User login

Antithrombotics appear safe in BCVI with concomitant injuries

SAN ANTONIO – Don’t withhold antiplatelet or heparin therapy in patients with blunt cerebrovascular injury, even if they have concomitant traumatic brain or solid organ injuries, advised researchers from the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis.

With close monitoring, “initiation of early antithrombotic therapy for patients with BCVI [blunt cerebrovascular injury] and concomitant TBI [traumatic brain injury] or SOI [solid organ injury] does not increase the risk of worsening TBI or SOI above baseline.” It is safe, effective, and “should not be withheld,” the researchers concluded after a review of 119 BCVI patients with concomitant injuries.

Seventy four (62%) had TBIs, 26 (22%) had SOIs, and 19 (16%) had both. At some institutions, antithrombotic therapy – the mainstay for BCVI to prevent secondary ischemic stroke – would have been delayed or withheld for fear of triggering hemorrhagic complications.

But at the Health Science Center in Memphis, “we have an extremely cooperative group of neurosurgeons who take BCVI as seriously as we do, and actually allow us, more often than not, to start antithrombotic therapy pretty much immediately after the injury is identified,” investigator and surgery resident Dr. Charles Shahan said at the annual scientific assembly of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

As a result, 85 patients (71%) received heparin infusions with goal-activated partial thromboplastin times of 45-60 seconds, and the rest antiplatelet therapy, typically 81-mg aspirin. The center generally uses heparin for TBI patients because of its short half-life, and aspirin for others.

Antithrombosed BCVI patients did as well as did historical controls. TBIs deteriorated – meaning worsening on clinical or CT exam, or delayed operative intervention – in 7%, vs. 10% of TBI patients without BCVI (P = .34). Three percent of SOI patients had delayed laparotomies vs. 5% of SOI patients without BCVI (P = .54). None of the BCVI patients stopped antithrombotics because of complications.

The results held regardless of the type of TBI, SOI, or antithrombotic used.

Overall, 11 patients (9%) had BCVI-related strokes. Without antithrombotic therapy, stroke rates in BCVI can approach 40%.

“Our extremely early use of antithrombotic therapy does not appear to increase our rate of worsening of our hemorrhagic injures and also gets our stroke rate within acceptable limits,” Dr. Shahan said.

The mean age in the study was 38, and just over half the subjects were men.

Dr. Shahan had no disclosures

SAN ANTONIO – Don’t withhold antiplatelet or heparin therapy in patients with blunt cerebrovascular injury, even if they have concomitant traumatic brain or solid organ injuries, advised researchers from the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis.

With close monitoring, “initiation of early antithrombotic therapy for patients with BCVI [blunt cerebrovascular injury] and concomitant TBI [traumatic brain injury] or SOI [solid organ injury] does not increase the risk of worsening TBI or SOI above baseline.” It is safe, effective, and “should not be withheld,” the researchers concluded after a review of 119 BCVI patients with concomitant injuries.

Seventy four (62%) had TBIs, 26 (22%) had SOIs, and 19 (16%) had both. At some institutions, antithrombotic therapy – the mainstay for BCVI to prevent secondary ischemic stroke – would have been delayed or withheld for fear of triggering hemorrhagic complications.

But at the Health Science Center in Memphis, “we have an extremely cooperative group of neurosurgeons who take BCVI as seriously as we do, and actually allow us, more often than not, to start antithrombotic therapy pretty much immediately after the injury is identified,” investigator and surgery resident Dr. Charles Shahan said at the annual scientific assembly of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

As a result, 85 patients (71%) received heparin infusions with goal-activated partial thromboplastin times of 45-60 seconds, and the rest antiplatelet therapy, typically 81-mg aspirin. The center generally uses heparin for TBI patients because of its short half-life, and aspirin for others.

Antithrombosed BCVI patients did as well as did historical controls. TBIs deteriorated – meaning worsening on clinical or CT exam, or delayed operative intervention – in 7%, vs. 10% of TBI patients without BCVI (P = .34). Three percent of SOI patients had delayed laparotomies vs. 5% of SOI patients without BCVI (P = .54). None of the BCVI patients stopped antithrombotics because of complications.

The results held regardless of the type of TBI, SOI, or antithrombotic used.

Overall, 11 patients (9%) had BCVI-related strokes. Without antithrombotic therapy, stroke rates in BCVI can approach 40%.

“Our extremely early use of antithrombotic therapy does not appear to increase our rate of worsening of our hemorrhagic injures and also gets our stroke rate within acceptable limits,” Dr. Shahan said.

The mean age in the study was 38, and just over half the subjects were men.

Dr. Shahan had no disclosures

SAN ANTONIO – Don’t withhold antiplatelet or heparin therapy in patients with blunt cerebrovascular injury, even if they have concomitant traumatic brain or solid organ injuries, advised researchers from the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis.

With close monitoring, “initiation of early antithrombotic therapy for patients with BCVI [blunt cerebrovascular injury] and concomitant TBI [traumatic brain injury] or SOI [solid organ injury] does not increase the risk of worsening TBI or SOI above baseline.” It is safe, effective, and “should not be withheld,” the researchers concluded after a review of 119 BCVI patients with concomitant injuries.

Seventy four (62%) had TBIs, 26 (22%) had SOIs, and 19 (16%) had both. At some institutions, antithrombotic therapy – the mainstay for BCVI to prevent secondary ischemic stroke – would have been delayed or withheld for fear of triggering hemorrhagic complications.

But at the Health Science Center in Memphis, “we have an extremely cooperative group of neurosurgeons who take BCVI as seriously as we do, and actually allow us, more often than not, to start antithrombotic therapy pretty much immediately after the injury is identified,” investigator and surgery resident Dr. Charles Shahan said at the annual scientific assembly of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

As a result, 85 patients (71%) received heparin infusions with goal-activated partial thromboplastin times of 45-60 seconds, and the rest antiplatelet therapy, typically 81-mg aspirin. The center generally uses heparin for TBI patients because of its short half-life, and aspirin for others.

Antithrombosed BCVI patients did as well as did historical controls. TBIs deteriorated – meaning worsening on clinical or CT exam, or delayed operative intervention – in 7%, vs. 10% of TBI patients without BCVI (P = .34). Three percent of SOI patients had delayed laparotomies vs. 5% of SOI patients without BCVI (P = .54). None of the BCVI patients stopped antithrombotics because of complications.

The results held regardless of the type of TBI, SOI, or antithrombotic used.

Overall, 11 patients (9%) had BCVI-related strokes. Without antithrombotic therapy, stroke rates in BCVI can approach 40%.

“Our extremely early use of antithrombotic therapy does not appear to increase our rate of worsening of our hemorrhagic injures and also gets our stroke rate within acceptable limits,” Dr. Shahan said.

The mean age in the study was 38, and just over half the subjects were men.

Dr. Shahan had no disclosures

AT THE EAST SCIENTIFIC ASSEMBLY

Key clinical point: Antithrombotics for BCVI do not make concomitant brain and solid organ injuries worse.

Major finding: TBIs deteriorated in 7% of BCVI patients on heparin infusion, versus 10% of TBI patients without BCVI (P = .34).

Data source: Review of 119 BCVI patients.

Disclosures: The lead investigator had no disclosures.

Save the Date for ACS Clinical Congress 2016, October 16−20

Save the date for the American College of Surgeons Clinical Congress 2016, October 16−20 in Washington, DC, at the Walter E. Washington Convention Center. The Marriot Marquis Washington, DC, located next to the convention center, will serve as the headquarters hotel.

The theme of this year’s meeting, Challenges for the Second Century, recognizes the College’s second 100 years of ensuring quality surgical patient care. Clinical Congress 2016 will present hundreds of educational sessions, including Panel Sessions, Postgraduate Didactic and Skills-Oriented Courses, Meet-the-Expert Luncheons, Names Lectures, Scientific Paper Sessions, and Poster Presentations. View an ACS press release at https://www.facs.org/media/press-releases/2016/clincon0316#sthash.SnHNsOJB.dpuf for more information on Clinical Congress 2016.

Save the date for the American College of Surgeons Clinical Congress 2016, October 16−20 in Washington, DC, at the Walter E. Washington Convention Center. The Marriot Marquis Washington, DC, located next to the convention center, will serve as the headquarters hotel.

The theme of this year’s meeting, Challenges for the Second Century, recognizes the College’s second 100 years of ensuring quality surgical patient care. Clinical Congress 2016 will present hundreds of educational sessions, including Panel Sessions, Postgraduate Didactic and Skills-Oriented Courses, Meet-the-Expert Luncheons, Names Lectures, Scientific Paper Sessions, and Poster Presentations. View an ACS press release at https://www.facs.org/media/press-releases/2016/clincon0316#sthash.SnHNsOJB.dpuf for more information on Clinical Congress 2016.

Save the date for the American College of Surgeons Clinical Congress 2016, October 16−20 in Washington, DC, at the Walter E. Washington Convention Center. The Marriot Marquis Washington, DC, located next to the convention center, will serve as the headquarters hotel.

The theme of this year’s meeting, Challenges for the Second Century, recognizes the College’s second 100 years of ensuring quality surgical patient care. Clinical Congress 2016 will present hundreds of educational sessions, including Panel Sessions, Postgraduate Didactic and Skills-Oriented Courses, Meet-the-Expert Luncheons, Names Lectures, Scientific Paper Sessions, and Poster Presentations. View an ACS press release at https://www.facs.org/media/press-releases/2016/clincon0316#sthash.SnHNsOJB.dpuf for more information on Clinical Congress 2016.

ART cycles, live births up in 2014

More than 65,000 babies were born following about 190,000 cycles of IVF and other assisted reproductive technologies in 2014, according to data from the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology.

The report – which includes data from 375 member clinics of the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology (SART) – shows an increase both in assisted reproductive technology (ART) procedures performed and in the number of subsequent live births, compared with 2013.

Another trend in the 2014 data is a decline in the number of multiple births, due largely to increased use of single-embryo transfer.

Singleton births reached 78% from the 2014 cycles, up from 75.5% the previous year. Single-embryo transfer cycles accounted for 27.2% of all cycles in 2014, compared with 20.6% in 2013.

“The latest data reflect the success of our efforts to improve ART practice from ovarian stimulation through transfer,” Dr. Bradley Van Voorhis, SART president, said in a statement. “We are proud of the progress we have made improving live birth rates – the true measure of a cycle’s success – and in improving maternal and child health outcomes for our patients through lower multiple birth rates.”

Read the national summary report for SART clinics here.

On Twitter @maryellenny

More than 65,000 babies were born following about 190,000 cycles of IVF and other assisted reproductive technologies in 2014, according to data from the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology.

The report – which includes data from 375 member clinics of the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology (SART) – shows an increase both in assisted reproductive technology (ART) procedures performed and in the number of subsequent live births, compared with 2013.

Another trend in the 2014 data is a decline in the number of multiple births, due largely to increased use of single-embryo transfer.

Singleton births reached 78% from the 2014 cycles, up from 75.5% the previous year. Single-embryo transfer cycles accounted for 27.2% of all cycles in 2014, compared with 20.6% in 2013.

“The latest data reflect the success of our efforts to improve ART practice from ovarian stimulation through transfer,” Dr. Bradley Van Voorhis, SART president, said in a statement. “We are proud of the progress we have made improving live birth rates – the true measure of a cycle’s success – and in improving maternal and child health outcomes for our patients through lower multiple birth rates.”

Read the national summary report for SART clinics here.

On Twitter @maryellenny

More than 65,000 babies were born following about 190,000 cycles of IVF and other assisted reproductive technologies in 2014, according to data from the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology.

The report – which includes data from 375 member clinics of the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology (SART) – shows an increase both in assisted reproductive technology (ART) procedures performed and in the number of subsequent live births, compared with 2013.

Another trend in the 2014 data is a decline in the number of multiple births, due largely to increased use of single-embryo transfer.

Singleton births reached 78% from the 2014 cycles, up from 75.5% the previous year. Single-embryo transfer cycles accounted for 27.2% of all cycles in 2014, compared with 20.6% in 2013.

“The latest data reflect the success of our efforts to improve ART practice from ovarian stimulation through transfer,” Dr. Bradley Van Voorhis, SART president, said in a statement. “We are proud of the progress we have made improving live birth rates – the true measure of a cycle’s success – and in improving maternal and child health outcomes for our patients through lower multiple birth rates.”

Read the national summary report for SART clinics here.

On Twitter @maryellenny

JAMA Surgery publishes research agenda developed at NIH-ACS symposium on disparities

An article in the March 16 issue of JAMA Surgery summarizes the research and funding priorities for addressing health care disparities in the United States, which were identified at the inaugural National Institutes of Health (NIH)–American College of Surgeons (ACS) Symposium on Surgical Disparities Research.1 The ACS and the National Institute on Minority Health and Disparities (NIMHD) cohosted the conference, which took place in May 2015 at the NIH campus, Bethesda, MD.2

“The goal of the symposium was to create a national research agenda that could be used to prioritize funding for research. We conducted an extensive literature review of existing research, organized the results by theme, and asked attendees to identify what they saw as the top priorities for each theme,” said Adil Haider, MD, MPH, FACS. Dr. Haider is the lead author of the JAMA Surgery article; Vice-Chair, ACS Committee on Health Care Disparities; and Kessler Director, Center for Surgery and Public Health, a joint initiative of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston.

Defining themes and priorities

The themes discussed at the symposium were as follows: patient and host factors, systemic factors and access issues, clinical care and quality, provider factors, and postoperative care and rehabilitation. The leading research and funding priorities – identified by the more than 60 researchers, surgeon-scientists, and federal leaders who attended the symposium, and articulated in the JAMA Surgery article – are as follows:

• Improve patient-provider communication by teaching providers to deliver culturally dexterous care and measuring its impact on elimination of surgical disparities.

• Foster engagement and community outreach and use technology to optimize patient education, health literacy, and shared decision making in a culturally relevant way; disseminate these techniques; and evaluate their impact on reducing surgical disparities.

• Evaluate regionalization of care versus strengthening safety-net hospitals within the context of differential access and surgical disparities.

• Gauge the long-term impact of intervention and rehabilitation support within the critical period on functional outcomes and patient-defined perceptions of quality of life.

• Improve patient engagement and identify patient expectations for postoperative and postinjury recovery, as well as their values regarding advanced health care planning and palliative care.

The authors of the JAMA Surgery article concluded that “The NIH-ACS Symposium on Surgical Disparities Research succeeded in identifying a comprehensive research agenda.” In particular, they noted that future research is needed in the areas of patients’ perspectives, workforce diversification and training, and systematic evaluation of health technologies to reduce surgical disparities. Within the context of the larger literature focused on disparity-related research, results also call for ongoing evaluation of evidence-based practice, rigorous research methodologies, incentives for standardization of care, and building on existing infrastructure to support these advances.

Just the beginning

The ACS is “confident that this is just the beginning of a much larger effort and hopeful that the National Institutes of Health and the NIMHD will continue to work with the ACS to build upon the foundation that was set during the symposium by establishing a funding stream to support this important research. Together, we can foster systemic change, effectively eliminating surgical and other health care disparities,” said L.D. Britt, MD, MPH, DSc(Hon), FACS, FCCM, FRCSEng(Hon), FRCSEd(Hon), FWACS(Hon), FRCSI(Hon), FCS(SA)(Hon), FRCSGlasg(Hon), ACS Past-President and Chair, ACS Committee on Health Care Disparities. Dr. Britt is the Brickhouse Professor of Surgery, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, and played a critical role in the creation of the committee and in defining the committee’s deliverables, which included a national symposium.

1. Haider AH, Dankwa-Mullan I, Maragh-Bass, et al. Setting a national agenda for surgical disparities research: Recommendations from the National Institutes of Health and American College of Surgeons Summit. JAMA Surg. March 16, 2016. Available at http://archsurg.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=2503437. Accessed March 28, 2016.

2. Schneidman D. No quality without access: ACS and NIH collaborate to ensure access to optimal care. Bull Am Coll Surg. 2015;100(8):52-62. Available at: bulletin.facs.org/2015/08/no-quality-without-access-acs-and-nih-collaborate-to-ensure-access-to-optimal-care. Accessed March 28, 2016.

An article in the March 16 issue of JAMA Surgery summarizes the research and funding priorities for addressing health care disparities in the United States, which were identified at the inaugural National Institutes of Health (NIH)–American College of Surgeons (ACS) Symposium on Surgical Disparities Research.1 The ACS and the National Institute on Minority Health and Disparities (NIMHD) cohosted the conference, which took place in May 2015 at the NIH campus, Bethesda, MD.2

“The goal of the symposium was to create a national research agenda that could be used to prioritize funding for research. We conducted an extensive literature review of existing research, organized the results by theme, and asked attendees to identify what they saw as the top priorities for each theme,” said Adil Haider, MD, MPH, FACS. Dr. Haider is the lead author of the JAMA Surgery article; Vice-Chair, ACS Committee on Health Care Disparities; and Kessler Director, Center for Surgery and Public Health, a joint initiative of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston.

Defining themes and priorities

The themes discussed at the symposium were as follows: patient and host factors, systemic factors and access issues, clinical care and quality, provider factors, and postoperative care and rehabilitation. The leading research and funding priorities – identified by the more than 60 researchers, surgeon-scientists, and federal leaders who attended the symposium, and articulated in the JAMA Surgery article – are as follows:

• Improve patient-provider communication by teaching providers to deliver culturally dexterous care and measuring its impact on elimination of surgical disparities.

• Foster engagement and community outreach and use technology to optimize patient education, health literacy, and shared decision making in a culturally relevant way; disseminate these techniques; and evaluate their impact on reducing surgical disparities.

• Evaluate regionalization of care versus strengthening safety-net hospitals within the context of differential access and surgical disparities.

• Gauge the long-term impact of intervention and rehabilitation support within the critical period on functional outcomes and patient-defined perceptions of quality of life.

• Improve patient engagement and identify patient expectations for postoperative and postinjury recovery, as well as their values regarding advanced health care planning and palliative care.

The authors of the JAMA Surgery article concluded that “The NIH-ACS Symposium on Surgical Disparities Research succeeded in identifying a comprehensive research agenda.” In particular, they noted that future research is needed in the areas of patients’ perspectives, workforce diversification and training, and systematic evaluation of health technologies to reduce surgical disparities. Within the context of the larger literature focused on disparity-related research, results also call for ongoing evaluation of evidence-based practice, rigorous research methodologies, incentives for standardization of care, and building on existing infrastructure to support these advances.

Just the beginning

The ACS is “confident that this is just the beginning of a much larger effort and hopeful that the National Institutes of Health and the NIMHD will continue to work with the ACS to build upon the foundation that was set during the symposium by establishing a funding stream to support this important research. Together, we can foster systemic change, effectively eliminating surgical and other health care disparities,” said L.D. Britt, MD, MPH, DSc(Hon), FACS, FCCM, FRCSEng(Hon), FRCSEd(Hon), FWACS(Hon), FRCSI(Hon), FCS(SA)(Hon), FRCSGlasg(Hon), ACS Past-President and Chair, ACS Committee on Health Care Disparities. Dr. Britt is the Brickhouse Professor of Surgery, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, and played a critical role in the creation of the committee and in defining the committee’s deliverables, which included a national symposium.

1. Haider AH, Dankwa-Mullan I, Maragh-Bass, et al. Setting a national agenda for surgical disparities research: Recommendations from the National Institutes of Health and American College of Surgeons Summit. JAMA Surg. March 16, 2016. Available at http://archsurg.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=2503437. Accessed March 28, 2016.

2. Schneidman D. No quality without access: ACS and NIH collaborate to ensure access to optimal care. Bull Am Coll Surg. 2015;100(8):52-62. Available at: bulletin.facs.org/2015/08/no-quality-without-access-acs-and-nih-collaborate-to-ensure-access-to-optimal-care. Accessed March 28, 2016.

An article in the March 16 issue of JAMA Surgery summarizes the research and funding priorities for addressing health care disparities in the United States, which were identified at the inaugural National Institutes of Health (NIH)–American College of Surgeons (ACS) Symposium on Surgical Disparities Research.1 The ACS and the National Institute on Minority Health and Disparities (NIMHD) cohosted the conference, which took place in May 2015 at the NIH campus, Bethesda, MD.2

“The goal of the symposium was to create a national research agenda that could be used to prioritize funding for research. We conducted an extensive literature review of existing research, organized the results by theme, and asked attendees to identify what they saw as the top priorities for each theme,” said Adil Haider, MD, MPH, FACS. Dr. Haider is the lead author of the JAMA Surgery article; Vice-Chair, ACS Committee on Health Care Disparities; and Kessler Director, Center for Surgery and Public Health, a joint initiative of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston.

Defining themes and priorities

The themes discussed at the symposium were as follows: patient and host factors, systemic factors and access issues, clinical care and quality, provider factors, and postoperative care and rehabilitation. The leading research and funding priorities – identified by the more than 60 researchers, surgeon-scientists, and federal leaders who attended the symposium, and articulated in the JAMA Surgery article – are as follows:

• Improve patient-provider communication by teaching providers to deliver culturally dexterous care and measuring its impact on elimination of surgical disparities.

• Foster engagement and community outreach and use technology to optimize patient education, health literacy, and shared decision making in a culturally relevant way; disseminate these techniques; and evaluate their impact on reducing surgical disparities.

• Evaluate regionalization of care versus strengthening safety-net hospitals within the context of differential access and surgical disparities.

• Gauge the long-term impact of intervention and rehabilitation support within the critical period on functional outcomes and patient-defined perceptions of quality of life.

• Improve patient engagement and identify patient expectations for postoperative and postinjury recovery, as well as their values regarding advanced health care planning and palliative care.

The authors of the JAMA Surgery article concluded that “The NIH-ACS Symposium on Surgical Disparities Research succeeded in identifying a comprehensive research agenda.” In particular, they noted that future research is needed in the areas of patients’ perspectives, workforce diversification and training, and systematic evaluation of health technologies to reduce surgical disparities. Within the context of the larger literature focused on disparity-related research, results also call for ongoing evaluation of evidence-based practice, rigorous research methodologies, incentives for standardization of care, and building on existing infrastructure to support these advances.

Just the beginning

The ACS is “confident that this is just the beginning of a much larger effort and hopeful that the National Institutes of Health and the NIMHD will continue to work with the ACS to build upon the foundation that was set during the symposium by establishing a funding stream to support this important research. Together, we can foster systemic change, effectively eliminating surgical and other health care disparities,” said L.D. Britt, MD, MPH, DSc(Hon), FACS, FCCM, FRCSEng(Hon), FRCSEd(Hon), FWACS(Hon), FRCSI(Hon), FCS(SA)(Hon), FRCSGlasg(Hon), ACS Past-President and Chair, ACS Committee on Health Care Disparities. Dr. Britt is the Brickhouse Professor of Surgery, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, and played a critical role in the creation of the committee and in defining the committee’s deliverables, which included a national symposium.

1. Haider AH, Dankwa-Mullan I, Maragh-Bass, et al. Setting a national agenda for surgical disparities research: Recommendations from the National Institutes of Health and American College of Surgeons Summit. JAMA Surg. March 16, 2016. Available at http://archsurg.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=2503437. Accessed March 28, 2016.

2. Schneidman D. No quality without access: ACS and NIH collaborate to ensure access to optimal care. Bull Am Coll Surg. 2015;100(8):52-62. Available at: bulletin.facs.org/2015/08/no-quality-without-access-acs-and-nih-collaborate-to-ensure-access-to-optimal-care. Accessed March 28, 2016.

Ripple effect of complications in lung transplant

As the frequency of lung transplants rises, so too has the strain on resources to manage in-hospital complications after those operations. Researchers from the University of Pittsburgh have identified independent predictors of short-term complications that can compromise long-term survival in these patients in what they said is the first study to systematically evaluate and profile such complications.

“These results may identify important targets for best practice guidelines and quality-of-care measures after lung transplantation,” reported Dr. Ernest G. Chan and colleagues (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2016 April;151:1171-80).

The study involved 748 patients in the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Transplant Patient Management System database who had in-hospital complications after single- or double-lung transplant from January 2007 to October 2013. The researchers analyzed 3,381 such complications in 92.78% of these patients, grading the complications via the extended Accordion Severity Grading System (ASGS). The median follow-up of the cohort was 5.4 years.

The researchers also classified complications that carried significant decrease in 5-year survival into three categories: renal complications, with a hazard ratio (HR) of 2.58; hepatic, with an HR of 4.08; and cardiac, with an HR of 1.95.

“Multivariate analysis identified a weighted ASGS sum of greater than 10 and renal, cardiac, and vascular complications as predictors of decreased long-term survival,” Dr. Chan and colleagues noted.

In-hospital complications are important predictors of long-term survival, Dr. Chan and coauthors wrote, citing studies from Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York and the University of Minnesota. (N Engl J Med. 2001;345:181-8;Ann Surg. 2011;254:368-74). They also noted variable findings of several studies with regard to the impact center volume can have on long-term survival, particularly because high-volume centers may be better prepared to manage those complications.

“These important finding highlight the need for further in-depth analysis into an intriguing aspect of surgical management of complications after high-risk procedures,” the researchers wrote. Their goal was to create a postoperative complication profile for lung transplant patients.

Of the 748 patients in the study, 7.22% (54) had an uneventful postoperative course. The noncomplication group had a cumulative 5-year survival of around 73.8% vs. 53.3% for the complications group. On average, each patient in the complication group had almost five different complications. The most common were pulmonary in nature (71.66%), followed by infections (69.52%), pleural space–related problems (46.12%), renal complications (36.23%), and cardiac (35.83%). Renal complications accounted for the greatest decrease in 5-year survival at 35.4% vs. 64.4% in patients who did not have renal complications.

Survival rates for other categories of complications vs. the absence of those complications were: hepatic, 18.1% vs. 57.3%; cardiac, 39.5% vs. 62.3%; vascular, 29.4% vs. 58.5%; neurologic, 32.6% vs. 57.1%; musculoskeletal, 27.4% vs. 56.8%; and pleural-space complications, 48.7% vs. 60.3%.

The multivariate analysis assigned hazard ratios to these predictors: age older than 65 years, 1.01; renal events, 1.70; cardiac events, 1.29; vascular events, 1.33; and weighted ASGS sum, 1.08. Besides ASGS severity, the researchers considered Charlson Comorbidity Index analysis, but found that it had no significant effect on hazard ratio, the researchers said.

“With appropriate patients selection and contemporary surgical techniques, vigilant postoperative management and avoidance of adverse events may potentially offer patients better long-term outcomes,” Dr. Chan and colleagues noted. “The overall 90-day postoperative course has an influence on long-term survival.”

Among those factors that influence survival are the severity of the intervention to treat the complication and the occurrence of less-severe complications, they added. “The next step is to identify interventions that effectively reduce the incidence, as well as severity, of in-hospital, postoperative complications.”

The researchers had no financial relationships to disclose.

The study findings show not only that complications after lung transplantation “are nearly ubiquitous” but also that clinicians need better management strategies to address them, Katie Kinaschuk and Dr. Jayan Nagendran said in their invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;151:1181-2).

The multivariate analysis by Dr. Chan and colleagues shows a strong correlation between nonpulmonary complications and decreased long-term survival in patients who have had lung transplants, but this does not downplay the significance of pulmonary and infectious complications, Ms. Kinaschuk and Dr. Nagendran noted. “Thus, despite the need to improve treatment algorithms of highly predictive non–allograft-related complications, the greatest opportunity to decrease the overall rates of complications still exists within pulmonary and infectious etiologies.”

Noteworthy among the study findings was that the Charlson Comorbidity Index values were not a predictor for long-term survival, they wrote. That may suggest that factors of the operation itself, along with donor tissue, may have important roles in the link between postoperative complications and decreased long-term survival. “This may represent the need for careful reporting and consideration of non–allograft-related postoperative complications in assessing new technologies for donor lung management,” they said.

The “ripple effect” of early postoperative complications “may warrant more vigilant long-term surveillance once a complication has occurred,” the commentators noted. “Ultimately, determination of preventive measures by identifying predictors of complications will have the greatest positive effect on survival,” an area that needs further investigation, they wrote.

Ms. Kinaschuk and Dr. Nagendran had no relationships to disclose.

The study findings show not only that complications after lung transplantation “are nearly ubiquitous” but also that clinicians need better management strategies to address them, Katie Kinaschuk and Dr. Jayan Nagendran said in their invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;151:1181-2).

The multivariate analysis by Dr. Chan and colleagues shows a strong correlation between nonpulmonary complications and decreased long-term survival in patients who have had lung transplants, but this does not downplay the significance of pulmonary and infectious complications, Ms. Kinaschuk and Dr. Nagendran noted. “Thus, despite the need to improve treatment algorithms of highly predictive non–allograft-related complications, the greatest opportunity to decrease the overall rates of complications still exists within pulmonary and infectious etiologies.”

Noteworthy among the study findings was that the Charlson Comorbidity Index values were not a predictor for long-term survival, they wrote. That may suggest that factors of the operation itself, along with donor tissue, may have important roles in the link between postoperative complications and decreased long-term survival. “This may represent the need for careful reporting and consideration of non–allograft-related postoperative complications in assessing new technologies for donor lung management,” they said.

The “ripple effect” of early postoperative complications “may warrant more vigilant long-term surveillance once a complication has occurred,” the commentators noted. “Ultimately, determination of preventive measures by identifying predictors of complications will have the greatest positive effect on survival,” an area that needs further investigation, they wrote.

Ms. Kinaschuk and Dr. Nagendran had no relationships to disclose.

The study findings show not only that complications after lung transplantation “are nearly ubiquitous” but also that clinicians need better management strategies to address them, Katie Kinaschuk and Dr. Jayan Nagendran said in their invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;151:1181-2).

The multivariate analysis by Dr. Chan and colleagues shows a strong correlation between nonpulmonary complications and decreased long-term survival in patients who have had lung transplants, but this does not downplay the significance of pulmonary and infectious complications, Ms. Kinaschuk and Dr. Nagendran noted. “Thus, despite the need to improve treatment algorithms of highly predictive non–allograft-related complications, the greatest opportunity to decrease the overall rates of complications still exists within pulmonary and infectious etiologies.”

Noteworthy among the study findings was that the Charlson Comorbidity Index values were not a predictor for long-term survival, they wrote. That may suggest that factors of the operation itself, along with donor tissue, may have important roles in the link between postoperative complications and decreased long-term survival. “This may represent the need for careful reporting and consideration of non–allograft-related postoperative complications in assessing new technologies for donor lung management,” they said.

The “ripple effect” of early postoperative complications “may warrant more vigilant long-term surveillance once a complication has occurred,” the commentators noted. “Ultimately, determination of preventive measures by identifying predictors of complications will have the greatest positive effect on survival,” an area that needs further investigation, they wrote.

Ms. Kinaschuk and Dr. Nagendran had no relationships to disclose.

As the frequency of lung transplants rises, so too has the strain on resources to manage in-hospital complications after those operations. Researchers from the University of Pittsburgh have identified independent predictors of short-term complications that can compromise long-term survival in these patients in what they said is the first study to systematically evaluate and profile such complications.

“These results may identify important targets for best practice guidelines and quality-of-care measures after lung transplantation,” reported Dr. Ernest G. Chan and colleagues (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2016 April;151:1171-80).

The study involved 748 patients in the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Transplant Patient Management System database who had in-hospital complications after single- or double-lung transplant from January 2007 to October 2013. The researchers analyzed 3,381 such complications in 92.78% of these patients, grading the complications via the extended Accordion Severity Grading System (ASGS). The median follow-up of the cohort was 5.4 years.

The researchers also classified complications that carried significant decrease in 5-year survival into three categories: renal complications, with a hazard ratio (HR) of 2.58; hepatic, with an HR of 4.08; and cardiac, with an HR of 1.95.

“Multivariate analysis identified a weighted ASGS sum of greater than 10 and renal, cardiac, and vascular complications as predictors of decreased long-term survival,” Dr. Chan and colleagues noted.

In-hospital complications are important predictors of long-term survival, Dr. Chan and coauthors wrote, citing studies from Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York and the University of Minnesota. (N Engl J Med. 2001;345:181-8;Ann Surg. 2011;254:368-74). They also noted variable findings of several studies with regard to the impact center volume can have on long-term survival, particularly because high-volume centers may be better prepared to manage those complications.

“These important finding highlight the need for further in-depth analysis into an intriguing aspect of surgical management of complications after high-risk procedures,” the researchers wrote. Their goal was to create a postoperative complication profile for lung transplant patients.

Of the 748 patients in the study, 7.22% (54) had an uneventful postoperative course. The noncomplication group had a cumulative 5-year survival of around 73.8% vs. 53.3% for the complications group. On average, each patient in the complication group had almost five different complications. The most common were pulmonary in nature (71.66%), followed by infections (69.52%), pleural space–related problems (46.12%), renal complications (36.23%), and cardiac (35.83%). Renal complications accounted for the greatest decrease in 5-year survival at 35.4% vs. 64.4% in patients who did not have renal complications.

Survival rates for other categories of complications vs. the absence of those complications were: hepatic, 18.1% vs. 57.3%; cardiac, 39.5% vs. 62.3%; vascular, 29.4% vs. 58.5%; neurologic, 32.6% vs. 57.1%; musculoskeletal, 27.4% vs. 56.8%; and pleural-space complications, 48.7% vs. 60.3%.

The multivariate analysis assigned hazard ratios to these predictors: age older than 65 years, 1.01; renal events, 1.70; cardiac events, 1.29; vascular events, 1.33; and weighted ASGS sum, 1.08. Besides ASGS severity, the researchers considered Charlson Comorbidity Index analysis, but found that it had no significant effect on hazard ratio, the researchers said.

“With appropriate patients selection and contemporary surgical techniques, vigilant postoperative management and avoidance of adverse events may potentially offer patients better long-term outcomes,” Dr. Chan and colleagues noted. “The overall 90-day postoperative course has an influence on long-term survival.”

Among those factors that influence survival are the severity of the intervention to treat the complication and the occurrence of less-severe complications, they added. “The next step is to identify interventions that effectively reduce the incidence, as well as severity, of in-hospital, postoperative complications.”

The researchers had no financial relationships to disclose.

As the frequency of lung transplants rises, so too has the strain on resources to manage in-hospital complications after those operations. Researchers from the University of Pittsburgh have identified independent predictors of short-term complications that can compromise long-term survival in these patients in what they said is the first study to systematically evaluate and profile such complications.

“These results may identify important targets for best practice guidelines and quality-of-care measures after lung transplantation,” reported Dr. Ernest G. Chan and colleagues (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2016 April;151:1171-80).

The study involved 748 patients in the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Transplant Patient Management System database who had in-hospital complications after single- or double-lung transplant from January 2007 to October 2013. The researchers analyzed 3,381 such complications in 92.78% of these patients, grading the complications via the extended Accordion Severity Grading System (ASGS). The median follow-up of the cohort was 5.4 years.

The researchers also classified complications that carried significant decrease in 5-year survival into three categories: renal complications, with a hazard ratio (HR) of 2.58; hepatic, with an HR of 4.08; and cardiac, with an HR of 1.95.

“Multivariate analysis identified a weighted ASGS sum of greater than 10 and renal, cardiac, and vascular complications as predictors of decreased long-term survival,” Dr. Chan and colleagues noted.

In-hospital complications are important predictors of long-term survival, Dr. Chan and coauthors wrote, citing studies from Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York and the University of Minnesota. (N Engl J Med. 2001;345:181-8;Ann Surg. 2011;254:368-74). They also noted variable findings of several studies with regard to the impact center volume can have on long-term survival, particularly because high-volume centers may be better prepared to manage those complications.

“These important finding highlight the need for further in-depth analysis into an intriguing aspect of surgical management of complications after high-risk procedures,” the researchers wrote. Their goal was to create a postoperative complication profile for lung transplant patients.

Of the 748 patients in the study, 7.22% (54) had an uneventful postoperative course. The noncomplication group had a cumulative 5-year survival of around 73.8% vs. 53.3% for the complications group. On average, each patient in the complication group had almost five different complications. The most common were pulmonary in nature (71.66%), followed by infections (69.52%), pleural space–related problems (46.12%), renal complications (36.23%), and cardiac (35.83%). Renal complications accounted for the greatest decrease in 5-year survival at 35.4% vs. 64.4% in patients who did not have renal complications.

Survival rates for other categories of complications vs. the absence of those complications were: hepatic, 18.1% vs. 57.3%; cardiac, 39.5% vs. 62.3%; vascular, 29.4% vs. 58.5%; neurologic, 32.6% vs. 57.1%; musculoskeletal, 27.4% vs. 56.8%; and pleural-space complications, 48.7% vs. 60.3%.

The multivariate analysis assigned hazard ratios to these predictors: age older than 65 years, 1.01; renal events, 1.70; cardiac events, 1.29; vascular events, 1.33; and weighted ASGS sum, 1.08. Besides ASGS severity, the researchers considered Charlson Comorbidity Index analysis, but found that it had no significant effect on hazard ratio, the researchers said.

“With appropriate patients selection and contemporary surgical techniques, vigilant postoperative management and avoidance of adverse events may potentially offer patients better long-term outcomes,” Dr. Chan and colleagues noted. “The overall 90-day postoperative course has an influence on long-term survival.”

Among those factors that influence survival are the severity of the intervention to treat the complication and the occurrence of less-severe complications, they added. “The next step is to identify interventions that effectively reduce the incidence, as well as severity, of in-hospital, postoperative complications.”

The researchers had no financial relationships to disclose.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THORACIC AND CARDIOVASCULAR SURGERY

Key clinical point: Early complications after lung transplant surgery can negatively impact survival and long-term outcomes.

Major finding: Postoperative complications occurred in 92.78% of patients. Median follow-up was 5.4 years.

Data source: Retrospective analysis of 748 patients in the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Transplant Patient Management System who had lung transplants from January 2007 to October 2013.

Disclosures: The study investigators had no relationships to disclose.

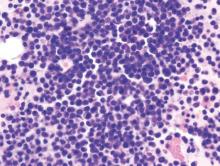

CML: T3151 plus additional mutations predicts poor response to ponatinib

Depending on the number and type of BCR-ABL1 mutations, certain patients with chronic myeloid leukemia may have a better response to ponatinib than to other tyrosine kinase inhibitors, according to a report published in Blood.

For patients with CML treated with first- or second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as imatinib, nilotinib, and dasatinib, the most common cause of treatment failure is the acquisition of mutations in the BCR-ABL1 gene, particularly the T315I mutation, which interfere with drug binding and eventually confer drug resistance. Some of these cancers have proved susceptible to ponatinib, but treatment response varies among patients, said Dr. Wendy T. Parker of the Australian Cancer Research Foundation (ACRF) Cancer Genomics Facility, the Center for Cancer Biology, and the University of Adelaide (Australia) and her associates.

They retrospectively assessed peripheral blood samples from 363 CML patients who had taken part in a phase II study of ponatinib therapy, using their newly developed mass spectrometry–based mutation detection assay to determine which mutations correlated with which treatment outcomes. These study participants contributed blood samples before, during, and after ponatinib treatment. The mass spectrometry–based assay can detect BCR-ABL1 KD mutations present at levels between 10- and 100-fold below those detectable using conventional Sanger sequencing, the researchers said (Blood. 2016;127[15]:1870-80).

Patients who had the T315I mutation plus additional mutations at baseline (32% of the study population) had significantly worse treatment responses and significantly worse outcomes than those who had only the T315I mutation at baseline. “Consequently, these patients may benefit from close monitoring, experimental approaches, or stem-cell transplantation to reduce the risk of tyrosine kinase inhibitor failure,” Dr. Parker and her associates said.

In addition, patients who didn’t have the T315I mutation but had multiple other mutations at baseline responded well to ponatinib. Historically, such patients have not responded well to first- or second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors, but ponatinib may prove to be a particularly effective option for this patient population, the investigators said (Blood. 2016;127[15]:1870-80).

These findings demonstrate that mutation analysis, such as that provided by their mass spectrometry–based assay, can be used to guide therapy even after patients have failed on some tyrosine kinase inhibitors, they added.

The study was supported by the maker of ponatinib (Iclusig) Ariad Pharmaceuticals, the Leukemia Foundation of Australia, and the A.R. Clarkson Foundation. Dr. Parker reported having no relevant financial disclosures; some of her associates were employed by Ariad.

Depending on the number and type of BCR-ABL1 mutations, certain patients with chronic myeloid leukemia may have a better response to ponatinib than to other tyrosine kinase inhibitors, according to a report published in Blood.

For patients with CML treated with first- or second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as imatinib, nilotinib, and dasatinib, the most common cause of treatment failure is the acquisition of mutations in the BCR-ABL1 gene, particularly the T315I mutation, which interfere with drug binding and eventually confer drug resistance. Some of these cancers have proved susceptible to ponatinib, but treatment response varies among patients, said Dr. Wendy T. Parker of the Australian Cancer Research Foundation (ACRF) Cancer Genomics Facility, the Center for Cancer Biology, and the University of Adelaide (Australia) and her associates.

They retrospectively assessed peripheral blood samples from 363 CML patients who had taken part in a phase II study of ponatinib therapy, using their newly developed mass spectrometry–based mutation detection assay to determine which mutations correlated with which treatment outcomes. These study participants contributed blood samples before, during, and after ponatinib treatment. The mass spectrometry–based assay can detect BCR-ABL1 KD mutations present at levels between 10- and 100-fold below those detectable using conventional Sanger sequencing, the researchers said (Blood. 2016;127[15]:1870-80).

Patients who had the T315I mutation plus additional mutations at baseline (32% of the study population) had significantly worse treatment responses and significantly worse outcomes than those who had only the T315I mutation at baseline. “Consequently, these patients may benefit from close monitoring, experimental approaches, or stem-cell transplantation to reduce the risk of tyrosine kinase inhibitor failure,” Dr. Parker and her associates said.

In addition, patients who didn’t have the T315I mutation but had multiple other mutations at baseline responded well to ponatinib. Historically, such patients have not responded well to first- or second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors, but ponatinib may prove to be a particularly effective option for this patient population, the investigators said (Blood. 2016;127[15]:1870-80).

These findings demonstrate that mutation analysis, such as that provided by their mass spectrometry–based assay, can be used to guide therapy even after patients have failed on some tyrosine kinase inhibitors, they added.

The study was supported by the maker of ponatinib (Iclusig) Ariad Pharmaceuticals, the Leukemia Foundation of Australia, and the A.R. Clarkson Foundation. Dr. Parker reported having no relevant financial disclosures; some of her associates were employed by Ariad.

Depending on the number and type of BCR-ABL1 mutations, certain patients with chronic myeloid leukemia may have a better response to ponatinib than to other tyrosine kinase inhibitors, according to a report published in Blood.

For patients with CML treated with first- or second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as imatinib, nilotinib, and dasatinib, the most common cause of treatment failure is the acquisition of mutations in the BCR-ABL1 gene, particularly the T315I mutation, which interfere with drug binding and eventually confer drug resistance. Some of these cancers have proved susceptible to ponatinib, but treatment response varies among patients, said Dr. Wendy T. Parker of the Australian Cancer Research Foundation (ACRF) Cancer Genomics Facility, the Center for Cancer Biology, and the University of Adelaide (Australia) and her associates.

They retrospectively assessed peripheral blood samples from 363 CML patients who had taken part in a phase II study of ponatinib therapy, using their newly developed mass spectrometry–based mutation detection assay to determine which mutations correlated with which treatment outcomes. These study participants contributed blood samples before, during, and after ponatinib treatment. The mass spectrometry–based assay can detect BCR-ABL1 KD mutations present at levels between 10- and 100-fold below those detectable using conventional Sanger sequencing, the researchers said (Blood. 2016;127[15]:1870-80).

Patients who had the T315I mutation plus additional mutations at baseline (32% of the study population) had significantly worse treatment responses and significantly worse outcomes than those who had only the T315I mutation at baseline. “Consequently, these patients may benefit from close monitoring, experimental approaches, or stem-cell transplantation to reduce the risk of tyrosine kinase inhibitor failure,” Dr. Parker and her associates said.

In addition, patients who didn’t have the T315I mutation but had multiple other mutations at baseline responded well to ponatinib. Historically, such patients have not responded well to first- or second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors, but ponatinib may prove to be a particularly effective option for this patient population, the investigators said (Blood. 2016;127[15]:1870-80).

These findings demonstrate that mutation analysis, such as that provided by their mass spectrometry–based assay, can be used to guide therapy even after patients have failed on some tyrosine kinase inhibitors, they added.

The study was supported by the maker of ponatinib (Iclusig) Ariad Pharmaceuticals, the Leukemia Foundation of Australia, and the A.R. Clarkson Foundation. Dr. Parker reported having no relevant financial disclosures; some of her associates were employed by Ariad.

FROM BLOOD

Key clinical point: The third-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitor ponatinib appears to be more effective than its predecessors against certain cases of chronic myeloid leukemia defined by the number and type of BCR-ABL1 mutations that patients have.

Major finding: Patients who had the T315I mutation plus additional mutations at baseline (32% of the study population) had significantly worse treatment responses and outcomes than those who had only the T315I mutation and those who had multiple other mutations.

Data source: A retrospective secondary analysis of data from a phase II clinical trial involving 363 patients with CML.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the maker of ponatinib (Iclusig) Ariad Pharmaceuticals, the Leukemia Foundation of Australia, and the A.R. Clarkson Foundation. Dr. Parker reported having no relevant financial disclosures; some of her associates were employed by Ariad.

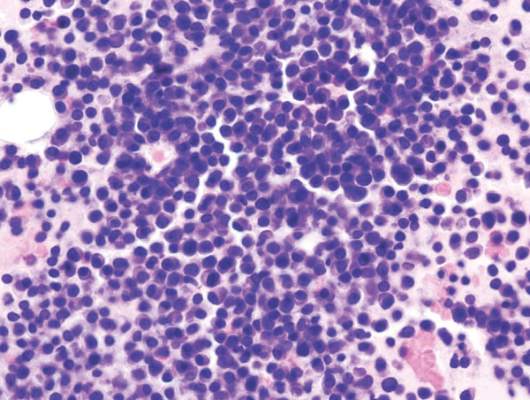

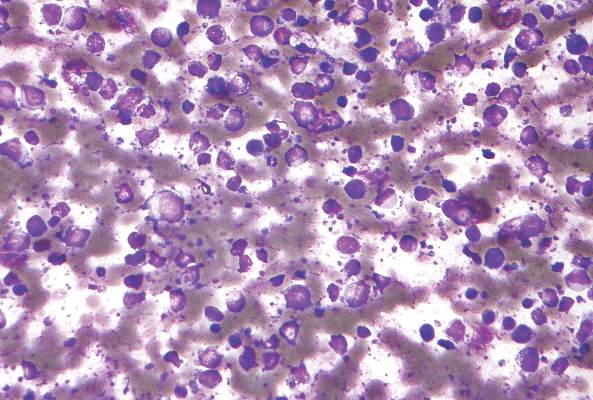

Daratumumab well tolerated, effective in heavily treated multiple myeloma

Daratumumab monotherapy was associated with an overall response rate of 29.2% and was well tolerated in 106 heavily treated patients with multiple myeloma, based on results from the SIRIUS trial.

Of 106 patients who received daratumumab at 16 mg/kg, 3% achieved a stringent complete response, 9% had a very good partial response, and 17% had a partial response. The median progression-free survival was 3.7 months and median duration of response was 7.4 months. The 12-month overall survival was 64·8%, and, at a subsequent cutoff, median overall survival was 17.5 months.

All of the study patients had been treated with proteasome inhibitors and immunomodulatory drugs, with a median of five previous therapies. Most patients (80%) had received autologous stem cell transplantation, and 97% were refractory to the last line of therapy before study enrollment.

“Resistance to any previous therapy had no effect on the activity of daratumumab, lending support to a novel mechanism of action, but these findings need to be confirmed in larger studies,” wrote Dr. Sagar Lonial of Emory University, Atlanta, and colleagues (Lancet 2016;387:1551-60). Response rates were similar for patients with moderate renal impairment, those over age 75, and those with extramedullary disease or high-risk baseline cytogenetic characteristics.

Daratumumab was well tolerated, and none of the patients discontinued treatment because of treatment-related adverse events. The most common adverse events of any grade were anemia (33%), thrombocytopenia (25%), and neutropenia (23%). Additional supportive care in the form of red blood cell transfusions was received by 38% of patients, platelet transfusions by 13%, and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor by 8%. Fatigue (40%) and nausea (29%) were the most common nonhematologic adverse events. Serious adverse events were observed in 30% of patients.

Daratumumab compares favorably with other regimens such as pomalidomide alone or with dexamethasone or carfilzomib monotherapy, according to the investigators.

The favorable safety profile of daratumumab makes it an attractive candidate for combination regimens, the authors noted, and daratumumab combined with other backbone agents are currently under investigation.

This study was sponsored by Janssen, maker of daratumumab (Darzalex). Dr. Lonial reported consulting or advisory roles with Janssen and several other drug companies.

With its novel mechanism of action, single-agent activity, absence of crossresistance, and tolerability, daratumumab may prove to be a transformative new treatment for multiple myeloma.

|

| Patrice Wendling/Frontline Medical News Dr. S. Vincent Rajkumar |

The single-agent activity of daratumumab (29%) exceeds that of bortezomib (27%), lenalidomide (26%), carfilzomib (24%), or pomalidomide (18%), even in a heavily pretreated population.

The safety profile is outstanding, and therein lies the reason for enthusiasm: Daratumumab can probably be combined with currently used triplet combinations in multiple myeloma, and can potentially take these highly active regimens to new heights.

Similar to rituximab, daratumumab will probably be added to many active triplet combinations. Daratumumab will likely move rapidly to a front-line setting in clinical trials for treatment of newly diagnosed multiple myeloma, maintenance therapy, and even smoldering multiple myeloma.

However, the data are insufficient to determine the cytogenetic subtypes that respond best to daratumumab. That information will be necessary in order to best sequence drugs according to the subtype of myeloma.

It will be important also to understand how daratumumab, an anti-CD38 drug, can work optimally with elotuzumab, another newly approved monoclonal antibody that targets SLAMF7.

Dr. S. Vincent Rajkumar is with the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. These remarks were part of an editorial (Lancet 2016; 387:1490-91) accompanying the study in the Lancet.

With its novel mechanism of action, single-agent activity, absence of crossresistance, and tolerability, daratumumab may prove to be a transformative new treatment for multiple myeloma.

|

| Patrice Wendling/Frontline Medical News Dr. S. Vincent Rajkumar |

The single-agent activity of daratumumab (29%) exceeds that of bortezomib (27%), lenalidomide (26%), carfilzomib (24%), or pomalidomide (18%), even in a heavily pretreated population.

The safety profile is outstanding, and therein lies the reason for enthusiasm: Daratumumab can probably be combined with currently used triplet combinations in multiple myeloma, and can potentially take these highly active regimens to new heights.

Similar to rituximab, daratumumab will probably be added to many active triplet combinations. Daratumumab will likely move rapidly to a front-line setting in clinical trials for treatment of newly diagnosed multiple myeloma, maintenance therapy, and even smoldering multiple myeloma.

However, the data are insufficient to determine the cytogenetic subtypes that respond best to daratumumab. That information will be necessary in order to best sequence drugs according to the subtype of myeloma.

It will be important also to understand how daratumumab, an anti-CD38 drug, can work optimally with elotuzumab, another newly approved monoclonal antibody that targets SLAMF7.

Dr. S. Vincent Rajkumar is with the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. These remarks were part of an editorial (Lancet 2016; 387:1490-91) accompanying the study in the Lancet.

With its novel mechanism of action, single-agent activity, absence of crossresistance, and tolerability, daratumumab may prove to be a transformative new treatment for multiple myeloma.

|

| Patrice Wendling/Frontline Medical News Dr. S. Vincent Rajkumar |

The single-agent activity of daratumumab (29%) exceeds that of bortezomib (27%), lenalidomide (26%), carfilzomib (24%), or pomalidomide (18%), even in a heavily pretreated population.

The safety profile is outstanding, and therein lies the reason for enthusiasm: Daratumumab can probably be combined with currently used triplet combinations in multiple myeloma, and can potentially take these highly active regimens to new heights.

Similar to rituximab, daratumumab will probably be added to many active triplet combinations. Daratumumab will likely move rapidly to a front-line setting in clinical trials for treatment of newly diagnosed multiple myeloma, maintenance therapy, and even smoldering multiple myeloma.

However, the data are insufficient to determine the cytogenetic subtypes that respond best to daratumumab. That information will be necessary in order to best sequence drugs according to the subtype of myeloma.

It will be important also to understand how daratumumab, an anti-CD38 drug, can work optimally with elotuzumab, another newly approved monoclonal antibody that targets SLAMF7.

Dr. S. Vincent Rajkumar is with the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. These remarks were part of an editorial (Lancet 2016; 387:1490-91) accompanying the study in the Lancet.

Daratumumab monotherapy was associated with an overall response rate of 29.2% and was well tolerated in 106 heavily treated patients with multiple myeloma, based on results from the SIRIUS trial.

Of 106 patients who received daratumumab at 16 mg/kg, 3% achieved a stringent complete response, 9% had a very good partial response, and 17% had a partial response. The median progression-free survival was 3.7 months and median duration of response was 7.4 months. The 12-month overall survival was 64·8%, and, at a subsequent cutoff, median overall survival was 17.5 months.

All of the study patients had been treated with proteasome inhibitors and immunomodulatory drugs, with a median of five previous therapies. Most patients (80%) had received autologous stem cell transplantation, and 97% were refractory to the last line of therapy before study enrollment.

“Resistance to any previous therapy had no effect on the activity of daratumumab, lending support to a novel mechanism of action, but these findings need to be confirmed in larger studies,” wrote Dr. Sagar Lonial of Emory University, Atlanta, and colleagues (Lancet 2016;387:1551-60). Response rates were similar for patients with moderate renal impairment, those over age 75, and those with extramedullary disease or high-risk baseline cytogenetic characteristics.

Daratumumab was well tolerated, and none of the patients discontinued treatment because of treatment-related adverse events. The most common adverse events of any grade were anemia (33%), thrombocytopenia (25%), and neutropenia (23%). Additional supportive care in the form of red blood cell transfusions was received by 38% of patients, platelet transfusions by 13%, and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor by 8%. Fatigue (40%) and nausea (29%) were the most common nonhematologic adverse events. Serious adverse events were observed in 30% of patients.

Daratumumab compares favorably with other regimens such as pomalidomide alone or with dexamethasone or carfilzomib monotherapy, according to the investigators.

The favorable safety profile of daratumumab makes it an attractive candidate for combination regimens, the authors noted, and daratumumab combined with other backbone agents are currently under investigation.

This study was sponsored by Janssen, maker of daratumumab (Darzalex). Dr. Lonial reported consulting or advisory roles with Janssen and several other drug companies.

Daratumumab monotherapy was associated with an overall response rate of 29.2% and was well tolerated in 106 heavily treated patients with multiple myeloma, based on results from the SIRIUS trial.

Of 106 patients who received daratumumab at 16 mg/kg, 3% achieved a stringent complete response, 9% had a very good partial response, and 17% had a partial response. The median progression-free survival was 3.7 months and median duration of response was 7.4 months. The 12-month overall survival was 64·8%, and, at a subsequent cutoff, median overall survival was 17.5 months.

All of the study patients had been treated with proteasome inhibitors and immunomodulatory drugs, with a median of five previous therapies. Most patients (80%) had received autologous stem cell transplantation, and 97% were refractory to the last line of therapy before study enrollment.

“Resistance to any previous therapy had no effect on the activity of daratumumab, lending support to a novel mechanism of action, but these findings need to be confirmed in larger studies,” wrote Dr. Sagar Lonial of Emory University, Atlanta, and colleagues (Lancet 2016;387:1551-60). Response rates were similar for patients with moderate renal impairment, those over age 75, and those with extramedullary disease or high-risk baseline cytogenetic characteristics.

Daratumumab was well tolerated, and none of the patients discontinued treatment because of treatment-related adverse events. The most common adverse events of any grade were anemia (33%), thrombocytopenia (25%), and neutropenia (23%). Additional supportive care in the form of red blood cell transfusions was received by 38% of patients, platelet transfusions by 13%, and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor by 8%. Fatigue (40%) and nausea (29%) were the most common nonhematologic adverse events. Serious adverse events were observed in 30% of patients.

Daratumumab compares favorably with other regimens such as pomalidomide alone or with dexamethasone or carfilzomib monotherapy, according to the investigators.

The favorable safety profile of daratumumab makes it an attractive candidate for combination regimens, the authors noted, and daratumumab combined with other backbone agents are currently under investigation.

This study was sponsored by Janssen, maker of daratumumab (Darzalex). Dr. Lonial reported consulting or advisory roles with Janssen and several other drug companies.

FROM THE LANCET

Key clinical point: Daratumumab was well tolerated and showed encouraging activity in heavily treated patients with multiple myeloma.

Major finding: In 106 patients previously treated with a median of five lines of therapy, the overall response rate to daratumumab at 16 mg/kg was 29.2%; 3% achieved a stringent complete response, 9% a very good partial response, and 17% a partial response.

Data sources: Data from the SIRIUS trial for 106 patients in the 16-mg/kg group.

Disclosures: This study was sponsored by Janssen, maker of daratumumab (Darzalex). Dr. Lonial reported consulting or advisory roles with Janssen and several other drug companies.

Hybrid option ‘reasonable’ for HLHS?

Although the classic Norwood palliation for infants with hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) has been well established, the procedure has had its drawbacks, namely the need for cardiopulmonary bypass with hypothermia and a because it rules out biventricular correction months later. A hybrid procedure avoids the need for bypass and accommodates short-term biventricular correction, but it has lacked strong evidence.

Researchers from Justus-Liebig University Giessen, Germany, reported on 182 patients with HLHS who had the three-stage Giessen hybrid procedure, noting 10-year survival of almost 80% with almost a third of patients requiring no artery intervention in that time (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016 April;151:1112-23).

“In view of the early results and long-term outcome after Giessen hybrid palliation, the hybrid approach has become a reasonable alternative to the conventional strategy to treat neonates with HLHS and variants,” wrote Dr. Can Yerebakan and colleagues. “Further refinements are warranted to decrease patient morbidity.”

The Giessen hybrid procedure uses a technique to control pulmonary blood flow that is different from the Norwood procedure. The hybrid approach involves stenting of the arterial duct or prostaglandin therapy to maintain systemic perfusion combined with off-pump bilateral banding of the pulmonary arteries (bPAB) in the neonatal period. The Giessen hybrid operation defers the Norwood-type palliation using cardiopulmonary bypass that involves an aortic arch reconstruction, including a superior cavopulmonary connection or a biventricular correction, if indicated, until the infant is 4-8 months of age.

“In recent years, hybrid treatment has moved from a myth to an alternative modality in a growing number of institutions globally,” Dr. Yerebakan and colleagues said. The hybrid procedure has been used in high-risk patients. One report claimed higher morbidity in the hybrid procedure due to bPAB (Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96:1382-8). Another study raised concerns about an adequate pulmonary artery rehabilitation at the time of the Fontan operation, the third stage in the hybrid strategy (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;147:706-12).

But with the hybrid approach, patients retain the potential to receive a biventricular correction up to 8 months later without compromising survival, “postponing an immediate definitive decision in the newborn period in comparison with the classic Norwood palliation,” Dr. Yerebakan and coauthors noted.

The doctors at the Pediatric Heart Center Giessen treat all types and variants of HLHS with the modified Giessen hybrid strategy. Between 1998 and 2015, 182 patients with HLHS had the Giessen hybrid stage I operation, including 126 patients who received univentricular palliation or a heart transplant. The median age of stage I recipients was 6 days, and median weight 3.2 kg. The stage II operation was performed at 4.5 months, with a range of 2.9 to 39.5 months, and Fontan completion was established at 33.7 months, with a range of 21 to 108 months.

Median follow-up after the stage I procedure was 4.6 years, and the death rate was 2.5%. After stage II, mortality was 4.9%; no deaths were reported after Fontan completion. Body weight less than 2.5 kg and aortic atresia had no significant effect on survival. Mortality rates were 8.9% between stages I and II and 5.3% between stage II and Fontan completion. “Cumulative interstage mortality was 14.2%,” Dr. Yerebakan and colleagues noted. “At 10 years, the probability of survival is 77.8%.”

Also at 10 years, 32.2% of patients were free from further pulmonary artery intervention, and 16.7% needed aortic arch reconstruction. Two patients required reoperations for aortic arch reconstruction.

Dr. Yerebakan and colleagues suggested several steps to improve outcomes with the hybrid approach: “intense collaboration” with anesthesiology and pediatric cardiology during and after the procedure to risk stratify individual patients; implementation of standards for management of all stages, including out-of-hospital care, in all departments that participate in a case; and liberalized indications for use of MRI before the stage II and Fontan completion.

Among the limitations of the study the authors noted were its retrospective nature and a median follow-up of only 5 years when the center has some cases with up to 15 years of follow-up. But Dr. Yerebakan and coauthors said they could not determine if the patients benefit from the hybrid treatment in the long-term.

The researchers had no disclosures.

The study by Dr. Yerebakan and colleagues is one of the largest single-center series of patients with HLHS who routinely undergo a hybrid palliation to date, and while the study is open to criticisms, “the authors should be applauded,” Dr. Ralph S. Mosca of New York University said in his invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;151:1123-25).

Among the criticisms Dr. Mosca mentioned are that the hybrid approach requires a more extensive stage II reconstruction, “often further complicated by the presence of significant branch PA stenosis and a difficult aortic arch reconstruction”; that there is “appreciable” interstage mortality at 12.2%; and that there is an absence of data on renal or respiratory insufficiency, infection rates, and neurologic outcomes.

Dr. Mosca cited the cause for applause, however: “Through their persistence and collective experience, [the authors] have achieved commendable results in this difficult patient population.”

Yet, Dr. Mosca also noted a number of “potential problems” with the hybrid approach: bilateral banding of the pulmonary artery is a “crude procedure”; arterial duct stenting can lead to retrograde aortic arch reduction; and the interstage mortality “remains significant.”

Results of the hybrid and Norwood procedures are “strikingly similar,” Dr. Mosca said. While the hybrid approach may lower neonatal mortality, it may also carry longer-term consequences “predicated upon the need to closely observe and intervene,” he said. Clinicians need more information on hybrid outcomes, but in time it will likely take its place as an option for HLHS alongside the Norwood procedure, Dr. Mosca said.

The study by Dr. Yerebakan and colleagues is one of the largest single-center series of patients with HLHS who routinely undergo a hybrid palliation to date, and while the study is open to criticisms, “the authors should be applauded,” Dr. Ralph S. Mosca of New York University said in his invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;151:1123-25).

Among the criticisms Dr. Mosca mentioned are that the hybrid approach requires a more extensive stage II reconstruction, “often further complicated by the presence of significant branch PA stenosis and a difficult aortic arch reconstruction”; that there is “appreciable” interstage mortality at 12.2%; and that there is an absence of data on renal or respiratory insufficiency, infection rates, and neurologic outcomes.

Dr. Mosca cited the cause for applause, however: “Through their persistence and collective experience, [the authors] have achieved commendable results in this difficult patient population.”

Yet, Dr. Mosca also noted a number of “potential problems” with the hybrid approach: bilateral banding of the pulmonary artery is a “crude procedure”; arterial duct stenting can lead to retrograde aortic arch reduction; and the interstage mortality “remains significant.”

Results of the hybrid and Norwood procedures are “strikingly similar,” Dr. Mosca said. While the hybrid approach may lower neonatal mortality, it may also carry longer-term consequences “predicated upon the need to closely observe and intervene,” he said. Clinicians need more information on hybrid outcomes, but in time it will likely take its place as an option for HLHS alongside the Norwood procedure, Dr. Mosca said.

The study by Dr. Yerebakan and colleagues is one of the largest single-center series of patients with HLHS who routinely undergo a hybrid palliation to date, and while the study is open to criticisms, “the authors should be applauded,” Dr. Ralph S. Mosca of New York University said in his invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;151:1123-25).

Among the criticisms Dr. Mosca mentioned are that the hybrid approach requires a more extensive stage II reconstruction, “often further complicated by the presence of significant branch PA stenosis and a difficult aortic arch reconstruction”; that there is “appreciable” interstage mortality at 12.2%; and that there is an absence of data on renal or respiratory insufficiency, infection rates, and neurologic outcomes.

Dr. Mosca cited the cause for applause, however: “Through their persistence and collective experience, [the authors] have achieved commendable results in this difficult patient population.”