User login

AAN recommends against routine closure of patent foramen ovale for secondary stroke prevention

An updated practice advisory from the American Academy of Neurology does not recommend the routine use of catheter-based closure of patent foramen ovale in patients with a history of cryptogenic ischemic stroke.

“Because of the limitations of the efficacy evidence and the potential for serious adverse effects, we judge the risk-benefit trade-offs of PFO [patent foramen ovale] closure by either the STARFlex or AMPLATZER PFO Occluder to be uncertain,” wrote Steven Messé, MD, associate professor of neurology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and his associates. “In rare circumstances, such as recurrent strokes despite adequate medical therapy with no other mechanism identified, clinicians may offer the AMPLATZER PFO Occluder if it is available,” they noted.

They also supported antiplatelet agents over anticoagulants unless patients have another indication for blood thinners, noting “the uncertainty surrounding the benefit of anticoagulation in the setting of PFO, and anticoagulation’s well-known harm profile.”

PFO affects about one in four individuals overall and up to half of cryptogenic stroke patients. The previous (2004) version of this practice advisory cited insufficient evidence to guide optimal therapy for secondary stroke prevention in these patients (Neurology. 2004;Apr 13;62[7]:1042-50). To update the guideline, Dr. Messé and his associates searched the literature for relevant randomized studies, excluding transient ischemic attacks when feasible because of their subjective nature, and focusing on intention-to-treat analyses to reduce bias (Neurology. 2016 Jul 27;doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002961).

Among 809 initial articles, 5 were considered relevant – a randomized, open-label, multicenter study of the STARFlex device (CLOSURE I), two randomized, controlled trials of the AMPLATZER PFO Occluder (PC Trial and RESPECT), and two randomized studies of warfarin versus aspirin in cryptogenic stroke patients, the experts said.

Percutaneous PFO closure with the STARFlex device did not appear to prevent secondary stroke, compared with medical therapy alone, based on a small positive estimated difference in risk of about 0.1%, and a 95% confidence interval that crossed zero (–2.2% to 2.0%). In contrast, the AMPLATZER PFO Occluder decreased the risk of secondary stroke by about 1.7% (95% CI, –3.2% to –0.2%), but upped the risk of procedural complications by more than 3%, and also slightly increased the risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation (1.6%; 95% CI, 0.1% to 3.2%).

Efficacy data were insufficient to clearly support anticoagulants over antiplatelet therapy for recurrent stroke prevention, the experts concluded. Compared with antiplatelet therapy, anticoagulation was associated with a 2% increase in risk of recurrent stroke, but the 95% confidence interval for this estimate was wide and crossed zero. “In the absence of another indication for anticoagulation, clinicians may routinely offer antiplatelet medications instead of anticoagulation to patients with cryptogenic stroke and PFO,” they wrote. “In rare circumstances, such as stroke that recurs while a patient is undergoing antiplatelet therapy, clinicians may offer anticoagulation to patients with cryptogenic stroke and PFO.”

Their strongest recommendation was to counsel patients who are considering percutaneous PFO closure “that having a PFO is common; it occurs in about 1 in 4 people; it is impossible to determine with certainty whether their PFOs caused their strokes or TIAs; the effectiveness of the procedure for reducing stroke risk remains uncertain; and the procedure is associated with relatively uncommon, yet potentially serious, complications.”

The practice advisory was supported by the American Academy of Neurology. Dr. Messé disclosed ties to GlaxoSmithKline and WL Gore & Associates and has been an investigator for the REDUCE and CLOSURE-I trials. Five of his coauthors have been investigators for RESPECT, CLOSURE-I, and REDUCE, have been editors for Neurology, and have received compensation from Genentech, Pfizer, Gilead Sciences, and other pharmaceutical companies. One coauthor had no disclosures.

An updated practice advisory from the American Academy of Neurology does not recommend the routine use of catheter-based closure of patent foramen ovale in patients with a history of cryptogenic ischemic stroke.

“Because of the limitations of the efficacy evidence and the potential for serious adverse effects, we judge the risk-benefit trade-offs of PFO [patent foramen ovale] closure by either the STARFlex or AMPLATZER PFO Occluder to be uncertain,” wrote Steven Messé, MD, associate professor of neurology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and his associates. “In rare circumstances, such as recurrent strokes despite adequate medical therapy with no other mechanism identified, clinicians may offer the AMPLATZER PFO Occluder if it is available,” they noted.

They also supported antiplatelet agents over anticoagulants unless patients have another indication for blood thinners, noting “the uncertainty surrounding the benefit of anticoagulation in the setting of PFO, and anticoagulation’s well-known harm profile.”

PFO affects about one in four individuals overall and up to half of cryptogenic stroke patients. The previous (2004) version of this practice advisory cited insufficient evidence to guide optimal therapy for secondary stroke prevention in these patients (Neurology. 2004;Apr 13;62[7]:1042-50). To update the guideline, Dr. Messé and his associates searched the literature for relevant randomized studies, excluding transient ischemic attacks when feasible because of their subjective nature, and focusing on intention-to-treat analyses to reduce bias (Neurology. 2016 Jul 27;doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002961).

Among 809 initial articles, 5 were considered relevant – a randomized, open-label, multicenter study of the STARFlex device (CLOSURE I), two randomized, controlled trials of the AMPLATZER PFO Occluder (PC Trial and RESPECT), and two randomized studies of warfarin versus aspirin in cryptogenic stroke patients, the experts said.

Percutaneous PFO closure with the STARFlex device did not appear to prevent secondary stroke, compared with medical therapy alone, based on a small positive estimated difference in risk of about 0.1%, and a 95% confidence interval that crossed zero (–2.2% to 2.0%). In contrast, the AMPLATZER PFO Occluder decreased the risk of secondary stroke by about 1.7% (95% CI, –3.2% to –0.2%), but upped the risk of procedural complications by more than 3%, and also slightly increased the risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation (1.6%; 95% CI, 0.1% to 3.2%).

Efficacy data were insufficient to clearly support anticoagulants over antiplatelet therapy for recurrent stroke prevention, the experts concluded. Compared with antiplatelet therapy, anticoagulation was associated with a 2% increase in risk of recurrent stroke, but the 95% confidence interval for this estimate was wide and crossed zero. “In the absence of another indication for anticoagulation, clinicians may routinely offer antiplatelet medications instead of anticoagulation to patients with cryptogenic stroke and PFO,” they wrote. “In rare circumstances, such as stroke that recurs while a patient is undergoing antiplatelet therapy, clinicians may offer anticoagulation to patients with cryptogenic stroke and PFO.”

Their strongest recommendation was to counsel patients who are considering percutaneous PFO closure “that having a PFO is common; it occurs in about 1 in 4 people; it is impossible to determine with certainty whether their PFOs caused their strokes or TIAs; the effectiveness of the procedure for reducing stroke risk remains uncertain; and the procedure is associated with relatively uncommon, yet potentially serious, complications.”

The practice advisory was supported by the American Academy of Neurology. Dr. Messé disclosed ties to GlaxoSmithKline and WL Gore & Associates and has been an investigator for the REDUCE and CLOSURE-I trials. Five of his coauthors have been investigators for RESPECT, CLOSURE-I, and REDUCE, have been editors for Neurology, and have received compensation from Genentech, Pfizer, Gilead Sciences, and other pharmaceutical companies. One coauthor had no disclosures.

An updated practice advisory from the American Academy of Neurology does not recommend the routine use of catheter-based closure of patent foramen ovale in patients with a history of cryptogenic ischemic stroke.

“Because of the limitations of the efficacy evidence and the potential for serious adverse effects, we judge the risk-benefit trade-offs of PFO [patent foramen ovale] closure by either the STARFlex or AMPLATZER PFO Occluder to be uncertain,” wrote Steven Messé, MD, associate professor of neurology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and his associates. “In rare circumstances, such as recurrent strokes despite adequate medical therapy with no other mechanism identified, clinicians may offer the AMPLATZER PFO Occluder if it is available,” they noted.

They also supported antiplatelet agents over anticoagulants unless patients have another indication for blood thinners, noting “the uncertainty surrounding the benefit of anticoagulation in the setting of PFO, and anticoagulation’s well-known harm profile.”

PFO affects about one in four individuals overall and up to half of cryptogenic stroke patients. The previous (2004) version of this practice advisory cited insufficient evidence to guide optimal therapy for secondary stroke prevention in these patients (Neurology. 2004;Apr 13;62[7]:1042-50). To update the guideline, Dr. Messé and his associates searched the literature for relevant randomized studies, excluding transient ischemic attacks when feasible because of their subjective nature, and focusing on intention-to-treat analyses to reduce bias (Neurology. 2016 Jul 27;doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002961).

Among 809 initial articles, 5 were considered relevant – a randomized, open-label, multicenter study of the STARFlex device (CLOSURE I), two randomized, controlled trials of the AMPLATZER PFO Occluder (PC Trial and RESPECT), and two randomized studies of warfarin versus aspirin in cryptogenic stroke patients, the experts said.

Percutaneous PFO closure with the STARFlex device did not appear to prevent secondary stroke, compared with medical therapy alone, based on a small positive estimated difference in risk of about 0.1%, and a 95% confidence interval that crossed zero (–2.2% to 2.0%). In contrast, the AMPLATZER PFO Occluder decreased the risk of secondary stroke by about 1.7% (95% CI, –3.2% to –0.2%), but upped the risk of procedural complications by more than 3%, and also slightly increased the risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation (1.6%; 95% CI, 0.1% to 3.2%).

Efficacy data were insufficient to clearly support anticoagulants over antiplatelet therapy for recurrent stroke prevention, the experts concluded. Compared with antiplatelet therapy, anticoagulation was associated with a 2% increase in risk of recurrent stroke, but the 95% confidence interval for this estimate was wide and crossed zero. “In the absence of another indication for anticoagulation, clinicians may routinely offer antiplatelet medications instead of anticoagulation to patients with cryptogenic stroke and PFO,” they wrote. “In rare circumstances, such as stroke that recurs while a patient is undergoing antiplatelet therapy, clinicians may offer anticoagulation to patients with cryptogenic stroke and PFO.”

Their strongest recommendation was to counsel patients who are considering percutaneous PFO closure “that having a PFO is common; it occurs in about 1 in 4 people; it is impossible to determine with certainty whether their PFOs caused their strokes or TIAs; the effectiveness of the procedure for reducing stroke risk remains uncertain; and the procedure is associated with relatively uncommon, yet potentially serious, complications.”

The practice advisory was supported by the American Academy of Neurology. Dr. Messé disclosed ties to GlaxoSmithKline and WL Gore & Associates and has been an investigator for the REDUCE and CLOSURE-I trials. Five of his coauthors have been investigators for RESPECT, CLOSURE-I, and REDUCE, have been editors for Neurology, and have received compensation from Genentech, Pfizer, Gilead Sciences, and other pharmaceutical companies. One coauthor had no disclosures.

FROM NEUROLOGY

Experts offer blueprint for transitioning youth with neurologic conditions

Until now, there was no blueprint for how to effectively transition pediatric patients with neurologic conditions to adult care: Hard science on the topic is almost nonexistent.

“There is not very much data, yet there is a lot of suggestion that if you do it badly things don’t turn out so well,” said Peter Camfield, MD, a child neurologist and professor emeritus at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia, who has written extensively on the topic (Ann Neurol. 2011;69[3]:437-44 and Epilepsy Curr. 2012;12[Suppl. 3]:13-21). He recalled hearing one story of an adolescent girl who came to see a child neurologist every 6 months, always with her parents. “She had some significant learning disabilities and she didn’t finish high school; she dropped out,” he said. “She was sent to an adult neurologist just with a transfer note and to a nephrologist just with a transfer note.”

The patient never visited the nephrologist. The adult neurologist saw her once, “but she said he was kind of rude and that he wouldn’t see her again,” Dr. Camfield said. “She lived with her boyfriend and eventually at about age 24 she was found dead in bed. She hadn’t taken her medications regularly. The presumption is she died from a seizure. If she had been more prepared for adult medical care, she could have engaged better with the adult neurologist, the kidney part of this thing wouldn’t have been let go, and she presumably would be still alive and making her way.”

In an effort to avoid such tragedies and to define the neurologist’s role in transitioning youth with neurologic conditions into adult care, an interdisciplinary team of child neurologists and other experts spent more than 2 years developing a consensus statement, published online July 27 in Neurology (doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002965). Spearheaded by Lawrence W. Brown, MD, director of the pediatric neuropsychiatry program at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, the consensus statement, “The neurologist’s role in supporting transition to adult health care” is endorsed by the Child Neurology Society, the American Academy of Neurology, and the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Despite broad-based efforts over more than a decade to improve transition of care, such as the Consensus Policy Statement on Health Care Transitions for Young Adults With Special Needs, the Clinical Report: Supporting Health Care Transition from Adolescence to Adulthood in the Medical Home, and the Got Transition Center for Health Care Transition Improvement (a federally funded program located at the National Alliance to Advance Adolescent Health), Dr. Brown expressed his belief that neurologists were unlikely to adopt these recommendations “because they were very hard to put in place, to concretize, and to make practical. We also recognized that child neurology was in many ways behind the eight ball compared to other specialties, at least compared to certain disease-oriented areas such as cystic fibrosis, sickle cell disease, congenital heart disease, and rheumatoid arthritis. These conditions already had attempts to show what the expectations were for the kids and for the doctors, and there were some practical solutions out there.” If transition to adult care is going to be successful, he continued, “it’s not just the neurologist acting in a vacuum, but the neurologist working with the youth and his caregivers as well as with his primary care physician and with other specialists.”

Dr. Brown characterized the new consensus statement as an outline of “common principles that all child neurologists should try to respect” based on a review of the best medical literature and best practices. The first of eight principles contained in the statement recommends that the child neurology team start talking early about the concept of transition to the adult health care system with the youth and caregivers, and document that discussion “no later than the youth’s 13th birthday.”

Mary L. Zupanc, MD, one of the experts who helped author the consensus document, underscored the importance of introducing the notion of transition before the youth turns 13 years of age. Otherwise, “you are playing catch-up all the time,” she said. “Families have to get used to the concept of transition because we have long-term relationships with these individuals and their families. They come to think of us as part of their family. When you first bring up the topic of transition they about have a heart attack, because they can’t imagine a life without including you in it.”

The document’s second common principle recommends that the neurology team assess the youth’s self-management skills annually beginning at age 12. According to the authors, self-management of a medical condition “includes a youth’s understanding of his or her condition and any related limitations, knowledge about and responsibility for his or her own care plan and the need to make informed decisions, and the importance of self-advocacy.”

The statement also recommends phased transition planning at least annually beginning when the youth is 13 years of age. Topics to be discussed at such planning sessions range from the youth’s medical condition and current medications to genetic counseling and issues of puberty and sexuality. The validated Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire can be used as well (Acad Pediatr. 2014;14[4]:415-22).

Another principle contained in the consensus statement calls for a comprehensive transition plan by the time the youth is 14 years of age, ideally coordinated by the youth’s primary care provider in collaboration with the youth, caregivers, other health care providers, school personnel, vocational professionals, community services providers, and legal services regarding all aspects of health, financial, and legal care. It tasks the child neurology team with three responsibilities toward the comprehensive care plan: “assuring that an appropriate plan exists” and is created in partnership with the youth and family; “identifying the professional(s) with primary responsibility for overseeing and updating the entire transition plan,” and “providing and updating the neurologic component to this plan – including the ‘transfer packet,’ ” which contains important medical and social information.

In 2011, Dr. Zupanc, division chief of pediatric neurology at Children’s Hospital of Orange County in Orange, Calif., created a multidisciplinary clinic for epilepsy patients that includes nurse practitioners, registered nurses, a pharmacist, a dietitian, a social worker, a neuropsychologist, and a child psychiatrist. When Dr. Zupanc addresses the notion of transition with patients and their families for the first time, it’s not uncommon for her to be accompanied by the social worker and the neuropsychologist, “which I find helpful because parents may start to ask questions about guardianship,” she said. “Many of these parents do not even realize that there has to be an appointed guardian at age 18. We usually seek verification of competency via neuropsychometric testing or school evaluations. This information has to go before a judge to decide whether or not the patient is capable of taking care of himself/herself or if there should be an appointed guardian, typically one or both parents.”

Dr. Zupanc goes on to tell patients and their families that transition of care is a process that’s going to occur over the next 6-8 years. “Some of the patients don’t transition at age 18 years, because they are covered by California Children’s Services until age 22 years,” she said. The age of transition may vary from state to state, depending on insurance coverage and other issues. “Parents and patients get used to the idea that the transition isn’t going to happen tomorrow,” she said. “We explain the whole process. We let them know that we will help them. We also mention that we have adult provider colleagues in the community who are very knowledgeable about epilepsy or their child’s genetic syndrome. We partner with these colleagues, many of whom we have identified over time as willing to take our neurologically complex patients. As the transition process proceeds, we develop a transition packet of important medical information and social information. We will personally have conversations with the physician to whom we are transitioning care. Sometimes, our colleagues at University of California, Irvine, come over to our clinic before the final hand-off, so that the adult provider and the pediatric provider can meet together with the parents and patients in the same room. To us, that is the ideal situation. In this way, both the patients and the parents do not feel as if they are being abandoned.”

Dr. Zupanc, professor of pediatrics at the University of California–Irvine School of Medicine, said that a chief barrier to effective transition of care for pediatric patients with complex neurological problems is identifying clinicians who are willing to accept them into their practice. For example, many young patients with intractable epilepsy have significant concomitant cognitive issues and behavioral issues and/or autistic spectrum disorder. “If you look at surveys of adult providers, they feel enormously uncomfortable and uneducated about autistic spectrum disorder. They do not want to touch these young adolescents/adults,” Dr. Zupanc said. “They’re willing to take a piece of their care but not the entire package, which is problematic.”

The way Dr. Camfield sees it, neurologists have a moral obligation to play an active role in transitioning pediatric patients to adult care. “In many ways, it’s the No. 1 issue for tertiary care pediatrics now: What happens to young people in adulthood; what kind of citizens they turn out to be and how we help that to take place,” said Dr. Camfield, who helped write the consensus statement. “It’s no longer just enough to think, ‘as your child gets to be 16, 17, or 18, that’s it. We’re finished. Our job is done.’ That doesn’t make sense to me.”

In the consensus statement, he and his coauthors call for additional research on transition care practices in neurology moving forward. “Possible metrics for assessment include the rate of appointment completion and follow-up in the adult setting, patient and family satisfaction with transition and the new provider, stable or improved neurologic condition, adherence to care plans, decreased emergency utilization, rate of ‘bounce back’ to pediatric providers, and improved quality of life,” they wrote.

The consensus statement was funded in part by Eisai. Dr. Brown and Dr. Zupanc reported having no financial disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Dr. Camfield disclosed that he has received a speakers honorarium from Biocodex. Neurology Reviews, a publication of Frontline Medical Communications, is a member of the President’s Council of the Child Neurology Foundation.

Until now, there was no blueprint for how to effectively transition pediatric patients with neurologic conditions to adult care: Hard science on the topic is almost nonexistent.

“There is not very much data, yet there is a lot of suggestion that if you do it badly things don’t turn out so well,” said Peter Camfield, MD, a child neurologist and professor emeritus at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia, who has written extensively on the topic (Ann Neurol. 2011;69[3]:437-44 and Epilepsy Curr. 2012;12[Suppl. 3]:13-21). He recalled hearing one story of an adolescent girl who came to see a child neurologist every 6 months, always with her parents. “She had some significant learning disabilities and she didn’t finish high school; she dropped out,” he said. “She was sent to an adult neurologist just with a transfer note and to a nephrologist just with a transfer note.”

The patient never visited the nephrologist. The adult neurologist saw her once, “but she said he was kind of rude and that he wouldn’t see her again,” Dr. Camfield said. “She lived with her boyfriend and eventually at about age 24 she was found dead in bed. She hadn’t taken her medications regularly. The presumption is she died from a seizure. If she had been more prepared for adult medical care, she could have engaged better with the adult neurologist, the kidney part of this thing wouldn’t have been let go, and she presumably would be still alive and making her way.”

In an effort to avoid such tragedies and to define the neurologist’s role in transitioning youth with neurologic conditions into adult care, an interdisciplinary team of child neurologists and other experts spent more than 2 years developing a consensus statement, published online July 27 in Neurology (doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002965). Spearheaded by Lawrence W. Brown, MD, director of the pediatric neuropsychiatry program at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, the consensus statement, “The neurologist’s role in supporting transition to adult health care” is endorsed by the Child Neurology Society, the American Academy of Neurology, and the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Despite broad-based efforts over more than a decade to improve transition of care, such as the Consensus Policy Statement on Health Care Transitions for Young Adults With Special Needs, the Clinical Report: Supporting Health Care Transition from Adolescence to Adulthood in the Medical Home, and the Got Transition Center for Health Care Transition Improvement (a federally funded program located at the National Alliance to Advance Adolescent Health), Dr. Brown expressed his belief that neurologists were unlikely to adopt these recommendations “because they were very hard to put in place, to concretize, and to make practical. We also recognized that child neurology was in many ways behind the eight ball compared to other specialties, at least compared to certain disease-oriented areas such as cystic fibrosis, sickle cell disease, congenital heart disease, and rheumatoid arthritis. These conditions already had attempts to show what the expectations were for the kids and for the doctors, and there were some practical solutions out there.” If transition to adult care is going to be successful, he continued, “it’s not just the neurologist acting in a vacuum, but the neurologist working with the youth and his caregivers as well as with his primary care physician and with other specialists.”

Dr. Brown characterized the new consensus statement as an outline of “common principles that all child neurologists should try to respect” based on a review of the best medical literature and best practices. The first of eight principles contained in the statement recommends that the child neurology team start talking early about the concept of transition to the adult health care system with the youth and caregivers, and document that discussion “no later than the youth’s 13th birthday.”

Mary L. Zupanc, MD, one of the experts who helped author the consensus document, underscored the importance of introducing the notion of transition before the youth turns 13 years of age. Otherwise, “you are playing catch-up all the time,” she said. “Families have to get used to the concept of transition because we have long-term relationships with these individuals and their families. They come to think of us as part of their family. When you first bring up the topic of transition they about have a heart attack, because they can’t imagine a life without including you in it.”

The document’s second common principle recommends that the neurology team assess the youth’s self-management skills annually beginning at age 12. According to the authors, self-management of a medical condition “includes a youth’s understanding of his or her condition and any related limitations, knowledge about and responsibility for his or her own care plan and the need to make informed decisions, and the importance of self-advocacy.”

The statement also recommends phased transition planning at least annually beginning when the youth is 13 years of age. Topics to be discussed at such planning sessions range from the youth’s medical condition and current medications to genetic counseling and issues of puberty and sexuality. The validated Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire can be used as well (Acad Pediatr. 2014;14[4]:415-22).

Another principle contained in the consensus statement calls for a comprehensive transition plan by the time the youth is 14 years of age, ideally coordinated by the youth’s primary care provider in collaboration with the youth, caregivers, other health care providers, school personnel, vocational professionals, community services providers, and legal services regarding all aspects of health, financial, and legal care. It tasks the child neurology team with three responsibilities toward the comprehensive care plan: “assuring that an appropriate plan exists” and is created in partnership with the youth and family; “identifying the professional(s) with primary responsibility for overseeing and updating the entire transition plan,” and “providing and updating the neurologic component to this plan – including the ‘transfer packet,’ ” which contains important medical and social information.

In 2011, Dr. Zupanc, division chief of pediatric neurology at Children’s Hospital of Orange County in Orange, Calif., created a multidisciplinary clinic for epilepsy patients that includes nurse practitioners, registered nurses, a pharmacist, a dietitian, a social worker, a neuropsychologist, and a child psychiatrist. When Dr. Zupanc addresses the notion of transition with patients and their families for the first time, it’s not uncommon for her to be accompanied by the social worker and the neuropsychologist, “which I find helpful because parents may start to ask questions about guardianship,” she said. “Many of these parents do not even realize that there has to be an appointed guardian at age 18. We usually seek verification of competency via neuropsychometric testing or school evaluations. This information has to go before a judge to decide whether or not the patient is capable of taking care of himself/herself or if there should be an appointed guardian, typically one or both parents.”

Dr. Zupanc goes on to tell patients and their families that transition of care is a process that’s going to occur over the next 6-8 years. “Some of the patients don’t transition at age 18 years, because they are covered by California Children’s Services until age 22 years,” she said. The age of transition may vary from state to state, depending on insurance coverage and other issues. “Parents and patients get used to the idea that the transition isn’t going to happen tomorrow,” she said. “We explain the whole process. We let them know that we will help them. We also mention that we have adult provider colleagues in the community who are very knowledgeable about epilepsy or their child’s genetic syndrome. We partner with these colleagues, many of whom we have identified over time as willing to take our neurologically complex patients. As the transition process proceeds, we develop a transition packet of important medical information and social information. We will personally have conversations with the physician to whom we are transitioning care. Sometimes, our colleagues at University of California, Irvine, come over to our clinic before the final hand-off, so that the adult provider and the pediatric provider can meet together with the parents and patients in the same room. To us, that is the ideal situation. In this way, both the patients and the parents do not feel as if they are being abandoned.”

Dr. Zupanc, professor of pediatrics at the University of California–Irvine School of Medicine, said that a chief barrier to effective transition of care for pediatric patients with complex neurological problems is identifying clinicians who are willing to accept them into their practice. For example, many young patients with intractable epilepsy have significant concomitant cognitive issues and behavioral issues and/or autistic spectrum disorder. “If you look at surveys of adult providers, they feel enormously uncomfortable and uneducated about autistic spectrum disorder. They do not want to touch these young adolescents/adults,” Dr. Zupanc said. “They’re willing to take a piece of their care but not the entire package, which is problematic.”

The way Dr. Camfield sees it, neurologists have a moral obligation to play an active role in transitioning pediatric patients to adult care. “In many ways, it’s the No. 1 issue for tertiary care pediatrics now: What happens to young people in adulthood; what kind of citizens they turn out to be and how we help that to take place,” said Dr. Camfield, who helped write the consensus statement. “It’s no longer just enough to think, ‘as your child gets to be 16, 17, or 18, that’s it. We’re finished. Our job is done.’ That doesn’t make sense to me.”

In the consensus statement, he and his coauthors call for additional research on transition care practices in neurology moving forward. “Possible metrics for assessment include the rate of appointment completion and follow-up in the adult setting, patient and family satisfaction with transition and the new provider, stable or improved neurologic condition, adherence to care plans, decreased emergency utilization, rate of ‘bounce back’ to pediatric providers, and improved quality of life,” they wrote.

The consensus statement was funded in part by Eisai. Dr. Brown and Dr. Zupanc reported having no financial disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Dr. Camfield disclosed that he has received a speakers honorarium from Biocodex. Neurology Reviews, a publication of Frontline Medical Communications, is a member of the President’s Council of the Child Neurology Foundation.

Until now, there was no blueprint for how to effectively transition pediatric patients with neurologic conditions to adult care: Hard science on the topic is almost nonexistent.

“There is not very much data, yet there is a lot of suggestion that if you do it badly things don’t turn out so well,” said Peter Camfield, MD, a child neurologist and professor emeritus at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia, who has written extensively on the topic (Ann Neurol. 2011;69[3]:437-44 and Epilepsy Curr. 2012;12[Suppl. 3]:13-21). He recalled hearing one story of an adolescent girl who came to see a child neurologist every 6 months, always with her parents. “She had some significant learning disabilities and she didn’t finish high school; she dropped out,” he said. “She was sent to an adult neurologist just with a transfer note and to a nephrologist just with a transfer note.”

The patient never visited the nephrologist. The adult neurologist saw her once, “but she said he was kind of rude and that he wouldn’t see her again,” Dr. Camfield said. “She lived with her boyfriend and eventually at about age 24 she was found dead in bed. She hadn’t taken her medications regularly. The presumption is she died from a seizure. If she had been more prepared for adult medical care, she could have engaged better with the adult neurologist, the kidney part of this thing wouldn’t have been let go, and she presumably would be still alive and making her way.”

In an effort to avoid such tragedies and to define the neurologist’s role in transitioning youth with neurologic conditions into adult care, an interdisciplinary team of child neurologists and other experts spent more than 2 years developing a consensus statement, published online July 27 in Neurology (doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002965). Spearheaded by Lawrence W. Brown, MD, director of the pediatric neuropsychiatry program at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, the consensus statement, “The neurologist’s role in supporting transition to adult health care” is endorsed by the Child Neurology Society, the American Academy of Neurology, and the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Despite broad-based efforts over more than a decade to improve transition of care, such as the Consensus Policy Statement on Health Care Transitions for Young Adults With Special Needs, the Clinical Report: Supporting Health Care Transition from Adolescence to Adulthood in the Medical Home, and the Got Transition Center for Health Care Transition Improvement (a federally funded program located at the National Alliance to Advance Adolescent Health), Dr. Brown expressed his belief that neurologists were unlikely to adopt these recommendations “because they were very hard to put in place, to concretize, and to make practical. We also recognized that child neurology was in many ways behind the eight ball compared to other specialties, at least compared to certain disease-oriented areas such as cystic fibrosis, sickle cell disease, congenital heart disease, and rheumatoid arthritis. These conditions already had attempts to show what the expectations were for the kids and for the doctors, and there were some practical solutions out there.” If transition to adult care is going to be successful, he continued, “it’s not just the neurologist acting in a vacuum, but the neurologist working with the youth and his caregivers as well as with his primary care physician and with other specialists.”

Dr. Brown characterized the new consensus statement as an outline of “common principles that all child neurologists should try to respect” based on a review of the best medical literature and best practices. The first of eight principles contained in the statement recommends that the child neurology team start talking early about the concept of transition to the adult health care system with the youth and caregivers, and document that discussion “no later than the youth’s 13th birthday.”

Mary L. Zupanc, MD, one of the experts who helped author the consensus document, underscored the importance of introducing the notion of transition before the youth turns 13 years of age. Otherwise, “you are playing catch-up all the time,” she said. “Families have to get used to the concept of transition because we have long-term relationships with these individuals and their families. They come to think of us as part of their family. When you first bring up the topic of transition they about have a heart attack, because they can’t imagine a life without including you in it.”

The document’s second common principle recommends that the neurology team assess the youth’s self-management skills annually beginning at age 12. According to the authors, self-management of a medical condition “includes a youth’s understanding of his or her condition and any related limitations, knowledge about and responsibility for his or her own care plan and the need to make informed decisions, and the importance of self-advocacy.”

The statement also recommends phased transition planning at least annually beginning when the youth is 13 years of age. Topics to be discussed at such planning sessions range from the youth’s medical condition and current medications to genetic counseling and issues of puberty and sexuality. The validated Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire can be used as well (Acad Pediatr. 2014;14[4]:415-22).

Another principle contained in the consensus statement calls for a comprehensive transition plan by the time the youth is 14 years of age, ideally coordinated by the youth’s primary care provider in collaboration with the youth, caregivers, other health care providers, school personnel, vocational professionals, community services providers, and legal services regarding all aspects of health, financial, and legal care. It tasks the child neurology team with three responsibilities toward the comprehensive care plan: “assuring that an appropriate plan exists” and is created in partnership with the youth and family; “identifying the professional(s) with primary responsibility for overseeing and updating the entire transition plan,” and “providing and updating the neurologic component to this plan – including the ‘transfer packet,’ ” which contains important medical and social information.

In 2011, Dr. Zupanc, division chief of pediatric neurology at Children’s Hospital of Orange County in Orange, Calif., created a multidisciplinary clinic for epilepsy patients that includes nurse practitioners, registered nurses, a pharmacist, a dietitian, a social worker, a neuropsychologist, and a child psychiatrist. When Dr. Zupanc addresses the notion of transition with patients and their families for the first time, it’s not uncommon for her to be accompanied by the social worker and the neuropsychologist, “which I find helpful because parents may start to ask questions about guardianship,” she said. “Many of these parents do not even realize that there has to be an appointed guardian at age 18. We usually seek verification of competency via neuropsychometric testing or school evaluations. This information has to go before a judge to decide whether or not the patient is capable of taking care of himself/herself or if there should be an appointed guardian, typically one or both parents.”

Dr. Zupanc goes on to tell patients and their families that transition of care is a process that’s going to occur over the next 6-8 years. “Some of the patients don’t transition at age 18 years, because they are covered by California Children’s Services until age 22 years,” she said. The age of transition may vary from state to state, depending on insurance coverage and other issues. “Parents and patients get used to the idea that the transition isn’t going to happen tomorrow,” she said. “We explain the whole process. We let them know that we will help them. We also mention that we have adult provider colleagues in the community who are very knowledgeable about epilepsy or their child’s genetic syndrome. We partner with these colleagues, many of whom we have identified over time as willing to take our neurologically complex patients. As the transition process proceeds, we develop a transition packet of important medical information and social information. We will personally have conversations with the physician to whom we are transitioning care. Sometimes, our colleagues at University of California, Irvine, come over to our clinic before the final hand-off, so that the adult provider and the pediatric provider can meet together with the parents and patients in the same room. To us, that is the ideal situation. In this way, both the patients and the parents do not feel as if they are being abandoned.”

Dr. Zupanc, professor of pediatrics at the University of California–Irvine School of Medicine, said that a chief barrier to effective transition of care for pediatric patients with complex neurological problems is identifying clinicians who are willing to accept them into their practice. For example, many young patients with intractable epilepsy have significant concomitant cognitive issues and behavioral issues and/or autistic spectrum disorder. “If you look at surveys of adult providers, they feel enormously uncomfortable and uneducated about autistic spectrum disorder. They do not want to touch these young adolescents/adults,” Dr. Zupanc said. “They’re willing to take a piece of their care but not the entire package, which is problematic.”

The way Dr. Camfield sees it, neurologists have a moral obligation to play an active role in transitioning pediatric patients to adult care. “In many ways, it’s the No. 1 issue for tertiary care pediatrics now: What happens to young people in adulthood; what kind of citizens they turn out to be and how we help that to take place,” said Dr. Camfield, who helped write the consensus statement. “It’s no longer just enough to think, ‘as your child gets to be 16, 17, or 18, that’s it. We’re finished. Our job is done.’ That doesn’t make sense to me.”

In the consensus statement, he and his coauthors call for additional research on transition care practices in neurology moving forward. “Possible metrics for assessment include the rate of appointment completion and follow-up in the adult setting, patient and family satisfaction with transition and the new provider, stable or improved neurologic condition, adherence to care plans, decreased emergency utilization, rate of ‘bounce back’ to pediatric providers, and improved quality of life,” they wrote.

The consensus statement was funded in part by Eisai. Dr. Brown and Dr. Zupanc reported having no financial disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Dr. Camfield disclosed that he has received a speakers honorarium from Biocodex. Neurology Reviews, a publication of Frontline Medical Communications, is a member of the President’s Council of the Child Neurology Foundation.

FROM NEUROLOGY

Alzheimer’s anti-tau drug fails phase III, but posts some benefit in monotherapy subanalysis

TORONTO – A highly anticipated phase III trial of an anti-tau drug has posted negative topline results, conferring no cognitive or functional benefits when given in conjunction with standard-of-care Alzheimer’s disease medications.

The drug, LTMX (TauRx, Singapore), also did not slow the progression of brain atrophy on imaging in either of two doses tested, according to a company press release.

Although the study didn’t meet its clinical endpoints in the overall cohort of 891 patients with mild-moderate disease, TauRx promoted it as “promising,” based on a subgroup analysis of the 15% of patients who took the drug as monotherapy.

Among these patients, LMTX was associated with dose-dependent, statistically significant improvements in the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale measures of cognition (ADAS-cog) and Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Activities of Daily Living inventory (ADCS-ADL). The drug was also associated with a slowing of brain ventricular expansion, compared with controls, suggesting that it could be preserving brain mass.

Nevertheless, the trial must be read as another negative one, said David S. Knopman, MD, who moderated a press briefing where the data were presented.

“I must say I am disappointed by the results because in my view of clinical trials forged from 30 years of experience, the only thing that really counts is the prespecified primary outcome,” said Dr. Knopman of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. “I think the secondary results are interesting, especially imaging findings. But our experience of secondary analyses in this field is that they are fraught with hidden biases. And because this is a small subset of just 15%, it’s very difficult to interpret.”

Details of the study

The 15-month study comprised 891 patients with mild-moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Most of these (85%) were taking standard-of-care symptomatic Alzheimer’s disease medications. Patients were randomized to 75 mg twice daily, 125 mg twice daily, or placebo, which necessarily consisted of a small amount of the medication. LMTX is a derivative of the dye methylene blue and colors urine when excreted. The inactive dose is enough to provide that color so that blinding can be maintained.

Patients were grouped according to whether they took the study drug as add-on therapy (85%) or as monotherapy (15%). However, the results were presented in a somewhat unusual way, with the placebo patients in each therapeutic regimen grouped together. Thus, there was no way to compare the placebo-treated patients who did not receive standard-of-care medications against those who received LMTX monotherapy without standard-of-care medications; instead, the benefits reported in the active monotherapy group were compared with the results seen in placebo patients in both the mono- and add-on groups.

The reason for this was that the numbers in each group were small, said Serge Gauthier, MD, who presented the LMTX data at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2016. Among the monotherapy group, 42 took 75 mg twice daily, 40 took 125 mg twice daily, and 54 took placebo. He suggested that these numbers could be pooled with those in a similar phase III trial of LMTX in about 800 patients with mild disease, which will be completed this fall.

“My proposal would be to combine these groups and then we would really be able to understand what we’re seeing in the control monotherapy versus the study drug monotherapy groups,” said Dr. Gauthier of McGill University, Montreal.

The study was conducted at 115 sites across 16 countries in Europe, North America, and Asia. All of the patients had a clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease; no one underwent amyloid PET imaging. The patients’ mean age was 70.6 years, and their baseline Mini Mental State Exam score was 18.7.

At the study’s end, patients in the monotherapy group taking 75 mg twice daily had declined 6.3 points less on the ADAS-cog than did the grouped placebo patients, indicating preserved cognition. Those taking 125 mg twice daily declined 5.8 points less than did the grouped placebo patients. On the ADCS-ADL, patients taking 75 mg twice daily scored 6.5 points higher than did the placebo group, indicating better function, and those taking 125 mg twice daily scored 6.9 points higher than did the placebo group.

Lateral ventricular volume expansion on MRI was significantly less than that seen in placebo-treated patients. For those taking 75 mg twice a day, ventricular expansion was reduced by 38%; for those taking 125 mg twice a day, expansion was reduced by 33%. This was accompanied by significant slowing of whole brain atrophy, Dr. Gauthier said, adding that this finding has never been reported in an Alzheimer’s drug trial.

Speculation on lack of effect with standard-of-care medications

Confoundingly, however, LMTX showed no benefit at all in the patients who were taking the usual Alzheimer’s medications. Nor were there similar changes in brain volume.

“We are struggling with this information,” Dr. Gauthier said. “Why this difference in the 15%? They were not older, they did not have milder disease, and there were no obvious differences. The only thing we saw was that they were more likely to have come from Eastern Europe, where access to these drugs is reduced.”

That, however, could play a key role in the findings, Dr. Knopman said in an interview.

“To be honest, I think people who entered the study not on standard of care were in regions where they were not getting any good medical care, and when they became part of this trial they began to get better medical care and experienced a pronounced placebo effect.”

He couldn’t explain how a placebo effect could be related to the MRI findings, although he did say that other medical conditions can be related to changes in brain volume. Quitting alcohol is a big one – alcoholics who stop drinking do experience increases in whole brain volume. And, Dr. Knopman pointed out, alcoholism is rampant in Eastern Europe, where most of these patients lived.

The finding is more problematic because there’s no way to compare the active monotherapy group with the placebo monotherapy group, he said.

“My suspicion is that if they had shown the differences between the monotherapy placebo and the monotherapy active groups, the curves would have looked a lot like what we saw in the add-on therapy groups.”

In an interview, Claude Wischik, MD, PhD, cofounder and executive chair of TauRx and primary investigator on all of the LMTX studies, dismissed Dr. Knopman’s suggestion.

“There’s no geography in the world that can change brain volume,” he said. “You can’t shift the brain simply by wanting it.” And while he fell short of suggesting that LMTX is affecting neurogenesis, he did say that the drug is directly responsible for modifying brain physiology.

Dr. Knopman also pointed out that the lack of baseline amyloid PET imaging almost certainly means that there were patients with other, non-Alzheimer’s dementias in the trial. Baseline amyloid PET imaging is now standard because up to 30% of patients in older antiamyloid studies have now been shown to have not even had the disease. Without baseline amyloid PET imaging to confirm diagnosis, “there’s no telling what they were treating” with LMTX, he said.

The drug’s failure as an add-on therapy is problematic, Dr. Knopman said. The symptomatic Alzheimer’s medications are generally considered to have a very low interaction profile with any other drug. This lack of efficacy, he suggested, is another hint that the benefit in the monotherapy group could be a fluke.

Dr. Wischik said this is not due to pharmacokinetics, but rather to the induction of a cellular clearance pathway called the P-glycoprotein 1 transport pathway.

“The most plausible explanation is this transporter hypothesis. If you’re taking a drug chronically – like an Alzheimer’s medication – this extrusion pathway is turned on. Its net effect is to excrete the drugs from the brain and enhance kidney excretion.” This would accelerate LMTX clearance to the point of inactivity, he said.

When asked if this would be problematic for other drugs taken chronically – statins, for example – Dr. Wischik said the cholinesterase inhibitors were responsible for activating the P-glycoprotein 1 transport pathway. He said there were no other drug interactions observed to inhibit the effect of LMTX.

Dr. Gauthier said research will proceed on LMTX, probably targeting patients with mild Alzheimer’s – or even prodromal disease – who are not yet taking an Alzheimer’s medication. In fact, he suggested that any future it might have would most likely be as part of a staged treatment. LMTX could be given early with the aim of delaying symptom onset, at which time treatment could accelerate to a symptomatic medication, and then, perhaps, to more aggressive measures like an antiamyloid, should one ever come to market.

Dr. Gauthier is on the TauRx advisory board. Dr. Knopman is an investigator on a trial of LMTX in frontotemporal dementia, but has no financial ties with the company.

On Twitter @alz_gal

TORONTO – A highly anticipated phase III trial of an anti-tau drug has posted negative topline results, conferring no cognitive or functional benefits when given in conjunction with standard-of-care Alzheimer’s disease medications.

The drug, LTMX (TauRx, Singapore), also did not slow the progression of brain atrophy on imaging in either of two doses tested, according to a company press release.

Although the study didn’t meet its clinical endpoints in the overall cohort of 891 patients with mild-moderate disease, TauRx promoted it as “promising,” based on a subgroup analysis of the 15% of patients who took the drug as monotherapy.

Among these patients, LMTX was associated with dose-dependent, statistically significant improvements in the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale measures of cognition (ADAS-cog) and Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Activities of Daily Living inventory (ADCS-ADL). The drug was also associated with a slowing of brain ventricular expansion, compared with controls, suggesting that it could be preserving brain mass.

Nevertheless, the trial must be read as another negative one, said David S. Knopman, MD, who moderated a press briefing where the data were presented.

“I must say I am disappointed by the results because in my view of clinical trials forged from 30 years of experience, the only thing that really counts is the prespecified primary outcome,” said Dr. Knopman of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. “I think the secondary results are interesting, especially imaging findings. But our experience of secondary analyses in this field is that they are fraught with hidden biases. And because this is a small subset of just 15%, it’s very difficult to interpret.”

Details of the study

The 15-month study comprised 891 patients with mild-moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Most of these (85%) were taking standard-of-care symptomatic Alzheimer’s disease medications. Patients were randomized to 75 mg twice daily, 125 mg twice daily, or placebo, which necessarily consisted of a small amount of the medication. LMTX is a derivative of the dye methylene blue and colors urine when excreted. The inactive dose is enough to provide that color so that blinding can be maintained.

Patients were grouped according to whether they took the study drug as add-on therapy (85%) or as monotherapy (15%). However, the results were presented in a somewhat unusual way, with the placebo patients in each therapeutic regimen grouped together. Thus, there was no way to compare the placebo-treated patients who did not receive standard-of-care medications against those who received LMTX monotherapy without standard-of-care medications; instead, the benefits reported in the active monotherapy group were compared with the results seen in placebo patients in both the mono- and add-on groups.

The reason for this was that the numbers in each group were small, said Serge Gauthier, MD, who presented the LMTX data at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2016. Among the monotherapy group, 42 took 75 mg twice daily, 40 took 125 mg twice daily, and 54 took placebo. He suggested that these numbers could be pooled with those in a similar phase III trial of LMTX in about 800 patients with mild disease, which will be completed this fall.

“My proposal would be to combine these groups and then we would really be able to understand what we’re seeing in the control monotherapy versus the study drug monotherapy groups,” said Dr. Gauthier of McGill University, Montreal.

The study was conducted at 115 sites across 16 countries in Europe, North America, and Asia. All of the patients had a clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease; no one underwent amyloid PET imaging. The patients’ mean age was 70.6 years, and their baseline Mini Mental State Exam score was 18.7.

At the study’s end, patients in the monotherapy group taking 75 mg twice daily had declined 6.3 points less on the ADAS-cog than did the grouped placebo patients, indicating preserved cognition. Those taking 125 mg twice daily declined 5.8 points less than did the grouped placebo patients. On the ADCS-ADL, patients taking 75 mg twice daily scored 6.5 points higher than did the placebo group, indicating better function, and those taking 125 mg twice daily scored 6.9 points higher than did the placebo group.

Lateral ventricular volume expansion on MRI was significantly less than that seen in placebo-treated patients. For those taking 75 mg twice a day, ventricular expansion was reduced by 38%; for those taking 125 mg twice a day, expansion was reduced by 33%. This was accompanied by significant slowing of whole brain atrophy, Dr. Gauthier said, adding that this finding has never been reported in an Alzheimer’s drug trial.

Speculation on lack of effect with standard-of-care medications

Confoundingly, however, LMTX showed no benefit at all in the patients who were taking the usual Alzheimer’s medications. Nor were there similar changes in brain volume.

“We are struggling with this information,” Dr. Gauthier said. “Why this difference in the 15%? They were not older, they did not have milder disease, and there were no obvious differences. The only thing we saw was that they were more likely to have come from Eastern Europe, where access to these drugs is reduced.”

That, however, could play a key role in the findings, Dr. Knopman said in an interview.

“To be honest, I think people who entered the study not on standard of care were in regions where they were not getting any good medical care, and when they became part of this trial they began to get better medical care and experienced a pronounced placebo effect.”

He couldn’t explain how a placebo effect could be related to the MRI findings, although he did say that other medical conditions can be related to changes in brain volume. Quitting alcohol is a big one – alcoholics who stop drinking do experience increases in whole brain volume. And, Dr. Knopman pointed out, alcoholism is rampant in Eastern Europe, where most of these patients lived.

The finding is more problematic because there’s no way to compare the active monotherapy group with the placebo monotherapy group, he said.

“My suspicion is that if they had shown the differences between the monotherapy placebo and the monotherapy active groups, the curves would have looked a lot like what we saw in the add-on therapy groups.”

In an interview, Claude Wischik, MD, PhD, cofounder and executive chair of TauRx and primary investigator on all of the LMTX studies, dismissed Dr. Knopman’s suggestion.

“There’s no geography in the world that can change brain volume,” he said. “You can’t shift the brain simply by wanting it.” And while he fell short of suggesting that LMTX is affecting neurogenesis, he did say that the drug is directly responsible for modifying brain physiology.

Dr. Knopman also pointed out that the lack of baseline amyloid PET imaging almost certainly means that there were patients with other, non-Alzheimer’s dementias in the trial. Baseline amyloid PET imaging is now standard because up to 30% of patients in older antiamyloid studies have now been shown to have not even had the disease. Without baseline amyloid PET imaging to confirm diagnosis, “there’s no telling what they were treating” with LMTX, he said.

The drug’s failure as an add-on therapy is problematic, Dr. Knopman said. The symptomatic Alzheimer’s medications are generally considered to have a very low interaction profile with any other drug. This lack of efficacy, he suggested, is another hint that the benefit in the monotherapy group could be a fluke.

Dr. Wischik said this is not due to pharmacokinetics, but rather to the induction of a cellular clearance pathway called the P-glycoprotein 1 transport pathway.

“The most plausible explanation is this transporter hypothesis. If you’re taking a drug chronically – like an Alzheimer’s medication – this extrusion pathway is turned on. Its net effect is to excrete the drugs from the brain and enhance kidney excretion.” This would accelerate LMTX clearance to the point of inactivity, he said.

When asked if this would be problematic for other drugs taken chronically – statins, for example – Dr. Wischik said the cholinesterase inhibitors were responsible for activating the P-glycoprotein 1 transport pathway. He said there were no other drug interactions observed to inhibit the effect of LMTX.

Dr. Gauthier said research will proceed on LMTX, probably targeting patients with mild Alzheimer’s – or even prodromal disease – who are not yet taking an Alzheimer’s medication. In fact, he suggested that any future it might have would most likely be as part of a staged treatment. LMTX could be given early with the aim of delaying symptom onset, at which time treatment could accelerate to a symptomatic medication, and then, perhaps, to more aggressive measures like an antiamyloid, should one ever come to market.

Dr. Gauthier is on the TauRx advisory board. Dr. Knopman is an investigator on a trial of LMTX in frontotemporal dementia, but has no financial ties with the company.

On Twitter @alz_gal

TORONTO – A highly anticipated phase III trial of an anti-tau drug has posted negative topline results, conferring no cognitive or functional benefits when given in conjunction with standard-of-care Alzheimer’s disease medications.

The drug, LTMX (TauRx, Singapore), also did not slow the progression of brain atrophy on imaging in either of two doses tested, according to a company press release.

Although the study didn’t meet its clinical endpoints in the overall cohort of 891 patients with mild-moderate disease, TauRx promoted it as “promising,” based on a subgroup analysis of the 15% of patients who took the drug as monotherapy.

Among these patients, LMTX was associated with dose-dependent, statistically significant improvements in the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale measures of cognition (ADAS-cog) and Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Activities of Daily Living inventory (ADCS-ADL). The drug was also associated with a slowing of brain ventricular expansion, compared with controls, suggesting that it could be preserving brain mass.

Nevertheless, the trial must be read as another negative one, said David S. Knopman, MD, who moderated a press briefing where the data were presented.

“I must say I am disappointed by the results because in my view of clinical trials forged from 30 years of experience, the only thing that really counts is the prespecified primary outcome,” said Dr. Knopman of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. “I think the secondary results are interesting, especially imaging findings. But our experience of secondary analyses in this field is that they are fraught with hidden biases. And because this is a small subset of just 15%, it’s very difficult to interpret.”

Details of the study

The 15-month study comprised 891 patients with mild-moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Most of these (85%) were taking standard-of-care symptomatic Alzheimer’s disease medications. Patients were randomized to 75 mg twice daily, 125 mg twice daily, or placebo, which necessarily consisted of a small amount of the medication. LMTX is a derivative of the dye methylene blue and colors urine when excreted. The inactive dose is enough to provide that color so that blinding can be maintained.

Patients were grouped according to whether they took the study drug as add-on therapy (85%) or as monotherapy (15%). However, the results were presented in a somewhat unusual way, with the placebo patients in each therapeutic regimen grouped together. Thus, there was no way to compare the placebo-treated patients who did not receive standard-of-care medications against those who received LMTX monotherapy without standard-of-care medications; instead, the benefits reported in the active monotherapy group were compared with the results seen in placebo patients in both the mono- and add-on groups.

The reason for this was that the numbers in each group were small, said Serge Gauthier, MD, who presented the LMTX data at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2016. Among the monotherapy group, 42 took 75 mg twice daily, 40 took 125 mg twice daily, and 54 took placebo. He suggested that these numbers could be pooled with those in a similar phase III trial of LMTX in about 800 patients with mild disease, which will be completed this fall.

“My proposal would be to combine these groups and then we would really be able to understand what we’re seeing in the control monotherapy versus the study drug monotherapy groups,” said Dr. Gauthier of McGill University, Montreal.

The study was conducted at 115 sites across 16 countries in Europe, North America, and Asia. All of the patients had a clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease; no one underwent amyloid PET imaging. The patients’ mean age was 70.6 years, and their baseline Mini Mental State Exam score was 18.7.

At the study’s end, patients in the monotherapy group taking 75 mg twice daily had declined 6.3 points less on the ADAS-cog than did the grouped placebo patients, indicating preserved cognition. Those taking 125 mg twice daily declined 5.8 points less than did the grouped placebo patients. On the ADCS-ADL, patients taking 75 mg twice daily scored 6.5 points higher than did the placebo group, indicating better function, and those taking 125 mg twice daily scored 6.9 points higher than did the placebo group.

Lateral ventricular volume expansion on MRI was significantly less than that seen in placebo-treated patients. For those taking 75 mg twice a day, ventricular expansion was reduced by 38%; for those taking 125 mg twice a day, expansion was reduced by 33%. This was accompanied by significant slowing of whole brain atrophy, Dr. Gauthier said, adding that this finding has never been reported in an Alzheimer’s drug trial.

Speculation on lack of effect with standard-of-care medications

Confoundingly, however, LMTX showed no benefit at all in the patients who were taking the usual Alzheimer’s medications. Nor were there similar changes in brain volume.

“We are struggling with this information,” Dr. Gauthier said. “Why this difference in the 15%? They were not older, they did not have milder disease, and there were no obvious differences. The only thing we saw was that they were more likely to have come from Eastern Europe, where access to these drugs is reduced.”

That, however, could play a key role in the findings, Dr. Knopman said in an interview.

“To be honest, I think people who entered the study not on standard of care were in regions where they were not getting any good medical care, and when they became part of this trial they began to get better medical care and experienced a pronounced placebo effect.”

He couldn’t explain how a placebo effect could be related to the MRI findings, although he did say that other medical conditions can be related to changes in brain volume. Quitting alcohol is a big one – alcoholics who stop drinking do experience increases in whole brain volume. And, Dr. Knopman pointed out, alcoholism is rampant in Eastern Europe, where most of these patients lived.

The finding is more problematic because there’s no way to compare the active monotherapy group with the placebo monotherapy group, he said.

“My suspicion is that if they had shown the differences between the monotherapy placebo and the monotherapy active groups, the curves would have looked a lot like what we saw in the add-on therapy groups.”

In an interview, Claude Wischik, MD, PhD, cofounder and executive chair of TauRx and primary investigator on all of the LMTX studies, dismissed Dr. Knopman’s suggestion.

“There’s no geography in the world that can change brain volume,” he said. “You can’t shift the brain simply by wanting it.” And while he fell short of suggesting that LMTX is affecting neurogenesis, he did say that the drug is directly responsible for modifying brain physiology.

Dr. Knopman also pointed out that the lack of baseline amyloid PET imaging almost certainly means that there were patients with other, non-Alzheimer’s dementias in the trial. Baseline amyloid PET imaging is now standard because up to 30% of patients in older antiamyloid studies have now been shown to have not even had the disease. Without baseline amyloid PET imaging to confirm diagnosis, “there’s no telling what they were treating” with LMTX, he said.

The drug’s failure as an add-on therapy is problematic, Dr. Knopman said. The symptomatic Alzheimer’s medications are generally considered to have a very low interaction profile with any other drug. This lack of efficacy, he suggested, is another hint that the benefit in the monotherapy group could be a fluke.

Dr. Wischik said this is not due to pharmacokinetics, but rather to the induction of a cellular clearance pathway called the P-glycoprotein 1 transport pathway.

“The most plausible explanation is this transporter hypothesis. If you’re taking a drug chronically – like an Alzheimer’s medication – this extrusion pathway is turned on. Its net effect is to excrete the drugs from the brain and enhance kidney excretion.” This would accelerate LMTX clearance to the point of inactivity, he said.

When asked if this would be problematic for other drugs taken chronically – statins, for example – Dr. Wischik said the cholinesterase inhibitors were responsible for activating the P-glycoprotein 1 transport pathway. He said there were no other drug interactions observed to inhibit the effect of LMTX.

Dr. Gauthier said research will proceed on LMTX, probably targeting patients with mild Alzheimer’s – or even prodromal disease – who are not yet taking an Alzheimer’s medication. In fact, he suggested that any future it might have would most likely be as part of a staged treatment. LMTX could be given early with the aim of delaying symptom onset, at which time treatment could accelerate to a symptomatic medication, and then, perhaps, to more aggressive measures like an antiamyloid, should one ever come to market.

Dr. Gauthier is on the TauRx advisory board. Dr. Knopman is an investigator on a trial of LMTX in frontotemporal dementia, but has no financial ties with the company.

On Twitter @alz_gal

AT AAIC 2016

Key clinical point: The anti-tau drug LMTX didn’t improve cognition or function as add-on therapy for Alzheimer’s disease, but did offer hints of benefit as a monotherapy.

Major finding: Patients who took LMTX as monotherapy declined 6 points less on the ADAS-cog scale over 15 months, compared with those who took placebo.

Data source: The trial randomized 891 patients to placebo or to LMTX 75 mg twice daily or LMTX 125 mg twice daily .

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by TauRx. Dr. Serge Gauthier is on the company’s advisory board. Dr. David Knopman is an investigator on a LMTX study for frontotemporal dementia, but has no financial ties with the company.

The benefits of doing ultrasound exams in your office

Point-of-care ultrasound is increasingly being integrated into clinical practice, as an adjunct to the physical examination and patient history,1 and into medical school curricula across North America.2,3 Research confirms that this technology improves patient survival in emergency medicine settings;4 however, the benefits of point-of-care ultrasound administered by family physicians (FPs) in the office setting are less well documented.

Here we provide a comprehensive review of the indications for ultrasound in the office setting, which range from diagnosing musculoskeletal injuries and guiding injections to screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA). We also address the accuracy and cost-effectiveness of ultrasound use and the training needed to make family medicine ultrasound (FAMUS) successful.

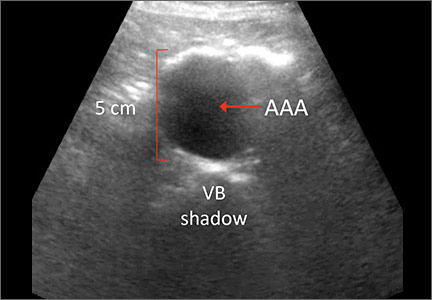

Ultrasound: A useful screening tool for abdominal aortic aneurysm

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends one-time screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) in men ages 65 to 75 years who have ever smoked (See: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/abdominal-aortic-aneurysm-screening.) Ultrasound is a reliable tool for identifying AAA5 (FIGURE 1); its sensitivity and specificity range from 94% to 98.9% and 98% to 100%, respectively.6-9 It is also superior to physical examination for AAAs,10 which has a sensitivity of 29% for small AAAs (30-39 mm) and 76% for larger AAAs (>50 mm).11

Most importantly, research has demonstrated that long-term mortality benefits are associated with ultrasound screening of asymptomatic patients for AAA. For example, one study found that screening asymptomatic men ages 65 to 74 (a population-based sample, with no particular risk factors) for AAA resulted in a reduction in all-cause mortality and that the benefit of AAA-related mortality continued to accumulate throughout follow-up.12

In fact, nationwide programs to screen for AAA using ultrasound have been established in England, Northern Ireland, Scotland, Sweden, the United States, and Wales to help prevent deaths associated with AAA rupture.13 Despite the documented benefits of ultrasound screening for AAA, a large retrospective cohort study conducted in an American integrated health care system found that only about 9% of patients eligible for screening according to USPSTF guidelines were screened for AAA with ultrasound in primary care practices in 2012.14

While most AAA screening occurs in the hospital, screening for the condition can be just as easily and effectively performed in an FP’s office or outpatient clinic. A Canadian prospective observational study demonstrated that aortic diameter measurements were comparable whether they were obtained by ultrasound performed by an office-based physician (who had completed an emergency ultrasonography course and performed at least 50 ultrasonographer-supervised ultrasound scans of the aorta), or by a hospital-based technologist whose scans were then reviewed by a radiologist.15 (See the TABLE for an overview of the research involving family medicine ultrasound.)

The office-based scans had a high degree of correlation (0.81) with the hospital-based ones, a sensitivity and specificity of 100%, and lasted a mean of 3.5 minutes. The researchers concluded that ultrasound screening for AAA can be safely performed in the office setting by FPs who are trained to use point-of-care ultrasound technology, and that the screening can be completed within the time constraints of a typical family practice office visit.15

In a separate study, cardiologists compared hand-held ultrasound screening for AAA to standard 2-dimensional echocardiography. This study found that screening for AAA in an outpatient clinic with a hand-held ultrasound device is feasible and accurate with a sensitivity of 88% and a specificity of 98%.16

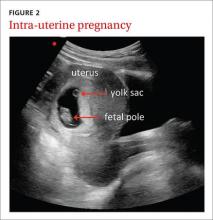

Ultrasound in the obstetrician’s office—and the FP’s office, too

The use of ultrasound in obstetrics (FIGURE 2) is particularly well documented, with evidence supporting the use of FAMUS for various obstetrical indications dating back 30 years.17 The American Academy of Family Physicians has a position paper endorsing diagnostic ultrasound for women’s health care and has offered obstetric ultrasound courses organized by, and for, FPs since 1989.18

In a prospective observational study conducted in the United Kingdom, an FP and a nurse midwife used ultrasound to assess 240 pregnant women presenting with vaginal bleeding in early pregnancy.19 Fetal heartbeat detection by an office ultrasound scan predicted fetal progression to 20 weeks with a sensitivity of 97% and a specificity of 98%. The clinicians also detected anomalies such as molar pregnancy, blighted ovum, and ectopic pregnancy.

FAMUS and its ability to accurately estimate delivery date was examined in another prospective study involving 186 patients at a community health center.20 Accuracy for the estimated date of delivery was 96% using stratified confidence intervals for first-, second-, and third-trimester examinations. The office-based ultrasound scans also detected one case of placenta previa, one fetal death, and 2 unsuspected twin pregnancies. Another study showed no difference in estimations of gestational age provided by ultrasound performed by supervised FP residents with 3 years’ ultrasound training (including 3 lectures per year and an annual 4-hour workshop), and radiologists.21