phenomenal,” especially in reducing nightmares (Am. J. Psychiatry 2013;170:1003-10).

One drug class to avoid using with PTSD patients is benzodiazepines, he said. “Every study has shown that benzodiazepines in PTSD do not work, and they come with a high rate of substance abuse in this population.”

*Dr. Nemeroff disclosed that he receives research and grant support from the National Institutes of Health. He also serves as a consultant for several companies, including Xhale, Takeda, SK Pharma, Shire, Roche, Lilly, Allergan, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Development America, Taisho Pharmaceutical, Lundbeck, Prismic Pharmaceuticals, and Clintara LLC. He is a stockholder in Xhale, Celgene, Seattle Genetics, Abbvie, Titan Pharmaceuticals, and OPKO Health.

In addition, he holds financial/proprietary interest in patents for method/devices for the transdermal delivery of lithium and for a method of assessing antidepressant drug therapy.

*Correction, 4/10/2015: An earlier version of this story misstated Dr. Nemeroff's disclosures.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

LAS VEGAS– There is no cure for posttraumatic stress disorder, but helping its sufferers reduce symptoms, improve resistance, and achieve a better quality of life is possible.

“We have no idea what the best treatments are for PTSD,” Dr. Charles B. Nemeroff, the Leonard M. Miller Professor, and chairman of the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of Miami, told an audience at the annual psychopharmacology update held by the Nevada Psychiatric Association.

Whether to rely upon psychosocial or pharmacologic interventions, or a combination of the two, to help shift PTSD from a debilitating condition into a manageable, chronic one, it is important to understand PTSD as a brain disease. “To accurately treat PTSD, consider it within a neurobiological context,” Dr. Nemeroff said. “Ordinarily, the brain is evolved to deal with stress, but it can be compromised.”

In chronic PTSD, brain studies have shown a noted shrinkage in the hippocampus, contributing to memory impairment, similar to the reduced hippocampal volume in child-abuse victims. Additionally, cortical function in the brain is affected in PTSD, creating difficulty with exercising judgment and good decision making.

“One way to think about PTSD is that the cortex is unable to reign in the limbic system,” Dr. Nemeroff said. “The hippocampus is impaired, the amygdala is hyperactive, and there is a tremendous emotional drive, so the ‘thinking’ part of the brain can’t [overcome] the emotional, reptilian brain.”

The result is that a person remains stuck in a hyperaroused state. “We know that the neurobiological basis for PTSD involves a prolonged, vigilant response to stress [involving] a multitude of brain circuits ... and of course the sympathetic nervous system and the pituitary and adrenal systems,” Dr. Nemeroff said.

Beyond brain changes, a genetic predisposition to PTSD accounts for a third of all cases, while an additional one-third are attributable to additional biological risk factors, according to Dr. Nemeroff (Nature 2011;470:492-7).

Just as with all anxiety-related disorders, women are more PTSD susceptible than are men. One of the “few things everybody agrees on,” Dr. Nemeroff said, is that early-life trauma such as neglect or abuse is a definite risk factor for PTSD, in part because early-life stress is thought to permanently program the brain regions involved in stress- and anxiety-mediation. Add to that, any adult level trauma, and they two “synergize. The more adult trauma coupled with early childhood abuse or neglect, the higher the level of PTSD.”

Meanwhile, poor social support, especially after the occurrence of a traumatic event, is a traditional prognosticator of poor recovery from PTSD, as are a family history of mood disorders, lower I.Q. and education, and experiencing other stressors the year before or after a traumatic event.

Dr. Nemeroff said that although the goals of treatment are reduced core symptoms, improved quality of life and function, strength, and resilience against subsequent stress, “the sad fact of the matter is that we don’t have a clue what the best treatment is, because we have no predictors of treatment response for PTSD.”

The most common treatments for PTSD are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), although the best data available suggest that prolonged imaginal exposure therapy is the most effective, Dr. Nemeroff said. It can be provided either virtually or in person, and includes breathing techniques, psychoeducation, and cognitive therapy. The Institute of Medicine gives exposure therapy its highest rating for scientific evidence, said Dr. Nemeroff, who is a board member of the institute.

Pharmacologic treatments approved by the Food and Drug Administration for PTSD treatment include sertraline and paroxetine, although other antidepressants can be prescribed off-label to some effect.

With sertraline, there is a “pretty low bar” of efficacy, according to Dr. Nemeroff, since only a 30% improvement in symptoms was recorded in 60% of study participants for FDA approval. It’s important to remember the treatment-response in PTSD is much slower than in major depression, Dr. Nemeroff said. “It can take as much as 9 months, so don’t give up.”

Combining sertraline with prolonged exposure therapy is even more effective, he said (J. Trauma Stress 2006;19:625-38). Meanwhile, other data show what paroxetine alone performed better than placebo, but the data are mixed for the drug in combination with prolonged exposure therapy (Am. J. Psychiatry 2012;169:80-8), (J. Clin. Psychiatry 2008;69:400-5), (J. Clin. Neurosci. 2008;62:646-52), and (Am. J. Psychiatry 2001;158:1982-8).

Dr. Nemeroff said lately, he has been treating PTSD patients with venlafaxine 450 mg, which is much higher than the usual dose of about 220 mg, with “considerably good results” (Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2006;63:1158-65).

Improvements in memory and hippocampal volume generally are found with SSRI treatments, as well as reductions in symptom severity, according to Dr. Nemeroff.

For PTSD patients who are struggling with insomnia and other sleep-related problems, Dr. Nemeroff said prazosin has been “phenomenal,” especially in reducing nightmares (Am. J. Psychiatry 2013;170:1003-10).

One drug class to avoid using with PTSD patients is benzodiazepines, he said. “Every study has shown that benzodiazepines in PTSD do not work, and they come with a high rate of substance abuse in this population.”

*Dr. Nemeroff disclosed that he receives research and grant support from the National Institutes of Health. He also serves as a consultant for several companies, including Xhale, Takeda, SK Pharma, Shire, Roche, Lilly, Allergan, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Development America, Taisho Pharmaceutical, Lundbeck, Prismic Pharmaceuticals, and Clintara LLC. He is a stockholder in Xhale, Celgene, Seattle Genetics, Abbvie, Titan Pharmaceuticals, and OPKO Health.

In addition, he holds financial/proprietary interest in patents for method/devices for the transdermal delivery of lithium and for a method of assessing antidepressant drug therapy.

*Correction, 4/10/2015: An earlier version of this story misstated Dr. Nemeroff's disclosures.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE NPA PSYCHOPHARMOCOLOGY UPDATE

Scalp Hyperkeratosis in Children With Skin of Color: Diagnostic and Therapeutic Considerations