User login

Surprising finding in upfront use of idelalisib monotherapy

Photo courtesy of ASH

ORLANDO, FL—Investigators have observed early fulminant hepatotoxicity in a subset of primarily younger chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients treated with idelalisib monotherapy in the frontline setting.

In a phase 2 study of idelalisib plus ofatumumab, 52% of the 24 patients enrolled experienced grade 3 or higher hepatotoxicity shortly after idelalisib was started.

The investigators say this may occur because a proportion of regulatory T cells in the peripheral blood decreases while patients are on idelalisib. The team believes this early hepatotoxicity is immune-mediated.

Benjamin Lampson, MD, PhD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts, described these surprising findings at the 2015 ASH Annual Meeting as abstract 497.*

Study design and patient demographics

Patients received 150 mg of idelalisib twice daily as monotherapy on days 1 through 56. They then received combination therapy with idelalisib plus ofatumumab for 8 weekly infusions, followed by 4 monthly infusions through day 225, and then idelalisib monotherapy indefinitely.

The primary endpoint of overall response rate was assessed 2 months after the completion of combination therapy.

“This dosing strategy is slightly different than what has been previously used in trials combining these particular drugs,” Dr Lampson said. “Specifically, previously reported trials started these agents simultaneously without a lead-in period of monotherapy.”

The investigators monitored the patients weekly for toxicities during the 2-month monotherapy lead-in period.

Three-quarters of the patients are male. Their median age is 67.4 years (range, 57.6–84.9), 54% have unmutated IgHV, 17% have deletion 17p or TP53 mutation, 4% have deletion 11q, and 54% have deletion 13q.

The patients received no prior therapies.

Results

The trial is currently ongoing.

The 24 patients enrolled as of early November have been on therapy a median of 7.7 months, for a median follow-up time of 14.7 months.

“What we began to notice after enrolling just a few subjects on the trial was that severe hepatotoxicity was occurring shortly after initiating idelalisib,” Dr Lampson said.

In the first 2 months of therapy, 52% of patients developed transaminitis, and 13% developed colitis or diarrhea, all grade 3 or higher. Thirteen percent developed pneumonitis of any grade.

Younger age is a risk factor for early hepatotoxicity, Dr Lampson said, with a significance of P=0.02. All subjects age 65 or younger (n=7) required systemic steroids to treat their toxicities.

Hepatotoxicity developed in a median of 28 days, he said, “and the hepatotoxicity is typically occurring before the first dose of ofatumumab is administered at week 8, suggesting that idelalisib alone is the cause of the hepatotoxicity.”

Dr Lampson noted that toxicities resolved rapidly with steroids.

“I do want to point out that all subjects evaluable for a response have had a response,” he added. “Additionally, in all subjects where treatment has been discontinued, the discontinuation was due to adverse events rather than disease progression.”

Twelve patients with grade 2 or higher transaminitis were re-challenged with idelalisib after holding the drug for toxicity.

Five patients were re-challenged while off steroids, and 4 developed recurrent transaminitis within 4 days. Seven patients were re-challenged while on steroids, and 2 developed recurrent transaminitis within 4 days.

“In general, our experience has been, if idelalisib is resumed while the subject remains on steroids, the drug is more likely to be tolerated and the subject can eventually be taken off steroids,” Dr Lampson said.

Comparison with earlier studies

The investigators compared the frequency of toxicity in their trial to earlier studies of idelalisib (Brown, Blood 2014; Coutre, EHA 2015, abstr P588; O’Brien, Blood 2015).

They found that grade 3 or higher transaminitis (52%) and any grade pneumonitis (13%) were higher in their trial than in the 3 other trials.

Colitis/diarrhea was about the same in 2 of the 3 other trials. But in the paper by O’Brien et al, 42% of patients experienced grade 3 or greater colitis/diarrhea.

The lower rate of colitis in the present trial may be due to the shorter follow-up, Dr Lampson said, as colitis is a late adverse event.

The O’Brien trial was also an upfront study, so patients had no prior therapies. The investigators observed that toxicities appeared to be more common in less heavily pretreated patients.

“As the median number of prior therapies decreases,” Dr Lampson said, “the frequency of adverse events increases.”

He noted that, in the O’Brien trial, idelalisib was started simultaneously with the other drugs, perhaps accounting for its somewhat lower rate (21%) of grade 3 or higher transaminitis.

Additionally, the patient population in the O’Brien trial was older than the population in the current trial, which could account for the higher rate of transaminitis, as younger age is a risk factor.

Decrease in regulatory T cells

Investigators noted a decrease in regulatory T cells while patients were on therapy. Eleven of 15 patients (73%) with matched samples had a significant (P<0.05) decrease in the percentage of T cells over time.

This, they say, could provide a possible explanation for the development of early hepatotoxicity.

The trial is investigator-initiated and funded by Gilead Sciences. ![]()

*Data in the presentation differs from the abstract.

Photo courtesy of ASH

ORLANDO, FL—Investigators have observed early fulminant hepatotoxicity in a subset of primarily younger chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients treated with idelalisib monotherapy in the frontline setting.

In a phase 2 study of idelalisib plus ofatumumab, 52% of the 24 patients enrolled experienced grade 3 or higher hepatotoxicity shortly after idelalisib was started.

The investigators say this may occur because a proportion of regulatory T cells in the peripheral blood decreases while patients are on idelalisib. The team believes this early hepatotoxicity is immune-mediated.

Benjamin Lampson, MD, PhD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts, described these surprising findings at the 2015 ASH Annual Meeting as abstract 497.*

Study design and patient demographics

Patients received 150 mg of idelalisib twice daily as monotherapy on days 1 through 56. They then received combination therapy with idelalisib plus ofatumumab for 8 weekly infusions, followed by 4 monthly infusions through day 225, and then idelalisib monotherapy indefinitely.

The primary endpoint of overall response rate was assessed 2 months after the completion of combination therapy.

“This dosing strategy is slightly different than what has been previously used in trials combining these particular drugs,” Dr Lampson said. “Specifically, previously reported trials started these agents simultaneously without a lead-in period of monotherapy.”

The investigators monitored the patients weekly for toxicities during the 2-month monotherapy lead-in period.

Three-quarters of the patients are male. Their median age is 67.4 years (range, 57.6–84.9), 54% have unmutated IgHV, 17% have deletion 17p or TP53 mutation, 4% have deletion 11q, and 54% have deletion 13q.

The patients received no prior therapies.

Results

The trial is currently ongoing.

The 24 patients enrolled as of early November have been on therapy a median of 7.7 months, for a median follow-up time of 14.7 months.

“What we began to notice after enrolling just a few subjects on the trial was that severe hepatotoxicity was occurring shortly after initiating idelalisib,” Dr Lampson said.

In the first 2 months of therapy, 52% of patients developed transaminitis, and 13% developed colitis or diarrhea, all grade 3 or higher. Thirteen percent developed pneumonitis of any grade.

Younger age is a risk factor for early hepatotoxicity, Dr Lampson said, with a significance of P=0.02. All subjects age 65 or younger (n=7) required systemic steroids to treat their toxicities.

Hepatotoxicity developed in a median of 28 days, he said, “and the hepatotoxicity is typically occurring before the first dose of ofatumumab is administered at week 8, suggesting that idelalisib alone is the cause of the hepatotoxicity.”

Dr Lampson noted that toxicities resolved rapidly with steroids.

“I do want to point out that all subjects evaluable for a response have had a response,” he added. “Additionally, in all subjects where treatment has been discontinued, the discontinuation was due to adverse events rather than disease progression.”

Twelve patients with grade 2 or higher transaminitis were re-challenged with idelalisib after holding the drug for toxicity.

Five patients were re-challenged while off steroids, and 4 developed recurrent transaminitis within 4 days. Seven patients were re-challenged while on steroids, and 2 developed recurrent transaminitis within 4 days.

“In general, our experience has been, if idelalisib is resumed while the subject remains on steroids, the drug is more likely to be tolerated and the subject can eventually be taken off steroids,” Dr Lampson said.

Comparison with earlier studies

The investigators compared the frequency of toxicity in their trial to earlier studies of idelalisib (Brown, Blood 2014; Coutre, EHA 2015, abstr P588; O’Brien, Blood 2015).

They found that grade 3 or higher transaminitis (52%) and any grade pneumonitis (13%) were higher in their trial than in the 3 other trials.

Colitis/diarrhea was about the same in 2 of the 3 other trials. But in the paper by O’Brien et al, 42% of patients experienced grade 3 or greater colitis/diarrhea.

The lower rate of colitis in the present trial may be due to the shorter follow-up, Dr Lampson said, as colitis is a late adverse event.

The O’Brien trial was also an upfront study, so patients had no prior therapies. The investigators observed that toxicities appeared to be more common in less heavily pretreated patients.

“As the median number of prior therapies decreases,” Dr Lampson said, “the frequency of adverse events increases.”

He noted that, in the O’Brien trial, idelalisib was started simultaneously with the other drugs, perhaps accounting for its somewhat lower rate (21%) of grade 3 or higher transaminitis.

Additionally, the patient population in the O’Brien trial was older than the population in the current trial, which could account for the higher rate of transaminitis, as younger age is a risk factor.

Decrease in regulatory T cells

Investigators noted a decrease in regulatory T cells while patients were on therapy. Eleven of 15 patients (73%) with matched samples had a significant (P<0.05) decrease in the percentage of T cells over time.

This, they say, could provide a possible explanation for the development of early hepatotoxicity.

The trial is investigator-initiated and funded by Gilead Sciences. ![]()

*Data in the presentation differs from the abstract.

Photo courtesy of ASH

ORLANDO, FL—Investigators have observed early fulminant hepatotoxicity in a subset of primarily younger chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients treated with idelalisib monotherapy in the frontline setting.

In a phase 2 study of idelalisib plus ofatumumab, 52% of the 24 patients enrolled experienced grade 3 or higher hepatotoxicity shortly after idelalisib was started.

The investigators say this may occur because a proportion of regulatory T cells in the peripheral blood decreases while patients are on idelalisib. The team believes this early hepatotoxicity is immune-mediated.

Benjamin Lampson, MD, PhD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts, described these surprising findings at the 2015 ASH Annual Meeting as abstract 497.*

Study design and patient demographics

Patients received 150 mg of idelalisib twice daily as monotherapy on days 1 through 56. They then received combination therapy with idelalisib plus ofatumumab for 8 weekly infusions, followed by 4 monthly infusions through day 225, and then idelalisib monotherapy indefinitely.

The primary endpoint of overall response rate was assessed 2 months after the completion of combination therapy.

“This dosing strategy is slightly different than what has been previously used in trials combining these particular drugs,” Dr Lampson said. “Specifically, previously reported trials started these agents simultaneously without a lead-in period of monotherapy.”

The investigators monitored the patients weekly for toxicities during the 2-month monotherapy lead-in period.

Three-quarters of the patients are male. Their median age is 67.4 years (range, 57.6–84.9), 54% have unmutated IgHV, 17% have deletion 17p or TP53 mutation, 4% have deletion 11q, and 54% have deletion 13q.

The patients received no prior therapies.

Results

The trial is currently ongoing.

The 24 patients enrolled as of early November have been on therapy a median of 7.7 months, for a median follow-up time of 14.7 months.

“What we began to notice after enrolling just a few subjects on the trial was that severe hepatotoxicity was occurring shortly after initiating idelalisib,” Dr Lampson said.

In the first 2 months of therapy, 52% of patients developed transaminitis, and 13% developed colitis or diarrhea, all grade 3 or higher. Thirteen percent developed pneumonitis of any grade.

Younger age is a risk factor for early hepatotoxicity, Dr Lampson said, with a significance of P=0.02. All subjects age 65 or younger (n=7) required systemic steroids to treat their toxicities.

Hepatotoxicity developed in a median of 28 days, he said, “and the hepatotoxicity is typically occurring before the first dose of ofatumumab is administered at week 8, suggesting that idelalisib alone is the cause of the hepatotoxicity.”

Dr Lampson noted that toxicities resolved rapidly with steroids.

“I do want to point out that all subjects evaluable for a response have had a response,” he added. “Additionally, in all subjects where treatment has been discontinued, the discontinuation was due to adverse events rather than disease progression.”

Twelve patients with grade 2 or higher transaminitis were re-challenged with idelalisib after holding the drug for toxicity.

Five patients were re-challenged while off steroids, and 4 developed recurrent transaminitis within 4 days. Seven patients were re-challenged while on steroids, and 2 developed recurrent transaminitis within 4 days.

“In general, our experience has been, if idelalisib is resumed while the subject remains on steroids, the drug is more likely to be tolerated and the subject can eventually be taken off steroids,” Dr Lampson said.

Comparison with earlier studies

The investigators compared the frequency of toxicity in their trial to earlier studies of idelalisib (Brown, Blood 2014; Coutre, EHA 2015, abstr P588; O’Brien, Blood 2015).

They found that grade 3 or higher transaminitis (52%) and any grade pneumonitis (13%) were higher in their trial than in the 3 other trials.

Colitis/diarrhea was about the same in 2 of the 3 other trials. But in the paper by O’Brien et al, 42% of patients experienced grade 3 or greater colitis/diarrhea.

The lower rate of colitis in the present trial may be due to the shorter follow-up, Dr Lampson said, as colitis is a late adverse event.

The O’Brien trial was also an upfront study, so patients had no prior therapies. The investigators observed that toxicities appeared to be more common in less heavily pretreated patients.

“As the median number of prior therapies decreases,” Dr Lampson said, “the frequency of adverse events increases.”

He noted that, in the O’Brien trial, idelalisib was started simultaneously with the other drugs, perhaps accounting for its somewhat lower rate (21%) of grade 3 or higher transaminitis.

Additionally, the patient population in the O’Brien trial was older than the population in the current trial, which could account for the higher rate of transaminitis, as younger age is a risk factor.

Decrease in regulatory T cells

Investigators noted a decrease in regulatory T cells while patients were on therapy. Eleven of 15 patients (73%) with matched samples had a significant (P<0.05) decrease in the percentage of T cells over time.

This, they say, could provide a possible explanation for the development of early hepatotoxicity.

The trial is investigator-initiated and funded by Gilead Sciences. ![]()

*Data in the presentation differs from the abstract.

CAR T-cell therapy dubbed ‘promising’ for MM

Photo courtesy of ASH

ORLANDO, FL—Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells can have “powerful activity” in patients with multiple myeloma (MM), according to a speaker at the 2015 ASH Annual Meeting.

The CAR T cells in question are directed against the B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA), a protein expressed by normal and malignant plasma cells.

In a phase 1 study of patients with previously treated MM, CAR-BCMA T cells eliminated plasma cells without causing direct damage to essential organs.

The therapy did produce “substantial” toxicity similar to that observed in previous CAR T-cell trials, but this was reversible, said James N. Kochenderfer, MD, of the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, Maryland.

Dr Kochenderfer presented these results as a late-breaking abstract at the meeting (LBA-1). He received research funding from bluebird bio, the company developing CAR-BCMA T-cell therapy along with Celgene and Baylor College of Medicine.

The researchers enrolled 12 patients on this study. The patients had received at least 3 prior lines of therapy, had “essentially normal” major organ function, and had clear, uniform expression of BCMA on myeloma cells by flow cytometry or immunohistochemistry.

The patients’ own T cells were genetically modified to express the CAR with a gamma-retroviral vector. The CAR-BCMA incorporates an anti-BCMA

single-chain variable fragment, a CD28 domain, and a CD3-zeta T-cell activation domain. It was previously described in Clinical Cancer Research in 2013.

Before receiving CAR-BCMA T-cell infusions, patients received chemotherapy—cyclophosphamide at 300 mg/m2 daily for 3 days and fludarabine at 30 mg/m2 daily for 3 days.

Two days later, patients received a single infusion of CAR-BCMA T cells. The doses were escalated based on the number of CAR-positive T cells/kg. The doses were 0.3 x 106, 1 x 106, 3 x 106, and 9 x 106 CAR-positive T cells/kg.

Response and toxicity

“[O]n the lower 2 dose levels, toxicity was minimal—just a couple of fevers,” Dr Kochenderfer noted. “When we got to the higher dose levels, patients started to have more significant toxicity, along with more impressive responses.”

One patient, Patient 10, had a stringent complete response to the highest dose of CAR-BCMA T cells (9 x 106). This response is ongoing and has lasted longer than 12 weeks.

Patient 8, who received a CAR-BCMA T-cell dose of 3 x 106, achieved a very good partial response that lasted 8 weeks. A PET scan showed complete clearance of myeloma in this patient.

Two patients achieved partial responses. One response occurred on the lowest dose of CAR-BCMA T cells (0.3 x 106) and lasted 2 weeks.

The other partial response occurred in Patient 11, who received the highest dose of CAR-BCMA T cells. This response is ongoing and has lasted more than 6 weeks.

The remaining 8 patients had stable disease that lasted anywhere from 2 weeks to 16 weeks.

Best responders

Patient 10, who achieved a stringent complete response, had chemotherapy-resistant IgA MM at baseline. He had received 3 prior lines of therapy and had relapsed with 90% bone marrow plasma cells 3 months after autologous transplant.

“BCMA expression was uniform but dim on his myeloma cells,” Dr Kochenderfer noted.

Within 4 hours of receiving CAR-BCMA T cells, Patient 10 became febrile. He showed other signs of cytokine release syndrome as well, including tachycardia, hypotension, elevated liver enzymes, and elevated creatinine kinase. But all of these symptoms resolved within 2 weeks.

Patient 10’s absolute neutrophil count was less than 500/µL at the time of CAR-BCMA T-cell infusion and remained less than 500/µL for 40 days after infusion. The patient was platelet-transfusion-dependent for 9 weeks after infusion.

Patient 11, who achieved the ongoing partial response, had received 5 prior lines of therapy. MM made up 80% of his bone marrow cells at baseline.

The patient experienced a rapid decrease in markers of MM after CAR-BCMA T-cell infusion, and his M protein levels continue to decrease.

Patient 11 also experienced fever, tachycardia, hypotension, acute kidney injury, dyspnea, delirium, and prolonged thrombocytopenia, but all of these toxicities have resolved completely.

Dr Kochenderfer noted that patients who had significant responses (Patients 8, 10, and 11) had the highest blood levels of CAR-BCMA T cells. They also had the most severe clinical signs of cytokine release syndrome and much higher serum levels of IL-6 than the other patients.

“We have demonstrated, for the first time, that CAR T cells can have powerful activity against measurable myeloma,” Dr Kochenderfer said in closing. “Anti-BCMA CAR T cells are a promising therapy for multiple myeloma.” ![]()

Photo courtesy of ASH

ORLANDO, FL—Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells can have “powerful activity” in patients with multiple myeloma (MM), according to a speaker at the 2015 ASH Annual Meeting.

The CAR T cells in question are directed against the B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA), a protein expressed by normal and malignant plasma cells.

In a phase 1 study of patients with previously treated MM, CAR-BCMA T cells eliminated plasma cells without causing direct damage to essential organs.

The therapy did produce “substantial” toxicity similar to that observed in previous CAR T-cell trials, but this was reversible, said James N. Kochenderfer, MD, of the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, Maryland.

Dr Kochenderfer presented these results as a late-breaking abstract at the meeting (LBA-1). He received research funding from bluebird bio, the company developing CAR-BCMA T-cell therapy along with Celgene and Baylor College of Medicine.

The researchers enrolled 12 patients on this study. The patients had received at least 3 prior lines of therapy, had “essentially normal” major organ function, and had clear, uniform expression of BCMA on myeloma cells by flow cytometry or immunohistochemistry.

The patients’ own T cells were genetically modified to express the CAR with a gamma-retroviral vector. The CAR-BCMA incorporates an anti-BCMA

single-chain variable fragment, a CD28 domain, and a CD3-zeta T-cell activation domain. It was previously described in Clinical Cancer Research in 2013.

Before receiving CAR-BCMA T-cell infusions, patients received chemotherapy—cyclophosphamide at 300 mg/m2 daily for 3 days and fludarabine at 30 mg/m2 daily for 3 days.

Two days later, patients received a single infusion of CAR-BCMA T cells. The doses were escalated based on the number of CAR-positive T cells/kg. The doses were 0.3 x 106, 1 x 106, 3 x 106, and 9 x 106 CAR-positive T cells/kg.

Response and toxicity

“[O]n the lower 2 dose levels, toxicity was minimal—just a couple of fevers,” Dr Kochenderfer noted. “When we got to the higher dose levels, patients started to have more significant toxicity, along with more impressive responses.”

One patient, Patient 10, had a stringent complete response to the highest dose of CAR-BCMA T cells (9 x 106). This response is ongoing and has lasted longer than 12 weeks.

Patient 8, who received a CAR-BCMA T-cell dose of 3 x 106, achieved a very good partial response that lasted 8 weeks. A PET scan showed complete clearance of myeloma in this patient.

Two patients achieved partial responses. One response occurred on the lowest dose of CAR-BCMA T cells (0.3 x 106) and lasted 2 weeks.

The other partial response occurred in Patient 11, who received the highest dose of CAR-BCMA T cells. This response is ongoing and has lasted more than 6 weeks.

The remaining 8 patients had stable disease that lasted anywhere from 2 weeks to 16 weeks.

Best responders

Patient 10, who achieved a stringent complete response, had chemotherapy-resistant IgA MM at baseline. He had received 3 prior lines of therapy and had relapsed with 90% bone marrow plasma cells 3 months after autologous transplant.

“BCMA expression was uniform but dim on his myeloma cells,” Dr Kochenderfer noted.

Within 4 hours of receiving CAR-BCMA T cells, Patient 10 became febrile. He showed other signs of cytokine release syndrome as well, including tachycardia, hypotension, elevated liver enzymes, and elevated creatinine kinase. But all of these symptoms resolved within 2 weeks.

Patient 10’s absolute neutrophil count was less than 500/µL at the time of CAR-BCMA T-cell infusion and remained less than 500/µL for 40 days after infusion. The patient was platelet-transfusion-dependent for 9 weeks after infusion.

Patient 11, who achieved the ongoing partial response, had received 5 prior lines of therapy. MM made up 80% of his bone marrow cells at baseline.

The patient experienced a rapid decrease in markers of MM after CAR-BCMA T-cell infusion, and his M protein levels continue to decrease.

Patient 11 also experienced fever, tachycardia, hypotension, acute kidney injury, dyspnea, delirium, and prolonged thrombocytopenia, but all of these toxicities have resolved completely.

Dr Kochenderfer noted that patients who had significant responses (Patients 8, 10, and 11) had the highest blood levels of CAR-BCMA T cells. They also had the most severe clinical signs of cytokine release syndrome and much higher serum levels of IL-6 than the other patients.

“We have demonstrated, for the first time, that CAR T cells can have powerful activity against measurable myeloma,” Dr Kochenderfer said in closing. “Anti-BCMA CAR T cells are a promising therapy for multiple myeloma.” ![]()

Photo courtesy of ASH

ORLANDO, FL—Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells can have “powerful activity” in patients with multiple myeloma (MM), according to a speaker at the 2015 ASH Annual Meeting.

The CAR T cells in question are directed against the B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA), a protein expressed by normal and malignant plasma cells.

In a phase 1 study of patients with previously treated MM, CAR-BCMA T cells eliminated plasma cells without causing direct damage to essential organs.

The therapy did produce “substantial” toxicity similar to that observed in previous CAR T-cell trials, but this was reversible, said James N. Kochenderfer, MD, of the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, Maryland.

Dr Kochenderfer presented these results as a late-breaking abstract at the meeting (LBA-1). He received research funding from bluebird bio, the company developing CAR-BCMA T-cell therapy along with Celgene and Baylor College of Medicine.

The researchers enrolled 12 patients on this study. The patients had received at least 3 prior lines of therapy, had “essentially normal” major organ function, and had clear, uniform expression of BCMA on myeloma cells by flow cytometry or immunohistochemistry.

The patients’ own T cells were genetically modified to express the CAR with a gamma-retroviral vector. The CAR-BCMA incorporates an anti-BCMA

single-chain variable fragment, a CD28 domain, and a CD3-zeta T-cell activation domain. It was previously described in Clinical Cancer Research in 2013.

Before receiving CAR-BCMA T-cell infusions, patients received chemotherapy—cyclophosphamide at 300 mg/m2 daily for 3 days and fludarabine at 30 mg/m2 daily for 3 days.

Two days later, patients received a single infusion of CAR-BCMA T cells. The doses were escalated based on the number of CAR-positive T cells/kg. The doses were 0.3 x 106, 1 x 106, 3 x 106, and 9 x 106 CAR-positive T cells/kg.

Response and toxicity

“[O]n the lower 2 dose levels, toxicity was minimal—just a couple of fevers,” Dr Kochenderfer noted. “When we got to the higher dose levels, patients started to have more significant toxicity, along with more impressive responses.”

One patient, Patient 10, had a stringent complete response to the highest dose of CAR-BCMA T cells (9 x 106). This response is ongoing and has lasted longer than 12 weeks.

Patient 8, who received a CAR-BCMA T-cell dose of 3 x 106, achieved a very good partial response that lasted 8 weeks. A PET scan showed complete clearance of myeloma in this patient.

Two patients achieved partial responses. One response occurred on the lowest dose of CAR-BCMA T cells (0.3 x 106) and lasted 2 weeks.

The other partial response occurred in Patient 11, who received the highest dose of CAR-BCMA T cells. This response is ongoing and has lasted more than 6 weeks.

The remaining 8 patients had stable disease that lasted anywhere from 2 weeks to 16 weeks.

Best responders

Patient 10, who achieved a stringent complete response, had chemotherapy-resistant IgA MM at baseline. He had received 3 prior lines of therapy and had relapsed with 90% bone marrow plasma cells 3 months after autologous transplant.

“BCMA expression was uniform but dim on his myeloma cells,” Dr Kochenderfer noted.

Within 4 hours of receiving CAR-BCMA T cells, Patient 10 became febrile. He showed other signs of cytokine release syndrome as well, including tachycardia, hypotension, elevated liver enzymes, and elevated creatinine kinase. But all of these symptoms resolved within 2 weeks.

Patient 10’s absolute neutrophil count was less than 500/µL at the time of CAR-BCMA T-cell infusion and remained less than 500/µL for 40 days after infusion. The patient was platelet-transfusion-dependent for 9 weeks after infusion.

Patient 11, who achieved the ongoing partial response, had received 5 prior lines of therapy. MM made up 80% of his bone marrow cells at baseline.

The patient experienced a rapid decrease in markers of MM after CAR-BCMA T-cell infusion, and his M protein levels continue to decrease.

Patient 11 also experienced fever, tachycardia, hypotension, acute kidney injury, dyspnea, delirium, and prolonged thrombocytopenia, but all of these toxicities have resolved completely.

Dr Kochenderfer noted that patients who had significant responses (Patients 8, 10, and 11) had the highest blood levels of CAR-BCMA T cells. They also had the most severe clinical signs of cytokine release syndrome and much higher serum levels of IL-6 than the other patients.

“We have demonstrated, for the first time, that CAR T cells can have powerful activity against measurable myeloma,” Dr Kochenderfer said in closing. “Anti-BCMA CAR T cells are a promising therapy for multiple myeloma.” ![]()

Genes can stop onset of AML, study suggests

Image by Lance Liotta

Two genes can stop the development of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), according to research published in the Journal of Experimental Medicine.

The work suggests that Hif-1α and Hif-2α work together to stop the formation of leukemic stem cells, and blocking either Hif-2α or both genes

accelerates AML development.

Investigators said these findings are surprising because previous research suggested that blocking Hif-1α or Hif-2α might stop AML progression.

But their study suggests that therapies designed to block these genes might worsen AML or at least have no impact on the disease.

Conversely, designing new therapies that promote the activity of Hif-1α and Hif-2α could help treat AML or stop relapse after chemotherapy.

“Our discovery that Hif-1α and Hif-2α molecules act together to stop leukemia development is a major milestone in our efforts to combat leukemia,” said study author Kamil R. Kranc, DPhil, of the University of Edinburgh in Scotland.

“We now intend to harness this knowledge to develop curative therapies that eliminate leukemic stem cells, which are the underlying cause of AML.” ![]()

Image by Lance Liotta

Two genes can stop the development of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), according to research published in the Journal of Experimental Medicine.

The work suggests that Hif-1α and Hif-2α work together to stop the formation of leukemic stem cells, and blocking either Hif-2α or both genes

accelerates AML development.

Investigators said these findings are surprising because previous research suggested that blocking Hif-1α or Hif-2α might stop AML progression.

But their study suggests that therapies designed to block these genes might worsen AML or at least have no impact on the disease.

Conversely, designing new therapies that promote the activity of Hif-1α and Hif-2α could help treat AML or stop relapse after chemotherapy.

“Our discovery that Hif-1α and Hif-2α molecules act together to stop leukemia development is a major milestone in our efforts to combat leukemia,” said study author Kamil R. Kranc, DPhil, of the University of Edinburgh in Scotland.

“We now intend to harness this knowledge to develop curative therapies that eliminate leukemic stem cells, which are the underlying cause of AML.” ![]()

Image by Lance Liotta

Two genes can stop the development of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), according to research published in the Journal of Experimental Medicine.

The work suggests that Hif-1α and Hif-2α work together to stop the formation of leukemic stem cells, and blocking either Hif-2α or both genes

accelerates AML development.

Investigators said these findings are surprising because previous research suggested that blocking Hif-1α or Hif-2α might stop AML progression.

But their study suggests that therapies designed to block these genes might worsen AML or at least have no impact on the disease.

Conversely, designing new therapies that promote the activity of Hif-1α and Hif-2α could help treat AML or stop relapse after chemotherapy.

“Our discovery that Hif-1α and Hif-2α molecules act together to stop leukemia development is a major milestone in our efforts to combat leukemia,” said study author Kamil R. Kranc, DPhil, of the University of Edinburgh in Scotland.

“We now intend to harness this knowledge to develop curative therapies that eliminate leukemic stem cells, which are the underlying cause of AML.” ![]()

Group finds inconsistencies in genome sequencing procedures

Photo courtesy of NIGMS

Researchers say they have identified substantial differences in the procedures and quality of cancer genome sequencing between sequencing centers.

And this led to dramatic discrepancies in the number and types of somatic mutations detected when using the same cancer genome sequences for analysis.

The group’s study involved 83 researchers from 78 institutions participating in the International Cancer Genomics Consortium (ICGC).

The ICGC is an international effort to establish a comprehensive description of genomic, transcriptomic, and epigenomic changes in 50 different tumor types and/or subtypes that are thought to be of clinical and societal importance across the globe.

The consortium is characterizing more than 25,000 cancer genomes and carrying out 78 projects supported by different national and international funding agencies.

For the current project, which was published in Nature Communications, researchers studied a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia and a patient with medulloblastoma.

The team analyzed the entire tumor genome of each patient and compared it to the normal genome of the same patient to decipher the molecular causes for these cancers.

The researchers said they saw “widely varying mutation call rates and low concordance among analysis pipelines.”

So they established a reference mutation dataset to assess analytical procedures. They said this “gold-set” reference database has helped the ICGC community improve procedures for identifying more true somatic mutations in cancer genomes and making fewer false-positive calls.

“The findings of our study have far-reaching implications for cancer genome analysis,” said Ivo Gut, of Centro Nacional de Analisis Genómico in Barcelona, Spain.

“We have found many inconsistencies in both the sequencing of cancer genomes and the data analysis at different sites. We are making our findings available to the scientific and diagnostic community so that they can improve their systems and generate more standardized and consistent results.” ![]()

Photo courtesy of NIGMS

Researchers say they have identified substantial differences in the procedures and quality of cancer genome sequencing between sequencing centers.

And this led to dramatic discrepancies in the number and types of somatic mutations detected when using the same cancer genome sequences for analysis.

The group’s study involved 83 researchers from 78 institutions participating in the International Cancer Genomics Consortium (ICGC).

The ICGC is an international effort to establish a comprehensive description of genomic, transcriptomic, and epigenomic changes in 50 different tumor types and/or subtypes that are thought to be of clinical and societal importance across the globe.

The consortium is characterizing more than 25,000 cancer genomes and carrying out 78 projects supported by different national and international funding agencies.

For the current project, which was published in Nature Communications, researchers studied a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia and a patient with medulloblastoma.

The team analyzed the entire tumor genome of each patient and compared it to the normal genome of the same patient to decipher the molecular causes for these cancers.

The researchers said they saw “widely varying mutation call rates and low concordance among analysis pipelines.”

So they established a reference mutation dataset to assess analytical procedures. They said this “gold-set” reference database has helped the ICGC community improve procedures for identifying more true somatic mutations in cancer genomes and making fewer false-positive calls.

“The findings of our study have far-reaching implications for cancer genome analysis,” said Ivo Gut, of Centro Nacional de Analisis Genómico in Barcelona, Spain.

“We have found many inconsistencies in both the sequencing of cancer genomes and the data analysis at different sites. We are making our findings available to the scientific and diagnostic community so that they can improve their systems and generate more standardized and consistent results.” ![]()

Photo courtesy of NIGMS

Researchers say they have identified substantial differences in the procedures and quality of cancer genome sequencing between sequencing centers.

And this led to dramatic discrepancies in the number and types of somatic mutations detected when using the same cancer genome sequences for analysis.

The group’s study involved 83 researchers from 78 institutions participating in the International Cancer Genomics Consortium (ICGC).

The ICGC is an international effort to establish a comprehensive description of genomic, transcriptomic, and epigenomic changes in 50 different tumor types and/or subtypes that are thought to be of clinical and societal importance across the globe.

The consortium is characterizing more than 25,000 cancer genomes and carrying out 78 projects supported by different national and international funding agencies.

For the current project, which was published in Nature Communications, researchers studied a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia and a patient with medulloblastoma.

The team analyzed the entire tumor genome of each patient and compared it to the normal genome of the same patient to decipher the molecular causes for these cancers.

The researchers said they saw “widely varying mutation call rates and low concordance among analysis pipelines.”

So they established a reference mutation dataset to assess analytical procedures. They said this “gold-set” reference database has helped the ICGC community improve procedures for identifying more true somatic mutations in cancer genomes and making fewer false-positive calls.

“The findings of our study have far-reaching implications for cancer genome analysis,” said Ivo Gut, of Centro Nacional de Analisis Genómico in Barcelona, Spain.

“We have found many inconsistencies in both the sequencing of cancer genomes and the data analysis at different sites. We are making our findings available to the scientific and diagnostic community so that they can improve their systems and generate more standardized and consistent results.” ![]()

Readmissions in Medicaid Beneficiaries

Hospital readmissions that occur within 30 days of discharge are an important measure for assessing performance of the healthcare system and the quality of patient care.[1, 2] According to the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), there were approximately 3.3 million adults with all‐cause 30‐day readmissions in the United States in 2011, incurring nearly $41.3 billion in hospital costs.[3] Reducing 30‐day readmissions has become a priority for payers, providers, and policymakers seeking to achieve improved quality of care at lower costs.

The implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) provided the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) statutory authority under the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program to reduce payments for certain hospital readmissions that it deemed avoidable.[4] Although initial focus was on Medicare readmissions related to heart failure, myocardial infarction, and pneumonia, CMS is now considering expanding the list beyond the 3 conditions covered by the program.[4, 5] Therefore, it is important to understand major risk factors for readmissions in beneficiaries with chronic conditions.

Medicaid consists of the largest number of beneficiaries among all payers in the United States, with approximately 62 million beneficiaries in 2013.[5] The Medicaid population is further expected to increase with the coverage expansions under the ACA. In addition, the state Medicaid programs incur an estimated $374 billion in healthcare expenditures and provide healthcare services to the vulnerable, indigent, and disabled. It is estimated that 61% of adult Medicaid beneficiaries have chronic or disabling conditions that place them at an increased risk of hospitalization.[6] A series of HCUP statistical briefs reported several findings. First, Medicaid all‐cause readmission rates were comparable with Medicare but double the rate of private insurance.[7] Second, for readmissions following nonsurgical hospitalizations, 30‐day Medicaid readmission rates were higher than Medicare and private insurance for both acute and chronic conditions.[1] The effects of such costly utilization patterns, for this large and growing population necessitates heightened attention under healthcare reform.

The balance between hospital efficiency and quality of care is another crucial aspect for our healthcare system. However, length of stay (LOS), a proxy marker for efficiency, may conflict with hospital readmission rates, an indicator of quality. Further, CMS plans to bundle 30‐day readmission rates to reimbursement for the index hospitalization.[8]

The effect of LOS on readmission rates is complex, and previous studies have provided conflicting data regarding the relationship between LOS and subsequent readmission risk. Some indicate that shorter LOS is associated with a higher risk of readmission,[8, 9] whereas others suggest that extended LOS is associated with a higher risk of readmission.[10, 11, 12] However, most research on readmissions has focused on Medicare beneficiaries.[11, 13, 14] The readmission patterns of Medicaid beneficiaries differ from those of the geriatric Medicare beneficiaries, from a clinical and socioeconomic perspective. Considering the importance of 30‐day readmission for payers and policy makers, there is a need to understand the role of LOS and implications for treatment and management strategies.

Our study examined the association between index hospitalization characteristics (LOS and reason for admission) and all‐cause 30‐day readmission risk in fee‐for‐service high‐risk Medicaid beneficiaries. The study is limited to patients with selected chronic conditions and examines the differentiating factors within this high‐risk population. For the purpose of our study, variables were selected based on a priori knowledge and Andersen's behavioral model of health service utilization. This model suggests that potential health service use is determined by interactions among predisposing (demographics, index hospitalization characteristics), enabling (county level [eg, socioeconomic status]), and need (health status) characteristics of individuals and also the healthcare systems in the communities where they reside.[15]

METHODS

Study Design

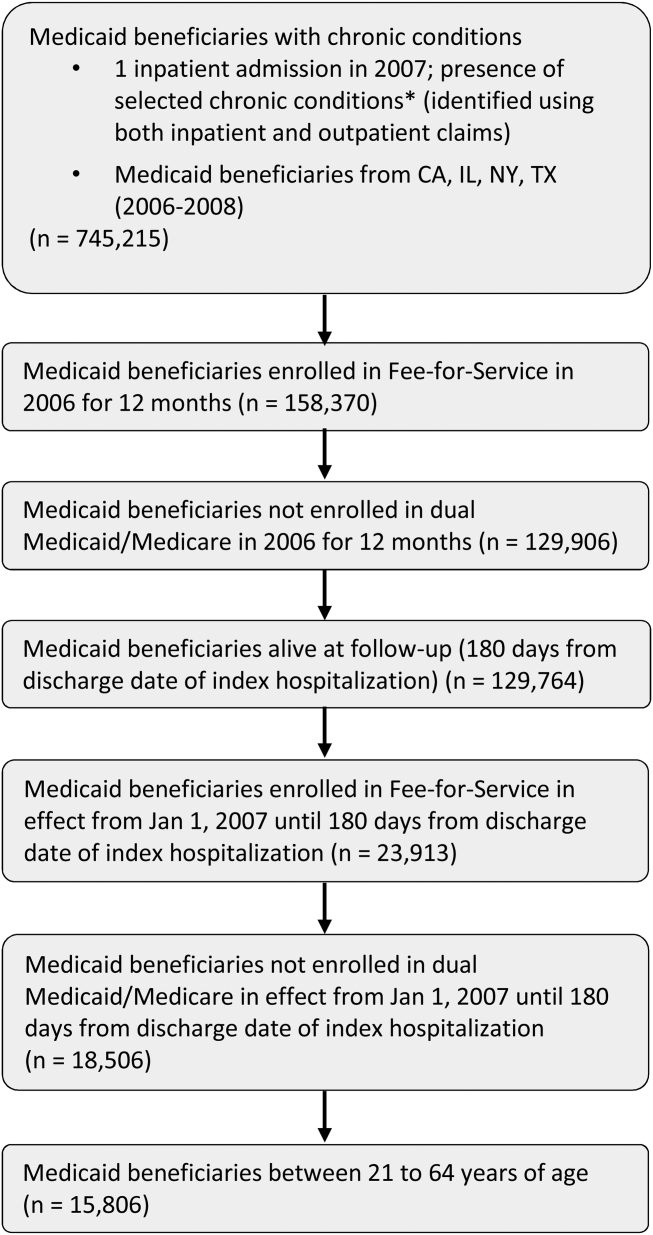

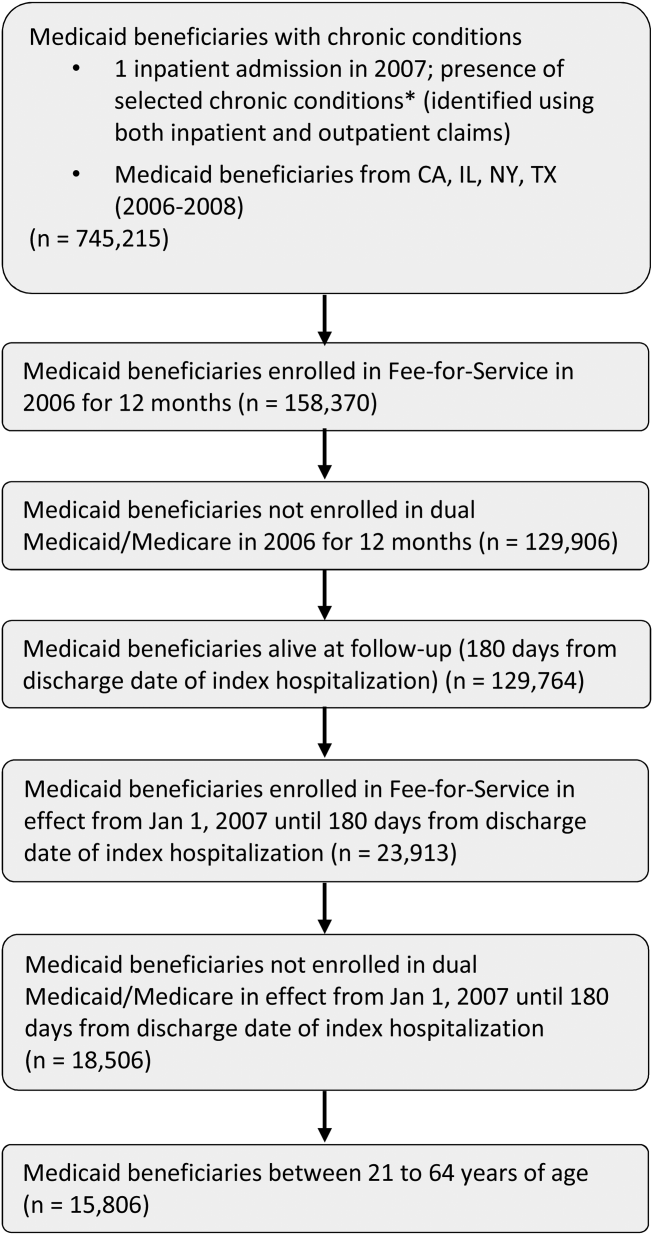

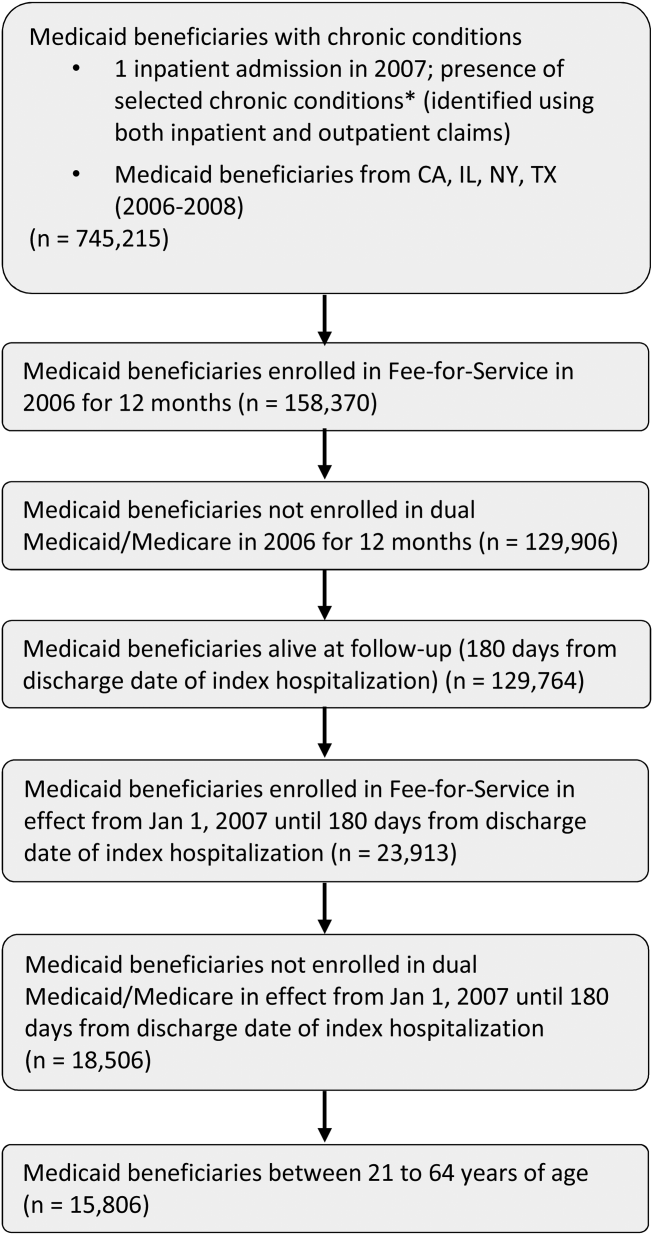

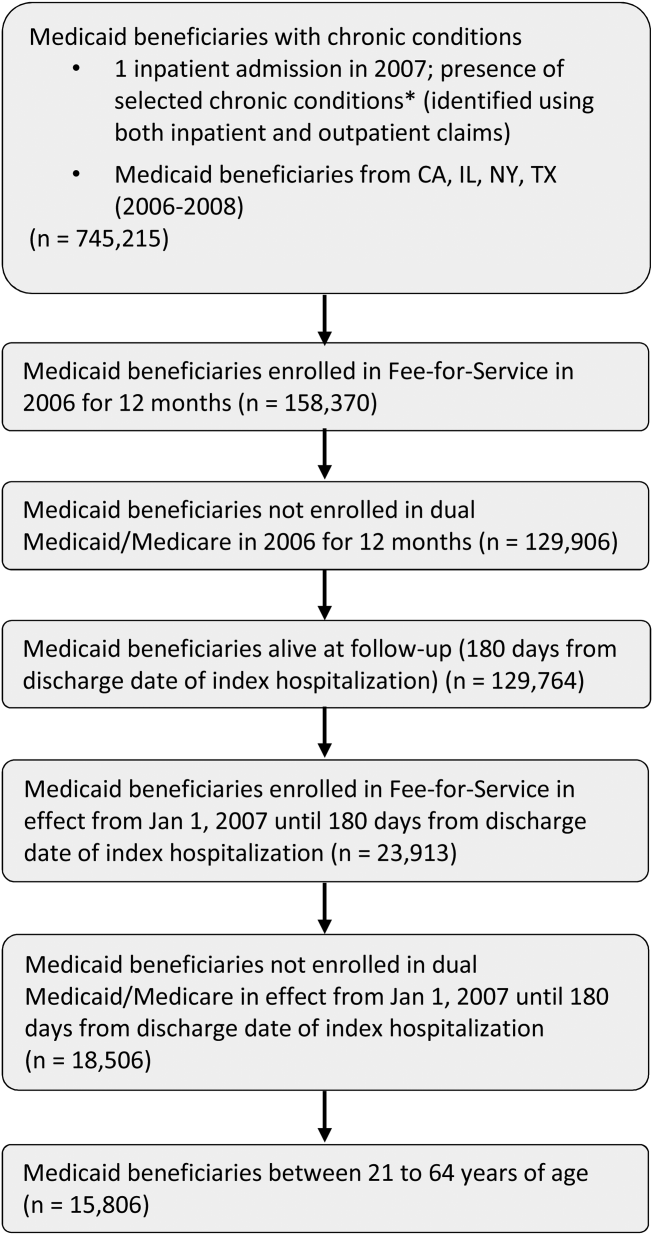

A retrospective cohort approach was used with baseline and follow‐up periods. The baseline period was defined as the admission date of the index hospitalization (first observed hospitalization) between January 1, 2007 and December 31, 2007. Patients were followed for 180 days after discharge date of the associated index hospitalization.

Data Source

Medicaid administrative claims files from California, Illinois, New York, and Texas, between 2006 and 2008, were used. The personal summary file included information on demographics, Medicaid enrollment, and eligibility status. Outpatient and Inpatient files included claims for services provided in ambulatory and inpatient settings and contained International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification codes. Information on county‐level characteristics were obtained from the 2009 Area Health Resource File (AHRF), which was linked to Medicaid administrative claims files using state and county codes where each beneficiary resided.

Study Population

The study population consisted of nonelderly (2164 years old) fee‐for‐service Medicaid‐only beneficiaries with selected chronic conditions and continuous enrollment during baseline and follow‐up period (Figure 1). Analyses were restricted to those who had at least 1 inpatient admission in 2007 and were conducted at the person‐level.

For the purpose of this study, Medicaid beneficiaries with 19 chronic conditions were selected: asthma, arthritis, cardiac arrhythmias, coronary artery disease, cancer, congestive heart failure, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, dementia, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, hepatitis, human immunodeficiency virus osteoporosis, stroke, depression, schizophrenia, and substance use disorders. These conditions were identified based on the strategic framework developed and adopted by the Department of Health and Human Services for research, policy, program, and practice.[16]

Dependent Variable

Individuals were categorized into 2 groups, those with and without all‐cause 30‐day readmission. All‐cause 30‐day readmission was identified as subsequent hospitalization within 30 days of discharge date of the index hospitalization.

Key Independent Variables

These were index hospitalization characteristics, where LOS was the primary independent variable, reason for admission was the secondary independent variable, and month of index hospitalization (included to control for potential seasonal effect).

Other Independent Variables

Patient‐level characteristics included demographics (age, gender, and race/ethnicity) and Medicaid eligibility status (cash and medical need). Primary care access included continuity of care measured using a previously published continuity index (Modified Modified Continuity Index) and coordination of care, measured as primary care visit within 14 days of discharge date. Healthcare utilization was measured as an emergency room visit within 6 months prior to the index hospitalization.

Variables accounting for county socioeconomic status included educational attainment, per capita income, employment rate, poverty level, and metropolitan statistical area. Variables related to availability of providers and healthcare facilities were AHRF designations for primary/mental healthcare shortage areas, presence of federally qualified health centers, rural health centers, and community mental health centers. Hospital and primary care provider density was defined as total number of hospitals or primary care providers per 100,000 individuals, respectively.

Statistical Techniques

2 tests of independence were used for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables to determine group differences in patient‐level and county‐level characteristics and all‐cause 30‐day readmission. Multilevel logistic regression models, which accounted for beneficiaries nested within counties, were used to examine the association between all‐cause 30‐day readmission and index hospitalization characteristics. The reference group for the dependent variable was no 30‐day readmission. Model 1 controlled for only patient‐level characteristics. Model 2 controlled for both patient‐level and county‐level characteristics. In both models, county was specified as a random intercept using the GLIMMIX procedure. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

After the exclusion criteria, there were 15,806 Medicaid beneficiaries with selected chronic conditions and at least 1 inpatient encounter in 2007. Overall, 16.7% experienced all‐cause 30‐day readmissions. A description of the study population and unadjusted associations between independent variables and all‐cause 30‐day readmission are presented in Table 1.

| Variables | 30‐Day Readmission, 2,633 (16.7%) | No 30‐Day Readmission, 13,173 (83.3%) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Demographic and Medicaid eligibility characteristics | |||

| Gender, N (%) | * | ||

| Female | 1,715 (65.1%) | 9,274 (70.4%) | |

| Male | 918 (34.9%) | 3,899 (29.6%) | |

| Age group, N (%) | * | ||

| 2124 years | 301 (11.4%) | 1,675 (12.7%) | |

| 2534 years | 567 (21.5%) | 3,578 (27.2%) | |

| 3544 years | 517 (19.6%) | 2,498 (19.0%) | |

| 4554 years | 673 (25.6%) | 2,971 (22.6%) | |

| 5564 years | 575 (21.8%) | 2,451 (18.6%) | |

| Race/ethnicity, N (%) | * | ||

| Caucasian | 847 (32.2%) | 3,831 (29.1%) | |

| African American | 988 (37.5%) | 4,270(32.4%) | |

| Hispanic | 608 (23.1%) | 4,245 (32.2%) | |

| Asian/AI/PI | 39 (1.5%) | 169 (1.3%) | |

| Other | 151 (5.7%) | 658 (5.0%) | |

| Cash eligibility, N (%) | 1,529 (58.1%) | 6,666 (50.6%) | * |

| Medical need eligibility, N (%) | 876 (33.3%) | 3769 (28.6%) | * |

| Index hospitalization characteristics | |||

| Length of stay, mean [SD] | 6.62 [9.09] | 4.29 [6.35] | * |

| Chronic conditions at admission, N (%) | |||

| Arthritis/osteoporosis | 99 (3.8%) | 464 (3.5%) | |

| Cancer | 134 (5.1%) | 429 (3.3%) | * |

| Cardiovascular conditions | 995 (37.8%) | 3,733 (28.3%) | * |

| COPD/asthma | 541 (20.5%) | 2,197 (16.7%) | * |

| Diabetes | 575 (21.8%) | 2,103 (16.0%) | * |

| HIV/hepatitis | 305 (11.6%) | 1,185 (9.0%) | * |

| Mental health conditions | 1,491 (56.6%) | 4,352 (33.0%) | * |

| Season of readmission, N (%) | * | ||

| Spring | 730 (27.7%) | 3,944 (29.9%) | |

| Summer | 401 (15.2%) | 2,332 (17.7%) | |

| Fall | 211 (8.0%) | 1,605 (12.2%) | |

| Winter | 1,291 (49.0%) | 5,292 (40.2%) | |

| Primary care access, N (%) | |||

| Coordination of primary care | 326 (12.4%) | 1,747 (13.3%) | |

| Continuity of primary care, N (%) | |||

| Complete care continuity | 349 (13.3%) | 1,764 (13.4%) | |

| Some care continuity | 634 (24.1%) | 2,960 (22.5%) | |

| No care continuity | 1650 (62.7%) | 8,449 (64.1%) | |

| Healthcare utilization, N (%) | |||

| Emergency room visit | 893 (33.9%) | 4,449 (33.8%) | |

| County‐level characteristics | |||

| Metropolitan status, N (%) | |||

| Nonmetro | 267 (10.1%) | 1,285 (9.8%) | |

| Metro | 2,366 (89.9%) | 11,888 (90.2%) | |

| Primary care shortage area, N (%) | |||

| Whole county | 2,034 (77.3%) | 10,147 (77.0%) | |

| Part county | 429 (16.3%) | 2,312 (17.6%) | |

| No shortage | 170 (6.5%) | 714 (5.4%) | |

| Mental healthcare shortage area, N (%) | |||

| Whole county | 2,015 (76.5%) | 9,925 (75.3%) | |

| Part county | 388 (14.7%) | 2,242 (17.0%) | |

| No shortage | 230 (8.7%) | 1,006 (7.6%) | |

| CMHC, mean [SD] | 0.81 [1.23] | 0.94 [1.24] | * |

| Rural health center, mean [SD] | 0.62 [3.03] | 1.06 [4.41] | * |

| FQHC, mean [SD] | 37.69 [44.31] | 37.78 [42.98] | |

| Education rate, 4+ years, mean [SD] | 25.39 [10.98] | 23.77 [10.51] | * |

| Unemployment rate, mean [SD] | 4.57 [0.71] | 4.67 [0.90] | * |

| % Below poverty level, mean [SD] | 15.11 [3.73] | 15.06 [3.80] | |

| Per capita income (US dollars), mean [SD] | 58,761.96 [33,697.42] | 54,029.16 [31,265.86] | * |

| Nonfederal PCP density, mean [SD] | 307.10 [192.29] | 279.97 [179.22] | * |

| Hospital density, mean [SD] | 1.74 [1.37] | 1.65 [1.14] | * |

Multilevel logistic regressions of all‐cause 30‐day readmissions are summarized in Table 2. Beneficiaries with longer LOS had significantly higher odds of 30‐day readmission. In addition, presence of cancer, cardiovascular conditions, diabetes, and mental health conditions at index hospitalization significantly increased the odds of readmission. In addition, beneficiaries with cash or medical need eligibility had significantly higher odds of 30‐day readmission.

| AOR | 95% CI | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Length of stay | 1.03 | [1.031.04] | * |

| Chronic conditions at admission | |||

| Arthritis/osteoporosis | 0.90 | [0.721.13] | |

| Cancer | 1.55 | [1.261.90] | * |

| Cardiovascular conditions | 1.20 | [1.081.33] | * |

| COPD/asthma | 1.01 | [0.901.12] | |

| Diabetes | 1.23 | [1.101.39] | * |

| HIV/hepatitis | 0.98 | [0.851.12] | |

| Mental health conditions | 2.17 | [1.982.38] | * |

| Season of readmission | |||

| Spring | 0.79 | [0.710.88] | * |

| Summer | 0.77 | [0.680.88] | * |

| Fall | 0.58 | [0.490.68] | * |

| Winter | Reference | ||

| Cash eligibility | 1.14 | [1.011.27] | |

| Medical need eligibility | 1.21 | [1.081.36] | |

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study examining patient‐level and county‐level characteristics associated with all‐cause 30‐day readmission in Medicaid beneficiaries with chronic conditions. In addition, our findings add to the nascent literature on readmissions among Medicaid beneficiaries, with findings discussed below.

LOS has been reported as a risk factor for readmission both in elderly and nonelderly populations.[11] Our findings indicate that longer LOS is associated with increased odds of 30‐day readmission, which could be attributed to severity of illness at index hospitalization.[10] This finding could be related to unmeasured clinical severity (our models account for some comorbidities) and socioeconomic issues (as noted in the introduction). This may have implications for discharge planning efforts and focusing on chronic disease management, which has previously shown to be effective in reducing readmissions.[17] Our findings suggest 30‐day readmissions can be predicted using variables that are readily available, few in number, and simple to incorporate in discharge planning. Comprehensive discharge planning which takes into account chronic conditions and index hospitalization characteristics may help organize postdischarge services, including coordination of care with physicians, medication reconciliation, follow‐up care, and appropriate self‐management for chronic conditions.

Our findings of increased risk of 30‐day hospital readmissions as well as longer LOS among Medicaid beneficiaries with cancer, cardiovascular conditions, diabetes, and mental health conditions at index hospitalization suggests that patient complexity/poor health status increases the risk of readmission. A more focused approach in treatment of these diseases can help reduce readmissions. Integrated care management interventions after hospital discharge have been shown to reduce readmissions among those with heart disease; a coordinated care team including cardiologists, specialized nurses, and primary care physicians, and provision of integrated care following hospitalizations have shown benefit.[18, 19] Emerging models of delivery such as accountable care organizations and patient‐centered medical homes, which offer comprehensive, well‐coordinated primary care services, may be needed to reduce readmission among Medicaid beneficiaries with chronic health conditions. In this respect, 3 of the 4 states represented (California, New York, and Texas) are CMS Innovation Model partner states and are presently awardees of Medicaid Incentives for the Prevention of Chronic Disease state grants.[20] It remains to be seen whether such programs can reduce the high prevalence of readmissions in a Medicaid population.

Although our findings may have implications in reducing readmission risk, these results need to be interpreted in the light of study limitations. Our study was based on beneficiaries from only 4 states and cannot be generalized to the entire US Medicaid population. We also excluded individuals who were not enrolled in Medicaid health maintenance organizations. Given that less than one‐third of the population receives fee‐for‐service care in Medicaid, our study may have selection bias. Our study design utilized a retrospective cohort approach and cannot be used to establish causal relationships. Further, our study did not include adjustment for variables related to discharge planning or care coordination other than a primary care visit 14 days post discharge, which might influence the readmission risk of complex patients. Our study utilized data from administrative claims files.

Overall, our analyses revealed that patient complexities increased the risk of all‐cause 30‐day readmission for high‐risk Medicaid beneficiaries with chronic conditions, thus warranting the need for comprehensive care for those with chronic conditions. Programs designed to reduce the risk of 30‐day readmissions may need to focus on appropriate disease management and better coordinated care post hospitalization.

Disclosures

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Training Program in the Behavioral and Biomedical Sciences at West Virginia University, National Institute of General Medical Sciences grant number T32 GM08174, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number U54GM104942, and the Benedum Foundation. The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analyses, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Hospital readmissions that occur within 30 days of discharge are an important measure for assessing performance of the healthcare system and the quality of patient care.[1, 2] According to the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), there were approximately 3.3 million adults with all‐cause 30‐day readmissions in the United States in 2011, incurring nearly $41.3 billion in hospital costs.[3] Reducing 30‐day readmissions has become a priority for payers, providers, and policymakers seeking to achieve improved quality of care at lower costs.

The implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) provided the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) statutory authority under the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program to reduce payments for certain hospital readmissions that it deemed avoidable.[4] Although initial focus was on Medicare readmissions related to heart failure, myocardial infarction, and pneumonia, CMS is now considering expanding the list beyond the 3 conditions covered by the program.[4, 5] Therefore, it is important to understand major risk factors for readmissions in beneficiaries with chronic conditions.

Medicaid consists of the largest number of beneficiaries among all payers in the United States, with approximately 62 million beneficiaries in 2013.[5] The Medicaid population is further expected to increase with the coverage expansions under the ACA. In addition, the state Medicaid programs incur an estimated $374 billion in healthcare expenditures and provide healthcare services to the vulnerable, indigent, and disabled. It is estimated that 61% of adult Medicaid beneficiaries have chronic or disabling conditions that place them at an increased risk of hospitalization.[6] A series of HCUP statistical briefs reported several findings. First, Medicaid all‐cause readmission rates were comparable with Medicare but double the rate of private insurance.[7] Second, for readmissions following nonsurgical hospitalizations, 30‐day Medicaid readmission rates were higher than Medicare and private insurance for both acute and chronic conditions.[1] The effects of such costly utilization patterns, for this large and growing population necessitates heightened attention under healthcare reform.

The balance between hospital efficiency and quality of care is another crucial aspect for our healthcare system. However, length of stay (LOS), a proxy marker for efficiency, may conflict with hospital readmission rates, an indicator of quality. Further, CMS plans to bundle 30‐day readmission rates to reimbursement for the index hospitalization.[8]

The effect of LOS on readmission rates is complex, and previous studies have provided conflicting data regarding the relationship between LOS and subsequent readmission risk. Some indicate that shorter LOS is associated with a higher risk of readmission,[8, 9] whereas others suggest that extended LOS is associated with a higher risk of readmission.[10, 11, 12] However, most research on readmissions has focused on Medicare beneficiaries.[11, 13, 14] The readmission patterns of Medicaid beneficiaries differ from those of the geriatric Medicare beneficiaries, from a clinical and socioeconomic perspective. Considering the importance of 30‐day readmission for payers and policy makers, there is a need to understand the role of LOS and implications for treatment and management strategies.

Our study examined the association between index hospitalization characteristics (LOS and reason for admission) and all‐cause 30‐day readmission risk in fee‐for‐service high‐risk Medicaid beneficiaries. The study is limited to patients with selected chronic conditions and examines the differentiating factors within this high‐risk population. For the purpose of our study, variables were selected based on a priori knowledge and Andersen's behavioral model of health service utilization. This model suggests that potential health service use is determined by interactions among predisposing (demographics, index hospitalization characteristics), enabling (county level [eg, socioeconomic status]), and need (health status) characteristics of individuals and also the healthcare systems in the communities where they reside.[15]

METHODS

Study Design

A retrospective cohort approach was used with baseline and follow‐up periods. The baseline period was defined as the admission date of the index hospitalization (first observed hospitalization) between January 1, 2007 and December 31, 2007. Patients were followed for 180 days after discharge date of the associated index hospitalization.

Data Source

Medicaid administrative claims files from California, Illinois, New York, and Texas, between 2006 and 2008, were used. The personal summary file included information on demographics, Medicaid enrollment, and eligibility status. Outpatient and Inpatient files included claims for services provided in ambulatory and inpatient settings and contained International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification codes. Information on county‐level characteristics were obtained from the 2009 Area Health Resource File (AHRF), which was linked to Medicaid administrative claims files using state and county codes where each beneficiary resided.

Study Population

The study population consisted of nonelderly (2164 years old) fee‐for‐service Medicaid‐only beneficiaries with selected chronic conditions and continuous enrollment during baseline and follow‐up period (Figure 1). Analyses were restricted to those who had at least 1 inpatient admission in 2007 and were conducted at the person‐level.

For the purpose of this study, Medicaid beneficiaries with 19 chronic conditions were selected: asthma, arthritis, cardiac arrhythmias, coronary artery disease, cancer, congestive heart failure, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, dementia, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, hepatitis, human immunodeficiency virus osteoporosis, stroke, depression, schizophrenia, and substance use disorders. These conditions were identified based on the strategic framework developed and adopted by the Department of Health and Human Services for research, policy, program, and practice.[16]

Dependent Variable

Individuals were categorized into 2 groups, those with and without all‐cause 30‐day readmission. All‐cause 30‐day readmission was identified as subsequent hospitalization within 30 days of discharge date of the index hospitalization.

Key Independent Variables

These were index hospitalization characteristics, where LOS was the primary independent variable, reason for admission was the secondary independent variable, and month of index hospitalization (included to control for potential seasonal effect).

Other Independent Variables

Patient‐level characteristics included demographics (age, gender, and race/ethnicity) and Medicaid eligibility status (cash and medical need). Primary care access included continuity of care measured using a previously published continuity index (Modified Modified Continuity Index) and coordination of care, measured as primary care visit within 14 days of discharge date. Healthcare utilization was measured as an emergency room visit within 6 months prior to the index hospitalization.

Variables accounting for county socioeconomic status included educational attainment, per capita income, employment rate, poverty level, and metropolitan statistical area. Variables related to availability of providers and healthcare facilities were AHRF designations for primary/mental healthcare shortage areas, presence of federally qualified health centers, rural health centers, and community mental health centers. Hospital and primary care provider density was defined as total number of hospitals or primary care providers per 100,000 individuals, respectively.

Statistical Techniques

2 tests of independence were used for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables to determine group differences in patient‐level and county‐level characteristics and all‐cause 30‐day readmission. Multilevel logistic regression models, which accounted for beneficiaries nested within counties, were used to examine the association between all‐cause 30‐day readmission and index hospitalization characteristics. The reference group for the dependent variable was no 30‐day readmission. Model 1 controlled for only patient‐level characteristics. Model 2 controlled for both patient‐level and county‐level characteristics. In both models, county was specified as a random intercept using the GLIMMIX procedure. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

After the exclusion criteria, there were 15,806 Medicaid beneficiaries with selected chronic conditions and at least 1 inpatient encounter in 2007. Overall, 16.7% experienced all‐cause 30‐day readmissions. A description of the study population and unadjusted associations between independent variables and all‐cause 30‐day readmission are presented in Table 1.

| Variables | 30‐Day Readmission, 2,633 (16.7%) | No 30‐Day Readmission, 13,173 (83.3%) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Demographic and Medicaid eligibility characteristics | |||

| Gender, N (%) | * | ||

| Female | 1,715 (65.1%) | 9,274 (70.4%) | |

| Male | 918 (34.9%) | 3,899 (29.6%) | |

| Age group, N (%) | * | ||

| 2124 years | 301 (11.4%) | 1,675 (12.7%) | |

| 2534 years | 567 (21.5%) | 3,578 (27.2%) | |

| 3544 years | 517 (19.6%) | 2,498 (19.0%) | |

| 4554 years | 673 (25.6%) | 2,971 (22.6%) | |

| 5564 years | 575 (21.8%) | 2,451 (18.6%) | |

| Race/ethnicity, N (%) | * | ||

| Caucasian | 847 (32.2%) | 3,831 (29.1%) | |

| African American | 988 (37.5%) | 4,270(32.4%) | |

| Hispanic | 608 (23.1%) | 4,245 (32.2%) | |

| Asian/AI/PI | 39 (1.5%) | 169 (1.3%) | |

| Other | 151 (5.7%) | 658 (5.0%) | |

| Cash eligibility, N (%) | 1,529 (58.1%) | 6,666 (50.6%) | * |

| Medical need eligibility, N (%) | 876 (33.3%) | 3769 (28.6%) | * |

| Index hospitalization characteristics | |||

| Length of stay, mean [SD] | 6.62 [9.09] | 4.29 [6.35] | * |

| Chronic conditions at admission, N (%) | |||

| Arthritis/osteoporosis | 99 (3.8%) | 464 (3.5%) | |

| Cancer | 134 (5.1%) | 429 (3.3%) | * |

| Cardiovascular conditions | 995 (37.8%) | 3,733 (28.3%) | * |

| COPD/asthma | 541 (20.5%) | 2,197 (16.7%) | * |

| Diabetes | 575 (21.8%) | 2,103 (16.0%) | * |

| HIV/hepatitis | 305 (11.6%) | 1,185 (9.0%) | * |

| Mental health conditions | 1,491 (56.6%) | 4,352 (33.0%) | * |

| Season of readmission, N (%) | * | ||

| Spring | 730 (27.7%) | 3,944 (29.9%) | |

| Summer | 401 (15.2%) | 2,332 (17.7%) | |

| Fall | 211 (8.0%) | 1,605 (12.2%) | |

| Winter | 1,291 (49.0%) | 5,292 (40.2%) | |

| Primary care access, N (%) | |||

| Coordination of primary care | 326 (12.4%) | 1,747 (13.3%) | |

| Continuity of primary care, N (%) | |||

| Complete care continuity | 349 (13.3%) | 1,764 (13.4%) | |

| Some care continuity | 634 (24.1%) | 2,960 (22.5%) | |

| No care continuity | 1650 (62.7%) | 8,449 (64.1%) | |

| Healthcare utilization, N (%) | |||

| Emergency room visit | 893 (33.9%) | 4,449 (33.8%) | |

| County‐level characteristics | |||

| Metropolitan status, N (%) | |||

| Nonmetro | 267 (10.1%) | 1,285 (9.8%) | |

| Metro | 2,366 (89.9%) | 11,888 (90.2%) | |

| Primary care shortage area, N (%) | |||

| Whole county | 2,034 (77.3%) | 10,147 (77.0%) | |

| Part county | 429 (16.3%) | 2,312 (17.6%) | |

| No shortage | 170 (6.5%) | 714 (5.4%) | |

| Mental healthcare shortage area, N (%) | |||

| Whole county | 2,015 (76.5%) | 9,925 (75.3%) | |

| Part county | 388 (14.7%) | 2,242 (17.0%) | |

| No shortage | 230 (8.7%) | 1,006 (7.6%) | |

| CMHC, mean [SD] | 0.81 [1.23] | 0.94 [1.24] | * |

| Rural health center, mean [SD] | 0.62 [3.03] | 1.06 [4.41] | * |

| FQHC, mean [SD] | 37.69 [44.31] | 37.78 [42.98] | |

| Education rate, 4+ years, mean [SD] | 25.39 [10.98] | 23.77 [10.51] | * |

| Unemployment rate, mean [SD] | 4.57 [0.71] | 4.67 [0.90] | * |

| % Below poverty level, mean [SD] | 15.11 [3.73] | 15.06 [3.80] | |

| Per capita income (US dollars), mean [SD] | 58,761.96 [33,697.42] | 54,029.16 [31,265.86] | * |

| Nonfederal PCP density, mean [SD] | 307.10 [192.29] | 279.97 [179.22] | * |

| Hospital density, mean [SD] | 1.74 [1.37] | 1.65 [1.14] | * |

Multilevel logistic regressions of all‐cause 30‐day readmissions are summarized in Table 2. Beneficiaries with longer LOS had significantly higher odds of 30‐day readmission. In addition, presence of cancer, cardiovascular conditions, diabetes, and mental health conditions at index hospitalization significantly increased the odds of readmission. In addition, beneficiaries with cash or medical need eligibility had significantly higher odds of 30‐day readmission.

| AOR | 95% CI | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Length of stay | 1.03 | [1.031.04] | * |

| Chronic conditions at admission | |||

| Arthritis/osteoporosis | 0.90 | [0.721.13] | |

| Cancer | 1.55 | [1.261.90] | * |

| Cardiovascular conditions | 1.20 | [1.081.33] | * |

| COPD/asthma | 1.01 | [0.901.12] | |

| Diabetes | 1.23 | [1.101.39] | * |

| HIV/hepatitis | 0.98 | [0.851.12] | |

| Mental health conditions | 2.17 | [1.982.38] | * |

| Season of readmission | |||

| Spring | 0.79 | [0.710.88] | * |

| Summer | 0.77 | [0.680.88] | * |

| Fall | 0.58 | [0.490.68] | * |

| Winter | Reference | ||

| Cash eligibility | 1.14 | [1.011.27] | |

| Medical need eligibility | 1.21 | [1.081.36] | |

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study examining patient‐level and county‐level characteristics associated with all‐cause 30‐day readmission in Medicaid beneficiaries with chronic conditions. In addition, our findings add to the nascent literature on readmissions among Medicaid beneficiaries, with findings discussed below.

LOS has been reported as a risk factor for readmission both in elderly and nonelderly populations.[11] Our findings indicate that longer LOS is associated with increased odds of 30‐day readmission, which could be attributed to severity of illness at index hospitalization.[10] This finding could be related to unmeasured clinical severity (our models account for some comorbidities) and socioeconomic issues (as noted in the introduction). This may have implications for discharge planning efforts and focusing on chronic disease management, which has previously shown to be effective in reducing readmissions.[17] Our findings suggest 30‐day readmissions can be predicted using variables that are readily available, few in number, and simple to incorporate in discharge planning. Comprehensive discharge planning which takes into account chronic conditions and index hospitalization characteristics may help organize postdischarge services, including coordination of care with physicians, medication reconciliation, follow‐up care, and appropriate self‐management for chronic conditions.

Our findings of increased risk of 30‐day hospital readmissions as well as longer LOS among Medicaid beneficiaries with cancer, cardiovascular conditions, diabetes, and mental health conditions at index hospitalization suggests that patient complexity/poor health status increases the risk of readmission. A more focused approach in treatment of these diseases can help reduce readmissions. Integrated care management interventions after hospital discharge have been shown to reduce readmissions among those with heart disease; a coordinated care team including cardiologists, specialized nurses, and primary care physicians, and provision of integrated care following hospitalizations have shown benefit.[18, 19] Emerging models of delivery such as accountable care organizations and patient‐centered medical homes, which offer comprehensive, well‐coordinated primary care services, may be needed to reduce readmission among Medicaid beneficiaries with chronic health conditions. In this respect, 3 of the 4 states represented (California, New York, and Texas) are CMS Innovation Model partner states and are presently awardees of Medicaid Incentives for the Prevention of Chronic Disease state grants.[20] It remains to be seen whether such programs can reduce the high prevalence of readmissions in a Medicaid population.

Although our findings may have implications in reducing readmission risk, these results need to be interpreted in the light of study limitations. Our study was based on beneficiaries from only 4 states and cannot be generalized to the entire US Medicaid population. We also excluded individuals who were not enrolled in Medicaid health maintenance organizations. Given that less than one‐third of the population receives fee‐for‐service care in Medicaid, our study may have selection bias. Our study design utilized a retrospective cohort approach and cannot be used to establish causal relationships. Further, our study did not include adjustment for variables related to discharge planning or care coordination other than a primary care visit 14 days post discharge, which might influence the readmission risk of complex patients. Our study utilized data from administrative claims files.

Overall, our analyses revealed that patient complexities increased the risk of all‐cause 30‐day readmission for high‐risk Medicaid beneficiaries with chronic conditions, thus warranting the need for comprehensive care for those with chronic conditions. Programs designed to reduce the risk of 30‐day readmissions may need to focus on appropriate disease management and better coordinated care post hospitalization.

Disclosures

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Training Program in the Behavioral and Biomedical Sciences at West Virginia University, National Institute of General Medical Sciences grant number T32 GM08174, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number U54GM104942, and the Benedum Foundation. The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analyses, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.